User login

HIV increases risk for severe COVID-19

according to a report from the World Health Organization on COVID-19 outcomes among people living with HIV. The study primarily included people from South Africa but also some data from other parts of the world, including the United States.

However, the report, presented at the 11th IAS Conference on HIV Science (IAS 2021), couldn’t answer some crucial questions clinicians have been wondering about since the COVID-19 pandemic began. For example, was the increase in COVID risk a result of the presence of HIV or because of the immune compromise caused by untreated HIV?

The report didn’t include data on viral load or CD counts, both used to evaluate the health of a person’s immune system. On effective treatment, people living with HIV have a lifespan close to their HIV-negative peers. And effective treatment causes undetectable viral loads which, when maintained for 6 months or more, eliminates transmission of HIV to sexual partners.

What’s clear is that in people with HIV, as in people without HIV, older people, men, and people with diabetes, hypertension, or obesity had the worst outcomes and were most likely to die from COVID-19.

For David Malebranche, MD, MPH, an internal medicine doctor who provides primary care for people in Atlanta, and who was not involved in the study, the WHO study didn’t add anything new. He already recommends the COVID-19 vaccine for all of his patients, HIV-positive or not.

“We don’t have any information from this about the T-cell counts [or] the rates of viral suppression, which I think is tremendously important,” he told this news organization. “To bypass that and not include that in any of the discussion puts the results in a questionable place for me.”

The results come from the WHO Clinical Platform, which culls data from WHO member country surveillance as well as manual case reports from all over the world. By April 29, data on 268,412 people hospitalized with COVID-19 from 37 countries were reported to the platform. Of those, 22,640 people are from the U.S.

A total of 15,522 participants worldwide were living with HIV, 664 in the United States. All U.S. cases were reported from the New York City Health and Hospitals system, Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, and BronxCare Health System in New York City. Almost all of the remaining participants lived in South Africa – 14,682 of the 15,522, or 94.5%.

Of the 15,522 people living with HIV in the overall group, 37.1% of participants were male, and their median age was 45 years. More than 1 in 3 (36.2%) were admitted with severe or critical COVID-19, and nearly one quarter – 23.1% – with a known outcome died. More than half had one or more chronic conditions, including those that themselves are associated with worse COVID-19 outcomes, such as hypertension (in 33.2% of the participants), diabetes (22.7%), and BMIs above 30 (16.9%). In addition, 8.9% were smokers, 6.6% had chronic pulmonary disease, and 4.3% had chronic heart disease.

After adjusting for those chronic conditions, age, and sex, people living with HIV had a 6% higher rate of severe or critical COVID-19 illness. When investigators adjusted the analysis additionally to differentiate outcomes based on not just the presence of comorbid conditions but the number of them a person had, that increased risk rose to 13%. HIV itself is a comorbid condition, though it wasn’t counted as one in this adjusted analysis.

It didn’t matter whether researchers looked at risk for severe outcomes or deaths after removing the significant co-occurring conditions or if they looked at number of chronic illnesses (aside from HIV), said Silvia Bertagnolio, MD, medical officer at the World Health Organization and co-author of the analysis.

“Both models show almost identical [adjusted odds ratios], meaning that HIV was independently significantly associated with severe/critical presentation,” she told this news organization.

As for death, the analysis showed that, overall, people living with HIV were 30% more likely to die of COVID-19 compared with those not living with HIV. And while this held true even when they adjusted the data for comorbidities, people with HIV were more likely to die if they were over age 65 (risk increased by 82%), male (risk increased by 21%), had diabetes (risk increased by 50%), or had hypertension (risk increased by 26%).

When they broke down the data by WHO region – Africa, Europe, the Americas – investigators found that the increased risk for death held true in Africa. But there were not enough data from the other regions to model mortality risk. What’s more, when they broke the data down by country and excluded South Africa, they found that the elevated risk for death in people living with HIV did not reach statistical significance. Dr. Bertagnolio said she suspects that the small sample sizes from other regions made it impossible to detect a difference, but one could still be present.

One thing conspicuously absent from the analysis was information on viral load, CD4 T-cell count, progression of HIV to AIDS, and whether individuals were in HIV care. The first three factors were not reported in the platform, and the fourth was available for 60% of participants but was not included in the analysis. Dr. Bertagnolio pointed out that, for those 60% of participants, 91.8% were on antiretroviral treatment (ART).

“The majority of patients come from South Africa, and we know that in South Africa, over 90% of people receiving ART are virologically suppressed,” she told this news organization. “So we could speculate that this effect persists despite the use of ART, in a population likely to be virally suppressed, although we cannot assess this with certainty through the data set we had.”

A much smaller study of 749 people living with HIV and diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2, also presented at the conference, found that detectable HIV viral load was significantly associated with a slightly higher risk of severe outcomes (P < .039), but CD4 counts less than 200 cells/mm3 was not (P = .15).

And although both Dr. Bertagnolio and conference organizers presented this data as proof that HIV increases the risk for poor COVID-19 outcomes, Dr. Malebranche isn’t so sure. He estimates that only about half his patients have received the COVID-19 vaccine. But this study is unlikely to make him forcefully recommend a COVID-19 vaccination with young, otherwise healthy, and undetectable people in his care who express particular concern about long-term effects of the vaccine. He also manages a lot of people with HIV who have undetectable viral loads and CD4 counts of up to 1,200 but are older, with diabetes, obesity, and high blood pressure. Those are the people he will target with stronger messages regarding the vaccine.

“The young patients who are healthy, virally suppressed, and doing well may very much argue with me, ‘I’m not going to push it,’ but I will bring it up on the next visit,” he said. The analysis “just helps reinforce in me that I need to have these conversations and be a little bit more persuasive to my older patients with comorbid conditions.”

Dr. Bertagnolio has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Malebranche serves on the pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) speakers bureau for Gilead Sciences and has consulted and advised for ViiV Healthcare. This study was funded by the World Health Organization.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a report from the World Health Organization on COVID-19 outcomes among people living with HIV. The study primarily included people from South Africa but also some data from other parts of the world, including the United States.

However, the report, presented at the 11th IAS Conference on HIV Science (IAS 2021), couldn’t answer some crucial questions clinicians have been wondering about since the COVID-19 pandemic began. For example, was the increase in COVID risk a result of the presence of HIV or because of the immune compromise caused by untreated HIV?

The report didn’t include data on viral load or CD counts, both used to evaluate the health of a person’s immune system. On effective treatment, people living with HIV have a lifespan close to their HIV-negative peers. And effective treatment causes undetectable viral loads which, when maintained for 6 months or more, eliminates transmission of HIV to sexual partners.

What’s clear is that in people with HIV, as in people without HIV, older people, men, and people with diabetes, hypertension, or obesity had the worst outcomes and were most likely to die from COVID-19.

For David Malebranche, MD, MPH, an internal medicine doctor who provides primary care for people in Atlanta, and who was not involved in the study, the WHO study didn’t add anything new. He already recommends the COVID-19 vaccine for all of his patients, HIV-positive or not.

“We don’t have any information from this about the T-cell counts [or] the rates of viral suppression, which I think is tremendously important,” he told this news organization. “To bypass that and not include that in any of the discussion puts the results in a questionable place for me.”

The results come from the WHO Clinical Platform, which culls data from WHO member country surveillance as well as manual case reports from all over the world. By April 29, data on 268,412 people hospitalized with COVID-19 from 37 countries were reported to the platform. Of those, 22,640 people are from the U.S.

A total of 15,522 participants worldwide were living with HIV, 664 in the United States. All U.S. cases were reported from the New York City Health and Hospitals system, Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, and BronxCare Health System in New York City. Almost all of the remaining participants lived in South Africa – 14,682 of the 15,522, or 94.5%.

Of the 15,522 people living with HIV in the overall group, 37.1% of participants were male, and their median age was 45 years. More than 1 in 3 (36.2%) were admitted with severe or critical COVID-19, and nearly one quarter – 23.1% – with a known outcome died. More than half had one or more chronic conditions, including those that themselves are associated with worse COVID-19 outcomes, such as hypertension (in 33.2% of the participants), diabetes (22.7%), and BMIs above 30 (16.9%). In addition, 8.9% were smokers, 6.6% had chronic pulmonary disease, and 4.3% had chronic heart disease.

After adjusting for those chronic conditions, age, and sex, people living with HIV had a 6% higher rate of severe or critical COVID-19 illness. When investigators adjusted the analysis additionally to differentiate outcomes based on not just the presence of comorbid conditions but the number of them a person had, that increased risk rose to 13%. HIV itself is a comorbid condition, though it wasn’t counted as one in this adjusted analysis.

