User login

Clinical Presentation of Subacute Combined Degeneration in a Patient With Chronic B12 Deficiency

Subacute combined degeneration (SCD) is an acquired neurologic complication of vitamin B12 (cobalamin) or, rarely, vitamin B9 (folate) deficiency. SCD is characterized by progressive demyelination of the dorsal and lateral spinal cord, resulting in peripheral neuropathy; gait ataxia; impaired proprioception, vibration, and fine touch; optic neuropathy; and cognitive impairment.1 In addition to SCD, other neurologic manifestations of B12 deficiency include dementia, depression, visual symptoms due to optic atrophy, and behavioral changes.2 The prevalence of SCD in the US has not been well documented, but B12 deficiency is reported at 6% in those aged < 60 years and 20% in those > 60 years.3

Causes of B12 and B9 deficiency include advanced age, low nutritional intake (eg, vegan diet), impaired absorption (eg, inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune pernicious anemia, gastrectomy, pancreatic disease), alcohol use, tapeworm infection, medications, and high metabolic states.2,4 Impaired B12 absorption is common in patients taking medications, such as metformin and proton pump inhibitors (PPI), due to suppression of ileal membrane transport and intrinsic factor activity.5-7 B-vitamin deficiency can be exacerbated by states of increased cellular turnover, such as polycythemia vera, due to elevated DNA synthesis.

Patients may experience permanent neurologic damage when the diagnosis and treatment of SCD are missed or delayed. Early diagnosis of SCD can be challenging due to lack of specific hematologic markers. In addition, many other conditions such as diabetic neuropathy, malnutrition, toxic neuropathy, sarcoidosis, HIV, multiple sclerosis, polycythemia vera, and iron deficiency anemia have similar presentations and clinical findings.8 Anemia and/or macrocytosis are not specific to B12 deficiency.4 In addition, patients with B12 deficiency may have a normal complete blood count (CBC); those with concomitant iron deficiency may have minimal or no mean corpuscular volume (MCV) elevation.4 In patients suspected to have B12 deficiency based on clinical presentation or laboratory findings of macrocytosis, serum methylmalonic acid (MMA) can serve as a direct measure of B12 activity, with levels > 0.75 μmol/L almost always indicating cobalamin deficiency. 9 On the other hand, plasma total homocysteine (tHcy) is a sensitive marker for B12 deficiency. The active form of B12, holotranscobalamin, has also emerged as a specific measure of B12 deficiency.9 However, in patients with SCD, measurement of these markers may be unnecessary due to the severity of their clinical symptoms.

The diagnosis of SCD is further complicated because not all individuals who develop B12 or B9 deficiency will develop SCD. It is difficult to determine which patients will develop SCD because the minimum level of serum B12 required for normal function is unknown, and recent studies indicate that SCD may occur even at low-normal B12 and B9 levels.2,4,10 Commonly, a serum B12 level of < 200 pg/mL is considered deficient, while a level between 200 and 300 pg/mL is considered borderline.4 The goal level of serum B12 is > 300 pg/mL, which is considered normal.4 While serologic findings of B-vitamin deficiency are only moderately specific, radiographic findings are highly sensitive and specific for SCD. According to Briani and colleagues, the most consistent finding in SCD on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a “symmetrical, abnormally increased T2 signal intensity, commonly confined to posterior or posterior and lateral columns in the cervical and thoracic spinal cord.”2

We present a case of SCD in a patient with low-normal vitamin B12 levels who presented with progressive sensorimotor deficits and vision loss. The patient was subsequently diagnosed with SCD by radiologic workup. His course was complicated by worsening neurologic deficits despite B12 replacement. The progression of his clinical symptoms demonstrates the need for prompt, aggressive B12 replacement in patients diagnosed with SCD.

Case Presentation

A 63-year-old man presented for neurologic evaluation of progressive gait disturbance, paresthesia, blurred vision, and increasing falls despite use of a walker. Pertinent medical history included polycythemia vera requiring phlebotomy for approximately 9 years, alcohol use disorder (18 servings weekly), type 2 diabetes mellitus, and a remote episode of transient ischemic attack (TIA). The patient reported a 5-year history of burning pain in all extremities. A prior physician diagnosis attributed the symptoms to polyneuropathy secondary to iron deficiency anemia in the setting of chronic phlebotomy for polycythemia vera and high erythrogenesis. He was prescribed gabapentin 600 mg 3 times daily for pain control. B12 deficiency was considered an unlikely etiology due to a low-normal serum level of 305 pg/mL (reference range, 190-950 pg/mL) and normocytosis, with MCV of 88 fL (reference range, 80-100 fL). The patient also reported a 3-year history of blurred vision, which was initially attributed to be secondary to diabetic retinopathy. One week prior to presenting to our clinic, he was evaluated by ophthalmology for new-onset, bilateral central visual field defects, and he was diagnosed with nutritional optic neuropathy.

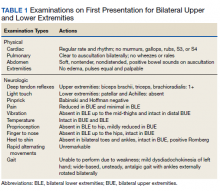

Ophthalmology suspected B12 deficiency. Notable findings included reduced deep tendon reflexes (DTRs) in the upper extremities and absent DTRs in the lower extremities, reduced sensation to light touch in all extremities, absent sensation to pinprick, vibration, and temperature in the lower extremities, positive Romberg sign, and a wide-based antalgic gait with the ankles externally rotated bilaterally (Table 1)

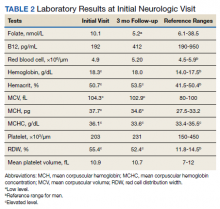

Previous cardiac evaluation failed to provide a diagnosis for syncopal episodes. MRI of the brain revealed nonspecific white matter changes consistent with chronic microvascular ischemic disease. Electromyography was limited due to pain but showed severe peripheral neuropathy. Laboratory results showed megalocytosis, low-normal serum B12 levels, and low serum folate levels (Table 2). The patient was diagnosed with polyneuropathy and was given intramuscular (IM) vitamin B12 1000 mcg once and a daily multivitamin (containing 25 mcg of B12). He was counseled on alcohol abstinence and medication adherence and was scheduled for follow-up in 3 months. He continued outpatient phlebotomy every 6 weeks for polycythemia.

At 3-month follow-up, the patient reported medication adherence, continued alcohol use, and worsening of symptoms. Falls, which now occurred 2 to 3 times weekly despite proper use of a walker, were described as sudden loss of bilateral lower extremity strength without loss of consciousness, palpitations, or other prodrome. Laboratory results showed minimal changes. Physical examination of the patient demonstrated similar deficits as on initial presentation. The patient received one additional B12 1000 mcg IM. Gabapentin was replaced with pregabalin 75 mg twice daily due to persistent uncontrolled pain and paresthesia. The patient was scheduled for a 3-month followup (6 months from initial visit) and repeat serology.

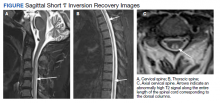

At 6-month follow-up, the patient showed continued progression of disease with significant difficulty using the walker, worsening falls, and wheelchair use required. Physical examination showed decreased sensation bilaterally up to the knees, absent bilateral patellar and Achilles reflexes, and unsteady gait. Laboratory results showed persistent subclinical B12 deficiency. MRI of the brain and spine showed high T2 signaling in a pattern highly specific for SCD. A formal diagnosis of SCD was made. The patient received an additional B12 1000 mcg IM once. Follow-up phone call with the patient 1 month later revealed no progression or improvement of symptoms.

Radiographic Findings

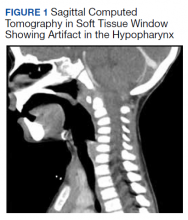

MRI of the cervical and thoracic spine demonstrated abnormal high T2 signal starting from C2 and extending along the course of the cervical and thoracic spinal cord (Figure). MRI in SCD classically shows symmetric, bilateral high T2 signal within the dorsal columns; on axial images, there is typically an inverted “V” sign.2,4 There can also be abnormal cerebral white matter change; however, MRI of the brain in this patient did not show any abnormalities.2 The imaging differential for this appearance includes other metabolic deficiencies/toxicities: copper deficiency; vitamin E deficiency; methotrexateinduced myelopathy, and infectious causes: HIV vacuolar myelopathy; and neurosyphilis (tabes dorsalis).4

Discussion

This case demonstrates the clinical and radiographic findings of SCD and underscores the need for high-intensity dosing of B12 replacement in patients with SCD to prevent progression of the disease and development of morbidities.

Symptoms of SCD may manifest even when the vitamin levels are in low-normal levels. Its presentation is often nonspecific, thus radiologic workup is beneficial to elucidate the clinical picture. We support the use of spinal MRI in patients with clinical suspicion of SCD to help rule out other causes of myelopathy. However, an MRI is not indicated in all patients with B12 deficiency, especially those without myelopathic symptoms. Additionally, follow-up spinal MRIs are useful in monitoring the progression or improvement of SCD after B12 replacement.2 It is important to note that the MRI findings in SCD are not specific to B12 deficiency; other causes may present with similar radiographic findings.4 Therefore, radiologic findings must be correlated with a patient’s clinical presentation.

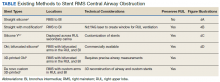

B12 replacement improves and may resolve clinical symptoms and abnormal radiographic findings of SCD. The treatment duration of B12 deficiency depends on the underlying etiology. Reversible causes, such as metformin use > 4 months, PPI use > 12 months, and dietary deficiency, require treatment until appropriate levels are reached and symptoms are resolved.4,11 The need for chronic metformin and PPI use should also be reassessed regularly. In patients who require long-term metformin use, IM administration of B12 1000 mcg annually should be considered, which will ensure adequate storage for more than 1 year.12,13 In patients who require long-term PPI use, the risk and benefits of continued use should be measured, and if needed, the lowest possible effective PPI dose is recommended.14 Irreversible causes of B12 deficiency, such as advanced age, prior gastrectomy, chronic pancreatitis, or autoimmune pernicious anemia, require lifelong supplementation of B12.4,11

In general, oral vitamin B12 replacement at 1000 to 2000 mcg daily may be as effective as parenteral replacement in patients with mild to moderate deficiency or neurologic symptoms.11 On the other hand, patients with SCD often require parenteral replacement of B12 due to the severity of their deficiency or neurologic symptoms, need for more rapid improvement in symptoms, and prevention of irreversible neurological deficits. 4,11 Appropriate B12 replacement in SCD requires intensive initial therapy which may involve IM B12 1000 mcg every other day for 2 weeks and additional IM supplementation every 2 to 3 months afterward until resolution of deficiency.4,14 IM replacement may also be considered in patients who are nonadherent to oral replacement or have an underlying gastrointestinal condition that impairs enteral absorption.4,11

B12 deficiency is frequently undertreated and can lead to progression of disease with significant morbidity. The need for highintensity dosing of B12 replacement is crucial in patients with SCD. Failure to respond to treatment, as shown from the lack of improvement of serum markers or symptoms, likely suggests undertreatment, treatment nonadherence, iron deficiency anemia, an unidentified malabsorption syndrome, or other diagnoses. In our case, significant undertreatment, compounded by his suspected iron deficiency anemia secondary to his polycythemia vera and chronic phlebotomies, are the most likel etiologies for his lack of clinical improvement.

