User login

The EHR Report Podcast: Meaningful Use, Part 1

Welcome to the debut of the EHR Report Podcast!

Starting this month, the authors of the EHR Report column, Dr. Neil Skolnik and Dr. Chris Notte, will deliver even more of their EHR know-how via their new podcast. Tune in regularly for candid analyses of EHR strategies, advanced tips on best practices, and one-on-one interviews with innovators in the field of EHRs.

In this, the first of a two-part series, Dr. Skolnik and Dr. Notte offer listeners an in-depth discussion of exactly what it takes for physicians to achieve meaningful use of their electronic health records software and earn federal incentives.

To download the podcast, click here.

To read the related column, click here.

To listen via this Web page, click on the player below:

Welcome to the debut of the EHR Report Podcast!

Starting this month, the authors of the EHR Report column, Dr. Neil Skolnik and Dr. Chris Notte, will deliver even more of their EHR know-how via their new podcast. Tune in regularly for candid analyses of EHR strategies, advanced tips on best practices, and one-on-one interviews with innovators in the field of EHRs.

In this, the first of a two-part series, Dr. Skolnik and Dr. Notte offer listeners an in-depth discussion of exactly what it takes for physicians to achieve meaningful use of their electronic health records software and earn federal incentives.

To download the podcast, click here.

To read the related column, click here.

To listen via this Web page, click on the player below:

Welcome to the debut of the EHR Report Podcast!

Starting this month, the authors of the EHR Report column, Dr. Neil Skolnik and Dr. Chris Notte, will deliver even more of their EHR know-how via their new podcast. Tune in regularly for candid analyses of EHR strategies, advanced tips on best practices, and one-on-one interviews with innovators in the field of EHRs.

In this, the first of a two-part series, Dr. Skolnik and Dr. Notte offer listeners an in-depth discussion of exactly what it takes for physicians to achieve meaningful use of their electronic health records software and earn federal incentives.

To download the podcast, click here.

To read the related column, click here.

To listen via this Web page, click on the player below:

The EHR Report Podcast: Meaningful Use, Part 1

Welcome to the debut of the EHR Report Podcast!

Starting this month, the authors of the EHR Report column, Dr. Neil Skolnik and Dr. Chris Notte, will deliver even more of their EHR know-how via their new podcast. Tune in regularly for candid analyses of EHR strategies, advanced tips on best practices, and one-on-one interviews with innovators in the field of EHRs.

In this, the first of a two-part series, Dr. Skolnik and Dr. Notte offer listeners an in-depth discussion of exactly what it takes for physicians to achieve meaningful use of their electronic health records software and earn federal incentives.

To download the podcast, click here.

To read the related column, click here.

To listen via this Web page, click on the player below:

Welcome to the debut of the EHR Report Podcast!

Starting this month, the authors of the EHR Report column, Dr. Neil Skolnik and Dr. Chris Notte, will deliver even more of their EHR know-how via their new podcast. Tune in regularly for candid analyses of EHR strategies, advanced tips on best practices, and one-on-one interviews with innovators in the field of EHRs.

In this, the first of a two-part series, Dr. Skolnik and Dr. Notte offer listeners an in-depth discussion of exactly what it takes for physicians to achieve meaningful use of their electronic health records software and earn federal incentives.

To download the podcast, click here.

To read the related column, click here.

To listen via this Web page, click on the player below:

Welcome to the debut of the EHR Report Podcast!

Starting this month, the authors of the EHR Report column, Dr. Neil Skolnik and Dr. Chris Notte, will deliver even more of their EHR know-how via their new podcast. Tune in regularly for candid analyses of EHR strategies, advanced tips on best practices, and one-on-one interviews with innovators in the field of EHRs.

In this, the first of a two-part series, Dr. Skolnik and Dr. Notte offer listeners an in-depth discussion of exactly what it takes for physicians to achieve meaningful use of their electronic health records software and earn federal incentives.

To download the podcast, click here.

To read the related column, click here.

To listen via this Web page, click on the player below:

When Your Patient With Depression Has a Family

Julie Totten was 24 years old when her brother Mark took his life. Shortly after, she helped her father, who had been suffering from undiagnosed depression all his life, get treated for the illness. In dealing with the depression that afflicted her father and brother, she felt alone, lost, and responsible. She thought there must be a lot of other families like hers.

So, 10 years after Mark’s death, Julie founded Families for Depression Awareness, a nonprofit organization to help families, including family caregivers like her, recognize and cope with depressive disorders to get people well and prevent suicides. The organization’s website, helps families recognize and cope with depression, and focuses on getting people into treatment to prevent suicide.

Dr. Bill Beardslee, chairman of psychiatry at Children’s Hospital Boston, lost an older sister to suicide when he was in medical school. "The depression took her over and after a valiant struggle against it, she took her own life some years later.

"It has taken me many years to deal with that and many conversations with my father, my mother and my wife, my friends, and, more recently, my children. Above all, it has given me a sense of how awful this illness can be for families," he wrote on the Hachette Book Group website. In his book, Out of the Darkened Room (New York: Little, Brown & Co., 2002), he describes the experiences of families with depression and strategies that families find helpful. It is highly recommended to psychiatrists to share with their patients and families.

Parents with depression worry that their children are suffering. Dr. Beardslee, who also is the Gardner-Monks Professor of Child Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston, has developed interventions with his colleagues aimed at helping these families. A major goal is "breaking the silence and helping the family talk together about depression." He conceptualizes depression as a chronic medical illness but also a family calamity and has developed an intervention to help families talk together and make meaning together.

His website, Families Preventing and Overcoming Depression provides details on the Family Talk Preventive Intervention. This is a public health, strength-based, and family-centered intervention designed to support families in which one or both parents have depression. This evidence-based practice partners with families to improve relationships and functioning by educating families on depression risk factors and understanding the benefits of applying protective factors to promote resilience.

Dr. Beardslee has many international collaborators in many different countries: Australia, Finland, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Columbia, Costa Rica, and Iceland. Family interventions in these countries are supported by government, and in the public health, and medical and mental health systems. Interventions in these countries are more widespread and systematically available than they are in the United States.

A symposium on this topic will be held at the American Psychiatric Association’s annual meeting in Philadelphia, moderated by Dr. Ellen Berman. It is called "When Your Patient Is a Parent: Supporting the Family and Addressing the Needs of Children." As part of that symposium, Dr. Beardslee will present "Clinical Implications of Evidence-Based Preventive Interventions for Families With Parental Depression." Finally, Ms. Totten will present "A Family Perspective," and I will present "Overview of Needs of the Children of Parents With Mental Illness." See you there!

Dr. Heru is an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She has been a member of the Association of Family Psychiatrists since 2002 and currently serves as the organization’s treasurer. In addition, she is the coauthor of two books on working with families and is the author of numerous articles on this topic

Julie Totten was 24 years old when her brother Mark took his life. Shortly after, she helped her father, who had been suffering from undiagnosed depression all his life, get treated for the illness. In dealing with the depression that afflicted her father and brother, she felt alone, lost, and responsible. She thought there must be a lot of other families like hers.

So, 10 years after Mark’s death, Julie founded Families for Depression Awareness, a nonprofit organization to help families, including family caregivers like her, recognize and cope with depressive disorders to get people well and prevent suicides. The organization’s website, helps families recognize and cope with depression, and focuses on getting people into treatment to prevent suicide.

Dr. Bill Beardslee, chairman of psychiatry at Children’s Hospital Boston, lost an older sister to suicide when he was in medical school. "The depression took her over and after a valiant struggle against it, she took her own life some years later.

"It has taken me many years to deal with that and many conversations with my father, my mother and my wife, my friends, and, more recently, my children. Above all, it has given me a sense of how awful this illness can be for families," he wrote on the Hachette Book Group website. In his book, Out of the Darkened Room (New York: Little, Brown & Co., 2002), he describes the experiences of families with depression and strategies that families find helpful. It is highly recommended to psychiatrists to share with their patients and families.

Parents with depression worry that their children are suffering. Dr. Beardslee, who also is the Gardner-Monks Professor of Child Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston, has developed interventions with his colleagues aimed at helping these families. A major goal is "breaking the silence and helping the family talk together about depression." He conceptualizes depression as a chronic medical illness but also a family calamity and has developed an intervention to help families talk together and make meaning together.

His website, Families Preventing and Overcoming Depression provides details on the Family Talk Preventive Intervention. This is a public health, strength-based, and family-centered intervention designed to support families in which one or both parents have depression. This evidence-based practice partners with families to improve relationships and functioning by educating families on depression risk factors and understanding the benefits of applying protective factors to promote resilience.

Dr. Beardslee has many international collaborators in many different countries: Australia, Finland, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Columbia, Costa Rica, and Iceland. Family interventions in these countries are supported by government, and in the public health, and medical and mental health systems. Interventions in these countries are more widespread and systematically available than they are in the United States.

A symposium on this topic will be held at the American Psychiatric Association’s annual meeting in Philadelphia, moderated by Dr. Ellen Berman. It is called "When Your Patient Is a Parent: Supporting the Family and Addressing the Needs of Children." As part of that symposium, Dr. Beardslee will present "Clinical Implications of Evidence-Based Preventive Interventions for Families With Parental Depression." Finally, Ms. Totten will present "A Family Perspective," and I will present "Overview of Needs of the Children of Parents With Mental Illness." See you there!

