User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Telehealth abortions are 95% effective, similar to in-person care

Telehealth abortion may be just as safe and effective as in-person care, according to a small study published online in JAMA Network Open.

Of the 110 women from whom researchers collected remote abortion outcome data, 95% had a complete abortion without additional medical interventions, such as aspiration or surgery, and none experienced adverse events. Researchers said this efficacy rate is similar to in-person visits.

“There was no reason to expect that the medications prescribed [via telemedicine] and delivered through the mail would have different outcomes from when a patient traveled to a clinic,” study author Ushma D. Upadhyay, PhD, MPH, associate professor in the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview.

Medication abortion, which usually involves taking mifepristone (Mifeprex) followed by misoprostol (Cytotec) during the first 10 weeks of pregnancy, has been available in the United States since 2000. The Food and Drug Administration’s Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy requires that mifepristone be dispensed in a medical office, clinic, or hospital, prohibiting dispensing from pharmacies in an effort to reduce potential risk for complications.

In April 2021, the FDA lifted the in-person dispensing requirement for mifepristone for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, Dr. Upadhyay hopes the findings of her current study will make this suspension permanent.

For the study, Dr. Upadhyay and colleagues examined the safety and efficacy of fully remote, medication abortion care. Eligibility for the medication was assessed using an online form that relies on patient history, or patients recalling their last period, to assess pregnancy duration and screen for ectopic pregnancy risks. Nurse practitioners reviewed the form and referred patients with unknown last menstrual period date or ectopic pregnancy risk factors for ultrasonography. A mail-order pharmacy delivered medications to eligible patients. The protocol involved three follow-up contacts: confirmation of medication administration, a 3-day assessment of symptoms, and a home pregnancy test after 4 weeks. Follow-up interactions were conducted by text, secure messaging, or telephone.

Researchers found that in addition to the 95% of the patients having a complete abortion without intervention, 5% (five) of patients required addition medical care to complete the abortion. Two of those patients were treated in EDs.

Gillian Burkhardt, MD, who was not involved in the study, said Dr. Upadhyay’s study proves what has been known all along, that medication is super safe and that women “can help to determine their own eligibility as well as in conjunction with the provider.”

“I hope that this will be one more study that the FDA can use when thinking about changing the risk evaluation administration strategy so that it’s removing the requirement that a person be in the dispensing medical office,” Dr. Burkhardt, assistant professor of family planning in the department of obstetrics & gynecology at the University of New Mexico Hospital, Albuquerque, said in an interview. “I hope it also makes providers feel more comfortable as well, because I think there’s some hesitancy among providers to provide abortion without doing an ultrasound or without seeing the patient typically in front of them.”

This isn’t the first study to suggest the safety of telemedicine abortion. A 2019 study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, which analyzed records from nearly 6,000 patients receiving medication abortion either through telemedicine or in person at 26 Planned Parenthood health centers in four states found that ongoing pregnancy and aspiration procedures were less common among telemedicine patients. Another 2017 study published in BMJ found that women who used an online consultation service and self-sourced medical abortion during a 3-year period were able to successfully end their pregnancies with few adverse events.

Dr. Upadhyay said one limitation of the current study is its sample size, so more studies should be conducted to prove telemedicine abortion’s safety.

“I think that we need continued research on this model of care just so we have more multiple studies that contribute to the evidence that can convince providers as well that they don’t need a lot of tests and that they can mail,” Dr. Upadhyay said.

Neither Dr. Upadhyay nor Dr. Burkhardt reported conflicts of interests.

Telehealth abortion may be just as safe and effective as in-person care, according to a small study published online in JAMA Network Open.

Of the 110 women from whom researchers collected remote abortion outcome data, 95% had a complete abortion without additional medical interventions, such as aspiration or surgery, and none experienced adverse events. Researchers said this efficacy rate is similar to in-person visits.

“There was no reason to expect that the medications prescribed [via telemedicine] and delivered through the mail would have different outcomes from when a patient traveled to a clinic,” study author Ushma D. Upadhyay, PhD, MPH, associate professor in the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview.

Medication abortion, which usually involves taking mifepristone (Mifeprex) followed by misoprostol (Cytotec) during the first 10 weeks of pregnancy, has been available in the United States since 2000. The Food and Drug Administration’s Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy requires that mifepristone be dispensed in a medical office, clinic, or hospital, prohibiting dispensing from pharmacies in an effort to reduce potential risk for complications.

In April 2021, the FDA lifted the in-person dispensing requirement for mifepristone for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, Dr. Upadhyay hopes the findings of her current study will make this suspension permanent.

For the study, Dr. Upadhyay and colleagues examined the safety and efficacy of fully remote, medication abortion care. Eligibility for the medication was assessed using an online form that relies on patient history, or patients recalling their last period, to assess pregnancy duration and screen for ectopic pregnancy risks. Nurse practitioners reviewed the form and referred patients with unknown last menstrual period date or ectopic pregnancy risk factors for ultrasonography. A mail-order pharmacy delivered medications to eligible patients. The protocol involved three follow-up contacts: confirmation of medication administration, a 3-day assessment of symptoms, and a home pregnancy test after 4 weeks. Follow-up interactions were conducted by text, secure messaging, or telephone.

Researchers found that in addition to the 95% of the patients having a complete abortion without intervention, 5% (five) of patients required addition medical care to complete the abortion. Two of those patients were treated in EDs.

Gillian Burkhardt, MD, who was not involved in the study, said Dr. Upadhyay’s study proves what has been known all along, that medication is super safe and that women “can help to determine their own eligibility as well as in conjunction with the provider.”

“I hope that this will be one more study that the FDA can use when thinking about changing the risk evaluation administration strategy so that it’s removing the requirement that a person be in the dispensing medical office,” Dr. Burkhardt, assistant professor of family planning in the department of obstetrics & gynecology at the University of New Mexico Hospital, Albuquerque, said in an interview. “I hope it also makes providers feel more comfortable as well, because I think there’s some hesitancy among providers to provide abortion without doing an ultrasound or without seeing the patient typically in front of them.”

This isn’t the first study to suggest the safety of telemedicine abortion. A 2019 study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, which analyzed records from nearly 6,000 patients receiving medication abortion either through telemedicine or in person at 26 Planned Parenthood health centers in four states found that ongoing pregnancy and aspiration procedures were less common among telemedicine patients. Another 2017 study published in BMJ found that women who used an online consultation service and self-sourced medical abortion during a 3-year period were able to successfully end their pregnancies with few adverse events.

Dr. Upadhyay said one limitation of the current study is its sample size, so more studies should be conducted to prove telemedicine abortion’s safety.

“I think that we need continued research on this model of care just so we have more multiple studies that contribute to the evidence that can convince providers as well that they don’t need a lot of tests and that they can mail,” Dr. Upadhyay said.

Neither Dr. Upadhyay nor Dr. Burkhardt reported conflicts of interests.

Telehealth abortion may be just as safe and effective as in-person care, according to a small study published online in JAMA Network Open.

Of the 110 women from whom researchers collected remote abortion outcome data, 95% had a complete abortion without additional medical interventions, such as aspiration or surgery, and none experienced adverse events. Researchers said this efficacy rate is similar to in-person visits.

“There was no reason to expect that the medications prescribed [via telemedicine] and delivered through the mail would have different outcomes from when a patient traveled to a clinic,” study author Ushma D. Upadhyay, PhD, MPH, associate professor in the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview.

Medication abortion, which usually involves taking mifepristone (Mifeprex) followed by misoprostol (Cytotec) during the first 10 weeks of pregnancy, has been available in the United States since 2000. The Food and Drug Administration’s Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy requires that mifepristone be dispensed in a medical office, clinic, or hospital, prohibiting dispensing from pharmacies in an effort to reduce potential risk for complications.

In April 2021, the FDA lifted the in-person dispensing requirement for mifepristone for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, Dr. Upadhyay hopes the findings of her current study will make this suspension permanent.

