User login

Do cosmetic breast implants hinder the detection of malignancy and reduce breast cancer–specific survival?

Most epidemiologic studies have found no elevated risk of breast cancer among women who undergo cosmetic breast augmentation. However, there is concern that implants, which are radio-opaque, may limit our ability to diagnose malignancies at an early stage using screening mammography.

In this study, investigators compared the stage distribution of breast cancers at diagnosis and documented breast cancer–specific survival among women with and without cosmetic breast implants. Twelve cross-sectional studies published after 2000 in the United States had evaluated stage distribution of breast cancer among women with and without cosmetic implants. As stated above, investigators found an elevated risk of nonlocalized breast cancer among women with implants in their meta-analysis of these studies (OR, 1.26), but this elevated risk did not achieve statistical significance. A second analysis of five studies found an elevated risk of breast cancer–specific mortality (OR, 1.38), compared with the general population (no implants), which did achieve significance.

MRI may be helpful—but is the expense justified?

More than 300,000 women underwent cosmetic breast augmentation in 2011 in the United States, an increase of roughly 800% since the early 1990s. The impaired visualization of breast tissue via mammography in these women ranges from 22% to 83%. In addition, the implants limit compression of the breasts during mammography, and capsular contraction further contributes to this problem.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be helpful in screening women with cosmetic breast implants, but this technology is expensive, and evidence supporting its routine use in this population is limited.

Some mammographers use special techniques to better visualize the breast tissue of women with implants. These techniques include displacing the implant posteriorly and pulling the breast tissue in front of it. However, even with such strategies, as much as one-third of the breast tissue may be inadequately assessed.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

These findings underscore the importance of sharing the risks of nonlocalized breast malignancy and increased breast cancer mortality with patients who are considering cosmetic breast implants, as well as with women who have already undergone this common procedure. Future studies are needed to address relevant issues, including the role of 3-D (tomosynthesis) technology in screening women with breast implants and optimal screening intervals in this subgroup.

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD

We want to hear from you. Tell us what you think.

Most epidemiologic studies have found no elevated risk of breast cancer among women who undergo cosmetic breast augmentation. However, there is concern that implants, which are radio-opaque, may limit our ability to diagnose malignancies at an early stage using screening mammography.

In this study, investigators compared the stage distribution of breast cancers at diagnosis and documented breast cancer–specific survival among women with and without cosmetic breast implants. Twelve cross-sectional studies published after 2000 in the United States had evaluated stage distribution of breast cancer among women with and without cosmetic implants. As stated above, investigators found an elevated risk of nonlocalized breast cancer among women with implants in their meta-analysis of these studies (OR, 1.26), but this elevated risk did not achieve statistical significance. A second analysis of five studies found an elevated risk of breast cancer–specific mortality (OR, 1.38), compared with the general population (no implants), which did achieve significance.

MRI may be helpful—but is the expense justified?

More than 300,000 women underwent cosmetic breast augmentation in 2011 in the United States, an increase of roughly 800% since the early 1990s. The impaired visualization of breast tissue via mammography in these women ranges from 22% to 83%. In addition, the implants limit compression of the breasts during mammography, and capsular contraction further contributes to this problem.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be helpful in screening women with cosmetic breast implants, but this technology is expensive, and evidence supporting its routine use in this population is limited.

Some mammographers use special techniques to better visualize the breast tissue of women with implants. These techniques include displacing the implant posteriorly and pulling the breast tissue in front of it. However, even with such strategies, as much as one-third of the breast tissue may be inadequately assessed.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

These findings underscore the importance of sharing the risks of nonlocalized breast malignancy and increased breast cancer mortality with patients who are considering cosmetic breast implants, as well as with women who have already undergone this common procedure. Future studies are needed to address relevant issues, including the role of 3-D (tomosynthesis) technology in screening women with breast implants and optimal screening intervals in this subgroup.

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD

We want to hear from you. Tell us what you think.

Most epidemiologic studies have found no elevated risk of breast cancer among women who undergo cosmetic breast augmentation. However, there is concern that implants, which are radio-opaque, may limit our ability to diagnose malignancies at an early stage using screening mammography.

In this study, investigators compared the stage distribution of breast cancers at diagnosis and documented breast cancer–specific survival among women with and without cosmetic breast implants. Twelve cross-sectional studies published after 2000 in the United States had evaluated stage distribution of breast cancer among women with and without cosmetic implants. As stated above, investigators found an elevated risk of nonlocalized breast cancer among women with implants in their meta-analysis of these studies (OR, 1.26), but this elevated risk did not achieve statistical significance. A second analysis of five studies found an elevated risk of breast cancer–specific mortality (OR, 1.38), compared with the general population (no implants), which did achieve significance.

MRI may be helpful—but is the expense justified?

More than 300,000 women underwent cosmetic breast augmentation in 2011 in the United States, an increase of roughly 800% since the early 1990s. The impaired visualization of breast tissue via mammography in these women ranges from 22% to 83%. In addition, the implants limit compression of the breasts during mammography, and capsular contraction further contributes to this problem.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be helpful in screening women with cosmetic breast implants, but this technology is expensive, and evidence supporting its routine use in this population is limited.

Some mammographers use special techniques to better visualize the breast tissue of women with implants. These techniques include displacing the implant posteriorly and pulling the breast tissue in front of it. However, even with such strategies, as much as one-third of the breast tissue may be inadequately assessed.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

These findings underscore the importance of sharing the risks of nonlocalized breast malignancy and increased breast cancer mortality with patients who are considering cosmetic breast implants, as well as with women who have already undergone this common procedure. Future studies are needed to address relevant issues, including the role of 3-D (tomosynthesis) technology in screening women with breast implants and optimal screening intervals in this subgroup.

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD

We want to hear from you. Tell us what you think.

The “Canoe” Technique to Insert Lumbar Pedicle Screws: Consistent, Safe, and Simple

Successful treatment of chronic vaginitis

Gadzooks! In preparing for the morning office practice session you notice that two patients with chronic vaginitis have been scheduled back to back in 15-minute slots.

Ms. A has chronic bacterial vaginosis. Ms. B has chronic yeast vaginitis. What are you going to do?

Chronic bacterial vaginosis

The normal vaginal microbiome is dominated by Lactobacillus crispatus and Lactobacillus jensenii. These organisms produce hydrogen peroxide and keep the vaginal pH ≤4.5. When Gardnerella vaginalis and associated anaerobic bacteria gain dominance in the vagina, bacterial vaginosis ensues. This infection is characterized by1:

- homogenous, thin, grayish-white discharge that smoothly coats the vaginal epithelium

- pH >4.5

- fishy odor when potassium hydroxide is added to a sample of the discharge

- clue cells on a saline wet mount.

Why is it prone to recur? If bacterial vaginosis was a simple infection, treatment with metronidazole or clindamycin should be very effective. But in many women the relief from symptoms provided by a single course of antibiotics is short-lived, and many patients experience recurrent bacterial vaginosis in the next few months.

The cause of this resistance to antibiotic treatment may be that G vaginalis and other anaerobes, such as Atopobium species, aggregate in vaginal biofilms that prevent the antibiotic from reaching the organism.2 The biofilm provides a safe haven for the bacteria to regrow following a single course of treatment.3 In addition, the nutrient-limited environment inside the encapsulated biofilm helps the bacteria to resist the toxic effects of the antibiotic.4

Another potential mechanism for bacterial vaginosis recurrence is that women destined to develop repeat infection often harbor G vaginalis encapsulated in biofilms in the mouth. These extravaginal bacteria often are found again in the vagina, suggesting that bacterial vaginosis can be acquired from extravaginal bacterial reservoirs.5 Investigators are developing approaches, such as intravaginal treatment with DNase, to destroy the vaginal biofilm in order to enhance the efficacy of antibiotic treatment.6

Treatment

Options for initial infection. There are three treatments for an initial occurrence of bacterial vaginosis7:

- oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 7 days

- 0.75% metronidazole gel one applicator intravaginally once daily for 5 days, or

- 2% clindamycin cream one applicator intravaginally at bedtime for 7 days.

