User login

Pathologic superstition

When you believe in things that you don’t understand

Then you suffer

Superstition ain’t the way

– Stevie Wonder

I have always found it odd that airplanes don’t have a 13th row and hotels don’t have a 13th floor. Well, of course they do, but they are not labeled that way. Many people would hesitate to sit in the 13th row of an airplane since 13 is such an unlucky number. At least many people in the United States think the number 13 is unlucky. Thirteen is just a number in much of Asia. There, the number 4 is just as threatening as 13 is to us.

Superstitions like these are familiar to all of us.

One of my favorites is the belief that vacuum cups attached to the skin will somehow draw out toxins and generally improve health. “Cupping,” as the practice is known, is endorsed by several celebrities and famous athletes. After the treatment, a cupped patient exhibits circles of hyperemia, and no other apparent harm. I suspect that about a third of cupped patients truly think they have benefited from a good cupping, about the same number that would benefit from an orally administered placebo.

Superstitions are everywhere. Whether it is a black cat in the United States, infinite reflecting mirrors in Mexico, going back to your house after a wake in the Philippines, or whistling indoors in Lithuania, superstitions are pervasive, deeply held, and generally harmless. They are good for a good laugh as we recognize how ludicrous these unfounded fears are.

Some superstitions, though, are no laughing matter. They can be quite harmful. They are pathologic superstitions.

For example, some people believe vaccines cause autism in children. That pathologic superstition has consequences. A recent CDC report revealed that the population of unvaccinated children in the United States has quadrupled since 2001. This comes as no surprise as we hear about more measles outbreaks – and the deaths associated with them – in populations of unvaccinated children every year. A similar and pervasive pathologic superstition is the fear that an influenza vaccine will cause the flu. I wonder how many people die from this misconception.

Other people believe that their cancer can be treated, if not cured, with unproven, unconventional treatments. I cannot understand how this pathologic superstition developed. The purveyors of unconventional treatment hold much of the blame, but gullibility and ignorance may play a larger role. The consequences are tragic. A recent report demonstrated an approximately twofold increased risk of death in patients who used complementary therapies, compared with those who did not (JAMA Oncol. 2018 Oct 1;4[10]:1375-81).

These are sobering data for those of us who have in the past relented when our patients asked if they could take this or that supplement because we did not think they would cause significant harm.

Superstitions apparently are part of the human condition, evolved to attribute causation and provide order. They are a learned phenomenon. They are learned by reasonable people with normal intelligence and rational thinking. A superstition is born when someone is exposed to a false statement by someone or something they trust – a trusted other.

Trusted others exude certainty. Once established, superstitions are regrettably difficult to remove by those who are less certain, like physicians. How willing are we to say that the flu vaccine is 100% safe? Without certainty, how can a physician debunk a superstition? The techniques that we have been taught usually work, but not when faced with a pathologic superstition.

Science and experience teach us that firmly held superstitions cannot be broken with logical, stepwise reasoning. Jonathan Haidt provides a useful metaphor for this problem in his book “The Happiness Hypothesis” (Basic Books, 2006). He describes a rider on an elephant. The rider represents our rational thought and the elephant represents our emotional foundation. The rider thinks he controls the elephant, but the opposite is more likely true. In order to move the elephant in a certain direction, the rider needs to make the elephant want to turn in that direction. Otherwise, all the cajoling and arguing in the world won’t make the elephant turn. A rational argument made to someone emotionally invested in the counter argument will fail. That is why we cannot convince antivaccine parents to vaccinate their children by trying to persuade them with facts. Neither can we convince global warming skeptics to stop burning coal, gun advocates to vote for restrictions on gun ownership, or cancer patients to accept curative treatment if their values and morals are being challenged.

In a later book, “The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion” (Vintage Books, 2012), Mr. Haidt expands his hypothesis to declare that to change minds, we must appeal to underlying moral values. The challenge is to identify those moral underpinnings in our patients in order to develop an appeal likely to resonate with their emotions and values.

Superstition derives from something people learn either from trusted others or from personal experience. It does no good for physicians to deride patient beliefs and denigrate their agency in an attempt to persuade them to abandon what we consider irrational beliefs. For physicians to penetrate pathologic superstitions, they will have to become the trusted other, to understand moral foundations, to emotionally connect. That does not usually happen the first day we meet a new patient, especially a skeptical one. It takes time, and effort, to reach out and bond with the patient and their family. Only then can pathologic superstitions dissolve and a better patient-doctor relationship evolve.

During this season rife with superstition, remember that your patient’s own superstitions are part of their belief system, and your belief system may be threatening to them. Make your beliefs less threatening, become a trusted other, and appeal to their foundational values, and you can successfully break a pathologic superstition.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at [email protected].

When you believe in things that you don’t understand

Then you suffer

Superstition ain’t the way

– Stevie Wonder

I have always found it odd that airplanes don’t have a 13th row and hotels don’t have a 13th floor. Well, of course they do, but they are not labeled that way. Many people would hesitate to sit in the 13th row of an airplane since 13 is such an unlucky number. At least many people in the United States think the number 13 is unlucky. Thirteen is just a number in much of Asia. There, the number 4 is just as threatening as 13 is to us.

Superstitions like these are familiar to all of us.

One of my favorites is the belief that vacuum cups attached to the skin will somehow draw out toxins and generally improve health. “Cupping,” as the practice is known, is endorsed by several celebrities and famous athletes. After the treatment, a cupped patient exhibits circles of hyperemia, and no other apparent harm. I suspect that about a third of cupped patients truly think they have benefited from a good cupping, about the same number that would benefit from an orally administered placebo.

Superstitions are everywhere. Whether it is a black cat in the United States, infinite reflecting mirrors in Mexico, going back to your house after a wake in the Philippines, or whistling indoors in Lithuania, superstitions are pervasive, deeply held, and generally harmless. They are good for a good laugh as we recognize how ludicrous these unfounded fears are.

Some superstitions, though, are no laughing matter. They can be quite harmful. They are pathologic superstitions.

For example, some people believe vaccines cause autism in children. That pathologic superstition has consequences. A recent CDC report revealed that the population of unvaccinated children in the United States has quadrupled since 2001. This comes as no surprise as we hear about more measles outbreaks – and the deaths associated with them – in populations of unvaccinated children every year. A similar and pervasive pathologic superstition is the fear that an influenza vaccine will cause the flu. I wonder how many people die from this misconception.

Other people believe that their cancer can be treated, if not cured, with unproven, unconventional treatments. I cannot understand how this pathologic superstition developed. The purveyors of unconventional treatment hold much of the blame, but gullibility and ignorance may play a larger role. The consequences are tragic. A recent report demonstrated an approximately twofold increased risk of death in patients who used complementary therapies, compared with those who did not (JAMA Oncol. 2018 Oct 1;4[10]:1375-81).

These are sobering data for those of us who have in the past relented when our patients asked if they could take this or that supplement because we did not think they would cause significant harm.

Superstitions apparently are part of the human condition, evolved to attribute causation and provide order. They are a learned phenomenon. They are learned by reasonable people with normal intelligence and rational thinking. A superstition is born when someone is exposed to a false statement by someone or something they trust – a trusted other.

Trusted others exude certainty. Once established, superstitions are regrettably difficult to remove by those who are less certain, like physicians. How willing are we to say that the flu vaccine is 100% safe? Without certainty, how can a physician debunk a superstition? The techniques that we have been taught usually work, but not when faced with a pathologic superstition.