Multiple factors may affect the prognosis of SCD. Males aged < 50 years with absence of anemia, spinal cord atrophy, Romberg sign, Babinski sign, or sensory deficits on examination have increased likelihood of eventual recovery of signs and symptoms of SCD; those with less spinal cord involvement (< 7 cord segments), contrast enhancement, and spinal cord edema also have improved outcomes.4,15

Conclusion

SCD is a rare but serious complication of chronic vitamin B12 deficiency that presents with a variety of neurological findings and may be easily confused with other illnesses. The condition is easily overlooked or misdiagnosed; thus, it is crucial to differentiate B12 deficiency from other common causes of neurologic symptoms. Specific findings on MRI are useful to support the clinical diagnosis of SCD and guide clinical decisions. Given the prevalence of B12 deficiency in the older adult population, clinicians should remain alert to the possibility of these conditions in patients who present with progressive neuropathy. Once a patient is diagnosed with SCD secondary to a B12 deficiency, appropriate B12 replacement is critical. Appropriate B12 replacement is aggressive and involves IM B12 1000 mcg every other day for 2 to 3 weeks, followed by additional IM administration every 2 months before transitioning to oral therapy. As seen in this case, failure to adequately replenish B12 can lead to progression or lack of resolution of SCD symptoms.

1. Gürsoy AE, Kolukısa M, Babacan-Yıldız G, Celebi A. Subacute Combined Degeneration of the Spinal Cord due to Different Etiologies and Improvement of MRI Findings. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2013;2013:159649. doi:10.1155/2013/159649

2. Briani C, Dalla Torre C, Citton V, et al. Cobalamin deficiency: clinical picture and radiological findings. Nutrients. 2013;5(11):4521-4539. Published 2013 Nov 15. doi:10.3390/nu5114521

3. Hunt A, Harrington D, Robinson S. Vitamin B12 deficiency. BMJ. 2014;349:g5226. Published 2014 Sep 4. doi:10.1136/bmj.g5226

4. Qudsiya Z, De Jesus O. Subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord. [Updated 2021 Feb 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Updated August 30, 2021. Accessed January 5, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books /NBK559316/

5. de Jager J, Kooy A, Lehert P, et al. Long term treatment with metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes and risk of vitamin B-12 deficiency: randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c2181. Published 2010 May 20. doi:10.1136/bmj.c2181

6. Aroda VR, Edelstein SL, Goldberg RB, et al. Longterm Metformin Use and Vitamin B12 Deficiency in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(4):1754-1761. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-3754

7. Lam JR, Schneider JL, Zhao W, Corley DA. Proton pump inhibitor and histamine 2 receptor antagonist use and vitamin B12 deficiency. JAMA. 2013;310(22):2435-2442. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.280490

8. Mihalj M, Titlic´ M, Bonacin D, Dogaš Z. Sensomotor axonal peripheral neuropathy as a first complication of polycythemia rubra vera: A report of 3 cases. Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:385-387. Published 2013 Sep 25. doi:10.12659/AJCR.884016

9. Devalia V, Hamilton MS, Molloy AM; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cobalamin and folate disorders. Br J Haematol. 2014;166(4):496-513. doi:10.1111/bjh.12959

10. Cao J, Xu S, Liu C. Is serum vitamin B12 decrease a necessity for the diagnosis of subacute combined degeneration?: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(14):e19700.doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000019700

11. Langan RC, Goodbred AJ. Vitamin B12 Deficiency: Recognition and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(6):384-389.

12. Mazokopakis EE, Starakis IK. Recommendations for diagnosis and management of metformin-induced vitamin B12 (Cbl) deficiency. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;97(3):359-367. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2012.06.001

13. Mahajan R, Gupta K. Revisiting Metformin: Annual Vitamin B12 Supplementation may become Mandatory with Long-Term Metformin Use. J Young Pharm. 2010;2(4):428-429. doi:10.4103/0975-1483.71621

14. Parks NE. Metabolic and Toxic Myelopathies. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2021;27(1):143-162. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000963

15. Vasconcelos OM, Poehm EH, McCarter RJ, Campbell WW, Quezado ZM. Potential outcome factors in subacute combined degeneration: review of observational studies. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(10):1063-1068. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00525.x

Subacute combined degeneration (SCD) is an acquired neurologic complication of vitamin B12 (cobalamin) or, rarely, vitamin B9 (folate) deficiency. SCD is characterized by progressive demyelination of the dorsal and lateral spinal cord, resulting in peripheral neuropathy; gait ataxia; impaired proprioception, vibration, and fine touch; optic neuropathy; and cognitive impairment.1 In addition to SCD, other neurologic manifestations of B12 deficiency include dementia, depression, visual symptoms due to optic atrophy, and behavioral changes.2 The prevalence of SCD in the US has not been well documented, but B12 deficiency is reported at 6% in those aged < 60 years and 20% in those > 60 years.3

Causes of B12 and B9 deficiency include advanced age, low nutritional intake (eg, vegan diet), impaired absorption (eg, inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune pernicious anemia, gastrectomy, pancreatic disease), alcohol use, tapeworm infection, medications, and high metabolic states.2,4 Impaired B12 absorption is common in patients taking medications, such as metformin and proton pump inhibitors (PPI), due to suppression of ileal membrane transport and intrinsic factor activity.5-7 B-vitamin deficiency can be exacerbated by states of increased cellular turnover, such as polycythemia vera, due to elevated DNA synthesis.

Patients may experience permanent neurologic damage when the diagnosis and treatment of SCD are missed or delayed. Early diagnosis of SCD can be challenging due to lack of specific hematologic markers. In addition, many other conditions such as diabetic neuropathy, malnutrition, toxic neuropathy, sarcoidosis, HIV, multiple sclerosis, polycythemia vera, and iron deficiency anemia have similar presentations and clinical findings.8 Anemia and/or macrocytosis are not specific to B12 deficiency.4 In addition, patients with B12 deficiency may have a normal complete blood count (CBC); those with concomitant iron deficiency may have minimal or no mean corpuscular volume (MCV) elevation.4 In patients suspected to have B12 deficiency based on clinical presentation or laboratory findings of macrocytosis, serum methylmalonic acid (MMA) can serve as a direct measure of B12 activity, with levels > 0.75 μmol/L almost always indicating cobalamin deficiency. 9 On the other hand, plasma total homocysteine (tHcy) is a sensitive marker for B12 deficiency. The active form of B12, holotranscobalamin, has also emerged as a specific measure of B12 deficiency.9 However, in patients with SCD, measurement of these markers may be unnecessary due to the severity of their clinical symptoms.

The diagnosis of SCD is further complicated because not all individuals who develop B12 or B9 deficiency will develop SCD. It is difficult to determine which patients will develop SCD because the minimum level of serum B12 required for normal function is unknown, and recent studies indicate that SCD may occur even at low-normal B12 and B9 levels.2,4,10 Commonly, a serum B12 level of < 200 pg/mL is considered deficient, while a level between 200 and 300 pg/mL is considered borderline.4 The goal level of serum B12 is > 300 pg/mL, which is considered normal.4 While serologic findings of B-vitamin deficiency are only moderately specific, radiographic findings are highly sensitive and specific for SCD. According to Briani and colleagues, the most consistent finding in SCD on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a “symmetrical, abnormally increased T2 signal intensity, commonly confined to posterior or posterior and lateral columns in the cervical and thoracic spinal cord.”2

We present a case of SCD in a patient with low-normal vitamin B12 levels who presented with progressive sensorimotor deficits and vision loss. The patient was subsequently diagnosed with SCD by radiologic workup. His course was complicated by worsening neurologic deficits despite B12 replacement. The progression of his clinical symptoms demonstrates the need for prompt, aggressive B12 replacement in patients diagnosed with SCD.

Case Presentation

A 63-year-old man presented for neurologic evaluation of progressive gait disturbance, paresthesia, blurred vision, and increasing falls despite use of a walker. Pertinent medical history included polycythemia vera requiring phlebotomy for approximately 9 years, alcohol use disorder (18 servings weekly), type 2 diabetes mellitus, and a remote episode of transient ischemic attack (TIA). The patient reported a 5-year history of burning pain in all extremities. A prior physician diagnosis attributed the symptoms to polyneuropathy secondary to iron deficiency anemia in the setting of chronic phlebotomy for polycythemia vera and high erythrogenesis. He was prescribed gabapentin 600 mg 3 times daily for pain control. B12 deficiency was considered an unlikely etiology due to a low-normal serum level of 305 pg/mL (reference range, 190-950 pg/mL) and normocytosis, with MCV of 88 fL (reference range, 80-100 fL). The patient also reported a 3-year history of blurred vision, which was initially attributed to be secondary to diabetic retinopathy. One week prior to presenting to our clinic, he was evaluated by ophthalmology for new-onset, bilateral central visual field defects, and he was diagnosed with nutritional optic neuropathy.

Ophthalmology suspected B12 deficiency. Notable findings included reduced deep tendon reflexes (DTRs) in the upper extremities and absent DTRs in the lower extremities, reduced sensation to light touch in all extremities, absent sensation to pinprick, vibration, and temperature in the lower extremities, positive Romberg sign, and a wide-based antalgic gait with the ankles externally rotated bilaterally (Table 1)

Previous cardiac evaluation failed to provide a diagnosis for syncopal episodes. MRI of the brain revealed nonspecific white matter changes consistent with chronic microvascular ischemic disease. Electromyography was limited due to pain but showed severe peripheral neuropathy. Laboratory results showed megalocytosis, low-normal serum B12 levels, and low serum folate levels (Table 2). The patient was diagnosed with polyneuropathy and was given intramuscular (IM) vitamin B12 1000 mcg once and a daily multivitamin (containing 25 mcg of B12). He was counseled on alcohol abstinence and medication adherence and was scheduled for follow-up in 3 months. He continued outpatient phlebotomy every 6 weeks for polycythemia.

At 3-month follow-up, the patient reported medication adherence, continued alcohol use, and worsening of symptoms. Falls, which now occurred 2 to 3 times weekly despite proper use of a walker, were described as sudden loss of bilateral lower extremity strength without loss of consciousness, palpitations, or other prodrome. Laboratory results showed minimal changes. Physical examination of the patient demonstrated similar deficits as on initial presentation. The patient received one additional B12 1000 mcg IM. Gabapentin was replaced with pregabalin 75 mg twice daily due to persistent uncontrolled pain and paresthesia. The patient was scheduled for a 3-month followup (6 months from initial visit) and repeat serology.

At 6-month follow-up, the patient showed continued progression of disease with significant difficulty using the walker, worsening falls, and wheelchair use required. Physical examination showed decreased sensation bilaterally up to the knees, absent bilateral patellar and Achilles reflexes, and unsteady gait. Laboratory results showed persistent subclinical B12 deficiency. MRI of the brain and spine showed high T2 signaling in a pattern highly specific for SCD. A formal diagnosis of SCD was made. The patient received an additional B12 1000 mcg IM once. Follow-up phone call with the patient 1 month later revealed no progression or improvement of symptoms.

Radiographic Findings

MRI of the cervical and thoracic spine demonstrated abnormal high T2 signal starting from C2 and extending along the course of the cervical and thoracic spinal cord (Figure). MRI in SCD classically shows symmetric, bilateral high T2 signal within the dorsal columns; on axial images, there is typically an inverted “V” sign.2,4 There can also be abnormal cerebral white matter change; however, MRI of the brain in this patient did not show any abnormalities.2 The imaging differential for this appearance includes other metabolic deficiencies/toxicities: copper deficiency; vitamin E deficiency; methotrexateinduced myelopathy, and infectious causes: HIV vacuolar myelopathy; and neurosyphilis (tabes dorsalis).4

Discussion

This case demonstrates the clinical and radiographic findings of SCD and underscores the need for high-intensity dosing of B12 replacement in patients with SCD to prevent progression of the disease and development of morbidities.

