User login

Palmoplantar exacerbation of psoriasis after nivolumab for lung cancer

Nivolumab is a full human immunoglobulin antibody to the programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) immune checkpoint receptor on T cells. This programmed cell death inhibitor is a targeted immunotherapy used to treat patients with melanoma, among other malignancies.1 More recently, nivolumab has been used for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) after failure of previous chemotherapeutic agents. It was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the NSCLC indication in 2015.2

PD-1 inhibitors are efficacious in treating advanced malignancies, although their immune-mediated functions can lead to undesirable side effects. Patients treated with nivolumab have been reported to develop thyroid disease,1,3,4 diabetes,3 hypophysitis,1,3 hypopituitarism,3 and pneumonitis,4,2 as well as other autoimmune conditions.3 Although nivolumab is often used to treat skin diseases such as melanoma, it can have many cutaneous side effects including pruritus,1,3-6 rash,1,3,4,6,7 vitiligo,1,3,7,6 mouth sores,3 injection site reactions,3,6 and alopecia.5 Herein, we describe a patient who was treated with nivolumab and developed an exacerbation of pre-existing psoriasis.

Case presentation and summary

A 57-year-old man with metastatic NSCLC and a history of plaque psoriasis presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of new lesions on his palms and soles. The patient had been previously treated with numerous therapies for NSCLC, including chemotherapy and radiation. Previous chemotherapeutic agents included the cisplatin plus etoposide combination, with doxetaxel and pemetrexed. The patient was not able to tolerate the chemotherapy and instead opted for hospice care. After several months, he chose to restart therapy, and was started on the programmed cell death (PD)-1 inhibitor, nivolumab, at a dose of 3 mg/kg for a total of 6 cycles. He received his first dose 5 weeks before his current presentation to the clinic, and his second dose 2 weeks before.

The patient reported a 20-year history of plaque psoriasis, characterized by psoriatic plaques on the elbows and shins and for which he was treated with topical therapies with good effect. Every few months, he would develop one or two small plaques of psoriasis on his palms and soles. The lesions were inconsequential to the patient, as he never experienced more than one or two small palmoplantar lesions at a time. One week after his second cycle of nivolumab, the patient developed an eruption of lesions on his palms and soles. He observed that the lesions seemed to be similar to his previous palmoplantar psoriatic plaques but with significantly greater skin involvement. The patient denied any new-onset joint pain.

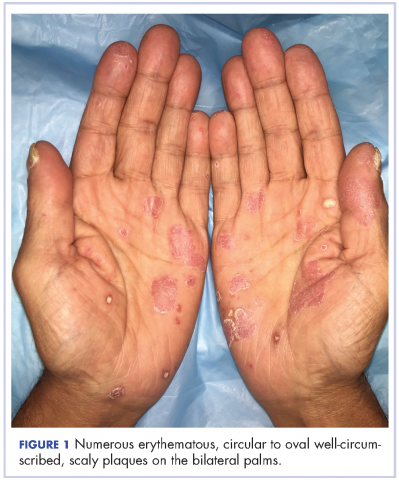

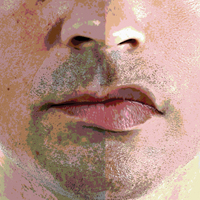

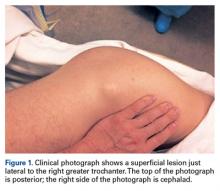

The results of a physical examination revealed a cachectic man in no acute distress, with more than 30 erythematous circular to oval circumscribed plaques with yellow to whitish scales on the bilateral palms (Figure 1) and soles (Figure 2).

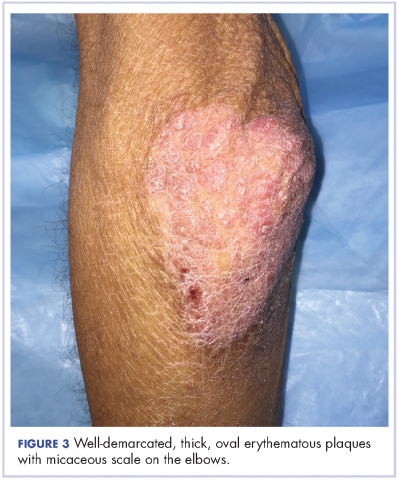

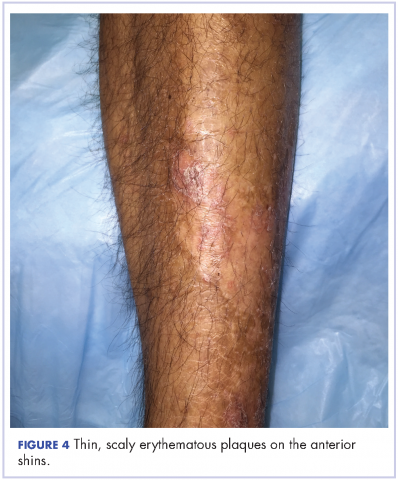

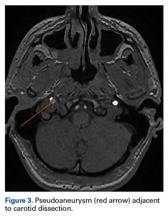

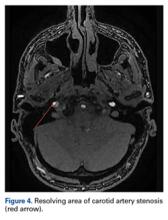

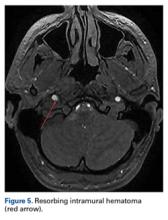

The patient also had well-demarcated, thick oval erythematous plaques with micaceous scales on the bilateral elbows (Figure 3), and thin scaly erythematous plaques on the anterior shins (Figure 4). There were no psoriatic plaques on the remainder of the trunk or extremities. Mucosal surfaces, scalp, and nails were uninvolved.

A clinical diagnosis of exacerbation of pre-existing psoriasis owing to nivolumab therapy was made. The patient was started on clobetasol 0.05% ointment twice daily under occlusion with plastic wrap to the affected areas, and he was continued on nivolumab for his NSCLC.

Discussion

Treatment with nivolumab can lead to a range of autoimmune side effects, and as shown in this case, psoriasis is one of the cutaneous findings that could be exacerbated by treatment with nivolumab. To date, two cases of exacerbation of psoriasis in patients treated with nivolumab for melanoma have been reported in the literature.8,9 In the first case, the patient had well-controlled plaque psoriasis at baseline and he subsequently developed psoriatic plaques on the trunk and extremities after the second infusion of nivolumab for metastatic melanoma. A biopsy showed regular acanthosis with hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis in addition to dilated vessels in the papillary dermis.8 In the second case, the patient had a history of psoriasis vulgaris with no active lesions. Three weeks after his first course of nivolumab for metastatic oral mucosal melanoma, he developed new, well-circumscribed erythematous scaly plaques on the trunk and extremities that were clinically diagnosed as psoriasis.9 In a third case, a patient without a prior history of psoriasis experienced a psoriasiform eruption on the trunk and extremities after the fourth dose of nivolumab for oral mucosal melanoma.10 Thus, our case is the third reported case of exacerbation of preexisting psoriasis in a patient treated with nivolumab. Furthermore, our patient is the first reported case of a patient treated with nivolumab for NSCLC to develop this adverse event. Whereas the previously reported cases were characterized by widespread trunk and extremity involvement, our patient developed focal exacerbation of the palmoplantar areas.

Additional studies are needed to more clearly characterize the specific cutaneous toxicities of nivolumab and to determine if particular skin reactions may indicate a better response to the anticancer agent. Side effects such as psoriasis can often be managed with topical therapies and may not require withdrawal of the medication. We encourage the collaboration of dermatologists and oncologists to enhance the diagnosis and management of these cutaneous side effects in cancer patients.

1. Larkin J, Lao CD, Urba WJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of Nivolumab in patients with BRAF V600 mutant and BRAF wild-type advanced melanoma: a pooled analysis of 4 clinical trials. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(4):433-440.

2. Gettinger SN, Horn L, Gandhi L, et al. Overall survival and long-term safety of nivolumab (anti-programmed death 1 antibody, BMS-936558, ONO-4538) in patients with previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(18):2004-2012.

3. Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(26):2443-2454.

4. Rizvi NA, Mazieres J, Planchard D, et al. Activity and safety of nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, for patients with advanced, refractory squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 063): a phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(3):257-265.

5. Weber JS, D’Angelo SP, Minor D, et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(4):375-384.

6. Weber JS, Kudchadkar RR, Yu B, et al. Safety, efficacy, and biomarkers of nivolumab with vaccine in ipilimumab-refractory or -naive melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(34):4311-4318.

7. Freeman-Keller M, Kim Y, Cronin H, Richards A, Gibney G, Weber J. Nivolumab in resected and unresectable metastatic melanoma: characteristics of immune-related adverse events and association with outcomes. Clin Cancer Res. 2015.

8. Matsumura N, Ohtsuka M, Kikuchi N, Yamamoto T. Exacerbation of psoriasis during nivolumab therapy for metastatic melanoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96(2):259-260.

9. Kato Y, Otsuka A, Miyachi Y, Kabashima K. Exacerbation of psoriasis vulgaris during nivolumab for oral mucosal melanoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(10):e89-e91.

10. Ohtsuka M, Miura T, Mori T, Ishikawa M, Yamamoto T. Occurrence of psoriasiform eruption during nivolumab therapy for primary oral mucosal melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(7):797-799.

Nivolumab is a full human immunoglobulin antibody to the programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) immune checkpoint receptor on T cells. This programmed cell death inhibitor is a targeted immunotherapy used to treat patients with melanoma, among other malignancies.1 More recently, nivolumab has been used for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) after failure of previous chemotherapeutic agents. It was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the NSCLC indication in 2015.2

PD-1 inhibitors are efficacious in treating advanced malignancies, although their immune-mediated functions can lead to undesirable side effects. Patients treated with nivolumab have been reported to develop thyroid disease,1,3,4 diabetes,3 hypophysitis,1,3 hypopituitarism,3 and pneumonitis,4,2 as well as other autoimmune conditions.3 Although nivolumab is often used to treat skin diseases such as melanoma, it can have many cutaneous side effects including pruritus,1,3-6 rash,1,3,4,6,7 vitiligo,1,3,7,6 mouth sores,3 injection site reactions,3,6 and alopecia.5 Herein, we describe a patient who was treated with nivolumab and developed an exacerbation of pre-existing psoriasis.

Case presentation and summary

A 57-year-old man with metastatic NSCLC and a history of plaque psoriasis presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of new lesions on his palms and soles. The patient had been previously treated with numerous therapies for NSCLC, including chemotherapy and radiation. Previous chemotherapeutic agents included the cisplatin plus etoposide combination, with doxetaxel and pemetrexed. The patient was not able to tolerate the chemotherapy and instead opted for hospice care. After several months, he chose to restart therapy, and was started on the programmed cell death (PD)-1 inhibitor, nivolumab, at a dose of 3 mg/kg for a total of 6 cycles. He received his first dose 5 weeks before his current presentation to the clinic, and his second dose 2 weeks before.

The patient reported a 20-year history of plaque psoriasis, characterized by psoriatic plaques on the elbows and shins and for which he was treated with topical therapies with good effect. Every few months, he would develop one or two small plaques of psoriasis on his palms and soles. The lesions were inconsequential to the patient, as he never experienced more than one or two small palmoplantar lesions at a time. One week after his second cycle of nivolumab, the patient developed an eruption of lesions on his palms and soles. He observed that the lesions seemed to be similar to his previous palmoplantar psoriatic plaques but with significantly greater skin involvement. The patient denied any new-onset joint pain.

The results of a physical examination revealed a cachectic man in no acute distress, with more than 30 erythematous circular to oval circumscribed plaques with yellow to whitish scales on the bilateral palms (Figure 1) and soles (Figure 2).

