User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Iatrogenic hyponatremia in a patient with bipolar disorder

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Bipolar disorder is a chronic mental disorder, often with onset at a young age. An estimated 4.4% of US adults experience bipolar disorder at some time in their lives.

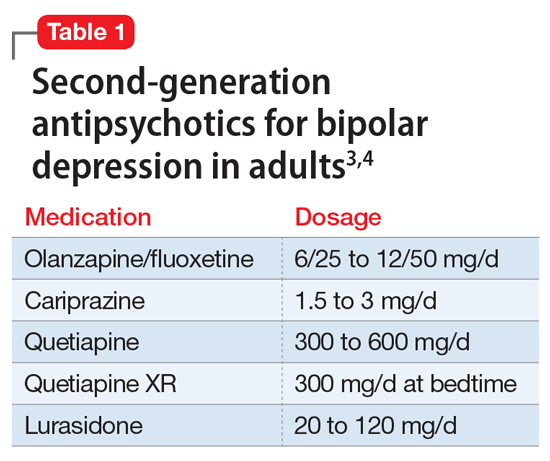

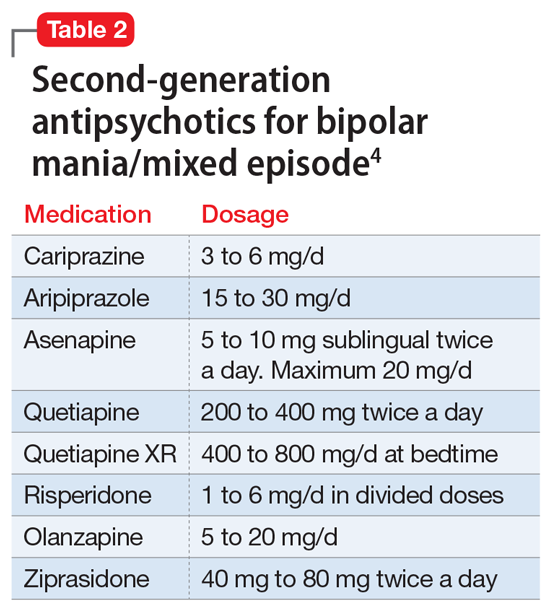

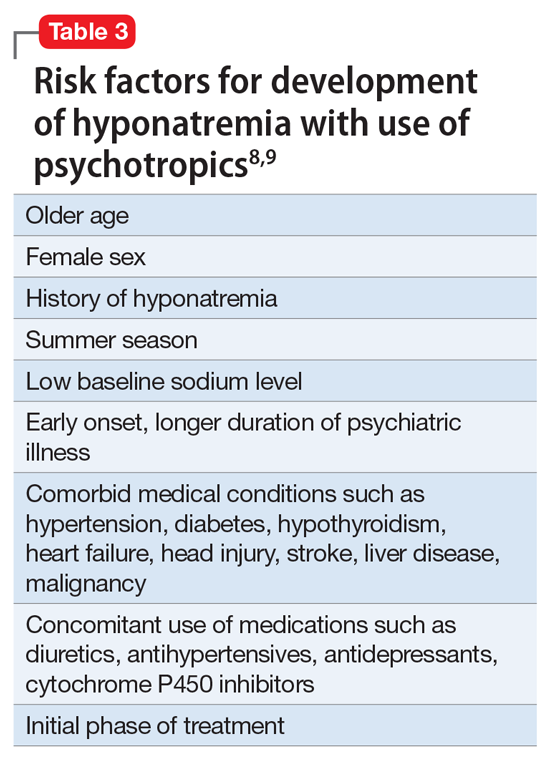

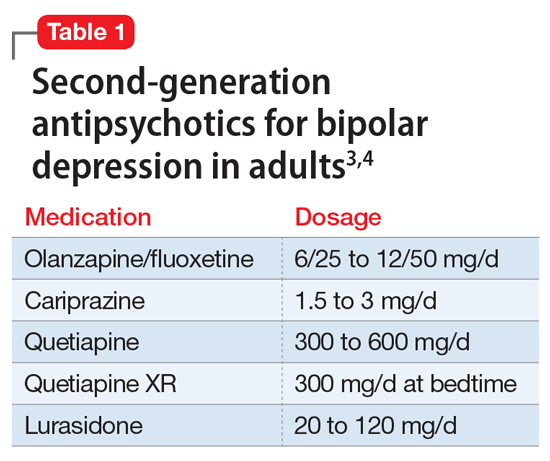

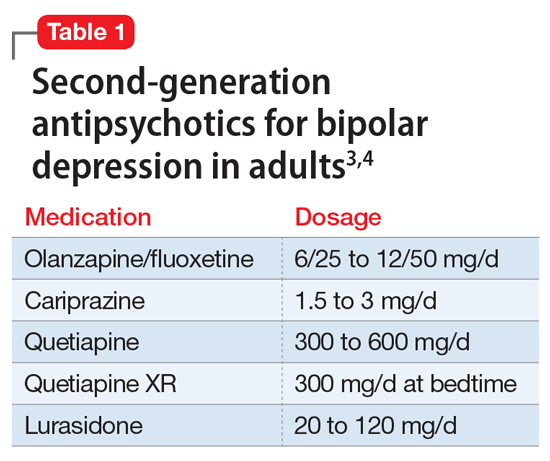

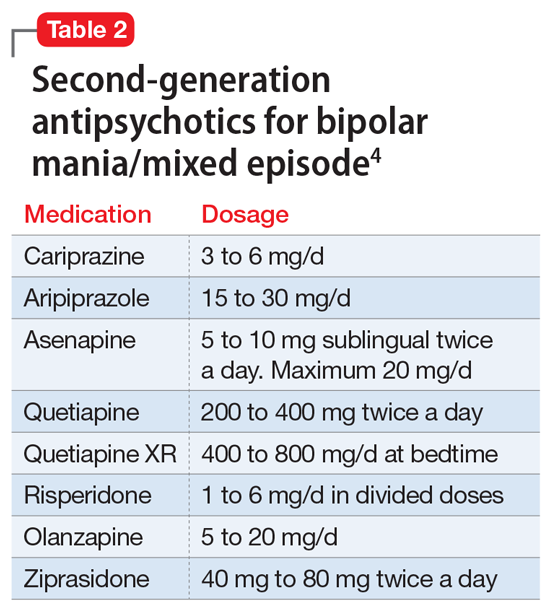

A variety of medications—including mood stabilizers, lithium, and antipsychotics (Table 1,3,4 and Table 2,4)—and somatic treatments such as electroconvulsive therapy and transcranial magnetic stimulation are used to manage the depressive and manic/mixed episodes of bipolar disorder. Treatment should be individualized based on the patient’s symptom severity, sensitivity, response to treatment, and preferences.

The most common reason for discontinuing a medication is intolerance to adverse effects. Some adverse effects are mild and may lessen over time. Others can be life-threatening. Thus, medications should be chosen carefully and started at low doses, and patients should be closely monitored for adverse effects at regular intervals.

Here I describe the case of a patient with bipolar disorder who developed hyponatremia while being treated with the second-generation antipsychotic lurasidone.

Continue to: CASE REPORT...

CASE REPORT

Mrs. G, age 65, lives with her husband. She has a history of bipolar disorder, chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus type 2, obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension associated with hyperaldosteronism, and obesity, for which she has undergone bariatric surgery. Symptoms of bipolar disorder started when she was in her 30s, following the death of her father. Her initial symptoms included depressed mood, anger, irritability, difficulty sleeping, racing thoughts, and impulsive spending. She did not have any suicidal ideation or homicidal ideation. She did not have anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms. She was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. For some time, she took perphenazine, 16 mg/d, divalproex sodium, 1,500 mg/d, and temazepam, 30 mg/d at bedtime. These doses were reduced as her mood stabilized. Over time, divalproex sodium was tapered and discontinued, and perphenazine was reduced to 4 mg/d at bedtime. Lithium was tried briefly but discontinued because Mrs. G did not tolerate it well. She has never been hospitalized for mental health issues, but did have one emergency department visit a very long time ago. She has no history of suicide attempts, and there is no family history of completed suicide. There is a family history of bipolar disorder in her mother.

Mrs. G was born and raised outside the United States in a stable, two-parent home. She had no maltreatment during childhood. She has a bachelor’s degree and was employed. She is a social drinker, with no history of treatment for alcohol use disorder.

Mrs. G was stable on perphenazine, 4 mg/d, and temazepam, 30 mg/d, until 5 years ago. In 2016, she became concerned about her weight and overall health, and underwent bariatric surgery (gastric sleeve). After this surgery, Mrs. G experienced changes in mood and thought. She felt paranoid and had ideas of reference, social sensitivity, increased irritability, and poor self-esteem. Perphenazine was discontinued, divalproex was reintroduced, and lurasidone was started. Lurasidone was titrated up to 120 mg/d, and divalproex up to 1,500 mg/d. Temazepam, 30 mg/d at bedtime, was continued for her insomnia. She also occasionally took over-the-counter melatonin, 5 to 10 mg, as needed for insomnia.

Mrs. G improved on this combination, and became stable and euthymic in September 2017. Other than a brief hypomanic episode in Spring 2018 that resolved quickly, she remained euthymic. During routine follow-up visits, Mrs. G’s nephrologist noticed that her sodium levels had been fluctuating. Mrs. G said her nephrologist was not sure exactly what was causing these fluctuations, and she continued to take the same medications.

In June 2018, Mrs. G developed tremors, slowing, and lethargy. Lurasidone was gradually reduced to 60 mg/d and divalproex to 750 mg/d. Temazepam, 30 mg/d at bedtime, was continued. In July 2018, divalproex was further reduced to 500 mg/d because Mrs. G’s free valproic acid levels were elevated. In February 2019, lurasidone was further reduced to 40 mg/d due to blunted affect, and in April 2019, escitalopram, 10 mg/d, was added for symptoms of depression (off-label), and anxiety. In June 2019, Mrs. G’s sodium level was 127 mEq/L (reference range: 135 to 145 mEq/L). Because escitalopram can cause hyponatremia, it was discontinued in August 2019, but Mrs. G continued to take lurasidone, 40 mg/d, divalproex, 500 mg/d, and temazepam, 30 mg/d.

