User login

Paranoia and slowed cognition

CASE: Behavioral changes

Mr. K, age 45, is brought to the emergency department (ED) by his wife for severe paranoia, combative behavior, confusion, and slowed cognition. Mr. K tells the ED staff that a chemical abrasion he sustained a few weeks earlier has spread to his penis, and insists that his penis is retracting into his body. He has tied a string around his penis to keep it from disappearing into his body. According to Mr. K’s wife, he went to an urgent care clinic 2 weeks ago after he sustained chemical abrasions from exposure to cleaning solution at home. The provider at the urgent care clinic started Mr. K on an unknown dose of oral prednisone.

Mr. K’s wife reports that her husband had a dysphoric episode approximately 6 months ago when his business was struggling but his mood improved without psychiatric care. Mr. K’s medical history includes episodic sarcoidosis of the eyes, skin, and lungs. In the past these symptoms remitted after he received oral prednisone.

ED clinicians consider neurosarcoidosis and substance-induced delirium in the differential diagnosis (Table).1 A CT scan of the head fails to show lesions suggestive of neurosarcoidosis. Chest radiography does not reveal lesions suggestive of lung sarcoids and Mr. K has no skin lesions.

Table

DSM-IV-TR criteria for substance-induced delirium

|

| Source: Reference 1 |

Mr. K is admitted to the psychiatric inpatient unit for acute stabilization, where he remains aggressive and combative. He throws chairs at his peers and staff on the unit and is placed in physical restraints. He requires several doses of IM haloperidol, 5 mg, lorazepam, 2 mg, and diphenhydramine, 50 mg, for severe agitation. Mr. K is guarded, perseverative, and selectively mute. He avoids eye contact and has poor grooming. He has slow thought processing and displays concrete thought process. Prednisone is discontinued and olanzapine, titrated to 30 mg/d, and mirtazapine, titrated to 30 mg/d, are started for psychosis and depression.

Mr. K’s mood and behavior eventually return to baseline but slowed cognition persists. He is discharged from our facility.

The authors’ observations

Cortisone was first used to treat rheumatoid arthritis in 1948 and corticosteroids have been linked to multiple neuropsychiatric complications that have been broadly defined as steroid psychosis. This syndrome includes reversible behavioral manifestations such as hypomania, irritability, mood reactivity, anxiety, and insomnia in addition to more severe symptoms such as depression, mania, and psychosis.2 Although mild cognitive deficits have been noted in patients taking corticosteroids, most published cases have focused on steroid-induced psychosis.

In 1984, Varney et al3 noted a phenomenon they called “steroid dementia” in 6 patients treated with corticosteroids. On first evaluation, these patients presented with symptoms similar to early Alzheimer’s dementia—impaired memory, attention, and concentration. Three patients initially were diagnosed first with Alzheimer’s dementia until their symptoms spontaneously improved when steroids were reduced or discontinued. Although their presentation resembled Alzheimer’s dementia, patients with steroid dementia had a specific cognitive presentation associated with corticosteroid use. Symptoms included impaired verbal memory and spatial thinking but normal procedural memory. These patients showed intact immediate recall but impaired delayed recall with difficulty tracking conversations and word finding. Overall, patients with steroid dementia showed a predominance of verbal declarative memory deficits out of proportion to other cognitive symptoms. These symptoms and recent corticosteroid exposure differentiated steroid dementia from other forms of dementia.

In a later article, Varney reviewed electroencephalography (EEG) and CT findings associated with steroid dementia, noting bilateral EEG abnormalities and acute cortical atrophy on CT.4 Steroid dementia largely was reversible, resolving 3 to 11 months after corticosteroid discontinuation. Additionally, Varney noted that patients who had psychosis and dementia had more severe and longer-lasting dementia.

TREATMENT: Progressive decline

Mr. K is college educated, has been married for 15 years, has 2 children, age 9 and 11, and owns a successful basketball coaching business. He has no history of substance abuse, legal issues, or violence. He reports a good childhood with normal developmental milestones and no history of trauma.

In the 6 months after his initial psychiatric admission, Mr. K sees various outpatient providers, who change his psychotropics multiple times. He also receives 4 courses of prednisone for ocular sarcoidosis. He is admitted twice to other psychiatric facilities. After he has paranoid interactions with colleagues and families of the youth he coaches, his business fails.

After his third psychiatric inpatient hospitalization, Mr. K becomes severely paranoid, believing his wife is having an affair. He becomes physically abusive to his wife, who obtains a restraining order and leaves with their children. Mr. K barely leaves his house and stops grooming. A friend notes that Mr. K’s home has become uninhabitable, and it goes into foreclosure. After Mr. K’s neighbors report combative behavior and paranoia, police bring him in on an involuntary hold for a fourth psychiatric hospitalization (the second in our facility).

During this hospitalization—6 months after the initial ED presentation—the neurology team conducts a repeat medical workup. EEG shows generalized slowing. Head CT and MRI show diffuse cortical atrophy that was not seen in previous imaging. Mr. K has ocular lesions characteristic of ocular sarcoidosis. His mental status examination is similar to his first presentation except that the psychosis and thought disorganization are considerably worse. His cognitive functioning also shows significant decline. Cognitive screening reveals intact remote memory with impaired recent memory. His thinking is concrete and his verbal memory is markedly impaired. His Mini-Mental State Examination score is 27/30, indicating functional capacity that is better than his clinical presentation. Because of difficulty with concentration and verbal processing, Mr. K is unable to complete the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory despite substantial assistance. On most days he cannot recall recent conversations with his wife, staff, or physicians. He is taking no medications at this time.

Mr. K is restarted on olanzapine, titrated to 30 mg/d, to control his psychosis; this medication was effective during his last stay in our facility. Oral prednisone is discontinued and methotrexate, 10 mg/week, is initiated for ocular sarcoidosis. Based on recommendations from a case series report,5 we start Mr. K on lithium, titrated to 600 mg twice a day, for steroid-induced mood symptoms, Mr. K’s psychosis and mood improve dramatically once he reaches a therapeutic lithium level; however, his cognition remains slowed and he is unable to care for his basic needs.

The authors’ observations

Steroid dementia may be the result of effects in the medial temporal lobe, specifically dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which impairs working memory, and the parahippocampal gyrus.6,7 The cognitive presentation of steroid dementia Varney et al3 described has been replicated in healthy volunteers who received corticosteroids.3 Patients with Cushing’s syndrome also have been noted to have diminished hippocampal volume and similar cognitive deficits. Cognitive impairment experienced by patients treated with corticosteroids may be caused by neuronal death in the hippocampus and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. The etiology of cell death is multifactorial and includes glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity, activation of proinflammatory pathways, inhibited utilization of glucose in the hippocampus, telomere shortening, and diminished cell repair by brain-derived neurotrophic factor. The net result is significant, widespread damage that in some cases is irreversible.8

Because of the severity of Mr. K’s psychosis and personality change from baseline, his cognitive symptoms were largely overlooked during his first psychiatric hospitalization. The affective flattening, delayed verbal response, and markedly concrete thought process were considered within the spectrum of resolving psychosis. After further hospitalizations and abnormal results on cognitive testing, Mr. K’s cognitive impairment was fully noted. His symptoms match those of previously documented cases of steroid dementia, including verbal deficits out of proportion to other impairment, acute cerebral atrophy on CT after corticosteroid treatment, and gradual improvement of symptoms when corticosteroids were discontinued.

Management recommendations

Educate patients taking steroids about possible side effects of mood changes, psychosis, and cognitive deficits. Close monitoring of patients on corticosteroids is paramount. If psychiatric or cognitive symptoms develop, gradually discontinue the corticosteroid and seek other treatments.

Randomized, placebo-controlled trials of lamotrigine and memantine have shown these medications are cognitively protective for patients taking prednisone.9

OUTCOME: Long-term deficits

After a 33-day stay in our adult inpatient psychiatric facility, the county places Mr. K in a permanent conservatorship for severe grave disability. He is discharged to a long-term psychiatric care locked facility for ongoing management. Mr. K spends 20 months in the long-term care facility while his family remains hopeful for his recovery and return home. He is admitted to our facility for acute stabilization of psychotic symptoms after he is released from the locked facility. Although no imaging studies are conducted, he remains significantly forgetful. Additionally, his paranoia persists.

