User login

Hospitals Reap Potential of Data Mining

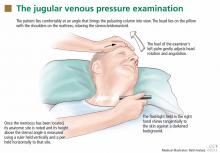

In one recently publicized demonstration of data mining’s potential, Austin, Texas-based Seton Healthcare Family used software developed by IBM to pore over doctors’ notes and predict the risk of readmission among patients with congestive heart failure. Among the shortlist of biggest predictors, the analysis pointed to a lack of emotional support and a bulging jugular vein—factors that could be easily identified through inpatient screening but might otherwise be overlooked by staff.

Similarly, New York-Presbyterian Hospital used a system by Microsoft to help reduce the rates of blood clotting in patients through an objective analysis of such risk factors as cancer, smoking, and bed confinement.

In June, Deloitte and Utah-based Intermountain Healthcare announced the launch of OutcomesMiner, an analytics tool that uses electronic health records to ferret out important variations and associations among patient populations. Brett Davis, general manager of Deloitte Health Informatics, says understanding asthma patients who are in different age brackets, have different comorbidities, and are on different drugs, for example, can allow providers to better manage the population. Merely using ICD-9 codes often results in inaccurate patient classifications, he warns. Instead, capturing and analyzing data from medications and clinical encounters can be vital for properly defining an asthma patient and separating the signal from the noise.

In one recently publicized demonstration of data mining’s potential, Austin, Texas-based Seton Healthcare Family used software developed by IBM to pore over doctors’ notes and predict the risk of readmission among patients with congestive heart failure. Among the shortlist of biggest predictors, the analysis pointed to a lack of emotional support and a bulging jugular vein—factors that could be easily identified through inpatient screening but might otherwise be overlooked by staff.

Similarly, New York-Presbyterian Hospital used a system by Microsoft to help reduce the rates of blood clotting in patients through an objective analysis of such risk factors as cancer, smoking, and bed confinement.

In June, Deloitte and Utah-based Intermountain Healthcare announced the launch of OutcomesMiner, an analytics tool that uses electronic health records to ferret out important variations and associations among patient populations. Brett Davis, general manager of Deloitte Health Informatics, says understanding asthma patients who are in different age brackets, have different comorbidities, and are on different drugs, for example, can allow providers to better manage the population. Merely using ICD-9 codes often results in inaccurate patient classifications, he warns. Instead, capturing and analyzing data from medications and clinical encounters can be vital for properly defining an asthma patient and separating the signal from the noise.

In one recently publicized demonstration of data mining’s potential, Austin, Texas-based Seton Healthcare Family used software developed by IBM to pore over doctors’ notes and predict the risk of readmission among patients with congestive heart failure. Among the shortlist of biggest predictors, the analysis pointed to a lack of emotional support and a bulging jugular vein—factors that could be easily identified through inpatient screening but might otherwise be overlooked by staff.

Similarly, New York-Presbyterian Hospital used a system by Microsoft to help reduce the rates of blood clotting in patients through an objective analysis of such risk factors as cancer, smoking, and bed confinement.

In June, Deloitte and Utah-based Intermountain Healthcare announced the launch of OutcomesMiner, an analytics tool that uses electronic health records to ferret out important variations and associations among patient populations. Brett Davis, general manager of Deloitte Health Informatics, says understanding asthma patients who are in different age brackets, have different comorbidities, and are on different drugs, for example, can allow providers to better manage the population. Merely using ICD-9 codes often results in inaccurate patient classifications, he warns. Instead, capturing and analyzing data from medications and clinical encounters can be vital for properly defining an asthma patient and separating the signal from the noise.

Hospitalist Groups Extract New Solutions Via Data Mining

One hospital wanted to reduce readmissions among patients with congestive heart failure. Another hoped to improve upon its sepsis mortality rates. A third sought to determine whether its doctors were providing cost-effective care for pneumonia patients. All of them adopted the same type of technology to help identify a solution.

As the healthcare industry tilts toward accountable care, pay for performance and an increasingly

cost-conscious mindset, hospitalists and other providers are tapping into a fast-growing analytical tool collectively known as data mining to help make sense of the growing mounds of information. Although no single technology can be considered a cure-all, HM leaders are so optimistic about data mining’s potential to address cost, outcome, and performance issues that some have labeled it a “game changer” for hospitalists.

Karim Godamunne, MD, MBA, SFHM, chief medical officer at North Fulton Hospital in Roswell, Ga., and a member of SHM’s Practice Management Committee, says he can’t overstate the importance of hospitalists’ involvement in physician data mining. “From my perspective, we’re looking to hospitalists to help drive this quality-utilization bandwagon, to be the real leaders in it,” he says. With the tremendous value that can be generated through understanding and using the information, “it’s good for your group and can be good to your hospital as a whole.”

So what is data mining? The technology fully emerged in the mid-1990s as a way to help scientists analyze large and often disparate bodies of data, present relevant information in new ways, and illuminate previously unknown relationships.1 In the healthcare industry, early adopters realized that the insights gleaned from data mining could help inform their clinical decision-making; organizations used the new tools to help predict health insurance fraud and identify at-risk patients, for example.

Cynthia Burghard, research director of Accountable Care IT Strategies at IDC Health Insights in Framingham, Mass., says researchers in academic medical centers initially conducted most of the clinical analytical work. Within the past few years, however, the increasing availability of data has allowed more hospitals to begin analyzing chronic disease, readmissions, and other areas of concern. In addition, Burghard says, new tools based on natural language processing are giving hospitals better access to unstructured clinical data, such as notes written by doctors and nurses.

“What I’m seeing both in my surveys as well as in conversations with hospitals is that analytics is the top of the investment priority for both hospitals and health plans,” Burghard says. According to IDC estimates, total spending for clinical analytics in the U.S. reached $3.7 billion in 2012 and is expected to grow to $5.14 billion by 2016. Much of the growth, she notes, is being driven by healthcare reform. “If your mandate is to manage populations of patients, it behooves you to know who those patients are and what their illnesses are, and to monitor what you’re doing for them,” she says.

Practice Improvement

Accordingly, a major goal of all this data-mining technology is to change practice behavior in a way that achieves the triple aim of improving quality of care, controlling costs, and bettering patient outcomes.

A growing number of companies are releasing tools that can compile and analyze the separate bits of information captured from claims and billing systems, Medicare reporting requirements, internal benchmarks, and other sources. Unlike passive data sources, such as Medicare’s Hospital Compare website, more active analytics can help their users zoom down to the level of an individual doctor or patient, pan out to the level of a hospitalist group, or expand out even more for a broader comparison among peer institutions.

Some newer data-mining tools with names like CRIMSON, Truven, Iodine, and Imagine are billing themselves as hospitalist-friendly performance-improvement aids and giving individual providers the ability to access and analyze the data themselves. A few of these applications can even provide real-time data via mobile devices (see “Physician Performance Aids,”).

Thomas Frederickson, MD, MBA, SFHM, medical director of the HM service at Alegent Creighton Health in Omaha, Neb., and a member of SHM’s Practice Management Committee, sees the biggest potential of this data-mining technology in its ability to help drive practice consistency. “You can use the database to analyze practice patterns of large groups, or even individuals, and see where variability exists,” he says. “And then, based on that, you can analyze why the variability exists and begin to address whether it’s variability that’s clinically indicated or not.”

When Alegent Creighton Health was scrutinizing the care of its pneumonia patients, for example, officials could compare the number of chest X-rays per pneumonia patient by hospital or across the entire CRIMSON database. At a deeper level, the officials could see how often individual providers ordered the tests compared to their peers. For outliers, they could follow up to determine whether the variability was warranted.

