User login

ERRATUM

The author list for the June 2019 PURL (“A better approach to the diagnosis of PE.” J Fam Pract. 2019;68:286,287,295) should have read: Andrew H. Slattengren, DO; Shailendra Prasad, MBBS, MPH; David C. Bury, DO; Michael M. Dickman, DO; Nick Bennett, DO; Ashley Smith, MD; Robert Oh, MD, MPH, FAAFP; Robert Marshall, MD, MPH, MISHM, FAAFP; North Memorial Family Medicine Residency, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis (Drs. Slattengren and Prasad); Madigan Family Medicine Residency, Gig Harbor, Washington (Drs. Bury, Dickman, Bennett, Smith, Oh, and Marshall).

The author list for the June 2019 PURL (“A better approach to the diagnosis of PE.” J Fam Pract. 2019;68:286,287,295) should have read: Andrew H. Slattengren, DO; Shailendra Prasad, MBBS, MPH; David C. Bury, DO; Michael M. Dickman, DO; Nick Bennett, DO; Ashley Smith, MD; Robert Oh, MD, MPH, FAAFP; Robert Marshall, MD, MPH, MISHM, FAAFP; North Memorial Family Medicine Residency, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis (Drs. Slattengren and Prasad); Madigan Family Medicine Residency, Gig Harbor, Washington (Drs. Bury, Dickman, Bennett, Smith, Oh, and Marshall).

The author list for the June 2019 PURL (“A better approach to the diagnosis of PE.” J Fam Pract. 2019;68:286,287,295) should have read: Andrew H. Slattengren, DO; Shailendra Prasad, MBBS, MPH; David C. Bury, DO; Michael M. Dickman, DO; Nick Bennett, DO; Ashley Smith, MD; Robert Oh, MD, MPH, FAAFP; Robert Marshall, MD, MPH, MISHM, FAAFP; North Memorial Family Medicine Residency, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis (Drs. Slattengren and Prasad); Madigan Family Medicine Residency, Gig Harbor, Washington (Drs. Bury, Dickman, Bennett, Smith, Oh, and Marshall).

Doing our part to dismantle the opioid crisis

When the Joint Commission dubbed pain assessment the “fifth vital sign” in 2001 and insisted that all outpatients be assessed for pain at each office visit, they had no idea of the unintended consequences that would result.

The problem they wanted to solve was undertreatment of postoperative pain, but the problem they helped create far outweighed any benefit to hospitalized patients. They would have been wise to listen to R.E.M.’s song “Everybody Hurts” and recognize that pain is a fact of life that doesn’t always require medical intervention. Combined with aggressive marketing of opioids by pharmaceutical companies, these 2 factors led to the opioid epidemic we currently find ourselves in.

The good news is that there has been a significant drop in opioid prescribing in recent years. Between 2014 and 2017, opioid prescriptions declined from 7.4% to 6.4%, based on a national electronic health record review.1 Reducing opioid prescribing for patients with chronic noncancer pain, however, is difficult. Although there are no truly evidence-based methods, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has provided expert advice on improving opioid prescribing, and Drs. Mendoza and Russell provide thoughtful recommendations for tapering opioids in patients on chronic therapy in this issue of JFP.

In addition, Patchett et al describe their experience with a practice-wide approach to reducing chronic opioid prescribing in their practice at Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz. Using a systematic approach, they were able to reduce the number of patients on chronic opioid therapy by 22%.

And there is more good news from a 2018 JAMA study.2

All family physicians should share the results of this study with their chronic pain patients and follow Pachett’s lead in a practice-wide approach to reducing opioid prescribing. We were part of the problem and must be part of the solution.

1. García MC, Heilig CM, Lee SH, et al. Opioid prescribing rates in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan counties among primary care providers using an electronic health record system — United States, 2014–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:25–30.

2. Krebs EE, Gravely A, Nugent S, et al. Effect of opioid vs nonopioid medications on pain-related function in patients with chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis pain. The SPACE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:872-882.

When the Joint Commission dubbed pain assessment the “fifth vital sign” in 2001 and insisted that all outpatients be assessed for pain at each office visit, they had no idea of the unintended consequences that would result.

The problem they wanted to solve was undertreatment of postoperative pain, but the problem they helped create far outweighed any benefit to hospitalized patients. They would have been wise to listen to R.E.M.’s song “Everybody Hurts” and recognize that pain is a fact of life that doesn’t always require medical intervention. Combined with aggressive marketing of opioids by pharmaceutical companies, these 2 factors led to the opioid epidemic we currently find ourselves in.

The good news is that there has been a significant drop in opioid prescribing in recent years. Between 2014 and 2017, opioid prescriptions declined from 7.4% to 6.4%, based on a national electronic health record review.1 Reducing opioid prescribing for patients with chronic noncancer pain, however, is difficult. Although there are no truly evidence-based methods, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has provided expert advice on improving opioid prescribing, and Drs. Mendoza and Russell provide thoughtful recommendations for tapering opioids in patients on chronic therapy in this issue of JFP.

In addition, Patchett et al describe their experience with a practice-wide approach to reducing chronic opioid prescribing in their practice at Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz. Using a systematic approach, they were able to reduce the number of patients on chronic opioid therapy by 22%.

And there is more good news from a 2018 JAMA study.2

All family physicians should share the results of this study with their chronic pain patients and follow Pachett’s lead in a practice-wide approach to reducing opioid prescribing. We were part of the problem and must be part of the solution.

When the Joint Commission dubbed pain assessment the “fifth vital sign” in 2001 and insisted that all outpatients be assessed for pain at each office visit, they had no idea of the unintended consequences that would result.

The problem they wanted to solve was undertreatment of postoperative pain, but the problem they helped create far outweighed any benefit to hospitalized patients. They would have been wise to listen to R.E.M.’s song “Everybody Hurts” and recognize that pain is a fact of life that doesn’t always require medical intervention. Combined with aggressive marketing of opioids by pharmaceutical companies, these 2 factors led to the opioid epidemic we currently find ourselves in.

The good news is that there has been a significant drop in opioid prescribing in recent years. Between 2014 and 2017, opioid prescriptions declined from 7.4% to 6.4%, based on a national electronic health record review.1 Reducing opioid prescribing for patients with chronic noncancer pain, however, is difficult. Although there are no truly evidence-based methods, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has provided expert advice on improving opioid prescribing, and Drs. Mendoza and Russell provide thoughtful recommendations for tapering opioids in patients on chronic therapy in this issue of JFP.

In addition, Patchett et al describe their experience with a practice-wide approach to reducing chronic opioid prescribing in their practice at Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz. Using a systematic approach, they were able to reduce the number of patients on chronic opioid therapy by 22%.

And there is more good news from a 2018 JAMA study.2

All family physicians should share the results of this study with their chronic pain patients and follow Pachett’s lead in a practice-wide approach to reducing opioid prescribing. We were part of the problem and must be part of the solution.

1. García MC, Heilig CM, Lee SH, et al. Opioid prescribing rates in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan counties among primary care providers using an electronic health record system — United States, 2014–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:25–30.

2. Krebs EE, Gravely A, Nugent S, et al. Effect of opioid vs nonopioid medications on pain-related function in patients with chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis pain. The SPACE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:872-882.

1. García MC, Heilig CM, Lee SH, et al. Opioid prescribing rates in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan counties among primary care providers using an electronic health record system — United States, 2014–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:25–30.

2. Krebs EE, Gravely A, Nugent S, et al. Effect of opioid vs nonopioid medications on pain-related function in patients with chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis pain. The SPACE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:872-882.

Fetal alcohol exposure overlooked again?

New study on large youth sample is well done – with a glaring exception

In 2016, two researchers published a meta-analysis on gray matter abnormalities in youth who had conduct problems.

