User login

Getting Hip to Vitamin D

Hip fracture is a common clinical problem, with an incidence of 957 cases/100,000 adults in the United States.[1] Studies have found a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among elderly patients with fragility fractures, though many of these studies were performed in high latitude regions.[2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10] Endocrine Society clinical practice guidelines recommend screening patients with fragility fractures for vitamin D deficiency.[11]

Our hospitalist group practices in an academic tertiary care facility in the southeastern United States. Beginning in June 2010, all patients with acute hip fracture were admitted to our service with consultative comanagement from orthopedics. Our group did not have a standardized approach for the assessment or treatment of vitamin D deficiency in this population. Preliminary analysis of a subgroup of our patients with acute hip fracture revealed that only 29% had been screened for vitamin D deficiency. Of these patients, 68% were deficient or insufficient, yet less than half had been discharged on an appropriate dose of vitamin D. We concluded that our group practice was both varied and substandard.

In this report we describe the creation and implementation of a process for improving the assessment and treatment of vitamin D deficiency in elderly patients with fragility hip fracture. We evaluated the effect of our process on the percentages of patients screened and treated appropriately for vitamin D deficiency.

METHODS

Creation of Intervention

We assembled a task force, consisting of 4 hospitalist physicians. The task force reviewed available literature on the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in elderly patients with fragility fracture and major practice guidelines related to vitamin D. We utilized Endocrine Society clinical practice guidelines to define vitamin D deficiency, insufficiency, and recommended treatment dosing for each condition[11] (Table 1).

| Vitamin D Level (25‐OH) | Vitamin D Status | Treatment Dose Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| 019 ng/mL | Deficient | 50,000 IU/week for 68 weeks |

| 2029 ng/mL | Insufficient | 1,000 to 2,000 IU/day or 50,000 IU/month |

We developed 2 processes for improving group practice. First, we presented a review of evidence and preliminary data from our group practice at a meeting of hospitalist staff. Second, we revised the computerized physician order entry (CPOE) set for patients with hip fractures to include 2 new orders: (1) an automatic order for 25‐OH vitamin D level to be drawn the morning after admission and (2) an order for initiation of 1000 IU daily of vitamin D at admission.

The reasons for starting empiric vitamin D supplementation were 2fold. First was to prompt dosing of vitamin D at the time of discharge by already having it on the patient's medication list. Second was to conform to US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines for fall prevention.[12] The dose of 1000 IU was selected due to its being adequate treatment for insufficient (though not deficient) patients, and yet a low enough dose to minimize risk of toxicity.

Providers

Our hospitalist group includes 21 physicians and 3 physician extenders. Two nocturnist positions were added to our group in July 2013, part way through our intervention. There were no other additions or subtractions to the staff during the study period.

Patients

Patients were identified by search of University of North Carolina (UNC) Hospitals' database using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision codes for femoral neck fracture (821.x) and femur fracture NOS (820.x), linked to hospital services covered by our group. Exclusion criteria included age 50 years, fracture due to high‐speed trauma, fracture due to malignancy, end‐stage renal disease, and death or transition to comfort care during the index hospitalization.

Outcome Measures

Primary outcome measures were the percentage of patients with acute hip fracture with vitamin D level checked during hospitalization and the percentage of deficient patients discharged on the recommended dose of vitamin D. Outcomes were measured for the 28 months before intervention (when our group assumed direct care for hip fracture patients) and were compared with the 12 months after intervention. We also report the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in our population.

Laboratory Methodology

25‐OH vitamin D assays were performed by UNC Hospitals' core laboratories. Assays were performed using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectroscopy technique. Methodology remained constant through the study period.

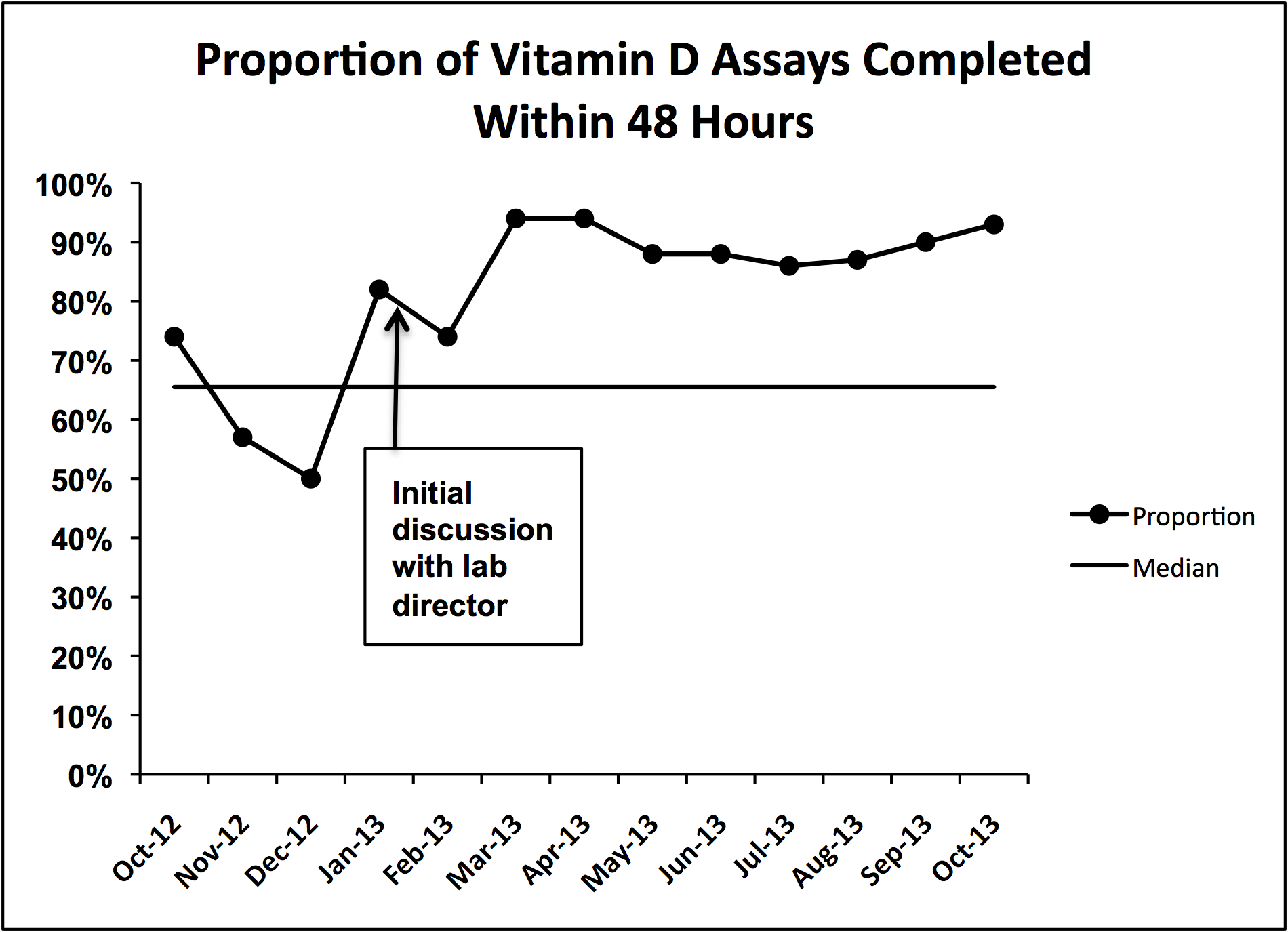

During implementation of the project, we identified slow turnaround time in reporting of the vitamin D assays as an issue. We subsequently plotted the percentage of assays returned within 48 hours for each month of the study period on a run chart.

Analysis

Primary outcome measures and demographic data were tested for statistical significance with the 2 test. As a separate means of analysis, we plotted a control chart for the percentage of patients with vitamin D level checked and a run chart for the percentage of deficient or insufficient patients discharged on the recommended dose of vitamin D. To ensure a constant sample size, consecutive samples of patients were plotted in chronologic order. Results were interpreted with standard Shewhart rules.[13] 2 testing and plotting of control and run charts were performed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) and QI Charts (Process Improvement Products, Austin, TX).

Implementation

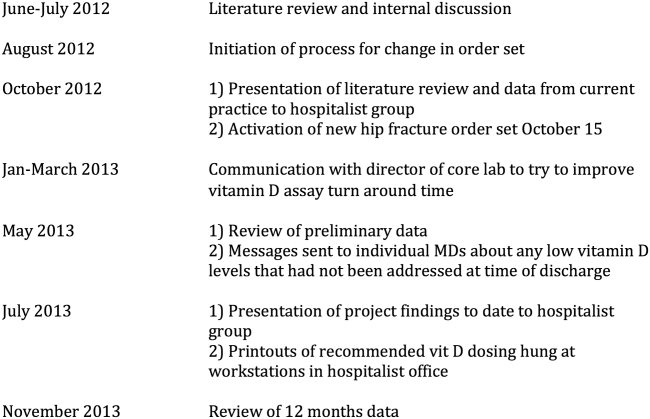

In October 2012, we presented the review of evidence and preliminary data to the hospitalist group and made the new CPOE hip fracture order set available. Implementation was monitored by solicitation of qualitative feedback from group physicians and analysis of outcome data every 6 months. Issues that arose during implementation are described in a project timeline (Figure 1) and discussed in detail in manuscript discussion. We received institutional review board approval to study the project's implementation.

