User login

Understanding valvular heart disease in patients with systemic autoimmune diseases

Melanoma Screening Behavior Among Primary Care Physicians

Is nedocromil effective in preventing asthmatic attacks in patients with asthma?

Nedocromil (Tilade) is effective for the treatment of mild persistent asthma. It has not been shown to be effective in more severe forms of asthma for both children and adults. Although no studies looked specifically at exacerbation rates, multiple clinical and biologic outcomes (symptom scores, quality of life measures, bronchodilator use, forced expiratory flow in 1 second [FEV1], and peak expiratory flow rate [PEFR]) improved with nedocromil use compared with placebo.

The most effective dose for preventing exacerbations appears to be 4 mg (2 puffs) 4 times a day (SOR: A, multiple randomized controlled trials [RCTs] and meta-analyses). More severe forms of asthma respond better to inhaled steroids than to nedocromil (SOR: A, multiple RCTs). Nedocromil may allow some patients with severe asthma to use lower doses of inhaled steroids (SOR: C, conflicting RCTs). Nedocromil is also effective for the treatment of exercise-induced asthma (SOR: A, multiple RCTs and meta-analyses).

In general, about 50% to 70% of patients respond to nedocromil (SOR: A, multiple RCTs and meta-analyses). Unfortunately, which patients respond is not predictable from clinical parameters.1 Nedocromil is worth trying in mild persistent asthma, particularly for children where the parents are worried about the growth issues associated with inhaled steroids. Side effects (sore throat, nausea, and headache) are mild and infrequent. Maximal efficacy is usually seen after 6 to 8 weeks.

Evidence summary

A systematic review encompassing 127 trial centers and 4723 patients concluded that inhaled nedocromil was effective for a variety of patients with asthma. Significant improvements were noted in FEV1, PEFR, use of bronchodilators, symptom scores, and quality of life scores. The reviewers found nedocromil to be most effective for patients with moderate disease already taking bronchodilators,2 corresponding to the “mild persistent asthma” category ( Table ).

A contemporaneous European RCT, not included in the review, compared 4 mg of inhaled nedocromil 4 times daily with inhaled placebo among 209 asthmatic children for 12 weeks.3 After 8 weeks, they found a statistically significant reduction in total daily asthma symptom scores (50% nedocromil vs 9% placebo; P<.01). The proportion of parents and children rating treatment as moderately or very effective was 78% in the treatment group and 59% in the placebo group (number needed to treat [NNT]=5.2; P<.01); clinicians’ ratings were 73% for nedocromil and 50% for placebo (NNT=4.3; P<.01). The frequency of side effects—including nausea, headache, and sleepiness—did not reach statistical significance; however, the nedocromil group reported up to a 20% incidence of sore throat. Most of the studies reported no dropouts due to side effects.

When patients are already using inhaled steroids, the evidence is less clear whether nedocromil confers additional benefits, such as fewer exacerbations or lower inhaled steroid doses. Two small studies of patients either already on inhaled steroids4 or considered to be steroid-resistant5 found nonsignificant trends towards reductions in bronchodilator use, increased PEFR, increased FEV1, and improved quality of life. Although both studies were underpowered, the study on steroid-resistant asthma did find a statistically significant 20% improvement in PEFR and decreased bronchodilator use for 50% of patients at 8 and 12 weeks.

The inherent waxing and waning nature of asthma makes demonstrating benefits difficult. Furthermore, nedocromil tends to have an all-ornothing effect rather than a dose-response gradient. Unfortunately, none of these trials found useful predictors to help clinicians determine which patients respond.1,5

In a Cochrane Review, 20 RCTs involving 280 participants showed that 4 mg (2 puffs) of nedocromil inhaled 15 to 60 minutes prior to exercise significantly reduced the severity and duration of exercise-induced asthma for both adults and children. The maximum percentage fall in FEV1 improved significantly compared with placebo, with a weighted mean difference of 15.5% (95% confidence interval, 13.2–18.1). In addition, the time to complete recovery was shortened from 30 minutes with placebo to 10 minutes with nedocromil.6

TABLE

Classification of asthma

| Classification | Symptom frequency | Spirometry findings |

|---|---|---|

| Severe persistent | Continual symptoms | PEFR <60% Variability >30% |

| Moderate persistent | Daily symptoms, more than 1 night per week | PEFR >60% but <80% Variability >30% |

| Mild persistent | More than twice per week but less than daily; more than 2 nights per month | PEFR >80% Variability 20%–30% |

| Mild intermittent | Less than once per week; less than or equal to 2 nights per month | PEFR >80% Variability <20% |

| Source: Global Initiative for Asthma, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute 2003.7 | ||

Recommendations from others

The Global Initiative for Asthma and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Expert Panel Report list nedocromil as an option for the treatment of exercise-induced asthma and mild persistent asthma for adults and children. However, it is listed as a second choice to the use of inhaled steroids in the case of mild persistent asthma. It is not recommended for moderate or severe persistent asthma, or for mild intermittent asthma.7

Nedocromil and cromolyn sodium are safe but many patients do not respond

Ron Baldwin, MD

University of Wyoming Family Practice Residency at Casper

Inhaled nedocromil and cromolyn sodium have long been recognized as agents with an excellent safety profile. Unfortunately, as pointed about above, many patients do not respond to these agents. In addition, 4-times-daily dosing makes compliance difficult. Clinicians and parents must weigh the theoretical risk of inhaled corticosteroid-induced growth retardation with this potential differential in effectiveness.

1. Parish RC, Miller LJ. Nedocromil sodium. Ann Pharmacother 1993;27:599-606.

2. Edwards AM, Stevens MT. The clinical efficacy of inhaled nedocromil sodium (Tilade) in the treatment of asthma. Eur Respir J 1993;6:35-41.

3. Armenio L, Baldini G, Baldare M, et al. Double blind, placebo controlled study of nedocromil sodium in asthma. Arch Dis Child 1993;68:193-197.

4. O’Hickey SP, Rees PJ. High dose nedocromil sodium as an addition to inhaled corticosteroids in the treatment of asthma. Respir Med 1994;88:499-502.

5. Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Garcia R, Ejea MV. Effects of nedocromil sodium in steroid-resistant asthma: a randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1996;97:602-610.

6. Spooner CH, Saunders LD, Rowe BH. Nedocromil sodium for preventing exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library, Issue 4, 2003. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

7. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. Bethesda, Md: Global Initiative for Asthma, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; 2003.

Nedocromil (Tilade) is effective for the treatment of mild persistent asthma. It has not been shown to be effective in more severe forms of asthma for both children and adults. Although no studies looked specifically at exacerbation rates, multiple clinical and biologic outcomes (symptom scores, quality of life measures, bronchodilator use, forced expiratory flow in 1 second [FEV1], and peak expiratory flow rate [PEFR]) improved with nedocromil use compared with placebo.

The most effective dose for preventing exacerbations appears to be 4 mg (2 puffs) 4 times a day (SOR: A, multiple randomized controlled trials [RCTs] and meta-analyses). More severe forms of asthma respond better to inhaled steroids than to nedocromil (SOR: A, multiple RCTs). Nedocromil may allow some patients with severe asthma to use lower doses of inhaled steroids (SOR: C, conflicting RCTs). Nedocromil is also effective for the treatment of exercise-induced asthma (SOR: A, multiple RCTs and meta-analyses).

