User login

Walking the walk

In March 2018, the Human Rights Campaign (HRC), an advocacy organization dedicated to improving the lives of LGBTQ people, released its 11th Annual Healthcare Equality Index. The HEI is an indicator of how inclusive and equitable health care facilities are in providing care for their LGBTQ patients. My own institution, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, scored very high on this index and received the “Leader in LGBTQ Healthcare Equality” designation. The process of receiving this designation is very rigorous, and I am proud of my institution for making great strides in expanding health care access for LGBTQ patients, especially transgender patients. However, this is no time to rest on one’s laurels, as many transgender people still experience challenges and barriers in navigating the health care system.

Insurance access continues to be a problem. I wrote a column in June 2017 about obtaining health care insurance for transgender patients. Preauthorization is common for obtaining cross-sex hormones or pubertal blockers even for insurance companies that are willing to pay for them – a process that can take weeks, even months, to complete. This creates delays in obtaining necessary care for transgender patients. This is just one of the many barriers transgender people face in navigating the health care system.

Increasing access to health care services for transgender patients is more about improving health outcomes than patient satisfaction. Even the smallest policy change may have a meaningful impact on the lives of transgender individuals. A study by Russell et al., in the April 2018 issue of Journal of Adolescent Health found that transgender youth allowed to use their chosen name (instead of the name assigned to them by their parents at birth) were more likely to have fewer depressive symptoms and lower rates of suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior.3 These findings highlight that even a small change can have a huge impact on the health and well-being of this patient population.

What can you do to expand access? First, you must educate yourself and teach others. Many providers report never having received education on LGBTQ health during their training,4 and most barriers for transgender patients stem from this lack of training. Second, work with the transgender community – it is very tempting to see your institution’s name on the HEI and think all the work is done, but the lived experiences of transgender patients sometimes are different than what is seen on paper (or online). Team up with local organizations such as PFLAG (formerly known as Parents and Families of Lesbians and Gays) that can create support groups for both transgender youth and their families. Help create a network of referral systems for your transgender patients – the community is often small enough that they know which providers or establishments are safe for transgender individuals. Many transgender patients find this extremely helpful.5 You still wield significant influence in the community, so work with the health care and insurance systems to improve access and coverage for gender-related services. The HRC HEI is becoming coveted by health care institutions. This is a prime opportunity to be involved in committees seeking to improve health care access for transgender individuals. Finally, as there are champions for transgender health in your clinic, there also are champions for transgender health in insurance companies. They often are well known in the community, so find that individual for counseling on how to navigate the insurance system for your transgender patients.

Although an increasing number of health care institutions and clinics are recognizing the health care needs of transgender patients and providing appropriate care, the health care system remains challenging for transgender individuals to navigate. Small policy changes may have a substantial impact on the health and well-being of transgender individuals. Although creating change within an institution may seem like a monumental task, you do have the agency to help create this type change within the system to expand health care access for transgender patients.

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC. Email him at [email protected].

Resources

- HRC HEI: If you’re interested in learning what policies are inclusive and equitable for LGBT patients, check out the HRC HEI scoring criteria. It’s a good place to start if you want to expand health care access for transgender individuals.

- To find out more about the health care legal protections transgender individuals are entitled to, check out the National Center for Transgender Equality.

References

1. Psychol Bull. 2003 Sep;129(5):674-97.

2. “Injustice at every turn: A report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey.” (Washington: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011.)

3. J. Adolesc Health. 2018 Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.02.003.

4. Int J Transgenderism. 2008. doi: 10.1300/J485v08n02_08.

5. Transgend Health. 2016 Nov 1;1(1):238-49.

In March 2018, the Human Rights Campaign (HRC), an advocacy organization dedicated to improving the lives of LGBTQ people, released its 11th Annual Healthcare Equality Index. The HEI is an indicator of how inclusive and equitable health care facilities are in providing care for their LGBTQ patients. My own institution, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, scored very high on this index and received the “Leader in LGBTQ Healthcare Equality” designation. The process of receiving this designation is very rigorous, and I am proud of my institution for making great strides in expanding health care access for LGBTQ patients, especially transgender patients. However, this is no time to rest on one’s laurels, as many transgender people still experience challenges and barriers in navigating the health care system.

Insurance access continues to be a problem. I wrote a column in June 2017 about obtaining health care insurance for transgender patients. Preauthorization is common for obtaining cross-sex hormones or pubertal blockers even for insurance companies that are willing to pay for them – a process that can take weeks, even months, to complete. This creates delays in obtaining necessary care for transgender patients. This is just one of the many barriers transgender people face in navigating the health care system.

Increasing access to health care services for transgender patients is more about improving health outcomes than patient satisfaction. Even the smallest policy change may have a meaningful impact on the lives of transgender individuals. A study by Russell et al., in the April 2018 issue of Journal of Adolescent Health found that transgender youth allowed to use their chosen name (instead of the name assigned to them by their parents at birth) were more likely to have fewer depressive symptoms and lower rates of suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior.3 These findings highlight that even a small change can have a huge impact on the health and well-being of this patient population.

What can you do to expand access? First, you must educate yourself and teach others. Many providers report never having received education on LGBTQ health during their training,4 and most barriers for transgender patients stem from this lack of training. Second, work with the transgender community – it is very tempting to see your institution’s name on the HEI and think all the work is done, but the lived experiences of transgender patients sometimes are different than what is seen on paper (or online). Team up with local organizations such as PFLAG (formerly known as Parents and Families of Lesbians and Gays) that can create support groups for both transgender youth and their families. Help create a network of referral systems for your transgender patients – the community is often small enough that they know which providers or establishments are safe for transgender individuals. Many transgender patients find this extremely helpful.5 You still wield significant influence in the community, so work with the health care and insurance systems to improve access and coverage for gender-related services. The HRC HEI is becoming coveted by health care institutions. This is a prime opportunity to be involved in committees seeking to improve health care access for transgender individuals. Finally, as there are champions for transgender health in your clinic, there also are champions for transgender health in insurance companies. They often are well known in the community, so find that individual for counseling on how to navigate the insurance system for your transgender patients.

Although an increasing number of health care institutions and clinics are recognizing the health care needs of transgender patients and providing appropriate care, the health care system remains challenging for transgender individuals to navigate. Small policy changes may have a substantial impact on the health and well-being of transgender individuals. Although creating change within an institution may seem like a monumental task, you do have the agency to help create this type change within the system to expand health care access for transgender patients.

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC. Email him at [email protected].

Resources

- HRC HEI: If you’re interested in learning what policies are inclusive and equitable for LGBT patients, check out the HRC HEI scoring criteria. It’s a good place to start if you want to expand health care access for transgender individuals.

- To find out more about the health care legal protections transgender individuals are entitled to, check out the National Center for Transgender Equality.

References

1. Psychol Bull. 2003 Sep;129(5):674-97.

2. “Injustice at every turn: A report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey.” (Washington: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011.)

3. J. Adolesc Health. 2018 Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.02.003.

4. Int J Transgenderism. 2008. doi: 10.1300/J485v08n02_08.

5. Transgend Health. 2016 Nov 1;1(1):238-49.

In March 2018, the Human Rights Campaign (HRC), an advocacy organization dedicated to improving the lives of LGBTQ people, released its 11th Annual Healthcare Equality Index. The HEI is an indicator of how inclusive and equitable health care facilities are in providing care for their LGBTQ patients. My own institution, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, scored very high on this index and received the “Leader in LGBTQ Healthcare Equality” designation. The process of receiving this designation is very rigorous, and I am proud of my institution for making great strides in expanding health care access for LGBTQ patients, especially transgender patients. However, this is no time to rest on one’s laurels, as many transgender people still experience challenges and barriers in navigating the health care system.

Insurance access continues to be a problem. I wrote a column in June 2017 about obtaining health care insurance for transgender patients. Preauthorization is common for obtaining cross-sex hormones or pubertal blockers even for insurance companies that are willing to pay for them – a process that can take weeks, even months, to complete. This creates delays in obtaining necessary care for transgender patients. This is just one of the many barriers transgender people face in navigating the health care system.

