User login

Grad Student With Palpitations

ANSWER

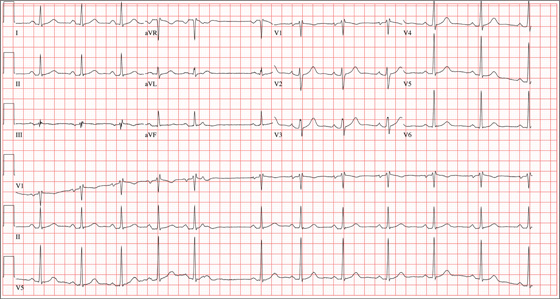

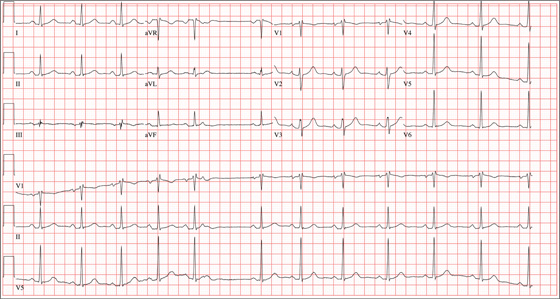

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes sinus rhythm with marked sinus arrhythmia and a blocked premature atrial contraction (PAC).

Sinus rhythm is defined as a heart rate between 60 and 100 beats/min, with a P wave for every QRS complex, a QRS complex for every P wave, and a consistent PR interval between 120 and 200 ms.

A sinus arrhythmia is defined as a variation of the P-P interval ≥ 120 ms in the presence of normal P waves and a normal PR interval. The most common cause of a sinus arrhythmia is respiratory variation.

A blocked PAC is seen following the fifth QRS complex. Careful inspection of the terminal portion of the T wave reveals a P wave without a corresponding QRS complex. There is no QRS complex because the PAC occurs while the AV node is refractory. The subsequent pause occurs because the PAC blocks the sinus node and resets the sinus rate.

The palpitations were correlated to PACs observed on a continuous rhythm strip, and the patient was reassured.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes sinus rhythm with marked sinus arrhythmia and a blocked premature atrial contraction (PAC).

Sinus rhythm is defined as a heart rate between 60 and 100 beats/min, with a P wave for every QRS complex, a QRS complex for every P wave, and a consistent PR interval between 120 and 200 ms.

A sinus arrhythmia is defined as a variation of the P-P interval ≥ 120 ms in the presence of normal P waves and a normal PR interval. The most common cause of a sinus arrhythmia is respiratory variation.

A blocked PAC is seen following the fifth QRS complex. Careful inspection of the terminal portion of the T wave reveals a P wave without a corresponding QRS complex. There is no QRS complex because the PAC occurs while the AV node is refractory. The subsequent pause occurs because the PAC blocks the sinus node and resets the sinus rate.

The palpitations were correlated to PACs observed on a continuous rhythm strip, and the patient was reassured.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes sinus rhythm with marked sinus arrhythmia and a blocked premature atrial contraction (PAC).

Sinus rhythm is defined as a heart rate between 60 and 100 beats/min, with a P wave for every QRS complex, a QRS complex for every P wave, and a consistent PR interval between 120 and 200 ms.

A sinus arrhythmia is defined as a variation of the P-P interval ≥ 120 ms in the presence of normal P waves and a normal PR interval. The most common cause of a sinus arrhythmia is respiratory variation.

A blocked PAC is seen following the fifth QRS complex. Careful inspection of the terminal portion of the T wave reveals a P wave without a corresponding QRS complex. There is no QRS complex because the PAC occurs while the AV node is refractory. The subsequent pause occurs because the PAC blocks the sinus node and resets the sinus rate.

The palpitations were correlated to PACs observed on a continuous rhythm strip, and the patient was reassured.

A 24-year-old graduate student presents to the student clinic with a history of palpitations. He first noticed them while snowboarding two months ago, but says they’re now occurring daily and much more frequently. He is concerned about the risk for “another” episode of tachycardia, which, through careful questioning, you learn he has experienced twice before. He recalls that each of the episodes—which occurred while he was “pulling all-nighters” for final exams during his undergrad years—began abruptly and lasted for approximately an hour. He had no chest pain, symptoms of near-syncope, or syncope, but recalls feeling very “jittery,” which he attributed to drinking a full pot of coffee while studying. The patient has no prior cardiac or pulmonary history and considers himself to be in excellent health. He has run two half-marathons in the preceding six months and is an avid snowboarder. He also competes in local road cycling competitions with reasonable success. Medical history is remarkable only for fractures of the right ankle and the left clavicle. He takes no medications and has no drug allergies. Family history is significant for stroke (paternal grandfather), diabetes (maternal grandmother), and hypertension (father). He consumes alcohol socially, primarily on weekends, and does not binge drink. He smokes marijuana during snowboard season but denies use at other times of the year. A 12-point review of systems is positive only for athlete’s foot and psoriasis on both upper extremities. The physical exam reveals a healthy, athletic-appearing male in no distress. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 126/68 mm Hg; pulse, 78 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min; and O2 saturation, 99% on room air. He is afebrile. His height is 70” and weight, 158 lb. Auscultation of the heart reveals no murmurs, rubs, or gallops, but you do detect several pauses. As you listen, he emphatically states, “There’s one … there’s another.” Following the physical exam, the patient asks you to order an ECG. The resultant tracing reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 70 beats/min; PR interval, 178 ms; QRS duration, 90 ms; QT/QTc interval, 402/434 ms; P axis, 23°, R axis, 38°; and T axis, 31°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

The Sunshine Act

This month, yet another new bureaucracy unfolds: Under the Physician Payment Sunshine Act – part of the Affordable Care Act – manufacturers of drugs, devices, and biological and medical supplies covered by federal health care programs are now required to begin reporting financial interactions with physicians and teaching hospitals to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Ownership or investment interests in the manufacturers by physicians and their family members also must be disclosed. Most of the data will be published online by September 2014.

In addition to reporting the type of financial exchange and the dollar amount, manufacturers are required to report the reason for the interaction, including consulting, food, ownership or investment interest, direct compensation for speakers at education programs (whether or not they are accredited or certified), and research. There are exclusions, including drug samples intended for distribution to patients. Medical students and residents are excluded entirely. You will be allowed to review your data and seek corrections before it is published; and you will have an additional 2 years to pursue corrections.

Compensation for conducting clinical trials will be reported, but not posted on the website until the product receives Food and Drug Administration approval, or until 4 years after the payment, whichever is earlier. Payments for trials involving a new indication for an approved drug will be posted immediately.

So what will be the likely effects on research, industry-sponsored meetings, meals provided by drug reps, and the like? The short answer is that no one knows. Much will depend on how the information is reported, and how patients interpret the data that they see – if they take notice at all.

Sunshine laws are already in effect in six states – California, Colorado, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Vermont, and West Virginia – and the District of Columbia. (Maine repealed its law in 2011.) Observers disagree on their impact. Data from Maine and West Virginia showed no significant changes in prescribing patterns after the laws took effect, according to a 2012 article in Archives of Internal Medicine (now JAMA Internal Medicine).

Evidence indicates that physicians have already decreased their industry interaction on their own: About a quarter of all private practices now refuse to see pharmaceutical reps; most medical schools prohibit samples, gifts, and on-site meals, and many prohibit on-site interaction of any kind between reps and residents.

How the disclosure legislation translates into physician-patient interaction remains equally unclear. Do patients think less of doctors who accept the occasional industry-sponsored lunch for their employees? Do they think more of doctors who conduct industry-sponsored clinical research? There are no objective data, so far as I know.

My guess – based on no evidence but 30 years of experience – is that attorneys, activists, and the occasional reporter will data-mine the website, but few patients will ever bother to visit. Nevertheless, you should prepare now to ensure the accuracy of anything posted about you when the database launches next year. Mark your calendar; the data must be reported to the CMS by March 31 annually, so you will need to set aside time each April or May to review it. If you have many or complex industry relationships, you should probably contact each of the manufacturers in January or February and ask to see the data before they are submitted. Then review the information again once the CMS gets it, to be sure nothing was changed. Maintaining accurate financial records has always been important, but it will be even more so now, to effectively dispute any inconsistencies.

If you don’t see drug reps or give sponsored talks, don’t assume that you won’t be on the website. Check anyway; you might be indirectly involved in compensation that you were not aware of, or you may have been reported in error.

