User login

Help wanted

In a Pediatrics article, Hsuan-hsiu Annie Chen, MD, offers a very personal and candid narrative of her struggle with depression during medical school and residency (Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1210). Dr. Chen knows from personal experience that she was not alone in her cohort as she faced the challenges of sleep deprivation and emotional trauma that continue to be a part of a physician’s education and training. In her discussion of how future medical trainees might be spared some of the long hours she endured, Dr. Chen suggests that this country consider expanding its physician workforce by “increasing the number of medical schools and recruiting foreign medical graduates” as some European countries have done. Dr. Chen now works in the pediatric residency office at Children’s Hospital, Los Angeles.

Ironically, or maybe it was intentionally, the editors of Pediatrics chose to open the same issue in which Dr. Chen’s personal story appears with a Pediatrics Perspective commentary that looks into the murky waters of physician workforce research (Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0469). Gary L. Freed, MD, MPH, at the Child Health Evaluation and Research Center at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, claims that, in general, the data currently being generated by workforce research must be interpreted with caution because many of the studies are flawed by one or more biases.

You may have survived the gauntlet of medical school and residency relatively unscathed. But Is part of the problem that your clinic is seeing too many patients with too few physicians? Do your colleagues share your opinion? Is the administration actively recruiting more physicians, but failing to find interested and qualified doctors? Is this a strictly local phenomenon limited to your community, or is it a regional shortage? Do you think your situation reflects a national trend that deserves attention?

Like Dr. Chen, do you think that more medical schools and active recruitment of foreign medical students would allow you to work less hours? Obviously, even if you were a teenager when you entered your residency, opening more medical schools is not going to allow you to shorten your workday. But are more medical schools the best solution for this country’s overworked physicians even in the long term? Dr. Freed’s observations should make you hesitant to even venture a guess.

You, I, and Dr. Chen only can report on how we perceive our own work environment. Your local physician shortage may be in part because the school system in your community has a poor reputation and young physicians don’t want to move there. It may be that the hospital that owns your practice is struggling and can’t afford to offer a competitive salary. Producing more physicians may not be the answer to the physician shortage in communities like yours, even in the long run.

This is a very large country with relatively porous boundaries between the states for physicians. Physician supply and demand seldom dictates where physicians choose to practice. In fact, a medically needy community is probably the least likely place a physician just finishing her training will choose to settle.

Although adding another physician to your practice may decrease your workload, can your personal finances handle the hit that might occur as you see less patients? Particularly, if the new hire turns out to be a rock star who siphons off more of your patients than you anticipated. On the other hand, there is always the chance that, despite careful vetting, your group hires a lemon who ends up creating more trouble than he is worth.

As Dr. Freed suggests, trying to determine just how many and what kind of physicians we need is complicated. It may be just a roll of the dice at best.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

In a Pediatrics article, Hsuan-hsiu Annie Chen, MD, offers a very personal and candid narrative of her struggle with depression during medical school and residency (Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1210). Dr. Chen knows from personal experience that she was not alone in her cohort as she faced the challenges of sleep deprivation and emotional trauma that continue to be a part of a physician’s education and training. In her discussion of how future medical trainees might be spared some of the long hours she endured, Dr. Chen suggests that this country consider expanding its physician workforce by “increasing the number of medical schools and recruiting foreign medical graduates” as some European countries have done. Dr. Chen now works in the pediatric residency office at Children’s Hospital, Los Angeles.

Ironically, or maybe it was intentionally, the editors of Pediatrics chose to open the same issue in which Dr. Chen’s personal story appears with a Pediatrics Perspective commentary that looks into the murky waters of physician workforce research (Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0469). Gary L. Freed, MD, MPH, at the Child Health Evaluation and Research Center at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, claims that, in general, the data currently being generated by workforce research must be interpreted with caution because many of the studies are flawed by one or more biases.

You may have survived the gauntlet of medical school and residency relatively unscathed. But Is part of the problem that your clinic is seeing too many patients with too few physicians? Do your colleagues share your opinion? Is the administration actively recruiting more physicians, but failing to find interested and qualified doctors? Is this a strictly local phenomenon limited to your community, or is it a regional shortage? Do you think your situation reflects a national trend that deserves attention?

Like Dr. Chen, do you think that more medical schools and active recruitment of foreign medical students would allow you to work less hours? Obviously, even if you were a teenager when you entered your residency, opening more medical schools is not going to allow you to shorten your workday. But are more medical schools the best solution for this country’s overworked physicians even in the long term? Dr. Freed’s observations should make you hesitant to even venture a guess.

You, I, and Dr. Chen only can report on how we perceive our own work environment. Your local physician shortage may be in part because the school system in your community has a poor reputation and young physicians don’t want to move there. It may be that the hospital that owns your practice is struggling and can’t afford to offer a competitive salary. Producing more physicians may not be the answer to the physician shortage in communities like yours, even in the long run.

This is a very large country with relatively porous boundaries between the states for physicians. Physician supply and demand seldom dictates where physicians choose to practice. In fact, a medically needy community is probably the least likely place a physician just finishing her training will choose to settle.

Although adding another physician to your practice may decrease your workload, can your personal finances handle the hit that might occur as you see less patients? Particularly, if the new hire turns out to be a rock star who siphons off more of your patients than you anticipated. On the other hand, there is always the chance that, despite careful vetting, your group hires a lemon who ends up creating more trouble than he is worth.

As Dr. Freed suggests, trying to determine just how many and what kind of physicians we need is complicated. It may be just a roll of the dice at best.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

In a Pediatrics article, Hsuan-hsiu Annie Chen, MD, offers a very personal and candid narrative of her struggle with depression during medical school and residency (Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1210). Dr. Chen knows from personal experience that she was not alone in her cohort as she faced the challenges of sleep deprivation and emotional trauma that continue to be a part of a physician’s education and training. In her discussion of how future medical trainees might be spared some of the long hours she endured, Dr. Chen suggests that this country consider expanding its physician workforce by “increasing the number of medical schools and recruiting foreign medical graduates” as some European countries have done. Dr. Chen now works in the pediatric residency office at Children’s Hospital, Los Angeles.

Ironically, or maybe it was intentionally, the editors of Pediatrics chose to open the same issue in which Dr. Chen’s personal story appears with a Pediatrics Perspective commentary that looks into the murky waters of physician workforce research (Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0469). Gary L. Freed, MD, MPH, at the Child Health Evaluation and Research Center at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, claims that, in general, the data currently being generated by workforce research must be interpreted with caution because many of the studies are flawed by one or more biases.

You may have survived the gauntlet of medical school and residency relatively unscathed. But Is part of the problem that your clinic is seeing too many patients with too few physicians? Do your colleagues share your opinion? Is the administration actively recruiting more physicians, but failing to find interested and qualified doctors? Is this a strictly local phenomenon limited to your community, or is it a regional shortage? Do you think your situation reflects a national trend that deserves attention?

Like Dr. Chen, do you think that more medical schools and active recruitment of foreign medical students would allow you to work less hours? Obviously, even if you were a teenager when you entered your residency, opening more medical schools is not going to allow you to shorten your workday. But are more medical schools the best solution for this country’s overworked physicians even in the long term? Dr. Freed’s observations should make you hesitant to even venture a guess.

You, I, and Dr. Chen only can report on how we perceive our own work environment. Your local physician shortage may be in part because the school system in your community has a poor reputation and young physicians don’t want to move there. It may be that the hospital that owns your practice is struggling and can’t afford to offer a competitive salary. Producing more physicians may not be the answer to the physician shortage in communities like yours, even in the long run.

This is a very large country with relatively porous boundaries between the states for physicians. Physician supply and demand seldom dictates where physicians choose to practice. In fact, a medically needy community is probably the least likely place a physician just finishing her training will choose to settle.

Although adding another physician to your practice may decrease your workload, can your personal finances handle the hit that might occur as you see less patients? Particularly, if the new hire turns out to be a rock star who siphons off more of your patients than you anticipated. On the other hand, there is always the chance that, despite careful vetting, your group hires a lemon who ends up creating more trouble than he is worth.

As Dr. Freed suggests, trying to determine just how many and what kind of physicians we need is complicated. It may be just a roll of the dice at best.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

It’s all in the timing

It is often fun and sometimes exhausting watching the speed with which children run around or switch from one game to another. A lot of us were attracted to pediatrics to share the quick joy of children and also the speed of their physical recovery. We get to see premature infants gain an ounce a day, and see wounds heal in less than a week. We give advice on sleep and see success in a month. We and the families get used to quick fixes.

Parents and children are forewarned and reassured by our knowledge about how long things typically take: Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) peaks in 5 days, colic lessens in 3 months, changing sleep patterns takes 3 weeks, habit formation 6 weeks, menses come 2 years after breast development, and so on. But the timing of daily parenting is rarely as predictable. Sometimes a child’s clock is running fast, making waiting even seconds for a snack or a bathroom difficult; other times are slow, as when walking down the sidewalk noticing every leaf. The child’s clock is independent of the adult’s – and complicated by clocks of siblings.

