User login

What Neglected Tropical Diseases Teach Us About Stigma

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are a group of 20 diseases that typically are chronic and cause long-term disability, which negatively impacts work productivity, child survival, and school performance and attendance with adverse effect on future earnings.1 Data from the 2013 Global Burden of Disease study revealed that half of the world’s NTDs occur in poor populations living in wealthy countries.2 Neglected tropical diseases with skin manifestations include parasitic infections (eg, American trypanosomiasis, African trypanosomiasis, dracunculiasis, echinococcosis, foodborne trematodiases, leishmaniasis, lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, scabies and other ectoparasites, schistosomiasis, soil-transmitted helminths, taeniasis/cysticercosis), bacterial infections (eg, Buruli ulcer, leprosy, yaws), fungal infections (eg, mycetoma, chromoblastomycosis, deep mycoses), and viral infections (eg, dengue, chikungunya). Rabies and snakebite envenomization involve the skin through inoculation. Within the larger group of NTDs, the World Health Organization has identified “skin NTDs” as a subgroup of NTDs that present primarily with changes in the skin.3 In the absence of early diagnosis and treatment of these diseases, chronic and lifelong disfigurement, disability, stigma, and socioeconomic losses ensue.

The Department of Health of the Government of Western Australia stated:

Stigma is a mark of disgrace that sets a person apart from others. When a person is labeled by their illness they are no longer seen as an individual but as part of a stereotyped group. Negative attitudes and beliefs toward this group create prejudice which leads to negative actions and discrimination.4

Stigma associated with skin NTDs exemplifies how skin diseases can have enduring impact on individuals.5 For example, scarring from inactive cutaneous leishmaniasis carries heavy psychosocial burden. Young women reported that facial scarring from cutaneous leishmaniasis led to marriage rejections.6 Some even reported extreme suicidal ideations.7 Recently, major depressive disorder associated with scarring from inactive cutaneous leishmaniasis has been recognized as a notable contributor to disease burden from cutaneous leishmaniasis.8

Lymphatic filariasis is a major cause of leg and scrotal lymphedema worldwide. Even when the condition is treated, lymphedema often persists due to chronic irreversible lymphatic damage. A systematic review of 18 stigma studies in lymphatic filariasis found common themes related to the deleterious consequences of stigma on social relationships; work and education opportunities; health outcomes from reduced treatment-seeking behavior; and mental health, including anxiety, depression, and suicidal tendencies.9 In one subdistrict in India, implementation of a community-based lymphedema management program that consisted of teaching hygiene and limb care for more than 20,000 lymphedema patients and performing community outreach activities (eg, street plays, radio programs, informational brochures) to teach people about lymphatic filariasis and lymphedema care was associated with community members being accepting of patients and an improvement in their understanding of disease etiology.10

Skin involvement from onchocerciasis infection (onchocercal skin disease) is another condition associated with notable stigma.9 Through the African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control, annual mass drug administration of ivermectin in onchocerciasis-endemic communities has reduced the rate of onchocercal skin disease in these communities. In looking at perception of stigma in onchocercal skin diseases before community-directed ivermectin therapy and 7 to 10 years after, avoidance of people with onchocercal skin disease decreased from 32.7% to 4.3%. There also was an improvement in relationships between healthy people and those with onchocercal skin disease.11

One of the most stigmatizing conditions is leprosy, often referred to as Hansen disease to give credit to the person who discovered that leprosy was caused by Mycobacterium leprae and not from sin, being cursed, or genetic inheritance. Even with this knowledge, stigma persists that can lead to family abandonment and social isolation, which further impacts afflicted individuals’ willingness to seek care, thus leading to disease progression. More recently, there has been research looking at interventions to reduce the stigma that individuals afflicted with leprosy face. In a study from Indonesia where individuals with leprosy were randomized to counseling, socioeconomic development, or contact between community members and affected people, all interventions were associated with a reduction in stigma.12 A rights-based counseling module integrated individual, family, and group forms of counseling and consisted of 5 sessions that focused on medical knowledge of leprosy and rights of individuals with leprosy, along with elements of cognitive behavioral therapy. Socioeconomic development involved opportunities for business training, creation of community groups through which microfinance services were administered, and other assistance to improve livelihood. Informed by evidence from the field of human immunodeficiency virus and mental health that co

Although steps are being taken to address the psychosocial burden of skin NTDs, there is still much work to be done. From the public health lens that largely governs the policies and approaches toward addressing NTDs, the focus often is on interrupting and eliminating disease transmission. Morbidity management, including reduction in stigma and functional impairment, is not always the priority. It is in this space that dermatologists are uniquely positioned to advocate for management approaches that address the morbidity associated with skin NTDs. We have an intimate understanding of how impactful skin diseases can be, even if they are not commonly fatal. Globally, skin diseases are the fourth leading cause of nonfatal disease burden,14 yet dermatology lacks effective evidence-based interventions for reducing stigma in our patients with visible chronic diseases.15

Every day, we see firsthand how skin diseases affect not only our patients but also their families, friends, and caregivers. Although we may not see skin NTDs on a regular basis in our clinics, we can understand almost intuitively how devastating skin NTDs could be on individuals, families, and communities. For patients with skin NTDs, receiving medical therapy is only one component of treatment. In addition to optimizing early diagnosis and treatment, interventions taken to educate families and communities affected by skin NTDs are vitally important. Stigma reduction is possible, as we have seen from the aforementioned interventions used in communities with lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, and leprosy. We call upon our fellow dermatologists to take interest in creating, evaluating, and promoting interventions that address stigma in skin NTDs; it is critical in achieving and maintaining health and well-being for our patients.

- Neglected tropical diseases. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/diseases/en/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Hotez PJ, Damania A, Naghavi M. Blue Marble Health and the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:E0004744.

- Skin NTDs. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/skin-ntds/en/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Government of Western Australia Department of Health. Stigma, discrimination and mental illness. February 2009. http://www.health.wa.gov.au/docreg/Education/Population/Health_Problems/Mental_Illness/Mentalhealth_stigma_fact.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Hotez PJ. Stigma: the stealth weapon of the NTD. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:E230.

- Bennis I, Belaid L, De Brouwere V, et al. “The mosquitoes that destroy your face.” social impact of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Southeastern Morocco, a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2017;12:E0189906.

- Bennis I, Thys S, Filali H, et al. Psychosocial impact of scars due to cutaneous leishmaniasis on high school students in Errachidia province, Morocco. Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6:46.

- Bailey F, Mondragon-Shem K, Haines LR, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis and co-morbid major depressive disorder: a systematic review with burden estimates. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:E0007092.

- Hofstraat K, van Brakel WH. Social stigma towards neglected tropical diseases: a systematic review. Int Health. 2016;8(suppl 1):I53-I70.

- Cassidy T, Worrell CM, Little K, et al. Experiences of a community-based lymphedema management program for lymphatic filariasis in Odisha State, India: an analysis of focus group discussions with patients, families, community members and program volunteers. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:E0004424.

- Tchounkeu YF, Onyeneho NG, Wanji S, et al. Changes in stigma and discrimination of onchocerciasis in Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106:340-347.

- Dadun D, Van Brakel WH, Peters RMH, et al. Impact of socio-economic development, contact and peer counselling on stigma against persons affected by leprosy in Cirebon, Indonesia—a randomised controlled trial. Lepr Rev. 2017;88:2-22.

- Kumar A, Lambert S, Lockwood DNJ. Picturing health: a new face for leprosy. Lancet. 2019;393:629-638.

- Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1527-1534.

- Topp J, Andrees V, Weinberger NA, et al. Strategies to reduce stigma related to visible chronic skin diseases: a systematic review [published online June 8, 2019]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.15734.

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are a group of 20 diseases that typically are chronic and cause long-term disability, which negatively impacts work productivity, child survival, and school performance and attendance with adverse effect on future earnings.1 Data from the 2013 Global Burden of Disease study revealed that half of the world’s NTDs occur in poor populations living in wealthy countries.2 Neglected tropical diseases with skin manifestations include parasitic infections (eg, American trypanosomiasis, African trypanosomiasis, dracunculiasis, echinococcosis, foodborne trematodiases, leishmaniasis, lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, scabies and other ectoparasites, schistosomiasis, soil-transmitted helminths, taeniasis/cysticercosis), bacterial infections (eg, Buruli ulcer, leprosy, yaws), fungal infections (eg, mycetoma, chromoblastomycosis, deep mycoses), and viral infections (eg, dengue, chikungunya). Rabies and snakebite envenomization involve the skin through inoculation. Within the larger group of NTDs, the World Health Organization has identified “skin NTDs” as a subgroup of NTDs that present primarily with changes in the skin.3 In the absence of early diagnosis and treatment of these diseases, chronic and lifelong disfigurement, disability, stigma, and socioeconomic losses ensue.

