User login

How to identify and localize IUDs on ultrasound

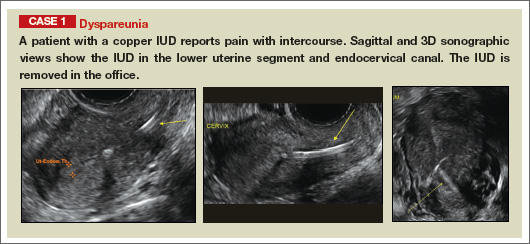

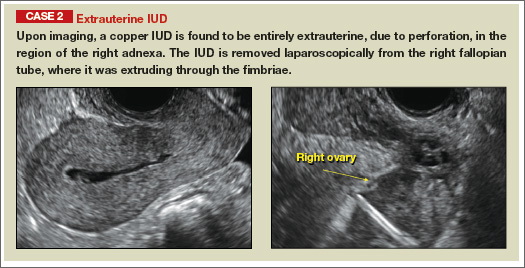

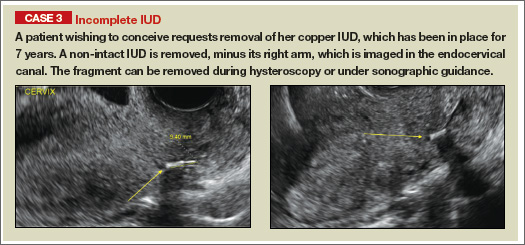

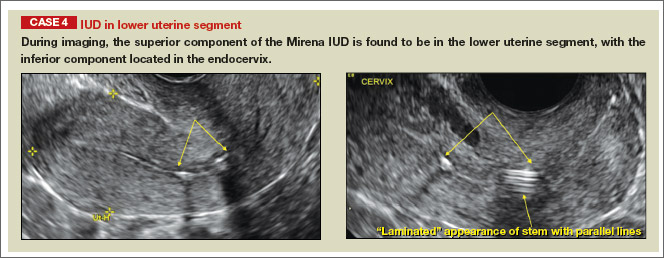

Although an ultrasound is not required after uncomplicated placement of an intrauterine device (IUD) or during routine management of women who are doing well with an IUD, it is invaluable in the evaluation of patients who present with pain or other symptoms suggestive of IUD malpositioning.

In this article, we outline the sonographic features of the IUDs available today in the United States and describe the basics of localization by ultrasound.

Related articles: STOP relying on 2D ultrasound for IUD localization. Steven R. Goldstein, MD, and Chrystie Fujimoto, MD (August 2014)

Update on Contraception. Melissa J. Chen, MD, MPH, and Mitchell D. Creinin, MD (August 2014)

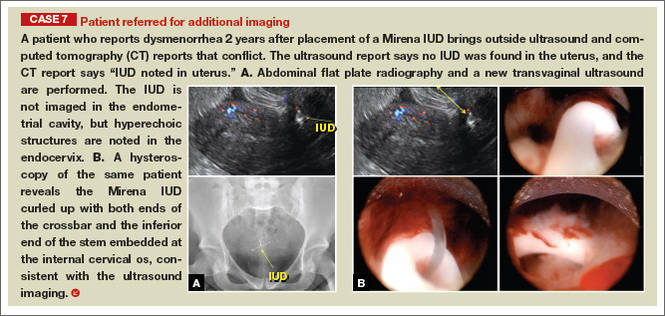

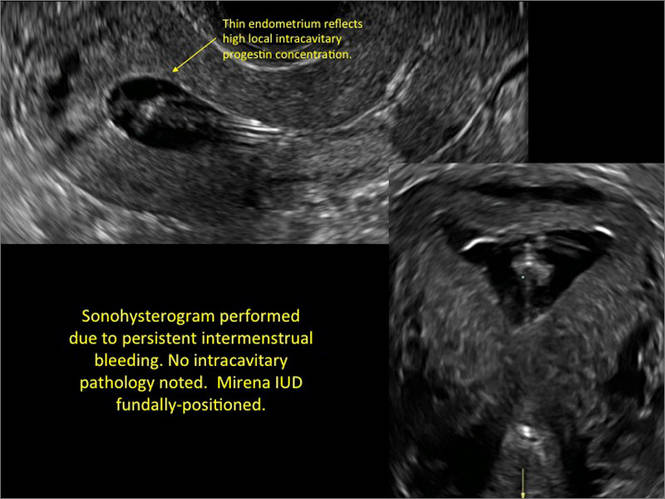

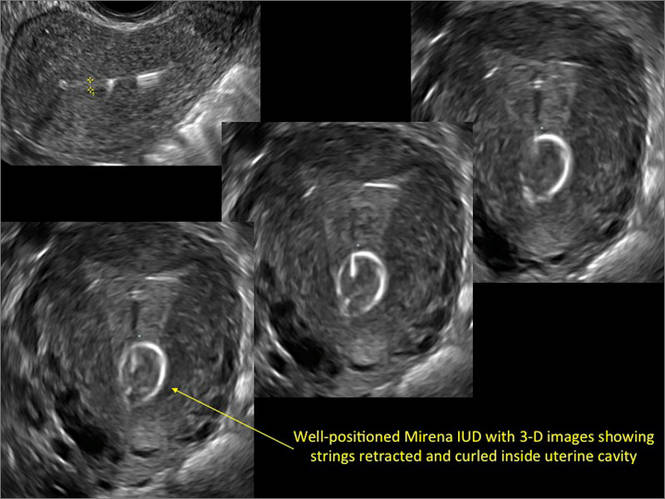

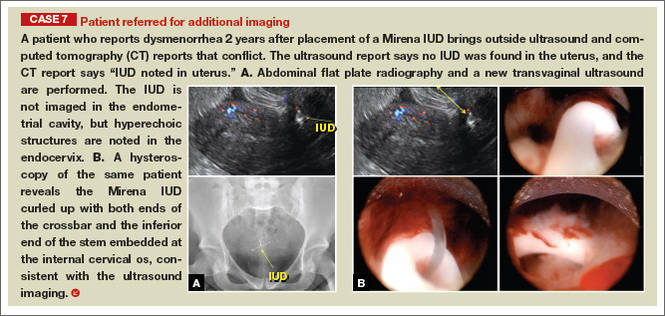

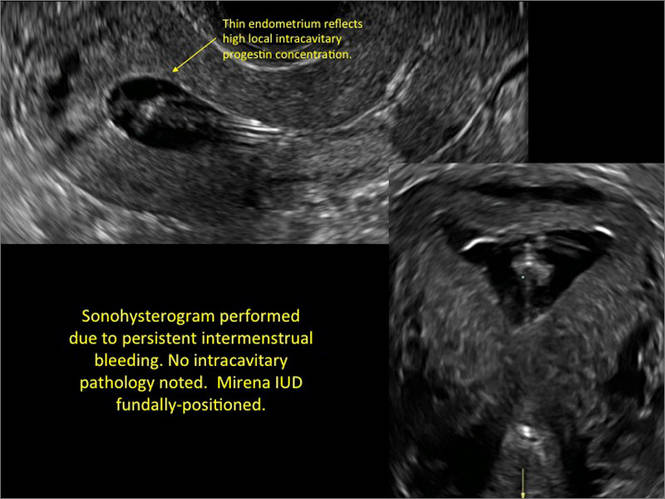

Ultrasound features of IUDsWhen positioned normally, an IUD is centrally located within the endometrial cavity, with the crossbar positioned in the fundal area.1 Copper and progestin-releasing IUDs can be identified easily on ultrasound if one is familiar with their basic sonographic features:

