User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Psychiatry is Neurology: White matter pathology permeates psychiatric disorders

Ask neurologists or psychiatrists to name a white matter (WM) brain disease and they are very likely to say multiple sclerosis (MS), a demyelinating brain disorder caused by immune-mediated destruction of oligodendrocytes, the glial cells that manufacture myelin without which brain communications would come to a standstill.

MS is often associated with mood or psychotic disorders, yet it is regarded as a neurologic illness, not a psychiatric disorder.

Many neurologists and psychiatrists may not be aware that during the past few years, multiple diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) studies have revealed that many psychiatric disorders are associated with WM pathology.1

Most people think that the brain is composed mostly of neurons, but in fact the bulk of brain volume (60%) is comprised of WM and only 40% is gray matter, which includes both neurons and glial cells (astroglia, microglia, and oligodendroglia). WM includes >137,000 km of myelinated fibers, an extensive network that connects all brain regions and integrates its complex, multifaceted functions, culminating in a unified sense of self and agency.

The role of the corpus callosum

Early in my research career, I became interested in the corpus callosum, the largest interhemispheric WM commissure connecting homologous areas across the 2 cerebral hemispheres. It is comprised of 200 million fibers of various diameters. Reasons for my fascination with the corpus callosum were:

The studies of Roger Sperry, the 1981 Nobel Laureate who led the team that was awarded the prize for split-brain research, which involved patients whose corpus callosum was cut to prevent the transfer of intractable epilepsy from 1 hemisphere to the other. Using a tachistoscope that he designed, Sperry discovered that the right and left hemispheres are 2 independent spheres of consciousness (ie, 2 individuals) with different skills.2 Cerebral dominance (laterality) fully integrates the 2 hemispheres via the corpus callosum, with a verbal hemisphere (the left, in 90% of people) dominating the other hemisphere and serving as the “spokesman self.” Thus, we all have 2 persons in our brain completely integrated into 1 “self.”2 This led me to wonder about the effects of an impaired corpus callosum on the “unified self.”

Postmortem and MRI studies conducted by our research group showed a significant difference in the thickness of the corpus callosum in a group of patients with schizophrenia vs healthy controls, which implied abnormal connectivity across the left and right hemispheres.3

Continue to: I then conducted a clinical study

I then conducted a clinical study examining patients with tumors impinging on the corpus callosum, which revealed that they developed psychotic symptoms (delusions and hallucinations).4 This study suggested that disrupting the integrity of the callosal inter-hemispheric fibers can trigger fixed false beliefs and perceptual anomalies.4

A ‘dysconnection’ between hemispheres

I translated those observations about the corpus callosum into a published hypothesis5 in which I proposed that Schneider’s First-Rank Symptoms of schizophrenia of thought insertion, thought withdrawal, and thought broadcasting—as well as delusional experiences of “external control”—may be due to a neurobiologic abnormality in the corpus callosum that disrupts the flow of ongoing bits of information transmitted from the left to the right hemisphere, and vice versa. I proposed in my model that this disruption leads to the verbal left hemisphere of a psychotic patient to describe having thoughts inserted into it from an alien source, failing to recognize that the thoughts it is receiving are being transmitted from the disconnected right hemisphere, which is no longer part of the “self.” Similarly, impulses from the right hemispheric consciousness are now perceived by the patient’s verbal left hemisphere (which talks to the examining physician) as “external control.” Thus, I postulated that an abnormal corpus callosum structure would lead to a “dysconnection” (not “disconnection”) between the 2 hemispheres, and that anomalous dysconnectivity may generate both delusions and hallucinations. 6

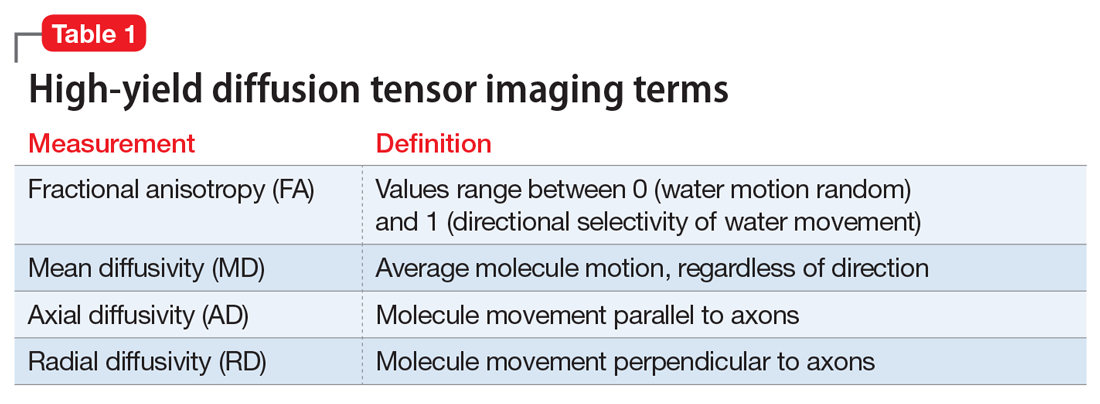

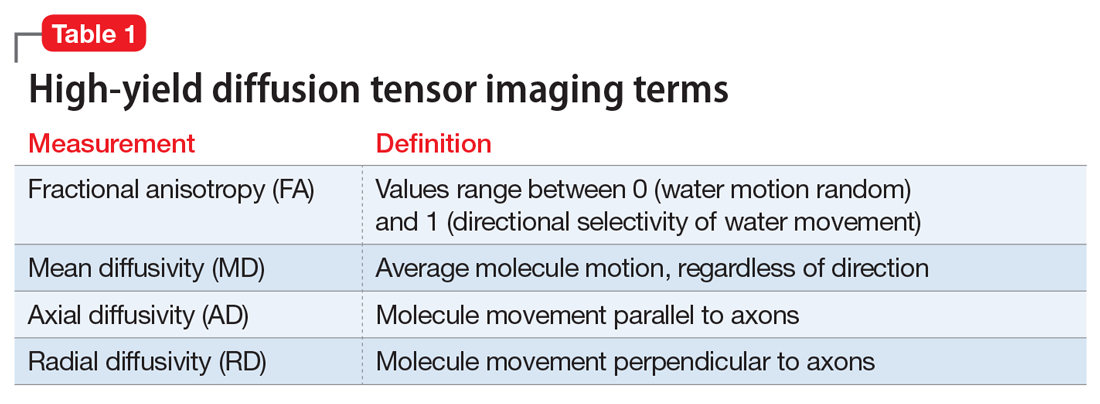

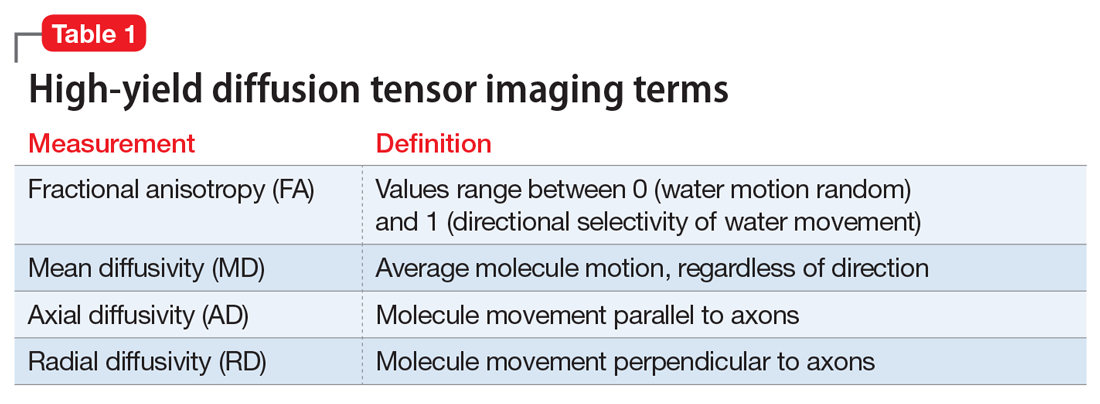

Two decades later, my assumptions were vindicated when DTI was invented, enabling the measurement of WM integrity, including the corpus callosum, the largest body of WM in the brain. Table 1 defines the main parameters of WM integrity, anisotropy and diffusivity, which measure water flow inside WM fibers.

During the past 15 years, many studies have confirmed the presence of significant abnormalities in the myelinated fibers of the corpus callosum in schizophrenia, which can be considered a validation of my hypothesis that the corpus callosum becomes a dysfunctional channel of communications between the right and left hemisphere. Subsequently, DTI studies have reported a spectrum of WM pathologies in various other cerebral bundles and not only in schizophrenia, but also in other major psychiatric disorders (Table 27-19).

The pathophysiology of WM pathology in many psychiatric disorders may include neurodevelopmental aberrations (genetic, environmental, or both, which may alter WM structure and/or myelination), neuroinflammation, or oxidative stress (free radicals), which can cause disintegration of the vital myelin sheaths, leading to disruption of brain connectivity.6,7 Researchers now consider the brain’s WM network dysconnectivity as generating a variety of psychiatric symptoms, including psychosis, depression, mania, anxiety, autism, aggression, impulsivity, psychopathy, and cognitive impairments.