Science and experience teach us that firmly held superstitions cannot be broken with logical, stepwise reasoning. Jonathan Haidt provides a useful metaphor for this problem in his book “The Happiness Hypothesis” (Basic Books, 2006). He describes a rider on an elephant. The rider represents our rational thought and the elephant represents our emotional foundation. The rider thinks he controls the elephant, but the opposite is more likely true. In order to move the elephant in a certain direction, the rider needs to make the elephant want to turn in that direction. Otherwise, all the cajoling and arguing in the world won’t make the elephant turn. A rational argument made to someone emotionally invested in the counter argument will fail. That is why we cannot convince antivaccine parents to vaccinate their children by trying to persuade them with facts. Neither can we convince global warming skeptics to stop burning coal, gun advocates to vote for restrictions on gun ownership, or cancer patients to accept curative treatment if their values and morals are being challenged.

In a later book, “The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion” (Vintage Books, 2012), Mr. Haidt expands his hypothesis to declare that to change minds, we must appeal to underlying moral values. The challenge is to identify those moral underpinnings in our patients in order to develop an appeal likely to resonate with their emotions and values.

Superstition derives from something people learn either from trusted others or from personal experience. It does no good for physicians to deride patient beliefs and denigrate their agency in an attempt to persuade them to abandon what we consider irrational beliefs. For physicians to penetrate pathologic superstitions, they will have to become the trusted other, to understand moral foundations, to emotionally connect. That does not usually happen the first day we meet a new patient, especially a skeptical one. It takes time, and effort, to reach out and bond with the patient and their family. Only then can pathologic superstitions dissolve and a better patient-doctor relationship evolve.

During this season rife with superstition, remember that your patient’s own superstitions are part of their belief system, and your belief system may be threatening to them. Make your beliefs less threatening, become a trusted other, and appeal to their foundational values, and you can successfully break a pathologic superstition.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at [email protected].

When you believe in things that you don’t understand

Then you suffer

Superstition ain’t the way

– Stevie Wonder

I have always found it odd that airplanes don’t have a 13th row and hotels don’t have a 13th floor. Well, of course they do, but they are not labeled that way. Many people would hesitate to sit in the 13th row of an airplane since 13 is such an unlucky number. At least many people in the United States think the number 13 is unlucky. Thirteen is just a number in much of Asia. There, the number 4 is just as threatening as 13 is to us.

Superstitions like these are familiar to all of us.

One of my favorites is the belief that vacuum cups attached to the skin will somehow draw out toxins and generally improve health. “Cupping,” as the practice is known, is endorsed by several celebrities and famous athletes. After the treatment, a cupped patient exhibits circles of hyperemia, and no other apparent harm. I suspect that about a third of cupped patients truly think they have benefited from a good cupping, about the same number that would benefit from an orally administered placebo.

Superstitions are everywhere. Whether it is a black cat in the United States, infinite reflecting mirrors in Mexico, going back to your house after a wake in the Philippines, or whistling indoors in Lithuania, superstitions are pervasive, deeply held, and generally harmless. They are good for a good laugh as we recognize how ludicrous these unfounded fears are.

Some superstitions, though, are no laughing matter. They can be quite harmful. They are pathologic superstitions.

For example, some people believe vaccines cause autism in children. That pathologic superstition has consequences. A recent CDC report revealed that the population of unvaccinated children in the United States has quadrupled since 2001. This comes as no surprise as we hear about more measles outbreaks – and the deaths associated with them – in populations of unvaccinated children every year. A similar and pervasive pathologic superstition is the fear that an influenza vaccine will cause the flu. I wonder how many people die from this misconception.

Other people believe that their cancer can be treated, if not cured, with unproven, unconventional treatments. I cannot understand how this pathologic superstition developed. The purveyors of unconventional treatment hold much of the blame, but gullibility and ignorance may play a larger role. The consequences are tragic. A recent report demonstrated an approximately twofold increased risk of death in patients who used complementary therapies, compared with those who did not (JAMA Oncol. 2018 Oct 1;4[10]:1375-81).

These are sobering data for those of us who have in the past relented when our patients asked if they could take this or that supplement because we did not think they would cause significant harm.

Superstitions apparently are part of the human condition, evolved to attribute causation and provide order. They are a learned phenomenon. They are learned by reasonable people with normal intelligence and rational thinking. A superstition is born when someone is exposed to a false statement by someone or something they trust – a trusted other.

Trusted others exude certainty. Once established, superstitions are regrettably difficult to remove by those who are less certain, like physicians. How willing are we to say that the flu vaccine is 100% safe? Without certainty, how can a physician debunk a superstition? The techniques that we have been taught usually work, but not when faced with a pathologic superstition.

Science and experience teach us that firmly held superstitions cannot be broken with logical, stepwise reasoning. Jonathan Haidt provides a useful metaphor for this problem in his book “The Happiness Hypothesis” (Basic Books, 2006). He describes a rider on an elephant. The rider represents our rational thought and the elephant represents our emotional foundation. The rider thinks he controls the elephant, but the opposite is more likely true. In order to move the elephant in a certain direction, the rider needs to make the elephant want to turn in that direction. Otherwise, all the cajoling and arguing in the world won’t make the elephant turn. A rational argument made to someone emotionally invested in the counter argument will fail. That is why we cannot convince antivaccine parents to vaccinate their children by trying to persuade them with facts. Neither can we convince global warming skeptics to stop burning coal, gun advocates to vote for restrictions on gun ownership, or cancer patients to accept curative treatment if their values and morals are being challenged.

In a later book, “The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion” (Vintage Books, 2012), Mr. Haidt expands his hypothesis to declare that to change minds, we must appeal to underlying moral values. The challenge is to identify those moral underpinnings in our patients in order to develop an appeal likely to resonate with their emotions and values.

Superstition derives from something people learn either from trusted others or from personal experience. It does no good for physicians to deride patient beliefs and denigrate their agency in an attempt to persuade them to abandon what we consider irrational beliefs. For physicians to penetrate pathologic superstitions, they will have to become the trusted other, to understand moral foundations, to emotionally connect. That does not usually happen the first day we meet a new patient, especially a skeptical one. It takes time, and effort, to reach out and bond with the patient and their family. Only then can pathologic superstitions dissolve and a better patient-doctor relationship evolve.

During this season rife with superstition, remember that your patient’s own superstitions are part of their belief system, and your belief system may be threatening to them. Make your beliefs less threatening, become a trusted other, and appeal to their foundational values, and you can successfully break a pathologic superstition.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at [email protected].

Tribute: Herb Kleber’s ‘generosity of spirit’ matched by few

Editors’ Note: Herbert D. Kleber, MD, a pioneer in the field of addiction medicine, died Oct. 5, at the age of 84. At the time of his death, Dr. Kleber was professor of psychiatry and emeritus director of the division on substance use disorders at Columbia University in New York.

I met Herb Kleber in the fall of 1967, when my center at National Institute of Mental Health funded six new programs to treat opiate addiction in selected cities across the United States. Fifty-one years later, only one still survives – in New Haven, Conn.

Herb began his work at Yale University in an academic/psychoanalytic environment that, with few exceptions, had too little respect for, or understanding of, his work; with a state mental health administration that placed addiction treatment at the very bottom of its priorities; and, in a racially polarized community reeling from a murder and a highly politicized jury trial.

It was Herb’s creative genius that led to the formation and maintenance of the APT Foundation with a laserlike focus on successive waves of heroin, crack cocaine, and other drug epidemics. The board structure, the clientele, and the challenges of building and maintaining a program that supported cutting-edge treatment, education, and research could have made him feel like the principal character in a book by Mario Puzo. But Herb generated loyalty in those who worked for and with him not by fear, but by his generosity of spirit, his crediting the work of others, his supporting the advancement of junior colleagues, and by his deep respect and appreciation for everyone on the team. When I last checked, Roz (his dedicated administrator) was still on the job – and the program was still being led by people whom he trained.

