User login

Be Careful What You Ask For

I pose here a list of questions to consider before embarking on the creation of a new specialty in hospital medicine

1) What distinguishes the body of knowledge of hospital medicine from internal medicine (or pediatrics, for our colleagues in that field)?

While there is a body of literature supporting operational aspects of hospital care, as far as I can tell there is no difference in the way a hospitalist or office-based internist should treat pneumonia. Hospitalists develop areas of expertise in case management, understanding of hospital-based quality-improvement systems, communication skills, etc, but these fall short of a body of knowledge for a medical specialty. Books on hospital medicine do not differ from standard medicine texts in terms of disease pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, or management. What then is the new body of knowledge?

2) Does hospital medicine really want to exclude office-based primary care doctors from managing their own cases in the hospital if they so choose?

Creating a new specialty of hospital medicine certainly would tend to do that. Let’s look at emergency medicine, for example. It used to be common for internists and surgeons to work in emergency rooms. That no longer is the case in many parts of this country because of the emergence of a new specialty. Do we want the same to be true for office-based doctors who care for their own patients?

3) Creating a new specialty requires special training. What is that going to be? Who teaches it and who will do it?

New subspecialties require additional training. For instance, electrophysiology is now a subspecialty of cardiology and requires an additional one or two years of training after a three-year cardiology fellowship. Working for 2-3 years as Dr. Nelson has proposed in the field of hospital medicine is not additional training, it is just additional practice. What is the formal training that the Society of Hospital Medicine proposes to qualify someone as a Board-certified hospitalist? Is it likely that young doctors are going to want to add on an additional 2 or 3 years of training beyond their internal medicine residency before they can start paying off their medical school loans? What will this training actually entail, and how will it merge with the internal medicine training programs that already exist?

I would point out that residents in fact are hospitalists in training. Certainly the vast majority of their clinical experience occurs in the hospital. Except for primary care residencies, I would estimate that 2/3 of the clinical care that internal medicine residents experience is in the hospital.

4) What about the primary care doctor or hospitalist who wants to switch careers?

Is the Society of Hospital Medicine going to require that a physician who has been in practice for 5 or 10 years and decides to switch to hospital medicine go through further training? Is that likely to occur? Alternatively, what about the hospitalist who gets tired of that field and wishes to become a primary care doctor? Might not office-based internists move to create their own specialty and thereby exclude hospitalists from work in that setting?

5) What about the malpractice risks that a new specialty will create?

Let’s imagine a world in which there are internists certified as hospitalists or as primary care physicians. Imagine this malpractice scenario. An office-based doctor caring for his/her own patients in the hospital is sued for some issue or another. The plaintiff attorney standing near the jury faces the doctor and asks “Doctor [he sighs, looking gravely serious], I understand there is a subspecialty in hospital medicine. Are you [now facing the jury] certified in that specialty? The doctor responds “No.” The attorney [turning abruptly back towards the nervous doctor] asks “No? Why not?” Let’s imagine another scenario. A hospitalist working part-time in an office-based practice 1 or 2 days a week faces a similar malpractice situation where he or she is sued. Attorney: “Doctor, I understand there is a subspecialty in primary care medicine? Are you certified in that specialty? Doctor: “No.” Attorney: “No? Why not?”

6) Why create more tests and expenses?

Enough said!

7) Do you want to bite the hand that feeds you?

In our hospital the vast majority of hospitalist admissions are from primary care doctors. Try to eliminate their admitting privileges and see what happens. It will be like the Flu vaccine fiasco this year. There is little vaccine available, but now everyone who has never gotten it in the past is asking for it. My guess is that most primary care doctors will protect their privileges and start admitting and caring for their own patients.

Why don’t we consider a more modest proposal? Here are three ideas.

First, identify areas of expertise that hospitalists actually develop. For instance, can they become procedural experts? Certainly the performance of lumbar punctures, thoracenteses, paracenteses, and central lines is something that most office-based doctors are not comfortable in carrying out any longer. Can we help create credentialing for these important procedures? That would go a long way towards initiating a set of skills that differentiates a hospitalist from an office-based doctor. Why not become a credentialing society for performance of these and other procedures? Monitoring numbers of procedures might constitute one measure, for example, of how to initiate credentialing. For instance, most centers no longer allow a cardiologist who has not performed a certain number of cardiac catheterizations a year to maintain privileges for that procedure. This does not seem discriminatory. It seems wise. I do not think office-based doctors would view credentialing for procedures as discriminatory.

Secondly, what about working to modify existing internal medicine training to perhaps provide added qualifications within hospital medicine for residents committed to the field? The board exams might actually differ then for primary care residents and for those interested in hospital medicine.

Thirdly, what about concentrating efforts on recertification? My guess is that very few residents coming out of practice would not feel qualified to take the hospital medicine or the ambulatory portion of an internal medicine exam. On the other hand, 10 years later during recertification many office-based doctors will not feel qualified to take an exam that emphasizes the treatment of vancomycin-resistant enterococci or management of cardiac arrests. Perhaps the recertification exam is the time to ask doctors to differentiate themselves. Some may wish to maintain certification in both hospital-based and ambulatory care, while others may choose one path or the other.

SHM has become the great organization it is in part because it reached out to hospitalists working in both community and teaching hospitals. Can we not bridge the gap with our office-based colleagues as well? In the field of internal medicine are we going to set ourselves up to become blue and red states? How about a nice shade of violet?

I pose here a list of questions to consider before embarking on the creation of a new specialty in hospital medicine

1) What distinguishes the body of knowledge of hospital medicine from internal medicine (or pediatrics, for our colleagues in that field)?

While there is a body of literature supporting operational aspects of hospital care, as far as I can tell there is no difference in the way a hospitalist or office-based internist should treat pneumonia. Hospitalists develop areas of expertise in case management, understanding of hospital-based quality-improvement systems, communication skills, etc, but these fall short of a body of knowledge for a medical specialty. Books on hospital medicine do not differ from standard medicine texts in terms of disease pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, or management. What then is the new body of knowledge?

2) Does hospital medicine really want to exclude office-based primary care doctors from managing their own cases in the hospital if they so choose?

Creating a new specialty of hospital medicine certainly would tend to do that. Let’s look at emergency medicine, for example. It used to be common for internists and surgeons to work in emergency rooms. That no longer is the case in many parts of this country because of the emergence of a new specialty. Do we want the same to be true for office-based doctors who care for their own patients?

3) Creating a new specialty requires special training. What is that going to be? Who teaches it and who will do it?

New subspecialties require additional training. For instance, electrophysiology is now a subspecialty of cardiology and requires an additional one or two years of training after a three-year cardiology fellowship. Working for 2-3 years as Dr. Nelson has proposed in the field of hospital medicine is not additional training, it is just additional practice. What is the formal training that the Society of Hospital Medicine proposes to qualify someone as a Board-certified hospitalist? Is it likely that young doctors are going to want to add on an additional 2 or 3 years of training beyond their internal medicine residency before they can start paying off their medical school loans? What will this training actually entail, and how will it merge with the internal medicine training programs that already exist?

I would point out that residents in fact are hospitalists in training. Certainly the vast majority of their clinical experience occurs in the hospital. Except for primary care residencies, I would estimate that 2/3 of the clinical care that internal medicine residents experience is in the hospital.

4) What about the primary care doctor or hospitalist who wants to switch careers?

Is the Society of Hospital Medicine going to require that a physician who has been in practice for 5 or 10 years and decides to switch to hospital medicine go through further training? Is that likely to occur? Alternatively, what about the hospitalist who gets tired of that field and wishes to become a primary care doctor? Might not office-based internists move to create their own specialty and thereby exclude hospitalists from work in that setting?

5) What about the malpractice risks that a new specialty will create?

