User login

PSA cancer screening: A case for shared decision-making

Prostate cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer in men and the third leading cause of cancer death in men worldwide.1 An estimated 174,650 new cases are diagnosed each year in the United States; 31,620 American men die annually from the disease.2 Although prostate cancer can be a serious disease, many men do not die from it. In fact, 2.9 million men who were diagnosed with prostate cancer at some point are alive today.3

Risk factors. Prostate cancer develops mainly in men ages ≥ 65 years and rarely occurs before age 40. In addition to age, family history and African American ethnicity are the major nonmodifiable risk factors for prostate cancer.4 From the 1970s to the most recent statistical analysis of the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program, African American men have continued to have significantly higher incidence of, and mortality rates from, prostate cancer than their European American counterparts. African American men are also more likely than men of European ancestry to have aggressive prostate cancers.5 Other risk factors include geographic location (higher risk in Northern Europe, North America, and Australia; lower risk in Asia, Africa, and South and Central America), mutations in the BRCA2 gene, and hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer syndrome.4

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) was first used as a screening tool for prostate cancer in 1991.6 Prostate cancer incidence, especially organ-confined disease, has dramatically increased since then.7 PSA testing has a low sensitivity and specificity for the detection of prostate cancer, and there is no clear threshold at which biopsy can or should be offered. The most commonly used cutoff value of 4 ng/mL has a false-positive rate of about 70%.8

Benign prostatic conditions such as hypertrophy and infection can elevate PSA levels. In addition, the PSA test does not distinguish between aggressive and slow-growing cancers, and about 15% of patients with prostate cancer have a normal PSA level.9

A word about the digital rectal exam. While PSA testing has been the mainstay of prostate cancer screening, a few studies have included digital rectal exam (DRE) in their protocols. Data from the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial showed that DRE captured an additional 2% of men with prostate cancer in the setting of a normal PSA test result.10 In the Rotterdam arm of the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) trial, the overall detection rate for prostate cancer was found to be better when DRE was combined with PSA and prostate biopsy than when DRE was used alone (4.5% vs 2.5%).11 Nevertheless, generally speaking, DRE can be omitted in the era of PSA screening.

Screening guidelines vary

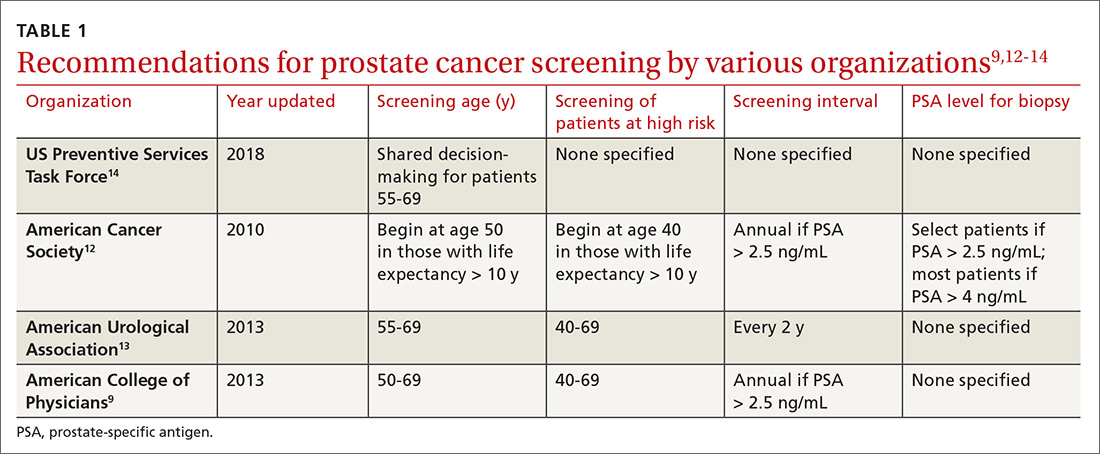

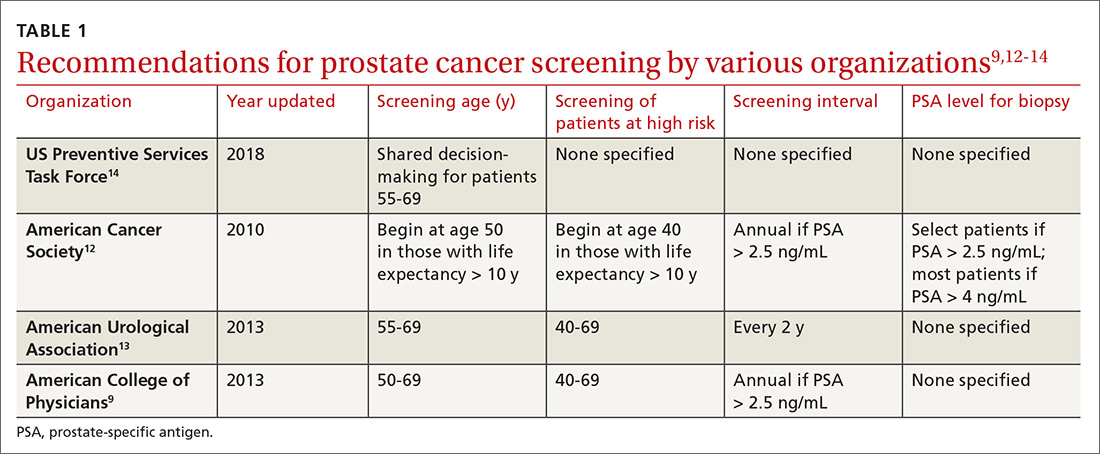

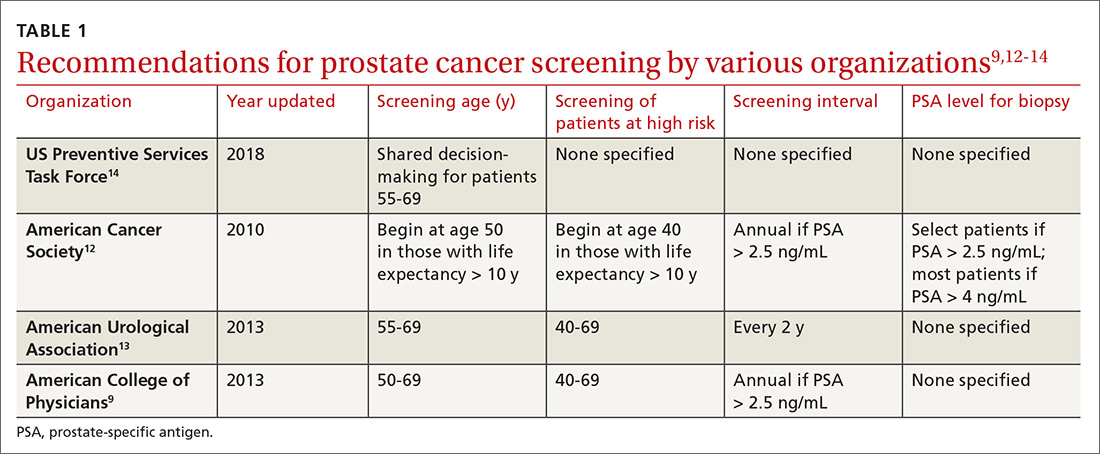

Recommendations for prostate cancer screening vary by organization and are summarized in TABLE 1.9,12-14 In 2012, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended against PSA-based screening for prostate cancer (Category D).15 In 2018, USPSTF provided an update with a new recommendation that clinicians inform men ages 55 to 69 years about the potential benefits and harms of PSA-based screening (Category C).14 The USPSTF continues to recommend against PSA-based screening for men ages ≥ 70 years (Category D).14

Does PSA-based screening improve patient-centered outcomes?

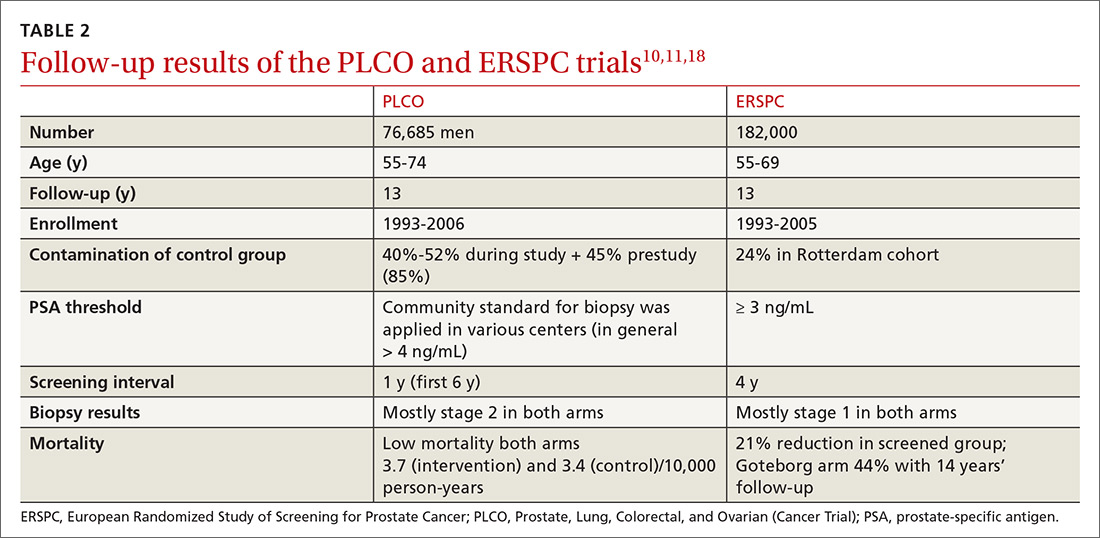

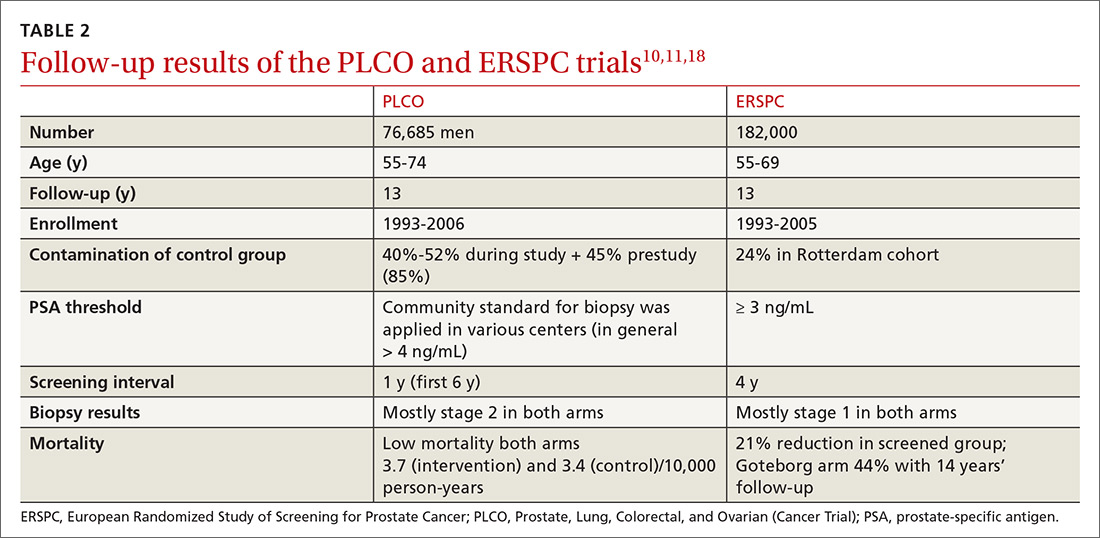

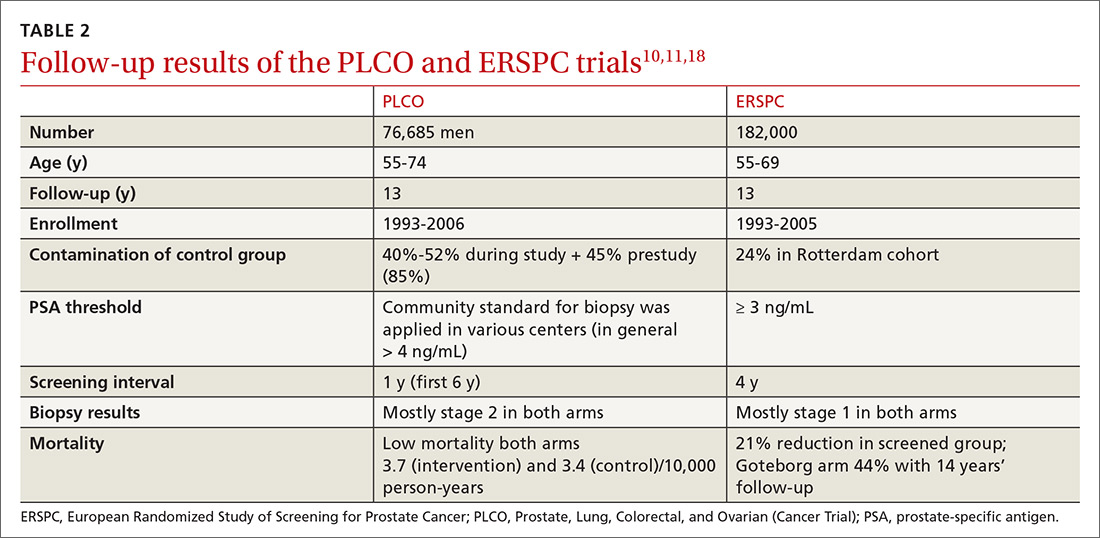

Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) such as the Quebec Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial,16 the Norrköping Sweden Study,17 ERSPC,11 and PLCO10 have been conducted to assess the benefits of PSA testing. PLCO and ERSPC have contributed significantly to our understanding of prostate cancer screening even though their 13-year follow-up results are conflicting (TABLE 2).10,11,18

Continue to: In the ERSPC 13-year follow-up publication...

