User login

Could a vaccine (and more) fix the fentanyl crisis?

This discussion was recorded on Aug. 31, 2022. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert Glatter, MD: Welcome. I’m Dr. Robert Glatter, medical advisor for Medscape Emergency Medicine. Today we have Dr. Paul Christo, a pain specialist in the Division of Pain Medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland, and host of the national radio show Aches and Gains on SiriusXM Radio, joining us to discuss the ongoing and worsening fentanyl crisis in the U.S.

Welcome, Dr Christo.

Paul J. Christo, MD, MBA: Thanks so much for having me.

Dr. Glatter: I want to begin with a sobering statistic regarding overdoses. , based on recent data from the CDC.

Let’s start by having you explain how deadly fentanyl is in terms of its potency compared with morphine and heroin.

Dr. Christo: Fentanyl is considered a synthetic opioid. It’s not a naturally occurring opioid like morphine, for example, or codeine. We use this drug, fentanyl, often in the anesthesia well. We’ve used it for many years as an anesthetic for surgery very safely. In the chronic pain world, we’ve used it to help reduce chronic pain in the form of a patch.

What we’re seeing now, though, is something entirely different, which is the use of synthetic fentanyl as a mind- and mood-altering substance for those who don’t have pain, and essentially those who are buying this off the street. Fentanyl is about 80-100 times more potent than morphine, so you can put that in perspective in terms of its danger.

Dr. Glatter: Let me have you take us through an evolution of the opioid crisis from the 1990s, from long-acting opioid OxyContin, which was approved in 1995, to where we are now. There are different phases. If you could, educate our audience on how we got to where fentanyl is now the most common opiate involved in drug overdoses.

Dr. Christo: It really stems from the epidemic related to chronic pain. We have over 100 million people in the United States alone who suffer from chronic pain. Most chronic pain, sadly, is undertreated or untreated. In the ‘90s, in the quest to reduce chronic pain to a better extent, we saw more and more literature and studies related to the use of opioids for noncancer pain (e.g., for lower back pain).

There were many primary care doctors and pain specialists who started using opioids, probably for patients who didn’t really need it. I think it was done out of good conscience in the sense that they were trying to reduce pain. We have other methods of pain relief, but we needed more. At that time, in the ‘90s, we had a greater use of opioids to treat noncancer pain.

Then from that point, we transitioned to the use of heroin. Again, this isn’t among the chronic pain population, but it was the nonchronic pain population that starting using heroin. Today we see synthetic fentanyl.

Addressing the synthetic opioid crisis

Dr. Glatter: With fentanyl being the most common opiate we’re seeing, we’re having problems trying to save patients. We’re trying to use naloxone, but obviously in increasing amounts, and sometimes it’s not adequate and we have to intubate patients.

In terms of addressing this issue of supply, the fentanyl is coming from Mexico, China, and it’s manufactured here in the United States. How do we address this crisis? What are the steps that you would recommend we take?

Dr. Christo: I think that we need to better support law enforcement to crack down on those who are manufacturing fentanyl in the United States, and also to crack down on those who are transporting it from, say, Mexico – I think it’s primarily coming from Mexico – but from outside the United States to the United States. I feel like that’s important to do.

Two, we need to better educate those who are using these mind- and mood-altering substances. We’re seeing more and more that it’s the young-adult population, those between the ages of 13 and 25, who are starting to use these substances, and they’re very dangerous.

Dr. Glatter: Are these teens seeking out heroin and it happens to be laced with fentanyl, or are they actually seeking pure fentanyl? Are they trying to buy the colorful pills that we know about? What’s your experience in terms of the population you’re treating and what you could tell us?

Dr. Christo: I think it’s both. We’re seeing young adults who are interested in the use of fentanyl as a mind- and mood-altering substance. We’re also seeing young and older adults use other drugs, like cocaine and heroin, that are laced with fentanyl, and they don’t know it. That’s exponentially more dangerous.

Fentanyl test strips

Dr. Glatter: People are unaware that there is fentanyl in what they’re using, and it is certainly leading to overdoses and deaths. I think that parents really need to be aware of this.

Dr. Christo: Yes, for sure. I think we need better educational methods in the schools to educate that population that we’re talking about (between the ages of 13 and 25). Let them know the dangers, because I don’t think they’re aware of the danger, and how potent fentanyl is in terms of its lethality, and that you don’t need very much to take in a form of a pill or to inhale or to inject intravenously to kill yourself. That is key – education at that level – and to let those who are going to use these substances (specifically, synthetic fentanyl) know that they should consider the use of fentanyl test strips.

Fentanyl test strips would be primarily used for those who are thinking that they’re using heroin but there may be fentanyl in there, or methamphetamine and there may be fentanyl, and they don’t know. The test strip gives them that knowledge.

The other harm reduction strategies would be the use of naloxone, known as Narcan. That’s a lifesaver. You just have to spritz it into the nostril. You don’t do it yourself if you’re using the substance, but you’ve got others who can do it for you. No question, that’s a lifesaver. We need to make sure that there’s greater availability of that throughout the entire country, and we’re seeing some of that in certain states. In certain states, you don’t need a prescription to get naloxone from the pharmacy.

Dr. Glatter: I think it’s so important that it should be widely available. Certainly, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the number of overdoses we saw. Are overdoses coming down or are we still at a level that’s close to 2020?

Dr. Christo: Unfortunately, we’re still seeing the same level, if not seeing it escalate. Certainly, the pandemic, because of the economic cost associated with the pandemic – loss of employment, underemployment – as well as the emotional stress of the pandemic led many people to use substances on the street in order to cope. They’re coping mechanisms, and we really haven’t seen it abate quite yet.

Dr. Glatter: Do you have a message for the lawmakers on Capitol Hill as to what we can do regarding the illegal manufacturing and distribution, how we can really crack down? Are there other approaches that we could implement that might be more tangible?

Dr. Christo: Yes. No. 1 would be to support law enforcement. No. 2 would be to create and make available more overdose prevention centers. The first was in New York City. If you look at the data on overdose prevention centers, in Canada, for example, they’ve seen a 35% reduction in overdose deaths. These are places where people who are using can go to get clean needles and clean syringes. This is where people basically oversee the use of the drug and intervene if necessary.

It seems sort of antithetical. It seems like, “Boy, why would you fund a center for people to use drugs?” The data from Canada and outside Canada are such that it can be very helpful. That would be one of my messages to lawmakers as well.

Vaccines to combat the synthetic opioid crisis

Dr. Glatter: Do you think that the legislators could approach some of these factories as a way to crack down, and have law enforcement be more aggressive? Is that another possible solution?

Dr. Christo: It is. Law enforcement needs to be supported by the government, by the Biden administration, so that we can prevent the influx of fentanyl and other drugs into the United States, and also to crack down on those in the United States who are manufacturing these drugs – synthetic fentanyl, first and foremost – because we’re seeing a lot of deaths related to synthetic fentanyl.

Also, we’re seeing — and this is pretty intriguing and interesting – the use of vaccines to help prevent overdose. The first human trial is underway right now for a vaccine against oxycodone. Not only that, but there are other vaccines that are in animal trials now against heroin, cocaine, or fentanyl. There’s hope there that we can use vaccines to also help reduce deaths related to overdose from fentanyl and other opioids.

Dr. Glatter: Do you think this would be given widely to the population or only to those at higher risk?

Dr. Christo: It would probably be targeting those who are at higher risk and have a history of drug abuse. I don’t think it would be something that would be given to the entire population, but it certainly could be effective, and we’re seeing encouraging results from the human trial right now.

Dr. Glatter: That’s very intriguing. That’s something that certainly could be quite helpful in the future.

One thing I did want to address is law enforcement and first responders who have been exposed to dust, or inhaled dust possibly, or had fentanyl on their skin. There has been lots of controversy. The recent literature has dispelled the controversy that people who had supposedly passed out and required Narcan after exposure to intact skin, or even compromised skin, had an overdose of fentanyl. Maybe you could speak to that and dispel that myth.

Dr. Christo: Yes, I’ve been asked this question a couple of times in the past. It’s not sufficient just to have contact with fentanyl on the skin to lead to an overdose. You really need to ingest it. That is, take it by mouth in the form of a pill, inhale it, or inject it intravenously. Skin contact is very unlikely going to lead to an overdose and death.

Dr. Glatter: I want to thank you for a very informative interview. Do you have one or two pearls you’d like to give our audience as a takeaway?

