User login

Does Young Athlete Have Cause for Concern?

ANSWER

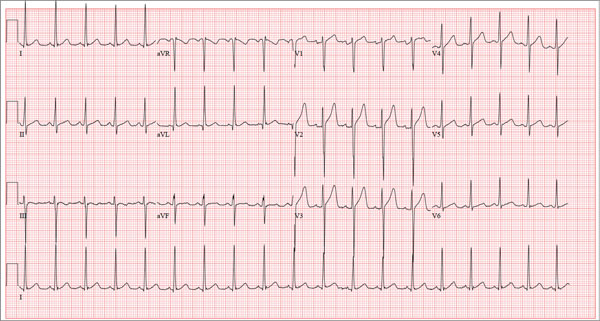

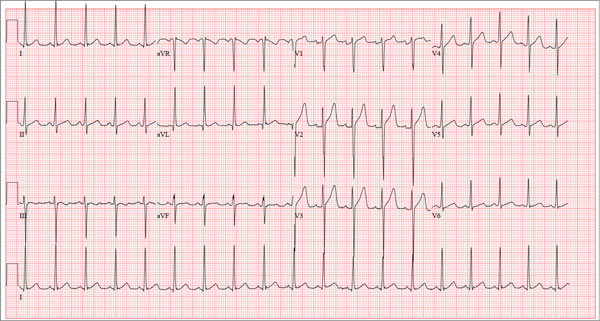

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes sinus tachycardia and left ventricular hypertrophy.

Sinus tachycardia is evidenced by an atrial rate greater than 100 beats/min with a P wave for every QRS complex and a QRS complex for every P wave.

Left ventricular hypertrophy is present when either the sum of the R wave voltage in lead I and the S wave in lead III is 25 mm or higher or the sum of the S wave in lead V1 and the R wave in either V5 or V6 is 35 mm or higher.

In follow-up to these findings, an echocardiogram was recommended and performed. It revealed a normal heart consistent with that of a young athlete.

The patient and his parents were reassured as to the young man’s condition but decided to seek a second opinion.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes sinus tachycardia and left ventricular hypertrophy.

Sinus tachycardia is evidenced by an atrial rate greater than 100 beats/min with a P wave for every QRS complex and a QRS complex for every P wave.

Left ventricular hypertrophy is present when either the sum of the R wave voltage in lead I and the S wave in lead III is 25 mm or higher or the sum of the S wave in lead V1 and the R wave in either V5 or V6 is 35 mm or higher.

In follow-up to these findings, an echocardiogram was recommended and performed. It revealed a normal heart consistent with that of a young athlete.

The patient and his parents were reassured as to the young man’s condition but decided to seek a second opinion.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes sinus tachycardia and left ventricular hypertrophy.

Sinus tachycardia is evidenced by an atrial rate greater than 100 beats/min with a P wave for every QRS complex and a QRS complex for every P wave.

Left ventricular hypertrophy is present when either the sum of the R wave voltage in lead I and the S wave in lead III is 25 mm or higher or the sum of the S wave in lead V1 and the R wave in either V5 or V6 is 35 mm or higher.

In follow-up to these findings, an echocardiogram was recommended and performed. It revealed a normal heart consistent with that of a young athlete.

The patient and his parents were reassured as to the young man’s condition but decided to seek a second opinion.

A 17-year-old male athlete recently graduated high school and received a full scholarship to play baseball for a major university. As part of his preparation for college, his parents bring him to your clinic for a complete physical examination, noting that he contracted several colds during the past school year. He has been symptom free for the past two months. The patient asks to be examined without his parents present. After they exit the room, he informs you that he has recently become sexually active, hasn’t used condoms on two occasions, and wants to be tested for sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Medical history is unremarkable, with the exception of a fractured left clavicle sustained when the patient was 12. He currently takes no medications, denies tobacco, alcohol, or recreational drug use, and has no known drug allergies. He lives at home with his parents and two siblings. A detailed review of systems reveals no complaints or symptoms. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 104/58 mm Hg; pulse, 100 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min-1; and temperature, 97.2°F. His weight is 204 lb and his height, 79 in. He appears anxious and apologizes for having sweaty palms. A thorough physical exam yields completely normal results, with the exception of a palpable callus over the mid portion of the left clavicle (consistent with his history of a fracture). Lung sounds are clear in all fields; there are no murmurs, bruits, rubs, or extra heart sounds; and a strong PMI (point of maximum impulse) is easily palpable over the left chest at the seventh and eighth intercostal spaces. The patient is sent to the lab, where blood is drawn for a routine chemistry panel, complete blood count, and STI surveillance panel. When he returns and his parents reenter the room, they insist on ECG for their son. You explain that there’s no clear indication for it; however, they insist and state they will pay out of pocket if not covered by insurance. You reluctantly agree. The ECG shows the following: a ventricular rate of 112 beats/min; PR interval, 132 ms; QRS duration, 756 ms; QT/QTc interval, 326/444 ms; P axis, 59°; R axis, –8°; and T axis, 26°. What is your interpretation?

Overcoming ibrutinib resistance in MCL

Credit: Rhoda Baer

Investigators have identified drug combinations that may overcome resistance to ibrutinib in patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

The group discovered a mutation in Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) that confers resistance to the drug.

They also found that high levels of PI3K-AKT and CDK4 signaling could explain innate resistance to ibrutinib, so combining a CDK4 inhibitor and a PI3K inhibitor might be effective in patients who don’t respond to ibrutinib.

Selina Chen-Kiang, PhD, of Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, and her colleagues detailed these findings in Cancer Discovery. Some of Dr Chen-Kiang’s colleagues reported relationships with Janssen and Pharmacyclics, the companies developing ibrutinib.

“[Ibrutinib] doesn’t work for about 32% of patients, and their lymphomas are said to have primary resistance to ibrutinib,” Dr Chen-Kiang noted. “We are also learning that most patients whose lymphomas respond to ibrutinib eventually relapse because their tumors acquire resistance to the drug.”

“The knowledge that we gained from longitudinal RNA and genomic sequencing of mantle cell lymphomas with primary and acquired resistance to ibrutinib allowed us to identify rational drug combinations that may overcome resistance in these 2 settings.”

Dr Chen-Kiang and her colleagues conducted whole-exome and whole-transcriptome analyses of 5 serial biopsies from a patient with MCL who initially responded to ibrutinib before progressing.

After comparing these data with results from an analysis of healthy tissues from the same patient, the investigators found that a mutation in BTK, the C481S mutation, appeared at relapse.

The researchers found the same mutation at relapse in a second MCL patient with acquired resistance to ibrutinib but not in any patients with primary resistance to the drug.

Further analyses revealed the consequences of the relapse-specific BTK C481S mutation, including activation of the PI3K and CDK4 signaling pathways, which promote cell survival and proliferation.

Inhibiting CDK4 with the investigational anticancer drug palbociclib made ibrutinib-resistant lymphoma cells carrying the BTK C481S mutation sensitive to investigational drugs that inhibit PI3K.

And palbociclib made ibrutinib-resistant lymphoma cells harboring normal BTK sensitive to both ibrutinib and investigational drugs that inhibit PI3K. The researchers recently opened a clinical trial to test ibrutinib and palbociclib in combination (NCT02159755).

“We are very excited to have generated data . . . that may be meaningful for patients,” Dr Chen-Kiang said. “It is also exciting because CDK4 is a new kind of drug target. It controls the cell cycle, which is a central cancer pathway. As such, it is not just important for mantle cell lymphoma but for many forms of cancer.” ![]()

Credit: Rhoda Baer

Investigators have identified drug combinations that may overcome resistance to ibrutinib in patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

The group discovered a mutation in Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) that confers resistance to the drug.

They also found that high levels of PI3K-AKT and CDK4 signaling could explain innate resistance to ibrutinib, so combining a CDK4 inhibitor and a PI3K inhibitor might be effective in patients who don’t respond to ibrutinib.

Selina Chen-Kiang, PhD, of Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, and her colleagues detailed these findings in Cancer Discovery. Some of Dr Chen-Kiang’s colleagues reported relationships with Janssen and Pharmacyclics, the companies developing ibrutinib.

“[Ibrutinib] doesn’t work for about 32% of patients, and their lymphomas are said to have primary resistance to ibrutinib,” Dr Chen-Kiang noted. “We are also learning that most patients whose lymphomas respond to ibrutinib eventually relapse because their tumors acquire resistance to the drug.”

“The knowledge that we gained from longitudinal RNA and genomic sequencing of mantle cell lymphomas with primary and acquired resistance to ibrutinib allowed us to identify rational drug combinations that may overcome resistance in these 2 settings.”

Dr Chen-Kiang and her colleagues conducted whole-exome and whole-transcriptome analyses of 5 serial biopsies from a patient with MCL who initially responded to ibrutinib before progressing.

After comparing these data with results from an analysis of healthy tissues from the same patient, the investigators found that a mutation in BTK, the C481S mutation, appeared at relapse.

The researchers found the same mutation at relapse in a second MCL patient with acquired resistance to ibrutinib but not in any patients with primary resistance to the drug.

Further analyses revealed the consequences of the relapse-specific BTK C481S mutation, including activation of the PI3K and CDK4 signaling pathways, which promote cell survival and proliferation.

Inhibiting CDK4 with the investigational anticancer drug palbociclib made ibrutinib-resistant lymphoma cells carrying the BTK C481S mutation sensitive to investigational drugs that inhibit PI3K.

And palbociclib made ibrutinib-resistant lymphoma cells harboring normal BTK sensitive to both ibrutinib and investigational drugs that inhibit PI3K. The researchers recently opened a clinical trial to test ibrutinib and palbociclib in combination (NCT02159755).

“We are very excited to have generated data . . . that may be meaningful for patients,” Dr Chen-Kiang said. “It is also exciting because CDK4 is a new kind of drug target. It controls the cell cycle, which is a central cancer pathway. As such, it is not just important for mantle cell lymphoma but for many forms of cancer.” ![]()

Credit: Rhoda Baer

Investigators have identified drug combinations that may overcome resistance to ibrutinib in patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

The group discovered a mutation in Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) that confers resistance to the drug.

