User login

Gastroparesis referrals often based on misdiagnosis

, a new retrospective review suggests.

The researchers analyzed the records of 339 patients referred for tertiary evaluation of GP at one center. Overall, 19.5% of patients were confirmed to have GP, whereas 80.5% were given an alternative diagnosis, with FD being the most common (44.5%).

Contributing to initial misdiagnosis are the similarity in presentation between patients with GP and FD and low rates of gastric emptying evaluation using the recommended test protocol, lead author David J. Cangemi, MD, division of gastroenterology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla., and colleagues write.

The findings “reaffirm guidelines noting that gastroparesis cannot be diagnosed based on symptoms alone,” they write.

Because FD is more prevalent than GP, FD “should be considered first in patients with characteristic upper GI symptoms,” they add.

The review was published online in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Similarities breed confusion

GP and FD are the two most common sensorimotor disorders of the stomach, and both are characterized by abdominal pain, nausea, early satiety, and vomiting, the researchers write.

While GP is defined by delayed gastric emptying, it is also seen in 20%-30% of patients with FD. This overlap and symptom commonality make “the diagnosis difficult for many health care providers,” they write.

The researchers hypothesized that GP is frequently incorrectly overdiagnosed in the community and that FD, along with other disorders that mimic GP, are underdiagnosed.

Their retrospective review involved adult patients referred to their institution for the evaluation of GP between January 2019 and July 2021.

The team gathered information on patient demographics, medical comorbidities, diagnostic tests, and laboratory results. Researchers determined a final diagnosis after reviewing clinical notes, communications, and the results of tests conducted by experts.

Of the 339 patients, 82.1% were female and 85.6% were White.

Diabetes was diagnosed in 21.7% of patients, of whom 59.7% had type 2 disease. Most patients (71.7%) had previously been diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux disease, and 5.6% had been diagnosed with Helicobacter pylori. Anxiety and depression were also seen in 56.9% and 38.8% of patients, respectively.

The team found that 14.5% of patients were taking opioids, and 19.2% were using cannabis. Less than half (41.3%) had undergone cholecystectomy and 6.8% a fundoplication procedure.

The most common presenting symptom was nausea, in 89.1% of patients, followed by abdominal pain in 76.4%, constipation in 70.5%, and vomiting in 65.8%.

Related treatments included at least one pyloric injection of botulinum toxin in 13% of patients, whereas 2.4% had a gastric electrical stimulator implanted.

Importantly, only 57.8% of the patients had received a definitive evaluation with a gastric emptying study (GES), of whom 38.3% had undergone the recommended 4-hour study, and just 6.8% had ingested radiolabeled eggs as the test meal, the study notes.

Besides FD, alternative final diagnoses included rapid gastric emptying (12.1% of patients), pelvic floor dysfunction (9.9%), constipation (8.4%), and cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (7%).

Patient differences found

Compared with patients with a definitive GP diagnosis, patients with alternative diagnoses were younger (P = .001) and had a lower median body mass index (P = .017).

Patients who were correctly diagnosed with GP more often had diabetes (P < .001) and a history of Barrett’s esophagus (P = .042) and were less likely to have chronic kidney disease (P = .036) and rheumatoid arthritis (P = .035).

Patients with confirmed GP were also more likely to have undergone cholecystectomy (P = .008), fundoplication (P = .025), and botulinum toxin injection of the pylorus (P = .013) than those with an alternative diagnosis. They were also more likely to use a proton pump inhibitor (P < .001) and less likely to use less cannabis (P = .034).

After tertiary evaluation, patients with a definitive diagnosis of GP were more likely to be treated with metoclopramide (P < .001), prucalopride (P < .001), ondansetron (P = .005), promethazine (P = .05), and dietary interventions (P = .024) than those with alternative diagnoses.

On the other hand, patients with alternative diagnoses more often received a tricyclic antidepressant (P = .039) and were advised to discontinue cannabis (P = .05) than those confirmed as having GP.

‘Striking’ finding

Although researchers predicted that GP was overdiagnosed in the community, the finding that nearly 80% of people referred for tertiary evaluation did not have the condition was “quite striking,” Dr. Cangemi told this news organization.

The findings regarding gastric emptying evaluations highlight the result of a previous study “demonstrating low compliance with gastric emptying protocol guidelines among U.S. medical institutions,” the researchers write.

“Improperly performed GES appears to play a critical role in misdiagnosis of GP,” they add.

The study’s main message is the “importance of performing a proper gastric emptying study,” Dr. Cangemi said. If GES isn’t conducted according to the guidelines, the results may be “misleading,” he added.

Another key point is that FD is a much more prevalent disorder, affecting approximately 10% of the United States population, while GP is “much rarer,” Dr. Cangemi said.

“That might be another reason why patients are mislabeled with gastroparesis – the lack of recognition of functional dyspepsia as a common disorder of gut-brain interaction – and perhaps some hesitation of among some providers to make a confident clinical diagnosis of functional dyspepsia,” he said.

Moreover, Dr. Cangemi said, patients can “go back and forth” between the two disorders. A recent study demonstrated that roughly 40% of patients transition between the two over the course of a year, he noted.

“So being locked into one diagnosis is, I think, not appropriate anymore. Providers really need to keep an open mind and think critically about the results of a gastric emptying study, especially if it was not done recently and especially if the test did not adhere to standard protocol,” he said.

No funding was declared. Co-author Brian E. Lacy, MD, PhD, declared relationships with Ironwood, Urovant, Salix, Sanofi, and Viver. No other relevant financial relationships were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a new retrospective review suggests.

The researchers analyzed the records of 339 patients referred for tertiary evaluation of GP at one center. Overall, 19.5% of patients were confirmed to have GP, whereas 80.5% were given an alternative diagnosis, with FD being the most common (44.5%).

Contributing to initial misdiagnosis are the similarity in presentation between patients with GP and FD and low rates of gastric emptying evaluation using the recommended test protocol, lead author David J. Cangemi, MD, division of gastroenterology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla., and colleagues write.

The findings “reaffirm guidelines noting that gastroparesis cannot be diagnosed based on symptoms alone,” they write.

Because FD is more prevalent than GP, FD “should be considered first in patients with characteristic upper GI symptoms,” they add.

The review was published online in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Similarities breed confusion

GP and FD are the two most common sensorimotor disorders of the stomach, and both are characterized by abdominal pain, nausea, early satiety, and vomiting, the researchers write.

While GP is defined by delayed gastric emptying, it is also seen in 20%-30% of patients with FD. This overlap and symptom commonality make “the diagnosis difficult for many health care providers,” they write.

The researchers hypothesized that GP is frequently incorrectly overdiagnosed in the community and that FD, along with other disorders that mimic GP, are underdiagnosed.

Their retrospective review involved adult patients referred to their institution for the evaluation of GP between January 2019 and July 2021.

The team gathered information on patient demographics, medical comorbidities, diagnostic tests, and laboratory results. Researchers determined a final diagnosis after reviewing clinical notes, communications, and the results of tests conducted by experts.

Of the 339 patients, 82.1% were female and 85.6% were White.

Diabetes was diagnosed in 21.7% of patients, of whom 59.7% had type 2 disease. Most patients (71.7%) had previously been diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux disease, and 5.6% had been diagnosed with Helicobacter pylori. Anxiety and depression were also seen in 56.9% and 38.8% of patients, respectively.

The team found that 14.5% of patients were taking opioids, and 19.2% were using cannabis. Less than half (41.3%) had undergone cholecystectomy and 6.8% a fundoplication procedure.

The most common presenting symptom was nausea, in 89.1% of patients, followed by abdominal pain in 76.4%, constipation in 70.5%, and vomiting in 65.8%.

Related treatments included at least one pyloric injection of botulinum toxin in 13% of patients, whereas 2.4% had a gastric electrical stimulator implanted.

Importantly, only 57.8% of the patients had received a definitive evaluation with a gastric emptying study (GES), of whom 38.3% had undergone the recommended 4-hour study, and just 6.8% had ingested radiolabeled eggs as the test meal, the study notes.

Besides FD, alternative final diagnoses included rapid gastric emptying (12.1% of patients), pelvic floor dysfunction (9.9%), constipation (8.4%), and cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (7%).

Patient differences found

Compared with patients with a definitive GP diagnosis, patients with alternative diagnoses were younger (P = .001) and had a lower median body mass index (P = .017).

Patients who were correctly diagnosed with GP more often had diabetes (P < .001) and a history of Barrett’s esophagus (P = .042) and were less likely to have chronic kidney disease (P = .036) and rheumatoid arthritis (P = .035).

Patients with confirmed GP were also more likely to have undergone cholecystectomy (P = .008), fundoplication (P = .025), and botulinum toxin injection of the pylorus (P = .013) than those with an alternative diagnosis. They were also more likely to use a proton pump inhibitor (P < .001) and less likely to use less cannabis (P = .034).

After tertiary evaluation, patients with a definitive diagnosis of GP were more likely to be treated with metoclopramide (P < .001), prucalopride (P < .001), ondansetron (P = .005), promethazine (P = .05), and dietary interventions (P = .024) than those with alternative diagnoses.

On the other hand, patients with alternative diagnoses more often received a tricyclic antidepressant (P = .039) and were advised to discontinue cannabis (P = .05) than those confirmed as having GP.

‘Striking’ finding

Although researchers predicted that GP was overdiagnosed in the community, the finding that nearly 80% of people referred for tertiary evaluation did not have the condition was “quite striking,” Dr. Cangemi told this news organization.