The Department of Health of the Government of Western Australia stated:

Stigma is a mark of disgrace that sets a person apart from others. When a person is labeled by their illness they are no longer seen as an individual but as part of a stereotyped group. Negative attitudes and beliefs toward this group create prejudice which leads to negative actions and discrimination.4

Stigma associated with skin NTDs exemplifies how skin diseases can have enduring impact on individuals.5 For example, scarring from inactive cutaneous leishmaniasis carries heavy psychosocial burden. Young women reported that facial scarring from cutaneous leishmaniasis led to marriage rejections.6 Some even reported extreme suicidal ideations.7 Recently, major depressive disorder associated with scarring from inactive cutaneous leishmaniasis has been recognized as a notable contributor to disease burden from cutaneous leishmaniasis.8

Lymphatic filariasis is a major cause of leg and scrotal lymphedema worldwide. Even when the condition is treated, lymphedema often persists due to chronic irreversible lymphatic damage. A systematic review of 18 stigma studies in lymphatic filariasis found common themes related to the deleterious consequences of stigma on social relationships; work and education opportunities; health outcomes from reduced treatment-seeking behavior; and mental health, including anxiety, depression, and suicidal tendencies.9 In one subdistrict in India, implementation of a community-based lymphedema management program that consisted of teaching hygiene and limb care for more than 20,000 lymphedema patients and performing community outreach activities (eg, street plays, radio programs, informational brochures) to teach people about lymphatic filariasis and lymphedema care was associated with community members being accepting of patients and an improvement in their understanding of disease etiology.10

Skin involvement from onchocerciasis infection (onchocercal skin disease) is another condition associated with notable stigma.9 Through the African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control, annual mass drug administration of ivermectin in onchocerciasis-endemic communities has reduced the rate of onchocercal skin disease in these communities. In looking at perception of stigma in onchocercal skin diseases before community-directed ivermectin therapy and 7 to 10 years after, avoidance of people with onchocercal skin disease decreased from 32.7% to 4.3%. There also was an improvement in relationships between healthy people and those with onchocercal skin disease.11

One of the most stigmatizing conditions is leprosy, often referred to as Hansen disease to give credit to the person who discovered that leprosy was caused by Mycobacterium leprae and not from sin, being cursed, or genetic inheritance. Even with this knowledge, stigma persists that can lead to family abandonment and social isolation, which further impacts afflicted individuals’ willingness to seek care, thus leading to disease progression. More recently, there has been research looking at interventions to reduce the stigma that individuals afflicted with leprosy face. In a study from Indonesia where individuals with leprosy were randomized to counseling, socioeconomic development, or contact between community members and affected people, all interventions were associated with a reduction in stigma.12 A rights-based counseling module integrated individual, family, and group forms of counseling and consisted of 5 sessions that focused on medical knowledge of leprosy and rights of individuals with leprosy, along with elements of cognitive behavioral therapy. Socioeconomic development involved opportunities for business training, creation of community groups through which microfinance services were administered, and other assistance to improve livelihood. Informed by evidence from the field of human immunodeficiency virus and mental health that co

Although steps are being taken to address the psychosocial burden of skin NTDs, there is still much work to be done. From the public health lens that largely governs the policies and approaches toward addressing NTDs, the focus often is on interrupting and eliminating disease transmission. Morbidity management, including reduction in stigma and functional impairment, is not always the priority. It is in this space that dermatologists are uniquely positioned to advocate for management approaches that address the morbidity associated with skin NTDs. We have an intimate understanding of how impactful skin diseases can be, even if they are not commonly fatal. Globally, skin diseases are the fourth leading cause of nonfatal disease burden,14 yet dermatology lacks effective evidence-based interventions for reducing stigma in our patients with visible chronic diseases.15

Every day, we see firsthand how skin diseases affect not only our patients but also their families, friends, and caregivers. Although we may not see skin NTDs on a regular basis in our clinics, we can understand almost intuitively how devastating skin NTDs could be on individuals, families, and communities. For patients with skin NTDs, receiving medical therapy is only one component of treatment. In addition to optimizing early diagnosis and treatment, interventions taken to educate families and communities affected by skin NTDs are vitally important. Stigma reduction is possible, as we have seen from the aforementioned interventions used in communities with lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, and leprosy. We call upon our fellow dermatologists to take interest in creating, evaluating, and promoting interventions that address stigma in skin NTDs; it is critical in achieving and maintaining health and well-being for our patients.

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are a group of 20 diseases that typically are chronic and cause long-term disability, which negatively impacts work productivity, child survival, and school performance and attendance with adverse effect on future earnings.1 Data from the 2013 Global Burden of Disease study revealed that half of the world’s NTDs occur in poor populations living in wealthy countries.2 Neglected tropical diseases with skin manifestations include parasitic infections (eg, American trypanosomiasis, African trypanosomiasis, dracunculiasis, echinococcosis, foodborne trematodiases, leishmaniasis, lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, scabies and other ectoparasites, schistosomiasis, soil-transmitted helminths, taeniasis/cysticercosis), bacterial infections (eg, Buruli ulcer, leprosy, yaws), fungal infections (eg, mycetoma, chromoblastomycosis, deep mycoses), and viral infections (eg, dengue, chikungunya). Rabies and snakebite envenomization involve the skin through inoculation. Within the larger group of NTDs, the World Health Organization has identified “skin NTDs” as a subgroup of NTDs that present primarily with changes in the skin.3 In the absence of early diagnosis and treatment of these diseases, chronic and lifelong disfigurement, disability, stigma, and socioeconomic losses ensue.

The Department of Health of the Government of Western Australia stated:

Stigma is a mark of disgrace that sets a person apart from others. When a person is labeled by their illness they are no longer seen as an individual but as part of a stereotyped group. Negative attitudes and beliefs toward this group create prejudice which leads to negative actions and discrimination.4

Stigma associated with skin NTDs exemplifies how skin diseases can have enduring impact on individuals.5 For example, scarring from inactive cutaneous leishmaniasis carries heavy psychosocial burden. Young women reported that facial scarring from cutaneous leishmaniasis led to marriage rejections.6 Some even reported extreme suicidal ideations.7 Recently, major depressive disorder associated with scarring from inactive cutaneous leishmaniasis has been recognized as a notable contributor to disease burden from cutaneous leishmaniasis.8

Lymphatic filariasis is a major cause of leg and scrotal lymphedema worldwide. Even when the condition is treated, lymphedema often persists due to chronic irreversible lymphatic damage. A systematic review of 18 stigma studies in lymphatic filariasis found common themes related to the deleterious consequences of stigma on social relationships; work and education opportunities; health outcomes from reduced treatment-seeking behavior; and mental health, including anxiety, depression, and suicidal tendencies.9 In one subdistrict in India, implementation of a community-based lymphedema management program that consisted of teaching hygiene and limb care for more than 20,000 lymphedema patients and performing community outreach activities (eg, street plays, radio programs, informational brochures) to teach people about lymphatic filariasis and lymphedema care was associated with community members being accepting of patients and an improvement in their understanding of disease etiology.10

Skin involvement from onchocerciasis infection (onchocercal skin disease) is another condition associated with notable stigma.9 Through the African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control, annual mass drug administration of ivermectin in onchocerciasis-endemic communities has reduced the rate of onchocercal skin disease in these communities. In looking at perception of stigma in onchocercal skin diseases before community-directed ivermectin therapy and 7 to 10 years after, avoidance of people with onchocercal skin disease decreased from 32.7% to 4.3%. There also was an improvement in relationships between healthy people and those with onchocercal skin disease.11