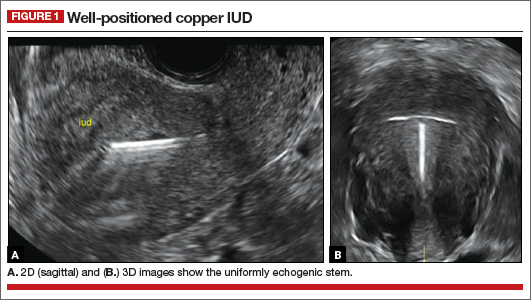

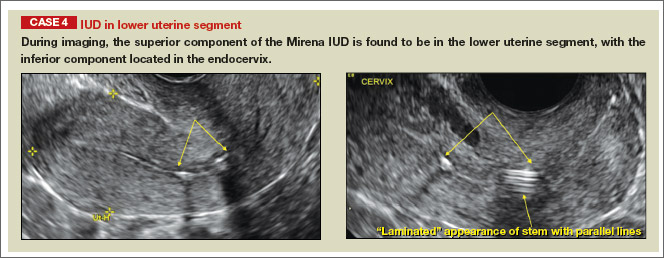

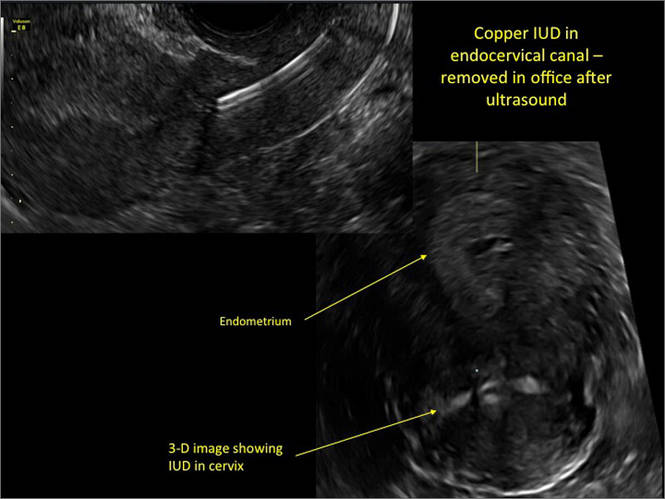

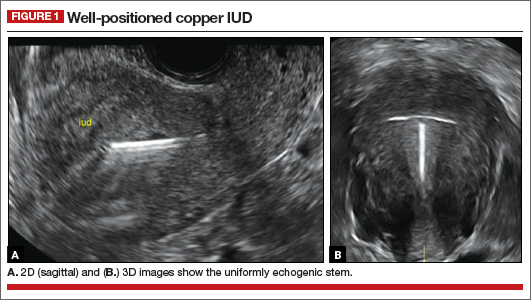

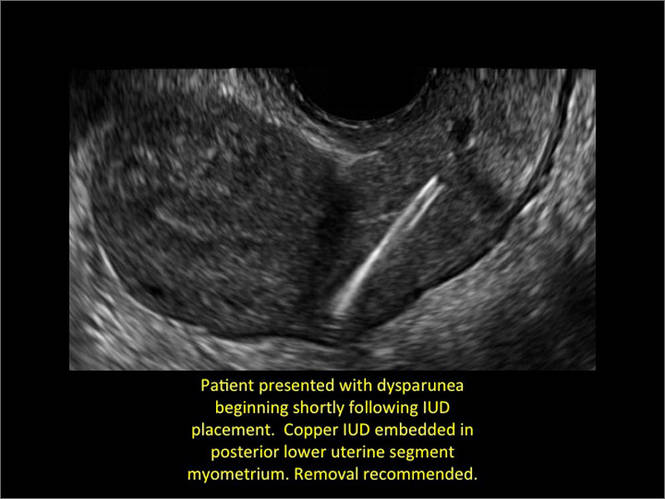

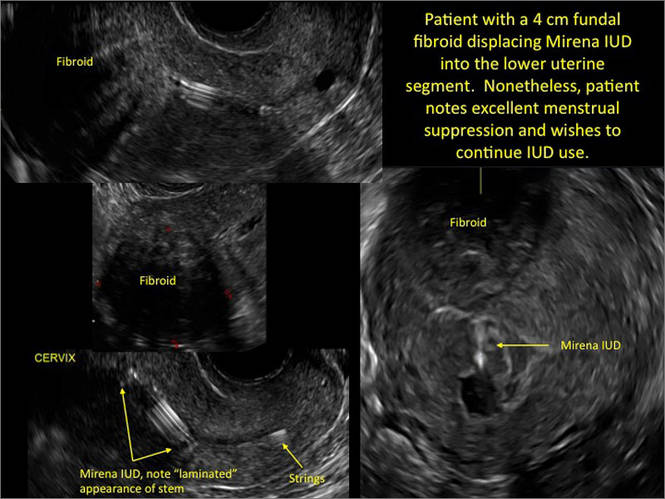

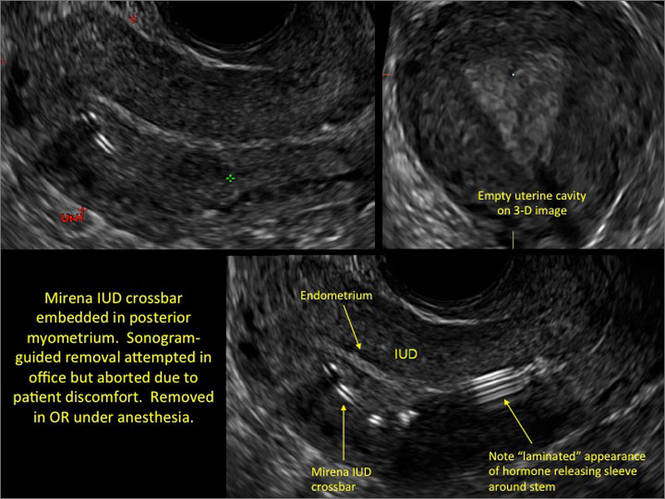

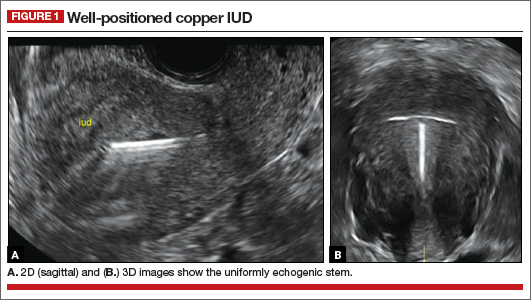

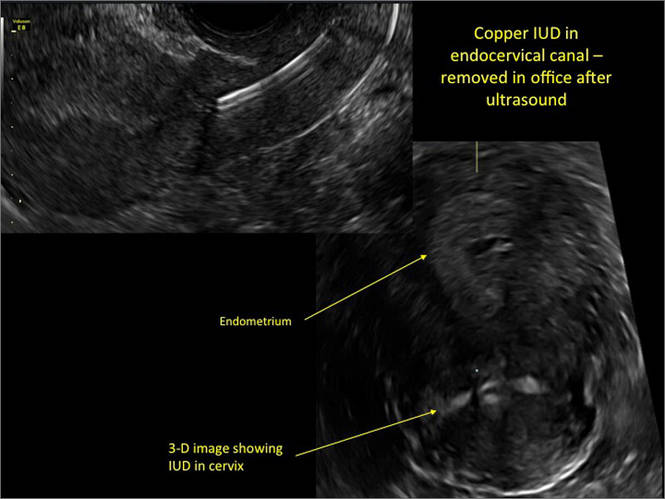

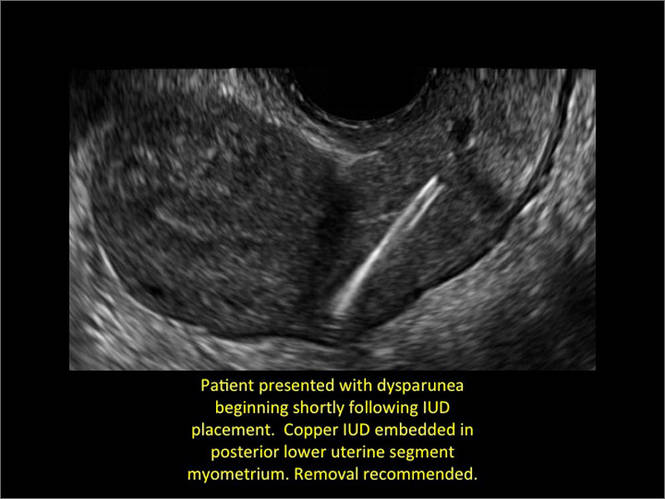

- Copper IUD: The central stem is uniformly echogenic due to its copper coils (FIGURE 1)

