User login

Back at the American Psychiatric Association annual meeting again, in person

It was wonderful to see long-term friends and colleagues again in New Orleans! Warmed me from the bottom of my COVID-scarred heart.

I had trepidation and anxiety about further COVID exposure, as I am sure many of you all did. I have carefully resumed traveling, although the rules on masking continue to change and confuse us all.

But I did it. I went to the American Psychiatric Association meeting in New Orleans and am so glad I did.

There was of course a lot of discussion about the pandemic, which separated us physically for 3 years – too many virtual meetings. And quiet discussions of grief and loss, both before and during the APA.

I just learned that Joe Napoli, MD, died. He was one of the hearts of the APA Disaster Psychiatry Committee. Others were lost as well, and I am processing those losses.

I do not want this column to be just a promotion for the APA, although it has been my home organization for decades. So, let me define further the cons and pros of going to the meeting. (Yes, I am deliberately reversing the order of these words.) I warn all the readers in advance that this is a soapbox.

Cons

The convention center in New Orleans is ridiculously long. Our convention was in Hall G down at end of its telescoping length. Only a couple of doors were open – clearly quite a challenge for folks with disabilities, or those aging into possible disability, like myself. I helped a psychiatrist with impaired vision down the endless hall and of course, felt good about it. (My motto: “Perform acts of kindness, and you will feel better yourself.”)

Another con: Too much going on at the same time. That’s a perpetual problem.

And the noise at the parties was way too loud. We could not hear each other.

Pros

Seeing people I have known for 40 years – with masks, without masks. Hugs or bows (on my part, I bow I do not yet hug in COVID times).

The receptions. Great networking. Mid-level psychiatrists who I had forgotten I had mentored. The “young ones” – the psychiatry residents. They seem to be a great and ambitious group.

I did several talks, including one on female veterans, and another on clinical management of the homeless population. The audiences were large and engaged. I am wondering how to make these topics an APA priority, especially engagement with strategies to take care of the unhoused/homeless folks.

Let me give you a brief synopsis of both of those talks, as they represent some of my passions. The first on female veterans. We tend to focus on PTSD and military sexual trauma. I am also concerned about reproductive and musculoskeletal concerns. Too many female service members get pregnant, then quit the military as they cannot manage being a Service member and a mother. They think they can make it (go to school, get a job) but they cannot manage it all.

Veterans services usually focus on single older men. There are not enough rooms and services for female veterans with children. In fairness to the Department of Veterans Affairs, they are trying to remedy this lack.

Transitioning to the homeless population in general, this is an incredible problem which is not easily solved. The VA has done an incredible job here, but the whole country should be mobilized.

My focus at the talk was the importance of assessing and treating medical problems. Again, homeless women are at high risk for barriers to contraception, sexual assault, pregnancy, and the corresponding difficulties of finding housing that will accept infants and small children.

Then there are the numerous medical issues in the unhoused population. Diabetes, hypertension, ulcers on the feet leading to cellulitis and amputation. I am advocating that we psychiatrists behave as medical doctors and think of the whole person, not just of the mind.

Another pro of the APA meeting: such desire to share what we know with the world. I found a few more potential authors for book chapters, specifically Dr. Anne Hansen to write a chapter in my capacity volume. And getting recruited myself, by Maria Llorente, MD, for one on centenarians (people who aged over 100.) Not sure if I know very much now, but I will try.

But another con: We have plenty of business for all, in this never-ending anxiety tide of COVID.

Another con: I tested positive for COVID after my return, as did several of my friends.

I am sure our readers have many more takes on returning to the APA. These are a few of my thoughts.

Dr. Ritchie is chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center. She is a member of the Clinical Psychiatry News editorial advisory board, and has no conflicts of interest.

It was wonderful to see long-term friends and colleagues again in New Orleans! Warmed me from the bottom of my COVID-scarred heart.

I had trepidation and anxiety about further COVID exposure, as I am sure many of you all did. I have carefully resumed traveling, although the rules on masking continue to change and confuse us all.

But I did it. I went to the American Psychiatric Association meeting in New Orleans and am so glad I did.

There was of course a lot of discussion about the pandemic, which separated us physically for 3 years – too many virtual meetings. And quiet discussions of grief and loss, both before and during the APA.

I just learned that Joe Napoli, MD, died. He was one of the hearts of the APA Disaster Psychiatry Committee. Others were lost as well, and I am processing those losses.

I do not want this column to be just a promotion for the APA, although it has been my home organization for decades. So, let me define further the cons and pros of going to the meeting. (Yes, I am deliberately reversing the order of these words.) I warn all the readers in advance that this is a soapbox.

Cons

The convention center in New Orleans is ridiculously long. Our convention was in Hall G down at end of its telescoping length. Only a couple of doors were open – clearly quite a challenge for folks with disabilities, or those aging into possible disability, like myself. I helped a psychiatrist with impaired vision down the endless hall and of course, felt good about it. (My motto: “Perform acts of kindness, and you will feel better yourself.”)

Another con: Too much going on at the same time. That’s a perpetual problem.

And the noise at the parties was way too loud. We could not hear each other.

Pros

Seeing people I have known for 40 years – with masks, without masks. Hugs or bows (on my part, I bow I do not yet hug in COVID times).

The receptions. Great networking. Mid-level psychiatrists who I had forgotten I had mentored. The “young ones” – the psychiatry residents. They seem to be a great and ambitious group.

I did several talks, including one on female veterans, and another on clinical management of the homeless population. The audiences were large and engaged. I am wondering how to make these topics an APA priority, especially engagement with strategies to take care of the unhoused/homeless folks.

Let me give you a brief synopsis of both of those talks, as they represent some of my passions. The first on female veterans. We tend to focus on PTSD and military sexual trauma. I am also concerned about reproductive and musculoskeletal concerns. Too many female service members get pregnant, then quit the military as they cannot manage being a Service member and a mother. They think they can make it (go to school, get a job) but they cannot manage it all.

Veterans services usually focus on single older men. There are not enough rooms and services for female veterans with children. In fairness to the Department of Veterans Affairs, they are trying to remedy this lack.

Transitioning to the homeless population in general, this is an incredible problem which is not easily solved. The VA has done an incredible job here, but the whole country should be mobilized.

My focus at the talk was the importance of assessing and treating medical problems. Again, homeless women are at high risk for barriers to contraception, sexual assault, pregnancy, and the corresponding difficulties of finding housing that will accept infants and small children.

Then there are the numerous medical issues in the unhoused population. Diabetes, hypertension, ulcers on the feet leading to cellulitis and amputation. I am advocating that we psychiatrists behave as medical doctors and think of the whole person, not just of the mind.

Another pro of the APA meeting: such desire to share what we know with the world. I found a few more potential authors for book chapters, specifically Dr. Anne Hansen to write a chapter in my capacity volume. And getting recruited myself, by Maria Llorente, MD, for one on centenarians (people who aged over 100.) Not sure if I know very much now, but I will try.

But another con: We have plenty of business for all, in this never-ending anxiety tide of COVID.

Another con: I tested positive for COVID after my return, as did several of my friends.

I am sure our readers have many more takes on returning to the APA. These are a few of my thoughts.

Dr. Ritchie is chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center. She is a member of the Clinical Psychiatry News editorial advisory board, and has no conflicts of interest.

It was wonderful to see long-term friends and colleagues again in New Orleans! Warmed me from the bottom of my COVID-scarred heart.

I had trepidation and anxiety about further COVID exposure, as I am sure many of you all did. I have carefully resumed traveling, although the rules on masking continue to change and confuse us all.

But I did it. I went to the American Psychiatric Association meeting in New Orleans and am so glad I did.

There was of course a lot of discussion about the pandemic, which separated us physically for 3 years – too many virtual meetings. And quiet discussions of grief and loss, both before and during the APA.

