User login

Prior authorization revisited: An update from the APA

You may have noticed that one of topics I like to write about in this column is the assault on the practice of medicine: the obligations that steal our time from patients without either the value or outcomes our patients see. It is these extraneous demands on our time and on our psyches that dehumanize medical practice as experienced by our patients and contribute to physician burnout. High on my list is the requirement for prior authorization for medications.

In 2015, I wrote a column, “Prior Authorization for Medications: Who oversees placement of the hoops?” The article followed my unsuccessful 6-week-long endeavor to get modafinil authorized for a patient. My efforts included interactions with the insurance company’s chief medical officer, the insurance commissioners in three states, my U.S. senator, and finally, the American Psychiatric Association’s attorney, Colleen Coyle, who has been working on this issue along with the American Medical Association and other medical specialty organizations for years now. The irony of the article is that, after it came out, a reader informed me that modafinil could be obtained from Costco for $34 for 30 pills, while every pharmacy I had checked was selling the generic medication for nearly $1,000 for the same number of pills!

One might make the case that prior authorization saves money by rationing the most expensive medications. And I might counter that physicians should be willing to try less expensive medications first – if we only knew the price of the medications we are prescribing. There is, however, no clear logic to the tremendous variability in price across pharmacies, which can amount to hundreds of dollars a month in the cost to an uninsured patient, and none of which reflects what might be a negotiated cost for those using health insurance. The newest medications are expensive from any retailer, but when it comes to older generics, it’s a crapshoot.

Years have passed since my prior authorization fiasco. Today, I keep a GoodRx app on my phone and often reference it when prescribing medications that might be expensive at one pharmacy but not at another. The app tells me that I can now buy 30 pills of the modafinil for $40.34 at grocery store pharmacy that is 2.7 miles from my office or for $305.50 at Walgreens, 3.6 miles away. A quick call to Costco shows that the price there has gone up to $40.89. For the prescriptions that I have written since that article, I have told patients that their insurance providers may not authorize the medication and if that is the case, they should price shop, as I don’t have the tenacity to go through the prior authorization process I endured in 2015.

So what progress has the APA made over the past 4 years? I wrote back to the APA’s attorney, Ms. Coyle, to ask for an update. Ms. Coyle was kind enough to respond in some detail. , and there is one less obstacle to obtaining care for a growing number of patients during our overdose epidemic.

Other news, however, is not all good. Medicare plans to increase the use of prior authorization.

Ms. Coyle provided data that confirmed what most physicians suspected. “The AMA did a survey1 and found 92% of physicians report that ‘prior authorizations programs have a negative impact on patient clinical outcomes.’ The AMA study revealed that ‘every week a medical practice completes an average of 29.1 prior authorization requirements per physician, which takes an average of 14.6 hours to process – the equivalent of nearly two business days.’ ”

She recounted the efforts the APA has made on behalf of psychiatrists. “We are working with the AMA and other physician groups to address the issue and recommended [Health and Human Services] address the burden of prior authorization as part of its Patients over Paperwork Initiative.2 Through our website and the helpline, we collected stories from our members about the burden it causes and the negative impact it has on patient care. We’ve shared the stories with the American Medical Association to use in joint advocacy efforts with the administration and private insurers.”

Finally, the APA has written a letter to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in opposition to a proposal for increased utilization review of Medicare Part D protected classes medications, which include antipsychotics and antidepressants. “We strongly oppose the proposal,” Ms. Coyle noted, “and asked our district branches to also submit letters in opposition.”

What can individual psychiatrists do to advocate? I noted that many of my efforts were futile. My U.S. senator responded with a letter that said my problem was not in his domain.

“As for the best way to approach the issue in the state, we recommend working with the state medical society to push for legislation. The AMA has draft legislation that may be used. It would also be helpful to collect the stories from the members about their challenges with prior authorization and impact on patient care/outcomes to share with state legislatures. It may also be beneficial to share these concerns with the state insurance commissioner and Department of Health and Human Services,” Ms. Coyle wrote. She noted it would be helpful for members to work directly with the district branches of the APA.

I am still left with some sense of futility. In 2014, Danielle Ofri, MD, PhD, a physician and writer, wrote an op-ed3 for the New York Times, “Adventures in ‘Prior Authorization,’ ” where she detailed the egregious practice. In the past 5 years, not much has changed, and insurers have not taken to the idea that preserving physician time for clinical care and face-to-face interactions with patients is the priority that we all might like it to be.

Dr. Miller is the coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice in Baltimore.

References

1. AMA Prior Authorization Physician Survey, 2017.

2. CMS Patients Over Paperwork Initiative, CMS.gov.

3. New York Times, Aug. 3, 2014.

You may have noticed that one of topics I like to write about in this column is the assault on the practice of medicine: the obligations that steal our time from patients without either the value or outcomes our patients see. It is these extraneous demands on our time and on our psyches that dehumanize medical practice as experienced by our patients and contribute to physician burnout. High on my list is the requirement for prior authorization for medications.

In 2015, I wrote a column, “Prior Authorization for Medications: Who oversees placement of the hoops?” The article followed my unsuccessful 6-week-long endeavor to get modafinil authorized for a patient. My efforts included interactions with the insurance company’s chief medical officer, the insurance commissioners in three states, my U.S. senator, and finally, the American Psychiatric Association’s attorney, Colleen Coyle, who has been working on this issue along with the American Medical Association and other medical specialty organizations for years now. The irony of the article is that, after it came out, a reader informed me that modafinil could be obtained from Costco for $34 for 30 pills, while every pharmacy I had checked was selling the generic medication for nearly $1,000 for the same number of pills!

One might make the case that prior authorization saves money by rationing the most expensive medications. And I might counter that physicians should be willing to try less expensive medications first – if we only knew the price of the medications we are prescribing. There is, however, no clear logic to the tremendous variability in price across pharmacies, which can amount to hundreds of dollars a month in the cost to an uninsured patient, and none of which reflects what might be a negotiated cost for those using health insurance. The newest medications are expensive from any retailer, but when it comes to older generics, it’s a crapshoot.

Years have passed since my prior authorization fiasco. Today, I keep a GoodRx app on my phone and often reference it when prescribing medications that might be expensive at one pharmacy but not at another. The app tells me that I can now buy 30 pills of the modafinil for $40.34 at grocery store pharmacy that is 2.7 miles from my office or for $305.50 at Walgreens, 3.6 miles away. A quick call to Costco shows that the price there has gone up to $40.89. For the prescriptions that I have written since that article, I have told patients that their insurance providers may not authorize the medication and if that is the case, they should price shop, as I don’t have the tenacity to go through the prior authorization process I endured in 2015.

So what progress has the APA made over the past 4 years? I wrote back to the APA’s attorney, Ms. Coyle, to ask for an update. Ms. Coyle was kind enough to respond in some detail. , and there is one less obstacle to obtaining care for a growing number of patients during our overdose epidemic.

Other news, however, is not all good. Medicare plans to increase the use of prior authorization.

Ms. Coyle provided data that confirmed what most physicians suspected. “The AMA did a survey1 and found 92% of physicians report that ‘prior authorizations programs have a negative impact on patient clinical outcomes.’ The AMA study revealed that ‘every week a medical practice completes an average of 29.1 prior authorization requirements per physician, which takes an average of 14.6 hours to process – the equivalent of nearly two business days.’ ”

She recounted the efforts the APA has made on behalf of psychiatrists. “We are working with the AMA and other physician groups to address the issue and recommended [Health and Human Services] address the burden of prior authorization as part of its Patients over Paperwork Initiative.2 Through our website and the helpline, we collected stories from our members about the burden it causes and the negative impact it has on patient care. We’ve shared the stories with the American Medical Association to use in joint advocacy efforts with the administration and private insurers.”