In the ERSPC 13-year follow-up publication, the authors concluded that a substantial reduction in prostate cancer mortality is attributable to testing with PSA.18 Despite limitations in the study design (eg, France entered after 2 years, screening intervals varied between 2 and 4 years, biopsy indications varied, and screening was discontinued at different times), PSA screening detected more prostate cancer than was detected in the control arm (10.2% vs 6.8%).

In the initial 11 years of follow-up, the study group experienced a 21% reduction in prostate cancer mortality, even though the absolute decrease ranged from only 0.6% (545 per 89,352) to 0.5% (355 per 72,891). The updated absolute risk reduction of death from prostate cancer at 13 years of follow-up showed a larger benefit: 0.11 per 1000 person-years or 1.28 per 1000 men randomized, which is equivalent to 1 prostate cancer death averted per 781 (95% confidence interval [CI], 490-1929) men invited for screening, or 1 per 27 (17-66) additional prostate cancers detected.

The PLCO trial did not show any significant difference in prostate cancer detection (11.1% screened vs 9.9% control), and there was no improvement in prostate cancer mortality (3.7 vs 3.4 death per 10,000 person-years).10 However, the PLCO trial suffered from issues of contamination, which may have influenced the overall results. About 52% of men in the control (usual care) group received a PSA test at some point during the study. And more than two-thirds of the men who had a prostate biopsy because of a positive PSA test did not have prostate cancer.

Community standards for the PSA threshold for biopsy were applied in various centers (> 4 ng/ml in general) in PLCO, whereas in ERSPC, a cut-off PSA value ≥ 3 ng/mL was used for biopsy. Because of the lower PSA threshold, ERSPC may have identified cancers that would have had good outcomes without any intervention.

The harms of PSA screening

While it is unclear whether PSA screening results in any improvement in patient-centered outcomes, it does lead to downstream intervention due to overdiagnosis, which precipitates unnecessary anxiety, biopsies, and overtreatment (eg, excess radiation, overuse of androgen deprivation therapy).19 Biopsies carry the risk of hematuria (22.6%), hematospermia (50.4%), and urinary tract infection.20 Data from SEER-Medicare showed that prostate biopsy was associated with a 2.65-fold increased risk of hospitalization within 30 days of the procedure compared to a control population.21

Continue to: Overdiagnosis leads to overtreatment...

Overdiagnosis leads to overtreatment of low-risk prostate cancer. Both traditional treatment options for prostate cancer—radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy—are associated with urinary incontinence, erectile dysfunction, and issues with bowel function.22,23

The Prostate Cancer Intervention vs Observation Trial (PIVOT),24 the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group Study Number 4 (SPCG-4),25 and the Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment (ProtecT) trial,22,23 are the major RCTs that looked at the outcomes of treatment modalities for localized prostate cancer in the modern era of PSA testing.

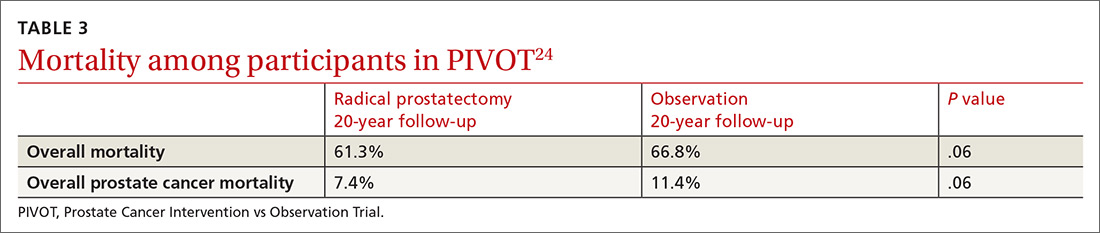

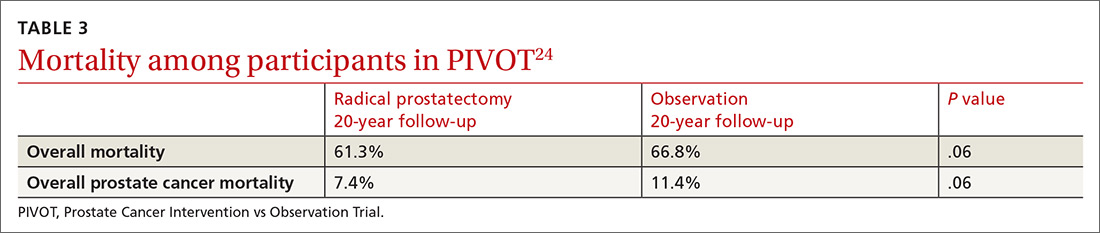

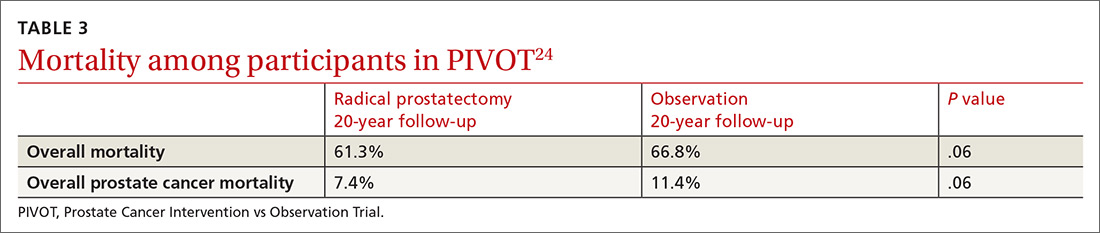

PIVOT compared passive observation with radical prostatectomy.24 After 20 years of follow-up on 731 patients, the researchers concluded that radical prostatectomy did not reduce all-cause or prostate cancer–related mortality (TABLE 3).24

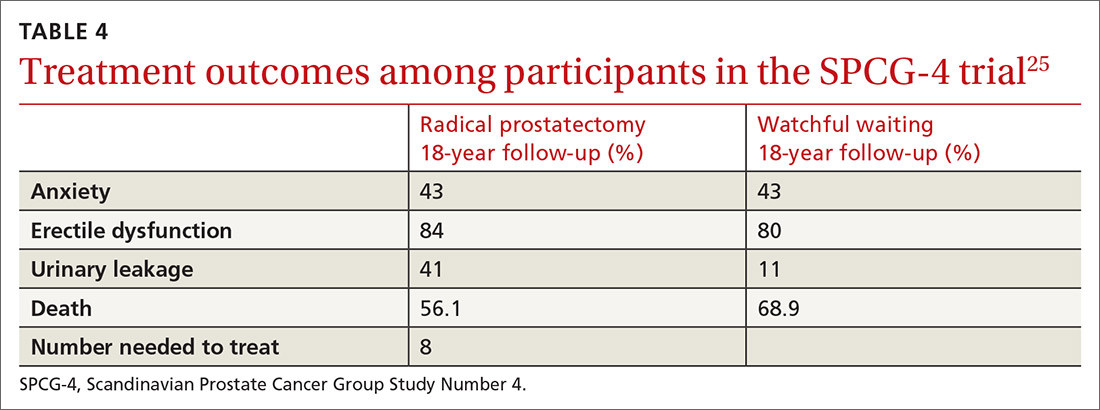

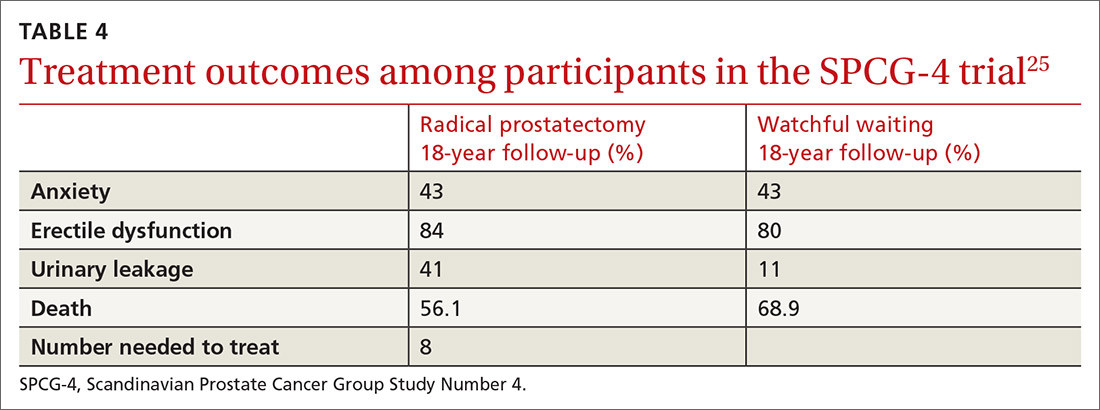

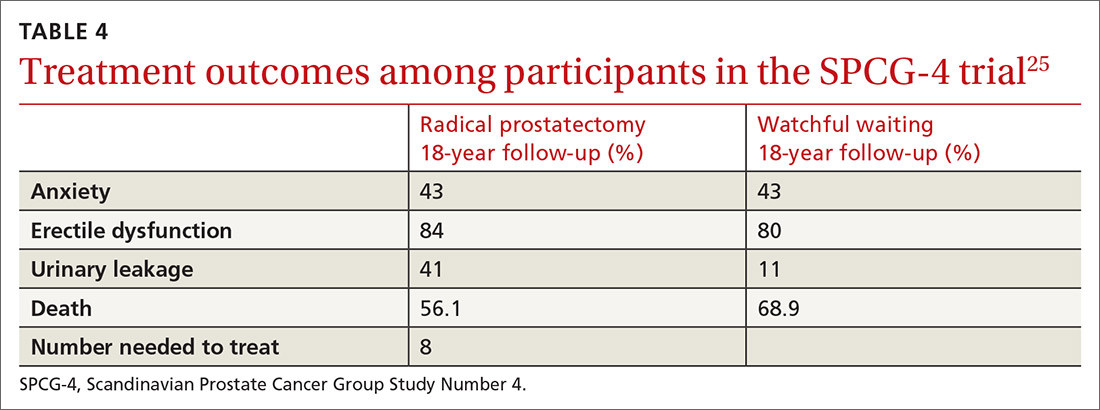

SPCG-4 showed survival benefits for men who underwent radical prostatectomy compared with men in a watchful waiting group, but only 5% of the study cohort had cancer detected by PSA screening (TABLE 4).25 The rest had either palpable tumors or symptoms of a tumor.