Parent pace also is determined by many factors unrelated to the child: work demands, deadlines, train schedules, something in the oven, needs of siblings, and so on. To those can be added intrinsic factors affecting parent’s tolerance to shifting pace to the child’s such as temperament, fatigue, illness, pain, or even adult ADHD. And don’t forget caffeine (or other drugs) affecting the internal metronome. When impatience with the child is a complaint, it is useful to ask, “What makes waiting for your child difficult for you?”

When discussing time, I find it important to discuss the poison “s-word” of parenting – “should.” This trickster often comes from time illusions in childrearing. After seeing so many behaviors change quickly, parents expect all change to be equally fast. She should be able to sleep through the night by now! He should be able to dress and get to the table in 5 minutes. And sometimes it is the parent’s s-word that creates pain – I should love pushing for as long as she wants to swing, if I am a good parent. The problem with thinking “should” is that it implies willful or moral behavior, and it may prompt a judgmental or punitive parental response.

Otherwise well intentioned, cooperative children who take longer to shift their attention from homework to shower can be seen as oppositional. Worse yet, if the example used is from playing video games (something fun) to getting to the bus stop (an undesirable shift), you may hear parents critically say, “He only wants to do what he wants to do.” When examining examples (always key to helping with behavior), pointing out that all kinds of transitions are difficult for this child may be educational and allow for a more reasoned response. And specifically being on electronics puts adults as well as children in a time warp which is hard to escape.

There are many kinds of thwarted expectations, but expectations about how long things take are pretty universal. Frustration generates anger and even can lead to violence, such as road rage. Children – who all step to the beat of a different drummer, especially those with different “clocks” such as in ADHD – may experience frustration most of the day. This can manifest as irritability for them and sometimes as an irritable response back from the parent.

The first step in adapting to differences in parent and child pace is to realize that time is the problem. Naming it, saying “we are on toddler time,” can be a “signal to self” to slow down. Generations of children loved Mr. Rogers because he always conveyed having all the time in the world for the person he was with. It actually does not take as long as it feels at first to do this. Listening while keeping eye contact, breathing deeply, and waiting until two breaths after the child goes silent before speaking or moving conveys your interest and respect. For some behaviors, such as tantrums, such quiet attention may be all that is needed to resolve the issue. We adults can practice this, but even infants can be helped to develop patience by reinforcement with brief attention from their caregivers for tiny increments of waiting.

I sometimes suggest that parents time behaviors to develop perspective, reset expectations, practice waiting, and perhaps even distract themselves from intervening and making things worse by lending attention to negative behaviors. Timing as observation can be helpful for tantrums, breath holding spells, whining, and sibling squabbles; maximum times for baths and video games; minimum times for meals, sitting to poop, and special time. Timers are not just for Time Out! “Visual timers” that show green then yellow then red and sometimes flashing lights as warnings of an upcoming stopping point are helpful for children preschool and older. These timers help them to develop a better sense of time and begin managing their own transitions. A game of guessing how long things take can build timing skills and patience. I think every child past preschool benefits from a wristwatch, first to build time sense, and second to avoid looking at a smartphone to see the hour, then being distracted by content! Diaries of behaviors over time are a staple of behavior change plans, with the added benefit of lending perspective on actually how often and how long a troublesome behavior occurs. Practicing mindfulness – nonjudgmental watching of our thoughts and feelings, often with deep breathing and relaxation – also can help both children and adults build time tolerance.

Children have little control over their daily schedule. Surrendering when you can for them to do things at their own pace can reduce their frustration, build the parent-child relationship, and promote positive behaviors. Plus family life is more enjoyable lived slower. You even can remind parents that “the days are long but the years are short” before their children will be grown and gone.

Dr. Howard is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS. She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. Email her at [email protected].

It is often fun and sometimes exhausting watching the speed with which children run around or switch from one game to another. A lot of us were attracted to pediatrics to share the quick joy of children and also the speed of their physical recovery. We get to see premature infants gain an ounce a day, and see wounds heal in less than a week. We give advice on sleep and see success in a month. We and the families get used to quick fixes.

Parents and children are forewarned and reassured by our knowledge about how long things typically take: Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) peaks in 5 days, colic lessens in 3 months, changing sleep patterns takes 3 weeks, habit formation 6 weeks, menses come 2 years after breast development, and so on. But the timing of daily parenting is rarely as predictable. Sometimes a child’s clock is running fast, making waiting even seconds for a snack or a bathroom difficult; other times are slow, as when walking down the sidewalk noticing every leaf. The child’s clock is independent of the adult’s – and complicated by clocks of siblings.

Parent pace also is determined by many factors unrelated to the child: work demands, deadlines, train schedules, something in the oven, needs of siblings, and so on. To those can be added intrinsic factors affecting parent’s tolerance to shifting pace to the child’s such as temperament, fatigue, illness, pain, or even adult ADHD. And don’t forget caffeine (or other drugs) affecting the internal metronome. When impatience with the child is a complaint, it is useful to ask, “What makes waiting for your child difficult for you?”

When discussing time, I find it important to discuss the poison “s-word” of parenting – “should.” This trickster often comes from time illusions in childrearing. After seeing so many behaviors change quickly, parents expect all change to be equally fast. She should be able to sleep through the night by now! He should be able to dress and get to the table in 5 minutes. And sometimes it is the parent’s s-word that creates pain – I should love pushing for as long as she wants to swing, if I am a good parent. The problem with thinking “should” is that it implies willful or moral behavior, and it may prompt a judgmental or punitive parental response.

Otherwise well intentioned, cooperative children who take longer to shift their attention from homework to shower can be seen as oppositional. Worse yet, if the example used is from playing video games (something fun) to getting to the bus stop (an undesirable shift), you may hear parents critically say, “He only wants to do what he wants to do.” When examining examples (always key to helping with behavior), pointing out that all kinds of transitions are difficult for this child may be educational and allow for a more reasoned response. And specifically being on electronics puts adults as well as children in a time warp which is hard to escape.

There are many kinds of thwarted expectations, but expectations about how long things take are pretty universal. Frustration generates anger and even can lead to violence, such as road rage. Children – who all step to the beat of a different drummer, especially those with different “clocks” such as in ADHD – may experience frustration most of the day. This can manifest as irritability for them and sometimes as an irritable response back from the parent.

The first step in adapting to differences in parent and child pace is to realize that time is the problem. Naming it, saying “we are on toddler time,” can be a “signal to self” to slow down. Generations of children loved Mr. Rogers because he always conveyed having all the time in the world for the person he was with. It actually does not take as long as it feels at first to do this. Listening while keeping eye contact, breathing deeply, and waiting until two breaths after the child goes silent before speaking or moving conveys your interest and respect. For some behaviors, such as tantrums, such quiet attention may be all that is needed to resolve the issue. We adults can practice this, but even infants can be helped to develop patience by reinforcement with brief attention from their caregivers for tiny increments of waiting.

I sometimes suggest that parents time behaviors to develop perspective, reset expectations, practice waiting, and perhaps even distract themselves from intervening and making things worse by lending attention to negative behaviors. Timing as observation can be helpful for tantrums, breath holding spells, whining, and sibling squabbles; maximum times for baths and video games; minimum times for meals, sitting to poop, and special time. Timers are not just for Time Out! “Visual timers” that show green then yellow then red and sometimes flashing lights as warnings of an upcoming stopping point are helpful for children preschool and older. These timers help them to develop a better sense of time and begin managing their own transitions. A game of guessing how long things take can build timing skills and patience. I think every child past preschool benefits from a wristwatch, first to build time sense, and second to avoid looking at a smartphone to see the hour, then being distracted by content! Diaries of behaviors over time are a staple of behavior change plans, with the added benefit of lending perspective on actually how often and how long a troublesome behavior occurs. Practicing mindfulness – nonjudgmental watching of our thoughts and feelings, often with deep breathing and relaxation – also can help both children and adults build time tolerance.

Children have little control over their daily schedule. Surrendering when you can for them to do things at their own pace can reduce their frustration, build the parent-child relationship, and promote positive behaviors. Plus family life is more enjoyable lived slower. You even can remind parents that “the days are long but the years are short” before their children will be grown and gone.

Dr. Howard is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS. She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. Email her at [email protected].

It is often fun and sometimes exhausting watching the speed with which children run around or switch from one game to another. A lot of us were attracted to pediatrics to share the quick joy of children and also the speed of their physical recovery. We get to see premature infants gain an ounce a day, and see wounds heal in less than a week. We give advice on sleep and see success in a month. We and the families get used to quick fixes.