Finally, the APA has written a letter to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in opposition to a proposal for increased utilization review of Medicare Part D protected classes medications, which include antipsychotics and antidepressants. “We strongly oppose the proposal,” Ms. Coyle noted, “and asked our district branches to also submit letters in opposition.”

What can individual psychiatrists do to advocate? I noted that many of my efforts were futile. My U.S. senator responded with a letter that said my problem was not in his domain.

“As for the best way to approach the issue in the state, we recommend working with the state medical society to push for legislation. The AMA has draft legislation that may be used. It would also be helpful to collect the stories from the members about their challenges with prior authorization and impact on patient care/outcomes to share with state legislatures. It may also be beneficial to share these concerns with the state insurance commissioner and Department of Health and Human Services,” Ms. Coyle wrote. She noted it would be helpful for members to work directly with the district branches of the APA.

I am still left with some sense of futility. In 2014, Danielle Ofri, MD, PhD, a physician and writer, wrote an op-ed3 for the New York Times, “Adventures in ‘Prior Authorization,’ ” where she detailed the egregious practice. In the past 5 years, not much has changed, and insurers have not taken to the idea that preserving physician time for clinical care and face-to-face interactions with patients is the priority that we all might like it to be.

Dr. Miller is the coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice in Baltimore.

References

1. AMA Prior Authorization Physician Survey, 2017.

2. CMS Patients Over Paperwork Initiative, CMS.gov.

3. New York Times, Aug. 3, 2014.

You may have noticed that one of topics I like to write about in this column is the assault on the practice of medicine: the obligations that steal our time from patients without either the value or outcomes our patients see. It is these extraneous demands on our time and on our psyches that dehumanize medical practice as experienced by our patients and contribute to physician burnout. High on my list is the requirement for prior authorization for medications.

In 2015, I wrote a column, “Prior Authorization for Medications: Who oversees placement of the hoops?” The article followed my unsuccessful 6-week-long endeavor to get modafinil authorized for a patient. My efforts included interactions with the insurance company’s chief medical officer, the insurance commissioners in three states, my U.S. senator, and finally, the American Psychiatric Association’s attorney, Colleen Coyle, who has been working on this issue along with the American Medical Association and other medical specialty organizations for years now. The irony of the article is that, after it came out, a reader informed me that modafinil could be obtained from Costco for $34 for 30 pills, while every pharmacy I had checked was selling the generic medication for nearly $1,000 for the same number of pills!

One might make the case that prior authorization saves money by rationing the most expensive medications. And I might counter that physicians should be willing to try less expensive medications first – if we only knew the price of the medications we are prescribing. There is, however, no clear logic to the tremendous variability in price across pharmacies, which can amount to hundreds of dollars a month in the cost to an uninsured patient, and none of which reflects what might be a negotiated cost for those using health insurance. The newest medications are expensive from any retailer, but when it comes to older generics, it’s a crapshoot.

Years have passed since my prior authorization fiasco. Today, I keep a GoodRx app on my phone and often reference it when prescribing medications that might be expensive at one pharmacy but not at another. The app tells me that I can now buy 30 pills of the modafinil for $40.34 at grocery store pharmacy that is 2.7 miles from my office or for $305.50 at Walgreens, 3.6 miles away. A quick call to Costco shows that the price there has gone up to $40.89. For the prescriptions that I have written since that article, I have told patients that their insurance providers may not authorize the medication and if that is the case, they should price shop, as I don’t have the tenacity to go through the prior authorization process I endured in 2015.

So what progress has the APA made over the past 4 years? I wrote back to the APA’s attorney, Ms. Coyle, to ask for an update. Ms. Coyle was kind enough to respond in some detail. , and there is one less obstacle to obtaining care for a growing number of patients during our overdose epidemic.

Other news, however, is not all good. Medicare plans to increase the use of prior authorization.

Ms. Coyle provided data that confirmed what most physicians suspected. “The AMA did a survey1 and found 92% of physicians report that ‘prior authorizations programs have a negative impact on patient clinical outcomes.’ The AMA study revealed that ‘every week a medical practice completes an average of 29.1 prior authorization requirements per physician, which takes an average of 14.6 hours to process – the equivalent of nearly two business days.’ ”

She recounted the efforts the APA has made on behalf of psychiatrists. “We are working with the AMA and other physician groups to address the issue and recommended [Health and Human Services] address the burden of prior authorization as part of its Patients over Paperwork Initiative.2 Through our website and the helpline, we collected stories from our members about the burden it causes and the negative impact it has on patient care. We’ve shared the stories with the American Medical Association to use in joint advocacy efforts with the administration and private insurers.”

Finally, the APA has written a letter to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in opposition to a proposal for increased utilization review of Medicare Part D protected classes medications, which include antipsychotics and antidepressants. “We strongly oppose the proposal,” Ms. Coyle noted, “and asked our district branches to also submit letters in opposition.”

What can individual psychiatrists do to advocate? I noted that many of my efforts were futile. My U.S. senator responded with a letter that said my problem was not in his domain.

“As for the best way to approach the issue in the state, we recommend working with the state medical society to push for legislation. The AMA has draft legislation that may be used. It would also be helpful to collect the stories from the members about their challenges with prior authorization and impact on patient care/outcomes to share with state legislatures. It may also be beneficial to share these concerns with the state insurance commissioner and Department of Health and Human Services,” Ms. Coyle wrote. She noted it would be helpful for members to work directly with the district branches of the APA.

I am still left with some sense of futility. In 2014, Danielle Ofri, MD, PhD, a physician and writer, wrote an op-ed3 for the New York Times, “Adventures in ‘Prior Authorization,’ ” where she detailed the egregious practice. In the past 5 years, not much has changed, and insurers have not taken to the idea that preserving physician time for clinical care and face-to-face interactions with patients is the priority that we all might like it to be.

Dr. Miller is the coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice in Baltimore.

References

1. AMA Prior Authorization Physician Survey, 2017.

2. CMS Patients Over Paperwork Initiative, CMS.gov.

3. New York Times, Aug. 3, 2014.

Peer-Review Transparency

Federal health care providers live under a microscope, so it seems only fair that we at Fed Pract honor that reality and open ourselves up to scrutiny as well.1 We hope that by shedding light on our peer-review process and manuscript acceptance rate, we will not only highlight our accomplishments, but identify areas for improvement.

Free access to Fed Pract content has always been our priority. While many journals charge authors or readers, Fed Pract has been and will remain free for readers and authors.2 Advertising enables the journal to support this free model of publishing, but we take care to ensure that advertisements do not influence content in any way. Our advertising policy can be found at www.mdedge.com/fedprac/page/advertising.

In January 2019, Fed Pract placed > 400 peer-reviewed articles published since January 2015 in the PubMed Central (PMC) database (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc). The full text of these and all future Fed Pract peer-reviewed articles will be available at PMC (no registration required), and the citations also will be included in PubMed. We hope that this process will make it even easier for anyone to access our authors’ works.

In 2018 about 36,000 federal health care providers (HCPs) received hard copies of this journal. The print journal is free, but circulation is limited to HCPs who work at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), US Department of Defense (DoD), and the US Public Health Service (PHS). The mdedge.com/fedprac website, which includes every article published since 2003, had 1.4 million page views in 2018. After reading 3 online articles, readers in the US are asked to complete a simple registration form to help us better customize the reader experience. In some cases, international readers may be asked to pay for access to articles online; however, any VA, DoD, or PHS officer stationed overseas can contact the editorial staff ([email protected]) to ensure that they can access the articles for free.