I just learned that Joe Napoli, MD, died. He was one of the hearts of the APA Disaster Psychiatry Committee. Others were lost as well, and I am processing those losses.

I do not want this column to be just a promotion for the APA, although it has been my home organization for decades. So, let me define further the cons and pros of going to the meeting. (Yes, I am deliberately reversing the order of these words.) I warn all the readers in advance that this is a soapbox.

Cons

The convention center in New Orleans is ridiculously long. Our convention was in Hall G down at end of its telescoping length. Only a couple of doors were open – clearly quite a challenge for folks with disabilities, or those aging into possible disability, like myself. I helped a psychiatrist with impaired vision down the endless hall and of course, felt good about it. (My motto: “Perform acts of kindness, and you will feel better yourself.”)

Another con: Too much going on at the same time. That’s a perpetual problem.

And the noise at the parties was way too loud. We could not hear each other.

Pros

Seeing people I have known for 40 years – with masks, without masks. Hugs or bows (on my part, I bow I do not yet hug in COVID times).

The receptions. Great networking. Mid-level psychiatrists who I had forgotten I had mentored. The “young ones” – the psychiatry residents. They seem to be a great and ambitious group.

I did several talks, including one on female veterans, and another on clinical management of the homeless population. The audiences were large and engaged. I am wondering how to make these topics an APA priority, especially engagement with strategies to take care of the unhoused/homeless folks.

Let me give you a brief synopsis of both of those talks, as they represent some of my passions. The first on female veterans. We tend to focus on PTSD and military sexual trauma. I am also concerned about reproductive and musculoskeletal concerns. Too many female service members get pregnant, then quit the military as they cannot manage being a Service member and a mother. They think they can make it (go to school, get a job) but they cannot manage it all.

Veterans services usually focus on single older men. There are not enough rooms and services for female veterans with children. In fairness to the Department of Veterans Affairs, they are trying to remedy this lack.

Transitioning to the homeless population in general, this is an incredible problem which is not easily solved. The VA has done an incredible job here, but the whole country should be mobilized.

My focus at the talk was the importance of assessing and treating medical problems. Again, homeless women are at high risk for barriers to contraception, sexual assault, pregnancy, and the corresponding difficulties of finding housing that will accept infants and small children.

Then there are the numerous medical issues in the unhoused population. Diabetes, hypertension, ulcers on the feet leading to cellulitis and amputation. I am advocating that we psychiatrists behave as medical doctors and think of the whole person, not just of the mind.

Another pro of the APA meeting: such desire to share what we know with the world. I found a few more potential authors for book chapters, specifically Dr. Anne Hansen to write a chapter in my capacity volume. And getting recruited myself, by Maria Llorente, MD, for one on centenarians (people who aged over 100.) Not sure if I know very much now, but I will try.

But another con: We have plenty of business for all, in this never-ending anxiety tide of COVID.

Another con: I tested positive for COVID after my return, as did several of my friends.

I am sure our readers have many more takes on returning to the APA. These are a few of my thoughts.

Dr. Ritchie is chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center. She is a member of the Clinical Psychiatry News editorial advisory board, and has no conflicts of interest.

Is hepatitis C an STI?

A 32-year-old woman had sex with a man she met while on vacation 6 weeks ago. She was intoxicated at the time and does not know much about the person. She recalls having engaged in vaginal intercourse without a condom. She does not have any symptoms.

She previously received baseline lab testing per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines 2 years ago with a negative HIV test and negative hepatitis C test. She asks for testing for STIs. What would you recommend?

A. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and human papillomavirus

B. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and herpes simplex virus

C. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, and chlamydia

D. HIV, gonorrhea, and chlamydia

E. Gonorrhea and chlamydia

HIV risk estimate

The most practical answer is E, check for gonorrhea and chlamydia. Many protocols in place for evaluating people for STIs will test for hepatitis C as well as HIV with single exposures. In this column, we will look at the lack of evidence of heterosexual sexual transmission of hepatitis C.

In regards to HIV risk, the estimated risk of transmission male to female from an HIV-infected individual is 0.08% per sexual encounter.1 The prevalence in the United States – where HIV occurs in about 0.5% of the adult population – was used to estimate the risk of a person with unknown HIV status acquiring HIV. The calculated risk from one sexual encounter would be 0.0004 (1 in 250,000).

Studies of hepatitis C transmission

Tahan and colleagues did a prospective study of 600 heterosexual couples where one partner had hepatitis C and the other didn’t. Over a mean of 3 years of follow-up, none of the seronegative spouses developed hepatitis C.2

Terrault and colleagues completed a cross-sectional study of hepatitis C virus (HCV)–positive individuals and their monogamous heterosexual partners to evaluate risk of sexual transmission of HCV.3 Based on 8,377 person-years of follow-up, the estimated maximum transmission rate was 0.07%/year, which was about 1/190,000 sexual contacts. No specific sexual practices were associated with transmission. The authors of this study concurred with CDC recommendations that persons with HCV infection in long-term monogamous relationships need not change their sexual practices.4

Vandelli and colleagues followed 776 heterosexual partners of HCV-infected individuals over 10 years.5 None of the couples reported condom use. Over the follow up period, three HCV infections occurred, but based on discordance of the typing of viral isolates, sexual transmission was excluded.

Jin and colleagues completed a systematic review of studies looking at possible sexual transmission of HCV in gay and bisexual men.6 HIV-positive men had a HCV incidence of 6.4 per 1,000 person-years, compared with 0.4 per 1000 person-years in HIV-negative men. The authors discussed several possible causes for increased transmission risk in HIV-infected individuals including coexisting STIs and higher HCV viral load in semen of HIV-infected individuals, as well as lower immunity.

Summary

In hepatitis C–discordant heterosexual couples, hepatitis C does not appear to be sexually transmitted.

The risk of sexual transmission of hepatitis C to non–HIV-infected individuals appears to be exceedingly low.

Many thanks to Hunter Handsfield, MD, for suggesting this topic and sharing supporting articles.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at [email protected].

1. Boily MC et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009 Feb;9(2):118-29.

2. Tahan V et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:821-4.

3. Terrault NA et al. Hepatology. 2013;57:881-9

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47:1-38.

5. Vandelli C et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:855-9.

6. Jin F et al. Sexual Health.2017;14:28-41.

A 32-year-old woman had sex with a man she met while on vacation 6 weeks ago. She was intoxicated at the time and does not know much about the person. She recalls having engaged in vaginal intercourse without a condom. She does not have any symptoms.

She previously received baseline lab testing per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines 2 years ago with a negative HIV test and negative hepatitis C test. She asks for testing for STIs. What would you recommend?

A. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and human papillomavirus

B. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and herpes simplex virus

C. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, and chlamydia

D. HIV, gonorrhea, and chlamydia

E. Gonorrhea and chlamydia

HIV risk estimate

The most practical answer is E, check for gonorrhea and chlamydia. Many protocols in place for evaluating people for STIs will test for hepatitis C as well as HIV with single exposures. In this column, we will look at the lack of evidence of heterosexual sexual transmission of hepatitis C.

In regards to HIV risk, the estimated risk of transmission male to female from an HIV-infected individual is 0.08% per sexual encounter.1 The prevalence in the United States – where HIV occurs in about 0.5% of the adult population – was used to estimate the risk of a person with unknown HIV status acquiring HIV. The calculated risk from one sexual encounter would be 0.0004 (1 in 250,000).

