User login

Advise lifestyle change to obese but metabolically healthy women

AMSTERDAM – Obese women with no metabolic disorders had the same cardiovascular disease risk as their normal-weight counterparts, according to a 5-year follow-up of more than 260,000 Danish women in their early 30s.

Meanwhile, during the same follow-up period, women with metabolic disorders had a fourfold increase in cardiovascular disease risk, regardless of their body mass index, according to Dr. Michelle D. Schmiegelow, who presented her findings at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The absolute risks were still low in this young population, but given the findings, Dr. Schmiegelow said that physicians should have an "increased awareness of these young metabolically healthy overweight and obese women, because there might be a window of opportunity in which they could change their lifestyle and thereby reduce their risk of metabolic disorders and possibly reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease substantially."

The study was one of several presented at the meeting addressing the ongoing discussions about the obesity paradox.

"If you want to rely on the question on what is my future CVD risk, it’s not as easy to just measure your body weight,’ said Dr. Diethelm Tschöpe of Ruhr University, Bochum, Germany, in a video interview. "It’s a complex situation, which consists of body weight, risk factors, comorbidities, and the genetic background, which at the moment is hard to measure."

Dr. Schmiegelow of Gentofte Hospital, Hellerup, Denmark, and her colleagues examined the risk of myocardial infarctions, ischemic stroke, and all-cause mortality in more than 260,000 women who had given birth between 2004 and 2010, at a mean age of 31 years old. These women were identified in a nationwide registry of birth records. The median follow-up was 5.5 years after childbirth.

The women were considered metabolically unhealthy is they had a hypertensive disorder such as gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, or hypertension; an abnormal glucose metabolism such as diabetes or gestational diabetes; or dyslipidemia.

They were separated to four groups based on metabolic health status and prepregnancy body mass index (BMI): Metabolically healthy with a BMI less than 25 kg/m2; metabolically health with a BMI greater than or equal to 25; metabolically unhealthy with a BMI less than 25; and metabolically unhealthy with a BMI of greater than or equal to 25.

Data were adjusted for age and calendar year. The combined primary endpoints were the risks of MI, ischemic stroke, and all-cause mortality, using the metabolically healthy women with a BMI of less than 25 as reference.

The incidence rate (IR) of the combined endpoints for the normal weight, metabolically healthy women was 0.41 (number of events equaled 375); obese but metabolically healthy women had an IR of .45 (n = 51), and rate ratio (RR) of 1.16; normal weight but metabolically unhealthy women had an IR of .91 (n = 175), RR of 2.11; and obese and metabolically unhealthy women had an IR of 1.25 (n = 86), with an RR of 2.81.

"When you have an obese individual in front of you, that should be the first step, figuring out what their risk profile is," said Dr. Schmiegelow. "If they have metabolic disorders, that means they’re at an increased risk. If they do not have metabolic disorders, that means they’re at an increased risk of developing that, and you should really try and motivate them to change their lifestyle."

Dr. Schmiegelow and Dr. Tschöpe had no disclosures.

On Twitter @NaseemSMiller

AMSTERDAM – Obese women with no metabolic disorders had the same cardiovascular disease risk as their normal-weight counterparts, according to a 5-year follow-up of more than 260,000 Danish women in their early 30s.

Meanwhile, during the same follow-up period, women with metabolic disorders had a fourfold increase in cardiovascular disease risk, regardless of their body mass index, according to Dr. Michelle D. Schmiegelow, who presented her findings at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The absolute risks were still low in this young population, but given the findings, Dr. Schmiegelow said that physicians should have an "increased awareness of these young metabolically healthy overweight and obese women, because there might be a window of opportunity in which they could change their lifestyle and thereby reduce their risk of metabolic disorders and possibly reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease substantially."

The study was one of several presented at the meeting addressing the ongoing discussions about the obesity paradox.

"If you want to rely on the question on what is my future CVD risk, it’s not as easy to just measure your body weight,’ said Dr. Diethelm Tschöpe of Ruhr University, Bochum, Germany, in a video interview. "It’s a complex situation, which consists of body weight, risk factors, comorbidities, and the genetic background, which at the moment is hard to measure."

Dr. Schmiegelow of Gentofte Hospital, Hellerup, Denmark, and her colleagues examined the risk of myocardial infarctions, ischemic stroke, and all-cause mortality in more than 260,000 women who had given birth between 2004 and 2010, at a mean age of 31 years old. These women were identified in a nationwide registry of birth records. The median follow-up was 5.5 years after childbirth.

The women were considered metabolically unhealthy is they had a hypertensive disorder such as gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, or hypertension; an abnormal glucose metabolism such as diabetes or gestational diabetes; or dyslipidemia.

They were separated to four groups based on metabolic health status and prepregnancy body mass index (BMI): Metabolically healthy with a BMI less than 25 kg/m2; metabolically health with a BMI greater than or equal to 25; metabolically unhealthy with a BMI less than 25; and metabolically unhealthy with a BMI of greater than or equal to 25.

Data were adjusted for age and calendar year. The combined primary endpoints were the risks of MI, ischemic stroke, and all-cause mortality, using the metabolically healthy women with a BMI of less than 25 as reference.

The incidence rate (IR) of the combined endpoints for the normal weight, metabolically healthy women was 0.41 (number of events equaled 375); obese but metabolically healthy women had an IR of .45 (n = 51), and rate ratio (RR) of 1.16; normal weight but metabolically unhealthy women had an IR of .91 (n = 175), RR of 2.11; and obese and metabolically unhealthy women had an IR of 1.25 (n = 86), with an RR of 2.81.

"When you have an obese individual in front of you, that should be the first step, figuring out what their risk profile is," said Dr. Schmiegelow. "If they have metabolic disorders, that means they’re at an increased risk. If they do not have metabolic disorders, that means they’re at an increased risk of developing that, and you should really try and motivate them to change their lifestyle."

Dr. Schmiegelow and Dr. Tschöpe had no disclosures.

On Twitter @NaseemSMiller

AMSTERDAM – Obese women with no metabolic disorders had the same cardiovascular disease risk as their normal-weight counterparts, according to a 5-year follow-up of more than 260,000 Danish women in their early 30s.

Meanwhile, during the same follow-up period, women with metabolic disorders had a fourfold increase in cardiovascular disease risk, regardless of their body mass index, according to Dr. Michelle D. Schmiegelow, who presented her findings at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The absolute risks were still low in this young population, but given the findings, Dr. Schmiegelow said that physicians should have an "increased awareness of these young metabolically healthy overweight and obese women, because there might be a window of opportunity in which they could change their lifestyle and thereby reduce their risk of metabolic disorders and possibly reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease substantially."

The study was one of several presented at the meeting addressing the ongoing discussions about the obesity paradox.

"If you want to rely on the question on what is my future CVD risk, it’s not as easy to just measure your body weight,’ said Dr. Diethelm Tschöpe of Ruhr University, Bochum, Germany, in a video interview. "It’s a complex situation, which consists of body weight, risk factors, comorbidities, and the genetic background, which at the moment is hard to measure."

Dr. Schmiegelow of Gentofte Hospital, Hellerup, Denmark, and her colleagues examined the risk of myocardial infarctions, ischemic stroke, and all-cause mortality in more than 260,000 women who had given birth between 2004 and 2010, at a mean age of 31 years old. These women were identified in a nationwide registry of birth records. The median follow-up was 5.5 years after childbirth.

The women were considered metabolically unhealthy is they had a hypertensive disorder such as gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, or hypertension; an abnormal glucose metabolism such as diabetes or gestational diabetes; or dyslipidemia.

They were separated to four groups based on metabolic health status and prepregnancy body mass index (BMI): Metabolically healthy with a BMI less than 25 kg/m2; metabolically health with a BMI greater than or equal to 25; metabolically unhealthy with a BMI less than 25; and metabolically unhealthy with a BMI of greater than or equal to 25.