Most importantly, in spite of his very busy work schedule, his top priority was his family.

In 1977, I became chairman of the department of psychiatry at the University of Connecticut. In 1978, my group received a 4-year center grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. By 1982, we had recruited three full professors and a talented assistant professor to our affiliated Veterans Affairs hospital. But in 1985, unfavorable changes at the Newington VA hospital led to the departure of those key faculty. Herb generously agreed to my request that we try to build collaborative bridges between our center and his programs in New Haven. This made it possible for Hank Kranzler at UConn and Stephanie O’Malley at Yale to launch their careers in clinical trials research. The collaboration that Herb generously provided likely saved our alcohol center. On a personal level, Herb and I began to have lunches halfway between New Haven and Farmington. We looked for ways to strengthen each other’s programs – but in 1989, Herb accepted an offer from President George H.W. Bush to join with William Bennett to launch a new White House Office of National Drug Control Policy.

On a trip to Washington, I visited Herb in his White House office. I watched as he mentored young staff about the intricacies of federal drug policy, and he proudly showed off the first draft of the national action plan. When Bill Bennett decided to move on, Herb and his wife, Marian Fischman, got an offer from Herb Pardes (then chair of psychiatry and dean of the College of Medicine at Columbia) to create a dedicated addiction research center at that institution. Their success at Columbia was unprecedented in an environment that had no previous commitment to addiction treatment and research. The result has been a research program that spans neuroscience, clinical trials, and clinical quality improvement. Herb enabled the research careers of a whole new generation of leaders. Combining his years at Yale and Columbia, : in the numbers, diversity, and success of his mentees.

In 1993, my wife and I moved to Washington. Despite the distance between New York and Washington, Herb and I remained good friends. Herb and Marian attended our daughter’s wedding. When Marian became ill, we feared the worst. After she died, we felt the depth of Herb’s loss. When, several years later, we met Annie Burlock Lawver, we felt profound joy. We were honored to be present at their wedding – and we truly enjoyed traveling together with them in Colombia, Spain, and Iceland.

Herb and Annie were on vacation in Greece with his son and daughter-in-law when he died suddenly of a heart attack while on the island of Santorini. When Annie called from Athens to tell us of Herb’s death, I felt a powerful unease – a sense that the world suddenly seemed more vulnerable. Especially in the age of Trump, Herb’s honesty, integrity, humility, and effectiveness served as an essential counterweight to frustration and despair.

To those who knew his love (like Annie, his children, grandchildren, and great granddaughter, and his dog Sparky), it was total and unconditional. He brought this boundless caring to mentorship and to friendship. His humor could light up a room. His generosity of spirit is matched by too few leaders in academia. It was my privilege to be counted among his friends. He was one of a kind, and I will miss him.

Dr. Meyer is former chair of psychiatry at the University of Connecticut, New Haven. He also served as principal investigator of the Alcohol Research Center and executive dean at UConn. In addition, Dr. Meyer is former vice president of health affairs at George Washington University in Washington, former CEO of Best Practice Project Management (a consulting company), and former professor of psychiatry at Pennsylvania State University, Hershey.

Editors’ Note: Herbert D. Kleber, MD, a pioneer in the field of addiction medicine, died Oct. 5, at the age of 84. At the time of his death, Dr. Kleber was professor of psychiatry and emeritus director of the division on substance use disorders at Columbia University in New York.

I met Herb Kleber in the fall of 1967, when my center at National Institute of Mental Health funded six new programs to treat opiate addiction in selected cities across the United States. Fifty-one years later, only one still survives – in New Haven, Conn.

Herb began his work at Yale University in an academic/psychoanalytic environment that, with few exceptions, had too little respect for, or understanding of, his work; with a state mental health administration that placed addiction treatment at the very bottom of its priorities; and, in a racially polarized community reeling from a murder and a highly politicized jury trial.

It was Herb’s creative genius that led to the formation and maintenance of the APT Foundation with a laserlike focus on successive waves of heroin, crack cocaine, and other drug epidemics. The board structure, the clientele, and the challenges of building and maintaining a program that supported cutting-edge treatment, education, and research could have made him feel like the principal character in a book by Mario Puzo. But Herb generated loyalty in those who worked for and with him not by fear, but by his generosity of spirit, his crediting the work of others, his supporting the advancement of junior colleagues, and by his deep respect and appreciation for everyone on the team. When I last checked, Roz (his dedicated administrator) was still on the job – and the program was still being led by people whom he trained.

Most importantly, in spite of his very busy work schedule, his top priority was his family.

In 1977, I became chairman of the department of psychiatry at the University of Connecticut. In 1978, my group received a 4-year center grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. By 1982, we had recruited three full professors and a talented assistant professor to our affiliated Veterans Affairs hospital. But in 1985, unfavorable changes at the Newington VA hospital led to the departure of those key faculty. Herb generously agreed to my request that we try to build collaborative bridges between our center and his programs in New Haven. This made it possible for Hank Kranzler at UConn and Stephanie O’Malley at Yale to launch their careers in clinical trials research. The collaboration that Herb generously provided likely saved our alcohol center. On a personal level, Herb and I began to have lunches halfway between New Haven and Farmington. We looked for ways to strengthen each other’s programs – but in 1989, Herb accepted an offer from President George H.W. Bush to join with William Bennett to launch a new White House Office of National Drug Control Policy.

On a trip to Washington, I visited Herb in his White House office. I watched as he mentored young staff about the intricacies of federal drug policy, and he proudly showed off the first draft of the national action plan. When Bill Bennett decided to move on, Herb and his wife, Marian Fischman, got an offer from Herb Pardes (then chair of psychiatry and dean of the College of Medicine at Columbia) to create a dedicated addiction research center at that institution. Their success at Columbia was unprecedented in an environment that had no previous commitment to addiction treatment and research. The result has been a research program that spans neuroscience, clinical trials, and clinical quality improvement. Herb enabled the research careers of a whole new generation of leaders. Combining his years at Yale and Columbia, : in the numbers, diversity, and success of his mentees.

In 1993, my wife and I moved to Washington. Despite the distance between New York and Washington, Herb and I remained good friends. Herb and Marian attended our daughter’s wedding. When Marian became ill, we feared the worst. After she died, we felt the depth of Herb’s loss. When, several years later, we met Annie Burlock Lawver, we felt profound joy. We were honored to be present at their wedding – and we truly enjoyed traveling together with them in Colombia, Spain, and Iceland.

Herb and Annie were on vacation in Greece with his son and daughter-in-law when he died suddenly of a heart attack while on the island of Santorini. When Annie called from Athens to tell us of Herb’s death, I felt a powerful unease – a sense that the world suddenly seemed more vulnerable. Especially in the age of Trump, Herb’s honesty, integrity, humility, and effectiveness served as an essential counterweight to frustration and despair.

To those who knew his love (like Annie, his children, grandchildren, and great granddaughter, and his dog Sparky), it was total and unconditional. He brought this boundless caring to mentorship and to friendship. His humor could light up a room. His generosity of spirit is matched by too few leaders in academia. It was my privilege to be counted among his friends. He was one of a kind, and I will miss him.

Dr. Meyer is former chair of psychiatry at the University of Connecticut, New Haven. He also served as principal investigator of the Alcohol Research Center and executive dean at UConn. In addition, Dr. Meyer is former vice president of health affairs at George Washington University in Washington, former CEO of Best Practice Project Management (a consulting company), and former professor of psychiatry at Pennsylvania State University, Hershey.

Editors’ Note: Herbert D. Kleber, MD, a pioneer in the field of addiction medicine, died Oct. 5, at the age of 84. At the time of his death, Dr. Kleber was professor of psychiatry and emeritus director of the division on substance use disorders at Columbia University in New York.