Symptoms of SCD may manifest even when the vitamin levels are in low-normal levels. Its presentation is often nonspecific, thus radiologic workup is beneficial to elucidate the clinical picture. We support the use of spinal MRI in patients with clinical suspicion of SCD to help rule out other causes of myelopathy. However, an MRI is not indicated in all patients with B12 deficiency, especially those without myelopathic symptoms. Additionally, follow-up spinal MRIs are useful in monitoring the progression or improvement of SCD after B12 replacement.2 It is important to note that the MRI findings in SCD are not specific to B12 deficiency; other causes may present with similar radiographic findings.4 Therefore, radiologic findings must be correlated with a patient’s clinical presentation.

B12 replacement improves and may resolve clinical symptoms and abnormal radiographic findings of SCD. The treatment duration of B12 deficiency depends on the underlying etiology. Reversible causes, such as metformin use > 4 months, PPI use > 12 months, and dietary deficiency, require treatment until appropriate levels are reached and symptoms are resolved.4,11 The need for chronic metformin and PPI use should also be reassessed regularly. In patients who require long-term metformin use, IM administration of B12 1000 mcg annually should be considered, which will ensure adequate storage for more than 1 year.12,13 In patients who require long-term PPI use, the risk and benefits of continued use should be measured, and if needed, the lowest possible effective PPI dose is recommended.14 Irreversible causes of B12 deficiency, such as advanced age, prior gastrectomy, chronic pancreatitis, or autoimmune pernicious anemia, require lifelong supplementation of B12.4,11

In general, oral vitamin B12 replacement at 1000 to 2000 mcg daily may be as effective as parenteral replacement in patients with mild to moderate deficiency or neurologic symptoms.11 On the other hand, patients with SCD often require parenteral replacement of B12 due to the severity of their deficiency or neurologic symptoms, need for more rapid improvement in symptoms, and prevention of irreversible neurological deficits. 4,11 Appropriate B12 replacement in SCD requires intensive initial therapy which may involve IM B12 1000 mcg every other day for 2 weeks and additional IM supplementation every 2 to 3 months afterward until resolution of deficiency.4,14 IM replacement may also be considered in patients who are nonadherent to oral replacement or have an underlying gastrointestinal condition that impairs enteral absorption.4,11

B12 deficiency is frequently undertreated and can lead to progression of disease with significant morbidity. The need for highintensity dosing of B12 replacement is crucial in patients with SCD. Failure to respond to treatment, as shown from the lack of improvement of serum markers or symptoms, likely suggests undertreatment, treatment nonadherence, iron deficiency anemia, an unidentified malabsorption syndrome, or other diagnoses. In our case, significant undertreatment, compounded by his suspected iron deficiency anemia secondary to his polycythemia vera and chronic phlebotomies, are the most likel etiologies for his lack of clinical improvement.

Multiple factors may affect the prognosis of SCD. Males aged < 50 years with absence of anemia, spinal cord atrophy, Romberg sign, Babinski sign, or sensory deficits on examination have increased likelihood of eventual recovery of signs and symptoms of SCD; those with less spinal cord involvement (< 7 cord segments), contrast enhancement, and spinal cord edema also have improved outcomes.4,15

Conclusion

SCD is a rare but serious complication of chronic vitamin B12 deficiency that presents with a variety of neurological findings and may be easily confused with other illnesses. The condition is easily overlooked or misdiagnosed; thus, it is crucial to differentiate B12 deficiency from other common causes of neurologic symptoms. Specific findings on MRI are useful to support the clinical diagnosis of SCD and guide clinical decisions. Given the prevalence of B12 deficiency in the older adult population, clinicians should remain alert to the possibility of these conditions in patients who present with progressive neuropathy. Once a patient is diagnosed with SCD secondary to a B12 deficiency, appropriate B12 replacement is critical. Appropriate B12 replacement is aggressive and involves IM B12 1000 mcg every other day for 2 to 3 weeks, followed by additional IM administration every 2 months before transitioning to oral therapy. As seen in this case, failure to adequately replenish B12 can lead to progression or lack of resolution of SCD symptoms.

Subacute combined degeneration (SCD) is an acquired neurologic complication of vitamin B12 (cobalamin) or, rarely, vitamin B9 (folate) deficiency. SCD is characterized by progressive demyelination of the dorsal and lateral spinal cord, resulting in peripheral neuropathy; gait ataxia; impaired proprioception, vibration, and fine touch; optic neuropathy; and cognitive impairment.1 In addition to SCD, other neurologic manifestations of B12 deficiency include dementia, depression, visual symptoms due to optic atrophy, and behavioral changes.2 The prevalence of SCD in the US has not been well documented, but B12 deficiency is reported at 6% in those aged < 60 years and 20% in those > 60 years.3

Causes of B12 and B9 deficiency include advanced age, low nutritional intake (eg, vegan diet), impaired absorption (eg, inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune pernicious anemia, gastrectomy, pancreatic disease), alcohol use, tapeworm infection, medications, and high metabolic states.2,4 Impaired B12 absorption is common in patients taking medications, such as metformin and proton pump inhibitors (PPI), due to suppression of ileal membrane transport and intrinsic factor activity.5-7 B-vitamin deficiency can be exacerbated by states of increased cellular turnover, such as polycythemia vera, due to elevated DNA synthesis.

Patients may experience permanent neurologic damage when the diagnosis and treatment of SCD are missed or delayed. Early diagnosis of SCD can be challenging due to lack of specific hematologic markers. In addition, many other conditions such as diabetic neuropathy, malnutrition, toxic neuropathy, sarcoidosis, HIV, multiple sclerosis, polycythemia vera, and iron deficiency anemia have similar presentations and clinical findings.8 Anemia and/or macrocytosis are not specific to B12 deficiency.4 In addition, patients with B12 deficiency may have a normal complete blood count (CBC); those with concomitant iron deficiency may have minimal or no mean corpuscular volume (MCV) elevation.4 In patients suspected to have B12 deficiency based on clinical presentation or laboratory findings of macrocytosis, serum methylmalonic acid (MMA) can serve as a direct measure of B12 activity, with levels > 0.75 μmol/L almost always indicating cobalamin deficiency. 9 On the other hand, plasma total homocysteine (tHcy) is a sensitive marker for B12 deficiency. The active form of B12, holotranscobalamin, has also emerged as a specific measure of B12 deficiency.9 However, in patients with SCD, measurement of these markers may be unnecessary due to the severity of their clinical symptoms.

The diagnosis of SCD is further complicated because not all individuals who develop B12 or B9 deficiency will develop SCD. It is difficult to determine which patients will develop SCD because the minimum level of serum B12 required for normal function is unknown, and recent studies indicate that SCD may occur even at low-normal B12 and B9 levels.2,4,10 Commonly, a serum B12 level of < 200 pg/mL is considered deficient, while a level between 200 and 300 pg/mL is considered borderline.4 The goal level of serum B12 is > 300 pg/mL, which is considered normal.4 While serologic findings of B-vitamin deficiency are only moderately specific, radiographic findings are highly sensitive and specific for SCD. According to Briani and colleagues, the most consistent finding in SCD on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a “symmetrical, abnormally increased T2 signal intensity, commonly confined to posterior or posterior and lateral columns in the cervical and thoracic spinal cord.”2

We present a case of SCD in a patient with low-normal vitamin B12 levels who presented with progressive sensorimotor deficits and vision loss. The patient was subsequently diagnosed with SCD by radiologic workup. His course was complicated by worsening neurologic deficits despite B12 replacement. The progression of his clinical symptoms demonstrates the need for prompt, aggressive B12 replacement in patients diagnosed with SCD.

Case Presentation

A 63-year-old man presented for neurologic evaluation of progressive gait disturbance, paresthesia, blurred vision, and increasing falls despite use of a walker. Pertinent medical history included polycythemia vera requiring phlebotomy for approximately 9 years, alcohol use disorder (18 servings weekly), type 2 diabetes mellitus, and a remote episode of transient ischemic attack (TIA). The patient reported a 5-year history of burning pain in all extremities. A prior physician diagnosis attributed the symptoms to polyneuropathy secondary to iron deficiency anemia in the setting of chronic phlebotomy for polycythemia vera and high erythrogenesis. He was prescribed gabapentin 600 mg 3 times daily for pain control. B12 deficiency was considered an unlikely etiology due to a low-normal serum level of 305 pg/mL (reference range, 190-950 pg/mL) and normocytosis, with MCV of 88 fL (reference range, 80-100 fL). The patient also reported a 3-year history of blurred vision, which was initially attributed to be secondary to diabetic retinopathy. One week prior to presenting to our clinic, he was evaluated by ophthalmology for new-onset, bilateral central visual field defects, and he was diagnosed with nutritional optic neuropathy.

Ophthalmology suspected B12 deficiency. Notable findings included reduced deep tendon reflexes (DTRs) in the upper extremities and absent DTRs in the lower extremities, reduced sensation to light touch in all extremities, absent sensation to pinprick, vibration, and temperature in the lower extremities, positive Romberg sign, and a wide-based antalgic gait with the ankles externally rotated bilaterally (Table 1)

Previous cardiac evaluation failed to provide a diagnosis for syncopal episodes. MRI of the brain revealed nonspecific white matter changes consistent with chronic microvascular ischemic disease. Electromyography was limited due to pain but showed severe peripheral neuropathy. Laboratory results showed megalocytosis, low-normal serum B12 levels, and low serum folate levels (Table 2). The patient was diagnosed with polyneuropathy and was given intramuscular (IM) vitamin B12 1000 mcg once and a daily multivitamin (containing 25 mcg of B12). He was counseled on alcohol abstinence and medication adherence and was scheduled for follow-up in 3 months. He continued outpatient phlebotomy every 6 weeks for polycythemia.

At 3-month follow-up, the patient reported medication adherence, continued alcohol use, and worsening of symptoms. Falls, which now occurred 2 to 3 times weekly despite proper use of a walker, were described as sudden loss of bilateral lower extremity strength without loss of consciousness, palpitations, or other prodrome. Laboratory results showed minimal changes. Physical examination of the patient demonstrated similar deficits as on initial presentation. The patient received one additional B12 1000 mcg IM. Gabapentin was replaced with pregabalin 75 mg twice daily due to persistent uncontrolled pain and paresthesia. The patient was scheduled for a 3-month followup (6 months from initial visit) and repeat serology.

At 6-month follow-up, the patient showed continued progression of disease with significant difficulty using the walker, worsening falls, and wheelchair use required. Physical examination showed decreased sensation bilaterally up to the knees, absent bilateral patellar and Achilles reflexes, and unsteady gait. Laboratory results showed persistent subclinical B12 deficiency. MRI of the brain and spine showed high T2 signaling in a pattern highly specific for SCD. A formal diagnosis of SCD was made. The patient received an additional B12 1000 mcg IM once. Follow-up phone call with the patient 1 month later revealed no progression or improvement of symptoms.