The findings regarding gastric emptying evaluations highlight the result of a previous study “demonstrating low compliance with gastric emptying protocol guidelines among U.S. medical institutions,” the researchers write.

“Improperly performed GES appears to play a critical role in misdiagnosis of GP,” they add.

The study’s main message is the “importance of performing a proper gastric emptying study,” Dr. Cangemi said. If GES isn’t conducted according to the guidelines, the results may be “misleading,” he added.

Another key point is that FD is a much more prevalent disorder, affecting approximately 10% of the United States population, while GP is “much rarer,” Dr. Cangemi said.

“That might be another reason why patients are mislabeled with gastroparesis – the lack of recognition of functional dyspepsia as a common disorder of gut-brain interaction – and perhaps some hesitation of among some providers to make a confident clinical diagnosis of functional dyspepsia,” he said.

Moreover, Dr. Cangemi said, patients can “go back and forth” between the two disorders. A recent study demonstrated that roughly 40% of patients transition between the two over the course of a year, he noted.

“So being locked into one diagnosis is, I think, not appropriate anymore. Providers really need to keep an open mind and think critically about the results of a gastric emptying study, especially if it was not done recently and especially if the test did not adhere to standard protocol,” he said.

No funding was declared. Co-author Brian E. Lacy, MD, PhD, declared relationships with Ironwood, Urovant, Salix, Sanofi, and Viver. No other relevant financial relationships were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a new retrospective review suggests.

The researchers analyzed the records of 339 patients referred for tertiary evaluation of GP at one center. Overall, 19.5% of patients were confirmed to have GP, whereas 80.5% were given an alternative diagnosis, with FD being the most common (44.5%).

Contributing to initial misdiagnosis are the similarity in presentation between patients with GP and FD and low rates of gastric emptying evaluation using the recommended test protocol, lead author David J. Cangemi, MD, division of gastroenterology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla., and colleagues write.

The findings “reaffirm guidelines noting that gastroparesis cannot be diagnosed based on symptoms alone,” they write.

Because FD is more prevalent than GP, FD “should be considered first in patients with characteristic upper GI symptoms,” they add.

The review was published online in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Similarities breed confusion

GP and FD are the two most common sensorimotor disorders of the stomach, and both are characterized by abdominal pain, nausea, early satiety, and vomiting, the researchers write.

While GP is defined by delayed gastric emptying, it is also seen in 20%-30% of patients with FD. This overlap and symptom commonality make “the diagnosis difficult for many health care providers,” they write.

The researchers hypothesized that GP is frequently incorrectly overdiagnosed in the community and that FD, along with other disorders that mimic GP, are underdiagnosed.

Their retrospective review involved adult patients referred to their institution for the evaluation of GP between January 2019 and July 2021.

The team gathered information on patient demographics, medical comorbidities, diagnostic tests, and laboratory results. Researchers determined a final diagnosis after reviewing clinical notes, communications, and the results of tests conducted by experts.

Of the 339 patients, 82.1% were female and 85.6% were White.

Diabetes was diagnosed in 21.7% of patients, of whom 59.7% had type 2 disease. Most patients (71.7%) had previously been diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux disease, and 5.6% had been diagnosed with Helicobacter pylori. Anxiety and depression were also seen in 56.9% and 38.8% of patients, respectively.

The team found that 14.5% of patients were taking opioids, and 19.2% were using cannabis. Less than half (41.3%) had undergone cholecystectomy and 6.8% a fundoplication procedure.

The most common presenting symptom was nausea, in 89.1% of patients, followed by abdominal pain in 76.4%, constipation in 70.5%, and vomiting in 65.8%.

Related treatments included at least one pyloric injection of botulinum toxin in 13% of patients, whereas 2.4% had a gastric electrical stimulator implanted.

Importantly, only 57.8% of the patients had received a definitive evaluation with a gastric emptying study (GES), of whom 38.3% had undergone the recommended 4-hour study, and just 6.8% had ingested radiolabeled eggs as the test meal, the study notes.

Besides FD, alternative final diagnoses included rapid gastric emptying (12.1% of patients), pelvic floor dysfunction (9.9%), constipation (8.4%), and cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (7%).

Patient differences found

Compared with patients with a definitive GP diagnosis, patients with alternative diagnoses were younger (P = .001) and had a lower median body mass index (P = .017).

Patients who were correctly diagnosed with GP more often had diabetes (P < .001) and a history of Barrett’s esophagus (P = .042) and were less likely to have chronic kidney disease (P = .036) and rheumatoid arthritis (P = .035).

Patients with confirmed GP were also more likely to have undergone cholecystectomy (P = .008), fundoplication (P = .025), and botulinum toxin injection of the pylorus (P = .013) than those with an alternative diagnosis. They were also more likely to use a proton pump inhibitor (P < .001) and less likely to use less cannabis (P = .034).

After tertiary evaluation, patients with a definitive diagnosis of GP were more likely to be treated with metoclopramide (P < .001), prucalopride (P < .001), ondansetron (P = .005), promethazine (P = .05), and dietary interventions (P = .024) than those with alternative diagnoses.

On the other hand, patients with alternative diagnoses more often received a tricyclic antidepressant (P = .039) and were advised to discontinue cannabis (P = .05) than those confirmed as having GP.

‘Striking’ finding

Although researchers predicted that GP was overdiagnosed in the community, the finding that nearly 80% of people referred for tertiary evaluation did not have the condition was “quite striking,” Dr. Cangemi told this news organization.

The findings regarding gastric emptying evaluations highlight the result of a previous study “demonstrating low compliance with gastric emptying protocol guidelines among U.S. medical institutions,” the researchers write.

“Improperly performed GES appears to play a critical role in misdiagnosis of GP,” they add.

The study’s main message is the “importance of performing a proper gastric emptying study,” Dr. Cangemi said. If GES isn’t conducted according to the guidelines, the results may be “misleading,” he added.

Another key point is that FD is a much more prevalent disorder, affecting approximately 10% of the United States population, while GP is “much rarer,” Dr. Cangemi said.

“That might be another reason why patients are mislabeled with gastroparesis – the lack of recognition of functional dyspepsia as a common disorder of gut-brain interaction – and perhaps some hesitation of among some providers to make a confident clinical diagnosis of functional dyspepsia,” he said.

Moreover, Dr. Cangemi said, patients can “go back and forth” between the two disorders. A recent study demonstrated that roughly 40% of patients transition between the two over the course of a year, he noted.

“So being locked into one diagnosis is, I think, not appropriate anymore. Providers really need to keep an open mind and think critically about the results of a gastric emptying study, especially if it was not done recently and especially if the test did not adhere to standard protocol,” he said.

No funding was declared. Co-author Brian E. Lacy, MD, PhD, declared relationships with Ironwood, Urovant, Salix, Sanofi, and Viver. No other relevant financial relationships were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Meta-analysis throws more shade aspirin’s way

A new meta-analysis has added evidence questioning the utility and efficacy of prophylactic low-dose aspirin for preventing cardiovascular events in people who don’t have atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), whether or not they’re also taking statins, and finds that at every level of ASCVD risk the aspirin carries a risk of major bleeding that exceeds its potentially protective benefits.

In a study published online in JACC: Advances, the researchers, led by Safi U. Khan, MD, MS, analyzed data from 16 trials with 171,215 individuals, with a median age of 64 years. Of the population analyzed, 35% were taking statins.

“This study focused on patients without ASCVD who are taking aspirin with or without statin therapy to prevent ASCVD events,” Dr. Khan, a cardiovascular disease fellow at Houston Methodist DeBakey Heart and Vascular Institute, told this news organization. “We noted that the absolute risk of major bleeding in this patient population exceeds the absolute reduction in MI by aspirin across different ASCVD risk categories. Furthermore, concomitant statin therapy use further diminishes aspirin’s cardiovascular effects without influencing bleeding risk.”

Across the 16 studies, people taking aspirin had a relative risk reduction of 15% for MI vs. controls (RR .85; 95% confidence interval [CI], .77 to .95; P < .001). However, they had a 48% greater risk of major bleeding (RR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.31-1.66; P < .001).

The meta-analysis also found that aspirin, either as monotherapy or with a statin, carried a slight to significant benefit depending on the estimated risk of developing ASCVD. The risk of major bleeding exceeded the benefit across all three risk-stratified groups. The greatest benefit, and greatest risk, was in the groups with high to very-high ASCVD risk groups, defined as a 20%-30% and 30% or greater ASCVD risk, respectively: 20-37 fewer MIs per 10,000 with monotherapy and 27-49 fewer with statin, but 78-98 more major bleeding events with monotherapy and 74-95 more with statin.

And aspirin, either as monotherapy or with statin, didn’t reduce the risk of other key endpoints: stroke, all-cause mortality, or cardiovascular mortality. While aspirin was associated with a lower risk of nonfatal MI (RR, .82; 95% CI, .72 to .94; P ≤. 001), it wasn’t associated with reducing the risk of nonfatal stroke. Aspirin patients had a significantly 32% greater risk of intracranial hemorrhage (RR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.12-1.55; P ≤ .001) and 51% increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding (RR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.33-1.72; P ≤ .001).

“We used randomized data from all key primary prevention of aspirin trials and estimated the absolute effects of aspirin therapy with or without concomitant statin across different baseline risks of the patients,” Dr. Khan said. “This approach allowed us to identify aspirin therapy’s risk-benefit equilibrium, which is tilted towards more harm than benefit.”