Parents and children are forewarned and reassured by our knowledge about how long things typically take: Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) peaks in 5 days, colic lessens in 3 months, changing sleep patterns takes 3 weeks, habit formation 6 weeks, menses come 2 years after breast development, and so on. But the timing of daily parenting is rarely as predictable. Sometimes a child’s clock is running fast, making waiting even seconds for a snack or a bathroom difficult; other times are slow, as when walking down the sidewalk noticing every leaf. The child’s clock is independent of the adult’s – and complicated by clocks of siblings.

Parent pace also is determined by many factors unrelated to the child: work demands, deadlines, train schedules, something in the oven, needs of siblings, and so on. To those can be added intrinsic factors affecting parent’s tolerance to shifting pace to the child’s such as temperament, fatigue, illness, pain, or even adult ADHD. And don’t forget caffeine (or other drugs) affecting the internal metronome. When impatience with the child is a complaint, it is useful to ask, “What makes waiting for your child difficult for you?”

When discussing time, I find it important to discuss the poison “s-word” of parenting – “should.” This trickster often comes from time illusions in childrearing. After seeing so many behaviors change quickly, parents expect all change to be equally fast. She should be able to sleep through the night by now! He should be able to dress and get to the table in 5 minutes. And sometimes it is the parent’s s-word that creates pain – I should love pushing for as long as she wants to swing, if I am a good parent. The problem with thinking “should” is that it implies willful or moral behavior, and it may prompt a judgmental or punitive parental response.

Otherwise well intentioned, cooperative children who take longer to shift their attention from homework to shower can be seen as oppositional. Worse yet, if the example used is from playing video games (something fun) to getting to the bus stop (an undesirable shift), you may hear parents critically say, “He only wants to do what he wants to do.” When examining examples (always key to helping with behavior), pointing out that all kinds of transitions are difficult for this child may be educational and allow for a more reasoned response. And specifically being on electronics puts adults as well as children in a time warp which is hard to escape.

There are many kinds of thwarted expectations, but expectations about how long things take are pretty universal. Frustration generates anger and even can lead to violence, such as road rage. Children – who all step to the beat of a different drummer, especially those with different “clocks” such as in ADHD – may experience frustration most of the day. This can manifest as irritability for them and sometimes as an irritable response back from the parent.

The first step in adapting to differences in parent and child pace is to realize that time is the problem. Naming it, saying “we are on toddler time,” can be a “signal to self” to slow down. Generations of children loved Mr. Rogers because he always conveyed having all the time in the world for the person he was with. It actually does not take as long as it feels at first to do this. Listening while keeping eye contact, breathing deeply, and waiting until two breaths after the child goes silent before speaking or moving conveys your interest and respect. For some behaviors, such as tantrums, such quiet attention may be all that is needed to resolve the issue. We adults can practice this, but even infants can be helped to develop patience by reinforcement with brief attention from their caregivers for tiny increments of waiting.

I sometimes suggest that parents time behaviors to develop perspective, reset expectations, practice waiting, and perhaps even distract themselves from intervening and making things worse by lending attention to negative behaviors. Timing as observation can be helpful for tantrums, breath holding spells, whining, and sibling squabbles; maximum times for baths and video games; minimum times for meals, sitting to poop, and special time. Timers are not just for Time Out! “Visual timers” that show green then yellow then red and sometimes flashing lights as warnings of an upcoming stopping point are helpful for children preschool and older. These timers help them to develop a better sense of time and begin managing their own transitions. A game of guessing how long things take can build timing skills and patience. I think every child past preschool benefits from a wristwatch, first to build time sense, and second to avoid looking at a smartphone to see the hour, then being distracted by content! Diaries of behaviors over time are a staple of behavior change plans, with the added benefit of lending perspective on actually how often and how long a troublesome behavior occurs. Practicing mindfulness – nonjudgmental watching of our thoughts and feelings, often with deep breathing and relaxation – also can help both children and adults build time tolerance.

Children have little control over their daily schedule. Surrendering when you can for them to do things at their own pace can reduce their frustration, build the parent-child relationship, and promote positive behaviors. Plus family life is more enjoyable lived slower. You even can remind parents that “the days are long but the years are short” before their children will be grown and gone.

Dr. Howard is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS. She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. Email her at [email protected].

When can I retire?

Whenever Don McLean is asked what the lyrics to his iconic song “American Pie” mean, he answers: “They mean that I don’t have to work anymore.”

It would be nice if those of us who have never written an enigmatic hit tune could receive an unequivocal signal when it’s safe to retire. Unfortunately, the road to retirement is fraught with challenges, not least of which is locating the right off-ramp.

We tend to live longer than planned, so we run the risk of outliving our savings, which are often underfunded to begin with. And we don’t face facts about end-of-life care. Few of us have long-term care insurance, or the means to self-fund an extended long-term care situation, as I will discuss next month.

Many of us lack a clear idea of where our retirement income will come from, or if it will be there when we arrive. Doctors in particular are notorious for mismanaging their investments. Many try to self-manage retirement plans and personal savings without adequate time or knowledge to do it right. Involving a qualified financial professional is usually a far better strategy than going it alone.

So, As with everything else, it depends; but to arrive at any sort of reliable ballpark figure, you’ll need to know three things: how much you realistically expect to spend annually after retirement; how much principal will throw off that amount in interest and dividends each year; and how far your present savings are from that target.

An oft-quoted rule of thumb is that, in retirement, your expenses will be about 70% of what they are now. In my opinion, that’s nonsense. While a few bills, such as disability and malpractice insurance premiums, will go away, other costs, such as recreation and medical care, will increase. I suggest assuming that your spending will not diminish significantly in retirement. Those of us who love travel or fancy toys may need even more.

Once you have an estimate of your annual retirement expenses, you’ll need to determine how much principal you’ll need – usually in fixed pensions and invested assets – to generate that income. Most financial advisors use the 5% rule: Assume your nest egg will pay you a conservative 5% of its value each year in dividends and interest. That rule has worked well, on average, over the long term. So if you estimate your postretirement spending will be around $100,000 per year (in today’s dollars), you’ll need about $2 million in assets. For $200,000 annual spending, you’ll need $4 million. (Should you factor in Social Security? Yes, if you’re 50 years or older; if you’re younger, I wouldn’t count on receiving any entitlements, and be pleasantly surprised if you do.)

How do you accumulate that kind of money? Financial experts say too many physicians invest too aggressively. For retirement, safety is the key. The most foolproof strategy – seldom employed, because it’s boring – is to sock away a fixed amount per month (after your retirement plan has been funded) in a mutual fund. $1,000 per month for 25 years with the market earning 10% (its historic long-term average) comes to almost $2 million, with the power of compounded interest working for you. And the earlier you start, the better.

It is never too soon to think about retirement. Young physicians often defer contributing to their retirement plans because they want to save for a new house or for college for their children. But there are tangible tax benefits that you get now, because your contributions usually reduce your taxable income, and your funds grow tax free until you withdraw them, presumably in a lower tax bracket.

At any age, it’s hard to motivate yourself to save, because it generally requires spending less money now. The way I do it is to pay myself first; that is, each month I make my regular savings contribution before considering any new purchases.

In the end, the strategy is very straightforward: Fill your retirement plan to its legal limit and let it grow, tax deferred. Then invest for the long term, with your target amount in mind. And once again, the earlier you start, the better.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Whenever Don McLean is asked what the lyrics to his iconic song “American Pie” mean, he answers: “They mean that I don’t have to work anymore.”

It would be nice if those of us who have never written an enigmatic hit tune could receive an unequivocal signal when it’s safe to retire. Unfortunately, the road to retirement is fraught with challenges, not least of which is locating the right off-ramp.

We tend to live longer than planned, so we run the risk of outliving our savings, which are often underfunded to begin with. And we don’t face facts about end-of-life care. Few of us have long-term care insurance, or the means to self-fund an extended long-term care situation, as I will discuss next month.

Many of us lack a clear idea of where our retirement income will come from, or if it will be there when we arrive. Doctors in particular are notorious for mismanaging their investments. Many try to self-manage retirement plans and personal savings without adequate time or knowledge to do it right. Involving a qualified financial professional is usually a far better strategy than going it alone.

So, As with everything else, it depends; but to arrive at any sort of reliable ballpark figure, you’ll need to know three things: how much you realistically expect to spend annually after retirement; how much principal will throw off that amount in interest and dividends each year; and how far your present savings are from that target.

An oft-quoted rule of thumb is that, in retirement, your expenses will be about 70% of what they are now. In my opinion, that’s nonsense. While a few bills, such as disability and malpractice insurance premiums, will go away, other costs, such as recreation and medical care, will increase. I suggest assuming that your spending will not diminish significantly in retirement. Those of us who love travel or fancy toys may need even more.

