User login

Giving Cash to Improve Health

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It doesn’t really matter what disease you are looking at — cancer, heart disease, dementia, drug abuse, psychiatric disorders. In every case, poverty is associated with worse disease.

But the word “associated” is doing a lot of work there. Many of us feel that poverty itself is causally linked to worse disease outcomes through things like poor access to care and poor access to medicines.

And there is an argument that the arrow goes the other way; perhaps people with worse illness are more likely to be poor because, in this country at least, being sick is incredibly expensive.

Causality is what all medical research is fundamentally about. We want to know if A causes B, because if A causes B, then changing A changes B. If poverty causes bad health outcomes, then alleviating poverty should alleviate bad health outcomes.

But that’s a hard proposition to test. You can’t exactly randomize some people to get extra money and some not to, right? Actually, you can. And in Massachusetts, they did.

What happened in Chelsea, Massachusetts, wasn’t exactly a randomized trial of cash supplementation to avoid bad health outcomes. It was actually a government program instituted during the pandemic. Chelsea has a large immigrant population, many of whom are living in poverty. From April to August 2020, the city ran a food distribution program to aid those in need. But the decision was then made to convert the money spent on that program to cash distributions — free of obligations. Chelsea residents making less than 30% of the median income for the Boston metro area — around $30,000 per family — were invited to enter a lottery. Only one member of any given family could enter. If selected, an individual would receive $200 a month, or $300 for a family of two, or $400 for a family of three or more. These payments went on for about 9 months.

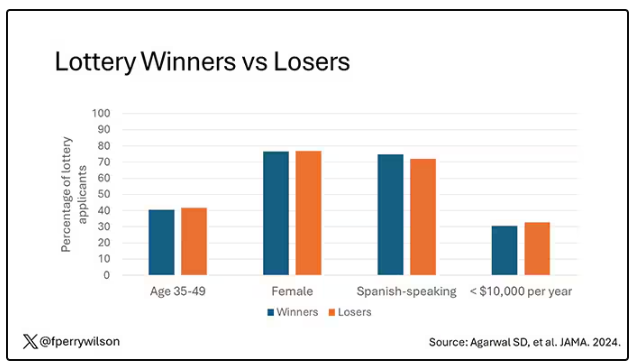

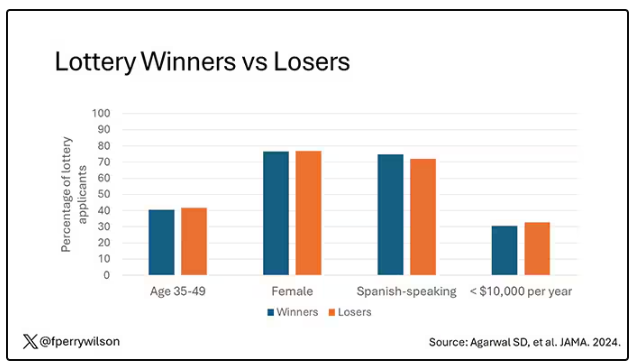

The key thing here is that not everyone won the lottery. The lottery picked winners randomly; 1746 individuals were selected to receive the benefits in the form of a reloadable gift card, and 1134 applied but did not receive any assistance.

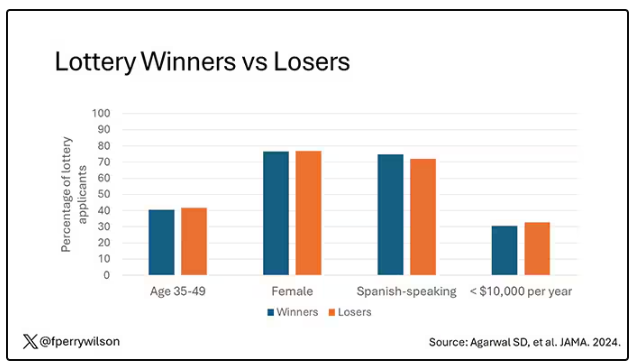

This is a perfect natural experiment. As you can see here — and as expected, given that the lottery winners were chosen randomly — winners and losers were similar in terms of age, sex, race, language, income, and more.

Researchers, led by Sumit Agarwal at the Brigham, leveraged that randomization to ask how these cash benefits would affect healthcare utilization. Their results appeared this week in JAMA.

I know what you’re thinking: Is $400 a month really enough to make a difference? Does $400 a month, less than $5000 a year, really fix poverty? We’ll get to that. But I will point out that the average family income of individuals in this study was about $1400 a month. An extra $400 might not change someone’s life, but it may really make a difference.

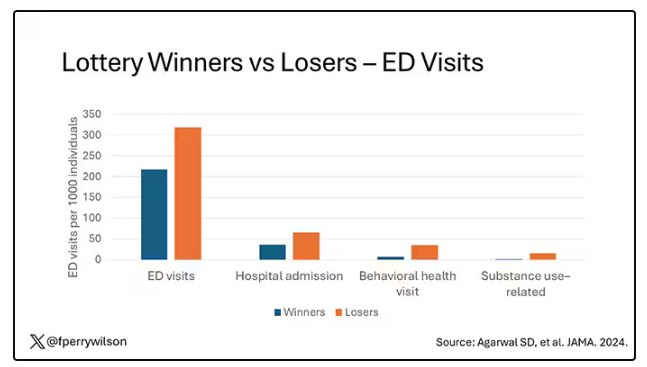

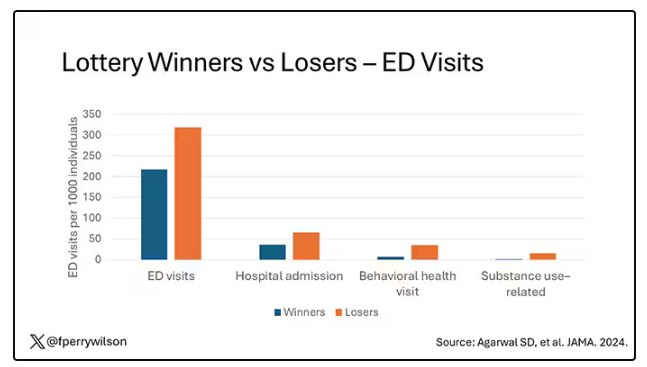

The primary outcome of this study was ED visits. There are a few ways this could go. Perhaps the money would lead to improved health and thus fewer ED visits. Or perhaps it would help people get transportation to primary care or other services that would offload the ED. Or maybe it would make things worse. Some folks have suggested that cash payments could increase the use of drugs and alcohol, and lead to more ED visits associated with the complications of using those substances.

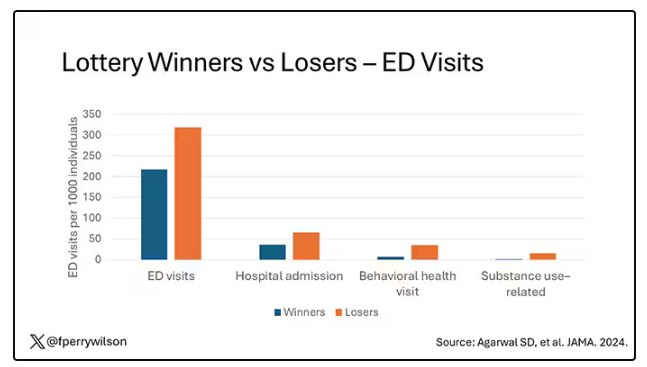

Here are the actual data. Per 1000 individuals, there were 217 ED visits in the cash-benefit group, 318 in the no-benefit group. That was a statistically significant finding.

Breaking those ED visits down, you can see that fewer visits resulted in hospital admission, with fewer behavioral health–related visits and — a key finding — fewer visits for substance use disorder. This puts the lie to the idea that cash benefits increase drug use.