Long-term metronidazole for recurrence. Approximately half of women who respond to initial treatment will have bacterial vaginosis again within 1 year. If vaginitis caused by recurrent bacterial vaginosisis diagnosed, a prolonged course of antibiotic treatment is warranted. Treatment starts with an induction regimen of the standard treatments listed in the paragraph above. This is followed by a long-term maintenance regimen using 0.75% metronidazole vaginal gel one applicator twice weekly for 4 to 6 months.8

Recurrent Candida vulvovaginitis

Four or more occurrences of symptomatic Candida vulvovaginitis in 12 months indicates recurrent infection. Recurrence is usually caused by reinfection with the same organism from a vaginal reservoir. For women with such repeat infection, vaginal cultures should be obtained to confirm Candida and to search for treatment-resistant species, such as Candida glabrata. (Many C glabrata organisms are resistant to standard fluconazole treatment.)

Treatment options

Long courses of oral or vaginal antimycotic agents can be effective treatment for recurrent Candida vulvovaginitis.

Fluconazole. One regimen is fluconazole 150 mg orally every 72 hours for 3 doses, followed by fluconazole 150 mg once weekly for 6 months.9 If patients relapse from this regimen, then the vaginitis should be retreated with fluconazole 150 mg orally every 72 hours for 3 doses, followed by fluconazole 150 mg weekly for 12 months.

Boric acid. If C glabrata is thought to be the cause of the infection, it may be difficult to eradicate with fluconazole. A regimen to treat recurrent vaginitis caused by C glabrata is intravaginal boric acid, a 600 mg capsule once nightly for 14 days.10,11This medication is not FDA-approved for this purpose and must be made by a compounding pharmacy. Boric acid can be fatal if swallowed rather than used intravaginally. Care must be taken to avoid access to these capsules by children.

Boric acid vaginal capsules also can be used to treat chronic bacterial vaginosis in combination with antibiotic therapy.12

Flucytosine. An alternative regimen to treat C glabrata is flucytosine vaginal cream one applicator nightly for 14 days. This vaginal cream must be compounded because it is not available as a commercial medication.

You are armed and ready

In retrospect, you realize that the morning office session schedule is going to be fine. You will treat Ms. A with a long course of metronidazole and Ms. B with a long course of fluconazole. Hopefully, they will both find relief from their symptoms.

Tell us what you think, at [email protected]. Please include your name and city and state.

- Eschenbach DA, Hillier S, Critchlow C, Stevens C, DeRouen T, Holmes KK. Diagnosis and clinical manifestations of bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158(4):819–828.

- Swidinski A, Mendling W, Loening-Baucke V, et al. Adherent biofilms in bacterial vaginosis.Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(5 pt 1):1013–1023.

- Swidinski A, Mendling W, Loening-Baucke V, et al. An adherent Gardnerella vaginalis biofilm persists on the vaginal epithelium after standard therapy with oral metronidazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(1):97e1–e6.

- Monds RD, O’Toole GA. The developmental model of microbial biofilm: ten years of a paradigm up for review. Trends Microbiol. 2009;17(2):73–87.

- Marrazzo JM, Friedler TL, Srinivasan S, et al. Extravaginal reservoirs of vaginal bacteria as risk factors for incident bacterial vaginosis. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(10):1580–1588.

- Hymes SR, Randis TM, Sun TY, Ratner AJ. DNase inhibits Gardnerella vaginalis biofilms in vitro and in vivo. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(10):1491–1497.

- Workowski KA, Berman S; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010; 59(RR-12):1–110.

- Sobel JD, Ferris D, Schwebke J, et al. Suppressive antibacterial therapy with 0.75% metronidazole vaginal gel to prevent recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(5):1283–1289.

- Sobel JD, Wiesenfeld HC, Martens M, et al. Maintenance fluconazole therapy for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(9):876–883.

- Savini V, Catavitello C, Bianco A, Balbinot A, D’Antonio F, D’Antonio D. Azole resistant Candida glabrata vulvovaginitis treated with boric acid. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;147(1):112.

- Iavazzo C, Gkegkes ID, Zarkada IM, Falagas ME. Boric acid for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: the clinical evidence. J Womens Health(Larchmt). 2011;20(8):1245–1255.

- Reichman O, Akins R, Sobel JD. Boric acid addition to suppressive antimicrobial therapy for recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(11):732–734.

Gadzooks! In preparing for the morning office practice session you notice that two patients with chronic vaginitis have been scheduled back to back in 15-minute slots.

Ms. A has chronic bacterial vaginosis. Ms. B has chronic yeast vaginitis. What are you going to do?

Chronic bacterial vaginosis

The normal vaginal microbiome is dominated by Lactobacillus crispatus and Lactobacillus jensenii. These organisms produce hydrogen peroxide and keep the vaginal pH ≤4.5. When Gardnerella vaginalis and associated anaerobic bacteria gain dominance in the vagina, bacterial vaginosis ensues. This infection is characterized by1:

- homogenous, thin, grayish-white discharge that smoothly coats the vaginal epithelium

- pH >4.5

- fishy odor when potassium hydroxide is added to a sample of the discharge

- clue cells on a saline wet mount.

Why is it prone to recur? If bacterial vaginosis was a simple infection, treatment with metronidazole or clindamycin should be very effective. But in many women the relief from symptoms provided by a single course of antibiotics is short-lived, and many patients experience recurrent bacterial vaginosis in the next few months.

The cause of this resistance to antibiotic treatment may be that G vaginalis and other anaerobes, such as Atopobium species, aggregate in vaginal biofilms that prevent the antibiotic from reaching the organism.2 The biofilm provides a safe haven for the bacteria to regrow following a single course of treatment.3 In addition, the nutrient-limited environment inside the encapsulated biofilm helps the bacteria to resist the toxic effects of the antibiotic.4

Another potential mechanism for bacterial vaginosis recurrence is that women destined to develop repeat infection often harbor G vaginalis encapsulated in biofilms in the mouth. These extravaginal bacteria often are found again in the vagina, suggesting that bacterial vaginosis can be acquired from extravaginal bacterial reservoirs.5 Investigators are developing approaches, such as intravaginal treatment with DNase, to destroy the vaginal biofilm in order to enhance the efficacy of antibiotic treatment.6

Treatment

Options for initial infection. There are three treatments for an initial occurrence of bacterial vaginosis7:

- oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 7 days

- 0.75% metronidazole gel one applicator intravaginally once daily for 5 days, or

- 2% clindamycin cream one applicator intravaginally at bedtime for 7 days.

Long-term metronidazole for recurrence. Approximately half of women who respond to initial treatment will have bacterial vaginosis again within 1 year. If vaginitis caused by recurrent bacterial vaginosisis diagnosed, a prolonged course of antibiotic treatment is warranted. Treatment starts with an induction regimen of the standard treatments listed in the paragraph above. This is followed by a long-term maintenance regimen using 0.75% metronidazole vaginal gel one applicator twice weekly for 4 to 6 months.8

Recurrent Candida vulvovaginitis

Four or more occurrences of symptomatic Candida vulvovaginitis in 12 months indicates recurrent infection. Recurrence is usually caused by reinfection with the same organism from a vaginal reservoir. For women with such repeat infection, vaginal cultures should be obtained to confirm Candida and to search for treatment-resistant species, such as Candida glabrata. (Many C glabrata organisms are resistant to standard fluconazole treatment.)

Treatment options

Long courses of oral or vaginal antimycotic agents can be effective treatment for recurrent Candida vulvovaginitis.

Fluconazole. One regimen is fluconazole 150 mg orally every 72 hours for 3 doses, followed by fluconazole 150 mg once weekly for 6 months.9 If patients relapse from this regimen, then the vaginitis should be retreated with fluconazole 150 mg orally every 72 hours for 3 doses, followed by fluconazole 150 mg weekly for 12 months.

Boric acid. If C glabrata is thought to be the cause of the infection, it may be difficult to eradicate with fluconazole. A regimen to treat recurrent vaginitis caused by C glabrata is intravaginal boric acid, a 600 mg capsule once nightly for 14 days.10,11This medication is not FDA-approved for this purpose and must be made by a compounding pharmacy. Boric acid can be fatal if swallowed rather than used intravaginally. Care must be taken to avoid access to these capsules by children.

Boric acid vaginal capsules also can be used to treat chronic bacterial vaginosis in combination with antibiotic therapy.12

Flucytosine. An alternative regimen to treat C glabrata is flucytosine vaginal cream one applicator nightly for 14 days. This vaginal cream must be compounded because it is not available as a commercial medication.

You are armed and ready

In retrospect, you realize that the morning office session schedule is going to be fine. You will treat Ms. A with a long course of metronidazole and Ms. B with a long course of fluconazole. Hopefully, they will both find relief from their symptoms.

