User login

High-Value, Cost-Conscious Evaluation for PCOS: Which Tests Should Be Routinely Ordered in Acne Patients?

The adult female patient presenting with severe acne vulgaris may raise special diagnostic concerns, including consideration of an underlying hormonal disorder. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrine disorder in women of reproductive age with an estimated prevalence as high as 12%.1 Many women with undiagnosed PCOS may be referred to dermatologists for evaluation of its cutaneous manifestations of hyperandrogenism including acne, hirsutism, and androgenic alopecia.2 Given the prevalence of PCOS and its long-term health implications, dermatologists can play an important role in the initial evaluation of these patients. Acne and androgenic alopecia, however, are quite common, and in the absence of red flags such as menstrual irregularities, virilization, visual field deficits, or signs of Cushing syndrome,3 clinicians must decide when to pursue limited versus comprehensive evaluation.

Despite being common in patients with PCOS, a recent study suggests that acne is an unreliable marker of biochemical hyperandrogenism, and specific features of acne (ie, lesion counts, lesional types, distribution) cannot reliably discriminate women who meet PCOS diagnostic criteria from those who do not.4 Similarly, the study found that androgenic alopecia was not associated with biochemical hyperandrogenism and was no more common in women with PCOS than women of similar age in a high-risk population. Unlike acne and androgenic alopecia, however, the study identified hirsutism, especially truncal hirsutism, as a reliable indicator of hyperandrogenemia and PCOS. Hirsutism also is associated with metabolic sequelae of PCOS. These findings suggest that hirsutism, but not acne or androgenic alopecia, in a female of reproductive age warrants a workup for PCOS.4 This report is consistent with a recommendation from the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society (AE-PCOS) to pursue a diagnostic evaluation in any woman presenting with hirsutism.5 Acanthosis nigricans also was found to be a reliable indicator of hyperandrogenemia, PCOS, and associated metabolic derangement. Thus, although recent evidence indicates that acne as an isolated cutaneous finding does not warrant further diagnostic evaluation, acne in the setting of hirsutism, acanthosis nigricans, menstrual irregularities, or additional specific signs of endocrine dysregulation should prompt focused workup.4

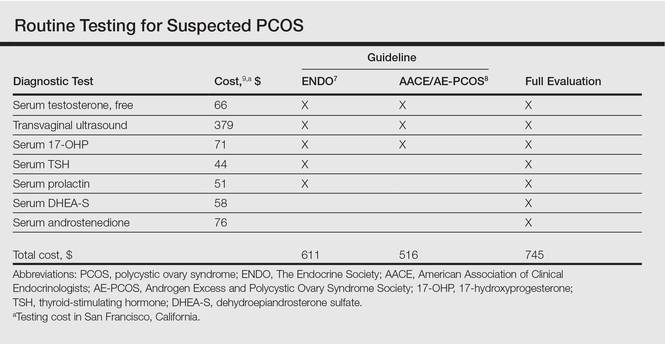

Multiple clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation of hirsutism and PCOS based on literature review and expert opinion have been proposed5-8; however, these guidelines vary in recommendations for routine diagnostic steps to exclude mimickers of PCOS such as prolactinoma/pituitary adenoma and congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH)(Table). In 2009, an AE-PCOS task force suggested that routine testing of thyroid function and serum prolactin in the absence of additional clinical signs may not be necessary based on the low prevalence of thyroid disorders and hyperprolactinemia in patients presenting with hyperandrogenism.6 In 2013, the Endocrine Society’s (ENDO) clinical guideline, however, recommended routine measurement of serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) to exclude thyroid disease and serum prolactin to exclude hyperprolactinemia in all women before making a diagnosis of PCOS.7 In 2015, the AE-PCOS collaborated with the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and American College of Endocrinology to publish an updated guideline for best practices, which was consistent with the prior AE-PCOS recommendation in 2009 for routine screening including to test 17-hydroxyprogesterone to exclude nonclassical CAH.8