In 2018 the journal received 164 manuscripts and published 94 articles written by 357 different federal HCPs. The 164 manuscript submissions represented a 45% growth over previous years. Not surprisingly, the increased rate of submissions began shortly after the May 2018 announcement that journal articles would be included in PMC. Most of those articles (83%) were submitted unsolicited.

Fed Pract has always prided itself on being an early promoter of interdisciplinary health care professional publications. Nearly half of its listed authors were physicians (48%), while pharmacists made up the next largest cohort (18%). There were smaller numbers of PhDs, nurses, social workers, and physical therapists. The majority were written by HCPs affiliated with the VA (95% of articles and 93% of authors), and no articles in 2018 were written by PHS officers. Physicians comprise about two-thirds of the audience, while pharmacists make up 17% and nurses 9%. PHS and DoD HCPs make up 19% of the Fed Pract audience, suggesting that the journal needs to do more work to encourage these HCPs to contribute articles to the journal.3

Articles published in 2018 covered a broad range of topics from “Anesthesia Care Practice Models in the VHA” and “Army Behavioral Health System” to “Vitreous Hemorrhage in the Setting of a Vascular Loop” and “A Workforce Assessment of VA Home-Based Primary Care Pharmacists.” Categorizing the articles is a challenge. Few health care topics fit neatly into a single topic or specialty. This is especially true in federal health care where much of the care is delivered by multidisciplinary patient-centered medical homes or patient aligned care teams. Nevertheless, a few broad outlines can be discerned. Articles were roughly split between primary care and hospital-based and/or specialty care topics; one-quarter of the articles were case studies or case series articles, and about 20% were editorials or opinion columns. Nineteen articles dealt explicitly with chronic conditions, and 10 articles focused on mental health care.

Peer reviewers are an essential part of the process. Reviewers are blinded to the identityof the authors, ensuring fairness and reducing potential conflicts of interest. We are extremely grateful to each and every reviewer for the time and energy they contribute to the journal. Peer reviewers do not get nearly enough recognition for their important work. In 2018 Fed Pract invited 1,205 reviewers for 164 manuscript submissions and 94 manuscript revisions. More than 200 different reviewers submitted 487 reviews with a median (SD) of 2 reviews (1.8) and a range of 1 to 10. The top 20 reviewers completed 134 reviews with a median (SD) of 6 reviews (1.2). The results stand in contrast to some journals that must offer many invitations per review and depend on a small number of reviewers.1,4-6

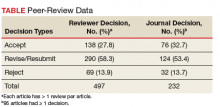

The reviewers recommended to reject 14% and to revise 26% of the articles, which is a much lower rejection rate than many other journals (Table).4

These data suggest that Fed Pract and its peer-review process is on a sound foundation but needs to make improvements. Moving into 2019, the journal expects that an increasing number of submissions will require a higher rejection rate. Moreover, we will need to do a better job reaching out to underrepresented portions of our audience. To decrease the time to publication for accepted manuscripts, in 2019 we will publish more articles online ahead of the print publication as we strive to improve the experience for authors, reviewers, readers, and the entire Fed Pract audience.

None of this work can be done without our small and dedicated staff. I would like to thank Managing Editor Joyce Brody who sent out each and every one of those reviewer invitations, Deputy Editor Robert Fee, who manages the special issues, Web Editor Teraya Smith, who runs our entire digital operation, and of course, Editor in Chief Cynthia Geppert, who oversees it all. Finally, it is important that you let us know how we are doing and whether we are meeting your needs. Visit mdedge.com/fedprac to take the readership survey or reach out to me at [email protected].

1. Geppert CMA. Caring under a microscope. Fed Pract. 2018;35(7):6-7.

2. Smith R. Peer review: a flawed process at the heart of science and journals. J R Soc Med. 2006;99(4):178-182.

3. BPA Worldwide. Federal Practitioner brand report for the 6 month period ending June 2018. https://www.frontlinemedcom.com/wp-content/uploads/FEDPRAC_BPA.pdf. Updated June 2018. Accessed March 5, 2019.

4. Fontanarosa PB, Bauchner H, Golub RM. Thank you to JAMA authors, peer reviewers, and readers. JAMA. 2017;317(8):812-813.

5. Publons, Clarivate Analytics. 2018 global state of peer review. https://publons.com/static/Publons-Global-State-Of-Peer-Review-2018.pdf. Published September 2018. Accessed March 5, 2019.

6. Malcom D. It’s time we fix the peer review system. Am J Pharm Educ. 2018;82(5):7144.

Federal health care providers live under a microscope, so it seems only fair that we at Fed Pract honor that reality and open ourselves up to scrutiny as well.1 We hope that by shedding light on our peer-review process and manuscript acceptance rate, we will not only highlight our accomplishments, but identify areas for improvement.

Free access to Fed Pract content has always been our priority. While many journals charge authors or readers, Fed Pract has been and will remain free for readers and authors.2 Advertising enables the journal to support this free model of publishing, but we take care to ensure that advertisements do not influence content in any way. Our advertising policy can be found at www.mdedge.com/fedprac/page/advertising.

In January 2019, Fed Pract placed > 400 peer-reviewed articles published since January 2015 in the PubMed Central (PMC) database (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc). The full text of these and all future Fed Pract peer-reviewed articles will be available at PMC (no registration required), and the citations also will be included in PubMed. We hope that this process will make it even easier for anyone to access our authors’ works.

In 2018 about 36,000 federal health care providers (HCPs) received hard copies of this journal. The print journal is free, but circulation is limited to HCPs who work at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), US Department of Defense (DoD), and the US Public Health Service (PHS). The mdedge.com/fedprac website, which includes every article published since 2003, had 1.4 million page views in 2018. After reading 3 online articles, readers in the US are asked to complete a simple registration form to help us better customize the reader experience. In some cases, international readers may be asked to pay for access to articles online; however, any VA, DoD, or PHS officer stationed overseas can contact the editorial staff ([email protected]) to ensure that they can access the articles for free.

In 2018 the journal received 164 manuscripts and published 94 articles written by 357 different federal HCPs. The 164 manuscript submissions represented a 45% growth over previous years. Not surprisingly, the increased rate of submissions began shortly after the May 2018 announcement that journal articles would be included in PMC. Most of those articles (83%) were submitted unsolicited.

Fed Pract has always prided itself on being an early promoter of interdisciplinary health care professional publications. Nearly half of its listed authors were physicians (48%), while pharmacists made up the next largest cohort (18%). There were smaller numbers of PhDs, nurses, social workers, and physical therapists. The majority were written by HCPs affiliated with the VA (95% of articles and 93% of authors), and no articles in 2018 were written by PHS officers. Physicians comprise about two-thirds of the audience, while pharmacists make up 17% and nurses 9%. PHS and DoD HCPs make up 19% of the Fed Pract audience, suggesting that the journal needs to do more work to encourage these HCPs to contribute articles to the journal.3

Articles published in 2018 covered a broad range of topics from “Anesthesia Care Practice Models in the VHA” and “Army Behavioral Health System” to “Vitreous Hemorrhage in the Setting of a Vascular Loop” and “A Workforce Assessment of VA Home-Based Primary Care Pharmacists.” Categorizing the articles is a challenge. Few health care topics fit neatly into a single topic or specialty. This is especially true in federal health care where much of the care is delivered by multidisciplinary patient-centered medical homes or patient aligned care teams. Nevertheless, a few broad outlines can be discerned. Articles were roughly split between primary care and hospital-based and/or specialty care topics; one-quarter of the articles were case studies or case series articles, and about 20% were editorials or opinion columns. Nineteen articles dealt explicitly with chronic conditions, and 10 articles focused on mental health care.

