User login

Dr. Carl Bell always asked the hard questions

Carl C. Bell, MD, started his career by asking the hard questions that no one dared to ask. His curiosity, courage, and compassion for all communities would lead him to impact the world in ways that few psychiatrists could ever imagine.

His accomplishments were many and far-reaching, dating back over 4 decades of service and research. He was a prolific author and researcher, having written more than 400 books, chapters, and articles. His research covered a lot of ground, but four critical areas of focus were childhood trauma, violence prevention, criminal justice reform, and most recently, fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

The word “visionary” is frequently overused. But when we apply it to Dr. Carl Bell, the word does not do him justice. If you take a closer look at all four of those areas, you can see a common thread: What are the elements of a society that can tear communities apart?

When I look at Dr. Bell’s research, I see a man with a dedicated vision to addressing each of those elements in systematic way, and a determination to bring the results of that research into his Southside Chicago community in numerous ways, including by serving as president and CEO of the Community Mental Health Council, and as director of the Institute for Juvenile Research at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Dr. Bell was a leader for his patients as well as for black psychiatrists. He was a founding member of Black Psychiatrists of America and served as a mentor in some way to the vast majority of black psychiatrists currently practicing in the country. As a black male psychiatrist, I saw Dr. Bell as a source of inspiration in my career and the standard by which I measured myself. I’m not talking about awards or accomplishments, as Dr. Bell has countless accolades, including most recently, being presented this year with the American Psychiatric Association’s Adolph Meyer Award for Lifetime Achievement in Psychiatric Research and the National Medical Association’s Scroll of Merit. I am referring to Dr. Bell’s willingness to walk away from something he thought was wrong.

For every accolade he won or prestigious committee he served on, I would wager that he declined or stepped way from just as many. Dr. Bell’s character and vision for psychiatry in general, and the mental health of African American communities specifically, would not allow him to pay lip service to agendas that were self-serving, and did not push the field and communities forward.

During his service as an editorial advisory board member for Clinical Psychiatry News, Dr. Bell could always be relied upon to offer an insightful perspective to any discussion, ranging from violence prevention to the social determinants of health and their role in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

What I will remember most about Dr. Bell is his strong character. My guess is that he was never shy about stating the truth to a patient or a president of the United States. He possessed the intellect to back up any of his views while also having the humility of a dedicated community psychiatrist who worked for no other reason than to serve his patients.

When I first met Dr. Bell, he was giving a grand rounds at the George Washington University department of psychiatry. He was wearing a hat during the lecture and a belt with the Superman logo. I thought to myself, “Whoa, this is a different type of guy,” then I sat and listened to the talk, and was utterly astounded by his intellect, humor, honesty, and passion for his patients. I had never heard a psychiatrist speak with a combination of such command and approachability, and again, I thought to myself, “Whoa, this is a different type of guy.”

Little did I know that Dr. Bell and I would end up serving together on the editorial board of CPN. I loved seeing Dr. Bell, and catching up and gleaning from his wisdom. I was very humbled by how generous Dr. Bell was with his time and the extent to which he would make himself available as a mentor. During a CPN board meeting, we were trying to come up with a mantra that would capture the mission of the new MDedge Psychiatry website. Dr. Bell (in a hat, of course) let everyone else talk, and then, in a calm voice, said: “We ask the hard questions.” As editor in chief of MDedge Psychiatry, I knew this had to be the mantra. It was aspirational, gave us an identity, and held our feet to the fire – to always ask hard questions in the service of patients and readers. I looked forward to discussing the evolution of the site, seeing him at meetings and conferences, brainstorming the implications of new advances in the field, and simply walking down the street and laughing.

Those events will never occur again, because Carl left us on Thursday, Aug 1. Carl has left us with a legacy of work that we are still coming to appreciate. He left us with a mandate to pursue the truth and make an impact in our communities. He taught black psychiatrists what it meant to stand up unapologetically for your community and society. As I reflect on the scope of his life, I have one last hard question for Carl: “Why did you have to leave us so soon?”

Dr. Norris is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at George Washington University, Washington. He also serves as assistant dean of student affairs at the university, and medical director of psychiatric and behavioral sciences at GWU Hospital. Dr. Norris also is host of the MDedge Psychcast.

Carl C. Bell, MD, started his career by asking the hard questions that no one dared to ask. His curiosity, courage, and compassion for all communities would lead him to impact the world in ways that few psychiatrists could ever imagine.

His accomplishments were many and far-reaching, dating back over 4 decades of service and research. He was a prolific author and researcher, having written more than 400 books, chapters, and articles. His research covered a lot of ground, but four critical areas of focus were childhood trauma, violence prevention, criminal justice reform, and most recently, fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

The word “visionary” is frequently overused. But when we apply it to Dr. Carl Bell, the word does not do him justice. If you take a closer look at all four of those areas, you can see a common thread: What are the elements of a society that can tear communities apart?

When I look at Dr. Bell’s research, I see a man with a dedicated vision to addressing each of those elements in systematic way, and a determination to bring the results of that research into his Southside Chicago community in numerous ways, including by serving as president and CEO of the Community Mental Health Council, and as director of the Institute for Juvenile Research at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Dr. Bell was a leader for his patients as well as for black psychiatrists. He was a founding member of Black Psychiatrists of America and served as a mentor in some way to the vast majority of black psychiatrists currently practicing in the country. As a black male psychiatrist, I saw Dr. Bell as a source of inspiration in my career and the standard by which I measured myself. I’m not talking about awards or accomplishments, as Dr. Bell has countless accolades, including most recently, being presented this year with the American Psychiatric Association’s Adolph Meyer Award for Lifetime Achievement in Psychiatric Research and the National Medical Association’s Scroll of Merit. I am referring to Dr. Bell’s willingness to walk away from something he thought was wrong.

For every accolade he won or prestigious committee he served on, I would wager that he declined or stepped way from just as many. Dr. Bell’s character and vision for psychiatry in general, and the mental health of African American communities specifically, would not allow him to pay lip service to agendas that were self-serving, and did not push the field and communities forward.

During his service as an editorial advisory board member for Clinical Psychiatry News, Dr. Bell could always be relied upon to offer an insightful perspective to any discussion, ranging from violence prevention to the social determinants of health and their role in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

What I will remember most about Dr. Bell is his strong character. My guess is that he was never shy about stating the truth to a patient or a president of the United States. He possessed the intellect to back up any of his views while also having the humility of a dedicated community psychiatrist who worked for no other reason than to serve his patients.

When I first met Dr. Bell, he was giving a grand rounds at the George Washington University department of psychiatry. He was wearing a hat during the lecture and a belt with the Superman logo. I thought to myself, “Whoa, this is a different type of guy,” then I sat and listened to the talk, and was utterly astounded by his intellect, humor, honesty, and passion for his patients. I had never heard a psychiatrist speak with a combination of such command and approachability, and again, I thought to myself, “Whoa, this is a different type of guy.”

Little did I know that Dr. Bell and I would end up serving together on the editorial board of CPN. I loved seeing Dr. Bell, and catching up and gleaning from his wisdom. I was very humbled by how generous Dr. Bell was with his time and the extent to which he would make himself available as a mentor. During a CPN board meeting, we were trying to come up with a mantra that would capture the mission of the new MDedge Psychiatry website. Dr. Bell (in a hat, of course) let everyone else talk, and then, in a calm voice, said: “We ask the hard questions.” As editor in chief of MDedge Psychiatry, I knew this had to be the mantra. It was aspirational, gave us an identity, and held our feet to the fire – to always ask hard questions in the service of patients and readers. I looked forward to discussing the evolution of the site, seeing him at meetings and conferences, brainstorming the implications of new advances in the field, and simply walking down the street and laughing.

Those events will never occur again, because Carl left us on Thursday, Aug 1. Carl has left us with a legacy of work that we are still coming to appreciate. He left us with a mandate to pursue the truth and make an impact in our communities. He taught black psychiatrists what it meant to stand up unapologetically for your community and society. As I reflect on the scope of his life, I have one last hard question for Carl: “Why did you have to leave us so soon?”

Dr. Norris is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at George Washington University, Washington. He also serves as assistant dean of student affairs at the university, and medical director of psychiatric and behavioral sciences at GWU Hospital. Dr. Norris also is host of the MDedge Psychcast.