Pharmaceutical companies face stiff penalties if they do not comply with the Sunshine Act. Those that fail to report can be fined up to $150,000 annually, and those fines can rise to $1 million for those that intentionally fail to report. This means that the information will be disclosed. If you have any financial relationships with the pharmaceutical industry, you will need to anticipate the implications of the increased scrutiny that may (or may not) result.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J.

This month, yet another new bureaucracy unfolds: Under the Physician Payment Sunshine Act – part of the Affordable Care Act – manufacturers of drugs, devices, and biological and medical supplies covered by federal health care programs are now required to begin reporting financial interactions with physicians and teaching hospitals to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Ownership or investment interests in the manufacturers by physicians and their family members also must be disclosed. Most of the data will be published online by September 2014.

In addition to reporting the type of financial exchange and the dollar amount, manufacturers are required to report the reason for the interaction, including consulting, food, ownership or investment interest, direct compensation for speakers at education programs (whether or not they are accredited or certified), and research. There are exclusions, including drug samples intended for distribution to patients. Medical students and residents are excluded entirely. You will be allowed to review your data and seek corrections before it is published; and you will have an additional 2 years to pursue corrections.

Compensation for conducting clinical trials will be reported, but not posted on the website until the product receives Food and Drug Administration approval, or until 4 years after the payment, whichever is earlier. Payments for trials involving a new indication for an approved drug will be posted immediately.

So what will be the likely effects on research, industry-sponsored meetings, meals provided by drug reps, and the like? The short answer is that no one knows. Much will depend on how the information is reported, and how patients interpret the data that they see – if they take notice at all.

Sunshine laws are already in effect in six states – California, Colorado, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Vermont, and West Virginia – and the District of Columbia. (Maine repealed its law in 2011.) Observers disagree on their impact. Data from Maine and West Virginia showed no significant changes in prescribing patterns after the laws took effect, according to a 2012 article in Archives of Internal Medicine (now JAMA Internal Medicine).

Evidence indicates that physicians have already decreased their industry interaction on their own: About a quarter of all private practices now refuse to see pharmaceutical reps; most medical schools prohibit samples, gifts, and on-site meals, and many prohibit on-site interaction of any kind between reps and residents.

How the disclosure legislation translates into physician-patient interaction remains equally unclear. Do patients think less of doctors who accept the occasional industry-sponsored lunch for their employees? Do they think more of doctors who conduct industry-sponsored clinical research? There are no objective data, so far as I know.

My guess – based on no evidence but 30 years of experience – is that attorneys, activists, and the occasional reporter will data-mine the website, but few patients will ever bother to visit. Nevertheless, you should prepare now to ensure the accuracy of anything posted about you when the database launches next year. Mark your calendar; the data must be reported to the CMS by March 31 annually, so you will need to set aside time each April or May to review it. If you have many or complex industry relationships, you should probably contact each of the manufacturers in January or February and ask to see the data before they are submitted. Then review the information again once the CMS gets it, to be sure nothing was changed. Maintaining accurate financial records has always been important, but it will be even more so now, to effectively dispute any inconsistencies.

If you don’t see drug reps or give sponsored talks, don’t assume that you won’t be on the website. Check anyway; you might be indirectly involved in compensation that you were not aware of, or you may have been reported in error.

Pharmaceutical companies face stiff penalties if they do not comply with the Sunshine Act. Those that fail to report can be fined up to $150,000 annually, and those fines can rise to $1 million for those that intentionally fail to report. This means that the information will be disclosed. If you have any financial relationships with the pharmaceutical industry, you will need to anticipate the implications of the increased scrutiny that may (or may not) result.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J.

This month, yet another new bureaucracy unfolds: Under the Physician Payment Sunshine Act – part of the Affordable Care Act – manufacturers of drugs, devices, and biological and medical supplies covered by federal health care programs are now required to begin reporting financial interactions with physicians and teaching hospitals to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Ownership or investment interests in the manufacturers by physicians and their family members also must be disclosed. Most of the data will be published online by September 2014.

In addition to reporting the type of financial exchange and the dollar amount, manufacturers are required to report the reason for the interaction, including consulting, food, ownership or investment interest, direct compensation for speakers at education programs (whether or not they are accredited or certified), and research. There are exclusions, including drug samples intended for distribution to patients. Medical students and residents are excluded entirely. You will be allowed to review your data and seek corrections before it is published; and you will have an additional 2 years to pursue corrections.

Compensation for conducting clinical trials will be reported, but not posted on the website until the product receives Food and Drug Administration approval, or until 4 years after the payment, whichever is earlier. Payments for trials involving a new indication for an approved drug will be posted immediately.

So what will be the likely effects on research, industry-sponsored meetings, meals provided by drug reps, and the like? The short answer is that no one knows. Much will depend on how the information is reported, and how patients interpret the data that they see – if they take notice at all.

Sunshine laws are already in effect in six states – California, Colorado, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Vermont, and West Virginia – and the District of Columbia. (Maine repealed its law in 2011.) Observers disagree on their impact. Data from Maine and West Virginia showed no significant changes in prescribing patterns after the laws took effect, according to a 2012 article in Archives of Internal Medicine (now JAMA Internal Medicine).

Evidence indicates that physicians have already decreased their industry interaction on their own: About a quarter of all private practices now refuse to see pharmaceutical reps; most medical schools prohibit samples, gifts, and on-site meals, and many prohibit on-site interaction of any kind between reps and residents.

How the disclosure legislation translates into physician-patient interaction remains equally unclear. Do patients think less of doctors who accept the occasional industry-sponsored lunch for their employees? Do they think more of doctors who conduct industry-sponsored clinical research? There are no objective data, so far as I know.

My guess – based on no evidence but 30 years of experience – is that attorneys, activists, and the occasional reporter will data-mine the website, but few patients will ever bother to visit. Nevertheless, you should prepare now to ensure the accuracy of anything posted about you when the database launches next year. Mark your calendar; the data must be reported to the CMS by March 31 annually, so you will need to set aside time each April or May to review it. If you have many or complex industry relationships, you should probably contact each of the manufacturers in January or February and ask to see the data before they are submitted. Then review the information again once the CMS gets it, to be sure nothing was changed. Maintaining accurate financial records has always been important, but it will be even more so now, to effectively dispute any inconsistencies.

If you don’t see drug reps or give sponsored talks, don’t assume that you won’t be on the website. Check anyway; you might be indirectly involved in compensation that you were not aware of, or you may have been reported in error.

Pharmaceutical companies face stiff penalties if they do not comply with the Sunshine Act. Those that fail to report can be fined up to $150,000 annually, and those fines can rise to $1 million for those that intentionally fail to report. This means that the information will be disclosed. If you have any financial relationships with the pharmaceutical industry, you will need to anticipate the implications of the increased scrutiny that may (or may not) result.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J.

Will a novel antibody fix the anticoagulant-bleeding problem?

It seems inescapable: If patients are made less able to form blood clots, they bleed more.

Bleeding is the perennial problem for anticoagulants. Whether it’s the traditional anticoagulants (heparin, warfarin, and the low-molecular-weight heparins) or new drugs (fondaparinux, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban), as the anticoagulant’s potency or dosage increases to stop blood clots from forming, the inevitable downside is increased bleeding.

Maybe not.

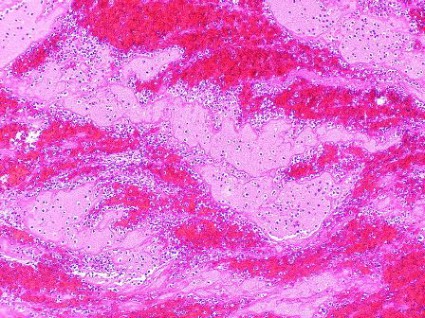

A newly developed, synthetic human IgG antibody appears, in animal and in vitro models, to allow normal clotting to occur and stop bleeding at vessel tears and cuts, while short-circuiting pathologic clotting in intravascular spaces – the sorts of clots that cause venous thromboembolisms, myocardial infarctions, and strokes.

"It seems too good to be true. It’s beyond comprehension," said Dr. Trevor Baglin, the University of Cambridge, England, hematologist who discovered the first identified, naturally occurring example of this antibody, in IgA form, in a patient he initially saw in 2008. "All we can do is go forward and see if it genuinely is as good as it seems," he said while presenting his group’s initial animal findings with the antibody at the Congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis in Amsterdam earlier this month.

