User login

CCR7 Predicts Cervical Metastasis in Oral Cancer

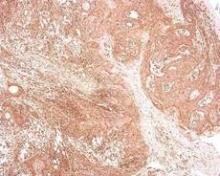

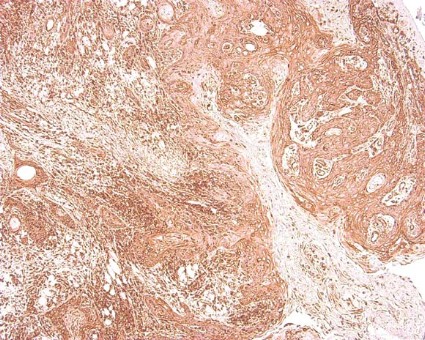

WASHINGTON – Chemokine receptor CCR7 expression is a significant predictor of cervical metastases in patients with squamous cell carcinoma in the oral cavity, based on data from 60 adults.

Metastatic spread of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is common, but the mechanisms behind the spread remain unclear, said Dr. Levi G. Ledgerwood of the University of California, Davis. "There has been a great deal of work that has looked at lymphocyte entry into lymphatics," he said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation.

Recent research has focused on the chemokine receptor CCR7, a cell-surface molecule that is required for T-cell entry from the bloodstream and peripheral tissues into lymphatics, he noted. Data from previous studies suggest that CCR7 might play a role in various cancers in the metastases of the lymph nodes.

Dr. Ledgerwood and his colleagues reviewed tissue samples from primary tumors in 60 oral SCC patients who underwent surgical resection at a single center between 2006 and 2011. The study included 30 samples from patients with metastases and 30 samples from patients without metastases. There were no significant demographic differences between the groups, although each group had more male than female patients, Dr. Ledgerwood noted. A total of 30 patients were node positive, and 30 were node negative.

Overall, patients with cervical metastases showed significantly higher CCR7 expression than those without cervical metastases (P less than .001). A total of 97% of node-positive patients were positive for CCR7 expression, but only 43% of patients without cervical metastases were positive for CCR7.

When the lymph nodes of the samples from metastatic cancer patients were examined, all 30 node-positive patients showed expression of CCR7, Dr. Ledgerwood added.

Although the study was limited by its small size, the results suggest a possible role for CCR7 in T-cell access to lymphatics, said Dr. Ledgerwood.

"This is a preliminary study, but we feel that this receptor could provide a very interesting target for future drug therapies and could also help in predicting the behavior of tumors," he said.

Dr. Ledgerwood had no financial conflicts to disclose.

WASHINGTON – Chemokine receptor CCR7 expression is a significant predictor of cervical metastases in patients with squamous cell carcinoma in the oral cavity, based on data from 60 adults.

Metastatic spread of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is common, but the mechanisms behind the spread remain unclear, said Dr. Levi G. Ledgerwood of the University of California, Davis. "There has been a great deal of work that has looked at lymphocyte entry into lymphatics," he said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation.

Recent research has focused on the chemokine receptor CCR7, a cell-surface molecule that is required for T-cell entry from the bloodstream and peripheral tissues into lymphatics, he noted. Data from previous studies suggest that CCR7 might play a role in various cancers in the metastases of the lymph nodes.

Dr. Ledgerwood and his colleagues reviewed tissue samples from primary tumors in 60 oral SCC patients who underwent surgical resection at a single center between 2006 and 2011. The study included 30 samples from patients with metastases and 30 samples from patients without metastases. There were no significant demographic differences between the groups, although each group had more male than female patients, Dr. Ledgerwood noted. A total of 30 patients were node positive, and 30 were node negative.

Overall, patients with cervical metastases showed significantly higher CCR7 expression than those without cervical metastases (P less than .001). A total of 97% of node-positive patients were positive for CCR7 expression, but only 43% of patients without cervical metastases were positive for CCR7.

When the lymph nodes of the samples from metastatic cancer patients were examined, all 30 node-positive patients showed expression of CCR7, Dr. Ledgerwood added.

Although the study was limited by its small size, the results suggest a possible role for CCR7 in T-cell access to lymphatics, said Dr. Ledgerwood.

"This is a preliminary study, but we feel that this receptor could provide a very interesting target for future drug therapies and could also help in predicting the behavior of tumors," he said.

Dr. Ledgerwood had no financial conflicts to disclose.

WASHINGTON – Chemokine receptor CCR7 expression is a significant predictor of cervical metastases in patients with squamous cell carcinoma in the oral cavity, based on data from 60 adults.

Metastatic spread of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is common, but the mechanisms behind the spread remain unclear, said Dr. Levi G. Ledgerwood of the University of California, Davis. "There has been a great deal of work that has looked at lymphocyte entry into lymphatics," he said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation.

Recent research has focused on the chemokine receptor CCR7, a cell-surface molecule that is required for T-cell entry from the bloodstream and peripheral tissues into lymphatics, he noted. Data from previous studies suggest that CCR7 might play a role in various cancers in the metastases of the lymph nodes.

Dr. Ledgerwood and his colleagues reviewed tissue samples from primary tumors in 60 oral SCC patients who underwent surgical resection at a single center between 2006 and 2011. The study included 30 samples from patients with metastases and 30 samples from patients without metastases. There were no significant demographic differences between the groups, although each group had more male than female patients, Dr. Ledgerwood noted. A total of 30 patients were node positive, and 30 were node negative.

Overall, patients with cervical metastases showed significantly higher CCR7 expression than those without cervical metastases (P less than .001). A total of 97% of node-positive patients were positive for CCR7 expression, but only 43% of patients without cervical metastases were positive for CCR7.

When the lymph nodes of the samples from metastatic cancer patients were examined, all 30 node-positive patients showed expression of CCR7, Dr. Ledgerwood added.

Although the study was limited by its small size, the results suggest a possible role for CCR7 in T-cell access to lymphatics, said Dr. Ledgerwood.

"This is a preliminary study, but we feel that this receptor could provide a very interesting target for future drug therapies and could also help in predicting the behavior of tumors," he said.

Dr. Ledgerwood had no financial conflicts to disclose.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF OTOLARYNGOLOGY-HEAD AND NECK SURGERY FOUNDATION

Open Surgery Tied to Small-Bowel Obstruction Risk

The risk of developing a small-bowel obstruction after open surgery is about fourfold higher when compared with laparoscopic surgery in nine commonly performed abdominal and pelvic procedures, including cholecystectomy, hysterectomy, and appendectomy, investigators reported.

Other factors such as patient age, , prior abdominal surgery, and comorbidities also contributed to the risk of SBO, the study showed. However, laparoscopy "exceeded other risk factors in reduction of the risk of SBO for most of the surgical procedures," wrote Dr. Eva Angenete and her colleagues (Arch. Surg. 2012;147:359-65).

"This study shows that, beyond important factors such as age, previous abdominal surgery, and comorbidity, the surgical technique is the most important factor related to SBO," the authors wrote. "Compared with laparoscopic surgery, open surgery seems to increase the risk of SBO at least four times."

It’s likely that the study results will hold up to further scrutiny because the study was population based and the sample size – 108,141 patients – is large, the authors said.

Still, laparoscopic surgery did not seem to reduce the incidence of SBO in some groups, including hysterectomy patients. "One hypothesis is that this result may be related to a limited dissection in the pelvis," but the small number of laparoscopic hysterectomy patients included in the study could have affected the study’s results, the authors wrote. In addition, there were no clear risk factors for SBO in patients undergoing bariatric surgery, they wrote.

The investigators used the Inpatient Register of the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare to analyze the risk of SBO in nine procedures, including cholecystectomy, hysterectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, bowel resection, anterior resection, abdominoperineal resection, rectopexy, appendectomy, and bariatric surgery performed from 2002 to 2004. The database included information on demographic characteristics, comorbidities, previous abdominal surgery, and deaths.