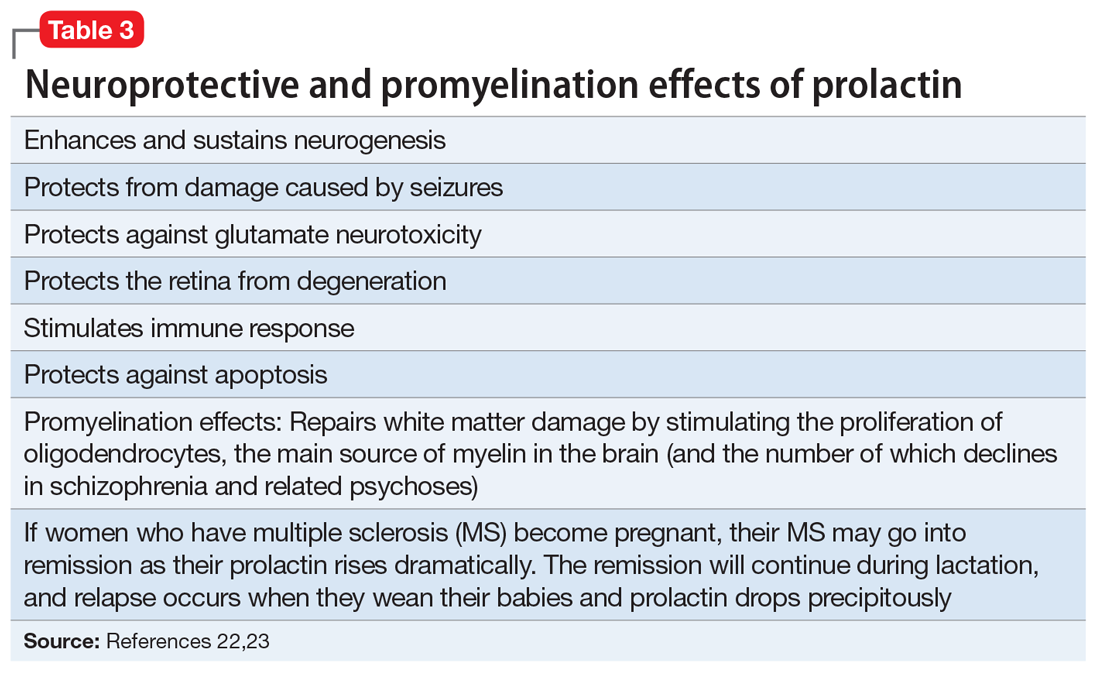

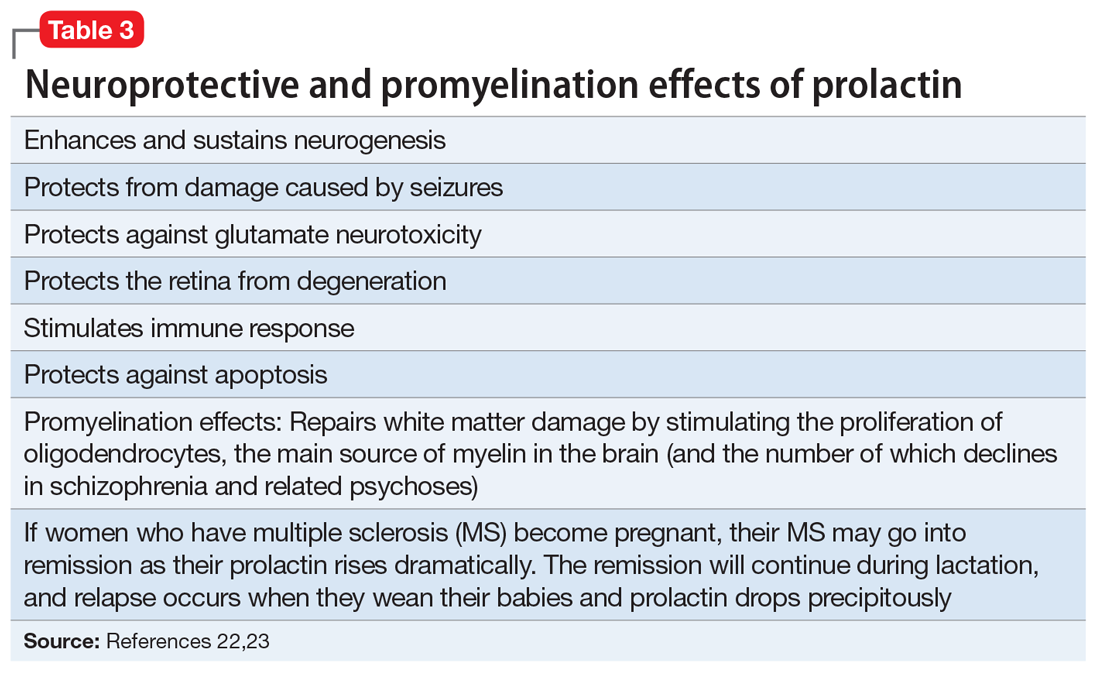

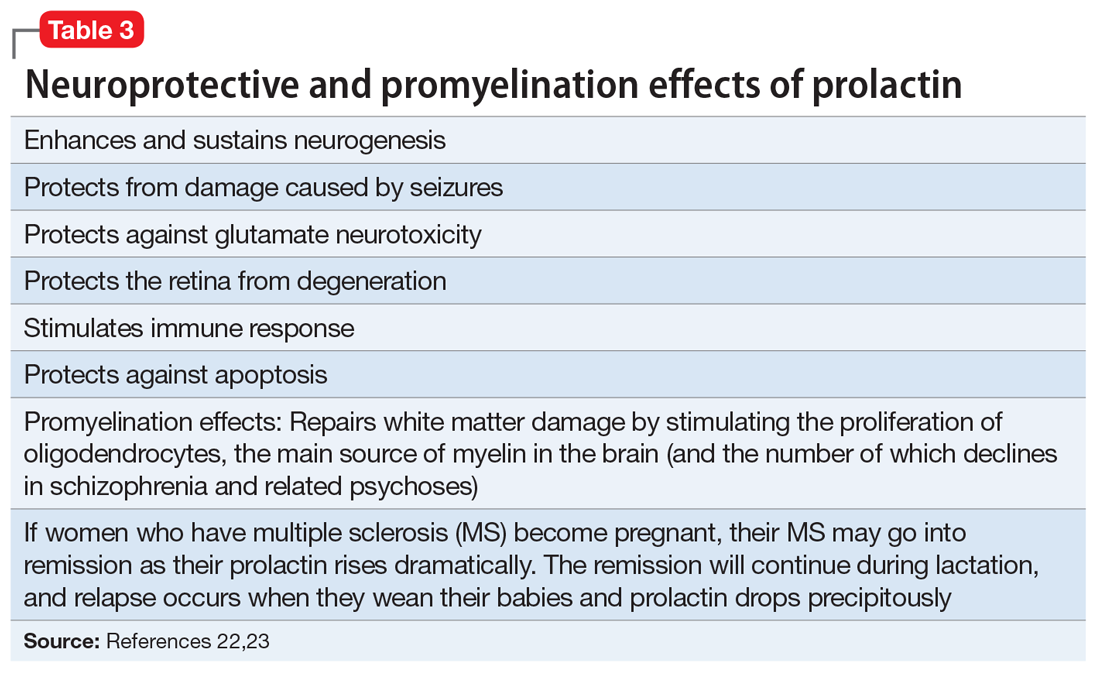

It is not surprising that WM repair has become a therapeutic target in psychiatry and neurology. Among the strategies being investigated are inhibiting the Nogo-A signaling pathways20 or modulating the Lingo-1 signaling.21 However, the most well-established myelin repair pathway is prolactin, a neuroprotective hormone with several beneficial effects on the brain (Table 322,23), including the proliferation of oligodendroglia, the main source of myelin (and the number of which declines in schizophrenia). Antipsychotics that increase prolactin have been shown to increase WM volume.24,25 It has even been proposed that a decline in oligodendrocytes and low myelin synthesis may be one of the neurobiologic pathologies in schizophrenia.26 One of the 24 neuroprotective properties of the second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) is the restoration of WM integrity.27 It’s worth noting that WM pathology has been found to be present at the onset of schizophrenia before treatment, and that SGAs have been reported to correct it.28

Continue to: In conclusion...

In conclusion, psychiatric disorders, usually referred to as “mental illnesses,” are unquestionably neurologic disorders. Similarly, all neurologic disorders are associated with psychiatric manifestations. WM pathology is only 1 of numerous structural brain abnormalities that have been documented across psychiatric disorders, which proves that psychiatry is a clinical neuroscience, just like neurology. I strongly advocate that psychiatry and neurology reunite into a single medical specialty. Both focus on disorders of brain structure and/or function, and these disorders also share much more than WM pathology.29

1. Sagarwala R and Nasrallah HA. White matter pathology is shared across multiple psychiatric brain disorders: Is abnormal diffusivity a transdiagnostic biomarker for psychopathology? Biomarkers in Neuropsychiatry. 2020;2:00010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bionps.2019.100010

2. Pearce JMS; FRCP. The “split brain” and Roger Wolcott Sperry (1913-1994). Rev Neurol (Paris). 2019;175(4):217-220.

3. Nasrallah HA, Andreasen NC, Coffman JA, et al. A controlled magnetic resonance imaging study of corpus callosum thickness in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1986;21(3):274-282.

4. Nasrallah HA, McChesney CM. Psychopathology of corpus callosum tumors. Biol Psychiatry. 1981;16(7):663-669.

5. Nasrallah HA. The unintegrated right cerebral hemispheric consciousness as alien intruder: a possible mechanism for Schneiderian delusions in schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 1985;26(3):273-282.

6. Friston K, Brown HR, Siemerkus J, et al. The dysconnection hypothesis (2016). Schizophr Res. 2016;176(2-3):83-94.

7. Najjar S, Pearlman DM. Neuroinflammation and white matter pathology in schizophrenia: systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2015;161(1):102-112.