Once you have an estimate of your annual retirement expenses, you’ll need to determine how much principal you’ll need – usually in fixed pensions and invested assets – to generate that income. Most financial advisors use the 5% rule: Assume your nest egg will pay you a conservative 5% of its value each year in dividends and interest. That rule has worked well, on average, over the long term. So if you estimate your postretirement spending will be around $100,000 per year (in today’s dollars), you’ll need about $2 million in assets. For $200,000 annual spending, you’ll need $4 million. (Should you factor in Social Security? Yes, if you’re 50 years or older; if you’re younger, I wouldn’t count on receiving any entitlements, and be pleasantly surprised if you do.)

How do you accumulate that kind of money? Financial experts say too many physicians invest too aggressively. For retirement, safety is the key. The most foolproof strategy – seldom employed, because it’s boring – is to sock away a fixed amount per month (after your retirement plan has been funded) in a mutual fund. $1,000 per month for 25 years with the market earning 10% (its historic long-term average) comes to almost $2 million, with the power of compounded interest working for you. And the earlier you start, the better.

It is never too soon to think about retirement. Young physicians often defer contributing to their retirement plans because they want to save for a new house or for college for their children. But there are tangible tax benefits that you get now, because your contributions usually reduce your taxable income, and your funds grow tax free until you withdraw them, presumably in a lower tax bracket.

At any age, it’s hard to motivate yourself to save, because it generally requires spending less money now. The way I do it is to pay myself first; that is, each month I make my regular savings contribution before considering any new purchases.

In the end, the strategy is very straightforward: Fill your retirement plan to its legal limit and let it grow, tax deferred. Then invest for the long term, with your target amount in mind. And once again, the earlier you start, the better.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Whenever Don McLean is asked what the lyrics to his iconic song “American Pie” mean, he answers: “They mean that I don’t have to work anymore.”

It would be nice if those of us who have never written an enigmatic hit tune could receive an unequivocal signal when it’s safe to retire. Unfortunately, the road to retirement is fraught with challenges, not least of which is locating the right off-ramp.

We tend to live longer than planned, so we run the risk of outliving our savings, which are often underfunded to begin with. And we don’t face facts about end-of-life care. Few of us have long-term care insurance, or the means to self-fund an extended long-term care situation, as I will discuss next month.

Many of us lack a clear idea of where our retirement income will come from, or if it will be there when we arrive. Doctors in particular are notorious for mismanaging their investments. Many try to self-manage retirement plans and personal savings without adequate time or knowledge to do it right. Involving a qualified financial professional is usually a far better strategy than going it alone.

So, As with everything else, it depends; but to arrive at any sort of reliable ballpark figure, you’ll need to know three things: how much you realistically expect to spend annually after retirement; how much principal will throw off that amount in interest and dividends each year; and how far your present savings are from that target.

An oft-quoted rule of thumb is that, in retirement, your expenses will be about 70% of what they are now. In my opinion, that’s nonsense. While a few bills, such as disability and malpractice insurance premiums, will go away, other costs, such as recreation and medical care, will increase. I suggest assuming that your spending will not diminish significantly in retirement. Those of us who love travel or fancy toys may need even more.

Once you have an estimate of your annual retirement expenses, you’ll need to determine how much principal you’ll need – usually in fixed pensions and invested assets – to generate that income. Most financial advisors use the 5% rule: Assume your nest egg will pay you a conservative 5% of its value each year in dividends and interest. That rule has worked well, on average, over the long term. So if you estimate your postretirement spending will be around $100,000 per year (in today’s dollars), you’ll need about $2 million in assets. For $200,000 annual spending, you’ll need $4 million. (Should you factor in Social Security? Yes, if you’re 50 years or older; if you’re younger, I wouldn’t count on receiving any entitlements, and be pleasantly surprised if you do.)

How do you accumulate that kind of money? Financial experts say too many physicians invest too aggressively. For retirement, safety is the key. The most foolproof strategy – seldom employed, because it’s boring – is to sock away a fixed amount per month (after your retirement plan has been funded) in a mutual fund. $1,000 per month for 25 years with the market earning 10% (its historic long-term average) comes to almost $2 million, with the power of compounded interest working for you. And the earlier you start, the better.

It is never too soon to think about retirement. Young physicians often defer contributing to their retirement plans because they want to save for a new house or for college for their children. But there are tangible tax benefits that you get now, because your contributions usually reduce your taxable income, and your funds grow tax free until you withdraw them, presumably in a lower tax bracket.

At any age, it’s hard to motivate yourself to save, because it generally requires spending less money now. The way I do it is to pay myself first; that is, each month I make my regular savings contribution before considering any new purchases.

In the end, the strategy is very straightforward: Fill your retirement plan to its legal limit and let it grow, tax deferred. Then invest for the long term, with your target amount in mind. And once again, the earlier you start, the better.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

#MomsNeedToKnow mental health awareness campaign set to launch

One goal is to use social media to encourage women to let go of stigma

Pregnancy-related mental health conditions are the most common complication of pregnancy, yet half of all women suffering will not be treated.

I wanted to address the stigma associated with these conditions as well as the rampant misinformation online. So, I reached out to Jen Schwartz, patient advocate and founder of Motherhood Understand, an online community for moms impacted by maternal mental health conditions. Together, we conceived the idea for the #MomsNeedToKnow maternal mental health awareness campaign, which will run from Oct. 14 to 25. This is an evidence-based campaign, complete with references and citations, that speaks to patients where they are at, i.e., social media.

With my clinical expertise and Jen’s reach, we felt like it was a natural partnership, as well as an innovative approach to empowering women to take control of their mental health during the perinatal period. We teamed up with Jamina Bone, an illustrator, and developed 2 weeks of Instagram posts, focused on the themes of lesser-known diagnoses, maternal mental health myths, and treatment options. This campaign is designed to help women understand risk factors for perinatal mood and anxiety disorders, as well as the signs of these conditions. It will cover lesser-known diagnoses like postpartum obsessive-compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder, and will address topics such as the impact of infertility on mental health and clarify the roles of different clinicians who can help.

Moreover, the campaign aims to address stigma and myths around psychiatric treatment during pregnancy – and also provides resources.

Dr. Lakshmin, a perinatal psychiatrist, is clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at George Washington University in Washington.

This article was updated 10/12/19.

One goal is to use social media to encourage women to let go of stigma

One goal is to use social media to encourage women to let go of stigma

Pregnancy-related mental health conditions are the most common complication of pregnancy, yet half of all women suffering will not be treated.

I wanted to address the stigma associated with these conditions as well as the rampant misinformation online. So, I reached out to Jen Schwartz, patient advocate and founder of Motherhood Understand, an online community for moms impacted by maternal mental health conditions. Together, we conceived the idea for the #MomsNeedToKnow maternal mental health awareness campaign, which will run from Oct. 14 to 25. This is an evidence-based campaign, complete with references and citations, that speaks to patients where they are at, i.e., social media.

With my clinical expertise and Jen’s reach, we felt like it was a natural partnership, as well as an innovative approach to empowering women to take control of their mental health during the perinatal period. We teamed up with Jamina Bone, an illustrator, and developed 2 weeks of Instagram posts, focused on the themes of lesser-known diagnoses, maternal mental health myths, and treatment options. This campaign is designed to help women understand risk factors for perinatal mood and anxiety disorders, as well as the signs of these conditions. It will cover lesser-known diagnoses like postpartum obsessive-compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder, and will address topics such as the impact of infertility on mental health and clarify the roles of different clinicians who can help.

Moreover, the campaign aims to address stigma and myths around psychiatric treatment during pregnancy – and also provides resources.

Dr. Lakshmin, a perinatal psychiatrist, is clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at George Washington University in Washington.

This article was updated 10/12/19.

Pregnancy-related mental health conditions are the most common complication of pregnancy, yet half of all women suffering will not be treated.

I wanted to address the stigma associated with these conditions as well as the rampant misinformation online. So, I reached out to Jen Schwartz, patient advocate and founder of Motherhood Understand, an online community for moms impacted by maternal mental health conditions. Together, we conceived the idea for the #MomsNeedToKnow maternal mental health awareness campaign, which will run from Oct. 14 to 25. This is an evidence-based campaign, complete with references and citations, that speaks to patients where they are at, i.e., social media.

With my clinical expertise and Jen’s reach, we felt like it was a natural partnership, as well as an innovative approach to empowering women to take control of their mental health during the perinatal period. We teamed up with Jamina Bone, an illustrator, and developed 2 weeks of Instagram posts, focused on the themes of lesser-known diagnoses, maternal mental health myths, and treatment options. This campaign is designed to help women understand risk factors for perinatal mood and anxiety disorders, as well as the signs of these conditions. It will cover lesser-known diagnoses like postpartum obsessive-compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder, and will address topics such as the impact of infertility on mental health and clarify the roles of different clinicians who can help.

Moreover, the campaign aims to address stigma and myths around psychiatric treatment during pregnancy – and also provides resources.

Dr. Lakshmin, a perinatal psychiatrist, is clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at George Washington University in Washington.

This article was updated 10/12/19.

