User login

Mild cognitive impairment: Hope for stability, plan for progression

As our population ages, people are thinking more about preserving their quality of life, especially with regard to maintaining their cognitive and functional abilities. Older patients and caregivers often raise concerns about cognitive issues to their primary care providers: many patients have memory complaints, are worried about whether these are merely part of normal aging or symptoms of early dementia, and want strategies to forestall the progression of cognitive impairment.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a heterogeneous syndrome that in some cases represents a transition between normal aging and dementia. However, this condition is not yet well understood. Although some patients progress to dementia, others remain stable, or even improve. This article will review the current definitions and the underlying physiology of MCI, as well as diagnostic and management strategies.

COGNITIVE CHANGES OCCUR WITH NORMAL AGING

Cognition is defined as a means of acquiring and processing information about ourselves and our world. It includes memory as well as other domains such as attention, visuospatial skills, mental processing speed, language, and executive function. Cognitive abilities typically peak between ages 30 and 40, plateau in our 50s and 60s, and decline in our late 70s.

With age come detectable changes in the brain: brain weight declines by 10% by age 80, blood flow diminishes, neurons are lost throughout life, and nerve conduction slows. Despite these changes, the brain has a great deal of functional reserve capacity.

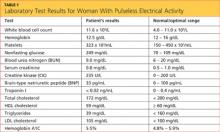

Table 1 compares the signs of normal aging, MCI, and dementia. Normally, cognitive abilities decline gradually with age without affecting overall function or activities of daily living. Even in normal aging, the processing of new information (new learning) is reduced. Mental processing becomes less efficient and slower. Visuospatial skills gradually decline, recall slows, and ultimately, the speed of performance slows as well. Additionally, distractibility increases. On the other hand, normal aging does not affect recognition, intelligence, or long-term memory.1

The line between the normal effects of aging on cognition and true pathologic cognitive decline is blurry. In a busy clinical practice, it is often difficult to determine whether problems with memory and cognition that elderly patients and their family members describe represent true pathologic decline. In general, the clinical presentation of MCI is more profound than that of age-associated cognitive impairment: whereas normal aging may involve forgetting names and words and misplacing things, MCI frequently involves forgetting conversations, information that one would ordinarily remember, appointments, and planned events.

BETWEEN NORMAL AGING AND DEMENTIA

MCI is a transitional state between normal cognition and dementia. But the course is not inevitably downward: on follow-up, patients with MCI may be better, stable, or worse (see PROGNOSIS VARIES, below).

On autopsy studies, the brains of people with MCI appear intermediate between normal brains and brains of people with Alzheimer-type dementia, which have neurofibrillary tangles, amyloid senile plaques, and neuronal degeneration.

Definitions of MCI vary

True cognitive decline that is more profound than normal aging was named and defined differently in different studies, making comparisons difficult. The concept of MCI arose from the term “benign senescent forgetfulness,” used by Kral in 1962.2 Other early terms include “cognitive impairment no dementia,” “memory impairment,” “mild cognitive disorder,” and “mild neurocognitive disorder.”3,4

MCI was first defined as a precursor to Alzheimer dementia. The term later described a sometimes reversible but abnormal state. It is a heterogeneous syndrome in terms of etiology, incidence, prevalence, presentation, and overall prognosis.

Most recently, MCI has been defined as5,6:

- Subjective memory complaints, preferably qualified by another person

- Memory impairment, with consideration for age and education

- Preserved general cognitive function

- Intact activities of daily living

- Absence of overt dementia.

MCI may arise from vascular, neurodegenerative, traumatic, metabolic, psychiatric, and other underlying medical disorders.7–9

The prevalence of MCI is difficult to determine because of the various definitions, populations studied (eg, clinic-based vs community-dwelling), and evaluation techniques. Published rates vary from 2% to 4% in all patients to 10% to 20% in the elderly. Incidence rates in the elderly vary from 14 to 75 per 1,000 patient-years.10–14

EARLY RECOGNITION ALLOWS PROMPT EVALUATION AND PLANNING

Pathologic cognitive decline is best detected early, for many reasons. Early recognition and intervention may help delay further decline. Establishing a diagnosis can also lessen family and caregiver stress and misunderstanding. Education of caregivers is important so that they can prepare for likely behavioral changes and plan for future care. Advance care planning, including advance directives, power of attorney, and designation of proxy for decision-making, is extremely important and is best considered before cognitive impairment becomes severe.

The diagnosis of MCI also provides the opportunity to assess safety concerns related to driving, working, medication compliance, the home environment, and firearms. Because patients with MCI are still highly functional, these issues need not be fully evaluated and should be handled on a case-by-case basis, depending on concerns raised. For example, if depression is an active concern, firearms safety should be addressed.

MEMORY LOSS MAY NOT BE THE PRIMARY CONCERN

MCI is categorized into two types based on whether memory loss is the primary cognitive deficit.

The amnestic type predominantly involves memory problems and is more common. Generally, several years elapse between initial memory concerns and a clinical diagnosis of MCI. Patients with amnestic MCI that progresses to dementia are more likely to develop Alzheimer disease.2,15

Nonamnestic types involve domains of cognition other than memory, such as executive function, attention, visuospatial ability, and language. Nonamnestic MCI can be subcategorized through extensive neuropsychological evaluation as involving single or multiple impaired domains.16,17 Such categorization is particularly important in determining prognosis, as patients with involvement of multiple domains are at higher risk of progressing to dementia.

Patients with nonamnestic MCI who progress to dementia are more likely to have non-Alzheimer types of dementia, such as Lewy body dementia and frontotemporal dementias.10

HISTORY SHOULD FOCUS ON FUNCTION, MEDICATIONS, AND DEPRESSION

Cognitive impairment should be clinically evaluated within the context of cognition, function, and behavior. Clinicians should focus on the time course of cognitive concerns, the specifics of the concerns, and their impact on day-to-day living and functioning. In assessing functional capacity, it is important to determine the level of assistance the patient needs to perform specific activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living (ie, the more advanced skills needed to live independently) (Table 2).

A thorough history includes consideration of baseline education, intellect, and previous learning disabilities; sensory impairments with emphasis on sight and hearing impairments; uncontrolled pain; head trauma; sleep disorders; concurrent medical and psychosocial illnesses such as depression and anxiety; substance abuse; and polypharmacy.

Depression, delirium, and the use of anticholinergic drugs are particularly important to evaluate, as these can result in cognitive deficits associated with MCI. The cognitive deficits may resolve with treatment or with stopping the drug.

Behavioral concerns such as wandering, agitation, and anger and sleep concerns, eating habits, and social etiquette are also important to evaluate.

PHYSICAL EVALUATION: RULE OUT REVERSIBLE CONDITIONS

The differential diagnosis of MCI includes delirium, depression, dementia, possibly reversible conditions affecting cognition (vitamin B12 deficiency, hypothyroidism, effects of anticholinergic drugs), and uncommonly, central nervous system conditions (normal pressure hydrocephalus, subdural hematoma, tumor, stroke), and others (Table 3).18

A thorough physical examination should include neurologic, cardiovascular, hearing, and vision examinations, as well as an evaluation of functional status.

Laboratory studies. Although evidence is lacking to support a laboratory diagnostic workup for MCI, a selective evaluation including a comprehensive metabolic profile, complete blood count, thyroid studies, and a vitamin B12 level can be useful. Occasionally, a treatable cause of impaired cognition such as vitamin B12 deficiency or thyroid disease can be identified and resolved. A further comprehensive laboratory evaluation should be obtained if a patient progresses to dementia.

Imaging can be used in conjunction with other supportive evidence but should not be used solely to establish a diagnosis of MCI. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can detect metastatic disease, normal pressure hydrocephalus, and subdural hematoma, in addition to traumatic, inflammatory, infectious, and vascular causes of cognitive impairment. MRI can also determine focal areas of atrophy; temporal lobe atrophy is a risk factor for progression to dementia.