8. Benedetti F, Bollettini I. Recent findings on the role of white matter pathology in bipolar disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2014;22(6):338-341.

9. Zheng H, Bergamino M, Ford BN, et al; Tulsa 1000 Investigators. Replicable association between human cytomegalovirus infection and reduced white matter fractional anisotropy in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021;46(5):928-938.

10. Sagarwala R, Nasrallah HA. A systematic review of diffusion tensor imaging studies in drug-naïve OCD patients before and after pharmacotherapy. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2020;32(1):42-47.

11. Lee KS, Lee SH. White matter-based structural brain network of anxiety. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1191:61-70.

12. Swanson MR, Hazlett HC. White matter as a monitoring biomarker for neurodevelopmental disorder intervention studies. J Neurodev Disord. 2019;11(1):33.

13. Hampton WH, Hanik IM, Olson IR. Substance abuse and white matter: findings, limitations, and future of diffusion tensor imaging research. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;197:288-298.

14. Waller R, Dotterer HL, Murray L, et al. White-matter tract abnormalities and antisocial behavior: a systematic review of diffusion tensor imaging studies across development. Neuroimage Clin. 2017;14:201-215.

15. Wolf RC, Pujara MS, Motzkin JC, et al. Interpersonal traits of psychopathy linked to reduced integrity of the uncinate fasciculus. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36(10):4202-4209.

16. Puzzo I, Seunarine K, Sully K, et al. Altered white-matter microstructure in conduct disorder is specifically associated with elevated callous-unemotional traits. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2018;46(7):1451-1466.

17. Finger EC, Marsh A, Blair KS, et al. Impaired functional but preserved structural connectivity in limbic white matter tracts in youth with conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder plus psychopathic traits. Psychiatry Res. 2012;202(3):239-244.

18. Li C, Dong M, Womer FY, et al. Transdiagnostic time-varying dysconnectivity across major psychiatric disorders. Hum Brain Mapp. 2021;42(4):1182-1196.

19. Khanbabaei M, Hughes E, Ellegood J, et al. Precocious myelination in a mouse model of autism. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):251.

20. Petratos S, Theotokis P, Kim MJ, et al. That’s a wrap! Molecular drivers governing neuronal nogo receptor-dependent myelin plasticity and integrity. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020;14:227

21. Fernandez-Enright F, Andrews JL, Newell KA, et al. Novel implications of Lingo-1 and its signaling partners in schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry. 2014;4(1):e348. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.121

22. Bartzokis G, Lu PH, Stewart SB, et al. In vivo evidence of differential impact of typical and atypical antipsychotics on intracortical myelin in adults with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;113(2-3):322-331.

23. Bartzokis G, Lu PH, Amar CP, et al. Long acting injection versus oral risperidone in first-episode schizophrenia: differential impact on white matter myelination trajectory. Schizophr Res. 2011 Oct;132(1):35-41

24. Tishler TA, Bartzokis G, Lu PH, et al. Abnormal trajectory of intracortical myelination in schizophrenia implicates white matter in disease pathophysiology and the therapeutic mechanism of action of antipsychotics. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2018;3(5):454-462.

25. Ren Y, Wang H, Xiao L. Improving myelin/oligodendrocyte-related dysfunction: a new mechanism of antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia? Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16(3):691-700.

26. Dietz AG, Goldman SA, Nedergaard M. Glial cells in schizophrenia: a unified hypothesis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(3):272-281.

27. Chen AT, Nasrallah HA. Neuroprotective effects of the second generation antipsychotics. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:1-7

28. Sagarwala R, Nasrallah HA. (In press.) The effect of antipsychotic medications on white matter integrity in first-episode drug naïve patients with psychosis. Asian Journal of Psychiatry.

29. Nasrallah HA. Let’s tear down the silos and reunify psychiatry and neurology. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(8):9-10.

Ask neurologists or psychiatrists to name a white matter (WM) brain disease and they are very likely to say multiple sclerosis (MS), a demyelinating brain disorder caused by immune-mediated destruction of oligodendrocytes, the glial cells that manufacture myelin without which brain communications would come to a standstill.

MS is often associated with mood or psychotic disorders, yet it is regarded as a neurologic illness, not a psychiatric disorder.

Many neurologists and psychiatrists may not be aware that during the past few years, multiple diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) studies have revealed that many psychiatric disorders are associated with WM pathology.1

Most people think that the brain is composed mostly of neurons, but in fact the bulk of brain volume (60%) is comprised of WM and only 40% is gray matter, which includes both neurons and glial cells (astroglia, microglia, and oligodendroglia). WM includes >137,000 km of myelinated fibers, an extensive network that connects all brain regions and integrates its complex, multifaceted functions, culminating in a unified sense of self and agency.

The role of the corpus callosum

Early in my research career, I became interested in the corpus callosum, the largest interhemispheric WM commissure connecting homologous areas across the 2 cerebral hemispheres. It is comprised of 200 million fibers of various diameters. Reasons for my fascination with the corpus callosum were:

The studies of Roger Sperry, the 1981 Nobel Laureate who led the team that was awarded the prize for split-brain research, which involved patients whose corpus callosum was cut to prevent the transfer of intractable epilepsy from 1 hemisphere to the other. Using a tachistoscope that he designed, Sperry discovered that the right and left hemispheres are 2 independent spheres of consciousness (ie, 2 individuals) with different skills.2 Cerebral dominance (laterality) fully integrates the 2 hemispheres via the corpus callosum, with a verbal hemisphere (the left, in 90% of people) dominating the other hemisphere and serving as the “spokesman self.” Thus, we all have 2 persons in our brain completely integrated into 1 “self.”2 This led me to wonder about the effects of an impaired corpus callosum on the “unified self.”

Postmortem and MRI studies conducted by our research group showed a significant difference in the thickness of the corpus callosum in a group of patients with schizophrenia vs healthy controls, which implied abnormal connectivity across the left and right hemispheres.3

Continue to: I then conducted a clinical study

I then conducted a clinical study examining patients with tumors impinging on the corpus callosum, which revealed that they developed psychotic symptoms (delusions and hallucinations).4 This study suggested that disrupting the integrity of the callosal inter-hemispheric fibers can trigger fixed false beliefs and perceptual anomalies.4

A ‘dysconnection’ between hemispheres

I translated those observations about the corpus callosum into a published hypothesis5 in which I proposed that Schneider’s First-Rank Symptoms of schizophrenia of thought insertion, thought withdrawal, and thought broadcasting—as well as delusional experiences of “external control”—may be due to a neurobiologic abnormality in the corpus callosum that disrupts the flow of ongoing bits of information transmitted from the left to the right hemisphere, and vice versa. I proposed in my model that this disruption leads to the verbal left hemisphere of a psychotic patient to describe having thoughts inserted into it from an alien source, failing to recognize that the thoughts it is receiving are being transmitted from the disconnected right hemisphere, which is no longer part of the “self.” Similarly, impulses from the right hemispheric consciousness are now perceived by the patient’s verbal left hemisphere (which talks to the examining physician) as “external control.” Thus, I postulated that an abnormal corpus callosum structure would lead to a “dysconnection” (not “disconnection”) between the 2 hemispheres, and that anomalous dysconnectivity may generate both delusions and hallucinations. 6

Two decades later, my assumptions were vindicated when DTI was invented, enabling the measurement of WM integrity, including the corpus callosum, the largest body of WM in the brain. Table 1 defines the main parameters of WM integrity, anisotropy and diffusivity, which measure water flow inside WM fibers.

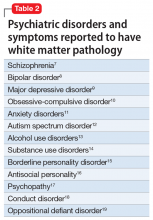

During the past 15 years, many studies have confirmed the presence of significant abnormalities in the myelinated fibers of the corpus callosum in schizophrenia, which can be considered a validation of my hypothesis that the corpus callosum becomes a dysfunctional channel of communications between the right and left hemisphere. Subsequently, DTI studies have reported a spectrum of WM pathologies in various other cerebral bundles and not only in schizophrenia, but also in other major psychiatric disorders (Table 27-19).

The pathophysiology of WM pathology in many psychiatric disorders may include neurodevelopmental aberrations (genetic, environmental, or both, which may alter WM structure and/or myelination), neuroinflammation, or oxidative stress (free radicals), which can cause disintegration of the vital myelin sheaths, leading to disruption of brain connectivity.6,7 Researchers now consider the brain’s WM network dysconnectivity as generating a variety of psychiatric symptoms, including psychosis, depression, mania, anxiety, autism, aggression, impulsivity, psychopathy, and cognitive impairments.

It is not surprising that WM repair has become a therapeutic target in psychiatry and neurology. Among the strategies being investigated are inhibiting the Nogo-A signaling pathways20 or modulating the Lingo-1 signaling.21 However, the most well-established myelin repair pathway is prolactin, a neuroprotective hormone with several beneficial effects on the brain (Table 322,23), including the proliferation of oligodendroglia, the main source of myelin (and the number of which declines in schizophrenia). Antipsychotics that increase prolactin have been shown to increase WM volume.24,25 It has even been proposed that a decline in oligodendrocytes and low myelin synthesis may be one of the neurobiologic pathologies in schizophrenia.26 One of the 24 neuroprotective properties of the second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) is the restoration of WM integrity.27 It’s worth noting that WM pathology has been found to be present at the onset of schizophrenia before treatment, and that SGAs have been reported to correct it.28

Continue to: In conclusion...

