User login

How to avoid 3 common errors in dementia screening

› Use age- and education-corrected normative data when using dementia screening tools. C

› Use verbatim instructions and the same size stimuli and response pages provided in a test’s manual. C

› Ensure that norms used for comparisons are current. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Treatment options for dementia are expanding and improving, giving extra impetus to detecting this progressive disease as early as possible. For example, research on the cholinesterase inhibitor donepezil has shown it can delay cognitive decline by 6 months or more compared with controls1,2 and possibly postpone institutionalization. With the number of elderly individuals and cases of dementia projected to grow significantly over the next 20 years,3 primary care physicians will increasingly be screening for cognitive impairment. Given the time constraints and patient loads in today’s practices, it’s not surprising that physicians tend to use evaluation tools that are brief and simple to administer. However, there are also serious pitfalls in the use of these tools.

When to screen. Many health-related organizations address screening for dementia4,5 and offer screening criteria (eg, the Alzheimer’s Association,6 the US Preventive Services Task Force7). Our experience suggests that specific behavioral changes are reasonable indicators of suspected dementia that should prompt cognitive screening. Using the Kingston Standardized Behavioural Assessment,8 we demonstrated a consistent pattern of earliest behavior change in a community-dwelling group with dementia.9 Meaningful clues are a decreased ability to engage in specific functional activities (including participation in favorite pastimes, ability to eat properly if left to prepare one’s own food, handling of personal finances, word finding, and reading) and unsteadiness. These specific behavioral changes reported by family or a caregiver suggest the need for cognitive screening.

Pitfalls associated with common screening tools, if not taken into account, can seriously limit the usefulness of information gained during assessment and potentially lead to a wrong conclusion. Screening tools are just that: a means of detecting the possible existence of a condition. Results are based on probability and subject to error. Therefore, a single test score is insufficient to render a diagnosis of dementia, and is one variable in a set of diagnostic criteria.

The purpose of this article is to review some of the most commonly used tools and procedures for dementia screening, identify procedural or interpretive errors made in everyday clinical practice, and suggest practical yet simple strategies to address these problems and improve the accuracy of assessments. We illustrate key points with clinical examples and vignettes using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE),10 an Animal Naming Task, and the Trail Making Test.11

Common error #1: Reliance on simple, single cutoff scores

There are a number of important considerations to keep in mind when trying to make sense of scores from the many available cognitive tests.

The range of normal test results is wide. The normal range for most physiologic measures, such as glucose levels or hemoglobin counts, is relatively narrow. However, human cognitive functions can naturally differ from person to person, and the range of normal can be extremely large.

A single, all-purpose cutoff score ignores critical factors. Very often, clinicians have dealt with the issue of wide variance in cognition scores by establishing a general cutoff point to serve as a pass-fail mark. But this practice can result in both under- and overidentification of dementia, and it ignores the 2 components that chiefly determine how individuals differ cognitively: age and intelligence.

Practical fix: Use age-, intelligence-corrected normative data

Level of cognitive performance can be revealing when adjustments are made for age and intelligence. Not taking these factors into account can lead to many errors in clinical decision making.

Age matters. Many cognitive capacities decline as part of normal aging even in otherwise healthy individuals (eg, reaction time, spatial abilities, flexibility in novel problem solving).12 With this in mind, psychologists often have made the distinction between “hold” tests (remaining stable or even improving with age) and “no-hold” tests (declining with age).13 Therefore it is critical to ask, “What is normal, given a particular patient’s age?” If normative data corrected for age are available for a given test, use them.

Intelligence is a factor, too. Intelligence, like most human qualities, is distributed along a bell-shaped curve of normal distribution, wherein most people fall somewhere in the middle and a smaller number will be at the lower and higher tails of the curve. Not all of us fall into the average range of intelligence; indeed, psychometrically, only half of us do. The other half are found somewhere in the more extreme ends. In evaluating a person for dementia, it is critical to compare test results with those found in the appropriate intellectual group. But how does the physician looking for a brief assessment strategy determine a patient’s premorbid level of intellectual functioning?

A widely used and accepted heuristic for gauging intelligence is “years of education.” Of course, education is not perfectly correlated with intelligence, particularly as those who are now elderly may have been denied the opportunity to attend school due to the Great Depression, war, or other life events. Nevertheless, with these limitations in mind, level of education is a reasonable approximation of intelligence. In practical application, premorbid intellectual level is determined by using education-corrected normative data.

Typically with cognitive tests, cutoff scores and score ranges are defined for general levels of education (eg, less than grade 12 or more than grade 12; elementary school, high school, post-secondary, etc). Adjusted norms for age and education are usually determined by taking large samples of subjects and stratifying the distribution by subgroups—eg, 5-year age groups; levels of education such as elementary school or high school—and then statistically analyzing each group and noting the relative differences between them.

Illustration: MMSE. Although not designed for the overall measurement of cognitive impairment in dementia, the MMSE10 has become widely used for that purpose. It is fairly insensitive to cognitive changes associated with earlier stages of dementia,14 and is intended only as a means of identifying patients in need of more comprehensive assessment. However, the MMSE is increasingly used to make a diagnosis of dementia.15 In some areas (eg, Ontario, Canada), it is used to justify paying for treatment with cognitive enhancers.

The universal cutoff score proves inadequate. Although several dementia cutoff scores for the MMSE have been proposed, it is common practice to use an MMSE score ≥24 to rule out dementia.16 In our clinical practice, however, many patients who ultimately are diagnosed with early dementia often perform well on the MMSE, although rather poorly on other dementia screens, such as the Kingston Standardized Cognitive Assessment-Revised (KSCAr)17 or the mini-KSCAr.18

Recently, we reviewed cases of >70 individuals from our outpatient clinic who were given the MMSE and were also diagnosed as having dementia by both DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders)19 and the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association20 criteria. Over three-quarters (78%) of these cases had an MMSE score of ≥24. Based on MMSE scores alone, these individuals would have been declared “not demented.”17

Correcting for age and intelligence increases accuracy. Published age and education norms are available for the MMSE.21 In applying these norms to our sample described above, the number of misidentified patients drops to approximately one-third (35.7%). This means that instead of misidentifying 2 out of 3 cases, the age and education corrections reduced this to about one out of 3, thereby increasing sensitivity and specificity. While this is still an unacceptably high rate of false negatives, it shows the considerable value of using age and education corrections.

The challenge of optimizing sensitivity and specificity of dementia screening tools is ongoing. As a matter of interest, we include TABLE 1,4,18,22-24 which shows calculated sensitivities and specificities of some commonly used screening tests.

Another practical fix: Use distributions and percentile-based normative data

Instead of simple cutoff scores, test scores can be, and often are, translated into percentiles to provide a meaningful context for evaluation and to make it easier to compare scores between patients. Someone with a score at the 70th percentile has performed as well as or better than 70% of others in the group who have taken the test. Usually, the average range of a normal population is defined as being between the 25th to 75th percentiles, encompassing 50% of that population. In general, percentiles make interpreting performance easier. Percentile-based test norms can also help determine with increased accuracy if there has been a decline over time.