Dr. Heru is an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She has been a member of the Association of Family Psychiatrists since 2002 and currently serves as the organization’s treasurer. In addition, she is the coauthor of two books on working with families and is the author of numerous articles on this topic

Julie Totten was 24 years old when her brother Mark took his life. Shortly after, she helped her father, who had been suffering from undiagnosed depression all his life, get treated for the illness. In dealing with the depression that afflicted her father and brother, she felt alone, lost, and responsible. She thought there must be a lot of other families like hers.

So, 10 years after Mark’s death, Julie founded Families for Depression Awareness, a nonprofit organization to help families, including family caregivers like her, recognize and cope with depressive disorders to get people well and prevent suicides. The organization’s website, helps families recognize and cope with depression, and focuses on getting people into treatment to prevent suicide.

Dr. Bill Beardslee, chairman of psychiatry at Children’s Hospital Boston, lost an older sister to suicide when he was in medical school. "The depression took her over and after a valiant struggle against it, she took her own life some years later.

"It has taken me many years to deal with that and many conversations with my father, my mother and my wife, my friends, and, more recently, my children. Above all, it has given me a sense of how awful this illness can be for families," he wrote on the Hachette Book Group website. In his book, Out of the Darkened Room (New York: Little, Brown & Co., 2002), he describes the experiences of families with depression and strategies that families find helpful. It is highly recommended to psychiatrists to share with their patients and families.

Parents with depression worry that their children are suffering. Dr. Beardslee, who also is the Gardner-Monks Professor of Child Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston, has developed interventions with his colleagues aimed at helping these families. A major goal is "breaking the silence and helping the family talk together about depression." He conceptualizes depression as a chronic medical illness but also a family calamity and has developed an intervention to help families talk together and make meaning together.

His website, Families Preventing and Overcoming Depression provides details on the Family Talk Preventive Intervention. This is a public health, strength-based, and family-centered intervention designed to support families in which one or both parents have depression. This evidence-based practice partners with families to improve relationships and functioning by educating families on depression risk factors and understanding the benefits of applying protective factors to promote resilience.

Dr. Beardslee has many international collaborators in many different countries: Australia, Finland, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Columbia, Costa Rica, and Iceland. Family interventions in these countries are supported by government, and in the public health, and medical and mental health systems. Interventions in these countries are more widespread and systematically available than they are in the United States.

A symposium on this topic will be held at the American Psychiatric Association’s annual meeting in Philadelphia, moderated by Dr. Ellen Berman. It is called "When Your Patient Is a Parent: Supporting the Family and Addressing the Needs of Children." As part of that symposium, Dr. Beardslee will present "Clinical Implications of Evidence-Based Preventive Interventions for Families With Parental Depression." Finally, Ms. Totten will present "A Family Perspective," and I will present "Overview of Needs of the Children of Parents With Mental Illness." See you there!

Dr. Heru is an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She has been a member of the Association of Family Psychiatrists since 2002 and currently serves as the organization’s treasurer. In addition, she is the coauthor of two books on working with families and is the author of numerous articles on this topic

FDA Investigates Major Bleeding Events in Dabigatran Patients

A little more than a year after the new anticoagulant dabigatran (Pradaxa) was approved for stroke prevention in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) patients, the FDA is evaluating post-marketing reports of serious bleeds in patients taking the drug.

The FDA is trying to determine if patients on Pradaxa are experiencing severe bleeding more than expected based on results of the clinical trial that led to Pradaxa’s approval, according to FDA spokeswoman Sandy Walsh.

“At this time, FDA continues to believe that Pradaxa provides an important health benefit when used as directed and recommends that healthcare professionals who prescribe Pradaxa follow the recommendations in the approved drug label,” Walsh tells The Hospitalist.

—Robert Pendleton, MD, director of the hospitalist program, University of Utah Healthcare; medical director, University Healthcare Thrombosis Service

Patients should not stop taking dabigatran without first talking to their doctors, the FDA announcement cautions. While “serious, even fatal events have been reported,” according to the FDA’s announcement, Walsh says the FDA isn’t prepared to say how many reports of serious bleeding events have been received because they’re still being reviewed.

“We often put out ‘early’ communications when we learn of drug safety issues,” she says. “We want to be transparent and make [the] public [aware of] what we do know, but our analysis is not final. At this point, the FDA is still evaluating this issue.”

Bleeding that leads to serious or fatal outcomes is a well-recognized complication of all anticoagulant therapies.

Dabigatran, a direct thrombin inhibitor, was approved in October 2010, becoming the first new oral anticoagulant approved in 50 years. It was the first approved among several new anti-coagulants that are poised to enter the market and are expected to challenge warfarin (Coumadin), the longtime standard of care.

The new drugs—including rivaroxaban (Xarelto), a Factor Xa-inhibitor that was approved in 2011—have been eagerly anticipated because they don’t require frequent blood draws for monitoring, as warfarin does. Hospitalists are especially interested in the new anticoagulant therapies because they treat numerous patients at an increased risk of clotting.

In the RE-LY trial, the 18,000-patient clinical trial comparing dabigatran and warfarin, major bleeding events occurred at similar rates with the two drugs.

Dabigatran manufacturer Boehringer Ingelheim is working with the FDA to evaluate the major bleeding reports, but spokeswoman Anna Moses says the drug has been performing according to expectations.

“Global data collected to date on major bleeding are consistent with our expectations based on the RE-LY trial and are in alignment with the U.S. Prescribing Information, which clearly state the benefits and risks associated with Pradaxa,” Moses says. “Overall, the positive-benefit-risk ratio of Pradaxa in NVAF remains unchanged.” (Visit the manufacturer website for prescribing information [PDF].)

Robert Pendleton, MD, director of the hospitalist program at the University of Utah Healthcare and Medical Director of the University Healthcare Thrombosis Service, expressed no surprise at the FDA’s statement.

“Although the data with new anticoagulants like Pradaxa is very favorable in a clinical trial setting, there’s great risk of enhanced demonstration of harm in the real-world setting if it’s not used optimally,” Dr. Pendleton says. “There will be more liberal sort of prescribing in a less-pure patient population.

So if people are not particularly cognizant of a patient’s renal function, their body weight, prior history of bleeding, etc., then you’re sort of applying new drugs in patients who are even more prone to bleed.”

Dr. Pendleton notes that in subgroup analyses, the slight benefits of the new drugs have come in patients with poor warfarin control, so if patients with good warfarin control are switched, outcomes could generally be expected not to be better, and could be worse.

“It won’t cause me to take people who I have prescribed Pradaxa and switch them back to warfarin,” he says, “but part of that is [that] here, in our healthcare system, we’re pretty cautious in who gets put on one of the new agents. And so those that do are patients who are most like those in the clinical trial.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in Florida.

A little more than a year after the new anticoagulant dabigatran (Pradaxa) was approved for stroke prevention in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) patients, the FDA is evaluating post-marketing reports of serious bleeds in patients taking the drug.

The FDA is trying to determine if patients on Pradaxa are experiencing severe bleeding more than expected based on results of the clinical trial that led to Pradaxa’s approval, according to FDA spokeswoman Sandy Walsh.

“At this time, FDA continues to believe that Pradaxa provides an important health benefit when used as directed and recommends that healthcare professionals who prescribe Pradaxa follow the recommendations in the approved drug label,” Walsh tells The Hospitalist.

—Robert Pendleton, MD, director of the hospitalist program, University of Utah Healthcare; medical director, University Healthcare Thrombosis Service

Patients should not stop taking dabigatran without first talking to their doctors, the FDA announcement cautions. While “serious, even fatal events have been reported,” according to the FDA’s announcement, Walsh says the FDA isn’t prepared to say how many reports of serious bleeding events have been received because they’re still being reviewed.

“We often put out ‘early’ communications when we learn of drug safety issues,” she says. “We want to be transparent and make [the] public [aware of] what we do know, but our analysis is not final. At this point, the FDA is still evaluating this issue.”

Bleeding that leads to serious or fatal outcomes is a well-recognized complication of all anticoagulant therapies.

Dabigatran, a direct thrombin inhibitor, was approved in October 2010, becoming the first new oral anticoagulant approved in 50 years. It was the first approved among several new anti-coagulants that are poised to enter the market and are expected to challenge warfarin (Coumadin), the longtime standard of care.

The new drugs—including rivaroxaban (Xarelto), a Factor Xa-inhibitor that was approved in 2011—have been eagerly anticipated because they don’t require frequent blood draws for monitoring, as warfarin does. Hospitalists are especially interested in the new anticoagulant therapies because they treat numerous patients at an increased risk of clotting.

In the RE-LY trial, the 18,000-patient clinical trial comparing dabigatran and warfarin, major bleeding events occurred at similar rates with the two drugs.

Dabigatran manufacturer Boehringer Ingelheim is working with the FDA to evaluate the major bleeding reports, but spokeswoman Anna Moses says the drug has been performing according to expectations.

“Global data collected to date on major bleeding are consistent with our expectations based on the RE-LY trial and are in alignment with the U.S. Prescribing Information, which clearly state the benefits and risks associated with Pradaxa,” Moses says. “Overall, the positive-benefit-risk ratio of Pradaxa in NVAF remains unchanged.” (Visit the manufacturer website for prescribing information [PDF].)

Robert Pendleton, MD, director of the hospitalist program at the University of Utah Healthcare and Medical Director of the University Healthcare Thrombosis Service, expressed no surprise at the FDA’s statement.

“Although the data with new anticoagulants like Pradaxa is very favorable in a clinical trial setting, there’s great risk of enhanced demonstration of harm in the real-world setting if it’s not used optimally,” Dr. Pendleton says. “There will be more liberal sort of prescribing in a less-pure patient population.