In October and November 2020, Mrs. G’s sodium level remained low at 123 and 127 mEq/L. Our treatment team wondered if lurasidone could be causing Mrs. G’s sodium levels to fall. Lurasidone was tapered over 3 days and discontinued. Repeat blood work showed that Mrs. G’s sodium levels soon returned to normal range. In January through March 2021, her sodium levels were 138, 139, and 136 mEq/L, all of which were within normal range. This confirmed our suspicion that lurasidone had caused the hyponatremia, though briefly it may have been made worse by escitalopram. Currently, Mrs. G is stable on perphenazine, 4 mg twice a day, divalproex, 500 mg/d, temazepam, 30 mg/d at bedtime, and melatonin, 5 mg at bedtime.

Continue to: Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion...

Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion

Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) secretion can result in hyponatremia. Classes of medications that can cause SIADH include antidepressants, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, cytotoxic agents, and pain medications.5 The class of drugs most commonly associated with SIADH is selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, particularly citalopram.5 Among the antipsychotics, risperidone is most associated with hyponatremia. The proposed mechanism of medication-induced SIADH is an increase in the release of ADH.6 Treatment options include discontinuing the offending medication(s) or switching to a different medication.

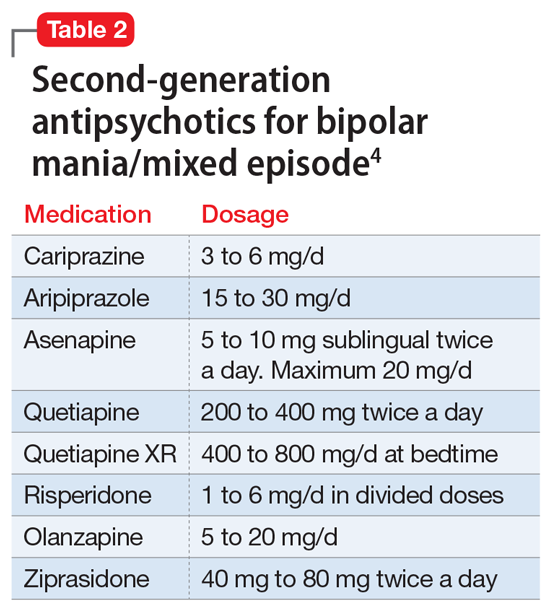

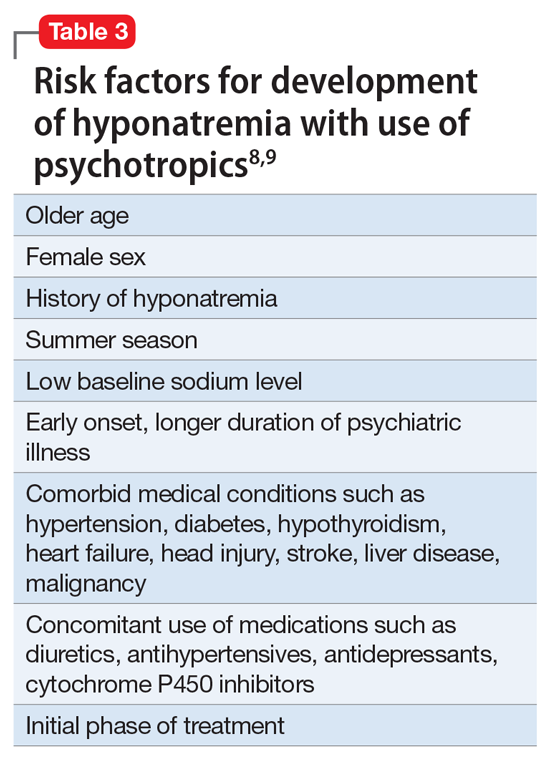

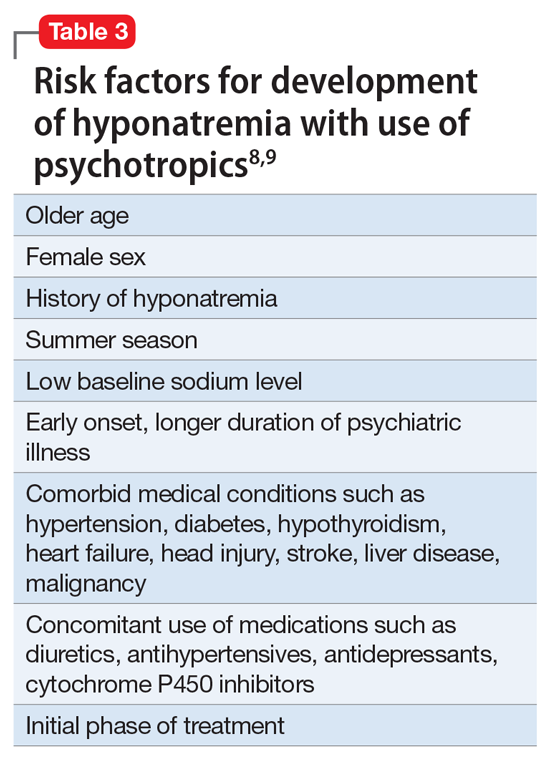

Hyponatremia is a rare adverse effect of lurasidone, with a reported incidence <1%.7 Although hyponatremia is potentially life-threatening, there is no recommendation to routinely monitor sodium levels in patients treated with lurasidone or other psychotropics, and patients who are prescribed lurasidone are not routinely monitored for sodium deficiency. Table 38,9 outlines risk factors for developing hyponatremia among patients taking psychotropic medications.

Mrs. G had been taking lurasidone for a few years and experienced fluctuating sodium levels. She had been taking divalproex, which by itself could cause hyponatremia and could have added to the effects of lurasidone in lowering sodium levels. Escitalopram briefly made her hyponatremia worse. Given Mrs. G’s medical illnesses, our focus had been on her underlying medical conditions rather than on a suspected medication-induced adverse effect.

In summary, patients who are prescribed lurasidone may benefit from regular monitoring of sodium levels. Monitoring sodium levels in geriatric patients who have multiple comorbid medical conditions and take multiple medications may reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with SIADH.

1. National Institute of Mental Health. Bipolar disorder. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/bipolar-disorder

2. Müller JK, Leweke FM. Bipolar disorder: clinical overview. Med Monatsschr Pharm. 2016;39(9):363-369.

3. Bobo WV, Shelton RC. Bipolar major depression in adults: Efficacy and adverse effects of second-generation antipsychotics. UpToDate. Updated September 1, 2020. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/bipolar-major-depression-in-adults-efficacy-and-adverse-effects-of-second-generation-antipsychotics

4. Epocrates. Version 21.9.1. Accessed October 14, 2021. https://www.epocrates.com

5. Shepshelovich D, Schechter A, Calvarysky B, et al. Medication-induced SIADH: distribution and characterization according to medication class. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83(8):1801-1807.

6. Guirguis E, Grace Y, Seetaram M. Management of hyponatremia: focus on psychiatric patients. US Pharm. 2013;38(11):HS3-HS6.

7. Drugs.com. Latuda side effects. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.drugs.com/sfx/latuda-side-effects.html

8. Ali SN, Bazzano LA. Hyponatremia in association with second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review of case reports. Ochsner J. 2018;18(3):230-235.

9. Sahoo S, Grover S. Hyponatremia and psychotropics. J Geriatr Ment Health. 2016;3(2):108-122.

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Bipolar disorder is a chronic mental disorder, often with onset at a young age. An estimated 4.4% of US adults experience bipolar disorder at some time in their lives.

A variety of medications—including mood stabilizers, lithium, and antipsychotics (Table 1,3,4 and Table 2,4)—and somatic treatments such as electroconvulsive therapy and transcranial magnetic stimulation are used to manage the depressive and manic/mixed episodes of bipolar disorder. Treatment should be individualized based on the patient’s symptom severity, sensitivity, response to treatment, and preferences.

The most common reason for discontinuing a medication is intolerance to adverse effects. Some adverse effects are mild and may lessen over time. Others can be life-threatening. Thus, medications should be chosen carefully and started at low doses, and patients should be closely monitored for adverse effects at regular intervals.

Here I describe the case of a patient with bipolar disorder who developed hyponatremia while being treated with the second-generation antipsychotic lurasidone.

Continue to: CASE REPORT...

CASE REPORT

Mrs. G, age 65, lives with her husband. She has a history of bipolar disorder, chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus type 2, obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension associated with hyperaldosteronism, and obesity, for which she has undergone bariatric surgery. Symptoms of bipolar disorder started when she was in her 30s, following the death of her father. Her initial symptoms included depressed mood, anger, irritability, difficulty sleeping, racing thoughts, and impulsive spending. She did not have any suicidal ideation or homicidal ideation. She did not have anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms. She was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. For some time, she took perphenazine, 16 mg/d, divalproex sodium, 1,500 mg/d, and temazepam, 30 mg/d at bedtime. These doses were reduced as her mood stabilized. Over time, divalproex sodium was tapered and discontinued, and perphenazine was reduced to 4 mg/d at bedtime. Lithium was tried briefly but discontinued because Mrs. G did not tolerate it well. She has never been hospitalized for mental health issues, but did have one emergency department visit a very long time ago. She has no history of suicide attempts, and there is no family history of completed suicide. There is a family history of bipolar disorder in her mother.

Mrs. G was born and raised outside the United States in a stable, two-parent home. She had no maltreatment during childhood. She has a bachelor’s degree and was employed. She is a social drinker, with no history of treatment for alcohol use disorder.

Mrs. G was stable on perphenazine, 4 mg/d, and temazepam, 30 mg/d, until 5 years ago. In 2016, she became concerned about her weight and overall health, and underwent bariatric surgery (gastric sleeve). After this surgery, Mrs. G experienced changes in mood and thought. She felt paranoid and had ideas of reference, social sensitivity, increased irritability, and poor self-esteem. Perphenazine was discontinued, divalproex was reintroduced, and lurasidone was started. Lurasidone was titrated up to 120 mg/d, and divalproex up to 1,500 mg/d. Temazepam, 30 mg/d at bedtime, was continued for her insomnia. She also occasionally took over-the-counter melatonin, 5 to 10 mg, as needed for insomnia.

Mrs. G improved on this combination, and became stable and euthymic in September 2017. Other than a brief hypomanic episode in Spring 2018 that resolved quickly, she remained euthymic. During routine follow-up visits, Mrs. G’s nephrologist noticed that her sodium levels had been fluctuating. Mrs. G said her nephrologist was not sure exactly what was causing these fluctuations, and she continued to take the same medications.