The rate of SBO was lowest after cholecystectomy, occurring in just 0.4% of all cases, and was highest, at 13.9%, in abdominoperineal resection patients. For most surgical procedures, patients who had SBO were older on average. SBO was also more common in patients with previous abdominal surgery.

In those who underwent cholecystectomy, bowel resection, or appendectomy, a higher level of comorbidity was associated with a greater incidence of SBO, the authors said. In the group of complicated cholecystectomy patients as well as the group of anterior resection patients, SBO was more common among men.

SBO was linked with an increased risk of death within 5 years, the study found.

"The aim of this study was to identify the incidence and risk factors for mechanical SBO after a number of common abdominal and pelvic procedures," the authors wrote. "Small-bowel obstruction is a substantial health care challenge, and correctly identified risk factors can provide improved tools to reduce the risk of SBO after an abdominal surgical procedure."

"The safety and the short-term benefits of laparoscopy are already known, and it is possible that laparoscopy should be regarded as the preferred technique in an attempt to further reduce the complications of surgery," the authors concluded.

The project was supported by grants from the Swedish Cancer Foundation, the Swedish Medical Association, the Gothenburg Medical Association, the Assar Gabrielsson Foundation, the Magn Berwall’s Foundation, and the Swedish Research Council. None of the funding sources had any role in the study or the preparation of the manuscript. The authors reported no financial conflicts of interest.

Replacing open abdominal surgery with laparoscopy when possible may offer an opportunity for improved quality of life and decreased morbidity for many patients, along with health care system cost savings, said Dr. Luke M. Funk and Dr. Stanley W. Ashley in an invited critique accompanying the study on small-bowel obstruction (SBO) risk (Arch Surg. 2012;147:365 [doi:10.1001/archsurg.2012.157]).

The finding that SBO risk was lower with laparoscopy even after accounting for patient factors such as age, comorbidities, and previous surgery, has important implications for both the quality and cost of surgical care, Dr. Funk and Dr. Ashley said in their commentary.

"For surgeons, it highlights another potential benefit of minimally invasive surgery and challenges us to continue to offer less invasive procedures whenever they are feasible," they wrote. "For payers and health care policy leaders, it suggests that substantial cost savings could be achieved if open surgery [were] replaced with laparoscopic surgery more often."

Inpatient expenses on adhesiolysis-related complications exceed $2 billion in the United States, they added.

However, to fully realize the benefits of laparoscopy, newer payment models such as bundled or episode-based payments would need to account for the higher initial cost of laparoscopy but lower long-term costs related to shorter hospitalizations, lower complication rates, fewer readmissions, and fewer reoperations, the two surgeons said.

Still, the study’s authors "have provided strong evidence that minimal invasion often results in maximal benefit," Dr. Funk and Dr. Ashley wrote.

Dr. Funk is a general surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Dr. Ashley is vice chairman of the department of surgery at Brigham and Women’s.

Replacing open abdominal surgery with laparoscopy when possible may offer an opportunity for improved quality of life and decreased morbidity for many patients, along with health care system cost savings, said Dr. Luke M. Funk and Dr. Stanley W. Ashley in an invited critique accompanying the study on small-bowel obstruction (SBO) risk (Arch Surg. 2012;147:365 [doi:10.1001/archsurg.2012.157]).

The finding that SBO risk was lower with laparoscopy even after accounting for patient factors such as age, comorbidities, and previous surgery, has important implications for both the quality and cost of surgical care, Dr. Funk and Dr. Ashley said in their commentary.

"For surgeons, it highlights another potential benefit of minimally invasive surgery and challenges us to continue to offer less invasive procedures whenever they are feasible," they wrote. "For payers and health care policy leaders, it suggests that substantial cost savings could be achieved if open surgery [were] replaced with laparoscopic surgery more often."

Inpatient expenses on adhesiolysis-related complications exceed $2 billion in the United States, they added.

However, to fully realize the benefits of laparoscopy, newer payment models such as bundled or episode-based payments would need to account for the higher initial cost of laparoscopy but lower long-term costs related to shorter hospitalizations, lower complication rates, fewer readmissions, and fewer reoperations, the two surgeons said.

Still, the study’s authors "have provided strong evidence that minimal invasion often results in maximal benefit," Dr. Funk and Dr. Ashley wrote.

Dr. Funk is a general surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Dr. Ashley is vice chairman of the department of surgery at Brigham and Women’s.

Replacing open abdominal surgery with laparoscopy when possible may offer an opportunity for improved quality of life and decreased morbidity for many patients, along with health care system cost savings, said Dr. Luke M. Funk and Dr. Stanley W. Ashley in an invited critique accompanying the study on small-bowel obstruction (SBO) risk (Arch Surg. 2012;147:365 [doi:10.1001/archsurg.2012.157]).

The finding that SBO risk was lower with laparoscopy even after accounting for patient factors such as age, comorbidities, and previous surgery, has important implications for both the quality and cost of surgical care, Dr. Funk and Dr. Ashley said in their commentary.

"For surgeons, it highlights another potential benefit of minimally invasive surgery and challenges us to continue to offer less invasive procedures whenever they are feasible," they wrote. "For payers and health care policy leaders, it suggests that substantial cost savings could be achieved if open surgery [were] replaced with laparoscopic surgery more often."

Inpatient expenses on adhesiolysis-related complications exceed $2 billion in the United States, they added.

However, to fully realize the benefits of laparoscopy, newer payment models such as bundled or episode-based payments would need to account for the higher initial cost of laparoscopy but lower long-term costs related to shorter hospitalizations, lower complication rates, fewer readmissions, and fewer reoperations, the two surgeons said.

Still, the study’s authors "have provided strong evidence that minimal invasion often results in maximal benefit," Dr. Funk and Dr. Ashley wrote.

Dr. Funk is a general surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Dr. Ashley is vice chairman of the department of surgery at Brigham and Women’s.

The risk of developing a small-bowel obstruction after open surgery is about fourfold higher when compared with laparoscopic surgery in nine commonly performed abdominal and pelvic procedures, including cholecystectomy, hysterectomy, and appendectomy, investigators reported.

Other factors such as patient age, , prior abdominal surgery, and comorbidities also contributed to the risk of SBO, the study showed. However, laparoscopy "exceeded other risk factors in reduction of the risk of SBO for most of the surgical procedures," wrote Dr. Eva Angenete and her colleagues (Arch. Surg. 2012;147:359-65).

"This study shows that, beyond important factors such as age, previous abdominal surgery, and comorbidity, the surgical technique is the most important factor related to SBO," the authors wrote. "Compared with laparoscopic surgery, open surgery seems to increase the risk of SBO at least four times."

It’s likely that the study results will hold up to further scrutiny because the study was population based and the sample size – 108,141 patients – is large, the authors said.

Still, laparoscopic surgery did not seem to reduce the incidence of SBO in some groups, including hysterectomy patients. "One hypothesis is that this result may be related to a limited dissection in the pelvis," but the small number of laparoscopic hysterectomy patients included in the study could have affected the study’s results, the authors wrote. In addition, there were no clear risk factors for SBO in patients undergoing bariatric surgery, they wrote.

The investigators used the Inpatient Register of the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare to analyze the risk of SBO in nine procedures, including cholecystectomy, hysterectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, bowel resection, anterior resection, abdominoperineal resection, rectopexy, appendectomy, and bariatric surgery performed from 2002 to 2004. The database included information on demographic characteristics, comorbidities, previous abdominal surgery, and deaths.

The rate of SBO was lowest after cholecystectomy, occurring in just 0.4% of all cases, and was highest, at 13.9%, in abdominoperineal resection patients. For most surgical procedures, patients who had SBO were older on average. SBO was also more common in patients with previous abdominal surgery.

In those who underwent cholecystectomy, bowel resection, or appendectomy, a higher level of comorbidity was associated with a greater incidence of SBO, the authors said. In the group of complicated cholecystectomy patients as well as the group of anterior resection patients, SBO was more common among men.