It didn’t matter whether researchers looked at risk for severe outcomes or deaths after removing the significant co-occurring conditions or if they looked at number of chronic illnesses (aside from HIV), said Silvia Bertagnolio, MD, medical officer at the World Health Organization and co-author of the analysis.

“Both models show almost identical [adjusted odds ratios], meaning that HIV was independently significantly associated with severe/critical presentation,” she told this news organization.

As for death, the analysis showed that, overall, people living with HIV were 30% more likely to die of COVID-19 compared with those not living with HIV. And while this held true even when they adjusted the data for comorbidities, people with HIV were more likely to die if they were over age 65 (risk increased by 82%), male (risk increased by 21%), had diabetes (risk increased by 50%), or had hypertension (risk increased by 26%).

When they broke down the data by WHO region – Africa, Europe, the Americas – investigators found that the increased risk for death held true in Africa. But there were not enough data from the other regions to model mortality risk. What’s more, when they broke the data down by country and excluded South Africa, they found that the elevated risk for death in people living with HIV did not reach statistical significance. Dr. Bertagnolio said she suspects that the small sample sizes from other regions made it impossible to detect a difference, but one could still be present.

One thing conspicuously absent from the analysis was information on viral load, CD4 T-cell count, progression of HIV to AIDS, and whether individuals were in HIV care. The first three factors were not reported in the platform, and the fourth was available for 60% of participants but was not included in the analysis. Dr. Bertagnolio pointed out that, for those 60% of participants, 91.8% were on antiretroviral treatment (ART).

“The majority of patients come from South Africa, and we know that in South Africa, over 90% of people receiving ART are virologically suppressed,” she told this news organization. “So we could speculate that this effect persists despite the use of ART, in a population likely to be virally suppressed, although we cannot assess this with certainty through the data set we had.”

A much smaller study of 749 people living with HIV and diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2, also presented at the conference, found that detectable HIV viral load was significantly associated with a slightly higher risk of severe outcomes (P < .039), but CD4 counts less than 200 cells/mm3 was not (P = .15).

And although both Dr. Bertagnolio and conference organizers presented this data as proof that HIV increases the risk for poor COVID-19 outcomes, Dr. Malebranche isn’t so sure. He estimates that only about half his patients have received the COVID-19 vaccine. But this study is unlikely to make him forcefully recommend a COVID-19 vaccination with young, otherwise healthy, and undetectable people in his care who express particular concern about long-term effects of the vaccine. He also manages a lot of people with HIV who have undetectable viral loads and CD4 counts of up to 1,200 but are older, with diabetes, obesity, and high blood pressure. Those are the people he will target with stronger messages regarding the vaccine.

“The young patients who are healthy, virally suppressed, and doing well may very much argue with me, ‘I’m not going to push it,’ but I will bring it up on the next visit,” he said. The analysis “just helps reinforce in me that I need to have these conversations and be a little bit more persuasive to my older patients with comorbid conditions.”

Dr. Bertagnolio has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Malebranche serves on the pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) speakers bureau for Gilead Sciences and has consulted and advised for ViiV Healthcare. This study was funded by the World Health Organization.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a report from the World Health Organization on COVID-19 outcomes among people living with HIV. The study primarily included people from South Africa but also some data from other parts of the world, including the United States.

However, the report, presented at the 11th IAS Conference on HIV Science (IAS 2021), couldn’t answer some crucial questions clinicians have been wondering about since the COVID-19 pandemic began. For example, was the increase in COVID risk a result of the presence of HIV or because of the immune compromise caused by untreated HIV?

The report didn’t include data on viral load or CD counts, both used to evaluate the health of a person’s immune system. On effective treatment, people living with HIV have a lifespan close to their HIV-negative peers. And effective treatment causes undetectable viral loads which, when maintained for 6 months or more, eliminates transmission of HIV to sexual partners.

What’s clear is that in people with HIV, as in people without HIV, older people, men, and people with diabetes, hypertension, or obesity had the worst outcomes and were most likely to die from COVID-19.

For David Malebranche, MD, MPH, an internal medicine doctor who provides primary care for people in Atlanta, and who was not involved in the study, the WHO study didn’t add anything new. He already recommends the COVID-19 vaccine for all of his patients, HIV-positive or not.

“We don’t have any information from this about the T-cell counts [or] the rates of viral suppression, which I think is tremendously important,” he told this news organization. “To bypass that and not include that in any of the discussion puts the results in a questionable place for me.”

The results come from the WHO Clinical Platform, which culls data from WHO member country surveillance as well as manual case reports from all over the world. By April 29, data on 268,412 people hospitalized with COVID-19 from 37 countries were reported to the platform. Of those, 22,640 people are from the U.S.

A total of 15,522 participants worldwide were living with HIV, 664 in the United States. All U.S. cases were reported from the New York City Health and Hospitals system, Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, and BronxCare Health System in New York City. Almost all of the remaining participants lived in South Africa – 14,682 of the 15,522, or 94.5%.

Of the 15,522 people living with HIV in the overall group, 37.1% of participants were male, and their median age was 45 years. More than 1 in 3 (36.2%) were admitted with severe or critical COVID-19, and nearly one quarter – 23.1% – with a known outcome died. More than half had one or more chronic conditions, including those that themselves are associated with worse COVID-19 outcomes, such as hypertension (in 33.2% of the participants), diabetes (22.7%), and BMIs above 30 (16.9%). In addition, 8.9% were smokers, 6.6% had chronic pulmonary disease, and 4.3% had chronic heart disease.

After adjusting for those chronic conditions, age, and sex, people living with HIV had a 6% higher rate of severe or critical COVID-19 illness. When investigators adjusted the analysis additionally to differentiate outcomes based on not just the presence of comorbid conditions but the number of them a person had, that increased risk rose to 13%. HIV itself is a comorbid condition, though it wasn’t counted as one in this adjusted analysis.

It didn’t matter whether researchers looked at risk for severe outcomes or deaths after removing the significant co-occurring conditions or if they looked at number of chronic illnesses (aside from HIV), said Silvia Bertagnolio, MD, medical officer at the World Health Organization and co-author of the analysis.

“Both models show almost identical [adjusted odds ratios], meaning that HIV was independently significantly associated with severe/critical presentation,” she told this news organization.

As for death, the analysis showed that, overall, people living with HIV were 30% more likely to die of COVID-19 compared with those not living with HIV. And while this held true even when they adjusted the data for comorbidities, people with HIV were more likely to die if they were over age 65 (risk increased by 82%), male (risk increased by 21%), had diabetes (risk increased by 50%), or had hypertension (risk increased by 26%).

When they broke down the data by WHO region – Africa, Europe, the Americas – investigators found that the increased risk for death held true in Africa. But there were not enough data from the other regions to model mortality risk. What’s more, when they broke the data down by country and excluded South Africa, they found that the elevated risk for death in people living with HIV did not reach statistical significance. Dr. Bertagnolio said she suspects that the small sample sizes from other regions made it impossible to detect a difference, but one could still be present.

One thing conspicuously absent from the analysis was information on viral load, CD4 T-cell count, progression of HIV to AIDS, and whether individuals were in HIV care. The first three factors were not reported in the platform, and the fourth was available for 60% of participants but was not included in the analysis. Dr. Bertagnolio pointed out that, for those 60% of participants, 91.8% were on antiretroviral treatment (ART).

“The majority of patients come from South Africa, and we know that in South Africa, over 90% of people receiving ART are virologically suppressed,” she told this news organization. “So we could speculate that this effect persists despite the use of ART, in a population likely to be virally suppressed, although we cannot assess this with certainty through the data set we had.”

A much smaller study of 749 people living with HIV and diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2, also presented at the conference, found that detectable HIV viral load was significantly associated with a slightly higher risk of severe outcomes (P < .039), but CD4 counts less than 200 cells/mm3 was not (P = .15).

And although both Dr. Bertagnolio and conference organizers presented this data as proof that HIV increases the risk for poor COVID-19 outcomes, Dr. Malebranche isn’t so sure. He estimates that only about half his patients have received the COVID-19 vaccine. But this study is unlikely to make him forcefully recommend a COVID-19 vaccination with young, otherwise healthy, and undetectable people in his care who express particular concern about long-term effects of the vaccine. He also manages a lot of people with HIV who have undetectable viral loads and CD4 counts of up to 1,200 but are older, with diabetes, obesity, and high blood pressure. Those are the people he will target with stronger messages regarding the vaccine.

“The young patients who are healthy, virally suppressed, and doing well may very much argue with me, ‘I’m not going to push it,’ but I will bring it up on the next visit,” he said. The analysis “just helps reinforce in me that I need to have these conversations and be a little bit more persuasive to my older patients with comorbid conditions.”