Dr. Christo: I would say two things. One is, don’t give up if you have chronic pain because there is hope. We have nonopioid treatments that can be effective. Two, don’t give up if you have a substance use disorder. Talk to your primary care doctor or talk to emergency room physicians if you’re in the emergency room. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration is a good resource, too. SAMHSA has an 800 number for support and a website. Take the opportunity to use the resources that are available.

Dr. Glatter is assistant professor of emergency medicine at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City and at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y. He is an editorial advisor and hosts the Hot Topics in EM series on Medscape. He is also a medical contributor for Forbes.

Dr. Christo is an associate professor and a pain specialist in the department of anesthesiology and critical care medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. He also serves as director of the multidisciplinary pain fellowship program at Johns Hopkins Hospital. Christo is the author of Aches and Gains, A Comprehensive Guide to Overcoming Your Pain, and hosts an award-winning, nationally syndicated SiriusXM radio talk show on overcoming pain, called Aches and Gains.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This discussion was recorded on Aug. 31, 2022. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert Glatter, MD: Welcome. I’m Dr. Robert Glatter, medical advisor for Medscape Emergency Medicine. Today we have Dr. Paul Christo, a pain specialist in the Division of Pain Medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland, and host of the national radio show Aches and Gains on SiriusXM Radio, joining us to discuss the ongoing and worsening fentanyl crisis in the U.S.

Welcome, Dr Christo.

Paul J. Christo, MD, MBA: Thanks so much for having me.

Dr. Glatter: I want to begin with a sobering statistic regarding overdoses. , based on recent data from the CDC.

Let’s start by having you explain how deadly fentanyl is in terms of its potency compared with morphine and heroin.

Dr. Christo: Fentanyl is considered a synthetic opioid. It’s not a naturally occurring opioid like morphine, for example, or codeine. We use this drug, fentanyl, often in the anesthesia well. We’ve used it for many years as an anesthetic for surgery very safely. In the chronic pain world, we’ve used it to help reduce chronic pain in the form of a patch.

What we’re seeing now, though, is something entirely different, which is the use of synthetic fentanyl as a mind- and mood-altering substance for those who don’t have pain, and essentially those who are buying this off the street. Fentanyl is about 80-100 times more potent than morphine, so you can put that in perspective in terms of its danger.

Dr. Glatter: Let me have you take us through an evolution of the opioid crisis from the 1990s, from long-acting opioid OxyContin, which was approved in 1995, to where we are now. There are different phases. If you could, educate our audience on how we got to where fentanyl is now the most common opiate involved in drug overdoses.

Dr. Christo: It really stems from the epidemic related to chronic pain. We have over 100 million people in the United States alone who suffer from chronic pain. Most chronic pain, sadly, is undertreated or untreated. In the ‘90s, in the quest to reduce chronic pain to a better extent, we saw more and more literature and studies related to the use of opioids for noncancer pain (e.g., for lower back pain).

There were many primary care doctors and pain specialists who started using opioids, probably for patients who didn’t really need it. I think it was done out of good conscience in the sense that they were trying to reduce pain. We have other methods of pain relief, but we needed more. At that time, in the ‘90s, we had a greater use of opioids to treat noncancer pain.

Then from that point, we transitioned to the use of heroin. Again, this isn’t among the chronic pain population, but it was the nonchronic pain population that starting using heroin. Today we see synthetic fentanyl.

Addressing the synthetic opioid crisis

Dr. Glatter: With fentanyl being the most common opiate we’re seeing, we’re having problems trying to save patients. We’re trying to use naloxone, but obviously in increasing amounts, and sometimes it’s not adequate and we have to intubate patients.

In terms of addressing this issue of supply, the fentanyl is coming from Mexico, China, and it’s manufactured here in the United States. How do we address this crisis? What are the steps that you would recommend we take?

Dr. Christo: I think that we need to better support law enforcement to crack down on those who are manufacturing fentanyl in the United States, and also to crack down on those who are transporting it from, say, Mexico – I think it’s primarily coming from Mexico – but from outside the United States to the United States. I feel like that’s important to do.

Two, we need to better educate those who are using these mind- and mood-altering substances. We’re seeing more and more that it’s the young-adult population, those between the ages of 13 and 25, who are starting to use these substances, and they’re very dangerous.

Dr. Glatter: Are these teens seeking out heroin and it happens to be laced with fentanyl, or are they actually seeking pure fentanyl? Are they trying to buy the colorful pills that we know about? What’s your experience in terms of the population you’re treating and what you could tell us?

Dr. Christo: I think it’s both. We’re seeing young adults who are interested in the use of fentanyl as a mind- and mood-altering substance. We’re also seeing young and older adults use other drugs, like cocaine and heroin, that are laced with fentanyl, and they don’t know it. That’s exponentially more dangerous.

Fentanyl test strips

Dr. Glatter: People are unaware that there is fentanyl in what they’re using, and it is certainly leading to overdoses and deaths. I think that parents really need to be aware of this.

Dr. Christo: Yes, for sure. I think we need better educational methods in the schools to educate that population that we’re talking about (between the ages of 13 and 25). Let them know the dangers, because I don’t think they’re aware of the danger, and how potent fentanyl is in terms of its lethality, and that you don’t need very much to take in a form of a pill or to inhale or to inject intravenously to kill yourself. That is key – education at that level – and to let those who are going to use these substances (specifically, synthetic fentanyl) know that they should consider the use of fentanyl test strips.

Fentanyl test strips would be primarily used for those who are thinking that they’re using heroin but there may be fentanyl in there, or methamphetamine and there may be fentanyl, and they don’t know. The test strip gives them that knowledge.

The other harm reduction strategies would be the use of naloxone, known as Narcan. That’s a lifesaver. You just have to spritz it into the nostril. You don’t do it yourself if you’re using the substance, but you’ve got others who can do it for you. No question, that’s a lifesaver. We need to make sure that there’s greater availability of that throughout the entire country, and we’re seeing some of that in certain states. In certain states, you don’t need a prescription to get naloxone from the pharmacy.

Dr. Glatter: I think it’s so important that it should be widely available. Certainly, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the number of overdoses we saw. Are overdoses coming down or are we still at a level that’s close to 2020?

Dr. Christo: Unfortunately, we’re still seeing the same level, if not seeing it escalate. Certainly, the pandemic, because of the economic cost associated with the pandemic – loss of employment, underemployment – as well as the emotional stress of the pandemic led many people to use substances on the street in order to cope. They’re coping mechanisms, and we really haven’t seen it abate quite yet.

Dr. Glatter: Do you have a message for the lawmakers on Capitol Hill as to what we can do regarding the illegal manufacturing and distribution, how we can really crack down? Are there other approaches that we could implement that might be more tangible?

Dr. Christo: Yes. No. 1 would be to support law enforcement. No. 2 would be to create and make available more overdose prevention centers. The first was in New York City. If you look at the data on overdose prevention centers, in Canada, for example, they’ve seen a 35% reduction in overdose deaths. These are places where people who are using can go to get clean needles and clean syringes. This is where people basically oversee the use of the drug and intervene if necessary.

It seems sort of antithetical. It seems like, “Boy, why would you fund a center for people to use drugs?” The data from Canada and outside Canada are such that it can be very helpful. That would be one of my messages to lawmakers as well.

Vaccines to combat the synthetic opioid crisis

Dr. Glatter: Do you think that the legislators could approach some of these factories as a way to crack down, and have law enforcement be more aggressive? Is that another possible solution?

Dr. Christo: It is. Law enforcement needs to be supported by the government, by the Biden administration, so that we can prevent the influx of fentanyl and other drugs into the United States, and also to crack down on those in the United States who are manufacturing these drugs – synthetic fentanyl, first and foremost – because we’re seeing a lot of deaths related to synthetic fentanyl.

Also, we’re seeing — and this is pretty intriguing and interesting – the use of vaccines to help prevent overdose. The first human trial is underway right now for a vaccine against oxycodone. Not only that, but there are other vaccines that are in animal trials now against heroin, cocaine, or fentanyl. There’s hope there that we can use vaccines to also help reduce deaths related to overdose from fentanyl and other opioids.

Dr. Glatter: Do you think this would be given widely to the population or only to those at higher risk?

Dr. Christo: It would probably be targeting those who are at higher risk and have a history of drug abuse. I don’t think it would be something that would be given to the entire population, but it certainly could be effective, and we’re seeing encouraging results from the human trial right now.