He acknowledged study limitations included using study-level rather than patient-level meta-analysis, and the inability to calculate effects in younger populations at high absolute risk.

The investigators acknowledged the controversy surrounding aspirin use to prevent ASCVD, noting the three major guidelines: the 2019 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and the 2021 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for aspirin only among asymptomatic individuals with high risk of ASCVD events, low bleeding risk, and age 70 years and younger; and the United States Preventive Services Task Force guidelines, updated in 2022, recommending individualized low-dose aspirin only among adults ages 40-59 years with 10-year ASCVD risk of 10% or greater and a low bleeding risk.

The findings are not a clarion call to halt aspirin therapy, Dr. Khan said. “This research focuses only on patients who do not have ASCVD,” he said. “Patients who do have ASCVD should continue with aspirin and statin therapy. However, we noted that aspirin has a limited role for patients who do not have ASCVD beyond lifestyle modifications, smoking cessation, exercise, and preventive statin therapy. Therefore, they should only consider using aspirin if their physicians suggest that the risk of having a cardiovascular event exceeds their bleeding risk. Otherwise, they should discuss with their physicians about omitting aspirin.”

The study confirms the move away from low-dose aspirin to prevent ASCVD, said Tahmid Rahman, MD, cardiologist and associate director of the Center for Advanced Lipid Management at Stony Brook (N.Y.) Heart Institute. “The study really continues to add to essentially what we already know,” he said. “There was a big push that aspirin, initially before the major statin trials, was the way to go to prevent heart disease, but with later studies, and especially now with newer antiplatelet therapies and longer duration of medication for people with both secondary prevention and primary prevention, we are getting away from routine aspirin, especially in primary prevention.”

Lowering LDL cholesterol is the definitive target for lowering risk for MI and stroke, Dr. Rahman said. “Statins don’t lead to a bleeding risk,” he said, “so my recommendation is to be aggressive with lowering your cholesterol and getting the LDL as low possible to really reduce outcomes, especially in secondary prevention, as well as in high-risk patients for primary prevention, especially diabetics.”

He added, however, lifestyle modification also has a key role for preventing ASCVD. “No matter what we have with medication, the most important thing is following a proper diet, especially something like the Mediterranean diet, as well as exercising regularly,” he said.

Dr. Khan and Dr. Rahman have no relevant disclosures.

A new meta-analysis has added evidence questioning the utility and efficacy of prophylactic low-dose aspirin for preventing cardiovascular events in people who don’t have atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), whether or not they’re also taking statins, and finds that at every level of ASCVD risk the aspirin carries a risk of major bleeding that exceeds its potentially protective benefits.

In a study published online in JACC: Advances, the researchers, led by Safi U. Khan, MD, MS, analyzed data from 16 trials with 171,215 individuals, with a median age of 64 years. Of the population analyzed, 35% were taking statins.

“This study focused on patients without ASCVD who are taking aspirin with or without statin therapy to prevent ASCVD events,” Dr. Khan, a cardiovascular disease fellow at Houston Methodist DeBakey Heart and Vascular Institute, told this news organization. “We noted that the absolute risk of major bleeding in this patient population exceeds the absolute reduction in MI by aspirin across different ASCVD risk categories. Furthermore, concomitant statin therapy use further diminishes aspirin’s cardiovascular effects without influencing bleeding risk.”

Across the 16 studies, people taking aspirin had a relative risk reduction of 15% for MI vs. controls (RR .85; 95% confidence interval [CI], .77 to .95; P < .001). However, they had a 48% greater risk of major bleeding (RR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.31-1.66; P < .001).

The meta-analysis also found that aspirin, either as monotherapy or with a statin, carried a slight to significant benefit depending on the estimated risk of developing ASCVD. The risk of major bleeding exceeded the benefit across all three risk-stratified groups. The greatest benefit, and greatest risk, was in the groups with high to very-high ASCVD risk groups, defined as a 20%-30% and 30% or greater ASCVD risk, respectively: 20-37 fewer MIs per 10,000 with monotherapy and 27-49 fewer with statin, but 78-98 more major bleeding events with monotherapy and 74-95 more with statin.

And aspirin, either as monotherapy or with statin, didn’t reduce the risk of other key endpoints: stroke, all-cause mortality, or cardiovascular mortality. While aspirin was associated with a lower risk of nonfatal MI (RR, .82; 95% CI, .72 to .94; P ≤. 001), it wasn’t associated with reducing the risk of nonfatal stroke. Aspirin patients had a significantly 32% greater risk of intracranial hemorrhage (RR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.12-1.55; P ≤ .001) and 51% increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding (RR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.33-1.72; P ≤ .001).

“We used randomized data from all key primary prevention of aspirin trials and estimated the absolute effects of aspirin therapy with or without concomitant statin across different baseline risks of the patients,” Dr. Khan said. “This approach allowed us to identify aspirin therapy’s risk-benefit equilibrium, which is tilted towards more harm than benefit.”

He acknowledged study limitations included using study-level rather than patient-level meta-analysis, and the inability to calculate effects in younger populations at high absolute risk.

The investigators acknowledged the controversy surrounding aspirin use to prevent ASCVD, noting the three major guidelines: the 2019 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and the 2021 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for aspirin only among asymptomatic individuals with high risk of ASCVD events, low bleeding risk, and age 70 years and younger; and the United States Preventive Services Task Force guidelines, updated in 2022, recommending individualized low-dose aspirin only among adults ages 40-59 years with 10-year ASCVD risk of 10% or greater and a low bleeding risk.

The findings are not a clarion call to halt aspirin therapy, Dr. Khan said. “This research focuses only on patients who do not have ASCVD,” he said. “Patients who do have ASCVD should continue with aspirin and statin therapy. However, we noted that aspirin has a limited role for patients who do not have ASCVD beyond lifestyle modifications, smoking cessation, exercise, and preventive statin therapy. Therefore, they should only consider using aspirin if their physicians suggest that the risk of having a cardiovascular event exceeds their bleeding risk. Otherwise, they should discuss with their physicians about omitting aspirin.”

The study confirms the move away from low-dose aspirin to prevent ASCVD, said Tahmid Rahman, MD, cardiologist and associate director of the Center for Advanced Lipid Management at Stony Brook (N.Y.) Heart Institute. “The study really continues to add to essentially what we already know,” he said. “There was a big push that aspirin, initially before the major statin trials, was the way to go to prevent heart disease, but with later studies, and especially now with newer antiplatelet therapies and longer duration of medication for people with both secondary prevention and primary prevention, we are getting away from routine aspirin, especially in primary prevention.”

Lowering LDL cholesterol is the definitive target for lowering risk for MI and stroke, Dr. Rahman said. “Statins don’t lead to a bleeding risk,” he said, “so my recommendation is to be aggressive with lowering your cholesterol and getting the LDL as low possible to really reduce outcomes, especially in secondary prevention, as well as in high-risk patients for primary prevention, especially diabetics.”

He added, however, lifestyle modification also has a key role for preventing ASCVD. “No matter what we have with medication, the most important thing is following a proper diet, especially something like the Mediterranean diet, as well as exercising regularly,” he said.

Dr. Khan and Dr. Rahman have no relevant disclosures.

A new meta-analysis has added evidence questioning the utility and efficacy of prophylactic low-dose aspirin for preventing cardiovascular events in people who don’t have atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), whether or not they’re also taking statins, and finds that at every level of ASCVD risk the aspirin carries a risk of major bleeding that exceeds its potentially protective benefits.

In a study published online in JACC: Advances, the researchers, led by Safi U. Khan, MD, MS, analyzed data from 16 trials with 171,215 individuals, with a median age of 64 years. Of the population analyzed, 35% were taking statins.

“This study focused on patients without ASCVD who are taking aspirin with or without statin therapy to prevent ASCVD events,” Dr. Khan, a cardiovascular disease fellow at Houston Methodist DeBakey Heart and Vascular Institute, told this news organization. “We noted that the absolute risk of major bleeding in this patient population exceeds the absolute reduction in MI by aspirin across different ASCVD risk categories. Furthermore, concomitant statin therapy use further diminishes aspirin’s cardiovascular effects without influencing bleeding risk.”

Across the 16 studies, people taking aspirin had a relative risk reduction of 15% for MI vs. controls (RR .85; 95% confidence interval [CI], .77 to .95; P < .001). However, they had a 48% greater risk of major bleeding (RR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.31-1.66; P < .001).

The meta-analysis also found that aspirin, either as monotherapy or with a statin, carried a slight to significant benefit depending on the estimated risk of developing ASCVD. The risk of major bleeding exceeded the benefit across all three risk-stratified groups. The greatest benefit, and greatest risk, was in the groups with high to very-high ASCVD risk groups, defined as a 20%-30% and 30% or greater ASCVD risk, respectively: 20-37 fewer MIs per 10,000 with monotherapy and 27-49 fewer with statin, but 78-98 more major bleeding events with monotherapy and 74-95 more with statin.

And aspirin, either as monotherapy or with statin, didn’t reduce the risk of other key endpoints: stroke, all-cause mortality, or cardiovascular mortality. While aspirin was associated with a lower risk of nonfatal MI (RR, .82; 95% CI, .72 to .94; P ≤. 001), it wasn’t associated with reducing the risk of nonfatal stroke. Aspirin patients had a significantly 32% greater risk of intracranial hemorrhage (RR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.12-1.55; P ≤ .001) and 51% increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding (RR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.33-1.72; P ≤ .001).