RESULTS

Patients

There were 220 patients identified in the 28 months before implementation. Twenty‐four were excluded by criteria, leaving 196 for analysis. One hundred thirteen patients were identified after implementation. Six patients were excluded by criteria, leaving 107 for analysis.

The mean patient age was 80 years, and the median age was 83 years. Seventy‐five percent were female. Race categories were 85% Caucasian, 8% African American, 3% Asian, 1% Native American, 1% Hispanic, and 3% other.

The preintervention group had mean and median ages of 80 and 82 years, respectively, compared with 81 and 84 years, respectively, in the postintervention group. Seventy‐five percent of the preintervention group was female, compared with 74% postintervention. The only statistically significant difference was in the percentage of Caucasian patients81% of preintervention group compared with 91% of the postintervention group (P = 0.028).

Primary Outcomes

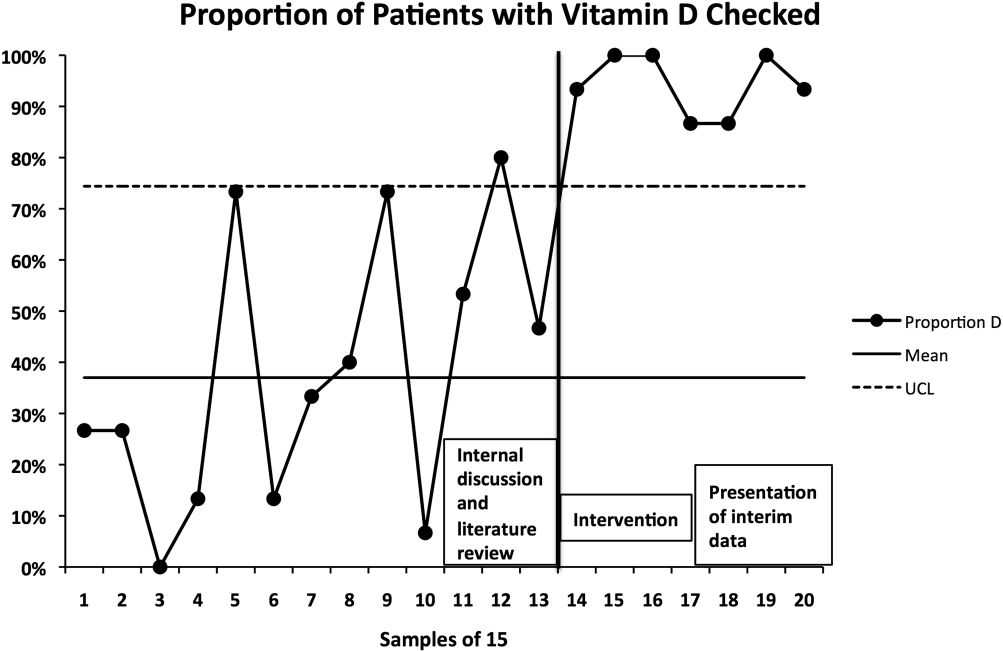

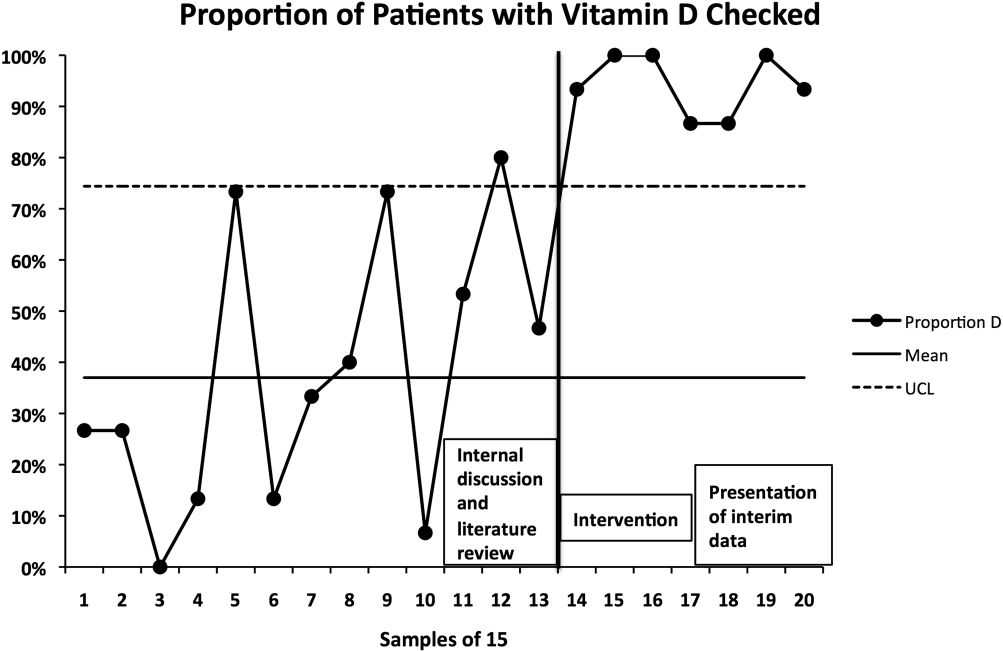

The percentage of patients with acute hip fracture with vitamin D level checked before project implementation was 37.2% (n = 196). After implementation, the percentage improved to 93.5% (n = 107, P < 0.001).

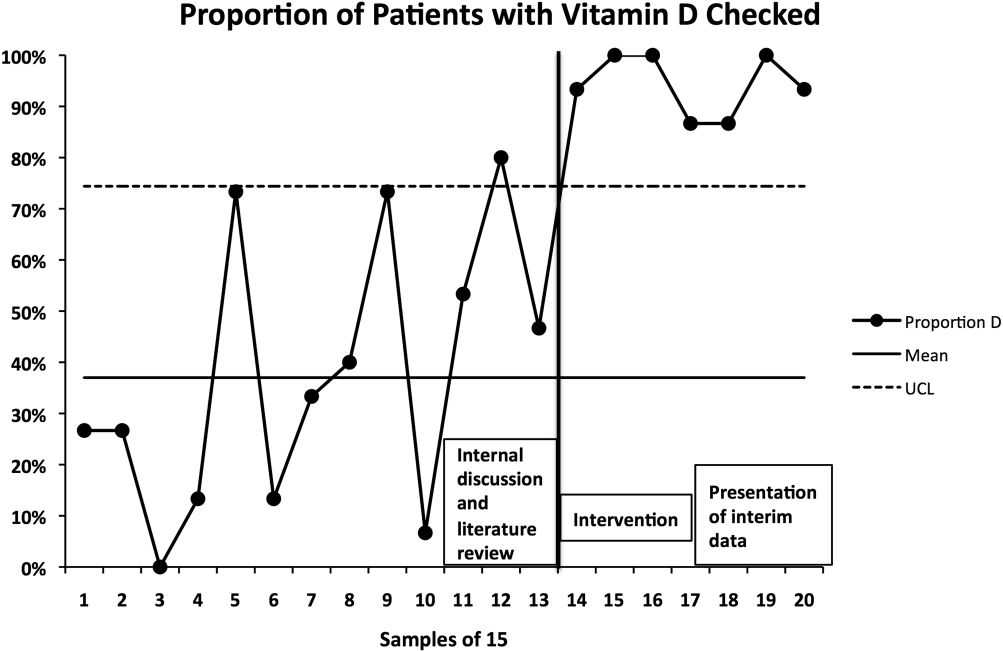

The proportion chart plot of the same data (Figure 2) shows evidence of a fundamental change after intervention. Data points showing the proportion of consecutive samples of 15 patients were plotted chronologically. All points after implementation were above the upper control limit, meeting Shewhart control chart rules for special cause variation.[13]

