User login

The Best of DDW 2022: Feel the history

“The Best of DDW” elicits in the minds of most readers a compilation of the most important clinical and scientific content presented at DDW.

But I am not referring to that.

The “Best of DDW 2022” was the American Gastroenterological Association Presidential Plenary Session thanks to the humanity and vision of outgoing AGA President John Inadomi, MD.1 I sat in the audience, misty eyed, as each presenter addressed issues that strike deep into our humanity – the social determinants of health that have festered for far too long, leading to intolerable differences in health outcomes based on accidents of birth, and amplified by racism.

As the table on stage slowly filled in, an amazing picture took shape. A majority of the speakers were Black gastroenterologists and hepatologists, and among them many were young women. As I watched the video of a group of young Black gastroenterologists and hepatologists reaching out to the community, I asked myself “Has anything like this ever happened at a major national medical association meeting in the United States? Ever?” And then it occurred to me: “And just imagine, this exactly 2 days before the 2-year anniversary of the death of George Floyd.”

The plenary session happened on May 23, and I was conscious about the dates because I will never forget that George Floyd was killed on May 25, 2020 – my 55th birthday. The juxtaposition of his death and my birthday 2 years ago shook me profoundly, prompting me to write down my reflections and my hope that, in the national reactions that followed, we were seeing the beginning of true change.2 Two years later, despite our national divisions and serious challenges, I have reasons for hope.

On May 24, I ran into a colleague who was a Black woman. I have stopped being afraid to bring up previously untouchable subjects. I asked her what she thought about the remarkable AGA Plenary. She said she was glad that she is here to see it – that her parents never got the chance.

I admitted to her that I often ask myself what more I could and should be doing. I’m trying to do what I can in recruitment, education, in my personal life. What more? She said that one thing we really need is for people who look like me to amplify the message.

So here it is: Readers, listen to the plenary talks if you were not there. At minimum, behold the following line-up of speakers and topics. Feel the history.

This was the Best of DDW 2022:

- Julius Friedenwald Recognition of Timothy Wang. – John Inadomi.

- Presidential Address: Don’t Talk: Act. The relevance of DEI to gastroenterologists and hepatologists and the imperative for action. – John Inadomi.

- AGA Equity Project: Accomplishments and what lies ahead. – Byron L. Cryer, Sandra M. Quezada.

- The genesis and goals of the Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists. – Sophie M. Balzora.

- Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in clinical trials: What we need to do. – Monica Webb Hooper.

- Reducing disparities in colorectal cancer. – Rachel Blankson Issaka.

- Reducing disparities in liver disease. – Lauren Nephew.

- Reducing disparities in IBD. – Fernando Velayos.

Uri Ladabaum, MD, MS, is with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology in the department of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. He reports serving on the advisory board for UniversalDx and Lean Medical and as a consultant for Medtronic, Clinical Genomics, Guardant Health, and Freenome. Dr. Ladabaum made these comments during the AGA Institute Presidential Plenary at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

References

1. Inadomi JM. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jun;162(7):1855-7.

2. Ladabaum U. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Dec 1;173(11):938-9.

“The Best of DDW” elicits in the minds of most readers a compilation of the most important clinical and scientific content presented at DDW.

But I am not referring to that.

The “Best of DDW 2022” was the American Gastroenterological Association Presidential Plenary Session thanks to the humanity and vision of outgoing AGA President John Inadomi, MD.1 I sat in the audience, misty eyed, as each presenter addressed issues that strike deep into our humanity – the social determinants of health that have festered for far too long, leading to intolerable differences in health outcomes based on accidents of birth, and amplified by racism.

As the table on stage slowly filled in, an amazing picture took shape. A majority of the speakers were Black gastroenterologists and hepatologists, and among them many were young women. As I watched the video of a group of young Black gastroenterologists and hepatologists reaching out to the community, I asked myself “Has anything like this ever happened at a major national medical association meeting in the United States? Ever?” And then it occurred to me: “And just imagine, this exactly 2 days before the 2-year anniversary of the death of George Floyd.”

The plenary session happened on May 23, and I was conscious about the dates because I will never forget that George Floyd was killed on May 25, 2020 – my 55th birthday. The juxtaposition of his death and my birthday 2 years ago shook me profoundly, prompting me to write down my reflections and my hope that, in the national reactions that followed, we were seeing the beginning of true change.2 Two years later, despite our national divisions and serious challenges, I have reasons for hope.

On May 24, I ran into a colleague who was a Black woman. I have stopped being afraid to bring up previously untouchable subjects. I asked her what she thought about the remarkable AGA Plenary. She said she was glad that she is here to see it – that her parents never got the chance.

I admitted to her that I often ask myself what more I could and should be doing. I’m trying to do what I can in recruitment, education, in my personal life. What more? She said that one thing we really need is for people who look like me to amplify the message.

So here it is: Readers, listen to the plenary talks if you were not there. At minimum, behold the following line-up of speakers and topics. Feel the history.

This was the Best of DDW 2022:

- Julius Friedenwald Recognition of Timothy Wang. – John Inadomi.

- Presidential Address: Don’t Talk: Act. The relevance of DEI to gastroenterologists and hepatologists and the imperative for action. – John Inadomi.

- AGA Equity Project: Accomplishments and what lies ahead. – Byron L. Cryer, Sandra M. Quezada.

- The genesis and goals of the Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists. – Sophie M. Balzora.

- Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in clinical trials: What we need to do. – Monica Webb Hooper.

- Reducing disparities in colorectal cancer. – Rachel Blankson Issaka.

- Reducing disparities in liver disease. – Lauren Nephew.

- Reducing disparities in IBD. – Fernando Velayos.

Uri Ladabaum, MD, MS, is with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology in the department of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. He reports serving on the advisory board for UniversalDx and Lean Medical and as a consultant for Medtronic, Clinical Genomics, Guardant Health, and Freenome. Dr. Ladabaum made these comments during the AGA Institute Presidential Plenary at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

References

1. Inadomi JM. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jun;162(7):1855-7.

2. Ladabaum U. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Dec 1;173(11):938-9.

“The Best of DDW” elicits in the minds of most readers a compilation of the most important clinical and scientific content presented at DDW.

But I am not referring to that.

The “Best of DDW 2022” was the American Gastroenterological Association Presidential Plenary Session thanks to the humanity and vision of outgoing AGA President John Inadomi, MD.1 I sat in the audience, misty eyed, as each presenter addressed issues that strike deep into our humanity – the social determinants of health that have festered for far too long, leading to intolerable differences in health outcomes based on accidents of birth, and amplified by racism.

As the table on stage slowly filled in, an amazing picture took shape. A majority of the speakers were Black gastroenterologists and hepatologists, and among them many were young women. As I watched the video of a group of young Black gastroenterologists and hepatologists reaching out to the community, I asked myself “Has anything like this ever happened at a major national medical association meeting in the United States? Ever?” And then it occurred to me: “And just imagine, this exactly 2 days before the 2-year anniversary of the death of George Floyd.”

The plenary session happened on May 23, and I was conscious about the dates because I will never forget that George Floyd was killed on May 25, 2020 – my 55th birthday. The juxtaposition of his death and my birthday 2 years ago shook me profoundly, prompting me to write down my reflections and my hope that, in the national reactions that followed, we were seeing the beginning of true change.2 Two years later, despite our national divisions and serious challenges, I have reasons for hope.

On May 24, I ran into a colleague who was a Black woman. I have stopped being afraid to bring up previously untouchable subjects. I asked her what she thought about the remarkable AGA Plenary. She said she was glad that she is here to see it – that her parents never got the chance.

I admitted to her that I often ask myself what more I could and should be doing. I’m trying to do what I can in recruitment, education, in my personal life. What more? She said that one thing we really need is for people who look like me to amplify the message.

So here it is: Readers, listen to the plenary talks if you were not there. At minimum, behold the following line-up of speakers and topics. Feel the history.

This was the Best of DDW 2022:

- Julius Friedenwald Recognition of Timothy Wang. – John Inadomi.

- Presidential Address: Don’t Talk: Act. The relevance of DEI to gastroenterologists and hepatologists and the imperative for action. – John Inadomi.

- AGA Equity Project: Accomplishments and what lies ahead. – Byron L. Cryer, Sandra M. Quezada.

- The genesis and goals of the Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists. – Sophie M. Balzora.

- Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in clinical trials: What we need to do. – Monica Webb Hooper.

- Reducing disparities in colorectal cancer. – Rachel Blankson Issaka.

- Reducing disparities in liver disease. – Lauren Nephew.

- Reducing disparities in IBD. – Fernando Velayos.

Uri Ladabaum, MD, MS, is with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology in the department of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. He reports serving on the advisory board for UniversalDx and Lean Medical and as a consultant for Medtronic, Clinical Genomics, Guardant Health, and Freenome. Dr. Ladabaum made these comments during the AGA Institute Presidential Plenary at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

References

1. Inadomi JM. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jun;162(7):1855-7.

2. Ladabaum U. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Dec 1;173(11):938-9.

Reversing depression: A plethora of therapeutic strategies and mechanisms

Despite much progress, major depressive disorder (MDD) continues to be a challenging and life-threatening neuropsychiatric disorder. It is highly prevalent and afflicts tens of millions of Americans.