So if people are not particularly cognizant of a patient’s renal function, their body weight, prior history of bleeding, etc., then you’re sort of applying new drugs in patients who are even more prone to bleed.”

Dr. Pendleton notes that in subgroup analyses, the slight benefits of the new drugs have come in patients with poor warfarin control, so if patients with good warfarin control are switched, outcomes could generally be expected not to be better, and could be worse.

“It won’t cause me to take people who I have prescribed Pradaxa and switch them back to warfarin,” he says, “but part of that is [that] here, in our healthcare system, we’re pretty cautious in who gets put on one of the new agents. And so those that do are patients who are most like those in the clinical trial.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in Florida.

A little more than a year after the new anticoagulant dabigatran (Pradaxa) was approved for stroke prevention in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) patients, the FDA is evaluating post-marketing reports of serious bleeds in patients taking the drug.

The FDA is trying to determine if patients on Pradaxa are experiencing severe bleeding more than expected based on results of the clinical trial that led to Pradaxa’s approval, according to FDA spokeswoman Sandy Walsh.

“At this time, FDA continues to believe that Pradaxa provides an important health benefit when used as directed and recommends that healthcare professionals who prescribe Pradaxa follow the recommendations in the approved drug label,” Walsh tells The Hospitalist.

—Robert Pendleton, MD, director of the hospitalist program, University of Utah Healthcare; medical director, University Healthcare Thrombosis Service

Patients should not stop taking dabigatran without first talking to their doctors, the FDA announcement cautions. While “serious, even fatal events have been reported,” according to the FDA’s announcement, Walsh says the FDA isn’t prepared to say how many reports of serious bleeding events have been received because they’re still being reviewed.

“We often put out ‘early’ communications when we learn of drug safety issues,” she says. “We want to be transparent and make [the] public [aware of] what we do know, but our analysis is not final. At this point, the FDA is still evaluating this issue.”

Bleeding that leads to serious or fatal outcomes is a well-recognized complication of all anticoagulant therapies.

Dabigatran, a direct thrombin inhibitor, was approved in October 2010, becoming the first new oral anticoagulant approved in 50 years. It was the first approved among several new anti-coagulants that are poised to enter the market and are expected to challenge warfarin (Coumadin), the longtime standard of care.

The new drugs—including rivaroxaban (Xarelto), a Factor Xa-inhibitor that was approved in 2011—have been eagerly anticipated because they don’t require frequent blood draws for monitoring, as warfarin does. Hospitalists are especially interested in the new anticoagulant therapies because they treat numerous patients at an increased risk of clotting.

In the RE-LY trial, the 18,000-patient clinical trial comparing dabigatran and warfarin, major bleeding events occurred at similar rates with the two drugs.

Dabigatran manufacturer Boehringer Ingelheim is working with the FDA to evaluate the major bleeding reports, but spokeswoman Anna Moses says the drug has been performing according to expectations.

“Global data collected to date on major bleeding are consistent with our expectations based on the RE-LY trial and are in alignment with the U.S. Prescribing Information, which clearly state the benefits and risks associated with Pradaxa,” Moses says. “Overall, the positive-benefit-risk ratio of Pradaxa in NVAF remains unchanged.” (Visit the manufacturer website for prescribing information [PDF].)

Robert Pendleton, MD, director of the hospitalist program at the University of Utah Healthcare and Medical Director of the University Healthcare Thrombosis Service, expressed no surprise at the FDA’s statement.

“Although the data with new anticoagulants like Pradaxa is very favorable in a clinical trial setting, there’s great risk of enhanced demonstration of harm in the real-world setting if it’s not used optimally,” Dr. Pendleton says. “There will be more liberal sort of prescribing in a less-pure patient population.

So if people are not particularly cognizant of a patient’s renal function, their body weight, prior history of bleeding, etc., then you’re sort of applying new drugs in patients who are even more prone to bleed.”

Dr. Pendleton notes that in subgroup analyses, the slight benefits of the new drugs have come in patients with poor warfarin control, so if patients with good warfarin control are switched, outcomes could generally be expected not to be better, and could be worse.

“It won’t cause me to take people who I have prescribed Pradaxa and switch them back to warfarin,” he says, “but part of that is [that] here, in our healthcare system, we’re pretty cautious in who gets put on one of the new agents. And so those that do are patients who are most like those in the clinical trial.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in Florida.

VIDEO: Car Seat Safety

In this video, Dr. Beers explains why a rear facing car seat is safer for your child. Safety data show that the use of rear facing seats in the first 2 years of life provides better support for a child's back and neck muscles in addition to providing maximum protection in the event of an auto accident.

In this video, Dr. Beers explains why a rear facing car seat is safer for your child. Safety data show that the use of rear facing seats in the first 2 years of life provides better support for a child's back and neck muscles in addition to providing maximum protection in the event of an auto accident.

In this video, Dr. Beers explains why a rear facing car seat is safer for your child. Safety data show that the use of rear facing seats in the first 2 years of life provides better support for a child's back and neck muscles in addition to providing maximum protection in the event of an auto accident.

Blinatumomab Induces Complete Remissions in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

SAN DIEGO – The novel antibody blinatumomab induced high complete remission rates in adults with relapsed B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia in early clinical trials, according to Dr. Max S. Topp.

In a phase II study with a dose-finding phase, 9 of 12 patients who received blinatumomab 5 mcg/m2 per day for 1 week, followed by a 15-mcg dose on subsequent weeks, had either a complete remission (CR) or a CR with partial hematologic recovery (CRh), Dr. Topp of the University of Würzburg (Germany) said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

"We have exceptionally high rates of hematological complete remissions in these patients, and it ought to be noted that every patient has achieved MRD [minimal residual disease] negativity," said Dr. Topp.

At a median follow-up of 9.7 months, the median overall survival had not been reached, he added.

Blinatumomab is a bispecific T-cell engager designed to direct cytotoxic T cells to cancer cells expressing the CD19 receptor. It has shown good activity in a phase I clinical trial in patients with relapsed non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and in a study of patients with B-ALL who were positive for MRD (J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:2493-8).

The MT 103-206 trial was an open-label, multicenter phase II trial of blinatumomab in patients with relapsed/refractory B-precursor ALL, or Philadelphia chromosome–positive ALL (Ph+ALL) who were ineligible for tyrosine kinase inhibitors or who were in relapse following an allogeneic stem cell transplant.

The trial had a dose-finding run-in phase, with four patient cohorts. Dr. Topp focused on cohorts 2a and 3, in which patients received the selected dose schedule: an initial dose of 5 mcg/m2 IV daily for the 1st week of cycle 1, followed by 15 mcg/m2 per day for weeks 2-4 of every 4-week cycle, and every subsequent cycle. Patients had 2 weeks off between each cycle.

Patients who had a CR or CRh within the first two treatment cycles underwent consolidation with three additional cycles of blinatumonab and allogeneic stem cell transplant.

At the selected dose, the most common clinical adverse events were fever in 67%, headache in 33%, and tremor in 33%. Most of the events occurred during the first cycle, and no patients had to permanently discontinue therapy because of adverse events.

Among all cohorts (totaling 25 patients), there were 17 who had a CR or CRh: 5 of 7 patients who received a 15-mcg dose throughout treatment (cohort 1); 3 of 6 patients who received escalating doses of 5-, 15-, and 30-mcg doses (cohort 2b); and 9 of 12 patients in cohorts 2a and 3 combined. All patients with a CR or CRh were also MRD negative, defined as an MRD less than 104 measured by polymerase chain reaction evaluation of individual rearrangement of immunoglobulin or T-cell receptor genes by a central laboratory.

Dr. Topp explained that there were high response rates among all patient subgroups, including patients with Ph+ALL, and those with the t(4,11) translocation.

As of early November 2011, 6 of 17 patients with complete responses had relapses. One of four patients who had undergone allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant had a medullary relapse; this patient was CD19 negative. A total of 5 of 13 patients had a relapse prior to transplant – 2 medullary relapses (1 CD19-negative and 1 positive) and 3 extramedullary relapses (1 CD19 negative and 2 positive).

One patient who had a medullary relapse but retained CD19 expression was retreated with blinatumomab and had a CRh of 7 months’ duration; the patient achieved a second, ongoing CRh after more blinatumomab.

The median duration of complete hematologic remission was 7.1 months (218 days) among 18 patients (12 responders) in cohorts 1, 2a, and 2b.

Asked in an interview whether an agent targeted against CD19 might work in combination with an anti-CD20 agent such as rituximab (Rituxan), Dr. Alan S. Wayne, a leukemia specialist and session comoderator who was not involved in the study, said that CD20 is not as attractive a target in ALL as it is in lymphoma or other hematologic malignancies.

"The question of CD20 in ALL is a little challenging, because the expression is less universal and even within individual cases across blasts," said Dr. Wayne, who is also head of the hematologic disease division of the pediatric oncology branch at the National Cancer Institute.

He noted, however, that there is evidence to suggest that pretreatment of patients with steroids may increase CD20 expression.

"This is an exciting new era for combining agents with a variety of different mechanisms of action, and also toxicity profiles. One could imagine, for example, [using] steroid to increase CD20 expression, rituximab, and then another CD19- or CD22-targeting agent," he said.

The MT 103-206 trial was supported by Micromet. Dr. Topp and coauthors Dr. Ralf Bargou and Dr. Nicola Goekbuget disclosed consulting for and/or receiving honoraria from the company. Three other coauthors are employees of the company. Dr. Wayne reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The novel antibody blinatumomab induced high complete remission rates in adults with relapsed B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia in early clinical trials, according to Dr. Max S. Topp.

