User login

Mounjaro Beats Ozempic, So Why Isn’t It More Popular?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It’s July, which means our hospital is filled with new interns, residents, and fellows all eager to embark on a new stage of their career. It’s an exciting time — a bit of a scary time — but it’s also the time when the medical strategies I’ve been taking for granted get called into question. At this point in the year, I tend to get a lot of “why” questions. Why did you order that test? Why did you suspect that diagnosis? Why did you choose that medication?

Meds are the hardest, I find. Sure, I can explain that I prescribed a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist because the patient had diabetes and was overweight, and multiple studies show that this class of drug leads to weight loss and reduced mortality risk. But then I get the follow-up: Sure, but why THAT GLP-1 drug? Why did you pick semaglutide (Ozempic) over tirzepatide (Mounjaro)?

Here’s where I run out of good answers. Sometimes I choose a drug because that’s what the patient’s insurance has on their formulary. Sometimes it’s because it’s cheaper in general. Sometimes, it’s just force of habit. I know the correct dose, I have experience with the side effects — it’s comfortable.

What I can’t say is that I have solid evidence that one drug is superior to another, say from a randomized trial of semaglutide vs tirzepatide. I don’t have that evidence because that trial has never happened and, as I’ll explain in a minute, may never happen at all.

But we might have the next best thing. And the results may surprise you.

Why don’t we see more head-to-head trials of competitor drugs? The answer is pretty simple, honestly: risk management. For drugs that are on patent, like the GLP-1s, conducting a trial without the buy-in of the pharmaceutical company is simply too expensive — we can’t run a trial unless someone provides the drug for free. That gives the companies a lot of say in what trials get done, and it seems that most pharma companies have reached the same conclusion: A head-to-head trial is too risky. Be happy with the market share you have, and try to nibble away at the edges through good old-fashioned marketing.

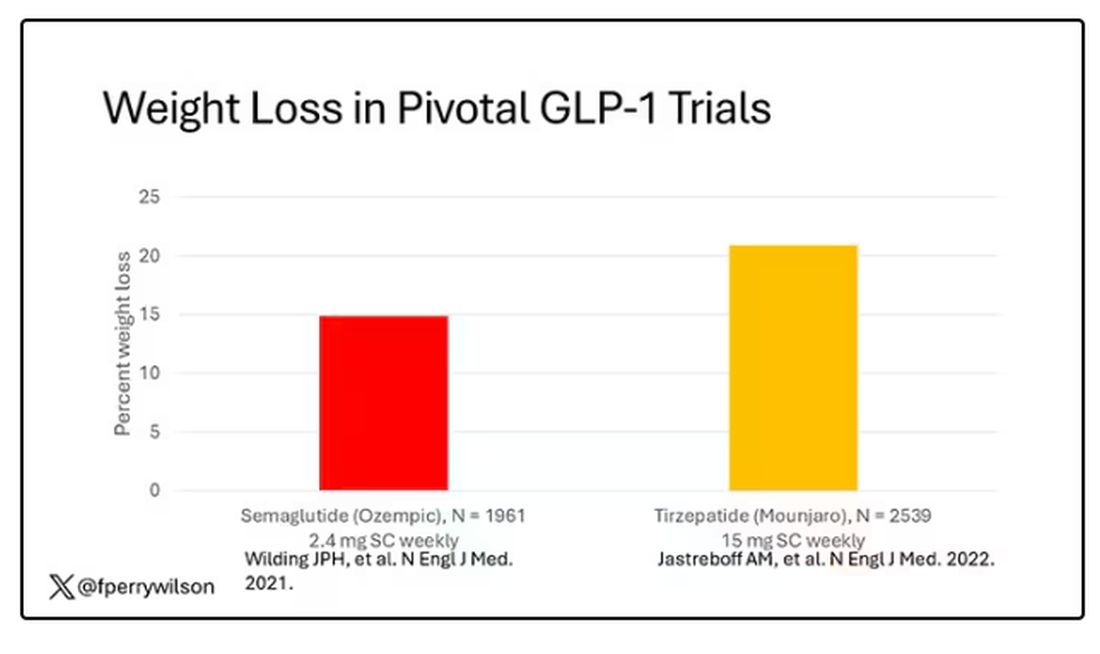

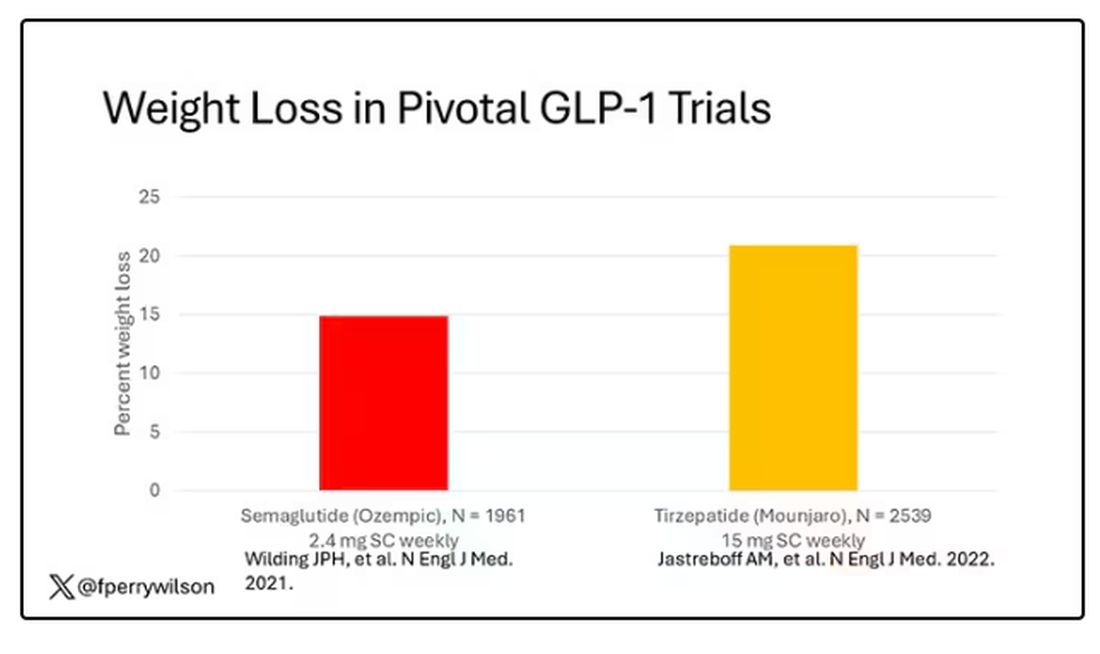

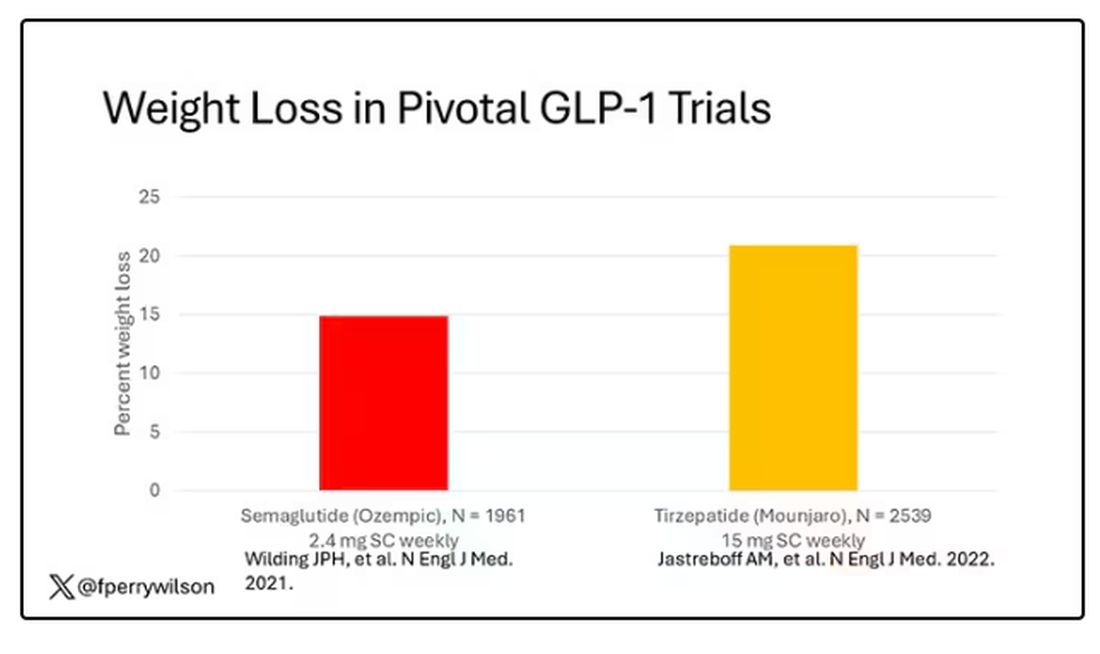

But if you look at the data that are out there, you might wonder why Ozempic is the market leader. I mean, sure, it’s a heck of a weight loss drug. But the weight loss in the trials of Mounjaro was actually a bit higher. It’s worth noting here that tirzepatide (Mounjaro) is not just a GLP-1 receptor agonist; it is also a gastric inhibitory polypeptide agonist.

But it’s very hard to compare the results of a trial pitting Ozempic against placebo with a totally different trial pitting Mounjaro against placebo. You can always argue that the patients studied were just too different at baseline — an apples and oranges situation.

Newly published, a study appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine uses real-world data and propensity-score matching to turn oranges back into apples. I’ll walk you through it.

The data and analysis here come from Truveta, a collective of various US healthcare systems that share a broad swath of electronic health record data. Researchers identified 41,222 adults with overweight or obesity who were prescribed semaglutide or tirzepatide between May 2022 and September 2023.