Carl C. Bell, MD, started his career by asking the hard questions that no one dared to ask. His curiosity, courage, and compassion for all communities would lead him to impact the world in ways that few psychiatrists could ever imagine.

His accomplishments were many and far-reaching, dating back over 4 decades of service and research. He was a prolific author and researcher, having written more than 400 books, chapters, and articles. His research covered a lot of ground, but four critical areas of focus were childhood trauma, violence prevention, criminal justice reform, and most recently, fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

The word “visionary” is frequently overused. But when we apply it to Dr. Carl Bell, the word does not do him justice. If you take a closer look at all four of those areas, you can see a common thread: What are the elements of a society that can tear communities apart?

When I look at Dr. Bell’s research, I see a man with a dedicated vision to addressing each of those elements in systematic way, and a determination to bring the results of that research into his Southside Chicago community in numerous ways, including by serving as president and CEO of the Community Mental Health Council, and as director of the Institute for Juvenile Research at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Dr. Bell was a leader for his patients as well as for black psychiatrists. He was a founding member of Black Psychiatrists of America and served as a mentor in some way to the vast majority of black psychiatrists currently practicing in the country. As a black male psychiatrist, I saw Dr. Bell as a source of inspiration in my career and the standard by which I measured myself. I’m not talking about awards or accomplishments, as Dr. Bell has countless accolades, including most recently, being presented this year with the American Psychiatric Association’s Adolph Meyer Award for Lifetime Achievement in Psychiatric Research and the National Medical Association’s Scroll of Merit. I am referring to Dr. Bell’s willingness to walk away from something he thought was wrong.

For every accolade he won or prestigious committee he served on, I would wager that he declined or stepped way from just as many. Dr. Bell’s character and vision for psychiatry in general, and the mental health of African American communities specifically, would not allow him to pay lip service to agendas that were self-serving, and did not push the field and communities forward.

During his service as an editorial advisory board member for Clinical Psychiatry News, Dr. Bell could always be relied upon to offer an insightful perspective to any discussion, ranging from violence prevention to the social determinants of health and their role in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

What I will remember most about Dr. Bell is his strong character. My guess is that he was never shy about stating the truth to a patient or a president of the United States. He possessed the intellect to back up any of his views while also having the humility of a dedicated community psychiatrist who worked for no other reason than to serve his patients.

When I first met Dr. Bell, he was giving a grand rounds at the George Washington University department of psychiatry. He was wearing a hat during the lecture and a belt with the Superman logo. I thought to myself, “Whoa, this is a different type of guy,” then I sat and listened to the talk, and was utterly astounded by his intellect, humor, honesty, and passion for his patients. I had never heard a psychiatrist speak with a combination of such command and approachability, and again, I thought to myself, “Whoa, this is a different type of guy.”

Little did I know that Dr. Bell and I would end up serving together on the editorial board of CPN. I loved seeing Dr. Bell, and catching up and gleaning from his wisdom. I was very humbled by how generous Dr. Bell was with his time and the extent to which he would make himself available as a mentor. During a CPN board meeting, we were trying to come up with a mantra that would capture the mission of the new MDedge Psychiatry website. Dr. Bell (in a hat, of course) let everyone else talk, and then, in a calm voice, said: “We ask the hard questions.” As editor in chief of MDedge Psychiatry, I knew this had to be the mantra. It was aspirational, gave us an identity, and held our feet to the fire – to always ask hard questions in the service of patients and readers. I looked forward to discussing the evolution of the site, seeing him at meetings and conferences, brainstorming the implications of new advances in the field, and simply walking down the street and laughing.

Those events will never occur again, because Carl left us on Thursday, Aug 1. Carl has left us with a legacy of work that we are still coming to appreciate. He left us with a mandate to pursue the truth and make an impact in our communities. He taught black psychiatrists what it meant to stand up unapologetically for your community and society. As I reflect on the scope of his life, I have one last hard question for Carl: “Why did you have to leave us so soon?”

Dr. Norris is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at George Washington University, Washington. He also serves as assistant dean of student affairs at the university, and medical director of psychiatric and behavioral sciences at GWU Hospital. Dr. Norris also is host of the MDedge Psychcast.

In memory of Dr. Carl Compton Bell

It was a simple message in the body of an email: “A strong voice in and for psychiatry is now silent.”

That is how I shared the news of the passing of Carl Compton Bell, MD, with the leadership of the American Psychiatric Association and what I think Carl would have approved be shared. Although he was a member of APA, he was never interested in the trappings of leadership there or any other organizations of which he was a longtime member, really. He preferred to “do the work” and was known to not suffer fools who were in it to promote themselves. He was always ready, willing, and able to offer guidance or assistance in your work and never failed to have an opinion on what else you needed to do. Some of my favorite memories of Carl are the talks he initiated at the drop of a hat where he “dropped some knowledge” about what he was doing or what you should be doing.

Upon hearing of his death, I described him to someone as fearless, unapologetic, smart, and ready to advocate for black people at the drop of one of the many hats he wore over the years. In fact, his decades of wardrobes is one the other things many of us will remember – the CMHC baseball cap with the “Stop Black on Black” crime T-shirt, the Obama cap paired with an assortment of message T-shirts (depending on what issue he was focused on at the time), and, most recently, the longer hair sticking out from under the wide brim leather cowboy hat with the highway patrol polarized sunglasses.

And whether it was the Surgeon General or an audience at the Carter Center, the message was consistent and powerful. An international researcher, clinician, teacher, and author of more than 500 books, chapters, and articles, he spent most of his career directly addressing issues of violence and HIV prevention, misdiagnosis of psychiatric disorders in African Americans, and the psychological effects on children exposed to violence.

Honoring the legacy of Carl Bell is about more than how we can all follow in his footsteps and more about being like him – unapologetically fearless and focused on improving the health, mental health, and overall well-being of black people. He was very clear that his talents, his skills, his focus – whether it was clinical care, training, or research – would be on black people, and he was often amused at the response, mostly from white people, when he stated clearly that this was his focus. He was often challenged by them, and his response as I frequently heard him say was: “I care about black people; I want to help black people.” I think he basically felt that, if it was good for black people, it would also benefit everyone else.

So, there’s a lesson for us as we heap on the well-deserved accolades on him and his life’s work, and reminisce about our personal encounters and experiences with him over the decades. As we reflect on what he meant to each of us as a friend, a colleague, and a history maker, I think the lesson is that if Carl were here today, he’d say: “OK, that’s all good, thank you for the nice words but what are you doing for black people today? What are you doing to improve their health and life condition today?” I think if we really want to honor his legacy and continue his work, we must be as fearless and focused as he was as we follow his lead and carry on with the work that promotes mental health in the black community. And when we are challenged for wanting to do this work, we must be just as unapologetic and thoughtful as he was, even channeling our own “Carl Bell” moment if needed. As a lifelong martial arts practitioner, I will end with this: “The bamboo which bends in the wind is stronger than the mighty oak which breaks in a storm.” Carl was the bamboo, and he’s with the Ancestors now, encouraging us to do the work and bend not break. Rest, my brother; job well done!

Dr. Stewart is immediate past president of the American Psychiatric Association.

It was a simple message in the body of an email: “A strong voice in and for psychiatry is now silent.”

That is how I shared the news of the passing of Carl Compton Bell, MD, with the leadership of the American Psychiatric Association and what I think Carl would have approved be shared. Although he was a member of APA, he was never interested in the trappings of leadership there or any other organizations of which he was a longtime member, really. He preferred to “do the work” and was known to not suffer fools who were in it to promote themselves. He was always ready, willing, and able to offer guidance or assistance in your work and never failed to have an opinion on what else you needed to do. Some of my favorite memories of Carl are the talks he initiated at the drop of a hat where he “dropped some knowledge” about what he was doing or what you should be doing.

Upon hearing of his death, I described him to someone as fearless, unapologetic, smart, and ready to advocate for black people at the drop of one of the many hats he wore over the years. In fact, his decades of wardrobes is one the other things many of us will remember – the CMHC baseball cap with the “Stop Black on Black” crime T-shirt, the Obama cap paired with an assortment of message T-shirts (depending on what issue he was focused on at the time), and, most recently, the longer hair sticking out from under the wide brim leather cowboy hat with the highway patrol polarized sunglasses.