In June 2018, Mrs. G developed tremors, slowing, and lethargy. Lurasidone was gradually reduced to 60 mg/d and divalproex to 750 mg/d. Temazepam, 30 mg/d at bedtime, was continued. In July 2018, divalproex was further reduced to 500 mg/d because Mrs. G’s free valproic acid levels were elevated. In February 2019, lurasidone was further reduced to 40 mg/d due to blunted affect, and in April 2019, escitalopram, 10 mg/d, was added for symptoms of depression (off-label), and anxiety. In June 2019, Mrs. G’s sodium level was 127 mEq/L (reference range: 135 to 145 mEq/L). Because escitalopram can cause hyponatremia, it was discontinued in August 2019, but Mrs. G continued to take lurasidone, 40 mg/d, divalproex, 500 mg/d, and temazepam, 30 mg/d.

In October and November 2020, Mrs. G’s sodium level remained low at 123 and 127 mEq/L. Our treatment team wondered if lurasidone could be causing Mrs. G’s sodium levels to fall. Lurasidone was tapered over 3 days and discontinued. Repeat blood work showed that Mrs. G’s sodium levels soon returned to normal range. In January through March 2021, her sodium levels were 138, 139, and 136 mEq/L, all of which were within normal range. This confirmed our suspicion that lurasidone had caused the hyponatremia, though briefly it may have been made worse by escitalopram. Currently, Mrs. G is stable on perphenazine, 4 mg twice a day, divalproex, 500 mg/d, temazepam, 30 mg/d at bedtime, and melatonin, 5 mg at bedtime.

Continue to: Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion...

Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion

Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) secretion can result in hyponatremia. Classes of medications that can cause SIADH include antidepressants, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, cytotoxic agents, and pain medications.5 The class of drugs most commonly associated with SIADH is selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, particularly citalopram.5 Among the antipsychotics, risperidone is most associated with hyponatremia. The proposed mechanism of medication-induced SIADH is an increase in the release of ADH.6 Treatment options include discontinuing the offending medication(s) or switching to a different medication.

Hyponatremia is a rare adverse effect of lurasidone, with a reported incidence <1%.7 Although hyponatremia is potentially life-threatening, there is no recommendation to routinely monitor sodium levels in patients treated with lurasidone or other psychotropics, and patients who are prescribed lurasidone are not routinely monitored for sodium deficiency. Table 38,9 outlines risk factors for developing hyponatremia among patients taking psychotropic medications.

Mrs. G had been taking lurasidone for a few years and experienced fluctuating sodium levels. She had been taking divalproex, which by itself could cause hyponatremia and could have added to the effects of lurasidone in lowering sodium levels. Escitalopram briefly made her hyponatremia worse. Given Mrs. G’s medical illnesses, our focus had been on her underlying medical conditions rather than on a suspected medication-induced adverse effect.

In summary, patients who are prescribed lurasidone may benefit from regular monitoring of sodium levels. Monitoring sodium levels in geriatric patients who have multiple comorbid medical conditions and take multiple medications may reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with SIADH.

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Bipolar disorder is a chronic mental disorder, often with onset at a young age. An estimated 4.4% of US adults experience bipolar disorder at some time in their lives.

A variety of medications—including mood stabilizers, lithium, and antipsychotics (Table 1,3,4 and Table 2,4)—and somatic treatments such as electroconvulsive therapy and transcranial magnetic stimulation are used to manage the depressive and manic/mixed episodes of bipolar disorder. Treatment should be individualized based on the patient’s symptom severity, sensitivity, response to treatment, and preferences.

The most common reason for discontinuing a medication is intolerance to adverse effects. Some adverse effects are mild and may lessen over time. Others can be life-threatening. Thus, medications should be chosen carefully and started at low doses, and patients should be closely monitored for adverse effects at regular intervals.

Here I describe the case of a patient with bipolar disorder who developed hyponatremia while being treated with the second-generation antipsychotic lurasidone.

Continue to: CASE REPORT...

CASE REPORT

Mrs. G, age 65, lives with her husband. She has a history of bipolar disorder, chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus type 2, obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension associated with hyperaldosteronism, and obesity, for which she has undergone bariatric surgery. Symptoms of bipolar disorder started when she was in her 30s, following the death of her father. Her initial symptoms included depressed mood, anger, irritability, difficulty sleeping, racing thoughts, and impulsive spending. She did not have any suicidal ideation or homicidal ideation. She did not have anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms. She was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. For some time, she took perphenazine, 16 mg/d, divalproex sodium, 1,500 mg/d, and temazepam, 30 mg/d at bedtime. These doses were reduced as her mood stabilized. Over time, divalproex sodium was tapered and discontinued, and perphenazine was reduced to 4 mg/d at bedtime. Lithium was tried briefly but discontinued because Mrs. G did not tolerate it well. She has never been hospitalized for mental health issues, but did have one emergency department visit a very long time ago. She has no history of suicide attempts, and there is no family history of completed suicide. There is a family history of bipolar disorder in her mother.

Mrs. G was born and raised outside the United States in a stable, two-parent home. She had no maltreatment during childhood. She has a bachelor’s degree and was employed. She is a social drinker, with no history of treatment for alcohol use disorder.

Mrs. G was stable on perphenazine, 4 mg/d, and temazepam, 30 mg/d, until 5 years ago. In 2016, she became concerned about her weight and overall health, and underwent bariatric surgery (gastric sleeve). After this surgery, Mrs. G experienced changes in mood and thought. She felt paranoid and had ideas of reference, social sensitivity, increased irritability, and poor self-esteem. Perphenazine was discontinued, divalproex was reintroduced, and lurasidone was started. Lurasidone was titrated up to 120 mg/d, and divalproex up to 1,500 mg/d. Temazepam, 30 mg/d at bedtime, was continued for her insomnia. She also occasionally took over-the-counter melatonin, 5 to 10 mg, as needed for insomnia.

Mrs. G improved on this combination, and became stable and euthymic in September 2017. Other than a brief hypomanic episode in Spring 2018 that resolved quickly, she remained euthymic. During routine follow-up visits, Mrs. G’s nephrologist noticed that her sodium levels had been fluctuating. Mrs. G said her nephrologist was not sure exactly what was causing these fluctuations, and she continued to take the same medications.

In June 2018, Mrs. G developed tremors, slowing, and lethargy. Lurasidone was gradually reduced to 60 mg/d and divalproex to 750 mg/d. Temazepam, 30 mg/d at bedtime, was continued. In July 2018, divalproex was further reduced to 500 mg/d because Mrs. G’s free valproic acid levels were elevated. In February 2019, lurasidone was further reduced to 40 mg/d due to blunted affect, and in April 2019, escitalopram, 10 mg/d, was added for symptoms of depression (off-label), and anxiety. In June 2019, Mrs. G’s sodium level was 127 mEq/L (reference range: 135 to 145 mEq/L). Because escitalopram can cause hyponatremia, it was discontinued in August 2019, but Mrs. G continued to take lurasidone, 40 mg/d, divalproex, 500 mg/d, and temazepam, 30 mg/d.

In October and November 2020, Mrs. G’s sodium level remained low at 123 and 127 mEq/L. Our treatment team wondered if lurasidone could be causing Mrs. G’s sodium levels to fall. Lurasidone was tapered over 3 days and discontinued. Repeat blood work showed that Mrs. G’s sodium levels soon returned to normal range. In January through March 2021, her sodium levels were 138, 139, and 136 mEq/L, all of which were within normal range. This confirmed our suspicion that lurasidone had caused the hyponatremia, though briefly it may have been made worse by escitalopram. Currently, Mrs. G is stable on perphenazine, 4 mg twice a day, divalproex, 500 mg/d, temazepam, 30 mg/d at bedtime, and melatonin, 5 mg at bedtime.

Continue to: Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion...

Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion

Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) secretion can result in hyponatremia. Classes of medications that can cause SIADH include antidepressants, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, cytotoxic agents, and pain medications.5 The class of drugs most commonly associated with SIADH is selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, particularly citalopram.5 Among the antipsychotics, risperidone is most associated with hyponatremia. The proposed mechanism of medication-induced SIADH is an increase in the release of ADH.6 Treatment options include discontinuing the offending medication(s) or switching to a different medication.

Hyponatremia is a rare adverse effect of lurasidone, with a reported incidence <1%.7 Although hyponatremia is potentially life-threatening, there is no recommendation to routinely monitor sodium levels in patients treated with lurasidone or other psychotropics, and patients who are prescribed lurasidone are not routinely monitored for sodium deficiency. Table 38,9 outlines risk factors for developing hyponatremia among patients taking psychotropic medications.

Mrs. G had been taking lurasidone for a few years and experienced fluctuating sodium levels. She had been taking divalproex, which by itself could cause hyponatremia and could have added to the effects of lurasidone in lowering sodium levels. Escitalopram briefly made her hyponatremia worse. Given Mrs. G’s medical illnesses, our focus had been on her underlying medical conditions rather than on a suspected medication-induced adverse effect.

In summary, patients who are prescribed lurasidone may benefit from regular monitoring of sodium levels. Monitoring sodium levels in geriatric patients who have multiple comorbid medical conditions and take multiple medications may reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with SIADH.

1. National Institute of Mental Health. Bipolar disorder. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/bipolar-disorder

2. Müller JK, Leweke FM. Bipolar disorder: clinical overview. Med Monatsschr Pharm. 2016;39(9):363-369.

3. Bobo WV, Shelton RC. Bipolar major depression in adults: Efficacy and adverse effects of second-generation antipsychotics. UpToDate. Updated September 1, 2020. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/bipolar-major-depression-in-adults-efficacy-and-adverse-effects-of-second-generation-antipsychotics

4. Epocrates. Version 21.9.1. Accessed October 14, 2021. https://www.epocrates.com

5. Shepshelovich D, Schechter A, Calvarysky B, et al. Medication-induced SIADH: distribution and characterization according to medication class. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83(8):1801-1807.

6. Guirguis E, Grace Y, Seetaram M. Management of hyponatremia: focus on psychiatric patients. US Pharm. 2013;38(11):HS3-HS6.

7. Drugs.com. Latuda side effects. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.drugs.com/sfx/latuda-side-effects.html

8. Ali SN, Bazzano LA. Hyponatremia in association with second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review of case reports. Ochsner J. 2018;18(3):230-235.