“We used randomized data from all key primary prevention of aspirin trials and estimated the absolute effects of aspirin therapy with or without concomitant statin across different baseline risks of the patients,” Dr. Khan said. “This approach allowed us to identify aspirin therapy’s risk-benefit equilibrium, which is tilted towards more harm than benefit.”

He acknowledged study limitations included using study-level rather than patient-level meta-analysis, and the inability to calculate effects in younger populations at high absolute risk.

The investigators acknowledged the controversy surrounding aspirin use to prevent ASCVD, noting the three major guidelines: the 2019 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and the 2021 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for aspirin only among asymptomatic individuals with high risk of ASCVD events, low bleeding risk, and age 70 years and younger; and the United States Preventive Services Task Force guidelines, updated in 2022, recommending individualized low-dose aspirin only among adults ages 40-59 years with 10-year ASCVD risk of 10% or greater and a low bleeding risk.

The findings are not a clarion call to halt aspirin therapy, Dr. Khan said. “This research focuses only on patients who do not have ASCVD,” he said. “Patients who do have ASCVD should continue with aspirin and statin therapy. However, we noted that aspirin has a limited role for patients who do not have ASCVD beyond lifestyle modifications, smoking cessation, exercise, and preventive statin therapy. Therefore, they should only consider using aspirin if their physicians suggest that the risk of having a cardiovascular event exceeds their bleeding risk. Otherwise, they should discuss with their physicians about omitting aspirin.”

The study confirms the move away from low-dose aspirin to prevent ASCVD, said Tahmid Rahman, MD, cardiologist and associate director of the Center for Advanced Lipid Management at Stony Brook (N.Y.) Heart Institute. “The study really continues to add to essentially what we already know,” he said. “There was a big push that aspirin, initially before the major statin trials, was the way to go to prevent heart disease, but with later studies, and especially now with newer antiplatelet therapies and longer duration of medication for people with both secondary prevention and primary prevention, we are getting away from routine aspirin, especially in primary prevention.”

Lowering LDL cholesterol is the definitive target for lowering risk for MI and stroke, Dr. Rahman said. “Statins don’t lead to a bleeding risk,” he said, “so my recommendation is to be aggressive with lowering your cholesterol and getting the LDL as low possible to really reduce outcomes, especially in secondary prevention, as well as in high-risk patients for primary prevention, especially diabetics.”

He added, however, lifestyle modification also has a key role for preventing ASCVD. “No matter what we have with medication, the most important thing is following a proper diet, especially something like the Mediterranean diet, as well as exercising regularly,” he said.

Dr. Khan and Dr. Rahman have no relevant disclosures.