Peer reviewers are an essential part of the process. Reviewers are blinded to the identityof the authors, ensuring fairness and reducing potential conflicts of interest. We are extremely grateful to each and every reviewer for the time and energy they contribute to the journal. Peer reviewers do not get nearly enough recognition for their important work. In 2018 Fed Pract invited 1,205 reviewers for 164 manuscript submissions and 94 manuscript revisions. More than 200 different reviewers submitted 487 reviews with a median (SD) of 2 reviews (1.8) and a range of 1 to 10. The top 20 reviewers completed 134 reviews with a median (SD) of 6 reviews (1.2). The results stand in contrast to some journals that must offer many invitations per review and depend on a small number of reviewers.1,4-6

The reviewers recommended to reject 14% and to revise 26% of the articles, which is a much lower rejection rate than many other journals (Table).4

These data suggest that Fed Pract and its peer-review process is on a sound foundation but needs to make improvements. Moving into 2019, the journal expects that an increasing number of submissions will require a higher rejection rate. Moreover, we will need to do a better job reaching out to underrepresented portions of our audience. To decrease the time to publication for accepted manuscripts, in 2019 we will publish more articles online ahead of the print publication as we strive to improve the experience for authors, reviewers, readers, and the entire Fed Pract audience.

None of this work can be done without our small and dedicated staff. I would like to thank Managing Editor Joyce Brody who sent out each and every one of those reviewer invitations, Deputy Editor Robert Fee, who manages the special issues, Web Editor Teraya Smith, who runs our entire digital operation, and of course, Editor in Chief Cynthia Geppert, who oversees it all. Finally, it is important that you let us know how we are doing and whether we are meeting your needs. Visit mdedge.com/fedprac to take the readership survey or reach out to me at [email protected].

Federal health care providers live under a microscope, so it seems only fair that we at Fed Pract honor that reality and open ourselves up to scrutiny as well.1 We hope that by shedding light on our peer-review process and manuscript acceptance rate, we will not only highlight our accomplishments, but identify areas for improvement.

Free access to Fed Pract content has always been our priority. While many journals charge authors or readers, Fed Pract has been and will remain free for readers and authors.2 Advertising enables the journal to support this free model of publishing, but we take care to ensure that advertisements do not influence content in any way. Our advertising policy can be found at www.mdedge.com/fedprac/page/advertising.

In January 2019, Fed Pract placed > 400 peer-reviewed articles published since January 2015 in the PubMed Central (PMC) database (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc). The full text of these and all future Fed Pract peer-reviewed articles will be available at PMC (no registration required), and the citations also will be included in PubMed. We hope that this process will make it even easier for anyone to access our authors’ works.

In 2018 about 36,000 federal health care providers (HCPs) received hard copies of this journal. The print journal is free, but circulation is limited to HCPs who work at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), US Department of Defense (DoD), and the US Public Health Service (PHS). The mdedge.com/fedprac website, which includes every article published since 2003, had 1.4 million page views in 2018. After reading 3 online articles, readers in the US are asked to complete a simple registration form to help us better customize the reader experience. In some cases, international readers may be asked to pay for access to articles online; however, any VA, DoD, or PHS officer stationed overseas can contact the editorial staff ([email protected]) to ensure that they can access the articles for free.

In 2018 the journal received 164 manuscripts and published 94 articles written by 357 different federal HCPs. The 164 manuscript submissions represented a 45% growth over previous years. Not surprisingly, the increased rate of submissions began shortly after the May 2018 announcement that journal articles would be included in PMC. Most of those articles (83%) were submitted unsolicited.

Fed Pract has always prided itself on being an early promoter of interdisciplinary health care professional publications. Nearly half of its listed authors were physicians (48%), while pharmacists made up the next largest cohort (18%). There were smaller numbers of PhDs, nurses, social workers, and physical therapists. The majority were written by HCPs affiliated with the VA (95% of articles and 93% of authors), and no articles in 2018 were written by PHS officers. Physicians comprise about two-thirds of the audience, while pharmacists make up 17% and nurses 9%. PHS and DoD HCPs make up 19% of the Fed Pract audience, suggesting that the journal needs to do more work to encourage these HCPs to contribute articles to the journal.3

Articles published in 2018 covered a broad range of topics from “Anesthesia Care Practice Models in the VHA” and “Army Behavioral Health System” to “Vitreous Hemorrhage in the Setting of a Vascular Loop” and “A Workforce Assessment of VA Home-Based Primary Care Pharmacists.” Categorizing the articles is a challenge. Few health care topics fit neatly into a single topic or specialty. This is especially true in federal health care where much of the care is delivered by multidisciplinary patient-centered medical homes or patient aligned care teams. Nevertheless, a few broad outlines can be discerned. Articles were roughly split between primary care and hospital-based and/or specialty care topics; one-quarter of the articles were case studies or case series articles, and about 20% were editorials or opinion columns. Nineteen articles dealt explicitly with chronic conditions, and 10 articles focused on mental health care.

Peer reviewers are an essential part of the process. Reviewers are blinded to the identityof the authors, ensuring fairness and reducing potential conflicts of interest. We are extremely grateful to each and every reviewer for the time and energy they contribute to the journal. Peer reviewers do not get nearly enough recognition for their important work. In 2018 Fed Pract invited 1,205 reviewers for 164 manuscript submissions and 94 manuscript revisions. More than 200 different reviewers submitted 487 reviews with a median (SD) of 2 reviews (1.8) and a range of 1 to 10. The top 20 reviewers completed 134 reviews with a median (SD) of 6 reviews (1.2). The results stand in contrast to some journals that must offer many invitations per review and depend on a small number of reviewers.1,4-6

The reviewers recommended to reject 14% and to revise 26% of the articles, which is a much lower rejection rate than many other journals (Table).4

These data suggest that Fed Pract and its peer-review process is on a sound foundation but needs to make improvements. Moving into 2019, the journal expects that an increasing number of submissions will require a higher rejection rate. Moreover, we will need to do a better job reaching out to underrepresented portions of our audience. To decrease the time to publication for accepted manuscripts, in 2019 we will publish more articles online ahead of the print publication as we strive to improve the experience for authors, reviewers, readers, and the entire Fed Pract audience.

None of this work can be done without our small and dedicated staff. I would like to thank Managing Editor Joyce Brody who sent out each and every one of those reviewer invitations, Deputy Editor Robert Fee, who manages the special issues, Web Editor Teraya Smith, who runs our entire digital operation, and of course, Editor in Chief Cynthia Geppert, who oversees it all. Finally, it is important that you let us know how we are doing and whether we are meeting your needs. Visit mdedge.com/fedprac to take the readership survey or reach out to me at [email protected].

1. Geppert CMA. Caring under a microscope. Fed Pract. 2018;35(7):6-7.

2. Smith R. Peer review: a flawed process at the heart of science and journals. J R Soc Med. 2006;99(4):178-182.

3. BPA Worldwide. Federal Practitioner brand report for the 6 month period ending June 2018. https://www.frontlinemedcom.com/wp-content/uploads/FEDPRAC_BPA.pdf. Updated June 2018. Accessed March 5, 2019.