Data were adjusted for age and calendar year. The combined primary endpoints were the risks of MI, ischemic stroke, and all-cause mortality, using the metabolically healthy women with a BMI of less than 25 as reference.

The incidence rate (IR) of the combined endpoints for the normal weight, metabolically healthy women was 0.41 (number of events equaled 375); obese but metabolically healthy women had an IR of .45 (n = 51), and rate ratio (RR) of 1.16; normal weight but metabolically unhealthy women had an IR of .91 (n = 175), RR of 2.11; and obese and metabolically unhealthy women had an IR of 1.25 (n = 86), with an RR of 2.81.

"When you have an obese individual in front of you, that should be the first step, figuring out what their risk profile is," said Dr. Schmiegelow. "If they have metabolic disorders, that means they’re at an increased risk. If they do not have metabolic disorders, that means they’re at an increased risk of developing that, and you should really try and motivate them to change their lifestyle."

Dr. Schmiegelow and Dr. Tschöpe had no disclosures.

On Twitter @NaseemSMiller

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2013

Order Out of Chaos: Emergency Department Integration Software

Sweet Syndrome: The Uncommon Painful Rash

Comparison of a Veterans-Directed Home Care Program vs Community Nursing Home Placement

Women Who Are Not Getting Cervical Screening

Low, high dose vancomycin equally effective in C. difficile

DENVER – Oral vancomycin at a dose of 125 mg four times daily is just as effective as is a dose of 250 mg or higher given at the same frequency in the treatment of diarrhea associated with Clostridium difficile infection, judging from the results from a retrospective study.

Use of the lower dosing regimen has the potential to decrease treatment costs without worsening outcomes, Philip Chung, Pharm.D., said in an interview before the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, where the study was presented.

According to current recommendations, oral vancomycin 125 mg q.i.d. is the treatment of choice for severe uncomplicated C. difficile infection. To date, no studies have shown the use of oral vancomycin doses higher than 125 mg q.i.d. to be more efficacious than the recommended 125 mg q.i.d. in this setting, said Dr. Chung, clinical pharmacy manager of infectious diseases at Montefiore Medical Center, New York.

"Prior to 2008, prescribers at our institution frequently requested vancomycin doses higher than the recommended 125 mg q.i.d. for treatment of [C. difficile infection] despite the absence of data showing added benefits with the higher dosing regimens," he said. "This practice not only increases medication and/or preparation costs, but it may also increase the potential for untoward effects in patients being treated with the higher doses (e.g., increased risks for vancomycin-resistant enterococci colonization or higher likelihood to further alter the GI flora)."

Since the inception of the Antimicrobial Stewardship Program at Montefiore Medical Center in 2008, Dr. Chung and his associates observed a shift in oral vancomycin prescribing practices from a higher dosing regimen to a lower dosing regimen. "Because of this change in practice, we wished to evaluate the efficacy of the different oral vancomycin dosing regimen in order to ensure treatment outcomes remained unchanged at our institution," he said. To do so, the researchers retrospectively reviewed clinical outcomes of 300 adult patients treated with oral vancomycin at the medical center between 2006 and 2010. They looked at clinical parameters, concomitant antibiotics, in-hospital mortality, and 30-day readmission.

The primary endpoint was clinical improvement at 72 hours of oral vancomycin. Secondary endpoints included clinical improvement at end of therapy or discharge, length of stay, in-hospital mortality, and 30-day readmission rate.

Of the 300 patients, 197 were prescribed oral vancomycin 125 mg q.i.d. (low-dose group) and 103 patients were prescribed 250 mg or higher q.i.d. (high-dose group). Dr. Chung and his associates reported that clinical improvement assessed 72 hours after starting oral vancomycin therapy was observed in 85% and 86% of patients in the low- and high-dose groups, respectively (P less than 0.05). Rates of clinical improvement at end of therapy or time of hospital discharge between the two groups were also found to be similar (93% vs. 96%), as were total length of hospital stay (20 days vs. 19 days), in-hospital mortality (15% vs. 23%), and rates of 30-day readmission (34% vs. 24%).

"The finding that oral vancomycin 125 mg q.i.d. works as well as higher doses for severe uncomplicated C. difficile infection for the most part is not a surprise to us, as some evidence already exists in the literature," said Dr. Chung, also of Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York. "Our finding only confirmed what is already known."

Limitations include the fact that this is a single-center study, and that it is subject to selection bias because of its retrospective design, Dr. Chung said. "However, we took steps to ensure that all patients treated with oral vancomycin who had laboratory-confirmed [C. difficile infection] and symptoms consistent with [C. difficile infection] were included in the study," he said.

Dr. Chung said that he had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

DENVER – Oral vancomycin at a dose of 125 mg four times daily is just as effective as is a dose of 250 mg or higher given at the same frequency in the treatment of diarrhea associated with Clostridium difficile infection, judging from the results from a retrospective study.

Use of the lower dosing regimen has the potential to decrease treatment costs without worsening outcomes, Philip Chung, Pharm.D., said in an interview before the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, where the study was presented.

According to current recommendations, oral vancomycin 125 mg q.i.d. is the treatment of choice for severe uncomplicated C. difficile infection. To date, no studies have shown the use of oral vancomycin doses higher than 125 mg q.i.d. to be more efficacious than the recommended 125 mg q.i.d. in this setting, said Dr. Chung, clinical pharmacy manager of infectious diseases at Montefiore Medical Center, New York.

"Prior to 2008, prescribers at our institution frequently requested vancomycin doses higher than the recommended 125 mg q.i.d. for treatment of [C. difficile infection] despite the absence of data showing added benefits with the higher dosing regimens," he said. "This practice not only increases medication and/or preparation costs, but it may also increase the potential for untoward effects in patients being treated with the higher doses (e.g., increased risks for vancomycin-resistant enterococci colonization or higher likelihood to further alter the GI flora)."

Since the inception of the Antimicrobial Stewardship Program at Montefiore Medical Center in 2008, Dr. Chung and his associates observed a shift in oral vancomycin prescribing practices from a higher dosing regimen to a lower dosing regimen. "Because of this change in practice, we wished to evaluate the efficacy of the different oral vancomycin dosing regimen in order to ensure treatment outcomes remained unchanged at our institution," he said. To do so, the researchers retrospectively reviewed clinical outcomes of 300 adult patients treated with oral vancomycin at the medical center between 2006 and 2010. They looked at clinical parameters, concomitant antibiotics, in-hospital mortality, and 30-day readmission.

The primary endpoint was clinical improvement at 72 hours of oral vancomycin. Secondary endpoints included clinical improvement at end of therapy or discharge, length of stay, in-hospital mortality, and 30-day readmission rate.

Of the 300 patients, 197 were prescribed oral vancomycin 125 mg q.i.d. (low-dose group) and 103 patients were prescribed 250 mg or higher q.i.d. (high-dose group). Dr. Chung and his associates reported that clinical improvement assessed 72 hours after starting oral vancomycin therapy was observed in 85% and 86% of patients in the low- and high-dose groups, respectively (P less than 0.05). Rates of clinical improvement at end of therapy or time of hospital discharge between the two groups were also found to be similar (93% vs. 96%), as were total length of hospital stay (20 days vs. 19 days), in-hospital mortality (15% vs. 23%), and rates of 30-day readmission (34% vs. 24%).

"The finding that oral vancomycin 125 mg q.i.d. works as well as higher doses for severe uncomplicated C. difficile infection for the most part is not a surprise to us, as some evidence already exists in the literature," said Dr. Chung, also of Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York. "Our finding only confirmed what is already known."

Limitations include the fact that this is a single-center study, and that it is subject to selection bias because of its retrospective design, Dr. Chung said. "However, we took steps to ensure that all patients treated with oral vancomycin who had laboratory-confirmed [C. difficile infection] and symptoms consistent with [C. difficile infection] were included in the study," he said.

