User login

Is anticoagulation appropriate for all patients with portal vein thrombosis?

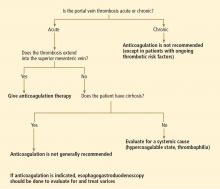

No. in general, the decision to treat portal vein thrombosis with anticoagulant drugs is complex and depends on whether the thrombosis is acute or chronic, and whether the cause is a local factor, cirrhosis of the liver, or a systemic condition (Table 1). A “one-size-fits-all” approach should be avoided (Figure 1).

ACUTE PORTAL VEIN THROMBOSIS WITHOUT CIRRHOSIS

No randomized controlled trial has yet evaluated anticoagulation in acute portal vein thrombosis. But a prospective study published in 2010 showed that the portal vein and its left or right branch were patent in 39% of anticoagulated patients (vs 13% initially), the splenic vein in 80% (vs 57% initially), and the superior mesenteric vein in 73% (vs 42% initially).1 Further, there appears to be a 20% reduction in the overall mortality rate associated with anticoagulation for acute portal vein thrombosis in retrospective studies.2

In the absence of contraindications, anticoagulation with heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin is recommended, with complete bridging to oral anticoagulation with a vitamin K antagonist. Anticoagulation should be continued for at least 3 months, and indefinitely in patients with permanent hypercoaguable risk factors.3

CHRONIC PORTAL VEIN THROMBOSIS WITHOUT CIRRHOSIS

All patients with chronic portal vein thrombosis should undergo esophagogastroduodenoscopy to evaluate for varices. Patients with large varices should be treated orally with a nonselective beta-adrenergic blocker or endoscopically. Though no prospective study has validated this practice, a retrospective analysis showed a decreased risk of first or recurrent bleeding.4

In 2007, a retrospective study showed a lower rate of death in patients with portomesenteric venous thrombosis treated with an oral vitamin K antagonist.5 Patients with chronic portal vein thrombosis with ongoing thrombotic risk factors should be treated with long-term anticoagulation after screening for varices, and if varices are present, primary prophylaxis should be started.3 With this approach, less than 5% of patients died from classic complications of portal vein thrombosis at 5 years of follow-up.4

ACUTE OR CHRONIC PORTAL VEIN THROMBOSIS WITH CIRRHOSIS

Portal vein thrombosis is common in patients with underlying cirrhosis. The risk in patients with cirrhosis significantly increases as liver function worsens. In patients with well-compensated cirrhosis, the risk is less than 1% vs 8% to 25% in those with advanced cirrhosis.6

In patients awaiting liver transplantation, a large retrospective study7 showed that the rate of partial or complete recanalization of the splanchnic veins was significantly higher in those who received anticoagulation (8 of 19) than in those who did not (0 of 10, P = .002). The rate of survival was significantly lower in those who had complete thrombotic obstruction of the portal vein at the time of surgery (P = .04). However, there was no difference in survival rates between those with partial obstruction who received anticoagulation and those with a patent portal vein.7

A later retrospective study8 showed no significant benefit in the rate of transplantation-free survival or survival after liver transplantation in patients with or without chronic portal vein thrombosis.8

Unfortunately, we have no data from prospective controlled trials and only limited data from retrospective studies to make a strong recommendation for or against anticoagulation in either acute and chronic portal vein thrombosis associated with cirrhosis. As such, each case must be evaluated on an individual basis in association with expert consultation.

In our experience, the risk of bleeding in patients with liver cirrhosis is substantial because of the decreased synthesis of coagulation factors and the presence of varices, whereas the efficacy and the benefits of recanalizing the portal vein in asymptomatic patients with liver cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis are unknown. Therefore, unless the thrombosis extends into the mesenteric vein, thus posing a risk of mesenteric ischemia, we do not generally recommend anticoagulation in asymptomatic portal vein thrombosis in patients with cirrhosis.

- Plessier A, Darwish-Murad S, Hernandez-Guerra M, et al; European Network for Vascular Disorders of the Liver (EN-Vie). Acute portal vein thrombosis unrelated to cirrhosis: a prospective multicenter follow-up study. Hepatology 2010; 51:210–218.

- Kumar S, Sarr MG, Kamath PS. Mesenteric venous thrombosis. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:1683–1688.

- de Franchis R. Evolving consensus in portal hypertension. Report of the Baveno IV consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol 2005; 43:167–176.

- Condat B, Pessione F, Hillaire S, et al. Current outcome of portal vein thrombosis in adults: risk and benefit of anticoagulant therapy. Gastroenterology 2001; 120:490–497.

- Orr DW, Harrison PM, Devlin J, et al. Chronic mesenteric venous thrombosis: evaluation and determinants of survival during long-term follow-up. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 5:80–86.

- DeLeve LD, Valla DC, Garcia-Tsao G; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Vascular disorders of the liver. Hepatology 2009; 49:1729–1764.

- Francoz C, Belghiti J, Vilgrain V, et al. Splanchnic vein thrombosis in candidates for liver transplantation: usefulness of screening and anticoagulation. Gut 2005; 54:691–697.

- John BV, Konjeti VR, Aggarwal A, et al. The impact of portal vein thrombosis (PVT) on cirrhotics awaiting liver transplantation (abstract). Hepatology 2010; 52(suppl1):888A–889A.

No. in general, the decision to treat portal vein thrombosis with anticoagulant drugs is complex and depends on whether the thrombosis is acute or chronic, and whether the cause is a local factor, cirrhosis of the liver, or a systemic condition (Table 1). A “one-size-fits-all” approach should be avoided (Figure 1).

ACUTE PORTAL VEIN THROMBOSIS WITHOUT CIRRHOSIS

No randomized controlled trial has yet evaluated anticoagulation in acute portal vein thrombosis. But a prospective study published in 2010 showed that the portal vein and its left or right branch were patent in 39% of anticoagulated patients (vs 13% initially), the splenic vein in 80% (vs 57% initially), and the superior mesenteric vein in 73% (vs 42% initially).1 Further, there appears to be a 20% reduction in the overall mortality rate associated with anticoagulation for acute portal vein thrombosis in retrospective studies.2

In the absence of contraindications, anticoagulation with heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin is recommended, with complete bridging to oral anticoagulation with a vitamin K antagonist. Anticoagulation should be continued for at least 3 months, and indefinitely in patients with permanent hypercoaguable risk factors.3

CHRONIC PORTAL VEIN THROMBOSIS WITHOUT CIRRHOSIS

All patients with chronic portal vein thrombosis should undergo esophagogastroduodenoscopy to evaluate for varices. Patients with large varices should be treated orally with a nonselective beta-adrenergic blocker or endoscopically. Though no prospective study has validated this practice, a retrospective analysis showed a decreased risk of first or recurrent bleeding.4

In 2007, a retrospective study showed a lower rate of death in patients with portomesenteric venous thrombosis treated with an oral vitamin K antagonist.5 Patients with chronic portal vein thrombosis with ongoing thrombotic risk factors should be treated with long-term anticoagulation after screening for varices, and if varices are present, primary prophylaxis should be started.3 With this approach, less than 5% of patients died from classic complications of portal vein thrombosis at 5 years of follow-up.4

ACUTE OR CHRONIC PORTAL VEIN THROMBOSIS WITH CIRRHOSIS

Portal vein thrombosis is common in patients with underlying cirrhosis. The risk in patients with cirrhosis significantly increases as liver function worsens. In patients with well-compensated cirrhosis, the risk is less than 1% vs 8% to 25% in those with advanced cirrhosis.6

In patients awaiting liver transplantation, a large retrospective study7 showed that the rate of partial or complete recanalization of the splanchnic veins was significantly higher in those who received anticoagulation (8 of 19) than in those who did not (0 of 10, P = .002). The rate of survival was significantly lower in those who had complete thrombotic obstruction of the portal vein at the time of surgery (P = .04). However, there was no difference in survival rates between those with partial obstruction who received anticoagulation and those with a patent portal vein.7

A later retrospective study8 showed no significant benefit in the rate of transplantation-free survival or survival after liver transplantation in patients with or without chronic portal vein thrombosis.8

Unfortunately, we have no data from prospective controlled trials and only limited data from retrospective studies to make a strong recommendation for or against anticoagulation in either acute and chronic portal vein thrombosis associated with cirrhosis. As such, each case must be evaluated on an individual basis in association with expert consultation.