Other studies. Structural MRI using techniques to evaluate the hippocampus, functional imaging, genetic testing for ApoE4 alleles, and biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid are currently under evaluation to identify those at risk of progression to dementia. Recently published guidelines by the Alzheimer’s Association and the National Institute on Aging indicate that pathophysiologic findings in MCI that may predict future Alzheimer disease are meant to guide research and are not part of clinical practice at this time.19

COGNITIVE AND NEUROLOGIC TESTING IDENTIFIES DEFICITS

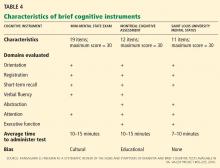

A number of global measures of cognition can be used in the office in clinical practice to help in evaluating significant cognitive concerns and to determine areas and severity of deficits at presentation. These include the Mini-Mental State Examination, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, the Saint Louis University Mental Status, and many others (Table 4).20

Caveats about interpreting the results: each of these tests has different sensitivities and specificities for detecting MCI. Also, we need to take into account the patient’s level of education, as highly educated people tend to do better on these tests.21–23 It is important to note that some patients with MCI have normal results or only minimally abnormal results on these tests.

Neuropsychological testing is reserved for patients needing further evaluation, eg, those with atypical or complex cases, and those in whom the specific domains of cognition involved need to be identified. It can also provide additional insight into the contribution of depression to cognitive deficits. Neuropsychological testing is usually very time-intensive and requires patients to be able to perform complicated cognitive tasks. Not all patients are good candidates for this testing; sensory and motor impairments must be considered to determine if patients can adequately participate in testing. The cost of neuropsychological testing for MCI may not be covered by insurance and should be discussed with patients before referral. Specific concerns about cognitive problems that need further evaluation should be stated in the referral.

No one test should be used to make a diagnosis of MCI or dementia; clinical judgment is also necessary. The need for referral to a neurologist, geriatrician, or psychiatrist depends on the nature of the cognitive and behavioral concerns, the complexity of making a diagnosis, the need for further assessment of functional ability, and the need for evaluation of risk of progression to dementia.

MEDICATIONS HAVE LITTLE ROLE IN MANAGEMENT

No drug has yet been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treating MCI.

The acetylcholinesterase inhibitors donepezil (Aricept), galantamine (Razadyne), and rivastigmine (Exelon) have undergone clinical trials for treatment of MCI but have not been definitely shown to significantly reduce the risk of progression to dementia.24

On the other hand, Diniz et al25 performed a meta-analysis of the use of cholinesterase inhibitors in patients with MCI as a means of delaying the progression to Alzheimer disease.25 They calculated that 15.4% of patients who received these drugs progressed to dementia, compared with 20.4% of those who received placebo, for a relative risk of 0.75 (95% confidence interval 0.66–0.87, P < .001). They concluded that the use of these drugs in patients with MCI “may attenuate the risk of progression” to Alzheimer disease and dementia.

In addition to not being approved for this indication and showing mixed evidence of efficacy, these drugs have well-known side effects such as diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and rhinitis, as well as significant but lesser-known side effects such as syncope, bradycardia, gastrointestinal bleeding, and vivid dreams.26

Nevertheless, some patients with MCI, particularly those at high risk with amnestic MCI, may still want to try these medications. In these cases, the risks and possible benefits (or lack of them) should be reviewed thoroughly with the patient and family, and the discussion should be documented before starting therapy. The lowest starting dose of acetylcholinesterase inhibitor should be used to determine tolerability; generally, the dose is increased after 4 weeks to a maintenance dosage, with particular consideration of side effects.

Other agents have also been evaluated for MCI but have shown no evidence of benefit. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have not been found to either improve symptoms or delay progression to dementia. Ginkgo biloba has shown unclear benefit in achieving important treatment goals for MCI,27 and it increases the risk of bleeding in the elderly. Vitamin E was evaluated in one study and did not slow progression to dementia.28

STAYING HEALTHY AND ACTIVE MAY HELP

We recommend optimizing vascular risk factors such as diabetes, blood pressure, smoking, and lipid levels in managing MCI, given that uncontrolled vascular risk factors may lead to progression to dementia. However, we can point to no research to support this recommendation.

Cognitive rehabilitation involves training in deficient domains and developing strategies to compensate for deficits. Different interventions are used, including computerized simulation exercises, memory aids, organizational techniques, personal digital assistants, crossword puzzles, mind games, and other mentally engaging activities.29

Increasing physical activity is another aspect of treatment. Some studies have shown that it improves cognitive performance in MCI, at least in the short term.30,31

Optimizing mood and emotions is also important. If present, depression should be identified and optimally treated. Social activity can be useful and leads to less emotional stress and to better coping mechanisms.

A multidisciplinary approach may help patients and may also help relieve the burden on the caregiver. Periodic reassessment of cognitive and functional symptoms may be warranted.

Maintaining disease-specific registries of patients who have MCI may be useful to longitudinally follow patients and ensure that they get the care they need.

PROGNOSIS VARIES

MCI is a heterogeneous condition that often does not predictably progress to dementia. Patients and families should be told that having MCI does not mean that the patient will necessarily get dementia.

Several studies have shown that the annual risk of progression to dementia for patients with MCI is 5% to 10% in community-dwelling populations and up to 15% in specialty-clinic patients.24,32 In comparison, the incidence of dementia in the general elderly population is 1% to 3% per year.

On the other hand, a number of studies show that MCI improves significantly in up to 15% to 40% of patients and sometimes reverts to a normal cognitive state.33,34 But prospective studies of patients with clinically diagnosed MCI usually find a low rate of reversion to a normal state.35,36 Many are short-term follow-up studies of different populations, making generalizations difficult.14

Patients with impairment in instrumental activities of daily living may be more likely to have nonreversible MCI and may be at higher risk of progressing to dementia.37

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION AND FOLLOW-UP CONSIDERATIONS

Caregiver education and stress management are important components of managing patients with MCI. Formally assessing caregiver stress is useful. Steps to prevent caregiver burnout include making use of respite care, counseling, education, and community resources such as adult day care and those offered by the Alzheimer’s Association.

Clinicians should follow patients with MCI closely to evaluate progression, address specific concerns, minimize risks, emphasize healthy habits, manage concurrent illnesses, and evaluate management.

Functional status, as demonstrated by activities of daily living, is the most important determinant of progression of MCI to dementia and should be evaluated at each visit. Repeat cognitive testing should be done on patients who have significant loss of functional status. Changes in work habits also warrant further attention.

Patients diagnosed with MCI or those who have persistent cognitive concerns should be considered for neuropsychological evaluation after 1 year to assess specific deficits and progression of cognitive impairment.

Finally, consideration should be given to current clinical research, and referrals should be made to research centers that focus on MCI management and treatment.

- Keefover RW. Aging and cognition. Neurol Clin 1998; 16:635–648.

- Kral VA. Senescent forgetfulness: benign and malignant. Can Med Assoc J 1962; 86:257–260.

- Bischkopf J, Busse A, Angermeyer MC. Mild cognitive impairment—a review of prevalence, incidence and outcome according to current approaches. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2002; 106:403–414.

- Petersen RC, Stevens JC, Ganguli M, Tangalos EG, Cummings JL, DeKosky ST. Practice parameter: early detection of dementia: mild cognitive impairment (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2001; 56:1133–1142.

- Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol 1999; 56:303–308.

- Petersen RC, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: ten years later. Arch Neurol 2009; 66:1447–1455.

- Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Bienias JL, et al. Mild cognitive impairment is related to Alzheimer disease pathology and cerebral infarctions. Neurology 2005; 64:834–841.

- Petersen RC, Parisi JE, Dickson DW, et al. Neuropathologic features of amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 2006; 63:665–672.

- Guillozet AL, Weintraub S, Mash DC, Mesulam MM. Neurofibrillary tangles, amyloid, and memory in aging and mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 2003; 60:729–736.

- Molano J, Boeve B, Ferman T, et al. Mild cognitive impairment associated with limbic and neocortical Lewy body disease: a clinicopathological study. Brain 2010; 133:540–556.

- Lopez OL, Jagust WJ, DeKosky ST, et al. Prevalence and classification of mild cognitive impairment in the Cardiovascular Health Study Cognition Study: part 1. Arch Neurol 2003; 60:1385–1389.