They also found that high levels of PI3K-AKT and CDK4 signaling could explain innate resistance to ibrutinib, so combining a CDK4 inhibitor and a PI3K inhibitor might be effective in patients who don’t respond to ibrutinib.

Selina Chen-Kiang, PhD, of Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, and her colleagues detailed these findings in Cancer Discovery. Some of Dr Chen-Kiang’s colleagues reported relationships with Janssen and Pharmacyclics, the companies developing ibrutinib.

“[Ibrutinib] doesn’t work for about 32% of patients, and their lymphomas are said to have primary resistance to ibrutinib,” Dr Chen-Kiang noted. “We are also learning that most patients whose lymphomas respond to ibrutinib eventually relapse because their tumors acquire resistance to the drug.”

“The knowledge that we gained from longitudinal RNA and genomic sequencing of mantle cell lymphomas with primary and acquired resistance to ibrutinib allowed us to identify rational drug combinations that may overcome resistance in these 2 settings.”

Dr Chen-Kiang and her colleagues conducted whole-exome and whole-transcriptome analyses of 5 serial biopsies from a patient with MCL who initially responded to ibrutinib before progressing.

After comparing these data with results from an analysis of healthy tissues from the same patient, the investigators found that a mutation in BTK, the C481S mutation, appeared at relapse.

The researchers found the same mutation at relapse in a second MCL patient with acquired resistance to ibrutinib but not in any patients with primary resistance to the drug.

Further analyses revealed the consequences of the relapse-specific BTK C481S mutation, including activation of the PI3K and CDK4 signaling pathways, which promote cell survival and proliferation.

Inhibiting CDK4 with the investigational anticancer drug palbociclib made ibrutinib-resistant lymphoma cells carrying the BTK C481S mutation sensitive to investigational drugs that inhibit PI3K.

And palbociclib made ibrutinib-resistant lymphoma cells harboring normal BTK sensitive to both ibrutinib and investigational drugs that inhibit PI3K. The researchers recently opened a clinical trial to test ibrutinib and palbociclib in combination (NCT02159755).

“We are very excited to have generated data . . . that may be meaningful for patients,” Dr Chen-Kiang said. “It is also exciting because CDK4 is a new kind of drug target. It controls the cell cycle, which is a central cancer pathway. As such, it is not just important for mantle cell lymphoma but for many forms of cancer.” ![]()

New insight into thalassemia, sickle cell anemia

Credit: Graham Beards

Researchers have found evidence suggesting that beneficial variants of a gene controlling hematopoiesis exist in nearly all human populations.

The team analyzed genomic data from world populations, looking at HMIP-2, a human quantitative trait locus that affects the production of fetal hemoglobin in adults.

The analysis revealed 2 alleles that promote fetal hemoglobin production and can therefore reduce the severity of thalassemia and sickle cell anemia (SCA).

“Patients who have milder versions of [these] blood disorders, thanks to their ability to keep producing fetal hemoglobin, carry genetic clues that are helping us to understand the function of the genes and biological pathways involved in these diseases,” said Stephan Menzel, MD, of King’s College London in the UK.

He and his colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in Annals of Human Genetics.

The researchers noted that HMIP (HBS1L-MYB intergenic polymorphism) on chromosome 6q23.3 was first detected in a large Asian Indian family, where it was shown to be responsible for the persistence of fetal hemoglobin production in adulthood.

And HMIP-2 occupies a 24-kb stretch of DNA that acts as a distal upstream enhancer for MYB, the gene for cMYB, which is essential to hematopoiesis.

While studying 4 groups of SCA patients of diverse African descent, Dr Menzel and his colleagues discovered 2 alleles at HMIP-2 that promote fetal hemoglobin—HMIP-2A and HMIP2-B.

Subsequent analyses revealed the alleles were present, either alone or together, in major human populations and nearly all of the ethnic groups studied.

Both HMIP-2A and HMIP2-B occur in Sub-Saharan Africa, but only at low frequencies. In much of the rest of the world, the alleles have combined, forming HMIP-2A-B, and this combination is relatively common in Europe, South Asia, and China. HMIP-2B alone is common in Far-East Asian peoples and in Amerindians.

The researchers also analyzed genomic data from Neanderthals, Denisovans, and Great Apes, but detected neither HMIP-2A nor HMIP-2B.

The team said these results suggest MYB enhancer variants that modulate the severity of SCA and thalassemia have arisen twice in modern humans, in Africa, and then spread to the rest of the world.

However, this likely occurred long before inherited blood disorders became prevalent, so the environmental factors that favored such variants in these early humans are not clear.

For the next stage of this research, Dr Menzel and his colleagues plan to explore which selection pressures or benefits might have contributed to the present population distribution of the variants.

Selection pressures could include nutritional factors, such as the availability of iron in the diet, or specific demands on red blood cell production, such as adaptation to high altitudes. ![]()

Credit: Graham Beards

Researchers have found evidence suggesting that beneficial variants of a gene controlling hematopoiesis exist in nearly all human populations.

The team analyzed genomic data from world populations, looking at HMIP-2, a human quantitative trait locus that affects the production of fetal hemoglobin in adults.

The analysis revealed 2 alleles that promote fetal hemoglobin production and can therefore reduce the severity of thalassemia and sickle cell anemia (SCA).

“Patients who have milder versions of [these] blood disorders, thanks to their ability to keep producing fetal hemoglobin, carry genetic clues that are helping us to understand the function of the genes and biological pathways involved in these diseases,” said Stephan Menzel, MD, of King’s College London in the UK.

He and his colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in Annals of Human Genetics.

The researchers noted that HMIP (HBS1L-MYB intergenic polymorphism) on chromosome 6q23.3 was first detected in a large Asian Indian family, where it was shown to be responsible for the persistence of fetal hemoglobin production in adulthood.

And HMIP-2 occupies a 24-kb stretch of DNA that acts as a distal upstream enhancer for MYB, the gene for cMYB, which is essential to hematopoiesis.

While studying 4 groups of SCA patients of diverse African descent, Dr Menzel and his colleagues discovered 2 alleles at HMIP-2 that promote fetal hemoglobin—HMIP-2A and HMIP2-B.

Subsequent analyses revealed the alleles were present, either alone or together, in major human populations and nearly all of the ethnic groups studied.

Both HMIP-2A and HMIP2-B occur in Sub-Saharan Africa, but only at low frequencies. In much of the rest of the world, the alleles have combined, forming HMIP-2A-B, and this combination is relatively common in Europe, South Asia, and China. HMIP-2B alone is common in Far-East Asian peoples and in Amerindians.

The researchers also analyzed genomic data from Neanderthals, Denisovans, and Great Apes, but detected neither HMIP-2A nor HMIP-2B.

The team said these results suggest MYB enhancer variants that modulate the severity of SCA and thalassemia have arisen twice in modern humans, in Africa, and then spread to the rest of the world.

However, this likely occurred long before inherited blood disorders became prevalent, so the environmental factors that favored such variants in these early humans are not clear.

For the next stage of this research, Dr Menzel and his colleagues plan to explore which selection pressures or benefits might have contributed to the present population distribution of the variants.

Selection pressures could include nutritional factors, such as the availability of iron in the diet, or specific demands on red blood cell production, such as adaptation to high altitudes. ![]()

Credit: Graham Beards

Researchers have found evidence suggesting that beneficial variants of a gene controlling hematopoiesis exist in nearly all human populations.

The team analyzed genomic data from world populations, looking at HMIP-2, a human quantitative trait locus that affects the production of fetal hemoglobin in adults.

The analysis revealed 2 alleles that promote fetal hemoglobin production and can therefore reduce the severity of thalassemia and sickle cell anemia (SCA).

“Patients who have milder versions of [these] blood disorders, thanks to their ability to keep producing fetal hemoglobin, carry genetic clues that are helping us to understand the function of the genes and biological pathways involved in these diseases,” said Stephan Menzel, MD, of King’s College London in the UK.

He and his colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in Annals of Human Genetics.

The researchers noted that HMIP (HBS1L-MYB intergenic polymorphism) on chromosome 6q23.3 was first detected in a large Asian Indian family, where it was shown to be responsible for the persistence of fetal hemoglobin production in adulthood.

And HMIP-2 occupies a 24-kb stretch of DNA that acts as a distal upstream enhancer for MYB, the gene for cMYB, which is essential to hematopoiesis.

While studying 4 groups of SCA patients of diverse African descent, Dr Menzel and his colleagues discovered 2 alleles at HMIP-2 that promote fetal hemoglobin—HMIP-2A and HMIP2-B.

Subsequent analyses revealed the alleles were present, either alone or together, in major human populations and nearly all of the ethnic groups studied.

Both HMIP-2A and HMIP2-B occur in Sub-Saharan Africa, but only at low frequencies. In much of the rest of the world, the alleles have combined, forming HMIP-2A-B, and this combination is relatively common in Europe, South Asia, and China. HMIP-2B alone is common in Far-East Asian peoples and in Amerindians.

The researchers also analyzed genomic data from Neanderthals, Denisovans, and Great Apes, but detected neither HMIP-2A nor HMIP-2B.

The team said these results suggest MYB enhancer variants that modulate the severity of SCA and thalassemia have arisen twice in modern humans, in Africa, and then spread to the rest of the world.

However, this likely occurred long before inherited blood disorders became prevalent, so the environmental factors that favored such variants in these early humans are not clear.

For the next stage of this research, Dr Menzel and his colleagues plan to explore which selection pressures or benefits might have contributed to the present population distribution of the variants.

Selection pressures could include nutritional factors, such as the availability of iron in the diet, or specific demands on red blood cell production, such as adaptation to high altitudes. ![]()

Efficacy of malaria vaccine varies with age, over time

Credit: Caitlin Kleiboer

A candidate malaria vaccine is more effective in children aged 5 months to 17 months than in infants 3 months of age or younger, results of a phase 3 study suggest.