Radiographic Findings

MRI of the cervical and thoracic spine demonstrated abnormal high T2 signal starting from C2 and extending along the course of the cervical and thoracic spinal cord (Figure). MRI in SCD classically shows symmetric, bilateral high T2 signal within the dorsal columns; on axial images, there is typically an inverted “V” sign.2,4 There can also be abnormal cerebral white matter change; however, MRI of the brain in this patient did not show any abnormalities.2 The imaging differential for this appearance includes other metabolic deficiencies/toxicities: copper deficiency; vitamin E deficiency; methotrexateinduced myelopathy, and infectious causes: HIV vacuolar myelopathy; and neurosyphilis (tabes dorsalis).4

Discussion

This case demonstrates the clinical and radiographic findings of SCD and underscores the need for high-intensity dosing of B12 replacement in patients with SCD to prevent progression of the disease and development of morbidities.

Symptoms of SCD may manifest even when the vitamin levels are in low-normal levels. Its presentation is often nonspecific, thus radiologic workup is beneficial to elucidate the clinical picture. We support the use of spinal MRI in patients with clinical suspicion of SCD to help rule out other causes of myelopathy. However, an MRI is not indicated in all patients with B12 deficiency, especially those without myelopathic symptoms. Additionally, follow-up spinal MRIs are useful in monitoring the progression or improvement of SCD after B12 replacement.2 It is important to note that the MRI findings in SCD are not specific to B12 deficiency; other causes may present with similar radiographic findings.4 Therefore, radiologic findings must be correlated with a patient’s clinical presentation.

B12 replacement improves and may resolve clinical symptoms and abnormal radiographic findings of SCD. The treatment duration of B12 deficiency depends on the underlying etiology. Reversible causes, such as metformin use > 4 months, PPI use > 12 months, and dietary deficiency, require treatment until appropriate levels are reached and symptoms are resolved.4,11 The need for chronic metformin and PPI use should also be reassessed regularly. In patients who require long-term metformin use, IM administration of B12 1000 mcg annually should be considered, which will ensure adequate storage for more than 1 year.12,13 In patients who require long-term PPI use, the risk and benefits of continued use should be measured, and if needed, the lowest possible effective PPI dose is recommended.14 Irreversible causes of B12 deficiency, such as advanced age, prior gastrectomy, chronic pancreatitis, or autoimmune pernicious anemia, require lifelong supplementation of B12.4,11

In general, oral vitamin B12 replacement at 1000 to 2000 mcg daily may be as effective as parenteral replacement in patients with mild to moderate deficiency or neurologic symptoms.11 On the other hand, patients with SCD often require parenteral replacement of B12 due to the severity of their deficiency or neurologic symptoms, need for more rapid improvement in symptoms, and prevention of irreversible neurological deficits. 4,11 Appropriate B12 replacement in SCD requires intensive initial therapy which may involve IM B12 1000 mcg every other day for 2 weeks and additional IM supplementation every 2 to 3 months afterward until resolution of deficiency.4,14 IM replacement may also be considered in patients who are nonadherent to oral replacement or have an underlying gastrointestinal condition that impairs enteral absorption.4,11

B12 deficiency is frequently undertreated and can lead to progression of disease with significant morbidity. The need for highintensity dosing of B12 replacement is crucial in patients with SCD. Failure to respond to treatment, as shown from the lack of improvement of serum markers or symptoms, likely suggests undertreatment, treatment nonadherence, iron deficiency anemia, an unidentified malabsorption syndrome, or other diagnoses. In our case, significant undertreatment, compounded by his suspected iron deficiency anemia secondary to his polycythemia vera and chronic phlebotomies, are the most likel etiologies for his lack of clinical improvement.

Multiple factors may affect the prognosis of SCD. Males aged < 50 years with absence of anemia, spinal cord atrophy, Romberg sign, Babinski sign, or sensory deficits on examination have increased likelihood of eventual recovery of signs and symptoms of SCD; those with less spinal cord involvement (< 7 cord segments), contrast enhancement, and spinal cord edema also have improved outcomes.4,15

Conclusion

SCD is a rare but serious complication of chronic vitamin B12 deficiency that presents with a variety of neurological findings and may be easily confused with other illnesses. The condition is easily overlooked or misdiagnosed; thus, it is crucial to differentiate B12 deficiency from other common causes of neurologic symptoms. Specific findings on MRI are useful to support the clinical diagnosis of SCD and guide clinical decisions. Given the prevalence of B12 deficiency in the older adult population, clinicians should remain alert to the possibility of these conditions in patients who present with progressive neuropathy. Once a patient is diagnosed with SCD secondary to a B12 deficiency, appropriate B12 replacement is critical. Appropriate B12 replacement is aggressive and involves IM B12 1000 mcg every other day for 2 to 3 weeks, followed by additional IM administration every 2 months before transitioning to oral therapy. As seen in this case, failure to adequately replenish B12 can lead to progression or lack of resolution of SCD symptoms.

1. Gürsoy AE, Kolukısa M, Babacan-Yıldız G, Celebi A. Subacute Combined Degeneration of the Spinal Cord due to Different Etiologies and Improvement of MRI Findings. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2013;2013:159649. doi:10.1155/2013/159649

2. Briani C, Dalla Torre C, Citton V, et al. Cobalamin deficiency: clinical picture and radiological findings. Nutrients. 2013;5(11):4521-4539. Published 2013 Nov 15. doi:10.3390/nu5114521

3. Hunt A, Harrington D, Robinson S. Vitamin B12 deficiency. BMJ. 2014;349:g5226. Published 2014 Sep 4. doi:10.1136/bmj.g5226

4. Qudsiya Z, De Jesus O. Subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord. [Updated 2021 Feb 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Updated August 30, 2021. Accessed January 5, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books /NBK559316/

5. de Jager J, Kooy A, Lehert P, et al. Long term treatment with metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes and risk of vitamin B-12 deficiency: randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c2181. Published 2010 May 20. doi:10.1136/bmj.c2181

6. Aroda VR, Edelstein SL, Goldberg RB, et al. Longterm Metformin Use and Vitamin B12 Deficiency in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(4):1754-1761. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-3754

7. Lam JR, Schneider JL, Zhao W, Corley DA. Proton pump inhibitor and histamine 2 receptor antagonist use and vitamin B12 deficiency. JAMA. 2013;310(22):2435-2442. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.280490

8. Mihalj M, Titlic´ M, Bonacin D, Dogaš Z. Sensomotor axonal peripheral neuropathy as a first complication of polycythemia rubra vera: A report of 3 cases. Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:385-387. Published 2013 Sep 25. doi:10.12659/AJCR.884016

9. Devalia V, Hamilton MS, Molloy AM; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cobalamin and folate disorders. Br J Haematol. 2014;166(4):496-513. doi:10.1111/bjh.12959

10. Cao J, Xu S, Liu C. Is serum vitamin B12 decrease a necessity for the diagnosis of subacute combined degeneration?: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(14):e19700.doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000019700

11. Langan RC, Goodbred AJ. Vitamin B12 Deficiency: Recognition and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(6):384-389.

12. Mazokopakis EE, Starakis IK. Recommendations for diagnosis and management of metformin-induced vitamin B12 (Cbl) deficiency. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;97(3):359-367. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2012.06.001

13. Mahajan R, Gupta K. Revisiting Metformin: Annual Vitamin B12 Supplementation may become Mandatory with Long-Term Metformin Use. J Young Pharm. 2010;2(4):428-429. doi:10.4103/0975-1483.71621

14. Parks NE. Metabolic and Toxic Myelopathies. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2021;27(1):143-162. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000963

15. Vasconcelos OM, Poehm EH, McCarter RJ, Campbell WW, Quezado ZM. Potential outcome factors in subacute combined degeneration: review of observational studies. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(10):1063-1068. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00525.x

1. Gürsoy AE, Kolukısa M, Babacan-Yıldız G, Celebi A. Subacute Combined Degeneration of the Spinal Cord due to Different Etiologies and Improvement of MRI Findings. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2013;2013:159649. doi:10.1155/2013/159649

2. Briani C, Dalla Torre C, Citton V, et al. Cobalamin deficiency: clinical picture and radiological findings. Nutrients. 2013;5(11):4521-4539. Published 2013 Nov 15. doi:10.3390/nu5114521

3. Hunt A, Harrington D, Robinson S. Vitamin B12 deficiency. BMJ. 2014;349:g5226. Published 2014 Sep 4. doi:10.1136/bmj.g5226

4. Qudsiya Z, De Jesus O. Subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord. [Updated 2021 Feb 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Updated August 30, 2021. Accessed January 5, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books /NBK559316/

5. de Jager J, Kooy A, Lehert P, et al. Long term treatment with metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes and risk of vitamin B-12 deficiency: randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c2181. Published 2010 May 20. doi:10.1136/bmj.c2181

6. Aroda VR, Edelstein SL, Goldberg RB, et al. Longterm Metformin Use and Vitamin B12 Deficiency in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(4):1754-1761. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-3754

7. Lam JR, Schneider JL, Zhao W, Corley DA. Proton pump inhibitor and histamine 2 receptor antagonist use and vitamin B12 deficiency. JAMA. 2013;310(22):2435-2442. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.280490

8. Mihalj M, Titlic´ M, Bonacin D, Dogaš Z. Sensomotor axonal peripheral neuropathy as a first complication of polycythemia rubra vera: A report of 3 cases. Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:385-387. Published 2013 Sep 25. doi:10.12659/AJCR.884016

9. Devalia V, Hamilton MS, Molloy AM; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cobalamin and folate disorders. Br J Haematol. 2014;166(4):496-513. doi:10.1111/bjh.12959

10. Cao J, Xu S, Liu C. Is serum vitamin B12 decrease a necessity for the diagnosis of subacute combined degeneration?: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(14):e19700.doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000019700

11. Langan RC, Goodbred AJ. Vitamin B12 Deficiency: Recognition and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(6):384-389.

12. Mazokopakis EE, Starakis IK. Recommendations for diagnosis and management of metformin-induced vitamin B12 (Cbl) deficiency. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;97(3):359-367. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2012.06.001

13. Mahajan R, Gupta K. Revisiting Metformin: Annual Vitamin B12 Supplementation may become Mandatory with Long-Term Metformin Use. J Young Pharm. 2010;2(4):428-429. doi:10.4103/0975-1483.71621

14. Parks NE. Metabolic and Toxic Myelopathies. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2021;27(1):143-162. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000963

15. Vasconcelos OM, Poehm EH, McCarter RJ, Campbell WW, Quezado ZM. Potential outcome factors in subacute combined degeneration: review of observational studies. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(10):1063-1068. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00525.x

Reactivation of a BCG Vaccination Scar Following the First Dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in notable morbidity and mortality worldwide. In December 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration issued an Emergency Use Authorization for 2 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines—produced by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna—for the prevention of COVID-19. Phase 3 trials of the vaccine developed by Moderna showed 94.1% efficacy at preventing COVID-19 after 2 doses.1

Common cutaneous adverse effects of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine include injection-site reactions, such as pain, induration, and erythema. Less frequently reported dermatologic adverse effects include diffuse bullous rash and hypersensitivity reactions.1 We report a case of reactivation of a BCG vaccination scar after the first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine.

Case Report

A 48-year-old Asian man who was otherwise healthy presented with erythema, induration, and mild pruritus on the deltoid muscle of the left arm, near the scar from an earlier BCG vaccine, which he received at approximately 5 years of age when living in Taiwan. The patient received the first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine approximately 5 to 7 cm distant from the BCG vaccination scar. One to 2 days after inoculation, the patient endorsed tenderness at the site of COVID-19 vaccination but denied systemic symptoms. He had never been given a diagnosis of COVID-19. His SARS-CoV-2 antibody status was unknown.