The antibody – which has been patented, synthesized, and is in extensive preclinical testing – has been named ichorcumab. In Greek mythology, "ichor" was the blood factor in gods that made them immortal.

The secret behind ichorcumab is that it binds to and inactivates exosite 1, the part of the thrombin molecule that cleaves fibrinogen into fibrin, an effective brake on clotting. Study results suggest that whether the exosite 1 portion of thrombin is exposed or hidden at various body sites accounts for ichorcumab’s varied effects.

"Our hypothesis is that exosite 1 is protected from the antibody [when a thrombin molecule sits] on a cell or clot surface, so hemostasis is unaffected, but thrombosis occurs in the luminal space, where exosite 1 is exposed an available to the antibody," Dr. Baglin explained.

"While before we thought of just one type of clot, [the work with ichorcumab so far] suggests there is not one clotting mechanism but two," he noted, one that leads to clot formation that stops bleeding, and a second mechanism that produces clots that cause thrombosis. Ichorcumab blocks the bad clots but not the good ones, because the clots form at different locations that affect the way that exosite 1 on thrombin is exposed.

It may sound farfetched, but it’s a way for the researchers to explain the curious patient whom Dr. Baglin first met in 2008, a 53-year old woman who spontaneously makes and carries the IgA prototype of ichorcumab in her blood.

Dr. Baglin said that he consulted on her case after a preprocedural clotting screen revealed that her blood was unclottable by standard tests, yet she had no history of any bleeding disorder. In fact, her history showed that she had undergone knee surgery (when no clotting screen had been done) 5 months before Dr. Baglin first saw her without any hint of a bleeding incident. She subsequently cut the tip of a finger while slicing with a mandolin, but her bleeding stopped spontaneously.

The patient goes through life with this antibody in her blood at a level of about 3 g/L with no bleeding problems whatsoever; yet in a mouse model, a substantially lower level of the mimic antibody, ichorcumab, effectively blocked thrombosis. In the mouse model, this effective dose of ichorcumab does not cause bleeding if the mouse’s tail is cut.

Dr. Baglin and his associates started a company in Cambridge, XO1, to fund the preclinical work and eventually commercialize ichorcumab. They believe it will be another 2 years before any person receives a dose of the antibody.

–BY MITCHEL L. ZOLER

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

It seems inescapable: If patients are made less able to form blood clots, they bleed more.

Bleeding is the perennial problem for anticoagulants. Whether it’s the traditional anticoagulants (heparin, warfarin, and the low-molecular-weight heparins) or new drugs (fondaparinux, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban), as the anticoagulant’s potency or dosage increases to stop blood clots from forming, the inevitable downside is increased bleeding.

Maybe not.

A newly developed, synthetic human IgG antibody appears, in animal and in vitro models, to allow normal clotting to occur and stop bleeding at vessel tears and cuts, while short-circuiting pathologic clotting in intravascular spaces – the sorts of clots that cause venous thromboembolisms, myocardial infarctions, and strokes.

"It seems too good to be true. It’s beyond comprehension," said Dr. Trevor Baglin, the University of Cambridge, England, hematologist who discovered the first identified, naturally occurring example of this antibody, in IgA form, in a patient he initially saw in 2008. "All we can do is go forward and see if it genuinely is as good as it seems," he said while presenting his group’s initial animal findings with the antibody at the Congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis in Amsterdam earlier this month.

The antibody – which has been patented, synthesized, and is in extensive preclinical testing – has been named ichorcumab. In Greek mythology, "ichor" was the blood factor in gods that made them immortal.

The secret behind ichorcumab is that it binds to and inactivates exosite 1, the part of the thrombin molecule that cleaves fibrinogen into fibrin, an effective brake on clotting. Study results suggest that whether the exosite 1 portion of thrombin is exposed or hidden at various body sites accounts for ichorcumab’s varied effects.

"Our hypothesis is that exosite 1 is protected from the antibody [when a thrombin molecule sits] on a cell or clot surface, so hemostasis is unaffected, but thrombosis occurs in the luminal space, where exosite 1 is exposed an available to the antibody," Dr. Baglin explained.

"While before we thought of just one type of clot, [the work with ichorcumab so far] suggests there is not one clotting mechanism but two," he noted, one that leads to clot formation that stops bleeding, and a second mechanism that produces clots that cause thrombosis. Ichorcumab blocks the bad clots but not the good ones, because the clots form at different locations that affect the way that exosite 1 on thrombin is exposed.

It may sound farfetched, but it’s a way for the researchers to explain the curious patient whom Dr. Baglin first met in 2008, a 53-year old woman who spontaneously makes and carries the IgA prototype of ichorcumab in her blood.

Dr. Baglin said that he consulted on her case after a preprocedural clotting screen revealed that her blood was unclottable by standard tests, yet she had no history of any bleeding disorder. In fact, her history showed that she had undergone knee surgery (when no clotting screen had been done) 5 months before Dr. Baglin first saw her without any hint of a bleeding incident. She subsequently cut the tip of a finger while slicing with a mandolin, but her bleeding stopped spontaneously.

The patient goes through life with this antibody in her blood at a level of about 3 g/L with no bleeding problems whatsoever; yet in a mouse model, a substantially lower level of the mimic antibody, ichorcumab, effectively blocked thrombosis. In the mouse model, this effective dose of ichorcumab does not cause bleeding if the mouse’s tail is cut.

Dr. Baglin and his associates started a company in Cambridge, XO1, to fund the preclinical work and eventually commercialize ichorcumab. They believe it will be another 2 years before any person receives a dose of the antibody.

–BY MITCHEL L. ZOLER

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

It seems inescapable: If patients are made less able to form blood clots, they bleed more.

Bleeding is the perennial problem for anticoagulants. Whether it’s the traditional anticoagulants (heparin, warfarin, and the low-molecular-weight heparins) or new drugs (fondaparinux, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban), as the anticoagulant’s potency or dosage increases to stop blood clots from forming, the inevitable downside is increased bleeding.

Maybe not.

A newly developed, synthetic human IgG antibody appears, in animal and in vitro models, to allow normal clotting to occur and stop bleeding at vessel tears and cuts, while short-circuiting pathologic clotting in intravascular spaces – the sorts of clots that cause venous thromboembolisms, myocardial infarctions, and strokes.

"It seems too good to be true. It’s beyond comprehension," said Dr. Trevor Baglin, the University of Cambridge, England, hematologist who discovered the first identified, naturally occurring example of this antibody, in IgA form, in a patient he initially saw in 2008. "All we can do is go forward and see if it genuinely is as good as it seems," he said while presenting his group’s initial animal findings with the antibody at the Congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis in Amsterdam earlier this month.

The antibody – which has been patented, synthesized, and is in extensive preclinical testing – has been named ichorcumab. In Greek mythology, "ichor" was the blood factor in gods that made them immortal.

The secret behind ichorcumab is that it binds to and inactivates exosite 1, the part of the thrombin molecule that cleaves fibrinogen into fibrin, an effective brake on clotting. Study results suggest that whether the exosite 1 portion of thrombin is exposed or hidden at various body sites accounts for ichorcumab’s varied effects.

"Our hypothesis is that exosite 1 is protected from the antibody [when a thrombin molecule sits] on a cell or clot surface, so hemostasis is unaffected, but thrombosis occurs in the luminal space, where exosite 1 is exposed an available to the antibody," Dr. Baglin explained.

"While before we thought of just one type of clot, [the work with ichorcumab so far] suggests there is not one clotting mechanism but two," he noted, one that leads to clot formation that stops bleeding, and a second mechanism that produces clots that cause thrombosis. Ichorcumab blocks the bad clots but not the good ones, because the clots form at different locations that affect the way that exosite 1 on thrombin is exposed.

It may sound farfetched, but it’s a way for the researchers to explain the curious patient whom Dr. Baglin first met in 2008, a 53-year old woman who spontaneously makes and carries the IgA prototype of ichorcumab in her blood.

Dr. Baglin said that he consulted on her case after a preprocedural clotting screen revealed that her blood was unclottable by standard tests, yet she had no history of any bleeding disorder. In fact, her history showed that she had undergone knee surgery (when no clotting screen had been done) 5 months before Dr. Baglin first saw her without any hint of a bleeding incident. She subsequently cut the tip of a finger while slicing with a mandolin, but her bleeding stopped spontaneously.