Let’s imagine a world in which there are internists certified as hospitalists or as primary care physicians. Imagine this malpractice scenario. An office-based doctor caring for his/her own patients in the hospital is sued for some issue or another. The plaintiff attorney standing near the jury faces the doctor and asks “Doctor [he sighs, looking gravely serious], I understand there is a subspecialty in hospital medicine. Are you [now facing the jury] certified in that specialty? The doctor responds “No.” The attorney [turning abruptly back towards the nervous doctor] asks “No? Why not?” Let’s imagine another scenario. A hospitalist working part-time in an office-based practice 1 or 2 days a week faces a similar malpractice situation where he or she is sued. Attorney: “Doctor, I understand there is a subspecialty in primary care medicine? Are you certified in that specialty? Doctor: “No.” Attorney: “No? Why not?”

6) Why create more tests and expenses?

Enough said!

7) Do you want to bite the hand that feeds you?

In our hospital the vast majority of hospitalist admissions are from primary care doctors. Try to eliminate their admitting privileges and see what happens. It will be like the Flu vaccine fiasco this year. There is little vaccine available, but now everyone who has never gotten it in the past is asking for it. My guess is that most primary care doctors will protect their privileges and start admitting and caring for their own patients.

Why don’t we consider a more modest proposal? Here are three ideas.

First, identify areas of expertise that hospitalists actually develop. For instance, can they become procedural experts? Certainly the performance of lumbar punctures, thoracenteses, paracenteses, and central lines is something that most office-based doctors are not comfortable in carrying out any longer. Can we help create credentialing for these important procedures? That would go a long way towards initiating a set of skills that differentiates a hospitalist from an office-based doctor. Why not become a credentialing society for performance of these and other procedures? Monitoring numbers of procedures might constitute one measure, for example, of how to initiate credentialing. For instance, most centers no longer allow a cardiologist who has not performed a certain number of cardiac catheterizations a year to maintain privileges for that procedure. This does not seem discriminatory. It seems wise. I do not think office-based doctors would view credentialing for procedures as discriminatory.

Secondly, what about working to modify existing internal medicine training to perhaps provide added qualifications within hospital medicine for residents committed to the field? The board exams might actually differ then for primary care residents and for those interested in hospital medicine.

Thirdly, what about concentrating efforts on recertification? My guess is that very few residents coming out of practice would not feel qualified to take the hospital medicine or the ambulatory portion of an internal medicine exam. On the other hand, 10 years later during recertification many office-based doctors will not feel qualified to take an exam that emphasizes the treatment of vancomycin-resistant enterococci or management of cardiac arrests. Perhaps the recertification exam is the time to ask doctors to differentiate themselves. Some may wish to maintain certification in both hospital-based and ambulatory care, while others may choose one path or the other.

SHM has become the great organization it is in part because it reached out to hospitalists working in both community and teaching hospitals. Can we not bridge the gap with our office-based colleagues as well? In the field of internal medicine are we going to set ourselves up to become blue and red states? How about a nice shade of violet?

I pose here a list of questions to consider before embarking on the creation of a new specialty in hospital medicine

1) What distinguishes the body of knowledge of hospital medicine from internal medicine (or pediatrics, for our colleagues in that field)?

While there is a body of literature supporting operational aspects of hospital care, as far as I can tell there is no difference in the way a hospitalist or office-based internist should treat pneumonia. Hospitalists develop areas of expertise in case management, understanding of hospital-based quality-improvement systems, communication skills, etc, but these fall short of a body of knowledge for a medical specialty. Books on hospital medicine do not differ from standard medicine texts in terms of disease pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, or management. What then is the new body of knowledge?

2) Does hospital medicine really want to exclude office-based primary care doctors from managing their own cases in the hospital if they so choose?

Creating a new specialty of hospital medicine certainly would tend to do that. Let’s look at emergency medicine, for example. It used to be common for internists and surgeons to work in emergency rooms. That no longer is the case in many parts of this country because of the emergence of a new specialty. Do we want the same to be true for office-based doctors who care for their own patients?

3) Creating a new specialty requires special training. What is that going to be? Who teaches it and who will do it?

New subspecialties require additional training. For instance, electrophysiology is now a subspecialty of cardiology and requires an additional one or two years of training after a three-year cardiology fellowship. Working for 2-3 years as Dr. Nelson has proposed in the field of hospital medicine is not additional training, it is just additional practice. What is the formal training that the Society of Hospital Medicine proposes to qualify someone as a Board-certified hospitalist? Is it likely that young doctors are going to want to add on an additional 2 or 3 years of training beyond their internal medicine residency before they can start paying off their medical school loans? What will this training actually entail, and how will it merge with the internal medicine training programs that already exist?

I would point out that residents in fact are hospitalists in training. Certainly the vast majority of their clinical experience occurs in the hospital. Except for primary care residencies, I would estimate that 2/3 of the clinical care that internal medicine residents experience is in the hospital.

4) What about the primary care doctor or hospitalist who wants to switch careers?

Is the Society of Hospital Medicine going to require that a physician who has been in practice for 5 or 10 years and decides to switch to hospital medicine go through further training? Is that likely to occur? Alternatively, what about the hospitalist who gets tired of that field and wishes to become a primary care doctor? Might not office-based internists move to create their own specialty and thereby exclude hospitalists from work in that setting?

5) What about the malpractice risks that a new specialty will create?

Let’s imagine a world in which there are internists certified as hospitalists or as primary care physicians. Imagine this malpractice scenario. An office-based doctor caring for his/her own patients in the hospital is sued for some issue or another. The plaintiff attorney standing near the jury faces the doctor and asks “Doctor [he sighs, looking gravely serious], I understand there is a subspecialty in hospital medicine. Are you [now facing the jury] certified in that specialty? The doctor responds “No.” The attorney [turning abruptly back towards the nervous doctor] asks “No? Why not?” Let’s imagine another scenario. A hospitalist working part-time in an office-based practice 1 or 2 days a week faces a similar malpractice situation where he or she is sued. Attorney: “Doctor, I understand there is a subspecialty in primary care medicine? Are you certified in that specialty? Doctor: “No.” Attorney: “No? Why not?”

6) Why create more tests and expenses?

Enough said!

7) Do you want to bite the hand that feeds you?

In our hospital the vast majority of hospitalist admissions are from primary care doctors. Try to eliminate their admitting privileges and see what happens. It will be like the Flu vaccine fiasco this year. There is little vaccine available, but now everyone who has never gotten it in the past is asking for it. My guess is that most primary care doctors will protect their privileges and start admitting and caring for their own patients.

Why don’t we consider a more modest proposal? Here are three ideas.

First, identify areas of expertise that hospitalists actually develop. For instance, can they become procedural experts? Certainly the performance of lumbar punctures, thoracenteses, paracenteses, and central lines is something that most office-based doctors are not comfortable in carrying out any longer. Can we help create credentialing for these important procedures? That would go a long way towards initiating a set of skills that differentiates a hospitalist from an office-based doctor. Why not become a credentialing society for performance of these and other procedures? Monitoring numbers of procedures might constitute one measure, for example, of how to initiate credentialing. For instance, most centers no longer allow a cardiologist who has not performed a certain number of cardiac catheterizations a year to maintain privileges for that procedure. This does not seem discriminatory. It seems wise. I do not think office-based doctors would view credentialing for procedures as discriminatory.

Secondly, what about working to modify existing internal medicine training to perhaps provide added qualifications within hospital medicine for residents committed to the field? The board exams might actually differ then for primary care residents and for those interested in hospital medicine.

Thirdly, what about concentrating efforts on recertification? My guess is that very few residents coming out of practice would not feel qualified to take the hospital medicine or the ambulatory portion of an internal medicine exam. On the other hand, 10 years later during recertification many office-based doctors will not feel qualified to take an exam that emphasizes the treatment of vancomycin-resistant enterococci or management of cardiac arrests. Perhaps the recertification exam is the time to ask doctors to differentiate themselves. Some may wish to maintain certification in both hospital-based and ambulatory care, while others may choose one path or the other.