Dr. Chung said that he had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

DENVER – Oral vancomycin at a dose of 125 mg four times daily is just as effective as is a dose of 250 mg or higher given at the same frequency in the treatment of diarrhea associated with Clostridium difficile infection, judging from the results from a retrospective study.

Use of the lower dosing regimen has the potential to decrease treatment costs without worsening outcomes, Philip Chung, Pharm.D., said in an interview before the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, where the study was presented.

According to current recommendations, oral vancomycin 125 mg q.i.d. is the treatment of choice for severe uncomplicated C. difficile infection. To date, no studies have shown the use of oral vancomycin doses higher than 125 mg q.i.d. to be more efficacious than the recommended 125 mg q.i.d. in this setting, said Dr. Chung, clinical pharmacy manager of infectious diseases at Montefiore Medical Center, New York.

"Prior to 2008, prescribers at our institution frequently requested vancomycin doses higher than the recommended 125 mg q.i.d. for treatment of [C. difficile infection] despite the absence of data showing added benefits with the higher dosing regimens," he said. "This practice not only increases medication and/or preparation costs, but it may also increase the potential for untoward effects in patients being treated with the higher doses (e.g., increased risks for vancomycin-resistant enterococci colonization or higher likelihood to further alter the GI flora)."

Since the inception of the Antimicrobial Stewardship Program at Montefiore Medical Center in 2008, Dr. Chung and his associates observed a shift in oral vancomycin prescribing practices from a higher dosing regimen to a lower dosing regimen. "Because of this change in practice, we wished to evaluate the efficacy of the different oral vancomycin dosing regimen in order to ensure treatment outcomes remained unchanged at our institution," he said. To do so, the researchers retrospectively reviewed clinical outcomes of 300 adult patients treated with oral vancomycin at the medical center between 2006 and 2010. They looked at clinical parameters, concomitant antibiotics, in-hospital mortality, and 30-day readmission.

The primary endpoint was clinical improvement at 72 hours of oral vancomycin. Secondary endpoints included clinical improvement at end of therapy or discharge, length of stay, in-hospital mortality, and 30-day readmission rate.

Of the 300 patients, 197 were prescribed oral vancomycin 125 mg q.i.d. (low-dose group) and 103 patients were prescribed 250 mg or higher q.i.d. (high-dose group). Dr. Chung and his associates reported that clinical improvement assessed 72 hours after starting oral vancomycin therapy was observed in 85% and 86% of patients in the low- and high-dose groups, respectively (P less than 0.05). Rates of clinical improvement at end of therapy or time of hospital discharge between the two groups were also found to be similar (93% vs. 96%), as were total length of hospital stay (20 days vs. 19 days), in-hospital mortality (15% vs. 23%), and rates of 30-day readmission (34% vs. 24%).

"The finding that oral vancomycin 125 mg q.i.d. works as well as higher doses for severe uncomplicated C. difficile infection for the most part is not a surprise to us, as some evidence already exists in the literature," said Dr. Chung, also of Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York. "Our finding only confirmed what is already known."

Limitations include the fact that this is a single-center study, and that it is subject to selection bias because of its retrospective design, Dr. Chung said. "However, we took steps to ensure that all patients treated with oral vancomycin who had laboratory-confirmed [C. difficile infection] and symptoms consistent with [C. difficile infection] were included in the study," he said.

Dr. Chung said that he had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

AT ICAAC 2013

AHA statement spotlights severe pediatric obesity

Earn 0.25 hours AMA PRA Category 1 credit: Read this article, and click the link at the end to take the post-test.

An estimated 4%-6% of children and adolescents in the United States are severely obese, and the prevalence appears to be on the uptick.

At the same time, existing treatments for the condition are limited in effectiveness and lack widespread availability, a nine-member writing group of experts led by Aaron S. Kelly, Ph.D., reported in a scientific statement from the American Heart Association.

"Severe obesity in young people has grave health consequences," said Dr. Kelly in a press statement. "It’s a much more serious childhood disease than obesity."

The condition "demands attention and clinical management, because if left unchecked, it will have a profound effect on those it afflicts and will place a significant economic and clinical services burden on the future health care system," the writing group cautionedonline Sept. 9 in Circulation. It emphasized that stakeholders at all levels "will need to work together to engage the growing problem of severe pediatric obesity."

The 17-page statement includes a recommendation to define children over age 2 as severely obese if they have either a body mass index that’s at least 20%higher than the 95th percentile for their sex and age, or a BMI score of 35 kg/mm2 or higher (Circulation 2013 Sept. 9 [doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182a5cfb3]). According to estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey dating back to 1999, 4%-6% of children and adolescents in the United States currently fall into this category. Those same data suggest that severe obesity is the fastest-growing subcategory of obesity in youth.

Dr. Kelly of the division of epidemiology and clinical research in the department of pediatrics at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and his associates discussed numerous associated health risks from being severely obese as a child, in particular the mounting evidence from clinical and population-based studies regarding its link to the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD). "Importantly, obesity and CVD risk factors associated with obesity have been linked to early atherosclerosis in pathological studies of the coronary arteries and aorta in adolescents and young adults," the writing group stated.

Other associated health risks that threaten this subset of patients include hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance, and prediabetes; obstructive sleep apnea syndrome; nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; musculoskeletal problems; depression and other psychosocial problems; and disordered eating.

Although data regarding the long-term risks of severe pediatric obesity are sparse, the authors noted, "it is well established that obese youth (probably because of the strong tracking of adiposity into adulthood) are more likely to have adverse levels of cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors later in life. Higher BMI is associated with tracking in the higher levels of both blood pressure and lipids in longitudinal pediatric cohort studies. Adolescents with a higher degree of obesity are also much more likely to demonstrate CVD risk factor clustering over time. Rate and degree of obesity development are also important."

The writing group characterized current treatment options for severe pediatric obesity as limited, as most standard approaches to weight loss are insufficient for this group. As for medications, orlistat is the only agent approved for weight loss in adolescents. The largest study of its use in adolescents reported a 2.4% reduction in BMI over the course of 12 months (JAMA 2005;293:2873-83). Other agents that have been studied for pediatric obesity include metformin and exenatide. To date, the "results have demonstrated that treatment elicits only modest reductions in BMI/weight and has relatively little impact on the cardiometabolic risk factor profile in obese youth," the experts wrote. Two weight loss medications recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat obesity in adults, lorcaserin and the combination of phentermine and topiramate, have never been studied in children.

Dr. Kelly and his associates went on to note that bariatric surgery "has generally been effective in reducing body mass index and improving cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors; however, reports of long-term outcomes are few, many youth with severe obesity do not qualify for surgery, and access is limited by lack of insurance coverage."

The scientific statement, which is endorsed by the Obesity Society, includes "a call to action" for innovative ways to "fill the gap between lifestyle/medication and surgery." Proposals include conducting more research on bariatric surgery’s effects and safety; evaluating the effectiveness of lifestyle modification interventions, including adherence to dietary and physical activity plans; funding research to find other useful interventions, including better drugs and medical devices; and recognizing severe obesity as a chronic disease requiring ongoing care and management.

"The task ahead will be arduous and complicated, but the high prevalence and serious consequences of severe obesity require us to commit time, intellectual capital, and financial resources to address it," the writing group concluded.

Dr. Kelly disclosed that he has received research grants from Amylin Pharmaceuticals, the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the Thrasher Research Fund. He is also a consultant to Novo Nordisk. One other writing group member, Dr. Thomas H. Inge, disclosed that he has received a research grant from Ethicon Endosurgery.

To earn 0.25 hours AMA PRA Category 1 credit after reading this article, take the post-test here.