As champions of process improvement, Dr. Frederickson says, hospitalists can make particularly good use of database analytics. “It’s part of the process of making hospitalists invaluable to their hospitals and their systems,” he says. “Part of that is building up expertise on process improvement and safety, and familiarity with these kinds of tools is one thing that will help us do that.”

North Fulton Hospital used CRIMSON to analyze how its doctors care for patients with sepsis and to establish new benchmarks. Dr. Godamunne says the tools allowed the hospital to track its doctors’ progress over time and identify potential problems. “If a patient with sepsis is staying too long, you can see who admitted the patient and see if, a few months ago, the same physician was having similar problems,” he says. Similarly, the hospital was able to track the top DRGs resulting in excess length of stay among patients, to identify potential bottlenecks in the care and discharge processes.

Some tools require only two-day training sessions for basic proficiency, though more advanced manipulations often require a bigger commitment, like the 12-week training session that Dr. Godamunne completed. That training included one hour of online learning and one hour of homework every week, and most of the cases highlighted during his coursework, he says, focused on hospitalists—another sign of the major role he believes HM will play in harnessing data to improve performance quality.

—Thomas Frederickson, MD, MBA, SFHM, medical director, hospital medicine service, Alegent Creighton Health, Omaha, Neb., SHM Practice Management Committee member

Slow—Construction Ahead

The best information is meaningful, individualized, and timely, says Steven Deitelzweig, MD, SFHM, system chairman for hospital medicine and medical director of regional business development at Ochsner Health System in New Orleans. “If you get something back six months after you’ve delivered the care, you’ll have a limited opportunity to improve, versus if you get it back in a week or two, or ideally, in real time,” says Dr. Deitelzweig, chair of SHM’s Practice Management Committee.

In examining length of stay, Dr. Deitelzweig says doctors could use data mining to look at time-stamped elements of patient flow and the timeliness of provider response: how patients go through the ED, and when they receive written orders or lab results. “It could be really powerful, and right now it’s a little bit of a black hole,” he says.

Based on her conversations with hospital executives and leaders, however, Burghard cautions that some real-time mobile applications, although technologically impressive, may be less useful or necessary in practice. “If it’s performance measurement, why do you need that in real time? It’s not going to change your behavior in the moment,” she says. “What you may want to get is an alert that your patient, who is in the hospital, has had some sort of negative event.”

Data mining has other potential limitations. “There’s always going to be questions of attribution, and you need to have clinical knowledge of your location,” Dr. Godamunne says. And data mining is only as good as the data that have been documented, underscoring the importance of securing provider cooperation.

Dr. Frederickson says physician acceptance, in fact, might be one of the biggest obstacles—a major reason why he recommends introducing the technology slowly and explaining why and how it will be used. If introduced too quickly and without adequate explanation about what a hospital or health system hopes to accomplish, he says, “there certainly is the potential for suspicion.” The key, he says, is to emphasize that the tools provide a valuable mechanism for gleaning new insights into doctors’ practice patterns, “not something that’s going to be used against them.”

Paul Roscoe, CEO of the Washington, D.C.-based Advisory Board Company's Crimson division, agrees that personally engaging physicians is essential for a good return on investment in analytical tools like his company’s suite of CRIMSON products. “If you can’t work with the physicians to get them to understand the data and actively use the data in their practice patterns, it becomes a bit meaningless,” he says.

—Karim Godamunne, MD, MBA, SFHM, chief medical officer, North Fulton Hospital, Roswell, Ga., SHM Practice Management Committee member

Roscoe sees big opportunities in prospectively examining information while a patient is still in the hospital and when a change of course by providers could avert a bad outcome. “Suggesting a set of interventions that they could do differently is really the value-add,” he says. But he cautions that those suggestions must be worded carefully to avoid alienating physicians.

“If doctors don’t feel like they’re being judged, they’ll engage with you,” Roscoe says.

Similar nuances can affect how users perceive the tools themselves. After hearing feedback from members that the words “data mining” didn’t conjure trust and confidence, the Advisory Board Company dropped the phrase altogether in favor of “data analytics,” “physician engagement,” and similar descriptors. “It’s simple things like that that can very quickly either turn a physician on or off,” Roscoe says.

Once users take the time to understand data-mining tools and how they can be properly harnessed, advocates say, the technology can lead to a host of unanticipated benefits. When a hospital bills the federal government for a Medicare patient, for example, it must submit an HCC code that describes the patient’s condition. By doing a better job of mining the data, Burghard says, a hospital can more accurately reflect that patient’s contdition. For example, if a hospital is treating a diabetic who comes in with a broken leg, the hospital could receive a lower payment rate if it does not properly identify and record both conditions.

And by using the tools prospectively, Burghard says, “I think there’s the opportunity to make a quantum leap from what we’re doing today. We usually just report on facts, and usually retrospectively. With some of the new technology that’s available, the healthcare industry can begin to do discovery analytics—you’re identifying insights, patterns, and relationships.”

Better integration of computerized physician order entry with data-mining ports, Dr. Godamunne predicts, will allow for much better attribution and finer parsing of the data. As the transparency increases, though, hospitalists will have to adapt to a new reality in which stronger analytical tools may point out individual outliers. And that level of detail, in turn, will require some hospitalists to justify why they’re different than their peers.

Even so, Roscoe says, he’s found that hospitalists are very open to using data to improve performance and that they make up a high percentage of CRIMSON users. “There isn’t a physician group that is in a better position to help drive this quality- and data-driven culture,” he says.

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

Reference

One hospital wanted to reduce readmissions among patients with congestive heart failure. Another hoped to improve upon its sepsis mortality rates. A third sought to determine whether its doctors were providing cost-effective care for pneumonia patients. All of them adopted the same type of technology to help identify a solution.

As the healthcare industry tilts toward accountable care, pay for performance and an increasingly

cost-conscious mindset, hospitalists and other providers are tapping into a fast-growing analytical tool collectively known as data mining to help make sense of the growing mounds of information. Although no single technology can be considered a cure-all, HM leaders are so optimistic about data mining’s potential to address cost, outcome, and performance issues that some have labeled it a “game changer” for hospitalists.

Karim Godamunne, MD, MBA, SFHM, chief medical officer at North Fulton Hospital in Roswell, Ga., and a member of SHM’s Practice Management Committee, says he can’t overstate the importance of hospitalists’ involvement in physician data mining. “From my perspective, we’re looking to hospitalists to help drive this quality-utilization bandwagon, to be the real leaders in it,” he says. With the tremendous value that can be generated through understanding and using the information, “it’s good for your group and can be good to your hospital as a whole.”

So what is data mining? The technology fully emerged in the mid-1990s as a way to help scientists analyze large and often disparate bodies of data, present relevant information in new ways, and illuminate previously unknown relationships.1 In the healthcare industry, early adopters realized that the insights gleaned from data mining could help inform their clinical decision-making; organizations used the new tools to help predict health insurance fraud and identify at-risk patients, for example.

Cynthia Burghard, research director of Accountable Care IT Strategies at IDC Health Insights in Framingham, Mass., says researchers in academic medical centers initially conducted most of the clinical analytical work. Within the past few years, however, the increasing availability of data has allowed more hospitals to begin analyzing chronic disease, readmissions, and other areas of concern. In addition, Burghard says, new tools based on natural language processing are giving hospitals better access to unstructured clinical data, such as notes written by doctors and nurses.

“What I’m seeing both in my surveys as well as in conversations with hospitals is that analytics is the top of the investment priority for both hospitals and health plans,” Burghard says. According to IDC estimates, total spending for clinical analytics in the U.S. reached $3.7 billion in 2012 and is expected to grow to $5.14 billion by 2016. Much of the growth, she notes, is being driven by healthcare reform. “If your mandate is to manage populations of patients, it behooves you to know who those patients are and what their illnesses are, and to monitor what you’re doing for them,” she says.