Importantly, these recommendations for routine testing for mimickers of PCOS are based on the rare prevalence of these etiologies in multiple studies of women presenting for hyperandrogenism. One study included 873 women presenting to an academic reproductive endocrine clinic for evaluation of symptoms potentially related to androgen excess. In addition to cutaneous manifestations of hirsutism, acne, and alopecia, the study also included women presenting with oligomenorrhea/amenorrhea, ovulatory dysfunction, and even virilization.10 A second study included 950 women presenting to academic endocrine departments with hirsutism, acne, or androgenic alopecia.11 Both studies defined hirsutism as having a modified Ferriman-Gallwey score of 6 or greater. Both studies also only measured serum prolactin or TSH when clinically indicated (ie, patients with ovulatory dysfunction).10,11

The diagnostic yield of tests for mimickers of PCOS was exceedingly low in both studies. For example, of the patients evaluated, only 0.4% to 0.7% had thyroid dysfunction, 0% to 0.3% had hyperprolactinemia, 0.2% had androgen-secreting neoplasms, 2.1% to 4.3% had nonclassical CAH, 0.7% had CAH, and 3.8% had HAIR-AN (hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, and acanthosis nigricans) syndrome.10,11 Because patients in both studies were only tested for hyperprolactinemia and thyroid dysfunction when clinically indicated, it is probable that routine screening without clinical indication would result in even lower yields.

Given the increasing importance of high-value, cost-conscious care,12 clinicians must consider the costs associated with testing in the face of low pretest probability. Although some studies have examined the cost-effectiveness of fertility treatments in PCOS,13,14 no studies have examined the cost-effectiveness of diagnostic strategies for PCOS. Cost-effectiveness studies are emerging to provide important guidance on high-value, cost-conscious diagnostic evaluation and monitoring15 and are much needed in dermatology.16,17

In the case of PCOS, the costs of some diagnostic tests are relatively low. For example, based on estimates from Healthcare Bluebook,9 serum TSH and prolactin tests in San Francisco, California, are $44 and $51, respectively. However, the cumulative costs for even the most stringent routine workup for PCOS recommended in the AACE/AE-PCOS guideline consisting of a free testosterone measurement, 17-hydroxyprogesterone, and transvaginal ultrasound would still cost a total of $516. Additional TSH and prolactin tests recommended by ENDO would increase the cost of PCOS testing by approximately 18%. Routine testing for additional serum androgens—dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) and androstenedione—would further increase this amount by an additional $134 to a total cost of $745. The ENDO guideline only recommends DHEA-S testing to assist in the diagnosis of an androgen-secreting tumor when signs of virilization are present, while the AACE/AE-PCOS guideline discourages routine testing for DHEA-S and androstenedione based on the low frequency of cases in which these androgens are elevated in isolation.7,8

Although the selection of tests influences total cost, the setting of tests (ie, hospitals, physician offices, independent test settings) also can contribute to wide variations in cost. For example, Healthcare Bluebook’s estimates for transvaginal ultrasound in Chicago, Illinois, range from $236 to more than $740.9 When the separate physician visit fees are included, the total cost of a routine diagnostic evaluation of a patient with acne or hirsutism concerning for PCOS is not trivial.

Large national clinical registries and formal cost-effectiveness analyses are necessary to shed light on this issue, but it is clear that clinicians should rely on their clinical judgment when ordering laboratory tests in the evaluation for PCOS given the apparent low yield of routine screening for PCOS mimickers in the absence of clinical indications. For example, a TSH would not be warranted in a patient without evidence of thyroid dysfunction (ie, weight gain, fatigue, constipation, menstrual irregularities). Similarly, clinicians should routinely consider the principle of high-value care: whether the results of a test will change management of the patient. For example, a woman with amenorrhea and severe acne who already meets diagnostic criteria for PCOS would benefit from a combined oral contraceptive for both acne and endometrial protection. An ovarian ultrasound may not be needed to confirm the diagnosis unless there is suspicion for an ovarian condition other than PCOS causing the symptoms.