Previous research indicated the vaccine— RTS,S/AS01—may prevent malaria in young children, but its efficacy wanes over time.

Now, researchers have reported that RTS,S/AS01 can sometimes prevent clinical malaria, severe malaria, and malaria hospitalization in children aged 5 to 17 months.

In the younger age group, the vaccine offered some protection against clinical malaria but did not significantly impact the rates of severe malaria or hospitalization.

The RTS,S Clinical Trials Partnership committee reported these findings in PLOS Medicine.

The study was sponsored by GSK Biologicals SA, the developer and manufacturer of RTS,S/AS01, and funded by both GSK Biologicals SA and the PATH Malaria Vaccine Initiative.

The researchers studied 6537 infants aged 6 to 12 weeks and 8923 children aged 5 to 17 months treated at 11 sites in Africa.

Subjects were randomized to receive 3 doses of RTS,S/AS01 or a comparator vaccine—a rabies vaccine (VeroRab) for the children and a meningococcal C conjugate vaccine (Menjugate) for the infants.

The primary outcome, vaccine efficacy (VE), was the reduction in malaria incidence among subjects who received RTS,S/AS01 compared to the incidence among subjects who received a comparator vaccine.

In the 18 months following vaccination, VE was 46% in children aged 5 to 17 months and 27% in infants aged 6 to 12 weeks. In both age groups, VE was highest in the first 6 months after vaccination.

RTS,S/AS01 averted an average of 829 cases of clinical malaria per 1000 children vaccinated (range, 37 to 2365) and 449 cases per 1000 infants (range, -10 to 1402) within 18 months of vaccination.

In children aged 5 to 17 months, VE was 34% for severe malaria, 41% for malaria hospitalization, and 19% for all-cause hospitalization. In the infants, there was no significant protection against severe malaria, malaria hospitalization, or all-cause hospitalization.

Serious adverse events occurred less often in children who received RTS,S/AS01 than in those who received a comparator vaccine—18.6% and 22.7%, respectively. In infants, the rate of serious adverse events was similar between the 2 vaccination groups.

Meningitis was more common in subjects who received RTS,S/AS01 than in those who received a comparator. However, the researchers have not established a causal relationship.

There were 16 cases of meningitis among the 5949 children in the RTS,S/AS01 group, 1 case among the 2974 children in the control group, 9 cases among the 4358 infants in the RTS,S/AS01 group, and 3 cases among the 2179 infants in the control group.

Despite the adverse events associated with RTS,S/AS01 and its decreased efficacy over time, the researchers believe the vaccine shows promise. They noted that, “even at modest levels of VE, the number of malaria cases averted was substantial.”

Now, the group is evaluating whether a booster immunization given 18 months after the primary vaccination can improve the efficacy of RTS,S/AS01.

Results of this study were previously reported at the Multilateral Initiative on Malaria Pan African Conference in October 2013 and published in The New England Journal of Medicine in October 2011 and November 2012. Long-term results of a phase 2 trial of RTS,S/AS01 were published in The New England Journal of Medicine in March 2013. ![]()

Credit: Caitlin Kleiboer

A candidate malaria vaccine is more effective in children aged 5 months to 17 months than in infants 3 months of age or younger, results of a phase 3 study suggest.

Previous research indicated the vaccine— RTS,S/AS01—may prevent malaria in young children, but its efficacy wanes over time.

Now, researchers have reported that RTS,S/AS01 can sometimes prevent clinical malaria, severe malaria, and malaria hospitalization in children aged 5 to 17 months.

In the younger age group, the vaccine offered some protection against clinical malaria but did not significantly impact the rates of severe malaria or hospitalization.

The RTS,S Clinical Trials Partnership committee reported these findings in PLOS Medicine.

The study was sponsored by GSK Biologicals SA, the developer and manufacturer of RTS,S/AS01, and funded by both GSK Biologicals SA and the PATH Malaria Vaccine Initiative.

The researchers studied 6537 infants aged 6 to 12 weeks and 8923 children aged 5 to 17 months treated at 11 sites in Africa.

Subjects were randomized to receive 3 doses of RTS,S/AS01 or a comparator vaccine—a rabies vaccine (VeroRab) for the children and a meningococcal C conjugate vaccine (Menjugate) for the infants.

The primary outcome, vaccine efficacy (VE), was the reduction in malaria incidence among subjects who received RTS,S/AS01 compared to the incidence among subjects who received a comparator vaccine.

In the 18 months following vaccination, VE was 46% in children aged 5 to 17 months and 27% in infants aged 6 to 12 weeks. In both age groups, VE was highest in the first 6 months after vaccination.

RTS,S/AS01 averted an average of 829 cases of clinical malaria per 1000 children vaccinated (range, 37 to 2365) and 449 cases per 1000 infants (range, -10 to 1402) within 18 months of vaccination.

In children aged 5 to 17 months, VE was 34% for severe malaria, 41% for malaria hospitalization, and 19% for all-cause hospitalization. In the infants, there was no significant protection against severe malaria, malaria hospitalization, or all-cause hospitalization.

Serious adverse events occurred less often in children who received RTS,S/AS01 than in those who received a comparator vaccine—18.6% and 22.7%, respectively. In infants, the rate of serious adverse events was similar between the 2 vaccination groups.

Meningitis was more common in subjects who received RTS,S/AS01 than in those who received a comparator. However, the researchers have not established a causal relationship.

There were 16 cases of meningitis among the 5949 children in the RTS,S/AS01 group, 1 case among the 2974 children in the control group, 9 cases among the 4358 infants in the RTS,S/AS01 group, and 3 cases among the 2179 infants in the control group.

Despite the adverse events associated with RTS,S/AS01 and its decreased efficacy over time, the researchers believe the vaccine shows promise. They noted that, “even at modest levels of VE, the number of malaria cases averted was substantial.”

Now, the group is evaluating whether a booster immunization given 18 months after the primary vaccination can improve the efficacy of RTS,S/AS01.

Results of this study were previously reported at the Multilateral Initiative on Malaria Pan African Conference in October 2013 and published in The New England Journal of Medicine in October 2011 and November 2012. Long-term results of a phase 2 trial of RTS,S/AS01 were published in The New England Journal of Medicine in March 2013. ![]()

Credit: Caitlin Kleiboer

A candidate malaria vaccine is more effective in children aged 5 months to 17 months than in infants 3 months of age or younger, results of a phase 3 study suggest.

Previous research indicated the vaccine— RTS,S/AS01—may prevent malaria in young children, but its efficacy wanes over time.

Now, researchers have reported that RTS,S/AS01 can sometimes prevent clinical malaria, severe malaria, and malaria hospitalization in children aged 5 to 17 months.

In the younger age group, the vaccine offered some protection against clinical malaria but did not significantly impact the rates of severe malaria or hospitalization.

The RTS,S Clinical Trials Partnership committee reported these findings in PLOS Medicine.

The study was sponsored by GSK Biologicals SA, the developer and manufacturer of RTS,S/AS01, and funded by both GSK Biologicals SA and the PATH Malaria Vaccine Initiative.

The researchers studied 6537 infants aged 6 to 12 weeks and 8923 children aged 5 to 17 months treated at 11 sites in Africa.

Subjects were randomized to receive 3 doses of RTS,S/AS01 or a comparator vaccine—a rabies vaccine (VeroRab) for the children and a meningococcal C conjugate vaccine (Menjugate) for the infants.

The primary outcome, vaccine efficacy (VE), was the reduction in malaria incidence among subjects who received RTS,S/AS01 compared to the incidence among subjects who received a comparator vaccine.

In the 18 months following vaccination, VE was 46% in children aged 5 to 17 months and 27% in infants aged 6 to 12 weeks. In both age groups, VE was highest in the first 6 months after vaccination.

RTS,S/AS01 averted an average of 829 cases of clinical malaria per 1000 children vaccinated (range, 37 to 2365) and 449 cases per 1000 infants (range, -10 to 1402) within 18 months of vaccination.

In children aged 5 to 17 months, VE was 34% for severe malaria, 41% for malaria hospitalization, and 19% for all-cause hospitalization. In the infants, there was no significant protection against severe malaria, malaria hospitalization, or all-cause hospitalization.

Serious adverse events occurred less often in children who received RTS,S/AS01 than in those who received a comparator vaccine—18.6% and 22.7%, respectively. In infants, the rate of serious adverse events was similar between the 2 vaccination groups.

Meningitis was more common in subjects who received RTS,S/AS01 than in those who received a comparator. However, the researchers have not established a causal relationship.

There were 16 cases of meningitis among the 5949 children in the RTS,S/AS01 group, 1 case among the 2974 children in the control group, 9 cases among the 4358 infants in the RTS,S/AS01 group, and 3 cases among the 2179 infants in the control group.

Despite the adverse events associated with RTS,S/AS01 and its decreased efficacy over time, the researchers believe the vaccine shows promise. They noted that, “even at modest levels of VE, the number of malaria cases averted was substantial.”

Now, the group is evaluating whether a booster immunization given 18 months after the primary vaccination can improve the efficacy of RTS,S/AS01.

Results of this study were previously reported at the Multilateral Initiative on Malaria Pan African Conference in October 2013 and published in The New England Journal of Medicine in October 2011 and November 2012. Long-term results of a phase 2 trial of RTS,S/AS01 were published in The New England Journal of Medicine in March 2013. ![]()

Drug-resistant malaria spreading

Credit: James Gathany

Drug-resistant malaria parasites have spread to critical border regions of Southeast Asia, according to a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The study confirms that resistance to the world’s most effective antimalarial drug, artemisinin, is now widespread in Southeast Asia.

This is not the first time malaria parasites have developed resistance to front-line drugs, and, each time, resistance has emerged from the same corner of Asia on the Cambodia-Thailand border.