The patient also had well-demarcated, thick oval erythematous plaques with micaceous scales on the bilateral elbows (Figure 3), and thin scaly erythematous plaques on the anterior shins (Figure 4). There were no psoriatic plaques on the remainder of the trunk or extremities. Mucosal surfaces, scalp, and nails were uninvolved.

A clinical diagnosis of exacerbation of pre-existing psoriasis owing to nivolumab therapy was made. The patient was started on clobetasol 0.05% ointment twice daily under occlusion with plastic wrap to the affected areas, and he was continued on nivolumab for his NSCLC.

Discussion

Treatment with nivolumab can lead to a range of autoimmune side effects, and as shown in this case, psoriasis is one of the cutaneous findings that could be exacerbated by treatment with nivolumab. To date, two cases of exacerbation of psoriasis in patients treated with nivolumab for melanoma have been reported in the literature.8,9 In the first case, the patient had well-controlled plaque psoriasis at baseline and he subsequently developed psoriatic plaques on the trunk and extremities after the second infusion of nivolumab for metastatic melanoma. A biopsy showed regular acanthosis with hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis in addition to dilated vessels in the papillary dermis.8 In the second case, the patient had a history of psoriasis vulgaris with no active lesions. Three weeks after his first course of nivolumab for metastatic oral mucosal melanoma, he developed new, well-circumscribed erythematous scaly plaques on the trunk and extremities that were clinically diagnosed as psoriasis.9 In a third case, a patient without a prior history of psoriasis experienced a psoriasiform eruption on the trunk and extremities after the fourth dose of nivolumab for oral mucosal melanoma.10 Thus, our case is the third reported case of exacerbation of preexisting psoriasis in a patient treated with nivolumab. Furthermore, our patient is the first reported case of a patient treated with nivolumab for NSCLC to develop this adverse event. Whereas the previously reported cases were characterized by widespread trunk and extremity involvement, our patient developed focal exacerbation of the palmoplantar areas.

Additional studies are needed to more clearly characterize the specific cutaneous toxicities of nivolumab and to determine if particular skin reactions may indicate a better response to the anticancer agent. Side effects such as psoriasis can often be managed with topical therapies and may not require withdrawal of the medication. We encourage the collaboration of dermatologists and oncologists to enhance the diagnosis and management of these cutaneous side effects in cancer patients.

Nivolumab is a full human immunoglobulin antibody to the programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) immune checkpoint receptor on T cells. This programmed cell death inhibitor is a targeted immunotherapy used to treat patients with melanoma, among other malignancies.1 More recently, nivolumab has been used for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) after failure of previous chemotherapeutic agents. It was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the NSCLC indication in 2015.2

PD-1 inhibitors are efficacious in treating advanced malignancies, although their immune-mediated functions can lead to undesirable side effects. Patients treated with nivolumab have been reported to develop thyroid disease,1,3,4 diabetes,3 hypophysitis,1,3 hypopituitarism,3 and pneumonitis,4,2 as well as other autoimmune conditions.3 Although nivolumab is often used to treat skin diseases such as melanoma, it can have many cutaneous side effects including pruritus,1,3-6 rash,1,3,4,6,7 vitiligo,1,3,7,6 mouth sores,3 injection site reactions,3,6 and alopecia.5 Herein, we describe a patient who was treated with nivolumab and developed an exacerbation of pre-existing psoriasis.

Case presentation and summary

A 57-year-old man with metastatic NSCLC and a history of plaque psoriasis presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of new lesions on his palms and soles. The patient had been previously treated with numerous therapies for NSCLC, including chemotherapy and radiation. Previous chemotherapeutic agents included the cisplatin plus etoposide combination, with doxetaxel and pemetrexed. The patient was not able to tolerate the chemotherapy and instead opted for hospice care. After several months, he chose to restart therapy, and was started on the programmed cell death (PD)-1 inhibitor, nivolumab, at a dose of 3 mg/kg for a total of 6 cycles. He received his first dose 5 weeks before his current presentation to the clinic, and his second dose 2 weeks before.

The patient reported a 20-year history of plaque psoriasis, characterized by psoriatic plaques on the elbows and shins and for which he was treated with topical therapies with good effect. Every few months, he would develop one or two small plaques of psoriasis on his palms and soles. The lesions were inconsequential to the patient, as he never experienced more than one or two small palmoplantar lesions at a time. One week after his second cycle of nivolumab, the patient developed an eruption of lesions on his palms and soles. He observed that the lesions seemed to be similar to his previous palmoplantar psoriatic plaques but with significantly greater skin involvement. The patient denied any new-onset joint pain.

The results of a physical examination revealed a cachectic man in no acute distress, with more than 30 erythematous circular to oval circumscribed plaques with yellow to whitish scales on the bilateral palms (Figure 1) and soles (Figure 2).

The patient also had well-demarcated, thick oval erythematous plaques with micaceous scales on the bilateral elbows (Figure 3), and thin scaly erythematous plaques on the anterior shins (Figure 4). There were no psoriatic plaques on the remainder of the trunk or extremities. Mucosal surfaces, scalp, and nails were uninvolved.

A clinical diagnosis of exacerbation of pre-existing psoriasis owing to nivolumab therapy was made. The patient was started on clobetasol 0.05% ointment twice daily under occlusion with plastic wrap to the affected areas, and he was continued on nivolumab for his NSCLC.

Discussion

Treatment with nivolumab can lead to a range of autoimmune side effects, and as shown in this case, psoriasis is one of the cutaneous findings that could be exacerbated by treatment with nivolumab. To date, two cases of exacerbation of psoriasis in patients treated with nivolumab for melanoma have been reported in the literature.8,9 In the first case, the patient had well-controlled plaque psoriasis at baseline and he subsequently developed psoriatic plaques on the trunk and extremities after the second infusion of nivolumab for metastatic melanoma. A biopsy showed regular acanthosis with hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis in addition to dilated vessels in the papillary dermis.8 In the second case, the patient had a history of psoriasis vulgaris with no active lesions. Three weeks after his first course of nivolumab for metastatic oral mucosal melanoma, he developed new, well-circumscribed erythematous scaly plaques on the trunk and extremities that were clinically diagnosed as psoriasis.9 In a third case, a patient without a prior history of psoriasis experienced a psoriasiform eruption on the trunk and extremities after the fourth dose of nivolumab for oral mucosal melanoma.10 Thus, our case is the third reported case of exacerbation of preexisting psoriasis in a patient treated with nivolumab. Furthermore, our patient is the first reported case of a patient treated with nivolumab for NSCLC to develop this adverse event. Whereas the previously reported cases were characterized by widespread trunk and extremity involvement, our patient developed focal exacerbation of the palmoplantar areas.

Additional studies are needed to more clearly characterize the specific cutaneous toxicities of nivolumab and to determine if particular skin reactions may indicate a better response to the anticancer agent. Side effects such as psoriasis can often be managed with topical therapies and may not require withdrawal of the medication. We encourage the collaboration of dermatologists and oncologists to enhance the diagnosis and management of these cutaneous side effects in cancer patients.

1. Larkin J, Lao CD, Urba WJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of Nivolumab in patients with BRAF V600 mutant and BRAF wild-type advanced melanoma: a pooled analysis of 4 clinical trials. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(4):433-440.

2. Gettinger SN, Horn L, Gandhi L, et al. Overall survival and long-term safety of nivolumab (anti-programmed death 1 antibody, BMS-936558, ONO-4538) in patients with previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(18):2004-2012.

3. Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(26):2443-2454.

4. Rizvi NA, Mazieres J, Planchard D, et al. Activity and safety of nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, for patients with advanced, refractory squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 063): a phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(3):257-265.

5. Weber JS, D’Angelo SP, Minor D, et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(4):375-384.

6. Weber JS, Kudchadkar RR, Yu B, et al. Safety, efficacy, and biomarkers of nivolumab with vaccine in ipilimumab-refractory or -naive melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(34):4311-4318.

7. Freeman-Keller M, Kim Y, Cronin H, Richards A, Gibney G, Weber J. Nivolumab in resected and unresectable metastatic melanoma: characteristics of immune-related adverse events and association with outcomes. Clin Cancer Res. 2015.

8. Matsumura N, Ohtsuka M, Kikuchi N, Yamamoto T. Exacerbation of psoriasis during nivolumab therapy for metastatic melanoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96(2):259-260.

9. Kato Y, Otsuka A, Miyachi Y, Kabashima K. Exacerbation of psoriasis vulgaris during nivolumab for oral mucosal melanoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(10):e89-e91.

10. Ohtsuka M, Miura T, Mori T, Ishikawa M, Yamamoto T. Occurrence of psoriasiform eruption during nivolumab therapy for primary oral mucosal melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(7):797-799.

1. Larkin J, Lao CD, Urba WJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of Nivolumab in patients with BRAF V600 mutant and BRAF wild-type advanced melanoma: a pooled analysis of 4 clinical trials. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(4):433-440.

2. Gettinger SN, Horn L, Gandhi L, et al. Overall survival and long-term safety of nivolumab (anti-programmed death 1 antibody, BMS-936558, ONO-4538) in patients with previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(18):2004-2012.

3. Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(26):2443-2454.

4. Rizvi NA, Mazieres J, Planchard D, et al. Activity and safety of nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, for patients with advanced, refractory squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 063): a phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(3):257-265.

5. Weber JS, D’Angelo SP, Minor D, et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(4):375-384.

6. Weber JS, Kudchadkar RR, Yu B, et al. Safety, efficacy, and biomarkers of nivolumab with vaccine in ipilimumab-refractory or -naive melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(34):4311-4318.

7. Freeman-Keller M, Kim Y, Cronin H, Richards A, Gibney G, Weber J. Nivolumab in resected and unresectable metastatic melanoma: characteristics of immune-related adverse events and association with outcomes. Clin Cancer Res. 2015.

8. Matsumura N, Ohtsuka M, Kikuchi N, Yamamoto T. Exacerbation of psoriasis during nivolumab therapy for metastatic melanoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96(2):259-260.

9. Kato Y, Otsuka A, Miyachi Y, Kabashima K. Exacerbation of psoriasis vulgaris during nivolumab for oral mucosal melanoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(10):e89-e91.

10. Ohtsuka M, Miura T, Mori T, Ishikawa M, Yamamoto T. Occurrence of psoriasiform eruption during nivolumab therapy for primary oral mucosal melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(7):797-799.

Peripheral Exudative Hemorrhagic Chorioretinopathy in Patients With Nonexudative Age-Related Macular Degeneration

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a common condition that affects the elderly white population. About 6.5% of Americans have been diagnosed with AMD, and 0.8% have received an end-stage AMD diagnosis.1 Exudative AMD is typically more visually debilitating and comprises between 10% and 15% of all AMD cases, with conversion from dry to wet about 10%.1

A thorough examination of the posterior pole is of utmost importance in patients with dry AMD in order to ensure there is no conversion to the exudative form. However, it also is imperative to perform a peripheral evaluation in these patients due to the incidence of peripheral choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM) and its potential visual significance.

Case Report 1

An 80-year-old white male with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) without retinopathy, dry AMD, and epiretinal membranes (ERM) in both eyes presented to the eye clinic for a 6-month follow-up. On examination, he had visual acuity (VA) of 20/25 in both eyes and reported no ocular problems. The intraocular pressures were 17 mm Hg in the right eye and 20 mm Hg in the left eye. Slit-lamp examination of the anterior segment of both eyes was significant for 2+ nuclear sclerotic cataracts.