It is also ranked as the No. 1 disabling medical (not just psychiatric) condition by the World Health Organization.1 A significant proportion of patients with MDD do not respond adequately to several rounds of antidepressant medications,2 and many are labeled as having “treatment-resistant depression” (TRD).

In a previous article, I provocatively proposed that TRD is a myth.3 What I meant is that in a heterogeneous syndrome such as depression, failure to respond to 1, 2, or even 3 antidepressants should not imply TRD, because there is a “right treatment” that has not yet been identified for a given depressed patient. Most of those labeled as TRD have simply not yet received the pharmacotherapy or somatic therapy with the requisite mechanism of action for their variant of depression within a heterogeneous syndrome. IV ketamine, which, astonishingly, often reverses severe TRD of chronic duration within a few hours, is a prime example of why the term TRD is often used prematurely. Ketamine’s mechanism of action (immediate neuroplasticity via glutamate N-methyl-

Some clinicians may not be aware of the abundance of mechanisms of action currently available for the treatment of MDD as well as bipolar depression. Many practitioners, in both psychiatry and primary care, usually start the treatment of depression with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and if that does not produce a response or remission, they might switch to a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. If that does not control the patient’s depressive symptoms, they start entertaining the notion that the patient may have TRD, not realizing that they have barely scratched the surface of the many therapeutic options and mechanisms of action, one of which could be the “best match” for a given patient.4

There will come a day when “precision psychiatry” finally arrives, and specific biomarkers will be developed to identify the “right” treatment for each patient within the heterogenous syndrome of depression.5 Until that day arrives, the treatment of depression will continue to be a process of trial and error, and hit or miss. But research will eventually discover genetic, neurochemical, neurophysiological, neuroimaging, or neuroimmune biomarkers that will rapidly guide clinicians to the correct treatment. This is critical to avoid inordinate delays in achieving remission and avert the ever-present risk of suicidal behavior.

