User login

Win Whitcomb: Introducing Neuroquality and Neurosafety

The prefix “neuro” has become quite popular the last couple of years. We have neuroeconomics, neuroplasticity, neuroergonomics, and, of course, neurohospitalist. The explosion of interest in the brain can be seen in the popular press, television, blogs, and the Journal of the American Medical Association.

I predict that recent breakthroughs in brain science and related fields (cognitive psychology, neurobiology, molecular biology, linguistics, and artificial intelligence, among others) will have a profound impact on the fields of quality improvement (QI) and patient safety, and, consequently on HM. To date, the patient safety movement has focused on systems issues in an effort to reduce harm induced by the healthcare system. I submit that for healthcare to be reliable and error-free in the future, we must leverage the innate strengths of the brain. Here I mention four areas where brain science breakthroughs can enable us to improve patient safety practices.

Diagnostic Error

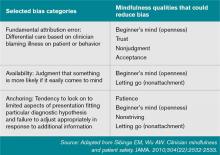

Patrick Croskerry, an emergency physician and researcher, has described errors in diagnosis as stemming in part from cognitive bias. He offers “de-biasing strategies” as an approach to decreasing diagnostic error.

One of the most powerful de-biasing strategies is metacognition, or awareness of one’s own thinking processes. Closely related to metacognition is mindfulness, defined as the “nonjudgmental awareness of the present moment.” A growing body of literature makes the case that enhancing mindfulness might reduce the impact bias has on diagnostic error.1 Table 1 (right) mentions a subset of bias types and how mindfulness might mitigate them. I’m sure you can think of cases you’ve encountered where bias has affected the diagnostic outcome.

Empathy and Patient Experience

As the focus on patient experience grows, approaches to improving performance on patient satisfaction surveys are proliferating. Whatever technical components you choose to employ, a capacity for caregiver empathy is a crucial underlying factor to a better patient experience. Harvard psychiatrist Helen Riess, MD, points out that we are now beginning to understand the neurobiological basis of empathy. She and others present evidence that we may be able to “up-regulate” empathy through education or cognitive practices.2 Several studies suggest we might be able to realize improved therapeutic relationships between physicians and patients, and they have led to programs, such as the ones at Stanford and Emory universities, that train caregivers to enhance empathy and compassion.

Interruptions and Cognitive Error

It has been customary in high-risk industries to ensure that certain procedures are free of interruptions. There is recognition that disturbances during high-stakes tasks, such as airline takeoff, carry disastrous consequences. We now know that multitasking is a myth and that the brain instead switches between tasks sequentially. But task-switching comes at the high cost of a marked increase in the rate of cognitive error.3 As we learn more, decreasing interruptions or delineating “interruption-free” zones in healthcare could be a way to mitigate an inherent vulnerability in our cognitive abilities.

Fatigue and Medical Error

It is well documented that sleep deprivation correlates with a decline in cognitive

performance in a number of classes of healthcare workers. Fatigue has also increased diagnostic error among residents. A 2011 Sentinel Alert from The Joint Commission creates a standard that healthcare organizations implement a fatigue-management plan to mitigate the potential harm caused by tired professionals.

Most of the approaches to improving outcomes in the hospital have focused on process improvement and systems thinking. But errors also occur due to the thinking process of clinicians. In the book “Brain Rules,” author John Medina argues that schools and businesses create an environment that is less than friendly to the brain, citing current classroom design and cubicles for office workers. As a result, he states, we often have poor educational and business performance. I have little doubt that if Medina spent a few hours in a hospital, he would come to a similar conclusion: We don’t do the brain any favors when it comes to creating a healthy environment for providing safe and reliable care to our patients.

References

- Sibinga EM, Wu AW. Clinician mindfulness and patient safety. JAMA. 2010;304(22):2532-2533.

- Riess H. Empathy in medicine─a neurobiological perspective. JAMA. 2010;304(14):1604-1605.

- Rogers RD, Monsell S. The costs of a predictable switch between simple cognitive tasks. J Exper Psychol. 1995;124(2):207–231.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

The prefix “neuro” has become quite popular the last couple of years. We have neuroeconomics, neuroplasticity, neuroergonomics, and, of course, neurohospitalist. The explosion of interest in the brain can be seen in the popular press, television, blogs, and the Journal of the American Medical Association.

I predict that recent breakthroughs in brain science and related fields (cognitive psychology, neurobiology, molecular biology, linguistics, and artificial intelligence, among others) will have a profound impact on the fields of quality improvement (QI) and patient safety, and, consequently on HM. To date, the patient safety movement has focused on systems issues in an effort to reduce harm induced by the healthcare system. I submit that for healthcare to be reliable and error-free in the future, we must leverage the innate strengths of the brain. Here I mention four areas where brain science breakthroughs can enable us to improve patient safety practices.

Diagnostic Error

Patrick Croskerry, an emergency physician and researcher, has described errors in diagnosis as stemming in part from cognitive bias. He offers “de-biasing strategies” as an approach to decreasing diagnostic error.

One of the most powerful de-biasing strategies is metacognition, or awareness of one’s own thinking processes. Closely related to metacognition is mindfulness, defined as the “nonjudgmental awareness of the present moment.” A growing body of literature makes the case that enhancing mindfulness might reduce the impact bias has on diagnostic error.1 Table 1 (right) mentions a subset of bias types and how mindfulness might mitigate them. I’m sure you can think of cases you’ve encountered where bias has affected the diagnostic outcome.

Empathy and Patient Experience

As the focus on patient experience grows, approaches to improving performance on patient satisfaction surveys are proliferating. Whatever technical components you choose to employ, a capacity for caregiver empathy is a crucial underlying factor to a better patient experience. Harvard psychiatrist Helen Riess, MD, points out that we are now beginning to understand the neurobiological basis of empathy. She and others present evidence that we may be able to “up-regulate” empathy through education or cognitive practices.2 Several studies suggest we might be able to realize improved therapeutic relationships between physicians and patients, and they have led to programs, such as the ones at Stanford and Emory universities, that train caregivers to enhance empathy and compassion.

Interruptions and Cognitive Error

It has been customary in high-risk industries to ensure that certain procedures are free of interruptions. There is recognition that disturbances during high-stakes tasks, such as airline takeoff, carry disastrous consequences. We now know that multitasking is a myth and that the brain instead switches between tasks sequentially. But task-switching comes at the high cost of a marked increase in the rate of cognitive error.3 As we learn more, decreasing interruptions or delineating “interruption-free” zones in healthcare could be a way to mitigate an inherent vulnerability in our cognitive abilities.

Fatigue and Medical Error

It is well documented that sleep deprivation correlates with a decline in cognitive

performance in a number of classes of healthcare workers. Fatigue has also increased diagnostic error among residents. A 2011 Sentinel Alert from The Joint Commission creates a standard that healthcare organizations implement a fatigue-management plan to mitigate the potential harm caused by tired professionals.

Most of the approaches to improving outcomes in the hospital have focused on process improvement and systems thinking. But errors also occur due to the thinking process of clinicians. In the book “Brain Rules,” author John Medina argues that schools and businesses create an environment that is less than friendly to the brain, citing current classroom design and cubicles for office workers. As a result, he states, we often have poor educational and business performance. I have little doubt that if Medina spent a few hours in a hospital, he would come to a similar conclusion: We don’t do the brain any favors when it comes to creating a healthy environment for providing safe and reliable care to our patients.

References

- Sibinga EM, Wu AW. Clinician mindfulness and patient safety. JAMA. 2010;304(22):2532-2533.

- Riess H. Empathy in medicine─a neurobiological perspective. JAMA. 2010;304(14):1604-1605.

- Rogers RD, Monsell S. The costs of a predictable switch between simple cognitive tasks. J Exper Psychol. 1995;124(2):207–231.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

The prefix “neuro” has become quite popular the last couple of years. We have neuroeconomics, neuroplasticity, neuroergonomics, and, of course, neurohospitalist. The explosion of interest in the brain can be seen in the popular press, television, blogs, and the Journal of the American Medical Association.