In general, about 50% to 70% of patients respond to nedocromil (SOR: A, multiple RCTs and meta-analyses). Unfortunately, which patients respond is not predictable from clinical parameters.1 Nedocromil is worth trying in mild persistent asthma, particularly for children where the parents are worried about the growth issues associated with inhaled steroids. Side effects (sore throat, nausea, and headache) are mild and infrequent. Maximal efficacy is usually seen after 6 to 8 weeks.

Evidence summary

A systematic review encompassing 127 trial centers and 4723 patients concluded that inhaled nedocromil was effective for a variety of patients with asthma. Significant improvements were noted in FEV1, PEFR, use of bronchodilators, symptom scores, and quality of life scores. The reviewers found nedocromil to be most effective for patients with moderate disease already taking bronchodilators,2 corresponding to the “mild persistent asthma” category ( Table ).

A contemporaneous European RCT, not included in the review, compared 4 mg of inhaled nedocromil 4 times daily with inhaled placebo among 209 asthmatic children for 12 weeks.3 After 8 weeks, they found a statistically significant reduction in total daily asthma symptom scores (50% nedocromil vs 9% placebo; P<.01). The proportion of parents and children rating treatment as moderately or very effective was 78% in the treatment group and 59% in the placebo group (number needed to treat [NNT]=5.2; P<.01); clinicians’ ratings were 73% for nedocromil and 50% for placebo (NNT=4.3; P<.01). The frequency of side effects—including nausea, headache, and sleepiness—did not reach statistical significance; however, the nedocromil group reported up to a 20% incidence of sore throat. Most of the studies reported no dropouts due to side effects.

When patients are already using inhaled steroids, the evidence is less clear whether nedocromil confers additional benefits, such as fewer exacerbations or lower inhaled steroid doses. Two small studies of patients either already on inhaled steroids4 or considered to be steroid-resistant5 found nonsignificant trends towards reductions in bronchodilator use, increased PEFR, increased FEV1, and improved quality of life. Although both studies were underpowered, the study on steroid-resistant asthma did find a statistically significant 20% improvement in PEFR and decreased bronchodilator use for 50% of patients at 8 and 12 weeks.

The inherent waxing and waning nature of asthma makes demonstrating benefits difficult. Furthermore, nedocromil tends to have an all-ornothing effect rather than a dose-response gradient. Unfortunately, none of these trials found useful predictors to help clinicians determine which patients respond.1,5

In a Cochrane Review, 20 RCTs involving 280 participants showed that 4 mg (2 puffs) of nedocromil inhaled 15 to 60 minutes prior to exercise significantly reduced the severity and duration of exercise-induced asthma for both adults and children. The maximum percentage fall in FEV1 improved significantly compared with placebo, with a weighted mean difference of 15.5% (95% confidence interval, 13.2–18.1). In addition, the time to complete recovery was shortened from 30 minutes with placebo to 10 minutes with nedocromil.6

TABLE

Classification of asthma

| Classification | Symptom frequency | Spirometry findings |

|---|---|---|

| Severe persistent | Continual symptoms | PEFR <60% Variability >30% |

| Moderate persistent | Daily symptoms, more than 1 night per week | PEFR >60% but <80% Variability >30% |

| Mild persistent | More than twice per week but less than daily; more than 2 nights per month | PEFR >80% Variability 20%–30% |

| Mild intermittent | Less than once per week; less than or equal to 2 nights per month | PEFR >80% Variability <20% |

| Source: Global Initiative for Asthma, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute 2003.7 | ||

Recommendations from others

The Global Initiative for Asthma and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Expert Panel Report list nedocromil as an option for the treatment of exercise-induced asthma and mild persistent asthma for adults and children. However, it is listed as a second choice to the use of inhaled steroids in the case of mild persistent asthma. It is not recommended for moderate or severe persistent asthma, or for mild intermittent asthma.7

Nedocromil and cromolyn sodium are safe but many patients do not respond

Ron Baldwin, MD

University of Wyoming Family Practice Residency at Casper

Inhaled nedocromil and cromolyn sodium have long been recognized as agents with an excellent safety profile. Unfortunately, as pointed about above, many patients do not respond to these agents. In addition, 4-times-daily dosing makes compliance difficult. Clinicians and parents must weigh the theoretical risk of inhaled corticosteroid-induced growth retardation with this potential differential in effectiveness.

Nedocromil (Tilade) is effective for the treatment of mild persistent asthma. It has not been shown to be effective in more severe forms of asthma for both children and adults. Although no studies looked specifically at exacerbation rates, multiple clinical and biologic outcomes (symptom scores, quality of life measures, bronchodilator use, forced expiratory flow in 1 second [FEV1], and peak expiratory flow rate [PEFR]) improved with nedocromil use compared with placebo.

The most effective dose for preventing exacerbations appears to be 4 mg (2 puffs) 4 times a day (SOR: A, multiple randomized controlled trials [RCTs] and meta-analyses). More severe forms of asthma respond better to inhaled steroids than to nedocromil (SOR: A, multiple RCTs). Nedocromil may allow some patients with severe asthma to use lower doses of inhaled steroids (SOR: C, conflicting RCTs). Nedocromil is also effective for the treatment of exercise-induced asthma (SOR: A, multiple RCTs and meta-analyses).

In general, about 50% to 70% of patients respond to nedocromil (SOR: A, multiple RCTs and meta-analyses). Unfortunately, which patients respond is not predictable from clinical parameters.1 Nedocromil is worth trying in mild persistent asthma, particularly for children where the parents are worried about the growth issues associated with inhaled steroids. Side effects (sore throat, nausea, and headache) are mild and infrequent. Maximal efficacy is usually seen after 6 to 8 weeks.

Evidence summary

A systematic review encompassing 127 trial centers and 4723 patients concluded that inhaled nedocromil was effective for a variety of patients with asthma. Significant improvements were noted in FEV1, PEFR, use of bronchodilators, symptom scores, and quality of life scores. The reviewers found nedocromil to be most effective for patients with moderate disease already taking bronchodilators,2 corresponding to the “mild persistent asthma” category ( Table ).

A contemporaneous European RCT, not included in the review, compared 4 mg of inhaled nedocromil 4 times daily with inhaled placebo among 209 asthmatic children for 12 weeks.3 After 8 weeks, they found a statistically significant reduction in total daily asthma symptom scores (50% nedocromil vs 9% placebo; P<.01). The proportion of parents and children rating treatment as moderately or very effective was 78% in the treatment group and 59% in the placebo group (number needed to treat [NNT]=5.2; P<.01); clinicians’ ratings were 73% for nedocromil and 50% for placebo (NNT=4.3; P<.01). The frequency of side effects—including nausea, headache, and sleepiness—did not reach statistical significance; however, the nedocromil group reported up to a 20% incidence of sore throat. Most of the studies reported no dropouts due to side effects.

When patients are already using inhaled steroids, the evidence is less clear whether nedocromil confers additional benefits, such as fewer exacerbations or lower inhaled steroid doses. Two small studies of patients either already on inhaled steroids4 or considered to be steroid-resistant5 found nonsignificant trends towards reductions in bronchodilator use, increased PEFR, increased FEV1, and improved quality of life. Although both studies were underpowered, the study on steroid-resistant asthma did find a statistically significant 20% improvement in PEFR and decreased bronchodilator use for 50% of patients at 8 and 12 weeks.