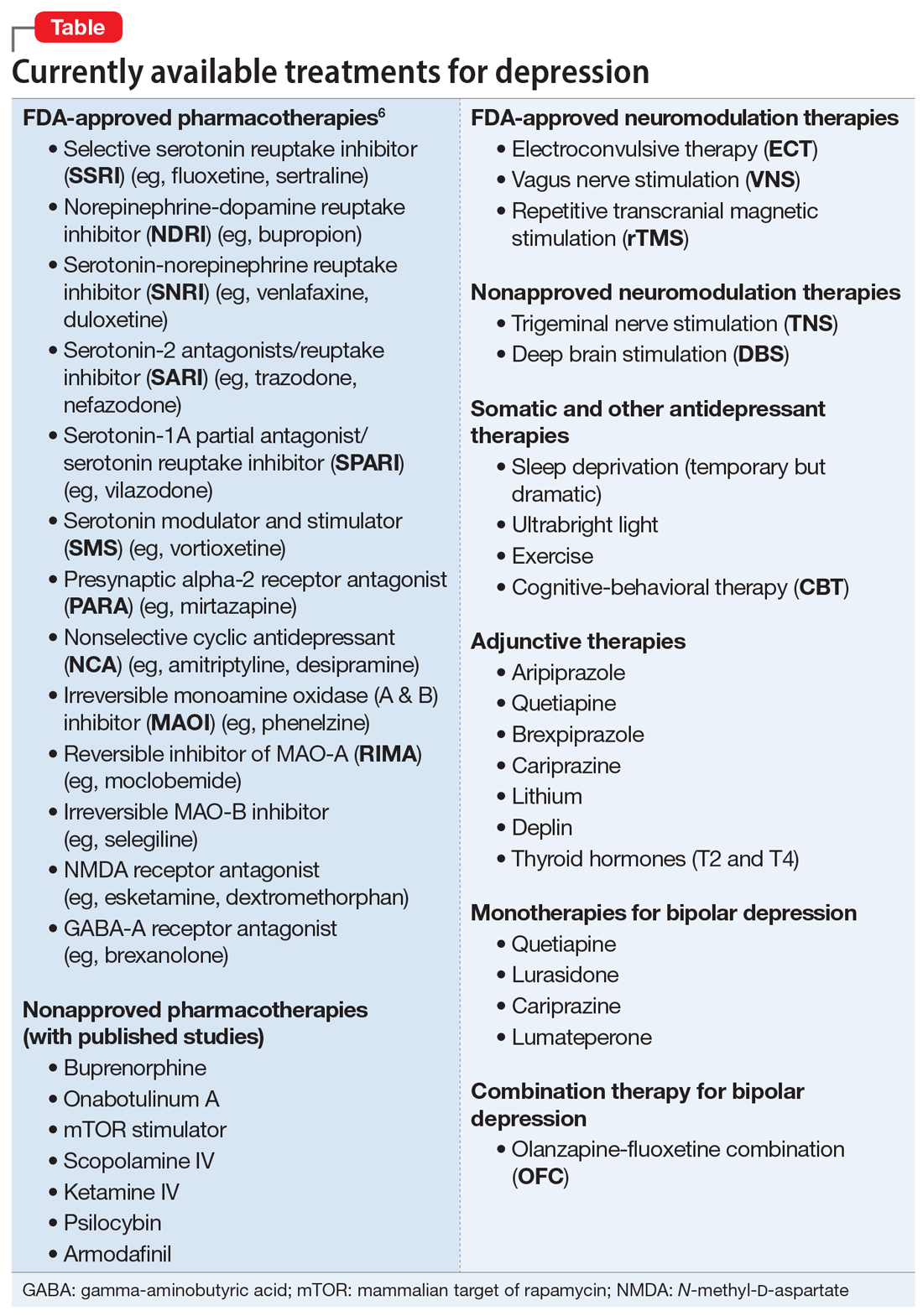

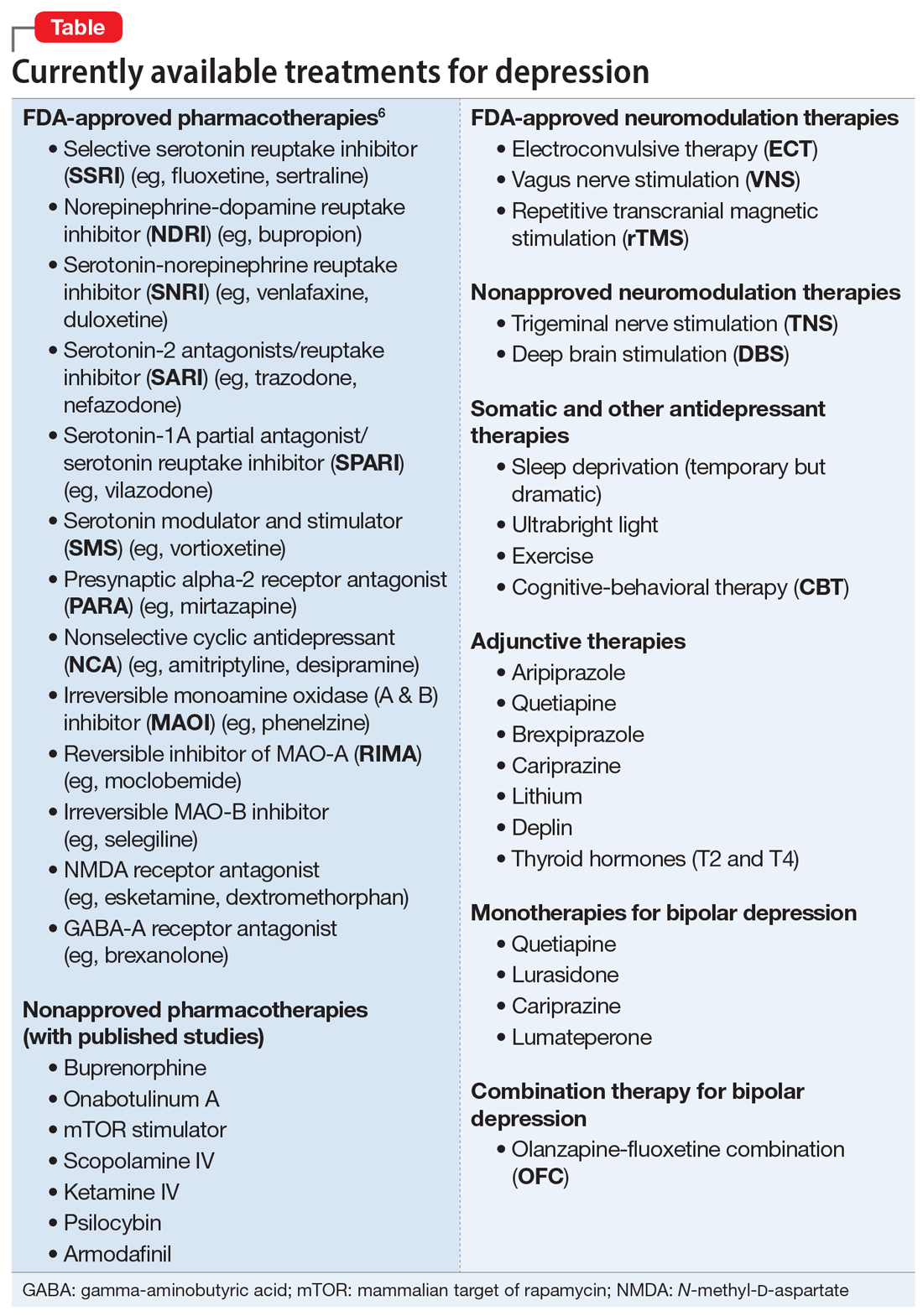

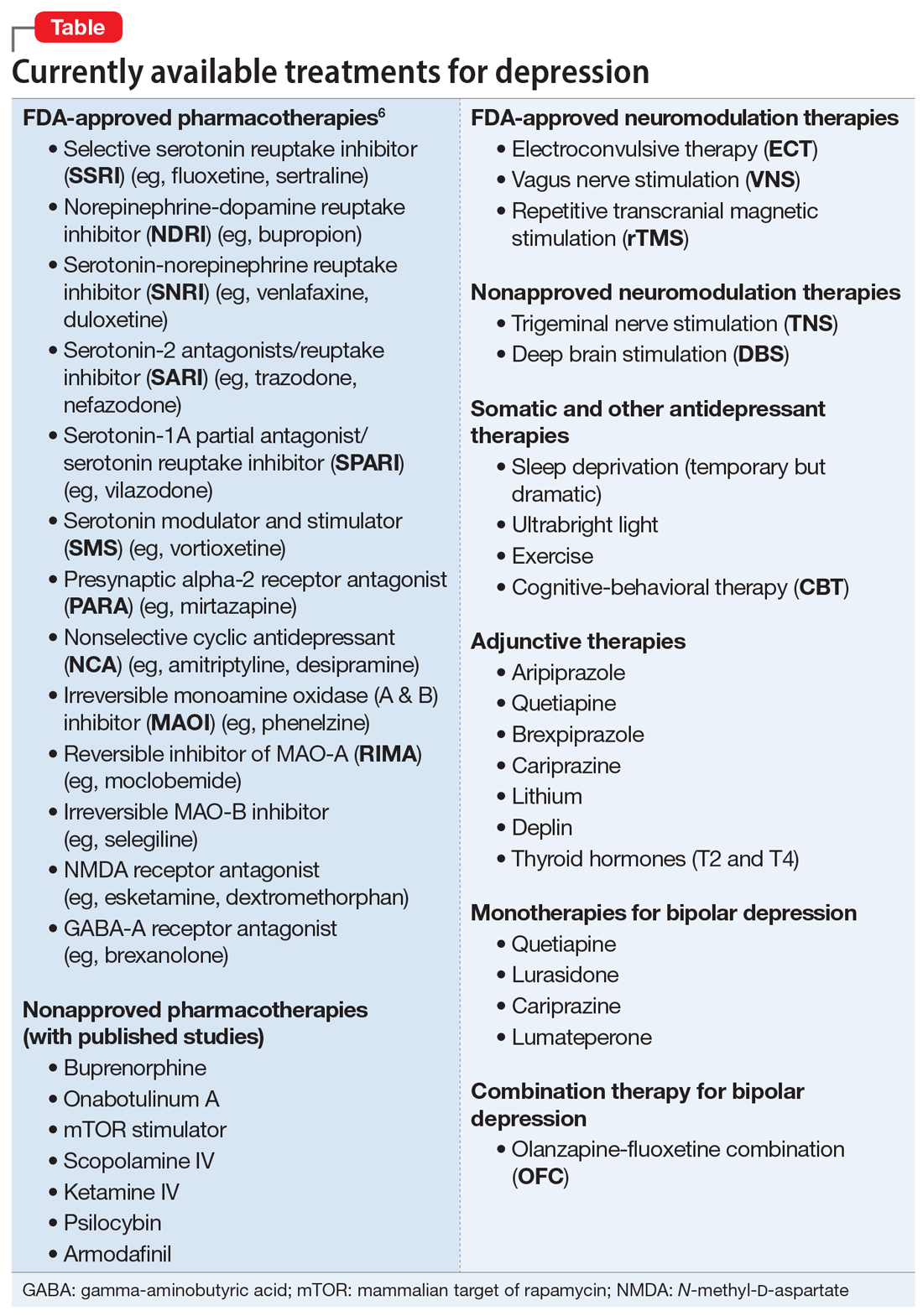

The Table6 provides an overview of the numerous treatments currently available to manage depression. All increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor and restore healthy neuroplasticity and neurogenesis, which are impaired in MDD and currently believed to be a final common pathway for all depression treatments.7

These 41 therapeutic approaches to treating MDD or bipolar depression reflect the heterogeneity of mechanisms of action to address an equally heterogeneous syndrome. This implies that clinicians have a wide array of on-label options to manage patients with depression, aiming for remission, not just a good response, which typically is defined as a ≥50% reduction in total score on one of the validated rating scales used to quantify depression severity, such as the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, or Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia.

Continue to: When several FDA-approved pharmacotherapies...

When several FDA-approved pharmacotherapies fall short and produce a suboptimal response, clinicians can resort to other treatment options known to have a higher efficacy than oral antidepressants. These include electroconvulsive therapy, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, and vagus nerve stimulation. Other on-label options include adjunctive therapy with one of the approved second-generation antipsychotic agents or with adjunctive esketamine.

But if the patient still does not improve, one of many emerging off-label treatment options may work. One of the exciting new discoveries is the hallucinogen psilocybin, whose mechanism of action is truly unique. Unlike standard antidepressant medications, which modulate neurotransmitters, psilocybin increases the brain’s network flexibility, decreases the modularity of several key brain networks (especially the default-brain network, or DMN), and alters the dark and distorted mental perspective of depression to a much healthier and optimistic outlook about the self and the world.8 Such novel breakthroughs in the treatment of severe depression will shed some unprecedented insights into the core neurobiology of depression, and may lead to early intervention and prevention.

As the saying goes, all roads lead to Rome. Psychiatric clinicians should rejoice that there are abundant approaches and therapeutic mechanisms to relieve their severely melancholic (and often suicidal) patients from the grips of this disabling and life-altering brain syndrome.

1. World Health Organization. Depression: let’s talk says WHO, as depression tops list of causes of ill health. March 30, 2017. Accessed July 5, 2022. www.who.int/news/item/30-03-2017--depression-let-s-talk-says-who-as-depression-tops-list-of-causes-of-ill-health

2. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Eng J Med. 2006;354(12)1243-1252.

3. Nasrallah HA. Treatment resistance is a myth! Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(3):14-16,28.

4. Nasrallah HA. 10 Recent paradigm shifts in the neurobiology and treatment of depression. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):10-13.

5. Nasrallah HA. Biomarkers in neuropsychiatric disorders: translating research to clinical applications. Biomarkers in Neuropsychiatry. 2019;1:100001. doi:10.1016/j.bionps.2019.100001

6. Procyshyn RM, Bezchlibnyk-Butler KZ, Jeffries JJ. Clinical Handbook of Psychotropic Drugs. 23rd ed. Hogrefe; 2019.

7. Tartt AN, Mariani, MB, Hen R, et al. Dysregulation of adult hippocampal neuroplasticity in major depression: pathogenesis and therapeutic implications. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(6):2689-2699.

8. Lowe H, Toyang N, Steele B, et al. The therapeutic potential of psilocybin. Molecules. 2021;26(10):2948. doi: 10.3390/molecules26102948

Despite much progress, major depressive disorder (MDD) continues to be a challenging and life-threatening neuropsychiatric disorder. It is highly prevalent and afflicts tens of millions of Americans.

It is also ranked as the No. 1 disabling medical (not just psychiatric) condition by the World Health Organization.1 A significant proportion of patients with MDD do not respond adequately to several rounds of antidepressant medications,2 and many are labeled as having “treatment-resistant depression” (TRD).

In a previous article, I provocatively proposed that TRD is a myth.3 What I meant is that in a heterogeneous syndrome such as depression, failure to respond to 1, 2, or even 3 antidepressants should not imply TRD, because there is a “right treatment” that has not yet been identified for a given depressed patient. Most of those labeled as TRD have simply not yet received the pharmacotherapy or somatic therapy with the requisite mechanism of action for their variant of depression within a heterogeneous syndrome. IV ketamine, which, astonishingly, often reverses severe TRD of chronic duration within a few hours, is a prime example of why the term TRD is often used prematurely. Ketamine’s mechanism of action (immediate neuroplasticity via glutamate N-methyl-

Some clinicians may not be aware of the abundance of mechanisms of action currently available for the treatment of MDD as well as bipolar depression. Many practitioners, in both psychiatry and primary care, usually start the treatment of depression with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and if that does not produce a response or remission, they might switch to a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. If that does not control the patient’s depressive symptoms, they start entertaining the notion that the patient may have TRD, not realizing that they have barely scratched the surface of the many therapeutic options and mechanisms of action, one of which could be the “best match” for a given patient.4

There will come a day when “precision psychiatry” finally arrives, and specific biomarkers will be developed to identify the “right” treatment for each patient within the heterogenous syndrome of depression.5 Until that day arrives, the treatment of depression will continue to be a process of trial and error, and hit or miss. But research will eventually discover genetic, neurochemical, neurophysiological, neuroimaging, or neuroimmune biomarkers that will rapidly guide clinicians to the correct treatment. This is critical to avoid inordinate delays in achieving remission and avert the ever-present risk of suicidal behavior.