9. Sahoo S, Grover S. Hyponatremia and psychotropics. J Geriatr Ment Health. 2016;3(2):108-122.

1. National Institute of Mental Health. Bipolar disorder. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/bipolar-disorder

2. Müller JK, Leweke FM. Bipolar disorder: clinical overview. Med Monatsschr Pharm. 2016;39(9):363-369.

3. Bobo WV, Shelton RC. Bipolar major depression in adults: Efficacy and adverse effects of second-generation antipsychotics. UpToDate. Updated September 1, 2020. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/bipolar-major-depression-in-adults-efficacy-and-adverse-effects-of-second-generation-antipsychotics

4. Epocrates. Version 21.9.1. Accessed October 14, 2021. https://www.epocrates.com

5. Shepshelovich D, Schechter A, Calvarysky B, et al. Medication-induced SIADH: distribution and characterization according to medication class. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83(8):1801-1807.

6. Guirguis E, Grace Y, Seetaram M. Management of hyponatremia: focus on psychiatric patients. US Pharm. 2013;38(11):HS3-HS6.

7. Drugs.com. Latuda side effects. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.drugs.com/sfx/latuda-side-effects.html

8. Ali SN, Bazzano LA. Hyponatremia in association with second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review of case reports. Ochsner J. 2018;18(3):230-235.

9. Sahoo S, Grover S. Hyponatremia and psychotropics. J Geriatr Ment Health. 2016;3(2):108-122.

Antidepressant may cut COVID-19–related hospitalization, mortality: TOGETHER

The antidepressant fluvoxamine (Luvox) may prevent hospitalization and death in outpatients with COVID-19, new research suggests.

Results from the placebo-controlled, multisite, phase 3 TOGETHER trial showed that in COVID-19 outpatients at high risk for complications, hospitalizations were cut by 66% and deaths were reduced by 91% in those who tolerated fluvoxamine.

“Our trial has found that fluvoxamine, an inexpensive existing drug, reduces the need for advanced disease care in this high-risk population,” wrote the investigators, led by Gilmar Reis, MD, PhD, research division, Cardresearch, Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

The findings were published online Oct. 27 in The Lancet Global Health.

Alternative mechanisms

Fluvoxamine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), is an antidepressant commonly prescribed for obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Besides its known effects on serotonin, the drug acts in other molecular pathways to dampen the production of inflammatory cytokines. Those alternative mechanisms are the ones believed to help patients with COVID-19, said coinvestigator Angela Reiersen, MD, child psychiatrist at Washington University, St. Louis.

Based on cell culture and mouse studies showing effects of the molecule’s binding to the sigma-1 receptor in the endoplasmic reticulum, Dr. Reiersen came up with the idea of testing if fluvoxamine could keep COVID-19 from progressing in newly infected patients.

Dr. Reiersen and psychiatrist Eric Lenze, MD, also from Washington University, led the phase 2 trial that initially suggested fluvoxamine’s promise as an outpatient medication. They are coinvestigators on the new phase 3 adaptive platform trial called TOGETHER, which was conducted by an international team of investigators in Brazil, Canada, and the United States.

For this latest study, researchers at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., partnered with the research clinic Cardresearch in Brazil to recruit unvaccinated, high-risk adults within 7 days of developing flu-like symptoms from COVID-19. They analyzed 1,497 newly symptomatic COVID-19 patients at 11 clinical sites in Brazil.

Patients entered the trial between January and August 2021 and were assigned to receive 100 mg fluvoxamine or placebo pills twice a day for 10 days. Investigators monitored participants through 28 days post treatment, noting whether complications developed requiring hospitalization or more than 6 hours of emergency care.

In the placebo group, 119 of 756 patients (15.7%) worsened to this extent. In comparison, 79 of 741 (10.7%) fluvoxamine-treated patients met these primary criteria. This represented a 32% reduction in hospitalizations and emergency visits.

Additional analysis requested

As Lancet Global Health reviewed these findings from the submitted manuscript, journal reviewers requested an additional “pre-protocol analysis” that was not specified in the trial’s original protocol. The request was to examine the subgroup of patients with good adherence (74% of treated group, 82% of placebo group).

Among these three quarters of patients who took at least 80% of their doses, benefits were better.

Fluvoxamine cut serious complications in this group by 66% and reduced mortality by 91%. In the placebo group, 12 people died compared with one who received the study drug.

from complications of the infection.

However, clinicians should note that the drug can cause side effects such as nausea, dizziness, and insomnia, she added. In addition, because it prevents the body from metabolizing caffeine, patients should limit their daily intake to half of a small cup of coffee or one can of soda or one tea while taking the drug.

Previous research has shown that fluvoxamine affects the metabolism of some drugs, such as theophylline, clozapine, olanzapine, and tizanidine.

Despite huge challenges with studying generic drugs as early COVID-19 treatment, the TOGETHER trial shows it is possible to produce quality evidence during a pandemic on a shoestring budget, noted co-principal investigator Edward Mills, PhD, professor in the department of health research methods, evidence, and impact at McMaster University.

To screen more than 12,000 patients and enroll 4,000 to test nine interventions, “our total budget was less than $8 million,” Dr. Mills said. The trial was funded by Fast Grants and the Rainwater Charitable Foundation.

‘A $10 medicine’

Commenting on the findings, David Boulware, MD, MPH, an infectious disease physician-researcher at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, noted fluvoxamine is “a $10 medicine that’s available and has a very good safety record.”

By comparison, a 5-day course of Merck’s antiviral molnupiravir, another oral drug that the company says can cut hospitalizations in COVID-19 outpatients, costs $700. However, the data have not been peer reviewed – and molnupiravir is not currently available and has unknown long-term safety implications, Dr. Boulware said.

Pharmaceutical companies typically spend tens of thousands of dollars on a trial evaluating a single drug, he noted.

In addition, the National Institutes of Health’s ACTIV-6 study, a nationwide trial on the effect of fluvoxamine and other repurposed generic drugs on thousands of COVID-19 outpatients, is a $110 million effort, according to Dr. Boulware, who cochairs its steering committee.

ACTIV-6 is currently enrolling outpatients with COVID-19 to test a lower dose of fluvoxamine, at 50 mg twice daily instead of the 100-mg dose used in the TOGETHER trial, as well as ivermectin and inhaled fluticasone. The COVID-OUT trial is also recruiting newly diagnosed COVID-19 patients to test various combinations of fluvoxamine, ivermectin, and the diabetes drug metformin.

Unanswered safety, efficacy questions

In an accompanying editorial in The Lancet Global Health, Otavio Berwanger, MD, cardiologist and clinical trialist, Academic Research Organization, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, Brazil, commends the investigators for rapidly generating evidence during the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, despite the important findings, “some questions related to efficacy and safety of fluvoxamine for patients with COVID-19 remain open,” Dr. Berwanger wrote.

The effects of the drug on reducing both mortality and hospitalizations also “still need addressing,” he noted.

“In addition, it remains to be established whether fluvoxamine has an additive effect to other therapies such as monoclonal antibodies and budesonide, and what is the optimal fluvoxamine therapeutic scheme,” wrote Dr. Berwanger.

In an interview, he noted that 74% of the Brazil population have currently received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine and 52% have received two doses. In addition, deaths have gone down from 4,000 per day during the March-April second wave to about 400 per day. “That is still unfortunate and far from ideal,” he said. In total, they have had about 600,000 deaths because of COVID-19.

Asked whether public health authorities are now recommending fluvoxamine as an early treatment for COVID-19 based on the TOGETHER trial data, Dr. Berwanger answered, “Not yet.

“I believe medical and scientific societies will need to critically appraise the manuscript in order to inform their decisions and recommendations. This interesting trial adds another important piece of information in this regard,” he said.

Dr. Reiersen and Dr. Lenze are inventors on a patent application related to methods for treating COVID-19, which was filed by Washington University. Dr. Mills reports no relevant financial relationships, as does Dr. Boulware – except that the TOGETHER trial funders are also funding the University of Minnesota COVID-OUT trial. Dr. Berwanger reports having received research grants outside of the submitted work that were paid to his institution by AstraZeneca, Bayer, Amgen, Servier, Novartis, Pfizer, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The antidepressant fluvoxamine (Luvox) may prevent hospitalization and death in outpatients with COVID-19, new research suggests.

Results from the placebo-controlled, multisite, phase 3 TOGETHER trial showed that in COVID-19 outpatients at high risk for complications, hospitalizations were cut by 66% and deaths were reduced by 91% in those who tolerated fluvoxamine.

“Our trial has found that fluvoxamine, an inexpensive existing drug, reduces the need for advanced disease care in this high-risk population,” wrote the investigators, led by Gilmar Reis, MD, PhD, research division, Cardresearch, Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

The findings were published online Oct. 27 in The Lancet Global Health.

Alternative mechanisms

Fluvoxamine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), is an antidepressant commonly prescribed for obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Besides its known effects on serotonin, the drug acts in other molecular pathways to dampen the production of inflammatory cytokines. Those alternative mechanisms are the ones believed to help patients with COVID-19, said coinvestigator Angela Reiersen, MD, child psychiatrist at Washington University, St. Louis.

Based on cell culture and mouse studies showing effects of the molecule’s binding to the sigma-1 receptor in the endoplasmic reticulum, Dr. Reiersen came up with the idea of testing if fluvoxamine could keep COVID-19 from progressing in newly infected patients.

Dr. Reiersen and psychiatrist Eric Lenze, MD, also from Washington University, led the phase 2 trial that initially suggested fluvoxamine’s promise as an outpatient medication. They are coinvestigators on the new phase 3 adaptive platform trial called TOGETHER, which was conducted by an international team of investigators in Brazil, Canada, and the United States.

For this latest study, researchers at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., partnered with the research clinic Cardresearch in Brazil to recruit unvaccinated, high-risk adults within 7 days of developing flu-like symptoms from COVID-19. They analyzed 1,497 newly symptomatic COVID-19 patients at 11 clinical sites in Brazil.

Patients entered the trial between January and August 2021 and were assigned to receive 100 mg fluvoxamine or placebo pills twice a day for 10 days. Investigators monitored participants through 28 days post treatment, noting whether complications developed requiring hospitalization or more than 6 hours of emergency care.

In the placebo group, 119 of 756 patients (15.7%) worsened to this extent. In comparison, 79 of 741 (10.7%) fluvoxamine-treated patients met these primary criteria. This represented a 32% reduction in hospitalizations and emergency visits.

Additional analysis requested

As Lancet Global Health reviewed these findings from the submitted manuscript, journal reviewers requested an additional “pre-protocol analysis” that was not specified in the trial’s original protocol. The request was to examine the subgroup of patients with good adherence (74% of treated group, 82% of placebo group).

