User login

Applications of office hysteroscopy for the infertility patient

What role does diagnostic office hysteroscopy play in an infertility evaluation?

.1

More specifically, hysteroscopy is the gold standard for assessing the uterine cavity. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive and negative predictive values of hysterosalpingography (HSG) in evaluating uterine cavity abnormalities were 44.83%; 86.67%; 56.52%; and 80.25%, respectively.2 Given the poor sensitivity of HSG, a diagnosis of endometrial polyps and/or chronic endometritis is more likely to be missed.

Our crossover trial comparing HSG to office hysteroscopy for tubal patency showed that women were 110 times more likely to have the maximum level of pain with HSG than diagnostic hysteroscopy when using a 2.8-mm flexible hysteroscope.3 Further, infection rates and vasovagal events were far lower with hysteroscopy.1

Finally, compared with HSG, we showed 98%-100% sensitivity and 84% specificity for tubal occlusion with hysteroscopy by air-infused saline. Conversely, HSG typically is associated with 76%-96% sensitivity and 67%-100% specificity.4 Additionally, we can often perform diagnostic hysteroscopies for approximately $35 per procedure for total fixed and disposable equipment costs.

How should physicians perform office hysteroscopy to minimize patient discomfort?

The classic paradigm has been to focus on paracervical blocks, anxiolytics, and a supportive environment (such as mood music). However, those are far more important when your hysteroscope is larger than the natural cervical lumen. If you can use small hysteroscopes (< 3 mm for the nulliparous cervix, < 4 mm for the parous cervix), most women will not require cervical dilation, which further enhances the patient experience.

Using a flexible hysteroscope for suspected pathology, making sure not to overdistend the uterus (particularly in high-risk patients such as those with tubal occlusion and cervical stenosis), and vaginoscopy can all minimize patient discomfort. We have published data showing that by using a 2.8-mm flexible diagnostic hysteroscope in a group of mostly nulliparous women, greater than 50% have no discomfort, and more than 90% will have mild to no discomfort.3

What operative hysteroscopy procedures can be performed safely in a physician’s office, and what equipment is required?

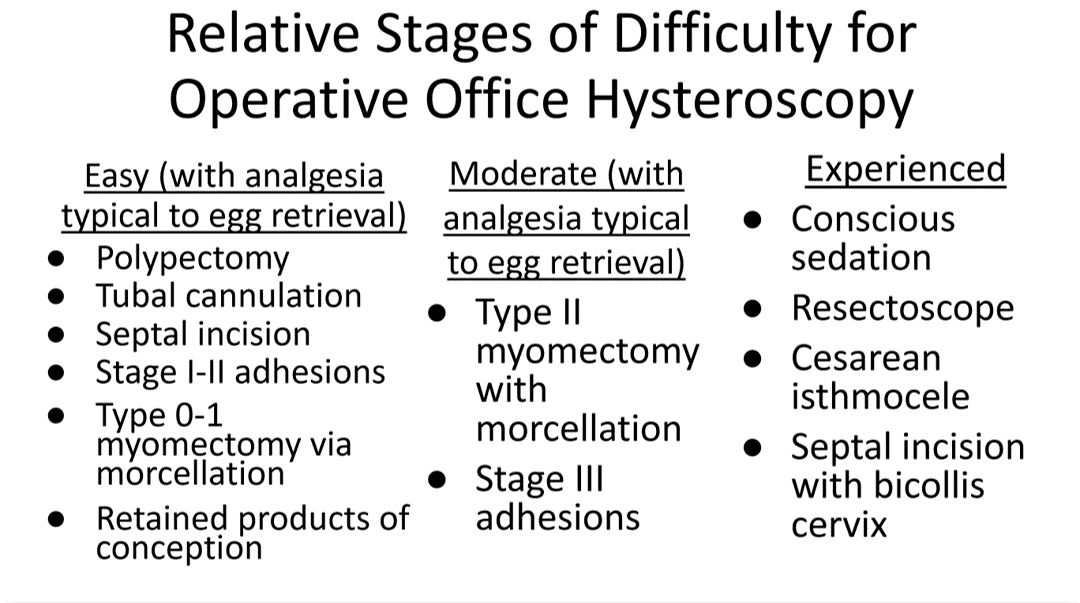

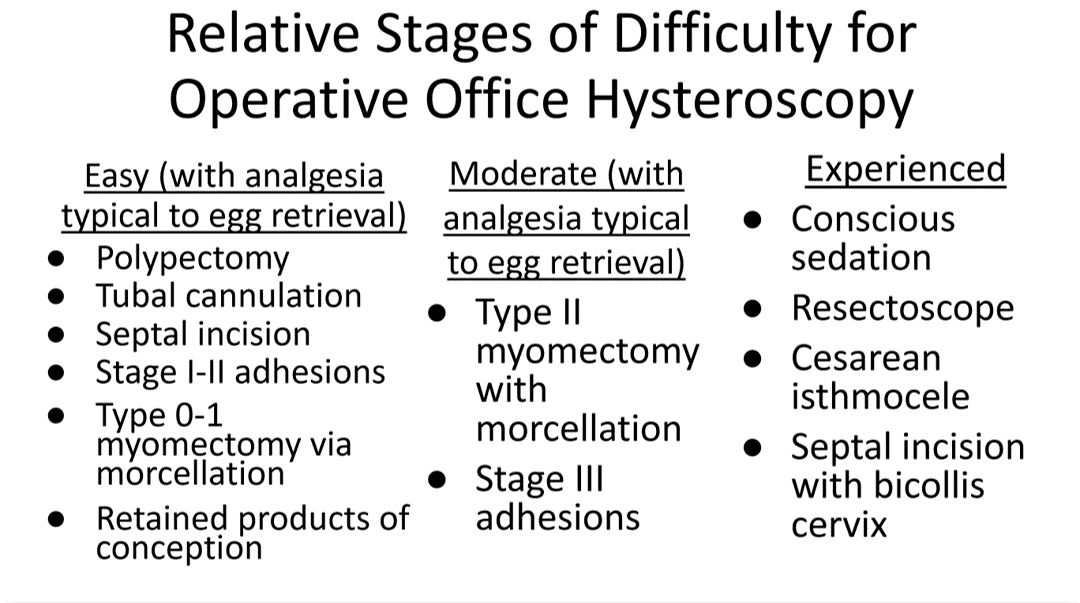

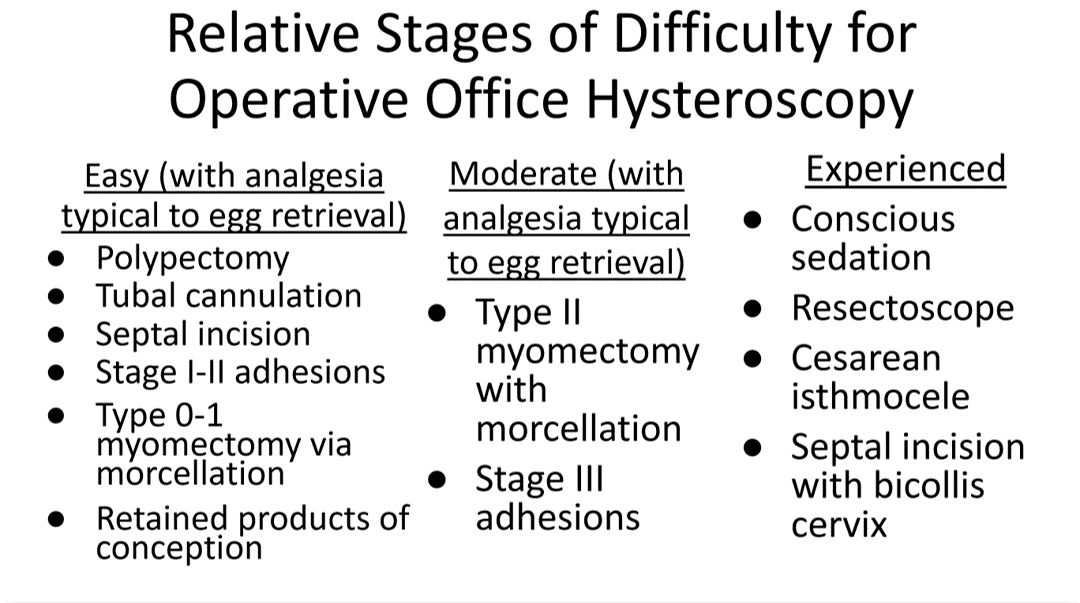

Though highly dependent on experience and resources, reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialists (REIs) arguably have the easiest transition to operative office hysteroscopy by utilizing the analgesia and procedure room that is standard for oocyte retrieval and simply adding hysteroscopic procedures. The accompanying table stratifies general hysteroscopic procedures by difficulty.

If one can use propofol or a similar level of sedation (which is routinely utilized for oocyte aspiration), there are few hysteroscopies that cannot be accomplished in the office. However, the less sedation and analgesia, the more judicious one must be in patient selection. Moreover, there are trade-offs between visualization, comfort, and instrumentation.

The greater the uterine distention and diameter of the hysteroscope, the more patients experience pain. One-third of patients (especially nulliparous) will discontinue a procedure with a 5-mm hysteroscope because of discomfort.5 However, as one drops to 4.5 mm and smaller operative hysteroscopes, instruments often occupy the inflow channel, limiting distention and visualization, which also can affect completion rates and safety.

When is operative hysteroscopy best suited for the OR?

