User login

Digital Ischemia From Accidental Epinephrine Injection

Patients presenting to the ED with injuries due to accidental self-injection with an epinephrine pen typically receive treatment to alleviate symptoms and reduce the potential of digital ischemia leading to gangrene and loss of tissue and function. Although there is no consensus or set guidelines in the literature regarding the management protocol of such cases, many reports support pharmacological intervention. There are, however, other reports that advocate conservative, nonpharmaceutical management (eg, immersing the affected digit in warm water) or an observation-only approach.

We present the first case report in Saudi Arabia of digital ischemia due to accidental injection of an epinephrine autoinjector, along with a review of the literature and management recommendations.

Case

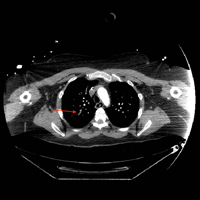

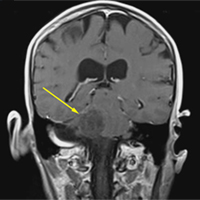

A 28-year-old woman presented to the ED in significant pain and discomfort 20 minutes after she accidentally injected the entire contents of her aunt’s epinephrine autoinjector (0.3 mg of 1:1000) into her right thumb. The patient, who was in significant pain and discomfort, stated that she was unable to remove the injector needle, which was firmly embedded in the bone of the palmer aspect of the distal phalanx in a manner similar to that of an intraosseous injection (Figure 1).

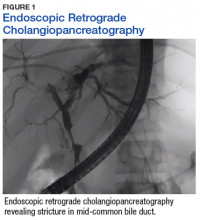

The patient’s vital signs and oxygen saturation on presentation were within normal limits. The emergency physician successfully removed the embedded needle through moderate countertraction. On examination, the patient’s right thumb was pale and cold, and had poor capillary refill (Figure 2). Due to concerns of the potential for digital tissue ischemia leading to tissue loss and gangrene, warm, moist compresses were applied to the affected thumb, followed by 2% topical nitroglycerin paste, after which the thumb was covered with an occlusive dressing. Since there was no improvement in circulation after 20 minutes, an infiltrate of 5 mg (0.5 mL of 10 mg/mL) of phentolamine (α-agonist) mixed with 2.5 mL of 2% lidocaine was injected at the puncture site and base of the right thumb.1 Hyperemia developed immediately at both injection sites, and the patient’s right thumb returned to a normal color and sensation 1 hour later, with a return to normal capillary refill. She remained in stable condition and was discharged home. Prior to discharge, the patient was educated on the proper handling and administration of an epinephrine autoinjector.

Discussion

Epinephrine is an ὰ- and β-adrenergic agonist that binds to the ὰ-adrenergic receptors of blood vessels, causing an increase in vascular resistance and vasoconstriction. Although the plasma half-life of epinephrine is approximately 2 to 3 minutes, subcutaneous or intramuscular injection resulting in local vasoconstriction may delay absorption; therefore, the effects of epinephrine may last much longer than its half-life.

The incidence of accidental injection from an epinephrine autoinjector is estimated to be 1 per 50,000 units dispensed.2 To date, there are no established treatment guidelines on managing cases of digital injection. An online PubMed and Google Scholar search of the literature found one systematic review,3 four observational studies,4-7 seven case series,8-14 and several case reports1,15-33 on the subject. Most of the patients in the published retrospective studies (71%) were treated conservatively with warming of the affected hand and observation, and the majority of patients in the case reports (87%) were treated pharmacologically, most commonly with topical nitroglycerin and phentolamine.1,3-34 All of the patients in both the retrospective studies and case reports had restoration of perfusion without necrosis, irrespective of treatment modality. However, patients who were managed conservatively or who were treated with topical nitroglycerin required a longer duration of stay in the ED, suffered from severe reperfusion pain, and in some cases, had a longer time to complete recovery (≥10 weeks).8

Pharmaceutical and Nonpharmaceutical Management

Phentolamine. Phentolamine is a nonselective ὰ-adrenergic antagonist that binds to ὰ1 and ὰ2 receptors of blood vessels, resulting in a decrease in peripheral vascular resistance and vasodilation. Phentolamine directly antagonizes the effect of epinephrine by blocking the ὰ-adrenergic receptors, which in our patient resulted in immediate return of digital circulation and full resolution of symptoms.

Topical Nitroglycerin. Nitroglycerin is a nitrate vasodilator that when metabolically converted to nitric oxide, results in smooth muscle relaxation, venodilation, and arteriodilation. Patients suffering from digital ischemia and vasoconstriction may be treated with topical nitroglycerin paste to reverse ischemia by causing smooth muscle relaxation of digital blood vessels. Conservative Management. As previously noted, not all cases of digital epinephrine injection are treated pharmacologically. Some patients are not treated, but kept in observation until the ischemic effects of epinephrine have resolved. Likewise, some patients are treated conservatively with warm water compresses or by fully immersing the affected digit in warm water to facilitate reversal of vasoconstriction and ischemia.3,8

Treatment Efficacy

In 2007, Fitzcharles-Bowe et al8 published a review of 59 cases of digital injection with high-dose epinephrine from 1989 to 2005. In this review, 32 of the 59 patients received no treatment, 25 patients received pharmacological treatment and in two patients, the treatment was unknown. Phentolamine was the most commonly used pharmacological agent (15 of 25 cases or 60%). Although none of the patients experienced digital necrosis, those treated with a local infiltration of phentolamine experienced a faster resolution of symptoms and normalization of perfusion. In 2004, Turner1 reported a case of a 10-year-old boy who was treated with phentolamine following an accidental injection of epinephrine into his left hand. While circulation returned to the affected digit within 5 minutes of receiving the phentolamine injection, the patient continued to experience reduced sensation in the digit 6 weeks later.8

Interestingly, one of the coauthors of the Fitzcharles-Bowe et al8 report intentionally injected three of the digits of his left hand (middle, ring, and small fingers) at the same time with high-dose epinephrine to carefully observe and document the outcomes. All three of the digits became very pale and cool, with decreased sensation. The author treated himself conservatively (observation-only). He experienced spontaneous return of circulation in two of the digits within 6 to 10 hours. Although there was some spontaneous return of circulation to the third digit after 13 hours, the author noted prolonged, intense reperfusion pain 4 hours after return of circulation. He also suffered from neuropraxia in the third digit, which did not fully resolve until 10 weeks after the injury.8

A review of the literature shows phentolamine to be a safe and effective treatment for patients presenting with digital ischemia, with no long-term adverse effects or complications. Moreover, phentolamine appears to be safe and effective for use in both adult and pediatric patients.3,8,35-38

Accidental Injection Prevention

Some of the cases of accidental epinephrine injection are due to user error. For example, a novice user may be holding the incorrect end of the injector in his or her hand when attempting to administer/deploy the device, resulting in premature dislodgement of the needle.39

Although, most of the autoinjector devices available today are user-friendly, we believe the addition of a safety feature such as a trigger or safety-lock may further help to reduce accidents. The European Medicines Agency recommends that all patients and caregivers receive training on the proper handling and administration of epinephrine autoinjectors, citing this as the most important factor to ensure successful use of an epinephrine autoinjector and reduce accidental injury.40 The patient in this case had not received any formal education or training regarding autoinjector use prior to this incident.

Safety of Lidocaine-Containing Epinephrine in Digital Anesthesia

Aside from cases of accidental digital epinephrine injection, clinicians have traditionally been taught to avoid using lidocaine with epinephrine for digital anesthesia. However, since the introduction of commercial lidocaine with epinephrine in 1948, there are no case reports of digital gangrene from commercially available lidocaine-epinephrine formulations.41,42 In a multicenter prospective study by Lalonde et al43 of 3,110 consecutive cases of elective injection of low-dose epinephrine in the hand, the authors concluded the likelihood of finger infarction is remote, particularly with possible phentolamine rescue therapy. Moreover, lidocaine-containing epinephrine (1%-2%) has a much lower concentration of epinephrine per mL of solution (5-10 mcg/mL) and appears to be safe for digital use.

Conclusion

This case describes the presentation and treatment of accidental digital injection of epinephrine, highlighting and supporting the benefits of local infiltration with phentolamine and observation until full recovery of perfusion. Local treatment with phentolamine not only facilitates recovery and return of capillary refill, but also shortens the duration of symptoms and alleviates vasoconstriction. In less severe cases, watchful waiting and observation may be appropriate and effective.

This case also underscores the importance of patient and caregiver education on the proper handling and administration of epinephrine autoinjectors to decrease the incidence of accidental injection.

1. Turner MJ. Accidental Epipen injection into a digit - the value of a Google search. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2004;86(3):218-219. doi:10.1308/003588404323043391.

2. McGovern SJ. Treatment of accidental digital injection of adrenaline from an auto-injector device. J Accid Emerg Med. 1997;14(6):379-380.

3. Wright M. Treatment after accidental injection with epinephrine autoinjector: a systematic review. J Allergy & Therapy. 2014;5(3):1000175. doi:10.4172/2155-6121.1000175.