I predict that recent breakthroughs in brain science and related fields (cognitive psychology, neurobiology, molecular biology, linguistics, and artificial intelligence, among others) will have a profound impact on the fields of quality improvement (QI) and patient safety, and, consequently on HM. To date, the patient safety movement has focused on systems issues in an effort to reduce harm induced by the healthcare system. I submit that for healthcare to be reliable and error-free in the future, we must leverage the innate strengths of the brain. Here I mention four areas where brain science breakthroughs can enable us to improve patient safety practices.

Diagnostic Error

Patrick Croskerry, an emergency physician and researcher, has described errors in diagnosis as stemming in part from cognitive bias. He offers “de-biasing strategies” as an approach to decreasing diagnostic error.

One of the most powerful de-biasing strategies is metacognition, or awareness of one’s own thinking processes. Closely related to metacognition is mindfulness, defined as the “nonjudgmental awareness of the present moment.” A growing body of literature makes the case that enhancing mindfulness might reduce the impact bias has on diagnostic error.1 Table 1 (right) mentions a subset of bias types and how mindfulness might mitigate them. I’m sure you can think of cases you’ve encountered where bias has affected the diagnostic outcome.

Empathy and Patient Experience

As the focus on patient experience grows, approaches to improving performance on patient satisfaction surveys are proliferating. Whatever technical components you choose to employ, a capacity for caregiver empathy is a crucial underlying factor to a better patient experience. Harvard psychiatrist Helen Riess, MD, points out that we are now beginning to understand the neurobiological basis of empathy. She and others present evidence that we may be able to “up-regulate” empathy through education or cognitive practices.2 Several studies suggest we might be able to realize improved therapeutic relationships between physicians and patients, and they have led to programs, such as the ones at Stanford and Emory universities, that train caregivers to enhance empathy and compassion.

Interruptions and Cognitive Error

It has been customary in high-risk industries to ensure that certain procedures are free of interruptions. There is recognition that disturbances during high-stakes tasks, such as airline takeoff, carry disastrous consequences. We now know that multitasking is a myth and that the brain instead switches between tasks sequentially. But task-switching comes at the high cost of a marked increase in the rate of cognitive error.3 As we learn more, decreasing interruptions or delineating “interruption-free” zones in healthcare could be a way to mitigate an inherent vulnerability in our cognitive abilities.

Fatigue and Medical Error

It is well documented that sleep deprivation correlates with a decline in cognitive

performance in a number of classes of healthcare workers. Fatigue has also increased diagnostic error among residents. A 2011 Sentinel Alert from The Joint Commission creates a standard that healthcare organizations implement a fatigue-management plan to mitigate the potential harm caused by tired professionals.

Most of the approaches to improving outcomes in the hospital have focused on process improvement and systems thinking. But errors also occur due to the thinking process of clinicians. In the book “Brain Rules,” author John Medina argues that schools and businesses create an environment that is less than friendly to the brain, citing current classroom design and cubicles for office workers. As a result, he states, we often have poor educational and business performance. I have little doubt that if Medina spent a few hours in a hospital, he would come to a similar conclusion: We don’t do the brain any favors when it comes to creating a healthy environment for providing safe and reliable care to our patients.

References

- Sibinga EM, Wu AW. Clinician mindfulness and patient safety. JAMA. 2010;304(22):2532-2533.

- Riess H. Empathy in medicine─a neurobiological perspective. JAMA. 2010;304(14):1604-1605.

- Rogers RD, Monsell S. The costs of a predictable switch between simple cognitive tasks. J Exper Psychol. 1995;124(2):207–231.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

Hospitalists' Morale Is More Than Mere Job Satisfaction

An abstract poster presented at HM12 in San Diego called the “Hospitalist Morale Assessment” a validated tool for identifying HM groups’ strengths and weaknesses by quantifying their members’ morale. Morale involves more than just job satisfaction, says Shalini Chandra, MD, MS, a hospitalist at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore and lead author of both the abstract and the assessment instrument.

“We’ve been measuring morale here since 2006. We’ve tried to drill down to what drives hospitalists’ morale. We’ve learned that it is not one-size-fits-all,” Dr. Chandra says.

The tool has gradually been refined to quantify both importance of and contentment with 36 domains of hospitalist morale.

Five hospitals and 93 physicians participated in the 2011 survey. Each hospital received a “morale report” that broke out its results. Overall, survey respondents ranked “family time” as the most important morale factor. “Supportive and effective leadership” was rated as next important.

At Johns Hopkins Bayview, results from the annual surveys have led to the opening of a lactation room to accommodate physicians who are new mothers and to the elimination of mandatory double shifts when staffing is short.

Morale is a critical issue in staff retention and in the prevention of costly and time-consuming recruitment searches to address turnover.

“You can’t expect to have happy patients if you don’t have happy providers who exude an air that suggests to patients, ‘I’m happy to be here and you’re my No. 1 priority,’” Dr. Chandra says. “From my perspective, it is important to address morale as an issue if we’re going to keep growing as hospitalist groups and as a specialty.”

For more information or to join future morale surveys, contact Dr. Chandra at [email protected].

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

An abstract poster presented at HM12 in San Diego called the “Hospitalist Morale Assessment” a validated tool for identifying HM groups’ strengths and weaknesses by quantifying their members’ morale. Morale involves more than just job satisfaction, says Shalini Chandra, MD, MS, a hospitalist at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore and lead author of both the abstract and the assessment instrument.

“We’ve been measuring morale here since 2006. We’ve tried to drill down to what drives hospitalists’ morale. We’ve learned that it is not one-size-fits-all,” Dr. Chandra says.

The tool has gradually been refined to quantify both importance of and contentment with 36 domains of hospitalist morale.

Five hospitals and 93 physicians participated in the 2011 survey. Each hospital received a “morale report” that broke out its results. Overall, survey respondents ranked “family time” as the most important morale factor. “Supportive and effective leadership” was rated as next important.

At Johns Hopkins Bayview, results from the annual surveys have led to the opening of a lactation room to accommodate physicians who are new mothers and to the elimination of mandatory double shifts when staffing is short.

Morale is a critical issue in staff retention and in the prevention of costly and time-consuming recruitment searches to address turnover.

“You can’t expect to have happy patients if you don’t have happy providers who exude an air that suggests to patients, ‘I’m happy to be here and you’re my No. 1 priority,’” Dr. Chandra says. “From my perspective, it is important to address morale as an issue if we’re going to keep growing as hospitalist groups and as a specialty.”

For more information or to join future morale surveys, contact Dr. Chandra at [email protected].

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

An abstract poster presented at HM12 in San Diego called the “Hospitalist Morale Assessment” a validated tool for identifying HM groups’ strengths and weaknesses by quantifying their members’ morale. Morale involves more than just job satisfaction, says Shalini Chandra, MD, MS, a hospitalist at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore and lead author of both the abstract and the assessment instrument.

“We’ve been measuring morale here since 2006. We’ve tried to drill down to what drives hospitalists’ morale. We’ve learned that it is not one-size-fits-all,” Dr. Chandra says.

The tool has gradually been refined to quantify both importance of and contentment with 36 domains of hospitalist morale.

Five hospitals and 93 physicians participated in the 2011 survey. Each hospital received a “morale report” that broke out its results. Overall, survey respondents ranked “family time” as the most important morale factor. “Supportive and effective leadership” was rated as next important.

At Johns Hopkins Bayview, results from the annual surveys have led to the opening of a lactation room to accommodate physicians who are new mothers and to the elimination of mandatory double shifts when staffing is short.

Morale is a critical issue in staff retention and in the prevention of costly and time-consuming recruitment searches to address turnover.

“You can’t expect to have happy patients if you don’t have happy providers who exude an air that suggests to patients, ‘I’m happy to be here and you’re my No. 1 priority,’” Dr. Chandra says. “From my perspective, it is important to address morale as an issue if we’re going to keep growing as hospitalist groups and as a specialty.”