Finally, clinicians should discuss testing options and involve patients in decisions around testing. Although PCOS treatments generally target individual symptoms rather than the syndrome as a whole, confirmation of a PCOS diagnosis importantly informs women of their risk for cardiovascular and metabolic disease. The ENDO recommends screening for impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity, family history of early cardiovascular disease, tobacco use, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obstructive sleep apnea in all women with PCOS, including nonobese patients.7 Ongoing efforts to gain and understand evidence to support high-value, cost-conscious care should be prioritized and kept in balance with shared decision-making in individual patients suspected of having PCOS.

- March WA, Moore VM, Willson KJ, et al. The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in a community sample assessed under contrasting diagnostic criteria. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:544-551.

- Sivayoganathan D, Maruthini D, Glanville JM, et al. Full investigation of patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) presenting to four different clinical specialties reveals significant differences and undiagnosed morbidity. Hum Fertil. 2011;14:261-265.

- Schmidt TH, Shinkai K. Evidence-based approach to cutaneous hyperandrogenism in women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:672-690.

- Schmidt TH, Khanijow K, Cedars MI, et al. Cutaneous findings and systemic associations in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;152:391-398.

- Escobar-Morreale HF, Carmina E, Dewailly D, et al. Epidemiology, diagnosis and management of hirsutism: a consensus statement by the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society. Hum Reprod Update. 2012;18:146-170.

- Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D, et al. The Androgen Excess and PCOS Society criteria for the polycystic ovary syndrome: the complete task force report. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:456-488.

- Legro RS, Arslanian SA, Ehermann DA, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline [published online October 22, 2013]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:4565-4592.

- Goodman NF, Cobin RH, Futterweit W, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology, and Androgen Excess and PCOS Society disease state clinical review: guide to the best practices in the evaluation and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome—part 1. Endocr Pract. 2015;21:1291-1300.

- Healthcare Bluebook. https://healthcarebluebook.com. Accessed June 13, 2016.

- Azziz R, Sanchez LA, Knochenhauer ES, et al. Androgen excess in women: experience with over 1000 consecutive patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:453-462.

- Carmina E, Rosato F, Jannì A, et al. Relative prevalence of different androgen excess disorders in 950 women referred because of clinical hyperandrogenism [published online November 1, 2005]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2-6.

- Owens DK, Qaseem A, Chou R, et al. High-value, cost-conscious health care: concepts for clinicians to evaluate the benefits, harms, and costs of medical interventions. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:174-180.

- Nahuis MJ, Oude Lohuis E, Kose N, et al. Long-term follow-up of laparoscopic electrocautery of the ovaries versus ovulation induction with recombinant FSH in clomiphene citrate-resistant women with polycystic ovary syndrome: an economic evaluation. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2012;27:3577-3582.

- Moolenaar LM, Nahuis MJ, Hompes PG, et al. Cost-effectiveness of treatment strategies in women with PCOS who do not conceive after six cycles of clomiphene citrate. Reprod Biomed Online. 2014;28:606-613.

- Chogle A, Saps M. Yield and cost of performing screening tests for constipation in children. Can J Gastroenterol. 2013;27:E35-E38.

- Lee YH, Scharnitz TP, Muscat J, et al. Laboratory monitoring during isotretinoin therapy for acne: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:35-44.

- Shinkai K, McMichael A, Linos E. Isotretinoin laboratory test monitoring—a call to decrease testing in an era of high-value, cost-conscious care. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:17-19.

The adult female patient presenting with severe acne vulgaris may raise special diagnostic concerns, including consideration of an underlying hormonal disorder. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrine disorder in women of reproductive age with an estimated prevalence as high as 12%.1 Many women with undiagnosed PCOS may be referred to dermatologists for evaluation of its cutaneous manifestations of hyperandrogenism including acne, hirsutism, and androgenic alopecia.2 Given the prevalence of PCOS and its long-term health implications, dermatologists can play an important role in the initial evaluation of these patients. Acne and androgenic alopecia, however, are quite common, and in the absence of red flags such as menstrual irregularities, virilization, visual field deficits, or signs of Cushing syndrome,3 clinicians must decide when to pursue limited versus comprehensive evaluation.