Dr. Bertagnolio has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Malebranche serves on the pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) speakers bureau for Gilead Sciences and has consulted and advised for ViiV Healthcare. This study was funded by the World Health Organization.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pharmacologic and electrical cardioversion of acute Afib reduces hospital admissions

Background: Atrial fibrillation (Afib) is the most common arrhythmia requiring treatment in the ED. There is a paucity of literature regarding the management of acute (onset < 48 h) atrial fibrillation in this setting and no conclusive evidence exists regarding the superiority of pharmacologic vs. electrical cardioversion.

Study design: Multicenter, single-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: 11 Canadian academic medical centers.

Synopsis: In this trial of 396 patients with acute Afib, half were randomly assigned to pharmacologic cardioversion with procainamide infusion (followed by DC cardioversion, if unsuccessful), while half were given a placebo infusion then DC cardioversion. The primary outcome was conversion to sinus rhythm, with maintenance of sinus rhythm at 30 minutes. A secondary protocol evaluated the difference in efficacy between anterolateral (AL) and anteroposterior (AP) pad placement

The “drug-shock” group achieved and maintained sinus rhythm in 96% of cases, compared to 92% in the “placebo-shock” group (statistically insignificant difference). The procainamide infusion alone achieved and maintained sinus rhythm in 52% of recipients, who thereby avoided the need for procedural sedation and monitoring. Notably, only 2% of patients in the study required admission to the hospital. Pad placement was equally efficacious in the AL or AP positions. The most common adverse event observed was transient hypotension during infusion of procainamide. No strokes were observed in either arm. Follow-up ECGs obtained 14 days later showed that 95% of patients remained in sinus rhythm.

Bottom line: Pharmacologic cardioversion with procainamide infusion and/or electrical cardioversion is a safe and efficacious initial management strategy for acute atrial fibrillation, and all but eliminates the need for hospital admission.

Citation: Stiell IG et al. Electrical versus pharmacological cardioversion for emergency department patients with acute atrial fibrillation (RAFF2): a partial factorial randomized trial. Lancet. 2020 Feb 1;395(10221):339-49.

Dr. Lawson is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Atrial fibrillation (Afib) is the most common arrhythmia requiring treatment in the ED. There is a paucity of literature regarding the management of acute (onset < 48 h) atrial fibrillation in this setting and no conclusive evidence exists regarding the superiority of pharmacologic vs. electrical cardioversion.

Study design: Multicenter, single-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: 11 Canadian academic medical centers.

Synopsis: In this trial of 396 patients with acute Afib, half were randomly assigned to pharmacologic cardioversion with procainamide infusion (followed by DC cardioversion, if unsuccessful), while half were given a placebo infusion then DC cardioversion. The primary outcome was conversion to sinus rhythm, with maintenance of sinus rhythm at 30 minutes. A secondary protocol evaluated the difference in efficacy between anterolateral (AL) and anteroposterior (AP) pad placement

The “drug-shock” group achieved and maintained sinus rhythm in 96% of cases, compared to 92% in the “placebo-shock” group (statistically insignificant difference). The procainamide infusion alone achieved and maintained sinus rhythm in 52% of recipients, who thereby avoided the need for procedural sedation and monitoring. Notably, only 2% of patients in the study required admission to the hospital. Pad placement was equally efficacious in the AL or AP positions. The most common adverse event observed was transient hypotension during infusion of procainamide. No strokes were observed in either arm. Follow-up ECGs obtained 14 days later showed that 95% of patients remained in sinus rhythm.

Bottom line: Pharmacologic cardioversion with procainamide infusion and/or electrical cardioversion is a safe and efficacious initial management strategy for acute atrial fibrillation, and all but eliminates the need for hospital admission.

Citation: Stiell IG et al. Electrical versus pharmacological cardioversion for emergency department patients with acute atrial fibrillation (RAFF2): a partial factorial randomized trial. Lancet. 2020 Feb 1;395(10221):339-49.

Dr. Lawson is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Atrial fibrillation (Afib) is the most common arrhythmia requiring treatment in the ED. There is a paucity of literature regarding the management of acute (onset < 48 h) atrial fibrillation in this setting and no conclusive evidence exists regarding the superiority of pharmacologic vs. electrical cardioversion.

Study design: Multicenter, single-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: 11 Canadian academic medical centers.

Synopsis: In this trial of 396 patients with acute Afib, half were randomly assigned to pharmacologic cardioversion with procainamide infusion (followed by DC cardioversion, if unsuccessful), while half were given a placebo infusion then DC cardioversion. The primary outcome was conversion to sinus rhythm, with maintenance of sinus rhythm at 30 minutes. A secondary protocol evaluated the difference in efficacy between anterolateral (AL) and anteroposterior (AP) pad placement

The “drug-shock” group achieved and maintained sinus rhythm in 96% of cases, compared to 92% in the “placebo-shock” group (statistically insignificant difference). The procainamide infusion alone achieved and maintained sinus rhythm in 52% of recipients, who thereby avoided the need for procedural sedation and monitoring. Notably, only 2% of patients in the study required admission to the hospital. Pad placement was equally efficacious in the AL or AP positions. The most common adverse event observed was transient hypotension during infusion of procainamide. No strokes were observed in either arm. Follow-up ECGs obtained 14 days later showed that 95% of patients remained in sinus rhythm.

Bottom line: Pharmacologic cardioversion with procainamide infusion and/or electrical cardioversion is a safe and efficacious initial management strategy for acute atrial fibrillation, and all but eliminates the need for hospital admission.

Citation: Stiell IG et al. Electrical versus pharmacological cardioversion for emergency department patients with acute atrial fibrillation (RAFF2): a partial factorial randomized trial. Lancet. 2020 Feb 1;395(10221):339-49.

Dr. Lawson is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Long COVID seen in patients with severe and mild disease

Findings from the cohort, composed of 113 COVID-19 survivors who developed ARDS after admission to a single center before to April 16, 2020, were presented online at the 31st European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases by Judit Aranda, MD, from Complex Hospitalari Moisés Broggi in Barcelona.

Median age of the participants was 64 years, and 70% were male. At least one persistent symptom was experienced during follow-up by 81% of the cohort, with 45% reporting shortness of breath, 50% reporting muscle pain, 43% reporting memory impairment, and 46% reporting physical weakness of at least 5 on a 10-point scale.

Of the 104 participants who completed a 6-minute walk test, 30% had a decrease in oxygen saturation level of at least 4%, and 5% had an initial or final level below 88%. Of the 46 participants who underwent a pulmonary function test, 15% had a forced expiratory volume in 1 second below 70%.

And of the 49% of participants with pathologic findings on chest x-ray, most were bilateral interstitial infiltrates (88%).

In addition, more than 90% of participants developed depression, anxiety, or PTSD, Dr. Aranda reported.

Not the whole picture

This study shows that sicker people – “those in intensive care units with acute respiratory distress syndrome” – are “more likely to be struggling with more severe symptoms,” said Christopher Terndrup, MD, from the division of general internal medicine and geriatrics at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

But a Swiss study, also presented at the meeting, “shows how even mild COVID cases can lead to debilitating symptoms,” Dr. Terndrup said in an interview.

The investigation of long-term COVID symptoms in outpatients was presented online by Florian Desgranges, MD, from Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital. He and his colleagues found that more than half of those with a mild to moderate disease had persistent symptoms at least 3 months after diagnosis.

The prevalence of long COVID has varied in previous research, from 15% in a study of health care workers, to 46% in a study of patients with mild COVID, 52% in a study of young COVID outpatients, and 76% in a study of patients hospitalized with COVID.

Dr. Desgranges and colleagues evaluated patients seen in an ED or outpatient clinic from February to April 2020.

The 418 patients with a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis were compared with a control group of 89 patients who presented to the same centers during the same time frame with similar symptoms – cough, shortness of breath, or fever – but had a negative SARS-CoV-2 test.

The number of patients with comorbidities was similar in the COVID and control groups (34% vs. 36%), as was median age (41 vs. 36 years) and the prevalence of women (62% vs 64%), but the proportion of health care workers was lower in the COVID group (64% vs 82%; P =.006).

