User login

Vorinostat demonstrates antitumor activity in FL

Single-agent treatment with the HDAC inhibitor vorinostat can be effective in certain patients with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), according to research published in the British Journal of Haematology.

In the phase 2 study, vorinostat prompted a 49% overall response rate among 39 patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma (FL).

However, none of the 4 patients with previously treated mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) achieved a response.

Michinori Ogura, MD, PhD, of Nagoya Daini Red Cross Hospital in Japan, and his colleagues set out to analyze the effects of vorinostat in 56 patients with indolent NHL. Six patients were excluded from the final analysis, as their diseases could not be classified.

Thirty-nine patients had FL, 4 had extranodal marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) of MALT type, 4 had MCL, 2 had small B-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified (NOS), and 1 had small lymphocytic lymphoma.

The median age was 60 years (range, 33-75), and the median number of prior therapies was 2 (range, 1-4). These therapies included rituximab (n=40), alkylating agents (n=7), purine analogs (n=5), and radioimmunotherapy (n=3).

The patients received vorinostat for a median of 8 months. The planned dosage was 200 mg twice daily for 14 consecutive days in a 21-day cycle.

At the first data cutoff point (1 year from the last patient’s enrollment), 18 patients remained on treatment. Thirty-eight had discontinued due to disease progression (n=25), drug-related adverse events (n=9), or withdrawn consent (n=4).

The overall response rate was 49% among FL patients. Ten percent (n=4) achieved a complete response, 8% (n=3) achieved an unconfirmed complete response, and 31% (n=12) achieved a partial response.

None of the patients with MCL responded, but 3 of the 7 (43%) patients with other indolent NHLs achieved a response.

That included 2 patients with small B-cell lymphoma NOS and 1 with extranodal MZL of MALT type. One of the patients with small B-cell lymphoma NOS achieved a complete response.

Approximately 81% of all 56 patients remained alive at 2 years after the last patients had enrolled (the second data cutoff point).

At that point, the median overall survival had not been reached. And the median progression-free survival was 26 months among the FL patients who responded.

There were no treatment-related deaths. The most common drug-related events (in all 56 patients) were thrombocytopenia (93%), diarrhea (68%), neutropenia (68%), decreased appetite (63%), nausea (61%), leukopenia (55%), and fatigue (52%).

Eighty percent of patients (n=45) experienced grade 3/4 adverse events, the most common of which were thrombocytopenia (23% grade 3; 25% grade 4) and neutropenia (36% grade 3; 5% grade 4).

However, all of the patients with thrombocytopenia or neutropenia recovered after they received adequate supportive care and their vorinostat dose was reduced or treatment was interrupted or discontinued.

Taking these results together, the researchers concluded that vorinostat offers sustained antitumor activity and has an acceptable safety profile for patients with relapsed or refractory FL. The team noted, however, that because this was a single-arm study with limited data, a comparative study is needed. ![]()

Single-agent treatment with the HDAC inhibitor vorinostat can be effective in certain patients with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), according to research published in the British Journal of Haematology.

In the phase 2 study, vorinostat prompted a 49% overall response rate among 39 patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma (FL).

However, none of the 4 patients with previously treated mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) achieved a response.

Michinori Ogura, MD, PhD, of Nagoya Daini Red Cross Hospital in Japan, and his colleagues set out to analyze the effects of vorinostat in 56 patients with indolent NHL. Six patients were excluded from the final analysis, as their diseases could not be classified.

Thirty-nine patients had FL, 4 had extranodal marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) of MALT type, 4 had MCL, 2 had small B-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified (NOS), and 1 had small lymphocytic lymphoma.

The median age was 60 years (range, 33-75), and the median number of prior therapies was 2 (range, 1-4). These therapies included rituximab (n=40), alkylating agents (n=7), purine analogs (n=5), and radioimmunotherapy (n=3).

The patients received vorinostat for a median of 8 months. The planned dosage was 200 mg twice daily for 14 consecutive days in a 21-day cycle.

At the first data cutoff point (1 year from the last patient’s enrollment), 18 patients remained on treatment. Thirty-eight had discontinued due to disease progression (n=25), drug-related adverse events (n=9), or withdrawn consent (n=4).

The overall response rate was 49% among FL patients. Ten percent (n=4) achieved a complete response, 8% (n=3) achieved an unconfirmed complete response, and 31% (n=12) achieved a partial response.

None of the patients with MCL responded, but 3 of the 7 (43%) patients with other indolent NHLs achieved a response.

That included 2 patients with small B-cell lymphoma NOS and 1 with extranodal MZL of MALT type. One of the patients with small B-cell lymphoma NOS achieved a complete response.

Approximately 81% of all 56 patients remained alive at 2 years after the last patients had enrolled (the second data cutoff point).

At that point, the median overall survival had not been reached. And the median progression-free survival was 26 months among the FL patients who responded.

There were no treatment-related deaths. The most common drug-related events (in all 56 patients) were thrombocytopenia (93%), diarrhea (68%), neutropenia (68%), decreased appetite (63%), nausea (61%), leukopenia (55%), and fatigue (52%).

Eighty percent of patients (n=45) experienced grade 3/4 adverse events, the most common of which were thrombocytopenia (23% grade 3; 25% grade 4) and neutropenia (36% grade 3; 5% grade 4).

However, all of the patients with thrombocytopenia or neutropenia recovered after they received adequate supportive care and their vorinostat dose was reduced or treatment was interrupted or discontinued.

Taking these results together, the researchers concluded that vorinostat offers sustained antitumor activity and has an acceptable safety profile for patients with relapsed or refractory FL. The team noted, however, that because this was a single-arm study with limited data, a comparative study is needed. ![]()

Single-agent treatment with the HDAC inhibitor vorinostat can be effective in certain patients with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), according to research published in the British Journal of Haematology.

In the phase 2 study, vorinostat prompted a 49% overall response rate among 39 patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma (FL).

However, none of the 4 patients with previously treated mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) achieved a response.

Michinori Ogura, MD, PhD, of Nagoya Daini Red Cross Hospital in Japan, and his colleagues set out to analyze the effects of vorinostat in 56 patients with indolent NHL. Six patients were excluded from the final analysis, as their diseases could not be classified.

Thirty-nine patients had FL, 4 had extranodal marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) of MALT type, 4 had MCL, 2 had small B-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified (NOS), and 1 had small lymphocytic lymphoma.

The median age was 60 years (range, 33-75), and the median number of prior therapies was 2 (range, 1-4). These therapies included rituximab (n=40), alkylating agents (n=7), purine analogs (n=5), and radioimmunotherapy (n=3).

The patients received vorinostat for a median of 8 months. The planned dosage was 200 mg twice daily for 14 consecutive days in a 21-day cycle.

At the first data cutoff point (1 year from the last patient’s enrollment), 18 patients remained on treatment. Thirty-eight had discontinued due to disease progression (n=25), drug-related adverse events (n=9), or withdrawn consent (n=4).

The overall response rate was 49% among FL patients. Ten percent (n=4) achieved a complete response, 8% (n=3) achieved an unconfirmed complete response, and 31% (n=12) achieved a partial response.