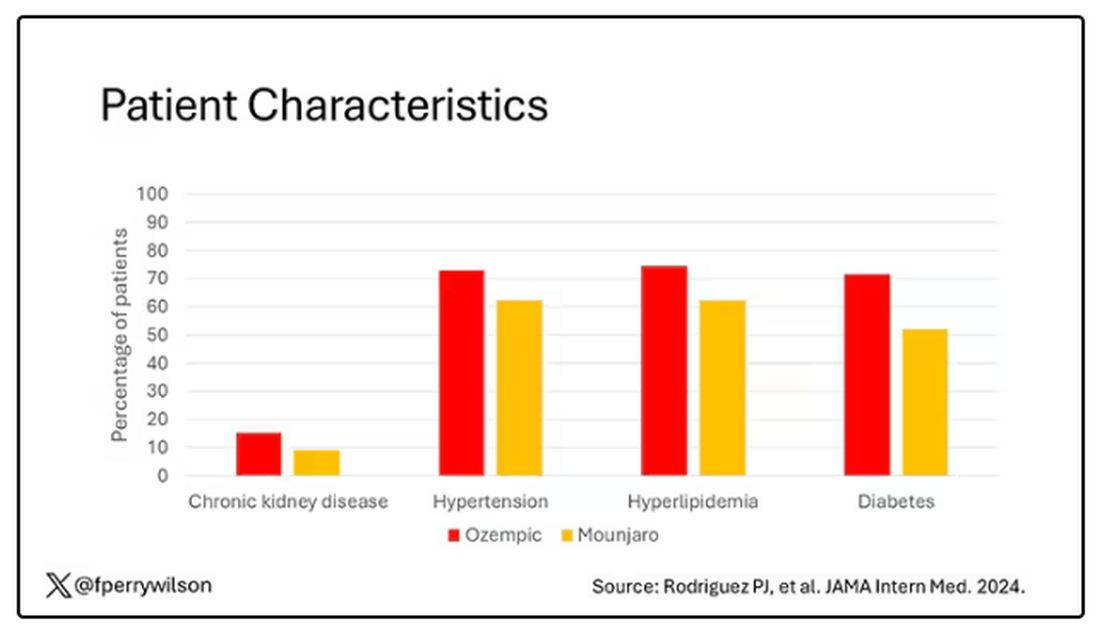

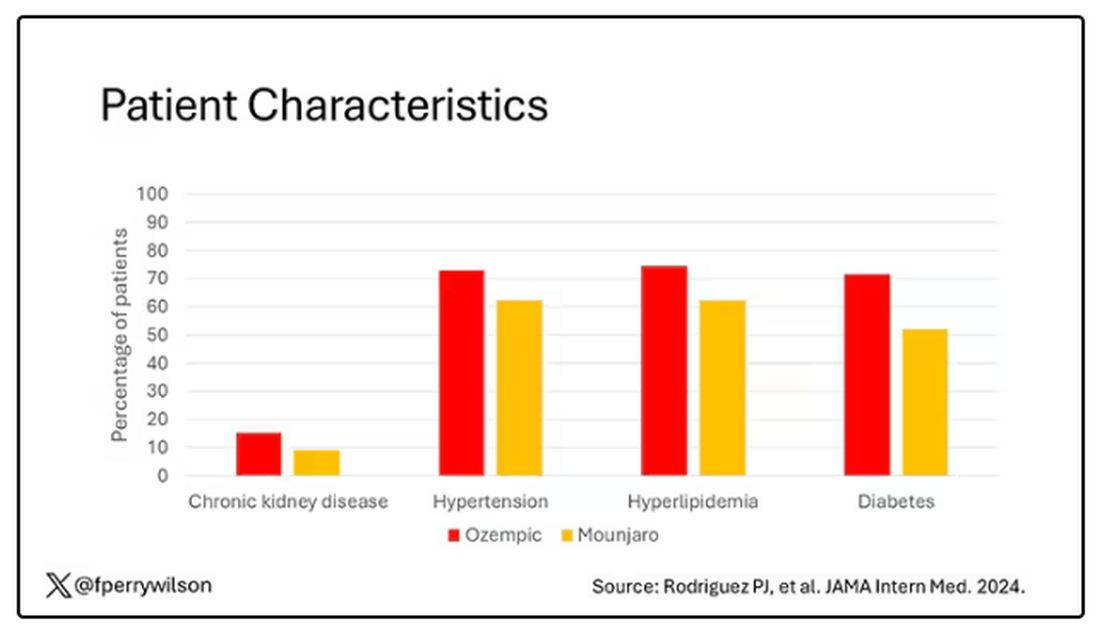

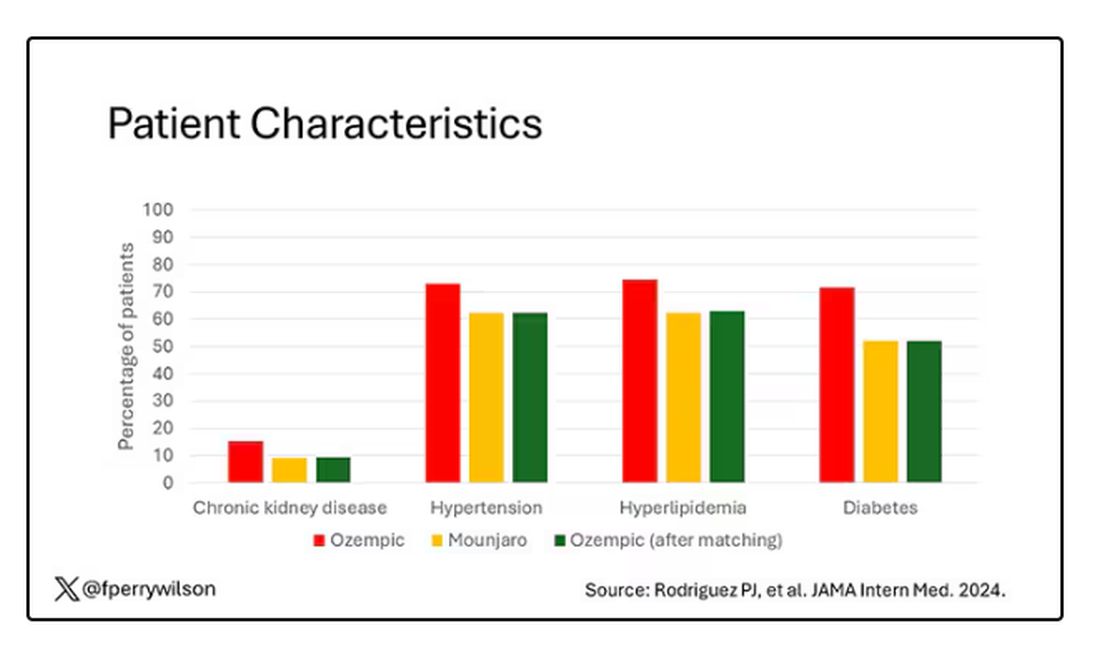

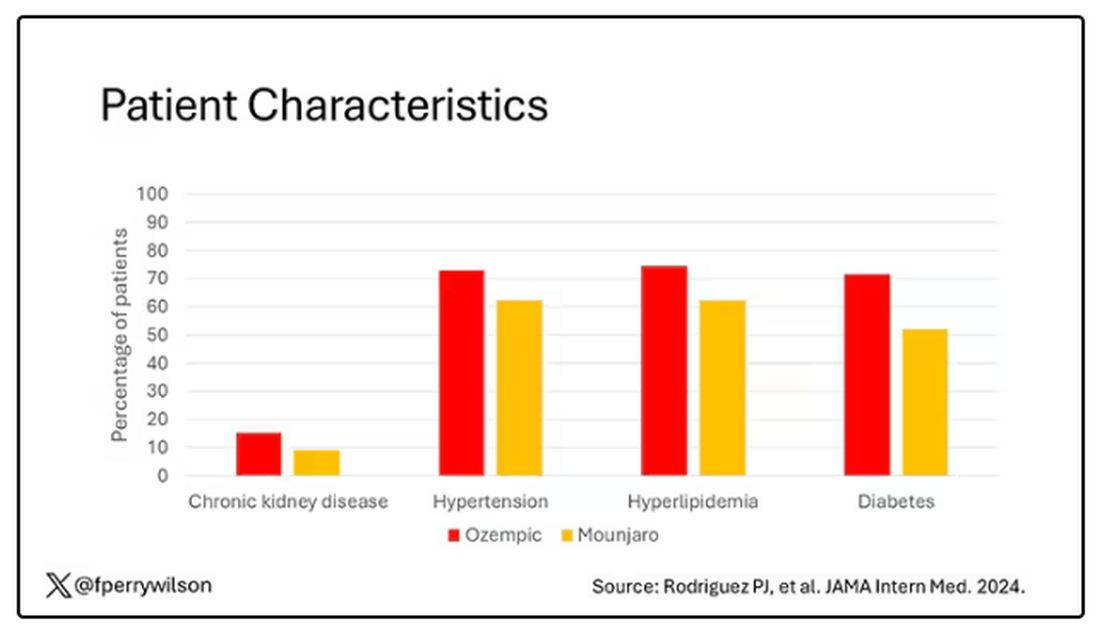

You’d be tempted to just see which group lost more weight over time, but that is the apples and oranges problem. People prescribed Mounjaro were different from people who were prescribed Ozempic. There are a variety of factors to look at here, but the vibe is that the Mounjaro group seems healthier at baseline. They were younger and had less kidney disease, less hypertension, and less hyperlipidemia. They had higher incomes and were more likely to be White. They were also dramatically less likely to have diabetes.

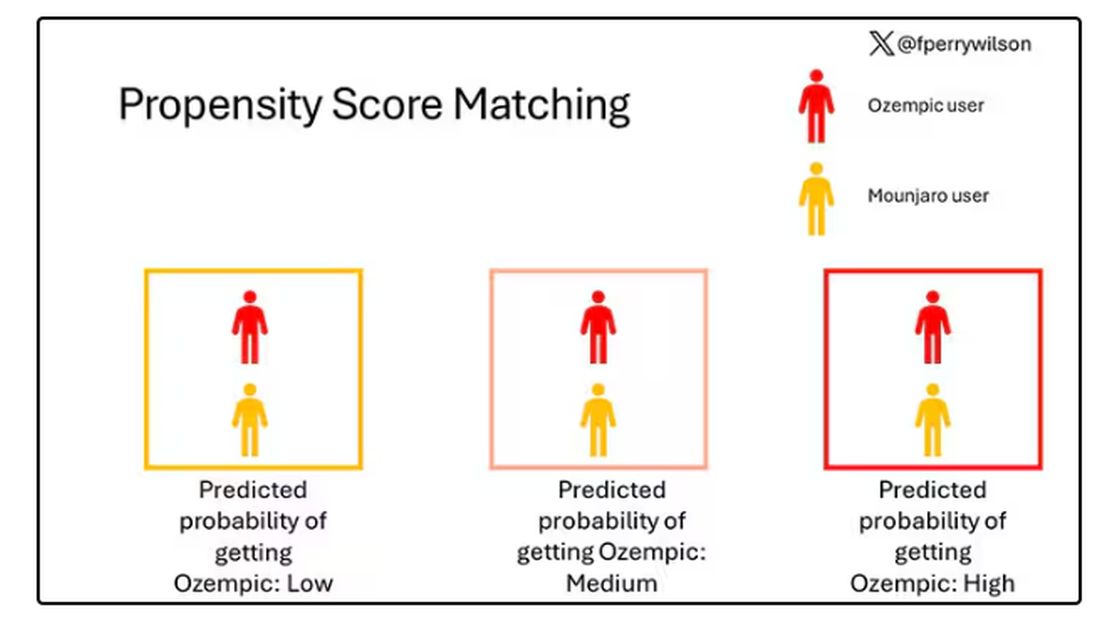

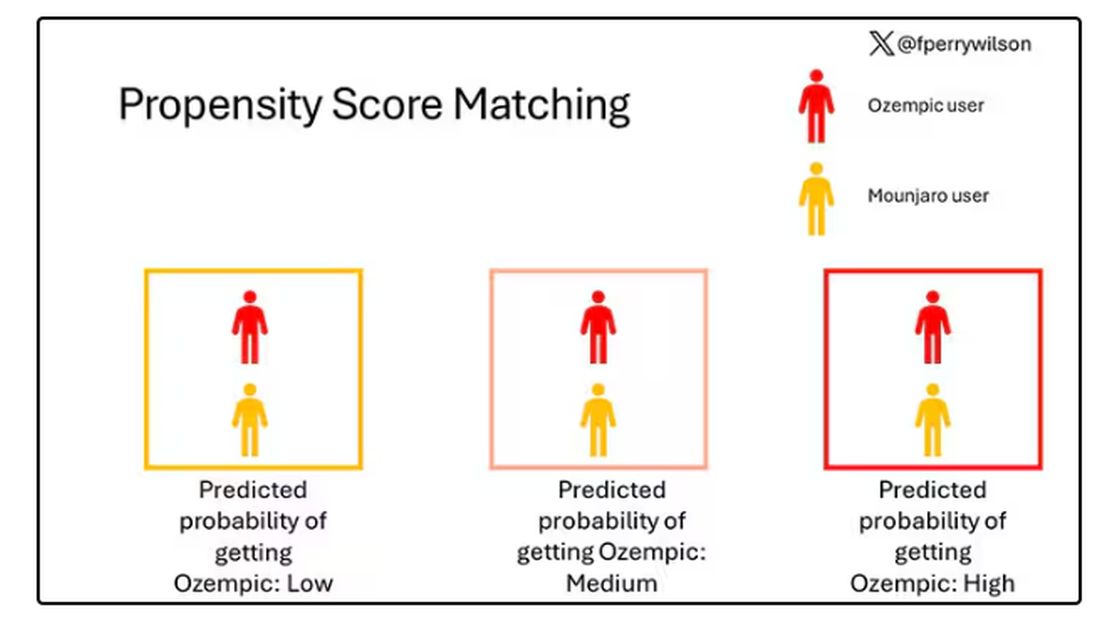

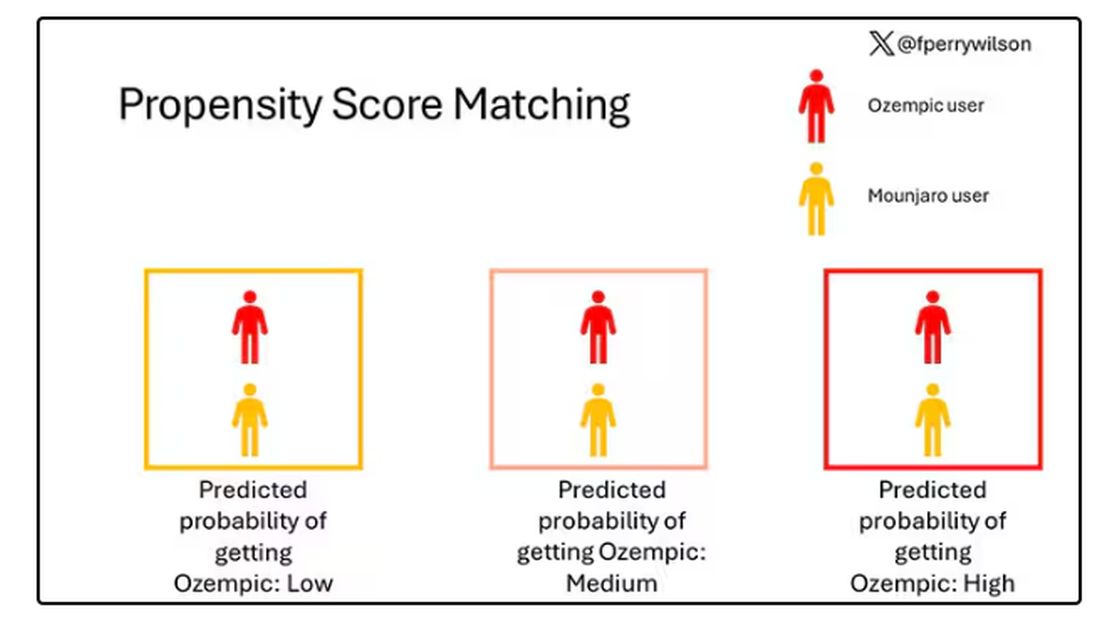

To account for this, the researchers used a statistical technique called propensity-score matching. Briefly, you create a model based on a variety of patient factors to predict who would be prescribed Ozempic and who would be prescribed Mounjaro. You then identify pairs of patients with similar probability (or propensity) of receiving, say, Ozempic, where one member of the pair got Ozempic and one got Mounjaro. Any unmatched individuals simply get dropped from the analysis.