For the study, Dr. Upadhyay and colleagues examined the safety and efficacy of fully remote, medication abortion care. Eligibility for the medication was assessed using an online form that relies on patient history, or patients recalling their last period, to assess pregnancy duration and screen for ectopic pregnancy risks. Nurse practitioners reviewed the form and referred patients with unknown last menstrual period date or ectopic pregnancy risk factors for ultrasonography. A mail-order pharmacy delivered medications to eligible patients. The protocol involved three follow-up contacts: confirmation of medication administration, a 3-day assessment of symptoms, and a home pregnancy test after 4 weeks. Follow-up interactions were conducted by text, secure messaging, or telephone.

Researchers found that in addition to the 95% of the patients having a complete abortion without intervention, 5% (five) of patients required addition medical care to complete the abortion. Two of those patients were treated in EDs.

Gillian Burkhardt, MD, who was not involved in the study, said Dr. Upadhyay’s study proves what has been known all along, that medication is super safe and that women “can help to determine their own eligibility as well as in conjunction with the provider.”

“I hope that this will be one more study that the FDA can use when thinking about changing the risk evaluation administration strategy so that it’s removing the requirement that a person be in the dispensing medical office,” Dr. Burkhardt, assistant professor of family planning in the department of obstetrics & gynecology at the University of New Mexico Hospital, Albuquerque, said in an interview. “I hope it also makes providers feel more comfortable as well, because I think there’s some hesitancy among providers to provide abortion without doing an ultrasound or without seeing the patient typically in front of them.”

This isn’t the first study to suggest the safety of telemedicine abortion. A 2019 study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, which analyzed records from nearly 6,000 patients receiving medication abortion either through telemedicine or in person at 26 Planned Parenthood health centers in four states found that ongoing pregnancy and aspiration procedures were less common among telemedicine patients. Another 2017 study published in BMJ found that women who used an online consultation service and self-sourced medical abortion during a 3-year period were able to successfully end their pregnancies with few adverse events.

Dr. Upadhyay said one limitation of the current study is its sample size, so more studies should be conducted to prove telemedicine abortion’s safety.

“I think that we need continued research on this model of care just so we have more multiple studies that contribute to the evidence that can convince providers as well that they don’t need a lot of tests and that they can mail,” Dr. Upadhyay said.

Neither Dr. Upadhyay nor Dr. Burkhardt reported conflicts of interests.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

How is a woman determined to have dense breast tissue?

Breasts that are heterogeneously dense or extremely dense on mammography are considered “dense breasts.” Breast density matters for 2 reasons: Dense tissue can mask cancer on a mammogram, and having dense breasts increases the risk of developing breast cancer.

Breast density measurement

A woman’s breast density is usually determined during her breast cancer screening with mammography by her radiologist through visual evaluation of the images taken. Breast density also can be measured from individual mammograms by computer software, and it can be estimated on computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In the United States, information about breast density is usually included in a report sent from the radiologist to the referring clinician after a mammogram is taken, and may also be included in the patient letter following up screening mammography. In Europe, national reporting guidelines for physicians vary.

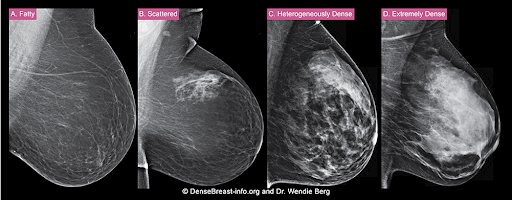

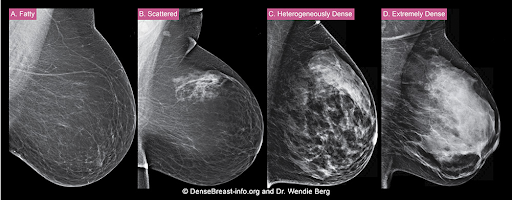

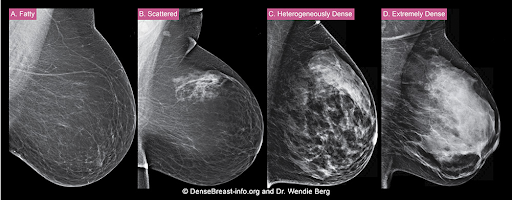

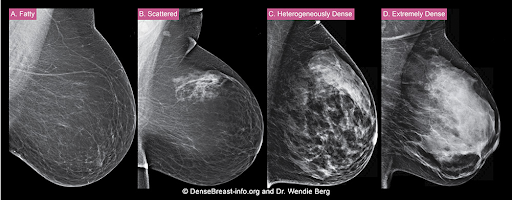

The density of a woman’s breast tissue is described using one of four BI-RADS® breast composition categories1 as shown in the FIGURE.

A. ALMOST ENTIRELY FATTY – On a mammogram, most of the tissue appears dark gray or black, while small amounts of dense (or fibroglandular) tissue display as light gray or white. About 13% of women aged 40 to 74 have breasts considered to be “fatty.”2

B. SCATTERED FIBROGLANDULAR DENSITY – There are scattered areas of dense (fibroglandular) tissue mixed with fat. Even in breasts with scattered areas of breast tissue, cancers can sometimes be missed when they look like areas of normal tissue or are within an area of denser tissue. About 43% of women aged 40 to 74 have breasts with scattered fibroglandular tissue.2

C. HETEROGENEOUSLY DENSE – There are large portions of the breast where dense (fibroglandular) tissue could hide small masses. About 36% of all women aged 40 to 74 have heterogeneously dense breasts.2

D. EXTREMELY DENSE – Most of the breast appears to consist of dense (fibroglandular) tissue, creating a “white out” situation and making it extremely difficult to see through and lowering the sensitivity of mammography. About 7% of all women aged 40 to 74 have extremely dense breasts.2

Factors that may impact breast density

Age. Breasts tend to become less dense as women get older, especially after menopause (as the glandular tissue atrophies and the breasts may appear more fatty-replaced).

Postmenopausal hormone therapy. An increase in mammographic density is more common among women taking continuous combined hormonal therapy than for those using oral low-dose estrogen or transdermal estrogen therapy.

Lactation. Breast density increases with lactation.

Weight changes. Weight gain can increase the amount of fat relative to dense tissue, resulting in slightly lower density as a proportion of breast tissue overall. Similarly, weight loss can decrease the amount of fat in the breasts, making breast density appear greater overall. Importantly, there is no change in the amount of glandular tissue; only the relative proportions change.

Tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors. These medications can slightly reduce breast density.

Because breast density may change with age and other factors, it should be assessed every year.

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org.

Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

1. Sickles EA, D’Orsi CJ, Bassett LW, et al. ACR BI-RADS Mammography. ACR BI-RADS Atlas, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2013.

2. Sprague BL, Gangnon RE, Burt V, et al. Prevalence of mammographically dense breasts in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju255. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju255.

Breasts that are heterogeneously dense or extremely dense on mammography are considered “dense breasts.” Breast density matters for 2 reasons: Dense tissue can mask cancer on a mammogram, and having dense breasts increases the risk of developing breast cancer.

Breast density measurement

A woman’s breast density is usually determined during her breast cancer screening with mammography by her radiologist through visual evaluation of the images taken. Breast density also can be measured from individual mammograms by computer software, and it can be estimated on computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In the United States, information about breast density is usually included in a report sent from the radiologist to the referring clinician after a mammogram is taken, and may also be included in the patient letter following up screening mammography. In Europe, national reporting guidelines for physicians vary.

The density of a woman’s breast tissue is described using one of four BI-RADS® breast composition categories1 as shown in the FIGURE.