4. Fontanarosa PB, Bauchner H, Golub RM. Thank you to JAMA authors, peer reviewers, and readers. JAMA. 2017;317(8):812-813.

5. Publons, Clarivate Analytics. 2018 global state of peer review. https://publons.com/static/Publons-Global-State-Of-Peer-Review-2018.pdf. Published September 2018. Accessed March 5, 2019.

6. Malcom D. It’s time we fix the peer review system. Am J Pharm Educ. 2018;82(5):7144.

1. Geppert CMA. Caring under a microscope. Fed Pract. 2018;35(7):6-7.

2. Smith R. Peer review: a flawed process at the heart of science and journals. J R Soc Med. 2006;99(4):178-182.

3. BPA Worldwide. Federal Practitioner brand report for the 6 month period ending June 2018. https://www.frontlinemedcom.com/wp-content/uploads/FEDPRAC_BPA.pdf. Updated June 2018. Accessed March 5, 2019.

4. Fontanarosa PB, Bauchner H, Golub RM. Thank you to JAMA authors, peer reviewers, and readers. JAMA. 2017;317(8):812-813.

5. Publons, Clarivate Analytics. 2018 global state of peer review. https://publons.com/static/Publons-Global-State-Of-Peer-Review-2018.pdf. Published September 2018. Accessed March 5, 2019.

6. Malcom D. It’s time we fix the peer review system. Am J Pharm Educ. 2018;82(5):7144.

Patient, heal thyself!

Octavio has prostate cancer. His prostate growth is large but localized.

“What do your doctors suggest?” I asked him.

“They sent me to two specialists at the medical center,” he said. “One does robotic surgery, the other does radiation. Each one told me why they recommend their technique.”

“How will you decide?”

“I’ll do some reading,” he said.

“What about the doctor who sent you to them?”

“He hasn’t discussed the choice with me, just sent me to get opinions. I have to make up own mind.”

Out of training for some time, I gather from students and family medical interactions that patient autonomy is now a reigning principle. Here is one definition:

. Patient autonomy does allow for health care providers to educate the patient but does not allow the health care provider to make the decision for the patient.

This sounds sensible, even admirable: no more paternalistic physicians talking down to patients and ordering them around. Yet a closer look shows a contradiction:

1. The second sentence says that patient autonomy “does not allow the health care provider to make the decision for the patient.”

2. But the first one says that patients should decide, “without their health care provider trying to influence the decision.”

Is “trying to influence” the same as making the decision for the patient?

Some would argue that it is: The power discrepancy between the parties makes a doctor’s attempt to influence amount to coercion.

Do you agree, esteemed colleagues, those of you who, like me, treat patients all day? If the choice is between freezing an actinic keratosis, burning it, or using topical chemotherapy, do you just lay all three options out there and ask the patient to pick one? What if your patient works in public and doesn’t have 2 weeks to wait while the reaction to topical 5-fluorouracil that makes his skin look like raw lobster subsides? Can you point that out? Or would that be “trying to influence” and thus not allowed?

You and I can think of many other examples, about medical choices large and small, where we could pose similar questions. This is not abstract philosophy; it is what we do all day.

Look up robot-assisted surgery and radiation for prostate cancer. You will find proponents of both, each making claims concerning survival, recurrence, discomfort, complications. Which is more important – a 15% greater chance of living 2 years longer or a 22% lower risk of incontinence? Will reading such statistics make your choice easier? What if other studies show different numbers?

Octavio chose surgery. I asked him how he decided.

“I talked with an internist I know socially,” he said. “He shared his experience with patients he’s referred for my problem and advised surgery as the better choice. I also saw a story online about a lawyer who chose one method, then 5 years later had to do the other.”

Octavio is sophisticated and well read. He lives near Boston, the self-described hub of medical expertise and academic excellence. Yet he makes up his mind the way everybody does: by asking a trusted adviser, by hearing an arresting anecdote. It’s not science. It’s how people think.

You don’t have to be a behavioral psychologist to know how hard it is for patients, especially frightened ones, to interpret statistical variances or compare disparate categories. Which is better – shorter life with less pain or longer life with more? How much less? How much more? There are ways to address such questions, but having an expert, trusted, and sympathetic adviser is a pretty good way to start. Only an abstract ethicist with no practical exposure to (or sympathy with) actual existing patients and their actual existing providers could possibly think otherwise.

“Let’s freeze those actinics off,” I suggest to a patient. “That won’t scar, you won’t need a dozen shots of lidocaine, and you won’t have to hide for 3 weeks.”

Did I influence her health care decision? Sure. Guilty as charged, with no apologies. When I am a patient, I want nothing less for myself: sympathetic, experienced guidance, shared by someone who knows me and appears to care one way or the other how I do.

Lord preserve us, doctors and patients both, from dogmatists who would demand otherwise.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

Octavio has prostate cancer. His prostate growth is large but localized.

“What do your doctors suggest?” I asked him.

“They sent me to two specialists at the medical center,” he said. “One does robotic surgery, the other does radiation. Each one told me why they recommend their technique.”

“How will you decide?”

“I’ll do some reading,” he said.

“What about the doctor who sent you to them?”

“He hasn’t discussed the choice with me, just sent me to get opinions. I have to make up own mind.”

Out of training for some time, I gather from students and family medical interactions that patient autonomy is now a reigning principle. Here is one definition:

. Patient autonomy does allow for health care providers to educate the patient but does not allow the health care provider to make the decision for the patient.

This sounds sensible, even admirable: no more paternalistic physicians talking down to patients and ordering them around. Yet a closer look shows a contradiction:

1. The second sentence says that patient autonomy “does not allow the health care provider to make the decision for the patient.”

2. But the first one says that patients should decide, “without their health care provider trying to influence the decision.”

Is “trying to influence” the same as making the decision for the patient?

Some would argue that it is: The power discrepancy between the parties makes a doctor’s attempt to influence amount to coercion.

Do you agree, esteemed colleagues, those of you who, like me, treat patients all day? If the choice is between freezing an actinic keratosis, burning it, or using topical chemotherapy, do you just lay all three options out there and ask the patient to pick one? What if your patient works in public and doesn’t have 2 weeks to wait while the reaction to topical 5-fluorouracil that makes his skin look like raw lobster subsides? Can you point that out? Or would that be “trying to influence” and thus not allowed?

You and I can think of many other examples, about medical choices large and small, where we could pose similar questions. This is not abstract philosophy; it is what we do all day.

Look up robot-assisted surgery and radiation for prostate cancer. You will find proponents of both, each making claims concerning survival, recurrence, discomfort, complications. Which is more important – a 15% greater chance of living 2 years longer or a 22% lower risk of incontinence? Will reading such statistics make your choice easier? What if other studies show different numbers?

Octavio chose surgery. I asked him how he decided.

“I talked with an internist I know socially,” he said. “He shared his experience with patients he’s referred for my problem and advised surgery as the better choice. I also saw a story online about a lawyer who chose one method, then 5 years later had to do the other.”

Octavio is sophisticated and well read. He lives near Boston, the self-described hub of medical expertise and academic excellence. Yet he makes up his mind the way everybody does: by asking a trusted adviser, by hearing an arresting anecdote. It’s not science. It’s how people think.

You don’t have to be a behavioral psychologist to know how hard it is for patients, especially frightened ones, to interpret statistical variances or compare disparate categories. Which is better – shorter life with less pain or longer life with more? How much less? How much more? There are ways to address such questions, but having an expert, trusted, and sympathetic adviser is a pretty good way to start. Only an abstract ethicist with no practical exposure to (or sympathy with) actual existing patients and their actual existing providers could possibly think otherwise.