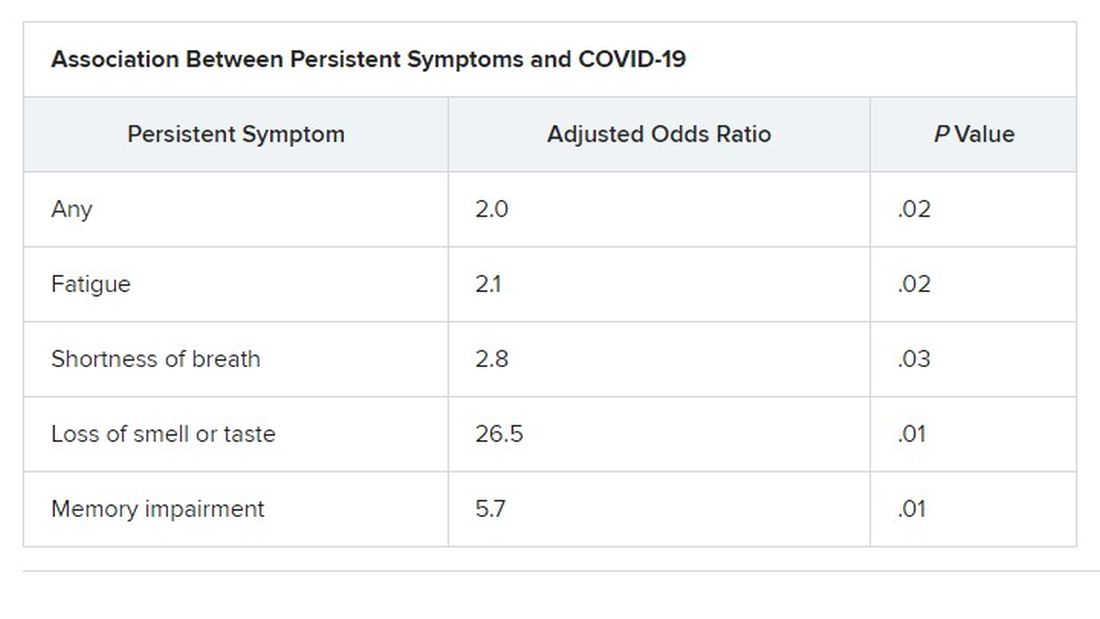

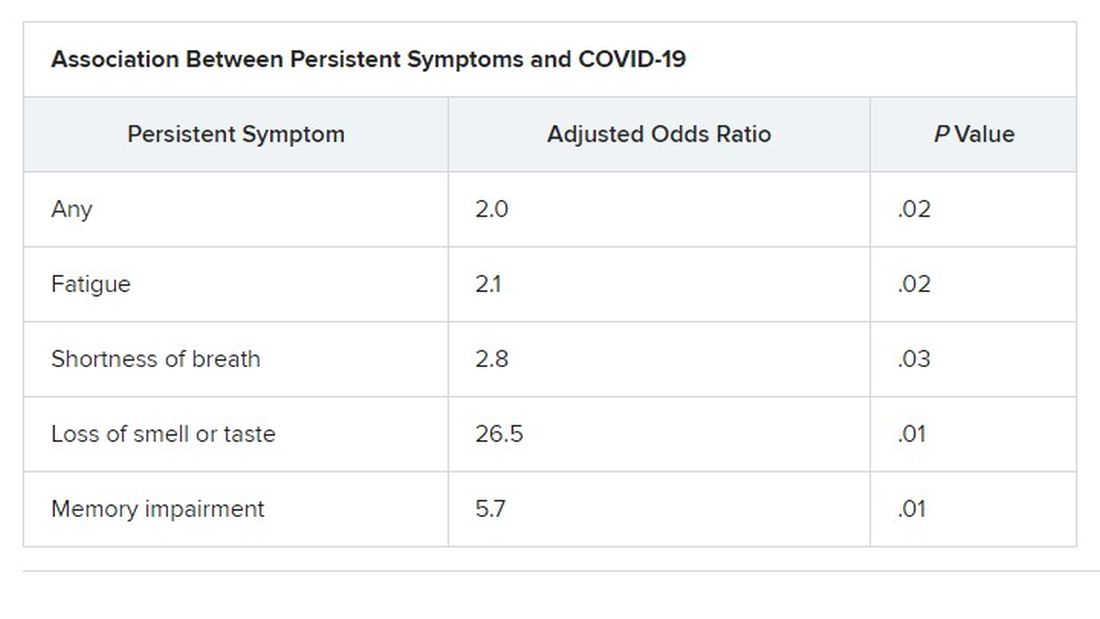

Symptoms that persisted for at least 3 months were more common in the COVID than in the control group (53% vs. 37%). And patients in the COVID group reported more symptoms than those in the control group after adjustment for age, gender, smoking status, comorbidities, and timing of the survey phone call.

Levels of sleeping problems and headache were similar in the two groups.

“We have to remember that with COVID-19 came the psychosocial changes of the pandemic situation” Dr. Desgranges said.

This study suggests that some long-COVID symptoms – such as the fatigue, headache, and sleep disorders reported in the control group – could be related to the pandemic itself, which has caused psychosocial distress, Dr. Terndrup said.

Another study that looked at outpatients “has some fantastic long-term follow-up data, and shows that many patients are still engaging in rehabilitation programs nearly a year after their diagnosis,” he explained.

The COVID HOME study

That prospective longitudinal COVID HOME study, which assessed long-term symptoms in people who were never hospitalized for COVID, was presented online by Adriana Tami, MD, PhD, from the University Medical Center Groningen (the Netherlands).

The researchers visited the homes of patients to collect data, blood samples, and perform polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing 1, 2, and 3 weeks after a diagnosis of COVID-19. If their PCR test was still positive, testing continued until week 6 or a negative test. In addition, participants completed questionnaires at week 2 and at months 3, 6 and 12 to assess fatigue, quality of life, and symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Three-month follow-up data were available for 134 of the 276 people initially enrolled in the study. Questionnaires were completed by 85 participants at 3 months, 62 participants at 6 months, and 10 participants at 12 months.

At least 40% of participants reported long-lasting symptoms at some point during follow-up, and at least 30% said they didn’t feel fully recovered at 12 months. The most common symptom was persistent fatigue, reported at 3, 6, and 12 months by at least 44% of participants. Other common symptoms – reported by at least 20% of respondents at 3, 6, and 12 months – were headache, mental or neurologic symptoms, and sleep disorders, shortness of breath, lack of smell or taste, and severe fatigue.

“We have a high proportion of nonhospitalized individuals who suffer from long COVID after more than 12 months,” Dr. Tami concluded, adding that the study is ongoing. “We have other variables that we want to look at, including duration viral shedding and serological results and variants.”

“These cohort studies are very helpful, but they can lead to inaccurate conclusions,” Dr. Terndrup cautioned.

They only provide pieces of the big picture, but they “do add to a growing body of knowledge about a significant portion of COVID patients still struggling with symptoms long after their initial infection. The symptoms can be quite variable but are dominated by both physical and mental fatigue, and tend to be worse in patients who were sicker at initial infection,” he said in an interview.

As a whole, these studies reinforce the need for treatment programs to help patients who suffer from long COVID, he added, but “I advise caution to folks suffering out there who seek ‘miracle cures’; across the world, we are collaborating to find solutions that are safe and effective.”

We are in desperate need of an equity lens in these studies.

“There is still a great deal to learn about long COVID,” said Dr. Terndrup. Data on underrepresented populations – such as Black, Indigenous, and people of color – are lacking from these and others studies, he explained. “We are in desperate need of an equity lens in these studies,” particularly in the United States, where there are “significant disparities” in the treatment of different populations.

However, “I do hope that this work can lead to a better understanding of how other viral infections can cause long-lasting symptoms,” said Dr. Terndrup.

“We have long proposed that after acute presentation, some microbes can cause chronic symptoms, like fatigue and widespread pain. Perhaps we can learn how to better care for these patients after learning from COVID’s significant impact on our societies across the globe.”

Dr. Aranda and Dr. Desgranges have disclosed no relevant financial relationships or study funding. The study by Dr. Tami’s team was funded by the University Medical Center Groningen Organization for Health Research and Development, and Connecting European Cohorts to Increase Common and Effective Response to SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Dr. Terndrup disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Findings from the cohort, composed of 113 COVID-19 survivors who developed ARDS after admission to a single center before to April 16, 2020, were presented online at the 31st European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases by Judit Aranda, MD, from Complex Hospitalari Moisés Broggi in Barcelona.

Median age of the participants was 64 years, and 70% were male. At least one persistent symptom was experienced during follow-up by 81% of the cohort, with 45% reporting shortness of breath, 50% reporting muscle pain, 43% reporting memory impairment, and 46% reporting physical weakness of at least 5 on a 10-point scale.

Of the 104 participants who completed a 6-minute walk test, 30% had a decrease in oxygen saturation level of at least 4%, and 5% had an initial or final level below 88%. Of the 46 participants who underwent a pulmonary function test, 15% had a forced expiratory volume in 1 second below 70%.

