User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Rethinking the language of substance abuse

In December 2019, Seattle Seahawks wide receiver Josh Gordon was suspended indefinitely from the NFL for violation of the league’s substance abuse policy. Gordon, once known as one of the most promising wide receivers of the last few decades, had a tumultuous relationship with the NFL as a result of his struggles with substance use. However, the headlines from major sports and news outlets often describe Gordon and other professional and collegiate athletes who struggle with substance use as “violating policies of abuse.” Media coverage of such athletes frequently imposes labels such as “violation” and “abuse,” implying a greater level of personal responsibility and willful misconduct than the biological process of addiction would typically allow. Gordon’s story brought attention not only to the adversity and impairments of substance use, but also the stigmatizing language that often accompanies it.

Shifting to less stigmatizing terminology

In DMS-5, use of the terminology substance use disorder fosters a more biologically-based model of behavior, and encourages recovery-oriented terminology.1 However, for most collegiate and professional sports leagues, the policies regarding substance use often use the term substance abuse, which can perpetuate stigma and a misunderstanding of the underpinnings of substance use, insinuating a sense of personal responsibility, deliberate misconduct, and criminality. When an individual is referred to as an “abuser” of substances, this might suggest that they are willful perpetrators of the disease on themselves, and thus may be undeserving of care.2 Individuals referred to as “substance abusers” rather than having a substance use disorder are more likely to be subjected to negative perceptions and evaluations of their behaviors, particularly by clinicians.

Individuals with substance use disorders are often viewed more negatively than individuals with physical or other psychiatric disorders, and are among the most stigmatized and marginalized groups in health care.4,5 Today, lawmakers, advocates, and health care professionals across the country are working to integrate destigmatizing language into media, policy, and educational settings in order to characterize substance use as a neurobiological process rather than a moral fault.6 For example, legislation in Maine passed in 2018 removed references to stigmatizing terms in policies related to substance use, replacing substance abuse and drug addict with recovery-oriented terminology such as substance use disorder and person with a substance use disorder.7

Individuals with substance use disorders often fear judgment and stigma during clinical encounters, and commonly cite this as a reason to avoid seeking care.8 Words matter, and if we are not careful, the language we use can convey meaning and attitudes that perpetuate the stigma that prevents so many from accessing treatment.9,10 Individuals with a substance use disorder should feel institutionally supported, and the language of policies and the clinicians who treat these patients should reflect this as well.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Wakeman SE. Language and addiction: choosing words wisely. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(4):e1‐e2.

3. Kelly JF, Westerhoff CM. Does it matter how we refer to individuals with substance-related conditions? A randomized study of two commonly used terms. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21(3):202‐207.

4. Corrigan PW, Kuwabara SA, O’Shaughnessy J. The public stigma of mental illness and drug addiction: findings from a stratified random sample. Journal of Social Work. 2009;9(2):139-147.

5. Barry CL, McGinty EE, Pescosolido BA, et al. Stigma, discrimination, treatment effectiveness, and policy: public views about drug addiction and mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(10):1269‐1272.

6. Office of National Drug Control Policy. Changing the language of addiction. https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/images/Memo%20-%20Changing%20Federal%20Terminology%20Regrading%20Substance%20Use%20and%20Substance%20Use%20Disorders.pdf. Published January 9, 2017. Accessed June 8, 2020.

7. Flaherty N. Why language matters when describing substance use disorder in Maine. http://www.mainepublic.org/post/why-language-matters-when-describing-substance-use-disorder-maine. Published May 16, 2018. Accessed June 8, 2020.

8. Merrill JO, Rhodes LA, Deyo RA, et al. Mutual mistrust in the medical care of drug users: the keys to the “narc” cabinet. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(5):327‐333.

9. Yang LH, Wong LY, Grivel MM, et al. Stigma and substance use disorders: an international phenomenon. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2017;30(5):378‐388.

10. Broyles LM, Binswanger IA, Jenkins JA, et al. Confronting inadvertent stigma and pejorative language in addiction scholarship: a recognition and response. Subst Abus. 2014;35(3):217‐221.

In December 2019, Seattle Seahawks wide receiver Josh Gordon was suspended indefinitely from the NFL for violation of the league’s substance abuse policy. Gordon, once known as one of the most promising wide receivers of the last few decades, had a tumultuous relationship with the NFL as a result of his struggles with substance use. However, the headlines from major sports and news outlets often describe Gordon and other professional and collegiate athletes who struggle with substance use as “violating policies of abuse.” Media coverage of such athletes frequently imposes labels such as “violation” and “abuse,” implying a greater level of personal responsibility and willful misconduct than the biological process of addiction would typically allow. Gordon’s story brought attention not only to the adversity and impairments of substance use, but also the stigmatizing language that often accompanies it.

Shifting to less stigmatizing terminology

In DMS-5, use of the terminology substance use disorder fosters a more biologically-based model of behavior, and encourages recovery-oriented terminology.1 However, for most collegiate and professional sports leagues, the policies regarding substance use often use the term substance abuse, which can perpetuate stigma and a misunderstanding of the underpinnings of substance use, insinuating a sense of personal responsibility, deliberate misconduct, and criminality. When an individual is referred to as an “abuser” of substances, this might suggest that they are willful perpetrators of the disease on themselves, and thus may be undeserving of care.2 Individuals referred to as “substance abusers” rather than having a substance use disorder are more likely to be subjected to negative perceptions and evaluations of their behaviors, particularly by clinicians.

Individuals with substance use disorders are often viewed more negatively than individuals with physical or other psychiatric disorders, and are among the most stigmatized and marginalized groups in health care.4,5 Today, lawmakers, advocates, and health care professionals across the country are working to integrate destigmatizing language into media, policy, and educational settings in order to characterize substance use as a neurobiological process rather than a moral fault.6 For example, legislation in Maine passed in 2018 removed references to stigmatizing terms in policies related to substance use, replacing substance abuse and drug addict with recovery-oriented terminology such as substance use disorder and person with a substance use disorder.7

Individuals with substance use disorders often fear judgment and stigma during clinical encounters, and commonly cite this as a reason to avoid seeking care.8 Words matter, and if we are not careful, the language we use can convey meaning and attitudes that perpetuate the stigma that prevents so many from accessing treatment.9,10 Individuals with a substance use disorder should feel institutionally supported, and the language of policies and the clinicians who treat these patients should reflect this as well.

In December 2019, Seattle Seahawks wide receiver Josh Gordon was suspended indefinitely from the NFL for violation of the league’s substance abuse policy. Gordon, once known as one of the most promising wide receivers of the last few decades, had a tumultuous relationship with the NFL as a result of his struggles with substance use. However, the headlines from major sports and news outlets often describe Gordon and other professional and collegiate athletes who struggle with substance use as “violating policies of abuse.” Media coverage of such athletes frequently imposes labels such as “violation” and “abuse,” implying a greater level of personal responsibility and willful misconduct than the biological process of addiction would typically allow. Gordon’s story brought attention not only to the adversity and impairments of substance use, but also the stigmatizing language that often accompanies it.

Shifting to less stigmatizing terminology

In DMS-5, use of the terminology substance use disorder fosters a more biologically-based model of behavior, and encourages recovery-oriented terminology.1 However, for most collegiate and professional sports leagues, the policies regarding substance use often use the term substance abuse, which can perpetuate stigma and a misunderstanding of the underpinnings of substance use, insinuating a sense of personal responsibility, deliberate misconduct, and criminality. When an individual is referred to as an “abuser” of substances, this might suggest that they are willful perpetrators of the disease on themselves, and thus may be undeserving of care.2 Individuals referred to as “substance abusers” rather than having a substance use disorder are more likely to be subjected to negative perceptions and evaluations of their behaviors, particularly by clinicians.