Increasing access to health care services for transgender patients is more about improving health outcomes than patient satisfaction. Even the smallest policy change may have a meaningful impact on the lives of transgender individuals. A study by Russell et al., in the April 2018 issue of Journal of Adolescent Health found that transgender youth allowed to use their chosen name (instead of the name assigned to them by their parents at birth) were more likely to have fewer depressive symptoms and lower rates of suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior.3 These findings highlight that even a small change can have a huge impact on the health and well-being of this patient population.

What can you do to expand access? First, you must educate yourself and teach others. Many providers report never having received education on LGBTQ health during their training,4 and most barriers for transgender patients stem from this lack of training. Second, work with the transgender community – it is very tempting to see your institution’s name on the HEI and think all the work is done, but the lived experiences of transgender patients sometimes are different than what is seen on paper (or online). Team up with local organizations such as PFLAG (formerly known as Parents and Families of Lesbians and Gays) that can create support groups for both transgender youth and their families. Help create a network of referral systems for your transgender patients – the community is often small enough that they know which providers or establishments are safe for transgender individuals. Many transgender patients find this extremely helpful.5 You still wield significant influence in the community, so work with the health care and insurance systems to improve access and coverage for gender-related services. The HRC HEI is becoming coveted by health care institutions. This is a prime opportunity to be involved in committees seeking to improve health care access for transgender individuals. Finally, as there are champions for transgender health in your clinic, there also are champions for transgender health in insurance companies. They often are well known in the community, so find that individual for counseling on how to navigate the insurance system for your transgender patients.

Although an increasing number of health care institutions and clinics are recognizing the health care needs of transgender patients and providing appropriate care, the health care system remains challenging for transgender individuals to navigate. Small policy changes may have a substantial impact on the health and well-being of transgender individuals. Although creating change within an institution may seem like a monumental task, you do have the agency to help create this type change within the system to expand health care access for transgender patients.

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC. Email him at [email protected].

Resources

- HRC HEI: If you’re interested in learning what policies are inclusive and equitable for LGBT patients, check out the HRC HEI scoring criteria. It’s a good place to start if you want to expand health care access for transgender individuals.

- To find out more about the health care legal protections transgender individuals are entitled to, check out the National Center for Transgender Equality.

References

1. Psychol Bull. 2003 Sep;129(5):674-97.

2. “Injustice at every turn: A report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey.” (Washington: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011.)

3. J. Adolesc Health. 2018 Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.02.003.

4. Int J Transgenderism. 2008. doi: 10.1300/J485v08n02_08.

5. Transgend Health. 2016 Nov 1;1(1):238-49.

On cardiology training

I recently received a letter from a former fellow who completed his training almost 25 years ago, thanking me for guiding him through his education and to his successful medical career. It’s one of those letters that we all have received and that makes us feel that it is all worth it. When he went through his requisite 2 years of training, it seemed to me that my responsibility was to provide a model of how to provide excellent care at the bedside and clinic with expertise and compassion.

Percutaneous coronary angiography, echocardiography, radioisotope imaging, and new dramatically effective lifesaving drugs such as beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, and thrombolytic therapies were developed almost overnight. Their application to the patient became a challenge, and an exciting period of clinical research ensued. As a training director, it seemed that our responsibility was not only to continue to provide a model of competent care but also to create an environment in which our new tools of diagnosis and therapy could be applied at the bedside. At the time, it became apparent that there was a need for staff members to develop expertise in all of these areas in order to provide an adequate teaching environment. These new developments also provided a unique opportunity to conduct clinical research in order develop the full range of the new therapeutic and diagnostic potentials.

Within a few years, we changed from being the bedside cardiologists who could do everything in a very limited way, to a staff focused on special areas of expertise in order to provide an optimal teaching environment. This led to the development of subspecialty areas of cardiac care, which became the future framework of the contemporary cardiology unit. It resulted in a decreased time on bedside care and a greater emphasis on pursuing specialty care. Many of the aspects of interpersonal relationships at the bedside became less important in order to provide trainees with the sufficient experience in the newly developing subspecialty areas. The competence of a cardiology fellow was no longer judged by his commitment to patient care but rather, by the achievement of sufficient number of procedures to meet certification exams. Both students and teachers became focused on the numbers game.

It is clear that the body of cardiology knowledge has expanded to a point where most of us cannot handle it all, and we need to turn to our colleagues with special expertise for help. This transition, which is not unique to cardiology, removed the teacher-practitioners from their role as the model of ethical and compassionate caregiver to that of the provider of procedures. Now, more than ever, there is a need to return to the model of the compassionate and concerned doctor. The need for expertise is undeniable, but in the process of achieving that, we cannot forget that we are doctors to patients and not just procedure readers and number crunchers. There is still time in our day to do that. If there isn’t, we need to find it.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

I recently received a letter from a former fellow who completed his training almost 25 years ago, thanking me for guiding him through his education and to his successful medical career. It’s one of those letters that we all have received and that makes us feel that it is all worth it. When he went through his requisite 2 years of training, it seemed to me that my responsibility was to provide a model of how to provide excellent care at the bedside and clinic with expertise and compassion.

Percutaneous coronary angiography, echocardiography, radioisotope imaging, and new dramatically effective lifesaving drugs such as beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, and thrombolytic therapies were developed almost overnight. Their application to the patient became a challenge, and an exciting period of clinical research ensued. As a training director, it seemed that our responsibility was not only to continue to provide a model of competent care but also to create an environment in which our new tools of diagnosis and therapy could be applied at the bedside. At the time, it became apparent that there was a need for staff members to develop expertise in all of these areas in order to provide an adequate teaching environment. These new developments also provided a unique opportunity to conduct clinical research in order develop the full range of the new therapeutic and diagnostic potentials.

Within a few years, we changed from being the bedside cardiologists who could do everything in a very limited way, to a staff focused on special areas of expertise in order to provide an optimal teaching environment. This led to the development of subspecialty areas of cardiac care, which became the future framework of the contemporary cardiology unit. It resulted in a decreased time on bedside care and a greater emphasis on pursuing specialty care. Many of the aspects of interpersonal relationships at the bedside became less important in order to provide trainees with the sufficient experience in the newly developing subspecialty areas. The competence of a cardiology fellow was no longer judged by his commitment to patient care but rather, by the achievement of sufficient number of procedures to meet certification exams. Both students and teachers became focused on the numbers game.

It is clear that the body of cardiology knowledge has expanded to a point where most of us cannot handle it all, and we need to turn to our colleagues with special expertise for help. This transition, which is not unique to cardiology, removed the teacher-practitioners from their role as the model of ethical and compassionate caregiver to that of the provider of procedures. Now, more than ever, there is a need to return to the model of the compassionate and concerned doctor. The need for expertise is undeniable, but in the process of achieving that, we cannot forget that we are doctors to patients and not just procedure readers and number crunchers. There is still time in our day to do that. If there isn’t, we need to find it.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

I recently received a letter from a former fellow who completed his training almost 25 years ago, thanking me for guiding him through his education and to his successful medical career. It’s one of those letters that we all have received and that makes us feel that it is all worth it. When he went through his requisite 2 years of training, it seemed to me that my responsibility was to provide a model of how to provide excellent care at the bedside and clinic with expertise and compassion.

Percutaneous coronary angiography, echocardiography, radioisotope imaging, and new dramatically effective lifesaving drugs such as beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, and thrombolytic therapies were developed almost overnight. Their application to the patient became a challenge, and an exciting period of clinical research ensued. As a training director, it seemed that our responsibility was not only to continue to provide a model of competent care but also to create an environment in which our new tools of diagnosis and therapy could be applied at the bedside. At the time, it became apparent that there was a need for staff members to develop expertise in all of these areas in order to provide an adequate teaching environment. These new developments also provided a unique opportunity to conduct clinical research in order develop the full range of the new therapeutic and diagnostic potentials.

Within a few years, we changed from being the bedside cardiologists who could do everything in a very limited way, to a staff focused on special areas of expertise in order to provide an optimal teaching environment. This led to the development of subspecialty areas of cardiac care, which became the future framework of the contemporary cardiology unit. It resulted in a decreased time on bedside care and a greater emphasis on pursuing specialty care. Many of the aspects of interpersonal relationships at the bedside became less important in order to provide trainees with the sufficient experience in the newly developing subspecialty areas. The competence of a cardiology fellow was no longer judged by his commitment to patient care but rather, by the achievement of sufficient number of procedures to meet certification exams. Both students and teachers became focused on the numbers game.

