User login

VA Ketamine Controversies

To the Editor: We read with interest the editorial on the clinical use of intranasal esketamine in treatment-resistant depression by Editor-in-Chief Cynthia Geppert in the October 2019 issue of Federal Practitioner.1 A recent case report published in your journal illustrated the success of IV ketamine in alleviating refractory chronic pain caused by a rare disease.2 Ketamine has been well established as an appropriate adjuvant as well as an alternative to opioids in attenuating acute postoperative pain and in certain chronic pain syndromes.3 We write out of concern for the rapidity of adoption of intranasal esketamine without considering the merits of IV ketamine.

When adopting new treatments or extending established drugs for newer indications, clinicians must balance beneficence and nonmaleficence. There is an urgent need for better treatment options for depression, suicidality, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and chronic pain in the veteran population. However, one must proceed with caution before wide adoption of a treatment that lacks real-world data on sustained or long-term benefits.4 Enthusiasm for this drug must also be tempered by the documented adverse effect (AE) of hepatic injury and the lack of data tracking this AE from repeated, long-term use.5 With these considerations in mind, reliable dosing and predictable pharmacokinetics are of great importance.

In addition to outpatient esketamine, outpatient IV administration of racemic ketamine remains an advantageous option with unique benefits compared with esketamine. Pharmacokinetically, IV ketamine is superior to intranasal esketamine. The bioavailability of intranasal esketamine is likely to be variable. A patient with a poor intranasal application or poor absorption might be falsely labeled an esketamine nonresponder. Increasing intranasal esketamine dosage to avoid false nonresponders may place other patients at risk for overdose and undesired AEs, including dysphoria and hallucinations. The variable bioavailability of intranasal ketamine adds complexity to the examination of its clinical effectiveness. IV ketamine should provide a predictable drug level and more reliable data. One might retort that esketamine is not the same as ketamine. True, esketamine is the S-enantiomer of ketamine, whereas ketamine is a racemic mixture of S- and R-ketamine. However, there is no clear evidence of clinically relevant differences between these formulations.5

Psychomimetic effects and cardiovascular changes are the most common short-term AEs resulting from ketamine.5 An IV infusion allows the treating physician to slowly titrate the administered ketamine to reach an effective concentration at the target site. Unlike an all-or-none intranasal administration, an infusion can be stopped at the first appearance of an AE. Psychomimetic effects, such as hallucinations, visual disturbances, and dysphoria are thought to occur in a dose-dependent fashion and remit once a ketamine infusion is stopped.5 Furthermore, cardiovascular AEs, such as hypertension and tachycardia, are commonly in patients with a body mass index > 30, with IV administration on a mg/kg basis. This suggests that calculated ideal body weight is a safer denominator, and reliable dosing is important to mitigating AEs.6

We urge caution with the widespread adoption of intranasal esketamine and suggest the advantages of the IV route, which offers predictability of AEs and titratability of dose. Questions remain regarding the appropriate dose and formulation of ketamine, rate of infusion, and route of administration for chronic pain and psychiatric indications.5,7 It is our responsibility to further study the long-term safety profile of ketamine and determine an appropriate dose of ketamine. The IV route allows many veterans to be helped in a safe and controllable manner.

Eugene Raggi, MD; and Srikantha L. Rao, MD, MS, FAS

1. Geppert CMA. The VA ketamine controversies. Fed Pract. 2019;36(10):446-447.

2. Eliason AH, Seo Y, Murphy D, Beal C. Adiposis dolorosa pain management. Fed Pract. 2019;36(11):530-533.

3. Orhurhu V, Orhurhu MS, Bhatia A, Cohen SP. Ketamine infusions for chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesth Analg. 2019;129(1):241-254.

4. Talbot J, Phillips JL, Blier P. Ketamine for chronic depression: two cautionary tales. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2019;44(6):384-385.

5. Cohen SP, Bhatia A, Buvanendran A, et al. Consensus guidelines on the use of intravenous ketamine infusions for chronic pain from the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, the American Academy of Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43(5):521-546.

6. Sanacora G, Frye MA, McDonald W, et al; American Psychiatric Association (APA) Council of Research Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments. A consensus statement on the use of ketamine in the treatment of mood disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(4):399-405.

7. Andrade C. Ketamine for depression, 4: in what dose, at what rate, by what route, for how long, and at what frequency? J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(7):e852-e857.

To the Editor: We read with interest the editorial on the clinical use of intranasal esketamine in treatment-resistant depression by Editor-in-Chief Cynthia Geppert in the October 2019 issue of Federal Practitioner.1 A recent case report published in your journal illustrated the success of IV ketamine in alleviating refractory chronic pain caused by a rare disease.2 Ketamine has been well established as an appropriate adjuvant as well as an alternative to opioids in attenuating acute postoperative pain and in certain chronic pain syndromes.3 We write out of concern for the rapidity of adoption of intranasal esketamine without considering the merits of IV ketamine.

When adopting new treatments or extending established drugs for newer indications, clinicians must balance beneficence and nonmaleficence. There is an urgent need for better treatment options for depression, suicidality, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and chronic pain in the veteran population. However, one must proceed with caution before wide adoption of a treatment that lacks real-world data on sustained or long-term benefits.4 Enthusiasm for this drug must also be tempered by the documented adverse effect (AE) of hepatic injury and the lack of data tracking this AE from repeated, long-term use.5 With these considerations in mind, reliable dosing and predictable pharmacokinetics are of great importance.

In addition to outpatient esketamine, outpatient IV administration of racemic ketamine remains an advantageous option with unique benefits compared with esketamine. Pharmacokinetically, IV ketamine is superior to intranasal esketamine. The bioavailability of intranasal esketamine is likely to be variable. A patient with a poor intranasal application or poor absorption might be falsely labeled an esketamine nonresponder. Increasing intranasal esketamine dosage to avoid false nonresponders may place other patients at risk for overdose and undesired AEs, including dysphoria and hallucinations. The variable bioavailability of intranasal ketamine adds complexity to the examination of its clinical effectiveness. IV ketamine should provide a predictable drug level and more reliable data. One might retort that esketamine is not the same as ketamine. True, esketamine is the S-enantiomer of ketamine, whereas ketamine is a racemic mixture of S- and R-ketamine. However, there is no clear evidence of clinically relevant differences between these formulations.5

Psychomimetic effects and cardiovascular changes are the most common short-term AEs resulting from ketamine.5 An IV infusion allows the treating physician to slowly titrate the administered ketamine to reach an effective concentration at the target site. Unlike an all-or-none intranasal administration, an infusion can be stopped at the first appearance of an AE. Psychomimetic effects, such as hallucinations, visual disturbances, and dysphoria are thought to occur in a dose-dependent fashion and remit once a ketamine infusion is stopped.5 Furthermore, cardiovascular AEs, such as hypertension and tachycardia, are commonly in patients with a body mass index > 30, with IV administration on a mg/kg basis. This suggests that calculated ideal body weight is a safer denominator, and reliable dosing is important to mitigating AEs.6

We urge caution with the widespread adoption of intranasal esketamine and suggest the advantages of the IV route, which offers predictability of AEs and titratability of dose. Questions remain regarding the appropriate dose and formulation of ketamine, rate of infusion, and route of administration for chronic pain and psychiatric indications.5,7 It is our responsibility to further study the long-term safety profile of ketamine and determine an appropriate dose of ketamine. The IV route allows many veterans to be helped in a safe and controllable manner.

Eugene Raggi, MD; and Srikantha L. Rao, MD, MS, FAS

To the Editor: We read with interest the editorial on the clinical use of intranasal esketamine in treatment-resistant depression by Editor-in-Chief Cynthia Geppert in the October 2019 issue of Federal Practitioner.1 A recent case report published in your journal illustrated the success of IV ketamine in alleviating refractory chronic pain caused by a rare disease.2 Ketamine has been well established as an appropriate adjuvant as well as an alternative to opioids in attenuating acute postoperative pain and in certain chronic pain syndromes.3 We write out of concern for the rapidity of adoption of intranasal esketamine without considering the merits of IV ketamine.