Among these three quarters of patients who took at least 80% of their doses, benefits were better.

Fluvoxamine cut serious complications in this group by 66% and reduced mortality by 91%. In the placebo group, 12 people died compared with one who received the study drug.

from complications of the infection.

However, clinicians should note that the drug can cause side effects such as nausea, dizziness, and insomnia, she added. In addition, because it prevents the body from metabolizing caffeine, patients should limit their daily intake to half of a small cup of coffee or one can of soda or one tea while taking the drug.

Previous research has shown that fluvoxamine affects the metabolism of some drugs, such as theophylline, clozapine, olanzapine, and tizanidine.

Despite huge challenges with studying generic drugs as early COVID-19 treatment, the TOGETHER trial shows it is possible to produce quality evidence during a pandemic on a shoestring budget, noted co-principal investigator Edward Mills, PhD, professor in the department of health research methods, evidence, and impact at McMaster University.

To screen more than 12,000 patients and enroll 4,000 to test nine interventions, “our total budget was less than $8 million,” Dr. Mills said. The trial was funded by Fast Grants and the Rainwater Charitable Foundation.

‘A $10 medicine’

Commenting on the findings, David Boulware, MD, MPH, an infectious disease physician-researcher at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, noted fluvoxamine is “a $10 medicine that’s available and has a very good safety record.”

By comparison, a 5-day course of Merck’s antiviral molnupiravir, another oral drug that the company says can cut hospitalizations in COVID-19 outpatients, costs $700. However, the data have not been peer reviewed – and molnupiravir is not currently available and has unknown long-term safety implications, Dr. Boulware said.

Pharmaceutical companies typically spend tens of thousands of dollars on a trial evaluating a single drug, he noted.

In addition, the National Institutes of Health’s ACTIV-6 study, a nationwide trial on the effect of fluvoxamine and other repurposed generic drugs on thousands of COVID-19 outpatients, is a $110 million effort, according to Dr. Boulware, who cochairs its steering committee.

ACTIV-6 is currently enrolling outpatients with COVID-19 to test a lower dose of fluvoxamine, at 50 mg twice daily instead of the 100-mg dose used in the TOGETHER trial, as well as ivermectin and inhaled fluticasone. The COVID-OUT trial is also recruiting newly diagnosed COVID-19 patients to test various combinations of fluvoxamine, ivermectin, and the diabetes drug metformin.

Unanswered safety, efficacy questions

In an accompanying editorial in The Lancet Global Health, Otavio Berwanger, MD, cardiologist and clinical trialist, Academic Research Organization, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, Brazil, commends the investigators for rapidly generating evidence during the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, despite the important findings, “some questions related to efficacy and safety of fluvoxamine for patients with COVID-19 remain open,” Dr. Berwanger wrote.

The effects of the drug on reducing both mortality and hospitalizations also “still need addressing,” he noted.

“In addition, it remains to be established whether fluvoxamine has an additive effect to other therapies such as monoclonal antibodies and budesonide, and what is the optimal fluvoxamine therapeutic scheme,” wrote Dr. Berwanger.

In an interview, he noted that 74% of the Brazil population have currently received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine and 52% have received two doses. In addition, deaths have gone down from 4,000 per day during the March-April second wave to about 400 per day. “That is still unfortunate and far from ideal,” he said. In total, they have had about 600,000 deaths because of COVID-19.

Asked whether public health authorities are now recommending fluvoxamine as an early treatment for COVID-19 based on the TOGETHER trial data, Dr. Berwanger answered, “Not yet.

“I believe medical and scientific societies will need to critically appraise the manuscript in order to inform their decisions and recommendations. This interesting trial adds another important piece of information in this regard,” he said.

Dr. Reiersen and Dr. Lenze are inventors on a patent application related to methods for treating COVID-19, which was filed by Washington University. Dr. Mills reports no relevant financial relationships, as does Dr. Boulware – except that the TOGETHER trial funders are also funding the University of Minnesota COVID-OUT trial. Dr. Berwanger reports having received research grants outside of the submitted work that were paid to his institution by AstraZeneca, Bayer, Amgen, Servier, Novartis, Pfizer, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The antidepressant fluvoxamine (Luvox) may prevent hospitalization and death in outpatients with COVID-19, new research suggests.

Results from the placebo-controlled, multisite, phase 3 TOGETHER trial showed that in COVID-19 outpatients at high risk for complications, hospitalizations were cut by 66% and deaths were reduced by 91% in those who tolerated fluvoxamine.

“Our trial has found that fluvoxamine, an inexpensive existing drug, reduces the need for advanced disease care in this high-risk population,” wrote the investigators, led by Gilmar Reis, MD, PhD, research division, Cardresearch, Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

The findings were published online Oct. 27 in The Lancet Global Health.

Alternative mechanisms

Fluvoxamine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), is an antidepressant commonly prescribed for obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Besides its known effects on serotonin, the drug acts in other molecular pathways to dampen the production of inflammatory cytokines. Those alternative mechanisms are the ones believed to help patients with COVID-19, said coinvestigator Angela Reiersen, MD, child psychiatrist at Washington University, St. Louis.

Based on cell culture and mouse studies showing effects of the molecule’s binding to the sigma-1 receptor in the endoplasmic reticulum, Dr. Reiersen came up with the idea of testing if fluvoxamine could keep COVID-19 from progressing in newly infected patients.

Dr. Reiersen and psychiatrist Eric Lenze, MD, also from Washington University, led the phase 2 trial that initially suggested fluvoxamine’s promise as an outpatient medication. They are coinvestigators on the new phase 3 adaptive platform trial called TOGETHER, which was conducted by an international team of investigators in Brazil, Canada, and the United States.

For this latest study, researchers at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., partnered with the research clinic Cardresearch in Brazil to recruit unvaccinated, high-risk adults within 7 days of developing flu-like symptoms from COVID-19. They analyzed 1,497 newly symptomatic COVID-19 patients at 11 clinical sites in Brazil.

Patients entered the trial between January and August 2021 and were assigned to receive 100 mg fluvoxamine or placebo pills twice a day for 10 days. Investigators monitored participants through 28 days post treatment, noting whether complications developed requiring hospitalization or more than 6 hours of emergency care.

In the placebo group, 119 of 756 patients (15.7%) worsened to this extent. In comparison, 79 of 741 (10.7%) fluvoxamine-treated patients met these primary criteria. This represented a 32% reduction in hospitalizations and emergency visits.

Additional analysis requested

As Lancet Global Health reviewed these findings from the submitted manuscript, journal reviewers requested an additional “pre-protocol analysis” that was not specified in the trial’s original protocol. The request was to examine the subgroup of patients with good adherence (74% of treated group, 82% of placebo group).

Among these three quarters of patients who took at least 80% of their doses, benefits were better.

Fluvoxamine cut serious complications in this group by 66% and reduced mortality by 91%. In the placebo group, 12 people died compared with one who received the study drug.

from complications of the infection.

However, clinicians should note that the drug can cause side effects such as nausea, dizziness, and insomnia, she added. In addition, because it prevents the body from metabolizing caffeine, patients should limit their daily intake to half of a small cup of coffee or one can of soda or one tea while taking the drug.

Previous research has shown that fluvoxamine affects the metabolism of some drugs, such as theophylline, clozapine, olanzapine, and tizanidine.

Despite huge challenges with studying generic drugs as early COVID-19 treatment, the TOGETHER trial shows it is possible to produce quality evidence during a pandemic on a shoestring budget, noted co-principal investigator Edward Mills, PhD, professor in the department of health research methods, evidence, and impact at McMaster University.

To screen more than 12,000 patients and enroll 4,000 to test nine interventions, “our total budget was less than $8 million,” Dr. Mills said. The trial was funded by Fast Grants and the Rainwater Charitable Foundation.

‘A $10 medicine’

Commenting on the findings, David Boulware, MD, MPH, an infectious disease physician-researcher at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, noted fluvoxamine is “a $10 medicine that’s available and has a very good safety record.”

By comparison, a 5-day course of Merck’s antiviral molnupiravir, another oral drug that the company says can cut hospitalizations in COVID-19 outpatients, costs $700. However, the data have not been peer reviewed – and molnupiravir is not currently available and has unknown long-term safety implications, Dr. Boulware said.

Pharmaceutical companies typically spend tens of thousands of dollars on a trial evaluating a single drug, he noted.

In addition, the National Institutes of Health’s ACTIV-6 study, a nationwide trial on the effect of fluvoxamine and other repurposed generic drugs on thousands of COVID-19 outpatients, is a $110 million effort, according to Dr. Boulware, who cochairs its steering committee.

ACTIV-6 is currently enrolling outpatients with COVID-19 to test a lower dose of fluvoxamine, at 50 mg twice daily instead of the 100-mg dose used in the TOGETHER trial, as well as ivermectin and inhaled fluticasone. The COVID-OUT trial is also recruiting newly diagnosed COVID-19 patients to test various combinations of fluvoxamine, ivermectin, and the diabetes drug metformin.

Unanswered safety, efficacy questions

In an accompanying editorial in The Lancet Global Health, Otavio Berwanger, MD, cardiologist and clinical trialist, Academic Research Organization, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, Brazil, commends the investigators for rapidly generating evidence during the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, despite the important findings, “some questions related to efficacy and safety of fluvoxamine for patients with COVID-19 remain open,” Dr. Berwanger wrote.

The effects of the drug on reducing both mortality and hospitalizations also “still need addressing,” he noted.

“In addition, it remains to be established whether fluvoxamine has an additive effect to other therapies such as monoclonal antibodies and budesonide, and what is the optimal fluvoxamine therapeutic scheme,” wrote Dr. Berwanger.

In an interview, he noted that 74% of the Brazil population have currently received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine and 52% have received two doses. In addition, deaths have gone down from 4,000 per day during the March-April second wave to about 400 per day. “That is still unfortunate and far from ideal,” he said. In total, they have had about 600,000 deaths because of COVID-19.

Asked whether public health authorities are now recommending fluvoxamine as an early treatment for COVID-19 based on the TOGETHER trial data, Dr. Berwanger answered, “Not yet.

“I believe medical and scientific societies will need to critically appraise the manuscript in order to inform their decisions and recommendations. This interesting trial adds another important piece of information in this regard,” he said.