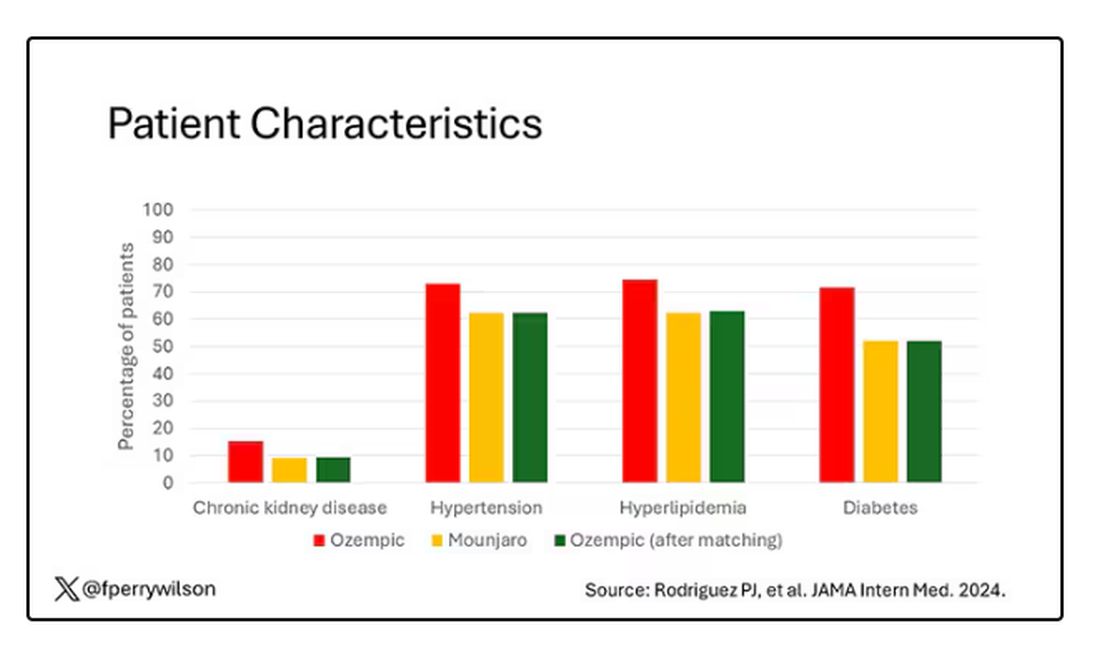

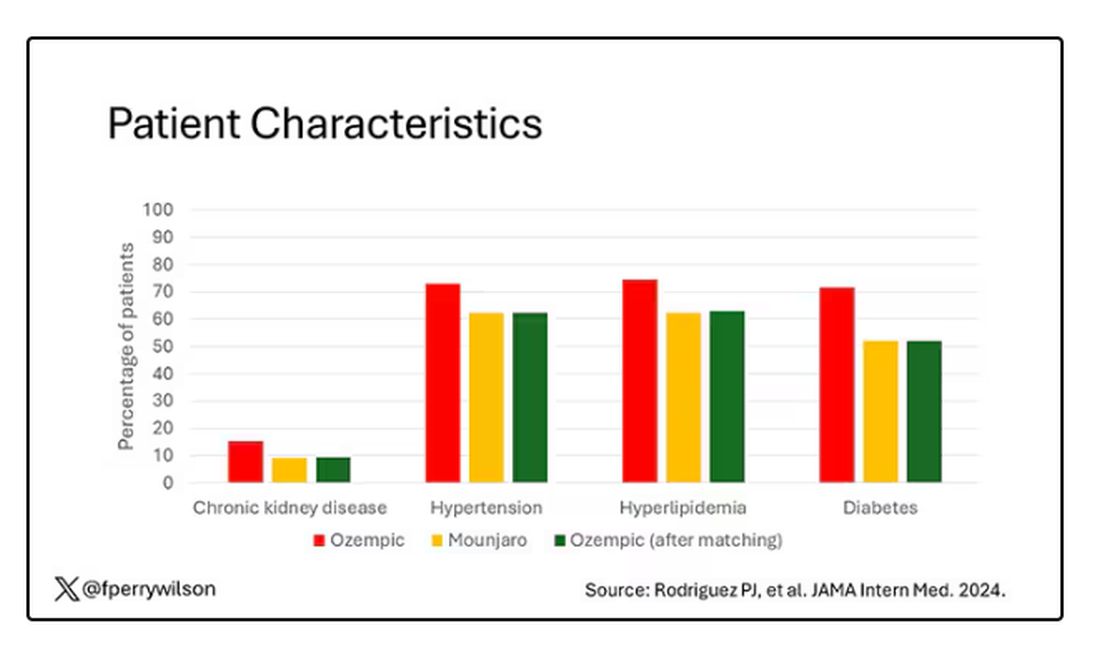

Thus, the researchers took the 41,222 individuals who started the analysis, of whom 9193 received Mounjaro, and identified the 9193 patients who got Ozempic that most closely matched the Mounjaro crowd. I know, it sounds confusing. But as an example, in the original dataset, 51.9% of those who got Mounjaro had diabetes compared with 71.5% of those who got Ozempic. Among the 9193 individuals who remained in the Ozempic group after matching, 52.1% had diabetes. By matching in this way, you balance your baseline characteristics. Turning apples into oranges. Or, maybe the better metaphor would be plucking the oranges out of a big pile of mostly apples.

Once that’s done, we can go back to do what we wanted to do in the beginning, which is to look at the weight loss between the groups.

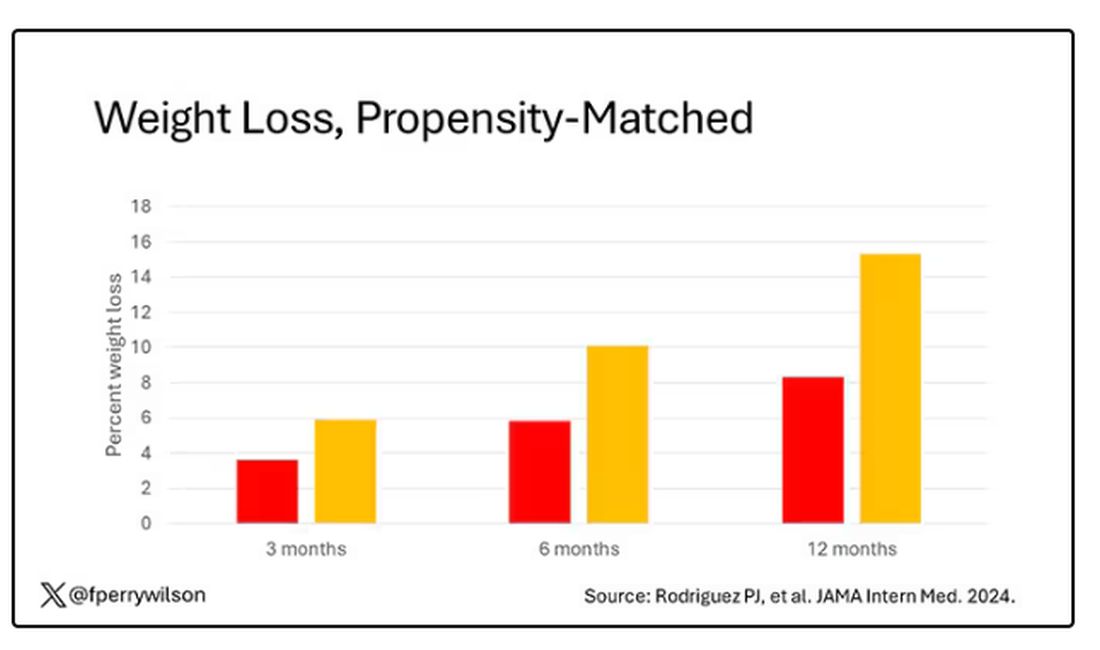

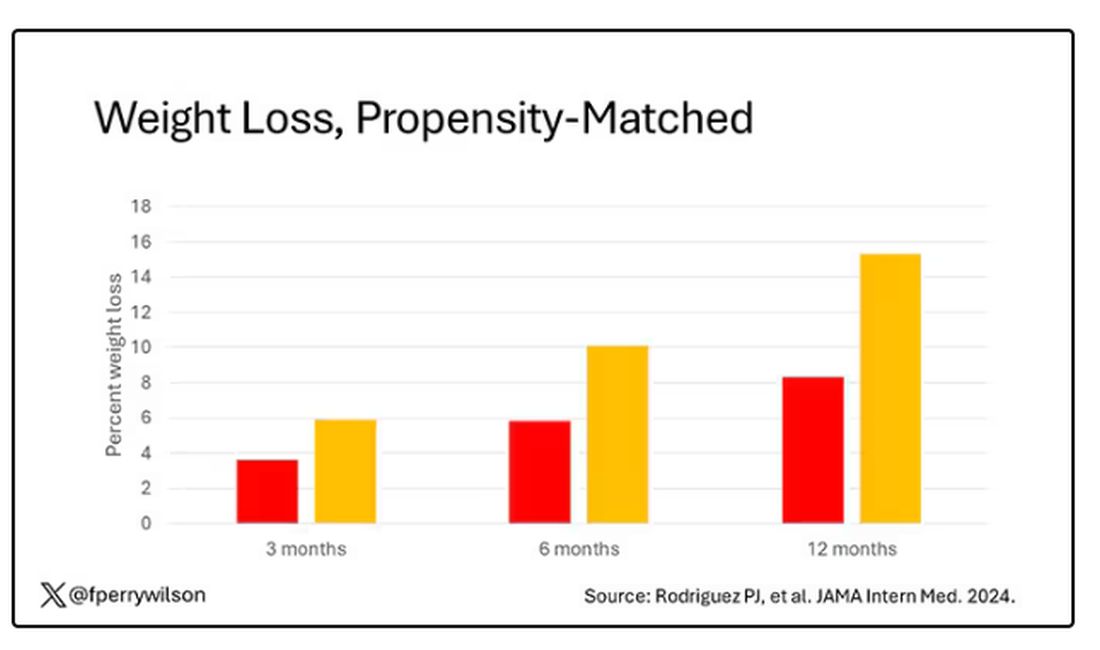

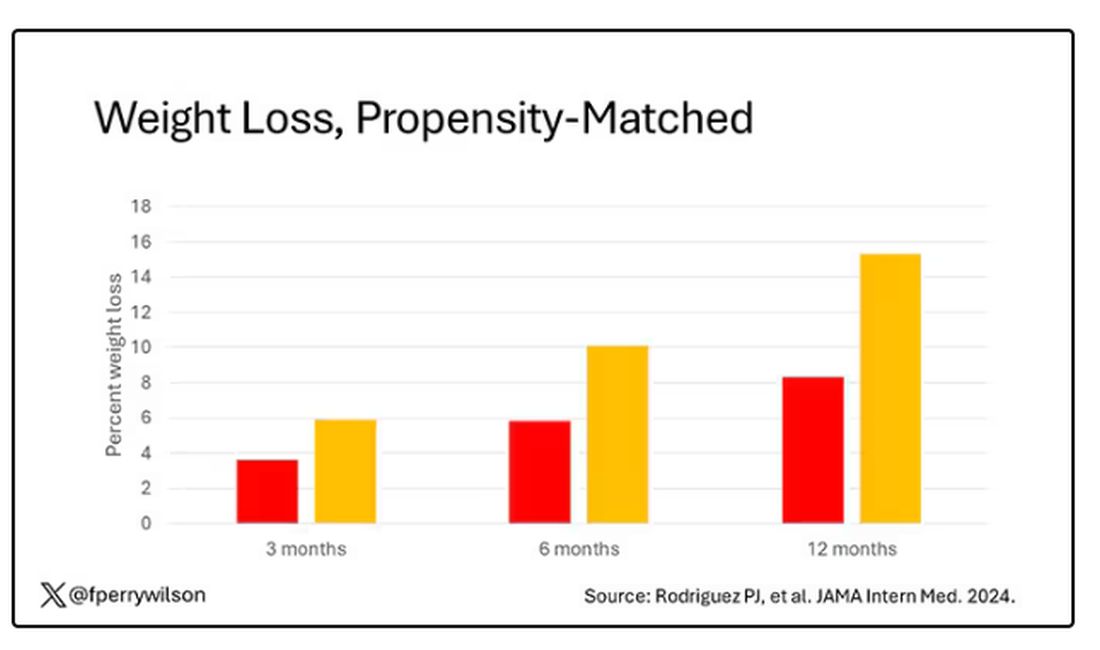

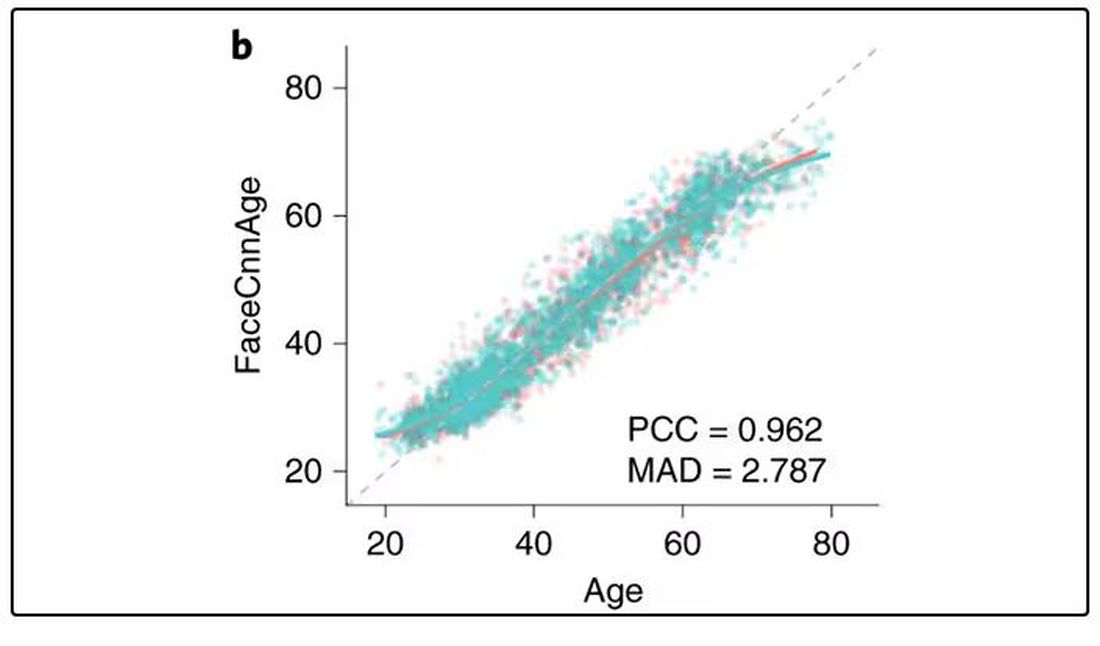

What I’m showing you here is the average percent change in body weight at 3, 6, and 12 months across the two drugs in the matched cohort. By a year out, you have basically 15% weight loss in the Mounjaro group compared with 8% or so in the Ozempic group.