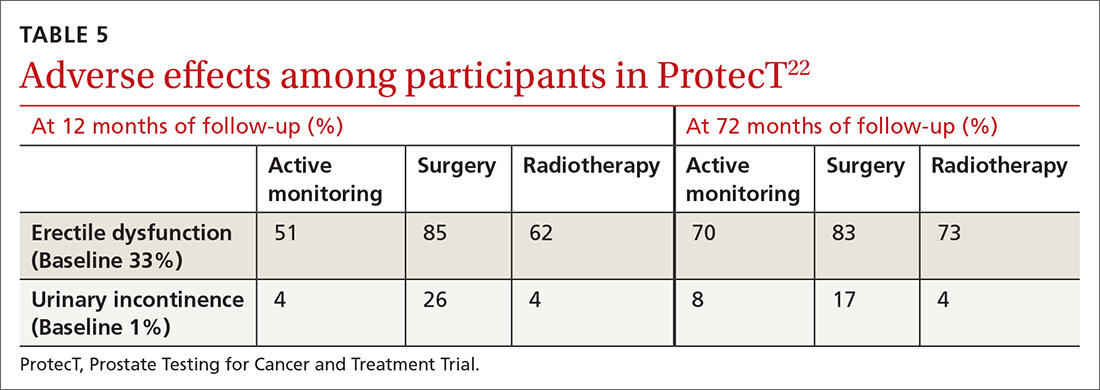

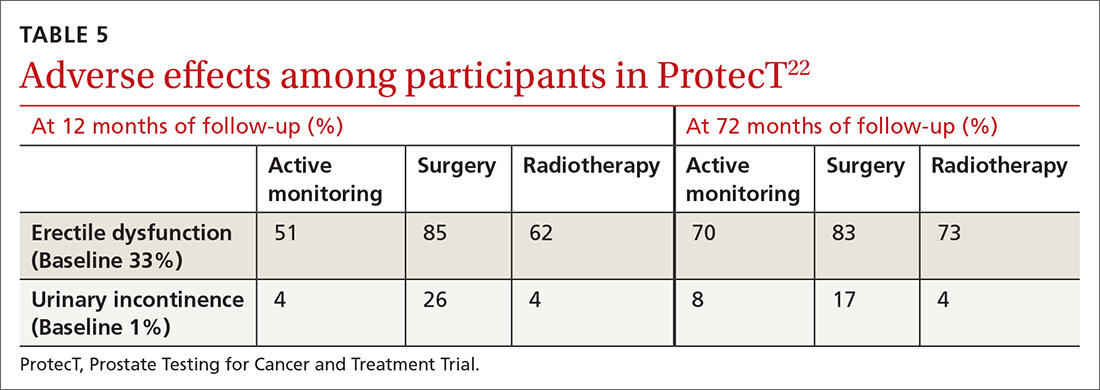

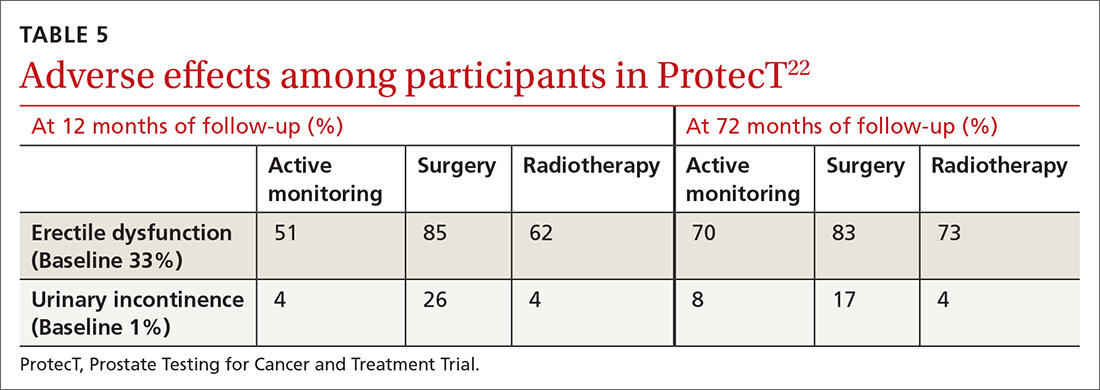

ProtecT, which followed patients with localized prostate cancer for more than 10 years,compared the outcomes and adverse effects of active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, and radiotherapy.23 Prostate cancer–specific mortality was low irrespective of the treatment,23 and there was no significant difference in all-cause mortality or prostate cancer–specific mortality between the 3 treatment groups.23 The active surveillance group had considerably fewer adverse events.22,23 The incidence rates of erectile dysfunction and urinary incontinence at the 1- and 6-year follow-up marks are outlined in TABLE 5.22

Continue to: The purpose of active monitoring...

The purpose of active monitoring is to minimize overtreatment by avoiding immediate radical intervention. Radical treatments with curative intent can be undertaken at any point while patients are being actively monitored. It is important to note that the active monitoring that took place in ProtecT23 was very different from the passive surveillance of PIVOT24 and SPCG-4.25 In ProtecT, once an elevated serum PSA level was noted, PSA levels were monitored every 3 months in the first year and every 6 to 12 months thereafter.23 Triggers to reassess patients and consider a change in clinical management were based largely on changes in PSA levels. Participants with an increase of at least 50% in PSA level during the previous 12 months were offered either continued monitoring or treatment after further testing.

Making individualized decisions about prostate cancer screening

Traditionally, the goal of cancer screening has been to maximize the number of people screened. Generally, the information provided to patients about cancer screening emphasizes the benefits and minimizes the harms. Recently, however, there has been a shift in communication about cancer screening with the emphasis now being placed on informed decision-making and encouraging patients to make individual decisions about screening participation.26

The treatment option of active surveillance, with its lower incidence of adverse outcomes, is an important reason for patients to make individualized decisions about prostate cancer screening.

Another reason relates to 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors. Although their role in the management of prostate cancer is currently not well defined, a reduction of almost 25% in the risk of prostate cancer and improvement in the performance of PSA has been reported.27

And yet another reason is that there are alternate strategies to manage the majority of patients who have been diagnosed with low-risk disease through transrectal ultrasound biopsy. The ERSPC study mentions multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging combined with targeted biopsy to identify high-grade disease.28,29 Genetic and epigenetic assays of the biopsied tissue can help grade disease based on aggressiveness.30 Transperineal mapping biopsy using a mapping software program can identify specific disease sites within the prostate gland, so that patients can be offered the option of targeted therapy.30