Despite being common in patients with PCOS, a recent study suggests that acne is an unreliable marker of biochemical hyperandrogenism, and specific features of acne (ie, lesion counts, lesional types, distribution) cannot reliably discriminate women who meet PCOS diagnostic criteria from those who do not.4 Similarly, the study found that androgenic alopecia was not associated with biochemical hyperandrogenism and was no more common in women with PCOS than women of similar age in a high-risk population. Unlike acne and androgenic alopecia, however, the study identified hirsutism, especially truncal hirsutism, as a reliable indicator of hyperandrogenemia and PCOS. Hirsutism also is associated with metabolic sequelae of PCOS. These findings suggest that hirsutism, but not acne or androgenic alopecia, in a female of reproductive age warrants a workup for PCOS.4 This report is consistent with a recommendation from the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society (AE-PCOS) to pursue a diagnostic evaluation in any woman presenting with hirsutism.5 Acanthosis nigricans also was found to be a reliable indicator of hyperandrogenemia, PCOS, and associated metabolic derangement. Thus, although recent evidence indicates that acne as an isolated cutaneous finding does not warrant further diagnostic evaluation, acne in the setting of hirsutism, acanthosis nigricans, menstrual irregularities, or additional specific signs of endocrine dysregulation should prompt focused workup.4

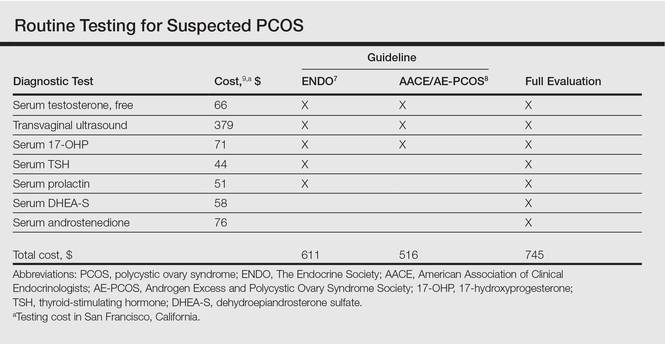

Multiple clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation of hirsutism and PCOS based on literature review and expert opinion have been proposed5-8; however, these guidelines vary in recommendations for routine diagnostic steps to exclude mimickers of PCOS such as prolactinoma/pituitary adenoma and congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH)(Table). In 2009, an AE-PCOS task force suggested that routine testing of thyroid function and serum prolactin in the absence of additional clinical signs may not be necessary based on the low prevalence of thyroid disorders and hyperprolactinemia in patients presenting with hyperandrogenism.6 In 2013, the Endocrine Society’s (ENDO) clinical guideline, however, recommended routine measurement of serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) to exclude thyroid disease and serum prolactin to exclude hyperprolactinemia in all women before making a diagnosis of PCOS.7 In 2015, the AE-PCOS collaborated with the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and American College of Endocrinology to publish an updated guideline for best practices, which was consistent with the prior AE-PCOS recommendation in 2009 for routine screening including to test 17-hydroxyprogesterone to exclude nonclassical CAH.8

Importantly, these recommendations for routine testing for mimickers of PCOS are based on the rare prevalence of these etiologies in multiple studies of women presenting for hyperandrogenism. One study included 873 women presenting to an academic reproductive endocrine clinic for evaluation of symptoms potentially related to androgen excess. In addition to cutaneous manifestations of hirsutism, acne, and alopecia, the study also included women presenting with oligomenorrhea/amenorrhea, ovulatory dysfunction, and even virilization.10 A second study included 950 women presenting to academic endocrine departments with hirsutism, acne, or androgenic alopecia.11 Both studies defined hirsutism as having a modified Ferriman-Gallwey score of 6 or greater. Both studies also only measured serum prolactin or TSH when clinically indicated (ie, patients with ovulatory dysfunction).10,11

The diagnostic yield of tests for mimickers of PCOS was exceedingly low in both studies. For example, of the patients evaluated, only 0.4% to 0.7% had thyroid dysfunction, 0% to 0.3% had hyperprolactinemia, 0.2% had androgen-secreting neoplasms, 2.1% to 4.3% had nonclassical CAH, 0.7% had CAH, and 3.8% had HAIR-AN (hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, and acanthosis nigricans) syndrome.10,11 Because patients in both studies were only tested for hyperprolactinemia and thyroid dysfunction when clinically indicated, it is probable that routine screening without clinical indication would result in even lower yields.