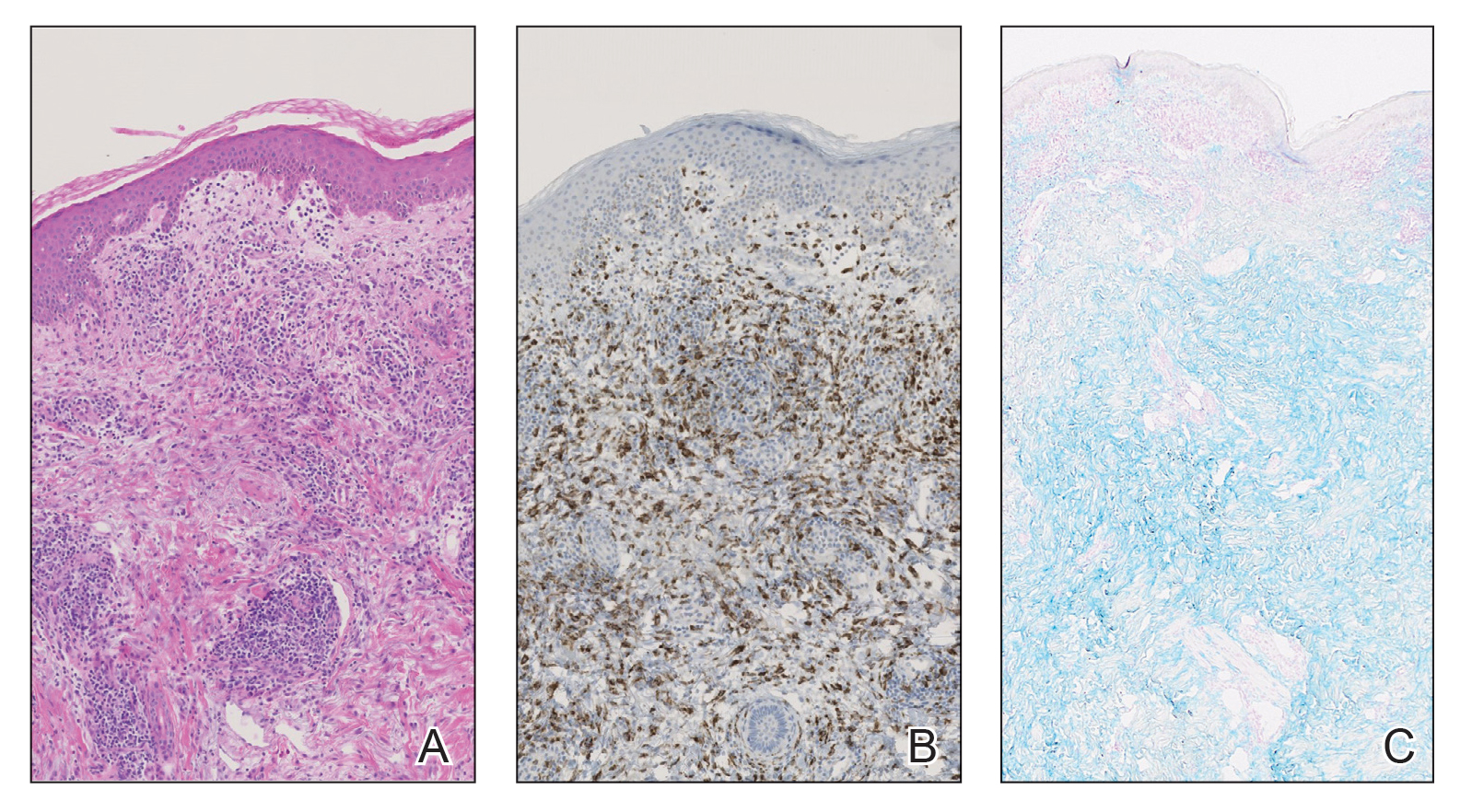

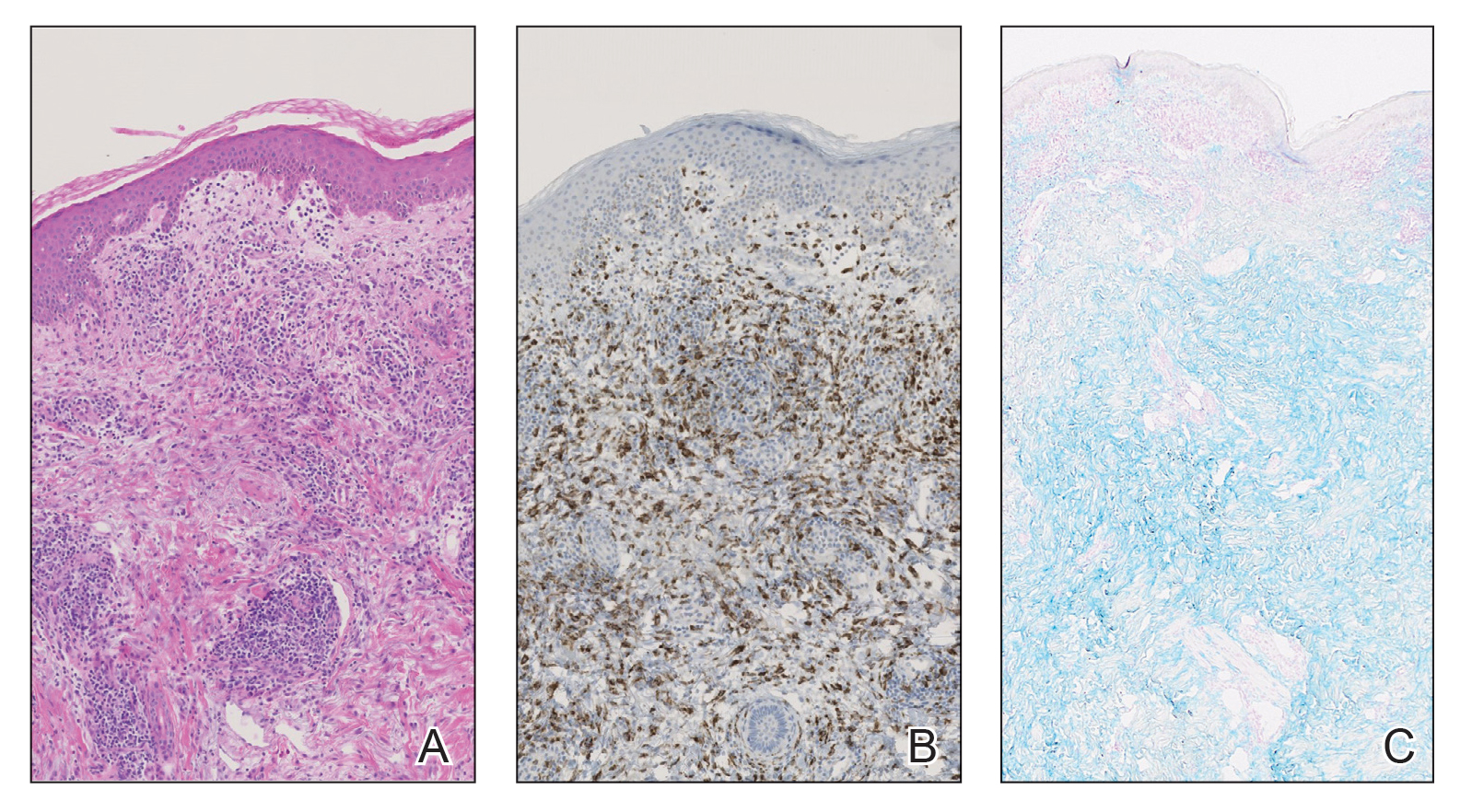

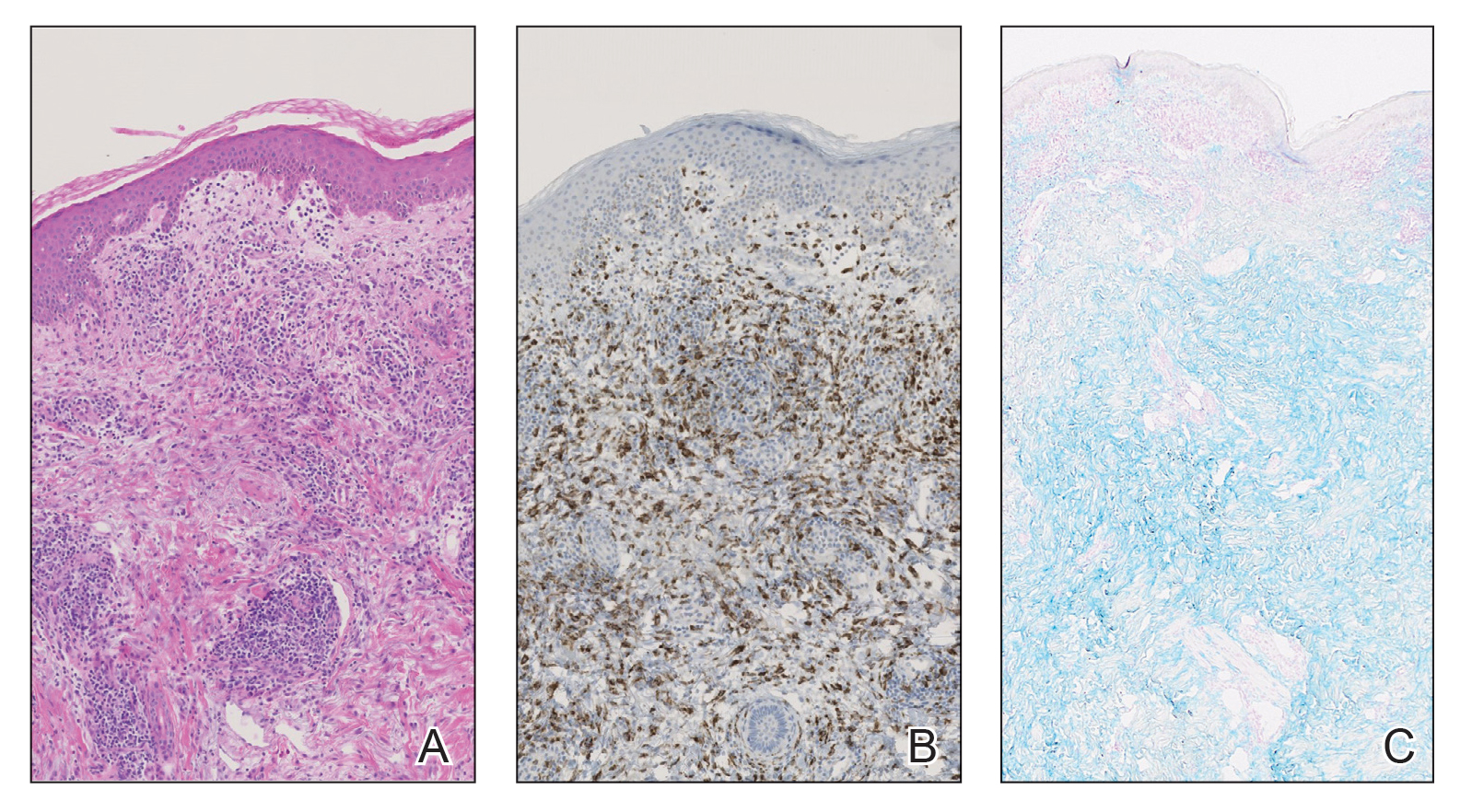

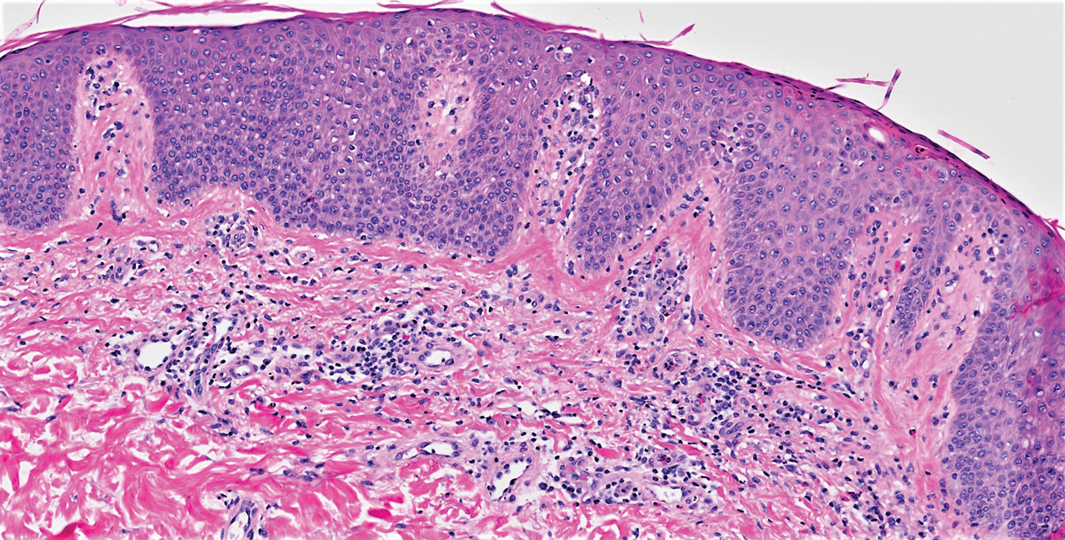

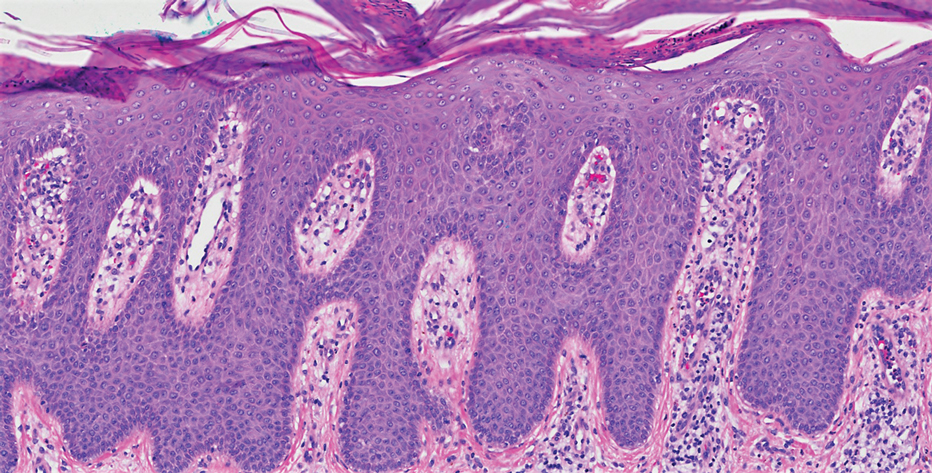

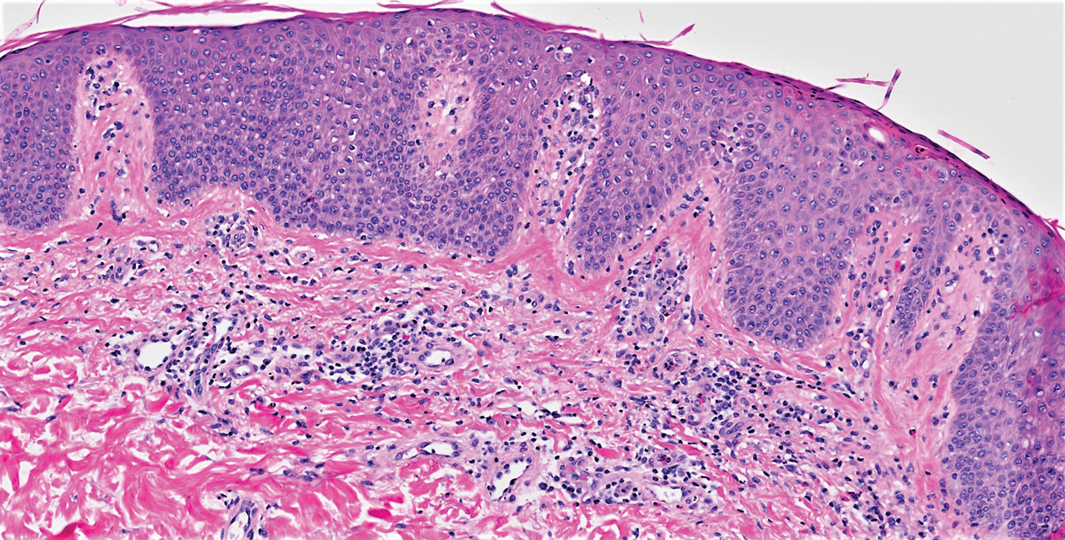

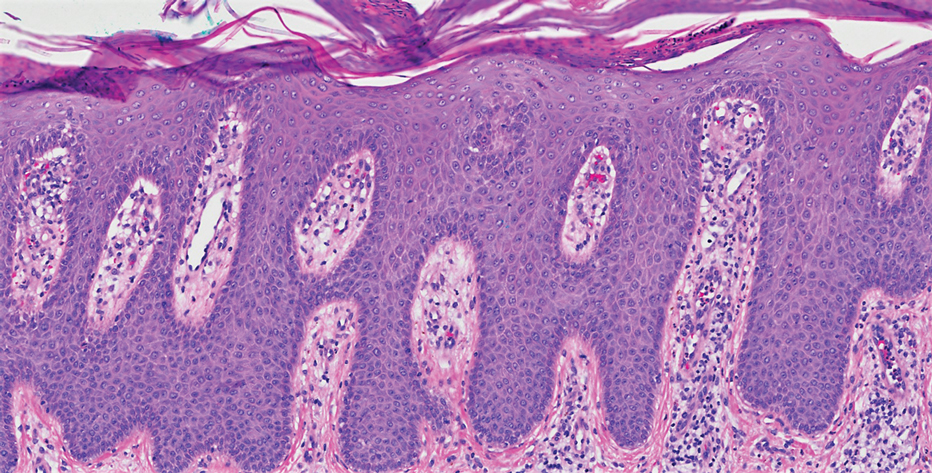

Eight days later, the patient noticed a well-defined, erythematous, indurated plaque with mild itchiness overlying and around the BCG vaccination scar that did not involve the COVID-19 vaccination site. The following day, the redness and induration became worse (Figure).

The patient was otherwise well. Vital signs were normal; there was no lymphadenopathy. The rash resolved without treatment over the next 4 days.

Comment

The BCG vaccine is an intradermal live attenuated virus vaccine used to prevent certain forms of tuberculosis and potentially other Mycobacterium infections. Although the vaccine is not routinely administered in the United States, it is part of the vaccination schedule in most countries, administered most often to newborns and infants. Administration of the BCG vaccine commonly results in mild localized erythema, swelling, and pain at the injection site. Most inoculated patients also develop an ulcer that heals with the characteristic BCG vaccination scar.2,3

There is evidence that the BCG vaccine can enhance the innate immune system response and might decrease the rate of infection by unrelated pathogens, including viruses.4 Several epidemiologic studies have suggested that the BCG vaccine might offer some protection against COVID-19, possibly due to a resemblance of the amino acid sequences of BCG and SARS-CoV-2, which might provoke cross-reactive T cells.5,6 Further studies are underway to determine whether the BCG vaccine is truly protective against COVID-19.

BCG vaccination scar reactivation presents as redness, swelling, or ulceration at the BCG injection site months to years after inoculation. Although erythema and induration of the BCG scar are not included in the diagnostic criteria of Kawasaki disease, likely due to variable vaccine requirements in different countries, these findings are largely recognized as specific for Kawasaki disease and present in approximately half of affected patients who received the BCG vaccine.2

Heat Shock Proteins—Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are produced by cells in response to stressors. The proposed mechanism of BCG vaccination scar reactivation is a cross-reaction between human homologue HSP 63 and Mycobacterium HSP 65, leading to hyperactivity of the immune system against BCG.7 There also are reports of reactivation of a BCG vaccination scar from measles infection and influenza vaccination.2,8,9 Most prior reports of BCG vaccination scar reactivation have been in pediatric patients; our patient is an adult who received the BCG vaccine more than 40 years ago.

Mechanism of Reactivation—The mechanism of BCG vaccination scar reactivation in our patient, who received the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine, is unclear. Possible mechanisms include (1) release of HSP mediated by the COVID-19 vaccine, leading to an immune response at the BCG vaccine scar, or (2) another immune-mediated cross-reaction between BCG and the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine mRNA nanoparticle or encoded spike protein antigen. It has been hypothesized that the BCG vaccine might offer some protection against COVID-19; this remains uncertain and is under further investigation.10 A recent retrospective cohort study showed that a BCG vaccination booster may decrease COVID-19 infection rates in higher-risk populations.11