Studies of hepatitis C transmission

Tahan and colleagues did a prospective study of 600 heterosexual couples where one partner had hepatitis C and the other didn’t. Over a mean of 3 years of follow-up, none of the seronegative spouses developed hepatitis C.2

Terrault and colleagues completed a cross-sectional study of hepatitis C virus (HCV)–positive individuals and their monogamous heterosexual partners to evaluate risk of sexual transmission of HCV.3 Based on 8,377 person-years of follow-up, the estimated maximum transmission rate was 0.07%/year, which was about 1/190,000 sexual contacts. No specific sexual practices were associated with transmission. The authors of this study concurred with CDC recommendations that persons with HCV infection in long-term monogamous relationships need not change their sexual practices.4

Vandelli and colleagues followed 776 heterosexual partners of HCV-infected individuals over 10 years.5 None of the couples reported condom use. Over the follow up period, three HCV infections occurred, but based on discordance of the typing of viral isolates, sexual transmission was excluded.

Jin and colleagues completed a systematic review of studies looking at possible sexual transmission of HCV in gay and bisexual men.6 HIV-positive men had a HCV incidence of 6.4 per 1,000 person-years, compared with 0.4 per 1000 person-years in HIV-negative men. The authors discussed several possible causes for increased transmission risk in HIV-infected individuals including coexisting STIs and higher HCV viral load in semen of HIV-infected individuals, as well as lower immunity.

Summary

In hepatitis C–discordant heterosexual couples, hepatitis C does not appear to be sexually transmitted.

The risk of sexual transmission of hepatitis C to non–HIV-infected individuals appears to be exceedingly low.

Many thanks to Hunter Handsfield, MD, for suggesting this topic and sharing supporting articles.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at [email protected].

1. Boily MC et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009 Feb;9(2):118-29.

2. Tahan V et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:821-4.

3. Terrault NA et al. Hepatology. 2013;57:881-9

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47:1-38.

5. Vandelli C et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:855-9.

6. Jin F et al. Sexual Health.2017;14:28-41.

A 32-year-old woman had sex with a man she met while on vacation 6 weeks ago. She was intoxicated at the time and does not know much about the person. She recalls having engaged in vaginal intercourse without a condom. She does not have any symptoms.

She previously received baseline lab testing per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines 2 years ago with a negative HIV test and negative hepatitis C test. She asks for testing for STIs. What would you recommend?

A. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and human papillomavirus

B. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and herpes simplex virus

C. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, and chlamydia

D. HIV, gonorrhea, and chlamydia

E. Gonorrhea and chlamydia

HIV risk estimate

The most practical answer is E, check for gonorrhea and chlamydia. Many protocols in place for evaluating people for STIs will test for hepatitis C as well as HIV with single exposures. In this column, we will look at the lack of evidence of heterosexual sexual transmission of hepatitis C.

In regards to HIV risk, the estimated risk of transmission male to female from an HIV-infected individual is 0.08% per sexual encounter.1 The prevalence in the United States – where HIV occurs in about 0.5% of the adult population – was used to estimate the risk of a person with unknown HIV status acquiring HIV. The calculated risk from one sexual encounter would be 0.0004 (1 in 250,000).

Studies of hepatitis C transmission

Tahan and colleagues did a prospective study of 600 heterosexual couples where one partner had hepatitis C and the other didn’t. Over a mean of 3 years of follow-up, none of the seronegative spouses developed hepatitis C.2

Terrault and colleagues completed a cross-sectional study of hepatitis C virus (HCV)–positive individuals and their monogamous heterosexual partners to evaluate risk of sexual transmission of HCV.3 Based on 8,377 person-years of follow-up, the estimated maximum transmission rate was 0.07%/year, which was about 1/190,000 sexual contacts. No specific sexual practices were associated with transmission. The authors of this study concurred with CDC recommendations that persons with HCV infection in long-term monogamous relationships need not change their sexual practices.4

Vandelli and colleagues followed 776 heterosexual partners of HCV-infected individuals over 10 years.5 None of the couples reported condom use. Over the follow up period, three HCV infections occurred, but based on discordance of the typing of viral isolates, sexual transmission was excluded.

Jin and colleagues completed a systematic review of studies looking at possible sexual transmission of HCV in gay and bisexual men.6 HIV-positive men had a HCV incidence of 6.4 per 1,000 person-years, compared with 0.4 per 1000 person-years in HIV-negative men. The authors discussed several possible causes for increased transmission risk in HIV-infected individuals including coexisting STIs and higher HCV viral load in semen of HIV-infected individuals, as well as lower immunity.

Summary

In hepatitis C–discordant heterosexual couples, hepatitis C does not appear to be sexually transmitted.

The risk of sexual transmission of hepatitis C to non–HIV-infected individuals appears to be exceedingly low.

Many thanks to Hunter Handsfield, MD, for suggesting this topic and sharing supporting articles.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at [email protected].

1. Boily MC et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009 Feb;9(2):118-29.

2. Tahan V et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:821-4.

3. Terrault NA et al. Hepatology. 2013;57:881-9

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47:1-38.

5. Vandelli C et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:855-9.

6. Jin F et al. Sexual Health.2017;14:28-41.

Registered Dietitian Nutritionists’ Role in Hospital in Home

Hospital in Home (HIH) is the delivery of acute care services in a patient’s home as an alternative to hospitalization.1 Compared with traditional inpatient care, HIH programs have been associated with reduced costs, as well as patient and caregiver satisfaction, diseasespecific outcomes, and mortality rates that were similar or improved compared with inpatient admissions.1-4

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and other hospital systems are increasingly adopting HIH models.2-4 At the time of this writing, there were 12 HIH programs in VHA (personal communication, D. Cooper, 2/28/2022). In addition to physicians and nurses, the interdisciplinary HIH team may include a pharmacist, social worker, and registered dietitian nutritionist (RDN).2,5 HIH programs have been shown to improve nutritional status as measured by the Mini Nutritional Assessment Score, but overall, there is a paucity of published information regarding the provision of nutrition care in HIH.6 The role of the RDN has varied within VHA. Some sites, such as the Sacramento VA Medical Center in California, include a distinct RDN position on the HIH team, whereas others, such as the Spark M. Matsunaga VA Medical Center in Honolulu, Hawaii, and the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital in Tampa, Florida, consult clinic RDNs.

Since HIH programs typically treat conditions for which diet is an inherent part of the treatment (eg, congestive heart failure [CHF]), there is a need to precisely define the role of the RDN within the HIH model.2,3,7 Drawing from my experience as an HIH RDN, I will describe how the inclusion of an RDN position within the HIH team is optimal for health care delivery and how HIH practitioners can best utilize RDN services.

RDN Role in HIH Team

Delegating nutrition services to an RDN enhances patient care by empowering HIH team members to function at the highest level of their scope of practice. RDNs have been recognized by physicians as the most qualified health care professionals to help patients with diet-related conditions, such as obesity, and physicians also have reported a desire for additional training in nutrition.8 Although home-health nurses have frequently performed nutrition assessments and interventions, survey results have indicated that many nurses do not feel confident in teaching complex nutritional information.9 In my experience, many HIH patients are nutritionally complex, with more than one condition requiring nutrition intervention. For example, patients may be admitted to HIH for management of CHF, but they may also have diabetes mellitus (DM), obesity, and low socioeconomic status. The HIH RDN can address the nutrition aspects of these conditions, freeing time for physicians and nurses to focus on their respective areas of expertise.9,10 Moreover, the RDN can also provide dietary education to the HIH team to increase their knowledge of nutritional topics and promote consistent messaging to patients.

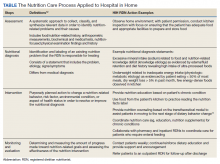

Including an RDN on the HIH team enables patients to have comprehensive, personalized nutrition care. Rather than merely offering generalized nutrition education, RDNs are trained to provide medical nutrition therapy (MNT), which has been shown to improve health outcomes and be cost-effective for conditions such as type 2 DM, chronic kidney disease, hypertension, and obesity.10,11 In MNT, RDNs use the standardized 4-stepnutrition care process (NCP).12 The Table shows examples of how the NCP can be applied in HIH settings. Furthermore, in my experience, MNT from an RDN also contributes to patient satisfaction. Subjective observations from my team have indicated that patients often express more confidence in managing their diets by the time of HIH discharge.