- Petersen RC, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, et al. Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment is higher in men. The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Neurology 2010; 75:889–897.

- Manly JJ, Tang MX, Schupf N, Stern Y, Vonsattel JP, Mayeux R. Frequency and course of mild cognitive impairment in a multiethnic community. Ann Neurol 2008; 63:494–506.

- Luck T, Luppa M, Briel S, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: incidence and risk factors: results of the Leipzig Longitudinal Study of the Aged. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010; 58:1903–1910.

- Roberts RO, Geda YE, Knopman DS, et al. The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging: design and sampling, participation, baseline measures and sample characteristics. Neuroepidemiology 2008; 30:58–69.

- Bozoki A, Giordani B, Heidebrink JL, Berent S, Foster NL. Mild cognitive impairments predict dementia in nondemented elderly patients with memory loss. Arch Neurol 2001; 58:411–416.

- DeCarli C. Mild cognitive impairment: prevalence, prognosis, aetiology, and treatment. Lancet Neurol 2003; 2:15–21.

- Graham JE, Rockwood K, Beattie BL, et al. Prevalence and severity of cognitive impairment with and without dementia in an elderly population. Lancet 1997; 349:1793–1796.

- Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011; 7:270–279.

- Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, Perry MH, Morley JE. Comparison of the Saint Louis University mental status examination and the Mini-Mental State Examination for detecting dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder—a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006; 14:900–910.

- Tang-Wai DF, Knopman DS, Geda YE, et al. Comparison of the short test of mental status and the Mini-Mental State Examination in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 2003; 60:1777–1781.

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53:695–699.

- Banks WA, Morley JE. Memories are made of this: recent advances in understanding cognitive impairments and dementia. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2003; 58:314–321.

- Petersen RC. Clinical practice. Mild cognitive impairment. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:2227–2234.

- Diniz BS, Pinto JA, Gonzaga MLC, Guimaraes FM, Gattaz WF, Forlenza OV. To treat or not to treat? A meta-analysis of the use of cholinesterase inhibitors in mild cognitive impairment for delaying progression to Alzheimer’s disease. Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurosci 2009; 259:248–256.

- Patel BB, Holland NW. Adverse effects of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Clin Geriatr 2011; 19:27–30.

- Birks J, Grimley Evans J. Ginkgo biloba for cognitive impairment and dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; 1:CD003120.

- Petersen RC, Thomas RG, Grundman M, et al; Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Group. Vitamin E and donepezil for the treatment of mild cognitive impairment. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:2379–2388.

- Jean L, Bergeron ME, Thivierge S, Simard M. Cognitive intervention programs for individuals with mild cognitive impairment: systematic review of the literature. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2010; 18:281–296.

- Lautenschlager NT, Cox KL, Flicker L, et al. Effect of physical activity on cognitive function in older adults at risk for Alzheimer disease: a randomized trial. JAMA 2008; 300:1027–1037.

- van Uffelen JG, Chinapaw MJ, van Mechelen W, Hopman-Rock M. Walking or vitamin B for cognition in older adults with mild cognitive impairment? A randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med 2008; 42:344–351.

- Farias ST, Mungas D, Reed BR, Harvey D, DeCarli C. Progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia in clinic-vs community-based cohorts. Arch Neurol 2009; 66:1151–1157.

- Ritchie K, Artero S, Touchon J. Classification criteria for mild cognitive impairment: a population-based validation study. Neurology 2001; 56:37–42.

- Larrieu S, Letenneur L, Orgogozo JM, et al. Incidence and outcome of mild cognitive impairment in a population-based prospective cohort. Neurology 2002; 59:1594–1599.

- Busse A, Hensel A, Gühne U, Angermeyer MC, Riedel-Heller SG. Mild cognitive impairment: long-term course of four clinical subtypes. Neurology 2006; 67:2176–2185.

- Fischer P, Jungwirth S, Zehetmayer S, et al. Conversion from subtypes of mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer dementia. Neurology 2007; 68:288–291.

- Pérès K, Chrysostome V, Fabrigoule C, Orgogozo JM, Dartigues JF, Barberger-Gateau P. Restriction in complex activities of daily living in MCI: impact on outcome. Neurology 2006; 67:461–466.

As our population ages, people are thinking more about preserving their quality of life, especially with regard to maintaining their cognitive and functional abilities. Older patients and caregivers often raise concerns about cognitive issues to their primary care providers: many patients have memory complaints, are worried about whether these are merely part of normal aging or symptoms of early dementia, and want strategies to forestall the progression of cognitive impairment.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a heterogeneous syndrome that in some cases represents a transition between normal aging and dementia. However, this condition is not yet well understood. Although some patients progress to dementia, others remain stable, or even improve. This article will review the current definitions and the underlying physiology of MCI, as well as diagnostic and management strategies.

COGNITIVE CHANGES OCCUR WITH NORMAL AGING

Cognition is defined as a means of acquiring and processing information about ourselves and our world. It includes memory as well as other domains such as attention, visuospatial skills, mental processing speed, language, and executive function. Cognitive abilities typically peak between ages 30 and 40, plateau in our 50s and 60s, and decline in our late 70s.

With age come detectable changes in the brain: brain weight declines by 10% by age 80, blood flow diminishes, neurons are lost throughout life, and nerve conduction slows. Despite these changes, the brain has a great deal of functional reserve capacity.

Table 1 compares the signs of normal aging, MCI, and dementia. Normally, cognitive abilities decline gradually with age without affecting overall function or activities of daily living. Even in normal aging, the processing of new information (new learning) is reduced. Mental processing becomes less efficient and slower. Visuospatial skills gradually decline, recall slows, and ultimately, the speed of performance slows as well. Additionally, distractibility increases. On the other hand, normal aging does not affect recognition, intelligence, or long-term memory.1

The line between the normal effects of aging on cognition and true pathologic cognitive decline is blurry. In a busy clinical practice, it is often difficult to determine whether problems with memory and cognition that elderly patients and their family members describe represent true pathologic decline. In general, the clinical presentation of MCI is more profound than that of age-associated cognitive impairment: whereas normal aging may involve forgetting names and words and misplacing things, MCI frequently involves forgetting conversations, information that one would ordinarily remember, appointments, and planned events.

BETWEEN NORMAL AGING AND DEMENTIA

MCI is a transitional state between normal cognition and dementia. But the course is not inevitably downward: on follow-up, patients with MCI may be better, stable, or worse (see PROGNOSIS VARIES, below).

On autopsy studies, the brains of people with MCI appear intermediate between normal brains and brains of people with Alzheimer-type dementia, which have neurofibrillary tangles, amyloid senile plaques, and neuronal degeneration.

Definitions of MCI vary

True cognitive decline that is more profound than normal aging was named and defined differently in different studies, making comparisons difficult. The concept of MCI arose from the term “benign senescent forgetfulness,” used by Kral in 1962.2 Other early terms include “cognitive impairment no dementia,” “memory impairment,” “mild cognitive disorder,” and “mild neurocognitive disorder.”3,4

MCI was first defined as a precursor to Alzheimer dementia. The term later described a sometimes reversible but abnormal state. It is a heterogeneous syndrome in terms of etiology, incidence, prevalence, presentation, and overall prognosis.

Most recently, MCI has been defined as5,6:

- Subjective memory complaints, preferably qualified by another person

- Memory impairment, with consideration for age and education

- Preserved general cognitive function

- Intact activities of daily living

- Absence of overt dementia.

MCI may arise from vascular, neurodegenerative, traumatic, metabolic, psychiatric, and other underlying medical disorders.7–9

The prevalence of MCI is difficult to determine because of the various definitions, populations studied (eg, clinic-based vs community-dwelling), and evaluation techniques. Published rates vary from 2% to 4% in all patients to 10% to 20% in the elderly. Incidence rates in the elderly vary from 14 to 75 per 1,000 patient-years.10–14

EARLY RECOGNITION ALLOWS PROMPT EVALUATION AND PLANNING

Pathologic cognitive decline is best detected early, for many reasons. Early recognition and intervention may help delay further decline. Establishing a diagnosis can also lessen family and caregiver stress and misunderstanding. Education of caregivers is important so that they can prepare for likely behavioral changes and plan for future care. Advance care planning, including advance directives, power of attorney, and designation of proxy for decision-making, is extremely important and is best considered before cognitive impairment becomes severe.