The study by Jack C. Rogers, PhD, and Stephane A. De Brito, PhD, found 13 well-done studies that included 394 youth with conduct problems and 390 typically developing youth. Compared with the typically developing youth, the conduct-disordered youth had decreased gray matter volume (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Jan;73[1]:64-72).

As I knew one of the researchers in one of the studies that made the cut, I called him up and asked whether their research had controlled for fetal alcohol exposure. They had not. I found this very curious because my experience is that youth who have been labeled with conduct disorder often have histories of prenatal fetal alcohol exposure. In addition, my understanding is that youth who have been exposed to prenatal alcohol often have symptoms of conduct disorder. Furthermore, research has shown that such youth have smaller brains (Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001 Mar;43[3]:148-54). I wondered whether the youth studied in that trial had been exposed to alcohol prenatally.

More recently, this problem has resurfaced. An article by Antonia N. Kaczkurkin, PhD, and associates about a large sample of youth was nicely done. But again, the variable of fetal alcohol exposure was not considered. The study was an elegant one that provides a strong rationale for consideration of a “psychopathology factor” in human life (Am J Psychiatry. 2019 Jun 24. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.1807035). It shored up that argument by doing neuroimaging studies on a reasonably large sample of youth and showed that reduced cortical thickness (gray matter volume) was associated with overall psychopathology. With the exception of failing to consider the variable of fetal alcohol exposure, the study is a valuable addition to our understanding of what might be going on with psychiatric disorders.

Unfortunately – while hating to sound like a broken record – I noticed that there was no consideration of fetal alcohol exposure as a cause for the findings of the study. It does not seem like a large leap to hypothesize some of these brain imaging studies that find smaller brain components associated with psychopathology and conduct disorder to be a dynamic of fetal alcohol exposure.

It seems to me that we made a huge mistake in public health in asking women only whether they were drinking while they were pregnant because it was the wrong question. The right question is – “When did you realize you were pregnant, and were you doing any social drinking before you knew you were pregnant?”

The former editor of the American Journal of Psychiatry – Robert A. Freedman, MD – suggests that by giving phosphatidyl choline to pregnant women, such problems could be prevented.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital’s Medical/Surgical-Psychiatry Inpatient Unit in Chicago, clinical psychiatrist emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago, former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council, and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago. In 2019, he was awarded the Adolph Meyer Award by the American Psychiatric Association for lifetime achievement in psychiatric research.

New study on large youth sample is well done – with a glaring exception

New study on large youth sample is well done – with a glaring exception

In 2016, two researchers published a meta-analysis on gray matter abnormalities in youth who had conduct problems.

The study by Jack C. Rogers, PhD, and Stephane A. De Brito, PhD, found 13 well-done studies that included 394 youth with conduct problems and 390 typically developing youth. Compared with the typically developing youth, the conduct-disordered youth had decreased gray matter volume (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Jan;73[1]:64-72).

As I knew one of the researchers in one of the studies that made the cut, I called him up and asked whether their research had controlled for fetal alcohol exposure. They had not. I found this very curious because my experience is that youth who have been labeled with conduct disorder often have histories of prenatal fetal alcohol exposure. In addition, my understanding is that youth who have been exposed to prenatal alcohol often have symptoms of conduct disorder. Furthermore, research has shown that such youth have smaller brains (Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001 Mar;43[3]:148-54). I wondered whether the youth studied in that trial had been exposed to alcohol prenatally.

More recently, this problem has resurfaced. An article by Antonia N. Kaczkurkin, PhD, and associates about a large sample of youth was nicely done. But again, the variable of fetal alcohol exposure was not considered. The study was an elegant one that provides a strong rationale for consideration of a “psychopathology factor” in human life (Am J Psychiatry. 2019 Jun 24. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.1807035). It shored up that argument by doing neuroimaging studies on a reasonably large sample of youth and showed that reduced cortical thickness (gray matter volume) was associated with overall psychopathology. With the exception of failing to consider the variable of fetal alcohol exposure, the study is a valuable addition to our understanding of what might be going on with psychiatric disorders.

Unfortunately – while hating to sound like a broken record – I noticed that there was no consideration of fetal alcohol exposure as a cause for the findings of the study. It does not seem like a large leap to hypothesize some of these brain imaging studies that find smaller brain components associated with psychopathology and conduct disorder to be a dynamic of fetal alcohol exposure.

It seems to me that we made a huge mistake in public health in asking women only whether they were drinking while they were pregnant because it was the wrong question. The right question is – “When did you realize you were pregnant, and were you doing any social drinking before you knew you were pregnant?”

The former editor of the American Journal of Psychiatry – Robert A. Freedman, MD – suggests that by giving phosphatidyl choline to pregnant women, such problems could be prevented.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital’s Medical/Surgical-Psychiatry Inpatient Unit in Chicago, clinical psychiatrist emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago, former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council, and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago. In 2019, he was awarded the Adolph Meyer Award by the American Psychiatric Association for lifetime achievement in psychiatric research.

In 2016, two researchers published a meta-analysis on gray matter abnormalities in youth who had conduct problems.

The study by Jack C. Rogers, PhD, and Stephane A. De Brito, PhD, found 13 well-done studies that included 394 youth with conduct problems and 390 typically developing youth. Compared with the typically developing youth, the conduct-disordered youth had decreased gray matter volume (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Jan;73[1]:64-72).

As I knew one of the researchers in one of the studies that made the cut, I called him up and asked whether their research had controlled for fetal alcohol exposure. They had not. I found this very curious because my experience is that youth who have been labeled with conduct disorder often have histories of prenatal fetal alcohol exposure. In addition, my understanding is that youth who have been exposed to prenatal alcohol often have symptoms of conduct disorder. Furthermore, research has shown that such youth have smaller brains (Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001 Mar;43[3]:148-54). I wondered whether the youth studied in that trial had been exposed to alcohol prenatally.

More recently, this problem has resurfaced. An article by Antonia N. Kaczkurkin, PhD, and associates about a large sample of youth was nicely done. But again, the variable of fetal alcohol exposure was not considered. The study was an elegant one that provides a strong rationale for consideration of a “psychopathology factor” in human life (Am J Psychiatry. 2019 Jun 24. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.1807035). It shored up that argument by doing neuroimaging studies on a reasonably large sample of youth and showed that reduced cortical thickness (gray matter volume) was associated with overall psychopathology. With the exception of failing to consider the variable of fetal alcohol exposure, the study is a valuable addition to our understanding of what might be going on with psychiatric disorders.

Unfortunately – while hating to sound like a broken record – I noticed that there was no consideration of fetal alcohol exposure as a cause for the findings of the study. It does not seem like a large leap to hypothesize some of these brain imaging studies that find smaller brain components associated with psychopathology and conduct disorder to be a dynamic of fetal alcohol exposure.

It seems to me that we made a huge mistake in public health in asking women only whether they were drinking while they were pregnant because it was the wrong question. The right question is – “When did you realize you were pregnant, and were you doing any social drinking before you knew you were pregnant?”

The former editor of the American Journal of Psychiatry – Robert A. Freedman, MD – suggests that by giving phosphatidyl choline to pregnant women, such problems could be prevented.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital’s Medical/Surgical-Psychiatry Inpatient Unit in Chicago, clinical psychiatrist emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago, former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council, and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago. In 2019, he was awarded the Adolph Meyer Award by the American Psychiatric Association for lifetime achievement in psychiatric research.

Entresto, inpatient therapy, and surrogate markers

The recently published PIONEER-HF study attempts to move sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) therapy to the inpatient environment to improve patient and physician acceptance of this therapy for patients with heart failure (N Engl J Med. 2019 Feb 7;380;539-48).