Conclusion

We present a case of BCG vaccine scar reactivation occurring after a dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine, a likely underreported, self-limiting, cutaneous adverse effect of this mRNA vaccine.

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al; COVE Study Group. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;384:403-416. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2035389

- Muthuvelu S, Lim KS, Huang L-Y, et al. Measles infection causing bacillus Calmette-Guérin reactivation: a case report. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19:251. doi:10.1186/s12887-019-1635-z

- Fatima S, Kumari A, Das G, et al. Tuberculosis vaccine: a journey from BCG to present. Life Sci. 2020;252:117594. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117594

- O’Neill LAJ, Netea MG. BCG-induced trained immunity: can it offer protection against COVID-19? Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:335-337. doi:10.1038/s41577-020-0337-y

- Brooks NA, Puri A, Garg S, et al. The association of coronavirus disease-19 mortality and prior bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccination: a robust ecological analysis using unsupervised machine learning. Sci Rep. 2021;11:774. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-80787-z

- Tomita Y, Sato R, Ikeda T, et al. BCG vaccine may generate cross-reactive T-cells against SARS-CoV-2: in silico analyses and a hypothesis. Vaccine. 2020;38:6352-6356. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.045

- Lim KYY, Chua MC, Tan NWH, et al. Reactivation of BCG inoculation site in a child with febrile exanthema of 3 days duration: an early indicator of incomplete Kawasaki disease. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:E239648. doi:10.1136/bcr-2020-239648

- Kondo M, Goto H, Yamamoto S. First case of redness and erosion at bacillus Calmette-Guérin inoculation site after vaccination against influenza. J Dermatol. 2016;43:1229-1231. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13365

- Chavarri-Guerra Y, Soto-Pérez-de-Celis E. Erythema at the bacillus Calmette-Guerin scar after influenza vaccination. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2019;53:E20190390. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0390-2019

- Fu W, Ho P-C, Liu C-L, et al. Reconcile the debate over protective effects of BCG vaccine against COVID-19. Sci Rep. 2021;11:8356. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-87731-9

- Amirlak L, Haddad R, Hardy JD, et al. Effectiveness of booster BCG vaccination in preventing COVID-19 infection. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17:3913-3915. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1956228

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in notable morbidity and mortality worldwide. In December 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration issued an Emergency Use Authorization for 2 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines—produced by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna—for the prevention of COVID-19. Phase 3 trials of the vaccine developed by Moderna showed 94.1% efficacy at preventing COVID-19 after 2 doses.1

Common cutaneous adverse effects of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine include injection-site reactions, such as pain, induration, and erythema. Less frequently reported dermatologic adverse effects include diffuse bullous rash and hypersensitivity reactions.1 We report a case of reactivation of a BCG vaccination scar after the first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine.