I met Herb Kleber in the fall of 1967, when my center at National Institute of Mental Health funded six new programs to treat opiate addiction in selected cities across the United States. Fifty-one years later, only one still survives – in New Haven, Conn.

Herb began his work at Yale University in an academic/psychoanalytic environment that, with few exceptions, had too little respect for, or understanding of, his work; with a state mental health administration that placed addiction treatment at the very bottom of its priorities; and, in a racially polarized community reeling from a murder and a highly politicized jury trial.

It was Herb’s creative genius that led to the formation and maintenance of the APT Foundation with a laserlike focus on successive waves of heroin, crack cocaine, and other drug epidemics. The board structure, the clientele, and the challenges of building and maintaining a program that supported cutting-edge treatment, education, and research could have made him feel like the principal character in a book by Mario Puzo. But Herb generated loyalty in those who worked for and with him not by fear, but by his generosity of spirit, his crediting the work of others, his supporting the advancement of junior colleagues, and by his deep respect and appreciation for everyone on the team. When I last checked, Roz (his dedicated administrator) was still on the job – and the program was still being led by people whom he trained.

Most importantly, in spite of his very busy work schedule, his top priority was his family.

In 1977, I became chairman of the department of psychiatry at the University of Connecticut. In 1978, my group received a 4-year center grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. By 1982, we had recruited three full professors and a talented assistant professor to our affiliated Veterans Affairs hospital. But in 1985, unfavorable changes at the Newington VA hospital led to the departure of those key faculty. Herb generously agreed to my request that we try to build collaborative bridges between our center and his programs in New Haven. This made it possible for Hank Kranzler at UConn and Stephanie O’Malley at Yale to launch their careers in clinical trials research. The collaboration that Herb generously provided likely saved our alcohol center. On a personal level, Herb and I began to have lunches halfway between New Haven and Farmington. We looked for ways to strengthen each other’s programs – but in 1989, Herb accepted an offer from President George H.W. Bush to join with William Bennett to launch a new White House Office of National Drug Control Policy.

On a trip to Washington, I visited Herb in his White House office. I watched as he mentored young staff about the intricacies of federal drug policy, and he proudly showed off the first draft of the national action plan. When Bill Bennett decided to move on, Herb and his wife, Marian Fischman, got an offer from Herb Pardes (then chair of psychiatry and dean of the College of Medicine at Columbia) to create a dedicated addiction research center at that institution. Their success at Columbia was unprecedented in an environment that had no previous commitment to addiction treatment and research. The result has been a research program that spans neuroscience, clinical trials, and clinical quality improvement. Herb enabled the research careers of a whole new generation of leaders. Combining his years at Yale and Columbia, : in the numbers, diversity, and success of his mentees.

In 1993, my wife and I moved to Washington. Despite the distance between New York and Washington, Herb and I remained good friends. Herb and Marian attended our daughter’s wedding. When Marian became ill, we feared the worst. After she died, we felt the depth of Herb’s loss. When, several years later, we met Annie Burlock Lawver, we felt profound joy. We were honored to be present at their wedding – and we truly enjoyed traveling together with them in Colombia, Spain, and Iceland.

Herb and Annie were on vacation in Greece with his son and daughter-in-law when he died suddenly of a heart attack while on the island of Santorini. When Annie called from Athens to tell us of Herb’s death, I felt a powerful unease – a sense that the world suddenly seemed more vulnerable. Especially in the age of Trump, Herb’s honesty, integrity, humility, and effectiveness served as an essential counterweight to frustration and despair.

To those who knew his love (like Annie, his children, grandchildren, and great granddaughter, and his dog Sparky), it was total and unconditional. He brought this boundless caring to mentorship and to friendship. His humor could light up a room. His generosity of spirit is matched by too few leaders in academia. It was my privilege to be counted among his friends. He was one of a kind, and I will miss him.

Dr. Meyer is former chair of psychiatry at the University of Connecticut, New Haven. He also served as principal investigator of the Alcohol Research Center and executive dean at UConn. In addition, Dr. Meyer is former vice president of health affairs at George Washington University in Washington, former CEO of Best Practice Project Management (a consulting company), and former professor of psychiatry at Pennsylvania State University, Hershey.

Food for Thought

This special issue is dedicated to resident education on psoriasis. With that in mind, we hope to address many topics of interest to those in training. Over the years, diet has been a hot topic among psoriasis patients. They want to know how diet affects psoriasis and what changes can be made to their diet to improve their condition. Although they have expected specific answers, my response has usually been that they should, of course, eat an overall healthy and balanced diet, and lose weight if necessary. I have continued, however, that no specific diet has been recommended. However, now we have some information that may start to give us some answers.

The Mediterranean diet has been regarded as a healthy regimen.1 This diet emphasizes eating primarily plant-based foods, such as fruits and vegetables; whole grains; legumes; and nuts. Other recommendations include replacing butter with healthy fats such as olive oil and canola oil, using herbs and spices instead of salt to flavor foods, and limiting red meat to no more than a few times a month.1

As we know, psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease. The Mediterranean diet has been shown to reduce chronic inflammation and has a positive effect on the risk for metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular events.1 Phan et al1 hypothesized a positive effect of the Mediterranean diet on psoriasis. They performed a study to assess the association between a score that reflects the adhesion to a Mediterranean diet (MEDI-LITE) and the onset and/or severity of psoriasis.1

The NutriNet-Santé program is an ongoing, observational, web-based questionnaire cohort study launched in France in May 2009.1 Data were collected and analyzed between April 2017 and June 2017. Individuals with psoriasis were identified utilizing a validated online questionnaire and then categorized by disease severity into 1 of 3 groups: severe psoriasis, nonsevere psoriasis, and psoriasis free.1

During the initial 2 years of participation in the cohort, data on dietary intake (including alcohol) were gathered to calculate the MEDI-LITE score, ranging from 0 (no adherence) to 18 (maximum adherence).1 Of the 158,361 total web-based participants, 35,735 (23%) replied to the psoriasis questionnaire.1 Of the respondents, 3557 (10%) individuals reported having psoriasis. The condition was severe in 878 cases (24.7%), and 299 (8.4%) incident cases were recorded (cases occurring >2 years after participant inclusion in the cohort). After adjustment for confounding factors, the investigators found a significant inverse relationship between the MEDI-LITE score and having severe psoriasis (odds ratio [OR], 0.71; 95% CI, 0.55-0.92 for the MEDI-LITE score’s second tertile [score of 8 to 9]; and OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.59-1.01 for the third tertile [score of 10 to 18]).1

The authors noted that patients with severe psoriasis displayed low levels of adherence to the Mediterranean diet.1 They commented that this finding supports the hypothesis that the Mediterranean diet may slow the progression of psoriasis. If these findings are confirmed, adherence to a Mediterranean diet should be integrated into the routine management of moderate to severe psoriasis.1 These findings are by no means definitive, but it is a first step in helping us define more specific dietary recommendations for psoriasis.

This issue includes several articles looking at various facets of psoriasis important to residents, including the pathophysiology of psoriasis,2 treatment approach using biologic therapies,3 risk factors and triggers for psoriasis,4 and the psychosocial impact of psoriasis.5 We hope that you find this issue enjoyable and informative.

- Phan C, Touvier M, Kesse-Guyot E, et al. Association between Mediterranean anti-inflammatory dietary profile and severity of psoriasis: results from the NutriNet-Santé cohort [published online July 25, 2018]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2127.

- Hugh JM, Weinberg JM. Update on the pathophysiology of psoriasis. Cutis. 2018;102(suppl 5):6-12.