Given the increasing importance of high-value, cost-conscious care,12 clinicians must consider the costs associated with testing in the face of low pretest probability. Although some studies have examined the cost-effectiveness of fertility treatments in PCOS,13,14 no studies have examined the cost-effectiveness of diagnostic strategies for PCOS. Cost-effectiveness studies are emerging to provide important guidance on high-value, cost-conscious diagnostic evaluation and monitoring15 and are much needed in dermatology.16,17

In the case of PCOS, the costs of some diagnostic tests are relatively low. For example, based on estimates from Healthcare Bluebook,9 serum TSH and prolactin tests in San Francisco, California, are $44 and $51, respectively. However, the cumulative costs for even the most stringent routine workup for PCOS recommended in the AACE/AE-PCOS guideline consisting of a free testosterone measurement, 17-hydroxyprogesterone, and transvaginal ultrasound would still cost a total of $516. Additional TSH and prolactin tests recommended by ENDO would increase the cost of PCOS testing by approximately 18%. Routine testing for additional serum androgens—dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) and androstenedione—would further increase this amount by an additional $134 to a total cost of $745. The ENDO guideline only recommends DHEA-S testing to assist in the diagnosis of an androgen-secreting tumor when signs of virilization are present, while the AACE/AE-PCOS guideline discourages routine testing for DHEA-S and androstenedione based on the low frequency of cases in which these androgens are elevated in isolation.7,8

Although the selection of tests influences total cost, the setting of tests (ie, hospitals, physician offices, independent test settings) also can contribute to wide variations in cost. For example, Healthcare Bluebook’s estimates for transvaginal ultrasound in Chicago, Illinois, range from $236 to more than $740.9 When the separate physician visit fees are included, the total cost of a routine diagnostic evaluation of a patient with acne or hirsutism concerning for PCOS is not trivial.

Large national clinical registries and formal cost-effectiveness analyses are necessary to shed light on this issue, but it is clear that clinicians should rely on their clinical judgment when ordering laboratory tests in the evaluation for PCOS given the apparent low yield of routine screening for PCOS mimickers in the absence of clinical indications. For example, a TSH would not be warranted in a patient without evidence of thyroid dysfunction (ie, weight gain, fatigue, constipation, menstrual irregularities). Similarly, clinicians should routinely consider the principle of high-value care: whether the results of a test will change management of the patient. For example, a woman with amenorrhea and severe acne who already meets diagnostic criteria for PCOS would benefit from a combined oral contraceptive for both acne and endometrial protection. An ovarian ultrasound may not be needed to confirm the diagnosis unless there is suspicion for an ovarian condition other than PCOS causing the symptoms.

Finally, clinicians should discuss testing options and involve patients in decisions around testing. Although PCOS treatments generally target individual symptoms rather than the syndrome as a whole, confirmation of a PCOS diagnosis importantly informs women of their risk for cardiovascular and metabolic disease. The ENDO recommends screening for impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity, family history of early cardiovascular disease, tobacco use, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obstructive sleep apnea in all women with PCOS, including nonobese patients.7 Ongoing efforts to gain and understand evidence to support high-value, cost-conscious care should be prioritized and kept in balance with shared decision-making in individual patients suspected of having PCOS.

