User login

NICE recommends bortezomib for untreated MM

Credit: Bill Branson

In a new draft guidance, the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has recommended bortezomib (Velcade) for certain patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM).

NICE is recommending the drug in combination with dexamethasone, or with dexamethasone and thalidomide, as induction treatment for adults with previously untreated MM who are eligible for high-dose chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

An appraisal committee said these regimens are clinically effective for this patient population. Trial data suggest the regimens confer a “clear advantage” over standard therapy with respect to induction response.

And it’s plausible that this may translate to improved survival, the committee said. (Standard treatment in the UK is a combination of cyclophosphamide, thalidomide, and dexamethasone.)

“Clinical specialists told the committee that induction treatment with bortezomib would enable a greater number of patients to proceed to [HSCT] and, consequently, prevent the disease from progressing for longer,” said Sir Andrew Dillon, NICE Chief Executive.

In addition, the committee said the bortezomib regimens are cost-effective for this patient population. The cost of bortezomib is £762.38 per 3.5 mg vial.

On average, a course of treatment with bortezomib given with dexamethasone costs £12,260.91. And a course of bortezomib given with dexamethasone and thalidomide costs £24,840.10.

The cost for bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone compared to thalidomide and dexamethasone is likely to be below £30,000 per quality-adjusted life-year gained.

The same is true when comparing bortezomib and dexamethasone to cyclophosphamide, thalidomide, and dexamethasone as well as vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone.

This draft guidance is now with consultees, who have the opportunity to appeal against it.

Other NICE recommendations for MM

NICE already recommends bortezomib monotherapy as a treatment option for MM patients at first relapse who have received one prior therapy and who have undergone, or are unsuitable for, HSCT.

Thalidomide in combination with an alkylating agent and a corticosteroid is recommended as a first-line treatment option in MM patients for whom high-dose chemotherapy with HSCT is considered inappropriate.

Bortezomib is also recommended under these circumstances, if the patient is unable to tolerate or has contraindications to thalidomide.

Lenalidomide in combination with dexamethasone is recommended as a treatment option for people with MM who have received 2 or more prior therapies. ![]()

Credit: Bill Branson

In a new draft guidance, the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has recommended bortezomib (Velcade) for certain patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM).

NICE is recommending the drug in combination with dexamethasone, or with dexamethasone and thalidomide, as induction treatment for adults with previously untreated MM who are eligible for high-dose chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

An appraisal committee said these regimens are clinically effective for this patient population. Trial data suggest the regimens confer a “clear advantage” over standard therapy with respect to induction response.

And it’s plausible that this may translate to improved survival, the committee said. (Standard treatment in the UK is a combination of cyclophosphamide, thalidomide, and dexamethasone.)

“Clinical specialists told the committee that induction treatment with bortezomib would enable a greater number of patients to proceed to [HSCT] and, consequently, prevent the disease from progressing for longer,” said Sir Andrew Dillon, NICE Chief Executive.

In addition, the committee said the bortezomib regimens are cost-effective for this patient population. The cost of bortezomib is £762.38 per 3.5 mg vial.

On average, a course of treatment with bortezomib given with dexamethasone costs £12,260.91. And a course of bortezomib given with dexamethasone and thalidomide costs £24,840.10.

The cost for bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone compared to thalidomide and dexamethasone is likely to be below £30,000 per quality-adjusted life-year gained.

The same is true when comparing bortezomib and dexamethasone to cyclophosphamide, thalidomide, and dexamethasone as well as vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone.

This draft guidance is now with consultees, who have the opportunity to appeal against it.

Other NICE recommendations for MM

NICE already recommends bortezomib monotherapy as a treatment option for MM patients at first relapse who have received one prior therapy and who have undergone, or are unsuitable for, HSCT.

Thalidomide in combination with an alkylating agent and a corticosteroid is recommended as a first-line treatment option in MM patients for whom high-dose chemotherapy with HSCT is considered inappropriate.

Bortezomib is also recommended under these circumstances, if the patient is unable to tolerate or has contraindications to thalidomide.

Lenalidomide in combination with dexamethasone is recommended as a treatment option for people with MM who have received 2 or more prior therapies. ![]()

Credit: Bill Branson

In a new draft guidance, the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has recommended bortezomib (Velcade) for certain patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM).

NICE is recommending the drug in combination with dexamethasone, or with dexamethasone and thalidomide, as induction treatment for adults with previously untreated MM who are eligible for high-dose chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

An appraisal committee said these regimens are clinically effective for this patient population. Trial data suggest the regimens confer a “clear advantage” over standard therapy with respect to induction response.

And it’s plausible that this may translate to improved survival, the committee said. (Standard treatment in the UK is a combination of cyclophosphamide, thalidomide, and dexamethasone.)

“Clinical specialists told the committee that induction treatment with bortezomib would enable a greater number of patients to proceed to [HSCT] and, consequently, prevent the disease from progressing for longer,” said Sir Andrew Dillon, NICE Chief Executive.

In addition, the committee said the bortezomib regimens are cost-effective for this patient population. The cost of bortezomib is £762.38 per 3.5 mg vial.

On average, a course of treatment with bortezomib given with dexamethasone costs £12,260.91. And a course of bortezomib given with dexamethasone and thalidomide costs £24,840.10.

The cost for bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone compared to thalidomide and dexamethasone is likely to be below £30,000 per quality-adjusted life-year gained.

The same is true when comparing bortezomib and dexamethasone to cyclophosphamide, thalidomide, and dexamethasone as well as vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone.

This draft guidance is now with consultees, who have the opportunity to appeal against it.

Other NICE recommendations for MM

NICE already recommends bortezomib monotherapy as a treatment option for MM patients at first relapse who have received one prior therapy and who have undergone, or are unsuitable for, HSCT.

Thalidomide in combination with an alkylating agent and a corticosteroid is recommended as a first-line treatment option in MM patients for whom high-dose chemotherapy with HSCT is considered inappropriate.

Bortezomib is also recommended under these circumstances, if the patient is unable to tolerate or has contraindications to thalidomide.

Lenalidomide in combination with dexamethasone is recommended as a treatment option for people with MM who have received 2 or more prior therapies. ![]()

How low levels of oxygen, nitric oxide worsen SCD

Medical College of Georgia

Low levels of oxygen and nitric oxide have an unfortunate synergy in sickle cell disease (SCD), according to preclinical research published in Blood.

The study indicates that these conditions dramatically increase red blood cells’ adhesion to endothelial cells and intensify the debilitating pain crises that can result.

The good news is that restoring normal levels of nitric oxide can substantially reduce red blood cell adhesion, said study author Tohru Ikuta, MD, PhD, of the Medical College of Georgia at Georgia Regents University in Augusta.

The study also points to a potential therapeutic target—the self-adhesion molecule P-selectin, which the researchers found played a central role in increased red blood cell adhesion. Low levels of oxygen and nitric oxide both increase expression of P-selectin.

To understand the relationship between hypoxia and nitric oxide, the researchers infused sickled red blood cells into mice incapable of producing nitric oxide.

The cells immediately began sticking to blood vessel walls, while normal mice were unaffected. In the face of low oxygen levels, cell adhesion increased significantly in the nitric oxide-deficient mice.

“It’s a synergy,” Dr Ikuta said. “This shows that hypoxia and low nitric oxide levels work together in a bad way for sickle cell patients.”

When the researchers restored normal nitric oxide levels by having mice breathe in the short-lived gas, cell adhesion did not increase when oxygen levels decreased.

And there was no additional benefit from increasing nitric oxide levels beyond normal. Rather, restoring normal nitric oxide levels appears the most efficient, effective way to reduce red blood cell adhesion, the researchers said.

They noted that clinical trials of nitric oxide therapy to ease pain in SCD patients have yielded conflicting results, with some patients reporting increased pain.