And of the 49% of participants with pathologic findings on chest x-ray, most were bilateral interstitial infiltrates (88%).

In addition, more than 90% of participants developed depression, anxiety, or PTSD, Dr. Aranda reported.

Not the whole picture

This study shows that sicker people – “those in intensive care units with acute respiratory distress syndrome” – are “more likely to be struggling with more severe symptoms,” said Christopher Terndrup, MD, from the division of general internal medicine and geriatrics at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

But a Swiss study, also presented at the meeting, “shows how even mild COVID cases can lead to debilitating symptoms,” Dr. Terndrup said in an interview.

The investigation of long-term COVID symptoms in outpatients was presented online by Florian Desgranges, MD, from Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital. He and his colleagues found that more than half of those with a mild to moderate disease had persistent symptoms at least 3 months after diagnosis.

The prevalence of long COVID has varied in previous research, from 15% in a study of health care workers, to 46% in a study of patients with mild COVID, 52% in a study of young COVID outpatients, and 76% in a study of patients hospitalized with COVID.

Dr. Desgranges and colleagues evaluated patients seen in an ED or outpatient clinic from February to April 2020.

The 418 patients with a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis were compared with a control group of 89 patients who presented to the same centers during the same time frame with similar symptoms – cough, shortness of breath, or fever – but had a negative SARS-CoV-2 test.

The number of patients with comorbidities was similar in the COVID and control groups (34% vs. 36%), as was median age (41 vs. 36 years) and the prevalence of women (62% vs 64%), but the proportion of health care workers was lower in the COVID group (64% vs 82%; P =.006).

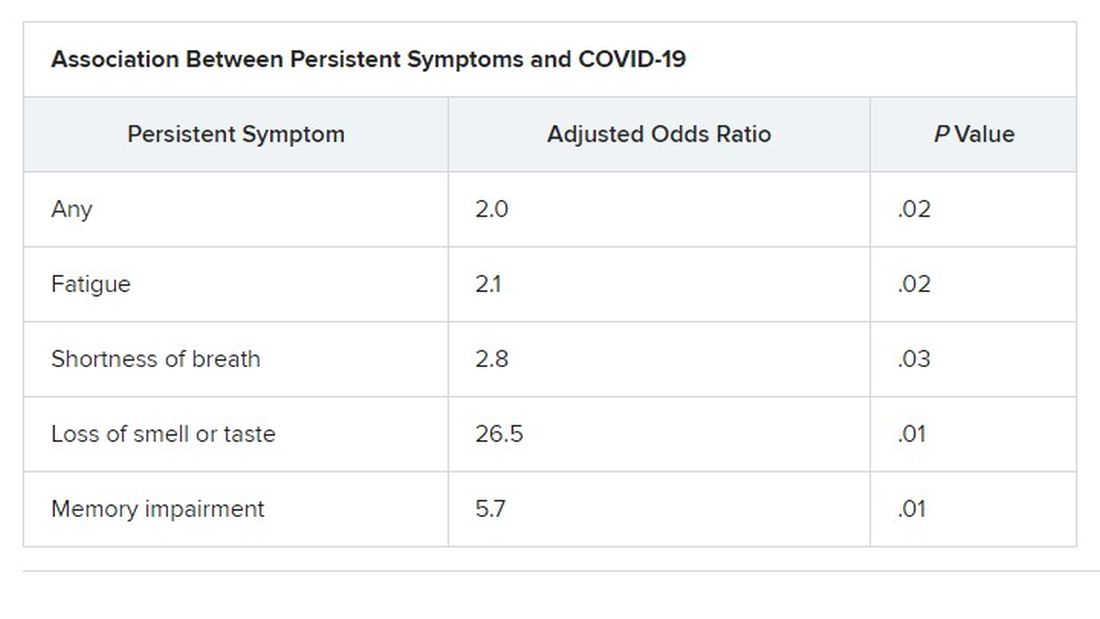

Symptoms that persisted for at least 3 months were more common in the COVID than in the control group (53% vs. 37%). And patients in the COVID group reported more symptoms than those in the control group after adjustment for age, gender, smoking status, comorbidities, and timing of the survey phone call.

Levels of sleeping problems and headache were similar in the two groups.

“We have to remember that with COVID-19 came the psychosocial changes of the pandemic situation” Dr. Desgranges said.

This study suggests that some long-COVID symptoms – such as the fatigue, headache, and sleep disorders reported in the control group – could be related to the pandemic itself, which has caused psychosocial distress, Dr. Terndrup said.

Another study that looked at outpatients “has some fantastic long-term follow-up data, and shows that many patients are still engaging in rehabilitation programs nearly a year after their diagnosis,” he explained.

The COVID HOME study

That prospective longitudinal COVID HOME study, which assessed long-term symptoms in people who were never hospitalized for COVID, was presented online by Adriana Tami, MD, PhD, from the University Medical Center Groningen (the Netherlands).

The researchers visited the homes of patients to collect data, blood samples, and perform polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing 1, 2, and 3 weeks after a diagnosis of COVID-19. If their PCR test was still positive, testing continued until week 6 or a negative test. In addition, participants completed questionnaires at week 2 and at months 3, 6 and 12 to assess fatigue, quality of life, and symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Three-month follow-up data were available for 134 of the 276 people initially enrolled in the study. Questionnaires were completed by 85 participants at 3 months, 62 participants at 6 months, and 10 participants at 12 months.

At least 40% of participants reported long-lasting symptoms at some point during follow-up, and at least 30% said they didn’t feel fully recovered at 12 months. The most common symptom was persistent fatigue, reported at 3, 6, and 12 months by at least 44% of participants. Other common symptoms – reported by at least 20% of respondents at 3, 6, and 12 months – were headache, mental or neurologic symptoms, and sleep disorders, shortness of breath, lack of smell or taste, and severe fatigue.

“We have a high proportion of nonhospitalized individuals who suffer from long COVID after more than 12 months,” Dr. Tami concluded, adding that the study is ongoing. “We have other variables that we want to look at, including duration viral shedding and serological results and variants.”

“These cohort studies are very helpful, but they can lead to inaccurate conclusions,” Dr. Terndrup cautioned.

They only provide pieces of the big picture, but they “do add to a growing body of knowledge about a significant portion of COVID patients still struggling with symptoms long after their initial infection. The symptoms can be quite variable but are dominated by both physical and mental fatigue, and tend to be worse in patients who were sicker at initial infection,” he said in an interview.

As a whole, these studies reinforce the need for treatment programs to help patients who suffer from long COVID, he added, but “I advise caution to folks suffering out there who seek ‘miracle cures’; across the world, we are collaborating to find solutions that are safe and effective.”

We are in desperate need of an equity lens in these studies.

“There is still a great deal to learn about long COVID,” said Dr. Terndrup. Data on underrepresented populations – such as Black, Indigenous, and people of color – are lacking from these and others studies, he explained. “We are in desperate need of an equity lens in these studies,” particularly in the United States, where there are “significant disparities” in the treatment of different populations.

However, “I do hope that this work can lead to a better understanding of how other viral infections can cause long-lasting symptoms,” said Dr. Terndrup.

“We have long proposed that after acute presentation, some microbes can cause chronic symptoms, like fatigue and widespread pain. Perhaps we can learn how to better care for these patients after learning from COVID’s significant impact on our societies across the globe.”

Dr. Aranda and Dr. Desgranges have disclosed no relevant financial relationships or study funding. The study by Dr. Tami’s team was funded by the University Medical Center Groningen Organization for Health Research and Development, and Connecting European Cohorts to Increase Common and Effective Response to SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Dr. Terndrup disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Findings from the cohort, composed of 113 COVID-19 survivors who developed ARDS after admission to a single center before to April 16, 2020, were presented online at the 31st European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases by Judit Aranda, MD, from Complex Hospitalari Moisés Broggi in Barcelona.

Median age of the participants was 64 years, and 70% were male. At least one persistent symptom was experienced during follow-up by 81% of the cohort, with 45% reporting shortness of breath, 50% reporting muscle pain, 43% reporting memory impairment, and 46% reporting physical weakness of at least 5 on a 10-point scale.

Of the 104 participants who completed a 6-minute walk test, 30% had a decrease in oxygen saturation level of at least 4%, and 5% had an initial or final level below 88%. Of the 46 participants who underwent a pulmonary function test, 15% had a forced expiratory volume in 1 second below 70%.

And of the 49% of participants with pathologic findings on chest x-ray, most were bilateral interstitial infiltrates (88%).

In addition, more than 90% of participants developed depression, anxiety, or PTSD, Dr. Aranda reported.