The diagnosis of MCI also provides the opportunity to assess safety concerns related to driving, working, medication compliance, the home environment, and firearms. Because patients with MCI are still highly functional, these issues need not be fully evaluated and should be handled on a case-by-case basis, depending on concerns raised. For example, if depression is an active concern, firearms safety should be addressed.

MEMORY LOSS MAY NOT BE THE PRIMARY CONCERN

MCI is categorized into two types based on whether memory loss is the primary cognitive deficit.

The amnestic type predominantly involves memory problems and is more common. Generally, several years elapse between initial memory concerns and a clinical diagnosis of MCI. Patients with amnestic MCI that progresses to dementia are more likely to develop Alzheimer disease.2,15

Nonamnestic types involve domains of cognition other than memory, such as executive function, attention, visuospatial ability, and language. Nonamnestic MCI can be subcategorized through extensive neuropsychological evaluation as involving single or multiple impaired domains.16,17 Such categorization is particularly important in determining prognosis, as patients with involvement of multiple domains are at higher risk of progressing to dementia.

Patients with nonamnestic MCI who progress to dementia are more likely to have non-Alzheimer types of dementia, such as Lewy body dementia and frontotemporal dementias.10

HISTORY SHOULD FOCUS ON FUNCTION, MEDICATIONS, AND DEPRESSION

Cognitive impairment should be clinically evaluated within the context of cognition, function, and behavior. Clinicians should focus on the time course of cognitive concerns, the specifics of the concerns, and their impact on day-to-day living and functioning. In assessing functional capacity, it is important to determine the level of assistance the patient needs to perform specific activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living (ie, the more advanced skills needed to live independently) (Table 2).

A thorough history includes consideration of baseline education, intellect, and previous learning disabilities; sensory impairments with emphasis on sight and hearing impairments; uncontrolled pain; head trauma; sleep disorders; concurrent medical and psychosocial illnesses such as depression and anxiety; substance abuse; and polypharmacy.

Depression, delirium, and the use of anticholinergic drugs are particularly important to evaluate, as these can result in cognitive deficits associated with MCI. The cognitive deficits may resolve with treatment or with stopping the drug.

Behavioral concerns such as wandering, agitation, and anger and sleep concerns, eating habits, and social etiquette are also important to evaluate.

PHYSICAL EVALUATION: RULE OUT REVERSIBLE CONDITIONS

The differential diagnosis of MCI includes delirium, depression, dementia, possibly reversible conditions affecting cognition (vitamin B12 deficiency, hypothyroidism, effects of anticholinergic drugs), and uncommonly, central nervous system conditions (normal pressure hydrocephalus, subdural hematoma, tumor, stroke), and others (Table 3).18

A thorough physical examination should include neurologic, cardiovascular, hearing, and vision examinations, as well as an evaluation of functional status.

Laboratory studies. Although evidence is lacking to support a laboratory diagnostic workup for MCI, a selective evaluation including a comprehensive metabolic profile, complete blood count, thyroid studies, and a vitamin B12 level can be useful. Occasionally, a treatable cause of impaired cognition such as vitamin B12 deficiency or thyroid disease can be identified and resolved. A further comprehensive laboratory evaluation should be obtained if a patient progresses to dementia.

Imaging can be used in conjunction with other supportive evidence but should not be used solely to establish a diagnosis of MCI. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can detect metastatic disease, normal pressure hydrocephalus, and subdural hematoma, in addition to traumatic, inflammatory, infectious, and vascular causes of cognitive impairment. MRI can also determine focal areas of atrophy; temporal lobe atrophy is a risk factor for progression to dementia.

Other studies. Structural MRI using techniques to evaluate the hippocampus, functional imaging, genetic testing for ApoE4 alleles, and biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid are currently under evaluation to identify those at risk of progression to dementia. Recently published guidelines by the Alzheimer’s Association and the National Institute on Aging indicate that pathophysiologic findings in MCI that may predict future Alzheimer disease are meant to guide research and are not part of clinical practice at this time.19

COGNITIVE AND NEUROLOGIC TESTING IDENTIFIES DEFICITS

A number of global measures of cognition can be used in the office in clinical practice to help in evaluating significant cognitive concerns and to determine areas and severity of deficits at presentation. These include the Mini-Mental State Examination, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, the Saint Louis University Mental Status, and many others (Table 4).20

Caveats about interpreting the results: each of these tests has different sensitivities and specificities for detecting MCI. Also, we need to take into account the patient’s level of education, as highly educated people tend to do better on these tests.21–23 It is important to note that some patients with MCI have normal results or only minimally abnormal results on these tests.

Neuropsychological testing is reserved for patients needing further evaluation, eg, those with atypical or complex cases, and those in whom the specific domains of cognition involved need to be identified. It can also provide additional insight into the contribution of depression to cognitive deficits. Neuropsychological testing is usually very time-intensive and requires patients to be able to perform complicated cognitive tasks. Not all patients are good candidates for this testing; sensory and motor impairments must be considered to determine if patients can adequately participate in testing. The cost of neuropsychological testing for MCI may not be covered by insurance and should be discussed with patients before referral. Specific concerns about cognitive problems that need further evaluation should be stated in the referral.

No one test should be used to make a diagnosis of MCI or dementia; clinical judgment is also necessary. The need for referral to a neurologist, geriatrician, or psychiatrist depends on the nature of the cognitive and behavioral concerns, the complexity of making a diagnosis, the need for further assessment of functional ability, and the need for evaluation of risk of progression to dementia.

MEDICATIONS HAVE LITTLE ROLE IN MANAGEMENT

No drug has yet been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treating MCI.

The acetylcholinesterase inhibitors donepezil (Aricept), galantamine (Razadyne), and rivastigmine (Exelon) have undergone clinical trials for treatment of MCI but have not been definitely shown to significantly reduce the risk of progression to dementia.24

On the other hand, Diniz et al25 performed a meta-analysis of the use of cholinesterase inhibitors in patients with MCI as a means of delaying the progression to Alzheimer disease.25 They calculated that 15.4% of patients who received these drugs progressed to dementia, compared with 20.4% of those who received placebo, for a relative risk of 0.75 (95% confidence interval 0.66–0.87, P < .001). They concluded that the use of these drugs in patients with MCI “may attenuate the risk of progression” to Alzheimer disease and dementia.

In addition to not being approved for this indication and showing mixed evidence of efficacy, these drugs have well-known side effects such as diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and rhinitis, as well as significant but lesser-known side effects such as syncope, bradycardia, gastrointestinal bleeding, and vivid dreams.26

Nevertheless, some patients with MCI, particularly those at high risk with amnestic MCI, may still want to try these medications. In these cases, the risks and possible benefits (or lack of them) should be reviewed thoroughly with the patient and family, and the discussion should be documented before starting therapy. The lowest starting dose of acetylcholinesterase inhibitor should be used to determine tolerability; generally, the dose is increased after 4 weeks to a maintenance dosage, with particular consideration of side effects.

Other agents have also been evaluated for MCI but have shown no evidence of benefit. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have not been found to either improve symptoms or delay progression to dementia. Ginkgo biloba has shown unclear benefit in achieving important treatment goals for MCI,27 and it increases the risk of bleeding in the elderly. Vitamin E was evaluated in one study and did not slow progression to dementia.28

STAYING HEALTHY AND ACTIVE MAY HELP

We recommend optimizing vascular risk factors such as diabetes, blood pressure, smoking, and lipid levels in managing MCI, given that uncontrolled vascular risk factors may lead to progression to dementia. However, we can point to no research to support this recommendation.

Cognitive rehabilitation involves training in deficient domains and developing strategies to compensate for deficits. Different interventions are used, including computerized simulation exercises, memory aids, organizational techniques, personal digital assistants, crossword puzzles, mind games, and other mentally engaging activities.29

Increasing physical activity is another aspect of treatment. Some studies have shown that it improves cognitive performance in MCI, at least in the short term.30,31

Optimizing mood and emotions is also important. If present, depression should be identified and optimally treated. Social activity can be useful and leads to less emotional stress and to better coping mechanisms.