Dr. Reiersen and Dr. Lenze are inventors on a patent application related to methods for treating COVID-19, which was filed by Washington University. Dr. Mills reports no relevant financial relationships, as does Dr. Boulware – except that the TOGETHER trial funders are also funding the University of Minnesota COVID-OUT trial. Dr. Berwanger reports having received research grants outside of the submitted work that were paid to his institution by AstraZeneca, Bayer, Amgen, Servier, Novartis, Pfizer, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clinicians underprescribe behavior therapy for preschool ADHD

The majority of families of preschool children with a diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder were not offered behavior therapy as a first-line treatment, according to data from nearly 200 children.

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ current clinical practice guidelines recommend parent training in behavior management (PTBM) as a first-line treatment for children aged 4-5 years diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or symptoms of ADHD such as hyperactivity or impulsivity, but data on how well primary care providers follow this recommendation in practice are lacking, wrote Yair Bannett, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues.

To investigate the rates of PTBM recommendations, the researchers reviewed electronic health records for 22,714 children aged 48-71 months who had at least two visits to any 1 of 10 primary care practices in a California pediatric health network between Oct. 1, 2015, and Dec. 31, 2019. Children with an autism diagnosis were excluded; ADHD-related visits were identified via ADHD diagnosis codes or symptom-level diagnosis codes.

In the study, published in JAMA Pediatrics, 192 children (1%) had either an ADHD diagnosis or ADHD symptoms; of these, 21 (11%) received referrals for PTBM during ADHD-related primary care visits. Records showed an additional 55 patients (29%) had a mention of counseling on PTBM by a primary care provider, including handouts.

PCPs prescribed ADHD medications for 32 children; 9 of these had documented PTBM recommendations, and in 4 cases, the PCPs recommended PTBM before prescribing a first medication.

A majority (73%) of the children were male, 64% were privately insured, 56% had subspecialists involved in their care, and 17% were prescribed ADHD medications (88% of which were stimulants).

In a multivariate analysis, children with public insurance were significantly less likely to receive a PTBM recommendation than were those with private insurance (adjusted relative risk 0.87).

The most common recommendation overall was routine/habit modifications (for 79 children), such as reducing sugar or adding supplements to the diet; improving sleep hygiene; and limiting screen time.

The low rates of PTBM among publicly insured patients in particular highlight the need to identify factors behind disparities in recommended treatments, the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the reliance on primary care provider documentation during the study period and the inclusion only of medical record reviews with diagnostic codes for ADHD, the researchers noted. Further studies beyond a single health care system are needed to assess generalizability, they added.

However, the results present an opportunity for primary care providers to improve adherence to clinical practice guidelines and establish behavioral treatment at an early age to mitigate long-term morbidity, they concluded.

Low rates highlight barriers and opportunities

“We were surprised to find very low rates of documented recommendations for behavioral treatment mentioned by PCPs,” Dr. Bannett said in an interview. The researchers were surprised that recommendations for changes in daily routines and habits, such as reduced sugar intake, regular exercise, better sleep, and reduced screen time, were the most common recommendations for families of children presenting with symptoms of ADHD. “Though these are good recommendations that can support the general health of any young child, there is no evidence to support their benefit in alleviating symptoms of ADHD,” he said.

Dr. Bannett acknowledged the challenge for pediatricians to stay current on where and how families can access this type of behavioral treatment, but the evidence supports behavior therapy over medication in preschool children, he said.

“I think that it is important for primary care clinicians to know that there are options for parent training in behavioral management for both privately and publicly insured patients,” said Dr. Bannett. “In California, for example, parent training programs are offered through county mental health services. In some counties, there are other organizations that offer parent training for underserved populations and those with public insurance,” he said.

Dr. Bannett noted that online treatments, including behavioral treatments, may be possible for some families.

He cited Triple P, an evidence-based curriculum for parent training in behavior management, which offers an online course for parents at triplep-parenting.com, and an online parent training course offered through the CHADD website (chadd.org/parent-to-parent/).

Dr. Bannett noted that the researchers are planning a follow-up study to investigate the reasons behind the low referral rates for PTBM. “A known barrier is the limited availability of therapists who can provide this type of therapy,” Dr. Bannett said. “Research is needed on the effectiveness of online versions of parent training, which can overcome some of the access barriers many families experience,” he added.

“Additionally, since behavioral treatment requires a significant effort on the part of the parents and caregivers, who often are not able to complete the therapy, there is a need for research on ways to enhance parent and family engagement and participation in these important evidence-based treatments,” as well as a need to research ways to increase adherence to evidence-based practices, said Dr. Bannett. “We are currently planning intervention studies that will enhance primary care clinicians’ knowledge and clinical practice; for example, decision support tools in the electronic health record, and up-to-date information about available resources and behavioral therapists in their community that they can share with families,” he said.

Barriers make it difficult to adhere to guidelines

The study authors missed a significant element of the AAP guidelines by failing to acknowledge the extensive accompanying section on barriers to adoption, which details why most pediatricians in clinical practice do not prescribe PTBM, Herschel Lessin, MD, of Children’s Medical Group, Poughkeepsie, N.Y., said in an interview.

“Academically, it is a wonderful article,” said Dr. Lessin, who was a member of the authoring committee of the AAP guidelines and a major contributor to the section on barriers. The AAP guidelines recommend PTBM because it is evidence based, but the barrier section is essential to understanding that this evidence-based recommendation is nearly impossible to follow in real-world clinical practice, he emphasized.

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ “Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents,” published in October of 2019 in Pediatrics, included a full subsection on barriers as to why the guidelines might not be followed in many cases in a real-world setting, and the study authors failed to acknowledge this section and its implications, said Dr. Lessin. Notably, the barriers section was originally published in Pediatrics under a Supplemental Data tab that might easily be overlooked by someone reviewing the main practice guideline recommendations, he said.

In most areas of the country, PTBM is simply unavailable, Dr. Lessin said.

There is a dearth of mental health providers in the United States in general, and “a monstrous shortage of mental health practitioners for young children,” he said. Children in underserved areas barely have access to a medical home, let alone mental health subspecialists, he added.

Even in areas where specialized behavior therapy may be available, it can be prohibitively expensive for all but the wealthiest patients, Dr. Lessin noted. Insurance does not cover this type of behavior therapy, and most mental health professionals don’t accept Medicaid, nor commercial insurance, he said.

“I don’t even bother with those referrals, because they are not available,” said Dr. Lessin. The take-home message is that most community-based pediatricians are not following the guidelines because the barriers are so enormous, he said.

The study was supported by a research grant from the Society of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics and salary support through the Instructor Support Program at the department of pediatrics, Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, to Dr. Bannett. The researchers had no other financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Lessin had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

The majority of families of preschool children with a diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder were not offered behavior therapy as a first-line treatment, according to data from nearly 200 children.

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ current clinical practice guidelines recommend parent training in behavior management (PTBM) as a first-line treatment for children aged 4-5 years diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or symptoms of ADHD such as hyperactivity or impulsivity, but data on how well primary care providers follow this recommendation in practice are lacking, wrote Yair Bannett, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues.

To investigate the rates of PTBM recommendations, the researchers reviewed electronic health records for 22,714 children aged 48-71 months who had at least two visits to any 1 of 10 primary care practices in a California pediatric health network between Oct. 1, 2015, and Dec. 31, 2019. Children with an autism diagnosis were excluded; ADHD-related visits were identified via ADHD diagnosis codes or symptom-level diagnosis codes.

In the study, published in JAMA Pediatrics, 192 children (1%) had either an ADHD diagnosis or ADHD symptoms; of these, 21 (11%) received referrals for PTBM during ADHD-related primary care visits. Records showed an additional 55 patients (29%) had a mention of counseling on PTBM by a primary care provider, including handouts.

PCPs prescribed ADHD medications for 32 children; 9 of these had documented PTBM recommendations, and in 4 cases, the PCPs recommended PTBM before prescribing a first medication.

A majority (73%) of the children were male, 64% were privately insured, 56% had subspecialists involved in their care, and 17% were prescribed ADHD medications (88% of which were stimulants).

In a multivariate analysis, children with public insurance were significantly less likely to receive a PTBM recommendation than were those with private insurance (adjusted relative risk 0.87).

The most common recommendation overall was routine/habit modifications (for 79 children), such as reducing sugar or adding supplements to the diet; improving sleep hygiene; and limiting screen time.

The low rates of PTBM among publicly insured patients in particular highlight the need to identify factors behind disparities in recommended treatments, the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the reliance on primary care provider documentation during the study period and the inclusion only of medical record reviews with diagnostic codes for ADHD, the researchers noted. Further studies beyond a single health care system are needed to assess generalizability, they added.

However, the results present an opportunity for primary care providers to improve adherence to clinical practice guidelines and establish behavioral treatment at an early age to mitigate long-term morbidity, they concluded.

Low rates highlight barriers and opportunities

“We were surprised to find very low rates of documented recommendations for behavioral treatment mentioned by PCPs,” Dr. Bannett said in an interview. The researchers were surprised that recommendations for changes in daily routines and habits, such as reduced sugar intake, regular exercise, better sleep, and reduced screen time, were the most common recommendations for families of children presenting with symptoms of ADHD. “Though these are good recommendations that can support the general health of any young child, there is no evidence to support their benefit in alleviating symptoms of ADHD,” he said.

Dr. Bannett acknowledged the challenge for pediatricians to stay current on where and how families can access this type of behavioral treatment, but the evidence supports behavior therapy over medication in preschool children, he said.

“I think that it is important for primary care clinicians to know that there are options for parent training in behavioral management for both privately and publicly insured patients,” said Dr. Bannett. “In California, for example, parent training programs are offered through county mental health services. In some counties, there are other organizations that offer parent training for underserved populations and those with public insurance,” he said.

Dr. Bannett noted that online treatments, including behavioral treatments, may be possible for some families.

He cited Triple P, an evidence-based curriculum for parent training in behavior management, which offers an online course for parents at triplep-parenting.com, and an online parent training course offered through the CHADD website (chadd.org/parent-to-parent/).

Dr. Bannett noted that the researchers are planning a follow-up study to investigate the reasons behind the low referral rates for PTBM. “A known barrier is the limited availability of therapists who can provide this type of therapy,” Dr. Bannett said. “Research is needed on the effectiveness of online versions of parent training, which can overcome some of the access barriers many families experience,” he added.

“Additionally, since behavioral treatment requires a significant effort on the part of the parents and caregivers, who often are not able to complete the therapy, there is a need for research on ways to enhance parent and family engagement and participation in these important evidence-based treatments,” as well as a need to research ways to increase adherence to evidence-based practices, said Dr. Bannett. “We are currently planning intervention studies that will enhance primary care clinicians’ knowledge and clinical practice; for example, decision support tools in the electronic health record, and up-to-date information about available resources and behavioral therapists in their community that they can share with families,” he said.