And whether it was the Surgeon General or an audience at the Carter Center, the message was consistent and powerful. An international researcher, clinician, teacher, and author of more than 500 books, chapters, and articles, he spent most of his career directly addressing issues of violence and HIV prevention, misdiagnosis of psychiatric disorders in African Americans, and the psychological effects on children exposed to violence.

Honoring the legacy of Carl Bell is about more than how we can all follow in his footsteps and more about being like him – unapologetically fearless and focused on improving the health, mental health, and overall well-being of black people. He was very clear that his talents, his skills, his focus – whether it was clinical care, training, or research – would be on black people, and he was often amused at the response, mostly from white people, when he stated clearly that this was his focus. He was often challenged by them, and his response as I frequently heard him say was: “I care about black people; I want to help black people.” I think he basically felt that, if it was good for black people, it would also benefit everyone else.

So, there’s a lesson for us as we heap on the well-deserved accolades on him and his life’s work, and reminisce about our personal encounters and experiences with him over the decades. As we reflect on what he meant to each of us as a friend, a colleague, and a history maker, I think the lesson is that if Carl were here today, he’d say: “OK, that’s all good, thank you for the nice words but what are you doing for black people today? What are you doing to improve their health and life condition today?” I think if we really want to honor his legacy and continue his work, we must be as fearless and focused as he was as we follow his lead and carry on with the work that promotes mental health in the black community. And when we are challenged for wanting to do this work, we must be just as unapologetic and thoughtful as he was, even channeling our own “Carl Bell” moment if needed. As a lifelong martial arts practitioner, I will end with this: “The bamboo which bends in the wind is stronger than the mighty oak which breaks in a storm.” Carl was the bamboo, and he’s with the Ancestors now, encouraging us to do the work and bend not break. Rest, my brother; job well done!

Dr. Stewart is immediate past president of the American Psychiatric Association.

It was a simple message in the body of an email: “A strong voice in and for psychiatry is now silent.”

That is how I shared the news of the passing of Carl Compton Bell, MD, with the leadership of the American Psychiatric Association and what I think Carl would have approved be shared. Although he was a member of APA, he was never interested in the trappings of leadership there or any other organizations of which he was a longtime member, really. He preferred to “do the work” and was known to not suffer fools who were in it to promote themselves. He was always ready, willing, and able to offer guidance or assistance in your work and never failed to have an opinion on what else you needed to do. Some of my favorite memories of Carl are the talks he initiated at the drop of a hat where he “dropped some knowledge” about what he was doing or what you should be doing.

Upon hearing of his death, I described him to someone as fearless, unapologetic, smart, and ready to advocate for black people at the drop of one of the many hats he wore over the years. In fact, his decades of wardrobes is one the other things many of us will remember – the CMHC baseball cap with the “Stop Black on Black” crime T-shirt, the Obama cap paired with an assortment of message T-shirts (depending on what issue he was focused on at the time), and, most recently, the longer hair sticking out from under the wide brim leather cowboy hat with the highway patrol polarized sunglasses.

And whether it was the Surgeon General or an audience at the Carter Center, the message was consistent and powerful. An international researcher, clinician, teacher, and author of more than 500 books, chapters, and articles, he spent most of his career directly addressing issues of violence and HIV prevention, misdiagnosis of psychiatric disorders in African Americans, and the psychological effects on children exposed to violence.

Honoring the legacy of Carl Bell is about more than how we can all follow in his footsteps and more about being like him – unapologetically fearless and focused on improving the health, mental health, and overall well-being of black people. He was very clear that his talents, his skills, his focus – whether it was clinical care, training, or research – would be on black people, and he was often amused at the response, mostly from white people, when he stated clearly that this was his focus. He was often challenged by them, and his response as I frequently heard him say was: “I care about black people; I want to help black people.” I think he basically felt that, if it was good for black people, it would also benefit everyone else.

So, there’s a lesson for us as we heap on the well-deserved accolades on him and his life’s work, and reminisce about our personal encounters and experiences with him over the decades. As we reflect on what he meant to each of us as a friend, a colleague, and a history maker, I think the lesson is that if Carl were here today, he’d say: “OK, that’s all good, thank you for the nice words but what are you doing for black people today? What are you doing to improve their health and life condition today?” I think if we really want to honor his legacy and continue his work, we must be as fearless and focused as he was as we follow his lead and carry on with the work that promotes mental health in the black community. And when we are challenged for wanting to do this work, we must be just as unapologetic and thoughtful as he was, even channeling our own “Carl Bell” moment if needed. As a lifelong martial arts practitioner, I will end with this: “The bamboo which bends in the wind is stronger than the mighty oak which breaks in a storm.” Carl was the bamboo, and he’s with the Ancestors now, encouraging us to do the work and bend not break. Rest, my brother; job well done!

Dr. Stewart is immediate past president of the American Psychiatric Association.

Why do so many women aged 65 years and older die of cervical cancer?

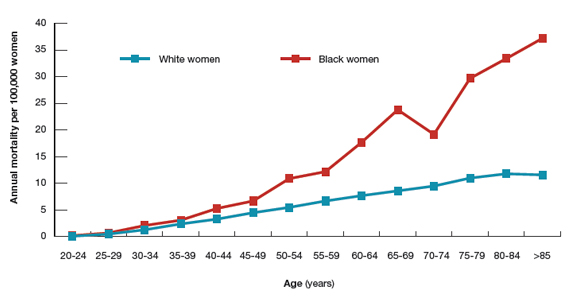

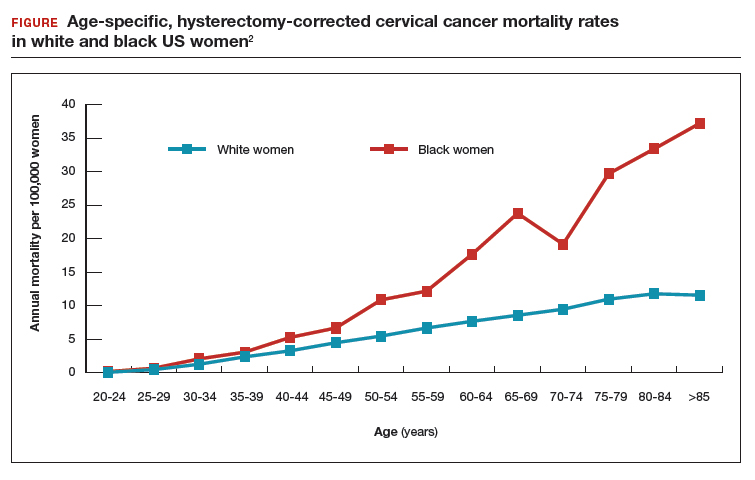

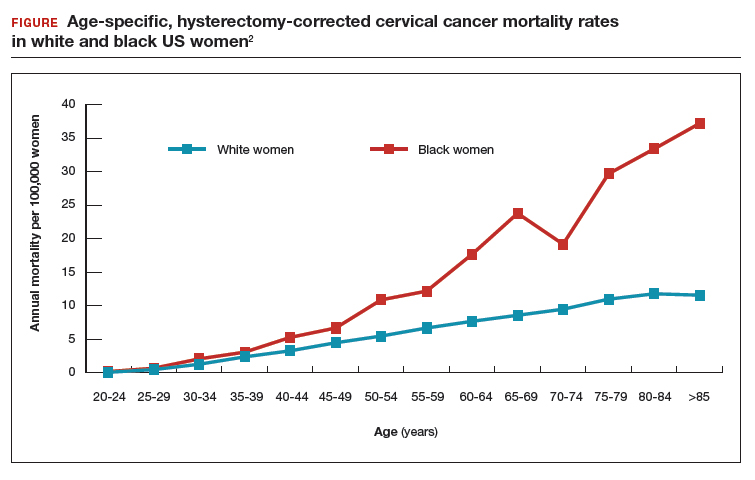

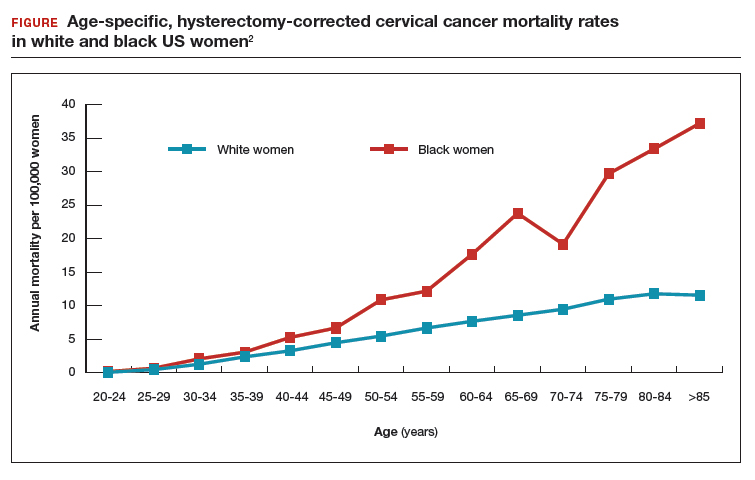

Surprisingly, the cervical cancer death rate is greater among women aged >65 years than among younger women1,2 (FIGURE). Paradoxically, most of our screening programs focus on women <65 years of age. A nationwide study from Denmark estimated that the cervical cancer death rate per 100,000 women at ages 40 to 44 and 65 to 69 was 3.8 and 9.0, respectively.1 In other words, the cervical cancer death rate at age 65 to 69 years was 2.36 times higher than at age 40 to 44 years.1