One of the most stigmatizing conditions is leprosy, often referred to as Hansen disease to give credit to the person who discovered that leprosy was caused by Mycobacterium leprae and not from sin, being cursed, or genetic inheritance. Even with this knowledge, stigma persists that can lead to family abandonment and social isolation, which further impacts afflicted individuals’ willingness to seek care, thus leading to disease progression. More recently, there has been research looking at interventions to reduce the stigma that individuals afflicted with leprosy face. In a study from Indonesia where individuals with leprosy were randomized to counseling, socioeconomic development, or contact between community members and affected people, all interventions were associated with a reduction in stigma.12 A rights-based counseling module integrated individual, family, and group forms of counseling and consisted of 5 sessions that focused on medical knowledge of leprosy and rights of individuals with leprosy, along with elements of cognitive behavioral therapy. Socioeconomic development involved opportunities for business training, creation of community groups through which microfinance services were administered, and other assistance to improve livelihood. Informed by evidence from the field of human immunodeficiency virus and mental health that co

Although steps are being taken to address the psychosocial burden of skin NTDs, there is still much work to be done. From the public health lens that largely governs the policies and approaches toward addressing NTDs, the focus often is on interrupting and eliminating disease transmission. Morbidity management, including reduction in stigma and functional impairment, is not always the priority. It is in this space that dermatologists are uniquely positioned to advocate for management approaches that address the morbidity associated with skin NTDs. We have an intimate understanding of how impactful skin diseases can be, even if they are not commonly fatal. Globally, skin diseases are the fourth leading cause of nonfatal disease burden,14 yet dermatology lacks effective evidence-based interventions for reducing stigma in our patients with visible chronic diseases.15

Every day, we see firsthand how skin diseases affect not only our patients but also their families, friends, and caregivers. Although we may not see skin NTDs on a regular basis in our clinics, we can understand almost intuitively how devastating skin NTDs could be on individuals, families, and communities. For patients with skin NTDs, receiving medical therapy is only one component of treatment. In addition to optimizing early diagnosis and treatment, interventions taken to educate families and communities affected by skin NTDs are vitally important. Stigma reduction is possible, as we have seen from the aforementioned interventions used in communities with lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, and leprosy. We call upon our fellow dermatologists to take interest in creating, evaluating, and promoting interventions that address stigma in skin NTDs; it is critical in achieving and maintaining health and well-being for our patients.

- Neglected tropical diseases. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/diseases/en/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Hotez PJ, Damania A, Naghavi M. Blue Marble Health and the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:E0004744.

- Skin NTDs. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/skin-ntds/en/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Government of Western Australia Department of Health. Stigma, discrimination and mental illness. February 2009. http://www.health.wa.gov.au/docreg/Education/Population/Health_Problems/Mental_Illness/Mentalhealth_stigma_fact.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Hotez PJ. Stigma: the stealth weapon of the NTD. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:E230.

- Bennis I, Belaid L, De Brouwere V, et al. “The mosquitoes that destroy your face.” social impact of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Southeastern Morocco, a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2017;12:E0189906.

- Bennis I, Thys S, Filali H, et al. Psychosocial impact of scars due to cutaneous leishmaniasis on high school students in Errachidia province, Morocco. Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6:46.

- Bailey F, Mondragon-Shem K, Haines LR, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis and co-morbid major depressive disorder: a systematic review with burden estimates. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:E0007092.

- Hofstraat K, van Brakel WH. Social stigma towards neglected tropical diseases: a systematic review. Int Health. 2016;8(suppl 1):I53-I70.

- Cassidy T, Worrell CM, Little K, et al. Experiences of a community-based lymphedema management program for lymphatic filariasis in Odisha State, India: an analysis of focus group discussions with patients, families, community members and program volunteers. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:E0004424.

- Tchounkeu YF, Onyeneho NG, Wanji S, et al. Changes in stigma and discrimination of onchocerciasis in Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106:340-347.

- Dadun D, Van Brakel WH, Peters RMH, et al. Impact of socio-economic development, contact and peer counselling on stigma against persons affected by leprosy in Cirebon, Indonesia—a randomised controlled trial. Lepr Rev. 2017;88:2-22.

- Kumar A, Lambert S, Lockwood DNJ. Picturing health: a new face for leprosy. Lancet. 2019;393:629-638.

- Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1527-1534.

- Topp J, Andrees V, Weinberger NA, et al. Strategies to reduce stigma related to visible chronic skin diseases: a systematic review [published online June 8, 2019]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.15734.

- Neglected tropical diseases. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/diseases/en/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Hotez PJ, Damania A, Naghavi M. Blue Marble Health and the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:E0004744.

- Skin NTDs. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/skin-ntds/en/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Government of Western Australia Department of Health. Stigma, discrimination and mental illness. February 2009. http://www.health.wa.gov.au/docreg/Education/Population/Health_Problems/Mental_Illness/Mentalhealth_stigma_fact.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Hotez PJ. Stigma: the stealth weapon of the NTD. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:E230.

- Bennis I, Belaid L, De Brouwere V, et al. “The mosquitoes that destroy your face.” social impact of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Southeastern Morocco, a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2017;12:E0189906.

- Bennis I, Thys S, Filali H, et al. Psychosocial impact of scars due to cutaneous leishmaniasis on high school students in Errachidia province, Morocco. Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6:46.

- Bailey F, Mondragon-Shem K, Haines LR, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis and co-morbid major depressive disorder: a systematic review with burden estimates. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:E0007092.

- Hofstraat K, van Brakel WH. Social stigma towards neglected tropical diseases: a systematic review. Int Health. 2016;8(suppl 1):I53-I70.

- Cassidy T, Worrell CM, Little K, et al. Experiences of a community-based lymphedema management program for lymphatic filariasis in Odisha State, India: an analysis of focus group discussions with patients, families, community members and program volunteers. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:E0004424.

- Tchounkeu YF, Onyeneho NG, Wanji S, et al. Changes in stigma and discrimination of onchocerciasis in Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106:340-347.

- Dadun D, Van Brakel WH, Peters RMH, et al. Impact of socio-economic development, contact and peer counselling on stigma against persons affected by leprosy in Cirebon, Indonesia—a randomised controlled trial. Lepr Rev. 2017;88:2-22.

- Kumar A, Lambert S, Lockwood DNJ. Picturing health: a new face for leprosy. Lancet. 2019;393:629-638.

- Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1527-1534.

- Topp J, Andrees V, Weinberger NA, et al. Strategies to reduce stigma related to visible chronic skin diseases: a systematic review [published online June 8, 2019]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.15734.

The VA Ketamine Controversies

"Extreme remedies are very appropriate for extreme diseases"

- Hippocrates Aphorisms

On March 5, 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a nasal spray formulation of the drug ketamine, an old anesthetic that has been put to a new use over the past 10 years as therapy for treatment-resistant severe depression. Ketamine, known on the street as Special K, has long been known to cause dissociation, hallucinations, and other hallucinogenic effects. In many randomized controlled trials, subanesthetic doses administered intravenously have demonstrated rapid and often dramatic relief of depressive symptoms.

Neuroscientists have heralded ketamine as the paradigm

When the FDA approved Spravato (esketamine), a nasal administration of ketamine, many people hoped that researchers had succeeded in overcoming these barriers. The risks of serious adverse events (AEs) as well as the potential for abuse and diversion led the FDA to limit prescriptions under a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS).3 Patients self-administer the nasal spray but only in a certified medical facility under the observation of a health care practitioner. Patients also must agree to remain on site for 2 hours after administration of the drug to ensure their safety. The FDA recommends the drug be given twice a week for 4 weeks along with a conventional monoamine-acting antidepressant.When the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) cleared the way for use of esketamine, less than 2 weeks after the FDA approval, it also launched a series of controversies over how to use the drug in its massive health care system, which is the subject of this editorial. On March 19, 2019, the VA announced that VA practitioners would be able to prescribe the nasal spray for patients who were determined to have treatment-resistant depression but only after appropriate clinical assessment and in accordance with their patients’ preferences.