Illustration: Animal naming task. In a common version of this task, patients are asked to name as many animals as they can in 60 seconds. This task has its roots in neuro- psychological tests of verbal fluency, such as the Controlled Oral Word Association Task.25 Verbal fluency tasks such as naming animals tap verbal generativity/problem-solving and self-monitoring, but are also highly dependent on vocabulary (word knowledge), a cognitive ability that is quite stable and even improves as one ages until individuals are well into their 80s.26

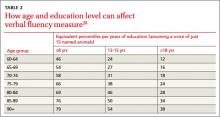

It is common practice with this procedure to consider a cutoff score of 15 as a minimally acceptable level of performance.27 Here again, there are potentially great differences in expected performance based on age and intelligence. TABLE 2 shows the effect of age and education on verbal fluency, expressed as percentiles, using a raw score of 15.28 For an individual in their early 60s who has a university degree, naming just 15 animals puts their performance at the 12th percentile (below average). The same performance for someone in their 90s who has only 8 years of education puts them in the 79th percentile (above the average range of 25th-75th percentiles). This performance would indicate impairment for the 60-year-old university-educated individual, but strong cognitive function for the 90-year-old.

Common error #2: Deviating from standardized procedures

While clinicians specifically trained in cognitive measurement are familiar with the rigor by which tests are constructed, those with less training are often unaware that even seemingly minor deviations in procedure can contaminate results as surely as using nonsterile containers in biologic testing, leading to inaccurate interpretations of cognition.

Practical fix: Administer tests using verbatim instructions

Failing to follow instructions can significantly bias acquired data, particularly when using performance tests that are timed.

Illustration: Trail Making Test. Trail Making is an old 2-part test developed for the United States Army in the 1940s,11 and used in the Halstead-Reitan neuropsychological battery. Part A is a timed measure of an individual’s ability to join up a series of numbered circles in ascending order. Part B measures the ability to alternately switch between 2 related tasks: namely, alternately joining numbered and lettered circles, in ascending order. This is considered a measure of complex attention, which is often disrupted in early dementia.29

The test uses a specific standardized set of instructions, and Part B’s interpretation depends on having first administered Part A. Anecdotally, we have increasingly seen clinician reports using only Part B. Eliminating Part A removes a significant opportunity for patients to become familiar with the task’s demands, placing them at a considerable disadvantage on Part B and thereby invalidating the normative data.

In addition, follow the exact phrasing of the instructions and use stimuli and response pages that are the same size as those provided in the manual. If a patient errs at any point, it’s important that the test administrator reads, verbatim, the provided correction statements because these statements influence the amount of time spent correcting an error and therefore the final score.

Common error #3: Using outdated normative data

Neglecting to use updated norms that reflect current cohort differences can compromise screening accuracy.

Practical fix: Ensure current norms are used for comparisons

Societal influences—computers and other technologies, nutrition, etc—have led to steady improvements in cognitive and physical abilities. In basic psychology, this pattern of improving cognition, documented as an approximate increase of 3 IQ points per decade, is referred to as the Flynn effect.30 Therefore, not only do age and education need to be controlled for, but normative data must be current.

Cognitive screening tools are usually published with norms compiled at the time of the test’s development. However, scores are periodically “re-normed” to reflect current levels of ability. These updated norms are readily available in published journal articles or online. (Current norms for each of the tests used as examples in this article are provided in the references).21,28,31

Illustration: Trail Making Test. The normative data for this test are not only age- and education-sensitive, but are also highly sensitive to cohort effects. Early norms such as those of Davies,32 while often still quoted in literature and even in some training initiatives, are now seriously outdated and should not be used for interpretation. TABLE 3 shows how an average individual (ie, 50th percentile) in the 1960s, in one of 2 age groups, would compare in speed to an individual of similar age today.31 A time score that was at the 50th percentile in 1968 is now at or below the 1st percentile. More recent norms are also usually corrected for education, as are those provided by Tombaugh.31

In “A 'case' for using optimal procedures” (below), TABLE 4 shows the results of using outdated Trail Making norms vs current Trail Making norms.

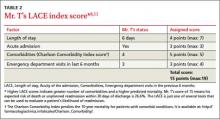

George is a 77-year-old retired school teacher with >15 years of education who was referred to us for complaints of memory loss and suspicion of progressive cognitive deficits. On cognitive screening he scored 26/30 on the Mini-Mental State Examination, generated 16 animal names in 60 seconds, and completed Parts A and B of the Trail Making test in 80 seconds and 196 seconds, respectively. TABLE 4 summarizes test scores and interpretation with and without appropriate corrections.

George’s case dramatically illustrates the clinical impact of using (or not using) optimal interpretive procedures—ie, age and education corrections and current (not outdated) norms. Using the basic cutoff scores without corrections, George’s performance is within acceptable limits on all 3 screening tests, and he is sent home with the comforting news that his performance was within normal limits. However, by using appropriate comparative data, the same scores on all 3 screens indicate impairment. A likely next step would be referral for specialized testing. Monitoring for progressive deterioration is advisable, and perhaps initiation of medication.

TABLE 4

Trail Making: Outdated norms vs current norms

| Version 1 – No corrections for age or education for MMSE or COWAT; outdated Trail Making norms | |||

| Test | Score | Results | Suggests dementia |

| MMSE | 26 | ≥24 within normal limits10 | No |

| COWAT | 16 | >15 within normal limits25 | No |

| Trail Making A | 80 secs | 50th percentile32 | No |

| Trail Making B | 196 secs | 50th percentile32 | No |

| Decision: Negative for dementia | |||

|

|

|

|

|

| Version 2 – Applied age and education corrections for MMSE and COWAT; current Trail Making norms | |||

| Test | Score | Results | Suggests dementia |

| MMSE | 26 | Expected = 2822 | Yes |

| COWAT | 16 | 38th percentile28 | Yes |

| Trail Making A | 80 secs | <1st percentile31 | Yes |

| Trail Making B | 196 secs | <2nd percentile31 | Yes |

| Decision: Positive for dementia | |||

COWAT, Controlled Oral Word Association Task; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination.

Patients deserve an accurate assessment

A diagnosis of dementia profoundly affects patients and families. Progressive dementia such as Alzheimer’s disease means an individual will spend the rest of his or her life (usually 8-10 years) with decreasing cognitive capacity and quality of life.33-35 It also means families will spend years providing or arranging for care, and watching their family member deteriorate. Early detection can afford affected individuals and families the opportunity to make plans for fulfilling wishes and dreams before increased impairment makes such plans unattainable. The importance of rigor in assessment is therefore essential.

Optimizing accuracy in screening for dementia also can enable physicians to reasonably reassure patients that they likely do not suffer from a dementia at the present time, or to at least recommend that they be further assessed by a specialist. Without rigor, time and resources are wasted and the important question that triggered the referral is neither satisfactorily—nor accurately—addressed. Thus, there is a need to use not just simple cutoff scores but to apply the most current age and education normative data, and adhere to administrative instructions verbatim.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lindy A. Kilik, PhD, Geriatric Psychiatry Program, Providence Care Mental Health Services, PO Bag 603, Kingston, Ontario, Canada K7L 4X3; [email protected]

1. Loveman E, Green C, Kirby J, et al. The clinical and cost-effectiveness of donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine and memantine for Alzheimer’s disease. Health Technol Assess. 2006;10:iii-iv,ix- xi,1-160.

2. Medical Care Corporation. Delaying the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Prevent AD Web site. Available at: http://www.preventad.com/pdf/support/article/DelayingADProgression.pdf. Accessed June 18, 2014.

3. Hopkins RW. Dementia projections for the counties, regional municipalities and districts of Ontario. Geriatric Psychiatry Unit Clinical/Research Bulletin, No. 16. Providence Care Web site. Available at: http://www.providencecare.ca/clinical-tools/Documents/Ontario-Dementia-Projections-2010.pdf. Accessed June 18, 2014.

4. Simmons BB, Hartmann B, Dejoseph D. Evaluation of suspected dementia. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:895-902.

5. McCarten JR, Borson S. Should family physicians routinely screen patients for cognitive impairment? Yes: screening is the first step toward improving care. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89: 861-862.