A study from the United States estimated that the cervical cancer death rate per 100,000 white women at ages 40 to 44 and 65 to 69 was 3.3 and 8.6, respectively,2 very similar to the findings from Denmark. The same US study estimated that the cervical cancer death rate per 100,000 black women at ages 40 to 44 and 65 to 69 was 5.3 and 23.8, highlighting the fact that, in the United States, cervical cancer disease burden is disproportionately greater among black than among white women.2 In addition, the cervical cancer death rate among black women at age 65 to 69 was 4.49 times higher than at age 40 to 44 years.2

Given the high death rate from cervical cancer in women >65 years of age, it is paradoxical that most professional society guidelines recommend discontinuing cervical cancer screening at 65 years of age, if previous cervical cancer screening is normal.3,4 Is the problem due to an inability to implement the current guidelines? Or is the problem that the guidelines are not optimally designed to reduce cervical cancer risk in women >65 years of age?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommend against cervical cancer screening in women >65 years of age who have had adequate prior screening and are not otherwise at high risk for cervical cancer. However, ACOG and the USPSTF caution that there are many groups of women that may benefit from continued screening after 65 years of age, including women with HIV infection, a compromised immune system, or previous high-grade precancerous lesion or cervicalcancer; women with limited access to care; women from racial/ethnic minority groups; and migrant women.4 Many clinicians remember the guidance, “discontinue cervical cancer screening at 65 years” but do not recall all the clinical factors that might warrant continued screening past age 65. Of special concern is that black,2 Hispanic,5 and migrant women6 are at much higher risk for invasive cervical cancer than white or US-born women.

The optimal implementation of the ACOG and USPSTF guidelines are undermined by a fractured health care system, where key pieces of information may be unavailable to the clinician tasked with making a decision about discontinuing cervical cancer screening. Imagine the case in which a 65-year-old woman pre‑sents to her primary care physician for cervical cancer screening. The clinician performs a cervical cytology test and obtains a report of “no intraepithelial lesion or malignancy.” The clinician then recommends that the patient discontinue cervical cancer screening. Unbeknownst to the clinician, the patient had a positive HPV 16/18/45 test within the past 10 years in another health system. In this case, it would be inappropriate to terminate the patient from cervical cancer screening.

Continue to: Testing for hrHPV is superior to cervical cytology in women >65 years...

Testing for hrHPV is superior to cervical cytology in women >65 years

In Sweden, about 30% of cervical cancer cases occur in women aged >60 years.7 To assess the prevalence of oncogenic high-risk HPV (hrHPV), women at ages 60, 65, 70, and 75 years were invited to send sequential self-collected vaginal samples for nucleic acid testing for hrHPV. The prevalence of hrHPV was found to be 4.4%. Women with a second positive, self-collected, hrHPV test were invited for colposcopy, cervical biopsy, and cytology testing. Among the women with two positive hrHPV tests, cervical biopsy revealed 7 cases of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 (CIN2), 6 cases of CIN1, and 4 biopsies without CIN. In these women 94% of the cervical cytology samples returned, “no intraepithelial lesion or malignancy” and 6% revealed atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance. This study suggests that, in women aged >65 years, cervical cytology may have a high rate of false-negative results, possibly due to epithelial atrophy. An evolving clinical pearl is that, when using the current cervical cancer screening guidelines, the final screen for cervical cancer must include a nucleic acid test for hrHPV.

In women 65 to 90 years, the prevalence of hrHPV is approximately 5%

In a study of 40,382 women aged 14 to 95 years, the prevalence of hrHPV was 46% in 20- to 23-year-old women and 5.7% in women older than 65 years of age.8 In a study of more than 108,000 women aged 69 to >89 years the prevalence of hrHPV was 4.3%, and similar prevalence rates were seen across all ages from 69 to >89 years.9 The carcinogenic role of persistent hrHPV infection in women >65 years is an important area for future research.

Latent HPV virus infection

Following a primary varicella-zoster infection (chickenpox), the virus may remain in a latent state in sensory ganglia, reactivating later in life to cause shingles. Thirty percent of people who have a primary chickenpox infection eventually will develop a case of shingles. Immunocompromised populations are at an increased risk of developing shingles because of reduced T-cell mediated immunity.

A recent hypothesis is that in immunocompromised and older women, latent HPV can reactivate and cause clinically significant infection.10 Following renal transplantation investigators have reported a significant increase in the prevalence of genital HPV, without a change in sexual behavior.11 In cervical tissue from women with no evidence of active HPV infection, highly sensitive PCR-based assays detected HPV16 virus in a latent state in some women, possibly due to disruption of the viral E2 gene.12 If latent HPV infection is a valid biological concept, it suggests that there is no “safe age” at which to discontinue screening for HPV infection because the virus cannot be detected in screening samples while it is latent.

Options for cervical cancer screening in women >65 years

Three options might reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with cervical cancer in women >65 years.

Option 1: Double-down on trying to effectively implement current guidelines. The high rate of cervical cancer mortality in women >65 years of age indicates that the current guidelines, as implemented in real clinical practice, are not working. A problem with the current screening guidelines is that clinicians are expected to be capable of finding all relevant cervical cancer test results and properly interpreting the results. Clinicians are over-taxed and fallible, and the current approach is not likely to be successful unless additional information technology solutions are implemented.

Continue to: Health systems could use information...

Health systems could use information technology to mitigate these problems. For example, health systems could deploy software to assemble every cervical screening result on each woman and pre‑sent those results to clinicians in a single integrated view in the electronic record. Additionally, once all lifetime screening results are consolidated in one view, artificial intelligence systems could be used to analyze the totality of results and identify women who would benefit by continued screening past age 65 and women who could safely discontinue screening.

Option 2: Adopt the Australian approach to cervical cancer screening. The current Australian approach to cervical cancer screening is built on 3 pillars: 1) school-based vaccination of all children against hrHPV, 2) screening all women from 25 to 74 years of age every 5 years using nucleic acid testing for hrHPV, and 3) providing a system for the testing of samples self-collected by women who are reluctant to visit a clinician for screening.13 Australia has one of the lowest cervical cancer death rates in the world.

Option 3: Continue screening most women past age 65. Women >65 years of age are known to be infected with hrHPV genotypes. hrHPV infection causes cervical cancer. Cervical cancer causes many deaths in women aged >65 years. There is no strong rationale for ignoring these three facts. hrHPV screening every 5 years as long as the woman is healthy and has a reasonable life expectancy is an option that could be evaluated in randomized studies.

Given the high rate of cervical cancer death in women >65 years of age, I plan to be very cautious about discontinuing cervical cancer screening until I can personally ensure that my patient has no evidence of hrHPV infection.