In our experience, the risk of bleeding in patients with liver cirrhosis is substantial because of the decreased synthesis of coagulation factors and the presence of varices, whereas the efficacy and the benefits of recanalizing the portal vein in asymptomatic patients with liver cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis are unknown. Therefore, unless the thrombosis extends into the mesenteric vein, thus posing a risk of mesenteric ischemia, we do not generally recommend anticoagulation in asymptomatic portal vein thrombosis in patients with cirrhosis.

No. in general, the decision to treat portal vein thrombosis with anticoagulant drugs is complex and depends on whether the thrombosis is acute or chronic, and whether the cause is a local factor, cirrhosis of the liver, or a systemic condition (Table 1). A “one-size-fits-all” approach should be avoided (Figure 1).

ACUTE PORTAL VEIN THROMBOSIS WITHOUT CIRRHOSIS

No randomized controlled trial has yet evaluated anticoagulation in acute portal vein thrombosis. But a prospective study published in 2010 showed that the portal vein and its left or right branch were patent in 39% of anticoagulated patients (vs 13% initially), the splenic vein in 80% (vs 57% initially), and the superior mesenteric vein in 73% (vs 42% initially).1 Further, there appears to be a 20% reduction in the overall mortality rate associated with anticoagulation for acute portal vein thrombosis in retrospective studies.2

In the absence of contraindications, anticoagulation with heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin is recommended, with complete bridging to oral anticoagulation with a vitamin K antagonist. Anticoagulation should be continued for at least 3 months, and indefinitely in patients with permanent hypercoaguable risk factors.3

CHRONIC PORTAL VEIN THROMBOSIS WITHOUT CIRRHOSIS

All patients with chronic portal vein thrombosis should undergo esophagogastroduodenoscopy to evaluate for varices. Patients with large varices should be treated orally with a nonselective beta-adrenergic blocker or endoscopically. Though no prospective study has validated this practice, a retrospective analysis showed a decreased risk of first or recurrent bleeding.4

In 2007, a retrospective study showed a lower rate of death in patients with portomesenteric venous thrombosis treated with an oral vitamin K antagonist.5 Patients with chronic portal vein thrombosis with ongoing thrombotic risk factors should be treated with long-term anticoagulation after screening for varices, and if varices are present, primary prophylaxis should be started.3 With this approach, less than 5% of patients died from classic complications of portal vein thrombosis at 5 years of follow-up.4

ACUTE OR CHRONIC PORTAL VEIN THROMBOSIS WITH CIRRHOSIS

Portal vein thrombosis is common in patients with underlying cirrhosis. The risk in patients with cirrhosis significantly increases as liver function worsens. In patients with well-compensated cirrhosis, the risk is less than 1% vs 8% to 25% in those with advanced cirrhosis.6

In patients awaiting liver transplantation, a large retrospective study7 showed that the rate of partial or complete recanalization of the splanchnic veins was significantly higher in those who received anticoagulation (8 of 19) than in those who did not (0 of 10, P = .002). The rate of survival was significantly lower in those who had complete thrombotic obstruction of the portal vein at the time of surgery (P = .04). However, there was no difference in survival rates between those with partial obstruction who received anticoagulation and those with a patent portal vein.7

A later retrospective study8 showed no significant benefit in the rate of transplantation-free survival or survival after liver transplantation in patients with or without chronic portal vein thrombosis.8

Unfortunately, we have no data from prospective controlled trials and only limited data from retrospective studies to make a strong recommendation for or against anticoagulation in either acute and chronic portal vein thrombosis associated with cirrhosis. As such, each case must be evaluated on an individual basis in association with expert consultation.

In our experience, the risk of bleeding in patients with liver cirrhosis is substantial because of the decreased synthesis of coagulation factors and the presence of varices, whereas the efficacy and the benefits of recanalizing the portal vein in asymptomatic patients with liver cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis are unknown. Therefore, unless the thrombosis extends into the mesenteric vein, thus posing a risk of mesenteric ischemia, we do not generally recommend anticoagulation in asymptomatic portal vein thrombosis in patients with cirrhosis.

- Plessier A, Darwish-Murad S, Hernandez-Guerra M, et al; European Network for Vascular Disorders of the Liver (EN-Vie). Acute portal vein thrombosis unrelated to cirrhosis: a prospective multicenter follow-up study. Hepatology 2010; 51:210–218.

- Kumar S, Sarr MG, Kamath PS. Mesenteric venous thrombosis. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:1683–1688.

- de Franchis R. Evolving consensus in portal hypertension. Report of the Baveno IV consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol 2005; 43:167–176.

- Condat B, Pessione F, Hillaire S, et al. Current outcome of portal vein thrombosis in adults: risk and benefit of anticoagulant therapy. Gastroenterology 2001; 120:490–497.

- Orr DW, Harrison PM, Devlin J, et al. Chronic mesenteric venous thrombosis: evaluation and determinants of survival during long-term follow-up. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 5:80–86.

- DeLeve LD, Valla DC, Garcia-Tsao G; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Vascular disorders of the liver. Hepatology 2009; 49:1729–1764.

- Francoz C, Belghiti J, Vilgrain V, et al. Splanchnic vein thrombosis in candidates for liver transplantation: usefulness of screening and anticoagulation. Gut 2005; 54:691–697.

- John BV, Konjeti VR, Aggarwal A, et al. The impact of portal vein thrombosis (PVT) on cirrhotics awaiting liver transplantation (abstract). Hepatology 2010; 52(suppl1):888A–889A.

- Plessier A, Darwish-Murad S, Hernandez-Guerra M, et al; European Network for Vascular Disorders of the Liver (EN-Vie). Acute portal vein thrombosis unrelated to cirrhosis: a prospective multicenter follow-up study. Hepatology 2010; 51:210–218.

- Kumar S, Sarr MG, Kamath PS. Mesenteric venous thrombosis. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:1683–1688.

- de Franchis R. Evolving consensus in portal hypertension. Report of the Baveno IV consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol 2005; 43:167–176.

- Condat B, Pessione F, Hillaire S, et al. Current outcome of portal vein thrombosis in adults: risk and benefit of anticoagulant therapy. Gastroenterology 2001; 120:490–497.

- Orr DW, Harrison PM, Devlin J, et al. Chronic mesenteric venous thrombosis: evaluation and determinants of survival during long-term follow-up. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 5:80–86.

- DeLeve LD, Valla DC, Garcia-Tsao G; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Vascular disorders of the liver. Hepatology 2009; 49:1729–1764.

- Francoz C, Belghiti J, Vilgrain V, et al. Splanchnic vein thrombosis in candidates for liver transplantation: usefulness of screening and anticoagulation. Gut 2005; 54:691–697.

- John BV, Konjeti VR, Aggarwal A, et al. The impact of portal vein thrombosis (PVT) on cirrhotics awaiting liver transplantation (abstract). Hepatology 2010; 52(suppl1):888A–889A.

An uncommon syndrome makes us reflect on our approach to diagnosis

In this issue of the Journal, Dr. Soumya Chatterjee and colleagues discuss the antisynthetase syndrome. Although uncommon, this syndrome is important for internists and subspecialists to be aware of. Patients present in several different ways, and potentially life-threatening organ involvement may initially not be recognized or may not be linked with other components of the syndrome, such as involvement of the lungs, muscles, heart, and esophagus and fever.

I am currently on our inpatient rheumatology consultation service, and so I am reminded daily of the challenges hospitalists and subspecialists confront in ordering tests while trying to balance limiting length of stay with cost-efficiency and the desire to obtain a correct diagnosis. And I am repeatedly sensitized to several common test-ordering pitfalls intrinsic to the evaluation of patients with multisystem disease, including myositis. Most have a shared theme—limited time is spent in thoughtful reflection before ordering.

Patients with myositis rarely present with the textbook description of proximal muscle weakness. They describe fatigue, malaise, and sometimes a generalized sense of weakness. It is the probing questioning of their functional capacity and focused examination that reveal that the weakness is characterized by difficulty getting up off the floor, out of a low chair, or off the toilet. Then, with further questioning, some patients note that their fatigue and tiredness may also include getting winded easily with exertion, such as when climbing stairs, thus raising the question of cardiac dysfunction, pulmonary hypertension, or interstitial lung disease.

The responses to those probing questions and the subsequent examination should transform the interpretation of elevated aminotransferase levels (“liver tests”: AST and ALT) from liver disease into suspicion of muscle disease and the appropriate ordering of the creatine kinase level (avoiding liver imaging and hepatology consultation). The carefully repeated and now focused neurologic examination distinguishes the initial “poor cooperation” from the proximal weakness of myopathy. The probing interview leads to the performance of a focused physical examination that frames the appropriate interpretation of the routinely obtained “admission lab studies”!