It is clear that the body of cardiology knowledge has expanded to a point where most of us cannot handle it all, and we need to turn to our colleagues with special expertise for help. This transition, which is not unique to cardiology, removed the teacher-practitioners from their role as the model of ethical and compassionate caregiver to that of the provider of procedures. Now, more than ever, there is a need to return to the model of the compassionate and concerned doctor. The need for expertise is undeniable, but in the process of achieving that, we cannot forget that we are doctors to patients and not just procedure readers and number crunchers. There is still time in our day to do that. If there isn’t, we need to find it.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

Ketamine formulation study is ‘groundbreaking’

It is remarkable to consider that we now have more than 30 medications approved by the Food and Drug Administration as monotherapy or augmentation for the treatment of major depressive disorder. And yet, we know very little about how these medications perform for patients at high risk for suicide.

Historically, suicidal patients have been excluded from phase 3 antidepressant trials, which provide the basis for regulatory approval. Even studies in treatment-resistant depression (TRD) have tended to exclude patients with the highest risk of suicide. Further, the FDA does not mandate that a new antidepressant medication demonstrate any benefit for suicidal ideation.

Focus on high-risk patients

The recent report by Canuso et al.3 in the American Journal of Psychiatry is a groundbreaking study: Previous placebo-controlled trials of intravenous ketamine in depressed patients with clinically significant suicidal ideation have used only one-time dose administrations4,5,6.

This phase 2, proof-of-concept trial randomized 68 adults with MDD at 11 U.S. sites, which were primarily academic medical centers. In contrast to previous ketamine studies, which recruited patients via advertisement or clinician referral, patients were identified and screened in an emergency department or an inpatient psychiatric unit. Participants had to voluntarily agree to hospitalization for 5 days following randomization, with the remainder of the study conducted on an outpatient basis. Intranasal esketamine (84 mg) or placebo was administered twice per week over 4 weeks, in addition to standard-of-care antidepressant treatment. The primary outcome was the change in the Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score from baseline to 4 hours after first dose of study medication.

For the primary MADRS outcome, esketamine statistically separated from placebo at 4 hours and 24 hours, with moderate effect sizes (0.61 to 0.65). There were no significant differences at the end of the double-blind period at day 25 and at posttreatment follow-up at day 81. For the suicidal thoughts item of the MADRS, esketamine’s efficacy was greater than placebo at 4 hours, but not at 24 hours or at day 25. Clinician global judgment of suicide risk was not statistically different between groups at any time point, although the esketamine group had numerically greater improvements at 4 hours and 24 hours. There were no group differences in self-report measures (Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation or Beck Hopelessness Scale) at any time point.

Regarding safety and tolerability, adverse events led to early termination for 5 patients in the esketamine group, compared with one in the placebo group. The most common adverse events were nausea, dizziness, dissociation, unpleasant taste, and headache, which were more frequent in the esketamine group. Transient elevations in blood pressure and dissociative symptoms generally peaked at 40 minutes after dosing and returned to baseline by 2 hours.

Putting findings in perspective

Several aspects of the trial are noteworthy. First, enrolled patients were markedly depressed, and half required additional suicide precautions in addition to hospitalization. Three patients (all in the placebo group) made suicide attempts during the follow-up period, further evidence that these patients were extremely high risk. Second, the sample was significantly more racially diverse (38% black or African American) than most previous ketamine studies. Third, psychiatric hospitalization plus the initiation of standard antidepressant medication resulted in substantial improvements for many patients randomized to intranasal placebo spray. Inflated short-term placebo responses are commonly seen even in severely depressed patients, making signal detection especially challenging for new drugs. Finally, it is difficult to compare the results of this study with the few placebo-controlled trials of intravenous ketamine for patients with MDD and significant suicidal ideation, because of differences in outcomes measures, patient populations, doses, and route of administration. This study used the Suicide Ideation and Behavior Assessment Tool, a computerized, modular instrument with patient-reported and clinician-reported assessments, which was developed specifically to measure rapid changes in suicidality and awaits further validation in ongoing studies.

Limitations of this study include the absence of reported plasma esketamine levels. Is it possible that higher doses of esketamine, or a different dosing schedule, would have had resulted in greater efficacy? The 84-mg dose used in this trial recently was found to be safe and effective in patients with TRD2, and was reported to have similar plasma levels as IV esketamine 0.2 mg/kg2. This dose, in turn, corresponds to a racemic ketamine dose of approximately 0.31 mg/kg1. Future studies will need to examine the antisuicidal and antidepressant effects of the most commonly used racemic ketamine dose (0.5 mg/kg), compared with 84 mg intranasal esketamine. The twice per week dosing schedule was supported empirically from a previous study of intravenous ketamine showing that twice weekly infusions were equally effective to thrice weekly administrations7. It is unknown, however, whether even less-frequent administrations (such as once weekly) would have been more effective than twice-weekly over the 4-week, double-blind period. Finally, the authors raise the possibility of functional unblinding, which always is a concern in ketamine studies. Although the placebo solution contained a bittering agent to simulate the taste of esketamine intranasal solution, the integrity of the blind was not reported.

Conclusion

Overall, this study is a promising start. In my view, the risk to benefit ratio for this approach is acceptable, given the morbidity and mortality associated with suicidal depression. The fact that esketamine nasal spray would be administered only under the observation of a clinician in a medical setting, and not be dispensed for at-home use, is reassuring and would mitigate the potential for abuse. In the meantime, our field awaits the results of larger phase 3 studies for patients with MDD at imminent risk for suicide.

Dr. Mathew is affiliated with the Michael E. Debakey VA Medical Center, and the Menninger Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. Over the last 12 months, he has served as a paid consultant to Alkermes and Fortress Biotech. He also has served as an investigator on clinical trials sponsored by Janssen Research and Development, the manufacturer of intranasal esketamine, and as an investigator on a trial sponsored by NeuroRx.

References

1. Biol Psychiatry. 2016 Sep 15;80(6):424-31.

2. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Feb 1;75(2):139-48.

3. Am J Psychiatry. 2018 Apr 16. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17060720.

4. Am J Psychiatry. 2018 Apr 1;175(4]):327-35.

5. Psychol Med. 2015 Dec;45(16):3571-80.

6. Am J Psychiatry. 2018 Feb 1;175(2):150-8.

7. Am J Psychiatry. 2016 Aug 1;173(8):816-26.

It is remarkable to consider that we now have more than 30 medications approved by the Food and Drug Administration as monotherapy or augmentation for the treatment of major depressive disorder. And yet, we know very little about how these medications perform for patients at high risk for suicide.

Historically, suicidal patients have been excluded from phase 3 antidepressant trials, which provide the basis for regulatory approval. Even studies in treatment-resistant depression (TRD) have tended to exclude patients with the highest risk of suicide. Further, the FDA does not mandate that a new antidepressant medication demonstrate any benefit for suicidal ideation.

Focus on high-risk patients

The recent report by Canuso et al.3 in the American Journal of Psychiatry is a groundbreaking study: Previous placebo-controlled trials of intravenous ketamine in depressed patients with clinically significant suicidal ideation have used only one-time dose administrations4,5,6.

This phase 2, proof-of-concept trial randomized 68 adults with MDD at 11 U.S. sites, which were primarily academic medical centers. In contrast to previous ketamine studies, which recruited patients via advertisement or clinician referral, patients were identified and screened in an emergency department or an inpatient psychiatric unit. Participants had to voluntarily agree to hospitalization for 5 days following randomization, with the remainder of the study conducted on an outpatient basis. Intranasal esketamine (84 mg) or placebo was administered twice per week over 4 weeks, in addition to standard-of-care antidepressant treatment. The primary outcome was the change in the Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score from baseline to 4 hours after first dose of study medication.