Tell us what you think, at [email protected]. Please include your name and city and state.

Gadzooks! In preparing for the morning office practice session you notice that two patients with chronic vaginitis have been scheduled back to back in 15-minute slots.

Ms. A has chronic bacterial vaginosis. Ms. B has chronic yeast vaginitis. What are you going to do?

Chronic bacterial vaginosis

The normal vaginal microbiome is dominated by Lactobacillus crispatus and Lactobacillus jensenii. These organisms produce hydrogen peroxide and keep the vaginal pH ≤4.5. When Gardnerella vaginalis and associated anaerobic bacteria gain dominance in the vagina, bacterial vaginosis ensues. This infection is characterized by1:

- homogenous, thin, grayish-white discharge that smoothly coats the vaginal epithelium

- pH >4.5

- fishy odor when potassium hydroxide is added to a sample of the discharge

- clue cells on a saline wet mount.

Why is it prone to recur? If bacterial vaginosis was a simple infection, treatment with metronidazole or clindamycin should be very effective. But in many women the relief from symptoms provided by a single course of antibiotics is short-lived, and many patients experience recurrent bacterial vaginosis in the next few months.

The cause of this resistance to antibiotic treatment may be that G vaginalis and other anaerobes, such as Atopobium species, aggregate in vaginal biofilms that prevent the antibiotic from reaching the organism.2 The biofilm provides a safe haven for the bacteria to regrow following a single course of treatment.3 In addition, the nutrient-limited environment inside the encapsulated biofilm helps the bacteria to resist the toxic effects of the antibiotic.4

Another potential mechanism for bacterial vaginosis recurrence is that women destined to develop repeat infection often harbor G vaginalis encapsulated in biofilms in the mouth. These extravaginal bacteria often are found again in the vagina, suggesting that bacterial vaginosis can be acquired from extravaginal bacterial reservoirs.5 Investigators are developing approaches, such as intravaginal treatment with DNase, to destroy the vaginal biofilm in order to enhance the efficacy of antibiotic treatment.6

Treatment

Options for initial infection. There are three treatments for an initial occurrence of bacterial vaginosis7:

- oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 7 days

- 0.75% metronidazole gel one applicator intravaginally once daily for 5 days, or

- 2% clindamycin cream one applicator intravaginally at bedtime for 7 days.

Long-term metronidazole for recurrence. Approximately half of women who respond to initial treatment will have bacterial vaginosis again within 1 year. If vaginitis caused by recurrent bacterial vaginosisis diagnosed, a prolonged course of antibiotic treatment is warranted. Treatment starts with an induction regimen of the standard treatments listed in the paragraph above. This is followed by a long-term maintenance regimen using 0.75% metronidazole vaginal gel one applicator twice weekly for 4 to 6 months.8

Recurrent Candida vulvovaginitis

Four or more occurrences of symptomatic Candida vulvovaginitis in 12 months indicates recurrent infection. Recurrence is usually caused by reinfection with the same organism from a vaginal reservoir. For women with such repeat infection, vaginal cultures should be obtained to confirm Candida and to search for treatment-resistant species, such as Candida glabrata. (Many C glabrata organisms are resistant to standard fluconazole treatment.)

Treatment options

Long courses of oral or vaginal antimycotic agents can be effective treatment for recurrent Candida vulvovaginitis.

Fluconazole. One regimen is fluconazole 150 mg orally every 72 hours for 3 doses, followed by fluconazole 150 mg once weekly for 6 months.9 If patients relapse from this regimen, then the vaginitis should be retreated with fluconazole 150 mg orally every 72 hours for 3 doses, followed by fluconazole 150 mg weekly for 12 months.

Boric acid. If C glabrata is thought to be the cause of the infection, it may be difficult to eradicate with fluconazole. A regimen to treat recurrent vaginitis caused by C glabrata is intravaginal boric acid, a 600 mg capsule once nightly for 14 days.10,11This medication is not FDA-approved for this purpose and must be made by a compounding pharmacy. Boric acid can be fatal if swallowed rather than used intravaginally. Care must be taken to avoid access to these capsules by children.

Boric acid vaginal capsules also can be used to treat chronic bacterial vaginosis in combination with antibiotic therapy.12

Flucytosine. An alternative regimen to treat C glabrata is flucytosine vaginal cream one applicator nightly for 14 days. This vaginal cream must be compounded because it is not available as a commercial medication.

You are armed and ready

In retrospect, you realize that the morning office session schedule is going to be fine. You will treat Ms. A with a long course of metronidazole and Ms. B with a long course of fluconazole. Hopefully, they will both find relief from their symptoms.

Tell us what you think, at [email protected]. Please include your name and city and state.

- Eschenbach DA, Hillier S, Critchlow C, Stevens C, DeRouen T, Holmes KK. Diagnosis and clinical manifestations of bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158(4):819–828.

- Swidinski A, Mendling W, Loening-Baucke V, et al. Adherent biofilms in bacterial vaginosis.Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(5 pt 1):1013–1023.

- Swidinski A, Mendling W, Loening-Baucke V, et al. An adherent Gardnerella vaginalis biofilm persists on the vaginal epithelium after standard therapy with oral metronidazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(1):97e1–e6.

- Monds RD, O’Toole GA. The developmental model of microbial biofilm: ten years of a paradigm up for review. Trends Microbiol. 2009;17(2):73–87.

- Marrazzo JM, Friedler TL, Srinivasan S, et al. Extravaginal reservoirs of vaginal bacteria as risk factors for incident bacterial vaginosis. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(10):1580–1588.

- Hymes SR, Randis TM, Sun TY, Ratner AJ. DNase inhibits Gardnerella vaginalis biofilms in vitro and in vivo. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(10):1491–1497.

- Workowski KA, Berman S; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010; 59(RR-12):1–110.

- Sobel JD, Ferris D, Schwebke J, et al. Suppressive antibacterial therapy with 0.75% metronidazole vaginal gel to prevent recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(5):1283–1289.

- Sobel JD, Wiesenfeld HC, Martens M, et al. Maintenance fluconazole therapy for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(9):876–883.

- Savini V, Catavitello C, Bianco A, Balbinot A, D’Antonio F, D’Antonio D. Azole resistant Candida glabrata vulvovaginitis treated with boric acid. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;147(1):112.

- Iavazzo C, Gkegkes ID, Zarkada IM, Falagas ME. Boric acid for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: the clinical evidence. J Womens Health(Larchmt). 2011;20(8):1245–1255.

- Reichman O, Akins R, Sobel JD. Boric acid addition to suppressive antimicrobial therapy for recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(11):732–734.

- Eschenbach DA, Hillier S, Critchlow C, Stevens C, DeRouen T, Holmes KK. Diagnosis and clinical manifestations of bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158(4):819–828.

- Swidinski A, Mendling W, Loening-Baucke V, et al. Adherent biofilms in bacterial vaginosis.Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(5 pt 1):1013–1023.

- Swidinski A, Mendling W, Loening-Baucke V, et al. An adherent Gardnerella vaginalis biofilm persists on the vaginal epithelium after standard therapy with oral metronidazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(1):97e1–e6.

- Monds RD, O’Toole GA. The developmental model of microbial biofilm: ten years of a paradigm up for review. Trends Microbiol. 2009;17(2):73–87.

- Marrazzo JM, Friedler TL, Srinivasan S, et al. Extravaginal reservoirs of vaginal bacteria as risk factors for incident bacterial vaginosis. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(10):1580–1588.

- Hymes SR, Randis TM, Sun TY, Ratner AJ. DNase inhibits Gardnerella vaginalis biofilms in vitro and in vivo. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(10):1491–1497.

- Workowski KA, Berman S; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010; 59(RR-12):1–110.

- Sobel JD, Ferris D, Schwebke J, et al. Suppressive antibacterial therapy with 0.75% metronidazole vaginal gel to prevent recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(5):1283–1289.

- Sobel JD, Wiesenfeld HC, Martens M, et al. Maintenance fluconazole therapy for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(9):876–883.

- Savini V, Catavitello C, Bianco A, Balbinot A, D’Antonio F, D’Antonio D. Azole resistant Candida glabrata vulvovaginitis treated with boric acid. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;147(1):112.