The thoughtful history and examination are the basic stuff of clinical medicine that can easily be pushed aside by any of us as we deal with the tensions of high-volume, “high-throughput” medical care. It is a low-resistance path from hearing the symptom of fatigue with elevated “liver enzymes” to immediately checking ferritin, ceruloplasmin, and a hepatitis screen in preparation for getting a liver biopsy. It is easy to go through the motions without reflection. Easy, but sometimes wrong. And it is just as easy (but likely to be costly and unhelpful) to identify a patient prematurely with “possible autoimmune disease” and to immediately order a panoply of antinuclear and autoimmune serologies, including the Jo-1 autoantibody test.

As Dr. Chatterjee et al point out, we must continuously reflect on our diagnoses, for even after we navigate the pitfalls and avoid missing the diagnosis of myositis, if we don’t continuously assess all the patient’s symptoms, repeat the examination in a directed manner, and then look for circulating Jo-1 antibody when appropriate, we may well miss the opportunity to recognize that our patient’s ongoing fatigue with exertion is a reflection of the well-described association of myositis with interstitial lung disease (which may warrant a change in therapy), and not steroid myopathy or just poor conditioning.

Alternatively, in evaluating a patient who describes a year of feeling tired, suffering generalized muscle pains with low-grade fevers with temperatures of 99.8°F, and total exhaustion for 3 days after cleaning the oven, testing for antinuclear antibodies, extractable nuclear antigen antibodies, and a “vasculitis panel” in anticipation of a rheumatology consultation is not likely to be useful therapeutically or diagnostically.

Despite the daily pressures, we need to keep ourselves grounded in the fundamentals of clinical care: careful listening, purposeful examination, and directed use of laboratory tests and imaging. The downstream consequences of ordering tests for the sake of efficient throughput are quite real, and thoughtful test ordering is one step toward quality care, as well as cost-effective care.

In future months, the Journal will delve more deeply into test ordering when, in a joint effort with the American College of Physicians, we will be discussing the use and misuse of specific tests.

In this issue of the Journal, Dr. Soumya Chatterjee and colleagues discuss the antisynthetase syndrome. Although uncommon, this syndrome is important for internists and subspecialists to be aware of. Patients present in several different ways, and potentially life-threatening organ involvement may initially not be recognized or may not be linked with other components of the syndrome, such as involvement of the lungs, muscles, heart, and esophagus and fever.

I am currently on our inpatient rheumatology consultation service, and so I am reminded daily of the challenges hospitalists and subspecialists confront in ordering tests while trying to balance limiting length of stay with cost-efficiency and the desire to obtain a correct diagnosis. And I am repeatedly sensitized to several common test-ordering pitfalls intrinsic to the evaluation of patients with multisystem disease, including myositis. Most have a shared theme—limited time is spent in thoughtful reflection before ordering.

Patients with myositis rarely present with the textbook description of proximal muscle weakness. They describe fatigue, malaise, and sometimes a generalized sense of weakness. It is the probing questioning of their functional capacity and focused examination that reveal that the weakness is characterized by difficulty getting up off the floor, out of a low chair, or off the toilet. Then, with further questioning, some patients note that their fatigue and tiredness may also include getting winded easily with exertion, such as when climbing stairs, thus raising the question of cardiac dysfunction, pulmonary hypertension, or interstitial lung disease.

The responses to those probing questions and the subsequent examination should transform the interpretation of elevated aminotransferase levels (“liver tests”: AST and ALT) from liver disease into suspicion of muscle disease and the appropriate ordering of the creatine kinase level (avoiding liver imaging and hepatology consultation). The carefully repeated and now focused neurologic examination distinguishes the initial “poor cooperation” from the proximal weakness of myopathy. The probing interview leads to the performance of a focused physical examination that frames the appropriate interpretation of the routinely obtained “admission lab studies”!

The thoughtful history and examination are the basic stuff of clinical medicine that can easily be pushed aside by any of us as we deal with the tensions of high-volume, “high-throughput” medical care. It is a low-resistance path from hearing the symptom of fatigue with elevated “liver enzymes” to immediately checking ferritin, ceruloplasmin, and a hepatitis screen in preparation for getting a liver biopsy. It is easy to go through the motions without reflection. Easy, but sometimes wrong. And it is just as easy (but likely to be costly and unhelpful) to identify a patient prematurely with “possible autoimmune disease” and to immediately order a panoply of antinuclear and autoimmune serologies, including the Jo-1 autoantibody test.

As Dr. Chatterjee et al point out, we must continuously reflect on our diagnoses, for even after we navigate the pitfalls and avoid missing the diagnosis of myositis, if we don’t continuously assess all the patient’s symptoms, repeat the examination in a directed manner, and then look for circulating Jo-1 antibody when appropriate, we may well miss the opportunity to recognize that our patient’s ongoing fatigue with exertion is a reflection of the well-described association of myositis with interstitial lung disease (which may warrant a change in therapy), and not steroid myopathy or just poor conditioning.

Alternatively, in evaluating a patient who describes a year of feeling tired, suffering generalized muscle pains with low-grade fevers with temperatures of 99.8°F, and total exhaustion for 3 days after cleaning the oven, testing for antinuclear antibodies, extractable nuclear antigen antibodies, and a “vasculitis panel” in anticipation of a rheumatology consultation is not likely to be useful therapeutically or diagnostically.

Despite the daily pressures, we need to keep ourselves grounded in the fundamentals of clinical care: careful listening, purposeful examination, and directed use of laboratory tests and imaging. The downstream consequences of ordering tests for the sake of efficient throughput are quite real, and thoughtful test ordering is one step toward quality care, as well as cost-effective care.

In future months, the Journal will delve more deeply into test ordering when, in a joint effort with the American College of Physicians, we will be discussing the use and misuse of specific tests.

In this issue of the Journal, Dr. Soumya Chatterjee and colleagues discuss the antisynthetase syndrome. Although uncommon, this syndrome is important for internists and subspecialists to be aware of. Patients present in several different ways, and potentially life-threatening organ involvement may initially not be recognized or may not be linked with other components of the syndrome, such as involvement of the lungs, muscles, heart, and esophagus and fever.

I am currently on our inpatient rheumatology consultation service, and so I am reminded daily of the challenges hospitalists and subspecialists confront in ordering tests while trying to balance limiting length of stay with cost-efficiency and the desire to obtain a correct diagnosis. And I am repeatedly sensitized to several common test-ordering pitfalls intrinsic to the evaluation of patients with multisystem disease, including myositis. Most have a shared theme—limited time is spent in thoughtful reflection before ordering.

Patients with myositis rarely present with the textbook description of proximal muscle weakness. They describe fatigue, malaise, and sometimes a generalized sense of weakness. It is the probing questioning of their functional capacity and focused examination that reveal that the weakness is characterized by difficulty getting up off the floor, out of a low chair, or off the toilet. Then, with further questioning, some patients note that their fatigue and tiredness may also include getting winded easily with exertion, such as when climbing stairs, thus raising the question of cardiac dysfunction, pulmonary hypertension, or interstitial lung disease.

The responses to those probing questions and the subsequent examination should transform the interpretation of elevated aminotransferase levels (“liver tests”: AST and ALT) from liver disease into suspicion of muscle disease and the appropriate ordering of the creatine kinase level (avoiding liver imaging and hepatology consultation). The carefully repeated and now focused neurologic examination distinguishes the initial “poor cooperation” from the proximal weakness of myopathy. The probing interview leads to the performance of a focused physical examination that frames the appropriate interpretation of the routinely obtained “admission lab studies”!

The thoughtful history and examination are the basic stuff of clinical medicine that can easily be pushed aside by any of us as we deal with the tensions of high-volume, “high-throughput” medical care. It is a low-resistance path from hearing the symptom of fatigue with elevated “liver enzymes” to immediately checking ferritin, ceruloplasmin, and a hepatitis screen in preparation for getting a liver biopsy. It is easy to go through the motions without reflection. Easy, but sometimes wrong. And it is just as easy (but likely to be costly and unhelpful) to identify a patient prematurely with “possible autoimmune disease” and to immediately order a panoply of antinuclear and autoimmune serologies, including the Jo-1 autoantibody test.

As Dr. Chatterjee et al point out, we must continuously reflect on our diagnoses, for even after we navigate the pitfalls and avoid missing the diagnosis of myositis, if we don’t continuously assess all the patient’s symptoms, repeat the examination in a directed manner, and then look for circulating Jo-1 antibody when appropriate, we may well miss the opportunity to recognize that our patient’s ongoing fatigue with exertion is a reflection of the well-described association of myositis with interstitial lung disease (which may warrant a change in therapy), and not steroid myopathy or just poor conditioning.