The patient goes through life with this antibody in her blood at a level of about 3 g/L with no bleeding problems whatsoever; yet in a mouse model, a substantially lower level of the mimic antibody, ichorcumab, effectively blocked thrombosis. In the mouse model, this effective dose of ichorcumab does not cause bleeding if the mouse’s tail is cut.

Dr. Baglin and his associates started a company in Cambridge, XO1, to fund the preclinical work and eventually commercialize ichorcumab. They believe it will be another 2 years before any person receives a dose of the antibody.

–BY MITCHEL L. ZOLER

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Risks for poorer outcomes of ASO for TGA

Neoaortic root dilation and neoaortic valve regurgitation are common complications in infants with transposition of the great arteries who undergo an arterial switch operation for repair, and the risk of developing these changes in the neoaorta increases over time, according to the results of a retrospective database study of patients at Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin.

In addition, when dilation occurs, the dimensions may progressively enlarge over time, making it important to maintain lifelong surveillance of this population.

Although perioperative mortality and long-term survival (assessed up to 30 years) has improved in more recent eras for use of an arterial switch operation (ASO) for transposition of the great arteries (TGA), these long-term studies have also shown important late complications that may contribute to late morbidity and the need for reoperation, according to Dr. Jennifer G. Co-Vu and her colleagues at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

They performed their study to determine the prevalence of neoaortic root dilation and neoaortic valve regurgitation in patients treated at their institution and to determine risk factors involved in the development of these late complications.

Out of 247 patients with TGA treated with an ASO at the hospital, there were 124 patients who had at least one available postoperative transthoracic echocardiogram at least 1 year after the ASO. Median age of these patients was 0.2 months at the time of their ASO and 7.2 years at their last follow-up; 71% were boys (Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2013;95:1654-9).

Retrospective measurements of the neoaortic annulus and root were performed on all available transthoracic echocardiograms and the severity of neoaortic valve regurgitation was determined by assessing the width of the color Doppler jet of regurgitation measured at the level of the valve in the parasternal long-axis view. A jet width of 1-4 mm was defined as trivial to mild; 4-6 mm was defined as moderate; and greater than 6 mm indicated severe regurgitation, according to the researchers. Significant regurgitation was defined as moderate or severe. Significant neoaortic annulus dilation was defined as a z score of 2.5 or greater.

They evaluated potential risk factors for the development of neoaortic root dilation, annulus dilation, and neoaortic valve regurgitation.

Significant neoaortic root dilation developed in 88 of 124 (66%) of the patients during follow-up, with the probability of being free from a root diameter z score of 2.5 or greater of 84%, 67%, 47%, and 32% at 1, 5, 10, and 15 years, respectively. Significant risk factors predicting neoaortic root dilation using multivariate analysis were a history of double outlet right ventricle (DORV), previous pulmonary artery (PA) banding, and length of follow-up. A history of ventricular septal defect (VSD), coarctation, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, and age at ASO were not significant risk factors.

Significant annulus dilation occurred in 54% of patients, with significant risk factors including a history of VSD, history of DORV, and the presence of a dilated neoaortic root. History of PA banding and length of follow-up were not significant. Moderate or severe neoaortic valve regurgitation occurred in 17 of 124 (14%) of the patients, with a probability of being free of these levels of regurgitation of 96%, 92%, 89%, and 75% at 1, 5, 10, and 15 years, respectively. The significant risk factors for regurgitation were history of DORV, VSD, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, and length of follow-up. No patient in the series required reintervention on the neoaorta.

The authors had no disclosures.

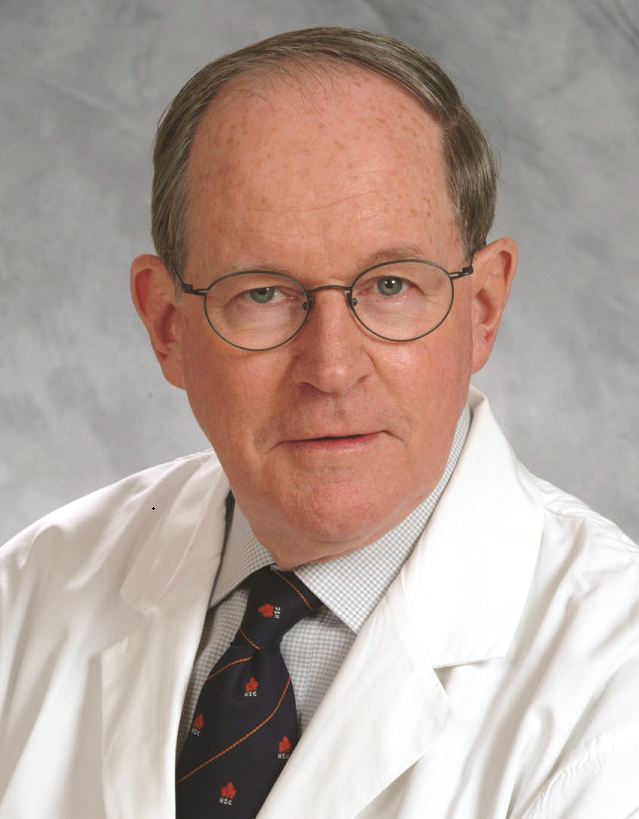

Most people living with congenital heart disease are now adults. Unfortunately the majority of these adults, for unclear reasons, are not receiving expert care by congenital heart specialists. Perhaps some of these adults have a misperception that they are cured. Dr. Co-Vu and coauthors at the Medical College of Wisconsin confirm that the highly successful arterial switch operation is not a "cure."

| Dr. Williams |

Their important, carefully executed echo study demonstrates important progressive increases in measured diameters of the neoaortic annulus and neoaortic root over the first 15 years of life. The

authors point out that the dilation has not as yet led to a need for reintervention, and the late prevalence of neoaortic regurgitation is not high, although it too is slowly increasing over time. Their message is a clarion call for lifelong clinical surveillance following an arterial switch operation – a message that should be applied to all patients with congenital heart disease.

Dr. William G. Williams is executive director of the Congenital Heart Surgeons’ Society Data Center, Toronto, and emeritus professor of surgery, University of Toronto, and an associate medical editor for Thoracic Surgery News.

Most people living with congenital heart disease are now adults. Unfortunately the majority of these adults, for unclear reasons, are not receiving expert care by congenital heart specialists. Perhaps some of these adults have a misperception that they are cured. Dr. Co-Vu and coauthors at the Medical College of Wisconsin confirm that the highly successful arterial switch operation is not a "cure."

| Dr. Williams |

Their important, carefully executed echo study demonstrates important progressive increases in measured diameters of the neoaortic annulus and neoaortic root over the first 15 years of life. The

authors point out that the dilation has not as yet led to a need for reintervention, and the late prevalence of neoaortic regurgitation is not high, although it too is slowly increasing over time. Their message is a clarion call for lifelong clinical surveillance following an arterial switch operation – a message that should be applied to all patients with congenital heart disease.

Dr. William G. Williams is executive director of the Congenital Heart Surgeons’ Society Data Center, Toronto, and emeritus professor of surgery, University of Toronto, and an associate medical editor for Thoracic Surgery News.

Most people living with congenital heart disease are now adults. Unfortunately the majority of these adults, for unclear reasons, are not receiving expert care by congenital heart specialists. Perhaps some of these adults have a misperception that they are cured. Dr. Co-Vu and coauthors at the Medical College of Wisconsin confirm that the highly successful arterial switch operation is not a "cure."

| Dr. Williams |

Their important, carefully executed echo study demonstrates important progressive increases in measured diameters of the neoaortic annulus and neoaortic root over the first 15 years of life. The

authors point out that the dilation has not as yet led to a need for reintervention, and the late prevalence of neoaortic regurgitation is not high, although it too is slowly increasing over time. Their message is a clarion call for lifelong clinical surveillance following an arterial switch operation – a message that should be applied to all patients with congenital heart disease.

Dr. William G. Williams is executive director of the Congenital Heart Surgeons’ Society Data Center, Toronto, and emeritus professor of surgery, University of Toronto, and an associate medical editor for Thoracic Surgery News.

Neoaortic root dilation and neoaortic valve regurgitation are common complications in infants with transposition of the great arteries who undergo an arterial switch operation for repair, and the risk of developing these changes in the neoaorta increases over time, according to the results of a retrospective database study of patients at Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin.

In addition, when dilation occurs, the dimensions may progressively enlarge over time, making it important to maintain lifelong surveillance of this population.

