User login

One in three cancer articles on social media has wrong info

Of the 200 most popular articles (50 each for prostate, lung, breast, and colorectal cancer), about a third (32.5%, n = 65) contained misinformation.

Among these articles containing misinformation, 76.9% (50/65) contained harmful information.

“The Internet is a leading source of health misinformation,” the study authors wrote. This is “particularly true for social media, where false information spreads faster and more broadly than fact-checked information,” they said, citing other research.

“We need to address these issues head on,” said lead author Skyler Johnson, MD, of the University of Utah’s Huntsman Cancer Institute in Salt Lake City.

“As a medical community, we can’t ignore the problem of cancer misinformation on social media or ask our patients to ignore it. We must empathize with our patients and help them when they encounter this type of information,” he said in a statement. “My goal is to help answer their questions, and provide cancer patients with accurate information that will give them the best chance for the best outcome.”

The study was published online July 22 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

The study period ran from 2018 to 2019, and looked at articles posted on social media platforms Facebook, Reddit, Twitter, or Pinterest. Popularity was measured by engagement with readers, such as upvotes, comments, reactions, and shares.

Some of the articles came from long-established news entities such as CBS News, The New York Times, and medical journals, while others came from fleeting crowdfunding web pages and fledging nontraditional news sites.

One example of popular and harmful misinformation highlighted by Dr. Johnson in an interview was titled, “44-Year-Old Mother Claims CBD Oil Cured Her of Breast Cancer within 5 Months.” Posted on truththeory.com in February 2018, the article is tagged as “opinion” by the publisher and in turn links to another news story about the same woman in the UK’s Daily Mail newspaper.

The ideas and claims in such articles can be very influential, Jennifer L. Lycette, MD, suggested in a recent blog post.

“After 18 years as a cancer doctor, it sadly doesn’t come as a surprise anymore when a patient declines treatment recommendations and instead opts for ‘alternative’ treatment,” she wrote.

Sometimes, misinformation is not sensational but is still effective via clever wording and presentation, observed Brian G. Southwell, PhD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., who has studied patients and misinformation.

“It isn’t the falsehood that is somehow magically attractive, per se, but the way that misinformation is often framed that can make it attractive,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Southwell recommends that clinicians be proactive about medical misinformation.

“Rather than expect patients to raise concerns without prompting, health care providers should invite conversations about potential misinformation with their patients,” he wrote in a recent essay in the American Journal of Public Health.

In short, ask patients what they know about the treatment of their cancer, he suggests.

“Patients don’t typically know that the misinformation they are encountering is misinformation,” said Dr. Southwell. “Approaching patients with compassion and empathy is a good first step.”

Study details

For the study, reported by Johnson et al., two National Comprehensive Cancer Network panel members were selected as content experts for each of the four cancers and were tasked with reviewing the primary medical claims in each article. The experts then completed a set of ratings to arrive at the proportion of misinformation and potential for harm in each article.

Of the 200 articles, 41.5% were from nontraditional news (digital only), 37.5% were from traditional news sources (online versions of print and/or broadcast media), 17% were from medical journals, 3% were from a crowdfunding site, and 1% were from personal blogs.

This expert review concluded that nearly one-third of the articles contained misinformation, as noted above. The misinformation was described as misleading (title not supported by text or statistics/data do not support conclusion, 28.8%), strength of the evidence mischaracterized (weak evidence portrayed as strong or vice versa, 27.7%) and unproven therapies (not studied or insufficient evidence, 26.7%).

Notably, the median number of engagements, such as likes on Twitter, for articles with misinformation was greater than that of factual articles (median, 2,300 vs. 1,600; P = .05).

In total, 30.5% of all 200 articles contained harmful information. This was described as harmful inaction (could lead to delay or not seeking medical attention for treatable/curable condition, 31.0%), economic harm (out-of-pocket financial costs associated with treatment/travel, 27.7%), harmful action (potentially toxic effects of the suggested test/treatment, 17.0%), and harmful interactions (known/unknown medical interactions with curative therapies, 16.2%).

The median number of engagements for articles with harmful information was statistically significantly greater than that of articles with correct information (median, 2,300 vs. 1,500; P = .007).

A limitation of the study is that it included only the most popular English language cancer articles.

This study was funded in part by the Huntsman Cancer Institute. Dr. Johnson, Dr. Lycette, and Dr. Southwell have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Some study authors have ties to the pharmaceutical industry.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Of the 200 most popular articles (50 each for prostate, lung, breast, and colorectal cancer), about a third (32.5%, n = 65) contained misinformation.

Among these articles containing misinformation, 76.9% (50/65) contained harmful information.

“The Internet is a leading source of health misinformation,” the study authors wrote. This is “particularly true for social media, where false information spreads faster and more broadly than fact-checked information,” they said, citing other research.

“We need to address these issues head on,” said lead author Skyler Johnson, MD, of the University of Utah’s Huntsman Cancer Institute in Salt Lake City.

“As a medical community, we can’t ignore the problem of cancer misinformation on social media or ask our patients to ignore it. We must empathize with our patients and help them when they encounter this type of information,” he said in a statement. “My goal is to help answer their questions, and provide cancer patients with accurate information that will give them the best chance for the best outcome.”

The study was published online July 22 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

The study period ran from 2018 to 2019, and looked at articles posted on social media platforms Facebook, Reddit, Twitter, or Pinterest. Popularity was measured by engagement with readers, such as upvotes, comments, reactions, and shares.

Some of the articles came from long-established news entities such as CBS News, The New York Times, and medical journals, while others came from fleeting crowdfunding web pages and fledging nontraditional news sites.

One example of popular and harmful misinformation highlighted by Dr. Johnson in an interview was titled, “44-Year-Old Mother Claims CBD Oil Cured Her of Breast Cancer within 5 Months.” Posted on truththeory.com in February 2018, the article is tagged as “opinion” by the publisher and in turn links to another news story about the same woman in the UK’s Daily Mail newspaper.

The ideas and claims in such articles can be very influential, Jennifer L. Lycette, MD, suggested in a recent blog post.

“After 18 years as a cancer doctor, it sadly doesn’t come as a surprise anymore when a patient declines treatment recommendations and instead opts for ‘alternative’ treatment,” she wrote.

Sometimes, misinformation is not sensational but is still effective via clever wording and presentation, observed Brian G. Southwell, PhD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., who has studied patients and misinformation.

“It isn’t the falsehood that is somehow magically attractive, per se, but the way that misinformation is often framed that can make it attractive,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Southwell recommends that clinicians be proactive about medical misinformation.

“Rather than expect patients to raise concerns without prompting, health care providers should invite conversations about potential misinformation with their patients,” he wrote in a recent essay in the American Journal of Public Health.

In short, ask patients what they know about the treatment of their cancer, he suggests.

“Patients don’t typically know that the misinformation they are encountering is misinformation,” said Dr. Southwell. “Approaching patients with compassion and empathy is a good first step.”

Study details

For the study, reported by Johnson et al., two National Comprehensive Cancer Network panel members were selected as content experts for each of the four cancers and were tasked with reviewing the primary medical claims in each article. The experts then completed a set of ratings to arrive at the proportion of misinformation and potential for harm in each article.

Of the 200 articles, 41.5% were from nontraditional news (digital only), 37.5% were from traditional news sources (online versions of print and/or broadcast media), 17% were from medical journals, 3% were from a crowdfunding site, and 1% were from personal blogs.

This expert review concluded that nearly one-third of the articles contained misinformation, as noted above. The misinformation was described as misleading (title not supported by text or statistics/data do not support conclusion, 28.8%), strength of the evidence mischaracterized (weak evidence portrayed as strong or vice versa, 27.7%) and unproven therapies (not studied or insufficient evidence, 26.7%).

Notably, the median number of engagements, such as likes on Twitter, for articles with misinformation was greater than that of factual articles (median, 2,300 vs. 1,600; P = .05).

In total, 30.5% of all 200 articles contained harmful information. This was described as harmful inaction (could lead to delay or not seeking medical attention for treatable/curable condition, 31.0%), economic harm (out-of-pocket financial costs associated with treatment/travel, 27.7%), harmful action (potentially toxic effects of the suggested test/treatment, 17.0%), and harmful interactions (known/unknown medical interactions with curative therapies, 16.2%).

The median number of engagements for articles with harmful information was statistically significantly greater than that of articles with correct information (median, 2,300 vs. 1,500; P = .007).

A limitation of the study is that it included only the most popular English language cancer articles.

This study was funded in part by the Huntsman Cancer Institute. Dr. Johnson, Dr. Lycette, and Dr. Southwell have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Some study authors have ties to the pharmaceutical industry.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Of the 200 most popular articles (50 each for prostate, lung, breast, and colorectal cancer), about a third (32.5%, n = 65) contained misinformation.

Among these articles containing misinformation, 76.9% (50/65) contained harmful information.

“The Internet is a leading source of health misinformation,” the study authors wrote. This is “particularly true for social media, where false information spreads faster and more broadly than fact-checked information,” they said, citing other research.

“We need to address these issues head on,” said lead author Skyler Johnson, MD, of the University of Utah’s Huntsman Cancer Institute in Salt Lake City.

“As a medical community, we can’t ignore the problem of cancer misinformation on social media or ask our patients to ignore it. We must empathize with our patients and help them when they encounter this type of information,” he said in a statement. “My goal is to help answer their questions, and provide cancer patients with accurate information that will give them the best chance for the best outcome.”

The study was published online July 22 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

The study period ran from 2018 to 2019, and looked at articles posted on social media platforms Facebook, Reddit, Twitter, or Pinterest. Popularity was measured by engagement with readers, such as upvotes, comments, reactions, and shares.

Some of the articles came from long-established news entities such as CBS News, The New York Times, and medical journals, while others came from fleeting crowdfunding web pages and fledging nontraditional news sites.

One example of popular and harmful misinformation highlighted by Dr. Johnson in an interview was titled, “44-Year-Old Mother Claims CBD Oil Cured Her of Breast Cancer within 5 Months.” Posted on truththeory.com in February 2018, the article is tagged as “opinion” by the publisher and in turn links to another news story about the same woman in the UK’s Daily Mail newspaper.

The ideas and claims in such articles can be very influential, Jennifer L. Lycette, MD, suggested in a recent blog post.

“After 18 years as a cancer doctor, it sadly doesn’t come as a surprise anymore when a patient declines treatment recommendations and instead opts for ‘alternative’ treatment,” she wrote.

Sometimes, misinformation is not sensational but is still effective via clever wording and presentation, observed Brian G. Southwell, PhD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., who has studied patients and misinformation.

“It isn’t the falsehood that is somehow magically attractive, per se, but the way that misinformation is often framed that can make it attractive,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Southwell recommends that clinicians be proactive about medical misinformation.

“Rather than expect patients to raise concerns without prompting, health care providers should invite conversations about potential misinformation with their patients,” he wrote in a recent essay in the American Journal of Public Health.

In short, ask patients what they know about the treatment of their cancer, he suggests.

“Patients don’t typically know that the misinformation they are encountering is misinformation,” said Dr. Southwell. “Approaching patients with compassion and empathy is a good first step.”

Study details

For the study, reported by Johnson et al., two National Comprehensive Cancer Network panel members were selected as content experts for each of the four cancers and were tasked with reviewing the primary medical claims in each article. The experts then completed a set of ratings to arrive at the proportion of misinformation and potential for harm in each article.

Of the 200 articles, 41.5% were from nontraditional news (digital only), 37.5% were from traditional news sources (online versions of print and/or broadcast media), 17% were from medical journals, 3% were from a crowdfunding site, and 1% were from personal blogs.

This expert review concluded that nearly one-third of the articles contained misinformation, as noted above. The misinformation was described as misleading (title not supported by text or statistics/data do not support conclusion, 28.8%), strength of the evidence mischaracterized (weak evidence portrayed as strong or vice versa, 27.7%) and unproven therapies (not studied or insufficient evidence, 26.7%).

Notably, the median number of engagements, such as likes on Twitter, for articles with misinformation was greater than that of factual articles (median, 2,300 vs. 1,600; P = .05).

In total, 30.5% of all 200 articles contained harmful information. This was described as harmful inaction (could lead to delay or not seeking medical attention for treatable/curable condition, 31.0%), economic harm (out-of-pocket financial costs associated with treatment/travel, 27.7%), harmful action (potentially toxic effects of the suggested test/treatment, 17.0%), and harmful interactions (known/unknown medical interactions with curative therapies, 16.2%).

The median number of engagements for articles with harmful information was statistically significantly greater than that of articles with correct information (median, 2,300 vs. 1,500; P = .007).

A limitation of the study is that it included only the most popular English language cancer articles.

This study was funded in part by the Huntsman Cancer Institute. Dr. Johnson, Dr. Lycette, and Dr. Southwell have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Some study authors have ties to the pharmaceutical industry.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Becoming vaccine ambassadors: A new role for psychiatrists

After more than 600,000 deaths in the United States from the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), several safe and effective vaccines against the virus have become available. Vaccines are the most effective preventive measure against COVID-19 and the most promising way to achieve herd immunity to end the current pandemic. However, obstacles to reaching this goal include vaccine skepticism, structural barriers, or simple inertia to get vaccinated. These challenges provide opportunities for psychiatrists to use their medical knowledge and expertise, applying behavior management techniques such as motivational interviewing and nudging to encourage their patients to get vaccinated. In particular, marginalized patients with serious mental illness (SMI), who are subject to disproportionately high rates of COVID-19 infection and more severe outcomes,1 have much to gain if psychiatrists become involved in the COVID-19 vaccination campaign.