To assess the extent of artemisinin resistance, researchers analyzed blood samples from 1241 malaria patients in 10 countries across Asia and Africa.

This revealed that artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum is now firmly established in western Cambodia, Thailand, Vietnam, eastern Myanmar, and northern Cambodia. There are also signs of emerging resistance in central Myanmar, southern Laos, and northeastern Cambodia.

There are no signs of resistance in the 3 African sites included in the study, located in Kenya, Nigeria, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The study also suggested that extending the course of antimalarial treatment in areas with established resistance—for 6 days rather than the standard 3 days—could offer a temporary solution to this worsening problem.

“It may still be possible to prevent the spread of artemisinin-resistant malaria parasites across Asia and then to Africa by eliminating them, but that window of opportunity is closing fast,” said study author Nicholas White, FRS, of the University of Oxford in the UK.

“Conventional malaria control approaches won’t be enough. We will need to take more radical action and make this a global public health priority, without delay.”

He and his colleagues conducted this study by analyzing malaria-infected adults and children at 15 trial sites in 10 malaria-endemic countries between May 2011 and April 2013.

Patients received a 6-day antimalarial treatment—3 days of an artemisinin derivative and a 3-day course of artemisinin combination treatment (ACT). Then, the researchers analyzed patients’ blood to determine the rate at which the parasites were cleared.

The median parasite clearance half-life ranged from 1.8 hours in the Democratic Republic of the Congo to 7 hours at the Thailand-Cambodia border, where artemisinin resistance has been known to exist since 2005.

The proportion of patients with parasites in their blood 72 hours after treatment, a widely used test for artemisinin resistance, ranged from 0% in Kenya to 68% in Eastern Thailand.

Malaria infections that were slow to clear were strongly associated with a single point mutation in a P falciparum gene called kelch 13, an important validation of the recently discovered genetic marker (k13) in the DNA of the malaria parasite.

The researchers also found that patients who had slow-clearing infections were more likely to have parasite stages that can infect mosquitoes. This suggests artemisinin-resistant P falciparum parasites have a transmission advantage over parasites that are not resistant, which drives their spread.

“Frontline ACTs are still very effective at curing the majority of patients, but we need to be vigilant, as cure rates have fallen in areas where artemisinin resistance is established,” said study author Elizabeth Ashley, MBBS, PhD, also of the University of Oxford.

“Action is needed to prevent the spread of resistance from Myanmar into neighboring Bangladesh and India. The artemisinin drugs are arguably the best antimalarials we have ever had. We need to conserve them in areas where they are still working well.” ![]()

Credit: James Gathany

Drug-resistant malaria parasites have spread to critical border regions of Southeast Asia, according to a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The study confirms that resistance to the world’s most effective antimalarial drug, artemisinin, is now widespread in Southeast Asia.

This is not the first time malaria parasites have developed resistance to front-line drugs, and, each time, resistance has emerged from the same corner of Asia on the Cambodia-Thailand border.

To assess the extent of artemisinin resistance, researchers analyzed blood samples from 1241 malaria patients in 10 countries across Asia and Africa.

This revealed that artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum is now firmly established in western Cambodia, Thailand, Vietnam, eastern Myanmar, and northern Cambodia. There are also signs of emerging resistance in central Myanmar, southern Laos, and northeastern Cambodia.

There are no signs of resistance in the 3 African sites included in the study, located in Kenya, Nigeria, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The study also suggested that extending the course of antimalarial treatment in areas with established resistance—for 6 days rather than the standard 3 days—could offer a temporary solution to this worsening problem.

“It may still be possible to prevent the spread of artemisinin-resistant malaria parasites across Asia and then to Africa by eliminating them, but that window of opportunity is closing fast,” said study author Nicholas White, FRS, of the University of Oxford in the UK.

“Conventional malaria control approaches won’t be enough. We will need to take more radical action and make this a global public health priority, without delay.”

He and his colleagues conducted this study by analyzing malaria-infected adults and children at 15 trial sites in 10 malaria-endemic countries between May 2011 and April 2013.

Patients received a 6-day antimalarial treatment—3 days of an artemisinin derivative and a 3-day course of artemisinin combination treatment (ACT). Then, the researchers analyzed patients’ blood to determine the rate at which the parasites were cleared.

The median parasite clearance half-life ranged from 1.8 hours in the Democratic Republic of the Congo to 7 hours at the Thailand-Cambodia border, where artemisinin resistance has been known to exist since 2005.

The proportion of patients with parasites in their blood 72 hours after treatment, a widely used test for artemisinin resistance, ranged from 0% in Kenya to 68% in Eastern Thailand.

Malaria infections that were slow to clear were strongly associated with a single point mutation in a P falciparum gene called kelch 13, an important validation of the recently discovered genetic marker (k13) in the DNA of the malaria parasite.

The researchers also found that patients who had slow-clearing infections were more likely to have parasite stages that can infect mosquitoes. This suggests artemisinin-resistant P falciparum parasites have a transmission advantage over parasites that are not resistant, which drives their spread.

“Frontline ACTs are still very effective at curing the majority of patients, but we need to be vigilant, as cure rates have fallen in areas where artemisinin resistance is established,” said study author Elizabeth Ashley, MBBS, PhD, also of the University of Oxford.

“Action is needed to prevent the spread of resistance from Myanmar into neighboring Bangladesh and India. The artemisinin drugs are arguably the best antimalarials we have ever had. We need to conserve them in areas where they are still working well.” ![]()

Credit: James Gathany

Drug-resistant malaria parasites have spread to critical border regions of Southeast Asia, according to a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The study confirms that resistance to the world’s most effective antimalarial drug, artemisinin, is now widespread in Southeast Asia.

This is not the first time malaria parasites have developed resistance to front-line drugs, and, each time, resistance has emerged from the same corner of Asia on the Cambodia-Thailand border.

To assess the extent of artemisinin resistance, researchers analyzed blood samples from 1241 malaria patients in 10 countries across Asia and Africa.

This revealed that artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum is now firmly established in western Cambodia, Thailand, Vietnam, eastern Myanmar, and northern Cambodia. There are also signs of emerging resistance in central Myanmar, southern Laos, and northeastern Cambodia.

There are no signs of resistance in the 3 African sites included in the study, located in Kenya, Nigeria, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The study also suggested that extending the course of antimalarial treatment in areas with established resistance—for 6 days rather than the standard 3 days—could offer a temporary solution to this worsening problem.

“It may still be possible to prevent the spread of artemisinin-resistant malaria parasites across Asia and then to Africa by eliminating them, but that window of opportunity is closing fast,” said study author Nicholas White, FRS, of the University of Oxford in the UK.

“Conventional malaria control approaches won’t be enough. We will need to take more radical action and make this a global public health priority, without delay.”

He and his colleagues conducted this study by analyzing malaria-infected adults and children at 15 trial sites in 10 malaria-endemic countries between May 2011 and April 2013.

Patients received a 6-day antimalarial treatment—3 days of an artemisinin derivative and a 3-day course of artemisinin combination treatment (ACT). Then, the researchers analyzed patients’ blood to determine the rate at which the parasites were cleared.

The median parasite clearance half-life ranged from 1.8 hours in the Democratic Republic of the Congo to 7 hours at the Thailand-Cambodia border, where artemisinin resistance has been known to exist since 2005.

The proportion of patients with parasites in their blood 72 hours after treatment, a widely used test for artemisinin resistance, ranged from 0% in Kenya to 68% in Eastern Thailand.

Malaria infections that were slow to clear were strongly associated with a single point mutation in a P falciparum gene called kelch 13, an important validation of the recently discovered genetic marker (k13) in the DNA of the malaria parasite.

The researchers also found that patients who had slow-clearing infections were more likely to have parasite stages that can infect mosquitoes. This suggests artemisinin-resistant P falciparum parasites have a transmission advantage over parasites that are not resistant, which drives their spread.

“Frontline ACTs are still very effective at curing the majority of patients, but we need to be vigilant, as cure rates have fallen in areas where artemisinin resistance is established,” said study author Elizabeth Ashley, MBBS, PhD, also of the University of Oxford.

“Action is needed to prevent the spread of resistance from Myanmar into neighboring Bangladesh and India. The artemisinin drugs are arguably the best antimalarials we have ever had. We need to conserve them in areas where they are still working well.” ![]()

Staffing Following Residency Work Hours

Long work hours with abnormal schedules and extended on‐call periods are common for physicians. Prior to resident work‐hour restrictions, studies showed that sleep‐deprived residents were at increased risk for making errors with decreased decision‐making abilities.[1, 2] Resident work‐hour restrictions and increased attending supervision regulations were initially implemented in 1989 in New York due to concerns for patient safety.[3] In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) adopted this 80‐hour work week standard nationally and restricted residents to a maximum of 30 hours of continuous clinical responsibilities.[4] Due to concern that residents working extending periods of time were at risk for making serious medical errors,[5, 6, 7] the ACGME mandated additional resident work‐hour restrictions in July 2011.8 These changes reduced the maximum hours of continuous clinical responsibilities from 30 to 16 hours for interns, and 28 hours for upper‐level residents, including 4 hours for transition of patient care. Continuous on‐site supervision by attending physicians is not mandated, but programs had to accommodate for the increased emphasis on attending services and supervision of residents, especially at night.[6, 8] Our previous study in 2010, prior to the implementation of new resident work hours, showed 84% of pediatric residency programs had pediatric hospitalists. Of those, 24% had 24/7 pediatric hospitalist coverage, 22% of pediatric residency programs had no in‐house attendings at night, and 31% of programs at that time planned on adding 24/7 pediatric hospitalist coverage within the next 5 years if further resident work‐hour restrictions were implemented.[9]

The objective of this study was to determine how inpatient staffing of teaching services within pediatric residency programs has changed following this recent transition of additional resident work hours. We also sought to define current attending physician staffing and explore attending physicians' overnight responsibilities following new ACGME standards, specifically looking at the role of pediatric hospitalists.