4. Mrvos R, Anderson BD, Krenzelok EP. Accidental injection of epinephrine from an autoinjector: invasive treatment not always required. South Med J. 2002;95(3):318-320.

5. Muck AE, Bebarta VS, Borys DJ, Morgan DL. Six years of epinephrine digital injections: absence of significant local or systemic effects. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(3):270-274. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.02.019.

6. Simons FE, Edwards ES, Read EJ Jr, Clark S, Liebelt EL. Voluntarily reported unintentional injections from epinephrine auto-injectors. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2):419-423. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.056.

7. Blume-Odom CM, Scalzo AJ, Weber JA. EpiPen accidental injection-134 cases over 10 years. Clin Toxicol. 2010;48:651.

8. Fitzcharles-Bowe C, Denkler K, Lalonde D. Finger injection with high-dose (1:1,000) epinephrine: Does it cause finger necrosis and should it be treated? Hand. 2007;2(1):5-11. doi:10.1007/s11552-006-9012-4.

9. Velissariou I, Cottrell S, Berry K, Wilson B. Management of adrenaline (epinephrine) induced digital ischaemia in children after accidental injection from an EpiPen. Emerg Med J. 2004;21(3):387-388.

10. ElMaraghy MW, ElMaraghy AW, Evans HB. Digital adrenaline injection injuries: a case series and review. Can J Plast Surg. 1998;6:196-200.

11. Skorpinski EW, McGeady SJ, Yousef E. Two cases of accidental epinephrine injection into a finger. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(2):463-464.

12. Nagaraj J, Reddy S, Murray R, Murphy N. Use of glyceryl trinitrate patches in the treatment of accidental digital injection of epinephrine from an autoinjector. Eur J Emerg Med. 2009;16(4):227-228. doi:10.1097/MEJ.0b013e328306f0ee.

13. Stier PA, Bogner MP, Webster K, Leikin JB, Burda A. Use of subcutaneous terbutaline to reverse peripheral ischemia. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17(1):91-94.

14. Lee G, Thomas PC. Accidental digital injection of adrenaline from an autoinjector device. J Accid Emerg Med. 1998;15(4):287.

15. Baris S, Saricoban HE, Ak K, Ozdemir C. Papaverine chloride as a topical vasodilator in accidental injection of adrenaline into a digital finger. Allergy. 2011;66(11):1495-1496. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02664.x.

16. Buse K, Hein W, Drager N. Making Sense of Global Health Governance: A Policy Perspective. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan UK; 2009.

17. Sherman SC. Digital Epipen® injection: a case of conservative management. J Emerg Med. 2011;41(6):672-674. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.07.027.

18. Janssen RL, Roeleveld-Versteegh AB, Wessels-Basten SJ, Hendriks T. [Auto-injection with epinephrine in the finger of a 5-year-old child]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2008;152(17):1005-1008.

19. Singh T, Randhawa S, Khanna R. The EpiPen and the ischaemic finger. Eur J Emerg Med. 2007;14(4):222-223.

20. Barkhordarian AR, Wakelin SH, Paes TR. Accidental digital injection of adrenaline from an autoinjector device. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143(6):1359.

21. Deshmukh N, Tolland JT. Treatment of accidental epinephrine injection in a finger. J Emerg Med. 1989;7(4):408.

22. Hinterberger JW, Kintzi HE. Phentolamine reversal of epinephrine-induced digital vasospasm. How to save an ischemic finger. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3(2):193-195.

23. Peyko V, Cohen V, Jellinek-Cohen SP, Pearl-Davis M. Evaluation and treatment of accidental autoinjection of epinephrine. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(9):778-781. doi:10.2146/ajhp120316.

24. Hardy SJ, Agostini DE. Accidental epinephrine auto-injector-induced digital ischemia reversed by phentolamine digital block. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1995;95(6):377-378.

25. Kaspersen J, Vedsted P. [Accidental injection of adrenaline in a finger with EpiPen]. Ugeskr Laeger. 1998;160(45):6531-6532.

26. Schintler MV, Arbab E, Aberer W, Spendel S, Scharnagl E. Accidental perforating bone injury using the EpiPen autoinjection device. Allergy. 2005;60(2):259-260.

27. Khairalla E. Epinephrine-induced digital ischemia relieved by phentolamine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108(6):1831-1832.

28. Murali KS, Nayeem N. Accidental digital injection of adrenaline from an autoinjector device. J Accid Emerg Med. 1998;15(4):287.

29. Sellens C, Morrison L. Accidental injection of epinephrine by a child: a unique approach to treatment. CJEM. 1999;1(1):34-36.

30. Klemawesch P. Hyperbaric oxygen relieves severe digital ischaemia from accidental EpiPen injection. 2009 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Annual Meeting.

31. McCauley WA, Gerace RV, Scilley C. Treatment of accidental digital injection of epinephrine. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20(6):665-668.

32. Mathez C, Favrat B, Staeger P. Management options for accidental injection of epinephrine from an autoinjector: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:7268. doi:10.4076/1752-1947-3-7268.

33. Molony D. Adrenaline-induced digital ischaemia reversed with phentolamine. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76(12):1125-1126.

34. Carrascosa MF, Gallastegui-Menéndez A, Teja-Santamaría C, Caviedes JR. Accidental finger ischaemia induced by epinephrine autoinjector. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013. pii:bcr2013200783. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-200783.

35. Patel R, Kumar H. Epinephrine induced digital ischemia after accidental injection from an auto-injector device. Indian Pediatr. 2013;50(2):247.

36. Xu J, Holt A. Use of Phentolamine in the treatment of Epipen induced digital ischemia. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012. doi:10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5450.

37. McNeil C, Copeland J. Accidental digital epinephrine injection: to treat or not to treat? Can Fam Physician. 2014;60(8):726-728.

38. Bodkin RP, Acquisto NM, Gunyan H, Wiegand TJ. Two cases of accidental injection of epinephrine into a digit treated with subcutaneous phentolamine injections. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2013;2013:586207. doi:10.1155/2013/586207.

39. Simons FE, Lieberman PL, Read EJ Jr, Edwards ES. Hazards of unintentional injection of epinephrine from autoinjectors: a systematic review. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;102(4):282-287. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60332-8.

40. European Medicines Agency. Better training tools recommended to support patients using adrenaline auto-injectors. European Medicines Agency, 2015.

41. Denkler K. A comprehensive review of epinephrine in the finger: to do or not to do.

42. Thomson CJ, Lalonde DH, Denkler KA, Feicht AJ. A critical look at the evidence for and against elective epinephrine use in the finger. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(1):260-266.

43. Lalonde D, Bell M, Benoit P, Sparkes G, Denkler K, Chang P. A multicenter prospective study of 3,110 consecutive cases of elective epinephrine use in the fingers and hand: the Dalhousie Project clinical phase. J Hand Surg Am. 2005;30(5):1061-1067. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.05.006.

Patients presenting to the ED with injuries due to accidental self-injection with an epinephrine pen typically receive treatment to alleviate symptoms and reduce the potential of digital ischemia leading to gangrene and loss of tissue and function. Although there is no consensus or set guidelines in the literature regarding the management protocol of such cases, many reports support pharmacological intervention. There are, however, other reports that advocate conservative, nonpharmaceutical management (eg, immersing the affected digit in warm water) or an observation-only approach.

We present the first case report in Saudi Arabia of digital ischemia due to accidental injection of an epinephrine autoinjector, along with a review of the literature and management recommendations.

Case

A 28-year-old woman presented to the ED in significant pain and discomfort 20 minutes after she accidentally injected the entire contents of her aunt’s epinephrine autoinjector (0.3 mg of 1:1000) into her right thumb. The patient, who was in significant pain and discomfort, stated that she was unable to remove the injector needle, which was firmly embedded in the bone of the palmer aspect of the distal phalanx in a manner similar to that of an intraosseous injection (Figure 1).

The patient’s vital signs and oxygen saturation on presentation were within normal limits. The emergency physician successfully removed the embedded needle through moderate countertraction. On examination, the patient’s right thumb was pale and cold, and had poor capillary refill (Figure 2). Due to concerns of the potential for digital tissue ischemia leading to tissue loss and gangrene, warm, moist compresses were applied to the affected thumb, followed by 2% topical nitroglycerin paste, after which the thumb was covered with an occlusive dressing. Since there was no improvement in circulation after 20 minutes, an infiltrate of 5 mg (0.5 mL of 10 mg/mL) of phentolamine (α-agonist) mixed with 2.5 mL of 2% lidocaine was injected at the puncture site and base of the right thumb.1 Hyperemia developed immediately at both injection sites, and the patient’s right thumb returned to a normal color and sensation 1 hour later, with a return to normal capillary refill. She remained in stable condition and was discharged home. Prior to discharge, the patient was educated on the proper handling and administration of an epinephrine autoinjector.