The Table6 provides an overview of the numerous treatments currently available to manage depression. All increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor and restore healthy neuroplasticity and neurogenesis, which are impaired in MDD and currently believed to be a final common pathway for all depression treatments.7

These 41 therapeutic approaches to treating MDD or bipolar depression reflect the heterogeneity of mechanisms of action to address an equally heterogeneous syndrome. This implies that clinicians have a wide array of on-label options to manage patients with depression, aiming for remission, not just a good response, which typically is defined as a ≥50% reduction in total score on one of the validated rating scales used to quantify depression severity, such as the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, or Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia.

Continue to: When several FDA-approved pharmacotherapies...

When several FDA-approved pharmacotherapies fall short and produce a suboptimal response, clinicians can resort to other treatment options known to have a higher efficacy than oral antidepressants. These include electroconvulsive therapy, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, and vagus nerve stimulation. Other on-label options include adjunctive therapy with one of the approved second-generation antipsychotic agents or with adjunctive esketamine.

But if the patient still does not improve, one of many emerging off-label treatment options may work. One of the exciting new discoveries is the hallucinogen psilocybin, whose mechanism of action is truly unique. Unlike standard antidepressant medications, which modulate neurotransmitters, psilocybin increases the brain’s network flexibility, decreases the modularity of several key brain networks (especially the default-brain network, or DMN), and alters the dark and distorted mental perspective of depression to a much healthier and optimistic outlook about the self and the world.8 Such novel breakthroughs in the treatment of severe depression will shed some unprecedented insights into the core neurobiology of depression, and may lead to early intervention and prevention.

As the saying goes, all roads lead to Rome. Psychiatric clinicians should rejoice that there are abundant approaches and therapeutic mechanisms to relieve their severely melancholic (and often suicidal) patients from the grips of this disabling and life-altering brain syndrome.

Despite much progress, major depressive disorder (MDD) continues to be a challenging and life-threatening neuropsychiatric disorder. It is highly prevalent and afflicts tens of millions of Americans.

It is also ranked as the No. 1 disabling medical (not just psychiatric) condition by the World Health Organization.1 A significant proportion of patients with MDD do not respond adequately to several rounds of antidepressant medications,2 and many are labeled as having “treatment-resistant depression” (TRD).

In a previous article, I provocatively proposed that TRD is a myth.3 What I meant is that in a heterogeneous syndrome such as depression, failure to respond to 1, 2, or even 3 antidepressants should not imply TRD, because there is a “right treatment” that has not yet been identified for a given depressed patient. Most of those labeled as TRD have simply not yet received the pharmacotherapy or somatic therapy with the requisite mechanism of action for their variant of depression within a heterogeneous syndrome. IV ketamine, which, astonishingly, often reverses severe TRD of chronic duration within a few hours, is a prime example of why the term TRD is often used prematurely. Ketamine’s mechanism of action (immediate neuroplasticity via glutamate N-methyl-

Some clinicians may not be aware of the abundance of mechanisms of action currently available for the treatment of MDD as well as bipolar depression. Many practitioners, in both psychiatry and primary care, usually start the treatment of depression with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and if that does not produce a response or remission, they might switch to a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. If that does not control the patient’s depressive symptoms, they start entertaining the notion that the patient may have TRD, not realizing that they have barely scratched the surface of the many therapeutic options and mechanisms of action, one of which could be the “best match” for a given patient.4

There will come a day when “precision psychiatry” finally arrives, and specific biomarkers will be developed to identify the “right” treatment for each patient within the heterogenous syndrome of depression.5 Until that day arrives, the treatment of depression will continue to be a process of trial and error, and hit or miss. But research will eventually discover genetic, neurochemical, neurophysiological, neuroimaging, or neuroimmune biomarkers that will rapidly guide clinicians to the correct treatment. This is critical to avoid inordinate delays in achieving remission and avert the ever-present risk of suicidal behavior.

The Table6 provides an overview of the numerous treatments currently available to manage depression. All increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor and restore healthy neuroplasticity and neurogenesis, which are impaired in MDD and currently believed to be a final common pathway for all depression treatments.7

These 41 therapeutic approaches to treating MDD or bipolar depression reflect the heterogeneity of mechanisms of action to address an equally heterogeneous syndrome. This implies that clinicians have a wide array of on-label options to manage patients with depression, aiming for remission, not just a good response, which typically is defined as a ≥50% reduction in total score on one of the validated rating scales used to quantify depression severity, such as the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, or Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia.

Continue to: When several FDA-approved pharmacotherapies...

When several FDA-approved pharmacotherapies fall short and produce a suboptimal response, clinicians can resort to other treatment options known to have a higher efficacy than oral antidepressants. These include electroconvulsive therapy, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, and vagus nerve stimulation. Other on-label options include adjunctive therapy with one of the approved second-generation antipsychotic agents or with adjunctive esketamine.

But if the patient still does not improve, one of many emerging off-label treatment options may work. One of the exciting new discoveries is the hallucinogen psilocybin, whose mechanism of action is truly unique. Unlike standard antidepressant medications, which modulate neurotransmitters, psilocybin increases the brain’s network flexibility, decreases the modularity of several key brain networks (especially the default-brain network, or DMN), and alters the dark and distorted mental perspective of depression to a much healthier and optimistic outlook about the self and the world.8 Such novel breakthroughs in the treatment of severe depression will shed some unprecedented insights into the core neurobiology of depression, and may lead to early intervention and prevention.

As the saying goes, all roads lead to Rome. Psychiatric clinicians should rejoice that there are abundant approaches and therapeutic mechanisms to relieve their severely melancholic (and often suicidal) patients from the grips of this disabling and life-altering brain syndrome.

1. World Health Organization. Depression: let’s talk says WHO, as depression tops list of causes of ill health. March 30, 2017. Accessed July 5, 2022. www.who.int/news/item/30-03-2017--depression-let-s-talk-says-who-as-depression-tops-list-of-causes-of-ill-health

2. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Eng J Med. 2006;354(12)1243-1252.

3. Nasrallah HA. Treatment resistance is a myth! Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(3):14-16,28.

4. Nasrallah HA. 10 Recent paradigm shifts in the neurobiology and treatment of depression. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):10-13.

5. Nasrallah HA. Biomarkers in neuropsychiatric disorders: translating research to clinical applications. Biomarkers in Neuropsychiatry. 2019;1:100001. doi:10.1016/j.bionps.2019.100001

6. Procyshyn RM, Bezchlibnyk-Butler KZ, Jeffries JJ. Clinical Handbook of Psychotropic Drugs. 23rd ed. Hogrefe; 2019.

7. Tartt AN, Mariani, MB, Hen R, et al. Dysregulation of adult hippocampal neuroplasticity in major depression: pathogenesis and therapeutic implications. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(6):2689-2699.

8. Lowe H, Toyang N, Steele B, et al. The therapeutic potential of psilocybin. Molecules. 2021;26(10):2948. doi: 10.3390/molecules26102948

1. World Health Organization. Depression: let’s talk says WHO, as depression tops list of causes of ill health. March 30, 2017. Accessed July 5, 2022. www.who.int/news/item/30-03-2017--depression-let-s-talk-says-who-as-depression-tops-list-of-causes-of-ill-health

2. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Eng J Med. 2006;354(12)1243-1252.

3. Nasrallah HA. Treatment resistance is a myth! Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(3):14-16,28.

4. Nasrallah HA. 10 Recent paradigm shifts in the neurobiology and treatment of depression. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):10-13.

5. Nasrallah HA. Biomarkers in neuropsychiatric disorders: translating research to clinical applications. Biomarkers in Neuropsychiatry. 2019;1:100001. doi:10.1016/j.bionps.2019.100001

6. Procyshyn RM, Bezchlibnyk-Butler KZ, Jeffries JJ. Clinical Handbook of Psychotropic Drugs. 23rd ed. Hogrefe; 2019.

7. Tartt AN, Mariani, MB, Hen R, et al. Dysregulation of adult hippocampal neuroplasticity in major depression: pathogenesis and therapeutic implications. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(6):2689-2699.

8. Lowe H, Toyang N, Steele B, et al. The therapeutic potential of psilocybin. Molecules. 2021;26(10):2948. doi: 10.3390/molecules26102948

Hope, help, and humor when facing a life-threatening illness

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

My father, Morty Sosland, MD, was a psychiatrist in a community health setting when he was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS; Lou Gehrig’s disease) in April 2020. He continued to work until February 2021 and credits his ongoing resilience to what he refers to as “the 3 Hs”: hope, help, and humor. Although he can no longer speak, I was able to interview him over the advanced technology that is text messaging.

Sarah: Hi, Dad.

Morty: It’s Doctor Dad to you.

Sarah: I guess we are starting with humor, then?

Humor

Research has demonstrated that humor can have serious health benefits, such as decreasing stress-making hormones and altering dopamine activity.1 For individuals facing a life-threatening illness, humor can help them gain a sense of perspective in a situation that would otherwise feel overwhelming.