When adopting new treatments or extending established drugs for newer indications, clinicians must balance beneficence and nonmaleficence. There is an urgent need for better treatment options for depression, suicidality, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and chronic pain in the veteran population. However, one must proceed with caution before wide adoption of a treatment that lacks real-world data on sustained or long-term benefits.4 Enthusiasm for this drug must also be tempered by the documented adverse effect (AE) of hepatic injury and the lack of data tracking this AE from repeated, long-term use.5 With these considerations in mind, reliable dosing and predictable pharmacokinetics are of great importance.

In addition to outpatient esketamine, outpatient IV administration of racemic ketamine remains an advantageous option with unique benefits compared with esketamine. Pharmacokinetically, IV ketamine is superior to intranasal esketamine. The bioavailability of intranasal esketamine is likely to be variable. A patient with a poor intranasal application or poor absorption might be falsely labeled an esketamine nonresponder. Increasing intranasal esketamine dosage to avoid false nonresponders may place other patients at risk for overdose and undesired AEs, including dysphoria and hallucinations. The variable bioavailability of intranasal ketamine adds complexity to the examination of its clinical effectiveness. IV ketamine should provide a predictable drug level and more reliable data. One might retort that esketamine is not the same as ketamine. True, esketamine is the S-enantiomer of ketamine, whereas ketamine is a racemic mixture of S- and R-ketamine. However, there is no clear evidence of clinically relevant differences between these formulations.5

Psychomimetic effects and cardiovascular changes are the most common short-term AEs resulting from ketamine.5 An IV infusion allows the treating physician to slowly titrate the administered ketamine to reach an effective concentration at the target site. Unlike an all-or-none intranasal administration, an infusion can be stopped at the first appearance of an AE. Psychomimetic effects, such as hallucinations, visual disturbances, and dysphoria are thought to occur in a dose-dependent fashion and remit once a ketamine infusion is stopped.5 Furthermore, cardiovascular AEs, such as hypertension and tachycardia, are commonly in patients with a body mass index > 30, with IV administration on a mg/kg basis. This suggests that calculated ideal body weight is a safer denominator, and reliable dosing is important to mitigating AEs.6

We urge caution with the widespread adoption of intranasal esketamine and suggest the advantages of the IV route, which offers predictability of AEs and titratability of dose. Questions remain regarding the appropriate dose and formulation of ketamine, rate of infusion, and route of administration for chronic pain and psychiatric indications.5,7 It is our responsibility to further study the long-term safety profile of ketamine and determine an appropriate dose of ketamine. The IV route allows many veterans to be helped in a safe and controllable manner.

Eugene Raggi, MD; and Srikantha L. Rao, MD, MS, FAS

1. Geppert CMA. The VA ketamine controversies. Fed Pract. 2019;36(10):446-447.

2. Eliason AH, Seo Y, Murphy D, Beal C. Adiposis dolorosa pain management. Fed Pract. 2019;36(11):530-533.

3. Orhurhu V, Orhurhu MS, Bhatia A, Cohen SP. Ketamine infusions for chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesth Analg. 2019;129(1):241-254.

4. Talbot J, Phillips JL, Blier P. Ketamine for chronic depression: two cautionary tales. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2019;44(6):384-385.

5. Cohen SP, Bhatia A, Buvanendran A, et al. Consensus guidelines on the use of intravenous ketamine infusions for chronic pain from the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, the American Academy of Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43(5):521-546.

6. Sanacora G, Frye MA, McDonald W, et al; American Psychiatric Association (APA) Council of Research Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments. A consensus statement on the use of ketamine in the treatment of mood disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(4):399-405.

7. Andrade C. Ketamine for depression, 4: in what dose, at what rate, by what route, for how long, and at what frequency? J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(7):e852-e857.

1. Geppert CMA. The VA ketamine controversies. Fed Pract. 2019;36(10):446-447.

2. Eliason AH, Seo Y, Murphy D, Beal C. Adiposis dolorosa pain management. Fed Pract. 2019;36(11):530-533.

3. Orhurhu V, Orhurhu MS, Bhatia A, Cohen SP. Ketamine infusions for chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesth Analg. 2019;129(1):241-254.

4. Talbot J, Phillips JL, Blier P. Ketamine for chronic depression: two cautionary tales. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2019;44(6):384-385.

5. Cohen SP, Bhatia A, Buvanendran A, et al. Consensus guidelines on the use of intravenous ketamine infusions for chronic pain from the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, the American Academy of Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43(5):521-546.

6. Sanacora G, Frye MA, McDonald W, et al; American Psychiatric Association (APA) Council of Research Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments. A consensus statement on the use of ketamine in the treatment of mood disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(4):399-405.

7. Andrade C. Ketamine for depression, 4: in what dose, at what rate, by what route, for how long, and at what frequency? J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(7):e852-e857.

The Worst and the Best of 2019

Readers may recall that at the end of each calendar as opposed to fiscal year—I know it is hard to believe time exists outside the Federal system—Federal Practitioner publishes my ethics-focused version of the familiar year-end roundup. This year I am reversing the typical order of most annual rankings by putting the worst first for 2 morally salient reasons.

The first is that, sadly, it is almost always easier to identify multiple incidents that compete ignominiously for the “worst” of federal health care. Even more disappointing, it is comparatively difficult to find stories for the “best” that are of the same scale and scope as the bad news. This is not to say that every day there are not individual narratives of courage and compassion reported in US Department of Defense, US Public Health Service, and US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and hundreds more unsung heroes.

The second reason is that as human beings our psychology is such that we gravitate toward the worst things more powerfully and persistently than we do the best. This is in part why it is more difficult to find uplifting stories and why the demoralizing ones affect us so strongly. In an exhaustive review of the subject, psychologists Roy Baumeister and colleagues conclude that,

When equal measures of good and bad are present, however, the psychological effects of bad ones outweigh those of the good ones. This may in fact be a general principle or law of psychological phenomena, possibly reflecting the innate predispositions of the psyche or at least reflecting the almost inevitable adaptation of each individual to the exigencies of daily life.2

I am thus saving the best for last in the hope that it will be more memorable and impactful than the worst.

Unique to this year’s look-back, both the negative and the positive accounts come from the domain of end-of-life care. And unlike prior reviews where the lack of administrative vigilance and professional competence affected hundreds of patients, families, and staff, each of this year’s incidents involve a single patient.

An incident that occurred in September 2019 at a VA Community Living Center (CLC) in Georgia stood out in infamy apart from all others. It was the report of a veteran in a VA nursing home who had been bitten more than 100 times by ants crawling all over his room. He died shortly afterward. In a scene out of a horror movie tapping into the most primeval human fears, his daughter Laquana Ross described her father, a Vietnam Air Force veteran with cancer, to media and VA officials in graphic terms. “I understand mistakes happen,” she said. “I’ve had ants. But he was bit by ants two days in a row. They feasted on him.”3

In this new era of holding its senior executive service accountable, the outraged chair of the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee demanded that heads roll, and the VA acted rapidly to comply.4 The VA Central Office placed the network director on administrative leave, reassigned the chief medical officer, and initiated quality and safety reviews as well as an administrative investigative board to scrutinize how the parent Atlanta VA medical center managed the situation. In total, 9 officials connected to the incident were placed on leave. The VA apologized, with VA Secretary Robert Wilke zeroing in on the core values involved in the tragedy, “This is about basic humanity and dignity,” he said. “I don’t care what steps were taken to address the issues. We did not treat a vet with the dignity that he and his family deserved.”5 Yet it was the veteran’s daughter, with unbelievable charity, who asked the most crucial question that must be answered within the framework of a just culture if similar tragedies are not to occur in the future, “I know the staff, without a shadow of doubt, respected my dad and even loved him,” Ross said. “But what’s their ability to assess situations and fix things?”3

To begin to give Ms. Ross the answer she deserves, we must understand that the antithesis of love is not hate but indifference; of compassion, it is not cruelty but coldness. A true just culture reserves individual blame for those who have ill-will and adopts a systems perspective of organizational improvement toward most other types of errors.6 This means that the deplorable conditions in the CLC cannot be charged to the failure of a single staff member to fulfil their obligations but to collective collapse at many levels of the organization. Just culture is ethically laudable and far superior to the history in federal service of capricious punishment or institutional apathy that far too often were the default reactions to media exposures or congressional ire. Justice, though necessary, is not sufficient to achieve virtue. Those who work in health care also must be inspired to offer mercy, kindness, and compassion, especially in our most sacred privilege to provide care of the dying.