The inherent waxing and waning nature of asthma makes demonstrating benefits difficult. Furthermore, nedocromil tends to have an all-ornothing effect rather than a dose-response gradient. Unfortunately, none of these trials found useful predictors to help clinicians determine which patients respond.1,5

In a Cochrane Review, 20 RCTs involving 280 participants showed that 4 mg (2 puffs) of nedocromil inhaled 15 to 60 minutes prior to exercise significantly reduced the severity and duration of exercise-induced asthma for both adults and children. The maximum percentage fall in FEV1 improved significantly compared with placebo, with a weighted mean difference of 15.5% (95% confidence interval, 13.2–18.1). In addition, the time to complete recovery was shortened from 30 minutes with placebo to 10 minutes with nedocromil.6

TABLE

Classification of asthma

| Classification | Symptom frequency | Spirometry findings |

|---|---|---|

| Severe persistent | Continual symptoms | PEFR <60% Variability >30% |

| Moderate persistent | Daily symptoms, more than 1 night per week | PEFR >60% but <80% Variability >30% |

| Mild persistent | More than twice per week but less than daily; more than 2 nights per month | PEFR >80% Variability 20%–30% |

| Mild intermittent | Less than once per week; less than or equal to 2 nights per month | PEFR >80% Variability <20% |

| Source: Global Initiative for Asthma, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute 2003.7 | ||

Recommendations from others

The Global Initiative for Asthma and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Expert Panel Report list nedocromil as an option for the treatment of exercise-induced asthma and mild persistent asthma for adults and children. However, it is listed as a second choice to the use of inhaled steroids in the case of mild persistent asthma. It is not recommended for moderate or severe persistent asthma, or for mild intermittent asthma.7

Nedocromil and cromolyn sodium are safe but many patients do not respond

Ron Baldwin, MD

University of Wyoming Family Practice Residency at Casper

Inhaled nedocromil and cromolyn sodium have long been recognized as agents with an excellent safety profile. Unfortunately, as pointed about above, many patients do not respond to these agents. In addition, 4-times-daily dosing makes compliance difficult. Clinicians and parents must weigh the theoretical risk of inhaled corticosteroid-induced growth retardation with this potential differential in effectiveness.

1. Parish RC, Miller LJ. Nedocromil sodium. Ann Pharmacother 1993;27:599-606.

2. Edwards AM, Stevens MT. The clinical efficacy of inhaled nedocromil sodium (Tilade) in the treatment of asthma. Eur Respir J 1993;6:35-41.

3. Armenio L, Baldini G, Baldare M, et al. Double blind, placebo controlled study of nedocromil sodium in asthma. Arch Dis Child 1993;68:193-197.

4. O’Hickey SP, Rees PJ. High dose nedocromil sodium as an addition to inhaled corticosteroids in the treatment of asthma. Respir Med 1994;88:499-502.

5. Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Garcia R, Ejea MV. Effects of nedocromil sodium in steroid-resistant asthma: a randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1996;97:602-610.

6. Spooner CH, Saunders LD, Rowe BH. Nedocromil sodium for preventing exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library, Issue 4, 2003. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

7. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. Bethesda, Md: Global Initiative for Asthma, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; 2003.

1. Parish RC, Miller LJ. Nedocromil sodium. Ann Pharmacother 1993;27:599-606.

2. Edwards AM, Stevens MT. The clinical efficacy of inhaled nedocromil sodium (Tilade) in the treatment of asthma. Eur Respir J 1993;6:35-41.

3. Armenio L, Baldini G, Baldare M, et al. Double blind, placebo controlled study of nedocromil sodium in asthma. Arch Dis Child 1993;68:193-197.

4. O’Hickey SP, Rees PJ. High dose nedocromil sodium as an addition to inhaled corticosteroids in the treatment of asthma. Respir Med 1994;88:499-502.

5. Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Garcia R, Ejea MV. Effects of nedocromil sodium in steroid-resistant asthma: a randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1996;97:602-610.

6. Spooner CH, Saunders LD, Rowe BH. Nedocromil sodium for preventing exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library, Issue 4, 2003. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

7. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. Bethesda, Md: Global Initiative for Asthma, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; 2003.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Blocking the ‘munchies’ receptor: A novel approach to obesity

Marijuana has long been known to stimulate appetite, particularly for sweet foods.1 The naughty boys in my fraternity called it “the munchies;” the professionals call it hyperphagia. Cannabinoid receptor (CB1) stimulation by marijuana’s main active component—9-THC—is believed to induce this behavior. Clinicians have successfully used this effect to treat AIDS-related wasting syndrome and other anorexic conditions.2

CB1 is widely expressed throughout the brain and seems to inhibit release of various neurotransmitters.3 How this effect leads to increased appetite is unclear, but it may result from a decrease in the appetite-suppressing effects of hormones such as leptin. In other words, tweaking the CB1 receptor may take the “brakes” off appetite.

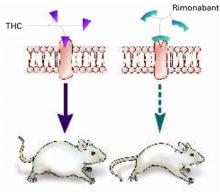

Some researchers have speculated that if stimulating CB1 triggers appetite, blocking the receptor might inhibit it (Figure 1).

THE ‘MUNCHIES’ IN MICE

Rimonabant (SR141716), an experimental agent, is a potent and selective CB1 antagonist.

Ravinet Trillou et al fed mice a high-fat diet known to induce obesity.4 The mice were randomized to receive rimonabant or placebo while maintained on the highly palatable diet. The authors asked: Would rimonabant help the mice lose weight even when they could eat as much delicious fatty food as they wanted?

Figure 1 Blocking CB1 may prevent weight gain

Δ9-THC activates the cannabinoid receptor (CB1), stimulating appetite and leading to weight gain in mice (left). When the same receptor is blocked, appetite is controlled (right).

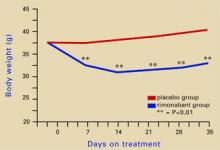

Source: Illustration for CURRENT PSYCHIATRY by Marcia HartsockRimonabant induced a sustained body weight reduction of approximately 20% in the treatment group compared with the placebo group across 5 weeks (Figure 2). Estimated fat stores among the treatment group were depleted by slightly more than 50%.

The authors noted that the mice in the treatment group had decreased their food intake, but the decrease was not sufficient to explain the weight loss. They speculate that rimonabant could activate metabolic processes and decrease intake.

RIMONABANT’S ROLE IN PSYCHIATRY

Phase III human trials of rimonabant are under way for obesity as well as smoking cessation.5 In uncontrolled studies, rimonabant has been shown to help people avoid weight gain while quitting smoking.5

If rimonabant shows effectiveness in controlled trials and is safe in humans, it could be most valuable. Obesity in industrial countries is epidemic and causes serious secondary morbidity, including diabetes, arthritis, and hypertension. Rimonabant, if approved by the FDA, could reach the market by early 2006.6

It is unknown whether rimonabant’s metabolic effects could offset those of many psychotropics. As psychiatrists, we often must stop an effective antipsychotic or antidepressant because it is causing significant weight gain. A treatment that would prevent medication-induced weight gain could improve patient compliance and, ultimately, outcomes.