SBO was linked with an increased risk of death within 5 years, the study found.

"The aim of this study was to identify the incidence and risk factors for mechanical SBO after a number of common abdominal and pelvic procedures," the authors wrote. "Small-bowel obstruction is a substantial health care challenge, and correctly identified risk factors can provide improved tools to reduce the risk of SBO after an abdominal surgical procedure."

"The safety and the short-term benefits of laparoscopy are already known, and it is possible that laparoscopy should be regarded as the preferred technique in an attempt to further reduce the complications of surgery," the authors concluded.

The project was supported by grants from the Swedish Cancer Foundation, the Swedish Medical Association, the Gothenburg Medical Association, the Assar Gabrielsson Foundation, the Magn Berwall’s Foundation, and the Swedish Research Council. None of the funding sources had any role in the study or the preparation of the manuscript. The authors reported no financial conflicts of interest.

The risk of developing a small-bowel obstruction after open surgery is about fourfold higher when compared with laparoscopic surgery in nine commonly performed abdominal and pelvic procedures, including cholecystectomy, hysterectomy, and appendectomy, investigators reported.

Other factors such as patient age, , prior abdominal surgery, and comorbidities also contributed to the risk of SBO, the study showed. However, laparoscopy "exceeded other risk factors in reduction of the risk of SBO for most of the surgical procedures," wrote Dr. Eva Angenete and her colleagues (Arch. Surg. 2012;147:359-65).

"This study shows that, beyond important factors such as age, previous abdominal surgery, and comorbidity, the surgical technique is the most important factor related to SBO," the authors wrote. "Compared with laparoscopic surgery, open surgery seems to increase the risk of SBO at least four times."

It’s likely that the study results will hold up to further scrutiny because the study was population based and the sample size – 108,141 patients – is large, the authors said.

Still, laparoscopic surgery did not seem to reduce the incidence of SBO in some groups, including hysterectomy patients. "One hypothesis is that this result may be related to a limited dissection in the pelvis," but the small number of laparoscopic hysterectomy patients included in the study could have affected the study’s results, the authors wrote. In addition, there were no clear risk factors for SBO in patients undergoing bariatric surgery, they wrote.

The investigators used the Inpatient Register of the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare to analyze the risk of SBO in nine procedures, including cholecystectomy, hysterectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, bowel resection, anterior resection, abdominoperineal resection, rectopexy, appendectomy, and bariatric surgery performed from 2002 to 2004. The database included information on demographic characteristics, comorbidities, previous abdominal surgery, and deaths.

The rate of SBO was lowest after cholecystectomy, occurring in just 0.4% of all cases, and was highest, at 13.9%, in abdominoperineal resection patients. For most surgical procedures, patients who had SBO were older on average. SBO was also more common in patients with previous abdominal surgery.

In those who underwent cholecystectomy, bowel resection, or appendectomy, a higher level of comorbidity was associated with a greater incidence of SBO, the authors said. In the group of complicated cholecystectomy patients as well as the group of anterior resection patients, SBO was more common among men.

SBO was linked with an increased risk of death within 5 years, the study found.

"The aim of this study was to identify the incidence and risk factors for mechanical SBO after a number of common abdominal and pelvic procedures," the authors wrote. "Small-bowel obstruction is a substantial health care challenge, and correctly identified risk factors can provide improved tools to reduce the risk of SBO after an abdominal surgical procedure."

"The safety and the short-term benefits of laparoscopy are already known, and it is possible that laparoscopy should be regarded as the preferred technique in an attempt to further reduce the complications of surgery," the authors concluded.

The project was supported by grants from the Swedish Cancer Foundation, the Swedish Medical Association, the Gothenburg Medical Association, the Assar Gabrielsson Foundation, the Magn Berwall’s Foundation, and the Swedish Research Council. None of the funding sources had any role in the study or the preparation of the manuscript. The authors reported no financial conflicts of interest.

Major Finding: The risk of small-bowel obstruction is four times higher in patients who undergo open surgery than in patients who undergo laparoscopy for nine commonly performed procedures.

Data Source: Data were analyzed from 108,141 cases between 2002 and 2004 from the Inpatient Register of the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare.

Disclosures: The project was supported by grants from the Swedish Cancer Foundation, the Swedish Medical Association, the Gothenburg Medical Association, the Assar Gabrielsson Foundation, the Magn Berwall’s Foundation, and the Swedish Research Council. None of the funding sources had any role in the study or the preparation of the manuscript. The authors reported no financial conflicts of interest.

Panel Backs Approval of Second Biologic for Ulcerative Colitis

SILVER SPRING, MD. – The approval of a second anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment option for ulcerative colitis is likely, now that the majority of a Food and Drug Administration advisory panel has recommended approval of adalimumab for treating people with moderately to severely active disease.

At a meeting on Aug. 28, the FDA’s Gastrointestinal Drugs Advisory Committee voted 15-2 that the expected benefits of adalimumab – a subcutaneously administered tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blocker – outweighed its potential risks as a treatment for patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis (UC) who have not had an adequate response with conventional treatments. The panel’s recommendation for approval was based on the results of two studies comparing adalimumab against placebo in such patients. But their support for approval came with caveats. While most of the panel agreed that the dose used in the studies had been shown to be clinically effective, they agreed that the optimal dose for treating UC had not yet been determined and that post-approval studies were needed to address dosing, subpopulations of patients who may benefit most from treatment, and long-term safety.

Panel members voting in favor of approval cited the need for more treatments and for a subcutaneous TNF blocker for these patients, as well as its potential steroid-sparing effects. And although the differences in clinical remission rates between placebo and treatment at 8 weeks and at 1 year were less than 10% – one of the main issues raised by FDA reviewers – most of the panel members said that these differences still represented a clinically meaningful benefit. Infliximab (Remicade), an intravenous TNF blocker, is approved for treating UC and Crohn’s disease in pediatric and adult patients.

Like other panelists, Dr. Andelka LoSavio of the department of gastroenterology and nutrition, Loyola University, Maywood, Ill., said that the outstanding issues should not hold up approval of adalimumab for UC. "Once the drug is on the marketplace, we will have more insight into subpopulations where the drug may be more effective," which was the case with Crohn’s disease and adalimumab.

Although the remission rates in the studies were low, these are difficult-to-treat patients, and the responses were statistically significant, with evidence of a steroid-sparing effect, said panelist Dr. Marc Wishingrad, a gastroenterologist who practices in Santa Monica, Calif. "So it seems to me in a global sense that there is enough benefit here, that overall I would recommend that this drug be approved for this indication," he added.

Panelists supported the manufacturer’s recommendation that if a patient does not respond after 8 weeks of treatment, that treatment should be stopped.

The two statisticians on the panel did not support approval, voting no on the risk-benefit question for reasons that included the modest effects on clinical remission rates, uncertain durability of these effects, inadequate long-term data, missing data, and uncertainties about the dose.

Adalimumab – marketed as Humira by Abbott Laboratories – was first approved in 2002 for treating moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis in adults, and was approved in 2007 for treating moderate to severe Crohn’s disease. It has also been approved for psoriasis, ankylosing spondylitis, and juvenile idiopathic arthritis indications.

The recommended dosing schedule for UC is one 160-mg starting dose, followed by 80 mg on day 15, and then 40 mg every other week starting at day 29, continuing treatment only in people who have responded within the first 8 weeks.

Abbott filed for approval in January 2011, but the FDA raised questions about whether a higher dose would be more effective and about the strength of the results in the two pivotal trials, including whether the differences in clinical remission rates at 8 and 52 weeks between placebo and treatment were clinically meaningful. The company resubmitted the application for approval, with a slightly different proposed indication: reducing the signs and symptoms, and achieving (instead of inducing and maintaining induction of) clinical remission in adults with moderately to severely active UC, who have had an inadequate response to conventional therapy.