Individuals with substance use disorders are often viewed more negatively than individuals with physical or other psychiatric disorders, and are among the most stigmatized and marginalized groups in health care.4,5 Today, lawmakers, advocates, and health care professionals across the country are working to integrate destigmatizing language into media, policy, and educational settings in order to characterize substance use as a neurobiological process rather than a moral fault.6 For example, legislation in Maine passed in 2018 removed references to stigmatizing terms in policies related to substance use, replacing substance abuse and drug addict with recovery-oriented terminology such as substance use disorder and person with a substance use disorder.7

Individuals with substance use disorders often fear judgment and stigma during clinical encounters, and commonly cite this as a reason to avoid seeking care.8 Words matter, and if we are not careful, the language we use can convey meaning and attitudes that perpetuate the stigma that prevents so many from accessing treatment.9,10 Individuals with a substance use disorder should feel institutionally supported, and the language of policies and the clinicians who treat these patients should reflect this as well.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Wakeman SE. Language and addiction: choosing words wisely. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(4):e1‐e2.

3. Kelly JF, Westerhoff CM. Does it matter how we refer to individuals with substance-related conditions? A randomized study of two commonly used terms. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21(3):202‐207.

4. Corrigan PW, Kuwabara SA, O’Shaughnessy J. The public stigma of mental illness and drug addiction: findings from a stratified random sample. Journal of Social Work. 2009;9(2):139-147.

5. Barry CL, McGinty EE, Pescosolido BA, et al. Stigma, discrimination, treatment effectiveness, and policy: public views about drug addiction and mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(10):1269‐1272.

6. Office of National Drug Control Policy. Changing the language of addiction. https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/images/Memo%20-%20Changing%20Federal%20Terminology%20Regrading%20Substance%20Use%20and%20Substance%20Use%20Disorders.pdf. Published January 9, 2017. Accessed June 8, 2020.

7. Flaherty N. Why language matters when describing substance use disorder in Maine. http://www.mainepublic.org/post/why-language-matters-when-describing-substance-use-disorder-maine. Published May 16, 2018. Accessed June 8, 2020.

8. Merrill JO, Rhodes LA, Deyo RA, et al. Mutual mistrust in the medical care of drug users: the keys to the “narc” cabinet. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(5):327‐333.

9. Yang LH, Wong LY, Grivel MM, et al. Stigma and substance use disorders: an international phenomenon. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2017;30(5):378‐388.

10. Broyles LM, Binswanger IA, Jenkins JA, et al. Confronting inadvertent stigma and pejorative language in addiction scholarship: a recognition and response. Subst Abus. 2014;35(3):217‐221.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Wakeman SE. Language and addiction: choosing words wisely. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(4):e1‐e2.

3. Kelly JF, Westerhoff CM. Does it matter how we refer to individuals with substance-related conditions? A randomized study of two commonly used terms. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21(3):202‐207.

4. Corrigan PW, Kuwabara SA, O’Shaughnessy J. The public stigma of mental illness and drug addiction: findings from a stratified random sample. Journal of Social Work. 2009;9(2):139-147.

5. Barry CL, McGinty EE, Pescosolido BA, et al. Stigma, discrimination, treatment effectiveness, and policy: public views about drug addiction and mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(10):1269‐1272.

6. Office of National Drug Control Policy. Changing the language of addiction. https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/images/Memo%20-%20Changing%20Federal%20Terminology%20Regrading%20Substance%20Use%20and%20Substance%20Use%20Disorders.pdf. Published January 9, 2017. Accessed June 8, 2020.

7. Flaherty N. Why language matters when describing substance use disorder in Maine. http://www.mainepublic.org/post/why-language-matters-when-describing-substance-use-disorder-maine. Published May 16, 2018. Accessed June 8, 2020.

8. Merrill JO, Rhodes LA, Deyo RA, et al. Mutual mistrust in the medical care of drug users: the keys to the “narc” cabinet. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(5):327‐333.

9. Yang LH, Wong LY, Grivel MM, et al. Stigma and substance use disorders: an international phenomenon. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2017;30(5):378‐388.

10. Broyles LM, Binswanger IA, Jenkins JA, et al. Confronting inadvertent stigma and pejorative language in addiction scholarship: a recognition and response. Subst Abus. 2014;35(3):217‐221.

More on the travesty of pre-authorization

We were delighted to read Dr. Nasrallah’s coruscating editorial about the deceptive, unethical, and clinically harmful practice of insurance companies requiring pre-authorization before granting coverage of psychotropic medications that are not on their short list of inexpensive alternatives (“Pre-authorization is illegal, unethical, and adversely disrupts patient care.” From the Editor,

Brian S. Barnett, MD

Staff Psychiatrist

Cleveland Clinic

Lutheran Hospital

Cleveland, Ohio

J. Alexander Bodkin, MD

Chief

Clinical Psychopharmacology

Research Program

McLean Hospital

Harvard Medical School

Belmont, Massachusetts

Disclosures: The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

I thank Dr. Nasrallah for bringing up the issue of pre-authorization in his editorial and could not agree with him more. As a practicing geriatric psychiatrist—for several decades—I experienced all of what he so nicely summarized, and more. The amount and degree of humiliation, frustration, and (mainly) waste of time have been painful and unacceptable. As he said: It must be stopped! The question is “How?” Hopefully this editorial triggers some activity against pre-authorization. It was time somebody addressed this problem.

Istvan Boksay, MD, PhD

Private psychiatric practice

New York, New York

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Continue to: I thank Dr. Nasrallah...

I thank Dr. Nasrallah for his editorial about pre-authorization, which was well organized and had a perfect headline. In succinct paragraphs, it says what we practitioners have wanted to say for years. If only the American Psychiatric Association and American Medical Association would take up the cause, perhaps some limitations might be put on this corporate intrusion into our practice. Pre-authorization may save insurance companies money, but its cost in time, frustration, and clinical outcomes adds a considerable burden to the financial problems of health care in the United States.

John Buckley, MD

Private psychiatric practice

Glen Arm, Maryland

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

I thank Dr. Nasrallah so much for his editorial. These types of clinically useless administrative tasks are invisible barriers to mental health care access, because the time utilized to complete these tasks can easily be used to see one more patient who needs to be treated. However, I also wonder how we as psychiatrists can move forward so that our psychiatric organizations and legislative bodies can take further action to the real barriers to health care and effective interventions.

Ranvinder Kaur Rai, MD

Private psychiatric practice

Fremont, California

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Continue to: I read with interest...

I read with interest Dr. Nasrallah’s editorials “We are physicians, not providers, and we treat patients, not clients!” (From the Editor,

Dr. Nasrallah’s strong advocacy against the use of the term “provider” is long overdue. I distinctly remember the insidious onset of the use of the terms provider and “consumer” during my years as a medical director of a mental health center. The inception of the provider/consumer terminology can be construed as striving for cultural correctness when psychiatry was going through its own identity crisis in response to deinstitutionalization and the destruction of the so-called myth of psychiatrists as paternalistic and all-powerful. Managed care as the business model of medicine further destroyed the perception of the psychiatric physician as noble and caring, and demythologized the physician–patient relationship. It is amazing how the term provider has persisted and become part of the language of medicine. During the last 20 years or so, psychiatric and medical professional organizations have done little to squash the usage of the term.

Furthermore, the concept of pre-authorization is not new to medicine, but has insidiously become part of the tasks of the psychiatric physician. It has morphed into more than having to obtain approval for using a branded medication over a cheaper generic alternative to having to obtain approval for the use of any medication that does not fall under the approved tier. Even antipsychotics (generally a protected class) have not been immune.

Both the use of the term provider and the concept of pre-authorization require more than the frustration and indignation of a clinical psychiatrist. It requires the determination of professional psychiatric organizations and those with power to fight the gradual but ever-deteriorating authority of medical practice and the role of the psychiatric physician.

