User login

Intervention may improve genetic testing for HBOC

Researchers from general obstetrics and gynecology (ob.gyn.) practices in New York and Connecticut have shown that (HBOC).

Genetic screening and testing can reduce the morbidity and mortality from breast, ovarian, and endometrial cancers through prevention and early detection. Mark S. DeFrancesco, MD, of Westwood Women’s Health, Waterbury, Conn., and his colleagues reported that, in spite of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ recommendation for ob.gyns. to regularly screen, counsel, and refer accordingly for HBOC (Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:153843), the “incorporation of hereditary cancer risk assessment and testing remains underutilized in the [ob.gyn.] setting.” The authors have addressed this issue in their own practice with promising results and important caveats (Obstet Gynecol 2018;132:1121-9).

The intervention included a process evaluation, improvements to patient work flow, and training of providers by genetic counselors and engineering personnel from the testing laboratory (Myriad Genetics), which provided support for the study. Patients in the study completed a family history questionnaire and, those meeting National Comprehensive Cancer Center Network criteria for genetic testing, were given pretest counseling and offered testing on the same day or referral for testing within 2 weeks.

Of the 3,811 women who completed the questionnaire, 24% (906) met NCCN criteria, 90% of whom were offered testing. However, only 52% (165) of patients who agreed to testing underwent genetic evaluation. This included 70% of patients who were offered same-day testing and 35% of patients who were offered a referral appointment for testing.

Conversations about HBOC and genetic testing can be complicated and may not be a patient’s initial priority. The authors should be commended for identifying the vast majority of high-risk patients. However, only half of patients meeting criteria completed testing and 10% who should have been offered testing were not – numbers still well below target.

Incorporation of family history questionnaires should become commonplace in the generalist’s office and optimizing EHRs may be an opportunity for rapid risk interpretation. As the success of same-day genetic testing was striking, opportunities for partnerships with insurance companies and private laboratories are likely needed to make this a more feasible option. Lastly, assessing women’s knowledge and attitudes around genetic testing could help to more specifically address barriers to testing in future interventions.

Improving genetic screening and testing completion rates requires a coordinated effort. Using tools and applications to optimize convenience (same-day testing, telemedicine) and simplification (electronic screening platforms), we can strive to appropriately detect all women at high risk for hereditary breast and ovarian cancers.

Michelle Lightfoot is a gynecologic oncology fellow at the Ohio State University in Columbus. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Researchers from general obstetrics and gynecology (ob.gyn.) practices in New York and Connecticut have shown that (HBOC).

Genetic screening and testing can reduce the morbidity and mortality from breast, ovarian, and endometrial cancers through prevention and early detection. Mark S. DeFrancesco, MD, of Westwood Women’s Health, Waterbury, Conn., and his colleagues reported that, in spite of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ recommendation for ob.gyns. to regularly screen, counsel, and refer accordingly for HBOC (Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:153843), the “incorporation of hereditary cancer risk assessment and testing remains underutilized in the [ob.gyn.] setting.” The authors have addressed this issue in their own practice with promising results and important caveats (Obstet Gynecol 2018;132:1121-9).

The intervention included a process evaluation, improvements to patient work flow, and training of providers by genetic counselors and engineering personnel from the testing laboratory (Myriad Genetics), which provided support for the study. Patients in the study completed a family history questionnaire and, those meeting National Comprehensive Cancer Center Network criteria for genetic testing, were given pretest counseling and offered testing on the same day or referral for testing within 2 weeks.

Of the 3,811 women who completed the questionnaire, 24% (906) met NCCN criteria, 90% of whom were offered testing. However, only 52% (165) of patients who agreed to testing underwent genetic evaluation. This included 70% of patients who were offered same-day testing and 35% of patients who were offered a referral appointment for testing.

Conversations about HBOC and genetic testing can be complicated and may not be a patient’s initial priority. The authors should be commended for identifying the vast majority of high-risk patients. However, only half of patients meeting criteria completed testing and 10% who should have been offered testing were not – numbers still well below target.

Incorporation of family history questionnaires should become commonplace in the generalist’s office and optimizing EHRs may be an opportunity for rapid risk interpretation. As the success of same-day genetic testing was striking, opportunities for partnerships with insurance companies and private laboratories are likely needed to make this a more feasible option. Lastly, assessing women’s knowledge and attitudes around genetic testing could help to more specifically address barriers to testing in future interventions.

Improving genetic screening and testing completion rates requires a coordinated effort. Using tools and applications to optimize convenience (same-day testing, telemedicine) and simplification (electronic screening platforms), we can strive to appropriately detect all women at high risk for hereditary breast and ovarian cancers.

Michelle Lightfoot is a gynecologic oncology fellow at the Ohio State University in Columbus. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Researchers from general obstetrics and gynecology (ob.gyn.) practices in New York and Connecticut have shown that (HBOC).

Genetic screening and testing can reduce the morbidity and mortality from breast, ovarian, and endometrial cancers through prevention and early detection. Mark S. DeFrancesco, MD, of Westwood Women’s Health, Waterbury, Conn., and his colleagues reported that, in spite of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ recommendation for ob.gyns. to regularly screen, counsel, and refer accordingly for HBOC (Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:153843), the “incorporation of hereditary cancer risk assessment and testing remains underutilized in the [ob.gyn.] setting.” The authors have addressed this issue in their own practice with promising results and important caveats (Obstet Gynecol 2018;132:1121-9).

The intervention included a process evaluation, improvements to patient work flow, and training of providers by genetic counselors and engineering personnel from the testing laboratory (Myriad Genetics), which provided support for the study. Patients in the study completed a family history questionnaire and, those meeting National Comprehensive Cancer Center Network criteria for genetic testing, were given pretest counseling and offered testing on the same day or referral for testing within 2 weeks.

Of the 3,811 women who completed the questionnaire, 24% (906) met NCCN criteria, 90% of whom were offered testing. However, only 52% (165) of patients who agreed to testing underwent genetic evaluation. This included 70% of patients who were offered same-day testing and 35% of patients who were offered a referral appointment for testing.

Conversations about HBOC and genetic testing can be complicated and may not be a patient’s initial priority. The authors should be commended for identifying the vast majority of high-risk patients. However, only half of patients meeting criteria completed testing and 10% who should have been offered testing were not – numbers still well below target.

Incorporation of family history questionnaires should become commonplace in the generalist’s office and optimizing EHRs may be an opportunity for rapid risk interpretation. As the success of same-day genetic testing was striking, opportunities for partnerships with insurance companies and private laboratories are likely needed to make this a more feasible option. Lastly, assessing women’s knowledge and attitudes around genetic testing could help to more specifically address barriers to testing in future interventions.

Improving genetic screening and testing completion rates requires a coordinated effort. Using tools and applications to optimize convenience (same-day testing, telemedicine) and simplification (electronic screening platforms), we can strive to appropriately detect all women at high risk for hereditary breast and ovarian cancers.

Michelle Lightfoot is a gynecologic oncology fellow at the Ohio State University in Columbus. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Surgical quality: How do we measure something so difficult to define?

Quality in medicine is a peculiar thing. It is clearly apparent, and yet, can be very difficult to measure and quantify. Surgery, a performance art of sorts, can be even more challenging to qualify or rate. However, as a means to elevate the quality of care for all patients, hospital systems and care providers have aggressively made attempts to do so. This is a noble objective.

In September 2018, the Committee of Gynecologic Practice of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists released ACOG Committee Opinion Number 750, titled, “Perioperative Pathways: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery.”1

The goals of this committee opinion were to advocate for gynecologic surgeons using the “ERAS” pathways in their perioperative care as part of an evidenced-based approach to quality improvement. ERAS pathways have been previously discussed in this column and feature bundled perioperative pathways that incorporate various concepts such as avoidance of prolonged preoperative fasting, early postoperative feeding, multimodal analgesia (with an avoidance of opiates), and inclusion of antibiotic and antiembolic prophylaxis, among other elements.

What was alarming upon closer review of this ACOG Committee Opinion was its omission of the randomized controlled trial by Dickson et al., the only randomized trial published in gynecologic surgery evaluating ERAS pathways.2 This trial compared the length of stay for patients receiving laparotomy for gynecologic cancer surgery who received perioperative care according the ERAS pathway versus those who received standard perioperative care. They found no difference in length of stay – the primary outcome – between the two groups, an impressive 3 days for both. The secondary outcome of postoperative pain was improved for the ERAS group for some of the time points. It was likely that the excellent outcomes in both groups resulted from a Hawthorne effect in which the behavior of study participants is influenced by the fact that they were being observed, in addition to the fact that the physicians involved in the study already were practicing high quality care as part of their “standard” regimen. It simply may be that the act of trying to improve quality is what improves outcomes, not a specific pathway. As senior author, Dr. Peter A. Argenta, explained to me, many of the ERAS elements are “simply good medicine.”

ERAS pathways are an example of process measures of quality. They include elements of care or processes in the delivery of care that are thought to be associated with improved outcomes. Prescription of antibiotics or venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis are other examples of process measures thought to be associated with improved surgical quality. Rather than rating surgeons’ outcomes (surgical site infection), surgeons are rated on their compliance with a process (the rate of appropriate perioperative antibiotic prescription). However, high compliance with these processes is not automatically associated with improved observed outcomes. For example, hospitals that meet the definition of high quality by virtue of structural measures (such as procedural volume and use of hospital-level quality initiatives) are associated with worse risk-adjusted VTE rates despite demonstrating higher adherence to VTE prophylaxis.3 This is felt to be a function of surveillance bias and the fact that these same hospitals have better capabilities to capture events as part of a feedback mechanism built into their quality initiatives.

What ERAS has favorably done for surgical care is to shine a glaring light on and challenge the unnecessary, old-fashioned, and non–patient-centric interventions that were considered dogma by many. For example, minimizing preoperative fasting is most certainly a patient-friendly adjustment that should absolutely be embraced, regardless of whether or not it speeds up time to discharge. Multimodal approaches to analgesia consistently have been shown to preserve or improve postoperative pain levels with a focus on minimizing opiate use, once again a noble and patient-centered objective.

However, all too many surgical quality interventions focus on their ability to reduce postoperative length of stay. Length of stay is an important driver of health care cost, and an indirect measure of perioperative complications; however, it is not a patient-centered outcome. So long as patients recover from their surgery quickly with respect to pain and function, the location of that recovery (home versus hospital) is less of a focus for most patients. In addition, in the pursuit of shorter hospital stays and less perioperative morbidity, we may encourage practices with unintentional adverse patient-centered outcomes. For example, to preserve a surgeon’s quality metrics, patients who are at high risk for complications may not be offered surgery at all. Long-term ovarian cancer outcomes, such as survival, can be negatively impacted when surgeons opt for less morbid, less radical surgical approaches which have favorable short-term morbidity such as surgical complications and readmissions.4

Ultimately we are most likely to see improvement in quality with a complex, nuanced approach to metrics, not simplistic interventions or pathways. We should recognize interventions that are consistently associated with better outcomes such as high procedural volume, consolidating less common procedures to fewer surgeons, data ascertainment, and reporting data to surgeons.5 Physicians need to take ownership and involvement in the quality metrics that are created to assess the care we provide. Hospital administrators may not fully understand the confounders, such as comorbidities, that contribute to outcomes, which can lead to mischaracterization, cause unfair comparisons between surgeons, or create unintentional incentives that are not patient-centered.6

We all need to understand the epidemiologic science behind evidence-based medicine and to be sophisticated in our ability to review and appraise data so that we can be sensible in what interventions we promote as supported by good evidence. If we fail to correctly identify and characterize what is truly good quality, if we miss the point of what is driving outcomes, or overstate the value of certain interventions, we miss the opportunity to intervene in ways that actually do make a meaningful difference.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She said she had no conflicts of interest. Email Dr. Rossi at [email protected].