For more information or to join future morale surveys, contact Dr. Chandra at [email protected].

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

12 Things Hospitalists Need to Know About Nephrology

One number alone should be enough for hospitalists to want to know everything they can about kidney disease: 26 million. It’s the number of Americans that the National Kidney Foundation estimates to have chronic kidney disease (CKD). That’s about the same number as the American Diabetes Association’s estimate for Americans battling diabetes.

And a lot of people who have CKD don’t even know they have it, kidney specialists warn, making it that much more important to be a knowledgeable watchdog looking out for people admitted to the hospital.

The Hospitalist talked to a half-dozen experts on kidney disease, requesting their words of wisdom for hospitalists. The following are 12 things the experts believe hospitalists should keep in mind as they care for patients with kidney disease.

1) Coordination is key, especially with regard to medications and dialysis after discharge.

A goal should be to develop a “tacit understanding of who does what and just trying to see each day that everyone’s working toward the same goal, so I’m not stopping fluids and then you’re starting fluids, or vice versa,” says Ted Shaikewitz, MD, attending nephrologist at Durham (N.C.) Regional Medical Center and a nephrologist at Durham Nephrology Associates.

A key component of hospitalist-nephrologist collaboration is examining and reconciling medications.

“If it looks like they’re on too many medications, then call the specialist, as opposed to each of you expecting the other one to do it,” he says. “Just pare things down and get rid of things that are unnecessary.”

Often, Dr. Shaikewitz says, the hospitalist and the nephrologist both are reluctant to stop or tweak a medication because someone else started the patient on it. He stresses that the more a medication regimen can be simplified, the better.

Coordination is especially important for dialysis patients who are being sent home, says Ruben Velez, MD, president of the Renal Physicians Association (RPA) and president of Dallas Nephrology Associates. If a nephrologist hasn’t been contacted at discharge, the nephrologist hasn’t contacted the patient’s dialysis center to arrange treatment after the hospitalization. And that treatment likely needs to be altered from what it was before the hospitalization, Dr. Velez explains.

The dialysis center needs to get a small discharge summary, so it’s important to get that ball rolling right away, he adds.

“It’s not uncommon for a nephrologist to round in the morning and suddenly realize that the patient was sent home last night,” he says. “We go, ‘Oops. Did somebody call the dialysis center?’ and we don’t know.”

Informing the nephrologist about discharge helps them do their jobs better, he says.

“My job and my clinical responsibility is, I need to contact the treating nephrologist. I need to contact the dialysis clinic,” he says. “I need to tell them, ‘Change your medications.’ I need to tell them there’s been added antibiotics or other things. I need to tell them what they came in with and what was done. And I need to tell them if there has been a change in their weight....The dialysis clinic has difficulty in dialyzing that patient unless they get this information.”

2) Acknowledge the significance of small, early changes.

A jump in serum creatinine levels at the lower end of the range is far more serious than jumps when the creatinine already is at higher levels, says Lynda Szczech, MD, president of the National Kidney Foundation and medical director at Pharmaceutical Product Development.

“The amount of kidney function that’s described by a [serum creatinine] change of 0.1 when that 0.1” is between 1 and 2, “meaning going from 1.1 to 1.2 or 1.3 to 1.4, is huge compared to the amount of kidney function that is described by a change of 0.1 when you’re higher, when you’re going from 3.0 to 3.1,” Dr. Szczech says. “That’s important, because the earlier changes of going from 0.9 to 1.1 might not trigger a cause for concern, but they actually should be the biggest concern. When you go from a creatinine of 1 to 2, you’ve lost 50 percent of your kidney function. When you go from a creatinine of 3 to 4, you’ve probably lost about 10 percent.”

Hospitalists need to understand both the significance of the change and know “how to jump on something,” Dr. Szczech says. “That is probably the most important thing.”

3) Avoid NSAIDs in patients with advanced CKD and transplant patients.

“The nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can make your renal function much worse,” Dr. Velez says. “Those can finish your kidneys off, and you end up on dialysis.”

That concept is so simple that it’s commonly forgotten, he adds. Patients come to the hospital and are put on an NSAID and the kidneys are damaged.

“It’s horrible,” Dr. Velez says. “That’s one of the worst, and we want to avoid more damage to their kidney function.”

It’s such a common occurrence that the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) included it on their short list of suggestions for the American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) Choosing Wisely campaign, which aims to arm patients and providers with better information, promote evidence-based care, and reduce unnecessary testing and cost.

4) Don’t place PICC lines in advanced CKD and ESRD patients.

Placement of peripheral intravenous central catheter (PICC) lines in advanced CKD and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients is something hospitalists should “avoid as much as possible,” Dr. Velez says, “or forever.”

“PICC lines will destroy veins that we will need to use to create fistulas” needed for dialysis or potential dialysis, he explains.

This item also appears on the Choosing Wisely list.

—Michael Shapiro, MD, MBA, FACP, CPE, president, Denver Nephrology

5) Take basic steps in cases of acute kidney injury (AKI), but be careful about ordering too many tests.

Dr. Shaikewitz says there is little point in hospitalists “ordering everything they can” before the nephrologist is even consulted. That said, certain basic steps—ultrasound, urinalysis, stopping NSAIDs, stopping angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and hydration—should be taken very early, he says.

But hydrating the patient really means achieving a “euvolemic state,” he explains.

“You don’t want to drown the patient,” Dr. Shaikewitz says. Once patients “clearly have enough fluid on board, then you can stop.”

Plus, while it might sound basic, looking back at old creatinine levels is crucial.

“Oftentimes, a lot of what is going on with a patient will become obvious, and the differential will become obvious, when you have more data,” he says.

He also says it’s important to keep in mind that “patients who are in flux with kidney issues often times can tolerate higher blood pressures,” and the goal should be to get it going in the right direction, not necessarily hitting a specific number.

6) Don’t wait for AKI to progress to needing dialysis before consulting the nephrologist.

As Michael Shapiro, MD, MBA, FACP, CPE, president of Denver Nephrology, puts it, “it doesn’t have to be a catastrophe or an emergency for us to be there within a very quick period of time.”

Nephrologists would rather help out earlier than later.

“What we hate to do is have [hospitalists] spend most of the day trying to manage a problem and then calling us late in the day or in the evening, especially if a procedure like dialysis would be needed at that point in time,” he says. “It’s a lot harder to manage those troops, so to speak, once we let the day go. It’s a little bit more of a crash as opposed to a nice plan.”

Hospitalists should adopt the “earlier is better” mantra for cases of electrolyte problems, such as hypokalemia, hyperkalemia, and significant hyponatremia, or low salt levels, he notes.

“We don’t mind being curb-sided,” Dr. Shapiro says. If the specialist gets a simple heads-up about a patient on the fourth floor—even if it doesn’t require immediate action—he can then pop in and check on the status of that patient when he’s there on his rounds, he says.

Dr. Shaikewitz admits that some kidney specialists prefer not to be called in very early; therefore, it’s important for hospitalists to develop relationships and understand individual preferences. But in his case, an early referral is favorable.

“When in doubt, refer a little bit on the early side,” he says. “It’s actually kind of a fun teamwork with the hospitalists, trying to manage the patient and doing everything as a group.”

—Ruben Velez, MD, president, Renal Physicians Association, president, Dallas Nephrology Associates

7) Always call a nephrologist when a kidney transplant patient is admitted.

Robert Kossmann, MD, president-elect of the RPA, and other experts agree that it’s a good idea to at least call and inform a nephrologist that a transplant patient has been admitted. The call can go something like, “I have this patient coming in to the hospital, their kidney transplant function is fine, but they’re here with X, Y, or Z,” he says. “Is there something that we should be paying particular attention to or do you need to come see that patient?”

Dr. Kossmann says hospitalists don’t need to automatically consult a nephrologist every time, but “it’s probably a good idea to call and talk to the nephrologist every time.”

Dr. Velez says he’s seen a lot of unnecessary mistakes around transplant patients.