- McKay C, Kondratuk KE, Miller JP, et al. Biologic therapy in psoriasis: navigating the options. Cutis. 2018;102(suppl 5):13-17.

- Lee EB, Wu KK, Lee MP, et al. Psoriasis risk factors and triggers. Cutis. 2018;102(suppl 5):18-20.

- Kolli SS, Amin SD, Pona A, et al. Psychosocial impact of psoriasis: a review for dermatology residents. Cutis. 2018;102(suppl 5):21-25.

This special issue is dedicated to resident education on psoriasis. With that in mind, we hope to address many topics of interest to those in training. Over the years, diet has been a hot topic among psoriasis patients. They want to know how diet affects psoriasis and what changes can be made to their diet to improve their condition. Although they have expected specific answers, my response has usually been that they should, of course, eat an overall healthy and balanced diet, and lose weight if necessary. I have continued, however, that no specific diet has been recommended. However, now we have some information that may start to give us some answers.

The Mediterranean diet has been regarded as a healthy regimen.1 This diet emphasizes eating primarily plant-based foods, such as fruits and vegetables; whole grains; legumes; and nuts. Other recommendations include replacing butter with healthy fats such as olive oil and canola oil, using herbs and spices instead of salt to flavor foods, and limiting red meat to no more than a few times a month.1

As we know, psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease. The Mediterranean diet has been shown to reduce chronic inflammation and has a positive effect on the risk for metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular events.1 Phan et al1 hypothesized a positive effect of the Mediterranean diet on psoriasis. They performed a study to assess the association between a score that reflects the adhesion to a Mediterranean diet (MEDI-LITE) and the onset and/or severity of psoriasis.1

The NutriNet-Santé program is an ongoing, observational, web-based questionnaire cohort study launched in France in May 2009.1 Data were collected and analyzed between April 2017 and June 2017. Individuals with psoriasis were identified utilizing a validated online questionnaire and then categorized by disease severity into 1 of 3 groups: severe psoriasis, nonsevere psoriasis, and psoriasis free.1

During the initial 2 years of participation in the cohort, data on dietary intake (including alcohol) were gathered to calculate the MEDI-LITE score, ranging from 0 (no adherence) to 18 (maximum adherence).1 Of the 158,361 total web-based participants, 35,735 (23%) replied to the psoriasis questionnaire.1 Of the respondents, 3557 (10%) individuals reported having psoriasis. The condition was severe in 878 cases (24.7%), and 299 (8.4%) incident cases were recorded (cases occurring >2 years after participant inclusion in the cohort). After adjustment for confounding factors, the investigators found a significant inverse relationship between the MEDI-LITE score and having severe psoriasis (odds ratio [OR], 0.71; 95% CI, 0.55-0.92 for the MEDI-LITE score’s second tertile [score of 8 to 9]; and OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.59-1.01 for the third tertile [score of 10 to 18]).1

The authors noted that patients with severe psoriasis displayed low levels of adherence to the Mediterranean diet.1 They commented that this finding supports the hypothesis that the Mediterranean diet may slow the progression of psoriasis. If these findings are confirmed, adherence to a Mediterranean diet should be integrated into the routine management of moderate to severe psoriasis.1 These findings are by no means definitive, but it is a first step in helping us define more specific dietary recommendations for psoriasis.

This issue includes several articles looking at various facets of psoriasis important to residents, including the pathophysiology of psoriasis,2 treatment approach using biologic therapies,3 risk factors and triggers for psoriasis,4 and the psychosocial impact of psoriasis.5 We hope that you find this issue enjoyable and informative.

This special issue is dedicated to resident education on psoriasis. With that in mind, we hope to address many topics of interest to those in training. Over the years, diet has been a hot topic among psoriasis patients. They want to know how diet affects psoriasis and what changes can be made to their diet to improve their condition. Although they have expected specific answers, my response has usually been that they should, of course, eat an overall healthy and balanced diet, and lose weight if necessary. I have continued, however, that no specific diet has been recommended. However, now we have some information that may start to give us some answers.

The Mediterranean diet has been regarded as a healthy regimen.1 This diet emphasizes eating primarily plant-based foods, such as fruits and vegetables; whole grains; legumes; and nuts. Other recommendations include replacing butter with healthy fats such as olive oil and canola oil, using herbs and spices instead of salt to flavor foods, and limiting red meat to no more than a few times a month.1

As we know, psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease. The Mediterranean diet has been shown to reduce chronic inflammation and has a positive effect on the risk for metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular events.1 Phan et al1 hypothesized a positive effect of the Mediterranean diet on psoriasis. They performed a study to assess the association between a score that reflects the adhesion to a Mediterranean diet (MEDI-LITE) and the onset and/or severity of psoriasis.1

The NutriNet-Santé program is an ongoing, observational, web-based questionnaire cohort study launched in France in May 2009.1 Data were collected and analyzed between April 2017 and June 2017. Individuals with psoriasis were identified utilizing a validated online questionnaire and then categorized by disease severity into 1 of 3 groups: severe psoriasis, nonsevere psoriasis, and psoriasis free.1

During the initial 2 years of participation in the cohort, data on dietary intake (including alcohol) were gathered to calculate the MEDI-LITE score, ranging from 0 (no adherence) to 18 (maximum adherence).1 Of the 158,361 total web-based participants, 35,735 (23%) replied to the psoriasis questionnaire.1 Of the respondents, 3557 (10%) individuals reported having psoriasis. The condition was severe in 878 cases (24.7%), and 299 (8.4%) incident cases were recorded (cases occurring >2 years after participant inclusion in the cohort). After adjustment for confounding factors, the investigators found a significant inverse relationship between the MEDI-LITE score and having severe psoriasis (odds ratio [OR], 0.71; 95% CI, 0.55-0.92 for the MEDI-LITE score’s second tertile [score of 8 to 9]; and OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.59-1.01 for the third tertile [score of 10 to 18]).1

The authors noted that patients with severe psoriasis displayed low levels of adherence to the Mediterranean diet.1 They commented that this finding supports the hypothesis that the Mediterranean diet may slow the progression of psoriasis. If these findings are confirmed, adherence to a Mediterranean diet should be integrated into the routine management of moderate to severe psoriasis.1 These findings are by no means definitive, but it is a first step in helping us define more specific dietary recommendations for psoriasis.

This issue includes several articles looking at various facets of psoriasis important to residents, including the pathophysiology of psoriasis,2 treatment approach using biologic therapies,3 risk factors and triggers for psoriasis,4 and the psychosocial impact of psoriasis.5 We hope that you find this issue enjoyable and informative.

- Phan C, Touvier M, Kesse-Guyot E, et al. Association between Mediterranean anti-inflammatory dietary profile and severity of psoriasis: results from the NutriNet-Santé cohort [published online July 25, 2018]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2127.

- Hugh JM, Weinberg JM. Update on the pathophysiology of psoriasis. Cutis. 2018;102(suppl 5):6-12.

- McKay C, Kondratuk KE, Miller JP, et al. Biologic therapy in psoriasis: navigating the options. Cutis. 2018;102(suppl 5):13-17.

- Lee EB, Wu KK, Lee MP, et al. Psoriasis risk factors and triggers. Cutis. 2018;102(suppl 5):18-20.

- Kolli SS, Amin SD, Pona A, et al. Psychosocial impact of psoriasis: a review for dermatology residents. Cutis. 2018;102(suppl 5):21-25.

- Phan C, Touvier M, Kesse-Guyot E, et al. Association between Mediterranean anti-inflammatory dietary profile and severity of psoriasis: results from the NutriNet-Santé cohort [published online July 25, 2018]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2127.

- Hugh JM, Weinberg JM. Update on the pathophysiology of psoriasis. Cutis. 2018;102(suppl 5):6-12.