- Iavazzo C, Gkegkes ID, Zarkada IM, Falagas ME. Boric acid for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: the clinical evidence. J Womens Health(Larchmt). 2011;20(8):1245–1255.

- Reichman O, Akins R, Sobel JD. Boric acid addition to suppressive antimicrobial therapy for recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(11):732–734.

Type IIb Bony Mallet Finger: Is Anatomical Reduction of the Fracture Necessary?

Travelers' diarrhea: Prevention, treatment, and post-trip evaluation

1. Recommend antibiotic chemoprophylaxis for travelers at high risk for travelers’ diarrhea (TD) and those at high risk for complications. It is also appropriate for travelers who have an inflexible itinerary. B

2. Recommend bismuth subsalicylate chemoprophylaxis for travelers at high risk for TD who are willing to comply with the regimen and want to avoid antibiotic prophylaxis. B

3. Advise travelers to initiate self-treatment for TD with a fluoroquinolone (or azithromycin, if in South or Southeast Asia) at the onset of diarrhea if it is bloody or accompanied by fever. A

NOTE: This practice recommendation in the print version of this article stated that travelers should also take loperamide; however, both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Infectious Diseases Society of America advise against the use of loperamide by travelers with fever or bloody diarrhea [corrected August 27, 2013].

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 40-year-old female patient, a childhood immigrant from India, is seeking advice regarding her upcoming 2-week trip to Mumbai. She is taking her 2 children, ages 16 years and 16 months, to visit their grandparents for the first time. She has made this trip alone a few times and has invariably experienced short bouts of self-limited diarrheal illness. She wonders what she might do to prevent travelers’ diarrhea. Her only medical problem is rheumatoid arthritis, which has been well controlled with methotrexate. Her children are healthy. What would you recommend?

Recommendations regarding travelers’ diarrhea (TD) address prevention and management. Prevention encompasses advice about personal behaviors and the use of chemoprophylaxis (antimicrobial and non-antimicrobial) and vaccinations. Since international travelers are known to treat themselves for diarrheal illnesses during their trips,1 recommendations regarding management should assume self-treatment and include the use of both antibiotics and non-antibiotic remedies. Pretravel recommendations will of course be most effective if they account for the individual’s risk for TD.

Innate patient susceptibility, destination, and dietary choices determine TD risk

TD is generally defined as the passage of 3 of more loose stools in a 24-hour period, with associated symptoms of enteric infection—eg, fever, nausea, vomiting, or abdominal cramping. Defined in this manner, TD is thought to occur in 60% to 70% of individuals who travel from developed countries to less-developed countries.2,4 Risk of TD is influenced both by intrinsic personal factors and by factors specific to the trip.

Personal risk factorsIndividual variation in susceptibility to TD might result from a genetic predisposition arising from single nucleotide polymorphisms governing various inflammatory marker proteins.5 A history of multiple episodes of TD, especially if fellow travelers were spared, can suggest this kind of individual susceptibility. Other factors that increase vulnerability to TD are immunodeficiency, achlorhydric states such as atrophic gastritis, and chronic use of proton pump inhibitors.6,7 However, the trip itself is much more important in assessing risk for TD.

Trip-related risk factors

The destination. The most salient risk factor for TD is the geographic destination. Regions of the world can be divided into TD risk strata:2

- Very high: South Asia

- High: South America, Sub-Saharan Africa

- Medium: Central America, Mexico, Caribbean, Middle East, North Africa, Southeast Asia, Oceania

- Low: Europe, North America (excluding Mexico), Australasia, Northeast Asia.

Particularly notable countries, in descending order of risk, are Nepal, India, Myanmar, Bolivia, Sri Lanka, Ecuador, Peru, Kenya, and Guatemala.2

Dietary choices. Additionally, since travelers acquire TD by ingesting food or beverages contaminated with pathogenic fecal microbes, dietary behaviors during the trip affect their susceptibility. At least risk are business travelers and tourists who confine their activities to more affluent settings in which food and beverages are prepared and stored hygienically.1,4,8,9 At greater risk are travelers who immerse themselves in local culture, visiting locations that are more impoverished and not as well equipped with sanitation systems, especially if their stay is at least 2 to 3 weeks.1,4,8,9

Also, the older a traveler is, the lower his or her risk of TD.1,9 An exception to this might be infants whose diet consists solely of breast milk or formula prepared under sanitary conditions.

Mandates and options for preventing TD

Emphasize food and beverage precautions

It might be reasonable to expect that travelers who are circumspect about their food and beverage choices on trips will be able to avoid TD. Indeed, this is the basis for the aphorism, “Boil it, peel it, or forget it.” Guidelines routinely recommend that travelers restrict their selection of foods to those that have been well cooked and are served while still very hot, and to fruits and vegetables that they peel themselves. Likewise, they should drink only beverages that have been boiled or are in sealed bottles or under carbonation and served without ice.10-12 Many travelers might find these recommendations too restrictive to follow faithfully. Moreover, studies suggest it may not be possible for even the most assiduous traveler to fully avoid the risk of TD.13,14 The hygienic characteristics of the travel destination may be more determinative, as illustrated by the successful reduction of TD rates in Jamaica by improving sanitation in tourist resorts.15

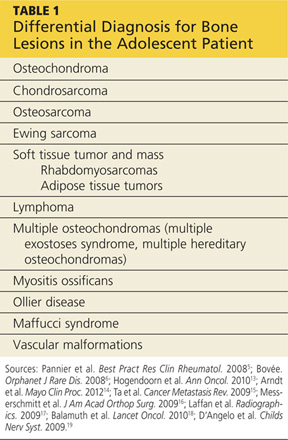

Antibiotic chemoprophylaxis: A debated practice with limited consensusThe etiologic agents of TD are multiple and vary somewhat in predominance according to geographic region.3,16,17 TABLE 1 depicts variance by region.16 The most common pathogens are strains of the bacterium Escherichia coli, particularly enterotoxigenic (ETEC), enteroaggregative (EAEC), and enteropathogenic (EPEC) strains.16 Other bacteria of importance are Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Shigella. Viruses, particularly norovirus (notably connected with cruise ships), can also cause TD, although it is implicated in no more than 17% of cases.18 Parasitic pathogens are even less common causes of TD (4%-10%) and mainly involve the protozoa, Giardia lamblia, and, to a lesser extent, Entamoeba histolytica and Cryptosporidium.

Although some pathogens often have a characteristic presentation—such as frothy, greasy diarrhea in the case of G lamblia—they generally cannot be reliably distinguished from one another clinically. Notably, up to 50% of stool samples from TD patients do not yield any pathogen,16 raising the suspicion that current diagnostic technology is not sufficiently sensitive to routinely identify certain bacteria.

There is no consensus on recommending antibiotic chemoprophylaxis against TD.

Opponents of this practice10-12,19,20 point out that TD is generally a brief (3-5 days), self-limited illness. Moreover, concerns about antibiotic resistance have come to pass. Previously used agents, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and doxycycline, are no longer effective in preventing or treating TD. In addition, antibiotic use carries the risk of allergic reactions as well as other adverse effects including, ironically, the development of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and Clostridium difficile diarrhea.

Proponents of antibiotic chemoprophylaxis21,22 point to its demonstrated efficacy in reducing the risk of TD by 4% to 40%.11 They also argue that at least 20% to 25% of travelers who get TD must significantly curtail their activities for a day or more.1,23 This change in travel plans is associated not only with significant personal loss but also imposes a financial burden.23 Furthermore, TD is known to have longer-term effects. Up to 10% of sufferers develop postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome (PI-IBS) that can last for 5 or 6 years.21,22,24,25 It is not known, however, whether the use of antibiotic chemoprophylaxis significantly reduces the incidence of PI-IBS.

Finally, the luminal antibiotic, rifaximin, nonabsorbable as it is, is very well-tolerated and holds promise for not inciting antibiotic resistance.22 However, while its efficacy in preventing TD has been demonstrated in various settings,22,26,27 it is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for this indication. Also, concerns persist that it might not be effective in preventing TD caused by invasive pathogens.19

Indications on which all agree. Even opponents of antibiotic chemoprophylaxis grant that it is probably warranted for 2 groups of travelers.10-12 The first is those whose trip schedule is of such importance that any deviation would be intolerable. The second is travelers with comorbidities that would render them at high risk for serious inconvenience or illness if they developed TD. Examples of the latter include patients with enterostomies, mobility impairments, immune suppression, inflammatory bowel disease, and renal or metabolic diseases.