A. ALMOST ENTIRELY FATTY – On a mammogram, most of the tissue appears dark gray or black, while small amounts of dense (or fibroglandular) tissue display as light gray or white. About 13% of women aged 40 to 74 have breasts considered to be “fatty.”2

B. SCATTERED FIBROGLANDULAR DENSITY – There are scattered areas of dense (fibroglandular) tissue mixed with fat. Even in breasts with scattered areas of breast tissue, cancers can sometimes be missed when they look like areas of normal tissue or are within an area of denser tissue. About 43% of women aged 40 to 74 have breasts with scattered fibroglandular tissue.2

C. HETEROGENEOUSLY DENSE – There are large portions of the breast where dense (fibroglandular) tissue could hide small masses. About 36% of all women aged 40 to 74 have heterogeneously dense breasts.2

D. EXTREMELY DENSE – Most of the breast appears to consist of dense (fibroglandular) tissue, creating a “white out” situation and making it extremely difficult to see through and lowering the sensitivity of mammography. About 7% of all women aged 40 to 74 have extremely dense breasts.2

Factors that may impact breast density

Age. Breasts tend to become less dense as women get older, especially after menopause (as the glandular tissue atrophies and the breasts may appear more fatty-replaced).

Postmenopausal hormone therapy. An increase in mammographic density is more common among women taking continuous combined hormonal therapy than for those using oral low-dose estrogen or transdermal estrogen therapy.

Lactation. Breast density increases with lactation.

Weight changes. Weight gain can increase the amount of fat relative to dense tissue, resulting in slightly lower density as a proportion of breast tissue overall. Similarly, weight loss can decrease the amount of fat in the breasts, making breast density appear greater overall. Importantly, there is no change in the amount of glandular tissue; only the relative proportions change.

Tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors. These medications can slightly reduce breast density.

Because breast density may change with age and other factors, it should be assessed every year.

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org.

Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

Breasts that are heterogeneously dense or extremely dense on mammography are considered “dense breasts.” Breast density matters for 2 reasons: Dense tissue can mask cancer on a mammogram, and having dense breasts increases the risk of developing breast cancer.

Breast density measurement

A woman’s breast density is usually determined during her breast cancer screening with mammography by her radiologist through visual evaluation of the images taken. Breast density also can be measured from individual mammograms by computer software, and it can be estimated on computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In the United States, information about breast density is usually included in a report sent from the radiologist to the referring clinician after a mammogram is taken, and may also be included in the patient letter following up screening mammography. In Europe, national reporting guidelines for physicians vary.

The density of a woman’s breast tissue is described using one of four BI-RADS® breast composition categories1 as shown in the FIGURE.

A. ALMOST ENTIRELY FATTY – On a mammogram, most of the tissue appears dark gray or black, while small amounts of dense (or fibroglandular) tissue display as light gray or white. About 13% of women aged 40 to 74 have breasts considered to be “fatty.”2

B. SCATTERED FIBROGLANDULAR DENSITY – There are scattered areas of dense (fibroglandular) tissue mixed with fat. Even in breasts with scattered areas of breast tissue, cancers can sometimes be missed when they look like areas of normal tissue or are within an area of denser tissue. About 43% of women aged 40 to 74 have breasts with scattered fibroglandular tissue.2

C. HETEROGENEOUSLY DENSE – There are large portions of the breast where dense (fibroglandular) tissue could hide small masses. About 36% of all women aged 40 to 74 have heterogeneously dense breasts.2

D. EXTREMELY DENSE – Most of the breast appears to consist of dense (fibroglandular) tissue, creating a “white out” situation and making it extremely difficult to see through and lowering the sensitivity of mammography. About 7% of all women aged 40 to 74 have extremely dense breasts.2

Factors that may impact breast density

Age. Breasts tend to become less dense as women get older, especially after menopause (as the glandular tissue atrophies and the breasts may appear more fatty-replaced).

Postmenopausal hormone therapy. An increase in mammographic density is more common among women taking continuous combined hormonal therapy than for those using oral low-dose estrogen or transdermal estrogen therapy.

Lactation. Breast density increases with lactation.

Weight changes. Weight gain can increase the amount of fat relative to dense tissue, resulting in slightly lower density as a proportion of breast tissue overall. Similarly, weight loss can decrease the amount of fat in the breasts, making breast density appear greater overall. Importantly, there is no change in the amount of glandular tissue; only the relative proportions change.

Tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors. These medications can slightly reduce breast density.

Because breast density may change with age and other factors, it should be assessed every year.

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org.

Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

1. Sickles EA, D’Orsi CJ, Bassett LW, et al. ACR BI-RADS Mammography. ACR BI-RADS Atlas, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2013.

2. Sprague BL, Gangnon RE, Burt V, et al. Prevalence of mammographically dense breasts in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju255. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju255.

1. Sickles EA, D’Orsi CJ, Bassett LW, et al. ACR BI-RADS Mammography. ACR BI-RADS Atlas, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2013.

2. Sprague BL, Gangnon RE, Burt V, et al. Prevalence of mammographically dense breasts in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju255. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju255.

‘Countdown to zero’: Endocrine disruptors and worldwide sperm counts

In medical school, I remember thinking that telling a patient “you have cancer” would be the most professionally challenging phrase I would ever utter. And don’t get me wrong – it certainly isn’t easy; but, compared with telling someone “you are infertile,” it’s a cakewalk.

Maybe it’s because people “have” cancer and cancer is something you “fight.” Or maybe because, unlike infertility, cancer has become a part of public life (think lapel pins and support groups) and is now easier to accept. On the other hand, someone “is” infertile. The condition is a source of embarrassment for the couple and is often hidden from society.

Here’s another concerning point of contrast: While the overall rate of cancer death has declined since the early 1990s, infertility is increasing. Reports now show that one in six couples have problems conceiving and the use of assisted reproductive technologies is increasing by 5%-10% per year. Many theories exist to explain these trends, chief among them the rise in average maternal age and the increasing incidence of obesity, as well as various other male- and female-specific factors.

But interestingly, recent data suggest that the most male of all male-specific factors – total sperm count – may be specifically to blame.

According to a recent meta-analysis, the average total sperm count in men declined by 59.3% between 1973 and 2011. While these data certainly have limitations – including the exclusion of non-English publications, the reliance on total sperm count and not sperm motility, and the potential bias of those patients willing to give a semen sample – the overall trend nevertheless seems to be clearly downward. What’s more concerning, if you believe the data presented, is that there does not appear to be a leveling off of the downward curve in total sperm count.

Think about that last statement. At the current rate of decline, the average sperm count will be zero in 2045. One of the lead authors on the meta-analysis, Hagai Levine, MD, MPH, goes so far as to state, “We should hope for the best and prepare for the worst.”

As a matter of personal philosophy, I’m not a huge fan of end-of-the-world predictions because they tend not to come true (think Montanism back in the 2nd century; the 2012 Mayan calendar scare; or my personal favorite, the Prophet Hen of Leeds). On the other hand, the overall trend of decreased total sperm count in the English-speaking world seems to be true and it raises the interesting question of why.

According to the Mayo Clinic, causes of decreased sperm count include everything from anatomical factors (like varicoceles and ejaculatory issues) and lifestyle issues (such as recreational drugs, weight gain, and emotional stress) to environmental exposures (heavy metal or radiation). The senior author of the aforementioned meta-analysis, Shanna Swan, PhD, has championed another theory: the widespread exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals in everyday plastics.

It turns out that at least two chemicals used in the plastics industry, bisphenol A and phthalates, can mimic the effect of estrogen when ingested into the body. Even low levels of these chemicals in our bodies can lead to health problems.

Consider for a moment the presence of plastics in your life: the plastic wrappings on your food, plastic containers for shampoos and beauty products, and even the coatings of our oral supplements. A study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention looked at the urine of people participating in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and found detectable concentrations of both of these chemicals in nearly all participants.

In 2045, I intend to be retired. But in the meantime, I think we all need to be aware of the potential impact that various endocrine-disrupting chemicals could be having on humanity. We need more research. If indeed the connection between endocrine disruptors and decreased sperm count is borne out, changes in our environmental exposure to these chemicals need to be made.