The best of 2019 illustrates this distinction movingly. This account also involves a Vietnam veteran, this time a Marine also dying of cancer, which happened just about a month after the earlier report. To be transparent it occurred at my home VA medical center in New Mexico. I was peripherally involved in the case as a consultant but had no role in the wondrous things that transpired. The last wish of a patient dying in the hospice unit on campus was to see his beloved dog who had been taken to the local city animal shelter when he was hospitalized because he had no friends or family to look after the companion animal. A social worker on the palliative care team called the animal shelter and explained the patient did not have much time left but wanted to see his dog before he died. Working together with support from facility leadership, shelter workers brought the dog to visit with the patient for an entire day while hospice staff cried with joy and sadness.7

As the epigraph for this editorial from Dame Cicely Saunders, the founder of the modern hospice movement, says, the difference between unspeakable pain and meaningful suffering can be measured in the depth of compassion caregivers show to the dying. It is this quality of mercy that in one case condemns, and in the other praises, us all as health care and administrative professionals in the service of our country. Baumeister and colleagues suggest that the human tendency to magnify the bad and minimize the good in everyday myopia may in a wider vision actually be a reason for hope:

It may be that humans and animals show heightened awareness of and responded more quickly to negative information because it signals a need for change. Hence, the adaptiveness of self-regulation partly lies in the organism’s ability to detect when response modifications are necessary and when they are unnecessary. Moreover, the lessons learned from bad events should ideally be retained permanently so that the same dangers or costs are not encountered repeatedly. Meanwhile, good events (such as those that provide a feeling of satisfaction and contentment) should ideally wear off so that the organism is motivated to continue searching for more and better outcomes.2

Let us all take this lesson into our work in 2020 so that when it comes time to write this column next year in the chilling cold of late autumn there will be more stories of light than darkness from which to choose.

1. Saunders C. The management of patients in the terminal stage. In: Raven R, ed. Cancer, Vol. 6. London: Butterworth and Company; 1960:403-417.

2. Baumeister RF, Bratslavasky E, Finkenauer C, Vohs KD. Bad is stronger than good. Rev General Psychol. 2001;5(4);323-370.

3. Knowles H. ‘They feasted on him’: Ants at VA nursing home bite a veteran 100 times before his death, daughter says. Washington Post. September 17, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2019/09/13/they-feasted-him-ants-va-nursing-home-bit-veteran-times-before-his-death-daughter-says. Accessed November 25, 2019.

4. Axelrod T. GOP senator presses VA after veteran reportedly bitten by ants in nursing home. https://thehill.com/homenews/senate/461196-gop-senator-presses-va-after-veteran-reportedly-bitten-by-ants-at-nursing. Published September 12, 2019. Accessed November 25, 2019.

5. Kime P. Nine VA leaders, staff placed on leave amid anti-bite scandal. https://www.military.com/daily-news/2019/09/17/nine-va-leaders-staff-placed-leave-amid-ant-bite-scandal.html. Published September 17, 2019. Accessed November 22, 2019.

6. Sculli GL, Hemphill R. Culture of safety and just culture. https://www.patientsafety.va.gov/docs/joe/just_culture_2013_tagged.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2019.

7. Hughes M. A Vietnam veteran in hospice care got to see his beloved dog one last time. https://www.cnn.com/2019/10/21/us/veteran-dying-wish-dog-trnd/index.html. Published October 21, 2019. Accessed November 22, 2019.

Readers may recall that at the end of each calendar as opposed to fiscal year—I know it is hard to believe time exists outside the Federal system—Federal Practitioner publishes my ethics-focused version of the familiar year-end roundup. This year I am reversing the typical order of most annual rankings by putting the worst first for 2 morally salient reasons.

The first is that, sadly, it is almost always easier to identify multiple incidents that compete ignominiously for the “worst” of federal health care. Even more disappointing, it is comparatively difficult to find stories for the “best” that are of the same scale and scope as the bad news. This is not to say that every day there are not individual narratives of courage and compassion reported in US Department of Defense, US Public Health Service, and US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and hundreds more unsung heroes.

The second reason is that as human beings our psychology is such that we gravitate toward the worst things more powerfully and persistently than we do the best. This is in part why it is more difficult to find uplifting stories and why the demoralizing ones affect us so strongly. In an exhaustive review of the subject, psychologists Roy Baumeister and colleagues conclude that,

When equal measures of good and bad are present, however, the psychological effects of bad ones outweigh those of the good ones. This may in fact be a general principle or law of psychological phenomena, possibly reflecting the innate predispositions of the psyche or at least reflecting the almost inevitable adaptation of each individual to the exigencies of daily life.2

I am thus saving the best for last in the hope that it will be more memorable and impactful than the worst.

Unique to this year’s look-back, both the negative and the positive accounts come from the domain of end-of-life care. And unlike prior reviews where the lack of administrative vigilance and professional competence affected hundreds of patients, families, and staff, each of this year’s incidents involve a single patient.

An incident that occurred in September 2019 at a VA Community Living Center (CLC) in Georgia stood out in infamy apart from all others. It was the report of a veteran in a VA nursing home who had been bitten more than 100 times by ants crawling all over his room. He died shortly afterward. In a scene out of a horror movie tapping into the most primeval human fears, his daughter Laquana Ross described her father, a Vietnam Air Force veteran with cancer, to media and VA officials in graphic terms. “I understand mistakes happen,” she said. “I’ve had ants. But he was bit by ants two days in a row. They feasted on him.”3

In this new era of holding its senior executive service accountable, the outraged chair of the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee demanded that heads roll, and the VA acted rapidly to comply.4 The VA Central Office placed the network director on administrative leave, reassigned the chief medical officer, and initiated quality and safety reviews as well as an administrative investigative board to scrutinize how the parent Atlanta VA medical center managed the situation. In total, 9 officials connected to the incident were placed on leave. The VA apologized, with VA Secretary Robert Wilke zeroing in on the core values involved in the tragedy, “This is about basic humanity and dignity,” he said. “I don’t care what steps were taken to address the issues. We did not treat a vet with the dignity that he and his family deserved.”5 Yet it was the veteran’s daughter, with unbelievable charity, who asked the most crucial question that must be answered within the framework of a just culture if similar tragedies are not to occur in the future, “I know the staff, without a shadow of doubt, respected my dad and even loved him,” Ross said. “But what’s their ability to assess situations and fix things?”3

To begin to give Ms. Ross the answer she deserves, we must understand that the antithesis of love is not hate but indifference; of compassion, it is not cruelty but coldness. A true just culture reserves individual blame for those who have ill-will and adopts a systems perspective of organizational improvement toward most other types of errors.6 This means that the deplorable conditions in the CLC cannot be charged to the failure of a single staff member to fulfil their obligations but to collective collapse at many levels of the organization. Just culture is ethically laudable and far superior to the history in federal service of capricious punishment or institutional apathy that far too often were the default reactions to media exposures or congressional ire. Justice, though necessary, is not sufficient to achieve virtue. Those who work in health care also must be inspired to offer mercy, kindness, and compassion, especially in our most sacred privilege to provide care of the dying.