Case Report

A 48-year-old Asian man who was otherwise healthy presented with erythema, induration, and mild pruritus on the deltoid muscle of the left arm, near the scar from an earlier BCG vaccine, which he received at approximately 5 years of age when living in Taiwan. The patient received the first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine approximately 5 to 7 cm distant from the BCG vaccination scar. One to 2 days after inoculation, the patient endorsed tenderness at the site of COVID-19 vaccination but denied systemic symptoms. He had never been given a diagnosis of COVID-19. His SARS-CoV-2 antibody status was unknown.

Eight days later, the patient noticed a well-defined, erythematous, indurated plaque with mild itchiness overlying and around the BCG vaccination scar that did not involve the COVID-19 vaccination site. The following day, the redness and induration became worse (Figure).

The patient was otherwise well. Vital signs were normal; there was no lymphadenopathy. The rash resolved without treatment over the next 4 days.

Comment

The BCG vaccine is an intradermal live attenuated virus vaccine used to prevent certain forms of tuberculosis and potentially other Mycobacterium infections. Although the vaccine is not routinely administered in the United States, it is part of the vaccination schedule in most countries, administered most often to newborns and infants. Administration of the BCG vaccine commonly results in mild localized erythema, swelling, and pain at the injection site. Most inoculated patients also develop an ulcer that heals with the characteristic BCG vaccination scar.2,3

There is evidence that the BCG vaccine can enhance the innate immune system response and might decrease the rate of infection by unrelated pathogens, including viruses.4 Several epidemiologic studies have suggested that the BCG vaccine might offer some protection against COVID-19, possibly due to a resemblance of the amino acid sequences of BCG and SARS-CoV-2, which might provoke cross-reactive T cells.5,6 Further studies are underway to determine whether the BCG vaccine is truly protective against COVID-19.

BCG vaccination scar reactivation presents as redness, swelling, or ulceration at the BCG injection site months to years after inoculation. Although erythema and induration of the BCG scar are not included in the diagnostic criteria of Kawasaki disease, likely due to variable vaccine requirements in different countries, these findings are largely recognized as specific for Kawasaki disease and present in approximately half of affected patients who received the BCG vaccine.2

Heat Shock Proteins—Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are produced by cells in response to stressors. The proposed mechanism of BCG vaccination scar reactivation is a cross-reaction between human homologue HSP 63 and Mycobacterium HSP 65, leading to hyperactivity of the immune system against BCG.7 There also are reports of reactivation of a BCG vaccination scar from measles infection and influenza vaccination.2,8,9 Most prior reports of BCG vaccination scar reactivation have been in pediatric patients; our patient is an adult who received the BCG vaccine more than 40 years ago.

Mechanism of Reactivation—The mechanism of BCG vaccination scar reactivation in our patient, who received the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine, is unclear. Possible mechanisms include (1) release of HSP mediated by the COVID-19 vaccine, leading to an immune response at the BCG vaccine scar, or (2) another immune-mediated cross-reaction between BCG and the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine mRNA nanoparticle or encoded spike protein antigen. It has been hypothesized that the BCG vaccine might offer some protection against COVID-19; this remains uncertain and is under further investigation.10 A recent retrospective cohort study showed that a BCG vaccination booster may decrease COVID-19 infection rates in higher-risk populations.11

Conclusion

We present a case of BCG vaccine scar reactivation occurring after a dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine, a likely underreported, self-limiting, cutaneous adverse effect of this mRNA vaccine.

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in notable morbidity and mortality worldwide. In December 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration issued an Emergency Use Authorization for 2 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines—produced by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna—for the prevention of COVID-19. Phase 3 trials of the vaccine developed by Moderna showed 94.1% efficacy at preventing COVID-19 after 2 doses.1

Common cutaneous adverse effects of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine include injection-site reactions, such as pain, induration, and erythema. Less frequently reported dermatologic adverse effects include diffuse bullous rash and hypersensitivity reactions.1 We report a case of reactivation of a BCG vaccination scar after the first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine.

Case Report

A 48-year-old Asian man who was otherwise healthy presented with erythema, induration, and mild pruritus on the deltoid muscle of the left arm, near the scar from an earlier BCG vaccine, which he received at approximately 5 years of age when living in Taiwan. The patient received the first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine approximately 5 to 7 cm distant from the BCG vaccination scar. One to 2 days after inoculation, the patient endorsed tenderness at the site of COVID-19 vaccination but denied systemic symptoms. He had never been given a diagnosis of COVID-19. His SARS-CoV-2 antibody status was unknown.

Eight days later, the patient noticed a well-defined, erythematous, indurated plaque with mild itchiness overlying and around the BCG vaccination scar that did not involve the COVID-19 vaccination site. The following day, the redness and induration became worse (Figure).

The patient was otherwise well. Vital signs were normal; there was no lymphadenopathy. The rash resolved without treatment over the next 4 days.

Comment

The BCG vaccine is an intradermal live attenuated virus vaccine used to prevent certain forms of tuberculosis and potentially other Mycobacterium infections. Although the vaccine is not routinely administered in the United States, it is part of the vaccination schedule in most countries, administered most often to newborns and infants. Administration of the BCG vaccine commonly results in mild localized erythema, swelling, and pain at the injection site. Most inoculated patients also develop an ulcer that heals with the characteristic BCG vaccination scar.2,3

There is evidence that the BCG vaccine can enhance the innate immune system response and might decrease the rate of infection by unrelated pathogens, including viruses.4 Several epidemiologic studies have suggested that the BCG vaccine might offer some protection against COVID-19, possibly due to a resemblance of the amino acid sequences of BCG and SARS-CoV-2, which might provoke cross-reactive T cells.5,6 Further studies are underway to determine whether the BCG vaccine is truly protective against COVID-19.

BCG vaccination scar reactivation presents as redness, swelling, or ulceration at the BCG injection site months to years after inoculation. Although erythema and induration of the BCG scar are not included in the diagnostic criteria of Kawasaki disease, likely due to variable vaccine requirements in different countries, these findings are largely recognized as specific for Kawasaki disease and present in approximately half of affected patients who received the BCG vaccine.2

Heat Shock Proteins—Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are produced by cells in response to stressors. The proposed mechanism of BCG vaccination scar reactivation is a cross-reaction between human homologue HSP 63 and Mycobacterium HSP 65, leading to hyperactivity of the immune system against BCG.7 There also are reports of reactivation of a BCG vaccination scar from measles infection and influenza vaccination.2,8,9 Most prior reports of BCG vaccination scar reactivation have been in pediatric patients; our patient is an adult who received the BCG vaccine more than 40 years ago.

Mechanism of Reactivation—The mechanism of BCG vaccination scar reactivation in our patient, who received the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine, is unclear. Possible mechanisms include (1) release of HSP mediated by the COVID-19 vaccine, leading to an immune response at the BCG vaccine scar, or (2) another immune-mediated cross-reaction between BCG and the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine mRNA nanoparticle or encoded spike protein antigen. It has been hypothesized that the BCG vaccine might offer some protection against COVID-19; this remains uncertain and is under further investigation.10 A recent retrospective cohort study showed that a BCG vaccination booster may decrease COVID-19 infection rates in higher-risk populations.11

Conclusion

We present a case of BCG vaccine scar reactivation occurring after a dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine, a likely underreported, self-limiting, cutaneous adverse effect of this mRNA vaccine.

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al; COVE Study Group. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;384:403-416. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2035389

- Muthuvelu S, Lim KS, Huang L-Y, et al. Measles infection causing bacillus Calmette-Guérin reactivation: a case report. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19:251. doi:10.1186/s12887-019-1635-z

- Fatima S, Kumari A, Das G, et al. Tuberculosis vaccine: a journey from BCG to present. Life Sci. 2020;252:117594. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117594

- O’Neill LAJ, Netea MG. BCG-induced trained immunity: can it offer protection against COVID-19? Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:335-337. doi:10.1038/s41577-020-0337-y

- Brooks NA, Puri A, Garg S, et al. The association of coronavirus disease-19 mortality and prior bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccination: a robust ecological analysis using unsupervised machine learning. Sci Rep. 2021;11:774. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-80787-z

- Tomita Y, Sato R, Ikeda T, et al. BCG vaccine may generate cross-reactive T-cells against SARS-CoV-2: in silico analyses and a hypothesis. Vaccine. 2020;38:6352-6356. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.045

- Lim KYY, Chua MC, Tan NWH, et al. Reactivation of BCG inoculation site in a child with febrile exanthema of 3 days duration: an early indicator of incomplete Kawasaki disease. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:E239648. doi:10.1136/bcr-2020-239648

- Kondo M, Goto H, Yamamoto S. First case of redness and erosion at bacillus Calmette-Guérin inoculation site after vaccination against influenza. J Dermatol. 2016;43:1229-1231. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13365

- Chavarri-Guerra Y, Soto-Pérez-de-Celis E. Erythema at the bacillus Calmette-Guerin scar after influenza vaccination. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2019;53:E20190390. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0390-2019

- Fu W, Ho P-C, Liu C-L, et al. Reconcile the debate over protective effects of BCG vaccine against COVID-19. Sci Rep. 2021;11:8356. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-87731-9

- Amirlak L, Haddad R, Hardy JD, et al. Effectiveness of booster BCG vaccination in preventing COVID-19 infection. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17:3913-3915. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1956228

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al; COVE Study Group. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;384:403-416. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2035389

- Muthuvelu S, Lim KS, Huang L-Y, et al. Measles infection causing bacillus Calmette-Guérin reactivation: a case report. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19:251. doi:10.1186/s12887-019-1635-z

- Fatima S, Kumari A, Das G, et al. Tuberculosis vaccine: a journey from BCG to present. Life Sci. 2020;252:117594. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117594

- O’Neill LAJ, Netea MG. BCG-induced trained immunity: can it offer protection against COVID-19? Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:335-337. doi:10.1038/s41577-020-0337-y

- Brooks NA, Puri A, Garg S, et al. The association of coronavirus disease-19 mortality and prior bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccination: a robust ecological analysis using unsupervised machine learning. Sci Rep. 2021;11:774. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-80787-z

- Tomita Y, Sato R, Ikeda T, et al. BCG vaccine may generate cross-reactive T-cells against SARS-CoV-2: in silico analyses and a hypothesis. Vaccine. 2020;38:6352-6356. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.045

- Lim KYY, Chua MC, Tan NWH, et al. Reactivation of BCG inoculation site in a child with febrile exanthema of 3 days duration: an early indicator of incomplete Kawasaki disease. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:E239648. doi:10.1136/bcr-2020-239648

- Kondo M, Goto H, Yamamoto S. First case of redness and erosion at bacillus Calmette-Guérin inoculation site after vaccination against influenza. J Dermatol. 2016;43:1229-1231. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13365

- Chavarri-Guerra Y, Soto-Pérez-de-Celis E. Erythema at the bacillus Calmette-Guerin scar after influenza vaccination. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2019;53:E20190390. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0390-2019

- Fu W, Ho P-C, Liu C-L, et al. Reconcile the debate over protective effects of BCG vaccine against COVID-19. Sci Rep. 2021;11:8356. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-87731-9

- Amirlak L, Haddad R, Hardy JD, et al. Effectiveness of booster BCG vaccination in preventing COVID-19 infection. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17:3913-3915. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1956228

Practice Points

- BCG vaccination scar reactivation is a potential benign, self-limited reaction in patients who receive the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine.