None of the patients with MCL responded, but 3 of the 7 (43%) patients with other indolent NHLs achieved a response.

That included 2 patients with small B-cell lymphoma NOS and 1 with extranodal MZL of MALT type. One of the patients with small B-cell lymphoma NOS achieved a complete response.

Approximately 81% of all 56 patients remained alive at 2 years after the last patients had enrolled (the second data cutoff point).

At that point, the median overall survival had not been reached. And the median progression-free survival was 26 months among the FL patients who responded.

There were no treatment-related deaths. The most common drug-related events (in all 56 patients) were thrombocytopenia (93%), diarrhea (68%), neutropenia (68%), decreased appetite (63%), nausea (61%), leukopenia (55%), and fatigue (52%).

Eighty percent of patients (n=45) experienced grade 3/4 adverse events, the most common of which were thrombocytopenia (23% grade 3; 25% grade 4) and neutropenia (36% grade 3; 5% grade 4).

However, all of the patients with thrombocytopenia or neutropenia recovered after they received adequate supportive care and their vorinostat dose was reduced or treatment was interrupted or discontinued.

Taking these results together, the researchers concluded that vorinostat offers sustained antitumor activity and has an acceptable safety profile for patients with relapsed or refractory FL. The team noted, however, that because this was a single-arm study with limited data, a comparative study is needed. ![]()

Immunotherapy shows promise in CBCL

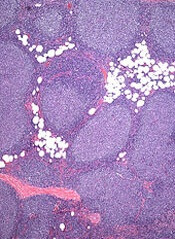

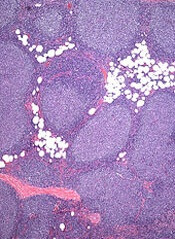

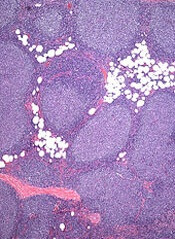

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Credit: Leszek Woźniak

& Krzysztof W. Zieliński

An immunotherapeutic agent can confer clinical benefit in patients with relapsed cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL), results of a small phase 2 study suggest.

The therapy, TG1042, is human adenovirus type 5 engineered to express interferon-gamma.

Repeat injections of TG1042 elicited responses in 11 of 12 evaluable patients, with complete responses in 7.

All 13 of the patients enrolled on the study experienced an adverse event that may have been related to TG1042, but most were grade 1 or 2 in severity.

“Intralesional TG1042 therapy is well-tolerated and results in lasting tumor regressions,” said study author Reinhard Dummer, MD, of the University of Zurich in Switzerland.

He and his colleagues reported these results in PLOS ONE. The study was sponsored by Transgene SA, makers of TG1042.

The trial consisted of 13 patients with primary CBCL, including primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, primary cutaneous follicle center B-cell lymphoma, primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma other than leg type, and T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma.

Patients were required to have either relapsed or active disease after at least 1 first-line treatment.

The patients received intralesional injections of TG1042 at 5 x 1010 viral particles per lesion. They could receive injections in up to 6 lesions, which were treated simultaneously on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 4-week cycle.

Patients did not receive treatment during the fourth week. At the end of the cycle, the researchers evaluated tumors for response.

If patients’ disease did not progress, they could receive an additional cycle, up to a maximum of 4. If patients responded to treatment and their lesions disappeared, they were eligible to receive a second series of injections in untreated lesions.

Of the 13 patients treated, 12 were evaluable for response. Eleven of the patients (85%) achieved an objective response—7 complete responses and 4 partial responses. One patient had stable disease.

All reviewed skin biopsies showed that lesions improved after treatment, with a decrease of the lymphoid infiltrate.

The median time to first objective response was 3.2 months (rage, 1-17.5 months). Among complete responders, the median time to response was 4.3 months (range, 1.4-17.5 months).

The median time to progression was 23.5 months (range, 6.5-26.4+ months).

All 13 patients were included in the safety evaluation, and all experienced 1 or more adverse events that were considered possibly or probably related to the treatment.

One patient discontinued treatment due to influenza-like illness, pyrexia, headache, and skin blisters that were possibly related to TG1042.

Another patient had grade 3 increased lipase, but this was thought to be unrelated to TG1042. And it resolved without treatment.

All other adverse events were grade 1 or 2 in nature. They included fatigue, headache, pyrexia, chills, influenza-like illness, injection site irritation, injection site erythema, and injection site pain.

All of these reactions resolved after treatment discontinuation. ![]()

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Credit: Leszek Woźniak

& Krzysztof W. Zieliński

An immunotherapeutic agent can confer clinical benefit in patients with relapsed cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL), results of a small phase 2 study suggest.

The therapy, TG1042, is human adenovirus type 5 engineered to express interferon-gamma.

Repeat injections of TG1042 elicited responses in 11 of 12 evaluable patients, with complete responses in 7.

All 13 of the patients enrolled on the study experienced an adverse event that may have been related to TG1042, but most were grade 1 or 2 in severity.

“Intralesional TG1042 therapy is well-tolerated and results in lasting tumor regressions,” said study author Reinhard Dummer, MD, of the University of Zurich in Switzerland.

He and his colleagues reported these results in PLOS ONE. The study was sponsored by Transgene SA, makers of TG1042.

The trial consisted of 13 patients with primary CBCL, including primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, primary cutaneous follicle center B-cell lymphoma, primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma other than leg type, and T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma.

Patients were required to have either relapsed or active disease after at least 1 first-line treatment.

The patients received intralesional injections of TG1042 at 5 x 1010 viral particles per lesion. They could receive injections in up to 6 lesions, which were treated simultaneously on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 4-week cycle.

Patients did not receive treatment during the fourth week. At the end of the cycle, the researchers evaluated tumors for response.

If patients’ disease did not progress, they could receive an additional cycle, up to a maximum of 4. If patients responded to treatment and their lesions disappeared, they were eligible to receive a second series of injections in untreated lesions.

Of the 13 patients treated, 12 were evaluable for response. Eleven of the patients (85%) achieved an objective response—7 complete responses and 4 partial responses. One patient had stable disease.

All reviewed skin biopsies showed that lesions improved after treatment, with a decrease of the lymphoid infiltrate.

The median time to first objective response was 3.2 months (rage, 1-17.5 months). Among complete responders, the median time to response was 4.3 months (range, 1.4-17.5 months).

The median time to progression was 23.5 months (range, 6.5-26.4+ months).

All 13 patients were included in the safety evaluation, and all experienced 1 or more adverse events that were considered possibly or probably related to the treatment.

One patient discontinued treatment due to influenza-like illness, pyrexia, headache, and skin blisters that were possibly related to TG1042.

Another patient had grade 3 increased lipase, but this was thought to be unrelated to TG1042. And it resolved without treatment.

All other adverse events were grade 1 or 2 in nature. They included fatigue, headache, pyrexia, chills, influenza-like illness, injection site irritation, injection site erythema, and injection site pain.

All of these reactions resolved after treatment discontinuation. ![]()

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Credit: Leszek Woźniak

& Krzysztof W. Zieliński

An immunotherapeutic agent can confer clinical benefit in patients with relapsed cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL), results of a small phase 2 study suggest.