Although perioperative mortality and long-term survival (assessed up to 30 years) has improved in more recent eras for use of an arterial switch operation (ASO) for transposition of the great arteries (TGA), these long-term studies have also shown important late complications that may contribute to late morbidity and the need for reoperation, according to Dr. Jennifer G. Co-Vu and her colleagues at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

They performed their study to determine the prevalence of neoaortic root dilation and neoaortic valve regurgitation in patients treated at their institution and to determine risk factors involved in the development of these late complications.

Out of 247 patients with TGA treated with an ASO at the hospital, there were 124 patients who had at least one available postoperative transthoracic echocardiogram at least 1 year after the ASO. Median age of these patients was 0.2 months at the time of their ASO and 7.2 years at their last follow-up; 71% were boys (Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2013;95:1654-9).

Retrospective measurements of the neoaortic annulus and root were performed on all available transthoracic echocardiograms and the severity of neoaortic valve regurgitation was determined by assessing the width of the color Doppler jet of regurgitation measured at the level of the valve in the parasternal long-axis view. A jet width of 1-4 mm was defined as trivial to mild; 4-6 mm was defined as moderate; and greater than 6 mm indicated severe regurgitation, according to the researchers. Significant regurgitation was defined as moderate or severe. Significant neoaortic annulus dilation was defined as a z score of 2.5 or greater.

They evaluated potential risk factors for the development of neoaortic root dilation, annulus dilation, and neoaortic valve regurgitation.

Significant neoaortic root dilation developed in 88 of 124 (66%) of the patients during follow-up, with the probability of being free from a root diameter z score of 2.5 or greater of 84%, 67%, 47%, and 32% at 1, 5, 10, and 15 years, respectively. Significant risk factors predicting neoaortic root dilation using multivariate analysis were a history of double outlet right ventricle (DORV), previous pulmonary artery (PA) banding, and length of follow-up. A history of ventricular septal defect (VSD), coarctation, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, and age at ASO were not significant risk factors.

Significant annulus dilation occurred in 54% of patients, with significant risk factors including a history of VSD, history of DORV, and the presence of a dilated neoaortic root. History of PA banding and length of follow-up were not significant. Moderate or severe neoaortic valve regurgitation occurred in 17 of 124 (14%) of the patients, with a probability of being free of these levels of regurgitation of 96%, 92%, 89%, and 75% at 1, 5, 10, and 15 years, respectively. The significant risk factors for regurgitation were history of DORV, VSD, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, and length of follow-up. No patient in the series required reintervention on the neoaorta.

The authors had no disclosures.

Neoaortic root dilation and neoaortic valve regurgitation are common complications in infants with transposition of the great arteries who undergo an arterial switch operation for repair, and the risk of developing these changes in the neoaorta increases over time, according to the results of a retrospective database study of patients at Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin.

In addition, when dilation occurs, the dimensions may progressively enlarge over time, making it important to maintain lifelong surveillance of this population.

Although perioperative mortality and long-term survival (assessed up to 30 years) has improved in more recent eras for use of an arterial switch operation (ASO) for transposition of the great arteries (TGA), these long-term studies have also shown important late complications that may contribute to late morbidity and the need for reoperation, according to Dr. Jennifer G. Co-Vu and her colleagues at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

They performed their study to determine the prevalence of neoaortic root dilation and neoaortic valve regurgitation in patients treated at their institution and to determine risk factors involved in the development of these late complications.

Out of 247 patients with TGA treated with an ASO at the hospital, there were 124 patients who had at least one available postoperative transthoracic echocardiogram at least 1 year after the ASO. Median age of these patients was 0.2 months at the time of their ASO and 7.2 years at their last follow-up; 71% were boys (Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2013;95:1654-9).

Retrospective measurements of the neoaortic annulus and root were performed on all available transthoracic echocardiograms and the severity of neoaortic valve regurgitation was determined by assessing the width of the color Doppler jet of regurgitation measured at the level of the valve in the parasternal long-axis view. A jet width of 1-4 mm was defined as trivial to mild; 4-6 mm was defined as moderate; and greater than 6 mm indicated severe regurgitation, according to the researchers. Significant regurgitation was defined as moderate or severe. Significant neoaortic annulus dilation was defined as a z score of 2.5 or greater.

They evaluated potential risk factors for the development of neoaortic root dilation, annulus dilation, and neoaortic valve regurgitation.

Significant neoaortic root dilation developed in 88 of 124 (66%) of the patients during follow-up, with the probability of being free from a root diameter z score of 2.5 or greater of 84%, 67%, 47%, and 32% at 1, 5, 10, and 15 years, respectively. Significant risk factors predicting neoaortic root dilation using multivariate analysis were a history of double outlet right ventricle (DORV), previous pulmonary artery (PA) banding, and length of follow-up. A history of ventricular septal defect (VSD), coarctation, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, and age at ASO were not significant risk factors.

Significant annulus dilation occurred in 54% of patients, with significant risk factors including a history of VSD, history of DORV, and the presence of a dilated neoaortic root. History of PA banding and length of follow-up were not significant. Moderate or severe neoaortic valve regurgitation occurred in 17 of 124 (14%) of the patients, with a probability of being free of these levels of regurgitation of 96%, 92%, 89%, and 75% at 1, 5, 10, and 15 years, respectively. The significant risk factors for regurgitation were history of DORV, VSD, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, and length of follow-up. No patient in the series required reintervention on the neoaorta.

The authors had no disclosures.

Imperforate hymen in your adolescent patient: Don’t miss the diagnosis

Many gynecologists encounter imperforate hymen, a congenital vaginal anomaly, in general practice. As such, it is important to have a basic understanding of the condition and to be aware of appropriate screening, evaluation, and management. This knowledge will allow you to differentiate imperforate hymen from more complex anomalies—preventing significant morbidity that could result from performing the wrong surgical procedure on this condition—and to provide optimal surgical management.

How often and why does it occur?

Imperforate hymen occurs in approximately 1/1000 newborn girls. It is the most common obstructive anomaly of the female reproductive tract.1,2

The hymen consists of fibrous connective tissue attached to the vaginal wall. In the perinatal period, the hymen serves to separate the vaginal lumen from the urogenital sinus (UGS); this is usually perforated during embryonic life by canalization of the most caudal portion of the vaginal plate at the UGS. This establishes a connection between the lumen of the vaginal canal and the vaginal vestibule.3 Failure of the hymen to perforate completely in the perinatal period can result in varying anomalies, including imperforate (FIGURE 1), microperforate, cribiform, or septated hymen.

Figure 1. Imperforate hymen

How does it present?

Its presentation is variable and frequently asymptomatic in infants and children.4 As a result, the diagnosis is often delayed until puberty.3

In infancy. Newborns typically will present with a hymenal bulge from hydrocolpos or mucocolpos, which result from maternal estrogen secretion on the newborn’s vaginal epithelium.5 This is usually asymptomatic and self limited.

Rarely, large hydrocolpos/mucocolpos may become symptomatic and can lead to urinary obstruction, or they can present as an abdominal mass or intestinal obstruction.4

In adolescence. The majority of adolescents will present with cyclic or persistent pelvic pain and primary amenorrhea. If significant hematometra is present, an abdominal mass also may be palpated. In extreme cases, the patient may present with mass effect symptoms, including back pain, pain with defecation, constipation, nausea and vomiting, urinary retention, or hydronephrosis.6 Retrograde passage of blood into the fallopian tubes can cause hematosalpinx, which can lead to endometriosis and adhesion formation. Blood also may pass freely into the peritoneal cavity, forming hemoperitoneum.3

Related article: Your age-based guide to comprehensive well-woman care

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (October 2012)

Imperforate hymen, vaginal septum, or distal vaginal atresia?

When in doubt, refer. Imperforate hymen can be confused with distal vaginal atresia or low transverse vaginal septum. Often, the patient may present with similar signs and symptoms in all 3 cases. Accurately differentiating imperforate hymen from the former two more complex congenital anomalies prior to surgery is of utmost importance because management is very different, and performing the wrong procedure can result in serious morbidity. As such, it is important to appropriately define the anatomy and refer the complex cases to a specialist comfortable and skilled in managing congenital anomalies, usually a pediatric and adolescent gynecologist or reproductive endocrinologist.

Imperforate hymen

Examination of the external genitalia reveals a perineal bulge secondary to hematocolpos.7 This finding, coupled with a rectal examination and pelvic ultrasonography is usually sufficient to make the diagnosis.6,8 However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis should be obtained in cases where the diagnosis is uncertain or the physical exam is more consistent with vaginal septum or agenesis.