These new findings and the fact that SCD patients have significant variability in their nitric oxide levels—even during a pain crisis—likely explains why, Dr Ikuta said. Nitric oxide therapy likely would benefit only patients with intermittent or chronically low levels of nitric oxide.

“The answer is that some patients may not need this,” Dr Ikuta said. “And our studies indicate that there is no therapeutic benefit to increasing levels beyond physiologic levels.” ![]()

Medical College of Georgia

Low levels of oxygen and nitric oxide have an unfortunate synergy in sickle cell disease (SCD), according to preclinical research published in Blood.

The study indicates that these conditions dramatically increase red blood cells’ adhesion to endothelial cells and intensify the debilitating pain crises that can result.

The good news is that restoring normal levels of nitric oxide can substantially reduce red blood cell adhesion, said study author Tohru Ikuta, MD, PhD, of the Medical College of Georgia at Georgia Regents University in Augusta.

The study also points to a potential therapeutic target—the self-adhesion molecule P-selectin, which the researchers found played a central role in increased red blood cell adhesion. Low levels of oxygen and nitric oxide both increase expression of P-selectin.

To understand the relationship between hypoxia and nitric oxide, the researchers infused sickled red blood cells into mice incapable of producing nitric oxide.

The cells immediately began sticking to blood vessel walls, while normal mice were unaffected. In the face of low oxygen levels, cell adhesion increased significantly in the nitric oxide-deficient mice.

“It’s a synergy,” Dr Ikuta said. “This shows that hypoxia and low nitric oxide levels work together in a bad way for sickle cell patients.”

When the researchers restored normal nitric oxide levels by having mice breathe in the short-lived gas, cell adhesion did not increase when oxygen levels decreased.

And there was no additional benefit from increasing nitric oxide levels beyond normal. Rather, restoring normal nitric oxide levels appears the most efficient, effective way to reduce red blood cell adhesion, the researchers said.

They noted that clinical trials of nitric oxide therapy to ease pain in SCD patients have yielded conflicting results, with some patients reporting increased pain.

These new findings and the fact that SCD patients have significant variability in their nitric oxide levels—even during a pain crisis—likely explains why, Dr Ikuta said. Nitric oxide therapy likely would benefit only patients with intermittent or chronically low levels of nitric oxide.

“The answer is that some patients may not need this,” Dr Ikuta said. “And our studies indicate that there is no therapeutic benefit to increasing levels beyond physiologic levels.” ![]()

Medical College of Georgia

Low levels of oxygen and nitric oxide have an unfortunate synergy in sickle cell disease (SCD), according to preclinical research published in Blood.

The study indicates that these conditions dramatically increase red blood cells’ adhesion to endothelial cells and intensify the debilitating pain crises that can result.

The good news is that restoring normal levels of nitric oxide can substantially reduce red blood cell adhesion, said study author Tohru Ikuta, MD, PhD, of the Medical College of Georgia at Georgia Regents University in Augusta.

The study also points to a potential therapeutic target—the self-adhesion molecule P-selectin, which the researchers found played a central role in increased red blood cell adhesion. Low levels of oxygen and nitric oxide both increase expression of P-selectin.

To understand the relationship between hypoxia and nitric oxide, the researchers infused sickled red blood cells into mice incapable of producing nitric oxide.

The cells immediately began sticking to blood vessel walls, while normal mice were unaffected. In the face of low oxygen levels, cell adhesion increased significantly in the nitric oxide-deficient mice.

“It’s a synergy,” Dr Ikuta said. “This shows that hypoxia and low nitric oxide levels work together in a bad way for sickle cell patients.”

When the researchers restored normal nitric oxide levels by having mice breathe in the short-lived gas, cell adhesion did not increase when oxygen levels decreased.

And there was no additional benefit from increasing nitric oxide levels beyond normal. Rather, restoring normal nitric oxide levels appears the most efficient, effective way to reduce red blood cell adhesion, the researchers said.

They noted that clinical trials of nitric oxide therapy to ease pain in SCD patients have yielded conflicting results, with some patients reporting increased pain.

These new findings and the fact that SCD patients have significant variability in their nitric oxide levels—even during a pain crisis—likely explains why, Dr Ikuta said. Nitric oxide therapy likely would benefit only patients with intermittent or chronically low levels of nitric oxide.

“The answer is that some patients may not need this,” Dr Ikuta said. “And our studies indicate that there is no therapeutic benefit to increasing levels beyond physiologic levels.” ![]()

Nanotherapies make inroads in wound regeneration

DENVER – Move over, gauze, bandages, and moist wound-healing techniques. Nanomaterials are making significant inroads in wound regeneration.

Dr. Adam Friedman, director of dermatologic research at the Montefiore-Einstein College of Medicine, New York, highlighted four nanotherapies in the field of wound care.

• Antimicrobial nano-based dressings. The antibacterial properties of silver have been documented since 1000 B.C., said Dr. Friedman of the departments of dermatology and of physiology and biophysics at the medical school. Silver ions are believed to directly disrupt pathogen cell walls/membranes and suppress respiratory enzymes and electron transport components. Silver has been used commercially for decades, with demonstrated antimicrobial effects (Crede’s 1% silver nitrate eyedrops were used to prevent mother to child transmission of gonococcal eye infection); anti-inflammatory properties (silver nitrate is used in pleurodesis); and infection protection (silver nanoparticle–impregnated wound dressings prevent infection and enhance wound healing).

Silver nanoparticles have an "increased likelihood of directly interacting with the target bacteria or virus," Dr. Friedman said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. "They bind to and/or disturb bacterial cell membrane activity as well as release silver ions much more readily then their bulk counterparts." Silver dressings currently on the market include Silvercel, Aquacel, and Acticoat.

Similarly to nanometals, the biological activity of curcumin (a water-insoluble polyphenolic compound derived from tumeric) can be used in the nanoform and has been shown to both effectively clear methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in burn wound infections and accelerate the healing of thermal burn wounds.

• Immunomodulating antimicrobial nanoparticles. One of the most promising immunomodulators in wound healing is the gaseous molecule nitric oxide (NO). This potential has yet to be realized, Dr. Friedman said, as NO is highly unstable and its site of action is often microns from its source of generation. Nanotechnology can allow for controlled and sustained release of this evasive biomolecule and make therapeutic translation a reality. "At Einstein, we are utilizing NO-generating nanoparticles to accelerate wound healing and eradicate multidrug resistant pathogens," he said. "But, because NO is integral to so many biological processes, it can do so much more. This technology is also being studied for the treatment of cardiovascular disease and even the topical treatment of erectile dysfunction."

• Gene modifying/silencing technologies. RNA interference is an endogenous mechanism to control gene expression in a variety of organisms. "We can take advantage of this process using siRNA (small interfering RNA) to manipulate limitless biological processes," Dr. Friedman explained. "While a hot area, translation to the bedside has been difficult as siRNA are very unstable and have a difficult time reaching their targets inside cells. Nanoparticles have been shown to overcome these limitations." Dr. Friedman noted how siRNA encapsulate nanoparticles targeting fidgetin-like 2 (an ATPase that cleaves microtubules), can knock down this gene in vivo, resulting in accelerated epithelial cell migration and hastened wound closure in both excisional and burn wound mouse models.

• Growth factor–releasing nanoparticles. Growth factors have been found to speed the healing of acute and chronic wounds in humans, including Regranex, a analogue of platelet-derived growth factor that is FDA-approved for treating leg and foot ulcers in diabetic patients, epidermal growth factor (donor-site wounds), fibroblast growth factor (burn wounds), and growth hormone (donor sites in burned children). "Nanomaterials offer many advantages here, from allowing for temporal release depending on the wound environment to delivering multiple factors at the same or different times, to even serving as a structural foundation for wound healing while releasing factors simultaneously," Dr. Friedman said. "The possibilities are limitless."

Dr. Friedman characterized nanomedicine as "a newborn branch of science. These promising and innovative tools should help us overcome limitations of traditional wound care, improve direct intervention on phases of wound healing, and provide better solutions for wound dressing that induce favorable wound healing environments. More work – and funding – is needed."