In this article, we define vaccine hesitancy and highlight what makes psychiatrists ideal vaccine ambassadors, given their unique skill set and longitudinal, trust-based connection with their patients. We expand on the particular vulnerabilities of patients with SMI, including structural barriers to vaccination that lead to health disparities and inequity. Finally, building on “The ABCs of successful vaccinations” framework published in

What is vaccine hesitancy?

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines vaccine hesitancy as a “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccine services.”3,4 Vaccine hesitancy occurs on a continuum ranging from uncertainty about accepting a vaccine to absolute refusal.4,5 It involves a complex decision-making process driven by contextual, individual, and social influences, and vaccine-specific issues.4 In the “3C” model developed by the WHO Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) Working Group, vaccine hesitancy is influenced by confidence (trust in vaccines, in the health care system, and in policy makers), complacency (lower perceived risk), and convenience (availability, affordability, accessibility, language and health literacy, appeal of vaccination program).4

In 2019, the WHO named vaccine hesitancy as one of the top 10 global health threats.3 Hesitancy to receive COVID-19 vaccines may be particularly high because of their rapid development. In addition, the tumultuous political environment that often featured inconsistent messaging about the virus, its dangers, and its transmission since the early days of the pandemic created widespread public confusion and doubt as scientific understandings evolved. “Anti-vaxxer” movements that completely rejected vaccine efficacy disseminated misinformation online. Followers of these movements may have such extreme overvalued ideas that any effort to persuade them otherwise with scientific evidence will accomplish very little.6,7 Therefore, focusing on individuals who are “sitting on the fence” about getting vaccinated can be more productive because they represent a much larger group than those who adamantly refuse vaccines, and they may be more amenable to changing beliefs and behaviors.8

The US Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey asked, “How likely are you to accept the vaccine?”9 As of late June 2021, 11.4% of US adults reported they would “definitely not get a vaccine” or “probably not get a vaccine,” and that number increases to 16.9% when including those who are “unsure,” although there is wide geographical variability.10

A recent study in Denmark showed that willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine was slightly lower among patients with mental illness (84.8%) compared with the general population (89.5%).11 Given the small difference, vaccine hesitancy was not considered to be a major barrier for vaccination among patients with mental illness in Denmark. This is similar to the findings of a pre-pandemic study at a community mental health clinic in the United States involving other vaccinations, which suggested that 84% of patients with SMI perceived vaccinations as safe, effective, and important.12 In this clinic, identified barriers to vaccinations in general among patients with SMI included lack of awareness and knowledge (42.2%), accessibility (16.3%), personal cost (13.3%), fears about immunization (10.4%), and lack of recommendations by primary care providers (PCPs) (1.5%).12

It is critical to distinguish attitude-driven vaccine hesitancy from a lack of education and opportunity to receive a vaccine. Particularly disadvantaged communities may be mislabeled as “vaccine hesitant” when in fact they may not have the ability to be as proactive as other population groups (eg, difficulty scheduling appointments over the Internet).

Continue to: What makes psychiatrists ideal vaccine ambassadors?

What makes psychiatrists ideal vaccine ambassadors?

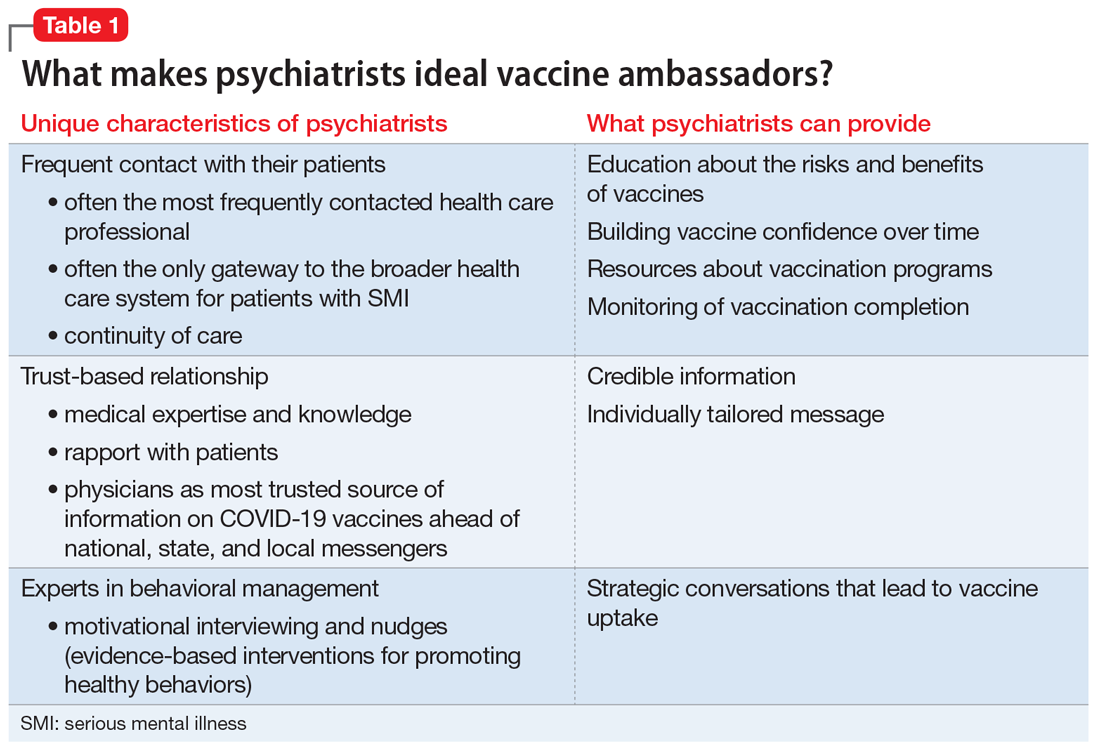

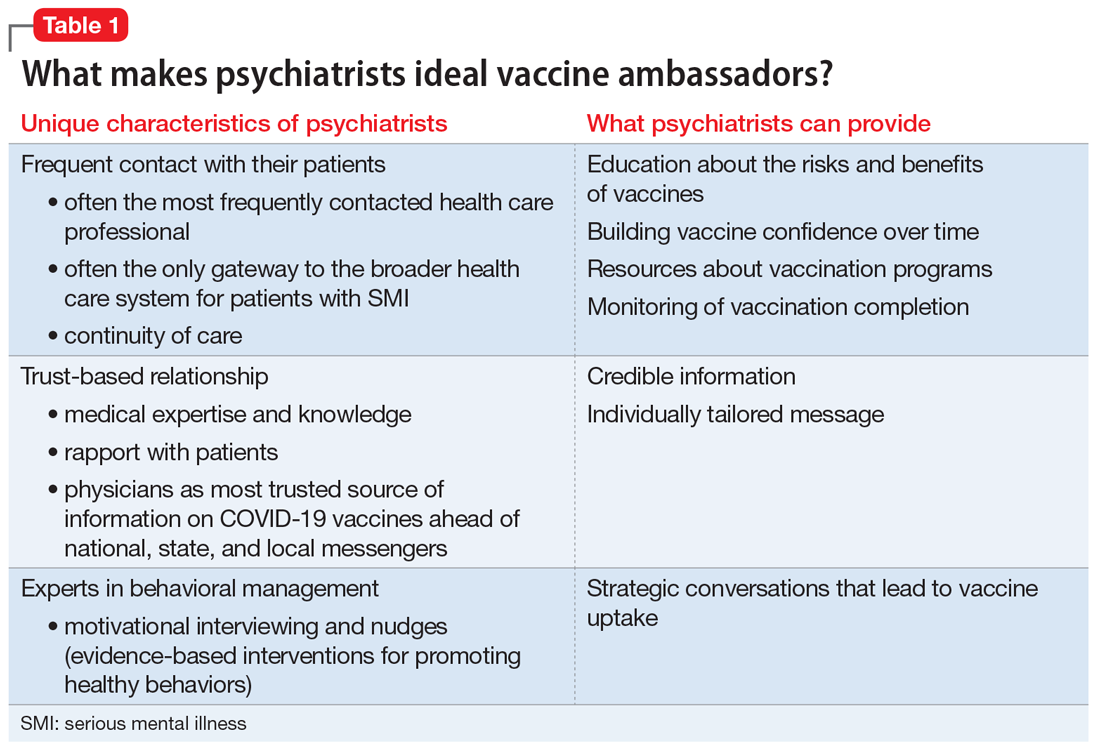

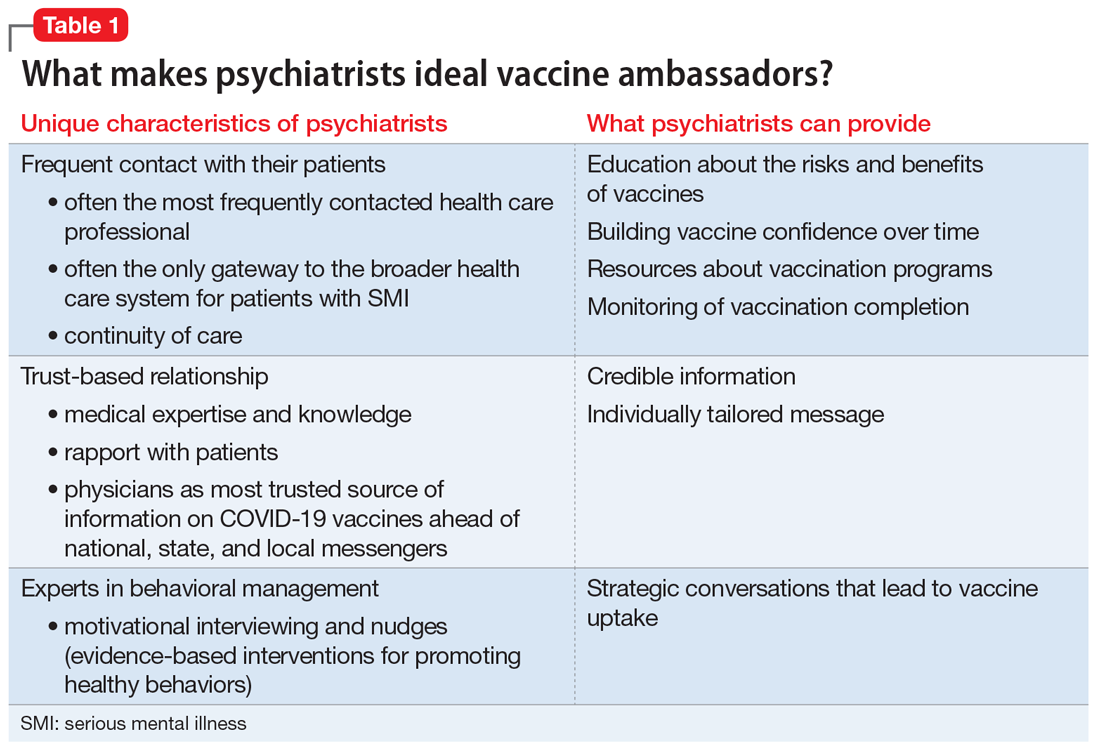

There are several reasons psychiatrists can be well-positioned to contribute to the success of vaccination campaigns (Table 1). These include their frequent contact with patients and their care teams, the high trust those patients have in them, and their medical expertise and skills in applied behavioral and social science techniques, including motivational interviewing and nudging. Vaccination efforts and outreach are more effective when led by the clinician with whom the patient has the most contact because resolving vaccine hesitancy is not a one-time discussion but requires ongoing communication, persistence, and consistency.13 Patients may contact their psychiatrists more frequently than their other clinicians, including PCPs. For this reason, psychiatrists can serve as the gateway to health care, particularly for patients with SMI.14 In addition, interruptions in nonemergency services caused by the COVID-19 pandemic may affect vaccine delivery because patients may have been unable to see their PCPs regularly during the pandemic.15

Psychiatrists’ medical expertise and their ability to develop rapport with their patients promote trust-building. Receiving credible information from a trusted source such as a patient’s psychiatrist can be impactful. A recent poll suggested that individual health care clinicians have been consistently identified as the most trusted sources for vaccine information, including for the COVID-19 vaccines.16 There is also higher trust when there is greater continuity of care both in terms of length of time the patient has known the clinician and the number of consultations,17 an inherent part of psychiatric practice. In addition, research has shown that patients trust their psychiatrists as much as they trust their general practitioners.18

Psychiatrists are experts in behavior change, promoting healthy behaviors through motivational interviewing and nudging. They also have experience with managing patients who hold overvalued ideas as well as dealing with uncertainty, given their scientific and medical training.

Motivational interviewing is a patient-centered, collaborative approach widely used by psychiatrists to treat unhealthy behaviors such as substance use. Clinicians elicit and strengthen the patient’s desire and motivation for change while respecting their autonomy. Instead of presenting persuasive facts, the clinician creates a welcoming, nonthreatening, safe environment by engaging patients in open dialogue, reflecting back the patients’ concerns with empathy, helping them realize contradictions in behavior, and supporting self-sufficiency.19 In a nonpsychiatric setting, studies have shown the effectiveness of motivational interviewing in increasing uptake of human papillomavirus vaccines and of pediatric vaccines.20

Nudging, which comes from behavioral economics and psychology, underscores the importance of structuring a choice architecture in changing the way people make their everyday decisions.21 Nudging still gives people a choice and respects autonomy, but it leads patients to more efficient and productive decision-making. Many nudges are based around giving good “default options” because people often do not make efforts to deviate from default options. In addition, social nudges are powerful, giving people a social reference point and normalizing certain behaviors.21 Psychiatrists have become skilled in nudging from working with patients with varying levels of insight and cognitive capabilities. That is, they give simple choices, prompts, and frequent feedback to reinforce “good” decisions and to discourage “bad” decisions.