Transverse vaginal septum

A reverse septum results from failure of the müllerian duct derivatives and UGS to fuse or canalize. This can occur in the lower, middle, or upper portion of the vagina, and septa may be thick or thin.6 Low transverse septa are more easily confused with imperforate hymen. Examination usually reveals a normal hymen with a short vagina posteriorly. In cases of extreme hematocolpos, vaginal septa also may present with a perineal bulge but, again, this will be posterior to a normal hymen.

Distal vaginal atresia

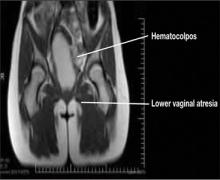

This condition occurs during embryonic development when the UGS fails to contribute to the lower portion of the vagina (FIGURE 2).5 In cases of distal vaginal atresia there is a lack of vaginal orifice, or only a vaginal dimple may be present.5,6 Rectovaginal examination will reveal a palpable mass if the upper vagina is distended with blood.6

Figure 2. Lower vaginal atresia

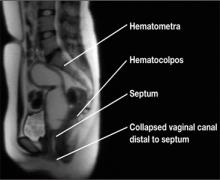

MRI is vital to firm diagnosis

In addition to pelvic ultrasonography, pelvic MRI is necessary to delineate the anatomy with both vaginal septum (FIGURE 3) and lower vaginal atresia (FIGURE 4), as preoperative evaluation of location and thickness of a vaginal septum as well as measurement of the total length of agenesis is imperative.6-8 Misdiagnosis of the vaginal septa or atresia as an imperforate hymen can lead to significant scarring and stenosis and can make corrective surgical procedures difficult or suboptimal.

| Figure 3. MRI of transverse vaginal septum |

Figure 4. MRI of lower vaginal atresia

Surgical management: hymenectomy

Imperforate hymen is managed surgically with hymenectomy. Repair is generally reserved for the newborn period or, ideally, in adolescence, as at puberty the presence of estrogen aids in surgical repair and healing.5 Simple aspiration of hematocolpos/ mucocolpos can lead to ascending infection, and pyocolpos and should be avoided.6

The goal of hymenectomy is to:

-

open the hymeneal membrane to allow egress of fluid and menstrual flow

-

allow for tampon use

The procedure is relatively straightforward and usually is performed under general anesthesia, although regional anesthesia also is an option.

Steps to the varying hymenectomy incisions

Cruciate incision

1. Incise the hymen at the 2-, 4-, 8-, and 10-o’clock positions into four quadrants.

2. Excise the quadrants along the lateral wall of the vagina.

Elliptical incision

1. Make a circumferential incision with the Bovie electrocautery, incising the hymenal membrane close to the hymenal ring.

U-incision

1. Similar to the elliptical incision, use the Bovie electrocautery to incise the tissue close to the hymenal ring posterior and laterally in a “u” shape.

2. Make a horizontal incision superiorly to remove the extra tissue.

Vertical incision

This incision has been described in cases where there is an attempt to spare the hymen for religious or cultural preference.

1. Make a midline vertical hymenotomy less than 1 cm. Drain the borders of the hymen.

2. Apply suture obliquely to form a circular opening.

References

1. Dominguez C, Rock J, Horowitz I. Surgical conditions of the vagina and urethra. In: TeLinde’s Operative Gynecology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1997.

2. Basaran M, Usal D, Aydemir C. Hymen sparing surgery for imperforate hymen: case reports and review of literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22(4):e61–e64.

Tips to a successful procedure

Ensure adequate suctioning. Before starting the procedure, insert a Foley catheter to completely drain the bladder and delineate the urethra. Making an initial incision into the hymen usually results in the expulsion of the old blood and mucus, which can be very thick and viscous; therefore, it is important to have adequate suction tubing.

Prevent scarring. After evacuating the old blood and mucus, excise the hymeneal membrane with a cruciate incision as is traditionally described. Alternatively, some experts use an elliptical incision or u-incision. (See “Steps to the varying hymenectomy incisions”.) Prevent excision of the hymenal tissue too close to the vaginal mucosa, as this can lead to scarring and stenosis and dyspareunia.3

Suturing the mucosal margins is likely unnecessary in adolescent patients. After excision of the hymenal tissue, one option is to suture the mucosal margins of the hymenal ring in an interrupted fashion with a fine, delayed-absorbable suture. Alternatively, at our institution, where we employ the u-incision (FIGURE 5), we assure hemostasis of the mucosal margins and do not suture the margins. Suturing the margins is believed to prevent adherence of the edges; however, in the pubertal girl, adherence is unlikely secondary to estrogen exposure.

Figure 5. Surgical correction with u-incision

Avoid infection; do not irrigate. We do not recommend that you irrigate the vagina and perform unnecessary uterine manipulation, as this may introduce bacteria into the dilated cervix and uterus.3,8

Septate/microperforate/cribiform hymen

These other hymeneal anomalies also may require surgical correction if they become clinically significant. Patients may present with difficulty inserting or removing a tampon, insertional dyspareunia, or incomplete drainage of menstrual blood.6

Imaging is usually not indicated to diagnose these hymenal anomalies, as physical examination will reveal a patent vaginal tract. A moistened Q-tip can be placed into the orifice or behind the septate hymen for confirmation (FIGURE 6).

Surgical correction of a microperforate or cribiform hymen is performed using the same principles as imperforate hymen.

Surgical correction of a septate hymen involves tying and suturing or clamping with a hemostat the upper and lower edges, with the excess hymenal tissue between the sutures then excised.8

Figure 6. Septate hymen

Postop care and follow up

Postoperative analgesia with lidocaine jelly or ice packs is usually sufficient for pain management. Reinforce proper hygienic care measures. At 2- to 3-week follow up, assess the patient for healing and evaluate the size of the hymenal orifice.

Key takeaways

-Differentiating imperforate hymen from low transverse vaginal septum or distal vaginal agenesis prior to surgery is of utmost importance because management is very different, and performing the wrong procedure can result in serious morbidity.

-With imperforate hymen, examination of the external genitalia reveals a perineal bulge secondary to hematocolpos.

-Pelvic MRI is essential to delineate the anatomy with both vaginal septum and agenesis, for preoperative evaluation of location and thickness of septum as well as measurement of total length of agenesis.

-Hymenectomy is relatively straightforward and may be performed using a cruciate, elliptical, or u-incision.

-Care should be taken to prevent excision of hymeneal tissue too close to the vaginal mucosa, as this can lead to scarring and stenosis, and later lead to dyspareunia.

Many gynecologists encounter imperforate hymen, a congenital vaginal anomaly, in general practice. As such, it is important to have a basic understanding of the condition and to be aware of appropriate screening, evaluation, and management. This knowledge will allow you to differentiate imperforate hymen from more complex anomalies—preventing significant morbidity that could result from performing the wrong surgical procedure on this condition—and to provide optimal surgical management.

How often and why does it occur?

Imperforate hymen occurs in approximately 1/1000 newborn girls. It is the most common obstructive anomaly of the female reproductive tract.1,2

The hymen consists of fibrous connective tissue attached to the vaginal wall. In the perinatal period, the hymen serves to separate the vaginal lumen from the urogenital sinus (UGS); this is usually perforated during embryonic life by canalization of the most caudal portion of the vaginal plate at the UGS. This establishes a connection between the lumen of the vaginal canal and the vaginal vestibule.3 Failure of the hymen to perforate completely in the perinatal period can result in varying anomalies, including imperforate (FIGURE 1), microperforate, cribiform, or septated hymen.

Figure 1. Imperforate hymen

How does it present?

Its presentation is variable and frequently asymptomatic in infants and children.4 As a result, the diagnosis is often delayed until puberty.3

In infancy. Newborns typically will present with a hymenal bulge from hydrocolpos or mucocolpos, which result from maternal estrogen secretion on the newborn’s vaginal epithelium.5 This is usually asymptomatic and self limited.