In 2008, Harald zur Hausen, MD, received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering that human papilloma virus (HPV) caused cervical cancer. In a recent study, 74% of cervical cancers were associated with HPV 16 or 18 infections. A total of 89% of the cancers were associated with one of the high-risk HPV genotypes, including HPV 16/18/31/33/45/52/58.1

Recently, HPV has been shown to be a major cause of oropharyngeal cancer. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calculated that in CY2015 in the United States there were 18,917 cases of HPV-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer and 11,788 cases of cervical cancer.2 Most cases of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer occur in men, and HPV vaccination of boys may help to prevent this cancer type. Oncogenic HPV produce two proteins (E6 and E7) that promote viral replication and squamous cell growth by inhibiting the function of p53 and retinoblastoma protein. The immortalized HeLa cell line, derived from Ms. Henrietta Lack's cervical cancer, contains integrated HPV18 nucleic acid sequences.3,4

The discovery that HPV causes cancer catalyzed the development of nucleic acid tests to identify high-risk oncogenic HPV and vaccines against high-risk oncogenic HPV genotypes that prevent cervical cancer. From a public health perspective, it is more effective to vaccinate the population against oncogenic HPV genotypes than to screen and treat cancer. In the United States, vaccination rates range from a high of 92% (District of Columbia) and 89% (Rhode Island) to a low of 47% (Wyoming) and 50% (Kentucky and Mississippi).5 To reduce HPV-associated cancer mortality, the gap in vaccination compliance must be closed.

References

- Kjaer SK, Munk C, Junge J, et al. Carcinogenic HPV prevalence and age-specific type distribution in 40,382 women with normal cervical cytology, ACSUC/LSIL, HSIL, or cervical cancer: what is the potential for prevention? Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:179-189.

- Van Dyne EA, Henley SJ, Saraiya M, et al. Trends in human papillomavirus-associated cancers - United States, 1999-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:918-924.

- Rosl F, Westphal EM, zur Hausen H. Chromatin structure and transcriptional regulation of human papillomavirus type 18 DNA in HeLa cells. Mol Carcinog. 1989;2:72-80.

- Adey A, Burton JN, Kitzman, et al. The haplotype-resolved genome and epigenome of the aneuploid HeLa cancer cell line. Nature. 2013;500:207-211.

- Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Singleton JA, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:874-882.

- Hammer A, Kahlert J, Gravitt PE, et al. Hysterectomy-corrected cervical cancer mortality rates in Denmark during 2002-2015: a registry-based cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98:1063-1069.

- Beavis AL, Gravitt PE, Rositch AF. Hysterectomy-corrected cervical cancer mortality rates reveal a larger racial disparity in the United States. Cancer. 2017;123:1044-1050.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins--Gynecology. Practice Bulletin No. 168: cervical cancer screening and prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e111-30.

- Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

- Stang A, Hawk H, Knowlton R, et al. Hysterectomy-corrected incidence rates of cervical and uterine cancers in Massachusetts, 1995-2010. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24:849-854.

- Hallowell BD, Endeshaw M, McKenna MT, et al. Cervical cancer death rates among U.S.- and foreign-born women: U.S., 2005-2014. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56:869-874.

- Lindström AK, Hermansson RS, Gustavsson I, et al. Cervical dysplasia in elderly women performing repeated self-sampling for HPV testing. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0207714.

- Kjaer SK, Munk C, Junge J, et al. Carcinogenic HPV prevalence and age-specific type distribution in 40,382 women with normal cervical cytology, ACSUC/LSIL, HSIL, or cervical cancer: what is the potential for prevention? Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:179-189.

- Andersen B, Christensen BS, Christensen J, et al. HPV-prevalence in elderly women in Denmark. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;154:118-123.

- Gravitt PE, Winer RL. Natural history of HPV infection across the lifespan: role of viral latency. Viruses. 2017;9:E267.

- Hinten F, Hilbrands LB, Meeuwis KAP, et al. Reactivation of latent HPV infections after renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:1563-1573.

- Leonard SM, Pereira M, Roberts S, et al. Evidence of disrupted high-risk human papillomavirus DNA in morphologically normal cervices of older women. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20847.

- Cervical cancer screening. Cancer Council website. https://www.cancer.org.au/about-cancer/early-detection/screening-programs/cervical-cancer-screening.html. Updated March 15, 2019. Accessed July 23, 2019.

Surprisingly, the cervical cancer death rate is greater among women aged >65 years than among younger women1,2 (FIGURE). Paradoxically, most of our screening programs focus on women <65 years of age. A nationwide study from Denmark estimated that the cervical cancer death rate per 100,000 women at ages 40 to 44 and 65 to 69 was 3.8 and 9.0, respectively.1 In other words, the cervical cancer death rate at age 65 to 69 years was 2.36 times higher than at age 40 to 44 years.1

A study from the United States estimated that the cervical cancer death rate per 100,000 white women at ages 40 to 44 and 65 to 69 was 3.3 and 8.6, respectively,2 very similar to the findings from Denmark. The same US study estimated that the cervical cancer death rate per 100,000 black women at ages 40 to 44 and 65 to 69 was 5.3 and 23.8, highlighting the fact that, in the United States, cervical cancer disease burden is disproportionately greater among black than among white women.2 In addition, the cervical cancer death rate among black women at age 65 to 69 was 4.49 times higher than at age 40 to 44 years.2

Given the high death rate from cervical cancer in women >65 years of age, it is paradoxical that most professional society guidelines recommend discontinuing cervical cancer screening at 65 years of age, if previous cervical cancer screening is normal.3,4 Is the problem due to an inability to implement the current guidelines? Or is the problem that the guidelines are not optimally designed to reduce cervical cancer risk in women >65 years of age?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommend against cervical cancer screening in women >65 years of age who have had adequate prior screening and are not otherwise at high risk for cervical cancer. However, ACOG and the USPSTF caution that there are many groups of women that may benefit from continued screening after 65 years of age, including women with HIV infection, a compromised immune system, or previous high-grade precancerous lesion or cervicalcancer; women with limited access to care; women from racial/ethnic minority groups; and migrant women.4 Many clinicians remember the guidance, “discontinue cervical cancer screening at 65 years” but do not recall all the clinical factors that might warrant continued screening past age 65. Of special concern is that black,2 Hispanic,5 and migrant women6 are at much higher risk for invasive cervical cancer than white or US-born women.

The optimal implementation of the ACOG and USPSTF guidelines are undermined by a fractured health care system, where key pieces of information may be unavailable to the clinician tasked with making a decision about discontinuing cervical cancer screening. Imagine the case in which a 65-year-old woman pre‑sents to her primary care physician for cervical cancer screening. The clinician performs a cervical cytology test and obtains a report of “no intraepithelial lesion or malignancy.” The clinician then recommends that the patient discontinue cervical cancer screening. Unbeknownst to the clinician, the patient had a positive HPV 16/18/45 test within the past 10 years in another health system. In this case, it would be inappropriate to terminate the patient from cervical cancer screening.

Continue to: Testing for hrHPV is superior to cervical cytology in women >65 years...

Testing for hrHPV is superior to cervical cytology in women >65 years

In Sweden, about 30% of cervical cancer cases occur in women aged >60 years.7 To assess the prevalence of oncogenic high-risk HPV (hrHPV), women at ages 60, 65, 70, and 75 years were invited to send sequential self-collected vaginal samples for nucleic acid testing for hrHPV. The prevalence of hrHPV was found to be 4.4%. Women with a second positive, self-collected, hrHPV test were invited for colposcopy, cervical biopsy, and cytology testing. Among the women with two positive hrHPV tests, cervical biopsy revealed 7 cases of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 (CIN2), 6 cases of CIN1, and 4 biopsies without CIN. In these women 94% of the cervical cytology samples returned, “no intraepithelial lesion or malignancy” and 6% revealed atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance. This study suggests that, in women aged >65 years, cervical cytology may have a high rate of false-negative results, possibly due to epithelial atrophy. An evolving clinical pearl is that, when using the current cervical cancer screening guidelines, the final screen for cervical cancer must include a nucleic acid test for hrHPV.

In women 65 to 90 years, the prevalence of hrHPV is approximately 5%

In a study of 40,382 women aged 14 to 95 years, the prevalence of hrHPV was 46% in 20- to 23-year-old women and 5.7% in women older than 65 years of age.8 In a study of more than 108,000 women aged 69 to >89 years the prevalence of hrHPV was 4.3%, and similar prevalence rates were seen across all ages from 69 to >89 years.9 The carcinogenic role of persistent hrHPV infection in women >65 years is an important area for future research.

Latent HPV virus infection

Following a primary varicella-zoster infection (chickenpox), the virus may remain in a latent state in sensory ganglia, reactivating later in life to cause shingles. Thirty percent of people who have a primary chickenpox infection eventually will develop a case of shingles. Immunocompromised populations are at an increased risk of developing shingles because of reduced T-cell mediated immunity.