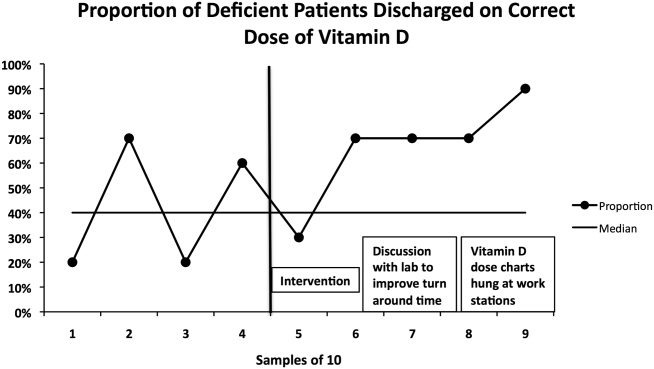

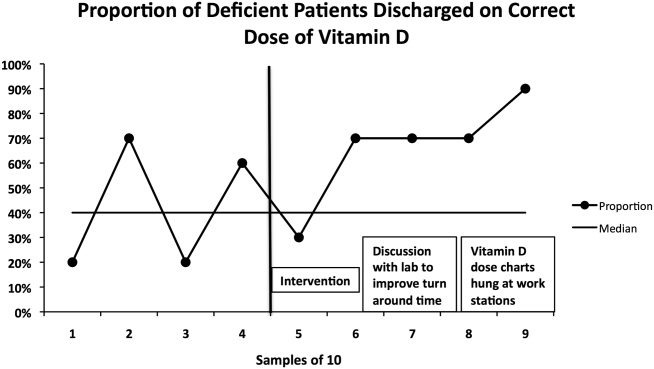

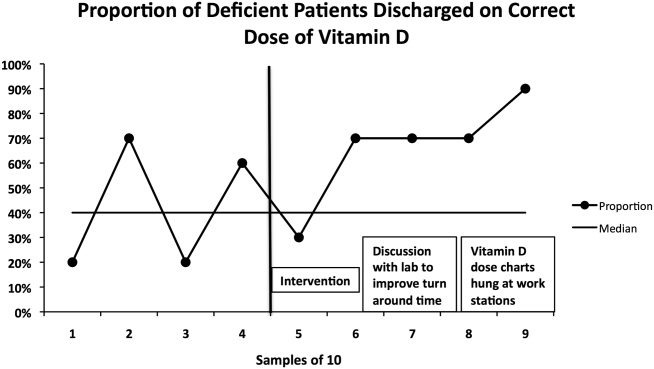

The percentage of vitamin D deficient/emnsufficient patients discharged on the recommended dose of vitamin D also improved, rising from 40.9% (n = 44) before to 68.0% (n = 50) after implementation (P = 0.008). Because there were fewer candidates for this outcome, we plotted samples of 10 patients consecutively on a run chart (Figure 3). Although there were insufficient data to establish a trend by run chart rules, the last 4 consecutive data points showed sequential improvement.

Prevalence of Vitamin D Insufficiency and Deficiency

Before implementation, 44 of the 73 patients (60.3%) with vitamin D levels checked were deficient or insufficient (25‐OH vitamin D <30 ng/mL); of those 44 patients, 21 (28.8% of total checked) had 25‐OH vitamin D levels <20 ng/mL. After implementation, 50 of 100 patients with levels checked were identified as deficient or insufficient (50%); of those 50 patients, 23 (23% of total) had 25‐OH vitamin D levels <20 ng/mL.

DISCUSSION

Our interventions correlated with significant improvements in the assessment and treatment of vitamin D deficiency in elderly patients with fragility hip fractures. Our study demonstrates a systematic method groups may use to adopt and reliably implement practice guidelines. Moreover, we report several steps to implementation that enhanced our ability to standardize clinical care.

The prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency we identified50.0% after change implementationis within the range reported in prior studies, though our result is notable for being in a southern region of the United States. The prevalence we found before implementation (60.3%) may have been subject to selection bias in screening, so 50.0% is likely the more correct prevalence. Other US studies of vitamin D deficiency prevalence in hip fracture patients report rates from 50% to 65.8%.[2, 8, 10]

The percentage of hip fracture patients screened for vitamin D deficiency showed significant improvement after our interventions, rising to 93.5%. As a comparison with our results, a 2008 study after implementation of a hip fracture pathway reported only screening 37% of patients for vitamin D deficiency.[14] The main barrier we identified was occasional failure to use the electronic order set. This was in large part due to moonlighting physicians, who occasionally cover hospitalist shifts. They accounted for 5 of the 7 missed patients. The other 2 misses were due to group physicians not using the order set. These findings were first identified after 6 months of data were analyzed. These data were presented to the hospitalist group, with reminders to reinforce order set use with moonlighters and to manually order levels after admission if the order set was not utilized.

We found more difficulty with discharging deficient patients on the recommended dose of vitamin D. Our low level at the time of implementation40.9%was actually higher than a recent Swiss study, which found that only 27% of patients with acute hip fracture were discharged on any vitamin D, despite 91% of patients having 25‐OH vitamin D levels <30 ng/mL.[15] However, our proportion of deficient patients discharged on the recommended vitamin D dose only improved to 68.0% during our interventions. This is similar to Glowacki et al., who reported discharging 76% of hip fracture patients on vitamin D and/or calcium through utilization of a discharge pathway, though they did not differentiate vitamin D from calcium in results or attempt to identify patient‐specific vitamin D dosing based on serum levels.[14]

We did identify and address several barriers to discharging patients on the recommended dose. First, we experienced slow turnaround time in measurement of 25‐OH vitamin D. Early into the project, we received several reports of patients being discharged before vitamin D levels had returned. We communicated with the director of UNC Hospitals' core laboratories. A major issue was that the special chemistry section of the core laboratory did not report results directly into the hospital's main electronic reporting system, so that the results had to be hand entered. Over several months, the laboratory worked to improve turnaround times. A run chart plot of the percentage of assays reported within 48 hours for each month showed significant improvement with these efforts (see Supporting Information, Figure 1, in the online version of this article). All 9 data points after our initial discussion with the laboratory director were above the mean established during the prior 4 months, meeting run chart rules for a fundamental change in the system.[13]

The second issue identified was that the ranges for deficiency and insufficiency recommended by Endocrine Society guidelines did not match the reference ranges provided by UNC Hospitals. UNC Hospitals reported levels of 25‐OH vitamin D as normal if above 24, whereas the Endocrine Society defined normal as above 29. When analyzing data after 6 months, we found several patients who had been screened appropriately with results available and noted by the discharging physician, but with results in the normal range per our laboratory. Several of these patients, though low in vitamin D by Endocrine Society standards, were not treated. The laboratory director was again contacted, who noted that the UNC reference ranges had been formed before the Endocrine Society guidelines had been published. We elected to continue with the more conservative ranges recommended by the Endocrine Society. We presented results to the group after 6 months of data had been collected and emphasized our recommended reference ranges and vitamin D dosing (Table 1). We also created reference charts with this information and hung them by all computer workstations in the hospitalist office. With this continued assessment of data and provider education, we did note further improvement through the implementation period, with 90.0% of the last sample of deficient/emnsufficient patients discharged on the recommended dose of vitamin D (Figure 3).

We debated whether to include calcium supplementation as part of our intervention, but given known potential harms from calcium supplementation, including nephrolithiasis and possible increased cardiovascular risk,[16] we elected to focus exclusively on vitamin D. Although studies of primary and secondary fragility fracture prevention with vitamin D have not demonstrated consistently positive results, the studies were not specifically targeted to vitamin D‐deficient patients.[17, 18] Even in the absence of definitively proven secondary fracture prevention, given the multiple health issues associated with vitamin D deficiency, we believe that screening high prevalence populations and treating appropriately is best practice. With minimal patient costs (our institution charges $93 per assay) and a high prevalence (50% in our population), we believe universal screening of elderly patients with hip fracture for vitamin D deficiency is also cost‐effective.

Our project was specifically designed to address the issue of vitamin D deficiency in elderly hip fracture patients, but most of these patients also have osteoporosis. Although vitamin D deficiency contributes to osteoporosis, it is certainly not the only factor. It is also recognized that a minority of patients with fragility fractures receives subsequent evaluation and treatment for osteoporosis, <20% in a recent large population‐based study.[19] The American Orthopedic Association has recently launched a website and campaign entitled Own the Bone to improve the quality of care for patients after osteoporotic fracture.[20] A number of measures have been studied to improve the deficit in care, often termed the osteoporosis treatment gap. Edwards and colleagues recently described an intervention based on their institutional electronic medical record.[21] The intervention included order sets for diagnosing osteoporosis and educational materials for patients and providers, but did not demonstrate any change in percentage of patients evaluated for osteoporosis after fragility fracture. Successful randomized controlled trials have been reported using mail notification of physicians and patients after osteoporotic fracture[22]; multifaceted telephone, education and mail notification interventions after wrist fracture[23]; and through the use of a central osteoporosis coordinator to coordinate osteoporosis treatment after a fragility fracture.[24] These successful trials were broad in scope and yet reported modest (10%20%) gains in improvement.

Although bisphophonate therapy is of proven benefit in secondary fracture prevention, there are a number of barriers to initiating it in the acute setting after fragility fracture, as the difficulty in getting large improvement during the above trials suggests. These include recommendations from some experts for bone density testing before starting treatment and theoretic concerns of impairing fracture healing in the initial weeks after acute fracture. Both of these concerns make a hospitalist‐based intervention for osteoporosis evaluation and treatment challenging and beyond the scope of our project's quality improvement efforts.

Our study has some limitations. It was conducted in a single institution and electronic order entry system, which could limit the ability to generalize the results. We did not assess vitamin D compliance or follow‐up after hospitalization, so we are unable to determine if patients successfully completed treatment after it was prescribed. We also found slight differences in race between the pre‐ and postintervention groups. Although we did not perform multivariable regression to account for these differences, we feel such analyses would be unlikely to alter our results. Last, it should be noted that there may be unintended consequences from preselected orders, such as the ones we utilized for vitamin D assays and empiric supplementation. For example, patients with a recently checked vitamin D assay would have duplication of that lab. Similarly, patients who were already taking vitamin D could theoretically be placed on double therapy at admission. With safeguards in the electronic system to flag duplicate medications, low toxicity of standard doses of vitamin D, and minimal economic harm with duplicate laboratory therapy in the context of a hospitalization for hip fracture, we believe the risks are outweighed by the benefits of screening.