When given to outpatients in the PARADIGM-HF trial, the combination was superior to enalapril for reducing the risks of death and hospitalization for heart failure (N Engl J Med 2014;371:993-1004.) Specifically, sacubitril/valsartan decreased mortality by 15% and hospitalization by 21% as an outpatient therapy for patients with systolic heart failure. Nevertheless, there has not been widespread adoption of this approach. It is well known that , one of the first drugs shown to be effective in heart failure therapy (Entresto costs more than $4,000 per year; enalapril costs about $120 per year).

The investigators in the PIONEER-HF study compared Entresto to enalapril over a 2-month period in patients hospitalized with systolic heart failure. To accelerate the trial, the investigators used the proportional change in patients’ N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels as the primary endpoint rather than the traditional outcome of morbidity and mortality. In the short term, no significant clinical benefits were observed, but there was a significant decrease in NT-proBNP of about 30% (P less than .001).

The investigators suggested that this finding extended the previous benefit observed with Entresto during outpatient initiation and could be used as a rationale for initiating Entresto therapy in the hospital. This earlier application of the therapy could make the drug more widely acceptable.

Considerable investigation in BNP measurement has occurred over the last few years, and although it is clear that BNP is elevated in heart failure patients, there is no evidence to confirm that the decrease in BNP is associated with improved outcome. BNP will fall with decrease in ventricular volume, which may have significant physiologic mechanisms but ventricular volume could decrease with fall in blood pressure that may have occurred in this population since hypotension tended to be more frequent with Entresto than with enalapril. The traditional measure of heart failure benefit with beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, and aldosterone antagonists in the inpatient and early postdischarge period has depended on clinical outcomes.

Regardless of the physiologic explanation of this fall in BNP, we must pause in our assumptions when a surrogate measure is used to assess clinical benefit as inpatient therapy. The Food and Drug Administration has long given up using surrogate measures as proof of efficacy, and rightly so. Clinical medicine is replete with dubious drug benefits based on surrogate measures. Let’s not forget that only a few years ago suppression of premature ventricular contractions was considered to be a measure of the pharmacologic prevention of sudden death. We have come a long way from that and other clinical missteps to use BNP, an uncertain marker at best of clinical improvement, as a surrogate for the improvement in heart failure.

There is a substantial amount of data supporting the benefit of Entresto in the clinical management of outpatients with heart failure without using the PIONEER-HF trial results as a pretense to initiate therapy when patients are hospitalized. One might suggest that if Novartis is concerned about introducing the drug in the clinical management of heart failure, the company might consider the possibility of decreasing its price.

Dr. Goldstein is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and the division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit.

The recently published PIONEER-HF study attempts to move sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) therapy to the inpatient environment to improve patient and physician acceptance of this therapy for patients with heart failure (N Engl J Med. 2019 Feb 7;380;539-48).

When given to outpatients in the PARADIGM-HF trial, the combination was superior to enalapril for reducing the risks of death and hospitalization for heart failure (N Engl J Med 2014;371:993-1004.) Specifically, sacubitril/valsartan decreased mortality by 15% and hospitalization by 21% as an outpatient therapy for patients with systolic heart failure. Nevertheless, there has not been widespread adoption of this approach. It is well known that , one of the first drugs shown to be effective in heart failure therapy (Entresto costs more than $4,000 per year; enalapril costs about $120 per year).

The investigators in the PIONEER-HF study compared Entresto to enalapril over a 2-month period in patients hospitalized with systolic heart failure. To accelerate the trial, the investigators used the proportional change in patients’ N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels as the primary endpoint rather than the traditional outcome of morbidity and mortality. In the short term, no significant clinical benefits were observed, but there was a significant decrease in NT-proBNP of about 30% (P less than .001).

The investigators suggested that this finding extended the previous benefit observed with Entresto during outpatient initiation and could be used as a rationale for initiating Entresto therapy in the hospital. This earlier application of the therapy could make the drug more widely acceptable.

Considerable investigation in BNP measurement has occurred over the last few years, and although it is clear that BNP is elevated in heart failure patients, there is no evidence to confirm that the decrease in BNP is associated with improved outcome. BNP will fall with decrease in ventricular volume, which may have significant physiologic mechanisms but ventricular volume could decrease with fall in blood pressure that may have occurred in this population since hypotension tended to be more frequent with Entresto than with enalapril. The traditional measure of heart failure benefit with beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, and aldosterone antagonists in the inpatient and early postdischarge period has depended on clinical outcomes.

Regardless of the physiologic explanation of this fall in BNP, we must pause in our assumptions when a surrogate measure is used to assess clinical benefit as inpatient therapy. The Food and Drug Administration has long given up using surrogate measures as proof of efficacy, and rightly so. Clinical medicine is replete with dubious drug benefits based on surrogate measures. Let’s not forget that only a few years ago suppression of premature ventricular contractions was considered to be a measure of the pharmacologic prevention of sudden death. We have come a long way from that and other clinical missteps to use BNP, an uncertain marker at best of clinical improvement, as a surrogate for the improvement in heart failure.

There is a substantial amount of data supporting the benefit of Entresto in the clinical management of outpatients with heart failure without using the PIONEER-HF trial results as a pretense to initiate therapy when patients are hospitalized. One might suggest that if Novartis is concerned about introducing the drug in the clinical management of heart failure, the company might consider the possibility of decreasing its price.

Dr. Goldstein is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and the division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit.

The recently published PIONEER-HF study attempts to move sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) therapy to the inpatient environment to improve patient and physician acceptance of this therapy for patients with heart failure (N Engl J Med. 2019 Feb 7;380;539-48).

When given to outpatients in the PARADIGM-HF trial, the combination was superior to enalapril for reducing the risks of death and hospitalization for heart failure (N Engl J Med 2014;371:993-1004.) Specifically, sacubitril/valsartan decreased mortality by 15% and hospitalization by 21% as an outpatient therapy for patients with systolic heart failure. Nevertheless, there has not been widespread adoption of this approach. It is well known that , one of the first drugs shown to be effective in heart failure therapy (Entresto costs more than $4,000 per year; enalapril costs about $120 per year).

The investigators in the PIONEER-HF study compared Entresto to enalapril over a 2-month period in patients hospitalized with systolic heart failure. To accelerate the trial, the investigators used the proportional change in patients’ N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels as the primary endpoint rather than the traditional outcome of morbidity and mortality. In the short term, no significant clinical benefits were observed, but there was a significant decrease in NT-proBNP of about 30% (P less than .001).

The investigators suggested that this finding extended the previous benefit observed with Entresto during outpatient initiation and could be used as a rationale for initiating Entresto therapy in the hospital. This earlier application of the therapy could make the drug more widely acceptable.

Considerable investigation in BNP measurement has occurred over the last few years, and although it is clear that BNP is elevated in heart failure patients, there is no evidence to confirm that the decrease in BNP is associated with improved outcome. BNP will fall with decrease in ventricular volume, which may have significant physiologic mechanisms but ventricular volume could decrease with fall in blood pressure that may have occurred in this population since hypotension tended to be more frequent with Entresto than with enalapril. The traditional measure of heart failure benefit with beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, and aldosterone antagonists in the inpatient and early postdischarge period has depended on clinical outcomes.

Regardless of the physiologic explanation of this fall in BNP, we must pause in our assumptions when a surrogate measure is used to assess clinical benefit as inpatient therapy. The Food and Drug Administration has long given up using surrogate measures as proof of efficacy, and rightly so. Clinical medicine is replete with dubious drug benefits based on surrogate measures. Let’s not forget that only a few years ago suppression of premature ventricular contractions was considered to be a measure of the pharmacologic prevention of sudden death. We have come a long way from that and other clinical missteps to use BNP, an uncertain marker at best of clinical improvement, as a surrogate for the improvement in heart failure.