Practice Improvement

Accordingly, a major goal of all this data-mining technology is to change practice behavior in a way that achieves the triple aim of improving quality of care, controlling costs, and bettering patient outcomes.

A growing number of companies are releasing tools that can compile and analyze the separate bits of information captured from claims and billing systems, Medicare reporting requirements, internal benchmarks, and other sources. Unlike passive data sources, such as Medicare’s Hospital Compare website, more active analytics can help their users zoom down to the level of an individual doctor or patient, pan out to the level of a hospitalist group, or expand out even more for a broader comparison among peer institutions.

Some newer data-mining tools with names like CRIMSON, Truven, Iodine, and Imagine are billing themselves as hospitalist-friendly performance-improvement aids and giving individual providers the ability to access and analyze the data themselves. A few of these applications can even provide real-time data via mobile devices (see “Physician Performance Aids,”).

Thomas Frederickson, MD, MBA, SFHM, medical director of the HM service at Alegent Creighton Health in Omaha, Neb., and a member of SHM’s Practice Management Committee, sees the biggest potential of this data-mining technology in its ability to help drive practice consistency. “You can use the database to analyze practice patterns of large groups, or even individuals, and see where variability exists,” he says. “And then, based on that, you can analyze why the variability exists and begin to address whether it’s variability that’s clinically indicated or not.”

When Alegent Creighton Health was scrutinizing the care of its pneumonia patients, for example, officials could compare the number of chest X-rays per pneumonia patient by hospital or across the entire CRIMSON database. At a deeper level, the officials could see how often individual providers ordered the tests compared to their peers. For outliers, they could follow up to determine whether the variability was warranted.

As champions of process improvement, Dr. Frederickson says, hospitalists can make particularly good use of database analytics. “It’s part of the process of making hospitalists invaluable to their hospitals and their systems,” he says. “Part of that is building up expertise on process improvement and safety, and familiarity with these kinds of tools is one thing that will help us do that.”

North Fulton Hospital used CRIMSON to analyze how its doctors care for patients with sepsis and to establish new benchmarks. Dr. Godamunne says the tools allowed the hospital to track its doctors’ progress over time and identify potential problems. “If a patient with sepsis is staying too long, you can see who admitted the patient and see if, a few months ago, the same physician was having similar problems,” he says. Similarly, the hospital was able to track the top DRGs resulting in excess length of stay among patients, to identify potential bottlenecks in the care and discharge processes.

Some tools require only two-day training sessions for basic proficiency, though more advanced manipulations often require a bigger commitment, like the 12-week training session that Dr. Godamunne completed. That training included one hour of online learning and one hour of homework every week, and most of the cases highlighted during his coursework, he says, focused on hospitalists—another sign of the major role he believes HM will play in harnessing data to improve performance quality.

—Thomas Frederickson, MD, MBA, SFHM, medical director, hospital medicine service, Alegent Creighton Health, Omaha, Neb., SHM Practice Management Committee member

Slow—Construction Ahead

The best information is meaningful, individualized, and timely, says Steven Deitelzweig, MD, SFHM, system chairman for hospital medicine and medical director of regional business development at Ochsner Health System in New Orleans. “If you get something back six months after you’ve delivered the care, you’ll have a limited opportunity to improve, versus if you get it back in a week or two, or ideally, in real time,” says Dr. Deitelzweig, chair of SHM’s Practice Management Committee.

In examining length of stay, Dr. Deitelzweig says doctors could use data mining to look at time-stamped elements of patient flow and the timeliness of provider response: how patients go through the ED, and when they receive written orders or lab results. “It could be really powerful, and right now it’s a little bit of a black hole,” he says.

Based on her conversations with hospital executives and leaders, however, Burghard cautions that some real-time mobile applications, although technologically impressive, may be less useful or necessary in practice. “If it’s performance measurement, why do you need that in real time? It’s not going to change your behavior in the moment,” she says. “What you may want to get is an alert that your patient, who is in the hospital, has had some sort of negative event.”

Data mining has other potential limitations. “There’s always going to be questions of attribution, and you need to have clinical knowledge of your location,” Dr. Godamunne says. And data mining is only as good as the data that have been documented, underscoring the importance of securing provider cooperation.

Dr. Frederickson says physician acceptance, in fact, might be one of the biggest obstacles—a major reason why he recommends introducing the technology slowly and explaining why and how it will be used. If introduced too quickly and without adequate explanation about what a hospital or health system hopes to accomplish, he says, “there certainly is the potential for suspicion.” The key, he says, is to emphasize that the tools provide a valuable mechanism for gleaning new insights into doctors’ practice patterns, “not something that’s going to be used against them.”

Paul Roscoe, CEO of the Washington, D.C.-based Advisory Board Company's Crimson division, agrees that personally engaging physicians is essential for a good return on investment in analytical tools like his company’s suite of CRIMSON products. “If you can’t work with the physicians to get them to understand the data and actively use the data in their practice patterns, it becomes a bit meaningless,” he says.

—Karim Godamunne, MD, MBA, SFHM, chief medical officer, North Fulton Hospital, Roswell, Ga., SHM Practice Management Committee member

Roscoe sees big opportunities in prospectively examining information while a patient is still in the hospital and when a change of course by providers could avert a bad outcome. “Suggesting a set of interventions that they could do differently is really the value-add,” he says. But he cautions that those suggestions must be worded carefully to avoid alienating physicians.

“If doctors don’t feel like they’re being judged, they’ll engage with you,” Roscoe says.

Similar nuances can affect how users perceive the tools themselves. After hearing feedback from members that the words “data mining” didn’t conjure trust and confidence, the Advisory Board Company dropped the phrase altogether in favor of “data analytics,” “physician engagement,” and similar descriptors. “It’s simple things like that that can very quickly either turn a physician on or off,” Roscoe says.

Once users take the time to understand data-mining tools and how they can be properly harnessed, advocates say, the technology can lead to a host of unanticipated benefits. When a hospital bills the federal government for a Medicare patient, for example, it must submit an HCC code that describes the patient’s condition. By doing a better job of mining the data, Burghard says, a hospital can more accurately reflect that patient’s contdition. For example, if a hospital is treating a diabetic who comes in with a broken leg, the hospital could receive a lower payment rate if it does not properly identify and record both conditions.

And by using the tools prospectively, Burghard says, “I think there’s the opportunity to make a quantum leap from what we’re doing today. We usually just report on facts, and usually retrospectively. With some of the new technology that’s available, the healthcare industry can begin to do discovery analytics—you’re identifying insights, patterns, and relationships.”

Better integration of computerized physician order entry with data-mining ports, Dr. Godamunne predicts, will allow for much better attribution and finer parsing of the data. As the transparency increases, though, hospitalists will have to adapt to a new reality in which stronger analytical tools may point out individual outliers. And that level of detail, in turn, will require some hospitalists to justify why they’re different than their peers.

Even so, Roscoe says, he’s found that hospitalists are very open to using data to improve performance and that they make up a high percentage of CRIMSON users. “There isn’t a physician group that is in a better position to help drive this quality- and data-driven culture,” he says.

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

Reference

One hospital wanted to reduce readmissions among patients with congestive heart failure. Another hoped to improve upon its sepsis mortality rates. A third sought to determine whether its doctors were providing cost-effective care for pneumonia patients. All of them adopted the same type of technology to help identify a solution.