The two double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III studies compared adalimumab against placebo in 1,094 treatment-refractory patients with moderately to severely active UC with a total Mayo score of 6 to 12 points, and an endoscopy sub-score of 2 or 3, despite current or previous steroid and/or immunosuppressant therapy. In one 8-week study, which did not include patients who had previously been treated with a TNF blocker, the clinical remission rate at 8 weeks was 18.5% among those on adalimumab vs. 9.2% in those on placebo, a 9.3% difference that was significant.

In the second study, which followed patients for 1 year and included some who had been treated with infliximab (40%), the clinical remission rate at 8 weeks was 16.5% among those on adalimumab, vs. 9.3% among those on placebo, a 7.2% difference that was statistically significant. At 52 weeks, the remission rate was 17.3% among those on adalimumab, vs. 8.5% among those on placebo, an 8.8% difference that also was statistically significant.

In different votes, the panel nearly unanimously agreed that the 8 week and 52 week clinical remission rates in the studies represented "clinically meaningful benefits."

However, in the second study, 8.5% of the patients on adalimumab were in clinical remission at both weeks 8 and 52, vs. 4.1% among those on placebo. The panel was less unanimous about whether the 4.4% difference between the two groups represented a clinically meaningful benefit of treatment, voting 10-6 with 1 abstention on this question.

Other findings in the 52-week study included a higher steroid discontinuation rate among those on adalimumab, a secondary endpoint: About 13% of those on adalimumab were able to go off steroid treatment before the 52nd week of treatment and had achieved a clinical remission, compared with 5.7% of those on placebo, a statistically significant difference. In addition, the patients on azathioprine or 6-MP at baseline in this study did not appear to benefit from adalimumab: In this subgroup, the remission rate at week 8 among those on adalimumab (12.9%) was similar to the rate among those on placebo (15%). But for those who were not on the immunomodulatory drugs at baseline, the remission rate was nearly 19% among those on adalimumab vs. 6.6% of those on placebo, the FDA reviewer pointed out. In the studies, the safety profile of adalimumab was similar to the placebo, other than a higher rate of injection site reactions among those on adalimumab, and no new safety signals for adalimumab were identified in the trials, according to Abbott.

If the FDA grants approval, adalimumab will be the only self-administered biologic therapy available for patients with UC, the company pointed out. In April 2012, adalimumab was approved in the European Union for treating adults with moderately to severely active UC who have had an inadequate response to conventional therapy, based on the same data submitted to the FDA for the UC indication, according to Abbott.

The company is planning an international registry of patients with UC treated with adalimumab in typical clinical settings to collect long-term safety data, which will include patients in the EU, and, if approved, in the United States. The FDA usually follows the recommendations of its advisory panels, which are not binding. The company expects a decision on approval by the end of the year, according to an Abbott spokesperson.

Panelists have been cleared of potential conflicts of interest related to the topic of the meeting. Occasionally, a panelist may be given a waiver, but not at this meeting.

SILVER SPRING, MD. – The approval of a second anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment option for ulcerative colitis is likely, now that the majority of a Food and Drug Administration advisory panel has recommended approval of adalimumab for treating people with moderately to severely active disease.

At a meeting on Aug. 28, the FDA’s Gastrointestinal Drugs Advisory Committee voted 15-2 that the expected benefits of adalimumab – a subcutaneously administered tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blocker – outweighed its potential risks as a treatment for patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis (UC) who have not had an adequate response with conventional treatments. The panel’s recommendation for approval was based on the results of two studies comparing adalimumab against placebo in such patients. But their support for approval came with caveats. While most of the panel agreed that the dose used in the studies had been shown to be clinically effective, they agreed that the optimal dose for treating UC had not yet been determined and that post-approval studies were needed to address dosing, subpopulations of patients who may benefit most from treatment, and long-term safety.

Panel members voting in favor of approval cited the need for more treatments and for a subcutaneous TNF blocker for these patients, as well as its potential steroid-sparing effects. And although the differences in clinical remission rates between placebo and treatment at 8 weeks and at 1 year were less than 10% – one of the main issues raised by FDA reviewers – most of the panel members said that these differences still represented a clinically meaningful benefit. Infliximab (Remicade), an intravenous TNF blocker, is approved for treating UC and Crohn’s disease in pediatric and adult patients.

Like other panelists, Dr. Andelka LoSavio of the department of gastroenterology and nutrition, Loyola University, Maywood, Ill., said that the outstanding issues should not hold up approval of adalimumab for UC. "Once the drug is on the marketplace, we will have more insight into subpopulations where the drug may be more effective," which was the case with Crohn’s disease and adalimumab.

Although the remission rates in the studies were low, these are difficult-to-treat patients, and the responses were statistically significant, with evidence of a steroid-sparing effect, said panelist Dr. Marc Wishingrad, a gastroenterologist who practices in Santa Monica, Calif. "So it seems to me in a global sense that there is enough benefit here, that overall I would recommend that this drug be approved for this indication," he added.

Panelists supported the manufacturer’s recommendation that if a patient does not respond after 8 weeks of treatment, that treatment should be stopped.

The two statisticians on the panel did not support approval, voting no on the risk-benefit question for reasons that included the modest effects on clinical remission rates, uncertain durability of these effects, inadequate long-term data, missing data, and uncertainties about the dose.

Adalimumab – marketed as Humira by Abbott Laboratories – was first approved in 2002 for treating moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis in adults, and was approved in 2007 for treating moderate to severe Crohn’s disease. It has also been approved for psoriasis, ankylosing spondylitis, and juvenile idiopathic arthritis indications.

The recommended dosing schedule for UC is one 160-mg starting dose, followed by 80 mg on day 15, and then 40 mg every other week starting at day 29, continuing treatment only in people who have responded within the first 8 weeks.

Abbott filed for approval in January 2011, but the FDA raised questions about whether a higher dose would be more effective and about the strength of the results in the two pivotal trials, including whether the differences in clinical remission rates at 8 and 52 weeks between placebo and treatment were clinically meaningful. The company resubmitted the application for approval, with a slightly different proposed indication: reducing the signs and symptoms, and achieving (instead of inducing and maintaining induction of) clinical remission in adults with moderately to severely active UC, who have had an inadequate response to conventional therapy.

The two double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III studies compared adalimumab against placebo in 1,094 treatment-refractory patients with moderately to severely active UC with a total Mayo score of 6 to 12 points, and an endoscopy sub-score of 2 or 3, despite current or previous steroid and/or immunosuppressant therapy. In one 8-week study, which did not include patients who had previously been treated with a TNF blocker, the clinical remission rate at 8 weeks was 18.5% among those on adalimumab vs. 9.2% in those on placebo, a 9.3% difference that was significant.

In the second study, which followed patients for 1 year and included some who had been treated with infliximab (40%), the clinical remission rate at 8 weeks was 16.5% among those on adalimumab, vs. 9.3% among those on placebo, a 7.2% difference that was statistically significant. At 52 weeks, the remission rate was 17.3% among those on adalimumab, vs. 8.5% among those on placebo, an 8.8% difference that also was statistically significant.

In different votes, the panel nearly unanimously agreed that the 8 week and 52 week clinical remission rates in the studies represented "clinically meaningful benefits."

However, in the second study, 8.5% of the patients on adalimumab were in clinical remission at both weeks 8 and 52, vs. 4.1% among those on placebo. The panel was less unanimous about whether the 4.4% difference between the two groups represented a clinically meaningful benefit of treatment, voting 10-6 with 1 abstention on this question.

Other findings in the 52-week study included a higher steroid discontinuation rate among those on adalimumab, a secondary endpoint: About 13% of those on adalimumab were able to go off steroid treatment before the 52nd week of treatment and had achieved a clinical remission, compared with 5.7% of those on placebo, a statistically significant difference. In addition, the patients on azathioprine or 6-MP at baseline in this study did not appear to benefit from adalimumab: In this subgroup, the remission rate at week 8 among those on adalimumab (12.9%) was similar to the rate among those on placebo (15%). But for those who were not on the immunomodulatory drugs at baseline, the remission rate was nearly 19% among those on adalimumab vs. 6.6% of those on placebo, the FDA reviewer pointed out. In the studies, the safety profile of adalimumab was similar to the placebo, other than a higher rate of injection site reactions among those on adalimumab, and no new safety signals for adalimumab were identified in the trials, according to Abbott.