Mr. K is poorly compliant with his psychotropics, which include divalproex, 1,000 mg/d, and olanzapine, 30 mg/d. Although he is discharged home with his family, his functional capacity is less than expected and he requires continuous support. Insisting that Mr. K abstain from steroids after the first psychiatric hospitalization might have prevented this seemingly irreversible dementia.

Related Resources

- Sacks O, Shulman M. Steroid dementia: an overlooked diagnosis? Neurology. 2005;64(4):707-709.

- Cipriani G, Picchi L, Vedovello M, et al. Reversible dementia from corticosteroid therapy. Clinical Geriatrics. 2012;20(7):38-41.

Drug Brand Names

- Diphenhydramine • Benadryl

- Divalproex • Depakote

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Memantine • Namenda

- Methotrexate • Rheumatrex, Trexall

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Prednisone • Deltasone, Meticorten, others

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 4th ed, text rev. Arlington VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

2. Warrington TP, Bostwick JM. Psychiatric adverse effects of corticosteroids. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(10):1361-1367.

3. Varney NR, Alexander B, MacIndoe JH. Reversible steroid dementia in patients without steroid psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141(3):369-372.

4. Varney NR. A case of reversible steroid dementia. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1997;12(2):167-171.

5. Sirois F. Steroid psychosis: a review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25(1):27-33.

6. Wolkowitz OM, Burke H, Epel ES, et al. Glucocorticoids: mood, memory, and mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1179:19-40.

7. Lupien SJ, McEwen BS. The acute effects of corticosteroids on cognition: integration of animal and human model studies. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1997;24(1):1-27.

8. Sapolsky RM. The physiological relevance of glucocorticoid endangerment of the hippocampus. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1994;746:294-304.

9. Brown ES. Effects of glucocorticoids on mood memory and the hippocampus. Treatment and preventative therapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1179:41-55.

CASE: Behavioral changes

Mr. K, age 45, is brought to the emergency department (ED) by his wife for severe paranoia, combative behavior, confusion, and slowed cognition. Mr. K tells the ED staff that a chemical abrasion he sustained a few weeks earlier has spread to his penis, and insists that his penis is retracting into his body. He has tied a string around his penis to keep it from disappearing into his body. According to Mr. K’s wife, he went to an urgent care clinic 2 weeks ago after he sustained chemical abrasions from exposure to cleaning solution at home. The provider at the urgent care clinic started Mr. K on an unknown dose of oral prednisone.

Mr. K’s wife reports that her husband had a dysphoric episode approximately 6 months ago when his business was struggling but his mood improved without psychiatric care. Mr. K’s medical history includes episodic sarcoidosis of the eyes, skin, and lungs. In the past these symptoms remitted after he received oral prednisone.

ED clinicians consider neurosarcoidosis and substance-induced delirium in the differential diagnosis (Table).1 A CT scan of the head fails to show lesions suggestive of neurosarcoidosis. Chest radiography does not reveal lesions suggestive of lung sarcoids and Mr. K has no skin lesions.

Table

DSM-IV-TR criteria for substance-induced delirium

|

| Source: Reference 1 |

Mr. K is admitted to the psychiatric inpatient unit for acute stabilization, where he remains aggressive and combative. He throws chairs at his peers and staff on the unit and is placed in physical restraints. He requires several doses of IM haloperidol, 5 mg, lorazepam, 2 mg, and diphenhydramine, 50 mg, for severe agitation. Mr. K is guarded, perseverative, and selectively mute. He avoids eye contact and has poor grooming. He has slow thought processing and displays concrete thought process. Prednisone is discontinued and olanzapine, titrated to 30 mg/d, and mirtazapine, titrated to 30 mg/d, are started for psychosis and depression.

Mr. K’s mood and behavior eventually return to baseline but slowed cognition persists. He is discharged from our facility.

The authors’ observations

Cortisone was first used to treat rheumatoid arthritis in 1948 and corticosteroids have been linked to multiple neuropsychiatric complications that have been broadly defined as steroid psychosis. This syndrome includes reversible behavioral manifestations such as hypomania, irritability, mood reactivity, anxiety, and insomnia in addition to more severe symptoms such as depression, mania, and psychosis.2 Although mild cognitive deficits have been noted in patients taking corticosteroids, most published cases have focused on steroid-induced psychosis.

In 1984, Varney et al3 noted a phenomenon they called “steroid dementia” in 6 patients treated with corticosteroids. On first evaluation, these patients presented with symptoms similar to early Alzheimer’s dementia—impaired memory, attention, and concentration. Three patients initially were diagnosed first with Alzheimer’s dementia until their symptoms spontaneously improved when steroids were reduced or discontinued. Although their presentation resembled Alzheimer’s dementia, patients with steroid dementia had a specific cognitive presentation associated with corticosteroid use. Symptoms included impaired verbal memory and spatial thinking but normal procedural memory. These patients showed intact immediate recall but impaired delayed recall with difficulty tracking conversations and word finding. Overall, patients with steroid dementia showed a predominance of verbal declarative memory deficits out of proportion to other cognitive symptoms. These symptoms and recent corticosteroid exposure differentiated steroid dementia from other forms of dementia.

In a later article, Varney reviewed electroencephalography (EEG) and CT findings associated with steroid dementia, noting bilateral EEG abnormalities and acute cortical atrophy on CT.4 Steroid dementia largely was reversible, resolving 3 to 11 months after corticosteroid discontinuation. Additionally, Varney noted that patients who had psychosis and dementia had more severe and longer-lasting dementia.

TREATMENT: Progressive decline

Mr. K is college educated, has been married for 15 years, has 2 children, age 9 and 11, and owns a successful basketball coaching business. He has no history of substance abuse, legal issues, or violence. He reports a good childhood with normal developmental milestones and no history of trauma.

In the 6 months after his initial psychiatric admission, Mr. K sees various outpatient providers, who change his psychotropics multiple times. He also receives 4 courses of prednisone for ocular sarcoidosis. He is admitted twice to other psychiatric facilities. After he has paranoid interactions with colleagues and families of the youth he coaches, his business fails.

After his third psychiatric inpatient hospitalization, Mr. K becomes severely paranoid, believing his wife is having an affair. He becomes physically abusive to his wife, who obtains a restraining order and leaves with their children. Mr. K barely leaves his house and stops grooming. A friend notes that Mr. K’s home has become uninhabitable, and it goes into foreclosure. After Mr. K’s neighbors report combative behavior and paranoia, police bring him in on an involuntary hold for a fourth psychiatric hospitalization (the second in our facility).

During this hospitalization—6 months after the initial ED presentation—the neurology team conducts a repeat medical workup. EEG shows generalized slowing. Head CT and MRI show diffuse cortical atrophy that was not seen in previous imaging. Mr. K has ocular lesions characteristic of ocular sarcoidosis. His mental status examination is similar to his first presentation except that the psychosis and thought disorganization are considerably worse. His cognitive functioning also shows significant decline. Cognitive screening reveals intact remote memory with impaired recent memory. His thinking is concrete and his verbal memory is markedly impaired. His Mini-Mental State Examination score is 27/30, indicating functional capacity that is better than his clinical presentation. Because of difficulty with concentration and verbal processing, Mr. K is unable to complete the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory despite substantial assistance. On most days he cannot recall recent conversations with his wife, staff, or physicians. He is taking no medications at this time.

Mr. K is restarted on olanzapine, titrated to 30 mg/d, to control his psychosis; this medication was effective during his last stay in our facility. Oral prednisone is discontinued and methotrexate, 10 mg/week, is initiated for ocular sarcoidosis. Based on recommendations from a case series report,5 we start Mr. K on lithium, titrated to 600 mg twice a day, for steroid-induced mood symptoms, Mr. K’s psychosis and mood improve dramatically once he reaches a therapeutic lithium level; however, his cognition remains slowed and he is unable to care for his basic needs.