Continue to: Applying shared decision-making to prostate cancer screening

Applying shared decision-making to prostate cancer screening

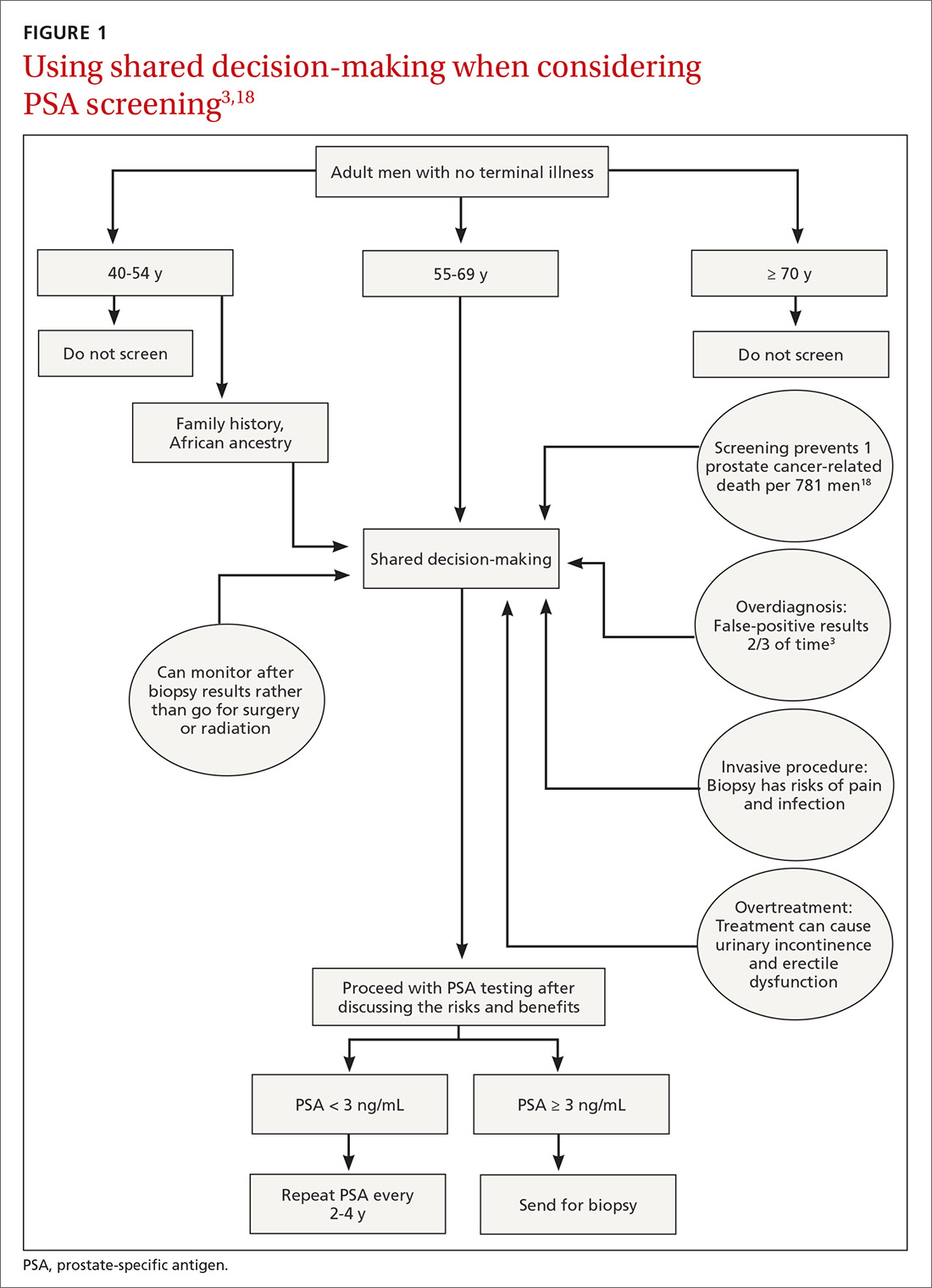

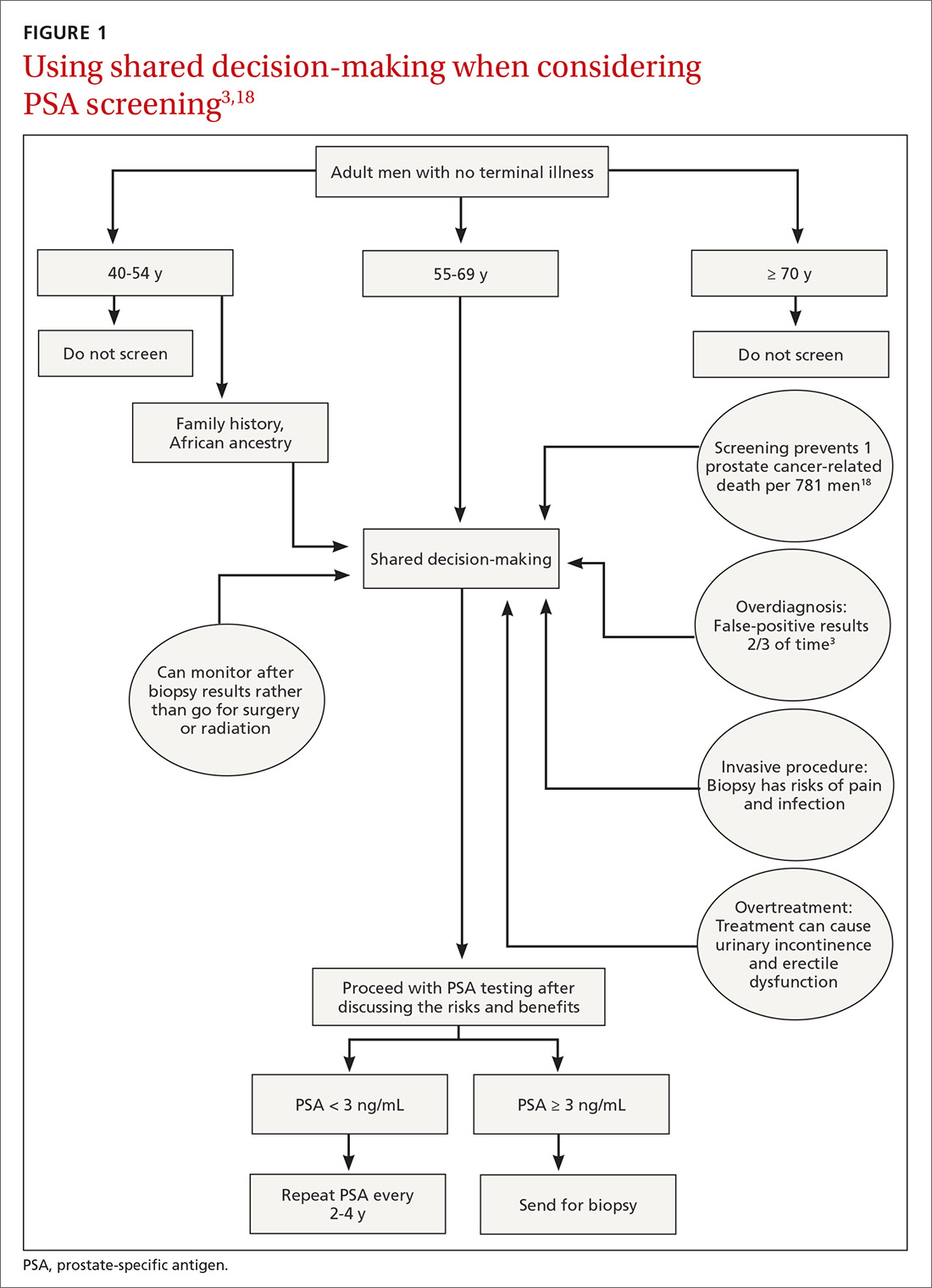

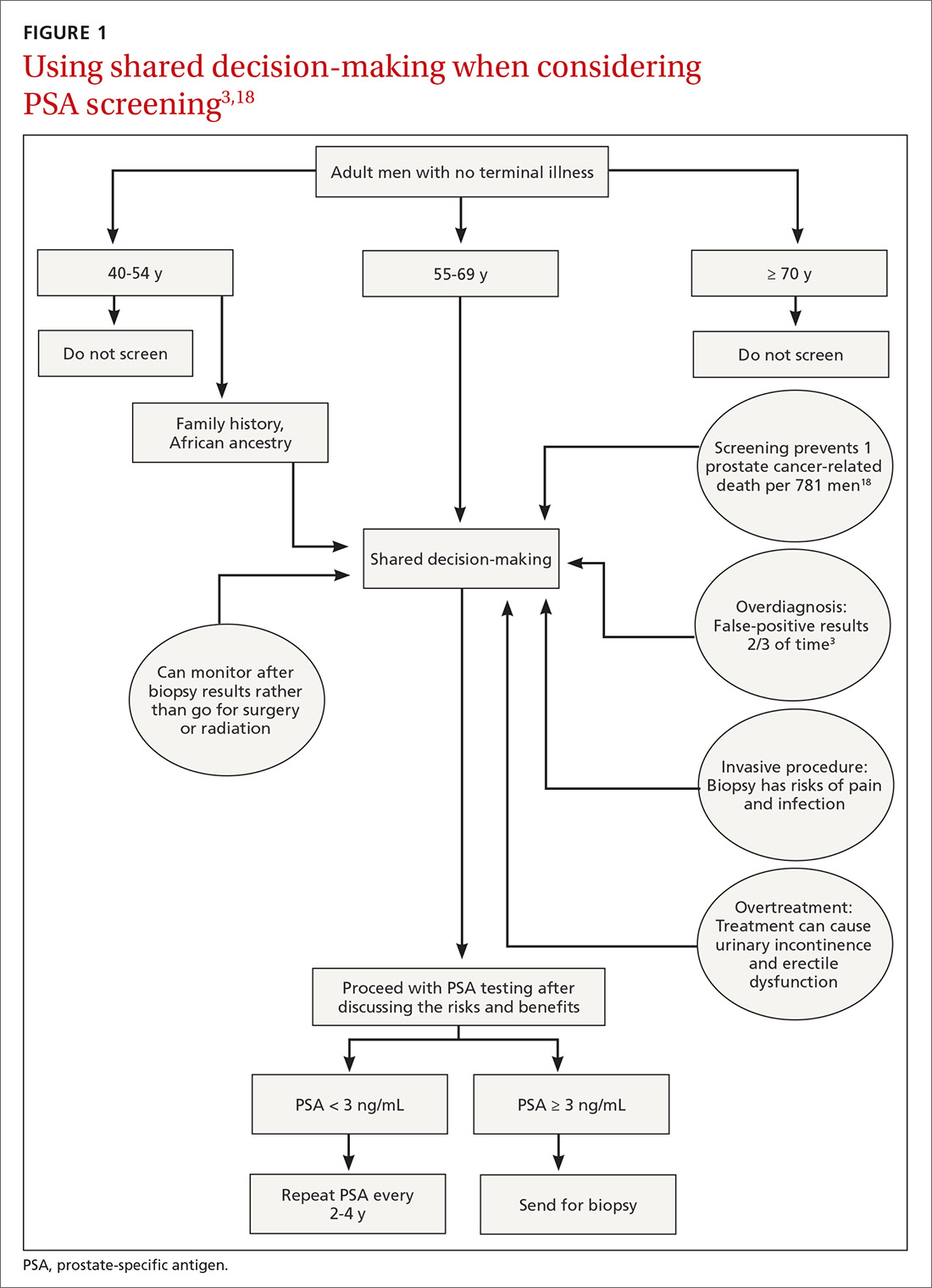

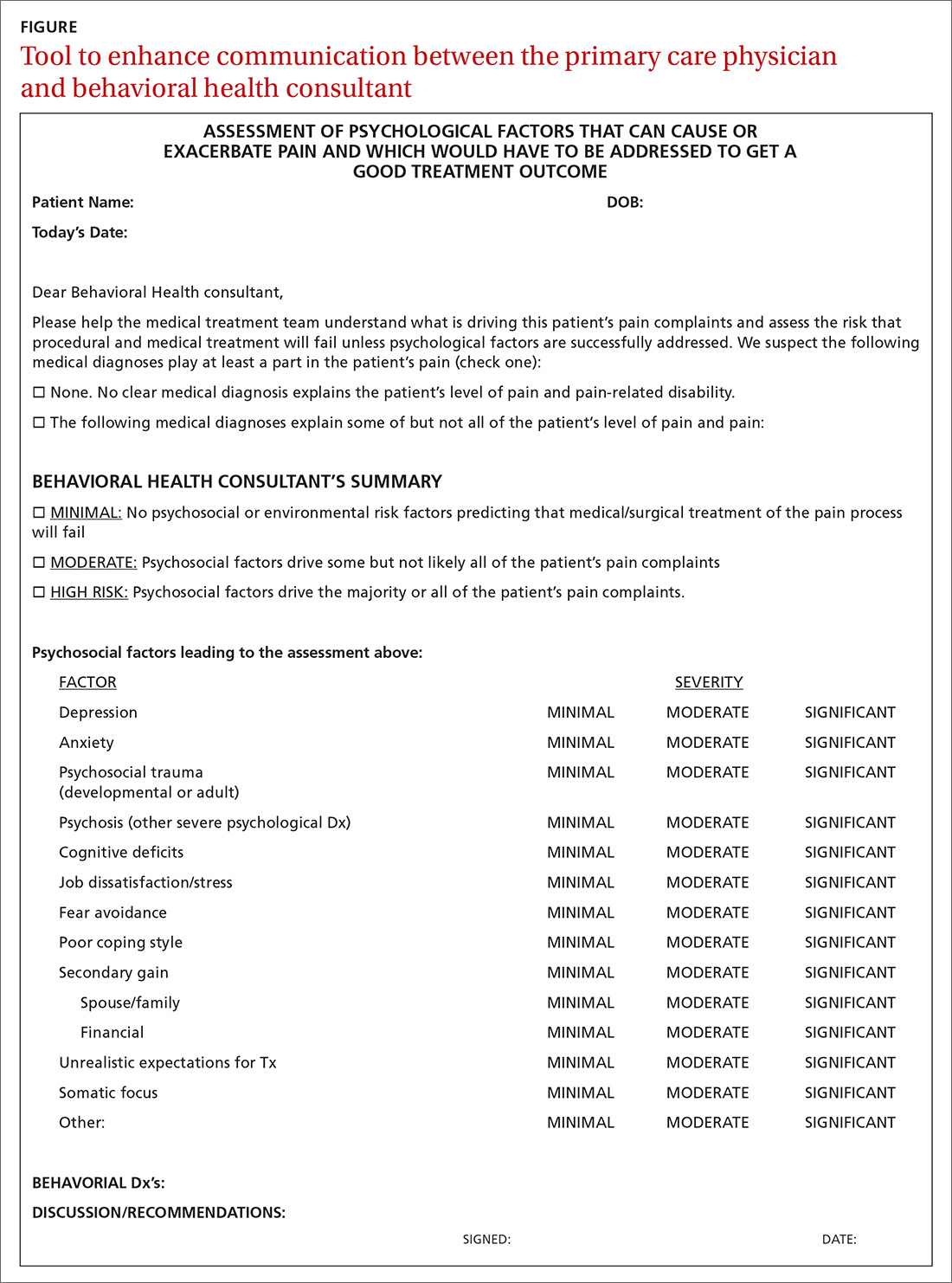

Balancing errors of omission with errors of commission is challenging. Shared decision-making (SDM) is an approach whereby clinicians and patients share the best available evidence when faced with the task of medical decision-making and in which patients are supported while they consider their options and achieve their preferences.31 SDM is well supported by evidence from a number of RCTs and results in increased knowledge, involvement, and confidence on the part of patients.32 An individualized approach using the schematic diagram (FIGURE 13,18) may be helpful.

Barriers to SDM success. Many factors can interfere with the success of SDM including limited or poor communication; lack of time during busy office visits; and patients’ cultural, informational, and/or emotional needs. To improve patient-centered communication, we can: (1) make information understandable and available to patients and families; (2) prioritize training in communication; (3) use decision aid tools to facilitate communication; and (4) work to improve the payment model to incentivize patient-centered communication. Tools that facilitate SDM include videotapes, patient group discussions, brief scripts read to patients, and informational pamphlets. One such tool is the American Society for Clinical Oncology’s decision aid tool for PSA testing.33

Limited knowledge among patients. Decisions regarding treatment among men diagnosed with localized prostate cancer can be difficult because there are several treatment options with similar prognoses, but there are differences in adverse effects. One population-based cohort study of men with newly diagnosed localized prostate cancer found that most men had significant knowledge deficits regarding the survival benefits of the 2 major treatment options—surgery and radiation.34 In a large population-based study, 38% of men with localized prostate cancer reported receiving help from their primary care providers in the decision-making process for treatment.35

Learning to employ SDM. Elwyn et al proposed a 3-step model to incorporate SDM into clinical practice.31 They described key steps that include: choice talk (making sure patients are informed about the reasonable options), option talk (providing more detailed information about the options), and decision talk (supporting the work of patients considering their preferences and deciding what is best). Properly employing these methods requires training using simulations.31

The bottom line

Although current guidelines regarding PSA screening differ by organization, generally speaking PSA screening should be offered only to men with a life expectancy > 10 years. The PSA test has low sensitivity and specificity and lacks a clear cut-off value that warrants prostate biopsy. Men who choose to have PSA testing increase their chances of detecting prostate cancer, but most prostate cancers are slow growing and do not cause death. The decision to undergo PSA screening should be made by both the provider and the patient, after a discussion of the limited benefits and associated harms. The interval of follow-up screening may vary from 2 to 4 years depending on patient age, level of PSA, and whether a patient is taking medications such as 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jaividhya Dasarathy, MD, FAAFP, 2500 Metro Health Medical Drive, Cleveland, Ohio 44109; [email protected].

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7-30.

2. National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Prostate Cancer. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html. Accessed January 16, 2020.

3. American Cancer Society. Key statistics for prostate cancer. Last revised August 1, 2019. www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/about/key-statistics.html. Accessed January 16, 2020.