If the FDA grants approval, adalimumab will be the only self-administered biologic therapy available for patients with UC, the company pointed out. In April 2012, adalimumab was approved in the European Union for treating adults with moderately to severely active UC who have had an inadequate response to conventional therapy, based on the same data submitted to the FDA for the UC indication, according to Abbott.

The company is planning an international registry of patients with UC treated with adalimumab in typical clinical settings to collect long-term safety data, which will include patients in the EU, and, if approved, in the United States. The FDA usually follows the recommendations of its advisory panels, which are not binding. The company expects a decision on approval by the end of the year, according to an Abbott spokesperson.

Panelists have been cleared of potential conflicts of interest related to the topic of the meeting. Occasionally, a panelist may be given a waiver, but not at this meeting.

SILVER SPRING, MD. – The approval of a second anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment option for ulcerative colitis is likely, now that the majority of a Food and Drug Administration advisory panel has recommended approval of adalimumab for treating people with moderately to severely active disease.

At a meeting on Aug. 28, the FDA’s Gastrointestinal Drugs Advisory Committee voted 15-2 that the expected benefits of adalimumab – a subcutaneously administered tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blocker – outweighed its potential risks as a treatment for patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis (UC) who have not had an adequate response with conventional treatments. The panel’s recommendation for approval was based on the results of two studies comparing adalimumab against placebo in such patients. But their support for approval came with caveats. While most of the panel agreed that the dose used in the studies had been shown to be clinically effective, they agreed that the optimal dose for treating UC had not yet been determined and that post-approval studies were needed to address dosing, subpopulations of patients who may benefit most from treatment, and long-term safety.

Panel members voting in favor of approval cited the need for more treatments and for a subcutaneous TNF blocker for these patients, as well as its potential steroid-sparing effects. And although the differences in clinical remission rates between placebo and treatment at 8 weeks and at 1 year were less than 10% – one of the main issues raised by FDA reviewers – most of the panel members said that these differences still represented a clinically meaningful benefit. Infliximab (Remicade), an intravenous TNF blocker, is approved for treating UC and Crohn’s disease in pediatric and adult patients.

Like other panelists, Dr. Andelka LoSavio of the department of gastroenterology and nutrition, Loyola University, Maywood, Ill., said that the outstanding issues should not hold up approval of adalimumab for UC. "Once the drug is on the marketplace, we will have more insight into subpopulations where the drug may be more effective," which was the case with Crohn’s disease and adalimumab.

Although the remission rates in the studies were low, these are difficult-to-treat patients, and the responses were statistically significant, with evidence of a steroid-sparing effect, said panelist Dr. Marc Wishingrad, a gastroenterologist who practices in Santa Monica, Calif. "So it seems to me in a global sense that there is enough benefit here, that overall I would recommend that this drug be approved for this indication," he added.

Panelists supported the manufacturer’s recommendation that if a patient does not respond after 8 weeks of treatment, that treatment should be stopped.

The two statisticians on the panel did not support approval, voting no on the risk-benefit question for reasons that included the modest effects on clinical remission rates, uncertain durability of these effects, inadequate long-term data, missing data, and uncertainties about the dose.

Adalimumab – marketed as Humira by Abbott Laboratories – was first approved in 2002 for treating moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis in adults, and was approved in 2007 for treating moderate to severe Crohn’s disease. It has also been approved for psoriasis, ankylosing spondylitis, and juvenile idiopathic arthritis indications.

The recommended dosing schedule for UC is one 160-mg starting dose, followed by 80 mg on day 15, and then 40 mg every other week starting at day 29, continuing treatment only in people who have responded within the first 8 weeks.

Abbott filed for approval in January 2011, but the FDA raised questions about whether a higher dose would be more effective and about the strength of the results in the two pivotal trials, including whether the differences in clinical remission rates at 8 and 52 weeks between placebo and treatment were clinically meaningful. The company resubmitted the application for approval, with a slightly different proposed indication: reducing the signs and symptoms, and achieving (instead of inducing and maintaining induction of) clinical remission in adults with moderately to severely active UC, who have had an inadequate response to conventional therapy.

The two double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III studies compared adalimumab against placebo in 1,094 treatment-refractory patients with moderately to severely active UC with a total Mayo score of 6 to 12 points, and an endoscopy sub-score of 2 or 3, despite current or previous steroid and/or immunosuppressant therapy. In one 8-week study, which did not include patients who had previously been treated with a TNF blocker, the clinical remission rate at 8 weeks was 18.5% among those on adalimumab vs. 9.2% in those on placebo, a 9.3% difference that was significant.

In the second study, which followed patients for 1 year and included some who had been treated with infliximab (40%), the clinical remission rate at 8 weeks was 16.5% among those on adalimumab, vs. 9.3% among those on placebo, a 7.2% difference that was statistically significant. At 52 weeks, the remission rate was 17.3% among those on adalimumab, vs. 8.5% among those on placebo, an 8.8% difference that also was statistically significant.

In different votes, the panel nearly unanimously agreed that the 8 week and 52 week clinical remission rates in the studies represented "clinically meaningful benefits."

However, in the second study, 8.5% of the patients on adalimumab were in clinical remission at both weeks 8 and 52, vs. 4.1% among those on placebo. The panel was less unanimous about whether the 4.4% difference between the two groups represented a clinically meaningful benefit of treatment, voting 10-6 with 1 abstention on this question.

Other findings in the 52-week study included a higher steroid discontinuation rate among those on adalimumab, a secondary endpoint: About 13% of those on adalimumab were able to go off steroid treatment before the 52nd week of treatment and had achieved a clinical remission, compared with 5.7% of those on placebo, a statistically significant difference. In addition, the patients on azathioprine or 6-MP at baseline in this study did not appear to benefit from adalimumab: In this subgroup, the remission rate at week 8 among those on adalimumab (12.9%) was similar to the rate among those on placebo (15%). But for those who were not on the immunomodulatory drugs at baseline, the remission rate was nearly 19% among those on adalimumab vs. 6.6% of those on placebo, the FDA reviewer pointed out. In the studies, the safety profile of adalimumab was similar to the placebo, other than a higher rate of injection site reactions among those on adalimumab, and no new safety signals for adalimumab were identified in the trials, according to Abbott.

If the FDA grants approval, adalimumab will be the only self-administered biologic therapy available for patients with UC, the company pointed out. In April 2012, adalimumab was approved in the European Union for treating adults with moderately to severely active UC who have had an inadequate response to conventional therapy, based on the same data submitted to the FDA for the UC indication, according to Abbott.

The company is planning an international registry of patients with UC treated with adalimumab in typical clinical settings to collect long-term safety data, which will include patients in the EU, and, if approved, in the United States. The FDA usually follows the recommendations of its advisory panels, which are not binding. The company expects a decision on approval by the end of the year, according to an Abbott spokesperson.

Panelists have been cleared of potential conflicts of interest related to the topic of the meeting. Occasionally, a panelist may be given a waiver, but not at this meeting.

Topical Pain Relievers: FDA Issues Burn Warning

Rare cases of chemical burns caused by over-the-counter topical muscle and joint pain relievers has prompted the Food and Drug Administration to issue an advisory about the use of the products, with recommendations for both consumers and health professionals.

The single- or combination-ingredient products contain menthol, methyl salicylate, or capsaicin. The products included in the advisory are marketed under various names, including Bengay, Capzasin, Flexall, Icy Hot, and Mentholatum, according to the FDA communication.

Injuries prompting the advisory have ranged from first- to third-degree chemical burns, some of which required hospitalization. "In many cases, the burns occurred after only one application of the OTC muscle and joint pain reliever, with severe burning or blistering occurring within 24 hours of the first application," according to the FDA statement.