Chemoprophylaxis regimens. If you prescribe an antibiotic prophylactically, consider daily doses of a fluoroquinolone (eg, ciprofloxacin 500 mg orally once daily, not twice daily as for treatment) or rifaximin 200 mg orally once or twice a day, for no longer than 2 to 3 weeks.10

Non-antimicrobial chemoprophylaxis

Bismuth subsalicylate has reduced the incidence of TD from 40% to just 14% when taken in doses of 2 chewable tablets or 60 mL of liquid 4 times daily. 11,19,22 However, the dosing frequency can hinder adherence. Moreover, the relatively high doses required raise the risk of adverse drug reactions such as blackening of the tongue and stool, nausea, constipation, Reye syndrome (in children under 12 years), and possibly tinnitus. The salicylate component of the drug poses a threat to patients with aspirin allergy, renal disease, and those taking anticoagulants. Drug interactions with probenecid and methotrexate are also possible. Bismuth is not recommended for use for longer than 3 weeks, or for children younger than 3 years or pregnant women in their third trimester.

Other non-antimicrobial chemoprophylaxis agents include probiotics such as Lactobacillus andSaccharomyces. These preparations of bacteria and fungi are marketed either singly or in blends of varying composition and proportion. The evidence is divided on their efficacy, and even though some meta-analyses have concluded probiotics such as Saccharomyces boulardii are useful in preventing TD, endorsement in clinical guidelines is muted.10-12,28-30

Immunizations have limited value so farNatural immunity to E coli gastrointestinal infection among indigenous people in less developed countries has raised the possibility of a role for vaccines in preventing TD. Some strains of ETEC produce a heat-labile toxin (LT) that bears significant resemblance to the toxin produced by Vibrio cholerae. Therefore, the oral cholera vaccine, Dukoral, has been marketed outside the United States for the prevention of TD.19,22 However, only ≤7% of TD cases worldwide would be prevented by routine use of this vaccine.31 A transdermal LT vaccine, which involves the antigen-presenting Langerhans cells in the superficial skin layers, is promising but not yet available for routine use.19,22

Treating TD and associated symptoms

Antibiotic treatment

Given that most cases of TD are caused by bacterial pathogens, antibiotics are considered the mainstay of treatment. Concerns about the ill effects of antibiotic use in the case of enterohemorrhagic E coli(EHEC O157:H7) can be allayed because this strain is rarely a cause of TD.9Patient factors that increase vulnerability to TD are immunodeficiency, achlorhydric states such as atrophic gastritis, and chronic use of proton pump inhibitors.

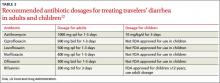

Consider local resistance patterns and risk of invasive infection. Which antibiotic to recommend is governed by the antibiotic resistance patterns prevalent in the travel destinations and by the risk of infection by invasive pathogens. Invasive TD is generally caused by Campylobacter, Shigella, or Salmonella and manifests clinically with bloody diarrhea, fever, or both. Rifaximin at a dose of 200 mg orally 3 times daily is effective for noninvasive TD.31,32 However, travelers who develop invasive TD need an alternative to rifaximin. (Those who advocate reserving antibiotic treatment only for invasive diarrhea will not see a role for rifaximin in the first place.) In most invasive cases, a fluoroquinolone will suffice.10-12,19,32 However, increasing prevalence of fluoroquinolone-resistantCampylobacter species has been reported in South and Southeast Asia. In those locations, azithromycin is an effective alternative, albeit with risk of nausea.33TABLE 212 provides details of recommended antibiotic dosages for adults and children. The duration of treatment is generally 1 day unless symptoms persist, in which case a 3-day course is recommended.10-12,19,32 If the traveler experiences persistent, new, or worsening symptoms beyond this point, immediate evaluation by a physician is required.

Non-antibiotic treatment

The antimotility agent loperamide is a well-established antidiarrheal agent. Its effective and safe use as an adjunct to antibiotics in the treatment of TD has been demonstrated in several studies.10-12,19,32,34 It is generally not used to treat children with TD9

No other non-antibiotic treatment for TD has significant guideline or clinical trial support. Bismuth subsalicylate can be helpful as an antidiarrheal agent,35 but is not often recommended because the regimen makes adherence difficult and because antibiotics and loperamide are effective.

Oral rehydration is usually a mainstay of treating gastrointestinal disease among infants and children. However, it, too, has a limited role in cases of TD because dehydration is not usually a significant part of the clinical presentation, perhaps because vomiting is not often prominent.

CASE Advice regarding safe food and beverage choices is essential for the patient and her children. Despite the increased risk for TD due to her history and her use of the immunosuppressant methotrexate, she decides not to pursue antibiotic prophylaxis. Bismuth is also contraindicated because of the methotrexate. Her teenage daughter declines bismuth prophylaxis, and her toddler is too young for it.

The patient does accept a prescription for azithromycin for her and her daughters in case they experience TD. This choice is appropriate given the destination of India and concern about Campylobacterresistance to fluoroquinolones. You also recommend loperamide for use by the mother and older child, in conjunction with the antibiotic.

Two weeks after their trip abroad, the travelers return for an office visit. On the trip, the mother and toddler suffered diarrhea, which responded well to your recommended management. The older child was well during the trip, but she developed diarrhea, abdominal pain, and anorexia one week after returning to the United States. These symptoms have persisted despite a 3-day course of azithromycin and loperamide.

Post-travel evaluation

TD generally occurs within one to 2 weeks of arrival at the travel destination and usually lasts no longer than 4 to 5 days.19 This scenario is typical of a bacterial infection. When it occurs later or lasts longer, or both, consider several alternative possibilities.19,36 First, the likelihood of a protozoal parasitic infection is increased. Although giardiasis is most likely, other protozoa such as Entamoeba, Cyclospora, Isospora, and Cryptosporidium are also possibilities. Second, if diarrhea persists, it might be due, not to continued infection, but to a self-limited post-infectious enteropathy or to PI-IBS. Third, TD is known to precipitate the clinical manifestation of underlying gastrointestinal disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), celiac disease, or even cancer.37

With an atypical disease course, it’s advisable to send 3 stool samples for laboratory evaluation for ova and parasites and for antigen assays for Giardia. If results of these tests are negative, given the difficulty inherent in diagnosing Giardia, consider empiric treatment with metronidazole in lieu of duodenal sampling.36 If the diarrhea persists, investigate serologic markers for celiac disease and IBD. If these are not revealing, referral for colonoscopy is prudent.

CASE The teenager’s 3 stool samples were negative for ova and parasites and for Giardia antigen. Following empirical treatment with oral metronidazole 250 mg, 3 times daily for 7 days, the diarrhea resolved.

CORRESPONDENCE Dilip Nair, MD, Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine at Marshall University, 1600 Medical Center Drive, Suite 1500, Huntington, WV 25701; [email protected]

1. Hill DR. Occurrence and self-treatment of diarrhea in a large cohort of Americans traveling to developing countries. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62:585–589.

2. Greenwood Z, Black J, Weld L, et al. for the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Gastrointestinal infection among international travelers globally. J Travel Med. 2008;15:221–228.

3. DuPont HL. Systematic review: the epidemiology and clinical features of travellers’ diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:187–196.

4. Steffen R, Tornieporth N, Clemens SA, et al. Epidemiology of travelers’ diarrhea: details of a global survey. J Travel Med. 2004;11:231–237.

5. de la Cabada Bauche J, DuPont HL. New developments in traveler’s diarrhea. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;7:88–95.

6. Cabada MM, White AC. Travelers’ diarrhea: an update on susceptibility, prevention, and treatment. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2008;10:473–479.

7. Ericsson CD. Travellers with pre-existing medical conditions. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;21:181–188.

8. Cabada MM, Maldonado F, Quispe W, et al. Risk factors associated with diarrhea among international visitors to Cuzco, Peru. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:968–972.

9. Mackell S. Traveler’s diarrhea in the pediatric population: etiology and impact. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(suppl 8):S547–S552.

10. Hill DR, Ericsson CD, Pearson RD, et al. The practice of travel medicine: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1499–1539.

11. Connor BA. Travelers’ diarrhea. Available at:http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2012/chapter-2-the-pre-travel-consultation/travelers-diarrhea.htm. Accessed August 20, 2012.