There is a substantial amount of data supporting the benefit of Entresto in the clinical management of outpatients with heart failure without using the PIONEER-HF trial results as a pretense to initiate therapy when patients are hospitalized. One might suggest that if Novartis is concerned about introducing the drug in the clinical management of heart failure, the company might consider the possibility of decreasing its price.

Dr. Goldstein is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and the division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit.

Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of ovarian remnant syndrome

Ovarian remnant syndrome (ORS) is an uncommon problem, but one that seems to be increasing in incidence and one that is important to diagnose and treat properly, as well as prevent. Retrospective cohort studies published in the past 15 years or so have improved our understanding of its presentation and the outcomes of surgical management – and recent literature has demonstrated that a minimally invasive surgical approach with either conventional laparoscopy or robot-assisted laparoscopy yields improved outcomes in a skilled surgeon’s hands.

Diagnosis is based on clinical history and should be further supported with imaging and laboratory evaluation. A definitive diagnosis of the disease comes through surgical intervention and pathological findings.

Surgery therefore is technically challenging, usually requiring complete ureterolysis, careful adhesiolysis (often enterolysis), and excision of much of the pelvic sidewall peritoneum with extirpation of the remnant and endometriosis. High ligation of the ovarian vasculature also often is required.

This complexity and the consequent risk of intraoperative injury to the bowel, bladder, and ureters requires careful preoperative preparation. When an ovarian remnant is suspected, it may be important to have other surgeons – such as gynecologic oncologists, urologists, colorectal surgeons, or general surgeons – either present or on standby during the surgical intervention. In expert hands, surgical intervention has been shown to resolve or improve pain in the majority of patients, with no recurrence of the syndrome.

Diagnosis of ORS

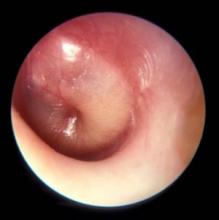

Courtesy Dr. Charles E. Miller and Dr. Kirsten J. Sasaki

Patients with ORS have had previous oophorectomies with incomplete removal of ovarian tissue. Pelvic pain, either cyclical or most commonly chronic, is a common symptom. Other symptoms can include dyspareunia, dysuria and other urinary symptoms, and bowel symptoms. Ovarian remnants may have an expanding cystic structure – oftentimes secondary to endometriosis – that causes mass-like effects leading to pain and inflammation and to symptoms such as low back pain, constipation, and even urinary retention.

It also is important to discuss the patient’s history of menopausal symptoms, because the absence of these symptoms after oophorectomy may be a sign that ovarian tissue has been left behind. Menopausal symptoms do not exclude the diagnosis, however. Endometriosis, extensive surgical history, and other diseases that lead to significant adhesion formation – and a higher risk of incomplete removal of ovarian tissue, theoretically – also should be explored during history-taking.

Laboratory assessment of serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and estradiol can be helpful. Values that are indicative of ovarian function – FSH less than 30 mIU/mL and estradiol greater than 35 pg/mL – point towards ORS, but the absence of such premenopausal values should not rule out the possibility of an ovarian remnant.

The literature shows that FSH and estradiol levels are variable in women with ORS. A retrospective review published in 2005 by Paul M. Magtibay, MD, and colleagues at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., and Rochester, Minn., involved 186 patients treated surgically from 1985 to 2003 with a mean follow-up, via questionnaire, of 1.2 years. This is the largest series published thus far of patients with pathologically confirmed ORS. It reported premenopausal levels of FSH and estradiol in 69% and 63% of patients, respectively, who had preoperative hormonal evaluations.1

In another retrospective cohort study published in 2011 of 30 women – also with pathologically confirmed ovarian remnants – Deborah Arden, MD, and Ted Lee, MD, of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center reported premenopausal levels of FSH and estradiol in 59% and 71%, respectively, of women whose concentrations were measured.2

ORS often involves a pelvic mass, and preoperative imaging is important in this regard. In Dr. Magtibay’s series, a pelvic mass was identified in 93%, 92%, and 78% of those who were imaged presurgically with ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging, respectively.1 As with laboratory testing, however, a negative result does not rule out the presence of an ovarian remnant.

Some authors have advocated the use of clomiphene citrate stimulation before preoperative imaging – or before repeat imaging – to identify remnant ovarian tissue. Typically, clomiphene citrate 100 mg is administered for 10 days prior to imaging to potentially induce ovulation in patients with suspected ORS. Alternatively, at the Advanced Gynecologic Surgery Institute in Naperville and Park Ridge, Ill., ovarian stimulation is performed using FSH 300 IUs for 5 days. A finding of cystic structures consistent with ovarian follicles will help narrow the diagnosis.

Use of gonadotropins is superior in that an intact pituitary-ovarian axis is not required. Moreover, monitoring can be in real time; increasing estradiol levels and increasing mass size on ultrasound can be monitored as gonadotropin treatment is rendered. Again, however, negative findings should not necessarily rule out ORS. Unfortunately, there have been no clinical studies looking at the use of controlled ovarian stimulation as a definitive test.

The differential diagnosis includes supernumerary ovary (a rare gynecologic congenital anomaly) and residual ovary syndrome (a condition in which an ovary is intentionally or unintentionally left in place during a hysterectomy, as well as often an intended bilateral oophorectomy, and later causes pain). The latter occurs when surgical anatomy is poor and the surgery is consequently very difficult.

Surgical principles and approach

Previously, laparotomy was believed to be the best approach for minimizing intraoperative complications and achieving the extensive dissections necessary for effective treatment of ORS. In recent years, conventional laparoscopy and robot-assisted laparoscopy have been shown in retrospective reviews such as that by Arden et al.2 and a 2007 review by Rosanne M. Kho, MD,3 to be just as safe and effective provided that the same surgical principles – extensive retroperitoneal dissections and ureterolysis – are applied.

Good outcomes can be achieved with less blood loss, shorter operating room time, and less time in the hospital. The better visualization with greater magnification afforded by a minimally invasive approach offers a distinct advantage for such complex dissections.

A remnant of ovarian tissue can be located anywhere along the pelvic sidewall, which makes the surgical protocol largely individualized and based on the suspected location of the remnant.

Still, there are certain standard components of any surgical approach to ORS: The retroperitoneum should be entered at the level of the pelvic brim and the ureter must be clearly identified; usually, a partial or complete ureterolysis is necessary. Then, a window into the broad ligament inferior to the infundibulopelvic (IP) ligament is created, or the peritoneum of the broad ligament is removed, in order to completely isolate both the IP ligament and the ureter.

Once the ovarian remnant is isolated, a wide excision at least 2 cm from all ovarian tissue is performed. This wide surgical clearance is critical to prevent recurrence.

These standard components form the crux of the most basic and straightforward surgery for ORS. In some cases, more extensive dissections such as a cystectomy or even a bowel resection might be necessary. Ligation of the IP ligament as high because its connection to the aortic bifurcation also may be necessary – depending, again, on the location of the ovarian remnant.

The risk of intraoperative injury to the bowel, bladder, and ureters is not insignificant, but with careful planning and the involvement of other surgeons in the most complex cases, these risks can be minimized.

For patients who have a significant surgical history and do not want more surgery, pharmacologic therapy, such as leuprolide (Lupron) or danazol, is an option for ORS. It’s important to note, however, that no studies have been done to demonstrate that medical therapy is a curative option. In addition, one must consider the small risk that remnants may harbor or develop malignancy.

Malignancy has been reported in ovarian remnant tissue. While the risk is believed to be very small, 2 of the 20 patients in Dr. Kho’s cohort had malignancy in remnant tissue,3 and it is generally recommended that surgeons send frozen sections of suspected ovarian tissue to pathology. Frozen-section diagnosis of ovarian tissue is about 95% accurate.