Alternatively, in evaluating a patient who describes a year of feeling tired, suffering generalized muscle pains with low-grade fevers with temperatures of 99.8°F, and total exhaustion for 3 days after cleaning the oven, testing for antinuclear antibodies, extractable nuclear antigen antibodies, and a “vasculitis panel” in anticipation of a rheumatology consultation is not likely to be useful therapeutically or diagnostically.

Despite the daily pressures, we need to keep ourselves grounded in the fundamentals of clinical care: careful listening, purposeful examination, and directed use of laboratory tests and imaging. The downstream consequences of ordering tests for the sake of efficient throughput are quite real, and thoughtful test ordering is one step toward quality care, as well as cost-effective care.

In future months, the Journal will delve more deeply into test ordering when, in a joint effort with the American College of Physicians, we will be discussing the use and misuse of specific tests.

Antisynthetase syndrome: Not just an inflammatory myopathy

A 66-year-old man was initially seen in clinic in March 2004 with a 5-month history of polyarthritis (affecting the finger joints, wrists, and knees) and several hours of morning stiffness. He also had significant proximal muscle weakness, progressive exertional dyspnea, and a nonproductive cough. There was no history of fever, chills, rash, dysphagia, or sicca symptoms. Findings on initial tests:

- His creatine kinase level was 700 U/L (reference range 30–220), which later rose to 1,664 U/L.

- He was positive for antinuclear antibody with a 5.7 optical density ratio (normal < 1.5) and for anti-Jo-1 antibody.

- An electromyogram was consistent with a necrotizing myopathy. Left rectus femoris biopsy revealed scattered degenerating and regenerating muscle fibers but no evidence of endomysial inflammation.

- On pulmonary function testing, his forced vital capacity was 80% of predicted, and his carbon monoxide diffusion capacity was 67% of predicted.

- High-resolution computed tomography revealed evidence of interstitial lung disease, characterized by bilateral patchy ground-glass opacities suggestive of active alveolitis, most extensive at the lung bases.

- Bronchoalveolar lavage indicated alveolitis, and transbronchial biopsy revealed pathologic changes consistent with cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. All cultures were negative.

This constellation of clinical manifestations, including myositis, interstitial lung disease, and polyarthritis, along with positive anti-Jo-1 antibody, confirmed the diagnosis of antisynthetase syndrome.

In June 2004, for his interstitial lung disease, he was started on daily oral cyclophosphamide along with high-dose oral prednisone. Three months later the skin of the tips and radial margins of his fingers started thickening and cracking, the appearance of which is classically described as “mechanic’s hands,” a well-described manifestation of antisynthetase syndrome (Figure 1).

Cyclophosphamide was continued for about a year. Subsequently, along with prednisone, he sequentially received various other immunosuppressive medications (methotrexate, tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and rituximab) over the next few years in an attempt to control his progressive interstitial lung disease. All of these agents were only partially and temporarily effective. Ultimately, despite all of these therapies, as his interstitial lung disease progressed, he needed supplemental oxygen and enrollment in a pulmonary rehabilitation program.

In March 2010, he was admitted with worsening dyspnea and significant peripheral edema and was found to have severe pulmonary arterial hypertension. He was started on bosentan. Eight months later sildenafil was added for progressive pulmonary arterial hypertension. However, his oxygenation status continued to decline.

In July 2011, he presented with chills, increasing shortness of breath, and a mild productive cough. As he was severely hypoxic, he was admitted to the intensive care unit and started on mechanical ventilation and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Despite escalation of oxygen therapy, his respiratory status rapidly deteriorated, and he developed hypotension requiring vasopressors. He ultimately died of cardiac arrest secondary to respiratory failure.

A CONSTELLATION OF MANIFESTATIONS

Antisynthetase syndrome, associated with anti-aminoacyl-transfer RNA (tRNA) synthetase antibodies, is characterized by a constellation of manifestations that include myositis, interstitial lung disease, mechanic’s hands, fever, Raynaud phenomenon, and nonerosive symmetric polyarthritis of the small joints.1

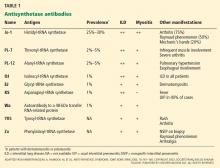

Anti-Jo-1 antibody (anti-histidyl-tRNA synthetase) is the most common of the antibodies and also was the first one to be identified (Table 1). It was named after John P, a patient with polymyositis and interstitial lung disease, in whom it was first detected in 1980.2 The onset of the syndrome associated with anti-Jo-1 antibody is often acute, and the myositis is usually steroid-responsive. However, not uncommonly, severe disease can develop over time, with a tendency to relapse and with a poor long-term prognosis.

RARE BUT UNDERRECOGNIZED

The true population prevalence of antisynthetase syndrome is unknown. Because this syndrome is rare, comprehensive epidemiologic studies are difficult to perform.

In several retrospective studies, the annual incidence of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies has been reported to be 2 to 10 new cases per million adults per year.3 Antisynthetase antibodies are detected in 20% to 40% of such cases.4–6 The disease is two to three times more common in women than in men.7

Early diagnosis is difficult because the clinical presentation is varied and often nonspecific, clinically milder disease may escape detection, and many general practitioners lack familiarity with this syndrome and consequently do not recognize it. Moreover, tests for myositis-specific antibodies (including antisynthetase antibodies) are often not ordered in the evaluation of myositis, and hence the diagnosis of antisynthetase syndrome cannot be substantiated. Furthermore, interstitial lung disease can predominate or can be the sole manifestation in the absence of clinically apparent myositis,8–10 and patients can be misdiagnosed as having idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis when underlying antisynthetase syndrome is not suspected. This distinction may be important because these conditions differ in their pathology and treatment. Histologically, the predominant pattern of lung injury in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is “usual interstitial pneumonia” which does not respond to immunosuppressive therapy, and hence lung transplantation is the only therapeutic option. On the other hand, in antisynthetase syndrome, the usual pattern of lung injury is “nonspecific interstitial pneumonia,” in which immunosuppressive therapy has a role.

Anti-Jo-1 antibody is detected in 15% to 25% of patients with polymyositis and in up to 70% of myositis patients with concomitant interstitial lung disease.11 Autoantibodies to seven other, less frequently targeted, aminoacyl tRNA synthetases have also been described in patients with polymyositis and interstitial lung disease (Table 1).11,12 In addition, an autoantibody to a 48-kDa transfer RNA-related protein (Wa) has been described.13 These non-Jo-1 antisynthetase antibodies are detected in only about 3% of myositis patients.14

ROLE OF ANTISYNTHETASE ANTIBODIES

Synthetases play a central role in protein synthesis by catalyzing the acetylation of tRNAs. The propensity of organ involvement in antisynthetase syndrome suggests that tissue-specific changes in muscle or lung lead to the production of unique forms of target autoantigens, the aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. There is evidence that these enzymes themselves may be involved in recruiting both antigen-presenting and inflammatory cells to the site of muscle or lung injury.15 However, the molecular pathway that initiates and propagates this autoimmune response and the specific role of the antisynthetase antibodies in the pathogenesis of this syndrome are presently unknown.

SIX SALIENT CLINICAL FEATURES

There are six predominant clinical manifestations, which may be present at disease onset or appear later as the disease progresses:

- Fever

- Myositis

- Interstitial lung disease

- Mechanic’s hands

- Raynaud phenomenon

- Inflammatory polyarthritis.

There is considerable clinical heterogeneity, and one or other manifestation can predominate or can be the only expression of the syndrome. Furthermore, in the same patient, the individual features can prevail at different times and may develop years after onset of the disease. Therefore, in addition to patients with myositis, it would be important to suspect antisynthetase syndrome in patients presenting with isolated lung involvement (amyopathic interstitial lung disease), as there are therapeutic implications. Studies have demonstrated the efficacy of immunosuppressive agents in interstitial lung disease associated with antisynthetase syndrome (where the predominant pattern of lung injury is “nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis”), whereas lung transplantation has so far been the only treatment option in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Fever

About 20% of patients have a fever at disease onset or associated with relapses. Sometimes the fever can persist until treatment of antisynthetase syndrome is started.

Myositis

Muscle disease is seen in more than 90% of patients with anti-Jo-1 antisynthetase syndrome. It can be subclinical (in the absence of proximal myopathy), manifested by transient creatine kinase elevation only, which may normalize after therapy is initiated.