Dr. Glatter: That’s very intriguing. That’s something that certainly could be quite helpful in the future.

One thing I did want to address is law enforcement and first responders who have been exposed to dust, or inhaled dust possibly, or had fentanyl on their skin. There has been lots of controversy. The recent literature has dispelled the controversy that people who had supposedly passed out and required Narcan after exposure to intact skin, or even compromised skin, had an overdose of fentanyl. Maybe you could speak to that and dispel that myth.

Dr. Christo: Yes, I’ve been asked this question a couple of times in the past. It’s not sufficient just to have contact with fentanyl on the skin to lead to an overdose. You really need to ingest it. That is, take it by mouth in the form of a pill, inhale it, or inject it intravenously. Skin contact is very unlikely going to lead to an overdose and death.

Dr. Glatter: I want to thank you for a very informative interview. Do you have one or two pearls you’d like to give our audience as a takeaway?

Dr. Christo: I would say two things. One is, don’t give up if you have chronic pain because there is hope. We have nonopioid treatments that can be effective. Two, don’t give up if you have a substance use disorder. Talk to your primary care doctor or talk to emergency room physicians if you’re in the emergency room. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration is a good resource, too. SAMHSA has an 800 number for support and a website. Take the opportunity to use the resources that are available.

Dr. Glatter is assistant professor of emergency medicine at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City and at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y. He is an editorial advisor and hosts the Hot Topics in EM series on Medscape. He is also a medical contributor for Forbes.

Dr. Christo is an associate professor and a pain specialist in the department of anesthesiology and critical care medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. He also serves as director of the multidisciplinary pain fellowship program at Johns Hopkins Hospital. Christo is the author of Aches and Gains, A Comprehensive Guide to Overcoming Your Pain, and hosts an award-winning, nationally syndicated SiriusXM radio talk show on overcoming pain, called Aches and Gains.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This discussion was recorded on Aug. 31, 2022. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert Glatter, MD: Welcome. I’m Dr. Robert Glatter, medical advisor for Medscape Emergency Medicine. Today we have Dr. Paul Christo, a pain specialist in the Division of Pain Medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland, and host of the national radio show Aches and Gains on SiriusXM Radio, joining us to discuss the ongoing and worsening fentanyl crisis in the U.S.

Welcome, Dr Christo.

Paul J. Christo, MD, MBA: Thanks so much for having me.

Dr. Glatter: I want to begin with a sobering statistic regarding overdoses. , based on recent data from the CDC.

Let’s start by having you explain how deadly fentanyl is in terms of its potency compared with morphine and heroin.

Dr. Christo: Fentanyl is considered a synthetic opioid. It’s not a naturally occurring opioid like morphine, for example, or codeine. We use this drug, fentanyl, often in the anesthesia well. We’ve used it for many years as an anesthetic for surgery very safely. In the chronic pain world, we’ve used it to help reduce chronic pain in the form of a patch.

What we’re seeing now, though, is something entirely different, which is the use of synthetic fentanyl as a mind- and mood-altering substance for those who don’t have pain, and essentially those who are buying this off the street. Fentanyl is about 80-100 times more potent than morphine, so you can put that in perspective in terms of its danger.

Dr. Glatter: Let me have you take us through an evolution of the opioid crisis from the 1990s, from long-acting opioid OxyContin, which was approved in 1995, to where we are now. There are different phases. If you could, educate our audience on how we got to where fentanyl is now the most common opiate involved in drug overdoses.

Dr. Christo: It really stems from the epidemic related to chronic pain. We have over 100 million people in the United States alone who suffer from chronic pain. Most chronic pain, sadly, is undertreated or untreated. In the ‘90s, in the quest to reduce chronic pain to a better extent, we saw more and more literature and studies related to the use of opioids for noncancer pain (e.g., for lower back pain).

There were many primary care doctors and pain specialists who started using opioids, probably for patients who didn’t really need it. I think it was done out of good conscience in the sense that they were trying to reduce pain. We have other methods of pain relief, but we needed more. At that time, in the ‘90s, we had a greater use of opioids to treat noncancer pain.

Then from that point, we transitioned to the use of heroin. Again, this isn’t among the chronic pain population, but it was the nonchronic pain population that starting using heroin. Today we see synthetic fentanyl.

Addressing the synthetic opioid crisis

Dr. Glatter: With fentanyl being the most common opiate we’re seeing, we’re having problems trying to save patients. We’re trying to use naloxone, but obviously in increasing amounts, and sometimes it’s not adequate and we have to intubate patients.

In terms of addressing this issue of supply, the fentanyl is coming from Mexico, China, and it’s manufactured here in the United States. How do we address this crisis? What are the steps that you would recommend we take?

Dr. Christo: I think that we need to better support law enforcement to crack down on those who are manufacturing fentanyl in the United States, and also to crack down on those who are transporting it from, say, Mexico – I think it’s primarily coming from Mexico – but from outside the United States to the United States. I feel like that’s important to do.

Two, we need to better educate those who are using these mind- and mood-altering substances. We’re seeing more and more that it’s the young-adult population, those between the ages of 13 and 25, who are starting to use these substances, and they’re very dangerous.

Dr. Glatter: Are these teens seeking out heroin and it happens to be laced with fentanyl, or are they actually seeking pure fentanyl? Are they trying to buy the colorful pills that we know about? What’s your experience in terms of the population you’re treating and what you could tell us?

Dr. Christo: I think it’s both. We’re seeing young adults who are interested in the use of fentanyl as a mind- and mood-altering substance. We’re also seeing young and older adults use other drugs, like cocaine and heroin, that are laced with fentanyl, and they don’t know it. That’s exponentially more dangerous.

Fentanyl test strips

Dr. Glatter: People are unaware that there is fentanyl in what they’re using, and it is certainly leading to overdoses and deaths. I think that parents really need to be aware of this.

Dr. Christo: Yes, for sure. I think we need better educational methods in the schools to educate that population that we’re talking about (between the ages of 13 and 25). Let them know the dangers, because I don’t think they’re aware of the danger, and how potent fentanyl is in terms of its lethality, and that you don’t need very much to take in a form of a pill or to inhale or to inject intravenously to kill yourself. That is key – education at that level – and to let those who are going to use these substances (specifically, synthetic fentanyl) know that they should consider the use of fentanyl test strips.

Fentanyl test strips would be primarily used for those who are thinking that they’re using heroin but there may be fentanyl in there, or methamphetamine and there may be fentanyl, and they don’t know. The test strip gives them that knowledge.

The other harm reduction strategies would be the use of naloxone, known as Narcan. That’s a lifesaver. You just have to spritz it into the nostril. You don’t do it yourself if you’re using the substance, but you’ve got others who can do it for you. No question, that’s a lifesaver. We need to make sure that there’s greater availability of that throughout the entire country, and we’re seeing some of that in certain states. In certain states, you don’t need a prescription to get naloxone from the pharmacy.

Dr. Glatter: I think it’s so important that it should be widely available. Certainly, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the number of overdoses we saw. Are overdoses coming down or are we still at a level that’s close to 2020?

Dr. Christo: Unfortunately, we’re still seeing the same level, if not seeing it escalate. Certainly, the pandemic, because of the economic cost associated with the pandemic – loss of employment, underemployment – as well as the emotional stress of the pandemic led many people to use substances on the street in order to cope. They’re coping mechanisms, and we really haven’t seen it abate quite yet.

Dr. Glatter: Do you have a message for the lawmakers on Capitol Hill as to what we can do regarding the illegal manufacturing and distribution, how we can really crack down? Are there other approaches that we could implement that might be more tangible?

Dr. Christo: Yes. No. 1 would be to support law enforcement. No. 2 would be to create and make available more overdose prevention centers. The first was in New York City. If you look at the data on overdose prevention centers, in Canada, for example, they’ve seen a 35% reduction in overdose deaths. These are places where people who are using can go to get clean needles and clean syringes. This is where people basically oversee the use of the drug and intervene if necessary.

It seems sort of antithetical. It seems like, “Boy, why would you fund a center for people to use drugs?” The data from Canada and outside Canada are such that it can be very helpful. That would be one of my messages to lawmakers as well.

Vaccines to combat the synthetic opioid crisis

Dr. Glatter: Do you think that the legislators could approach some of these factories as a way to crack down, and have law enforcement be more aggressive? Is that another possible solution?