A recent hypothesis is that in immunocompromised and older women, latent HPV can reactivate and cause clinically significant infection.10 Following renal transplantation investigators have reported a significant increase in the prevalence of genital HPV, without a change in sexual behavior.11 In cervical tissue from women with no evidence of active HPV infection, highly sensitive PCR-based assays detected HPV16 virus in a latent state in some women, possibly due to disruption of the viral E2 gene.12 If latent HPV infection is a valid biological concept, it suggests that there is no “safe age” at which to discontinue screening for HPV infection because the virus cannot be detected in screening samples while it is latent.

Options for cervical cancer screening in women >65 years

Three options might reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with cervical cancer in women >65 years.

Option 1: Double-down on trying to effectively implement current guidelines. The high rate of cervical cancer mortality in women >65 years of age indicates that the current guidelines, as implemented in real clinical practice, are not working. A problem with the current screening guidelines is that clinicians are expected to be capable of finding all relevant cervical cancer test results and properly interpreting the results. Clinicians are over-taxed and fallible, and the current approach is not likely to be successful unless additional information technology solutions are implemented.

Continue to: Health systems could use information...

Health systems could use information technology to mitigate these problems. For example, health systems could deploy software to assemble every cervical screening result on each woman and pre‑sent those results to clinicians in a single integrated view in the electronic record. Additionally, once all lifetime screening results are consolidated in one view, artificial intelligence systems could be used to analyze the totality of results and identify women who would benefit by continued screening past age 65 and women who could safely discontinue screening.

Option 2: Adopt the Australian approach to cervical cancer screening. The current Australian approach to cervical cancer screening is built on 3 pillars: 1) school-based vaccination of all children against hrHPV, 2) screening all women from 25 to 74 years of age every 5 years using nucleic acid testing for hrHPV, and 3) providing a system for the testing of samples self-collected by women who are reluctant to visit a clinician for screening.13 Australia has one of the lowest cervical cancer death rates in the world.

Option 3: Continue screening most women past age 65. Women >65 years of age are known to be infected with hrHPV genotypes. hrHPV infection causes cervical cancer. Cervical cancer causes many deaths in women aged >65 years. There is no strong rationale for ignoring these three facts. hrHPV screening every 5 years as long as the woman is healthy and has a reasonable life expectancy is an option that could be evaluated in randomized studies.

Given the high rate of cervical cancer death in women >65 years of age, I plan to be very cautious about discontinuing cervical cancer screening until I can personally ensure that my patient has no evidence of hrHPV infection.

In 2008, Harald zur Hausen, MD, received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering that human papilloma virus (HPV) caused cervical cancer. In a recent study, 74% of cervical cancers were associated with HPV 16 or 18 infections. A total of 89% of the cancers were associated with one of the high-risk HPV genotypes, including HPV 16/18/31/33/45/52/58.1

Recently, HPV has been shown to be a major cause of oropharyngeal cancer. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calculated that in CY2015 in the United States there were 18,917 cases of HPV-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer and 11,788 cases of cervical cancer.2 Most cases of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer occur in men, and HPV vaccination of boys may help to prevent this cancer type. Oncogenic HPV produce two proteins (E6 and E7) that promote viral replication and squamous cell growth by inhibiting the function of p53 and retinoblastoma protein. The immortalized HeLa cell line, derived from Ms. Henrietta Lack's cervical cancer, contains integrated HPV18 nucleic acid sequences.3,4

The discovery that HPV causes cancer catalyzed the development of nucleic acid tests to identify high-risk oncogenic HPV and vaccines against high-risk oncogenic HPV genotypes that prevent cervical cancer. From a public health perspective, it is more effective to vaccinate the population against oncogenic HPV genotypes than to screen and treat cancer. In the United States, vaccination rates range from a high of 92% (District of Columbia) and 89% (Rhode Island) to a low of 47% (Wyoming) and 50% (Kentucky and Mississippi).5 To reduce HPV-associated cancer mortality, the gap in vaccination compliance must be closed.

References

- Kjaer SK, Munk C, Junge J, et al. Carcinogenic HPV prevalence and age-specific type distribution in 40,382 women with normal cervical cytology, ACSUC/LSIL, HSIL, or cervical cancer: what is the potential for prevention? Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:179-189.

- Van Dyne EA, Henley SJ, Saraiya M, et al. Trends in human papillomavirus-associated cancers - United States, 1999-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:918-924.

- Rosl F, Westphal EM, zur Hausen H. Chromatin structure and transcriptional regulation of human papillomavirus type 18 DNA in HeLa cells. Mol Carcinog. 1989;2:72-80.

- Adey A, Burton JN, Kitzman, et al. The haplotype-resolved genome and epigenome of the aneuploid HeLa cancer cell line. Nature. 2013;500:207-211.

- Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Singleton JA, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:874-882.

Surprisingly, the cervical cancer death rate is greater among women aged >65 years than among younger women1,2 (FIGURE). Paradoxically, most of our screening programs focus on women <65 years of age. A nationwide study from Denmark estimated that the cervical cancer death rate per 100,000 women at ages 40 to 44 and 65 to 69 was 3.8 and 9.0, respectively.1 In other words, the cervical cancer death rate at age 65 to 69 years was 2.36 times higher than at age 40 to 44 years.1

A study from the United States estimated that the cervical cancer death rate per 100,000 white women at ages 40 to 44 and 65 to 69 was 3.3 and 8.6, respectively,2 very similar to the findings from Denmark. The same US study estimated that the cervical cancer death rate per 100,000 black women at ages 40 to 44 and 65 to 69 was 5.3 and 23.8, highlighting the fact that, in the United States, cervical cancer disease burden is disproportionately greater among black than among white women.2 In addition, the cervical cancer death rate among black women at age 65 to 69 was 4.49 times higher than at age 40 to 44 years.2

Given the high death rate from cervical cancer in women >65 years of age, it is paradoxical that most professional society guidelines recommend discontinuing cervical cancer screening at 65 years of age, if previous cervical cancer screening is normal.3,4 Is the problem due to an inability to implement the current guidelines? Or is the problem that the guidelines are not optimally designed to reduce cervical cancer risk in women >65 years of age?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommend against cervical cancer screening in women >65 years of age who have had adequate prior screening and are not otherwise at high risk for cervical cancer. However, ACOG and the USPSTF caution that there are many groups of women that may benefit from continued screening after 65 years of age, including women with HIV infection, a compromised immune system, or previous high-grade precancerous lesion or cervicalcancer; women with limited access to care; women from racial/ethnic minority groups; and migrant women.4 Many clinicians remember the guidance, “discontinue cervical cancer screening at 65 years” but do not recall all the clinical factors that might warrant continued screening past age 65. Of special concern is that black,2 Hispanic,5 and migrant women6 are at much higher risk for invasive cervical cancer than white or US-born women.

The optimal implementation of the ACOG and USPSTF guidelines are undermined by a fractured health care system, where key pieces of information may be unavailable to the clinician tasked with making a decision about discontinuing cervical cancer screening. Imagine the case in which a 65-year-old woman pre‑sents to her primary care physician for cervical cancer screening. The clinician performs a cervical cytology test and obtains a report of “no intraepithelial lesion or malignancy.” The clinician then recommends that the patient discontinue cervical cancer screening. Unbeknownst to the clinician, the patient had a positive HPV 16/18/45 test within the past 10 years in another health system. In this case, it would be inappropriate to terminate the patient from cervical cancer screening.

Continue to: Testing for hrHPV is superior to cervical cytology in women >65 years...

Testing for hrHPV is superior to cervical cytology in women >65 years

In Sweden, about 30% of cervical cancer cases occur in women aged >60 years.7 To assess the prevalence of oncogenic high-risk HPV (hrHPV), women at ages 60, 65, 70, and 75 years were invited to send sequential self-collected vaginal samples for nucleic acid testing for hrHPV. The prevalence of hrHPV was found to be 4.4%. Women with a second positive, self-collected, hrHPV test were invited for colposcopy, cervical biopsy, and cytology testing. Among the women with two positive hrHPV tests, cervical biopsy revealed 7 cases of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 (CIN2), 6 cases of CIN1, and 4 biopsies without CIN. In these women 94% of the cervical cytology samples returned, “no intraepithelial lesion or malignancy” and 6% revealed atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance. This study suggests that, in women aged >65 years, cervical cytology may have a high rate of false-negative results, possibly due to epithelial atrophy. An evolving clinical pearl is that, when using the current cervical cancer screening guidelines, the final screen for cervical cancer must include a nucleic acid test for hrHPV.