References

1. Obstet Gynecol 2018;132:e120-e30.

2. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Feb;129(2):355-62.

3. JAMA. 2013 Oct 9;310(14):1482-9.

4. Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Dec;147(3):607-11.

5. J Am Coll Surg. 2004 Apr;198(4):626-32.

6. Gynecol Oncol. 2018 Oct;151(1):141-4.

Quality in medicine is a peculiar thing. It is clearly apparent, and yet, can be very difficult to measure and quantify. Surgery, a performance art of sorts, can be even more challenging to qualify or rate. However, as a means to elevate the quality of care for all patients, hospital systems and care providers have aggressively made attempts to do so. This is a noble objective.

In September 2018, the Committee of Gynecologic Practice of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists released ACOG Committee Opinion Number 750, titled, “Perioperative Pathways: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery.”1

The goals of this committee opinion were to advocate for gynecologic surgeons using the “ERAS” pathways in their perioperative care as part of an evidenced-based approach to quality improvement. ERAS pathways have been previously discussed in this column and feature bundled perioperative pathways that incorporate various concepts such as avoidance of prolonged preoperative fasting, early postoperative feeding, multimodal analgesia (with an avoidance of opiates), and inclusion of antibiotic and antiembolic prophylaxis, among other elements.

What was alarming upon closer review of this ACOG Committee Opinion was its omission of the randomized controlled trial by Dickson et al., the only randomized trial published in gynecologic surgery evaluating ERAS pathways.2 This trial compared the length of stay for patients receiving laparotomy for gynecologic cancer surgery who received perioperative care according the ERAS pathway versus those who received standard perioperative care. They found no difference in length of stay – the primary outcome – between the two groups, an impressive 3 days for both. The secondary outcome of postoperative pain was improved for the ERAS group for some of the time points. It was likely that the excellent outcomes in both groups resulted from a Hawthorne effect in which the behavior of study participants is influenced by the fact that they were being observed, in addition to the fact that the physicians involved in the study already were practicing high quality care as part of their “standard” regimen. It simply may be that the act of trying to improve quality is what improves outcomes, not a specific pathway. As senior author, Dr. Peter A. Argenta, explained to me, many of the ERAS elements are “simply good medicine.”

ERAS pathways are an example of process measures of quality. They include elements of care or processes in the delivery of care that are thought to be associated with improved outcomes. Prescription of antibiotics or venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis are other examples of process measures thought to be associated with improved surgical quality. Rather than rating surgeons’ outcomes (surgical site infection), surgeons are rated on their compliance with a process (the rate of appropriate perioperative antibiotic prescription). However, high compliance with these processes is not automatically associated with improved observed outcomes. For example, hospitals that meet the definition of high quality by virtue of structural measures (such as procedural volume and use of hospital-level quality initiatives) are associated with worse risk-adjusted VTE rates despite demonstrating higher adherence to VTE prophylaxis.3 This is felt to be a function of surveillance bias and the fact that these same hospitals have better capabilities to capture events as part of a feedback mechanism built into their quality initiatives.

What ERAS has favorably done for surgical care is to shine a glaring light on and challenge the unnecessary, old-fashioned, and non–patient-centric interventions that were considered dogma by many. For example, minimizing preoperative fasting is most certainly a patient-friendly adjustment that should absolutely be embraced, regardless of whether or not it speeds up time to discharge. Multimodal approaches to analgesia consistently have been shown to preserve or improve postoperative pain levels with a focus on minimizing opiate use, once again a noble and patient-centered objective.

However, all too many surgical quality interventions focus on their ability to reduce postoperative length of stay. Length of stay is an important driver of health care cost, and an indirect measure of perioperative complications; however, it is not a patient-centered outcome. So long as patients recover from their surgery quickly with respect to pain and function, the location of that recovery (home versus hospital) is less of a focus for most patients. In addition, in the pursuit of shorter hospital stays and less perioperative morbidity, we may encourage practices with unintentional adverse patient-centered outcomes. For example, to preserve a surgeon’s quality metrics, patients who are at high risk for complications may not be offered surgery at all. Long-term ovarian cancer outcomes, such as survival, can be negatively impacted when surgeons opt for less morbid, less radical surgical approaches which have favorable short-term morbidity such as surgical complications and readmissions.4

Ultimately we are most likely to see improvement in quality with a complex, nuanced approach to metrics, not simplistic interventions or pathways. We should recognize interventions that are consistently associated with better outcomes such as high procedural volume, consolidating less common procedures to fewer surgeons, data ascertainment, and reporting data to surgeons.5 Physicians need to take ownership and involvement in the quality metrics that are created to assess the care we provide. Hospital administrators may not fully understand the confounders, such as comorbidities, that contribute to outcomes, which can lead to mischaracterization, cause unfair comparisons between surgeons, or create unintentional incentives that are not patient-centered.6

We all need to understand the epidemiologic science behind evidence-based medicine and to be sophisticated in our ability to review and appraise data so that we can be sensible in what interventions we promote as supported by good evidence. If we fail to correctly identify and characterize what is truly good quality, if we miss the point of what is driving outcomes, or overstate the value of certain interventions, we miss the opportunity to intervene in ways that actually do make a meaningful difference.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She said she had no conflicts of interest. Email Dr. Rossi at [email protected].

References

1. Obstet Gynecol 2018;132:e120-e30.

2. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Feb;129(2):355-62.

3. JAMA. 2013 Oct 9;310(14):1482-9.

4. Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Dec;147(3):607-11.

5. J Am Coll Surg. 2004 Apr;198(4):626-32.

6. Gynecol Oncol. 2018 Oct;151(1):141-4.

Quality in medicine is a peculiar thing. It is clearly apparent, and yet, can be very difficult to measure and quantify. Surgery, a performance art of sorts, can be even more challenging to qualify or rate. However, as a means to elevate the quality of care for all patients, hospital systems and care providers have aggressively made attempts to do so. This is a noble objective.

In September 2018, the Committee of Gynecologic Practice of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists released ACOG Committee Opinion Number 750, titled, “Perioperative Pathways: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery.”1

The goals of this committee opinion were to advocate for gynecologic surgeons using the “ERAS” pathways in their perioperative care as part of an evidenced-based approach to quality improvement. ERAS pathways have been previously discussed in this column and feature bundled perioperative pathways that incorporate various concepts such as avoidance of prolonged preoperative fasting, early postoperative feeding, multimodal analgesia (with an avoidance of opiates), and inclusion of antibiotic and antiembolic prophylaxis, among other elements.

What was alarming upon closer review of this ACOG Committee Opinion was its omission of the randomized controlled trial by Dickson et al., the only randomized trial published in gynecologic surgery evaluating ERAS pathways.2 This trial compared the length of stay for patients receiving laparotomy for gynecologic cancer surgery who received perioperative care according the ERAS pathway versus those who received standard perioperative care. They found no difference in length of stay – the primary outcome – between the two groups, an impressive 3 days for both. The secondary outcome of postoperative pain was improved for the ERAS group for some of the time points. It was likely that the excellent outcomes in both groups resulted from a Hawthorne effect in which the behavior of study participants is influenced by the fact that they were being observed, in addition to the fact that the physicians involved in the study already were practicing high quality care as part of their “standard” regimen. It simply may be that the act of trying to improve quality is what improves outcomes, not a specific pathway. As senior author, Dr. Peter A. Argenta, explained to me, many of the ERAS elements are “simply good medicine.”

ERAS pathways are an example of process measures of quality. They include elements of care or processes in the delivery of care that are thought to be associated with improved outcomes. Prescription of antibiotics or venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis are other examples of process measures thought to be associated with improved surgical quality. Rather than rating surgeons’ outcomes (surgical site infection), surgeons are rated on their compliance with a process (the rate of appropriate perioperative antibiotic prescription). However, high compliance with these processes is not automatically associated with improved observed outcomes. For example, hospitals that meet the definition of high quality by virtue of structural measures (such as procedural volume and use of hospital-level quality initiatives) are associated with worse risk-adjusted VTE rates despite demonstrating higher adherence to VTE prophylaxis.3 This is felt to be a function of surveillance bias and the fact that these same hospitals have better capabilities to capture events as part of a feedback mechanism built into their quality initiatives.

What ERAS has favorably done for surgical care is to shine a glaring light on and challenge the unnecessary, old-fashioned, and non–patient-centric interventions that were considered dogma by many. For example, minimizing preoperative fasting is most certainly a patient-friendly adjustment that should absolutely be embraced, regardless of whether or not it speeds up time to discharge. Multimodal approaches to analgesia consistently have been shown to preserve or improve postoperative pain levels with a focus on minimizing opiate use, once again a noble and patient-centered objective.

However, all too many surgical quality interventions focus on their ability to reduce postoperative length of stay. Length of stay is an important driver of health care cost, and an indirect measure of perioperative complications; however, it is not a patient-centered outcome. So long as patients recover from their surgery quickly with respect to pain and function, the location of that recovery (home versus hospital) is less of a focus for most patients. In addition, in the pursuit of shorter hospital stays and less perioperative morbidity, we may encourage practices with unintentional adverse patient-centered outcomes. For example, to preserve a surgeon’s quality metrics, patients who are at high risk for complications may not be offered surgery at all. Long-term ovarian cancer outcomes, such as survival, can be negatively impacted when surgeons opt for less morbid, less radical surgical approaches which have favorable short-term morbidity such as surgical complications and readmissions.4

Ultimately we are most likely to see improvement in quality with a complex, nuanced approach to metrics, not simplistic interventions or pathways. We should recognize interventions that are consistently associated with better outcomes such as high procedural volume, consolidating less common procedures to fewer surgeons, data ascertainment, and reporting data to surgeons.5 Physicians need to take ownership and involvement in the quality metrics that are created to assess the care we provide. Hospital administrators may not fully understand the confounders, such as comorbidities, that contribute to outcomes, which can lead to mischaracterization, cause unfair comparisons between surgeons, or create unintentional incentives that are not patient-centered.6

We all need to understand the epidemiologic science behind evidence-based medicine and to be sophisticated in our ability to review and appraise data so that we can be sensible in what interventions we promote as supported by good evidence. If we fail to correctly identify and characterize what is truly good quality, if we miss the point of what is driving outcomes, or overstate the value of certain interventions, we miss the opportunity to intervene in ways that actually do make a meaningful difference.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She said she had no conflicts of interest. Email Dr. Rossi at [email protected].

References

1. Obstet Gynecol 2018;132:e120-e30.

2. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Feb;129(2):355-62.

3. JAMA. 2013 Oct 9;310(14):1482-9.

4. Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Dec;147(3):607-11.