Elizabeth A. Varas, MD

Private psychiatric practice

Westwood, New Jersey

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

We were delighted to read Dr. Nasrallah’s coruscating editorial about the deceptive, unethical, and clinically harmful practice of insurance companies requiring pre-authorization before granting coverage of psychotropic medications that are not on their short list of inexpensive alternatives (“Pre-authorization is illegal, unethical, and adversely disrupts patient care.” From the Editor,

Brian S. Barnett, MD

Staff Psychiatrist

Cleveland Clinic

Lutheran Hospital

Cleveland, Ohio

J. Alexander Bodkin, MD

Chief

Clinical Psychopharmacology

Research Program

McLean Hospital

Harvard Medical School

Belmont, Massachusetts

Disclosures: The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

I thank Dr. Nasrallah for bringing up the issue of pre-authorization in his editorial and could not agree with him more. As a practicing geriatric psychiatrist—for several decades—I experienced all of what he so nicely summarized, and more. The amount and degree of humiliation, frustration, and (mainly) waste of time have been painful and unacceptable. As he said: It must be stopped! The question is “How?” Hopefully this editorial triggers some activity against pre-authorization. It was time somebody addressed this problem.

Istvan Boksay, MD, PhD

Private psychiatric practice

New York, New York

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Continue to: I thank Dr. Nasrallah...

I thank Dr. Nasrallah for his editorial about pre-authorization, which was well organized and had a perfect headline. In succinct paragraphs, it says what we practitioners have wanted to say for years. If only the American Psychiatric Association and American Medical Association would take up the cause, perhaps some limitations might be put on this corporate intrusion into our practice. Pre-authorization may save insurance companies money, but its cost in time, frustration, and clinical outcomes adds a considerable burden to the financial problems of health care in the United States.

John Buckley, MD

Private psychiatric practice

Glen Arm, Maryland

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

I thank Dr. Nasrallah so much for his editorial. These types of clinically useless administrative tasks are invisible barriers to mental health care access, because the time utilized to complete these tasks can easily be used to see one more patient who needs to be treated. However, I also wonder how we as psychiatrists can move forward so that our psychiatric organizations and legislative bodies can take further action to the real barriers to health care and effective interventions.

Ranvinder Kaur Rai, MD

Private psychiatric practice

Fremont, California

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Continue to: I read with interest...

I read with interest Dr. Nasrallah’s editorials “We are physicians, not providers, and we treat patients, not clients!” (From the Editor,

Dr. Nasrallah’s strong advocacy against the use of the term “provider” is long overdue. I distinctly remember the insidious onset of the use of the terms provider and “consumer” during my years as a medical director of a mental health center. The inception of the provider/consumer terminology can be construed as striving for cultural correctness when psychiatry was going through its own identity crisis in response to deinstitutionalization and the destruction of the so-called myth of psychiatrists as paternalistic and all-powerful. Managed care as the business model of medicine further destroyed the perception of the psychiatric physician as noble and caring, and demythologized the physician–patient relationship. It is amazing how the term provider has persisted and become part of the language of medicine. During the last 20 years or so, psychiatric and medical professional organizations have done little to squash the usage of the term.

Furthermore, the concept of pre-authorization is not new to medicine, but has insidiously become part of the tasks of the psychiatric physician. It has morphed into more than having to obtain approval for using a branded medication over a cheaper generic alternative to having to obtain approval for the use of any medication that does not fall under the approved tier. Even antipsychotics (generally a protected class) have not been immune.

Both the use of the term provider and the concept of pre-authorization require more than the frustration and indignation of a clinical psychiatrist. It requires the determination of professional psychiatric organizations and those with power to fight the gradual but ever-deteriorating authority of medical practice and the role of the psychiatric physician.

Elizabeth A. Varas, MD

Private psychiatric practice

Westwood, New Jersey

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

We were delighted to read Dr. Nasrallah’s coruscating editorial about the deceptive, unethical, and clinically harmful practice of insurance companies requiring pre-authorization before granting coverage of psychotropic medications that are not on their short list of inexpensive alternatives (“Pre-authorization is illegal, unethical, and adversely disrupts patient care.” From the Editor,

Brian S. Barnett, MD

Staff Psychiatrist

Cleveland Clinic

Lutheran Hospital

Cleveland, Ohio

J. Alexander Bodkin, MD

Chief

Clinical Psychopharmacology

Research Program

McLean Hospital

Harvard Medical School

Belmont, Massachusetts

Disclosures: The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

I thank Dr. Nasrallah for bringing up the issue of pre-authorization in his editorial and could not agree with him more. As a practicing geriatric psychiatrist—for several decades—I experienced all of what he so nicely summarized, and more. The amount and degree of humiliation, frustration, and (mainly) waste of time have been painful and unacceptable. As he said: It must be stopped! The question is “How?” Hopefully this editorial triggers some activity against pre-authorization. It was time somebody addressed this problem.

Istvan Boksay, MD, PhD

Private psychiatric practice

New York, New York

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Continue to: I thank Dr. Nasrallah...

I thank Dr. Nasrallah for his editorial about pre-authorization, which was well organized and had a perfect headline. In succinct paragraphs, it says what we practitioners have wanted to say for years. If only the American Psychiatric Association and American Medical Association would take up the cause, perhaps some limitations might be put on this corporate intrusion into our practice. Pre-authorization may save insurance companies money, but its cost in time, frustration, and clinical outcomes adds a considerable burden to the financial problems of health care in the United States.

John Buckley, MD

Private psychiatric practice

Glen Arm, Maryland

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

I thank Dr. Nasrallah so much for his editorial. These types of clinically useless administrative tasks are invisible barriers to mental health care access, because the time utilized to complete these tasks can easily be used to see one more patient who needs to be treated. However, I also wonder how we as psychiatrists can move forward so that our psychiatric organizations and legislative bodies can take further action to the real barriers to health care and effective interventions.

Ranvinder Kaur Rai, MD

Private psychiatric practice

Fremont, California

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Continue to: I read with interest...

I read with interest Dr. Nasrallah’s editorials “We are physicians, not providers, and we treat patients, not clients!” (From the Editor,

Dr. Nasrallah’s strong advocacy against the use of the term “provider” is long overdue. I distinctly remember the insidious onset of the use of the terms provider and “consumer” during my years as a medical director of a mental health center. The inception of the provider/consumer terminology can be construed as striving for cultural correctness when psychiatry was going through its own identity crisis in response to deinstitutionalization and the destruction of the so-called myth of psychiatrists as paternalistic and all-powerful. Managed care as the business model of medicine further destroyed the perception of the psychiatric physician as noble and caring, and demythologized the physician–patient relationship. It is amazing how the term provider has persisted and become part of the language of medicine. During the last 20 years or so, psychiatric and medical professional organizations have done little to squash the usage of the term.

Furthermore, the concept of pre-authorization is not new to medicine, but has insidiously become part of the tasks of the psychiatric physician. It has morphed into more than having to obtain approval for using a branded medication over a cheaper generic alternative to having to obtain approval for the use of any medication that does not fall under the approved tier. Even antipsychotics (generally a protected class) have not been immune.

Both the use of the term provider and the concept of pre-authorization require more than the frustration and indignation of a clinical psychiatrist. It requires the determination of professional psychiatric organizations and those with power to fight the gradual but ever-deteriorating authority of medical practice and the role of the psychiatric physician.

Elizabeth A. Varas, MD

Private psychiatric practice

Westwood, New Jersey

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

COVID-19 and the precipitous dismantlement of societal norms

As the life-altering coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic gradually ebbs, we are all its survivors. Now, we are experiencing COVID-19 fatigue, trying to emerge from its dense fog that pervaded every facet of our lives. We are fully cognizant that there will not be a return to the previous “normal.” The pernicious virus had a transformative effect that did not spare any component of our society. Full recovery will not be easy.