The adult female patient presenting with severe acne vulgaris may raise special diagnostic concerns, including consideration of an underlying hormonal disorder. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrine disorder in women of reproductive age with an estimated prevalence as high as 12%.1 Many women with undiagnosed PCOS may be referred to dermatologists for evaluation of its cutaneous manifestations of hyperandrogenism including acne, hirsutism, and androgenic alopecia.2 Given the prevalence of PCOS and its long-term health implications, dermatologists can play an important role in the initial evaluation of these patients. Acne and androgenic alopecia, however, are quite common, and in the absence of red flags such as menstrual irregularities, virilization, visual field deficits, or signs of Cushing syndrome,3 clinicians must decide when to pursue limited versus comprehensive evaluation.

Despite being common in patients with PCOS, a recent study suggests that acne is an unreliable marker of biochemical hyperandrogenism, and specific features of acne (ie, lesion counts, lesional types, distribution) cannot reliably discriminate women who meet PCOS diagnostic criteria from those who do not.4 Similarly, the study found that androgenic alopecia was not associated with biochemical hyperandrogenism and was no more common in women with PCOS than women of similar age in a high-risk population. Unlike acne and androgenic alopecia, however, the study identified hirsutism, especially truncal hirsutism, as a reliable indicator of hyperandrogenemia and PCOS. Hirsutism also is associated with metabolic sequelae of PCOS. These findings suggest that hirsutism, but not acne or androgenic alopecia, in a female of reproductive age warrants a workup for PCOS.4 This report is consistent with a recommendation from the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society (AE-PCOS) to pursue a diagnostic evaluation in any woman presenting with hirsutism.5 Acanthosis nigricans also was found to be a reliable indicator of hyperandrogenemia, PCOS, and associated metabolic derangement. Thus, although recent evidence indicates that acne as an isolated cutaneous finding does not warrant further diagnostic evaluation, acne in the setting of hirsutism, acanthosis nigricans, menstrual irregularities, or additional specific signs of endocrine dysregulation should prompt focused workup.4

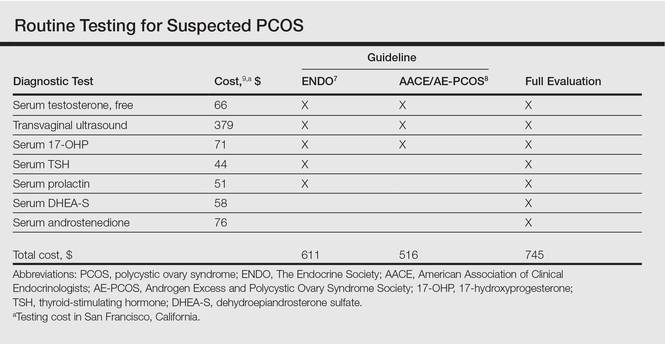

Multiple clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation of hirsutism and PCOS based on literature review and expert opinion have been proposed5-8; however, these guidelines vary in recommendations for routine diagnostic steps to exclude mimickers of PCOS such as prolactinoma/pituitary adenoma and congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH)(Table). In 2009, an AE-PCOS task force suggested that routine testing of thyroid function and serum prolactin in the absence of additional clinical signs may not be necessary based on the low prevalence of thyroid disorders and hyperprolactinemia in patients presenting with hyperandrogenism.6 In 2013, the Endocrine Society’s (ENDO) clinical guideline, however, recommended routine measurement of serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) to exclude thyroid disease and serum prolactin to exclude hyperprolactinemia in all women before making a diagnosis of PCOS.7 In 2015, the AE-PCOS collaborated with the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and American College of Endocrinology to publish an updated guideline for best practices, which was consistent with the prior AE-PCOS recommendation in 2009 for routine screening including to test 17-hydroxyprogesterone to exclude nonclassical CAH.8

Importantly, these recommendations for routine testing for mimickers of PCOS are based on the rare prevalence of these etiologies in multiple studies of women presenting for hyperandrogenism. One study included 873 women presenting to an academic reproductive endocrine clinic for evaluation of symptoms potentially related to androgen excess. In addition to cutaneous manifestations of hirsutism, acne, and alopecia, the study also included women presenting with oligomenorrhea/amenorrhea, ovulatory dysfunction, and even virilization.10 A second study included 950 women presenting to academic endocrine departments with hirsutism, acne, or androgenic alopecia.11 Both studies defined hirsutism as having a modified Ferriman-Gallwey score of 6 or greater. Both studies also only measured serum prolactin or TSH when clinically indicated (ie, patients with ovulatory dysfunction).10,11