In summary, with review of evidence, modification of a computerized physician order set, provider education and feedback, and collaboration with our clinical laboratory, we were able to standardize and improve group practice for the assessment and treatment of vitamin D deficiency in elderly patients with hip fracture. We believe that our model could be applied to other institutions to further improve patient care. Given the extremely high incidence of hip fracture and consistently high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in this population across studies, these findings have important implications for the care of this commonly encountered and vulnerable group of patients.

Disclosures: Data from this project were presented in abstract form at the Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meetings in 2013 and 2014 and as an abstract at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting in 2014. Dr. Catherine Hammett‐Stabler, Director of UNC Hospitals McLendon Core Laboratories, provided data on vitamin D assay turnaround times. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , . Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United States. JAMA. 2009;302(14):1573–1579.

- , , , , , . Occult vitamin D deficiency in postmenopausal US women with acute hip fracture. JAMA. 1999;281(16):1505–1511.

- , , , , , . Prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy in Scottish adults with non‐vertebral fragility fractures. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(9):1355–1361.

- , , . Prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy in osteoporotic hip fracture patients in London. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(12):1891–1894.

- , , , et al. Half of the patients with an acute hip fracture suffer from hypovitaminosis D: a prospective study in southeastern Finland. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(12):2018–2024.

- , , , et al. Prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy in Belfast following fragility fracture. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(1):101–105.

- , , , , , . High prevalence of hypovitaminosis D and K in patients with hip fracture. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2011;20(1):56–61.

- , , , . Vitamin D insufficiency in patients with acute hip fractures of all ages and both sexes in a sunny climate. J Orthop Trauma. 2013;27(12):e275–e280.

- , , , et al. Vitamin D and intact PTH status in patients with hip fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(11):1608–1614.

- , , , et al. Distribution and correlates of serum 25‐hydroxyvitamin D levels in a sample of patients with hip fracture. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5(4):335–340.

- , , , et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(7):1911–1930.

- , . Prevention of falls in community‐dwelling older adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(3):197–204.

- , . The Health Care Data Guide: Learning From Data for Improvement. 1st ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass; 2011.

- , , , , . Importance of vitamin D in hospital‐based fracture care pathways. J Nutr Health Aging. 2008;12(5):291–293.

- , , , et al. Before and after hip fracture, vitamin D deficiency may not be treated sufficiently. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(11):2765–2773.

- , , , et al. Effect of calcium supplements on risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular events: meta‐analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c3691.

- , , , et al. A pooled analysis of vitamin D dose requirements for fracture prevention. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(1):40–49.

- , , , et al. Oral vitamin D3 and calcium for secondary prevention of low‐trauma fractures in elderly people (Randomised Evaluation of Calcium Or vitamin D, RECORD): a randomised placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9471):1621–1628.

- , , , et al. A population‐based analysis of the post‐fracture care gap 1996–2008: the situation is not improving. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(5):1623–1629.

- American Orthopedic Association. Own the Bone website. 2011. Available at: http://www.ownthebone.org. Accessed August 1, 2014.

- , , , et al. Development of an electronic medical record based intervention to improve medical care of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(10):2489–2498.

- , , , , . Closing the gap in postfracture care at the population level: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2012;184(3):290–296.

- , , , et al. Multifaceted intervention to improve diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis in patients with recent wrist fracture: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2008;178(5):569–575.

- , , , et al. Impact of a centralized osteoporosis coordinator on post‐fracture osteoporosis management: a cluster randomized trial. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(1):87–95.

Hip fracture is a common clinical problem, with an incidence of 957 cases/100,000 adults in the United States.[1] Studies have found a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among elderly patients with fragility fractures, though many of these studies were performed in high latitude regions.[2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10] Endocrine Society clinical practice guidelines recommend screening patients with fragility fractures for vitamin D deficiency.[11]

Our hospitalist group practices in an academic tertiary care facility in the southeastern United States. Beginning in June 2010, all patients with acute hip fracture were admitted to our service with consultative comanagement from orthopedics. Our group did not have a standardized approach for the assessment or treatment of vitamin D deficiency in this population. Preliminary analysis of a subgroup of our patients with acute hip fracture revealed that only 29% had been screened for vitamin D deficiency. Of these patients, 68% were deficient or insufficient, yet less than half had been discharged on an appropriate dose of vitamin D. We concluded that our group practice was both varied and substandard.

In this report we describe the creation and implementation of a process for improving the assessment and treatment of vitamin D deficiency in elderly patients with fragility hip fracture. We evaluated the effect of our process on the percentages of patients screened and treated appropriately for vitamin D deficiency.

METHODS

Creation of Intervention

We assembled a task force, consisting of 4 hospitalist physicians. The task force reviewed available literature on the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in elderly patients with fragility fracture and major practice guidelines related to vitamin D. We utilized Endocrine Society clinical practice guidelines to define vitamin D deficiency, insufficiency, and recommended treatment dosing for each condition[11] (Table 1).

| Vitamin D Level (25‐OH) | Vitamin D Status | Treatment Dose Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| 019 ng/mL | Deficient | 50,000 IU/week for 68 weeks |

| 2029 ng/mL | Insufficient | 1,000 to 2,000 IU/day or 50,000 IU/month |

We developed 2 processes for improving group practice. First, we presented a review of evidence and preliminary data from our group practice at a meeting of hospitalist staff. Second, we revised the computerized physician order entry (CPOE) set for patients with hip fractures to include 2 new orders: (1) an automatic order for 25‐OH vitamin D level to be drawn the morning after admission and (2) an order for initiation of 1000 IU daily of vitamin D at admission.

The reasons for starting empiric vitamin D supplementation were 2fold. First was to prompt dosing of vitamin D at the time of discharge by already having it on the patient's medication list. Second was to conform to US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines for fall prevention.[12] The dose of 1000 IU was selected due to its being adequate treatment for insufficient (though not deficient) patients, and yet a low enough dose to minimize risk of toxicity.

Providers

Our hospitalist group includes 21 physicians and 3 physician extenders. Two nocturnist positions were added to our group in July 2013, part way through our intervention. There were no other additions or subtractions to the staff during the study period.

Patients

Patients were identified by search of University of North Carolina (UNC) Hospitals' database using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision codes for femoral neck fracture (821.x) and femur fracture NOS (820.x), linked to hospital services covered by our group. Exclusion criteria included age 50 years, fracture due to high‐speed trauma, fracture due to malignancy, end‐stage renal disease, and death or transition to comfort care during the index hospitalization.

Outcome Measures

Primary outcome measures were the percentage of patients with acute hip fracture with vitamin D level checked during hospitalization and the percentage of deficient patients discharged on the recommended dose of vitamin D. Outcomes were measured for the 28 months before intervention (when our group assumed direct care for hip fracture patients) and were compared with the 12 months after intervention. We also report the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in our population.

Laboratory Methodology

25‐OH vitamin D assays were performed by UNC Hospitals' core laboratories. Assays were performed using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectroscopy technique. Methodology remained constant through the study period.

During implementation of the project, we identified slow turnaround time in reporting of the vitamin D assays as an issue. We subsequently plotted the percentage of assays returned within 48 hours for each month of the study period on a run chart.

Analysis

Primary outcome measures and demographic data were tested for statistical significance with the 2 test. As a separate means of analysis, we plotted a control chart for the percentage of patients with vitamin D level checked and a run chart for the percentage of deficient or insufficient patients discharged on the recommended dose of vitamin D. To ensure a constant sample size, consecutive samples of patients were plotted in chronologic order. Results were interpreted with standard Shewhart rules.[13] 2 testing and plotting of control and run charts were performed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) and QI Charts (Process Improvement Products, Austin, TX).

Implementation

In October 2012, we presented the review of evidence and preliminary data to the hospitalist group and made the new CPOE hip fracture order set available. Implementation was monitored by solicitation of qualitative feedback from group physicians and analysis of outcome data every 6 months. Issues that arose during implementation are described in a project timeline (Figure 1) and discussed in detail in manuscript discussion. We received institutional review board approval to study the project's implementation.

RESULTS

Patients

There were 220 patients identified in the 28 months before implementation. Twenty‐four were excluded by criteria, leaving 196 for analysis. One hundred thirteen patients were identified after implementation. Six patients were excluded by criteria, leaving 107 for analysis.

The mean patient age was 80 years, and the median age was 83 years. Seventy‐five percent were female. Race categories were 85% Caucasian, 8% African American, 3% Asian, 1% Native American, 1% Hispanic, and 3% other.

The preintervention group had mean and median ages of 80 and 82 years, respectively, compared with 81 and 84 years, respectively, in the postintervention group. Seventy‐five percent of the preintervention group was female, compared with 74% postintervention. The only statistically significant difference was in the percentage of Caucasian patients81% of preintervention group compared with 91% of the postintervention group (P = 0.028).

Primary Outcomes

The percentage of patients with acute hip fracture with vitamin D level checked before project implementation was 37.2% (n = 196). After implementation, the percentage improved to 93.5% (n = 107, P < 0.001).