As the healthcare industry tilts toward accountable care, pay for performance and an increasingly

cost-conscious mindset, hospitalists and other providers are tapping into a fast-growing analytical tool collectively known as data mining to help make sense of the growing mounds of information. Although no single technology can be considered a cure-all, HM leaders are so optimistic about data mining’s potential to address cost, outcome, and performance issues that some have labeled it a “game changer” for hospitalists.

Karim Godamunne, MD, MBA, SFHM, chief medical officer at North Fulton Hospital in Roswell, Ga., and a member of SHM’s Practice Management Committee, says he can’t overstate the importance of hospitalists’ involvement in physician data mining. “From my perspective, we’re looking to hospitalists to help drive this quality-utilization bandwagon, to be the real leaders in it,” he says. With the tremendous value that can be generated through understanding and using the information, “it’s good for your group and can be good to your hospital as a whole.”

So what is data mining? The technology fully emerged in the mid-1990s as a way to help scientists analyze large and often disparate bodies of data, present relevant information in new ways, and illuminate previously unknown relationships.1 In the healthcare industry, early adopters realized that the insights gleaned from data mining could help inform their clinical decision-making; organizations used the new tools to help predict health insurance fraud and identify at-risk patients, for example.

Cynthia Burghard, research director of Accountable Care IT Strategies at IDC Health Insights in Framingham, Mass., says researchers in academic medical centers initially conducted most of the clinical analytical work. Within the past few years, however, the increasing availability of data has allowed more hospitals to begin analyzing chronic disease, readmissions, and other areas of concern. In addition, Burghard says, new tools based on natural language processing are giving hospitals better access to unstructured clinical data, such as notes written by doctors and nurses.

“What I’m seeing both in my surveys as well as in conversations with hospitals is that analytics is the top of the investment priority for both hospitals and health plans,” Burghard says. According to IDC estimates, total spending for clinical analytics in the U.S. reached $3.7 billion in 2012 and is expected to grow to $5.14 billion by 2016. Much of the growth, she notes, is being driven by healthcare reform. “If your mandate is to manage populations of patients, it behooves you to know who those patients are and what their illnesses are, and to monitor what you’re doing for them,” she says.

Practice Improvement

Accordingly, a major goal of all this data-mining technology is to change practice behavior in a way that achieves the triple aim of improving quality of care, controlling costs, and bettering patient outcomes.

A growing number of companies are releasing tools that can compile and analyze the separate bits of information captured from claims and billing systems, Medicare reporting requirements, internal benchmarks, and other sources. Unlike passive data sources, such as Medicare’s Hospital Compare website, more active analytics can help their users zoom down to the level of an individual doctor or patient, pan out to the level of a hospitalist group, or expand out even more for a broader comparison among peer institutions.

Some newer data-mining tools with names like CRIMSON, Truven, Iodine, and Imagine are billing themselves as hospitalist-friendly performance-improvement aids and giving individual providers the ability to access and analyze the data themselves. A few of these applications can even provide real-time data via mobile devices (see “Physician Performance Aids,”).

Thomas Frederickson, MD, MBA, SFHM, medical director of the HM service at Alegent Creighton Health in Omaha, Neb., and a member of SHM’s Practice Management Committee, sees the biggest potential of this data-mining technology in its ability to help drive practice consistency. “You can use the database to analyze practice patterns of large groups, or even individuals, and see where variability exists,” he says. “And then, based on that, you can analyze why the variability exists and begin to address whether it’s variability that’s clinically indicated or not.”

When Alegent Creighton Health was scrutinizing the care of its pneumonia patients, for example, officials could compare the number of chest X-rays per pneumonia patient by hospital or across the entire CRIMSON database. At a deeper level, the officials could see how often individual providers ordered the tests compared to their peers. For outliers, they could follow up to determine whether the variability was warranted.

As champions of process improvement, Dr. Frederickson says, hospitalists can make particularly good use of database analytics. “It’s part of the process of making hospitalists invaluable to their hospitals and their systems,” he says. “Part of that is building up expertise on process improvement and safety, and familiarity with these kinds of tools is one thing that will help us do that.”

North Fulton Hospital used CRIMSON to analyze how its doctors care for patients with sepsis and to establish new benchmarks. Dr. Godamunne says the tools allowed the hospital to track its doctors’ progress over time and identify potential problems. “If a patient with sepsis is staying too long, you can see who admitted the patient and see if, a few months ago, the same physician was having similar problems,” he says. Similarly, the hospital was able to track the top DRGs resulting in excess length of stay among patients, to identify potential bottlenecks in the care and discharge processes.

Some tools require only two-day training sessions for basic proficiency, though more advanced manipulations often require a bigger commitment, like the 12-week training session that Dr. Godamunne completed. That training included one hour of online learning and one hour of homework every week, and most of the cases highlighted during his coursework, he says, focused on hospitalists—another sign of the major role he believes HM will play in harnessing data to improve performance quality.

—Thomas Frederickson, MD, MBA, SFHM, medical director, hospital medicine service, Alegent Creighton Health, Omaha, Neb., SHM Practice Management Committee member

Slow—Construction Ahead

The best information is meaningful, individualized, and timely, says Steven Deitelzweig, MD, SFHM, system chairman for hospital medicine and medical director of regional business development at Ochsner Health System in New Orleans. “If you get something back six months after you’ve delivered the care, you’ll have a limited opportunity to improve, versus if you get it back in a week or two, or ideally, in real time,” says Dr. Deitelzweig, chair of SHM’s Practice Management Committee.

In examining length of stay, Dr. Deitelzweig says doctors could use data mining to look at time-stamped elements of patient flow and the timeliness of provider response: how patients go through the ED, and when they receive written orders or lab results. “It could be really powerful, and right now it’s a little bit of a black hole,” he says.

Based on her conversations with hospital executives and leaders, however, Burghard cautions that some real-time mobile applications, although technologically impressive, may be less useful or necessary in practice. “If it’s performance measurement, why do you need that in real time? It’s not going to change your behavior in the moment,” she says. “What you may want to get is an alert that your patient, who is in the hospital, has had some sort of negative event.”

Data mining has other potential limitations. “There’s always going to be questions of attribution, and you need to have clinical knowledge of your location,” Dr. Godamunne says. And data mining is only as good as the data that have been documented, underscoring the importance of securing provider cooperation.

Dr. Frederickson says physician acceptance, in fact, might be one of the biggest obstacles—a major reason why he recommends introducing the technology slowly and explaining why and how it will be used. If introduced too quickly and without adequate explanation about what a hospital or health system hopes to accomplish, he says, “there certainly is the potential for suspicion.” The key, he says, is to emphasize that the tools provide a valuable mechanism for gleaning new insights into doctors’ practice patterns, “not something that’s going to be used against them.”

Paul Roscoe, CEO of the Washington, D.C.-based Advisory Board Company's Crimson division, agrees that personally engaging physicians is essential for a good return on investment in analytical tools like his company’s suite of CRIMSON products. “If you can’t work with the physicians to get them to understand the data and actively use the data in their practice patterns, it becomes a bit meaningless,” he says.

—Karim Godamunne, MD, MBA, SFHM, chief medical officer, North Fulton Hospital, Roswell, Ga., SHM Practice Management Committee member

Roscoe sees big opportunities in prospectively examining information while a patient is still in the hospital and when a change of course by providers could avert a bad outcome. “Suggesting a set of interventions that they could do differently is really the value-add,” he says. But he cautions that those suggestions must be worded carefully to avoid alienating physicians.

“If doctors don’t feel like they’re being judged, they’ll engage with you,” Roscoe says.

Similar nuances can affect how users perceive the tools themselves. After hearing feedback from members that the words “data mining” didn’t conjure trust and confidence, the Advisory Board Company dropped the phrase altogether in favor of “data analytics,” “physician engagement,” and similar descriptors. “It’s simple things like that that can very quickly either turn a physician on or off,” Roscoe says.