In addition to physician experience and clinical resources, the critical factors guiding our choices for selecting the OR rather than the office, include:

- Loss of landmarks. Though Dr. Parry now does most severe intrauterine adhesion cases in the office with ultrasound guidance, when neither ostia can be visualized there is meaningful risk for perforation. Preoperative estrogen, development of planes with the diagnostic hysteroscope prior, and preparing the patient for a possible multistage procedure are all important.

- Use of energy. There are many excellent hysteroscopic surgeons who use the resectoscope well in the office. However, with possible patient movement and potential perforation with energy leading to a bowel injury, there can be greater risk when using energy relative to other methods (such as forceps, scissors, and mechanical morcellation).

- Deeper fibroids. Fibroids displace rather than invade the myometrium, and one can sonographically visualize the myometrium reapproximate over a fibroid as it herniates more into the uterine cavity. Nevertheless, the closer a fibroid comes to the serosa, the more mindful one should be of risks and balances for hysteroscopic removal.

In a patient with a severely stenotic cervix or tortuous endocervical canal, what preprocedure methods do you find helpful, and do you utilize abdominal ultrasound guidance?

If using a 2.8-mm flexible diagnostic hysteroscope, we find 99.8%-99.9% of cervices can be successfully cannulated in the office, with rare exception, that is, following cryotherapy or chlamydia cervicitis. This is the equivalent of your dilator having a camera on the tip and fully articulating to adjust to the cervical path.

Transvaginal sonography prior to hysteroscopy where one maps the cervical lumen helps anticipate problems (along with being familiar with the patient’s history). For the rare dilation under anesthesia, concurrent sonography with a 2.8-mm flexible hysteroscope and intermittent dilator use has been sufficient for our exceptions without the need for lacrimal dilators, vasopressin, misoprostol, and other adjuncts. Of note, we use a 1080p flexible endoscope, as lower resolution would make this more challenging.

In patients with recurrent implantation failure following IVF, is hysteroscopy superior to 3D saline infusion sonogram?

At an American Society of Reproductive Medicine 2021 session, Ilan Tur-Kaspa, MD, and Dr. Parry debated the topic of 2D ultrasound combined with hysteroscopy vs. 3D saline infusion sonography. Core areas of agreement were that expert hands for any approach are better than nonexpert, and high-resolution technology is better than lower resolution. There was also agreement that extrauterine and myometrial disease, such as intramural fibroids and adenomyosis, are contributory factors.

So, sonography will always have a role. However, existing and forthcoming data show hysteroscopy to improve live birth rates for patients with recurrent implantation failure after IVF. Dr. Parry finds diagnostic hysteroscopy easier for identifying endometritis, sessile and cornual polyps, retained products of conception (which are often isoechogenic with the endometrium) and lateral adhesions.

The reality is that there is variability among physicians and midlevel providers in both sonographic and diagnostic hysteroscopic skill. If one wants to verify findings with another team member, acknowledging that there can be nuances to identifying these pathologies by sonography, it is easier to share and discuss findings through hysteroscopic video than sonographic records.

When is endometrial biopsy indicated during office hysteroscopy?

The patients of an REI are very unlikely to have endometrial cancer (or even hyperplasia) outside of polyps (or arguably hypervascular areas of overgrowth), so the focus is on resecting visualized pathology relative to random biopsy.

However, the threshold for biopsy should be adjusted to the patient population, as well as to individual findings and risk. RVUs are greatly increased (11.1 > 41.57) with biopsy, helping sustainability. Additionally, if one places the hysteroscope on endometrium and applies suction through the inflow channel, one can obtain a sample with small-caliber diagnostic hysteroscopes and without having to use forceps.

What is your threshold for fluid deficit in hysteroscopy?

We follow AAGL guidelines, which for operative hysteroscopy are 2,500 mL of isotonic fluids or 1,000 mL of hypotonic fluids in low-risk patients. This should be further reduced to 500 mL of isotonic fluids in the elderly and even 300 mL in those with cardiovascular compromise.6

For patients who request sedation for office hysteroscopy, which option do you recommend – paracervical block alone, nitrous oxide, or the combination?

For diagnostic, greater than 95% of our patients do not require even over-the-counter analgesic medications. For operative, we consider all permissible resources that allow for a safe combination that is appropriate to the pathology and clinical setting, such as paracervical blocks, nitrous oxide, NSAIDs such as ketorolac, anxiolytics, and more.

The goal is to optimize the patient experience. However, the top three criteria that influence successful operative office hysteroscopy for a conscious patient are a parous cervix, judicious patient selection, and pre- and intraoperative verbal analgesia. Informed consent and engagement improve the experience of both the patient and physician.

Dr. Parry is the founder of Positive Steps Fertility in Madison, Miss. Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

References

1. Parry JP et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017 May-Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2017.02.010.

2. Wadhwa L et al. 2017 Apr-Jun. doi: 10.4103/jhrs.JHRS_123_16.

3. Parry JP et al. Fertil Steril. 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.07.1159.

4. Penzias A et al. Fertil Steril. 2021 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.08.038.

5. Campo R et al. Hum Reprod. 2005 Jan;20(1):258-63. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh559.

6. AAGL AAGL practice report: Practice guidelines for the management of hysteroscopic distending media. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013 Mar-Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2012.12.002.

What role does diagnostic office hysteroscopy play in an infertility evaluation?

.1

More specifically, hysteroscopy is the gold standard for assessing the uterine cavity. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive and negative predictive values of hysterosalpingography (HSG) in evaluating uterine cavity abnormalities were 44.83%; 86.67%; 56.52%; and 80.25%, respectively.2 Given the poor sensitivity of HSG, a diagnosis of endometrial polyps and/or chronic endometritis is more likely to be missed.

Our crossover trial comparing HSG to office hysteroscopy for tubal patency showed that women were 110 times more likely to have the maximum level of pain with HSG than diagnostic hysteroscopy when using a 2.8-mm flexible hysteroscope.3 Further, infection rates and vasovagal events were far lower with hysteroscopy.1

Finally, compared with HSG, we showed 98%-100% sensitivity and 84% specificity for tubal occlusion with hysteroscopy by air-infused saline. Conversely, HSG typically is associated with 76%-96% sensitivity and 67%-100% specificity.4 Additionally, we can often perform diagnostic hysteroscopies for approximately $35 per procedure for total fixed and disposable equipment costs.

How should physicians perform office hysteroscopy to minimize patient discomfort?

The classic paradigm has been to focus on paracervical blocks, anxiolytics, and a supportive environment (such as mood music). However, those are far more important when your hysteroscope is larger than the natural cervical lumen. If you can use small hysteroscopes (< 3 mm for the nulliparous cervix, < 4 mm for the parous cervix), most women will not require cervical dilation, which further enhances the patient experience.

Using a flexible hysteroscope for suspected pathology, making sure not to overdistend the uterus (particularly in high-risk patients such as those with tubal occlusion and cervical stenosis), and vaginoscopy can all minimize patient discomfort. We have published data showing that by using a 2.8-mm flexible diagnostic hysteroscope in a group of mostly nulliparous women, greater than 50% have no discomfort, and more than 90% will have mild to no discomfort.3

What operative hysteroscopy procedures can be performed safely in a physician’s office, and what equipment is required?

Though highly dependent on experience and resources, reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialists (REIs) arguably have the easiest transition to operative office hysteroscopy by utilizing the analgesia and procedure room that is standard for oocyte retrieval and simply adding hysteroscopic procedures. The accompanying table stratifies general hysteroscopic procedures by difficulty.

If one can use propofol or a similar level of sedation (which is routinely utilized for oocyte aspiration), there are few hysteroscopies that cannot be accomplished in the office. However, the less sedation and analgesia, the more judicious one must be in patient selection. Moreover, there are trade-offs between visualization, comfort, and instrumentation.

The greater the uterine distention and diameter of the hysteroscope, the more patients experience pain. One-third of patients (especially nulliparous) will discontinue a procedure with a 5-mm hysteroscope because of discomfort.5 However, as one drops to 4.5 mm and smaller operative hysteroscopes, instruments often occupy the inflow channel, limiting distention and visualization, which also can affect completion rates and safety.

When is operative hysteroscopy best suited for the OR?

In addition to physician experience and clinical resources, the critical factors guiding our choices for selecting the OR rather than the office, include:

- Loss of landmarks. Though Dr. Parry now does most severe intrauterine adhesion cases in the office with ultrasound guidance, when neither ostia can be visualized there is meaningful risk for perforation. Preoperative estrogen, development of planes with the diagnostic hysteroscope prior, and preparing the patient for a possible multistage procedure are all important.

- Use of energy. There are many excellent hysteroscopic surgeons who use the resectoscope well in the office. However, with possible patient movement and potential perforation with energy leading to a bowel injury, there can be greater risk when using energy relative to other methods (such as forceps, scissors, and mechanical morcellation).

- Deeper fibroids. Fibroids displace rather than invade the myometrium, and one can sonographically visualize the myometrium reapproximate over a fibroid as it herniates more into the uterine cavity. Nevertheless, the closer a fibroid comes to the serosa, the more mindful one should be of risks and balances for hysteroscopic removal.

In a patient with a severely stenotic cervix or tortuous endocervical canal, what preprocedure methods do you find helpful, and do you utilize abdominal ultrasound guidance?

If using a 2.8-mm flexible diagnostic hysteroscope, we find 99.8%-99.9% of cervices can be successfully cannulated in the office, with rare exception, that is, following cryotherapy or chlamydia cervicitis. This is the equivalent of your dilator having a camera on the tip and fully articulating to adjust to the cervical path.