The authors’ observations

Steroid dementia may be the result of effects in the medial temporal lobe, specifically dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which impairs working memory, and the parahippocampal gyrus.6,7 The cognitive presentation of steroid dementia Varney et al3 described has been replicated in healthy volunteers who received corticosteroids.3 Patients with Cushing’s syndrome also have been noted to have diminished hippocampal volume and similar cognitive deficits. Cognitive impairment experienced by patients treated with corticosteroids may be caused by neuronal death in the hippocampus and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. The etiology of cell death is multifactorial and includes glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity, activation of proinflammatory pathways, inhibited utilization of glucose in the hippocampus, telomere shortening, and diminished cell repair by brain-derived neurotrophic factor. The net result is significant, widespread damage that in some cases is irreversible.8

Because of the severity of Mr. K’s psychosis and personality change from baseline, his cognitive symptoms were largely overlooked during his first psychiatric hospitalization. The affective flattening, delayed verbal response, and markedly concrete thought process were considered within the spectrum of resolving psychosis. After further hospitalizations and abnormal results on cognitive testing, Mr. K’s cognitive impairment was fully noted. His symptoms match those of previously documented cases of steroid dementia, including verbal deficits out of proportion to other impairment, acute cerebral atrophy on CT after corticosteroid treatment, and gradual improvement of symptoms when corticosteroids were discontinued.

Management recommendations

Educate patients taking steroids about possible side effects of mood changes, psychosis, and cognitive deficits. Close monitoring of patients on corticosteroids is paramount. If psychiatric or cognitive symptoms develop, gradually discontinue the corticosteroid and seek other treatments.

Randomized, placebo-controlled trials of lamotrigine and memantine have shown these medications are cognitively protective for patients taking prednisone.9

OUTCOME: Long-term deficits

After a 33-day stay in our adult inpatient psychiatric facility, the county places Mr. K in a permanent conservatorship for severe grave disability. He is discharged to a long-term psychiatric care locked facility for ongoing management. Mr. K spends 20 months in the long-term care facility while his family remains hopeful for his recovery and return home. He is admitted to our facility for acute stabilization of psychotic symptoms after he is released from the locked facility. Although no imaging studies are conducted, he remains significantly forgetful. Additionally, his paranoia persists.

Mr. K is poorly compliant with his psychotropics, which include divalproex, 1,000 mg/d, and olanzapine, 30 mg/d. Although he is discharged home with his family, his functional capacity is less than expected and he requires continuous support. Insisting that Mr. K abstain from steroids after the first psychiatric hospitalization might have prevented this seemingly irreversible dementia.

Related Resources

- Sacks O, Shulman M. Steroid dementia: an overlooked diagnosis? Neurology. 2005;64(4):707-709.

- Cipriani G, Picchi L, Vedovello M, et al. Reversible dementia from corticosteroid therapy. Clinical Geriatrics. 2012;20(7):38-41.

Drug Brand Names

- Diphenhydramine • Benadryl

- Divalproex • Depakote

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Memantine • Namenda

- Methotrexate • Rheumatrex, Trexall

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Prednisone • Deltasone, Meticorten, others

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE: Behavioral changes

Mr. K, age 45, is brought to the emergency department (ED) by his wife for severe paranoia, combative behavior, confusion, and slowed cognition. Mr. K tells the ED staff that a chemical abrasion he sustained a few weeks earlier has spread to his penis, and insists that his penis is retracting into his body. He has tied a string around his penis to keep it from disappearing into his body. According to Mr. K’s wife, he went to an urgent care clinic 2 weeks ago after he sustained chemical abrasions from exposure to cleaning solution at home. The provider at the urgent care clinic started Mr. K on an unknown dose of oral prednisone.

Mr. K’s wife reports that her husband had a dysphoric episode approximately 6 months ago when his business was struggling but his mood improved without psychiatric care. Mr. K’s medical history includes episodic sarcoidosis of the eyes, skin, and lungs. In the past these symptoms remitted after he received oral prednisone.

ED clinicians consider neurosarcoidosis and substance-induced delirium in the differential diagnosis (Table).1 A CT scan of the head fails to show lesions suggestive of neurosarcoidosis. Chest radiography does not reveal lesions suggestive of lung sarcoids and Mr. K has no skin lesions.

Table

DSM-IV-TR criteria for substance-induced delirium

|

| Source: Reference 1 |

Mr. K is admitted to the psychiatric inpatient unit for acute stabilization, where he remains aggressive and combative. He throws chairs at his peers and staff on the unit and is placed in physical restraints. He requires several doses of IM haloperidol, 5 mg, lorazepam, 2 mg, and diphenhydramine, 50 mg, for severe agitation. Mr. K is guarded, perseverative, and selectively mute. He avoids eye contact and has poor grooming. He has slow thought processing and displays concrete thought process. Prednisone is discontinued and olanzapine, titrated to 30 mg/d, and mirtazapine, titrated to 30 mg/d, are started for psychosis and depression.

Mr. K’s mood and behavior eventually return to baseline but slowed cognition persists. He is discharged from our facility.

The authors’ observations

Cortisone was first used to treat rheumatoid arthritis in 1948 and corticosteroids have been linked to multiple neuropsychiatric complications that have been broadly defined as steroid psychosis. This syndrome includes reversible behavioral manifestations such as hypomania, irritability, mood reactivity, anxiety, and insomnia in addition to more severe symptoms such as depression, mania, and psychosis.2 Although mild cognitive deficits have been noted in patients taking corticosteroids, most published cases have focused on steroid-induced psychosis.

In 1984, Varney et al3 noted a phenomenon they called “steroid dementia” in 6 patients treated with corticosteroids. On first evaluation, these patients presented with symptoms similar to early Alzheimer’s dementia—impaired memory, attention, and concentration. Three patients initially were diagnosed first with Alzheimer’s dementia until their symptoms spontaneously improved when steroids were reduced or discontinued. Although their presentation resembled Alzheimer’s dementia, patients with steroid dementia had a specific cognitive presentation associated with corticosteroid use. Symptoms included impaired verbal memory and spatial thinking but normal procedural memory. These patients showed intact immediate recall but impaired delayed recall with difficulty tracking conversations and word finding. Overall, patients with steroid dementia showed a predominance of verbal declarative memory deficits out of proportion to other cognitive symptoms. These symptoms and recent corticosteroid exposure differentiated steroid dementia from other forms of dementia.

In a later article, Varney reviewed electroencephalography (EEG) and CT findings associated with steroid dementia, noting bilateral EEG abnormalities and acute cortical atrophy on CT.4 Steroid dementia largely was reversible, resolving 3 to 11 months after corticosteroid discontinuation. Additionally, Varney noted that patients who had psychosis and dementia had more severe and longer-lasting dementia.

TREATMENT: Progressive decline

Mr. K is college educated, has been married for 15 years, has 2 children, age 9 and 11, and owns a successful basketball coaching business. He has no history of substance abuse, legal issues, or violence. He reports a good childhood with normal developmental milestones and no history of trauma.

In the 6 months after his initial psychiatric admission, Mr. K sees various outpatient providers, who change his psychotropics multiple times. He also receives 4 courses of prednisone for ocular sarcoidosis. He is admitted twice to other psychiatric facilities. After he has paranoid interactions with colleagues and families of the youth he coaches, his business fails.

After his third psychiatric inpatient hospitalization, Mr. K becomes severely paranoid, believing his wife is having an affair. He becomes physically abusive to his wife, who obtains a restraining order and leaves with their children. Mr. K barely leaves his house and stops grooming. A friend notes that Mr. K’s home has become uninhabitable, and it goes into foreclosure. After Mr. K’s neighbors report combative behavior and paranoia, police bring him in on an involuntary hold for a fourth psychiatric hospitalization (the second in our facility).

During this hospitalization—6 months after the initial ED presentation—the neurology team conducts a repeat medical workup. EEG shows generalized slowing. Head CT and MRI show diffuse cortical atrophy that was not seen in previous imaging. Mr. K has ocular lesions characteristic of ocular sarcoidosis. His mental status examination is similar to his first presentation except that the psychosis and thought disorganization are considerably worse. His cognitive functioning also shows significant decline. Cognitive screening reveals intact remote memory with impaired recent memory. His thinking is concrete and his verbal memory is markedly impaired. His Mini-Mental State Examination score is 27/30, indicating functional capacity that is better than his clinical presentation. Because of difficulty with concentration and verbal processing, Mr. K is unable to complete the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory despite substantial assistance. On most days he cannot recall recent conversations with his wife, staff, or physicians. He is taking no medications at this time.