Rarely, large hydrocolpos/mucocolpos may become symptomatic and can lead to urinary obstruction, or they can present as an abdominal mass or intestinal obstruction.4

In adolescence. The majority of adolescents will present with cyclic or persistent pelvic pain and primary amenorrhea. If significant hematometra is present, an abdominal mass also may be palpated. In extreme cases, the patient may present with mass effect symptoms, including back pain, pain with defecation, constipation, nausea and vomiting, urinary retention, or hydronephrosis.6 Retrograde passage of blood into the fallopian tubes can cause hematosalpinx, which can lead to endometriosis and adhesion formation. Blood also may pass freely into the peritoneal cavity, forming hemoperitoneum.3

Related article: Your age-based guide to comprehensive well-woman care

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (October 2012)

Imperforate hymen, vaginal septum, or distal vaginal atresia?

When in doubt, refer. Imperforate hymen can be confused with distal vaginal atresia or low transverse vaginal septum. Often, the patient may present with similar signs and symptoms in all 3 cases. Accurately differentiating imperforate hymen from the former two more complex congenital anomalies prior to surgery is of utmost importance because management is very different, and performing the wrong procedure can result in serious morbidity. As such, it is important to appropriately define the anatomy and refer the complex cases to a specialist comfortable and skilled in managing congenital anomalies, usually a pediatric and adolescent gynecologist or reproductive endocrinologist.

Imperforate hymen

Examination of the external genitalia reveals a perineal bulge secondary to hematocolpos.7 This finding, coupled with a rectal examination and pelvic ultrasonography is usually sufficient to make the diagnosis.6,8 However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis should be obtained in cases where the diagnosis is uncertain or the physical exam is more consistent with vaginal septum or agenesis.

Transverse vaginal septum

A reverse septum results from failure of the müllerian duct derivatives and UGS to fuse or canalize. This can occur in the lower, middle, or upper portion of the vagina, and septa may be thick or thin.6 Low transverse septa are more easily confused with imperforate hymen. Examination usually reveals a normal hymen with a short vagina posteriorly. In cases of extreme hematocolpos, vaginal septa also may present with a perineal bulge but, again, this will be posterior to a normal hymen.

Distal vaginal atresia

This condition occurs during embryonic development when the UGS fails to contribute to the lower portion of the vagina (FIGURE 2).5 In cases of distal vaginal atresia there is a lack of vaginal orifice, or only a vaginal dimple may be present.5,6 Rectovaginal examination will reveal a palpable mass if the upper vagina is distended with blood.6

Figure 2. Lower vaginal atresia

MRI is vital to firm diagnosis

In addition to pelvic ultrasonography, pelvic MRI is necessary to delineate the anatomy with both vaginal septum (FIGURE 3) and lower vaginal atresia (FIGURE 4), as preoperative evaluation of location and thickness of a vaginal septum as well as measurement of the total length of agenesis is imperative.6-8 Misdiagnosis of the vaginal septa or atresia as an imperforate hymen can lead to significant scarring and stenosis and can make corrective surgical procedures difficult or suboptimal.

| Figure 3. MRI of transverse vaginal septum |

Figure 4. MRI of lower vaginal atresia

Surgical management: hymenectomy

Imperforate hymen is managed surgically with hymenectomy. Repair is generally reserved for the newborn period or, ideally, in adolescence, as at puberty the presence of estrogen aids in surgical repair and healing.5 Simple aspiration of hematocolpos/ mucocolpos can lead to ascending infection, and pyocolpos and should be avoided.6

The goal of hymenectomy is to:

-

open the hymeneal membrane to allow egress of fluid and menstrual flow

-

allow for tampon use

The procedure is relatively straightforward and usually is performed under general anesthesia, although regional anesthesia also is an option.

Steps to the varying hymenectomy incisions

Cruciate incision

1. Incise the hymen at the 2-, 4-, 8-, and 10-o’clock positions into four quadrants.

2. Excise the quadrants along the lateral wall of the vagina.

Elliptical incision

1. Make a circumferential incision with the Bovie electrocautery, incising the hymenal membrane close to the hymenal ring.

U-incision

1. Similar to the elliptical incision, use the Bovie electrocautery to incise the tissue close to the hymenal ring posterior and laterally in a “u” shape.

2. Make a horizontal incision superiorly to remove the extra tissue.

Vertical incision

This incision has been described in cases where there is an attempt to spare the hymen for religious or cultural preference.

1. Make a midline vertical hymenotomy less than 1 cm. Drain the borders of the hymen.

2. Apply suture obliquely to form a circular opening.

References

1. Dominguez C, Rock J, Horowitz I. Surgical conditions of the vagina and urethra. In: TeLinde’s Operative Gynecology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1997.

2. Basaran M, Usal D, Aydemir C. Hymen sparing surgery for imperforate hymen: case reports and review of literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22(4):e61–e64.

Tips to a successful procedure

Ensure adequate suctioning. Before starting the procedure, insert a Foley catheter to completely drain the bladder and delineate the urethra. Making an initial incision into the hymen usually results in the expulsion of the old blood and mucus, which can be very thick and viscous; therefore, it is important to have adequate suction tubing.

Prevent scarring. After evacuating the old blood and mucus, excise the hymeneal membrane with a cruciate incision as is traditionally described. Alternatively, some experts use an elliptical incision or u-incision. (See “Steps to the varying hymenectomy incisions”.) Prevent excision of the hymenal tissue too close to the vaginal mucosa, as this can lead to scarring and stenosis and dyspareunia.3

Suturing the mucosal margins is likely unnecessary in adolescent patients. After excision of the hymenal tissue, one option is to suture the mucosal margins of the hymenal ring in an interrupted fashion with a fine, delayed-absorbable suture. Alternatively, at our institution, where we employ the u-incision (FIGURE 5), we assure hemostasis of the mucosal margins and do not suture the margins. Suturing the margins is believed to prevent adherence of the edges; however, in the pubertal girl, adherence is unlikely secondary to estrogen exposure.

Figure 5. Surgical correction with u-incision

Avoid infection; do not irrigate. We do not recommend that you irrigate the vagina and perform unnecessary uterine manipulation, as this may introduce bacteria into the dilated cervix and uterus.3,8

Septate/microperforate/cribiform hymen

These other hymeneal anomalies also may require surgical correction if they become clinically significant. Patients may present with difficulty inserting or removing a tampon, insertional dyspareunia, or incomplete drainage of menstrual blood.6

Imaging is usually not indicated to diagnose these hymenal anomalies, as physical examination will reveal a patent vaginal tract. A moistened Q-tip can be placed into the orifice or behind the septate hymen for confirmation (FIGURE 6).

Surgical correction of a microperforate or cribiform hymen is performed using the same principles as imperforate hymen.

Surgical correction of a septate hymen involves tying and suturing or clamping with a hemostat the upper and lower edges, with the excess hymenal tissue between the sutures then excised.8

Figure 6. Septate hymen

Postop care and follow up

Postoperative analgesia with lidocaine jelly or ice packs is usually sufficient for pain management. Reinforce proper hygienic care measures. At 2- to 3-week follow up, assess the patient for healing and evaluate the size of the hymenal orifice.

Key takeaways

-Differentiating imperforate hymen from low transverse vaginal septum or distal vaginal agenesis prior to surgery is of utmost importance because management is very different, and performing the wrong procedure can result in serious morbidity.

-With imperforate hymen, examination of the external genitalia reveals a perineal bulge secondary to hematocolpos.

-Pelvic MRI is essential to delineate the anatomy with both vaginal septum and agenesis, for preoperative evaluation of location and thickness of septum as well as measurement of total length of agenesis.

-Hymenectomy is relatively straightforward and may be performed using a cruciate, elliptical, or u-incision.

-Care should be taken to prevent excision of hymeneal tissue too close to the vaginal mucosa, as this can lead to scarring and stenosis, and later lead to dyspareunia.

Many gynecologists encounter imperforate hymen, a congenital vaginal anomaly, in general practice. As such, it is important to have a basic understanding of the condition and to be aware of appropriate screening, evaluation, and management. This knowledge will allow you to differentiate imperforate hymen from more complex anomalies—preventing significant morbidity that could result from performing the wrong surgical procedure on this condition—and to provide optimal surgical management.

How often and why does it occur?

Imperforate hymen occurs in approximately 1/1000 newborn girls. It is the most common obstructive anomaly of the female reproductive tract.1,2

The hymen consists of fibrous connective tissue attached to the vaginal wall. In the perinatal period, the hymen serves to separate the vaginal lumen from the urogenital sinus (UGS); this is usually perforated during embryonic life by canalization of the most caudal portion of the vaginal plate at the UGS. This establishes a connection between the lumen of the vaginal canal and the vaginal vestibule.3 Failure of the hymen to perforate completely in the perinatal period can result in varying anomalies, including imperforate (FIGURE 1), microperforate, cribiform, or septated hymen.