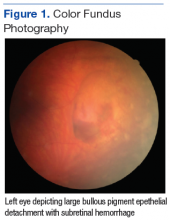

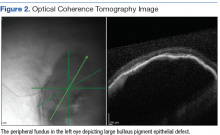

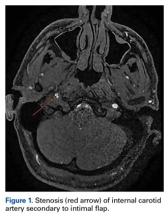

On dilated fundus exam, there were macular drusen and ERM in both eyes; peripherally in the right eye, there was cobblestone degeneration and pigmentary changes. Peripherally in the left eye, there was a large retinal pigment epithelial detachment (PED) with subretinal hemorrhage in the inferior temporal quadrant (Figure 1) along with cobblestone degeneration and pigmentary changes. Peripheral optical coherence tomography (OCT) in the left eye showed a large PED in the location of the hemorrhage (Figure 2).

Case Report 2

An 88-year-old white male presented to the eye clinic reporting blurred vision at distance and dry eyes. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for vascular and heart disease, treated with warfarin. The patient also had insulin controlled DM, with no prior history of retinopathy. His past ocular history included hard drusen in the macula, peripheral drusen, pavingstone degeneration, and a fibrotic scar temporally in the right eye.

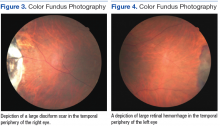

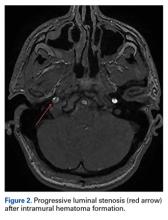

At his annual eye examination, the patient’s vision was correctable to 20/25 in both eyes. His anterior segment slit-lamp exam was remarkable for posterior chamber intraocular lenses, clear and centered in each eye. His posterior pole exam was remarkable for small hard drusen at the macula in both eyes. Peripherally in the right eye, there was a large disciform fibrotic scar temporally (Figure 3) as well as cobblestone degeneration and peripheral drusen. The left eye revealed a large disciform hemorrhage temporally (Figure 4) with cobblestone degeneration and peripheral drusen.

Both patients currently are being closely monitored for any encroachment of the peripheral lesions into the posterior poles.

Discussion

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR), also referred to in the literature as eccentric disciform CNVM, peripheral CNVM, and peripheral age-related degeneration, is a rare condition more prevalent in elderly white females.2-4 Mean age ranges from 70 to 82 years, with bilateral involvement ranging from 18% to 37%.2-4 The mid-periphery or periphery is the most common location for these lesions, more specifically, in the inferior temporal quadrant.2,3,5,6

Age-related macular degeneration is not pathognomonic for PEHCR. Mantel and colleagues reported that 68.9% of the patients in their study had AMD.3 Visual acuity ranges from 20/20 to light perception, dependent upon ocular comorbidities.2,3 As reported by Mantel and colleagues, patients with symptomatic PEHCR commonly experience visual loss, floaters, photopsias, metamorphopsia, and scotoma.3

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is a hemorrhagic or exudative process that can occur either as an isolated lesion or as multiple lesions that consist of a PED along with hemorrhage, subretinal fluid and/or fibrotic scarring.2-5 Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is not visually significant unless a vitreous hemorrhage is evident or the blood and/or fluid extends to the macular region.2,5

The exact etiology of peripheral CNVM remains unknown; however, ischemia, mechanical forces, and defects in Bruch’s membrane all have been speculated as causative factors.2,3,6 Others have hypothesized that PEHCR is a form of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy.3,7,8 A rupture in Bruch’s membrane with a vascular complex contributes to the pathophysiology and histology of this condition.3,6

Given the propensity for cardiovascular diseases, such as DM and hypertension, to lead to retinal ischemia, it is important to take a good case history.2,4,6 Additionally, anticoagulants have been shown to exacerbate bleeding.2,5 Due to PEHCR’s location in the periphery, as well as its appearance as an elevated dark mass, it is important to differentiate these lesions from a choroidal melanoma.2,6 Recognition of PEHCR can save the patient from unnecessary treatment with radiation or enucleation.

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is a self-limiting condition that generally requires close observation only. Long-term follow-up studies show resolution, regression, or stability of the peripheral lesions.4,5,8 If a hemorrhage is present, the blood will resolve and leave a disciform scar with pigmentary changes.2-4 In cases where vision is threatened, CNVM has been treated with photocoagulation, cryopexy, and more recently, intravitreal anti-VEGF injections.4,5,9,10 Given that VEGF is more prevalent in the presence of a choroidal neovascular complex, the goal of anti-VEGF therapy is to prevent the growth of and further damage from these abnormal blood vessels.5

Conclusion

The authors have described 2 cases of asymptomatic PEHCR in elderly white males who are both currently being observed closely. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is an uncommon finding; therefore, knowledge of this condition also may be rare. Through this article and these cases, the importance of routine peripheral fundus examination to detect PEHCR should be stressed. It also is important to include PEHCR as a differential diagnosis when evaluating a peripheral dark elevated lesion to distinguish from peripheral melanomas and avoid unnecessary treatments. If identified, these lesions often require close observation only, and a retina referral is warranted if there is macular involvement or a rapidly progressive lesion.5

1. Pron G. Optical coherence tomography monitoring strategies for A-VEGF–treated age-related macular degeneration: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2014;14(10):1–64.

2. Annesley WH Jr. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1980;78:321-364.

3. Mantel I, Uffer S, Zografos L. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: a clinical angiographic, and histologic study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(6):932-938.

4. Pinarci EY, Kilic I, Bayar SA, Sizmaz S, Akkoyun I, Yilmaz G. Clinical characteristics of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy and its response to bevacizumab therapy. Eye (Lond). 2013;27(1):111-112.

5. Seibel I, Hager A, Duncker T, et al. Anti-VEGF therapy in symptomatic peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR) involving the macula. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;254(4):653-659.

6. Collaer N, James C. Peripheral exudative and hemorrhagic chorio-retinopathy…the peripheral form of age-related macular degeneration? Report on 2 cases. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol. 2007;(305):23-26.

7. Goldman DR, Freund KB, McCannel CA, Sarraf D. Peripheral polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy as a cause of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: A report of 10 eyes. Retina. 2013;33(1):48-55.

8. Mashayekhi A, Shields CL, Shields JA. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: a variant of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy? J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2013;8(3):264-267.

9. Takayama K, Enoki T, Kojima T, Ishikawa S, Takeuchi M. Treatment of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy by intravitreal injections of ranibizumab. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:865-869.

10. Barkmeier AJ, Kadikoy H, Holz ER, Carvounis PE. Regression of serous macular detachment due to peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy following intravitreal bevacizumab. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21(4):506-508.

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a common condition that affects the elderly white population. About 6.5% of Americans have been diagnosed with AMD, and 0.8% have received an end-stage AMD diagnosis.1 Exudative AMD is typically more visually debilitating and comprises between 10% and 15% of all AMD cases, with conversion from dry to wet about 10%.1

A thorough examination of the posterior pole is of utmost importance in patients with dry AMD in order to ensure there is no conversion to the exudative form. However, it also is imperative to perform a peripheral evaluation in these patients due to the incidence of peripheral choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM) and its potential visual significance.

Case Report 1

An 80-year-old white male with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) without retinopathy, dry AMD, and epiretinal membranes (ERM) in both eyes presented to the eye clinic for a 6-month follow-up. On examination, he had visual acuity (VA) of 20/25 in both eyes and reported no ocular problems. The intraocular pressures were 17 mm Hg in the right eye and 20 mm Hg in the left eye. Slit-lamp examination of the anterior segment of both eyes was significant for 2+ nuclear sclerotic cataracts.

On dilated fundus exam, there were macular drusen and ERM in both eyes; peripherally in the right eye, there was cobblestone degeneration and pigmentary changes. Peripherally in the left eye, there was a large retinal pigment epithelial detachment (PED) with subretinal hemorrhage in the inferior temporal quadrant (Figure 1) along with cobblestone degeneration and pigmentary changes. Peripheral optical coherence tomography (OCT) in the left eye showed a large PED in the location of the hemorrhage (Figure 2).

Case Report 2

An 88-year-old white male presented to the eye clinic reporting blurred vision at distance and dry eyes. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for vascular and heart disease, treated with warfarin. The patient also had insulin controlled DM, with no prior history of retinopathy. His past ocular history included hard drusen in the macula, peripheral drusen, pavingstone degeneration, and a fibrotic scar temporally in the right eye.

At his annual eye examination, the patient’s vision was correctable to 20/25 in both eyes. His anterior segment slit-lamp exam was remarkable for posterior chamber intraocular lenses, clear and centered in each eye. His posterior pole exam was remarkable for small hard drusen at the macula in both eyes. Peripherally in the right eye, there was a large disciform fibrotic scar temporally (Figure 3) as well as cobblestone degeneration and peripheral drusen. The left eye revealed a large disciform hemorrhage temporally (Figure 4) with cobblestone degeneration and peripheral drusen.

Both patients currently are being closely monitored for any encroachment of the peripheral lesions into the posterior poles.

Discussion

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR), also referred to in the literature as eccentric disciform CNVM, peripheral CNVM, and peripheral age-related degeneration, is a rare condition more prevalent in elderly white females.2-4 Mean age ranges from 70 to 82 years, with bilateral involvement ranging from 18% to 37%.2-4 The mid-periphery or periphery is the most common location for these lesions, more specifically, in the inferior temporal quadrant.2,3,5,6

Age-related macular degeneration is not pathognomonic for PEHCR. Mantel and colleagues reported that 68.9% of the patients in their study had AMD.3 Visual acuity ranges from 20/20 to light perception, dependent upon ocular comorbidities.2,3 As reported by Mantel and colleagues, patients with symptomatic PEHCR commonly experience visual loss, floaters, photopsias, metamorphopsia, and scotoma.3

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is a hemorrhagic or exudative process that can occur either as an isolated lesion or as multiple lesions that consist of a PED along with hemorrhage, subretinal fluid and/or fibrotic scarring.2-5 Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is not visually significant unless a vitreous hemorrhage is evident or the blood and/or fluid extends to the macular region.2,5

The exact etiology of peripheral CNVM remains unknown; however, ischemia, mechanical forces, and defects in Bruch’s membrane all have been speculated as causative factors.2,3,6 Others have hypothesized that PEHCR is a form of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy.3,7,8 A rupture in Bruch’s membrane with a vascular complex contributes to the pathophysiology and histology of this condition.3,6

Given the propensity for cardiovascular diseases, such as DM and hypertension, to lead to retinal ischemia, it is important to take a good case history.2,4,6 Additionally, anticoagulants have been shown to exacerbate bleeding.2,5 Due to PEHCR’s location in the periphery, as well as its appearance as an elevated dark mass, it is important to differentiate these lesions from a choroidal melanoma.2,6 Recognition of PEHCR can save the patient from unnecessary treatment with radiation or enucleation.

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is a self-limiting condition that generally requires close observation only. Long-term follow-up studies show resolution, regression, or stability of the peripheral lesions.4,5,8 If a hemorrhage is present, the blood will resolve and leave a disciform scar with pigmentary changes.2-4 In cases where vision is threatened, CNVM has been treated with photocoagulation, cryopexy, and more recently, intravitreal anti-VEGF injections.4,5,9,10 Given that VEGF is more prevalent in the presence of a choroidal neovascular complex, the goal of anti-VEGF therapy is to prevent the growth of and further damage from these abnormal blood vessels.5

Conclusion

The authors have described 2 cases of asymptomatic PEHCR in elderly white males who are both currently being observed closely. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is an uncommon finding; therefore, knowledge of this condition also may be rare. Through this article and these cases, the importance of routine peripheral fundus examination to detect PEHCR should be stressed. It also is important to include PEHCR as a differential diagnosis when evaluating a peripheral dark elevated lesion to distinguish from peripheral melanomas and avoid unnecessary treatments. If identified, these lesions often require close observation only, and a retina referral is warranted if there is macular involvement or a rapidly progressive lesion.5

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a common condition that affects the elderly white population. About 6.5% of Americans have been diagnosed with AMD, and 0.8% have received an end-stage AMD diagnosis.1 Exudative AMD is typically more visually debilitating and comprises between 10% and 15% of all AMD cases, with conversion from dry to wet about 10%.1

A thorough examination of the posterior pole is of utmost importance in patients with dry AMD in order to ensure there is no conversion to the exudative form. However, it also is imperative to perform a peripheral evaluation in these patients due to the incidence of peripheral choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM) and its potential visual significance.