As the uncertainty lingers about another devastating return of the pandemic later this year, we can see the reverberation of this invisible assault on human existence. Although a relatively small fraction of the population lost their lives, the rest of us are valiantly trying to readjust to the multiple ways our world has changed. Consider the following abrupt and sweeping burdens inflicted by the pandemic within a few short weeks:

Mental health. The acute stress of thanatophobia generated a triad of anxiety, depression, and nosophobia on a large scale. The demand for psychiatric care rapidly escalated. Suicide rate increased not only because of the stress of being locked down at home (alien to most people’s lifestyle) but because of the coincidental timing of the pandemic during April and May, the peak time of year for suicide. Animal researchers use immobilization as a paradigm to stress a rat or mouse. Many humans immobilized during the pandemic have developed exquisite empathy towards those rodents! The impact on children may also have long-term effects because playing and socializing with friends is a vital part of their lives. Parents have noticed dysphoria and acting out among their children, and an intense compensatory preoccupation with video games and electronic communications with friends.

Physical health. Medical care focused heavily on COVID-19 victims, to the detriment of all other medical conditions. Non-COVID-19 hospital admissions plummeted, and all elective surgeries and procedures were put on hold, depriving many people of medical care they badly needed. Emergency department (ED) visits also declined dramatically, including the usual flow of heart attacks, stroke, pulmonary embolus, asthma attacks, etc. The minimization of driving greatly reduced the admission of accident victims to EDs. Colonoscopies, cardiac stents, hip replacements, MRIs, mammography, and other procedures that are vital to maintain health and quality of life were halted. Dentists shuttered their practices due to the high risk of infection from exposure to oral secretions and breathing. One can only imagine the suffering of having a toothache with no dental help available, and how that might lead to narcotic abuse.

Social health. The imperative of social distancing disrupted most ordinary human activities, such as dining out, sitting in an auditorium for Grand Rounds or a lecture, visiting friends at their homes, the cherished interactions between grandparents and grandchildren (the lack of which I painfully experienced), and even seeing each other’s smiles behind the ubiquitous masks. And forget about hugging or kissing. The aversion to being near anyone who is coughing or sneezing led to an adaptive social paranoia and the social shunning of anyone who appeared to have an upper respiratory infection, even if it was unrelated to COVID-19.

Redemption for the pharmaceutical industry. The deadly pandemic intensified the public’s awareness of the importance of developing treatments and vaccines for COVID-19. The often-demonized pharmaceutical companies, with their extensive R&D infrastructure, emerged as a major source of hope for discovering an effective treatment for the coronavirus infection, or—better still—one or more vaccines that will enable society to return to its normal functions. It was quite impressive how many pharmaceutical companies “came to the rescue” with clinical trials to repurpose existing medications or to develop new ones. It was very encouraging to see multiple vaccine candidates being developed and expedited for testing around the world. A process that usually takes years was reduced to a few months, thanks to the existing technical infrastructure and thousands of scientists who enable rapid drug development. It is possible that the public may gradually modify its perception of the pharmaceutical industry from a “corporate villain” to an “indispensable health industry” for urgent medical crises such as a pandemic, and also for hundreds of medical diseases that are still in need of safe, effective therapies.

Economic burden. The unimaginable nightmare scenario of a total shutdown of all businesses led to the unprecedented loss of millions of jobs and livelihoods, reflected in miles-long lines of families at food banks. Overnight, the government switched from worrying about its $20-trillion deficit to printing several more trillion dollars to rescue the economy from collapse. The huge magnitude of a trillion can be appreciated if one is aware that it takes roughly 32 years to count to 1 billion, and 32,000 years to count to 1 trillion. Stimulating the economy while the gross domestic product threatens to sink by terrifying percentages (20% to 30%) was urgently needed, even though it meant mortgaging the future, especially when interest rates, and servicing the debt, will inevitably rise from the current zero to much higher levels in the future. The collapse of the once-thriving airline industry (bookings were down an estimated 98%) is an example of why desperate measures were needed to salvage an economy paralyzed by a viral pandemic.

Continue to: Political repercussions

Political repercussions. In our already hyperpartisan country, the COVID-19 crisis created more fissures across party lines. The blame game escalated as each side tried to exploit the crisis for political gain during a presidential election year. None of the leaders, from mayors to governors to the president, had any notion of how to wisely manage an unforeseen catastrophic pandemic. Thus, a political cacophony has developed, further exacerbating the public’s anxiety and uncertainty, especially about how and when the pandemic will end.

Education disruption. Never before have all schools and colleges around the country abruptly closed and sent students of all ages to shelter at home. Massive havoc ensued, with a wholesale switch to solitary online learning, the loss of the unique school and college social experience in the classroom and on campus, and the loss of experiencing commencement to receive a diploma (an important milestone for every graduate). Even medical students were not allowed to complete their clinical rotations and were sent home to attend online classes. A complete paradigm shift emerged about entrance exams: the SAT and ACT were eliminated for college applicants, and the MCAT for medical school applicants. This was unthinkable before the pandemic descended upon us, but benchmarks suddenly evaporated to adjust to the new reality. Then there followed disastrous financial losses by institutions of higher learning as well as academic medical centers and teaching hospitals, all slashing their budgets, furloughing employees, cutting salaries, and eliminating programs. Even the “sacred” tenure of senior faculty became a casualty of the financial “exigency.” Children’s nutrition suffered, especially among those in lower socioeconomic groups for whom the main meal of the day was the school lunch, and was made worse by their parents’ loss of income. For millions of people, the emotional toll was inevitable following the draconian measure of closing all educational institutions to contain the spread of the pandemic.

Family burden. Sheltering at home might have been fun for a few days, but after many weeks, it festered into a major stress, especially for those living in a small house, condominium, or apartment. The resilience of many families was tested as the exercise of freedoms collided with the fear of getting infected. Families were deprived of celebrating birthdays, weddings, funerals, graduation parties, retirement parties, Mother’s Day, Father’s Day, and various religious holidays, including Easter, Passover, and Eid al-Fitr.

Sexual burden. Intimacy and sexual contact between consenting adults living apart were sacrificed on the altar of the pernicious viral pandemic. Mandatory social distancing of 6 feet or more to avoid each other’s droplets emanating from simple speech, not just sneezing or coughing, makes intimacy practically impossible. Thus, physical closeness became taboo, and avoiding another person’s saliva or body secretions became a must to avoid contracting the virus. Being single was quite a lonely experience during this pandemic!

Entertainment deprivation. Americans are known to thrive on an extensive diet of spectator sports. Going to football, basketball, baseball, or hockey games to root for one’s team is intrinsically American. The pursuit of happiness extends to attending concerts, movies, Broadway shows, theme parks, and cruises with thousands of others. The pandemic ripped all those pleasurable leisure activities from our daily lives, leaving a big hole in people’s lives at the precise time fun activities were needed as a useful diversion from the dismal stress of a pandemic. To make things worse, it is uncertain when (if ever) such group activities will be restored, especially if the pandemic returns with another wave. But optimists would hurry to remind us that the “Roaring 20s” blossomed in the decade following the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic.

Continue to: Legal system

Legal system. Astounding changes were instigated by the pandemic, such as the release of thousands of inmates, including felons, to avoid the spread of the virus in crowded prisons. For us psychiatrists, the silver lining in that unexpected action is that many of those released were patients with mental illness who were incarcerated because of the lack of hospitals that would take them. The police started issuing citations instead of arresting and jailing violators. Enforcement of the law was welcome when it targeted those who gouged the public for personal profit during the scarcity of masks, sanitizers, or even toilet paper and soap.

Medical practice. In addition to delaying medical care for patients, the freeze on so-called elective surgeries or procedures (many of which were actually necessary) was financially ruinous for physicians. Another regrettable consequence of the pandemic is a drop in pediatric vaccinations because parents were reluctant to take their children to the pediatrician. On a more positive note, the massive switch to telehealth was advantageous for both patients and psychiatrists because this technology is well-suited for psychiatric care. Fortunately, regulations that hampered telepsychiatry practice were substantially loosened or eliminated, and even the usually sacrosanct HIPAA regulations were temporarily sidelined.