In a phase II study with a dose-finding phase, 9 of 12 patients who received blinatumomab 5 mcg/m2 per day for 1 week, followed by a 15-mcg dose on subsequent weeks, had either a complete remission (CR) or a CR with partial hematologic recovery (CRh), Dr. Topp of the University of Würzburg (Germany) said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

"We have exceptionally high rates of hematological complete remissions in these patients, and it ought to be noted that every patient has achieved MRD [minimal residual disease] negativity," said Dr. Topp.

At a median follow-up of 9.7 months, the median overall survival had not been reached, he added.

Blinatumomab is a bispecific T-cell engager designed to direct cytotoxic T cells to cancer cells expressing the CD19 receptor. It has shown good activity in a phase I clinical trial in patients with relapsed non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and in a study of patients with B-ALL who were positive for MRD (J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:2493-8).

The MT 103-206 trial was an open-label, multicenter phase II trial of blinatumomab in patients with relapsed/refractory B-precursor ALL, or Philadelphia chromosome–positive ALL (Ph+ALL) who were ineligible for tyrosine kinase inhibitors or who were in relapse following an allogeneic stem cell transplant.

The trial had a dose-finding run-in phase, with four patient cohorts. Dr. Topp focused on cohorts 2a and 3, in which patients received the selected dose schedule: an initial dose of 5 mcg/m2 IV daily for the 1st week of cycle 1, followed by 15 mcg/m2 per day for weeks 2-4 of every 4-week cycle, and every subsequent cycle. Patients had 2 weeks off between each cycle.

Patients who had a CR or CRh within the first two treatment cycles underwent consolidation with three additional cycles of blinatumonab and allogeneic stem cell transplant.

At the selected dose, the most common clinical adverse events were fever in 67%, headache in 33%, and tremor in 33%. Most of the events occurred during the first cycle, and no patients had to permanently discontinue therapy because of adverse events.

Among all cohorts (totaling 25 patients), there were 17 who had a CR or CRh: 5 of 7 patients who received a 15-mcg dose throughout treatment (cohort 1); 3 of 6 patients who received escalating doses of 5-, 15-, and 30-mcg doses (cohort 2b); and 9 of 12 patients in cohorts 2a and 3 combined. All patients with a CR or CRh were also MRD negative, defined as an MRD less than 104 measured by polymerase chain reaction evaluation of individual rearrangement of immunoglobulin or T-cell receptor genes by a central laboratory.

Dr. Topp explained that there were high response rates among all patient subgroups, including patients with Ph+ALL, and those with the t(4,11) translocation.

As of early November 2011, 6 of 17 patients with complete responses had relapses. One of four patients who had undergone allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant had a medullary relapse; this patient was CD19 negative. A total of 5 of 13 patients had a relapse prior to transplant – 2 medullary relapses (1 CD19-negative and 1 positive) and 3 extramedullary relapses (1 CD19 negative and 2 positive).

One patient who had a medullary relapse but retained CD19 expression was retreated with blinatumomab and had a CRh of 7 months’ duration; the patient achieved a second, ongoing CRh after more blinatumomab.

The median duration of complete hematologic remission was 7.1 months (218 days) among 18 patients (12 responders) in cohorts 1, 2a, and 2b.

Asked in an interview whether an agent targeted against CD19 might work in combination with an anti-CD20 agent such as rituximab (Rituxan), Dr. Alan S. Wayne, a leukemia specialist and session comoderator who was not involved in the study, said that CD20 is not as attractive a target in ALL as it is in lymphoma or other hematologic malignancies.

"The question of CD20 in ALL is a little challenging, because the expression is less universal and even within individual cases across blasts," said Dr. Wayne, who is also head of the hematologic disease division of the pediatric oncology branch at the National Cancer Institute.

He noted, however, that there is evidence to suggest that pretreatment of patients with steroids may increase CD20 expression.

"This is an exciting new era for combining agents with a variety of different mechanisms of action, and also toxicity profiles. One could imagine, for example, [using] steroid to increase CD20 expression, rituximab, and then another CD19- or CD22-targeting agent," he said.

The MT 103-206 trial was supported by Micromet. Dr. Topp and coauthors Dr. Ralf Bargou and Dr. Nicola Goekbuget disclosed consulting for and/or receiving honoraria from the company. Three other coauthors are employees of the company. Dr. Wayne reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The novel antibody blinatumomab induced high complete remission rates in adults with relapsed B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia in early clinical trials, according to Dr. Max S. Topp.

In a phase II study with a dose-finding phase, 9 of 12 patients who received blinatumomab 5 mcg/m2 per day for 1 week, followed by a 15-mcg dose on subsequent weeks, had either a complete remission (CR) or a CR with partial hematologic recovery (CRh), Dr. Topp of the University of Würzburg (Germany) said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

"We have exceptionally high rates of hematological complete remissions in these patients, and it ought to be noted that every patient has achieved MRD [minimal residual disease] negativity," said Dr. Topp.

At a median follow-up of 9.7 months, the median overall survival had not been reached, he added.

Blinatumomab is a bispecific T-cell engager designed to direct cytotoxic T cells to cancer cells expressing the CD19 receptor. It has shown good activity in a phase I clinical trial in patients with relapsed non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and in a study of patients with B-ALL who were positive for MRD (J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:2493-8).

The MT 103-206 trial was an open-label, multicenter phase II trial of blinatumomab in patients with relapsed/refractory B-precursor ALL, or Philadelphia chromosome–positive ALL (Ph+ALL) who were ineligible for tyrosine kinase inhibitors or who were in relapse following an allogeneic stem cell transplant.

The trial had a dose-finding run-in phase, with four patient cohorts. Dr. Topp focused on cohorts 2a and 3, in which patients received the selected dose schedule: an initial dose of 5 mcg/m2 IV daily for the 1st week of cycle 1, followed by 15 mcg/m2 per day for weeks 2-4 of every 4-week cycle, and every subsequent cycle. Patients had 2 weeks off between each cycle.

Patients who had a CR or CRh within the first two treatment cycles underwent consolidation with three additional cycles of blinatumonab and allogeneic stem cell transplant.

At the selected dose, the most common clinical adverse events were fever in 67%, headache in 33%, and tremor in 33%. Most of the events occurred during the first cycle, and no patients had to permanently discontinue therapy because of adverse events.

Among all cohorts (totaling 25 patients), there were 17 who had a CR or CRh: 5 of 7 patients who received a 15-mcg dose throughout treatment (cohort 1); 3 of 6 patients who received escalating doses of 5-, 15-, and 30-mcg doses (cohort 2b); and 9 of 12 patients in cohorts 2a and 3 combined. All patients with a CR or CRh were also MRD negative, defined as an MRD less than 104 measured by polymerase chain reaction evaluation of individual rearrangement of immunoglobulin or T-cell receptor genes by a central laboratory.

Dr. Topp explained that there were high response rates among all patient subgroups, including patients with Ph+ALL, and those with the t(4,11) translocation.

As of early November 2011, 6 of 17 patients with complete responses had relapses. One of four patients who had undergone allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant had a medullary relapse; this patient was CD19 negative. A total of 5 of 13 patients had a relapse prior to transplant – 2 medullary relapses (1 CD19-negative and 1 positive) and 3 extramedullary relapses (1 CD19 negative and 2 positive).

One patient who had a medullary relapse but retained CD19 expression was retreated with blinatumomab and had a CRh of 7 months’ duration; the patient achieved a second, ongoing CRh after more blinatumomab.

The median duration of complete hematologic remission was 7.1 months (218 days) among 18 patients (12 responders) in cohorts 1, 2a, and 2b.

Asked in an interview whether an agent targeted against CD19 might work in combination with an anti-CD20 agent such as rituximab (Rituxan), Dr. Alan S. Wayne, a leukemia specialist and session comoderator who was not involved in the study, said that CD20 is not as attractive a target in ALL as it is in lymphoma or other hematologic malignancies.

"The question of CD20 in ALL is a little challenging, because the expression is less universal and even within individual cases across blasts," said Dr. Wayne, who is also head of the hematologic disease division of the pediatric oncology branch at the National Cancer Institute.

He noted, however, that there is evidence to suggest that pretreatment of patients with steroids may increase CD20 expression.

"This is an exciting new era for combining agents with a variety of different mechanisms of action, and also toxicity profiles. One could imagine, for example, [using] steroid to increase CD20 expression, rituximab, and then another CD19- or CD22-targeting agent," he said.

The MT 103-206 trial was supported by Micromet. Dr. Topp and coauthors Dr. Ralf Bargou and Dr. Nicola Goekbuget disclosed consulting for and/or receiving honoraria from the company. Three other coauthors are employees of the company. Dr. Wayne reported no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF HEMATOLOGY

Major Finding: A total of 9 of 12 patients with relapsed B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia who received blinatumomab 5 mcg/m2 per day for 1 week, followed by a 15-mcg dose on subsequent weeks, had either a complete remission or a complete response with partial hematologic recovery,

Data Source: Open-label phase II trial with a dose-finding phase.