Dr. Christo: It is. Law enforcement needs to be supported by the government, by the Biden administration, so that we can prevent the influx of fentanyl and other drugs into the United States, and also to crack down on those in the United States who are manufacturing these drugs – synthetic fentanyl, first and foremost – because we’re seeing a lot of deaths related to synthetic fentanyl.

Also, we’re seeing — and this is pretty intriguing and interesting – the use of vaccines to help prevent overdose. The first human trial is underway right now for a vaccine against oxycodone. Not only that, but there are other vaccines that are in animal trials now against heroin, cocaine, or fentanyl. There’s hope there that we can use vaccines to also help reduce deaths related to overdose from fentanyl and other opioids.

Dr. Glatter: Do you think this would be given widely to the population or only to those at higher risk?

Dr. Christo: It would probably be targeting those who are at higher risk and have a history of drug abuse. I don’t think it would be something that would be given to the entire population, but it certainly could be effective, and we’re seeing encouraging results from the human trial right now.

Dr. Glatter: That’s very intriguing. That’s something that certainly could be quite helpful in the future.

One thing I did want to address is law enforcement and first responders who have been exposed to dust, or inhaled dust possibly, or had fentanyl on their skin. There has been lots of controversy. The recent literature has dispelled the controversy that people who had supposedly passed out and required Narcan after exposure to intact skin, or even compromised skin, had an overdose of fentanyl. Maybe you could speak to that and dispel that myth.

Dr. Christo: Yes, I’ve been asked this question a couple of times in the past. It’s not sufficient just to have contact with fentanyl on the skin to lead to an overdose. You really need to ingest it. That is, take it by mouth in the form of a pill, inhale it, or inject it intravenously. Skin contact is very unlikely going to lead to an overdose and death.

Dr. Glatter: I want to thank you for a very informative interview. Do you have one or two pearls you’d like to give our audience as a takeaway?

Dr. Christo: I would say two things. One is, don’t give up if you have chronic pain because there is hope. We have nonopioid treatments that can be effective. Two, don’t give up if you have a substance use disorder. Talk to your primary care doctor or talk to emergency room physicians if you’re in the emergency room. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration is a good resource, too. SAMHSA has an 800 number for support and a website. Take the opportunity to use the resources that are available.

Dr. Glatter is assistant professor of emergency medicine at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City and at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y. He is an editorial advisor and hosts the Hot Topics in EM series on Medscape. He is also a medical contributor for Forbes.

Dr. Christo is an associate professor and a pain specialist in the department of anesthesiology and critical care medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. He also serves as director of the multidisciplinary pain fellowship program at Johns Hopkins Hospital. Christo is the author of Aches and Gains, A Comprehensive Guide to Overcoming Your Pain, and hosts an award-winning, nationally syndicated SiriusXM radio talk show on overcoming pain, called Aches and Gains.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Is exercise effective for constipation?

I recently presented a clinical scenario about a patient of mine named Brenda. This 35-year-old woman came to me with symptoms that had been going on for a year already. I asked for readers’ comments about my management of Brenda.

I appreciate the comments I received regarding this case. The most common suggestion was to encourage Brenda to exercise, and a systematic review of randomized clinical trials published in 2019 supports this recommendation. This review included nine studies with a total of 680 participants, and the overall effect of exercise was a twofold improvement in symptoms associated with constipation. Walking was the most common exercise intervention, and along with qigong (which combines body position, breathing, and meditation), these two modes of exercise were effective in improving constipation. However, the one study evaluating resistance training failed to demonstrate a significant effect. Importantly, the reviewers considered the collective research to be at a high risk of bias.

Exercise will probably help Brenda, although some brainstorming might be necessary to help her fit exercise into her busy schedule. Another suggestion focused on her risk for colorectal cancer, and Dr. Cooke and Dr. Boboc both astutely noted that colorectal cancer is increasingly common among adults at early middle age. This stands in contrast to a steady decline in the prevalence of colorectal cancer among U.S. adults at age 65 years or older. Whereas colorectal cancer declined by 3.3% annually among U.S. older adults from 2011 to 2016, there was a reversal of this favorable trend among individuals between 50 and 64 years of age, with rates increasing by 1% annually.

The increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer among adults 50-64 years of age has been outpaced by the increase among adults younger than 50 years, who have experienced a 2.2% increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer annually between 2012 and 2016. Previously, the increase in colorectal cancer among early middle-aged adults was driven by higher rates of rectal cancer, but more recently this trend has included higher rates of proximal and distal colon tumors. In 2020, 12% of new cases of colorectal cancer were expected to be among individuals younger than 50 years.

So how do we act on this context in the case of Brenda? Her history suggests no overt warning signs for cancer. The history did not address a family history of gastrointestinal symptoms or colorectal cancer, which is an important omission.

Although the number of cases of cancer among persons younger than 50 years may be rising, the overall prevalence of colorectal cancer among younger adults is well under 1%. At 35 years of age, it is not necessary to evaluate Brenda for colorectal cancer. However, persistent or worsening symptoms could prompt a referral for colonoscopy at a later time.

Finally, let’s address how to practically manage Brenda’s case, because many options are available. I would begin with recommendations regarding her lifestyle, including regular exercise, adequate sleep, and whatever she can achieve in the FODMAP diet. I would also recommend psyllium as a soluble fiber and expect that these changes would help her constipation. But they might be less effective for abdominal cramping, so I would also recommend peppermint oil at this time.

If Brenda commits to these recommendations, she will very likely improve. If she does not, I will be more concerned regarding anxiety and depression complicating her illness. Treating those disorders can make a big difference.

In addition, if there is an inadequate response to initial therapy, I will initiate linaclotide or lubiprostone. Plecanatide is another reasonable option. At this point, I will also consider referral to a gastroenterologist for a recalcitrant case and will certainly refer if one of these specific treatments fails in Brenda. Conditions such as pelvic floor dysfunction can mimic irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and merit consideration.

However, I really believe that Brenda will feel better. Thanks for all of the insightful and interesting comments. It is easy to see how we are all invested in improving patients’ lives.

Dr. Vega is a clinical professor of family medicine at the University of California, Irvine. He reported disclosures with McNeil Pharmaceuticals. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I recently presented a clinical scenario about a patient of mine named Brenda. This 35-year-old woman came to me with symptoms that had been going on for a year already. I asked for readers’ comments about my management of Brenda.

I appreciate the comments I received regarding this case. The most common suggestion was to encourage Brenda to exercise, and a systematic review of randomized clinical trials published in 2019 supports this recommendation. This review included nine studies with a total of 680 participants, and the overall effect of exercise was a twofold improvement in symptoms associated with constipation. Walking was the most common exercise intervention, and along with qigong (which combines body position, breathing, and meditation), these two modes of exercise were effective in improving constipation. However, the one study evaluating resistance training failed to demonstrate a significant effect. Importantly, the reviewers considered the collective research to be at a high risk of bias.

Exercise will probably help Brenda, although some brainstorming might be necessary to help her fit exercise into her busy schedule. Another suggestion focused on her risk for colorectal cancer, and Dr. Cooke and Dr. Boboc both astutely noted that colorectal cancer is increasingly common among adults at early middle age. This stands in contrast to a steady decline in the prevalence of colorectal cancer among U.S. adults at age 65 years or older. Whereas colorectal cancer declined by 3.3% annually among U.S. older adults from 2011 to 2016, there was a reversal of this favorable trend among individuals between 50 and 64 years of age, with rates increasing by 1% annually.

The increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer among adults 50-64 years of age has been outpaced by the increase among adults younger than 50 years, who have experienced a 2.2% increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer annually between 2012 and 2016. Previously, the increase in colorectal cancer among early middle-aged adults was driven by higher rates of rectal cancer, but more recently this trend has included higher rates of proximal and distal colon tumors. In 2020, 12% of new cases of colorectal cancer were expected to be among individuals younger than 50 years.

So how do we act on this context in the case of Brenda? Her history suggests no overt warning signs for cancer. The history did not address a family history of gastrointestinal symptoms or colorectal cancer, which is an important omission.

Although the number of cases of cancer among persons younger than 50 years may be rising, the overall prevalence of colorectal cancer among younger adults is well under 1%. At 35 years of age, it is not necessary to evaluate Brenda for colorectal cancer. However, persistent or worsening symptoms could prompt a referral for colonoscopy at a later time.