The therapy, TG1042, is human adenovirus type 5 engineered to express interferon-gamma.

Repeat injections of TG1042 elicited responses in 11 of 12 evaluable patients, with complete responses in 7.

All 13 of the patients enrolled on the study experienced an adverse event that may have been related to TG1042, but most were grade 1 or 2 in severity.

“Intralesional TG1042 therapy is well-tolerated and results in lasting tumor regressions,” said study author Reinhard Dummer, MD, of the University of Zurich in Switzerland.

He and his colleagues reported these results in PLOS ONE. The study was sponsored by Transgene SA, makers of TG1042.

The trial consisted of 13 patients with primary CBCL, including primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, primary cutaneous follicle center B-cell lymphoma, primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma other than leg type, and T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma.

Patients were required to have either relapsed or active disease after at least 1 first-line treatment.

The patients received intralesional injections of TG1042 at 5 x 1010 viral particles per lesion. They could receive injections in up to 6 lesions, which were treated simultaneously on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 4-week cycle.

Patients did not receive treatment during the fourth week. At the end of the cycle, the researchers evaluated tumors for response.

If patients’ disease did not progress, they could receive an additional cycle, up to a maximum of 4. If patients responded to treatment and their lesions disappeared, they were eligible to receive a second series of injections in untreated lesions.

Of the 13 patients treated, 12 were evaluable for response. Eleven of the patients (85%) achieved an objective response—7 complete responses and 4 partial responses. One patient had stable disease.

All reviewed skin biopsies showed that lesions improved after treatment, with a decrease of the lymphoid infiltrate.

The median time to first objective response was 3.2 months (rage, 1-17.5 months). Among complete responders, the median time to response was 4.3 months (range, 1.4-17.5 months).

The median time to progression was 23.5 months (range, 6.5-26.4+ months).

All 13 patients were included in the safety evaluation, and all experienced 1 or more adverse events that were considered possibly or probably related to the treatment.

One patient discontinued treatment due to influenza-like illness, pyrexia, headache, and skin blisters that were possibly related to TG1042.

Another patient had grade 3 increased lipase, but this was thought to be unrelated to TG1042. And it resolved without treatment.

All other adverse events were grade 1 or 2 in nature. They included fatigue, headache, pyrexia, chills, influenza-like illness, injection site irritation, injection site erythema, and injection site pain.

All of these reactions resolved after treatment discontinuation. ![]()

Device measures drugs’ antithrombotic activity

on a microfluidic chip

Credit: Rob Felt

New research suggests a microfluidic device could help physicians choose the appropriate antiplatelet therapy for patients in need of thromboprophylaxis.

Study investigators ran patient blood samples through the microfluidic device to compare the effects of 3 antiplatelet agents—aspirin, eptifibatide, and heparin—on occlusion times and thrombus detachment.

They found that shear rates had a significant impact on treatment effects.

Although aspirin was effective at low shear rates, it proved largely ineffective at high shear rates, even with increasing doses. And the same was true of heparin.

Eptifibatide was affected by shear rates but still lengthened occlusion times and decreased the risk of thrombus detachment. At higher doses, the drug could prevent occlusion regardless of shear rate.

Melissa Li, PhD, of the University of Washington in Seattle, and her colleagues reported these results in PLOS ONE.

“Doctors have many drug options, and it is difficult for them to determine how well each of those options is going to work for a patient,” Dr Li said. “This study is the first time that a prototype benchtop diagnostic device has tried to address this problem using varying shear rates and patient dosing and tried to make it more personalized.”

The researchers used the microfluidic device to measure occlusion times and thrombus detachment for a range of shear rates (500, 1500, 4000, and 10000 s-1) and drug concentrations (0-2.4 μM for eptifibatide, 0-2 mM for aspirin, and 3.5-40 units/L for heparin).

The team took blood samples from healthy patients, added the drugs to the samples, and ran them through the device. The device has 4 channels that mimic the coronary arteries, which allowed the investigators to study clotting under a variety of conditions.

Results showed that eptifibatide lengthened occlusion time, but the time decreased as shear rates increased. Increasing doses of the drug reduced the risk of occlusion, however. At doses greater than 1.2 μM, eptifibatide prevented occlusion at all shear rates.

Aspirin was unable to fully prevent occlusive thrombosis at high shear rates (4000 and 10000 s-1), even at doses of 2 mM, which is 20 times the recommended daily oral dose.

However, the drug did prevent nearly all occlusive thromboses at low shear rates (500 and 1500 s-1), even at the lowest doses tested. The researchers said they observed identical trends in aspirin and heparin.

When they controlled for shear rate, dosage, and inter-subject variability, the investigators found that occlusion rates were significantly different with the 3 therapies.

Compared to samples treated with eptifibatide, those treated with aspirin had a 4-fold greater risk of occlusion, and those treated with heparin had a 9-fold greater risk. An untreated sample had 14 times the risk of occlusion as an eptifibatide-treated sample.

The researchers also assessed the risk of thrombus detachment and found that eptifibatide lowered the risk, while aspirin raised it. Compared to no therapy, the odds ratios were 0.72 for eptifibatide and 4.48 for aspirin.

Dr Li said this evidence suggests that aspirin can prevent thrombosis in some patients but may not be effective in others, particularly those with atherosclerosis. The team’s device could one day help physicians identify which patients can benefit from aspirin and which cannot, although more testing is needed.

“This finding is something that’s been echoed in the literature by physicians who would find that a number of patients who would take aspirin were not receiving any clinical benefit,” Dr Li said. “What we showed is a good explanation for the conditions under which aspirin resistance occurs and one that matches up with what other people have found.”

On the other hand, as eptifibatide could prevent thrombosis across all shear rates, this research suggests the drug (and other GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors) could be effective for patients whether or not they had atherosclerosis. Dr Li noted that clinical evidence supports this finding. ![]()

on a microfluidic chip

Credit: Rob Felt

New research suggests a microfluidic device could help physicians choose the appropriate antiplatelet therapy for patients in need of thromboprophylaxis.

Study investigators ran patient blood samples through the microfluidic device to compare the effects of 3 antiplatelet agents—aspirin, eptifibatide, and heparin—on occlusion times and thrombus detachment.

They found that shear rates had a significant impact on treatment effects.

Although aspirin was effective at low shear rates, it proved largely ineffective at high shear rates, even with increasing doses. And the same was true of heparin.

Eptifibatide was affected by shear rates but still lengthened occlusion times and decreased the risk of thrombus detachment. At higher doses, the drug could prevent occlusion regardless of shear rate.

Melissa Li, PhD, of the University of Washington in Seattle, and her colleagues reported these results in PLOS ONE.

“Doctors have many drug options, and it is difficult for them to determine how well each of those options is going to work for a patient,” Dr Li said. “This study is the first time that a prototype benchtop diagnostic device has tried to address this problem using varying shear rates and patient dosing and tried to make it more personalized.”

The researchers used the microfluidic device to measure occlusion times and thrombus detachment for a range of shear rates (500, 1500, 4000, and 10000 s-1) and drug concentrations (0-2.4 μM for eptifibatide, 0-2 mM for aspirin, and 3.5-40 units/L for heparin).