Figure 1. Imperforate hymen

How does it present?

Its presentation is variable and frequently asymptomatic in infants and children.4 As a result, the diagnosis is often delayed until puberty.3

In infancy. Newborns typically will present with a hymenal bulge from hydrocolpos or mucocolpos, which result from maternal estrogen secretion on the newborn’s vaginal epithelium.5 This is usually asymptomatic and self limited.

Rarely, large hydrocolpos/mucocolpos may become symptomatic and can lead to urinary obstruction, or they can present as an abdominal mass or intestinal obstruction.4

In adolescence. The majority of adolescents will present with cyclic or persistent pelvic pain and primary amenorrhea. If significant hematometra is present, an abdominal mass also may be palpated. In extreme cases, the patient may present with mass effect symptoms, including back pain, pain with defecation, constipation, nausea and vomiting, urinary retention, or hydronephrosis.6 Retrograde passage of blood into the fallopian tubes can cause hematosalpinx, which can lead to endometriosis and adhesion formation. Blood also may pass freely into the peritoneal cavity, forming hemoperitoneum.3

Related article: Your age-based guide to comprehensive well-woman care

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (October 2012)

Imperforate hymen, vaginal septum, or distal vaginal atresia?

When in doubt, refer. Imperforate hymen can be confused with distal vaginal atresia or low transverse vaginal septum. Often, the patient may present with similar signs and symptoms in all 3 cases. Accurately differentiating imperforate hymen from the former two more complex congenital anomalies prior to surgery is of utmost importance because management is very different, and performing the wrong procedure can result in serious morbidity. As such, it is important to appropriately define the anatomy and refer the complex cases to a specialist comfortable and skilled in managing congenital anomalies, usually a pediatric and adolescent gynecologist or reproductive endocrinologist.

Imperforate hymen

Examination of the external genitalia reveals a perineal bulge secondary to hematocolpos.7 This finding, coupled with a rectal examination and pelvic ultrasonography is usually sufficient to make the diagnosis.6,8 However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis should be obtained in cases where the diagnosis is uncertain or the physical exam is more consistent with vaginal septum or agenesis.

Transverse vaginal septum

A reverse septum results from failure of the müllerian duct derivatives and UGS to fuse or canalize. This can occur in the lower, middle, or upper portion of the vagina, and septa may be thick or thin.6 Low transverse septa are more easily confused with imperforate hymen. Examination usually reveals a normal hymen with a short vagina posteriorly. In cases of extreme hematocolpos, vaginal septa also may present with a perineal bulge but, again, this will be posterior to a normal hymen.

Distal vaginal atresia

This condition occurs during embryonic development when the UGS fails to contribute to the lower portion of the vagina (FIGURE 2).5 In cases of distal vaginal atresia there is a lack of vaginal orifice, or only a vaginal dimple may be present.5,6 Rectovaginal examination will reveal a palpable mass if the upper vagina is distended with blood.6

Figure 2. Lower vaginal atresia

MRI is vital to firm diagnosis

In addition to pelvic ultrasonography, pelvic MRI is necessary to delineate the anatomy with both vaginal septum (FIGURE 3) and lower vaginal atresia (FIGURE 4), as preoperative evaluation of location and thickness of a vaginal septum as well as measurement of the total length of agenesis is imperative.6-8 Misdiagnosis of the vaginal septa or atresia as an imperforate hymen can lead to significant scarring and stenosis and can make corrective surgical procedures difficult or suboptimal.

| Figure 3. MRI of transverse vaginal septum |

Figure 4. MRI of lower vaginal atresia

Surgical management: hymenectomy

Imperforate hymen is managed surgically with hymenectomy. Repair is generally reserved for the newborn period or, ideally, in adolescence, as at puberty the presence of estrogen aids in surgical repair and healing.5 Simple aspiration of hematocolpos/ mucocolpos can lead to ascending infection, and pyocolpos and should be avoided.6

The goal of hymenectomy is to:

-

open the hymeneal membrane to allow egress of fluid and menstrual flow

-

allow for tampon use

The procedure is relatively straightforward and usually is performed under general anesthesia, although regional anesthesia also is an option.

Steps to the varying hymenectomy incisions

Cruciate incision

1. Incise the hymen at the 2-, 4-, 8-, and 10-o’clock positions into four quadrants.

2. Excise the quadrants along the lateral wall of the vagina.

Elliptical incision

1. Make a circumferential incision with the Bovie electrocautery, incising the hymenal membrane close to the hymenal ring.

U-incision

1. Similar to the elliptical incision, use the Bovie electrocautery to incise the tissue close to the hymenal ring posterior and laterally in a “u” shape.

2. Make a horizontal incision superiorly to remove the extra tissue.

Vertical incision

This incision has been described in cases where there is an attempt to spare the hymen for religious or cultural preference.

1. Make a midline vertical hymenotomy less than 1 cm. Drain the borders of the hymen.

2. Apply suture obliquely to form a circular opening.

References

1. Dominguez C, Rock J, Horowitz I. Surgical conditions of the vagina and urethra. In: TeLinde’s Operative Gynecology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1997.

2. Basaran M, Usal D, Aydemir C. Hymen sparing surgery for imperforate hymen: case reports and review of literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22(4):e61–e64.

Tips to a successful procedure

Ensure adequate suctioning. Before starting the procedure, insert a Foley catheter to completely drain the bladder and delineate the urethra. Making an initial incision into the hymen usually results in the expulsion of the old blood and mucus, which can be very thick and viscous; therefore, it is important to have adequate suction tubing.

Prevent scarring. After evacuating the old blood and mucus, excise the hymeneal membrane with a cruciate incision as is traditionally described. Alternatively, some experts use an elliptical incision or u-incision. (See “Steps to the varying hymenectomy incisions”.) Prevent excision of the hymenal tissue too close to the vaginal mucosa, as this can lead to scarring and stenosis and dyspareunia.3

Suturing the mucosal margins is likely unnecessary in adolescent patients. After excision of the hymenal tissue, one option is to suture the mucosal margins of the hymenal ring in an interrupted fashion with a fine, delayed-absorbable suture. Alternatively, at our institution, where we employ the u-incision (FIGURE 5), we assure hemostasis of the mucosal margins and do not suture the margins. Suturing the margins is believed to prevent adherence of the edges; however, in the pubertal girl, adherence is unlikely secondary to estrogen exposure.

Figure 5. Surgical correction with u-incision

Avoid infection; do not irrigate. We do not recommend that you irrigate the vagina and perform unnecessary uterine manipulation, as this may introduce bacteria into the dilated cervix and uterus.3,8

Septate/microperforate/cribiform hymen

These other hymeneal anomalies also may require surgical correction if they become clinically significant. Patients may present with difficulty inserting or removing a tampon, insertional dyspareunia, or incomplete drainage of menstrual blood.6

Imaging is usually not indicated to diagnose these hymenal anomalies, as physical examination will reveal a patent vaginal tract. A moistened Q-tip can be placed into the orifice or behind the septate hymen for confirmation (FIGURE 6).

Surgical correction of a microperforate or cribiform hymen is performed using the same principles as imperforate hymen.

Surgical correction of a septate hymen involves tying and suturing or clamping with a hemostat the upper and lower edges, with the excess hymenal tissue between the sutures then excised.8

Figure 6. Septate hymen

Postop care and follow up

Postoperative analgesia with lidocaine jelly or ice packs is usually sufficient for pain management. Reinforce proper hygienic care measures. At 2- to 3-week follow up, assess the patient for healing and evaluate the size of the hymenal orifice.

Key takeaways

-Differentiating imperforate hymen from low transverse vaginal septum or distal vaginal agenesis prior to surgery is of utmost importance because management is very different, and performing the wrong procedure can result in serious morbidity.

-With imperforate hymen, examination of the external genitalia reveals a perineal bulge secondary to hematocolpos.

-Pelvic MRI is essential to delineate the anatomy with both vaginal septum and agenesis, for preoperative evaluation of location and thickness of septum as well as measurement of total length of agenesis.

-Hymenectomy is relatively straightforward and may be performed using a cruciate, elliptical, or u-incision.

-Care should be taken to prevent excision of hymeneal tissue too close to the vaginal mucosa, as this can lead to scarring and stenosis, and later lead to dyspareunia.

The Affordable Care Act and the drive for electronic health records: Are small practices being squeezed?