METHODS

We developed a Web‐based electronic survey consisting of 23 questions. Many of these questions were multiple choice or numerical values with the option to comment. The survey gathered data on the demographics of pediatric residency programs including: the number of residents in each program, patient admission caps (the total number of patients the resident team can admit overnight), and the use of resident night floats (a resident team working the overnight shift, admitting and cross‐covering patients who will be handed over to a day team in the morning).

We also examined the number of pediatric providers at night, the use of pediatric hospitalists, and specifically the use of attendings in‐house at night and their overnight responsibilities.

The survey was first pilot tested by pediatric hospitalists for face validity. It was reviewed and approved by the Association of Pediatric Program Directors (APPD) research task force. The survey was sent to 198 US pediatric residency programs via the APPD listserve in May 2012. Program directors were given the option of completing it themselves or designating someone else to complete it. We sent 2 e‐mail reminders via the listserve with individual e‐mail reminders to nonresponding programs. We sent follow‐up e‐mails and phone calls to programs with current night float systems to clarify their use of resident night float prior to implementation of new work‐hour restrictions. Duplicate responses from a program were removed by initially removing the 1 with incomplete data. If both responses were complete, we removed the second response. We analyzed the use of resident night float systems and admission caps, as well as the use of attending physicians in‐house at night, using a z‐score and [2] test.

The institutional review board of the Indiana University School of Medicine reviewed this study.

RESULTS

Out of 198 pediatric ACGME programs contacted, 152 responses were received, which is a 77% response rate. This represented 7828 pediatric residents, or 79% of total US pediatric residents. Average program size was 52 residents (range, 6168 residents; median, 41). This average program size was similar to the ACGME average program size of 50 residents. Sorting our response rate by program size, all 58 large ACGME programs responded (programs with over 50 residents). Eighty‐four percent (57 programs) of medium‐sized programs responded (programs with 3050 residents). Fifty‐one percent (37 programs) of small programs responded (programs with <30 residents).

Changes in Resident Staffing

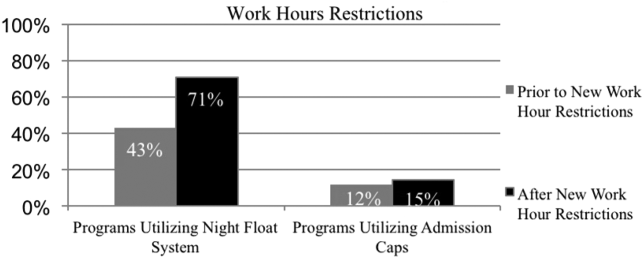

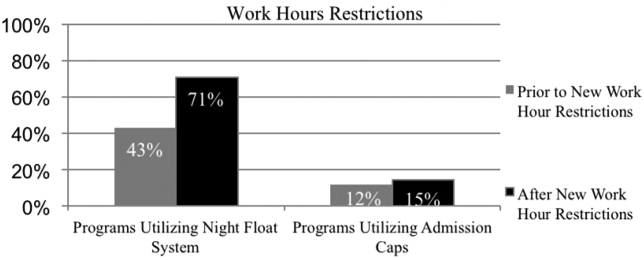

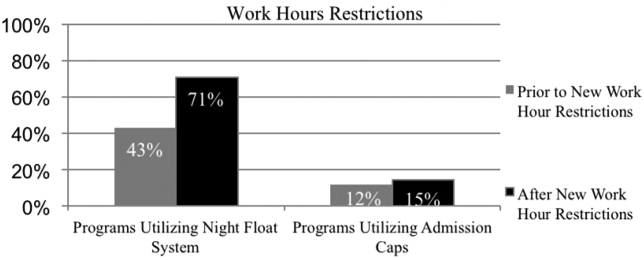

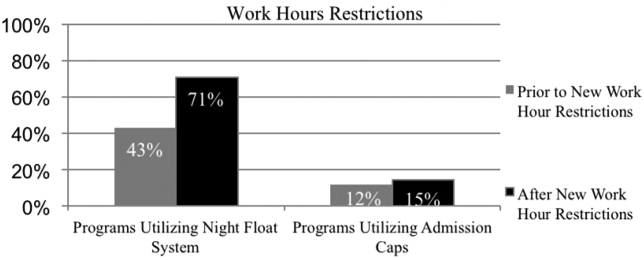

Residency programs utilizing night float systems increased from 43% before to 71% after new work hours were implemented (P<0.0001). Overall use of resident admission caps did not significantly change (12%14.5%, P=0.52) (Figure 1).

Changes in Attending Physicians In‐House at Night

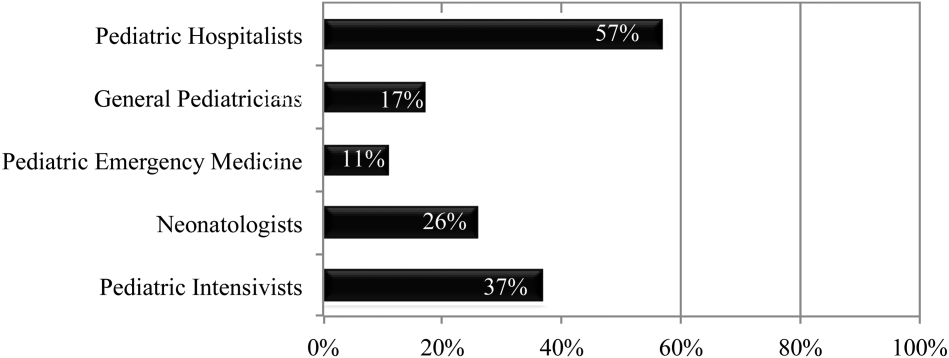

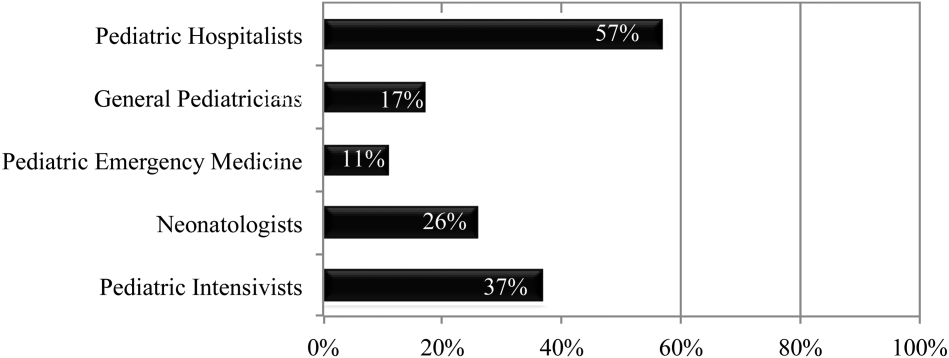

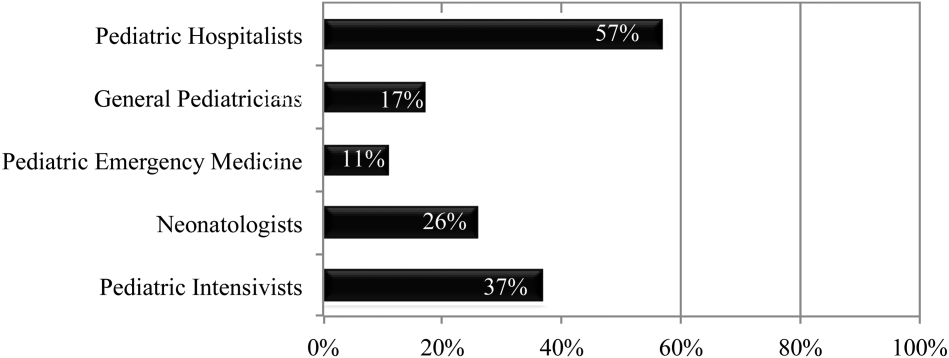

Following implementation of new resident work‐hour restrictions, 23% of programs increased the number of attending physicians in‐house at night. Of these programs, 57% (20 programs) increased the number of pediatric hospitalist attendings in‐house at night, whereas 37% increased the number of pediatric intensive care unit attendings (Figure 2). When asked the reason for increased attending physician presence in‐house, 71% of programs attributed this change to increased resident work‐hour restrictions, and 37% attributed it to increased patient census. Other common reasons cited included increased patient acuity as well as improved resident supervision and education.