FROM JACC: ADVANCES

Asymptomatic Soft Tumor on the Forearm

The Diagnosis: Aneurysmal Dermatofibroma

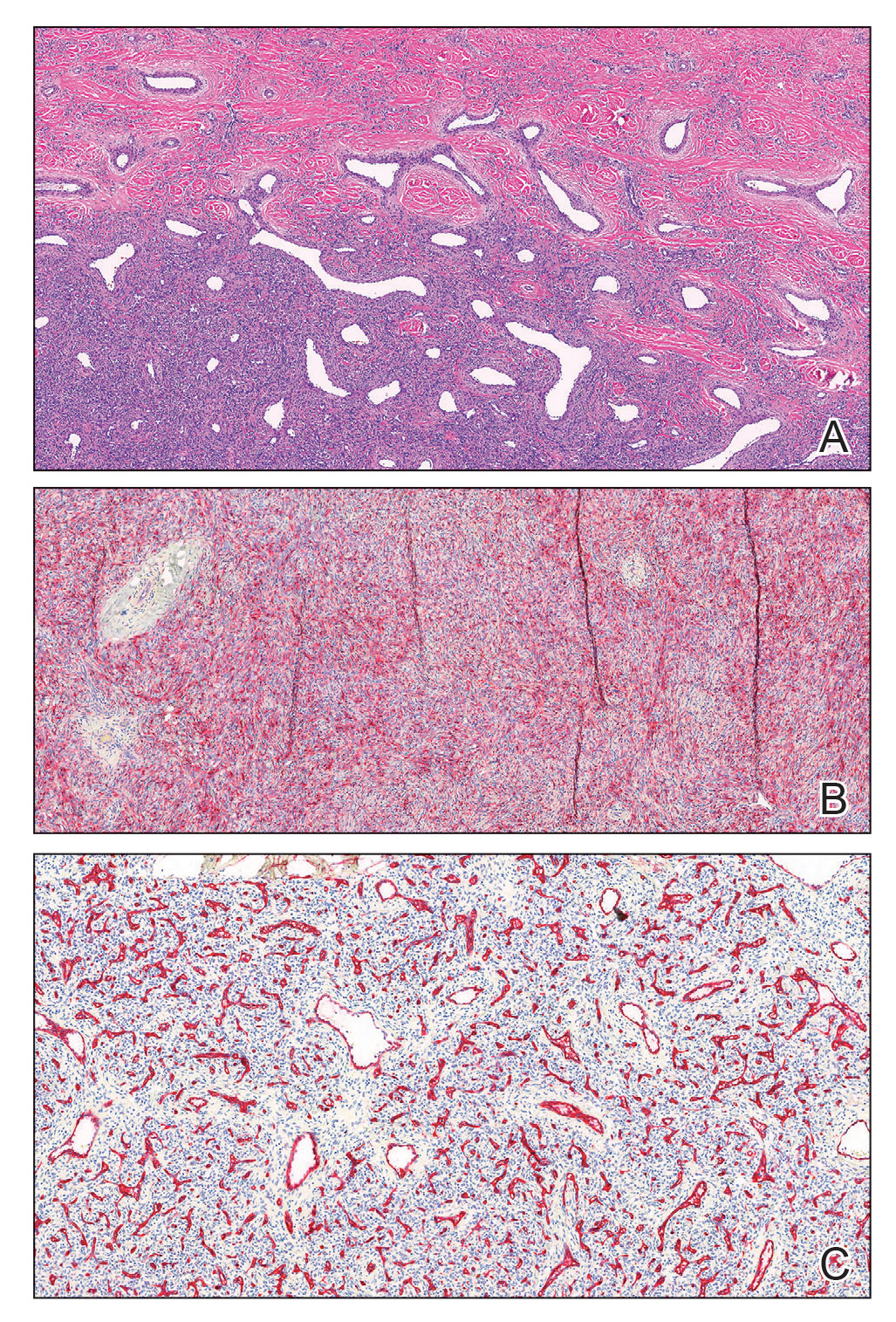

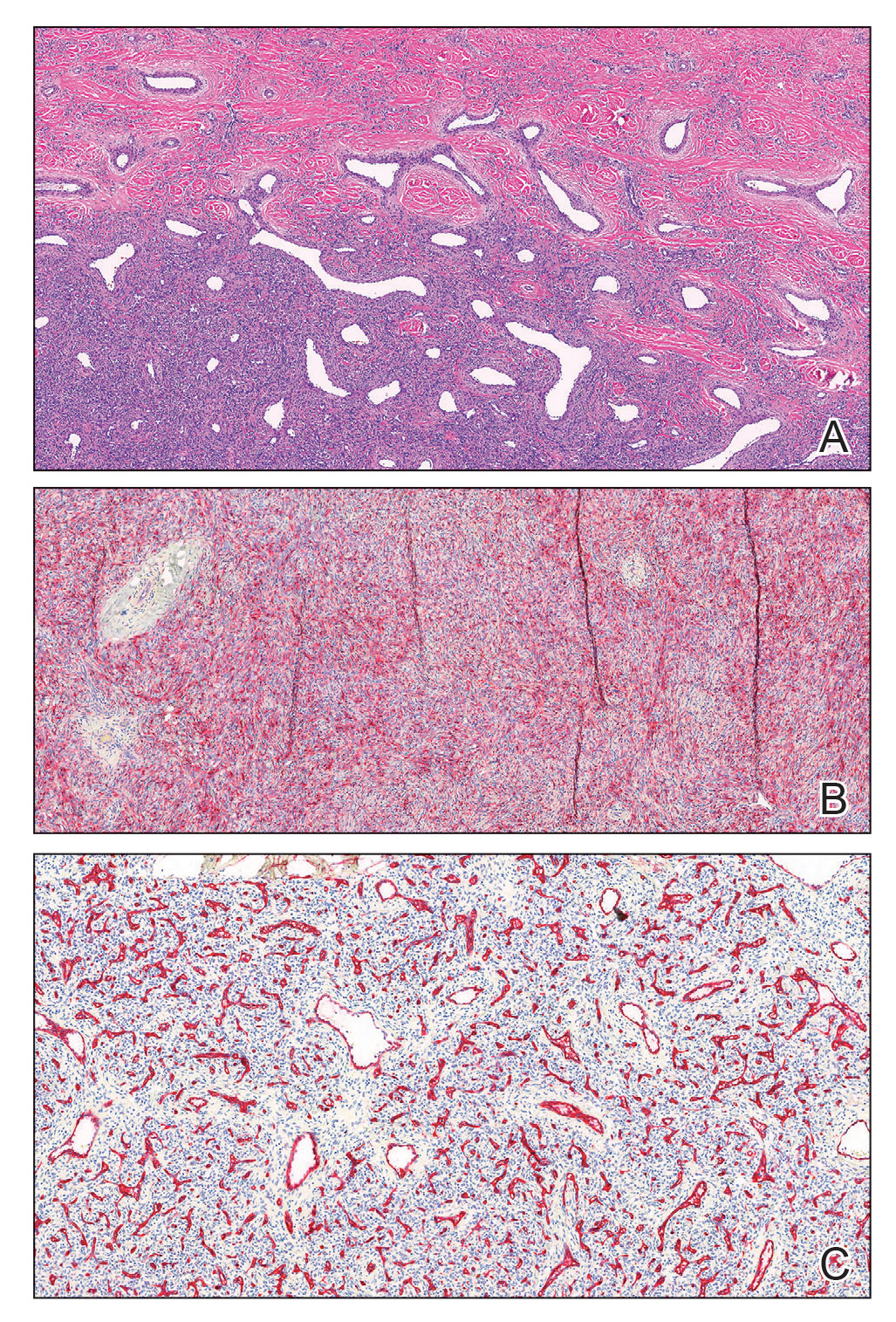

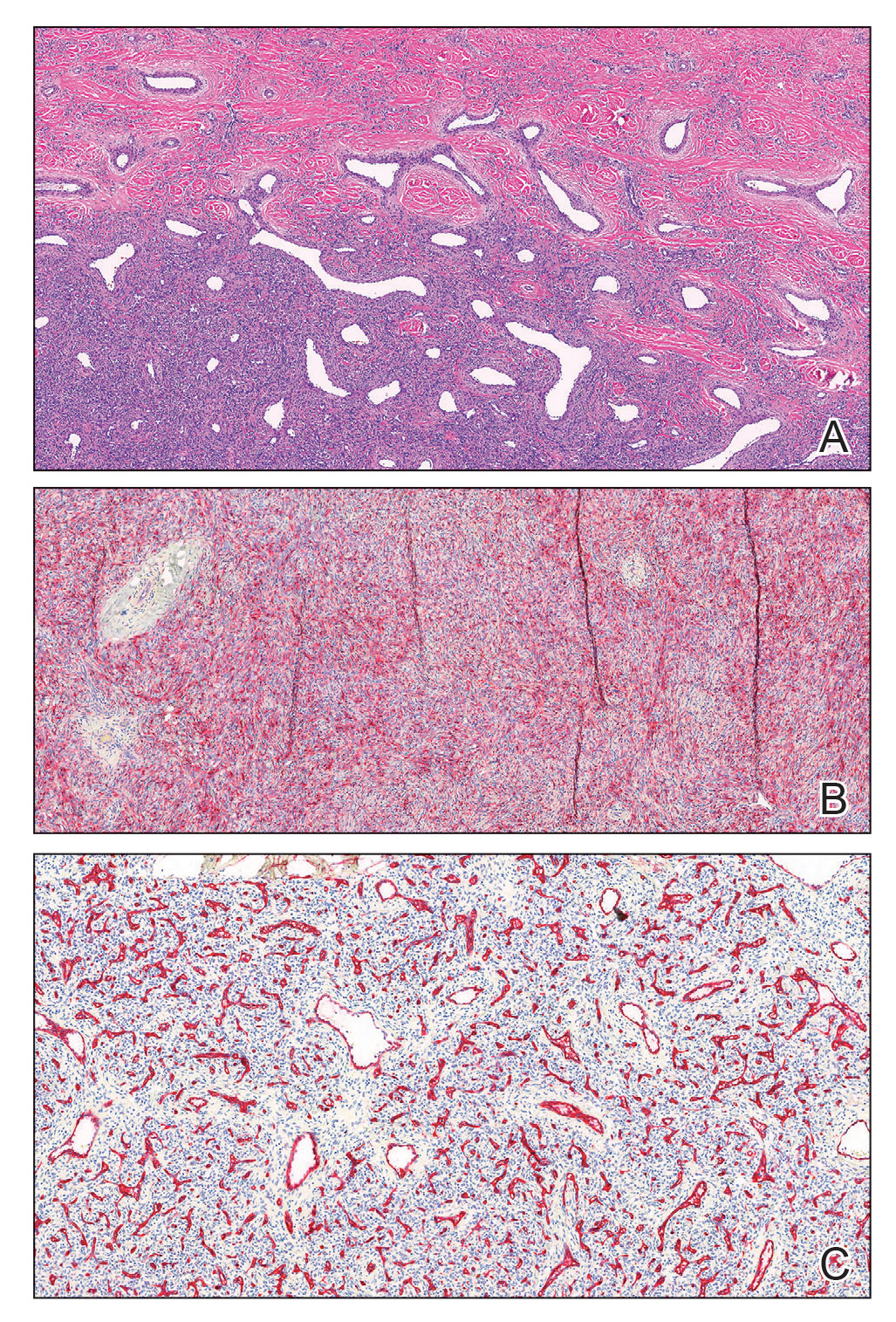

A shave biopsy of the entire tumor was performed at the initial visit. Histologic examination with hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a fibrohistiocytic infiltrate containing cleftlike cavernous spaces lined by epithelial cells (Figure, A). Immunohistochemical staining revealed factor XIIIa expression on fibrohistiocytic cells (Figure, B). CD34 was expressed on vascular endothelial cells, but it failed to highlight the fibrohistiocytic space (Figure, C). Overall, these findings supported the diagnosis of aneurysmal dermatofibroma. The lesion healed without complications, and the patient was counseled on the risk for recurrence. He was offered localized excision but opted for conservative management without excision and close follow-up and monitoring.

Dermatofibromas are common benign cutaneous nodules that often are asymptomatic and occur on the extremities. Dermatofibromas also are known as cutaneous fibrous histiocytomas and have numerous histologic variants. Aneurysmal dermatofibroma (also called aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma) is a rare histologic variant of dermatofibroma presenting as a slow-growing exophytic tumor that can be purple, red, brown, or blue. Although classic dermatofibromas typically constitute a straightforward diagnosis, aneurysmal dermatofibromas often are more challenging to clinically differentiate from other cutaneous neoplasms. Additionally, due to the exophytic nature and larger size (0.5–4.0 cm), aneurysmal dermatofibromas do not exhibit the characteristic dimple (Fitzpatrick) sign found in many dermatofibromas. Aneurysmal dermatofibromas are 10 times more likely to recur than classic dermatofibromas.1-4

Aneurysmal dermatofibromas can mimic other cutaneous neoplasms, some indolent and others more aggressive. Similar to aneurysmal dermatofibromas, solitary neurofibromas and nevi lipomatosus can appear as asymptomatic exophytic nodules with a similar spectrum of color and indolent clinical courses. In nevus lipomatosus, the dermis is almost entirely replaced by mature adipose tissue.5 Solitary neurofibromas represent a proliferation of neuromesenchymal cells with haphazardly arranged, wavy nuclei characteristic of nerve cells.6 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans can be distinguished from aneurysmal dermatofibroma by lack of factor XIIIa expression and diffuse positivity for CD34.7 Finally, aneurysmal dermatofibromas may resemble vascular tumors such as nodular Kaposi sarcoma. Kaposi sarcoma can be differentiated from an aneurysmal dermatofibroma by the presence of characteristic vascular wrapping, the absence of fibrohistiocytic cells, and expression of human herpesvirus 8 latent nuclear antigen-1.1,8 Although aneurysmal dermatofibromas are of low malignant potential, they are associated with a higher rate of recurrence compared to common dermatofibromas.9 Definitive treatment involves complete excision with follow-up to ensure no signs of recurrence.10 Incomplete excision can increase the likelihood of recurrence, especially for larger aneurysmal dermatofibromas. Aneurysmal dermatofibromas are one of the subtypes of dermatofibromas that may extend into the subcutaneous tissue. Han et al2 found that 77.8% of aneurysmal dermatofibromas extended into subcutaneous tissue. Recognizing the clinical and pathological features of this rare subtype of dermatofibroma can aid dermatologists in appropriate recognition and management.

- Burr DM, Peterson WA, Peterson MW. Aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Am Osteopath. June 2018;40. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.aocd.org/resource/resmgr/jaocd/contents/volume40/40-04.pdf

- Han TY, Chang HS, Lee JHK, et al. A clinical and histopathological study of 122 cases of dermatofibroma (benign fibrous histiocytoma). Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:185-192.

- Morariu SH, Suciu M, Vartolomei MD, et al. Aneurysmal dermatofibroma mimicking both clinical and dermoscopic malignant melanoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:1221-1224.

- Calonje E, Fletcher CDM. Aneurysmal benign fibrous histiocytoma: clinicopathological analysis of 40 cases of a tumour frequently misdiagnosed as a vascular neoplasm. Histopathology. 1995;26:323-331.

- Pujani M, Choudhury M, Garg T, et al. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis: a rare cutaneous hamartoma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:109-110.

- Strike SA, Puhaindran ME. Nerve tumors of the upper extremity. Clin Plast Surg. 2019;46:347-350.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Farhood AI. Dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: differential expression of CD34 and factor XIIIa. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:573-574.

- Kandal S, Ozmen S, Demir HY, et al. Aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma of the skin: a rare variant of dermatofibroma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:2050-2051.

- Hornick JL. Cutaneous soft tissue tumors: how do we make sense of fibrous and “fibrohistiocytic” tumors with confusing names and similar appearances? Mod Pathol. 2020;33:56-65.

- Das A, Das A, Bandyopadhyay D, et al. Aneurysmal benign fibrous histiocytoma presenting as a giant acrochordon on thigh. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:436.