MANAGING SCHIZOPHRENIA

Some evidence also suggests that rimonabant may offer additional benefits for patients with schizophrenia beyond weight reduction or smoking cessation.

Figure 2 Rimonabant’s effects on weight in mice on a high-fat diet

Source: Adapted from reference 4.Leweke et al found increased endogenous cannabinoids in the CSF of patients with schizophrenia, suggesting that a cannabinoid signaling imbalance may contribute to the disorder’s pathogenesis.7 However, 72 patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who took rimonabant for 6 weeks showed no improvement compared with a placebo group.8

1. Abel EL. Cannabis: effects on hunger and thirst. Behav Biol 1975;15:255-81.

2. Beal JE, Olson R, Laubenstein L, et al. Dronabinol as a treatment for anorexia associated with weight loss in patients with AIDS. J Pain Symptom Manage 1995;10:89-97.

3. Iversen L. Cannabis and the brain. Brain 2003;126:1252-70.

4. Ravinet Trillou C, Arnone M, Delgorge C, et al. Anti-obesity effect of SR141716, a CB1 receptor antagonist, in diet-induced obese mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2003;284:R345-53.

5. Fernandez JR, Allison DB. Rimonabant Sanofi-Synthelabo. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 2004;5:430-5.

6. The Website for the Drug Development Industry. Acomplia (rimonabant)—investigational agent for the management of obesity. London: SPGMedia. Available at: http://www. drugdevelopment-technology.com/projects/rimonabant/. Accessed Oct. 14, 2004.

7. Leweke FM, Giuffrida A, Wurster U, et al. Elevated endogenous cannabinoids in schizophrenia. Neuroreport 1999;10:1665-9.

8. Meltzer HY, Arvanitis L, Bauer D, et al. Placebo-controlled evaluation of four novel compounds for the treatment of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:975-84.

Marijuana has long been known to stimulate appetite, particularly for sweet foods.1 The naughty boys in my fraternity called it “the munchies;” the professionals call it hyperphagia. Cannabinoid receptor (CB1) stimulation by marijuana’s main active component—9-THC—is believed to induce this behavior. Clinicians have successfully used this effect to treat AIDS-related wasting syndrome and other anorexic conditions.2

CB1 is widely expressed throughout the brain and seems to inhibit release of various neurotransmitters.3 How this effect leads to increased appetite is unclear, but it may result from a decrease in the appetite-suppressing effects of hormones such as leptin. In other words, tweaking the CB1 receptor may take the “brakes” off appetite.

Some researchers have speculated that if stimulating CB1 triggers appetite, blocking the receptor might inhibit it (Figure 1).

THE ‘MUNCHIES’ IN MICE

Rimonabant (SR141716), an experimental agent, is a potent and selective CB1 antagonist.

Ravinet Trillou et al fed mice a high-fat diet known to induce obesity.4 The mice were randomized to receive rimonabant or placebo while maintained on the highly palatable diet. The authors asked: Would rimonabant help the mice lose weight even when they could eat as much delicious fatty food as they wanted?

Figure 1 Blocking CB1 may prevent weight gain

Δ9-THC activates the cannabinoid receptor (CB1), stimulating appetite and leading to weight gain in mice (left). When the same receptor is blocked, appetite is controlled (right).

Source: Illustration for CURRENT PSYCHIATRY by Marcia HartsockRimonabant induced a sustained body weight reduction of approximately 20% in the treatment group compared with the placebo group across 5 weeks (Figure 2). Estimated fat stores among the treatment group were depleted by slightly more than 50%.

The authors noted that the mice in the treatment group had decreased their food intake, but the decrease was not sufficient to explain the weight loss. They speculate that rimonabant could activate metabolic processes and decrease intake.

RIMONABANT’S ROLE IN PSYCHIATRY

Phase III human trials of rimonabant are under way for obesity as well as smoking cessation.5 In uncontrolled studies, rimonabant has been shown to help people avoid weight gain while quitting smoking.5

If rimonabant shows effectiveness in controlled trials and is safe in humans, it could be most valuable. Obesity in industrial countries is epidemic and causes serious secondary morbidity, including diabetes, arthritis, and hypertension. Rimonabant, if approved by the FDA, could reach the market by early 2006.6

It is unknown whether rimonabant’s metabolic effects could offset those of many psychotropics. As psychiatrists, we often must stop an effective antipsychotic or antidepressant because it is causing significant weight gain. A treatment that would prevent medication-induced weight gain could improve patient compliance and, ultimately, outcomes.

MANAGING SCHIZOPHRENIA

Some evidence also suggests that rimonabant may offer additional benefits for patients with schizophrenia beyond weight reduction or smoking cessation.

Figure 2 Rimonabant’s effects on weight in mice on a high-fat diet

Source: Adapted from reference 4.Leweke et al found increased endogenous cannabinoids in the CSF of patients with schizophrenia, suggesting that a cannabinoid signaling imbalance may contribute to the disorder’s pathogenesis.7 However, 72 patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who took rimonabant for 6 weeks showed no improvement compared with a placebo group.8

Marijuana has long been known to stimulate appetite, particularly for sweet foods.1 The naughty boys in my fraternity called it “the munchies;” the professionals call it hyperphagia. Cannabinoid receptor (CB1) stimulation by marijuana’s main active component—9-THC—is believed to induce this behavior. Clinicians have successfully used this effect to treat AIDS-related wasting syndrome and other anorexic conditions.2

CB1 is widely expressed throughout the brain and seems to inhibit release of various neurotransmitters.3 How this effect leads to increased appetite is unclear, but it may result from a decrease in the appetite-suppressing effects of hormones such as leptin. In other words, tweaking the CB1 receptor may take the “brakes” off appetite.

Some researchers have speculated that if stimulating CB1 triggers appetite, blocking the receptor might inhibit it (Figure 1).

THE ‘MUNCHIES’ IN MICE

Rimonabant (SR141716), an experimental agent, is a potent and selective CB1 antagonist.

Ravinet Trillou et al fed mice a high-fat diet known to induce obesity.4 The mice were randomized to receive rimonabant or placebo while maintained on the highly palatable diet. The authors asked: Would rimonabant help the mice lose weight even when they could eat as much delicious fatty food as they wanted?

Figure 1 Blocking CB1 may prevent weight gain

Δ9-THC activates the cannabinoid receptor (CB1), stimulating appetite and leading to weight gain in mice (left). When the same receptor is blocked, appetite is controlled (right).

Source: Illustration for CURRENT PSYCHIATRY by Marcia HartsockRimonabant induced a sustained body weight reduction of approximately 20% in the treatment group compared with the placebo group across 5 weeks (Figure 2). Estimated fat stores among the treatment group were depleted by slightly more than 50%.

The authors noted that the mice in the treatment group had decreased their food intake, but the decrease was not sufficient to explain the weight loss. They speculate that rimonabant could activate metabolic processes and decrease intake.

RIMONABANT’S ROLE IN PSYCHIATRY

Phase III human trials of rimonabant are under way for obesity as well as smoking cessation.5 In uncontrolled studies, rimonabant has been shown to help people avoid weight gain while quitting smoking.5

If rimonabant shows effectiveness in controlled trials and is safe in humans, it could be most valuable. Obesity in industrial countries is epidemic and causes serious secondary morbidity, including diabetes, arthritis, and hypertension. Rimonabant, if approved by the FDA, could reach the market by early 2006.6

It is unknown whether rimonabant’s metabolic effects could offset those of many psychotropics. As psychiatrists, we often must stop an effective antipsychotic or antidepressant because it is causing significant weight gain. A treatment that would prevent medication-induced weight gain could improve patient compliance and, ultimately, outcomes.