SHM has become the great organization it is in part because it reached out to hospitalists working in both community and teaching hospitals. Can we not bridge the gap with our office-based colleagues as well? In the field of internal medicine are we going to set ourselves up to become blue and red states? How about a nice shade of violet?

An Ongoing Analysis of the 2003-04 SHM Productivity and Compensation Survey

The survey analysis of productivity breaks this performance measure into two categories:

- Inputs: The hours worked by hospitalists. Three categories of hours worked are analyzed in this chapter: inpatient hours worked, non-patient hours worked, and on-call hours worked. Please note, the analysis excludes outpatient hours worked because only 15% of the survey respondents reported any outpatient hours.

- Outputs: The work completed by hospitalists. This includes charges generated, collections generated, patient encounters, patient admissions and consults, and relative value units (RVUs) of work completed. These measures are analyzed in chapter 5 (to be published in the March/April Hospitalist issue.

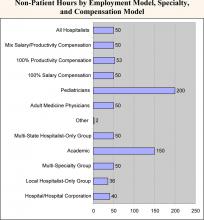

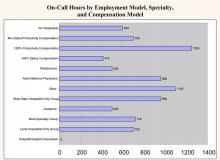

Overall, surveyed physician hospitalists worked a median of 2,100 inpatient hours per year. They had a median of 50 non-patient hours per year (about one per week) and worked a median of 600 on-call hours per year. The analyses below look at productivity inputs by region, employment model, specialty/provider type, and compensation model.

- Academic hospitalists work the least amount of inpatient hours (1,700 vs. an overall median of 2,100). However, they work significantly more non‑patient hours (150 vs. 50), probably because of their teaching responsibilities.

- Hospitalists that work for hospitalist-only groups work more inpatient hours than the overall median: multistate hospitalist only groups are 14% higher (2,400 vs. 2,100), while local hospitalist-only groups are 5% higher (2,210 vs. 2,100).

- Regarding on-call hours, hospitalists that work for hospital-based groups have a median of zero. This is probably because only 27% of hospital-based groups have call-based staffing, significantly less than other employment categories (see Chapter 1). This also is probably the explanation for the median of zero for eastern hospitalists, as that region has a high proportion of hospital-based groups.

- Adult medicine hospitalists work 24% more inpatient hours than pediatric hospitalists (2,111 vs. 1,700). Conversely, pediatric hospitalists have four times as many non-patient hours (200 vs. 50). This is likely explained by the fact that pediatricians are twice as likely to work in academia (see chapter 1).

- Non-physician hospitalists have a median of 1,900 inpatient hours and a median of only 10 non-patient hours

- There is a strong relationship between compensation model and hours worked. Hospitalists that work under a 100% productivity model have a median number of inpatient hours that is 30% more than those that work in a 100% salary model (2,500 vs. 1,930). Hospitalists that work in a mixed model fall in the middle (2,184).

- There is minimal difference in the non-patient hours worked among the three categories (approximately 50). However, 100% productivity-model hospitalists have a median number of on-call hours, which is almost 3 times greater than that of 100% salary-based hospitalists (1,250 vs. 416). Again, mixed-model hospitalists fall in the middle (700).

The survey analysis of productivity breaks this performance measure into two categories:

- Inputs: The hours worked by hospitalists. Three categories of hours worked are analyzed in this chapter: inpatient hours worked, non-patient hours worked, and on-call hours worked. Please note, the analysis excludes outpatient hours worked because only 15% of the survey respondents reported any outpatient hours.

- Outputs: The work completed by hospitalists. This includes charges generated, collections generated, patient encounters, patient admissions and consults, and relative value units (RVUs) of work completed. These measures are analyzed in chapter 5 (to be published in the March/April Hospitalist issue.

Overall, surveyed physician hospitalists worked a median of 2,100 inpatient hours per year. They had a median of 50 non-patient hours per year (about one per week) and worked a median of 600 on-call hours per year. The analyses below look at productivity inputs by region, employment model, specialty/provider type, and compensation model.

- Academic hospitalists work the least amount of inpatient hours (1,700 vs. an overall median of 2,100). However, they work significantly more non‑patient hours (150 vs. 50), probably because of their teaching responsibilities.

- Hospitalists that work for hospitalist-only groups work more inpatient hours than the overall median: multistate hospitalist only groups are 14% higher (2,400 vs. 2,100), while local hospitalist-only groups are 5% higher (2,210 vs. 2,100).

- Regarding on-call hours, hospitalists that work for hospital-based groups have a median of zero. This is probably because only 27% of hospital-based groups have call-based staffing, significantly less than other employment categories (see Chapter 1). This also is probably the explanation for the median of zero for eastern hospitalists, as that region has a high proportion of hospital-based groups.

- Adult medicine hospitalists work 24% more inpatient hours than pediatric hospitalists (2,111 vs. 1,700). Conversely, pediatric hospitalists have four times as many non-patient hours (200 vs. 50). This is likely explained by the fact that pediatricians are twice as likely to work in academia (see chapter 1).

- Non-physician hospitalists have a median of 1,900 inpatient hours and a median of only 10 non-patient hours

- There is a strong relationship between compensation model and hours worked. Hospitalists that work under a 100% productivity model have a median number of inpatient hours that is 30% more than those that work in a 100% salary model (2,500 vs. 1,930). Hospitalists that work in a mixed model fall in the middle (2,184).

- There is minimal difference in the non-patient hours worked among the three categories (approximately 50). However, 100% productivity-model hospitalists have a median number of on-call hours, which is almost 3 times greater than that of 100% salary-based hospitalists (1,250 vs. 416). Again, mixed-model hospitalists fall in the middle (700).

The survey analysis of productivity breaks this performance measure into two categories:

- Inputs: The hours worked by hospitalists. Three categories of hours worked are analyzed in this chapter: inpatient hours worked, non-patient hours worked, and on-call hours worked. Please note, the analysis excludes outpatient hours worked because only 15% of the survey respondents reported any outpatient hours.

- Outputs: The work completed by hospitalists. This includes charges generated, collections generated, patient encounters, patient admissions and consults, and relative value units (RVUs) of work completed. These measures are analyzed in chapter 5 (to be published in the March/April Hospitalist issue.

Overall, surveyed physician hospitalists worked a median of 2,100 inpatient hours per year. They had a median of 50 non-patient hours per year (about one per week) and worked a median of 600 on-call hours per year. The analyses below look at productivity inputs by region, employment model, specialty/provider type, and compensation model.

- Academic hospitalists work the least amount of inpatient hours (1,700 vs. an overall median of 2,100). However, they work significantly more non‑patient hours (150 vs. 50), probably because of their teaching responsibilities.

- Hospitalists that work for hospitalist-only groups work more inpatient hours than the overall median: multistate hospitalist only groups are 14% higher (2,400 vs. 2,100), while local hospitalist-only groups are 5% higher (2,210 vs. 2,100).

- Regarding on-call hours, hospitalists that work for hospital-based groups have a median of zero. This is probably because only 27% of hospital-based groups have call-based staffing, significantly less than other employment categories (see Chapter 1). This also is probably the explanation for the median of zero for eastern hospitalists, as that region has a high proportion of hospital-based groups.

- Adult medicine hospitalists work 24% more inpatient hours than pediatric hospitalists (2,111 vs. 1,700). Conversely, pediatric hospitalists have four times as many non-patient hours (200 vs. 50). This is likely explained by the fact that pediatricians are twice as likely to work in academia (see chapter 1).

- Non-physician hospitalists have a median of 1,900 inpatient hours and a median of only 10 non-patient hours

- There is a strong relationship between compensation model and hours worked. Hospitalists that work under a 100% productivity model have a median number of inpatient hours that is 30% more than those that work in a 100% salary model (2,500 vs. 1,930). Hospitalists that work in a mixed model fall in the middle (2,184).