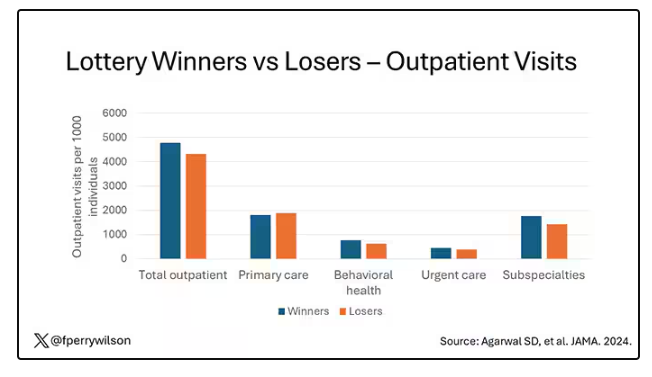

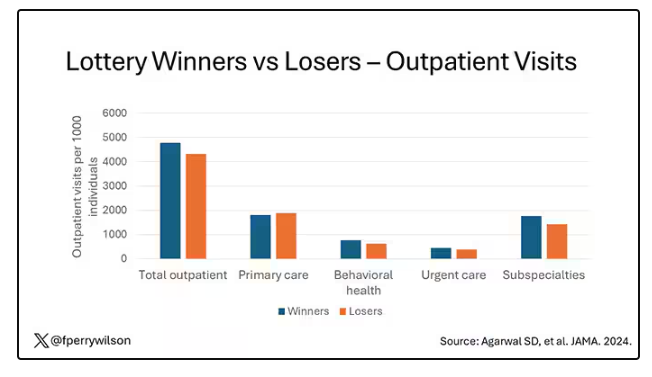

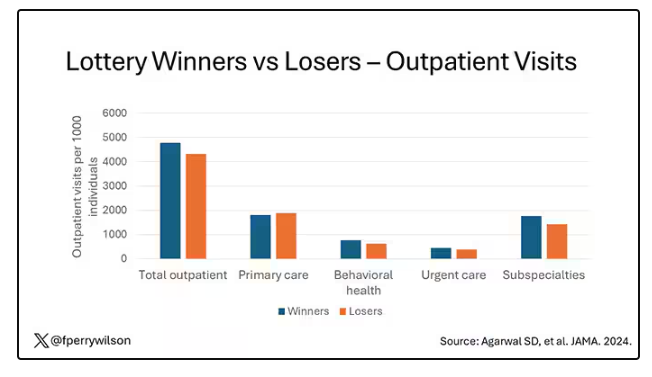

But the authors also looked at other causes of healthcare utilization. Outpatient visits were slightly higher in the cash-benefit group, driven largely by an increase in specialty care visits. The authors note that this is likely due to the fact that reaching a specialist often requires more travel, which can be costly. Indeed, this effect was most pronounced among the people living furthest from a specialty center.

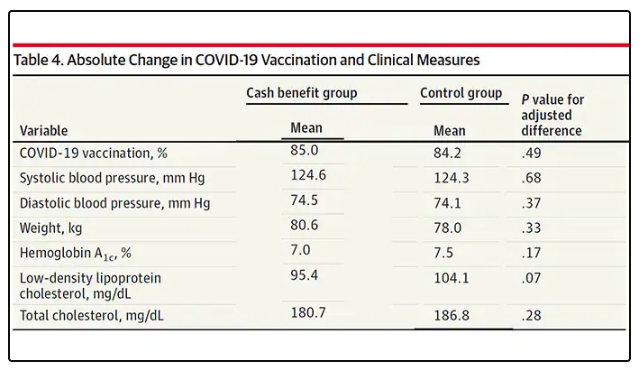

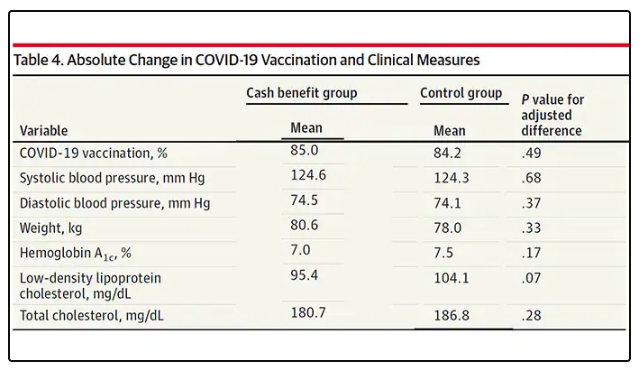

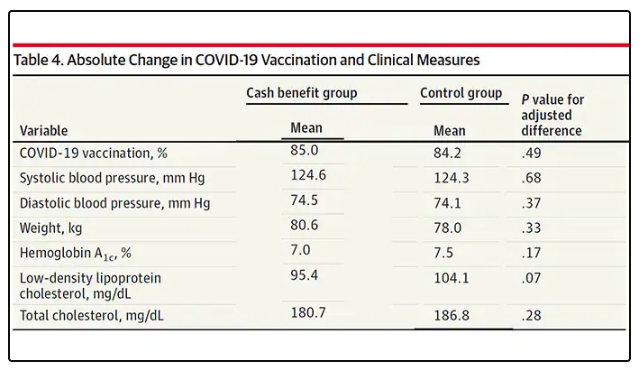

Outside of utilization, the researchers examined a variety of individual health markers — things like blood pressure — to see if the cash benefit had any effect. A bit of caution here because these data were available only among those who interacted with the healthcare system, which may bias the results a bit. Regardless, no major differences were seen in blood pressure, weight, hemoglobin A1c, cholesterol, or COVID vaccination.

So, it seems that $400 a month doesn’t move the needle too much on risk factors for cardiovascular disease, but the effect on ED visits on their own is fairly impressive.

Is it worth it? The authors did their best to calculate the net effect of this program, accounting for the reduced ED visits and hospitalizations (that’s a big one), but also for the increased number of specialty visits. All told, the program saves about $450 per person in healthcare costs over 9 months. That’s about one seventh of the cost of the overall program.

But remember that they only looked at outcomes for the individual who got the gift cards; it’s likely that there were benefits to their family members as well. And, of course, programs like this can recoup costs indirectly though increases in economic activity, a phenomenon known as the multiplier effect.

I’m not here to tell you whether this program was a good idea; people tend to have quite strong feelings about this sort of thing. But I can tell you what it tells me about healthcare in America. It may not be surprising, but it confirms that access is far from fairly distributed.

I started this story asking about the arrow of causality between poverty and poor health. The truth is, you probably have causality in both directions.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It doesn’t really matter what disease you are looking at — cancer, heart disease, dementia, drug abuse, psychiatric disorders. In every case, poverty is associated with worse disease.

But the word “associated” is doing a lot of work there. Many of us feel that poverty itself is causally linked to worse disease outcomes through things like poor access to care and poor access to medicines.

And there is an argument that the arrow goes the other way; perhaps people with worse illness are more likely to be poor because, in this country at least, being sick is incredibly expensive.

Causality is what all medical research is fundamentally about. We want to know if A causes B, because if A causes B, then changing A changes B. If poverty causes bad health outcomes, then alleviating poverty should alleviate bad health outcomes.

But that’s a hard proposition to test. You can’t exactly randomize some people to get extra money and some not to, right? Actually, you can. And in Massachusetts, they did.

What happened in Chelsea, Massachusetts, wasn’t exactly a randomized trial of cash supplementation to avoid bad health outcomes. It was actually a government program instituted during the pandemic. Chelsea has a large immigrant population, many of whom are living in poverty. From April to August 2020, the city ran a food distribution program to aid those in need. But the decision was then made to convert the money spent on that program to cash distributions — free of obligations. Chelsea residents making less than 30% of the median income for the Boston metro area — around $30,000 per family — were invited to enter a lottery. Only one member of any given family could enter. If selected, an individual would receive $200 a month, or $300 for a family of two, or $400 for a family of three or more. These payments went on for about 9 months.

The key thing here is that not everyone won the lottery. The lottery picked winners randomly; 1746 individuals were selected to receive the benefits in the form of a reloadable gift card, and 1134 applied but did not receive any assistance.

This is a perfect natural experiment. As you can see here — and as expected, given that the lottery winners were chosen randomly — winners and losers were similar in terms of age, sex, race, language, income, and more.

Researchers, led by Sumit Agarwal at the Brigham, leveraged that randomization to ask how these cash benefits would affect healthcare utilization. Their results appeared this week in JAMA.

I know what you’re thinking: Is $400 a month really enough to make a difference? Does $400 a month, less than $5000 a year, really fix poverty? We’ll get to that. But I will point out that the average family income of individuals in this study was about $1400 a month. An extra $400 might not change someone’s life, but it may really make a difference.

The primary outcome of this study was ED visits. There are a few ways this could go. Perhaps the money would lead to improved health and thus fewer ED visits. Or perhaps it would help people get transportation to primary care or other services that would offload the ED. Or maybe it would make things worse. Some folks have suggested that cash payments could increase the use of drugs and alcohol, and lead to more ED visits associated with the complications of using those substances.

Here are the actual data. Per 1000 individuals, there were 217 ED visits in the cash-benefit group, 318 in the no-benefit group. That was a statistically significant finding.

Breaking those ED visits down, you can see that fewer visits resulted in hospital admission, with fewer behavioral health–related visits and — a key finding — fewer visits for substance use disorder. This puts the lie to the idea that cash benefits increase drug use.

But the authors also looked at other causes of healthcare utilization. Outpatient visits were slightly higher in the cash-benefit group, driven largely by an increase in specialty care visits. The authors note that this is likely due to the fact that reaching a specialist often requires more travel, which can be costly. Indeed, this effect was most pronounced among the people living furthest from a specialty center.

Outside of utilization, the researchers examined a variety of individual health markers — things like blood pressure — to see if the cash benefit had any effect. A bit of caution here because these data were available only among those who interacted with the healthcare system, which may bias the results a bit. Regardless, no major differences were seen in blood pressure, weight, hemoglobin A1c, cholesterol, or COVID vaccination.

So, it seems that $400 a month doesn’t move the needle too much on risk factors for cardiovascular disease, but the effect on ED visits on their own is fairly impressive.