For the primary MADRS outcome, esketamine statistically separated from placebo at 4 hours and 24 hours, with moderate effect sizes (0.61 to 0.65). There were no significant differences at the end of the double-blind period at day 25 and at posttreatment follow-up at day 81. For the suicidal thoughts item of the MADRS, esketamine’s efficacy was greater than placebo at 4 hours, but not at 24 hours or at day 25. Clinician global judgment of suicide risk was not statistically different between groups at any time point, although the esketamine group had numerically greater improvements at 4 hours and 24 hours. There were no group differences in self-report measures (Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation or Beck Hopelessness Scale) at any time point.

Regarding safety and tolerability, adverse events led to early termination for 5 patients in the esketamine group, compared with one in the placebo group. The most common adverse events were nausea, dizziness, dissociation, unpleasant taste, and headache, which were more frequent in the esketamine group. Transient elevations in blood pressure and dissociative symptoms generally peaked at 40 minutes after dosing and returned to baseline by 2 hours.

Putting findings in perspective

Several aspects of the trial are noteworthy. First, enrolled patients were markedly depressed, and half required additional suicide precautions in addition to hospitalization. Three patients (all in the placebo group) made suicide attempts during the follow-up period, further evidence that these patients were extremely high risk. Second, the sample was significantly more racially diverse (38% black or African American) than most previous ketamine studies. Third, psychiatric hospitalization plus the initiation of standard antidepressant medication resulted in substantial improvements for many patients randomized to intranasal placebo spray. Inflated short-term placebo responses are commonly seen even in severely depressed patients, making signal detection especially challenging for new drugs. Finally, it is difficult to compare the results of this study with the few placebo-controlled trials of intravenous ketamine for patients with MDD and significant suicidal ideation, because of differences in outcomes measures, patient populations, doses, and route of administration. This study used the Suicide Ideation and Behavior Assessment Tool, a computerized, modular instrument with patient-reported and clinician-reported assessments, which was developed specifically to measure rapid changes in suicidality and awaits further validation in ongoing studies.

Limitations of this study include the absence of reported plasma esketamine levels. Is it possible that higher doses of esketamine, or a different dosing schedule, would have had resulted in greater efficacy? The 84-mg dose used in this trial recently was found to be safe and effective in patients with TRD2, and was reported to have similar plasma levels as IV esketamine 0.2 mg/kg2. This dose, in turn, corresponds to a racemic ketamine dose of approximately 0.31 mg/kg1. Future studies will need to examine the antisuicidal and antidepressant effects of the most commonly used racemic ketamine dose (0.5 mg/kg), compared with 84 mg intranasal esketamine. The twice per week dosing schedule was supported empirically from a previous study of intravenous ketamine showing that twice weekly infusions were equally effective to thrice weekly administrations7. It is unknown, however, whether even less-frequent administrations (such as once weekly) would have been more effective than twice-weekly over the 4-week, double-blind period. Finally, the authors raise the possibility of functional unblinding, which always is a concern in ketamine studies. Although the placebo solution contained a bittering agent to simulate the taste of esketamine intranasal solution, the integrity of the blind was not reported.

Conclusion

Overall, this study is a promising start. In my view, the risk to benefit ratio for this approach is acceptable, given the morbidity and mortality associated with suicidal depression. The fact that esketamine nasal spray would be administered only under the observation of a clinician in a medical setting, and not be dispensed for at-home use, is reassuring and would mitigate the potential for abuse. In the meantime, our field awaits the results of larger phase 3 studies for patients with MDD at imminent risk for suicide.

Dr. Mathew is affiliated with the Michael E. Debakey VA Medical Center, and the Menninger Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. Over the last 12 months, he has served as a paid consultant to Alkermes and Fortress Biotech. He also has served as an investigator on clinical trials sponsored by Janssen Research and Development, the manufacturer of intranasal esketamine, and as an investigator on a trial sponsored by NeuroRx.

References

1. Biol Psychiatry. 2016 Sep 15;80(6):424-31.

2. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Feb 1;75(2):139-48.

3. Am J Psychiatry. 2018 Apr 16. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17060720.

4. Am J Psychiatry. 2018 Apr 1;175(4]):327-35.

5. Psychol Med. 2015 Dec;45(16):3571-80.

6. Am J Psychiatry. 2018 Feb 1;175(2):150-8.

7. Am J Psychiatry. 2016 Aug 1;173(8):816-26.

It is remarkable to consider that we now have more than 30 medications approved by the Food and Drug Administration as monotherapy or augmentation for the treatment of major depressive disorder. And yet, we know very little about how these medications perform for patients at high risk for suicide.

Historically, suicidal patients have been excluded from phase 3 antidepressant trials, which provide the basis for regulatory approval. Even studies in treatment-resistant depression (TRD) have tended to exclude patients with the highest risk of suicide. Further, the FDA does not mandate that a new antidepressant medication demonstrate any benefit for suicidal ideation.

Focus on high-risk patients

The recent report by Canuso et al.3 in the American Journal of Psychiatry is a groundbreaking study: Previous placebo-controlled trials of intravenous ketamine in depressed patients with clinically significant suicidal ideation have used only one-time dose administrations4,5,6.

This phase 2, proof-of-concept trial randomized 68 adults with MDD at 11 U.S. sites, which were primarily academic medical centers. In contrast to previous ketamine studies, which recruited patients via advertisement or clinician referral, patients were identified and screened in an emergency department or an inpatient psychiatric unit. Participants had to voluntarily agree to hospitalization for 5 days following randomization, with the remainder of the study conducted on an outpatient basis. Intranasal esketamine (84 mg) or placebo was administered twice per week over 4 weeks, in addition to standard-of-care antidepressant treatment. The primary outcome was the change in the Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score from baseline to 4 hours after first dose of study medication.

For the primary MADRS outcome, esketamine statistically separated from placebo at 4 hours and 24 hours, with moderate effect sizes (0.61 to 0.65). There were no significant differences at the end of the double-blind period at day 25 and at posttreatment follow-up at day 81. For the suicidal thoughts item of the MADRS, esketamine’s efficacy was greater than placebo at 4 hours, but not at 24 hours or at day 25. Clinician global judgment of suicide risk was not statistically different between groups at any time point, although the esketamine group had numerically greater improvements at 4 hours and 24 hours. There were no group differences in self-report measures (Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation or Beck Hopelessness Scale) at any time point.

Regarding safety and tolerability, adverse events led to early termination for 5 patients in the esketamine group, compared with one in the placebo group. The most common adverse events were nausea, dizziness, dissociation, unpleasant taste, and headache, which were more frequent in the esketamine group. Transient elevations in blood pressure and dissociative symptoms generally peaked at 40 minutes after dosing and returned to baseline by 2 hours.

Putting findings in perspective

Several aspects of the trial are noteworthy. First, enrolled patients were markedly depressed, and half required additional suicide precautions in addition to hospitalization. Three patients (all in the placebo group) made suicide attempts during the follow-up period, further evidence that these patients were extremely high risk. Second, the sample was significantly more racially diverse (38% black or African American) than most previous ketamine studies. Third, psychiatric hospitalization plus the initiation of standard antidepressant medication resulted in substantial improvements for many patients randomized to intranasal placebo spray. Inflated short-term placebo responses are commonly seen even in severely depressed patients, making signal detection especially challenging for new drugs. Finally, it is difficult to compare the results of this study with the few placebo-controlled trials of intravenous ketamine for patients with MDD and significant suicidal ideation, because of differences in outcomes measures, patient populations, doses, and route of administration. This study used the Suicide Ideation and Behavior Assessment Tool, a computerized, modular instrument with patient-reported and clinician-reported assessments, which was developed specifically to measure rapid changes in suicidality and awaits further validation in ongoing studies.