Finally, let’s address how to practically manage Brenda’s case, because many options are available. I would begin with recommendations regarding her lifestyle, including regular exercise, adequate sleep, and whatever she can achieve in the FODMAP diet. I would also recommend psyllium as a soluble fiber and expect that these changes would help her constipation. But they might be less effective for abdominal cramping, so I would also recommend peppermint oil at this time.

If Brenda commits to these recommendations, she will very likely improve. If she does not, I will be more concerned regarding anxiety and depression complicating her illness. Treating those disorders can make a big difference.

In addition, if there is an inadequate response to initial therapy, I will initiate linaclotide or lubiprostone. Plecanatide is another reasonable option. At this point, I will also consider referral to a gastroenterologist for a recalcitrant case and will certainly refer if one of these specific treatments fails in Brenda. Conditions such as pelvic floor dysfunction can mimic irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and merit consideration.

However, I really believe that Brenda will feel better. Thanks for all of the insightful and interesting comments. It is easy to see how we are all invested in improving patients’ lives.

Dr. Vega is a clinical professor of family medicine at the University of California, Irvine. He reported disclosures with McNeil Pharmaceuticals. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I recently presented a clinical scenario about a patient of mine named Brenda. This 35-year-old woman came to me with symptoms that had been going on for a year already. I asked for readers’ comments about my management of Brenda.

I appreciate the comments I received regarding this case. The most common suggestion was to encourage Brenda to exercise, and a systematic review of randomized clinical trials published in 2019 supports this recommendation. This review included nine studies with a total of 680 participants, and the overall effect of exercise was a twofold improvement in symptoms associated with constipation. Walking was the most common exercise intervention, and along with qigong (which combines body position, breathing, and meditation), these two modes of exercise were effective in improving constipation. However, the one study evaluating resistance training failed to demonstrate a significant effect. Importantly, the reviewers considered the collective research to be at a high risk of bias.

Exercise will probably help Brenda, although some brainstorming might be necessary to help her fit exercise into her busy schedule. Another suggestion focused on her risk for colorectal cancer, and Dr. Cooke and Dr. Boboc both astutely noted that colorectal cancer is increasingly common among adults at early middle age. This stands in contrast to a steady decline in the prevalence of colorectal cancer among U.S. adults at age 65 years or older. Whereas colorectal cancer declined by 3.3% annually among U.S. older adults from 2011 to 2016, there was a reversal of this favorable trend among individuals between 50 and 64 years of age, with rates increasing by 1% annually.

The increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer among adults 50-64 years of age has been outpaced by the increase among adults younger than 50 years, who have experienced a 2.2% increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer annually between 2012 and 2016. Previously, the increase in colorectal cancer among early middle-aged adults was driven by higher rates of rectal cancer, but more recently this trend has included higher rates of proximal and distal colon tumors. In 2020, 12% of new cases of colorectal cancer were expected to be among individuals younger than 50 years.

So how do we act on this context in the case of Brenda? Her history suggests no overt warning signs for cancer. The history did not address a family history of gastrointestinal symptoms or colorectal cancer, which is an important omission.

Although the number of cases of cancer among persons younger than 50 years may be rising, the overall prevalence of colorectal cancer among younger adults is well under 1%. At 35 years of age, it is not necessary to evaluate Brenda for colorectal cancer. However, persistent or worsening symptoms could prompt a referral for colonoscopy at a later time.

Finally, let’s address how to practically manage Brenda’s case, because many options are available. I would begin with recommendations regarding her lifestyle, including regular exercise, adequate sleep, and whatever she can achieve in the FODMAP diet. I would also recommend psyllium as a soluble fiber and expect that these changes would help her constipation. But they might be less effective for abdominal cramping, so I would also recommend peppermint oil at this time.

If Brenda commits to these recommendations, she will very likely improve. If she does not, I will be more concerned regarding anxiety and depression complicating her illness. Treating those disorders can make a big difference.

In addition, if there is an inadequate response to initial therapy, I will initiate linaclotide or lubiprostone. Plecanatide is another reasonable option. At this point, I will also consider referral to a gastroenterologist for a recalcitrant case and will certainly refer if one of these specific treatments fails in Brenda. Conditions such as pelvic floor dysfunction can mimic irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and merit consideration.

However, I really believe that Brenda will feel better. Thanks for all of the insightful and interesting comments. It is easy to see how we are all invested in improving patients’ lives.

Dr. Vega is a clinical professor of family medicine at the University of California, Irvine. He reported disclosures with McNeil Pharmaceuticals. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The role of repeat uterine curettage in postmolar gestational trophoblastic neoplasia