A multidisciplinary approach may help patients and may also help relieve the burden on the caregiver. Periodic reassessment of cognitive and functional symptoms may be warranted.

Maintaining disease-specific registries of patients who have MCI may be useful to longitudinally follow patients and ensure that they get the care they need.

PROGNOSIS VARIES

MCI is a heterogeneous condition that often does not predictably progress to dementia. Patients and families should be told that having MCI does not mean that the patient will necessarily get dementia.

Several studies have shown that the annual risk of progression to dementia for patients with MCI is 5% to 10% in community-dwelling populations and up to 15% in specialty-clinic patients.24,32 In comparison, the incidence of dementia in the general elderly population is 1% to 3% per year.

On the other hand, a number of studies show that MCI improves significantly in up to 15% to 40% of patients and sometimes reverts to a normal cognitive state.33,34 But prospective studies of patients with clinically diagnosed MCI usually find a low rate of reversion to a normal state.35,36 Many are short-term follow-up studies of different populations, making generalizations difficult.14

Patients with impairment in instrumental activities of daily living may be more likely to have nonreversible MCI and may be at higher risk of progressing to dementia.37

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION AND FOLLOW-UP CONSIDERATIONS

Caregiver education and stress management are important components of managing patients with MCI. Formally assessing caregiver stress is useful. Steps to prevent caregiver burnout include making use of respite care, counseling, education, and community resources such as adult day care and those offered by the Alzheimer’s Association.

Clinicians should follow patients with MCI closely to evaluate progression, address specific concerns, minimize risks, emphasize healthy habits, manage concurrent illnesses, and evaluate management.

Functional status, as demonstrated by activities of daily living, is the most important determinant of progression of MCI to dementia and should be evaluated at each visit. Repeat cognitive testing should be done on patients who have significant loss of functional status. Changes in work habits also warrant further attention.

Patients diagnosed with MCI or those who have persistent cognitive concerns should be considered for neuropsychological evaluation after 1 year to assess specific deficits and progression of cognitive impairment.

Finally, consideration should be given to current clinical research, and referrals should be made to research centers that focus on MCI management and treatment.

As our population ages, people are thinking more about preserving their quality of life, especially with regard to maintaining their cognitive and functional abilities. Older patients and caregivers often raise concerns about cognitive issues to their primary care providers: many patients have memory complaints, are worried about whether these are merely part of normal aging or symptoms of early dementia, and want strategies to forestall the progression of cognitive impairment.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a heterogeneous syndrome that in some cases represents a transition between normal aging and dementia. However, this condition is not yet well understood. Although some patients progress to dementia, others remain stable, or even improve. This article will review the current definitions and the underlying physiology of MCI, as well as diagnostic and management strategies.

COGNITIVE CHANGES OCCUR WITH NORMAL AGING

Cognition is defined as a means of acquiring and processing information about ourselves and our world. It includes memory as well as other domains such as attention, visuospatial skills, mental processing speed, language, and executive function. Cognitive abilities typically peak between ages 30 and 40, plateau in our 50s and 60s, and decline in our late 70s.

With age come detectable changes in the brain: brain weight declines by 10% by age 80, blood flow diminishes, neurons are lost throughout life, and nerve conduction slows. Despite these changes, the brain has a great deal of functional reserve capacity.

Table 1 compares the signs of normal aging, MCI, and dementia. Normally, cognitive abilities decline gradually with age without affecting overall function or activities of daily living. Even in normal aging, the processing of new information (new learning) is reduced. Mental processing becomes less efficient and slower. Visuospatial skills gradually decline, recall slows, and ultimately, the speed of performance slows as well. Additionally, distractibility increases. On the other hand, normal aging does not affect recognition, intelligence, or long-term memory.1

The line between the normal effects of aging on cognition and true pathologic cognitive decline is blurry. In a busy clinical practice, it is often difficult to determine whether problems with memory and cognition that elderly patients and their family members describe represent true pathologic decline. In general, the clinical presentation of MCI is more profound than that of age-associated cognitive impairment: whereas normal aging may involve forgetting names and words and misplacing things, MCI frequently involves forgetting conversations, information that one would ordinarily remember, appointments, and planned events.

BETWEEN NORMAL AGING AND DEMENTIA

MCI is a transitional state between normal cognition and dementia. But the course is not inevitably downward: on follow-up, patients with MCI may be better, stable, or worse (see PROGNOSIS VARIES, below).

On autopsy studies, the brains of people with MCI appear intermediate between normal brains and brains of people with Alzheimer-type dementia, which have neurofibrillary tangles, amyloid senile plaques, and neuronal degeneration.

Definitions of MCI vary

True cognitive decline that is more profound than normal aging was named and defined differently in different studies, making comparisons difficult. The concept of MCI arose from the term “benign senescent forgetfulness,” used by Kral in 1962.2 Other early terms include “cognitive impairment no dementia,” “memory impairment,” “mild cognitive disorder,” and “mild neurocognitive disorder.”3,4

MCI was first defined as a precursor to Alzheimer dementia. The term later described a sometimes reversible but abnormal state. It is a heterogeneous syndrome in terms of etiology, incidence, prevalence, presentation, and overall prognosis.

Most recently, MCI has been defined as5,6:

- Subjective memory complaints, preferably qualified by another person

- Memory impairment, with consideration for age and education

- Preserved general cognitive function

- Intact activities of daily living

- Absence of overt dementia.

MCI may arise from vascular, neurodegenerative, traumatic, metabolic, psychiatric, and other underlying medical disorders.7–9

The prevalence of MCI is difficult to determine because of the various definitions, populations studied (eg, clinic-based vs community-dwelling), and evaluation techniques. Published rates vary from 2% to 4% in all patients to 10% to 20% in the elderly. Incidence rates in the elderly vary from 14 to 75 per 1,000 patient-years.10–14

EARLY RECOGNITION ALLOWS PROMPT EVALUATION AND PLANNING

Pathologic cognitive decline is best detected early, for many reasons. Early recognition and intervention may help delay further decline. Establishing a diagnosis can also lessen family and caregiver stress and misunderstanding. Education of caregivers is important so that they can prepare for likely behavioral changes and plan for future care. Advance care planning, including advance directives, power of attorney, and designation of proxy for decision-making, is extremely important and is best considered before cognitive impairment becomes severe.

The diagnosis of MCI also provides the opportunity to assess safety concerns related to driving, working, medication compliance, the home environment, and firearms. Because patients with MCI are still highly functional, these issues need not be fully evaluated and should be handled on a case-by-case basis, depending on concerns raised. For example, if depression is an active concern, firearms safety should be addressed.

MEMORY LOSS MAY NOT BE THE PRIMARY CONCERN

MCI is categorized into two types based on whether memory loss is the primary cognitive deficit.

The amnestic type predominantly involves memory problems and is more common. Generally, several years elapse between initial memory concerns and a clinical diagnosis of MCI. Patients with amnestic MCI that progresses to dementia are more likely to develop Alzheimer disease.2,15

Nonamnestic types involve domains of cognition other than memory, such as executive function, attention, visuospatial ability, and language. Nonamnestic MCI can be subcategorized through extensive neuropsychological evaluation as involving single or multiple impaired domains.16,17 Such categorization is particularly important in determining prognosis, as patients with involvement of multiple domains are at higher risk of progressing to dementia.

Patients with nonamnestic MCI who progress to dementia are more likely to have non-Alzheimer types of dementia, such as Lewy body dementia and frontotemporal dementias.10

HISTORY SHOULD FOCUS ON FUNCTION, MEDICATIONS, AND DEPRESSION

Cognitive impairment should be clinically evaluated within the context of cognition, function, and behavior. Clinicians should focus on the time course of cognitive concerns, the specifics of the concerns, and their impact on day-to-day living and functioning. In assessing functional capacity, it is important to determine the level of assistance the patient needs to perform specific activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living (ie, the more advanced skills needed to live independently) (Table 2).