In conclusion, psychiatric disorders, usually referred to as “mental illnesses,” are unquestionably neurologic disorders. Similarly, all neurologic disorders are associated with psychiatric manifestations. WM pathology is only 1 of numerous structural brain abnormalities that have been documented across psychiatric disorders, which proves that psychiatry is a clinical neuroscience, just like neurology. I strongly advocate that psychiatry and neurology reunite into a single medical specialty. Both focus on disorders of brain structure and/or function, and these disorders also share much more than WM pathology.29

Ask neurologists or psychiatrists to name a white matter (WM) brain disease and they are very likely to say multiple sclerosis (MS), a demyelinating brain disorder caused by immune-mediated destruction of oligodendrocytes, the glial cells that manufacture myelin without which brain communications would come to a standstill.

MS is often associated with mood or psychotic disorders, yet it is regarded as a neurologic illness, not a psychiatric disorder.

Many neurologists and psychiatrists may not be aware that during the past few years, multiple diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) studies have revealed that many psychiatric disorders are associated with WM pathology.1

Most people think that the brain is composed mostly of neurons, but in fact the bulk of brain volume (60%) is comprised of WM and only 40% is gray matter, which includes both neurons and glial cells (astroglia, microglia, and oligodendroglia). WM includes >137,000 km of myelinated fibers, an extensive network that connects all brain regions and integrates its complex, multifaceted functions, culminating in a unified sense of self and agency.

The role of the corpus callosum

Early in my research career, I became interested in the corpus callosum, the largest interhemispheric WM commissure connecting homologous areas across the 2 cerebral hemispheres. It is comprised of 200 million fibers of various diameters. Reasons for my fascination with the corpus callosum were:

The studies of Roger Sperry, the 1981 Nobel Laureate who led the team that was awarded the prize for split-brain research, which involved patients whose corpus callosum was cut to prevent the transfer of intractable epilepsy from 1 hemisphere to the other. Using a tachistoscope that he designed, Sperry discovered that the right and left hemispheres are 2 independent spheres of consciousness (ie, 2 individuals) with different skills.2 Cerebral dominance (laterality) fully integrates the 2 hemispheres via the corpus callosum, with a verbal hemisphere (the left, in 90% of people) dominating the other hemisphere and serving as the “spokesman self.” Thus, we all have 2 persons in our brain completely integrated into 1 “self.”2 This led me to wonder about the effects of an impaired corpus callosum on the “unified self.”

Postmortem and MRI studies conducted by our research group showed a significant difference in the thickness of the corpus callosum in a group of patients with schizophrenia vs healthy controls, which implied abnormal connectivity across the left and right hemispheres.3

Continue to: I then conducted a clinical study

I then conducted a clinical study examining patients with tumors impinging on the corpus callosum, which revealed that they developed psychotic symptoms (delusions and hallucinations).4 This study suggested that disrupting the integrity of the callosal inter-hemispheric fibers can trigger fixed false beliefs and perceptual anomalies.4

A ‘dysconnection’ between hemispheres

I translated those observations about the corpus callosum into a published hypothesis5 in which I proposed that Schneider’s First-Rank Symptoms of schizophrenia of thought insertion, thought withdrawal, and thought broadcasting—as well as delusional experiences of “external control”—may be due to a neurobiologic abnormality in the corpus callosum that disrupts the flow of ongoing bits of information transmitted from the left to the right hemisphere, and vice versa. I proposed in my model that this disruption leads to the verbal left hemisphere of a psychotic patient to describe having thoughts inserted into it from an alien source, failing to recognize that the thoughts it is receiving are being transmitted from the disconnected right hemisphere, which is no longer part of the “self.” Similarly, impulses from the right hemispheric consciousness are now perceived by the patient’s verbal left hemisphere (which talks to the examining physician) as “external control.” Thus, I postulated that an abnormal corpus callosum structure would lead to a “dysconnection” (not “disconnection”) between the 2 hemispheres, and that anomalous dysconnectivity may generate both delusions and hallucinations. 6

Two decades later, my assumptions were vindicated when DTI was invented, enabling the measurement of WM integrity, including the corpus callosum, the largest body of WM in the brain. Table 1 defines the main parameters of WM integrity, anisotropy and diffusivity, which measure water flow inside WM fibers.

During the past 15 years, many studies have confirmed the presence of significant abnormalities in the myelinated fibers of the corpus callosum in schizophrenia, which can be considered a validation of my hypothesis that the corpus callosum becomes a dysfunctional channel of communications between the right and left hemisphere. Subsequently, DTI studies have reported a spectrum of WM pathologies in various other cerebral bundles and not only in schizophrenia, but also in other major psychiatric disorders (Table 27-19).

The pathophysiology of WM pathology in many psychiatric disorders may include neurodevelopmental aberrations (genetic, environmental, or both, which may alter WM structure and/or myelination), neuroinflammation, or oxidative stress (free radicals), which can cause disintegration of the vital myelin sheaths, leading to disruption of brain connectivity.6,7 Researchers now consider the brain’s WM network dysconnectivity as generating a variety of psychiatric symptoms, including psychosis, depression, mania, anxiety, autism, aggression, impulsivity, psychopathy, and cognitive impairments.

It is not surprising that WM repair has become a therapeutic target in psychiatry and neurology. Among the strategies being investigated are inhibiting the Nogo-A signaling pathways20 or modulating the Lingo-1 signaling.21 However, the most well-established myelin repair pathway is prolactin, a neuroprotective hormone with several beneficial effects on the brain (Table 322,23), including the proliferation of oligodendroglia, the main source of myelin (and the number of which declines in schizophrenia). Antipsychotics that increase prolactin have been shown to increase WM volume.24,25 It has even been proposed that a decline in oligodendrocytes and low myelin synthesis may be one of the neurobiologic pathologies in schizophrenia.26 One of the 24 neuroprotective properties of the second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) is the restoration of WM integrity.27 It’s worth noting that WM pathology has been found to be present at the onset of schizophrenia before treatment, and that SGAs have been reported to correct it.28

Continue to: In conclusion...

In conclusion, psychiatric disorders, usually referred to as “mental illnesses,” are unquestionably neurologic disorders. Similarly, all neurologic disorders are associated with psychiatric manifestations. WM pathology is only 1 of numerous structural brain abnormalities that have been documented across psychiatric disorders, which proves that psychiatry is a clinical neuroscience, just like neurology. I strongly advocate that psychiatry and neurology reunite into a single medical specialty. Both focus on disorders of brain structure and/or function, and these disorders also share much more than WM pathology.29

1. Sagarwala R and Nasrallah HA. White matter pathology is shared across multiple psychiatric brain disorders: Is abnormal diffusivity a transdiagnostic biomarker for psychopathology? Biomarkers in Neuropsychiatry. 2020;2:00010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bionps.2019.100010

2. Pearce JMS; FRCP. The “split brain” and Roger Wolcott Sperry (1913-1994). Rev Neurol (Paris). 2019;175(4):217-220.

3. Nasrallah HA, Andreasen NC, Coffman JA, et al. A controlled magnetic resonance imaging study of corpus callosum thickness in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1986;21(3):274-282.

4. Nasrallah HA, McChesney CM. Psychopathology of corpus callosum tumors. Biol Psychiatry. 1981;16(7):663-669.

5. Nasrallah HA. The unintegrated right cerebral hemispheric consciousness as alien intruder: a possible mechanism for Schneiderian delusions in schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 1985;26(3):273-282.

6. Friston K, Brown HR, Siemerkus J, et al. The dysconnection hypothesis (2016). Schizophr Res. 2016;176(2-3):83-94.

7. Najjar S, Pearlman DM. Neuroinflammation and white matter pathology in schizophrenia: systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2015;161(1):102-112.

8. Benedetti F, Bollettini I. Recent findings on the role of white matter pathology in bipolar disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2014;22(6):338-341.

9. Zheng H, Bergamino M, Ford BN, et al; Tulsa 1000 Investigators. Replicable association between human cytomegalovirus infection and reduced white matter fractional anisotropy in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021;46(5):928-938.

10. Sagarwala R, Nasrallah HA. A systematic review of diffusion tensor imaging studies in drug-naïve OCD patients before and after pharmacotherapy. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2020;32(1):42-47.

11. Lee KS, Lee SH. White matter-based structural brain network of anxiety. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1191:61-70.

12. Swanson MR, Hazlett HC. White matter as a monitoring biomarker for neurodevelopmental disorder intervention studies. J Neurodev Disord. 2019;11(1):33.

13. Hampton WH, Hanik IM, Olson IR. Substance abuse and white matter: findings, limitations, and future of diffusion tensor imaging research. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;197:288-298.

14. Waller R, Dotterer HL, Murray L, et al. White-matter tract abnormalities and antisocial behavior: a systematic review of diffusion tensor imaging studies across development. Neuroimage Clin. 2017;14:201-215.

15. Wolf RC, Pujara MS, Motzkin JC, et al. Interpersonal traits of psychopathy linked to reduced integrity of the uncinate fasciculus. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36(10):4202-4209.

16. Puzzo I, Seunarine K, Sully K, et al. Altered white-matter microstructure in conduct disorder is specifically associated with elevated callous-unemotional traits. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2018;46(7):1451-1466.

17. Finger EC, Marsh A, Blair KS, et al. Impaired functional but preserved structural connectivity in limbic white matter tracts in youth with conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder plus psychopathic traits. Psychiatry Res. 2012;202(3):239-244.

18. Li C, Dong M, Womer FY, et al. Transdiagnostic time-varying dysconnectivity across major psychiatric disorders. Hum Brain Mapp. 2021;42(4):1182-1196.

19. Khanbabaei M, Hughes E, Ellegood J, et al. Precocious myelination in a mouse model of autism. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):251.