Once users take the time to understand data-mining tools and how they can be properly harnessed, advocates say, the technology can lead to a host of unanticipated benefits. When a hospital bills the federal government for a Medicare patient, for example, it must submit an HCC code that describes the patient’s condition. By doing a better job of mining the data, Burghard says, a hospital can more accurately reflect that patient’s contdition. For example, if a hospital is treating a diabetic who comes in with a broken leg, the hospital could receive a lower payment rate if it does not properly identify and record both conditions.

And by using the tools prospectively, Burghard says, “I think there’s the opportunity to make a quantum leap from what we’re doing today. We usually just report on facts, and usually retrospectively. With some of the new technology that’s available, the healthcare industry can begin to do discovery analytics—you’re identifying insights, patterns, and relationships.”

Better integration of computerized physician order entry with data-mining ports, Dr. Godamunne predicts, will allow for much better attribution and finer parsing of the data. As the transparency increases, though, hospitalists will have to adapt to a new reality in which stronger analytical tools may point out individual outliers. And that level of detail, in turn, will require some hospitalists to justify why they’re different than their peers.

Even so, Roscoe says, he’s found that hospitalists are very open to using data to improve performance and that they make up a high percentage of CRIMSON users. “There isn’t a physician group that is in a better position to help drive this quality- and data-driven culture,” he says.

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

Reference

The end of the warfarin era

For over a half a century, the vitamin K antagonists coumarin and warfarin have been the only anticoagulants available to prevent clot formation in a variety of cardiovascular clinical settings. They are now about to be replaced with direct thrombin and factor Xa inhibitors. Vitamin K antagonists have not only dominated anticoagulant therapy, they have created an entire industry within the cardiovascular domain for the monitoring and control of its dose administration.

The story began in 1933 when Karl Paul Link, Ph.D., working in a laboratory at the University of Wisconsin School of Agriculture, was asked to examine the blood of cows dying of hemorrhage thought to be due to the ingestion of spoiled sweet clover. After years of research, Link was able to isolate an anticoagulant from the clover feed, called dicumarol, and he initially patented it in 1941 as rat poison. The marketed drug was called warfarin, after the Wisconsin Agricultural Research Foundation (WARF). Based on that patent, billions of dollars were generated for future research at the WARF.

Warfarin began to be used in the 1950s by a number of clinical investigators to prevent pulmonary embolism in the setting of an acute myocardial infarction (Lancet 1954;266:92-5). At that time, 1 month of complete bed rest was standard therapy for an AMI, and thrombophlebitis together with pulmonary and systemic embolism were the main causes of mortality. When early ambulation became acceptable for AMI patients, warfarin use tapered off. As clinicians became more focused on the prevention of intravascular thrombus formation after prosthetic valve surgery, and to prevent thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation, warfarin therapy became more widely used, and the definition of the therapeutic dose of warfarin became important.

It soon became evident that vitamin K antagonists had a very narrow therapeutic window, framed by excessive bleeding at high doses and inefficacy at lower dose. As a result, the need for closer dose monitoring became important, and this led to the establishment of anticoagulant clinics. However, even with the establishment of these clinics, it became obvious that the clinical status of patients and dietary variability played major roles in dosing. The need for frequent blood sampling and the logistics of dose management were frustrations for both the patient and physician for decades.

As the need for better anticoagulant therapy became evident, drugs were developed that had a wider therapeutic range and that could be administered orally without the need of blood monitoring. The development of direct-acting thrombin and factor Xa inhibitors have led to major advances in anticoagulant therapy, resulting in safer oral fixed-dose drugs with therapeutic efficacy comparable to or better than vitamin K antagonists. In addition, they appear to be free from the effects of dietary variation. The factor Xa inhibitors apixaban and rivaroxaban have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the prevention of systemic emboli in patients with atrial fibrillation. Rivaroxaban is also indicated for preventing and treating deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran has also been approved for the prevention of thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation. The only settings for which the new anticoagulants have not been approved are acute coronary syndrome and prevention of thromboembolism with prosthetic valves.

The development of new anticoagulants provides an opportunity to improve therapy and witness the retirement of a ponderous and complicated dosing program that has been inconvenient to both patients and doctors. The retirement of warfarin and the death of the anticoagulant clinic will be appreciated by all.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

For over a half a century, the vitamin K antagonists coumarin and warfarin have been the only anticoagulants available to prevent clot formation in a variety of cardiovascular clinical settings. They are now about to be replaced with direct thrombin and factor Xa inhibitors. Vitamin K antagonists have not only dominated anticoagulant therapy, they have created an entire industry within the cardiovascular domain for the monitoring and control of its dose administration.

The story began in 1933 when Karl Paul Link, Ph.D., working in a laboratory at the University of Wisconsin School of Agriculture, was asked to examine the blood of cows dying of hemorrhage thought to be due to the ingestion of spoiled sweet clover. After years of research, Link was able to isolate an anticoagulant from the clover feed, called dicumarol, and he initially patented it in 1941 as rat poison. The marketed drug was called warfarin, after the Wisconsin Agricultural Research Foundation (WARF). Based on that patent, billions of dollars were generated for future research at the WARF.

Warfarin began to be used in the 1950s by a number of clinical investigators to prevent pulmonary embolism in the setting of an acute myocardial infarction (Lancet 1954;266:92-5). At that time, 1 month of complete bed rest was standard therapy for an AMI, and thrombophlebitis together with pulmonary and systemic embolism were the main causes of mortality. When early ambulation became acceptable for AMI patients, warfarin use tapered off. As clinicians became more focused on the prevention of intravascular thrombus formation after prosthetic valve surgery, and to prevent thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation, warfarin therapy became more widely used, and the definition of the therapeutic dose of warfarin became important.

It soon became evident that vitamin K antagonists had a very narrow therapeutic window, framed by excessive bleeding at high doses and inefficacy at lower dose. As a result, the need for closer dose monitoring became important, and this led to the establishment of anticoagulant clinics. However, even with the establishment of these clinics, it became obvious that the clinical status of patients and dietary variability played major roles in dosing. The need for frequent blood sampling and the logistics of dose management were frustrations for both the patient and physician for decades.

As the need for better anticoagulant therapy became evident, drugs were developed that had a wider therapeutic range and that could be administered orally without the need of blood monitoring. The development of direct-acting thrombin and factor Xa inhibitors have led to major advances in anticoagulant therapy, resulting in safer oral fixed-dose drugs with therapeutic efficacy comparable to or better than vitamin K antagonists. In addition, they appear to be free from the effects of dietary variation. The factor Xa inhibitors apixaban and rivaroxaban have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the prevention of systemic emboli in patients with atrial fibrillation. Rivaroxaban is also indicated for preventing and treating deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran has also been approved for the prevention of thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation. The only settings for which the new anticoagulants have not been approved are acute coronary syndrome and prevention of thromboembolism with prosthetic valves.

The development of new anticoagulants provides an opportunity to improve therapy and witness the retirement of a ponderous and complicated dosing program that has been inconvenient to both patients and doctors. The retirement of warfarin and the death of the anticoagulant clinic will be appreciated by all.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

For over a half a century, the vitamin K antagonists coumarin and warfarin have been the only anticoagulants available to prevent clot formation in a variety of cardiovascular clinical settings. They are now about to be replaced with direct thrombin and factor Xa inhibitors. Vitamin K antagonists have not only dominated anticoagulant therapy, they have created an entire industry within the cardiovascular domain for the monitoring and control of its dose administration.