Transvaginal sonography prior to hysteroscopy where one maps the cervical lumen helps anticipate problems (along with being familiar with the patient’s history). For the rare dilation under anesthesia, concurrent sonography with a 2.8-mm flexible hysteroscope and intermittent dilator use has been sufficient for our exceptions without the need for lacrimal dilators, vasopressin, misoprostol, and other adjuncts. Of note, we use a 1080p flexible endoscope, as lower resolution would make this more challenging.

In patients with recurrent implantation failure following IVF, is hysteroscopy superior to 3D saline infusion sonogram?

At an American Society of Reproductive Medicine 2021 session, Ilan Tur-Kaspa, MD, and Dr. Parry debated the topic of 2D ultrasound combined with hysteroscopy vs. 3D saline infusion sonography. Core areas of agreement were that expert hands for any approach are better than nonexpert, and high-resolution technology is better than lower resolution. There was also agreement that extrauterine and myometrial disease, such as intramural fibroids and adenomyosis, are contributory factors.

So, sonography will always have a role. However, existing and forthcoming data show hysteroscopy to improve live birth rates for patients with recurrent implantation failure after IVF. Dr. Parry finds diagnostic hysteroscopy easier for identifying endometritis, sessile and cornual polyps, retained products of conception (which are often isoechogenic with the endometrium) and lateral adhesions.

The reality is that there is variability among physicians and midlevel providers in both sonographic and diagnostic hysteroscopic skill. If one wants to verify findings with another team member, acknowledging that there can be nuances to identifying these pathologies by sonography, it is easier to share and discuss findings through hysteroscopic video than sonographic records.

When is endometrial biopsy indicated during office hysteroscopy?

The patients of an REI are very unlikely to have endometrial cancer (or even hyperplasia) outside of polyps (or arguably hypervascular areas of overgrowth), so the focus is on resecting visualized pathology relative to random biopsy.

However, the threshold for biopsy should be adjusted to the patient population, as well as to individual findings and risk. RVUs are greatly increased (11.1 > 41.57) with biopsy, helping sustainability. Additionally, if one places the hysteroscope on endometrium and applies suction through the inflow channel, one can obtain a sample with small-caliber diagnostic hysteroscopes and without having to use forceps.

What is your threshold for fluid deficit in hysteroscopy?

We follow AAGL guidelines, which for operative hysteroscopy are 2,500 mL of isotonic fluids or 1,000 mL of hypotonic fluids in low-risk patients. This should be further reduced to 500 mL of isotonic fluids in the elderly and even 300 mL in those with cardiovascular compromise.6

For patients who request sedation for office hysteroscopy, which option do you recommend – paracervical block alone, nitrous oxide, or the combination?

For diagnostic, greater than 95% of our patients do not require even over-the-counter analgesic medications. For operative, we consider all permissible resources that allow for a safe combination that is appropriate to the pathology and clinical setting, such as paracervical blocks, nitrous oxide, NSAIDs such as ketorolac, anxiolytics, and more.

The goal is to optimize the patient experience. However, the top three criteria that influence successful operative office hysteroscopy for a conscious patient are a parous cervix, judicious patient selection, and pre- and intraoperative verbal analgesia. Informed consent and engagement improve the experience of both the patient and physician.

Dr. Parry is the founder of Positive Steps Fertility in Madison, Miss. Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

References

1. Parry JP et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017 May-Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2017.02.010.

2. Wadhwa L et al. 2017 Apr-Jun. doi: 10.4103/jhrs.JHRS_123_16.

3. Parry JP et al. Fertil Steril. 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.07.1159.

4. Penzias A et al. Fertil Steril. 2021 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.08.038.

5. Campo R et al. Hum Reprod. 2005 Jan;20(1):258-63. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh559.

6. AAGL AAGL practice report: Practice guidelines for the management of hysteroscopic distending media. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013 Mar-Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2012.12.002.

What role does diagnostic office hysteroscopy play in an infertility evaluation?

.1

More specifically, hysteroscopy is the gold standard for assessing the uterine cavity. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive and negative predictive values of hysterosalpingography (HSG) in evaluating uterine cavity abnormalities were 44.83%; 86.67%; 56.52%; and 80.25%, respectively.2 Given the poor sensitivity of HSG, a diagnosis of endometrial polyps and/or chronic endometritis is more likely to be missed.

Our crossover trial comparing HSG to office hysteroscopy for tubal patency showed that women were 110 times more likely to have the maximum level of pain with HSG than diagnostic hysteroscopy when using a 2.8-mm flexible hysteroscope.3 Further, infection rates and vasovagal events were far lower with hysteroscopy.1

Finally, compared with HSG, we showed 98%-100% sensitivity and 84% specificity for tubal occlusion with hysteroscopy by air-infused saline. Conversely, HSG typically is associated with 76%-96% sensitivity and 67%-100% specificity.4 Additionally, we can often perform diagnostic hysteroscopies for approximately $35 per procedure for total fixed and disposable equipment costs.

How should physicians perform office hysteroscopy to minimize patient discomfort?

The classic paradigm has been to focus on paracervical blocks, anxiolytics, and a supportive environment (such as mood music). However, those are far more important when your hysteroscope is larger than the natural cervical lumen. If you can use small hysteroscopes (< 3 mm for the nulliparous cervix, < 4 mm for the parous cervix), most women will not require cervical dilation, which further enhances the patient experience.

Using a flexible hysteroscope for suspected pathology, making sure not to overdistend the uterus (particularly in high-risk patients such as those with tubal occlusion and cervical stenosis), and vaginoscopy can all minimize patient discomfort. We have published data showing that by using a 2.8-mm flexible diagnostic hysteroscope in a group of mostly nulliparous women, greater than 50% have no discomfort, and more than 90% will have mild to no discomfort.3

What operative hysteroscopy procedures can be performed safely in a physician’s office, and what equipment is required?

Though highly dependent on experience and resources, reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialists (REIs) arguably have the easiest transition to operative office hysteroscopy by utilizing the analgesia and procedure room that is standard for oocyte retrieval and simply adding hysteroscopic procedures. The accompanying table stratifies general hysteroscopic procedures by difficulty.

If one can use propofol or a similar level of sedation (which is routinely utilized for oocyte aspiration), there are few hysteroscopies that cannot be accomplished in the office. However, the less sedation and analgesia, the more judicious one must be in patient selection. Moreover, there are trade-offs between visualization, comfort, and instrumentation.

The greater the uterine distention and diameter of the hysteroscope, the more patients experience pain. One-third of patients (especially nulliparous) will discontinue a procedure with a 5-mm hysteroscope because of discomfort.5 However, as one drops to 4.5 mm and smaller operative hysteroscopes, instruments often occupy the inflow channel, limiting distention and visualization, which also can affect completion rates and safety.

When is operative hysteroscopy best suited for the OR?

In addition to physician experience and clinical resources, the critical factors guiding our choices for selecting the OR rather than the office, include:

- Loss of landmarks. Though Dr. Parry now does most severe intrauterine adhesion cases in the office with ultrasound guidance, when neither ostia can be visualized there is meaningful risk for perforation. Preoperative estrogen, development of planes with the diagnostic hysteroscope prior, and preparing the patient for a possible multistage procedure are all important.

- Use of energy. There are many excellent hysteroscopic surgeons who use the resectoscope well in the office. However, with possible patient movement and potential perforation with energy leading to a bowel injury, there can be greater risk when using energy relative to other methods (such as forceps, scissors, and mechanical morcellation).

- Deeper fibroids. Fibroids displace rather than invade the myometrium, and one can sonographically visualize the myometrium reapproximate over a fibroid as it herniates more into the uterine cavity. Nevertheless, the closer a fibroid comes to the serosa, the more mindful one should be of risks and balances for hysteroscopic removal.

In a patient with a severely stenotic cervix or tortuous endocervical canal, what preprocedure methods do you find helpful, and do you utilize abdominal ultrasound guidance?

If using a 2.8-mm flexible diagnostic hysteroscope, we find 99.8%-99.9% of cervices can be successfully cannulated in the office, with rare exception, that is, following cryotherapy or chlamydia cervicitis. This is the equivalent of your dilator having a camera on the tip and fully articulating to adjust to the cervical path.

Transvaginal sonography prior to hysteroscopy where one maps the cervical lumen helps anticipate problems (along with being familiar with the patient’s history). For the rare dilation under anesthesia, concurrent sonography with a 2.8-mm flexible hysteroscope and intermittent dilator use has been sufficient for our exceptions without the need for lacrimal dilators, vasopressin, misoprostol, and other adjuncts. Of note, we use a 1080p flexible endoscope, as lower resolution would make this more challenging.

In patients with recurrent implantation failure following IVF, is hysteroscopy superior to 3D saline infusion sonogram?

At an American Society of Reproductive Medicine 2021 session, Ilan Tur-Kaspa, MD, and Dr. Parry debated the topic of 2D ultrasound combined with hysteroscopy vs. 3D saline infusion sonography. Core areas of agreement were that expert hands for any approach are better than nonexpert, and high-resolution technology is better than lower resolution. There was also agreement that extrauterine and myometrial disease, such as intramural fibroids and adenomyosis, are contributory factors.

So, sonography will always have a role. However, existing and forthcoming data show hysteroscopy to improve live birth rates for patients with recurrent implantation failure after IVF. Dr. Parry finds diagnostic hysteroscopy easier for identifying endometritis, sessile and cornual polyps, retained products of conception (which are often isoechogenic with the endometrium) and lateral adhesions.