This is a wonderful and yet frightening manuscript that summarizes why we must be so concerned about childhood obesity and overweight. Additionally worrisome is the high prevalence of severe obesity in very young children. More research is definitely warranted and needed, particularly regarding effective interventions, but with so many children already affected and suffering, we can't wait to act. However, currently the majority of pediatricians across the United States are unable to see a child for "only" having childhood obesity or overweight because these visits are rejected for payment by the majority of Medicaid and private insurance carriers in most states. There are some states and insurance carriers that reimburse an obesity or weight management visit, but for most pediatricians and other health professionals, we have to wait until the child develops a complication of their weight before we can see them to address their excess weight. This is very frustrating.

|

| Dr. Stephen Pont |

In November 2011, Medicare approved intensive outpatient treatment for adults with obesity; however, the majority of insurance providers for children, both Medicaid and private payers, still do not recognize childhood obesity as a reimbursable reason for a child to visit their pediatrician - or other health care professional - to address their weight. If you are interested in working in this area of advocacy, the American Academy of Pediatrics section on obesity would love to work with you. Beyond the walls of our clinics, pediatricians and other health professionals must also work in our communities. We must advocate and lead healthy community change so that healthy choices are easier to make where our patients live. Then as we help empower our patients in our clinics, they can return to communities where the healthier choice is much easier to make.

Stephen Pont, M.D., M.P.H., is a pediatrician at Dell Children's Medical Center in Austin, Tex., and chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics section on obesity. (On Twitter @DrStephenPont). He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

This is a wonderful and yet frightening manuscript that summarizes why we must be so concerned about childhood obesity and overweight. Additionally worrisome is the high prevalence of severe obesity in very young children. More research is definitely warranted and needed, particularly regarding effective interventions, but with so many children already affected and suffering, we can't wait to act. However, currently the majority of pediatricians across the United States are unable to see a child for "only" having childhood obesity or overweight because these visits are rejected for payment by the majority of Medicaid and private insurance carriers in most states. There are some states and insurance carriers that reimburse an obesity or weight management visit, but for most pediatricians and other health professionals, we have to wait until the child develops a complication of their weight before we can see them to address their excess weight. This is very frustrating.

|

| Dr. Stephen Pont |

In November 2011, Medicare approved intensive outpatient treatment for adults with obesity; however, the majority of insurance providers for children, both Medicaid and private payers, still do not recognize childhood obesity as a reimbursable reason for a child to visit their pediatrician - or other health care professional - to address their weight. If you are interested in working in this area of advocacy, the American Academy of Pediatrics section on obesity would love to work with you. Beyond the walls of our clinics, pediatricians and other health professionals must also work in our communities. We must advocate and lead healthy community change so that healthy choices are easier to make where our patients live. Then as we help empower our patients in our clinics, they can return to communities where the healthier choice is much easier to make.

Stephen Pont, M.D., M.P.H., is a pediatrician at Dell Children's Medical Center in Austin, Tex., and chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics section on obesity. (On Twitter @DrStephenPont). He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

This is a wonderful and yet frightening manuscript that summarizes why we must be so concerned about childhood obesity and overweight. Additionally worrisome is the high prevalence of severe obesity in very young children. More research is definitely warranted and needed, particularly regarding effective interventions, but with so many children already affected and suffering, we can't wait to act. However, currently the majority of pediatricians across the United States are unable to see a child for "only" having childhood obesity or overweight because these visits are rejected for payment by the majority of Medicaid and private insurance carriers in most states. There are some states and insurance carriers that reimburse an obesity or weight management visit, but for most pediatricians and other health professionals, we have to wait until the child develops a complication of their weight before we can see them to address their excess weight. This is very frustrating.

|

| Dr. Stephen Pont |

In November 2011, Medicare approved intensive outpatient treatment for adults with obesity; however, the majority of insurance providers for children, both Medicaid and private payers, still do not recognize childhood obesity as a reimbursable reason for a child to visit their pediatrician - or other health care professional - to address their weight. If you are interested in working in this area of advocacy, the American Academy of Pediatrics section on obesity would love to work with you. Beyond the walls of our clinics, pediatricians and other health professionals must also work in our communities. We must advocate and lead healthy community change so that healthy choices are easier to make where our patients live. Then as we help empower our patients in our clinics, they can return to communities where the healthier choice is much easier to make.

Stephen Pont, M.D., M.P.H., is a pediatrician at Dell Children's Medical Center in Austin, Tex., and chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics section on obesity. (On Twitter @DrStephenPont). He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Earn 0.25 hours AMA PRA Category 1 credit: Read this article, and click the link at the end to take the post-test.

An estimated 4%-6% of children and adolescents in the United States are severely obese, and the prevalence appears to be on the uptick.

At the same time, existing treatments for the condition are limited in effectiveness and lack widespread availability, a nine-member writing group of experts led by Aaron S. Kelly, Ph.D., reported in a scientific statement from the American Heart Association.

"Severe obesity in young people has grave health consequences," said Dr. Kelly in a press statement. "It’s a much more serious childhood disease than obesity."

The condition "demands attention and clinical management, because if left unchecked, it will have a profound effect on those it afflicts and will place a significant economic and clinical services burden on the future health care system," the writing group cautionedonline Sept. 9 in Circulation. It emphasized that stakeholders at all levels "will need to work together to engage the growing problem of severe pediatric obesity."

The 17-page statement includes a recommendation to define children over age 2 as severely obese if they have either a body mass index that’s at least 20%higher than the 95th percentile for their sex and age, or a BMI score of 35 kg/mm2 or higher (Circulation 2013 Sept. 9 [doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182a5cfb3]). According to estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey dating back to 1999, 4%-6% of children and adolescents in the United States currently fall into this category. Those same data suggest that severe obesity is the fastest-growing subcategory of obesity in youth.

Dr. Kelly of the division of epidemiology and clinical research in the department of pediatrics at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and his associates discussed numerous associated health risks from being severely obese as a child, in particular the mounting evidence from clinical and population-based studies regarding its link to the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD). "Importantly, obesity and CVD risk factors associated with obesity have been linked to early atherosclerosis in pathological studies of the coronary arteries and aorta in adolescents and young adults," the writing group stated.

Other associated health risks that threaten this subset of patients include hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance, and prediabetes; obstructive sleep apnea syndrome; nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; musculoskeletal problems; depression and other psychosocial problems; and disordered eating.

Although data regarding the long-term risks of severe pediatric obesity are sparse, the authors noted, "it is well established that obese youth (probably because of the strong tracking of adiposity into adulthood) are more likely to have adverse levels of cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors later in life. Higher BMI is associated with tracking in the higher levels of both blood pressure and lipids in longitudinal pediatric cohort studies. Adolescents with a higher degree of obesity are also much more likely to demonstrate CVD risk factor clustering over time. Rate and degree of obesity development are also important."

The writing group characterized current treatment options for severe pediatric obesity as limited, as most standard approaches to weight loss are insufficient for this group. As for medications, orlistat is the only agent approved for weight loss in adolescents. The largest study of its use in adolescents reported a 2.4% reduction in BMI over the course of 12 months (JAMA 2005;293:2873-83). Other agents that have been studied for pediatric obesity include metformin and exenatide. To date, the "results have demonstrated that treatment elicits only modest reductions in BMI/weight and has relatively little impact on the cardiometabolic risk factor profile in obese youth," the experts wrote. Two weight loss medications recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat obesity in adults, lorcaserin and the combination of phentermine and topiramate, have never been studied in children.

Dr. Kelly and his associates went on to note that bariatric surgery "has generally been effective in reducing body mass index and improving cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors; however, reports of long-term outcomes are few, many youth with severe obesity do not qualify for surgery, and access is limited by lack of insurance coverage."