Dr. Friedman disclosed that he is a consultant and/or a member of the scientific advisory board for SanovaWorks, Prodigy, Oakstone Institute, Liquidia Technologies, L’Oréal, Amgen, Onset, Aveeno, GSK, MicroCures, and Nano Bio-Med. He is also a speaker for Onset and Amgen.

This article was updated March 24, 2014.

DENVER – Move over, gauze, bandages, and moist wound-healing techniques. Nanomaterials are making significant inroads in wound regeneration.

Dr. Adam Friedman, director of dermatologic research at the Montefiore-Einstein College of Medicine, New York, highlighted four nanotherapies in the field of wound care.

• Antimicrobial nano-based dressings. The antibacterial properties of silver have been documented since 1000 B.C., said Dr. Friedman of the departments of dermatology and of physiology and biophysics at the medical school. Silver ions are believed to directly disrupt pathogen cell walls/membranes and suppress respiratory enzymes and electron transport components. Silver has been used commercially for decades, with demonstrated antimicrobial effects (Crede’s 1% silver nitrate eyedrops were used to prevent mother to child transmission of gonococcal eye infection); anti-inflammatory properties (silver nitrate is used in pleurodesis); and infection protection (silver nanoparticle–impregnated wound dressings prevent infection and enhance wound healing).

Silver nanoparticles have an "increased likelihood of directly interacting with the target bacteria or virus," Dr. Friedman said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. "They bind to and/or disturb bacterial cell membrane activity as well as release silver ions much more readily then their bulk counterparts." Silver dressings currently on the market include Silvercel, Aquacel, and Acticoat.

Similarly to nanometals, the biological activity of curcumin (a water-insoluble polyphenolic compound derived from tumeric) can be used in the nanoform and has been shown to both effectively clear methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in burn wound infections and accelerate the healing of thermal burn wounds.

• Immunomodulating antimicrobial nanoparticles. One of the most promising immunomodulators in wound healing is the gaseous molecule nitric oxide (NO). This potential has yet to be realized, Dr. Friedman said, as NO is highly unstable and its site of action is often microns from its source of generation. Nanotechnology can allow for controlled and sustained release of this evasive biomolecule and make therapeutic translation a reality. "At Einstein, we are utilizing NO-generating nanoparticles to accelerate wound healing and eradicate multidrug resistant pathogens," he said. "But, because NO is integral to so many biological processes, it can do so much more. This technology is also being studied for the treatment of cardiovascular disease and even the topical treatment of erectile dysfunction."

• Gene modifying/silencing technologies. RNA interference is an endogenous mechanism to control gene expression in a variety of organisms. "We can take advantage of this process using siRNA (small interfering RNA) to manipulate limitless biological processes," Dr. Friedman explained. "While a hot area, translation to the bedside has been difficult as siRNA are very unstable and have a difficult time reaching their targets inside cells. Nanoparticles have been shown to overcome these limitations." Dr. Friedman noted how siRNA encapsulate nanoparticles targeting fidgetin-like 2 (an ATPase that cleaves microtubules), can knock down this gene in vivo, resulting in accelerated epithelial cell migration and hastened wound closure in both excisional and burn wound mouse models.

• Growth factor–releasing nanoparticles. Growth factors have been found to speed the healing of acute and chronic wounds in humans, including Regranex, a analogue of platelet-derived growth factor that is FDA-approved for treating leg and foot ulcers in diabetic patients, epidermal growth factor (donor-site wounds), fibroblast growth factor (burn wounds), and growth hormone (donor sites in burned children). "Nanomaterials offer many advantages here, from allowing for temporal release depending on the wound environment to delivering multiple factors at the same or different times, to even serving as a structural foundation for wound healing while releasing factors simultaneously," Dr. Friedman said. "The possibilities are limitless."

Dr. Friedman characterized nanomedicine as "a newborn branch of science. These promising and innovative tools should help us overcome limitations of traditional wound care, improve direct intervention on phases of wound healing, and provide better solutions for wound dressing that induce favorable wound healing environments. More work – and funding – is needed."

Dr. Friedman disclosed that he is a consultant and/or a member of the scientific advisory board for SanovaWorks, Prodigy, Oakstone Institute, Liquidia Technologies, L’Oréal, Amgen, Onset, Aveeno, GSK, MicroCures, and Nano Bio-Med. He is also a speaker for Onset and Amgen.

This article was updated March 24, 2014.

DENVER – Move over, gauze, bandages, and moist wound-healing techniques. Nanomaterials are making significant inroads in wound regeneration.

Dr. Adam Friedman, director of dermatologic research at the Montefiore-Einstein College of Medicine, New York, highlighted four nanotherapies in the field of wound care.

• Antimicrobial nano-based dressings. The antibacterial properties of silver have been documented since 1000 B.C., said Dr. Friedman of the departments of dermatology and of physiology and biophysics at the medical school. Silver ions are believed to directly disrupt pathogen cell walls/membranes and suppress respiratory enzymes and electron transport components. Silver has been used commercially for decades, with demonstrated antimicrobial effects (Crede’s 1% silver nitrate eyedrops were used to prevent mother to child transmission of gonococcal eye infection); anti-inflammatory properties (silver nitrate is used in pleurodesis); and infection protection (silver nanoparticle–impregnated wound dressings prevent infection and enhance wound healing).

Silver nanoparticles have an "increased likelihood of directly interacting with the target bacteria or virus," Dr. Friedman said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. "They bind to and/or disturb bacterial cell membrane activity as well as release silver ions much more readily then their bulk counterparts." Silver dressings currently on the market include Silvercel, Aquacel, and Acticoat.

Similarly to nanometals, the biological activity of curcumin (a water-insoluble polyphenolic compound derived from tumeric) can be used in the nanoform and has been shown to both effectively clear methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in burn wound infections and accelerate the healing of thermal burn wounds.

• Immunomodulating antimicrobial nanoparticles. One of the most promising immunomodulators in wound healing is the gaseous molecule nitric oxide (NO). This potential has yet to be realized, Dr. Friedman said, as NO is highly unstable and its site of action is often microns from its source of generation. Nanotechnology can allow for controlled and sustained release of this evasive biomolecule and make therapeutic translation a reality. "At Einstein, we are utilizing NO-generating nanoparticles to accelerate wound healing and eradicate multidrug resistant pathogens," he said. "But, because NO is integral to so many biological processes, it can do so much more. This technology is also being studied for the treatment of cardiovascular disease and even the topical treatment of erectile dysfunction."

• Gene modifying/silencing technologies. RNA interference is an endogenous mechanism to control gene expression in a variety of organisms. "We can take advantage of this process using siRNA (small interfering RNA) to manipulate limitless biological processes," Dr. Friedman explained. "While a hot area, translation to the bedside has been difficult as siRNA are very unstable and have a difficult time reaching their targets inside cells. Nanoparticles have been shown to overcome these limitations." Dr. Friedman noted how siRNA encapsulate nanoparticles targeting fidgetin-like 2 (an ATPase that cleaves microtubules), can knock down this gene in vivo, resulting in accelerated epithelial cell migration and hastened wound closure in both excisional and burn wound mouse models.

• Growth factor–releasing nanoparticles. Growth factors have been found to speed the healing of acute and chronic wounds in humans, including Regranex, a analogue of platelet-derived growth factor that is FDA-approved for treating leg and foot ulcers in diabetic patients, epidermal growth factor (donor-site wounds), fibroblast growth factor (burn wounds), and growth hormone (donor sites in burned children). "Nanomaterials offer many advantages here, from allowing for temporal release depending on the wound environment to delivering multiple factors at the same or different times, to even serving as a structural foundation for wound healing while releasing factors simultaneously," Dr. Friedman said. "The possibilities are limitless."