Mr. K is restarted on olanzapine, titrated to 30 mg/d, to control his psychosis; this medication was effective during his last stay in our facility. Oral prednisone is discontinued and methotrexate, 10 mg/week, is initiated for ocular sarcoidosis. Based on recommendations from a case series report,5 we start Mr. K on lithium, titrated to 600 mg twice a day, for steroid-induced mood symptoms, Mr. K’s psychosis and mood improve dramatically once he reaches a therapeutic lithium level; however, his cognition remains slowed and he is unable to care for his basic needs.

The authors’ observations

Steroid dementia may be the result of effects in the medial temporal lobe, specifically dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which impairs working memory, and the parahippocampal gyrus.6,7 The cognitive presentation of steroid dementia Varney et al3 described has been replicated in healthy volunteers who received corticosteroids.3 Patients with Cushing’s syndrome also have been noted to have diminished hippocampal volume and similar cognitive deficits. Cognitive impairment experienced by patients treated with corticosteroids may be caused by neuronal death in the hippocampus and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. The etiology of cell death is multifactorial and includes glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity, activation of proinflammatory pathways, inhibited utilization of glucose in the hippocampus, telomere shortening, and diminished cell repair by brain-derived neurotrophic factor. The net result is significant, widespread damage that in some cases is irreversible.8

Because of the severity of Mr. K’s psychosis and personality change from baseline, his cognitive symptoms were largely overlooked during his first psychiatric hospitalization. The affective flattening, delayed verbal response, and markedly concrete thought process were considered within the spectrum of resolving psychosis. After further hospitalizations and abnormal results on cognitive testing, Mr. K’s cognitive impairment was fully noted. His symptoms match those of previously documented cases of steroid dementia, including verbal deficits out of proportion to other impairment, acute cerebral atrophy on CT after corticosteroid treatment, and gradual improvement of symptoms when corticosteroids were discontinued.

Management recommendations

Educate patients taking steroids about possible side effects of mood changes, psychosis, and cognitive deficits. Close monitoring of patients on corticosteroids is paramount. If psychiatric or cognitive symptoms develop, gradually discontinue the corticosteroid and seek other treatments.

Randomized, placebo-controlled trials of lamotrigine and memantine have shown these medications are cognitively protective for patients taking prednisone.9

OUTCOME: Long-term deficits

After a 33-day stay in our adult inpatient psychiatric facility, the county places Mr. K in a permanent conservatorship for severe grave disability. He is discharged to a long-term psychiatric care locked facility for ongoing management. Mr. K spends 20 months in the long-term care facility while his family remains hopeful for his recovery and return home. He is admitted to our facility for acute stabilization of psychotic symptoms after he is released from the locked facility. Although no imaging studies are conducted, he remains significantly forgetful. Additionally, his paranoia persists.

Mr. K is poorly compliant with his psychotropics, which include divalproex, 1,000 mg/d, and olanzapine, 30 mg/d. Although he is discharged home with his family, his functional capacity is less than expected and he requires continuous support. Insisting that Mr. K abstain from steroids after the first psychiatric hospitalization might have prevented this seemingly irreversible dementia.

Related Resources

- Sacks O, Shulman M. Steroid dementia: an overlooked diagnosis? Neurology. 2005;64(4):707-709.

- Cipriani G, Picchi L, Vedovello M, et al. Reversible dementia from corticosteroid therapy. Clinical Geriatrics. 2012;20(7):38-41.

Drug Brand Names

- Diphenhydramine • Benadryl

- Divalproex • Depakote

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Memantine • Namenda

- Methotrexate • Rheumatrex, Trexall

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Prednisone • Deltasone, Meticorten, others

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 4th ed, text rev. Arlington VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

2. Warrington TP, Bostwick JM. Psychiatric adverse effects of corticosteroids. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(10):1361-1367.

3. Varney NR, Alexander B, MacIndoe JH. Reversible steroid dementia in patients without steroid psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141(3):369-372.

4. Varney NR. A case of reversible steroid dementia. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1997;12(2):167-171.

5. Sirois F. Steroid psychosis: a review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25(1):27-33.

6. Wolkowitz OM, Burke H, Epel ES, et al. Glucocorticoids: mood, memory, and mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1179:19-40.

7. Lupien SJ, McEwen BS. The acute effects of corticosteroids on cognition: integration of animal and human model studies. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1997;24(1):1-27.

8. Sapolsky RM. The physiological relevance of glucocorticoid endangerment of the hippocampus. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1994;746:294-304.

9. Brown ES. Effects of glucocorticoids on mood memory and the hippocampus. Treatment and preventative therapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1179:41-55.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 4th ed, text rev. Arlington VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

2. Warrington TP, Bostwick JM. Psychiatric adverse effects of corticosteroids. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(10):1361-1367.

3. Varney NR, Alexander B, MacIndoe JH. Reversible steroid dementia in patients without steroid psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141(3):369-372.

4. Varney NR. A case of reversible steroid dementia. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1997;12(2):167-171.

5. Sirois F. Steroid psychosis: a review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25(1):27-33.

6. Wolkowitz OM, Burke H, Epel ES, et al. Glucocorticoids: mood, memory, and mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1179:19-40.

7. Lupien SJ, McEwen BS. The acute effects of corticosteroids on cognition: integration of animal and human model studies. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1997;24(1):1-27.

8. Sapolsky RM. The physiological relevance of glucocorticoid endangerment of the hippocampus. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1994;746:294-304.

9. Brown ES. Effects of glucocorticoids on mood memory and the hippocampus. Treatment and preventative therapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1179:41-55.

Erythematous penile lesion

A 63-YEAR-OLD MAN came to our clinic complaining of a rash on his penis. He indicated that the rash had been there for almost 2 years and that he’d seen 2 other doctors about it, but they’d been unable to make a diagnosis.

The patient said the rash was mildly painful and tender. He denied pain on urination, discharge, fever, malaise, or arthralgias. He also denied any sexual contact outside of his marriage and indicated that he had not been able to have intimate contact with his wife because of the problem.

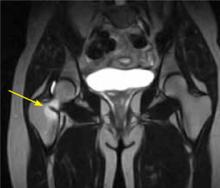

The patient was uncircumcised and when the foreskin was retracted, a bright red erythematous nonscaly circumferential plaque was visible on the glans penis, spreading to the foreskin (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1

A nonscaly, circumferential plaque on the glans penis

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Zoon’s balanitis

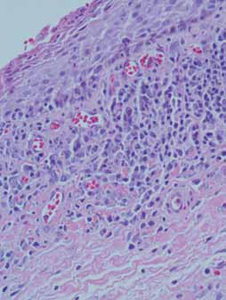

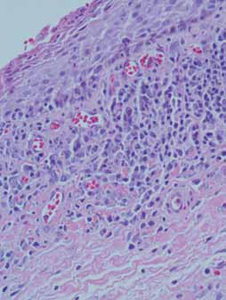

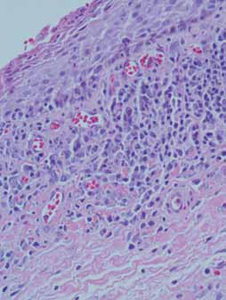

We ordered a biopsy because we suspected that the cause of the rash was either erythroplasia of Queyrat (a premalignant condition also known as Bowen’s disease of the glans penis) or Zoon’s balanitis (plasma cell balanitis or balanitis circumscripta plasmacellularis). The biopsy report confirmed the diagnosis of Zoon’s balanitis and showed no signs of malignancy. The features of Zoon’s balanitis include epidermal atrophy, loss of rete ridges, spongiosis, and subepidermal plasma cell infiltrate without evidence of malignancy (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 2

Dense plasmacytic infiltration underlying the mucosal epidermis

Condition affects older, uncircumcised men

Zoon’s balanitis is thought to be a benign condition that typically affects uncircumcised middle-aged to elderly men.1,2 Worldwide prevalence among uncircumcised men is approximately 3%.2 The etiology is unknown; it’s thought that this condition may be caused by friction, trauma, heat, lack of hygiene, exogenous or infectious agents, an IgE hypersensitivity, or a chronic infection with Mycobacterium smegmatis.1,2

Typically, the appearance of the lesion precedes diagnosis by about one to 2 years.1 The patient usually complains of mild pruritus and tenderness. Undergarments may be bloodstained.