Continue to: Managing overvalued ideas

Managing overvalued ideas. Psychiatrists are also well-versed in having discussions with patients who hold irrational beliefs (psychosis) or overvalued ideas. For example, psychiatrists frequently manage anorexia nervosa and hypochondria, which are rooted in overvalued ideas.7 While psychiatrists may not be able to directly confront the overvalued ideas, they can work around such ideas while waiting for more flexible moments. Similarly, managing patients with intense emotional commitment7 to commonly held anti-vaccination ideas may not be much different. Psychiatrists can work around resistance until patients may be less strongly attached to those overvalued ideas in instances when other techniques, such as motivational interviewing and nudging, may be more effective.

Managing uncertainty. Psychiatrists are experts in managing “not knowing” and uncertainty. Due to their medical scientific training, they are familiar with the process of science, and how understanding changes through trial and error. In contrast, most patients usually only see the end product (ie, a drug comes to market). Discussions with patients that acknowledge uncertainty and emphasize that changes in what is known are expected and appropriate as scientific knowledge evolves could help preempt skepticism when messages are updated.

Why do patients with SMI need more help?

SMI as a high-risk group. Patients with SMI are part of a “tragic” epidemiologic triad of agent-host-environment15 that places them at remarkably elevated risk for COVID-19 infection and more serious complications and death when infected.1 After age, a diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder is the second largest predictor of mortality from COVID-19, with a 2.7-fold increase in mortality.22 This is how the elements of the triad come together: SARS-Cov-2 is a highly infectious agent affecting individuals who are vulnerable hosts because of their high frequency of medical comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and respiratory tract diseases, which are all risk factors for worse outcomes due to COVID-19.23 In addition, SMI is associated with socioeconomic risk factors for SARS-Cov-2 infection, including poverty, homelessness, and crowded settings such as jails, group homes, hospitals, and shelters, which constitute ideal environments for high transmission of the virus.

Structural barriers to vaccination. Studies have suggested lower rates of vaccination among people with SMI for various other infectious diseases compared with the general population.12 For example, in 1 outpatient mental health setting, influenza vaccination rates were 24% to 28%, which was lower than the national vaccination rate of 40.9% for the same influenza season (2010 to 2011).24 More recently, a study in Israel examining the COVID-19 vaccination rate among >25,000 patients with schizophrenia suggested under-vaccination of this cohort. The results showed that the odds of getting the COVID-19 vaccination were significantly lower in the schizophrenia group compared with the general population (odds ratio = 0.80, 95% CI: 0.77 to 0.83).25

Patients with SMI encounter considerable system-level barriers to vaccinations in general, such as reduced access to health care due to cost and a lack of transportation,12 the digital divide given their reduced access to the internet and computers for information and scheduling,26 and lack of vaccination recommendations from their PCPs.12 Studies have also shown that patients with SMI often receive suboptimal medical care because of stigmatization and discrimination.27 They also have lower rates of preventive care utilization, seeking medical services only in times of crisis and seeking mental health services more often than physical health care.28-30

Continue to: Patients with SMI face...

Patients with SMI face additional individual challenges that impede vaccine uptake, such as lack of knowledge and awareness about the virus and vaccinations, general cognitive impairment, low digital literacy skills,31 low language literacy and educational attainment, baseline delusions, and negative symptoms such as apathy, avolition, and anhedonia.1 Thus, even if they overcome the external barriers and obtain vaccine-related information, these patients may experience difficulty in understanding the content and applying this information to their personal circumstances as a result of low health literacy.

How psychiatrists can help

The concept of using mental health care sites and trained clinicians to increase medical disease prevention is not new. The rigorously tested intervention model STIRR (Screen, Test, Immunize, Reduce risk, and Refer) uses co-located nurse practitioners in community mental health centers to provide risk assessment, counseling, and blood testing for hepatitis and HIV, as well as on-site vaccinations for hepatitis to patients dually diagnosed with SMI and substance use disorders.32

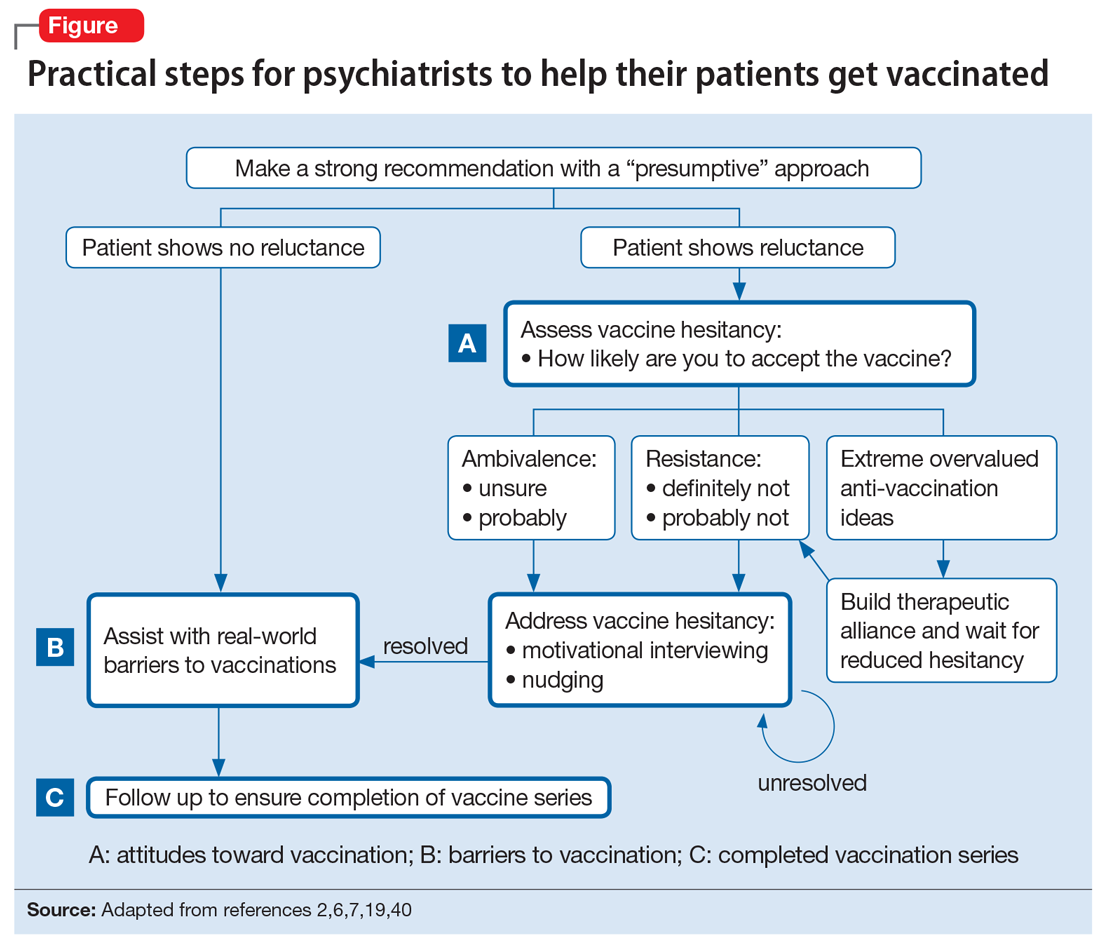

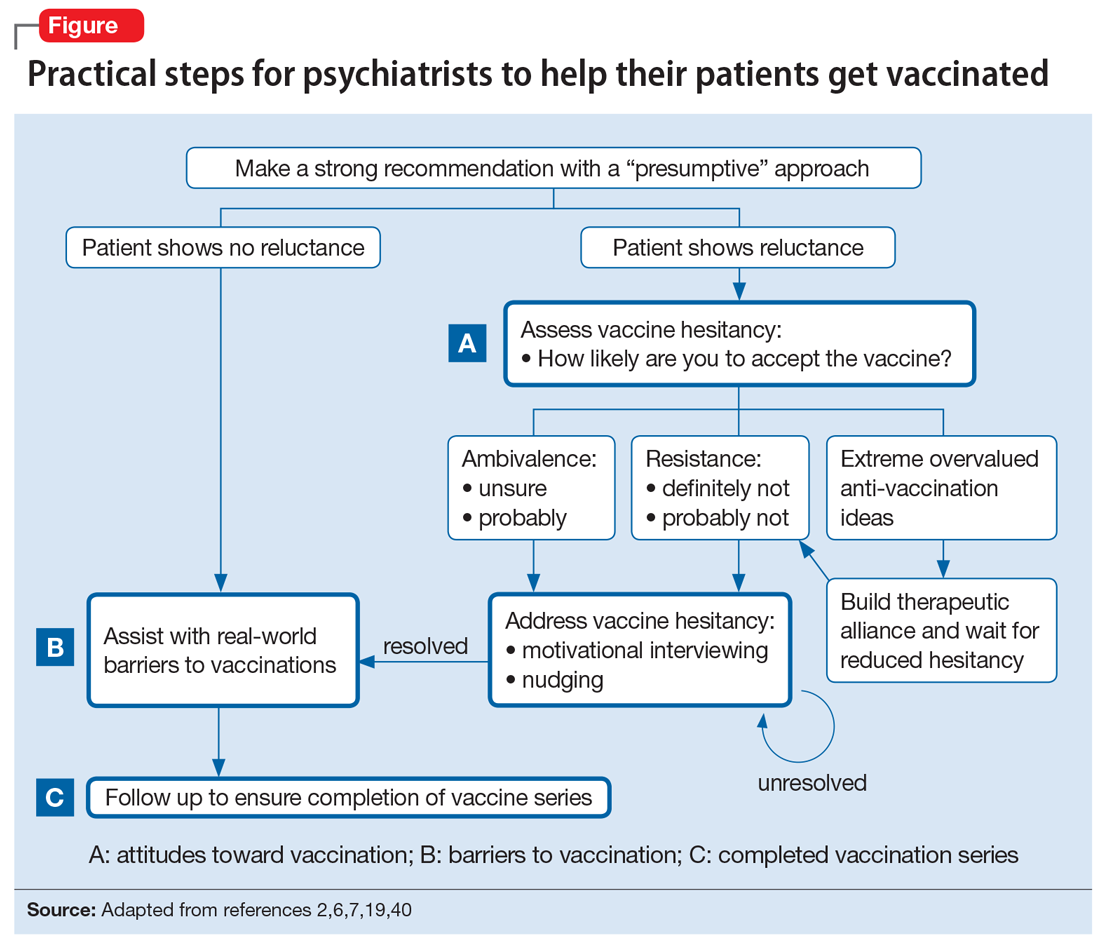

Prioritization of patients with SMI for vaccine eligibility does not directly lead to vaccine uptake. Patients with SMI need extra support from their primary point of health care contact, namely their psychiatrists. Psychiatrists may bring a set of specialized skills uniquely suited to this moment to address vaccine hesitancy and overall lack of vaccine resources and awareness. Freudenreich et al2 recently proposed “The ABCs of Successful Vaccinations” framework that psychiatrists can use in their interactions with patients to encourage vaccination by focusing on:

- attitudes towards vaccination

- barriers to vaccination

- completed vaccination series.