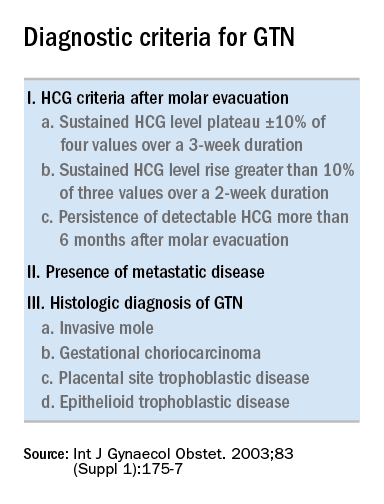

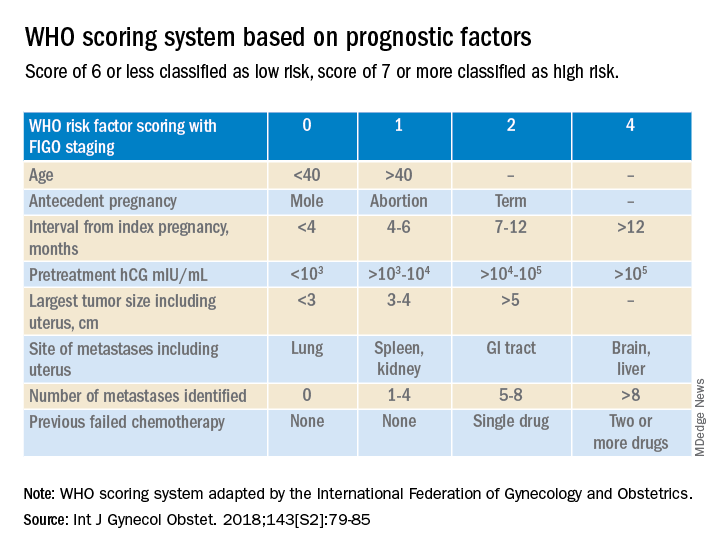

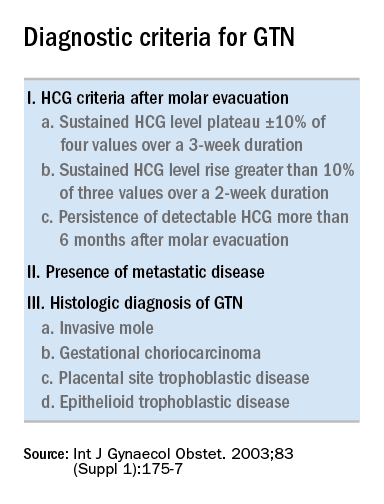

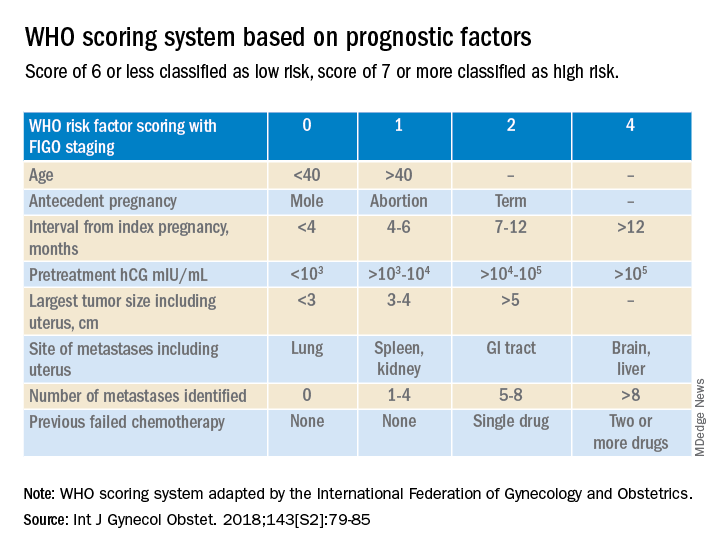

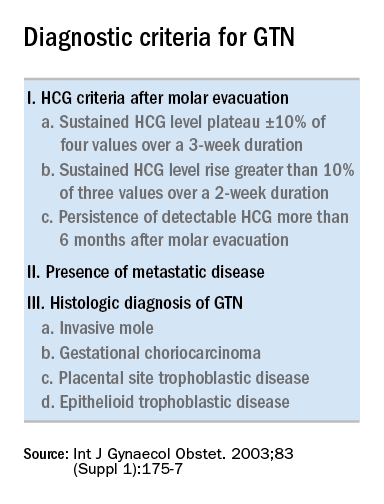

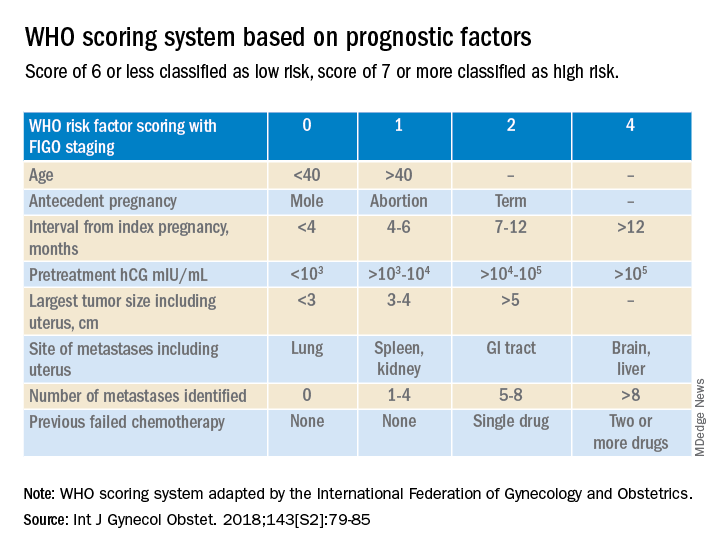

Trophoblastic tissue is responsible for formation of the placenta during pregnancy. Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD), a group comprising benign (hydatidiform moles) and malignant tumors, occurs when gestational trophoblastic tissue behaves in an abnormal manner. Hydatidiform moles, which are thought to be caused by errors in fertilization, occur in approximately 1 in 1,200 pregnancies in the United States. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) refers to the subgroup of these trophoblastic or placental tumors with malignant behavior and includes postmolar GTN, invasive mole, gestational choriocarcinoma, placental-site trophoblastic tumor (PSTT), and epithelioid trophoblastic tumor. Postmolar GTN arises after evacuation of a molar pregnancy and is most frequently diagnosed by a plateau or increase in human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG).1 The risk of postmolar GTN is much higher after a complete mole (7%-30%) compared with a partial mole (2.5%-7.5%).2 Once postmolar GTN is diagnosed, a World Health Organization score is assigned to determine if patients have low- or high-risk disease.3 The primary treatment for most GTN is chemotherapy. A patient’s WHO score helps determine whether they would benefit from single-agent or multiagent chemotherapy. The standard of care for low-risk disease is single-agent chemotherapy with either methotrexate or actinomycin D.

The role of a second uterine curettage, after the diagnosis of low-risk postmolar GTN, has been controversial because of the limited data and disparate outcomes reported. In older retrospective series, a second curettage affected treatment or produced remission in only 9%-20% of patients and caused uterine perforation or major hemorrhage in 5%-8% of patients.4,5 Given relatively high rates of major complications compared with surgical cure or decreased chemotherapy cycles needed, only a limited number of patients seemed to benefit from a second procedure. On the other hand, an observational study of 544 patients who underwent second uterine evacuation after a presumed diagnosis of persistent GTD found that up to 60% of patients did not require chemotherapy afterward.6 Those with hCG levels greater than 1,500 IU/L or histologic evidence of GTD were less likely to have a surgical cure after second curettage. The indications for uterine evacuations were varied across these studies and make it nearly impossible to compare their results.

More recently, there have been two prospective trials that have tackled the question of the utility of second uterine evacuation in low-risk, nonmetastatic GTN. The Gynecologic Oncology Group performed a single-arm prospective study in the United States that enrolled patients with postmolar GTN to undergo second curettage as initial treatment of their disease.7 Of 60 eligible patients, 40% had a surgical cure (defined as normalization of hCG followed by at least 6 months of subsequent normal hCG values). Overall, 47% of patients were able to avoid chemotherapy. All surgical cures were seen in patients with WHO scores between 0 and 4. Importantly, three women were diagnosed with PSTT, which tends to be resistant to methotrexate and actinomycin D (treatment for nonmetastatic PSTT is definitive surgery with hysterectomy). The study found that hCG was a poor discriminator for achieving surgical cure. While age appeared to have an association with surgical cure (cure less likely for younger and older ages, younger than 19 and older than 40), patient numbers were too small to make a statistical conclusion. There were no uterine perforations and one patient had a grade 3 hemorrhage (requiring transfusion).

In the second prospective trial, performed in Iran, 62 patients were randomized to either second uterine evacuation or standard treatment after diagnosis of postmolar GTN.8 All patients in the surgical arm received a cervical ripening agent prior to their procedure, had their procedure under ultrasound guidance, and received misoprostol afterward to prevent uterine bleeding. Among those undergoing second uterine evacuation, 50% were cured (no need for chemotherapy). Among those needing chemotherapy after surgery, the mean number of cycles of chemotherapy needed (3.07 vs. 6.69) and the time it took to achieve negative hCG (3.23 vs. 9.19 weeks) were significantly less compared with patients who did not undergo surgery. hCG prior to second uterine evacuation could distinguish response to surgery compared with those needing chemotherapy (hCG of 1,983 IU/L or less was the level determined to best predict response). No complications related to surgery were reported.

Given prospective data available, second uterine evacuation for treatment of nonmetastatic, low-risk postmolar GTN is a reasonable treatment option and one that should be considered and discussed with patients given the potential to avoid chemotherapy or decrease the number of cycles needed. It may be prudent to limit the procedure to patients with an hCG less than 1,500-2,000 IU/L and to those between the ages of 20 and 40. While uterine hemorrhage and perforation have been reported in the literature, more recent data suggest low rates of these complications. Unfortunately, given the rarity of the disease and the historically controversial use of second curettage, little is known about the effects on future fertility that this procedure may have, including the development of uterine synechiae.

Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

1. Ngan HY et al, FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003 Oct;83 Suppl 1:175-7. Erratum in: Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Dec;155(3):563.

2. Soper JT. Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Feb.;137(2):355-70.

3. Ngan HY et al. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;143:79-85.

4. Schlaerth JB et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Jun;162(6):1465-70.

5. van Trommel NE et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 Oct;99(1):6-13.

6. Pezeshki M et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2004 Dec;95(3):423-9.

7. Osborne RJ et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep;128(3):535-42.

8. Ayatollahi H et al. Int J Womens Health. 2017 Sep 21;9:665-71.

Trophoblastic tissue is responsible for formation of the placenta during pregnancy. Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD), a group comprising benign (hydatidiform moles) and malignant tumors, occurs when gestational trophoblastic tissue behaves in an abnormal manner. Hydatidiform moles, which are thought to be caused by errors in fertilization, occur in approximately 1 in 1,200 pregnancies in the United States. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) refers to the subgroup of these trophoblastic or placental tumors with malignant behavior and includes postmolar GTN, invasive mole, gestational choriocarcinoma, placental-site trophoblastic tumor (PSTT), and epithelioid trophoblastic tumor. Postmolar GTN arises after evacuation of a molar pregnancy and is most frequently diagnosed by a plateau or increase in human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG).1 The risk of postmolar GTN is much higher after a complete mole (7%-30%) compared with a partial mole (2.5%-7.5%).2 Once postmolar GTN is diagnosed, a World Health Organization score is assigned to determine if patients have low- or high-risk disease.3 The primary treatment for most GTN is chemotherapy. A patient’s WHO score helps determine whether they would benefit from single-agent or multiagent chemotherapy. The standard of care for low-risk disease is single-agent chemotherapy with either methotrexate or actinomycin D.