The differential for penile lesions is extensive, and includes psoriasis, nummular eczema, candidiasis, herpes simplex, scabies, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus or lichen planus, syphilis, balanitis, and erythroplasia of Queyrat.

The lesion associated with Zoon’s balanitis is a solitary, glistening, shiny, red-to-orange plaque of the glans penis or prepuce of an uncircumcised male. Pinpoint erythematous spots or “cayenne pepper spots” may also be associated with this condition.

Patients with erythroplasia of Queyrat have either a solitary or multiple nonhealing erythematous plaques on the glans penis. These lesions may also affect the adjacent mucosal epithelium. As is true with Zoon’s balanitis, the typical patient is uncircumcised and middle-aged to elderly.1,2

Presentations may be similar, but treatment differs

Because the treatments for Zoon’s balanitis and erythroplasia of Queyrat are different, a biopsy is imperative. Erythroplasia of Queyrat is a premalignant condition that is treated with topical fluorouracil or surgical excision.3 Treatment for Zoon’s balanitis consists of a topical corticosteroid with or without topical anticandidal agents and circumcision after the acute inflammation resolves.1,2 (If a skin biopsy cannot be obtained in the clinic, the foreskin [if affected] can be sent for biopsy after the circumcision.)

If resolution is not seen with topical steroid treatment, other treatments have demonstrated efficacy. These include topical tacrolimus, as well as YAG and carbon dioxide laser treatments.4-6

Although information is limited on rates of recurrence, circumcision is considered the treatment of choice and is usually curative.1

Ointment does the trick for our patient

Our patient was treated with a single combined topical ointment consisting of nystatin and triamcinolone cream with zinc oxide. The lesion resolved completely after 10 days. We requested a urology consult so that a circumcision could be performed.

CORRESPONDENCE Matthew R. Noss, DO, MSEd, Fort Belvoir Community Hospital Family Medicine Clinic, 1st Floor, Eagle Pavilion, 9300 Dewitt Loop, Ft. Belvoir, VA 22060; [email protected]

1. Scheinfeld NS, Keough GC, Lehman DS. Balanitis circumscripta plasmacellularis. Medscape. June 8, 2012. Available at: emedicine.medscape.com/article/1122283. Accessed October 26, 2012.

2. Barrisford GW. Balanitis and balanoposthitis in adults. UpToDate. December 19, 2011. Available at: www.uptodate.com/contents/balanitis-and-balanoposthitis-in-adults. Accessed October 26, 2012.

3. Egan KM, Maino KL. Erythroplasia of Queyrat (Bowen disease of the glans penis). Medscape. May 31, 2012. Available at: emedicine.medscape.com/article/1100317. Accessed October 26, 2012.

4. Santos-Juanes J, Sanchez del Rio J, Galache C, et al. Topical tacrolimus: an effective therapy for Zoon balanitis. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1538-1539.

5. Wollina U. Ablative erbium: YAG laser treatment of idiopathic chronic inflammatory non-cicatricial balanoposthitis (Zoon’s disease)—a series of 20 patients with long-term outcome. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2010;12:120-123.

6. Retamar RA, Kien MC, Couela EN. Zoon’s balanitis: presentation of 15 patients, five treated with a carbon dioxide laser. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:305-307.

A 63-YEAR-OLD MAN came to our clinic complaining of a rash on his penis. He indicated that the rash had been there for almost 2 years and that he’d seen 2 other doctors about it, but they’d been unable to make a diagnosis.

The patient said the rash was mildly painful and tender. He denied pain on urination, discharge, fever, malaise, or arthralgias. He also denied any sexual contact outside of his marriage and indicated that he had not been able to have intimate contact with his wife because of the problem.

The patient was uncircumcised and when the foreskin was retracted, a bright red erythematous nonscaly circumferential plaque was visible on the glans penis, spreading to the foreskin (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1

A nonscaly, circumferential plaque on the glans penis

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Zoon’s balanitis

We ordered a biopsy because we suspected that the cause of the rash was either erythroplasia of Queyrat (a premalignant condition also known as Bowen’s disease of the glans penis) or Zoon’s balanitis (plasma cell balanitis or balanitis circumscripta plasmacellularis). The biopsy report confirmed the diagnosis of Zoon’s balanitis and showed no signs of malignancy. The features of Zoon’s balanitis include epidermal atrophy, loss of rete ridges, spongiosis, and subepidermal plasma cell infiltrate without evidence of malignancy (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 2

Dense plasmacytic infiltration underlying the mucosal epidermis

Condition affects older, uncircumcised men

Zoon’s balanitis is thought to be a benign condition that typically affects uncircumcised middle-aged to elderly men.1,2 Worldwide prevalence among uncircumcised men is approximately 3%.2 The etiology is unknown; it’s thought that this condition may be caused by friction, trauma, heat, lack of hygiene, exogenous or infectious agents, an IgE hypersensitivity, or a chronic infection with Mycobacterium smegmatis.1,2

Typically, the appearance of the lesion precedes diagnosis by about one to 2 years.1 The patient usually complains of mild pruritus and tenderness. Undergarments may be bloodstained.

The differential for penile lesions is extensive, and includes psoriasis, nummular eczema, candidiasis, herpes simplex, scabies, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus or lichen planus, syphilis, balanitis, and erythroplasia of Queyrat.

The lesion associated with Zoon’s balanitis is a solitary, glistening, shiny, red-to-orange plaque of the glans penis or prepuce of an uncircumcised male. Pinpoint erythematous spots or “cayenne pepper spots” may also be associated with this condition.

Patients with erythroplasia of Queyrat have either a solitary or multiple nonhealing erythematous plaques on the glans penis. These lesions may also affect the adjacent mucosal epithelium. As is true with Zoon’s balanitis, the typical patient is uncircumcised and middle-aged to elderly.1,2

Presentations may be similar, but treatment differs

Because the treatments for Zoon’s balanitis and erythroplasia of Queyrat are different, a biopsy is imperative. Erythroplasia of Queyrat is a premalignant condition that is treated with topical fluorouracil or surgical excision.3 Treatment for Zoon’s balanitis consists of a topical corticosteroid with or without topical anticandidal agents and circumcision after the acute inflammation resolves.1,2 (If a skin biopsy cannot be obtained in the clinic, the foreskin [if affected] can be sent for biopsy after the circumcision.)

If resolution is not seen with topical steroid treatment, other treatments have demonstrated efficacy. These include topical tacrolimus, as well as YAG and carbon dioxide laser treatments.4-6

Although information is limited on rates of recurrence, circumcision is considered the treatment of choice and is usually curative.1

Ointment does the trick for our patient

Our patient was treated with a single combined topical ointment consisting of nystatin and triamcinolone cream with zinc oxide. The lesion resolved completely after 10 days. We requested a urology consult so that a circumcision could be performed.

CORRESPONDENCE Matthew R. Noss, DO, MSEd, Fort Belvoir Community Hospital Family Medicine Clinic, 1st Floor, Eagle Pavilion, 9300 Dewitt Loop, Ft. Belvoir, VA 22060; [email protected]

A 63-YEAR-OLD MAN came to our clinic complaining of a rash on his penis. He indicated that the rash had been there for almost 2 years and that he’d seen 2 other doctors about it, but they’d been unable to make a diagnosis.

The patient said the rash was mildly painful and tender. He denied pain on urination, discharge, fever, malaise, or arthralgias. He also denied any sexual contact outside of his marriage and indicated that he had not been able to have intimate contact with his wife because of the problem.

The patient was uncircumcised and when the foreskin was retracted, a bright red erythematous nonscaly circumferential plaque was visible on the glans penis, spreading to the foreskin (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1

A nonscaly, circumferential plaque on the glans penis

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Zoon’s balanitis

We ordered a biopsy because we suspected that the cause of the rash was either erythroplasia of Queyrat (a premalignant condition also known as Bowen’s disease of the glans penis) or Zoon’s balanitis (plasma cell balanitis or balanitis circumscripta plasmacellularis). The biopsy report confirmed the diagnosis of Zoon’s balanitis and showed no signs of malignancy. The features of Zoon’s balanitis include epidermal atrophy, loss of rete ridges, spongiosis, and subepidermal plasma cell infiltrate without evidence of malignancy (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 2

Dense plasmacytic infiltration underlying the mucosal epidermis

Condition affects older, uncircumcised men

Zoon’s balanitis is thought to be a benign condition that typically affects uncircumcised middle-aged to elderly men.1,2 Worldwide prevalence among uncircumcised men is approximately 3%.2 The etiology is unknown; it’s thought that this condition may be caused by friction, trauma, heat, lack of hygiene, exogenous or infectious agents, an IgE hypersensitivity, or a chronic infection with Mycobacterium smegmatis.1,2

Typically, the appearance of the lesion precedes diagnosis by about one to 2 years.1 The patient usually complains of mild pruritus and tenderness. Undergarments may be bloodstained.