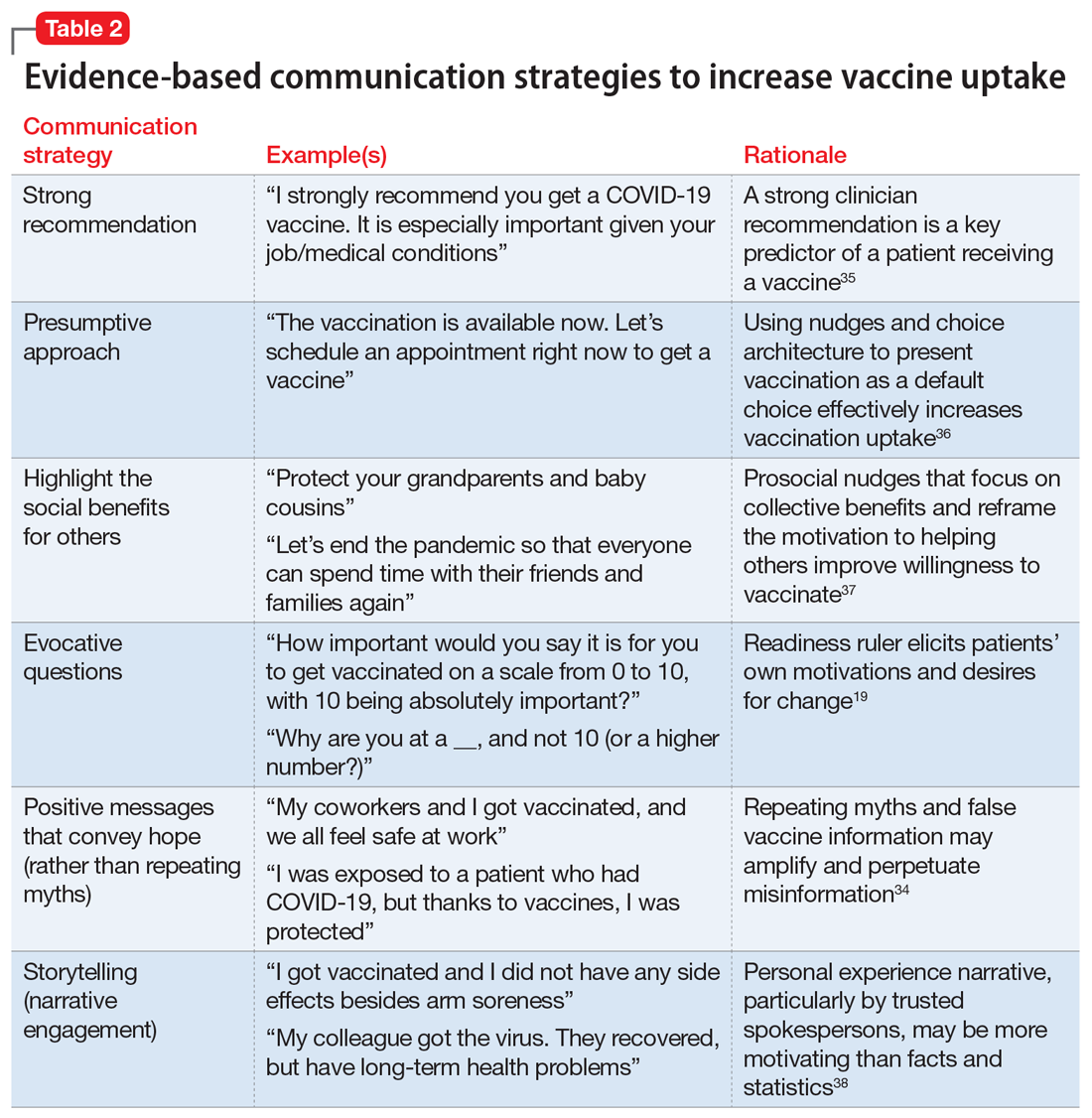

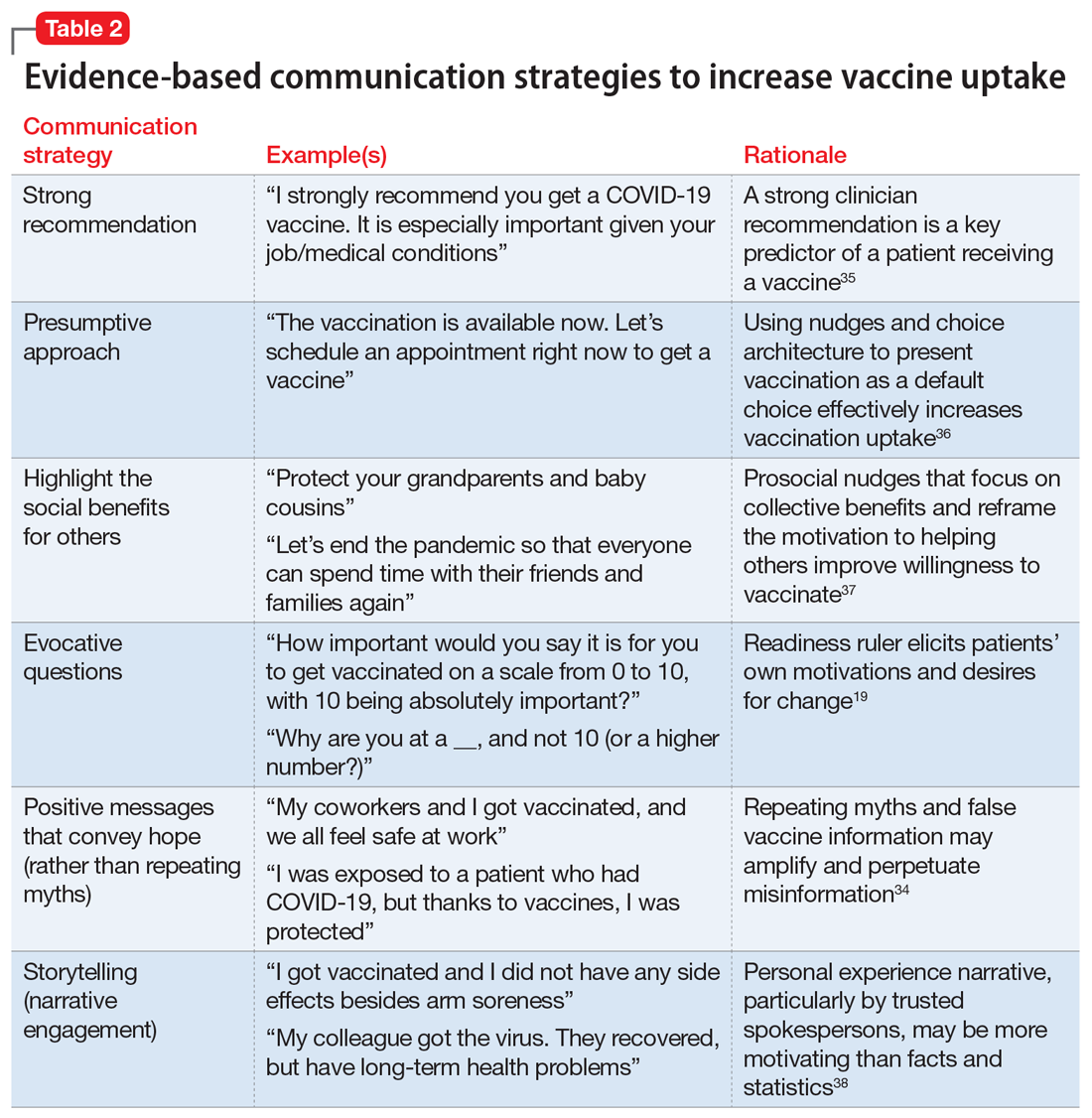

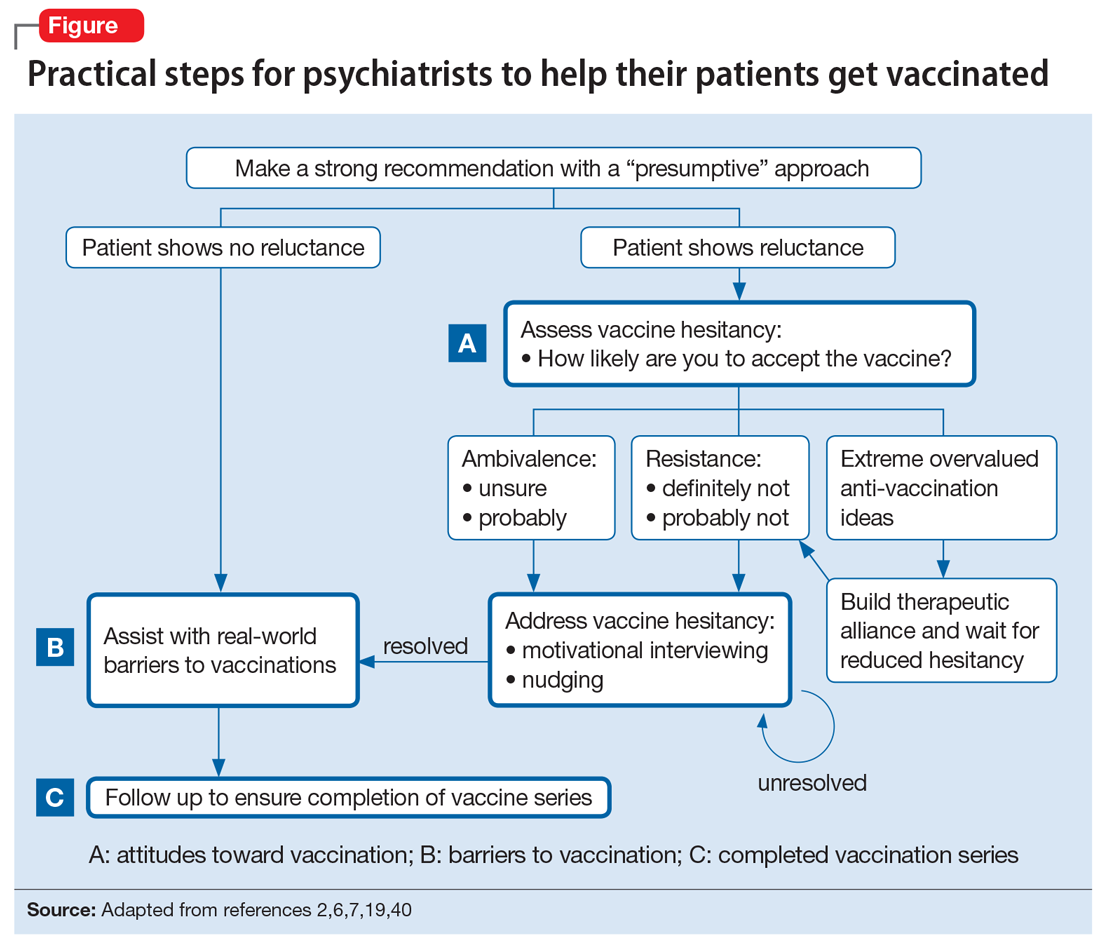

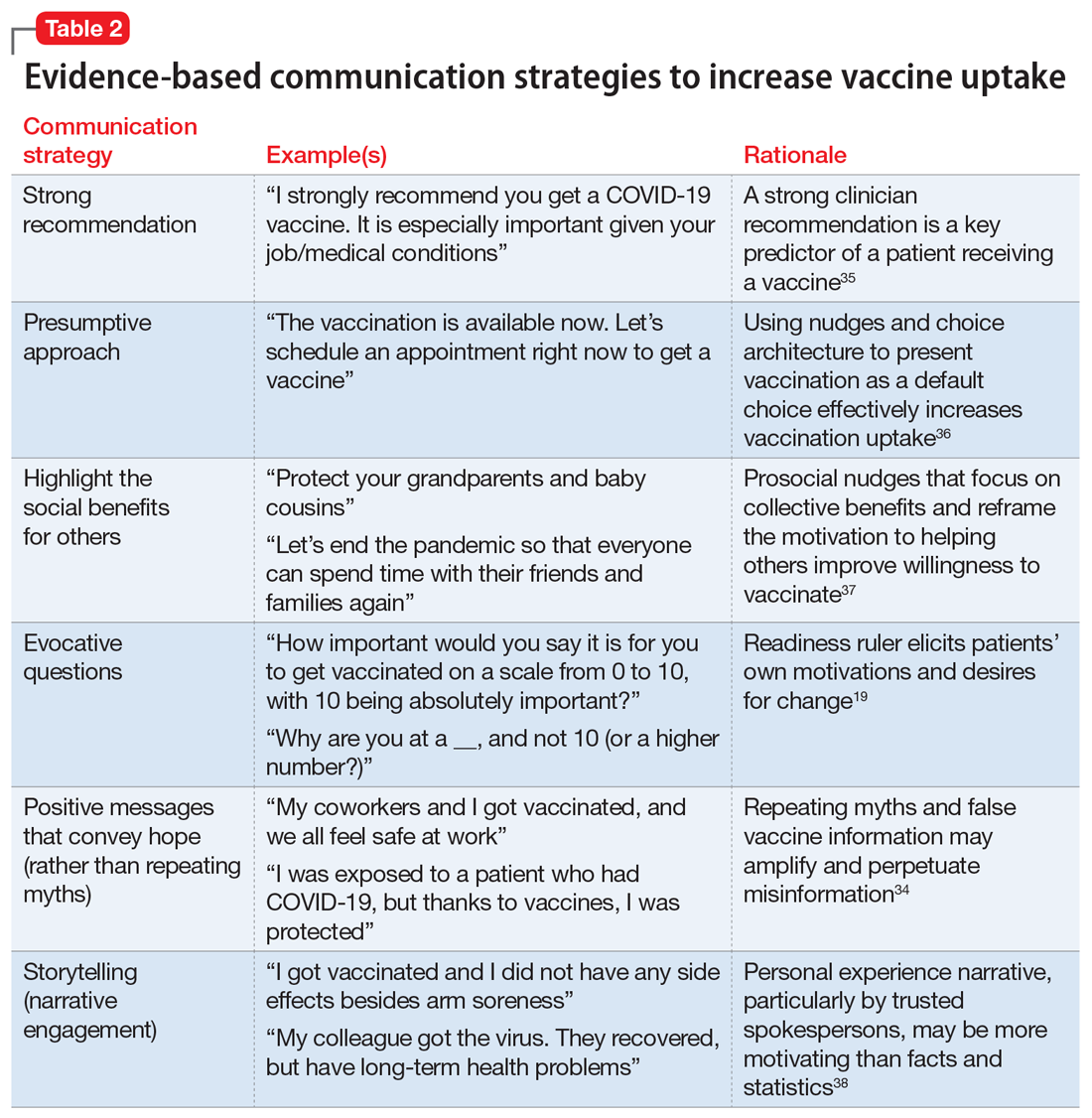

Understand attitudes toward vaccination. Decision-making may be an emotional and psychological experience that is informed by thoughts and feelings,34 and psychiatrists are uniquely positioned to tailor messages to individual patients by using motivational interviewing and applying nudging techniques.8 Given the large role of the pandemic in everyday life, it would be natural to address vaccine-related concerns in the course of routine rapport-building. Table 219,34-38 shows example phrases of COVID-19 vaccine messages that are based on communication strategies that have demonstrated success in health behavior domains (including vaccinations).39

Continue to: First, a strong recommendation...