Discussion

Epinephrine is an ὰ- and β-adrenergic agonist that binds to the ὰ-adrenergic receptors of blood vessels, causing an increase in vascular resistance and vasoconstriction. Although the plasma half-life of epinephrine is approximately 2 to 3 minutes, subcutaneous or intramuscular injection resulting in local vasoconstriction may delay absorption; therefore, the effects of epinephrine may last much longer than its half-life.

The incidence of accidental injection from an epinephrine autoinjector is estimated to be 1 per 50,000 units dispensed.2 To date, there are no established treatment guidelines on managing cases of digital injection. An online PubMed and Google Scholar search of the literature found one systematic review,3 four observational studies,4-7 seven case series,8-14 and several case reports1,15-33 on the subject. Most of the patients in the published retrospective studies (71%) were treated conservatively with warming of the affected hand and observation, and the majority of patients in the case reports (87%) were treated pharmacologically, most commonly with topical nitroglycerin and phentolamine.1,3-34 All of the patients in both the retrospective studies and case reports had restoration of perfusion without necrosis, irrespective of treatment modality. However, patients who were managed conservatively or who were treated with topical nitroglycerin required a longer duration of stay in the ED, suffered from severe reperfusion pain, and in some cases, had a longer time to complete recovery (≥10 weeks).8

Pharmaceutical and Nonpharmaceutical Management

Phentolamine. Phentolamine is a nonselective ὰ-adrenergic antagonist that binds to ὰ1 and ὰ2 receptors of blood vessels, resulting in a decrease in peripheral vascular resistance and vasodilation. Phentolamine directly antagonizes the effect of epinephrine by blocking the ὰ-adrenergic receptors, which in our patient resulted in immediate return of digital circulation and full resolution of symptoms.

Topical Nitroglycerin. Nitroglycerin is a nitrate vasodilator that when metabolically converted to nitric oxide, results in smooth muscle relaxation, venodilation, and arteriodilation. Patients suffering from digital ischemia and vasoconstriction may be treated with topical nitroglycerin paste to reverse ischemia by causing smooth muscle relaxation of digital blood vessels. Conservative Management. As previously noted, not all cases of digital epinephrine injection are treated pharmacologically. Some patients are not treated, but kept in observation until the ischemic effects of epinephrine have resolved. Likewise, some patients are treated conservatively with warm water compresses or by fully immersing the affected digit in warm water to facilitate reversal of vasoconstriction and ischemia.3,8

Treatment Efficacy

In 2007, Fitzcharles-Bowe et al8 published a review of 59 cases of digital injection with high-dose epinephrine from 1989 to 2005. In this review, 32 of the 59 patients received no treatment, 25 patients received pharmacological treatment and in two patients, the treatment was unknown. Phentolamine was the most commonly used pharmacological agent (15 of 25 cases or 60%). Although none of the patients experienced digital necrosis, those treated with a local infiltration of phentolamine experienced a faster resolution of symptoms and normalization of perfusion. In 2004, Turner1 reported a case of a 10-year-old boy who was treated with phentolamine following an accidental injection of epinephrine into his left hand. While circulation returned to the affected digit within 5 minutes of receiving the phentolamine injection, the patient continued to experience reduced sensation in the digit 6 weeks later.8

Interestingly, one of the coauthors of the Fitzcharles-Bowe et al8 report intentionally injected three of the digits of his left hand (middle, ring, and small fingers) at the same time with high-dose epinephrine to carefully observe and document the outcomes. All three of the digits became very pale and cool, with decreased sensation. The author treated himself conservatively (observation-only). He experienced spontaneous return of circulation in two of the digits within 6 to 10 hours. Although there was some spontaneous return of circulation to the third digit after 13 hours, the author noted prolonged, intense reperfusion pain 4 hours after return of circulation. He also suffered from neuropraxia in the third digit, which did not fully resolve until 10 weeks after the injury.8

A review of the literature shows phentolamine to be a safe and effective treatment for patients presenting with digital ischemia, with no long-term adverse effects or complications. Moreover, phentolamine appears to be safe and effective for use in both adult and pediatric patients.3,8,35-38

Accidental Injection Prevention

Some of the cases of accidental epinephrine injection are due to user error. For example, a novice user may be holding the incorrect end of the injector in his or her hand when attempting to administer/deploy the device, resulting in premature dislodgement of the needle.39

Although, most of the autoinjector devices available today are user-friendly, we believe the addition of a safety feature such as a trigger or safety-lock may further help to reduce accidents. The European Medicines Agency recommends that all patients and caregivers receive training on the proper handling and administration of epinephrine autoinjectors, citing this as the most important factor to ensure successful use of an epinephrine autoinjector and reduce accidental injury.40 The patient in this case had not received any formal education or training regarding autoinjector use prior to this incident.

Safety of Lidocaine-Containing Epinephrine in Digital Anesthesia

Aside from cases of accidental digital epinephrine injection, clinicians have traditionally been taught to avoid using lidocaine with epinephrine for digital anesthesia. However, since the introduction of commercial lidocaine with epinephrine in 1948, there are no case reports of digital gangrene from commercially available lidocaine-epinephrine formulations.41,42 In a multicenter prospective study by Lalonde et al43 of 3,110 consecutive cases of elective injection of low-dose epinephrine in the hand, the authors concluded the likelihood of finger infarction is remote, particularly with possible phentolamine rescue therapy. Moreover, lidocaine-containing epinephrine (1%-2%) has a much lower concentration of epinephrine per mL of solution (5-10 mcg/mL) and appears to be safe for digital use.

Conclusion

This case describes the presentation and treatment of accidental digital injection of epinephrine, highlighting and supporting the benefits of local infiltration with phentolamine and observation until full recovery of perfusion. Local treatment with phentolamine not only facilitates recovery and return of capillary refill, but also shortens the duration of symptoms and alleviates vasoconstriction. In less severe cases, watchful waiting and observation may be appropriate and effective.

This case also underscores the importance of patient and caregiver education on the proper handling and administration of epinephrine autoinjectors to decrease the incidence of accidental injection.

Patients presenting to the ED with injuries due to accidental self-injection with an epinephrine pen typically receive treatment to alleviate symptoms and reduce the potential of digital ischemia leading to gangrene and loss of tissue and function. Although there is no consensus or set guidelines in the literature regarding the management protocol of such cases, many reports support pharmacological intervention. There are, however, other reports that advocate conservative, nonpharmaceutical management (eg, immersing the affected digit in warm water) or an observation-only approach.

We present the first case report in Saudi Arabia of digital ischemia due to accidental injection of an epinephrine autoinjector, along with a review of the literature and management recommendations.

Case

A 28-year-old woman presented to the ED in significant pain and discomfort 20 minutes after she accidentally injected the entire contents of her aunt’s epinephrine autoinjector (0.3 mg of 1:1000) into her right thumb. The patient, who was in significant pain and discomfort, stated that she was unable to remove the injector needle, which was firmly embedded in the bone of the palmer aspect of the distal phalanx in a manner similar to that of an intraosseous injection (Figure 1).

The patient’s vital signs and oxygen saturation on presentation were within normal limits. The emergency physician successfully removed the embedded needle through moderate countertraction. On examination, the patient’s right thumb was pale and cold, and had poor capillary refill (Figure 2). Due to concerns of the potential for digital tissue ischemia leading to tissue loss and gangrene, warm, moist compresses were applied to the affected thumb, followed by 2% topical nitroglycerin paste, after which the thumb was covered with an occlusive dressing. Since there was no improvement in circulation after 20 minutes, an infiltrate of 5 mg (0.5 mL of 10 mg/mL) of phentolamine (α-agonist) mixed with 2.5 mL of 2% lidocaine was injected at the puncture site and base of the right thumb.1 Hyperemia developed immediately at both injection sites, and the patient’s right thumb returned to a normal color and sensation 1 hour later, with a return to normal capillary refill. She remained in stable condition and was discharged home. Prior to discharge, the patient was educated on the proper handling and administration of an epinephrine autoinjector.

Discussion

Epinephrine is an ὰ- and β-adrenergic agonist that binds to the ὰ-adrenergic receptors of blood vessels, causing an increase in vascular resistance and vasoconstriction. Although the plasma half-life of epinephrine is approximately 2 to 3 minutes, subcutaneous or intramuscular injection resulting in local vasoconstriction may delay absorption; therefore, the effects of epinephrine may last much longer than its half-life.

The incidence of accidental injection from an epinephrine autoinjector is estimated to be 1 per 50,000 units dispensed.2 To date, there are no established treatment guidelines on managing cases of digital injection. An online PubMed and Google Scholar search of the literature found one systematic review,3 four observational studies,4-7 seven case series,8-14 and several case reports1,15-33 on the subject. Most of the patients in the published retrospective studies (71%) were treated conservatively with warming of the affected hand and observation, and the majority of patients in the case reports (87%) were treated pharmacologically, most commonly with topical nitroglycerin and phentolamine.1,3-34 All of the patients in both the retrospective studies and case reports had restoration of perfusion without necrosis, irrespective of treatment modality. However, patients who were managed conservatively or who were treated with topical nitroglycerin required a longer duration of stay in the ED, suffered from severe reperfusion pain, and in some cases, had a longer time to complete recovery (≥10 weeks).8

Pharmaceutical and Nonpharmaceutical Management

Phentolamine. Phentolamine is a nonselective ὰ-adrenergic antagonist that binds to ὰ1 and ὰ2 receptors of blood vessels, resulting in a decrease in peripheral vascular resistance and vasodilation. Phentolamine directly antagonizes the effect of epinephrine by blocking the ὰ-adrenergic receptors, which in our patient resulted in immediate return of digital circulation and full resolution of symptoms.