RDNs can guide physicians and pharmacists in ordering oral nutrition supplements (ONS). Within the VHA, a “food first” approach is preferred to increase caloric intake, and patients must meet specific criteria for prescription of an ONS.13 Furthermore, ONS designed for specific medical conditions (eg, chronic kidney disease) are considered nonformulary and require an RDN evaluation.13 Including an RDN on the HIH team allows this evaluation process to begin early in the patient’s admission to the program and ensures that provision of ONS is clinically appropriate and cost-effective.

Care Coordination

HIH is highly interdisciplinary. Team members perform their respective roles and communicate with the team throughout the day. RDNs can help monitor patients and alert physicians for changes in blood glucose, gastrointestinal concerns, and weight. This is especially helpful for patients who do not have a planned nursing visit on the day of an RDN evaluation. The HIH RDN can also collaborate with other team members to address patient needs. For example, for patients with limited financial resources, the HIH RDN can provide nutrition education regarding cooking on a budget, and the HIH social worker can arrange free or low-cost meal services.

Tips

When hiring an HIH RDN, seek candidates with experience in inpatient, outpatient, and home care settings. As a hybrid of these 3 areas, the HIH RDN position requires a unique combination of acute care skills and health coaching. Additionally, in my experience, the HIH RDN interacts more frequently with the HIH team than other RDN colleagues, so it is important that candidates can work independently and take initiative. This type of position would not be suitable for entry-level RDNs.

Stagger HIH team visits to prevent overwhelming the patient and caregivers. Early in our program, my team quickly learned that patients and caregivers can feel overwhelmed with too many home visits upon admission to HIH. After seeing multiple HIH team members the same day, they were often too tired to focus well on diet education during my visit. Staggering visits (eg, completing the initial nutrition assessment 1 day to 1 week after the initial medical and pharmacy visits) has been an effective strategy to address this problem. Furthermore, some patients prefer that the initial RDN appointment is conducted by telephone, with an inperson reassessment the following week. In my experience, HIH workflow is dynamic by nature, so it is crucial to remain flexible and accommodate individual patient needs as much as possible.

Dietary behavior change is a long-term process, and restrictive hospital diets can be challenging to replicate at home. In a hospital setting, clinicians can order a specialized diet (eg, low sodium with fluid restriction for CHF patients), whereas efforts to implement these restrictions in the home setting can be cumbersome and negatively impact quality of life.7,14 Nevertheless, the effectiveness of medical treatment is compromised when patients do not adhere to dietary recommendations. Meal delivery services that offer specialized diets can be a useful resource for patients and caregivers who are unable to cook, and the HIH RDN can assist patients in ordering these services.

HIH patients may vary in terms of readiness to make dietary changes, and in addition to nutrition education, nutrition counseling is usually needed to effect behavior change. My team has found that consideration of the transtheoretical/ stages of change model can be a helpful approach. 15 The HIH RDN can tailor nutrition interventions to the patient’s stage of change. For example, for patients in the precontemplation stage, the HIH RDN would focus on providing information and addressing emotional aspects of dietary change. In contrast, for patients in the action stage of change, the HIH RDN might emphasize behavioral skill training and social support.15 Particularly for patients in the early stages of change, it may be unrealistic to expect full adoption of the recommended diet within the 30 days of the HIH program. However, by acknowledging the reality of the patient’s stage of change, the HIH RDN and team can then collaborate to support the patient in moving toward the next stage. Patients who are not ready for dietary behavior change during the 30 days of HIH may benefit from longer-term support, and the HIH RDN can arrange followup care with an outpatient RDN.

Conclusions

As the HIH model continues to be adopted across the VHA and other health care systems, it is crucial to consider the value and expertise of an RDN for guiding nutrition care in the HIH setting. The HIH RDN contributes to optimal health care delivery by leading nutritional aspects of patient care, offering personalized MNT, and coordinating and collaborating with team members to meet individual patient needs. An RDN can serve as a valuable resource for nutrition information and enhance the team’s overall services, with the potential to impact clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction.

1. Levine DM, Ouchi K, Blanchfield B, et al. Hospitallevel care at home for acutely ill adults: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(2):77-85. doi:10.7326/M19-0600

2. Cai S, Grubbs A, Makineni R, Kinosian B, Phibbs CS, Intrator O. Evaluation of the Cincinnati Veterans Affairs medical center hospital-in-home program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(7):1392-1398. doi:10.1111/jgs.15382

3. Cai S, Laurel PA, Makineni R, Marks ML. Evaluation of a hospital-in-home program implemented among veterans. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(8):482-487.

4. Conley J, O’Brien CW, Leff BA, Bolen S, Zulman D. Alternative strategies to inpatient hospitalization for acute medical conditions: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1693-1702. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5974

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1144: Hospital in Home program, Appendix A, Hospital in Home program standards. January 19, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2022. https://www .va.gov/VHApublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub _ID=9157

6. Tibaldi V, Isaia G, Scarafiotti C, et al. Hospital at home for elderly patients with acute decompensation of chronic heart failure: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(17):1569-1575. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.267

7. Abshire M, Xu J, Baptiste D, et al. Nutritional interventions in heart failure: a systematic review of the literature. J Card Fail. 2015;21(12):989-999. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.10.004

8. Bleich SN, Bennett WL, Gudzune KA, Cooper LA. National survey of US primary care physicians’ perspectives about causes of obesity and solutions to improve care. BMJ Open. 2012;2(6):e001871. Published 2012 Dec 20. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001871

9. Sousa AM. Benefits of dietitian home visits. J Am Diet Assoc. 1994;94(10):1149-1151. doi:10.1016/0002-8223(94)91136-3

10. Casas-Agustench P, Megías-Rangil I, Babio N. Economic benefit of dietetic-nutritional treatment in the multidisciplinary primary care team. Beneficio económico del tratamiento dietético-nutricional en el equipo multidisciplinario de atención primaria. Nutr Hosp. 2020;37(4):863-874. doi:10.20960/nh.03025

11. Lee J, Briggs Early K, Kovesdy CP, Lancaster K, Brown N, Steiber AL. The impact of RDNs on non-communicable diseases: proceedings from The State of Food and Nutrition Series Forum. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2022;122(1):166-174. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2021.02.021

12. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Evidence analysis library, nutrition care process. Accessed May 5, 2022. https://www.andeal.org/ncp

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1438, clinical nutrition management and therapy. Appendix A, nutrition support therapy. September 19, 2019. Accessed January 20, 2022. https://www.va.gov/VHAPUBLICATIONS/ViewPublication .asp?pub_ID=8512

14. Vogelzang JL. Fifteen ways to enhance client outcomes by using your registered dietitian. Home Healthc Nurse. 2002;20(4):227-229. doi:10.1097/00004045-200204000-00005

15. Kristal AR, Glanz K, Curry SJ, Patterson RE. How can stages of change be best used in dietary interventions?. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99(6):679-684. doi:10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00165-0

Hospital in Home (HIH) is the delivery of acute care services in a patient’s home as an alternative to hospitalization.1 Compared with traditional inpatient care, HIH programs have been associated with reduced costs, as well as patient and caregiver satisfaction, diseasespecific outcomes, and mortality rates that were similar or improved compared with inpatient admissions.1-4

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and other hospital systems are increasingly adopting HIH models.2-4 At the time of this writing, there were 12 HIH programs in VHA (personal communication, D. Cooper, 2/28/2022). In addition to physicians and nurses, the interdisciplinary HIH team may include a pharmacist, social worker, and registered dietitian nutritionist (RDN).2,5 HIH programs have been shown to improve nutritional status as measured by the Mini Nutritional Assessment Score, but overall, there is a paucity of published information regarding the provision of nutrition care in HIH.6 The role of the RDN has varied within VHA. Some sites, such as the Sacramento VA Medical Center in California, include a distinct RDN position on the HIH team, whereas others, such as the Spark M. Matsunaga VA Medical Center in Honolulu, Hawaii, and the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital in Tampa, Florida, consult clinic RDNs.