First, a strong recommendation should be made using the presumptive approach.40 If vaccine hesitancy is detected, psychiatrists should next attempt to understand patients’ reasoning with open-ended questions to probe vaccine-related concerns. Motivational interviewing can then be used to target the fence sitters (rather than anti-vaxxers).6 Psychiatrists can also communicate with therapists about the need for further follow up on patients’ hesitancies.

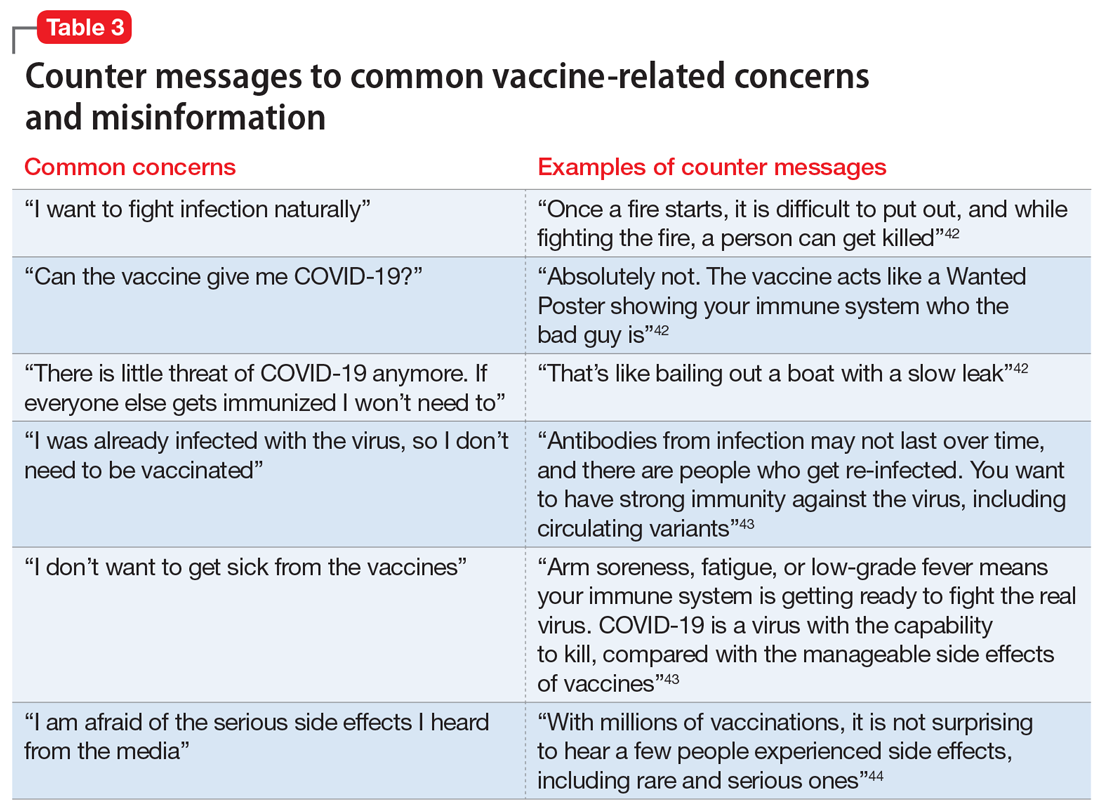

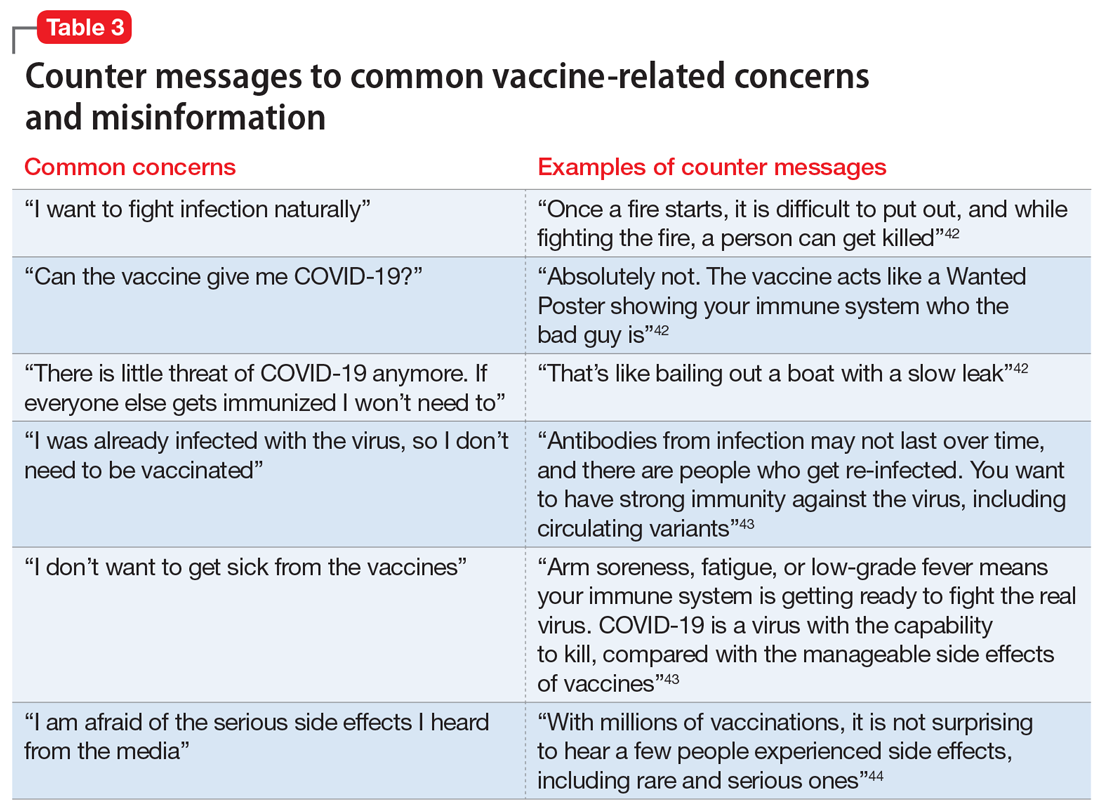

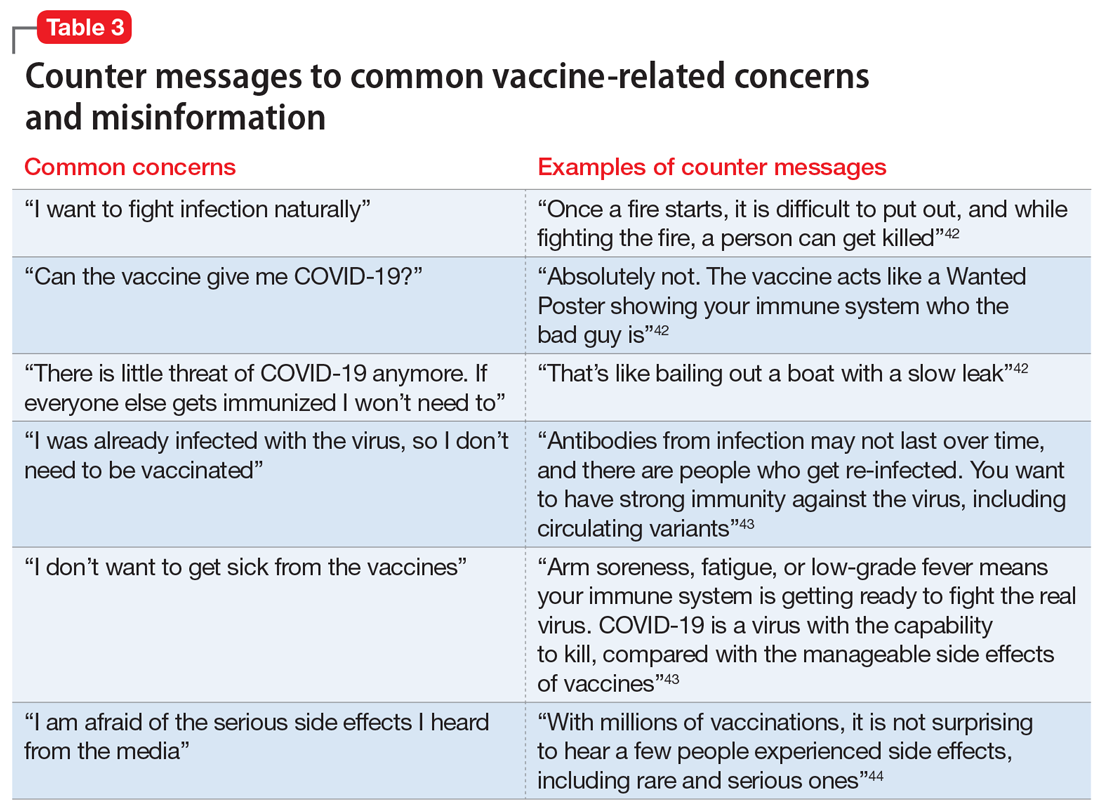

When assuring patients of vaccine safety and efficacy, it is helpful to explain the vaccine development process, including FDA approval, extensive clinical trials, monitoring, and the distribution process. Providing clear, transparent, accurate information about the risks and benefits of the vaccines is important, as well as monitoring misinformation and developing convincing counter messages that elicit positive emotions toward the vaccines.41 Examples of messages to counter common vaccine-related concerns and misinformation are shown in Table 3.42-44