Topical Nitroglycerin. Nitroglycerin is a nitrate vasodilator that when metabolically converted to nitric oxide, results in smooth muscle relaxation, venodilation, and arteriodilation. Patients suffering from digital ischemia and vasoconstriction may be treated with topical nitroglycerin paste to reverse ischemia by causing smooth muscle relaxation of digital blood vessels. Conservative Management. As previously noted, not all cases of digital epinephrine injection are treated pharmacologically. Some patients are not treated, but kept in observation until the ischemic effects of epinephrine have resolved. Likewise, some patients are treated conservatively with warm water compresses or by fully immersing the affected digit in warm water to facilitate reversal of vasoconstriction and ischemia.3,8

Treatment Efficacy

In 2007, Fitzcharles-Bowe et al8 published a review of 59 cases of digital injection with high-dose epinephrine from 1989 to 2005. In this review, 32 of the 59 patients received no treatment, 25 patients received pharmacological treatment and in two patients, the treatment was unknown. Phentolamine was the most commonly used pharmacological agent (15 of 25 cases or 60%). Although none of the patients experienced digital necrosis, those treated with a local infiltration of phentolamine experienced a faster resolution of symptoms and normalization of perfusion. In 2004, Turner1 reported a case of a 10-year-old boy who was treated with phentolamine following an accidental injection of epinephrine into his left hand. While circulation returned to the affected digit within 5 minutes of receiving the phentolamine injection, the patient continued to experience reduced sensation in the digit 6 weeks later.8

Interestingly, one of the coauthors of the Fitzcharles-Bowe et al8 report intentionally injected three of the digits of his left hand (middle, ring, and small fingers) at the same time with high-dose epinephrine to carefully observe and document the outcomes. All three of the digits became very pale and cool, with decreased sensation. The author treated himself conservatively (observation-only). He experienced spontaneous return of circulation in two of the digits within 6 to 10 hours. Although there was some spontaneous return of circulation to the third digit after 13 hours, the author noted prolonged, intense reperfusion pain 4 hours after return of circulation. He also suffered from neuropraxia in the third digit, which did not fully resolve until 10 weeks after the injury.8

A review of the literature shows phentolamine to be a safe and effective treatment for patients presenting with digital ischemia, with no long-term adverse effects or complications. Moreover, phentolamine appears to be safe and effective for use in both adult and pediatric patients.3,8,35-38

Accidental Injection Prevention

Some of the cases of accidental epinephrine injection are due to user error. For example, a novice user may be holding the incorrect end of the injector in his or her hand when attempting to administer/deploy the device, resulting in premature dislodgement of the needle.39

Although, most of the autoinjector devices available today are user-friendly, we believe the addition of a safety feature such as a trigger or safety-lock may further help to reduce accidents. The European Medicines Agency recommends that all patients and caregivers receive training on the proper handling and administration of epinephrine autoinjectors, citing this as the most important factor to ensure successful use of an epinephrine autoinjector and reduce accidental injury.40 The patient in this case had not received any formal education or training regarding autoinjector use prior to this incident.

Safety of Lidocaine-Containing Epinephrine in Digital Anesthesia

Aside from cases of accidental digital epinephrine injection, clinicians have traditionally been taught to avoid using lidocaine with epinephrine for digital anesthesia. However, since the introduction of commercial lidocaine with epinephrine in 1948, there are no case reports of digital gangrene from commercially available lidocaine-epinephrine formulations.41,42 In a multicenter prospective study by Lalonde et al43 of 3,110 consecutive cases of elective injection of low-dose epinephrine in the hand, the authors concluded the likelihood of finger infarction is remote, particularly with possible phentolamine rescue therapy. Moreover, lidocaine-containing epinephrine (1%-2%) has a much lower concentration of epinephrine per mL of solution (5-10 mcg/mL) and appears to be safe for digital use.

Conclusion

This case describes the presentation and treatment of accidental digital injection of epinephrine, highlighting and supporting the benefits of local infiltration with phentolamine and observation until full recovery of perfusion. Local treatment with phentolamine not only facilitates recovery and return of capillary refill, but also shortens the duration of symptoms and alleviates vasoconstriction. In less severe cases, watchful waiting and observation may be appropriate and effective.

This case also underscores the importance of patient and caregiver education on the proper handling and administration of epinephrine autoinjectors to decrease the incidence of accidental injection.

1. Turner MJ. Accidental Epipen injection into a digit - the value of a Google search. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2004;86(3):218-219. doi:10.1308/003588404323043391.

2. McGovern SJ. Treatment of accidental digital injection of adrenaline from an auto-injector device. J Accid Emerg Med. 1997;14(6):379-380.

3. Wright M. Treatment after accidental injection with epinephrine autoinjector: a systematic review. J Allergy & Therapy. 2014;5(3):1000175. doi:10.4172/2155-6121.1000175.

4. Mrvos R, Anderson BD, Krenzelok EP. Accidental injection of epinephrine from an autoinjector: invasive treatment not always required. South Med J. 2002;95(3):318-320.

5. Muck AE, Bebarta VS, Borys DJ, Morgan DL. Six years of epinephrine digital injections: absence of significant local or systemic effects. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(3):270-274. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.02.019.

6. Simons FE, Edwards ES, Read EJ Jr, Clark S, Liebelt EL. Voluntarily reported unintentional injections from epinephrine auto-injectors. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2):419-423. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.056.

7. Blume-Odom CM, Scalzo AJ, Weber JA. EpiPen accidental injection-134 cases over 10 years. Clin Toxicol. 2010;48:651.

8. Fitzcharles-Bowe C, Denkler K, Lalonde D. Finger injection with high-dose (1:1,000) epinephrine: Does it cause finger necrosis and should it be treated? Hand. 2007;2(1):5-11. doi:10.1007/s11552-006-9012-4.

9. Velissariou I, Cottrell S, Berry K, Wilson B. Management of adrenaline (epinephrine) induced digital ischaemia in children after accidental injection from an EpiPen. Emerg Med J. 2004;21(3):387-388.

10. ElMaraghy MW, ElMaraghy AW, Evans HB. Digital adrenaline injection injuries: a case series and review. Can J Plast Surg. 1998;6:196-200.

11. Skorpinski EW, McGeady SJ, Yousef E. Two cases of accidental epinephrine injection into a finger. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(2):463-464.

12. Nagaraj J, Reddy S, Murray R, Murphy N. Use of glyceryl trinitrate patches in the treatment of accidental digital injection of epinephrine from an autoinjector. Eur J Emerg Med. 2009;16(4):227-228. doi:10.1097/MEJ.0b013e328306f0ee.

13. Stier PA, Bogner MP, Webster K, Leikin JB, Burda A. Use of subcutaneous terbutaline to reverse peripheral ischemia. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17(1):91-94.

14. Lee G, Thomas PC. Accidental digital injection of adrenaline from an autoinjector device. J Accid Emerg Med. 1998;15(4):287.

15. Baris S, Saricoban HE, Ak K, Ozdemir C. Papaverine chloride as a topical vasodilator in accidental injection of adrenaline into a digital finger. Allergy. 2011;66(11):1495-1496. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02664.x.

16. Buse K, Hein W, Drager N. Making Sense of Global Health Governance: A Policy Perspective. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan UK; 2009.

17. Sherman SC. Digital Epipen® injection: a case of conservative management. J Emerg Med. 2011;41(6):672-674. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.07.027.

18. Janssen RL, Roeleveld-Versteegh AB, Wessels-Basten SJ, Hendriks T. [Auto-injection with epinephrine in the finger of a 5-year-old child]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2008;152(17):1005-1008.

19. Singh T, Randhawa S, Khanna R. The EpiPen and the ischaemic finger. Eur J Emerg Med. 2007;14(4):222-223.

20. Barkhordarian AR, Wakelin SH, Paes TR. Accidental digital injection of adrenaline from an autoinjector device. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143(6):1359.

21. Deshmukh N, Tolland JT. Treatment of accidental epinephrine injection in a finger. J Emerg Med. 1989;7(4):408.

22. Hinterberger JW, Kintzi HE. Phentolamine reversal of epinephrine-induced digital vasospasm. How to save an ischemic finger. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3(2):193-195.

23. Peyko V, Cohen V, Jellinek-Cohen SP, Pearl-Davis M. Evaluation and treatment of accidental autoinjection of epinephrine. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(9):778-781. doi:10.2146/ajhp120316.