Henry Rosevear, MD, is a private-practice urologist based in Colorado Springs. He comes from a long line of doctors, but before entering medicine he served in the U.S. Navy as an officer aboard the USS Pittsburgh, a fast-attack submarine based out of New London, Conn. During his time in the Navy, he served in two deployments to the Persian Gulf, including combat experience as part of Operation Iraqi Freedom. Dr. Rosevear disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In medical school, I remember thinking that telling a patient “you have cancer” would be the most professionally challenging phrase I would ever utter. And don’t get me wrong – it certainly isn’t easy; but, compared with telling someone “you are infertile,” it’s a cakewalk.

Maybe it’s because people “have” cancer and cancer is something you “fight.” Or maybe because, unlike infertility, cancer has become a part of public life (think lapel pins and support groups) and is now easier to accept. On the other hand, someone “is” infertile. The condition is a source of embarrassment for the couple and is often hidden from society.

Here’s another concerning point of contrast: While the overall rate of cancer death has declined since the early 1990s, infertility is increasing. Reports now show that one in six couples have problems conceiving and the use of assisted reproductive technologies is increasing by 5%-10% per year. Many theories exist to explain these trends, chief among them the rise in average maternal age and the increasing incidence of obesity, as well as various other male- and female-specific factors.

But interestingly, recent data suggest that the most male of all male-specific factors – total sperm count – may be specifically to blame.

According to a recent meta-analysis, the average total sperm count in men declined by 59.3% between 1973 and 2011. While these data certainly have limitations – including the exclusion of non-English publications, the reliance on total sperm count and not sperm motility, and the potential bias of those patients willing to give a semen sample – the overall trend nevertheless seems to be clearly downward. What’s more concerning, if you believe the data presented, is that there does not appear to be a leveling off of the downward curve in total sperm count.

Think about that last statement. At the current rate of decline, the average sperm count will be zero in 2045. One of the lead authors on the meta-analysis, Hagai Levine, MD, MPH, goes so far as to state, “We should hope for the best and prepare for the worst.”

As a matter of personal philosophy, I’m not a huge fan of end-of-the-world predictions because they tend not to come true (think Montanism back in the 2nd century; the 2012 Mayan calendar scare; or my personal favorite, the Prophet Hen of Leeds). On the other hand, the overall trend of decreased total sperm count in the English-speaking world seems to be true and it raises the interesting question of why.

According to the Mayo Clinic, causes of decreased sperm count include everything from anatomical factors (like varicoceles and ejaculatory issues) and lifestyle issues (such as recreational drugs, weight gain, and emotional stress) to environmental exposures (heavy metal or radiation). The senior author of the aforementioned meta-analysis, Shanna Swan, PhD, has championed another theory: the widespread exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals in everyday plastics.

It turns out that at least two chemicals used in the plastics industry, bisphenol A and phthalates, can mimic the effect of estrogen when ingested into the body. Even low levels of these chemicals in our bodies can lead to health problems.

Consider for a moment the presence of plastics in your life: the plastic wrappings on your food, plastic containers for shampoos and beauty products, and even the coatings of our oral supplements. A study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention looked at the urine of people participating in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and found detectable concentrations of both of these chemicals in nearly all participants.

In 2045, I intend to be retired. But in the meantime, I think we all need to be aware of the potential impact that various endocrine-disrupting chemicals could be having on humanity. We need more research. If indeed the connection between endocrine disruptors and decreased sperm count is borne out, changes in our environmental exposure to these chemicals need to be made.

Henry Rosevear, MD, is a private-practice urologist based in Colorado Springs. He comes from a long line of doctors, but before entering medicine he served in the U.S. Navy as an officer aboard the USS Pittsburgh, a fast-attack submarine based out of New London, Conn. During his time in the Navy, he served in two deployments to the Persian Gulf, including combat experience as part of Operation Iraqi Freedom. Dr. Rosevear disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In medical school, I remember thinking that telling a patient “you have cancer” would be the most professionally challenging phrase I would ever utter. And don’t get me wrong – it certainly isn’t easy; but, compared with telling someone “you are infertile,” it’s a cakewalk.

Maybe it’s because people “have” cancer and cancer is something you “fight.” Or maybe because, unlike infertility, cancer has become a part of public life (think lapel pins and support groups) and is now easier to accept. On the other hand, someone “is” infertile. The condition is a source of embarrassment for the couple and is often hidden from society.

Here’s another concerning point of contrast: While the overall rate of cancer death has declined since the early 1990s, infertility is increasing. Reports now show that one in six couples have problems conceiving and the use of assisted reproductive technologies is increasing by 5%-10% per year. Many theories exist to explain these trends, chief among them the rise in average maternal age and the increasing incidence of obesity, as well as various other male- and female-specific factors.

But interestingly, recent data suggest that the most male of all male-specific factors – total sperm count – may be specifically to blame.

According to a recent meta-analysis, the average total sperm count in men declined by 59.3% between 1973 and 2011. While these data certainly have limitations – including the exclusion of non-English publications, the reliance on total sperm count and not sperm motility, and the potential bias of those patients willing to give a semen sample – the overall trend nevertheless seems to be clearly downward. What’s more concerning, if you believe the data presented, is that there does not appear to be a leveling off of the downward curve in total sperm count.

Think about that last statement. At the current rate of decline, the average sperm count will be zero in 2045. One of the lead authors on the meta-analysis, Hagai Levine, MD, MPH, goes so far as to state, “We should hope for the best and prepare for the worst.”

As a matter of personal philosophy, I’m not a huge fan of end-of-the-world predictions because they tend not to come true (think Montanism back in the 2nd century; the 2012 Mayan calendar scare; or my personal favorite, the Prophet Hen of Leeds). On the other hand, the overall trend of decreased total sperm count in the English-speaking world seems to be true and it raises the interesting question of why.

According to the Mayo Clinic, causes of decreased sperm count include everything from anatomical factors (like varicoceles and ejaculatory issues) and lifestyle issues (such as recreational drugs, weight gain, and emotional stress) to environmental exposures (heavy metal or radiation). The senior author of the aforementioned meta-analysis, Shanna Swan, PhD, has championed another theory: the widespread exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals in everyday plastics.

It turns out that at least two chemicals used in the plastics industry, bisphenol A and phthalates, can mimic the effect of estrogen when ingested into the body. Even low levels of these chemicals in our bodies can lead to health problems.

Consider for a moment the presence of plastics in your life: the plastic wrappings on your food, plastic containers for shampoos and beauty products, and even the coatings of our oral supplements. A study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention looked at the urine of people participating in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and found detectable concentrations of both of these chemicals in nearly all participants.

In 2045, I intend to be retired. But in the meantime, I think we all need to be aware of the potential impact that various endocrine-disrupting chemicals could be having on humanity. We need more research. If indeed the connection between endocrine disruptors and decreased sperm count is borne out, changes in our environmental exposure to these chemicals need to be made.

Henry Rosevear, MD, is a private-practice urologist based in Colorado Springs. He comes from a long line of doctors, but before entering medicine he served in the U.S. Navy as an officer aboard the USS Pittsburgh, a fast-attack submarine based out of New London, Conn. During his time in the Navy, he served in two deployments to the Persian Gulf, including combat experience as part of Operation Iraqi Freedom. Dr. Rosevear disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A hot dog a day takes 36 minutes away

The death ‘dog’

Imagine you’re out in your backyard managing the grill for a big family barbecue. You’ve got a dazzling assortment of meat assorted on your fancy new propane grill, all charring nicely. Naturally, the hot dogs finish first, and as you pull them off, you figure you’ll help yourself to one now. After all, you are the chef, you deserve a reward. But, as you bite into your smoking hot sandwich, a cold, bony finger taps you on the shoulder. You turn and come face to face with the Grim Reaper. “YOU JUST LOST 36 MINUTES,” Death says. “ALSO, MAY I HAVE ONE OF THOSE? THEY LOOK DELICIOUS.”