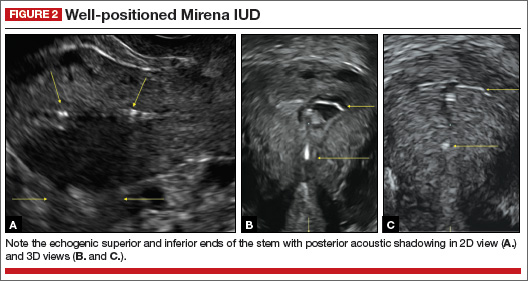

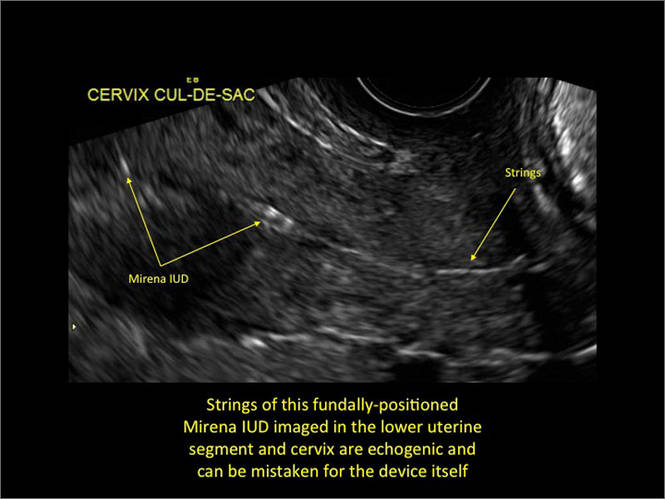

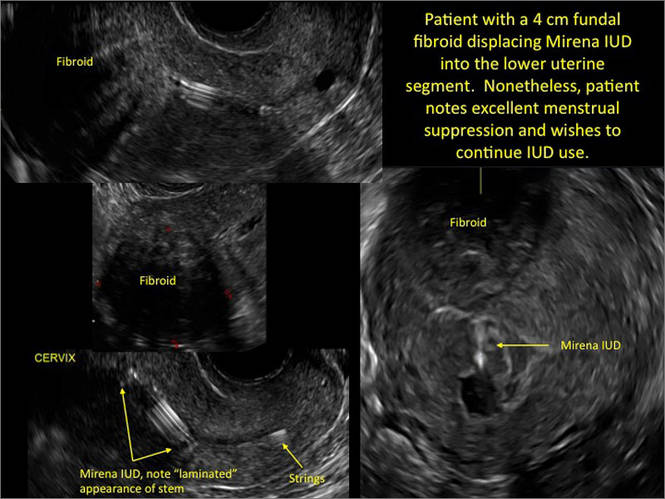

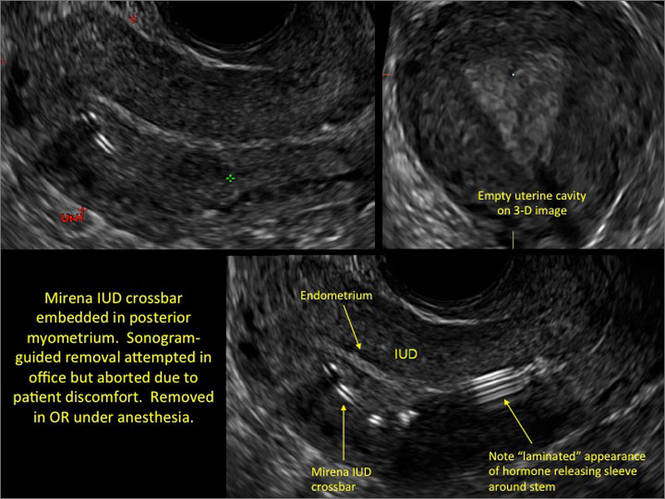

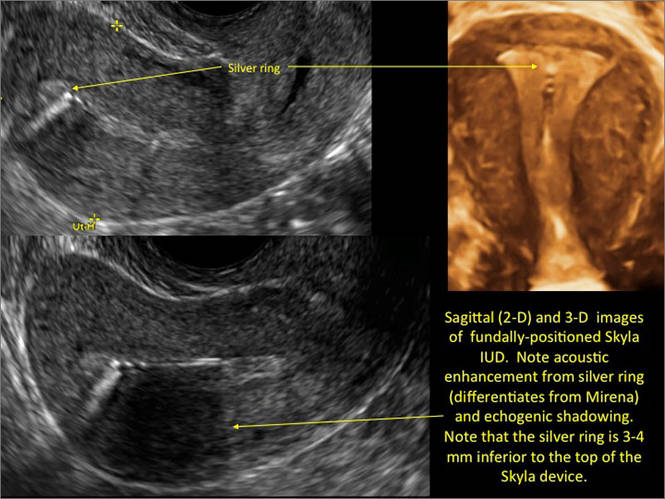

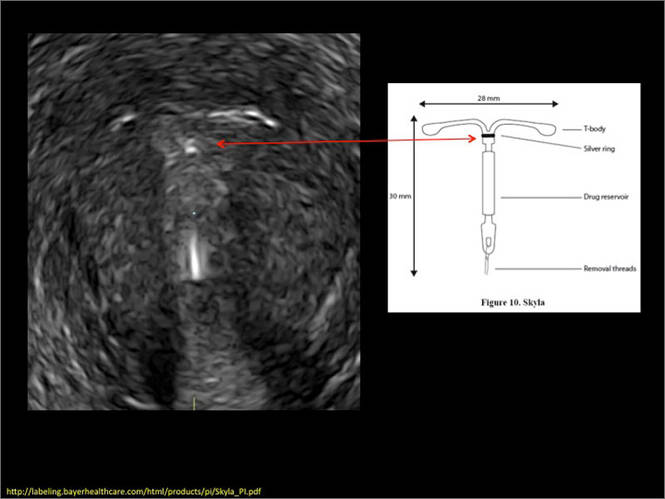

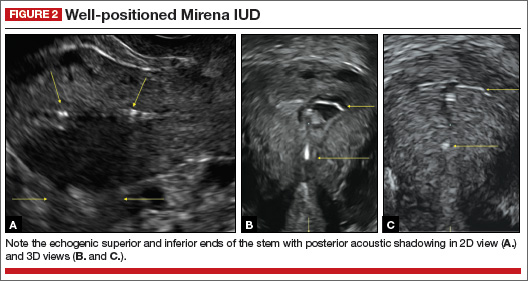

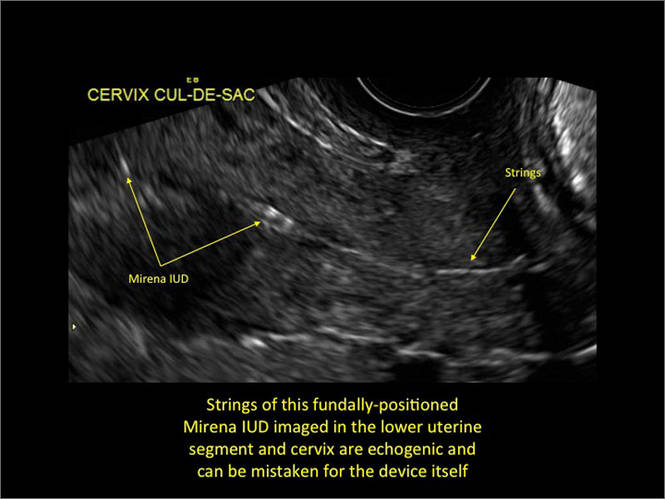

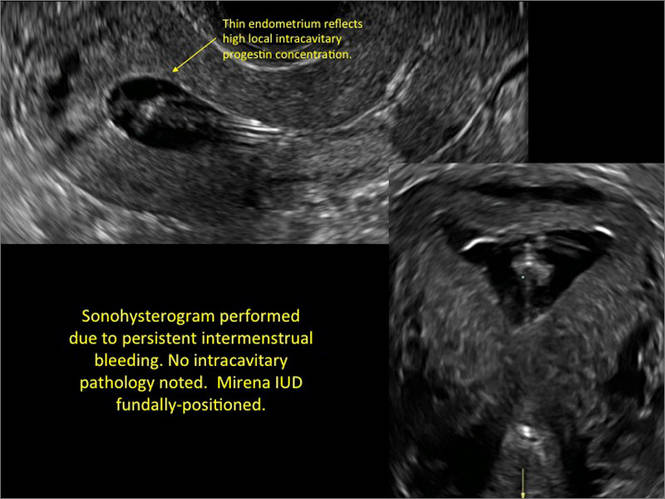

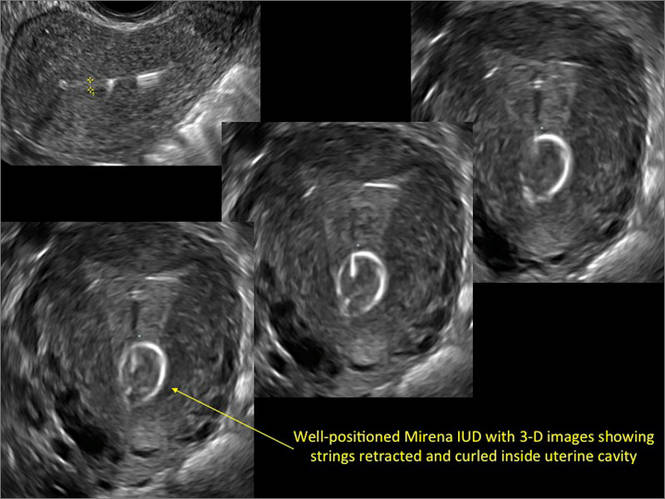

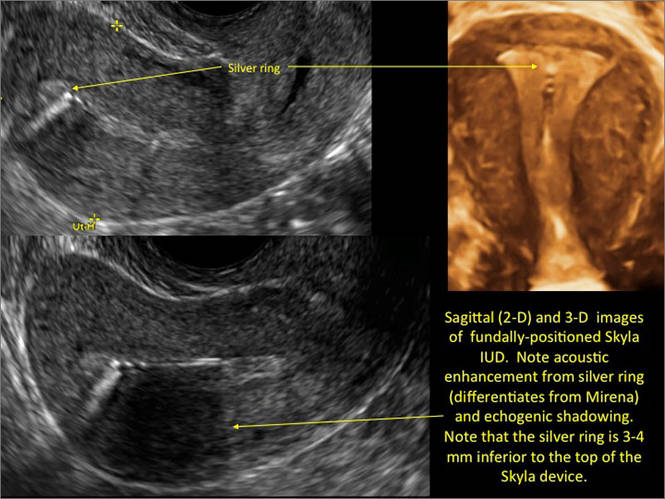

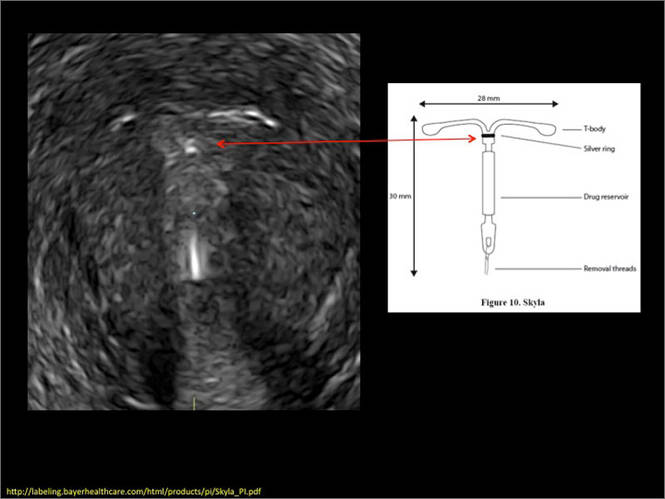

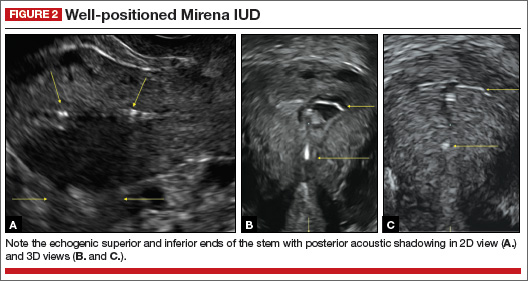

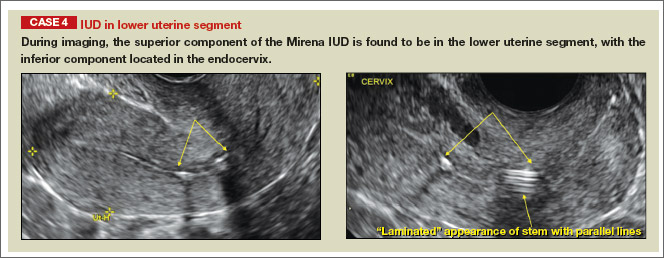

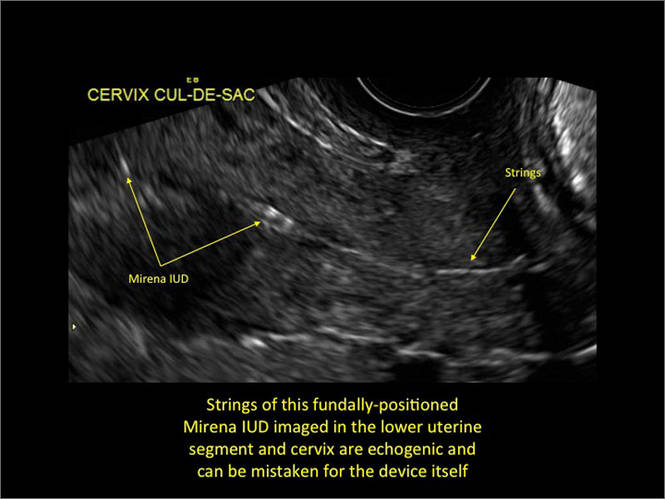

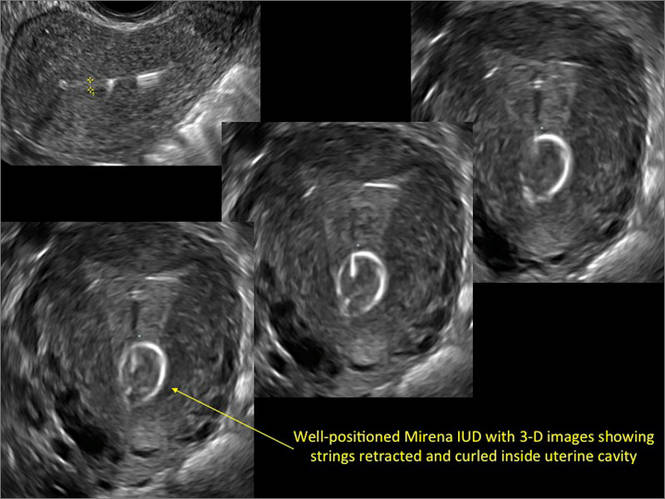

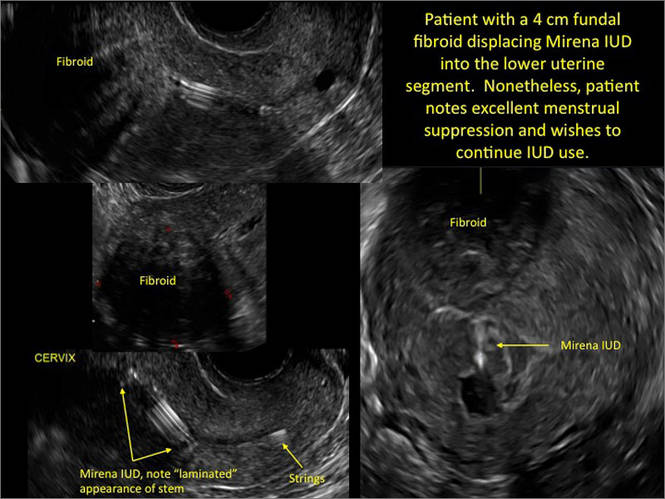

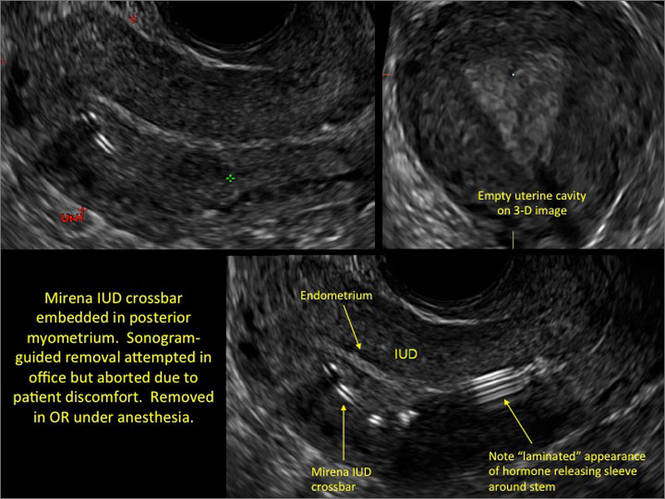

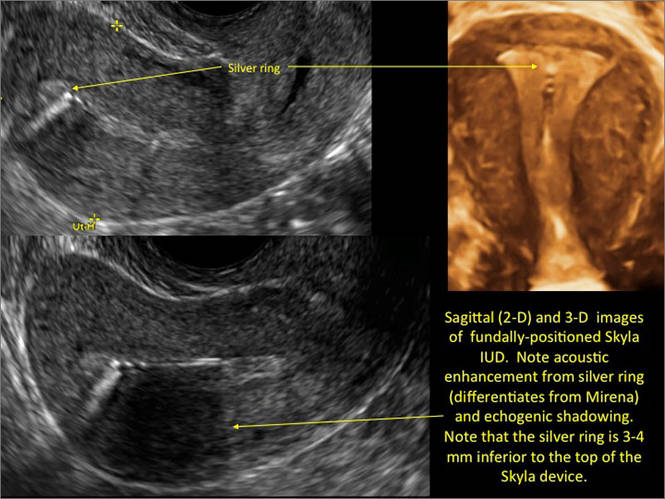

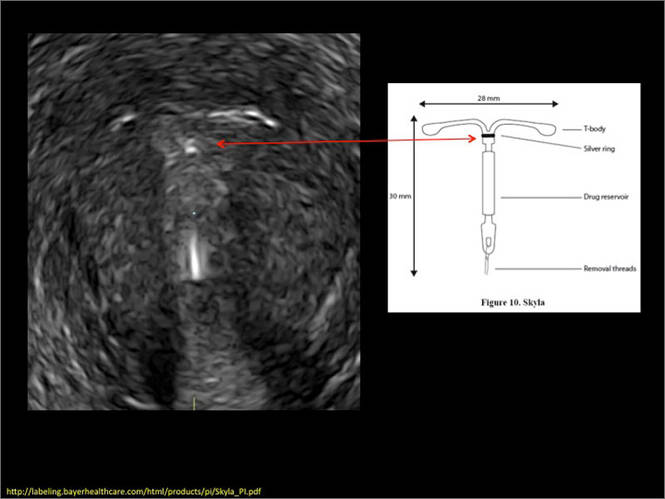

- Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS): The LNG-IUS consists of a plastic sleeve that contains the progestin and surrounds a central stem. This configuration causes acoustic shadowing and has a characteristic “laminated” sonographic appearance with parallel lines (FIGURE 2). The Mirena IUD has echogenic arms due to barium sulfate, as well as an echogenic distal tip, with acoustic shadowing from the stem. Skyla is similar except for a highly echogenic silver ring on the stem approximately 3 to 4 mm inferior to the crossbar. On occasion, the echogenic strings of Mirena and Skyla can be mistaken for the device.

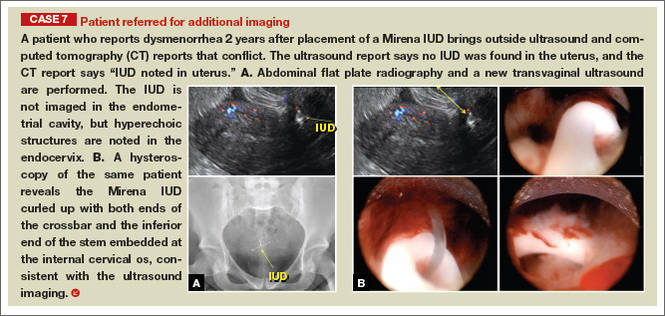

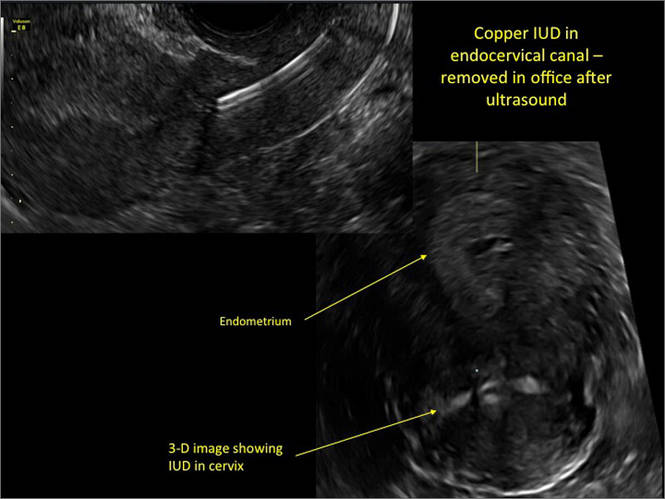

Three-dimensional ultrasound is useful in imaging of an IUD. If a patient’s IUD cannot be visualized by ultrasound, plain radiography of the kidney, ureter, and bladder may be helpful. If an IUD is not apparent on plain film, consider that it may have been expelled.