Since HIH programs typically treat conditions for which diet is an inherent part of the treatment (eg, congestive heart failure [CHF]), there is a need to precisely define the role of the RDN within the HIH model.2,3,7 Drawing from my experience as an HIH RDN, I will describe how the inclusion of an RDN position within the HIH team is optimal for health care delivery and how HIH practitioners can best utilize RDN services.

RDN Role in HIH Team

Delegating nutrition services to an RDN enhances patient care by empowering HIH team members to function at the highest level of their scope of practice. RDNs have been recognized by physicians as the most qualified health care professionals to help patients with diet-related conditions, such as obesity, and physicians also have reported a desire for additional training in nutrition.8 Although home-health nurses have frequently performed nutrition assessments and interventions, survey results have indicated that many nurses do not feel confident in teaching complex nutritional information.9 In my experience, many HIH patients are nutritionally complex, with more than one condition requiring nutrition intervention. For example, patients may be admitted to HIH for management of CHF, but they may also have diabetes mellitus (DM), obesity, and low socioeconomic status. The HIH RDN can address the nutrition aspects of these conditions, freeing time for physicians and nurses to focus on their respective areas of expertise.9,10 Moreover, the RDN can also provide dietary education to the HIH team to increase their knowledge of nutritional topics and promote consistent messaging to patients.

Including an RDN on the HIH team enables patients to have comprehensive, personalized nutrition care. Rather than merely offering generalized nutrition education, RDNs are trained to provide medical nutrition therapy (MNT), which has been shown to improve health outcomes and be cost-effective for conditions such as type 2 DM, chronic kidney disease, hypertension, and obesity.10,11 In MNT, RDNs use the standardized 4-stepnutrition care process (NCP).12 The Table shows examples of how the NCP can be applied in HIH settings. Furthermore, in my experience, MNT from an RDN also contributes to patient satisfaction. Subjective observations from my team have indicated that patients often express more confidence in managing their diets by the time of HIH discharge.

RDNs can guide physicians and pharmacists in ordering oral nutrition supplements (ONS). Within the VHA, a “food first” approach is preferred to increase caloric intake, and patients must meet specific criteria for prescription of an ONS.13 Furthermore, ONS designed for specific medical conditions (eg, chronic kidney disease) are considered nonformulary and require an RDN evaluation.13 Including an RDN on the HIH team allows this evaluation process to begin early in the patient’s admission to the program and ensures that provision of ONS is clinically appropriate and cost-effective.

Care Coordination

HIH is highly interdisciplinary. Team members perform their respective roles and communicate with the team throughout the day. RDNs can help monitor patients and alert physicians for changes in blood glucose, gastrointestinal concerns, and weight. This is especially helpful for patients who do not have a planned nursing visit on the day of an RDN evaluation. The HIH RDN can also collaborate with other team members to address patient needs. For example, for patients with limited financial resources, the HIH RDN can provide nutrition education regarding cooking on a budget, and the HIH social worker can arrange free or low-cost meal services.

Tips

When hiring an HIH RDN, seek candidates with experience in inpatient, outpatient, and home care settings. As a hybrid of these 3 areas, the HIH RDN position requires a unique combination of acute care skills and health coaching. Additionally, in my experience, the HIH RDN interacts more frequently with the HIH team than other RDN colleagues, so it is important that candidates can work independently and take initiative. This type of position would not be suitable for entry-level RDNs.

Stagger HIH team visits to prevent overwhelming the patient and caregivers. Early in our program, my team quickly learned that patients and caregivers can feel overwhelmed with too many home visits upon admission to HIH. After seeing multiple HIH team members the same day, they were often too tired to focus well on diet education during my visit. Staggering visits (eg, completing the initial nutrition assessment 1 day to 1 week after the initial medical and pharmacy visits) has been an effective strategy to address this problem. Furthermore, some patients prefer that the initial RDN appointment is conducted by telephone, with an inperson reassessment the following week. In my experience, HIH workflow is dynamic by nature, so it is crucial to remain flexible and accommodate individual patient needs as much as possible.

Dietary behavior change is a long-term process, and restrictive hospital diets can be challenging to replicate at home. In a hospital setting, clinicians can order a specialized diet (eg, low sodium with fluid restriction for CHF patients), whereas efforts to implement these restrictions in the home setting can be cumbersome and negatively impact quality of life.7,14 Nevertheless, the effectiveness of medical treatment is compromised when patients do not adhere to dietary recommendations. Meal delivery services that offer specialized diets can be a useful resource for patients and caregivers who are unable to cook, and the HIH RDN can assist patients in ordering these services.

HIH patients may vary in terms of readiness to make dietary changes, and in addition to nutrition education, nutrition counseling is usually needed to effect behavior change. My team has found that consideration of the transtheoretical/ stages of change model can be a helpful approach. 15 The HIH RDN can tailor nutrition interventions to the patient’s stage of change. For example, for patients in the precontemplation stage, the HIH RDN would focus on providing information and addressing emotional aspects of dietary change. In contrast, for patients in the action stage of change, the HIH RDN might emphasize behavioral skill training and social support.15 Particularly for patients in the early stages of change, it may be unrealistic to expect full adoption of the recommended diet within the 30 days of the HIH program. However, by acknowledging the reality of the patient’s stage of change, the HIH RDN and team can then collaborate to support the patient in moving toward the next stage. Patients who are not ready for dietary behavior change during the 30 days of HIH may benefit from longer-term support, and the HIH RDN can arrange followup care with an outpatient RDN.

Conclusions

As the HIH model continues to be adopted across the VHA and other health care systems, it is crucial to consider the value and expertise of an RDN for guiding nutrition care in the HIH setting. The HIH RDN contributes to optimal health care delivery by leading nutritional aspects of patient care, offering personalized MNT, and coordinating and collaborating with team members to meet individual patient needs. An RDN can serve as a valuable resource for nutrition information and enhance the team’s overall services, with the potential to impact clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction.

Hospital in Home (HIH) is the delivery of acute care services in a patient’s home as an alternative to hospitalization.1 Compared with traditional inpatient care, HIH programs have been associated with reduced costs, as well as patient and caregiver satisfaction, diseasespecific outcomes, and mortality rates that were similar or improved compared with inpatient admissions.1-4

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and other hospital systems are increasingly adopting HIH models.2-4 At the time of this writing, there were 12 HIH programs in VHA (personal communication, D. Cooper, 2/28/2022). In addition to physicians and nurses, the interdisciplinary HIH team may include a pharmacist, social worker, and registered dietitian nutritionist (RDN).2,5 HIH programs have been shown to improve nutritional status as measured by the Mini Nutritional Assessment Score, but overall, there is a paucity of published information regarding the provision of nutrition care in HIH.6 The role of the RDN has varied within VHA. Some sites, such as the Sacramento VA Medical Center in California, include a distinct RDN position on the HIH team, whereas others, such as the Spark M. Matsunaga VA Medical Center in Honolulu, Hawaii, and the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital in Tampa, Florida, consult clinic RDNs.

Since HIH programs typically treat conditions for which diet is an inherent part of the treatment (eg, congestive heart failure [CHF]), there is a need to precisely define the role of the RDN within the HIH model.2,3,7 Drawing from my experience as an HIH RDN, I will describe how the inclusion of an RDN position within the HIH team is optimal for health care delivery and how HIH practitioners can best utilize RDN services.