The best of 2019 illustrates this distinction movingly. This account also involves a Vietnam veteran, this time a Marine also dying of cancer, which happened just about a month after the earlier report. To be transparent it occurred at my home VA medical center in New Mexico. I was peripherally involved in the case as a consultant but had no role in the wondrous things that transpired. The last wish of a patient dying in the hospice unit on campus was to see his beloved dog who had been taken to the local city animal shelter when he was hospitalized because he had no friends or family to look after the companion animal. A social worker on the palliative care team called the animal shelter and explained the patient did not have much time left but wanted to see his dog before he died. Working together with support from facility leadership, shelter workers brought the dog to visit with the patient for an entire day while hospice staff cried with joy and sadness.7

As the epigraph for this editorial from Dame Cicely Saunders, the founder of the modern hospice movement, says, the difference between unspeakable pain and meaningful suffering can be measured in the depth of compassion caregivers show to the dying. It is this quality of mercy that in one case condemns, and in the other praises, us all as health care and administrative professionals in the service of our country. Baumeister and colleagues suggest that the human tendency to magnify the bad and minimize the good in everyday myopia may in a wider vision actually be a reason for hope:

It may be that humans and animals show heightened awareness of and responded more quickly to negative information because it signals a need for change. Hence, the adaptiveness of self-regulation partly lies in the organism’s ability to detect when response modifications are necessary and when they are unnecessary. Moreover, the lessons learned from bad events should ideally be retained permanently so that the same dangers or costs are not encountered repeatedly. Meanwhile, good events (such as those that provide a feeling of satisfaction and contentment) should ideally wear off so that the organism is motivated to continue searching for more and better outcomes.2

Let us all take this lesson into our work in 2020 so that when it comes time to write this column next year in the chilling cold of late autumn there will be more stories of light than darkness from which to choose.

Readers may recall that at the end of each calendar as opposed to fiscal year—I know it is hard to believe time exists outside the Federal system—Federal Practitioner publishes my ethics-focused version of the familiar year-end roundup. This year I am reversing the typical order of most annual rankings by putting the worst first for 2 morally salient reasons.

The first is that, sadly, it is almost always easier to identify multiple incidents that compete ignominiously for the “worst” of federal health care. Even more disappointing, it is comparatively difficult to find stories for the “best” that are of the same scale and scope as the bad news. This is not to say that every day there are not individual narratives of courage and compassion reported in US Department of Defense, US Public Health Service, and US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and hundreds more unsung heroes.

The second reason is that as human beings our psychology is such that we gravitate toward the worst things more powerfully and persistently than we do the best. This is in part why it is more difficult to find uplifting stories and why the demoralizing ones affect us so strongly. In an exhaustive review of the subject, psychologists Roy Baumeister and colleagues conclude that,

When equal measures of good and bad are present, however, the psychological effects of bad ones outweigh those of the good ones. This may in fact be a general principle or law of psychological phenomena, possibly reflecting the innate predispositions of the psyche or at least reflecting the almost inevitable adaptation of each individual to the exigencies of daily life.2

I am thus saving the best for last in the hope that it will be more memorable and impactful than the worst.

Unique to this year’s look-back, both the negative and the positive accounts come from the domain of end-of-life care. And unlike prior reviews where the lack of administrative vigilance and professional competence affected hundreds of patients, families, and staff, each of this year’s incidents involve a single patient.

An incident that occurred in September 2019 at a VA Community Living Center (CLC) in Georgia stood out in infamy apart from all others. It was the report of a veteran in a VA nursing home who had been bitten more than 100 times by ants crawling all over his room. He died shortly afterward. In a scene out of a horror movie tapping into the most primeval human fears, his daughter Laquana Ross described her father, a Vietnam Air Force veteran with cancer, to media and VA officials in graphic terms. “I understand mistakes happen,” she said. “I’ve had ants. But he was bit by ants two days in a row. They feasted on him.”3

In this new era of holding its senior executive service accountable, the outraged chair of the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee demanded that heads roll, and the VA acted rapidly to comply.4 The VA Central Office placed the network director on administrative leave, reassigned the chief medical officer, and initiated quality and safety reviews as well as an administrative investigative board to scrutinize how the parent Atlanta VA medical center managed the situation. In total, 9 officials connected to the incident were placed on leave. The VA apologized, with VA Secretary Robert Wilke zeroing in on the core values involved in the tragedy, “This is about basic humanity and dignity,” he said. “I don’t care what steps were taken to address the issues. We did not treat a vet with the dignity that he and his family deserved.”5 Yet it was the veteran’s daughter, with unbelievable charity, who asked the most crucial question that must be answered within the framework of a just culture if similar tragedies are not to occur in the future, “I know the staff, without a shadow of doubt, respected my dad and even loved him,” Ross said. “But what’s their ability to assess situations and fix things?”3

To begin to give Ms. Ross the answer she deserves, we must understand that the antithesis of love is not hate but indifference; of compassion, it is not cruelty but coldness. A true just culture reserves individual blame for those who have ill-will and adopts a systems perspective of organizational improvement toward most other types of errors.6 This means that the deplorable conditions in the CLC cannot be charged to the failure of a single staff member to fulfil their obligations but to collective collapse at many levels of the organization. Just culture is ethically laudable and far superior to the history in federal service of capricious punishment or institutional apathy that far too often were the default reactions to media exposures or congressional ire. Justice, though necessary, is not sufficient to achieve virtue. Those who work in health care also must be inspired to offer mercy, kindness, and compassion, especially in our most sacred privilege to provide care of the dying.

The best of 2019 illustrates this distinction movingly. This account also involves a Vietnam veteran, this time a Marine also dying of cancer, which happened just about a month after the earlier report. To be transparent it occurred at my home VA medical center in New Mexico. I was peripherally involved in the case as a consultant but had no role in the wondrous things that transpired. The last wish of a patient dying in the hospice unit on campus was to see his beloved dog who had been taken to the local city animal shelter when he was hospitalized because he had no friends or family to look after the companion animal. A social worker on the palliative care team called the animal shelter and explained the patient did not have much time left but wanted to see his dog before he died. Working together with support from facility leadership, shelter workers brought the dog to visit with the patient for an entire day while hospice staff cried with joy and sadness.7

As the epigraph for this editorial from Dame Cicely Saunders, the founder of the modern hospice movement, says, the difference between unspeakable pain and meaningful suffering can be measured in the depth of compassion caregivers show to the dying. It is this quality of mercy that in one case condemns, and in the other praises, us all as health care and administrative professionals in the service of our country. Baumeister and colleagues suggest that the human tendency to magnify the bad and minimize the good in everyday myopia may in a wider vision actually be a reason for hope:

It may be that humans and animals show heightened awareness of and responded more quickly to negative information because it signals a need for change. Hence, the adaptiveness of self-regulation partly lies in the organism’s ability to detect when response modifications are necessary and when they are unnecessary. Moreover, the lessons learned from bad events should ideally be retained permanently so that the same dangers or costs are not encountered repeatedly. Meanwhile, good events (such as those that provide a feeling of satisfaction and contentment) should ideally wear off so that the organism is motivated to continue searching for more and better outcomes.2

Let us all take this lesson into our work in 2020 so that when it comes time to write this column next year in the chilling cold of late autumn there will be more stories of light than darkness from which to choose.

1. Saunders C. The management of patients in the terminal stage. In: Raven R, ed. Cancer, Vol. 6. London: Butterworth and Company; 1960:403-417.

2. Baumeister RF, Bratslavasky E, Finkenauer C, Vohs KD. Bad is stronger than good. Rev General Psychol. 2001;5(4);323-370.

3. Knowles H. ‘They feasted on him’: Ants at VA nursing home bite a veteran 100 times before his death, daughter says. Washington Post. September 17, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2019/09/13/they-feasted-him-ants-va-nursing-home-bit-veteran-times-before-his-death-daughter-says. Accessed November 25, 2019.

4. Axelrod T. GOP senator presses VA after veteran reportedly bitten by ants in nursing home. https://thehill.com/homenews/senate/461196-gop-senator-presses-va-after-veteran-reportedly-bitten-by-ants-at-nursing. Published September 12, 2019. Accessed November 25, 2019.