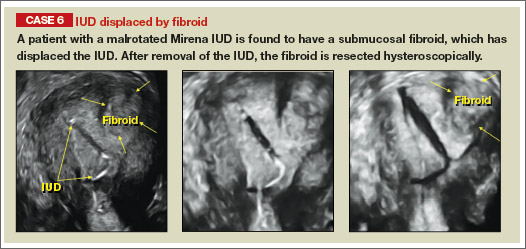

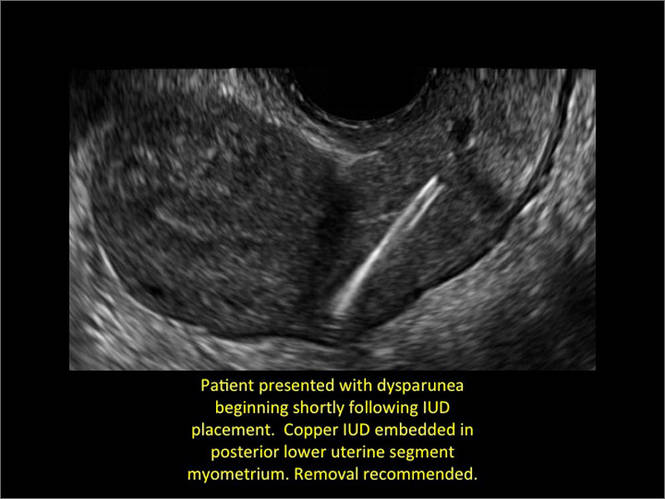

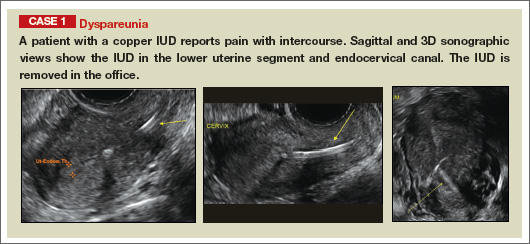

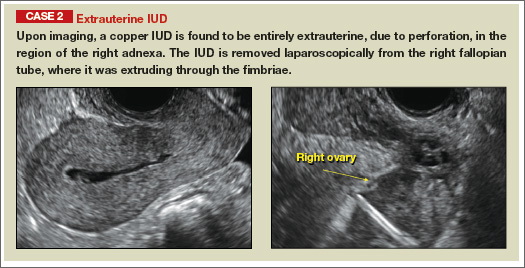

Potential malpositioningA malpositioned IUD may be partially expelled, rotated, embedded in the myometrium, or perforating the uterine serosa.

Related article: Malpositioned IUDs: When you should intervene (and when you should not). Kari Braaten, MD, MPH, and Alisa B. Goldberg, MD, MPH (August 2012)

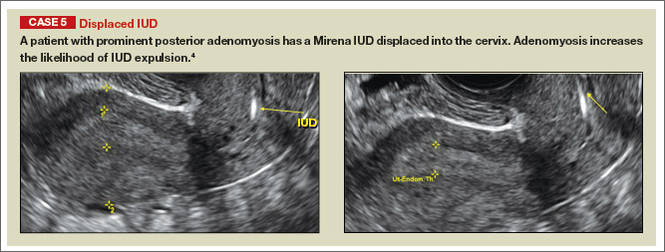

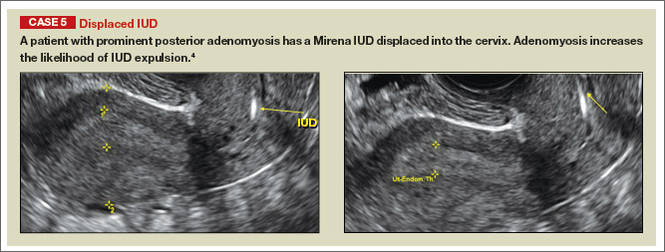

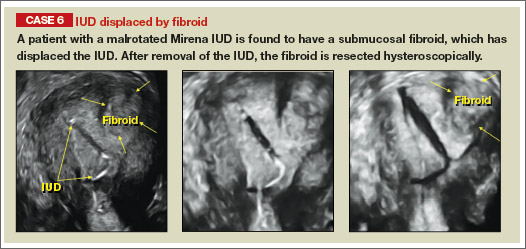

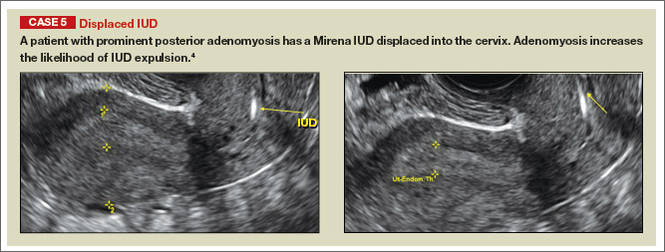

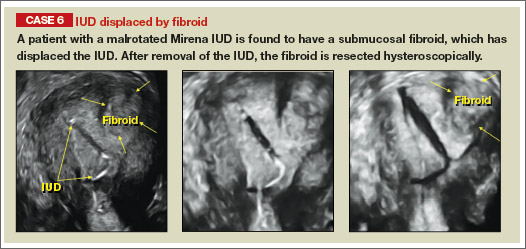

In a retrospective case-control study that compared 182 women with sonographicallyidentified malpositioned IUDs with 182 women with properly positioned IUDs, Braaten and colleagues found that suspected adenomyosis was associated with malpositioning (odds ratio [OR], 3.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.08–8.52), but a history of vaginal delivery was protective (OR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.32–0.87).2 A distorted uterine cavity also increases the risk of malpositioning.3

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

Although no uterine perforations were reported in a review of the LNG-IUS, expulsions were reported and may be more common among women who use the IUD for heavy menstrual bleeding.4

Additional images

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU! Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

1. Peri N, Graha D, Levine D. Imaging of intrauterine contraceptive devices. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26(10):1389–1401.

2. Braaten KP, Benson CB, Maurer R, Goldberg AB. Malpositioned intrauterine contraceptive devices: Risk factors, outcomes, and future pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(5):1014–1020.

3. Braaten KP, Goldberg AB. Malpositioned IUDs: When you should intervene and when you should not. OBG Manag. 2012;24(8):39–46.

4. Kaunitz AM, Inki P. The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in heavy menstrual bleeding: a benefit-risk review. Drugs. 2012;72(2):193–215.

Although an ultrasound is not required after uncomplicated placement of an intrauterine device (IUD) or during routine management of women who are doing well with an IUD, it is invaluable in the evaluation of patients who present with pain or other symptoms suggestive of IUD malpositioning.

In this article, we outline the sonographic features of the IUDs available today in the United States and describe the basics of localization by ultrasound.

Related articles: STOP relying on 2D ultrasound for IUD localization. Steven R. Goldstein, MD, and Chrystie Fujimoto, MD (August 2014)

Update on Contraception. Melissa J. Chen, MD, MPH, and Mitchell D. Creinin, MD (August 2014)

Ultrasound features of IUDsWhen positioned normally, an IUD is centrally located within the endometrial cavity, with the crossbar positioned in the fundal area.1 Copper and progestin-releasing IUDs can be identified easily on ultrasound if one is familiar with their basic sonographic features:

- Copper IUD: The central stem is uniformly echogenic due to its copper coils (FIGURE 1)

- Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS): The LNG-IUS consists of a plastic sleeve that contains the progestin and surrounds a central stem. This configuration causes acoustic shadowing and has a characteristic “laminated” sonographic appearance with parallel lines (FIGURE 2). The Mirena IUD has echogenic arms due to barium sulfate, as well as an echogenic distal tip, with acoustic shadowing from the stem. Skyla is similar except for a highly echogenic silver ring on the stem approximately 3 to 4 mm inferior to the crossbar. On occasion, the echogenic strings of Mirena and Skyla can be mistaken for the device.

Three-dimensional ultrasound is useful in imaging of an IUD. If a patient’s IUD cannot be visualized by ultrasound, plain radiography of the kidney, ureter, and bladder may be helpful. If an IUD is not apparent on plain film, consider that it may have been expelled.

Potential malpositioningA malpositioned IUD may be partially expelled, rotated, embedded in the myometrium, or perforating the uterine serosa.

Related article: Malpositioned IUDs: When you should intervene (and when you should not). Kari Braaten, MD, MPH, and Alisa B. Goldberg, MD, MPH (August 2012)

In a retrospective case-control study that compared 182 women with sonographicallyidentified malpositioned IUDs with 182 women with properly positioned IUDs, Braaten and colleagues found that suspected adenomyosis was associated with malpositioning (odds ratio [OR], 3.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.08–8.52), but a history of vaginal delivery was protective (OR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.32–0.87).2 A distorted uterine cavity also increases the risk of malpositioning.3

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

Although no uterine perforations were reported in a review of the LNG-IUS, expulsions were reported and may be more common among women who use the IUD for heavy menstrual bleeding.4

Additional images

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU! Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

Although an ultrasound is not required after uncomplicated placement of an intrauterine device (IUD) or during routine management of women who are doing well with an IUD, it is invaluable in the evaluation of patients who present with pain or other symptoms suggestive of IUD malpositioning.

In this article, we outline the sonographic features of the IUDs available today in the United States and describe the basics of localization by ultrasound.

Related articles: STOP relying on 2D ultrasound for IUD localization. Steven R. Goldstein, MD, and Chrystie Fujimoto, MD (August 2014)

Update on Contraception. Melissa J. Chen, MD, MPH, and Mitchell D. Creinin, MD (August 2014)

Ultrasound features of IUDsWhen positioned normally, an IUD is centrally located within the endometrial cavity, with the crossbar positioned in the fundal area.1 Copper and progestin-releasing IUDs can be identified easily on ultrasound if one is familiar with their basic sonographic features:

- Copper IUD: The central stem is uniformly echogenic due to its copper coils (FIGURE 1)

- Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS): The LNG-IUS consists of a plastic sleeve that contains the progestin and surrounds a central stem. This configuration causes acoustic shadowing and has a characteristic “laminated” sonographic appearance with parallel lines (FIGURE 2). The Mirena IUD has echogenic arms due to barium sulfate, as well as an echogenic distal tip, with acoustic shadowing from the stem. Skyla is similar except for a highly echogenic silver ring on the stem approximately 3 to 4 mm inferior to the crossbar. On occasion, the echogenic strings of Mirena and Skyla can be mistaken for the device.

Three-dimensional ultrasound is useful in imaging of an IUD. If a patient’s IUD cannot be visualized by ultrasound, plain radiography of the kidney, ureter, and bladder may be helpful. If an IUD is not apparent on plain film, consider that it may have been expelled.

Potential malpositioningA malpositioned IUD may be partially expelled, rotated, embedded in the myometrium, or perforating the uterine serosa.

Related article: Malpositioned IUDs: When you should intervene (and when you should not). Kari Braaten, MD, MPH, and Alisa B. Goldberg, MD, MPH (August 2012)

In a retrospective case-control study that compared 182 women with sonographicallyidentified malpositioned IUDs with 182 women with properly positioned IUDs, Braaten and colleagues found that suspected adenomyosis was associated with malpositioning (odds ratio [OR], 3.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.08–8.52), but a history of vaginal delivery was protective (OR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.32–0.87).2 A distorted uterine cavity also increases the risk of malpositioning.3

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

Although no uterine perforations were reported in a review of the LNG-IUS, expulsions were reported and may be more common among women who use the IUD for heavy menstrual bleeding.4

Additional images

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU! Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

1. Peri N, Graha D, Levine D. Imaging of intrauterine contraceptive devices. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26(10):1389–1401.

2. Braaten KP, Benson CB, Maurer R, Goldberg AB. Malpositioned intrauterine contraceptive devices: Risk factors, outcomes, and future pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(5):1014–1020.

3. Braaten KP, Goldberg AB. Malpositioned IUDs: When you should intervene and when you should not. OBG Manag. 2012;24(8):39–46.

4. Kaunitz AM, Inki P. The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in heavy menstrual bleeding: a benefit-risk review. Drugs. 2012;72(2):193–215.

1. Peri N, Graha D, Levine D. Imaging of intrauterine contraceptive devices. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26(10):1389–1401.

2. Braaten KP, Benson CB, Maurer R, Goldberg AB. Malpositioned intrauterine contraceptive devices: Risk factors, outcomes, and future pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(5):1014–1020.

3. Braaten KP, Goldberg AB. Malpositioned IUDs: When you should intervene and when you should not. OBG Manag. 2012;24(8):39–46.

4. Kaunitz AM, Inki P. The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in heavy menstrual bleeding: a benefit-risk review. Drugs. 2012;72(2):193–215.

Hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation

One of the hottest and most controversial topics in gynecologic surgery, at present, is laparoscopic electromechanical power morcellation.

In April of this year, the Food and Drug Administration sent out a news release regarding the potential risk of spread of sarcomatous tissue at the time of this procedure. In that release, the agency "discouraged" use of laparoscopic electromechanical power morcellation. Responses came from many societies, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the AAGL, which indicated that laparoscopic electromechanical power morcellation could be used if proper care was taken.

I am personally proud that the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery has been very proactive and diligent in its discussion of laparoscopic electromechanical power morcellation. This is the third in our series regarding this topic.