The differential for penile lesions is extensive, and includes psoriasis, nummular eczema, candidiasis, herpes simplex, scabies, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus or lichen planus, syphilis, balanitis, and erythroplasia of Queyrat.

The lesion associated with Zoon’s balanitis is a solitary, glistening, shiny, red-to-orange plaque of the glans penis or prepuce of an uncircumcised male. Pinpoint erythematous spots or “cayenne pepper spots” may also be associated with this condition.

Patients with erythroplasia of Queyrat have either a solitary or multiple nonhealing erythematous plaques on the glans penis. These lesions may also affect the adjacent mucosal epithelium. As is true with Zoon’s balanitis, the typical patient is uncircumcised and middle-aged to elderly.1,2

Presentations may be similar, but treatment differs

Because the treatments for Zoon’s balanitis and erythroplasia of Queyrat are different, a biopsy is imperative. Erythroplasia of Queyrat is a premalignant condition that is treated with topical fluorouracil or surgical excision.3 Treatment for Zoon’s balanitis consists of a topical corticosteroid with or without topical anticandidal agents and circumcision after the acute inflammation resolves.1,2 (If a skin biopsy cannot be obtained in the clinic, the foreskin [if affected] can be sent for biopsy after the circumcision.)

If resolution is not seen with topical steroid treatment, other treatments have demonstrated efficacy. These include topical tacrolimus, as well as YAG and carbon dioxide laser treatments.4-6

Although information is limited on rates of recurrence, circumcision is considered the treatment of choice and is usually curative.1

Ointment does the trick for our patient

Our patient was treated with a single combined topical ointment consisting of nystatin and triamcinolone cream with zinc oxide. The lesion resolved completely after 10 days. We requested a urology consult so that a circumcision could be performed.

CORRESPONDENCE Matthew R. Noss, DO, MSEd, Fort Belvoir Community Hospital Family Medicine Clinic, 1st Floor, Eagle Pavilion, 9300 Dewitt Loop, Ft. Belvoir, VA 22060; [email protected]

1. Scheinfeld NS, Keough GC, Lehman DS. Balanitis circumscripta plasmacellularis. Medscape. June 8, 2012. Available at: emedicine.medscape.com/article/1122283. Accessed October 26, 2012.

2. Barrisford GW. Balanitis and balanoposthitis in adults. UpToDate. December 19, 2011. Available at: www.uptodate.com/contents/balanitis-and-balanoposthitis-in-adults. Accessed October 26, 2012.

3. Egan KM, Maino KL. Erythroplasia of Queyrat (Bowen disease of the glans penis). Medscape. May 31, 2012. Available at: emedicine.medscape.com/article/1100317. Accessed October 26, 2012.

4. Santos-Juanes J, Sanchez del Rio J, Galache C, et al. Topical tacrolimus: an effective therapy for Zoon balanitis. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1538-1539.

5. Wollina U. Ablative erbium: YAG laser treatment of idiopathic chronic inflammatory non-cicatricial balanoposthitis (Zoon’s disease)—a series of 20 patients with long-term outcome. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2010;12:120-123.

6. Retamar RA, Kien MC, Couela EN. Zoon’s balanitis: presentation of 15 patients, five treated with a carbon dioxide laser. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:305-307.

1. Scheinfeld NS, Keough GC, Lehman DS. Balanitis circumscripta plasmacellularis. Medscape. June 8, 2012. Available at: emedicine.medscape.com/article/1122283. Accessed October 26, 2012.

2. Barrisford GW. Balanitis and balanoposthitis in adults. UpToDate. December 19, 2011. Available at: www.uptodate.com/contents/balanitis-and-balanoposthitis-in-adults. Accessed October 26, 2012.

3. Egan KM, Maino KL. Erythroplasia of Queyrat (Bowen disease of the glans penis). Medscape. May 31, 2012. Available at: emedicine.medscape.com/article/1100317. Accessed October 26, 2012.

4. Santos-Juanes J, Sanchez del Rio J, Galache C, et al. Topical tacrolimus: an effective therapy for Zoon balanitis. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1538-1539.

5. Wollina U. Ablative erbium: YAG laser treatment of idiopathic chronic inflammatory non-cicatricial balanoposthitis (Zoon’s disease)—a series of 20 patients with long-term outcome. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2010;12:120-123.

6. Retamar RA, Kien MC, Couela EN. Zoon’s balanitis: presentation of 15 patients, five treated with a carbon dioxide laser. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:305-307.

Death follows a normal EKG ...Kidney failure after multiple meds

Death follows a normal EKG

MID-CHEST DISCOMFORT, A COUGH, AND SWEATING brought a 59-year-old man to his primary care physician. The patient had normal vital signs and reported that belching relieved the chest discomfort. He had a history of severe coronary artery disease and had undergone angioplasty and stenting several years earlier.

The primary care physician performed an electrocardiogram (EKG), which was normal and unchanged from one done the year before. The doctor suspected bronchitis, but prescribed omeprazole because the patient had previously been diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux disease. He ordered a chemical stress test to be performed within a month and a chest radiograph to be done if the patient’s symptoms didn’t improve.

Two hours after returning home, the patient called an ambulance. He told paramedics that he’d been having chest pain for an hour. While they were putting the patient into the ambulance, he went into cardiac arrest. Four defibrillation attempts en route to the hospital and additional resuscitation attempts in the ED failed; he was pronounced dead 3½ hours after leaving his physician’s office.

No autopsy was performed. The patient’s widow found the omeprazole bottle, with one pill missing, and fast-food hamburger wrappers on the kitchen table.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The primary care physician should have sent the patient to the ED to determine whether the chest pain had a cardiac cause; the patient was suffering from acute cardiac syndrome when the doctor saw him.

THE DEFENSE The patient’s normal EKG and vital signs and the fact that belching relieved his chest symptoms indicated that the complaints did not arise from cardiac causes or require emergency assessment. The patient didn’t report chest pain at the office visit; the later cardiac arrest probably resulted from a sudden plaque rupture unrelated to the earlier chest discomfort.

VERDICT $1.5 million Illinois verdict.

COMMENT I hope most doctors won’t have to learn this lesson from their own experience. A normal EKG does not rule out acute ischemia in a high-risk patient with chest pain and sweating. Admit such patients immediately to a cardiac observation unit.

Kidney failure after multiple meds

A MAN WAS TAKING MULTIPLE MEDICATIONS: 3 blood pressure drugs prescribed by his primary care physician, an NSAID prescribed by another doctor, and sizable doses of BC Powder, an over-the-counter analgesic containing aspirin, salicylamide, and caffeine. After 4 years on this medication regimen, the patient’s kidneys failed.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The primary care physician failed to properly monitor kidney function with blood and urine tests while his patient was taking the medications. Proper testing would have resulted in a diagnosis of kidney disease before the patient’s kidneys failed completely. In addition, the primary care physician failed to explain the risks and side effects of the medications to the patient.

THE DEFENSE The patient refused kidney function testing and did not follow medical advice. He consumed excessive amounts of alcohol against medical advice, did not tell the primary care physician about other drugs he was taking, and had allowed his supply of blood pressure medication to run out.

VERDICT $2 million gross verdict in Georgia, with a finding of 47% comparative negligence.

COMMENT This case offers several lessons: First, each BC Powder packet contains the equivalent of 2 aspirin. Second, chronic, high-dose NSAIDs can cause renal failure, especially in patients whose renal function is compromised by hypertension. Third, all patients with hypertension should undergo periodic monitoring of renal function.

Death follows a normal EKG

MID-CHEST DISCOMFORT, A COUGH, AND SWEATING brought a 59-year-old man to his primary care physician. The patient had normal vital signs and reported that belching relieved the chest discomfort. He had a history of severe coronary artery disease and had undergone angioplasty and stenting several years earlier.