There were 43 reports of burns caused by application of these OTC products (in patch, balm, and cream formulations) identified in a search of the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System from 1969 to April 2011, the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System – Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance database from 2004 to 2010, and a 1987 report in the medical literature. The literature report described a patient who developed full-thickness skin and muscle necrosis and persistent interstitial nephritis after topical application of methyl salicylate and menthol, followed by the use of a heating pad (Cutis 1987;39:442-4).

Most of the second- and third-degree burns were associated with products that contain menthol as the single active ingredient and with products that contain a combination of menthol (concentration greater than 3%) and methyl salicylate (concentration greater than 10%). Only a few cases involved a product that contained capsaicin.

The advisory noted that health care professionals should counsel patients on how to safely use the products and on when they are recommended and to advise patients to stop using the products if they develop pain, swelling, or blistering at the application site. Consumers are advised to seek medical attention if they develop any of these effects – and to avoid tightly bandaging or applying heat to the application sites.

Currently, a warning about the risk of serious buns is not required on the label of these products.

Serious adverse reactions associated with these products should be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch program at 800-332-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch/.

Rare cases of chemical burns caused by over-the-counter topical muscle and joint pain relievers has prompted the Food and Drug Administration to issue an advisory about the use of the products, with recommendations for both consumers and health professionals.

The single- or combination-ingredient products contain menthol, methyl salicylate, or capsaicin. The products included in the advisory are marketed under various names, including Bengay, Capzasin, Flexall, Icy Hot, and Mentholatum, according to the FDA communication.

Injuries prompting the advisory have ranged from first- to third-degree chemical burns, some of which required hospitalization. "In many cases, the burns occurred after only one application of the OTC muscle and joint pain reliever, with severe burning or blistering occurring within 24 hours of the first application," according to the FDA statement.

There were 43 reports of burns caused by application of these OTC products (in patch, balm, and cream formulations) identified in a search of the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System from 1969 to April 2011, the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System – Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance database from 2004 to 2010, and a 1987 report in the medical literature. The literature report described a patient who developed full-thickness skin and muscle necrosis and persistent interstitial nephritis after topical application of methyl salicylate and menthol, followed by the use of a heating pad (Cutis 1987;39:442-4).

Most of the second- and third-degree burns were associated with products that contain menthol as the single active ingredient and with products that contain a combination of menthol (concentration greater than 3%) and methyl salicylate (concentration greater than 10%). Only a few cases involved a product that contained capsaicin.

The advisory noted that health care professionals should counsel patients on how to safely use the products and on when they are recommended and to advise patients to stop using the products if they develop pain, swelling, or blistering at the application site. Consumers are advised to seek medical attention if they develop any of these effects – and to avoid tightly bandaging or applying heat to the application sites.

Currently, a warning about the risk of serious buns is not required on the label of these products.

Serious adverse reactions associated with these products should be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch program at 800-332-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch/.

Rare cases of chemical burns caused by over-the-counter topical muscle and joint pain relievers has prompted the Food and Drug Administration to issue an advisory about the use of the products, with recommendations for both consumers and health professionals.

The single- or combination-ingredient products contain menthol, methyl salicylate, or capsaicin. The products included in the advisory are marketed under various names, including Bengay, Capzasin, Flexall, Icy Hot, and Mentholatum, according to the FDA communication.

Injuries prompting the advisory have ranged from first- to third-degree chemical burns, some of which required hospitalization. "In many cases, the burns occurred after only one application of the OTC muscle and joint pain reliever, with severe burning or blistering occurring within 24 hours of the first application," according to the FDA statement.

There were 43 reports of burns caused by application of these OTC products (in patch, balm, and cream formulations) identified in a search of the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System from 1969 to April 2011, the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System – Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance database from 2004 to 2010, and a 1987 report in the medical literature. The literature report described a patient who developed full-thickness skin and muscle necrosis and persistent interstitial nephritis after topical application of methyl salicylate and menthol, followed by the use of a heating pad (Cutis 1987;39:442-4).

Most of the second- and third-degree burns were associated with products that contain menthol as the single active ingredient and with products that contain a combination of menthol (concentration greater than 3%) and methyl salicylate (concentration greater than 10%). Only a few cases involved a product that contained capsaicin.

The advisory noted that health care professionals should counsel patients on how to safely use the products and on when they are recommended and to advise patients to stop using the products if they develop pain, swelling, or blistering at the application site. Consumers are advised to seek medical attention if they develop any of these effects – and to avoid tightly bandaging or applying heat to the application sites.

Currently, a warning about the risk of serious buns is not required on the label of these products.

Serious adverse reactions associated with these products should be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch program at 800-332-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch/.

Report: Hospitalists Can Trim Wasteful Healthcare Spending

An author of a report that estimates the national cost of unnecessary or wasteful healthcare at $750 billion per year hopes its findings will serve as a platform for hospitalists to spearhead improvements in healthcare delivery in the U.S.

The Institute of Medicine report, "Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America" [PDF], offers 10 broad recommendations that include reforming payment, adopting digital infrastructure, and simplifying transitional care. The paper was published earlier this month by a national committee of healthcare leaders, including Gary Kaplan, MD, FACP, FACMPE, FACPE, chairman and chief executive officer of Virginia Mason Health System in Seattle.

"The hospitalist is in a very unique position," Dr. Kaplan says. "They really are at the nexus of what we see as several of our key recommendations going forward."

In particular, Dr. Kaplan notes that healthcare delivery organizations should develop, implement, and fine-tune their "systems, engineering tools and process-improvement methods." Making such changes would help to "eliminate inefficiencies, remove unnecessary burdens on clinicians and staff, enhance patient experience, and improve patient health outcomes," he says.

"The hospitalists and the care teams with which the hospitalist connects are very critical to streamlining operations," Dr. Kaplan adds.

Many of the report's complaints about unnecessary testing, poor communication, and inefficient care delivery dovetail with the quality initiatives and practice-management improvements HM groups already push, Dr. Kaplan adds. To advance healthcare delivery's evolution, hospitalists should view the task of reform as an opportunity, not a challenge.

"There are very powerful opportunities for the hospitalist now to have great impact," he says. "To not just be the passive participants in a broken and dysfunctional system, but in many ways, [to be] one of the architects of an improved care system going forward."

An author of a report that estimates the national cost of unnecessary or wasteful healthcare at $750 billion per year hopes its findings will serve as a platform for hospitalists to spearhead improvements in healthcare delivery in the U.S.

The Institute of Medicine report, "Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America" [PDF], offers 10 broad recommendations that include reforming payment, adopting digital infrastructure, and simplifying transitional care. The paper was published earlier this month by a national committee of healthcare leaders, including Gary Kaplan, MD, FACP, FACMPE, FACPE, chairman and chief executive officer of Virginia Mason Health System in Seattle.

"The hospitalist is in a very unique position," Dr. Kaplan says. "They really are at the nexus of what we see as several of our key recommendations going forward."

In particular, Dr. Kaplan notes that healthcare delivery organizations should develop, implement, and fine-tune their "systems, engineering tools and process-improvement methods." Making such changes would help to "eliminate inefficiencies, remove unnecessary burdens on clinicians and staff, enhance patient experience, and improve patient health outcomes," he says.

"The hospitalists and the care teams with which the hospitalist connects are very critical to streamlining operations," Dr. Kaplan adds.

Many of the report's complaints about unnecessary testing, poor communication, and inefficient care delivery dovetail with the quality initiatives and practice-management improvements HM groups already push, Dr. Kaplan adds. To advance healthcare delivery's evolution, hospitalists should view the task of reform as an opportunity, not a challenge.

"There are very powerful opportunities for the hospitalist now to have great impact," he says. "To not just be the passive participants in a broken and dysfunctional system, but in many ways, [to be] one of the architects of an improved care system going forward."