12. Advice for travelers. Treat Guidel Med Lett. 2012;10:45–56.

13. Shlim DR. Looking for evidence that personal hygiene precautions prevent travelers’ diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(suppl 8):S531–S535.

14. Laverone E, Boccalini S, Bechini A, et al. Travelers’ compliance to prophylactic measures and behavior during stay abroad: results of a retrospective study of subjects returning to a travel medicine center in Italy. J Travel Med. 2006;13:338–344.

15. Ashley DV, Walters C, Dockery-Brown C, et al. Interventions to prevent and control food-borne diseases associated with a reduction in traveler’s diarrhea in tourists to Jamaica. J Travel Med. 2004;11:364–367.

16. Shah N, DuPont HL, Ramsey DJ. Global etiology of travelers’ diarrhea: systematic review from 1973 to the present. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:609–614.

17. Riddle MS, Sanders JW, Putnam SD, et al. Incidence, etiology, and impact of diarrhea among long-term travelers (US military and similar populations): a systematic review. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:891–900.

18. Koo HL, Ajami NJ, Jiang ZD, et al. Noroviruses as a cause of diarrhea in travelers to Guatemala, India, and Mexico. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:1673–1676.

19. Hill DR, Ryan ET. Management of travellers’ diarrhoea. BMJ. 2008;337:863–867.

20. Rendi-Wagner P, Kollaritsch H. Drug prophylaxis for travelers’ diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:628–633.

21. Pimentel M, Riddle MS. Prevention of traveler’s diarrhea: a call to reconvene. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:151–152.

22. DuPont HL. Systematic review: prevention of travellers’ diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:741–751.

23. Wang M, Szucs TD, Steffen R. Economic aspects of travelers’ diarrhea. J Travel Med. 2008;15:110–118.

24. Neal KR, Barker L, Spiller RC. Prognosis in post-infective irritable bowel syndrome: a six year follow up study. Gut. 2002;51:410–413.

25. Tornblom H, Holmvall P, Svenungsson B, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms after infectious diarrhea: a five-year follow-up in a Swedish cohort of adults. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:461–464.

26. DuPont HL, Jiang ZD, Okhuysen PC, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of rifaximin to prevent travelers’ diarrhea. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:805–812.

27. Taylor DN, McKenzie R, Durbin A, et al. Rifaximin, a nonabsorbed oral antibiotic, prevents shigellosis after experimental challenge. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1283–1288.

28. Sazawal S, Hiremath G, Dhingra U, et al. Efficacy of probiotics in prevention of acute diarrhoea: a meta-analysis of masked, randomised, placebo-controlled trials. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:374–382.

29. Bri V, Buffet P, Genty S, et al. Absence of efficacy of nonviable Lactobacillus acidophilus for the prevention of traveler’s diarrhea: a randomized, double-blind, controlled study. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1170–1175.

30. Hill DR, Ford L, Lalloo DG. Oral cholera vaccines—use in clinical practice. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:361–373.

31. Taylor DN, Bourgeois AL, Ericsson CD, et al. A randomized double-blind, multicenter study of rifaximin compared with placebo and with ciprofloxacin in the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:1060–1066.

32. DuPont HL, Ericsson CD, Farthing MJG, et al. Expert review of the evidence base for self-therapy of travelers’ diarrhea. J Travel Med. 2009;16:161–171.

33. Tribble DR, Sanders JW, Pang LW, et al. Traveler’s diarrhea in Thailand: randomized, double-blind trial comparing single-dose and 3-day azithromycin-based regimens with a 3-day levofloxacin regimen. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:338–346.

34. Riddle MS, Arnold S, Tribble DR. Effect of adjunctive loperamide in combination with antibiotics on treatment outcomes in travelers’ diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1007–1014.

35. Steffen R. Worldwide efficacy of bismuth subsalicylate in the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12(suppl 1):S80–S86.

36. Connor BA. Persistent travelers’ diarrhea. Available at:http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2012/chapter-5-post-travel-evaluation/persistent-travelers-diarrhea.htm. Accessed August 20, 2012.

37.Landzberg BR, Connor BA. Persistent diarrhea in the returning traveler: think beyond persistent infection. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:112–114.

1. Recommend antibiotic chemoprophylaxis for travelers at high risk for travelers’ diarrhea (TD) and those at high risk for complications. It is also appropriate for travelers who have an inflexible itinerary. B

2. Recommend bismuth subsalicylate chemoprophylaxis for travelers at high risk for TD who are willing to comply with the regimen and want to avoid antibiotic prophylaxis. B

3. Advise travelers to initiate self-treatment for TD with a fluoroquinolone (or azithromycin, if in South or Southeast Asia) at the onset of diarrhea if it is bloody or accompanied by fever. A

NOTE: This practice recommendation in the print version of this article stated that travelers should also take loperamide; however, both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Infectious Diseases Society of America advise against the use of loperamide by travelers with fever or bloody diarrhea [corrected August 27, 2013].

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 40-year-old female patient, a childhood immigrant from India, is seeking advice regarding her upcoming 2-week trip to Mumbai. She is taking her 2 children, ages 16 years and 16 months, to visit their grandparents for the first time. She has made this trip alone a few times and has invariably experienced short bouts of self-limited diarrheal illness. She wonders what she might do to prevent travelers’ diarrhea. Her only medical problem is rheumatoid arthritis, which has been well controlled with methotrexate. Her children are healthy. What would you recommend?

Recommendations regarding travelers’ diarrhea (TD) address prevention and management. Prevention encompasses advice about personal behaviors and the use of chemoprophylaxis (antimicrobial and non-antimicrobial) and vaccinations. Since international travelers are known to treat themselves for diarrheal illnesses during their trips,1 recommendations regarding management should assume self-treatment and include the use of both antibiotics and non-antibiotic remedies. Pretravel recommendations will of course be most effective if they account for the individual’s risk for TD.

Innate patient susceptibility, destination, and dietary choices determine TD risk

TD is generally defined as the passage of 3 of more loose stools in a 24-hour period, with associated symptoms of enteric infection—eg, fever, nausea, vomiting, or abdominal cramping. Defined in this manner, TD is thought to occur in 60% to 70% of individuals who travel from developed countries to less-developed countries.2,4 Risk of TD is influenced both by intrinsic personal factors and by factors specific to the trip.

Personal risk factorsIndividual variation in susceptibility to TD might result from a genetic predisposition arising from single nucleotide polymorphisms governing various inflammatory marker proteins.5 A history of multiple episodes of TD, especially if fellow travelers were spared, can suggest this kind of individual susceptibility. Other factors that increase vulnerability to TD are immunodeficiency, achlorhydric states such as atrophic gastritis, and chronic use of proton pump inhibitors.6,7 However, the trip itself is much more important in assessing risk for TD.

Trip-related risk factors

The destination. The most salient risk factor for TD is the geographic destination. Regions of the world can be divided into TD risk strata:2

- Very high: South Asia

- High: South America, Sub-Saharan Africa

- Medium: Central America, Mexico, Caribbean, Middle East, North Africa, Southeast Asia, Oceania

- Low: Europe, North America (excluding Mexico), Australasia, Northeast Asia.

Particularly notable countries, in descending order of risk, are Nepal, India, Myanmar, Bolivia, Sri Lanka, Ecuador, Peru, Kenya, and Guatemala.2

Dietary choices. Additionally, since travelers acquire TD by ingesting food or beverages contaminated with pathogenic fecal microbes, dietary behaviors during the trip affect their susceptibility. At least risk are business travelers and tourists who confine their activities to more affluent settings in which food and beverages are prepared and stored hygienically.1,4,8,9 At greater risk are travelers who immerse themselves in local culture, visiting locations that are more impoverished and not as well equipped with sanitation systems, especially if their stay is at least 2 to 3 weeks.1,4,8,9

Also, the older a traveler is, the lower his or her risk of TD.1,9 An exception to this might be infants whose diet consists solely of breast milk or formula prepared under sanitary conditions.