The reality is that there is variability among physicians and midlevel providers in both sonographic and diagnostic hysteroscopic skill. If one wants to verify findings with another team member, acknowledging that there can be nuances to identifying these pathologies by sonography, it is easier to share and discuss findings through hysteroscopic video than sonographic records.

When is endometrial biopsy indicated during office hysteroscopy?

The patients of an REI are very unlikely to have endometrial cancer (or even hyperplasia) outside of polyps (or arguably hypervascular areas of overgrowth), so the focus is on resecting visualized pathology relative to random biopsy.

However, the threshold for biopsy should be adjusted to the patient population, as well as to individual findings and risk. RVUs are greatly increased (11.1 > 41.57) with biopsy, helping sustainability. Additionally, if one places the hysteroscope on endometrium and applies suction through the inflow channel, one can obtain a sample with small-caliber diagnostic hysteroscopes and without having to use forceps.

What is your threshold for fluid deficit in hysteroscopy?

We follow AAGL guidelines, which for operative hysteroscopy are 2,500 mL of isotonic fluids or 1,000 mL of hypotonic fluids in low-risk patients. This should be further reduced to 500 mL of isotonic fluids in the elderly and even 300 mL in those with cardiovascular compromise.6

For patients who request sedation for office hysteroscopy, which option do you recommend – paracervical block alone, nitrous oxide, or the combination?

For diagnostic, greater than 95% of our patients do not require even over-the-counter analgesic medications. For operative, we consider all permissible resources that allow for a safe combination that is appropriate to the pathology and clinical setting, such as paracervical blocks, nitrous oxide, NSAIDs such as ketorolac, anxiolytics, and more.

The goal is to optimize the patient experience. However, the top three criteria that influence successful operative office hysteroscopy for a conscious patient are a parous cervix, judicious patient selection, and pre- and intraoperative verbal analgesia. Informed consent and engagement improve the experience of both the patient and physician.

Dr. Parry is the founder of Positive Steps Fertility in Madison, Miss. Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

References

1. Parry JP et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017 May-Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2017.02.010.

2. Wadhwa L et al. 2017 Apr-Jun. doi: 10.4103/jhrs.JHRS_123_16.

3. Parry JP et al. Fertil Steril. 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.07.1159.

4. Penzias A et al. Fertil Steril. 2021 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.08.038.

5. Campo R et al. Hum Reprod. 2005 Jan;20(1):258-63. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh559.

6. AAGL AAGL practice report: Practice guidelines for the management of hysteroscopic distending media. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013 Mar-Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2012.12.002.

The diagnostic and therapeutic challenges of syringoma

Pain and pruritus are the most common complaints in patients who present to vulvar clinics.1 These symptoms can be related to a variety of conditions, including vulvar lesions. There are both common and uncommon vulvar lesions. Vulvar lesions can be skin colored, yellow, and red. Certain lesions can be diagnosed with history and physical examination alone. Some more common lesions include acrochordons (skin tags), benign growths that are common in patients with diabetes, obesity, and pregnancy.2,3 Other common vulvar lesions are papillomatosis, lichen simplex chronicus, and epidermoid cysts. Other lesions include low- and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL).4 These lesions require biopsy for diagnosis as high-grade lesions require treatment. HSIL of the vulva is considered a premalignancy that necessitates treatment.5 Other lesions that can present with vulvar complaints are molluscum contagiosum, Bartholin gland duct cyst, intradermal melanocytic nevus, and squamous cell carcinoma.

Rarely, other less common conditions can present as vulvar lesions. Syringomas are benign eccrine sweat gland neoplasms. They are more commonly found on the face, neck, or chest.6 On the vulva they are generally small subcutaneous skin-colored papules.7 They may be asymptomatic and noted only on routine examination.

Vulvar syringomas also may present with symptoms. On the vulva, syringomas often present as pruritic papules that can be isolated or multifocal. Often on the labia majora they range in size from 2 to 20 mm.8

They can coalesce to form a larger lesion. They also may be described as painful. When syringomas are pruritic, the overlying skin may appear thickened from rubbing or scratching, and excoriations may be present.

Since vulvar syringomas are rare, there is no standard treatment. Biopsy is necessary for definitive diagnosis. For asymptomatic cases, expectant management is warranted. In symptomatic cases treatment can be considered. Treatment options include cryotherapy, laser ablation, and intralesional electrodissection.8 Intralesional electrodissection and curettage also has been described as treatment.9 Other treatment options include surgical excision of individual lesions or larger excisions if multifocal.

The case study described in "Case letter: Vulvar syringoma" highlights the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges associated with rare lesions of the vulva. Referral to a specialty clinic may be warranted in these challenging cases. ●

- Hansen A, Carr K, Jensen JT. Characteristics and initial diagnoses in women presenting to a referral center for vulvovaginal disorders in 1996–2000. J Reprod Med. 2002; 47: 854-860.

- Boza JC, Trindade EN, Peruzzo J, et al. Skin manifestations of obesity: a comparative study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1220-1223.

- Winton GB, Lewis CW. Dermatoses of pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;6:977-998.

- Bornstein J, Bogliatto F, Haefner HK, et al; ISSVD Terminology Committee. The 2015 International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) terminology of vulvar squamous intraepithelial lesions. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2016;20:11-14.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 675: management of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e178-e182.

- Heller DS. Benign tumors and tumor-like lesions of the vulva. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;58:526-535.

- Shalabi MMK, Homan K, Bicknell L. Vulvar syringomas. Proc (Bayl Univer Med Cent). 2022;35:113-114.

- Ozdemir O, Sari ME, Sen E, et al. Vulvar syringoma in a postmenopausal woman: a case report. J Reprod Med. 2015;60:452-454.

- Stevenson TR, Swanson NA. Syringoma: removal by electrodesiccation and curettage. Ann Plast Surg. 1985;15:151-154.

Pain and pruritus are the most common complaints in patients who present to vulvar clinics.1 These symptoms can be related to a variety of conditions, including vulvar lesions. There are both common and uncommon vulvar lesions. Vulvar lesions can be skin colored, yellow, and red. Certain lesions can be diagnosed with history and physical examination alone. Some more common lesions include acrochordons (skin tags), benign growths that are common in patients with diabetes, obesity, and pregnancy.2,3 Other common vulvar lesions are papillomatosis, lichen simplex chronicus, and epidermoid cysts. Other lesions include low- and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL).4 These lesions require biopsy for diagnosis as high-grade lesions require treatment. HSIL of the vulva is considered a premalignancy that necessitates treatment.5 Other lesions that can present with vulvar complaints are molluscum contagiosum, Bartholin gland duct cyst, intradermal melanocytic nevus, and squamous cell carcinoma.

Rarely, other less common conditions can present as vulvar lesions. Syringomas are benign eccrine sweat gland neoplasms. They are more commonly found on the face, neck, or chest.6 On the vulva they are generally small subcutaneous skin-colored papules.7 They may be asymptomatic and noted only on routine examination.

Vulvar syringomas also may present with symptoms. On the vulva, syringomas often present as pruritic papules that can be isolated or multifocal. Often on the labia majora they range in size from 2 to 20 mm.8

They can coalesce to form a larger lesion. They also may be described as painful. When syringomas are pruritic, the overlying skin may appear thickened from rubbing or scratching, and excoriations may be present.

Since vulvar syringomas are rare, there is no standard treatment. Biopsy is necessary for definitive diagnosis. For asymptomatic cases, expectant management is warranted. In symptomatic cases treatment can be considered. Treatment options include cryotherapy, laser ablation, and intralesional electrodissection.8 Intralesional electrodissection and curettage also has been described as treatment.9 Other treatment options include surgical excision of individual lesions or larger excisions if multifocal.

The case study described in "Case letter: Vulvar syringoma" highlights the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges associated with rare lesions of the vulva. Referral to a specialty clinic may be warranted in these challenging cases. ●

Pain and pruritus are the most common complaints in patients who present to vulvar clinics.1 These symptoms can be related to a variety of conditions, including vulvar lesions. There are both common and uncommon vulvar lesions. Vulvar lesions can be skin colored, yellow, and red. Certain lesions can be diagnosed with history and physical examination alone. Some more common lesions include acrochordons (skin tags), benign growths that are common in patients with diabetes, obesity, and pregnancy.2,3 Other common vulvar lesions are papillomatosis, lichen simplex chronicus, and epidermoid cysts. Other lesions include low- and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL).4 These lesions require biopsy for diagnosis as high-grade lesions require treatment. HSIL of the vulva is considered a premalignancy that necessitates treatment.5 Other lesions that can present with vulvar complaints are molluscum contagiosum, Bartholin gland duct cyst, intradermal melanocytic nevus, and squamous cell carcinoma.

Rarely, other less common conditions can present as vulvar lesions. Syringomas are benign eccrine sweat gland neoplasms. They are more commonly found on the face, neck, or chest.6 On the vulva they are generally small subcutaneous skin-colored papules.7 They may be asymptomatic and noted only on routine examination.

Vulvar syringomas also may present with symptoms. On the vulva, syringomas often present as pruritic papules that can be isolated or multifocal. Often on the labia majora they range in size from 2 to 20 mm.8

They can coalesce to form a larger lesion. They also may be described as painful. When syringomas are pruritic, the overlying skin may appear thickened from rubbing or scratching, and excoriations may be present.

Since vulvar syringomas are rare, there is no standard treatment. Biopsy is necessary for definitive diagnosis. For asymptomatic cases, expectant management is warranted. In symptomatic cases treatment can be considered. Treatment options include cryotherapy, laser ablation, and intralesional electrodissection.8 Intralesional electrodissection and curettage also has been described as treatment.9 Other treatment options include surgical excision of individual lesions or larger excisions if multifocal.