Not the whole picture

This study shows that sicker people – “those in intensive care units with acute respiratory distress syndrome” – are “more likely to be struggling with more severe symptoms,” said Christopher Terndrup, MD, from the division of general internal medicine and geriatrics at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

But a Swiss study, also presented at the meeting, “shows how even mild COVID cases can lead to debilitating symptoms,” Dr. Terndrup said in an interview.

The investigation of long-term COVID symptoms in outpatients was presented online by Florian Desgranges, MD, from Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital. He and his colleagues found that more than half of those with a mild to moderate disease had persistent symptoms at least 3 months after diagnosis.

The prevalence of long COVID has varied in previous research, from 15% in a study of health care workers, to 46% in a study of patients with mild COVID, 52% in a study of young COVID outpatients, and 76% in a study of patients hospitalized with COVID.

Dr. Desgranges and colleagues evaluated patients seen in an ED or outpatient clinic from February to April 2020.

The 418 patients with a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis were compared with a control group of 89 patients who presented to the same centers during the same time frame with similar symptoms – cough, shortness of breath, or fever – but had a negative SARS-CoV-2 test.

The number of patients with comorbidities was similar in the COVID and control groups (34% vs. 36%), as was median age (41 vs. 36 years) and the prevalence of women (62% vs 64%), but the proportion of health care workers was lower in the COVID group (64% vs 82%; P =.006).

Symptoms that persisted for at least 3 months were more common in the COVID than in the control group (53% vs. 37%). And patients in the COVID group reported more symptoms than those in the control group after adjustment for age, gender, smoking status, comorbidities, and timing of the survey phone call.

Levels of sleeping problems and headache were similar in the two groups.

“We have to remember that with COVID-19 came the psychosocial changes of the pandemic situation” Dr. Desgranges said.

This study suggests that some long-COVID symptoms – such as the fatigue, headache, and sleep disorders reported in the control group – could be related to the pandemic itself, which has caused psychosocial distress, Dr. Terndrup said.

Another study that looked at outpatients “has some fantastic long-term follow-up data, and shows that many patients are still engaging in rehabilitation programs nearly a year after their diagnosis,” he explained.

The COVID HOME study

That prospective longitudinal COVID HOME study, which assessed long-term symptoms in people who were never hospitalized for COVID, was presented online by Adriana Tami, MD, PhD, from the University Medical Center Groningen (the Netherlands).

The researchers visited the homes of patients to collect data, blood samples, and perform polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing 1, 2, and 3 weeks after a diagnosis of COVID-19. If their PCR test was still positive, testing continued until week 6 or a negative test. In addition, participants completed questionnaires at week 2 and at months 3, 6 and 12 to assess fatigue, quality of life, and symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Three-month follow-up data were available for 134 of the 276 people initially enrolled in the study. Questionnaires were completed by 85 participants at 3 months, 62 participants at 6 months, and 10 participants at 12 months.

At least 40% of participants reported long-lasting symptoms at some point during follow-up, and at least 30% said they didn’t feel fully recovered at 12 months. The most common symptom was persistent fatigue, reported at 3, 6, and 12 months by at least 44% of participants. Other common symptoms – reported by at least 20% of respondents at 3, 6, and 12 months – were headache, mental or neurologic symptoms, and sleep disorders, shortness of breath, lack of smell or taste, and severe fatigue.

“We have a high proportion of nonhospitalized individuals who suffer from long COVID after more than 12 months,” Dr. Tami concluded, adding that the study is ongoing. “We have other variables that we want to look at, including duration viral shedding and serological results and variants.”

“These cohort studies are very helpful, but they can lead to inaccurate conclusions,” Dr. Terndrup cautioned.

They only provide pieces of the big picture, but they “do add to a growing body of knowledge about a significant portion of COVID patients still struggling with symptoms long after their initial infection. The symptoms can be quite variable but are dominated by both physical and mental fatigue, and tend to be worse in patients who were sicker at initial infection,” he said in an interview.

As a whole, these studies reinforce the need for treatment programs to help patients who suffer from long COVID, he added, but “I advise caution to folks suffering out there who seek ‘miracle cures’; across the world, we are collaborating to find solutions that are safe and effective.”

We are in desperate need of an equity lens in these studies.

“There is still a great deal to learn about long COVID,” said Dr. Terndrup. Data on underrepresented populations – such as Black, Indigenous, and people of color – are lacking from these and others studies, he explained. “We are in desperate need of an equity lens in these studies,” particularly in the United States, where there are “significant disparities” in the treatment of different populations.

However, “I do hope that this work can lead to a better understanding of how other viral infections can cause long-lasting symptoms,” said Dr. Terndrup.

“We have long proposed that after acute presentation, some microbes can cause chronic symptoms, like fatigue and widespread pain. Perhaps we can learn how to better care for these patients after learning from COVID’s significant impact on our societies across the globe.”

Dr. Aranda and Dr. Desgranges have disclosed no relevant financial relationships or study funding. The study by Dr. Tami’s team was funded by the University Medical Center Groningen Organization for Health Research and Development, and Connecting European Cohorts to Increase Common and Effective Response to SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Dr. Terndrup disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EUROPEAN CONGRESS OF CLINICAL MICROBIOLOGY & INFECTIOUS DISEASES

The febrile infant: New AAP guidance for the first 2 months of life

Sixteen years in the making, the American Academy of Pediatrics just released a new clinical practice guideline (CPG), “Evaluation and Management of Well-Appearing Febrile Infants 8-60 Days Old”. The recommendations were derived from interpretations of sequential studies in young, febrile, but well-appearing infants that covered invasive bacterial infection (IBI) incidence, diagnostic modalities, and treatment during the first 2 months of life, further refining approaches to evaluation and empirical treatment.

Pediatricians have long had solid information to help assess the risk for IBI among febrile infants aged 0-3 months, but there has been an ongoing desire to further refine the suggested evaluation of these very young infants. A study of febrile infants from the Pediatric Research in Office Settings network along with subsequent evidence has identified the first 3 weeks of life as the period of highest risk for IBI, with risk declining in a graded fashion aged between 22 and 56 days.

Critical caveats

First, some caveats. Infants 0-7 days are not addressed in the CPG, and all should be treated as high risk and receive full IBI evaluation according to newborn protocols. Second, the recommendations apply only to “well-appearing” infants. Any ill-appearing infant should be treated as high risk and receive full IBI evaluation and begun on empirical antimicrobials. Third, even though the CPG deals with infants as young as 8-21 days old, the recommendations are to treat all infants in this age group as high risk, even if well-appearing, and complete full IBI evaluation and empirical therapy while awaiting results. Fourth, these guidelines apply only to infants born at 37 weeks’ gestation or more. Finally, the new CPG action statements are meant to be recommendations rather than a standard of medical care, leaving some leeway for clinician interpretation of individual patient scenarios. Where appropriate, parents’ values and preferences should be incorporated as part of shared decision-making.

The CPG divides young, febrile infants into three cohorts based on age:

- 8-21 days old

- 22-28 days old

- 29-60 days old

Age 8-21 days

For well-appearing febrile infants 8-21 days old, the CPG recommends a complete IBI evaluation that includes urine, blood, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for culture, approaching all infants in this cohort as high risk. Inflammatory markers may be obtained, but the evidence is not comprehensive enough to evaluate their role in decision-making for this age group. A two-step urine evaluation method (urine analysis followed by culture if the urine analysis looks concerning) is not recommended for infants aged 8-21 days. Urine samples for culture from these young infants should be obtained by catheterization or suprapubic aspiration.

The CPG recommends drawing blood cultures and CSF by lumbar puncture from this cohort. These infants should be admitted to the hospital, treated empirically with antimicrobials, and actively monitored. However, if the cultures are negative at 24-36 hours, the clinician should discontinue antimicrobials and discharge the infant if there is no other reason for continued hospitalization.

Age 22-28 days

Well-appearing, febrile infants 22-28 days old are in an intermediate-risk zone. The recommendation for infants in this cohort is to obtain a urine specimen by catheterization or suprapubic aspiration for both urine analysis and culture. Clinicians may consider obtaining urine samples for analysis noninvasively (e.g., urine bag) in this cohort, but this is not the preferred method.

Blood culture should be obtained from all infants in this group. Inflammatory markers can help clinicians identify infants at greater risk for IBI, including meningitis. Previous data suggested that inflammatory markers such as serum white blood cell counts greater than 11,000/mcL, a serum absolute neutrophil count of greater than 4,000/mcL, and elevated C-reactive protein and procalcitonin levels could help providers identify febrile infants with true IBI. A 2008 study demonstrated that procalcitonin had the best receiver operating characteristic curve in regard to predicting IBI in young febrile infants. Other research backed up that finding and identified cutoff values for procalcitonin levels greater than 1.0 ng/mL. The CPG recommends considering a procalcitonin value of 0.5 ng/mL or higher as positive, indicating that the infant is at greater risk for IBI and potentially should undergo an expanded IBI workup. Therefore, in infants aged 22-28 days, inflammatory markers can play a role in deciding whether to perform a lumbar puncture.