The role of a second uterine curettage, after the diagnosis of low-risk postmolar GTN, has been controversial because of the limited data and disparate outcomes reported. In older retrospective series, a second curettage affected treatment or produced remission in only 9%-20% of patients and caused uterine perforation or major hemorrhage in 5%-8% of patients.4,5 Given relatively high rates of major complications compared with surgical cure or decreased chemotherapy cycles needed, only a limited number of patients seemed to benefit from a second procedure. On the other hand, an observational study of 544 patients who underwent second uterine evacuation after a presumed diagnosis of persistent GTD found that up to 60% of patients did not require chemotherapy afterward.6 Those with hCG levels greater than 1,500 IU/L or histologic evidence of GTD were less likely to have a surgical cure after second curettage. The indications for uterine evacuations were varied across these studies and make it nearly impossible to compare their results.

More recently, there have been two prospective trials that have tackled the question of the utility of second uterine evacuation in low-risk, nonmetastatic GTN. The Gynecologic Oncology Group performed a single-arm prospective study in the United States that enrolled patients with postmolar GTN to undergo second curettage as initial treatment of their disease.7 Of 60 eligible patients, 40% had a surgical cure (defined as normalization of hCG followed by at least 6 months of subsequent normal hCG values). Overall, 47% of patients were able to avoid chemotherapy. All surgical cures were seen in patients with WHO scores between 0 and 4. Importantly, three women were diagnosed with PSTT, which tends to be resistant to methotrexate and actinomycin D (treatment for nonmetastatic PSTT is definitive surgery with hysterectomy). The study found that hCG was a poor discriminator for achieving surgical cure. While age appeared to have an association with surgical cure (cure less likely for younger and older ages, younger than 19 and older than 40), patient numbers were too small to make a statistical conclusion. There were no uterine perforations and one patient had a grade 3 hemorrhage (requiring transfusion).

In the second prospective trial, performed in Iran, 62 patients were randomized to either second uterine evacuation or standard treatment after diagnosis of postmolar GTN.8 All patients in the surgical arm received a cervical ripening agent prior to their procedure, had their procedure under ultrasound guidance, and received misoprostol afterward to prevent uterine bleeding. Among those undergoing second uterine evacuation, 50% were cured (no need for chemotherapy). Among those needing chemotherapy after surgery, the mean number of cycles of chemotherapy needed (3.07 vs. 6.69) and the time it took to achieve negative hCG (3.23 vs. 9.19 weeks) were significantly less compared with patients who did not undergo surgery. hCG prior to second uterine evacuation could distinguish response to surgery compared with those needing chemotherapy (hCG of 1,983 IU/L or less was the level determined to best predict response). No complications related to surgery were reported.

Given prospective data available, second uterine evacuation for treatment of nonmetastatic, low-risk postmolar GTN is a reasonable treatment option and one that should be considered and discussed with patients given the potential to avoid chemotherapy or decrease the number of cycles needed. It may be prudent to limit the procedure to patients with an hCG less than 1,500-2,000 IU/L and to those between the ages of 20 and 40. While uterine hemorrhage and perforation have been reported in the literature, more recent data suggest low rates of these complications. Unfortunately, given the rarity of the disease and the historically controversial use of second curettage, little is known about the effects on future fertility that this procedure may have, including the development of uterine synechiae.

Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

1. Ngan HY et al, FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003 Oct;83 Suppl 1:175-7. Erratum in: Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Dec;155(3):563.

2. Soper JT. Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Feb.;137(2):355-70.

3. Ngan HY et al. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;143:79-85.

4. Schlaerth JB et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Jun;162(6):1465-70.

5. van Trommel NE et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 Oct;99(1):6-13.

6. Pezeshki M et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2004 Dec;95(3):423-9.

7. Osborne RJ et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep;128(3):535-42.

8. Ayatollahi H et al. Int J Womens Health. 2017 Sep 21;9:665-71.

Trophoblastic tissue is responsible for formation of the placenta during pregnancy. Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD), a group comprising benign (hydatidiform moles) and malignant tumors, occurs when gestational trophoblastic tissue behaves in an abnormal manner. Hydatidiform moles, which are thought to be caused by errors in fertilization, occur in approximately 1 in 1,200 pregnancies in the United States. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) refers to the subgroup of these trophoblastic or placental tumors with malignant behavior and includes postmolar GTN, invasive mole, gestational choriocarcinoma, placental-site trophoblastic tumor (PSTT), and epithelioid trophoblastic tumor. Postmolar GTN arises after evacuation of a molar pregnancy and is most frequently diagnosed by a plateau or increase in human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG).1 The risk of postmolar GTN is much higher after a complete mole (7%-30%) compared with a partial mole (2.5%-7.5%).2 Once postmolar GTN is diagnosed, a World Health Organization score is assigned to determine if patients have low- or high-risk disease.3 The primary treatment for most GTN is chemotherapy. A patient’s WHO score helps determine whether they would benefit from single-agent or multiagent chemotherapy. The standard of care for low-risk disease is single-agent chemotherapy with either methotrexate or actinomycin D.

The role of a second uterine curettage, after the diagnosis of low-risk postmolar GTN, has been controversial because of the limited data and disparate outcomes reported. In older retrospective series, a second curettage affected treatment or produced remission in only 9%-20% of patients and caused uterine perforation or major hemorrhage in 5%-8% of patients.4,5 Given relatively high rates of major complications compared with surgical cure or decreased chemotherapy cycles needed, only a limited number of patients seemed to benefit from a second procedure. On the other hand, an observational study of 544 patients who underwent second uterine evacuation after a presumed diagnosis of persistent GTD found that up to 60% of patients did not require chemotherapy afterward.6 Those with hCG levels greater than 1,500 IU/L or histologic evidence of GTD were less likely to have a surgical cure after second curettage. The indications for uterine evacuations were varied across these studies and make it nearly impossible to compare their results.

More recently, there have been two prospective trials that have tackled the question of the utility of second uterine evacuation in low-risk, nonmetastatic GTN. The Gynecologic Oncology Group performed a single-arm prospective study in the United States that enrolled patients with postmolar GTN to undergo second curettage as initial treatment of their disease.7 Of 60 eligible patients, 40% had a surgical cure (defined as normalization of hCG followed by at least 6 months of subsequent normal hCG values). Overall, 47% of patients were able to avoid chemotherapy. All surgical cures were seen in patients with WHO scores between 0 and 4. Importantly, three women were diagnosed with PSTT, which tends to be resistant to methotrexate and actinomycin D (treatment for nonmetastatic PSTT is definitive surgery with hysterectomy). The study found that hCG was a poor discriminator for achieving surgical cure. While age appeared to have an association with surgical cure (cure less likely for younger and older ages, younger than 19 and older than 40), patient numbers were too small to make a statistical conclusion. There were no uterine perforations and one patient had a grade 3 hemorrhage (requiring transfusion).

In the second prospective trial, performed in Iran, 62 patients were randomized to either second uterine evacuation or standard treatment after diagnosis of postmolar GTN.8 All patients in the surgical arm received a cervical ripening agent prior to their procedure, had their procedure under ultrasound guidance, and received misoprostol afterward to prevent uterine bleeding. Among those undergoing second uterine evacuation, 50% were cured (no need for chemotherapy). Among those needing chemotherapy after surgery, the mean number of cycles of chemotherapy needed (3.07 vs. 6.69) and the time it took to achieve negative hCG (3.23 vs. 9.19 weeks) were significantly less compared with patients who did not undergo surgery. hCG prior to second uterine evacuation could distinguish response to surgery compared with those needing chemotherapy (hCG of 1,983 IU/L or less was the level determined to best predict response). No complications related to surgery were reported.

Given prospective data available, second uterine evacuation for treatment of nonmetastatic, low-risk postmolar GTN is a reasonable treatment option and one that should be considered and discussed with patients given the potential to avoid chemotherapy or decrease the number of cycles needed. It may be prudent to limit the procedure to patients with an hCG less than 1,500-2,000 IU/L and to those between the ages of 20 and 40. While uterine hemorrhage and perforation have been reported in the literature, more recent data suggest low rates of these complications. Unfortunately, given the rarity of the disease and the historically controversial use of second curettage, little is known about the effects on future fertility that this procedure may have, including the development of uterine synechiae.

Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

1. Ngan HY et al, FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003 Oct;83 Suppl 1:175-7. Erratum in: Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Dec;155(3):563.

2. Soper JT. Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Feb.;137(2):355-70.

3. Ngan HY et al. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;143:79-85.

4. Schlaerth JB et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Jun;162(6):1465-70.

5. van Trommel NE et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 Oct;99(1):6-13.