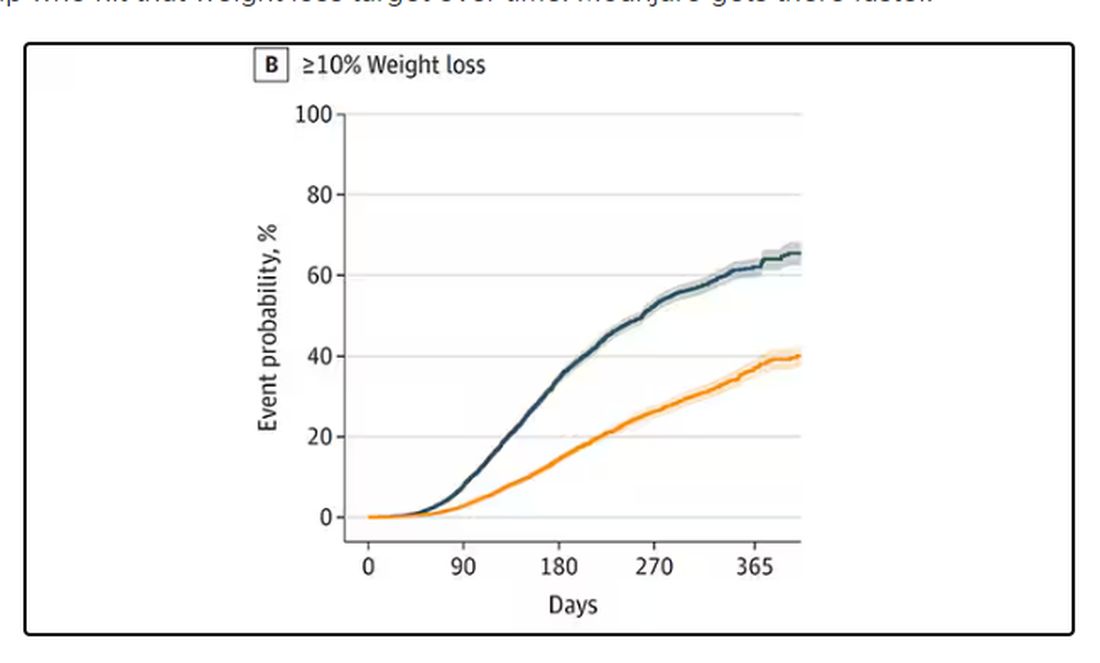

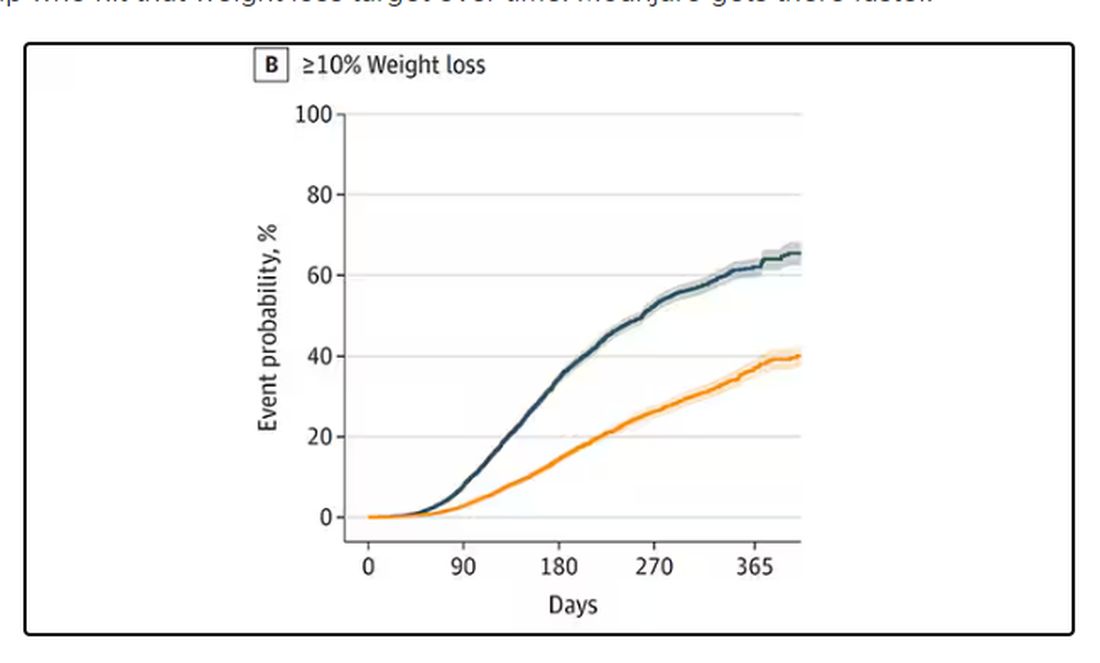

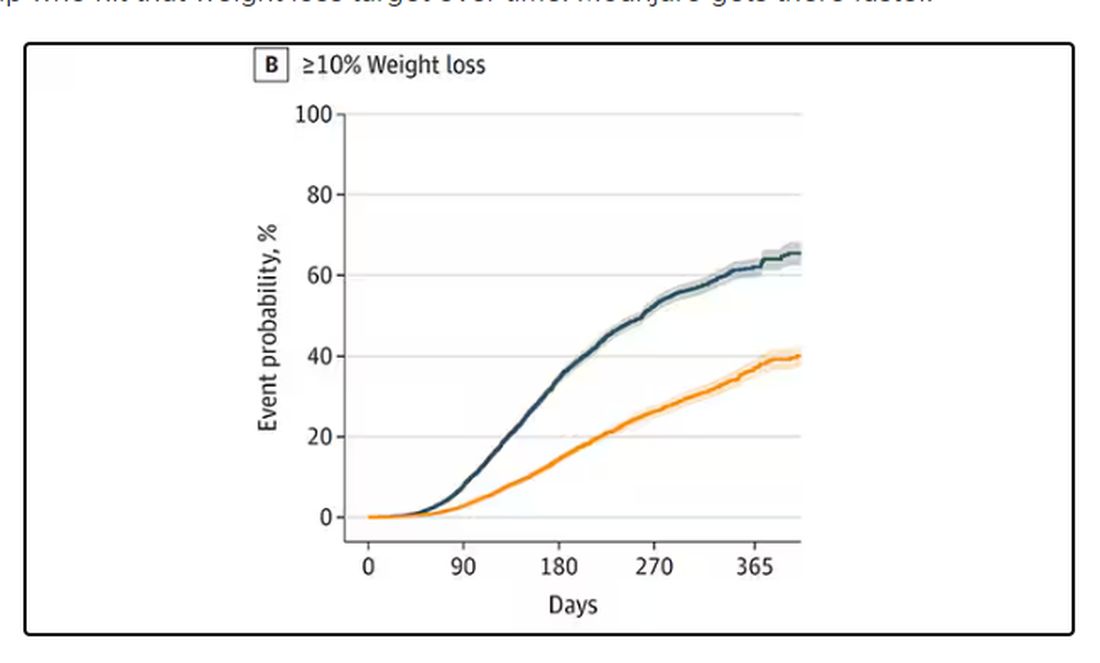

We can slice this a different way as well — asking what percent of people in each group achieve, say, 10% weight loss? This graph examines the percentage of each treatment group who hit that weight loss target over time. Mounjaro gets there faster.

I should point out that this was a so-called “on treatment” analysis: If people stopped taking either of the drugs, they were no longer included in the study. That tends to make drugs like this appear better than they are because as time goes on, you may weed out the people who stop the drug owing to lack of efficacy or to side effects. But in a sensitivity analysis, the authors see what happens if they just treat people as if they were taking the drug for the entire year once they had it prescribed, and the results, while not as dramatic, were broadly similar. Mounjaro still came out on top.

Adverse events— stuff like gastroparesis and pancreatitis — were rare, but rates were similar between the two groups.

It’s great to see studies like this that leverage real world data and a solid statistical underpinning to give us providers actionable information. Is it 100% definitive? No. But, especially considering the clinical trial data, I don’t think I’m going out on a limb to say that Mounjaro seems to be the more effective weight loss agent. That said, we don’t actually live in a world where we can prescribe medications based on a silly little thing like which is the most effective. Especially given the cost of these agents — the patient’s insurance status is going to guide our prescription pen more than this study ever could. And of course, given the demand for this class of agents and the fact that both are actually quite effective, you may be best off prescribing whatever you can get your hands on.

But I’d like to see more of this. When I do have a choice of a medication, when costs and availability are similar, I’d like to be able to answer that question of “why did you choose that one?” with an evidence-based answer: “It’s better.”

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It’s July, which means our hospital is filled with new interns, residents, and fellows all eager to embark on a new stage of their career. It’s an exciting time — a bit of a scary time — but it’s also the time when the medical strategies I’ve been taking for granted get called into question. At this point in the year, I tend to get a lot of “why” questions. Why did you order that test? Why did you suspect that diagnosis? Why did you choose that medication?

Meds are the hardest, I find. Sure, I can explain that I prescribed a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist because the patient had diabetes and was overweight, and multiple studies show that this class of drug leads to weight loss and reduced mortality risk. But then I get the follow-up: Sure, but why THAT GLP-1 drug? Why did you pick semaglutide (Ozempic) over tirzepatide (Mounjaro)?

Here’s where I run out of good answers. Sometimes I choose a drug because that’s what the patient’s insurance has on their formulary. Sometimes it’s because it’s cheaper in general. Sometimes, it’s just force of habit. I know the correct dose, I have experience with the side effects — it’s comfortable.

What I can’t say is that I have solid evidence that one drug is superior to another, say from a randomized trial of semaglutide vs tirzepatide. I don’t have that evidence because that trial has never happened and, as I’ll explain in a minute, may never happen at all.

But we might have the next best thing. And the results may surprise you.

Why don’t we see more head-to-head trials of competitor drugs? The answer is pretty simple, honestly: risk management. For drugs that are on patent, like the GLP-1s, conducting a trial without the buy-in of the pharmaceutical company is simply too expensive — we can’t run a trial unless someone provides the drug for free. That gives the companies a lot of say in what trials get done, and it seems that most pharma companies have reached the same conclusion: A head-to-head trial is too risky. Be happy with the market share you have, and try to nibble away at the edges through good old-fashioned marketing.

But if you look at the data that are out there, you might wonder why Ozempic is the market leader. I mean, sure, it’s a heck of a weight loss drug. But the weight loss in the trials of Mounjaro was actually a bit higher. It’s worth noting here that tirzepatide (Mounjaro) is not just a GLP-1 receptor agonist; it is also a gastric inhibitory polypeptide agonist.

But it’s very hard to compare the results of a trial pitting Ozempic against placebo with a totally different trial pitting Mounjaro against placebo. You can always argue that the patients studied were just too different at baseline — an apples and oranges situation.

Newly published, a study appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine uses real-world data and propensity-score matching to turn oranges back into apples. I’ll walk you through it.

The data and analysis here come from Truveta, a collective of various US healthcare systems that share a broad swath of electronic health record data. Researchers identified 41,222 adults with overweight or obesity who were prescribed semaglutide or tirzepatide between May 2022 and September 2023.

You’d be tempted to just see which group lost more weight over time, but that is the apples and oranges problem. People prescribed Mounjaro were different from people who were prescribed Ozempic. There are a variety of factors to look at here, but the vibe is that the Mounjaro group seems healthier at baseline. They were younger and had less kidney disease, less hypertension, and less hyperlipidemia. They had higher incomes and were more likely to be White. They were also dramatically less likely to have diabetes.

To account for this, the researchers used a statistical technique called propensity-score matching. Briefly, you create a model based on a variety of patient factors to predict who would be prescribed Ozempic and who would be prescribed Mounjaro. You then identify pairs of patients with similar probability (or propensity) of receiving, say, Ozempic, where one member of the pair got Ozempic and one got Mounjaro. Any unmatched individuals simply get dropped from the analysis.