In women 65 to 90 years, the prevalence of hrHPV is approximately 5%

In a study of 40,382 women aged 14 to 95 years, the prevalence of hrHPV was 46% in 20- to 23-year-old women and 5.7% in women older than 65 years of age.8 In a study of more than 108,000 women aged 69 to >89 years the prevalence of hrHPV was 4.3%, and similar prevalence rates were seen across all ages from 69 to >89 years.9 The carcinogenic role of persistent hrHPV infection in women >65 years is an important area for future research.

Latent HPV virus infection

Following a primary varicella-zoster infection (chickenpox), the virus may remain in a latent state in sensory ganglia, reactivating later in life to cause shingles. Thirty percent of people who have a primary chickenpox infection eventually will develop a case of shingles. Immunocompromised populations are at an increased risk of developing shingles because of reduced T-cell mediated immunity.

A recent hypothesis is that in immunocompromised and older women, latent HPV can reactivate and cause clinically significant infection.10 Following renal transplantation investigators have reported a significant increase in the prevalence of genital HPV, without a change in sexual behavior.11 In cervical tissue from women with no evidence of active HPV infection, highly sensitive PCR-based assays detected HPV16 virus in a latent state in some women, possibly due to disruption of the viral E2 gene.12 If latent HPV infection is a valid biological concept, it suggests that there is no “safe age” at which to discontinue screening for HPV infection because the virus cannot be detected in screening samples while it is latent.

Options for cervical cancer screening in women >65 years

Three options might reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with cervical cancer in women >65 years.

Option 1: Double-down on trying to effectively implement current guidelines. The high rate of cervical cancer mortality in women >65 years of age indicates that the current guidelines, as implemented in real clinical practice, are not working. A problem with the current screening guidelines is that clinicians are expected to be capable of finding all relevant cervical cancer test results and properly interpreting the results. Clinicians are over-taxed and fallible, and the current approach is not likely to be successful unless additional information technology solutions are implemented.

Continue to: Health systems could use information...

Health systems could use information technology to mitigate these problems. For example, health systems could deploy software to assemble every cervical screening result on each woman and pre‑sent those results to clinicians in a single integrated view in the electronic record. Additionally, once all lifetime screening results are consolidated in one view, artificial intelligence systems could be used to analyze the totality of results and identify women who would benefit by continued screening past age 65 and women who could safely discontinue screening.

Option 2: Adopt the Australian approach to cervical cancer screening. The current Australian approach to cervical cancer screening is built on 3 pillars: 1) school-based vaccination of all children against hrHPV, 2) screening all women from 25 to 74 years of age every 5 years using nucleic acid testing for hrHPV, and 3) providing a system for the testing of samples self-collected by women who are reluctant to visit a clinician for screening.13 Australia has one of the lowest cervical cancer death rates in the world.

Option 3: Continue screening most women past age 65. Women >65 years of age are known to be infected with hrHPV genotypes. hrHPV infection causes cervical cancer. Cervical cancer causes many deaths in women aged >65 years. There is no strong rationale for ignoring these three facts. hrHPV screening every 5 years as long as the woman is healthy and has a reasonable life expectancy is an option that could be evaluated in randomized studies.

Given the high rate of cervical cancer death in women >65 years of age, I plan to be very cautious about discontinuing cervical cancer screening until I can personally ensure that my patient has no evidence of hrHPV infection.

In 2008, Harald zur Hausen, MD, received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering that human papilloma virus (HPV) caused cervical cancer. In a recent study, 74% of cervical cancers were associated with HPV 16 or 18 infections. A total of 89% of the cancers were associated with one of the high-risk HPV genotypes, including HPV 16/18/31/33/45/52/58.1

Recently, HPV has been shown to be a major cause of oropharyngeal cancer. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calculated that in CY2015 in the United States there were 18,917 cases of HPV-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer and 11,788 cases of cervical cancer.2 Most cases of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer occur in men, and HPV vaccination of boys may help to prevent this cancer type. Oncogenic HPV produce two proteins (E6 and E7) that promote viral replication and squamous cell growth by inhibiting the function of p53 and retinoblastoma protein. The immortalized HeLa cell line, derived from Ms. Henrietta Lack's cervical cancer, contains integrated HPV18 nucleic acid sequences.3,4

The discovery that HPV causes cancer catalyzed the development of nucleic acid tests to identify high-risk oncogenic HPV and vaccines against high-risk oncogenic HPV genotypes that prevent cervical cancer. From a public health perspective, it is more effective to vaccinate the population against oncogenic HPV genotypes than to screen and treat cancer. In the United States, vaccination rates range from a high of 92% (District of Columbia) and 89% (Rhode Island) to a low of 47% (Wyoming) and 50% (Kentucky and Mississippi).5 To reduce HPV-associated cancer mortality, the gap in vaccination compliance must be closed.

References

- Kjaer SK, Munk C, Junge J, et al. Carcinogenic HPV prevalence and age-specific type distribution in 40,382 women with normal cervical cytology, ACSUC/LSIL, HSIL, or cervical cancer: what is the potential for prevention? Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:179-189.

- Van Dyne EA, Henley SJ, Saraiya M, et al. Trends in human papillomavirus-associated cancers - United States, 1999-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:918-924.

- Rosl F, Westphal EM, zur Hausen H. Chromatin structure and transcriptional regulation of human papillomavirus type 18 DNA in HeLa cells. Mol Carcinog. 1989;2:72-80.

- Adey A, Burton JN, Kitzman, et al. The haplotype-resolved genome and epigenome of the aneuploid HeLa cancer cell line. Nature. 2013;500:207-211.

- Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Singleton JA, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:874-882.

- Hammer A, Kahlert J, Gravitt PE, et al. Hysterectomy-corrected cervical cancer mortality rates in Denmark during 2002-2015: a registry-based cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98:1063-1069.

- Beavis AL, Gravitt PE, Rositch AF. Hysterectomy-corrected cervical cancer mortality rates reveal a larger racial disparity in the United States. Cancer. 2017;123:1044-1050.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins--Gynecology. Practice Bulletin No. 168: cervical cancer screening and prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e111-30.

- Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

- Stang A, Hawk H, Knowlton R, et al. Hysterectomy-corrected incidence rates of cervical and uterine cancers in Massachusetts, 1995-2010. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24:849-854.

- Hallowell BD, Endeshaw M, McKenna MT, et al. Cervical cancer death rates among U.S.- and foreign-born women: U.S., 2005-2014. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56:869-874.

- Lindström AK, Hermansson RS, Gustavsson I, et al. Cervical dysplasia in elderly women performing repeated self-sampling for HPV testing. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0207714.

- Kjaer SK, Munk C, Junge J, et al. Carcinogenic HPV prevalence and age-specific type distribution in 40,382 women with normal cervical cytology, ACSUC/LSIL, HSIL, or cervical cancer: what is the potential for prevention? Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:179-189.

- Andersen B, Christensen BS, Christensen J, et al. HPV-prevalence in elderly women in Denmark. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;154:118-123.

- Gravitt PE, Winer RL. Natural history of HPV infection across the lifespan: role of viral latency. Viruses. 2017;9:E267.

- Hinten F, Hilbrands LB, Meeuwis KAP, et al. Reactivation of latent HPV infections after renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:1563-1573.

- Leonard SM, Pereira M, Roberts S, et al. Evidence of disrupted high-risk human papillomavirus DNA in morphologically normal cervices of older women. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20847.

- Cervical cancer screening. Cancer Council website. https://www.cancer.org.au/about-cancer/early-detection/screening-programs/cervical-cancer-screening.html. Updated March 15, 2019. Accessed July 23, 2019.

- Hammer A, Kahlert J, Gravitt PE, et al. Hysterectomy-corrected cervical cancer mortality rates in Denmark during 2002-2015: a registry-based cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98:1063-1069.

- Beavis AL, Gravitt PE, Rositch AF. Hysterectomy-corrected cervical cancer mortality rates reveal a larger racial disparity in the United States. Cancer. 2017;123:1044-1050.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins--Gynecology. Practice Bulletin No. 168: cervical cancer screening and prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e111-30.

- Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

- Stang A, Hawk H, Knowlton R, et al. Hysterectomy-corrected incidence rates of cervical and uterine cancers in Massachusetts, 1995-2010. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24:849-854.

- Hallowell BD, Endeshaw M, McKenna MT, et al. Cervical cancer death rates among U.S.- and foreign-born women: U.S., 2005-2014. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56:869-874.

- Lindström AK, Hermansson RS, Gustavsson I, et al. Cervical dysplasia in elderly women performing repeated self-sampling for HPV testing. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0207714.

- Kjaer SK, Munk C, Junge J, et al. Carcinogenic HPV prevalence and age-specific type distribution in 40,382 women with normal cervical cytology, ACSUC/LSIL, HSIL, or cervical cancer: what is the potential for prevention? Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:179-189.

- Andersen B, Christensen BS, Christensen J, et al. HPV-prevalence in elderly women in Denmark. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;154:118-123.

- Gravitt PE, Winer RL. Natural history of HPV infection across the lifespan: role of viral latency. Viruses. 2017;9:E267.

- Hinten F, Hilbrands LB, Meeuwis KAP, et al. Reactivation of latent HPV infections after renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:1563-1573.

- Leonard SM, Pereira M, Roberts S, et al. Evidence of disrupted high-risk human papillomavirus DNA in morphologically normal cervices of older women. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20847.

- Cervical cancer screening. Cancer Council website. https://www.cancer.org.au/about-cancer/early-detection/screening-programs/cervical-cancer-screening.html. Updated March 15, 2019. Accessed July 23, 2019.

Technology, counseling, and CBT apps for primary care

There is probably no area where human contact is more important than in the area of counseling and psychotherapy. Or so most of us have thought. It turns out that, even in behavioral medicine, technology has made fantastic inroads in helping patients achieve real improvement in troublesome behavioral symptoms. We will not go over that evidence in this column, other than to say that the evidence is there, but rather we will review some of the best apps that those of us in primary care can utilize in the care of our patients. It is our opinion that these apps are best used in conjunction with our care to supplement the counseling we are giving our patients in the office. Many of the apps listed may be used for both anxiety and depression, as well as in areas related to problem solving, self-esteem, anger management, creating lifestyle changes, and coping with uncertainty.

MoodKit

MoodKit is a CBT app with four main tools: a collection of activities focused on coping self-efficacy (a person’s belief in success in specific situations) that includes individual productivity, social relationships, physical activity, and healthy habits; a thought checker; mood tracker; and journal. MoodKit is accessed in an unstructured way and can be used as an unguided self-help app. It is useful in patient interactions to access interventions in areas such as social engagement and options for choosing a healthy lifestyle. It is available in Apple’s App Store, and it costs $4.99.

Moodnotes

Based on CBT and positive psychology, Moodnotes assists in recognizing and learning about “traps” in thinking, as well as emphasizing healthier thinking habits. Traps in thinking include “catastrophic thinking” where patients with depression may think that a small error or behavioral indiscretion may lead to a consequence that far exceeds what is likely, or “mind-reading” where a person assumes that others are critical of them without actually having evidence that this is the case. Moodnotes tracks mood over a period of time while identifying factors that influence it. It is helpful in between visits to aid clinicians in gaining perspective on mood patterns. It is available in the App Store; it costs $4.99.

MoodMission

This app recommends strategies based in CBT after input of low moods or feelings of anxiety. MoodMission provides five “missions” to engage in that promote confidence in handling stressors and promotes coping self-efficacy. The app learns what style works best and tailors techniques according to when a patient uses it most frequently. Rewards in the app are used to promote motivation and to increase pleasure and self-confidence. It is useful for patients who could use a lift in mood or decrease in symptoms of anxiety and depression. It available in the App Store and Google Play, and it’s free.

What’s Up

In line with its development based on principles from CBT and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), What’s Up identifies common negative thinking patterns and methods to overcome them with useful metaphors, a catastrophe scale, grounding techniques, and breathing exercises. What’s Up syncs data across multiple devices and uses a unique passcode to protect this information. One of the abilities that separates it from other apps is that it can become active in forums where people discuss similar feelings and strategies that have been useful for them. It is available in the App Store and Google Play, and it’s free.

Moodpath

Moodpath uses daily screenings to create better understanding of thoughts, feelings, and emotions. If needed, it provides a discussion guide to talking with a medical professional based on answers to its daily screenings. Included in the app are over 150 psychological exercises and videos to promote and strengthen overall mental health. It is useful in introducing how to discuss mental health with a professional. It is available in the App Store and Google Play free of cost.

MindShift CBT

Designed to assist youth and young adults in coping with anxiety, MindShift constructs an individualized toolbox to help individuals deal with test anxiety, perfectionism, social anxiety, worry, panic, and conflict. The app includes directions on how to construct “belief experiments” to test common beliefs that fuel anxiety, guided relaxation, as well as tools and tips to help set and accomplish goals. It is useful in helping teens and young adults learn about helpful and unhelpful anxiety, as well as to overcome fears by gradually facing them in manageable steps. It is available in the App Store and Google Play for free.

CBT-i Coach

CBT-i Coach, based on principles of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-i), is a structured program to learn about sleep, develop positive sleep routines, and improve sleep environment. The CBT methods used attempt to change behaviors, which in turn provides confidence that patients will sleep better on a regular basis. It useful as a first-line intervention in treating symptoms of insomnia. It is available in the App Store and Google Play for no cost.

Getselfhelp.co.uk

This website provides free self-help and therapy resources grounded in methods that teach the change agents in CBT that can influence negative and destructive thought patterns. Negative thought patterns include thinking in terms of all or nothing: “Nothing ever works out for me,” fortune telling: “I shouldn’t even try,” and overgeneralization: “This didn’t work so this will not either.” Getselfhelp.co.uk provides handouts on a wide array of symptoms related to anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, panic attacks, social disorder, and more. The solution section of the website supplies interventions that can be printed and saved for future use. It is helpful for clinicians and patients in identifying an area of need and creating an action plan. It is also useful for clinicians to have as an augmented supplement for counseling and is free of cost.

The bottom line

When used correctly the resources that we have reviewed can essentially be deployed in a manner similar to how we use finger-stick blood sugar monitoring in the treatment of diabetes. Each of these technologies works best when combined with clinician input and periodic review. When used to supplement clinician counseling, the apps may help sustain motivation and provide insights and exercises that improve patient engagement and supplement the effect of counseling and/or medications that are prescribed in the office.

Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Aaron Sutton is a behavioral health consultant and faculty member in the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

There is probably no area where human contact is more important than in the area of counseling and psychotherapy. Or so most of us have thought. It turns out that, even in behavioral medicine, technology has made fantastic inroads in helping patients achieve real improvement in troublesome behavioral symptoms. We will not go over that evidence in this column, other than to say that the evidence is there, but rather we will review some of the best apps that those of us in primary care can utilize in the care of our patients. It is our opinion that these apps are best used in conjunction with our care to supplement the counseling we are giving our patients in the office. Many of the apps listed may be used for both anxiety and depression, as well as in areas related to problem solving, self-esteem, anger management, creating lifestyle changes, and coping with uncertainty.

MoodKit

MoodKit is a CBT app with four main tools: a collection of activities focused on coping self-efficacy (a person’s belief in success in specific situations) that includes individual productivity, social relationships, physical activity, and healthy habits; a thought checker; mood tracker; and journal. MoodKit is accessed in an unstructured way and can be used as an unguided self-help app. It is useful in patient interactions to access interventions in areas such as social engagement and options for choosing a healthy lifestyle. It is available in Apple’s App Store, and it costs $4.99.

Moodnotes

Based on CBT and positive psychology, Moodnotes assists in recognizing and learning about “traps” in thinking, as well as emphasizing healthier thinking habits. Traps in thinking include “catastrophic thinking” where patients with depression may think that a small error or behavioral indiscretion may lead to a consequence that far exceeds what is likely, or “mind-reading” where a person assumes that others are critical of them without actually having evidence that this is the case. Moodnotes tracks mood over a period of time while identifying factors that influence it. It is helpful in between visits to aid clinicians in gaining perspective on mood patterns. It is available in the App Store; it costs $4.99.