24. Hardy SJ, Agostini DE. Accidental epinephrine auto-injector-induced digital ischemia reversed by phentolamine digital block. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1995;95(6):377-378.

25. Kaspersen J, Vedsted P. [Accidental injection of adrenaline in a finger with EpiPen]. Ugeskr Laeger. 1998;160(45):6531-6532.

26. Schintler MV, Arbab E, Aberer W, Spendel S, Scharnagl E. Accidental perforating bone injury using the EpiPen autoinjection device. Allergy. 2005;60(2):259-260.

27. Khairalla E. Epinephrine-induced digital ischemia relieved by phentolamine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108(6):1831-1832.

28. Murali KS, Nayeem N. Accidental digital injection of adrenaline from an autoinjector device. J Accid Emerg Med. 1998;15(4):287.

29. Sellens C, Morrison L. Accidental injection of epinephrine by a child: a unique approach to treatment. CJEM. 1999;1(1):34-36.

30. Klemawesch P. Hyperbaric oxygen relieves severe digital ischaemia from accidental EpiPen injection. 2009 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Annual Meeting.

31. McCauley WA, Gerace RV, Scilley C. Treatment of accidental digital injection of epinephrine. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20(6):665-668.

32. Mathez C, Favrat B, Staeger P. Management options for accidental injection of epinephrine from an autoinjector: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:7268. doi:10.4076/1752-1947-3-7268.

33. Molony D. Adrenaline-induced digital ischaemia reversed with phentolamine. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76(12):1125-1126.

34. Carrascosa MF, Gallastegui-Menéndez A, Teja-Santamaría C, Caviedes JR. Accidental finger ischaemia induced by epinephrine autoinjector. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013. pii:bcr2013200783. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-200783.

35. Patel R, Kumar H. Epinephrine induced digital ischemia after accidental injection from an auto-injector device. Indian Pediatr. 2013;50(2):247.

36. Xu J, Holt A. Use of Phentolamine in the treatment of Epipen induced digital ischemia. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012. doi:10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5450.

37. McNeil C, Copeland J. Accidental digital epinephrine injection: to treat or not to treat? Can Fam Physician. 2014;60(8):726-728.

38. Bodkin RP, Acquisto NM, Gunyan H, Wiegand TJ. Two cases of accidental injection of epinephrine into a digit treated with subcutaneous phentolamine injections. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2013;2013:586207. doi:10.1155/2013/586207.

39. Simons FE, Lieberman PL, Read EJ Jr, Edwards ES. Hazards of unintentional injection of epinephrine from autoinjectors: a systematic review. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;102(4):282-287. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60332-8.

40. European Medicines Agency. Better training tools recommended to support patients using adrenaline auto-injectors. European Medicines Agency, 2015.

41. Denkler K. A comprehensive review of epinephrine in the finger: to do or not to do.

42. Thomson CJ, Lalonde DH, Denkler KA, Feicht AJ. A critical look at the evidence for and against elective epinephrine use in the finger. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(1):260-266.

43. Lalonde D, Bell M, Benoit P, Sparkes G, Denkler K, Chang P. A multicenter prospective study of 3,110 consecutive cases of elective epinephrine use in the fingers and hand: the Dalhousie Project clinical phase. J Hand Surg Am. 2005;30(5):1061-1067. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.05.006.

1. Turner MJ. Accidental Epipen injection into a digit - the value of a Google search. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2004;86(3):218-219. doi:10.1308/003588404323043391.

2. McGovern SJ. Treatment of accidental digital injection of adrenaline from an auto-injector device. J Accid Emerg Med. 1997;14(6):379-380.

3. Wright M. Treatment after accidental injection with epinephrine autoinjector: a systematic review. J Allergy & Therapy. 2014;5(3):1000175. doi:10.4172/2155-6121.1000175.

4. Mrvos R, Anderson BD, Krenzelok EP. Accidental injection of epinephrine from an autoinjector: invasive treatment not always required. South Med J. 2002;95(3):318-320.

5. Muck AE, Bebarta VS, Borys DJ, Morgan DL. Six years of epinephrine digital injections: absence of significant local or systemic effects. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(3):270-274. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.02.019.

6. Simons FE, Edwards ES, Read EJ Jr, Clark S, Liebelt EL. Voluntarily reported unintentional injections from epinephrine auto-injectors. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2):419-423. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.056.

7. Blume-Odom CM, Scalzo AJ, Weber JA. EpiPen accidental injection-134 cases over 10 years. Clin Toxicol. 2010;48:651.

8. Fitzcharles-Bowe C, Denkler K, Lalonde D. Finger injection with high-dose (1:1,000) epinephrine: Does it cause finger necrosis and should it be treated? Hand. 2007;2(1):5-11. doi:10.1007/s11552-006-9012-4.

9. Velissariou I, Cottrell S, Berry K, Wilson B. Management of adrenaline (epinephrine) induced digital ischaemia in children after accidental injection from an EpiPen. Emerg Med J. 2004;21(3):387-388.

10. ElMaraghy MW, ElMaraghy AW, Evans HB. Digital adrenaline injection injuries: a case series and review. Can J Plast Surg. 1998;6:196-200.

11. Skorpinski EW, McGeady SJ, Yousef E. Two cases of accidental epinephrine injection into a finger. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(2):463-464.

12. Nagaraj J, Reddy S, Murray R, Murphy N. Use of glyceryl trinitrate patches in the treatment of accidental digital injection of epinephrine from an autoinjector. Eur J Emerg Med. 2009;16(4):227-228. doi:10.1097/MEJ.0b013e328306f0ee.

13. Stier PA, Bogner MP, Webster K, Leikin JB, Burda A. Use of subcutaneous terbutaline to reverse peripheral ischemia. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17(1):91-94.

14. Lee G, Thomas PC. Accidental digital injection of adrenaline from an autoinjector device. J Accid Emerg Med. 1998;15(4):287.

15. Baris S, Saricoban HE, Ak K, Ozdemir C. Papaverine chloride as a topical vasodilator in accidental injection of adrenaline into a digital finger. Allergy. 2011;66(11):1495-1496. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02664.x.

16. Buse K, Hein W, Drager N. Making Sense of Global Health Governance: A Policy Perspective. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan UK; 2009.

17. Sherman SC. Digital Epipen® injection: a case of conservative management. J Emerg Med. 2011;41(6):672-674. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.07.027.

18. Janssen RL, Roeleveld-Versteegh AB, Wessels-Basten SJ, Hendriks T. [Auto-injection with epinephrine in the finger of a 5-year-old child]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2008;152(17):1005-1008.

19. Singh T, Randhawa S, Khanna R. The EpiPen and the ischaemic finger. Eur J Emerg Med. 2007;14(4):222-223.

20. Barkhordarian AR, Wakelin SH, Paes TR. Accidental digital injection of adrenaline from an autoinjector device. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143(6):1359.

21. Deshmukh N, Tolland JT. Treatment of accidental epinephrine injection in a finger. J Emerg Med. 1989;7(4):408.

22. Hinterberger JW, Kintzi HE. Phentolamine reversal of epinephrine-induced digital vasospasm. How to save an ischemic finger. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3(2):193-195.

23. Peyko V, Cohen V, Jellinek-Cohen SP, Pearl-Davis M. Evaluation and treatment of accidental autoinjection of epinephrine. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(9):778-781. doi:10.2146/ajhp120316.

24. Hardy SJ, Agostini DE. Accidental epinephrine auto-injector-induced digital ischemia reversed by phentolamine digital block. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1995;95(6):377-378.

25. Kaspersen J, Vedsted P. [Accidental injection of adrenaline in a finger with EpiPen]. Ugeskr Laeger. 1998;160(45):6531-6532.

26. Schintler MV, Arbab E, Aberer W, Spendel S, Scharnagl E. Accidental perforating bone injury using the EpiPen autoinjection device. Allergy. 2005;60(2):259-260.

27. Khairalla E. Epinephrine-induced digital ischemia relieved by phentolamine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108(6):1831-1832.

28. Murali KS, Nayeem N. Accidental digital injection of adrenaline from an autoinjector device. J Accid Emerg Med. 1998;15(4):287.

29. Sellens C, Morrison L. Accidental injection of epinephrine by a child: a unique approach to treatment. CJEM. 1999;1(1):34-36.

30. Klemawesch P. Hyperbaric oxygen relieves severe digital ischaemia from accidental EpiPen injection. 2009 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Annual Meeting.

31. McCauley WA, Gerace RV, Scilley C. Treatment of accidental digital injection of epinephrine. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20(6):665-668.

32. Mathez C, Favrat B, Staeger P. Management options for accidental injection of epinephrine from an autoinjector: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:7268. doi:10.4076/1752-1947-3-7268.

33. Molony D. Adrenaline-induced digital ischaemia reversed with phentolamine. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76(12):1125-1126.

34. Carrascosa MF, Gallastegui-Menéndez A, Teja-Santamaría C, Caviedes JR. Accidental finger ischaemia induced by epinephrine autoinjector. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013. pii:bcr2013200783. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-200783.