Dr. Friedman characterized nanomedicine as "a newborn branch of science. These promising and innovative tools should help us overcome limitations of traditional wound care, improve direct intervention on phases of wound healing, and provide better solutions for wound dressing that induce favorable wound healing environments. More work – and funding – is needed."

Dr. Friedman disclosed that he is a consultant and/or a member of the scientific advisory board for SanovaWorks, Prodigy, Oakstone Institute, Liquidia Technologies, L’Oréal, Amgen, Onset, Aveeno, GSK, MicroCures, and Nano Bio-Med. He is also a speaker for Onset and Amgen.

This article was updated March 24, 2014.

AT THE AAD ANNUAL MEETING

VIDEO: Vitiligo gene hunt could open door to eventual drug treatment

DENVER – Vitiligo has been known for thousands of years, but only in the past six decades have researchers begun to better understand it and uncover genes associated with the disorder.

Dr. Richard A. Spritz, one of the leaders in vitiligo research, says that scientists are very close to understanding the condition’s pathogenesis. He is embarking on another analysis of data from a large genetic study, which could double the number of known vitiligo genes, putting the disorder on par with other autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis.

At the Society of Pediatric Dermatology’s annual meeting, held immediately before the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Spritz spoke about what is known so far about vitiligo and what the future holds. Dr. Spritz is professor and director of the Human Medical Genetics and Genomics Program at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

On Twitter @naseemsmiller

DENVER – Vitiligo has been known for thousands of years, but only in the past six decades have researchers begun to better understand it and uncover genes associated with the disorder.

Dr. Richard A. Spritz, one of the leaders in vitiligo research, says that scientists are very close to understanding the condition’s pathogenesis. He is embarking on another analysis of data from a large genetic study, which could double the number of known vitiligo genes, putting the disorder on par with other autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis.

At the Society of Pediatric Dermatology’s annual meeting, held immediately before the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Spritz spoke about what is known so far about vitiligo and what the future holds. Dr. Spritz is professor and director of the Human Medical Genetics and Genomics Program at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

On Twitter @naseemsmiller

DENVER – Vitiligo has been known for thousands of years, but only in the past six decades have researchers begun to better understand it and uncover genes associated with the disorder.

Dr. Richard A. Spritz, one of the leaders in vitiligo research, says that scientists are very close to understanding the condition’s pathogenesis. He is embarking on another analysis of data from a large genetic study, which could double the number of known vitiligo genes, putting the disorder on par with other autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis.

At the Society of Pediatric Dermatology’s annual meeting, held immediately before the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Spritz spoke about what is known so far about vitiligo and what the future holds. Dr. Spritz is professor and director of the Human Medical Genetics and Genomics Program at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

On Twitter @naseemsmiller

AT A MEETING OF THE SOCIETY OF PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

Omitting RT can increase risk of relapse in HL

Credit: Sue Campbell

Interim results of a randomized trial suggest that omitting radiotherapy in Hodgkin lymphoma patients with an early negative PET scan can increase their risk of relapse.

Patients with stage I/II Hodgkin lymphoma who received involved-node radiotherapy after chemotherapy with ABVD (adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazin) were less likely to relapse than patients who received ABVD alone, regardless of prognosis.

However, patients who received chemotherapy alone still had a high rate of progression-free survival (PFS), at about 95%.

John M.M. Raemaekers, MD, PhD, of the Radboud University Medical Center in Nijmegen, The Netherlands, and his colleagues reported these results in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“Striking the right balance between initial cure through combined-modality treatment and accepting a higher risk of late complications, and a higher recurrence rate after omitting radiotherapy in subsets of patients who will subsequently need intensive salvage treatment, is a matter of unsettled debate,” Dr Raemaekers said.

So he and his colleagues set out to evaluate whether involved-node radiotherapy could be omitted without compromising PFS in patients with stage I/II Hodgkin lymphoma who had an early negative PET scan after treatment with ABVD.

The interim analysis included 1137 patients with untreated clinical stage I/II Hodgkin lymphoma. Of these, 444 patients had favorable prognoses, and 693 had unfavorable prognoses.

Patients in each prognostic group were randomized to receive standard treatment—2 cycles of ABVD followed by radiotherapy (n=188)—or experimental treatment—ABVD alone (n=193).

For patients with a favorable prognosis and an early negative PET scan, 1 progression occurred in the standard arm, and 9 occurred in the experimental arm. At 1 year, PFS rates were 100% and 94.9%, respectively.

For patients with unfavorable prognosis and an early negative PET scan, 7 events occurred in the standard arm, and 16 occurred in the experimental arm.

One patient died from toxicity without signs of progression, but all of the remaining events were progressions. At 1 year, the PFS rates were 97.3% and 94.7%, respectively.

Although there were few events and the median follow-up time was short, an independent data monitoring committee said it was unlikely that the final results would show non-inferiority for the experimental treatment. They therefore advised that randomization be stopped for early PET-negative patients. ![]()

Credit: Sue Campbell

Interim results of a randomized trial suggest that omitting radiotherapy in Hodgkin lymphoma patients with an early negative PET scan can increase their risk of relapse.

Patients with stage I/II Hodgkin lymphoma who received involved-node radiotherapy after chemotherapy with ABVD (adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazin) were less likely to relapse than patients who received ABVD alone, regardless of prognosis.

However, patients who received chemotherapy alone still had a high rate of progression-free survival (PFS), at about 95%.

John M.M. Raemaekers, MD, PhD, of the Radboud University Medical Center in Nijmegen, The Netherlands, and his colleagues reported these results in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“Striking the right balance between initial cure through combined-modality treatment and accepting a higher risk of late complications, and a higher recurrence rate after omitting radiotherapy in subsets of patients who will subsequently need intensive salvage treatment, is a matter of unsettled debate,” Dr Raemaekers said.

So he and his colleagues set out to evaluate whether involved-node radiotherapy could be omitted without compromising PFS in patients with stage I/II Hodgkin lymphoma who had an early negative PET scan after treatment with ABVD.

The interim analysis included 1137 patients with untreated clinical stage I/II Hodgkin lymphoma. Of these, 444 patients had favorable prognoses, and 693 had unfavorable prognoses.

Patients in each prognostic group were randomized to receive standard treatment—2 cycles of ABVD followed by radiotherapy (n=188)—or experimental treatment—ABVD alone (n=193).

For patients with a favorable prognosis and an early negative PET scan, 1 progression occurred in the standard arm, and 9 occurred in the experimental arm. At 1 year, PFS rates were 100% and 94.9%, respectively.

For patients with unfavorable prognosis and an early negative PET scan, 7 events occurred in the standard arm, and 16 occurred in the experimental arm.

One patient died from toxicity without signs of progression, but all of the remaining events were progressions. At 1 year, the PFS rates were 97.3% and 94.7%, respectively.

Although there were few events and the median follow-up time was short, an independent data monitoring committee said it was unlikely that the final results would show non-inferiority for the experimental treatment. They therefore advised that randomization be stopped for early PET-negative patients. ![]()

Credit: Sue Campbell

Interim results of a randomized trial suggest that omitting radiotherapy in Hodgkin lymphoma patients with an early negative PET scan can increase their risk of relapse.

Patients with stage I/II Hodgkin lymphoma who received involved-node radiotherapy after chemotherapy with ABVD (adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazin) were less likely to relapse than patients who received ABVD alone, regardless of prognosis.

However, patients who received chemotherapy alone still had a high rate of progression-free survival (PFS), at about 95%.

John M.M. Raemaekers, MD, PhD, of the Radboud University Medical Center in Nijmegen, The Netherlands, and his colleagues reported these results in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“Striking the right balance between initial cure through combined-modality treatment and accepting a higher risk of late complications, and a higher recurrence rate after omitting radiotherapy in subsets of patients who will subsequently need intensive salvage treatment, is a matter of unsettled debate,” Dr Raemaekers said.