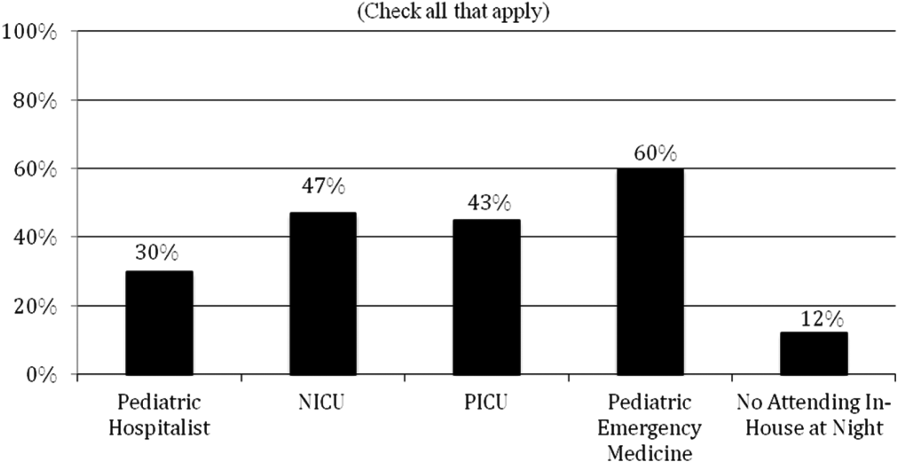

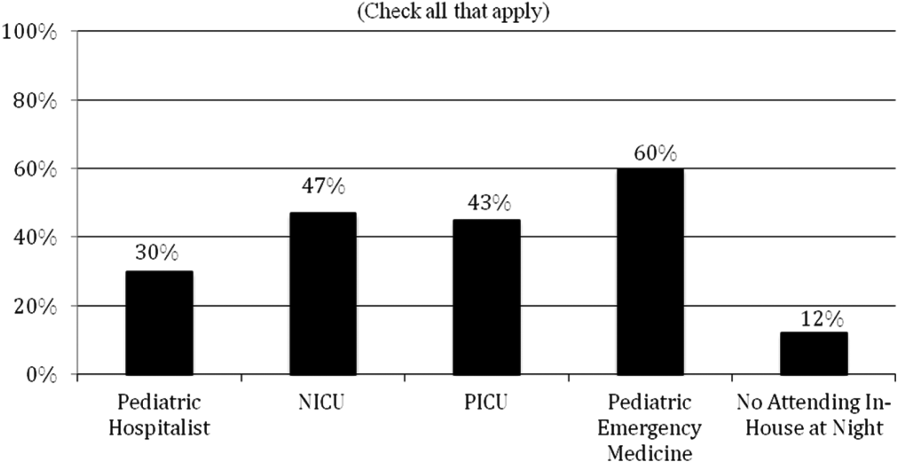

Currently, 30% of responding programs have pediatric hospitalists in‐house at night. This nighttime in‐house coverage includes both partial nighttime coverage (for example, until midnight) and overnight coverage. Forty‐seven percent have neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and 43% have pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) in‐house attending coverage. Sixty percent of responding programs have pediatric emergency medicine attendings in‐house at night. Only 12% of programs have no in‐house attending night coverage at all (Figure 3).

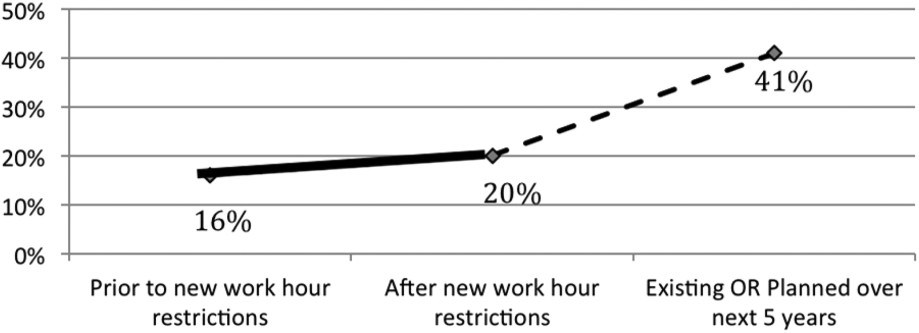

Although there was a trend toward increased pediatric hospitalist attendings in‐house 24/7, this did not meet statistical significance (16%20%, P=0.36). Programs with night hospitalist coverage were more likely to be small (<30 residents) or large (50+ residents), compared to medium‐sized programs (3049 residents) (P<0.0032). Thirty‐eight percent of small programs, 14% of medium programs, and 41% of large programs have in‐house night hospitalist coverage.

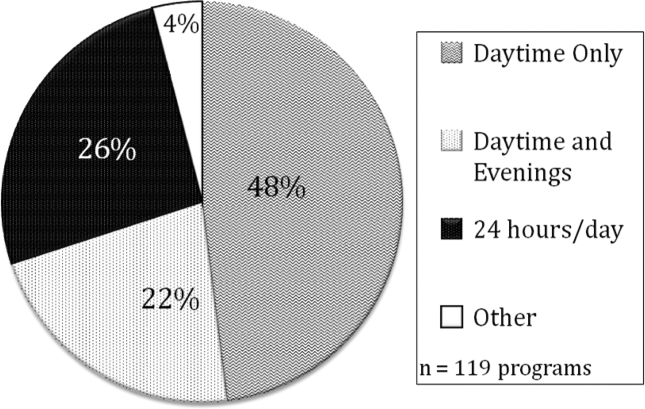

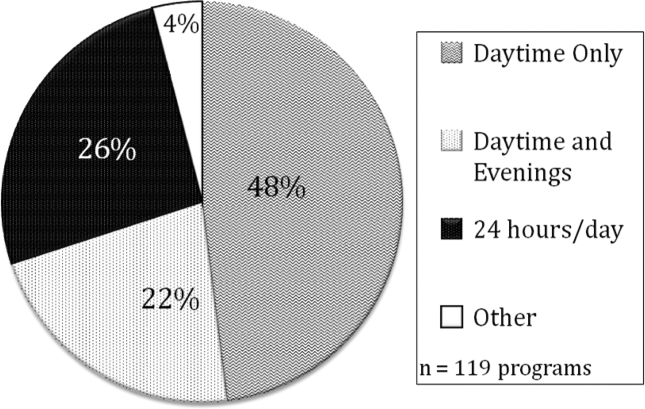

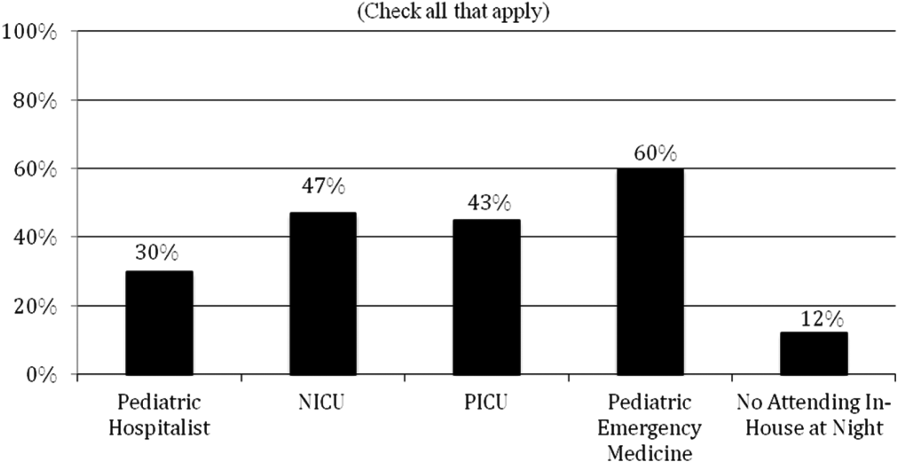

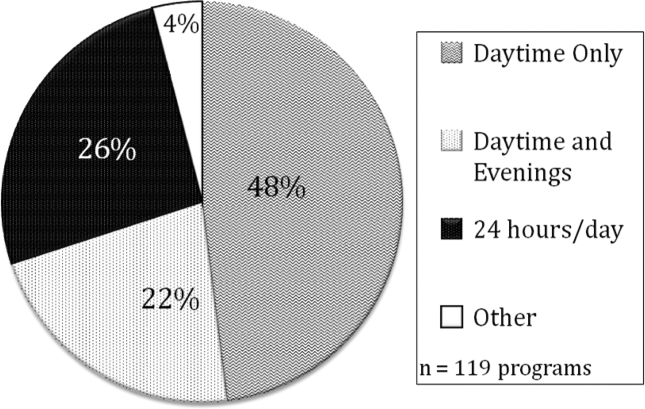

All large programs have some attending physicians in‐house at night (NICU, PICU, pediatric emergency medicine, or hospitalist). All programs with no attendings in‐house at night have fewer than 46 residents. Of programs with pediatric hospitalists (119), hospitalist attendings have in‐house daytime‐only coverage in approximately half the responding programs (48%). The other half of the programs is split between providing some evening coverage (22%) and 24/7 coverage (26%) (Figure 4).

Responsibilities of In‐House Pediatric Hospitalist Attendings at Night

Hospitalist attendings who are in‐house at night have a variety of night responsibilities including approving admission and transfers (65%), teaching residents (74%), consulting for other services (65%), and consulting for residents (65%). They vary in how they staff new patient admissions, with 65% of programs seeing select general pediatric admissions and 35% seeing all general pediatric admissions.

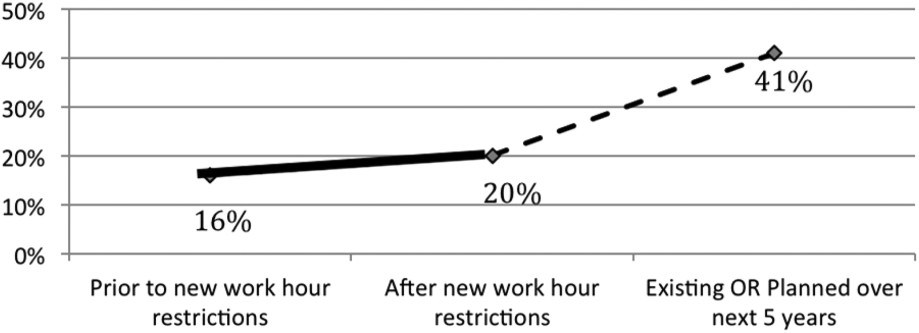

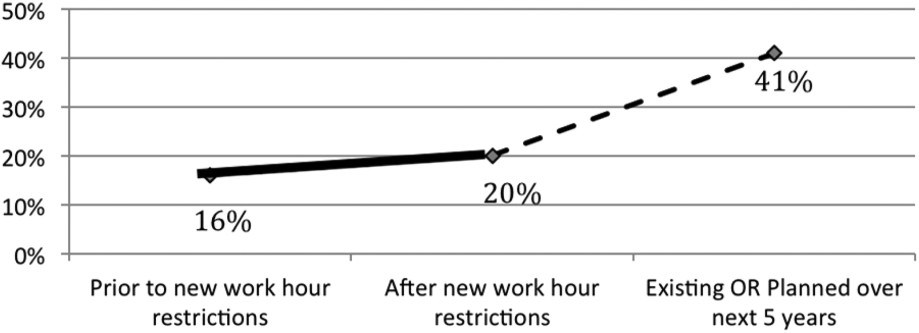

Of the programs without 24/7 pediatric hospital attending coverage, 26% reported that they are planning to add this coverage within the next 5 years. If this occurred, 41% of total responding pediatric residency programs would have 24/7 pediatric hospital coverage (P<0.0001) (Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

Great variation exists in night staffing of pediatric inpatient teaching services. Residency programs have adapted to changes in residency work hours and increased supervision regulations by utilizing night float systems and increasing in‐house attending coverage at night. The largest growth of in‐house attending physicians at night since these work‐hour changes has been pediatric hospitalist attendings. Although hospital medicine has been a rapidly growing field over the past 10 years, many program directors in our study felt that the change in resident work hours was the primary driver of increased in‐house attending physicians at night. At the time of this study, pediatric program directors are anticipating an even larger increase in this hospitalist coverage over the next 5 years.