35. Patel R, Kumar H. Epinephrine induced digital ischemia after accidental injection from an auto-injector device. Indian Pediatr. 2013;50(2):247.

36. Xu J, Holt A. Use of Phentolamine in the treatment of Epipen induced digital ischemia. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012. doi:10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5450.

37. McNeil C, Copeland J. Accidental digital epinephrine injection: to treat or not to treat? Can Fam Physician. 2014;60(8):726-728.

38. Bodkin RP, Acquisto NM, Gunyan H, Wiegand TJ. Two cases of accidental injection of epinephrine into a digit treated with subcutaneous phentolamine injections. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2013;2013:586207. doi:10.1155/2013/586207.

39. Simons FE, Lieberman PL, Read EJ Jr, Edwards ES. Hazards of unintentional injection of epinephrine from autoinjectors: a systematic review. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;102(4):282-287. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60332-8.

40. European Medicines Agency. Better training tools recommended to support patients using adrenaline auto-injectors. European Medicines Agency, 2015.

41. Denkler K. A comprehensive review of epinephrine in the finger: to do or not to do.

42. Thomson CJ, Lalonde DH, Denkler KA, Feicht AJ. A critical look at the evidence for and against elective epinephrine use in the finger. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(1):260-266.

43. Lalonde D, Bell M, Benoit P, Sparkes G, Denkler K, Chang P. A multicenter prospective study of 3,110 consecutive cases of elective epinephrine use in the fingers and hand: the Dalhousie Project clinical phase. J Hand Surg Am. 2005;30(5):1061-1067. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.05.006.

A Forgotten Cause of Cardiac Tamponade

Purulent pericarditis is an infection within the pericardial space rarely seen in the modern antibiotic era. Most cases are secondary to another infectious process of bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic origin.1,2 Predisposing factors include malignancy, chronic kidney disease, immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, and alcohol misuse disorder.1 Although purulent pericarditis has been described extensively in the literature, it is a challenging diagnosis if it is not initially considered within the differential diagnosis repertoire.1-4 Most authors agree that this may be because it has become an infrequent diagnosis.1,2 In addition, purulent pericarditis may have an atypical presentation when compared with a classic case of pericarditis.2,3 The authors believe that this forgotten entity will be revisited through this case.

Case Presentation

A 66-year-old-man was transferred to Veterans Affairs Caribbean Healthcare System (VACHS) from a community hospital with a diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and bilateral pleural effusions. Four days prior to arrival at the community hospital, the patient had developed diffuse, watery diarrhea, which resolved in 3 days. After resolution of diarrhea, he began experiencing shortness of breath on exertion that progressed to onset at rest. The patient reported no fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, cough, or contact with others who were not healthy. He had a history of alcohol misuse without liver cirrhosis and reported no chronic diseases or use of medications. The patient had no history of tuberculosis exposure or pneumococcal vaccination, and had a negative interferon gamma release assay.

On admission to the community hospital, the patient was treated for CAP with ceftriaxone and azithromycin. On hospital day 3, the patient developed hypoxemia and an altered mental status. He was started on supplemental oxygen and transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU). Antibiotic therapy consequently was changed to levofloxacin and meropenem. However, no clinical improvement was noted on the following days.

On hospital day 7, the patient developed acute respiratory failure that required mechanical ventilation while being transferred to VACHS via air ambulance. His vital signs on arrival were the following: temperature, 97° F; heart rate, 86 beats/min; blood pressure, 103/61 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min and SaO2 of 97%, measured while he breathed supplemental oxygen at an FiO2 of 0.4.

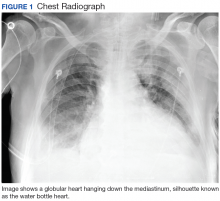

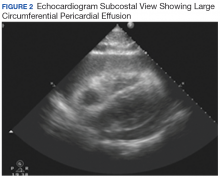

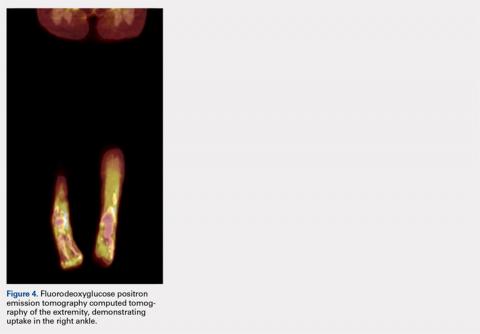

Hours after arrival, the patient developed sinus tachycardia and hypotension. A bedside 2D echocardiogram demonstrated a large pericardial effusion with diastolic collapse of the right atrium (Figure 2).

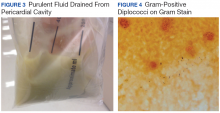

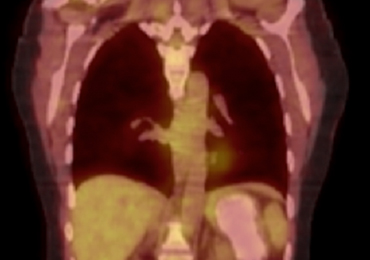

The patient’s clinical condition improved following drainage of pericardial fluid, with no further need for inotropic support. Antibiotic therapy was changed to vancomycin and meropenem. Initial microbiologic samples from pericardial fluid demonstrated Gram-positive diplococci, suggestive of Streptococcus pneumoniae (S pneumoniae) (Figure 4). Other diagnostic pericardial fluid test results included: WBC count 25,330 cmm, with 99% neutrophils and 1% lymphocytes; total protein, 3.8 mg/dL; glucose, < 2.0 mg/dL,LDH, > 2,500 U/L, potassium hydroxide preparation. The tests found no fungus, and the acid fast bacilli smear revealed no Bacillus. However, the pericardial fluid culture failed to demonstrate growth of any organism. Blood cultures also were negative.

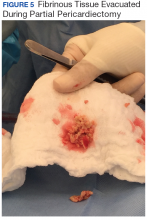

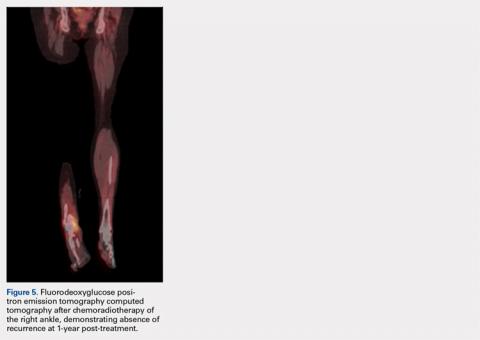

The patient underwent anterior thoracotomy with partial pericardiectomy, and a pericardial tube was left in place connected to drainage. During the procedure, an abundant amount of fibrinous tissue was evacuated from the pericardial space (Figure 5).

The patient was extubated, pericardial and pleural tubes were removed, and he was transferred to the internal medicine ward 24 days after admission to the ICU. He received in-patient physical rehabilitation while completing a 6-week course of IV antibiotics (vancomycin and meropenem). After completion of therapy, the patient received the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination, and an echocardiography was repeated. No significant re-accumulation of pericardial effusion or constrictive pattern was evidenced. The patient was discharged to his out-of-state home, and follow-up was consequently lost.

Discussion

Purulent pericarditis is an infection localized within the pericardial space. Most cases are secondary to an infectious process elsewhere, which could be of bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic etiology.1 Five mechanisms could lead the infecting organism to infect the pericardial space; contiguous spread from intrathoracic site, hematogenous spread, extension from myocardial site, perforating injury or surgery, and extension from a subdiaphragmatic site.1 Predisposing factors for the development of this condition include malignancy, chronic kidney disease, immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, and alcohol misuse. Pericarditis is an infection localized within the pericardial space.

Purulent pericarditis has become a rare entity in the antibiotic era.2 Prior to the development of antibiotics, most cases were secondary to S pneumoniae.1,2,5,6 As per Cilloniz and colleagues, about 40% to 50% of all cases of purulent pericarditis are caused by Gram-positive bacteria, mostly S pneumoniae.5 In this case study, bacterial culture did not reveal growth of an organism—most likely because the patient had received antibiotics elsewhere. However, Gram-positive cocci were seen within the initial pericardial aspirate. This organism was suspected to have spread contiguously from a pulmonary focus, which also led to pleural effusions.