The proportion chart plot of the same data (Figure 2) shows evidence of a fundamental change after intervention. Data points showing the proportion of consecutive samples of 15 patients were plotted chronologically. All points after implementation were above the upper control limit, meeting Shewhart control chart rules for special cause variation.[13]

The percentage of vitamin D deficient/emnsufficient patients discharged on the recommended dose of vitamin D also improved, rising from 40.9% (n = 44) before to 68.0% (n = 50) after implementation (P = 0.008). Because there were fewer candidates for this outcome, we plotted samples of 10 patients consecutively on a run chart (Figure 3). Although there were insufficient data to establish a trend by run chart rules, the last 4 consecutive data points showed sequential improvement.

Prevalence of Vitamin D Insufficiency and Deficiency

Before implementation, 44 of the 73 patients (60.3%) with vitamin D levels checked were deficient or insufficient (25‐OH vitamin D <30 ng/mL); of those 44 patients, 21 (28.8% of total checked) had 25‐OH vitamin D levels <20 ng/mL. After implementation, 50 of 100 patients with levels checked were identified as deficient or insufficient (50%); of those 50 patients, 23 (23% of total) had 25‐OH vitamin D levels <20 ng/mL.

DISCUSSION

Our interventions correlated with significant improvements in the assessment and treatment of vitamin D deficiency in elderly patients with fragility hip fractures. Our study demonstrates a systematic method groups may use to adopt and reliably implement practice guidelines. Moreover, we report several steps to implementation that enhanced our ability to standardize clinical care.

The prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency we identified50.0% after change implementationis within the range reported in prior studies, though our result is notable for being in a southern region of the United States. The prevalence we found before implementation (60.3%) may have been subject to selection bias in screening, so 50.0% is likely the more correct prevalence. Other US studies of vitamin D deficiency prevalence in hip fracture patients report rates from 50% to 65.8%.[2, 8, 10]

The percentage of hip fracture patients screened for vitamin D deficiency showed significant improvement after our interventions, rising to 93.5%. As a comparison with our results, a 2008 study after implementation of a hip fracture pathway reported only screening 37% of patients for vitamin D deficiency.[14] The main barrier we identified was occasional failure to use the electronic order set. This was in large part due to moonlighting physicians, who occasionally cover hospitalist shifts. They accounted for 5 of the 7 missed patients. The other 2 misses were due to group physicians not using the order set. These findings were first identified after 6 months of data were analyzed. These data were presented to the hospitalist group, with reminders to reinforce order set use with moonlighters and to manually order levels after admission if the order set was not utilized.

We found more difficulty with discharging deficient patients on the recommended dose of vitamin D. Our low level at the time of implementation40.9%was actually higher than a recent Swiss study, which found that only 27% of patients with acute hip fracture were discharged on any vitamin D, despite 91% of patients having 25‐OH vitamin D levels <30 ng/mL.[15] However, our proportion of deficient patients discharged on the recommended vitamin D dose only improved to 68.0% during our interventions. This is similar to Glowacki et al., who reported discharging 76% of hip fracture patients on vitamin D and/or calcium through utilization of a discharge pathway, though they did not differentiate vitamin D from calcium in results or attempt to identify patient‐specific vitamin D dosing based on serum levels.[14]

We did identify and address several barriers to discharging patients on the recommended dose. First, we experienced slow turnaround time in measurement of 25‐OH vitamin D. Early into the project, we received several reports of patients being discharged before vitamin D levels had returned. We communicated with the director of UNC Hospitals' core laboratories. A major issue was that the special chemistry section of the core laboratory did not report results directly into the hospital's main electronic reporting system, so that the results had to be hand entered. Over several months, the laboratory worked to improve turnaround times. A run chart plot of the percentage of assays reported within 48 hours for each month showed significant improvement with these efforts (see Supporting Information, Figure 1, in the online version of this article). All 9 data points after our initial discussion with the laboratory director were above the mean established during the prior 4 months, meeting run chart rules for a fundamental change in the system.[13]

The second issue identified was that the ranges for deficiency and insufficiency recommended by Endocrine Society guidelines did not match the reference ranges provided by UNC Hospitals. UNC Hospitals reported levels of 25‐OH vitamin D as normal if above 24, whereas the Endocrine Society defined normal as above 29. When analyzing data after 6 months, we found several patients who had been screened appropriately with results available and noted by the discharging physician, but with results in the normal range per our laboratory. Several of these patients, though low in vitamin D by Endocrine Society standards, were not treated. The laboratory director was again contacted, who noted that the UNC reference ranges had been formed before the Endocrine Society guidelines had been published. We elected to continue with the more conservative ranges recommended by the Endocrine Society. We presented results to the group after 6 months of data had been collected and emphasized our recommended reference ranges and vitamin D dosing (Table 1). We also created reference charts with this information and hung them by all computer workstations in the hospitalist office. With this continued assessment of data and provider education, we did note further improvement through the implementation period, with 90.0% of the last sample of deficient/emnsufficient patients discharged on the recommended dose of vitamin D (Figure 3).

We debated whether to include calcium supplementation as part of our intervention, but given known potential harms from calcium supplementation, including nephrolithiasis and possible increased cardiovascular risk,[16] we elected to focus exclusively on vitamin D. Although studies of primary and secondary fragility fracture prevention with vitamin D have not demonstrated consistently positive results, the studies were not specifically targeted to vitamin D‐deficient patients.[17, 18] Even in the absence of definitively proven secondary fracture prevention, given the multiple health issues associated with vitamin D deficiency, we believe that screening high prevalence populations and treating appropriately is best practice. With minimal patient costs (our institution charges $93 per assay) and a high prevalence (50% in our population), we believe universal screening of elderly patients with hip fracture for vitamin D deficiency is also cost‐effective.

Our project was specifically designed to address the issue of vitamin D deficiency in elderly hip fracture patients, but most of these patients also have osteoporosis. Although vitamin D deficiency contributes to osteoporosis, it is certainly not the only factor. It is also recognized that a minority of patients with fragility fractures receives subsequent evaluation and treatment for osteoporosis, <20% in a recent large population‐based study.[19] The American Orthopedic Association has recently launched a website and campaign entitled Own the Bone to improve the quality of care for patients after osteoporotic fracture.[20] A number of measures have been studied to improve the deficit in care, often termed the osteoporosis treatment gap. Edwards and colleagues recently described an intervention based on their institutional electronic medical record.[21] The intervention included order sets for diagnosing osteoporosis and educational materials for patients and providers, but did not demonstrate any change in percentage of patients evaluated for osteoporosis after fragility fracture. Successful randomized controlled trials have been reported using mail notification of physicians and patients after osteoporotic fracture[22]; multifaceted telephone, education and mail notification interventions after wrist fracture[23]; and through the use of a central osteoporosis coordinator to coordinate osteoporosis treatment after a fragility fracture.[24] These successful trials were broad in scope and yet reported modest (10%20%) gains in improvement.

Although bisphophonate therapy is of proven benefit in secondary fracture prevention, there are a number of barriers to initiating it in the acute setting after fragility fracture, as the difficulty in getting large improvement during the above trials suggests. These include recommendations from some experts for bone density testing before starting treatment and theoretic concerns of impairing fracture healing in the initial weeks after acute fracture. Both of these concerns make a hospitalist‐based intervention for osteoporosis evaluation and treatment challenging and beyond the scope of our project's quality improvement efforts.

Our study has some limitations. It was conducted in a single institution and electronic order entry system, which could limit the ability to generalize the results. We did not assess vitamin D compliance or follow‐up after hospitalization, so we are unable to determine if patients successfully completed treatment after it was prescribed. We also found slight differences in race between the pre‐ and postintervention groups. Although we did not perform multivariable regression to account for these differences, we feel such analyses would be unlikely to alter our results. Last, it should be noted that there may be unintended consequences from preselected orders, such as the ones we utilized for vitamin D assays and empiric supplementation. For example, patients with a recently checked vitamin D assay would have duplication of that lab. Similarly, patients who were already taking vitamin D could theoretically be placed on double therapy at admission. With safeguards in the electronic system to flag duplicate medications, low toxicity of standard doses of vitamin D, and minimal economic harm with duplicate laboratory therapy in the context of a hospitalization for hip fracture, we believe the risks are outweighed by the benefits of screening.

In summary, with review of evidence, modification of a computerized physician order set, provider education and feedback, and collaboration with our clinical laboratory, we were able to standardize and improve group practice for the assessment and treatment of vitamin D deficiency in elderly patients with hip fracture. We believe that our model could be applied to other institutions to further improve patient care. Given the extremely high incidence of hip fracture and consistently high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in this population across studies, these findings have important implications for the care of this commonly encountered and vulnerable group of patients.