The case study described in "Case letter: Vulvar syringoma" highlights the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges associated with rare lesions of the vulva. Referral to a specialty clinic may be warranted in these challenging cases. ●

- Hansen A, Carr K, Jensen JT. Characteristics and initial diagnoses in women presenting to a referral center for vulvovaginal disorders in 1996–2000. J Reprod Med. 2002; 47: 854-860.

- Boza JC, Trindade EN, Peruzzo J, et al. Skin manifestations of obesity: a comparative study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1220-1223.

- Winton GB, Lewis CW. Dermatoses of pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;6:977-998.

- Bornstein J, Bogliatto F, Haefner HK, et al; ISSVD Terminology Committee. The 2015 International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) terminology of vulvar squamous intraepithelial lesions. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2016;20:11-14.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 675: management of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e178-e182.

- Heller DS. Benign tumors and tumor-like lesions of the vulva. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;58:526-535.

- Shalabi MMK, Homan K, Bicknell L. Vulvar syringomas. Proc (Bayl Univer Med Cent). 2022;35:113-114.

- Ozdemir O, Sari ME, Sen E, et al. Vulvar syringoma in a postmenopausal woman: a case report. J Reprod Med. 2015;60:452-454.

- Stevenson TR, Swanson NA. Syringoma: removal by electrodesiccation and curettage. Ann Plast Surg. 1985;15:151-154.

- Hansen A, Carr K, Jensen JT. Characteristics and initial diagnoses in women presenting to a referral center for vulvovaginal disorders in 1996–2000. J Reprod Med. 2002; 47: 854-860.

- Boza JC, Trindade EN, Peruzzo J, et al. Skin manifestations of obesity: a comparative study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1220-1223.

- Winton GB, Lewis CW. Dermatoses of pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;6:977-998.

- Bornstein J, Bogliatto F, Haefner HK, et al; ISSVD Terminology Committee. The 2015 International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) terminology of vulvar squamous intraepithelial lesions. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2016;20:11-14.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 675: management of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e178-e182.

- Heller DS. Benign tumors and tumor-like lesions of the vulva. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;58:526-535.

- Shalabi MMK, Homan K, Bicknell L. Vulvar syringomas. Proc (Bayl Univer Med Cent). 2022;35:113-114.

- Ozdemir O, Sari ME, Sen E, et al. Vulvar syringoma in a postmenopausal woman: a case report. J Reprod Med. 2015;60:452-454.

- Stevenson TR, Swanson NA. Syringoma: removal by electrodesiccation and curettage. Ann Plast Surg. 1985;15:151-154.

Preventive antipyretics, antibiotics not needed in stroke

“The results of PRECIOUS do not support preventive use of antiemetic, antipyretic, or antibiotic drugs in older patients with acute stroke,” senior study author Bart van der Worp, MD, professor of acute neurology at University Medical Center, Utrecht, the Netherlands, concluded.

“This trial was all about prevention,” trial co-investigator, Philip Bath, MD, professor of stroke medicine at the University of Nottingham (England), said in an interview.

“It was trying to improve outcomes by preventing infection, fever, and aspiration pneumonia, but the message from these results is that while we should be on the lookout for these complications and treat them early when they occur, we don’t need to give these medications on a prophylactic basis.”

The PREvention of Complications to Improve OUtcome in elderly patients with acute Stroke (PRECIOUS) trial was presented at the annual European Stroke Organisation Conference, held in Munich.

Dr. Van der Worp explained that infections, fever, and aspiration pneumonia frequently occur following stroke, particularly in older patients, and these poststroke complications are associated with an increased risk of death and poor functional outcome.

“We assessed whether a pharmacological strategy to reduce the risk of infections and fever improves outcomes of elderly patients with moderately severe or severe stroke,” he said.

Previous studies looking at this approach have been performed in broad populations of stroke patients who had a relatively low risk of poststroke complications, thereby reducing the potential for benefit from these interventions.

The current PRECIOUS trial was therefore conducted in a more selective elderly population with more severe strokes, a group believed to be at higher risk of infection and fever.

The trial included patients aged 66 years or older with moderately severe to severe ischemic stroke (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score ≥ 6) or intracerebral hemorrhage.

They were randomized in a 3 x 2 factorial design to oral, rectal, or intravenous metoclopramide (10 mg three times a day); intravenous ceftriaxone (2,000 mg once daily); oral, rectal, or intravenous paracetamol (1,000 mg four times daily); or usual care.

Medications were started within 24 hours after symptom onset and continued for 4 days or until complete recovery or discharge from hospital, if earlier.

“We assessed these three simple, safe, and inexpensive therapies – paracetamol to prevent fever; the antiemetic, metoclopramide, to prevent aspiration; and ceftriaxone, which is the preferred antibiotic for post-stroke pneumonia in the Netherlands,” Dr. van der Worp said.

The primary outcome was modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score at 90 days.

The trial was aiming to enroll 3,800 patients from 67 European sites but was stopped after 1,493 patients had been included because of lack of funding. After excluding patients who withdrew consent or were lost to follow-up, 1,471 patients were included in the intention-to-treat analysis.

Results showed no effect on the primary outcome of any of the prophylactic treatments.

“None of the medications had any effect on the functional outcome at 90 days. This was a surprise to me,” Dr. Van der Worp commented. “I had expected that at least one of the medications would have been of benefit.”

A secondary outcome was the diagnosis of pneumonia, which again was not reduced by any of the medications.

“Remarkably, neither ceftriaxone nor metoclopramide had any effect on the risk of developing pneumonia. It was all quite disappointing,” van der Worp said.

There was, however, a reduction in the incidence of urinary tract infections in the ceftriaxone group.

Trying to explain why there was a reduction in urinary tract infections but not pneumonia with the antibiotic, Dr. Van der Worp pointed out that poststroke pneumonia is to a large extent caused by a mechanical process (aspiration), and bacteria may only play a minor role in its development.

He said he was therefore surprised that metoclopramide, which should prevent the mechanical process of aspiration, did not reduce the development of pneumonia.

He suggested that some patients may have already experienced aspiration before the metoclopramide was started, noting that many patients with acute stroke already have signs of pneumonia on CT scan in the first few hours after symptom onset.

A previous smaller study (MAPS) had shown a lower rate of pneumonia in stroke patients given metoclopramide, but in this study the drug was given for 3 weeks.

Discussing the PRECIOUS trial at the ESOC meeting, Christine Roffe, MD, professor of stroke medicine at Keele (England) University, and senior investigator of the MAPS study, suggested that a longer period of metoclopramide treatment may be needed than the 4 days given in the PRECIOUS study, as the risk of pneumonia persists for longer than just a few days.

She noted that another trial (MAPS-2) is now underway in the United Kingdom to try and confirm the first MAPS result with longer duration metoclopramide.

Dr. Van der Worp responded: “Certainly, I think that the MAPS-2 study should be continued. It is investigating a much longer duration of treatment, which may be beneficial, especially in patients with more severe strokes.”

On the reason for the disappointing results with paracetamol, Dr. Van der Worp elaborated: “We found that only a very few of these older patients developed a fever – only about 5% in the control group. Paracetamol did reduce the risk of fever, but because the proportion of patients who developed fever was so small, this may have been why it didn’t translate into any effect on the functional outcome.”

Dr. Roffe concluded that PRECIOUS was an important study. “There is also a positive message here. We have all been worried about using too many antibiotics. We need to make sure we use these drugs responsibly. I think this trial has told us there is little point in using antibiotics in a preventative way in these patients.”

She added that although the trial was stopped prematurely, it had produced decisive results.

“Yes, I believe that even if the trial was much larger, we still would not have shown an effect,” Dr. Van der Worp agreed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“The results of PRECIOUS do not support preventive use of antiemetic, antipyretic, or antibiotic drugs in older patients with acute stroke,” senior study author Bart van der Worp, MD, professor of acute neurology at University Medical Center, Utrecht, the Netherlands, concluded.

“This trial was all about prevention,” trial co-investigator, Philip Bath, MD, professor of stroke medicine at the University of Nottingham (England), said in an interview.

“It was trying to improve outcomes by preventing infection, fever, and aspiration pneumonia, but the message from these results is that while we should be on the lookout for these complications and treat them early when they occur, we don’t need to give these medications on a prophylactic basis.”

The PREvention of Complications to Improve OUtcome in elderly patients with acute Stroke (PRECIOUS) trial was presented at the annual European Stroke Organisation Conference, held in Munich.

Dr. Van der Worp explained that infections, fever, and aspiration pneumonia frequently occur following stroke, particularly in older patients, and these poststroke complications are associated with an increased risk of death and poor functional outcome.

“We assessed whether a pharmacological strategy to reduce the risk of infections and fever improves outcomes of elderly patients with moderately severe or severe stroke,” he said.

Previous studies looking at this approach have been performed in broad populations of stroke patients who had a relatively low risk of poststroke complications, thereby reducing the potential for benefit from these interventions.

The current PRECIOUS trial was therefore conducted in a more selective elderly population with more severe strokes, a group believed to be at higher risk of infection and fever.

The trial included patients aged 66 years or older with moderately severe to severe ischemic stroke (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score ≥ 6) or intracerebral hemorrhage.

They were randomized in a 3 x 2 factorial design to oral, rectal, or intravenous metoclopramide (10 mg three times a day); intravenous ceftriaxone (2,000 mg once daily); oral, rectal, or intravenous paracetamol (1,000 mg four times daily); or usual care.