Effects of Increased Resident Work‐Hour Restrictions on Patient Safety

The literature is unclear on whether patient safety has improved due to residency work‐hour restrictions. Several studies show decreased mortality among high‐risk patients, but there are conflicting reports on if patient complications have changed.[10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15] Two systematic reviews did not show evidence of improved patient safety with increased resident work‐hour restrictions. Some of the studies in these reviews showed a change in medical errors, but no increased patient morbidity and mortality. Although residents were less fatigued with new resident work hours, there is also concern that increased resident handoffs, especially with the increase in resident night float, could lead to medical errors.[16, 17]

Effects of Increased Resident Work‐Hour Restrictions on Resident Education

There is concern regarding dissatisfaction among residents, nursing, and training physicians with respect to resident education following the change in residency work‐hour regulations. A systematic review showed negative perceptions of resident education following resident work‐hour restrictions.[18] Another systematic review assessed all intervention studies that reduced resident work shifts over 16 hours, showing no change in resident education with improved patient safety.[19] However, multiple studies done following this systematic review show otherwise.[14, 15, 20, 21] A more recent study showed that although residents were better rested following the shortened work schedule, there was increased work‐load intensity while at work, with decreased patient ownership as well as decreased didactic education (a 25% reduction in ability to attend the noon conference).[20] This could be related to the increase in resident night float seen in our study, resulting in residents not being present during the daytime when much of the didactic education takes place. The number of patient handoffs dramatically increased with an association with higher rates of medical errors.[14, 15, 20, 21] A single‐center study looking specifically at resident education before and after resident work‐hour restrictions were implemented showed improved resident education. This study is hard to generalize due to increased educational programs and redesign of the inpatient services during this time.[22] Although the new resident work‐hour regulations were supposed to increase resident wakefulness, a study on surgical interns found that interns were actually more sleepy on the night float schedule, possibly due to multiple nights of poor sleep without a post‐call day to make it up.[23] Our hypothesis on these conflicting studies is that changes in work‐hour restrictions could result in improved quality of patient care and improved education with the right mix of increased educational programs (on handoffs) and redesign of inpatient services. It is also worth noting that all studies are biased by the constraint of minimal change in resident workload or residency duration. The basic structure of residency may require change to produce the potentially competing goals of improved patient safety and appropriate medical training.

Effects of Increased Resident Supervision and the Role of the In‐House Pediatric Hospitalist at Night

Although increased resident work hours were an important piece of new 2011 ACGME regulations, they also involved increased resident supervision. This may be more important on nights and weekends where there is increased likelihood of patient morbidity and mortality.[24] Our study shows an increase of in‐house attending coverage at night. Although the reasoning for this is likely multifactorial, a large proportion of program directors attributed it to changes in residency work hours. Our study also showed that many of the programs utilized pediatric hospitalist attendings to increase this coverage. A recent study showed that this increased supervision at night improved both the resident education and perception of patient care.[25] Despite this, there is still variation in overnight hospitalist attendings' supervision of trainees, even when hospitalist attendings are present. Our study showed the majority of hospitalist in‐house overnight attendings had roles in teaching and consulting for residents. A different study of internal medicine hospitalist attendings found 61% of these programs had hospitalist attendings in‐house overnight. Only 38% of these programs had formally defined supervisory roles, with almost 25% of the programs with overnight coverage involved in nonteaching services only.[26] although a majority of these hospitalist attending leaders felt formal overnight supervision would improve patient safety and resident education, they were concerned for decreased resident autonomy and increased hospitalist attending workload.[26]

There is little literature specifically on effects of increased resident supervision directly on patient safety since new resident work hours. One large pediatric residency program without 24/7 in‐house attending coverage found that decreasing attending presence by phone did not decrease quality of patient care.[27]

Like all studies, our study has limitations that warrant consideration. Program directors were the respondents in our study. Although they were knowledgeable on residency changes, there may be specific questions on attending responsibilities and future direction of pediatric hospitalist services that may be better answered by specific specialty directors. Although our survey asked for information on the responsibilities of pediatric hospitalist attendings at night, we did not specifically examine responsibilities of nonteaching services. We also did not clarify responsibilities of other attendings (PICU, NICU, emergency medicine) and their utilization of nonteaching services. We did have dropout bias toward the end of our survey. We cannot comment on differences between responding and nonresponding programs, although this is minimized by our large response rate, with similar average program size compared to ACGME data. We are limited by a smaller percentage of small programs responding compared to higher response rates of large and medium‐sized programs. Although program directors predicted large growth of in‐house 24/7 hospitalist coverage, recent economic changes in reimbursement may limit this.[28] Our initial study prior to implementation of 2011 work hours suggested 31% of programs planned to add 24/7 coverage within 5 years.[9] Our current study shows that whereas 24/7 hospitalist coverage is still projected to grow rapidly, it has not yet done so. This could be related to the time to implement 24/7 coverage (hiring staffing for this model and financial concerns) versus the ability of program directors to predict the future of pediatric hospital medicine divisions. Finally, although we feel that the changes in residency work hours likely contributed to the increase in 24/7 hospitalist coverage, this increase is probably multifactorial and could be related to financial and marketing reasons.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, our study shows that although programs vary in their response to changes in residency work hours, they most commonly utilize night float systems and increased in‐house attending coverage at night, especially among pediatric hospitalist attendings. These changes are likely multifactorial, but many programs attribute increased attending in‐house nighttime coverage to changes in residency work hours. Pediatric hospitalist attendings have had the largest growth of in‐house attending physicians at night, with many programs planning to increase in‐house pediatric hospitalist attending coverage at night in the next 5 years. Further investigation is needed to determine the impact of in‐house hospitalist attending coverage at night on patient outcomes, supervision, and resident education. In the current economic environment with reimbursement rates and national inpatient volumes continuing to decline, hospitals continue to explore options to lower expenses and boost productivity.[28, 29] The perceived need for 24/7 attending in‐house presence may prove to be a financial disincentive for smaller programs and accelerate the shift in pediatric beds to larger, tertiary care settings. A national study may be needed to determine the overall importance and necessity of in‐house hospitalist attending coverage at night, with regard to maintaining high levels of patient care and residency education while adapting to new economic constraints.

Disclosures: Dr. Oshimura designed the study, coordinated and supervised the data collection, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. She has had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Dr. Sperring and Dr. Bauer conceptualized and designed the study, reviewed the initial analyses, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Dr. Carroll critically reviewed the data collection instruments, analyzed and interpreted the data, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Dr. Rauch conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, reviewed the initial analysis, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. There was no funding source for the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , . A review of studies concerning effects of sleep deprivation and fatigue on residents' performance. Acad Med. 1991;66:687–693.

- , , , . The risks and implications of excessive daytime sleepiness in resident physicians. Acad Med. 2002;77:1019–1025.

- , . A brief history of duty hours and resident education. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PDFs/jgme‐11‐00‐5‐11%5B1%5D.pdf. Accessed July 26, 2014.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Statement of justification/impact for the final approval of common standards related to resident duty hours; September 2002. Available at: www.acgme.org. Accessed November 4, 2013.

- , . Fatigue among clinicians and the safety of patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1249–1255.

- Ulmer C, Wolman DM, Johns MME, eds. Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2008.

- , , , et al. Effect of reducing interns' weekly work hours on sleep and attentional failure. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(18):1829–1837.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME approved standards, effective July 2011. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PDFs/Common_Program_Requirements_07012011%5B2%5D.pdf. Accessed November 4, 2013.

- , , , . Inpatient staffing within pediatric residency programs: work hour restrictions and the evolving role of the pediatric hospitalist. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(4):299–303.

- , , , . Duty‐hour limits and patient care and resident outcomes: can high‐quality studies offer insight into complex relationships? Ann Rev Med. 2013;64:467–483.

- , , , et al. Effect of reducing interns' work hours on serious medical errors in intensive care units. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1838–1848.

- , , , , , . Implementation of resident work hour restrictions is associated with a reduction in mortality and provider‐related complications on the surgical service: a concurrent analysis of 14,610 patients. Ann Surg. 2009;250(2):316–321.

- , , , et al. Impact of the 80‐hour workweek on patient care at a level 1 trauma center. Arch Surg. 2007;142(8):708–714.

- , , , et al. Effects of the 2011 duty hour reforms on interns and their patients: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):657–662.

- , . Changes in hospital mortality associated with residency work‐hour regulations. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(2):73–80.

- , , , et al. Systematic review: effects of resident work hours on patient safety. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(11):851–857.

- , . Restricting resident work hours: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(3):960–966.

- , , , et al. Sleep deprivation in resident physicians, work hour limitations, and related outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Postgrad Med. 2012;124(4):241–249.

- , , . Effects of reducing or eliminating resident work shifts over 16 hours: a systematic review. Sleep. 2010;33(8):1043–1053.

- , , , et al. Effect of the 2011 vs 2003 duty hour regulation‐compliant models on sleep duration, trainee education, and continuity of patient care among internal medicine house staff. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):649–655.

- , , , , , . Better rested, but more stressed? Evidence of the effects of resident work hour restrictions. Acad Pediatr. 2012;12(4):335–343.

- , , . The effect of reducing maximum shift lengths to 16 hours on internal medicine interns' educational opportunities. Acad Med. 2013;88(4):512–518.