“There’s a lot of drug interactions with immunosuppressive drugs that these patients take that could have been prevented or avoided,” he says. “Even on patients that have fantastic renal function up to transplant … these patients can turn sour on a dime.”

8) Don’t forget the power of a simple urinalysis.

You can get a lot of diagnostic information from the urinalysis—“from a simple dipstick,” Dr. Szczech says. She points out the value of the specific gravity reading.

“A specific gravity of 1.010 in the setting of a rising creatinine [level] probably means you’ve got injury to the tubule,” she says.

The power of this simple tool can sometimes be overlooked, she says, as clinicians seek to understand how to use the newer biomarkers.

“In nephrology, we can make things quite complicated,” she adds. “We can’t forget about the low-tech stuff that we just take for granted.”

9) Simply looking at serum creatinine level is not enough.

It’s extremely important to calculate the glomerular filtration rate (GFR), says Katherine Tuttle, MD, clinical professor of medicine in the University of Washington’s division of nephrology. Some hospital labs will do this, but hospitalists need to “make sure they review the GFR values, not just the serum creatinine,” she says.

And those readings have important ripple effects.

“Everything from need for adjustment of drugs for low GFR to drug interactions to caution about, for example, using iodinated contrasts because of risk of acute kidney injury, increased risk of infection, increased risk of cardiovascular complications,” she says. “So it’s a very important part of the clinical assessment.”

10) Know the potential benefits of isolated ultrafiltration.

This dialysis-like procedure is becoming more widely recognized as helpful for patients with congestive heart failure who have recurrent readmissions.

“This is a very small group, but a very complicated group,” Dr. Kossmann says. “You can’t keep them out of the hospital.”

Isolated ultrafiltration can help “pull off quite a lot of fluid while they’re in the hospital or in a setting where you can do that,” he adds. “That’s something that I think hospitalists may be seeing more of as this unfolds into the future. It’s a small group of people, but there’s so much heart disease in this country that it winds up being a significant increase in number.”

11) Avoid using low-molecular-weight heparins, especially Lovenox, in advanced kidney disease and dialysis patients.

Don’t just follow the protocols for preventing thromboembolic events, says Dr. Velez, who adds it’s done “very frequently.”

“In this day and age of preventing thromboembolic [events], they have protocols where they just put them on it and they don’t realize they have advanced kidney disease or end-stage renal disease,” he says. “Heparin is fine. Lovenox should be avoided.”

Such mistakes are, in part, a product of operating within a protocol-driven environment.

“Dealing with a lot of protocols and algorithms and pressure from the hospital and you name it—and we’re all busy—we want to do the right thing,” Dr. Velez says. “But we don’t apply it to individual patients, and that’s a concern of having too many protocols and trying to treat everybody the same.”

Dr. Tuttle says the risk of “over-reliance” on protocols and guidelines is real.

“The problem with guidelines is people extrapolate them too far and they overinterpret them,” she says. “That happens in the hospital all the time.”

12) Take a moment and ask: Am I really comfortable handling this patient?

“It’s worth pausing at some point with yourself and sort of taking a self-assessment and saying—whether it’s nephrology, cardiology, or something else—‘Where do I feel confident and strong?’” Dr. Kossmann says. “Although it sounds overly basic, that’s an important starting point.”

He says he’s witnessed hospitalists with a wide range of comfort levels handle cases involving kidney dysfunction.

“There’s no one-size-fits-all,” he says. “Sometimes the question I get asked is, ‘Rob, what’s the general rule? When should a nephrologist be called for a consult?’ And that’s a terrible question, because it depends on the doctor who’s seeing the patient.”

Thomas Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

One number alone should be enough for hospitalists to want to know everything they can about kidney disease: 26 million. It’s the number of Americans that the National Kidney Foundation estimates to have chronic kidney disease (CKD). That’s about the same number as the American Diabetes Association’s estimate for Americans battling diabetes.

And a lot of people who have CKD don’t even know they have it, kidney specialists warn, making it that much more important to be a knowledgeable watchdog looking out for people admitted to the hospital.

The Hospitalist talked to a half-dozen experts on kidney disease, requesting their words of wisdom for hospitalists. The following are 12 things the experts believe hospitalists should keep in mind as they care for patients with kidney disease.

1) Coordination is key, especially with regard to medications and dialysis after discharge.

A goal should be to develop a “tacit understanding of who does what and just trying to see each day that everyone’s working toward the same goal, so I’m not stopping fluids and then you’re starting fluids, or vice versa,” says Ted Shaikewitz, MD, attending nephrologist at Durham (N.C.) Regional Medical Center and a nephrologist at Durham Nephrology Associates.

A key component of hospitalist-nephrologist collaboration is examining and reconciling medications.

“If it looks like they’re on too many medications, then call the specialist, as opposed to each of you expecting the other one to do it,” he says. “Just pare things down and get rid of things that are unnecessary.”

Often, Dr. Shaikewitz says, the hospitalist and the nephrologist both are reluctant to stop or tweak a medication because someone else started the patient on it. He stresses that the more a medication regimen can be simplified, the better.

Coordination is especially important for dialysis patients who are being sent home, says Ruben Velez, MD, president of the Renal Physicians Association (RPA) and president of Dallas Nephrology Associates. If a nephrologist hasn’t been contacted at discharge, the nephrologist hasn’t contacted the patient’s dialysis center to arrange treatment after the hospitalization. And that treatment likely needs to be altered from what it was before the hospitalization, Dr. Velez explains.

The dialysis center needs to get a small discharge summary, so it’s important to get that ball rolling right away, he adds.

“It’s not uncommon for a nephrologist to round in the morning and suddenly realize that the patient was sent home last night,” he says. “We go, ‘Oops. Did somebody call the dialysis center?’ and we don’t know.”

Informing the nephrologist about discharge helps them do their jobs better, he says.

“My job and my clinical responsibility is, I need to contact the treating nephrologist. I need to contact the dialysis clinic,” he says. “I need to tell them, ‘Change your medications.’ I need to tell them there’s been added antibiotics or other things. I need to tell them what they came in with and what was done. And I need to tell them if there has been a change in their weight....The dialysis clinic has difficulty in dialyzing that patient unless they get this information.”

2) Acknowledge the significance of small, early changes.

A jump in serum creatinine levels at the lower end of the range is far more serious than jumps when the creatinine already is at higher levels, says Lynda Szczech, MD, president of the National Kidney Foundation and medical director at Pharmaceutical Product Development.

“The amount of kidney function that’s described by a [serum creatinine] change of 0.1 when that 0.1” is between 1 and 2, “meaning going from 1.1 to 1.2 or 1.3 to 1.4, is huge compared to the amount of kidney function that is described by a change of 0.1 when you’re higher, when you’re going from 3.0 to 3.1,” Dr. Szczech says. “That’s important, because the earlier changes of going from 0.9 to 1.1 might not trigger a cause for concern, but they actually should be the biggest concern. When you go from a creatinine of 1 to 2, you’ve lost 50 percent of your kidney function. When you go from a creatinine of 3 to 4, you’ve probably lost about 10 percent.”

Hospitalists need to understand both the significance of the change and know “how to jump on something,” Dr. Szczech says. “That is probably the most important thing.”

3) Avoid NSAIDs in patients with advanced CKD and transplant patients.

“The nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can make your renal function much worse,” Dr. Velez says. “Those can finish your kidneys off, and you end up on dialysis.”

That concept is so simple that it’s commonly forgotten, he adds. Patients come to the hospital and are put on an NSAID and the kidneys are damaged.

“It’s horrible,” Dr. Velez says. “That’s one of the worst, and we want to avoid more damage to their kidney function.”

It’s such a common occurrence that the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) included it on their short list of suggestions for the American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) Choosing Wisely campaign, which aims to arm patients and providers with better information, promote evidence-based care, and reduce unnecessary testing and cost.

4) Don’t place PICC lines in advanced CKD and ESRD patients.