However, more commonly, patients develop profound proximal muscle weakness and sometimes muscle pain (Table 2). Weakness of the striated muscles of the upper esophagus, cricopharyngeus, and hypopharynx may cause dysphagia and makes these patients susceptible to aspiration pneumonia. Diaphragmatic and intercostal muscle weakness can contribute to shortness of breath in some patients. Myocarditis has also been reported.

Pulmonary disease

Interstitial lung disease develops in most patients with anti-Jo-1 antisynthetase syndrome, with a reported prevalence of about 90% in one series.16 Patients often present with acute, subacute, or insidious onset of exertional dyspnea. Sometimes there is an intractable nonproductive cough.

At the outset of antisynthetase syndrome, if the patient is profoundly weak because of myopathy or has inflammatory polyarthritis, mobility is significantly compromised, and exertional dyspnea may not be experienced. However, as the interstitial lung disease progresses, shortness of breath becomes overt, more so when the patient’s level of activity improves with treatment of myositis.

Inspiratory crackles on auscultation of the lung bases or changes on chest radiography are relatively insensitive findings and can miss early interstitial lung disease. Therefore, if antisynthetase syndrome is suspected or diagnosed, a baseline pulmonary function test (spirometry and carbon monoxide diffusion capacity) is indicated. It will often detect occult interstitial lung disease, and the diagnosis can then be confirmed with thoracic high-resolution computed tomography (Figure 2).

Pulmonary hypertension. Recent studies indicate that, similar to patients with other autoimmune rheumatic diseases, pulmonary hypertension can develop in patients with antisynthetase syndrome, with or without concomitant interstitial lung disease.17,18 This complication occurred in the case presented here. It has been found that when pulmonary hypertension coexists with interstitial lung disease, its degree may not correlate with the severity of the latter.17 Additionally, pulmonary hypertension, when present, has been found to contribute independently to prognosis and survival.

Mechanic’s hands

In about 30% of patients, the skin of the tips and margins of the fingers becomes thickened, hyperkeratotic, and fissured, the appearance of which is classically described as mechanic’s hands. It is a common manifestation of antisynthetase syndrome and is particularly prominent on the radial side of the index fingers (Figure 1). Biopsy of affected skin shows an interface psoriasiform dermatitis.19 In addition, some dermatomyositis patients with Gottron papules and a heliotrope rash have antisynthetase antibodies.

Raynaud phenomenon

Raynaud phenomenon develops in about 40% of patients. Some have nailfold capillary abnormalities.20 However, persistent or severe digital ischemia leading to digital ulceration or infarction is uncommon.21

Inflammatory arthritis

Arthralgias and arthritis are common (50%), the most common form being a symmetric polyarthritis of the small joints of the hands and feet. It is typically nonerosive but can sometimes be erosive and destructive.20

Because inflammatory arthritis mimics rheumatoid arthritis, antisynthetase syndrome should be considered in rheumatoid factor-negative patients presenting with polyarthritis.

ASSOCIATION WITH MALIGNANCY

Traditional teaching has been that antisynthetase antibody is protective against an underlying malignancy.22,23 However, several recently published case studies have reported various malignancies occurring within 6 to 12 months of the diagnosis of antisynthetase syndrome.7,24 The debate as to whether these are chance associations or causal (a paraneoplastic phenomenon) has not been resolved at this time.24

It is now recommended that patients with antisynthetase syndrome be screened for malignancies as appropriate for the patient’s age and sex. Screening should include a careful history and physical examination, complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, chest radiography, mammography, and a gynecologic examination for women.25 If abnormalities are found, a more thorough evaluation for cancer is appropriate.

DIAGNOSIS

Muscle enzyme levels are often elevated

Muscle enzymes (creatine kinase and aldolase) are often elevated. Serum creatine kinase levels can range between 5 to 50 times the upper limit of normal. In an established case, creatine kinase levels along with careful manual muscle strength testing may help evaluate myositis activity. However, in chronic and advanced disease, creatine kinase may be within the normal range despite active myositis, partly because of extensive loss of muscle mass. In myositis, it may be prudent to check both creatine kinase and aldolase; sometimes only serum aldolase level rises, when immune-mediated injury predominantly affects the early regenerative myocytes.26

Judicious use of autoantibody testing

The characteristic clinical presentation is the initial clue to the diagnosis of antisynthetase syndrome, which is then supported by serologic testing.

Injudicious testing for a long list of antibodies should be avoided, as the cost is considerable and it does not influence further management. However, ordering an anti-Jo-1 antibody test in the correct clinical setting is appropriate, as it has high specificity,27,28 and thus can help establish or refute the clinical suspicion of antisynthetase syndrome.

Screening pulmonary function testing and thoracic high-resolution computed tomography for all patients with polymyositis or dermatomyositis is not considered “standard of care” and will likely not be reimbursed by third-party payers. However, in a patient with symptoms and signs of myositis, the presence of an antisynthetase antibody should prompt screening for occult interstitial lung disease, even in the absence of symptoms. As lung disease ultimately determines the prognosis in antisynthetase syndrome, early diagnosis and management is the key. Therefore, these tests would likely be approved to establish the diagnosis of interstitial lung disease and evaluate its severity.

If a myositis patient is also found to have interstitial lung disease or develops mechanic’s hands, the likely diagnosis is antisynthetase syndrome, which can be confirmed by serologic testing for antisynthetase antibodies. Interstitial lung disease in antisynthetase syndrome is often from “nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis”; therefore, medications tested and proven effective for this condition should be approved and reimbursed by payers.29–32

The coexistence of myositis and interstitial lung disease increases the sensitivity of anti-Jo-1 antibody.11 Thus, the clinician can have more confidence in early recognition and initiation of aggressive but targeted disease-modifying therapy.

Various methods can be used for detecting antisynthetase antibodies, with comparable results.28 Anti-Jo-1 antibody testing costs about $140. If that test is negative and antisynthetase syndrome is still suspected, then testing for the non-Jo-1 antisynthetase antibodies may be justified (Table 1). Though the cost of this panel of autoantibodies is about $300, it helps to confirm the diagnosis, and it influences the choice of second-line immunosuppressive agents such as tacrolimus29 and rituximab32 in patients resistant to conventional immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine and methotrexate.

Often, anti-Ro52 SS-A antibodies are present concurrently in patients with anti-Jo-1 syndrome.33 In observational studies in patients with anti-Jo-1 antibody-associated interstitial lung disease, coexistence of anti-Ro52 SS-A antibody tended to predict a worse pulmonary outcome than in those with anti-Jo-1 antibody alone.34,35

Electromyography

Electromyography not only helps differentiate between myopathic and neuropathic weakness, but it may also support the diagnosis of “inflammatory” myopathy as suggested by prominent muscle membrane irritability (fibrillations, positive sharp waves) and abnormal motor unit action potentials (spontaneous activity showing small, short, polyphasic potentials and early recruitment). However, the findings can be nonspecific, and may even be normal in 10% to 15% of patients.36 Electromyographic abnormalities are most consistently observed in weak proximal muscles, and electromyography is also helpful in selecting a muscle for biopsy. Although no single electromyographic pattern is considered diagnostic for inflammatory myopathy, abnormalities are present in around 90% of patients (Table 2).3

Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging may show increased signal intensity in the affected muscles and surrounding tissues (Figure 3).37 Because it lacks sensitivity and specificity, magnetic resonance imaging is not helpful in diagnosing the disease. However, in the correct clinical setting, it may be used to guide muscle biopsy, and it can help in monitoring the disease progress.38

Muscle histopathology

Muscle biopsy, though often helpful, is not always diagnostic, and antisynthetase syndrome should still be suspected in the right clinical context, even in the absence of characteristic pathologic changes.

Biopsy of sites recently studied by electromyography should be avoided, and if the patient has undergone electromyography recently, the contralateral side should be selected for biopsy.

Reports of histopathologic findings in muscle biopsies in patients with antisynthetase syndrome document inflammatory myopathic features (Figure 4). In a series of patients with anti-Jo-1 syndrome, inflammation was noted in all cases, predominantly perimysial in location, with occasional endomysial and perivascular inflammation.39 Many of the inflammatory cells seen were macrophages and lymphocytes, in contrast to the predominantly lymphocytic infiltrates described in classic polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Perifascicular atrophy, similar to what is seen in dermatomyositis, was encountered; however, vascular changes, typical of dermatomyositis, were absent. Occasional degenerating and regenerating muscle fibers were also observed in most cases. Additionally, a characteristic perimysial connective tissue fragmentation was described, a feature less often seen in classic polymyositis and dermatomyositis.39

Pulmonary function testing

If antisynthetase syndrome is suspected or diagnosed, baseline pulmonary function testing (spirometry and carbon monoxide diffusion capacity) is indicated. It will often detect occult interstitial lung disease (reduced forced vital capacity and carbon monoxide diffusion capacity), and the diagnosis will be substantiated on thoracic high-resolution computed tomography. Respiratory muscle weakness can be detected with upright and supine spirometry.40 Weakness of these muscles contributes to shortness of breath, and patients may need ventilatory support.