Medical research. Both human and animal research came to a screeching halt, and many research assistants were furloughed. Data collection was disrupted, and a generation of scientific and medical discoveries became a casualty of the pandemic.

Medical literature. It was stunning to see how quickly COVID-19 occupied most of the pages of prominent journals. The scholarly articles were frankly quite useful, covering topics ranging from risk factors to early symptoms to treatment and pathophysiology across multiple organs. As with other paradigm shifts, there was an accelerated publication push, sometimes with expedited peer reviews to inform health care workers and the public while the pandemic was still raging. However, a couple of very prominent journals had to retract flawed articles that were hastily published without the usual due diligence and rigorous peer review. The pandemic clearly disrupted the science publishing process.

Travel effects. The steep reduction of flights (by 98%) was financially catastrophic, not only for airline companies but to business travel across the country. However, fewer cars on the road resulted in fewer accidents and deaths, and also reduced pollution. Paradoxically, to prevent crowding in subways, trains, and buses, officials reversed their traditional instructions and advised the public to drive their own cars instead of using public transportation!

Continue to: Heroism of front-line medical personnel

Heroism of front-line medical personnel. Everyone saluted and prayed for the health care professionals working at the bedside of highly infectious patients who needed 24/7 intensive care. Many have died while carrying out the noble but hazardous medical duties. Those heroes deserve our lasting respect and admiration.

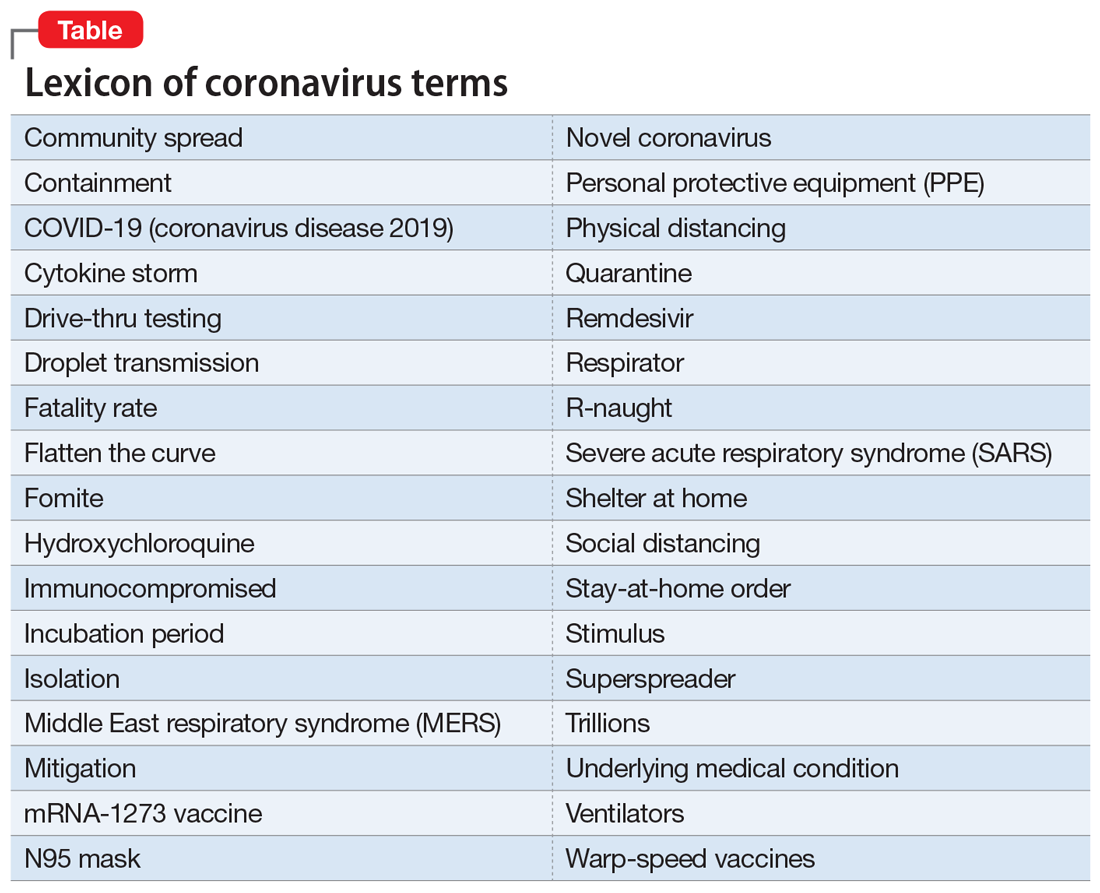

The COVID-19 pandemic insidiously permeated and altered every aspect of our complex society and revealed how fragile our “normal lifestyle” really is. It is possible that nothing will ever be the same again, and an uneasy sense of vulnerability will engulf us as we cautiously return to a “new normal.” Even our language has expanded with the lexicon of pandemic terminology (Table). We all pray and hope that this plague never returns. And let’s hope one or more vaccines are developed soon so we can manage future recurrences like the annual flu season. In the meantime, keep your masks and sanitizers close by…

Postscript: Shortly after I completed this editorial, the ongoing COVID-19 plague was overshadowed by the scourge of racism, with massive protests, at times laced by violence, triggered by the death of a black man in custody of the police, under condemnable circumstances. The COVID-19 pandemic and the necessary social distancing it requires were temporarily ignored during the ensuing protests. The combined effect of those overlapping scourges are jarring to the country’s psyche, complicating and perhaps sabotaging the social recovery from the pandemic.

As the life-altering coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic gradually ebbs, we are all its survivors. Now, we are experiencing COVID-19 fatigue, trying to emerge from its dense fog that pervaded every facet of our lives. We are fully cognizant that there will not be a return to the previous “normal.” The pernicious virus had a transformative effect that did not spare any component of our society. Full recovery will not be easy.

As the uncertainty lingers about another devastating return of the pandemic later this year, we can see the reverberation of this invisible assault on human existence. Although a relatively small fraction of the population lost their lives, the rest of us are valiantly trying to readjust to the multiple ways our world has changed. Consider the following abrupt and sweeping burdens inflicted by the pandemic within a few short weeks:

Mental health. The acute stress of thanatophobia generated a triad of anxiety, depression, and nosophobia on a large scale. The demand for psychiatric care rapidly escalated. Suicide rate increased not only because of the stress of being locked down at home (alien to most people’s lifestyle) but because of the coincidental timing of the pandemic during April and May, the peak time of year for suicide. Animal researchers use immobilization as a paradigm to stress a rat or mouse. Many humans immobilized during the pandemic have developed exquisite empathy towards those rodents! The impact on children may also have long-term effects because playing and socializing with friends is a vital part of their lives. Parents have noticed dysphoria and acting out among their children, and an intense compensatory preoccupation with video games and electronic communications with friends.

Physical health. Medical care focused heavily on COVID-19 victims, to the detriment of all other medical conditions. Non-COVID-19 hospital admissions plummeted, and all elective surgeries and procedures were put on hold, depriving many people of medical care they badly needed. Emergency department (ED) visits also declined dramatically, including the usual flow of heart attacks, stroke, pulmonary embolus, asthma attacks, etc. The minimization of driving greatly reduced the admission of accident victims to EDs. Colonoscopies, cardiac stents, hip replacements, MRIs, mammography, and other procedures that are vital to maintain health and quality of life were halted. Dentists shuttered their practices due to the high risk of infection from exposure to oral secretions and breathing. One can only imagine the suffering of having a toothache with no dental help available, and how that might lead to narcotic abuse.

Social health. The imperative of social distancing disrupted most ordinary human activities, such as dining out, sitting in an auditorium for Grand Rounds or a lecture, visiting friends at their homes, the cherished interactions between grandparents and grandchildren (the lack of which I painfully experienced), and even seeing each other’s smiles behind the ubiquitous masks. And forget about hugging or kissing. The aversion to being near anyone who is coughing or sneezing led to an adaptive social paranoia and the social shunning of anyone who appeared to have an upper respiratory infection, even if it was unrelated to COVID-19.