Limitations of this study include the absence of reported plasma esketamine levels. Is it possible that higher doses of esketamine, or a different dosing schedule, would have had resulted in greater efficacy? The 84-mg dose used in this trial recently was found to be safe and effective in patients with TRD2, and was reported to have similar plasma levels as IV esketamine 0.2 mg/kg2. This dose, in turn, corresponds to a racemic ketamine dose of approximately 0.31 mg/kg1. Future studies will need to examine the antisuicidal and antidepressant effects of the most commonly used racemic ketamine dose (0.5 mg/kg), compared with 84 mg intranasal esketamine. The twice per week dosing schedule was supported empirically from a previous study of intravenous ketamine showing that twice weekly infusions were equally effective to thrice weekly administrations7. It is unknown, however, whether even less-frequent administrations (such as once weekly) would have been more effective than twice-weekly over the 4-week, double-blind period. Finally, the authors raise the possibility of functional unblinding, which always is a concern in ketamine studies. Although the placebo solution contained a bittering agent to simulate the taste of esketamine intranasal solution, the integrity of the blind was not reported.

Conclusion

Overall, this study is a promising start. In my view, the risk to benefit ratio for this approach is acceptable, given the morbidity and mortality associated with suicidal depression. The fact that esketamine nasal spray would be administered only under the observation of a clinician in a medical setting, and not be dispensed for at-home use, is reassuring and would mitigate the potential for abuse. In the meantime, our field awaits the results of larger phase 3 studies for patients with MDD at imminent risk for suicide.

Dr. Mathew is affiliated with the Michael E. Debakey VA Medical Center, and the Menninger Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. Over the last 12 months, he has served as a paid consultant to Alkermes and Fortress Biotech. He also has served as an investigator on clinical trials sponsored by Janssen Research and Development, the manufacturer of intranasal esketamine, and as an investigator on a trial sponsored by NeuroRx.

References

1. Biol Psychiatry. 2016 Sep 15;80(6):424-31.

2. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Feb 1;75(2):139-48.

3. Am J Psychiatry. 2018 Apr 16. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17060720.

4. Am J Psychiatry. 2018 Apr 1;175(4]):327-35.

5. Psychol Med. 2015 Dec;45(16):3571-80.

6. Am J Psychiatry. 2018 Feb 1;175(2):150-8.

7. Am J Psychiatry. 2016 Aug 1;173(8):816-26.

Self-harm

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) has become more prevalent in youth over recent years and has many inherent risks. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), NSSI is a diagnosis suggested for further study, and criteria include engaging in self-injury for 5 or more days without suicidal intent as well as self-injury associated with at least 1 of the following: obtaining relief from negative thoughts or feelings, resolving interpersonal challenges, inducing positive feelings. It is associated with interpersonal difficulties or negative thoughts/feelings. The behavior causes significant impairment in functioning and is not better explained by another condition.1

Estimates of lifetime prevalence in community-based samples of youth range from 15% to 20%. Individuals often start during early adolescence. It can pose many risks including infection, permanent scarring or disfigurement, decreased self-esteem, interpersonal conflict, severe injury, or death. Reasons for engaging in self-harm can vary and include attempts to regulate negative affect, to manage feelings of emptiness/numbness, regain a sense of control over body, feelings, etc., or to provide a consequence for perceived faults. Youth often may start to engage in self-harm covertly, and it may first become apparent in emergency or primary care settings. However, upon discovery, the response given also may affect future behavior.

Efforts also have been underway to distinguish between youth who engage in self-harm with and without suicidal ideation. Girls are more likely than are boys to report NSSI, although male NSSI may present differently. In addition to cutting or more stereotypical self-injury, they may punch walls or engage in fights or other risky behaviors as a proxy for self-harm. Risk factors for boys with regard to suicide attempts include hopelessness and history of sexual abuse. Maladaptive eating patterns and hopelessness were the two most significant factors for girls.4

With regard to issues of confidentiality, it will be important to carefully gauge level of safety and to clearly communicate with the patient (and family) limits of confidentiality. This may result in working within shades of gray to help maintain the therapeutic relationship and the patient’s comfort in being able to disclose potentially sensitive information.

Families can struggle with how to manage this, and it can generate fear as well as other strong emotions.

Tips for parents and guardians

- Validate the underlying emotions while not validating the behavior. Self-injury is a coping strategy. Focus on the driving forces for the actions rather than the actions themselves.

- Approach your child from a nonjudgmental stance.

- Recognize that change may not happen overnight, and that there may be periods of regression.

- Acknowledge successes when they occur.

- Make yourself available for open communication. Open-ended questions may facilitate more dialogue.

- Take care of yourself as well. Ensure you use your supports and are engaging in healthy self-care.

- Take the behavior seriously. While this behavior is relatively common, do not assume it is “just a phase.”

- While remaining supportive, it is important to maintain a parental role and to keep expectations rather than “walking on eggshells.”

- Involve the child in identifying what can be of support.

- Become aware of local crisis resources in your community. National resources include Call 1-800-273-TALK for the national suicide hotline or Text 741741 to connect with a crisis counselor.

Things to avoid

- Avoid taking a punitive stance. While the behavior can be provocative, most likely the primary purpose is not for attention.

- Avoid engaging in power struggles.

- Avoid creating increased isolation for the child. This can be a delicate balance with regard to peer groups, but encouraging healthy social interactions and activities is a way to help build resilience.

- Avoid taking the behavior personally.5

In working with youth who engage in self-harm, it is important to work within a team, which may include family, primary care, mental health support, school, and potentially other community supports. Treatment evidence is relatively limited, but there is some evidence to support use of cognitive behavioral therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, and mentalization-based therapy. Regardless, work will likely be long term and at times intensive in addressing the problems leading to self-harm behavior.6

Dr. Strange is an assistant professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of Vermont Medical Center and University of Vermont Robert Larner College of Medicine, both in Burlington. She works with children and adolescents. She has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2013)

2. J Adolesc. 2014 Dec;37(8):1335-44.

3. Behav Ther. 2017 May; 48(3):366-79.

4. Acad Pediatr. 2012 May-Jun;12(3):205-13.

5. “Information for parents: What you need to know about self-injury.” The Fact Sheet Series, Cornell Research Program on Self-Injury and Recovery. 2009.

6. Clin Pediatr. 2016 Sep 13;55(11):1012-9.

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) has become more prevalent in youth over recent years and has many inherent risks. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), NSSI is a diagnosis suggested for further study, and criteria include engaging in self-injury for 5 or more days without suicidal intent as well as self-injury associated with at least 1 of the following: obtaining relief from negative thoughts or feelings, resolving interpersonal challenges, inducing positive feelings. It is associated with interpersonal difficulties or negative thoughts/feelings. The behavior causes significant impairment in functioning and is not better explained by another condition.1

Estimates of lifetime prevalence in community-based samples of youth range from 15% to 20%. Individuals often start during early adolescence. It can pose many risks including infection, permanent scarring or disfigurement, decreased self-esteem, interpersonal conflict, severe injury, or death. Reasons for engaging in self-harm can vary and include attempts to regulate negative affect, to manage feelings of emptiness/numbness, regain a sense of control over body, feelings, etc., or to provide a consequence for perceived faults. Youth often may start to engage in self-harm covertly, and it may first become apparent in emergency or primary care settings. However, upon discovery, the response given also may affect future behavior.

Efforts also have been underway to distinguish between youth who engage in self-harm with and without suicidal ideation. Girls are more likely than are boys to report NSSI, although male NSSI may present differently. In addition to cutting or more stereotypical self-injury, they may punch walls or engage in fights or other risky behaviors as a proxy for self-harm. Risk factors for boys with regard to suicide attempts include hopelessness and history of sexual abuse. Maladaptive eating patterns and hopelessness were the two most significant factors for girls.4

With regard to issues of confidentiality, it will be important to carefully gauge level of safety and to clearly communicate with the patient (and family) limits of confidentiality. This may result in working within shades of gray to help maintain the therapeutic relationship and the patient’s comfort in being able to disclose potentially sensitive information.

Families can struggle with how to manage this, and it can generate fear as well as other strong emotions.

Tips for parents and guardians

- Validate the underlying emotions while not validating the behavior. Self-injury is a coping strategy. Focus on the driving forces for the actions rather than the actions themselves.

- Approach your child from a nonjudgmental stance.

- Recognize that change may not happen overnight, and that there may be periods of regression.

- Acknowledge successes when they occur.

- Make yourself available for open communication. Open-ended questions may facilitate more dialogue.

- Take care of yourself as well. Ensure you use your supports and are engaging in healthy self-care.