A thorough history includes consideration of baseline education, intellect, and previous learning disabilities; sensory impairments with emphasis on sight and hearing impairments; uncontrolled pain; head trauma; sleep disorders; concurrent medical and psychosocial illnesses such as depression and anxiety; substance abuse; and polypharmacy.

Depression, delirium, and the use of anticholinergic drugs are particularly important to evaluate, as these can result in cognitive deficits associated with MCI. The cognitive deficits may resolve with treatment or with stopping the drug.

Behavioral concerns such as wandering, agitation, and anger and sleep concerns, eating habits, and social etiquette are also important to evaluate.

PHYSICAL EVALUATION: RULE OUT REVERSIBLE CONDITIONS

The differential diagnosis of MCI includes delirium, depression, dementia, possibly reversible conditions affecting cognition (vitamin B12 deficiency, hypothyroidism, effects of anticholinergic drugs), and uncommonly, central nervous system conditions (normal pressure hydrocephalus, subdural hematoma, tumor, stroke), and others (Table 3).18

A thorough physical examination should include neurologic, cardiovascular, hearing, and vision examinations, as well as an evaluation of functional status.

Laboratory studies. Although evidence is lacking to support a laboratory diagnostic workup for MCI, a selective evaluation including a comprehensive metabolic profile, complete blood count, thyroid studies, and a vitamin B12 level can be useful. Occasionally, a treatable cause of impaired cognition such as vitamin B12 deficiency or thyroid disease can be identified and resolved. A further comprehensive laboratory evaluation should be obtained if a patient progresses to dementia.

Imaging can be used in conjunction with other supportive evidence but should not be used solely to establish a diagnosis of MCI. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can detect metastatic disease, normal pressure hydrocephalus, and subdural hematoma, in addition to traumatic, inflammatory, infectious, and vascular causes of cognitive impairment. MRI can also determine focal areas of atrophy; temporal lobe atrophy is a risk factor for progression to dementia.

Other studies. Structural MRI using techniques to evaluate the hippocampus, functional imaging, genetic testing for ApoE4 alleles, and biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid are currently under evaluation to identify those at risk of progression to dementia. Recently published guidelines by the Alzheimer’s Association and the National Institute on Aging indicate that pathophysiologic findings in MCI that may predict future Alzheimer disease are meant to guide research and are not part of clinical practice at this time.19

COGNITIVE AND NEUROLOGIC TESTING IDENTIFIES DEFICITS

A number of global measures of cognition can be used in the office in clinical practice to help in evaluating significant cognitive concerns and to determine areas and severity of deficits at presentation. These include the Mini-Mental State Examination, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, the Saint Louis University Mental Status, and many others (Table 4).20

Caveats about interpreting the results: each of these tests has different sensitivities and specificities for detecting MCI. Also, we need to take into account the patient’s level of education, as highly educated people tend to do better on these tests.21–23 It is important to note that some patients with MCI have normal results or only minimally abnormal results on these tests.

Neuropsychological testing is reserved for patients needing further evaluation, eg, those with atypical or complex cases, and those in whom the specific domains of cognition involved need to be identified. It can also provide additional insight into the contribution of depression to cognitive deficits. Neuropsychological testing is usually very time-intensive and requires patients to be able to perform complicated cognitive tasks. Not all patients are good candidates for this testing; sensory and motor impairments must be considered to determine if patients can adequately participate in testing. The cost of neuropsychological testing for MCI may not be covered by insurance and should be discussed with patients before referral. Specific concerns about cognitive problems that need further evaluation should be stated in the referral.

No one test should be used to make a diagnosis of MCI or dementia; clinical judgment is also necessary. The need for referral to a neurologist, geriatrician, or psychiatrist depends on the nature of the cognitive and behavioral concerns, the complexity of making a diagnosis, the need for further assessment of functional ability, and the need for evaluation of risk of progression to dementia.

MEDICATIONS HAVE LITTLE ROLE IN MANAGEMENT

No drug has yet been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treating MCI.

The acetylcholinesterase inhibitors donepezil (Aricept), galantamine (Razadyne), and rivastigmine (Exelon) have undergone clinical trials for treatment of MCI but have not been definitely shown to significantly reduce the risk of progression to dementia.24

On the other hand, Diniz et al25 performed a meta-analysis of the use of cholinesterase inhibitors in patients with MCI as a means of delaying the progression to Alzheimer disease.25 They calculated that 15.4% of patients who received these drugs progressed to dementia, compared with 20.4% of those who received placebo, for a relative risk of 0.75 (95% confidence interval 0.66–0.87, P < .001). They concluded that the use of these drugs in patients with MCI “may attenuate the risk of progression” to Alzheimer disease and dementia.

In addition to not being approved for this indication and showing mixed evidence of efficacy, these drugs have well-known side effects such as diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and rhinitis, as well as significant but lesser-known side effects such as syncope, bradycardia, gastrointestinal bleeding, and vivid dreams.26

Nevertheless, some patients with MCI, particularly those at high risk with amnestic MCI, may still want to try these medications. In these cases, the risks and possible benefits (or lack of them) should be reviewed thoroughly with the patient and family, and the discussion should be documented before starting therapy. The lowest starting dose of acetylcholinesterase inhibitor should be used to determine tolerability; generally, the dose is increased after 4 weeks to a maintenance dosage, with particular consideration of side effects.

Other agents have also been evaluated for MCI but have shown no evidence of benefit. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have not been found to either improve symptoms or delay progression to dementia. Ginkgo biloba has shown unclear benefit in achieving important treatment goals for MCI,27 and it increases the risk of bleeding in the elderly. Vitamin E was evaluated in one study and did not slow progression to dementia.28

STAYING HEALTHY AND ACTIVE MAY HELP

We recommend optimizing vascular risk factors such as diabetes, blood pressure, smoking, and lipid levels in managing MCI, given that uncontrolled vascular risk factors may lead to progression to dementia. However, we can point to no research to support this recommendation.

Cognitive rehabilitation involves training in deficient domains and developing strategies to compensate for deficits. Different interventions are used, including computerized simulation exercises, memory aids, organizational techniques, personal digital assistants, crossword puzzles, mind games, and other mentally engaging activities.29

Increasing physical activity is another aspect of treatment. Some studies have shown that it improves cognitive performance in MCI, at least in the short term.30,31

Optimizing mood and emotions is also important. If present, depression should be identified and optimally treated. Social activity can be useful and leads to less emotional stress and to better coping mechanisms.

A multidisciplinary approach may help patients and may also help relieve the burden on the caregiver. Periodic reassessment of cognitive and functional symptoms may be warranted.

Maintaining disease-specific registries of patients who have MCI may be useful to longitudinally follow patients and ensure that they get the care they need.

PROGNOSIS VARIES

MCI is a heterogeneous condition that often does not predictably progress to dementia. Patients and families should be told that having MCI does not mean that the patient will necessarily get dementia.

Several studies have shown that the annual risk of progression to dementia for patients with MCI is 5% to 10% in community-dwelling populations and up to 15% in specialty-clinic patients.24,32 In comparison, the incidence of dementia in the general elderly population is 1% to 3% per year.

On the other hand, a number of studies show that MCI improves significantly in up to 15% to 40% of patients and sometimes reverts to a normal cognitive state.33,34 But prospective studies of patients with clinically diagnosed MCI usually find a low rate of reversion to a normal state.35,36 Many are short-term follow-up studies of different populations, making generalizations difficult.14

Patients with impairment in instrumental activities of daily living may be more likely to have nonreversible MCI and may be at higher risk of progressing to dementia.37

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION AND FOLLOW-UP CONSIDERATIONS

Caregiver education and stress management are important components of managing patients with MCI. Formally assessing caregiver stress is useful. Steps to prevent caregiver burnout include making use of respite care, counseling, education, and community resources such as adult day care and those offered by the Alzheimer’s Association.

Clinicians should follow patients with MCI closely to evaluate progression, address specific concerns, minimize risks, emphasize healthy habits, manage concurrent illnesses, and evaluate management.

Functional status, as demonstrated by activities of daily living, is the most important determinant of progression of MCI to dementia and should be evaluated at each visit. Repeat cognitive testing should be done on patients who have significant loss of functional status. Changes in work habits also warrant further attention.