Nonplussed and moving automatically, you scoop up another hot dog and place it in a bun. “WITH KETCHUP PLEASE,” Death says. “I NEVER CARED FOR MUSTARD.”

“I don’t understand,” you say. “Surely I won’t die at a family barbecue.”

“DO NOT CALL ME SHIRLEY,” Death says. “AND YOU WILL NOT. IT’S PART OF MY NEW CONTRACT.”

A new study, published in Nature Food, found that a person may lose up to 36 minutes for every hot dog consumed. Researchers from the University of Michigan analyzed nearly 6,000 different foods using a new nutritional index to quantify their health effects in minutes of healthy life lost or gained. Eating a serving of nuts adds an extra 26 minutes of life. The researchers determined that replacing just 10% of daily caloric intake from beef and processed foods with fruits, vegetables, and nuts can add 48 minutes per day. It would also reduce the daily carbon footprint by 33%.

“So you go around to everyone eating bad food and tell them how much life they’ve lost?” you ask when the Grim Reaper finishes his story. “Sounds like a drag.”

“IT IS. WE’VE HAD TO HIRE NEW BLOOD.” Death chuckles at its own bad pun. “NOW IF YOU’LL EXCUSE ME, I MUST CHASTISE A MAN IN FLORIDA FOR EATING A WELL-DONE STEAK.”

More stress, less sex

As the world becomes a more stressful place, the human population could face a 50% drop by the end of the century.

Think of stress as a one-two punch to the libido and human fertility. The more people are stressed out, the less likely they are to have quality interactions with others. Many of us would rather be alone with our wine and cheese to watch our favorite show.

Researchers have found that high stress levels have been known to drop sperm count, ovulation, and sexual activity. Guess what? There has been a 50% decrease in sperm counts over the last 50 years. That’s the second punch. But let’s not forget, the times are changing.

“Changes in reproductive behavior that contribute to the population drop include more young couples choosing to be ‘child-free,’ people having fewer children, and couples waiting longer to start families,” said Alexander Suvorov, PhD, of the University of Massachusetts, the paper’s author.

Let’s summarize: The more stress we’re dealing with, the less people want to deal with each other.

Who would have thought the future would be less fun?

‘You are not a horse. You are not a cow. Seriously, y’all. Stop it.’

WARNING: The following descriptions of COVID-19–related insanity may be offensive to some readers.

Greetings, ladies and gentlemen! Welcome to the first round of Pandemic Pandemonium. Let’s get right to the action.

This week’s preshow match-off involves face mask woes. The first comes to us from Alabama, where a woman wore a space helmet to a school board meeting to protest mask mandates. The second comes from Australia, in the form of mischievous magpies. We will explain.

It is not uncommon for magpies to attack those who come too close to their nests in the spring, or “swooping season,” as it’s affectionately called. The magpies are smart enough to recognize the faces of people they see regularly and not attack; however, it’s feared that mask wearing will change this.

While you’re chewing on that exciting appetizer, let’s take a look at our main course, which has a distinct governmental flavor. Jeff Landry is the attorney general of Louisiana, and, like our space-helmet wearer, he’s not a fan of mask mandates. According to Business Insider, Mr. Landry “drafted and distributed sample letters intended to help parents evade mask-wearing ordinances and COVID-19 vaccination requirements for their children in schools.”

Up against him is the Food and Drug Administration’s Twitter account. In an unrelated matter, the agency tweeted, “You are not a horse. You are not a cow. Seriously, y’all. Stop it.” This was in response to people using the nonhuman forms of ivermectin to treat very human COVID-19.

Well, there you have it. Who will win tonight’s exciting edition of Pandemic Pandemonium? The first reader to contact us gets to decide the fate of these worthy contestants.

From venomous poison to heart drug

It’s not likely that anyone who sees a giant, venomous spider is thinking, “Hey! That thing could save my life!” It’s usually quite the opposite. Honestly, we would run away from just about any spider. But what if one of the deadliest spiders in the world could also save you from dying of a heart attack?

You probably don’t believe us, right? That’s fair, but the deadly Fraser Island (K’gari) funnel web spider, might also be the most helpful. Investigators from the University of Queensland in Australia have found a way to extract a molecule from the spider’s venom that might help stop damage from heart attacks and may even preserve hearts being used for transplants. “The Hi1a protein from spider venom blocks acid-sensing ion channels in the heart, so the death message is blocked, cell death is reduced, and we see improved heart cell survival,” Nathan Palpant, PhD, of the university, noted in a written statement.

No one has ever developed a drug to stop the “death signal,” so maybe it’s time to befriend spiders instead of running away from them in horror. Just leave the venom extraction to the professionals.

The death ‘dog’

Imagine you’re out in your backyard managing the grill for a big family barbecue. You’ve got a dazzling assortment of meat assorted on your fancy new propane grill, all charring nicely. Naturally, the hot dogs finish first, and as you pull them off, you figure you’ll help yourself to one now. After all, you are the chef, you deserve a reward. But, as you bite into your smoking hot sandwich, a cold, bony finger taps you on the shoulder. You turn and come face to face with the Grim Reaper. “YOU JUST LOST 36 MINUTES,” Death says. “ALSO, MAY I HAVE ONE OF THOSE? THEY LOOK DELICIOUS.”

Nonplussed and moving automatically, you scoop up another hot dog and place it in a bun. “WITH KETCHUP PLEASE,” Death says. “I NEVER CARED FOR MUSTARD.”

“I don’t understand,” you say. “Surely I won’t die at a family barbecue.”

“DO NOT CALL ME SHIRLEY,” Death says. “AND YOU WILL NOT. IT’S PART OF MY NEW CONTRACT.”

A new study, published in Nature Food, found that a person may lose up to 36 minutes for every hot dog consumed. Researchers from the University of Michigan analyzed nearly 6,000 different foods using a new nutritional index to quantify their health effects in minutes of healthy life lost or gained. Eating a serving of nuts adds an extra 26 minutes of life. The researchers determined that replacing just 10% of daily caloric intake from beef and processed foods with fruits, vegetables, and nuts can add 48 minutes per day. It would also reduce the daily carbon footprint by 33%.

“So you go around to everyone eating bad food and tell them how much life they’ve lost?” you ask when the Grim Reaper finishes his story. “Sounds like a drag.”

“IT IS. WE’VE HAD TO HIRE NEW BLOOD.” Death chuckles at its own bad pun. “NOW IF YOU’LL EXCUSE ME, I MUST CHASTISE A MAN IN FLORIDA FOR EATING A WELL-DONE STEAK.”

More stress, less sex

As the world becomes a more stressful place, the human population could face a 50% drop by the end of the century.

Think of stress as a one-two punch to the libido and human fertility. The more people are stressed out, the less likely they are to have quality interactions with others. Many of us would rather be alone with our wine and cheese to watch our favorite show.

Researchers have found that high stress levels have been known to drop sperm count, ovulation, and sexual activity. Guess what? There has been a 50% decrease in sperm counts over the last 50 years. That’s the second punch. But let’s not forget, the times are changing.

“Changes in reproductive behavior that contribute to the population drop include more young couples choosing to be ‘child-free,’ people having fewer children, and couples waiting longer to start families,” said Alexander Suvorov, PhD, of the University of Massachusetts, the paper’s author.

Let’s summarize: The more stress we’re dealing with, the less people want to deal with each other.

Who would have thought the future would be less fun?

‘You are not a horse. You are not a cow. Seriously, y’all. Stop it.’

WARNING: The following descriptions of COVID-19–related insanity may be offensive to some readers.

Greetings, ladies and gentlemen! Welcome to the first round of Pandemic Pandemonium. Let’s get right to the action.

This week’s preshow match-off involves face mask woes. The first comes to us from Alabama, where a woman wore a space helmet to a school board meeting to protest mask mandates. The second comes from Australia, in the form of mischievous magpies. We will explain.