Is it worth it? The authors did their best to calculate the net effect of this program, accounting for the reduced ED visits and hospitalizations (that’s a big one), but also for the increased number of specialty visits. All told, the program saves about $450 per person in healthcare costs over 9 months. That’s about one seventh of the cost of the overall program.

But remember that they only looked at outcomes for the individual who got the gift cards; it’s likely that there were benefits to their family members as well. And, of course, programs like this can recoup costs indirectly though increases in economic activity, a phenomenon known as the multiplier effect.

I’m not here to tell you whether this program was a good idea; people tend to have quite strong feelings about this sort of thing. But I can tell you what it tells me about healthcare in America. It may not be surprising, but it confirms that access is far from fairly distributed.

I started this story asking about the arrow of causality between poverty and poor health. The truth is, you probably have causality in both directions.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It doesn’t really matter what disease you are looking at — cancer, heart disease, dementia, drug abuse, psychiatric disorders. In every case, poverty is associated with worse disease.

But the word “associated” is doing a lot of work there. Many of us feel that poverty itself is causally linked to worse disease outcomes through things like poor access to care and poor access to medicines.

And there is an argument that the arrow goes the other way; perhaps people with worse illness are more likely to be poor because, in this country at least, being sick is incredibly expensive.

Causality is what all medical research is fundamentally about. We want to know if A causes B, because if A causes B, then changing A changes B. If poverty causes bad health outcomes, then alleviating poverty should alleviate bad health outcomes.

But that’s a hard proposition to test. You can’t exactly randomize some people to get extra money and some not to, right? Actually, you can. And in Massachusetts, they did.

What happened in Chelsea, Massachusetts, wasn’t exactly a randomized trial of cash supplementation to avoid bad health outcomes. It was actually a government program instituted during the pandemic. Chelsea has a large immigrant population, many of whom are living in poverty. From April to August 2020, the city ran a food distribution program to aid those in need. But the decision was then made to convert the money spent on that program to cash distributions — free of obligations. Chelsea residents making less than 30% of the median income for the Boston metro area — around $30,000 per family — were invited to enter a lottery. Only one member of any given family could enter. If selected, an individual would receive $200 a month, or $300 for a family of two, or $400 for a family of three or more. These payments went on for about 9 months.

The key thing here is that not everyone won the lottery. The lottery picked winners randomly; 1746 individuals were selected to receive the benefits in the form of a reloadable gift card, and 1134 applied but did not receive any assistance.

This is a perfect natural experiment. As you can see here — and as expected, given that the lottery winners were chosen randomly — winners and losers were similar in terms of age, sex, race, language, income, and more.

Researchers, led by Sumit Agarwal at the Brigham, leveraged that randomization to ask how these cash benefits would affect healthcare utilization. Their results appeared this week in JAMA.

I know what you’re thinking: Is $400 a month really enough to make a difference? Does $400 a month, less than $5000 a year, really fix poverty? We’ll get to that. But I will point out that the average family income of individuals in this study was about $1400 a month. An extra $400 might not change someone’s life, but it may really make a difference.

The primary outcome of this study was ED visits. There are a few ways this could go. Perhaps the money would lead to improved health and thus fewer ED visits. Or perhaps it would help people get transportation to primary care or other services that would offload the ED. Or maybe it would make things worse. Some folks have suggested that cash payments could increase the use of drugs and alcohol, and lead to more ED visits associated with the complications of using those substances.

Here are the actual data. Per 1000 individuals, there were 217 ED visits in the cash-benefit group, 318 in the no-benefit group. That was a statistically significant finding.

Breaking those ED visits down, you can see that fewer visits resulted in hospital admission, with fewer behavioral health–related visits and — a key finding — fewer visits for substance use disorder. This puts the lie to the idea that cash benefits increase drug use.

But the authors also looked at other causes of healthcare utilization. Outpatient visits were slightly higher in the cash-benefit group, driven largely by an increase in specialty care visits. The authors note that this is likely due to the fact that reaching a specialist often requires more travel, which can be costly. Indeed, this effect was most pronounced among the people living furthest from a specialty center.

Outside of utilization, the researchers examined a variety of individual health markers — things like blood pressure — to see if the cash benefit had any effect. A bit of caution here because these data were available only among those who interacted with the healthcare system, which may bias the results a bit. Regardless, no major differences were seen in blood pressure, weight, hemoglobin A1c, cholesterol, or COVID vaccination.

So, it seems that $400 a month doesn’t move the needle too much on risk factors for cardiovascular disease, but the effect on ED visits on their own is fairly impressive.

Is it worth it? The authors did their best to calculate the net effect of this program, accounting for the reduced ED visits and hospitalizations (that’s a big one), but also for the increased number of specialty visits. All told, the program saves about $450 per person in healthcare costs over 9 months. That’s about one seventh of the cost of the overall program.

But remember that they only looked at outcomes for the individual who got the gift cards; it’s likely that there were benefits to their family members as well. And, of course, programs like this can recoup costs indirectly though increases in economic activity, a phenomenon known as the multiplier effect.

I’m not here to tell you whether this program was a good idea; people tend to have quite strong feelings about this sort of thing. But I can tell you what it tells me about healthcare in America. It may not be surprising, but it confirms that access is far from fairly distributed.

I started this story asking about the arrow of causality between poverty and poor health. The truth is, you probably have causality in both directions.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Which GI Side Effects Should GLP-1 Prescribers Worry About?

Several recent studies have sought to expound upon what role, if any, GLP-1 RAs may have in increasing the risk for specific gastrointestinal (GI) adverse events.

Herein is a summary of the most current information on this topic, as well as my best guidance for clinicians on integrating it into the clinical care of their patients.

Aspiration Risks

Albiglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide, liraglutide, lixisenatide, semaglutide, and tirzepatide are among the class of medications known as GLP-1 RAs. These medications all work by mimicking the action of hormonal incretins, which are released postprandially. Incretins affect the pancreatic glucose-dependent release of insulin, inhibit release of glucagon, stimulate satiety, and reduce gastric emptying. This last effect has raised concerns that patients taking GLP-1 RAs might be at an elevated risk for endoscopy-related aspiration.

In June 2023, the American Society of Anesthesiologists released recommendations asking providers to consider holding back GLP-1 RAs in patients with scheduled elective procedures.

In August 2023, five national GI societies — the American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition — issued their own joint statement on the issue.

In the absence of sufficient evidence, these groups suggested that healthcare providers “exercise best practices when performing endoscopy on these patients on GLP-1 [RAs].” They called for more data and encouraged key stakeholders to work together to develop the necessary evidence to provide guidance for these patients prior to elective endoscopy. A rapid clinical update issued by the American Gastroenterological Association in 2024 was consistent with these earlier multisociety recommendations.

Two studies presented at 2024’s Digestive Disease Week provided additional reassurance that concerns about aspiration with these medications were perhaps unwarranted.

The first (since published in The American Journal of Gastroenterology ) was a case-control study of 16,295 patients undergoing upper endoscopy, among whom 306 were taking GLP-1 RAs. It showed a higher rate of solid gastric residue among those taking GLP-1 RAs compared with controls (14% vs 4%, respectively). Patients who had prolonged fasting and clear liquids for concurrent colonoscopy had lower residue rates (2% vs 11%, respectively). However, there were no recorded incidents of procedural complications or aspiration.

The second was a retrospective cohort study using TriNetX, a federated cloud-based network pulling millions of data points from multiple US healthcare organizations. It found that the incidence of aspiration pneumonitis and emergent intubation during or immediately after esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy among those taking GLP-1 RAs was not increased compared with those not taking these medications.

These were followed in June 2024 by a systematic review and meta-analysis published by Hiramoto and colleagues, which included 15 studies. The researchers showed a 36-minute prolongation for solid-food emptying and no delay in liquid emptying for patients taking GLP-1 RAs vs controls. The authors concluded that the minimal delay in solid-food emptying would be offset by standard preprocedural fasting periods.

There is concern that patients with complicated type 2 diabetes may have a bit more of a risk for aspiration. However, this was not supported by an analysis from Barlowe and colleagues, who used a national claims database to identify 15,119 patients with type 2 diabetes on GLP-1 RAs. They found no increased events of pulmonary complications (ie, aspiration, pneumonia, respiratory failure) within 14 days following esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Additional evidence suggests that the risk for aspiration in these patients seems to be offset by prolonged fasting and intake of clear liquids.

Although physicians clearly need to use clinical judgment when performing endoscopic procedures on these patients, the emerging evidence on safety has been encouraging.

Association With GI Adverse Events

A recent retrospective analysis of real-world data from 10,328 new users of GLP-1 RAs with diabetes/obesity reported that the most common GI adverse events in this cohort were abdominal pain (57.6%), constipation (30.4%), diarrhea (32.7%), nausea and vomiting (23.4%), GI bleeding (15.9%), gastroparesis (5.1%), and pancreatitis (3.4%).