- McKay C, Kondratuk KE, Miller JP, et al. Biologic therapy in psoriasis: navigating the options. Cutis. 2018;102(suppl 5):13-17.

- Lee EB, Wu KK, Lee MP, et al. Psoriasis risk factors and triggers. Cutis. 2018;102(suppl 5):18-20.

- Kolli SS, Amin SD, Pona A, et al. Psychosocial impact of psoriasis: a review for dermatology residents. Cutis. 2018;102(suppl 5):21-25.

Heart cell transplant rejections

The concept that cell transplantation is the answer to the treatment of heart failure may have suffered a major setback as a result of a research scam perpetrated at Harvard University’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

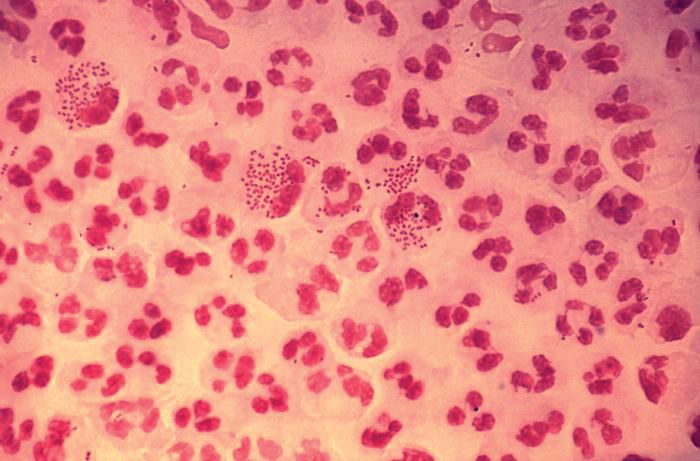

The fraudulent cardiac research at that institution was from the lab of Piero Anversa, MD, which falsified or fabricated data. Dr. Anversa was one of the leaders in pursuing the concept that adult cardiomyocytes can not only regenerate by cell division but can also be transplanted from one animal to another, in his case a mouse.

The original reports over a decade ago caused a major stir in heart failure research. They also were met with considerable skepticism in the research field and have not been reproduced in other laboratories. Numerous small trials in humans have been unsuccessful in demonstrating the survival of autologous cells transplanted in both animal and humans. Dr. Anversa’s research has been under scrutiny by Harvard and Brigham and Women’s since 2013, ultimately resulting in the call to retract 31 published studies in mid-October. In the meantime, admission of fraud in regard to the original Anversa papers resulted in a fine of $10 million paid by the institutions to the National Institutes of Health in a 2017 settlement. Dr. Anversa left Harvard in 2015.

Nevertheless Dr. Anversa’s concepts led to the initiation of an NIH-supported multicenter trial in humans of the implantation of autologous bone marrow cells using endocardial devices to transplant cells in 144 patients with heart failure. The Combination of Autologous Bone Marrow Derived Mesenchymal and C-Kit+ Cardiac Stem Cells as Regenerative Therapy for Heart Failure (CONCERT-HF) was started in 2015 and was still recruiting until Oct. 29, when the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute announced that a pause in recruitment was called in order to review the fraudulent data that led to the trial’s initiation. Patients were to be followed over a 1-year period using delayed-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DEMRI) scans to assess scar size and left ventricular function and structure at baseline and at 6 and 12 months post study product ad-ministration. For the purpose of the endpoint analysis and safety evaluations, the investigators planned to use an intention-to-treat study population evaluating a number of clinical parameters.

Anatomists and physiologists have long been of the opinion that adult human and mammalian cardiomyocytes are terminally differentiated and do not undergo cell division. However, over time, cardiomyocytes can undergo hypertrophy as a result of increased workload. Cells can die as a result of ischemia, infarction, or stress mediated through unchecked inflammatory processes. It also has been shown that cells can die as a result of apoptosis, particularly in areas in proximity to myocardial scars. It is generally believed that these three methods of cell depletion contribute to the progression of heart failure. Dr. Anversa also proposed that there is some degree of replication of cardiomyocytes but not to a degree that can have a meaningful replacement value.

The concept of cell transplantation in medicine certainly has been in the forefront of clinical research in medicine for the last decade based in part on research by Dr. Anversa and others in cardiology and numerous investigators in other medical disciplines. With few exceptions, there has been little support for the clinical benefit of these clinical studies. We are unfortunately now faced with the release of the tainted fraudulent research that led to CONCERT-HF. Whether there is anything of scientific value to come of the trial is highly unlikely.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

This article was updated Oct. 30, 2018.

The concept that cell transplantation is the answer to the treatment of heart failure may have suffered a major setback as a result of a research scam perpetrated at Harvard University’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The fraudulent cardiac research at that institution was from the lab of Piero Anversa, MD, which falsified or fabricated data. Dr. Anversa was one of the leaders in pursuing the concept that adult cardiomyocytes can not only regenerate by cell division but can also be transplanted from one animal to another, in his case a mouse.

The original reports over a decade ago caused a major stir in heart failure research. They also were met with considerable skepticism in the research field and have not been reproduced in other laboratories. Numerous small trials in humans have been unsuccessful in demonstrating the survival of autologous cells transplanted in both animal and humans. Dr. Anversa’s research has been under scrutiny by Harvard and Brigham and Women’s since 2013, ultimately resulting in the call to retract 31 published studies in mid-October. In the meantime, admission of fraud in regard to the original Anversa papers resulted in a fine of $10 million paid by the institutions to the National Institutes of Health in a 2017 settlement. Dr. Anversa left Harvard in 2015.

Nevertheless Dr. Anversa’s concepts led to the initiation of an NIH-supported multicenter trial in humans of the implantation of autologous bone marrow cells using endocardial devices to transplant cells in 144 patients with heart failure. The Combination of Autologous Bone Marrow Derived Mesenchymal and C-Kit+ Cardiac Stem Cells as Regenerative Therapy for Heart Failure (CONCERT-HF) was started in 2015 and was still recruiting until Oct. 29, when the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute announced that a pause in recruitment was called in order to review the fraudulent data that led to the trial’s initiation. Patients were to be followed over a 1-year period using delayed-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DEMRI) scans to assess scar size and left ventricular function and structure at baseline and at 6 and 12 months post study product ad-ministration. For the purpose of the endpoint analysis and safety evaluations, the investigators planned to use an intention-to-treat study population evaluating a number of clinical parameters.

Anatomists and physiologists have long been of the opinion that adult human and mammalian cardiomyocytes are terminally differentiated and do not undergo cell division. However, over time, cardiomyocytes can undergo hypertrophy as a result of increased workload. Cells can die as a result of ischemia, infarction, or stress mediated through unchecked inflammatory processes. It also has been shown that cells can die as a result of apoptosis, particularly in areas in proximity to myocardial scars. It is generally believed that these three methods of cell depletion contribute to the progression of heart failure. Dr. Anversa also proposed that there is some degree of replication of cardiomyocytes but not to a degree that can have a meaningful replacement value.

The concept of cell transplantation in medicine certainly has been in the forefront of clinical research in medicine for the last decade based in part on research by Dr. Anversa and others in cardiology and numerous investigators in other medical disciplines. With few exceptions, there has been little support for the clinical benefit of these clinical studies. We are unfortunately now faced with the release of the tainted fraudulent research that led to CONCERT-HF. Whether there is anything of scientific value to come of the trial is highly unlikely.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

This article was updated Oct. 30, 2018.

The concept that cell transplantation is the answer to the treatment of heart failure may have suffered a major setback as a result of a research scam perpetrated at Harvard University’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The fraudulent cardiac research at that institution was from the lab of Piero Anversa, MD, which falsified or fabricated data. Dr. Anversa was one of the leaders in pursuing the concept that adult cardiomyocytes can not only regenerate by cell division but can also be transplanted from one animal to another, in his case a mouse.