MANAGING SCHIZOPHRENIA

Some evidence also suggests that rimonabant may offer additional benefits for patients with schizophrenia beyond weight reduction or smoking cessation.

Figure 2 Rimonabant’s effects on weight in mice on a high-fat diet

Source: Adapted from reference 4.Leweke et al found increased endogenous cannabinoids in the CSF of patients with schizophrenia, suggesting that a cannabinoid signaling imbalance may contribute to the disorder’s pathogenesis.7 However, 72 patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who took rimonabant for 6 weeks showed no improvement compared with a placebo group.8

1. Abel EL. Cannabis: effects on hunger and thirst. Behav Biol 1975;15:255-81.

2. Beal JE, Olson R, Laubenstein L, et al. Dronabinol as a treatment for anorexia associated with weight loss in patients with AIDS. J Pain Symptom Manage 1995;10:89-97.

3. Iversen L. Cannabis and the brain. Brain 2003;126:1252-70.

4. Ravinet Trillou C, Arnone M, Delgorge C, et al. Anti-obesity effect of SR141716, a CB1 receptor antagonist, in diet-induced obese mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2003;284:R345-53.

5. Fernandez JR, Allison DB. Rimonabant Sanofi-Synthelabo. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 2004;5:430-5.

6. The Website for the Drug Development Industry. Acomplia (rimonabant)—investigational agent for the management of obesity. London: SPGMedia. Available at: http://www. drugdevelopment-technology.com/projects/rimonabant/. Accessed Oct. 14, 2004.

7. Leweke FM, Giuffrida A, Wurster U, et al. Elevated endogenous cannabinoids in schizophrenia. Neuroreport 1999;10:1665-9.

8. Meltzer HY, Arvanitis L, Bauer D, et al. Placebo-controlled evaluation of four novel compounds for the treatment of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:975-84.

1. Abel EL. Cannabis: effects on hunger and thirst. Behav Biol 1975;15:255-81.

2. Beal JE, Olson R, Laubenstein L, et al. Dronabinol as a treatment for anorexia associated with weight loss in patients with AIDS. J Pain Symptom Manage 1995;10:89-97.

3. Iversen L. Cannabis and the brain. Brain 2003;126:1252-70.

4. Ravinet Trillou C, Arnone M, Delgorge C, et al. Anti-obesity effect of SR141716, a CB1 receptor antagonist, in diet-induced obese mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2003;284:R345-53.

5. Fernandez JR, Allison DB. Rimonabant Sanofi-Synthelabo. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 2004;5:430-5.

6. The Website for the Drug Development Industry. Acomplia (rimonabant)—investigational agent for the management of obesity. London: SPGMedia. Available at: http://www. drugdevelopment-technology.com/projects/rimonabant/. Accessed Oct. 14, 2004.

7. Leweke FM, Giuffrida A, Wurster U, et al. Elevated endogenous cannabinoids in schizophrenia. Neuroreport 1999;10:1665-9.

8. Meltzer HY, Arvanitis L, Bauer D, et al. Placebo-controlled evaluation of four novel compounds for the treatment of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:975-84.

A ‘FRESH’ way to manage trauma

Ameliorating emotional trauma is key to avoiding long-term functional impairment. Consider a FRESH approach that involves families/friends, reassurance/retelling, education, addressing substance abuse, sleeplessness, and suicide risk, and taking a careful history.

Family and friends can be valuable to treatment but clinicians often overlook their importance. Overwhelmed or traumatized family members who are not counseled about the patient’s symptoms can undermine treatment by dismissing symptoms and withdrawing support. Involve them by emphasizing their supportive role. Alert them to normal and problematic trauma responses and stress disorder symptoms.

Reassurance/retelling. Explain that emotional pain is normal but usually fades with time. Consider effects of survivor guilt: Encourage the patient to retell the experience, but do not demand this. Help patients identify and correct thought distortions that foster avoidance. Though controversial,1 critical incident debriefing and cognitive-behavioral therapy can help the patient recount the trauma and ultimately restore a sense of self, enjoyment of life, and expectations of safety, control, and trust.2

Educate patients about normal variable stress responses. Warn traumatized patients against engaging in high-risk behaviors, through which they may try to deny their vulnerability, fear, and loss of control. Explain symptoms and risk factors for depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and other anxiety disorders.

Substance abuse, sleeplessness, and suicide are possible outcomes of trauma. Prescribe a non-narcotic sleep-promoting medication if insomnia is problematic. Alternately, consider a selective serotonin or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor3,4 at normal or low starting dosages if presenting symptoms suggest an emerging anxiety or mood disorder or PTSD. Watch for signs of survivor guilt—such as an unrealistic sense of responsibility for the trauma—that can lead to depression with suicide risk after a significant loss.

History. Watch for factors that predict PTSD and comorbid disorders (trauma severity and chronicity, involvement of interpersonal violence, fear of death). Previous trauma, PTSD, depression, anxiety, personality disorder, childhood victimization, substance abuse, and poor social support increase the risk. Avoidance, numbing, dissociation, high guilt, and low acknowledged anger correlate with increased PTSD risk. Follow up with patients who exhibit these risk factors every 1 to 2 weeks with medication and/or psychotherapy.

1. Cloak NL, Edwards P. Psychological first aid: Emergency care for terrorism and disaster survivors. Current Psychiatry 2004;3(5):12-23.

2. Bisson JI. Early interventions following traumatic events. Psychiatr Ann 2003;1:37-44.

3. Davidson JR, Rothbaum BO, van der Kolk BA, et al. Multicenter, double-blind comparison of sertraline and placebo in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58:485-92.

4. Marshall RD, Beebe KL, Oldham M, et al. Efficacy and safety of paroxetine treatment for chronic PTSD: a fixed-dose, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:1982-8.

Dr. Sobel is a clinical instructor, University of California-San Diego School of Medicine, and consulting psychiatrist, University of San Diego Counseling Center.

Ameliorating emotional trauma is key to avoiding long-term functional impairment. Consider a FRESH approach that involves families/friends, reassurance/retelling, education, addressing substance abuse, sleeplessness, and suicide risk, and taking a careful history.

Family and friends can be valuable to treatment but clinicians often overlook their importance. Overwhelmed or traumatized family members who are not counseled about the patient’s symptoms can undermine treatment by dismissing symptoms and withdrawing support. Involve them by emphasizing their supportive role. Alert them to normal and problematic trauma responses and stress disorder symptoms.

Reassurance/retelling. Explain that emotional pain is normal but usually fades with time. Consider effects of survivor guilt: Encourage the patient to retell the experience, but do not demand this. Help patients identify and correct thought distortions that foster avoidance. Though controversial,1 critical incident debriefing and cognitive-behavioral therapy can help the patient recount the trauma and ultimately restore a sense of self, enjoyment of life, and expectations of safety, control, and trust.2

Educate patients about normal variable stress responses. Warn traumatized patients against engaging in high-risk behaviors, through which they may try to deny their vulnerability, fear, and loss of control. Explain symptoms and risk factors for depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and other anxiety disorders.