Placement of peripheral intravenous central catheter (PICC) lines in advanced CKD and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients is something hospitalists should “avoid as much as possible,” Dr. Velez says, “or forever.”

“PICC lines will destroy veins that we will need to use to create fistulas” needed for dialysis or potential dialysis, he explains.

This item also appears on the Choosing Wisely list.

—Michael Shapiro, MD, MBA, FACP, CPE, president, Denver Nephrology

5) Take basic steps in cases of acute kidney injury (AKI), but be careful about ordering too many tests.

Dr. Shaikewitz says there is little point in hospitalists “ordering everything they can” before the nephrologist is even consulted. That said, certain basic steps—ultrasound, urinalysis, stopping NSAIDs, stopping angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and hydration—should be taken very early, he says.

But hydrating the patient really means achieving a “euvolemic state,” he explains.

“You don’t want to drown the patient,” Dr. Shaikewitz says. Once patients “clearly have enough fluid on board, then you can stop.”

Plus, while it might sound basic, looking back at old creatinine levels is crucial.

“Oftentimes, a lot of what is going on with a patient will become obvious, and the differential will become obvious, when you have more data,” he says.

He also says it’s important to keep in mind that “patients who are in flux with kidney issues often times can tolerate higher blood pressures,” and the goal should be to get it going in the right direction, not necessarily hitting a specific number.

6) Don’t wait for AKI to progress to needing dialysis before consulting the nephrologist.

As Michael Shapiro, MD, MBA, FACP, CPE, president of Denver Nephrology, puts it, “it doesn’t have to be a catastrophe or an emergency for us to be there within a very quick period of time.”

Nephrologists would rather help out earlier than later.

“What we hate to do is have [hospitalists] spend most of the day trying to manage a problem and then calling us late in the day or in the evening, especially if a procedure like dialysis would be needed at that point in time,” he says. “It’s a lot harder to manage those troops, so to speak, once we let the day go. It’s a little bit more of a crash as opposed to a nice plan.”

Hospitalists should adopt the “earlier is better” mantra for cases of electrolyte problems, such as hypokalemia, hyperkalemia, and significant hyponatremia, or low salt levels, he notes.

“We don’t mind being curb-sided,” Dr. Shapiro says. If the specialist gets a simple heads-up about a patient on the fourth floor—even if it doesn’t require immediate action—he can then pop in and check on the status of that patient when he’s there on his rounds, he says.

Dr. Shaikewitz admits that some kidney specialists prefer not to be called in very early; therefore, it’s important for hospitalists to develop relationships and understand individual preferences. But in his case, an early referral is favorable.

“When in doubt, refer a little bit on the early side,” he says. “It’s actually kind of a fun teamwork with the hospitalists, trying to manage the patient and doing everything as a group.”

—Ruben Velez, MD, president, Renal Physicians Association, president, Dallas Nephrology Associates

7) Always call a nephrologist when a kidney transplant patient is admitted.

Robert Kossmann, MD, president-elect of the RPA, and other experts agree that it’s a good idea to at least call and inform a nephrologist that a transplant patient has been admitted. The call can go something like, “I have this patient coming in to the hospital, their kidney transplant function is fine, but they’re here with X, Y, or Z,” he says. “Is there something that we should be paying particular attention to or do you need to come see that patient?”

Dr. Kossmann says hospitalists don’t need to automatically consult a nephrologist every time, but “it’s probably a good idea to call and talk to the nephrologist every time.”

Dr. Velez says he’s seen a lot of unnecessary mistakes around transplant patients.

“There’s a lot of drug interactions with immunosuppressive drugs that these patients take that could have been prevented or avoided,” he says. “Even on patients that have fantastic renal function up to transplant … these patients can turn sour on a dime.”

8) Don’t forget the power of a simple urinalysis.

You can get a lot of diagnostic information from the urinalysis—“from a simple dipstick,” Dr. Szczech says. She points out the value of the specific gravity reading.

“A specific gravity of 1.010 in the setting of a rising creatinine [level] probably means you’ve got injury to the tubule,” she says.

The power of this simple tool can sometimes be overlooked, she says, as clinicians seek to understand how to use the newer biomarkers.

“In nephrology, we can make things quite complicated,” she adds. “We can’t forget about the low-tech stuff that we just take for granted.”

9) Simply looking at serum creatinine level is not enough.

It’s extremely important to calculate the glomerular filtration rate (GFR), says Katherine Tuttle, MD, clinical professor of medicine in the University of Washington’s division of nephrology. Some hospital labs will do this, but hospitalists need to “make sure they review the GFR values, not just the serum creatinine,” she says.

And those readings have important ripple effects.

“Everything from need for adjustment of drugs for low GFR to drug interactions to caution about, for example, using iodinated contrasts because of risk of acute kidney injury, increased risk of infection, increased risk of cardiovascular complications,” she says. “So it’s a very important part of the clinical assessment.”

10) Know the potential benefits of isolated ultrafiltration.

This dialysis-like procedure is becoming more widely recognized as helpful for patients with congestive heart failure who have recurrent readmissions.

“This is a very small group, but a very complicated group,” Dr. Kossmann says. “You can’t keep them out of the hospital.”

Isolated ultrafiltration can help “pull off quite a lot of fluid while they’re in the hospital or in a setting where you can do that,” he adds. “That’s something that I think hospitalists may be seeing more of as this unfolds into the future. It’s a small group of people, but there’s so much heart disease in this country that it winds up being a significant increase in number.”

11) Avoid using low-molecular-weight heparins, especially Lovenox, in advanced kidney disease and dialysis patients.

Don’t just follow the protocols for preventing thromboembolic events, says Dr. Velez, who adds it’s done “very frequently.”

“In this day and age of preventing thromboembolic [events], they have protocols where they just put them on it and they don’t realize they have advanced kidney disease or end-stage renal disease,” he says. “Heparin is fine. Lovenox should be avoided.”

Such mistakes are, in part, a product of operating within a protocol-driven environment.

“Dealing with a lot of protocols and algorithms and pressure from the hospital and you name it—and we’re all busy—we want to do the right thing,” Dr. Velez says. “But we don’t apply it to individual patients, and that’s a concern of having too many protocols and trying to treat everybody the same.”

Dr. Tuttle says the risk of “over-reliance” on protocols and guidelines is real.

“The problem with guidelines is people extrapolate them too far and they overinterpret them,” she says. “That happens in the hospital all the time.”

12) Take a moment and ask: Am I really comfortable handling this patient?

“It’s worth pausing at some point with yourself and sort of taking a self-assessment and saying—whether it’s nephrology, cardiology, or something else—‘Where do I feel confident and strong?’” Dr. Kossmann says. “Although it sounds overly basic, that’s an important starting point.”

He says he’s witnessed hospitalists with a wide range of comfort levels handle cases involving kidney dysfunction.

“There’s no one-size-fits-all,” he says. “Sometimes the question I get asked is, ‘Rob, what’s the general rule? When should a nephrologist be called for a consult?’ And that’s a terrible question, because it depends on the doctor who’s seeing the patient.”

Thomas Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

One number alone should be enough for hospitalists to want to know everything they can about kidney disease: 26 million. It’s the number of Americans that the National Kidney Foundation estimates to have chronic kidney disease (CKD). That’s about the same number as the American Diabetes Association’s estimate for Americans battling diabetes.

And a lot of people who have CKD don’t even know they have it, kidney specialists warn, making it that much more important to be a knowledgeable watchdog looking out for people admitted to the hospital.

The Hospitalist talked to a half-dozen experts on kidney disease, requesting their words of wisdom for hospitalists. The following are 12 things the experts believe hospitalists should keep in mind as they care for patients with kidney disease.

1) Coordination is key, especially with regard to medications and dialysis after discharge.

A goal should be to develop a “tacit understanding of who does what and just trying to see each day that everyone’s working toward the same goal, so I’m not stopping fluids and then you’re starting fluids, or vice versa,” says Ted Shaikewitz, MD, attending nephrologist at Durham (N.C.) Regional Medical Center and a nephrologist at Durham Nephrology Associates.