4. Brawley OW. Trends in prostate cancer in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;2012:152-156.

5. Powell IJ. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of prostate cancer in African-American men. J Urol. 2007;177:444-449.

6. Catalona WJ, Smith DS, Ratliff TL, et al. Measurement of prostate-specific antigen in serum as a screening test for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1156-1161.

7. Jacobsen SJ, Katusic SK, Bergstraih EJ. Incidence of prostate cancer diagnosis in the eras before and after serum prostate-specific antigen testing. JAMA. 1995;274:1445-1449.

8. Mistry K, Cable G. Meta-analysis of prostate-specific antigen and digital rectal examination as screening tests for prostate carcinoma. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16:95-101.

9. Qaseem A, Barry MJ, Denberg TD, et al. Screening for prostate cancer: a guidance statement from the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Int Med. 2013;158:761-769.

10. Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL 3rd, et al. Prostate cancer screening in the randomized Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial: mortality results after 13 years of follow-up. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:125-132.

11. Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1320-1328.

12. American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society recommendations for prostate cancer early detection. Last revised August 1, 2019. www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/acs-recommendations.html. Accessed January 16, 2020.

13. American Urologic Association. Early detection of prostate cancer (2018). Reviewed 2018. https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/prostate-cancer-early-detection-guideline. Accessed January 16, 2020.

14. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Prostate Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319:1901-1913.

15 Moyer VA. Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Int Med. 2012;157:120-134.

16. Labrie F, Candas B, Dupont A, et al. Screening decreases prostate cancer death: first analysis of the 1988 Quebec prospective randomized controlled trial. Prostate. 1999;38:83-91.

17. Sandblom G, Varenhorst E, Rosell J, et al. Randomised prostate cancer screening trial: 20-year follow-up. BMJ. 2011;342:d1539.

18. Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet. 2014;384:2027-2035.

19. McNaughton-Collins M, Fowler FJ Jr, Caubet JF, et al. Psychological effects of a suspicious prostate cancer screening test followed by a benign biopsy result. Am J Med. 2004;117:719-725.

20 Raaijmakers R, Kirkels WJ, Roobol MJ, et al. Complication rates and risk factors of 5802 transrectal ultrasound-guided sextant biopsies of the prostate within a population-based screening program. Urology. 2002;60:826-830.

21. Loeb S, Carter HB, Berndt SI, et al. Complications after prostate biopsy: data from SEER-Medicare. J Urol. 2011;186:1830-1834.

22. Donovan J, Hamdy F, Lane J, et al. Patient-reported outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1425-1437.

23. Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al. 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1415-1424.

24. Wilt TJ, Jones KM, Barry MJ, et al. Follow-up of prostatectomy versus observation for early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:132-142.

25. Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Garmo H, et al. Radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2319-2329.

26. Hersch JK, Nickel BL, Ghanouni A, et al. Improving communication about cancer screening: moving towards informed decision making. Public Health Res Pract. 2017;27(2).

27. Cuzick J, Thorat MA, Andriole G, et al. Prevention and early detection of prostate cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e484-e492.

28. Pinto PA, Chung PH, Rastinehad AR, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging/ultrasound fusion guided prostate biopsy improves cancer detection following transrectal ultrasound biopsy and correlates with multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. J Urol. 2011;186:1281-1285.

29. Kuru TH, Roethke MC, Seidenader J, et al. Critical evaluation of magnetic resonance imaging targeted, transrectal ultrasound guided transperineal fusion biopsy for detection of prostate cancer. J Urol. 2013;190:1380-1386.

30. Crawford ED, Rove KO, Barqawi AB, et al. Clinical-pathologic correlation between transperineal mapping biopsies of the prostate and three-dimensional reconstruction of prostatectomy specimens. Prostate. 2013;73:778-787.

31. Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1361-1367.

32. Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD001431.

33. ASCO. Decision aid tool: prostate cancer screening with PSA testing. https://www.asco.org/sites/new-www.asco.org/files/content-files/practice-and-guidelines/documents/2012-psa-pco-decision-aid.pdf. Accessed January 16, 2020.

34. Daum LM, Reamer EN, Ruterbusch JJ, et al. Patient knowledge and qualities of treatment decisions for localized prostate cancer. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30:288-297.

35. Radhakrishnan A, Grande D, Ross M, et al. When primary care providers (PCPs) help patients choose prostate cancer treatment. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30:298-307.

Prostate cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer in men and the third leading cause of cancer death in men worldwide.1 An estimated 174,650 new cases are diagnosed each year in the United States; 31,620 American men die annually from the disease.2 Although prostate cancer can be a serious disease, many men do not die from it. In fact, 2.9 million men who were diagnosed with prostate cancer at some point are alive today.3

Risk factors. Prostate cancer develops mainly in men ages ≥ 65 years and rarely occurs before age 40. In addition to age, family history and African American ethnicity are the major nonmodifiable risk factors for prostate cancer.4 From the 1970s to the most recent statistical analysis of the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program, African American men have continued to have significantly higher incidence of, and mortality rates from, prostate cancer than their European American counterparts. African American men are also more likely than men of European ancestry to have aggressive prostate cancers.5 Other risk factors include geographic location (higher risk in Northern Europe, North America, and Australia; lower risk in Asia, Africa, and South and Central America), mutations in the BRCA2 gene, and hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer syndrome.4

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) was first used as a screening tool for prostate cancer in 1991.6 Prostate cancer incidence, especially organ-confined disease, has dramatically increased since then.7 PSA testing has a low sensitivity and specificity for the detection of prostate cancer, and there is no clear threshold at which biopsy can or should be offered. The most commonly used cutoff value of 4 ng/mL has a false-positive rate of about 70%.8

Benign prostatic conditions such as hypertrophy and infection can elevate PSA levels. In addition, the PSA test does not distinguish between aggressive and slow-growing cancers, and about 15% of patients with prostate cancer have a normal PSA level.9

A word about the digital rectal exam. While PSA testing has been the mainstay of prostate cancer screening, a few studies have included digital rectal exam (DRE) in their protocols. Data from the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial showed that DRE captured an additional 2% of men with prostate cancer in the setting of a normal PSA test result.10 In the Rotterdam arm of the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) trial, the overall detection rate for prostate cancer was found to be better when DRE was combined with PSA and prostate biopsy than when DRE was used alone (4.5% vs 2.5%).11 Nevertheless, generally speaking, DRE can be omitted in the era of PSA screening.

Screening guidelines vary

Recommendations for prostate cancer screening vary by organization and are summarized in TABLE 1.9,12-14 In 2012, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended against PSA-based screening for prostate cancer (Category D).15 In 2018, USPSTF provided an update with a new recommendation that clinicians inform men ages 55 to 69 years about the potential benefits and harms of PSA-based screening (Category C).14 The USPSTF continues to recommend against PSA-based screening for men ages ≥ 70 years (Category D).14

Does PSA-based screening improve patient-centered outcomes?

Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) such as the Quebec Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial,16 the Norrköping Sweden Study,17 ERSPC,11 and PLCO10 have been conducted to assess the benefits of PSA testing. PLCO and ERSPC have contributed significantly to our understanding of prostate cancer screening even though their 13-year follow-up results are conflicting (TABLE 2).10,11,18

Continue to: In the ERSPC 13-year follow-up publication...

In the ERSPC 13-year follow-up publication, the authors concluded that a substantial reduction in prostate cancer mortality is attributable to testing with PSA.18 Despite limitations in the study design (eg, France entered after 2 years, screening intervals varied between 2 and 4 years, biopsy indications varied, and screening was discontinued at different times), PSA screening detected more prostate cancer than was detected in the control arm (10.2% vs 6.8%).

In the initial 11 years of follow-up, the study group experienced a 21% reduction in prostate cancer mortality, even though the absolute decrease ranged from only 0.6% (545 per 89,352) to 0.5% (355 per 72,891). The updated absolute risk reduction of death from prostate cancer at 13 years of follow-up showed a larger benefit: 0.11 per 1000 person-years or 1.28 per 1000 men randomized, which is equivalent to 1 prostate cancer death averted per 781 (95% confidence interval [CI], 490-1929) men invited for screening, or 1 per 27 (17-66) additional prostate cancers detected.

The PLCO trial did not show any significant difference in prostate cancer detection (11.1% screened vs 9.9% control), and there was no improvement in prostate cancer mortality (3.7 vs 3.4 death per 10,000 person-years).10 However, the PLCO trial suffered from issues of contamination, which may have influenced the overall results. About 52% of men in the control (usual care) group received a PSA test at some point during the study. And more than two-thirds of the men who had a prostate biopsy because of a positive PSA test did not have prostate cancer.

Community standards for the PSA threshold for biopsy were applied in various centers (> 4 ng/ml in general) in PLCO, whereas in ERSPC, a cut-off PSA value ≥ 3 ng/mL was used for biopsy. Because of the lower PSA threshold, ERSPC may have identified cancers that would have had good outcomes without any intervention.

The harms of PSA screening

While it is unclear whether PSA screening results in any improvement in patient-centered outcomes, it does lead to downstream intervention due to overdiagnosis, which precipitates unnecessary anxiety, biopsies, and overtreatment (eg, excess radiation, overuse of androgen deprivation therapy).19 Biopsies carry the risk of hematuria (22.6%), hematospermia (50.4%), and urinary tract infection.20 Data from SEER-Medicare showed that prostate biopsy was associated with a 2.65-fold increased risk of hospitalization within 30 days of the procedure compared to a control population.21

Continue to: Overdiagnosis leads to overtreatment...

Overdiagnosis leads to overtreatment of low-risk prostate cancer. Both traditional treatment options for prostate cancer—radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy—are associated with urinary incontinence, erectile dysfunction, and issues with bowel function.22,23

The Prostate Cancer Intervention vs Observation Trial (PIVOT),24 the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group Study Number 4 (SPCG-4),25 and the Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment (ProtecT) trial,22,23 are the major RCTs that looked at the outcomes of treatment modalities for localized prostate cancer in the modern era of PSA testing.

PIVOT compared passive observation with radical prostatectomy.24 After 20 years of follow-up on 731 patients, the researchers concluded that radical prostatectomy did not reduce all-cause or prostate cancer–related mortality (TABLE 3).24

SPCG-4 showed survival benefits for men who underwent radical prostatectomy compared with men in a watchful waiting group, but only 5% of the study cohort had cancer detected by PSA screening (TABLE 4).25 The rest had either palpable tumors or symptoms of a tumor.

ProtecT, which followed patients with localized prostate cancer for more than 10 years,compared the outcomes and adverse effects of active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, and radiotherapy.23 Prostate cancer–specific mortality was low irrespective of the treatment,23 and there was no significant difference in all-cause mortality or prostate cancer–specific mortality between the 3 treatment groups.23 The active surveillance group had considerably fewer adverse events.22,23 The incidence rates of erectile dysfunction and urinary incontinence at the 1- and 6-year follow-up marks are outlined in TABLE 5.22

Continue to: The purpose of active monitoring...

The purpose of active monitoring is to minimize overtreatment by avoiding immediate radical intervention. Radical treatments with curative intent can be undertaken at any point while patients are being actively monitored. It is important to note that the active monitoring that took place in ProtecT23 was very different from the passive surveillance of PIVOT24 and SPCG-4.25 In ProtecT, once an elevated serum PSA level was noted, PSA levels were monitored every 3 months in the first year and every 6 to 12 months thereafter.23 Triggers to reassess patients and consider a change in clinical management were based largely on changes in PSA levels. Participants with an increase of at least 50% in PSA level during the previous 12 months were offered either continued monitoring or treatment after further testing.

Making individualized decisions about prostate cancer screening

Traditionally, the goal of cancer screening has been to maximize the number of people screened. Generally, the information provided to patients about cancer screening emphasizes the benefits and minimizes the harms. Recently, however, there has been a shift in communication about cancer screening with the emphasis now being placed on informed decision-making and encouraging patients to make individual decisions about screening participation.26

The treatment option of active surveillance, with its lower incidence of adverse outcomes, is an important reason for patients to make individualized decisions about prostate cancer screening.