Substance abuse, sleeplessness, and suicide are possible outcomes of trauma. Prescribe a non-narcotic sleep-promoting medication if insomnia is problematic. Alternately, consider a selective serotonin or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor3,4 at normal or low starting dosages if presenting symptoms suggest an emerging anxiety or mood disorder or PTSD. Watch for signs of survivor guilt—such as an unrealistic sense of responsibility for the trauma—that can lead to depression with suicide risk after a significant loss.

History. Watch for factors that predict PTSD and comorbid disorders (trauma severity and chronicity, involvement of interpersonal violence, fear of death). Previous trauma, PTSD, depression, anxiety, personality disorder, childhood victimization, substance abuse, and poor social support increase the risk. Avoidance, numbing, dissociation, high guilt, and low acknowledged anger correlate with increased PTSD risk. Follow up with patients who exhibit these risk factors every 1 to 2 weeks with medication and/or psychotherapy.

Ameliorating emotional trauma is key to avoiding long-term functional impairment. Consider a FRESH approach that involves families/friends, reassurance/retelling, education, addressing substance abuse, sleeplessness, and suicide risk, and taking a careful history.

Family and friends can be valuable to treatment but clinicians often overlook their importance. Overwhelmed or traumatized family members who are not counseled about the patient’s symptoms can undermine treatment by dismissing symptoms and withdrawing support. Involve them by emphasizing their supportive role. Alert them to normal and problematic trauma responses and stress disorder symptoms.

Reassurance/retelling. Explain that emotional pain is normal but usually fades with time. Consider effects of survivor guilt: Encourage the patient to retell the experience, but do not demand this. Help patients identify and correct thought distortions that foster avoidance. Though controversial,1 critical incident debriefing and cognitive-behavioral therapy can help the patient recount the trauma and ultimately restore a sense of self, enjoyment of life, and expectations of safety, control, and trust.2

Educate patients about normal variable stress responses. Warn traumatized patients against engaging in high-risk behaviors, through which they may try to deny their vulnerability, fear, and loss of control. Explain symptoms and risk factors for depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and other anxiety disorders.

Substance abuse, sleeplessness, and suicide are possible outcomes of trauma. Prescribe a non-narcotic sleep-promoting medication if insomnia is problematic. Alternately, consider a selective serotonin or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor3,4 at normal or low starting dosages if presenting symptoms suggest an emerging anxiety or mood disorder or PTSD. Watch for signs of survivor guilt—such as an unrealistic sense of responsibility for the trauma—that can lead to depression with suicide risk after a significant loss.

History. Watch for factors that predict PTSD and comorbid disorders (trauma severity and chronicity, involvement of interpersonal violence, fear of death). Previous trauma, PTSD, depression, anxiety, personality disorder, childhood victimization, substance abuse, and poor social support increase the risk. Avoidance, numbing, dissociation, high guilt, and low acknowledged anger correlate with increased PTSD risk. Follow up with patients who exhibit these risk factors every 1 to 2 weeks with medication and/or psychotherapy.

1. Cloak NL, Edwards P. Psychological first aid: Emergency care for terrorism and disaster survivors. Current Psychiatry 2004;3(5):12-23.

2. Bisson JI. Early interventions following traumatic events. Psychiatr Ann 2003;1:37-44.

3. Davidson JR, Rothbaum BO, van der Kolk BA, et al. Multicenter, double-blind comparison of sertraline and placebo in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58:485-92.

4. Marshall RD, Beebe KL, Oldham M, et al. Efficacy and safety of paroxetine treatment for chronic PTSD: a fixed-dose, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:1982-8.

Dr. Sobel is a clinical instructor, University of California-San Diego School of Medicine, and consulting psychiatrist, University of San Diego Counseling Center.

1. Cloak NL, Edwards P. Psychological first aid: Emergency care for terrorism and disaster survivors. Current Psychiatry 2004;3(5):12-23.

2. Bisson JI. Early interventions following traumatic events. Psychiatr Ann 2003;1:37-44.

3. Davidson JR, Rothbaum BO, van der Kolk BA, et al. Multicenter, double-blind comparison of sertraline and placebo in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58:485-92.

4. Marshall RD, Beebe KL, Oldham M, et al. Efficacy and safety of paroxetine treatment for chronic PTSD: a fixed-dose, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:1982-8.

Dr. Sobel is a clinical instructor, University of California-San Diego School of Medicine, and consulting psychiatrist, University of San Diego Counseling Center.

Liability in patient suicide

Clinical psychiatrists often find it hard to evaluate suicide risk and understand their potential legal liability. Prevalence of suicidality compounds this challenge: Up to one-third of the general population in the United States have suicidal thoughts at some point.1 Although most people who consider suicide do not act on those thoughts, 51% of psychiatrists report having had a patient who committed suicide.2

Because patient suicide risk is real, psychiatrists often worry about malpractice claims. Although post-suicide lawsuits account for the largest number of malpractice suits against psychiatrists,3,4 a psychiatrist’s risk of being sued for malpractice is still quite low.3 Even when sued, clinicians win up to 80% of cases.3

Still, with malpractice claims increasing overall, clinicians should understand their potential liability in preventing suicide and the basic principles behind a malpractice claim.

Patient jumps from window after suicide watch is called off

Los Angeles County (CA) superior court

A 24-year-old man was hospitalized after attempting suicide by ingesting prescription pills and alcohol. He was admitted to the general medical floor with a 24-hour sitter to guard against additional suicide attempts. When the psychiatrist tried to evaluate him, he found the patient unresponsive because of the pills’ effects.

The next day, the psychiatrist evaluated the patient and recommended that the patient be transferred to the psychiatric unit and that the sitter be continued. Four hours later, without a further evaluation, the psychiatrist recommended moving the patient to another room and canceling the sitter.

The next day, the patient jumped from his sixth-floor hospital room window. He sustained traumatic brain injury.

The patient’s guardian ad litem argued that discontinuing the sitter was negligent. The defendant argued that discontinuation was within the parameters of proper care.

- The jury found for the defense.

Patient commits suicide hours after ER discharge

Lake County (IL) circuit court

A 36-year-old man was being treated by a psychiatrist for major depressive disorder. The patient owned several guns for hunting and target shooting and had a state-issued firearm owner’s identification card.

In October 2003, the patient presented to the emergency room and was examined by a mental health assessment staff. The psychiatrist recommended voluntary admission to the psychiatric unit for 23 hours.

The patient’s father discouraged the admission and stated that the patient could lose his gun owner’s card as a result. The patient was subsequently discharged. Within 24 hours after discharge, the patient shot himself in the chest and died.

The deceased’s estate argued that the psychiatrist should have admitted the patient involuntarily. The psychiatrist claimed no obligation to involuntary admission and argued that the patient did not meet criteria typically used for such admission.

- The jury found for the defense.

Doctor’s hanging attempt in hospital causes permanent brain damage

Morris County (NJ) district court

A cardiologist was admitted to the hospital’s psychiatric unit after decompensating. While hospitalized, he attempted suicide by hanging in a clinic bathroom. He suffered permanent brain injury as a result of the hanging. Because the injury left him in a childlike state, he required constant care.