Preventing ovarian remnants

Oophorectomy is a common procedure performed by gynecologic surgeons. While routine, it is imperative that it be performed correctly to prevent ovarian remnants from occurring. When performing a laparoscopic or robot-assisted laparoscopic oophorectomy, it is important to optimize visualization of the ovary and the IP ligament, and to account for the significant magnification provided by laparoscopic cameras.

Surgeons must make sure all adhesions are completely cleared in order to optimally transect the IP ligament. Furthermore, wide excision around ovarian tissue is critical. Accessory ovarian tissue has been found up to 1.4 cm away from the ovary itself, which is why we recommend that surgeons excise at least 2-3 cm away from the IP in order to safely ensure complete removal of ovarian tissue.

Dr. Kooperman completed the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL) Fellowship Program in Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill., and will be starting practice at the Highland Park (Ill.) North Shore Hospital System in August 2019. He reported no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(6):2062-6.

2. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(2):194-9.

3. Fertil Steril. 2007;87(5):1005-9.

Ovarian remnant syndrome (ORS) is an uncommon problem, but one that seems to be increasing in incidence and one that is important to diagnose and treat properly, as well as prevent. Retrospective cohort studies published in the past 15 years or so have improved our understanding of its presentation and the outcomes of surgical management – and recent literature has demonstrated that a minimally invasive surgical approach with either conventional laparoscopy or robot-assisted laparoscopy yields improved outcomes in a skilled surgeon’s hands.

Diagnosis is based on clinical history and should be further supported with imaging and laboratory evaluation. A definitive diagnosis of the disease comes through surgical intervention and pathological findings.

Surgery therefore is technically challenging, usually requiring complete ureterolysis, careful adhesiolysis (often enterolysis), and excision of much of the pelvic sidewall peritoneum with extirpation of the remnant and endometriosis. High ligation of the ovarian vasculature also often is required.

This complexity and the consequent risk of intraoperative injury to the bowel, bladder, and ureters requires careful preoperative preparation. When an ovarian remnant is suspected, it may be important to have other surgeons – such as gynecologic oncologists, urologists, colorectal surgeons, or general surgeons – either present or on standby during the surgical intervention. In expert hands, surgical intervention has been shown to resolve or improve pain in the majority of patients, with no recurrence of the syndrome.

Diagnosis of ORS

Courtesy Dr. Charles E. Miller and Dr. Kirsten J. Sasaki

Patients with ORS have had previous oophorectomies with incomplete removal of ovarian tissue. Pelvic pain, either cyclical or most commonly chronic, is a common symptom. Other symptoms can include dyspareunia, dysuria and other urinary symptoms, and bowel symptoms. Ovarian remnants may have an expanding cystic structure – oftentimes secondary to endometriosis – that causes mass-like effects leading to pain and inflammation and to symptoms such as low back pain, constipation, and even urinary retention.

It also is important to discuss the patient’s history of menopausal symptoms, because the absence of these symptoms after oophorectomy may be a sign that ovarian tissue has been left behind. Menopausal symptoms do not exclude the diagnosis, however. Endometriosis, extensive surgical history, and other diseases that lead to significant adhesion formation – and a higher risk of incomplete removal of ovarian tissue, theoretically – also should be explored during history-taking.

Laboratory assessment of serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and estradiol can be helpful. Values that are indicative of ovarian function – FSH less than 30 mIU/mL and estradiol greater than 35 pg/mL – point towards ORS, but the absence of such premenopausal values should not rule out the possibility of an ovarian remnant.

The literature shows that FSH and estradiol levels are variable in women with ORS. A retrospective review published in 2005 by Paul M. Magtibay, MD, and colleagues at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., and Rochester, Minn., involved 186 patients treated surgically from 1985 to 2003 with a mean follow-up, via questionnaire, of 1.2 years. This is the largest series published thus far of patients with pathologically confirmed ORS. It reported premenopausal levels of FSH and estradiol in 69% and 63% of patients, respectively, who had preoperative hormonal evaluations.1

In another retrospective cohort study published in 2011 of 30 women – also with pathologically confirmed ovarian remnants – Deborah Arden, MD, and Ted Lee, MD, of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center reported premenopausal levels of FSH and estradiol in 59% and 71%, respectively, of women whose concentrations were measured.2

ORS often involves a pelvic mass, and preoperative imaging is important in this regard. In Dr. Magtibay’s series, a pelvic mass was identified in 93%, 92%, and 78% of those who were imaged presurgically with ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging, respectively.1 As with laboratory testing, however, a negative result does not rule out the presence of an ovarian remnant.

Some authors have advocated the use of clomiphene citrate stimulation before preoperative imaging – or before repeat imaging – to identify remnant ovarian tissue. Typically, clomiphene citrate 100 mg is administered for 10 days prior to imaging to potentially induce ovulation in patients with suspected ORS. Alternatively, at the Advanced Gynecologic Surgery Institute in Naperville and Park Ridge, Ill., ovarian stimulation is performed using FSH 300 IUs for 5 days. A finding of cystic structures consistent with ovarian follicles will help narrow the diagnosis.

Use of gonadotropins is superior in that an intact pituitary-ovarian axis is not required. Moreover, monitoring can be in real time; increasing estradiol levels and increasing mass size on ultrasound can be monitored as gonadotropin treatment is rendered. Again, however, negative findings should not necessarily rule out ORS. Unfortunately, there have been no clinical studies looking at the use of controlled ovarian stimulation as a definitive test.

The differential diagnosis includes supernumerary ovary (a rare gynecologic congenital anomaly) and residual ovary syndrome (a condition in which an ovary is intentionally or unintentionally left in place during a hysterectomy, as well as often an intended bilateral oophorectomy, and later causes pain). The latter occurs when surgical anatomy is poor and the surgery is consequently very difficult.

Surgical principles and approach

Previously, laparotomy was believed to be the best approach for minimizing intraoperative complications and achieving the extensive dissections necessary for effective treatment of ORS. In recent years, conventional laparoscopy and robot-assisted laparoscopy have been shown in retrospective reviews such as that by Arden et al.2 and a 2007 review by Rosanne M. Kho, MD,3 to be just as safe and effective provided that the same surgical principles – extensive retroperitoneal dissections and ureterolysis – are applied.

Good outcomes can be achieved with less blood loss, shorter operating room time, and less time in the hospital. The better visualization with greater magnification afforded by a minimally invasive approach offers a distinct advantage for such complex dissections.

A remnant of ovarian tissue can be located anywhere along the pelvic sidewall, which makes the surgical protocol largely individualized and based on the suspected location of the remnant.

Still, there are certain standard components of any surgical approach to ORS: The retroperitoneum should be entered at the level of the pelvic brim and the ureter must be clearly identified; usually, a partial or complete ureterolysis is necessary. Then, a window into the broad ligament inferior to the infundibulopelvic (IP) ligament is created, or the peritoneum of the broad ligament is removed, in order to completely isolate both the IP ligament and the ureter.

Once the ovarian remnant is isolated, a wide excision at least 2 cm from all ovarian tissue is performed. This wide surgical clearance is critical to prevent recurrence.

These standard components form the crux of the most basic and straightforward surgery for ORS. In some cases, more extensive dissections such as a cystectomy or even a bowel resection might be necessary. Ligation of the IP ligament as high because its connection to the aortic bifurcation also may be necessary – depending, again, on the location of the ovarian remnant.

The risk of intraoperative injury to the bowel, bladder, and ureters is not insignificant, but with careful planning and the involvement of other surgeons in the most complex cases, these risks can be minimized.