Thus, the researchers took the 41,222 individuals who started the analysis, of whom 9193 received Mounjaro, and identified the 9193 patients who got Ozempic that most closely matched the Mounjaro crowd. I know, it sounds confusing. But as an example, in the original dataset, 51.9% of those who got Mounjaro had diabetes compared with 71.5% of those who got Ozempic. Among the 9193 individuals who remained in the Ozempic group after matching, 52.1% had diabetes. By matching in this way, you balance your baseline characteristics. Turning apples into oranges. Or, maybe the better metaphor would be plucking the oranges out of a big pile of mostly apples.

Once that’s done, we can go back to do what we wanted to do in the beginning, which is to look at the weight loss between the groups.

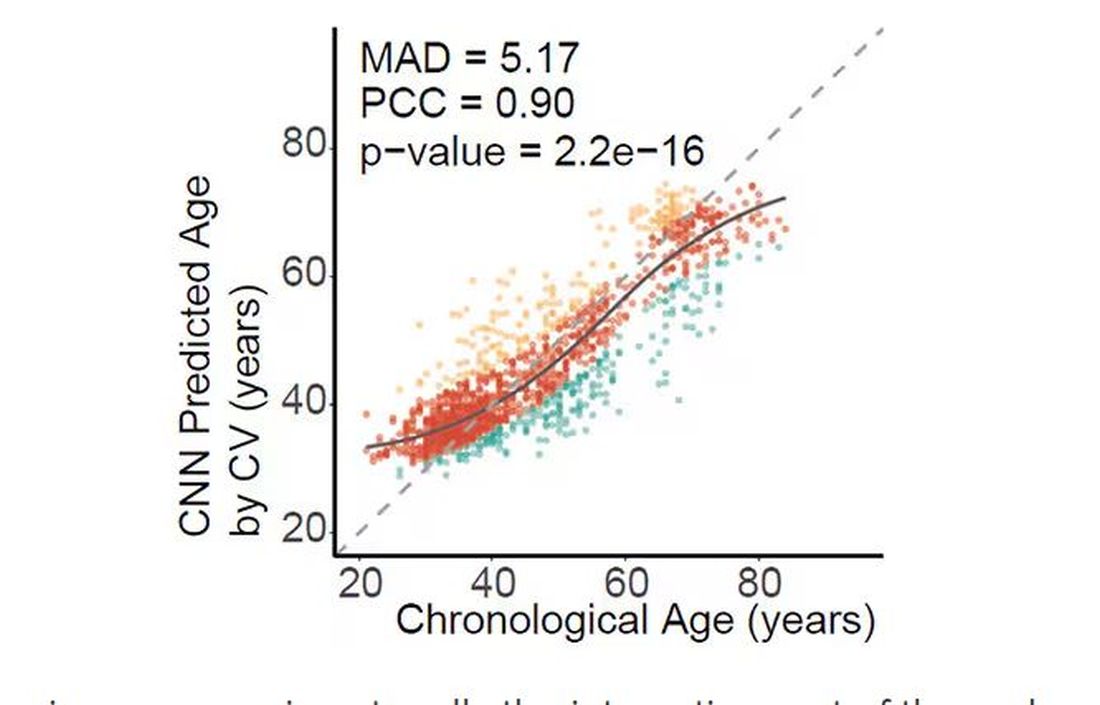

What I’m showing you here is the average percent change in body weight at 3, 6, and 12 months across the two drugs in the matched cohort. By a year out, you have basically 15% weight loss in the Mounjaro group compared with 8% or so in the Ozempic group.

We can slice this a different way as well — asking what percent of people in each group achieve, say, 10% weight loss? This graph examines the percentage of each treatment group who hit that weight loss target over time. Mounjaro gets there faster.

I should point out that this was a so-called “on treatment” analysis: If people stopped taking either of the drugs, they were no longer included in the study. That tends to make drugs like this appear better than they are because as time goes on, you may weed out the people who stop the drug owing to lack of efficacy or to side effects. But in a sensitivity analysis, the authors see what happens if they just treat people as if they were taking the drug for the entire year once they had it prescribed, and the results, while not as dramatic, were broadly similar. Mounjaro still came out on top.

Adverse events— stuff like gastroparesis and pancreatitis — were rare, but rates were similar between the two groups.

It’s great to see studies like this that leverage real world data and a solid statistical underpinning to give us providers actionable information. Is it 100% definitive? No. But, especially considering the clinical trial data, I don’t think I’m going out on a limb to say that Mounjaro seems to be the more effective weight loss agent. That said, we don’t actually live in a world where we can prescribe medications based on a silly little thing like which is the most effective. Especially given the cost of these agents — the patient’s insurance status is going to guide our prescription pen more than this study ever could. And of course, given the demand for this class of agents and the fact that both are actually quite effective, you may be best off prescribing whatever you can get your hands on.

But I’d like to see more of this. When I do have a choice of a medication, when costs and availability are similar, I’d like to be able to answer that question of “why did you choose that one?” with an evidence-based answer: “It’s better.”

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It’s July, which means our hospital is filled with new interns, residents, and fellows all eager to embark on a new stage of their career. It’s an exciting time — a bit of a scary time — but it’s also the time when the medical strategies I’ve been taking for granted get called into question. At this point in the year, I tend to get a lot of “why” questions. Why did you order that test? Why did you suspect that diagnosis? Why did you choose that medication?

Meds are the hardest, I find. Sure, I can explain that I prescribed a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist because the patient had diabetes and was overweight, and multiple studies show that this class of drug leads to weight loss and reduced mortality risk. But then I get the follow-up: Sure, but why THAT GLP-1 drug? Why did you pick semaglutide (Ozempic) over tirzepatide (Mounjaro)?

Here’s where I run out of good answers. Sometimes I choose a drug because that’s what the patient’s insurance has on their formulary. Sometimes it’s because it’s cheaper in general. Sometimes, it’s just force of habit. I know the correct dose, I have experience with the side effects — it’s comfortable.

What I can’t say is that I have solid evidence that one drug is superior to another, say from a randomized trial of semaglutide vs tirzepatide. I don’t have that evidence because that trial has never happened and, as I’ll explain in a minute, may never happen at all.

But we might have the next best thing. And the results may surprise you.

Why don’t we see more head-to-head trials of competitor drugs? The answer is pretty simple, honestly: risk management. For drugs that are on patent, like the GLP-1s, conducting a trial without the buy-in of the pharmaceutical company is simply too expensive — we can’t run a trial unless someone provides the drug for free. That gives the companies a lot of say in what trials get done, and it seems that most pharma companies have reached the same conclusion: A head-to-head trial is too risky. Be happy with the market share you have, and try to nibble away at the edges through good old-fashioned marketing.

But if you look at the data that are out there, you might wonder why Ozempic is the market leader. I mean, sure, it’s a heck of a weight loss drug. But the weight loss in the trials of Mounjaro was actually a bit higher. It’s worth noting here that tirzepatide (Mounjaro) is not just a GLP-1 receptor agonist; it is also a gastric inhibitory polypeptide agonist.

But it’s very hard to compare the results of a trial pitting Ozempic against placebo with a totally different trial pitting Mounjaro against placebo. You can always argue that the patients studied were just too different at baseline — an apples and oranges situation.

Newly published, a study appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine uses real-world data and propensity-score matching to turn oranges back into apples. I’ll walk you through it.

The data and analysis here come from Truveta, a collective of various US healthcare systems that share a broad swath of electronic health record data. Researchers identified 41,222 adults with overweight or obesity who were prescribed semaglutide or tirzepatide between May 2022 and September 2023.

You’d be tempted to just see which group lost more weight over time, but that is the apples and oranges problem. People prescribed Mounjaro were different from people who were prescribed Ozempic. There are a variety of factors to look at here, but the vibe is that the Mounjaro group seems healthier at baseline. They were younger and had less kidney disease, less hypertension, and less hyperlipidemia. They had higher incomes and were more likely to be White. They were also dramatically less likely to have diabetes.

To account for this, the researchers used a statistical technique called propensity-score matching. Briefly, you create a model based on a variety of patient factors to predict who would be prescribed Ozempic and who would be prescribed Mounjaro. You then identify pairs of patients with similar probability (or propensity) of receiving, say, Ozempic, where one member of the pair got Ozempic and one got Mounjaro. Any unmatched individuals simply get dropped from the analysis.

Thus, the researchers took the 41,222 individuals who started the analysis, of whom 9193 received Mounjaro, and identified the 9193 patients who got Ozempic that most closely matched the Mounjaro crowd. I know, it sounds confusing. But as an example, in the original dataset, 51.9% of those who got Mounjaro had diabetes compared with 71.5% of those who got Ozempic. Among the 9193 individuals who remained in the Ozempic group after matching, 52.1% had diabetes. By matching in this way, you balance your baseline characteristics. Turning apples into oranges. Or, maybe the better metaphor would be plucking the oranges out of a big pile of mostly apples.

Once that’s done, we can go back to do what we wanted to do in the beginning, which is to look at the weight loss between the groups.

What I’m showing you here is the average percent change in body weight at 3, 6, and 12 months across the two drugs in the matched cohort. By a year out, you have basically 15% weight loss in the Mounjaro group compared with 8% or so in the Ozempic group.

We can slice this a different way as well — asking what percent of people in each group achieve, say, 10% weight loss? This graph examines the percentage of each treatment group who hit that weight loss target over time. Mounjaro gets there faster.

I should point out that this was a so-called “on treatment” analysis: If people stopped taking either of the drugs, they were no longer included in the study. That tends to make drugs like this appear better than they are because as time goes on, you may weed out the people who stop the drug owing to lack of efficacy or to side effects. But in a sensitivity analysis, the authors see what happens if they just treat people as if they were taking the drug for the entire year once they had it prescribed, and the results, while not as dramatic, were broadly similar. Mounjaro still came out on top.

Adverse events— stuff like gastroparesis and pancreatitis — were rare, but rates were similar between the two groups.

It’s great to see studies like this that leverage real world data and a solid statistical underpinning to give us providers actionable information. Is it 100% definitive? No. But, especially considering the clinical trial data, I don’t think I’m going out on a limb to say that Mounjaro seems to be the more effective weight loss agent. That said, we don’t actually live in a world where we can prescribe medications based on a silly little thing like which is the most effective. Especially given the cost of these agents — the patient’s insurance status is going to guide our prescription pen more than this study ever could. And of course, given the demand for this class of agents and the fact that both are actually quite effective, you may be best off prescribing whatever you can get your hands on.

But I’d like to see more of this. When I do have a choice of a medication, when costs and availability are similar, I’d like to be able to answer that question of “why did you choose that one?” with an evidence-based answer: “It’s better.”

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Chronic Neck Pain: A Primary Care Approach

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome to The Curbsiders. I’m here with my great friend and America’s primary care physician, Dr. Paul Nelson Williams. We’re going to be talking about the evaluation of chronic neck pain, which is a really common complaint in primary care. So, Paul, what are the three buckets of neck pain?

Paul N. Williams, MD: Well, as our listeners probably know, neck pain is extraordinarily common. There are three big buckets. There is mechanical neck pain, which is sort of the bread-and-butter “my neck just hurts” — probably the one you’re going to see most commonly in the office. We’ll get into that in just a second.

The second bucket is cervical radiculopathy. We see a little bit more neurologic symptoms as part of the presentation. They may have weakness. They may have pain.

The third type of neck pain is cervical myelopathy, which is the one that probably warrants more aggressive follow-up and evaluation, and potentially even management. And that is typically your older patients in nontraumatic cases, who have bony impingement on the central spinal cord, often with upper motor neuron signs, and it can ultimately be very devastating. It’s almost a spectrum of presentations to worry about in terms of severity and outcomes.

We’ll start with the mechanical neck pain. It’s the one that we see the most commonly in the primary care office. We’ve all dealt with this. This is the patient who’s got localized neck pain that doesn’t really radiate anywhere; it kind of sits in the middle of the neck. In fact, if you actually poke back there where the patient says “ouch,” you’re probably in the right ballpark. The etiology and pathophysiology, weirdly, are still not super well-defined, but it’s probably mostly myofascial in etiology. And as such, it often gets better no matter what you do. It will probably get better with time.

You are not going to have neurologic deficits with this type of neck pain. There’s not going to be weakness, or radiation down the arm, or upper motor neuron signs. No one is mentioning the urinary symptoms with this. You can treat it with NSAIDs and physical therapy, which may be necessary if it persists. Massage can sometimes be helpful, but basically you’re just kind of supporting the patients through their own natural healing process. Physical therapy might help with the ergonomics and help make sure that they position themselves and move in a way that does not exacerbate the underlying structures. That is probably the one that we see the most and in some ways is probably the easiest to manage.

Dr. Watto: This is the one that we generally should be least worried about. But cervical radiculopathy, which is the second bucket, is not as severe as cervical myelopathy, so it’s kind of in between the two. Cervical radiculopathy is basically the patient who has neck pain that’s going down one arm or the other, usually not both arms because that would be weird for them to have symmetric radiculopathy. It’s a nerve being pinched somewhere, usually more on one side than the other.

The good news for patients is that the natural history is that it’s going to get better over time, almost no matter what we do. I almost think of this akin to sciatica. Usually sciatica and cervical radiculopathy do not have any motor weakness along with them. It’s really just the pain and maybe a little bit of mild sensory symptoms. So, you can reassure the patient that this usually goes away. Our guest said he sometimes gives gabapentin for this. That’s not my practice. I would be more likely to refer to physical therapy or try some NSAIDs if they’re really having trouble functioning or maybe some muscle relaxants. But they aren’t going to need to go to surgery.