Case Report 1

An 80-year-old white male with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) without retinopathy, dry AMD, and epiretinal membranes (ERM) in both eyes presented to the eye clinic for a 6-month follow-up. On examination, he had visual acuity (VA) of 20/25 in both eyes and reported no ocular problems. The intraocular pressures were 17 mm Hg in the right eye and 20 mm Hg in the left eye. Slit-lamp examination of the anterior segment of both eyes was significant for 2+ nuclear sclerotic cataracts.

On dilated fundus exam, there were macular drusen and ERM in both eyes; peripherally in the right eye, there was cobblestone degeneration and pigmentary changes. Peripherally in the left eye, there was a large retinal pigment epithelial detachment (PED) with subretinal hemorrhage in the inferior temporal quadrant (Figure 1) along with cobblestone degeneration and pigmentary changes. Peripheral optical coherence tomography (OCT) in the left eye showed a large PED in the location of the hemorrhage (Figure 2).

Case Report 2

An 88-year-old white male presented to the eye clinic reporting blurred vision at distance and dry eyes. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for vascular and heart disease, treated with warfarin. The patient also had insulin controlled DM, with no prior history of retinopathy. His past ocular history included hard drusen in the macula, peripheral drusen, pavingstone degeneration, and a fibrotic scar temporally in the right eye.

At his annual eye examination, the patient’s vision was correctable to 20/25 in both eyes. His anterior segment slit-lamp exam was remarkable for posterior chamber intraocular lenses, clear and centered in each eye. His posterior pole exam was remarkable for small hard drusen at the macula in both eyes. Peripherally in the right eye, there was a large disciform fibrotic scar temporally (Figure 3) as well as cobblestone degeneration and peripheral drusen. The left eye revealed a large disciform hemorrhage temporally (Figure 4) with cobblestone degeneration and peripheral drusen.

Both patients currently are being closely monitored for any encroachment of the peripheral lesions into the posterior poles.

Discussion

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR), also referred to in the literature as eccentric disciform CNVM, peripheral CNVM, and peripheral age-related degeneration, is a rare condition more prevalent in elderly white females.2-4 Mean age ranges from 70 to 82 years, with bilateral involvement ranging from 18% to 37%.2-4 The mid-periphery or periphery is the most common location for these lesions, more specifically, in the inferior temporal quadrant.2,3,5,6

Age-related macular degeneration is not pathognomonic for PEHCR. Mantel and colleagues reported that 68.9% of the patients in their study had AMD.3 Visual acuity ranges from 20/20 to light perception, dependent upon ocular comorbidities.2,3 As reported by Mantel and colleagues, patients with symptomatic PEHCR commonly experience visual loss, floaters, photopsias, metamorphopsia, and scotoma.3

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is a hemorrhagic or exudative process that can occur either as an isolated lesion or as multiple lesions that consist of a PED along with hemorrhage, subretinal fluid and/or fibrotic scarring.2-5 Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is not visually significant unless a vitreous hemorrhage is evident or the blood and/or fluid extends to the macular region.2,5

The exact etiology of peripheral CNVM remains unknown; however, ischemia, mechanical forces, and defects in Bruch’s membrane all have been speculated as causative factors.2,3,6 Others have hypothesized that PEHCR is a form of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy.3,7,8 A rupture in Bruch’s membrane with a vascular complex contributes to the pathophysiology and histology of this condition.3,6

Given the propensity for cardiovascular diseases, such as DM and hypertension, to lead to retinal ischemia, it is important to take a good case history.2,4,6 Additionally, anticoagulants have been shown to exacerbate bleeding.2,5 Due to PEHCR’s location in the periphery, as well as its appearance as an elevated dark mass, it is important to differentiate these lesions from a choroidal melanoma.2,6 Recognition of PEHCR can save the patient from unnecessary treatment with radiation or enucleation.

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is a self-limiting condition that generally requires close observation only. Long-term follow-up studies show resolution, regression, or stability of the peripheral lesions.4,5,8 If a hemorrhage is present, the blood will resolve and leave a disciform scar with pigmentary changes.2-4 In cases where vision is threatened, CNVM has been treated with photocoagulation, cryopexy, and more recently, intravitreal anti-VEGF injections.4,5,9,10 Given that VEGF is more prevalent in the presence of a choroidal neovascular complex, the goal of anti-VEGF therapy is to prevent the growth of and further damage from these abnormal blood vessels.5

Conclusion

The authors have described 2 cases of asymptomatic PEHCR in elderly white males who are both currently being observed closely. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is an uncommon finding; therefore, knowledge of this condition also may be rare. Through this article and these cases, the importance of routine peripheral fundus examination to detect PEHCR should be stressed. It also is important to include PEHCR as a differential diagnosis when evaluating a peripheral dark elevated lesion to distinguish from peripheral melanomas and avoid unnecessary treatments. If identified, these lesions often require close observation only, and a retina referral is warranted if there is macular involvement or a rapidly progressive lesion.5

1. Pron G. Optical coherence tomography monitoring strategies for A-VEGF–treated age-related macular degeneration: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2014;14(10):1–64.

2. Annesley WH Jr. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1980;78:321-364.

3. Mantel I, Uffer S, Zografos L. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: a clinical angiographic, and histologic study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(6):932-938.

4. Pinarci EY, Kilic I, Bayar SA, Sizmaz S, Akkoyun I, Yilmaz G. Clinical characteristics of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy and its response to bevacizumab therapy. Eye (Lond). 2013;27(1):111-112.

5. Seibel I, Hager A, Duncker T, et al. Anti-VEGF therapy in symptomatic peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR) involving the macula. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;254(4):653-659.

6. Collaer N, James C. Peripheral exudative and hemorrhagic chorio-retinopathy…the peripheral form of age-related macular degeneration? Report on 2 cases. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol. 2007;(305):23-26.

7. Goldman DR, Freund KB, McCannel CA, Sarraf D. Peripheral polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy as a cause of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: A report of 10 eyes. Retina. 2013;33(1):48-55.

8. Mashayekhi A, Shields CL, Shields JA. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: a variant of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy? J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2013;8(3):264-267.

9. Takayama K, Enoki T, Kojima T, Ishikawa S, Takeuchi M. Treatment of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy by intravitreal injections of ranibizumab. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:865-869.

10. Barkmeier AJ, Kadikoy H, Holz ER, Carvounis PE. Regression of serous macular detachment due to peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy following intravitreal bevacizumab. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21(4):506-508.

1. Pron G. Optical coherence tomography monitoring strategies for A-VEGF–treated age-related macular degeneration: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2014;14(10):1–64.

2. Annesley WH Jr. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1980;78:321-364.

3. Mantel I, Uffer S, Zografos L. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: a clinical angiographic, and histologic study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(6):932-938.

4. Pinarci EY, Kilic I, Bayar SA, Sizmaz S, Akkoyun I, Yilmaz G. Clinical characteristics of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy and its response to bevacizumab therapy. Eye (Lond). 2013;27(1):111-112.

5. Seibel I, Hager A, Duncker T, et al. Anti-VEGF therapy in symptomatic peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR) involving the macula. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;254(4):653-659.

6. Collaer N, James C. Peripheral exudative and hemorrhagic chorio-retinopathy…the peripheral form of age-related macular degeneration? Report on 2 cases. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol. 2007;(305):23-26.

7. Goldman DR, Freund KB, McCannel CA, Sarraf D. Peripheral polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy as a cause of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: A report of 10 eyes. Retina. 2013;33(1):48-55.

8. Mashayekhi A, Shields CL, Shields JA. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: a variant of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy? J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2013;8(3):264-267.

9. Takayama K, Enoki T, Kojima T, Ishikawa S, Takeuchi M. Treatment of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy by intravitreal injections of ranibizumab. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:865-869.

10. Barkmeier AJ, Kadikoy H, Holz ER, Carvounis PE. Regression of serous macular detachment due to peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy following intravitreal bevacizumab. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21(4):506-508.

Acquired Epidermodysplasia Verruciformis Occurring in a Renal Transplant Recipient

Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EDV) is a rare disorder occurring in patients with depressed cellular immunity, particularly individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Rare cases of acquired EDV have been reported in stem cell or solid organ transplant recipients. Weakened cellular immunity predisposes the patient to human papillomavirus (HPV) infections, with 92% of renal transplant recipients developing warts within 5 years posttransplantation.1 Specific EDV-HPV subtypes have been isolated from lesions in several immunosuppressed individuals, with HPV-5 and HPV-8 being the most commonly isolated subtypes.2,3 Herein, we present the clinical findings of a renal transplant recipient who presented for evaluation of multiple skin lesions characteristic of EDV 5 years following transplantation and initiation of immunosuppressive therapy. Additionally, we review the current diagnostic findings, management, and treatment of acquired EDV.

A 44-year-old white woman presented for evaluation of several pruritic cutaneous lesions that had developed on the chest and neck of 1 month’s duration. The patient had been on the immunosuppressant medications cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil for more than 5 years following renal transplantation 7 years prior to the current presentation. She also was on low-dose prednisone for chronic systemic lupus erythematosus. Her family history was negative for any pertinent skin conditions.