The team took blood samples from healthy patients, added the drugs to the samples, and ran them through the device. The device has 4 channels that mimic the coronary arteries, which allowed the investigators to study clotting under a variety of conditions.

Results showed that eptifibatide lengthened occlusion time, but the time decreased as shear rates increased. Increasing doses of the drug reduced the risk of occlusion, however. At doses greater than 1.2 μM, eptifibatide prevented occlusion at all shear rates.

Aspirin was unable to fully prevent occlusive thrombosis at high shear rates (4000 and 10000 s-1), even at doses of 2 mM, which is 20 times the recommended daily oral dose.

However, the drug did prevent nearly all occlusive thromboses at low shear rates (500 and 1500 s-1), even at the lowest doses tested. The researchers said they observed identical trends in aspirin and heparin.

When they controlled for shear rate, dosage, and inter-subject variability, the investigators found that occlusion rates were significantly different with the 3 therapies.

Compared to samples treated with eptifibatide, those treated with aspirin had a 4-fold greater risk of occlusion, and those treated with heparin had a 9-fold greater risk. An untreated sample had 14 times the risk of occlusion as an eptifibatide-treated sample.

The researchers also assessed the risk of thrombus detachment and found that eptifibatide lowered the risk, while aspirin raised it. Compared to no therapy, the odds ratios were 0.72 for eptifibatide and 4.48 for aspirin.

Dr Li said this evidence suggests that aspirin can prevent thrombosis in some patients but may not be effective in others, particularly those with atherosclerosis. The team’s device could one day help physicians identify which patients can benefit from aspirin and which cannot, although more testing is needed.

“This finding is something that’s been echoed in the literature by physicians who would find that a number of patients who would take aspirin were not receiving any clinical benefit,” Dr Li said. “What we showed is a good explanation for the conditions under which aspirin resistance occurs and one that matches up with what other people have found.”

On the other hand, as eptifibatide could prevent thrombosis across all shear rates, this research suggests the drug (and other GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors) could be effective for patients whether or not they had atherosclerosis. Dr Li noted that clinical evidence supports this finding. ![]()

on a microfluidic chip

Credit: Rob Felt

New research suggests a microfluidic device could help physicians choose the appropriate antiplatelet therapy for patients in need of thromboprophylaxis.

Study investigators ran patient blood samples through the microfluidic device to compare the effects of 3 antiplatelet agents—aspirin, eptifibatide, and heparin—on occlusion times and thrombus detachment.

They found that shear rates had a significant impact on treatment effects.

Although aspirin was effective at low shear rates, it proved largely ineffective at high shear rates, even with increasing doses. And the same was true of heparin.

Eptifibatide was affected by shear rates but still lengthened occlusion times and decreased the risk of thrombus detachment. At higher doses, the drug could prevent occlusion regardless of shear rate.

Melissa Li, PhD, of the University of Washington in Seattle, and her colleagues reported these results in PLOS ONE.

“Doctors have many drug options, and it is difficult for them to determine how well each of those options is going to work for a patient,” Dr Li said. “This study is the first time that a prototype benchtop diagnostic device has tried to address this problem using varying shear rates and patient dosing and tried to make it more personalized.”

The researchers used the microfluidic device to measure occlusion times and thrombus detachment for a range of shear rates (500, 1500, 4000, and 10000 s-1) and drug concentrations (0-2.4 μM for eptifibatide, 0-2 mM for aspirin, and 3.5-40 units/L for heparin).

The team took blood samples from healthy patients, added the drugs to the samples, and ran them through the device. The device has 4 channels that mimic the coronary arteries, which allowed the investigators to study clotting under a variety of conditions.

Results showed that eptifibatide lengthened occlusion time, but the time decreased as shear rates increased. Increasing doses of the drug reduced the risk of occlusion, however. At doses greater than 1.2 μM, eptifibatide prevented occlusion at all shear rates.

Aspirin was unable to fully prevent occlusive thrombosis at high shear rates (4000 and 10000 s-1), even at doses of 2 mM, which is 20 times the recommended daily oral dose.

However, the drug did prevent nearly all occlusive thromboses at low shear rates (500 and 1500 s-1), even at the lowest doses tested. The researchers said they observed identical trends in aspirin and heparin.

When they controlled for shear rate, dosage, and inter-subject variability, the investigators found that occlusion rates were significantly different with the 3 therapies.

Compared to samples treated with eptifibatide, those treated with aspirin had a 4-fold greater risk of occlusion, and those treated with heparin had a 9-fold greater risk. An untreated sample had 14 times the risk of occlusion as an eptifibatide-treated sample.

The researchers also assessed the risk of thrombus detachment and found that eptifibatide lowered the risk, while aspirin raised it. Compared to no therapy, the odds ratios were 0.72 for eptifibatide and 4.48 for aspirin.

Dr Li said this evidence suggests that aspirin can prevent thrombosis in some patients but may not be effective in others, particularly those with atherosclerosis. The team’s device could one day help physicians identify which patients can benefit from aspirin and which cannot, although more testing is needed.

“This finding is something that’s been echoed in the literature by physicians who would find that a number of patients who would take aspirin were not receiving any clinical benefit,” Dr Li said. “What we showed is a good explanation for the conditions under which aspirin resistance occurs and one that matches up with what other people have found.”

On the other hand, as eptifibatide could prevent thrombosis across all shear rates, this research suggests the drug (and other GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors) could be effective for patients whether or not they had atherosclerosis. Dr Li noted that clinical evidence supports this finding. ![]()

HM14 Special Report: Disaster Preparedness

Presenters: Dahlia Rizk, Alfred Burger, Reza Samad, Beth Israel Medical Center, New York City

Summary: Disasters can happen anywhere. The team at Beth Israel Medical Center shared their experience with disaster pre-planning and also with severe storm effects of Hurricane Sandy in lower Manhattan in New York City in 2012.

Disaster pre-planning is a very helpful tool. Beth Israel Medical Center (BIMC) had regular leadership planning meetings and mock disaster situations in advance of Hurricane Sandy. Their overall disaster plan included triage of existing patients to a lower acuity setting or discharge. Planning for staff needs, including places to stay if they cannot safely travel home, is part of the disaster plan.

Hurricane Sandy was a disaster in multiple areas including power loss, closure of other healthcare facilities, trauma, infrastructure impairment, and flooding. Some patients were trapped at home. Many ambulatory centers were closed including dialysis units. Hospitals only had partial power because they were working on emergency generators. Infrastructure was not functioning properly. Cell towers and paging system were not functioning.

BIMC received a surge of patients after the storm because of decreased access to medical care in the storm area. One way they dealt with the surge was opening new patient units on two revamped substance abuse units.

There were many lessons learned. A command center for internal communication is required. Communication with outside entities is also important.

Surge planning is also a key consideration. Making bed space, alternative use of staff, patient supplies, staff supplies, staff quarters are all aspects of planning. Disposition enhancement is important for patient care. Social workers and nursing home collaboration are needed. Human resources is needed for short and long term surge staffing. Relationships with other institutions and staffing companies can assist with staffing needs.