5. J Am Coll Surg. 2004 Apr;198(4):626-32.

6. Gynecol Oncol. 2018 Oct;151(1):141-4.

Keeping the sample closet out of medication decisions

When I first began practice the COX-2 inhibitors had first come to market. My sample closet was awash with Celebrex and Vioxx.

I was young and naive. These drugs were allegedly safer than NSAIDs, so shouldn’t I be using them? They were new, and therefore had to be better, than plain old naproxen and ibuprofen. And hey, the samples were free.

As a result, I handed them out for pretty much all musculoskeletal stuff. “Here, try this ... ”

Of course, that came to a crashing halt when I encountered the realities of payers and drug coverage. No history of GI issues, no previous tries/fails ... Why on earth are you prescribing this? Obviously, the answer “because the samples were free” wasn’t going to pass muster.

Granted, history wasn’t particularly kind to the COX-2 drugs. Out of the three that made it to market, two were withdrawn and Celebrex’s star faded with them. But the lesson is still there.

Today, 20 years later, I use more generics. Maybe it’s because I’m familiar with them (many came to market during my career). Maybe it’s because years of calls from patients, pharmacies, and insurance companies have taught me to try them first. Probably a mixture of both.

This isn’t to say I don’t use branded drugs. I prescribe my share. There are plenty of times a generic isn’t appropriate, or a new approach is needed after a treatment failure.

But I’ve also learned that .

We learn a lot about the many different medications available in medical school and residency. But learning facts about dosing, side effects, and mechanisms of action (while quite important) is quite different from the practical aspect of learning what is more likely to be covered and affordable. Only the experience of everyday practice will teach that.

It sure taught me.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

When I first began practice the COX-2 inhibitors had first come to market. My sample closet was awash with Celebrex and Vioxx.

I was young and naive. These drugs were allegedly safer than NSAIDs, so shouldn’t I be using them? They were new, and therefore had to be better, than plain old naproxen and ibuprofen. And hey, the samples were free.

As a result, I handed them out for pretty much all musculoskeletal stuff. “Here, try this ... ”

Of course, that came to a crashing halt when I encountered the realities of payers and drug coverage. No history of GI issues, no previous tries/fails ... Why on earth are you prescribing this? Obviously, the answer “because the samples were free” wasn’t going to pass muster.

Granted, history wasn’t particularly kind to the COX-2 drugs. Out of the three that made it to market, two were withdrawn and Celebrex’s star faded with them. But the lesson is still there.

Today, 20 years later, I use more generics. Maybe it’s because I’m familiar with them (many came to market during my career). Maybe it’s because years of calls from patients, pharmacies, and insurance companies have taught me to try them first. Probably a mixture of both.

This isn’t to say I don’t use branded drugs. I prescribe my share. There are plenty of times a generic isn’t appropriate, or a new approach is needed after a treatment failure.

But I’ve also learned that .

We learn a lot about the many different medications available in medical school and residency. But learning facts about dosing, side effects, and mechanisms of action (while quite important) is quite different from the practical aspect of learning what is more likely to be covered and affordable. Only the experience of everyday practice will teach that.

It sure taught me.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

When I first began practice the COX-2 inhibitors had first come to market. My sample closet was awash with Celebrex and Vioxx.

I was young and naive. These drugs were allegedly safer than NSAIDs, so shouldn’t I be using them? They were new, and therefore had to be better, than plain old naproxen and ibuprofen. And hey, the samples were free.

As a result, I handed them out for pretty much all musculoskeletal stuff. “Here, try this ... ”

Of course, that came to a crashing halt when I encountered the realities of payers and drug coverage. No history of GI issues, no previous tries/fails ... Why on earth are you prescribing this? Obviously, the answer “because the samples were free” wasn’t going to pass muster.

Granted, history wasn’t particularly kind to the COX-2 drugs. Out of the three that made it to market, two were withdrawn and Celebrex’s star faded with them. But the lesson is still there.

Today, 20 years later, I use more generics. Maybe it’s because I’m familiar with them (many came to market during my career). Maybe it’s because years of calls from patients, pharmacies, and insurance companies have taught me to try them first. Probably a mixture of both.

This isn’t to say I don’t use branded drugs. I prescribe my share. There are plenty of times a generic isn’t appropriate, or a new approach is needed after a treatment failure.

But I’ve also learned that .

We learn a lot about the many different medications available in medical school and residency. But learning facts about dosing, side effects, and mechanisms of action (while quite important) is quite different from the practical aspect of learning what is more likely to be covered and affordable. Only the experience of everyday practice will teach that.

It sure taught me.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Severe chronic malnutrition: What it is and how to diagnose it

My wife and I have traveled a number of times as far east as Kyrgyzstan and as far south as Paraguay to participate in short 1- to 2-week medical clinics. When I participated in a week-long medical clinic in Haiti in early 2017, the CEO of the hosting U.S. organization asked, “I wonder if we are doing any good here?” His organization had been to Onaville, Haiti for the last 4-5 years.

So my wife Stacy, a retired licensed practical nurse, and I, a general pediatrician with an interest in severe acute malnutrition, went on a 3-month medical sabbatical to Onaville. We were self-funded, with the exception of our home church in Senoia, Ga., paying the cost of our lodging during that time.

Prior to the 2010 Haiti earthquake, the government planned Onaville to be a retirement community area, with a population of only about 1,500, I was told. After the devastating temblor, it became one of several areas where the government sent people displaced from Port-au-Prince. The population today is possibly 250,000 or more.

The poverty in this area has “newer” flavor than areas such as Cité Soleil, which has been there for decades. What we found in Onaville – and probably all of Haiti – is an appalling lack of understanding and appreciation about the nature of malnutrition.

Methods and materials for study

The 1981 World Health Organization’s last printed monograph about severe acute nutrition remains essentially today’s cookbook recipe for treatment. Little seems to have changed since then in the literature I’ve reviewed. It didn’t take long after we started seeing the children in Onaville to shift that interest to something much more serious and widespread.

I wanted to start with basic health assessments in the Onaville children around 5 years and under. These children rarely see a physician, and only about half or so get any vaccine. Most parents do not have any immunization records in their possession to even review.

We decided to measure head size, mid-upper arm circumference, height, weight, and hemoglobin levels. Date of birth was recorded, if known or could at best be closely estimated. Vaccination was recorded as a yes or no response. All children also were examined for evidence of things like swelling, marasmic appearance (wasting, loss of body fat and muscle), yellowed hair, eye findings of vitamin A deficiency, etc. I wanted to get some impression about the health of these children in the same way that most mobile medical clinics do in Haiti.

Being a database programmer since I bought my first computer in 1985, and having written and deployed my office’s current EMR system in 2000, I decided before ever arriving in Haiti to write the software needed for this task. Unlike regular office EMRs, there were some special considerations.

Growth charts needed not only to be generated for individuals, but in aggregate. Hemoglobins levels, too, needed charting. While in the United States, I use Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth chart data, but for Haiti I used WHO growth data. I was able to procure hemoglobin charting data as well. Aggregate data turned out to be key to our conclusions.

We used a regular consumer quality digital bathroom scale for weights. A sewing tape attached with duct tape to a wall or pillar was used to measure height. Standard head circumference tapes were use to measure heads and arms.

The hemoglobin was measured with a HemoCue Hb 201+ instrument. Size, ruggedness, and cost dictated all our choices because, except for food, we had to carry everything with us. The cost of a new HemoCue was under $400 and each microcuvette test was about $1.50.

Severe anemia

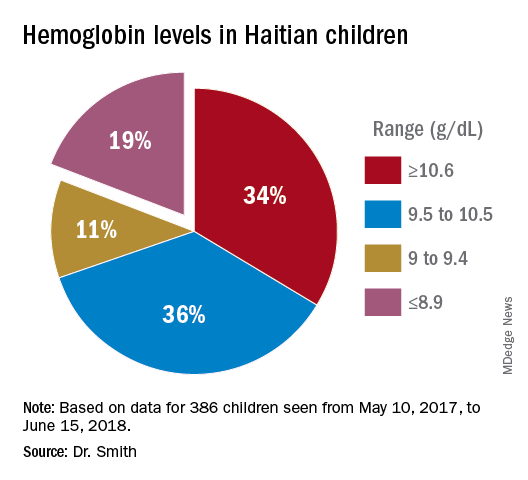

In total, we saw about 386 children, mostly 5 years and under, in Onaville. Toward the end of the 3 months, we were seeing some of those back as follow-ups. One of the first hemoglobins was 4.9 g/dL, with a 5.4 g/dL on repeat. This stunned us. In the first few days, we were seeing what we saw consistently throughout the course of 3 months.

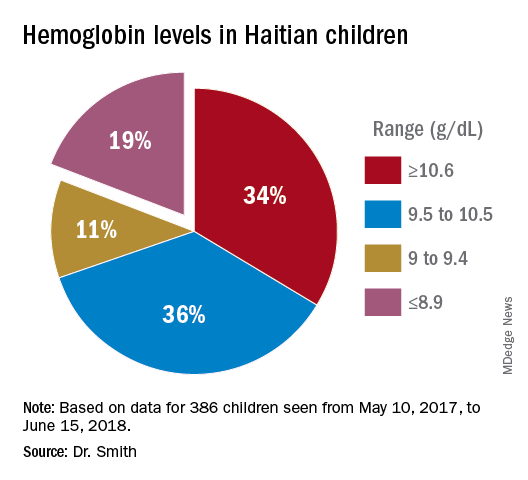

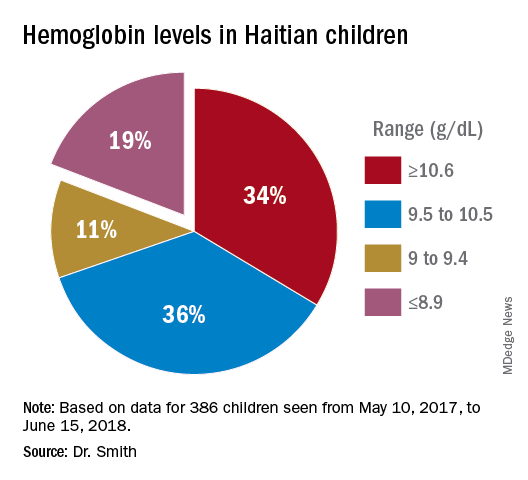

About 19% of these children had hemoglobins from below 9.0 g/dL to below 6 g/dL. More importantly, there was little on physical exam that would trigger one to do a hemoglobin. Low hemoglobins were not associated with yellow-orange hair. No cases of the swelling of kwashiorkor or pencil-like frames of marasmus were seen.