Mandates and options for preventing TD

Emphasize food and beverage precautions

It might be reasonable to expect that travelers who are circumspect about their food and beverage choices on trips will be able to avoid TD. Indeed, this is the basis for the aphorism, “Boil it, peel it, or forget it.” Guidelines routinely recommend that travelers restrict their selection of foods to those that have been well cooked and are served while still very hot, and to fruits and vegetables that they peel themselves. Likewise, they should drink only beverages that have been boiled or are in sealed bottles or under carbonation and served without ice.10-12 Many travelers might find these recommendations too restrictive to follow faithfully. Moreover, studies suggest it may not be possible for even the most assiduous traveler to fully avoid the risk of TD.13,14 The hygienic characteristics of the travel destination may be more determinative, as illustrated by the successful reduction of TD rates in Jamaica by improving sanitation in tourist resorts.15

Antibiotic chemoprophylaxis: A debated practice with limited consensusThe etiologic agents of TD are multiple and vary somewhat in predominance according to geographic region.3,16,17 TABLE 1 depicts variance by region.16 The most common pathogens are strains of the bacterium Escherichia coli, particularly enterotoxigenic (ETEC), enteroaggregative (EAEC), and enteropathogenic (EPEC) strains.16 Other bacteria of importance are Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Shigella. Viruses, particularly norovirus (notably connected with cruise ships), can also cause TD, although it is implicated in no more than 17% of cases.18 Parasitic pathogens are even less common causes of TD (4%-10%) and mainly involve the protozoa, Giardia lamblia, and, to a lesser extent, Entamoeba histolytica and Cryptosporidium.

Although some pathogens often have a characteristic presentation—such as frothy, greasy diarrhea in the case of G lamblia—they generally cannot be reliably distinguished from one another clinically. Notably, up to 50% of stool samples from TD patients do not yield any pathogen,16 raising the suspicion that current diagnostic technology is not sufficiently sensitive to routinely identify certain bacteria.

There is no consensus on recommending antibiotic chemoprophylaxis against TD.

Opponents of this practice10-12,19,20 point out that TD is generally a brief (3-5 days), self-limited illness. Moreover, concerns about antibiotic resistance have come to pass. Previously used agents, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and doxycycline, are no longer effective in preventing or treating TD. In addition, antibiotic use carries the risk of allergic reactions as well as other adverse effects including, ironically, the development of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and Clostridium difficile diarrhea.

Proponents of antibiotic chemoprophylaxis21,22 point to its demonstrated efficacy in reducing the risk of TD by 4% to 40%.11 They also argue that at least 20% to 25% of travelers who get TD must significantly curtail their activities for a day or more.1,23 This change in travel plans is associated not only with significant personal loss but also imposes a financial burden.23 Furthermore, TD is known to have longer-term effects. Up to 10% of sufferers develop postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome (PI-IBS) that can last for 5 or 6 years.21,22,24,25 It is not known, however, whether the use of antibiotic chemoprophylaxis significantly reduces the incidence of PI-IBS.

Finally, the luminal antibiotic, rifaximin, nonabsorbable as it is, is very well-tolerated and holds promise for not inciting antibiotic resistance.22 However, while its efficacy in preventing TD has been demonstrated in various settings,22,26,27 it is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for this indication. Also, concerns persist that it might not be effective in preventing TD caused by invasive pathogens.19

Indications on which all agree. Even opponents of antibiotic chemoprophylaxis grant that it is probably warranted for 2 groups of travelers.10-12 The first is those whose trip schedule is of such importance that any deviation would be intolerable. The second is travelers with comorbidities that would render them at high risk for serious inconvenience or illness if they developed TD. Examples of the latter include patients with enterostomies, mobility impairments, immune suppression, inflammatory bowel disease, and renal or metabolic diseases.

Chemoprophylaxis regimens. If you prescribe an antibiotic prophylactically, consider daily doses of a fluoroquinolone (eg, ciprofloxacin 500 mg orally once daily, not twice daily as for treatment) or rifaximin 200 mg orally once or twice a day, for no longer than 2 to 3 weeks.10

Non-antimicrobial chemoprophylaxis

Bismuth subsalicylate has reduced the incidence of TD from 40% to just 14% when taken in doses of 2 chewable tablets or 60 mL of liquid 4 times daily. 11,19,22 However, the dosing frequency can hinder adherence. Moreover, the relatively high doses required raise the risk of adverse drug reactions such as blackening of the tongue and stool, nausea, constipation, Reye syndrome (in children under 12 years), and possibly tinnitus. The salicylate component of the drug poses a threat to patients with aspirin allergy, renal disease, and those taking anticoagulants. Drug interactions with probenecid and methotrexate are also possible. Bismuth is not recommended for use for longer than 3 weeks, or for children younger than 3 years or pregnant women in their third trimester.

Other non-antimicrobial chemoprophylaxis agents include probiotics such as Lactobacillus andSaccharomyces. These preparations of bacteria and fungi are marketed either singly or in blends of varying composition and proportion. The evidence is divided on their efficacy, and even though some meta-analyses have concluded probiotics such as Saccharomyces boulardii are useful in preventing TD, endorsement in clinical guidelines is muted.10-12,28-30

Immunizations have limited value so farNatural immunity to E coli gastrointestinal infection among indigenous people in less developed countries has raised the possibility of a role for vaccines in preventing TD. Some strains of ETEC produce a heat-labile toxin (LT) that bears significant resemblance to the toxin produced by Vibrio cholerae. Therefore, the oral cholera vaccine, Dukoral, has been marketed outside the United States for the prevention of TD.19,22 However, only ≤7% of TD cases worldwide would be prevented by routine use of this vaccine.31 A transdermal LT vaccine, which involves the antigen-presenting Langerhans cells in the superficial skin layers, is promising but not yet available for routine use.19,22

Treating TD and associated symptoms

Antibiotic treatment

Given that most cases of TD are caused by bacterial pathogens, antibiotics are considered the mainstay of treatment. Concerns about the ill effects of antibiotic use in the case of enterohemorrhagic E coli(EHEC O157:H7) can be allayed because this strain is rarely a cause of TD.9Patient factors that increase vulnerability to TD are immunodeficiency, achlorhydric states such as atrophic gastritis, and chronic use of proton pump inhibitors.

Consider local resistance patterns and risk of invasive infection. Which antibiotic to recommend is governed by the antibiotic resistance patterns prevalent in the travel destinations and by the risk of infection by invasive pathogens. Invasive TD is generally caused by Campylobacter, Shigella, or Salmonella and manifests clinically with bloody diarrhea, fever, or both. Rifaximin at a dose of 200 mg orally 3 times daily is effective for noninvasive TD.31,32 However, travelers who develop invasive TD need an alternative to rifaximin. (Those who advocate reserving antibiotic treatment only for invasive diarrhea will not see a role for rifaximin in the first place.) In most invasive cases, a fluoroquinolone will suffice.10-12,19,32 However, increasing prevalence of fluoroquinolone-resistantCampylobacter species has been reported in South and Southeast Asia. In those locations, azithromycin is an effective alternative, albeit with risk of nausea.33TABLE 212 provides details of recommended antibiotic dosages for adults and children. The duration of treatment is generally 1 day unless symptoms persist, in which case a 3-day course is recommended.10-12,19,32 If the traveler experiences persistent, new, or worsening symptoms beyond this point, immediate evaluation by a physician is required.

Non-antibiotic treatment

The antimotility agent loperamide is a well-established antidiarrheal agent. Its effective and safe use as an adjunct to antibiotics in the treatment of TD has been demonstrated in several studies.10-12,19,32,34 It is generally not used to treat children with TD9

No other non-antibiotic treatment for TD has significant guideline or clinical trial support. Bismuth subsalicylate can be helpful as an antidiarrheal agent,35 but is not often recommended because the regimen makes adherence difficult and because antibiotics and loperamide are effective.

Oral rehydration is usually a mainstay of treating gastrointestinal disease among infants and children. However, it, too, has a limited role in cases of TD because dehydration is not usually a significant part of the clinical presentation, perhaps because vomiting is not often prominent.

CASE Advice regarding safe food and beverage choices is essential for the patient and her children. Despite the increased risk for TD due to her history and her use of the immunosuppressant methotrexate, she decides not to pursue antibiotic prophylaxis. Bismuth is also contraindicated because of the methotrexate. Her teenage daughter declines bismuth prophylaxis, and her toddler is too young for it.

The patient does accept a prescription for azithromycin for her and her daughters in case they experience TD. This choice is appropriate given the destination of India and concern about Campylobacterresistance to fluoroquinolones. You also recommend loperamide for use by the mother and older child, in conjunction with the antibiotic.

Two weeks after their trip abroad, the travelers return for an office visit. On the trip, the mother and toddler suffered diarrhea, which responded well to your recommended management. The older child was well during the trip, but she developed diarrhea, abdominal pain, and anorexia one week after returning to the United States. These symptoms have persisted despite a 3-day course of azithromycin and loperamide.