Since the patient in this case study had no history of thoracic surgery, malignancy, or other immunosuppression, the patient’s history of alcohol misuse was the only predisposing factor for development of purulent pericarditis. Contrary to the common presentation of pericarditis, purulent pericarditis may not have the common clinical findings, such as chest pain, pericardial friction rub, and distended neck veins.2,3 Furthermore, according to Parikh and colleagues, about 35% of affected patients may have a normal electrocardiogram.2 Hence, the diagnosis of purulent pericarditis often is missed because the classic signs of pericarditis are often absent, and other nonspecific symptoms are attributed to initial underlying infection.7

A high index of suspicion is needed to diagnose purulent pericarditis. Once a diagnosis is made, initial treatment should consist of prompt drainage of pericardial fluid combined with systemic antibiotic therapy. Vancomycin and a third-generation cephalosporin may be started empirically until results of pericardial fluid cultures become available.3 Drainage can be achieved by pericardiocentesis, pericardiotomy, or pericardiectomy (partial or total).1 In cases of hemodynamic instability due to cardiac tamponade, sonographically guided pericardiocentesis should be undertaken and an indwelling pericardial catheter left in place.1 Although this is the simplest and fastest method of evacuation, it may not be effective when dealing with thick, fibrinous fluid. In such cases, intrapericardial fibrinolysis may be considered. This approach may be undertaken early in the process, after drainage insertion, or as salvage therapy, when there has been incomplete evacuation of purulent material or open surgical drainage is not available.

Streptokinase, urokinase, and tissue plasminogen activator have been used for intrapericadial fibrinolysis.1 However, there is no definite data on dosage or frequency at which these medications should be administered. No matter the therapeutic approach, effective drainage of the pericardial fluid is crucial to avoid the development of pericardial constriction. Constrictive pericarditis occurs when fibrosis and adhesions create a dense pericardium that encases the heart. This causes impaired ventricular filling that can lead eventually to heart failure.4 Pericardiectomy is the definitive treatment for constrictive pericarditis.

Conclusion

Although purulent pericarditis has become a rare diagnosis since the development of antibiotics, knowledge of how to identify it is essential since mortality reaches 100% if the diagnosis is missed.4 Even when the condition is promptly diagnosed and treated, mortality is 40%, mainly due to cardiac tamponade, septic shock, or constriction.1 The case presented here illustrates the clinical features associated with this condition. Knowing these features can translate in a successful patient outcome.

1. Ferreira dos Santos L, Moreira D, Ribeiro P, et al. Purulent pericarditis: a rare diagnosis [in Portuguese]. Rev Port Cardiol. 2013;32(9):721-727.

2. Parikh SV, Memon N, Echols M, Shah J, McGuire DK, Keeley EC. Purulent pericarditis: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2009;88(1):52–65.

3. Go C, Asnis DS, Saltzman H. Pneumococcal pericarditis since 1980. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27(5):1338-1340.

4. Wada A, Craft J, Mazzaferri EL. Purulent pericarditis leading to constriction. Cardiol Res. 2014;5(6):188-190.

5. Cillóniz C, Rangel E, Barlascini C, Piroddi IMG, Torres A, Nicolini A. Streptococcus pneumoniae-associated pneumonia complicated by purulent pericarditis: case series [in English, Portuguese]. J Bras Pneumol. 2015;41(4):389-394.

6. Saenz RE, Sanders CV, Aldridge KE, Patel MM. Purulent pericarditis with associated cardiac tamponade caused by a Streptococcus pneumoniae strain highly resistant to penicillin, cefotaxime, and ceftriaxone. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26(3):762–763.

7. Sagristà-Sauleda J, Barrabés JA, Permanyer-Miralda G, Soler-Soler J. Purulent pericarditis: review of a 20-year experience in a general hospital. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993; 22(6):1661-1665.

Purulent pericarditis is an infection within the pericardial space rarely seen in the modern antibiotic era. Most cases are secondary to another infectious process of bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic origin.1,2 Predisposing factors include malignancy, chronic kidney disease, immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, and alcohol misuse disorder.1 Although purulent pericarditis has been described extensively in the literature, it is a challenging diagnosis if it is not initially considered within the differential diagnosis repertoire.1-4 Most authors agree that this may be because it has become an infrequent diagnosis.1,2 In addition, purulent pericarditis may have an atypical presentation when compared with a classic case of pericarditis.2,3 The authors believe that this forgotten entity will be revisited through this case.

Case Presentation

A 66-year-old-man was transferred to Veterans Affairs Caribbean Healthcare System (VACHS) from a community hospital with a diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and bilateral pleural effusions. Four days prior to arrival at the community hospital, the patient had developed diffuse, watery diarrhea, which resolved in 3 days. After resolution of diarrhea, he began experiencing shortness of breath on exertion that progressed to onset at rest. The patient reported no fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, cough, or contact with others who were not healthy. He had a history of alcohol misuse without liver cirrhosis and reported no chronic diseases or use of medications. The patient had no history of tuberculosis exposure or pneumococcal vaccination, and had a negative interferon gamma release assay.

On admission to the community hospital, the patient was treated for CAP with ceftriaxone and azithromycin. On hospital day 3, the patient developed hypoxemia and an altered mental status. He was started on supplemental oxygen and transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU). Antibiotic therapy consequently was changed to levofloxacin and meropenem. However, no clinical improvement was noted on the following days.

On hospital day 7, the patient developed acute respiratory failure that required mechanical ventilation while being transferred to VACHS via air ambulance. His vital signs on arrival were the following: temperature, 97° F; heart rate, 86 beats/min; blood pressure, 103/61 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min and SaO2 of 97%, measured while he breathed supplemental oxygen at an FiO2 of 0.4.

Hours after arrival, the patient developed sinus tachycardia and hypotension. A bedside 2D echocardiogram demonstrated a large pericardial effusion with diastolic collapse of the right atrium (Figure 2).

The patient’s clinical condition improved following drainage of pericardial fluid, with no further need for inotropic support. Antibiotic therapy was changed to vancomycin and meropenem. Initial microbiologic samples from pericardial fluid demonstrated Gram-positive diplococci, suggestive of Streptococcus pneumoniae (S pneumoniae) (Figure 4). Other diagnostic pericardial fluid test results included: WBC count 25,330 cmm, with 99% neutrophils and 1% lymphocytes; total protein, 3.8 mg/dL; glucose, < 2.0 mg/dL,LDH, > 2,500 U/L, potassium hydroxide preparation. The tests found no fungus, and the acid fast bacilli smear revealed no Bacillus. However, the pericardial fluid culture failed to demonstrate growth of any organism. Blood cultures also were negative.

The patient underwent anterior thoracotomy with partial pericardiectomy, and a pericardial tube was left in place connected to drainage. During the procedure, an abundant amount of fibrinous tissue was evacuated from the pericardial space (Figure 5).

The patient was extubated, pericardial and pleural tubes were removed, and he was transferred to the internal medicine ward 24 days after admission to the ICU. He received in-patient physical rehabilitation while completing a 6-week course of IV antibiotics (vancomycin and meropenem). After completion of therapy, the patient received the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination, and an echocardiography was repeated. No significant re-accumulation of pericardial effusion or constrictive pattern was evidenced. The patient was discharged to his out-of-state home, and follow-up was consequently lost.

Discussion

Purulent pericarditis is an infection localized within the pericardial space. Most cases are secondary to an infectious process elsewhere, which could be of bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic etiology.1 Five mechanisms could lead the infecting organism to infect the pericardial space; contiguous spread from intrathoracic site, hematogenous spread, extension from myocardial site, perforating injury or surgery, and extension from a subdiaphragmatic site.1 Predisposing factors for the development of this condition include malignancy, chronic kidney disease, immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, and alcohol misuse. Pericarditis is an infection localized within the pericardial space.

Purulent pericarditis has become a rare entity in the antibiotic era.2 Prior to the development of antibiotics, most cases were secondary to S pneumoniae.1,2,5,6 As per Cilloniz and colleagues, about 40% to 50% of all cases of purulent pericarditis are caused by Gram-positive bacteria, mostly S pneumoniae.5 In this case study, bacterial culture did not reveal growth of an organism—most likely because the patient had received antibiotics elsewhere. However, Gram-positive cocci were seen within the initial pericardial aspirate. This organism was suspected to have spread contiguously from a pulmonary focus, which also led to pleural effusions.

Since the patient in this case study had no history of thoracic surgery, malignancy, or other immunosuppression, the patient’s history of alcohol misuse was the only predisposing factor for development of purulent pericarditis. Contrary to the common presentation of pericarditis, purulent pericarditis may not have the common clinical findings, such as chest pain, pericardial friction rub, and distended neck veins.2,3 Furthermore, according to Parikh and colleagues, about 35% of affected patients may have a normal electrocardiogram.2 Hence, the diagnosis of purulent pericarditis often is missed because the classic signs of pericarditis are often absent, and other nonspecific symptoms are attributed to initial underlying infection.7

A high index of suspicion is needed to diagnose purulent pericarditis. Once a diagnosis is made, initial treatment should consist of prompt drainage of pericardial fluid combined with systemic antibiotic therapy. Vancomycin and a third-generation cephalosporin may be started empirically until results of pericardial fluid cultures become available.3 Drainage can be achieved by pericardiocentesis, pericardiotomy, or pericardiectomy (partial or total).1 In cases of hemodynamic instability due to cardiac tamponade, sonographically guided pericardiocentesis should be undertaken and an indwelling pericardial catheter left in place.1 Although this is the simplest and fastest method of evacuation, it may not be effective when dealing with thick, fibrinous fluid. In such cases, intrapericardial fibrinolysis may be considered. This approach may be undertaken early in the process, after drainage insertion, or as salvage therapy, when there has been incomplete evacuation of purulent material or open surgical drainage is not available.