Sarah: I feel like a lot of the humor you used with patients was to help them gain perspective.

Continue to: Morty

Morty: Yes. I’d have to know the client well enough, though—and timing is important. My patients would come to me with a long list of challenges they had faced in the week, and I would say, “But besides that, everything’s good?”

Sarah: And besides the ALS, everything’s good?

Morty: Exactly. I’d also use magic or math tricks to make kids like coming to therapy or to reinforce important concepts.

Sarah: How has humor helped you cope?

Morty: Thinking about things in humorous ways has always been helpful. I used to say my Olympic sport was walking to the dining room with my walker. Unfortunately, I can’t do that anymore, so now my Olympic sport is getting out of bed. It’s a team sport.

Sarah: And that’s a good segue to…

Help

Countless studies have shown the impact of social support on health. Good social support can increase resilience, protect against mental illness, and even increase life expectancy.2 Support becomes even more critical when you are physically dependent on others due to illness.

Continue to: Sarah

Sarah: Was it difficult for you to accept help at first?

Morty: I would say yes—but at the same time, I accepted it because the illness was so shocking. I learned early on this was a fight that my family would also fight alongside me.

Sarah: I remember you would quote Fred Rogers.

Morty: Actually, it was Fred Rogers’ mother. She would tell her son during hard times, “Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.” Helpers can be family members, friends, doctors, and aides, as well as others who have the same illness.

Hope

In the face of all life’s challenges, hope is important, but in the face of a life-threatening illness, hope must be multifaceted.3 In addition to hope for a cure, patients may focus their hopes on deepening relationships, maintaining dignity, or living each day to its fullest.

Morty: Early on in this illness, I chose to set a positive tone when I told people. I would say I have the top doctors and there is more research now than ever. Years ago, I wrote a children’s book with the mantra, “I say I can, I make a plan, I get right to it and then I do it.”4 My plan is to be around for at least 30 more years.

Sarah: Do you think it’s possible to hold acceptance and hope at the same time?

Morty: Acceptance and hope are not easy, but possible. I get down about this illness. In my dreams, I walk and talk, and most mornings I wake up and see my wheelchair and I think this is absurd or a different choice word. But I focus on the things I still can do, and that gives me a feeling of hope. I can read the latest research, I can enjoy moments of laughter, and I can spend time with my family and close friends.

1. Yim J. Therapeutic benefits of laughter in mental health: a theoretical review. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2016;239(3):243-249. doi:10.1620/tjem.239.243

2. Ozbay F, Johnson DC, Dimoulas E, et al. Social support and resilience to stress: from neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2007;4(5):35-40.

3. Hill DL, Feudnter C. Hope in the midst of terminal illness. In: Gallagher MW, Lopez SJ, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Hope. Oxford University Press; 2018:191-206.

4. Sosland MD. The Can Do Duck: A Story About Believing in Yourself. Can Do Duck Publishing; 2019.

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

My father, Morty Sosland, MD, was a psychiatrist in a community health setting when he was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS; Lou Gehrig’s disease) in April 2020. He continued to work until February 2021 and credits his ongoing resilience to what he refers to as “the 3 Hs”: hope, help, and humor. Although he can no longer speak, I was able to interview him over the advanced technology that is text messaging.

Sarah: Hi, Dad.

Morty: It’s Doctor Dad to you.

Sarah: I guess we are starting with humor, then?

Humor

Research has demonstrated that humor can have serious health benefits, such as decreasing stress-making hormones and altering dopamine activity.1 For individuals facing a life-threatening illness, humor can help them gain a sense of perspective in a situation that would otherwise feel overwhelming.

Sarah: I feel like a lot of the humor you used with patients was to help them gain perspective.

Continue to: Morty

Morty: Yes. I’d have to know the client well enough, though—and timing is important. My patients would come to me with a long list of challenges they had faced in the week, and I would say, “But besides that, everything’s good?”

Sarah: And besides the ALS, everything’s good?

Morty: Exactly. I’d also use magic or math tricks to make kids like coming to therapy or to reinforce important concepts.

Sarah: How has humor helped you cope?

Morty: Thinking about things in humorous ways has always been helpful. I used to say my Olympic sport was walking to the dining room with my walker. Unfortunately, I can’t do that anymore, so now my Olympic sport is getting out of bed. It’s a team sport.

Sarah: And that’s a good segue to…

Help

Countless studies have shown the impact of social support on health. Good social support can increase resilience, protect against mental illness, and even increase life expectancy.2 Support becomes even more critical when you are physically dependent on others due to illness.

Continue to: Sarah

Sarah: Was it difficult for you to accept help at first?

Morty: I would say yes—but at the same time, I accepted it because the illness was so shocking. I learned early on this was a fight that my family would also fight alongside me.

Sarah: I remember you would quote Fred Rogers.

Morty: Actually, it was Fred Rogers’ mother. She would tell her son during hard times, “Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.” Helpers can be family members, friends, doctors, and aides, as well as others who have the same illness.

Hope

In the face of all life’s challenges, hope is important, but in the face of a life-threatening illness, hope must be multifaceted.3 In addition to hope for a cure, patients may focus their hopes on deepening relationships, maintaining dignity, or living each day to its fullest.

Morty: Early on in this illness, I chose to set a positive tone when I told people. I would say I have the top doctors and there is more research now than ever. Years ago, I wrote a children’s book with the mantra, “I say I can, I make a plan, I get right to it and then I do it.”4 My plan is to be around for at least 30 more years.

Sarah: Do you think it’s possible to hold acceptance and hope at the same time?

Morty: Acceptance and hope are not easy, but possible. I get down about this illness. In my dreams, I walk and talk, and most mornings I wake up and see my wheelchair and I think this is absurd or a different choice word. But I focus on the things I still can do, and that gives me a feeling of hope. I can read the latest research, I can enjoy moments of laughter, and I can spend time with my family and close friends.

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

My father, Morty Sosland, MD, was a psychiatrist in a community health setting when he was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS; Lou Gehrig’s disease) in April 2020. He continued to work until February 2021 and credits his ongoing resilience to what he refers to as “the 3 Hs”: hope, help, and humor. Although he can no longer speak, I was able to interview him over the advanced technology that is text messaging.

Sarah: Hi, Dad.

Morty: It’s Doctor Dad to you.

Sarah: I guess we are starting with humor, then?

Humor

Research has demonstrated that humor can have serious health benefits, such as decreasing stress-making hormones and altering dopamine activity.1 For individuals facing a life-threatening illness, humor can help them gain a sense of perspective in a situation that would otherwise feel overwhelming.

Sarah: I feel like a lot of the humor you used with patients was to help them gain perspective.

Continue to: Morty

Morty: Yes. I’d have to know the client well enough, though—and timing is important. My patients would come to me with a long list of challenges they had faced in the week, and I would say, “But besides that, everything’s good?”

Sarah: And besides the ALS, everything’s good?

Morty: Exactly. I’d also use magic or math tricks to make kids like coming to therapy or to reinforce important concepts.

Sarah: How has humor helped you cope?

Morty: Thinking about things in humorous ways has always been helpful. I used to say my Olympic sport was walking to the dining room with my walker. Unfortunately, I can’t do that anymore, so now my Olympic sport is getting out of bed. It’s a team sport.

Sarah: And that’s a good segue to…

Help

Countless studies have shown the impact of social support on health. Good social support can increase resilience, protect against mental illness, and even increase life expectancy.2 Support becomes even more critical when you are physically dependent on others due to illness.

Continue to: Sarah

Sarah: Was it difficult for you to accept help at first?

Morty: I would say yes—but at the same time, I accepted it because the illness was so shocking. I learned early on this was a fight that my family would also fight alongside me.

Sarah: I remember you would quote Fred Rogers.

Morty: Actually, it was Fred Rogers’ mother. She would tell her son during hard times, “Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.” Helpers can be family members, friends, doctors, and aides, as well as others who have the same illness.

Hope

In the face of all life’s challenges, hope is important, but in the face of a life-threatening illness, hope must be multifaceted.3 In addition to hope for a cure, patients may focus their hopes on deepening relationships, maintaining dignity, or living each day to its fullest.

Morty: Early on in this illness, I chose to set a positive tone when I told people. I would say I have the top doctors and there is more research now than ever. Years ago, I wrote a children’s book with the mantra, “I say I can, I make a plan, I get right to it and then I do it.”4 My plan is to be around for at least 30 more years.

Sarah: Do you think it’s possible to hold acceptance and hope at the same time?

Morty: Acceptance and hope are not easy, but possible. I get down about this illness. In my dreams, I walk and talk, and most mornings I wake up and see my wheelchair and I think this is absurd or a different choice word. But I focus on the things I still can do, and that gives me a feeling of hope. I can read the latest research, I can enjoy moments of laughter, and I can spend time with my family and close friends.

1. Yim J. Therapeutic benefits of laughter in mental health: a theoretical review. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2016;239(3):243-249. doi:10.1620/tjem.239.243

2. Ozbay F, Johnson DC, Dimoulas E, et al. Social support and resilience to stress: from neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2007;4(5):35-40.

3. Hill DL, Feudnter C. Hope in the midst of terminal illness. In: Gallagher MW, Lopez SJ, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Hope. Oxford University Press; 2018:191-206.