Key Takeaways:

- Disasters happen and are often unpredictable.

- Preparation is essential.

- Leadership among staff is crucial.

- Teamwork is a must and will get the organization through a disaster.

Dr. Hale is a pediatric hospitalist at the Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, and a member of Team Hospitalist.

Presenters: Dahlia Rizk, Alfred Burger, Reza Samad, Beth Israel Medical Center, New York City

Summary: Disasters can happen anywhere. The team at Beth Israel Medical Center shared their experience with disaster pre-planning and also with severe storm effects of Hurricane Sandy in lower Manhattan in New York City in 2012.

Disaster pre-planning is a very helpful tool. Beth Israel Medical Center (BIMC) had regular leadership planning meetings and mock disaster situations in advance of Hurricane Sandy. Their overall disaster plan included triage of existing patients to a lower acuity setting or discharge. Planning for staff needs, including places to stay if they cannot safely travel home, is part of the disaster plan.

Hurricane Sandy was a disaster in multiple areas including power loss, closure of other healthcare facilities, trauma, infrastructure impairment, and flooding. Some patients were trapped at home. Many ambulatory centers were closed including dialysis units. Hospitals only had partial power because they were working on emergency generators. Infrastructure was not functioning properly. Cell towers and paging system were not functioning.

BIMC received a surge of patients after the storm because of decreased access to medical care in the storm area. One way they dealt with the surge was opening new patient units on two revamped substance abuse units.

There were many lessons learned. A command center for internal communication is required. Communication with outside entities is also important.

Surge planning is also a key consideration. Making bed space, alternative use of staff, patient supplies, staff supplies, staff quarters are all aspects of planning. Disposition enhancement is important for patient care. Social workers and nursing home collaboration are needed. Human resources is needed for short and long term surge staffing. Relationships with other institutions and staffing companies can assist with staffing needs.

Key Takeaways:

- Disasters happen and are often unpredictable.

- Preparation is essential.

- Leadership among staff is crucial.

- Teamwork is a must and will get the organization through a disaster.

Dr. Hale is a pediatric hospitalist at the Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, and a member of Team Hospitalist.

Presenters: Dahlia Rizk, Alfred Burger, Reza Samad, Beth Israel Medical Center, New York City

Summary: Disasters can happen anywhere. The team at Beth Israel Medical Center shared their experience with disaster pre-planning and also with severe storm effects of Hurricane Sandy in lower Manhattan in New York City in 2012.

Disaster pre-planning is a very helpful tool. Beth Israel Medical Center (BIMC) had regular leadership planning meetings and mock disaster situations in advance of Hurricane Sandy. Their overall disaster plan included triage of existing patients to a lower acuity setting or discharge. Planning for staff needs, including places to stay if they cannot safely travel home, is part of the disaster plan.

Hurricane Sandy was a disaster in multiple areas including power loss, closure of other healthcare facilities, trauma, infrastructure impairment, and flooding. Some patients were trapped at home. Many ambulatory centers were closed including dialysis units. Hospitals only had partial power because they were working on emergency generators. Infrastructure was not functioning properly. Cell towers and paging system were not functioning.

BIMC received a surge of patients after the storm because of decreased access to medical care in the storm area. One way they dealt with the surge was opening new patient units on two revamped substance abuse units.

There were many lessons learned. A command center for internal communication is required. Communication with outside entities is also important.

Surge planning is also a key consideration. Making bed space, alternative use of staff, patient supplies, staff supplies, staff quarters are all aspects of planning. Disposition enhancement is important for patient care. Social workers and nursing home collaboration are needed. Human resources is needed for short and long term surge staffing. Relationships with other institutions and staffing companies can assist with staffing needs.

Key Takeaways:

- Disasters happen and are often unpredictable.

- Preparation is essential.

- Leadership among staff is crucial.

- Teamwork is a must and will get the organization through a disaster.

Dr. Hale is a pediatric hospitalist at the Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, and a member of Team Hospitalist.

HM14 Special Report: HFNC in Bronchiolitis: Best Thing Since Sliced Bread?

Presenter: Shawn Ralston, MD, Children’s Hospital at Dartmouth and Giesel School of Medicine, Hanover, NH

As the evidence comes in, the use of HFNC in patients with bronchiolitis is likely to be an innovation in pediatric hospital medicine,” said Dr. Ralston, with a potentially large impact on the healthcare of hospitalized children in the U.S.

Key Takeaways

Dr. Ralson provided a succinct overview of the literature surrounding the use of HFNC in patients with bronchiolitis:

- Over the past 10 years, the incidence rates of bronchiolitis hospitalizations have declined in all age groups, but during the same time period in-hospital use of mechanical ventilation, and therefore hospital charges per case, have increased.

- Surprisingly, the definition of high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) is not uniform among institutions. Most would agree that it is a heated circuit of humidified oxygen at flow rates that exceed a patient’s respiratory demand.

- The goal of the nasal cannula in HFNC is to occupy at least 50% of the nares. If correctly sized, this will provide end-expiratory pressures that reduce the subjective work of breathing in infants.

- Can we predict the non-responders to HFNC? Failure to decrease respiratory rate (RR) at onset of therapy was associated with intubation, or failure of successful use of HFNC.

- One needs to be aware of potential biases when evaluating the literature on the use of HFNC in bronchiolitis. Seasonal disease variation, secular trends in ICU and/or ED training, and QI culture in hospital such as guidelines and protocols may all potentially impact study results.

James O’Callaghan is a Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Washington and a member of Team Hospitalist.

Presenter: Shawn Ralston, MD, Children’s Hospital at Dartmouth and Giesel School of Medicine, Hanover, NH

As the evidence comes in, the use of HFNC in patients with bronchiolitis is likely to be an innovation in pediatric hospital medicine,” said Dr. Ralston, with a potentially large impact on the healthcare of hospitalized children in the U.S.

Key Takeaways

Dr. Ralson provided a succinct overview of the literature surrounding the use of HFNC in patients with bronchiolitis:

- Over the past 10 years, the incidence rates of bronchiolitis hospitalizations have declined in all age groups, but during the same time period in-hospital use of mechanical ventilation, and therefore hospital charges per case, have increased.

- Surprisingly, the definition of high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) is not uniform among institutions. Most would agree that it is a heated circuit of humidified oxygen at flow rates that exceed a patient’s respiratory demand.

- The goal of the nasal cannula in HFNC is to occupy at least 50% of the nares. If correctly sized, this will provide end-expiratory pressures that reduce the subjective work of breathing in infants.

- Can we predict the non-responders to HFNC? Failure to decrease respiratory rate (RR) at onset of therapy was associated with intubation, or failure of successful use of HFNC.

- One needs to be aware of potential biases when evaluating the literature on the use of HFNC in bronchiolitis. Seasonal disease variation, secular trends in ICU and/or ED training, and QI culture in hospital such as guidelines and protocols may all potentially impact study results.

James O’Callaghan is a Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Washington and a member of Team Hospitalist.