6. Alzheimer’s Association. Health Care Professionals and Alzheimer’s. Alzheimer’s Association Web site. Available at: http://www.alz.org/health-care-professionals/cognitive-tests-patient-assessment.asp. Accessed June 18, 2014.

7. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cognitive impairment in older adults. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsdeme.htm. Accessed June 18, 2014.

8. Hopkins RW, Kilik LA, Day D, et al. Kingston Standardized Behavioural Assessment. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2006;21:339-346.

9. Kilik LA, Hopkins RW, Day D, et al. The progression of behaviour in dementia: an in-office guide for clinicians. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2008;23:242-249.

10. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189-198.

11. Army Individual Test Battery. Manual of Directions and Scoring. Washington, DC: War Department, Adjutant General’s Office; 1944.

12. Wechsler D. The Measurement and Appraisal of Adult Intelligence. 4th ed. The Williams & Wilkins Company: Baltimore, MD; 1958.

13. Larrabee GJ, Largen JW, Levin HS. Sensitivity of age-decline resistant (“hold”) WAIS subtests to Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1985;7:497-504.

14. Herndon RM. Assessment of the elderly with dementia. In: Handbook of Neurologic Rating Scales. 2nd ed. Demos Medical Publishing LLC: New York, NY; 2006:199.

15. Brugnolo A, Nobili F, Barbieri MP, et al. The factorial structure of the mini mental state examination (MMSE) in Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;49:180-185.

16. Folstein M, Anthony JC, Parhad I, et al. The meaning of cognitive impairment in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1985;33:228-235.

17. Hopkins RW, Kilik LA, Day DJ, et al. The Revised Kingston Standardized Cognitive Assessment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19:320-326.

18. Hopkins R, Kilik L. The mini-Kingston Standardized Cognitive Assessment. Kingston Scales Web site. Available at: http://www.kingstonscales.org. Accessed June 18, 2014.

19. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

20. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34: 939-944.

21. Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, et al. Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. JAMA. 1993;269:2386-2391.

22. O’Bryant SE, Humphreys JD, Smith GE, et al. Detecting dementia with the mini-mental state examination in highly educated individuals. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:963-967.

23. O’Sullivan M, Morris RG, Markus HS. Brief cognitive assessment for patients with cerebral small vessel disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1140-1145.

24. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695-699.

25. Benton AL, Hamsher K. Multilingual Aphasia Examination. 2nd ed. Iowa City, OA: AJA Associates, Inc; 1976.

26. Wechsler D. WAIS-III Administration and Scoring Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997.

27. Morris JC, Heyman A, Mohs RC, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assesment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1989;39:1159-1165.

28. Gladsjo JA, Miller SW, Heaton RK. Norms for Letter and Category Fluency: Demographic Corrections for Age, Education and Ethnicity. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1999.

29. Perry R, Hodges J. Attention and executive deficits in Alzheimer’s disease. A critical review. Brain. 1999;122(pt 3):383-404.

30. Flynn JR. The mean IQ of Americans: Massive gains 1932 to 1978. Psychol Bull. 1984;95:29-51.

31. Tombaugh TN. Trail Making Test A and B: normative data stratified by age and education. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2004;19: 203-214.

32. Davies A. The influence of age on trail making test performance. J Clin Psychol. 1968;24:96-98.

33. Bianchetti A, Trabucch M. Clinical aspects of Alzheimer’s disease. Aging (Milano). 2001;13:221-230.

34. Kay D, Forster DP, Newens AJ. Long-term survival, place of death, and death certification in clinically diagnosed pre-senile dementia in northern England. Follow-up after 8-12 years. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:156-162.

35. Chaussalet T, Thompson WA. Data requirements in a model of the natural history of Alzheimer’s disease. Health Care Manag Sci. 2001;4:13-19.

› Use age- and education-corrected normative data when using dementia screening tools. C

› Use verbatim instructions and the same size stimuli and response pages provided in a test’s manual. C

› Ensure that norms used for comparisons are current. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Treatment options for dementia are expanding and improving, giving extra impetus to detecting this progressive disease as early as possible. For example, research on the cholinesterase inhibitor donepezil has shown it can delay cognitive decline by 6 months or more compared with controls1,2 and possibly postpone institutionalization. With the number of elderly individuals and cases of dementia projected to grow significantly over the next 20 years,3 primary care physicians will increasingly be screening for cognitive impairment. Given the time constraints and patient loads in today’s practices, it’s not surprising that physicians tend to use evaluation tools that are brief and simple to administer. However, there are also serious pitfalls in the use of these tools.

When to screen. Many health-related organizations address screening for dementia4,5 and offer screening criteria (eg, the Alzheimer’s Association,6 the US Preventive Services Task Force7). Our experience suggests that specific behavioral changes are reasonable indicators of suspected dementia that should prompt cognitive screening. Using the Kingston Standardized Behavioural Assessment,8 we demonstrated a consistent pattern of earliest behavior change in a community-dwelling group with dementia.9 Meaningful clues are a decreased ability to engage in specific functional activities (including participation in favorite pastimes, ability to eat properly if left to prepare one’s own food, handling of personal finances, word finding, and reading) and unsteadiness. These specific behavioral changes reported by family or a caregiver suggest the need for cognitive screening.

Pitfalls associated with common screening tools, if not taken into account, can seriously limit the usefulness of information gained during assessment and potentially lead to a wrong conclusion. Screening tools are just that: a means of detecting the possible existence of a condition. Results are based on probability and subject to error. Therefore, a single test score is insufficient to render a diagnosis of dementia, and is one variable in a set of diagnostic criteria.

The purpose of this article is to review some of the most commonly used tools and procedures for dementia screening, identify procedural or interpretive errors made in everyday clinical practice, and suggest practical yet simple strategies to address these problems and improve the accuracy of assessments. We illustrate key points with clinical examples and vignettes using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE),10 an Animal Naming Task, and the Trail Making Test.11

Common error #1: Reliance on simple, single cutoff scores

There are a number of important considerations to keep in mind when trying to make sense of scores from the many available cognitive tests.

The range of normal test results is wide. The normal range for most physiologic measures, such as glucose levels or hemoglobin counts, is relatively narrow. However, human cognitive functions can naturally differ from person to person, and the range of normal can be extremely large.

A single, all-purpose cutoff score ignores critical factors. Very often, clinicians have dealt with the issue of wide variance in cognition scores by establishing a general cutoff point to serve as a pass-fail mark. But this practice can result in both under- and overidentification of dementia, and it ignores the 2 components that chiefly determine how individuals differ cognitively: age and intelligence.

Practical fix: Use age-, intelligence-corrected normative data

Level of cognitive performance can be revealing when adjustments are made for age and intelligence. Not taking these factors into account can lead to many errors in clinical decision making.

Age matters. Many cognitive capacities decline as part of normal aging even in otherwise healthy individuals (eg, reaction time, spatial abilities, flexibility in novel problem solving).12 With this in mind, psychologists often have made the distinction between “hold” tests (remaining stable or even improving with age) and “no-hold” tests (declining with age).13 Therefore it is critical to ask, “What is normal, given a particular patient’s age?” If normative data corrected for age are available for a given test, use them.

Intelligence is a factor, too. Intelligence, like most human qualities, is distributed along a bell-shaped curve of normal distribution, wherein most people fall somewhere in the middle and a smaller number will be at the lower and higher tails of the curve. Not all of us fall into the average range of intelligence; indeed, psychometrically, only half of us do. The other half are found somewhere in the more extreme ends. In evaluating a person for dementia, it is critical to compare test results with those found in the appropriate intellectual group. But how does the physician looking for a brief assessment strategy determine a patient’s premorbid level of intellectual functioning?