- There is minimal difference in the non-patient hours worked among the three categories (approximately 50). However, 100% productivity-model hospitalists have a median number of on-call hours, which is almost 3 times greater than that of 100% salary-based hospitalists (1,250 vs. 416). Again, mixed-model hospitalists fall in the middle (700).

Thanks for the Memories

This issue of The Hospitalist marks the beginning of my sixth year as the chief executive officer at SHM. Much has happened at SHM and in our specialty in the last 5 years, and

I thought I would use this space to share with everyone what we have accomplished together and to recognize the many individuals who have made all of this possible.

Past

When I first came to SHM in January of 2000, SHM had two employees, three or four committees, and about 500members. There were estimated to be 1000-2000 hospitalists in the country. SHM did stage an Annual Meeting with 300 attendees and published a newsletter of 16 pages with minimal ad revenue and a circulation of about 1000. SHM had no external grants and limited relationships with industry.

SHM was a fledgling national organization with no local presence. SHM had minimal assets or infrastructure and was very reliant on ACP for support and direction. Most of the innovation and direction fell to a few hospitalists around the country, who, while devoted to SHM (then NAIP) and our specialty, still had a very full plate just doing their day jobs, growing their hospital medicine groups. It was amazing what they had accomplished with minimal staff support or infrastructure.

At the start of the new millennium, SHM didn’t know how many hospitals had hospitalists. There was no data on how hard hospitalists should be expected to work or how much they should be paid. There was limited data on the background or training of those doctors who were going into hospital medicine, and there was no understanding of what the knowledge base was for this new specialty. There was a vague sense that the importance of hospitalists was more than just seeing their own patients, but there was little understanding of what value hospitalists could add to their health communities.

Present

Over the last 5 years, together we have made enormous progress. We have changed our name from the National Association of Inpatient Physicians to the Society of Hospital Medicine to better reflect all the stakeholders in our growing specialty. We have grown our Philadelphia staff to 13 and employ another five staff in Boston, Atlanta, and California. The Hospitalist newsletter is now the recognized publication in hospital medicine with 65-80 pages per issue, 2-3 supplements each year, and a circulation well over 10,000. There are more than $75,000 in recruitment ads in each issue, as much a testament to the growth of the specialty as anything else.

SHM’s Annual Meeting now attracts almost 1000 attendees and is the primary networking opportunity for the fastest-growing medical specialty. SHM has almost 5000 members, and there are an estimated 10,000-12,000 hospitalists now practicing in over 1500 hospitals. SHM currently has more than 40 local chapters meeting at least once a year throughout the country.

SHM has developed unique expertise in the management aspects of hospital medicine and holds practice management courses at least three times each year. In addition, SHM has realized that hospitalists will need to be the leaders of the hospitals of the future and has created Leadership Academies to train these future leaders. SHM has worked with grants from the Hartford Foundation to establish the hospitalist as the physician for the acutely ill elderly. SHM is working with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and others in helping to create the physical design of the hospital of the future.

SHM is just completing the Core Curriculum for Hospital Medicine, which will define the knowledge base for our specialty and serve as the basis for SHM’s growing educational enterprise. SHM is defining the value that hospitalists add beyond just direct patient care. This phenomenon has been the basis for hospitals looking for innovative ways to grow and support their hospital medicine groups. SHM will publish these white papers for hospitalists and hospital executives to use in designing their hospital medicine programs.

SHM has defined the productivity and compensation data for our specialty in our biannual surveys that are the best source for hospitalist data. SHM has developed a Washington presence and is defining the advocacy issues for hospital medicine, including substantial reform of payment to de-emphasize compensation based solely on the unit of the visit or the procedure.

SHM is now an organization with almost $3 million in assets, completely autonomous, and functioning on its own. We have a strong and growing relationship with ACP, and SHM has reached out to partner with many other organizations, including the AHA, ACCP, JCAHO, RWJ, Hartford Foundation, CDC, AACN, ASHP, ABIM, AAP, SGIM, AAIM and many others.

Future

And there is much to look forward to in the next 5 years. In the coming months, SHM will launch the first journal in hospital medicine in January 2006. SHM’s Web site will come into the 21st century with the ability for each member to have their own Web page. The Web site will be the one location that hospitalists can come to for CME and other educational information. SHM will be working with AACP, AACN, ASHP, and others to establish an Acute Care Collaborative, reorganizing hospital workflow to deliver measurable higher-quality health care using interdisciplinary teams of health professionals. This will help to define the hospital of the future.

There will be a certification for hospitalists in the near future. This will define how hospitalists add value and how we are different from other internists, pediatricians, and family practitioners. SHM will also be using the Core Curriculum to not only drive SHM post-graduate education, but to help redefine residency training to produce more and better-trained individuals for a future that includes 30,000 to 40,000 hospitalists.

This has been quite a ride in the last 5 years. I have been fortunate enough to have had a front row seat. And I am not going anywhere soon. This is way too much fun. I just wanted to share with you a few others who have been instrumental in growing SHM.

A Special Thank You to Those Who Did the Work

SHM Presidents

John Nelson

Win Whitcomb

Bob Wachter

Ron Angus

Mark Williams

Jeff Dichter

Jeanne Huddleston

SHM Board Members (in addition to all Presidents)

Bill Atchley

Brad Flansbaum

David Zipes

Diane Craig

Herb Rogove

Jan Merin

Lisa Kettering

Mark Aronson

Mary Jo Gorman

Mike Ruhlen

Mitch Wilson

Pat Cawley

Peter Lindenauer

Richard Slataper

Russ Holman

Steve Pantilat

Editors, The Hospitalist

Scott Flanders

Jim Pile

Committee & Council Chairs (in addition to Board members)

Alpesh Amin

Andy Auerbach

Don Krause

Jack Percelay

Joe Li

Lakshmi Halasyamani

Mike Pistoria

Natalie Correia

Neil Kripalani

Preetha Basaviah

Sanjay Saint

Shaun Frost

Stacy Goldsholl

Sylvia McKean

Teresa Jones

Tim Cornell

Vineet Arora

SHM Staff

Angela Musial

Erica Pearson

Jane Mihelic

Kevin Stevens

Marie Francois

Marilyn Rivera

Michelle D’Agostino

Vera Bensch

Vernita Jackson

Veronica BeUs

Joe Miller

Tina Budnitz

This issue of The Hospitalist marks the beginning of my sixth year as the chief executive officer at SHM. Much has happened at SHM and in our specialty in the last 5 years, and

I thought I would use this space to share with everyone what we have accomplished together and to recognize the many individuals who have made all of this possible.

Past

When I first came to SHM in January of 2000, SHM had two employees, three or four committees, and about 500members. There were estimated to be 1000-2000 hospitalists in the country. SHM did stage an Annual Meeting with 300 attendees and published a newsletter of 16 pages with minimal ad revenue and a circulation of about 1000. SHM had no external grants and limited relationships with industry.

SHM was a fledgling national organization with no local presence. SHM had minimal assets or infrastructure and was very reliant on ACP for support and direction. Most of the innovation and direction fell to a few hospitalists around the country, who, while devoted to SHM (then NAIP) and our specialty, still had a very full plate just doing their day jobs, growing their hospital medicine groups. It was amazing what they had accomplished with minimal staff support or infrastructure.

At the start of the new millennium, SHM didn’t know how many hospitals had hospitalists. There was no data on how hard hospitalists should be expected to work or how much they should be paid. There was limited data on the background or training of those doctors who were going into hospital medicine, and there was no understanding of what the knowledge base was for this new specialty. There was a vague sense that the importance of hospitalists was more than just seeing their own patients, but there was little understanding of what value hospitalists could add to their health communities.

Present

Over the last 5 years, together we have made enormous progress. We have changed our name from the National Association of Inpatient Physicians to the Society of Hospital Medicine to better reflect all the stakeholders in our growing specialty. We have grown our Philadelphia staff to 13 and employ another five staff in Boston, Atlanta, and California. The Hospitalist newsletter is now the recognized publication in hospital medicine with 65-80 pages per issue, 2-3 supplements each year, and a circulation well over 10,000. There are more than $75,000 in recruitment ads in each issue, as much a testament to the growth of the specialty as anything else.