5. Kime P. Nine VA leaders, staff placed on leave amid anti-bite scandal. https://www.military.com/daily-news/2019/09/17/nine-va-leaders-staff-placed-leave-amid-ant-bite-scandal.html. Published September 17, 2019. Accessed November 22, 2019.

6. Sculli GL, Hemphill R. Culture of safety and just culture. https://www.patientsafety.va.gov/docs/joe/just_culture_2013_tagged.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2019.

7. Hughes M. A Vietnam veteran in hospice care got to see his beloved dog one last time. https://www.cnn.com/2019/10/21/us/veteran-dying-wish-dog-trnd/index.html. Published October 21, 2019. Accessed November 22, 2019.

1. Saunders C. The management of patients in the terminal stage. In: Raven R, ed. Cancer, Vol. 6. London: Butterworth and Company; 1960:403-417.

2. Baumeister RF, Bratslavasky E, Finkenauer C, Vohs KD. Bad is stronger than good. Rev General Psychol. 2001;5(4);323-370.

3. Knowles H. ‘They feasted on him’: Ants at VA nursing home bite a veteran 100 times before his death, daughter says. Washington Post. September 17, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2019/09/13/they-feasted-him-ants-va-nursing-home-bit-veteran-times-before-his-death-daughter-says. Accessed November 25, 2019.

4. Axelrod T. GOP senator presses VA after veteran reportedly bitten by ants in nursing home. https://thehill.com/homenews/senate/461196-gop-senator-presses-va-after-veteran-reportedly-bitten-by-ants-at-nursing. Published September 12, 2019. Accessed November 25, 2019.

5. Kime P. Nine VA leaders, staff placed on leave amid anti-bite scandal. https://www.military.com/daily-news/2019/09/17/nine-va-leaders-staff-placed-leave-amid-ant-bite-scandal.html. Published September 17, 2019. Accessed November 22, 2019.

6. Sculli GL, Hemphill R. Culture of safety and just culture. https://www.patientsafety.va.gov/docs/joe/just_culture_2013_tagged.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2019.

7. Hughes M. A Vietnam veteran in hospice care got to see his beloved dog one last time. https://www.cnn.com/2019/10/21/us/veteran-dying-wish-dog-trnd/index.html. Published October 21, 2019. Accessed November 22, 2019.

Bariatric surgery should be considered in individuals with class 1 obesity

Mitchel L. Zoler’s article on Abstract A105, presented at Obesity Week 2019, addresses an important health concern and is timely.

Over the past 4 decades we have seen a rise in the prevalence of obesity and associated health complications, not just in the United States but across the world. The incidence of obesity (having a BMI greater than 30) was 35% for women and 31% for men in the United States, and associated deaths and disability were primarily attributed to diabetes and cardiovascular disease resulting from obesity.

This article references the benefits of bariatric/metabolic surgery in individuals with class 1 obesity. In the United States, more than half of those who meet the criteria for obesity come under the class 1 category (BMI, 30-34.9). Those in this class of obesity are at increased risk of developing diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, obstructive sleep apnea, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and bone and joint disorders.

There are several studies that document the significant reduction in incidence of the above cardiometabolic risks with sustained weight loss. Nonsurgical interventions in individuals with class 1 obesity through lifestyle modifications and pharmacotherapy have not demonstrated success in providing persistent weight loss or metabolic benefits. The data presented in this article are of great significance to patients and physicians alike as they highlight the long-term benefits and reversal of metabolic disorders.

Current guidelines for bariatric surgery for individuals with a BMI greater than 35 were published in 1991. Since then several safe surgical options including laparoscopic procedures, sleeve gastrectomy, and adjustable gastric banding have been developed with decreased surgical risks, morbidity, and mortality.

The International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders, the International Diabetes Federation, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence of the United Kingdom, have supported the option of bariatric surgery in class 1 obese individuals with metabolic disorders.

While lifestyle modifications with medications should be the first-line treatment for class 1 obesity, as a primary care physician I believe that, given the major changes in the surgical options, the proven long-term benefits, and the rising incidences of obesity and metabolic syndrome, it is time for the health care community, insurers, patients, and all other stakeholders to consider bariatric surgery in class 1 obese individuals as a potential and viable option.

Noel N. Deep, MD, is a general internist in a multispecialty group practice with Aspirus Antigo (Wis.) Clinic and the chief medical officer and a staff physician at Aspirus Langlade Hospital in Antigo. He is also assistant clinical professor at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Central Wisconsin Campus, Wausau, and the governor of the Wisconsin chapter of the American College of Physicians. Dr. Deep serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News.

He made these comments in response to questions from MDedge and had no relevant disclosures.

Mitchel L. Zoler’s article on Abstract A105, presented at Obesity Week 2019, addresses an important health concern and is timely.

Over the past 4 decades we have seen a rise in the prevalence of obesity and associated health complications, not just in the United States but across the world. The incidence of obesity (having a BMI greater than 30) was 35% for women and 31% for men in the United States, and associated deaths and disability were primarily attributed to diabetes and cardiovascular disease resulting from obesity.

This article references the benefits of bariatric/metabolic surgery in individuals with class 1 obesity. In the United States, more than half of those who meet the criteria for obesity come under the class 1 category (BMI, 30-34.9). Those in this class of obesity are at increased risk of developing diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, obstructive sleep apnea, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and bone and joint disorders.

There are several studies that document the significant reduction in incidence of the above cardiometabolic risks with sustained weight loss. Nonsurgical interventions in individuals with class 1 obesity through lifestyle modifications and pharmacotherapy have not demonstrated success in providing persistent weight loss or metabolic benefits. The data presented in this article are of great significance to patients and physicians alike as they highlight the long-term benefits and reversal of metabolic disorders.

Current guidelines for bariatric surgery for individuals with a BMI greater than 35 were published in 1991. Since then several safe surgical options including laparoscopic procedures, sleeve gastrectomy, and adjustable gastric banding have been developed with decreased surgical risks, morbidity, and mortality.

The International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders, the International Diabetes Federation, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence of the United Kingdom, have supported the option of bariatric surgery in class 1 obese individuals with metabolic disorders.

While lifestyle modifications with medications should be the first-line treatment for class 1 obesity, as a primary care physician I believe that, given the major changes in the surgical options, the proven long-term benefits, and the rising incidences of obesity and metabolic syndrome, it is time for the health care community, insurers, patients, and all other stakeholders to consider bariatric surgery in class 1 obese individuals as a potential and viable option.

Noel N. Deep, MD, is a general internist in a multispecialty group practice with Aspirus Antigo (Wis.) Clinic and the chief medical officer and a staff physician at Aspirus Langlade Hospital in Antigo. He is also assistant clinical professor at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Central Wisconsin Campus, Wausau, and the governor of the Wisconsin chapter of the American College of Physicians. Dr. Deep serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News.

He made these comments in response to questions from MDedge and had no relevant disclosures.

Mitchel L. Zoler’s article on Abstract A105, presented at Obesity Week 2019, addresses an important health concern and is timely.

Over the past 4 decades we have seen a rise in the prevalence of obesity and associated health complications, not just in the United States but across the world. The incidence of obesity (having a BMI greater than 30) was 35% for women and 31% for men in the United States, and associated deaths and disability were primarily attributed to diabetes and cardiovascular disease resulting from obesity.

This article references the benefits of bariatric/metabolic surgery in individuals with class 1 obesity. In the United States, more than half of those who meet the criteria for obesity come under the class 1 category (BMI, 30-34.9). Those in this class of obesity are at increased risk of developing diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, obstructive sleep apnea, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and bone and joint disorders.

There are several studies that document the significant reduction in incidence of the above cardiometabolic risks with sustained weight loss. Nonsurgical interventions in individuals with class 1 obesity through lifestyle modifications and pharmacotherapy have not demonstrated success in providing persistent weight loss or metabolic benefits. The data presented in this article are of great significance to patients and physicians alike as they highlight the long-term benefits and reversal of metabolic disorders.