20. Petratos S, Theotokis P, Kim MJ, et al. That’s a wrap! Molecular drivers governing neuronal nogo receptor-dependent myelin plasticity and integrity. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020;14:227

21. Fernandez-Enright F, Andrews JL, Newell KA, et al. Novel implications of Lingo-1 and its signaling partners in schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry. 2014;4(1):e348. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.121

22. Bartzokis G, Lu PH, Stewart SB, et al. In vivo evidence of differential impact of typical and atypical antipsychotics on intracortical myelin in adults with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;113(2-3):322-331.

23. Bartzokis G, Lu PH, Amar CP, et al. Long acting injection versus oral risperidone in first-episode schizophrenia: differential impact on white matter myelination trajectory. Schizophr Res. 2011 Oct;132(1):35-41

24. Tishler TA, Bartzokis G, Lu PH, et al. Abnormal trajectory of intracortical myelination in schizophrenia implicates white matter in disease pathophysiology and the therapeutic mechanism of action of antipsychotics. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2018;3(5):454-462.

25. Ren Y, Wang H, Xiao L. Improving myelin/oligodendrocyte-related dysfunction: a new mechanism of antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia? Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16(3):691-700.

26. Dietz AG, Goldman SA, Nedergaard M. Glial cells in schizophrenia: a unified hypothesis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(3):272-281.

27. Chen AT, Nasrallah HA. Neuroprotective effects of the second generation antipsychotics. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:1-7

28. Sagarwala R, Nasrallah HA. (In press.) The effect of antipsychotic medications on white matter integrity in first-episode drug naïve patients with psychosis. Asian Journal of Psychiatry.

29. Nasrallah HA. Let’s tear down the silos and reunify psychiatry and neurology. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(8):9-10.

1. Sagarwala R and Nasrallah HA. White matter pathology is shared across multiple psychiatric brain disorders: Is abnormal diffusivity a transdiagnostic biomarker for psychopathology? Biomarkers in Neuropsychiatry. 2020;2:00010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bionps.2019.100010

2. Pearce JMS; FRCP. The “split brain” and Roger Wolcott Sperry (1913-1994). Rev Neurol (Paris). 2019;175(4):217-220.

3. Nasrallah HA, Andreasen NC, Coffman JA, et al. A controlled magnetic resonance imaging study of corpus callosum thickness in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1986;21(3):274-282.

4. Nasrallah HA, McChesney CM. Psychopathology of corpus callosum tumors. Biol Psychiatry. 1981;16(7):663-669.

5. Nasrallah HA. The unintegrated right cerebral hemispheric consciousness as alien intruder: a possible mechanism for Schneiderian delusions in schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 1985;26(3):273-282.

6. Friston K, Brown HR, Siemerkus J, et al. The dysconnection hypothesis (2016). Schizophr Res. 2016;176(2-3):83-94.

7. Najjar S, Pearlman DM. Neuroinflammation and white matter pathology in schizophrenia: systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2015;161(1):102-112.

8. Benedetti F, Bollettini I. Recent findings on the role of white matter pathology in bipolar disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2014;22(6):338-341.

9. Zheng H, Bergamino M, Ford BN, et al; Tulsa 1000 Investigators. Replicable association between human cytomegalovirus infection and reduced white matter fractional anisotropy in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021;46(5):928-938.

10. Sagarwala R, Nasrallah HA. A systematic review of diffusion tensor imaging studies in drug-naïve OCD patients before and after pharmacotherapy. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2020;32(1):42-47.

11. Lee KS, Lee SH. White matter-based structural brain network of anxiety. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1191:61-70.

12. Swanson MR, Hazlett HC. White matter as a monitoring biomarker for neurodevelopmental disorder intervention studies. J Neurodev Disord. 2019;11(1):33.

13. Hampton WH, Hanik IM, Olson IR. Substance abuse and white matter: findings, limitations, and future of diffusion tensor imaging research. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;197:288-298.

14. Waller R, Dotterer HL, Murray L, et al. White-matter tract abnormalities and antisocial behavior: a systematic review of diffusion tensor imaging studies across development. Neuroimage Clin. 2017;14:201-215.

15. Wolf RC, Pujara MS, Motzkin JC, et al. Interpersonal traits of psychopathy linked to reduced integrity of the uncinate fasciculus. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36(10):4202-4209.

16. Puzzo I, Seunarine K, Sully K, et al. Altered white-matter microstructure in conduct disorder is specifically associated with elevated callous-unemotional traits. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2018;46(7):1451-1466.

17. Finger EC, Marsh A, Blair KS, et al. Impaired functional but preserved structural connectivity in limbic white matter tracts in youth with conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder plus psychopathic traits. Psychiatry Res. 2012;202(3):239-244.

18. Li C, Dong M, Womer FY, et al. Transdiagnostic time-varying dysconnectivity across major psychiatric disorders. Hum Brain Mapp. 2021;42(4):1182-1196.

19. Khanbabaei M, Hughes E, Ellegood J, et al. Precocious myelination in a mouse model of autism. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):251.

20. Petratos S, Theotokis P, Kim MJ, et al. That’s a wrap! Molecular drivers governing neuronal nogo receptor-dependent myelin plasticity and integrity. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020;14:227

21. Fernandez-Enright F, Andrews JL, Newell KA, et al. Novel implications of Lingo-1 and its signaling partners in schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry. 2014;4(1):e348. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.121

22. Bartzokis G, Lu PH, Stewart SB, et al. In vivo evidence of differential impact of typical and atypical antipsychotics on intracortical myelin in adults with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;113(2-3):322-331.

23. Bartzokis G, Lu PH, Amar CP, et al. Long acting injection versus oral risperidone in first-episode schizophrenia: differential impact on white matter myelination trajectory. Schizophr Res. 2011 Oct;132(1):35-41

24. Tishler TA, Bartzokis G, Lu PH, et al. Abnormal trajectory of intracortical myelination in schizophrenia implicates white matter in disease pathophysiology and the therapeutic mechanism of action of antipsychotics. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2018;3(5):454-462.

25. Ren Y, Wang H, Xiao L. Improving myelin/oligodendrocyte-related dysfunction: a new mechanism of antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia? Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16(3):691-700.

26. Dietz AG, Goldman SA, Nedergaard M. Glial cells in schizophrenia: a unified hypothesis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(3):272-281.

27. Chen AT, Nasrallah HA. Neuroprotective effects of the second generation antipsychotics. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:1-7

28. Sagarwala R, Nasrallah HA. (In press.) The effect of antipsychotic medications on white matter integrity in first-episode drug naïve patients with psychosis. Asian Journal of Psychiatry.

29. Nasrallah HA. Let’s tear down the silos and reunify psychiatry and neurology. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(8):9-10.

How to help vaccinated patients navigate FOGO (fear of going out)

Remember FOMO (fear of missing out)? The pandemic cured most of us of that! In its place, many are suffering from a new syndrome that has been coined “FOGO” (fear of going out). As the COVID-19 vaccines roll out, restrictions lessen, and cases decline, we face new challenges. The pandemic showed us that “we are all in it together.” Now our patients, family, friends – and even we, ourselves – may face similar anxieties as we transition back.

Our brains love routines. They save energy as we transverse the same pathway with ease. We created new patterns in the first 30 days of quarantine, and we spent more than a year engraining them. Many people are feeling even more anxiety as restrictions are lifting and expectations are rising. Those with preexisting anxiety disorders may have an even more difficult time resuming routine activities.

Since the virus is still among us, we need to maintain caution, so some degree of FOGO is wise. But when we limit our activities too much, we create a whole new host of issues. The pandemic gave us all a taste of the agoraphobic lifestyle. It is difficult to know where exactly to draw the line right now between healthy anxiety and anxiety that becomes the disease for ourselves, our families and friends – and our patients.

Recommendations for FOGO

- Talk to your families, friends, and patients about what activities you recommend, which they might resume and which they should continue to avoid. People should make plans to optimize their physical and mental health while continuing to protect themselves from COVID-19. If anxiety is becoming the main problem, psychotherapy or medication may be necessary to treat their symptoms.

- Continue to encourage those with FOGO to practice techniques to be calm. Suggest that they take deep breaths with long exhales. This breathing pattern activates the parasympathetic nervous system and will help them feel calmer. We have all been under chronic stress, and our sympathetic nervous system has been in overdrive. We need to be calm to make the best decisions so our frontal lobe can be in charge rather than our primitive, fear-based brain that has been running the show for more a year. Encourage calming activities, such as yoga, meditation, warm baths, spending time in nature, hugging a pet, and more.

- Advise sufferers to start slowly. They should resume activities where they feel the safest. Walking outside with a friend is a good way to start. We now know that transmission is remarkably low or nonexistent if both parties are vaccinated. Exercise is a great way to combat many psychological issues, including FOGO.

- FOGO sufferers should build confidence gradually. Recommend taking one day at a time and trying to find ways to enjoy new ventures out. Soon, our brains will adapt to the new routines and the days of COVID-19 will recede from our thoughts.

- Respect whatever feelings emerge. The closer we and our patients were to trauma, the more challenging it may be to recover. If you or your patients suffered from COVID-19 or had a close family member or friend who did, be prepared to reemerge more slowly. Don’t feel pressured by what others are doing. Go at your own pace. Only you can decide what is the right way to move forward in these times.

- Look for signs of substance overuse or misuse. FOGO sufferers may turn to drugs or alcohol to mask their anxiety. This is a common pothole and should be avoided. Be alert for this problem and discuss it with patients, friends, or family members who may be making unhealthy choices.