Many more nuanced recommendations for whether to and how to empirically treat with antimicrobials in this cohort can be found in the CPG, including whether to manage in the hospital or at home. Treatment recommendations vary greatly for this cohort on the basis of the tests obtained and whether tests were positive or negative at the initial evaluation.

Age 29-60 days

The CPG will be most helpful when clinicians are faced with well-appearing, febrile infants in the 29- to 60-day age group. As with the other groups, a urine evaluation is recommended; however, the CPG suggests that the two-step approach – obtaining a urine analysis by a noninvasive method and only obtaining culture if the urine analysis is positive – is reasonable. This means that a bag or free-flowing urine specimen would be appropriate for urinalysis, followed by catheterization/suprapubic aspiration if a culture is necessary. This would save approximately 90% of infants from invasive urine collection. Regardless, only catheter or suprapubic specimens are appropriate for urine culture.

The CPG also recommends that clinicians obtain blood culture on all of these infants. Inflammatory markers should be assessed in this cohort because avoiding lumbar puncture for CSF culture would be appropriate in this cohort if the inflammatory markers are negative. If CSF is obtained in this age cohort, enterovirus testing should be added to the testing regimen. Again, for any infant considered at higher risk for IBI on the basis of screening tests, the CPG recommends a 24- to 36-hour rule-out period with empirical antimicrobial treatment and active monitoring in the hospital.

Summary

The recommended approach for febrile infants 8-21 days old is relatively aggressive, with urine, blood, and CSF evaluation for IBI. Clinicians gain some leeway for infants age 22-28 days, but the guidelines recommend a more flexible approach to evaluating well-appearing, febrile infants age 29-60 days, when a two-step urine evaluation and inflammatory marker assessment can help clinicians and parents have a better discussion about the risk-benefit trade-offs of more aggressive testing and empirical treatment.

The author would like to thank Ken Roberts, MD, for his review and helpful comments on this summary of the CPG highlights. Summary points of the CPG were presented by the writing group at the 2021 Pediatric Academic Societies meeting.

William T. Basco, Jr, MD, MS, is a professor of pediatrics at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, and director of the division of general pediatrics. He is an active health services researcher and has published more than 60 manuscripts in the peer-reviewed literature.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Sixteen years in the making, the American Academy of Pediatrics just released a new clinical practice guideline (CPG), “Evaluation and Management of Well-Appearing Febrile Infants 8-60 Days Old”. The recommendations were derived from interpretations of sequential studies in young, febrile, but well-appearing infants that covered invasive bacterial infection (IBI) incidence, diagnostic modalities, and treatment during the first 2 months of life, further refining approaches to evaluation and empirical treatment.

Pediatricians have long had solid information to help assess the risk for IBI among febrile infants aged 0-3 months, but there has been an ongoing desire to further refine the suggested evaluation of these very young infants. A study of febrile infants from the Pediatric Research in Office Settings network along with subsequent evidence has identified the first 3 weeks of life as the period of highest risk for IBI, with risk declining in a graded fashion aged between 22 and 56 days.

Critical caveats

First, some caveats. Infants 0-7 days are not addressed in the CPG, and all should be treated as high risk and receive full IBI evaluation according to newborn protocols. Second, the recommendations apply only to “well-appearing” infants. Any ill-appearing infant should be treated as high risk and receive full IBI evaluation and begun on empirical antimicrobials. Third, even though the CPG deals with infants as young as 8-21 days old, the recommendations are to treat all infants in this age group as high risk, even if well-appearing, and complete full IBI evaluation and empirical therapy while awaiting results. Fourth, these guidelines apply only to infants born at 37 weeks’ gestation or more. Finally, the new CPG action statements are meant to be recommendations rather than a standard of medical care, leaving some leeway for clinician interpretation of individual patient scenarios. Where appropriate, parents’ values and preferences should be incorporated as part of shared decision-making.

The CPG divides young, febrile infants into three cohorts based on age:

- 8-21 days old

- 22-28 days old

- 29-60 days old

Age 8-21 days

For well-appearing febrile infants 8-21 days old, the CPG recommends a complete IBI evaluation that includes urine, blood, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for culture, approaching all infants in this cohort as high risk. Inflammatory markers may be obtained, but the evidence is not comprehensive enough to evaluate their role in decision-making for this age group. A two-step urine evaluation method (urine analysis followed by culture if the urine analysis looks concerning) is not recommended for infants aged 8-21 days. Urine samples for culture from these young infants should be obtained by catheterization or suprapubic aspiration.

The CPG recommends drawing blood cultures and CSF by lumbar puncture from this cohort. These infants should be admitted to the hospital, treated empirically with antimicrobials, and actively monitored. However, if the cultures are negative at 24-36 hours, the clinician should discontinue antimicrobials and discharge the infant if there is no other reason for continued hospitalization.

Age 22-28 days

Well-appearing, febrile infants 22-28 days old are in an intermediate-risk zone. The recommendation for infants in this cohort is to obtain a urine specimen by catheterization or suprapubic aspiration for both urine analysis and culture. Clinicians may consider obtaining urine samples for analysis noninvasively (e.g., urine bag) in this cohort, but this is not the preferred method.

Blood culture should be obtained from all infants in this group. Inflammatory markers can help clinicians identify infants at greater risk for IBI, including meningitis. Previous data suggested that inflammatory markers such as serum white blood cell counts greater than 11,000/mcL, a serum absolute neutrophil count of greater than 4,000/mcL, and elevated C-reactive protein and procalcitonin levels could help providers identify febrile infants with true IBI. A 2008 study demonstrated that procalcitonin had the best receiver operating characteristic curve in regard to predicting IBI in young febrile infants. Other research backed up that finding and identified cutoff values for procalcitonin levels greater than 1.0 ng/mL. The CPG recommends considering a procalcitonin value of 0.5 ng/mL or higher as positive, indicating that the infant is at greater risk for IBI and potentially should undergo an expanded IBI workup. Therefore, in infants aged 22-28 days, inflammatory markers can play a role in deciding whether to perform a lumbar puncture.

Many more nuanced recommendations for whether to and how to empirically treat with antimicrobials in this cohort can be found in the CPG, including whether to manage in the hospital or at home. Treatment recommendations vary greatly for this cohort on the basis of the tests obtained and whether tests were positive or negative at the initial evaluation.

Age 29-60 days

The CPG will be most helpful when clinicians are faced with well-appearing, febrile infants in the 29- to 60-day age group. As with the other groups, a urine evaluation is recommended; however, the CPG suggests that the two-step approach – obtaining a urine analysis by a noninvasive method and only obtaining culture if the urine analysis is positive – is reasonable. This means that a bag or free-flowing urine specimen would be appropriate for urinalysis, followed by catheterization/suprapubic aspiration if a culture is necessary. This would save approximately 90% of infants from invasive urine collection. Regardless, only catheter or suprapubic specimens are appropriate for urine culture.

The CPG also recommends that clinicians obtain blood culture on all of these infants. Inflammatory markers should be assessed in this cohort because avoiding lumbar puncture for CSF culture would be appropriate in this cohort if the inflammatory markers are negative. If CSF is obtained in this age cohort, enterovirus testing should be added to the testing regimen. Again, for any infant considered at higher risk for IBI on the basis of screening tests, the CPG recommends a 24- to 36-hour rule-out period with empirical antimicrobial treatment and active monitoring in the hospital.

Summary

The recommended approach for febrile infants 8-21 days old is relatively aggressive, with urine, blood, and CSF evaluation for IBI. Clinicians gain some leeway for infants age 22-28 days, but the guidelines recommend a more flexible approach to evaluating well-appearing, febrile infants age 29-60 days, when a two-step urine evaluation and inflammatory marker assessment can help clinicians and parents have a better discussion about the risk-benefit trade-offs of more aggressive testing and empirical treatment.

The author would like to thank Ken Roberts, MD, for his review and helpful comments on this summary of the CPG highlights. Summary points of the CPG were presented by the writing group at the 2021 Pediatric Academic Societies meeting.