Another reason relates to 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors. Although their role in the management of prostate cancer is currently not well defined, a reduction of almost 25% in the risk of prostate cancer and improvement in the performance of PSA has been reported.27

And yet another reason is that there are alternate strategies to manage the majority of patients who have been diagnosed with low-risk disease through transrectal ultrasound biopsy. The ERSPC study mentions multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging combined with targeted biopsy to identify high-grade disease.28,29 Genetic and epigenetic assays of the biopsied tissue can help grade disease based on aggressiveness.30 Transperineal mapping biopsy using a mapping software program can identify specific disease sites within the prostate gland, so that patients can be offered the option of targeted therapy.30

Continue to: Applying shared decision-making to prostate cancer screening

Applying shared decision-making to prostate cancer screening

Balancing errors of omission with errors of commission is challenging. Shared decision-making (SDM) is an approach whereby clinicians and patients share the best available evidence when faced with the task of medical decision-making and in which patients are supported while they consider their options and achieve their preferences.31 SDM is well supported by evidence from a number of RCTs and results in increased knowledge, involvement, and confidence on the part of patients.32 An individualized approach using the schematic diagram (FIGURE 13,18) may be helpful.

Barriers to SDM success. Many factors can interfere with the success of SDM including limited or poor communication; lack of time during busy office visits; and patients’ cultural, informational, and/or emotional needs. To improve patient-centered communication, we can: (1) make information understandable and available to patients and families; (2) prioritize training in communication; (3) use decision aid tools to facilitate communication; and (4) work to improve the payment model to incentivize patient-centered communication. Tools that facilitate SDM include videotapes, patient group discussions, brief scripts read to patients, and informational pamphlets. One such tool is the American Society for Clinical Oncology’s decision aid tool for PSA testing.33

Limited knowledge among patients. Decisions regarding treatment among men diagnosed with localized prostate cancer can be difficult because there are several treatment options with similar prognoses, but there are differences in adverse effects. One population-based cohort study of men with newly diagnosed localized prostate cancer found that most men had significant knowledge deficits regarding the survival benefits of the 2 major treatment options—surgery and radiation.34 In a large population-based study, 38% of men with localized prostate cancer reported receiving help from their primary care providers in the decision-making process for treatment.35

Learning to employ SDM. Elwyn et al proposed a 3-step model to incorporate SDM into clinical practice.31 They described key steps that include: choice talk (making sure patients are informed about the reasonable options), option talk (providing more detailed information about the options), and decision talk (supporting the work of patients considering their preferences and deciding what is best). Properly employing these methods requires training using simulations.31

The bottom line

Although current guidelines regarding PSA screening differ by organization, generally speaking PSA screening should be offered only to men with a life expectancy > 10 years. The PSA test has low sensitivity and specificity and lacks a clear cut-off value that warrants prostate biopsy. Men who choose to have PSA testing increase their chances of detecting prostate cancer, but most prostate cancers are slow growing and do not cause death. The decision to undergo PSA screening should be made by both the provider and the patient, after a discussion of the limited benefits and associated harms. The interval of follow-up screening may vary from 2 to 4 years depending on patient age, level of PSA, and whether a patient is taking medications such as 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jaividhya Dasarathy, MD, FAAFP, 2500 Metro Health Medical Drive, Cleveland, Ohio 44109; [email protected].

Prostate cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer in men and the third leading cause of cancer death in men worldwide.1 An estimated 174,650 new cases are diagnosed each year in the United States; 31,620 American men die annually from the disease.2 Although prostate cancer can be a serious disease, many men do not die from it. In fact, 2.9 million men who were diagnosed with prostate cancer at some point are alive today.3

Risk factors. Prostate cancer develops mainly in men ages ≥ 65 years and rarely occurs before age 40. In addition to age, family history and African American ethnicity are the major nonmodifiable risk factors for prostate cancer.4 From the 1970s to the most recent statistical analysis of the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program, African American men have continued to have significantly higher incidence of, and mortality rates from, prostate cancer than their European American counterparts. African American men are also more likely than men of European ancestry to have aggressive prostate cancers.5 Other risk factors include geographic location (higher risk in Northern Europe, North America, and Australia; lower risk in Asia, Africa, and South and Central America), mutations in the BRCA2 gene, and hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer syndrome.4

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) was first used as a screening tool for prostate cancer in 1991.6 Prostate cancer incidence, especially organ-confined disease, has dramatically increased since then.7 PSA testing has a low sensitivity and specificity for the detection of prostate cancer, and there is no clear threshold at which biopsy can or should be offered. The most commonly used cutoff value of 4 ng/mL has a false-positive rate of about 70%.8

Benign prostatic conditions such as hypertrophy and infection can elevate PSA levels. In addition, the PSA test does not distinguish between aggressive and slow-growing cancers, and about 15% of patients with prostate cancer have a normal PSA level.9

A word about the digital rectal exam. While PSA testing has been the mainstay of prostate cancer screening, a few studies have included digital rectal exam (DRE) in their protocols. Data from the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial showed that DRE captured an additional 2% of men with prostate cancer in the setting of a normal PSA test result.10 In the Rotterdam arm of the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) trial, the overall detection rate for prostate cancer was found to be better when DRE was combined with PSA and prostate biopsy than when DRE was used alone (4.5% vs 2.5%).11 Nevertheless, generally speaking, DRE can be omitted in the era of PSA screening.

Screening guidelines vary

Recommendations for prostate cancer screening vary by organization and are summarized in TABLE 1.9,12-14 In 2012, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended against PSA-based screening for prostate cancer (Category D).15 In 2018, USPSTF provided an update with a new recommendation that clinicians inform men ages 55 to 69 years about the potential benefits and harms of PSA-based screening (Category C).14 The USPSTF continues to recommend against PSA-based screening for men ages ≥ 70 years (Category D).14

Does PSA-based screening improve patient-centered outcomes?

Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) such as the Quebec Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial,16 the Norrköping Sweden Study,17 ERSPC,11 and PLCO10 have been conducted to assess the benefits of PSA testing. PLCO and ERSPC have contributed significantly to our understanding of prostate cancer screening even though their 13-year follow-up results are conflicting (TABLE 2).10,11,18

Continue to: In the ERSPC 13-year follow-up publication...

In the ERSPC 13-year follow-up publication, the authors concluded that a substantial reduction in prostate cancer mortality is attributable to testing with PSA.18 Despite limitations in the study design (eg, France entered after 2 years, screening intervals varied between 2 and 4 years, biopsy indications varied, and screening was discontinued at different times), PSA screening detected more prostate cancer than was detected in the control arm (10.2% vs 6.8%).

In the initial 11 years of follow-up, the study group experienced a 21% reduction in prostate cancer mortality, even though the absolute decrease ranged from only 0.6% (545 per 89,352) to 0.5% (355 per 72,891). The updated absolute risk reduction of death from prostate cancer at 13 years of follow-up showed a larger benefit: 0.11 per 1000 person-years or 1.28 per 1000 men randomized, which is equivalent to 1 prostate cancer death averted per 781 (95% confidence interval [CI], 490-1929) men invited for screening, or 1 per 27 (17-66) additional prostate cancers detected.

The PLCO trial did not show any significant difference in prostate cancer detection (11.1% screened vs 9.9% control), and there was no improvement in prostate cancer mortality (3.7 vs 3.4 death per 10,000 person-years).10 However, the PLCO trial suffered from issues of contamination, which may have influenced the overall results. About 52% of men in the control (usual care) group received a PSA test at some point during the study. And more than two-thirds of the men who had a prostate biopsy because of a positive PSA test did not have prostate cancer.

Community standards for the PSA threshold for biopsy were applied in various centers (> 4 ng/ml in general) in PLCO, whereas in ERSPC, a cut-off PSA value ≥ 3 ng/mL was used for biopsy. Because of the lower PSA threshold, ERSPC may have identified cancers that would have had good outcomes without any intervention.

The harms of PSA screening

While it is unclear whether PSA screening results in any improvement in patient-centered outcomes, it does lead to downstream intervention due to overdiagnosis, which precipitates unnecessary anxiety, biopsies, and overtreatment (eg, excess radiation, overuse of androgen deprivation therapy).19 Biopsies carry the risk of hematuria (22.6%), hematospermia (50.4%), and urinary tract infection.20 Data from SEER-Medicare showed that prostate biopsy was associated with a 2.65-fold increased risk of hospitalization within 30 days of the procedure compared to a control population.21

Continue to: Overdiagnosis leads to overtreatment...

Overdiagnosis leads to overtreatment of low-risk prostate cancer. Both traditional treatment options for prostate cancer—radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy—are associated with urinary incontinence, erectile dysfunction, and issues with bowel function.22,23

The Prostate Cancer Intervention vs Observation Trial (PIVOT),24 the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group Study Number 4 (SPCG-4),25 and the Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment (ProtecT) trial,22,23 are the major RCTs that looked at the outcomes of treatment modalities for localized prostate cancer in the modern era of PSA testing.

PIVOT compared passive observation with radical prostatectomy.24 After 20 years of follow-up on 731 patients, the researchers concluded that radical prostatectomy did not reduce all-cause or prostate cancer–related mortality (TABLE 3).24

SPCG-4 showed survival benefits for men who underwent radical prostatectomy compared with men in a watchful waiting group, but only 5% of the study cohort had cancer detected by PSA screening (TABLE 4).25 The rest had either palpable tumors or symptoms of a tumor.

ProtecT, which followed patients with localized prostate cancer for more than 10 years,compared the outcomes and adverse effects of active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, and radiotherapy.23 Prostate cancer–specific mortality was low irrespective of the treatment,23 and there was no significant difference in all-cause mortality or prostate cancer–specific mortality between the 3 treatment groups.23 The active surveillance group had considerably fewer adverse events.22,23 The incidence rates of erectile dysfunction and urinary incontinence at the 1- and 6-year follow-up marks are outlined in TABLE 5.22

Continue to: The purpose of active monitoring...

The purpose of active monitoring is to minimize overtreatment by avoiding immediate radical intervention. Radical treatments with curative intent can be undertaken at any point while patients are being actively monitored. It is important to note that the active monitoring that took place in ProtecT23 was very different from the passive surveillance of PIVOT24 and SPCG-4.25 In ProtecT, once an elevated serum PSA level was noted, PSA levels were monitored every 3 months in the first year and every 6 to 12 months thereafter.23 Triggers to reassess patients and consider a change in clinical management were based largely on changes in PSA levels. Participants with an increase of at least 50% in PSA level during the previous 12 months were offered either continued monitoring or treatment after further testing.

Making individualized decisions about prostate cancer screening

Traditionally, the goal of cancer screening has been to maximize the number of people screened. Generally, the information provided to patients about cancer screening emphasizes the benefits and minimizes the harms. Recently, however, there has been a shift in communication about cancer screening with the emphasis now being placed on informed decision-making and encouraging patients to make individual decisions about screening participation.26

The treatment option of active surveillance, with its lower incidence of adverse outcomes, is an important reason for patients to make individualized decisions about prostate cancer screening.

Another reason relates to 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors. Although their role in the management of prostate cancer is currently not well defined, a reduction of almost 25% in the risk of prostate cancer and improvement in the performance of PSA has been reported.27

And yet another reason is that there are alternate strategies to manage the majority of patients who have been diagnosed with low-risk disease through transrectal ultrasound biopsy. The ERSPC study mentions multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging combined with targeted biopsy to identify high-grade disease.28,29 Genetic and epigenetic assays of the biopsied tissue can help grade disease based on aggressiveness.30 Transperineal mapping biopsy using a mapping software program can identify specific disease sites within the prostate gland, so that patients can be offered the option of targeted therapy.30

Continue to: Applying shared decision-making to prostate cancer screening

Applying shared decision-making to prostate cancer screening

Balancing errors of omission with errors of commission is challenging. Shared decision-making (SDM) is an approach whereby clinicians and patients share the best available evidence when faced with the task of medical decision-making and in which patients are supported while they consider their options and achieve their preferences.31 SDM is well supported by evidence from a number of RCTs and results in increased knowledge, involvement, and confidence on the part of patients.32 An individualized approach using the schematic diagram (FIGURE 13,18) may be helpful.