Current guidelines for bariatric surgery for individuals with a BMI greater than 35 were published in 1991. Since then several safe surgical options including laparoscopic procedures, sleeve gastrectomy, and adjustable gastric banding have been developed with decreased surgical risks, morbidity, and mortality.

The International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders, the International Diabetes Federation, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence of the United Kingdom, have supported the option of bariatric surgery in class 1 obese individuals with metabolic disorders.

While lifestyle modifications with medications should be the first-line treatment for class 1 obesity, as a primary care physician I believe that, given the major changes in the surgical options, the proven long-term benefits, and the rising incidences of obesity and metabolic syndrome, it is time for the health care community, insurers, patients, and all other stakeholders to consider bariatric surgery in class 1 obese individuals as a potential and viable option.

Noel N. Deep, MD, is a general internist in a multispecialty group practice with Aspirus Antigo (Wis.) Clinic and the chief medical officer and a staff physician at Aspirus Langlade Hospital in Antigo. He is also assistant clinical professor at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Central Wisconsin Campus, Wausau, and the governor of the Wisconsin chapter of the American College of Physicians. Dr. Deep serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News.

He made these comments in response to questions from MDedge and had no relevant disclosures.

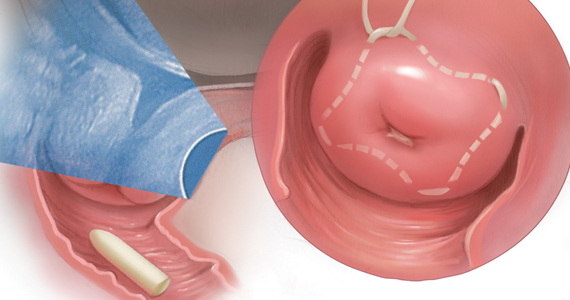

Progesterone supplementation does not PROLONG pregnancy in women at risk for preterm birth: What do we do now?

Preterm birth (PTB) remains a significant public health concern and a major cause of newborn morbidity and mortality. In the United States, 1 in 10 babies are born preterm (< 37 weeks), and this rate has changed little in 30 years.1

In 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved progesterone supplementation—specifically, α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P) injection (Makena)—to prevent recurrent PTB in women with a singleton pregnancy at high risk by virtue of a prior spontaneous PTB.2 This was the first-ever FDA-approved drug for PTB prevention, and it was the first drug approved by the FDA for use in pregnancy in more than 15 years. The approval of 17P utilized the FDA's Subpart H Accelerated Approval Pathway, which applies to therapies that: 1) treat serious conditions with unmet need, and 2) demonstrate safety and efficacy on surrogate end points reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit.3

By voting their approval of 17P in 2011, the FDA affirmed that PTB was a serious condition with unmet need, that birth < 37 weeks was an accepted surrogate end point, and that there was compelling evidence of safety and benefit. The compelling evidence presented was a single, randomized, vehicle-controlled clinical trial conducted by the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network, which showed significant reduction in recurrent PTB < 37 weeks (from 54.9% in the placebo group to 36.3% in the 17P group; P<.001; relative risk [RR], 0.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.81).4

In 2017, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) reaffirmed the use of 17P to prevent recurrent PTB and, that same year, it was estimated that 75% of eligible patients received 17P.5,6 Importantly, Subpart H approval requires one or more follow-up clinical trials confirming safety and efficacy. And the FDA has the right—the responsibility—to revisit approval if such trials are either not performed or are unfavorable.

The recently published PROLONG study by Blackwell and colleagues is this required postapproval confirmatory trial conducted to verify the clinical benefit of 17P supplementation.7

Continue to: Study design, and stunning results...

Study design, and stunning results

PROLONG (Progestin's Role in Optimizing Neonatal Gestation) was a randomized (2:1), double-blind, vehicle-controlled, multicenter international trial (2009-2018) conducted to assess the safety and efficacy of 17P injection in 1,708 women with a singleton pregnancy and one or more prior spontaneous PTBs.7 Women in the active treatment group (n = 1,130) received weekly intramuscular injections of 17P, while those in the control group (n = 578) received weekly injections of inert oil vehicle.

Results of the trial showed no significant reduction in the co-primary end points, which were PTB < 35 weeks (11.0% in the 17P group vs 11.5% in the placebo group; RR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.71-1.26) and neonatal morbidity index (5.6% in the 17P group vs 5.0% in the placebo group; RR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.68-1.61). There was no evidence of benefit for any subpopulation (geographic region, race, or other PTB risk factor). Maternal outcomes also were similar between the groups. No significant safety concerns were identified.

Important differences between MFMU and PROLONG trials

Strengths of the PROLONG trial include its randomized, placebo-controlled design, excellent follow-up rate, and use of a protocol that mirrored that of the MFMU trial. The primary limitation of PROLONG is that participants experienced a lower rate of PTB compared with those in the MFMU trial. The rate of PTB < 37 weeks was 54.9% in the control group of the MFMU trial compared with 21.9% in PROLONG.

Given the low rate of PTB in PROLONG, the study was underpowered for the co-primary outcomes. In addition, lower rates of PTB in PROLONG compared with in the MFMU trial likely reflected different patient populations.8 Moreover, PROLONG was an international trial. Of the 1,708 participants, most were recruited in Russia (36%) and Ukraine (25%); only 23% were from the United States. By contrast, participants in the MFMU trial were recruited from US academic medical centers. Also, participants in the MFMU trial were significantly more likely to have a short cervix, to have a history of more than one PTB, and to be African American.

Discrepant trial results create clinical quandary

In October 2019, the FDA's Bone, Reproductive and Urologic Drugs Advisory Committee voted 9-7 to withdraw approval for 17P. Committee members struggled with the conflicting data between the 2 trials and hesitated to remove a medication whose use has become standard practice. Ultimately, however, it was lack of substantial evidence of effectiveness of 17P that swayed the committee's vote. While the FDA generally follows the recommendation of an advisory committee, it is not bound to do so.

Societies' perspectives

So what are physicians and patients to do? It is possible that a small subgroup of women at extremely high risk for early PTB may benefit from 17P administration. SMFM stated: "...it is reasonable for providers to use 17-OHPC [17P] in women with a profile more representative of the very high-risk population reported in the Meis [MFMU] trial."8 Further, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) stated in a Practice Advisory dated October 25, 2019, that "ACOG is not changing our clinical recommendations at this time... [We] will be reviewing subsequent forthcoming analyses and will issue updated clinical guidance as appropriate."9

Where we stand on 17P use going forward

17P should be available to women who previously may have benefited from its use. However, 17P should not be recommended routinely to prevent recurrent spontaneous PTB in women with one prior PTB and no other risk factors. Of note, the PROLONG trial does not change recommendations for cervical length screening. Women with a history of a prior spontaneous PTB should undergo cervical length screening to identify those individuals who may benefit from an ultrasound-indicated cerclage.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins--Obstetrics. ACOG practice bulletin no. 127: Management of preterm labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:1308-1317.

- Makena [package insert]. Waltham, MA: AMAG Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2018. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/021945s012lbl.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2019.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Code of Federal Regulations Title 21. Subpart H--Acceleratedapproval of new drugs for serious or life-threatening illnesses. April 1, 2019. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=314&showFR=1&subpartNode=21:5.0.1.1.4.8. Accessed November 10, 2019.

- Meis PJ, Klebanoff M, Thom E, et al; for the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Prevention of recurrent preterm delivery by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2379-2385.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Publications Committee. The choice of progestogen for the prevention of preterm birth in women with singleton pregnancy and prior preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:B11-B13.

- Gallagher JR, Gudeman J, Heap K, et al. Understanding if, how, and why women with prior spontaneous preterm births are treated with progestogens: a national survey of obstetrician practice patterns. AJP Rep. 2018;8:e315-e324.