Disclosures: Data from this project were presented in abstract form at the Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meetings in 2013 and 2014 and as an abstract at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting in 2014. Dr. Catherine Hammett‐Stabler, Director of UNC Hospitals McLendon Core Laboratories, provided data on vitamin D assay turnaround times. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Hip fracture is a common clinical problem, with an incidence of 957 cases/100,000 adults in the United States.[1] Studies have found a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among elderly patients with fragility fractures, though many of these studies were performed in high latitude regions.[2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10] Endocrine Society clinical practice guidelines recommend screening patients with fragility fractures for vitamin D deficiency.[11]

Our hospitalist group practices in an academic tertiary care facility in the southeastern United States. Beginning in June 2010, all patients with acute hip fracture were admitted to our service with consultative comanagement from orthopedics. Our group did not have a standardized approach for the assessment or treatment of vitamin D deficiency in this population. Preliminary analysis of a subgroup of our patients with acute hip fracture revealed that only 29% had been screened for vitamin D deficiency. Of these patients, 68% were deficient or insufficient, yet less than half had been discharged on an appropriate dose of vitamin D. We concluded that our group practice was both varied and substandard.

In this report we describe the creation and implementation of a process for improving the assessment and treatment of vitamin D deficiency in elderly patients with fragility hip fracture. We evaluated the effect of our process on the percentages of patients screened and treated appropriately for vitamin D deficiency.

METHODS

Creation of Intervention

We assembled a task force, consisting of 4 hospitalist physicians. The task force reviewed available literature on the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in elderly patients with fragility fracture and major practice guidelines related to vitamin D. We utilized Endocrine Society clinical practice guidelines to define vitamin D deficiency, insufficiency, and recommended treatment dosing for each condition[11] (Table 1).

| Vitamin D Level (25‐OH) | Vitamin D Status | Treatment Dose Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| 019 ng/mL | Deficient | 50,000 IU/week for 68 weeks |

| 2029 ng/mL | Insufficient | 1,000 to 2,000 IU/day or 50,000 IU/month |

We developed 2 processes for improving group practice. First, we presented a review of evidence and preliminary data from our group practice at a meeting of hospitalist staff. Second, we revised the computerized physician order entry (CPOE) set for patients with hip fractures to include 2 new orders: (1) an automatic order for 25‐OH vitamin D level to be drawn the morning after admission and (2) an order for initiation of 1000 IU daily of vitamin D at admission.

The reasons for starting empiric vitamin D supplementation were 2fold. First was to prompt dosing of vitamin D at the time of discharge by already having it on the patient's medication list. Second was to conform to US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines for fall prevention.[12] The dose of 1000 IU was selected due to its being adequate treatment for insufficient (though not deficient) patients, and yet a low enough dose to minimize risk of toxicity.

Providers

Our hospitalist group includes 21 physicians and 3 physician extenders. Two nocturnist positions were added to our group in July 2013, part way through our intervention. There were no other additions or subtractions to the staff during the study period.

Patients

Patients were identified by search of University of North Carolina (UNC) Hospitals' database using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision codes for femoral neck fracture (821.x) and femur fracture NOS (820.x), linked to hospital services covered by our group. Exclusion criteria included age 50 years, fracture due to high‐speed trauma, fracture due to malignancy, end‐stage renal disease, and death or transition to comfort care during the index hospitalization.

Outcome Measures

Primary outcome measures were the percentage of patients with acute hip fracture with vitamin D level checked during hospitalization and the percentage of deficient patients discharged on the recommended dose of vitamin D. Outcomes were measured for the 28 months before intervention (when our group assumed direct care for hip fracture patients) and were compared with the 12 months after intervention. We also report the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in our population.

Laboratory Methodology

25‐OH vitamin D assays were performed by UNC Hospitals' core laboratories. Assays were performed using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectroscopy technique. Methodology remained constant through the study period.

During implementation of the project, we identified slow turnaround time in reporting of the vitamin D assays as an issue. We subsequently plotted the percentage of assays returned within 48 hours for each month of the study period on a run chart.

Analysis

Primary outcome measures and demographic data were tested for statistical significance with the 2 test. As a separate means of analysis, we plotted a control chart for the percentage of patients with vitamin D level checked and a run chart for the percentage of deficient or insufficient patients discharged on the recommended dose of vitamin D. To ensure a constant sample size, consecutive samples of patients were plotted in chronologic order. Results were interpreted with standard Shewhart rules.[13] 2 testing and plotting of control and run charts were performed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) and QI Charts (Process Improvement Products, Austin, TX).

Implementation

In October 2012, we presented the review of evidence and preliminary data to the hospitalist group and made the new CPOE hip fracture order set available. Implementation was monitored by solicitation of qualitative feedback from group physicians and analysis of outcome data every 6 months. Issues that arose during implementation are described in a project timeline (Figure 1) and discussed in detail in manuscript discussion. We received institutional review board approval to study the project's implementation.

RESULTS

Patients

There were 220 patients identified in the 28 months before implementation. Twenty‐four were excluded by criteria, leaving 196 for analysis. One hundred thirteen patients were identified after implementation. Six patients were excluded by criteria, leaving 107 for analysis.

The mean patient age was 80 years, and the median age was 83 years. Seventy‐five percent were female. Race categories were 85% Caucasian, 8% African American, 3% Asian, 1% Native American, 1% Hispanic, and 3% other.

The preintervention group had mean and median ages of 80 and 82 years, respectively, compared with 81 and 84 years, respectively, in the postintervention group. Seventy‐five percent of the preintervention group was female, compared with 74% postintervention. The only statistically significant difference was in the percentage of Caucasian patients81% of preintervention group compared with 91% of the postintervention group (P = 0.028).

Primary Outcomes

The percentage of patients with acute hip fracture with vitamin D level checked before project implementation was 37.2% (n = 196). After implementation, the percentage improved to 93.5% (n = 107, P < 0.001).

The proportion chart plot of the same data (Figure 2) shows evidence of a fundamental change after intervention. Data points showing the proportion of consecutive samples of 15 patients were plotted chronologically. All points after implementation were above the upper control limit, meeting Shewhart control chart rules for special cause variation.[13]

The percentage of vitamin D deficient/emnsufficient patients discharged on the recommended dose of vitamin D also improved, rising from 40.9% (n = 44) before to 68.0% (n = 50) after implementation (P = 0.008). Because there were fewer candidates for this outcome, we plotted samples of 10 patients consecutively on a run chart (Figure 3). Although there were insufficient data to establish a trend by run chart rules, the last 4 consecutive data points showed sequential improvement.

Prevalence of Vitamin D Insufficiency and Deficiency

Before implementation, 44 of the 73 patients (60.3%) with vitamin D levels checked were deficient or insufficient (25‐OH vitamin D <30 ng/mL); of those 44 patients, 21 (28.8% of total checked) had 25‐OH vitamin D levels <20 ng/mL. After implementation, 50 of 100 patients with levels checked were identified as deficient or insufficient (50%); of those 50 patients, 23 (23% of total) had 25‐OH vitamin D levels <20 ng/mL.

DISCUSSION

Our interventions correlated with significant improvements in the assessment and treatment of vitamin D deficiency in elderly patients with fragility hip fractures. Our study demonstrates a systematic method groups may use to adopt and reliably implement practice guidelines. Moreover, we report several steps to implementation that enhanced our ability to standardize clinical care.

The prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency we identified50.0% after change implementationis within the range reported in prior studies, though our result is notable for being in a southern region of the United States. The prevalence we found before implementation (60.3%) may have been subject to selection bias in screening, so 50.0% is likely the more correct prevalence. Other US studies of vitamin D deficiency prevalence in hip fracture patients report rates from 50% to 65.8%.[2, 8, 10]

The percentage of hip fracture patients screened for vitamin D deficiency showed significant improvement after our interventions, rising to 93.5%. As a comparison with our results, a 2008 study after implementation of a hip fracture pathway reported only screening 37% of patients for vitamin D deficiency.[14] The main barrier we identified was occasional failure to use the electronic order set. This was in large part due to moonlighting physicians, who occasionally cover hospitalist shifts. They accounted for 5 of the 7 missed patients. The other 2 misses were due to group physicians not using the order set. These findings were first identified after 6 months of data were analyzed. These data were presented to the hospitalist group, with reminders to reinforce order set use with moonlighters and to manually order levels after admission if the order set was not utilized.

We found more difficulty with discharging deficient patients on the recommended dose of vitamin D. Our low level at the time of implementation40.9%was actually higher than a recent Swiss study, which found that only 27% of patients with acute hip fracture were discharged on any vitamin D, despite 91% of patients having 25‐OH vitamin D levels <30 ng/mL.[15] However, our proportion of deficient patients discharged on the recommended vitamin D dose only improved to 68.0% during our interventions. This is similar to Glowacki et al., who reported discharging 76% of hip fracture patients on vitamin D and/or calcium through utilization of a discharge pathway, though they did not differentiate vitamin D from calcium in results or attempt to identify patient‐specific vitamin D dosing based on serum levels.[14]

We did identify and address several barriers to discharging patients on the recommended dose. First, we experienced slow turnaround time in measurement of 25‐OH vitamin D. Early into the project, we received several reports of patients being discharged before vitamin D levels had returned. We communicated with the director of UNC Hospitals' core laboratories. A major issue was that the special chemistry section of the core laboratory did not report results directly into the hospital's main electronic reporting system, so that the results had to be hand entered. Over several months, the laboratory worked to improve turnaround times. A run chart plot of the percentage of assays reported within 48 hours for each month showed significant improvement with these efforts (see Supporting Information, Figure 1, in the online version of this article). All 9 data points after our initial discussion with the laboratory director were above the mean established during the prior 4 months, meeting run chart rules for a fundamental change in the system.[13]

The second issue identified was that the ranges for deficiency and insufficiency recommended by Endocrine Society guidelines did not match the reference ranges provided by UNC Hospitals. UNC Hospitals reported levels of 25‐OH vitamin D as normal if above 24, whereas the Endocrine Society defined normal as above 29. When analyzing data after 6 months, we found several patients who had been screened appropriately with results available and noted by the discharging physician, but with results in the normal range per our laboratory. Several of these patients, though low in vitamin D by Endocrine Society standards, were not treated. The laboratory director was again contacted, who noted that the UNC reference ranges had been formed before the Endocrine Society guidelines had been published. We elected to continue with the more conservative ranges recommended by the Endocrine Society. We presented results to the group after 6 months of data had been collected and emphasized our recommended reference ranges and vitamin D dosing (Table 1). We also created reference charts with this information and hung them by all computer workstations in the hospitalist office. With this continued assessment of data and provider education, we did note further improvement through the implementation period, with 90.0% of the last sample of deficient/emnsufficient patients discharged on the recommended dose of vitamin D (Figure 3).