4. Sosland MD. The Can Do Duck: A Story About Believing in Yourself. Can Do Duck Publishing; 2019.

1. Yim J. Therapeutic benefits of laughter in mental health: a theoretical review. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2016;239(3):243-249. doi:10.1620/tjem.239.243

2. Ozbay F, Johnson DC, Dimoulas E, et al. Social support and resilience to stress: from neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2007;4(5):35-40.

3. Hill DL, Feudnter C. Hope in the midst of terminal illness. In: Gallagher MW, Lopez SJ, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Hope. Oxford University Press; 2018:191-206.

4. Sosland MD. The Can Do Duck: A Story About Believing in Yourself. Can Do Duck Publishing; 2019.

The impact of COVID-19 on adolescents’ mental health

While the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the mental health of a wide range of individuals, its adverse effects have been particularly detrimental to adolescents. In this article, I discuss evidence that shows the effects of the pandemic on adolescent patients, potential reasons for this increased distress, and what types of coping mechanisms adolescents have used to counter these effects.

Increases in multiple measures of psychopathology

Multiple online surveys and other studies have documented the pandemic’s impact on younger individuals. In the United States, visits to emergency departments by pediatric patients increased in the months after the first lockdown period.1 Several studies found increased rates of anxiety and depression among adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic.2,3 In an online survey of 359 children and 3,254 adolescents in China, 22% of respondents reported that they experienced depressive symptoms.3 In an online survey of 1,054 Canadian adolescents, 43% said they were “very concerned” about the pandemic.4 In an online survey of 7,353 adolescents in the United States, 37% reported suicidal ideation during the pandemic compared to 17% in 2017.5 A Chinese study found that smartphone and internet addiction was significantly associated with increased levels of depressive symptoms during the pandemic.3 In a survey in the Philippines, 16.3% of adolescents reported moderate-to-severe psychological impairment during the pandemic; the rates of COVID-19–related anxiety were higher among girls vs boys.6 Alcohol and cannabis use increased among Canadian adolescents during the pandemic, according to an online survey.7 Adolescents with anorexia nervosa reported a 70% increase in poor eating habits and more thoughts associated with eating disorders during the pandemic.8 A Danish study found that children and adolescents newly diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) or who had completed treatment exhibited worsening OCD, anxiety, and depressive symptoms during the pandemic.9 An online survey of 6,196 Chinese adolescents found that those with a higher number of pre-pandemic adverse childhood experiences, such as abuse and neglect, had elevated posttraumatic stress symptoms and anxiety during the onset of the pandemic.10

Underlying causes of pandemic-induced distress

Limited social connectedness during the pandemic is a major reason for distress among adolescents. A review of 80 studies found that social isolation and loneliness as a result of social distancing and quarantining were associated with an increased risk of depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and self-harm.11 Parents’ stress about the risks of COVID-19 was correlated with worsening mental health in their adolescent children.12 A Chinese study found that the amount of time students spent on smartphones and social media doubled during the pandemic.13 In an online survey of 7,890 Chinese adolescents, greater social media, internet, and smartphone use was associated with increased anxiety and depression.14 This may be in part the result of adolescents spending time reading COVID-related news.

Coping mechanisms to increase well-being

Researchers have identified several positive coping mechanisms adolescents employed during the pandemic. Although some data suggest that increased internet use raises the risk of COVID-related distress, for certain adolescents, using social media to stay connected with friends and relatives was a buffer for feelings of loneliness and might have increased mental well-being.15 Other common coping mechanisms include relying on faith, volunteering, and starting new hobbies.16 During the pandemic, there were higher rates of playing outside and increased physical activity, which correlated with positive mental health outcomes.16 An online survey of 1,040 adolescents found that those who looked to the future optimistically and confidently had a higher health-related quality of life.17

Continuing an emphasis on adolescent well-being

Although data are limited, adolescents can continue to use these coping mechanisms to maintain their well-being, even if COVID-related restrictions are lifted or reimplemented. During these difficult times, it is imperative for adolescents to get the mental health services they need, and for psychiatric clinicians to continue to find avenues to promote resilience and mental wellness among young patients.

1. Leeb RT, Bitsko RH, Radhakrishnan L, et al. Mental health–related emergency department visits among children aged <18 years during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, January 1-October 17, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(45):1675-1680. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6945a3

2. Oosterhoff B, Palmer CA, Wilson J, et al. Adolescents’ motivations to engage in social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: associations with mental and social health. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(2):179-185. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.004

3. Duan L, Shao X, Wang Y, et al. An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in China during the outbreak of COVID-19. J Affect Disord. 2020;275:112-118. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.029

4. Ellis WE, Dumas TM, Forbes LM. Physically isolated but socially connected: psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Can J Behav Sci. 2020;52(3):177-187. doi:10.1037/cbs0000215

5. Murata S, Rezeppa T, Thoma B, et al. The psychiatric sequelae of the COVID-19 pandemic in adolescents, adults, and health care workers. Depress Anxiety. 2021;38(2):233-246. doi:10.1002/da.23120

6. Tee ML, Tee CA, Anlacan JP, et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:379-391. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.043

7. Dumas TM, Ellis W, Litt DM. What does adolescent substance use look like during the COVID-19 pandemic? Examining changes in frequency, social contexts, and pandemic-related predictors. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(3):354-361. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.018

8. Schlegl S, Maier J, Meule A, et al. Eating disorders in times of the COVID-19 pandemic—results from an online survey of patients with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53:1791-1800. doi:10.1002/eat.23374.

9. Nissen JB, Højgaard D, Thomsen PH. The immediate effect of COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents with obsessive compulsive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):511. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02905-5

10. Guo J, Fu M, Liu D, et al. Is the psychological impact of exposure to COVID-19 stronger in adolescents with pre-pandemic maltreatment experiences? A survey of rural Chinese adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;110(Pt 2):104667. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104667

11. Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, et al. Rapid Systematic Review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(11):1218-1239.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009

12. Spinelli M, Lionetti F, Setti A, et al. Parenting stress during the COVID-19 outbreak: socioeconomic and environmental risk factors and implications for children emotion regulation. Fam Process. 2021;60(2):639-653. doi:10.1111/famp.12601

13. Chen IH, Chen CY, Pakpour AH, et al. Internet-related behaviors and psychological distress among schoolchildren during COVID-19 school suspension. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(10):1099-1102.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2020.06.007

14. Li W, Zhang Y, Wang J, et al. Association of home quarantine and mental health among teenagers in Wuhan, China, during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(3):313-316. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5499

15. Janssen, LHC, Kullberg, MJ, Verkuil B, et al. Does the COVID-19 pandemic impact parents’ and adolescents’ well-being? An EMA-study on daily affect and parenting. PLoS One. 2020;15(10):e0240962. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0240962

16. Banati P, Jones N, Youssef S. Intersecting vulnerabilities: the impacts of COVID-19 on the psycho-emotional lives of young people in low- and middle-income countries. Eur J Dev Res. 2020;32(5):1613-1638. doi:10.1057/s41287-020-00325-5

17. Ravens-Sieberer U, Kaman A, Otto C, et al. Mental health and quality of life in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic—results of the COPSY study. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;117(48):828-829. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2020.0828

While the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the mental health of a wide range of individuals, its adverse effects have been particularly detrimental to adolescents. In this article, I discuss evidence that shows the effects of the pandemic on adolescent patients, potential reasons for this increased distress, and what types of coping mechanisms adolescents have used to counter these effects.

Increases in multiple measures of psychopathology

Multiple online surveys and other studies have documented the pandemic’s impact on younger individuals. In the United States, visits to emergency departments by pediatric patients increased in the months after the first lockdown period.1 Several studies found increased rates of anxiety and depression among adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic.2,3 In an online survey of 359 children and 3,254 adolescents in China, 22% of respondents reported that they experienced depressive symptoms.3 In an online survey of 1,054 Canadian adolescents, 43% said they were “very concerned” about the pandemic.4 In an online survey of 7,353 adolescents in the United States, 37% reported suicidal ideation during the pandemic compared to 17% in 2017.5 A Chinese study found that smartphone and internet addiction was significantly associated with increased levels of depressive symptoms during the pandemic.3 In a survey in the Philippines, 16.3% of adolescents reported moderate-to-severe psychological impairment during the pandemic; the rates of COVID-19–related anxiety were higher among girls vs boys.6 Alcohol and cannabis use increased among Canadian adolescents during the pandemic, according to an online survey.7 Adolescents with anorexia nervosa reported a 70% increase in poor eating habits and more thoughts associated with eating disorders during the pandemic.8 A Danish study found that children and adolescents newly diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) or who had completed treatment exhibited worsening OCD, anxiety, and depressive symptoms during the pandemic.9 An online survey of 6,196 Chinese adolescents found that those with a higher number of pre-pandemic adverse childhood experiences, such as abuse and neglect, had elevated posttraumatic stress symptoms and anxiety during the onset of the pandemic.10

Underlying causes of pandemic-induced distress

Limited social connectedness during the pandemic is a major reason for distress among adolescents. A review of 80 studies found that social isolation and loneliness as a result of social distancing and quarantining were associated with an increased risk of depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and self-harm.11 Parents’ stress about the risks of COVID-19 was correlated with worsening mental health in their adolescent children.12 A Chinese study found that the amount of time students spent on smartphones and social media doubled during the pandemic.13 In an online survey of 7,890 Chinese adolescents, greater social media, internet, and smartphone use was associated with increased anxiety and depression.14 This may be in part the result of adolescents spending time reading COVID-related news.