- Blackwell SC, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Biggio JR Jr, et al. 17-OHPC to prevent recurrent preterm birth in singleton gestations (PROLONG study): a multicenter, international, randomized double-blind trial. Am J Perinatol. 2019. doi:10.1055/s-0039-3400227.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Publications Committee. SMFM statement: Use of 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate for prevention of recurrent preterm birth. https://els-jbs-prod-cdn.literatumonline.com/pb/assets/raw/Health%20Advance/journals/ymob/SMFM_Statement_PRO LONG-1572023839767.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2019.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice advisory: Clinical guidance for integration of the findings of the PROLONG study: progestin's role in optimizing neonatal gestation. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Practice-Advisories/Clinical-guidance-for-integration-of-the-findings-of-The-PROLONG-study-Progestins-Role-in-Optimizing?IsMobileSet=false. Accessed November 10, 2019.

Preterm birth (PTB) remains a significant public health concern and a major cause of newborn morbidity and mortality. In the United States, 1 in 10 babies are born preterm (< 37 weeks), and this rate has changed little in 30 years.1

In 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved progesterone supplementation—specifically, α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P) injection (Makena)—to prevent recurrent PTB in women with a singleton pregnancy at high risk by virtue of a prior spontaneous PTB.2 This was the first-ever FDA-approved drug for PTB prevention, and it was the first drug approved by the FDA for use in pregnancy in more than 15 years. The approval of 17P utilized the FDA's Subpart H Accelerated Approval Pathway, which applies to therapies that: 1) treat serious conditions with unmet need, and 2) demonstrate safety and efficacy on surrogate end points reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit.3

By voting their approval of 17P in 2011, the FDA affirmed that PTB was a serious condition with unmet need, that birth < 37 weeks was an accepted surrogate end point, and that there was compelling evidence of safety and benefit. The compelling evidence presented was a single, randomized, vehicle-controlled clinical trial conducted by the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network, which showed significant reduction in recurrent PTB < 37 weeks (from 54.9% in the placebo group to 36.3% in the 17P group; P<.001; relative risk [RR], 0.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.81).4

In 2017, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) reaffirmed the use of 17P to prevent recurrent PTB and, that same year, it was estimated that 75% of eligible patients received 17P.5,6 Importantly, Subpart H approval requires one or more follow-up clinical trials confirming safety and efficacy. And the FDA has the right—the responsibility—to revisit approval if such trials are either not performed or are unfavorable.

The recently published PROLONG study by Blackwell and colleagues is this required postapproval confirmatory trial conducted to verify the clinical benefit of 17P supplementation.7

Continue to: Study design, and stunning results...

Study design, and stunning results

PROLONG (Progestin's Role in Optimizing Neonatal Gestation) was a randomized (2:1), double-blind, vehicle-controlled, multicenter international trial (2009-2018) conducted to assess the safety and efficacy of 17P injection in 1,708 women with a singleton pregnancy and one or more prior spontaneous PTBs.7 Women in the active treatment group (n = 1,130) received weekly intramuscular injections of 17P, while those in the control group (n = 578) received weekly injections of inert oil vehicle.

Results of the trial showed no significant reduction in the co-primary end points, which were PTB < 35 weeks (11.0% in the 17P group vs 11.5% in the placebo group; RR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.71-1.26) and neonatal morbidity index (5.6% in the 17P group vs 5.0% in the placebo group; RR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.68-1.61). There was no evidence of benefit for any subpopulation (geographic region, race, or other PTB risk factor). Maternal outcomes also were similar between the groups. No significant safety concerns were identified.

Important differences between MFMU and PROLONG trials

Strengths of the PROLONG trial include its randomized, placebo-controlled design, excellent follow-up rate, and use of a protocol that mirrored that of the MFMU trial. The primary limitation of PROLONG is that participants experienced a lower rate of PTB compared with those in the MFMU trial. The rate of PTB < 37 weeks was 54.9% in the control group of the MFMU trial compared with 21.9% in PROLONG.

Given the low rate of PTB in PROLONG, the study was underpowered for the co-primary outcomes. In addition, lower rates of PTB in PROLONG compared with in the MFMU trial likely reflected different patient populations.8 Moreover, PROLONG was an international trial. Of the 1,708 participants, most were recruited in Russia (36%) and Ukraine (25%); only 23% were from the United States. By contrast, participants in the MFMU trial were recruited from US academic medical centers. Also, participants in the MFMU trial were significantly more likely to have a short cervix, to have a history of more than one PTB, and to be African American.

Discrepant trial results create clinical quandary

In October 2019, the FDA's Bone, Reproductive and Urologic Drugs Advisory Committee voted 9-7 to withdraw approval for 17P. Committee members struggled with the conflicting data between the 2 trials and hesitated to remove a medication whose use has become standard practice. Ultimately, however, it was lack of substantial evidence of effectiveness of 17P that swayed the committee's vote. While the FDA generally follows the recommendation of an advisory committee, it is not bound to do so.

Societies' perspectives

So what are physicians and patients to do? It is possible that a small subgroup of women at extremely high risk for early PTB may benefit from 17P administration. SMFM stated: "...it is reasonable for providers to use 17-OHPC [17P] in women with a profile more representative of the very high-risk population reported in the Meis [MFMU] trial."8 Further, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) stated in a Practice Advisory dated October 25, 2019, that "ACOG is not changing our clinical recommendations at this time... [We] will be reviewing subsequent forthcoming analyses and will issue updated clinical guidance as appropriate."9

Where we stand on 17P use going forward

17P should be available to women who previously may have benefited from its use. However, 17P should not be recommended routinely to prevent recurrent spontaneous PTB in women with one prior PTB and no other risk factors. Of note, the PROLONG trial does not change recommendations for cervical length screening. Women with a history of a prior spontaneous PTB should undergo cervical length screening to identify those individuals who may benefit from an ultrasound-indicated cerclage.

Preterm birth (PTB) remains a significant public health concern and a major cause of newborn morbidity and mortality. In the United States, 1 in 10 babies are born preterm (< 37 weeks), and this rate has changed little in 30 years.1

In 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved progesterone supplementation—specifically, α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P) injection (Makena)—to prevent recurrent PTB in women with a singleton pregnancy at high risk by virtue of a prior spontaneous PTB.2 This was the first-ever FDA-approved drug for PTB prevention, and it was the first drug approved by the FDA for use in pregnancy in more than 15 years. The approval of 17P utilized the FDA's Subpart H Accelerated Approval Pathway, which applies to therapies that: 1) treat serious conditions with unmet need, and 2) demonstrate safety and efficacy on surrogate end points reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit.3

By voting their approval of 17P in 2011, the FDA affirmed that PTB was a serious condition with unmet need, that birth < 37 weeks was an accepted surrogate end point, and that there was compelling evidence of safety and benefit. The compelling evidence presented was a single, randomized, vehicle-controlled clinical trial conducted by the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network, which showed significant reduction in recurrent PTB < 37 weeks (from 54.9% in the placebo group to 36.3% in the 17P group; P<.001; relative risk [RR], 0.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.81).4

In 2017, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) reaffirmed the use of 17P to prevent recurrent PTB and, that same year, it was estimated that 75% of eligible patients received 17P.5,6 Importantly, Subpart H approval requires one or more follow-up clinical trials confirming safety and efficacy. And the FDA has the right—the responsibility—to revisit approval if such trials are either not performed or are unfavorable.

The recently published PROLONG study by Blackwell and colleagues is this required postapproval confirmatory trial conducted to verify the clinical benefit of 17P supplementation.7

Continue to: Study design, and stunning results...

Study design, and stunning results

PROLONG (Progestin's Role in Optimizing Neonatal Gestation) was a randomized (2:1), double-blind, vehicle-controlled, multicenter international trial (2009-2018) conducted to assess the safety and efficacy of 17P injection in 1,708 women with a singleton pregnancy and one or more prior spontaneous PTBs.7 Women in the active treatment group (n = 1,130) received weekly intramuscular injections of 17P, while those in the control group (n = 578) received weekly injections of inert oil vehicle.