We debated whether to include calcium supplementation as part of our intervention, but given known potential harms from calcium supplementation, including nephrolithiasis and possible increased cardiovascular risk,[16] we elected to focus exclusively on vitamin D. Although studies of primary and secondary fragility fracture prevention with vitamin D have not demonstrated consistently positive results, the studies were not specifically targeted to vitamin D‐deficient patients.[17, 18] Even in the absence of definitively proven secondary fracture prevention, given the multiple health issues associated with vitamin D deficiency, we believe that screening high prevalence populations and treating appropriately is best practice. With minimal patient costs (our institution charges $93 per assay) and a high prevalence (50% in our population), we believe universal screening of elderly patients with hip fracture for vitamin D deficiency is also cost‐effective.

Our project was specifically designed to address the issue of vitamin D deficiency in elderly hip fracture patients, but most of these patients also have osteoporosis. Although vitamin D deficiency contributes to osteoporosis, it is certainly not the only factor. It is also recognized that a minority of patients with fragility fractures receives subsequent evaluation and treatment for osteoporosis, <20% in a recent large population‐based study.[19] The American Orthopedic Association has recently launched a website and campaign entitled Own the Bone to improve the quality of care for patients after osteoporotic fracture.[20] A number of measures have been studied to improve the deficit in care, often termed the osteoporosis treatment gap. Edwards and colleagues recently described an intervention based on their institutional electronic medical record.[21] The intervention included order sets for diagnosing osteoporosis and educational materials for patients and providers, but did not demonstrate any change in percentage of patients evaluated for osteoporosis after fragility fracture. Successful randomized controlled trials have been reported using mail notification of physicians and patients after osteoporotic fracture[22]; multifaceted telephone, education and mail notification interventions after wrist fracture[23]; and through the use of a central osteoporosis coordinator to coordinate osteoporosis treatment after a fragility fracture.[24] These successful trials were broad in scope and yet reported modest (10%20%) gains in improvement.

Although bisphophonate therapy is of proven benefit in secondary fracture prevention, there are a number of barriers to initiating it in the acute setting after fragility fracture, as the difficulty in getting large improvement during the above trials suggests. These include recommendations from some experts for bone density testing before starting treatment and theoretic concerns of impairing fracture healing in the initial weeks after acute fracture. Both of these concerns make a hospitalist‐based intervention for osteoporosis evaluation and treatment challenging and beyond the scope of our project's quality improvement efforts.

Our study has some limitations. It was conducted in a single institution and electronic order entry system, which could limit the ability to generalize the results. We did not assess vitamin D compliance or follow‐up after hospitalization, so we are unable to determine if patients successfully completed treatment after it was prescribed. We also found slight differences in race between the pre‐ and postintervention groups. Although we did not perform multivariable regression to account for these differences, we feel such analyses would be unlikely to alter our results. Last, it should be noted that there may be unintended consequences from preselected orders, such as the ones we utilized for vitamin D assays and empiric supplementation. For example, patients with a recently checked vitamin D assay would have duplication of that lab. Similarly, patients who were already taking vitamin D could theoretically be placed on double therapy at admission. With safeguards in the electronic system to flag duplicate medications, low toxicity of standard doses of vitamin D, and minimal economic harm with duplicate laboratory therapy in the context of a hospitalization for hip fracture, we believe the risks are outweighed by the benefits of screening.

In summary, with review of evidence, modification of a computerized physician order set, provider education and feedback, and collaboration with our clinical laboratory, we were able to standardize and improve group practice for the assessment and treatment of vitamin D deficiency in elderly patients with hip fracture. We believe that our model could be applied to other institutions to further improve patient care. Given the extremely high incidence of hip fracture and consistently high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in this population across studies, these findings have important implications for the care of this commonly encountered and vulnerable group of patients.

Disclosures: Data from this project were presented in abstract form at the Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meetings in 2013 and 2014 and as an abstract at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting in 2014. Dr. Catherine Hammett‐Stabler, Director of UNC Hospitals McLendon Core Laboratories, provided data on vitamin D assay turnaround times. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , . Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United States. JAMA. 2009;302(14):1573–1579.

- , , , , , . Occult vitamin D deficiency in postmenopausal US women with acute hip fracture. JAMA. 1999;281(16):1505–1511.

- , , , , , . Prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy in Scottish adults with non‐vertebral fragility fractures. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(9):1355–1361.

- , , . Prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy in osteoporotic hip fracture patients in London. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(12):1891–1894.

- , , , et al. Half of the patients with an acute hip fracture suffer from hypovitaminosis D: a prospective study in southeastern Finland. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(12):2018–2024.

- , , , et al. Prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy in Belfast following fragility fracture. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(1):101–105.

- , , , , , . High prevalence of hypovitaminosis D and K in patients with hip fracture. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2011;20(1):56–61.

- , , , . Vitamin D insufficiency in patients with acute hip fractures of all ages and both sexes in a sunny climate. J Orthop Trauma. 2013;27(12):e275–e280.

- , , , et al. Vitamin D and intact PTH status in patients with hip fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(11):1608–1614.

- , , , et al. Distribution and correlates of serum 25‐hydroxyvitamin D levels in a sample of patients with hip fracture. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5(4):335–340.

- , , , et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(7):1911–1930.

- , . Prevention of falls in community‐dwelling older adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(3):197–204.

- , . The Health Care Data Guide: Learning From Data for Improvement. 1st ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass; 2011.

- , , , , . Importance of vitamin D in hospital‐based fracture care pathways. J Nutr Health Aging. 2008;12(5):291–293.

- , , , et al. Before and after hip fracture, vitamin D deficiency may not be treated sufficiently. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(11):2765–2773.

- , , , et al. Effect of calcium supplements on risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular events: meta‐analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c3691.

- , , , et al. A pooled analysis of vitamin D dose requirements for fracture prevention. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(1):40–49.

- , , , et al. Oral vitamin D3 and calcium for secondary prevention of low‐trauma fractures in elderly people (Randomised Evaluation of Calcium Or vitamin D, RECORD): a randomised placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9471):1621–1628.

- , , , et al. A population‐based analysis of the post‐fracture care gap 1996–2008: the situation is not improving. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(5):1623–1629.

- American Orthopedic Association. Own the Bone website. 2011. Available at: http://www.ownthebone.org. Accessed August 1, 2014.

- , , , et al. Development of an electronic medical record based intervention to improve medical care of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(10):2489–2498.

- , , , , . Closing the gap in postfracture care at the population level: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2012;184(3):290–296.

- , , , et al. Multifaceted intervention to improve diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis in patients with recent wrist fracture: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2008;178(5):569–575.

- , , , et al. Impact of a centralized osteoporosis coordinator on post‐fracture osteoporosis management: a cluster randomized trial. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(1):87–95.

- , , , . Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United States. JAMA. 2009;302(14):1573–1579.

- , , , , , . Occult vitamin D deficiency in postmenopausal US women with acute hip fracture. JAMA. 1999;281(16):1505–1511.

- , , , , , . Prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy in Scottish adults with non‐vertebral fragility fractures. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(9):1355–1361.

- , , . Prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy in osteoporotic hip fracture patients in London. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(12):1891–1894.

- , , , et al. Half of the patients with an acute hip fracture suffer from hypovitaminosis D: a prospective study in southeastern Finland. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(12):2018–2024.

- , , , et al. Prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy in Belfast following fragility fracture. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(1):101–105.

- , , , , , . High prevalence of hypovitaminosis D and K in patients with hip fracture. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2011;20(1):56–61.

- , , , . Vitamin D insufficiency in patients with acute hip fractures of all ages and both sexes in a sunny climate. J Orthop Trauma. 2013;27(12):e275–e280.

- , , , et al. Vitamin D and intact PTH status in patients with hip fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(11):1608–1614.

- , , , et al. Distribution and correlates of serum 25‐hydroxyvitamin D levels in a sample of patients with hip fracture. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5(4):335–340.

- , , , et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(7):1911–1930.