The patient’s attorney argued that hospital personnel knew he was suicidal yet did not adequately supervise him. The attorney also argued that the injury cost his client $5 million in lost income.

The defense reported that the hospital had placed the patient on suicide watch and that staff checked him every 5 minutes. The defense also argued that the bathroom where the suicide was attempted was impossible to monitor.

- The jury found for the defense.

Dr. Grant’s observations

To win a malpractice claim, the injured party must show four things:

Duty to care for the patient existed based on the provider’s relationship with the patient. Whether on a hospital floor or in the emergency room, once a doctor-patient relationship has been established, the provider agrees to provide non-negligent care.

Negligence. The physician or hospital personnel acted negligently and violated the duty of care. This concept is based upon a “standard of care” —ie, what other psychiatrists would do in this situation.

Harm. Even if someone has acted negligently, a malpractice case cannot go forward if no harm has been suffered.

Causation. The negligent act caused the harm.

The defendants most likely won the cases cited above because the injured parties could not establish negligence. Clinicians are not negligent for merely failing to predict suicide, as the inability to predict suicide has been demonstrated.5,6 Clinicians, however, must follow the profession’s standard of care, assess the relative degree of risk, and form a treatment and safety plan consistent with that risk.4

Based on relevant case law, the following actions can decrease the risk of patient suicide—and a resultant malpractice claim:

- Conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the patient and his or her suicide risk. Ask about:

- Consider hospitalizing at-risk patients. If you decide against hospitalization, provide a comprehensive safety plan. In the gun owner’s case, such a plan would include arranging with the family to remove firearms. Implement additional anti-suicide precautions, such as more-intensive outpatient therapy or involving family members in treatment.

- Document suicide risk assessment and the reasons for your treatment decisions. Juries may interpret lack of documented information in the patient’s favor.

- Design a treatment plan for hospitalized patients to reduce suicide risk. Consider the patient’s reaction to constant surveillance. For example, checking a paranoid patient every 5 minutes may be more therapeutic than a constant watch while providing adequate safety. Thoroughly document your reasons behind the plan.

1. Hirschfeld RMA, Russell JM. Assessment and treatment of suicidal patients. N Engl J Med 1997;337:910-5.

2. Chemtob CM, Hamada RS, Bauer GB, et al. Patient suicide: frequency and impact on psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry 1988;145:224-8.

3. Baerger DR. Risk management with the suicidal patient: lessons from case law. Prof Psychol Res Pract 2001;32:359-66.

4. Packman WL, O’Connor Pennuto T, Bongar B, Orthwein J. Legal issues of professional negligence in suicide cases. Behav Sci Law 2004;22:697-713.

5. Pokorny AD. Prediction of suicide in psychiatric patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983;40:249-57.

6. Pokorny AD. Suicide prediction revisited. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1993;23:1-10.

7. Bell v. New York City Health and Hospitals Corp., 456 NYS 2d 787 (App. Div. 1982).

8. Simon RI. The suicidal patient. In: Lifson LE, Simon SI (eds). The mental health practitioner and the law: A comprehensive handbook. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998;166-86.

Clinical psychiatrists often find it hard to evaluate suicide risk and understand their potential legal liability. Prevalence of suicidality compounds this challenge: Up to one-third of the general population in the United States have suicidal thoughts at some point.1 Although most people who consider suicide do not act on those thoughts, 51% of psychiatrists report having had a patient who committed suicide.2

Because patient suicide risk is real, psychiatrists often worry about malpractice claims. Although post-suicide lawsuits account for the largest number of malpractice suits against psychiatrists,3,4 a psychiatrist’s risk of being sued for malpractice is still quite low.3 Even when sued, clinicians win up to 80% of cases.3

Still, with malpractice claims increasing overall, clinicians should understand their potential liability in preventing suicide and the basic principles behind a malpractice claim.

Patient jumps from window after suicide watch is called off

Los Angeles County (CA) superior court

A 24-year-old man was hospitalized after attempting suicide by ingesting prescription pills and alcohol. He was admitted to the general medical floor with a 24-hour sitter to guard against additional suicide attempts. When the psychiatrist tried to evaluate him, he found the patient unresponsive because of the pills’ effects.

The next day, the psychiatrist evaluated the patient and recommended that the patient be transferred to the psychiatric unit and that the sitter be continued. Four hours later, without a further evaluation, the psychiatrist recommended moving the patient to another room and canceling the sitter.

The next day, the patient jumped from his sixth-floor hospital room window. He sustained traumatic brain injury.

The patient’s guardian ad litem argued that discontinuing the sitter was negligent. The defendant argued that discontinuation was within the parameters of proper care.

- The jury found for the defense.

Patient commits suicide hours after ER discharge

Lake County (IL) circuit court

A 36-year-old man was being treated by a psychiatrist for major depressive disorder. The patient owned several guns for hunting and target shooting and had a state-issued firearm owner’s identification card.

In October 2003, the patient presented to the emergency room and was examined by a mental health assessment staff. The psychiatrist recommended voluntary admission to the psychiatric unit for 23 hours.

The patient’s father discouraged the admission and stated that the patient could lose his gun owner’s card as a result. The patient was subsequently discharged. Within 24 hours after discharge, the patient shot himself in the chest and died.

The deceased’s estate argued that the psychiatrist should have admitted the patient involuntarily. The psychiatrist claimed no obligation to involuntary admission and argued that the patient did not meet criteria typically used for such admission.

- The jury found for the defense.

Doctor’s hanging attempt in hospital causes permanent brain damage

Morris County (NJ) district court

A cardiologist was admitted to the hospital’s psychiatric unit after decompensating. While hospitalized, he attempted suicide by hanging in a clinic bathroom. He suffered permanent brain injury as a result of the hanging. Because the injury left him in a childlike state, he required constant care.

The patient’s attorney argued that hospital personnel knew he was suicidal yet did not adequately supervise him. The attorney also argued that the injury cost his client $5 million in lost income.

The defense reported that the hospital had placed the patient on suicide watch and that staff checked him every 5 minutes. The defense also argued that the bathroom where the suicide was attempted was impossible to monitor.

- The jury found for the defense.

Dr. Grant’s observations

To win a malpractice claim, the injured party must show four things:

Duty to care for the patient existed based on the provider’s relationship with the patient. Whether on a hospital floor or in the emergency room, once a doctor-patient relationship has been established, the provider agrees to provide non-negligent care.

Negligence. The physician or hospital personnel acted negligently and violated the duty of care. This concept is based upon a “standard of care” —ie, what other psychiatrists would do in this situation.

Harm. Even if someone has acted negligently, a malpractice case cannot go forward if no harm has been suffered.

Causation. The negligent act caused the harm.

The defendants most likely won the cases cited above because the injured parties could not establish negligence. Clinicians are not negligent for merely failing to predict suicide, as the inability to predict suicide has been demonstrated.5,6 Clinicians, however, must follow the profession’s standard of care, assess the relative degree of risk, and form a treatment and safety plan consistent with that risk.4

Based on relevant case law, the following actions can decrease the risk of patient suicide—and a resultant malpractice claim:

- Conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the patient and his or her suicide risk. Ask about:

- Consider hospitalizing at-risk patients. If you decide against hospitalization, provide a comprehensive safety plan. In the gun owner’s case, such a plan would include arranging with the family to remove firearms. Implement additional anti-suicide precautions, such as more-intensive outpatient therapy or involving family members in treatment.