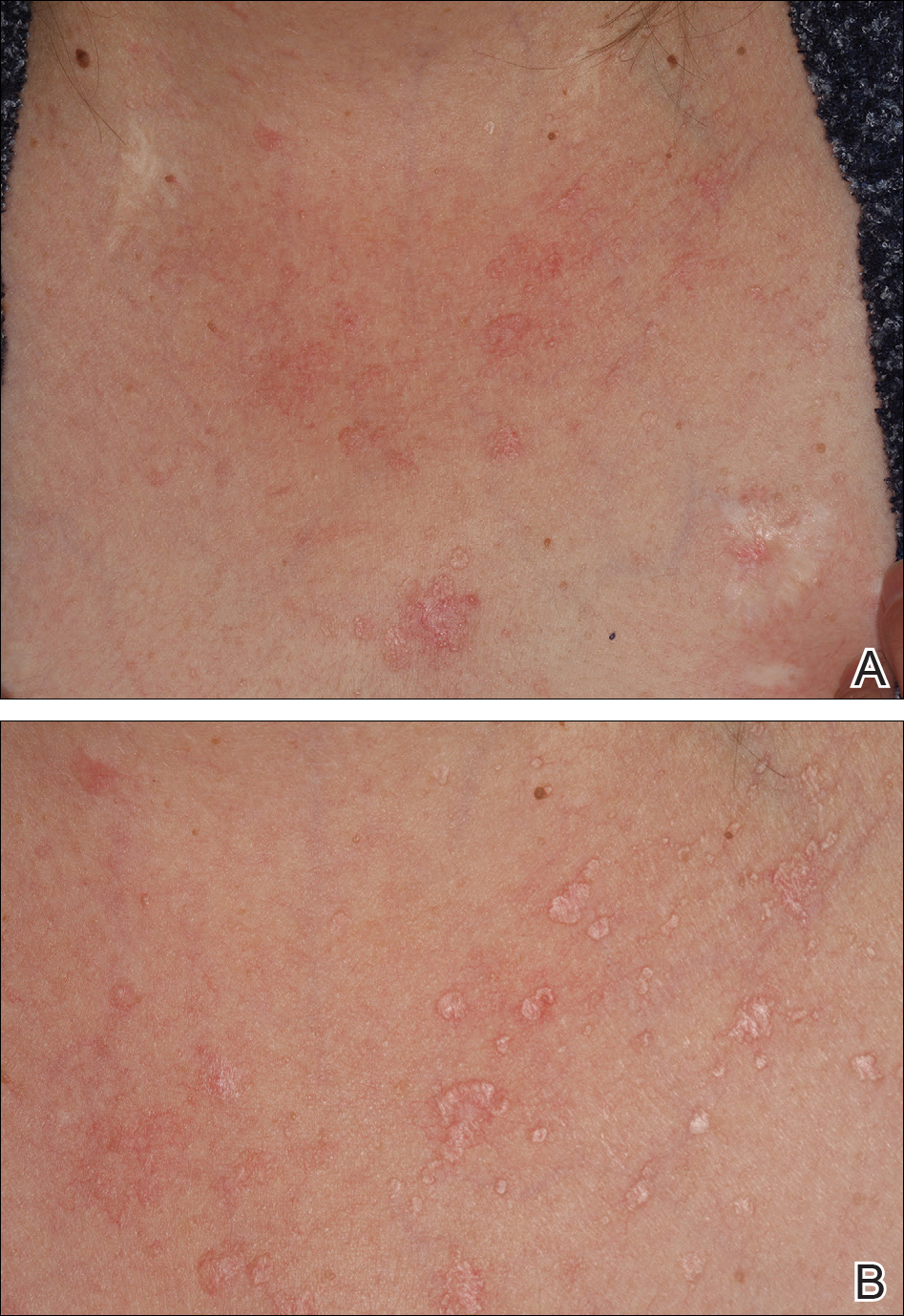

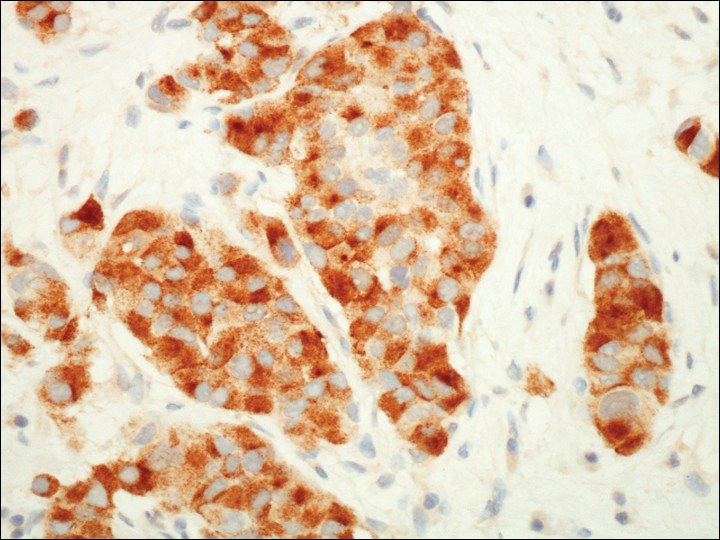

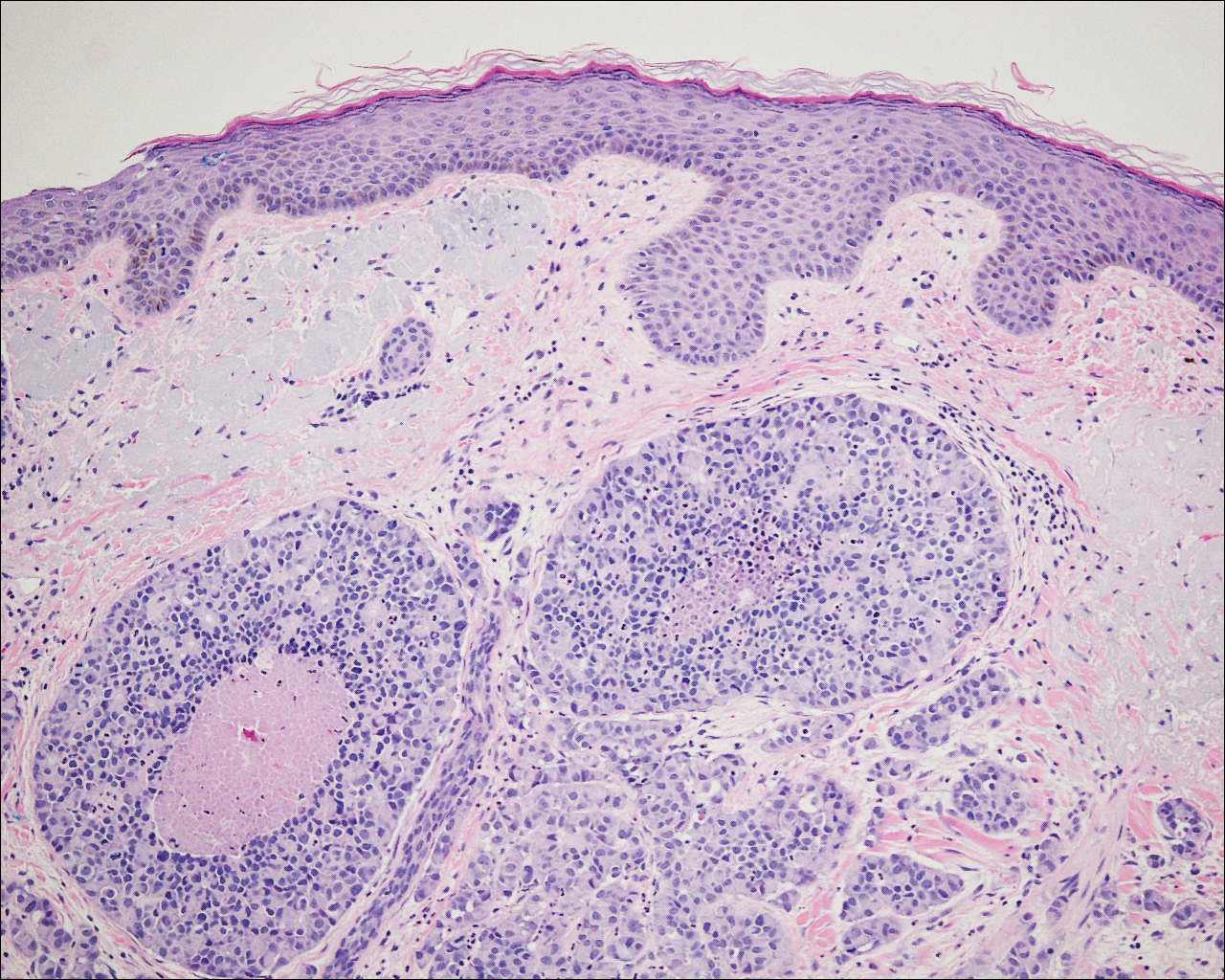

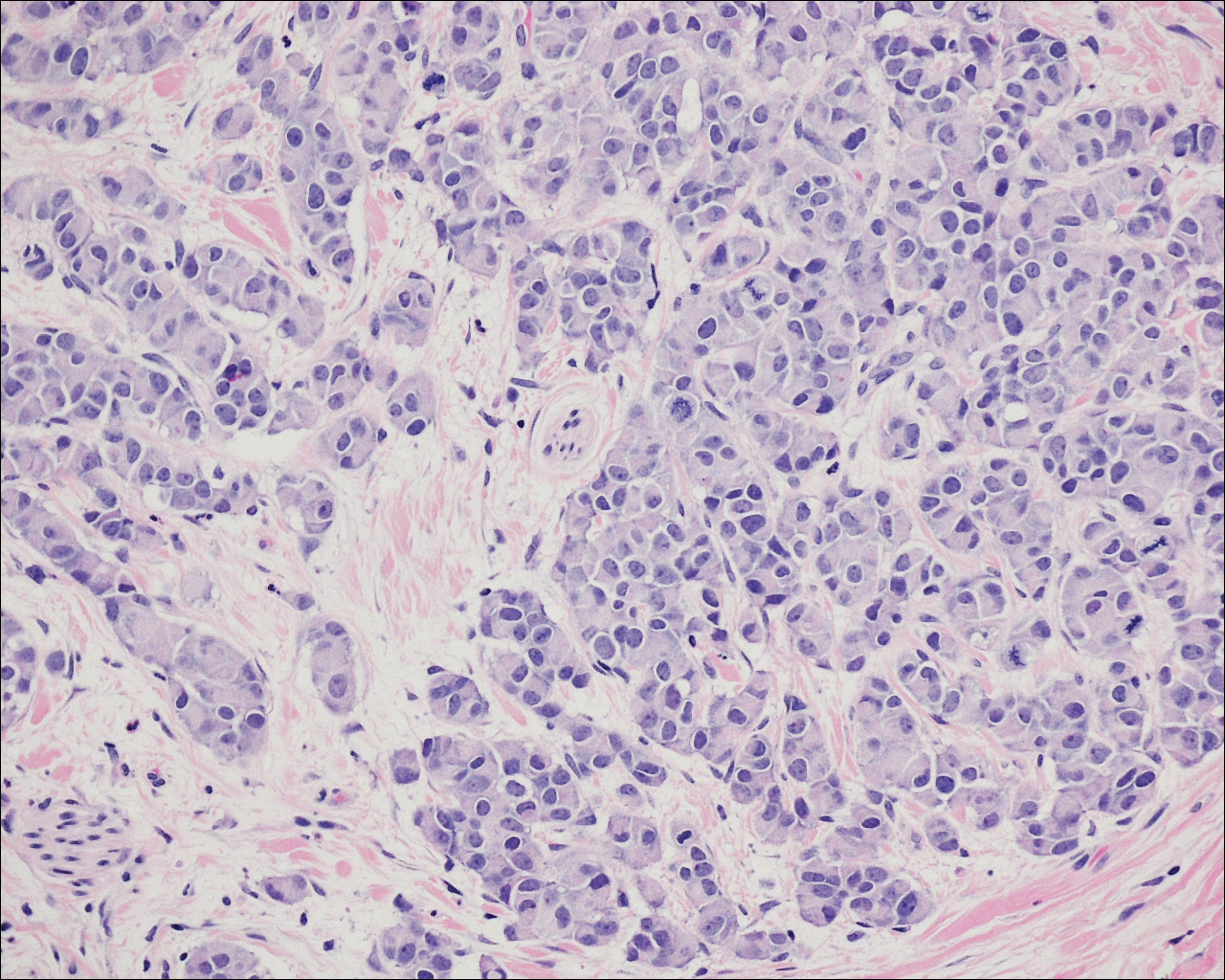

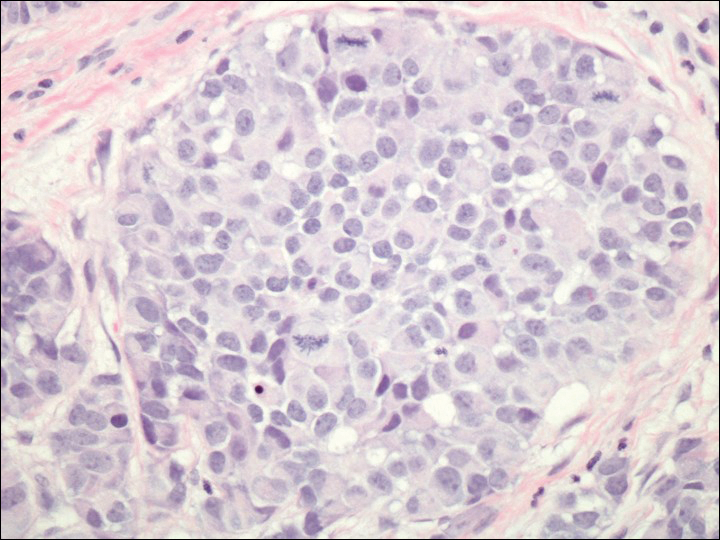

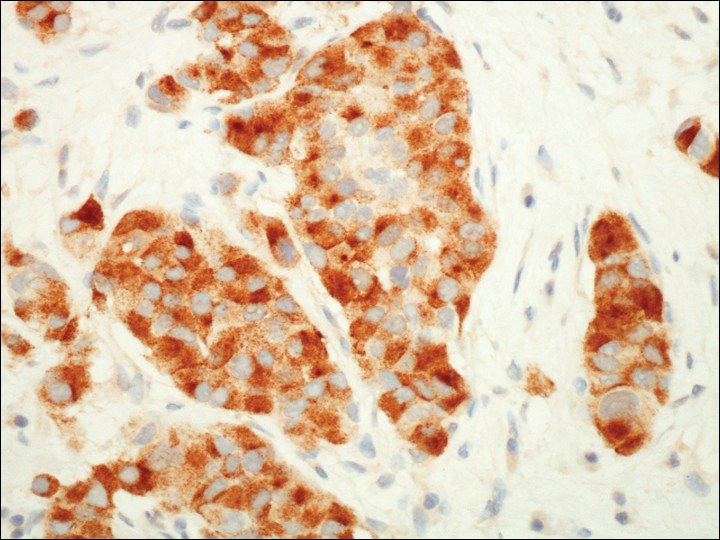

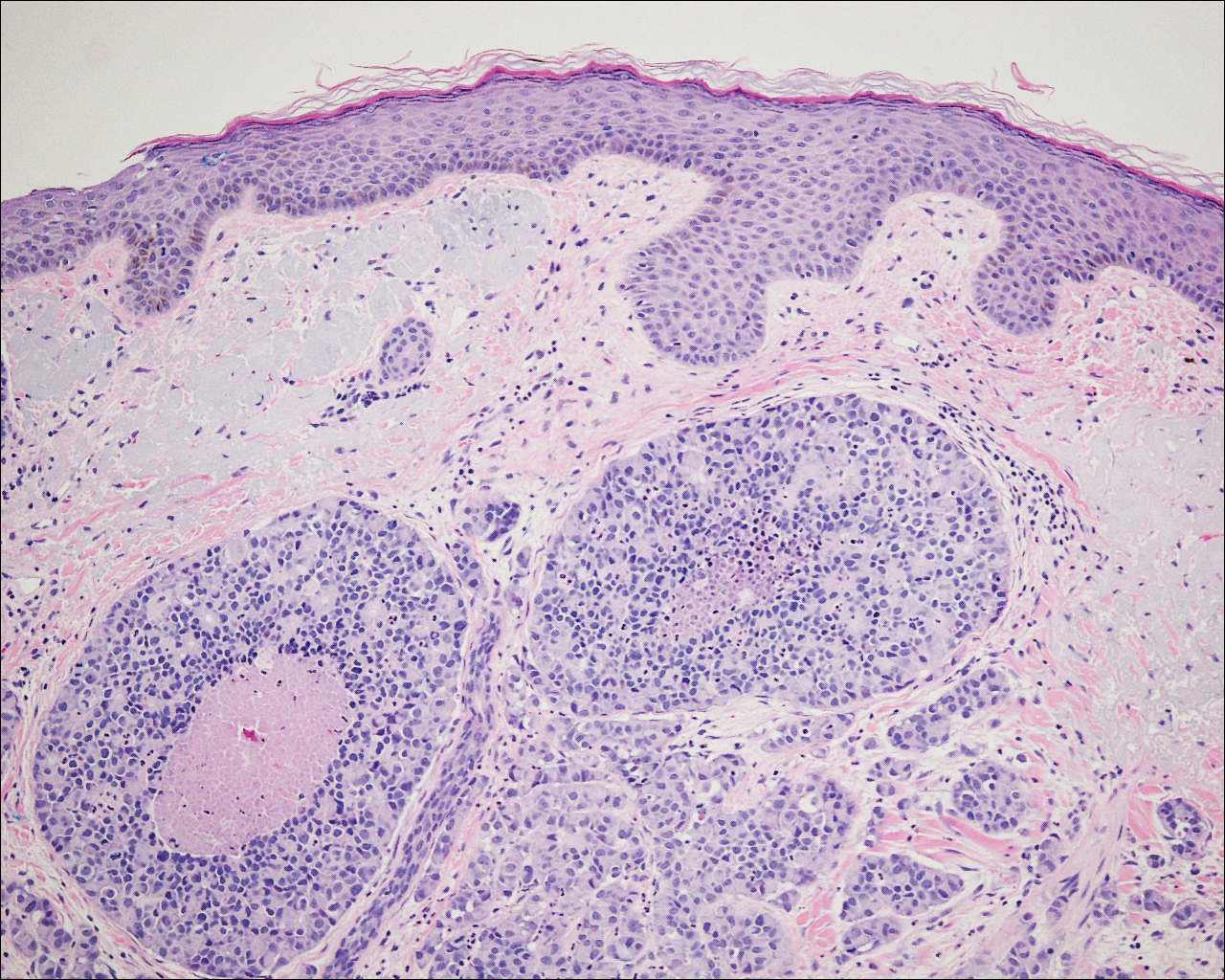

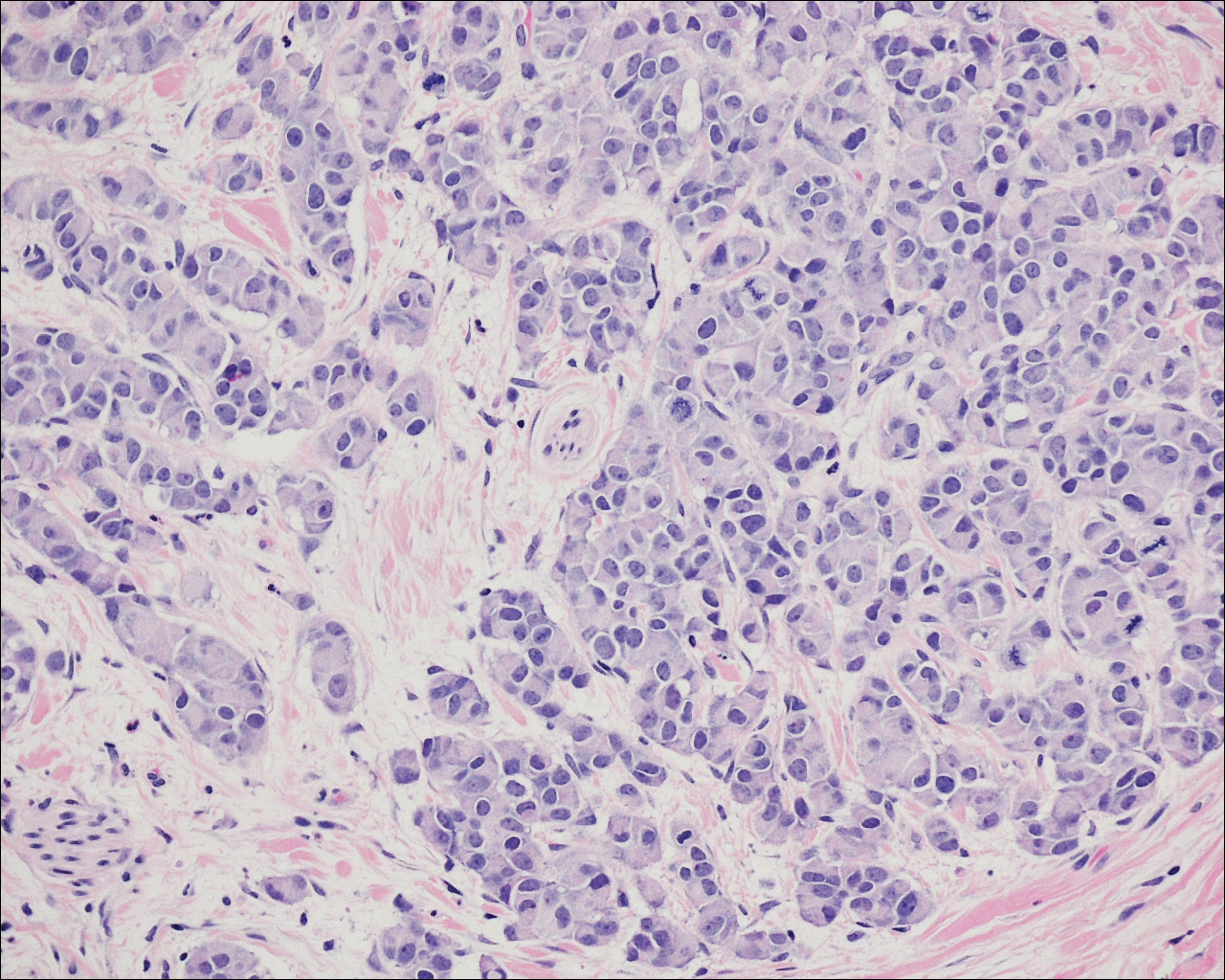

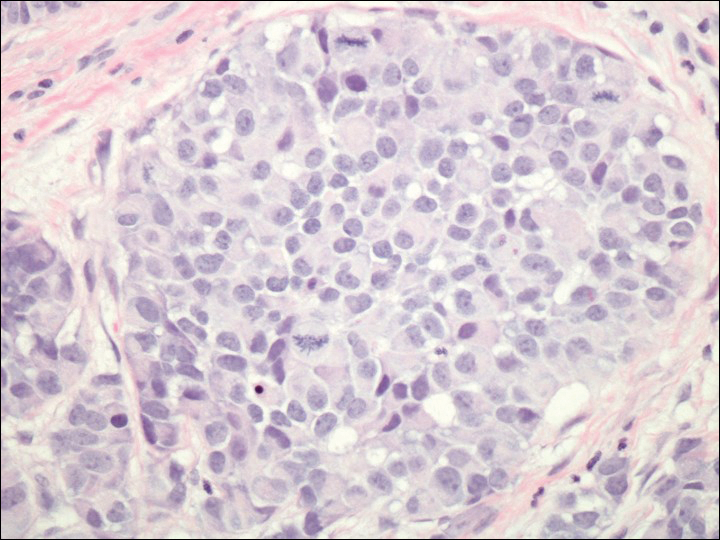

On physical examination the patient exhibited several grouped 0.5-cm, shiny, pink lichenoid macules located on the upper mid chest, anterior neck, and left leg clinically resembling the lesions of pityriasis versicolor (Figure 1). A shave biopsy was taken from one of the newest lesions on the left leg. Histopathology revealed viral epidermal cytopathic changes, blue cytoplasm, and coarse hypergranulosis characteristic of EDV (Figure 2). A diagnosis of acquired EDV was made based on the clinical and histopathologic findings.

The patient’s skin lesions became more widespread despite several different treatment regimens, including cryosurgery; tazarotene cream 0.05% nightly; imiquimod cream 5% once weekly; and intermittent short courses of 5-fluorouracil cream 5%, which provided the best response. At her most recent clinic visit 8 years after initial presentation, she continued to have more widespread lesions on the trunk, arms, and legs, but no evidence of malignant transformation.