In our first segment, I discussed the issue of electromechanical power morcellation relative to the inadvertent spread of sarcomatous tissue. In our second in the series, Dr. Ceana Nezhat, Dr. Bernard Taylor, and Dr. Tony Shibley discussed ways to minimize this risk – including morcellation in a bag. Videos of their individual techniques of electromechanical power morcellation, as well as that of Dr. Douglas Brown, can be viewed on SurgeryU. In addition, my partner, Dr. Aarathi Cholkeri-Singh, and I have a video on SurgeryU illustrating our technique of morcellation in a bag.

This current Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery is now devoted to hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation. In my discussions with physicians throughout the country relative to this technique, it has become evident that some institutions have not only banned the use of electromechanical power morcellation at time of laparoscopy, but have also stopped usage of hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation. While neither the FDA nor the lay press has ever questioned the use of hysteroscopic morcellators, I believe it is imperative that this topic be reviewed. I am sure that it will be obvious that hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation has thus far proved to be a safe and effective treatment option for various pathologic entities, including submucosal uterine fibroids.

To review hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation, I have invited Dr. Joseph S. Sanfilippo, professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Pittsburgh and director of the division of reproductive endocrinology and infertility at Magee-Womens Hospital in Pittsburgh.

Dr. Sanfilippo is a lecturer and educator. He has written an extensive number of peer-reviewed articles, and has been a contributor to several textbooks. In addition, Dr. Sanfilippo has been and remains a very active member of the AAGL.

It is a pleasure and honor to welcome Dr. Sanfilippo to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, the third installment on morcellation.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy, and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller disclosed that he is a consultant to Hologic and is on the speakers bureau for Smith & Nephew. Videos for this and past Master Class in Gynecology Surgery articles can be viewed on SurgeryU.

One of the hottest and most controversial topics in gynecologic surgery, at present, is laparoscopic electromechanical power morcellation.

In April of this year, the Food and Drug Administration sent out a news release regarding the potential risk of spread of sarcomatous tissue at the time of this procedure. In that release, the agency "discouraged" use of laparoscopic electromechanical power morcellation. Responses came from many societies, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the AAGL, which indicated that laparoscopic electromechanical power morcellation could be used if proper care was taken.

I am personally proud that the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery has been very proactive and diligent in its discussion of laparoscopic electromechanical power morcellation. This is the third in our series regarding this topic.

In our first segment, I discussed the issue of electromechanical power morcellation relative to the inadvertent spread of sarcomatous tissue. In our second in the series, Dr. Ceana Nezhat, Dr. Bernard Taylor, and Dr. Tony Shibley discussed ways to minimize this risk – including morcellation in a bag. Videos of their individual techniques of electromechanical power morcellation, as well as that of Dr. Douglas Brown, can be viewed on SurgeryU. In addition, my partner, Dr. Aarathi Cholkeri-Singh, and I have a video on SurgeryU illustrating our technique of morcellation in a bag.

This current Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery is now devoted to hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation. In my discussions with physicians throughout the country relative to this technique, it has become evident that some institutions have not only banned the use of electromechanical power morcellation at time of laparoscopy, but have also stopped usage of hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation. While neither the FDA nor the lay press has ever questioned the use of hysteroscopic morcellators, I believe it is imperative that this topic be reviewed. I am sure that it will be obvious that hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation has thus far proved to be a safe and effective treatment option for various pathologic entities, including submucosal uterine fibroids.

To review hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation, I have invited Dr. Joseph S. Sanfilippo, professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Pittsburgh and director of the division of reproductive endocrinology and infertility at Magee-Womens Hospital in Pittsburgh.

Dr. Sanfilippo is a lecturer and educator. He has written an extensive number of peer-reviewed articles, and has been a contributor to several textbooks. In addition, Dr. Sanfilippo has been and remains a very active member of the AAGL.

It is a pleasure and honor to welcome Dr. Sanfilippo to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, the third installment on morcellation.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy, and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller disclosed that he is a consultant to Hologic and is on the speakers bureau for Smith & Nephew. Videos for this and past Master Class in Gynecology Surgery articles can be viewed on SurgeryU.

One of the hottest and most controversial topics in gynecologic surgery, at present, is laparoscopic electromechanical power morcellation.

In April of this year, the Food and Drug Administration sent out a news release regarding the potential risk of spread of sarcomatous tissue at the time of this procedure. In that release, the agency "discouraged" use of laparoscopic electromechanical power morcellation. Responses came from many societies, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the AAGL, which indicated that laparoscopic electromechanical power morcellation could be used if proper care was taken.

I am personally proud that the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery has been very proactive and diligent in its discussion of laparoscopic electromechanical power morcellation. This is the third in our series regarding this topic.

In our first segment, I discussed the issue of electromechanical power morcellation relative to the inadvertent spread of sarcomatous tissue. In our second in the series, Dr. Ceana Nezhat, Dr. Bernard Taylor, and Dr. Tony Shibley discussed ways to minimize this risk – including morcellation in a bag. Videos of their individual techniques of electromechanical power morcellation, as well as that of Dr. Douglas Brown, can be viewed on SurgeryU. In addition, my partner, Dr. Aarathi Cholkeri-Singh, and I have a video on SurgeryU illustrating our technique of morcellation in a bag.

This current Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery is now devoted to hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation. In my discussions with physicians throughout the country relative to this technique, it has become evident that some institutions have not only banned the use of electromechanical power morcellation at time of laparoscopy, but have also stopped usage of hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation. While neither the FDA nor the lay press has ever questioned the use of hysteroscopic morcellators, I believe it is imperative that this topic be reviewed. I am sure that it will be obvious that hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation has thus far proved to be a safe and effective treatment option for various pathologic entities, including submucosal uterine fibroids.

To review hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation, I have invited Dr. Joseph S. Sanfilippo, professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Pittsburgh and director of the division of reproductive endocrinology and infertility at Magee-Womens Hospital in Pittsburgh.

Dr. Sanfilippo is a lecturer and educator. He has written an extensive number of peer-reviewed articles, and has been a contributor to several textbooks. In addition, Dr. Sanfilippo has been and remains a very active member of the AAGL.

It is a pleasure and honor to welcome Dr. Sanfilippo to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, the third installment on morcellation.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy, and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller disclosed that he is a consultant to Hologic and is on the speakers bureau for Smith & Nephew. Videos for this and past Master Class in Gynecology Surgery articles can be viewed on SurgeryU.

Hysteroscopic morcellation – a very different entity

Submucous leiomyomas are the most problematic type of fibroid and have been associated with abnormal uterine bleeding, infertility, and other clinical issues. Treatment has been shown to be effective in improving fertility and success rates with assisted reproduction.

Newer hysteroscopic surgical techniques and morcellation technology allow us to remove not only polyps, but selected submucous myomas, in a fashion that is not only minimally invasive but that also raises few if any concerns about spreading or upstaging an unsuspected leiomyosarcoma. In this respect, the controversy over laparoscopic power morcellation does not extend to hysteroscopic morcellation.

Such a distinction was made during opening remarks at a meeting in June 2014 of the Obstetrics & Gynecology Devices Panel of the Food and Drug Administration’s Medical Devices Advisory Committee, which was charged with addressing such concerns.

Dr. Aron Yustein, deputy director of clinical affairs and chief medical officer of the FDA’s Office of Surveillance and Biometrics, explained that the panel would not address hysteroscopic morcellators "as we do not believe that when used [as intended], they pose the same risk" as that of laparoscopic morcellation in terms of potentially disseminating and upstaging an undetected uterine malignancy.

In hysteroscopic morcellation, tissue is contained and delivered through the morcellation system into a trap, or collecting pouch. This allows for complete capture and histopathologic assessment of all fragments extracted from the uterine cavity.

Numerous equipment options are currently available to gynecologic surgeons for hysteroscopically-guided myomectomy: Newer systems such as the Gynecare VersaPoint (Ethicon Endo-Surgery), and the Symphion system (Boston Scientific) facilitate bipolar electrosurgical resection. MyoSure (Hologic) and TRUCLEAR (Smith & Nephew), on the other hand, are hysteroscopic morcellators; they both use mechanical energy rather than high-frequency electrical energy to simultaneously cut and aspirate tissue.

Common to each of these options are advanced, automated fluid management systems that continuously measure distending media input and output, intrauterine distension pressure, and fluid deficit volume throughout the procedure. Such monitoring is critical to preventing excess fluid absorption and its associated complications. The new fluid management systems allow excellent visualization of the intrauterine cavity.

Benefit of Treatment

Leiomyomas, synonymously known as myomas, are among the uterine bleeding abnormalities included in a new classification system introduced in 2011 by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics. The system classifies the causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-aged women; it is known by the acronym PALM-COEIN, for polyp, adenomyosis, leiomyoma, malignancy and hyperplasia, coagulopathy, ovulatory dysfunction, endometrial, iatrogenic, and not yet classified.

In a practice bulletin published in 2012, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists endorsed the nomenclature system and provided guidelines for evaluating reproductive-aged patients with abnormal uterine bleeding (Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;120:197-206).

The diagnosis and management of submucous leiomyomas is particularly important in cases of infertility, as these types of myomas (compared with intramural or subserosal) appear to have the greatest impact on pregnancy and implantation rates.

In general, uterine myomas are found in 5%-10% of women with infertility. In 1%-3% of infertility patients, myomas are the only abnormal findings. As described in a literature review, it is believed that myomas may interfere with sperm transport or access, and with implantation. Endometrial cavity deformity, cornual ostia obstruction, altered uterine contractility, and altered endometrial development may each play a role (Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 2006;33:145-52).

Studies evaluating the impact of myomectomy on fertility outcomes provide evidence that submucous myomas should be removed before assisted reproductive technology/in vitro fertilization. According to the AAGL’s practice guidelines on the diagnosis and management of submucous leiomyomas, it "seems clear from high-quality studies that pregnancy rates are higher after myomectomy than no or ‘placebo’ procedures" (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19:152-71).

The most widely used system for categorizing submucous myomas, developed by the European Society of Gynecological Endoscopy (ESGE), breaks them into three subtypes according to how much of the lesion’s diameter is contained within the myometrium: Type 0 myomas are entirely within the endometrial cavity, while type I have less than 50% myometrial extension, and type II are 50% or more within the myometrium.

It is the ESGE type 0 submucous myomas that are appropriate for resectoscopic surgery.

(Another system known as the STEPW classification system adds other categories, taking into account factors such as topography, extension of the base, and penetration. This system is becoming more recognized and may be useful in the future for evaluating patients for resectoscopic surgery and predicting outcomes, but it is not being used as often as the ESGE classification system.)

As the AAGL guidelines state, diagnosis is generally achieved with one or a combination of hysteroscopic and radiological techniques that may include transvaginal ultrasonography, saline infusion sonohysterography, and magnetic resonance imaging.

Research on safety

Hysteroscopic morcellation is the most recent operative hysteroscopic technique to be employed for the removal of submucous leiomyomas. In lieu of concerns about laparoscopic power morcellation, the question arises: Should we be concerned about cancer and hysteroscopy?

Numerous studies have looked at the question of whether hysteroscopic procedures produce intraperitoneal spread of endometrial cancer cells and, if so, whether this results in the "upstaging" of unsuspected cancer. Much of the research has involved diagnostic hysteroscopy, which includes the use of intrauterine cavity distension with fluid media, similar to that of operative hysteroscopy.

Investigators at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York, for instance, looked retrospectively at whether initial diagnostic procedures were associated with abnormal peritoneal washings (PW) in almost 300 women who were treated for endometrial carcinoma with hysterectomy and intraoperative PW. They found no association between the initial diagnostic procedures, including hysteroscopy, and the results of peritoneal cytology (Cancer 2000;90:143-7).

Similarly, physicians in the Czech Republic compared PW done at the start of surgery in 134 patients whose endometrial carcinoma had been diagnosed by hysteroscopy with 61 patients whose cancer had been diagnosed by dilation and curettage. The results, they said, suggest that hysteroscopy does not increase the risk of penetration of tumor cells into the peritoneal cavity more than does D&C (Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2001; 22:342-4).

Another retrospective study of 146 patients with endometrial cancer who underwent either D&C or office hysteroscopy showed that diagnostic hysteroscopy did not increase the risk of adnexal, abdominal, or retroperitoneal lymph node metastases, compared with D&C, although there was an increase in positive peritoneal cytology (Gynecol. Oncol. 2007;107:94-8).

At least two broader reviews/meta-analyses also show no evidence for an upstaging of cancer from hysteroscopic procedures performed in the presence of cancer.

A meta-analysis of 19 studies suggests that preoperative hysteroscopy resulted in a statistically significant higher risk of positive peritoneal cytology compared with no hysteroscopy, but there was no evidence to support avoiding diagnostic hysteroscopy prior to surgical intervention for endometrial cancer (Fertil. Steril. 2011;96:957-61).