The primary care physician performed an electrocardiogram (EKG), which was normal and unchanged from one done the year before. The doctor suspected bronchitis, but prescribed omeprazole because the patient had previously been diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux disease. He ordered a chemical stress test to be performed within a month and a chest radiograph to be done if the patient’s symptoms didn’t improve.

Two hours after returning home, the patient called an ambulance. He told paramedics that he’d been having chest pain for an hour. While they were putting the patient into the ambulance, he went into cardiac arrest. Four defibrillation attempts en route to the hospital and additional resuscitation attempts in the ED failed; he was pronounced dead 3½ hours after leaving his physician’s office.

No autopsy was performed. The patient’s widow found the omeprazole bottle, with one pill missing, and fast-food hamburger wrappers on the kitchen table.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The primary care physician should have sent the patient to the ED to determine whether the chest pain had a cardiac cause; the patient was suffering from acute cardiac syndrome when the doctor saw him.

THE DEFENSE The patient’s normal EKG and vital signs and the fact that belching relieved his chest symptoms indicated that the complaints did not arise from cardiac causes or require emergency assessment. The patient didn’t report chest pain at the office visit; the later cardiac arrest probably resulted from a sudden plaque rupture unrelated to the earlier chest discomfort.

VERDICT $1.5 million Illinois verdict.

COMMENT I hope most doctors won’t have to learn this lesson from their own experience. A normal EKG does not rule out acute ischemia in a high-risk patient with chest pain and sweating. Admit such patients immediately to a cardiac observation unit.

Kidney failure after multiple meds

A MAN WAS TAKING MULTIPLE MEDICATIONS: 3 blood pressure drugs prescribed by his primary care physician, an NSAID prescribed by another doctor, and sizable doses of BC Powder, an over-the-counter analgesic containing aspirin, salicylamide, and caffeine. After 4 years on this medication regimen, the patient’s kidneys failed.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The primary care physician failed to properly monitor kidney function with blood and urine tests while his patient was taking the medications. Proper testing would have resulted in a diagnosis of kidney disease before the patient’s kidneys failed completely. In addition, the primary care physician failed to explain the risks and side effects of the medications to the patient.

THE DEFENSE The patient refused kidney function testing and did not follow medical advice. He consumed excessive amounts of alcohol against medical advice, did not tell the primary care physician about other drugs he was taking, and had allowed his supply of blood pressure medication to run out.

VERDICT $2 million gross verdict in Georgia, with a finding of 47% comparative negligence.

COMMENT This case offers several lessons: First, each BC Powder packet contains the equivalent of 2 aspirin. Second, chronic, high-dose NSAIDs can cause renal failure, especially in patients whose renal function is compromised by hypertension. Third, all patients with hypertension should undergo periodic monitoring of renal function.

Death follows a normal EKG

MID-CHEST DISCOMFORT, A COUGH, AND SWEATING brought a 59-year-old man to his primary care physician. The patient had normal vital signs and reported that belching relieved the chest discomfort. He had a history of severe coronary artery disease and had undergone angioplasty and stenting several years earlier.

The primary care physician performed an electrocardiogram (EKG), which was normal and unchanged from one done the year before. The doctor suspected bronchitis, but prescribed omeprazole because the patient had previously been diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux disease. He ordered a chemical stress test to be performed within a month and a chest radiograph to be done if the patient’s symptoms didn’t improve.

Two hours after returning home, the patient called an ambulance. He told paramedics that he’d been having chest pain for an hour. While they were putting the patient into the ambulance, he went into cardiac arrest. Four defibrillation attempts en route to the hospital and additional resuscitation attempts in the ED failed; he was pronounced dead 3½ hours after leaving his physician’s office.

No autopsy was performed. The patient’s widow found the omeprazole bottle, with one pill missing, and fast-food hamburger wrappers on the kitchen table.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The primary care physician should have sent the patient to the ED to determine whether the chest pain had a cardiac cause; the patient was suffering from acute cardiac syndrome when the doctor saw him.

THE DEFENSE The patient’s normal EKG and vital signs and the fact that belching relieved his chest symptoms indicated that the complaints did not arise from cardiac causes or require emergency assessment. The patient didn’t report chest pain at the office visit; the later cardiac arrest probably resulted from a sudden plaque rupture unrelated to the earlier chest discomfort.

VERDICT $1.5 million Illinois verdict.

COMMENT I hope most doctors won’t have to learn this lesson from their own experience. A normal EKG does not rule out acute ischemia in a high-risk patient with chest pain and sweating. Admit such patients immediately to a cardiac observation unit.

Kidney failure after multiple meds

A MAN WAS TAKING MULTIPLE MEDICATIONS: 3 blood pressure drugs prescribed by his primary care physician, an NSAID prescribed by another doctor, and sizable doses of BC Powder, an over-the-counter analgesic containing aspirin, salicylamide, and caffeine. After 4 years on this medication regimen, the patient’s kidneys failed.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The primary care physician failed to properly monitor kidney function with blood and urine tests while his patient was taking the medications. Proper testing would have resulted in a diagnosis of kidney disease before the patient’s kidneys failed completely. In addition, the primary care physician failed to explain the risks and side effects of the medications to the patient.

THE DEFENSE The patient refused kidney function testing and did not follow medical advice. He consumed excessive amounts of alcohol against medical advice, did not tell the primary care physician about other drugs he was taking, and had allowed his supply of blood pressure medication to run out.

VERDICT $2 million gross verdict in Georgia, with a finding of 47% comparative negligence.

COMMENT This case offers several lessons: First, each BC Powder packet contains the equivalent of 2 aspirin. Second, chronic, high-dose NSAIDs can cause renal failure, especially in patients whose renal function is compromised by hypertension. Third, all patients with hypertension should undergo periodic monitoring of renal function.

Hepatitis C: New CDC screening recommendations

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently released new recommendations for screening for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection that include a one-time screening for everyone in the United States born between 1945 and 1965, regardless of risk.1 These new recommendations are an enhancement of, but not a replacement for, the recommendations for HCV screening made in 1998, which called for screening those at high risk.2

HCV causes considerable morbidity and mortality in this country. Approximately 17,000 new infections occurred in 2010.1 Between 2.7 and 3.9 million Americans (1%-1.5% of the population) are living with chronic HCV infection, and many do not know they are infected.1 This lack of awareness appears to be due to a failure of both health care providers to offer testing to those at known risk and patients to either acknowledge or recall past high-risk behaviors.

Those at highest risk for HCV infection are current or past users of illegal injected drugs and recipients of a blood transfusion before 1992 (when HCV screening of the blood supply was instituted). Other risk factors are listed in TABLE 1.1 Many of those with HCV infection do not report injection drug use or having received a transfusion prior to 1992, and they are not detected by current risk-based testing.

TABLE 1

Risk factors for HCV infection1

| Most common risks |

|

| Less common risks |

|

| HCV, hepatitis C virus |

Approximately three-fourths of those who acquire HCV are unable to clear the virus and become chronically infected.1 Twenty percent of these individuals will develop cirrhosis and 5% will die from an HCV-related liver disease, such as decompensated cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).3

New treatments. In 2011, 2 protease inhibitor drugs, telaprevir and boceprevir, were approved for the treatment of HCV geno-type 1. These are the first generation of a class of drugs called direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs). When a DAA is added to the standard therapy of ribavirin and pegylated interferon, the rate of viral clearance increases (from 44% to 75% for telaprevir and from 38% to 63% for boceprevir).1 However, the adverse reactions caused by these new drugs can lead to a 34% rise in the rate at which patients stop treatment.1 Twenty potential new HCV antivirals are in clinical trials, and it is expected that treatment recommendations will change rapidly as some of these are approved.

Does treatment improve long-term outcomes?

Clinical guidelines recommend antiviral treatment for anyone with HCV infection and biopsy evidence of bridging fibrosis, septal fibrosis, or cirrhosis.4

A look at Tx and all-cause mortality. Studies looking at patient-oriented outcomes such as all-cause mortality and incidence of HCC have been conducted with pegylated interferon and ribavirin, without the newer DAAs. The most commonly cited study assessed all-cause mortality in a large sample of veterans with multiple comorbidities.