A widely used and accepted heuristic for gauging intelligence is “years of education.” Of course, education is not perfectly correlated with intelligence, particularly as those who are now elderly may have been denied the opportunity to attend school due to the Great Depression, war, or other life events. Nevertheless, with these limitations in mind, level of education is a reasonable approximation of intelligence. In practical application, premorbid intellectual level is determined by using education-corrected normative data.

Typically with cognitive tests, cutoff scores and score ranges are defined for general levels of education (eg, less than grade 12 or more than grade 12; elementary school, high school, post-secondary, etc). Adjusted norms for age and education are usually determined by taking large samples of subjects and stratifying the distribution by subgroups—eg, 5-year age groups; levels of education such as elementary school or high school—and then statistically analyzing each group and noting the relative differences between them.

Illustration: MMSE. Although not designed for the overall measurement of cognitive impairment in dementia, the MMSE10 has become widely used for that purpose. It is fairly insensitive to cognitive changes associated with earlier stages of dementia,14 and is intended only as a means of identifying patients in need of more comprehensive assessment. However, the MMSE is increasingly used to make a diagnosis of dementia.15 In some areas (eg, Ontario, Canada), it is used to justify paying for treatment with cognitive enhancers.

The universal cutoff score proves inadequate. Although several dementia cutoff scores for the MMSE have been proposed, it is common practice to use an MMSE score ≥24 to rule out dementia.16 In our clinical practice, however, many patients who ultimately are diagnosed with early dementia often perform well on the MMSE, although rather poorly on other dementia screens, such as the Kingston Standardized Cognitive Assessment-Revised (KSCAr)17 or the mini-KSCAr.18

Recently, we reviewed cases of >70 individuals from our outpatient clinic who were given the MMSE and were also diagnosed as having dementia by both DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders)19 and the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association20 criteria. Over three-quarters (78%) of these cases had an MMSE score of ≥24. Based on MMSE scores alone, these individuals would have been declared “not demented.”17

Correcting for age and intelligence increases accuracy. Published age and education norms are available for the MMSE.21 In applying these norms to our sample described above, the number of misidentified patients drops to approximately one-third (35.7%). This means that instead of misidentifying 2 out of 3 cases, the age and education corrections reduced this to about one out of 3, thereby increasing sensitivity and specificity. While this is still an unacceptably high rate of false negatives, it shows the considerable value of using age and education corrections.

The challenge of optimizing sensitivity and specificity of dementia screening tools is ongoing. As a matter of interest, we include TABLE 1,4,18,22-24 which shows calculated sensitivities and specificities of some commonly used screening tests.

Another practical fix: Use distributions and percentile-based normative data

Instead of simple cutoff scores, test scores can be, and often are, translated into percentiles to provide a meaningful context for evaluation and to make it easier to compare scores between patients. Someone with a score at the 70th percentile has performed as well as or better than 70% of others in the group who have taken the test. Usually, the average range of a normal population is defined as being between the 25th to 75th percentiles, encompassing 50% of that population. In general, percentiles make interpreting performance easier. Percentile-based test norms can also help determine with increased accuracy if there has been a decline over time.

Illustration: Animal naming task. In a common version of this task, patients are asked to name as many animals as they can in 60 seconds. This task has its roots in neuro- psychological tests of verbal fluency, such as the Controlled Oral Word Association Task.25 Verbal fluency tasks such as naming animals tap verbal generativity/problem-solving and self-monitoring, but are also highly dependent on vocabulary (word knowledge), a cognitive ability that is quite stable and even improves as one ages until individuals are well into their 80s.26

It is common practice with this procedure to consider a cutoff score of 15 as a minimally acceptable level of performance.27 Here again, there are potentially great differences in expected performance based on age and intelligence. TABLE 2 shows the effect of age and education on verbal fluency, expressed as percentiles, using a raw score of 15.28 For an individual in their early 60s who has a university degree, naming just 15 animals puts their performance at the 12th percentile (below average). The same performance for someone in their 90s who has only 8 years of education puts them in the 79th percentile (above the average range of 25th-75th percentiles). This performance would indicate impairment for the 60-year-old university-educated individual, but strong cognitive function for the 90-year-old.

Common error #2: Deviating from standardized procedures

While clinicians specifically trained in cognitive measurement are familiar with the rigor by which tests are constructed, those with less training are often unaware that even seemingly minor deviations in procedure can contaminate results as surely as using nonsterile containers in biologic testing, leading to inaccurate interpretations of cognition.

Practical fix: Administer tests using verbatim instructions

Failing to follow instructions can significantly bias acquired data, particularly when using performance tests that are timed.

Illustration: Trail Making Test. Trail Making is an old 2-part test developed for the United States Army in the 1940s,11 and used in the Halstead-Reitan neuropsychological battery. Part A is a timed measure of an individual’s ability to join up a series of numbered circles in ascending order. Part B measures the ability to alternately switch between 2 related tasks: namely, alternately joining numbered and lettered circles, in ascending order. This is considered a measure of complex attention, which is often disrupted in early dementia.29

The test uses a specific standardized set of instructions, and Part B’s interpretation depends on having first administered Part A. Anecdotally, we have increasingly seen clinician reports using only Part B. Eliminating Part A removes a significant opportunity for patients to become familiar with the task’s demands, placing them at a considerable disadvantage on Part B and thereby invalidating the normative data.

In addition, follow the exact phrasing of the instructions and use stimuli and response pages that are the same size as those provided in the manual. If a patient errs at any point, it’s important that the test administrator reads, verbatim, the provided correction statements because these statements influence the amount of time spent correcting an error and therefore the final score.

Common error #3: Using outdated normative data

Neglecting to use updated norms that reflect current cohort differences can compromise screening accuracy.

Practical fix: Ensure current norms are used for comparisons

Societal influences—computers and other technologies, nutrition, etc—have led to steady improvements in cognitive and physical abilities. In basic psychology, this pattern of improving cognition, documented as an approximate increase of 3 IQ points per decade, is referred to as the Flynn effect.30 Therefore, not only do age and education need to be controlled for, but normative data must be current.

Cognitive screening tools are usually published with norms compiled at the time of the test’s development. However, scores are periodically “re-normed” to reflect current levels of ability. These updated norms are readily available in published journal articles or online. (Current norms for each of the tests used as examples in this article are provided in the references).21,28,31

Illustration: Trail Making Test. The normative data for this test are not only age- and education-sensitive, but are also highly sensitive to cohort effects. Early norms such as those of Davies,32 while often still quoted in literature and even in some training initiatives, are now seriously outdated and should not be used for interpretation. TABLE 3 shows how an average individual (ie, 50th percentile) in the 1960s, in one of 2 age groups, would compare in speed to an individual of similar age today.31 A time score that was at the 50th percentile in 1968 is now at or below the 1st percentile. More recent norms are also usually corrected for education, as are those provided by Tombaugh.31

In “A 'case' for using optimal procedures” (below), TABLE 4 shows the results of using outdated Trail Making norms vs current Trail Making norms.

George is a 77-year-old retired school teacher with >15 years of education who was referred to us for complaints of memory loss and suspicion of progressive cognitive deficits. On cognitive screening he scored 26/30 on the Mini-Mental State Examination, generated 16 animal names in 60 seconds, and completed Parts A and B of the Trail Making test in 80 seconds and 196 seconds, respectively. TABLE 4 summarizes test scores and interpretation with and without appropriate corrections.