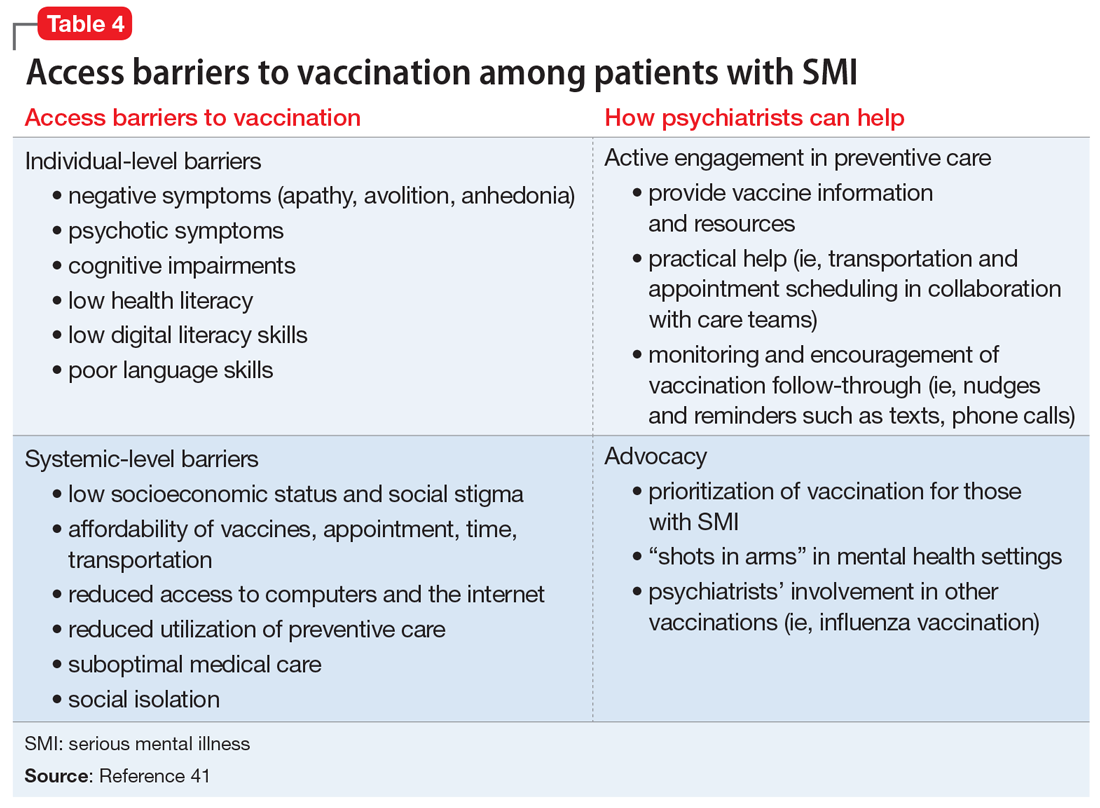

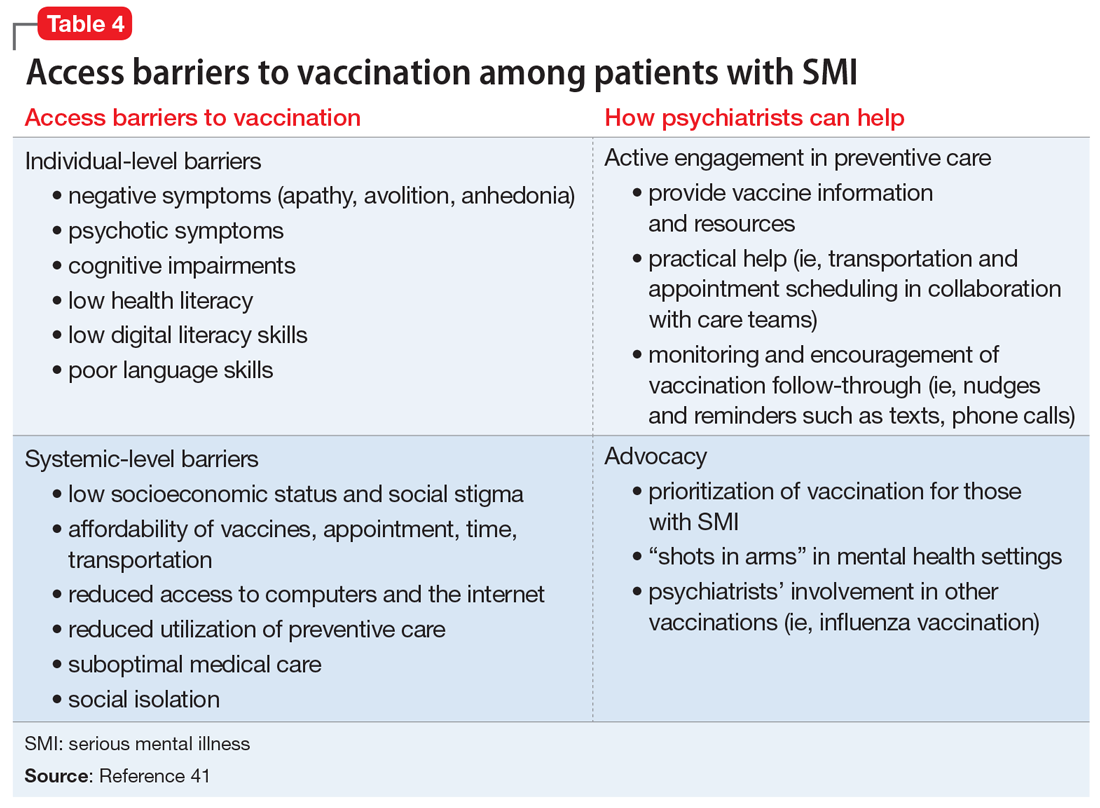

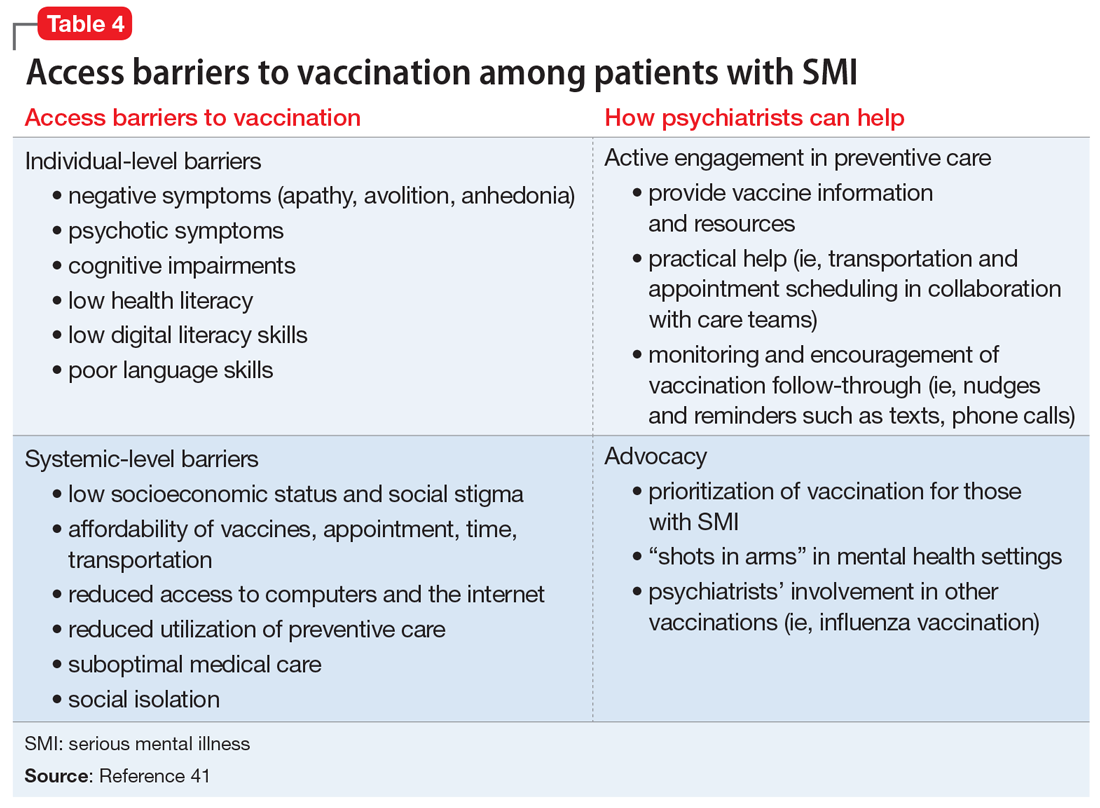

Know the barriers to vaccination. The role of the psychiatrist is to help patients, particularly those with SMIs, overcome logistical barriers and address hesitancy, which are both essential for vaccine uptake. Psychiatrists can help identify actual barriers (eg, transportation, digital access for information and scheduling) and perceived barriers, improve information access, and help patients obtain self-efficacy to take the actions needed to get vaccinated, particularly by collaborating with and communicating these concerns to other social services (Table 4).41

Monitor for vaccination series completion. Especially for vaccines that require more than a single dose over time, patients need more reminders, nudges, practical support, and encouragement to complete vaccination. A surprising degree of confusion regarding the timing of protection and benefit from the second COVID-19 injection (for the 2-injection vaccines) was uncovered in a recent survey of >1,000 US adults who had received their vaccinations in February 2021.45 Attentive monitoring of vaccination series completion by psychiatrists can thus increase the likelihood that a patient will follow through (Table 4).41 This can be as simple as asking about completion of the series during appointments, but further aided by communicating to the larger care team (social workers, care managers, care coordinators) when identifying that the patient may need further assistance.

The Figure2,6,7,19,40 summarizes the steps that psychiatrists can take to help patients get vaccinated by assessing attitudes towards vaccination (vaccine hesitancy), helping to remove barriers to vaccination, and ensuring via patient follow-up that a vaccine series is completed.

Continue to: Active involvement is key

Active involvement is key

The active involvement of psychiatrists in COVID-19 vaccination efforts can protect patients from the virus, reduce health disparities among patients with SMI, and promote herd immunity, helping to end the pandemic. Psychiatry practices can serve as ideal platforms to deliver evidence-based COVID-19 vaccine information and encourage vaccine uptake, particularly for marginalized populations.

Vaccination programs in mental health practices can even be conceptualized as a moral mandate in the spirit of addressing distributive injustice. The population management challenges of individual-level barriers and follow-through could be dramatically reduced—if not nearly eliminated—through policy-level changes that allow vaccinations to be administered in places where patients with SMI are already engaged: that is, “shots in arms” in mental health settings. As noted, some studies have shown that mental health settings can play a key role in other preventive care campaigns, such as the annual influenza and hepatitis vaccinations, and thus the incorporation of preventive care need not be limited to just COVID-19 vaccination efforts.

The COVID-19 pandemic is an opportunity to rethink the role of psychiatrists and psychiatric offices and clinics in preventive health care. The health risks and disparities of patients with SMI require the proactive involvement of psychiatrists at both the level of their individual patients and at the federal and state levels to advocate for policy changes that can benefit these populations. Overall, psychiatrists occupy a special role within the medical establishment that enables them to uniquely advocate for patients with SMI and ensure they are not forgotten during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists could apply behavior management techniques such as motivational interviewing and nudging to address vaccine hesitancy in their patients and move them to accepting the COVID-19 vaccination. This could be particularly valuable for patients with serious mental illness, who face increased risks from COVID-19 and additional barriers to getting vaccinated.

Related Resources

- American Psychiatric Association. APA coronavirus resources. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/covid-19-Coronavirus

- Baddeley M. Behavioural economics: a very short introduction. Oxford University Press; 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccines for COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/index.html

- Chou W, Burgdorf C, Gaysynsky A, et al. COVID-19 vaccination communication: applying behavioral and social science to address vaccine hesitancy and foster vaccine confidence. National Institutes of Health. Published 2020. https://obssr.od.nih.gov/sites/obssr/files/inline-files/OBSSR_VaccineWhitePaper_FINAL_508.pdf

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: helping people change. Guilford Press; 2012.

1. Mazereel V, Van Assche K, Detraux J, et al. COVID-19 vaccination for people with severe mental illness: why, what, and how? Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(5):444-450.

2. Freudenreich O, Van Alphen MU, Lim C. The ABCs of successful vaccinations: a role for psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(3):48-50.

3. World Health Organization (WHO). Ten threats to global health in 2019. Accessed July 2, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019

4. MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161-4164.

5. McClure CC, Cataldi JR, O’Leary ST. Vaccine hesitancy: where we are and where we are going. Clin Ther. 2017;39(8):1550-1562.

6. Betsch C, Korn L, Holtmann C. Don’t try to convert the antivaccinators, instead target the fence-sitters. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112(49):E6725-E6726.

7. Rahman T, Hartz SM, Xiong W, et al. Extreme overvalued beliefs. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2020;48(3):319-326.

8. Leask J. Target the fence-sitters. Nature. 2011;473(7348):443-445.

9. United States Census Bureau. Household Pulse Survey COVID-19 Vaccination Tracker. Updated June 30, 2021. Accessed July 2, 2021. https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/household-pulse-survey-covid-19-vaccination-tracker.html

10. United States Census Bureau. Measuring household experiences during the coronavirus pandemic. Updated May 5, 2021. Accessed July 2, 2021. https://www.census.gov/data/experimental-data-products/household-pulse-survey.html

11. Jefsen OH, Kølbæk P, Gil Y, et al. COVID-19 vaccine willingness among patients with mental illness compared with the general population. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2021:1-24. doi:10.1017/neu.2021.15

12. Miles LW, Williams N, Luthy KE, et al. Adult vaccination rates in the mentally ill population: an outpatient improvement project. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2020;26(2):172-180.

13. Lewandowsky S, Ecker UK, Seifert CM, et al. Misinformation and its correction: continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2012;13(3):106-131.

14. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA. Locus of mental health treatment in an integrated service system. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(7):890-892.

15. Freudenreich O, Kontos N, Querques J. COVID-19 and patients with serious mental illness. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(9):24-35.

16. Hamel L, Kirzinger A, Muñana C, et al. KFF COVID-19 vaccine monitor: December 2020. Accessed July 2, 2021. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/report/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-december-2020/

17. Kai J, Crosland A. Perspectives of people with enduring mental ill health from a community-based qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51(470):730-736.

18. Mather G, Baker D, Laugharne R. Patient trust in psychiatrists. Psychosis. 2012;4(2):161-167.

19. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: helping people change. Guilford Press; 2012.

20. Reno JE, O’Leary S, Garrett K, et al. Improving provider communication about HPV vaccines for vaccine-hesitant parents through the use of motivational interviewing. J Health Commun. 2018;23(4):313-320.

21. Baddeley M. Behavioural economics: a very short introduction. Volume 505. Oxford University Press; 2017.

22. Nemani K, Li C, Olfson M, et al. Association of psychiatric disorders with mortality among patients with COVID-19. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(4):380-386.

23. De Hert M, Correll CU, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011;10(1):52.

24. Lorenz RA, Norris MM, Norton LC, et al. Factors associated with influenza vaccination decisions among patients with mental illness. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2013;46(1):1-13.

25. Bitan DT. Patients with schizophrenia are under‐vaccinated for COVID‐19: a report from Israel. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(2):300.

26. Robotham D, Satkunanathan S, Doughty L, et al. Do we still have a digital divide in mental health? A five-year survey follow-up. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(11):e309.

27. De Hert M, Cohen D, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. II. Barriers to care, monitoring and treatment guidelines, plus recommendations at the system and individual level. World Psychiatry. 2011;10(2):138.

28. Carrà G, Bartoli F, Carretta D, et al. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in people with severe mental illness: a mediation analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(11):1739-1746.

29. Lin MT, Burgess JF, Carey K. The association between serious psychological distress and emergency department utilization among young adults in the USA. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(6):939-947.

30. DeCoux M. Acute versus primary care: the health care decision making process for individuals with severe mental illness. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2005;26(9):935-951.

31. Hoffman L, Wisniewski H, Hays R, et al. Digital opportunities for outcomes in recovery services (DOORS): a pragmatic hands-on group approach toward increasing digital health and smartphone competencies, autonomy, relatedness, and alliance for those with serious mental illness. J Psychiatr Pract. 2020;26(2):80-88.

32. Rosenberg SD, Goldberg RW, Dixon LB, et al. Assessing the STIRR model of best practices for blood-borne infections of clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(9):885-891.

33. Slade EP, Rosenberg S, Dixon LB, et al. Costs of a public health model to increase receipt of hepatitis-related services for persons with mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(2):127-133.

34. Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Rothman AJ, et al. Increasing vaccination: putting psychological science into action. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2017;18(3):149-207.

35. Nabet B, Gable J, Eder J, et al. PolicyLab evidence to action brief: addressing vaccine hesitancy to protect children & communities against preventable diseases. Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Published Spring 2017. Accessed July 2, 2021. https://policylab.chop.edu/sites/default/files/pdf/publications/Addressing_Vaccine_Hesitancy.pdf

36. Opel DJ, Heritage J, Taylor JA, et al. The architecture of provider-parent vaccine discussions at health supervision visits. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):1037-1046.