William T. Basco, Jr, MD, MS, is a professor of pediatrics at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, and director of the division of general pediatrics. He is an active health services researcher and has published more than 60 manuscripts in the peer-reviewed literature.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Sixteen years in the making, the American Academy of Pediatrics just released a new clinical practice guideline (CPG), “Evaluation and Management of Well-Appearing Febrile Infants 8-60 Days Old”. The recommendations were derived from interpretations of sequential studies in young, febrile, but well-appearing infants that covered invasive bacterial infection (IBI) incidence, diagnostic modalities, and treatment during the first 2 months of life, further refining approaches to evaluation and empirical treatment.

Pediatricians have long had solid information to help assess the risk for IBI among febrile infants aged 0-3 months, but there has been an ongoing desire to further refine the suggested evaluation of these very young infants. A study of febrile infants from the Pediatric Research in Office Settings network along with subsequent evidence has identified the first 3 weeks of life as the period of highest risk for IBI, with risk declining in a graded fashion aged between 22 and 56 days.

Critical caveats

First, some caveats. Infants 0-7 days are not addressed in the CPG, and all should be treated as high risk and receive full IBI evaluation according to newborn protocols. Second, the recommendations apply only to “well-appearing” infants. Any ill-appearing infant should be treated as high risk and receive full IBI evaluation and begun on empirical antimicrobials. Third, even though the CPG deals with infants as young as 8-21 days old, the recommendations are to treat all infants in this age group as high risk, even if well-appearing, and complete full IBI evaluation and empirical therapy while awaiting results. Fourth, these guidelines apply only to infants born at 37 weeks’ gestation or more. Finally, the new CPG action statements are meant to be recommendations rather than a standard of medical care, leaving some leeway for clinician interpretation of individual patient scenarios. Where appropriate, parents’ values and preferences should be incorporated as part of shared decision-making.

The CPG divides young, febrile infants into three cohorts based on age:

- 8-21 days old

- 22-28 days old

- 29-60 days old

Age 8-21 days

For well-appearing febrile infants 8-21 days old, the CPG recommends a complete IBI evaluation that includes urine, blood, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for culture, approaching all infants in this cohort as high risk. Inflammatory markers may be obtained, but the evidence is not comprehensive enough to evaluate their role in decision-making for this age group. A two-step urine evaluation method (urine analysis followed by culture if the urine analysis looks concerning) is not recommended for infants aged 8-21 days. Urine samples for culture from these young infants should be obtained by catheterization or suprapubic aspiration.

The CPG recommends drawing blood cultures and CSF by lumbar puncture from this cohort. These infants should be admitted to the hospital, treated empirically with antimicrobials, and actively monitored. However, if the cultures are negative at 24-36 hours, the clinician should discontinue antimicrobials and discharge the infant if there is no other reason for continued hospitalization.

Age 22-28 days

Well-appearing, febrile infants 22-28 days old are in an intermediate-risk zone. The recommendation for infants in this cohort is to obtain a urine specimen by catheterization or suprapubic aspiration for both urine analysis and culture. Clinicians may consider obtaining urine samples for analysis noninvasively (e.g., urine bag) in this cohort, but this is not the preferred method.

Blood culture should be obtained from all infants in this group. Inflammatory markers can help clinicians identify infants at greater risk for IBI, including meningitis. Previous data suggested that inflammatory markers such as serum white blood cell counts greater than 11,000/mcL, a serum absolute neutrophil count of greater than 4,000/mcL, and elevated C-reactive protein and procalcitonin levels could help providers identify febrile infants with true IBI. A 2008 study demonstrated that procalcitonin had the best receiver operating characteristic curve in regard to predicting IBI in young febrile infants. Other research backed up that finding and identified cutoff values for procalcitonin levels greater than 1.0 ng/mL. The CPG recommends considering a procalcitonin value of 0.5 ng/mL or higher as positive, indicating that the infant is at greater risk for IBI and potentially should undergo an expanded IBI workup. Therefore, in infants aged 22-28 days, inflammatory markers can play a role in deciding whether to perform a lumbar puncture.

Many more nuanced recommendations for whether to and how to empirically treat with antimicrobials in this cohort can be found in the CPG, including whether to manage in the hospital or at home. Treatment recommendations vary greatly for this cohort on the basis of the tests obtained and whether tests were positive or negative at the initial evaluation.

Age 29-60 days

The CPG will be most helpful when clinicians are faced with well-appearing, febrile infants in the 29- to 60-day age group. As with the other groups, a urine evaluation is recommended; however, the CPG suggests that the two-step approach – obtaining a urine analysis by a noninvasive method and only obtaining culture if the urine analysis is positive – is reasonable. This means that a bag or free-flowing urine specimen would be appropriate for urinalysis, followed by catheterization/suprapubic aspiration if a culture is necessary. This would save approximately 90% of infants from invasive urine collection. Regardless, only catheter or suprapubic specimens are appropriate for urine culture.

The CPG also recommends that clinicians obtain blood culture on all of these infants. Inflammatory markers should be assessed in this cohort because avoiding lumbar puncture for CSF culture would be appropriate in this cohort if the inflammatory markers are negative. If CSF is obtained in this age cohort, enterovirus testing should be added to the testing regimen. Again, for any infant considered at higher risk for IBI on the basis of screening tests, the CPG recommends a 24- to 36-hour rule-out period with empirical antimicrobial treatment and active monitoring in the hospital.

Summary

The recommended approach for febrile infants 8-21 days old is relatively aggressive, with urine, blood, and CSF evaluation for IBI. Clinicians gain some leeway for infants age 22-28 days, but the guidelines recommend a more flexible approach to evaluating well-appearing, febrile infants age 29-60 days, when a two-step urine evaluation and inflammatory marker assessment can help clinicians and parents have a better discussion about the risk-benefit trade-offs of more aggressive testing and empirical treatment.

The author would like to thank Ken Roberts, MD, for his review and helpful comments on this summary of the CPG highlights. Summary points of the CPG were presented by the writing group at the 2021 Pediatric Academic Societies meeting.

William T. Basco, Jr, MD, MS, is a professor of pediatrics at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, and director of the division of general pediatrics. He is an active health services researcher and has published more than 60 manuscripts in the peer-reviewed literature.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Treatment of opioid use disorder with buprenorphine and methadone effective but underutilized

Background: Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a chronic disease with a high health care and societal burden from overdose and complications requiring hospitalization. Though clinical trials demonstrate effectiveness of methadone and buprenorphine, most patients do not have access to these medications.

Study design: Retrospective comparative effectiveness study.

Setting: Nationwide claims database of commercial and Medicare Advantage Enrollees.

Synopsis: A total of 40,885 individuals aged 16 years or older with OUD were studied in an intent-to-treat analysis of six unique treatment pathways. Though used in just 12.5% of patients, only treatment with buprenorphine or methadone was protective against overdose at 3 and 12 months, compared with no treatment. Additionally, these medications and nonintensive behavioral health counseling were associated with lower incidence of acute care episodes from complications of opioid use. Notably, those treated with buprenorphine or methadone for more than 6 months received the greatest benefit. With use of only health care encounters, the results may underestimate incidence of complications of ongoing opioid misuse.

Bottom line: Buprenorphine and methadone for OUD were associated with reduced overdose and opioid-related morbidity, compared with opioid antagonist therapy, inpatient treatment, or intensive outpatient behavioral interventions and should be considered a first-line treatment.

Citation: Wakeman SE et al. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Feb 5;3(2):e1920622. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622.

Dr. Inofuentes is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a chronic disease with a high health care and societal burden from overdose and complications requiring hospitalization. Though clinical trials demonstrate effectiveness of methadone and buprenorphine, most patients do not have access to these medications.

Study design: Retrospective comparative effectiveness study.

Setting: Nationwide claims database of commercial and Medicare Advantage Enrollees.

Synopsis: A total of 40,885 individuals aged 16 years or older with OUD were studied in an intent-to-treat analysis of six unique treatment pathways. Though used in just 12.5% of patients, only treatment with buprenorphine or methadone was protective against overdose at 3 and 12 months, compared with no treatment. Additionally, these medications and nonintensive behavioral health counseling were associated with lower incidence of acute care episodes from complications of opioid use. Notably, those treated with buprenorphine or methadone for more than 6 months received the greatest benefit. With use of only health care encounters, the results may underestimate incidence of complications of ongoing opioid misuse.

Bottom line: Buprenorphine and methadone for OUD were associated with reduced overdose and opioid-related morbidity, compared with opioid antagonist therapy, inpatient treatment, or intensive outpatient behavioral interventions and should be considered a first-line treatment.

Citation: Wakeman SE et al. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Feb 5;3(2):e1920622. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622.

Dr. Inofuentes is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a chronic disease with a high health care and societal burden from overdose and complications requiring hospitalization. Though clinical trials demonstrate effectiveness of methadone and buprenorphine, most patients do not have access to these medications.