- Take the behavior seriously. While this behavior is relatively common, do not assume it is “just a phase.”

- While remaining supportive, it is important to maintain a parental role and to keep expectations rather than “walking on eggshells.”

- Involve the child in identifying what can be of support.

- Become aware of local crisis resources in your community. National resources include Call 1-800-273-TALK for the national suicide hotline or Text 741741 to connect with a crisis counselor.

Things to avoid

- Avoid taking a punitive stance. While the behavior can be provocative, most likely the primary purpose is not for attention.

- Avoid engaging in power struggles.

- Avoid creating increased isolation for the child. This can be a delicate balance with regard to peer groups, but encouraging healthy social interactions and activities is a way to help build resilience.

- Avoid taking the behavior personally.5

In working with youth who engage in self-harm, it is important to work within a team, which may include family, primary care, mental health support, school, and potentially other community supports. Treatment evidence is relatively limited, but there is some evidence to support use of cognitive behavioral therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, and mentalization-based therapy. Regardless, work will likely be long term and at times intensive in addressing the problems leading to self-harm behavior.6

Dr. Strange is an assistant professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of Vermont Medical Center and University of Vermont Robert Larner College of Medicine, both in Burlington. She works with children and adolescents. She has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2013)

2. J Adolesc. 2014 Dec;37(8):1335-44.

3. Behav Ther. 2017 May; 48(3):366-79.

4. Acad Pediatr. 2012 May-Jun;12(3):205-13.

5. “Information for parents: What you need to know about self-injury.” The Fact Sheet Series, Cornell Research Program on Self-Injury and Recovery. 2009.

6. Clin Pediatr. 2016 Sep 13;55(11):1012-9.

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) has become more prevalent in youth over recent years and has many inherent risks. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), NSSI is a diagnosis suggested for further study, and criteria include engaging in self-injury for 5 or more days without suicidal intent as well as self-injury associated with at least 1 of the following: obtaining relief from negative thoughts or feelings, resolving interpersonal challenges, inducing positive feelings. It is associated with interpersonal difficulties or negative thoughts/feelings. The behavior causes significant impairment in functioning and is not better explained by another condition.1

Estimates of lifetime prevalence in community-based samples of youth range from 15% to 20%. Individuals often start during early adolescence. It can pose many risks including infection, permanent scarring or disfigurement, decreased self-esteem, interpersonal conflict, severe injury, or death. Reasons for engaging in self-harm can vary and include attempts to regulate negative affect, to manage feelings of emptiness/numbness, regain a sense of control over body, feelings, etc., or to provide a consequence for perceived faults. Youth often may start to engage in self-harm covertly, and it may first become apparent in emergency or primary care settings. However, upon discovery, the response given also may affect future behavior.

Efforts also have been underway to distinguish between youth who engage in self-harm with and without suicidal ideation. Girls are more likely than are boys to report NSSI, although male NSSI may present differently. In addition to cutting or more stereotypical self-injury, they may punch walls or engage in fights or other risky behaviors as a proxy for self-harm. Risk factors for boys with regard to suicide attempts include hopelessness and history of sexual abuse. Maladaptive eating patterns and hopelessness were the two most significant factors for girls.4

With regard to issues of confidentiality, it will be important to carefully gauge level of safety and to clearly communicate with the patient (and family) limits of confidentiality. This may result in working within shades of gray to help maintain the therapeutic relationship and the patient’s comfort in being able to disclose potentially sensitive information.

Families can struggle with how to manage this, and it can generate fear as well as other strong emotions.

Tips for parents and guardians

- Validate the underlying emotions while not validating the behavior. Self-injury is a coping strategy. Focus on the driving forces for the actions rather than the actions themselves.

- Approach your child from a nonjudgmental stance.

- Recognize that change may not happen overnight, and that there may be periods of regression.

- Acknowledge successes when they occur.

- Make yourself available for open communication. Open-ended questions may facilitate more dialogue.

- Take care of yourself as well. Ensure you use your supports and are engaging in healthy self-care.

- Take the behavior seriously. While this behavior is relatively common, do not assume it is “just a phase.”

- While remaining supportive, it is important to maintain a parental role and to keep expectations rather than “walking on eggshells.”

- Involve the child in identifying what can be of support.

- Become aware of local crisis resources in your community. National resources include Call 1-800-273-TALK for the national suicide hotline or Text 741741 to connect with a crisis counselor.

Things to avoid

- Avoid taking a punitive stance. While the behavior can be provocative, most likely the primary purpose is not for attention.

- Avoid engaging in power struggles.

- Avoid creating increased isolation for the child. This can be a delicate balance with regard to peer groups, but encouraging healthy social interactions and activities is a way to help build resilience.

- Avoid taking the behavior personally.5

In working with youth who engage in self-harm, it is important to work within a team, which may include family, primary care, mental health support, school, and potentially other community supports. Treatment evidence is relatively limited, but there is some evidence to support use of cognitive behavioral therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, and mentalization-based therapy. Regardless, work will likely be long term and at times intensive in addressing the problems leading to self-harm behavior.6

Dr. Strange is an assistant professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of Vermont Medical Center and University of Vermont Robert Larner College of Medicine, both in Burlington. She works with children and adolescents. She has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2013)

2. J Adolesc. 2014 Dec;37(8):1335-44.

3. Behav Ther. 2017 May; 48(3):366-79.

4. Acad Pediatr. 2012 May-Jun;12(3):205-13.

5. “Information for parents: What you need to know about self-injury.” The Fact Sheet Series, Cornell Research Program on Self-Injury and Recovery. 2009.

6. Clin Pediatr. 2016 Sep 13;55(11):1012-9.

Hints of altered microRNA expression in women exposed to EDCs

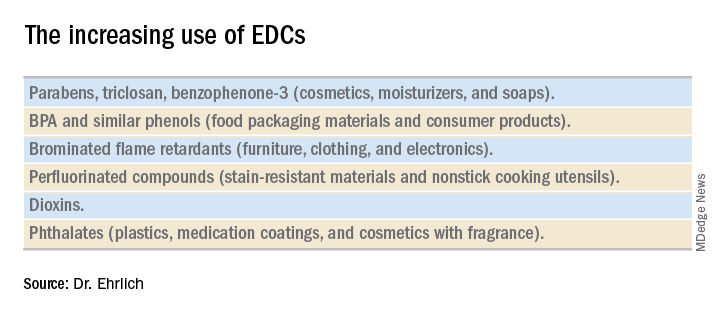

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are structurally similar to endogenous hormones and are therefore capable of mimicking these natural hormones, interfering with their biosynthesis, transport, binding action, and/or elimination. In animal studies and human clinical observational and epidemiologic studies of various EDCs, these chemicals have consistently been associated with diabetes mellitus, obesity, hormone-sensitive cancers, neurodevelopmental disorders in children exposed prenatally, and reproductive health.

In 2009, the Endocrine Society published a scientific statement in which it called EDCs a significant concern to human health (Endocr Rev. 2009;30[4]:293-342). Several years later, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine issued a Committee Opinion on Exposure to Toxic Environmental Agents, warning that patient exposure to EDCs and other toxic environmental agents can have a “profound and lasting effect” on reproductive health outcomes across the life course and calling the reduction of exposure a “critical area of intervention” for ob.gyns. and other reproductive health care professionals (Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122[4]:931-5).