ID Blog: The story of syphilis, part III

The tortured road to successful treatment

It is rare in this modern era for medicine to confront an infectious disease for which there is no cure. Today, there are comparatively few infectious diseases (in the developed world and in places where money is no object) for which medicine cannot offer at least a glimmer of hope to infected patients. Even at its most futile, modern medicine has achieved vast improvements in the efficacy of palliative care. But it wasn’t that long ago that HIV infection was a nearly inevitable death sentence from the complications of AIDS, with no available treatments. And however monstrous that suffering and death, which still continues in many areas of the developing world, it was decades rather than centuries before modern medicine came up with effective treatments. Recently, there is even significant hope on the Ebola virus front that curative treatments may soon become available.

Medicine has always been in the business of hope, even when true cures were not available. Today that hope is less often misplaced. But in previous centuries, the need to offer hope to – and perhaps to make money from – desperate patients was a hallmark of the doctor’s trade.

It was this need to give patients hope and for doctors to feel that they were being effective that led to some highly dubious and desperate efforts to cure syphilis throughout history. These efforts meant centuries of fruitless torture for countless patients until the rise of modern antibiotics.

For the most part, what we now look upon as horrors and insanity in treatment were the result of misguided scientific theories, half-baked folk wisdom, and the generally well-intentioned efforts of medical practitioners at a cure. There were the charlatans as well, seeking a quick buck from the truly hopeless.

However, the social stigma of syphilis as a venereal disease played a role in the courses of treatment.

By the 15th century, syphilis was recognized as being spread by sexual intercourse, and in a situation analogous with the early AIDS epidemic, “16th- and 17th-century writers and physicians were divided on the moral aspects of syphilis. Some thought it was a divine punishment for sin – and as such only harsh treatments would cure it – or that people with syphilis shouldn’t be treated at all.”

Mercury rising

In its earliest manifestations, syphilis was considered untreatable. In 1496, Sebastian Brandt, wrote a poem entitled “De pestilentiali Scorra sive mala de Franzos” detailing the disease’s early spread across Europe and how doctors had no remedy for it.

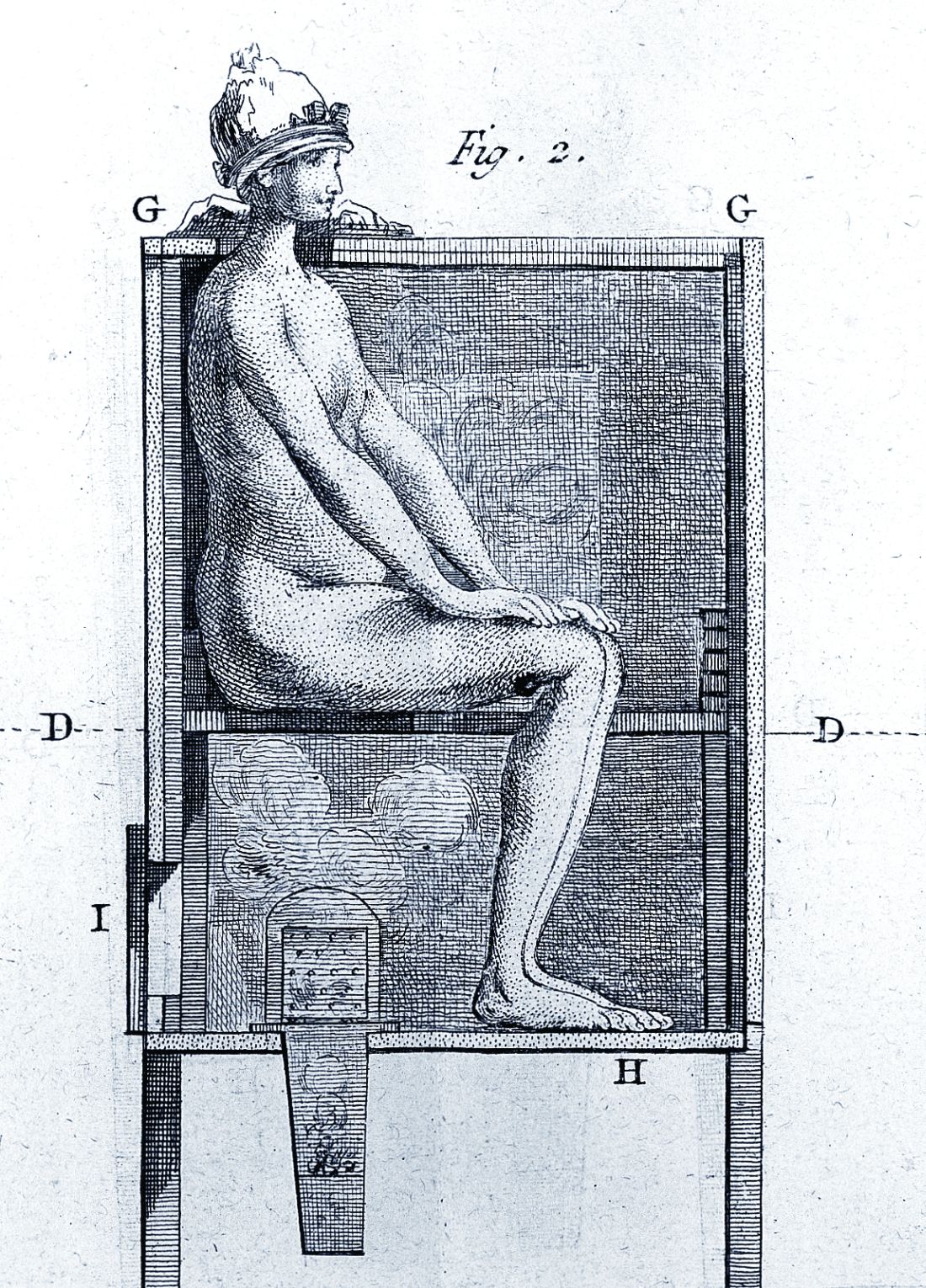

However, it wasn’t long before desperate physicians turned their quest for a cure to a reliable old standby treatment of the period – mercury, which had a history of being used for skin diseases. Mercury salves had been in use in the Arab world for leprosy and eczema, among other skin afflictions, and had been brought to Europe with the return of the medieval crusaders. Another way elemental mercury was administered was through the use of heated cinnabar (HgS), which gave off mercury vapors that could be absorbed by breathing and through the skin. In the 16th century, doctors would place a syphilis-infected individual inside an ovenlike chamber over pans of cinnabar, which were then heated at the person’s feet.

Oral mercury treatments were promoted by Paracelsus (1493?-1541), an alchemist and physician who prescribed calomel (HgCl), or mercury chloride, pills. Mercury treatment, administered at almost inevitably toxic doses, led to ulcerations of the lips, tongue, palate, and jaw; tooth loss; and fetid breath and excessive salivation. This last symptom was, in fact, considered the endpoint in mercury therapy for syphilis, which was “originally judged to be a copious secretion of saliva – ‘some few liters per diem.’ ” Even as recent as the late 19th century and early 20th century, syphilitic patients such as Oscar Wilde (whose teeth were blackened by the treatment), were prescribed calomel.

Looking to the “holy wood”

By 1519, an alternative treatment to mercury was available. In that year, Ulrich von Hutton, a German scholar who suffered from the “great pox,” described its treatment with guaiacum sanctum, or holy wood, in “De Morbo Gallico.” Four years later, despite such treatment, he was dead from the disease himself. But the lack of efficacy did not stop the faith that doctors placed in this botanical cure.

Holy wood was an herbal treatment derived from the bark of trees from the Guaiacum family. It was brought back on trading ships from the Caribbean and South America, the origin of syphilis’s foothold in Europe and the rest of the world. The use of holy wood matched a then-current theory that the cure to a disease could be found in the area from which it came. Other botanicals from around the world were also tried, but never came into routine use.

Guaiacum was the first treatment given to sufferers of syphilis in the Blatterhaus (pox hospital) in Augsburg after 1522, according to information from the archives at the Edward Worth Library in Dublin. The botanical therapy was given as a hot drink and followed by a sweating cure. Guaiacum extract acted as a sudorific, a compound which induces sweating when ingested. Even though the use of Guaiacum was initially popular, it was replaced almost exclusively by the use of mercury.

“Give me fever”

In the late 1800s, Julius Wagner von Jauregg (1857-1940), a Viennese neurologist, observed that Austrian army officers with neurosyphilis did not become partially paralyzed if they had also contracted malaria or relapsing fever. He initiated clinical trials in which he induced fever in syphilitics with tuberculin (1-10 mg) and observed in many the remissions their neuropsychiatric symptoms and signs. He also injected neurosyphilitic patients with a mild form of malaria to induce fever, which could then be suppressed with quinine treatment.