George’s case dramatically illustrates the clinical impact of using (or not using) optimal interpretive procedures—ie, age and education corrections and current (not outdated) norms. Using the basic cutoff scores without corrections, George’s performance is within acceptable limits on all 3 screening tests, and he is sent home with the comforting news that his performance was within normal limits. However, by using appropriate comparative data, the same scores on all 3 screens indicate impairment. A likely next step would be referral for specialized testing. Monitoring for progressive deterioration is advisable, and perhaps initiation of medication.

TABLE 4

Trail Making: Outdated norms vs current norms

| Version 1 – No corrections for age or education for MMSE or COWAT; outdated Trail Making norms | |||

| Test | Score | Results | Suggests dementia |

| MMSE | 26 | ≥24 within normal limits10 | No |

| COWAT | 16 | >15 within normal limits25 | No |

| Trail Making A | 80 secs | 50th percentile32 | No |

| Trail Making B | 196 secs | 50th percentile32 | No |

| Decision: Negative for dementia | |||

|

|

|

|

|

| Version 2 – Applied age and education corrections for MMSE and COWAT; current Trail Making norms | |||

| Test | Score | Results | Suggests dementia |

| MMSE | 26 | Expected = 2822 | Yes |

| COWAT | 16 | 38th percentile28 | Yes |

| Trail Making A | 80 secs | <1st percentile31 | Yes |

| Trail Making B | 196 secs | <2nd percentile31 | Yes |

| Decision: Positive for dementia | |||

COWAT, Controlled Oral Word Association Task; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination.

Patients deserve an accurate assessment

A diagnosis of dementia profoundly affects patients and families. Progressive dementia such as Alzheimer’s disease means an individual will spend the rest of his or her life (usually 8-10 years) with decreasing cognitive capacity and quality of life.33-35 It also means families will spend years providing or arranging for care, and watching their family member deteriorate. Early detection can afford affected individuals and families the opportunity to make plans for fulfilling wishes and dreams before increased impairment makes such plans unattainable. The importance of rigor in assessment is therefore essential.

Optimizing accuracy in screening for dementia also can enable physicians to reasonably reassure patients that they likely do not suffer from a dementia at the present time, or to at least recommend that they be further assessed by a specialist. Without rigor, time and resources are wasted and the important question that triggered the referral is neither satisfactorily—nor accurately—addressed. Thus, there is a need to use not just simple cutoff scores but to apply the most current age and education normative data, and adhere to administrative instructions verbatim.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lindy A. Kilik, PhD, Geriatric Psychiatry Program, Providence Care Mental Health Services, PO Bag 603, Kingston, Ontario, Canada K7L 4X3; [email protected]

› Use age- and education-corrected normative data when using dementia screening tools. C

› Use verbatim instructions and the same size stimuli and response pages provided in a test’s manual. C

› Ensure that norms used for comparisons are current. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Treatment options for dementia are expanding and improving, giving extra impetus to detecting this progressive disease as early as possible. For example, research on the cholinesterase inhibitor donepezil has shown it can delay cognitive decline by 6 months or more compared with controls1,2 and possibly postpone institutionalization. With the number of elderly individuals and cases of dementia projected to grow significantly over the next 20 years,3 primary care physicians will increasingly be screening for cognitive impairment. Given the time constraints and patient loads in today’s practices, it’s not surprising that physicians tend to use evaluation tools that are brief and simple to administer. However, there are also serious pitfalls in the use of these tools.

When to screen. Many health-related organizations address screening for dementia4,5 and offer screening criteria (eg, the Alzheimer’s Association,6 the US Preventive Services Task Force7). Our experience suggests that specific behavioral changes are reasonable indicators of suspected dementia that should prompt cognitive screening. Using the Kingston Standardized Behavioural Assessment,8 we demonstrated a consistent pattern of earliest behavior change in a community-dwelling group with dementia.9 Meaningful clues are a decreased ability to engage in specific functional activities (including participation in favorite pastimes, ability to eat properly if left to prepare one’s own food, handling of personal finances, word finding, and reading) and unsteadiness. These specific behavioral changes reported by family or a caregiver suggest the need for cognitive screening.

Pitfalls associated with common screening tools, if not taken into account, can seriously limit the usefulness of information gained during assessment and potentially lead to a wrong conclusion. Screening tools are just that: a means of detecting the possible existence of a condition. Results are based on probability and subject to error. Therefore, a single test score is insufficient to render a diagnosis of dementia, and is one variable in a set of diagnostic criteria.

The purpose of this article is to review some of the most commonly used tools and procedures for dementia screening, identify procedural or interpretive errors made in everyday clinical practice, and suggest practical yet simple strategies to address these problems and improve the accuracy of assessments. We illustrate key points with clinical examples and vignettes using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE),10 an Animal Naming Task, and the Trail Making Test.11

Common error #1: Reliance on simple, single cutoff scores

There are a number of important considerations to keep in mind when trying to make sense of scores from the many available cognitive tests.

The range of normal test results is wide. The normal range for most physiologic measures, such as glucose levels or hemoglobin counts, is relatively narrow. However, human cognitive functions can naturally differ from person to person, and the range of normal can be extremely large.

A single, all-purpose cutoff score ignores critical factors. Very often, clinicians have dealt with the issue of wide variance in cognition scores by establishing a general cutoff point to serve as a pass-fail mark. But this practice can result in both under- and overidentification of dementia, and it ignores the 2 components that chiefly determine how individuals differ cognitively: age and intelligence.

Practical fix: Use age-, intelligence-corrected normative data

Level of cognitive performance can be revealing when adjustments are made for age and intelligence. Not taking these factors into account can lead to many errors in clinical decision making.

Age matters. Many cognitive capacities decline as part of normal aging even in otherwise healthy individuals (eg, reaction time, spatial abilities, flexibility in novel problem solving).12 With this in mind, psychologists often have made the distinction between “hold” tests (remaining stable or even improving with age) and “no-hold” tests (declining with age).13 Therefore it is critical to ask, “What is normal, given a particular patient’s age?” If normative data corrected for age are available for a given test, use them.

Intelligence is a factor, too. Intelligence, like most human qualities, is distributed along a bell-shaped curve of normal distribution, wherein most people fall somewhere in the middle and a smaller number will be at the lower and higher tails of the curve. Not all of us fall into the average range of intelligence; indeed, psychometrically, only half of us do. The other half are found somewhere in the more extreme ends. In evaluating a person for dementia, it is critical to compare test results with those found in the appropriate intellectual group. But how does the physician looking for a brief assessment strategy determine a patient’s premorbid level of intellectual functioning?

A widely used and accepted heuristic for gauging intelligence is “years of education.” Of course, education is not perfectly correlated with intelligence, particularly as those who are now elderly may have been denied the opportunity to attend school due to the Great Depression, war, or other life events. Nevertheless, with these limitations in mind, level of education is a reasonable approximation of intelligence. In practical application, premorbid intellectual level is determined by using education-corrected normative data.

Typically with cognitive tests, cutoff scores and score ranges are defined for general levels of education (eg, less than grade 12 or more than grade 12; elementary school, high school, post-secondary, etc). Adjusted norms for age and education are usually determined by taking large samples of subjects and stratifying the distribution by subgroups—eg, 5-year age groups; levels of education such as elementary school or high school—and then statistically analyzing each group and noting the relative differences between them.

Illustration: MMSE. Although not designed for the overall measurement of cognitive impairment in dementia, the MMSE10 has become widely used for that purpose. It is fairly insensitive to cognitive changes associated with earlier stages of dementia,14 and is intended only as a means of identifying patients in need of more comprehensive assessment. However, the MMSE is increasingly used to make a diagnosis of dementia.15 In some areas (eg, Ontario, Canada), it is used to justify paying for treatment with cognitive enhancers.