Severe chronic malnutrition

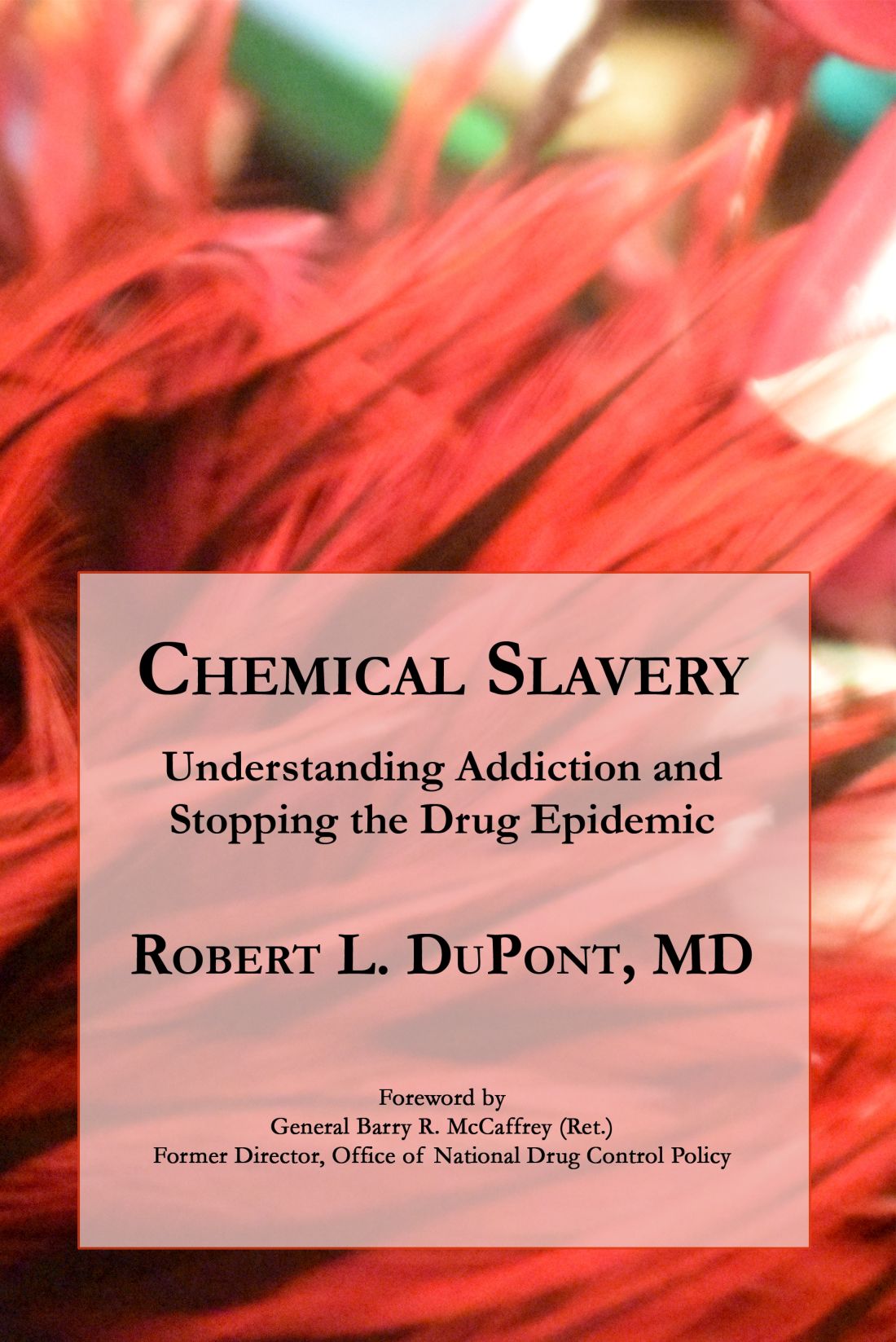

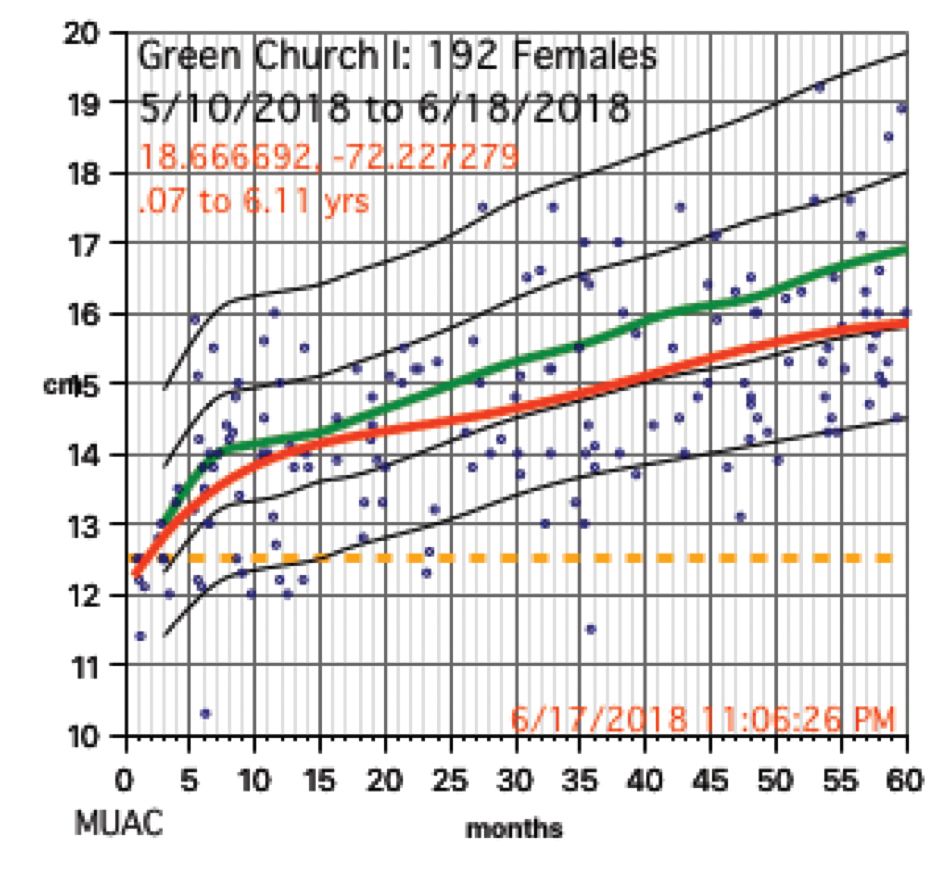

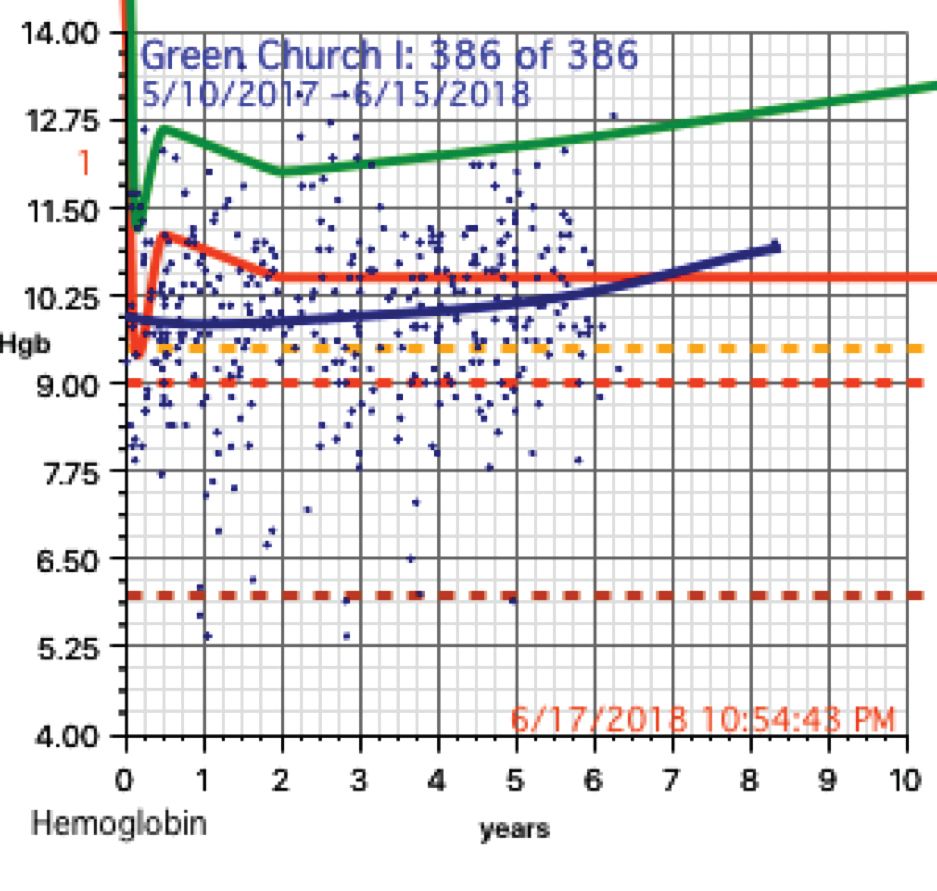

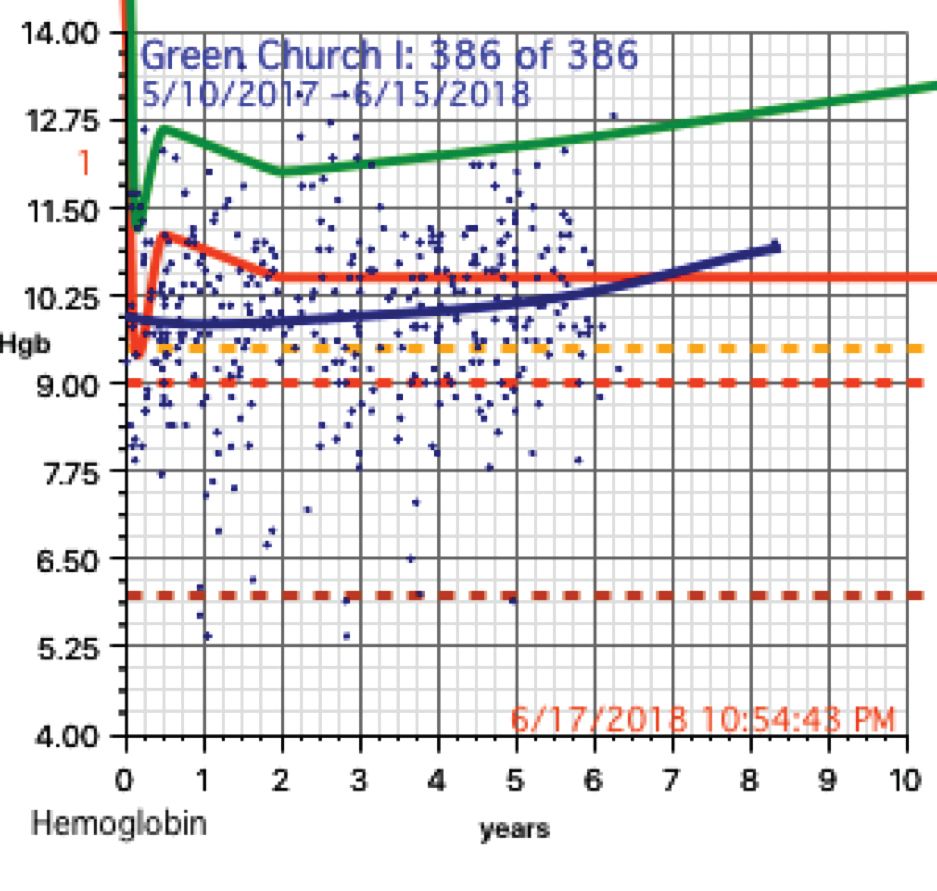

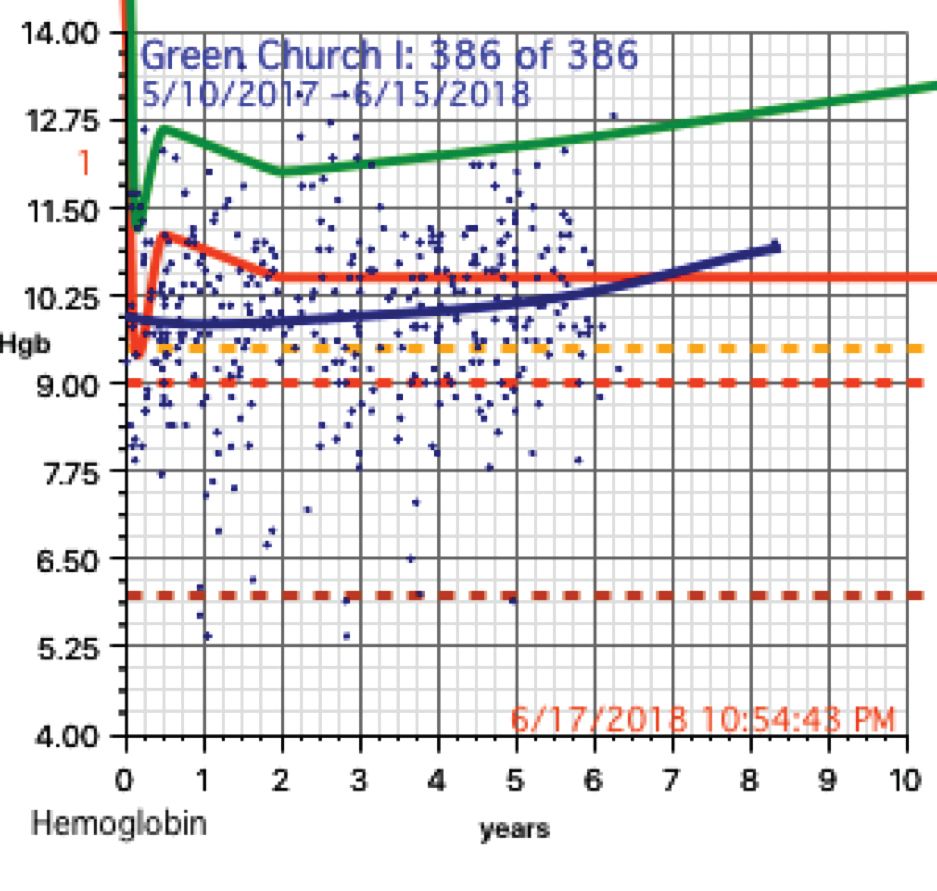

The scatter charts are very telling and the hemoglobin graphs are explosive. What is demonstrated is that this recent population is slowly starving to death. How can the hemoglobins be so very low in comparison to the only slightly lowered mean averages (the solid red line)?

In over 3 decades of pediatric medicine, I rarely have seen children in the United States with hemoglobins below 9.5 g/dL. Often they have other illnesses that clearly point to the cause. Could the 19% of children with severely lowered hemoglobins (below 9.0 g/dL) be caused by sickle cell disease or something else in these Haitian children?

A search for articles where sickle cell was studied revealed a study done at St. Damien Pediatrics Hospital in Port-au-Prince (Blood. 2012;120:4235). The overall incidence of sickle cell disease was this: “Of the 2,258 samples tested, 247 had HbS, fifty-seven had HbC, ten had HbSS, and three had HbSC.” Only 0.57% of these children had sickle or sickle-C disease where one could expect hemoglobins to be as low as in the children of Onaville. Applying that percentage to the 386 children we saw would account for about only 2 children who might have sickling anemia. Yet we had 73 children in our study with severely lowered hemoglobins below 9.0 g/dL. If you estimate that half of the 250,000 people in Onaville are children, that extrapolates to over 47,000 with severe anemia! I think that a study larger than ours needs to be done to better assess that, however.

My best thought is that these children who have little external evidence of abnormality and mildly lowered growth data represent a type of malnutrition that has not been defined, much less addressed. I call this severe chronic malnutrition. The very low hemoglobins indicate to me that this is not simply a lack of iron – although certainly that is a factor – but rather that these children are in a state of chronic protein deprivation. They represent a large pool of children who exist between those with normal nutritional states and those with the kwashiorkor or marasmus of severe acute malnutrition.