Post-travel evaluation

TD generally occurs within one to 2 weeks of arrival at the travel destination and usually lasts no longer than 4 to 5 days.19 This scenario is typical of a bacterial infection. When it occurs later or lasts longer, or both, consider several alternative possibilities.19,36 First, the likelihood of a protozoal parasitic infection is increased. Although giardiasis is most likely, other protozoa such as Entamoeba, Cyclospora, Isospora, and Cryptosporidium are also possibilities. Second, if diarrhea persists, it might be due, not to continued infection, but to a self-limited post-infectious enteropathy or to PI-IBS. Third, TD is known to precipitate the clinical manifestation of underlying gastrointestinal disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), celiac disease, or even cancer.37

With an atypical disease course, it’s advisable to send 3 stool samples for laboratory evaluation for ova and parasites and for antigen assays for Giardia. If results of these tests are negative, given the difficulty inherent in diagnosing Giardia, consider empiric treatment with metronidazole in lieu of duodenal sampling.36 If the diarrhea persists, investigate serologic markers for celiac disease and IBD. If these are not revealing, referral for colonoscopy is prudent.

CASE The teenager’s 3 stool samples were negative for ova and parasites and for Giardia antigen. Following empirical treatment with oral metronidazole 250 mg, 3 times daily for 7 days, the diarrhea resolved.

CORRESPONDENCE Dilip Nair, MD, Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine at Marshall University, 1600 Medical Center Drive, Suite 1500, Huntington, WV 25701; [email protected]

1. Recommend antibiotic chemoprophylaxis for travelers at high risk for travelers’ diarrhea (TD) and those at high risk for complications. It is also appropriate for travelers who have an inflexible itinerary. B

2. Recommend bismuth subsalicylate chemoprophylaxis for travelers at high risk for TD who are willing to comply with the regimen and want to avoid antibiotic prophylaxis. B

3. Advise travelers to initiate self-treatment for TD with a fluoroquinolone (or azithromycin, if in South or Southeast Asia) at the onset of diarrhea if it is bloody or accompanied by fever. A

NOTE: This practice recommendation in the print version of this article stated that travelers should also take loperamide; however, both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Infectious Diseases Society of America advise against the use of loperamide by travelers with fever or bloody diarrhea [corrected August 27, 2013].

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 40-year-old female patient, a childhood immigrant from India, is seeking advice regarding her upcoming 2-week trip to Mumbai. She is taking her 2 children, ages 16 years and 16 months, to visit their grandparents for the first time. She has made this trip alone a few times and has invariably experienced short bouts of self-limited diarrheal illness. She wonders what she might do to prevent travelers’ diarrhea. Her only medical problem is rheumatoid arthritis, which has been well controlled with methotrexate. Her children are healthy. What would you recommend?

Recommendations regarding travelers’ diarrhea (TD) address prevention and management. Prevention encompasses advice about personal behaviors and the use of chemoprophylaxis (antimicrobial and non-antimicrobial) and vaccinations. Since international travelers are known to treat themselves for diarrheal illnesses during their trips,1 recommendations regarding management should assume self-treatment and include the use of both antibiotics and non-antibiotic remedies. Pretravel recommendations will of course be most effective if they account for the individual’s risk for TD.

Innate patient susceptibility, destination, and dietary choices determine TD risk

TD is generally defined as the passage of 3 of more loose stools in a 24-hour period, with associated symptoms of enteric infection—eg, fever, nausea, vomiting, or abdominal cramping. Defined in this manner, TD is thought to occur in 60% to 70% of individuals who travel from developed countries to less-developed countries.2,4 Risk of TD is influenced both by intrinsic personal factors and by factors specific to the trip.

Personal risk factorsIndividual variation in susceptibility to TD might result from a genetic predisposition arising from single nucleotide polymorphisms governing various inflammatory marker proteins.5 A history of multiple episodes of TD, especially if fellow travelers were spared, can suggest this kind of individual susceptibility. Other factors that increase vulnerability to TD are immunodeficiency, achlorhydric states such as atrophic gastritis, and chronic use of proton pump inhibitors.6,7 However, the trip itself is much more important in assessing risk for TD.

Trip-related risk factors

The destination. The most salient risk factor for TD is the geographic destination. Regions of the world can be divided into TD risk strata:2

- Very high: South Asia

- High: South America, Sub-Saharan Africa

- Medium: Central America, Mexico, Caribbean, Middle East, North Africa, Southeast Asia, Oceania

- Low: Europe, North America (excluding Mexico), Australasia, Northeast Asia.

Particularly notable countries, in descending order of risk, are Nepal, India, Myanmar, Bolivia, Sri Lanka, Ecuador, Peru, Kenya, and Guatemala.2

Dietary choices. Additionally, since travelers acquire TD by ingesting food or beverages contaminated with pathogenic fecal microbes, dietary behaviors during the trip affect their susceptibility. At least risk are business travelers and tourists who confine their activities to more affluent settings in which food and beverages are prepared and stored hygienically.1,4,8,9 At greater risk are travelers who immerse themselves in local culture, visiting locations that are more impoverished and not as well equipped with sanitation systems, especially if their stay is at least 2 to 3 weeks.1,4,8,9

Also, the older a traveler is, the lower his or her risk of TD.1,9 An exception to this might be infants whose diet consists solely of breast milk or formula prepared under sanitary conditions.

Mandates and options for preventing TD

Emphasize food and beverage precautions

It might be reasonable to expect that travelers who are circumspect about their food and beverage choices on trips will be able to avoid TD. Indeed, this is the basis for the aphorism, “Boil it, peel it, or forget it.” Guidelines routinely recommend that travelers restrict their selection of foods to those that have been well cooked and are served while still very hot, and to fruits and vegetables that they peel themselves. Likewise, they should drink only beverages that have been boiled or are in sealed bottles or under carbonation and served without ice.10-12 Many travelers might find these recommendations too restrictive to follow faithfully. Moreover, studies suggest it may not be possible for even the most assiduous traveler to fully avoid the risk of TD.13,14 The hygienic characteristics of the travel destination may be more determinative, as illustrated by the successful reduction of TD rates in Jamaica by improving sanitation in tourist resorts.15

Antibiotic chemoprophylaxis: A debated practice with limited consensusThe etiologic agents of TD are multiple and vary somewhat in predominance according to geographic region.3,16,17 TABLE 1 depicts variance by region.16 The most common pathogens are strains of the bacterium Escherichia coli, particularly enterotoxigenic (ETEC), enteroaggregative (EAEC), and enteropathogenic (EPEC) strains.16 Other bacteria of importance are Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Shigella. Viruses, particularly norovirus (notably connected with cruise ships), can also cause TD, although it is implicated in no more than 17% of cases.18 Parasitic pathogens are even less common causes of TD (4%-10%) and mainly involve the protozoa, Giardia lamblia, and, to a lesser extent, Entamoeba histolytica and Cryptosporidium.

Although some pathogens often have a characteristic presentation—such as frothy, greasy diarrhea in the case of G lamblia—they generally cannot be reliably distinguished from one another clinically. Notably, up to 50% of stool samples from TD patients do not yield any pathogen,16 raising the suspicion that current diagnostic technology is not sufficiently sensitive to routinely identify certain bacteria.

There is no consensus on recommending antibiotic chemoprophylaxis against TD.

Opponents of this practice10-12,19,20 point out that TD is generally a brief (3-5 days), self-limited illness. Moreover, concerns about antibiotic resistance have come to pass. Previously used agents, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and doxycycline, are no longer effective in preventing or treating TD. In addition, antibiotic use carries the risk of allergic reactions as well as other adverse effects including, ironically, the development of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and Clostridium difficile diarrhea.

Proponents of antibiotic chemoprophylaxis21,22 point to its demonstrated efficacy in reducing the risk of TD by 4% to 40%.11 They also argue that at least 20% to 25% of travelers who get TD must significantly curtail their activities for a day or more.1,23 This change in travel plans is associated not only with significant personal loss but also imposes a financial burden.23 Furthermore, TD is known to have longer-term effects. Up to 10% of sufferers develop postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome (PI-IBS) that can last for 5 or 6 years.21,22,24,25 It is not known, however, whether the use of antibiotic chemoprophylaxis significantly reduces the incidence of PI-IBS.