RDN Role in HIH Team

Delegating nutrition services to an RDN enhances patient care by empowering HIH team members to function at the highest level of their scope of practice. RDNs have been recognized by physicians as the most qualified health care professionals to help patients with diet-related conditions, such as obesity, and physicians also have reported a desire for additional training in nutrition.8 Although home-health nurses have frequently performed nutrition assessments and interventions, survey results have indicated that many nurses do not feel confident in teaching complex nutritional information.9 In my experience, many HIH patients are nutritionally complex, with more than one condition requiring nutrition intervention. For example, patients may be admitted to HIH for management of CHF, but they may also have diabetes mellitus (DM), obesity, and low socioeconomic status. The HIH RDN can address the nutrition aspects of these conditions, freeing time for physicians and nurses to focus on their respective areas of expertise.9,10 Moreover, the RDN can also provide dietary education to the HIH team to increase their knowledge of nutritional topics and promote consistent messaging to patients.

Including an RDN on the HIH team enables patients to have comprehensive, personalized nutrition care. Rather than merely offering generalized nutrition education, RDNs are trained to provide medical nutrition therapy (MNT), which has been shown to improve health outcomes and be cost-effective for conditions such as type 2 DM, chronic kidney disease, hypertension, and obesity.10,11 In MNT, RDNs use the standardized 4-stepnutrition care process (NCP).12 The Table shows examples of how the NCP can be applied in HIH settings. Furthermore, in my experience, MNT from an RDN also contributes to patient satisfaction. Subjective observations from my team have indicated that patients often express more confidence in managing their diets by the time of HIH discharge.

RDNs can guide physicians and pharmacists in ordering oral nutrition supplements (ONS). Within the VHA, a “food first” approach is preferred to increase caloric intake, and patients must meet specific criteria for prescription of an ONS.13 Furthermore, ONS designed for specific medical conditions (eg, chronic kidney disease) are considered nonformulary and require an RDN evaluation.13 Including an RDN on the HIH team allows this evaluation process to begin early in the patient’s admission to the program and ensures that provision of ONS is clinically appropriate and cost-effective.

Care Coordination

HIH is highly interdisciplinary. Team members perform their respective roles and communicate with the team throughout the day. RDNs can help monitor patients and alert physicians for changes in blood glucose, gastrointestinal concerns, and weight. This is especially helpful for patients who do not have a planned nursing visit on the day of an RDN evaluation. The HIH RDN can also collaborate with other team members to address patient needs. For example, for patients with limited financial resources, the HIH RDN can provide nutrition education regarding cooking on a budget, and the HIH social worker can arrange free or low-cost meal services.

Tips

When hiring an HIH RDN, seek candidates with experience in inpatient, outpatient, and home care settings. As a hybrid of these 3 areas, the HIH RDN position requires a unique combination of acute care skills and health coaching. Additionally, in my experience, the HIH RDN interacts more frequently with the HIH team than other RDN colleagues, so it is important that candidates can work independently and take initiative. This type of position would not be suitable for entry-level RDNs.

Stagger HIH team visits to prevent overwhelming the patient and caregivers. Early in our program, my team quickly learned that patients and caregivers can feel overwhelmed with too many home visits upon admission to HIH. After seeing multiple HIH team members the same day, they were often too tired to focus well on diet education during my visit. Staggering visits (eg, completing the initial nutrition assessment 1 day to 1 week after the initial medical and pharmacy visits) has been an effective strategy to address this problem. Furthermore, some patients prefer that the initial RDN appointment is conducted by telephone, with an inperson reassessment the following week. In my experience, HIH workflow is dynamic by nature, so it is crucial to remain flexible and accommodate individual patient needs as much as possible.

Dietary behavior change is a long-term process, and restrictive hospital diets can be challenging to replicate at home. In a hospital setting, clinicians can order a specialized diet (eg, low sodium with fluid restriction for CHF patients), whereas efforts to implement these restrictions in the home setting can be cumbersome and negatively impact quality of life.7,14 Nevertheless, the effectiveness of medical treatment is compromised when patients do not adhere to dietary recommendations. Meal delivery services that offer specialized diets can be a useful resource for patients and caregivers who are unable to cook, and the HIH RDN can assist patients in ordering these services.

HIH patients may vary in terms of readiness to make dietary changes, and in addition to nutrition education, nutrition counseling is usually needed to effect behavior change. My team has found that consideration of the transtheoretical/ stages of change model can be a helpful approach. 15 The HIH RDN can tailor nutrition interventions to the patient’s stage of change. For example, for patients in the precontemplation stage, the HIH RDN would focus on providing information and addressing emotional aspects of dietary change. In contrast, for patients in the action stage of change, the HIH RDN might emphasize behavioral skill training and social support.15 Particularly for patients in the early stages of change, it may be unrealistic to expect full adoption of the recommended diet within the 30 days of the HIH program. However, by acknowledging the reality of the patient’s stage of change, the HIH RDN and team can then collaborate to support the patient in moving toward the next stage. Patients who are not ready for dietary behavior change during the 30 days of HIH may benefit from longer-term support, and the HIH RDN can arrange followup care with an outpatient RDN.

Conclusions

As the HIH model continues to be adopted across the VHA and other health care systems, it is crucial to consider the value and expertise of an RDN for guiding nutrition care in the HIH setting. The HIH RDN contributes to optimal health care delivery by leading nutritional aspects of patient care, offering personalized MNT, and coordinating and collaborating with team members to meet individual patient needs. An RDN can serve as a valuable resource for nutrition information and enhance the team’s overall services, with the potential to impact clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction.

1. Levine DM, Ouchi K, Blanchfield B, et al. Hospitallevel care at home for acutely ill adults: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(2):77-85. doi:10.7326/M19-0600

2. Cai S, Grubbs A, Makineni R, Kinosian B, Phibbs CS, Intrator O. Evaluation of the Cincinnati Veterans Affairs medical center hospital-in-home program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(7):1392-1398. doi:10.1111/jgs.15382

3. Cai S, Laurel PA, Makineni R, Marks ML. Evaluation of a hospital-in-home program implemented among veterans. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(8):482-487.

4. Conley J, O’Brien CW, Leff BA, Bolen S, Zulman D. Alternative strategies to inpatient hospitalization for acute medical conditions: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1693-1702. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5974

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1144: Hospital in Home program, Appendix A, Hospital in Home program standards. January 19, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2022. https://www .va.gov/VHApublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub _ID=9157

6. Tibaldi V, Isaia G, Scarafiotti C, et al. Hospital at home for elderly patients with acute decompensation of chronic heart failure: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(17):1569-1575. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.267

7. Abshire M, Xu J, Baptiste D, et al. Nutritional interventions in heart failure: a systematic review of the literature. J Card Fail. 2015;21(12):989-999. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.10.004

8. Bleich SN, Bennett WL, Gudzune KA, Cooper LA. National survey of US primary care physicians’ perspectives about causes of obesity and solutions to improve care. BMJ Open. 2012;2(6):e001871. Published 2012 Dec 20. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001871

9. Sousa AM. Benefits of dietitian home visits. J Am Diet Assoc. 1994;94(10):1149-1151. doi:10.1016/0002-8223(94)91136-3

10. Casas-Agustench P, Megías-Rangil I, Babio N. Economic benefit of dietetic-nutritional treatment in the multidisciplinary primary care team. Beneficio económico del tratamiento dietético-nutricional en el equipo multidisciplinario de atención primaria. Nutr Hosp. 2020;37(4):863-874. doi:10.20960/nh.03025

11. Lee J, Briggs Early K, Kovesdy CP, Lancaster K, Brown N, Steiber AL. The impact of RDNs on non-communicable diseases: proceedings from The State of Food and Nutrition Series Forum. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2022;122(1):166-174. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2021.02.021

12. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Evidence analysis library, nutrition care process. Accessed May 5, 2022. https://www.andeal.org/ncp

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1438, clinical nutrition management and therapy. Appendix A, nutrition support therapy. September 19, 2019. Accessed January 20, 2022. https://www.va.gov/VHAPUBLICATIONS/ViewPublication .asp?pub_ID=8512

14. Vogelzang JL. Fifteen ways to enhance client outcomes by using your registered dietitian. Home Healthc Nurse. 2002;20(4):227-229. doi:10.1097/00004045-200204000-00005

15. Kristal AR, Glanz K, Curry SJ, Patterson RE. How can stages of change be best used in dietary interventions?. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99(6):679-684. doi:10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00165-0

1. Levine DM, Ouchi K, Blanchfield B, et al. Hospitallevel care at home for acutely ill adults: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(2):77-85. doi:10.7326/M19-0600

2. Cai S, Grubbs A, Makineni R, Kinosian B, Phibbs CS, Intrator O. Evaluation of the Cincinnati Veterans Affairs medical center hospital-in-home program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(7):1392-1398. doi:10.1111/jgs.15382

3. Cai S, Laurel PA, Makineni R, Marks ML. Evaluation of a hospital-in-home program implemented among veterans. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(8):482-487.