SHM’s Annual Meeting now attracts almost 1000 attendees and is the primary networking opportunity for the fastest-growing medical specialty. SHM has almost 5000 members, and there are an estimated 10,000-12,000 hospitalists now practicing in over 1500 hospitals. SHM currently has more than 40 local chapters meeting at least once a year throughout the country.

SHM has developed unique expertise in the management aspects of hospital medicine and holds practice management courses at least three times each year. In addition, SHM has realized that hospitalists will need to be the leaders of the hospitals of the future and has created Leadership Academies to train these future leaders. SHM has worked with grants from the Hartford Foundation to establish the hospitalist as the physician for the acutely ill elderly. SHM is working with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and others in helping to create the physical design of the hospital of the future.

SHM is just completing the Core Curriculum for Hospital Medicine, which will define the knowledge base for our specialty and serve as the basis for SHM’s growing educational enterprise. SHM is defining the value that hospitalists add beyond just direct patient care. This phenomenon has been the basis for hospitals looking for innovative ways to grow and support their hospital medicine groups. SHM will publish these white papers for hospitalists and hospital executives to use in designing their hospital medicine programs.

SHM has defined the productivity and compensation data for our specialty in our biannual surveys that are the best source for hospitalist data. SHM has developed a Washington presence and is defining the advocacy issues for hospital medicine, including substantial reform of payment to de-emphasize compensation based solely on the unit of the visit or the procedure.

SHM is now an organization with almost $3 million in assets, completely autonomous, and functioning on its own. We have a strong and growing relationship with ACP, and SHM has reached out to partner with many other organizations, including the AHA, ACCP, JCAHO, RWJ, Hartford Foundation, CDC, AACN, ASHP, ABIM, AAP, SGIM, AAIM and many others.

Future

And there is much to look forward to in the next 5 years. In the coming months, SHM will launch the first journal in hospital medicine in January 2006. SHM’s Web site will come into the 21st century with the ability for each member to have their own Web page. The Web site will be the one location that hospitalists can come to for CME and other educational information. SHM will be working with AACP, AACN, ASHP, and others to establish an Acute Care Collaborative, reorganizing hospital workflow to deliver measurable higher-quality health care using interdisciplinary teams of health professionals. This will help to define the hospital of the future.

There will be a certification for hospitalists in the near future. This will define how hospitalists add value and how we are different from other internists, pediatricians, and family practitioners. SHM will also be using the Core Curriculum to not only drive SHM post-graduate education, but to help redefine residency training to produce more and better-trained individuals for a future that includes 30,000 to 40,000 hospitalists.

This has been quite a ride in the last 5 years. I have been fortunate enough to have had a front row seat. And I am not going anywhere soon. This is way too much fun. I just wanted to share with you a few others who have been instrumental in growing SHM.

A Special Thank You to Those Who Did the Work

SHM Presidents

John Nelson

Win Whitcomb

Bob Wachter

Ron Angus

Mark Williams

Jeff Dichter

Jeanne Huddleston

SHM Board Members (in addition to all Presidents)

Bill Atchley

Brad Flansbaum

David Zipes

Diane Craig

Herb Rogove

Jan Merin

Lisa Kettering

Mark Aronson

Mary Jo Gorman

Mike Ruhlen

Mitch Wilson

Pat Cawley

Peter Lindenauer

Richard Slataper

Russ Holman

Steve Pantilat

Editors, The Hospitalist

Scott Flanders

Jim Pile

Committee & Council Chairs (in addition to Board members)

Alpesh Amin

Andy Auerbach

Don Krause

Jack Percelay

Joe Li

Lakshmi Halasyamani

Mike Pistoria

Natalie Correia

Neil Kripalani

Preetha Basaviah

Sanjay Saint

Shaun Frost

Stacy Goldsholl

Sylvia McKean

Teresa Jones

Tim Cornell

Vineet Arora

SHM Staff

Angela Musial

Erica Pearson

Jane Mihelic

Kevin Stevens

Marie Francois

Marilyn Rivera

Michelle D’Agostino

Vera Bensch

Vernita Jackson

Veronica BeUs

Joe Miller

Tina Budnitz

This issue of The Hospitalist marks the beginning of my sixth year as the chief executive officer at SHM. Much has happened at SHM and in our specialty in the last 5 years, and

I thought I would use this space to share with everyone what we have accomplished together and to recognize the many individuals who have made all of this possible.

Past

When I first came to SHM in January of 2000, SHM had two employees, three or four committees, and about 500members. There were estimated to be 1000-2000 hospitalists in the country. SHM did stage an Annual Meeting with 300 attendees and published a newsletter of 16 pages with minimal ad revenue and a circulation of about 1000. SHM had no external grants and limited relationships with industry.

SHM was a fledgling national organization with no local presence. SHM had minimal assets or infrastructure and was very reliant on ACP for support and direction. Most of the innovation and direction fell to a few hospitalists around the country, who, while devoted to SHM (then NAIP) and our specialty, still had a very full plate just doing their day jobs, growing their hospital medicine groups. It was amazing what they had accomplished with minimal staff support or infrastructure.

At the start of the new millennium, SHM didn’t know how many hospitals had hospitalists. There was no data on how hard hospitalists should be expected to work or how much they should be paid. There was limited data on the background or training of those doctors who were going into hospital medicine, and there was no understanding of what the knowledge base was for this new specialty. There was a vague sense that the importance of hospitalists was more than just seeing their own patients, but there was little understanding of what value hospitalists could add to their health communities.

Present

Over the last 5 years, together we have made enormous progress. We have changed our name from the National Association of Inpatient Physicians to the Society of Hospital Medicine to better reflect all the stakeholders in our growing specialty. We have grown our Philadelphia staff to 13 and employ another five staff in Boston, Atlanta, and California. The Hospitalist newsletter is now the recognized publication in hospital medicine with 65-80 pages per issue, 2-3 supplements each year, and a circulation well over 10,000. There are more than $75,000 in recruitment ads in each issue, as much a testament to the growth of the specialty as anything else.

SHM’s Annual Meeting now attracts almost 1000 attendees and is the primary networking opportunity for the fastest-growing medical specialty. SHM has almost 5000 members, and there are an estimated 10,000-12,000 hospitalists now practicing in over 1500 hospitals. SHM currently has more than 40 local chapters meeting at least once a year throughout the country.

SHM has developed unique expertise in the management aspects of hospital medicine and holds practice management courses at least three times each year. In addition, SHM has realized that hospitalists will need to be the leaders of the hospitals of the future and has created Leadership Academies to train these future leaders. SHM has worked with grants from the Hartford Foundation to establish the hospitalist as the physician for the acutely ill elderly. SHM is working with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and others in helping to create the physical design of the hospital of the future.

SHM is just completing the Core Curriculum for Hospital Medicine, which will define the knowledge base for our specialty and serve as the basis for SHM’s growing educational enterprise. SHM is defining the value that hospitalists add beyond just direct patient care. This phenomenon has been the basis for hospitals looking for innovative ways to grow and support their hospital medicine groups. SHM will publish these white papers for hospitalists and hospital executives to use in designing their hospital medicine programs.

SHM has defined the productivity and compensation data for our specialty in our biannual surveys that are the best source for hospitalist data. SHM has developed a Washington presence and is defining the advocacy issues for hospital medicine, including substantial reform of payment to de-emphasize compensation based solely on the unit of the visit or the procedure.

SHM is now an organization with almost $3 million in assets, completely autonomous, and functioning on its own. We have a strong and growing relationship with ACP, and SHM has reached out to partner with many other organizations, including the AHA, ACCP, JCAHO, RWJ, Hartford Foundation, CDC, AACN, ASHP, ABIM, AAP, SGIM, AAIM and many others.