Barriers make it difficult to adhere to guidelines

The study authors missed a significant element of the AAP guidelines by failing to acknowledge the extensive accompanying section on barriers to adoption, which details why most pediatricians in clinical practice do not prescribe PTBM, Herschel Lessin, MD, of Children’s Medical Group, Poughkeepsie, N.Y., said in an interview.

“Academically, it is a wonderful article,” said Dr. Lessin, who was a member of the authoring committee of the AAP guidelines and a major contributor to the section on barriers. The AAP guidelines recommend PTBM because it is evidence based, but the barrier section is essential to understanding that this evidence-based recommendation is nearly impossible to follow in real-world clinical practice, he emphasized.

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ “Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents,” published in October of 2019 in Pediatrics, included a full subsection on barriers as to why the guidelines might not be followed in many cases in a real-world setting, and the study authors failed to acknowledge this section and its implications, said Dr. Lessin. Notably, the barriers section was originally published in Pediatrics under a Supplemental Data tab that might easily be overlooked by someone reviewing the main practice guideline recommendations, he said.

In most areas of the country, PTBM is simply unavailable, Dr. Lessin said.

There is a dearth of mental health providers in the United States in general, and “a monstrous shortage of mental health practitioners for young children,” he said. Children in underserved areas barely have access to a medical home, let alone mental health subspecialists, he added.

Even in areas where specialized behavior therapy may be available, it can be prohibitively expensive for all but the wealthiest patients, Dr. Lessin noted. Insurance does not cover this type of behavior therapy, and most mental health professionals don’t accept Medicaid, nor commercial insurance, he said.

“I don’t even bother with those referrals, because they are not available,” said Dr. Lessin. The take-home message is that most community-based pediatricians are not following the guidelines because the barriers are so enormous, he said.

The study was supported by a research grant from the Society of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics and salary support through the Instructor Support Program at the department of pediatrics, Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, to Dr. Bannett. The researchers had no other financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Lessin had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

The majority of families of preschool children with a diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder were not offered behavior therapy as a first-line treatment, according to data from nearly 200 children.

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ current clinical practice guidelines recommend parent training in behavior management (PTBM) as a first-line treatment for children aged 4-5 years diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or symptoms of ADHD such as hyperactivity or impulsivity, but data on how well primary care providers follow this recommendation in practice are lacking, wrote Yair Bannett, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues.

To investigate the rates of PTBM recommendations, the researchers reviewed electronic health records for 22,714 children aged 48-71 months who had at least two visits to any 1 of 10 primary care practices in a California pediatric health network between Oct. 1, 2015, and Dec. 31, 2019. Children with an autism diagnosis were excluded; ADHD-related visits were identified via ADHD diagnosis codes or symptom-level diagnosis codes.

In the study, published in JAMA Pediatrics, 192 children (1%) had either an ADHD diagnosis or ADHD symptoms; of these, 21 (11%) received referrals for PTBM during ADHD-related primary care visits. Records showed an additional 55 patients (29%) had a mention of counseling on PTBM by a primary care provider, including handouts.

PCPs prescribed ADHD medications for 32 children; 9 of these had documented PTBM recommendations, and in 4 cases, the PCPs recommended PTBM before prescribing a first medication.

A majority (73%) of the children were male, 64% were privately insured, 56% had subspecialists involved in their care, and 17% were prescribed ADHD medications (88% of which were stimulants).

In a multivariate analysis, children with public insurance were significantly less likely to receive a PTBM recommendation than were those with private insurance (adjusted relative risk 0.87).

The most common recommendation overall was routine/habit modifications (for 79 children), such as reducing sugar or adding supplements to the diet; improving sleep hygiene; and limiting screen time.

The low rates of PTBM among publicly insured patients in particular highlight the need to identify factors behind disparities in recommended treatments, the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the reliance on primary care provider documentation during the study period and the inclusion only of medical record reviews with diagnostic codes for ADHD, the researchers noted. Further studies beyond a single health care system are needed to assess generalizability, they added.

However, the results present an opportunity for primary care providers to improve adherence to clinical practice guidelines and establish behavioral treatment at an early age to mitigate long-term morbidity, they concluded.

Low rates highlight barriers and opportunities

“We were surprised to find very low rates of documented recommendations for behavioral treatment mentioned by PCPs,” Dr. Bannett said in an interview. The researchers were surprised that recommendations for changes in daily routines and habits, such as reduced sugar intake, regular exercise, better sleep, and reduced screen time, were the most common recommendations for families of children presenting with symptoms of ADHD. “Though these are good recommendations that can support the general health of any young child, there is no evidence to support their benefit in alleviating symptoms of ADHD,” he said.

Dr. Bannett acknowledged the challenge for pediatricians to stay current on where and how families can access this type of behavioral treatment, but the evidence supports behavior therapy over medication in preschool children, he said.

“I think that it is important for primary care clinicians to know that there are options for parent training in behavioral management for both privately and publicly insured patients,” said Dr. Bannett. “In California, for example, parent training programs are offered through county mental health services. In some counties, there are other organizations that offer parent training for underserved populations and those with public insurance,” he said.

Dr. Bannett noted that online treatments, including behavioral treatments, may be possible for some families.

He cited Triple P, an evidence-based curriculum for parent training in behavior management, which offers an online course for parents at triplep-parenting.com, and an online parent training course offered through the CHADD website (chadd.org/parent-to-parent/).

Dr. Bannett noted that the researchers are planning a follow-up study to investigate the reasons behind the low referral rates for PTBM. “A known barrier is the limited availability of therapists who can provide this type of therapy,” Dr. Bannett said. “Research is needed on the effectiveness of online versions of parent training, which can overcome some of the access barriers many families experience,” he added.

“Additionally, since behavioral treatment requires a significant effort on the part of the parents and caregivers, who often are not able to complete the therapy, there is a need for research on ways to enhance parent and family engagement and participation in these important evidence-based treatments,” as well as a need to research ways to increase adherence to evidence-based practices, said Dr. Bannett. “We are currently planning intervention studies that will enhance primary care clinicians’ knowledge and clinical practice; for example, decision support tools in the electronic health record, and up-to-date information about available resources and behavioral therapists in their community that they can share with families,” he said.

Barriers make it difficult to adhere to guidelines

The study authors missed a significant element of the AAP guidelines by failing to acknowledge the extensive accompanying section on barriers to adoption, which details why most pediatricians in clinical practice do not prescribe PTBM, Herschel Lessin, MD, of Children’s Medical Group, Poughkeepsie, N.Y., said in an interview.

“Academically, it is a wonderful article,” said Dr. Lessin, who was a member of the authoring committee of the AAP guidelines and a major contributor to the section on barriers. The AAP guidelines recommend PTBM because it is evidence based, but the barrier section is essential to understanding that this evidence-based recommendation is nearly impossible to follow in real-world clinical practice, he emphasized.

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ “Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents,” published in October of 2019 in Pediatrics, included a full subsection on barriers as to why the guidelines might not be followed in many cases in a real-world setting, and the study authors failed to acknowledge this section and its implications, said Dr. Lessin. Notably, the barriers section was originally published in Pediatrics under a Supplemental Data tab that might easily be overlooked by someone reviewing the main practice guideline recommendations, he said.

In most areas of the country, PTBM is simply unavailable, Dr. Lessin said.

There is a dearth of mental health providers in the United States in general, and “a monstrous shortage of mental health practitioners for young children,” he said. Children in underserved areas barely have access to a medical home, let alone mental health subspecialists, he added.

Even in areas where specialized behavior therapy may be available, it can be prohibitively expensive for all but the wealthiest patients, Dr. Lessin noted. Insurance does not cover this type of behavior therapy, and most mental health professionals don’t accept Medicaid, nor commercial insurance, he said.

“I don’t even bother with those referrals, because they are not available,” said Dr. Lessin. The take-home message is that most community-based pediatricians are not following the guidelines because the barriers are so enormous, he said.

The study was supported by a research grant from the Society of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics and salary support through the Instructor Support Program at the department of pediatrics, Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, to Dr. Bannett. The researchers had no other financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Lessin had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Borderline personality disorder: 6 studies of biological interventions

FIRST OF 2 PARTS

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is marked by an ongoing pattern of mood instability, cognitive distortions, problems with self-image, and impulsive behavior, often resulting in problems in relationships. BPD is associated with serious impairment in psychosocial functioning.1 Patients with BPD tend to use more mental health services than patients with other personality disorders or those with major depressive disorder (MDD).2 However, there has been little consensus on the best treatment(s) for this serious and debilitating disorder, and some clinicians view BPD as difficult to treat.