The original reports over a decade ago caused a major stir in heart failure research. They also were met with considerable skepticism in the research field and have not been reproduced in other laboratories. Numerous small trials in humans have been unsuccessful in demonstrating the survival of autologous cells transplanted in both animal and humans. Dr. Anversa’s research has been under scrutiny by Harvard and Brigham and Women’s since 2013, ultimately resulting in the call to retract 31 published studies in mid-October. In the meantime, admission of fraud in regard to the original Anversa papers resulted in a fine of $10 million paid by the institutions to the National Institutes of Health in a 2017 settlement. Dr. Anversa left Harvard in 2015.

Nevertheless Dr. Anversa’s concepts led to the initiation of an NIH-supported multicenter trial in humans of the implantation of autologous bone marrow cells using endocardial devices to transplant cells in 144 patients with heart failure. The Combination of Autologous Bone Marrow Derived Mesenchymal and C-Kit+ Cardiac Stem Cells as Regenerative Therapy for Heart Failure (CONCERT-HF) was started in 2015 and was still recruiting until Oct. 29, when the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute announced that a pause in recruitment was called in order to review the fraudulent data that led to the trial’s initiation. Patients were to be followed over a 1-year period using delayed-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DEMRI) scans to assess scar size and left ventricular function and structure at baseline and at 6 and 12 months post study product ad-ministration. For the purpose of the endpoint analysis and safety evaluations, the investigators planned to use an intention-to-treat study population evaluating a number of clinical parameters.

Anatomists and physiologists have long been of the opinion that adult human and mammalian cardiomyocytes are terminally differentiated and do not undergo cell division. However, over time, cardiomyocytes can undergo hypertrophy as a result of increased workload. Cells can die as a result of ischemia, infarction, or stress mediated through unchecked inflammatory processes. It also has been shown that cells can die as a result of apoptosis, particularly in areas in proximity to myocardial scars. It is generally believed that these three methods of cell depletion contribute to the progression of heart failure. Dr. Anversa also proposed that there is some degree of replication of cardiomyocytes but not to a degree that can have a meaningful replacement value.

The concept of cell transplantation in medicine certainly has been in the forefront of clinical research in medicine for the last decade based in part on research by Dr. Anversa and others in cardiology and numerous investigators in other medical disciplines. With few exceptions, there has been little support for the clinical benefit of these clinical studies. We are unfortunately now faced with the release of the tainted fraudulent research that led to CONCERT-HF. Whether there is anything of scientific value to come of the trial is highly unlikely.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

This article was updated Oct. 30, 2018.

Understanding hypertensive disorders in pregnancy

Preeclampsia is one of the most significant medical complications in pregnancy because of the acute onset it can have in so many affected patients. This acute onset may then rapidly progress to eclampsia and to severe consequences, including maternal death. In addition, the disorder can occur as early as the late second trimester and can thus impact the timing of delivery and fetal age at birth.

It is an obstetrical syndrome with serious implications for the fetus, the infant at birth, and the mother, and it is one whose incidence has been increasing. A full knowledge of the disease state – its pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and various therapeutic options, both medical and surgical – is critical for the health and well-being of both the mother and fetus.

A new classification system introduced in 2013 by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force Report on Hypertension in Pregnancy has added further complexity to an already complicated disease. On one hand, attempting to precisely achieve a diagnosis with such an imprecise and insidious disease seems ill advised. On the other hand, it is important to achieve some level of clarity with respect to diagnosis and management. In doing so, we must lean toward overdiagnosis and maintain a low threshold for treatment and intervention in the interest of the mother and infant.

I have engaged Baha M. Sibai, MD, professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Texas McGovern Medical School, Houston, to introduce a practical approach for interpreting and utilizing the ACOG report. This installment is the first of a two-part series in which we hope to provide practical clinical strategies for this complex disease.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

Preeclampsia is one of the most significant medical complications in pregnancy because of the acute onset it can have in so many affected patients. This acute onset may then rapidly progress to eclampsia and to severe consequences, including maternal death. In addition, the disorder can occur as early as the late second trimester and can thus impact the timing of delivery and fetal age at birth.

It is an obstetrical syndrome with serious implications for the fetus, the infant at birth, and the mother, and it is one whose incidence has been increasing. A full knowledge of the disease state – its pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and various therapeutic options, both medical and surgical – is critical for the health and well-being of both the mother and fetus.

A new classification system introduced in 2013 by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force Report on Hypertension in Pregnancy has added further complexity to an already complicated disease. On one hand, attempting to precisely achieve a diagnosis with such an imprecise and insidious disease seems ill advised. On the other hand, it is important to achieve some level of clarity with respect to diagnosis and management. In doing so, we must lean toward overdiagnosis and maintain a low threshold for treatment and intervention in the interest of the mother and infant.

I have engaged Baha M. Sibai, MD, professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Texas McGovern Medical School, Houston, to introduce a practical approach for interpreting and utilizing the ACOG report. This installment is the first of a two-part series in which we hope to provide practical clinical strategies for this complex disease.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

Preeclampsia is one of the most significant medical complications in pregnancy because of the acute onset it can have in so many affected patients. This acute onset may then rapidly progress to eclampsia and to severe consequences, including maternal death. In addition, the disorder can occur as early as the late second trimester and can thus impact the timing of delivery and fetal age at birth.

It is an obstetrical syndrome with serious implications for the fetus, the infant at birth, and the mother, and it is one whose incidence has been increasing. A full knowledge of the disease state – its pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and various therapeutic options, both medical and surgical – is critical for the health and well-being of both the mother and fetus.

A new classification system introduced in 2013 by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force Report on Hypertension in Pregnancy has added further complexity to an already complicated disease. On one hand, attempting to precisely achieve a diagnosis with such an imprecise and insidious disease seems ill advised. On the other hand, it is important to achieve some level of clarity with respect to diagnosis and management. In doing so, we must lean toward overdiagnosis and maintain a low threshold for treatment and intervention in the interest of the mother and infant.

I have engaged Baha M. Sibai, MD, professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Texas McGovern Medical School, Houston, to introduce a practical approach for interpreting and utilizing the ACOG report. This installment is the first of a two-part series in which we hope to provide practical clinical strategies for this complex disease.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

Clarifying the categories of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy

Prenatal care always has been in part about identifying women with medical complications including preeclampsia. We have long measured blood pressure, checked the urine for high levels of protein, and monitored weight gain. We still do.

However, over the years, the diagnostic criteria for preeclampsia have evolved, first with the exclusion of edema and more recently with the exclusion of proteinuria as a necessary element of the diagnosis. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force Report, Hypertension in Pregnancy, published in 2013, concluded that while preeclampsia may still be defined by the occurrence of hypertension with proteinuria, it also may be diagnosed when hypertension occurs in association with other multisystemic signs indicative of disease severity. The change came based on evidence that some women develop eclampsia, HELLP syndrome, and other serious complications in the absence of proteinuria.

The 2013 document also attempted to review and clarify various issues relating to the classifications, diagnosis, prediction and prevention, and management of hypertension during pregnancy, including the postpartum period. In many respects, it was successful in doing so. However, there is still much confusion regarding the diagnosis of certain categories of hypertensive disorders – particularly preeclampsia with severe features and superimposed preeclampsia with or without severe features.

While it is difficult to establish precise definitions given the often insidious nature of preeclampsia, it still is important to achieve a higher level of clarity with respect to these categories. Overdiagnosis may be preferable. However, improper classification also may influence management decisions that could prove detrimental to the fetus.