Notably, dulaglutide and liraglutide had higher rates of abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, and nausea and vomiting than did semaglutide and exenatide. Compared with semaglutide, dulaglutide and liraglutide had slightly higher odds of abdominal pain, gastroparesis, and nausea and vomiting. There were no significant differences between the GLP-1 RAs in the risk for GI bleeding or pancreatitis.

A 2023 report in JAMA observed that the risk for bowel obstruction is also elevated among patients using these agents for weight loss. Possible reasons for this are currently unknown.

Studies are needed to analyze possible variations in safety profiles between GLP-1 RAs to better guide selection of these drugs, particularly in patients with GI risk factors. Furthermore, the causal relationship between GLP-1 RAs with other concomitant medications requires further investigation.

Although relatively infrequent, the risk for GI adverse events should be given special consideration by providers when prescribing them for weight loss, because the risk/benefit ratios may be different from those in patients with diabetes.

A Lack of Hepatic Concerns

GLP-1 RAs have demonstrated a significant impact on body weight and glycemic control, as well as beneficial effects on clinical, biochemical, and histologic markers in patients with metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). These favorable changes are evident by reductions in the hepatic cytolysis markers (ie, aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase).

GLP-1 RAs may provide a protective function by reducing the accumulation of hepatic triglycerides and expression of several collagen genes. Some preclinical data suggest a risk reduction for progression to hepatocellular carcinoma, and animal studies indicate that complete suppression of hepatic carcinogenesis is achieved with liraglutide.

The most recent assessment of risk reduction for MASLD progression comes from a Scandinavian cohort analysis of national registries. In looking at 91,479 patients using GLP-1 RAs, investigators demonstrated this treatment was associated with a significant reduction in the composite primary endpoint of hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as both compensated and decompensated cirrhosis.

Given the various favorable hepatic effects of GLP-1 RAs, it is likely that the composite benefit on MASLD is multifactorial. The current literature is clear that it is safe to use these agents across the spectrum of MASLD with or without fibrosis, although it must be noted that GLP-1 RAs are not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this indication.

Dr. Johnson is professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, Virginia, and a past president of the American College of Gastroenterology. He disclosed ties with ISOTHRIVE and Johnson & Johnson.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Several recent studies have sought to expound upon what role, if any, GLP-1 RAs may have in increasing the risk for specific gastrointestinal (GI) adverse events.

Herein is a summary of the most current information on this topic, as well as my best guidance for clinicians on integrating it into the clinical care of their patients.

Aspiration Risks

Albiglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide, liraglutide, lixisenatide, semaglutide, and tirzepatide are among the class of medications known as GLP-1 RAs. These medications all work by mimicking the action of hormonal incretins, which are released postprandially. Incretins affect the pancreatic glucose-dependent release of insulin, inhibit release of glucagon, stimulate satiety, and reduce gastric emptying. This last effect has raised concerns that patients taking GLP-1 RAs might be at an elevated risk for endoscopy-related aspiration.

In June 2023, the American Society of Anesthesiologists released recommendations asking providers to consider holding back GLP-1 RAs in patients with scheduled elective procedures.

In August 2023, five national GI societies — the American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition — issued their own joint statement on the issue.

In the absence of sufficient evidence, these groups suggested that healthcare providers “exercise best practices when performing endoscopy on these patients on GLP-1 [RAs].” They called for more data and encouraged key stakeholders to work together to develop the necessary evidence to provide guidance for these patients prior to elective endoscopy. A rapid clinical update issued by the American Gastroenterological Association in 2024 was consistent with these earlier multisociety recommendations.

Two studies presented at 2024’s Digestive Disease Week provided additional reassurance that concerns about aspiration with these medications were perhaps unwarranted.

The first (since published in The American Journal of Gastroenterology ) was a case-control study of 16,295 patients undergoing upper endoscopy, among whom 306 were taking GLP-1 RAs. It showed a higher rate of solid gastric residue among those taking GLP-1 RAs compared with controls (14% vs 4%, respectively). Patients who had prolonged fasting and clear liquids for concurrent colonoscopy had lower residue rates (2% vs 11%, respectively). However, there were no recorded incidents of procedural complications or aspiration.

The second was a retrospective cohort study using TriNetX, a federated cloud-based network pulling millions of data points from multiple US healthcare organizations. It found that the incidence of aspiration pneumonitis and emergent intubation during or immediately after esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy among those taking GLP-1 RAs was not increased compared with those not taking these medications.

These were followed in June 2024 by a systematic review and meta-analysis published by Hiramoto and colleagues, which included 15 studies. The researchers showed a 36-minute prolongation for solid-food emptying and no delay in liquid emptying for patients taking GLP-1 RAs vs controls. The authors concluded that the minimal delay in solid-food emptying would be offset by standard preprocedural fasting periods.

There is concern that patients with complicated type 2 diabetes may have a bit more of a risk for aspiration. However, this was not supported by an analysis from Barlowe and colleagues, who used a national claims database to identify 15,119 patients with type 2 diabetes on GLP-1 RAs. They found no increased events of pulmonary complications (ie, aspiration, pneumonia, respiratory failure) within 14 days following esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Additional evidence suggests that the risk for aspiration in these patients seems to be offset by prolonged fasting and intake of clear liquids.

Although physicians clearly need to use clinical judgment when performing endoscopic procedures on these patients, the emerging evidence on safety has been encouraging.

Association With GI Adverse Events

A recent retrospective analysis of real-world data from 10,328 new users of GLP-1 RAs with diabetes/obesity reported that the most common GI adverse events in this cohort were abdominal pain (57.6%), constipation (30.4%), diarrhea (32.7%), nausea and vomiting (23.4%), GI bleeding (15.9%), gastroparesis (5.1%), and pancreatitis (3.4%).

Notably, dulaglutide and liraglutide had higher rates of abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, and nausea and vomiting than did semaglutide and exenatide. Compared with semaglutide, dulaglutide and liraglutide had slightly higher odds of abdominal pain, gastroparesis, and nausea and vomiting. There were no significant differences between the GLP-1 RAs in the risk for GI bleeding or pancreatitis.

A 2023 report in JAMA observed that the risk for bowel obstruction is also elevated among patients using these agents for weight loss. Possible reasons for this are currently unknown.

Studies are needed to analyze possible variations in safety profiles between GLP-1 RAs to better guide selection of these drugs, particularly in patients with GI risk factors. Furthermore, the causal relationship between GLP-1 RAs with other concomitant medications requires further investigation.

Although relatively infrequent, the risk for GI adverse events should be given special consideration by providers when prescribing them for weight loss, because the risk/benefit ratios may be different from those in patients with diabetes.

A Lack of Hepatic Concerns

GLP-1 RAs have demonstrated a significant impact on body weight and glycemic control, as well as beneficial effects on clinical, biochemical, and histologic markers in patients with metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). These favorable changes are evident by reductions in the hepatic cytolysis markers (ie, aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase).

GLP-1 RAs may provide a protective function by reducing the accumulation of hepatic triglycerides and expression of several collagen genes. Some preclinical data suggest a risk reduction for progression to hepatocellular carcinoma, and animal studies indicate that complete suppression of hepatic carcinogenesis is achieved with liraglutide.

The most recent assessment of risk reduction for MASLD progression comes from a Scandinavian cohort analysis of national registries. In looking at 91,479 patients using GLP-1 RAs, investigators demonstrated this treatment was associated with a significant reduction in the composite primary endpoint of hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as both compensated and decompensated cirrhosis.

Given the various favorable hepatic effects of GLP-1 RAs, it is likely that the composite benefit on MASLD is multifactorial. The current literature is clear that it is safe to use these agents across the spectrum of MASLD with or without fibrosis, although it must be noted that GLP-1 RAs are not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this indication.

Dr. Johnson is professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, Virginia, and a past president of the American College of Gastroenterology. He disclosed ties with ISOTHRIVE and Johnson & Johnson.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Several recent studies have sought to expound upon what role, if any, GLP-1 RAs may have in increasing the risk for specific gastrointestinal (GI) adverse events.

Herein is a summary of the most current information on this topic, as well as my best guidance for clinicians on integrating it into the clinical care of their patients.

Aspiration Risks

Albiglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide, liraglutide, lixisenatide, semaglutide, and tirzepatide are among the class of medications known as GLP-1 RAs. These medications all work by mimicking the action of hormonal incretins, which are released postprandially. Incretins affect the pancreatic glucose-dependent release of insulin, inhibit release of glucagon, stimulate satiety, and reduce gastric emptying. This last effect has raised concerns that patients taking GLP-1 RAs might be at an elevated risk for endoscopy-related aspiration.

In June 2023, the American Society of Anesthesiologists released recommendations asking providers to consider holding back GLP-1 RAs in patients with scheduled elective procedures.

In August 2023, five national GI societies — the American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition — issued their own joint statement on the issue.

In the absence of sufficient evidence, these groups suggested that healthcare providers “exercise best practices when performing endoscopy on these patients on GLP-1 [RAs].” They called for more data and encouraged key stakeholders to work together to develop the necessary evidence to provide guidance for these patients prior to elective endoscopy. A rapid clinical update issued by the American Gastroenterological Association in 2024 was consistent with these earlier multisociety recommendations.