37. Betsch C, Böhm R, Korn L, et al. On the benefits of explaining herd immunity in vaccine advocacy. Nat Hum Behav. 2017;1(3):1-6.

38. Shen F, Sheer VC, Li R. Impact of narratives on persuasion in health communication: a meta-analysis. J Advert. 2015;44(2):105-113.

39. Parkerson N, Leader A. Vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID. Population Health Leadership Series: PopTalk webinars. Paper 26. Published February 10, 2021. https://jdc.jefferson.edu/phlspoptalk/26/

40. Dempsey AF, O’Leary ST. Human papillomavirus vaccination: narrative review of studies on how providers’ vaccine communication affects attitudes and uptake. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2):S23-S27.

41. Chou W, Burgdorf C, Gaysynsky A, et al. COVID-19 vaccination communication: applying behavioral and social science to address vaccine hesitancy and foster vaccine confidence. National Institutes of Health. Published 2020. https://obssr.od.nih.gov/sites/obssr/files/inline-files/OBSSR_VaccineWhitePaper_FINAL_508.pdf

42. International Society for Vaccines and the MJH Life Sciences COVID-19 coalition. Building confidence in COVID-19 vaccination: a toolbox of talks from leaders in the field. March 9, 2021. https://globalmeet.webcasts.com/starthere.jsp?ei=1435659&tp_key=59ed660099

43. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Frequently asked questions about COVID-19 vaccination. Accessed July 2, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/faq.html

44. Singh BR, Gandharava S, Gandharva R. Covid-19 vaccines and community immunity. Infectious Diseases Research. 2021;2(1):5.

45. Goldfarb JL, Kreps S, Brownstein JS, et al. Beyond the first dose - Covid-19 vaccine follow-through and continued protective measures. N Engl J Med. 2021;85(2):101-103.

After more than 600,000 deaths in the United States from the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), several safe and effective vaccines against the virus have become available. Vaccines are the most effective preventive measure against COVID-19 and the most promising way to achieve herd immunity to end the current pandemic. However, obstacles to reaching this goal include vaccine skepticism, structural barriers, or simple inertia to get vaccinated. These challenges provide opportunities for psychiatrists to use their medical knowledge and expertise, applying behavior management techniques such as motivational interviewing and nudging to encourage their patients to get vaccinated. In particular, marginalized patients with serious mental illness (SMI), who are subject to disproportionately high rates of COVID-19 infection and more severe outcomes,1 have much to gain if psychiatrists become involved in the COVID-19 vaccination campaign.

In this article, we define vaccine hesitancy and highlight what makes psychiatrists ideal vaccine ambassadors, given their unique skill set and longitudinal, trust-based connection with their patients. We expand on the particular vulnerabilities of patients with SMI, including structural barriers to vaccination that lead to health disparities and inequity. Finally, building on “The ABCs of successful vaccinations” framework published in

What is vaccine hesitancy?

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines vaccine hesitancy as a “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccine services.”3,4 Vaccine hesitancy occurs on a continuum ranging from uncertainty about accepting a vaccine to absolute refusal.4,5 It involves a complex decision-making process driven by contextual, individual, and social influences, and vaccine-specific issues.4 In the “3C” model developed by the WHO Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) Working Group, vaccine hesitancy is influenced by confidence (trust in vaccines, in the health care system, and in policy makers), complacency (lower perceived risk), and convenience (availability, affordability, accessibility, language and health literacy, appeal of vaccination program).4

In 2019, the WHO named vaccine hesitancy as one of the top 10 global health threats.3 Hesitancy to receive COVID-19 vaccines may be particularly high because of their rapid development. In addition, the tumultuous political environment that often featured inconsistent messaging about the virus, its dangers, and its transmission since the early days of the pandemic created widespread public confusion and doubt as scientific understandings evolved. “Anti-vaxxer” movements that completely rejected vaccine efficacy disseminated misinformation online. Followers of these movements may have such extreme overvalued ideas that any effort to persuade them otherwise with scientific evidence will accomplish very little.6,7 Therefore, focusing on individuals who are “sitting on the fence” about getting vaccinated can be more productive because they represent a much larger group than those who adamantly refuse vaccines, and they may be more amenable to changing beliefs and behaviors.8

The US Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey asked, “How likely are you to accept the vaccine?”9 As of late June 2021, 11.4% of US adults reported they would “definitely not get a vaccine” or “probably not get a vaccine,” and that number increases to 16.9% when including those who are “unsure,” although there is wide geographical variability.10

A recent study in Denmark showed that willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine was slightly lower among patients with mental illness (84.8%) compared with the general population (89.5%).11 Given the small difference, vaccine hesitancy was not considered to be a major barrier for vaccination among patients with mental illness in Denmark. This is similar to the findings of a pre-pandemic study at a community mental health clinic in the United States involving other vaccinations, which suggested that 84% of patients with SMI perceived vaccinations as safe, effective, and important.12 In this clinic, identified barriers to vaccinations in general among patients with SMI included lack of awareness and knowledge (42.2%), accessibility (16.3%), personal cost (13.3%), fears about immunization (10.4%), and lack of recommendations by primary care providers (PCPs) (1.5%).12

It is critical to distinguish attitude-driven vaccine hesitancy from a lack of education and opportunity to receive a vaccine. Particularly disadvantaged communities may be mislabeled as “vaccine hesitant” when in fact they may not have the ability to be as proactive as other population groups (eg, difficulty scheduling appointments over the Internet).

Continue to: What makes psychiatrists ideal vaccine ambassadors?

What makes psychiatrists ideal vaccine ambassadors?

There are several reasons psychiatrists can be well-positioned to contribute to the success of vaccination campaigns (Table 1). These include their frequent contact with patients and their care teams, the high trust those patients have in them, and their medical expertise and skills in applied behavioral and social science techniques, including motivational interviewing and nudging. Vaccination efforts and outreach are more effective when led by the clinician with whom the patient has the most contact because resolving vaccine hesitancy is not a one-time discussion but requires ongoing communication, persistence, and consistency.13 Patients may contact their psychiatrists more frequently than their other clinicians, including PCPs. For this reason, psychiatrists can serve as the gateway to health care, particularly for patients with SMI.14 In addition, interruptions in nonemergency services caused by the COVID-19 pandemic may affect vaccine delivery because patients may have been unable to see their PCPs regularly during the pandemic.15

Psychiatrists’ medical expertise and their ability to develop rapport with their patients promote trust-building. Receiving credible information from a trusted source such as a patient’s psychiatrist can be impactful. A recent poll suggested that individual health care clinicians have been consistently identified as the most trusted sources for vaccine information, including for the COVID-19 vaccines.16 There is also higher trust when there is greater continuity of care both in terms of length of time the patient has known the clinician and the number of consultations,17 an inherent part of psychiatric practice. In addition, research has shown that patients trust their psychiatrists as much as they trust their general practitioners.18

Psychiatrists are experts in behavior change, promoting healthy behaviors through motivational interviewing and nudging. They also have experience with managing patients who hold overvalued ideas as well as dealing with uncertainty, given their scientific and medical training.

Motivational interviewing is a patient-centered, collaborative approach widely used by psychiatrists to treat unhealthy behaviors such as substance use. Clinicians elicit and strengthen the patient’s desire and motivation for change while respecting their autonomy. Instead of presenting persuasive facts, the clinician creates a welcoming, nonthreatening, safe environment by engaging patients in open dialogue, reflecting back the patients’ concerns with empathy, helping them realize contradictions in behavior, and supporting self-sufficiency.19 In a nonpsychiatric setting, studies have shown the effectiveness of motivational interviewing in increasing uptake of human papillomavirus vaccines and of pediatric vaccines.20

Nudging, which comes from behavioral economics and psychology, underscores the importance of structuring a choice architecture in changing the way people make their everyday decisions.21 Nudging still gives people a choice and respects autonomy, but it leads patients to more efficient and productive decision-making. Many nudges are based around giving good “default options” because people often do not make efforts to deviate from default options. In addition, social nudges are powerful, giving people a social reference point and normalizing certain behaviors.21 Psychiatrists have become skilled in nudging from working with patients with varying levels of insight and cognitive capabilities. That is, they give simple choices, prompts, and frequent feedback to reinforce “good” decisions and to discourage “bad” decisions.

Continue to: Managing overvalued ideas

Managing overvalued ideas. Psychiatrists are also well-versed in having discussions with patients who hold irrational beliefs (psychosis) or overvalued ideas. For example, psychiatrists frequently manage anorexia nervosa and hypochondria, which are rooted in overvalued ideas.7 While psychiatrists may not be able to directly confront the overvalued ideas, they can work around such ideas while waiting for more flexible moments. Similarly, managing patients with intense emotional commitment7 to commonly held anti-vaccination ideas may not be much different. Psychiatrists can work around resistance until patients may be less strongly attached to those overvalued ideas in instances when other techniques, such as motivational interviewing and nudging, may be more effective.

Managing uncertainty. Psychiatrists are experts in managing “not knowing” and uncertainty. Due to their medical scientific training, they are familiar with the process of science, and how understanding changes through trial and error. In contrast, most patients usually only see the end product (ie, a drug comes to market). Discussions with patients that acknowledge uncertainty and emphasize that changes in what is known are expected and appropriate as scientific knowledge evolves could help preempt skepticism when messages are updated.

Why do patients with SMI need more help?

SMI as a high-risk group. Patients with SMI are part of a “tragic” epidemiologic triad of agent-host-environment15 that places them at remarkably elevated risk for COVID-19 infection and more serious complications and death when infected.1 After age, a diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder is the second largest predictor of mortality from COVID-19, with a 2.7-fold increase in mortality.22 This is how the elements of the triad come together: SARS-Cov-2 is a highly infectious agent affecting individuals who are vulnerable hosts because of their high frequency of medical comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and respiratory tract diseases, which are all risk factors for worse outcomes due to COVID-19.23 In addition, SMI is associated with socioeconomic risk factors for SARS-Cov-2 infection, including poverty, homelessness, and crowded settings such as jails, group homes, hospitals, and shelters, which constitute ideal environments for high transmission of the virus.

Structural barriers to vaccination. Studies have suggested lower rates of vaccination among people with SMI for various other infectious diseases compared with the general population.12 For example, in 1 outpatient mental health setting, influenza vaccination rates were 24% to 28%, which was lower than the national vaccination rate of 40.9% for the same influenza season (2010 to 2011).24 More recently, a study in Israel examining the COVID-19 vaccination rate among >25,000 patients with schizophrenia suggested under-vaccination of this cohort. The results showed that the odds of getting the COVID-19 vaccination were significantly lower in the schizophrenia group compared with the general population (odds ratio = 0.80, 95% CI: 0.77 to 0.83).25

Patients with SMI encounter considerable system-level barriers to vaccinations in general, such as reduced access to health care due to cost and a lack of transportation,12 the digital divide given their reduced access to the internet and computers for information and scheduling,26 and lack of vaccination recommendations from their PCPs.12 Studies have also shown that patients with SMI often receive suboptimal medical care because of stigmatization and discrimination.27 They also have lower rates of preventive care utilization, seeking medical services only in times of crisis and seeking mental health services more often than physical health care.28-30

Continue to: Patients with SMI face...

Patients with SMI face additional individual challenges that impede vaccine uptake, such as lack of knowledge and awareness about the virus and vaccinations, general cognitive impairment, low digital literacy skills,31 low language literacy and educational attainment, baseline delusions, and negative symptoms such as apathy, avolition, and anhedonia.1 Thus, even if they overcome the external barriers and obtain vaccine-related information, these patients may experience difficulty in understanding the content and applying this information to their personal circumstances as a result of low health literacy.

How psychiatrists can help

The concept of using mental health care sites and trained clinicians to increase medical disease prevention is not new. The rigorously tested intervention model STIRR (Screen, Test, Immunize, Reduce risk, and Refer) uses co-located nurse practitioners in community mental health centers to provide risk assessment, counseling, and blood testing for hepatitis and HIV, as well as on-site vaccinations for hepatitis to patients dually diagnosed with SMI and substance use disorders.32

Prioritization of patients with SMI for vaccine eligibility does not directly lead to vaccine uptake. Patients with SMI need extra support from their primary point of health care contact, namely their psychiatrists. Psychiatrists may bring a set of specialized skills uniquely suited to this moment to address vaccine hesitancy and overall lack of vaccine resources and awareness. Freudenreich et al2 recently proposed “The ABCs of Successful Vaccinations” framework that psychiatrists can use in their interactions with patients to encourage vaccination by focusing on:

- attitudes towards vaccination

- barriers to vaccination

- completed vaccination series.

Understand attitudes toward vaccination. Decision-making may be an emotional and psychological experience that is informed by thoughts and feelings,34 and psychiatrists are uniquely positioned to tailor messages to individual patients by using motivational interviewing and applying nudging techniques.8 Given the large role of the pandemic in everyday life, it would be natural to address vaccine-related concerns in the course of routine rapport-building. Table 219,34-38 shows example phrases of COVID-19 vaccine messages that are based on communication strategies that have demonstrated success in health behavior domains (including vaccinations).39

Continue to: First, a strong recommendation...

First, a strong recommendation should be made using the presumptive approach.40 If vaccine hesitancy is detected, psychiatrists should next attempt to understand patients’ reasoning with open-ended questions to probe vaccine-related concerns. Motivational interviewing can then be used to target the fence sitters (rather than anti-vaxxers).6 Psychiatrists can also communicate with therapists about the need for further follow up on patients’ hesitancies.