Presenter: Shawn Ralston, MD, Children’s Hospital at Dartmouth and Giesel School of Medicine, Hanover, NH

As the evidence comes in, the use of HFNC in patients with bronchiolitis is likely to be an innovation in pediatric hospital medicine,” said Dr. Ralston, with a potentially large impact on the healthcare of hospitalized children in the U.S.

Key Takeaways

Dr. Ralson provided a succinct overview of the literature surrounding the use of HFNC in patients with bronchiolitis:

- Over the past 10 years, the incidence rates of bronchiolitis hospitalizations have declined in all age groups, but during the same time period in-hospital use of mechanical ventilation, and therefore hospital charges per case, have increased.

- Surprisingly, the definition of high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) is not uniform among institutions. Most would agree that it is a heated circuit of humidified oxygen at flow rates that exceed a patient’s respiratory demand.

- The goal of the nasal cannula in HFNC is to occupy at least 50% of the nares. If correctly sized, this will provide end-expiratory pressures that reduce the subjective work of breathing in infants.

- Can we predict the non-responders to HFNC? Failure to decrease respiratory rate (RR) at onset of therapy was associated with intubation, or failure of successful use of HFNC.

- One needs to be aware of potential biases when evaluating the literature on the use of HFNC in bronchiolitis. Seasonal disease variation, secular trends in ICU and/or ED training, and QI culture in hospital such as guidelines and protocols may all potentially impact study results.

James O’Callaghan is a Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Washington and a member of Team Hospitalist.

Hospitalists Focus on Matters of the Heart

LAS VEGAS—Hospitalist Michael Hoftiezer, MD, has been to pre-courses at annual meetings before HM14, but yesterday’s lineup offered a new option: “Cardiology: What Hospitalists Need to Know as Front-Line Providers.”

The eight-hour seminar was one of three new pre-courses at SHM’s annual meeting, along with “Efficient High-Value Evidence-Based Medicine for the Practicing Hospitalist” and “NP/PA Playbook for Hospital Medicine.” The offerings drew hundreds of hospitalists to the unofficial first day of HM14 at Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino.

“It’s nice to have an extra day of learning,” says Dr. Hoftiezer, who practices at Holy Family Memorial Medical Center in Manitowoc, Wis. And “it’s concentrated on one subject. It’s a good overview of a single subject, rather than bouncing around different things.” Course director Matthews Chacko, MD, of Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, says the time is right for hospitalists to devote a full-day pre-course focused on cardiology. “Cardiovascular disease is the most common reason we die,” he says.

“It’s something hospital-based practitioners see often. Providing a comprehensive but yet simplified overview of the way to manage some of these diseases with talks given by some of the leading experts in the field seemed very appropriate for this meeting.”

The course covered such topics as arrhythmia, heart failure, peripheral artery disease, and unstable myocardial infarction. Dr. Hoftiezer says he gleaned tips he can take back to his hospital—including the mechanisms of atrial fibrillation and when to measure rhythm versus rate—and that’s what made the pre-course valuable.

“The more relevant, the better,” he adds. “My favorite lectures are the ones that change something I do.”

LAS VEGAS—Hospitalist Michael Hoftiezer, MD, has been to pre-courses at annual meetings before HM14, but yesterday’s lineup offered a new option: “Cardiology: What Hospitalists Need to Know as Front-Line Providers.”

The eight-hour seminar was one of three new pre-courses at SHM’s annual meeting, along with “Efficient High-Value Evidence-Based Medicine for the Practicing Hospitalist” and “NP/PA Playbook for Hospital Medicine.” The offerings drew hundreds of hospitalists to the unofficial first day of HM14 at Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino.

“It’s nice to have an extra day of learning,” says Dr. Hoftiezer, who practices at Holy Family Memorial Medical Center in Manitowoc, Wis. And “it’s concentrated on one subject. It’s a good overview of a single subject, rather than bouncing around different things.” Course director Matthews Chacko, MD, of Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, says the time is right for hospitalists to devote a full-day pre-course focused on cardiology. “Cardiovascular disease is the most common reason we die,” he says.

“It’s something hospital-based practitioners see often. Providing a comprehensive but yet simplified overview of the way to manage some of these diseases with talks given by some of the leading experts in the field seemed very appropriate for this meeting.”

The course covered such topics as arrhythmia, heart failure, peripheral artery disease, and unstable myocardial infarction. Dr. Hoftiezer says he gleaned tips he can take back to his hospital—including the mechanisms of atrial fibrillation and when to measure rhythm versus rate—and that’s what made the pre-course valuable.

“The more relevant, the better,” he adds. “My favorite lectures are the ones that change something I do.”

LAS VEGAS—Hospitalist Michael Hoftiezer, MD, has been to pre-courses at annual meetings before HM14, but yesterday’s lineup offered a new option: “Cardiology: What Hospitalists Need to Know as Front-Line Providers.”

The eight-hour seminar was one of three new pre-courses at SHM’s annual meeting, along with “Efficient High-Value Evidence-Based Medicine for the Practicing Hospitalist” and “NP/PA Playbook for Hospital Medicine.” The offerings drew hundreds of hospitalists to the unofficial first day of HM14 at Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino.

“It’s nice to have an extra day of learning,” says Dr. Hoftiezer, who practices at Holy Family Memorial Medical Center in Manitowoc, Wis. And “it’s concentrated on one subject. It’s a good overview of a single subject, rather than bouncing around different things.” Course director Matthews Chacko, MD, of Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, says the time is right for hospitalists to devote a full-day pre-course focused on cardiology. “Cardiovascular disease is the most common reason we die,” he says.

“It’s something hospital-based practitioners see often. Providing a comprehensive but yet simplified overview of the way to manage some of these diseases with talks given by some of the leading experts in the field seemed very appropriate for this meeting.”

The course covered such topics as arrhythmia, heart failure, peripheral artery disease, and unstable myocardial infarction. Dr. Hoftiezer says he gleaned tips he can take back to his hospital—including the mechanisms of atrial fibrillation and when to measure rhythm versus rate—and that’s what made the pre-course valuable.

“The more relevant, the better,” he adds. “My favorite lectures are the ones that change something I do.”

Relevance Fuels HM14 Schedule Decisions

LAS VEGAS—For the next two and a half days at the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino, some 3,000 hospitalists attending SHM’s annual meeting will have 10 learning tracks and 115 educational sessions to choose from. Which raises a good question: How does a hospitalist make the difficult choice between two sessions of interest that are scheduled at the same time?

“What’s guiding me is: What’s more relevant to what I’m doing?” says hospitalist and first-time attendee Uzoeshi Anukam, MD, of Methodist Mansfield Medical Center in Texas. “What’s more relevant to my patient care? I see a lot of chest pain, so I’m going to jump on chest pain [sessions]. It’s relevant for me.”

The smorgasbord of educational tracks, rapid-fire sessions, and small-group workshops is a recipe for conflict, though. Multiple sessions could offer similar relevance.

“It’s pick your poison, sort of,” says Curt Lawrence, MD, a hospitalist who does locums tenens work in Miami. “To me, most of the topics are pretty interesting and informative. It’s a good problem to have, wanting to go to multiple things.”