Thoracic high-resolution computed tomography

Different patterns of lung injury can be seen in antisynthetase syndrome. Diffuse ground-glass opacification may suggest a nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis pattern, which is the most common form of interstitial lung disease (Figure 2), whereas coarse reticulation or honeycombing correlates with a usual interstitial pneumonitis pattern. Patchy consolidation or air-space disease can occur if cryptogenic organizing pneumonia is the predominant pattern of lung injury.

Swallowing evaluation

A comprehensive swallowing evaluation by a speech therapist may be necessary for evaluation of dysphagia (from oropharyngeal and striated esophageal muscle weakness) and determination of aspiration risk (Table 2).

Lung histopathology

If necessary, a surgical lung biopsy is needed to document the pathologic pattern of injury, including the amount of fibrosis in the lung. Historically, in idiopathic inflammatory myopathy patients in general, this has taken the form of usual interstitial pneumonia, organizing pneumonia, or diffuse alveolar damage.41 With the emergence of the definition of nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis and fibrosis as a documented and accepted pattern, more studies have found this to be the most common pattern of lung injury.16 It is characterized by diffuse involvement of the lung by an interstitial chronic inflammatory infiltrate, a cellular type of nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis that progresses in a uniform pattern to a fibrotic type (Figure 5). This form of fibrosis rarely results in significant remodeling, so-called honeycomb changes. In addition, anti-Jo-1 antibody patients may also have an increased incidence of acute lung injury, including acute diffuse alveolar damage that is often superimposed on the underlying chronic lung disease.42

In patients with pulmonary hypertension, histopathologic studies of the muscular pulmonary arteries often show moderate intimal fibroplasia, suggesting that a pulmonary arteriopathy with intimal thickening and luminal narrowing develops in some of these patients (Figure 5), independent of chronic hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction or vascular obstruction due to its entrapment within fibrotic lung tissue.17

TREATMENT

Glucocorticoids are the mainstay

Glucocorticoids are considered the mainstay of treatment. Patients should be advised that long-term use of glucocorticoids is necessary, though the response is variable. It is also important to discuss possible side effects of long-term glucocorticoid use.

Standard practice is to initiate treatment with high doses for the first 4 to 6 weeks to achieve disease control, followed by a slow taper over the next 9 to 12 months to the lowest effective dose to maintain remission. If the patient is profoundly weak, especially with respiratory muscle weakness or significant dysphagia and aspiration risk, hospital admission for intravenous methylprednisolone 1,000 mg daily for 3 to 5 days may be necessary. Otherwise, oral prednisone 1 mg/kg/day would be the usual starting dose.

If the patient’s muscle strength initially improves and then declines weeks to months later despite adequate therapy, glucocorticoid-induced myopathy should be suspected, especially if the muscle enzymes are within the reference range. This is more likely to occur if high-dose prednisone is continued for more than 6 to 8 weeks.

Improvement in muscle strength, which can take several weeks to several months, is a more reliable indicator of response to therapy than the serum creatine kinase level, which may take much longer to normalize. Relying on normalization of the creatine kinase level alone may lead to unnecessary prolongation of high-dose glucocorticoid therapy. It may take several months for the muscle enzymes to normalize, and there is usually a time lag between normalization of muscle enzymes and complete recovery of muscle strength.

Long-term use of high-dose prednisone leads to glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Therefore, patients should receive osteoporosis prophylaxis including antiresorptive therapy with a bisphosphonate. In addition, prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jirovecii is indicated for patients treated with high-dose glucocorticoids.

Additional immunosuppressive agents

Although glucocorticoids are considered the mainstay of treatment, additional immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine and methotrexate are often required, both as glucocorticoid-sparing agents and to achieve adequate disease control.10 Addition of such agents from the outset is particularly necessary in patients with profound muscle weakness or those who have concomitant symptomatic interstitial lung disease.

No randomized controlled trial comparing azathioprine and methotrexate has been conducted to date. Therefore, the choice is based on patient preference, presence of coexisting interstitial lung disease or liver disease, commitment to limit alcohol consumption, and thiopurine methyltransferase status. Most patients need prolonged therapy.

In a randomized clinical trial, concomitant therapy with prednisone and azathioprine resulted in better functional outcomes and a significantly lower prednisone dose requirement for maintenance therapy at 3 years than with prednisone alone.43,44 Although no such randomized study has been conducted using methotrexate, several retrospective studies have demonstrated 70% to 80% response rates, including those for whom monotherapy with glucocorticoids had failed.45,46 The combination of methotrexate and azathioprine may be beneficial in patients who previously had inadequate responses to either of these agents alone.47

For severe pulmonary involvement associated with antisynthetase syndrome, monthly intravenous infusion of cyclophosphamide has been shown to be effective.48,49

Some recent studies established the role of tacrolimus in the treatment of both interstitial lung disease and myositis associated with antisynthetase syndrome.29 Cyclosporine has also been successfully used in a case of interstitial lung disease associated with anti Jo-1 syndrome.30

Rituximab, a monoclonal antibody to Blymphocyte antigen CD20, can also be used successfully in refractory disease,31 including refractory interstitial lung disease.32

In an open-label prospective study, polymyositis refractory to glucocorticoids and multiple conventional immunosuppressive agents responded well to high-dose intravenous immune globulin in the short term.50 However, the antisynthetase antibody status in this cohort was unknown; therefore, no definite conclusion could be drawn about the efficacy of intravenous immune globulin specifically in antisynthetase syndrome.

General measures

In patients with profound muscle weakness, physical therapy and rehabilitation should begin early. The goal is to reduce further muscle wasting from disuse and prevent muscle contractures. Patients with oropharyngeal and esophageal dysmotility should be advised about aspiration precautions and may need a swallow evaluation by a speech therapist; some may need temporary parenteral hyper-alimentation or J-tube insertion.

PROGNOSIS

If skeletal muscle involvement is the sole manifestation of antisynthetase syndrome, patients usually respond to glucocorticoids and immunosuppressive therapy and do fairly well. However, the outcome is not so promising when patients also develop interstitial lung disease, and the severity and type of lung injury usually determine the prognosis. As expected, patients with a progressive course of interstitial lung disease fare poorly, whereas those with a nonprogressive course tend to do relatively better. Older age at onset (> 60 years), presence of a malignancy, and a negative antinuclear antibody test are associated with a poor prognosis.7

Acknowledgment: The authors are grateful to Dr. Stephen Hatem, MD, staff radiologist, musculoskeletal radiology, Cleveland Clinic Imaging Institute, for help in the preparation of the magnetic resonance images. We also thank Dr. Steven Shook, MD, staff neurologist, Cleveland Clinic Neurological Institute, for help in summarizing the EMG findings.

- Katzap E, Barilla-LaBarca ML, Marder G. Antisynthetase syndrome. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2011; 13:175–181.

- Nishikai M, Reichlin M. Heterogeneity of precipitating antibodies in polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Characterization of the Jo-1 antibody system. Arthritis Rheum 1980; 23:881–888.

- Nagaraju K, Lundberg IE. Inflammatory diseases of muscle and other myopathies. In:Firestein GS, Budd RC, Harris ED, McInnes IB, Ruddy S, Sergent JS, editors. Kelley’s Textbook of Rheumatology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2008:1353–1380.

- Brouwer R, Hengstman GJ, Vree Egberts W, et al. Autoantibody profiles in the sera of European patients with myositis. Ann Rheum Dis 2001; 60:116–123.

- Vázquez-Abad D, Rothfield NF. Sensitivity and specificity of anti-Jo-1 antibodies in autoimmune diseases with myositis. Arthritis Rheum 1996; 39:292–296.

- Arnett FC, Targoff IN, Mimori T, Goldstein R, Warner NB, Reveille JD. Interrelationship of major histocompatibility complex class II alleles and autoantibodies in four ethnic groups with various forms of myositis. Arthritis Rheum 1996; 39:1507–1518.

- Dugar M, Cox S, Limaye V, Blumbergs P, Roberts-Thomson PJ. Clinical heterogeneity and prognostic features of South Australian patients with antisynthetase autoantibodies. Intern Med J 2011; 41:674–679.