A number of controversies have emerged surrounding the VA adoption of esketamine, including its cost/benefit/risk ratio and who should be able to access the medication. Each of these issues has onion layers of political, regulatory, and ethical concerns that can only be superficially noted here and warrant fuller unpeeling. In June The New York Times featured a story alleging that in response to the tragic tide of ever-increasing veteran suicides, the VA sanctioned esketamine prescribing despite its cost and the serious questions experts raised about the data the FDA cited to establish its safety and efficacy. Although the cost to the VA of Spravato is unclear, it is much higher than generic IV ketamine.4

The access controversy is almost the ethical inverse of the first. In June 2019, a Veterans Health Administration advisory panel voted against allowing general use of esketamine, limiting it to individual cases of patients who are preapproved and have failed 2 antidepressant trials. Esketamine will not be on the VA formulary for widespread use. Congressional and public advocacy groups have noted that the formulary decision came in the wake of ongoing attention to the role of the pharmaceutical industry in the VA’s rapid adoption of the drug.5,6 For the thousands of veterans for whom the data show conventional antidepressants even in combination with other psychotropic medications and evidence-based psychotherapies resulted in AEs or only partial remission of depression symptoms, the VA’s restriction will likely seem unfair and even uncaring.7

As a practicing VA psychiatrist, I know firsthand how desperately we need new, more effective, and better-tolerated treatments for severe unipolar and bipolar depression. Although I have not prescribed ketamine or esketamine, several of my most respected colleagues do. I have seen patients with chronic, severe, depression respond and even recover in ways that seem just a little short of miraculous when compared with other therapies. Yet as a longtime student of the history of psychiatry, I have also seen that often the treatments that initially seem so auspicious, in time, turn out to have a dark side. Families, communities, the country, VA, and the US Department of Defense and its practitioners in and out of mental health cannot in any moral universe abide by the fact that 20 plus men and women who served take their lives every day.8

As the epigraph to this column notes, we must often try radical therapies for grave cases in drastic crises. Yet we must also in making serious public health decisions fraught with unseen consequences take all due and considered diligence that we do not violate the even more fundamental dictum of the Hippocratic School, “at least do not harm.” That means trying to balance safety and availability while VA conducts its own research in a precarious way that leaves almost no stakeholder completely happy.

1. Lener MS, Kadriu B, Zarate CA Jr. Ketamine and beyond: investigations into the potential of glutamatergic agents to treat depression. Drugs. 2017;77(4):381-401.

2. Thielking M. “Is the Ketamine Boon Getting out of Hand?” STAT. September 24, 2018. https://www.statnews.com/2018/09/24/ketamine-clinics-severe-depression-treatment. Accessed September 17, 2019.

3. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves new nasal spray medication for treatment-resistant depression: available only at a certified doctor’s office or clinic [press release]. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-nasal-spray-medication-treatment-resistant-depression-available-only-certified. Published March 5, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

4. Carey B, Steinhauser J. Veterans agency to offer new depression drug, despite safety and efficacy concerns. The New York Times. June 21, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/21/health/ketamine-depression-veterans.html. Accessed September 17, 2019.

5. US House of Representatives, Committee on Veterans Affairs. Chairman Takano statement following reports that VA fast-tracked controversial drug Spravato to treat veterans [press release]. https://veterans.house.gov/news/press-releases/chairman-takano-statement-following-reports-that-va-fast-tracked-controversial-drug-spravato-to-treat-veterans. Published June 18, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

6. Cary P. Trump’s praise put drug for vets on fast track, but experts are not sure it works. https://publicintegrity.org/federal-politics/trumps-raves-put-drug-for-vets-on-fast-track-but-experts-arent-sure-it-works. Published June 18, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

7. Zisook S, Tal I, Weingart K, et al. Characteristics of U.S. veteran patients with major depressive disorder who require ‘next-step’ treatments: A VAST-D report. J Affect Disord. 2016;206:232-240.

8. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. VA National Suicide Data Report 2005-2016. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/OMHSP_National_Suicide_Data_Report_2005-2016_508.pdf. Updated 2018. Accessed September 17, 2019.

"Extreme remedies are very appropriate for extreme diseases"

- Hippocrates Aphorisms

On March 5, 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a nasal spray formulation of the drug ketamine, an old anesthetic that has been put to a new use over the past 10 years as therapy for treatment-resistant severe depression. Ketamine, known on the street as Special K, has long been known to cause dissociation, hallucinations, and other hallucinogenic effects. In many randomized controlled trials, subanesthetic doses administered intravenously have demonstrated rapid and often dramatic relief of depressive symptoms.

Neuroscientists have heralded ketamine as the paradigm

When the FDA approved Spravato (esketamine), a nasal administration of ketamine, many people hoped that researchers had succeeded in overcoming these barriers. The risks of serious adverse events (AEs) as well as the potential for abuse and diversion led the FDA to limit prescriptions under a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS).3 Patients self-administer the nasal spray but only in a certified medical facility under the observation of a health care practitioner. Patients also must agree to remain on site for 2 hours after administration of the drug to ensure their safety. The FDA recommends the drug be given twice a week for 4 weeks along with a conventional monoamine-acting antidepressant.When the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) cleared the way for use of esketamine, less than 2 weeks after the FDA approval, it also launched a series of controversies over how to use the drug in its massive health care system, which is the subject of this editorial. On March 19, 2019, the VA announced that VA practitioners would be able to prescribe the nasal spray for patients who were determined to have treatment-resistant depression but only after appropriate clinical assessment and in accordance with their patients’ preferences.

A number of controversies have emerged surrounding the VA adoption of esketamine, including its cost/benefit/risk ratio and who should be able to access the medication. Each of these issues has onion layers of political, regulatory, and ethical concerns that can only be superficially noted here and warrant fuller unpeeling. In June The New York Times featured a story alleging that in response to the tragic tide of ever-increasing veteran suicides, the VA sanctioned esketamine prescribing despite its cost and the serious questions experts raised about the data the FDA cited to establish its safety and efficacy. Although the cost to the VA of Spravato is unclear, it is much higher than generic IV ketamine.4

The access controversy is almost the ethical inverse of the first. In June 2019, a Veterans Health Administration advisory panel voted against allowing general use of esketamine, limiting it to individual cases of patients who are preapproved and have failed 2 antidepressant trials. Esketamine will not be on the VA formulary for widespread use. Congressional and public advocacy groups have noted that the formulary decision came in the wake of ongoing attention to the role of the pharmaceutical industry in the VA’s rapid adoption of the drug.5,6 For the thousands of veterans for whom the data show conventional antidepressants even in combination with other psychotropic medications and evidence-based psychotherapies resulted in AEs or only partial remission of depression symptoms, the VA’s restriction will likely seem unfair and even uncaring.7

As a practicing VA psychiatrist, I know firsthand how desperately we need new, more effective, and better-tolerated treatments for severe unipolar and bipolar depression. Although I have not prescribed ketamine or esketamine, several of my most respected colleagues do. I have seen patients with chronic, severe, depression respond and even recover in ways that seem just a little short of miraculous when compared with other therapies. Yet as a longtime student of the history of psychiatry, I have also seen that often the treatments that initially seem so auspicious, in time, turn out to have a dark side. Families, communities, the country, VA, and the US Department of Defense and its practitioners in and out of mental health cannot in any moral universe abide by the fact that 20 plus men and women who served take their lives every day.8

As the epigraph to this column notes, we must often try radical therapies for grave cases in drastic crises. Yet we must also in making serious public health decisions fraught with unseen consequences take all due and considered diligence that we do not violate the even more fundamental dictum of the Hippocratic School, “at least do not harm.” That means trying to balance safety and availability while VA conducts its own research in a precarious way that leaves almost no stakeholder completely happy.

"Extreme remedies are very appropriate for extreme diseases"

- Hippocrates Aphorisms

On March 5, 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a nasal spray formulation of the drug ketamine, an old anesthetic that has been put to a new use over the past 10 years as therapy for treatment-resistant severe depression. Ketamine, known on the street as Special K, has long been known to cause dissociation, hallucinations, and other hallucinogenic effects. In many randomized controlled trials, subanesthetic doses administered intravenously have demonstrated rapid and often dramatic relief of depressive symptoms.

Neuroscientists have heralded ketamine as the paradigm

When the FDA approved Spravato (esketamine), a nasal administration of ketamine, many people hoped that researchers had succeeded in overcoming these barriers. The risks of serious adverse events (AEs) as well as the potential for abuse and diversion led the FDA to limit prescriptions under a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS).3 Patients self-administer the nasal spray but only in a certified medical facility under the observation of a health care practitioner. Patients also must agree to remain on site for 2 hours after administration of the drug to ensure their safety. The FDA recommends the drug be given twice a week for 4 weeks along with a conventional monoamine-acting antidepressant.When the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) cleared the way for use of esketamine, less than 2 weeks after the FDA approval, it also launched a series of controversies over how to use the drug in its massive health care system, which is the subject of this editorial. On March 19, 2019, the VA announced that VA practitioners would be able to prescribe the nasal spray for patients who were determined to have treatment-resistant depression but only after appropriate clinical assessment and in accordance with their patients’ preferences.