Barriers to SDM success. Many factors can interfere with the success of SDM including limited or poor communication; lack of time during busy office visits; and patients’ cultural, informational, and/or emotional needs. To improve patient-centered communication, we can: (1) make information understandable and available to patients and families; (2) prioritize training in communication; (3) use decision aid tools to facilitate communication; and (4) work to improve the payment model to incentivize patient-centered communication. Tools that facilitate SDM include videotapes, patient group discussions, brief scripts read to patients, and informational pamphlets. One such tool is the American Society for Clinical Oncology’s decision aid tool for PSA testing.33

Limited knowledge among patients. Decisions regarding treatment among men diagnosed with localized prostate cancer can be difficult because there are several treatment options with similar prognoses, but there are differences in adverse effects. One population-based cohort study of men with newly diagnosed localized prostate cancer found that most men had significant knowledge deficits regarding the survival benefits of the 2 major treatment options—surgery and radiation.34 In a large population-based study, 38% of men with localized prostate cancer reported receiving help from their primary care providers in the decision-making process for treatment.35

Learning to employ SDM. Elwyn et al proposed a 3-step model to incorporate SDM into clinical practice.31 They described key steps that include: choice talk (making sure patients are informed about the reasonable options), option talk (providing more detailed information about the options), and decision talk (supporting the work of patients considering their preferences and deciding what is best). Properly employing these methods requires training using simulations.31

The bottom line

Although current guidelines regarding PSA screening differ by organization, generally speaking PSA screening should be offered only to men with a life expectancy > 10 years. The PSA test has low sensitivity and specificity and lacks a clear cut-off value that warrants prostate biopsy. Men who choose to have PSA testing increase their chances of detecting prostate cancer, but most prostate cancers are slow growing and do not cause death. The decision to undergo PSA screening should be made by both the provider and the patient, after a discussion of the limited benefits and associated harms. The interval of follow-up screening may vary from 2 to 4 years depending on patient age, level of PSA, and whether a patient is taking medications such as 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jaividhya Dasarathy, MD, FAAFP, 2500 Metro Health Medical Drive, Cleveland, Ohio 44109; [email protected].

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7-30.

2. National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Prostate Cancer. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html. Accessed January 16, 2020.

3. American Cancer Society. Key statistics for prostate cancer. Last revised August 1, 2019. www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/about/key-statistics.html. Accessed January 16, 2020.

4. Brawley OW. Trends in prostate cancer in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;2012:152-156.

5. Powell IJ. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of prostate cancer in African-American men. J Urol. 2007;177:444-449.

6. Catalona WJ, Smith DS, Ratliff TL, et al. Measurement of prostate-specific antigen in serum as a screening test for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1156-1161.

7. Jacobsen SJ, Katusic SK, Bergstraih EJ. Incidence of prostate cancer diagnosis in the eras before and after serum prostate-specific antigen testing. JAMA. 1995;274:1445-1449.

8. Mistry K, Cable G. Meta-analysis of prostate-specific antigen and digital rectal examination as screening tests for prostate carcinoma. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16:95-101.

9. Qaseem A, Barry MJ, Denberg TD, et al. Screening for prostate cancer: a guidance statement from the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Int Med. 2013;158:761-769.

10. Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL 3rd, et al. Prostate cancer screening in the randomized Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial: mortality results after 13 years of follow-up. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:125-132.

11. Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1320-1328.

12. American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society recommendations for prostate cancer early detection. Last revised August 1, 2019. www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/acs-recommendations.html. Accessed January 16, 2020.

13. American Urologic Association. Early detection of prostate cancer (2018). Reviewed 2018. https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/prostate-cancer-early-detection-guideline. Accessed January 16, 2020.

14. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Prostate Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319:1901-1913.

15 Moyer VA. Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Int Med. 2012;157:120-134.

16. Labrie F, Candas B, Dupont A, et al. Screening decreases prostate cancer death: first analysis of the 1988 Quebec prospective randomized controlled trial. Prostate. 1999;38:83-91.

17. Sandblom G, Varenhorst E, Rosell J, et al. Randomised prostate cancer screening trial: 20-year follow-up. BMJ. 2011;342:d1539.

18. Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet. 2014;384:2027-2035.

19. McNaughton-Collins M, Fowler FJ Jr, Caubet JF, et al. Psychological effects of a suspicious prostate cancer screening test followed by a benign biopsy result. Am J Med. 2004;117:719-725.

20 Raaijmakers R, Kirkels WJ, Roobol MJ, et al. Complication rates and risk factors of 5802 transrectal ultrasound-guided sextant biopsies of the prostate within a population-based screening program. Urology. 2002;60:826-830.

21. Loeb S, Carter HB, Berndt SI, et al. Complications after prostate biopsy: data from SEER-Medicare. J Urol. 2011;186:1830-1834.

22. Donovan J, Hamdy F, Lane J, et al. Patient-reported outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1425-1437.

23. Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al. 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1415-1424.

24. Wilt TJ, Jones KM, Barry MJ, et al. Follow-up of prostatectomy versus observation for early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:132-142.

25. Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Garmo H, et al. Radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2319-2329.

26. Hersch JK, Nickel BL, Ghanouni A, et al. Improving communication about cancer screening: moving towards informed decision making. Public Health Res Pract. 2017;27(2).

27. Cuzick J, Thorat MA, Andriole G, et al. Prevention and early detection of prostate cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e484-e492.

28. Pinto PA, Chung PH, Rastinehad AR, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging/ultrasound fusion guided prostate biopsy improves cancer detection following transrectal ultrasound biopsy and correlates with multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. J Urol. 2011;186:1281-1285.

29. Kuru TH, Roethke MC, Seidenader J, et al. Critical evaluation of magnetic resonance imaging targeted, transrectal ultrasound guided transperineal fusion biopsy for detection of prostate cancer. J Urol. 2013;190:1380-1386.

30. Crawford ED, Rove KO, Barqawi AB, et al. Clinical-pathologic correlation between transperineal mapping biopsies of the prostate and three-dimensional reconstruction of prostatectomy specimens. Prostate. 2013;73:778-787.

31. Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1361-1367.

32. Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD001431.

33. ASCO. Decision aid tool: prostate cancer screening with PSA testing. https://www.asco.org/sites/new-www.asco.org/files/content-files/practice-and-guidelines/documents/2012-psa-pco-decision-aid.pdf. Accessed January 16, 2020.

34. Daum LM, Reamer EN, Ruterbusch JJ, et al. Patient knowledge and qualities of treatment decisions for localized prostate cancer. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30:288-297.

35. Radhakrishnan A, Grande D, Ross M, et al. When primary care providers (PCPs) help patients choose prostate cancer treatment. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30:298-307.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7-30.

2. National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Prostate Cancer. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html. Accessed January 16, 2020.

3. American Cancer Society. Key statistics for prostate cancer. Last revised August 1, 2019. www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/about/key-statistics.html. Accessed January 16, 2020.

4. Brawley OW. Trends in prostate cancer in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;2012:152-156.

5. Powell IJ. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of prostate cancer in African-American men. J Urol. 2007;177:444-449.

6. Catalona WJ, Smith DS, Ratliff TL, et al. Measurement of prostate-specific antigen in serum as a screening test for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1156-1161.

7. Jacobsen SJ, Katusic SK, Bergstraih EJ. Incidence of prostate cancer diagnosis in the eras before and after serum prostate-specific antigen testing. JAMA. 1995;274:1445-1449.

8. Mistry K, Cable G. Meta-analysis of prostate-specific antigen and digital rectal examination as screening tests for prostate carcinoma. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16:95-101.

9. Qaseem A, Barry MJ, Denberg TD, et al. Screening for prostate cancer: a guidance statement from the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Int Med. 2013;158:761-769.

10. Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL 3rd, et al. Prostate cancer screening in the randomized Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial: mortality results after 13 years of follow-up. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:125-132.

11. Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1320-1328.

12. American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society recommendations for prostate cancer early detection. Last revised August 1, 2019. www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/acs-recommendations.html. Accessed January 16, 2020.

13. American Urologic Association. Early detection of prostate cancer (2018). Reviewed 2018. https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/prostate-cancer-early-detection-guideline. Accessed January 16, 2020.

14. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Prostate Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319:1901-1913.

15 Moyer VA. Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Int Med. 2012;157:120-134.

16. Labrie F, Candas B, Dupont A, et al. Screening decreases prostate cancer death: first analysis of the 1988 Quebec prospective randomized controlled trial. Prostate. 1999;38:83-91.

17. Sandblom G, Varenhorst E, Rosell J, et al. Randomised prostate cancer screening trial: 20-year follow-up. BMJ. 2011;342:d1539.

18. Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet. 2014;384:2027-2035.

19. McNaughton-Collins M, Fowler FJ Jr, Caubet JF, et al. Psychological effects of a suspicious prostate cancer screening test followed by a benign biopsy result. Am J Med. 2004;117:719-725.

20 Raaijmakers R, Kirkels WJ, Roobol MJ, et al. Complication rates and risk factors of 5802 transrectal ultrasound-guided sextant biopsies of the prostate within a population-based screening program. Urology. 2002;60:826-830.

21. Loeb S, Carter HB, Berndt SI, et al. Complications after prostate biopsy: data from SEER-Medicare. J Urol. 2011;186:1830-1834.

22. Donovan J, Hamdy F, Lane J, et al. Patient-reported outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1425-1437.

23. Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al. 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1415-1424.

24. Wilt TJ, Jones KM, Barry MJ, et al. Follow-up of prostatectomy versus observation for early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:132-142.

25. Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Garmo H, et al. Radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2319-2329.

26. Hersch JK, Nickel BL, Ghanouni A, et al. Improving communication about cancer screening: moving towards informed decision making. Public Health Res Pract. 2017;27(2).

27. Cuzick J, Thorat MA, Andriole G, et al. Prevention and early detection of prostate cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e484-e492.

28. Pinto PA, Chung PH, Rastinehad AR, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging/ultrasound fusion guided prostate biopsy improves cancer detection following transrectal ultrasound biopsy and correlates with multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. J Urol. 2011;186:1281-1285.

29. Kuru TH, Roethke MC, Seidenader J, et al. Critical evaluation of magnetic resonance imaging targeted, transrectal ultrasound guided transperineal fusion biopsy for detection of prostate cancer. J Urol. 2013;190:1380-1386.

30. Crawford ED, Rove KO, Barqawi AB, et al. Clinical-pathologic correlation between transperineal mapping biopsies of the prostate and three-dimensional reconstruction of prostatectomy specimens. Prostate. 2013;73:778-787.

31. Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1361-1367.

32. Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD001431.

33. ASCO. Decision aid tool: prostate cancer screening with PSA testing. https://www.asco.org/sites/new-www.asco.org/files/content-files/practice-and-guidelines/documents/2012-psa-pco-decision-aid.pdf. Accessed January 16, 2020.

34. Daum LM, Reamer EN, Ruterbusch JJ, et al. Patient knowledge and qualities of treatment decisions for localized prostate cancer. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30:288-297.

35. Radhakrishnan A, Grande D, Ross M, et al. When primary care providers (PCPs) help patients choose prostate cancer treatment. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30:298-307.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Recommend individualized decision-making to men ages 55 to 69 years after discussing the potential benefits and risks of prostate-specific antigen (PSA)-based screening. B

› Do not use a PSA-based screening method for prostate cancer in men ages < 50 years or > 70 years or men with a life expectancy < 10 years. C

› Do not routinely recommend PSA-based screening to men with a family history of prostate cancer or to men who are African American. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

2020 Update on obstetrics

Attributed to the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus, and often quoted in contemporary times, is the expression “the only constant is change.” This sentiment rings true for the field of obstetrics this past year, as several bread-and-butter guidelines for managing common obstetric conditions were either challenged or altered.

The publication of the PROLONG trial called into question the use of intramuscular progesterone for the prevention of preterm birth. Prophylaxis guidelines for group B streptococcal disease were updated, including several significant clinical practice changes. Finally, there was a comprehensive overhaul of the guidelines for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, which replaced a landmark Task Force document from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) that was published only a few years ago.

Change is constant, and in obstetrics it is vital to keep up with the changing guidelines that result as new data become available for digestion and implementation into everyday clinical practice.

Results from the PROLONG trial may shake up treatment options for recurrent preterm birth

Blackwell SC, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Biggio JR Jr, et al. 17-OHPC to prevent recurrent preterm birth in singleton gestations (PROLONG study): a multicenter, international, randomized double-blind trial. Am J Perinatol. 2019. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-3400227.