Future

And there is much to look forward to in the next 5 years. In the coming months, SHM will launch the first journal in hospital medicine in January 2006. SHM’s Web site will come into the 21st century with the ability for each member to have their own Web page. The Web site will be the one location that hospitalists can come to for CME and other educational information. SHM will be working with AACP, AACN, ASHP, and others to establish an Acute Care Collaborative, reorganizing hospital workflow to deliver measurable higher-quality health care using interdisciplinary teams of health professionals. This will help to define the hospital of the future.

There will be a certification for hospitalists in the near future. This will define how hospitalists add value and how we are different from other internists, pediatricians, and family practitioners. SHM will also be using the Core Curriculum to not only drive SHM post-graduate education, but to help redefine residency training to produce more and better-trained individuals for a future that includes 30,000 to 40,000 hospitalists.

This has been quite a ride in the last 5 years. I have been fortunate enough to have had a front row seat. And I am not going anywhere soon. This is way too much fun. I just wanted to share with you a few others who have been instrumental in growing SHM.

A Special Thank You to Those Who Did the Work

SHM Presidents

John Nelson

Win Whitcomb

Bob Wachter

Ron Angus

Mark Williams

Jeff Dichter

Jeanne Huddleston

SHM Board Members (in addition to all Presidents)

Bill Atchley

Brad Flansbaum

David Zipes

Diane Craig

Herb Rogove

Jan Merin

Lisa Kettering

Mark Aronson

Mary Jo Gorman

Mike Ruhlen

Mitch Wilson

Pat Cawley

Peter Lindenauer

Richard Slataper

Russ Holman

Steve Pantilat

Editors, The Hospitalist

Scott Flanders

Jim Pile

Committee & Council Chairs (in addition to Board members)

Alpesh Amin

Andy Auerbach

Don Krause

Jack Percelay

Joe Li

Lakshmi Halasyamani

Mike Pistoria

Natalie Correia

Neil Kripalani

Preetha Basaviah

Sanjay Saint

Shaun Frost

Stacy Goldsholl

Sylvia McKean

Teresa Jones

Tim Cornell

Vineet Arora

SHM Staff

Angela Musial

Erica Pearson

Jane Mihelic

Kevin Stevens

Marie Francois

Marilyn Rivera

Michelle D’Agostino

Vera Bensch

Vernita Jackson

Veronica BeUs

Joe Miller

Tina Budnitz

The Campaign to Save 100,000 Lives

I am on a plane on my way back to Minnesota after being professionally rejuvenated by the content of the Institute of Healthcare Improvement’s 16th Annual Forum, in Orlando, FL. The theme of the meeting called on all hospitals, and hence I believe all hospitalists, to save lives. Dr. Donald Berwick, President and CEO of the Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI) kicked off this years’ Annual Forum with his plenary speech “Some is not a number, Soon is not a time.” Saving some lives, some time in the future is not a clear goal. “Some is not a number and soon is not a time.” So, he put the challenge forth for hospitals to join IHI in a campaign to save 100K lives by June 14, 2006 at 9:00 a.m. EDT.

“Some is not a number. Soon is not a time.” We all get “why” this is important, at least in so much as what we have been told by the Institute of Medicine Reports “To Err is Human” and “Crossing the Quality Chasm”. But “how” can this be done? By doing things that we already know impact mortality in a hospital setting. By engaging in the reliable care delivery of six changes that save lives. These include recommendations in each of the following areas: rapid response or emergency medical teams, reliable care for acute myocardial infarctions, reliable use of the ventilator pneumonia and central venous line “bundles”, surgical site infection prophylaxis, and prevention of adverse drug events with reconciliation. Each is described in more detail below.

- Rapid Response Teams (also known as Medical Emergency or Pre-Code Teams): This is a team of healthcare providers that may be summoned at any time by anyone in the hospital to assist in the care of a patient who appears acutely ill, before the patient has respiratory failure, a cardiac arrest or other adverse event. The aim is to prevent situations of “failure to rescue”, to recognize the early signs and symptoms of clinical deterioration prior to requiring transfer to the intensive care unit.

- Reliable Care for Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI): For appropriate AMI patients, reliable use of all of the following treatments: early administration of aspirin, aspirin at discharge, early administration of a beta-blocker, beta-blocker at discharge, ACE‑inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) at discharge (if systolic dysfunction), timely reperfusion, and smoking cessation counseling.

- Reliable use of the Ventilator Bundle: A number of hospitals have initiated the use of the ventilator bundle to prevent ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP). VAP carries a high mortality rate. The “bundle” is a grouping of 5 treatments/preventions measured as a composite (% of patients that get all 5).

- Elevate head of bed to 30 degrees

- Peptic ulcer prophylaxis

- Deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis

- Daily “sedation vacation”

- Daily assessment of readiness to extubate

Not all of the items have a specific relationship to VAP (e.g., DVT prophylaxis), but when reliably performed in concert with the other items, leads to a decrease in VAP.

- Reliable use of Central Venous Line Bundles: This is a grouping of 5 preventative measures that when done in concert and measured as a composite have had maximal effectiveness for the reduction of central line associated blood stream infections (CLABs) in some hospitals.

- Hand hygiene

- Maximal barrier precautions

- Chlorhexidine skin antisepsis

- Appropriate catheter site and administration system care

- No routine line replacement

- Surgical site infection (SSI) prophylaxis with a “SSI bundle”: Hospitals participating with the IHI in a variety of different formats have found the most substantial reduction/prevention of SSIs when 3 preventative measures are done in concert with each other for every surgical patient. These preventative measures include:

- Guideline-based use of prophylactic perioperative antibiotics (including both choice and timing of administration of antibiotic)

- Appropriate hair removal (avoiding shaving)

- Perioperative glucose control

- Prevention of adverse drug events with medication reconciliation: This refers to the procedures that can be put in place at the time of any transition of care to mitigate the increased risk of wrong dose of medication or even wrong drug being administered immediately following that transition. Each time we have to transfer information from one sheet of paper to another or from a sheet of paper to a computer, there is chance for human error. Medication reconciliation can virtually eliminate errors occurring at transitions in care.

I have placed in Table 1, the information (goals, background, proposed interventions and success stories) handed out during Dr. Donald Berwick’s opening plenary session, the kick-off for the campaign to save 100,000 lives.

Two key components of the descriptions above deserve further explanation. One of the key components is the concept of reliability. Reliability is how often something in health care does what it is supposed to do, in the time frame it is supposed to do it in. The formula is the number of times that something (delivery of a medication or service) is done correctly divided by the number of times that same something is attempted. In work published by Karl Weick, one common principle within high reliability organizations is that of a preoccupation with failure. As such, the notation of reliability is a measure of defects. Currently much of healthcare (including use of beta-blockers after AMI) functions at a 10-1 level of performance (one defect in 10 tries) or less than a 90% success rate. Organizations that have actively embraced this concept of reliability in their quality improvement work have rejected the usual satisfaction with 10-1 performance. Shouldn’t 99 out of 100 (or 999 out of a 1,000) patients with an AMI get what they are supposed to get?

The other key component embedded within some of the six items that save lives is the concept of bundles. Rather than considering individual measures for each of the items within a bundle, a composite or aggregate measure is reported. Bottom line is that doing any one or two of the items in a bundle is not good enough. It will not achieve the same reduction in hospital acquired infection rates or mortality, as doing all of the items in concert for every appropriate patient.

How can hospitalists help achieve this national goal, to participate in this campaign with the IHI? As individuals, we can be a hospital “precinct captain” or champion, speak to our hospital boards, convene colleagues to standardize to science, start medication reconciliation, and seek composite reliability in our own individual practices.

The IHI will measure this campaign in four ways.