The scientific statement, which is endorsed by the Obesity Society, includes "a call to action" for innovative ways to "fill the gap between lifestyle/medication and surgery." Proposals include conducting more research on bariatric surgery’s effects and safety; evaluating the effectiveness of lifestyle modification interventions, including adherence to dietary and physical activity plans; funding research to find other useful interventions, including better drugs and medical devices; and recognizing severe obesity as a chronic disease requiring ongoing care and management.

"The task ahead will be arduous and complicated, but the high prevalence and serious consequences of severe obesity require us to commit time, intellectual capital, and financial resources to address it," the writing group concluded.

Dr. Kelly disclosed that he has received research grants from Amylin Pharmaceuticals, the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the Thrasher Research Fund. He is also a consultant to Novo Nordisk. One other writing group member, Dr. Thomas H. Inge, disclosed that he has received a research grant from Ethicon Endosurgery.

To earn 0.25 hours AMA PRA Category 1 credit after reading this article, take the post-test here.

Earn 0.25 hours AMA PRA Category 1 credit: Read this article, and click the link at the end to take the post-test.

An estimated 4%-6% of children and adolescents in the United States are severely obese, and the prevalence appears to be on the uptick.

At the same time, existing treatments for the condition are limited in effectiveness and lack widespread availability, a nine-member writing group of experts led by Aaron S. Kelly, Ph.D., reported in a scientific statement from the American Heart Association.

"Severe obesity in young people has grave health consequences," said Dr. Kelly in a press statement. "It’s a much more serious childhood disease than obesity."

The condition "demands attention and clinical management, because if left unchecked, it will have a profound effect on those it afflicts and will place a significant economic and clinical services burden on the future health care system," the writing group cautionedonline Sept. 9 in Circulation. It emphasized that stakeholders at all levels "will need to work together to engage the growing problem of severe pediatric obesity."

The 17-page statement includes a recommendation to define children over age 2 as severely obese if they have either a body mass index that’s at least 20%higher than the 95th percentile for their sex and age, or a BMI score of 35 kg/mm2 or higher (Circulation 2013 Sept. 9 [doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182a5cfb3]). According to estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey dating back to 1999, 4%-6% of children and adolescents in the United States currently fall into this category. Those same data suggest that severe obesity is the fastest-growing subcategory of obesity in youth.

Dr. Kelly of the division of epidemiology and clinical research in the department of pediatrics at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and his associates discussed numerous associated health risks from being severely obese as a child, in particular the mounting evidence from clinical and population-based studies regarding its link to the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD). "Importantly, obesity and CVD risk factors associated with obesity have been linked to early atherosclerosis in pathological studies of the coronary arteries and aorta in adolescents and young adults," the writing group stated.

Other associated health risks that threaten this subset of patients include hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance, and prediabetes; obstructive sleep apnea syndrome; nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; musculoskeletal problems; depression and other psychosocial problems; and disordered eating.

Although data regarding the long-term risks of severe pediatric obesity are sparse, the authors noted, "it is well established that obese youth (probably because of the strong tracking of adiposity into adulthood) are more likely to have adverse levels of cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors later in life. Higher BMI is associated with tracking in the higher levels of both blood pressure and lipids in longitudinal pediatric cohort studies. Adolescents with a higher degree of obesity are also much more likely to demonstrate CVD risk factor clustering over time. Rate and degree of obesity development are also important."

The writing group characterized current treatment options for severe pediatric obesity as limited, as most standard approaches to weight loss are insufficient for this group. As for medications, orlistat is the only agent approved for weight loss in adolescents. The largest study of its use in adolescents reported a 2.4% reduction in BMI over the course of 12 months (JAMA 2005;293:2873-83). Other agents that have been studied for pediatric obesity include metformin and exenatide. To date, the "results have demonstrated that treatment elicits only modest reductions in BMI/weight and has relatively little impact on the cardiometabolic risk factor profile in obese youth," the experts wrote. Two weight loss medications recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat obesity in adults, lorcaserin and the combination of phentermine and topiramate, have never been studied in children.

Dr. Kelly and his associates went on to note that bariatric surgery "has generally been effective in reducing body mass index and improving cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors; however, reports of long-term outcomes are few, many youth with severe obesity do not qualify for surgery, and access is limited by lack of insurance coverage."

The scientific statement, which is endorsed by the Obesity Society, includes "a call to action" for innovative ways to "fill the gap between lifestyle/medication and surgery." Proposals include conducting more research on bariatric surgery’s effects and safety; evaluating the effectiveness of lifestyle modification interventions, including adherence to dietary and physical activity plans; funding research to find other useful interventions, including better drugs and medical devices; and recognizing severe obesity as a chronic disease requiring ongoing care and management.

"The task ahead will be arduous and complicated, but the high prevalence and serious consequences of severe obesity require us to commit time, intellectual capital, and financial resources to address it," the writing group concluded.

Dr. Kelly disclosed that he has received research grants from Amylin Pharmaceuticals, the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the Thrasher Research Fund. He is also a consultant to Novo Nordisk. One other writing group member, Dr. Thomas H. Inge, disclosed that he has received a research grant from Ethicon Endosurgery.

To earn 0.25 hours AMA PRA Category 1 credit after reading this article, take the post-test here.

FROM CIRCULATION

New Anticoagulants for Thromboprophylaxis After Total Knee Arthroplasty

Fecal incontinence: New therapies, age-old problem

Fecal incontinence is a socially embarrassing condition that affects approximately 18 million adults in the United States.1 Its true incidence is likely much higher than reported, however, as many patients are reluctant to discuss it.

A recent study found that nearly 20% of women experience fecal incontinence at least once a year, and 9.5% experience it al least once a month.2 Only 28% of these women had ever discussed their symptoms with a physician, however.3 Women who did seek care were more likely to consult a family physician or internist (75%) than a gynecologist (7%).3

Until recently, few options were available for patients with fecal incontinence who had not benefited from conservative measures. Many patients simply had to live with their symptoms or undergo a diverting ostomy to control the chronic involuntary drainage.

Recent years have seen the development of new minimally invasive and highly successful techniques to treat fecal incontinence. Greater awareness of the prevalence of fecal incontinence and its devastating impact on quality of life is needed for this problem to be fully addressed, however. In this article, we review the recommended evaluation of a patient who reports fecal incontinence and describe the range of treatment options.

Fecal incontinence is a symptom, not a diagnosis

Although the most common historical factor contributing to fecal incontinence is obstetric trauma, there are several other causes of this condition. A detailed history and physical examination are vital to determine whether the patient is experiencing true fecal incontinence, or whether she is leaking for other reasons—so-called pseudo-incontinence.

Conditions that can mimic fecal incontinence include:

- prolapsing hemorrhoids

- anal fistula

- sexually transmitted infection

- benign or malignant anorectal neoplasms

- dermatologic conditions.

True fecal incontinence may be active (loss of stool despite the patient’s best effort to control it) or passive (loss of stool without the patient’s awareness). Among the causes of true fecal incontinence are:

- anal sphincter injury (obstetric tear, anorectal surgery such as fistulotomy, or trauma)

- denervation of the pelvic floor from pudendal nerve injury during childbirth

- chronic rectal prolapse

- neurologic conditions (spina bifida, myelomeningocele)

- noncompliant rectum from inflammatory bowel disease

- radiation proctitis.

The maintenance of continence requires a complex interaction between the sphincter muscle, the puborectalis muscle (which acts as a sling), rectal capacity and compliance, stool volume and frequency, and neurologic mechanisms.

Diagnosis and management require an experienced physician

We believe that patients reporting fecal incontinence are best worked up and managed by a physician who is well versed in the various diagnoses associated with fecal incontinence, as well as the most current treatments.

Diagnosis entails some detective work

When a patient reports fecal incontinence, she should be asked to elaborate on the circumstances surrounding the complaint and the frequency of its occurrence, duration of symptoms, and nature of the incontinence (gas, liquid, or solid).