It is not uncommon for magpies to attack those who come too close to their nests in the spring, or “swooping season,” as it’s affectionately called. The magpies are smart enough to recognize the faces of people they see regularly and not attack; however, it’s feared that mask wearing will change this.

While you’re chewing on that exciting appetizer, let’s take a look at our main course, which has a distinct governmental flavor. Jeff Landry is the attorney general of Louisiana, and, like our space-helmet wearer, he’s not a fan of mask mandates. According to Business Insider, Mr. Landry “drafted and distributed sample letters intended to help parents evade mask-wearing ordinances and COVID-19 vaccination requirements for their children in schools.”

Up against him is the Food and Drug Administration’s Twitter account. In an unrelated matter, the agency tweeted, “You are not a horse. You are not a cow. Seriously, y’all. Stop it.” This was in response to people using the nonhuman forms of ivermectin to treat very human COVID-19.

Well, there you have it. Who will win tonight’s exciting edition of Pandemic Pandemonium? The first reader to contact us gets to decide the fate of these worthy contestants.

From venomous poison to heart drug

It’s not likely that anyone who sees a giant, venomous spider is thinking, “Hey! That thing could save my life!” It’s usually quite the opposite. Honestly, we would run away from just about any spider. But what if one of the deadliest spiders in the world could also save you from dying of a heart attack?

You probably don’t believe us, right? That’s fair, but the deadly Fraser Island (K’gari) funnel web spider, might also be the most helpful. Investigators from the University of Queensland in Australia have found a way to extract a molecule from the spider’s venom that might help stop damage from heart attacks and may even preserve hearts being used for transplants. “The Hi1a protein from spider venom blocks acid-sensing ion channels in the heart, so the death message is blocked, cell death is reduced, and we see improved heart cell survival,” Nathan Palpant, PhD, of the university, noted in a written statement.

No one has ever developed a drug to stop the “death signal,” so maybe it’s time to befriend spiders instead of running away from them in horror. Just leave the venom extraction to the professionals.

The death ‘dog’

Imagine you’re out in your backyard managing the grill for a big family barbecue. You’ve got a dazzling assortment of meat assorted on your fancy new propane grill, all charring nicely. Naturally, the hot dogs finish first, and as you pull them off, you figure you’ll help yourself to one now. After all, you are the chef, you deserve a reward. But, as you bite into your smoking hot sandwich, a cold, bony finger taps you on the shoulder. You turn and come face to face with the Grim Reaper. “YOU JUST LOST 36 MINUTES,” Death says. “ALSO, MAY I HAVE ONE OF THOSE? THEY LOOK DELICIOUS.”

Nonplussed and moving automatically, you scoop up another hot dog and place it in a bun. “WITH KETCHUP PLEASE,” Death says. “I NEVER CARED FOR MUSTARD.”

“I don’t understand,” you say. “Surely I won’t die at a family barbecue.”

“DO NOT CALL ME SHIRLEY,” Death says. “AND YOU WILL NOT. IT’S PART OF MY NEW CONTRACT.”

A new study, published in Nature Food, found that a person may lose up to 36 minutes for every hot dog consumed. Researchers from the University of Michigan analyzed nearly 6,000 different foods using a new nutritional index to quantify their health effects in minutes of healthy life lost or gained. Eating a serving of nuts adds an extra 26 minutes of life. The researchers determined that replacing just 10% of daily caloric intake from beef and processed foods with fruits, vegetables, and nuts can add 48 minutes per day. It would also reduce the daily carbon footprint by 33%.

“So you go around to everyone eating bad food and tell them how much life they’ve lost?” you ask when the Grim Reaper finishes his story. “Sounds like a drag.”

“IT IS. WE’VE HAD TO HIRE NEW BLOOD.” Death chuckles at its own bad pun. “NOW IF YOU’LL EXCUSE ME, I MUST CHASTISE A MAN IN FLORIDA FOR EATING A WELL-DONE STEAK.”

More stress, less sex

As the world becomes a more stressful place, the human population could face a 50% drop by the end of the century.

Think of stress as a one-two punch to the libido and human fertility. The more people are stressed out, the less likely they are to have quality interactions with others. Many of us would rather be alone with our wine and cheese to watch our favorite show.

Researchers have found that high stress levels have been known to drop sperm count, ovulation, and sexual activity. Guess what? There has been a 50% decrease in sperm counts over the last 50 years. That’s the second punch. But let’s not forget, the times are changing.

“Changes in reproductive behavior that contribute to the population drop include more young couples choosing to be ‘child-free,’ people having fewer children, and couples waiting longer to start families,” said Alexander Suvorov, PhD, of the University of Massachusetts, the paper’s author.

Let’s summarize: The more stress we’re dealing with, the less people want to deal with each other.

Who would have thought the future would be less fun?

‘You are not a horse. You are not a cow. Seriously, y’all. Stop it.’

WARNING: The following descriptions of COVID-19–related insanity may be offensive to some readers.

Greetings, ladies and gentlemen! Welcome to the first round of Pandemic Pandemonium. Let’s get right to the action.

This week’s preshow match-off involves face mask woes. The first comes to us from Alabama, where a woman wore a space helmet to a school board meeting to protest mask mandates. The second comes from Australia, in the form of mischievous magpies. We will explain.

It is not uncommon for magpies to attack those who come too close to their nests in the spring, or “swooping season,” as it’s affectionately called. The magpies are smart enough to recognize the faces of people they see regularly and not attack; however, it’s feared that mask wearing will change this.

While you’re chewing on that exciting appetizer, let’s take a look at our main course, which has a distinct governmental flavor. Jeff Landry is the attorney general of Louisiana, and, like our space-helmet wearer, he’s not a fan of mask mandates. According to Business Insider, Mr. Landry “drafted and distributed sample letters intended to help parents evade mask-wearing ordinances and COVID-19 vaccination requirements for their children in schools.”

Up against him is the Food and Drug Administration’s Twitter account. In an unrelated matter, the agency tweeted, “You are not a horse. You are not a cow. Seriously, y’all. Stop it.” This was in response to people using the nonhuman forms of ivermectin to treat very human COVID-19.

Well, there you have it. Who will win tonight’s exciting edition of Pandemic Pandemonium? The first reader to contact us gets to decide the fate of these worthy contestants.

From venomous poison to heart drug

It’s not likely that anyone who sees a giant, venomous spider is thinking, “Hey! That thing could save my life!” It’s usually quite the opposite. Honestly, we would run away from just about any spider. But what if one of the deadliest spiders in the world could also save you from dying of a heart attack?

You probably don’t believe us, right? That’s fair, but the deadly Fraser Island (K’gari) funnel web spider, might also be the most helpful. Investigators from the University of Queensland in Australia have found a way to extract a molecule from the spider’s venom that might help stop damage from heart attacks and may even preserve hearts being used for transplants. “The Hi1a protein from spider venom blocks acid-sensing ion channels in the heart, so the death message is blocked, cell death is reduced, and we see improved heart cell survival,” Nathan Palpant, PhD, of the university, noted in a written statement.

No one has ever developed a drug to stop the “death signal,” so maybe it’s time to befriend spiders instead of running away from them in horror. Just leave the venom extraction to the professionals.

Recommendations from a gynecologic oncologist to a general ob.gyn., part 2

In this month’s column we continue to discuss recommendations from the gynecologic oncologist to the general gynecologist.

Don’t screen average-risk women for ovarian cancer.