Level 1. Number of hospitals “signing up”

Level 2. Changes in process of care reported

Level 3. Actual changes in deaths and death rates (sample amongst volunteer hospitals)

Level 4. Hospital Standardized Mortality Rates (work of Brian Jarman)

More detailed and specific information about the campaign (and how to participate) can be found on IHI’s Web site (www.ihi.org/ihi/programs/campaign).

“Some is not a number. Soon is not a time.”

The number: 100,000 lives.

The time: June 14, 2006 – 9 a.m. EDT.

References

- Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction – executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:671-719.

- Antman EM, Lau J, Kupelnick B, Mosteller F, Chalmers TC. A comparison of results of meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials and recommendations of clinical experts: treatments for myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1992;268:240-8.

- Hennekens CH, Albert CM, Godfried SL, Gaziano JM, Buring JE. Adjunctive drug therapy of acute myocardial infarction – evidence from clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1660-7.

- McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2635-45.

- Adams K, Corrigan JM, eds. Priority areas for national action: transforming health care quality. Washington, DC: The National Academics Press, 2003.

- Lappe JM, Muhlstein JB, Lappe DL, et al. Improvements in 1-year cardiovascular clinical outcomes associated with a hospital-based discharge medication program. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:446-53.

- Hackensack University Medical Center AMI Report, Sept 10, 2004.

- McLeod Regional Medical Center Storyboard for the 2004 IHI National Forum.

- Craven DE, Steger KA. Nosocomial pneumonia in mechanically ventilated adult patients: epidemiology and prevention in 1996. Semin Respir Infect. 1996;11:32-53.

- Ibrahim EH, Tracy L, Hill C, Fraser VJ, Kollef MH. The occurrence of ventilator-associated pneumonia in a community hospital: risk factors and clinical outcomes. Chest. 2001;120:555-61.

- Rello J, Ollendorf DA, Oster G, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of ventilator associated pneumonia in a large U.S. database. Chest. 2002;122:2115-21.

- Guidelines for Preventing Health-Care-Associated Pneumonia, 2003. Recommendations of CDC and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Commi Tee. MMWR. 2004;53(No.RR‑3):1-36.

- Dodek P, Keenan S, Cook D, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline for the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:305-13.

- Rello J, Lorente C, Bodi M, Diaz E, Ricart M, Kollef MH. Why do physicians not follow evidence-based guidelines for preventing ventilator-associated pneumonia? A survey based on the opinions of an international panel of intensivists. Chest. 2002;122:656-61.

- Drakulovic MB, Torres A, Bauer TT, Nicolas JM, Nogue S, Ferrer M. Supine body position as a risk factor for nosocomial pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients: a randomized trial. Lancet. 1999;354:1851-58.

- Kress JP, Pohlman AS, O’Connor MF, Hall JB. Daily interruption of sedative infusions in critically ill patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1471-77.

- Cook DJ, Fuller HD, Guyatt GH, et al. Risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:377-81.

- Cook DJ, Reeve BK, Guyatt GH, et al. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in critically ill patients: resolving discordant meta-analyses. JAMA. 1996;275:308-314.

- Cook D, Guyatt G, Marshall J, et al. A comparison of sucralfate and ranitidine for the prevention of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients requiring mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:791-97.

- Cook D, Heyland, Griffith L, Cook R, Marshall J, Pagliarello J. Risk factors for clinically important upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients requiring mechanical ventilation. Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:2812-17.

- Attia J, Ray JG, Cook DJ, Douketis J, Ginsberg JS, Geerts WH. Deep vein thrombosis and its prevention in critically ill adults. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1268-79.

- Geerts WH, Pineo GF, Heit JA, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. The seventh ACCP conference on antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy. Chest. 2004;126:338S-400S.

- Berenholtz SM, Pronovost PJ, Lipsett PA, et al. Eliminating catheter-related bloodstream infections in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:2014-20.

- Pittet D, Tarara D, Wenzel RP. Nosocomial bloodstream infection in critically ill patients. Excess length of stay, extra costs, and aTributable mortality. JAMA. 1994;271:1598-1601.

- Saint S. Chapter 16. Prevention of intravascular catheter-related infection. Making health care safer: a critical analysis of patient safety practices. AHRQ evidence report, number 43, July 20, 2001. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/vooks.

- O’Grady NP; Alexander M, Dellinger EP, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. MMWR Morb Mort Wkly Rep. 2002;51(RR-10):1-29.

- Kirkland KB, et al. The impact of surgical-site infections in the 1990s: attributable mortality, excess length of hospitalization, and extra costs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:725-30.

- Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, et al. Guidelines for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:247-78.

- Classen DC, Pestotnik SL, Evans RS, Lloyd JF, Burke JP. Adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. Excess length of stay, extra costs, and attributable mortality. JAMA. 1997;277:301-06.

- Phillips DP, Christenfeld N, Glynn LM. Increase in U.S. medication-error deaths between 1983 and 1993. Lancet. 1998;351:643-4.

- Rothschild JM, Federic FA, Gandhi TK, Kaushal R, Williams DH, Bates DW. Analysis of medication-related malpractice claims. Causes, preventability, and costs. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2414-20.

- Pronovost P, Weast B, Schwarz M, et al. Medication reconciliation: a practical tool to reduce the risk of medication errors. J Crit Care. 2003;18:201-205.

- Rozich JD, Resar RK. Medication safety: one organization’s approach to the challenge. JCOM. 2001;8(10):27-34.

- Rozich JD, Howard RJ, Justeson JM, Macken PD, Lindsay ME, Resar RK. Standardization as a mechanism to improve safety in healthcare. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2004;30:5-14.

- Whittington J, Cohen H. OSF Healthcare’s journey in patient safety. Qual Manag Health Care. 2004;13:53-59.

- Needleman J, Buerhaus P, Mattke S, et al. Nursing-staffing levels and the quality of care in hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1715-22.

- Peberdy MA, Kaye W, Ornato JP, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation of adults in the hospital: a report of 14,270 cardiac arrests from the National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2003;58:297-308.

- Sandroni C, Ferro G, Santangelo S, et al. In-hospital cardiac arrest: survival depends mainly on the emergency response. Resuscitation. 2004;62:291-7.

- Schein RM, Hazday N, Pena M, et al. Clinical antecedents to in-hospital cardiopulmonary arrest. Chest. 1990;98:1388-92.

- Hillman K, Parr M, Flabouris A, Bishop G, Stewart A. Redefining in-hospital resuscitation: the concept of the medical emergency team. Resuscitation. 2001;48:105-10.

- Buist MD, Moore GE, Bernard SA, Waxman BP, Anderson JN, Nguyen TV. Effects of a medical emergency team on reduction of incidence of and mortality from unexpected cardiac arrests in hospital: preliminary study. BMJ. 2002;324:387-90.

- Bellomo R, Goldsmith D, Uchino S, et al. A prospective before-and-after trial of a medical emergency team. MJA. 2003;179:283-7.

- Bellomo R, Goldsmith D, Uchino S, et al. Prospective controlled trail of effect of medical emergency team on postoperative morbidity and mortality rates. Crit Car Med. 2004;32:916-21.

- Furnary AP, Zerr KJ, Grunkemeier GL, Starr AL. Continuous intravenous insulin infusion reduces the incidence of deep sternal wound infection in diabetic patients after cardiac surgical procedures. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67: 352-62.

- Van de Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, et all. Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1359-67.

I am on a plane on my way back to Minnesota after being professionally rejuvenated by the content of the Institute of Healthcare Improvement’s 16th Annual Forum, in Orlando, FL. The theme of the meeting called on all hospitals, and hence I believe all hospitalists, to save lives. Dr. Donald Berwick, President and CEO of the Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI) kicked off this years’ Annual Forum with his plenary speech “Some is not a number, Soon is not a time.” Saving some lives, some time in the future is not a clear goal. “Some is not a number and soon is not a time.” So, he put the challenge forth for hospitals to join IHI in a campaign to save 100K lives by June 14, 2006 at 9:00 a.m. EDT.