Those who achieved a sustained virological response after treatment exhibited a reduction in all-cause mortality >50% compared with nonresponders. This endpoint included substantially lower rates of liver-related deaths and cirrhosis complicated by ascites, variceal bleeding, or encephalopathy.5 However, in such a nonrandom clinical trial, an improved outcome for responders could be due to their relatively good health, with fewer comorbid conditions, and other undetected biases. While this study attempted to control for such biases, it didn’t provide evidence that treating infection detected by screening a low-risk population would improve intermediate or long-term outcomes.

Observational studies look at carcinoma incidence. Twelve observational studies have addressed treatment effects on HCC incidence. They showed a 75% reduction in HCC rates in those who achieved viral clearance compared with those who did not.1 Again, these studies did not compare treated and untreated patients in a controlled clinical trial; they looked only at treated individuals and compared the outcomes of responders and nonresponders.

HCV transmission research is lacking. The CDC found no studies in its evidence review that addressed the issue of HCV transmission. Nevertheless, the new recommendations state that HCV transmission was a critical factor in determining the strength of the recommendation for age cohort screening. It is expected that those who have a sustained viral response will be less likely to transmit the virus to others.

Why the 1945-1965 birth cohort?

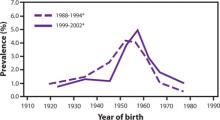

The prevalence of HCV infection in those born between 1945 and 1965 is 3.25%, and three-fourths of all those with HCV infection in the United States are in this cohort. The FIGURE depicts the large difference in prevalence between this age group and others. Within 3 cohorts defined by date of birth (1945-1965, 1950-1970, and 1945-1970), the prevalence of HCV infection is twice as high in men than in women, and in black non-Hispanics than in white non-Hispanics and Mexican Americans. However, extending the birth cohort to those born through 1970 yields only a marginal difference in prevalence figures. The CDC justifies restricting the new universal screening recommendation to the 1945-1965 age group mainly on the results of focus groups in which the public identified this cohort as “baby boomers” who would likely adopt the recommendation.

FIGURE

Prevalence of hepatitis C virus antibody by year of birth1

*National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 1988–1994 and 1999–2002.

Two-step screening process

Screen individuals using a test for antibodies to HCV (anti-HCV). If the anti-HCV test result is positive, order a test for HCV nucleic acid that gives either a quantitative measure of viral load or a qualitative assessment of presence or absence of virus. If the confirmatory nucleic acid test result is negative, the individual does not have chronic HCV infection and is among the approximately 25% who clear the virus on their own. They do not need further testing or treatment.

What to tell infected patients

If the confirmatory test result is positive, presume the patient has HCV infection and offer the advice contained in TABLE 2.1 Patients should undergo further assessment for possible chronic liver disease and, with the counsel of their physician, decide whether to initiate treatment. They should also take measures to protect the liver from further damage, such as reducing alcohol consumption, avoiding medication and herbal products that can damage the liver, maintaining an optimal weight, and receiving vaccines against hepatitis A and B, if still susceptible to these viruses. Finally, encourage patients to take steps to avoid transmission of HCV to others.

TABLE 2

Advice for your patients with HCV infection1

Consult a health care provider (either a primary care physician or specialist [eg, in hepatology, gastroenterology, or infectious disease]) for:

|

Protect the liver from further harm by:

|

Maintain optimal weight by:

|

Minimize the risk of infecting others by:

|

| BMI, body mass index; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus. |

The decision on whether to begin treatment immediately is complicated by the large number of new antivirals in development, which will be available in the near future and may be more effective with fewer adverse effects.

Lingering controversies

Given the lack of evidence of improved outcomes with HCV screening in the general population, it will be interesting to see how widely accepted the new CDC recommendations will be. The US Preventive Services Task Force is in the process of revising its HCV screening recommendations. Given the Task Force’s evidence-based methodology and the lack of evidence on the benefits and harms of screening those with no reported risks, there may be some differences with the new CDC recommendations.

If the CDC’s assumption proves correct—ie, that the benefits of treating high-risk populations will also occur with treating detected infection in the general population—and if the age cohort screening recommendation is fully implemented, 47,000 cases of HCC and 15,000 liver transplants will be prevented.1

1. CDC. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945-1965. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:1-18.Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr6104.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2012.

2. CDC. Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus infection and HCV-related chronic disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998;47(RR-19):1-54.

3. Alter HJ, Seeff LB. Recovery, persistence, and sequelae in hepatitis C virus infection: a perspective on long-term outcome. Semin Liver Dis. 2000;20:17-35.

4. Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, et al. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49:1335-1374.

5. Backus LI, Boothroyd DB, Phillips BR, et al. A sustained virological response reduces risk of all-cause mortality in patients with hepatitis C. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:509-516.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently released new recommendations for screening for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection that include a one-time screening for everyone in the United States born between 1945 and 1965, regardless of risk.1 These new recommendations are an enhancement of, but not a replacement for, the recommendations for HCV screening made in 1998, which called for screening those at high risk.2

HCV causes considerable morbidity and mortality in this country. Approximately 17,000 new infections occurred in 2010.1 Between 2.7 and 3.9 million Americans (1%-1.5% of the population) are living with chronic HCV infection, and many do not know they are infected.1 This lack of awareness appears to be due to a failure of both health care providers to offer testing to those at known risk and patients to either acknowledge or recall past high-risk behaviors.

Those at highest risk for HCV infection are current or past users of illegal injected drugs and recipients of a blood transfusion before 1992 (when HCV screening of the blood supply was instituted). Other risk factors are listed in TABLE 1.1 Many of those with HCV infection do not report injection drug use or having received a transfusion prior to 1992, and they are not detected by current risk-based testing.

TABLE 1

Risk factors for HCV infection1

| Most common risks |

|

| Less common risks |

|

| HCV, hepatitis C virus |

Approximately three-fourths of those who acquire HCV are unable to clear the virus and become chronically infected.1 Twenty percent of these individuals will develop cirrhosis and 5% will die from an HCV-related liver disease, such as decompensated cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).3

New treatments. In 2011, 2 protease inhibitor drugs, telaprevir and boceprevir, were approved for the treatment of HCV geno-type 1. These are the first generation of a class of drugs called direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs). When a DAA is added to the standard therapy of ribavirin and pegylated interferon, the rate of viral clearance increases (from 44% to 75% for telaprevir and from 38% to 63% for boceprevir).1 However, the adverse reactions caused by these new drugs can lead to a 34% rise in the rate at which patients stop treatment.1 Twenty potential new HCV antivirals are in clinical trials, and it is expected that treatment recommendations will change rapidly as some of these are approved.

Does treatment improve long-term outcomes?

Clinical guidelines recommend antiviral treatment for anyone with HCV infection and biopsy evidence of bridging fibrosis, septal fibrosis, or cirrhosis.4

A look at Tx and all-cause mortality. Studies looking at patient-oriented outcomes such as all-cause mortality and incidence of HCC have been conducted with pegylated interferon and ribavirin, without the newer DAAs. The most commonly cited study assessed all-cause mortality in a large sample of veterans with multiple comorbidities.

Those who achieved a sustained virological response after treatment exhibited a reduction in all-cause mortality >50% compared with nonresponders. This endpoint included substantially lower rates of liver-related deaths and cirrhosis complicated by ascites, variceal bleeding, or encephalopathy.5 However, in such a nonrandom clinical trial, an improved outcome for responders could be due to their relatively good health, with fewer comorbid conditions, and other undetected biases. While this study attempted to control for such biases, it didn’t provide evidence that treating infection detected by screening a low-risk population would improve intermediate or long-term outcomes.

Observational studies look at carcinoma incidence. Twelve observational studies have addressed treatment effects on HCC incidence. They showed a 75% reduction in HCC rates in those who achieved viral clearance compared with those who did not.1 Again, these studies did not compare treated and untreated patients in a controlled clinical trial; they looked only at treated individuals and compared the outcomes of responders and nonresponders.

HCV transmission research is lacking. The CDC found no studies in its evidence review that addressed the issue of HCV transmission. Nevertheless, the new recommendations state that HCV transmission was a critical factor in determining the strength of the recommendation for age cohort screening. It is expected that those who have a sustained viral response will be less likely to transmit the virus to others.

Why the 1945-1965 birth cohort?