Redemption for the pharmaceutical industry. The deadly pandemic intensified the public’s awareness of the importance of developing treatments and vaccines for COVID-19. The often-demonized pharmaceutical companies, with their extensive R&D infrastructure, emerged as a major source of hope for discovering an effective treatment for the coronavirus infection, or—better still—one or more vaccines that will enable society to return to its normal functions. It was quite impressive how many pharmaceutical companies “came to the rescue” with clinical trials to repurpose existing medications or to develop new ones. It was very encouraging to see multiple vaccine candidates being developed and expedited for testing around the world. A process that usually takes years was reduced to a few months, thanks to the existing technical infrastructure and thousands of scientists who enable rapid drug development. It is possible that the public may gradually modify its perception of the pharmaceutical industry from a “corporate villain” to an “indispensable health industry” for urgent medical crises such as a pandemic, and also for hundreds of medical diseases that are still in need of safe, effective therapies.

Economic burden. The unimaginable nightmare scenario of a total shutdown of all businesses led to the unprecedented loss of millions of jobs and livelihoods, reflected in miles-long lines of families at food banks. Overnight, the government switched from worrying about its $20-trillion deficit to printing several more trillion dollars to rescue the economy from collapse. The huge magnitude of a trillion can be appreciated if one is aware that it takes roughly 32 years to count to 1 billion, and 32,000 years to count to 1 trillion. Stimulating the economy while the gross domestic product threatens to sink by terrifying percentages (20% to 30%) was urgently needed, even though it meant mortgaging the future, especially when interest rates, and servicing the debt, will inevitably rise from the current zero to much higher levels in the future. The collapse of the once-thriving airline industry (bookings were down an estimated 98%) is an example of why desperate measures were needed to salvage an economy paralyzed by a viral pandemic.

Continue to: Political repercussions

Political repercussions. In our already hyperpartisan country, the COVID-19 crisis created more fissures across party lines. The blame game escalated as each side tried to exploit the crisis for political gain during a presidential election year. None of the leaders, from mayors to governors to the president, had any notion of how to wisely manage an unforeseen catastrophic pandemic. Thus, a political cacophony has developed, further exacerbating the public’s anxiety and uncertainty, especially about how and when the pandemic will end.

Education disruption. Never before have all schools and colleges around the country abruptly closed and sent students of all ages to shelter at home. Massive havoc ensued, with a wholesale switch to solitary online learning, the loss of the unique school and college social experience in the classroom and on campus, and the loss of experiencing commencement to receive a diploma (an important milestone for every graduate). Even medical students were not allowed to complete their clinical rotations and were sent home to attend online classes. A complete paradigm shift emerged about entrance exams: the SAT and ACT were eliminated for college applicants, and the MCAT for medical school applicants. This was unthinkable before the pandemic descended upon us, but benchmarks suddenly evaporated to adjust to the new reality. Then there followed disastrous financial losses by institutions of higher learning as well as academic medical centers and teaching hospitals, all slashing their budgets, furloughing employees, cutting salaries, and eliminating programs. Even the “sacred” tenure of senior faculty became a casualty of the financial “exigency.” Children’s nutrition suffered, especially among those in lower socioeconomic groups for whom the main meal of the day was the school lunch, and was made worse by their parents’ loss of income. For millions of people, the emotional toll was inevitable following the draconian measure of closing all educational institutions to contain the spread of the pandemic.

Family burden. Sheltering at home might have been fun for a few days, but after many weeks, it festered into a major stress, especially for those living in a small house, condominium, or apartment. The resilience of many families was tested as the exercise of freedoms collided with the fear of getting infected. Families were deprived of celebrating birthdays, weddings, funerals, graduation parties, retirement parties, Mother’s Day, Father’s Day, and various religious holidays, including Easter, Passover, and Eid al-Fitr.

Sexual burden. Intimacy and sexual contact between consenting adults living apart were sacrificed on the altar of the pernicious viral pandemic. Mandatory social distancing of 6 feet or more to avoid each other’s droplets emanating from simple speech, not just sneezing or coughing, makes intimacy practically impossible. Thus, physical closeness became taboo, and avoiding another person’s saliva or body secretions became a must to avoid contracting the virus. Being single was quite a lonely experience during this pandemic!

Entertainment deprivation. Americans are known to thrive on an extensive diet of spectator sports. Going to football, basketball, baseball, or hockey games to root for one’s team is intrinsically American. The pursuit of happiness extends to attending concerts, movies, Broadway shows, theme parks, and cruises with thousands of others. The pandemic ripped all those pleasurable leisure activities from our daily lives, leaving a big hole in people’s lives at the precise time fun activities were needed as a useful diversion from the dismal stress of a pandemic. To make things worse, it is uncertain when (if ever) such group activities will be restored, especially if the pandemic returns with another wave. But optimists would hurry to remind us that the “Roaring 20s” blossomed in the decade following the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic.

Continue to: Legal system

Legal system. Astounding changes were instigated by the pandemic, such as the release of thousands of inmates, including felons, to avoid the spread of the virus in crowded prisons. For us psychiatrists, the silver lining in that unexpected action is that many of those released were patients with mental illness who were incarcerated because of the lack of hospitals that would take them. The police started issuing citations instead of arresting and jailing violators. Enforcement of the law was welcome when it targeted those who gouged the public for personal profit during the scarcity of masks, sanitizers, or even toilet paper and soap.

Medical practice. In addition to delaying medical care for patients, the freeze on so-called elective surgeries or procedures (many of which were actually necessary) was financially ruinous for physicians. Another regrettable consequence of the pandemic is a drop in pediatric vaccinations because parents were reluctant to take their children to the pediatrician. On a more positive note, the massive switch to telehealth was advantageous for both patients and psychiatrists because this technology is well-suited for psychiatric care. Fortunately, regulations that hampered telepsychiatry practice were substantially loosened or eliminated, and even the usually sacrosanct HIPAA regulations were temporarily sidelined.

Medical research. Both human and animal research came to a screeching halt, and many research assistants were furloughed. Data collection was disrupted, and a generation of scientific and medical discoveries became a casualty of the pandemic.

Medical literature. It was stunning to see how quickly COVID-19 occupied most of the pages of prominent journals. The scholarly articles were frankly quite useful, covering topics ranging from risk factors to early symptoms to treatment and pathophysiology across multiple organs. As with other paradigm shifts, there was an accelerated publication push, sometimes with expedited peer reviews to inform health care workers and the public while the pandemic was still raging. However, a couple of very prominent journals had to retract flawed articles that were hastily published without the usual due diligence and rigorous peer review. The pandemic clearly disrupted the science publishing process.

Travel effects. The steep reduction of flights (by 98%) was financially catastrophic, not only for airline companies but to business travel across the country. However, fewer cars on the road resulted in fewer accidents and deaths, and also reduced pollution. Paradoxically, to prevent crowding in subways, trains, and buses, officials reversed their traditional instructions and advised the public to drive their own cars instead of using public transportation!

Continue to: Heroism of front-line medical personnel

Heroism of front-line medical personnel. Everyone saluted and prayed for the health care professionals working at the bedside of highly infectious patients who needed 24/7 intensive care. Many have died while carrying out the noble but hazardous medical duties. Those heroes deserve our lasting respect and admiration.