Medications were started within 24 hours after symptom onset and continued for 4 days or until complete recovery or discharge from hospital, if earlier.

“We assessed these three simple, safe, and inexpensive therapies – paracetamol to prevent fever; the antiemetic, metoclopramide, to prevent aspiration; and ceftriaxone, which is the preferred antibiotic for post-stroke pneumonia in the Netherlands,” Dr. van der Worp said.

The primary outcome was modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score at 90 days.

The trial was aiming to enroll 3,800 patients from 67 European sites but was stopped after 1,493 patients had been included because of lack of funding. After excluding patients who withdrew consent or were lost to follow-up, 1,471 patients were included in the intention-to-treat analysis.

Results showed no effect on the primary outcome of any of the prophylactic treatments.

“None of the medications had any effect on the functional outcome at 90 days. This was a surprise to me,” Dr. Van der Worp commented. “I had expected that at least one of the medications would have been of benefit.”

A secondary outcome was the diagnosis of pneumonia, which again was not reduced by any of the medications.

“Remarkably, neither ceftriaxone nor metoclopramide had any effect on the risk of developing pneumonia. It was all quite disappointing,” van der Worp said.

There was, however, a reduction in the incidence of urinary tract infections in the ceftriaxone group.

Trying to explain why there was a reduction in urinary tract infections but not pneumonia with the antibiotic, Dr. Van der Worp pointed out that poststroke pneumonia is to a large extent caused by a mechanical process (aspiration), and bacteria may only play a minor role in its development.

He said he was therefore surprised that metoclopramide, which should prevent the mechanical process of aspiration, did not reduce the development of pneumonia.

He suggested that some patients may have already experienced aspiration before the metoclopramide was started, noting that many patients with acute stroke already have signs of pneumonia on CT scan in the first few hours after symptom onset.

A previous smaller study (MAPS) had shown a lower rate of pneumonia in stroke patients given metoclopramide, but in this study the drug was given for 3 weeks.

Discussing the PRECIOUS trial at the ESOC meeting, Christine Roffe, MD, professor of stroke medicine at Keele (England) University, and senior investigator of the MAPS study, suggested that a longer period of metoclopramide treatment may be needed than the 4 days given in the PRECIOUS study, as the risk of pneumonia persists for longer than just a few days.

She noted that another trial (MAPS-2) is now underway in the United Kingdom to try and confirm the first MAPS result with longer duration metoclopramide.

Dr. Van der Worp responded: “Certainly, I think that the MAPS-2 study should be continued. It is investigating a much longer duration of treatment, which may be beneficial, especially in patients with more severe strokes.”

On the reason for the disappointing results with paracetamol, Dr. Van der Worp elaborated: “We found that only a very few of these older patients developed a fever – only about 5% in the control group. Paracetamol did reduce the risk of fever, but because the proportion of patients who developed fever was so small, this may have been why it didn’t translate into any effect on the functional outcome.”

Dr. Roffe concluded that PRECIOUS was an important study. “There is also a positive message here. We have all been worried about using too many antibiotics. We need to make sure we use these drugs responsibly. I think this trial has told us there is little point in using antibiotics in a preventative way in these patients.”

She added that although the trial was stopped prematurely, it had produced decisive results.

“Yes, I believe that even if the trial was much larger, we still would not have shown an effect,” Dr. Van der Worp agreed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“The results of PRECIOUS do not support preventive use of antiemetic, antipyretic, or antibiotic drugs in older patients with acute stroke,” senior study author Bart van der Worp, MD, professor of acute neurology at University Medical Center, Utrecht, the Netherlands, concluded.

“This trial was all about prevention,” trial co-investigator, Philip Bath, MD, professor of stroke medicine at the University of Nottingham (England), said in an interview.

“It was trying to improve outcomes by preventing infection, fever, and aspiration pneumonia, but the message from these results is that while we should be on the lookout for these complications and treat them early when they occur, we don’t need to give these medications on a prophylactic basis.”

The PREvention of Complications to Improve OUtcome in elderly patients with acute Stroke (PRECIOUS) trial was presented at the annual European Stroke Organisation Conference, held in Munich.

Dr. Van der Worp explained that infections, fever, and aspiration pneumonia frequently occur following stroke, particularly in older patients, and these poststroke complications are associated with an increased risk of death and poor functional outcome.

“We assessed whether a pharmacological strategy to reduce the risk of infections and fever improves outcomes of elderly patients with moderately severe or severe stroke,” he said.

Previous studies looking at this approach have been performed in broad populations of stroke patients who had a relatively low risk of poststroke complications, thereby reducing the potential for benefit from these interventions.

The current PRECIOUS trial was therefore conducted in a more selective elderly population with more severe strokes, a group believed to be at higher risk of infection and fever.

The trial included patients aged 66 years or older with moderately severe to severe ischemic stroke (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score ≥ 6) or intracerebral hemorrhage.

They were randomized in a 3 x 2 factorial design to oral, rectal, or intravenous metoclopramide (10 mg three times a day); intravenous ceftriaxone (2,000 mg once daily); oral, rectal, or intravenous paracetamol (1,000 mg four times daily); or usual care.

Medications were started within 24 hours after symptom onset and continued for 4 days or until complete recovery or discharge from hospital, if earlier.

“We assessed these three simple, safe, and inexpensive therapies – paracetamol to prevent fever; the antiemetic, metoclopramide, to prevent aspiration; and ceftriaxone, which is the preferred antibiotic for post-stroke pneumonia in the Netherlands,” Dr. van der Worp said.

The primary outcome was modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score at 90 days.

The trial was aiming to enroll 3,800 patients from 67 European sites but was stopped after 1,493 patients had been included because of lack of funding. After excluding patients who withdrew consent or were lost to follow-up, 1,471 patients were included in the intention-to-treat analysis.

Results showed no effect on the primary outcome of any of the prophylactic treatments.

“None of the medications had any effect on the functional outcome at 90 days. This was a surprise to me,” Dr. Van der Worp commented. “I had expected that at least one of the medications would have been of benefit.”

A secondary outcome was the diagnosis of pneumonia, which again was not reduced by any of the medications.

“Remarkably, neither ceftriaxone nor metoclopramide had any effect on the risk of developing pneumonia. It was all quite disappointing,” van der Worp said.

There was, however, a reduction in the incidence of urinary tract infections in the ceftriaxone group.

Trying to explain why there was a reduction in urinary tract infections but not pneumonia with the antibiotic, Dr. Van der Worp pointed out that poststroke pneumonia is to a large extent caused by a mechanical process (aspiration), and bacteria may only play a minor role in its development.

He said he was therefore surprised that metoclopramide, which should prevent the mechanical process of aspiration, did not reduce the development of pneumonia.

He suggested that some patients may have already experienced aspiration before the metoclopramide was started, noting that many patients with acute stroke already have signs of pneumonia on CT scan in the first few hours after symptom onset.

A previous smaller study (MAPS) had shown a lower rate of pneumonia in stroke patients given metoclopramide, but in this study the drug was given for 3 weeks.

Discussing the PRECIOUS trial at the ESOC meeting, Christine Roffe, MD, professor of stroke medicine at Keele (England) University, and senior investigator of the MAPS study, suggested that a longer period of metoclopramide treatment may be needed than the 4 days given in the PRECIOUS study, as the risk of pneumonia persists for longer than just a few days.

She noted that another trial (MAPS-2) is now underway in the United Kingdom to try and confirm the first MAPS result with longer duration metoclopramide.

Dr. Van der Worp responded: “Certainly, I think that the MAPS-2 study should be continued. It is investigating a much longer duration of treatment, which may be beneficial, especially in patients with more severe strokes.”

On the reason for the disappointing results with paracetamol, Dr. Van der Worp elaborated: “We found that only a very few of these older patients developed a fever – only about 5% in the control group. Paracetamol did reduce the risk of fever, but because the proportion of patients who developed fever was so small, this may have been why it didn’t translate into any effect on the functional outcome.”

Dr. Roffe concluded that PRECIOUS was an important study. “There is also a positive message here. We have all been worried about using too many antibiotics. We need to make sure we use these drugs responsibly. I think this trial has told us there is little point in using antibiotics in a preventative way in these patients.”

She added that although the trial was stopped prematurely, it had produced decisive results.

“Yes, I believe that even if the trial was much larger, we still would not have shown an effect,” Dr. Van der Worp agreed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ESOC 2023

Endocrinology pay steadily climbs, gender gap closes

Endocrinologists report steady increases in pay in the Medscape Endocrinologist Compensation Report 2023, but more doctors dropped insurers that pay the least, compared with last year, and only about two-thirds of respondents say they would choose medicine again as a career if given the chance.

In the survey of more than 10,000 physicians in over 29 specialties,

Those earnings still place them in the lowest five specialties in terms of pay, above infectious diseases, family medicine, pediatrics, and public health and preventive medicine. The latter is at the bottom of the list, with average annual earnings of $249,000.

Conversely, the top three specialties were plastic surgery, at an average of $619,000 per annum, followed by orthopedics, at $573,000, and cardiology, at $507,000.

Specialties in which the most significant changes in annual compensation occurred were led by oncology, with a 13% increase from 2022, followed by gastroenterology, with an 11% increase. On the opposite end, ophthalmologists experienced a 7% decline in earnings, while emergency medicine had a 6% decrease from 2022.