“Let’s freeze those actinics off,” I suggest to a patient. “That won’t scar, you won’t need a dozen shots of lidocaine, and you won’t have to hide for 3 weeks.”

Did I influence her health care decision? Sure. Guilty as charged, with no apologies. When I am a patient, I want nothing less for myself: sympathetic, experienced guidance, shared by someone who knows me and appears to care one way or the other how I do.

Lord preserve us, doctors and patients both, from dogmatists who would demand otherwise.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

Octavio has prostate cancer. His prostate growth is large but localized.

“What do your doctors suggest?” I asked him.

“They sent me to two specialists at the medical center,” he said. “One does robotic surgery, the other does radiation. Each one told me why they recommend their technique.”

“How will you decide?”

“I’ll do some reading,” he said.

“What about the doctor who sent you to them?”

“He hasn’t discussed the choice with me, just sent me to get opinions. I have to make up own mind.”

Out of training for some time, I gather from students and family medical interactions that patient autonomy is now a reigning principle. Here is one definition:

. Patient autonomy does allow for health care providers to educate the patient but does not allow the health care provider to make the decision for the patient.

This sounds sensible, even admirable: no more paternalistic physicians talking down to patients and ordering them around. Yet a closer look shows a contradiction:

1. The second sentence says that patient autonomy “does not allow the health care provider to make the decision for the patient.”

2. But the first one says that patients should decide, “without their health care provider trying to influence the decision.”

Is “trying to influence” the same as making the decision for the patient?

Some would argue that it is: The power discrepancy between the parties makes a doctor’s attempt to influence amount to coercion.

Do you agree, esteemed colleagues, those of you who, like me, treat patients all day? If the choice is between freezing an actinic keratosis, burning it, or using topical chemotherapy, do you just lay all three options out there and ask the patient to pick one? What if your patient works in public and doesn’t have 2 weeks to wait while the reaction to topical 5-fluorouracil that makes his skin look like raw lobster subsides? Can you point that out? Or would that be “trying to influence” and thus not allowed?

You and I can think of many other examples, about medical choices large and small, where we could pose similar questions. This is not abstract philosophy; it is what we do all day.

Look up robot-assisted surgery and radiation for prostate cancer. You will find proponents of both, each making claims concerning survival, recurrence, discomfort, complications. Which is more important – a 15% greater chance of living 2 years longer or a 22% lower risk of incontinence? Will reading such statistics make your choice easier? What if other studies show different numbers?

Octavio chose surgery. I asked him how he decided.

“I talked with an internist I know socially,” he said. “He shared his experience with patients he’s referred for my problem and advised surgery as the better choice. I also saw a story online about a lawyer who chose one method, then 5 years later had to do the other.”

Octavio is sophisticated and well read. He lives near Boston, the self-described hub of medical expertise and academic excellence. Yet he makes up his mind the way everybody does: by asking a trusted adviser, by hearing an arresting anecdote. It’s not science. It’s how people think.

You don’t have to be a behavioral psychologist to know how hard it is for patients, especially frightened ones, to interpret statistical variances or compare disparate categories. Which is better – shorter life with less pain or longer life with more? How much less? How much more? There are ways to address such questions, but having an expert, trusted, and sympathetic adviser is a pretty good way to start. Only an abstract ethicist with no practical exposure to (or sympathy with) actual existing patients and their actual existing providers could possibly think otherwise.

“Let’s freeze those actinics off,” I suggest to a patient. “That won’t scar, you won’t need a dozen shots of lidocaine, and you won’t have to hide for 3 weeks.”

Did I influence her health care decision? Sure. Guilty as charged, with no apologies. When I am a patient, I want nothing less for myself: sympathetic, experienced guidance, shared by someone who knows me and appears to care one way or the other how I do.

Lord preserve us, doctors and patients both, from dogmatists who would demand otherwise.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

Letters: National Suicide Strategy

To the Editor: Even one death by suicide is too many. Suicide is complex and a serious national public health issue that affects people from all walks of life—not just veterans—for a variety of reasons. While there is still a lot we can learn about suicide, we know that suicide is preventable, treatment works, and there is hope.

At the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), our suicide prevention efforts are guided by the National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide.1 Published in 2018, this long-term strategy expands beyond crisis intervention and provides a framework for identifying priorities, organizing efforts, and focusing national attention and community resources to prevent suicide among veterans through a broad public health approach with an emphasis on comprehensive, community-based engagement.

This approach is grounded in 4 key areas: Primary prevention focuses on preventing suicidal behavior before it occurs; whole health considers factors beyond mental health, such as physical health, alcohol or substance misuse, and life events; application of data and research emphasizes evidence-based approaches that can be tailored to the needs of veterans in local communities; and collaboration educates and empowers diverse communities to participate in suicide prevention efforts through coordination.

A recent article by Russell Lemle, PhD, noted that the National Strategy does not emphasize the work of the VA, and he is correct.2 Rather than perpetuate the myth that VA can address suicide alone, the strategy was intended to guide veteran suicide prevention efforts across the entire nation, not just within VA’s walls. It is a plan for how we can ALL work together to prevent veteran suicide. The National Strategy does not minimize VA’s role in suicide prevention. It enhances VA’s ability and expectation to engage in collaborative efforts across the nation.

Every year, about 6,000 veterans die by suicide, the majority of whom have not received recent VA care. We are mindful that some veterans may not receive any or all of their health care services from the VA, for various reasons, and want to be respectful and cognizant of those choices. To save lives, VA needs the support of partners across sectors. We need to ensure that multiple systems are working in a coordinated way to reach veterans where they live, work, and thrive.

Our philosophy is that there is no wrong door to care. That is why we focused on universal, non-VA community interventions. Preventing suicide among all of the nation’s 20 million veterans cannot be the sole responsibility of VA—it requires a nationwide effort. As there is no single cause of suicide, no single organization can tackle suicide prevention alone. Put simply, VA must ensure suicide prevention is a part of every aspect of veterans’ lives, not just their VA interactions. At VA, we know that the care and support that veterans need often comes before a mental health crisis occurs, and communities and families may be better equipped to provide these types of supports.

Activities or special interest groups can boost protective factors against suicide and combat risk factors. Communities can foster an environment where veterans can find connection and camaraderie, achieve a sense of purpose, bolster their coping skills, and live healthily. And partners like the National Shooting Sports Foundation help VA to address sensitive issues, such as lethal means safety, while correcting misconceptions about how VA handles gun ownership.

Data also are an integral piece of our public health approach, driving how VA defines the problem, targets its programs, and delivers and implements interventions. VA was one of the first institutions to implement comprehensive suicide analysis and predictive analytics, and VA has continuously improved data surveillance related to veteran suicide.

We began comprehensive suicide monitoring for the entire VA patient population in 2006, and in 2012, VA released its first report of suicide surveillance among all veterans in select partnering states. Though we are able to share data, we acknowledge the limitations Dr. Lemle highlighted in implementing predictive analytics program outside the VA. However, VA continues to improve reporting and surveillance efforts, especially to better understand the 20 veterans and service members who die by suicide each day.

As Lemle noted, little was previously known about the 14 of 20 veterans who die by suicide every day who weren’t recent users of VA health services. Since the September 2018 release of the National Strategy, VA has obtained additional data. In addition to sharing data, VA will focus on helping non-VA entities understand the problem so that they can help reach veterans who may never go to VA for care. Efforts are underway to better understand specific groups that are at elevated risk, such as veterans aged 18 to 34 years, women veterans, never federally activated guardsmen and reservists, recently separated veterans, and former service members with Other Than Honorable discharges.