Comment

Epidermodysplasia verruciformis was first recognized as an inherited condition, most commonly inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion; however, X-linked recessive cases have been reported.4,5 Patients with the inherited forms of this condition are prone to recurrent HPV infections secondary to a missense mutation in the epidermodysplasia verruciformis 1 and 2 genes, EVER1 and EVER2, on the EV1 locus located on chromosome 17q25.6 Because of this mutation, the patient’s cellular immunity becomes weakened. Cellular presentation of the EDV-HPV antigen to T lymphocytes becomes impaired, thereby inhibiting the body’s ability to successfully clear itself of the virus.5,6 The most commonly isolated EDV-HPV subtypes are HPV-5 and HPV-8, but HPV types 9, 12, 14, 15, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, and 50 also have been associated with EDV.1,3,7

Patients who have suppressed cellular immunity, such as transplant recipients on long-term immunosuppressant medications and individuals with HIV, graft-vs-host disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, and hematologic malignancies, are susceptible to EDV, as well as patients with atopic dermatitis being treated with topical calcineurin inhibitors.2,3,8-15 These patients acquire depressed cellular immunity and become increasingly susceptible to infections with the EDV-HPV subtypes. When clinical and histopathologic findings are consistent with EDV, a diagnosis of acquired EDV is given, which was further confirmed in a study conducted by Harwood et al.16 They found immunocompromised patients carry more EDV-HPV subtypes in skin lesions analyzed by polymerase chain reaction than immunocompetent individuals.16 Additionally, there is a positive correlation between the length of immunosuppression and the development of HPV lesions, with a majority of patients developing lesions within 5 years following initial immunosuppression.1,7,10,17

Epidermodysplasia verruciformis commonly presents with multiple hypopigmented to red macules that may coalesce into patches with a fine scale, clinically resembling the lesions of pityriasis versicolor.2,3,8-15 Epidermodysplasia verruciformis also may present as multiple flesh-colored, flat-topped, verrucous papules that clinically resemble the lesions of verruca plana on sun-exposed areas such as the face, arms, and legs.9 The characteristic histopathologic findings are enlarged keratinocytes with perinuclear halos and blue-gray cytoplasm as well as hypergranulosis.18 Immunocompromised hosts infected with EDV-HPV histologically tend to display more severe dysplasia than immunocompetent individuals.19 The differential diagnosis includes pityriasis versicolor, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and verruca plana. Tissue cultures and potassium hydroxide scrapings for microorganisms should be negative.

The specific EDV-HPV strains 5, 8, and 41 carry the highest oncogenic potential, with more than 60% of inherited EDV patients developing SCC by the fourth and fifth decades of life.16 Unlike inherited EDV, the clinical course of acquired EDV is less well known; however, UV light is thought to act synergistically with the EDV-HPV in oncogenic transformation of the lesions, as most of the SCCs develop on sun-exposed areas, and darker-skinned patients seem to have a decreased risk for malignant transformation of EDV lesions.4,9,20,21 Preventative measures such as strict sun protection and annual surveillance of lesions can help to prevent oncogenic progression of the lesions; however, several single- and multiple-agent regimens have been used in the treatment of EDV with variable results. Topical imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, tretinoin, and tazarotene have been used with variable success. Acitretin alone and in combination with interferon alfa-2a also has been used.22,23 Highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV has effectively decreased the number of lesions in a subset of patients.24 We (anecdotal) and others25 also have had success using photodynamic therapy. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in patients with EDV can be managed by excision or by Mohs micrographic surgery.

Conclusion

We report a rare case of acquired EDV in a solid organ transplant recipient. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis can be acquired in immunosuppressed patients such as ours, and these patients should be followed closely due to the potential for malignant transformation. More studies regarding the anticipated clinical course of skin lesions in patients with acquired EDV are needed to better predict the time frame for malignant transformation.

- Dyall-Smith D, Trowell H, Dyall-Smith ML. Benign human papillomavirus infection in renal transplant recipients. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:785-789.

- Lutzner MA, Orth G, Dutronquay V, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus type 5 DNA in skin cancers of an immunosuppressed renal allograft recipient. Lancet. 1983;2:422-424.

- Lutzner M, Croissant O, Ducasse MF, et al. A potentially oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV-5) found in two renal allograft recipients. J Invest Dermatol. 1980;75:353-356.

- Androphy EJ, Dvoretzky I, Lowy DR. X-linked inheritance of epidermodysplasia verruciformis. genetic and virologic studies of a kindred. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:864-868.

- Lutzner MA. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis. an autosomal recessive disease characterized by viral warts and skin cancer. a model for viral oncogenesis. Bull Cancer. 1978;65:169-182.

- Ramoz N, Rueda LA, Bouadjar B, et al. Mutations in two adjacent novel genes are associated with epidermodysplasia verruciformis. Nat Genet. 2002;32:579-581.

- Rüdlinger R, Smith IW, Bunney MH, et al. Human papillomavirus infections in a group of renal transplant recipients. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:681-692.

- Kawai K, Egawa N, Kiyono T, et al. Epidermodysplasia-verruciformis-like eruption associated with gamma-papillomavirus infection in a patient with adult T-cell leukemia. Dermatology. 2009;219:274-278.

- Barr BB, Benton EC, McLaren K, et al. Human papilloma virus infection and skin cancer in renal allograft recipients. Lancet. 1989;1:124-129.

- Tanigaki T, Kanda R, Sato K. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis (L-L, 1922) in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol Res. 1986;278:247-248.

- Holmes C, Chong AH, Tabrizi SN, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis-like syndrome in association with systemic lupus erythematosus. Australas J Dermatol. 2009;50:44-47.

- Gross G, Ellinger K, Roussaki A, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis in a patient with Hodgkin’s disease: characterization of a new papillomavirus type and interferon treatment. J Invest Dermatol. 1988;91:43-48.

- Fernandez KH, Rady P, Tyring S, et al. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis in a child with atopic dermatitis [published online September 3, 2012]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:400-402.

- Hultgren TL, Srinivasan SK, DiMaio DJ. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis occurring in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus: a case report. Cutis. 2007;79:307-311.

- Kunishige JH, Hymes SR, Madkan V, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis in the setting of graft-versus-host disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(5 suppl):S78-S80.

- Harwood CA, Surentheran T, McGregor JM, et al. Human papillomavirus infection and non-melanoma skin cancer in immunosuppressed and immunocompetent individuals. J Med Virol. 2000;61:289-297.

- Moloney FJ, Keane S, O’Kelly P, et al. The impact of skin disease following renal transplantation on quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:574-578.

- Tanigaki T, Endo H. A case of epidermodysplasia verruciformis (Lewandowsky-Lutz, 1922) with skin cancer: histopathology of malignant cutaneous changes. Dermatologica. 1984;169:97-101.

- Morrison C, Eliezri Y, Magro C, et al. The histologic spectrum of epidermodysplasia verruciformis in transplant and AIDS patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:480-489.

- Majewski S, Jabło´nska S. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis as a model of human papillomavirus-induced genetic cancer of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1312-1318.

- Jacyk WK, De Villiers EM. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis in Africans. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:806-810.

- Gubinelli E, Posteraro P, Cocuroccia B, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis with multiple mucosal carcinomas treated with pegylated interferon alfa and acitretin. J Dermatolog Treat. 2003;14:184-188.

- Anadolu R, Oskay T, Erdem C, et al. Treatment of epidermodysplasia verruciformis with a combination of acitretin and interferon alfa-2a. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:296-299.

- Haas N, Fuchs PG, Hermes B, et al. Remission of epidermodysplasia verruciformis-like skin eruption after highly active antiretroviral therapy in a human immunodeficiency virus-positive patient. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:669-670.

- Karrer S, Szeimies RM, Abels C, et al. Epidermo-dysplasia verruciformis treated using topical 5-aminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:935-938.

Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EDV) is a rare disorder occurring in patients with depressed cellular immunity, particularly individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Rare cases of acquired EDV have been reported in stem cell or solid organ transplant recipients. Weakened cellular immunity predisposes the patient to human papillomavirus (HPV) infections, with 92% of renal transplant recipients developing warts within 5 years posttransplantation.1 Specific EDV-HPV subtypes have been isolated from lesions in several immunosuppressed individuals, with HPV-5 and HPV-8 being the most commonly isolated subtypes.2,3 Herein, we present the clinical findings of a renal transplant recipient who presented for evaluation of multiple skin lesions characteristic of EDV 5 years following transplantation and initiation of immunosuppressive therapy. Additionally, we review the current diagnostic findings, management, and treatment of acquired EDV.

A 44-year-old white woman presented for evaluation of several pruritic cutaneous lesions that had developed on the chest and neck of 1 month’s duration. The patient had been on the immunosuppressant medications cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil for more than 5 years following renal transplantation 7 years prior to the current presentation. She also was on low-dose prednisone for chronic systemic lupus erythematosus. Her family history was negative for any pertinent skin conditions.

On physical examination the patient exhibited several grouped 0.5-cm, shiny, pink lichenoid macules located on the upper mid chest, anterior neck, and left leg clinically resembling the lesions of pityriasis versicolor (Figure 1). A shave biopsy was taken from one of the newest lesions on the left leg. Histopathology revealed viral epidermal cytopathic changes, blue cytoplasm, and coarse hypergranulosis characteristic of EDV (Figure 2). A diagnosis of acquired EDV was made based on the clinical and histopathologic findings.

The patient’s skin lesions became more widespread despite several different treatment regimens, including cryosurgery; tazarotene cream 0.05% nightly; imiquimod cream 5% once weekly; and intermittent short courses of 5-fluorouracil cream 5%, which provided the best response. At her most recent clinic visit 8 years after initial presentation, she continued to have more widespread lesions on the trunk, arms, and legs, but no evidence of malignant transformation.

Comment

Epidermodysplasia verruciformis was first recognized as an inherited condition, most commonly inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion; however, X-linked recessive cases have been reported.4,5 Patients with the inherited forms of this condition are prone to recurrent HPV infections secondary to a missense mutation in the epidermodysplasia verruciformis 1 and 2 genes, EVER1 and EVER2, on the EV1 locus located on chromosome 17q25.6 Because of this mutation, the patient’s cellular immunity becomes weakened. Cellular presentation of the EDV-HPV antigen to T lymphocytes becomes impaired, thereby inhibiting the body’s ability to successfully clear itself of the virus.5,6 The most commonly isolated EDV-HPV subtypes are HPV-5 and HPV-8, but HPV types 9, 12, 14, 15, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, and 50 also have been associated with EDV.1,3,7

Patients who have suppressed cellular immunity, such as transplant recipients on long-term immunosuppressant medications and individuals with HIV, graft-vs-host disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, and hematologic malignancies, are susceptible to EDV, as well as patients with atopic dermatitis being treated with topical calcineurin inhibitors.2,3,8-15 These patients acquire depressed cellular immunity and become increasingly susceptible to infections with the EDV-HPV subtypes. When clinical and histopathologic findings are consistent with EDV, a diagnosis of acquired EDV is given, which was further confirmed in a study conducted by Harwood et al.16 They found immunocompromised patients carry more EDV-HPV subtypes in skin lesions analyzed by polymerase chain reaction than immunocompetent individuals.16 Additionally, there is a positive correlation between the length of immunosuppression and the development of HPV lesions, with a majority of patients developing lesions within 5 years following initial immunosuppression.1,7,10,17

Epidermodysplasia verruciformis commonly presents with multiple hypopigmented to red macules that may coalesce into patches with a fine scale, clinically resembling the lesions of pityriasis versicolor.2,3,8-15 Epidermodysplasia verruciformis also may present as multiple flesh-colored, flat-topped, verrucous papules that clinically resemble the lesions of verruca plana on sun-exposed areas such as the face, arms, and legs.9 The characteristic histopathologic findings are enlarged keratinocytes with perinuclear halos and blue-gray cytoplasm as well as hypergranulosis.18 Immunocompromised hosts infected with EDV-HPV histologically tend to display more severe dysplasia than immunocompetent individuals.19 The differential diagnosis includes pityriasis versicolor, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and verruca plana. Tissue cultures and potassium hydroxide scrapings for microorganisms should be negative.