A search of the 69,823 ICD-10 codes in my database for “malnutrition” only turns up the ill-defined terms, “Unspecified severe protein-calorie malnutrition,” “Moderate, and Mild protein-calorie malnutrition,” “Unspecified protein-calorie malnutrition,” and “Sequelae of protein-calorie malnutrition.” Whatever each of those means is purely subjective in my opinion.

Without a clear understanding or definition of what is severe chronic malnutrition, we are like the Titanic trying to avoid icebergs on a moonless night. I think we must define severe chronic malnutrition before we really can understand the pathophysiology and treatment of severe acute malnutrition.

The WHO published its last printed monograph, “The treatment and management of severe acute protein-energy malnutrition,” in 1981. This publication is essentially a cookbook approach for what to do, with no clear presentation of the chemical processes and medicine involved. The primary focus for the WHO is mid-upper arm circumference and weight for height. Reading this document might lead one to believe that all malnutrition is acutely severe. It is most certainly not.

Conclusion

The answer to why some children show the swelling of kwashiorkor and some show marasmus probably will not be found in the study of severe acute malnutrition or refeeding syndrome alone. We must go far beyond the WHO’s cookbook recipe.

I think we must start with the study, definition, and treatment of severe chronic malnutrition.

While in Haiti, we shared these data with three organization that are working to provide nutrition in a starving nation. Together, the Baptist Haiti Mission, Mission of Hope Haiti, and Trinity Hope may well be supplying 175,000 meals a day through school lunches and other avenues throughout the country. Their response was telling. Those at Baptist Haiti Mission, an organization with a presence of almost 80 years there, told us that this information was a “big deal.”