When assuring patients of vaccine safety and efficacy, it is helpful to explain the vaccine development process, including FDA approval, extensive clinical trials, monitoring, and the distribution process. Providing clear, transparent, accurate information about the risks and benefits of the vaccines is important, as well as monitoring misinformation and developing convincing counter messages that elicit positive emotions toward the vaccines.41 Examples of messages to counter common vaccine-related concerns and misinformation are shown in Table 3.42-44

Know the barriers to vaccination. The role of the psychiatrist is to help patients, particularly those with SMIs, overcome logistical barriers and address hesitancy, which are both essential for vaccine uptake. Psychiatrists can help identify actual barriers (eg, transportation, digital access for information and scheduling) and perceived barriers, improve information access, and help patients obtain self-efficacy to take the actions needed to get vaccinated, particularly by collaborating with and communicating these concerns to other social services (Table 4).41

Monitor for vaccination series completion. Especially for vaccines that require more than a single dose over time, patients need more reminders, nudges, practical support, and encouragement to complete vaccination. A surprising degree of confusion regarding the timing of protection and benefit from the second COVID-19 injection (for the 2-injection vaccines) was uncovered in a recent survey of >1,000 US adults who had received their vaccinations in February 2021.45 Attentive monitoring of vaccination series completion by psychiatrists can thus increase the likelihood that a patient will follow through (Table 4).41 This can be as simple as asking about completion of the series during appointments, but further aided by communicating to the larger care team (social workers, care managers, care coordinators) when identifying that the patient may need further assistance.

The Figure2,6,7,19,40 summarizes the steps that psychiatrists can take to help patients get vaccinated by assessing attitudes towards vaccination (vaccine hesitancy), helping to remove barriers to vaccination, and ensuring via patient follow-up that a vaccine series is completed.

Continue to: Active involvement is key

Active involvement is key

The active involvement of psychiatrists in COVID-19 vaccination efforts can protect patients from the virus, reduce health disparities among patients with SMI, and promote herd immunity, helping to end the pandemic. Psychiatry practices can serve as ideal platforms to deliver evidence-based COVID-19 vaccine information and encourage vaccine uptake, particularly for marginalized populations.

Vaccination programs in mental health practices can even be conceptualized as a moral mandate in the spirit of addressing distributive injustice. The population management challenges of individual-level barriers and follow-through could be dramatically reduced—if not nearly eliminated—through policy-level changes that allow vaccinations to be administered in places where patients with SMI are already engaged: that is, “shots in arms” in mental health settings. As noted, some studies have shown that mental health settings can play a key role in other preventive care campaigns, such as the annual influenza and hepatitis vaccinations, and thus the incorporation of preventive care need not be limited to just COVID-19 vaccination efforts.

The COVID-19 pandemic is an opportunity to rethink the role of psychiatrists and psychiatric offices and clinics in preventive health care. The health risks and disparities of patients with SMI require the proactive involvement of psychiatrists at both the level of their individual patients and at the federal and state levels to advocate for policy changes that can benefit these populations. Overall, psychiatrists occupy a special role within the medical establishment that enables them to uniquely advocate for patients with SMI and ensure they are not forgotten during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists could apply behavior management techniques such as motivational interviewing and nudging to address vaccine hesitancy in their patients and move them to accepting the COVID-19 vaccination. This could be particularly valuable for patients with serious mental illness, who face increased risks from COVID-19 and additional barriers to getting vaccinated.

Related Resources

- American Psychiatric Association. APA coronavirus resources. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/covid-19-Coronavirus

- Baddeley M. Behavioural economics: a very short introduction. Oxford University Press; 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccines for COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/index.html

- Chou W, Burgdorf C, Gaysynsky A, et al. COVID-19 vaccination communication: applying behavioral and social science to address vaccine hesitancy and foster vaccine confidence. National Institutes of Health. Published 2020. https://obssr.od.nih.gov/sites/obssr/files/inline-files/OBSSR_VaccineWhitePaper_FINAL_508.pdf

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: helping people change. Guilford Press; 2012.

After more than 600,000 deaths in the United States from the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), several safe and effective vaccines against the virus have become available. Vaccines are the most effective preventive measure against COVID-19 and the most promising way to achieve herd immunity to end the current pandemic. However, obstacles to reaching this goal include vaccine skepticism, structural barriers, or simple inertia to get vaccinated. These challenges provide opportunities for psychiatrists to use their medical knowledge and expertise, applying behavior management techniques such as motivational interviewing and nudging to encourage their patients to get vaccinated. In particular, marginalized patients with serious mental illness (SMI), who are subject to disproportionately high rates of COVID-19 infection and more severe outcomes,1 have much to gain if psychiatrists become involved in the COVID-19 vaccination campaign.

In this article, we define vaccine hesitancy and highlight what makes psychiatrists ideal vaccine ambassadors, given their unique skill set and longitudinal, trust-based connection with their patients. We expand on the particular vulnerabilities of patients with SMI, including structural barriers to vaccination that lead to health disparities and inequity. Finally, building on “The ABCs of successful vaccinations” framework published in

What is vaccine hesitancy?

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines vaccine hesitancy as a “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccine services.”3,4 Vaccine hesitancy occurs on a continuum ranging from uncertainty about accepting a vaccine to absolute refusal.4,5 It involves a complex decision-making process driven by contextual, individual, and social influences, and vaccine-specific issues.4 In the “3C” model developed by the WHO Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) Working Group, vaccine hesitancy is influenced by confidence (trust in vaccines, in the health care system, and in policy makers), complacency (lower perceived risk), and convenience (availability, affordability, accessibility, language and health literacy, appeal of vaccination program).4

In 2019, the WHO named vaccine hesitancy as one of the top 10 global health threats.3 Hesitancy to receive COVID-19 vaccines may be particularly high because of their rapid development. In addition, the tumultuous political environment that often featured inconsistent messaging about the virus, its dangers, and its transmission since the early days of the pandemic created widespread public confusion and doubt as scientific understandings evolved. “Anti-vaxxer” movements that completely rejected vaccine efficacy disseminated misinformation online. Followers of these movements may have such extreme overvalued ideas that any effort to persuade them otherwise with scientific evidence will accomplish very little.6,7 Therefore, focusing on individuals who are “sitting on the fence” about getting vaccinated can be more productive because they represent a much larger group than those who adamantly refuse vaccines, and they may be more amenable to changing beliefs and behaviors.8

The US Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey asked, “How likely are you to accept the vaccine?”9 As of late June 2021, 11.4% of US adults reported they would “definitely not get a vaccine” or “probably not get a vaccine,” and that number increases to 16.9% when including those who are “unsure,” although there is wide geographical variability.10

A recent study in Denmark showed that willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine was slightly lower among patients with mental illness (84.8%) compared with the general population (89.5%).11 Given the small difference, vaccine hesitancy was not considered to be a major barrier for vaccination among patients with mental illness in Denmark. This is similar to the findings of a pre-pandemic study at a community mental health clinic in the United States involving other vaccinations, which suggested that 84% of patients with SMI perceived vaccinations as safe, effective, and important.12 In this clinic, identified barriers to vaccinations in general among patients with SMI included lack of awareness and knowledge (42.2%), accessibility (16.3%), personal cost (13.3%), fears about immunization (10.4%), and lack of recommendations by primary care providers (PCPs) (1.5%).12

It is critical to distinguish attitude-driven vaccine hesitancy from a lack of education and opportunity to receive a vaccine. Particularly disadvantaged communities may be mislabeled as “vaccine hesitant” when in fact they may not have the ability to be as proactive as other population groups (eg, difficulty scheduling appointments over the Internet).

Continue to: What makes psychiatrists ideal vaccine ambassadors?

What makes psychiatrists ideal vaccine ambassadors?

There are several reasons psychiatrists can be well-positioned to contribute to the success of vaccination campaigns (Table 1). These include their frequent contact with patients and their care teams, the high trust those patients have in them, and their medical expertise and skills in applied behavioral and social science techniques, including motivational interviewing and nudging. Vaccination efforts and outreach are more effective when led by the clinician with whom the patient has the most contact because resolving vaccine hesitancy is not a one-time discussion but requires ongoing communication, persistence, and consistency.13 Patients may contact their psychiatrists more frequently than their other clinicians, including PCPs. For this reason, psychiatrists can serve as the gateway to health care, particularly for patients with SMI.14 In addition, interruptions in nonemergency services caused by the COVID-19 pandemic may affect vaccine delivery because patients may have been unable to see their PCPs regularly during the pandemic.15

Psychiatrists’ medical expertise and their ability to develop rapport with their patients promote trust-building. Receiving credible information from a trusted source such as a patient’s psychiatrist can be impactful. A recent poll suggested that individual health care clinicians have been consistently identified as the most trusted sources for vaccine information, including for the COVID-19 vaccines.16 There is also higher trust when there is greater continuity of care both in terms of length of time the patient has known the clinician and the number of consultations,17 an inherent part of psychiatric practice. In addition, research has shown that patients trust their psychiatrists as much as they trust their general practitioners.18

Psychiatrists are experts in behavior change, promoting healthy behaviors through motivational interviewing and nudging. They also have experience with managing patients who hold overvalued ideas as well as dealing with uncertainty, given their scientific and medical training.

Motivational interviewing is a patient-centered, collaborative approach widely used by psychiatrists to treat unhealthy behaviors such as substance use. Clinicians elicit and strengthen the patient’s desire and motivation for change while respecting their autonomy. Instead of presenting persuasive facts, the clinician creates a welcoming, nonthreatening, safe environment by engaging patients in open dialogue, reflecting back the patients’ concerns with empathy, helping them realize contradictions in behavior, and supporting self-sufficiency.19 In a nonpsychiatric setting, studies have shown the effectiveness of motivational interviewing in increasing uptake of human papillomavirus vaccines and of pediatric vaccines.20

Nudging, which comes from behavioral economics and psychology, underscores the importance of structuring a choice architecture in changing the way people make their everyday decisions.21 Nudging still gives people a choice and respects autonomy, but it leads patients to more efficient and productive decision-making. Many nudges are based around giving good “default options” because people often do not make efforts to deviate from default options. In addition, social nudges are powerful, giving people a social reference point and normalizing certain behaviors.21 Psychiatrists have become skilled in nudging from working with patients with varying levels of insight and cognitive capabilities. That is, they give simple choices, prompts, and frequent feedback to reinforce “good” decisions and to discourage “bad” decisions.

Continue to: Managing overvalued ideas

Managing overvalued ideas. Psychiatrists are also well-versed in having discussions with patients who hold irrational beliefs (psychosis) or overvalued ideas. For example, psychiatrists frequently manage anorexia nervosa and hypochondria, which are rooted in overvalued ideas.7 While psychiatrists may not be able to directly confront the overvalued ideas, they can work around such ideas while waiting for more flexible moments. Similarly, managing patients with intense emotional commitment7 to commonly held anti-vaccination ideas may not be much different. Psychiatrists can work around resistance until patients may be less strongly attached to those overvalued ideas in instances when other techniques, such as motivational interviewing and nudging, may be more effective.

Managing uncertainty. Psychiatrists are experts in managing “not knowing” and uncertainty. Due to their medical scientific training, they are familiar with the process of science, and how understanding changes through trial and error. In contrast, most patients usually only see the end product (ie, a drug comes to market). Discussions with patients that acknowledge uncertainty and emphasize that changes in what is known are expected and appropriate as scientific knowledge evolves could help preempt skepticism when messages are updated.

Why do patients with SMI need more help?

SMI as a high-risk group. Patients with SMI are part of a “tragic” epidemiologic triad of agent-host-environment15 that places them at remarkably elevated risk for COVID-19 infection and more serious complications and death when infected.1 After age, a diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder is the second largest predictor of mortality from COVID-19, with a 2.7-fold increase in mortality.22 This is how the elements of the triad come together: SARS-Cov-2 is a highly infectious agent affecting individuals who are vulnerable hosts because of their high frequency of medical comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and respiratory tract diseases, which are all risk factors for worse outcomes due to COVID-19.23 In addition, SMI is associated with socioeconomic risk factors for SARS-Cov-2 infection, including poverty, homelessness, and crowded settings such as jails, group homes, hospitals, and shelters, which constitute ideal environments for high transmission of the virus.

Structural barriers to vaccination. Studies have suggested lower rates of vaccination among people with SMI for various other infectious diseases compared with the general population.12 For example, in 1 outpatient mental health setting, influenza vaccination rates were 24% to 28%, which was lower than the national vaccination rate of 40.9% for the same influenza season (2010 to 2011).24 More recently, a study in Israel examining the COVID-19 vaccination rate among >25,000 patients with schizophrenia suggested under-vaccination of this cohort. The results showed that the odds of getting the COVID-19 vaccination were significantly lower in the schizophrenia group compared with the general population (odds ratio = 0.80, 95% CI: 0.77 to 0.83).25

Patients with SMI encounter considerable system-level barriers to vaccinations in general, such as reduced access to health care due to cost and a lack of transportation,12 the digital divide given their reduced access to the internet and computers for information and scheduling,26 and lack of vaccination recommendations from their PCPs.12 Studies have also shown that patients with SMI often receive suboptimal medical care because of stigmatization and discrimination.27 They also have lower rates of preventive care utilization, seeking medical services only in times of crisis and seeking mental health services more often than physical health care.28-30

Continue to: Patients with SMI face...