A number of controversies have emerged surrounding the VA adoption of esketamine, including its cost/benefit/risk ratio and who should be able to access the medication. Each of these issues has onion layers of political, regulatory, and ethical concerns that can only be superficially noted here and warrant fuller unpeeling. In June The New York Times featured a story alleging that in response to the tragic tide of ever-increasing veteran suicides, the VA sanctioned esketamine prescribing despite its cost and the serious questions experts raised about the data the FDA cited to establish its safety and efficacy. Although the cost to the VA of Spravato is unclear, it is much higher than generic IV ketamine.4

The access controversy is almost the ethical inverse of the first. In June 2019, a Veterans Health Administration advisory panel voted against allowing general use of esketamine, limiting it to individual cases of patients who are preapproved and have failed 2 antidepressant trials. Esketamine will not be on the VA formulary for widespread use. Congressional and public advocacy groups have noted that the formulary decision came in the wake of ongoing attention to the role of the pharmaceutical industry in the VA’s rapid adoption of the drug.5,6 For the thousands of veterans for whom the data show conventional antidepressants even in combination with other psychotropic medications and evidence-based psychotherapies resulted in AEs or only partial remission of depression symptoms, the VA’s restriction will likely seem unfair and even uncaring.7

As a practicing VA psychiatrist, I know firsthand how desperately we need new, more effective, and better-tolerated treatments for severe unipolar and bipolar depression. Although I have not prescribed ketamine or esketamine, several of my most respected colleagues do. I have seen patients with chronic, severe, depression respond and even recover in ways that seem just a little short of miraculous when compared with other therapies. Yet as a longtime student of the history of psychiatry, I have also seen that often the treatments that initially seem so auspicious, in time, turn out to have a dark side. Families, communities, the country, VA, and the US Department of Defense and its practitioners in and out of mental health cannot in any moral universe abide by the fact that 20 plus men and women who served take their lives every day.8

As the epigraph to this column notes, we must often try radical therapies for grave cases in drastic crises. Yet we must also in making serious public health decisions fraught with unseen consequences take all due and considered diligence that we do not violate the even more fundamental dictum of the Hippocratic School, “at least do not harm.” That means trying to balance safety and availability while VA conducts its own research in a precarious way that leaves almost no stakeholder completely happy.

1. Lener MS, Kadriu B, Zarate CA Jr. Ketamine and beyond: investigations into the potential of glutamatergic agents to treat depression. Drugs. 2017;77(4):381-401.

2. Thielking M. “Is the Ketamine Boon Getting out of Hand?” STAT. September 24, 2018. https://www.statnews.com/2018/09/24/ketamine-clinics-severe-depression-treatment. Accessed September 17, 2019.

3. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves new nasal spray medication for treatment-resistant depression: available only at a certified doctor’s office or clinic [press release]. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-nasal-spray-medication-treatment-resistant-depression-available-only-certified. Published March 5, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

4. Carey B, Steinhauser J. Veterans agency to offer new depression drug, despite safety and efficacy concerns. The New York Times. June 21, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/21/health/ketamine-depression-veterans.html. Accessed September 17, 2019.

5. US House of Representatives, Committee on Veterans Affairs. Chairman Takano statement following reports that VA fast-tracked controversial drug Spravato to treat veterans [press release]. https://veterans.house.gov/news/press-releases/chairman-takano-statement-following-reports-that-va-fast-tracked-controversial-drug-spravato-to-treat-veterans. Published June 18, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

6. Cary P. Trump’s praise put drug for vets on fast track, but experts are not sure it works. https://publicintegrity.org/federal-politics/trumps-raves-put-drug-for-vets-on-fast-track-but-experts-arent-sure-it-works. Published June 18, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

7. Zisook S, Tal I, Weingart K, et al. Characteristics of U.S. veteran patients with major depressive disorder who require ‘next-step’ treatments: A VAST-D report. J Affect Disord. 2016;206:232-240.

8. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. VA National Suicide Data Report 2005-2016. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/OMHSP_National_Suicide_Data_Report_2005-2016_508.pdf. Updated 2018. Accessed September 17, 2019.

1. Lener MS, Kadriu B, Zarate CA Jr. Ketamine and beyond: investigations into the potential of glutamatergic agents to treat depression. Drugs. 2017;77(4):381-401.

2. Thielking M. “Is the Ketamine Boon Getting out of Hand?” STAT. September 24, 2018. https://www.statnews.com/2018/09/24/ketamine-clinics-severe-depression-treatment. Accessed September 17, 2019.

3. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves new nasal spray medication for treatment-resistant depression: available only at a certified doctor’s office or clinic [press release]. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-nasal-spray-medication-treatment-resistant-depression-available-only-certified. Published March 5, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

4. Carey B, Steinhauser J. Veterans agency to offer new depression drug, despite safety and efficacy concerns. The New York Times. June 21, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/21/health/ketamine-depression-veterans.html. Accessed September 17, 2019.

5. US House of Representatives, Committee on Veterans Affairs. Chairman Takano statement following reports that VA fast-tracked controversial drug Spravato to treat veterans [press release]. https://veterans.house.gov/news/press-releases/chairman-takano-statement-following-reports-that-va-fast-tracked-controversial-drug-spravato-to-treat-veterans. Published June 18, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

6. Cary P. Trump’s praise put drug for vets on fast track, but experts are not sure it works. https://publicintegrity.org/federal-politics/trumps-raves-put-drug-for-vets-on-fast-track-but-experts-arent-sure-it-works. Published June 18, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

7. Zisook S, Tal I, Weingart K, et al. Characteristics of U.S. veteran patients with major depressive disorder who require ‘next-step’ treatments: A VAST-D report. J Affect Disord. 2016;206:232-240.

8. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. VA National Suicide Data Report 2005-2016. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/OMHSP_National_Suicide_Data_Report_2005-2016_508.pdf. Updated 2018. Accessed September 17, 2019.

When providing contraceptive counseling to women with migraine headaches, how do you identify migraine with aura?

Most physicians know that migraine with aura is a risk factor for ischemic stroke and that the use of an estrogen-containing contraceptive further increases this risk.1-3 Additional important and prevalent risk factors for ischemic stroke include cigarette smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and ischemic heart disease.1 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)2 and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)3 recommend against the use of estrogen-containing contraceptives for women with migraine with aura because of the increased risk of ischemic stroke (Medical Eligibility Criteria [MEC] category 4—unacceptable health risk, method not to be used).

However, those who have migraine with aura can use nonhormonal and progestin-only forms of contraception, including copper- and levonorgestrel-intrauterine devices, the etonogestrel subdermal implant, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, and progestin-only pills (MEC category 1—no restriction).2,3 ACOG and the CDC advise that estrogen-containing contraceptives can be used for those with migraine without aura who have no other risk factors for stroke (MEC category 2—advantages generally outweigh theoretical or proven risks).2,3 Given the high prevalence of migraine in reproductive-age women, accurate diagnosis of aura is of paramount importance in order to provide appropriate contraceptive counseling.

When is migraine with aura the right diagnosis?

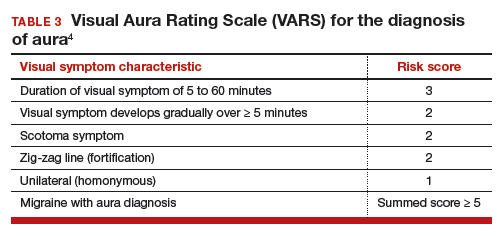

In clinical practice, there is a high level of confusion about the migraine symptoms that warrant a diagnosis of migraine with aura. One approach to improving the accuracy of such a diagnosis is to refer every woman seeking contraceptive counseling who has migraine headaches to a neurologist for expert adjudication of the presence or absence of aura. But in the clinical context of contraceptive counseling, neurology consultation is not always readily available, and requiring consultation increases barriers to care. However, there are tools—such as the Visual Aura Rating Scale (VARS), which is discussed below—that may help non-neurologists identify migraine with aura.4 First, let us review the data that links migraine with aura with increased risk of ischemic stroke.