4. Conley J, O’Brien CW, Leff BA, Bolen S, Zulman D. Alternative strategies to inpatient hospitalization for acute medical conditions: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1693-1702. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5974

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1144: Hospital in Home program, Appendix A, Hospital in Home program standards. January 19, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2022. https://www .va.gov/VHApublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub _ID=9157

6. Tibaldi V, Isaia G, Scarafiotti C, et al. Hospital at home for elderly patients with acute decompensation of chronic heart failure: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(17):1569-1575. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.267

7. Abshire M, Xu J, Baptiste D, et al. Nutritional interventions in heart failure: a systematic review of the literature. J Card Fail. 2015;21(12):989-999. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.10.004

8. Bleich SN, Bennett WL, Gudzune KA, Cooper LA. National survey of US primary care physicians’ perspectives about causes of obesity and solutions to improve care. BMJ Open. 2012;2(6):e001871. Published 2012 Dec 20. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001871

9. Sousa AM. Benefits of dietitian home visits. J Am Diet Assoc. 1994;94(10):1149-1151. doi:10.1016/0002-8223(94)91136-3

10. Casas-Agustench P, Megías-Rangil I, Babio N. Economic benefit of dietetic-nutritional treatment in the multidisciplinary primary care team. Beneficio económico del tratamiento dietético-nutricional en el equipo multidisciplinario de atención primaria. Nutr Hosp. 2020;37(4):863-874. doi:10.20960/nh.03025

11. Lee J, Briggs Early K, Kovesdy CP, Lancaster K, Brown N, Steiber AL. The impact of RDNs on non-communicable diseases: proceedings from The State of Food and Nutrition Series Forum. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2022;122(1):166-174. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2021.02.021

12. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Evidence analysis library, nutrition care process. Accessed May 5, 2022. https://www.andeal.org/ncp

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1438, clinical nutrition management and therapy. Appendix A, nutrition support therapy. September 19, 2019. Accessed January 20, 2022. https://www.va.gov/VHAPUBLICATIONS/ViewPublication .asp?pub_ID=8512

14. Vogelzang JL. Fifteen ways to enhance client outcomes by using your registered dietitian. Home Healthc Nurse. 2002;20(4):227-229. doi:10.1097/00004045-200204000-00005

15. Kristal AR, Glanz K, Curry SJ, Patterson RE. How can stages of change be best used in dietary interventions?. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99(6):679-684. doi:10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00165-0

Don’t overlook this cause of falls

I enjoyed reading “How to identify balance disorders and reduce fall risk” (J Fam Pract. 2022;71:20-30) from the January/February issue. I was, however, disappointed to see that normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) was not discussed in the article or tables.

Recently, I took care of a 72-year-old patient who presented after multiple falls. In conjunction with Neurology, the presumptive diagnosis of Parkinson disease was made. However, the patient continued to experience a health decline that included cognitive changes, nocturia, and the classic “magnetic gait” of NPH (mnemonic for diagnosing this triad of symptoms: weird, wet, wobbly). The presumptive diagnosis was then changed when the results of a fluorodopa F18 positron emission tomography scan (also known as a DaT scan) returned as normal, essentially excluding the diagnosis of Parkinson disease.

The patient has since seen a dramatic improvement in gait and cognitive and urinary symptoms following a high-volume lumbar puncture and placement of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt.

This case demonstrates the importance of considering NPH in the differential diagnosis for patients with balance disorders. Prompt diagnosis and management can result in a variable, but at times dramatic, reversal of symptoms.

Ernestine Lee, MD, MPH

Austin, TX

I enjoyed reading “How to identify balance disorders and reduce fall risk” (J Fam Pract. 2022;71:20-30) from the January/February issue. I was, however, disappointed to see that normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) was not discussed in the article or tables.

Recently, I took care of a 72-year-old patient who presented after multiple falls. In conjunction with Neurology, the presumptive diagnosis of Parkinson disease was made. However, the patient continued to experience a health decline that included cognitive changes, nocturia, and the classic “magnetic gait” of NPH (mnemonic for diagnosing this triad of symptoms: weird, wet, wobbly). The presumptive diagnosis was then changed when the results of a fluorodopa F18 positron emission tomography scan (also known as a DaT scan) returned as normal, essentially excluding the diagnosis of Parkinson disease.

The patient has since seen a dramatic improvement in gait and cognitive and urinary symptoms following a high-volume lumbar puncture and placement of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt.

This case demonstrates the importance of considering NPH in the differential diagnosis for patients with balance disorders. Prompt diagnosis and management can result in a variable, but at times dramatic, reversal of symptoms.

Ernestine Lee, MD, MPH

Austin, TX

I enjoyed reading “How to identify balance disorders and reduce fall risk” (J Fam Pract. 2022;71:20-30) from the January/February issue. I was, however, disappointed to see that normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) was not discussed in the article or tables.

Recently, I took care of a 72-year-old patient who presented after multiple falls. In conjunction with Neurology, the presumptive diagnosis of Parkinson disease was made. However, the patient continued to experience a health decline that included cognitive changes, nocturia, and the classic “magnetic gait” of NPH (mnemonic for diagnosing this triad of symptoms: weird, wet, wobbly). The presumptive diagnosis was then changed when the results of a fluorodopa F18 positron emission tomography scan (also known as a DaT scan) returned as normal, essentially excluding the diagnosis of Parkinson disease.

The patient has since seen a dramatic improvement in gait and cognitive and urinary symptoms following a high-volume lumbar puncture and placement of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt.

This case demonstrates the importance of considering NPH in the differential diagnosis for patients with balance disorders. Prompt diagnosis and management can result in a variable, but at times dramatic, reversal of symptoms.

Ernestine Lee, MD, MPH

Austin, TX

Taking the time to get it right

I cannot agree more with Dr. Hickner’s editorial, “The power of the pause to prevent diagnostic error” (J Fam Pract. 2022;71:102). In 1974, when I started at the Medical College of Virginia, I thought I was going to be a medical researcher. By mid-1978, I had completely changed my focus to family medicine. Fortunately, my drive for detail and accuracy remained, albeit at odds with a whirlwind residency and solo practice. I drove my staff (and wife) crazy because I frequently spent more than the “allotted” time with a patient. The time was not wasted; it was most important for me to gain the trust of the patient and then to get it right—or find a path to the answer.

Jeff Ginther, MD

Bristol, VA

I cannot agree more with Dr. Hickner’s editorial, “The power of the pause to prevent diagnostic error” (J Fam Pract. 2022;71:102). In 1974, when I started at the Medical College of Virginia, I thought I was going to be a medical researcher. By mid-1978, I had completely changed my focus to family medicine. Fortunately, my drive for detail and accuracy remained, albeit at odds with a whirlwind residency and solo practice. I drove my staff (and wife) crazy because I frequently spent more than the “allotted” time with a patient. The time was not wasted; it was most important for me to gain the trust of the patient and then to get it right—or find a path to the answer.