So he and his colleagues set out to evaluate whether involved-node radiotherapy could be omitted without compromising PFS in patients with stage I/II Hodgkin lymphoma who had an early negative PET scan after treatment with ABVD.

The interim analysis included 1137 patients with untreated clinical stage I/II Hodgkin lymphoma. Of these, 444 patients had favorable prognoses, and 693 had unfavorable prognoses.

Patients in each prognostic group were randomized to receive standard treatment—2 cycles of ABVD followed by radiotherapy (n=188)—or experimental treatment—ABVD alone (n=193).

For patients with a favorable prognosis and an early negative PET scan, 1 progression occurred in the standard arm, and 9 occurred in the experimental arm. At 1 year, PFS rates were 100% and 94.9%, respectively.

For patients with unfavorable prognosis and an early negative PET scan, 7 events occurred in the standard arm, and 16 occurred in the experimental arm.

One patient died from toxicity without signs of progression, but all of the remaining events were progressions. At 1 year, the PFS rates were 97.3% and 94.7%, respectively.

Although there were few events and the median follow-up time was short, an independent data monitoring committee said it was unlikely that the final results would show non-inferiority for the experimental treatment. They therefore advised that randomization be stopped for early PET-negative patients. ![]()

Finger prick yields ample iPSCs for banking

Credit: Salk Institute

Researchers say they’ve discovered an easy way to collect large quantities of viable, bankable stem cells.

Donors prick their own fingers to provide a single drop of blood, and the team generates induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from that sample.

“We show that a single drop of blood from a finger-prick sample is sufficient for performing cellular reprogramming, DNA sequencing, and blood typing in parallel,” said Jonathan Yuin-Han Loh, PhD, of the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) in Singapore.

“Our strategy has the potential of facilitating the development of large-scale human iPSC banking worldwide.”

The researchers described this strategy in STEM CELLS Translational Medicine.

“We gradually reduced the starting volume of blood (collected using a needle) and confirmed that reprogramming can be achieved with as little as 0.25 milliliters,” said Hong Kee Tan, a research officer in the Loh lab.

And this made the team wonder whether a do-it-yourself approach to blood collection might work too.

“To test this idea, we asked donors to prick their own fingers in a normal room environment and collect a single drop of blood sample into a tube,” Tan said. “The tube was placed on ice and delivered to the lab for reprogramming.”

The cells were treated with a buffer at 12-, 24- or 48-hour increments and observed under the microscope for viability and signs of contamination. After 12 days of expansion in medium, the cells appeared healthy and were actively dividing.

The researchers then succeeded in forcing the cells to become mesodermal, endodermal, and neural cells. They were also able to produce cells that gave rise to rhythmically beating cardiomyocytes.

The team said there was no noticeable reduction in reprogramming efficiency between the freshly collected finger-prick samples and the do-it-yourself samples.

“[W]e derived healthy iPSCs from tiny volumes of venipuncture and a single drop from finger-prick blood samples,” Dr Loh said. “We also report a high reprogramming yield of 100 to 600 colonies per milliliter of blood.” ![]()

Credit: Salk Institute

Researchers say they’ve discovered an easy way to collect large quantities of viable, bankable stem cells.

Donors prick their own fingers to provide a single drop of blood, and the team generates induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from that sample.

“We show that a single drop of blood from a finger-prick sample is sufficient for performing cellular reprogramming, DNA sequencing, and blood typing in parallel,” said Jonathan Yuin-Han Loh, PhD, of the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) in Singapore.

“Our strategy has the potential of facilitating the development of large-scale human iPSC banking worldwide.”

The researchers described this strategy in STEM CELLS Translational Medicine.

“We gradually reduced the starting volume of blood (collected using a needle) and confirmed that reprogramming can be achieved with as little as 0.25 milliliters,” said Hong Kee Tan, a research officer in the Loh lab.

And this made the team wonder whether a do-it-yourself approach to blood collection might work too.

“To test this idea, we asked donors to prick their own fingers in a normal room environment and collect a single drop of blood sample into a tube,” Tan said. “The tube was placed on ice and delivered to the lab for reprogramming.”

The cells were treated with a buffer at 12-, 24- or 48-hour increments and observed under the microscope for viability and signs of contamination. After 12 days of expansion in medium, the cells appeared healthy and were actively dividing.

The researchers then succeeded in forcing the cells to become mesodermal, endodermal, and neural cells. They were also able to produce cells that gave rise to rhythmically beating cardiomyocytes.

The team said there was no noticeable reduction in reprogramming efficiency between the freshly collected finger-prick samples and the do-it-yourself samples.

“[W]e derived healthy iPSCs from tiny volumes of venipuncture and a single drop from finger-prick blood samples,” Dr Loh said. “We also report a high reprogramming yield of 100 to 600 colonies per milliliter of blood.” ![]()

Credit: Salk Institute

Researchers say they’ve discovered an easy way to collect large quantities of viable, bankable stem cells.

Donors prick their own fingers to provide a single drop of blood, and the team generates induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from that sample.

“We show that a single drop of blood from a finger-prick sample is sufficient for performing cellular reprogramming, DNA sequencing, and blood typing in parallel,” said Jonathan Yuin-Han Loh, PhD, of the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) in Singapore.

“Our strategy has the potential of facilitating the development of large-scale human iPSC banking worldwide.”

The researchers described this strategy in STEM CELLS Translational Medicine.

“We gradually reduced the starting volume of blood (collected using a needle) and confirmed that reprogramming can be achieved with as little as 0.25 milliliters,” said Hong Kee Tan, a research officer in the Loh lab.

And this made the team wonder whether a do-it-yourself approach to blood collection might work too.

“To test this idea, we asked donors to prick their own fingers in a normal room environment and collect a single drop of blood sample into a tube,” Tan said. “The tube was placed on ice and delivered to the lab for reprogramming.”

The cells were treated with a buffer at 12-, 24- or 48-hour increments and observed under the microscope for viability and signs of contamination. After 12 days of expansion in medium, the cells appeared healthy and were actively dividing.

The researchers then succeeded in forcing the cells to become mesodermal, endodermal, and neural cells. They were also able to produce cells that gave rise to rhythmically beating cardiomyocytes.

The team said there was no noticeable reduction in reprogramming efficiency between the freshly collected finger-prick samples and the do-it-yourself samples.

“[W]e derived healthy iPSCs from tiny volumes of venipuncture and a single drop from finger-prick blood samples,” Dr Loh said. “We also report a high reprogramming yield of 100 to 600 colonies per milliliter of blood.” ![]()

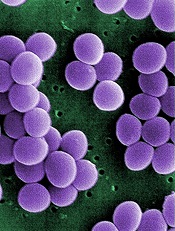

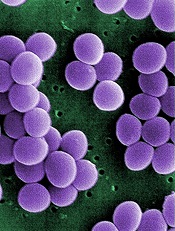

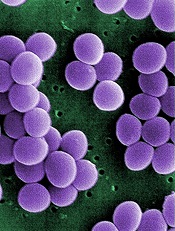

Bloodstream infections treated ‘inappropriately’

Credit: Janice Haney Carr

An analysis of 9 community hospitals showed that 1 in 3 patients with bloodstream infections received inappropriate therapy.

The study also revealed growing resistance to treatment and a high prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus bacteria in these hospitals.

Investigators said the findings, published in PLOS ONE, provide the most comprehensive look at bloodstream infections in community hospitals to date.

Much of the existing research on bloodstream infections focuses on tertiary care centers.

“Our study provides a much-needed update on what we’re seeing in community hospitals, and ultimately, we’re finding similar types of infections in these hospitals as in tertiary care centers,” said study author Deverick Anderson, MD, of Duke University in Durham North Carolina.

“It’s a challenge to identify bloodstream infections and treat them quickly and appropriately, but this study shows that there is room for improvement in both kinds of hospital settings.”