Migraine with aura is a risk factor for stroke

Multiple case-control studies report that migraine with aura is a risk factor for ischemic stroke.1,5,6 Studies also report that women with migraine with aura who use estrogen-containing contraceptives have an even greater risk of ischemic stroke. For example, one recent case-control study used a commercial claims database of 1,884 cases of ischemic stroke among individuals who identify as women 15 to 49 years of age matched to 7,536 controls without ischemic stroke.1 In this study, the risk of ischemic stroke was increased more than 2.5-fold by cigarette smoking (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.59), hypertension (aOR, 2.73), diabetes (aOR, 2.78), migraine with aura (aOR, 2.89), and ischemic heart disease (aOR, 5.49). For those with migraine with aura who also used an estrogen-containing contraceptive, the aOR for ischemic stroke was 6.08. By contrast, the risk for stroke among those with migraine with aura who were not using an estrogen-containing contraceptive was 2.65. Furthermore, among those with migraine without aura, the risk of ischemic stroke was only 1.77 with the use of an estrogen-containing contraceptive.

Continue to: Although women with migraine...

Although women with migraine with and without aura are at increased risk for stroke, the absolute risk is still very low. For example, one review reported that the incidence of ischemic stroke per 100,000 person-years among women 20 to 44 years of age was 2.5 for those without migraine not taking estrogen-containing contraceptives, 5.9 for those with migraine with aura not taking estrogen-containing contraceptives, and 14.5 among those with migraine with aura and taking estrogen-containing contraceptives.6 Another important observation is that the incidence of thrombotic stroke dramatically increases from adolescence (3.4 per 100,000 person-years) to 45-49 years of age (64.4 per 100,000 person-years).7 Therefore, older women with migraine are at greater risk for stroke than adolescents.

Diagnostic criteria for migraine with and without aura

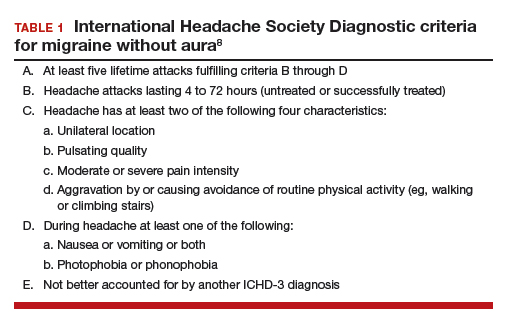

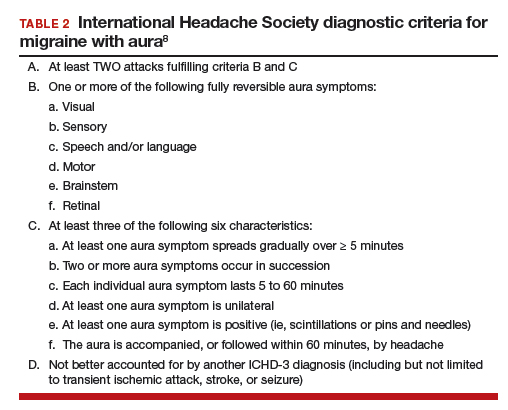

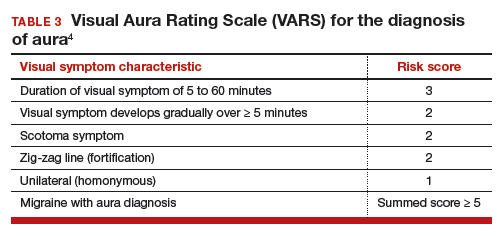

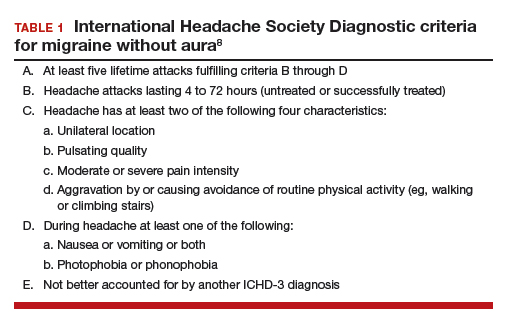

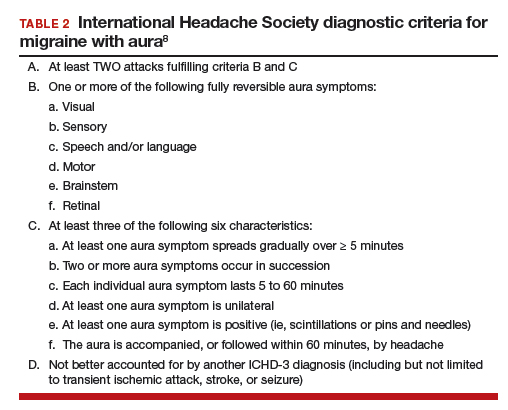

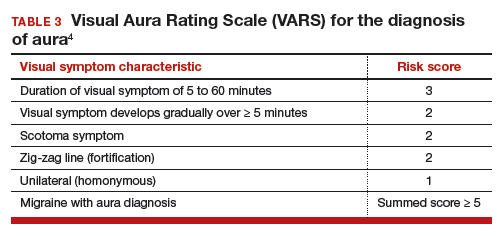

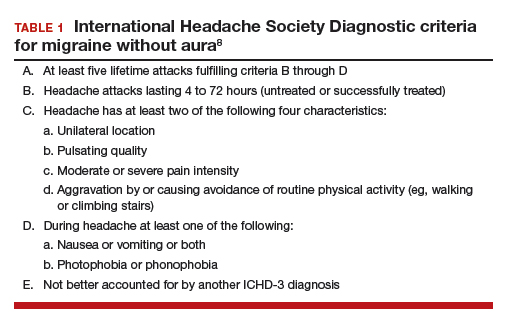

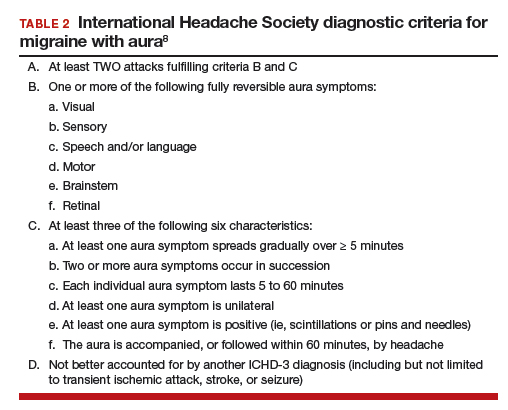

In contraceptive counseling, if an estrogen-containing contraceptive is being considered, it is important to identify women with migraine headache, determine migraine subtype, assess the frequency of migraines and identify other cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension and cigarette smoking. The International Headache Society has evolved the diagnostic criteria for migraine with and without aura, and now endorses the criteria published in the 3rd edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3; TABLES 1 and 2).8 For non-neurologists, these criteria may be difficult to remember and impractical to utilize in daily contraceptive counseling. Two simplified tools, the ID Migraine Questionnaire9 and the Visual Aura Rating Scale (TABLE 3)4 may help identify women who have migraine headaches and assess for the presence of aura.

The ID Migraine Questionnaire

In a study of 563 people seeking primary care who had headaches in the past 3 months, 3 questions were identified as being helpful in identifying women with migraine. This 3-question screening tool had reasonable sensitivity (81%), specificity (75%), and positive predictive value (93%) compared with expert diagnosis using the ICHD-3.9 The 3 questions in this screening tool, which are answered “Yes” or “No,” are:

During the last 3 months did you have the following symptoms with your headaches:

- Feel nauseated or sick to your stomach?

- Light bothered you?

- Your headaches limited your ability to work, study or do what you needed to do for at least 1 day?

If two questions are answered “Yes” the patient may have migraine headaches.

Visual Aura Rating Scale for the diagnosis of migraine with aura

More than 90% of women with migraine with aura have visual auras, leaving only a minority with non–visual aura, such as tingling or numbness in a limb, speech or language problems, or muscle weakness. Hence for non-neurologists, it is reasonable to focus on the accurate diagnosis of visual aura to identify those with migraine with aura.

In the clinical context of contraceptive counseling, the Visual Aura Rating Scale (VARS) is especially useful because it has good sensitivity and specificity, and it is easy to use in practice (TABLE 3).4 VARS assesses for 5 characteristics of a visual aura, and each characteristic is associated with a weighted risk score. The 5 symptoms assessed include:

- duration of visual symptom between 5 and 60 minutes (3 points)

- visual symptom develops gradually over 5 minutes (2 points)

- scotoma (2 points)

- zig-zag line (2 points)

- unilateral (1 point).