For patients who have a significant surgical history and do not want more surgery, pharmacologic therapy, such as leuprolide (Lupron) or danazol, is an option for ORS. It’s important to note, however, that no studies have been done to demonstrate that medical therapy is a curative option. In addition, one must consider the small risk that remnants may harbor or develop malignancy.

Malignancy has been reported in ovarian remnant tissue. While the risk is believed to be very small, 2 of the 20 patients in Dr. Kho’s cohort had malignancy in remnant tissue,3 and it is generally recommended that surgeons send frozen sections of suspected ovarian tissue to pathology. Frozen-section diagnosis of ovarian tissue is about 95% accurate.

Preventing ovarian remnants

Oophorectomy is a common procedure performed by gynecologic surgeons. While routine, it is imperative that it be performed correctly to prevent ovarian remnants from occurring. When performing a laparoscopic or robot-assisted laparoscopic oophorectomy, it is important to optimize visualization of the ovary and the IP ligament, and to account for the significant magnification provided by laparoscopic cameras.

Surgeons must make sure all adhesions are completely cleared in order to optimally transect the IP ligament. Furthermore, wide excision around ovarian tissue is critical. Accessory ovarian tissue has been found up to 1.4 cm away from the ovary itself, which is why we recommend that surgeons excise at least 2-3 cm away from the IP in order to safely ensure complete removal of ovarian tissue.

Dr. Kooperman completed the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL) Fellowship Program in Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill., and will be starting practice at the Highland Park (Ill.) North Shore Hospital System in August 2019. He reported no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(6):2062-6.

2. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(2):194-9.

3. Fertil Steril. 2007;87(5):1005-9.

Ovarian remnant syndrome (ORS) is an uncommon problem, but one that seems to be increasing in incidence and one that is important to diagnose and treat properly, as well as prevent. Retrospective cohort studies published in the past 15 years or so have improved our understanding of its presentation and the outcomes of surgical management – and recent literature has demonstrated that a minimally invasive surgical approach with either conventional laparoscopy or robot-assisted laparoscopy yields improved outcomes in a skilled surgeon’s hands.

Diagnosis is based on clinical history and should be further supported with imaging and laboratory evaluation. A definitive diagnosis of the disease comes through surgical intervention and pathological findings.

Surgery therefore is technically challenging, usually requiring complete ureterolysis, careful adhesiolysis (often enterolysis), and excision of much of the pelvic sidewall peritoneum with extirpation of the remnant and endometriosis. High ligation of the ovarian vasculature also often is required.

This complexity and the consequent risk of intraoperative injury to the bowel, bladder, and ureters requires careful preoperative preparation. When an ovarian remnant is suspected, it may be important to have other surgeons – such as gynecologic oncologists, urologists, colorectal surgeons, or general surgeons – either present or on standby during the surgical intervention. In expert hands, surgical intervention has been shown to resolve or improve pain in the majority of patients, with no recurrence of the syndrome.

Diagnosis of ORS

Courtesy Dr. Charles E. Miller and Dr. Kirsten J. Sasaki

Patients with ORS have had previous oophorectomies with incomplete removal of ovarian tissue. Pelvic pain, either cyclical or most commonly chronic, is a common symptom. Other symptoms can include dyspareunia, dysuria and other urinary symptoms, and bowel symptoms. Ovarian remnants may have an expanding cystic structure – oftentimes secondary to endometriosis – that causes mass-like effects leading to pain and inflammation and to symptoms such as low back pain, constipation, and even urinary retention.

It also is important to discuss the patient’s history of menopausal symptoms, because the absence of these symptoms after oophorectomy may be a sign that ovarian tissue has been left behind. Menopausal symptoms do not exclude the diagnosis, however. Endometriosis, extensive surgical history, and other diseases that lead to significant adhesion formation – and a higher risk of incomplete removal of ovarian tissue, theoretically – also should be explored during history-taking.

Laboratory assessment of serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and estradiol can be helpful. Values that are indicative of ovarian function – FSH less than 30 mIU/mL and estradiol greater than 35 pg/mL – point towards ORS, but the absence of such premenopausal values should not rule out the possibility of an ovarian remnant.

The literature shows that FSH and estradiol levels are variable in women with ORS. A retrospective review published in 2005 by Paul M. Magtibay, MD, and colleagues at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., and Rochester, Minn., involved 186 patients treated surgically from 1985 to 2003 with a mean follow-up, via questionnaire, of 1.2 years. This is the largest series published thus far of patients with pathologically confirmed ORS. It reported premenopausal levels of FSH and estradiol in 69% and 63% of patients, respectively, who had preoperative hormonal evaluations.1

In another retrospective cohort study published in 2011 of 30 women – also with pathologically confirmed ovarian remnants – Deborah Arden, MD, and Ted Lee, MD, of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center reported premenopausal levels of FSH and estradiol in 59% and 71%, respectively, of women whose concentrations were measured.2

ORS often involves a pelvic mass, and preoperative imaging is important in this regard. In Dr. Magtibay’s series, a pelvic mass was identified in 93%, 92%, and 78% of those who were imaged presurgically with ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging, respectively.1 As with laboratory testing, however, a negative result does not rule out the presence of an ovarian remnant.

Some authors have advocated the use of clomiphene citrate stimulation before preoperative imaging – or before repeat imaging – to identify remnant ovarian tissue. Typically, clomiphene citrate 100 mg is administered for 10 days prior to imaging to potentially induce ovulation in patients with suspected ORS. Alternatively, at the Advanced Gynecologic Surgery Institute in Naperville and Park Ridge, Ill., ovarian stimulation is performed using FSH 300 IUs for 5 days. A finding of cystic structures consistent with ovarian follicles will help narrow the diagnosis.

Use of gonadotropins is superior in that an intact pituitary-ovarian axis is not required. Moreover, monitoring can be in real time; increasing estradiol levels and increasing mass size on ultrasound can be monitored as gonadotropin treatment is rendered. Again, however, negative findings should not necessarily rule out ORS. Unfortunately, there have been no clinical studies looking at the use of controlled ovarian stimulation as a definitive test.

The differential diagnosis includes supernumerary ovary (a rare gynecologic congenital anomaly) and residual ovary syndrome (a condition in which an ovary is intentionally or unintentionally left in place during a hysterectomy, as well as often an intended bilateral oophorectomy, and later causes pain). The latter occurs when surgical anatomy is poor and the surgery is consequently very difficult.

Surgical principles and approach

Previously, laparotomy was believed to be the best approach for minimizing intraoperative complications and achieving the extensive dissections necessary for effective treatment of ORS. In recent years, conventional laparoscopy and robot-assisted laparoscopy have been shown in retrospective reviews such as that by Arden et al.2 and a 2007 review by Rosanne M. Kho, MD,3 to be just as safe and effective provided that the same surgical principles – extensive retroperitoneal dissections and ureterolysis – are applied.

Good outcomes can be achieved with less blood loss, shorter operating room time, and less time in the hospital. The better visualization with greater magnification afforded by a minimally invasive approach offers a distinct advantage for such complex dissections.

A remnant of ovarian tissue can be located anywhere along the pelvic sidewall, which makes the surgical protocol largely individualized and based on the suspected location of the remnant.

Still, there are certain standard components of any surgical approach to ORS: The retroperitoneum should be entered at the level of the pelvic brim and the ureter must be clearly identified; usually, a partial or complete ureterolysis is necessary. Then, a window into the broad ligament inferior to the infundibulopelvic (IP) ligament is created, or the peritoneum of the broad ligament is removed, in order to completely isolate both the IP ligament and the ureter.

Once the ovarian remnant is isolated, a wide excision at least 2 cm from all ovarian tissue is performed. This wide surgical clearance is critical to prevent recurrence.