The story began in 1933 when Karl Paul Link, Ph.D., working in a laboratory at the University of Wisconsin School of Agriculture, was asked to examine the blood of cows dying of hemorrhage thought to be due to the ingestion of spoiled sweet clover. After years of research, Link was able to isolate an anticoagulant from the clover feed, called dicumarol, and he initially patented it in 1941 as rat poison. The marketed drug was called warfarin, after the Wisconsin Agricultural Research Foundation (WARF). Based on that patent, billions of dollars were generated for future research at the WARF.

Warfarin began to be used in the 1950s by a number of clinical investigators to prevent pulmonary embolism in the setting of an acute myocardial infarction (Lancet 1954;266:92-5). At that time, 1 month of complete bed rest was standard therapy for an AMI, and thrombophlebitis together with pulmonary and systemic embolism were the main causes of mortality. When early ambulation became acceptable for AMI patients, warfarin use tapered off. As clinicians became more focused on the prevention of intravascular thrombus formation after prosthetic valve surgery, and to prevent thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation, warfarin therapy became more widely used, and the definition of the therapeutic dose of warfarin became important.

It soon became evident that vitamin K antagonists had a very narrow therapeutic window, framed by excessive bleeding at high doses and inefficacy at lower dose. As a result, the need for closer dose monitoring became important, and this led to the establishment of anticoagulant clinics. However, even with the establishment of these clinics, it became obvious that the clinical status of patients and dietary variability played major roles in dosing. The need for frequent blood sampling and the logistics of dose management were frustrations for both the patient and physician for decades.

As the need for better anticoagulant therapy became evident, drugs were developed that had a wider therapeutic range and that could be administered orally without the need of blood monitoring. The development of direct-acting thrombin and factor Xa inhibitors have led to major advances in anticoagulant therapy, resulting in safer oral fixed-dose drugs with therapeutic efficacy comparable to or better than vitamin K antagonists. In addition, they appear to be free from the effects of dietary variation. The factor Xa inhibitors apixaban and rivaroxaban have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the prevention of systemic emboli in patients with atrial fibrillation. Rivaroxaban is also indicated for preventing and treating deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran has also been approved for the prevention of thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation. The only settings for which the new anticoagulants have not been approved are acute coronary syndrome and prevention of thromboembolism with prosthetic valves.

The development of new anticoagulants provides an opportunity to improve therapy and witness the retirement of a ponderous and complicated dosing program that has been inconvenient to both patients and doctors. The retirement of warfarin and the death of the anticoagulant clinic will be appreciated by all.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

Hepatocellular carcinoma: Options for diagnosing and managing a deadly disease

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a common cause of death worldwide. However, it can be detected early in high-risk individuals by using effective screening strategies, resulting in the ability to provide curative treatment.

Here, we review the risk factors for HCC, strategies for surveillance and diagnosis, and therapies that can be used.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

HCC is the most common primary malignancy of the liver. Overall, it is the fifth most common type of cancer in men and the seventh most common in women.1

Cirrhosis is present in 80% to 90% of patients with HCC.

Male sex. The male-to-female ratio is from 2:1 to 4:1, depending on the region.2 In the United States, the overall male-to-female ratio has been reported2 as 2.4:1. In another report,3 the incidence rate of HCC per 100,000 person-years was 3.7 for men and 2.0 for women.

Geographic areas with a high incidence of HCC include sub-Saharan Africa and eastern Asia, whereas Canada and the United States are low-incidence areas. The difference has been because of a lower prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in North America. However, recent data show a downward trend in incidence of HCC in eastern Asia and an upward trend in North America (Figure 1).3,4

Viral hepatitis (ie, hepatitis B or hepatitis C) is the main risk factor for cirrhosis and HCC.

Diabetes mellitus can predispose to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, which can subsequently progress to cirrhosis. Thus, it increases the risk of HCC.

Obesity increases the risk of death from liver cancer, with obese people (body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2) having a higher HCC-related death rate than leaner individuals.5 And as obesity becomes more prevalent, the number of deaths from HCC could increase.

Other diseases that predispose to HCC include alcohol abuse, hereditary hemochromatosis, alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, and glycogen storage disease.

SURVEILLANCE OF PATIENTS AT RISK

Patients at high risk of developing liver cancer require frequent screening (Table 1).

Patients with cirrhosis. Sarasin et al6 calculated that surveillance is cost-effective and increases the odds of survival in patients with cirrhosis if the incidence of HCC exceeds 1.5% per year (which it does). In view of this finding, all patients with cirrhosis should be screened every 6 months, irrespective of the cause of the cirrhosis.

Hepatitis B carriers. Surveillance is also indicated in some hepatitis B carriers (Table 1), eg, those with a family history of HCC in a first-degree relative (an independent risk factor for developing the disease in this group).7 Also, Africans with hepatitis B tend to develop HCC early in life.8 Though it has been recommended that surveillance be started at a younger age in these patients,9 the age at which it should begin has not been clearly established. In addition, it is not clear if black people born outside Africa are at higher risk.

Benefit of surveillance

HCC surveillance has shown to lower the death rate. A randomized controlled trial in China compared screening (with abdominal ultrasonography and alpha-fetoprotein levels) vs no screening in patients with hepatitis B. It showed that screening led to a 37% decrease in the death rate.12 Studies have also established that patients with early-stage HCC have a better survival rate than patients with more-advanced disease.10,11 This survival benefit is largely explained by the availability of effective treatments for early-stage cancer, including liver transplantation. Therefore, early-stage asymptomatic patients diagnosed by a surveillance program should have a better survival rate than symptomatic patients.

Surveillance methods

The tests most often used in surveillance for HCC are serum alpha-fetoprotein levels and liver ultrasonography.

Serum alpha-fetoprotein levels by themselves have not been shown to be useful, whereas the combination of alpha-fetoprotein levels and ultrasonography has been shown to reduce the death rate when used for surveillance in a randomized trial.12 A 2012 study reported that the combination of alpha-fetoprotein testing and ultrasonography had a higher sensitivity (90%) than ultrasonography alone (58%), but at the expense of a lower specificity.13

Alpha-fetoprotein has a low sensitivity (ie, 54%) for HCC.14 Tumor size is one of the factors limiting the sensitivity of alpha-fetoprotein, 14 and this would imply that this test may not be helpful in detecting HCC at an early stage. Alpha-fetoprotein L3, an isoform of alpha-fetoprotein, may be helpful in patients with alpha-fetoprotein levels in the intermediate range, and it is currently being studied.

Liver ultrasonography is operator-dependent, and it may not be as accurate in overweight or obese people.

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are not recommended for surveillance. Serial CT poses risks of radiation-induced damage, contrast-related anaphylaxis, and renal failure, and MRI is not cost-effective and can also lead to gadolinium-induced nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in patients with renal failure.

Currently, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases9 recommends ultrasonography only, every 6 months, for surveillance for HCC. However, it may be premature to conclude that alpha-fetoprotein measurement is no longer required for surveillance, and if new data emerge that support its role, it may be reincorporated into the guidelines.

DIAGNOSING HEPATOCELLULAR CARCINOMA

Lesions larger than 1 cm on ultrasonography

The finding of a liver lesion larger than 1 cm on ultrasonography during surveillance warrants further testing.

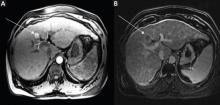

Noninvasive testing with four-phase multidetector CT or dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI is the next step. Typical findings on either of these imaging studies are sufficient to make a diagnosis of HCC, as they have a high specificity and positive predictive value.15 Arterial hyperenhancement with a venous-phase or delayed-phase washout of contrast medium confirms the diagnosis (Figure 2).9 If one of the two imaging studies is typical for HCC, liver biopsy is not needed.