Types of infection

To better understand the types of bloodstream infections found in community hospitals, Dr Anderson and his colleagues collected information on patients treated at these hospitals in Virginia and North Carolina from 2003 to 2006.

The investigators focused on 1470 patients diagnosed with bloodstream infections. The infections were classified depending on where and when they were contracted.

Infections resulting from prior hospitalization, surgery, invasive devices (such as catheters), or living in long-term care facilities were designated healthcare-associated infections.

Community-acquired infections were contracted outside of medical settings or shortly after being admitted to a hospital. And hospital-onset infections occurred after being in a hospital for several days.

The investigators found that 56% of bloodstream infections were healthcare-associated, but symptoms began prior to hospital admission. Community-acquired infections unrelated to medical care were seen in 29% of patients. And 15% had hospital-onset healthcare-associated infections.

S aureus was the most common pathogen, causing 28% of bloodstream infections. This was closely followed by Escherichia coli, which was found in 24% of patients.

Bloodstream infections due to multidrug-resistant pathogens occurred in 23% of patients—an increase over earlier studies. And methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) was the most common multidrug-resistant pathogen.

“Similar patterns of pathogens and drug resistance have been observed in tertiary care centers, suggesting that bloodstream infections in community hospitals aren’t that different from tertiary care centers,” Dr Anderson said.

“There’s a misconception that community hospitals don’t have to deal with S aureus and MRSA, but our findings dispel that myth, since community hospitals also see these serious infections.”

Inappropriate therapy

The investigators also found that approximately 38% of patients with bloodstream infections received inappropriate empiric antimicrobial therapy or were not initially prescribed an effective antibiotic while the cause of the infection was still unknown.

A multivariate analysis revealed several factors associated with receiving inappropriate therapy, including the hospital where the patient received care (P<0.001), the need for assistance with 3 or more “daily living” activities (P=0.005), and a high Charlson score (P=0.05).

Community-onset healthcare-associated infections (P=0.01) and hospital-onset healthcare-associated infections (P=0.02) were associated with the failure to receive appropriate therapy, when community-acquired infections were used as the reference.

The investigators also incorporated drug resistance into their analysis. And they found that infection due to a multidrug-resistant organism was strongly associated with the failure to receive appropriate therapy (P<0.0001).

But most of the predictors the team initially identified retained their significance. The patient’s hospital (P<0.001), need for assistance with activities (P=0.02), and type of infection remained significant (P=0.04), but the Charlson score did not (P=0.07).

Dr Anderson recommended that clinicians in community hospitals focus on these risk factors when choosing antibiotic therapy for patients with bloodstream infections. He noted that most risk factors for receiving inappropriate therapy are already recorded in electronic health records.

“Developing an intervention where electronic records automatically alert clinicians to these risk factors when they’re choosing antibiotics could help reduce the problem,” he said. “This is just a place to start, but it’s an example of an area where we could improve how we treat patients with bloodstream infections.” ![]()

Credit: Janice Haney Carr

An analysis of 9 community hospitals showed that 1 in 3 patients with bloodstream infections received inappropriate therapy.

The study also revealed growing resistance to treatment and a high prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus bacteria in these hospitals.

Investigators said the findings, published in PLOS ONE, provide the most comprehensive look at bloodstream infections in community hospitals to date.

Much of the existing research on bloodstream infections focuses on tertiary care centers.

“Our study provides a much-needed update on what we’re seeing in community hospitals, and ultimately, we’re finding similar types of infections in these hospitals as in tertiary care centers,” said study author Deverick Anderson, MD, of Duke University in Durham North Carolina.

“It’s a challenge to identify bloodstream infections and treat them quickly and appropriately, but this study shows that there is room for improvement in both kinds of hospital settings.”

Types of infection

To better understand the types of bloodstream infections found in community hospitals, Dr Anderson and his colleagues collected information on patients treated at these hospitals in Virginia and North Carolina from 2003 to 2006.

The investigators focused on 1470 patients diagnosed with bloodstream infections. The infections were classified depending on where and when they were contracted.

Infections resulting from prior hospitalization, surgery, invasive devices (such as catheters), or living in long-term care facilities were designated healthcare-associated infections.

Community-acquired infections were contracted outside of medical settings or shortly after being admitted to a hospital. And hospital-onset infections occurred after being in a hospital for several days.

The investigators found that 56% of bloodstream infections were healthcare-associated, but symptoms began prior to hospital admission. Community-acquired infections unrelated to medical care were seen in 29% of patients. And 15% had hospital-onset healthcare-associated infections.

S aureus was the most common pathogen, causing 28% of bloodstream infections. This was closely followed by Escherichia coli, which was found in 24% of patients.

Bloodstream infections due to multidrug-resistant pathogens occurred in 23% of patients—an increase over earlier studies. And methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) was the most common multidrug-resistant pathogen.

“Similar patterns of pathogens and drug resistance have been observed in tertiary care centers, suggesting that bloodstream infections in community hospitals aren’t that different from tertiary care centers,” Dr Anderson said.

“There’s a misconception that community hospitals don’t have to deal with S aureus and MRSA, but our findings dispel that myth, since community hospitals also see these serious infections.”

Inappropriate therapy

The investigators also found that approximately 38% of patients with bloodstream infections received inappropriate empiric antimicrobial therapy or were not initially prescribed an effective antibiotic while the cause of the infection was still unknown.

A multivariate analysis revealed several factors associated with receiving inappropriate therapy, including the hospital where the patient received care (P<0.001), the need for assistance with 3 or more “daily living” activities (P=0.005), and a high Charlson score (P=0.05).

Community-onset healthcare-associated infections (P=0.01) and hospital-onset healthcare-associated infections (P=0.02) were associated with the failure to receive appropriate therapy, when community-acquired infections were used as the reference.

The investigators also incorporated drug resistance into their analysis. And they found that infection due to a multidrug-resistant organism was strongly associated with the failure to receive appropriate therapy (P<0.0001).

But most of the predictors the team initially identified retained their significance. The patient’s hospital (P<0.001), need for assistance with activities (P=0.02), and type of infection remained significant (P=0.04), but the Charlson score did not (P=0.07).

Dr Anderson recommended that clinicians in community hospitals focus on these risk factors when choosing antibiotic therapy for patients with bloodstream infections. He noted that most risk factors for receiving inappropriate therapy are already recorded in electronic health records.

“Developing an intervention where electronic records automatically alert clinicians to these risk factors when they’re choosing antibiotics could help reduce the problem,” he said. “This is just a place to start, but it’s an example of an area where we could improve how we treat patients with bloodstream infections.” ![]()

Credit: Janice Haney Carr

An analysis of 9 community hospitals showed that 1 in 3 patients with bloodstream infections received inappropriate therapy.

The study also revealed growing resistance to treatment and a high prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus bacteria in these hospitals.

Investigators said the findings, published in PLOS ONE, provide the most comprehensive look at bloodstream infections in community hospitals to date.

Much of the existing research on bloodstream infections focuses on tertiary care centers.

“Our study provides a much-needed update on what we’re seeing in community hospitals, and ultimately, we’re finding similar types of infections in these hospitals as in tertiary care centers,” said study author Deverick Anderson, MD, of Duke University in Durham North Carolina.

“It’s a challenge to identify bloodstream infections and treat them quickly and appropriately, but this study shows that there is room for improvement in both kinds of hospital settings.”

Types of infection

To better understand the types of bloodstream infections found in community hospitals, Dr Anderson and his colleagues collected information on patients treated at these hospitals in Virginia and North Carolina from 2003 to 2006.

The investigators focused on 1470 patients diagnosed with bloodstream infections. The infections were classified depending on where and when they were contracted.

Infections resulting from prior hospitalization, surgery, invasive devices (such as catheters), or living in long-term care facilities were designated healthcare-associated infections.

Community-acquired infections were contracted outside of medical settings or shortly after being admitted to a hospital. And hospital-onset infections occurred after being in a hospital for several days.