Time is a great healer, and remind others that “this too shall pass.” FOGO will give rise to another yet-to-be named syndrome. We seem to be moving in a very positive direction at a remarkable pace. As Alexander Pope so wisely wrote, “Hope springs eternal.” Better times are ahead.

Dr. Ritvo, who has almost 30 years’ experience in psychiatry, practices in Miami Beach, Fla. She is the author of “Bekindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa. Momosa Publishing, 2018). Dr. Ritvo has no disclosures.

Remember FOMO (fear of missing out)? The pandemic cured most of us of that! In its place, many are suffering from a new syndrome that has been coined “FOGO” (fear of going out). As the COVID-19 vaccines roll out, restrictions lessen, and cases decline, we face new challenges. The pandemic showed us that “we are all in it together.” Now our patients, family, friends – and even we, ourselves – may face similar anxieties as we transition back.

Our brains love routines. They save energy as we transverse the same pathway with ease. We created new patterns in the first 30 days of quarantine, and we spent more than a year engraining them. Many people are feeling even more anxiety as restrictions are lifting and expectations are rising. Those with preexisting anxiety disorders may have an even more difficult time resuming routine activities.

Since the virus is still among us, we need to maintain caution, so some degree of FOGO is wise. But when we limit our activities too much, we create a whole new host of issues. The pandemic gave us all a taste of the agoraphobic lifestyle. It is difficult to know where exactly to draw the line right now between healthy anxiety and anxiety that becomes the disease for ourselves, our families and friends – and our patients.

Recommendations for FOGO

- Talk to your families, friends, and patients about what activities you recommend, which they might resume and which they should continue to avoid. People should make plans to optimize their physical and mental health while continuing to protect themselves from COVID-19. If anxiety is becoming the main problem, psychotherapy or medication may be necessary to treat their symptoms.

- Continue to encourage those with FOGO to practice techniques to be calm. Suggest that they take deep breaths with long exhales. This breathing pattern activates the parasympathetic nervous system and will help them feel calmer. We have all been under chronic stress, and our sympathetic nervous system has been in overdrive. We need to be calm to make the best decisions so our frontal lobe can be in charge rather than our primitive, fear-based brain that has been running the show for more a year. Encourage calming activities, such as yoga, meditation, warm baths, spending time in nature, hugging a pet, and more.

- Advise sufferers to start slowly. They should resume activities where they feel the safest. Walking outside with a friend is a good way to start. We now know that transmission is remarkably low or nonexistent if both parties are vaccinated. Exercise is a great way to combat many psychological issues, including FOGO.

- FOGO sufferers should build confidence gradually. Recommend taking one day at a time and trying to find ways to enjoy new ventures out. Soon, our brains will adapt to the new routines and the days of COVID-19 will recede from our thoughts.

- Respect whatever feelings emerge. The closer we and our patients were to trauma, the more challenging it may be to recover. If you or your patients suffered from COVID-19 or had a close family member or friend who did, be prepared to reemerge more slowly. Don’t feel pressured by what others are doing. Go at your own pace. Only you can decide what is the right way to move forward in these times.

- Look for signs of substance overuse or misuse. FOGO sufferers may turn to drugs or alcohol to mask their anxiety. This is a common pothole and should be avoided. Be alert for this problem and discuss it with patients, friends, or family members who may be making unhealthy choices.

Time is a great healer, and remind others that “this too shall pass.” FOGO will give rise to another yet-to-be named syndrome. We seem to be moving in a very positive direction at a remarkable pace. As Alexander Pope so wisely wrote, “Hope springs eternal.” Better times are ahead.

Dr. Ritvo, who has almost 30 years’ experience in psychiatry, practices in Miami Beach, Fla. She is the author of “Bekindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa. Momosa Publishing, 2018). Dr. Ritvo has no disclosures.

Remember FOMO (fear of missing out)? The pandemic cured most of us of that! In its place, many are suffering from a new syndrome that has been coined “FOGO” (fear of going out). As the COVID-19 vaccines roll out, restrictions lessen, and cases decline, we face new challenges. The pandemic showed us that “we are all in it together.” Now our patients, family, friends – and even we, ourselves – may face similar anxieties as we transition back.

Our brains love routines. They save energy as we transverse the same pathway with ease. We created new patterns in the first 30 days of quarantine, and we spent more than a year engraining them. Many people are feeling even more anxiety as restrictions are lifting and expectations are rising. Those with preexisting anxiety disorders may have an even more difficult time resuming routine activities.

Since the virus is still among us, we need to maintain caution, so some degree of FOGO is wise. But when we limit our activities too much, we create a whole new host of issues. The pandemic gave us all a taste of the agoraphobic lifestyle. It is difficult to know where exactly to draw the line right now between healthy anxiety and anxiety that becomes the disease for ourselves, our families and friends – and our patients.

Recommendations for FOGO

- Talk to your families, friends, and patients about what activities you recommend, which they might resume and which they should continue to avoid. People should make plans to optimize their physical and mental health while continuing to protect themselves from COVID-19. If anxiety is becoming the main problem, psychotherapy or medication may be necessary to treat their symptoms.

- Continue to encourage those with FOGO to practice techniques to be calm. Suggest that they take deep breaths with long exhales. This breathing pattern activates the parasympathetic nervous system and will help them feel calmer. We have all been under chronic stress, and our sympathetic nervous system has been in overdrive. We need to be calm to make the best decisions so our frontal lobe can be in charge rather than our primitive, fear-based brain that has been running the show for more a year. Encourage calming activities, such as yoga, meditation, warm baths, spending time in nature, hugging a pet, and more.

- Advise sufferers to start slowly. They should resume activities where they feel the safest. Walking outside with a friend is a good way to start. We now know that transmission is remarkably low or nonexistent if both parties are vaccinated. Exercise is a great way to combat many psychological issues, including FOGO.

- FOGO sufferers should build confidence gradually. Recommend taking one day at a time and trying to find ways to enjoy new ventures out. Soon, our brains will adapt to the new routines and the days of COVID-19 will recede from our thoughts.

- Respect whatever feelings emerge. The closer we and our patients were to trauma, the more challenging it may be to recover. If you or your patients suffered from COVID-19 or had a close family member or friend who did, be prepared to reemerge more slowly. Don’t feel pressured by what others are doing. Go at your own pace. Only you can decide what is the right way to move forward in these times.

- Look for signs of substance overuse or misuse. FOGO sufferers may turn to drugs or alcohol to mask their anxiety. This is a common pothole and should be avoided. Be alert for this problem and discuss it with patients, friends, or family members who may be making unhealthy choices.

Time is a great healer, and remind others that “this too shall pass.” FOGO will give rise to another yet-to-be named syndrome. We seem to be moving in a very positive direction at a remarkable pace. As Alexander Pope so wisely wrote, “Hope springs eternal.” Better times are ahead.

Dr. Ritvo, who has almost 30 years’ experience in psychiatry, practices in Miami Beach, Fla. She is the author of “Bekindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa. Momosa Publishing, 2018). Dr. Ritvo has no disclosures.

The end of happy hour? No safe level of alcohol for the brain

There is no safe amount of alcohol consumption for the brain; even moderate drinking adversely affects brain structure and function, according a British study of more 25,000 adults.

“This is one of the largest studies of alcohol and brain health to date,” Anya Topiwala, DPhil, University of Oxford (England), told this news organization.

“There have been previous claims the relationship between alcohol and brain health are J-shaped (ie., small amounts are protective), but we formally tested this and did not find it to be the case. In fact, we found that any level of alcohol was associated with poorer brain health, compared to no alcohol,” Dr. Topiwala added.

The study, which has not yet been peer reviewed, was published online May 12 in MedRxiv.

Global impact on the brain

Participants provided detailed information on their alcohol intake. The cohort included 691 never-drinkers, 617 former drinkers, and 24,069 current drinkers.

Median alcohol intake was 13.5 units (102 g) weekly. Almost half of the sample (48.2%) were drinking above current UK low-risk guidelines (14 units, 112 g weekly), but few were heavy drinkers (>50 units, 400 g weekly).

After adjusting for all known potential confounders and multiple comparisons, a higher volume of alcohol consumed per week was associated with lower gray matter in “almost all areas of the brain,” Dr. Topiwala said in an interview.

Alcohol consumption accounted for up to 0.8% of gray matter volume variance. “The size of the effect is small, albeit greater than any other modifiable risk factor. These brain changes have been previously linked to aging, poorer performance on memory changes, and dementia,” Dr. Topiwala said.

Widespread negative associations were also found between drinking alcohol and all the measures of white matter integrity that were assessed. There was a significant positive association between alcohol consumption and resting-state functional connectivity.

Higher blood pressure and body mass index “steepened” the negative associations between alcohol and brain health, and binge drinking had additive negative effects on brain structure beyond the absolute volume consumed.

There was no evidence that the risk for alcohol-related brain harm differs according to the type of alcohol consumed (wine, beer, or spirits).

A key limitation of the study is that the study population from the UK Biobank represents a sample that is healthier, better educated, and less deprived and is characterized by less ethnic diversity than the general population. “As with any observational study, we cannot infer causality from association,” the authors note.

What remains unclear, they say, is the duration of drinking needed to cause an effect on the brain. It may be that vulnerability is increased during periods of life in which dynamic brain changes occur, such as adolescence and older age.

They also note that some studies of alcohol-dependent individuals have suggested that at least some brain damage is reversible upon abstinence. Whether that is true for moderate drinkers is unknown.

On the basis of their findings, there is “no safe dose of alcohol for the brain,” Dr. Topiwala and colleagues conclude. They suggest that current low-risk drinking guidelines be revisited to take account of brain effects.