Disclosures: The MT 103-206 trial was supported by Micromet. Dr. Topp and coauthors Dr. Ralf Bargou and Dr. Nicola Goekbuget disclosed consulting for and/or receiving honoraria from the company. Three other coauthors are employees of the company. Dr. Wayne reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Intermediate Care: Role for Hospitalists

Hospitalized patients are becoming increasingly complex. The care of such patients may be impacted by the limited resources of the general ward and might benefit from more intensive monitoring in an intensive care unit (ICU)‐like setting. In light of this problem, the intermediate care units (ImCU) may provide a cost‐effective alternative by providing higher levels of staffing tailored to patient needs, without incurring the cost of an ICU admission. The ImCU can reduce costs and improves ICU utilization for sicker patients, decrease ICU readmissions, promote greater flexibility in patient triage, and decrease mortality rates in hospital wards.18

The characteristics of ImCUs depend on resource availability, institutional infrastructure, and the organization and funding of the parent healthcare system. The ImCU may function as a step‐up or step‐down unit, or may provide specialty care for cardiac, neurologic, respiratory, or surgical conditions.811 These units can expand opportunities for co‐management and, at the same time, offer the occasion for training residents to follow up patients through different levels of care (from the general ward to ImCU). In the same way, the multidisciplinary approach of the ImCU can improve the center's teaching potential.

Characterizing the ImCU population requires the assessment of their severity of illness, which is crucial for the evaluation of risk‐adjusted outcomes. The present study evaluated the impact of a hospitalist‐led ImCU on observed‐to‐expected mortality ratios, as well as its role in co‐management and teaching.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We performed a retrospective observational study, with data collected from April 2006 to April 2010 in a single academic medical center in Pamplona, Spain. The ImCU is a 9‐bed unit adjacent to, but independent from, the mixed ICU. Each bed is equipped with continuous telemetry, pulse oximetry, noninvasive arterial blood pressure, central venous pressure monitoring, and noninvasive pressure support ventilation. The signals are relayed to a central monitoring station and the nurse‐to‐patient ratio is 1:3.

The ImCU rounding team is multidisciplinary, and involves the hospital pharmacist, a nurse, the ImCU resident, the specialist or surgeon, and the attending hospitalist. After the triage process, ImCU patients were admitted to the attending hospitalist, who was responsible for admission and discharge of all ImCU patients. The hospitalist ordered diagnostic or therapeutic interventions as needed, with the exception of orders for procedures or consultations related with specialist/surgeon's specific needs.

Admission and discharge criteria for the ImCU were set according to guidelines defined by The American College of Critical Care Medicine,10 and also served as inclusion criteria for the present study. Exclusion criteria included: age less than 18 years old, severe respiratory failure, status epilepticus, and catastrophic brain illness. Patients admitted for drug administration and desensitization, and also ImCU readmissions, were excluded from data analysis. Patients came from medical and surgical wards, ICU, the operating room, and the emergency room.

A total of 756 patients were admitted to our ImCU during the study period. Patient demographics, past medical history, physiologic parameters at the time of admission, and survival to hospital discharge were recorded for all patients. Patient demographics include: age, gender, location before ImCU admission, length of stay before ImCU admission, reason for ImCU admission, anatomic site of surgery (if applicable), planned or unplanned admission, and infection status (nosocomial). Past medical history includes: the presence of arterial hypertension, diabetes, cirrhosis, chronic renal failure, chronic heart failure, cancer, hematological malignancy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS), immunosuppression, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, steroid treatment, and alcoholism. Physiologic parameters abstracted are described in Table 1. We used the Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II),12 as a prognostic and severity score. SAPS II is the only previously validated score in intermediate care.13 In‐hospital mortality was the clinical outcome measured.

|

| Vital signs |

| Glasgow Coma Scale |

| Serum bilirubin |

| Serum creatinine |

| Urea nitrogen |

| Leucocyte count |

| Serum sodium |

| Serum potassium |

| Bicarbonate levels |

| Urinary output in the first 24 hr |

| Oxygenation and ventilatory support |

Data were entered into a computer database by the authors. Statistical analysis was not blinded, and was performed using SPSS for Windows, version 15.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Continuous variables were reported as mean standard deviation or median (25%‐75% interquartile range). For nonparametric measure of statistical dependence of quantitative variables, we used Spearman's correlation coefficient. Discrimination was evaluated by calculating the area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC).

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at the Clnica Universidad de Navarra in Pamplona, Spain.

RESULTS

Four hundred fifty‐six patients were included in data analysis. Three hundred patients were excluded: 61 low‐risk patients (drug administration and desensitization), 147 readmissions, and 92 patients for missing variables. Patient characteristics, including probability of death following ImCU admission and discharge location, are summarized in Table 2. The mean age was 65.6 years, and about 35% of patients had a SAPS II‐based risk of death higher than 25% at the time of ImCU admission. The median length of stay was 4 (3‐7) days.

| |

| Age (yr) | 65.6 14.3 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 283 (62.1%) |