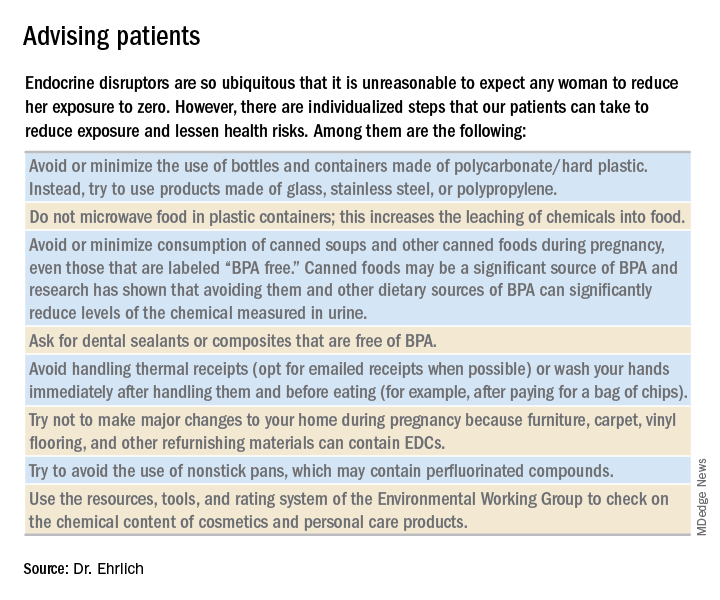

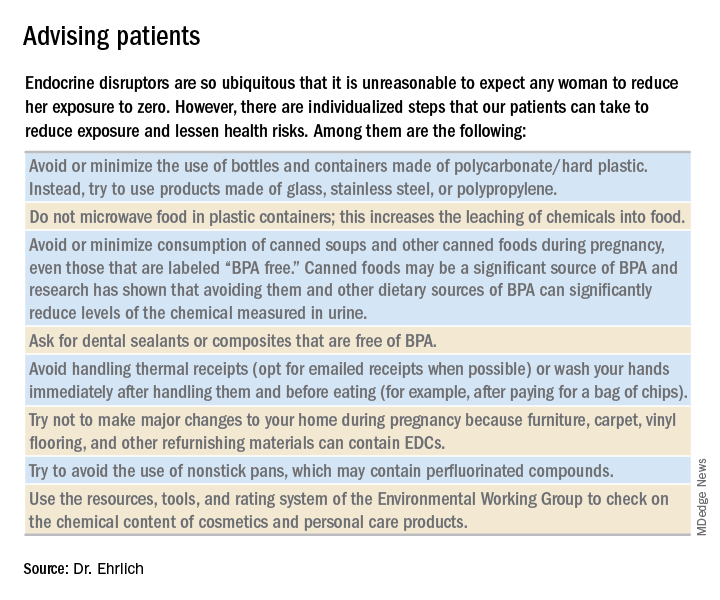

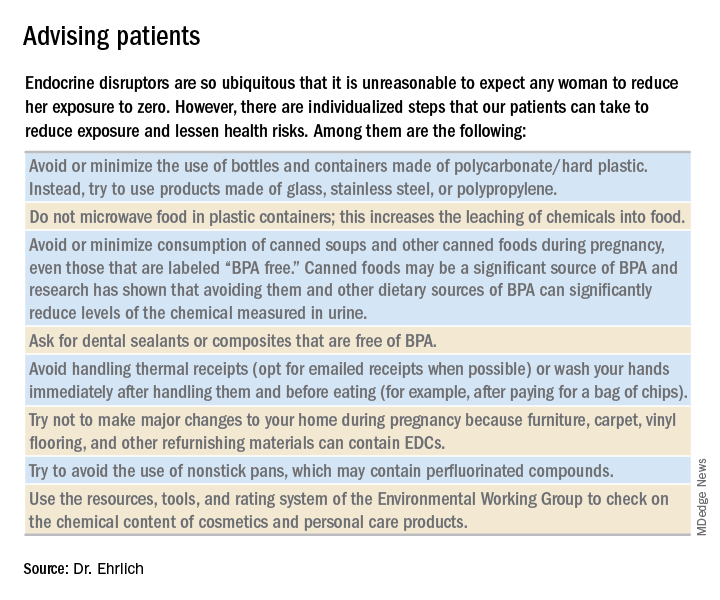

Despite strong calls by each of these organizations to not overlook EDCs in the clinical arena, as well as emerging evidence that EDCs may be a risk factor for gestational diabetes (GDM), EDC exposure may not be on the practicing ob.gyn.’s radar. Clinicians should know what these chemicals are and how to talk about them in preconception and prenatal visits. We should carefully consider their known – and potential – risks, and encourage our patients to identify and reduce exposure without being alarmist.

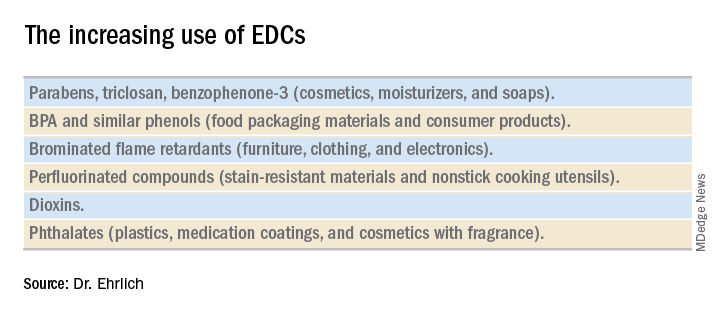

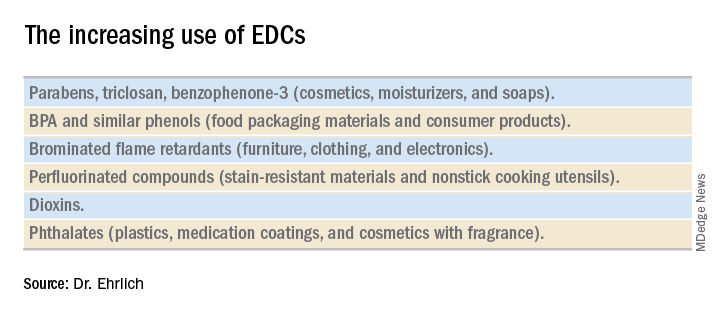

Low-dose effects

EDCs are used in the manufacture of pesticides, industrial chemicals, plastics and plasticizers, hand sanitizers, medical equipment, dental sealants, a variety of personal care products, cosmetics, and other common consumer and household products. They’re found, for example, in sunscreens, canned foods and beverages, food-packaging materials, baby bottles, flame-retardant furniture, stain-resistant carpet, and shoes. We are all ingesting and breathing them in to some degree.

Bisphenol A (BPA), one of the most extensively studied EDCs, is found in the thermal receipt paper routinely used by gas stations, supermarkets, and other stores. In a small study we conducted at Harvard, we found that urinary BPA concentrations increased after continual handling of receipts for 2 hours without gloves but did not increase significantly when gloves were used (JAMA. 2014 Feb 26;311[8]:859-60).

Informed consumers can then affect the market through their purchasing choices, but the removal of concerning chemicals from products takes a long time, and it’s not always immediately clear that replacement chemicals are safer. For instance, the BPA in “BPA-free” water bottles and canned foods has been replaced by bisphenol S (BPS), which has a very similar molecular structure to BPA. The potential adverse health effects of these replacement chemicals are now being examined in experimental and epidemiologic studies.

Through its National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported detection rates of between 75% and 99% for different EDCs in urine samples collected from a representative sample of the U.S. population. In other human research, several EDCs have been shown to cross the placenta and have been measured in maternal blood and urine and in cord blood and amniotic fluid, as well as in placental tissue at birth.

It is interesting to note that BPA’s structure is similar to that of diethylstilbestrol (DES). BPA was first shown to have estrogenic activity in 1936 and was originally considered for use in pharmaceuticals to prevent miscarriages, spontaneous abortions, and premature labor but was put aside in favor of DES. (DES was eventually found to be carcinogenic and was taken off the market.) In the 1950s, the use of BPA was resuscitated though not in pharmaceuticals.

A better understanding about the mechanisms of action and dose-response patterns of EDCs has indicated that EDCs can act at low doses, and in many cases a nonmonotonic dose-response association has been demonstrated. This is a paradigm shift for traditional toxicology in which it is “the dose that makes the poison,” and some toxicologists have been critical of the claims of low-dose potency for EDCs.

A team of epidemiologists, toxicologists, and other scientists, including myself, critically analyzed in vitro, animal, and epidemiologic studies as part of a National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences working group on BPA to determine the strength of the evidence for low-dose effects (doses lower than those tested in traditional toxicology assessments) of BPA. We found that consistent, reproducible, and often adverse low-dose effects have been demonstrated for BPA in cell lines, primary cells and tissues, laboratory animals, and human populations. We also concluded that EDCs can pose the greatest threats when exposure occurs during early development, organogenesis, and during critical postnatal periods when tissues are differentiating (Endocr Disruptors [Austin, Tex.]. 2013 Sep;1:e25078-1-13).