Other imaging studies, including contrast-enhanced ultrasonography, have not been shown to be specific for this diagnosis.16

Liver biopsy is indicated in patients in whom the imaging findings are atypical for HCC.9,17 Biopsy has very good sensitivity and specificity for cancer, but false-negative findings do occur.18 Therefore, a negative biopsy does not entirely exclude HCC. In this situation, patients should be followed by serial ultrasonography, and any further growth or change in character should be reevaluated.

Lesions smaller than 1 cm

For lesions smaller than 1 cm, the incidence of HCC is low, and currently available diagnostic tests are not reliable.15,19 Lesions of this size should be followed by serial ultrasonography every 3 to 4 months until they either enlarge to greater than 1 cm or remain stable at 2 years.9 If they remain stable at the end of 2 years, regular surveillance ultrasonography once every 6 months can be continued.

CURATIVE AND PALLIATIVE THERAPIES

Therapies for HCC (Table 2) can be divided into two categories: curative and palliative.

Curative treatments include surgical resection, liver transplantation, and radiofrequency ablation. All other treatments are palliative, including transarterial chemoembolization and medical therapy with sorafenib.

The choice of treatment depends on the characteristics of the tumor, the degree of liver dysfunction, and the patient’s current level of function. The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer classification is widely used in making these decisions, as it incorporates both clinical features and tumor stage.9 Figure 3 shows a simplified management algorithm.

SURGICAL RESECTION

Surgical resection is the preferred treatment for patients who have a solitary HCC lesion without cirrhosis.9 It is also indicated in patients with well-compensated cirrhosis who have normal portal pressure, a normal serum bilirubin level, and a platelet count greater than 100 × 109/L.20,21 In such patients, the 5-year survival rate is about 74%, compared with 25% in patients with portal hypertension and serum bilirubin levels higher than 1 mg/dL.21

Surgical resection is not recommended for patients with decompensated cirrhosis, as it can worsen liver function postoperatively and increase the risk of death.19,20 In Western countries, where cirrhosis from hepatitis C is the commonest cause of HCC, most patients have poorly preserved hepatic function at the time of diagnosis, leaving only a minority of patients as candidates for surgical resection.

After surgical resection of HCC, the recurrence rate can be as high as 70% to 80% at 5 years.22,23 Studies have consistently found larger tumor size and vascular invasion to be factors that predict recurrence.24,25 Vascular invasion was also found to predict poor survival after recurrence.24 Studies have so far not shown any conclusive benefit from post-surgical adjuvant chemotherapy in reducing the rate of recurrence of HCC.26,27

How to treat recurrent HCC after surgical resection has not been clearly established. Radiofrequency ablation, transarterial chemoembolization, repeat resection, and liver transplantation have all improved survival when used alone or in combination.28 However, randomized controlled trials are needed to establish the effective treatment strategy and the benefit of multimodal treatment of recurrent HCC.

LIVER TRANSPLANTATION

Orthotopic liver transplantation is the preferred treatment for patients with HCC complicated by cirrhosis and portal hypertension. It has the advantage not only of being potentially curative, but also of overcoming liver cirrhosis by replacing the liver.

To qualify for liver transplantation, patients must meet the Milan criteria (ie, have a single nodule less than 5 cm in diameter or up to three nodules, with the largest being less than 3 cm in diameter, with no evidence of vascular invasion or distant metastasis). These patients have an expected 4-year survival rate of 85% and a recurrence-free survival rate of 92% after transplantation, compared with 50% and 59%, respectively, in patients whose tumors exceeded these criteria.29

Some believe that the Milan criteria are too restrictive and could be expanded. Yao et al at the University of California-San Francisco30 reported that patients with HCC meeting the criteria of having a solitary tumor smaller than 6.5 cm or having up to three nodules, with the largest smaller than 4.5 cm, and total tumor diameter less than 8 cm, had survival rates of 90% at 1 year and 75.2% at 5 years after liver transplantation, compared with 50% at 1 year for patients with tumors exceeding these limits. (These have come to be known as the UCSF criteria.) However, the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) has not adopted these expanded criteria. UNOS has a point system for allocating livers for transplant called the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD). Patients who meet the Milan criteria receive extra points, putting them higher on the transplant list. This allows for early transplantation, thus reducing tumor progression and dropout from the transplant list. UNOS allocates a MELD score of 22 to all patients who meet the Milan criteria, and the score is further adjusted once every 3 months to reflect a 10% increase in the mortality rate. However, patients who have a single lesion smaller than 2 cm and are candidates for liver transplantation are not assigned additional MELD points per UNOS policy, as the risk of tumor progression beyond the Milan criteria in these patients is deemed to be low.

Therapies while awaiting transplantation

Even if they receive additional MELD points to give them priority on the waiting list, patients face a considerable wait before transplantation because of the limited availability of donor organs. In the interim, they have a risk of tumor progression beyond the Milan criteria and subsequent dropout from the transplant list.31 Patients on the waiting list may therefore undergo a locoregional therapy such as transarterial chemoembolization or radiofrequency ablation as bridging therapy.

These therapies have been shown to decrease dropout from the waiting list.31 A prospective study showed that in 48 patients who underwent transarterial chemoembolization while awaiting liver transplantation, none had tumor progression, and 41 did receive a transplant, with excellent posttransplantation survival rates.32 Similarly, radioembolization using yttrium-90-labeled microspheres or radiofrequency ablation while on the waiting list has been shown to significantly decrease the rate of dropout, with good posttransplantation outcomes.33,34

However, in spite of these benefits, these bridging therapies do not increase survival rates after transplantation. It is also unclear whether they are useful in regions with short waiting times for liver transplantation.

Adjuvant systemic chemotherapy has not been shown to improve survival in patients undergoing liver transplantation. For example, in a randomized controlled trial of doxorubicin given before, during, and after surgery, the survival rate at 5 years was 38% with doxorubicin and 40% without.35

ABLATIVE LOCOREGIONAL THERAPIES

Locoregional therapies play an important role in managing HCC. They are classified as ablative and perfusion-based.

Ablative locoregional therapies include chemical modalities such as percutaneous ethanol injection; thermal therapies such as radiofrequency ablation, microwave ablation, laser ablation, and cryotherapy; and newer methods such as irreversible electroporation and light-activated drug therapy. Of these, radiofrequency ablation is the most widely used.

Radiofrequency ablation

Radiofrequency ablation induces thermal injury, resulting in tumor necrosis. It can be used as an alternative to surgery in patients who have a single HCC lesion less than 3 to 5 cm in diameter, confined to the liver, and in a site amenable to this procedure and who have a reasonable coagulation profile. The procedure can be performed percutaneously or via laparoscopy.

Radiofrequency ablation is contraindicated in patients with decompensated cirrhosis, Child-Pugh class C cirrhosis (the most severe category), vascular or bile duct invasion, extrahepatic disease, or lesions that are not accessible or are adjacent to structures such as the gall bladder, bowel, stomach, or diaphragm.

Radiofrequency ablation has been compared with surgical resection in patients who had small tumors. Though a randomized controlled trial did not show any difference between the two treatment groups in terms of survival at 5 years and recurrence rates,36 a meta-analysis showed that overall survival rates at 3 years and 5 years were significantly higher with surgical resection than with radiofrequency ablation.37 Patients also had a higher rate of local recurrence with radiofrequency ablation than with surgical resection.37 In addition, radiofrequency ablation has been shown to be effective only in small tumors and does not perform as well in lesions larger than 2 or 3 cm.

Thus, based on current evidence, surgical resection is preferable to radiofrequency ablation as first-line treatment. The latter, however, is also used as a bridging therapy in patients awaiting liver transplantation.