A literature review covering studies published between 1980 and 2001 showed that while there might be an increased risk of peritoneal contamination by cancer cells after hysteroscopy, there is no evidence that these patients fare worse compared with patients who have undergone other diagnostic procedures (Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2004;59:280-4).

Surgical rather than diagnostic hysterectomy was the focus of one recent case report from Italy. The patient was a 52-year-old nulliparous woman with a leiomyosarcoma detected 2 months after a hysteroscopic resection of a presumed myoma. After resection, the myoma was determined to be an atypical "mitotically active" leiomyoma (Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2012;33:656-7).

The authors emphasize the "rarity" of this particular finding, and the available data overall offer no evidence for an upstaging of unsuspected endometrial cancer with hysteroscopic procedures. While hysteroscopy should not be used in cases of known cancer, as it does not facilitate treatment, there are no data that should lead us to be concerned about adverse effects in the presence of cancer.

Current systems

Traditionally, resectoscopy has posed numerous challenges for the removal of intracavitary lesions: Tissue removal has been difficult and time consuming. Visibility has been disrupted by gas bubbles, tissue fragments, blood clots, and cervical mucus. Multiple insertions have been required, raising the risk of embolism (a "piston effect"). There also have been concerns about the risk of perforation and about the learning curve.

Older resectoscopes – loop-electrode resectoscopes – were designed for monopolar electrosurgery, which requires the use of nonconductive, electrolyte-free solutions for uterine distension. This limited the amount of fluid absorption that could occur before procedures needed to be stopped.

The incorporation of bipolar instrumentation – and more recently, the development of hysteroscopic morcellation systems that use reciprocating blades driven by mechanical energy rather radiofrequency electrical energy – have enabled the use of electrolyte-containing distending media (saline or Ringer’s Lactate) and, consequently, a higher allowable amount of fluid absorption.

Saline is an ideal medium: It is isotonic, nonhemolytic, nonconductive, nontoxic, and rapidly cleared. The AAGL’s Practice Guidelines for the Management of Hysteroscopic Distending Media lists an intravasation safety limit of 2,500 cc for isotonic solution, compared with a maximum limit of 1,000 cc when using hypotonic solutions (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20:137-48). This higher cut-off means we can achieve the vast majority of myoma resections in one sitting.

Hysteroscopic morcellators have additional advantages, in my experience. They allow for the use of smaller-diameter hysteroscopes, which in turn requires less cervical dilation. They also have improved reciprocating blades that enable the resection of myomas in addition to endometrial polyps. Previously, the focus was primarily on hysteroscopic polypectomy.

As technology has advanced with tissue removal being instantaneous, there is simultaneous cutting and extraction, and resections are therefore quicker. Overall, there is better visualization and a lower risk of perforation. The learning curve is quicker.

In a randomized trial focused on polypectomy, hysteroscopic mechanical morcellation was superior to electrosurgical resection. The multicenter trial from the United Kingdom compared the two modalities for removal of endometrial polyps in 121 women, and found that hysteroscopic morcellation with a mechanical-based morcellator was significantly quicker for polyp removal (a median time of 5½ minutes, versus 10 minutes, approximately), less painful and more acceptable to women, and more likely to completely remove the polyps (98% compared with 83%), the investigators reported (Obstet. Gynecol. 2014;123:745-51).

The only surgical complications in either group were vasovagal reactions, which occurred in 2% (1 out of 62) and 10% (6 out of 59) of the hysteroscopic morcellation and electrosurgical resection procedures, respectively. There was one serious adverse event, with a woman treated 2 weeks after morcellation for endomyometritis.

Indeed, infection, perforation and cervical trauma, mechanical complications, and media-related complications (intravasation and gas embolism) are risks with all modalities of operative hysteroscopy and all indications. Bleeding appears rarely to be a problem with mechanical morcellation, however, as does perforation. Certainly, perforation that occurs with a nonelectrical morcellator will be significantly less complicating than when energy is engaged.

Our experience overall with resections of intracavitary polyps and small myomas via hysteroscopic morcellation in 50 cases indicates a mean operating time of 9.4 min, a mean fluid deficit of 329 milliliters, and a mean surgeon rating of 9, with 10 representing an excellent rating. We have had no intra-or postoperative hemorrhage, no obvious electrolyte changes, and uneventful recoveries.

The majority of our hysteroscopic morcellations are done under conscious sedation with the addition of a local anesthetic in the form of a paracervical block. A 200-mcg vaginal tablet of misoprostol (Cytotec) off label the night before surgery is the pretreatment strategy I most often employ for cervical preparation. To prevent infection, I prescribe one dose of a broad-spectrum antibiotic, such as a cephalosporin, to my patients receiving myomectomies.

To learn hysteroscopic morcellation, one should begin with polypectomy and move to myomectomy once comfortable. With the TRUCLEAR system, the system I use most frequently, the hysteroscopic sheath should be inserted with the obturator in place to lessen cervical trauma.

The early flow of saline will not only aid the insertion process, it will assist in achieving good visualization quickly, as will increasing the uterine pressure setting at the start of the process. After the beginning of the procedure, however, pressure is maintained at the lowest setting capable of achieving adequate distension and providing good visualization.

When morcellating pathology, one should work from the periphery to the base. The pathology is kept between the morcellator blade opening and the optics of the camera. Large myomas can be split in half, with each half approached from distal to proximal.

Running the morcellator in the open cavity for a short time will aid in clearing the visual field of debris. Overall, however, visualization with today’s hysteroscopic morcellators and advancements in fluid management is excellent. In our experience, hysteroscopic morcellation is proving to be a safe and effective tool for performing myomectomy and addressing problems of infertility and abnormal uterine bleeding.

Dr. Sanfilippo is professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Pittsburgh and director of the division of reproductive endocrinology and infertility at Magee-Womens Hospital in Pittsburgh. He is on the advisory board for Bayer Healthcare and Smith &Nephew. A lecturer and educator, Dr. Sanfilippo has written peer-reviewed articles and has been a contributor to several textbooks. He is a member of the AAGL.

Submucous leiomyomas are the most problematic type of fibroid and have been associated with abnormal uterine bleeding, infertility, and other clinical issues. Treatment has been shown to be effective in improving fertility and success rates with assisted reproduction.

Newer hysteroscopic surgical techniques and morcellation technology allow us to remove not only polyps, but selected submucous myomas, in a fashion that is not only minimally invasive but that also raises few if any concerns about spreading or upstaging an unsuspected leiomyosarcoma. In this respect, the controversy over laparoscopic power morcellation does not extend to hysteroscopic morcellation.

Such a distinction was made during opening remarks at a meeting in June 2014 of the Obstetrics & Gynecology Devices Panel of the Food and Drug Administration’s Medical Devices Advisory Committee, which was charged with addressing such concerns.

Dr. Aron Yustein, deputy director of clinical affairs and chief medical officer of the FDA’s Office of Surveillance and Biometrics, explained that the panel would not address hysteroscopic morcellators "as we do not believe that when used [as intended], they pose the same risk" as that of laparoscopic morcellation in terms of potentially disseminating and upstaging an undetected uterine malignancy.

In hysteroscopic morcellation, tissue is contained and delivered through the morcellation system into a trap, or collecting pouch. This allows for complete capture and histopathologic assessment of all fragments extracted from the uterine cavity.

Numerous equipment options are currently available to gynecologic surgeons for hysteroscopically-guided myomectomy: Newer systems such as the Gynecare VersaPoint (Ethicon Endo-Surgery), and the Symphion system (Boston Scientific) facilitate bipolar electrosurgical resection. MyoSure (Hologic) and TRUCLEAR (Smith & Nephew), on the other hand, are hysteroscopic morcellators; they both use mechanical energy rather than high-frequency electrical energy to simultaneously cut and aspirate tissue.

Common to each of these options are advanced, automated fluid management systems that continuously measure distending media input and output, intrauterine distension pressure, and fluid deficit volume throughout the procedure. Such monitoring is critical to preventing excess fluid absorption and its associated complications. The new fluid management systems allow excellent visualization of the intrauterine cavity.

Benefit of Treatment

Leiomyomas, synonymously known as myomas, are among the uterine bleeding abnormalities included in a new classification system introduced in 2011 by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics. The system classifies the causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-aged women; it is known by the acronym PALM-COEIN, for polyp, adenomyosis, leiomyoma, malignancy and hyperplasia, coagulopathy, ovulatory dysfunction, endometrial, iatrogenic, and not yet classified.

In a practice bulletin published in 2012, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists endorsed the nomenclature system and provided guidelines for evaluating reproductive-aged patients with abnormal uterine bleeding (Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;120:197-206).

The diagnosis and management of submucous leiomyomas is particularly important in cases of infertility, as these types of myomas (compared with intramural or subserosal) appear to have the greatest impact on pregnancy and implantation rates.

In general, uterine myomas are found in 5%-10% of women with infertility. In 1%-3% of infertility patients, myomas are the only abnormal findings. As described in a literature review, it is believed that myomas may interfere with sperm transport or access, and with implantation. Endometrial cavity deformity, cornual ostia obstruction, altered uterine contractility, and altered endometrial development may each play a role (Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 2006;33:145-52).

Studies evaluating the impact of myomectomy on fertility outcomes provide evidence that submucous myomas should be removed before assisted reproductive technology/in vitro fertilization. According to the AAGL’s practice guidelines on the diagnosis and management of submucous leiomyomas, it "seems clear from high-quality studies that pregnancy rates are higher after myomectomy than no or ‘placebo’ procedures" (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19:152-71).

The most widely used system for categorizing submucous myomas, developed by the European Society of Gynecological Endoscopy (ESGE), breaks them into three subtypes according to how much of the lesion’s diameter is contained within the myometrium: Type 0 myomas are entirely within the endometrial cavity, while type I have less than 50% myometrial extension, and type II are 50% or more within the myometrium.

It is the ESGE type 0 submucous myomas that are appropriate for resectoscopic surgery.

(Another system known as the STEPW classification system adds other categories, taking into account factors such as topography, extension of the base, and penetration. This system is becoming more recognized and may be useful in the future for evaluating patients for resectoscopic surgery and predicting outcomes, but it is not being used as often as the ESGE classification system.)

As the AAGL guidelines state, diagnosis is generally achieved with one or a combination of hysteroscopic and radiological techniques that may include transvaginal ultrasonography, saline infusion sonohysterography, and magnetic resonance imaging.

Research on safety

Hysteroscopic morcellation is the most recent operative hysteroscopic technique to be employed for the removal of submucous leiomyomas. In lieu of concerns about laparoscopic power morcellation, the question arises: Should we be concerned about cancer and hysteroscopy?

Numerous studies have looked at the question of whether hysteroscopic procedures produce intraperitoneal spread of endometrial cancer cells and, if so, whether this results in the "upstaging" of unsuspected cancer. Much of the research has involved diagnostic hysteroscopy, which includes the use of intrauterine cavity distension with fluid media, similar to that of operative hysteroscopy.

Investigators at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York, for instance, looked retrospectively at whether initial diagnostic procedures were associated with abnormal peritoneal washings (PW) in almost 300 women who were treated for endometrial carcinoma with hysterectomy and intraoperative PW. They found no association between the initial diagnostic procedures, including hysteroscopy, and the results of peritoneal cytology (Cancer 2000;90:143-7).

Similarly, physicians in the Czech Republic compared PW done at the start of surgery in 134 patients whose endometrial carcinoma had been diagnosed by hysteroscopy with 61 patients whose cancer had been diagnosed by dilation and curettage. The results, they said, suggest that hysteroscopy does not increase the risk of penetration of tumor cells into the peritoneal cavity more than does D&C (Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2001; 22:342-4).

Another retrospective study of 146 patients with endometrial cancer who underwent either D&C or office hysteroscopy showed that diagnostic hysteroscopy did not increase the risk of adnexal, abdominal, or retroperitoneal lymph node metastases, compared with D&C, although there was an increase in positive peritoneal cytology (Gynecol. Oncol. 2007;107:94-8).

At least two broader reviews/meta-analyses also show no evidence for an upstaging of cancer from hysteroscopic procedures performed in the presence of cancer.

A meta-analysis of 19 studies suggests that preoperative hysteroscopy resulted in a statistically significant higher risk of positive peritoneal cytology compared with no hysteroscopy, but there was no evidence to support avoiding diagnostic hysteroscopy prior to surgical intervention for endometrial cancer (Fertil. Steril. 2011;96:957-61).

A literature review covering studies published between 1980 and 2001 showed that while there might be an increased risk of peritoneal contamination by cancer cells after hysteroscopy, there is no evidence that these patients fare worse compared with patients who have undergone other diagnostic procedures (Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2004;59:280-4).

Surgical rather than diagnostic hysterectomy was the focus of one recent case report from Italy. The patient was a 52-year-old nulliparous woman with a leiomyosarcoma detected 2 months after a hysteroscopic resection of a presumed myoma. After resection, the myoma was determined to be an atypical "mitotically active" leiomyoma (Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2012;33:656-7).