The specific EDV-HPV strains 5, 8, and 41 carry the highest oncogenic potential, with more than 60% of inherited EDV patients developing SCC by the fourth and fifth decades of life.16 Unlike inherited EDV, the clinical course of acquired EDV is less well known; however, UV light is thought to act synergistically with the EDV-HPV in oncogenic transformation of the lesions, as most of the SCCs develop on sun-exposed areas, and darker-skinned patients seem to have a decreased risk for malignant transformation of EDV lesions.4,9,20,21 Preventative measures such as strict sun protection and annual surveillance of lesions can help to prevent oncogenic progression of the lesions; however, several single- and multiple-agent regimens have been used in the treatment of EDV with variable results. Topical imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, tretinoin, and tazarotene have been used with variable success. Acitretin alone and in combination with interferon alfa-2a also has been used.22,23 Highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV has effectively decreased the number of lesions in a subset of patients.24 We (anecdotal) and others25 also have had success using photodynamic therapy. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in patients with EDV can be managed by excision or by Mohs micrographic surgery.

Conclusion

We report a rare case of acquired EDV in a solid organ transplant recipient. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis can be acquired in immunosuppressed patients such as ours, and these patients should be followed closely due to the potential for malignant transformation. More studies regarding the anticipated clinical course of skin lesions in patients with acquired EDV are needed to better predict the time frame for malignant transformation.

Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EDV) is a rare disorder occurring in patients with depressed cellular immunity, particularly individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Rare cases of acquired EDV have been reported in stem cell or solid organ transplant recipients. Weakened cellular immunity predisposes the patient to human papillomavirus (HPV) infections, with 92% of renal transplant recipients developing warts within 5 years posttransplantation.1 Specific EDV-HPV subtypes have been isolated from lesions in several immunosuppressed individuals, with HPV-5 and HPV-8 being the most commonly isolated subtypes.2,3 Herein, we present the clinical findings of a renal transplant recipient who presented for evaluation of multiple skin lesions characteristic of EDV 5 years following transplantation and initiation of immunosuppressive therapy. Additionally, we review the current diagnostic findings, management, and treatment of acquired EDV.

A 44-year-old white woman presented for evaluation of several pruritic cutaneous lesions that had developed on the chest and neck of 1 month’s duration. The patient had been on the immunosuppressant medications cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil for more than 5 years following renal transplantation 7 years prior to the current presentation. She also was on low-dose prednisone for chronic systemic lupus erythematosus. Her family history was negative for any pertinent skin conditions.

On physical examination the patient exhibited several grouped 0.5-cm, shiny, pink lichenoid macules located on the upper mid chest, anterior neck, and left leg clinically resembling the lesions of pityriasis versicolor (Figure 1). A shave biopsy was taken from one of the newest lesions on the left leg. Histopathology revealed viral epidermal cytopathic changes, blue cytoplasm, and coarse hypergranulosis characteristic of EDV (Figure 2). A diagnosis of acquired EDV was made based on the clinical and histopathologic findings.

The patient’s skin lesions became more widespread despite several different treatment regimens, including cryosurgery; tazarotene cream 0.05% nightly; imiquimod cream 5% once weekly; and intermittent short courses of 5-fluorouracil cream 5%, which provided the best response. At her most recent clinic visit 8 years after initial presentation, she continued to have more widespread lesions on the trunk, arms, and legs, but no evidence of malignant transformation.

Comment

Epidermodysplasia verruciformis was first recognized as an inherited condition, most commonly inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion; however, X-linked recessive cases have been reported.4,5 Patients with the inherited forms of this condition are prone to recurrent HPV infections secondary to a missense mutation in the epidermodysplasia verruciformis 1 and 2 genes, EVER1 and EVER2, on the EV1 locus located on chromosome 17q25.6 Because of this mutation, the patient’s cellular immunity becomes weakened. Cellular presentation of the EDV-HPV antigen to T lymphocytes becomes impaired, thereby inhibiting the body’s ability to successfully clear itself of the virus.5,6 The most commonly isolated EDV-HPV subtypes are HPV-5 and HPV-8, but HPV types 9, 12, 14, 15, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, and 50 also have been associated with EDV.1,3,7

Patients who have suppressed cellular immunity, such as transplant recipients on long-term immunosuppressant medications and individuals with HIV, graft-vs-host disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, and hematologic malignancies, are susceptible to EDV, as well as patients with atopic dermatitis being treated with topical calcineurin inhibitors.2,3,8-15 These patients acquire depressed cellular immunity and become increasingly susceptible to infections with the EDV-HPV subtypes. When clinical and histopathologic findings are consistent with EDV, a diagnosis of acquired EDV is given, which was further confirmed in a study conducted by Harwood et al.16 They found immunocompromised patients carry more EDV-HPV subtypes in skin lesions analyzed by polymerase chain reaction than immunocompetent individuals.16 Additionally, there is a positive correlation between the length of immunosuppression and the development of HPV lesions, with a majority of patients developing lesions within 5 years following initial immunosuppression.1,7,10,17

Epidermodysplasia verruciformis commonly presents with multiple hypopigmented to red macules that may coalesce into patches with a fine scale, clinically resembling the lesions of pityriasis versicolor.2,3,8-15 Epidermodysplasia verruciformis also may present as multiple flesh-colored, flat-topped, verrucous papules that clinically resemble the lesions of verruca plana on sun-exposed areas such as the face, arms, and legs.9 The characteristic histopathologic findings are enlarged keratinocytes with perinuclear halos and blue-gray cytoplasm as well as hypergranulosis.18 Immunocompromised hosts infected with EDV-HPV histologically tend to display more severe dysplasia than immunocompetent individuals.19 The differential diagnosis includes pityriasis versicolor, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and verruca plana. Tissue cultures and potassium hydroxide scrapings for microorganisms should be negative.

The specific EDV-HPV strains 5, 8, and 41 carry the highest oncogenic potential, with more than 60% of inherited EDV patients developing SCC by the fourth and fifth decades of life.16 Unlike inherited EDV, the clinical course of acquired EDV is less well known; however, UV light is thought to act synergistically with the EDV-HPV in oncogenic transformation of the lesions, as most of the SCCs develop on sun-exposed areas, and darker-skinned patients seem to have a decreased risk for malignant transformation of EDV lesions.4,9,20,21 Preventative measures such as strict sun protection and annual surveillance of lesions can help to prevent oncogenic progression of the lesions; however, several single- and multiple-agent regimens have been used in the treatment of EDV with variable results. Topical imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, tretinoin, and tazarotene have been used with variable success. Acitretin alone and in combination with interferon alfa-2a also has been used.22,23 Highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV has effectively decreased the number of lesions in a subset of patients.24 We (anecdotal) and others25 also have had success using photodynamic therapy. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in patients with EDV can be managed by excision or by Mohs micrographic surgery.

Conclusion

We report a rare case of acquired EDV in a solid organ transplant recipient. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis can be acquired in immunosuppressed patients such as ours, and these patients should be followed closely due to the potential for malignant transformation. More studies regarding the anticipated clinical course of skin lesions in patients with acquired EDV are needed to better predict the time frame for malignant transformation.

- Dyall-Smith D, Trowell H, Dyall-Smith ML. Benign human papillomavirus infection in renal transplant recipients. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:785-789.

- Lutzner MA, Orth G, Dutronquay V, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus type 5 DNA in skin cancers of an immunosuppressed renal allograft recipient. Lancet. 1983;2:422-424.

- Lutzner M, Croissant O, Ducasse MF, et al. A potentially oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV-5) found in two renal allograft recipients. J Invest Dermatol. 1980;75:353-356.

- Androphy EJ, Dvoretzky I, Lowy DR. X-linked inheritance of epidermodysplasia verruciformis. genetic and virologic studies of a kindred. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:864-868.

- Lutzner MA. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis. an autosomal recessive disease characterized by viral warts and skin cancer. a model for viral oncogenesis. Bull Cancer. 1978;65:169-182.

- Ramoz N, Rueda LA, Bouadjar B, et al. Mutations in two adjacent novel genes are associated with epidermodysplasia verruciformis. Nat Genet. 2002;32:579-581.

- Rüdlinger R, Smith IW, Bunney MH, et al. Human papillomavirus infections in a group of renal transplant recipients. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:681-692.

- Kawai K, Egawa N, Kiyono T, et al. Epidermodysplasia-verruciformis-like eruption associated with gamma-papillomavirus infection in a patient with adult T-cell leukemia. Dermatology. 2009;219:274-278.

- Barr BB, Benton EC, McLaren K, et al. Human papilloma virus infection and skin cancer in renal allograft recipients. Lancet. 1989;1:124-129.

- Tanigaki T, Kanda R, Sato K. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis (L-L, 1922) in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol Res. 1986;278:247-248.

- Holmes C, Chong AH, Tabrizi SN, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis-like syndrome in association with systemic lupus erythematosus. Australas J Dermatol. 2009;50:44-47.

- Gross G, Ellinger K, Roussaki A, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis in a patient with Hodgkin’s disease: characterization of a new papillomavirus type and interferon treatment. J Invest Dermatol. 1988;91:43-48.

- Fernandez KH, Rady P, Tyring S, et al. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis in a child with atopic dermatitis [published online September 3, 2012]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:400-402.

- Hultgren TL, Srinivasan SK, DiMaio DJ. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis occurring in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus: a case report. Cutis. 2007;79:307-311.

- Kunishige JH, Hymes SR, Madkan V, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis in the setting of graft-versus-host disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(5 suppl):S78-S80.

- Harwood CA, Surentheran T, McGregor JM, et al. Human papillomavirus infection and non-melanoma skin cancer in immunosuppressed and immunocompetent individuals. J Med Virol. 2000;61:289-297.

- Moloney FJ, Keane S, O’Kelly P, et al. The impact of skin disease following renal transplantation on quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:574-578.

- Tanigaki T, Endo H. A case of epidermodysplasia verruciformis (Lewandowsky-Lutz, 1922) with skin cancer: histopathology of malignant cutaneous changes. Dermatologica. 1984;169:97-101.

- Morrison C, Eliezri Y, Magro C, et al. The histologic spectrum of epidermodysplasia verruciformis in transplant and AIDS patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:480-489.

- Majewski S, Jabło´nska S. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis as a model of human papillomavirus-induced genetic cancer of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1312-1318.

- Jacyk WK, De Villiers EM. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis in Africans. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:806-810.

- Gubinelli E, Posteraro P, Cocuroccia B, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis with multiple mucosal carcinomas treated with pegylated interferon alfa and acitretin. J Dermatolog Treat. 2003;14:184-188.

- Anadolu R, Oskay T, Erdem C, et al. Treatment of epidermodysplasia verruciformis with a combination of acitretin and interferon alfa-2a. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:296-299.

- Haas N, Fuchs PG, Hermes B, et al. Remission of epidermodysplasia verruciformis-like skin eruption after highly active antiretroviral therapy in a human immunodeficiency virus-positive patient. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:669-670.

- Karrer S, Szeimies RM, Abels C, et al. Epidermo-dysplasia verruciformis treated using topical 5-aminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:935-938.