- Document suicide risk assessment and the reasons for your treatment decisions. Juries may interpret lack of documented information in the patient’s favor.

- Design a treatment plan for hospitalized patients to reduce suicide risk. Consider the patient’s reaction to constant surveillance. For example, checking a paranoid patient every 5 minutes may be more therapeutic than a constant watch while providing adequate safety. Thoroughly document your reasons behind the plan.

Clinical psychiatrists often find it hard to evaluate suicide risk and understand their potential legal liability. Prevalence of suicidality compounds this challenge: Up to one-third of the general population in the United States have suicidal thoughts at some point.1 Although most people who consider suicide do not act on those thoughts, 51% of psychiatrists report having had a patient who committed suicide.2

Because patient suicide risk is real, psychiatrists often worry about malpractice claims. Although post-suicide lawsuits account for the largest number of malpractice suits against psychiatrists,3,4 a psychiatrist’s risk of being sued for malpractice is still quite low.3 Even when sued, clinicians win up to 80% of cases.3

Still, with malpractice claims increasing overall, clinicians should understand their potential liability in preventing suicide and the basic principles behind a malpractice claim.

Patient jumps from window after suicide watch is called off

Los Angeles County (CA) superior court

A 24-year-old man was hospitalized after attempting suicide by ingesting prescription pills and alcohol. He was admitted to the general medical floor with a 24-hour sitter to guard against additional suicide attempts. When the psychiatrist tried to evaluate him, he found the patient unresponsive because of the pills’ effects.

The next day, the psychiatrist evaluated the patient and recommended that the patient be transferred to the psychiatric unit and that the sitter be continued. Four hours later, without a further evaluation, the psychiatrist recommended moving the patient to another room and canceling the sitter.

The next day, the patient jumped from his sixth-floor hospital room window. He sustained traumatic brain injury.

The patient’s guardian ad litem argued that discontinuing the sitter was negligent. The defendant argued that discontinuation was within the parameters of proper care.

- The jury found for the defense.

Patient commits suicide hours after ER discharge

Lake County (IL) circuit court

A 36-year-old man was being treated by a psychiatrist for major depressive disorder. The patient owned several guns for hunting and target shooting and had a state-issued firearm owner’s identification card.

In October 2003, the patient presented to the emergency room and was examined by a mental health assessment staff. The psychiatrist recommended voluntary admission to the psychiatric unit for 23 hours.

The patient’s father discouraged the admission and stated that the patient could lose his gun owner’s card as a result. The patient was subsequently discharged. Within 24 hours after discharge, the patient shot himself in the chest and died.

The deceased’s estate argued that the psychiatrist should have admitted the patient involuntarily. The psychiatrist claimed no obligation to involuntary admission and argued that the patient did not meet criteria typically used for such admission.

- The jury found for the defense.

Doctor’s hanging attempt in hospital causes permanent brain damage

Morris County (NJ) district court

A cardiologist was admitted to the hospital’s psychiatric unit after decompensating. While hospitalized, he attempted suicide by hanging in a clinic bathroom. He suffered permanent brain injury as a result of the hanging. Because the injury left him in a childlike state, he required constant care.

The patient’s attorney argued that hospital personnel knew he was suicidal yet did not adequately supervise him. The attorney also argued that the injury cost his client $5 million in lost income.

The defense reported that the hospital had placed the patient on suicide watch and that staff checked him every 5 minutes. The defense also argued that the bathroom where the suicide was attempted was impossible to monitor.

- The jury found for the defense.

Dr. Grant’s observations

To win a malpractice claim, the injured party must show four things:

Duty to care for the patient existed based on the provider’s relationship with the patient. Whether on a hospital floor or in the emergency room, once a doctor-patient relationship has been established, the provider agrees to provide non-negligent care.

Negligence. The physician or hospital personnel acted negligently and violated the duty of care. This concept is based upon a “standard of care” —ie, what other psychiatrists would do in this situation.

Harm. Even if someone has acted negligently, a malpractice case cannot go forward if no harm has been suffered.

Causation. The negligent act caused the harm.

The defendants most likely won the cases cited above because the injured parties could not establish negligence. Clinicians are not negligent for merely failing to predict suicide, as the inability to predict suicide has been demonstrated.5,6 Clinicians, however, must follow the profession’s standard of care, assess the relative degree of risk, and form a treatment and safety plan consistent with that risk.4

Based on relevant case law, the following actions can decrease the risk of patient suicide—and a resultant malpractice claim:

- Conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the patient and his or her suicide risk. Ask about:

- Consider hospitalizing at-risk patients. If you decide against hospitalization, provide a comprehensive safety plan. In the gun owner’s case, such a plan would include arranging with the family to remove firearms. Implement additional anti-suicide precautions, such as more-intensive outpatient therapy or involving family members in treatment.

- Document suicide risk assessment and the reasons for your treatment decisions. Juries may interpret lack of documented information in the patient’s favor.

- Design a treatment plan for hospitalized patients to reduce suicide risk. Consider the patient’s reaction to constant surveillance. For example, checking a paranoid patient every 5 minutes may be more therapeutic than a constant watch while providing adequate safety. Thoroughly document your reasons behind the plan.

1. Hirschfeld RMA, Russell JM. Assessment and treatment of suicidal patients. N Engl J Med 1997;337:910-5.

2. Chemtob CM, Hamada RS, Bauer GB, et al. Patient suicide: frequency and impact on psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry 1988;145:224-8.

3. Baerger DR. Risk management with the suicidal patient: lessons from case law. Prof Psychol Res Pract 2001;32:359-66.

4. Packman WL, O’Connor Pennuto T, Bongar B, Orthwein J. Legal issues of professional negligence in suicide cases. Behav Sci Law 2004;22:697-713.

5. Pokorny AD. Prediction of suicide in psychiatric patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983;40:249-57.

6. Pokorny AD. Suicide prediction revisited. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1993;23:1-10.

7. Bell v. New York City Health and Hospitals Corp., 456 NYS 2d 787 (App. Div. 1982).

8. Simon RI. The suicidal patient. In: Lifson LE, Simon SI (eds). The mental health practitioner and the law: A comprehensive handbook. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998;166-86.

1. Hirschfeld RMA, Russell JM. Assessment and treatment of suicidal patients. N Engl J Med 1997;337:910-5.

2. Chemtob CM, Hamada RS, Bauer GB, et al. Patient suicide: frequency and impact on psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry 1988;145:224-8.

3. Baerger DR. Risk management with the suicidal patient: lessons from case law. Prof Psychol Res Pract 2001;32:359-66.

4. Packman WL, O’Connor Pennuto T, Bongar B, Orthwein J. Legal issues of professional negligence in suicide cases. Behav Sci Law 2004;22:697-713.

5. Pokorny AD. Prediction of suicide in psychiatric patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983;40:249-57.

6. Pokorny AD. Suicide prediction revisited. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1993;23:1-10.

7. Bell v. New York City Health and Hospitals Corp., 456 NYS 2d 787 (App. Div. 1982).

8. Simon RI. The suicidal patient. In: Lifson LE, Simon SI (eds). The mental health practitioner and the law: A comprehensive handbook. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998;166-86.