The universal cutoff score proves inadequate. Although several dementia cutoff scores for the MMSE have been proposed, it is common practice to use an MMSE score ≥24 to rule out dementia.16 In our clinical practice, however, many patients who ultimately are diagnosed with early dementia often perform well on the MMSE, although rather poorly on other dementia screens, such as the Kingston Standardized Cognitive Assessment-Revised (KSCAr)17 or the mini-KSCAr.18

Recently, we reviewed cases of >70 individuals from our outpatient clinic who were given the MMSE and were also diagnosed as having dementia by both DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders)19 and the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association20 criteria. Over three-quarters (78%) of these cases had an MMSE score of ≥24. Based on MMSE scores alone, these individuals would have been declared “not demented.”17

Correcting for age and intelligence increases accuracy. Published age and education norms are available for the MMSE.21 In applying these norms to our sample described above, the number of misidentified patients drops to approximately one-third (35.7%). This means that instead of misidentifying 2 out of 3 cases, the age and education corrections reduced this to about one out of 3, thereby increasing sensitivity and specificity. While this is still an unacceptably high rate of false negatives, it shows the considerable value of using age and education corrections.

The challenge of optimizing sensitivity and specificity of dementia screening tools is ongoing. As a matter of interest, we include TABLE 1,4,18,22-24 which shows calculated sensitivities and specificities of some commonly used screening tests.

Another practical fix: Use distributions and percentile-based normative data

Instead of simple cutoff scores, test scores can be, and often are, translated into percentiles to provide a meaningful context for evaluation and to make it easier to compare scores between patients. Someone with a score at the 70th percentile has performed as well as or better than 70% of others in the group who have taken the test. Usually, the average range of a normal population is defined as being between the 25th to 75th percentiles, encompassing 50% of that population. In general, percentiles make interpreting performance easier. Percentile-based test norms can also help determine with increased accuracy if there has been a decline over time.

Illustration: Animal naming task. In a common version of this task, patients are asked to name as many animals as they can in 60 seconds. This task has its roots in neuro- psychological tests of verbal fluency, such as the Controlled Oral Word Association Task.25 Verbal fluency tasks such as naming animals tap verbal generativity/problem-solving and self-monitoring, but are also highly dependent on vocabulary (word knowledge), a cognitive ability that is quite stable and even improves as one ages until individuals are well into their 80s.26

It is common practice with this procedure to consider a cutoff score of 15 as a minimally acceptable level of performance.27 Here again, there are potentially great differences in expected performance based on age and intelligence. TABLE 2 shows the effect of age and education on verbal fluency, expressed as percentiles, using a raw score of 15.28 For an individual in their early 60s who has a university degree, naming just 15 animals puts their performance at the 12th percentile (below average). The same performance for someone in their 90s who has only 8 years of education puts them in the 79th percentile (above the average range of 25th-75th percentiles). This performance would indicate impairment for the 60-year-old university-educated individual, but strong cognitive function for the 90-year-old.

Common error #2: Deviating from standardized procedures

While clinicians specifically trained in cognitive measurement are familiar with the rigor by which tests are constructed, those with less training are often unaware that even seemingly minor deviations in procedure can contaminate results as surely as using nonsterile containers in biologic testing, leading to inaccurate interpretations of cognition.

Practical fix: Administer tests using verbatim instructions

Failing to follow instructions can significantly bias acquired data, particularly when using performance tests that are timed.

Illustration: Trail Making Test. Trail Making is an old 2-part test developed for the United States Army in the 1940s,11 and used in the Halstead-Reitan neuropsychological battery. Part A is a timed measure of an individual’s ability to join up a series of numbered circles in ascending order. Part B measures the ability to alternately switch between 2 related tasks: namely, alternately joining numbered and lettered circles, in ascending order. This is considered a measure of complex attention, which is often disrupted in early dementia.29

The test uses a specific standardized set of instructions, and Part B’s interpretation depends on having first administered Part A. Anecdotally, we have increasingly seen clinician reports using only Part B. Eliminating Part A removes a significant opportunity for patients to become familiar with the task’s demands, placing them at a considerable disadvantage on Part B and thereby invalidating the normative data.

In addition, follow the exact phrasing of the instructions and use stimuli and response pages that are the same size as those provided in the manual. If a patient errs at any point, it’s important that the test administrator reads, verbatim, the provided correction statements because these statements influence the amount of time spent correcting an error and therefore the final score.

Common error #3: Using outdated normative data

Neglecting to use updated norms that reflect current cohort differences can compromise screening accuracy.

Practical fix: Ensure current norms are used for comparisons

Societal influences—computers and other technologies, nutrition, etc—have led to steady improvements in cognitive and physical abilities. In basic psychology, this pattern of improving cognition, documented as an approximate increase of 3 IQ points per decade, is referred to as the Flynn effect.30 Therefore, not only do age and education need to be controlled for, but normative data must be current.

Cognitive screening tools are usually published with norms compiled at the time of the test’s development. However, scores are periodically “re-normed” to reflect current levels of ability. These updated norms are readily available in published journal articles or online. (Current norms for each of the tests used as examples in this article are provided in the references).21,28,31

Illustration: Trail Making Test. The normative data for this test are not only age- and education-sensitive, but are also highly sensitive to cohort effects. Early norms such as those of Davies,32 while often still quoted in literature and even in some training initiatives, are now seriously outdated and should not be used for interpretation. TABLE 3 shows how an average individual (ie, 50th percentile) in the 1960s, in one of 2 age groups, would compare in speed to an individual of similar age today.31 A time score that was at the 50th percentile in 1968 is now at or below the 1st percentile. More recent norms are also usually corrected for education, as are those provided by Tombaugh.31

In “A 'case' for using optimal procedures” (below), TABLE 4 shows the results of using outdated Trail Making norms vs current Trail Making norms.

George is a 77-year-old retired school teacher with >15 years of education who was referred to us for complaints of memory loss and suspicion of progressive cognitive deficits. On cognitive screening he scored 26/30 on the Mini-Mental State Examination, generated 16 animal names in 60 seconds, and completed Parts A and B of the Trail Making test in 80 seconds and 196 seconds, respectively. TABLE 4 summarizes test scores and interpretation with and without appropriate corrections.

George’s case dramatically illustrates the clinical impact of using (or not using) optimal interpretive procedures—ie, age and education corrections and current (not outdated) norms. Using the basic cutoff scores without corrections, George’s performance is within acceptable limits on all 3 screening tests, and he is sent home with the comforting news that his performance was within normal limits. However, by using appropriate comparative data, the same scores on all 3 screens indicate impairment. A likely next step would be referral for specialized testing. Monitoring for progressive deterioration is advisable, and perhaps initiation of medication.

TABLE 4

Trail Making: Outdated norms vs current norms

| Version 1 – No corrections for age or education for MMSE or COWAT; outdated Trail Making norms | |||

| Test | Score | Results | Suggests dementia |

| MMSE | 26 | ≥24 within normal limits10 | No |

| COWAT | 16 | >15 within normal limits25 | No |

| Trail Making A | 80 secs | 50th percentile32 | No |

| Trail Making B | 196 secs | 50th percentile32 | No |

| Decision: Negative for dementia | |||

|

|

|

|

|

| Version 2 – Applied age and education corrections for MMSE and COWAT; current Trail Making norms | |||

| Test | Score | Results | Suggests dementia |

| MMSE | 26 | Expected = 2822 | Yes |

| COWAT | 16 | 38th percentile28 | Yes |

| Trail Making A | 80 secs | <1st percentile31 | Yes |

| Trail Making B | 196 secs | <2nd percentile31 | Yes |

| Decision: Positive for dementia | |||

COWAT, Controlled Oral Word Association Task; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination.