“Other physicians soon began using malariotherapy in uncontrolled studies of neurosyphilitics and reported clinical success rates of 33%-51% and only a 5% mortality. Persons with tabes dorsalis (the “wasting” paralysis of neurosyphilis) were hospitalized for 3 weeks of alternate-day fever therapy involving 5-hour long hot baths and extended periods wrapped in heavy blankets,” according to C.T. Ambrose, MD, of the University of Kentucky, Lexington.

A 1931 medical text summarizes in 35 studies involving 2,356 cases of general paresis treated with malaria and reported a 27.5% “full remission,” he added. A bacterial treatment developed in this period used a course of 18-23 injections of killed typhoid cells administered every 2-3 days in order to produce a fever of 103°–104°F. Animal studies of rabbits infected with syphilis showed that high temperatures could be curative.

Dr. Ambrose suggests that 16th-century syphilitics who had been subjected to mercury fumigation in ovenlike chambers endured severe sweating conditions and – for those who survived – the prolonged elevated body temperature (not the mercury) may have proved curative. Fever “was the common therapeutic denominator in the cinnabar-oven treatment, botanical sudorifics (guaiacum, China root), malarial infections (natural and iatrogenic), and bacterial (tuberculin) vaccine therapy.”

Prelude to modern antibiotics

German bacteriologist/immunologist Paul Ehrlich, MD, (1854-1915) investigated the use of atoxyl (sodium arsanilate) in syphilis, but the metallic drug had severe side effects, injuring the optic nerve and causing blindness. To overcome this problem, Ehrlich and his coworkers synthesized and tested related organic arsenicals. The antisyphilitic activity of arsphenamine (compound 606) was discovered by Sahachiro Hata, MD, (1879-1938) in 1909. This compound, known as Salvarsan, became “Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet,” for the treatment of syphilis in the 1910s, and it, and later, the less-toxic compound neoarsphenamine (compound 914) became mainstays of successful clinical treatment until the development and use of penicillin in the 1940s.

Selected sources

Ambrose, CT. Pre-antibiotic therapy of syphilis. NESSA J Infect Dis Immunology. 2016. 1(1);1-20.

Frith J. Syphilis: Its early history and treatment until penicillin and the debate on its origins. J Mil Veterans Health. 2012;20(4):49-58.

Tognotti B. The rise and fall of syphilis in Renaissance Italy. J Med Humanit. 2009 Jun;30(2):99-113.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor in the department of biochemistry and molecular & cellular biology at Georgetown University, Washington.

The tortured road to successful treatment

The tortured road to successful treatment

It is rare in this modern era for medicine to confront an infectious disease for which there is no cure. Today, there are comparatively few infectious diseases (in the developed world and in places where money is no object) for which medicine cannot offer at least a glimmer of hope to infected patients. Even at its most futile, modern medicine has achieved vast improvements in the efficacy of palliative care. But it wasn’t that long ago that HIV infection was a nearly inevitable death sentence from the complications of AIDS, with no available treatments. And however monstrous that suffering and death, which still continues in many areas of the developing world, it was decades rather than centuries before modern medicine came up with effective treatments. Recently, there is even significant hope on the Ebola virus front that curative treatments may soon become available.

Medicine has always been in the business of hope, even when true cures were not available. Today that hope is less often misplaced. But in previous centuries, the need to offer hope to – and perhaps to make money from – desperate patients was a hallmark of the doctor’s trade.

It was this need to give patients hope and for doctors to feel that they were being effective that led to some highly dubious and desperate efforts to cure syphilis throughout history. These efforts meant centuries of fruitless torture for countless patients until the rise of modern antibiotics.

For the most part, what we now look upon as horrors and insanity in treatment were the result of misguided scientific theories, half-baked folk wisdom, and the generally well-intentioned efforts of medical practitioners at a cure. There were the charlatans as well, seeking a quick buck from the truly hopeless.

However, the social stigma of syphilis as a venereal disease played a role in the courses of treatment.

By the 15th century, syphilis was recognized as being spread by sexual intercourse, and in a situation analogous with the early AIDS epidemic, “16th- and 17th-century writers and physicians were divided on the moral aspects of syphilis. Some thought it was a divine punishment for sin – and as such only harsh treatments would cure it – or that people with syphilis shouldn’t be treated at all.”

Mercury rising

In its earliest manifestations, syphilis was considered untreatable. In 1496, Sebastian Brandt, wrote a poem entitled “De pestilentiali Scorra sive mala de Franzos” detailing the disease’s early spread across Europe and how doctors had no remedy for it.

However, it wasn’t long before desperate physicians turned their quest for a cure to a reliable old standby treatment of the period – mercury, which had a history of being used for skin diseases. Mercury salves had been in use in the Arab world for leprosy and eczema, among other skin afflictions, and had been brought to Europe with the return of the medieval crusaders. Another way elemental mercury was administered was through the use of heated cinnabar (HgS), which gave off mercury vapors that could be absorbed by breathing and through the skin. In the 16th century, doctors would place a syphilis-infected individual inside an ovenlike chamber over pans of cinnabar, which were then heated at the person’s feet.

Oral mercury treatments were promoted by Paracelsus (1493?-1541), an alchemist and physician who prescribed calomel (HgCl), or mercury chloride, pills. Mercury treatment, administered at almost inevitably toxic doses, led to ulcerations of the lips, tongue, palate, and jaw; tooth loss; and fetid breath and excessive salivation. This last symptom was, in fact, considered the endpoint in mercury therapy for syphilis, which was “originally judged to be a copious secretion of saliva – ‘some few liters per diem.’ ” Even as recent as the late 19th century and early 20th century, syphilitic patients such as Oscar Wilde (whose teeth were blackened by the treatment), were prescribed calomel.

Looking to the “holy wood”

By 1519, an alternative treatment to mercury was available. In that year, Ulrich von Hutton, a German scholar who suffered from the “great pox,” described its treatment with guaiacum sanctum, or holy wood, in “De Morbo Gallico.” Four years later, despite such treatment, he was dead from the disease himself. But the lack of efficacy did not stop the faith that doctors placed in this botanical cure.

Holy wood was an herbal treatment derived from the bark of trees from the Guaiacum family. It was brought back on trading ships from the Caribbean and South America, the origin of syphilis’s foothold in Europe and the rest of the world. The use of holy wood matched a then-current theory that the cure to a disease could be found in the area from which it came. Other botanicals from around the world were also tried, but never came into routine use.

Guaiacum was the first treatment given to sufferers of syphilis in the Blatterhaus (pox hospital) in Augsburg after 1522, according to information from the archives at the Edward Worth Library in Dublin. The botanical therapy was given as a hot drink and followed by a sweating cure. Guaiacum extract acted as a sudorific, a compound which induces sweating when ingested. Even though the use of Guaiacum was initially popular, it was replaced almost exclusively by the use of mercury.

“Give me fever”

In the late 1800s, Julius Wagner von Jauregg (1857-1940), a Viennese neurologist, observed that Austrian army officers with neurosyphilis did not become partially paralyzed if they had also contracted malaria or relapsing fever. He initiated clinical trials in which he induced fever in syphilitics with tuberculin (1-10 mg) and observed in many the remissions their neuropsychiatric symptoms and signs. He also injected neurosyphilitic patients with a mild form of malaria to induce fever, which could then be suppressed with quinine treatment.

“Other physicians soon began using malariotherapy in uncontrolled studies of neurosyphilitics and reported clinical success rates of 33%-51% and only a 5% mortality. Persons with tabes dorsalis (the “wasting” paralysis of neurosyphilis) were hospitalized for 3 weeks of alternate-day fever therapy involving 5-hour long hot baths and extended periods wrapped in heavy blankets,” according to C.T. Ambrose, MD, of the University of Kentucky, Lexington.

A 1931 medical text summarizes in 35 studies involving 2,356 cases of general paresis treated with malaria and reported a 27.5% “full remission,” he added. A bacterial treatment developed in this period used a course of 18-23 injections of killed typhoid cells administered every 2-3 days in order to produce a fever of 103°–104°F. Animal studies of rabbits infected with syphilis showed that high temperatures could be curative.

Dr. Ambrose suggests that 16th-century syphilitics who had been subjected to mercury fumigation in ovenlike chambers endured severe sweating conditions and – for those who survived – the prolonged elevated body temperature (not the mercury) may have proved curative. Fever “was the common therapeutic denominator in the cinnabar-oven treatment, botanical sudorifics (guaiacum, China root), malarial infections (natural and iatrogenic), and bacterial (tuberculin) vaccine therapy.”

Prelude to modern antibiotics

German bacteriologist/immunologist Paul Ehrlich, MD, (1854-1915) investigated the use of atoxyl (sodium arsanilate) in syphilis, but the metallic drug had severe side effects, injuring the optic nerve and causing blindness. To overcome this problem, Ehrlich and his coworkers synthesized and tested related organic arsenicals. The antisyphilitic activity of arsphenamine (compound 606) was discovered by Sahachiro Hata, MD, (1879-1938) in 1909. This compound, known as Salvarsan, became “Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet,” for the treatment of syphilis in the 1910s, and it, and later, the less-toxic compound neoarsphenamine (compound 914) became mainstays of successful clinical treatment until the development and use of penicillin in the 1940s.