These standard components form the crux of the most basic and straightforward surgery for ORS. In some cases, more extensive dissections such as a cystectomy or even a bowel resection might be necessary. Ligation of the IP ligament as high because its connection to the aortic bifurcation also may be necessary – depending, again, on the location of the ovarian remnant.

The risk of intraoperative injury to the bowel, bladder, and ureters is not insignificant, but with careful planning and the involvement of other surgeons in the most complex cases, these risks can be minimized.

For patients who have a significant surgical history and do not want more surgery, pharmacologic therapy, such as leuprolide (Lupron) or danazol, is an option for ORS. It’s important to note, however, that no studies have been done to demonstrate that medical therapy is a curative option. In addition, one must consider the small risk that remnants may harbor or develop malignancy.

Malignancy has been reported in ovarian remnant tissue. While the risk is believed to be very small, 2 of the 20 patients in Dr. Kho’s cohort had malignancy in remnant tissue,3 and it is generally recommended that surgeons send frozen sections of suspected ovarian tissue to pathology. Frozen-section diagnosis of ovarian tissue is about 95% accurate.

Preventing ovarian remnants

Oophorectomy is a common procedure performed by gynecologic surgeons. While routine, it is imperative that it be performed correctly to prevent ovarian remnants from occurring. When performing a laparoscopic or robot-assisted laparoscopic oophorectomy, it is important to optimize visualization of the ovary and the IP ligament, and to account for the significant magnification provided by laparoscopic cameras.

Surgeons must make sure all adhesions are completely cleared in order to optimally transect the IP ligament. Furthermore, wide excision around ovarian tissue is critical. Accessory ovarian tissue has been found up to 1.4 cm away from the ovary itself, which is why we recommend that surgeons excise at least 2-3 cm away from the IP in order to safely ensure complete removal of ovarian tissue.

Dr. Kooperman completed the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL) Fellowship Program in Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill., and will be starting practice at the Highland Park (Ill.) North Shore Hospital System in August 2019. He reported no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(6):2062-6.

2. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(2):194-9.

3. Fertil Steril. 2007;87(5):1005-9.

The ovarian remnant syndrome

A 45-year old woman was referred by her physician to my clinic for continued pain after total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The patient initially had undergone a robot-assisted total laparoscopic hysterectomy, bilateral salpingectomy, and excision of stage 1 endometriosis secondary to pelvic pain. Because of continued pain and new onset of persistent ovarian cysts, she once again underwent robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery, this time to remove both ovaries. Interestingly, severe periadnexal adhesions were noted in the second surgical report. A hemorrhagic cyst and a corpus luteal cyst were noted. Unfortunately, the patient continued to have left lower abdominal pain; thus, the referral to my clinic.

Given the history of pelvic pain, especially in light of severe periadnexal adhesions at the second surgery, I voiced my concern about possible ovarian remnant syndrome. At the patient’s initial visit, an estradiol (E2), progesterone (P4) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) test were ordered. Interestingly, while the E2 and P4 were quite low, the FSH was 10.9 IU/mL. Certainly, this was not consistent with menopause but could point to ovarian remnant syndrome.

A follow-up examination and ultrasound revealed a 15-mm exquisitely tender left adnexal mass, again consistent with ovarian remnant syndrome. My plan now is to proceed with surgery with the presumptive diagnosis of ovarian remnant syndrome.

Ovarian remnant syndrome (ORS), first described by Shemwell and Weed in 1970, is defined as a pelvic mass with residual ovarian tissue postoophorectomy.1-3 ORS may be associated with endometriosis or ovarian cancer. Remnant ovarian tissue also may stimulate endometriosis and cyclic pelvic pain, similar to symptoms of the remnant itself.4

Pelvic adhesions may be secondary to previous surgery, intraoperative bleeding, previous appendectomy, inflammatory bowel disease, pelvic inflammatory disease, or endometriosis, the latter of which is the most common cause of initial oophorectomy. Moreover, surgical technique may be causal. This includes inability to achieve adequate exposure, inability to restore normal anatomy, and imprecise site of surgical incision.5-7

For this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have enlisted the assistance of Ryan S. Kooperman, DO, who recently completed his 2-year American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL) Fellowship in Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital in Park Ridge, Ill., where I am currently the program director.

In 2016, Dr. Kooperman was the recipient of the National Outstanding Resident of the Year in Obstetrics and Gynecology (American Osteopathic Foundation/Medical Education Foundation of the American College of Osteopathic Obstetricians and Gynecologists). Dr. Kooperman is a very skilled surgeon and adroit clinician. He will be starting practice at Highland Park (Ill.) North Shore Hospital System in August 2019. It is a pleasure to welcome Dr. Kooperman to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago and the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital. He has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 1970 Aug;36(2):299-303.

2. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989 Nov;29(4):433-5.

3. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Aug;24(4):210-4.

4. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1988 Feb;26(1):93-103.

5. Oncol Lett. 2014 Jul;8(1):3-6.

6. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011 Mar-Apr;18(2):194-9.

7. Fertil Steril. 2007 May;87(5):1005-9.

A 45-year old woman was referred by her physician to my clinic for continued pain after total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The patient initially had undergone a robot-assisted total laparoscopic hysterectomy, bilateral salpingectomy, and excision of stage 1 endometriosis secondary to pelvic pain. Because of continued pain and new onset of persistent ovarian cysts, she once again underwent robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery, this time to remove both ovaries. Interestingly, severe periadnexal adhesions were noted in the second surgical report. A hemorrhagic cyst and a corpus luteal cyst were noted. Unfortunately, the patient continued to have left lower abdominal pain; thus, the referral to my clinic.

Given the history of pelvic pain, especially in light of severe periadnexal adhesions at the second surgery, I voiced my concern about possible ovarian remnant syndrome. At the patient’s initial visit, an estradiol (E2), progesterone (P4) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) test were ordered. Interestingly, while the E2 and P4 were quite low, the FSH was 10.9 IU/mL. Certainly, this was not consistent with menopause but could point to ovarian remnant syndrome.

A follow-up examination and ultrasound revealed a 15-mm exquisitely tender left adnexal mass, again consistent with ovarian remnant syndrome. My plan now is to proceed with surgery with the presumptive diagnosis of ovarian remnant syndrome.

Ovarian remnant syndrome (ORS), first described by Shemwell and Weed in 1970, is defined as a pelvic mass with residual ovarian tissue postoophorectomy.1-3 ORS may be associated with endometriosis or ovarian cancer. Remnant ovarian tissue also may stimulate endometriosis and cyclic pelvic pain, similar to symptoms of the remnant itself.4

Pelvic adhesions may be secondary to previous surgery, intraoperative bleeding, previous appendectomy, inflammatory bowel disease, pelvic inflammatory disease, or endometriosis, the latter of which is the most common cause of initial oophorectomy. Moreover, surgical technique may be causal. This includes inability to achieve adequate exposure, inability to restore normal anatomy, and imprecise site of surgical incision.5-7

For this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have enlisted the assistance of Ryan S. Kooperman, DO, who recently completed his 2-year American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL) Fellowship in Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital in Park Ridge, Ill., where I am currently the program director.

In 2016, Dr. Kooperman was the recipient of the National Outstanding Resident of the Year in Obstetrics and Gynecology (American Osteopathic Foundation/Medical Education Foundation of the American College of Osteopathic Obstetricians and Gynecologists). Dr. Kooperman is a very skilled surgeon and adroit clinician. He will be starting practice at Highland Park (Ill.) North Shore Hospital System in August 2019. It is a pleasure to welcome Dr. Kooperman to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago and the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital. He has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 1970 Aug;36(2):299-303.

2. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989 Nov;29(4):433-5.

3. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Aug;24(4):210-4.

4. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1988 Feb;26(1):93-103.

5. Oncol Lett. 2014 Jul;8(1):3-6.

6. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011 Mar-Apr;18(2):194-9.