The investigators found that 56% of bloodstream infections were healthcare-associated, but symptoms began prior to hospital admission. Community-acquired infections unrelated to medical care were seen in 29% of patients. And 15% had hospital-onset healthcare-associated infections.

S aureus was the most common pathogen, causing 28% of bloodstream infections. This was closely followed by Escherichia coli, which was found in 24% of patients.

Bloodstream infections due to multidrug-resistant pathogens occurred in 23% of patients—an increase over earlier studies. And methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) was the most common multidrug-resistant pathogen.

“Similar patterns of pathogens and drug resistance have been observed in tertiary care centers, suggesting that bloodstream infections in community hospitals aren’t that different from tertiary care centers,” Dr Anderson said.

“There’s a misconception that community hospitals don’t have to deal with S aureus and MRSA, but our findings dispel that myth, since community hospitals also see these serious infections.”

Inappropriate therapy

The investigators also found that approximately 38% of patients with bloodstream infections received inappropriate empiric antimicrobial therapy or were not initially prescribed an effective antibiotic while the cause of the infection was still unknown.

A multivariate analysis revealed several factors associated with receiving inappropriate therapy, including the hospital where the patient received care (P<0.001), the need for assistance with 3 or more “daily living” activities (P=0.005), and a high Charlson score (P=0.05).

Community-onset healthcare-associated infections (P=0.01) and hospital-onset healthcare-associated infections (P=0.02) were associated with the failure to receive appropriate therapy, when community-acquired infections were used as the reference.

The investigators also incorporated drug resistance into their analysis. And they found that infection due to a multidrug-resistant organism was strongly associated with the failure to receive appropriate therapy (P<0.0001).

But most of the predictors the team initially identified retained their significance. The patient’s hospital (P<0.001), need for assistance with activities (P=0.02), and type of infection remained significant (P=0.04), but the Charlson score did not (P=0.07).

Dr Anderson recommended that clinicians in community hospitals focus on these risk factors when choosing antibiotic therapy for patients with bloodstream infections. He noted that most risk factors for receiving inappropriate therapy are already recorded in electronic health records.

“Developing an intervention where electronic records automatically alert clinicians to these risk factors when they’re choosing antibiotics could help reduce the problem,” he said. “This is just a place to start, but it’s an example of an area where we could improve how we treat patients with bloodstream infections.” ![]()

Group grows functional LSCs in culture

Two small-molecule compounds can help researchers maintain leukemic stem cells (LSCs) in culture, according to a paper published in Nature Methods.

Investigators said they created improved culture conditions for primary human acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells, based on serum-free medium supplemented with the small molecules SR1 and UM729.

These conditions increased the yield of phenotypically undifferentiated CD34+ AML cells and supported the ex vivo maintenance of LSCs that are typically lost in culture.

Caroline Pabst, MD, of the Institute for Research in Immunology and Cancer at the University of Montreal in Quebec, Canada, and her colleagues conducted this research using AML patient samples.

The team screened about 6000 compounds in an attempt to identify small molecules that promote the ex vivo expansion of undifferentiated AML cells.

And they found that suppressors of the aryl-hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) pathway were enriched among the hit compounds.

So the researchers decided to study 2 chemically distinct AhR suppressors: N-methyl-β-carboline-3-carboxamide (C05), which yielded the highest CD34+CD15- cell counts in secondary screens, and the known AhR antagonist SR1. They also studied the pyrimidoindole UM729, which had shown no effects on AhR target genes.

Experiments showed that the AhR pathway was “rapidly and robustly” activated in the AML samples upon culture. However, suppressing the pathway with SR1 and C05 enabled the expansion of CD34+ AML cells and supported the maintenance of LSCs.

In addition, UM729 had an additive effect with SR1 on the maintenance of AML stem and progenitor cells in vitro.

The investigators said these results should help establish defined conditions to overcome spontaneous differentiation and cell death in ex vivo cultures of primary human AML specimens.

The team believes at least 3 molecular targets could be involved in this process, and 2 of them are targeted by SR1 and UM729.

So these compounds could serve as a standardized supplement to culture media. They might aid studies of self-renewal mechanisms and help researchers identify new antileukemic drugs. ![]()

Two small-molecule compounds can help researchers maintain leukemic stem cells (LSCs) in culture, according to a paper published in Nature Methods.

Investigators said they created improved culture conditions for primary human acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells, based on serum-free medium supplemented with the small molecules SR1 and UM729.

These conditions increased the yield of phenotypically undifferentiated CD34+ AML cells and supported the ex vivo maintenance of LSCs that are typically lost in culture.

Caroline Pabst, MD, of the Institute for Research in Immunology and Cancer at the University of Montreal in Quebec, Canada, and her colleagues conducted this research using AML patient samples.

The team screened about 6000 compounds in an attempt to identify small molecules that promote the ex vivo expansion of undifferentiated AML cells.

And they found that suppressors of the aryl-hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) pathway were enriched among the hit compounds.

So the researchers decided to study 2 chemically distinct AhR suppressors: N-methyl-β-carboline-3-carboxamide (C05), which yielded the highest CD34+CD15- cell counts in secondary screens, and the known AhR antagonist SR1. They also studied the pyrimidoindole UM729, which had shown no effects on AhR target genes.

Experiments showed that the AhR pathway was “rapidly and robustly” activated in the AML samples upon culture. However, suppressing the pathway with SR1 and C05 enabled the expansion of CD34+ AML cells and supported the maintenance of LSCs.

In addition, UM729 had an additive effect with SR1 on the maintenance of AML stem and progenitor cells in vitro.

The investigators said these results should help establish defined conditions to overcome spontaneous differentiation and cell death in ex vivo cultures of primary human AML specimens.

The team believes at least 3 molecular targets could be involved in this process, and 2 of them are targeted by SR1 and UM729.

So these compounds could serve as a standardized supplement to culture media. They might aid studies of self-renewal mechanisms and help researchers identify new antileukemic drugs. ![]()

Two small-molecule compounds can help researchers maintain leukemic stem cells (LSCs) in culture, according to a paper published in Nature Methods.

Investigators said they created improved culture conditions for primary human acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells, based on serum-free medium supplemented with the small molecules SR1 and UM729.

These conditions increased the yield of phenotypically undifferentiated CD34+ AML cells and supported the ex vivo maintenance of LSCs that are typically lost in culture.

Caroline Pabst, MD, of the Institute for Research in Immunology and Cancer at the University of Montreal in Quebec, Canada, and her colleagues conducted this research using AML patient samples.

The team screened about 6000 compounds in an attempt to identify small molecules that promote the ex vivo expansion of undifferentiated AML cells.

And they found that suppressors of the aryl-hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) pathway were enriched among the hit compounds.

So the researchers decided to study 2 chemically distinct AhR suppressors: N-methyl-β-carboline-3-carboxamide (C05), which yielded the highest CD34+CD15- cell counts in secondary screens, and the known AhR antagonist SR1. They also studied the pyrimidoindole UM729, which had shown no effects on AhR target genes.

Experiments showed that the AhR pathway was “rapidly and robustly” activated in the AML samples upon culture. However, suppressing the pathway with SR1 and C05 enabled the expansion of CD34+ AML cells and supported the maintenance of LSCs.

In addition, UM729 had an additive effect with SR1 on the maintenance of AML stem and progenitor cells in vitro.

The investigators said these results should help establish defined conditions to overcome spontaneous differentiation and cell death in ex vivo cultures of primary human AML specimens.

The team believes at least 3 molecular targets could be involved in this process, and 2 of them are targeted by SR1 and UM729.

So these compounds could serve as a standardized supplement to culture media. They might aid studies of self-renewal mechanisms and help researchers identify new antileukemic drugs. ![]()

New cholesterol guidelines would add 13 million new statin users

Strict adherence to the new risk-based American College of Cardiology–American Heart Association guidelines for managing cholesterol would increase the number of adults eligible for statin therapy by nearly 13 million, a study suggests.