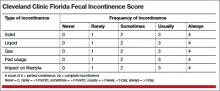

Validated quality-of-life instruments, such as the Cleveland Clinic Florida Fecal Incontinence Score (CCF-FIS) may be helpful in documenting the severity of the symptoms and improvement after treatment (TABLE).4

One factor that current scoring systems fail to capture is urgency. In many instances, urgency is the symptom most distressing to the patient. Be sure to ask about it.

A detailed obstetric history also is important. It is not uncommon for a patient to develop symptoms 20 years or longer after the injury. Also review the patient’s medical history for inflammatory bowel disease, neurologic disorders, and any history of pelvic radiation for help in determining the cause of symptoms.

In addition, ask the patient about any other pelvic floor symptoms, such as voiding dysfunction and problems with pelvic organ prolapse. And question her about stool consistency and frequency. In some cases, diarrhea can lead to fecal incontinence and is usually managed conservatively.

Physical exam: Focus on the perineum and anus

A detailed physical examination is warranted to determine the state of the patient’s sphincter musculature and rule out other causes of pseudo-incontinence, such as hemorrhoids or anal fistula. Inspect the perineum for thinning of the perineal body and scars from prior surgery.

A patulous anus may be a sign of rectal prolapse. To check for it, ask the patient to strain on the commode. If rectal prolapse is present, it will become apparent upon straining. If prolapse is detected, surgical treatment of the prolapse would be the first step in managing the incontinence.

A simple test of neurologic function is to try to elicit an anal “wink” in response to a pinprick.

A digital rectal exam allows the assessment of resting and squeeze tone, as well as the use of accessory muscles, such as the gluteus maximus, during squeezing.

Rigid or flexible proctoscopy may be indicated to rule out inflammatory bowel disease, radiation proctitis, and rectal neoplasm, depending on the patient’s history.

A few diagnostic adjuncts can help

Several adjuncts to physical examination can provide more detailed information about the patient’s condition and facilitate the development of an individualized treatment plan. For example, if rectal prolapse, rectocele with delayed emptying, or enterocele is suspected, consider defecography. If voiding dysfunction coexists with the fecal incontinence, urodynamic testing and cystoscopy may be indicated.

We routinely perform physiology testing and endoanal ultrasound if surgery is planned to address the fecal incontinence, although routine use of these adjuncts is controversial. Because many patients can be managed with conservative medical measures, we do not find it necessary to perform these tests at the time of the first visit.

Anal physiology testing includes manometry (a measure of both resting and squeeze tone) and pudendal nerve terminal motor latency testing.

Manometry can help quantify the severity of muscle weakness and determine the presence or absence of normal anal reflexes. Pudendal nerve testing assesses the innervation of the anal sphincter. There is some evidence that patients who have a pudendal neuropathy have a poor outcome with sphincteroplasty,5 although that evidence is controversial. The findings from physiology studies have not been correlated with outcomes of newer treatments, such as sacral neuromodulation (InterStim, Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minnesota). Each physiology lab uses different equipment, so “normal” values vary between institutions.

Endoanal ultrasound is easily performed in an office setting. It is well tolerated and provides anatomic detail of the sphincter musculature. We use a 13-MHz rotating probe to provide 3D imaging of the anal canal. The internal sphincter is represented by a hypoechoic circle surrounded by the hyperechoic external sphincter (FIGURE 1).

In the hands of an experienced examiner, the sensitivity and specificity of endoanal ultrasound in detecting sphincter defects approaches 100%.6,7 Ultrasound also enables measurement of the perineal body. A normal perineal body measures 10 to 15 mm.

For treatment, try conservative measures first

Bulking agents (fiber), constipating agents (loperamide, etc.), or a laxative regimen with scheduled disimpactions (in patients who have pelvic outlet constipation and overflow incontinence) often can control the symptoms of fecal incontinence, making further interventions unnecessary.

Biofeedback is another option. It uses visual, auditory, and sensory information to train patients to better control anal sphincter muscle function.

A recent randomized study found manometric biofeedback to be superior to simple Kegel exercises in improving fecal continence.8 In this study, 76% of patients in the biofeedback group experienced symptom improvement, compared with 41% of patients in the pelvic floor exercise group (P <.001). The long-term benefits of biofeedback are less clear, and patients often need to be reminded to perform their exercises at home and to attend occasional refresher-training sessions. Nevertheless, biofeedback is an important noninvasive option for patients in whom medical management has failed.

Minimally invasive options are now available

Over the past 2 years, minimally invasive treatments for fecal incontinence have emerged, including an implantable sacral neuromodulation device (InterStim) and an injectable dextranomer (Solesta; Salix Pharmaceuticals, Raleigh, North Carolina). Previously, the only surgical option for fecal incontinence was a sphincter repair if a defect was present. The new options may help patients improve their quality of life without having to undergo major surgery.

No one has directly compared the outcomes of these procedures when they are performed by a colorectal surgeon versus a physician of another specialty. It is our belief that the treating physician should have a strong interest in caring for these complex patients and a good working knowledge of the various treatment options.

Related Article Obstetric anal sphincter injury: 7 critical questions about care Ranee Thakar, MD, MRCOG (February 2008)

Sacral neuromodulation

This technique initially was developed for the treatment of overactive bladder and nonobstructive urinary retention and has been used in the United States for the past 15 years for these indications. Improvement in fecal continence was observed in these patients, prompting further studies of its efficacy. In 2011, it was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of fecal incontinence. It has since revolutionized the treatment of this disorder, offering a minimally invasive and highly successful alternative to sphincteroplasty.

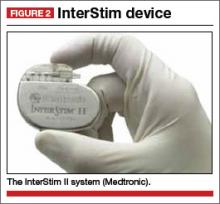

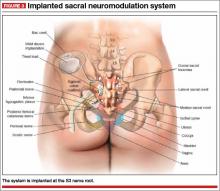

The InterStim procedure is the only therapeutic modality to include a test phase. The outpatient procedure involves sterile placement of an electrode through the S3 foramen to stimulate the S3 nerve root using fluoroscopic guidance (FIGURES 2 and 3). Patients who experience at least 50% improvement in symptoms are then offered placement of a permanent stimulator.

In most series, approximately 90% of patients have a positive test and progress to implantation. A recent US multicenter clinical trial indicated that 86% of patients achieved an improvement in continence of at least 50%, and 40% of patients were completely continent at 3 years.9 The number of episodes of incontinence decreased from a mean of 9.4/week to 1.7/week.9 Quality of life also improved greatly. Few complications have been reported, the most notable of which is infection (10.8% in the US multicenter trial9).

Another advantage of sacral neuromodulation: It can be used successfully in patients with external sphincter defects as large as 120º. A study by Tjandra and colleagues found that 65% of patients experienced improvement in symptoms of at least 50%, and 47% of patients (more than 50% of whom had external sphincter defects as large as 120º) became completely continent.10

The only variable shown to predict success with sacral neuromodulation is a positive response to the test implant procedure.

In our experience, this procedure is easy to perform and well tolerated, even in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities. The procedure has the additional advantage of potentially improving concomitant urinary symptoms as well.

The major disadvantage of sacral neuromodulation is its cost, although most major insurance carriers cover it. There is no well-conducted cost-effectiveness analysis comparing this modality to other treatments.

Related Article Interstim: An implantable device for implacable urinary symptoms Deborah L. Myers, MD (October 2006)

Injectable agents

Several biocompatible bulking agents have been tested in the treatment of fecal incontinence. These compounds traditionally have been used to treat mild fecal incontinence, or to treat patients with isolated internal sphincter defects.

More recently, an injectable dextranomer in stabilized hyaluronic acid was approved by the FDA and marketed as Solesta. Graf and colleagues randomly allocated 136 patients to injection and 70 patients to sham injection. Patients with external sphincter defects were excluded. At 6 months, 52% of patients in the active treatment group experienced an improvement in continence of at least 50%, compared with 31% of patients injected with placebo.11

The advantage of this procedure is its minimally invasive nature (submucosal injection performed in the office). The disadvantage: a lack of long-term efficacy data, although unpublished data suggest that patients who improve after an injection see a durable response at 3 years.