Since Medscape’s 2015 report, annual salaries for endocrinologists have increased by 36%. Similar patterns in compensation increases since 2015 occurred across all specialties. In contrast to some other specialties, endocrinologists did not experience a significant decline in earnings during the pandemic.

Across all specialties, men still earned more than women in the 2023 report – with a gap of 19% ($386,000 vs. $300,000). However, there appears to be progress, as the difference represents the lowest gender pay gap in 5 years.

This gradual improvement should likely continue as awareness of pay discrepancies grows and new generations emerge, said Theresa Rohr-Kirchgraber, MD, president of the American Medical Women’s Association and professor of medicine at AU/USA Medical Partnership, Athens, Ga., in the report.

“Due to efforts by many, some institutions and health care organizations have reviewed their salary lines and recognized the discrepancies not only between the sexes but also between new hires” and more established workers, she explained in the report.

“[The new hires] can be offered significantly more than those more senior physicians who have been working there for years and hired under a different pay structure,” she noted.

Nearly half of endocrinologists (45%) reported taking on extra work outside of their profession, up from 39% in the 2022 report. Among them, 31% reported other medical-related work, 8% reported “medical moonlighting,” 7% reported non–medical-related work, and 2% added more hours to their primary job as a physician.

Endocrinologists were in the lowest third of specialties in terms of their impressions of fair compensation, with only 45% reporting that they felt adequately paid. On the lowest end was infectious disease, with only 35% feeling their compensation is fair. By contrast, the highest response, 68%, was among psychiatrists.

Nevertheless, 85% of endocrinologists report that they would choose the same specialty again if given the chance. Responses ranged from 61% in internal medicine to 97% in plastic surgery.

Of note, fewer – 71% of endocrinologists – responded that they would choose medicine again, down from the 76% of endocrinologists who answered yes to the same question in 2022. At the bottom of the list was emergency medicine, with only 61% saying they would choose medicine again. The highest rates were in dermatology, at 86%, and allergy and immunology, at 84%.

In terms of time spent seeing patients, endocrinologists are more likely to see patients less than 30 hours per week, at 24%, compared with physicians overall, at 19%; 61% of endocrinologists report seeing patients 30-40 hours per week, versus 53% of all physicians.

Only 12% report seeing patients 41-50 hours per week, compared with 16% of all physicians. And 4% reported seeing patients 51 hours or more weekly, versus 11% of physicians overall.

The proportion of endocrinologists who reported that they would drop insurers that pay the least was notably up in the current report, at 25%, versus just 15% in the 2022 report; 22% indicated they would not drop insurers because “I need all payers”; 16% said no because “it’s inappropriate”; and the remainder responded no for other reasons.

Overall, the leading response by physicians for the most rewarding aspects of their job were “being good at what I am doing/finding answers, diagnoses,” reported by 32%, followed by “gratitude from/relationships with patients” (24%) and “making the world a better place (for example, helping others),” at 22%.

Conversely, the most challenging aspect, described by 20%, is “having so many rules and regulations,” followed by “difficulties getting fair reimbursement from or dealing with Medicare and/or other insurers (17%).”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Endocrinologists report steady increases in pay in the Medscape Endocrinologist Compensation Report 2023, but more doctors dropped insurers that pay the least, compared with last year, and only about two-thirds of respondents say they would choose medicine again as a career if given the chance.

In the survey of more than 10,000 physicians in over 29 specialties,

Those earnings still place them in the lowest five specialties in terms of pay, above infectious diseases, family medicine, pediatrics, and public health and preventive medicine. The latter is at the bottom of the list, with average annual earnings of $249,000.

Conversely, the top three specialties were plastic surgery, at an average of $619,000 per annum, followed by orthopedics, at $573,000, and cardiology, at $507,000.

Specialties in which the most significant changes in annual compensation occurred were led by oncology, with a 13% increase from 2022, followed by gastroenterology, with an 11% increase. On the opposite end, ophthalmologists experienced a 7% decline in earnings, while emergency medicine had a 6% decrease from 2022.

Since Medscape’s 2015 report, annual salaries for endocrinologists have increased by 36%. Similar patterns in compensation increases since 2015 occurred across all specialties. In contrast to some other specialties, endocrinologists did not experience a significant decline in earnings during the pandemic.

Across all specialties, men still earned more than women in the 2023 report – with a gap of 19% ($386,000 vs. $300,000). However, there appears to be progress, as the difference represents the lowest gender pay gap in 5 years.

This gradual improvement should likely continue as awareness of pay discrepancies grows and new generations emerge, said Theresa Rohr-Kirchgraber, MD, president of the American Medical Women’s Association and professor of medicine at AU/USA Medical Partnership, Athens, Ga., in the report.

“Due to efforts by many, some institutions and health care organizations have reviewed their salary lines and recognized the discrepancies not only between the sexes but also between new hires” and more established workers, she explained in the report.

“[The new hires] can be offered significantly more than those more senior physicians who have been working there for years and hired under a different pay structure,” she noted.

Nearly half of endocrinologists (45%) reported taking on extra work outside of their profession, up from 39% in the 2022 report. Among them, 31% reported other medical-related work, 8% reported “medical moonlighting,” 7% reported non–medical-related work, and 2% added more hours to their primary job as a physician.

Endocrinologists were in the lowest third of specialties in terms of their impressions of fair compensation, with only 45% reporting that they felt adequately paid. On the lowest end was infectious disease, with only 35% feeling their compensation is fair. By contrast, the highest response, 68%, was among psychiatrists.

Nevertheless, 85% of endocrinologists report that they would choose the same specialty again if given the chance. Responses ranged from 61% in internal medicine to 97% in plastic surgery.

Of note, fewer – 71% of endocrinologists – responded that they would choose medicine again, down from the 76% of endocrinologists who answered yes to the same question in 2022. At the bottom of the list was emergency medicine, with only 61% saying they would choose medicine again. The highest rates were in dermatology, at 86%, and allergy and immunology, at 84%.

In terms of time spent seeing patients, endocrinologists are more likely to see patients less than 30 hours per week, at 24%, compared with physicians overall, at 19%; 61% of endocrinologists report seeing patients 30-40 hours per week, versus 53% of all physicians.

Only 12% report seeing patients 41-50 hours per week, compared with 16% of all physicians. And 4% reported seeing patients 51 hours or more weekly, versus 11% of physicians overall.

The proportion of endocrinologists who reported that they would drop insurers that pay the least was notably up in the current report, at 25%, versus just 15% in the 2022 report; 22% indicated they would not drop insurers because “I need all payers”; 16% said no because “it’s inappropriate”; and the remainder responded no for other reasons.

Overall, the leading response by physicians for the most rewarding aspects of their job were “being good at what I am doing/finding answers, diagnoses,” reported by 32%, followed by “gratitude from/relationships with patients” (24%) and “making the world a better place (for example, helping others),” at 22%.

Conversely, the most challenging aspect, described by 20%, is “having so many rules and regulations,” followed by “difficulties getting fair reimbursement from or dealing with Medicare and/or other insurers (17%).”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Endocrinologists report steady increases in pay in the Medscape Endocrinologist Compensation Report 2023, but more doctors dropped insurers that pay the least, compared with last year, and only about two-thirds of respondents say they would choose medicine again as a career if given the chance.

In the survey of more than 10,000 physicians in over 29 specialties,

Those earnings still place them in the lowest five specialties in terms of pay, above infectious diseases, family medicine, pediatrics, and public health and preventive medicine. The latter is at the bottom of the list, with average annual earnings of $249,000.

Conversely, the top three specialties were plastic surgery, at an average of $619,000 per annum, followed by orthopedics, at $573,000, and cardiology, at $507,000.

Specialties in which the most significant changes in annual compensation occurred were led by oncology, with a 13% increase from 2022, followed by gastroenterology, with an 11% increase. On the opposite end, ophthalmologists experienced a 7% decline in earnings, while emergency medicine had a 6% decrease from 2022.

Since Medscape’s 2015 report, annual salaries for endocrinologists have increased by 36%. Similar patterns in compensation increases since 2015 occurred across all specialties. In contrast to some other specialties, endocrinologists did not experience a significant decline in earnings during the pandemic.

Across all specialties, men still earned more than women in the 2023 report – with a gap of 19% ($386,000 vs. $300,000). However, there appears to be progress, as the difference represents the lowest gender pay gap in 5 years.

This gradual improvement should likely continue as awareness of pay discrepancies grows and new generations emerge, said Theresa Rohr-Kirchgraber, MD, president of the American Medical Women’s Association and professor of medicine at AU/USA Medical Partnership, Athens, Ga., in the report.

“Due to efforts by many, some institutions and health care organizations have reviewed their salary lines and recognized the discrepancies not only between the sexes but also between new hires” and more established workers, she explained in the report.

“[The new hires] can be offered significantly more than those more senior physicians who have been working there for years and hired under a different pay structure,” she noted.

Nearly half of endocrinologists (45%) reported taking on extra work outside of their profession, up from 39% in the 2022 report. Among them, 31% reported other medical-related work, 8% reported “medical moonlighting,” 7% reported non–medical-related work, and 2% added more hours to their primary job as a physician.

Endocrinologists were in the lowest third of specialties in terms of their impressions of fair compensation, with only 45% reporting that they felt adequately paid. On the lowest end was infectious disease, with only 35% feeling their compensation is fair. By contrast, the highest response, 68%, was among psychiatrists.

Nevertheless, 85% of endocrinologists report that they would choose the same specialty again if given the chance. Responses ranged from 61% in internal medicine to 97% in plastic surgery.