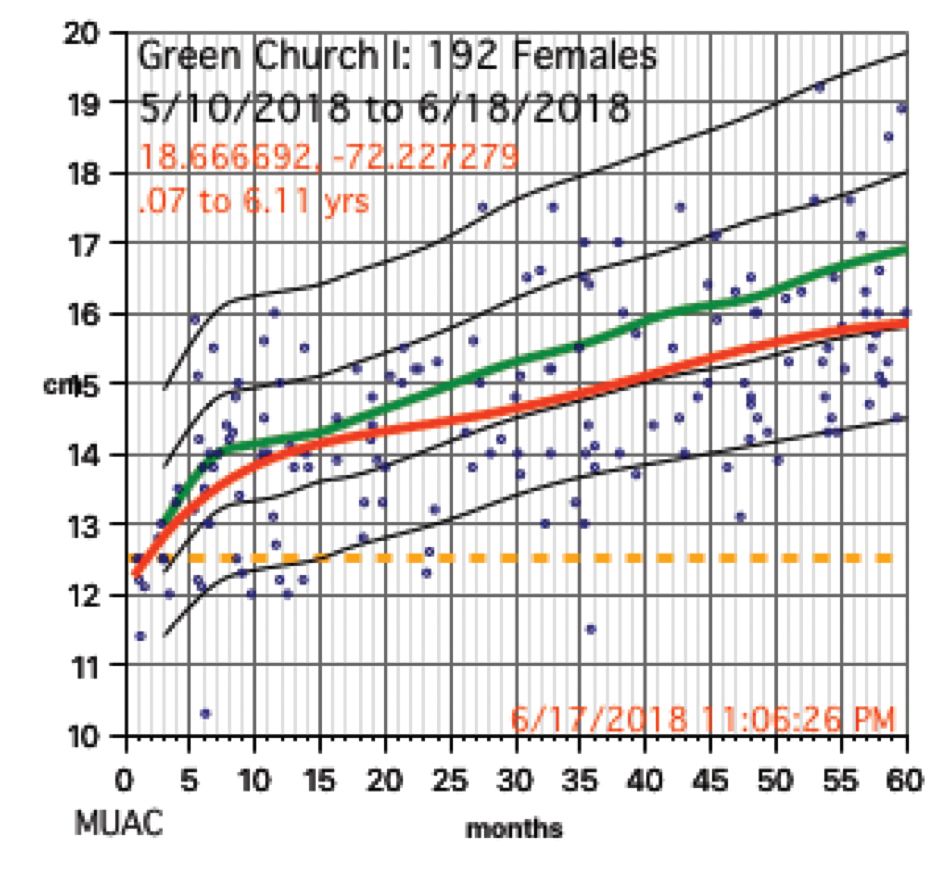

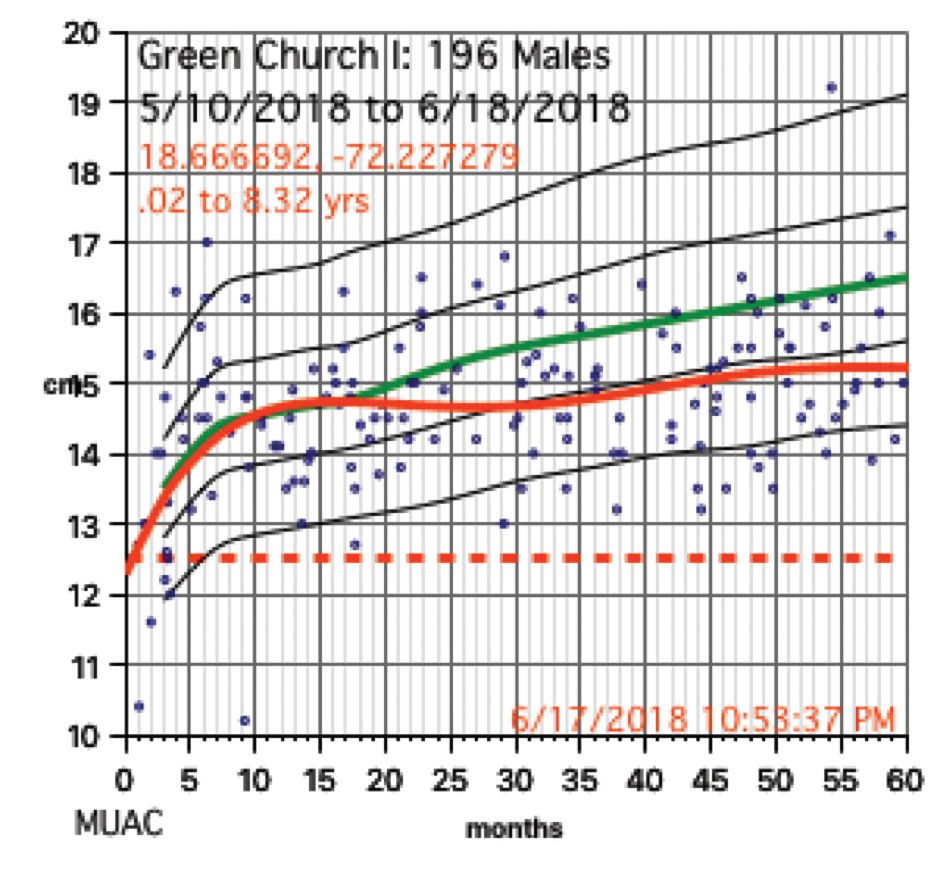

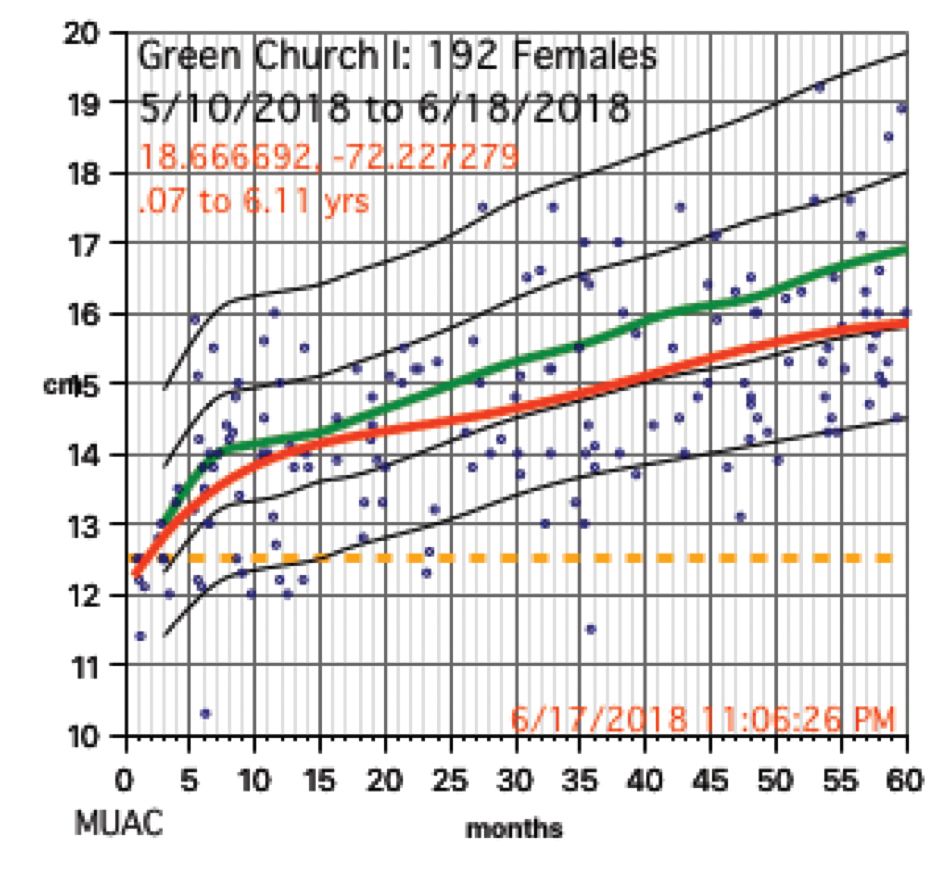

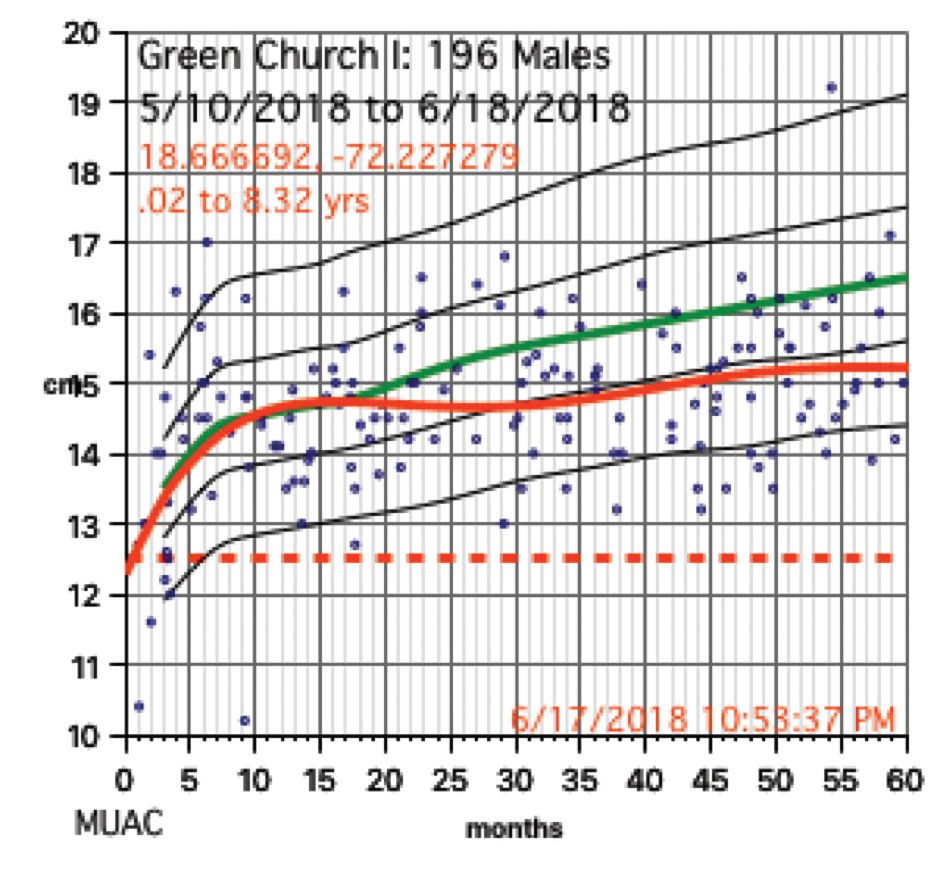

The issue for them is the answer to the question, “How can we tell if we are doing any good in our feeding programs?” A lot of money is being thrown into nutrition without tangible ways to assess impact. Clearly parameters such as mid-upper arm circumference and weight for height that WHO advocates is not adequate, as our plots revealed.

We think that a simple, cheap, hemoglobin finger stick can tell us who is falling through the cracks into severe chronic malnutrition and those at risk for severe acute malnutrition. I am an advocate for instituting hemoglobin surveillance as part of all feeding programs. Then we can come up with the cheapest and most effective in-country mechanisms to treat these children.

Indeed that is our next step in working in Haiti.

Dr. Smith is a board certified pediatrician working in McDonough, Ga., with an interest in malnutrition among the children of Haiti. Email him at [email protected].

My wife and I have traveled a number of times as far east as Kyrgyzstan and as far south as Paraguay to participate in short 1- to 2-week medical clinics. When I participated in a week-long medical clinic in Haiti in early 2017, the CEO of the hosting U.S. organization asked, “I wonder if we are doing any good here?” His organization had been to Onaville, Haiti for the last 4-5 years.

So my wife Stacy, a retired licensed practical nurse, and I, a general pediatrician with an interest in severe acute malnutrition, went on a 3-month medical sabbatical to Onaville. We were self-funded, with the exception of our home church in Senoia, Ga., paying the cost of our lodging during that time.

Prior to the 2010 Haiti earthquake, the government planned Onaville to be a retirement community area, with a population of only about 1,500, I was told. After the devastating temblor, it became one of several areas where the government sent people displaced from Port-au-Prince. The population today is possibly 250,000 or more.

The poverty in this area has “newer” flavor than areas such as Cité Soleil, which has been there for decades. What we found in Onaville – and probably all of Haiti – is an appalling lack of understanding and appreciation about the nature of malnutrition.

Methods and materials for study

The 1981 World Health Organization’s last printed monograph about severe acute nutrition remains essentially today’s cookbook recipe for treatment. Little seems to have changed since then in the literature I’ve reviewed. It didn’t take long after we started seeing the children in Onaville to shift that interest to something much more serious and widespread.

I wanted to start with basic health assessments in the Onaville children around 5 years and under. These children rarely see a physician, and only about half or so get any vaccine. Most parents do not have any immunization records in their possession to even review.

We decided to measure head size, mid-upper arm circumference, height, weight, and hemoglobin levels. Date of birth was recorded, if known or could at best be closely estimated. Vaccination was recorded as a yes or no response. All children also were examined for evidence of things like swelling, marasmic appearance (wasting, loss of body fat and muscle), yellowed hair, eye findings of vitamin A deficiency, etc. I wanted to get some impression about the health of these children in the same way that most mobile medical clinics do in Haiti.

Being a database programmer since I bought my first computer in 1985, and having written and deployed my office’s current EMR system in 2000, I decided before ever arriving in Haiti to write the software needed for this task. Unlike regular office EMRs, there were some special considerations.

Growth charts needed not only to be generated for individuals, but in aggregate. Hemoglobins levels, too, needed charting. While in the United States, I use Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth chart data, but for Haiti I used WHO growth data. I was able to procure hemoglobin charting data as well. Aggregate data turned out to be key to our conclusions.

We used a regular consumer quality digital bathroom scale for weights. A sewing tape attached with duct tape to a wall or pillar was used to measure height. Standard head circumference tapes were use to measure heads and arms.

The hemoglobin was measured with a HemoCue Hb 201+ instrument. Size, ruggedness, and cost dictated all our choices because, except for food, we had to carry everything with us. The cost of a new HemoCue was under $400 and each microcuvette test was about $1.50.

Severe anemia

In total, we saw about 386 children, mostly 5 years and under, in Onaville. Toward the end of the 3 months, we were seeing some of those back as follow-ups. One of the first hemoglobins was 4.9 g/dL, with a 5.4 g/dL on repeat. This stunned us. In the first few days, we were seeing what we saw consistently throughout the course of 3 months.

About 19% of these children had hemoglobins from below 9.0 g/dL to below 6 g/dL. More importantly, there was little on physical exam that would trigger one to do a hemoglobin. Low hemoglobins were not associated with yellow-orange hair. No cases of the swelling of kwashiorkor or pencil-like frames of marasmus were seen.

Severe chronic malnutrition

The scatter charts are very telling and the hemoglobin graphs are explosive. What is demonstrated is that this recent population is slowly starving to death. How can the hemoglobins be so very low in comparison to the only slightly lowered mean averages (the solid red line)?

In over 3 decades of pediatric medicine, I rarely have seen children in the United States with hemoglobins below 9.5 g/dL. Often they have other illnesses that clearly point to the cause. Could the 19% of children with severely lowered hemoglobins (below 9.0 g/dL) be caused by sickle cell disease or something else in these Haitian children?

A search for articles where sickle cell was studied revealed a study done at St. Damien Pediatrics Hospital in Port-au-Prince (Blood. 2012;120:4235). The overall incidence of sickle cell disease was this: “Of the 2,258 samples tested, 247 had HbS, fifty-seven had HbC, ten had HbSS, and three had HbSC.” Only 0.57% of these children had sickle or sickle-C disease where one could expect hemoglobins to be as low as in the children of Onaville. Applying that percentage to the 386 children we saw would account for about only 2 children who might have sickling anemia. Yet we had 73 children in our study with severely lowered hemoglobins below 9.0 g/dL. If you estimate that half of the 250,000 people in Onaville are children, that extrapolates to over 47,000 with severe anemia! I think that a study larger than ours needs to be done to better assess that, however.