Continue to: Of note, visual aura is usually...

Of note, visual aura is usually slow-spreading and persists for more than 5 minutes but less than 60 minutes. If a visual symptom has a sudden onset and persists for much longer than 60 minutes, concern is heightened for a more serious neurologic diagnosis such as transient ischemic attack or stroke. A summed score of 5 or more points supports the diagnosis of migraine with aura. In one study, VARS had a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 96% for identifying women with migraine with aura diagnosed by the ICHD-3 criteria.4

Consider using VARS to identify migraine with aura

Epidemiologic studies report that about 17% of adults have migraine, and about 5% have migraine with aura.10,11 Consequently, migraine with aura is one of the most common medical conditions encountered during contraceptive counseling. The CDC MEC recommend against the use of estrogen-containing contraceptives in women with migraine with aura (Category 4 rating). The VARS may help clinicians identify those who have migraine with aura who should not be offered estrogen-containing contraceptives. Equally important, the use of VARS could help reduce the number of women who are inappropriately diagnosed as having migraine with aura based on fleeting visual symptoms lasting far less than 5 minutes during a migraine headache.

- Champaloux SW, Tepper NK, Monsour M, et al. Use of combined hormonal contraceptives among women with migraine and risk of ischemic stroke. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:489.e1-e7.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 206: use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e128-e150.

- Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-103.

- Eriksen MK, Thomsen LL, Olesen J. The Visual Aura Rating Scale (VARS) for migraine aura diagnosis. Cephalalgia. 2005;25:801-810.

- Schürks M, Rist PM, Bigal ME, et al. Migraine and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b3914.

- Sacco S, Merki-Feld G, Aegidius KL, et al. Hormonal contraceptives and risk of ischemic stroke in women with migraine: a consensus statement from the European Headache Federation (EHF) and the European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health (ESC). J Headache Pain. 2017;18:108.

- Lidegaard Ø, Lokkegaard E, Jensen A, et al. Thrombotic stroke and myocardial infarction with hormonal contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2257-2266.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1-211.

- Lipton RB, Dodick D, Sadovsky R, et al. A self-administered screener for migraine in primary care: the ID Migraine validation study. Neurology. 2003;12;61:375-382.

- Lipton RB, Scher AI, Kolodner K, et al. Migraine in the United States: epidemiology and patterns of health care use. Neurology. 2002;58:885-894.

- Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al; AMPP Advisory Group. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68:343-349.

Most physicians know that migraine with aura is a risk factor for ischemic stroke and that the use of an estrogen-containing contraceptive further increases this risk.1-3 Additional important and prevalent risk factors for ischemic stroke include cigarette smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and ischemic heart disease.1 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)2 and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)3 recommend against the use of estrogen-containing contraceptives for women with migraine with aura because of the increased risk of ischemic stroke (Medical Eligibility Criteria [MEC] category 4—unacceptable health risk, method not to be used).

However, those who have migraine with aura can use nonhormonal and progestin-only forms of contraception, including copper- and levonorgestrel-intrauterine devices, the etonogestrel subdermal implant, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, and progestin-only pills (MEC category 1—no restriction).2,3 ACOG and the CDC advise that estrogen-containing contraceptives can be used for those with migraine without aura who have no other risk factors for stroke (MEC category 2—advantages generally outweigh theoretical or proven risks).2,3 Given the high prevalence of migraine in reproductive-age women, accurate diagnosis of aura is of paramount importance in order to provide appropriate contraceptive counseling.

When is migraine with aura the right diagnosis?

In clinical practice, there is a high level of confusion about the migraine symptoms that warrant a diagnosis of migraine with aura. One approach to improving the accuracy of such a diagnosis is to refer every woman seeking contraceptive counseling who has migraine headaches to a neurologist for expert adjudication of the presence or absence of aura. But in the clinical context of contraceptive counseling, neurology consultation is not always readily available, and requiring consultation increases barriers to care. However, there are tools—such as the Visual Aura Rating Scale (VARS), which is discussed below—that may help non-neurologists identify migraine with aura.4 First, let us review the data that links migraine with aura with increased risk of ischemic stroke.

Migraine with aura is a risk factor for stroke

Multiple case-control studies report that migraine with aura is a risk factor for ischemic stroke.1,5,6 Studies also report that women with migraine with aura who use estrogen-containing contraceptives have an even greater risk of ischemic stroke. For example, one recent case-control study used a commercial claims database of 1,884 cases of ischemic stroke among individuals who identify as women 15 to 49 years of age matched to 7,536 controls without ischemic stroke.1 In this study, the risk of ischemic stroke was increased more than 2.5-fold by cigarette smoking (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.59), hypertension (aOR, 2.73), diabetes (aOR, 2.78), migraine with aura (aOR, 2.89), and ischemic heart disease (aOR, 5.49). For those with migraine with aura who also used an estrogen-containing contraceptive, the aOR for ischemic stroke was 6.08. By contrast, the risk for stroke among those with migraine with aura who were not using an estrogen-containing contraceptive was 2.65. Furthermore, among those with migraine without aura, the risk of ischemic stroke was only 1.77 with the use of an estrogen-containing contraceptive.

Continue to: Although women with migraine...

Although women with migraine with and without aura are at increased risk for stroke, the absolute risk is still very low. For example, one review reported that the incidence of ischemic stroke per 100,000 person-years among women 20 to 44 years of age was 2.5 for those without migraine not taking estrogen-containing contraceptives, 5.9 for those with migraine with aura not taking estrogen-containing contraceptives, and 14.5 among those with migraine with aura and taking estrogen-containing contraceptives.6 Another important observation is that the incidence of thrombotic stroke dramatically increases from adolescence (3.4 per 100,000 person-years) to 45-49 years of age (64.4 per 100,000 person-years).7 Therefore, older women with migraine are at greater risk for stroke than adolescents.

Diagnostic criteria for migraine with and without aura

In contraceptive counseling, if an estrogen-containing contraceptive is being considered, it is important to identify women with migraine headache, determine migraine subtype, assess the frequency of migraines and identify other cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension and cigarette smoking. The International Headache Society has evolved the diagnostic criteria for migraine with and without aura, and now endorses the criteria published in the 3rd edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3; TABLES 1 and 2).8 For non-neurologists, these criteria may be difficult to remember and impractical to utilize in daily contraceptive counseling. Two simplified tools, the ID Migraine Questionnaire9 and the Visual Aura Rating Scale (TABLE 3)4 may help identify women who have migraine headaches and assess for the presence of aura.

The ID Migraine Questionnaire

In a study of 563 people seeking primary care who had headaches in the past 3 months, 3 questions were identified as being helpful in identifying women with migraine. This 3-question screening tool had reasonable sensitivity (81%), specificity (75%), and positive predictive value (93%) compared with expert diagnosis using the ICHD-3.9 The 3 questions in this screening tool, which are answered “Yes” or “No,” are:

During the last 3 months did you have the following symptoms with your headaches:

- Feel nauseated or sick to your stomach?

- Light bothered you?

- Your headaches limited your ability to work, study or do what you needed to do for at least 1 day?

If two questions are answered “Yes” the patient may have migraine headaches.

Visual Aura Rating Scale for the diagnosis of migraine with aura

More than 90% of women with migraine with aura have visual auras, leaving only a minority with non–visual aura, such as tingling or numbness in a limb, speech or language problems, or muscle weakness. Hence for non-neurologists, it is reasonable to focus on the accurate diagnosis of visual aura to identify those with migraine with aura.

In the clinical context of contraceptive counseling, the Visual Aura Rating Scale (VARS) is especially useful because it has good sensitivity and specificity, and it is easy to use in practice (TABLE 3).4 VARS assesses for 5 characteristics of a visual aura, and each characteristic is associated with a weighted risk score. The 5 symptoms assessed include:

- duration of visual symptom between 5 and 60 minutes (3 points)

- visual symptom develops gradually over 5 minutes (2 points)

- scotoma (2 points)

- zig-zag line (2 points)

- unilateral (1 point).

Continue to: Of note, visual aura is usually...