“Some is not a number. Soon is not a time.” We all get “why” this is important, at least in so much as what we have been told by the Institute of Medicine Reports “To Err is Human” and “Crossing the Quality Chasm”. But “how” can this be done? By doing things that we already know impact mortality in a hospital setting. By engaging in the reliable care delivery of six changes that save lives. These include recommendations in each of the following areas: rapid response or emergency medical teams, reliable care for acute myocardial infarctions, reliable use of the ventilator pneumonia and central venous line “bundles”, surgical site infection prophylaxis, and prevention of adverse drug events with reconciliation. Each is described in more detail below.

- Rapid Response Teams (also known as Medical Emergency or Pre-Code Teams): This is a team of healthcare providers that may be summoned at any time by anyone in the hospital to assist in the care of a patient who appears acutely ill, before the patient has respiratory failure, a cardiac arrest or other adverse event. The aim is to prevent situations of “failure to rescue”, to recognize the early signs and symptoms of clinical deterioration prior to requiring transfer to the intensive care unit.

- Reliable Care for Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI): For appropriate AMI patients, reliable use of all of the following treatments: early administration of aspirin, aspirin at discharge, early administration of a beta-blocker, beta-blocker at discharge, ACE‑inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) at discharge (if systolic dysfunction), timely reperfusion, and smoking cessation counseling.

- Reliable use of the Ventilator Bundle: A number of hospitals have initiated the use of the ventilator bundle to prevent ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP). VAP carries a high mortality rate. The “bundle” is a grouping of 5 treatments/preventions measured as a composite (% of patients that get all 5).

- Elevate head of bed to 30 degrees

- Peptic ulcer prophylaxis

- Deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis

- Daily “sedation vacation”

- Daily assessment of readiness to extubate

Not all of the items have a specific relationship to VAP (e.g., DVT prophylaxis), but when reliably performed in concert with the other items, leads to a decrease in VAP.

- Reliable use of Central Venous Line Bundles: This is a grouping of 5 preventative measures that when done in concert and measured as a composite have had maximal effectiveness for the reduction of central line associated blood stream infections (CLABs) in some hospitals.

- Hand hygiene

- Maximal barrier precautions

- Chlorhexidine skin antisepsis

- Appropriate catheter site and administration system care

- No routine line replacement

- Surgical site infection (SSI) prophylaxis with a “SSI bundle”: Hospitals participating with the IHI in a variety of different formats have found the most substantial reduction/prevention of SSIs when 3 preventative measures are done in concert with each other for every surgical patient. These preventative measures include:

- Guideline-based use of prophylactic perioperative antibiotics (including both choice and timing of administration of antibiotic)

- Appropriate hair removal (avoiding shaving)

- Perioperative glucose control

- Prevention of adverse drug events with medication reconciliation: This refers to the procedures that can be put in place at the time of any transition of care to mitigate the increased risk of wrong dose of medication or even wrong drug being administered immediately following that transition. Each time we have to transfer information from one sheet of paper to another or from a sheet of paper to a computer, there is chance for human error. Medication reconciliation can virtually eliminate errors occurring at transitions in care.

I have placed in Table 1, the information (goals, background, proposed interventions and success stories) handed out during Dr. Donald Berwick’s opening plenary session, the kick-off for the campaign to save 100,000 lives.

Two key components of the descriptions above deserve further explanation. One of the key components is the concept of reliability. Reliability is how often something in health care does what it is supposed to do, in the time frame it is supposed to do it in. The formula is the number of times that something (delivery of a medication or service) is done correctly divided by the number of times that same something is attempted. In work published by Karl Weick, one common principle within high reliability organizations is that of a preoccupation with failure. As such, the notation of reliability is a measure of defects. Currently much of healthcare (including use of beta-blockers after AMI) functions at a 10-1 level of performance (one defect in 10 tries) or less than a 90% success rate. Organizations that have actively embraced this concept of reliability in their quality improvement work have rejected the usual satisfaction with 10-1 performance. Shouldn’t 99 out of 100 (or 999 out of a 1,000) patients with an AMI get what they are supposed to get?

The other key component embedded within some of the six items that save lives is the concept of bundles. Rather than considering individual measures for each of the items within a bundle, a composite or aggregate measure is reported. Bottom line is that doing any one or two of the items in a bundle is not good enough. It will not achieve the same reduction in hospital acquired infection rates or mortality, as doing all of the items in concert for every appropriate patient.

How can hospitalists help achieve this national goal, to participate in this campaign with the IHI? As individuals, we can be a hospital “precinct captain” or champion, speak to our hospital boards, convene colleagues to standardize to science, start medication reconciliation, and seek composite reliability in our own individual practices.

The IHI will measure this campaign in four ways.

Level 1. Number of hospitals “signing up”

Level 2. Changes in process of care reported

Level 3. Actual changes in deaths and death rates (sample amongst volunteer hospitals)

Level 4. Hospital Standardized Mortality Rates (work of Brian Jarman)

More detailed and specific information about the campaign (and how to participate) can be found on IHI’s Web site (www.ihi.org/ihi/programs/campaign).

“Some is not a number. Soon is not a time.”

The number: 100,000 lives.

The time: June 14, 2006 – 9 a.m. EDT.

References

- Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction – executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:671-719.

- Antman EM, Lau J, Kupelnick B, Mosteller F, Chalmers TC. A comparison of results of meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials and recommendations of clinical experts: treatments for myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1992;268:240-8.

- Hennekens CH, Albert CM, Godfried SL, Gaziano JM, Buring JE. Adjunctive drug therapy of acute myocardial infarction – evidence from clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1660-7.

- McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2635-45.

- Adams K, Corrigan JM, eds. Priority areas for national action: transforming health care quality. Washington, DC: The National Academics Press, 2003.

- Lappe JM, Muhlstein JB, Lappe DL, et al. Improvements in 1-year cardiovascular clinical outcomes associated with a hospital-based discharge medication program. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:446-53.

- Hackensack University Medical Center AMI Report, Sept 10, 2004.

- McLeod Regional Medical Center Storyboard for the 2004 IHI National Forum.

- Craven DE, Steger KA. Nosocomial pneumonia in mechanically ventilated adult patients: epidemiology and prevention in 1996. Semin Respir Infect. 1996;11:32-53.

- Ibrahim EH, Tracy L, Hill C, Fraser VJ, Kollef MH. The occurrence of ventilator-associated pneumonia in a community hospital: risk factors and clinical outcomes. Chest. 2001;120:555-61.

- Rello J, Ollendorf DA, Oster G, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of ventilator associated pneumonia in a large U.S. database. Chest. 2002;122:2115-21.

- Guidelines for Preventing Health-Care-Associated Pneumonia, 2003. Recommendations of CDC and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Commi Tee. MMWR. 2004;53(No.RR‑3):1-36.

- Dodek P, Keenan S, Cook D, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline for the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:305-13.

- Rello J, Lorente C, Bodi M, Diaz E, Ricart M, Kollef MH. Why do physicians not follow evidence-based guidelines for preventing ventilator-associated pneumonia? A survey based on the opinions of an international panel of intensivists. Chest. 2002;122:656-61.

- Drakulovic MB, Torres A, Bauer TT, Nicolas JM, Nogue S, Ferrer M. Supine body position as a risk factor for nosocomial pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients: a randomized trial. Lancet. 1999;354:1851-58.

- Kress JP, Pohlman AS, O’Connor MF, Hall JB. Daily interruption of sedative infusions in critically ill patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1471-77.

- Cook DJ, Fuller HD, Guyatt GH, et al. Risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:377-81.

- Cook DJ, Reeve BK, Guyatt GH, et al. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in critically ill patients: resolving discordant meta-analyses. JAMA. 1996;275:308-314.

- Cook D, Guyatt G, Marshall J, et al. A comparison of sucralfate and ranitidine for the prevention of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients requiring mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:791-97.