This easy, office-based treatment is ideal for patients with minor incontinence or persistent symptoms after another procedure.

Sphincter repair

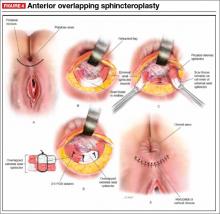

Anterior sphincteroplasty has been the mainstay of surgical treatment for patients with a sphincter defect. With the patient in a dorsal lithotomy or prone position on the operating-room table, a transverse perineal incision is made, and the ends of the severed sphincter muscle are located and mobilized. The repair then can be performed in an end-to-end manner or by overlapping the muscles in the anterior midline (FIGURE 4).

Some of the debatable technical issues of this procedure include:

- whether to overlap the muscles or scar tissue

- whether to repair internal and external defects together or separately

- how the age of the patient affects the outcome.

In regard to the first issue, there may be a superior outcome with overlapping repairs, but they carry a higher risk of dyspareunia and evacuation difficulties. Some surgeons will attempt a separate repair of the internal and external sphincter muscles if it appears feasible. Most often, both muscles are tethered together with scar tissue and separate repair is not possible. There are no conclusive data to demonstrate the superiority of either approach.

As for age, the traditional teaching was that older patients do not benefit from this procedure as much as younger patients do. However, a recent study found no differences in the CCF-FIS score in patients older than age 60, compared with younger patients.12 Investigators concluded that sphincteroplasty can be offered to both young and older patients.12

Although sphincteroplasty often leads to excellent short-term improvement, with 60% to 90% of patients experiencing a good or excellent outcome, nearly all series indicate a decline over the long term (>5 years). A recent systematic review found that as few as 12% of patients experience a good or excellent result, depending on the series.13

We offer sphincter repair to young women with a new sphincter defect after delivery. For older patients, we offer sacral neuromodulation as a first-line treatment.

Other surgical options

We believe that most patients with fecal incontinence can be managed using conservative measures, sacral neuromodulation, injectable dextranomer, or sphincter repair. However, several other options are available.

Artificial bowel sphincter

The artificial bowel sphincter was first described in 1987 and has been modified over the years. The system currently is marketed as the Acticon Neosphincter (American Medical Systems, Minnetonka, Minnesota). The procedure involves the creation of a subcutaneous tunnel around the anus so that an inflatable cuff can be positioned there. A pump then is tunneled through a Pfannenstiel incision to the labia or scrotum, and a reservoir is positioned in the space of Retzius. The device maintains continence by keeping the cuff inflated during the resting state and by pumping fluid from the cuff to the reservoir when the patient needs to evacuate.

The major barrier to utilization of the artificial bowel sphincter is infection. In a series of 112 patients who were implanted with the sphincter, 384 device-related adverse events occurred in 99 patients.14 A total of 73 revision operations were required in 51 patients (46%). Twenty-five percent of patients developed infection that required surgical revision, and 37% had the device explanted. Eighty-five percent of patients with a functional device had a successful outcome.14

Given the device-related challenges and infectious complications, patients should be considered for less invasive treatments before being offered an artificial bowel

sphincter.

Radiofrequency current

The Secca procedure (Curon Medical, Fremont, California) involves the application of radiofrequency current to the anal canal to generate thermal energy. This procedure causes contraction of collagen fibers, which are permanently shortened, and leads to tightening of the muscle. It is performed under intravenous sedation on an outpatient basis.

This approach is indicated for patients with mild to moderate fecal incontinence who have not responded to conservative management. An external sphincter defect is a contraindication.

Small, nonrandomized studies have found improvement in the CCF-FIS score in patients treated with this approach.15 The major limitation of this treatment is the lack of high-level clinical evidence demonstrating its efficacy and safety.

Antegrade continence enema

This approach, also known as the Malone procedure, is usually reserved for debilitating incontinence or constipation in the pediatric population. An appendicostomy is constructed at the navel, allowing daily introduction of a catheter and antegrade enema. The purpose is to perform rapid, controlled emptying of the colon at times chosen by the patient. It is also reserved as a last resort for patients considering an ostomy.

Adult patients with neurologic problems, such as spina bifida, may be candidates for this procedure, provided they are highly motivated.

Fecal diversion

Creation of a colostomy or ileostomy is usually the last resort for a patient with fecal incontinence. We are fortunate that there are an increasing number of options that may improve the patient’s condition before colostomy is required.

If fecal diversion is chosen by the patient, it is important to involve an enterostomal therapist for site marking and patient education. A well-constructed ostomy is essential, as this option often is permanent.

Up and coming options

A novel treatment approach for fecal incontinence is the magnetic anal sphincter. The device, marketed as the FENIX Continence Restoration System (Torax Medical, Shoreview, Minnesota) consists of a series of titanium beads with magnetic cores that are interlinked with titanium wires. The device is designed to encircle the external anal sphincter muscle, reinforce the sphincter, and expand to allow passage of stool at a socially appropriate time.

Preliminary data from 16 patients indicate a mean decrease in the number of episodes of incontinence from 7.2/week to 0.7/week, as well as a mean reduction in the CCF-FIS score from 17.2 to 8.7.16 Two devices were removed due to infection, and one device passed spontaneously after disconnection of the suture.16

This device is not approved by the FDA, but it may become a promising treatment if its safety and efficacy can be established in larger clinical trials.

The TOPAS sling (American Medical Systems) is currently being studied in a Phase 3, multicenter, nonrandomized, clinical trial (NCT01090739) for the treatment of fecal incontinence.17 The sling is implanted using a minimally invasive transobturator approach; two needle-passers deliver the sling assembly. Two small posterior incisions facilitate the postanal placement of the mesh.

This procedure replicates the anorectal angle created by the puborectalis muscle. Although it may become a minimally invasive treatment in the future, final results of the Phase 3 trial are not expected until 2016.

Tibial nerve stimulation is commonly used for urinary urge incontinence. Several small series have documented modest success with its application to fecal incontinence.18

The outpatient procedure involves the insertion of a needle electrode three fingerbreadths above the medial malleolus, followed by electrical stimulation. The current is slowly increased until a sensory or motor response (tingling under the sole of the foot or great toe plantar flexion) is elicited. Treatment necessitates several outpatient sessions.

In a recent series, the mean CCF-FIS decreased from 12.2/20 at baseline to 9.1/20 after treatment (P <.0001).18

The role of this procedure in the treatment algorithm for fecal incontinence remains to be determined.

What we offer patients

Fecal incontinence is a debilitating condition with an increasing number of potential therapeutic options. It clearly is under-recognized by patients and physicians alike.

After a thorough work-up, conservative treatment options should be offered first. When those fail, we generally recommend a trial of sacral neuromodulation for patients with no sphincter defect. When a sphincter defect is present, we counsel the patient about the merits of sphincter repair versus a trial of neuromodulation. These options have the most robust data supporting their clinical use, and have been used successfully in our own practices.

Given the continuous development of other therapeutic modalities, it is likely that future treatments will involve a stepwise progression of approaches. The need for colostomy should diminish in coming years as more minimally invasive techniques become available.

- Whitehead WE, Borrud L, Goode PS, et al. Fecal incontinence in US adults: epidemiology and risk factors. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(2):512–517.

- Brown HW, Wexner SD, Segall MM, et al. Accidental bowel leakage in the mature women’s health study: prevalence and predictors. Int Clin Pract. 2012;66(11):1101–1108.

- Brown HW, Wexner SD, Segall MM, et al. Quality of life in women with accidental bowel leakage. Int Clin Pract. 2012;66(11):1109–1116.