| Female | 173 (37.9%) |

| Location prior to admission | |

| General ward | 252 (55.3%) |

| Emergency room | 96 (21.1%) |

| ICU | 63 (13.8%) |

| Operating room | 28 (6.1%) |

| Other hospital | 17 (3.7%) |

| Probability of in‐hospital mortality based on SAPS II | |

| <10% | 128 (28.1%) |

| 11%‐25% | 176 (38.6%) |

| 26%‐50% | 107 (23.4%) |

| >50% | 45 (9.9%) |

| Global expected mortality (in‐hospital) | 23.2% |

| Global observed mortality (in‐hospital) | 20.6% (94/456) |

| O/E mortality ratio | 0.89 |

| Discharge location | |

| General ward | 352/456 (77.2%) |

| ICU | 65/456 (14.3%) |

| Home | 1/456 (0.2%) |

| Other hospital | 11/456 (2.4%) |

| Death location | |

| ImCU | 27/456 (5.9%) |

| ICU (transferred patients) | 32/65* (49.2%) |

| General ward | 35/352* (9.9%) |

Outcomes

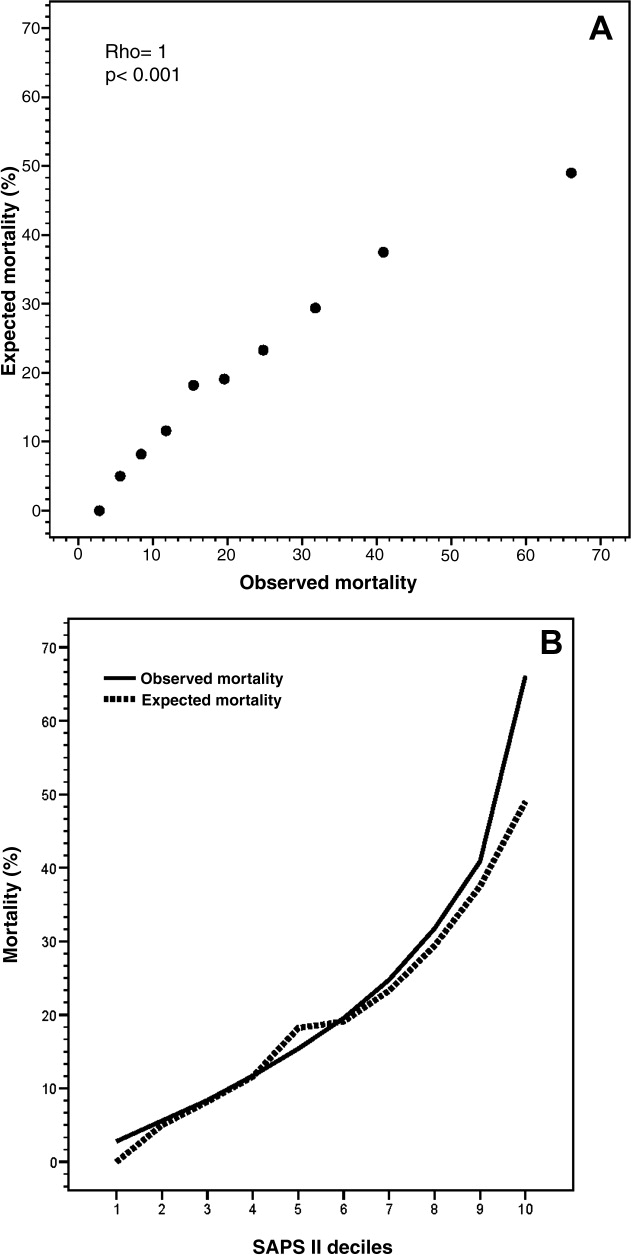

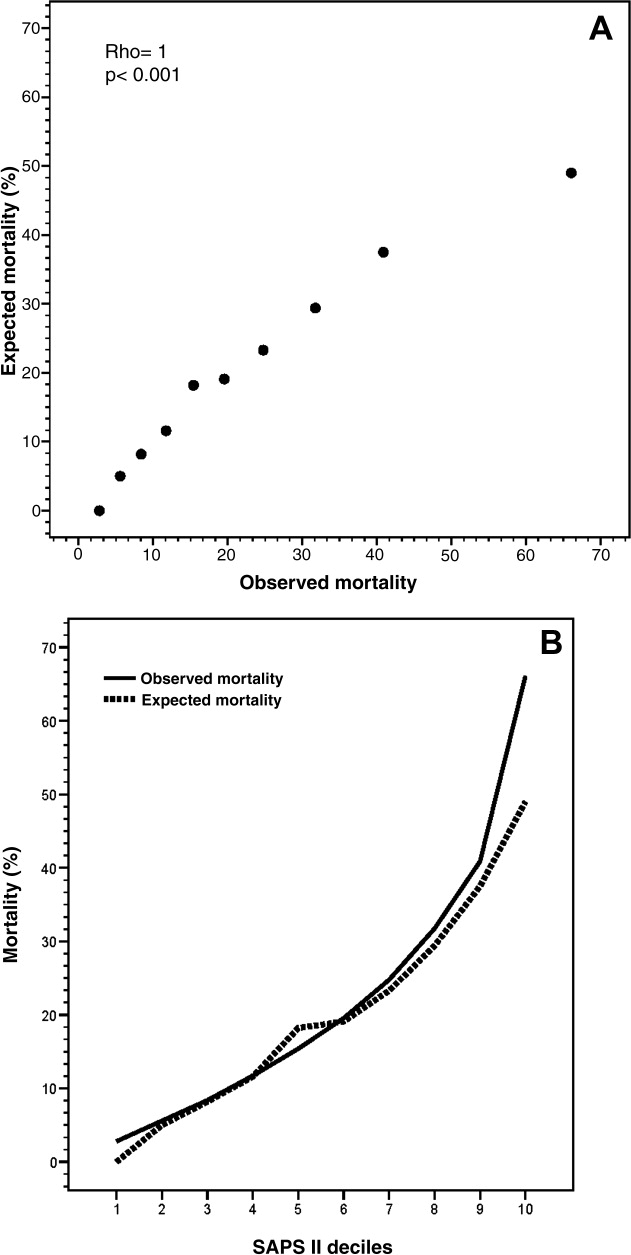

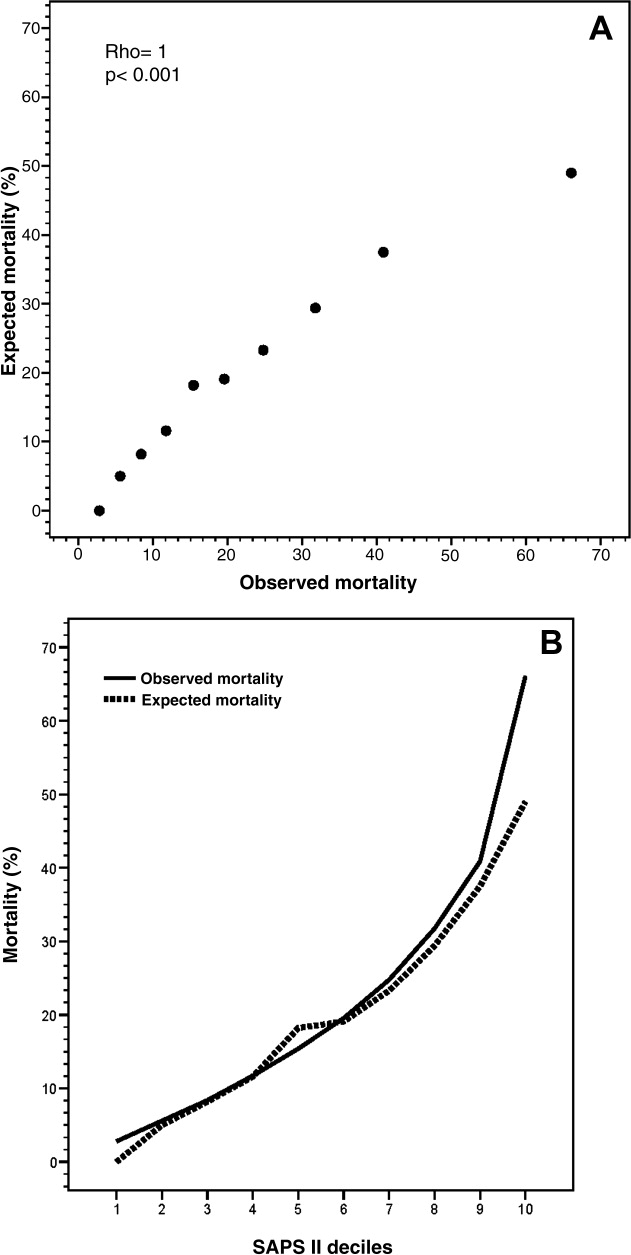

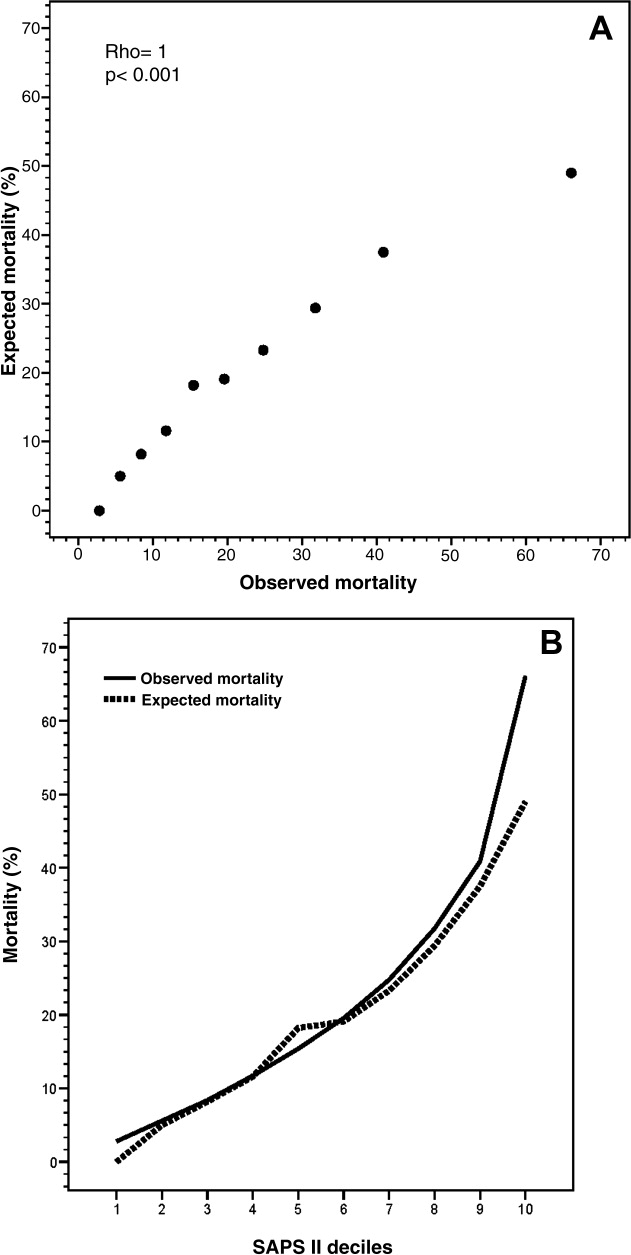

The mean SAPS II of the cohort was 37 12 points, and the expected mortality derived from this score was 23.2%. The observed in‐hospital mortality was 20.6% (94/456) resulting in an observed‐to‐expected mortality ratio of 0.89 (Table 2). Reasons for ImCU admission, as well as mortality ratios, are described in Table 3. The correlation between SAPS II predicted and observed death rates was accurate and statistically significant (Rho = 1.0, P < 0.001) (Figure 1). The AUROC for SAPS II predicting in‐hospital mortality was 0.75 (P < 0.001).

| Condition | Patients | SAPS II | Expected Mortality | Observed Mortality | O/E Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Respiratory failure | 153 (33.6%) | 36.1 9.7 | 21.5 15.3% | 25.5% (39) | 1.19 |

| Sepsis | 88 (19.3%) | 45.7 15.1 | 37.5 25.1% | 22.7% (20) | 0.61 |

| Cardiovascular | 72 (15.8%) | 35.7 11.0 | 21.3 16.6% | 23.6% (17) | 1.11 |

| Perioperative | 59 (12.9%) | 28.9 9.9 | 12.9 11.7% | 5.1% (3) | 0.40 |

| Complex monitoring | 34 (7.5%) | 33.2 12.1 | 19.1 16.3% | 14.7% (5) | 0.77 |

| GI complications | 33 (7.2%) | 32.1 8.3 | 15.6 10.7% | 12.1% (4) | 0.78 |

| Neurologic | 10 (2.2%) | 40.9 10.6 | 29.7 20.0% | 30.0% (3) | 1.01 |

| Liver failure | 7 (1.5%) | 42.1 17.2 | 30.9 29.4% | 42.9% (3) | 1.39 |

Co‐Management and Teaching

During the study period, 382/456 (83.8%) patients were co‐managed with 9 medical and 7 surgical teams (Table 4). From the period of 2006‐2008, a total of 37/106 (34.9%) patients were co‐managed with surgeons, and just 5/37 (13.5%) were co‐managed preoperatively before ImCU admission. In the next 2 years, the patient total increased to 69/106 (65.1%), and preoperative surgical co‐management significantly increased to 25/69 (36.2%) (P = 0.014).

| Medical | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical | |||

| |||

| Oncology | 100 (21.9%) | Neurology | 17 (3.7%) |

| Hepatology | 43 (9.4%) | Cardiology | 14 (3.1%) |

| Pulmonology | 36 (7.9%) | Nephrology | 14 (3.1%) |

| Hematology | 20 (4.4%) | Others | 13 (2.9%) |

| Gastroenterology | 19 (4.2%) | ||

| Total | 276 | ||

| General | 44 (9.6%) | Orthopedics | 6 (1.3%) |

| Vascular | 23 (5.0%) | Urology | 5 (1.1%) |

| Thoracic | 11 (2.4%) | Others | 10 (2.2%) |

| Neurosurgery | 7 (1.5%) | ||

| Total | 106 | ||

Our academic medical center enrolls 46 new residents every year. Since the creation of the ImCU in 2006, residents from different medical subspecialties and from general surgery received training in intermediate care and hospital medicine. All residents rotated into the ImCU for 1‐3 months working 8 hours a day. In 2006, when the unit was opened, 2 residents from internal medicine (4.3%) rotated in the ImCU. Thereafter, a significant increase in the number of training residents was observed, reaching 30.4% of the total resident pool (14/46) in 2010 (P = 0.002).