What about cervical myelopathy, Paul? Do those patients need surgery?

Dr. Williams: Yes. The idea with cervical myelopathy is to keep it from progressing. It typically occurs in older patients. It’s like arthritis — a sort of bony buildup that compresses on the spinal cord itself. These patients will often have neck pain but not always. It’s also associated with impairments in motor function and other neurologic deficits. So, the patients may report that they have difficulty buttoning their buttons or managing fine-motor skills. They may have radicular symptoms down their arms. They may have an abnormal physical examination. They may have weakness on exam, but they’ll have a positive Hoffmann’s test where you flick the middle finger and look for flexion of the first finger and the thumb. They may have abnormal tandem gait, or patellar or Achilles hyperreflexia. Their neuro exam will not be normal much of the time, and in later cases because it’s upper motor neuron disease, they may even report urinary symptoms like urinary hesitancy or just a feeling of general unsteadiness of the gait, even though we’re at the cervical level. If you suspect myelopathy — and the trick is to think about it and recognize it when you see it — then you should send them for an MRI. If it persists or they have rapid regression, you get the MRI and refer them to neurosurgery. It’s not necessarily a neurosurgical emergency, but things should move along fairly briskly once you’ve actually identified it.

Dr. Watto: Dr. Mikula made the point that if someone comes to you in a wheelchair, they are probably not going to regain the ability to walk. You’re really trying to prevent progression. If they are already severely disabled, they’re probably not going to get totally back to full functioning, even with surgery. You’re just trying to prevent things from getting worse. That’s the main reason to identify this and get the patient to surgery.

We covered a lot more about neck pain. This was a very superficial review of what we talked about with Dr. Anthony Mikula. Click here to listen to the full podcast.

Matthew F. Watto is clinical assistant professor, Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at University of Pennsylvania, and internist, Department of Medicine, Hospital Medicine Section, Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Paul N. Williams is associate professor of clinical medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, Lewis Katz School of Medicine, and staff physician, Department of General Internal Medicine, Temple Internal Medicine Associates, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for The Curbsiders; received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from The Curbsiders.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome to The Curbsiders. I’m here with my great friend and America’s primary care physician, Dr. Paul Nelson Williams. We’re going to be talking about the evaluation of chronic neck pain, which is a really common complaint in primary care. So, Paul, what are the three buckets of neck pain?

Paul N. Williams, MD: Well, as our listeners probably know, neck pain is extraordinarily common. There are three big buckets. There is mechanical neck pain, which is sort of the bread-and-butter “my neck just hurts” — probably the one you’re going to see most commonly in the office. We’ll get into that in just a second.

The second bucket is cervical radiculopathy. We see a little bit more neurologic symptoms as part of the presentation. They may have weakness. They may have pain.

The third type of neck pain is cervical myelopathy, which is the one that probably warrants more aggressive follow-up and evaluation, and potentially even management. And that is typically your older patients in nontraumatic cases, who have bony impingement on the central spinal cord, often with upper motor neuron signs, and it can ultimately be very devastating. It’s almost a spectrum of presentations to worry about in terms of severity and outcomes.

We’ll start with the mechanical neck pain. It’s the one that we see the most commonly in the primary care office. We’ve all dealt with this. This is the patient who’s got localized neck pain that doesn’t really radiate anywhere; it kind of sits in the middle of the neck. In fact, if you actually poke back there where the patient says “ouch,” you’re probably in the right ballpark. The etiology and pathophysiology, weirdly, are still not super well-defined, but it’s probably mostly myofascial in etiology. And as such, it often gets better no matter what you do. It will probably get better with time.

You are not going to have neurologic deficits with this type of neck pain. There’s not going to be weakness, or radiation down the arm, or upper motor neuron signs. No one is mentioning the urinary symptoms with this. You can treat it with NSAIDs and physical therapy, which may be necessary if it persists. Massage can sometimes be helpful, but basically you’re just kind of supporting the patients through their own natural healing process. Physical therapy might help with the ergonomics and help make sure that they position themselves and move in a way that does not exacerbate the underlying structures. That is probably the one that we see the most and in some ways is probably the easiest to manage.

Dr. Watto: This is the one that we generally should be least worried about. But cervical radiculopathy, which is the second bucket, is not as severe as cervical myelopathy, so it’s kind of in between the two. Cervical radiculopathy is basically the patient who has neck pain that’s going down one arm or the other, usually not both arms because that would be weird for them to have symmetric radiculopathy. It’s a nerve being pinched somewhere, usually more on one side than the other.

The good news for patients is that the natural history is that it’s going to get better over time, almost no matter what we do. I almost think of this akin to sciatica. Usually sciatica and cervical radiculopathy do not have any motor weakness along with them. It’s really just the pain and maybe a little bit of mild sensory symptoms. So, you can reassure the patient that this usually goes away. Our guest said he sometimes gives gabapentin for this. That’s not my practice. I would be more likely to refer to physical therapy or try some NSAIDs if they’re really having trouble functioning or maybe some muscle relaxants. But they aren’t going to need to go to surgery.

What about cervical myelopathy, Paul? Do those patients need surgery?

Dr. Williams: Yes. The idea with cervical myelopathy is to keep it from progressing. It typically occurs in older patients. It’s like arthritis — a sort of bony buildup that compresses on the spinal cord itself. These patients will often have neck pain but not always. It’s also associated with impairments in motor function and other neurologic deficits. So, the patients may report that they have difficulty buttoning their buttons or managing fine-motor skills. They may have radicular symptoms down their arms. They may have an abnormal physical examination. They may have weakness on exam, but they’ll have a positive Hoffmann’s test where you flick the middle finger and look for flexion of the first finger and the thumb. They may have abnormal tandem gait, or patellar or Achilles hyperreflexia. Their neuro exam will not be normal much of the time, and in later cases because it’s upper motor neuron disease, they may even report urinary symptoms like urinary hesitancy or just a feeling of general unsteadiness of the gait, even though we’re at the cervical level. If you suspect myelopathy — and the trick is to think about it and recognize it when you see it — then you should send them for an MRI. If it persists or they have rapid regression, you get the MRI and refer them to neurosurgery. It’s not necessarily a neurosurgical emergency, but things should move along fairly briskly once you’ve actually identified it.

Dr. Watto: Dr. Mikula made the point that if someone comes to you in a wheelchair, they are probably not going to regain the ability to walk. You’re really trying to prevent progression. If they are already severely disabled, they’re probably not going to get totally back to full functioning, even with surgery. You’re just trying to prevent things from getting worse. That’s the main reason to identify this and get the patient to surgery.

We covered a lot more about neck pain. This was a very superficial review of what we talked about with Dr. Anthony Mikula. Click here to listen to the full podcast.

Matthew F. Watto is clinical assistant professor, Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at University of Pennsylvania, and internist, Department of Medicine, Hospital Medicine Section, Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Paul N. Williams is associate professor of clinical medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, Lewis Katz School of Medicine, and staff physician, Department of General Internal Medicine, Temple Internal Medicine Associates, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for The Curbsiders; received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from The Curbsiders.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome to The Curbsiders. I’m here with my great friend and America’s primary care physician, Dr. Paul Nelson Williams. We’re going to be talking about the evaluation of chronic neck pain, which is a really common complaint in primary care. So, Paul, what are the three buckets of neck pain?

Paul N. Williams, MD: Well, as our listeners probably know, neck pain is extraordinarily common. There are three big buckets. There is mechanical neck pain, which is sort of the bread-and-butter “my neck just hurts” — probably the one you’re going to see most commonly in the office. We’ll get into that in just a second.

The second bucket is cervical radiculopathy. We see a little bit more neurologic symptoms as part of the presentation. They may have weakness. They may have pain.

The third type of neck pain is cervical myelopathy, which is the one that probably warrants more aggressive follow-up and evaluation, and potentially even management. And that is typically your older patients in nontraumatic cases, who have bony impingement on the central spinal cord, often with upper motor neuron signs, and it can ultimately be very devastating. It’s almost a spectrum of presentations to worry about in terms of severity and outcomes.

We’ll start with the mechanical neck pain. It’s the one that we see the most commonly in the primary care office. We’ve all dealt with this. This is the patient who’s got localized neck pain that doesn’t really radiate anywhere; it kind of sits in the middle of the neck. In fact, if you actually poke back there where the patient says “ouch,” you’re probably in the right ballpark. The etiology and pathophysiology, weirdly, are still not super well-defined, but it’s probably mostly myofascial in etiology. And as such, it often gets better no matter what you do. It will probably get better with time.

You are not going to have neurologic deficits with this type of neck pain. There’s not going to be weakness, or radiation down the arm, or upper motor neuron signs. No one is mentioning the urinary symptoms with this. You can treat it with NSAIDs and physical therapy, which may be necessary if it persists. Massage can sometimes be helpful, but basically you’re just kind of supporting the patients through their own natural healing process. Physical therapy might help with the ergonomics and help make sure that they position themselves and move in a way that does not exacerbate the underlying structures. That is probably the one that we see the most and in some ways is probably the easiest to manage.

Dr. Watto: This is the one that we generally should be least worried about. But cervical radiculopathy, which is the second bucket, is not as severe as cervical myelopathy, so it’s kind of in between the two. Cervical radiculopathy is basically the patient who has neck pain that’s going down one arm or the other, usually not both arms because that would be weird for them to have symmetric radiculopathy. It’s a nerve being pinched somewhere, usually more on one side than the other.

The good news for patients is that the natural history is that it’s going to get better over time, almost no matter what we do. I almost think of this akin to sciatica. Usually sciatica and cervical radiculopathy do not have any motor weakness along with them. It’s really just the pain and maybe a little bit of mild sensory symptoms. So, you can reassure the patient that this usually goes away. Our guest said he sometimes gives gabapentin for this. That’s not my practice. I would be more likely to refer to physical therapy or try some NSAIDs if they’re really having trouble functioning or maybe some muscle relaxants. But they aren’t going to need to go to surgery.

What about cervical myelopathy, Paul? Do those patients need surgery?

Dr. Williams: Yes. The idea with cervical myelopathy is to keep it from progressing. It typically occurs in older patients. It’s like arthritis — a sort of bony buildup that compresses on the spinal cord itself. These patients will often have neck pain but not always. It’s also associated with impairments in motor function and other neurologic deficits. So, the patients may report that they have difficulty buttoning their buttons or managing fine-motor skills. They may have radicular symptoms down their arms. They may have an abnormal physical examination. They may have weakness on exam, but they’ll have a positive Hoffmann’s test where you flick the middle finger and look for flexion of the first finger and the thumb. They may have abnormal tandem gait, or patellar or Achilles hyperreflexia. Their neuro exam will not be normal much of the time, and in later cases because it’s upper motor neuron disease, they may even report urinary symptoms like urinary hesitancy or just a feeling of general unsteadiness of the gait, even though we’re at the cervical level. If you suspect myelopathy — and the trick is to think about it and recognize it when you see it — then you should send them for an MRI. If it persists or they have rapid regression, you get the MRI and refer them to neurosurgery. It’s not necessarily a neurosurgical emergency, but things should move along fairly briskly once you’ve actually identified it.

Dr. Watto: Dr. Mikula made the point that if someone comes to you in a wheelchair, they are probably not going to regain the ability to walk. You’re really trying to prevent progression. If they are already severely disabled, they’re probably not going to get totally back to full functioning, even with surgery. You’re just trying to prevent things from getting worse. That’s the main reason to identify this and get the patient to surgery.

We covered a lot more about neck pain. This was a very superficial review of what we talked about with Dr. Anthony Mikula. Click here to listen to the full podcast.

Matthew F. Watto is clinical assistant professor, Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at University of Pennsylvania, and internist, Department of Medicine, Hospital Medicine Section, Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Paul N. Williams is associate professor of clinical medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, Lewis Katz School of Medicine, and staff physician, Department of General Internal Medicine, Temple Internal Medicine Associates, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for The Curbsiders; received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from The Curbsiders.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘The Oncologist Without the Pathologist Is Blind’: GI Cancer Updates at ASCO 2024

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hello. I’m Mark Lewis, director of gastrointestinal (GI) oncology at Intermountain Health in Utah.

If you allow me, I’d like to go in a craniocaudal fashion. It’s my anatomic mnemonic. I think that’s appropriate because our plenary session yesterday kicked off with some exciting data in esophageal cancer, specifically esophageal adenocarcinoma.

This was the long-awaited ESOPEC trial. It’s a phase 3 study looking at perioperative FLOT (5-FU/leucovorin/oxaliplatin/docetaxel), a chemo triplet, vs the CROSS protocol, which is neoadjuvant chemoradiation with carboplatin and paclitaxel. The primary endpoint was overall survival, and at first blush, FLOT looked to be the true winner. There were some really remarkable milestones in this study, and I have some reservations about the FLOT arm that I’ll raise in just a second.

The investigators are to be commended because in a truly deadly disease, they reported a 5-year overall survival in half of the patients who were receiving FLOT. That is truly commendable and really a milestone in our field. The reason I take a little bit of issue with the trial is that I still have some questions about methodology.

It wasn’t that long ago at ASCO GI that there was a really heated debate called “FLOT or Not” — not in this precise setting, but asking the question, do we think that patients with upper GI malignancy are even fit enough to handle a chemo triplet like FLOT?