Of note, fewer – 71% of endocrinologists – responded that they would choose medicine again, down from the 76% of endocrinologists who answered yes to the same question in 2022. At the bottom of the list was emergency medicine, with only 61% saying they would choose medicine again. The highest rates were in dermatology, at 86%, and allergy and immunology, at 84%.

In terms of time spent seeing patients, endocrinologists are more likely to see patients less than 30 hours per week, at 24%, compared with physicians overall, at 19%; 61% of endocrinologists report seeing patients 30-40 hours per week, versus 53% of all physicians.

Only 12% report seeing patients 41-50 hours per week, compared with 16% of all physicians. And 4% reported seeing patients 51 hours or more weekly, versus 11% of physicians overall.

The proportion of endocrinologists who reported that they would drop insurers that pay the least was notably up in the current report, at 25%, versus just 15% in the 2022 report; 22% indicated they would not drop insurers because “I need all payers”; 16% said no because “it’s inappropriate”; and the remainder responded no for other reasons.

Overall, the leading response by physicians for the most rewarding aspects of their job were “being good at what I am doing/finding answers, diagnoses,” reported by 32%, followed by “gratitude from/relationships with patients” (24%) and “making the world a better place (for example, helping others),” at 22%.

Conversely, the most challenging aspect, described by 20%, is “having so many rules and regulations,” followed by “difficulties getting fair reimbursement from or dealing with Medicare and/or other insurers (17%).”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

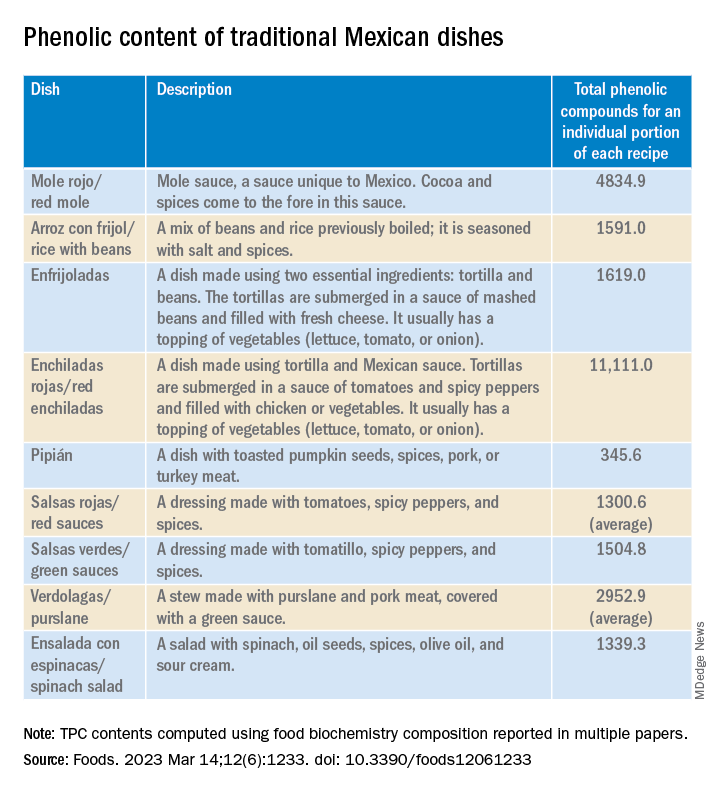

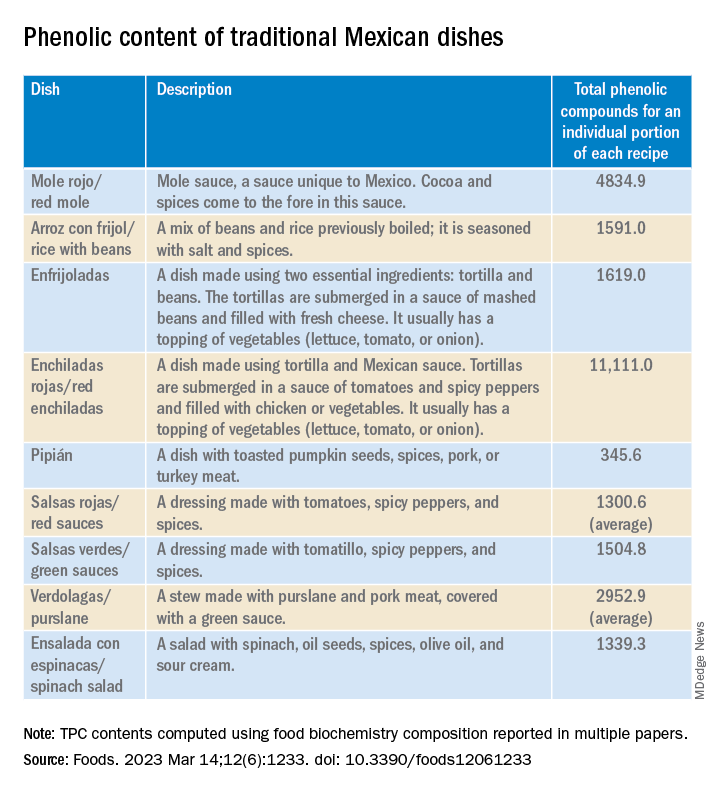

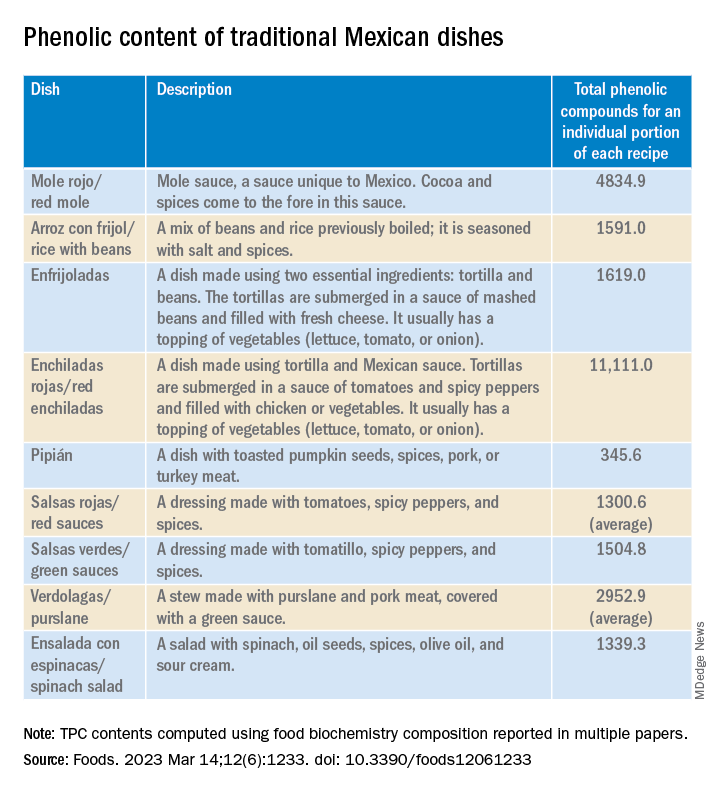

Traditional Mexican food has health benefits

, according to researchers from the Institute of Sciences at Benemérita Autonomous University of Puebla, Puebla, Mexico.

Their study, published in the journal Foods, is the first to produce tables showing the phenolic content of Mexican dishes. Physicians and nutritionists can use this information as a reference tool when drawing up diet recommendations for patients who could benefit from a higher intake of phenolic compounds (PC).

“Up until now, there hasn’t been a table that we – nutritionists and physicians – could look at and see exactly which foods were richest in these compounds. In the United States, European countries, Asian countries – they’ve all had food tables; in Mexico, we didn’t,” said lead author Julia Alatorre-Cruz, PhD, a biological scientist and postdoctoral researcher at BUAP. “So, it’s a fairly innovative contribution. As a bonus, the information can be used to analyze the relationship between diet and noncommunicable diseases in the Mexican population.”

In recent years, nutrition science has focused on counteracting nutrient deficiency and some diseases by identifying active-food components. Diet offers the possibility to improve the patient’s health conditions by using these components or functional food.

PCs are a diverse group of plant micronutrients, some of which modulate physiologic and molecular pathways involved in energy metabolism. They can act by different mechanisms; the most important of them are conducted by anti-inflammatory, antioxidant activities, and are antiallergic.

Moreover, recent studies explain how PCs positively affect certain illnesses, such as obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, thrombocytopenia, and metabolic syndrome. Several common features characterize these pathologies – among them are the redox balance and a notable inflammatory response that strongly alters the biochemical and functional characteristics of the affected tissues.

Traditional Mexican food is characterized by grains, tubers, legumes, vegetables, and spices, most of which are rich in PCs. However, the Mexican diet has changed over the past decades because traditional food has been replaced with ultraprocessed food with high-caloric values. Moreover, some vegetables and fruits are preferably consumed after processing, which affects the quantity, quality, and bioavailability of the PCs. In addition, diseases associated with eating habits have increased by more than 27% in the Mexican population.

The objective of the study was to determine whether participants with a higher PC intake from beverages or Mexican dishes have better health conditions than those with a lower intake.

A total of 973 adults (798 females, 175 males) aged 18-79 years were enrolled in this cross-sectional study. The data were obtained from a validated, self-administered food consumption survey that was posted on social media (Facebook) or sent via WhatsApp or email. In one section, there was a list of fruits, vegetables, cereals, legumes, seeds, spices, beverages, and Mexican dishes. The participants were asked to indicate how often in the past month they had consumed these items. There were also sections for providing identification data (for example, age, sex, marital status), height and weight information, and medical history.