Of note, visual aura is usually slow-spreading and persists for more than 5 minutes but less than 60 minutes. If a visual symptom has a sudden onset and persists for much longer than 60 minutes, concern is heightened for a more serious neurologic diagnosis such as transient ischemic attack or stroke. A summed score of 5 or more points supports the diagnosis of migraine with aura. In one study, VARS had a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 96% for identifying women with migraine with aura diagnosed by the ICHD-3 criteria.4

Consider using VARS to identify migraine with aura

Epidemiologic studies report that about 17% of adults have migraine, and about 5% have migraine with aura.10,11 Consequently, migraine with aura is one of the most common medical conditions encountered during contraceptive counseling. The CDC MEC recommend against the use of estrogen-containing contraceptives in women with migraine with aura (Category 4 rating). The VARS may help clinicians identify those who have migraine with aura who should not be offered estrogen-containing contraceptives. Equally important, the use of VARS could help reduce the number of women who are inappropriately diagnosed as having migraine with aura based on fleeting visual symptoms lasting far less than 5 minutes during a migraine headache.

Most physicians know that migraine with aura is a risk factor for ischemic stroke and that the use of an estrogen-containing contraceptive further increases this risk.1-3 Additional important and prevalent risk factors for ischemic stroke include cigarette smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and ischemic heart disease.1 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)2 and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)3 recommend against the use of estrogen-containing contraceptives for women with migraine with aura because of the increased risk of ischemic stroke (Medical Eligibility Criteria [MEC] category 4—unacceptable health risk, method not to be used).

However, those who have migraine with aura can use nonhormonal and progestin-only forms of contraception, including copper- and levonorgestrel-intrauterine devices, the etonogestrel subdermal implant, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, and progestin-only pills (MEC category 1—no restriction).2,3 ACOG and the CDC advise that estrogen-containing contraceptives can be used for those with migraine without aura who have no other risk factors for stroke (MEC category 2—advantages generally outweigh theoretical or proven risks).2,3 Given the high prevalence of migraine in reproductive-age women, accurate diagnosis of aura is of paramount importance in order to provide appropriate contraceptive counseling.

When is migraine with aura the right diagnosis?

In clinical practice, there is a high level of confusion about the migraine symptoms that warrant a diagnosis of migraine with aura. One approach to improving the accuracy of such a diagnosis is to refer every woman seeking contraceptive counseling who has migraine headaches to a neurologist for expert adjudication of the presence or absence of aura. But in the clinical context of contraceptive counseling, neurology consultation is not always readily available, and requiring consultation increases barriers to care. However, there are tools—such as the Visual Aura Rating Scale (VARS), which is discussed below—that may help non-neurologists identify migraine with aura.4 First, let us review the data that links migraine with aura with increased risk of ischemic stroke.

Migraine with aura is a risk factor for stroke

Multiple case-control studies report that migraine with aura is a risk factor for ischemic stroke.1,5,6 Studies also report that women with migraine with aura who use estrogen-containing contraceptives have an even greater risk of ischemic stroke. For example, one recent case-control study used a commercial claims database of 1,884 cases of ischemic stroke among individuals who identify as women 15 to 49 years of age matched to 7,536 controls without ischemic stroke.1 In this study, the risk of ischemic stroke was increased more than 2.5-fold by cigarette smoking (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.59), hypertension (aOR, 2.73), diabetes (aOR, 2.78), migraine with aura (aOR, 2.89), and ischemic heart disease (aOR, 5.49). For those with migraine with aura who also used an estrogen-containing contraceptive, the aOR for ischemic stroke was 6.08. By contrast, the risk for stroke among those with migraine with aura who were not using an estrogen-containing contraceptive was 2.65. Furthermore, among those with migraine without aura, the risk of ischemic stroke was only 1.77 with the use of an estrogen-containing contraceptive.

Continue to: Although women with migraine...

Although women with migraine with and without aura are at increased risk for stroke, the absolute risk is still very low. For example, one review reported that the incidence of ischemic stroke per 100,000 person-years among women 20 to 44 years of age was 2.5 for those without migraine not taking estrogen-containing contraceptives, 5.9 for those with migraine with aura not taking estrogen-containing contraceptives, and 14.5 among those with migraine with aura and taking estrogen-containing contraceptives.6 Another important observation is that the incidence of thrombotic stroke dramatically increases from adolescence (3.4 per 100,000 person-years) to 45-49 years of age (64.4 per 100,000 person-years).7 Therefore, older women with migraine are at greater risk for stroke than adolescents.

Diagnostic criteria for migraine with and without aura

In contraceptive counseling, if an estrogen-containing contraceptive is being considered, it is important to identify women with migraine headache, determine migraine subtype, assess the frequency of migraines and identify other cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension and cigarette smoking. The International Headache Society has evolved the diagnostic criteria for migraine with and without aura, and now endorses the criteria published in the 3rd edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3; TABLES 1 and 2).8 For non-neurologists, these criteria may be difficult to remember and impractical to utilize in daily contraceptive counseling. Two simplified tools, the ID Migraine Questionnaire9 and the Visual Aura Rating Scale (TABLE 3)4 may help identify women who have migraine headaches and assess for the presence of aura.

The ID Migraine Questionnaire

In a study of 563 people seeking primary care who had headaches in the past 3 months, 3 questions were identified as being helpful in identifying women with migraine. This 3-question screening tool had reasonable sensitivity (81%), specificity (75%), and positive predictive value (93%) compared with expert diagnosis using the ICHD-3.9 The 3 questions in this screening tool, which are answered “Yes” or “No,” are:

During the last 3 months did you have the following symptoms with your headaches:

- Feel nauseated or sick to your stomach?

- Light bothered you?

- Your headaches limited your ability to work, study or do what you needed to do for at least 1 day?

If two questions are answered “Yes” the patient may have migraine headaches.

Visual Aura Rating Scale for the diagnosis of migraine with aura

More than 90% of women with migraine with aura have visual auras, leaving only a minority with non–visual aura, such as tingling or numbness in a limb, speech or language problems, or muscle weakness. Hence for non-neurologists, it is reasonable to focus on the accurate diagnosis of visual aura to identify those with migraine with aura.

In the clinical context of contraceptive counseling, the Visual Aura Rating Scale (VARS) is especially useful because it has good sensitivity and specificity, and it is easy to use in practice (TABLE 3).4 VARS assesses for 5 characteristics of a visual aura, and each characteristic is associated with a weighted risk score. The 5 symptoms assessed include:

- duration of visual symptom between 5 and 60 minutes (3 points)

- visual symptom develops gradually over 5 minutes (2 points)

- scotoma (2 points)

- zig-zag line (2 points)

- unilateral (1 point).

Continue to: Of note, visual aura is usually...

Of note, visual aura is usually slow-spreading and persists for more than 5 minutes but less than 60 minutes. If a visual symptom has a sudden onset and persists for much longer than 60 minutes, concern is heightened for a more serious neurologic diagnosis such as transient ischemic attack or stroke. A summed score of 5 or more points supports the diagnosis of migraine with aura. In one study, VARS had a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 96% for identifying women with migraine with aura diagnosed by the ICHD-3 criteria.4

Consider using VARS to identify migraine with aura

Epidemiologic studies report that about 17% of adults have migraine, and about 5% have migraine with aura.10,11 Consequently, migraine with aura is one of the most common medical conditions encountered during contraceptive counseling. The CDC MEC recommend against the use of estrogen-containing contraceptives in women with migraine with aura (Category 4 rating). The VARS may help clinicians identify those who have migraine with aura who should not be offered estrogen-containing contraceptives. Equally important, the use of VARS could help reduce the number of women who are inappropriately diagnosed as having migraine with aura based on fleeting visual symptoms lasting far less than 5 minutes during a migraine headache.

- Champaloux SW, Tepper NK, Monsour M, et al. Use of combined hormonal contraceptives among women with migraine and risk of ischemic stroke. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:489.e1-e7.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 206: use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e128-e150.

- Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-103.

- Eriksen MK, Thomsen LL, Olesen J. The Visual Aura Rating Scale (VARS) for migraine aura diagnosis. Cephalalgia. 2005;25:801-810.

- Schürks M, Rist PM, Bigal ME, et al. Migraine and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b3914.

- Sacco S, Merki-Feld G, Aegidius KL, et al. Hormonal contraceptives and risk of ischemic stroke in women with migraine: a consensus statement from the European Headache Federation (EHF) and the European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health (ESC). J Headache Pain. 2017;18:108.

- Lidegaard Ø, Lokkegaard E, Jensen A, et al. Thrombotic stroke and myocardial infarction with hormonal contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2257-2266.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1-211.