The Diagnosis: Aneurysmal Dermatofibroma

A shave biopsy of the entire tumor was performed at the initial visit. Histologic examination with hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a fibrohistiocytic infiltrate containing cleftlike cavernous spaces lined by epithelial cells (Figure, A). Immunohistochemical staining revealed factor XIIIa expression on fibrohistiocytic cells (Figure, B). CD34 was expressed on vascular endothelial cells, but it failed to highlight the fibrohistiocytic space (Figure, C). Overall, these findings supported the diagnosis of aneurysmal dermatofibroma. The lesion healed without complications, and the patient was counseled on the risk for recurrence. He was offered localized excision but opted for conservative management without excision and close follow-up and monitoring.

Dermatofibromas are common benign cutaneous nodules that often are asymptomatic and occur on the extremities. Dermatofibromas also are known as cutaneous fibrous histiocytomas and have numerous histologic variants. Aneurysmal dermatofibroma (also called aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma) is a rare histologic variant of dermatofibroma presenting as a slow-growing exophytic tumor that can be purple, red, brown, or blue. Although classic dermatofibromas typically constitute a straightforward diagnosis, aneurysmal dermatofibromas often are more challenging to clinically differentiate from other cutaneous neoplasms. Additionally, due to the exophytic nature and larger size (0.5–4.0 cm), aneurysmal dermatofibromas do not exhibit the characteristic dimple (Fitzpatrick) sign found in many dermatofibromas. Aneurysmal dermatofibromas are 10 times more likely to recur than classic dermatofibromas.1-4

Aneurysmal dermatofibromas can mimic other cutaneous neoplasms, some indolent and others more aggressive. Similar to aneurysmal dermatofibromas, solitary neurofibromas and nevi lipomatosus can appear as asymptomatic exophytic nodules with a similar spectrum of color and indolent clinical courses. In nevus lipomatosus, the dermis is almost entirely replaced by mature adipose tissue.5 Solitary neurofibromas represent a proliferation of neuromesenchymal cells with haphazardly arranged, wavy nuclei characteristic of nerve cells.6 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans can be distinguished from aneurysmal dermatofibroma by lack of factor XIIIa expression and diffuse positivity for CD34.7 Finally, aneurysmal dermatofibromas may resemble vascular tumors such as nodular Kaposi sarcoma. Kaposi sarcoma can be differentiated from an aneurysmal dermatofibroma by the presence of characteristic vascular wrapping, the absence of fibrohistiocytic cells, and expression of human herpesvirus 8 latent nuclear antigen-1.1,8 Although aneurysmal dermatofibromas are of low malignant potential, they are associated with a higher rate of recurrence compared to common dermatofibromas.9 Definitive treatment involves complete excision with follow-up to ensure no signs of recurrence.10 Incomplete excision can increase the likelihood of recurrence, especially for larger aneurysmal dermatofibromas. Aneurysmal dermatofibromas are one of the subtypes of dermatofibromas that may extend into the subcutaneous tissue. Han et al2 found that 77.8% of aneurysmal dermatofibromas extended into subcutaneous tissue. Recognizing the clinical and pathological features of this rare subtype of dermatofibroma can aid dermatologists in appropriate recognition and management.

The Diagnosis: Aneurysmal Dermatofibroma

A shave biopsy of the entire tumor was performed at the initial visit. Histologic examination with hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a fibrohistiocytic infiltrate containing cleftlike cavernous spaces lined by epithelial cells (Figure, A). Immunohistochemical staining revealed factor XIIIa expression on fibrohistiocytic cells (Figure, B). CD34 was expressed on vascular endothelial cells, but it failed to highlight the fibrohistiocytic space (Figure, C). Overall, these findings supported the diagnosis of aneurysmal dermatofibroma. The lesion healed without complications, and the patient was counseled on the risk for recurrence. He was offered localized excision but opted for conservative management without excision and close follow-up and monitoring.

Dermatofibromas are common benign cutaneous nodules that often are asymptomatic and occur on the extremities. Dermatofibromas also are known as cutaneous fibrous histiocytomas and have numerous histologic variants. Aneurysmal dermatofibroma (also called aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma) is a rare histologic variant of dermatofibroma presenting as a slow-growing exophytic tumor that can be purple, red, brown, or blue. Although classic dermatofibromas typically constitute a straightforward diagnosis, aneurysmal dermatofibromas often are more challenging to clinically differentiate from other cutaneous neoplasms. Additionally, due to the exophytic nature and larger size (0.5–4.0 cm), aneurysmal dermatofibromas do not exhibit the characteristic dimple (Fitzpatrick) sign found in many dermatofibromas. Aneurysmal dermatofibromas are 10 times more likely to recur than classic dermatofibromas.1-4

Aneurysmal dermatofibromas can mimic other cutaneous neoplasms, some indolent and others more aggressive. Similar to aneurysmal dermatofibromas, solitary neurofibromas and nevi lipomatosus can appear as asymptomatic exophytic nodules with a similar spectrum of color and indolent clinical courses. In nevus lipomatosus, the dermis is almost entirely replaced by mature adipose tissue.5 Solitary neurofibromas represent a proliferation of neuromesenchymal cells with haphazardly arranged, wavy nuclei characteristic of nerve cells.6 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans can be distinguished from aneurysmal dermatofibroma by lack of factor XIIIa expression and diffuse positivity for CD34.7 Finally, aneurysmal dermatofibromas may resemble vascular tumors such as nodular Kaposi sarcoma. Kaposi sarcoma can be differentiated from an aneurysmal dermatofibroma by the presence of characteristic vascular wrapping, the absence of fibrohistiocytic cells, and expression of human herpesvirus 8 latent nuclear antigen-1.1,8 Although aneurysmal dermatofibromas are of low malignant potential, they are associated with a higher rate of recurrence compared to common dermatofibromas.9 Definitive treatment involves complete excision with follow-up to ensure no signs of recurrence.10 Incomplete excision can increase the likelihood of recurrence, especially for larger aneurysmal dermatofibromas. Aneurysmal dermatofibromas are one of the subtypes of dermatofibromas that may extend into the subcutaneous tissue. Han et al2 found that 77.8% of aneurysmal dermatofibromas extended into subcutaneous tissue. Recognizing the clinical and pathological features of this rare subtype of dermatofibroma can aid dermatologists in appropriate recognition and management.

- Burr DM, Peterson WA, Peterson MW. Aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Am Osteopath. June 2018;40. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.aocd.org/resource/resmgr/jaocd/contents/volume40/40-04.pdf

- Han TY, Chang HS, Lee JHK, et al. A clinical and histopathological study of 122 cases of dermatofibroma (benign fibrous histiocytoma). Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:185-192.

- Morariu SH, Suciu M, Vartolomei MD, et al. Aneurysmal dermatofibroma mimicking both clinical and dermoscopic malignant melanoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:1221-1224.

- Calonje E, Fletcher CDM. Aneurysmal benign fibrous histiocytoma: clinicopathological analysis of 40 cases of a tumour frequently misdiagnosed as a vascular neoplasm. Histopathology. 1995;26:323-331.

- Pujani M, Choudhury M, Garg T, et al. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis: a rare cutaneous hamartoma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:109-110.

- Strike SA, Puhaindran ME. Nerve tumors of the upper extremity. Clin Plast Surg. 2019;46:347-350.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Farhood AI. Dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: differential expression of CD34 and factor XIIIa. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:573-574.

- Kandal S, Ozmen S, Demir HY, et al. Aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma of the skin: a rare variant of dermatofibroma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:2050-2051.

- Hornick JL. Cutaneous soft tissue tumors: how do we make sense of fibrous and “fibrohistiocytic” tumors with confusing names and similar appearances? Mod Pathol. 2020;33:56-65.

- Das A, Das A, Bandyopadhyay D, et al. Aneurysmal benign fibrous histiocytoma presenting as a giant acrochordon on thigh. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:436.

- Burr DM, Peterson WA, Peterson MW. Aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Am Osteopath. June 2018;40. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.aocd.org/resource/resmgr/jaocd/contents/volume40/40-04.pdf

- Han TY, Chang HS, Lee JHK, et al. A clinical and histopathological study of 122 cases of dermatofibroma (benign fibrous histiocytoma). Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:185-192.

- Morariu SH, Suciu M, Vartolomei MD, et al. Aneurysmal dermatofibroma mimicking both clinical and dermoscopic malignant melanoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:1221-1224.

- Calonje E, Fletcher CDM. Aneurysmal benign fibrous histiocytoma: clinicopathological analysis of 40 cases of a tumour frequently misdiagnosed as a vascular neoplasm. Histopathology. 1995;26:323-331.

- Pujani M, Choudhury M, Garg T, et al. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis: a rare cutaneous hamartoma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:109-110.

- Strike SA, Puhaindran ME. Nerve tumors of the upper extremity. Clin Plast Surg. 2019;46:347-350.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Farhood AI. Dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: differential expression of CD34 and factor XIIIa. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:573-574.

- Kandal S, Ozmen S, Demir HY, et al. Aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma of the skin: a rare variant of dermatofibroma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:2050-2051.

- Hornick JL. Cutaneous soft tissue tumors: how do we make sense of fibrous and “fibrohistiocytic” tumors with confusing names and similar appearances? Mod Pathol. 2020;33:56-65.

- Das A, Das A, Bandyopadhyay D, et al. Aneurysmal benign fibrous histiocytoma presenting as a giant acrochordon on thigh. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:436.