- , , , , , . Effects of the new Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education work hour rules on surgical interns: a prospective study in a community teaching hospital. Am J Surg. 2012;205(2):163–168.

- Nocturnists help avoid night, weekend danger. Healthcare Benchmarks Qual Improv. 2011;18(11):127.

- , , , , , . Effects of increased overnight supervision on resident education, decision‐making, and autonomy. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(8):606–610.

- , , , et al. Survey of overnight academic hospitalist supervision of trainees. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:521–523.

- , , , , , . Tempering pediatric hospitalist supervision of residents improves admission process efficiency without decreasing quality of care. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):106–110.

- . CMS announces Medicare reimbursement changes for 2014. July 16, 2013. Available at: http://www.insidepatientfinance.com/revenue‐cycle‐news/cms‐announces‐medicare‐reimbursement‐changes‐for‐2014. Accessed September 12, 2013.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). National estimates on use of hospitals by children from the HCUP Kids Inpatient Database. Available at: http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/HCUPnet.jsp. Accessed September 12, 2013.

Long work hours with abnormal schedules and extended on‐call periods are common for physicians. Prior to resident work‐hour restrictions, studies showed that sleep‐deprived residents were at increased risk for making errors with decreased decision‐making abilities.[1, 2] Resident work‐hour restrictions and increased attending supervision regulations were initially implemented in 1989 in New York due to concerns for patient safety.[3] In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) adopted this 80‐hour work week standard nationally and restricted residents to a maximum of 30 hours of continuous clinical responsibilities.[4] Due to concern that residents working extending periods of time were at risk for making serious medical errors,[5, 6, 7] the ACGME mandated additional resident work‐hour restrictions in July 2011.8 These changes reduced the maximum hours of continuous clinical responsibilities from 30 to 16 hours for interns, and 28 hours for upper‐level residents, including 4 hours for transition of patient care. Continuous on‐site supervision by attending physicians is not mandated, but programs had to accommodate for the increased emphasis on attending services and supervision of residents, especially at night.[6, 8] Our previous study in 2010, prior to the implementation of new resident work hours, showed 84% of pediatric residency programs had pediatric hospitalists. Of those, 24% had 24/7 pediatric hospitalist coverage, 22% of pediatric residency programs had no in‐house attendings at night, and 31% of programs at that time planned on adding 24/7 pediatric hospitalist coverage within the next 5 years if further resident work‐hour restrictions were implemented.[9]

The objective of this study was to determine how inpatient staffing of teaching services within pediatric residency programs has changed following this recent transition of additional resident work hours. We also sought to define current attending physician staffing and explore attending physicians' overnight responsibilities following new ACGME standards, specifically looking at the role of pediatric hospitalists.

METHODS

We developed a Web‐based electronic survey consisting of 23 questions. Many of these questions were multiple choice or numerical values with the option to comment. The survey gathered data on the demographics of pediatric residency programs including: the number of residents in each program, patient admission caps (the total number of patients the resident team can admit overnight), and the use of resident night floats (a resident team working the overnight shift, admitting and cross‐covering patients who will be handed over to a day team in the morning).

We also examined the number of pediatric providers at night, the use of pediatric hospitalists, and specifically the use of attendings in‐house at night and their overnight responsibilities.

The survey was first pilot tested by pediatric hospitalists for face validity. It was reviewed and approved by the Association of Pediatric Program Directors (APPD) research task force. The survey was sent to 198 US pediatric residency programs via the APPD listserve in May 2012. Program directors were given the option of completing it themselves or designating someone else to complete it. We sent 2 e‐mail reminders via the listserve with individual e‐mail reminders to nonresponding programs. We sent follow‐up e‐mails and phone calls to programs with current night float systems to clarify their use of resident night float prior to implementation of new work‐hour restrictions. Duplicate responses from a program were removed by initially removing the 1 with incomplete data. If both responses were complete, we removed the second response. We analyzed the use of resident night float systems and admission caps, as well as the use of attending physicians in‐house at night, using a z‐score and [2] test.

The institutional review board of the Indiana University School of Medicine reviewed this study.

RESULTS

Out of 198 pediatric ACGME programs contacted, 152 responses were received, which is a 77% response rate. This represented 7828 pediatric residents, or 79% of total US pediatric residents. Average program size was 52 residents (range, 6168 residents; median, 41). This average program size was similar to the ACGME average program size of 50 residents. Sorting our response rate by program size, all 58 large ACGME programs responded (programs with over 50 residents). Eighty‐four percent (57 programs) of medium‐sized programs responded (programs with 3050 residents). Fifty‐one percent (37 programs) of small programs responded (programs with <30 residents).

Changes in Resident Staffing

Residency programs utilizing night float systems increased from 43% before to 71% after new work hours were implemented (P<0.0001). Overall use of resident admission caps did not significantly change (12%14.5%, P=0.52) (Figure 1).

Changes in Attending Physicians In‐House at Night

Following implementation of new resident work‐hour restrictions, 23% of programs increased the number of attending physicians in‐house at night. Of these programs, 57% (20 programs) increased the number of pediatric hospitalist attendings in‐house at night, whereas 37% increased the number of pediatric intensive care unit attendings (Figure 2). When asked the reason for increased attending physician presence in‐house, 71% of programs attributed this change to increased resident work‐hour restrictions, and 37% attributed it to increased patient census. Other common reasons cited included increased patient acuity as well as improved resident supervision and education.

Currently, 30% of responding programs have pediatric hospitalists in‐house at night. This nighttime in‐house coverage includes both partial nighttime coverage (for example, until midnight) and overnight coverage. Forty‐seven percent have neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and 43% have pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) in‐house attending coverage. Sixty percent of responding programs have pediatric emergency medicine attendings in‐house at night. Only 12% of programs have no in‐house attending night coverage at all (Figure 3).

Although there was a trend toward increased pediatric hospitalist attendings in‐house 24/7, this did not meet statistical significance (16%20%, P=0.36). Programs with night hospitalist coverage were more likely to be small (<30 residents) or large (50+ residents), compared to medium‐sized programs (3049 residents) (P<0.0032). Thirty‐eight percent of small programs, 14% of medium programs, and 41% of large programs have in‐house night hospitalist coverage.

All large programs have some attending physicians in‐house at night (NICU, PICU, pediatric emergency medicine, or hospitalist). All programs with no attendings in‐house at night have fewer than 46 residents. Of programs with pediatric hospitalists (119), hospitalist attendings have in‐house daytime‐only coverage in approximately half the responding programs (48%). The other half of the programs is split between providing some evening coverage (22%) and 24/7 coverage (26%) (Figure 4).

Responsibilities of In‐House Pediatric Hospitalist Attendings at Night

Hospitalist attendings who are in‐house at night have a variety of night responsibilities including approving admission and transfers (65%), teaching residents (74%), consulting for other services (65%), and consulting for residents (65%). They vary in how they staff new patient admissions, with 65% of programs seeing select general pediatric admissions and 35% seeing all general pediatric admissions.

Of the programs without 24/7 pediatric hospital attending coverage, 26% reported that they are planning to add this coverage within the next 5 years. If this occurred, 41% of total responding pediatric residency programs would have 24/7 pediatric hospital coverage (P<0.0001) (Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

Great variation exists in night staffing of pediatric inpatient teaching services. Residency programs have adapted to changes in residency work hours and increased supervision regulations by utilizing night float systems and increasing in‐house attending coverage at night. The largest growth of in‐house attending physicians at night since these work‐hour changes has been pediatric hospitalist attendings. Although hospital medicine has been a rapidly growing field over the past 10 years, many program directors in our study felt that the change in resident work hours was the primary driver of increased in‐house attending physicians at night. At the time of this study, pediatric program directors are anticipating an even larger increase in this hospitalist coverage over the next 5 years.

Effects of Increased Resident Work‐Hour Restrictions on Patient Safety

The literature is unclear on whether patient safety has improved due to residency work‐hour restrictions. Several studies show decreased mortality among high‐risk patients, but there are conflicting reports on if patient complications have changed.[10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15] Two systematic reviews did not show evidence of improved patient safety with increased resident work‐hour restrictions. Some of the studies in these reviews showed a change in medical errors, but no increased patient morbidity and mortality. Although residents were less fatigued with new resident work hours, there is also concern that increased resident handoffs, especially with the increase in resident night float, could lead to medical errors.[16, 17]

Effects of Increased Resident Work‐Hour Restrictions on Resident Education

There is concern regarding dissatisfaction among residents, nursing, and training physicians with respect to resident education following the change in residency work‐hour regulations. A systematic review showed negative perceptions of resident education following resident work‐hour restrictions.[18] Another systematic review assessed all intervention studies that reduced resident work shifts over 16 hours, showing no change in resident education with improved patient safety.[19] However, multiple studies done following this systematic review show otherwise.[14, 15, 20, 21] A more recent study showed that although residents were better rested following the shortened work schedule, there was increased work‐load intensity while at work, with decreased patient ownership as well as decreased didactic education (a 25% reduction in ability to attend the noon conference).[20] This could be related to the increase in resident night float seen in our study, resulting in residents not being present during the daytime when much of the didactic education takes place. The number of patient handoffs dramatically increased with an association with higher rates of medical errors.[14, 15, 20, 21] A single‐center study looking specifically at resident education before and after resident work‐hour restrictions were implemented showed improved resident education. This study is hard to generalize due to increased educational programs and redesign of the inpatient services during this time.[22] Although the new resident work‐hour regulations were supposed to increase resident wakefulness, a study on surgical interns found that interns were actually more sleepy on the night float schedule, possibly due to multiple nights of poor sleep without a post‐call day to make it up.[23] Our hypothesis on these conflicting studies is that changes in work‐hour restrictions could result in improved quality of patient care and improved education with the right mix of increased educational programs (on handoffs) and redesign of inpatient services. It is also worth noting that all studies are biased by the constraint of minimal change in resident workload or residency duration. The basic structure of residency may require change to produce the potentially competing goals of improved patient safety and appropriate medical training.