Results of the trial showed no significant reduction in the co-primary end points, which were PTB < 35 weeks (11.0% in the 17P group vs 11.5% in the placebo group; RR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.71-1.26) and neonatal morbidity index (5.6% in the 17P group vs 5.0% in the placebo group; RR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.68-1.61). There was no evidence of benefit for any subpopulation (geographic region, race, or other PTB risk factor). Maternal outcomes also were similar between the groups. No significant safety concerns were identified.

Important differences between MFMU and PROLONG trials

Strengths of the PROLONG trial include its randomized, placebo-controlled design, excellent follow-up rate, and use of a protocol that mirrored that of the MFMU trial. The primary limitation of PROLONG is that participants experienced a lower rate of PTB compared with those in the MFMU trial. The rate of PTB < 37 weeks was 54.9% in the control group of the MFMU trial compared with 21.9% in PROLONG.

Given the low rate of PTB in PROLONG, the study was underpowered for the co-primary outcomes. In addition, lower rates of PTB in PROLONG compared with in the MFMU trial likely reflected different patient populations.8 Moreover, PROLONG was an international trial. Of the 1,708 participants, most were recruited in Russia (36%) and Ukraine (25%); only 23% were from the United States. By contrast, participants in the MFMU trial were recruited from US academic medical centers. Also, participants in the MFMU trial were significantly more likely to have a short cervix, to have a history of more than one PTB, and to be African American.

Discrepant trial results create clinical quandary

In October 2019, the FDA's Bone, Reproductive and Urologic Drugs Advisory Committee voted 9-7 to withdraw approval for 17P. Committee members struggled with the conflicting data between the 2 trials and hesitated to remove a medication whose use has become standard practice. Ultimately, however, it was lack of substantial evidence of effectiveness of 17P that swayed the committee's vote. While the FDA generally follows the recommendation of an advisory committee, it is not bound to do so.

Societies' perspectives

So what are physicians and patients to do? It is possible that a small subgroup of women at extremely high risk for early PTB may benefit from 17P administration. SMFM stated: "...it is reasonable for providers to use 17-OHPC [17P] in women with a profile more representative of the very high-risk population reported in the Meis [MFMU] trial."8 Further, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) stated in a Practice Advisory dated October 25, 2019, that "ACOG is not changing our clinical recommendations at this time... [We] will be reviewing subsequent forthcoming analyses and will issue updated clinical guidance as appropriate."9

Where we stand on 17P use going forward

17P should be available to women who previously may have benefited from its use. However, 17P should not be recommended routinely to prevent recurrent spontaneous PTB in women with one prior PTB and no other risk factors. Of note, the PROLONG trial does not change recommendations for cervical length screening. Women with a history of a prior spontaneous PTB should undergo cervical length screening to identify those individuals who may benefit from an ultrasound-indicated cerclage.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins--Obstetrics. ACOG practice bulletin no. 127: Management of preterm labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:1308-1317.

- Makena [package insert]. Waltham, MA: AMAG Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2018. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/021945s012lbl.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2019.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Code of Federal Regulations Title 21. Subpart H--Acceleratedapproval of new drugs for serious or life-threatening illnesses. April 1, 2019. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=314&showFR=1&subpartNode=21:5.0.1.1.4.8. Accessed November 10, 2019.

- Meis PJ, Klebanoff M, Thom E, et al; for the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Prevention of recurrent preterm delivery by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2379-2385.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Publications Committee. The choice of progestogen for the prevention of preterm birth in women with singleton pregnancy and prior preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:B11-B13.

- Gallagher JR, Gudeman J, Heap K, et al. Understanding if, how, and why women with prior spontaneous preterm births are treated with progestogens: a national survey of obstetrician practice patterns. AJP Rep. 2018;8:e315-e324.

- Blackwell SC, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Biggio JR Jr, et al. 17-OHPC to prevent recurrent preterm birth in singleton gestations (PROLONG study): a multicenter, international, randomized double-blind trial. Am J Perinatol. 2019. doi:10.1055/s-0039-3400227.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Publications Committee. SMFM statement: Use of 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate for prevention of recurrent preterm birth. https://els-jbs-prod-cdn.literatumonline.com/pb/assets/raw/Health%20Advance/journals/ymob/SMFM_Statement_PRO LONG-1572023839767.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2019.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice advisory: Clinical guidance for integration of the findings of the PROLONG study: progestin's role in optimizing neonatal gestation. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Practice-Advisories/Clinical-guidance-for-integration-of-the-findings-of-The-PROLONG-study-Progestins-Role-in-Optimizing?IsMobileSet=false. Accessed November 10, 2019.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins--Obstetrics. ACOG practice bulletin no. 127: Management of preterm labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:1308-1317.

- Makena [package insert]. Waltham, MA: AMAG Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2018. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/021945s012lbl.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2019.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Code of Federal Regulations Title 21. Subpart H--Acceleratedapproval of new drugs for serious or life-threatening illnesses. April 1, 2019. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=314&showFR=1&subpartNode=21:5.0.1.1.4.8. Accessed November 10, 2019.

- Meis PJ, Klebanoff M, Thom E, et al; for the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Prevention of recurrent preterm delivery by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2379-2385.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Publications Committee. The choice of progestogen for the prevention of preterm birth in women with singleton pregnancy and prior preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:B11-B13.

- Gallagher JR, Gudeman J, Heap K, et al. Understanding if, how, and why women with prior spontaneous preterm births are treated with progestogens: a national survey of obstetrician practice patterns. AJP Rep. 2018;8:e315-e324.

- Blackwell SC, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Biggio JR Jr, et al. 17-OHPC to prevent recurrent preterm birth in singleton gestations (PROLONG study): a multicenter, international, randomized double-blind trial. Am J Perinatol. 2019. doi:10.1055/s-0039-3400227.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Publications Committee. SMFM statement: Use of 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate for prevention of recurrent preterm birth. https://els-jbs-prod-cdn.literatumonline.com/pb/assets/raw/Health%20Advance/journals/ymob/SMFM_Statement_PRO LONG-1572023839767.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2019.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice advisory: Clinical guidance for integration of the findings of the PROLONG study: progestin's role in optimizing neonatal gestation. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Practice-Advisories/Clinical-guidance-for-integration-of-the-findings-of-The-PROLONG-study-Progestins-Role-in-Optimizing?IsMobileSet=false. Accessed November 10, 2019.

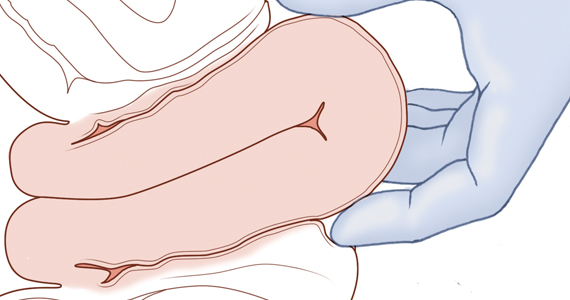

Retained placenta after vaginal birth: How long should you wait to manually remove the placenta?

You have just safely delivered the baby who is quietly resting on her mother’s chest. You begin active management of the third stage of labor, administering oxytocin, performing uterine massage and applying controlled tension on the umbilical cord. There is no evidence of excess postpartum bleeding.

How long will you wait to deliver the placenta?

Active management of the third stage of labor

Most authorities recommend active management of the third stage of labor because active management reduces the risk of maternal hemorrhage >1,000 mL (relative risk [RR], 0.34), postpartum hemoglobin levels < 9 g/dL (RR, 0.50), and maternal blood transfusion (RR, 0.35) compared with expectant management.1

The most important component of active management of the third stage of labor is the administration of a uterotonic after delivery of the newborn. In the United States, oxytocin is the uterotonic most often utilized for the active management of the third stage of labor. Authors of a recent randomized clinical trial reported that intravenous oxytocin is superior to intramuscular oxytocin for reducing postpartum blood loss (385 vs 445 mL), the frequency of blood loss greater than 1,000 mL (4.6% vs 8.1%), and the rate of maternal blood transfusion (1.5% vs 4.4%).2