- Friedman AW, Targoff IN, Arnett FC. Interstitial lung disease with autoantibodies against aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases in the absence of clinically apparent myositis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1996; 26:459–467.

- Yoshifuji H, Fujii T, Kobayashi S, et al. Anti-aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase antibodies in clinical course prediction of interstitial lung disease complicated with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Autoimmunity 2006; 39:233–241.

- Tillie-Leblond I, Wislez M, Valeyre D, et al. Interstitial lung disease and anti-Jo-1 antibodies: difference between acute and gradual onset. Thorax 2008; 63:53–59.

- Targoff IN. Update on myositis-specific and myositis-associated autoantibodies. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2000; 12:475–481.

- Ancuta CM, Ancuta E, Chirieac RM. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: an update on immunopathogenic significance, clinical and therapeutic implications. In:Gran JT, editor. Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathies - Recent Developments. Rijeka, Croatia: InTech; 2011:77–90.

- Kajihara M, Kuwana M, Tokuda H, et al. Myositis and interstitial lung disease associated with autoantibody to a transfer RNA-related protein Wa. J Rheumatol 2000; 27:2707–2710.

- Yamasaki Y, Yamada H, Nozaki T, et al. Unusually high frequency of autoantibodies to PL-7 associated with milder muscle disease in Japanese patients with polymyositis/dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum 2006; 54:2004–2009.

- Ascherman DP. The role of Jo-1 in the immunopathogenesis of polymyositis: current hypotheses. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2003; 5:425–430.

- Yousem SA, Gibson K, Kaminski N, Oddis CV, Ascherman DP. The pulmonary histopathologic manifestations of the anti-Jo-1 tRNA synthetase syndrome. Mod Pathol 2010; 23:874–880.

- Chatterjee S, Farver C. Severe pulmonary hypertension in anti-Jo-1 syndrome. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010; 62:425–429.

- Minai OA. Pulmonary hypertension in polymyositis-dermatomyositis: clinical and hemodynamic characteristics and response to vasoactive therapy. Lupus 2009; 18:1006–1010.

- Bugatti L, De Angelis R, Filosa G, Salaffi F. Bilateral, asymptomatic scaly and fissured cutaneous lesions of the fingers in a patient presenting with myositis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2005; 71:137–138.

- Mumm GE, McKown KM, Bell CL. Antisynthetase syndrome presenting as rheumatoid-like polyarthritis. J Clin Rheumatol 2010; 16:307–312.

- Hirakata M, Mimori T, Akizuki M, Craft J, Hardin JA, Homma M. Autoantibodies to small nuclear and cytoplasmic ribonucleoproteins in Japanese patients with inflammatory muscle disease. Arthritis Rheum 1992; 35:449–456.

- Love LA, Leff RL, Fraser DD, et al. A new approach to the classification of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy: myositis-specific autoantibodies define useful homogeneous patient groups. Medicine (Baltimore) 1991; 70:360–374.

- Chen YJ, Wu CY, Shen JL. Predicting factors of malignancy in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol 2001; 144:825–831.

- Legault D, McDermott J, Crous-Tsanaclis AM, Boire G. Cancer-associated myositis in the presence of anti-Jo1 autoantibodies and the antisynthetase syndrome. J Rheumatol 2008; 35:169–171.

- Selva-O’Callaghan A, Trallero-Araguás E, Grau-Junyent JM, Labrador-Horrillo M. Malignancy and myositis: novel autoantibodies and new insights. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2010; 22:627–632.

- Casciola-Rosen L, Hall JC, Mammen AL, Christopher-Stine L, Rosen A. Isolated elevation of aldolase in the serum of myositis patients: a potential biomarker of damaged early regenerating muscle cells. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2012; 30:548–553.

- Shovman O, Gilburd B, Barzilai O, et al. Evaluation of the BioPlex 2200 ANA screen: analysis of 510 healthy subjects: incidence of natural/predictive autoantibodies. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2005; 1050:380–388.

- Zampieri S, Ghirardello A, Iaccarino L, Tarricone E, Gambari PF, Doria A. Anti-Jo-1 antibodies. Autoimmunity 2005; 38:73–78.

- Wilkes MR, Sereika SM, Fertig N, Lucas MR, Oddis CV. Treatment of antisynthetase-associated interstitial lung disease with tacrolimus. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52:2439–2446.

- Jankowska M, Butto B, Debska-Slizien A, Rutkowski B. Beneficial effect of treatment with cyclosporin A in a case of refractory antisynthetase syndrome. Rheumatol Int 2007; 27:775–780.

- Limaye V, Hissaria P, Liew CL, Koszyka B. Efficacy of rituximab in refractory antisynthetase syndrome. Intern Med J 2012; 42:e4–e7.

- Marie I, Dominique S, Janvresse A, Levesque H, Menard JF. Rituximab therapy for refractory interstitial lung disease related to antisynthetase syndrome. Respir Med 2012; 106:581–587.

- Rutjes SA, Vree Egberts WT, Jongen P, Van Den Hoogen F, Pruijn GJ, Van Venrooij WJ. Anti-Ro52 antibodies frequently co-occur with anti-Jo-1 antibodies in sera from patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Clin Exp Immunol 1997; 109:32–40.

- La Corte R, Lo Mo Naco A, Locaputo A, Dolzani F, Trotta F. In patients with antisynthetase syndrome the occurrence of anti-Ro/SSA antibodies causes a more severe interstitial lung disease. Autoimmunity 2006; 39:249–253.

- Váncsa A, Csípo I, Németh J, Dévényi K, Gergely L, Dankó K. Characteristics of interstitial lung disease in SS-A positive/Jo-1 positive inflammatory myopathy patients. Rheumatol Int 2009; 29:989–994.

- Bohan A, Peter JB, Bowman RL, Pearson CM. Computer-assisted analysis of 153 patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Medicine (Baltimore) 1977; 56:255–286.

- Reimers CD, Finkenstaedt M. Muscle imaging in inflammatory myopathies. Curr Opin Rheumatol 1997; 9:475–485.

- O’Connell MJ. Whole-body MR imaging in the diagnosis of polymyositis. Am J Roentgenol 2002; 179:967–971.

- Mozaffar T, Pestronk A. Myopathy with anti-Jo-1 antibodies: pathology in perimysium and neighbouring muscle fibres. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000; 68:472–478.

- Fromageot C, Lofaso F, Annane D, et al. Supine fall in lung volumes in the assessment of diaphragmatic weakness in neuromuscular disorders. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001; 82:123–128.

- Leslie KO. Historical perspective: a pathologic approach to the classification of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Chest 2005; 128(suppl 1):513S–519S.

- Nicholson AG, Colby TV, du Bois RM, Hansell DM, Wells AU. The prognostic significance of the histologic pattern of interstitial pneumonia in patients presenting with the clinical entity of cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 162:2213–2217.

- Bunch TW, Worthington JW, Combs JJ, Ilstrup DM, Engel AG. Azathioprine with prednisone for polymyositis. A controlled, clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 1980; 92:365–369.

- Bunch TW. Prednisone and azathioprine for polymyositis: long-term followup. Arthritis Rheum 1981; 24:45–48.

- Metzger AL, Bohan A, Goldberg LS, Bluestone R, Pearson CM. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis: combined methotrexate and corticosteroid therapy. Ann Intern Med 1974; 81:182–189.

- Joffe MM, Love LA, Leff RL, et al. Drug therapy of the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: predictors of response to prednisone, azathioprine, and methotrexate and a comparison of their efficacy. Am J Med 1993; 94:379–387.

- Villalba L, Hicks JE, Adams EM, et al. Treatment of refractory myositis: a randomized crossover study of two new cytotoxic regimens. Arthritis Rheum 1998; 41:392–399.

- Yamasaki Y, Yamada H, Yamasaki M, et al. Intravenous cyclophosphamide therapy for progressive interstitial pneumonia in patients with polymyositis/dermatomyositis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007; 46:124–130.

- al-Janadi M, Smith CD, Karsh J. Cyclophosphamide treatment of interstitial pulmonary fibrosis in polymyositis/dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol 1989; 16:1592–1596.

- Cherin P, Pelletier S, Teixeira A, et al. Results and long-term followup of intravenous immunoglobulin infusions in chronic, refractory polymyositis: an open study with thirty-five adult patients. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 46:467–474.