Selected sources

Ambrose, CT. Pre-antibiotic therapy of syphilis. NESSA J Infect Dis Immunology. 2016. 1(1);1-20.

Frith J. Syphilis: Its early history and treatment until penicillin and the debate on its origins. J Mil Veterans Health. 2012;20(4):49-58.

Tognotti B. The rise and fall of syphilis in Renaissance Italy. J Med Humanit. 2009 Jun;30(2):99-113.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor in the department of biochemistry and molecular & cellular biology at Georgetown University, Washington.

It is rare in this modern era for medicine to confront an infectious disease for which there is no cure. Today, there are comparatively few infectious diseases (in the developed world and in places where money is no object) for which medicine cannot offer at least a glimmer of hope to infected patients. Even at its most futile, modern medicine has achieved vast improvements in the efficacy of palliative care. But it wasn’t that long ago that HIV infection was a nearly inevitable death sentence from the complications of AIDS, with no available treatments. And however monstrous that suffering and death, which still continues in many areas of the developing world, it was decades rather than centuries before modern medicine came up with effective treatments. Recently, there is even significant hope on the Ebola virus front that curative treatments may soon become available.

Medicine has always been in the business of hope, even when true cures were not available. Today that hope is less often misplaced. But in previous centuries, the need to offer hope to – and perhaps to make money from – desperate patients was a hallmark of the doctor’s trade.

It was this need to give patients hope and for doctors to feel that they were being effective that led to some highly dubious and desperate efforts to cure syphilis throughout history. These efforts meant centuries of fruitless torture for countless patients until the rise of modern antibiotics.

For the most part, what we now look upon as horrors and insanity in treatment were the result of misguided scientific theories, half-baked folk wisdom, and the generally well-intentioned efforts of medical practitioners at a cure. There were the charlatans as well, seeking a quick buck from the truly hopeless.

However, the social stigma of syphilis as a venereal disease played a role in the courses of treatment.

By the 15th century, syphilis was recognized as being spread by sexual intercourse, and in a situation analogous with the early AIDS epidemic, “16th- and 17th-century writers and physicians were divided on the moral aspects of syphilis. Some thought it was a divine punishment for sin – and as such only harsh treatments would cure it – or that people with syphilis shouldn’t be treated at all.”

Mercury rising

In its earliest manifestations, syphilis was considered untreatable. In 1496, Sebastian Brandt, wrote a poem entitled “De pestilentiali Scorra sive mala de Franzos” detailing the disease’s early spread across Europe and how doctors had no remedy for it.

However, it wasn’t long before desperate physicians turned their quest for a cure to a reliable old standby treatment of the period – mercury, which had a history of being used for skin diseases. Mercury salves had been in use in the Arab world for leprosy and eczema, among other skin afflictions, and had been brought to Europe with the return of the medieval crusaders. Another way elemental mercury was administered was through the use of heated cinnabar (HgS), which gave off mercury vapors that could be absorbed by breathing and through the skin. In the 16th century, doctors would place a syphilis-infected individual inside an ovenlike chamber over pans of cinnabar, which were then heated at the person’s feet.

Oral mercury treatments were promoted by Paracelsus (1493?-1541), an alchemist and physician who prescribed calomel (HgCl), or mercury chloride, pills. Mercury treatment, administered at almost inevitably toxic doses, led to ulcerations of the lips, tongue, palate, and jaw; tooth loss; and fetid breath and excessive salivation. This last symptom was, in fact, considered the endpoint in mercury therapy for syphilis, which was “originally judged to be a copious secretion of saliva – ‘some few liters per diem.’ ” Even as recent as the late 19th century and early 20th century, syphilitic patients such as Oscar Wilde (whose teeth were blackened by the treatment), were prescribed calomel.

Looking to the “holy wood”

By 1519, an alternative treatment to mercury was available. In that year, Ulrich von Hutton, a German scholar who suffered from the “great pox,” described its treatment with guaiacum sanctum, or holy wood, in “De Morbo Gallico.” Four years later, despite such treatment, he was dead from the disease himself. But the lack of efficacy did not stop the faith that doctors placed in this botanical cure.

Holy wood was an herbal treatment derived from the bark of trees from the Guaiacum family. It was brought back on trading ships from the Caribbean and South America, the origin of syphilis’s foothold in Europe and the rest of the world. The use of holy wood matched a then-current theory that the cure to a disease could be found in the area from which it came. Other botanicals from around the world were also tried, but never came into routine use.

Guaiacum was the first treatment given to sufferers of syphilis in the Blatterhaus (pox hospital) in Augsburg after 1522, according to information from the archives at the Edward Worth Library in Dublin. The botanical therapy was given as a hot drink and followed by a sweating cure. Guaiacum extract acted as a sudorific, a compound which induces sweating when ingested. Even though the use of Guaiacum was initially popular, it was replaced almost exclusively by the use of mercury.

“Give me fever”

In the late 1800s, Julius Wagner von Jauregg (1857-1940), a Viennese neurologist, observed that Austrian army officers with neurosyphilis did not become partially paralyzed if they had also contracted malaria or relapsing fever. He initiated clinical trials in which he induced fever in syphilitics with tuberculin (1-10 mg) and observed in many the remissions their neuropsychiatric symptoms and signs. He also injected neurosyphilitic patients with a mild form of malaria to induce fever, which could then be suppressed with quinine treatment.

“Other physicians soon began using malariotherapy in uncontrolled studies of neurosyphilitics and reported clinical success rates of 33%-51% and only a 5% mortality. Persons with tabes dorsalis (the “wasting” paralysis of neurosyphilis) were hospitalized for 3 weeks of alternate-day fever therapy involving 5-hour long hot baths and extended periods wrapped in heavy blankets,” according to C.T. Ambrose, MD, of the University of Kentucky, Lexington.

A 1931 medical text summarizes in 35 studies involving 2,356 cases of general paresis treated with malaria and reported a 27.5% “full remission,” he added. A bacterial treatment developed in this period used a course of 18-23 injections of killed typhoid cells administered every 2-3 days in order to produce a fever of 103°–104°F. Animal studies of rabbits infected with syphilis showed that high temperatures could be curative.

Dr. Ambrose suggests that 16th-century syphilitics who had been subjected to mercury fumigation in ovenlike chambers endured severe sweating conditions and – for those who survived – the prolonged elevated body temperature (not the mercury) may have proved curative. Fever “was the common therapeutic denominator in the cinnabar-oven treatment, botanical sudorifics (guaiacum, China root), malarial infections (natural and iatrogenic), and bacterial (tuberculin) vaccine therapy.”

Prelude to modern antibiotics

German bacteriologist/immunologist Paul Ehrlich, MD, (1854-1915) investigated the use of atoxyl (sodium arsanilate) in syphilis, but the metallic drug had severe side effects, injuring the optic nerve and causing blindness. To overcome this problem, Ehrlich and his coworkers synthesized and tested related organic arsenicals. The antisyphilitic activity of arsphenamine (compound 606) was discovered by Sahachiro Hata, MD, (1879-1938) in 1909. This compound, known as Salvarsan, became “Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet,” for the treatment of syphilis in the 1910s, and it, and later, the less-toxic compound neoarsphenamine (compound 914) became mainstays of successful clinical treatment until the development and use of penicillin in the 1940s.

Selected sources

Ambrose, CT. Pre-antibiotic therapy of syphilis. NESSA J Infect Dis Immunology. 2016. 1(1);1-20.

Frith J. Syphilis: Its early history and treatment until penicillin and the debate on its origins. J Mil Veterans Health. 2012;20(4):49-58.

Tognotti B. The rise and fall of syphilis in Renaissance Italy. J Med Humanit. 2009 Jun;30(2):99-113.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor in the department of biochemistry and molecular & cellular biology at Georgetown University, Washington.

Dismantling the opioid crisis

Dr. John Hickner’s editorial, “Doing our part to dismantle the opioid crisis” (J Fam Pract 2019;68:308) had important inaccuracies.

The Joint Commission, for which I serve as an executive vice president, did not “dub pain assessment the ‘fifth vital sign’. ” The concept of the fifth vital sign was developed by the American Pain Society in the 1990s.1 It gained national attention through a Veterans Health Administration initiative in 1999.2 And in 2001, the Joint Commission (then the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations or JCAHO) issued its Pain Standards.