The COVID-19 pandemic insidiously permeated and altered every aspect of our complex society and revealed how fragile our “normal lifestyle” really is. It is possible that nothing will ever be the same again, and an uneasy sense of vulnerability will engulf us as we cautiously return to a “new normal.” Even our language has expanded with the lexicon of pandemic terminology (Table). We all pray and hope that this plague never returns. And let’s hope one or more vaccines are developed soon so we can manage future recurrences like the annual flu season. In the meantime, keep your masks and sanitizers close by…

Postscript: Shortly after I completed this editorial, the ongoing COVID-19 plague was overshadowed by the scourge of racism, with massive protests, at times laced by violence, triggered by the death of a black man in custody of the police, under condemnable circumstances. The COVID-19 pandemic and the necessary social distancing it requires were temporarily ignored during the ensuing protests. The combined effect of those overlapping scourges are jarring to the country’s psyche, complicating and perhaps sabotaging the social recovery from the pandemic.

As the life-altering coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic gradually ebbs, we are all its survivors. Now, we are experiencing COVID-19 fatigue, trying to emerge from its dense fog that pervaded every facet of our lives. We are fully cognizant that there will not be a return to the previous “normal.” The pernicious virus had a transformative effect that did not spare any component of our society. Full recovery will not be easy.

As the uncertainty lingers about another devastating return of the pandemic later this year, we can see the reverberation of this invisible assault on human existence. Although a relatively small fraction of the population lost their lives, the rest of us are valiantly trying to readjust to the multiple ways our world has changed. Consider the following abrupt and sweeping burdens inflicted by the pandemic within a few short weeks:

Mental health. The acute stress of thanatophobia generated a triad of anxiety, depression, and nosophobia on a large scale. The demand for psychiatric care rapidly escalated. Suicide rate increased not only because of the stress of being locked down at home (alien to most people’s lifestyle) but because of the coincidental timing of the pandemic during April and May, the peak time of year for suicide. Animal researchers use immobilization as a paradigm to stress a rat or mouse. Many humans immobilized during the pandemic have developed exquisite empathy towards those rodents! The impact on children may also have long-term effects because playing and socializing with friends is a vital part of their lives. Parents have noticed dysphoria and acting out among their children, and an intense compensatory preoccupation with video games and electronic communications with friends.

Physical health. Medical care focused heavily on COVID-19 victims, to the detriment of all other medical conditions. Non-COVID-19 hospital admissions plummeted, and all elective surgeries and procedures were put on hold, depriving many people of medical care they badly needed. Emergency department (ED) visits also declined dramatically, including the usual flow of heart attacks, stroke, pulmonary embolus, asthma attacks, etc. The minimization of driving greatly reduced the admission of accident victims to EDs. Colonoscopies, cardiac stents, hip replacements, MRIs, mammography, and other procedures that are vital to maintain health and quality of life were halted. Dentists shuttered their practices due to the high risk of infection from exposure to oral secretions and breathing. One can only imagine the suffering of having a toothache with no dental help available, and how that might lead to narcotic abuse.

Social health. The imperative of social distancing disrupted most ordinary human activities, such as dining out, sitting in an auditorium for Grand Rounds or a lecture, visiting friends at their homes, the cherished interactions between grandparents and grandchildren (the lack of which I painfully experienced), and even seeing each other’s smiles behind the ubiquitous masks. And forget about hugging or kissing. The aversion to being near anyone who is coughing or sneezing led to an adaptive social paranoia and the social shunning of anyone who appeared to have an upper respiratory infection, even if it was unrelated to COVID-19.

Redemption for the pharmaceutical industry. The deadly pandemic intensified the public’s awareness of the importance of developing treatments and vaccines for COVID-19. The often-demonized pharmaceutical companies, with their extensive R&D infrastructure, emerged as a major source of hope for discovering an effective treatment for the coronavirus infection, or—better still—one or more vaccines that will enable society to return to its normal functions. It was quite impressive how many pharmaceutical companies “came to the rescue” with clinical trials to repurpose existing medications or to develop new ones. It was very encouraging to see multiple vaccine candidates being developed and expedited for testing around the world. A process that usually takes years was reduced to a few months, thanks to the existing technical infrastructure and thousands of scientists who enable rapid drug development. It is possible that the public may gradually modify its perception of the pharmaceutical industry from a “corporate villain” to an “indispensable health industry” for urgent medical crises such as a pandemic, and also for hundreds of medical diseases that are still in need of safe, effective therapies.

Economic burden. The unimaginable nightmare scenario of a total shutdown of all businesses led to the unprecedented loss of millions of jobs and livelihoods, reflected in miles-long lines of families at food banks. Overnight, the government switched from worrying about its $20-trillion deficit to printing several more trillion dollars to rescue the economy from collapse. The huge magnitude of a trillion can be appreciated if one is aware that it takes roughly 32 years to count to 1 billion, and 32,000 years to count to 1 trillion. Stimulating the economy while the gross domestic product threatens to sink by terrifying percentages (20% to 30%) was urgently needed, even though it meant mortgaging the future, especially when interest rates, and servicing the debt, will inevitably rise from the current zero to much higher levels in the future. The collapse of the once-thriving airline industry (bookings were down an estimated 98%) is an example of why desperate measures were needed to salvage an economy paralyzed by a viral pandemic.

Continue to: Political repercussions

Political repercussions. In our already hyperpartisan country, the COVID-19 crisis created more fissures across party lines. The blame game escalated as each side tried to exploit the crisis for political gain during a presidential election year. None of the leaders, from mayors to governors to the president, had any notion of how to wisely manage an unforeseen catastrophic pandemic. Thus, a political cacophony has developed, further exacerbating the public’s anxiety and uncertainty, especially about how and when the pandemic will end.

Education disruption. Never before have all schools and colleges around the country abruptly closed and sent students of all ages to shelter at home. Massive havoc ensued, with a wholesale switch to solitary online learning, the loss of the unique school and college social experience in the classroom and on campus, and the loss of experiencing commencement to receive a diploma (an important milestone for every graduate). Even medical students were not allowed to complete their clinical rotations and were sent home to attend online classes. A complete paradigm shift emerged about entrance exams: the SAT and ACT were eliminated for college applicants, and the MCAT for medical school applicants. This was unthinkable before the pandemic descended upon us, but benchmarks suddenly evaporated to adjust to the new reality. Then there followed disastrous financial losses by institutions of higher learning as well as academic medical centers and teaching hospitals, all slashing their budgets, furloughing employees, cutting salaries, and eliminating programs. Even the “sacred” tenure of senior faculty became a casualty of the financial “exigency.” Children’s nutrition suffered, especially among those in lower socioeconomic groups for whom the main meal of the day was the school lunch, and was made worse by their parents’ loss of income. For millions of people, the emotional toll was inevitable following the draconian measure of closing all educational institutions to contain the spread of the pandemic.

Family burden. Sheltering at home might have been fun for a few days, but after many weeks, it festered into a major stress, especially for those living in a small house, condominium, or apartment. The resilience of many families was tested as the exercise of freedoms collided with the fear of getting infected. Families were deprived of celebrating birthdays, weddings, funerals, graduation parties, retirement parties, Mother’s Day, Father’s Day, and various religious holidays, including Easter, Passover, and Eid al-Fitr.

Sexual burden. Intimacy and sexual contact between consenting adults living apart were sacrificed on the altar of the pernicious viral pandemic. Mandatory social distancing of 6 feet or more to avoid each other’s droplets emanating from simple speech, not just sneezing or coughing, makes intimacy practically impossible. Thus, physical closeness became taboo, and avoiding another person’s saliva or body secretions became a must to avoid contracting the virus. Being single was quite a lonely experience during this pandemic!

Entertainment deprivation. Americans are known to thrive on an extensive diet of spectator sports. Going to football, basketball, baseball, or hockey games to root for one’s team is intrinsically American. The pursuit of happiness extends to attending concerts, movies, Broadway shows, theme parks, and cruises with thousands of others. The pandemic ripped all those pleasurable leisure activities from our daily lives, leaving a big hole in people’s lives at the precise time fun activities were needed as a useful diversion from the dismal stress of a pandemic. To make things worse, it is uncertain when (if ever) such group activities will be restored, especially if the pandemic returns with another wave. But optimists would hurry to remind us that the “Roaring 20s” blossomed in the decade following the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic.