A 66-year-old man was initially seen in clinic in March 2004 with a 5-month history of polyarthritis (affecting the finger joints, wrists, and knees) and several hours of morning stiffness. He also had significant proximal muscle weakness, progressive exertional dyspnea, and a nonproductive cough. There was no history of fever, chills, rash, dysphagia, or sicca symptoms. Findings on initial tests:

- His creatine kinase level was 700 U/L (reference range 30–220), which later rose to 1,664 U/L.

- He was positive for antinuclear antibody with a 5.7 optical density ratio (normal < 1.5) and for anti-Jo-1 antibody.

- An electromyogram was consistent with a necrotizing myopathy. Left rectus femoris biopsy revealed scattered degenerating and regenerating muscle fibers but no evidence of endomysial inflammation.

- On pulmonary function testing, his forced vital capacity was 80% of predicted, and his carbon monoxide diffusion capacity was 67% of predicted.

- High-resolution computed tomography revealed evidence of interstitial lung disease, characterized by bilateral patchy ground-glass opacities suggestive of active alveolitis, most extensive at the lung bases.

- Bronchoalveolar lavage indicated alveolitis, and transbronchial biopsy revealed pathologic changes consistent with cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. All cultures were negative.

This constellation of clinical manifestations, including myositis, interstitial lung disease, and polyarthritis, along with positive anti-Jo-1 antibody, confirmed the diagnosis of antisynthetase syndrome.

In June 2004, for his interstitial lung disease, he was started on daily oral cyclophosphamide along with high-dose oral prednisone. Three months later the skin of the tips and radial margins of his fingers started thickening and cracking, the appearance of which is classically described as “mechanic’s hands,” a well-described manifestation of antisynthetase syndrome (Figure 1).

Cyclophosphamide was continued for about a year. Subsequently, along with prednisone, he sequentially received various other immunosuppressive medications (methotrexate, tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and rituximab) over the next few years in an attempt to control his progressive interstitial lung disease. All of these agents were only partially and temporarily effective. Ultimately, despite all of these therapies, as his interstitial lung disease progressed, he needed supplemental oxygen and enrollment in a pulmonary rehabilitation program.

In March 2010, he was admitted with worsening dyspnea and significant peripheral edema and was found to have severe pulmonary arterial hypertension. He was started on bosentan. Eight months later sildenafil was added for progressive pulmonary arterial hypertension. However, his oxygenation status continued to decline.

In July 2011, he presented with chills, increasing shortness of breath, and a mild productive cough. As he was severely hypoxic, he was admitted to the intensive care unit and started on mechanical ventilation and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Despite escalation of oxygen therapy, his respiratory status rapidly deteriorated, and he developed hypotension requiring vasopressors. He ultimately died of cardiac arrest secondary to respiratory failure.

A CONSTELLATION OF MANIFESTATIONS

Antisynthetase syndrome, associated with anti-aminoacyl-transfer RNA (tRNA) synthetase antibodies, is characterized by a constellation of manifestations that include myositis, interstitial lung disease, mechanic’s hands, fever, Raynaud phenomenon, and nonerosive symmetric polyarthritis of the small joints.1

Anti-Jo-1 antibody (anti-histidyl-tRNA synthetase) is the most common of the antibodies and also was the first one to be identified (Table 1). It was named after John P, a patient with polymyositis and interstitial lung disease, in whom it was first detected in 1980.2 The onset of the syndrome associated with anti-Jo-1 antibody is often acute, and the myositis is usually steroid-responsive. However, not uncommonly, severe disease can develop over time, with a tendency to relapse and with a poor long-term prognosis.

RARE BUT UNDERRECOGNIZED

The true population prevalence of antisynthetase syndrome is unknown. Because this syndrome is rare, comprehensive epidemiologic studies are difficult to perform.

In several retrospective studies, the annual incidence of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies has been reported to be 2 to 10 new cases per million adults per year.3 Antisynthetase antibodies are detected in 20% to 40% of such cases.4–6 The disease is two to three times more common in women than in men.7

Early diagnosis is difficult because the clinical presentation is varied and often nonspecific, clinically milder disease may escape detection, and many general practitioners lack familiarity with this syndrome and consequently do not recognize it. Moreover, tests for myositis-specific antibodies (including antisynthetase antibodies) are often not ordered in the evaluation of myositis, and hence the diagnosis of antisynthetase syndrome cannot be substantiated. Furthermore, interstitial lung disease can predominate or can be the sole manifestation in the absence of clinically apparent myositis,8–10 and patients can be misdiagnosed as having idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis when underlying antisynthetase syndrome is not suspected. This distinction may be important because these conditions differ in their pathology and treatment. Histologically, the predominant pattern of lung injury in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is “usual interstitial pneumonia” which does not respond to immunosuppressive therapy, and hence lung transplantation is the only therapeutic option. On the other hand, in antisynthetase syndrome, the usual pattern of lung injury is “nonspecific interstitial pneumonia,” in which immunosuppressive therapy has a role.

Anti-Jo-1 antibody is detected in 15% to 25% of patients with polymyositis and in up to 70% of myositis patients with concomitant interstitial lung disease.11 Autoantibodies to seven other, less frequently targeted, aminoacyl tRNA synthetases have also been described in patients with polymyositis and interstitial lung disease (Table 1).11,12 In addition, an autoantibody to a 48-kDa transfer RNA-related protein (Wa) has been described.13 These non-Jo-1 antisynthetase antibodies are detected in only about 3% of myositis patients.14

ROLE OF ANTISYNTHETASE ANTIBODIES

Synthetases play a central role in protein synthesis by catalyzing the acetylation of tRNAs. The propensity of organ involvement in antisynthetase syndrome suggests that tissue-specific changes in muscle or lung lead to the production of unique forms of target autoantigens, the aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. There is evidence that these enzymes themselves may be involved in recruiting both antigen-presenting and inflammatory cells to the site of muscle or lung injury.15 However, the molecular pathway that initiates and propagates this autoimmune response and the specific role of the antisynthetase antibodies in the pathogenesis of this syndrome are presently unknown.

SIX SALIENT CLINICAL FEATURES

There are six predominant clinical manifestations, which may be present at disease onset or appear later as the disease progresses:

- Fever

- Myositis

- Interstitial lung disease

- Mechanic’s hands

- Raynaud phenomenon

- Inflammatory polyarthritis.

There is considerable clinical heterogeneity, and one or other manifestation can predominate or can be the only expression of the syndrome. Furthermore, in the same patient, the individual features can prevail at different times and may develop years after onset of the disease. Therefore, in addition to patients with myositis, it would be important to suspect antisynthetase syndrome in patients presenting with isolated lung involvement (amyopathic interstitial lung disease), as there are therapeutic implications. Studies have demonstrated the efficacy of immunosuppressive agents in interstitial lung disease associated with antisynthetase syndrome (where the predominant pattern of lung injury is “nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis”), whereas lung transplantation has so far been the only treatment option in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Fever

About 20% of patients have a fever at disease onset or associated with relapses. Sometimes the fever can persist until treatment of antisynthetase syndrome is started.

Myositis

Muscle disease is seen in more than 90% of patients with anti-Jo-1 antisynthetase syndrome. It can be subclinical (in the absence of proximal myopathy), manifested by transient creatine kinase elevation only, which may normalize after therapy is initiated.

However, more commonly, patients develop profound proximal muscle weakness and sometimes muscle pain (Table 2). Weakness of the striated muscles of the upper esophagus, cricopharyngeus, and hypopharynx may cause dysphagia and makes these patients susceptible to aspiration pneumonia. Diaphragmatic and intercostal muscle weakness can contribute to shortness of breath in some patients. Myocarditis has also been reported.

Pulmonary disease

Interstitial lung disease develops in most patients with anti-Jo-1 antisynthetase syndrome, with a reported prevalence of about 90% in one series.16 Patients often present with acute, subacute, or insidious onset of exertional dyspnea. Sometimes there is an intractable nonproductive cough.

At the outset of antisynthetase syndrome, if the patient is profoundly weak because of myopathy or has inflammatory polyarthritis, mobility is significantly compromised, and exertional dyspnea may not be experienced. However, as the interstitial lung disease progresses, shortness of breath becomes overt, more so when the patient’s level of activity improves with treatment of myositis.

Inspiratory crackles on auscultation of the lung bases or changes on chest radiography are relatively insensitive findings and can miss early interstitial lung disease. Therefore, if antisynthetase syndrome is suspected or diagnosed, a baseline pulmonary function test (spirometry and carbon monoxide diffusion capacity) is indicated. It will often detect occult interstitial lung disease, and the diagnosis can then be confirmed with thoracic high-resolution computed tomography (Figure 2).