The reason I bring that up now in 2024 is that, to my surprise, and I think to many others’, there was a lower-than-expected completion rate of the patients in this trial who were receiving the CROSS regimen. The number of people who were able to complete that in full was about two-thirds, which compared with a historical control from a trial scheme that first emerged over a decade ago that used to be over 90% completion. I found that quite strange.

I also think this trial suffers a little bit, and unavoidably, from the evolution of care that’s happened since it was first enrolling. Of course, I refer to adjuvant immunotherapy. Now, the real question is whether there is synergy between patients who receive radiation upfront and then adjuvant nivolumab, as per CheckMate 577.

In her plenary discussion, I thought Dr. Karyn Goodman did a masterful job — I would encourage you to watch it on ASCO’s website —discussing how we can take all these data and reconcile them for optimal patient outcome. She ultimately suggested that we might deploy all four modalities in the management of these people.

She proposed a paradigm with a PET-adapted, upfront induction chemotherapy, then moving to chemoradiation, then moving to surgery, and finally moving to immunotherapy. That is all four of the traditional arms of oncology. I find that really rather remarkable. Watch that space. This is a great trial with really remarkable survival data, but I’m not entirely convinced that the CROSS arm was given its due.

Next up, I want to talk about pancreas cancer, which is something near and dear to my heart. It affects about one in four of my patients and it remains, unfortunately, a highly lethal disease. I think the top-line news from this meeting is that the KRAS mutation is druggable. I’m probably showing my age, but when I did my fellowship in 2009 through 2012, I was taught that KRAS was sort of the undruggable mutation par excellence. At this meeting, we’ve seen maturing data in regard to targeting KRAS G12C with both sotorasib and adagrasib. The disease control rates are astounding, at 80% and more, which is really remarkable. I wouldn’t have believed that even a few years ago.

I’m even more excited about how we bring a rising tide that can lift all boats and apply this to other KRAS mutations, and not just KRAS G12C but all KRAS mutations. I think that’s coming, hopefully, with the pan-RAS inhibitors, because once that happens — if that happens; I’ll try not to be irrationally exuberant — that would take the traditional mutation found in almost all pancreas cancers and really make it its own Achilles heel. I think that could be such a huge leap forward.

Another matter, however, that remains unresolved at this meeting is in the neoadjuvant setting with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. There’s still equipoise, actually, between neoadjuvant gemcitabine, paclitaxel, and FOLFIRINOX. I thought that that was very well spelled out by some of our Dutch colleagues, who continue to do great work in a variety of cancers, including colorectal.

Where I’d like to move next is colorectal cancer. Of course, immunotherapy remains a hot topic at all of these conferences. There were three different aspects of immunotherapy I’d like to highlight at this conference in regard to colon and rectal cancer.

First, Dr. Heinz-Josef Lenz presented updated data from CheckMate 8HW, which looked at nivolumab and ipilimumab (nivo/ipi) vs chemotherapy in the first line for MSI-high or mismatch repair–deficient colon cancer. Once again, the data we’ve had now for several years at the 2-year mark are incredibly impressive. The 2-year progression-free survival (PFS) rates for nivo/ipi are above 70% and down at around 14% for chemo.

What was impressive about this meeting is that Dr. Lenz presented PFS2, trying to determine the impact, if any, of subsequent therapy. What was going on here, which I think was ethically responsible by the investigators, was crossover. About two-thirds of the chemo arm crossed over to any form of immuno-oncology (IO), and just under a half crossed over to nivo and ipi. The PFS benefits continued with up-front IO. The way that Dr. Lenz phrased it is that you really never get the chance to win back the benefit that you would derive by giving immunotherapy first line to someone who has MSI-high or mismatch repair–deficient metastatic colon cancer.

One thing that’s still not settled in my mind, though, is, does this really dethrone single-agent immunotherapy, such as pembrolizumab in KEYNOTE-177? What I’m really driving at is the ipilimumab. Is the juice worth the squeeze? Is the addition of an anti-CTLA4 agent worth the toxicity that we know comes along with that mechanism of action? Watch this space.

I was also really interested in NEOPRISM-CRC, which looked at the role of immunotherapy in neoadjuvant down-staging of radiographically high-risk stage II or stage III colon cancer. Here, the investigators really make a strong case that, up front in these potentially respectable cases, not only should we know about mismatch repair deficiency but we should actually be interrogating further for tumor mutational burden (TMB).

They had TMB-high patients. In fact, the median TMB was 42 mutations per megabase, with really impressive down-staging using three cycles of every-3-week pembrolizumab before surgery. Again, I really think we’re at an exciting time where, even for colon cancer that looks operable up front, we might actually have the opportunity to improve pathologic and clinical complete responses before and after surgery.

Finally, I want to bring up what continues to amaze me. Two years ago, at ASCO 2022, we heard from Dr. Andrea Cercek and the Memorial Sloan Kettering group about the incredible experience they were having with neoadjuvant, or frankly, definitive dostarlimab in mismatch repair–deficient locally advanced rectal cancer.

I remember being at the conference and there was simultaneous publication of that abstract in The New York Times because it was so remarkable. There was a 100% clinical complete response. The patients didn’t require radiation, they didn’t require chemotherapy, and they didn’t require surgery for locally advanced rectal cancer, provided there was this vulnerability of mismatch-repair deficiency.

Now, 2 years later, Dr. Cercek and her group have updated those data with more than 40 patients, and again, a 100% clinical complete response, including mature, complete responses at over a year in about 20 patients. Again, we are really doing our rectal cancer patients a disservice if we’re not checking for mismatch-repair deficiency upfront, and especially if we’re not talking about them in multidisciplinary conferences.

One of the things that absolutely blows my mind about rectal cancer is just how complicated it’s becoming. I think it is the standard of care to discuss these cases upfront with radiation oncology, surgical oncology, medical oncology, and pathology.

Maybe the overarching message I would take from everything I’ve said today is that the oncologist without the pathologist is blind. It’s really a dyad, a partnership that guides optimal medical oncology care. As much as I love ASCO, I often wish we had more of our pathology colleagues here. I look forward to taking all the findings from this meeting back to the tumor board and really having a dynamic dialogue.

Dr. Lewis is director, Department of Gastrointestinal Oncology, Intermountain Health, Salt Lake City, Utah. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hello. I’m Mark Lewis, director of gastrointestinal (GI) oncology at Intermountain Health in Utah.

If you allow me, I’d like to go in a craniocaudal fashion. It’s my anatomic mnemonic. I think that’s appropriate because our plenary session yesterday kicked off with some exciting data in esophageal cancer, specifically esophageal adenocarcinoma.

This was the long-awaited ESOPEC trial. It’s a phase 3 study looking at perioperative FLOT (5-FU/leucovorin/oxaliplatin/docetaxel), a chemo triplet, vs the CROSS protocol, which is neoadjuvant chemoradiation with carboplatin and paclitaxel. The primary endpoint was overall survival, and at first blush, FLOT looked to be the true winner. There were some really remarkable milestones in this study, and I have some reservations about the FLOT arm that I’ll raise in just a second.

The investigators are to be commended because in a truly deadly disease, they reported a 5-year overall survival in half of the patients who were receiving FLOT. That is truly commendable and really a milestone in our field. The reason I take a little bit of issue with the trial is that I still have some questions about methodology.

It wasn’t that long ago at ASCO GI that there was a really heated debate called “FLOT or Not” — not in this precise setting, but asking the question, do we think that patients with upper GI malignancy are even fit enough to handle a chemo triplet like FLOT?

The reason I bring that up now in 2024 is that, to my surprise, and I think to many others’, there was a lower-than-expected completion rate of the patients in this trial who were receiving the CROSS regimen. The number of people who were able to complete that in full was about two-thirds, which compared with a historical control from a trial scheme that first emerged over a decade ago that used to be over 90% completion. I found that quite strange.

I also think this trial suffers a little bit, and unavoidably, from the evolution of care that’s happened since it was first enrolling. Of course, I refer to adjuvant immunotherapy. Now, the real question is whether there is synergy between patients who receive radiation upfront and then adjuvant nivolumab, as per CheckMate 577.

In her plenary discussion, I thought Dr. Karyn Goodman did a masterful job — I would encourage you to watch it on ASCO’s website —discussing how we can take all these data and reconcile them for optimal patient outcome. She ultimately suggested that we might deploy all four modalities in the management of these people.

She proposed a paradigm with a PET-adapted, upfront induction chemotherapy, then moving to chemoradiation, then moving to surgery, and finally moving to immunotherapy. That is all four of the traditional arms of oncology. I find that really rather remarkable. Watch that space. This is a great trial with really remarkable survival data, but I’m not entirely convinced that the CROSS arm was given its due.

Next up, I want to talk about pancreas cancer, which is something near and dear to my heart. It affects about one in four of my patients and it remains, unfortunately, a highly lethal disease. I think the top-line news from this meeting is that the KRAS mutation is druggable. I’m probably showing my age, but when I did my fellowship in 2009 through 2012, I was taught that KRAS was sort of the undruggable mutation par excellence. At this meeting, we’ve seen maturing data in regard to targeting KRAS G12C with both sotorasib and adagrasib. The disease control rates are astounding, at 80% and more, which is really remarkable. I wouldn’t have believed that even a few years ago.

I’m even more excited about how we bring a rising tide that can lift all boats and apply this to other KRAS mutations, and not just KRAS G12C but all KRAS mutations. I think that’s coming, hopefully, with the pan-RAS inhibitors, because once that happens — if that happens; I’ll try not to be irrationally exuberant — that would take the traditional mutation found in almost all pancreas cancers and really make it its own Achilles heel. I think that could be such a huge leap forward.

Another matter, however, that remains unresolved at this meeting is in the neoadjuvant setting with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. There’s still equipoise, actually, between neoadjuvant gemcitabine, paclitaxel, and FOLFIRINOX. I thought that that was very well spelled out by some of our Dutch colleagues, who continue to do great work in a variety of cancers, including colorectal.

Where I’d like to move next is colorectal cancer. Of course, immunotherapy remains a hot topic at all of these conferences. There were three different aspects of immunotherapy I’d like to highlight at this conference in regard to colon and rectal cancer.

First, Dr. Heinz-Josef Lenz presented updated data from CheckMate 8HW, which looked at nivolumab and ipilimumab (nivo/ipi) vs chemotherapy in the first line for MSI-high or mismatch repair–deficient colon cancer. Once again, the data we’ve had now for several years at the 2-year mark are incredibly impressive. The 2-year progression-free survival (PFS) rates for nivo/ipi are above 70% and down at around 14% for chemo.

What was impressive about this meeting is that Dr. Lenz presented PFS2, trying to determine the impact, if any, of subsequent therapy. What was going on here, which I think was ethically responsible by the investigators, was crossover. About two-thirds of the chemo arm crossed over to any form of immuno-oncology (IO), and just under a half crossed over to nivo and ipi. The PFS benefits continued with up-front IO. The way that Dr. Lenz phrased it is that you really never get the chance to win back the benefit that you would derive by giving immunotherapy first line to someone who has MSI-high or mismatch repair–deficient metastatic colon cancer.

One thing that’s still not settled in my mind, though, is, does this really dethrone single-agent immunotherapy, such as pembrolizumab in KEYNOTE-177? What I’m really driving at is the ipilimumab. Is the juice worth the squeeze? Is the addition of an anti-CTLA4 agent worth the toxicity that we know comes along with that mechanism of action? Watch this space.

I was also really interested in NEOPRISM-CRC, which looked at the role of immunotherapy in neoadjuvant down-staging of radiographically high-risk stage II or stage III colon cancer. Here, the investigators really make a strong case that, up front in these potentially respectable cases, not only should we know about mismatch repair deficiency but we should actually be interrogating further for tumor mutational burden (TMB).

They had TMB-high patients. In fact, the median TMB was 42 mutations per megabase, with really impressive down-staging using three cycles of every-3-week pembrolizumab before surgery. Again, I really think we’re at an exciting time where, even for colon cancer that looks operable up front, we might actually have the opportunity to improve pathologic and clinical complete responses before and after surgery.

Finally, I want to bring up what continues to amaze me. Two years ago, at ASCO 2022, we heard from Dr. Andrea Cercek and the Memorial Sloan Kettering group about the incredible experience they were having with neoadjuvant, or frankly, definitive dostarlimab in mismatch repair–deficient locally advanced rectal cancer.

I remember being at the conference and there was simultaneous publication of that abstract in The New York Times because it was so remarkable. There was a 100% clinical complete response. The patients didn’t require radiation, they didn’t require chemotherapy, and they didn’t require surgery for locally advanced rectal cancer, provided there was this vulnerability of mismatch-repair deficiency.

Now, 2 years later, Dr. Cercek and her group have updated those data with more than 40 patients, and again, a 100% clinical complete response, including mature, complete responses at over a year in about 20 patients. Again, we are really doing our rectal cancer patients a disservice if we’re not checking for mismatch-repair deficiency upfront, and especially if we’re not talking about them in multidisciplinary conferences.

One of the things that absolutely blows my mind about rectal cancer is just how complicated it’s becoming. I think it is the standard of care to discuss these cases upfront with radiation oncology, surgical oncology, medical oncology, and pathology.

Maybe the overarching message I would take from everything I’ve said today is that the oncologist without the pathologist is blind. It’s really a dyad, a partnership that guides optimal medical oncology care. As much as I love ASCO, I often wish we had more of our pathology colleagues here. I look forward to taking all the findings from this meeting back to the tumor board and really having a dynamic dialogue.