Patients deserve an accurate assessment

A diagnosis of dementia profoundly affects patients and families. Progressive dementia such as Alzheimer’s disease means an individual will spend the rest of his or her life (usually 8-10 years) with decreasing cognitive capacity and quality of life.33-35 It also means families will spend years providing or arranging for care, and watching their family member deteriorate. Early detection can afford affected individuals and families the opportunity to make plans for fulfilling wishes and dreams before increased impairment makes such plans unattainable. The importance of rigor in assessment is therefore essential.

Optimizing accuracy in screening for dementia also can enable physicians to reasonably reassure patients that they likely do not suffer from a dementia at the present time, or to at least recommend that they be further assessed by a specialist. Without rigor, time and resources are wasted and the important question that triggered the referral is neither satisfactorily—nor accurately—addressed. Thus, there is a need to use not just simple cutoff scores but to apply the most current age and education normative data, and adhere to administrative instructions verbatim.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lindy A. Kilik, PhD, Geriatric Psychiatry Program, Providence Care Mental Health Services, PO Bag 603, Kingston, Ontario, Canada K7L 4X3; [email protected]

1. Loveman E, Green C, Kirby J, et al. The clinical and cost-effectiveness of donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine and memantine for Alzheimer’s disease. Health Technol Assess. 2006;10:iii-iv,ix- xi,1-160.

2. Medical Care Corporation. Delaying the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Prevent AD Web site. Available at: http://www.preventad.com/pdf/support/article/DelayingADProgression.pdf. Accessed June 18, 2014.

3. Hopkins RW. Dementia projections for the counties, regional municipalities and districts of Ontario. Geriatric Psychiatry Unit Clinical/Research Bulletin, No. 16. Providence Care Web site. Available at: http://www.providencecare.ca/clinical-tools/Documents/Ontario-Dementia-Projections-2010.pdf. Accessed June 18, 2014.

4. Simmons BB, Hartmann B, Dejoseph D. Evaluation of suspected dementia. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:895-902.

5. McCarten JR, Borson S. Should family physicians routinely screen patients for cognitive impairment? Yes: screening is the first step toward improving care. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89: 861-862.

6. Alzheimer’s Association. Health Care Professionals and Alzheimer’s. Alzheimer’s Association Web site. Available at: http://www.alz.org/health-care-professionals/cognitive-tests-patient-assessment.asp. Accessed June 18, 2014.

7. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cognitive impairment in older adults. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsdeme.htm. Accessed June 18, 2014.

8. Hopkins RW, Kilik LA, Day D, et al. Kingston Standardized Behavioural Assessment. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2006;21:339-346.

9. Kilik LA, Hopkins RW, Day D, et al. The progression of behaviour in dementia: an in-office guide for clinicians. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2008;23:242-249.

10. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189-198.

11. Army Individual Test Battery. Manual of Directions and Scoring. Washington, DC: War Department, Adjutant General’s Office; 1944.

12. Wechsler D. The Measurement and Appraisal of Adult Intelligence. 4th ed. The Williams & Wilkins Company: Baltimore, MD; 1958.

13. Larrabee GJ, Largen JW, Levin HS. Sensitivity of age-decline resistant (“hold”) WAIS subtests to Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1985;7:497-504.

14. Herndon RM. Assessment of the elderly with dementia. In: Handbook of Neurologic Rating Scales. 2nd ed. Demos Medical Publishing LLC: New York, NY; 2006:199.

15. Brugnolo A, Nobili F, Barbieri MP, et al. The factorial structure of the mini mental state examination (MMSE) in Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;49:180-185.

16. Folstein M, Anthony JC, Parhad I, et al. The meaning of cognitive impairment in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1985;33:228-235.

17. Hopkins RW, Kilik LA, Day DJ, et al. The Revised Kingston Standardized Cognitive Assessment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19:320-326.

18. Hopkins R, Kilik L. The mini-Kingston Standardized Cognitive Assessment. Kingston Scales Web site. Available at: http://www.kingstonscales.org. Accessed June 18, 2014.

19. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

20. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34: 939-944.

21. Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, et al. Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. JAMA. 1993;269:2386-2391.

22. O’Bryant SE, Humphreys JD, Smith GE, et al. Detecting dementia with the mini-mental state examination in highly educated individuals. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:963-967.

23. O’Sullivan M, Morris RG, Markus HS. Brief cognitive assessment for patients with cerebral small vessel disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1140-1145.

24. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695-699.

25. Benton AL, Hamsher K. Multilingual Aphasia Examination. 2nd ed. Iowa City, OA: AJA Associates, Inc; 1976.

26. Wechsler D. WAIS-III Administration and Scoring Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997.

27. Morris JC, Heyman A, Mohs RC, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assesment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1989;39:1159-1165.

28. Gladsjo JA, Miller SW, Heaton RK. Norms for Letter and Category Fluency: Demographic Corrections for Age, Education and Ethnicity. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1999.

29. Perry R, Hodges J. Attention and executive deficits in Alzheimer’s disease. A critical review. Brain. 1999;122(pt 3):383-404.

30. Flynn JR. The mean IQ of Americans: Massive gains 1932 to 1978. Psychol Bull. 1984;95:29-51.

31. Tombaugh TN. Trail Making Test A and B: normative data stratified by age and education. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2004;19: 203-214.

32. Davies A. The influence of age on trail making test performance. J Clin Psychol. 1968;24:96-98.

33. Bianchetti A, Trabucch M. Clinical aspects of Alzheimer’s disease. Aging (Milano). 2001;13:221-230.

34. Kay D, Forster DP, Newens AJ. Long-term survival, place of death, and death certification in clinically diagnosed pre-senile dementia in northern England. Follow-up after 8-12 years. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:156-162.

35. Chaussalet T, Thompson WA. Data requirements in a model of the natural history of Alzheimer’s disease. Health Care Manag Sci. 2001;4:13-19.

1. Loveman E, Green C, Kirby J, et al. The clinical and cost-effectiveness of donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine and memantine for Alzheimer’s disease. Health Technol Assess. 2006;10:iii-iv,ix- xi,1-160.

2. Medical Care Corporation. Delaying the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Prevent AD Web site. Available at: http://www.preventad.com/pdf/support/article/DelayingADProgression.pdf. Accessed June 18, 2014.

3. Hopkins RW. Dementia projections for the counties, regional municipalities and districts of Ontario. Geriatric Psychiatry Unit Clinical/Research Bulletin, No. 16. Providence Care Web site. Available at: http://www.providencecare.ca/clinical-tools/Documents/Ontario-Dementia-Projections-2010.pdf. Accessed June 18, 2014.

4. Simmons BB, Hartmann B, Dejoseph D. Evaluation of suspected dementia. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:895-902.

5. McCarten JR, Borson S. Should family physicians routinely screen patients for cognitive impairment? Yes: screening is the first step toward improving care. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89: 861-862.

6. Alzheimer’s Association. Health Care Professionals and Alzheimer’s. Alzheimer’s Association Web site. Available at: http://www.alz.org/health-care-professionals/cognitive-tests-patient-assessment.asp. Accessed June 18, 2014.

7. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cognitive impairment in older adults. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsdeme.htm. Accessed June 18, 2014.

8. Hopkins RW, Kilik LA, Day D, et al. Kingston Standardized Behavioural Assessment. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2006;21:339-346.

9. Kilik LA, Hopkins RW, Day D, et al. The progression of behaviour in dementia: an in-office guide for clinicians. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2008;23:242-249.

10. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189-198.

11. Army Individual Test Battery. Manual of Directions and Scoring. Washington, DC: War Department, Adjutant General’s Office; 1944.