Jeff Ginther, MD

Bristol, VA

I cannot agree more with Dr. Hickner’s editorial, “The power of the pause to prevent diagnostic error” (J Fam Pract. 2022;71:102). In 1974, when I started at the Medical College of Virginia, I thought I was going to be a medical researcher. By mid-1978, I had completely changed my focus to family medicine. Fortunately, my drive for detail and accuracy remained, albeit at odds with a whirlwind residency and solo practice. I drove my staff (and wife) crazy because I frequently spent more than the “allotted” time with a patient. The time was not wasted; it was most important for me to gain the trust of the patient and then to get it right—or find a path to the answer.

Jeff Ginther, MD

Bristol, VA

Why do young men target schools for violent attacks? And what can we do about it?

Schools are intended to be a safe place to acquire knowledge, try out ideas, practice socializing, and build a foundation for adulthood. Many schools fulfill this mission for most children, but for children at both extremes of ability their school experience does not suffice.

When asked, “If you had the choice, would you rather stay home or go to school?” my patients almost universally prefer school. They all know that school is where they should be; they want to be normal, accepted by peers, getting ready for the world’s coming demands, and validation that they will make it as adults. Endorsement otherwise is a warning sign.

When such important tasks of childhood are thwarted children may despair, withdraw, give up, or a small number become furious. These may profoundly resent the children who are experiencing success when they could not. They may hate the teachers and the place where they experienced failure and humiliation. Lack of a positive connection to school characterizes children who are violent toward schools as well as those who drop out.

Schools may fail to support the basic needs of children for many reasons. Schools may avoid physical violence but fail to protect the children’s self-esteem. I have heard stories of teachers calling on children to perform who are clearly struggling or shy, insulting incorrect answers, calling names, putting names on the board, reading out failed grades, posting grades publicly, even allowing peers to mock students. Teachers may deny or disregard parent complaints, or even worsen treatment of the child. Although children may at times falsify complaints, children’s and parents’ reports must be taken seriously and remain anonymous. When we hear of such toxic situations for our patients, we can get details and contact school administrators without naming the child, as often the family feels they can’t. Repeated humiliation may require not only remediation, but consequences. We can advocate for a change in classroom or request a 504 Plan if emotional health is affected.

All children learn best and experience success and even joy when the tasks they face are at or slightly beyond their skill level. But with the wide range of abilities, especially for boys, education may need to be individualized. This is very difficult in larger classrooms with fewer resources, too few adult helpers, inexperienced teachers, or high levels of student misbehavior. Basing teacher promotion mainly on standardized test results makes individualizing instruction even less likely. Smaller class size is better; even the recommended (less than 20) or regulated (less than 30) class sizes are associated with suboptimal achievement, compared with smaller ones. Some ways to attain smaller class size include split days or alternate-day sessions, although these also have disadvantages.

While we can advocate for these changes, we can also encourage parents to promote academic skills by talking to and reading to their children of all ages, trying Reach Out and Read for young children, providing counting games, board games, and math songs! Besides screening for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, we can use standard paragraphs and math problems (for example, WRAT, Einstein) to check skills when performance is low or behavior is a problem the school denies. When concerned, we can write letters for parents to sign requesting testing and an individualized education plan to determine need for tutoring or special education.

While Federal legislation requiring the “least restrictive environment” for education was intended to avoid sidelining differently able children, some can’t learn in a regular class. Conversely, if instruction in a special class is adjusted to the child with the lowest skills, minimal learning may occur for others. Although we can speak with the teacher about “this child’s abilities among those in his class” we can first suggest that the parent visit class to observe. Outside tutoring or home schooling may help a child move up to a regular class.

Sometimes a child’s learning is hampered by classrooms with numerous children misbehaving; this is also a reason for resentment. We can inform school administrators about methods such as The Good Behavior Game (paxis.org) that can improve behavior and connection for the whole class.

While a social “pecking order” is universal, it is unacceptable for children to be allowed to humiliate or hurt a peer, or damage their reputation. While this moral teaching should occur at home, it needs to continue at school where peers are forced into groups they did not choose. Screening for bullying at pediatric visits is now a universal recommendation as 30% report being bullied. We need to ask all children about “mean kids in school” or gang involvement for older children.

Parents can support their children experiencing cyberbullying and switch them to a “dumb phone” with no texting option, limited phone time, or no phone at all. Policies against bullying coming from school administrators are most effective but we can inform schools about the STOPit app for children to report bullying anonymously as well as education for students to stand together against a bully (stopbullying.gov). A Lunch Bunch for younger children or a buddy system for older ones can be requested to help them make friends.

With diverse child aptitudes, schools need to offer students alternative opportunities for self-expression and contribution. We can ask about a child’s strengths and suggest related extracurriculars activities in school or outside, including volunteering. Participation on teams or in clubs must not be blocked for those with poor grades. Perhaps tying participation to tutoring would satisfy the school’s desire to motivate instead. Parents can be encouraged to advocate for music, art, and drama classes – programs that are often victims of budget cuts – that can create the essential school connection.

Students in many areas lack access to classes in trades early enough in their education. The requirements for English or math may be out of reach and result in students dropping out before trade classes are an option. We may identify our patients who may do better with a trade education and advise families to request transfer to a high school offering this.

The best connection a child can have to a school is an adult who values them. The child may identify a preferred teacher to us so that we, or the parent, can call to ask them to provide special attention. Facilitating times for students to get to know teachers may require alteration in bus schedules, lunch times, study halls, or breaks, or keeping the school open longer outside class hours. While more mental health providers are clearly needed, sometimes it is the groundskeeper, the secretary, or the lunch helper who can make the best connection with a child.

As pediatricians, we must listen to struggling youth, acknowledge their pain, and model this empathy for their parents who may be obsessing over grades. Problem-solving about how to get accommodations, informal or formal, can inspire hope. We can coach parents and youth to meet respectfully with the school about issues to avoid labeling the child as a problem.

As pediatricians, our recommendations for school funding and policies may carry extra weight. We may share ideas through talks at PTA meetings, serve on school boards, or endorse leaders planning greater resources for schools to optimize each child’s experience and connection to school.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. E-mail her at [email protected].

Schools are intended to be a safe place to acquire knowledge, try out ideas, practice socializing, and build a foundation for adulthood. Many schools fulfill this mission for most children, but for children at both extremes of ability their school experience does not suffice.

When asked, “If you had the choice, would you rather stay home or go to school?” my patients almost universally prefer school. They all know that school is where they should be; they want to be normal, accepted by peers, getting ready for the world’s coming demands, and validation that they will make it as adults. Endorsement otherwise is a warning sign.

When such important tasks of childhood are thwarted children may despair, withdraw, give up, or a small number become furious. These may profoundly resent the children who are experiencing success when they could not. They may hate the teachers and the place where they experienced failure and humiliation. Lack of a positive connection to school characterizes children who are violent toward schools as well as those who drop out.

Schools may fail to support the basic needs of children for many reasons. Schools may avoid physical violence but fail to protect the children’s self-esteem. I have heard stories of teachers calling on children to perform who are clearly struggling or shy, insulting incorrect answers, calling names, putting names on the board, reading out failed grades, posting grades publicly, even allowing peers to mock students. Teachers may deny or disregard parent complaints, or even worsen treatment of the child. Although children may at times falsify complaints, children’s and parents’ reports must be taken seriously and remain anonymous. When we hear of such toxic situations for our patients, we can get details and contact school administrators without naming the child, as often the family feels they can’t. Repeated humiliation may require not only remediation, but consequences. We can advocate for a change in classroom or request a 504 Plan if emotional health is affected.