To end veteran suicide, VA is relentlessly working to make improvements to existing suicide prevention programs, develop VA-specific plans to advance the National Strategy, find innovative ways to get people into care, and educate veterans and family members about VA care. Through Executive Order 13822, for example, VA has partnered with the Departments of Defense and Homeland Security, which allows us to educate service members about VA offerings before they become veterans. We also are making it easier for them to quickly find information online about VA mental health services.

We acknowledge VA is not a perfect organization, and a negative image can turn away veterans. VA is actively working with the media to get more good news stories published. We have many exciting things to talk about, such as a newly implemented Comprehensive Suicide Risk Assessment, and it is important for people to know that VA is providing the gold standard of care. Sometimes, those stories are better messaged and amplified by partners and non-VA entities, and this is a key part of our approach.

Lemle also raised a concern around funding this new public health initiative. While we recognize the challenges in advancing this new public health approach without additional funding, we are hopeful we can energize communities to work with us to find a solution.

The National Strategy is not the end of the conversation. It is a starting point. We are thankful for Lemle’s thoughtful questions and are actively pursuing and investigating solutions regarding veteran suicide studies, peer support, and community care guidelines for partners as we seek to improve our services. We also are putting pen to paper on a plan to strengthen family involvement and integrate suicide prevention within VA’s whole health and social services strategies.

The National Strategy is a call to action to every organization, system, and institution interested in preventing veteran suicide to help do this work where we cannot. For our part, VA will continue to energize communities to increase local involvement to reach all veterans, and we will continue to empower and equip ALL veterans with the resources and care they need to thrive.

To learn about the resources available for veterans and how you can #BeThere as a VA employee, family member, friend, community partner, or clinician, visit www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/resources.asp. If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide, contact the Veterans Crisis Line to receive free, confidential support and crisis intervention available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year. Call 800-273-8255 and press 1, text to 838255, or chat online at VeteransCrisisLine.net/Chat.

- Keita Franklin, LCSD, PhD

Author affiliations: Executive Director, Suicide Prevention VA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention.

Author disclosures: Keita Franklin participated in the development of the National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide .

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner , Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies.

Author Response: Keita Franklin, PhD, offers a valuable response to my December critique of the VA National Strategy to Prevent Veteran Suicide. Dr. Franklin thoughtfully articulates why public health approaches to prevent suicide must be a core component of a multifaceted strategy. She is right about that.

While I see considerable overlap between our statements, there are 2 important points where we diverge: (1) Unless Congress appropriates sufficient funds for extensive public health outreach, there is a danger that funds to implement it would be diverted from VA’s extant effective VA suicide prevention programs. (2) A prospective suicide prevention plan requires 3 prongs of universal, group, and individually focused strategies, because suicide cannot be prevented by any single strategy. The VA National Strategy as well as the March 2019 Executive Order on a National Roadmap to Empower Veterans and End Suicide, focus predominantly on universal strategies, and I believe its overall approach would be improved by also explicitly supporting VA’s targeted programs for at-risk veterans.

- Russell B. Lemle, PhD

Author affiliations: Policy Analyst at the Veterans Healthcare Policy Institute in Oakland, California.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. National strategy for preventing veteran suicide 2018–2028. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/docs/Office-of-Mental-Health-and-Suicide-Prevention-National-Strategy-for-Preventing-Veterans-Suicide.pdf. Published September 2018. Accessed February 19, 2019.

2. Lemle R. Communities emphasis could undercut VA successes in National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide. Fed Pract. 2018;35(12):16-17.

To the Editor: Even one death by suicide is too many. Suicide is complex and a serious national public health issue that affects people from all walks of life—not just veterans—for a variety of reasons. While there is still a lot we can learn about suicide, we know that suicide is preventable, treatment works, and there is hope.

At the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), our suicide prevention efforts are guided by the National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide.1 Published in 2018, this long-term strategy expands beyond crisis intervention and provides a framework for identifying priorities, organizing efforts, and focusing national attention and community resources to prevent suicide among veterans through a broad public health approach with an emphasis on comprehensive, community-based engagement.

This approach is grounded in 4 key areas: Primary prevention focuses on preventing suicidal behavior before it occurs; whole health considers factors beyond mental health, such as physical health, alcohol or substance misuse, and life events; application of data and research emphasizes evidence-based approaches that can be tailored to the needs of veterans in local communities; and collaboration educates and empowers diverse communities to participate in suicide prevention efforts through coordination.

A recent article by Russell Lemle, PhD, noted that the National Strategy does not emphasize the work of the VA, and he is correct.2 Rather than perpetuate the myth that VA can address suicide alone, the strategy was intended to guide veteran suicide prevention efforts across the entire nation, not just within VA’s walls. It is a plan for how we can ALL work together to prevent veteran suicide. The National Strategy does not minimize VA’s role in suicide prevention. It enhances VA’s ability and expectation to engage in collaborative efforts across the nation.

Every year, about 6,000 veterans die by suicide, the majority of whom have not received recent VA care. We are mindful that some veterans may not receive any or all of their health care services from the VA, for various reasons, and want to be respectful and cognizant of those choices. To save lives, VA needs the support of partners across sectors. We need to ensure that multiple systems are working in a coordinated way to reach veterans where they live, work, and thrive.

Our philosophy is that there is no wrong door to care. That is why we focused on universal, non-VA community interventions. Preventing suicide among all of the nation’s 20 million veterans cannot be the sole responsibility of VA—it requires a nationwide effort. As there is no single cause of suicide, no single organization can tackle suicide prevention alone. Put simply, VA must ensure suicide prevention is a part of every aspect of veterans’ lives, not just their VA interactions. At VA, we know that the care and support that veterans need often comes before a mental health crisis occurs, and communities and families may be better equipped to provide these types of supports.

Activities or special interest groups can boost protective factors against suicide and combat risk factors. Communities can foster an environment where veterans can find connection and camaraderie, achieve a sense of purpose, bolster their coping skills, and live healthily. And partners like the National Shooting Sports Foundation help VA to address sensitive issues, such as lethal means safety, while correcting misconceptions about how VA handles gun ownership.

Data also are an integral piece of our public health approach, driving how VA defines the problem, targets its programs, and delivers and implements interventions. VA was one of the first institutions to implement comprehensive suicide analysis and predictive analytics, and VA has continuously improved data surveillance related to veteran suicide.

We began comprehensive suicide monitoring for the entire VA patient population in 2006, and in 2012, VA released its first report of suicide surveillance among all veterans in select partnering states. Though we are able to share data, we acknowledge the limitations Dr. Lemle highlighted in implementing predictive analytics program outside the VA. However, VA continues to improve reporting and surveillance efforts, especially to better understand the 20 veterans and service members who die by suicide each day.

As Lemle noted, little was previously known about the 14 of 20 veterans who die by suicide every day who weren’t recent users of VA health services. Since the September 2018 release of the National Strategy, VA has obtained additional data. In addition to sharing data, VA will focus on helping non-VA entities understand the problem so that they can help reach veterans who may never go to VA for care. Efforts are underway to better understand specific groups that are at elevated risk, such as veterans aged 18 to 34 years, women veterans, never federally activated guardsmen and reservists, recently separated veterans, and former service members with Other Than Honorable discharges.