Dr. Lawrence says SHM’s online repository of presentations, podcasts, and on-demand videos helps to fill the gaps when he misses a session. And Dr. Anukam says the HM14 At Hand application for smartphones and tablets assists in winnowing down choices and setting goals for which sessions to attend.

“Objectives put things in perspective and guide what things to go to,” Dr. Lawrence says. “My goal is to get as much as information as you can. As a hospitalist, it’s go-go-go-go. I want to spend this time to just stop and get information.”

LAS VEGAS—For the next two and a half days at the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino, some 3,000 hospitalists attending SHM’s annual meeting will have 10 learning tracks and 115 educational sessions to choose from. Which raises a good question: How does a hospitalist make the difficult choice between two sessions of interest that are scheduled at the same time?

“What’s guiding me is: What’s more relevant to what I’m doing?” says hospitalist and first-time attendee Uzoeshi Anukam, MD, of Methodist Mansfield Medical Center in Texas. “What’s more relevant to my patient care? I see a lot of chest pain, so I’m going to jump on chest pain [sessions]. It’s relevant for me.”

The smorgasbord of educational tracks, rapid-fire sessions, and small-group workshops is a recipe for conflict, though. Multiple sessions could offer similar relevance.

“It’s pick your poison, sort of,” says Curt Lawrence, MD, a hospitalist who does locums tenens work in Miami. “To me, most of the topics are pretty interesting and informative. It’s a good problem to have, wanting to go to multiple things.”

Dr. Lawrence says SHM’s online repository of presentations, podcasts, and on-demand videos helps to fill the gaps when he misses a session. And Dr. Anukam says the HM14 At Hand application for smartphones and tablets assists in winnowing down choices and setting goals for which sessions to attend.

“Objectives put things in perspective and guide what things to go to,” Dr. Lawrence says. “My goal is to get as much as information as you can. As a hospitalist, it’s go-go-go-go. I want to spend this time to just stop and get information.”

LAS VEGAS—For the next two and a half days at the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino, some 3,000 hospitalists attending SHM’s annual meeting will have 10 learning tracks and 115 educational sessions to choose from. Which raises a good question: How does a hospitalist make the difficult choice between two sessions of interest that are scheduled at the same time?

“What’s guiding me is: What’s more relevant to what I’m doing?” says hospitalist and first-time attendee Uzoeshi Anukam, MD, of Methodist Mansfield Medical Center in Texas. “What’s more relevant to my patient care? I see a lot of chest pain, so I’m going to jump on chest pain [sessions]. It’s relevant for me.”

The smorgasbord of educational tracks, rapid-fire sessions, and small-group workshops is a recipe for conflict, though. Multiple sessions could offer similar relevance.

“It’s pick your poison, sort of,” says Curt Lawrence, MD, a hospitalist who does locums tenens work in Miami. “To me, most of the topics are pretty interesting and informative. It’s a good problem to have, wanting to go to multiple things.”

Dr. Lawrence says SHM’s online repository of presentations, podcasts, and on-demand videos helps to fill the gaps when he misses a session. And Dr. Anukam says the HM14 At Hand application for smartphones and tablets assists in winnowing down choices and setting goals for which sessions to attend.

“Objectives put things in perspective and guide what things to go to,” Dr. Lawrence says. “My goal is to get as much as information as you can. As a hospitalist, it’s go-go-go-go. I want to spend this time to just stop and get information.”

HM14 Special Report: Research in Medical Education

“Stare at who you want to become,” Scott Wright, MD, at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center told hospitalists at SHM’s annual meeting HM14. Look to others who have found success in researching medical education and “learn to steal without apology,” he added. Build upon the work of these mentors and then be sure to give them credit when due. To quote famed painter Pablo Picasso, Dr. Wright said, “Good artists copy, great artists steal.”

Key Takeaways

- Perform a self-assessment. Many of us start our careers with low competency in research skills. It is important to begin with an accurate self-assessment to find areas of weakness and then work with a research mentor to focus improvement on those areas;

- Expand your potential area of research. Medical education has traditionally been concerned with the education and training of residents, but it can also apply to younger clinical faculty and their acquisition of knowledge through continuing medical education;

- Understand how quality will be assessed. Learn how reviewers for journals judge quality and try to increase the quality of the study during the design stage, not the write-up stage; and

- Research new things to determine whether they can work, rather than big, already-implemented things to determine if they did work.

Dr. O’Callaghan is a Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Washington and a member of Team Hospitalist.

“Stare at who you want to become,” Scott Wright, MD, at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center told hospitalists at SHM’s annual meeting HM14. Look to others who have found success in researching medical education and “learn to steal without apology,” he added. Build upon the work of these mentors and then be sure to give them credit when due. To quote famed painter Pablo Picasso, Dr. Wright said, “Good artists copy, great artists steal.”

Key Takeaways

- Perform a self-assessment. Many of us start our careers with low competency in research skills. It is important to begin with an accurate self-assessment to find areas of weakness and then work with a research mentor to focus improvement on those areas;

- Expand your potential area of research. Medical education has traditionally been concerned with the education and training of residents, but it can also apply to younger clinical faculty and their acquisition of knowledge through continuing medical education;

- Understand how quality will be assessed. Learn how reviewers for journals judge quality and try to increase the quality of the study during the design stage, not the write-up stage; and

- Research new things to determine whether they can work, rather than big, already-implemented things to determine if they did work.

Dr. O’Callaghan is a Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Washington and a member of Team Hospitalist.

“Stare at who you want to become,” Scott Wright, MD, at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center told hospitalists at SHM’s annual meeting HM14. Look to others who have found success in researching medical education and “learn to steal without apology,” he added. Build upon the work of these mentors and then be sure to give them credit when due. To quote famed painter Pablo Picasso, Dr. Wright said, “Good artists copy, great artists steal.”

Key Takeaways

- Perform a self-assessment. Many of us start our careers with low competency in research skills. It is important to begin with an accurate self-assessment to find areas of weakness and then work with a research mentor to focus improvement on those areas;

- Expand your potential area of research. Medical education has traditionally been concerned with the education and training of residents, but it can also apply to younger clinical faculty and their acquisition of knowledge through continuing medical education;

- Understand how quality will be assessed. Learn how reviewers for journals judge quality and try to increase the quality of the study during the design stage, not the write-up stage; and

- Research new things to determine whether they can work, rather than big, already-implemented things to determine if they did work.

Dr. O’Callaghan is a Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Washington and a member of Team Hospitalist.

VIDEO: Battlefield lessons improve treatment of traumatic scars

DENVER – Military dermatologists have played an active role in helping wounded warriors with their scars, and those physicians’ practices, including the use of ablative fractional resurfacing, are now entering the civilian world to treat injuries from fire, car crashes, or blasts.

Earlier this year, a group of dermatologists published a consensus report to highlight best practices for laser treatment of traumatic scars. The groups, which included several military dermatologists, concluded that "laser treatment, particularly ablative fractional resurfacing, deserves a prominent role in future scar treatment paradigms, with the possible inclusion of early intervention for contracture avoidance and assistance with wound healing."