Continue to: Legal system

Legal system. Astounding changes were instigated by the pandemic, such as the release of thousands of inmates, including felons, to avoid the spread of the virus in crowded prisons. For us psychiatrists, the silver lining in that unexpected action is that many of those released were patients with mental illness who were incarcerated because of the lack of hospitals that would take them. The police started issuing citations instead of arresting and jailing violators. Enforcement of the law was welcome when it targeted those who gouged the public for personal profit during the scarcity of masks, sanitizers, or even toilet paper and soap.

Medical practice. In addition to delaying medical care for patients, the freeze on so-called elective surgeries or procedures (many of which were actually necessary) was financially ruinous for physicians. Another regrettable consequence of the pandemic is a drop in pediatric vaccinations because parents were reluctant to take their children to the pediatrician. On a more positive note, the massive switch to telehealth was advantageous for both patients and psychiatrists because this technology is well-suited for psychiatric care. Fortunately, regulations that hampered telepsychiatry practice were substantially loosened or eliminated, and even the usually sacrosanct HIPAA regulations were temporarily sidelined.

Medical research. Both human and animal research came to a screeching halt, and many research assistants were furloughed. Data collection was disrupted, and a generation of scientific and medical discoveries became a casualty of the pandemic.

Medical literature. It was stunning to see how quickly COVID-19 occupied most of the pages of prominent journals. The scholarly articles were frankly quite useful, covering topics ranging from risk factors to early symptoms to treatment and pathophysiology across multiple organs. As with other paradigm shifts, there was an accelerated publication push, sometimes with expedited peer reviews to inform health care workers and the public while the pandemic was still raging. However, a couple of very prominent journals had to retract flawed articles that were hastily published without the usual due diligence and rigorous peer review. The pandemic clearly disrupted the science publishing process.

Travel effects. The steep reduction of flights (by 98%) was financially catastrophic, not only for airline companies but to business travel across the country. However, fewer cars on the road resulted in fewer accidents and deaths, and also reduced pollution. Paradoxically, to prevent crowding in subways, trains, and buses, officials reversed their traditional instructions and advised the public to drive their own cars instead of using public transportation!

Continue to: Heroism of front-line medical personnel

Heroism of front-line medical personnel. Everyone saluted and prayed for the health care professionals working at the bedside of highly infectious patients who needed 24/7 intensive care. Many have died while carrying out the noble but hazardous medical duties. Those heroes deserve our lasting respect and admiration.

The COVID-19 pandemic insidiously permeated and altered every aspect of our complex society and revealed how fragile our “normal lifestyle” really is. It is possible that nothing will ever be the same again, and an uneasy sense of vulnerability will engulf us as we cautiously return to a “new normal.” Even our language has expanded with the lexicon of pandemic terminology (Table). We all pray and hope that this plague never returns. And let’s hope one or more vaccines are developed soon so we can manage future recurrences like the annual flu season. In the meantime, keep your masks and sanitizers close by…

Postscript: Shortly after I completed this editorial, the ongoing COVID-19 plague was overshadowed by the scourge of racism, with massive protests, at times laced by violence, triggered by the death of a black man in custody of the police, under condemnable circumstances. The COVID-19 pandemic and the necessary social distancing it requires were temporarily ignored during the ensuing protests. The combined effect of those overlapping scourges are jarring to the country’s psyche, complicating and perhaps sabotaging the social recovery from the pandemic.

New-onset psychosis while being treated for coronavirus

CASE Agitated, psychotic, and COVID-19–positive

Mr. G, age 56, is brought to the emergency department (ED) by emergency medical services (EMS) after his girlfriend reports that he was trying to climb into the “fiery furnace” to “burn the devil within him.” Mr. G had recently tested positive for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) via polymerase chain reaction and had been receiving treatment for it. In the ED, he is distressed and repeatedly exclaims, “The devil is alive!” He insists on covering himself with blankets, despite diaphoresis and soaking through his clothing within minutes. Because he does not respond to attempted redirection, the ED clinicians administer a single dose of IM haloperidol, 2 mg, for agitation.

HISTORY Multiple ED visits and hospitalizations

Mr. G, who has no known psychiatric history, lives with his girlfriend of 10 years. His medical history includes chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and prostate cancer. In 2015, he had a radical prostatectomy, without chemotherapy. His social history includes childhood neglect, which prompted him to leave home when he was a teenager. Mr. G had earned his general education development certificate and worked at a small retail store.

Mr. G had no previous history of mental health treatment per self-report, collateral information from his girlfriend, and chart review. He reported no known family psychiatric history. He did not endorse past psychiatric admissions or suicide attempts, nor previous periods of mania, depression, or psychosis. He said he used illicit substances as a teen, but denied using alcohol, tobacco products, or illicit substances in the past 20 years.

Mr. G recently had multiple ED visits and hospitalizations due to ongoing signs and symptoms associated with his COVID-19 diagnosis, primarily worsening shortness of breath and cough. Eleven days before EMS brought him to the ED at his girlfriend’s request, Mr. G had presented to the ED with chief complaints of shortness of breath and dry cough (Day 0). He reported that he had been “running a fever” for 2 days. In the ED, his initial vital signs were notable only for a temperature of 100.9°F (38.28°C). He was diagnosed with “acute viral syndrome” and received 1 dose of IV ceftriaxone, 2 g, and IV azithromycin, 500 mg. On Day 2, the ED clinicians prescribed a 4-day course of oral azithromycin, 250 mg/d, and discharged him home.

On Day 3, Mr. G returned to the ED with similar complaints—congestion and productive cough. He tested positive for COVID-19, and the ED discharged him home with quarantine instructions. Hours later, he returned to the ED via EMS with chief complaints of chest pain, diarrhea, and myalgias. He was prescribed a 5-day course ofoseltamivir, 75 mg twice daily, and azithromycin, 250 mg/d. The ED again discharged him home.

On Day 4, Mr. G returned to the ED for a fourth time. His chief complaint was worsening shortness of breath. His oxygen saturation was 94% on room air; it improved to 96% on 2 L of oxygen. His chest X-ray showed diffuse reticulonodular opacities throughout his bilateral lung fields and increased airspace opacification in the bilateral lower lobes. The ED admitted Mr. G to an internal medicine unit, where the primary treatment team enrolled him in a clinical trial. As part of the trial, Mr. G received hydroxychloroquine, 400 mg, on Day 4 and Day 5. The placebo-controlled component of the trial involved Mr. G receiving daily infusions of either remdesivir or placebo on Day 6 through Day 8. On Day 8, Mr. G was discharged home.

On Day 9, Mr. G returned to the ED with a chief complaint that his “thermometer wasn’t working” at home. The ED readmitted him to the internal medicine unit. On Day 9 through Day 11, Mr. G received daily doses of

Continue to: During the second hospitalization...

During the second hospitalization, nursing staff reported that Mr. G seemed religiously preoccupied and once reported seeing angels and demons. He was observed sitting in a chair praying to Allah that he would “come in on a horse to chop all the workers’ heads off.”

On Day 11, Mr. G was discharged home. Later that evening, the EMS brought him back in the ED due to his girlfriend’s concerns about his mental state.

EVALUATION Talks to God

On Day 12, psychiatry is consulted to evaluate Mr. G’s new-onset psychosis. Mr. G is alert and oriented to person, place, and time. His speech is loud, though the amount and rate are unremarkable. He displays no psychomotor agitation. His thought process is tangential and focuses on religious themes, specifically referring to Islam. He reports auditory hallucinations of God speaking directly to him. Mr. G states, “I am here because of a miraculous transformation from death back to life. Do you believe in God? Which God do you believe in? There are 2 Gods and only one of them is the true God. He is the God of all the 7 heavens and His true name is Allah, only one God, one faith. Allah is a ball of energy.”