Two studies presented at 2024’s Digestive Disease Week provided additional reassurance that concerns about aspiration with these medications were perhaps unwarranted.

The first (since published in The American Journal of Gastroenterology ) was a case-control study of 16,295 patients undergoing upper endoscopy, among whom 306 were taking GLP-1 RAs. It showed a higher rate of solid gastric residue among those taking GLP-1 RAs compared with controls (14% vs 4%, respectively). Patients who had prolonged fasting and clear liquids for concurrent colonoscopy had lower residue rates (2% vs 11%, respectively). However, there were no recorded incidents of procedural complications or aspiration.

The second was a retrospective cohort study using TriNetX, a federated cloud-based network pulling millions of data points from multiple US healthcare organizations. It found that the incidence of aspiration pneumonitis and emergent intubation during or immediately after esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy among those taking GLP-1 RAs was not increased compared with those not taking these medications.

These were followed in June 2024 by a systematic review and meta-analysis published by Hiramoto and colleagues, which included 15 studies. The researchers showed a 36-minute prolongation for solid-food emptying and no delay in liquid emptying for patients taking GLP-1 RAs vs controls. The authors concluded that the minimal delay in solid-food emptying would be offset by standard preprocedural fasting periods.

There is concern that patients with complicated type 2 diabetes may have a bit more of a risk for aspiration. However, this was not supported by an analysis from Barlowe and colleagues, who used a national claims database to identify 15,119 patients with type 2 diabetes on GLP-1 RAs. They found no increased events of pulmonary complications (ie, aspiration, pneumonia, respiratory failure) within 14 days following esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Additional evidence suggests that the risk for aspiration in these patients seems to be offset by prolonged fasting and intake of clear liquids.

Although physicians clearly need to use clinical judgment when performing endoscopic procedures on these patients, the emerging evidence on safety has been encouraging.

Association With GI Adverse Events

A recent retrospective analysis of real-world data from 10,328 new users of GLP-1 RAs with diabetes/obesity reported that the most common GI adverse events in this cohort were abdominal pain (57.6%), constipation (30.4%), diarrhea (32.7%), nausea and vomiting (23.4%), GI bleeding (15.9%), gastroparesis (5.1%), and pancreatitis (3.4%).

Notably, dulaglutide and liraglutide had higher rates of abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, and nausea and vomiting than did semaglutide and exenatide. Compared with semaglutide, dulaglutide and liraglutide had slightly higher odds of abdominal pain, gastroparesis, and nausea and vomiting. There were no significant differences between the GLP-1 RAs in the risk for GI bleeding or pancreatitis.

A 2023 report in JAMA observed that the risk for bowel obstruction is also elevated among patients using these agents for weight loss. Possible reasons for this are currently unknown.

Studies are needed to analyze possible variations in safety profiles between GLP-1 RAs to better guide selection of these drugs, particularly in patients with GI risk factors. Furthermore, the causal relationship between GLP-1 RAs with other concomitant medications requires further investigation.

Although relatively infrequent, the risk for GI adverse events should be given special consideration by providers when prescribing them for weight loss, because the risk/benefit ratios may be different from those in patients with diabetes.

A Lack of Hepatic Concerns

GLP-1 RAs have demonstrated a significant impact on body weight and glycemic control, as well as beneficial effects on clinical, biochemical, and histologic markers in patients with metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). These favorable changes are evident by reductions in the hepatic cytolysis markers (ie, aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase).

GLP-1 RAs may provide a protective function by reducing the accumulation of hepatic triglycerides and expression of several collagen genes. Some preclinical data suggest a risk reduction for progression to hepatocellular carcinoma, and animal studies indicate that complete suppression of hepatic carcinogenesis is achieved with liraglutide.

The most recent assessment of risk reduction for MASLD progression comes from a Scandinavian cohort analysis of national registries. In looking at 91,479 patients using GLP-1 RAs, investigators demonstrated this treatment was associated with a significant reduction in the composite primary endpoint of hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as both compensated and decompensated cirrhosis.

Given the various favorable hepatic effects of GLP-1 RAs, it is likely that the composite benefit on MASLD is multifactorial. The current literature is clear that it is safe to use these agents across the spectrum of MASLD with or without fibrosis, although it must be noted that GLP-1 RAs are not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this indication.

Dr. Johnson is professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, Virginia, and a past president of the American College of Gastroenterology. He disclosed ties with ISOTHRIVE and Johnson & Johnson.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

For Richer, for Poorer: Low-Carb Diets Work for All Incomes

For 3 years, Ajala Efem’s type 2 diabetes was so poorly controlled that her blood sugar often soared northward of 500 mg/dL despite insulin shots three to five times a day. She would experience dizziness, vomiting, severe headaches, and the neuropathy in her feet made walking painful. She was also — literally — frothing at the mouth. The 47-year-old single mother of two adult children with mental disabilities feared that she would die.

Ms. Efem lives in the South Bronx, which is among the poorest areas of New York City, where the combined rate of prediabetes and diabetes is close to 30%, the highest rate of any borough in the city.

She had to wait 8 months for an appointment with an endocrinologist, but that visit proved to be life-changing. She lost 28 pounds and got off 15 medications in a single month. She did not join a gym or count calories; she simply changed the food she ate and adopted a low-carb diet.

“I went from being sick to feeling so great,” she told her endocrinologist recently: “My feet aren’t hurting; I’m not in pain; I’m eating as much as I want, and I really enjoy my food so much.”

Ms. Efem’s life-changing visit was with Mariela Glandt, MD, at the offices of Essen Health Care. One month earlier, Dr. Glandt’s company, OwnaHealth, was contracted by Essen to conduct a 100-person pilot program for endocrinology patients. Essen is the largest Medicaid provider in New York City, and “they were desperate for an endocrinologist,” said Dr. Glandt, who trained at Columbia University in New York. So she came — all the way from Madrid, Spain. She commutes monthly, staying for a week each visit.

Dr. Glandt keeps up this punishing schedule because, as she explains, “it’s such a high for me to see these incredible transformations.” Her mostly Black and Hispanic patients are poor and lack resources, yet they lose significant amounts of weight, and their health issues resolve.

“Food is medicine” is an idea very much in vogue. The concept was central to the landmark White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health in 2022 and is now the focus of a number of a wide range of government programs. Recently, the Senate held a hearing aimed at further expanding food as medicine programs.

Still, only a single randomized controlled clinical trial has been conducted on this nutritional approach, with unexpectedly disappointing results. In the mid-Atlantic region, 456 food-insecure adults with type 2 diabetes were randomly assigned to usual care or the provision of weekly groceries for their entire families for about 1 year. Provisions for a Mediterranean-style diet included whole grains, fruits and vegetables, lean protein, low-fat dairy products, cereal, brown rice, and bread. In addition, participants received dietary consultations. Yet, those who got free food and coaching did not see improvements in their average blood sugar (the study’s primary outcome), and their low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels appeared to have worsened.

“To be honest, I was surprised,” the study’s lead author, Joseph Doyle, PhD, professor at the Sloan School of Management at MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts, told me. “I was hoping we would show improved outcomes, but the way to make progress is to do well-randomized trials to find out what works.”

I was not surprised by these results because a recent rigorous systematic review and meta-analysis in The BMJ did not show a Mediterranean-style diet to be the most effective for glycemic control. And Ms. Efem was not in fact following a Mediterranean-style diet.

Ms. Efem’s low-carb success story is anecdotal, but Dr. Glandt has an established track record from her 9 years’ experience as the medical director of the eponymous diabetes center she founded in Tel Aviv. A recent audit of 344 patients from the center found that after 6 months of following a very low–carbohydrate diet, 96.3% of those with diabetes saw their A1c fall from a median 7.6% to 6.3%. Weight loss was significant, with a median drop of 6.5 kg (14 pounds) for patients with diabetes and 5.7 kg for those with prediabetes. The diet comprises 5%-10% of calories from carbs, but Dr. Glandt does not use numeric targets with her patients.

Blood pressure, triglycerides, and liver enzymes also improved. And though LDL cholesterol went up by 8%, this result may have been offset by an accompanying 13% rise in HDL cholesterol. Of the 78 patients initially on insulin, 62 were able to stop this medication entirely.

Although these results aren’t from a clinical trial, they’re still highly meaningful because the current dietary standard of care for type 2 diabetes can only slow the progression of the disease, not cause remission. Indeed, the idea that type 2 diabetes could be put into remission was not seriously considered by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) until 2009. By 2019, an ADA report concluded that “[r]educing overall carbohydrate intake for individuals with diabetes has demonstrated the most evidence for improving glycemia.” In other words, the best way to improve the key factor in diabetes is to reduce total carbohydrates. Yet, the ADA still advocates filling one quarter of one’s plate with carbohydrate-based foods, an amount that will prevent remission. Given that the ADA’s vision statement is “a life free of diabetes,” it seems negligent not to tell people with a deadly condition that they can reverse this diagnosis.