A 43-year-old Black man with no notable medical history presented to our clinic with a progressively enlarging tumor on the right forearm of 12 months’ duration. Despite its progressive growth, the tumor was asymptomatic. Physical examination of the right forearm revealed a 3.7×3.0-cm, well-circumscribed, exophytic tumor with a mildly erythematous hue, scaly surface, and rubbery consistency. There was no surrounding erythema, edema, localized lymphadenopathy, or concurrent lymphedema.

Don’t keep your patients waiting

Recently, the results of a survey of consumers regarding their health care experiences were reported by Carta Healthcare. As you might expect, I’ve written about punctuality before, but this is such a ubiquitous problem that it bears repeating. Here are some suggestions:

Start on time. That seems obvious, but I’m always amazed at the number of doctors who admit to running late who also admit that they start late. If you’re in the hole before you even start, you can seldom dig yourself out. Sometimes an on-time start is the solution to the entire problem! If you doubt me, try it.

Book realistically. Everyone works at a different pace. Determine the number of patients you can comfortably see in an hour, and book only that number. If you want to see more patients, the solution is working longer hours or hiring physicians or physician extenders (or both), not overloading your schedule.

Time-stamp each chart. Pay attention to patient arrival times if your EHR records them, and step up your pace if you start to fall behind. If your EHR does not record arrival times or you are still using paper records, buy a time clock and have your receptionist time-stamp the “encounter form” that goes to the back with the patient. One glance at the stamp will tell you exactly how long that patient has been waiting.

Schedule all surgeries. If you haven’t scheduled the time necessary for a surgical procedure, don’t do it. It’s frequently tempting to “squeeze in” an excision, often because you feel guilty that the patient has already had to wait for you. But every unscheduled surgery puts you that much further behind. And hurrying through a procedure increases the risk of mistakes. Tell the patient that surgery requires extra time and it can’t be rushed, so you will have to schedule that time.

Work-ins come last, not first. Patients with urgent problems should be seen after scheduled patients. That may seem counterintuitive; receptionists often assume it’s better to squeeze them in early, while you’re still running on time. But doing that guarantees you will run late, and it isn’t fair to patients who have appointments and expect to be seen promptly.

Work-ins, on the other hand, expect a wait because they have no appointment. We tell them, “Our schedule is full today; but if you come at the end of hours, the doctor will see you. But you may have a wait.” Far from complaining, they invariably thank us for seeing them.

Seize the list. You know the list I mean. “Number 16: My right big toe itches. Number 17: I think I feel something on my back. Number 18: This weird chartreuse thing on my arm ...” One long list can leave an entire half-day schedule in shambles.

When a list is produced, the best option is to take it and read it yourself. Identify the most important two or three problems, and address them. For the rest, I will say, “This group of problems deserves a visit of its own, and we will schedule that visit.”

Ask if you can place the list (or a photocopy) in the patient’s chart. (It is, after all, important clinical information.) All of these problems are important to the patient and should be addressed – but on your schedule, not the patient’s.

Avoid interruptions. Especially phone calls. Unless it’s an emergency or an immediate family member, my receptionists say, “I’m sorry, the doctor is with patients. May I take a message?” Everyone – even other physicians – understands. But be sure to return those calls promptly.

Pharmaceutical reps should not be allowed to interrupt you, either. Have them make an appointment, just like everybody else.

There will be times, of course, when you run late. But these should be the exception rather than the rule. By streamlining your procedures and avoiding the pitfalls mentioned, you can give nearly every patient all the time he or she deserves without keeping the next patient waiting.

Incidentally, other common patient complaints in that survey were the following:

- Couldn’t schedule an appointment within a week.

- Spent too little time with me.

- Didn’t provide test results promptly.

- Didn’t respond to my phone calls promptly.

Now would be an excellent opportunity to identify and address any of those problems as well.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Recently, the results of a survey of consumers regarding their health care experiences were reported by Carta Healthcare. As you might expect, I’ve written about punctuality before, but this is such a ubiquitous problem that it bears repeating. Here are some suggestions:

Start on time. That seems obvious, but I’m always amazed at the number of doctors who admit to running late who also admit that they start late. If you’re in the hole before you even start, you can seldom dig yourself out. Sometimes an on-time start is the solution to the entire problem! If you doubt me, try it.

Book realistically. Everyone works at a different pace. Determine the number of patients you can comfortably see in an hour, and book only that number. If you want to see more patients, the solution is working longer hours or hiring physicians or physician extenders (or both), not overloading your schedule.

Time-stamp each chart. Pay attention to patient arrival times if your EHR records them, and step up your pace if you start to fall behind. If your EHR does not record arrival times or you are still using paper records, buy a time clock and have your receptionist time-stamp the “encounter form” that goes to the back with the patient. One glance at the stamp will tell you exactly how long that patient has been waiting.

Schedule all surgeries. If you haven’t scheduled the time necessary for a surgical procedure, don’t do it. It’s frequently tempting to “squeeze in” an excision, often because you feel guilty that the patient has already had to wait for you. But every unscheduled surgery puts you that much further behind. And hurrying through a procedure increases the risk of mistakes. Tell the patient that surgery requires extra time and it can’t be rushed, so you will have to schedule that time.

Work-ins come last, not first. Patients with urgent problems should be seen after scheduled patients. That may seem counterintuitive; receptionists often assume it’s better to squeeze them in early, while you’re still running on time. But doing that guarantees you will run late, and it isn’t fair to patients who have appointments and expect to be seen promptly.

Work-ins, on the other hand, expect a wait because they have no appointment. We tell them, “Our schedule is full today; but if you come at the end of hours, the doctor will see you. But you may have a wait.” Far from complaining, they invariably thank us for seeing them.

Seize the list. You know the list I mean. “Number 16: My right big toe itches. Number 17: I think I feel something on my back. Number 18: This weird chartreuse thing on my arm ...” One long list can leave an entire half-day schedule in shambles.

When a list is produced, the best option is to take it and read it yourself. Identify the most important two or three problems, and address them. For the rest, I will say, “This group of problems deserves a visit of its own, and we will schedule that visit.”

Ask if you can place the list (or a photocopy) in the patient’s chart. (It is, after all, important clinical information.) All of these problems are important to the patient and should be addressed – but on your schedule, not the patient’s.

Avoid interruptions. Especially phone calls. Unless it’s an emergency or an immediate family member, my receptionists say, “I’m sorry, the doctor is with patients. May I take a message?” Everyone – even other physicians – understands. But be sure to return those calls promptly.

Pharmaceutical reps should not be allowed to interrupt you, either. Have them make an appointment, just like everybody else.

There will be times, of course, when you run late. But these should be the exception rather than the rule. By streamlining your procedures and avoiding the pitfalls mentioned, you can give nearly every patient all the time he or she deserves without keeping the next patient waiting.

Incidentally, other common patient complaints in that survey were the following:

- Couldn’t schedule an appointment within a week.

- Spent too little time with me.

- Didn’t provide test results promptly.

- Didn’t respond to my phone calls promptly.

Now would be an excellent opportunity to identify and address any of those problems as well.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Recently, the results of a survey of consumers regarding their health care experiences were reported by Carta Healthcare. As you might expect, I’ve written about punctuality before, but this is such a ubiquitous problem that it bears repeating. Here are some suggestions:

Start on time. That seems obvious, but I’m always amazed at the number of doctors who admit to running late who also admit that they start late. If you’re in the hole before you even start, you can seldom dig yourself out. Sometimes an on-time start is the solution to the entire problem! If you doubt me, try it.

Book realistically. Everyone works at a different pace. Determine the number of patients you can comfortably see in an hour, and book only that number. If you want to see more patients, the solution is working longer hours or hiring physicians or physician extenders (or both), not overloading your schedule.

Time-stamp each chart. Pay attention to patient arrival times if your EHR records them, and step up your pace if you start to fall behind. If your EHR does not record arrival times or you are still using paper records, buy a time clock and have your receptionist time-stamp the “encounter form” that goes to the back with the patient. One glance at the stamp will tell you exactly how long that patient has been waiting.

Schedule all surgeries. If you haven’t scheduled the time necessary for a surgical procedure, don’t do it. It’s frequently tempting to “squeeze in” an excision, often because you feel guilty that the patient has already had to wait for you. But every unscheduled surgery puts you that much further behind. And hurrying through a procedure increases the risk of mistakes. Tell the patient that surgery requires extra time and it can’t be rushed, so you will have to schedule that time.

Work-ins come last, not first. Patients with urgent problems should be seen after scheduled patients. That may seem counterintuitive; receptionists often assume it’s better to squeeze them in early, while you’re still running on time. But doing that guarantees you will run late, and it isn’t fair to patients who have appointments and expect to be seen promptly.

Work-ins, on the other hand, expect a wait because they have no appointment. We tell them, “Our schedule is full today; but if you come at the end of hours, the doctor will see you. But you may have a wait.” Far from complaining, they invariably thank us for seeing them.

Seize the list. You know the list I mean. “Number 16: My right big toe itches. Number 17: I think I feel something on my back. Number 18: This weird chartreuse thing on my arm ...” One long list can leave an entire half-day schedule in shambles.

When a list is produced, the best option is to take it and read it yourself. Identify the most important two or three problems, and address them. For the rest, I will say, “This group of problems deserves a visit of its own, and we will schedule that visit.”

Ask if you can place the list (or a photocopy) in the patient’s chart. (It is, after all, important clinical information.) All of these problems are important to the patient and should be addressed – but on your schedule, not the patient’s.

Avoid interruptions. Especially phone calls. Unless it’s an emergency or an immediate family member, my receptionists say, “I’m sorry, the doctor is with patients. May I take a message?” Everyone – even other physicians – understands. But be sure to return those calls promptly.