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first description of hospitalists in intermediate care. In Spain, where hospital medicine is early in development but expanding, critical and intermediate care units are usually staffed by intensivists or anesthesiologists. Staffing an ImCU with hospitalists, using a multidisciplinary co‐management model, is a novel staffing solution for acutely ill patients.

Approximately 35% of ICU patients are low risk, admitted mainly for monitoring purposes.9, 14 In contrast, some patients are treated on general wards when they should receive more intensive care and monitoring.15 Intermediate care units could improve cost containment and triage flexibility, while tailoring treatments according to patient needs. In general, ImCUs require lower nurse‐to‐patient ratios, and less expensive equipment and supplies than ICUs, while retaining the capability of responding appropriately to acute events.16 Moreover, patient and family satisfaction may be increased as a result of more liberal visitation policies and a less noisy environment.17

This study was not designed to measure the cost‐effectiveness of the ImCU. Surprisingly, there are few reports in the last 2 decades demonstrating the efficacy and cost containment of intermediate care. The majority of the studies were retrospective or uncontrolled observations.27 To our knowledge, only 1 randomized controlled trial1 and 1 multicenter prospective cost study exist.8 Further research is needed in this area, with larger, prospective randomized controlled trials, before the benefits and limitations of intermediate care can be fully determined.

Description of the ImCU patients depends on accurate severity scoring. The efficacy and reliability of these scores has been described only for ICU patients and their role for predicting mortality in the ImCU is uncertain. There is only 1 report using SAPS II in intermediate care, showing good discriminant power and calibration in a cohort of 433 patients.13 Auriant et al described, in that cohort, an observed mortality rate of 8.1% with an expected mortality rate of 8.7%.13 In contrast, our expected mortality rate was considerably higher (23.2%). Although ImCUs are generally created for low‐risk patients and monitoring purposes, our population was more similar to an ICU population, with very high risk for major complications and mortality.1823 The contribution of oncologic patients (22% of the total series; most of them with advanced disease, elevated SAPS II [42.2 13.6] and do‐not‐resuscitate orders), probably contributed to the higher acuity of our ImCU population. The correlation of our present data supports the value of SAPS II as a prognostic score in intermediate care, even for patients sicker than those reported by Auriant et al.13 Intermediate care is also a valuable setting to expand a co‐management model with different medical and surgical specialties.

Similarly, since the creation of the ImCU at our institution in 2006, there is a substantial increase in the number of residents rotating through our ImCU. Previous studies showed positive results of hospitalists as clinical educators in various settings.24, 25

In conclusion, intermediate care serves as an expansion of role for hospitalists at our institution; and clinicians, trainees, and patients may benefit from co‐management and teaching opportunities at this unique level of care. An ImCU led by hospitalists showed encouraging results in terms of observed‐to‐expected mortality ratios for acutely ill patients. SAPS II is a useful tool for prognostic evaluation of ImCU patients. However, results of this study should be confirmed with larger, prospective trials at multiple centers.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Efren Manjarrez for the final manuscript revision, and the ImCU Nursing Staff for their unconditional support in patient care.

- ,,,,,.The cost‐effectiveness of a special care unit to care for the chronically critically ill.J Nurs Adm.1995;25:47–53.

- ,.Noninvasive respiratory care unit. A cost‐effective solution for the future.Chest.1988;93:390–394.

- ,,,.The noninvasive respiratory care unit. Patterns of use and financial implications.Chest.1991;99:205–208.

- ,,,,,.Decreases in mortality on a large urban medical service by facilitating access to critical care. An alternative to rationing.Arch Intern Med.1988;148:1403–1405.

- ,,,.Impact of an intermediate care area on ICU utilization after cardiac surgery.Crit Care Med.1986;14:869–872.

- ,,.Closure of an intermediate care unit. Impact on critical care utilization.Chest.1993;104:876–881.

- ,.A case‐control study of patients readmitted to the intensive care unit.Crit Care Med.1993;21:1547–1553.

- ,,, et al.Costs of the COPD. Differences between intensive care unit and respiratory intermediate care unit.Respir Med.2005;99:894–900.

- ,,,,.A multicenter description of intermediate‐care patients. Comparison with ICU low‐risk monitor patients.Chest.2002;121:1253–1261.

- ,,, et al.Guidelines on admission and discharge for adult intermediate care units. American College of Critical Care Medicine of the Society of Critical Care Medicine.Crit Care Med.1998;26:607–610.

- ,.Do we need intermediate care units?Intensive Care Med.1999;25:1345–1349.

- ,,.A new simplified acute physiology score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study.JAMA.1993;270:2957–2963.

- ,,,,.Simplified acute physiology score II for measuring severity of illness in intermediate care units.Crit Care Med.1998;26:1368–1371.

- ,,,,,.The use of risk predictions to identify candidates for intermediate care units. Implications for intensive care utilization and cost.Chest.1995;108:490–499.

- ,.Identifying patients with high risk of high cost.Chest1991;99:530–531.

- ,,.Structural models for intermediate care areas.Crit Care Med.1999;27:2266–2271.

- ,,,.Characteristics of pediatric intermediate care units in pediatric training programs.Crit Care Med.1991;19:1004–1007.

- ,,, et al.Prognostic performance and customization of the SAPS II: results of a multicenter Austrian study.Int Care Med.1999;25:192–197.

- ,,,,,.Comparison of Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) and Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II) scoring systems in a single Greek intensive care unit.Crit Care Med.2000;28:426–432.

- ,,,.External validation of the SAPS II, APACHE II and APACHE III prognostic models in South England: a multicentre study.Intensive Care Med.2003;29:249–256.

- ,,,,,.SAPS II revisited.Intensive Care Med.2005;31:416–423.

- ,,, et al.Mortality prediction using SAPS II: an update for French intensive care units.Crit Care.2005;9:R645–R652.

- ,,,.Predicting death and readmission after intensive care discharge.Br J Anaesth.2008;100:656–662.

- ,,, et al.Hospitalists as teachers.J Gen Intern Med.2004;19:8–15.

- ,,, et al.The positive impact of initiation of hospitalist clinician educators.J Gen Intern Med.2004;19:293–301.

Hospitalized patients are becoming increasingly complex. The care of such patients may be impacted by the limited resources of the general ward and might benefit from more intensive monitoring in an intensive care unit (ICU)‐like setting. In light of this problem, the intermediate care units (ImCU) may provide a cost‐effective alternative by providing higher levels of staffing tailored to patient needs, without incurring the cost of an ICU admission. The ImCU can reduce costs and improves ICU utilization for sicker patients, decrease ICU readmissions, promote greater flexibility in patient triage, and decrease mortality rates in hospital wards.18

The characteristics of ImCUs depend on resource availability, institutional infrastructure, and the organization and funding of the parent healthcare system. The ImCU may function as a step‐up or step‐down unit, or may provide specialty care for cardiac, neurologic, respiratory, or surgical conditions.811 These units can expand opportunities for co‐management and, at the same time, offer the occasion for training residents to follow up patients through different levels of care (from the general ward to ImCU). In the same way, the multidisciplinary approach of the ImCU can improve the center's teaching potential.

Characterizing the ImCU population requires the assessment of their severity of illness, which is crucial for the evaluation of risk‐adjusted outcomes. The present study evaluated the impact of a hospitalist‐led ImCU on observed‐to‐expected mortality ratios, as well as its role in co‐management and teaching.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We performed a retrospective observational study, with data collected from April 2006 to April 2010 in a single academic medical center in Pamplona, Spain. The ImCU is a 9‐bed unit adjacent to, but independent from, the mixed ICU. Each bed is equipped with continuous telemetry, pulse oximetry, noninvasive arterial blood pressure, central venous pressure monitoring, and noninvasive pressure support ventilation. The signals are relayed to a central monitoring station and the nurse‐to‐patient ratio is 1:3.

The ImCU rounding team is multidisciplinary, and involves the hospital pharmacist, a nurse, the ImCU resident, the specialist or surgeon, and the attending hospitalist. After the triage process, ImCU patients were admitted to the attending hospitalist, who was responsible for admission and discharge of all ImCU patients. The hospitalist ordered diagnostic or therapeutic interventions as needed, with the exception of orders for procedures or consultations related with specialist/surgeon's specific needs.

Admission and discharge criteria for the ImCU were set according to guidelines defined by The American College of Critical Care Medicine,10 and also served as inclusion criteria for the present study. Exclusion criteria included: age less than 18 years old, severe respiratory failure, status epilepticus, and catastrophic brain illness. Patients admitted for drug administration and desensitization, and also ImCU readmissions, were excluded from data analysis. Patients came from medical and surgical wards, ICU, the operating room, and the emergency room.

A total of 756 patients were admitted to our ImCU during the study period. Patient demographics, past medical history, physiologic parameters at the time of admission, and survival to hospital discharge were recorded for all patients. Patient demographics include: age, gender, location before ImCU admission, length of stay before ImCU admission, reason for ImCU admission, anatomic site of surgery (if applicable), planned or unplanned admission, and infection status (nosocomial). Past medical history includes: the presence of arterial hypertension, diabetes, cirrhosis, chronic renal failure, chronic heart failure, cancer, hematological malignancy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS), immunosuppression, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, steroid treatment, and alcoholism. Physiologic parameters abstracted are described in Table 1. We used the Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II),12 as a prognostic and severity score. SAPS II is the only previously validated score in intermediate care.13 In‐hospital mortality was the clinical outcome measured.

|

| Vital signs |

| Glasgow Coma Scale |

| Serum bilirubin |

| Serum creatinine |

| Urea nitrogen |

| Leucocyte count |

| Serum sodium |

| Serum potassium |

| Bicarbonate levels |

| Urinary output in the first 24 hr |

| Oxygenation and ventilatory support |

Data were entered into a computer database by the authors. Statistical analysis was not blinded, and was performed using SPSS for Windows, version 15.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Continuous variables were reported as mean standard deviation or median (25%‐75% interquartile range). For nonparametric measure of statistical dependence of quantitative variables, we used Spearman's correlation coefficient. Discrimination was evaluated by calculating the area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC).