A 2023 meta-analysis of 42 controlled clinical trials on 4809 patients showed that a very low–carbohydrate ketogenic diet (keto) was “superior” to alternatives for glycemic control. A more recent review of 11 clinical trials found that this diet was equal but not superior to other nutritional approaches in terms of blood sugar control, but this review also concluded that keto led to greater increases in HDL cholesterol and lower triglycerides.

Dr. Glandt’s patients in the Bronx might not seem like obvious low-carb candidates. The diet is considered expensive and difficult to sustain. My interviews with a half dozen patients revealed some of these difficulties, but even for a woman living in a homeless shelter, the obstacles are not insurmountable.

Jerrilyn, who preferred that I use only her first name, lives in a shelter in Queens. While we strolled through a nearby park, she told me about her desire to lose weight and recover from polycystic ovary syndrome, which terrified her because it had caused dramatic hair loss. When she landed in Dr. Glandt’s office at age 28, she weighed 180 pounds.

Less than 5 months later, Jerrilyn had lost 25 pounds, and her period had returned with some regularity. She said she used “food stamps,” known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), to buy most of her food at local delis because the meals served at the shelter were too heavy in starches. She starts her day with eggs, turkey bacon, and avocado.

“It was hard to give up carbohydrates because in my culture [Latina], we have nothing but carbs: rice, potatoes, yuca,” Jerrilyn shared. She noticed that carbs make her hungrier, but after 3 days of going low-carb, her cravings diminished. “It was like getting over an addiction,” she said.

Jerrilyn told me she’d seen many doctors but none as involved as Dr. Glandt. “It feels awesome to know that I have a lot of really useful information coming from her all the time.” The OwnaHealth app tracks weight, blood pressure, blood sugar, ketones, meals, mood, and cravings. Patients wear continuous glucose monitors and enter other information manually. Ketone bodies are used to measure dietary adherence and are obtained through finger pricks and test strips provided by OwnaHealth. Dr. Glandt gives patients her own food plan, along with free visual guides to low-carbohydrate foods by dietdoctor.com.

Dr. Glandt also sends her patients for regular blood work. She says she does not frequently see a rise in LDL cholesterol, which can sometimes occur on a low-carbohydrate diet. This effect is most common among people who are lean and fit. She says she doesn’t discontinue statins unless cholesterol levels improve significantly.

Samuel Gonzalez, age 56, weighed 275 pounds when he walked into Dr. Glandt’s office this past November. His A1c was 9.2%, but none of his previous doctors had diagnosed him with diabetes. “I was like a walking bag of sugar!” he joked.

A low-carbohydrate diet seemed absurd to a Puerto Rican like himself: “Having coffee without sugar? That’s like sacrilegious in my culture!” exclaimed Mr. Gonzalez. Still, he managed, with SNAP, to cook eggs and bacon for breakfast and some kind of protein for dinner. He keeps lunch light, “like tuna fish,” and finds checking in with the OwnaHealth app to be very helpful. “Every day, I’m on it,” he said. In the past 7 months, he’s lost 50 pounds, normalized his cholesterol and blood pressure levels, and lowered his A1c to 5.5%.

Mr. Gonzalez gets disability payments due to a back injury, and Ms. Efem receives government payments because her husband died serving in the military. Ms. Efem says her new diet challenges her budget, but Mr. Gonzalez says he manages easily.

Mélissa Cruz, a 28-year-old studying to be a nail technician while also doing back office work at a physical therapy practice, says she’s stretched thin. “I end up sad because I can’t put energy into looking up recipes and cooking for me and my boyfriend,” she told me. She’ll often cook rice and plantains for him and meat for herself, but “it’s frustrating when I’m low on funds and can’t figure out what to eat.”

Low-carbohydrate diets have a reputation for being expensive because people often start eating pricier foods, like meat and cheese, to replace cheaper starchy foods such as pasta and rice.

A 2019 cost analysis published in Nutrition & Dietetics compared a low-carbohydrate dietary pattern with the New Zealand government’s recommended guidelines (which are almost identical to those in the United States) and found that it cost only an extra $1.27 in US dollars per person per day. One explanation is that protein and fat are more satiating than carbohydrates, so people who mostly consume these macronutrients often cut back on snacks like packaged chips, crackers, and even fruits. Also, those on a ketogenic diet usually cut down on medications, so the additional $1.27 daily is likely offset by reduced spending at the pharmacy.

It’s not just Bronx residents with low socioeconomic status (SES) who adapt well to low-carbohydrate diets. Among Alabama state employees with diabetes enrolled in a low-carbohydrate dietary program provided by a company called Virta, the low SES population had the best outcomes. Virta also published survey data in 2023 showing that participants in a program with the Veteran’s Administration did not find additional costs to be an obstacle to dietary adherence. In fact, some participants saw cost reductions due to decreased spending on processed snacks and fast foods.

Ms. Cruz told me she struggles financially, yet she’s still lost nearly 30 pounds in 5 months, and her A1c went from 7.1% down to 5.9%, putting her diabetes into remission. Equally motivating for her are the improvements she’s seen in other hormonal issues. Since childhood, she’s had acanthosis, a condition that causes the skin to darken in velvety patches, and more recently, she developed severe hirsutism to the point of growing sideburns. “I had tried going vegan and fasting, but these just weren’t sustainable for me, and I was so overwhelmed with counting calories all the time.” Now, on a low-carbohydrate diet, which doesn’t require calorie counting, she’s finally seeing both these conditions improve significantly.

When I last checked in with Ms. Cruz, she said she had “kind of ghosted” Dr. Glandt due to her work and school constraints, but she hadn’t abandoned the diet. She appreciated, too, that Dr. Glandt had not given up on her and kept calling and messaging. “She’s not at all like a typical doctor who would just tell me to lose weight and shake their head at me,” Ms. Cruz said.

Because Dr. Glandt’s approach is time-intensive and high-touch, it might seem impractical to scale up, but Dr. Glandt’s app uses artificial intelligence to help with communications thus allowing her, with help from part-time health coaches, to care for patients.

This early success in one of the United States’ poorest and sickest neighborhoods should give us hope that type 2 diabetes need not to be a progressive irreversible disease, even among the disadvantaged.

OwnaHealth’s track record, along with that of Virta and other similar low-carbohydrate medical practices also give hope to the food-is-medicine idea. Diabetes can go into remission, and people can be healed, provided that health practitioners prescribe the right foods. And in truth, it’s not a diet. It’s a way of eating that must be maintained. The sustainability of low-carbohydrate diets has been a point of contention, but the Virta trial, with 38% of patients sustaining remission at 2 years, showed that it’s possible. (OwnaHealth, for its part, offers long-term maintenance plans to help patients stay very low-carb permanently.)

Given the tremendous costs and health burden of diabetes, this approach should no doubt be the first line of treatment for doctors and the ADA. The past two decades of clinical trial research have demonstrated that remission of type 2 diabetes is possible through diet alone. It turns out that for metabolic diseases, only certain foods are truly medicine.

Tools and Tips for Clinicians:

- Free two-page keto starter’s guide by OwnaHealth; Dr. Glandt uses this guide with her patients.

- Illustrated low-carb guides by dietdoctor.com

- Free low-carbohydrate starter guide by the Michigan Collaborative for Type 2 Diabetes

- Low-Carb for Any Budget, a free digital booklet by Mark Cucuzzella, MD, and Kristie Sullivan, PhD

- Recipe and meal ideas from Ruled.me, Keto-Mojo.com, and

Dr. Teicholz is the founder of Nutrition Coalition, an independent nonprofit dedicated to ensuring that US dietary guidelines align with current science. She disclosed receiving book royalties from The Big Fat Surprise, and received honorarium not exceeding $2000 for speeches from various sources.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

For 3 years, Ajala Efem’s type 2 diabetes was so poorly controlled that her blood sugar often soared northward of 500 mg/dL despite insulin shots three to five times a day. She would experience dizziness, vomiting, severe headaches, and the neuropathy in her feet made walking painful. She was also — literally — frothing at the mouth. The 47-year-old single mother of two adult children with mental disabilities feared that she would die.

Ms. Efem lives in the South Bronx, which is among the poorest areas of New York City, where the combined rate of prediabetes and diabetes is close to 30%, the highest rate of any borough in the city.

She had to wait 8 months for an appointment with an endocrinologist, but that visit proved to be life-changing. She lost 28 pounds and got off 15 medications in a single month. She did not join a gym or count calories; she simply changed the food she ate and adopted a low-carb diet.

“I went from being sick to feeling so great,” she told her endocrinologist recently: “My feet aren’t hurting; I’m not in pain; I’m eating as much as I want, and I really enjoy my food so much.”

Ms. Efem’s life-changing visit was with Mariela Glandt, MD, at the offices of Essen Health Care. One month earlier, Dr. Glandt’s company, OwnaHealth, was contracted by Essen to conduct a 100-person pilot program for endocrinology patients. Essen is the largest Medicaid provider in New York City, and “they were desperate for an endocrinologist,” said Dr. Glandt, who trained at Columbia University in New York. So she came — all the way from Madrid, Spain. She commutes monthly, staying for a week each visit.