Dr. Lewis is director, Department of Gastrointestinal Oncology, Intermountain Health, Salt Lake City, Utah. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hello. I’m Mark Lewis, director of gastrointestinal (GI) oncology at Intermountain Health in Utah.

If you allow me, I’d like to go in a craniocaudal fashion. It’s my anatomic mnemonic. I think that’s appropriate because our plenary session yesterday kicked off with some exciting data in esophageal cancer, specifically esophageal adenocarcinoma.

This was the long-awaited ESOPEC trial. It’s a phase 3 study looking at perioperative FLOT (5-FU/leucovorin/oxaliplatin/docetaxel), a chemo triplet, vs the CROSS protocol, which is neoadjuvant chemoradiation with carboplatin and paclitaxel. The primary endpoint was overall survival, and at first blush, FLOT looked to be the true winner. There were some really remarkable milestones in this study, and I have some reservations about the FLOT arm that I’ll raise in just a second.

The investigators are to be commended because in a truly deadly disease, they reported a 5-year overall survival in half of the patients who were receiving FLOT. That is truly commendable and really a milestone in our field. The reason I take a little bit of issue with the trial is that I still have some questions about methodology.

It wasn’t that long ago at ASCO GI that there was a really heated debate called “FLOT or Not” — not in this precise setting, but asking the question, do we think that patients with upper GI malignancy are even fit enough to handle a chemo triplet like FLOT?

The reason I bring that up now in 2024 is that, to my surprise, and I think to many others’, there was a lower-than-expected completion rate of the patients in this trial who were receiving the CROSS regimen. The number of people who were able to complete that in full was about two-thirds, which compared with a historical control from a trial scheme that first emerged over a decade ago that used to be over 90% completion. I found that quite strange.

I also think this trial suffers a little bit, and unavoidably, from the evolution of care that’s happened since it was first enrolling. Of course, I refer to adjuvant immunotherapy. Now, the real question is whether there is synergy between patients who receive radiation upfront and then adjuvant nivolumab, as per CheckMate 577.

In her plenary discussion, I thought Dr. Karyn Goodman did a masterful job — I would encourage you to watch it on ASCO’s website —discussing how we can take all these data and reconcile them for optimal patient outcome. She ultimately suggested that we might deploy all four modalities in the management of these people.

She proposed a paradigm with a PET-adapted, upfront induction chemotherapy, then moving to chemoradiation, then moving to surgery, and finally moving to immunotherapy. That is all four of the traditional arms of oncology. I find that really rather remarkable. Watch that space. This is a great trial with really remarkable survival data, but I’m not entirely convinced that the CROSS arm was given its due.

Next up, I want to talk about pancreas cancer, which is something near and dear to my heart. It affects about one in four of my patients and it remains, unfortunately, a highly lethal disease. I think the top-line news from this meeting is that the KRAS mutation is druggable. I’m probably showing my age, but when I did my fellowship in 2009 through 2012, I was taught that KRAS was sort of the undruggable mutation par excellence. At this meeting, we’ve seen maturing data in regard to targeting KRAS G12C with both sotorasib and adagrasib. The disease control rates are astounding, at 80% and more, which is really remarkable. I wouldn’t have believed that even a few years ago.

I’m even more excited about how we bring a rising tide that can lift all boats and apply this to other KRAS mutations, and not just KRAS G12C but all KRAS mutations. I think that’s coming, hopefully, with the pan-RAS inhibitors, because once that happens — if that happens; I’ll try not to be irrationally exuberant — that would take the traditional mutation found in almost all pancreas cancers and really make it its own Achilles heel. I think that could be such a huge leap forward.

Another matter, however, that remains unresolved at this meeting is in the neoadjuvant setting with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. There’s still equipoise, actually, between neoadjuvant gemcitabine, paclitaxel, and FOLFIRINOX. I thought that that was very well spelled out by some of our Dutch colleagues, who continue to do great work in a variety of cancers, including colorectal.

Where I’d like to move next is colorectal cancer. Of course, immunotherapy remains a hot topic at all of these conferences. There were three different aspects of immunotherapy I’d like to highlight at this conference in regard to colon and rectal cancer.

First, Dr. Heinz-Josef Lenz presented updated data from CheckMate 8HW, which looked at nivolumab and ipilimumab (nivo/ipi) vs chemotherapy in the first line for MSI-high or mismatch repair–deficient colon cancer. Once again, the data we’ve had now for several years at the 2-year mark are incredibly impressive. The 2-year progression-free survival (PFS) rates for nivo/ipi are above 70% and down at around 14% for chemo.

What was impressive about this meeting is that Dr. Lenz presented PFS2, trying to determine the impact, if any, of subsequent therapy. What was going on here, which I think was ethically responsible by the investigators, was crossover. About two-thirds of the chemo arm crossed over to any form of immuno-oncology (IO), and just under a half crossed over to nivo and ipi. The PFS benefits continued with up-front IO. The way that Dr. Lenz phrased it is that you really never get the chance to win back the benefit that you would derive by giving immunotherapy first line to someone who has MSI-high or mismatch repair–deficient metastatic colon cancer.

One thing that’s still not settled in my mind, though, is, does this really dethrone single-agent immunotherapy, such as pembrolizumab in KEYNOTE-177? What I’m really driving at is the ipilimumab. Is the juice worth the squeeze? Is the addition of an anti-CTLA4 agent worth the toxicity that we know comes along with that mechanism of action? Watch this space.

I was also really interested in NEOPRISM-CRC, which looked at the role of immunotherapy in neoadjuvant down-staging of radiographically high-risk stage II or stage III colon cancer. Here, the investigators really make a strong case that, up front in these potentially respectable cases, not only should we know about mismatch repair deficiency but we should actually be interrogating further for tumor mutational burden (TMB).

They had TMB-high patients. In fact, the median TMB was 42 mutations per megabase, with really impressive down-staging using three cycles of every-3-week pembrolizumab before surgery. Again, I really think we’re at an exciting time where, even for colon cancer that looks operable up front, we might actually have the opportunity to improve pathologic and clinical complete responses before and after surgery.

Finally, I want to bring up what continues to amaze me. Two years ago, at ASCO 2022, we heard from Dr. Andrea Cercek and the Memorial Sloan Kettering group about the incredible experience they were having with neoadjuvant, or frankly, definitive dostarlimab in mismatch repair–deficient locally advanced rectal cancer.

I remember being at the conference and there was simultaneous publication of that abstract in The New York Times because it was so remarkable. There was a 100% clinical complete response. The patients didn’t require radiation, they didn’t require chemotherapy, and they didn’t require surgery for locally advanced rectal cancer, provided there was this vulnerability of mismatch-repair deficiency.

Now, 2 years later, Dr. Cercek and her group have updated those data with more than 40 patients, and again, a 100% clinical complete response, including mature, complete responses at over a year in about 20 patients. Again, we are really doing our rectal cancer patients a disservice if we’re not checking for mismatch-repair deficiency upfront, and especially if we’re not talking about them in multidisciplinary conferences.

One of the things that absolutely blows my mind about rectal cancer is just how complicated it’s becoming. I think it is the standard of care to discuss these cases upfront with radiation oncology, surgical oncology, medical oncology, and pathology.

Maybe the overarching message I would take from everything I’ve said today is that the oncologist without the pathologist is blind. It’s really a dyad, a partnership that guides optimal medical oncology care. As much as I love ASCO, I often wish we had more of our pathology colleagues here. I look forward to taking all the findings from this meeting back to the tumor board and really having a dynamic dialogue.

Dr. Lewis is director, Department of Gastrointestinal Oncology, Intermountain Health, Salt Lake City, Utah. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

An Overview of Gender-Affirming Care for Children and Adolescents

As Pride Month drew to a close, the Supreme Court made a shocking announcement. For the first time in the history of the court, it is willing to hear a legal challenge regarding gender-affirming care for minors. The justices will review whether a 2023 Tennessee law, SB1, which bans hormone therapy, puberty blockers, and surgery for transgender minors, is unconstitutional. This is the first time the Supreme Court will directly weigh in on gender-affirming care.

There are few topics as politically and medically divisive as gender-affirming care for minors. When the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) released its updated Standards of Care, SOC8, one of the noticeable changes to the document was its approach to caring for transgender children and adolescents.

Before I highlight these recommendations and the ensuing controversy, it is imperative to establish proper terminology. Unfortunately, medical and legal terms often differ. Both activists and opponents use these terms interchangeably, which makes discourse about an already emotionally charged topic extremely difficult. From a legal perspective, the terms “minor” and “child” often refer to individuals under the age of majority. In the United States, the age of majority is 18. However, the term child also has a well-established medical definition. A child is an individual between the stages of infancy and puberty. Adolescence is a transitional period marked by the onset of puberty until adulthood (typically the age of majority). As medical providers, understanding these definitions is essential to identifying misinformation pertaining to this type of healthcare.

For the purposes of this article, I will be adhering to the medical terminology. Now, I want to be very clear. WPATH does not endorse surgical procedures on children. Furthermore, surgeons are not performing gender-affirming surgeries on children. On adolescents, rarely. But children, never.

According to the updated SOC8, the only acceptable gender-affirming intervention for children is psychosocial support.1 This does not include puberty blockers, hormones, or surgery, but rather allowing a child to explore their gender identity by experimenting with different clothing, toys, hairstyles, and even an alternative name that aligns more closely with their gender identity.1

It is only after children reach adolescence that medical, and in rare cases, surgical interventions, can be considered. Puberty blockers are appropriate for patients who have started puberty and experience gender dysphoria. These medications are reversible, and their purpose is to temporarily pause puberty to allow the adolescent to further explore their gender identity.

The most significant side effect of puberty blockers is decreased bone density.1 As a result, providers typically do not prescribe these medications for more than 2-3 years. After discontinuation of the medication, bone density returns to baseline.1 If the adolescent’s gender identity is marked and sustained over time, hormone therapy, such as testosterone or estrogen is then considered. Unlike puberty blockers, these medications can have permanent side effects. Testosterone use can lead to irreversible hair growth, alopecia, clitoromegaly, and voice deepening, while estrogen can cause permanent breast growth and halt sperm production.1 Future fertility and these side effects are discussed with the patient in detail prior to the initiation of these medications.

Contrary to the current political narrative, gender-affirming care for children and adolescents is not taken lightly. These individuals often receive years of multidisciplinary assessments, with a focus on gender identity development, social development and support, and diagnostic assessment of possible co-occurring mental health or developmental concerns and capacity for decision making.1 The clinical visits also occur with parental support and consent.

WPATH SOC8 also delineates the provider qualifications for health care professionals assessing these patients. Providers must be licensed by their statutory bodies and hold a postgraduate degree by a nationally accredited statutory institution; receive theoretical and evidence-based training and develop expertise in child, adolescent, and family mental health across the developmental spectrum; receive training and have expertise in gender identity development and gender diversity in children and adolescence; have the ability to assess capacity to assent/consent; receive training and develop expertise in autism spectrum disorders and other neurodevelopmental presentations; and to continue engaging in professional development in all areas relevant to gender-diverse children, adolescents, and families.1

The most controversial aspect of gender-affirming care for children and adolescents relates to surgical treatment. While the rates of gender-affirming surgeries have increased for this age group over the years, the overall rate of gender-affirming surgery for adolescents is markedly lower compared with other adolescents seeking cosmetic surgeries and compared with transgender adults undergoing gender-affirming surgery.

In a cohort study conducted between 2016 to 2020, 48,019 patients were identified who had undergone gender-affirming surgery.2 Only 3678 or 7.7% of patients were aged between 12 and 18, with the most common procedure being chest/breast surgery.2 So, under about 1000 cases per year were gender-affirming surgeries on patients under 18.

During 2020 alone, the number of cisgender adolescents between the ages of 13 and 19 who underwent breast augmentation and breast reduction was 3233 and 4666, respectively.3 The outrage about gender-affirming surgeries on transgender youth, yet the silence on cosmetic procedures in this same age group, speaks volumes.

All surgeries on adolescents should be taken seriously and with caution, regardless of gender identity. However, current legislation disproportionately targets only transgender youth. For whatever reason, surgeries on transgender individuals are labeled as “body mutilation,” whereas surgeries on cisgender youth are not even discussed. Such inflammatory rhetoric and complete lack of empathy impedes the common goal of all parties: what is in the best interest of the minor? Unfortunately, in a few short months, the answer to this question will be determined by a group of nine justices who have no experience in medicine or transgender health care, instead of by medical experts and the parents who care for these individuals.

Dr. Brandt is an ob.gyn. and fellowship-trained gender-affirming surgeon in West Reading, Pennsylvania. She has no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Coleman E et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. Int J Transgender Health. 2022;23(sup):S1-S259.

2. Wright JD et al. National estimates of gender affirming surgery in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Aug 1;6(8):e2330348.

3. American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Plastic Surgery Statistics Report. ASPS National Clearinghouse of Plastic Surgery Procedural Statistics. 2020.

As Pride Month drew to a close, the Supreme Court made a shocking announcement. For the first time in the history of the court, it is willing to hear a legal challenge regarding gender-affirming care for minors. The justices will review whether a 2023 Tennessee law, SB1, which bans hormone therapy, puberty blockers, and surgery for transgender minors, is unconstitutional. This is the first time the Supreme Court will directly weigh in on gender-affirming care.

There are few topics as politically and medically divisive as gender-affirming care for minors. When the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) released its updated Standards of Care, SOC8, one of the noticeable changes to the document was its approach to caring for transgender children and adolescents.