A key component of hospitalist-nephrologist collaboration is examining and reconciling medications.

“If it looks like they’re on too many medications, then call the specialist, as opposed to each of you expecting the other one to do it,” he says. “Just pare things down and get rid of things that are unnecessary.”

Often, Dr. Shaikewitz says, the hospitalist and the nephrologist both are reluctant to stop or tweak a medication because someone else started the patient on it. He stresses that the more a medication regimen can be simplified, the better.

Coordination is especially important for dialysis patients who are being sent home, says Ruben Velez, MD, president of the Renal Physicians Association (RPA) and president of Dallas Nephrology Associates. If a nephrologist hasn’t been contacted at discharge, the nephrologist hasn’t contacted the patient’s dialysis center to arrange treatment after the hospitalization. And that treatment likely needs to be altered from what it was before the hospitalization, Dr. Velez explains.

The dialysis center needs to get a small discharge summary, so it’s important to get that ball rolling right away, he adds.

“It’s not uncommon for a nephrologist to round in the morning and suddenly realize that the patient was sent home last night,” he says. “We go, ‘Oops. Did somebody call the dialysis center?’ and we don’t know.”

Informing the nephrologist about discharge helps them do their jobs better, he says.

“My job and my clinical responsibility is, I need to contact the treating nephrologist. I need to contact the dialysis clinic,” he says. “I need to tell them, ‘Change your medications.’ I need to tell them there’s been added antibiotics or other things. I need to tell them what they came in with and what was done. And I need to tell them if there has been a change in their weight....The dialysis clinic has difficulty in dialyzing that patient unless they get this information.”

2) Acknowledge the significance of small, early changes.

A jump in serum creatinine levels at the lower end of the range is far more serious than jumps when the creatinine already is at higher levels, says Lynda Szczech, MD, president of the National Kidney Foundation and medical director at Pharmaceutical Product Development.

“The amount of kidney function that’s described by a [serum creatinine] change of 0.1 when that 0.1” is between 1 and 2, “meaning going from 1.1 to 1.2 or 1.3 to 1.4, is huge compared to the amount of kidney function that is described by a change of 0.1 when you’re higher, when you’re going from 3.0 to 3.1,” Dr. Szczech says. “That’s important, because the earlier changes of going from 0.9 to 1.1 might not trigger a cause for concern, but they actually should be the biggest concern. When you go from a creatinine of 1 to 2, you’ve lost 50 percent of your kidney function. When you go from a creatinine of 3 to 4, you’ve probably lost about 10 percent.”

Hospitalists need to understand both the significance of the change and know “how to jump on something,” Dr. Szczech says. “That is probably the most important thing.”

3) Avoid NSAIDs in patients with advanced CKD and transplant patients.

“The nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can make your renal function much worse,” Dr. Velez says. “Those can finish your kidneys off, and you end up on dialysis.”

That concept is so simple that it’s commonly forgotten, he adds. Patients come to the hospital and are put on an NSAID and the kidneys are damaged.

“It’s horrible,” Dr. Velez says. “That’s one of the worst, and we want to avoid more damage to their kidney function.”

It’s such a common occurrence that the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) included it on their short list of suggestions for the American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) Choosing Wisely campaign, which aims to arm patients and providers with better information, promote evidence-based care, and reduce unnecessary testing and cost.

4) Don’t place PICC lines in advanced CKD and ESRD patients.

Placement of peripheral intravenous central catheter (PICC) lines in advanced CKD and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients is something hospitalists should “avoid as much as possible,” Dr. Velez says, “or forever.”

“PICC lines will destroy veins that we will need to use to create fistulas” needed for dialysis or potential dialysis, he explains.

This item also appears on the Choosing Wisely list.

—Michael Shapiro, MD, MBA, FACP, CPE, president, Denver Nephrology

5) Take basic steps in cases of acute kidney injury (AKI), but be careful about ordering too many tests.

Dr. Shaikewitz says there is little point in hospitalists “ordering everything they can” before the nephrologist is even consulted. That said, certain basic steps—ultrasound, urinalysis, stopping NSAIDs, stopping angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and hydration—should be taken very early, he says.

But hydrating the patient really means achieving a “euvolemic state,” he explains.

“You don’t want to drown the patient,” Dr. Shaikewitz says. Once patients “clearly have enough fluid on board, then you can stop.”

Plus, while it might sound basic, looking back at old creatinine levels is crucial.

“Oftentimes, a lot of what is going on with a patient will become obvious, and the differential will become obvious, when you have more data,” he says.

He also says it’s important to keep in mind that “patients who are in flux with kidney issues often times can tolerate higher blood pressures,” and the goal should be to get it going in the right direction, not necessarily hitting a specific number.

6) Don’t wait for AKI to progress to needing dialysis before consulting the nephrologist.

As Michael Shapiro, MD, MBA, FACP, CPE, president of Denver Nephrology, puts it, “it doesn’t have to be a catastrophe or an emergency for us to be there within a very quick period of time.”

Nephrologists would rather help out earlier than later.

“What we hate to do is have [hospitalists] spend most of the day trying to manage a problem and then calling us late in the day or in the evening, especially if a procedure like dialysis would be needed at that point in time,” he says. “It’s a lot harder to manage those troops, so to speak, once we let the day go. It’s a little bit more of a crash as opposed to a nice plan.”

Hospitalists should adopt the “earlier is better” mantra for cases of electrolyte problems, such as hypokalemia, hyperkalemia, and significant hyponatremia, or low salt levels, he notes.

“We don’t mind being curb-sided,” Dr. Shapiro says. If the specialist gets a simple heads-up about a patient on the fourth floor—even if it doesn’t require immediate action—he can then pop in and check on the status of that patient when he’s there on his rounds, he says.

Dr. Shaikewitz admits that some kidney specialists prefer not to be called in very early; therefore, it’s important for hospitalists to develop relationships and understand individual preferences. But in his case, an early referral is favorable.

“When in doubt, refer a little bit on the early side,” he says. “It’s actually kind of a fun teamwork with the hospitalists, trying to manage the patient and doing everything as a group.”

—Ruben Velez, MD, president, Renal Physicians Association, president, Dallas Nephrology Associates

7) Always call a nephrologist when a kidney transplant patient is admitted.

Robert Kossmann, MD, president-elect of the RPA, and other experts agree that it’s a good idea to at least call and inform a nephrologist that a transplant patient has been admitted. The call can go something like, “I have this patient coming in to the hospital, their kidney transplant function is fine, but they’re here with X, Y, or Z,” he says. “Is there something that we should be paying particular attention to or do you need to come see that patient?”

Dr. Kossmann says hospitalists don’t need to automatically consult a nephrologist every time, but “it’s probably a good idea to call and talk to the nephrologist every time.”

Dr. Velez says he’s seen a lot of unnecessary mistakes around transplant patients.

“There’s a lot of drug interactions with immunosuppressive drugs that these patients take that could have been prevented or avoided,” he says. “Even on patients that have fantastic renal function up to transplant … these patients can turn sour on a dime.”

8) Don’t forget the power of a simple urinalysis.

You can get a lot of diagnostic information from the urinalysis—“from a simple dipstick,” Dr. Szczech says. She points out the value of the specific gravity reading.

“A specific gravity of 1.010 in the setting of a rising creatinine [level] probably means you’ve got injury to the tubule,” she says.

The power of this simple tool can sometimes be overlooked, she says, as clinicians seek to understand how to use the newer biomarkers.

“In nephrology, we can make things quite complicated,” she adds. “We can’t forget about the low-tech stuff that we just take for granted.”

9) Simply looking at serum creatinine level is not enough.

It’s extremely important to calculate the glomerular filtration rate (GFR), says Katherine Tuttle, MD, clinical professor of medicine in the University of Washington’s division of nephrology. Some hospital labs will do this, but hospitalists need to “make sure they review the GFR values, not just the serum creatinine,” she says.

And those readings have important ripple effects.