Experts weigh in

Several experts weighed in on the study in a statement from the nonprofit UK Science Media Center.

Paul Matthews, MD, head of the department of brain sciences, Imperial College London, noted that this “carefully performed preliminary report extends our earlier UK Dementia Research Institute study of a smaller group from same UK Biobank population also showing that even moderate drinking is associated with greater atrophy of the brain, as well as injury to the heart and liver.”

Dr. Matthews said the investigators’ conclusion that there is no safe threshold below which alcohol consumption has no toxic effects “echoes our own. We join with them in suggesting that current public health guidelines concerning alcohol consumption may need to be revisited.”

Rebecca Dewey, PhD, research fellow in neuroimaging, University of Nottingham (England), cautioned that “the degree to which very small changes in brain volume are harmful” is unknown.

“While there was no threshold under which alcohol consumption did not cause changes in the brain, there may a degree of brain volume difference that is irrelevant to brain health. We don’t know what these people’s brains looked like before they drank alcohol, so the brain may have learned to cope/compensate,” Dewey said.

Sadie Boniface, PhD, head of research at the Institute of Alcohol Studies and visiting researcher at King’s College London, said, “While we can’t yet say for sure whether there is ‘no safe level’ of alcohol regarding brain health at the moment, it has been known for decades that heavy drinking is bad for brain health.

“We also shouldn’t forget alcohol affects all parts of the body and there are multiple health risks. For example, it is already known there is ‘no safe level’ of alcohol consumption for the seven types of cancer caused by alcohol, as identified by the UK chief medical officers,” Dr. Boniface said.

The study was supported in part by the Wellcome Trust, Li Ka Shing Center for Health Information and Discovery, the National Institutes of Health, and the UK Medical Research Council. Dr. Topiwala, Dr. Boniface, Dr. Dewey, and Dr. Matthews have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There is no safe amount of alcohol consumption for the brain; even moderate drinking adversely affects brain structure and function, according a British study of more 25,000 adults.

“This is one of the largest studies of alcohol and brain health to date,” Anya Topiwala, DPhil, University of Oxford (England), told this news organization.

“There have been previous claims the relationship between alcohol and brain health are J-shaped (ie., small amounts are protective), but we formally tested this and did not find it to be the case. In fact, we found that any level of alcohol was associated with poorer brain health, compared to no alcohol,” Dr. Topiwala added.

The study, which has not yet been peer reviewed, was published online May 12 in MedRxiv.

Global impact on the brain

Participants provided detailed information on their alcohol intake. The cohort included 691 never-drinkers, 617 former drinkers, and 24,069 current drinkers.

Median alcohol intake was 13.5 units (102 g) weekly. Almost half of the sample (48.2%) were drinking above current UK low-risk guidelines (14 units, 112 g weekly), but few were heavy drinkers (>50 units, 400 g weekly).

After adjusting for all known potential confounders and multiple comparisons, a higher volume of alcohol consumed per week was associated with lower gray matter in “almost all areas of the brain,” Dr. Topiwala said in an interview.

Alcohol consumption accounted for up to 0.8% of gray matter volume variance. “The size of the effect is small, albeit greater than any other modifiable risk factor. These brain changes have been previously linked to aging, poorer performance on memory changes, and dementia,” Dr. Topiwala said.

Widespread negative associations were also found between drinking alcohol and all the measures of white matter integrity that were assessed. There was a significant positive association between alcohol consumption and resting-state functional connectivity.

Higher blood pressure and body mass index “steepened” the negative associations between alcohol and brain health, and binge drinking had additive negative effects on brain structure beyond the absolute volume consumed.

There was no evidence that the risk for alcohol-related brain harm differs according to the type of alcohol consumed (wine, beer, or spirits).

A key limitation of the study is that the study population from the UK Biobank represents a sample that is healthier, better educated, and less deprived and is characterized by less ethnic diversity than the general population. “As with any observational study, we cannot infer causality from association,” the authors note.

What remains unclear, they say, is the duration of drinking needed to cause an effect on the brain. It may be that vulnerability is increased during periods of life in which dynamic brain changes occur, such as adolescence and older age.

They also note that some studies of alcohol-dependent individuals have suggested that at least some brain damage is reversible upon abstinence. Whether that is true for moderate drinkers is unknown.

On the basis of their findings, there is “no safe dose of alcohol for the brain,” Dr. Topiwala and colleagues conclude. They suggest that current low-risk drinking guidelines be revisited to take account of brain effects.

Experts weigh in

Several experts weighed in on the study in a statement from the nonprofit UK Science Media Center.

Paul Matthews, MD, head of the department of brain sciences, Imperial College London, noted that this “carefully performed preliminary report extends our earlier UK Dementia Research Institute study of a smaller group from same UK Biobank population also showing that even moderate drinking is associated with greater atrophy of the brain, as well as injury to the heart and liver.”

Dr. Matthews said the investigators’ conclusion that there is no safe threshold below which alcohol consumption has no toxic effects “echoes our own. We join with them in suggesting that current public health guidelines concerning alcohol consumption may need to be revisited.”

Rebecca Dewey, PhD, research fellow in neuroimaging, University of Nottingham (England), cautioned that “the degree to which very small changes in brain volume are harmful” is unknown.

“While there was no threshold under which alcohol consumption did not cause changes in the brain, there may a degree of brain volume difference that is irrelevant to brain health. We don’t know what these people’s brains looked like before they drank alcohol, so the brain may have learned to cope/compensate,” Dewey said.

Sadie Boniface, PhD, head of research at the Institute of Alcohol Studies and visiting researcher at King’s College London, said, “While we can’t yet say for sure whether there is ‘no safe level’ of alcohol regarding brain health at the moment, it has been known for decades that heavy drinking is bad for brain health.

“We also shouldn’t forget alcohol affects all parts of the body and there are multiple health risks. For example, it is already known there is ‘no safe level’ of alcohol consumption for the seven types of cancer caused by alcohol, as identified by the UK chief medical officers,” Dr. Boniface said.

The study was supported in part by the Wellcome Trust, Li Ka Shing Center for Health Information and Discovery, the National Institutes of Health, and the UK Medical Research Council. Dr. Topiwala, Dr. Boniface, Dr. Dewey, and Dr. Matthews have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There is no safe amount of alcohol consumption for the brain; even moderate drinking adversely affects brain structure and function, according a British study of more 25,000 adults.

“This is one of the largest studies of alcohol and brain health to date,” Anya Topiwala, DPhil, University of Oxford (England), told this news organization.

“There have been previous claims the relationship between alcohol and brain health are J-shaped (ie., small amounts are protective), but we formally tested this and did not find it to be the case. In fact, we found that any level of alcohol was associated with poorer brain health, compared to no alcohol,” Dr. Topiwala added.

The study, which has not yet been peer reviewed, was published online May 12 in MedRxiv.

Global impact on the brain

Participants provided detailed information on their alcohol intake. The cohort included 691 never-drinkers, 617 former drinkers, and 24,069 current drinkers.

Median alcohol intake was 13.5 units (102 g) weekly. Almost half of the sample (48.2%) were drinking above current UK low-risk guidelines (14 units, 112 g weekly), but few were heavy drinkers (>50 units, 400 g weekly).

After adjusting for all known potential confounders and multiple comparisons, a higher volume of alcohol consumed per week was associated with lower gray matter in “almost all areas of the brain,” Dr. Topiwala said in an interview.

Alcohol consumption accounted for up to 0.8% of gray matter volume variance. “The size of the effect is small, albeit greater than any other modifiable risk factor. These brain changes have been previously linked to aging, poorer performance on memory changes, and dementia,” Dr. Topiwala said.

Widespread negative associations were also found between drinking alcohol and all the measures of white matter integrity that were assessed. There was a significant positive association between alcohol consumption and resting-state functional connectivity.

Higher blood pressure and body mass index “steepened” the negative associations between alcohol and brain health, and binge drinking had additive negative effects on brain structure beyond the absolute volume consumed.

There was no evidence that the risk for alcohol-related brain harm differs according to the type of alcohol consumed (wine, beer, or spirits).

A key limitation of the study is that the study population from the UK Biobank represents a sample that is healthier, better educated, and less deprived and is characterized by less ethnic diversity than the general population. “As with any observational study, we cannot infer causality from association,” the authors note.

What remains unclear, they say, is the duration of drinking needed to cause an effect on the brain. It may be that vulnerability is increased during periods of life in which dynamic brain changes occur, such as adolescence and older age.

They also note that some studies of alcohol-dependent individuals have suggested that at least some brain damage is reversible upon abstinence. Whether that is true for moderate drinkers is unknown.

On the basis of their findings, there is “no safe dose of alcohol for the brain,” Dr. Topiwala and colleagues conclude. They suggest that current low-risk drinking guidelines be revisited to take account of brain effects.

Experts weigh in

Several experts weighed in on the study in a statement from the nonprofit UK Science Media Center.

Paul Matthews, MD, head of the department of brain sciences, Imperial College London, noted that this “carefully performed preliminary report extends our earlier UK Dementia Research Institute study of a smaller group from same UK Biobank population also showing that even moderate drinking is associated with greater atrophy of the brain, as well as injury to the heart and liver.”

Dr. Matthews said the investigators’ conclusion that there is no safe threshold below which alcohol consumption has no toxic effects “echoes our own. We join with them in suggesting that current public health guidelines concerning alcohol consumption may need to be revisited.”

Rebecca Dewey, PhD, research fellow in neuroimaging, University of Nottingham (England), cautioned that “the degree to which very small changes in brain volume are harmful” is unknown.