A potential risk factor for GDM

Quite a lot of research has been done on EDCs and the risk of type 2 diabetes. A recent meta-analysis that included 41 cross-sectional and 8 prospective studies found that serum concentrations of dioxins, polychlorinated biphenyls, and chlorinated pesticides – and urine concentrations of BPA and phthalates – were significantly associated with type 2 diabetes risk. Comparing the highest and lowest concentration categories, the pooled relative risk was 1.45 for BPA and phthalates. EDC concentrations also were associated with indicators of impaired fasting glucose and insulin resistance (J Diabetes. 2016 Jul;8[4]:516-32).

Despite the mounting evidence for an association between BPA and type 2 diabetes, and despite the fact that the increased incidence of GDM in the past 20 years has mirrored the increasing use of EDCs, there has been a dearth of research examining the possible relationship between EDCs and GDM. The effects of BPA on GDM were identified as a knowledge gap by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences after a review of the literature from 2007 to 2013 (Environ Health Perspect. 2014 Aug:122[8]:775-86).

To understand the association between EDCs and GDM and the underlying mechanistic pathway of EDCs, we are conducting research that uses a growing body of evidence that suggests that environmental toxins are involved in the control of microRNA (miRNA) expression in trophoblast cells.

MiRNA, a single-stranded, short, noncoding RNA that is involved in posttranslational gene expression, can be packaged along with other signaling molecules inside extracellular vesicles in the placenta called exosomes. These exosomes appear to be shed from the placenta into the maternal circulation as early as 6-7 weeks into pregnancy. Once released into the maternal circulation, research has shown that the exosomes can target and reprogram other cells via the transfer of noncoding miRNAs, thereby changing the gene expression in these cells.

Such an exosome-mediated signaling pathway provides us with the opportunity to isolate exosomes, sequence the miRNAs, and look at whether women who are exposed to higher levels of EDCs (as indicated in urine concentration) have a particular miRNA signature that correlates with GDM. In other words, we’re working to determine whether particular EDCs and exposure levels affect the miRNA placental profiles, and if these profiles are predictive of GDM.

Thus far, in a pilot prospective cohort study of pregnant women, we are seeing hints of altered miRNA expression in relation to GDM. We have selected study participants who are at high risk of developing GDM (for example, prepregnancy body mass index greater than 30, past pregnancy with GDM, or macrosomia) because we suspect that, in many women, EDCs are a tipping point for the development of GDM rather than a sole causative factor. In addition to understanding the impact of EDCs on GDM, it is our hope that miRNAs in maternal circulation will serve as a noninvasive biomarker for early detection of GDM development or susceptibility.

Dr. Ehrlich is an assistant professor of pediatrics and environmental health at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are structurally similar to endogenous hormones and are therefore capable of mimicking these natural hormones, interfering with their biosynthesis, transport, binding action, and/or elimination. In animal studies and human clinical observational and epidemiologic studies of various EDCs, these chemicals have consistently been associated with diabetes mellitus, obesity, hormone-sensitive cancers, neurodevelopmental disorders in children exposed prenatally, and reproductive health.

In 2009, the Endocrine Society published a scientific statement in which it called EDCs a significant concern to human health (Endocr Rev. 2009;30[4]:293-342). Several years later, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine issued a Committee Opinion on Exposure to Toxic Environmental Agents, warning that patient exposure to EDCs and other toxic environmental agents can have a “profound and lasting effect” on reproductive health outcomes across the life course and calling the reduction of exposure a “critical area of intervention” for ob.gyns. and other reproductive health care professionals (Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122[4]:931-5).

Despite strong calls by each of these organizations to not overlook EDCs in the clinical arena, as well as emerging evidence that EDCs may be a risk factor for gestational diabetes (GDM), EDC exposure may not be on the practicing ob.gyn.’s radar. Clinicians should know what these chemicals are and how to talk about them in preconception and prenatal visits. We should carefully consider their known – and potential – risks, and encourage our patients to identify and reduce exposure without being alarmist.

Low-dose effects

EDCs are used in the manufacture of pesticides, industrial chemicals, plastics and plasticizers, hand sanitizers, medical equipment, dental sealants, a variety of personal care products, cosmetics, and other common consumer and household products. They’re found, for example, in sunscreens, canned foods and beverages, food-packaging materials, baby bottles, flame-retardant furniture, stain-resistant carpet, and shoes. We are all ingesting and breathing them in to some degree.

Bisphenol A (BPA), one of the most extensively studied EDCs, is found in the thermal receipt paper routinely used by gas stations, supermarkets, and other stores. In a small study we conducted at Harvard, we found that urinary BPA concentrations increased after continual handling of receipts for 2 hours without gloves but did not increase significantly when gloves were used (JAMA. 2014 Feb 26;311[8]:859-60).

Informed consumers can then affect the market through their purchasing choices, but the removal of concerning chemicals from products takes a long time, and it’s not always immediately clear that replacement chemicals are safer. For instance, the BPA in “BPA-free” water bottles and canned foods has been replaced by bisphenol S (BPS), which has a very similar molecular structure to BPA. The potential adverse health effects of these replacement chemicals are now being examined in experimental and epidemiologic studies.

Through its National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported detection rates of between 75% and 99% for different EDCs in urine samples collected from a representative sample of the U.S. population. In other human research, several EDCs have been shown to cross the placenta and have been measured in maternal blood and urine and in cord blood and amniotic fluid, as well as in placental tissue at birth.

It is interesting to note that BPA’s structure is similar to that of diethylstilbestrol (DES). BPA was first shown to have estrogenic activity in 1936 and was originally considered for use in pharmaceuticals to prevent miscarriages, spontaneous abortions, and premature labor but was put aside in favor of DES. (DES was eventually found to be carcinogenic and was taken off the market.) In the 1950s, the use of BPA was resuscitated though not in pharmaceuticals.

A better understanding about the mechanisms of action and dose-response patterns of EDCs has indicated that EDCs can act at low doses, and in many cases a nonmonotonic dose-response association has been demonstrated. This is a paradigm shift for traditional toxicology in which it is “the dose that makes the poison,” and some toxicologists have been critical of the claims of low-dose potency for EDCs.

A team of epidemiologists, toxicologists, and other scientists, including myself, critically analyzed in vitro, animal, and epidemiologic studies as part of a National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences working group on BPA to determine the strength of the evidence for low-dose effects (doses lower than those tested in traditional toxicology assessments) of BPA. We found that consistent, reproducible, and often adverse low-dose effects have been demonstrated for BPA in cell lines, primary cells and tissues, laboratory animals, and human populations. We also concluded that EDCs can pose the greatest threats when exposure occurs during early development, organogenesis, and during critical postnatal periods when tissues are differentiating (Endocr Disruptors [Austin, Tex.]. 2013 Sep;1:e25078-1-13).

A potential risk factor for GDM

Quite a lot of research has been done on EDCs and the risk of type 2 diabetes. A recent meta-analysis that included 41 cross-sectional and 8 prospective studies found that serum concentrations of dioxins, polychlorinated biphenyls, and chlorinated pesticides – and urine concentrations of BPA and phthalates – were significantly associated with type 2 diabetes risk. Comparing the highest and lowest concentration categories, the pooled relative risk was 1.45 for BPA and phthalates. EDC concentrations also were associated with indicators of impaired fasting glucose and insulin resistance (J Diabetes. 2016 Jul;8[4]:516-32).

Despite the mounting evidence for an association between BPA and type 2 diabetes, and despite the fact that the increased incidence of GDM in the past 20 years has mirrored the increasing use of EDCs, there has been a dearth of research examining the possible relationship between EDCs and GDM. The effects of BPA on GDM were identified as a knowledge gap by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences after a review of the literature from 2007 to 2013 (Environ Health Perspect. 2014 Aug:122[8]:775-86).

To understand the association between EDCs and GDM and the underlying mechanistic pathway of EDCs, we are conducting research that uses a growing body of evidence that suggests that environmental toxins are involved in the control of microRNA (miRNA) expression in trophoblast cells.