My best thought is that these children who have little external evidence of abnormality and mildly lowered growth data represent a type of malnutrition that has not been defined, much less addressed. I call this severe chronic malnutrition. The very low hemoglobins indicate to me that this is not simply a lack of iron – although certainly that is a factor – but rather that these children are in a state of chronic protein deprivation. They represent a large pool of children who exist between those with normal nutritional states and those with the kwashiorkor or marasmus of severe acute malnutrition.

A search of the 69,823 ICD-10 codes in my database for “malnutrition” only turns up the ill-defined terms, “Unspecified severe protein-calorie malnutrition,” “Moderate, and Mild protein-calorie malnutrition,” “Unspecified protein-calorie malnutrition,” and “Sequelae of protein-calorie malnutrition.” Whatever each of those means is purely subjective in my opinion.

Without a clear understanding or definition of what is severe chronic malnutrition, we are like the Titanic trying to avoid icebergs on a moonless night. I think we must define severe chronic malnutrition before we really can understand the pathophysiology and treatment of severe acute malnutrition.

The WHO published its last printed monograph, “The treatment and management of severe acute protein-energy malnutrition,” in 1981. This publication is essentially a cookbook approach for what to do, with no clear presentation of the chemical processes and medicine involved. The primary focus for the WHO is mid-upper arm circumference and weight for height. Reading this document might lead one to believe that all malnutrition is acutely severe. It is most certainly not.

Conclusion

The answer to why some children show the swelling of kwashiorkor and some show marasmus probably will not be found in the study of severe acute malnutrition or refeeding syndrome alone. We must go far beyond the WHO’s cookbook recipe.

I think we must start with the study, definition, and treatment of severe chronic malnutrition.

While in Haiti, we shared these data with three organization that are working to provide nutrition in a starving nation. Together, the Baptist Haiti Mission, Mission of Hope Haiti, and Trinity Hope may well be supplying 175,000 meals a day through school lunches and other avenues throughout the country. Their response was telling. Those at Baptist Haiti Mission, an organization with a presence of almost 80 years there, told us that this information was a “big deal.”

The issue for them is the answer to the question, “How can we tell if we are doing any good in our feeding programs?” A lot of money is being thrown into nutrition without tangible ways to assess impact. Clearly parameters such as mid-upper arm circumference and weight for height that WHO advocates is not adequate, as our plots revealed.

We think that a simple, cheap, hemoglobin finger stick can tell us who is falling through the cracks into severe chronic malnutrition and those at risk for severe acute malnutrition. I am an advocate for instituting hemoglobin surveillance as part of all feeding programs. Then we can come up with the cheapest and most effective in-country mechanisms to treat these children.

Indeed that is our next step in working in Haiti.

Dr. Smith is a board certified pediatrician working in McDonough, Ga., with an interest in malnutrition among the children of Haiti. Email him at [email protected].

My wife and I have traveled a number of times as far east as Kyrgyzstan and as far south as Paraguay to participate in short 1- to 2-week medical clinics. When I participated in a week-long medical clinic in Haiti in early 2017, the CEO of the hosting U.S. organization asked, “I wonder if we are doing any good here?” His organization had been to Onaville, Haiti for the last 4-5 years.

So my wife Stacy, a retired licensed practical nurse, and I, a general pediatrician with an interest in severe acute malnutrition, went on a 3-month medical sabbatical to Onaville. We were self-funded, with the exception of our home church in Senoia, Ga., paying the cost of our lodging during that time.

Prior to the 2010 Haiti earthquake, the government planned Onaville to be a retirement community area, with a population of only about 1,500, I was told. After the devastating temblor, it became one of several areas where the government sent people displaced from Port-au-Prince. The population today is possibly 250,000 or more.

The poverty in this area has “newer” flavor than areas such as Cité Soleil, which has been there for decades. What we found in Onaville – and probably all of Haiti – is an appalling lack of understanding and appreciation about the nature of malnutrition.

Methods and materials for study

The 1981 World Health Organization’s last printed monograph about severe acute nutrition remains essentially today’s cookbook recipe for treatment. Little seems to have changed since then in the literature I’ve reviewed. It didn’t take long after we started seeing the children in Onaville to shift that interest to something much more serious and widespread.

I wanted to start with basic health assessments in the Onaville children around 5 years and under. These children rarely see a physician, and only about half or so get any vaccine. Most parents do not have any immunization records in their possession to even review.

We decided to measure head size, mid-upper arm circumference, height, weight, and hemoglobin levels. Date of birth was recorded, if known or could at best be closely estimated. Vaccination was recorded as a yes or no response. All children also were examined for evidence of things like swelling, marasmic appearance (wasting, loss of body fat and muscle), yellowed hair, eye findings of vitamin A deficiency, etc. I wanted to get some impression about the health of these children in the same way that most mobile medical clinics do in Haiti.

Being a database programmer since I bought my first computer in 1985, and having written and deployed my office’s current EMR system in 2000, I decided before ever arriving in Haiti to write the software needed for this task. Unlike regular office EMRs, there were some special considerations.

Growth charts needed not only to be generated for individuals, but in aggregate. Hemoglobins levels, too, needed charting. While in the United States, I use Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth chart data, but for Haiti I used WHO growth data. I was able to procure hemoglobin charting data as well. Aggregate data turned out to be key to our conclusions.

We used a regular consumer quality digital bathroom scale for weights. A sewing tape attached with duct tape to a wall or pillar was used to measure height. Standard head circumference tapes were use to measure heads and arms.

The hemoglobin was measured with a HemoCue Hb 201+ instrument. Size, ruggedness, and cost dictated all our choices because, except for food, we had to carry everything with us. The cost of a new HemoCue was under $400 and each microcuvette test was about $1.50.

Severe anemia

In total, we saw about 386 children, mostly 5 years and under, in Onaville. Toward the end of the 3 months, we were seeing some of those back as follow-ups. One of the first hemoglobins was 4.9 g/dL, with a 5.4 g/dL on repeat. This stunned us. In the first few days, we were seeing what we saw consistently throughout the course of 3 months.

About 19% of these children had hemoglobins from below 9.0 g/dL to below 6 g/dL. More importantly, there was little on physical exam that would trigger one to do a hemoglobin. Low hemoglobins were not associated with yellow-orange hair. No cases of the swelling of kwashiorkor or pencil-like frames of marasmus were seen.

Severe chronic malnutrition

The scatter charts are very telling and the hemoglobin graphs are explosive. What is demonstrated is that this recent population is slowly starving to death. How can the hemoglobins be so very low in comparison to the only slightly lowered mean averages (the solid red line)?

In over 3 decades of pediatric medicine, I rarely have seen children in the United States with hemoglobins below 9.5 g/dL. Often they have other illnesses that clearly point to the cause. Could the 19% of children with severely lowered hemoglobins (below 9.0 g/dL) be caused by sickle cell disease or something else in these Haitian children?

A search for articles where sickle cell was studied revealed a study done at St. Damien Pediatrics Hospital in Port-au-Prince (Blood. 2012;120:4235). The overall incidence of sickle cell disease was this: “Of the 2,258 samples tested, 247 had HbS, fifty-seven had HbC, ten had HbSS, and three had HbSC.” Only 0.57% of these children had sickle or sickle-C disease where one could expect hemoglobins to be as low as in the children of Onaville. Applying that percentage to the 386 children we saw would account for about only 2 children who might have sickling anemia. Yet we had 73 children in our study with severely lowered hemoglobins below 9.0 g/dL. If you estimate that half of the 250,000 people in Onaville are children, that extrapolates to over 47,000 with severe anemia! I think that a study larger than ours needs to be done to better assess that, however.

My best thought is that these children who have little external evidence of abnormality and mildly lowered growth data represent a type of malnutrition that has not been defined, much less addressed. I call this severe chronic malnutrition. The very low hemoglobins indicate to me that this is not simply a lack of iron – although certainly that is a factor – but rather that these children are in a state of chronic protein deprivation. They represent a large pool of children who exist between those with normal nutritional states and those with the kwashiorkor or marasmus of severe acute malnutrition.

A search of the 69,823 ICD-10 codes in my database for “malnutrition” only turns up the ill-defined terms, “Unspecified severe protein-calorie malnutrition,” “Moderate, and Mild protein-calorie malnutrition,” “Unspecified protein-calorie malnutrition,” and “Sequelae of protein-calorie malnutrition.” Whatever each of those means is purely subjective in my opinion.

Without a clear understanding or definition of what is severe chronic malnutrition, we are like the Titanic trying to avoid icebergs on a moonless night. I think we must define severe chronic malnutrition before we really can understand the pathophysiology and treatment of severe acute malnutrition.

The WHO published its last printed monograph, “The treatment and management of severe acute protein-energy malnutrition,” in 1981. This publication is essentially a cookbook approach for what to do, with no clear presentation of the chemical processes and medicine involved. The primary focus for the WHO is mid-upper arm circumference and weight for height. Reading this document might lead one to believe that all malnutrition is acutely severe. It is most certainly not.

Conclusion

The answer to why some children show the swelling of kwashiorkor and some show marasmus probably will not be found in the study of severe acute malnutrition or refeeding syndrome alone. We must go far beyond the WHO’s cookbook recipe.

I think we must start with the study, definition, and treatment of severe chronic malnutrition.

While in Haiti, we shared these data with three organization that are working to provide nutrition in a starving nation. Together, the Baptist Haiti Mission, Mission of Hope Haiti, and Trinity Hope may well be supplying 175,000 meals a day through school lunches and other avenues throughout the country. Their response was telling. Those at Baptist Haiti Mission, an organization with a presence of almost 80 years there, told us that this information was a “big deal.”

The issue for them is the answer to the question, “How can we tell if we are doing any good in our feeding programs?” A lot of money is being thrown into nutrition without tangible ways to assess impact. Clearly parameters such as mid-upper arm circumference and weight for height that WHO advocates is not adequate, as our plots revealed.

We think that a simple, cheap, hemoglobin finger stick can tell us who is falling through the cracks into severe chronic malnutrition and those at risk for severe acute malnutrition. I am an advocate for instituting hemoglobin surveillance as part of all feeding programs. Then we can come up with the cheapest and most effective in-country mechanisms to treat these children.

Indeed that is our next step in working in Haiti.

Dr. Smith is a board certified pediatrician working in McDonough, Ga., with an interest in malnutrition among the children of Haiti. Email him at [email protected].

Book Review: DuPont’s approach to addiction is tough, yet compassionate

What do Queen Silvia of Sweden, Pope Francis, and the first director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) have in common? They all share a deep and sobering commitment to fighting the global disease of addiction.

Robert L. DuPont, MD, has written a beautiful and surprisingly spiritual guide into the American addiction epidemic. He is the author of “The Selfish Brain: Learning From Addiction” (Center City, Minn.: Hazelden, 2000) and with his newest publication, “Chemical Slavery: Understanding Addiction and Stopping the Drug Epidemic” (Institute for Behavior and Health, 2018), he writes a clear-eyed tome detailing the history of drug and alcohol use within the United States and the current state of America’s drug epidemic.