Coping mechanisms to increase well-being

Researchers have identified several positive coping mechanisms adolescents employed during the pandemic. Although some data suggest that increased internet use raises the risk of COVID-related distress, for certain adolescents, using social media to stay connected with friends and relatives was a buffer for feelings of loneliness and might have increased mental well-being.15 Other common coping mechanisms include relying on faith, volunteering, and starting new hobbies.16 During the pandemic, there were higher rates of playing outside and increased physical activity, which correlated with positive mental health outcomes.16 An online survey of 1,040 adolescents found that those who looked to the future optimistically and confidently had a higher health-related quality of life.17

Continuing an emphasis on adolescent well-being

Although data are limited, adolescents can continue to use these coping mechanisms to maintain their well-being, even if COVID-related restrictions are lifted or reimplemented. During these difficult times, it is imperative for adolescents to get the mental health services they need, and for psychiatric clinicians to continue to find avenues to promote resilience and mental wellness among young patients.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the mental health of a wide range of individuals, its adverse effects have been particularly detrimental to adolescents. In this article, I discuss evidence that shows the effects of the pandemic on adolescent patients, potential reasons for this increased distress, and what types of coping mechanisms adolescents have used to counter these effects.

Increases in multiple measures of psychopathology

Multiple online surveys and other studies have documented the pandemic’s impact on younger individuals. In the United States, visits to emergency departments by pediatric patients increased in the months after the first lockdown period.1 Several studies found increased rates of anxiety and depression among adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic.2,3 In an online survey of 359 children and 3,254 adolescents in China, 22% of respondents reported that they experienced depressive symptoms.3 In an online survey of 1,054 Canadian adolescents, 43% said they were “very concerned” about the pandemic.4 In an online survey of 7,353 adolescents in the United States, 37% reported suicidal ideation during the pandemic compared to 17% in 2017.5 A Chinese study found that smartphone and internet addiction was significantly associated with increased levels of depressive symptoms during the pandemic.3 In a survey in the Philippines, 16.3% of adolescents reported moderate-to-severe psychological impairment during the pandemic; the rates of COVID-19–related anxiety were higher among girls vs boys.6 Alcohol and cannabis use increased among Canadian adolescents during the pandemic, according to an online survey.7 Adolescents with anorexia nervosa reported a 70% increase in poor eating habits and more thoughts associated with eating disorders during the pandemic.8 A Danish study found that children and adolescents newly diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) or who had completed treatment exhibited worsening OCD, anxiety, and depressive symptoms during the pandemic.9 An online survey of 6,196 Chinese adolescents found that those with a higher number of pre-pandemic adverse childhood experiences, such as abuse and neglect, had elevated posttraumatic stress symptoms and anxiety during the onset of the pandemic.10

Underlying causes of pandemic-induced distress

Limited social connectedness during the pandemic is a major reason for distress among adolescents. A review of 80 studies found that social isolation and loneliness as a result of social distancing and quarantining were associated with an increased risk of depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and self-harm.11 Parents’ stress about the risks of COVID-19 was correlated with worsening mental health in their adolescent children.12 A Chinese study found that the amount of time students spent on smartphones and social media doubled during the pandemic.13 In an online survey of 7,890 Chinese adolescents, greater social media, internet, and smartphone use was associated with increased anxiety and depression.14 This may be in part the result of adolescents spending time reading COVID-related news.

Coping mechanisms to increase well-being

Researchers have identified several positive coping mechanisms adolescents employed during the pandemic. Although some data suggest that increased internet use raises the risk of COVID-related distress, for certain adolescents, using social media to stay connected with friends and relatives was a buffer for feelings of loneliness and might have increased mental well-being.15 Other common coping mechanisms include relying on faith, volunteering, and starting new hobbies.16 During the pandemic, there were higher rates of playing outside and increased physical activity, which correlated with positive mental health outcomes.16 An online survey of 1,040 adolescents found that those who looked to the future optimistically and confidently had a higher health-related quality of life.17

Continuing an emphasis on adolescent well-being

Although data are limited, adolescents can continue to use these coping mechanisms to maintain their well-being, even if COVID-related restrictions are lifted or reimplemented. During these difficult times, it is imperative for adolescents to get the mental health services they need, and for psychiatric clinicians to continue to find avenues to promote resilience and mental wellness among young patients.

1. Leeb RT, Bitsko RH, Radhakrishnan L, et al. Mental health–related emergency department visits among children aged <18 years during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, January 1-October 17, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(45):1675-1680. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6945a3

2. Oosterhoff B, Palmer CA, Wilson J, et al. Adolescents’ motivations to engage in social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: associations with mental and social health. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(2):179-185. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.004

3. Duan L, Shao X, Wang Y, et al. An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in China during the outbreak of COVID-19. J Affect Disord. 2020;275:112-118. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.029

4. Ellis WE, Dumas TM, Forbes LM. Physically isolated but socially connected: psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Can J Behav Sci. 2020;52(3):177-187. doi:10.1037/cbs0000215

5. Murata S, Rezeppa T, Thoma B, et al. The psychiatric sequelae of the COVID-19 pandemic in adolescents, adults, and health care workers. Depress Anxiety. 2021;38(2):233-246. doi:10.1002/da.23120

6. Tee ML, Tee CA, Anlacan JP, et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:379-391. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.043

7. Dumas TM, Ellis W, Litt DM. What does adolescent substance use look like during the COVID-19 pandemic? Examining changes in frequency, social contexts, and pandemic-related predictors. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(3):354-361. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.018

8. Schlegl S, Maier J, Meule A, et al. Eating disorders in times of the COVID-19 pandemic—results from an online survey of patients with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53:1791-1800. doi:10.1002/eat.23374.

9. Nissen JB, Højgaard D, Thomsen PH. The immediate effect of COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents with obsessive compulsive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):511. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02905-5

10. Guo J, Fu M, Liu D, et al. Is the psychological impact of exposure to COVID-19 stronger in adolescents with pre-pandemic maltreatment experiences? A survey of rural Chinese adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;110(Pt 2):104667. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104667

11. Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, et al. Rapid Systematic Review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(11):1218-1239.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009

12. Spinelli M, Lionetti F, Setti A, et al. Parenting stress during the COVID-19 outbreak: socioeconomic and environmental risk factors and implications for children emotion regulation. Fam Process. 2021;60(2):639-653. doi:10.1111/famp.12601

13. Chen IH, Chen CY, Pakpour AH, et al. Internet-related behaviors and psychological distress among schoolchildren during COVID-19 school suspension. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(10):1099-1102.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2020.06.007

14. Li W, Zhang Y, Wang J, et al. Association of home quarantine and mental health among teenagers in Wuhan, China, during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(3):313-316. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5499

15. Janssen, LHC, Kullberg, MJ, Verkuil B, et al. Does the COVID-19 pandemic impact parents’ and adolescents’ well-being? An EMA-study on daily affect and parenting. PLoS One. 2020;15(10):e0240962. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0240962

16. Banati P, Jones N, Youssef S. Intersecting vulnerabilities: the impacts of COVID-19 on the psycho-emotional lives of young people in low- and middle-income countries. Eur J Dev Res. 2020;32(5):1613-1638. doi:10.1057/s41287-020-00325-5

17. Ravens-Sieberer U, Kaman A, Otto C, et al. Mental health and quality of life in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic—results of the COPSY study. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;117(48):828-829. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2020.0828

1. Leeb RT, Bitsko RH, Radhakrishnan L, et al. Mental health–related emergency department visits among children aged <18 years during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, January 1-October 17, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(45):1675-1680. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6945a3

2. Oosterhoff B, Palmer CA, Wilson J, et al. Adolescents’ motivations to engage in social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: associations with mental and social health. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(2):179-185. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.004

3. Duan L, Shao X, Wang Y, et al. An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in China during the outbreak of COVID-19. J Affect Disord. 2020;275:112-118. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.029

4. Ellis WE, Dumas TM, Forbes LM. Physically isolated but socially connected: psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Can J Behav Sci. 2020;52(3):177-187. doi:10.1037/cbs0000215

5. Murata S, Rezeppa T, Thoma B, et al. The psychiatric sequelae of the COVID-19 pandemic in adolescents, adults, and health care workers. Depress Anxiety. 2021;38(2):233-246. doi:10.1002/da.23120

6. Tee ML, Tee CA, Anlacan JP, et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:379-391. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.043

7. Dumas TM, Ellis W, Litt DM. What does adolescent substance use look like during the COVID-19 pandemic? Examining changes in frequency, social contexts, and pandemic-related predictors. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(3):354-361. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.018

8. Schlegl S, Maier J, Meule A, et al. Eating disorders in times of the COVID-19 pandemic—results from an online survey of patients with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53:1791-1800. doi:10.1002/eat.23374.