“While there was no threshold under which alcohol consumption did not cause changes in the brain, there may a degree of brain volume difference that is irrelevant to brain health. We don’t know what these people’s brains looked like before they drank alcohol, so the brain may have learned to cope/compensate,” Dewey said.

Sadie Boniface, PhD, head of research at the Institute of Alcohol Studies and visiting researcher at King’s College London, said, “While we can’t yet say for sure whether there is ‘no safe level’ of alcohol regarding brain health at the moment, it has been known for decades that heavy drinking is bad for brain health.

“We also shouldn’t forget alcohol affects all parts of the body and there are multiple health risks. For example, it is already known there is ‘no safe level’ of alcohol consumption for the seven types of cancer caused by alcohol, as identified by the UK chief medical officers,” Dr. Boniface said.

The study was supported in part by the Wellcome Trust, Li Ka Shing Center for Health Information and Discovery, the National Institutes of Health, and the UK Medical Research Council. Dr. Topiwala, Dr. Boniface, Dr. Dewey, and Dr. Matthews have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AHA reassures myocarditis rare after COVID vaccination, benefits overwhelm risks

The benefits of COVID-19 vaccination “enormously outweigh” the rare possible risk for heart-related complications, including myocarditis, the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (ASA) says in new statement.

The message follows a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that the agency is monitoring the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS) and the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) for cases of myocarditis that have been associated with the mRNA vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 from Pfizer and Moderna.

The “relatively few” reported cases myocarditis in adolescents or young adults have involved males more often than females, more often followed the second dose rather than the first, and were usually seen in the 4 days after vaccination, the CDC’s COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Technical Work Group (VaST) found.

“Most cases appear to be mild, and follow-up of cases is ongoing,” the CDC says. “Within CDC safety monitoring systems, rates of myocarditis reports in the window following COVID-19 vaccination have not differed from expected baseline rates.”

In their statement, the AHA/ASA “strongly urge” all adults and children 12 years and older to receive a COVID-19 vaccine as soon as possible.

“The evidence continues to indicate that the COVID-19 vaccines are nearly 100% effective at preventing death and hospitalization due to COVID-19 infection,” the groups say.

Although the investigation of cases of myocarditis related to COVID-19 vaccination is ongoing, the AHA/ASA notes that myocarditis is typically the result of an actual viral infection, “and it is yet to be determined if these cases have any correlation to receiving a COVID-19 vaccine.”

“We’ve lost hundreds of children, and there have been thousands who have been hospitalized, thousands who developed an inflammatory syndrome, and one of the pieces of that can be myocarditis,” Richard Besser, MD, president and CEO of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), said today on ABC’s Good Morning America.

Still, “from my perspective, the risk of COVID is so much greater than any theoretical risk from the vaccine,” said Dr. Besser, former acting director of the CDC.

The symptoms that can occur after COVID-19 vaccination include tiredness, headache, muscle pain, chills, fever, and nausea, reminds the AHA/ASA statement. Such symptoms would “typically appear within 24-48 hours and usually pass within 36-48 hours after receiving the vaccine.”

All health care providers should be aware of the “very rare” adverse events that could be related to a COVID-19 vaccine, including myocarditis, blood clots, low platelets, and symptoms of severe inflammation, it says.

“Health care professionals should strongly consider inquiring about the timing of any recent COVID vaccination among patients presenting with these conditions, as needed, in order to provide appropriate treatment quickly,” the statement advises.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The benefits of COVID-19 vaccination “enormously outweigh” the rare possible risk for heart-related complications, including myocarditis, the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (ASA) says in new statement.

The message follows a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that the agency is monitoring the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS) and the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) for cases of myocarditis that have been associated with the mRNA vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 from Pfizer and Moderna.

The “relatively few” reported cases myocarditis in adolescents or young adults have involved males more often than females, more often followed the second dose rather than the first, and were usually seen in the 4 days after vaccination, the CDC’s COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Technical Work Group (VaST) found.

“Most cases appear to be mild, and follow-up of cases is ongoing,” the CDC says. “Within CDC safety monitoring systems, rates of myocarditis reports in the window following COVID-19 vaccination have not differed from expected baseline rates.”

In their statement, the AHA/ASA “strongly urge” all adults and children 12 years and older to receive a COVID-19 vaccine as soon as possible.

“The evidence continues to indicate that the COVID-19 vaccines are nearly 100% effective at preventing death and hospitalization due to COVID-19 infection,” the groups say.

Although the investigation of cases of myocarditis related to COVID-19 vaccination is ongoing, the AHA/ASA notes that myocarditis is typically the result of an actual viral infection, “and it is yet to be determined if these cases have any correlation to receiving a COVID-19 vaccine.”

“We’ve lost hundreds of children, and there have been thousands who have been hospitalized, thousands who developed an inflammatory syndrome, and one of the pieces of that can be myocarditis,” Richard Besser, MD, president and CEO of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), said today on ABC’s Good Morning America.

Still, “from my perspective, the risk of COVID is so much greater than any theoretical risk from the vaccine,” said Dr. Besser, former acting director of the CDC.

The symptoms that can occur after COVID-19 vaccination include tiredness, headache, muscle pain, chills, fever, and nausea, reminds the AHA/ASA statement. Such symptoms would “typically appear within 24-48 hours and usually pass within 36-48 hours after receiving the vaccine.”

All health care providers should be aware of the “very rare” adverse events that could be related to a COVID-19 vaccine, including myocarditis, blood clots, low platelets, and symptoms of severe inflammation, it says.

“Health care professionals should strongly consider inquiring about the timing of any recent COVID vaccination among patients presenting with these conditions, as needed, in order to provide appropriate treatment quickly,” the statement advises.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The benefits of COVID-19 vaccination “enormously outweigh” the rare possible risk for heart-related complications, including myocarditis, the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (ASA) says in new statement.

The message follows a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that the agency is monitoring the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS) and the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) for cases of myocarditis that have been associated with the mRNA vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 from Pfizer and Moderna.

The “relatively few” reported cases myocarditis in adolescents or young adults have involved males more often than females, more often followed the second dose rather than the first, and were usually seen in the 4 days after vaccination, the CDC’s COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Technical Work Group (VaST) found.

“Most cases appear to be mild, and follow-up of cases is ongoing,” the CDC says. “Within CDC safety monitoring systems, rates of myocarditis reports in the window following COVID-19 vaccination have not differed from expected baseline rates.”

In their statement, the AHA/ASA “strongly urge” all adults and children 12 years and older to receive a COVID-19 vaccine as soon as possible.

“The evidence continues to indicate that the COVID-19 vaccines are nearly 100% effective at preventing death and hospitalization due to COVID-19 infection,” the groups say.

Although the investigation of cases of myocarditis related to COVID-19 vaccination is ongoing, the AHA/ASA notes that myocarditis is typically the result of an actual viral infection, “and it is yet to be determined if these cases have any correlation to receiving a COVID-19 vaccine.”

“We’ve lost hundreds of children, and there have been thousands who have been hospitalized, thousands who developed an inflammatory syndrome, and one of the pieces of that can be myocarditis,” Richard Besser, MD, president and CEO of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), said today on ABC’s Good Morning America.

Still, “from my perspective, the risk of COVID is so much greater than any theoretical risk from the vaccine,” said Dr. Besser, former acting director of the CDC.

The symptoms that can occur after COVID-19 vaccination include tiredness, headache, muscle pain, chills, fever, and nausea, reminds the AHA/ASA statement. Such symptoms would “typically appear within 24-48 hours and usually pass within 36-48 hours after receiving the vaccine.”

All health care providers should be aware of the “very rare” adverse events that could be related to a COVID-19 vaccine, including myocarditis, blood clots, low platelets, and symptoms of severe inflammation, it says.

“Health care professionals should strongly consider inquiring about the timing of any recent COVID vaccination among patients presenting with these conditions, as needed, in order to provide appropriate treatment quickly,” the statement advises.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Physicians’ trust in health care leadership drops in pandemic

according to a survey conducted by NORC at the University of Chicago on behalf of the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation.

Survey results, released May 21, indicate that 30% of physicians say their trust in the U.S. health care system and health care leadership has decreased during the pandemic. Only 18% reported an increase in trust.

Physicians, however, have great trust in their fellow clinicians.

In the survey of 600 physicians, 94% said they trust doctors within their practice; 85% trusted doctors outside of their practice; and 89% trusted nurses. That trust increased during the pandemic, with 41% saying their trust in fellow physicians rose and 37% saying their trust in nurses did.

In a separate survey, NORC asked patients about their trust in various aspects of health care. Among 2,069 respondents, a wide majority reported that they trust doctors (84%) and nurses (85%), but only 64% trusted the health care system as a whole. One in three consumers (32%) said their trust in the health care system decreased during the pandemic, compared with 11% who said their trust increased.

The ABIM Foundation released the research findings on May 21 as part of Building Trust, a national campaign that aims to boost trust among patients, clinicians, system leaders, researchers, and others.

Richard J. Baron, MD, president and chief executive officer of the ABIM Foundation, said in an interview, “Clearly there’s lower trust in health care organization leaders and executives, and that’s troubling.

“Science by itself is not enough,” he said. “Becoming trustworthy has to be a core project of everybody in health care.”

Deterioration in physicians’ trust during the pandemic comes in part from failed promises of adequate personal protective equipment and some physicians’ loss of income as a result of the crisis, Dr. Baron said.

He added that the vaccine rollout was very uneven and that policies as to which elective procedures could be performed were handled differently in different parts of the country.