Patients diagnosed with MCI or those who have persistent cognitive concerns should be considered for neuropsychological evaluation after 1 year to assess specific deficits and progression of cognitive impairment.

Finally, consideration should be given to current clinical research, and referrals should be made to research centers that focus on MCI management and treatment.

- Keefover RW. Aging and cognition. Neurol Clin 1998; 16:635–648.

- Kral VA. Senescent forgetfulness: benign and malignant. Can Med Assoc J 1962; 86:257–260.

- Bischkopf J, Busse A, Angermeyer MC. Mild cognitive impairment—a review of prevalence, incidence and outcome according to current approaches. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2002; 106:403–414.

- Petersen RC, Stevens JC, Ganguli M, Tangalos EG, Cummings JL, DeKosky ST. Practice parameter: early detection of dementia: mild cognitive impairment (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2001; 56:1133–1142.

- Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol 1999; 56:303–308.

- Petersen RC, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: ten years later. Arch Neurol 2009; 66:1447–1455.

- Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Bienias JL, et al. Mild cognitive impairment is related to Alzheimer disease pathology and cerebral infarctions. Neurology 2005; 64:834–841.

- Petersen RC, Parisi JE, Dickson DW, et al. Neuropathologic features of amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 2006; 63:665–672.

- Guillozet AL, Weintraub S, Mash DC, Mesulam MM. Neurofibrillary tangles, amyloid, and memory in aging and mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 2003; 60:729–736.

- Molano J, Boeve B, Ferman T, et al. Mild cognitive impairment associated with limbic and neocortical Lewy body disease: a clinicopathological study. Brain 2010; 133:540–556.

- Lopez OL, Jagust WJ, DeKosky ST, et al. Prevalence and classification of mild cognitive impairment in the Cardiovascular Health Study Cognition Study: part 1. Arch Neurol 2003; 60:1385–1389.

- Petersen RC, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, et al. Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment is higher in men. The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Neurology 2010; 75:889–897.

- Manly JJ, Tang MX, Schupf N, Stern Y, Vonsattel JP, Mayeux R. Frequency and course of mild cognitive impairment in a multiethnic community. Ann Neurol 2008; 63:494–506.

- Luck T, Luppa M, Briel S, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: incidence and risk factors: results of the Leipzig Longitudinal Study of the Aged. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010; 58:1903–1910.

- Roberts RO, Geda YE, Knopman DS, et al. The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging: design and sampling, participation, baseline measures and sample characteristics. Neuroepidemiology 2008; 30:58–69.

- Bozoki A, Giordani B, Heidebrink JL, Berent S, Foster NL. Mild cognitive impairments predict dementia in nondemented elderly patients with memory loss. Arch Neurol 2001; 58:411–416.

- DeCarli C. Mild cognitive impairment: prevalence, prognosis, aetiology, and treatment. Lancet Neurol 2003; 2:15–21.

- Graham JE, Rockwood K, Beattie BL, et al. Prevalence and severity of cognitive impairment with and without dementia in an elderly population. Lancet 1997; 349:1793–1796.

- Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011; 7:270–279.

- Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, Perry MH, Morley JE. Comparison of the Saint Louis University mental status examination and the Mini-Mental State Examination for detecting dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder—a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006; 14:900–910.

- Tang-Wai DF, Knopman DS, Geda YE, et al. Comparison of the short test of mental status and the Mini-Mental State Examination in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 2003; 60:1777–1781.

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53:695–699.

- Banks WA, Morley JE. Memories are made of this: recent advances in understanding cognitive impairments and dementia. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2003; 58:314–321.

- Petersen RC. Clinical practice. Mild cognitive impairment. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:2227–2234.

- Diniz BS, Pinto JA, Gonzaga MLC, Guimaraes FM, Gattaz WF, Forlenza OV. To treat or not to treat? A meta-analysis of the use of cholinesterase inhibitors in mild cognitive impairment for delaying progression to Alzheimer’s disease. Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurosci 2009; 259:248–256.

- Patel BB, Holland NW. Adverse effects of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Clin Geriatr 2011; 19:27–30.

- Birks J, Grimley Evans J. Ginkgo biloba for cognitive impairment and dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; 1:CD003120.

- Petersen RC, Thomas RG, Grundman M, et al; Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Group. Vitamin E and donepezil for the treatment of mild cognitive impairment. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:2379–2388.

- Jean L, Bergeron ME, Thivierge S, Simard M. Cognitive intervention programs for individuals with mild cognitive impairment: systematic review of the literature. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2010; 18:281–296.

- Lautenschlager NT, Cox KL, Flicker L, et al. Effect of physical activity on cognitive function in older adults at risk for Alzheimer disease: a randomized trial. JAMA 2008; 300:1027–1037.

- van Uffelen JG, Chinapaw MJ, van Mechelen W, Hopman-Rock M. Walking or vitamin B for cognition in older adults with mild cognitive impairment? A randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med 2008; 42:344–351.

- Farias ST, Mungas D, Reed BR, Harvey D, DeCarli C. Progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia in clinic-vs community-based cohorts. Arch Neurol 2009; 66:1151–1157.

- Ritchie K, Artero S, Touchon J. Classification criteria for mild cognitive impairment: a population-based validation study. Neurology 2001; 56:37–42.

- Larrieu S, Letenneur L, Orgogozo JM, et al. Incidence and outcome of mild cognitive impairment in a population-based prospective cohort. Neurology 2002; 59:1594–1599.

- Busse A, Hensel A, Gühne U, Angermeyer MC, Riedel-Heller SG. Mild cognitive impairment: long-term course of four clinical subtypes. Neurology 2006; 67:2176–2185.

- Fischer P, Jungwirth S, Zehetmayer S, et al. Conversion from subtypes of mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer dementia. Neurology 2007; 68:288–291.

- Pérès K, Chrysostome V, Fabrigoule C, Orgogozo JM, Dartigues JF, Barberger-Gateau P. Restriction in complex activities of daily living in MCI: impact on outcome. Neurology 2006; 67:461–466.

- Keefover RW. Aging and cognition. Neurol Clin 1998; 16:635–648.

- Kral VA. Senescent forgetfulness: benign and malignant. Can Med Assoc J 1962; 86:257–260.

- Bischkopf J, Busse A, Angermeyer MC. Mild cognitive impairment—a review of prevalence, incidence and outcome according to current approaches. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2002; 106:403–414.

- Petersen RC, Stevens JC, Ganguli M, Tangalos EG, Cummings JL, DeKosky ST. Practice parameter: early detection of dementia: mild cognitive impairment (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2001; 56:1133–1142.

- Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol 1999; 56:303–308.

- Petersen RC, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: ten years later. Arch Neurol 2009; 66:1447–1455.

- Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Bienias JL, et al. Mild cognitive impairment is related to Alzheimer disease pathology and cerebral infarctions. Neurology 2005; 64:834–841.

- Petersen RC, Parisi JE, Dickson DW, et al. Neuropathologic features of amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 2006; 63:665–672.

- Guillozet AL, Weintraub S, Mash DC, Mesulam MM. Neurofibrillary tangles, amyloid, and memory in aging and mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 2003; 60:729–736.

- Molano J, Boeve B, Ferman T, et al. Mild cognitive impairment associated with limbic and neocortical Lewy body disease: a clinicopathological study. Brain 2010; 133:540–556.

- Lopez OL, Jagust WJ, DeKosky ST, et al. Prevalence and classification of mild cognitive impairment in the Cardiovascular Health Study Cognition Study: part 1. Arch Neurol 2003; 60:1385–1389.

- Petersen RC, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, et al. Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment is higher in men. The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Neurology 2010; 75:889–897.

- Manly JJ, Tang MX, Schupf N, Stern Y, Vonsattel JP, Mayeux R. Frequency and course of mild cognitive impairment in a multiethnic community. Ann Neurol 2008; 63:494–506.

- Luck T, Luppa M, Briel S, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: incidence and risk factors: results of the Leipzig Longitudinal Study of the Aged. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010; 58:1903–1910.