In a video interview at the American Academy of Dermatology’s annual meeting, Lt. Col. Chad M. Hivnor, USAF, MC, FS, USA, a staff dermatologist for the San Antonio (Tex.) Military Health System, discussed the use of lasers in treating traumatic scars, talked about the psychology of scars, and shared a few of his own practice pearls.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @naseemmiller

DENVER – Military dermatologists have played an active role in helping wounded warriors with their scars, and those physicians’ practices, including the use of ablative fractional resurfacing, are now entering the civilian world to treat injuries from fire, car crashes, or blasts.

Earlier this year, a group of dermatologists published a consensus report to highlight best practices for laser treatment of traumatic scars. The groups, which included several military dermatologists, concluded that "laser treatment, particularly ablative fractional resurfacing, deserves a prominent role in future scar treatment paradigms, with the possible inclusion of early intervention for contracture avoidance and assistance with wound healing."

In a video interview at the American Academy of Dermatology’s annual meeting, Lt. Col. Chad M. Hivnor, USAF, MC, FS, USA, a staff dermatologist for the San Antonio (Tex.) Military Health System, discussed the use of lasers in treating traumatic scars, talked about the psychology of scars, and shared a few of his own practice pearls.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @naseemmiller

DENVER – Military dermatologists have played an active role in helping wounded warriors with their scars, and those physicians’ practices, including the use of ablative fractional resurfacing, are now entering the civilian world to treat injuries from fire, car crashes, or blasts.

Earlier this year, a group of dermatologists published a consensus report to highlight best practices for laser treatment of traumatic scars. The groups, which included several military dermatologists, concluded that "laser treatment, particularly ablative fractional resurfacing, deserves a prominent role in future scar treatment paradigms, with the possible inclusion of early intervention for contracture avoidance and assistance with wound healing."

In a video interview at the American Academy of Dermatology’s annual meeting, Lt. Col. Chad M. Hivnor, USAF, MC, FS, USA, a staff dermatologist for the San Antonio (Tex.) Military Health System, discussed the use of lasers in treating traumatic scars, talked about the psychology of scars, and shared a few of his own practice pearls.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @naseemmiller

AT THE AAD ANNUAL MEETING

HM14 Special Report: SHM Leadership Committee Meeting

This year’s SHM leadership committee meeting brought together a great group of thought leaders passionate about developing strong leaders for tomorrow. Hospitalists with an interest in leadership have at their disposal three SHM Leadership Academies. These academies build the foundations of effective leadership, teach team building and conflict resolution, and help leaders better understand finances in hospital medicine. In addition, the Certificate of Leadership in Hospital Medicine (CLHM) is a program through which hospitalists are recognized by SHM for their leadership skills and training.

Hospitalists receive expert consultation and guidance for a hospital system project that they would like to implement in their home institution and upon completion, receive a Certificate of Leadership in Hospital Medicine. One of the committee members also pointed out that as a certified leader himself, he has had more success with recruiting quality, career-oriented hospitalists.

Another exciting endeavor this year is our book club. Look for a definitive date in the near future for our second online book club meeting. I am most certainly excited about this meeting because our book of choice is one of my personal favorites: Lean in: women, work and the will to lead.

As an active community on HMX, we would like to hear from our SHM members, leaders and frontline hospitalists alike, about the kind of resources that you might need to help you become better hospitalist leaders at your institution.

Key Takeaways

- Explore SHM Leadership Academies: foundation of leadership, personal excellence and team building, advanced leadership;

- Receive mentorship from experts in our field for a project that you would like to implement at your hospital through SHM’s Certificate of Leadership in Hospital Medicine;

- Let us know what resources you need to help you lead more effectively; and

- Join in on the conversation at our next book club meeting where we will discuss Lean in: women, work, and the will to lead.

Dr. Kanikkannan is Hospitalist Medical Director and Assistant Professor of Medicine Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine and serves on the SHM Leadership Committee. She is a member of Team Hospitalist.

This year’s SHM leadership committee meeting brought together a great group of thought leaders passionate about developing strong leaders for tomorrow. Hospitalists with an interest in leadership have at their disposal three SHM Leadership Academies. These academies build the foundations of effective leadership, teach team building and conflict resolution, and help leaders better understand finances in hospital medicine. In addition, the Certificate of Leadership in Hospital Medicine (CLHM) is a program through which hospitalists are recognized by SHM for their leadership skills and training.

Hospitalists receive expert consultation and guidance for a hospital system project that they would like to implement in their home institution and upon completion, receive a Certificate of Leadership in Hospital Medicine. One of the committee members also pointed out that as a certified leader himself, he has had more success with recruiting quality, career-oriented hospitalists.

Another exciting endeavor this year is our book club. Look for a definitive date in the near future for our second online book club meeting. I am most certainly excited about this meeting because our book of choice is one of my personal favorites: Lean in: women, work and the will to lead.

As an active community on HMX, we would like to hear from our SHM members, leaders and frontline hospitalists alike, about the kind of resources that you might need to help you become better hospitalist leaders at your institution.

Key Takeaways

- Explore SHM Leadership Academies: foundation of leadership, personal excellence and team building, advanced leadership;

- Receive mentorship from experts in our field for a project that you would like to implement at your hospital through SHM’s Certificate of Leadership in Hospital Medicine;

- Let us know what resources you need to help you lead more effectively; and

- Join in on the conversation at our next book club meeting where we will discuss Lean in: women, work, and the will to lead.

Dr. Kanikkannan is Hospitalist Medical Director and Assistant Professor of Medicine Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine and serves on the SHM Leadership Committee. She is a member of Team Hospitalist.

This year’s SHM leadership committee meeting brought together a great group of thought leaders passionate about developing strong leaders for tomorrow. Hospitalists with an interest in leadership have at their disposal three SHM Leadership Academies. These academies build the foundations of effective leadership, teach team building and conflict resolution, and help leaders better understand finances in hospital medicine. In addition, the Certificate of Leadership in Hospital Medicine (CLHM) is a program through which hospitalists are recognized by SHM for their leadership skills and training.

Hospitalists receive expert consultation and guidance for a hospital system project that they would like to implement in their home institution and upon completion, receive a Certificate of Leadership in Hospital Medicine. One of the committee members also pointed out that as a certified leader himself, he has had more success with recruiting quality, career-oriented hospitalists.

Another exciting endeavor this year is our book club. Look for a definitive date in the near future for our second online book club meeting. I am most certainly excited about this meeting because our book of choice is one of my personal favorites: Lean in: women, work and the will to lead.

As an active community on HMX, we would like to hear from our SHM members, leaders and frontline hospitalists alike, about the kind of resources that you might need to help you become better hospitalist leaders at your institution.

Key Takeaways

- Explore SHM Leadership Academies: foundation of leadership, personal excellence and team building, advanced leadership;

- Receive mentorship from experts in our field for a project that you would like to implement at your hospital through SHM’s Certificate of Leadership in Hospital Medicine;

- Let us know what resources you need to help you lead more effectively; and

- Join in on the conversation at our next book club meeting where we will discuss Lean in: women, work, and the will to lead.

Dr. Kanikkannan is Hospitalist Medical Director and Assistant Professor of Medicine Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine and serves on the SHM Leadership Committee. She is a member of Team Hospitalist.