9. Nissen JB, Højgaard D, Thomsen PH. The immediate effect of COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents with obsessive compulsive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):511. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02905-5

10. Guo J, Fu M, Liu D, et al. Is the psychological impact of exposure to COVID-19 stronger in adolescents with pre-pandemic maltreatment experiences? A survey of rural Chinese adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;110(Pt 2):104667. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104667

11. Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, et al. Rapid Systematic Review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(11):1218-1239.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009

12. Spinelli M, Lionetti F, Setti A, et al. Parenting stress during the COVID-19 outbreak: socioeconomic and environmental risk factors and implications for children emotion regulation. Fam Process. 2021;60(2):639-653. doi:10.1111/famp.12601

13. Chen IH, Chen CY, Pakpour AH, et al. Internet-related behaviors and psychological distress among schoolchildren during COVID-19 school suspension. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(10):1099-1102.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2020.06.007

14. Li W, Zhang Y, Wang J, et al. Association of home quarantine and mental health among teenagers in Wuhan, China, during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(3):313-316. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5499

15. Janssen, LHC, Kullberg, MJ, Verkuil B, et al. Does the COVID-19 pandemic impact parents’ and adolescents’ well-being? An EMA-study on daily affect and parenting. PLoS One. 2020;15(10):e0240962. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0240962

16. Banati P, Jones N, Youssef S. Intersecting vulnerabilities: the impacts of COVID-19 on the psycho-emotional lives of young people in low- and middle-income countries. Eur J Dev Res. 2020;32(5):1613-1638. doi:10.1057/s41287-020-00325-5

17. Ravens-Sieberer U, Kaman A, Otto C, et al. Mental health and quality of life in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic—results of the COPSY study. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;117(48):828-829. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2020.0828

More on stigma

I just finished reading your editorial “A PSYCHIATRIC MANIFESTO: Stigma is hate speech and a hate crime” (

Our son went from an honor roll student before the pandemic to a child I barely recognized. Approximately 6 months into the pandemic, he was using drugs, vaping nicotine, destroying our property, and eloping at night. The journey of watching his decline and getting him help was agonizing. But the stigma around what was happening to him was an entirely separate animal.

Our society vilifies, ridicules, dismisses, and often makes fun of those with mental health issues. I experience it daily with my son and am on constant guard to shoot down any comments and to calmly teach those who say such cruel things. But the shame my son feels is the most devastating part. Although we keep reminding him that his condition is a medical condition like diabetes or heart disease, for a teenage boy, that makes no sense. He just wants to be “normal.” And living in a world that rarely represents mental illness this way, it’s almost a lost cause to get him to let go of this shame. All we can do is love him, be there for him, support him, and do what we can to educate those around us about the stigma of mental illness.

What a powerful and accurate article. Thank you for putting into words what I have been thinking and feeling, and for being as outraged as we are at how this vulnerable population is treated. My husband is a psychiatrist and we live in an affluent urban area, so we are not in the middle of nowhere with no knowledge of what is happening to our son. And despite that, we still suffer from the stigma.

Thank you, Dr. Nasrallah.

Name withheld

I need to take a moment to thank you for your editorial about stigma being hate speech and a hate crime. I really agree with you, and I think the way you formulated and articulated this message is very compelling.

I have focused on normalizing mental health differences among entrepreneurs as a destigmatization strategy (see https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0883902622000027 and https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11187-018-0059-8). Entrepreneurs clearly illustrate the fallacy of stigma. As a simple example, Elon Musk—the wealthiest person in the world—talks openly about being autistic, and possibly bipolar. These mental health differences help him create jobs and contribute to our shared prosperity. Nothing to be ashamed of there.

Thanks again for being such an effective advocate.

Michael A. Freeman, MD

Kentfield, California

Continue to: Thank you...

Thank you so much for your “Psychiatric Manifesto.” I will do my best to disseminate it amongst colleagues, patients, friends, family, and as many others as possible.

Daniel N. Pistone, MD

San Francisco, California

Once again, your words hit the pin on the head.

Robert W. Pollack, MD, ABPN, DLFAPA

Fort Myers, Florida

I just finished reading your editorial “A PSYCHIATRIC MANIFESTO: Stigma is hate speech and a hate crime” (

Our son went from an honor roll student before the pandemic to a child I barely recognized. Approximately 6 months into the pandemic, he was using drugs, vaping nicotine, destroying our property, and eloping at night. The journey of watching his decline and getting him help was agonizing. But the stigma around what was happening to him was an entirely separate animal.

Our society vilifies, ridicules, dismisses, and often makes fun of those with mental health issues. I experience it daily with my son and am on constant guard to shoot down any comments and to calmly teach those who say such cruel things. But the shame my son feels is the most devastating part. Although we keep reminding him that his condition is a medical condition like diabetes or heart disease, for a teenage boy, that makes no sense. He just wants to be “normal.” And living in a world that rarely represents mental illness this way, it’s almost a lost cause to get him to let go of this shame. All we can do is love him, be there for him, support him, and do what we can to educate those around us about the stigma of mental illness.

What a powerful and accurate article. Thank you for putting into words what I have been thinking and feeling, and for being as outraged as we are at how this vulnerable population is treated. My husband is a psychiatrist and we live in an affluent urban area, so we are not in the middle of nowhere with no knowledge of what is happening to our son. And despite that, we still suffer from the stigma.

Thank you, Dr. Nasrallah.

Name withheld

I need to take a moment to thank you for your editorial about stigma being hate speech and a hate crime. I really agree with you, and I think the way you formulated and articulated this message is very compelling.

I have focused on normalizing mental health differences among entrepreneurs as a destigmatization strategy (see https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0883902622000027 and https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11187-018-0059-8). Entrepreneurs clearly illustrate the fallacy of stigma. As a simple example, Elon Musk—the wealthiest person in the world—talks openly about being autistic, and possibly bipolar. These mental health differences help him create jobs and contribute to our shared prosperity. Nothing to be ashamed of there.

Thanks again for being such an effective advocate.

Michael A. Freeman, MD

Kentfield, California

Continue to: Thank you...

Thank you so much for your “Psychiatric Manifesto.” I will do my best to disseminate it amongst colleagues, patients, friends, family, and as many others as possible.

Daniel N. Pistone, MD

San Francisco, California

Once again, your words hit the pin on the head.

Robert W. Pollack, MD, ABPN, DLFAPA

Fort Myers, Florida

I just finished reading your editorial “A PSYCHIATRIC MANIFESTO: Stigma is hate speech and a hate crime” (

Our son went from an honor roll student before the pandemic to a child I barely recognized. Approximately 6 months into the pandemic, he was using drugs, vaping nicotine, destroying our property, and eloping at night. The journey of watching his decline and getting him help was agonizing. But the stigma around what was happening to him was an entirely separate animal.

Our society vilifies, ridicules, dismisses, and often makes fun of those with mental health issues. I experience it daily with my son and am on constant guard to shoot down any comments and to calmly teach those who say such cruel things. But the shame my son feels is the most devastating part. Although we keep reminding him that his condition is a medical condition like diabetes or heart disease, for a teenage boy, that makes no sense. He just wants to be “normal.” And living in a world that rarely represents mental illness this way, it’s almost a lost cause to get him to let go of this shame. All we can do is love him, be there for him, support him, and do what we can to educate those around us about the stigma of mental illness.

What a powerful and accurate article. Thank you for putting into words what I have been thinking and feeling, and for being as outraged as we are at how this vulnerable population is treated. My husband is a psychiatrist and we live in an affluent urban area, so we are not in the middle of nowhere with no knowledge of what is happening to our son. And despite that, we still suffer from the stigma.

Thank you, Dr. Nasrallah.

Name withheld

I need to take a moment to thank you for your editorial about stigma being hate speech and a hate crime. I really agree with you, and I think the way you formulated and articulated this message is very compelling.

I have focused on normalizing mental health differences among entrepreneurs as a destigmatization strategy (see https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0883902622000027 and https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11187-018-0059-8). Entrepreneurs clearly illustrate the fallacy of stigma. As a simple example, Elon Musk—the wealthiest person in the world—talks openly about being autistic, and possibly bipolar. These mental health differences help him create jobs and contribute to our shared prosperity. Nothing to be ashamed of there.

Thanks again for being such an effective advocate.

Michael A. Freeman, MD

Kentfield, California

Continue to: Thank you...

Thank you so much for your “Psychiatric Manifesto.” I will do my best to disseminate it amongst colleagues, patients, friends, family, and as many others as possible.

Daniel N. Pistone, MD

San Francisco, California

Once again, your words hit the pin on the head.

Robert W. Pollack, MD, ABPN, DLFAPA

Fort Myers, Florida

Then and now: Inflammatory bowel diseases

(IBD) creating a whole new landscape for the disease.

In 2007, IBD seemed to be primarily a disease of Caucasian and Jewish ancestry. While prevalence of IBD is still highest in the Western world, there is now increasing incidence, even accounting for detection bias, in people of all other ancestries globally. Incidence of IBD in children under the age of 18 years is also rising. Patients with IBD are living longer and, despite the notion that IBD is a disease primarily of younger adults, nearly one-third of Americans with IBD are 60 years and older.