- , . Prevention of falls in community‐dwelling older adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(3):197–204.

- , . The Health Care Data Guide: Learning From Data for Improvement. 1st ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass; 2011.

- , , , , . Importance of vitamin D in hospital‐based fracture care pathways. J Nutr Health Aging. 2008;12(5):291–293.

- , , , et al. Before and after hip fracture, vitamin D deficiency may not be treated sufficiently. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(11):2765–2773.

- , , , et al. Effect of calcium supplements on risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular events: meta‐analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c3691.

- , , , et al. A pooled analysis of vitamin D dose requirements for fracture prevention. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(1):40–49.

- , , , et al. Oral vitamin D3 and calcium for secondary prevention of low‐trauma fractures in elderly people (Randomised Evaluation of Calcium Or vitamin D, RECORD): a randomised placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9471):1621–1628.

- , , , et al. A population‐based analysis of the post‐fracture care gap 1996–2008: the situation is not improving. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(5):1623–1629.

- American Orthopedic Association. Own the Bone website. 2011. Available at: http://www.ownthebone.org. Accessed August 1, 2014.

- , , , et al. Development of an electronic medical record based intervention to improve medical care of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(10):2489–2498.

- , , , , . Closing the gap in postfracture care at the population level: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2012;184(3):290–296.

- , , , et al. Multifaceted intervention to improve diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis in patients with recent wrist fracture: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2008;178(5):569–575.

- , , , et al. Impact of a centralized osteoporosis coordinator on post‐fracture osteoporosis management: a cluster randomized trial. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(1):87–95.

© 2014 Society of Hospital Medicine

Systems Automation for Cancer Surveillance: A Useful Tool for Tracking the Care of Head and Neck Cancer Patients in the Ear, Nose, and Throat Clinic

Purpose: About 400,000 new cases of Head and Neck Cancer (HNC) are diagnosed and reported each year. HNC patients require frequent follow-up care and additional interventions due to the potential for disease recurrence and second primaries. A robust and automated HNC identification and surveillance program can aid in case identification and can track appointments and required care, using the guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). An automated tool would provide for optimal treatment interventions while preventing any patients from being inadvertently lost to follow-up, enhancing veteran centered care.

Methods: The ear, nose, and throat (ENT) Cancer Tracking System (CTS) queries the VA Corporate Data Warehouse each night to identify all patients recently diagnosed with a HNC. All patients residing in the Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Big Spring, Texas, catchment areas are included in the capture pool. Cases are identified by examining outpatient visits and inpatient discharge diagnosis International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes, surgical pathology Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine—Clinical Terms (SNOMED codes), and VistA problem list diagnoses. Patients identified as having cancer are presented, using an interactive report hosted on a secure SharePoint site. Newly identified patients are automatically assigned to “active” management status, minimizing the risk of missing a new patient. The coordinator can toggle a patient’s status between “inactive” and “active” at any time, but can never delete a patient from the CTS. Inactive patients with a new cancer diagnosis are automatically toggled to active status. The CTS report tracks and presents a number of pertinent medical indicators, including patient identifiers and residence location, most recent diagnosis date, days since last diagnosis, diagnosis ICD code, date captured on the CTS, most recent ear, nose, and throat (ENT) visit, most recent ENT appointment, days since last visit, date of last thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) test, and date of last PET scan. Cancellations, no-shows, and patients overdue for TSH testing are highlighted.

Results: Baseline data obtained in 2012 prior to the activation of the CTS revealed that about 31.1% of diagnosed HNC patients in the ENT clinic experienced delays in care or were lost to follow-up care through cancellations, no shows, and nonrescheduled appointments. A dedicated cancer care coordinator (CCC) was assigned to the ENT clinic to record, monitor, and track HNC patients manually using an Excel spreadsheet. Although cancer surveillance reports proved that launching a cancer surveillance program prevented patients with cancer from being lost to follow-up care, the manual tracking system was time consuming and labor intensive. The automated CTS has optimized cancer surveillance by providing the CCC with immediate identification of new HNC diagnoses, appointment tracking, alerts for HNC patients that have not been scheduled, alerts of overdue required lab tests, tracking of completed PET CT imaging, and improved timeliness in obtaining quality improvement data; all were accomplished without the CCC manually tracking anything.

Conclusions: During the first 4 months of operation (February to May 2014), 14 new HNC patients were identified automatically—patients that manual tracking might have missed or incurred delays in care. The CTS has proved to be a vital tool to the CCC and will continue to assist in the identification of new HNC patients, provide access to patient information on follow-up care, and improve access to recommended diagnostic procedures from NCCN guidelines. Other benefits of an electronic tracking system are optimized time, improved workflows, and improvements to patient safety by providing timely access to care and treatment.

Purpose: About 400,000 new cases of Head and Neck Cancer (HNC) are diagnosed and reported each year. HNC patients require frequent follow-up care and additional interventions due to the potential for disease recurrence and second primaries. A robust and automated HNC identification and surveillance program can aid in case identification and can track appointments and required care, using the guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). An automated tool would provide for optimal treatment interventions while preventing any patients from being inadvertently lost to follow-up, enhancing veteran centered care.

Methods: The ear, nose, and throat (ENT) Cancer Tracking System (CTS) queries the VA Corporate Data Warehouse each night to identify all patients recently diagnosed with a HNC. All patients residing in the Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Big Spring, Texas, catchment areas are included in the capture pool. Cases are identified by examining outpatient visits and inpatient discharge diagnosis International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes, surgical pathology Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine—Clinical Terms (SNOMED codes), and VistA problem list diagnoses. Patients identified as having cancer are presented, using an interactive report hosted on a secure SharePoint site. Newly identified patients are automatically assigned to “active” management status, minimizing the risk of missing a new patient. The coordinator can toggle a patient’s status between “inactive” and “active” at any time, but can never delete a patient from the CTS. Inactive patients with a new cancer diagnosis are automatically toggled to active status. The CTS report tracks and presents a number of pertinent medical indicators, including patient identifiers and residence location, most recent diagnosis date, days since last diagnosis, diagnosis ICD code, date captured on the CTS, most recent ear, nose, and throat (ENT) visit, most recent ENT appointment, days since last visit, date of last thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) test, and date of last PET scan. Cancellations, no-shows, and patients overdue for TSH testing are highlighted.

Results: Baseline data obtained in 2012 prior to the activation of the CTS revealed that about 31.1% of diagnosed HNC patients in the ENT clinic experienced delays in care or were lost to follow-up care through cancellations, no shows, and nonrescheduled appointments. A dedicated cancer care coordinator (CCC) was assigned to the ENT clinic to record, monitor, and track HNC patients manually using an Excel spreadsheet. Although cancer surveillance reports proved that launching a cancer surveillance program prevented patients with cancer from being lost to follow-up care, the manual tracking system was time consuming and labor intensive. The automated CTS has optimized cancer surveillance by providing the CCC with immediate identification of new HNC diagnoses, appointment tracking, alerts for HNC patients that have not been scheduled, alerts of overdue required lab tests, tracking of completed PET CT imaging, and improved timeliness in obtaining quality improvement data; all were accomplished without the CCC manually tracking anything.

Conclusions: During the first 4 months of operation (February to May 2014), 14 new HNC patients were identified automatically—patients that manual tracking might have missed or incurred delays in care. The CTS has proved to be a vital tool to the CCC and will continue to assist in the identification of new HNC patients, provide access to patient information on follow-up care, and improve access to recommended diagnostic procedures from NCCN guidelines. Other benefits of an electronic tracking system are optimized time, improved workflows, and improvements to patient safety by providing timely access to care and treatment.

Purpose: About 400,000 new cases of Head and Neck Cancer (HNC) are diagnosed and reported each year. HNC patients require frequent follow-up care and additional interventions due to the potential for disease recurrence and second primaries. A robust and automated HNC identification and surveillance program can aid in case identification and can track appointments and required care, using the guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). An automated tool would provide for optimal treatment interventions while preventing any patients from being inadvertently lost to follow-up, enhancing veteran centered care.

Methods: The ear, nose, and throat (ENT) Cancer Tracking System (CTS) queries the VA Corporate Data Warehouse each night to identify all patients recently diagnosed with a HNC. All patients residing in the Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Big Spring, Texas, catchment areas are included in the capture pool. Cases are identified by examining outpatient visits and inpatient discharge diagnosis International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes, surgical pathology Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine—Clinical Terms (SNOMED codes), and VistA problem list diagnoses. Patients identified as having cancer are presented, using an interactive report hosted on a secure SharePoint site. Newly identified patients are automatically assigned to “active” management status, minimizing the risk of missing a new patient. The coordinator can toggle a patient’s status between “inactive” and “active” at any time, but can never delete a patient from the CTS. Inactive patients with a new cancer diagnosis are automatically toggled to active status. The CTS report tracks and presents a number of pertinent medical indicators, including patient identifiers and residence location, most recent diagnosis date, days since last diagnosis, diagnosis ICD code, date captured on the CTS, most recent ear, nose, and throat (ENT) visit, most recent ENT appointment, days since last visit, date of last thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) test, and date of last PET scan. Cancellations, no-shows, and patients overdue for TSH testing are highlighted.