Dr. Glandt keeps up this punishing schedule because, as she explains, “it’s such a high for me to see these incredible transformations.” Her mostly Black and Hispanic patients are poor and lack resources, yet they lose significant amounts of weight, and their health issues resolve.

“Food is medicine” is an idea very much in vogue. The concept was central to the landmark White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health in 2022 and is now the focus of a number of a wide range of government programs. Recently, the Senate held a hearing aimed at further expanding food as medicine programs.

Still, only a single randomized controlled clinical trial has been conducted on this nutritional approach, with unexpectedly disappointing results. In the mid-Atlantic region, 456 food-insecure adults with type 2 diabetes were randomly assigned to usual care or the provision of weekly groceries for their entire families for about 1 year. Provisions for a Mediterranean-style diet included whole grains, fruits and vegetables, lean protein, low-fat dairy products, cereal, brown rice, and bread. In addition, participants received dietary consultations. Yet, those who got free food and coaching did not see improvements in their average blood sugar (the study’s primary outcome), and their low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels appeared to have worsened.

“To be honest, I was surprised,” the study’s lead author, Joseph Doyle, PhD, professor at the Sloan School of Management at MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts, told me. “I was hoping we would show improved outcomes, but the way to make progress is to do well-randomized trials to find out what works.”

I was not surprised by these results because a recent rigorous systematic review and meta-analysis in The BMJ did not show a Mediterranean-style diet to be the most effective for glycemic control. And Ms. Efem was not in fact following a Mediterranean-style diet.

Ms. Efem’s low-carb success story is anecdotal, but Dr. Glandt has an established track record from her 9 years’ experience as the medical director of the eponymous diabetes center she founded in Tel Aviv. A recent audit of 344 patients from the center found that after 6 months of following a very low–carbohydrate diet, 96.3% of those with diabetes saw their A1c fall from a median 7.6% to 6.3%. Weight loss was significant, with a median drop of 6.5 kg (14 pounds) for patients with diabetes and 5.7 kg for those with prediabetes. The diet comprises 5%-10% of calories from carbs, but Dr. Glandt does not use numeric targets with her patients.

Blood pressure, triglycerides, and liver enzymes also improved. And though LDL cholesterol went up by 8%, this result may have been offset by an accompanying 13% rise in HDL cholesterol. Of the 78 patients initially on insulin, 62 were able to stop this medication entirely.

Although these results aren’t from a clinical trial, they’re still highly meaningful because the current dietary standard of care for type 2 diabetes can only slow the progression of the disease, not cause remission. Indeed, the idea that type 2 diabetes could be put into remission was not seriously considered by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) until 2009. By 2019, an ADA report concluded that “[r]educing overall carbohydrate intake for individuals with diabetes has demonstrated the most evidence for improving glycemia.” In other words, the best way to improve the key factor in diabetes is to reduce total carbohydrates. Yet, the ADA still advocates filling one quarter of one’s plate with carbohydrate-based foods, an amount that will prevent remission. Given that the ADA’s vision statement is “a life free of diabetes,” it seems negligent not to tell people with a deadly condition that they can reverse this diagnosis.

A 2023 meta-analysis of 42 controlled clinical trials on 4809 patients showed that a very low–carbohydrate ketogenic diet (keto) was “superior” to alternatives for glycemic control. A more recent review of 11 clinical trials found that this diet was equal but not superior to other nutritional approaches in terms of blood sugar control, but this review also concluded that keto led to greater increases in HDL cholesterol and lower triglycerides.

Dr. Glandt’s patients in the Bronx might not seem like obvious low-carb candidates. The diet is considered expensive and difficult to sustain. My interviews with a half dozen patients revealed some of these difficulties, but even for a woman living in a homeless shelter, the obstacles are not insurmountable.

Jerrilyn, who preferred that I use only her first name, lives in a shelter in Queens. While we strolled through a nearby park, she told me about her desire to lose weight and recover from polycystic ovary syndrome, which terrified her because it had caused dramatic hair loss. When she landed in Dr. Glandt’s office at age 28, she weighed 180 pounds.

Less than 5 months later, Jerrilyn had lost 25 pounds, and her period had returned with some regularity. She said she used “food stamps,” known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), to buy most of her food at local delis because the meals served at the shelter were too heavy in starches. She starts her day with eggs, turkey bacon, and avocado.

“It was hard to give up carbohydrates because in my culture [Latina], we have nothing but carbs: rice, potatoes, yuca,” Jerrilyn shared. She noticed that carbs make her hungrier, but after 3 days of going low-carb, her cravings diminished. “It was like getting over an addiction,” she said.

Jerrilyn told me she’d seen many doctors but none as involved as Dr. Glandt. “It feels awesome to know that I have a lot of really useful information coming from her all the time.” The OwnaHealth app tracks weight, blood pressure, blood sugar, ketones, meals, mood, and cravings. Patients wear continuous glucose monitors and enter other information manually. Ketone bodies are used to measure dietary adherence and are obtained through finger pricks and test strips provided by OwnaHealth. Dr. Glandt gives patients her own food plan, along with free visual guides to low-carbohydrate foods by dietdoctor.com.

Dr. Glandt also sends her patients for regular blood work. She says she does not frequently see a rise in LDL cholesterol, which can sometimes occur on a low-carbohydrate diet. This effect is most common among people who are lean and fit. She says she doesn’t discontinue statins unless cholesterol levels improve significantly.

Samuel Gonzalez, age 56, weighed 275 pounds when he walked into Dr. Glandt’s office this past November. His A1c was 9.2%, but none of his previous doctors had diagnosed him with diabetes. “I was like a walking bag of sugar!” he joked.

A low-carbohydrate diet seemed absurd to a Puerto Rican like himself: “Having coffee without sugar? That’s like sacrilegious in my culture!” exclaimed Mr. Gonzalez. Still, he managed, with SNAP, to cook eggs and bacon for breakfast and some kind of protein for dinner. He keeps lunch light, “like tuna fish,” and finds checking in with the OwnaHealth app to be very helpful. “Every day, I’m on it,” he said. In the past 7 months, he’s lost 50 pounds, normalized his cholesterol and blood pressure levels, and lowered his A1c to 5.5%.

Mr. Gonzalez gets disability payments due to a back injury, and Ms. Efem receives government payments because her husband died serving in the military. Ms. Efem says her new diet challenges her budget, but Mr. Gonzalez says he manages easily.

Mélissa Cruz, a 28-year-old studying to be a nail technician while also doing back office work at a physical therapy practice, says she’s stretched thin. “I end up sad because I can’t put energy into looking up recipes and cooking for me and my boyfriend,” she told me. She’ll often cook rice and plantains for him and meat for herself, but “it’s frustrating when I’m low on funds and can’t figure out what to eat.”

Low-carbohydrate diets have a reputation for being expensive because people often start eating pricier foods, like meat and cheese, to replace cheaper starchy foods such as pasta and rice.

A 2019 cost analysis published in Nutrition & Dietetics compared a low-carbohydrate dietary pattern with the New Zealand government’s recommended guidelines (which are almost identical to those in the United States) and found that it cost only an extra $1.27 in US dollars per person per day. One explanation is that protein and fat are more satiating than carbohydrates, so people who mostly consume these macronutrients often cut back on snacks like packaged chips, crackers, and even fruits. Also, those on a ketogenic diet usually cut down on medications, so the additional $1.27 daily is likely offset by reduced spending at the pharmacy.

It’s not just Bronx residents with low socioeconomic status (SES) who adapt well to low-carbohydrate diets. Among Alabama state employees with diabetes enrolled in a low-carbohydrate dietary program provided by a company called Virta, the low SES population had the best outcomes. Virta also published survey data in 2023 showing that participants in a program with the Veteran’s Administration did not find additional costs to be an obstacle to dietary adherence. In fact, some participants saw cost reductions due to decreased spending on processed snacks and fast foods.

Ms. Cruz told me she struggles financially, yet she’s still lost nearly 30 pounds in 5 months, and her A1c went from 7.1% down to 5.9%, putting her diabetes into remission. Equally motivating for her are the improvements she’s seen in other hormonal issues. Since childhood, she’s had acanthosis, a condition that causes the skin to darken in velvety patches, and more recently, she developed severe hirsutism to the point of growing sideburns. “I had tried going vegan and fasting, but these just weren’t sustainable for me, and I was so overwhelmed with counting calories all the time.” Now, on a low-carbohydrate diet, which doesn’t require calorie counting, she’s finally seeing both these conditions improve significantly.

When I last checked in with Ms. Cruz, she said she had “kind of ghosted” Dr. Glandt due to her work and school constraints, but she hadn’t abandoned the diet. She appreciated, too, that Dr. Glandt had not given up on her and kept calling and messaging. “She’s not at all like a typical doctor who would just tell me to lose weight and shake their head at me,” Ms. Cruz said.