Severe gestational hypertension

ACOG’s 2013 Report on Hypertension in Pregnancy classifies hypertensive disorders of pregnancy into these categories: Gestational hypertension (GHTN), preeclampsia, preeclampsia with severe features (this includes HELLP), chronic hypertension (CHTN), superimposed preeclampsia with or without severe features, and eclampsia.

Some of the definitions and diagnostic criteria are clear. For instance, GHTN is defined as the new onset of hypertension after 20 weeks’ gestation in the absence of proteinuria or systemic findings such as thrombocytopenia or impaired liver function. CHTN is defined as hypertension that predates conception or is detected before 20 weeks’ gestation. In both cases there should be elevated blood pressure on two occasions at least 4 hours apart.

A major omission is the lack of a definition for severe GHTN. Removal of this previously well-understood classification category combined with unclear statements regarding preeclampsia with or without severe features has made it difficult for physicians to know in some cases of severe hypertension only what diagnosis a woman should receive and how she should be managed.

I recommend that we maintain the category of severe GHTN, and that it be defined as a systolic blood pressure (BP) greater than or equal to 160 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP greater than or equal to 110 mm Hg on at least two occasions at least 4 hours apart when antihypertensive medications have not been initiated. There should be no proteinuria or severe features such as thrombocytopenia or impaired liver function.

The physician may elect in these cases to administer antihypertensive medication and observe the patient in the hospital. An individualized decision can then be made regarding how the patient should be managed, including whether she should be admitted and whether the pregnancy should continue beyond 34 weeks. Blood pressure, gestational age at diagnosis, the presence or absence of symptoms, and laboratory tests all should be taken into consideration.

Preeclampsia with or without severe features

We need to clarify and simplify how we think about GHTN and preeclampsia with or without severe features.

Most cases of preeclampsia will involve new-onset proteinuria, with proteinuria being defined as greater than or equal to 300 mg/day or a protein-creatinine ratio of greater than or equal to 0.3 mg/dL. In cases in which a dipstick test must be used, proteinuria is suggested by a urine protein reading of 1+. (It is important to note that dipstick readings should be taken on two separate occasions.) According to the report, preeclampsia also may be established by the presence of GHTN in association with any one of a list of features that are generally referred to as “severe features.”

Various boxes and textual descriptions in the report offer a sometimes confusing picture, however, of the terms preeclampsia and preeclampsia with severe features and their differences. For clarification, I recommend that we define preeclampsia with severe features as GHTN (mild or severe) in association with any one of the severe features.

Severe features of preeclampsia

- Platelet count less than 100,000/microliter.

- Elevated hepatic transaminases greater than two times the upper limit of normal for specific laboratory adult reference ranges.

- Severe persistent right upper quadrant abdominal pain or epigastric pain unresponsive to analgesics and unexplained by other etiology.

- Serum creatinine greater than 1.1 mg/dL.

- Pulmonary edema.

- Persistent cerebral disturbances such as severe persistent new-onset headaches unresponsive to nonnarcotic analgesics, altered mental status or other neurologic deficits.

- Visual disturbances such as blurred vision, scotomata, photophobia, or loss of vision.

I also suggest that we think of “mild” GHTN (systolic BP of 140-159 mm Hg or diastolic BP 90-109 mm Hg) and preeclampsia without severe features as one in the same, and that we manage them similarly. The presence or absence of proteinuria is currently the only difference diagnostically. The only difference with respect to management – aside from a weekly urine protein check in the case of GHTN – is the frequency of nonstress testing (NST) and amniotic fluid index (AFI) measurement (currently once a week for GHTN and twice a week for preeclampsia).

Given that unnecessary time and energy may be spent differentiating the two when management is essentially the same, I suggest that preeclampsia be diagnosed in any patient with GHTN with or without proteinuria. All patients can then be managed with blood pressure checks twice a week; symptoms and kick count daily; NST and AFI twice a week; estimated fetal weight by ultrasound every third week; lab tests (CBC, liver enzymes, and creatinine) once a week, and delivery at 37 weeks.

Superimposed preeclampsia with or without severe features

As the report states, the recognition of preeclampsia superimposed on chronic hypertension is “perhaps the greatest challenge” in the diagnosis and management of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. Overdiagnosis “may be preferable,” the report says, given the high risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes with superimposed preeclampsia. On the other hand, it says, a “more stratified approach based on severity and predictors of adverse outcome may be useful” in avoiding unnecessary preterm births.

Ultimately, the task force proposed that we utilize the two categories of “superimposed preeclampsia” and “superimposed preeclampsia with severe features,” and in doing so, it noted that there “often is ambiguity in the diagnosis of superimposed preeclampsia and that the clinical spectrum of disease is broad.” Indeed, the diagnosis of superimposed preeclampsia as presented in the report remains vague and open to interpretation. In my institution, it has created significant confusion.

The report states that superimposed preeclampsia is likely when any of the following are present: 1) a sudden increase in blood pressure that was previously well controlled or escalation of antihypertensive medications to control blood pressure, or 2) new onset of proteinuria or a sudden increase in proteinuria in a woman with known proteinuria before or early in pregnancy.

It is not clear, however, what is considered a sudden increase in blood pressure, and it is concerning that any escalation of medication could potentially prompt this diagnosis. Is an increase in systolic blood pressure from 140 mm Hg to 150 mm Hg or an increase in diastolic blood pressure from 90 mm Hg to 100 mm Hg between two prenatal visits considered a “sudden increase”? Does an increase in methyldopa dosage from 250 mg daily to 500 mg daily to keep blood pressure within the range of mild hypertension mean that the patient should be diagnosed with superimposed preeclampsia? Hypertension is likely to increase and require an escalation of antihypertensive medications as patients with chronic hypertension progress through their pregnancies.

Similarly, a “sudden increase in proteinuria” – or “sudden, substantial, and sustained increases in protein excretion,” as written elsewhere in the report with respect to superimposed preeclampsia – also is undefined. What exactly does this mean? That we lack clinically meaningful parameters and clear descriptions of acceptable criteria/scenarios for observation rather than intervention is troubling, particularly because some of these women may have preexisting renal disease with expected increases and fluctuations in protein excretion during advanced gestation.

We must be cautious about making a diagnosis of superimposed preeclampsia based on changes in blood pressure or urinary protein alone, lest we have unnecessary hospitalizations and interventions. I recommend that the diagnosis of superimposed preeclampsia be made based on either the new onset of proteinuria in association with mild hypertension after 20 weeks or on elevation in blood pressure to severe ranges (systolic BP greater than or equal to160 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP greater than or equal to 110 mm Hg) despite the use of maximum doses of one antihypertensive drug.

Regarding superimposed preeclampsia with severe features, I recommend that in the case of blood pressure elevation, it be diagnosed only after maximal doses of two medications have been used. Specifically, I recommend that superimposed preeclampsia with severe features be defined as either CHTN or superimposed preeclampsia in association with either systolic BP greater than or equal to 160 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP greater than or equal to 110 mm Hg on at least two occasions despite use of maximum doses of labetalol (2,400 mg/day) plus long-acting nifedipine (120 mg/day), or with any of the other severe features.

In a second installment of the Master Class, I will elaborate on the treatment of severe GHTN and address the management of preeclampsia with severe features as well as postpartum management of hypertension during pregnancy.

Suggested diagnostic definitions

- Preeclampsia with severe features: GHTN in association with severe features.

- Superimposed preeclampsia: CHTN with either the new onset of proteinuria in association with mild hypertension after 20 weeks, or an elevation in blood pressure to severe ranges (systolic BP greater than or equal to 160 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP greater than or equal to 110 mm Hg) despite the use of the maximal dose of one antihypertensive drug.