“Everything from need for adjustment of drugs for low GFR to drug interactions to caution about, for example, using iodinated contrasts because of risk of acute kidney injury, increased risk of infection, increased risk of cardiovascular complications,” she says. “So it’s a very important part of the clinical assessment.”

10) Know the potential benefits of isolated ultrafiltration.

This dialysis-like procedure is becoming more widely recognized as helpful for patients with congestive heart failure who have recurrent readmissions.

“This is a very small group, but a very complicated group,” Dr. Kossmann says. “You can’t keep them out of the hospital.”

Isolated ultrafiltration can help “pull off quite a lot of fluid while they’re in the hospital or in a setting where you can do that,” he adds. “That’s something that I think hospitalists may be seeing more of as this unfolds into the future. It’s a small group of people, but there’s so much heart disease in this country that it winds up being a significant increase in number.”

11) Avoid using low-molecular-weight heparins, especially Lovenox, in advanced kidney disease and dialysis patients.

Don’t just follow the protocols for preventing thromboembolic events, says Dr. Velez, who adds it’s done “very frequently.”

“In this day and age of preventing thromboembolic [events], they have protocols where they just put them on it and they don’t realize they have advanced kidney disease or end-stage renal disease,” he says. “Heparin is fine. Lovenox should be avoided.”

Such mistakes are, in part, a product of operating within a protocol-driven environment.

“Dealing with a lot of protocols and algorithms and pressure from the hospital and you name it—and we’re all busy—we want to do the right thing,” Dr. Velez says. “But we don’t apply it to individual patients, and that’s a concern of having too many protocols and trying to treat everybody the same.”

Dr. Tuttle says the risk of “over-reliance” on protocols and guidelines is real.

“The problem with guidelines is people extrapolate them too far and they overinterpret them,” she says. “That happens in the hospital all the time.”

12) Take a moment and ask: Am I really comfortable handling this patient?

“It’s worth pausing at some point with yourself and sort of taking a self-assessment and saying—whether it’s nephrology, cardiology, or something else—‘Where do I feel confident and strong?’” Dr. Kossmann says. “Although it sounds overly basic, that’s an important starting point.”

He says he’s witnessed hospitalists with a wide range of comfort levels handle cases involving kidney dysfunction.

“There’s no one-size-fits-all,” he says. “Sometimes the question I get asked is, ‘Rob, what’s the general rule? When should a nephrologist be called for a consult?’ And that’s a terrible question, because it depends on the doctor who’s seeing the patient.”

Thomas Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

The Pros and Cons of Locum Tenens for Hospitalists

Michael Manning, MD, medical director of Murphy Medical Center in Murphy, N.C., needed a doctor. Tasked with building the hospitalist program for his 57-bed hospital 90 miles from the closest city, Dr. Manning turned to a locum tenens firm for help, and the company seemed to find a perfect fit. They found a physician who wanted to commit to a one-year stint. The physician was eminently competent, had lined up housing for the year, and, perhaps most important, was eager to serve the residents of seven rural counties in western North Carolina, northern Georgia, and eastern Tennessee.

Then the new hire had a change of heart and backed out of the position. As medical director, Dr. Manning has taken on up to 10 hospitalist shifts a month to cover the absence, and the hospital-employed group is now looking at paying temporary staffers even more as the nascent group struggles to reach its optimal staffing level. To Dr. Manning, the hope-to-heartburn scenario typifies the “two-edged sword” that is locum tenens.

“Overall, I would say it’s a necessary evil,” he says. “You’ve got to have your service staffed. You can’t go without physicians filling slots. The evil for us is the cost.”

The cost of paying temporary physicians over the long term can be overwhelming for cash-strapped hospitals and health systems. But that’s done little to stop hospitalists from becoming the leading specialty in the temporary staffing market, according to a proprietary annual review compiled by Staffing Industry Analysis of Mountain View, Calif., on behalf of the National Association of Locum Tenens Organizations (NALTO). Hospitalists accounted for 17% of locum tenens revenue generated in the first half of 2011, the report states. The only other specialty in double-digit figures was emergency medicine, which tallied 14% of the $548 million in revenue measured by the report. Survey respondents reported year-over-year revenue growth of 9.5% in the first half of 2011, with aggregate revenue generated by hospitalists jumping more than 34%.

A survey of hospitalists released in October showed that nearly 12% had worked locum tenens in the previous 12 months; 64% had done the work in addition to their full-time jobs.1 The survey, crafted by Locum Leaders of Alpharetta, Ga., was among the first to capture just how prevalent the practice of temporary staffing is and what motivates physicians to do the work.

The reasons hospitalists choose to work locums are as varied as HM practices. In the short term, hospital-based physicians are looking for geographic flexibility, higher earning potential, and the chance to “try something on for size before they buy,” says Robert Harrington Jr., MD, SFHM, chief medical officer for Locum Leaders and a SHM board member. Early-career hospitalists can use temporary work to determine what they want to do with their careers, while older physicians can use it to finish their careers focused solely on clinical care.

Regardless of motivation, hospital administrators can utilize temporary staffing to save money on health, retirement, and retention benefits, as well as costs related to training and career development. But staffing via locum tenens has downsides, too. Cost is the concern most commonly noted, with expenses including negotiated fees to locum companies and, depending on contracts, travel and lodging costs (most contracts cover malpractice costs, industry players say). Some critics question the quality of temporary physicians, while others worry about the potential of doctors distracted by their “day” jobs.

Detractors also note that using temporary physicians can have a deleterious effect on teamwork, as more transient workers are less invested in an institution’s mission, vision, and long-term goals. Patricia Stone, PhD, RN, FAAN, who has studied the use of agency nurses, says that how well a locum tenens worker integrates into a team setting depends on how willing that person is to bond with colleagues.

“There are things that happen in a hospital for which a team is needed,” says Stone, director of the Center for Health Policy and the PhD program at the Columbia University School of Nursing in New York City. “The nurse needs to know how much she can count on that physician. The physician needs to know how much they can count on that nurse.”

Hospitalists = Prime Targets

The use of locum tenens in HM has skyrocketed in recent years, as the number of hospitals adding hospitalists has grown. And, for now, it doesn’t seem like there’s any end in sight, particularly as cost-conscious hospitals look for ways to save money.

“Trees don’t grow to the sky, but...we’ll be very curious to see what the next survey tells us about how the second half of 2011 did,” says Tony Gregoire, senior research analyst for Staffing Industry Analysts. “But as of yet, we just can’t speak to any plateauing. It just seems like there is more room for growth here. The big factor will be supply shortage because there is such demand for hospitalists.”

To wit, the 2011 Survey of Temporary Physician Staffing Trends found that 85% of healthcare facilities managers reported using temporary physicians in 2010, up from 72% in 2009.2 And the number of facilities seeking locum tenens staffers is rising, despite the “downturn in physician utilization caused by the recession,” the report added. Some 41% of those surveyed were looking for locum tenens physicians in 2010, up 1% from the year before.

Brent Bormaster, divisional vice president of Staff Care of Dallas—whose firm publishes an annual report, the 2011 Survey on temporary staffing trends—says that the use of temporary staffing makes economic sense in a growing specialty such as HM because it allows programs to start up and staff up more quickly. And because turnover can be an issue in the early days of any group, temporary staffers can either fill in while the group recruits a permanent physician or can step in when a physician leaves, giving the practice time to run a proper search.

—Brent Bormaster, divisional vice president, Staff Care of Dallas

“You can still maintain your continuity of staff and continuity of care,” Bormaster says. “All the while, you’re still recruiting for your permanent physician and permanent replacement, which may take upwards of six to eight months.”

The temporary staffing market in HM has grown so competitive in recent years that one large hospitalist group started its own placement division for physicians. Robert Bessler, MD, president and CEO of Tacoma, Wash.-based Sound Physicians, says his company launched Echo Locum Tenens of Dallas in August 2011 to take advantage of the firm’s economies of scale. Sound employs more than 500 hospitalists and post-acute physicians, and partners with about 70 hospitals nationwide (see “DIY Locum?”, right).