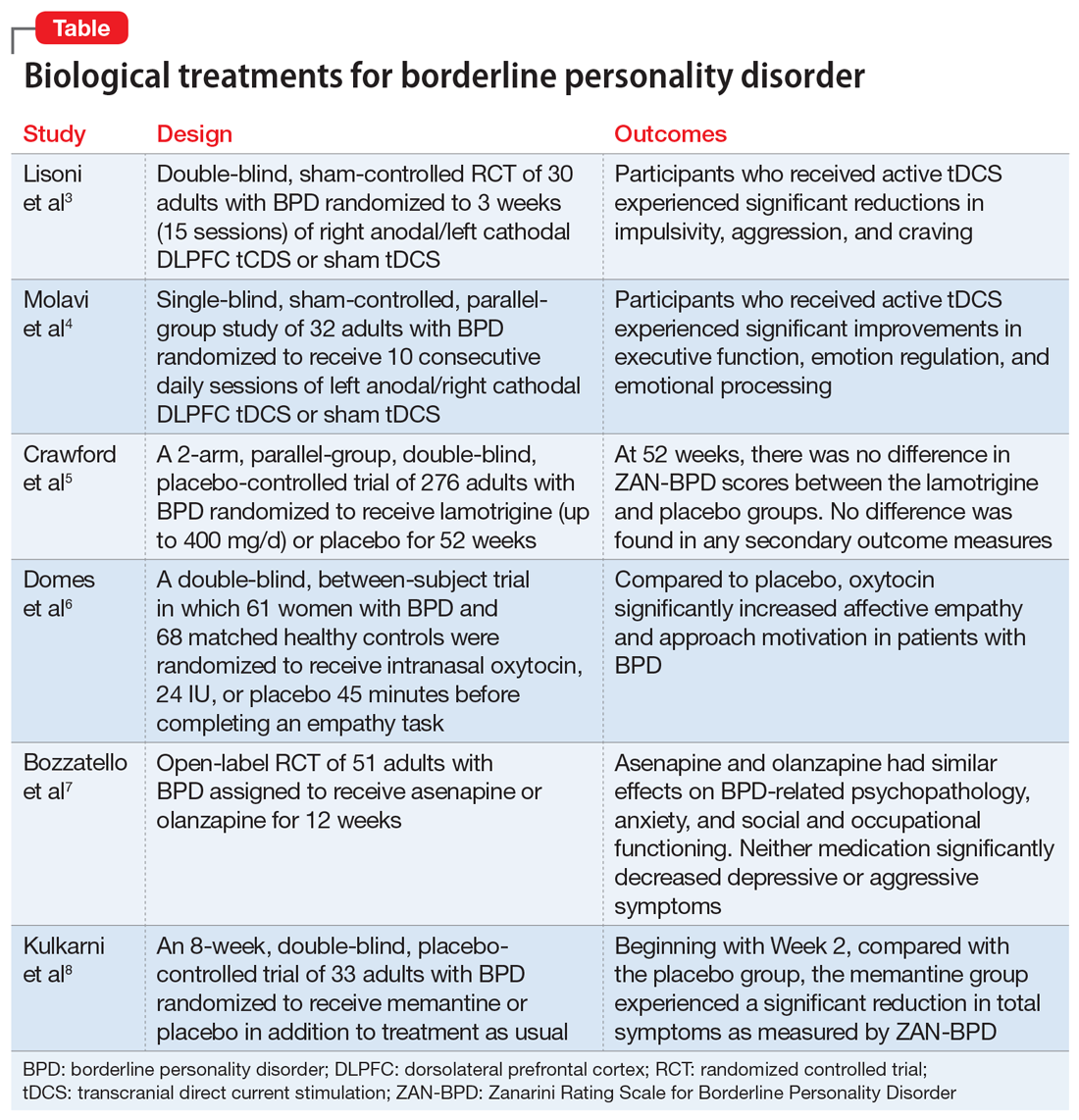

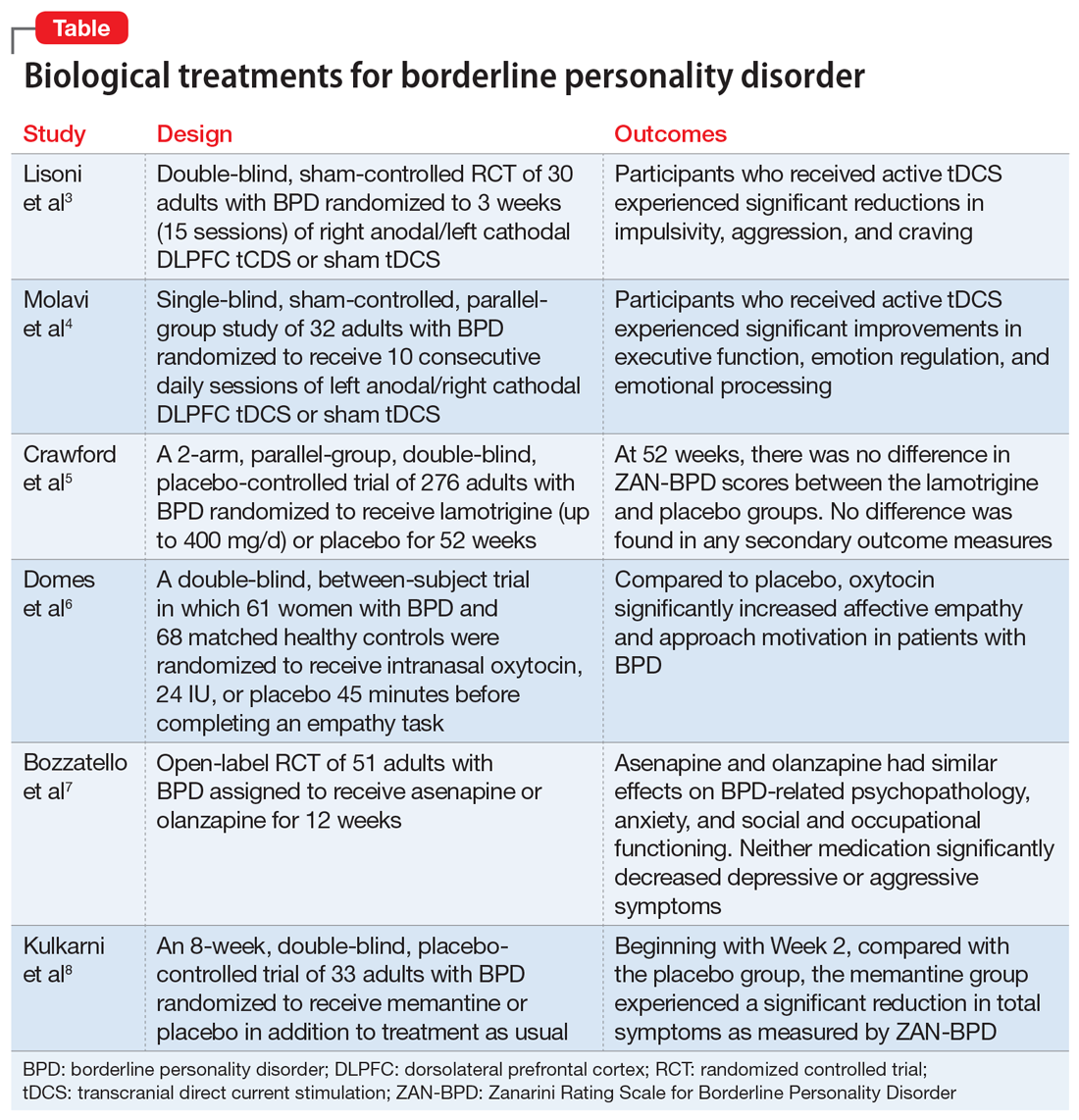

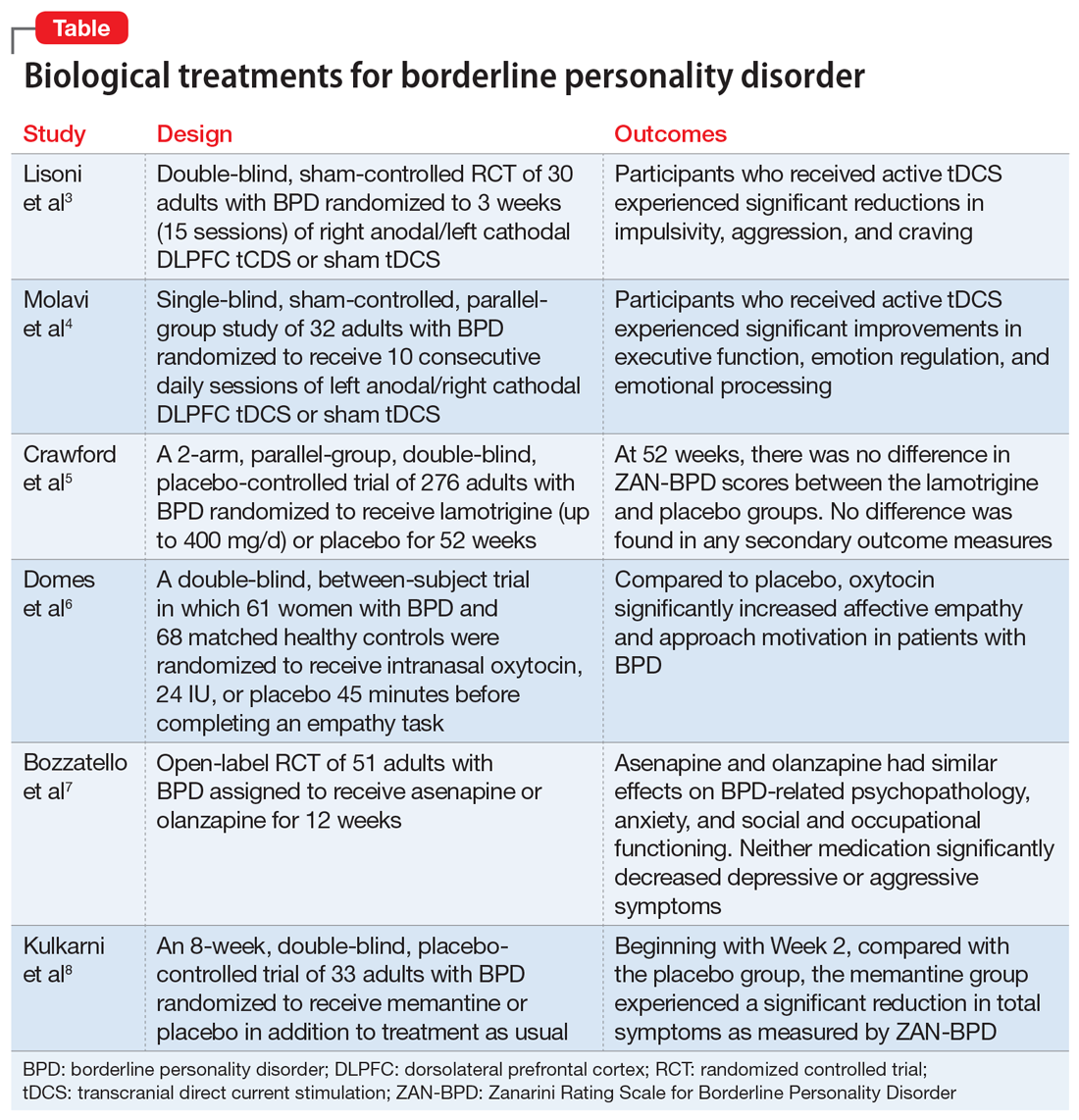

Current treatments for BPD include psychological and pharmacological interventions. Neuromodulation techniques, such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, may also positively affect BPD symptomatology. In recent years, there have been some promising findings in the treatment of BPD. In this 2-part article, we focus on current (within the last 5 years) findings from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of BPD treatments. Here in Part 1, we focus on 6 studies that evaluated biological interventions (Table,3-8). In Part 2, we will focus on RCTs that investigated psychological interventions.

1. Lisoni J, Miotto P, Barlati S, et al. Change in core symptoms of borderline personality disorder by tDCS: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113261. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113261