The authors emphasize the "rarity" of this particular finding, and the available data overall offer no evidence for an upstaging of unsuspected endometrial cancer with hysteroscopic procedures. While hysteroscopy should not be used in cases of known cancer, as it does not facilitate treatment, there are no data that should lead us to be concerned about adverse effects in the presence of cancer.

Current systems

Traditionally, resectoscopy has posed numerous challenges for the removal of intracavitary lesions: Tissue removal has been difficult and time consuming. Visibility has been disrupted by gas bubbles, tissue fragments, blood clots, and cervical mucus. Multiple insertions have been required, raising the risk of embolism (a "piston effect"). There also have been concerns about the risk of perforation and about the learning curve.

Older resectoscopes – loop-electrode resectoscopes – were designed for monopolar electrosurgery, which requires the use of nonconductive, electrolyte-free solutions for uterine distension. This limited the amount of fluid absorption that could occur before procedures needed to be stopped.

The incorporation of bipolar instrumentation – and more recently, the development of hysteroscopic morcellation systems that use reciprocating blades driven by mechanical energy rather radiofrequency electrical energy – have enabled the use of electrolyte-containing distending media (saline or Ringer’s Lactate) and, consequently, a higher allowable amount of fluid absorption.

Saline is an ideal medium: It is isotonic, nonhemolytic, nonconductive, nontoxic, and rapidly cleared. The AAGL’s Practice Guidelines for the Management of Hysteroscopic Distending Media lists an intravasation safety limit of 2,500 cc for isotonic solution, compared with a maximum limit of 1,000 cc when using hypotonic solutions (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20:137-48). This higher cut-off means we can achieve the vast majority of myoma resections in one sitting.

Hysteroscopic morcellators have additional advantages, in my experience. They allow for the use of smaller-diameter hysteroscopes, which in turn requires less cervical dilation. They also have improved reciprocating blades that enable the resection of myomas in addition to endometrial polyps. Previously, the focus was primarily on hysteroscopic polypectomy.

As technology has advanced with tissue removal being instantaneous, there is simultaneous cutting and extraction, and resections are therefore quicker. Overall, there is better visualization and a lower risk of perforation. The learning curve is quicker.

In a randomized trial focused on polypectomy, hysteroscopic mechanical morcellation was superior to electrosurgical resection. The multicenter trial from the United Kingdom compared the two modalities for removal of endometrial polyps in 121 women, and found that hysteroscopic morcellation with a mechanical-based morcellator was significantly quicker for polyp removal (a median time of 5½ minutes, versus 10 minutes, approximately), less painful and more acceptable to women, and more likely to completely remove the polyps (98% compared with 83%), the investigators reported (Obstet. Gynecol. 2014;123:745-51).

The only surgical complications in either group were vasovagal reactions, which occurred in 2% (1 out of 62) and 10% (6 out of 59) of the hysteroscopic morcellation and electrosurgical resection procedures, respectively. There was one serious adverse event, with a woman treated 2 weeks after morcellation for endomyometritis.

Indeed, infection, perforation and cervical trauma, mechanical complications, and media-related complications (intravasation and gas embolism) are risks with all modalities of operative hysteroscopy and all indications. Bleeding appears rarely to be a problem with mechanical morcellation, however, as does perforation. Certainly, perforation that occurs with a nonelectrical morcellator will be significantly less complicating than when energy is engaged.

Our experience overall with resections of intracavitary polyps and small myomas via hysteroscopic morcellation in 50 cases indicates a mean operating time of 9.4 min, a mean fluid deficit of 329 milliliters, and a mean surgeon rating of 9, with 10 representing an excellent rating. We have had no intra-or postoperative hemorrhage, no obvious electrolyte changes, and uneventful recoveries.

The majority of our hysteroscopic morcellations are done under conscious sedation with the addition of a local anesthetic in the form of a paracervical block. A 200-mcg vaginal tablet of misoprostol (Cytotec) off label the night before surgery is the pretreatment strategy I most often employ for cervical preparation. To prevent infection, I prescribe one dose of a broad-spectrum antibiotic, such as a cephalosporin, to my patients receiving myomectomies.

To learn hysteroscopic morcellation, one should begin with polypectomy and move to myomectomy once comfortable. With the TRUCLEAR system, the system I use most frequently, the hysteroscopic sheath should be inserted with the obturator in place to lessen cervical trauma.

The early flow of saline will not only aid the insertion process, it will assist in achieving good visualization quickly, as will increasing the uterine pressure setting at the start of the process. After the beginning of the procedure, however, pressure is maintained at the lowest setting capable of achieving adequate distension and providing good visualization.

When morcellating pathology, one should work from the periphery to the base. The pathology is kept between the morcellator blade opening and the optics of the camera. Large myomas can be split in half, with each half approached from distal to proximal.

Running the morcellator in the open cavity for a short time will aid in clearing the visual field of debris. Overall, however, visualization with today’s hysteroscopic morcellators and advancements in fluid management is excellent. In our experience, hysteroscopic morcellation is proving to be a safe and effective tool for performing myomectomy and addressing problems of infertility and abnormal uterine bleeding.

Dr. Sanfilippo is professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Pittsburgh and director of the division of reproductive endocrinology and infertility at Magee-Womens Hospital in Pittsburgh. He is on the advisory board for Bayer Healthcare and Smith &Nephew. A lecturer and educator, Dr. Sanfilippo has written peer-reviewed articles and has been a contributor to several textbooks. He is a member of the AAGL.

Submucous leiomyomas are the most problematic type of fibroid and have been associated with abnormal uterine bleeding, infertility, and other clinical issues. Treatment has been shown to be effective in improving fertility and success rates with assisted reproduction.

Newer hysteroscopic surgical techniques and morcellation technology allow us to remove not only polyps, but selected submucous myomas, in a fashion that is not only minimally invasive but that also raises few if any concerns about spreading or upstaging an unsuspected leiomyosarcoma. In this respect, the controversy over laparoscopic power morcellation does not extend to hysteroscopic morcellation.

Such a distinction was made during opening remarks at a meeting in June 2014 of the Obstetrics & Gynecology Devices Panel of the Food and Drug Administration’s Medical Devices Advisory Committee, which was charged with addressing such concerns.

Dr. Aron Yustein, deputy director of clinical affairs and chief medical officer of the FDA’s Office of Surveillance and Biometrics, explained that the panel would not address hysteroscopic morcellators "as we do not believe that when used [as intended], they pose the same risk" as that of laparoscopic morcellation in terms of potentially disseminating and upstaging an undetected uterine malignancy.

In hysteroscopic morcellation, tissue is contained and delivered through the morcellation system into a trap, or collecting pouch. This allows for complete capture and histopathologic assessment of all fragments extracted from the uterine cavity.

Numerous equipment options are currently available to gynecologic surgeons for hysteroscopically-guided myomectomy: Newer systems such as the Gynecare VersaPoint (Ethicon Endo-Surgery), and the Symphion system (Boston Scientific) facilitate bipolar electrosurgical resection. MyoSure (Hologic) and TRUCLEAR (Smith & Nephew), on the other hand, are hysteroscopic morcellators; they both use mechanical energy rather than high-frequency electrical energy to simultaneously cut and aspirate tissue.

Common to each of these options are advanced, automated fluid management systems that continuously measure distending media input and output, intrauterine distension pressure, and fluid deficit volume throughout the procedure. Such monitoring is critical to preventing excess fluid absorption and its associated complications. The new fluid management systems allow excellent visualization of the intrauterine cavity.

Benefit of Treatment

Leiomyomas, synonymously known as myomas, are among the uterine bleeding abnormalities included in a new classification system introduced in 2011 by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics. The system classifies the causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-aged women; it is known by the acronym PALM-COEIN, for polyp, adenomyosis, leiomyoma, malignancy and hyperplasia, coagulopathy, ovulatory dysfunction, endometrial, iatrogenic, and not yet classified.

In a practice bulletin published in 2012, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists endorsed the nomenclature system and provided guidelines for evaluating reproductive-aged patients with abnormal uterine bleeding (Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;120:197-206).

The diagnosis and management of submucous leiomyomas is particularly important in cases of infertility, as these types of myomas (compared with intramural or subserosal) appear to have the greatest impact on pregnancy and implantation rates.

In general, uterine myomas are found in 5%-10% of women with infertility. In 1%-3% of infertility patients, myomas are the only abnormal findings. As described in a literature review, it is believed that myomas may interfere with sperm transport or access, and with implantation. Endometrial cavity deformity, cornual ostia obstruction, altered uterine contractility, and altered endometrial development may each play a role (Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 2006;33:145-52).

Studies evaluating the impact of myomectomy on fertility outcomes provide evidence that submucous myomas should be removed before assisted reproductive technology/in vitro fertilization. According to the AAGL’s practice guidelines on the diagnosis and management of submucous leiomyomas, it "seems clear from high-quality studies that pregnancy rates are higher after myomectomy than no or ‘placebo’ procedures" (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19:152-71).

The most widely used system for categorizing submucous myomas, developed by the European Society of Gynecological Endoscopy (ESGE), breaks them into three subtypes according to how much of the lesion’s diameter is contained within the myometrium: Type 0 myomas are entirely within the endometrial cavity, while type I have less than 50% myometrial extension, and type II are 50% or more within the myometrium.

It is the ESGE type 0 submucous myomas that are appropriate for resectoscopic surgery.

(Another system known as the STEPW classification system adds other categories, taking into account factors such as topography, extension of the base, and penetration. This system is becoming more recognized and may be useful in the future for evaluating patients for resectoscopic surgery and predicting outcomes, but it is not being used as often as the ESGE classification system.)

As the AAGL guidelines state, diagnosis is generally achieved with one or a combination of hysteroscopic and radiological techniques that may include transvaginal ultrasonography, saline infusion sonohysterography, and magnetic resonance imaging.

Research on safety

Hysteroscopic morcellation is the most recent operative hysteroscopic technique to be employed for the removal of submucous leiomyomas. In lieu of concerns about laparoscopic power morcellation, the question arises: Should we be concerned about cancer and hysteroscopy?

Numerous studies have looked at the question of whether hysteroscopic procedures produce intraperitoneal spread of endometrial cancer cells and, if so, whether this results in the "upstaging" of unsuspected cancer. Much of the research has involved diagnostic hysteroscopy, which includes the use of intrauterine cavity distension with fluid media, similar to that of operative hysteroscopy.

Investigators at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York, for instance, looked retrospectively at whether initial diagnostic procedures were associated with abnormal peritoneal washings (PW) in almost 300 women who were treated for endometrial carcinoma with hysterectomy and intraoperative PW. They found no association between the initial diagnostic procedures, including hysteroscopy, and the results of peritoneal cytology (Cancer 2000;90:143-7).

Similarly, physicians in the Czech Republic compared PW done at the start of surgery in 134 patients whose endometrial carcinoma had been diagnosed by hysteroscopy with 61 patients whose cancer had been diagnosed by dilation and curettage. The results, they said, suggest that hysteroscopy does not increase the risk of penetration of tumor cells into the peritoneal cavity more than does D&C (Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2001; 22:342-4).

Another retrospective study of 146 patients with endometrial cancer who underwent either D&C or office hysteroscopy showed that diagnostic hysteroscopy did not increase the risk of adnexal, abdominal, or retroperitoneal lymph node metastases, compared with D&C, although there was an increase in positive peritoneal cytology (Gynecol. Oncol. 2007;107:94-8).

At least two broader reviews/meta-analyses also show no evidence for an upstaging of cancer from hysteroscopic procedures performed in the presence of cancer.

A meta-analysis of 19 studies suggests that preoperative hysteroscopy resulted in a statistically significant higher risk of positive peritoneal cytology compared with no hysteroscopy, but there was no evidence to support avoiding diagnostic hysteroscopy prior to surgical intervention for endometrial cancer (Fertil. Steril. 2011;96:957-61).

A literature review covering studies published between 1980 and 2001 showed that while there might be an increased risk of peritoneal contamination by cancer cells after hysteroscopy, there is no evidence that these patients fare worse compared with patients who have undergone other diagnostic procedures (Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2004;59:280-4).

Surgical rather than diagnostic hysterectomy was the focus of one recent case report from Italy. The patient was a 52-year-old nulliparous woman with a leiomyosarcoma detected 2 months after a hysteroscopic resection of a presumed myoma. After resection, the myoma was determined to be an atypical "mitotically active" leiomyoma (Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2012;33:656-7).

The authors emphasize the "rarity" of this particular finding, and the available data overall offer no evidence for an upstaging of unsuspected endometrial cancer with hysteroscopic procedures. While hysteroscopy should not be used in cases of known cancer, as it does not facilitate treatment, there are no data that should lead us to be concerned about adverse effects in the presence of cancer.