Most of the increase would be among older adults without cardiovascular disease, Michael J. Pencina, Ph.D., of the Duke Clinical Research Institute of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and his colleagues reported online March 19 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The investigators used fasting data from 3,773 adults aged 40-75 years who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) of 2005-2010 to estimate the number of individuals for whom statin therapy would be recommended under the new guidelines, published in November 2013, compared with the previously recommended 2007 guidelines from the Third Adult Treatment Panel (ATP III) of the National Cholesterol Education Program.

After extrapolating the results to the estimated population of U.S. adults aged 40-75 years (115.4 million adults), they determined that 14.4 million adults would be newly eligible for statin therapy based on the new guidelines, and that 1.6 million previously eligible adults would become ineligible under the new guidelines, for a net increase in the number of adults receiving or eligible for statin therapy from 43.2 million (38%) to 56.0 million (49%), the investigators said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014 March 19 [doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315665]).

Of the 12.8 million additional eligible adults, 10.4 million would be individuals without existing cardiovascular disease, and 8.4 million of those would be aged 60-75 years; among the 60- to 75-year-olds without cardiovascular disease, the percentage eligible would increase from 30% to 87% for men, and from 21% to 54% for women.

"The median age of adults who would be newly eligible for statin therapy under the new ACC-AHA guidelines would be 63.4 years, and 61.7% would be men. The median LDL cholesterol level for these adults is 105.2 mg per deciliter," the investigators wrote, adding that the new guidelines increase the estimated number of adults who would be eligible across all categories.

The largest increase would occur among adults who have an indication for primary prevention on the basis of their 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease (15.1 million by the new guidelines vs. 6.9 million by ATP III), they said.

"Furthermore, 2.4 million adults with prevalent cardiovascular disease and LDL cholesterol levels of less than 100 mg per deciliter who would not be eligible for statin therapy according to the ATP III guidelines would be eligible under the new ACC-AHA guidelines. Finally, the number of adults with diabetes who are eligible for statin therapy would increase from 4.5 million to 6.7 million as a result of the lowering of the threshold for LDL cholesterol treatment from 100 to 70 mg per deciliter," the investigators wrote.

According to the ATP III guidelines, patients with established cardiovascular disease or diabetes and LDL cholesterol levels of 100 mg/dL or higher were eligible for statin therapy. Those guidelines also recommended statins for primary prevention in patients on the basis of a combined assessment of LDL cholesterol and a 10-year risk of coronary heart disease.

The new ACC-AHA guidelines differ substantially from the ATP III guidelines in that they expand the treatment recommendation to all adults with known cardiovascular disease, regardless of LDL cholesterol level, and for primary prevention they recommend statin therapy for all those with an LDL cholesterol level of 70 mg/dL or higher and who also have diabetes or a 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease of 7.5% or greater based on new pooled-cohort equations.

"These new treatment recommendations have a larger effect in the older age group (60 to 75 years) than in the younger age group (40 to 59 years). Although up to 30% of adults in the younger age group without cardiovascular disease would be eligible for statin therapy for primary prevention, more than 77% of those in the older age group would be eligible. This difference might be partially explained by the addition of stroke to coronary heart disease as a target for prevention in the new pooled-cohort equations," they wrote. Because the prevalence of cardiovascular disease rises markedly with age, the large proportion of older adults who would be eligible for statin therapy may be justifiable, they added.

"Further research is required to determine whether more aggressive preventive strategies are needed for younger adults," they said.

Though limited by a number of factors, such as the extrapolation of data from 3,773 NHANES participants to 115.4 million U.S. adults, and by an inability to accurately quantify the effects of the new and old guidelines on patients currently receiving lipid-lowering therapy (since it was unclear why therapy was initiated), the findings nonetheless suggest a need for personalization with respect to applying the new guidelines.

The new guidelines "treat risk as the predominant reason for treating patients," according to one of the study’s lead authors, Dr. Eric D. Peterson of Duke University.

However, there is a paucity of data on the whether this approach works for older adults, Dr. Peterson said in an interview.

"I’m not willing to say we will be overtreating these patients [based on the new guidelines], but we need more data; this is a pretty big leap," he said.

Conversely, the new guidelines could lead to undertreatment of younger patients with high lipid levels, he added.

"This is kind of frightening," Dr. Peterson said, explaining that a younger patient who appears to have a relatively low 10-year risk of developing cardiovascular disease, but who has high lipid levels, would not be recommended for intervention – even though such a patient has a high likelihood of eventually developing cardiovascular disease.

"There is good research saying we should treat these patients, but these guidelines don’t recommend that. If we strictly follow the guidelines, we will undertreat younger patients," he said.

It is important to remember that the new guidelines are not "the letter of law," but rather are guides.

"Some degree of personalization for the patient in front of us is definitely needed right now," he said.

Dr. Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, cochair of the ACC-AHA guidelines, said he "agrees with the careful analysis" by Dr. Pencina, Dr. Peterson, and their colleagues.

"These findings are consistent with the analyses we reported in the guideline documents using NHANES data," said Dr. Lloyd-Jones, senior associate dean and professor and chair of preventive medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago.

Of note, the majority of the difference between the estimates based on the ATP III guidelines and the ACC-AHA guidelines is due to the lower threshold for consideration of treatment, which was derived directly from the evidence base from newer primary-prevention randomized clinical trials, he said.

"The authors recognized that the reported estimate is the maximum estimate of the increase in the number of people potentially eligible for statin therapy, because the guideline recommendation is for the clinician and patient to use the risk equations as the starting point for a risk discussion, not to mandate a statin prescription," he said.

Additionally, the results "refute the alarmist claims that we saw from a number of commentators in the media a few months ago that 70-100 million Americans would be put on statin therapy as a result of the new guidelines," Dr. Lloyd-Jones said.

"With one in three Americans dying of a preventable or postponable cardiovascular event, and more than half experiencing a major vascular event before they die, evidence-based guidelines that recommend that statins be considered for about half of American adults seem about right. Furthermore, we currently recommend that about 70 million Americans be treated for hypertension, so recommending that about 50 million should be considered for statins also seems about right," he said.

This study was funded by the Duke Clinical Research Institute and by grants from M. Jean de Granpre and Louis and Sylvia Vogel. Dr. Pencina reported receiving research fees (unrelated to this study) from McGill University Health Center and AbbVie. Dr. Peterson reported receiving grants from Eli Lilly and grant support and/or personal fees from Janssen and Boehringer Ingelheim. The remaining authors reported having nothing to disclose.

Strict adherence to the new risk-based American College of Cardiology–American Heart Association guidelines for managing cholesterol would increase the number of adults eligible for statin therapy by nearly 13 million, a study suggests.

Most of the increase would be among older adults without cardiovascular disease, Michael J. Pencina, Ph.D., of the Duke Clinical Research Institute of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and his colleagues reported online March 19 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The investigators used fasting data from 3,773 adults aged 40-75 years who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) of 2005-2010 to estimate the number of individuals for whom statin therapy would be recommended under the new guidelines, published in November 2013, compared with the previously recommended 2007 guidelines from the Third Adult Treatment Panel (ATP III) of the National Cholesterol Education Program.

After extrapolating the results to the estimated population of U.S. adults aged 40-75 years (115.4 million adults), they determined that 14.4 million adults would be newly eligible for statin therapy based on the new guidelines, and that 1.6 million previously eligible adults would become ineligible under the new guidelines, for a net increase in the number of adults receiving or eligible for statin therapy from 43.2 million (38%) to 56.0 million (49%), the investigators said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014 March 19 [doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315665]).

Of the 12.8 million additional eligible adults, 10.4 million would be individuals without existing cardiovascular disease, and 8.4 million of those would be aged 60-75 years; among the 60- to 75-year-olds without cardiovascular disease, the percentage eligible would increase from 30% to 87% for men, and from 21% to 54% for women.