Pharmaceutical reps should not be allowed to interrupt you, either. Have them make an appointment, just like everybody else.

There will be times, of course, when you run late. But these should be the exception rather than the rule. By streamlining your procedures and avoiding the pitfalls mentioned, you can give nearly every patient all the time he or she deserves without keeping the next patient waiting.

Incidentally, other common patient complaints in that survey were the following:

- Couldn’t schedule an appointment within a week.

- Spent too little time with me.

- Didn’t provide test results promptly.

- Didn’t respond to my phone calls promptly.

Now would be an excellent opportunity to identify and address any of those problems as well.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Longitudinal arm lesion

This linear pattern of hyper-pigmented, often verrucous tissue oriented along Blaschko skin lines is typical for linear epidermal nevi (LEN). In some cases, lesions are not in a linear pattern and are actually in more of a localized or whorled pattern (called epidermal nevi).

LEN are usually present at birth, as in this individual. They are frequently seen on the head and neck region and are often asymptomatic. LEN are considered a birthmark that develops because of a genetic abnormality that typically affects keratinocytes. This genetic mutation only affects a portion of the body (mosaicism) without affecting the overall genetics of the individual. This is important to note because LEN do not typically have a hereditary component or implications for offspring. While usually asymptomatic and localized, LEN can be associated with extracutaneous and neurologic difficulties. In these situations, it is called epidermal nevus syndrome, and is more common if the LEN occur on the face or head.1

Since LEN are usually asymptomatic, treatment is not required unless the lesions affect the function of adjacent structures, such as the eyes, lips, or nose. Due to their frequent presence on the face or other visible areas, some patients may choose to get these lesions treated for cosmetic purposes. In the past, full-thickness excision was recommended. Topical medications are ineffective, and superficial shave excision usually leads to recurrence. More recently, destructive laser treatments have been used, with success, to reduce the appearance of the lesions.2

This patient was not concerned about the appearance of the asymptomatic lesions and chose not to have any treatment.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Asch S, Sugarman JL. Epidermal nevus syndromes: new insights into whorls and swirls. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:21-29. doi: 10.1111/pde.13273

2. Alonso-Castro L, Boixeda P, Reig I, et al. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of epidermal nevi: response and long-term follow-up. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:910-8. doi: 10.1016/j.adengl.2012.10.001

This linear pattern of hyper-pigmented, often verrucous tissue oriented along Blaschko skin lines is typical for linear epidermal nevi (LEN). In some cases, lesions are not in a linear pattern and are actually in more of a localized or whorled pattern (called epidermal nevi).

LEN are usually present at birth, as in this individual. They are frequently seen on the head and neck region and are often asymptomatic. LEN are considered a birthmark that develops because of a genetic abnormality that typically affects keratinocytes. This genetic mutation only affects a portion of the body (mosaicism) without affecting the overall genetics of the individual. This is important to note because LEN do not typically have a hereditary component or implications for offspring. While usually asymptomatic and localized, LEN can be associated with extracutaneous and neurologic difficulties. In these situations, it is called epidermal nevus syndrome, and is more common if the LEN occur on the face or head.1

Since LEN are usually asymptomatic, treatment is not required unless the lesions affect the function of adjacent structures, such as the eyes, lips, or nose. Due to their frequent presence on the face or other visible areas, some patients may choose to get these lesions treated for cosmetic purposes. In the past, full-thickness excision was recommended. Topical medications are ineffective, and superficial shave excision usually leads to recurrence. More recently, destructive laser treatments have been used, with success, to reduce the appearance of the lesions.2

This patient was not concerned about the appearance of the asymptomatic lesions and chose not to have any treatment.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

This linear pattern of hyper-pigmented, often verrucous tissue oriented along Blaschko skin lines is typical for linear epidermal nevi (LEN). In some cases, lesions are not in a linear pattern and are actually in more of a localized or whorled pattern (called epidermal nevi).

LEN are usually present at birth, as in this individual. They are frequently seen on the head and neck region and are often asymptomatic. LEN are considered a birthmark that develops because of a genetic abnormality that typically affects keratinocytes. This genetic mutation only affects a portion of the body (mosaicism) without affecting the overall genetics of the individual. This is important to note because LEN do not typically have a hereditary component or implications for offspring. While usually asymptomatic and localized, LEN can be associated with extracutaneous and neurologic difficulties. In these situations, it is called epidermal nevus syndrome, and is more common if the LEN occur on the face or head.1

Since LEN are usually asymptomatic, treatment is not required unless the lesions affect the function of adjacent structures, such as the eyes, lips, or nose. Due to their frequent presence on the face or other visible areas, some patients may choose to get these lesions treated for cosmetic purposes. In the past, full-thickness excision was recommended. Topical medications are ineffective, and superficial shave excision usually leads to recurrence. More recently, destructive laser treatments have been used, with success, to reduce the appearance of the lesions.2

This patient was not concerned about the appearance of the asymptomatic lesions and chose not to have any treatment.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Asch S, Sugarman JL. Epidermal nevus syndromes: new insights into whorls and swirls. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:21-29. doi: 10.1111/pde.13273

2. Alonso-Castro L, Boixeda P, Reig I, et al. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of epidermal nevi: response and long-term follow-up. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:910-8. doi: 10.1016/j.adengl.2012.10.001

1. Asch S, Sugarman JL. Epidermal nevus syndromes: new insights into whorls and swirls. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:21-29. doi: 10.1111/pde.13273

2. Alonso-Castro L, Boixeda P, Reig I, et al. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of epidermal nevi: response and long-term follow-up. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:910-8. doi: 10.1016/j.adengl.2012.10.001

A Review of the Glycemia Reduction Approaches in Diabetes (GRADE) Study: Comparing the Effectiveness of Type 2 Diabetes Medications

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is a chronic, progressive disease marked by ongoing decline in insulin sensitivity and beta-cell function over time. Clinical trials have shown that lowering A1C to ∼7.0% (53 mmol/mol), especially after an early diagnosis, can markedly reduce the long-term complications of T2D. Metformin has become the generally recommended first therapeutic agent in treating T2D due to the drug’s long-term experience, effectiveness, and avoidance of hypoglycemia or weight gain. However, it is clear that additional agents are necessary to regain glucose control when metformin eventually fails due to the progressive nature of the disease.

Insufficient data on comparative efficacy and durability of effect has led to uncertainty in recommendations for the preferred second agent. Comparative effectiveness has been reported primarily in industry-sponsored trials of relatively short duration. With this in mind, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) sponsored the Glycemia Reduction Approaches in Diabetes: A Comparative Effectiveness (GRADE) Study. This landmark, randomized controlled study was initiated in 2013, enrolling patients on metformin alone within 10 years of diagnosis of T2D. It involved 36 research sites in the United States with a mean follow-up of 5 years. The participants were randomized to adding a dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitor (sitagliptin), a sulfonylurea (glimepiride), basal insulin (glargine), or a glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) (liraglutide), with the primary outcome being time to A1C over 7.0%.

The GRADE study was unique in several ways: its size, scope, length, and the fact that the financial support and design planning stemmed from a U34 planning grant from the NIDDK. The study population of 5047 participants was very diverse, reflecting the population affected by T2D. A mix of racial and ethnic groups were represented, including 19.8% Black participants and 18.6% Hispanic participants. It is unlikely that a similar comparative effectiveness trial of pharmacologic treatment of T2D will be performed again in the future, considering the high costs and length of time required for such a study amid the dynamic drug development environment today. In fact, the final implementation of study results is somewhat complicated by the subsequent approval of GLP-1 RAs of greater efficacy, weight loss, and convenience, as well as sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and, most recently, a dual GLP-1/gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) receptor agonist (tirzepatide). Many of these newer agents have demonstrated nonglycemic benefits, such as reduced risk of cardiovascular (CV) events or reduced progression of renal disease. The findings from the GRADE study, however, did provide important insight on the long-term management of T2D.

The GRADE study was the first to compare the efficacy of 4 US Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs for T2D in maintaining blood glucose levels for the longest amount of time in patients with T2D. It also monitored microvascular complications, CV events, and adverse drug effects.

An important message of the study that may be overlooked is that all of the studied agents’ ability to maintain an A1C under 7.0% was quite low—as 71% of all participants reached the primary outcome by 5 years; the best results for a group were 67% for glargine and 68% for liraglutide. In general, the results showed that liraglutide and insulin glargine were superior to glimepiride and sitagliptin in controlling blood sugars. They provided approximately 6 months’ more time with blood glucose levels in the desired range compared with sitagliptin, which was shown to provide the least amount of time in maintaining glucose levels. Fifty-five percent of the sitagliptin group experienced the primary outcome at 1 year. Sitagliptin was particularly ineffective for the patient subgroup with an A1C at baseline of 7.8% or higher, where 70% reached the primary outcome in 1 year. The results were uniform regarding age, race, sex, and ethnicity of the trial participants. The intention-to-treat design of the study limits the conclusions about A1C differences, as failure to maintain an A1C under 7.5% required addition of prandial insulin for the glargine group and the addition of glargine to the other 3 groups. Although subjects receiving glargine had an initial glucose-lowering effect that was less than that seen with liraglutide, the ability to keep titrating the glargine likely had an impact on the long-term benefit of that agent. When the glargine group neared or in some cases even passed the secondary outcome A1C level of 7.5%, the basal insulin was increased to lower the A1C, sometimes even when the protocol would recommend adding prandial insulin.