Percutaneous ethanol injection

Percutaneous ethanol injection is used less frequently than radiofrequency ablation, as studies have shown the latter to be superior in regard to local recurrence-free survival rates.38 However, percutaneous ethanol injection is used instead of radiofrequency ablation in a small number of patients, when the lesion is very close to organs such as the bile duct (which could be damaged by radiofrequency ablation) or the large vessels (which may make radiofrequency ablation less effective, since heat may dissipate as a result of excessive blood flow in this region).

Microwave ablation

Microwave ablation is an emerging therapy for HCC. Its advantage over radiofrequency ablation is that its use is not limited by blood vessels in close proximity to the ablation site.

Earlier studies did not show microwave ablation to be superior to radiofrequency ablation.39,40 However, current studies involving newer techniques of microwave ablation are more promising.41

PERFUSION-BASED LOCOREGIONAL THERAPIES

Perfusion-based locoregional therapies deliver embolic particles, chemotherapeutic agents, or radioactive materials into the artery feeding the tumor. The portal blood flow allows for preservation of vital liver tissue during arterial embolization of liver tumors. Perfusionbased therapies include transarterial chemoembolization, transarterial chemoembolization with doxorubicin-eluting beads (DEB-TACE), “bland” embolization, and radioembolization.

Transarterial chemoembolization

Transarterial chemoembolization is a minimally invasive procedure in which the hepatic artery is cannulated through a percutaneous puncture, the branches of the hepatic artery supplying the tumor are identified, and then embolic particles and chemotherapeutic agents are injected. This serves a dual purpose: it embolizes the feeding vessel that supplies the tumor, causing tumor necrosis, and it focuses the chemotherapy on the tumor and thus minimizes the systemic effects of the chemotherapeutic agent.

This therapy is contraindicated in patients with portal vein thrombosis, advanced liver dysfunction, or a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Side effects of the procedure include a postembolization syndrome of abdominal pain and fever (occurring in about 50% of patients from ischemic injury to the liver), hepatic abscesses, injury to the hepatic artery, development of ascites, liver dysfunction, and contrast-induced renal failure.

In addition to bridging patients to liver transplantation, transarterial chemoembolization is recommended as palliative treatment to prolong survival in patients with HCC who are not candidates for liver transplantation, surgical resection, or radiofrequency ablation.9,42 Patients who have Child-Pugh grade A or B cirrhosis but do not have main portal vein thrombosis or extrahepatic spread are candidates for this therapy. Patients such as these who undergo this therapy have a better survival rate at 2 years compared with untreated patients.43,44

Transarterial chemoembolization has also been used to reduce the size of (ie, to “downstage”) tumors that are outside the Milan criteria in patients who are otherwise candidates for liver transplantation. It induces tumor necrosis and has been shown to decrease the tumor size in a selected group of patients and to bring them within the Milan criteria, thus potentially enabling them to be put on the transplant list.45 Studies have shown that patients who receive a transplant after successful down-staging may achieve a 5-year survival rate comparable with that of patients who were initially within the Milan criteria and received a transplant without the need for down-staging.45 However, factors that predict successful down-staging have not been clearly established.

Newer techniques have been developed. A randomized controlled trial found transarterial chemoembolization with doxorubicin-eluting beads to be safer and better tolerated than conventional transarterial chemembolization.46

Bland embolization is transarterial embolization without chemotherapeutic agents and is performed in patients with significant liver dysfunction who might not tolerate chemotherapy. The benefits of this approach are yet to be determined.

Radioembolization

Radioembolization with yttrium-90 microspheres has recently been introduced as an alternative to transarterial chemoembolization, especially in patients with portal vein thrombosis, a portocaval shunt, or a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

In observational studies, radioembolization was as effective as transarterial chemoembolization, with a similar survival benefit.47 However, significant pulmonary shunting must be ruled out before radioembolization, as it would lead to radiation-induced pulmonary disease. Randomized controlled trials are under way to compare the efficacy of the two methods.

CHEMOTHERAPY

Sorafenib

Sorafenib is an oral antiangiogenic agent. A kinase inhibitor, it interacts with multiple intracellular and cell-surface kinases, including vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, platelet-derived growth factor receptor, and Raf proto-oncogene, inhibiting tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis.

Sorafenib has been shown to prolong survival in patients with advanced-stage HCC.48 A randomized placebo-controlled trial in patients with Child-Pugh grade A cirrhosis and advanced HCC who had not received chemotherapy showed that sorafenib increased the life expectancy by nearly 3 months compared with placebo.47 Sorafenib therapy is very expensive, but it is usually covered by insurance.

Sorafenib is recommended in patients who have advanced HCC with vascular invasion, extrahepatic dissemination, or minimal constitutional symptoms. It is not recommended for patients with severe advanced liver disease who have moderate to severe tumor-related constitutional symptoms or Child-Pugh grade C cirrhosis, or for patients with a life expectancy of less than 3 months.

The most common side effects of sorafenib are diarrhea, weight loss, and skin reactions on the hands and feet. These commonly lead to decreased tolerability and dose reductions.47 Doses should be adjusted on the basis of the bilirubin and albumin levels.49

Other chemotherapeutic agents

Several molecular targeted agents are undergoing clinical trials for the treatment of HCC. These include bevacizumab, erlotinib, brivanib, and ramucirumab. Chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin and everolimus are also being studied.

PALLIATIVE TREATMENT

Patients with end-stage HCC with moderate to severe constitutional symptoms, extrahepatic disease progression, and decompensated liver disease have a survival of less than 3 months and are treated for pain and symptom control.9

- Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer 2010; 127:2893–2917.

- El-Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology 2007; 132:2557–2576.

- El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2012; 142:1264–1273.e1.

- Altekruse SF, McGlynn KA, Reichman ME. Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence, mortality, and survival trends in the United States from 1975 to 2005. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27:1485–1491.

- Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of US adults. N Engl J Med 2003; 348:1625–1638.

- Sarasin FP, Giostra E, Hadengue A. Cost-effectiveness of screening for detection of small hepatocellular carcinoma in western patients with Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis. Am J Med 1996; 101:422–434.

- Yu MW, Chang HC, Liaw YF, et al. Familial risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among chronic hepatitis B carriers and their relatives. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000; 92:1159–1164.

- Kew MC, Macerollo P. Effect of age on the etiologic role of the hepatitis B virus in hepatocellular carcinoma in blacks. Gastroenterology 1988; 94:439–442.

- Bruix J, Sherman M; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology 2011; 53:1020–1022.

- Bruix J, Llovet JM. Major achievements in hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2009; 373:614–616.

- Gómez-Rodríguez R, Romero-Gutiérrez M, Artaza-Varasa T, et al. The value of the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer and alpha-fetoprotein in the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2012; 104:298–304.

- Zhang BH, Yang BH, Tang ZY. Randomized controlled trial of screening for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2004; 130:417–422.

- Giannini EG, Erroi V, Trevisani F. Effectiveness of a-fetoprotein for hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance: the return of the living-dead? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 6:441–444.

- Farinati F, Marino D, De Giorgio M, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic role of alpha-fetoprotein in hepatocellular carcinoma: both or neither? Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101:524–532.

- Forner A, Vilana R, Ayuso C, et al. Diagnosis of hepatic nodules 20 mm or smaller in cirrhosis: prospective validation of the noninvasive diagnostic criteria for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2008; 47:97–104.

- Vilana R, Forner A, Bianchi L, et al. Intrahepatic peripheral cholangiocarcinoma in cirrhosis patients may display a vascular pattern similar to hepatocellular carcinoma on contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Hepatology 2010; 51:2020–2029.

- Kojiro M. Pathological diagnosis at early stage: reaching international consensus. Oncology 2010; 78(suppl 1):31–35.