- Symptoms of BCG vaccination scar reactivation, which is seen more commonly in children with Kawasaki disease, include redness, swelling, and ulceration.

3-year-old girl • fever • cervical lymphadenopathy • leukocytosis • Dx?

THE CASE

A previously healthy 3-year-old girl presented to the emergency department with 4 days of fever and 2 days of right-side neck pain. The maximum temperature at home was 103 °F. The patient was irritable and vomited once. There were no other apparent or reported symptoms.

The neck exam was notable for nonfluctuant, swollen, and tender lymph nodes on the right side. Her sclera and conjunctiva were clear, and her oropharynx was unremarkable. Lab work revealed leukocytosis, with a white blood cell (WBC) count of 15.5 × 103/µL (normal range, 4.0-10.0 × 103/µL). She was given one 20 cc/kg normal saline bolus, started on intravenous clindamycin for presumed cervical lymphadenitis, and admitted to the hospital.

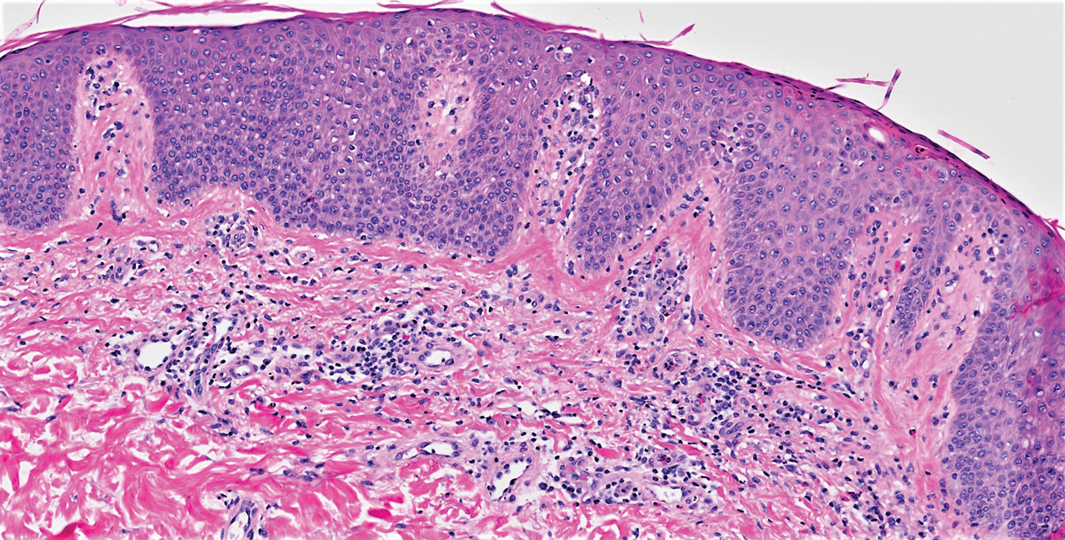

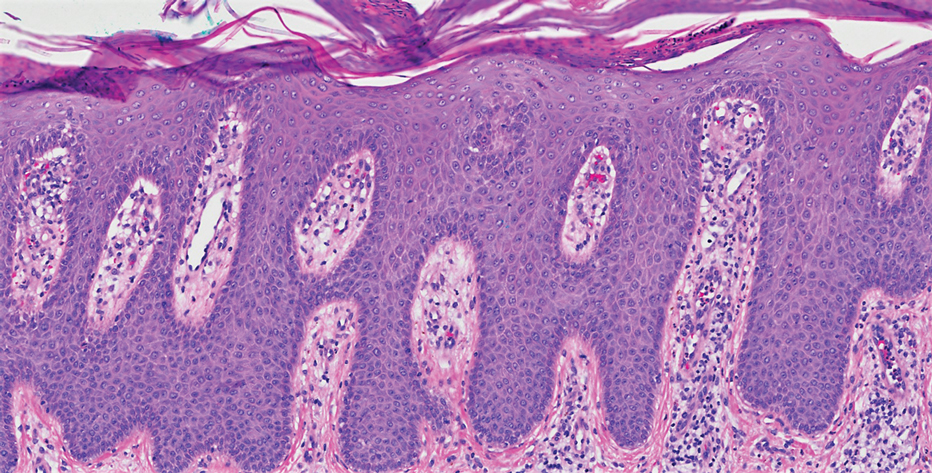

On Day 2, the patient developed a fine maculopapular rash on her chest, abdomen, and back. She had spiking fevers—as high as 102.2 °F—despite being on antibiotics for more than 24 hours. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 39 mm/h (0-20 mm/h), and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 71.4 mg/L (0.0-4.9 mg/L). Due to concern for abscess, a neck ultrasound was performed; it showed a chain of enlarged lymph nodes in the right neck (largest, 2.3 × 1.1 × 1.4 cm) and no abscess.

On Day 3, clindamycin was switched to intravenous ampicillin/sulbactam because a nasal swab for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus was negative. A swab for respiratory viral infections was also negative. The patient then developed notable facial swelling, bilateral bulbar conjunctival injection with limbic sparing, and swelling of her hands and feet.

THE DIAGNOSIS

By the end of Day 3, the patient’s lab studies demonstrated microcytic anemia and low albumin (2.5 g/dL), but no transaminitis, thrombocytosis, or sterile pyuria. An electrocardiogram was unremarkable. A pediatric echocardiogram revealed hyperemic coronaries, indicating inflammation. The coronary arteries were measured in the upper limits of normal, and the patient’s Z-scores were < 2.5. (A Z-score < 2 indicates no involvement, 2 to < 2.5 indicates dilation, and ≥ 2.5 indicates aneurysm abnormality.1) An ultrasound of the right upper quadrant revealed an enlarged/elongated gallbladder. The patient therefore met clinical criteria for Kawasaki disease.

DISCUSSION

Kawasaki disease is a self-limited vasculitis of childhood and the leading cause of acquired heart disease in children in developed countries.1 The annual incidence of Kawasaki disease in North America is about 25 cases per 100,000 children < 5 years of age.1 In the United States, incidence is highest in Asian and Pacific Islander populations (30 per 100,000) and is particularly high among those of Japanese ancestry (~200 per 100,000).2 Disease prevalence is also noteworthy in Non-Hispanic African American (17 per 100,000) and Hispanic (16 per 100,000) populations.2

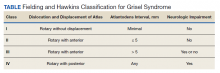

Diagnosis of Kawasaki disease requires presence of fever lasting at least 5 days and at least 4 of the following: bilateral bulbar conjunctival injection, oral mucous membrane changes (erythematous or cracked lips, erythematous pharynx, strawberry tongue), peripheral extremity changes (erythema of palms or soles, edema of hands or feet, and/or periungual desquamation), diffuse maculopapular rash, and cervical lymphadenopathy (≥ 1.5 cm, often unilateral). If ≥ 4 criteria are met, Kawasaki disease can be diagnosed on the fourth day of illness.1

Continue to: Laboratory findings suggesting...

Laboratory findings suggesting Kawasaki disease include a WBC count ≥ 15,000/mcL, normocytic, normochromic anemia, platelets ≥ 450,000/mcL after 7 days of illness, sterile pyuria (≥ 10 WBCs/high-power field), serum alanine aminotransferase level > 50 U/L, and serum albumin ≤ 3 g/dL.

Cardiac abnormalities are not included in the diagnostic criteria for Kawasaki disease but provide evidence in cases of incomplete Kawasaki disease if ≥ 4 criteria are not met and there is strong clinical suspicion.1 Incomplete Kawasaki disease should be considered in a patient with a CRP level ≥ 3 mg/dL and/or ESR ≥ 40 mm/h, ≥ 3 supplemental laboratory criteria, or a positive echocardiogram.1

Ultrasound imaging may reveal cervical lymph nodes resembling a “cluster of grapes.”3 The case patient’s imaging showed a “chain of enlarged lymph nodes.” She likely had gallbladder “hydrops” due to its increased longitudinal and horizontal diameter and lack of other anatomic changes.4

Prompt treatment is essential

Treatment for complete and incomplete Kawasaki disease is a single high dose of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) along with aspirin. Patients meeting criteria should be treated as soon as the diagnosis is established.5 A single high dose of IVIG (2 g/kg), administered over 10 to 12 hours, should be initiated within 5 to 10 days of disease onset. Administering IVIG in the acute phase of Kawasaki disease reduces the prevalence of coronary artery abnormalities.6 Corticosteroids may be used as adjunctive therapy for patients with high risk of IVIG resistance.1,7-9

Our patient was not deemed to be at high risk for IVIG resistance (Non-Japanese patient, age at fever onset > 6 months, absence of coronary artery aneurysm9) and was administered IVIG on Day 4. She was also given moderate-dose aspirin, then later transitioned to low-dose aspirin. The patient’s fevers improved, she was less irritable, and she had periods of playfulness. Physical exam then showed erythematous and cracked lips with peeling skin.

Continue to: The patient was discharged...

The patient was discharged home on Day 8, after her fever resolved, with instructions to continue low-dose aspirin and to obtain a repeat echocardiogram, gallbladder ultrasound, and lab work in 2 weeks. At her follow-up appointment, periungual desquamation was noted, and ultrasound showed continued enlarged/elongated gallbladder. A repeat echocardiogram was not available. Overall, the patient recovered from Kawasaki disease after therapeutic intervention.

THE TAKEAWAY

Kawasaki disease can be relatively rare in North American populations, but it is important for physicians to be able to recognize and treat it. Untreated children have a 25% chance of developing coronary artery aneurysms.1,10,11 Early treatment with IVIG can decrease risk to 5%, resulting in an excellent medium- to long-term prognosis for patients.10 Thorough physical examination and an appropriate degree of clinical suspicion was key in this case of Kawasaki disease.

Taisha Doo, MD, 1401 Madison Street, Suite #100, Seattle, WA 98104; [email protected]

1. McCrindle BW, Rowley AH, Newburger JW, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a scientific statement for health professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e927-e999. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000484

2. Holman RC, Belay ED, Christensen KY, et al. Hospitalizations for Kawasaki syndrome among children in the United States, 1997-2007. Pediatr Infect Dis. 2010;29:483-488. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181cf8705

3. Tashiro N, Matsubara T, Uchida M, et al. Ultrasonographic evaluation of cervical lymph nodes in Kawasaki disease. Pediatrics. 2002;109:e77. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.5.e77

4. Chen CJ, Huang FC, Taio MM, et al. Sonographic gallbladder abnormality is associated with intravenous immunoglobulin resistance in Kawasaki disease. Scientific World J. 2012;2012:485758. doi: 10.1100/2012/485758

5. Dominguez SR, Anderson MS, El-Adawy M, et al. Preventing coronary artery abnormalities: a need for earlier diagnosis and treatment of Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:1217-1220. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318266bcf9