- Roberts RO, Geda YE, Knopman DS, et al. The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging: design and sampling, participation, baseline measures and sample characteristics. Neuroepidemiology 2008; 30:58–69.

- Bozoki A, Giordani B, Heidebrink JL, Berent S, Foster NL. Mild cognitive impairments predict dementia in nondemented elderly patients with memory loss. Arch Neurol 2001; 58:411–416.

- DeCarli C. Mild cognitive impairment: prevalence, prognosis, aetiology, and treatment. Lancet Neurol 2003; 2:15–21.

- Graham JE, Rockwood K, Beattie BL, et al. Prevalence and severity of cognitive impairment with and without dementia in an elderly population. Lancet 1997; 349:1793–1796.

- Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011; 7:270–279.

- Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, Perry MH, Morley JE. Comparison of the Saint Louis University mental status examination and the Mini-Mental State Examination for detecting dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder—a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006; 14:900–910.

- Tang-Wai DF, Knopman DS, Geda YE, et al. Comparison of the short test of mental status and the Mini-Mental State Examination in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 2003; 60:1777–1781.

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53:695–699.

- Banks WA, Morley JE. Memories are made of this: recent advances in understanding cognitive impairments and dementia. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2003; 58:314–321.

- Petersen RC. Clinical practice. Mild cognitive impairment. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:2227–2234.

- Diniz BS, Pinto JA, Gonzaga MLC, Guimaraes FM, Gattaz WF, Forlenza OV. To treat or not to treat? A meta-analysis of the use of cholinesterase inhibitors in mild cognitive impairment for delaying progression to Alzheimer’s disease. Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurosci 2009; 259:248–256.

- Patel BB, Holland NW. Adverse effects of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Clin Geriatr 2011; 19:27–30.

- Birks J, Grimley Evans J. Ginkgo biloba for cognitive impairment and dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; 1:CD003120.

- Petersen RC, Thomas RG, Grundman M, et al; Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Group. Vitamin E and donepezil for the treatment of mild cognitive impairment. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:2379–2388.

- Jean L, Bergeron ME, Thivierge S, Simard M. Cognitive intervention programs for individuals with mild cognitive impairment: systematic review of the literature. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2010; 18:281–296.

- Lautenschlager NT, Cox KL, Flicker L, et al. Effect of physical activity on cognitive function in older adults at risk for Alzheimer disease: a randomized trial. JAMA 2008; 300:1027–1037.

- van Uffelen JG, Chinapaw MJ, van Mechelen W, Hopman-Rock M. Walking or vitamin B for cognition in older adults with mild cognitive impairment? A randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med 2008; 42:344–351.

- Farias ST, Mungas D, Reed BR, Harvey D, DeCarli C. Progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia in clinic-vs community-based cohorts. Arch Neurol 2009; 66:1151–1157.

- Ritchie K, Artero S, Touchon J. Classification criteria for mild cognitive impairment: a population-based validation study. Neurology 2001; 56:37–42.

- Larrieu S, Letenneur L, Orgogozo JM, et al. Incidence and outcome of mild cognitive impairment in a population-based prospective cohort. Neurology 2002; 59:1594–1599.

- Busse A, Hensel A, Gühne U, Angermeyer MC, Riedel-Heller SG. Mild cognitive impairment: long-term course of four clinical subtypes. Neurology 2006; 67:2176–2185.

- Fischer P, Jungwirth S, Zehetmayer S, et al. Conversion from subtypes of mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer dementia. Neurology 2007; 68:288–291.

- Pérès K, Chrysostome V, Fabrigoule C, Orgogozo JM, Dartigues JF, Barberger-Gateau P. Restriction in complex activities of daily living in MCI: impact on outcome. Neurology 2006; 67:461–466.

KEY POINTS

- MCI that primarily involves memory or multiple domains has a higher risk of progressing to dementia.

- Depression and the effects of anticholinergic medication can mimic MCI, and these should be looked for in patients presenting with cognitive loss.

- Impaired functional status as reflected in activities of daily living is an important sign of progression from MCI to dementia.

- Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are not approved for treating MCI, have shown little efficacy in altering progression to dementia, and have multiple side effects.

- Enhancing physical and mental health and developing strategies to compensate for deficits are key management approaches.

Bilateral adrenal masses

A 68-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with constipation and abdominal pain 13 days after left hip arthroplasty. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed possible bowel obstruction, left renal infarction, and a thrombus in the abdominal aorta near the left renal artery (Figure 1).

Because of the aortic thrombus, anticoagulation with intravenous heparin and with warfarin (Coumadin) was started. Three days later, her platelet count decreased to 54 × 109/L (reference range 150–400), her serum creatinine rose to 2.38 mg/dL (0.70–1.40), sodium was stable at 131 mmol/L (132–148), and potassium was 4.1 mmol/L (3.5–5.0).

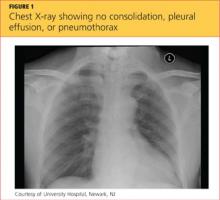

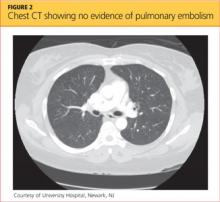

Physical examination revealed a temperature of 100.2°F (37.9°C), blood pressure 110/59 mm Hg, pulse 100 bpm, and no abdominal pain on palpation. Renal ultrasonography revealed a mass (2.4 × 2.1 × 3.6 cm) above the right kidney. Abdominal CT without contrast showed bilateral high-density adrenal masses (Figure 2).

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Metastasis to the adrenal glands

- Adrenal adenoma

- Pheochromocytoma

- Adrenal cortical carcinoma

- Adrenal gland hemorrhage

A: The correct diagnosis is adrenal gland hemorrhage.

Acute or subacute hemorrhage typically results in an oval hyperdense mass with an attenuation of 50 to 90 Hounsfield units (H) on noncontrast CT (Figure 2),1,2 and this attenuation does not increase with the use of contrast.2

In contrast, adrenal cortical carcinoma typically appears as a large heterogeneous mass, with some lesions demonstrating central necrosis or calcification. Pheochromocytoma is well defined, with intense enhancement after contrast is given. Adenoma is usually homogenous, with well-defined margins. Many adenomas have increased intracytoplasmic lipid content and, therefore, will have an attenuation of less than 10 H or will demonstrate rapid washout of contrast. Metastasis to the adrenal gland may not have a characteristic radiographic appearance but typically has a slower contrast washout rate than adenoma.1

This patient’s initial abdominal image showed normal-appearing adrenal glands, thus making adenoma, adrenal metastasis, pheochromocytoma, and adrenal cortical carcinoma unlikely.

The patient’s baseline cortisol level, a random afternoon reading, was 0.4 μg/dL (reference range 3.4–26.9), and a 1-hour cortrosyn-stimulated cortisol was 0 μg/dL, which is diagnostic of primary adrenal insufficiency in the context of this clinical setting. She received hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone, and 8 am cortisol measurements 3 weeks and 5 months later, after the patient was off hydrocortisone for 24 hours, remained undetectable.

The diagnosis of adrenal hemorrhage can be difficult because the symptoms can be nonspecific and attributable to other clinical factors. In a review of 141 patients with adrenal hemorrhage,3 only 19% of patients with bilateral adrenal hemorrhage developed hypotension with a systolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg, only 15% developed hyponatremia (sodium < 130 mmol/L), and only 24% developed hyperkalemia (potassium > 5 mmol/L).3

If unrecognized, adrenal insufficiency from adrenal hemorrhage is fatal. Abdominal CT or magnetic resonance imaging can diagnose adrenal hemorrhage. Adrenal function may recover (although it did not in this patient), and a morning cortisol level should be obtained to reevaluate adrenal function.3

Risk factors for adrenal hemorrhage include anticoagulation therapy, sepsis, surgery, hypotension, and coagulopathy as seen in heparininduced thrombocytopenia and disseminated intravascular coagulation. This patient had coagulopathy, as evidenced by her abdominal aortic thrombus, for which she was placed on anticoagulation. Patients without these risk factors for adrenal gland hemorrhage should be investigated for an underlying adrenal neoplasm or cyst.2