Streptokinase, urokinase, and tissue plasminogen activator have been used for intrapericadial fibrinolysis.1 However, there is no definite data on dosage or frequency at which these medications should be administered. No matter the therapeutic approach, effective drainage of the pericardial fluid is crucial to avoid the development of pericardial constriction. Constrictive pericarditis occurs when fibrosis and adhesions create a dense pericardium that encases the heart. This causes impaired ventricular filling that can lead eventually to heart failure.4 Pericardiectomy is the definitive treatment for constrictive pericarditis.

Conclusion

Although purulent pericarditis has become a rare diagnosis since the development of antibiotics, knowledge of how to identify it is essential since mortality reaches 100% if the diagnosis is missed.4 Even when the condition is promptly diagnosed and treated, mortality is 40%, mainly due to cardiac tamponade, septic shock, or constriction.1 The case presented here illustrates the clinical features associated with this condition. Knowing these features can translate in a successful patient outcome.

Purulent pericarditis is an infection within the pericardial space rarely seen in the modern antibiotic era. Most cases are secondary to another infectious process of bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic origin.1,2 Predisposing factors include malignancy, chronic kidney disease, immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, and alcohol misuse disorder.1 Although purulent pericarditis has been described extensively in the literature, it is a challenging diagnosis if it is not initially considered within the differential diagnosis repertoire.1-4 Most authors agree that this may be because it has become an infrequent diagnosis.1,2 In addition, purulent pericarditis may have an atypical presentation when compared with a classic case of pericarditis.2,3 The authors believe that this forgotten entity will be revisited through this case.

Case Presentation

A 66-year-old-man was transferred to Veterans Affairs Caribbean Healthcare System (VACHS) from a community hospital with a diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and bilateral pleural effusions. Four days prior to arrival at the community hospital, the patient had developed diffuse, watery diarrhea, which resolved in 3 days. After resolution of diarrhea, he began experiencing shortness of breath on exertion that progressed to onset at rest. The patient reported no fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, cough, or contact with others who were not healthy. He had a history of alcohol misuse without liver cirrhosis and reported no chronic diseases or use of medications. The patient had no history of tuberculosis exposure or pneumococcal vaccination, and had a negative interferon gamma release assay.

On admission to the community hospital, the patient was treated for CAP with ceftriaxone and azithromycin. On hospital day 3, the patient developed hypoxemia and an altered mental status. He was started on supplemental oxygen and transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU). Antibiotic therapy consequently was changed to levofloxacin and meropenem. However, no clinical improvement was noted on the following days.

On hospital day 7, the patient developed acute respiratory failure that required mechanical ventilation while being transferred to VACHS via air ambulance. His vital signs on arrival were the following: temperature, 97° F; heart rate, 86 beats/min; blood pressure, 103/61 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min and SaO2 of 97%, measured while he breathed supplemental oxygen at an FiO2 of 0.4.

Hours after arrival, the patient developed sinus tachycardia and hypotension. A bedside 2D echocardiogram demonstrated a large pericardial effusion with diastolic collapse of the right atrium (Figure 2).

The patient’s clinical condition improved following drainage of pericardial fluid, with no further need for inotropic support. Antibiotic therapy was changed to vancomycin and meropenem. Initial microbiologic samples from pericardial fluid demonstrated Gram-positive diplococci, suggestive of Streptococcus pneumoniae (S pneumoniae) (Figure 4). Other diagnostic pericardial fluid test results included: WBC count 25,330 cmm, with 99% neutrophils and 1% lymphocytes; total protein, 3.8 mg/dL; glucose, < 2.0 mg/dL,LDH, > 2,500 U/L, potassium hydroxide preparation. The tests found no fungus, and the acid fast bacilli smear revealed no Bacillus. However, the pericardial fluid culture failed to demonstrate growth of any organism. Blood cultures also were negative.

The patient underwent anterior thoracotomy with partial pericardiectomy, and a pericardial tube was left in place connected to drainage. During the procedure, an abundant amount of fibrinous tissue was evacuated from the pericardial space (Figure 5).

The patient was extubated, pericardial and pleural tubes were removed, and he was transferred to the internal medicine ward 24 days after admission to the ICU. He received in-patient physical rehabilitation while completing a 6-week course of IV antibiotics (vancomycin and meropenem). After completion of therapy, the patient received the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination, and an echocardiography was repeated. No significant re-accumulation of pericardial effusion or constrictive pattern was evidenced. The patient was discharged to his out-of-state home, and follow-up was consequently lost.

Discussion

Purulent pericarditis is an infection localized within the pericardial space. Most cases are secondary to an infectious process elsewhere, which could be of bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic etiology.1 Five mechanisms could lead the infecting organism to infect the pericardial space; contiguous spread from intrathoracic site, hematogenous spread, extension from myocardial site, perforating injury or surgery, and extension from a subdiaphragmatic site.1 Predisposing factors for the development of this condition include malignancy, chronic kidney disease, immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, and alcohol misuse. Pericarditis is an infection localized within the pericardial space.

Purulent pericarditis has become a rare entity in the antibiotic era.2 Prior to the development of antibiotics, most cases were secondary to S pneumoniae.1,2,5,6 As per Cilloniz and colleagues, about 40% to 50% of all cases of purulent pericarditis are caused by Gram-positive bacteria, mostly S pneumoniae.5 In this case study, bacterial culture did not reveal growth of an organism—most likely because the patient had received antibiotics elsewhere. However, Gram-positive cocci were seen within the initial pericardial aspirate. This organism was suspected to have spread contiguously from a pulmonary focus, which also led to pleural effusions.

Since the patient in this case study had no history of thoracic surgery, malignancy, or other immunosuppression, the patient’s history of alcohol misuse was the only predisposing factor for development of purulent pericarditis. Contrary to the common presentation of pericarditis, purulent pericarditis may not have the common clinical findings, such as chest pain, pericardial friction rub, and distended neck veins.2,3 Furthermore, according to Parikh and colleagues, about 35% of affected patients may have a normal electrocardiogram.2 Hence, the diagnosis of purulent pericarditis often is missed because the classic signs of pericarditis are often absent, and other nonspecific symptoms are attributed to initial underlying infection.7

A high index of suspicion is needed to diagnose purulent pericarditis. Once a diagnosis is made, initial treatment should consist of prompt drainage of pericardial fluid combined with systemic antibiotic therapy. Vancomycin and a third-generation cephalosporin may be started empirically until results of pericardial fluid cultures become available.3 Drainage can be achieved by pericardiocentesis, pericardiotomy, or pericardiectomy (partial or total).1 In cases of hemodynamic instability due to cardiac tamponade, sonographically guided pericardiocentesis should be undertaken and an indwelling pericardial catheter left in place.1 Although this is the simplest and fastest method of evacuation, it may not be effective when dealing with thick, fibrinous fluid. In such cases, intrapericardial fibrinolysis may be considered. This approach may be undertaken early in the process, after drainage insertion, or as salvage therapy, when there has been incomplete evacuation of purulent material or open surgical drainage is not available.

Streptokinase, urokinase, and tissue plasminogen activator have been used for intrapericadial fibrinolysis.1 However, there is no definite data on dosage or frequency at which these medications should be administered. No matter the therapeutic approach, effective drainage of the pericardial fluid is crucial to avoid the development of pericardial constriction. Constrictive pericarditis occurs when fibrosis and adhesions create a dense pericardium that encases the heart. This causes impaired ventricular filling that can lead eventually to heart failure.4 Pericardiectomy is the definitive treatment for constrictive pericarditis.

Conclusion

Although purulent pericarditis has become a rare diagnosis since the development of antibiotics, knowledge of how to identify it is essential since mortality reaches 100% if the diagnosis is missed.4 Even when the condition is promptly diagnosed and treated, mortality is 40%, mainly due to cardiac tamponade, septic shock, or constriction.1 The case presented here illustrates the clinical features associated with this condition. Knowing these features can translate in a successful patient outcome.

1. Ferreira dos Santos L, Moreira D, Ribeiro P, et al. Purulent pericarditis: a rare diagnosis [in Portuguese]. Rev Port Cardiol. 2013;32(9):721-727.

2. Parikh SV, Memon N, Echols M, Shah J, McGuire DK, Keeley EC. Purulent pericarditis: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2009;88(1):52–65.

3. Go C, Asnis DS, Saltzman H. Pneumococcal pericarditis since 1980. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27(5):1338-1340.

4. Wada A, Craft J, Mazzaferri EL. Purulent pericarditis leading to constriction. Cardiol Res. 2014;5(6):188-190.

5. Cillóniz C, Rangel E, Barlascini C, Piroddi IMG, Torres A, Nicolini A. Streptococcus pneumoniae-associated pneumonia complicated by purulent pericarditis: case series [in English, Portuguese]. J Bras Pneumol. 2015;41(4):389-394.