“We felt there was an opportunity to be a niche provider to serve our own needs … to fill the short-term demand for temporary help, whether we’re starting up a program quickly or have a gap in coverage due to illness or maternity leave or something else,” Dr. Bessler says. “We found that we could build a more accountable model by having it be part of our organization.”

Another reason for the growth in temporary staffing may be the appeal it has for physicians who want to focus simply on clinical care, says Dorothy Nemec, MD, MSPH, a board-certified internist who runs MDPA Locums in Punta Gordo, Fla., with her physician assistant husband, Larry Rand, PA-C. The couple started their temporary staffing firm in 1996 and has authored a book, “Finding Private Locums,” that outlines how to launch a career in locum tenens.3

“When we started our own business, what we found was we were able to do what we are trained to do, and you don’t have to deal with the politics,” Dr. Nemec explains. “You don’t have to deal with all of the other things that you get involved with when you’re in permanent practices. So you can devote all of your time to taking care of patients.”

The Cost Equation

The biggest question surrounding the use of locums is the cost-benefit analysis, a point not lost on hospital executives and locum physicians who answered Staff Care’s last report. Eighty-six percent of those surveyed said cost was the biggest drawback to the use of locum doctors, a dramatic increase from the previous year, when just 58% pointed to cost as the largest detriment. Locum physicians can gross 30% to 40% more per year for the same number of shifts as a typical FTE hospitalist.

But Dr. Harrington believes the ability to earn more money continues to push physicians into working locums. “Hospitals now realize that they have to have a hospitalist program,” Dr. Harrington says. “The issue for them is more around reimbursement and where that money is going to come from.”

Bormaster, of Staff Care, says that while the higher salaries for locum physicians can seem like an expensive proposition, the cost has to be viewed in context. Because the typical temporary physician is an independent contractor, compensation does not include many of the costly expenses tied to permanent hires.

“You’re paying us on an hourly basis, and you don’t have any ancillary benefits, healthcare, 401(k), malpractice insurance, anything like that,” Bormaster adds. “All you’re doing is paying straight for the hours worked or hours produced by that hospitalist that is contracted with us.”

Surveys show part-time and temporary physicians’ lack of familiarity with their work setting can be detrimental. It’s shortsighted to undervalue the role continuity plays in the hospital setting, as it can lower the quality of care delivered and impact both patient and worker satisfaction, says Stone, the Columbia University nurse-researcher.

“It’s not necessarily the cheapest way to go because of the decreased quality,” she says, adding she hopes the topic is one tackled in future research. “It needs to be looked at. The hospitalist environment has just grown so much....How to do it right? We just don’t know enough about it yet.”

Is the Sky the Limit?

It is often said that HM is the country’s fastest-growing medical specialty. Combined with the recent reduction in resident work-hours at academic centers and the impending physician shortfall nationwide, there may be a perfect storm looming.

“Supply will eventually adjust to the demand, but that demand is only going to keep increasing,” says Gregoire, the senior research analyst.

MaryAnn Stolgitis, vice president of operations for Boston-based national staffing firm Barton Associates, says hospitals and healthcare organizations will often have little choice but to continue using temporary physicians to bridge personnel gaps.

Stolgitis says that beyond the supply-demand curve, another factor in temporary staffing’s growth is the increased desire of physicians to generate additional revenue. The exact motivation will vary, from new physicians looking to pay off increasingly burdensome student loans to late-career physicians looking for financial security as they transition into retirement. Others will enjoy the idea of traveling the country via a spider web of locum tenens positions.

“We’re recruiting doctors who were full-time doctors, permanent doctors. There are a lot of people making that switch,” she says. “I think there’s not only increased demand for patient care, but there’s also a shortage of physicians out there willing to accept full-time jobs because now they see this other way of life and they’re willing to do that.”

Dr. Manning says that quality locum firms can take advantage of that situation by continually recruiting the strongest physicians.

“When you find a good company providing you physicians that want to work and do their job and are patient-friendly, you just need to go with it,” he says. “The only problem, is you’re going to pay more for it.”

Jason Daeffler, a marketing director for Barton, adds that the physician shortage in the coming years will only exacerbate the issue of staffing issues at hospitals. He says supplementing full-time hospitalists with locum doctors will offer HM group leaders the scheduling flexibility needed to maintain optimal coverage levels and maximize revenue generation. HM groups without that leverage could struggle to cover all shifts as effectively, he adds.

Plus, physicians who take on locum tenens work will create financial flexibility for themselves at a time when payrolls are under tremendous pressure from C-suite executives looking to trim budgets. Individually, each factor might not be as powerful, but when combined, Stolgitis says the stage is set for continued success.

“You’re going to see more and more locum tenens in the future,” she says. “Whether you’re looking at the retiree population, physicians right out of residency or fellowship training, or someone who’s been working two or three years...they are beginning to see locum tenens as a better lifestyle for them.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Locum Leaders. 2012 Hospitalist Locum Tenens Survey. Locum Leaders website. Available at http://www.locumleaders.com/assets/downloads/2012_hospitalist_locum_tenens_survey_locum_leaders.pdf. Accessed Oct. 1, 2012.

- Staff Care. 2011 Survey of Temporary Physician Staffing Trends. Staff Care website. Available at: http://www.staffcare.com/pdf/2011_Survey_of_Temporary_Physician_Staffing_Trends.pdf. Accessed Sept. 28, 2012.

- Nemec DK, Rand LD. Finding Private Locums. 1st edition. MDPA Locums Inc.: Punta Gordo, Fla.: 2006.

Michael Manning, MD, medical director of Murphy Medical Center in Murphy, N.C., needed a doctor. Tasked with building the hospitalist program for his 57-bed hospital 90 miles from the closest city, Dr. Manning turned to a locum tenens firm for help, and the company seemed to find a perfect fit. They found a physician who wanted to commit to a one-year stint. The physician was eminently competent, had lined up housing for the year, and, perhaps most important, was eager to serve the residents of seven rural counties in western North Carolina, northern Georgia, and eastern Tennessee.

Then the new hire had a change of heart and backed out of the position. As medical director, Dr. Manning has taken on up to 10 hospitalist shifts a month to cover the absence, and the hospital-employed group is now looking at paying temporary staffers even more as the nascent group struggles to reach its optimal staffing level. To Dr. Manning, the hope-to-heartburn scenario typifies the “two-edged sword” that is locum tenens.

“Overall, I would say it’s a necessary evil,” he says. “You’ve got to have your service staffed. You can’t go without physicians filling slots. The evil for us is the cost.”

The cost of paying temporary physicians over the long term can be overwhelming for cash-strapped hospitals and health systems. But that’s done little to stop hospitalists from becoming the leading specialty in the temporary staffing market, according to a proprietary annual review compiled by Staffing Industry Analysis of Mountain View, Calif., on behalf of the National Association of Locum Tenens Organizations (NALTO). Hospitalists accounted for 17% of locum tenens revenue generated in the first half of 2011, the report states. The only other specialty in double-digit figures was emergency medicine, which tallied 14% of the $548 million in revenue measured by the report. Survey respondents reported year-over-year revenue growth of 9.5% in the first half of 2011, with aggregate revenue generated by hospitalists jumping more than 34%.

A survey of hospitalists released in October showed that nearly 12% had worked locum tenens in the previous 12 months; 64% had done the work in addition to their full-time jobs.1 The survey, crafted by Locum Leaders of Alpharetta, Ga., was among the first to capture just how prevalent the practice of temporary staffing is and what motivates physicians to do the work.

The reasons hospitalists choose to work locums are as varied as HM practices. In the short term, hospital-based physicians are looking for geographic flexibility, higher earning potential, and the chance to “try something on for size before they buy,” says Robert Harrington Jr., MD, SFHM, chief medical officer for Locum Leaders and a SHM board member. Early-career hospitalists can use temporary work to determine what they want to do with their careers, while older physicians can use it to finish their careers focused solely on clinical care.