Ovarian cancer is most often diagnosed at an advanced stage, which limits the curability of the disease. Consequently, there is a strong focus on attempting to diagnose the disease at earlier, more curable stages. This leads to the impulse by some well-intentioned providers to implement screening tests, such as ultrasounds and tumor markers, for all women. Unfortunately, the screening of “average risk” women for ovarian cancer is not recommended. Randomized controlled trials of tens of thousands of women have not observed a clinically significant decrease in ovarian cancer mortality with the addition of screening with tumor markers and ultrasound.1 These studies did observe a false-positive rate of 5%. While that may seem like a low rate of false-positive testing, the definitive diagnostic test which follows is a major abdominal surgery (oophorectomy) and serious complications are encountered in 15% of patients undergoing surgery for false-positive ovarian cancer screening.1 Therefore, quite simply, the harms are not balanced by benefits.

The key to offering patients appropriate and effective screening is case selection. It is important to identify which patients are at higher risk for ovarian cancer and offer those women testing for germline mutations and screening strategies. An important component of a well-woman visit is to take a thorough family history of cancer. Women are considered at high risk for having hereditary predisposition to ovarian cancer if they have a first- or second-degree relative with breast cancer younger than 45-50 years, or any age if Ashkenazi Jewish, triple-negative breast cancer younger than 60 years of age, two or more primary breast cancers with the first diagnosed at less than 50 years of age, male breast cancer, ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer, a known BRCA 1/2 mutation, or a personal history of those same conditions. These women should be recommended to undergo genetic testing for BRCA 1, 2, and Lynch syndrome. They should not automatically be offered ovarian cancer screening. If a patient has a more remote family history for ovarian cancer, their personal risk may be somewhat elevated above the baseline population risk, however, not substantially enough to justify implementing screening in the absence of a confirmed genetic mutation.

While screening tests may not be appropriate for all patients, all patients should be asked about the early symptoms of ovarian cancer because these are consistently present, and frequently overlooked, prior to the eventual diagnosis of advanced disease. Those symptoms include abdominal discomfort, abdominal swelling and bloating, and urinary urgency.2 Consider offering all patients a dedicated ovarian cancer specific review of systems that includes inquiries about these symptoms at their annual wellness visits.

Opt for vertical midline incisions when surgery is anticipated to be complex

What is the first thing gynecologic oncologists do when called in to assist in a difficult gynecologic procedure? Get better exposure. Exposure is the cornerstone of safe, effective surgery. Sometimes this simply means placing a more effective retractor. In other cases, it might mean extending the incision. However, if the incision is a low transverse incision (the go-to for many gynecologists because of its favorable cosmetic and pain-producing profile) this proves to be difficult. Attempting to assist in a complicated case, such as a frozen pelvis, severed ureter or rectal injury, through a pfannensteil incision can be extraordinarily difficult, and while these incisions can be extended by incising the rectus muscle bellies, upper abdominal visualization remains elusive in most patients. This is particularly problematic if the ureter or splenic flexure need to be mobilized, or if extensive lysis of adhesions is necessary to ensure there is no occult enterotomy. As my mentor Dr. John Soper once described to me: “It’s like trying to scratch your armpit by reaching through your fly.”

While pfannensteil incisions come naturally, and comfortably, to most gynecologists, likely because of their frequent application during cesarean section, all gynecologists should be confident in the steps and anatomy for vertical midline, or paramedian incisions. This is not only beneficial for complex gynecologic cases, but also in the event of vascular emergency. In the hands of an experienced abdominal/pelvic surgeon, the vertical midline incision is the quickest way to safely enter the abdomen, and provides the kind of exposure that may be critical in safely repairing or controlling hemorrhage from a major vessel.

While low transverse incisions may be more cosmetic, less painful, and associated with fewer wound complications, our first concern as surgeons should be mitigating complications. In situations where risks of complications are high, it is best to not handicap ourselves with the incision location. And always remember, wound complications are highest when a transverse incision needs to be converted to a vertical one with a “T.”

It’s not just about diagnosis of cancer, it’s also prevention

Detection of cancer is an important role of the obstetrician gynecologist. However, equally important is being able to seize opportunities for cancer prevention. Cervical, vulvar, endometrial and ovarian cancer are all known to have preventative strategies.

All patients up to the age of 45 should be offered vaccination against HPV. Initial indications for HPV vaccination were for women up to age 26; however, recent data support the safety and efficacy of the vaccine in older women.3 HPV vaccination is most effective at preventing cancer when administered prior to exposure (ideally age 9-11), leaving this in the hands of our pediatrician colleagues. However, we must be vigilant to inquire about vaccination status for all our patients and encourage vaccines for those who were missed earlier in their life.

Patients should be counseled regarding the significant risk reduction for cancer that is gained from use of oral hormonal contraceptives and progestin-releasing IUDs (especially for endometrial and ovarian cancers). Providing them with knowledge of this information when considering options for contraception or menstrual cycle management is important in their decision-making process.

Endometrial cancer incidence is sadly on the rise in the United States, likely secondary to increasing rates of obesity. Pregnancy is a time when many women begin to gain, and accumulate, weight and therefore obstetric providers have a unique opportunity to assist patients in strategies to normalize their weight after pregnancy. Many of my patients with endometrial cancer state that they have never heard that it is associated with obesity. This suggests that more can be done to educate patients on the carcinogenic effect of obesity (for both endometrial and breast cancer), which may aid in motivating change of modifiable behaviors.

The fallopian tubes are the source of many ovarian cancers and knowledge of this has led to the recommendation to perform opportunistic salpingectomy as a cancer risk-reducing strategy. Hysterectomy and sterilization procedures are most apropos for this modification. While prospective data to confirm a reduced risk of ovarian cancer with opportunistic salpingectomy are lacking, a reduced incidence of cancer has been observed when the tubes have been removed for indicated surgeries; there appear to be no significant deleterious sequelae.4,5 A focus should be made on removal of the entire distal third of the tube, particularly the fimbriated ends, as this is the portion most implicated in malignancy.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no relevant disclosures. Contact her at [email protected].

References

1. Buys SS et al. JAMA. 2011;305(22):2295.

2. Goff BA et al. JAMA. 2004;291(22):2705.

3. Castellsagué X et al. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(1):28.

4. Yoon SH et al. Eur J Cancer. 2016 Mar;55:38-46.

5. Hanley GE et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(2):172.

In this month’s column we continue to discuss recommendations from the gynecologic oncologist to the general gynecologist.

Don’t screen average-risk women for ovarian cancer.

Ovarian cancer is most often diagnosed at an advanced stage, which limits the curability of the disease. Consequently, there is a strong focus on attempting to diagnose the disease at earlier, more curable stages. This leads to the impulse by some well-intentioned providers to implement screening tests, such as ultrasounds and tumor markers, for all women. Unfortunately, the screening of “average risk” women for ovarian cancer is not recommended. Randomized controlled trials of tens of thousands of women have not observed a clinically significant decrease in ovarian cancer mortality with the addition of screening with tumor markers and ultrasound.1 These studies did observe a false-positive rate of 5%. While that may seem like a low rate of false-positive testing, the definitive diagnostic test which follows is a major abdominal surgery (oophorectomy) and serious complications are encountered in 15% of patients undergoing surgery for false-positive ovarian cancer screening.1 Therefore, quite simply, the harms are not balanced by benefits.

The key to offering patients appropriate and effective screening is case selection. It is important to identify which patients are at higher risk for ovarian cancer and offer those women testing for germline mutations and screening strategies. An important component of a well-woman visit is to take a thorough family history of cancer. Women are considered at high risk for having hereditary predisposition to ovarian cancer if they have a first- or second-degree relative with breast cancer younger than 45-50 years, or any age if Ashkenazi Jewish, triple-negative breast cancer younger than 60 years of age, two or more primary breast cancers with the first diagnosed at less than 50 years of age, male breast cancer, ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer, a known BRCA 1/2 mutation, or a personal history of those same conditions. These women should be recommended to undergo genetic testing for BRCA 1, 2, and Lynch syndrome. They should not automatically be offered ovarian cancer screening. If a patient has a more remote family history for ovarian cancer, their personal risk may be somewhat elevated above the baseline population risk, however, not substantially enough to justify implementing screening in the absence of a confirmed genetic mutation.