6. Pezeshki M et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2004 Dec;95(3):423-9.

7. Osborne RJ et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep;128(3):535-42.

8. Ayatollahi H et al. Int J Womens Health. 2017 Sep 21;9:665-71.

Yes, we should talk politics and religion with patients

From our first days as medical students, we are told that politics and religion are topics to be avoided with patients, but I disagree. Knowing more about our patients allows us to deliver better care.

Politics and religion: New risk factors

The importance of politics and religion in the health of patients was clearly demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lives were needlessly lost because of stands taken based on religious beliefs or a political ideology. Families, friends, and the community at large were impacted.

Over my years of practice, I have found that while these are difficult topics to address, they should not be avoided. Studies have shown that open acknowledgement of religious beliefs can affect both clinical outcomes and well-being. Religion and spirituality are as much a part of our patient’s lives as the physical parameters that we measure. To neglect these significant aspects is to miss the very essence of the individual.

I made it a practice to ask patients about their religious beliefs, the extent to which religion shaped their life, and whether they were part of a church community. Knowing this allowed me to separate deep personal belief from stances based on personal freedom, misinformation, conspiracies, and politics.

I found that information about political leanings flowed naturally in discussions with patients as we trusted and respected each other over time. If I approached politics objectively and nonjudgmentally, it generally led to meaningful conversation. This helped me to understand the patient as an individual and informed my diagnosis and treatment plan.

Politics as stress

For example, on more than one occasion, a patient with atrial fibrillation presented with persistent elevated blood pressure and pulse rate despite adherence to the medical regimen that I had prescribed. After a few minutes of discussion, it was clear that excessive attention to political commentary on TV and social media raised their anxiety and anger level, putting them at greater risk for adverse outcomes. I advised that they refocus their leisure activities rather than change or increase medication.

It is disappointing to see how one of the great scientific advances of our lifetime, vaccination science, has been tarnished because of political or religious ideology and to see the extent to which these beliefs influenced COVID-19 vaccination compliance. As health care providers, we must promote information based on the scientific method. If patients challenge us and point out that recommendations based on science seem to change over time, we must explain that science evolves on the basis of new information objectively gathered. We need to find out what information the patient has gotten from the Internet, TV, or conspiracy theories and counter this with scientific facts. If we do not discuss religion and politics with our patients along with other risk factors, we may compromise our ability to give them the best advice and treatment.

Our patients have a right to their own spiritual and political ideology. If it differs dramatically from our own, this should not influence our commitment to care for them. But we have an obligation to challenge unfounded beliefs about medicine and counter with scientific facts. There are times when individual freedoms must be secondary to public health. Ultimately, it is up to the patient to choose, but they should not be given a “free pass” on the basis of religion or politics. If I know something is true and I would do it myself or recommend it for my family, I have an obligation to provide this recommendation to my patients.

Religious preference is included in medical records. It is not appropriate to add political preference, but the patient benefits if a long-term caregiver knows this information.

During the pandemic, for the first time in my 40+ years of practice, some patients questioned my recommendations and placed equal or greater weight on religion, politics, or conspiracy theories. This continues to be a very real struggle.

Knowing and understanding our patients as individuals is critical to providing optimum care and that means tackling these formally taboo topics. If having a potentially uncomfortable conversation with patients allows us to save one life, it is worth it.

Dr. Francis is a cardiologist at Inova Heart and Vascular Institute, McLean, Va. He disclosed no relevant conflict of interest. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

From our first days as medical students, we are told that politics and religion are topics to be avoided with patients, but I disagree. Knowing more about our patients allows us to deliver better care.

Politics and religion: New risk factors

The importance of politics and religion in the health of patients was clearly demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lives were needlessly lost because of stands taken based on religious beliefs or a political ideology. Families, friends, and the community at large were impacted.

Over my years of practice, I have found that while these are difficult topics to address, they should not be avoided. Studies have shown that open acknowledgement of religious beliefs can affect both clinical outcomes and well-being. Religion and spirituality are as much a part of our patient’s lives as the physical parameters that we measure. To neglect these significant aspects is to miss the very essence of the individual.

I made it a practice to ask patients about their religious beliefs, the extent to which religion shaped their life, and whether they were part of a church community. Knowing this allowed me to separate deep personal belief from stances based on personal freedom, misinformation, conspiracies, and politics.

I found that information about political leanings flowed naturally in discussions with patients as we trusted and respected each other over time. If I approached politics objectively and nonjudgmentally, it generally led to meaningful conversation. This helped me to understand the patient as an individual and informed my diagnosis and treatment plan.

Politics as stress

For example, on more than one occasion, a patient with atrial fibrillation presented with persistent elevated blood pressure and pulse rate despite adherence to the medical regimen that I had prescribed. After a few minutes of discussion, it was clear that excessive attention to political commentary on TV and social media raised their anxiety and anger level, putting them at greater risk for adverse outcomes. I advised that they refocus their leisure activities rather than change or increase medication.

It is disappointing to see how one of the great scientific advances of our lifetime, vaccination science, has been tarnished because of political or religious ideology and to see the extent to which these beliefs influenced COVID-19 vaccination compliance. As health care providers, we must promote information based on the scientific method. If patients challenge us and point out that recommendations based on science seem to change over time, we must explain that science evolves on the basis of new information objectively gathered. We need to find out what information the patient has gotten from the Internet, TV, or conspiracy theories and counter this with scientific facts. If we do not discuss religion and politics with our patients along with other risk factors, we may compromise our ability to give them the best advice and treatment.

Our patients have a right to their own spiritual and political ideology. If it differs dramatically from our own, this should not influence our commitment to care for them. But we have an obligation to challenge unfounded beliefs about medicine and counter with scientific facts. There are times when individual freedoms must be secondary to public health. Ultimately, it is up to the patient to choose, but they should not be given a “free pass” on the basis of religion or politics. If I know something is true and I would do it myself or recommend it for my family, I have an obligation to provide this recommendation to my patients.

Religious preference is included in medical records. It is not appropriate to add political preference, but the patient benefits if a long-term caregiver knows this information.

During the pandemic, for the first time in my 40+ years of practice, some patients questioned my recommendations and placed equal or greater weight on religion, politics, or conspiracy theories. This continues to be a very real struggle.

Knowing and understanding our patients as individuals is critical to providing optimum care and that means tackling these formally taboo topics. If having a potentially uncomfortable conversation with patients allows us to save one life, it is worth it.

Dr. Francis is a cardiologist at Inova Heart and Vascular Institute, McLean, Va. He disclosed no relevant conflict of interest. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

From our first days as medical students, we are told that politics and religion are topics to be avoided with patients, but I disagree. Knowing more about our patients allows us to deliver better care.

Politics and religion: New risk factors

The importance of politics and religion in the health of patients was clearly demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lives were needlessly lost because of stands taken based on religious beliefs or a political ideology. Families, friends, and the community at large were impacted.

Over my years of practice, I have found that while these are difficult topics to address, they should not be avoided. Studies have shown that open acknowledgement of religious beliefs can affect both clinical outcomes and well-being. Religion and spirituality are as much a part of our patient’s lives as the physical parameters that we measure. To neglect these significant aspects is to miss the very essence of the individual.

I made it a practice to ask patients about their religious beliefs, the extent to which religion shaped their life, and whether they were part of a church community. Knowing this allowed me to separate deep personal belief from stances based on personal freedom, misinformation, conspiracies, and politics.

I found that information about political leanings flowed naturally in discussions with patients as we trusted and respected each other over time. If I approached politics objectively and nonjudgmentally, it generally led to meaningful conversation. This helped me to understand the patient as an individual and informed my diagnosis and treatment plan.

Politics as stress

For example, on more than one occasion, a patient with atrial fibrillation presented with persistent elevated blood pressure and pulse rate despite adherence to the medical regimen that I had prescribed. After a few minutes of discussion, it was clear that excessive attention to political commentary on TV and social media raised their anxiety and anger level, putting them at greater risk for adverse outcomes. I advised that they refocus their leisure activities rather than change or increase medication.

It is disappointing to see how one of the great scientific advances of our lifetime, vaccination science, has been tarnished because of political or religious ideology and to see the extent to which these beliefs influenced COVID-19 vaccination compliance. As health care providers, we must promote information based on the scientific method. If patients challenge us and point out that recommendations based on science seem to change over time, we must explain that science evolves on the basis of new information objectively gathered. We need to find out what information the patient has gotten from the Internet, TV, or conspiracy theories and counter this with scientific facts. If we do not discuss religion and politics with our patients along with other risk factors, we may compromise our ability to give them the best advice and treatment.