7. Fertil Steril. 2007 May;87(5):1005-9.

A 45-year old woman was referred by her physician to my clinic for continued pain after total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The patient initially had undergone a robot-assisted total laparoscopic hysterectomy, bilateral salpingectomy, and excision of stage 1 endometriosis secondary to pelvic pain. Because of continued pain and new onset of persistent ovarian cysts, she once again underwent robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery, this time to remove both ovaries. Interestingly, severe periadnexal adhesions were noted in the second surgical report. A hemorrhagic cyst and a corpus luteal cyst were noted. Unfortunately, the patient continued to have left lower abdominal pain; thus, the referral to my clinic.

Given the history of pelvic pain, especially in light of severe periadnexal adhesions at the second surgery, I voiced my concern about possible ovarian remnant syndrome. At the patient’s initial visit, an estradiol (E2), progesterone (P4) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) test were ordered. Interestingly, while the E2 and P4 were quite low, the FSH was 10.9 IU/mL. Certainly, this was not consistent with menopause but could point to ovarian remnant syndrome.

A follow-up examination and ultrasound revealed a 15-mm exquisitely tender left adnexal mass, again consistent with ovarian remnant syndrome. My plan now is to proceed with surgery with the presumptive diagnosis of ovarian remnant syndrome.

Ovarian remnant syndrome (ORS), first described by Shemwell and Weed in 1970, is defined as a pelvic mass with residual ovarian tissue postoophorectomy.1-3 ORS may be associated with endometriosis or ovarian cancer. Remnant ovarian tissue also may stimulate endometriosis and cyclic pelvic pain, similar to symptoms of the remnant itself.4

Pelvic adhesions may be secondary to previous surgery, intraoperative bleeding, previous appendectomy, inflammatory bowel disease, pelvic inflammatory disease, or endometriosis, the latter of which is the most common cause of initial oophorectomy. Moreover, surgical technique may be causal. This includes inability to achieve adequate exposure, inability to restore normal anatomy, and imprecise site of surgical incision.5-7

For this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have enlisted the assistance of Ryan S. Kooperman, DO, who recently completed his 2-year American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL) Fellowship in Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital in Park Ridge, Ill., where I am currently the program director.

In 2016, Dr. Kooperman was the recipient of the National Outstanding Resident of the Year in Obstetrics and Gynecology (American Osteopathic Foundation/Medical Education Foundation of the American College of Osteopathic Obstetricians and Gynecologists). Dr. Kooperman is a very skilled surgeon and adroit clinician. He will be starting practice at Highland Park (Ill.) North Shore Hospital System in August 2019. It is a pleasure to welcome Dr. Kooperman to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago and the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital. He has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 1970 Aug;36(2):299-303.

2. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989 Nov;29(4):433-5.

3. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Aug;24(4):210-4.

4. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1988 Feb;26(1):93-103.

5. Oncol Lett. 2014 Jul;8(1):3-6.

6. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011 Mar-Apr;18(2):194-9.

7. Fertil Steril. 2007 May;87(5):1005-9.

Migrant children need safety net

ACEs tied to traumas threaten the emotional, physical health of a generation

An 11-year-old was caring for his toddler brother. Both were fending for themselves in a cell with dozens of other children. The little one was quiet with matted hair, a hacking cough, muddy pants, and eyes that fluttered with fatigue.

As the two brothers were reportedly interviewed, one fell asleep on two office chairs drawn together, probably the most comfortable bed he had used in weeks. They had been separated from an 18-year-old uncle and sent to the Clint Border Patrol Station in Texas. When they were interviewed in the news report, they had been there 3 weeks and counting.

Per news reports this summer, preteen migrant children have been asked to care for toddlers not related to them with no assistance from adults, and no beds, no food, and no change of clothing. Children were sleeping on concrete floors and eating the same unpalatable and unhealthy foods for close to a month: instant oatmeal, instant soup, and previously frozen burritos. Babies were roaming around in dirty diapers, fending for themselves, foraging for food. Two- and 3-year-old toddlers were sick with no adult comforting them.

When some people visited the border patrol station, they said they saw children trapped in cages like animals. Some were keening in pain while pining for their parents from whom they had been separated.

These children were forcibly separated from parents. In addition, they face living conditions that include hunger, dehydration, and lack of hygiene, to name a few. This sounds like some fantastical nightmare from a war-torn third-world country – but no these circumstances are real, and they are here in the USA.

We witness helplessly the helplessness created by a man-made disaster striking the world’s most vulnerable creature: the human child. This specter afflicting thousands of migrant children either seeking asylum or an immigrant status has far-reaching implications. This is even more ironic, given that, as a nation, we have embraced the concept of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and their impact on lifelong health challenges. Most of us reel with horror as these tales make their way to national headlines. But are we as a nation complicit in watching like bystanders while a generation of children is placed at risk from experiencing the long-term effects of ACEs on their physical and emotional health?

Surely if the psychological implications of ACEs do not warrant a change in course, the mere economics of the costs arising from the suffering caused by totally preventable medical problems in adulthood should be considered in policy decisions. However, that is beyond the scope of this commentary.

The human child is so utterly dependent on parents. He does not have the fairly quick physical independence from parents that we see in the animal kingdom. As soon as a child is born, a curious process of attachment begins within the mom and baby dyad, and eventually, this bond engulfs the father as well. The baby depends on the parent to understand his needs: be it when to eat, when he wants to be touched, when he needs to be left alone, when he needs to be cleaned or fed. Optimum crying serves so many purposes, and most parents are exquisitely attuned to the baby’s cry. From this relationship emerges a stable worldview, and, among many things, a stable neuroendocrine system.

Unique cultural backgrounds of individuals create the scaffolding for human variability, which in turn, confers a richness to the human race. However, development proceeds in a fairly uniform and universal fashion for children, regardless of where they come from. The progression of brain and body development moves lockstep with each other responding to a complex interplay between genetics, environment, and neurohormonal factors. It is remarkable just how resilient the human baby is in the face of the challenges that it often faces: accidental injury, illness, and even benign neglect.

However, there comes a breaking point similar to that described in the stories above, where the stress is toxic and intolerable. It is continuous, and it is relentless in its capacity to bathe the developing brain and body of the child with noxious endogenous substances that cause cell death and subsequent atrophy that is potentially irreversible.

We see such children in our clinics downstream: at ages 8, 13, or 16, after they have lost their ability to modulate emotions and are highly aggressive, or are withdrawn and depressed – or in the juvenile justice system after having repeatedly but impulsively violated the law. In other words, repeated trauma changes the wiring of the brain and neuromodulatory capacity. There is literature suggesting that traumatized children carry within them modified genes that affect their capacity to be nurturing parents. In other words, trauma has the potential to lead to multigenerational transmission of the experiences of suffering and often a psychological incapacity to parent – putting subsequent generations at risk.

So what should we do? Be bystanders, or become involved professionals?

The need to create a supportive safety net for these children is essential. Ideally, they should be reunited with their parents. The reunification of children with their parents is an absolute must if it can be done. Their parents are alive somewhere – and the best mitigators of the emotional damage already done. A strong case needs to be made for reunification, otherwise parental separation, deprivation on multiple levels, such as what these children are experiencing, will create a generation of compromised children.

A second-best option is that an emotional and physical safety net should be created that mimics a family for each child. Children need predictability and stability of caregivers with whom they can form an affective bond. This is essential for them to negotiate the cycle of inconsolable weeping, searching for their parent/s, reconciling the loss, and either reaching a level of adaptation or being engulfed in the despair that these toddlers, children, and teens continually face. In addition, these individuals/teams first and foremost should plan on giving equal consideration to the physical and emotional needs of the children.