Current systems

Traditionally, resectoscopy has posed numerous challenges for the removal of intracavitary lesions: Tissue removal has been difficult and time consuming. Visibility has been disrupted by gas bubbles, tissue fragments, blood clots, and cervical mucus. Multiple insertions have been required, raising the risk of embolism (a "piston effect"). There also have been concerns about the risk of perforation and about the learning curve.

Older resectoscopes – loop-electrode resectoscopes – were designed for monopolar electrosurgery, which requires the use of nonconductive, electrolyte-free solutions for uterine distension. This limited the amount of fluid absorption that could occur before procedures needed to be stopped.

The incorporation of bipolar instrumentation – and more recently, the development of hysteroscopic morcellation systems that use reciprocating blades driven by mechanical energy rather radiofrequency electrical energy – have enabled the use of electrolyte-containing distending media (saline or Ringer’s Lactate) and, consequently, a higher allowable amount of fluid absorption.

Saline is an ideal medium: It is isotonic, nonhemolytic, nonconductive, nontoxic, and rapidly cleared. The AAGL’s Practice Guidelines for the Management of Hysteroscopic Distending Media lists an intravasation safety limit of 2,500 cc for isotonic solution, compared with a maximum limit of 1,000 cc when using hypotonic solutions (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20:137-48). This higher cut-off means we can achieve the vast majority of myoma resections in one sitting.

Hysteroscopic morcellators have additional advantages, in my experience. They allow for the use of smaller-diameter hysteroscopes, which in turn requires less cervical dilation. They also have improved reciprocating blades that enable the resection of myomas in addition to endometrial polyps. Previously, the focus was primarily on hysteroscopic polypectomy.

As technology has advanced with tissue removal being instantaneous, there is simultaneous cutting and extraction, and resections are therefore quicker. Overall, there is better visualization and a lower risk of perforation. The learning curve is quicker.

In a randomized trial focused on polypectomy, hysteroscopic mechanical morcellation was superior to electrosurgical resection. The multicenter trial from the United Kingdom compared the two modalities for removal of endometrial polyps in 121 women, and found that hysteroscopic morcellation with a mechanical-based morcellator was significantly quicker for polyp removal (a median time of 5½ minutes, versus 10 minutes, approximately), less painful and more acceptable to women, and more likely to completely remove the polyps (98% compared with 83%), the investigators reported (Obstet. Gynecol. 2014;123:745-51).

The only surgical complications in either group were vasovagal reactions, which occurred in 2% (1 out of 62) and 10% (6 out of 59) of the hysteroscopic morcellation and electrosurgical resection procedures, respectively. There was one serious adverse event, with a woman treated 2 weeks after morcellation for endomyometritis.

Indeed, infection, perforation and cervical trauma, mechanical complications, and media-related complications (intravasation and gas embolism) are risks with all modalities of operative hysteroscopy and all indications. Bleeding appears rarely to be a problem with mechanical morcellation, however, as does perforation. Certainly, perforation that occurs with a nonelectrical morcellator will be significantly less complicating than when energy is engaged.

Our experience overall with resections of intracavitary polyps and small myomas via hysteroscopic morcellation in 50 cases indicates a mean operating time of 9.4 min, a mean fluid deficit of 329 milliliters, and a mean surgeon rating of 9, with 10 representing an excellent rating. We have had no intra-or postoperative hemorrhage, no obvious electrolyte changes, and uneventful recoveries.

The majority of our hysteroscopic morcellations are done under conscious sedation with the addition of a local anesthetic in the form of a paracervical block. A 200-mcg vaginal tablet of misoprostol (Cytotec) off label the night before surgery is the pretreatment strategy I most often employ for cervical preparation. To prevent infection, I prescribe one dose of a broad-spectrum antibiotic, such as a cephalosporin, to my patients receiving myomectomies.

To learn hysteroscopic morcellation, one should begin with polypectomy and move to myomectomy once comfortable. With the TRUCLEAR system, the system I use most frequently, the hysteroscopic sheath should be inserted with the obturator in place to lessen cervical trauma.

The early flow of saline will not only aid the insertion process, it will assist in achieving good visualization quickly, as will increasing the uterine pressure setting at the start of the process. After the beginning of the procedure, however, pressure is maintained at the lowest setting capable of achieving adequate distension and providing good visualization.

When morcellating pathology, one should work from the periphery to the base. The pathology is kept between the morcellator blade opening and the optics of the camera. Large myomas can be split in half, with each half approached from distal to proximal.

Running the morcellator in the open cavity for a short time will aid in clearing the visual field of debris. Overall, however, visualization with today’s hysteroscopic morcellators and advancements in fluid management is excellent. In our experience, hysteroscopic morcellation is proving to be a safe and effective tool for performing myomectomy and addressing problems of infertility and abnormal uterine bleeding.

Dr. Sanfilippo is professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Pittsburgh and director of the division of reproductive endocrinology and infertility at Magee-Womens Hospital in Pittsburgh. He is on the advisory board for Bayer Healthcare and Smith &Nephew. A lecturer and educator, Dr. Sanfilippo has written peer-reviewed articles and has been a contributor to several textbooks. He is a member of the AAGL.

Conventional DMARDs may be excluded from psoriatic arthritis enthesitis guidelines

NEW YORK – Conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs will not be included among acceptable treatments for enthesitis related to psoriatic arthritis, according to a draft of guidelines being prepared for publication.

"The only controlled trial with a DMARD [disease-modifying antirheumatic drug] for enthesitis was conducted with sulfasalazine, and it was negative," said Dr. Evan L. Siegel, who is in group practice in rheumatology in Rockville, Md. Dr. Siegel led a group of experts preparing psoriatic arthritis enthesitis treatment recommendations to be issued by the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA).

In a preliminary report on the planned treatment recommendations, which were delivered at the joint meetings of GRAPPA and the Spondyloarthritis Research & Treatment Network (SPARTAN), Dr. Siegel reported that the new recommendations will recognize only two gradations of enthesitis: mild or moderate/severe.

"It is difficult to differentiate moderate from severe because these have not been treated as distinct entities in the clinical trials," Dr. Siegel said. Patients experience severity in regard to intensity of pain and limitation of function, either or both of which may represent severe enthesitis in any given individual patient, according to Dr. Siegel, who also noted that the number of sites of activity is also generally unhelpful.

"Significant activity at a single site may be sufficient to produce a major functional deficit in one individual, whereas the activity at multiple sites may not produce much symptomatology or functional loss in another," Dr. Siegel said.

Enthesitis, an inflammation at the site where tendons or ligaments attach to bone, has been reported in up to 70% of patients with psoriatic arthritis. In some patients, it is the dominant symptom. However, the number of treatment trials in which control of enthesitis is the primary outcome continues to be limited, according to Dr. Siegel. He acknowledged that many of the proposed treatment recommendations owed more to expert opinion than to data.

This is true of the proposed first-line recommendation, he said, which is the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and physical therapy. For NSAIDs, the wording of the recommendation will emphasize the need to monitor side effects.

The expert opinion of the GRAPPA consensus group was nearly unanimous that NSAIDs and physical therapy are effective and should be tried initially in both mild and moderate/severe disease, even though Dr. Siegel said that the supportive data from controlled trials are limited.

For those with moderate/severe enthesitis not sufficiently controlled on NSAIDs, alternatives include tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, ustekinumab, and apremilast. Some supportive data are available for each of these options, even though the consensus group concluded that there is not enough comparative evidence "to recommend one over another," he said.

Rather, the consensus group is recommending that the choice of therapies beyond NSAIDs and physical therapy be individualized in relationship to comorbidities, personal preference, and other considerations.

Special wording is being developed in regard to the use of corticosteroid injections. This wording was partly inspired by a meta-analysis that associated corticosteroid injections with an adverse effect on the integrity of tendons. Although there were many criticisms of this report, there was sufficient concern among the consensus group to urge that this treatment be used with caution.

"We think that these injections should only be provided by experienced physicians," Dr. Siegel reported. The wording in the preliminary draft is that adjunctive corticosteroid injections "may be considered on an individual basis."

When published, the enthesitis guidelines will include grading for the quality of the evidence behind each recommendation as well as the relative strength of the recommendation conferred by the expert panel.

Dr. Siegel reported financial relationships with Amgen and AbbVie.

NEW YORK – Conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs will not be included among acceptable treatments for enthesitis related to psoriatic arthritis, according to a draft of guidelines being prepared for publication.

"The only controlled trial with a DMARD [disease-modifying antirheumatic drug] for enthesitis was conducted with sulfasalazine, and it was negative," said Dr. Evan L. Siegel, who is in group practice in rheumatology in Rockville, Md. Dr. Siegel led a group of experts preparing psoriatic arthritis enthesitis treatment recommendations to be issued by the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA).

In a preliminary report on the planned treatment recommendations, which were delivered at the joint meetings of GRAPPA and the Spondyloarthritis Research & Treatment Network (SPARTAN), Dr. Siegel reported that the new recommendations will recognize only two gradations of enthesitis: mild or moderate/severe.

"It is difficult to differentiate moderate from severe because these have not been treated as distinct entities in the clinical trials," Dr. Siegel said. Patients experience severity in regard to intensity of pain and limitation of function, either or both of which may represent severe enthesitis in any given individual patient, according to Dr. Siegel, who also noted that the number of sites of activity is also generally unhelpful.

"Significant activity at a single site may be sufficient to produce a major functional deficit in one individual, whereas the activity at multiple sites may not produce much symptomatology or functional loss in another," Dr. Siegel said.

Enthesitis, an inflammation at the site where tendons or ligaments attach to bone, has been reported in up to 70% of patients with psoriatic arthritis. In some patients, it is the dominant symptom. However, the number of treatment trials in which control of enthesitis is the primary outcome continues to be limited, according to Dr. Siegel. He acknowledged that many of the proposed treatment recommendations owed more to expert opinion than to data.

This is true of the proposed first-line recommendation, he said, which is the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and physical therapy. For NSAIDs, the wording of the recommendation will emphasize the need to monitor side effects.

The expert opinion of the GRAPPA consensus group was nearly unanimous that NSAIDs and physical therapy are effective and should be tried initially in both mild and moderate/severe disease, even though Dr. Siegel said that the supportive data from controlled trials are limited.

For those with moderate/severe enthesitis not sufficiently controlled on NSAIDs, alternatives include tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, ustekinumab, and apremilast. Some supportive data are available for each of these options, even though the consensus group concluded that there is not enough comparative evidence "to recommend one over another," he said.

Rather, the consensus group is recommending that the choice of therapies beyond NSAIDs and physical therapy be individualized in relationship to comorbidities, personal preference, and other considerations.

Special wording is being developed in regard to the use of corticosteroid injections. This wording was partly inspired by a meta-analysis that associated corticosteroid injections with an adverse effect on the integrity of tendons. Although there were many criticisms of this report, there was sufficient concern among the consensus group to urge that this treatment be used with caution.

"We think that these injections should only be provided by experienced physicians," Dr. Siegel reported. The wording in the preliminary draft is that adjunctive corticosteroid injections "may be considered on an individual basis."

When published, the enthesitis guidelines will include grading for the quality of the evidence behind each recommendation as well as the relative strength of the recommendation conferred by the expert panel.

Dr. Siegel reported financial relationships with Amgen and AbbVie.

NEW YORK – Conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs will not be included among acceptable treatments for enthesitis related to psoriatic arthritis, according to a draft of guidelines being prepared for publication.

"The only controlled trial with a DMARD [disease-modifying antirheumatic drug] for enthesitis was conducted with sulfasalazine, and it was negative," said Dr. Evan L. Siegel, who is in group practice in rheumatology in Rockville, Md. Dr. Siegel led a group of experts preparing psoriatic arthritis enthesitis treatment recommendations to be issued by the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA).

In a preliminary report on the planned treatment recommendations, which were delivered at the joint meetings of GRAPPA and the Spondyloarthritis Research & Treatment Network (SPARTAN), Dr. Siegel reported that the new recommendations will recognize only two gradations of enthesitis: mild or moderate/severe.

"It is difficult to differentiate moderate from severe because these have not been treated as distinct entities in the clinical trials," Dr. Siegel said. Patients experience severity in regard to intensity of pain and limitation of function, either or both of which may represent severe enthesitis in any given individual patient, according to Dr. Siegel, who also noted that the number of sites of activity is also generally unhelpful.

"Significant activity at a single site may be sufficient to produce a major functional deficit in one individual, whereas the activity at multiple sites may not produce much symptomatology or functional loss in another," Dr. Siegel said.

Enthesitis, an inflammation at the site where tendons or ligaments attach to bone, has been reported in up to 70% of patients with psoriatic arthritis. In some patients, it is the dominant symptom. However, the number of treatment trials in which control of enthesitis is the primary outcome continues to be limited, according to Dr. Siegel. He acknowledged that many of the proposed treatment recommendations owed more to expert opinion than to data.