Because Dr. Glandt’s approach is time-intensive and high-touch, it might seem impractical to scale up, but Dr. Glandt’s app uses artificial intelligence to help with communications thus allowing her, with help from part-time health coaches, to care for patients.

This early success in one of the United States’ poorest and sickest neighborhoods should give us hope that type 2 diabetes need not to be a progressive irreversible disease, even among the disadvantaged.

OwnaHealth’s track record, along with that of Virta and other similar low-carbohydrate medical practices also give hope to the food-is-medicine idea. Diabetes can go into remission, and people can be healed, provided that health practitioners prescribe the right foods. And in truth, it’s not a diet. It’s a way of eating that must be maintained. The sustainability of low-carbohydrate diets has been a point of contention, but the Virta trial, with 38% of patients sustaining remission at 2 years, showed that it’s possible. (OwnaHealth, for its part, offers long-term maintenance plans to help patients stay very low-carb permanently.)

Given the tremendous costs and health burden of diabetes, this approach should no doubt be the first line of treatment for doctors and the ADA. The past two decades of clinical trial research have demonstrated that remission of type 2 diabetes is possible through diet alone. It turns out that for metabolic diseases, only certain foods are truly medicine.

Tools and Tips for Clinicians:

- Free two-page keto starter’s guide by OwnaHealth; Dr. Glandt uses this guide with her patients.

- Illustrated low-carb guides by dietdoctor.com

- Free low-carbohydrate starter guide by the Michigan Collaborative for Type 2 Diabetes

- Low-Carb for Any Budget, a free digital booklet by Mark Cucuzzella, MD, and Kristie Sullivan, PhD

- Recipe and meal ideas from Ruled.me, Keto-Mojo.com, and

Dr. Teicholz is the founder of Nutrition Coalition, an independent nonprofit dedicated to ensuring that US dietary guidelines align with current science. She disclosed receiving book royalties from The Big Fat Surprise, and received honorarium not exceeding $2000 for speeches from various sources.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

For 3 years, Ajala Efem’s type 2 diabetes was so poorly controlled that her blood sugar often soared northward of 500 mg/dL despite insulin shots three to five times a day. She would experience dizziness, vomiting, severe headaches, and the neuropathy in her feet made walking painful. She was also — literally — frothing at the mouth. The 47-year-old single mother of two adult children with mental disabilities feared that she would die.

Ms. Efem lives in the South Bronx, which is among the poorest areas of New York City, where the combined rate of prediabetes and diabetes is close to 30%, the highest rate of any borough in the city.

She had to wait 8 months for an appointment with an endocrinologist, but that visit proved to be life-changing. She lost 28 pounds and got off 15 medications in a single month. She did not join a gym or count calories; she simply changed the food she ate and adopted a low-carb diet.

“I went from being sick to feeling so great,” she told her endocrinologist recently: “My feet aren’t hurting; I’m not in pain; I’m eating as much as I want, and I really enjoy my food so much.”

Ms. Efem’s life-changing visit was with Mariela Glandt, MD, at the offices of Essen Health Care. One month earlier, Dr. Glandt’s company, OwnaHealth, was contracted by Essen to conduct a 100-person pilot program for endocrinology patients. Essen is the largest Medicaid provider in New York City, and “they were desperate for an endocrinologist,” said Dr. Glandt, who trained at Columbia University in New York. So she came — all the way from Madrid, Spain. She commutes monthly, staying for a week each visit.

Dr. Glandt keeps up this punishing schedule because, as she explains, “it’s such a high for me to see these incredible transformations.” Her mostly Black and Hispanic patients are poor and lack resources, yet they lose significant amounts of weight, and their health issues resolve.

“Food is medicine” is an idea very much in vogue. The concept was central to the landmark White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health in 2022 and is now the focus of a number of a wide range of government programs. Recently, the Senate held a hearing aimed at further expanding food as medicine programs.

Still, only a single randomized controlled clinical trial has been conducted on this nutritional approach, with unexpectedly disappointing results. In the mid-Atlantic region, 456 food-insecure adults with type 2 diabetes were randomly assigned to usual care or the provision of weekly groceries for their entire families for about 1 year. Provisions for a Mediterranean-style diet included whole grains, fruits and vegetables, lean protein, low-fat dairy products, cereal, brown rice, and bread. In addition, participants received dietary consultations. Yet, those who got free food and coaching did not see improvements in their average blood sugar (the study’s primary outcome), and their low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels appeared to have worsened.

“To be honest, I was surprised,” the study’s lead author, Joseph Doyle, PhD, professor at the Sloan School of Management at MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts, told me. “I was hoping we would show improved outcomes, but the way to make progress is to do well-randomized trials to find out what works.”

I was not surprised by these results because a recent rigorous systematic review and meta-analysis in The BMJ did not show a Mediterranean-style diet to be the most effective for glycemic control. And Ms. Efem was not in fact following a Mediterranean-style diet.

Ms. Efem’s low-carb success story is anecdotal, but Dr. Glandt has an established track record from her 9 years’ experience as the medical director of the eponymous diabetes center she founded in Tel Aviv. A recent audit of 344 patients from the center found that after 6 months of following a very low–carbohydrate diet, 96.3% of those with diabetes saw their A1c fall from a median 7.6% to 6.3%. Weight loss was significant, with a median drop of 6.5 kg (14 pounds) for patients with diabetes and 5.7 kg for those with prediabetes. The diet comprises 5%-10% of calories from carbs, but Dr. Glandt does not use numeric targets with her patients.

Blood pressure, triglycerides, and liver enzymes also improved. And though LDL cholesterol went up by 8%, this result may have been offset by an accompanying 13% rise in HDL cholesterol. Of the 78 patients initially on insulin, 62 were able to stop this medication entirely.

Although these results aren’t from a clinical trial, they’re still highly meaningful because the current dietary standard of care for type 2 diabetes can only slow the progression of the disease, not cause remission. Indeed, the idea that type 2 diabetes could be put into remission was not seriously considered by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) until 2009. By 2019, an ADA report concluded that “[r]educing overall carbohydrate intake for individuals with diabetes has demonstrated the most evidence for improving glycemia.” In other words, the best way to improve the key factor in diabetes is to reduce total carbohydrates. Yet, the ADA still advocates filling one quarter of one’s plate with carbohydrate-based foods, an amount that will prevent remission. Given that the ADA’s vision statement is “a life free of diabetes,” it seems negligent not to tell people with a deadly condition that they can reverse this diagnosis.

A 2023 meta-analysis of 42 controlled clinical trials on 4809 patients showed that a very low–carbohydrate ketogenic diet (keto) was “superior” to alternatives for glycemic control. A more recent review of 11 clinical trials found that this diet was equal but not superior to other nutritional approaches in terms of blood sugar control, but this review also concluded that keto led to greater increases in HDL cholesterol and lower triglycerides.

Dr. Glandt’s patients in the Bronx might not seem like obvious low-carb candidates. The diet is considered expensive and difficult to sustain. My interviews with a half dozen patients revealed some of these difficulties, but even for a woman living in a homeless shelter, the obstacles are not insurmountable.

Jerrilyn, who preferred that I use only her first name, lives in a shelter in Queens. While we strolled through a nearby park, she told me about her desire to lose weight and recover from polycystic ovary syndrome, which terrified her because it had caused dramatic hair loss. When she landed in Dr. Glandt’s office at age 28, she weighed 180 pounds.

Less than 5 months later, Jerrilyn had lost 25 pounds, and her period had returned with some regularity. She said she used “food stamps,” known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), to buy most of her food at local delis because the meals served at the shelter were too heavy in starches. She starts her day with eggs, turkey bacon, and avocado.

“It was hard to give up carbohydrates because in my culture [Latina], we have nothing but carbs: rice, potatoes, yuca,” Jerrilyn shared. She noticed that carbs make her hungrier, but after 3 days of going low-carb, her cravings diminished. “It was like getting over an addiction,” she said.

Jerrilyn told me she’d seen many doctors but none as involved as Dr. Glandt. “It feels awesome to know that I have a lot of really useful information coming from her all the time.” The OwnaHealth app tracks weight, blood pressure, blood sugar, ketones, meals, mood, and cravings. Patients wear continuous glucose monitors and enter other information manually. Ketone bodies are used to measure dietary adherence and are obtained through finger pricks and test strips provided by OwnaHealth. Dr. Glandt gives patients her own food plan, along with free visual guides to low-carbohydrate foods by dietdoctor.com.

Dr. Glandt also sends her patients for regular blood work. She says she does not frequently see a rise in LDL cholesterol, which can sometimes occur on a low-carbohydrate diet. This effect is most common among people who are lean and fit. She says she doesn’t discontinue statins unless cholesterol levels improve significantly.

Samuel Gonzalez, age 56, weighed 275 pounds when he walked into Dr. Glandt’s office this past November. His A1c was 9.2%, but none of his previous doctors had diagnosed him with diabetes. “I was like a walking bag of sugar!” he joked.