12. Wechsler D. The Measurement and Appraisal of Adult Intelligence. 4th ed. The Williams & Wilkins Company: Baltimore, MD; 1958.

13. Larrabee GJ, Largen JW, Levin HS. Sensitivity of age-decline resistant (“hold”) WAIS subtests to Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1985;7:497-504.

14. Herndon RM. Assessment of the elderly with dementia. In: Handbook of Neurologic Rating Scales. 2nd ed. Demos Medical Publishing LLC: New York, NY; 2006:199.

15. Brugnolo A, Nobili F, Barbieri MP, et al. The factorial structure of the mini mental state examination (MMSE) in Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;49:180-185.

16. Folstein M, Anthony JC, Parhad I, et al. The meaning of cognitive impairment in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1985;33:228-235.

17. Hopkins RW, Kilik LA, Day DJ, et al. The Revised Kingston Standardized Cognitive Assessment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19:320-326.

18. Hopkins R, Kilik L. The mini-Kingston Standardized Cognitive Assessment. Kingston Scales Web site. Available at: http://www.kingstonscales.org. Accessed June 18, 2014.

19. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

20. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34: 939-944.

21. Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, et al. Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. JAMA. 1993;269:2386-2391.

22. O’Bryant SE, Humphreys JD, Smith GE, et al. Detecting dementia with the mini-mental state examination in highly educated individuals. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:963-967.

23. O’Sullivan M, Morris RG, Markus HS. Brief cognitive assessment for patients with cerebral small vessel disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1140-1145.

24. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695-699.

25. Benton AL, Hamsher K. Multilingual Aphasia Examination. 2nd ed. Iowa City, OA: AJA Associates, Inc; 1976.

26. Wechsler D. WAIS-III Administration and Scoring Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997.

27. Morris JC, Heyman A, Mohs RC, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assesment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1989;39:1159-1165.

28. Gladsjo JA, Miller SW, Heaton RK. Norms for Letter and Category Fluency: Demographic Corrections for Age, Education and Ethnicity. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1999.

29. Perry R, Hodges J. Attention and executive deficits in Alzheimer’s disease. A critical review. Brain. 1999;122(pt 3):383-404.

30. Flynn JR. The mean IQ of Americans: Massive gains 1932 to 1978. Psychol Bull. 1984;95:29-51.

31. Tombaugh TN. Trail Making Test A and B: normative data stratified by age and education. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2004;19: 203-214.

32. Davies A. The influence of age on trail making test performance. J Clin Psychol. 1968;24:96-98.

33. Bianchetti A, Trabucch M. Clinical aspects of Alzheimer’s disease. Aging (Milano). 2001;13:221-230.

34. Kay D, Forster DP, Newens AJ. Long-term survival, place of death, and death certification in clinically diagnosed pre-senile dementia in northern England. Follow-up after 8-12 years. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:156-162.

35. Chaussalet T, Thompson WA. Data requirements in a model of the natural history of Alzheimer’s disease. Health Care Manag Sci. 2001;4:13-19.

Deaf Hospitalist Focuses on Teaching, Co-Management, Patient-Centered Care

"What’s the bigger picture here?” Hospitalist Christopher Moreland, MD, MPH, FACP, drops his question neatly into the pause in resident Adrienne Victor, MD’s presentation of patient status and lab results.

We’re on the bustling 9th floor of University Hospital at the University of Texas Health Science Center (UTHSCSA) in San Antonio during fast-paced morning rounds. As attending physician, Dr. Moreland is focusing intently on Dr. Victor’s face, simultaneously monitoring the American Sign Language (ASL) interpretation of Todd Agan, CI/CT, BEI Master Interpreter. Immediately after his question to Dr. Victor, the discussion—conducted in both ASL and spoken English—shifts to the patient’s psychosocial issues and whether a palliative care consult would be advisable.

It’s clear that for Dr. Moreland, the work, not his lack of hearing, is the main point here. A hospitalist with the UTHSCSA team since 2010, Dr. Moreland quickly established himself not only as a valuable HM team member and educator, but also as a leader in other domains. For example, in addition to his academic appointment as assistant clinical professor of medicine, he previously was co-director of the medicine consult and co-management service at University Hospital and now serves as UTHSCSA’s associate program director for the internal medicine residency program.

Dr. Moreland’s question this morning is typical of his teaching, says Bret Simon, PhD, an educational development specialist and assistant professor with the division of hospital medicine at UTHSCSA.

–Christopher Moreland, MD, MPH, FACP

“He’s very good at using questions to teach, promoting reflection rather than simply telling the student what to do,” Dr. Simon explains.

Why Medicine?

Chris Moreland’s parents discovered their son was deaf at age two, by which time he had acquired very few spoken words. After multiple visits to healthcare professionals, a physician finally identified his deafness. The family then embarked on a bimodal approach to his education, using both signed and spoken English. He learned ASL in college. As a result, he communicates through a variety of channels: ASL with interpreters Agan and Keri Richardson, speech reading, and spoken English. When examining patients, he uses an electronic stethoscope that interfaces with his cochlear implant.

Medicine was not Dr. Moreland’s first academic choice.

“I went into college thinking I wanted to do computer science,” he says, speaking of his undergraduate studies at the University of Texas in Austin. When he realized computers were not for him, he switched his major to theater arts, continuing an interest he had had in high school. After that, research seemed appealing, and he became a research assistant in a lab in the Department of Anthropology. Finally, after shadowing a number of physicians, his interest in medical science was stimulated.

“Medicine,” he says, “became a nice culmination of everything I was interested in doing.” From computer science, he learned to appreciate an understanding of algorithms; from theater arts came the ability to understand where people are coming from; and from his link with research in linguistics and anthropology came the contribution of problem solving and methodology.

Fearless Communicator

Dr. Moreland says his deafness presents no impediments to his practice of medicine. “I grew up working with interpreters, so I’m used to that process,” he says. “It forces you to become less inhibited about what you’re doing. People have questions [‘who is that other person in the room?’], and you learn how to handle those questions quickly, without interfering with communication in order to advance the work.”

When Dr. Moreland started his clinical rotations as a third-year medical student, he grappled with the best way to introduce himself and his interpreter to patients. His first attempt at explaining the interpretive process “went on for quite a while” and was too much information. “It ended up overwhelming the patient,” he says.

The next time he chose not to introduce the interpreter but to simply address the patient directly. “That didn’t work either, because the patient’s eyes kept wandering to that other person in the room.”

Finally, “I realized that it wasn’t about me,” he says. “It was about the patient.” So he simply shortened the introduction to himself and the interpreter and asked the patients how they were doing.

“Once I became more professional about the situation, the more positive and patient-centered it became, and it went well.” He says he’s had no negative experiences since then, at least not related to his deafness. He approaches each new patient interaction proactively, and he and his interpreters become part of the flow of care.

Teaching’s Missing Pieces

As illustrated with his first question, Dr. Moreland intends for his trainees to learn to think globally about their patients.

“Although rote information has its role,” he explains later in the conference room, “I’m always afraid of overemphasizing it. When I trained in medical school, we didn’t learn that much about communication skills and teamwork. We talked a lot about information we use as physicians—the mechanism of disease, the drugs we use.

“What I try to emphasize with trainees is, what skills in communication, teamwork, and self-education can we develop so that we can use those skills continuously throughout our practice?”

Dr. Moreland takes setting resident-generated learning goals seriously, says Dr. Simon, for which he and trainees give him high marks.

“He is very supportive and encourages us to make our own management decisions,” Dr. Victor says. “Though, of course, he will let us know if something is likely the wrong choice, usually by discussing it first.”