- Jorge JM, Wexner SD. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36(1):77–97.

- Sangwan YP, Collar JA, Barrett RC, et al. Unilateral pudendal neuropathy. Impact on outcomes of anal sphincter repair. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39(6):686–689.

- Deen KI, Kumar D, Williams JG, et al. Anal sphincter defects. Correlation between endoanal ultrasound and surgery. Ann Surg. 1993;218(2):201–205.

- Oberwalder M, Thaler K, Baig MK, et al. Anal ultrasound and endosonographic measurement of perineal body thickness: a new evaluation for fecal incontinence in females. Surg Endosc. 2004;18(4):650–654.

- Heymen S, Scarlett Y, Jones K, et al. Randomized controlled trial shows biofeedback to be superior to pelvic floor exercises for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(10):1730–1737.

- Mellgren AF, Wexner SD, Coller JA, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011:54(9):1065–1075.

- Tjandra JJ, Chan MK, Yeh CH, et al. Sacral nerve stimulation is more effective than optimal medical therapy for severe fecal incontinence: a randomized, controlled study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(5):494–502.

- Graf W, Mellgren A, Matzel K, et al. Efficacy of a dextranomer in stabilized hyaluronic acid for treatment of faecal incontinence: a randomized, sham-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9770):997–1003.

- El-Gazzaz G, Zutshi M, Hannaway C, Gurland B, Hull T. Overlapping sphincter repair: does age matter? Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55(3):256–261.

- Glasgow SC, Lowry AC. Long-term outcomes of anal sphincter repair for fecal incontinence: a systematic review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55(4):482–490.

- Wong WD, Congliosi SM, Spencer MP, et al. The safety and efficacy of the artificial bowel sphincter for fecal incontinence: results from a multicenter cohort study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45(9):1139–1153.

- Takahashi T, Morales M, Garcia-Osogobio S, et al. Secca procedure for the treatment of fecal incontinence: results of five-year follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(3):355–359.

- Lehur PA, McNevin S, Buntzen S, et al. Magnetic anal sphincter augmentation for the treatment of fecal incontinence: a preliminary report from a feasibility study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53(12):1604–1610.

- TOPAS sling. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01090739. Accessed August 26, 2013.

- Hotouras A, Thaha MA, Allison ME, et al. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) in females with faecal incontinence: the impact of sphincter morphology and rectal sensation on the clinical outcome. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27(7):927–930.

Fecal incontinence is a socially embarrassing condition that affects approximately 18 million adults in the United States.1 Its true incidence is likely much higher than reported, however, as many patients are reluctant to discuss it.

A recent study found that nearly 20% of women experience fecal incontinence at least once a year, and 9.5% experience it al least once a month.2 Only 28% of these women had ever discussed their symptoms with a physician, however.3 Women who did seek care were more likely to consult a family physician or internist (75%) than a gynecologist (7%).3

Until recently, few options were available for patients with fecal incontinence who had not benefited from conservative measures. Many patients simply had to live with their symptoms or undergo a diverting ostomy to control the chronic involuntary drainage.

Recent years have seen the development of new minimally invasive and highly successful techniques to treat fecal incontinence. Greater awareness of the prevalence of fecal incontinence and its devastating impact on quality of life is needed for this problem to be fully addressed, however. In this article, we review the recommended evaluation of a patient who reports fecal incontinence and describe the range of treatment options.

Fecal incontinence is a symptom, not a diagnosis

Although the most common historical factor contributing to fecal incontinence is obstetric trauma, there are several other causes of this condition. A detailed history and physical examination are vital to determine whether the patient is experiencing true fecal incontinence, or whether she is leaking for other reasons—so-called pseudo-incontinence.

Conditions that can mimic fecal incontinence include:

- prolapsing hemorrhoids

- anal fistula

- sexually transmitted infection

- benign or malignant anorectal neoplasms

- dermatologic conditions.

True fecal incontinence may be active (loss of stool despite the patient’s best effort to control it) or passive (loss of stool without the patient’s awareness). Among the causes of true fecal incontinence are:

- anal sphincter injury (obstetric tear, anorectal surgery such as fistulotomy, or trauma)

- denervation of the pelvic floor from pudendal nerve injury during childbirth

- chronic rectal prolapse

- neurologic conditions (spina bifida, myelomeningocele)

- noncompliant rectum from inflammatory bowel disease

- radiation proctitis.

The maintenance of continence requires a complex interaction between the sphincter muscle, the puborectalis muscle (which acts as a sling), rectal capacity and compliance, stool volume and frequency, and neurologic mechanisms.

Diagnosis and management require an experienced physician

We believe that patients reporting fecal incontinence are best worked up and managed by a physician who is well versed in the various diagnoses associated with fecal incontinence, as well as the most current treatments.

Diagnosis entails some detective work

When a patient reports fecal incontinence, she should be asked to elaborate on the circumstances surrounding the complaint and the frequency of its occurrence, duration of symptoms, and nature of the incontinence (gas, liquid, or solid).

Validated quality-of-life instruments, such as the Cleveland Clinic Florida Fecal Incontinence Score (CCF-FIS) may be helpful in documenting the severity of the symptoms and improvement after treatment (TABLE).4

One factor that current scoring systems fail to capture is urgency. In many instances, urgency is the symptom most distressing to the patient. Be sure to ask about it.

A detailed obstetric history also is important. It is not uncommon for a patient to develop symptoms 20 years or longer after the injury. Also review the patient’s medical history for inflammatory bowel disease, neurologic disorders, and any history of pelvic radiation for help in determining the cause of symptoms.

In addition, ask the patient about any other pelvic floor symptoms, such as voiding dysfunction and problems with pelvic organ prolapse. And question her about stool consistency and frequency. In some cases, diarrhea can lead to fecal incontinence and is usually managed conservatively.

Physical exam: Focus on the perineum and anus

A detailed physical examination is warranted to determine the state of the patient’s sphincter musculature and rule out other causes of pseudo-incontinence, such as hemorrhoids or anal fistula. Inspect the perineum for thinning of the perineal body and scars from prior surgery.

A patulous anus may be a sign of rectal prolapse. To check for it, ask the patient to strain on the commode. If rectal prolapse is present, it will become apparent upon straining. If prolapse is detected, surgical treatment of the prolapse would be the first step in managing the incontinence.

A simple test of neurologic function is to try to elicit an anal “wink” in response to a pinprick.

A digital rectal exam allows the assessment of resting and squeeze tone, as well as the use of accessory muscles, such as the gluteus maximus, during squeezing.

Rigid or flexible proctoscopy may be indicated to rule out inflammatory bowel disease, radiation proctitis, and rectal neoplasm, depending on the patient’s history.

A few diagnostic adjuncts can help

Several adjuncts to physical examination can provide more detailed information about the patient’s condition and facilitate the development of an individualized treatment plan. For example, if rectal prolapse, rectocele with delayed emptying, or enterocele is suspected, consider defecography. If voiding dysfunction coexists with the fecal incontinence, urodynamic testing and cystoscopy may be indicated.

We routinely perform physiology testing and endoanal ultrasound if surgery is planned to address the fecal incontinence, although routine use of these adjuncts is controversial. Because many patients can be managed with conservative medical measures, we do not find it necessary to perform these tests at the time of the first visit.

Anal physiology testing includes manometry (a measure of both resting and squeeze tone) and pudendal nerve terminal motor latency testing.

Manometry can help quantify the severity of muscle weakness and determine the presence or absence of normal anal reflexes. Pudendal nerve testing assesses the innervation of the anal sphincter. There is some evidence that patients who have a pudendal neuropathy have a poor outcome with sphincteroplasty,5 although that evidence is controversial. The findings from physiology studies have not been correlated with outcomes of newer treatments, such as sacral neuromodulation (InterStim, Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minnesota). Each physiology lab uses different equipment, so “normal” values vary between institutions.