An author of a report that estimates the national cost of unnecessary or wasteful healthcare at $750 billion per year hopes its findings will serve as a platform for hospitalists to spearhead improvements in healthcare delivery in the U.S.

The Institute of Medicine report, "Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America" [PDF], offers 10 broad recommendations that include reforming payment, adopting digital infrastructure, and simplifying transitional care. The paper was published earlier this month by a national committee of healthcare leaders, including Gary Kaplan, MD, FACP, FACMPE, FACPE, chairman and chief executive officer of Virginia Mason Health System in Seattle.

"The hospitalist is in a very unique position," Dr. Kaplan says. "They really are at the nexus of what we see as several of our key recommendations going forward."

In particular, Dr. Kaplan notes that healthcare delivery organizations should develop, implement, and fine-tune their "systems, engineering tools and process-improvement methods." Making such changes would help to "eliminate inefficiencies, remove unnecessary burdens on clinicians and staff, enhance patient experience, and improve patient health outcomes," he says.

"The hospitalists and the care teams with which the hospitalist connects are very critical to streamlining operations," Dr. Kaplan adds.

Many of the report's complaints about unnecessary testing, poor communication, and inefficient care delivery dovetail with the quality initiatives and practice-management improvements HM groups already push, Dr. Kaplan adds. To advance healthcare delivery's evolution, hospitalists should view the task of reform as an opportunity, not a challenge.

"There are very powerful opportunities for the hospitalist now to have great impact," he says. "To not just be the passive participants in a broken and dysfunctional system, but in many ways, [to be] one of the architects of an improved care system going forward."

ITL: Physician Reviews of HM-Relevant Research

Clinical question: What is the optimal duration of oral ciprofloxacin in women with acute community-acquired pyelonephritis?

Background: Despite being a commonly encountered infection, there are little data on the appropriate duration of therapy for acute pyelonephritis in women.

Study design: Prospective, randomized, open-labeled, double-blinded, noninferiority trial.

Setting: Twenty-one infectious diseases centers in Sweden.

Synopsis: Two hundred forty-eight women aged 18 or older with a presumed diagnosis of pyelonephritis were randomized to treatment with seven or 14 days of oral ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily. One hundred fifty-six per protocol patients were analyzed, and short-term clinical cure was shown to be noninferior, with cure of 97% in the seven-day group and 96% in the 14-day group (90% confidence interval -6.5-4.8, P=0.004). Results were also shown to be valid for older women and those with more severe infections. With growing concerns of antibiotic resistance and adverse drug events, using shorter courses of antibiotics has come into favor. The authors warn that these findings should not be extrapolated to other classes of antibiotics.

Bottom line: Treatment of community-acquired acute pyelonephritis in women with ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily for seven days is not inferior to 14 days.

Citation: Sandberg T, Skoog G, Hermansson AB, et al. Ciprofloxacin for 7 days versus 14 days in women with acute pyelonephritis: a randomised, open-label and double-blind, placebo-controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2012; Jun 20: [Epub ahead of print].

Read more of our physician reviews of recent, HM-relevant literature.

Clinical question: What is the optimal duration of oral ciprofloxacin in women with acute community-acquired pyelonephritis?

Background: Despite being a commonly encountered infection, there are little data on the appropriate duration of therapy for acute pyelonephritis in women.

Study design: Prospective, randomized, open-labeled, double-blinded, noninferiority trial.

Setting: Twenty-one infectious diseases centers in Sweden.

Synopsis: Two hundred forty-eight women aged 18 or older with a presumed diagnosis of pyelonephritis were randomized to treatment with seven or 14 days of oral ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily. One hundred fifty-six per protocol patients were analyzed, and short-term clinical cure was shown to be noninferior, with cure of 97% in the seven-day group and 96% in the 14-day group (90% confidence interval -6.5-4.8, P=0.004). Results were also shown to be valid for older women and those with more severe infections. With growing concerns of antibiotic resistance and adverse drug events, using shorter courses of antibiotics has come into favor. The authors warn that these findings should not be extrapolated to other classes of antibiotics.

Bottom line: Treatment of community-acquired acute pyelonephritis in women with ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily for seven days is not inferior to 14 days.

Citation: Sandberg T, Skoog G, Hermansson AB, et al. Ciprofloxacin for 7 days versus 14 days in women with acute pyelonephritis: a randomised, open-label and double-blind, placebo-controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2012; Jun 20: [Epub ahead of print].

Read more of our physician reviews of recent, HM-relevant literature.

Clinical question: What is the optimal duration of oral ciprofloxacin in women with acute community-acquired pyelonephritis?

Background: Despite being a commonly encountered infection, there are little data on the appropriate duration of therapy for acute pyelonephritis in women.

Study design: Prospective, randomized, open-labeled, double-blinded, noninferiority trial.

Setting: Twenty-one infectious diseases centers in Sweden.

Synopsis: Two hundred forty-eight women aged 18 or older with a presumed diagnosis of pyelonephritis were randomized to treatment with seven or 14 days of oral ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily. One hundred fifty-six per protocol patients were analyzed, and short-term clinical cure was shown to be noninferior, with cure of 97% in the seven-day group and 96% in the 14-day group (90% confidence interval -6.5-4.8, P=0.004). Results were also shown to be valid for older women and those with more severe infections. With growing concerns of antibiotic resistance and adverse drug events, using shorter courses of antibiotics has come into favor. The authors warn that these findings should not be extrapolated to other classes of antibiotics.

Bottom line: Treatment of community-acquired acute pyelonephritis in women with ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily for seven days is not inferior to 14 days.

Citation: Sandberg T, Skoog G, Hermansson AB, et al. Ciprofloxacin for 7 days versus 14 days in women with acute pyelonephritis: a randomised, open-label and double-blind, placebo-controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2012; Jun 20: [Epub ahead of print].

Read more of our physician reviews of recent, HM-relevant literature.

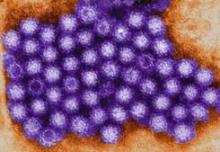

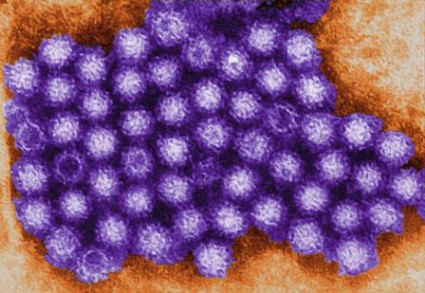

DNA Alone Inadequate to Identify HPV-Related Cancers

Testing for the presence of human papillomavirus DNA alone, especially using polymerase chain reaction methods, is not adequate to identify which head and neck squamous cell carcinomas are caused by the virus, according to two studies published online Sept. 18 in Cancer Research.

Identifying HPV-driven malignancies is important because they respond better to treatment and have better outcomes than those unrelated to HPV infection. Indeed, treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) may soon be guided by the tumor’s HPV status, since trials are now underway to determine whether de-escalation of chemo- and radiotherapy is safe and effective in such patients.

At present, however, the biomarkers that are best suited to making this identification are unclear.

Case Series Assesses Biomarkers

In the first study, researchers assessed the usefulness of four biomarkers in determining which HNSCCs in a case series were driven by HPV. They began by examining fresh-frozen tumor biopsy samples from 199 German adults diagnosed as having oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer between 1990 and 2008.

The four biomarkers were HPV-16 viral load, viral oncogene RNA (E6 and E7), p16INK4a, and RNA patterns similar to those characteristic of cervical carcinomas (CxCa RNA), said Dr. Dana Holzinger of the German Cancer Research Center at Heidelberg (Germany) University and her associates.

The simple presence of HPV DNA in a tumor sample was found to be a poor indicator of prognosis, likely because it often signaled past HPV infections or recent oral exposure, rather than active HPV infection that progressed to malignancy, the investigators said (Cancer Res. 2012 Sept. 18 [doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3934]).