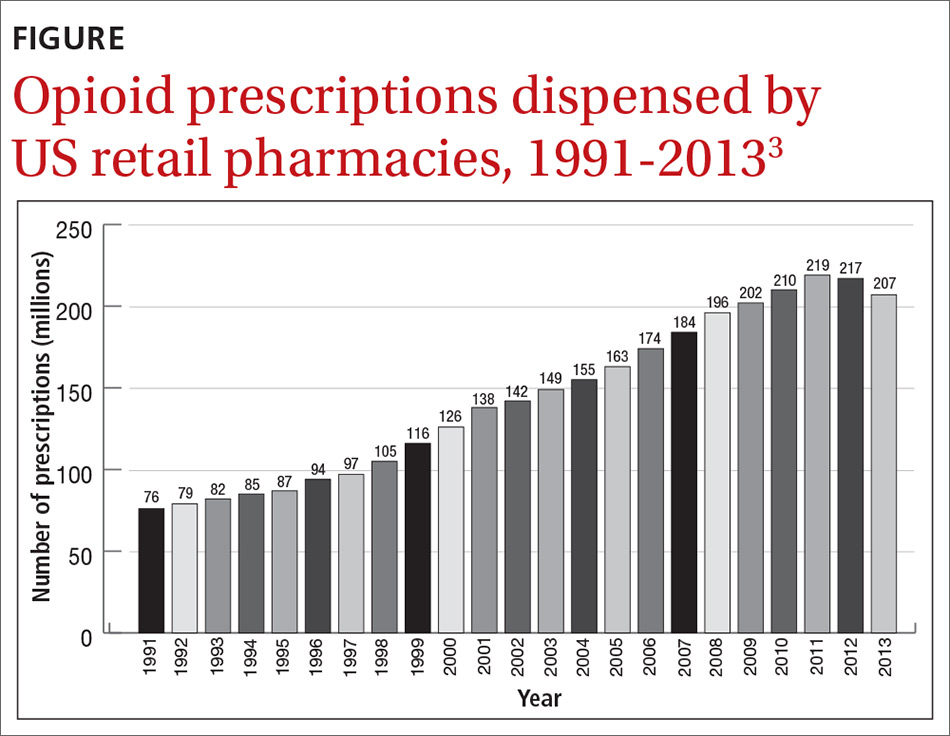

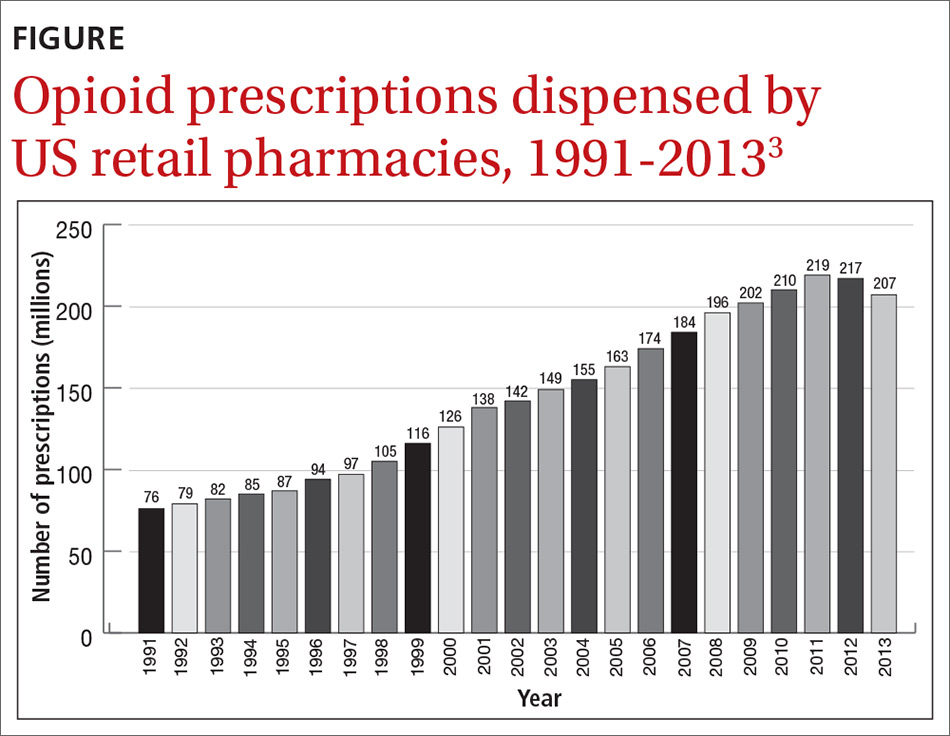

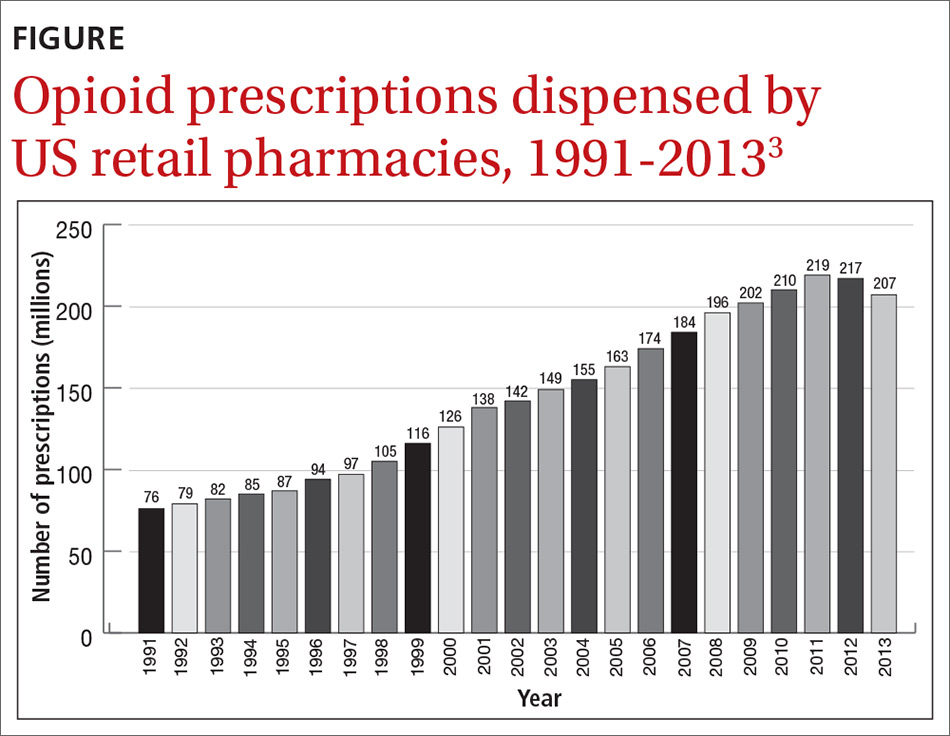

Dr. Hickner wrote that the push to assess for pain as the fifth vital sign was a central cause of the opioid epidemic; however, this is contrary to published data on the epidemic. Total opioid prescriptions had been steadily increasing in the United States for at least a decade before the Pain Standards went into effect in 2001 (FIGURE).3 Between 1991 and 1997, the number of prescriptions increased from 76 million to 97 million. The rate of increase from 1997 to 2011 appears to have been more rapid, which is likely due to the 1995 approval of the new sustained-release opioid OxyContin and the associated aggressive marketing campaigns to physicians.

Your readers should know that we, at the Joint Commission, are also “doing our part to dismantle the opioid crisis.” In 2016, we completely revised our Pain Standards, adding new criteria to help address the epidemic. Some adjustments include: requiring improved availability of nonpharmacologic therapy, encouraging engagement of patients in pain management plans, enhancing accessibility of Physician Drug Monitoring Program tools, and monitoring opioid prescribing.

David W. Baker, MD, FACP, executive vice president

The Joint Commission, Oakbrook Terrace, IL

1. American Pain Society. Principles of Analgesic Use in the Treatment of Acute Pain and Chronic Cancer Pain. 2nd ed. Skokie, Illinois: American Pain Society; 1989.

2. Department of Veteran’s Affairs. Pain: the fifth vital sign. www.va.gov/PAINMANAGEMENT/docs/Pain_As_the_5th_Vital_Sign_Toolkit.pdf. Published October 2000. Accessed September 30, 2019.

3 National Institute on Drug Abuse. America’s addiction to opioids: heroin and prescription drug abuse. https://archives.drugabuse.gov/testimonies/2014/americas-addiction-to-opioids-heroin-prescription-drug-abuse. Published May 14, 2014. Accessed September 30, 2019.

Dr. John Hickner’s editorial, “Doing our part to dismantle the opioid crisis” (J Fam Pract 2019;68:308) had important inaccuracies.

The Joint Commission, for which I serve as an executive vice president, did not “dub pain assessment the ‘fifth vital sign’. ” The concept of the fifth vital sign was developed by the American Pain Society in the 1990s.1 It gained national attention through a Veterans Health Administration initiative in 1999.2 And in 2001, the Joint Commission (then the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations or JCAHO) issued its Pain Standards.