To end veteran suicide, VA is relentlessly working to make improvements to existing suicide prevention programs, develop VA-specific plans to advance the National Strategy, find innovative ways to get people into care, and educate veterans and family members about VA care. Through Executive Order 13822, for example, VA has partnered with the Departments of Defense and Homeland Security, which allows us to educate service members about VA offerings before they become veterans. We also are making it easier for them to quickly find information online about VA mental health services.

We acknowledge VA is not a perfect organization, and a negative image can turn away veterans. VA is actively working with the media to get more good news stories published. We have many exciting things to talk about, such as a newly implemented Comprehensive Suicide Risk Assessment, and it is important for people to know that VA is providing the gold standard of care. Sometimes, those stories are better messaged and amplified by partners and non-VA entities, and this is a key part of our approach.

Lemle also raised a concern around funding this new public health initiative. While we recognize the challenges in advancing this new public health approach without additional funding, we are hopeful we can energize communities to work with us to find a solution.

The National Strategy is not the end of the conversation. It is a starting point. We are thankful for Lemle’s thoughtful questions and are actively pursuing and investigating solutions regarding veteran suicide studies, peer support, and community care guidelines for partners as we seek to improve our services. We also are putting pen to paper on a plan to strengthen family involvement and integrate suicide prevention within VA’s whole health and social services strategies.

The National Strategy is a call to action to every organization, system, and institution interested in preventing veteran suicide to help do this work where we cannot. For our part, VA will continue to energize communities to increase local involvement to reach all veterans, and we will continue to empower and equip ALL veterans with the resources and care they need to thrive.

To learn about the resources available for veterans and how you can #BeThere as a VA employee, family member, friend, community partner, or clinician, visit www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/resources.asp. If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide, contact the Veterans Crisis Line to receive free, confidential support and crisis intervention available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year. Call 800-273-8255 and press 1, text to 838255, or chat online at VeteransCrisisLine.net/Chat.

- Keita Franklin, LCSD, PhD

Author affiliations: Executive Director, Suicide Prevention VA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention.

Author disclosures: Keita Franklin participated in the development of the National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide .

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner , Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies.

Author Response: Keita Franklin, PhD, offers a valuable response to my December critique of the VA National Strategy to Prevent Veteran Suicide. Dr. Franklin thoughtfully articulates why public health approaches to prevent suicide must be a core component of a multifaceted strategy. She is right about that.

While I see considerable overlap between our statements, there are 2 important points where we diverge: (1) Unless Congress appropriates sufficient funds for extensive public health outreach, there is a danger that funds to implement it would be diverted from VA’s extant effective VA suicide prevention programs. (2) A prospective suicide prevention plan requires 3 prongs of universal, group, and individually focused strategies, because suicide cannot be prevented by any single strategy. The VA National Strategy as well as the March 2019 Executive Order on a National Roadmap to Empower Veterans and End Suicide, focus predominantly on universal strategies, and I believe its overall approach would be improved by also explicitly supporting VA’s targeted programs for at-risk veterans.

- Russell B. Lemle, PhD

Author affiliations: Policy Analyst at the Veterans Healthcare Policy Institute in Oakland, California.

To the Editor: Even one death by suicide is too many. Suicide is complex and a serious national public health issue that affects people from all walks of life—not just veterans—for a variety of reasons. While there is still a lot we can learn about suicide, we know that suicide is preventable, treatment works, and there is hope.

At the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), our suicide prevention efforts are guided by the National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide.1 Published in 2018, this long-term strategy expands beyond crisis intervention and provides a framework for identifying priorities, organizing efforts, and focusing national attention and community resources to prevent suicide among veterans through a broad public health approach with an emphasis on comprehensive, community-based engagement.

This approach is grounded in 4 key areas: Primary prevention focuses on preventing suicidal behavior before it occurs; whole health considers factors beyond mental health, such as physical health, alcohol or substance misuse, and life events; application of data and research emphasizes evidence-based approaches that can be tailored to the needs of veterans in local communities; and collaboration educates and empowers diverse communities to participate in suicide prevention efforts through coordination.

A recent article by Russell Lemle, PhD, noted that the National Strategy does not emphasize the work of the VA, and he is correct.2 Rather than perpetuate the myth that VA can address suicide alone, the strategy was intended to guide veteran suicide prevention efforts across the entire nation, not just within VA’s walls. It is a plan for how we can ALL work together to prevent veteran suicide. The National Strategy does not minimize VA’s role in suicide prevention. It enhances VA’s ability and expectation to engage in collaborative efforts across the nation.

Every year, about 6,000 veterans die by suicide, the majority of whom have not received recent VA care. We are mindful that some veterans may not receive any or all of their health care services from the VA, for various reasons, and want to be respectful and cognizant of those choices. To save lives, VA needs the support of partners across sectors. We need to ensure that multiple systems are working in a coordinated way to reach veterans where they live, work, and thrive.

Our philosophy is that there is no wrong door to care. That is why we focused on universal, non-VA community interventions. Preventing suicide among all of the nation’s 20 million veterans cannot be the sole responsibility of VA—it requires a nationwide effort. As there is no single cause of suicide, no single organization can tackle suicide prevention alone. Put simply, VA must ensure suicide prevention is a part of every aspect of veterans’ lives, not just their VA interactions. At VA, we know that the care and support that veterans need often comes before a mental health crisis occurs, and communities and families may be better equipped to provide these types of supports.

Activities or special interest groups can boost protective factors against suicide and combat risk factors. Communities can foster an environment where veterans can find connection and camaraderie, achieve a sense of purpose, bolster their coping skills, and live healthily. And partners like the National Shooting Sports Foundation help VA to address sensitive issues, such as lethal means safety, while correcting misconceptions about how VA handles gun ownership.

Data also are an integral piece of our public health approach, driving how VA defines the problem, targets its programs, and delivers and implements interventions. VA was one of the first institutions to implement comprehensive suicide analysis and predictive analytics, and VA has continuously improved data surveillance related to veteran suicide.

We began comprehensive suicide monitoring for the entire VA patient population in 2006, and in 2012, VA released its first report of suicide surveillance among all veterans in select partnering states. Though we are able to share data, we acknowledge the limitations Dr. Lemle highlighted in implementing predictive analytics program outside the VA. However, VA continues to improve reporting and surveillance efforts, especially to better understand the 20 veterans and service members who die by suicide each day.

As Lemle noted, little was previously known about the 14 of 20 veterans who die by suicide every day who weren’t recent users of VA health services. Since the September 2018 release of the National Strategy, VA has obtained additional data. In addition to sharing data, VA will focus on helping non-VA entities understand the problem so that they can help reach veterans who may never go to VA for care. Efforts are underway to better understand specific groups that are at elevated risk, such as veterans aged 18 to 34 years, women veterans, never federally activated guardsmen and reservists, recently separated veterans, and former service members with Other Than Honorable discharges.

To end veteran suicide, VA is relentlessly working to make improvements to existing suicide prevention programs, develop VA-specific plans to advance the National Strategy, find innovative ways to get people into care, and educate veterans and family members about VA care. Through Executive Order 13822, for example, VA has partnered with the Departments of Defense and Homeland Security, which allows us to educate service members about VA offerings before they become veterans. We also are making it easier for them to quickly find information online about VA mental health services.

We acknowledge VA is not a perfect organization, and a negative image can turn away veterans. VA is actively working with the media to get more good news stories published. We have many exciting things to talk about, such as a newly implemented Comprehensive Suicide Risk Assessment, and it is important for people to know that VA is providing the gold standard of care. Sometimes, those stories are better messaged and amplified by partners and non-VA entities, and this is a key part of our approach.