Instead, "we showed that high viral load and a cancer-specific pattern of viral gene expression are most suited to identify patients with HPV-driven tumors among patients with oropharyngeal cancer. Viral expression pattern is a completely new marker in this field, and viral load has hardly been analyzed before," Dr. Holzinger said in a press statement accompanying the publication of these findings.

"Once standardized assays for these markers, applicable in routine clinical laboratories, are established, they will allow precise identification" of cancers that are or are not HPV-driven, which will in turn influence prognosis and treatment, she added.

Results Back Combination Approach

In the second study, Dr. Caihua Liang of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and her associates examined 488 HNSCC samples as well as serum samples collected in a population-based study in the Boston area during 1999-2003.

As in the first study, these investigators found that the mere presence of HPV-16 DNA in these tumors, particularly when detected by PCR analysis, did not accurately predict overall survival or progression-free survival.

Instead, "our study strongly suggests that the combination of detection of HPV-16 DNA in HNSCC tumors [plus] p16 immunostaining with E6/E7 antibodies represents the most clinically valuable surrogate marker for the identification of patients . . . who have a better prognosis," they said (Cancer Res. 2012 Sept. 28 [doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3277]).

"Assessment of HPV DNA using polymerase chain reaction methods as a biomarker in individual head and neck cancers is a poor predictor of outcome, and is also poorly associated with antibody response indicative of exposure and/or infection by HPV," senior author Dr. Karl T. Kelsey added in the press statement.

"We may not be diagnosing these tumors as accurately and precisely as we need to for adjusting treatments," said Dr. Kelsey, a professor in the department of epidemiology and the department of pathology and laboratory medicine at Brown University.

Dr. Holzinger’s study was funded in part by the European Commission, BMBG/HGAF-Canceropole Grand-Est, and the German Research Foundation. Her associates reported ties to Qiagen and Roche. Dr. Liang’s study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute, and one associate reported ties to Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Both of these studies demonstrate that the HPV DNA status of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas should be interpreted with caution, said Dr. Eduardo Mendez.

"Further testing to confirm HPV active infection may be warranted, particularly in consideration of de-escalation regimens," he said. In addition, other prognostic factors should be taken into account, such as tumor classification and lymph node status.

Dr. Mendez is at the University of Washington/Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle. He reported ties to Intuitive Surgical. These remarks were taken from his commentary accompanying Dr. Holzinger’s and Dr. Liang’s reports (Cancer Res. 2012 Sept. 18 [doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3285]).

Both of these studies demonstrate that the HPV DNA status of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas should be interpreted with caution, said Dr. Eduardo Mendez.

"Further testing to confirm HPV active infection may be warranted, particularly in consideration of de-escalation regimens," he said. In addition, other prognostic factors should be taken into account, such as tumor classification and lymph node status.

Dr. Mendez is at the University of Washington/Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle. He reported ties to Intuitive Surgical. These remarks were taken from his commentary accompanying Dr. Holzinger’s and Dr. Liang’s reports (Cancer Res. 2012 Sept. 18 [doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3285]).

Both of these studies demonstrate that the HPV DNA status of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas should be interpreted with caution, said Dr. Eduardo Mendez.

"Further testing to confirm HPV active infection may be warranted, particularly in consideration of de-escalation regimens," he said. In addition, other prognostic factors should be taken into account, such as tumor classification and lymph node status.

Dr. Mendez is at the University of Washington/Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle. He reported ties to Intuitive Surgical. These remarks were taken from his commentary accompanying Dr. Holzinger’s and Dr. Liang’s reports (Cancer Res. 2012 Sept. 18 [doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3285]).

Testing for the presence of human papillomavirus DNA alone, especially using polymerase chain reaction methods, is not adequate to identify which head and neck squamous cell carcinomas are caused by the virus, according to two studies published online Sept. 18 in Cancer Research.

Identifying HPV-driven malignancies is important because they respond better to treatment and have better outcomes than those unrelated to HPV infection. Indeed, treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) may soon be guided by the tumor’s HPV status, since trials are now underway to determine whether de-escalation of chemo- and radiotherapy is safe and effective in such patients.

At present, however, the biomarkers that are best suited to making this identification are unclear.

Case Series Assesses Biomarkers

In the first study, researchers assessed the usefulness of four biomarkers in determining which HNSCCs in a case series were driven by HPV. They began by examining fresh-frozen tumor biopsy samples from 199 German adults diagnosed as having oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer between 1990 and 2008.

The four biomarkers were HPV-16 viral load, viral oncogene RNA (E6 and E7), p16INK4a, and RNA patterns similar to those characteristic of cervical carcinomas (CxCa RNA), said Dr. Dana Holzinger of the German Cancer Research Center at Heidelberg (Germany) University and her associates.

The simple presence of HPV DNA in a tumor sample was found to be a poor indicator of prognosis, likely because it often signaled past HPV infections or recent oral exposure, rather than active HPV infection that progressed to malignancy, the investigators said (Cancer Res. 2012 Sept. 18 [doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3934]).

Instead, "we showed that high viral load and a cancer-specific pattern of viral gene expression are most suited to identify patients with HPV-driven tumors among patients with oropharyngeal cancer. Viral expression pattern is a completely new marker in this field, and viral load has hardly been analyzed before," Dr. Holzinger said in a press statement accompanying the publication of these findings.

"Once standardized assays for these markers, applicable in routine clinical laboratories, are established, they will allow precise identification" of cancers that are or are not HPV-driven, which will in turn influence prognosis and treatment, she added.

Results Back Combination Approach

In the second study, Dr. Caihua Liang of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and her associates examined 488 HNSCC samples as well as serum samples collected in a population-based study in the Boston area during 1999-2003.

As in the first study, these investigators found that the mere presence of HPV-16 DNA in these tumors, particularly when detected by PCR analysis, did not accurately predict overall survival or progression-free survival.

Instead, "our study strongly suggests that the combination of detection of HPV-16 DNA in HNSCC tumors [plus] p16 immunostaining with E6/E7 antibodies represents the most clinically valuable surrogate marker for the identification of patients . . . who have a better prognosis," they said (Cancer Res. 2012 Sept. 28 [doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3277]).

"Assessment of HPV DNA using polymerase chain reaction methods as a biomarker in individual head and neck cancers is a poor predictor of outcome, and is also poorly associated with antibody response indicative of exposure and/or infection by HPV," senior author Dr. Karl T. Kelsey added in the press statement.

"We may not be diagnosing these tumors as accurately and precisely as we need to for adjusting treatments," said Dr. Kelsey, a professor in the department of epidemiology and the department of pathology and laboratory medicine at Brown University.

Dr. Holzinger’s study was funded in part by the European Commission, BMBG/HGAF-Canceropole Grand-Est, and the German Research Foundation. Her associates reported ties to Qiagen and Roche. Dr. Liang’s study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute, and one associate reported ties to Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Testing for the presence of human papillomavirus DNA alone, especially using polymerase chain reaction methods, is not adequate to identify which head and neck squamous cell carcinomas are caused by the virus, according to two studies published online Sept. 18 in Cancer Research.

Identifying HPV-driven malignancies is important because they respond better to treatment and have better outcomes than those unrelated to HPV infection. Indeed, treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) may soon be guided by the tumor’s HPV status, since trials are now underway to determine whether de-escalation of chemo- and radiotherapy is safe and effective in such patients.

At present, however, the biomarkers that are best suited to making this identification are unclear.

Case Series Assesses Biomarkers

In the first study, researchers assessed the usefulness of four biomarkers in determining which HNSCCs in a case series were driven by HPV. They began by examining fresh-frozen tumor biopsy samples from 199 German adults diagnosed as having oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer between 1990 and 2008.

The four biomarkers were HPV-16 viral load, viral oncogene RNA (E6 and E7), p16INK4a, and RNA patterns similar to those characteristic of cervical carcinomas (CxCa RNA), said Dr. Dana Holzinger of the German Cancer Research Center at Heidelberg (Germany) University and her associates.