The drug 17 α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17-OHPC, or 17P; Makena) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2011 for the prevention of spontaneous preterm birth (PTB) in women with a singleton pregnancy and a history of singleton spontaneous PTB. The results of the trial by Meis and colleagues of 17-OHPC played a major role in achieving that approval, as it demonstrated a 34% reduction in recurrent PTB and a reduction in some neonatal morbidities.1 Following the drug's approval, both ACOG and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) published guidelines recommending progesterone therapy, including 17-OHPC, for the prevention of recurrent spontaneous PTB.2

The FDA approval of 17-OHPC was granted under an accelerated conditional pathway that required a confirmatory trial evaluating efficacy, safety, and long-term infant follow-up to be performed by the sponsor. That trial, Progestin's Role in Optimizing Neonatal Gestation (PROLONG), was started in 2009, and its results were published on October 25, 2019.3

Continue to: Design of the trial...

Design of the trial

PROLONG was a multicenter (93 sites), randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study conducted in 9 countries (23% of participants were in the United States, 60% were in Russia and Ukraine). The co-primary outcome was PTB < 35 weeks and a composite neonatal morbidity and mortality index. The primary safety outcome was fetal/early infant death.

The study was designed to have 98% power to detect a 30% reduction in PTB < 35 weeks, and 90% power to detect a 35% reduction in the neonatal composite index. It included 1,708 participants (1,130 were treated with 17-OHPC, and 578 received placebo).

Trial outcomes. There was no difference in PTB < 35 weeks between the 17-OHPC and the placebo groups (11.0% vs 11.5%; relative risk [RR], 0.95; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.71-1.26). There was no difference in PTB < 32 or < 37 weeks.

The study revealed also that there was no difference between groups in the neonatal composite index (5.6% for 17-OHPC vs 5.0% for placebo; RR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.68-1.61). In addition, there was no difference in fetal/early infant death between the 17-OHPC and placebo groups (1.7% vs 1.9%; RR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.4-1.81).

Conclusions. The trial investigators concluded that 17-OHPC did not demonstrate a reduction in recurrent PTB and did not decrease neonatal morbidity.

Study limitations included underpowering and selection bias

The investigators noted that the PTB rate in PROLONG was unexpectedly almost 50% lower than that in the Meis trial, and that therefore the PROLONG trial was underpowered to assess the primary outcomes.

Further, the study populations of the 2 trials were very different: The Meis trial included women at higher baseline risk for PTB (> 1 prior PTB and at least 1 other risk factor for PTB). Additionally, while the PROLONG trial included mostly white (90%), married (90%), nonsmoking women (8% smoked), the Meis trial population was 59% black and 50% married, and 20% were smokers.

The availability and common use of 17-OHPC in the United States likely led to a selection bias for the PROLONG trial population, as the highest-risk patients were most likely already receiving treatment and were therefore excluded from the PROLONG trial.

Society, and FDA, responses to the new data

The results of the PROLONG trial call into question what has become standard practice for patients with a history of spontaneous PTB in the United States. While the safety profile of 17-OHPC has not been cited as a concern, whether or not the drug should be used at all has—as has its current FDA-approved status.

In response to the publication of the PROLONG trial results, ACOG released a Practice Advisory that acknowledged the study's findings but did not alter the current recommendations to continue to offer progesterone for the prevention of preterm birth, upholding ACOG's current Practice Bulletin guidance.2,4 Additional considerations for offering 17-OHPC use include the patients' preferences, available resources, and the setting for the intervention.

SMFM's response was more specific, stating that it is reasonable to continue to use 17-OHPC in high-risk patient populations consistent with those in the Meis trial.5 In the rest of the general population at risk for recurrent PTB, SMFM recommends that, due to uncertain benefit with 17-OHPC, the high cost, patient discomfort, and increased visits should be taken into account.

Four days after the publication of the PROLONG study, the FDA Bone, Reproductive, and Urologic Drugs Advisory Committee voted 9-7 to withdraw approval for 17-OHPC.6 In response, SMFM released a statement supporting continued access to 17-OHPC.7 The FDA's final decision on the status of the drug is expected within the next several months from this writing.

17-OHPC continues to be considered safe and still is recommended by both ACOG and SMFM for the prevention of recurrent preterm birth in high-risk patients. The high-risk patient population who may benefit most from this therapy is still not certain, but hopefully future studies will better delineate this. The landscape for 17-OHPC use may change dramatically if FDA approval is not upheld in the future. In my current practice, I am continuing to offer 17-OHPC to patients per the current ACOG guidelines, but I am counseling patients in a shared decision-making model regarding the findings of the PROLONG trial and the potential change in FDA approval.

Continue to: ACOG updates guidance on preventing early-onset GBS disease...

ACOG updates guidance on preventing early-onset GBS disease

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists—Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG committee opinion no. 782: prevention of early-onset group B streptococcal disease in newborns. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:e19-e40.

Group B streptococcus (GBS) is the leading cause of newborn infection and is associated with maternal infections as well as preterm labor and stillbirth. Early-onset GBS disease occurs within 7 days of birth and is linked to vertical transmission via maternal colonization of the genitourinary or gastrointestinal tract and fetal/neonatal aspiration at birth.

Preventing early-onset GBS disease with maternal screening and intrapartum prophylaxis according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines has reduced early-onset disease by 80% since the 1990s. By contrast, late-onset GBS infection, which occurs 7 days to 3 months after birth, usually is associated with horizontal maternal transmission or hospital or community infections, and it is not prevented by intrapartum treatment.

In 2018, the CDC transferred responsibility for GBS prophylaxis guidelines to ACOG and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). In July 2019, ACOG released its Committee Opinion on preventing early-onset GBS disease in newborns.8 This guidance replaces and updates the previous guidelines, with 3 notable changes.

The screening timing has changed

In the CDC's 2010 guidelines, GBS screening was recommended to start at 35 weeks' gestation. The new guidelines recommend universal vaginal-rectal screening at 36 to 37 6/7 weeks' gestation. The new timing of culture will shift the expected 5-week window in which GBS cultures are considered valid up to at least 41 weeks' gestation. The rationale for this change is that any GBS-unknown patient who previously would have been cultured under 37 weeks' would be an automatic candidate for empiric therapy and the lower rate of birth in the 35th versus the 41st week of gestation.

Identifying candidates for intrapartum treatment

The usual indications for intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis include a GBS-positive culture at 36 weeks or beyond, GBS bacteriuria at any point in pregnancy, a prior GBS-affected child, or unknown GBS status with any of the following: < 37 weeks, rupture of membranes ≥ 18 hours or temperature ≥ 100.4°F (38°C), and a positive rapid GBS culture in labor. In addition, antibiotics now should be considered for patients at term with unknown GBS status but with a history of GBS colonization in a prior pregnancy.

This represents a major practice change for women at ≥ 37 weeks with unknown GBS status and no other traditional risk factors. The rationale for this recommendation is that women who have been positive for GBS in a prior pregnancy have a 50% chance of being colonized in the current pregnancy, and their newborns are therefore at higher risk for early-onset GBS disease.

Managing patients with penicillin allergy

Intravenous penicillin (or ampicillin) remains the antibiotic of choice for intrapartum prophylaxis against GBS due to its efficacy and specific, narrow coverage of gram-positive organisms. The updated recommendations emphasize that it is important to carefully evaluate patients with reported penicillin allergies for several reasons: determining risk of anaphylaxis and clindamycin susceptibility testing in GBS evaluations are often overlooked by obstetric providers, the need for antibiotic stewardship to reduce the development of antibiotic resistance, and clarification of allergy status for future health care needs.

Three recommendations are made:

- Laboratory requisitions for cultures should specifically note a penicillin allergy so that clindamycin susceptibility testing can be performed.

- Penicillin allergy skin testing should be considered for patients at unknown or low risk for anaphylaxis, as it is considered safe in pregnancy and most patients (80%-90%) who report a penicillin allergy are actually penicillin tolerant.

- For patients at high risk for anaphylaxis to penicillin, the recommended vancomycin dosing has been changed from 1 g IV every 12 hours to 20 mg/kg IV every 8 hours (maximum single dose, 2 g). Renal function should be assessed prior to dosing. This weight- and renal function-based dosing increased neonatal therapeutic levels in several studies of different doses.

ACOG's key recommendations for preventing early-onset GBS disease in newborns include:

- Universal vaginal-rectal screening for GBS should be performed at 36 to 37 6/7 weeks' gestation.

- Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis should be considered for low-risk patients at term with unknown GBS status and a history of GBS colonization in a prior pregnancy.

- Patients with a reported penicillin allergy require careful evaluation of the nature of their allergy, including consideration of skin testing and GBS susceptibility evaluation in order to promote the best practices for antibiotic use.

- For GBS-positive patients at high risk for penicillin anaphylaxis, vancomycin 20 mg/kg IV every 8 hours (maximum single dose, 2 g) is recommended.

Continue to: Managing hypertension in pregnancy: New recommendations...

Managing hypertension in pregnancy: New recommendations

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 202. Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e1-e25.

In 2013, ACOG released "Hypertension in pregnancy," a 99-page comprehensive document developed by their Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy, to summarize knowledge on the subject, provide guidelines for management, and identify needed areas of research.9 I summarized key points from that document in the 2014 "Update on Obstetrics" (OBG Manag. 2013;26[1]:28-36). Now, ACOG has released 2 Practice Bulletins—"Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia" and "Chronic hypertension in pregnancy"—that replace the 2013 document.10,11 These Practice Bulletins are quite comprehensive and warrant a thorough read. Several noteworthy changes relevant to the practicing obstetrician are summarized below.

Highlights of revised guidance

Expectant management vs early delivery in preeclampsia with fetal growth restriction. Fetal growth restriction, which was removed from the definition of preeclampsia with severe features in 2013, is no longer an indication for delivery in preeclampsia with severe features (previously, if the estimated fetal weight was < 5th percentile for gestational age, delivery after steroid administration was recommended). Rather, expectant management is reasonable if fetal antenatal testing, amniotic fluid, and Doppler ultrasound studies are reassuring. Abnormal umbilical artery Doppler studies continue to be an indication for earlier delivery.

Postpartum NSAID use in hypertension. The 2013 document cautioned against nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use postpartum in women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy because of concern for exacerbating hypertension. The updated Practice Bulletins recommend NSAIDs as the preferred choice over opioid analgesics as data have not shown these drugs to increase blood pressure, antihypertensive requirements, or other adverse events in postpartum patients with blood pressure issues.

More women will be diagnosed with chronic hypertension. Recently, the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association changed the definition of hypertension. Stage 1 hypertension is now defined as a systolic blood pressure of 130-139 mm Hg or a diastolic blood pressure of 80-89 mm Hg. Treatment of stage 1 hypertension is recommended for nonpregnant adults with risk factors for current or future cardiovascular disease. The potential impact is that more women will enter pregnancy with a diagnosis of chronic hypertension, and more may be on prepregnancy antihypertensive therapy that will need to be addressed during the pregnancy.

Blood pressure goals. The target blood pressure range for pregnant women with chronic hypertension is recommended to be ≥ 120/80 mm Hg and < 160/110 mm Hg (this represents a slight change, as previously diastolic blood pressure was to be < 105 mm Hg). Postpartum blood pressure goals of < 150/100 mm Hg remain the same.

Managing acute hypertensive emergencies. Both Practice Bulletins emphasize the importance of aggressive management of acute hypertensive emergency, with options for 3 protocols: labetalol, nifedipine, and hydralazine. The goal is to administer antihypertensive therapy within 30 to 60 minutes, but administration as soon as feasibly possible after diagnosis of severe hypertension is ideal.

Timing of delivery. Recommended delivery timing in patients with chronic hypertension was slightly altered (previous recommendations included a range of 37 to 39 6/7 weeks). The lower limit of gestational age for recommended delivery timing in chronic hypertension has not changed—it remains not before 38 weeks if no antihypertensive therapy and stable, and not before 37 weeks if antihypertensive therapy and stable.

The upper limit of 39 6/7 weeks is challenged, however, because data support that induction of labor at either 38 or 39 weeks reduces the risk of severe hypertensive complications (such as superimposed preeclampsia and eclampsia) without increasing the risk of cesarean delivery. Therefore, for patients with chronic hypertension, expectant management beyond 39 weeks is cautioned, to be done only with careful consideration of risks and with close surveillance.