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at the Clnica Universidad de Navarra in Pamplona, Spain.

RESULTS

Four hundred fifty‐six patients were included in data analysis. Three hundred patients were excluded: 61 low‐risk patients (drug administration and desensitization), 147 readmissions, and 92 patients for missing variables. Patient characteristics, including probability of death following ImCU admission and discharge location, are summarized in Table 2. The mean age was 65.6 years, and about 35% of patients had a SAPS II‐based risk of death higher than 25% at the time of ImCU admission. The median length of stay was 4 (3‐7) days.

| |

| Age (yr) | 65.6 14.3 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 283 (62.1%) |

| Female | 173 (37.9%) |

| Location prior to admission | |

| General ward | 252 (55.3%) |

| Emergency room | 96 (21.1%) |

| ICU | 63 (13.8%) |

| Operating room | 28 (6.1%) |

| Other hospital | 17 (3.7%) |

| Probability of in‐hospital mortality based on SAPS II | |

| <10% | 128 (28.1%) |

| 11%‐25% | 176 (38.6%) |

| 26%‐50% | 107 (23.4%) |

| >50% | 45 (9.9%) |

| Global expected mortality (in‐hospital) | 23.2% |

| Global observed mortality (in‐hospital) | 20.6% (94/456) |

| O/E mortality ratio | 0.89 |

| Discharge location | |

| General ward | 352/456 (77.2%) |

| ICU | 65/456 (14.3%) |

| Home | 1/456 (0.2%) |

| Other hospital | 11/456 (2.4%) |

| Death location | |

| ImCU | 27/456 (5.9%) |

| ICU (transferred patients) | 32/65* (49.2%) |

| General ward | 35/352* (9.9%) |

Outcomes

The mean SAPS II of the cohort was 37 12 points, and the expected mortality derived from this score was 23.2%. The observed in‐hospital mortality was 20.6% (94/456) resulting in an observed‐to‐expected mortality ratio of 0.89 (Table 2). Reasons for ImCU admission, as well as mortality ratios, are described in Table 3. The correlation between SAPS II predicted and observed death rates was accurate and statistically significant (Rho = 1.0, P < 0.001) (Figure 1). The AUROC for SAPS II predicting in‐hospital mortality was 0.75 (P < 0.001).

| Condition | Patients | SAPS II | Expected Mortality | Observed Mortality | O/E Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Respiratory failure | 153 (33.6%) | 36.1 9.7 | 21.5 15.3% | 25.5% (39) | 1.19 |

| Sepsis | 88 (19.3%) | 45.7 15.1 | 37.5 25.1% | 22.7% (20) | 0.61 |

| Cardiovascular | 72 (15.8%) | 35.7 11.0 | 21.3 16.6% | 23.6% (17) | 1.11 |

| Perioperative | 59 (12.9%) | 28.9 9.9 | 12.9 11.7% | 5.1% (3) | 0.40 |

| Complex monitoring | 34 (7.5%) | 33.2 12.1 | 19.1 16.3% | 14.7% (5) | 0.77 |

| GI complications | 33 (7.2%) | 32.1 8.3 | 15.6 10.7% | 12.1% (4) | 0.78 |

| Neurologic | 10 (2.2%) | 40.9 10.6 | 29.7 20.0% | 30.0% (3) | 1.01 |

| Liver failure | 7 (1.5%) | 42.1 17.2 | 30.9 29.4% | 42.9% (3) | 1.39 |

Co‐Management and Teaching

During the study period, 382/456 (83.8%) patients were co‐managed with 9 medical and 7 surgical teams (Table 4). From the period of 2006‐2008, a total of 37/106 (34.9%) patients were co‐managed with surgeons, and just 5/37 (13.5%) were co‐managed preoperatively before ImCU admission. In the next 2 years, the patient total increased to 69/106 (65.1%), and preoperative surgical co‐management significantly increased to 25/69 (36.2%) (P = 0.014).

| Medical | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical | |||

| |||

| Oncology | 100 (21.9%) | Neurology | 17 (3.7%) |

| Hepatology | 43 (9.4%) | Cardiology | 14 (3.1%) |

| Pulmonology | 36 (7.9%) | Nephrology | 14 (3.1%) |

| Hematology | 20 (4.4%) | Others | 13 (2.9%) |

| Gastroenterology | 19 (4.2%) | ||

| Total | 276 | ||

| General | 44 (9.6%) | Orthopedics | 6 (1.3%) |

| Vascular | 23 (5.0%) | Urology | 5 (1.1%) |

| Thoracic | 11 (2.4%) | Others | 10 (2.2%) |

| Neurosurgery | 7 (1.5%) | ||

| Total | 106 | ||

Our academic medical center enrolls 46 new residents every year. Since the creation of the ImCU in 2006, residents from different medical subspecialties and from general surgery received training in intermediate care and hospital medicine. All residents rotated into the ImCU for 1‐3 months working 8 hours a day. In 2006, when the unit was opened, 2 residents from internal medicine (4.3%) rotated in the ImCU. Thereafter, a significant increase in the number of training residents was observed, reaching 30.4% of the total resident pool (14/46) in 2010 (P = 0.002).

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first description of hospitalists in intermediate care. In Spain, where hospital medicine is early in development but expanding, critical and intermediate care units are usually staffed by intensivists or anesthesiologists. Staffing an ImCU with hospitalists, using a multidisciplinary co‐management model, is a novel staffing solution for acutely ill patients.

Approximately 35% of ICU patients are low risk, admitted mainly for monitoring purposes.9, 14 In contrast, some patients are treated on general wards when they should receive more intensive care and monitoring.15 Intermediate care units could improve cost containment and triage flexibility, while tailoring treatments according to patient needs. In general, ImCUs require lower nurse‐to‐patient ratios, and less expensive equipment and supplies than ICUs, while retaining the capability of responding appropriately to acute events.16 Moreover, patient and family satisfaction may be increased as a result of more liberal visitation policies and a less noisy environment.17

This study was not designed to measure the cost‐effectiveness of the ImCU. Surprisingly, there are few reports in the last 2 decades demonstrating the efficacy and cost containment of intermediate care. The majority of the studies were retrospective or uncontrolled observations.27 To our knowledge, only 1 randomized controlled trial1 and 1 multicenter prospective cost study exist.8 Further research is needed in this area, with larger, prospective randomized controlled trials, before the benefits and limitations of intermediate care can be fully determined.

Description of the ImCU patients depends on accurate severity scoring. The efficacy and reliability of these scores has been described only for ICU patients and their role for predicting mortality in the ImCU is uncertain. There is only 1 report using SAPS II in intermediate care, showing good discriminant power and calibration in a cohort of 433 patients.13 Auriant et al described, in that cohort, an observed mortality rate of 8.1% with an expected mortality rate of 8.7%.13 In contrast, our expected mortality rate was considerably higher (23.2%). Although ImCUs are generally created for low‐risk patients and monitoring purposes, our population was more similar to an ICU population, with very high risk for major complications and mortality.1823 The contribution of oncologic patients (22% of the total series; most of them with advanced disease, elevated SAPS II [42.2 13.6] and do‐not‐resuscitate orders), probably contributed to the higher acuity of our ImCU population. The correlation of our present data supports the value of SAPS II as a prognostic score in intermediate care, even for patients sicker than those reported by Auriant et al.13 Intermediate care is also a valuable setting to expand a co‐management model with different medical and surgical specialties.

Similarly, since the creation of the ImCU at our institution in 2006, there is a substantial increase in the number of residents rotating through our ImCU. Previous studies showed positive results of hospitalists as clinical educators in various settings.24, 25

In conclusion, intermediate care serves as an expansion of role for hospitalists at our institution; and clinicians, trainees, and patients may benefit from co‐management and teaching opportunities at this unique level of care. An ImCU led by hospitalists showed encouraging results in terms of observed‐to‐expected mortality ratios for acutely ill patients. SAPS II is a useful tool for prognostic evaluation of ImCU patients. However, results of this study should be confirmed with larger, prospective trials at multiple centers.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Efren Manjarrez for the final manuscript revision, and the ImCU Nursing Staff for their unconditional support in patient care.

Hospitalized patients are becoming increasingly complex. The care of such patients may be impacted by the limited resources of the general ward and might benefit from more intensive monitoring in an intensive care unit (ICU)‐like setting. In light of this problem, the intermediate care units (ImCU) may provide a cost‐effective alternative by providing higher levels of staffing tailored to patient needs, without incurring the cost of an ICU admission. The ImCU can reduce costs and improves ICU utilization for sicker patients, decrease ICU readmissions, promote greater flexibility in patient triage, and decrease mortality rates in hospital wards.18

The characteristics of ImCUs depend on resource availability, institutional infrastructure, and the organization and funding of the parent healthcare system. The ImCU may function as a step‐up or step‐down unit, or may provide specialty care for cardiac, neurologic, respiratory, or surgical conditions.811 These units can expand opportunities for co‐management and, at the same time, offer the occasion for training residents to follow up patients through different levels of care (from the general ward to ImCU). In the same way, the multidisciplinary approach of the ImCU can improve the center's teaching potential.