While screening tests may not be appropriate for all patients, all patients should be asked about the early symptoms of ovarian cancer because these are consistently present, and frequently overlooked, prior to the eventual diagnosis of advanced disease. Those symptoms include abdominal discomfort, abdominal swelling and bloating, and urinary urgency.2 Consider offering all patients a dedicated ovarian cancer specific review of systems that includes inquiries about these symptoms at their annual wellness visits.

Opt for vertical midline incisions when surgery is anticipated to be complex

What is the first thing gynecologic oncologists do when called in to assist in a difficult gynecologic procedure? Get better exposure. Exposure is the cornerstone of safe, effective surgery. Sometimes this simply means placing a more effective retractor. In other cases, it might mean extending the incision. However, if the incision is a low transverse incision (the go-to for many gynecologists because of its favorable cosmetic and pain-producing profile) this proves to be difficult. Attempting to assist in a complicated case, such as a frozen pelvis, severed ureter or rectal injury, through a pfannensteil incision can be extraordinarily difficult, and while these incisions can be extended by incising the rectus muscle bellies, upper abdominal visualization remains elusive in most patients. This is particularly problematic if the ureter or splenic flexure need to be mobilized, or if extensive lysis of adhesions is necessary to ensure there is no occult enterotomy. As my mentor Dr. John Soper once described to me: “It’s like trying to scratch your armpit by reaching through your fly.”

While pfannensteil incisions come naturally, and comfortably, to most gynecologists, likely because of their frequent application during cesarean section, all gynecologists should be confident in the steps and anatomy for vertical midline, or paramedian incisions. This is not only beneficial for complex gynecologic cases, but also in the event of vascular emergency. In the hands of an experienced abdominal/pelvic surgeon, the vertical midline incision is the quickest way to safely enter the abdomen, and provides the kind of exposure that may be critical in safely repairing or controlling hemorrhage from a major vessel.

While low transverse incisions may be more cosmetic, less painful, and associated with fewer wound complications, our first concern as surgeons should be mitigating complications. In situations where risks of complications are high, it is best to not handicap ourselves with the incision location. And always remember, wound complications are highest when a transverse incision needs to be converted to a vertical one with a “T.”

It’s not just about diagnosis of cancer, it’s also prevention

Detection of cancer is an important role of the obstetrician gynecologist. However, equally important is being able to seize opportunities for cancer prevention. Cervical, vulvar, endometrial and ovarian cancer are all known to have preventative strategies.

All patients up to the age of 45 should be offered vaccination against HPV. Initial indications for HPV vaccination were for women up to age 26; however, recent data support the safety and efficacy of the vaccine in older women.3 HPV vaccination is most effective at preventing cancer when administered prior to exposure (ideally age 9-11), leaving this in the hands of our pediatrician colleagues. However, we must be vigilant to inquire about vaccination status for all our patients and encourage vaccines for those who were missed earlier in their life.

Patients should be counseled regarding the significant risk reduction for cancer that is gained from use of oral hormonal contraceptives and progestin-releasing IUDs (especially for endometrial and ovarian cancers). Providing them with knowledge of this information when considering options for contraception or menstrual cycle management is important in their decision-making process.

Endometrial cancer incidence is sadly on the rise in the United States, likely secondary to increasing rates of obesity. Pregnancy is a time when many women begin to gain, and accumulate, weight and therefore obstetric providers have a unique opportunity to assist patients in strategies to normalize their weight after pregnancy. Many of my patients with endometrial cancer state that they have never heard that it is associated with obesity. This suggests that more can be done to educate patients on the carcinogenic effect of obesity (for both endometrial and breast cancer), which may aid in motivating change of modifiable behaviors.

The fallopian tubes are the source of many ovarian cancers and knowledge of this has led to the recommendation to perform opportunistic salpingectomy as a cancer risk-reducing strategy. Hysterectomy and sterilization procedures are most apropos for this modification. While prospective data to confirm a reduced risk of ovarian cancer with opportunistic salpingectomy are lacking, a reduced incidence of cancer has been observed when the tubes have been removed for indicated surgeries; there appear to be no significant deleterious sequelae.4,5 A focus should be made on removal of the entire distal third of the tube, particularly the fimbriated ends, as this is the portion most implicated in malignancy.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no relevant disclosures. Contact her at [email protected].

References

1. Buys SS et al. JAMA. 2011;305(22):2295.

2. Goff BA et al. JAMA. 2004;291(22):2705.

3. Castellsagué X et al. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(1):28.

4. Yoon SH et al. Eur J Cancer. 2016 Mar;55:38-46.

5. Hanley GE et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(2):172.

In this month’s column we continue to discuss recommendations from the gynecologic oncologist to the general gynecologist.

Don’t screen average-risk women for ovarian cancer.

Ovarian cancer is most often diagnosed at an advanced stage, which limits the curability of the disease. Consequently, there is a strong focus on attempting to diagnose the disease at earlier, more curable stages. This leads to the impulse by some well-intentioned providers to implement screening tests, such as ultrasounds and tumor markers, for all women. Unfortunately, the screening of “average risk” women for ovarian cancer is not recommended. Randomized controlled trials of tens of thousands of women have not observed a clinically significant decrease in ovarian cancer mortality with the addition of screening with tumor markers and ultrasound.1 These studies did observe a false-positive rate of 5%. While that may seem like a low rate of false-positive testing, the definitive diagnostic test which follows is a major abdominal surgery (oophorectomy) and serious complications are encountered in 15% of patients undergoing surgery for false-positive ovarian cancer screening.1 Therefore, quite simply, the harms are not balanced by benefits.

The key to offering patients appropriate and effective screening is case selection. It is important to identify which patients are at higher risk for ovarian cancer and offer those women testing for germline mutations and screening strategies. An important component of a well-woman visit is to take a thorough family history of cancer. Women are considered at high risk for having hereditary predisposition to ovarian cancer if they have a first- or second-degree relative with breast cancer younger than 45-50 years, or any age if Ashkenazi Jewish, triple-negative breast cancer younger than 60 years of age, two or more primary breast cancers with the first diagnosed at less than 50 years of age, male breast cancer, ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer, a known BRCA 1/2 mutation, or a personal history of those same conditions. These women should be recommended to undergo genetic testing for BRCA 1, 2, and Lynch syndrome. They should not automatically be offered ovarian cancer screening. If a patient has a more remote family history for ovarian cancer, their personal risk may be somewhat elevated above the baseline population risk, however, not substantially enough to justify implementing screening in the absence of a confirmed genetic mutation.

While screening tests may not be appropriate for all patients, all patients should be asked about the early symptoms of ovarian cancer because these are consistently present, and frequently overlooked, prior to the eventual diagnosis of advanced disease. Those symptoms include abdominal discomfort, abdominal swelling and bloating, and urinary urgency.2 Consider offering all patients a dedicated ovarian cancer specific review of systems that includes inquiries about these symptoms at their annual wellness visits.

Opt for vertical midline incisions when surgery is anticipated to be complex

What is the first thing gynecologic oncologists do when called in to assist in a difficult gynecologic procedure? Get better exposure. Exposure is the cornerstone of safe, effective surgery. Sometimes this simply means placing a more effective retractor. In other cases, it might mean extending the incision. However, if the incision is a low transverse incision (the go-to for many gynecologists because of its favorable cosmetic and pain-producing profile) this proves to be difficult. Attempting to assist in a complicated case, such as a frozen pelvis, severed ureter or rectal injury, through a pfannensteil incision can be extraordinarily difficult, and while these incisions can be extended by incising the rectus muscle bellies, upper abdominal visualization remains elusive in most patients. This is particularly problematic if the ureter or splenic flexure need to be mobilized, or if extensive lysis of adhesions is necessary to ensure there is no occult enterotomy. As my mentor Dr. John Soper once described to me: “It’s like trying to scratch your armpit by reaching through your fly.”