Dr. DuPont is well known within the American addiction community as NIDA’s first director and as the second drug czar, under two presidents, Richard M. Nixon and Gerald R. Ford. His breadth of experience, spanning 50-plus years, dates from his early career with the District of Columbia Department of Corrections, into his work in public policy on drugs and alcohol. This experience infuses his book with the hard science of addiction and the common-sense compassion required to shepherd people into recovery. One of us has worked with and been influenced by him since the 1970s. The other, also an addiction psychiatrist, finished this book both invigorated and compelled to say thank you to Dr. DuPont and his life’s work! He remains relevant, insightful, and always optimistic about the future of addiction treatment.

Harm reduction explored

The book begins with a cogent history of drug and alcohol use in America. Dr. DuPont details this as well as the public policies that have evolved to address them. He weaves into our national history reasoning behind why, as a “mass consumer” culture, we are more prone to addiction than ever before. The loss of cultural and societal pressures has a role to play in the rise along with genetics and environmental stress. The adolescent brain is prominently discussed throughout this first section as a highly vulnerable organ that can lead to lifelong addiction if primed early by addictive chemicals.

Dr. DuPont addresses the biology of addiction, delving into both the biological mechanisms within the brain, making those details accessible and understandable – to a practicing physician as well as a family member or patient struggling with addiction.

He also addresses harm reduction, a fairly new concept within the field. Harm reduction has taken on more prominence with localities across the country providing people with addictions with safe places and clean needles to continue their substance use without risks of serious or life-threatening diseases and crime. He challenges the idea that harm reduction is active recovery from substance addiction. Instead, he opines that harm reduction must be tethered to and must lead to real recovery work or it risks becoming an organizational enabling of the addict’s behavior.

Dr. DuPont pulls no punches with his language. He uses words such as “fatal,” “addict,” and “alcoholic.” He addresses the concerns by some in the field that those kinds of words are harsh, derogatory, and prejudicial by calling out addiction as a disease hallmarked primarily by loss of control and by dishonesty. To shun those words is to perpetuate the disease, delaying life-saving treatment.

Compassion is a theme throughout. He says we must stigmatize the addiction but not the addict. He advocates for real consequences to addictive behaviors as a key to getting addicted physicians and others with this disease into recovery. Treatment works, but we also have studied specific approaches that work and why.1 His writing conveys a genuine empathy for his patients and argues that treatment is delayed when serious and negative consequences for patients are removed.

Focus on prevention

A clear passion for prevention is evident within his chapters on youth addiction. For adolescents, Dr. DuPont presents a “One Choice approach,” which requires complete abstinence from alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana. He also presents science showing that patients younger than age 21 will have a greater risk of developing lifelong and debilitating addictions if they use these chemicals prior to this age. His emphasis for the One Choice approach carries ramifications throughout the primary care, pediatric, and family practice communities.

Dr. DuPont is nothing if not an optimist. Though he clearly defines addiction as an often-fatal disease, he remains positive about the future of addiction treatment, both with changes in public policy and with advancements in the medicine of addiction. He makes a compelling argument regarding Sweden’s approach to the drug problem, citing Queen Silvia’s lifelong commitment to prevent, control, and treat drug and alcohol addiction. Sweden’s model is, indeed, intriguing, and that country’s outcomes present a strong argument for the marriage of the criminal justice system with medical intervention – an approach that the United States has adopted only in a patchwork fashion.

The book describes controversies throughout, such as Dr. DuPont’s furtherance of our work on how best to treat dual disorders.2 He is not impressed with the self-medication hypothesis as well as the dive into the U.S. national medical marijuana experiment. We had looked at college students having new-onset memory or attention-deficit/hyperactivity problems, only to find that it was likely psychostimulant seeking to reverse marijuana effects.3 Physicians, families, and patients would be well served to review his arguments on the clear definition of “medicine” with regard to marijuana and the risks taken when we medicalize a known addictive chemical. He tackles the push for legalization as well, and the risks of increased societal acceptance and commercialization power that comes with this. He has led the field in thinking about the role of early drug exposure, brain training, and hijacking in the addictive process. This gateway hypothesis can occur whether the first teen drugs are cannabis or tobacco4 or alcohol.

Dr. DuPont finishes his work with a detailed biography, in which he addresses his family history of addiction, and his own overuse of alcohol in his late teens and early 20s as well as a confession of onetime use of marijuana during medical school. He always has led the field in trying to explain the disease of addiction, intervention, treatment, and recovery. But this self-reflection and brutal honesty is refreshing and in step with themes in his book, which promote the idea of recovery as an embrace of honesty, in mind, body, and spirit.

Dr. Jorandby trained in addiction psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and works as an addiction psychiatrist with Amen Clinics in Washington. Dr. Gold is the 17th Distinguished Alumni Professor at the University of Florida, Gainesville, and professor of psychiatry (adjunct) at Washington University in St. Louis.

References

1. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009 Mar;36(2):159-71.

2. J Addict Dis. 2007;26 Suppl 1:13-23.

3. Am J Psychiatry. 2007 Jun;164(6):973.

4. J Addict Dis. 2003;22(3):51-62.

What do Queen Silvia of Sweden, Pope Francis, and the first director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) have in common? They all share a deep and sobering commitment to fighting the global disease of addiction.

Robert L. DuPont, MD, has written a beautiful and surprisingly spiritual guide into the American addiction epidemic. He is the author of “The Selfish Brain: Learning From Addiction” (Center City, Minn.: Hazelden, 2000) and with his newest publication, “Chemical Slavery: Understanding Addiction and Stopping the Drug Epidemic” (Institute for Behavior and Health, 2018), he writes a clear-eyed tome detailing the history of drug and alcohol use within the United States and the current state of America’s drug epidemic.

Dr. DuPont is well known within the American addiction community as NIDA’s first director and as the second drug czar, under two presidents, Richard M. Nixon and Gerald R. Ford. His breadth of experience, spanning 50-plus years, dates from his early career with the District of Columbia Department of Corrections, into his work in public policy on drugs and alcohol. This experience infuses his book with the hard science of addiction and the common-sense compassion required to shepherd people into recovery. One of us has worked with and been influenced by him since the 1970s. The other, also an addiction psychiatrist, finished this book both invigorated and compelled to say thank you to Dr. DuPont and his life’s work! He remains relevant, insightful, and always optimistic about the future of addiction treatment.

Harm reduction explored

The book begins with a cogent history of drug and alcohol use in America. Dr. DuPont details this as well as the public policies that have evolved to address them. He weaves into our national history reasoning behind why, as a “mass consumer” culture, we are more prone to addiction than ever before. The loss of cultural and societal pressures has a role to play in the rise along with genetics and environmental stress. The adolescent brain is prominently discussed throughout this first section as a highly vulnerable organ that can lead to lifelong addiction if primed early by addictive chemicals.

Dr. DuPont addresses the biology of addiction, delving into both the biological mechanisms within the brain, making those details accessible and understandable – to a practicing physician as well as a family member or patient struggling with addiction.

He also addresses harm reduction, a fairly new concept within the field. Harm reduction has taken on more prominence with localities across the country providing people with addictions with safe places and clean needles to continue their substance use without risks of serious or life-threatening diseases and crime. He challenges the idea that harm reduction is active recovery from substance addiction. Instead, he opines that harm reduction must be tethered to and must lead to real recovery work or it risks becoming an organizational enabling of the addict’s behavior.

Dr. DuPont pulls no punches with his language. He uses words such as “fatal,” “addict,” and “alcoholic.” He addresses the concerns by some in the field that those kinds of words are harsh, derogatory, and prejudicial by calling out addiction as a disease hallmarked primarily by loss of control and by dishonesty. To shun those words is to perpetuate the disease, delaying life-saving treatment.

Compassion is a theme throughout. He says we must stigmatize the addiction but not the addict. He advocates for real consequences to addictive behaviors as a key to getting addicted physicians and others with this disease into recovery. Treatment works, but we also have studied specific approaches that work and why.1 His writing conveys a genuine empathy for his patients and argues that treatment is delayed when serious and negative consequences for patients are removed.

Focus on prevention

A clear passion for prevention is evident within his chapters on youth addiction. For adolescents, Dr. DuPont presents a “One Choice approach,” which requires complete abstinence from alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana. He also presents science showing that patients younger than age 21 will have a greater risk of developing lifelong and debilitating addictions if they use these chemicals prior to this age. His emphasis for the One Choice approach carries ramifications throughout the primary care, pediatric, and family practice communities.

Dr. DuPont is nothing if not an optimist. Though he clearly defines addiction as an often-fatal disease, he remains positive about the future of addiction treatment, both with changes in public policy and with advancements in the medicine of addiction. He makes a compelling argument regarding Sweden’s approach to the drug problem, citing Queen Silvia’s lifelong commitment to prevent, control, and treat drug and alcohol addiction. Sweden’s model is, indeed, intriguing, and that country’s outcomes present a strong argument for the marriage of the criminal justice system with medical intervention – an approach that the United States has adopted only in a patchwork fashion.

The book describes controversies throughout, such as Dr. DuPont’s furtherance of our work on how best to treat dual disorders.2 He is not impressed with the self-medication hypothesis as well as the dive into the U.S. national medical marijuana experiment. We had looked at college students having new-onset memory or attention-deficit/hyperactivity problems, only to find that it was likely psychostimulant seeking to reverse marijuana effects.3 Physicians, families, and patients would be well served to review his arguments on the clear definition of “medicine” with regard to marijuana and the risks taken when we medicalize a known addictive chemical. He tackles the push for legalization as well, and the risks of increased societal acceptance and commercialization power that comes with this. He has led the field in thinking about the role of early drug exposure, brain training, and hijacking in the addictive process. This gateway hypothesis can occur whether the first teen drugs are cannabis or tobacco4 or alcohol.

Dr. DuPont finishes his work with a detailed biography, in which he addresses his family history of addiction, and his own overuse of alcohol in his late teens and early 20s as well as a confession of onetime use of marijuana during medical school. He always has led the field in trying to explain the disease of addiction, intervention, treatment, and recovery. But this self-reflection and brutal honesty is refreshing and in step with themes in his book, which promote the idea of recovery as an embrace of honesty, in mind, body, and spirit.

Dr. Jorandby trained in addiction psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and works as an addiction psychiatrist with Amen Clinics in Washington. Dr. Gold is the 17th Distinguished Alumni Professor at the University of Florida, Gainesville, and professor of psychiatry (adjunct) at Washington University in St. Louis.

References

1. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009 Mar;36(2):159-71.

2. J Addict Dis. 2007;26 Suppl 1:13-23.

3. Am J Psychiatry. 2007 Jun;164(6):973.

4. J Addict Dis. 2003;22(3):51-62.

What do Queen Silvia of Sweden, Pope Francis, and the first director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) have in common? They all share a deep and sobering commitment to fighting the global disease of addiction.

Robert L. DuPont, MD, has written a beautiful and surprisingly spiritual guide into the American addiction epidemic. He is the author of “The Selfish Brain: Learning From Addiction” (Center City, Minn.: Hazelden, 2000) and with his newest publication, “Chemical Slavery: Understanding Addiction and Stopping the Drug Epidemic” (Institute for Behavior and Health, 2018), he writes a clear-eyed tome detailing the history of drug and alcohol use within the United States and the current state of America’s drug epidemic.