The diagnostic yield of tests for mimickers of PCOS was exceedingly low in both studies. For example, of the patients evaluated, only 0.4% to 0.7% had thyroid dysfunction, 0% to 0.3% had hyperprolactinemia, 0.2% had androgen-secreting neoplasms, 2.1% to 4.3% had nonclassical CAH, 0.7% had CAH, and 3.8% had HAIR-AN (hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, and acanthosis nigricans) syndrome.10,11 Because patients in both studies were only tested for hyperprolactinemia and thyroid dysfunction when clinically indicated, it is probable that routine screening without clinical indication would result in even lower yields.

Given the increasing importance of high-value, cost-conscious care,12 clinicians must consider the costs associated with testing in the face of low pretest probability. Although some studies have examined the cost-effectiveness of fertility treatments in PCOS,13,14 no studies have examined the cost-effectiveness of diagnostic strategies for PCOS. Cost-effectiveness studies are emerging to provide important guidance on high-value, cost-conscious diagnostic evaluation and monitoring15 and are much needed in dermatology.16,17

In the case of PCOS, the costs of some diagnostic tests are relatively low. For example, based on estimates from Healthcare Bluebook,9 serum TSH and prolactin tests in San Francisco, California, are $44 and $51, respectively. However, the cumulative costs for even the most stringent routine workup for PCOS recommended in the AACE/AE-PCOS guideline consisting of a free testosterone measurement, 17-hydroxyprogesterone, and transvaginal ultrasound would still cost a total of $516. Additional TSH and prolactin tests recommended by ENDO would increase the cost of PCOS testing by approximately 18%. Routine testing for additional serum androgens—dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) and androstenedione—would further increase this amount by an additional $134 to a total cost of $745. The ENDO guideline only recommends DHEA-S testing to assist in the diagnosis of an androgen-secreting tumor when signs of virilization are present, while the AACE/AE-PCOS guideline discourages routine testing for DHEA-S and androstenedione based on the low frequency of cases in which these androgens are elevated in isolation.7,8

Although the selection of tests influences total cost, the setting of tests (ie, hospitals, physician offices, independent test settings) also can contribute to wide variations in cost. For example, Healthcare Bluebook’s estimates for transvaginal ultrasound in Chicago, Illinois, range from $236 to more than $740.9 When the separate physician visit fees are included, the total cost of a routine diagnostic evaluation of a patient with acne or hirsutism concerning for PCOS is not trivial.

Large national clinical registries and formal cost-effectiveness analyses are necessary to shed light on this issue, but it is clear that clinicians should rely on their clinical judgment when ordering laboratory tests in the evaluation for PCOS given the apparent low yield of routine screening for PCOS mimickers in the absence of clinical indications. For example, a TSH would not be warranted in a patient without evidence of thyroid dysfunction (ie, weight gain, fatigue, constipation, menstrual irregularities). Similarly, clinicians should routinely consider the principle of high-value care: whether the results of a test will change management of the patient. For example, a woman with amenorrhea and severe acne who already meets diagnostic criteria for PCOS would benefit from a combined oral contraceptive for both acne and endometrial protection. An ovarian ultrasound may not be needed to confirm the diagnosis unless there is suspicion for an ovarian condition other than PCOS causing the symptoms.

Finally, clinicians should discuss testing options and involve patients in decisions around testing. Although PCOS treatments generally target individual symptoms rather than the syndrome as a whole, confirmation of a PCOS diagnosis importantly informs women of their risk for cardiovascular and metabolic disease. The ENDO recommends screening for impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity, family history of early cardiovascular disease, tobacco use, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obstructive sleep apnea in all women with PCOS, including nonobese patients.7 Ongoing efforts to gain and understand evidence to support high-value, cost-conscious care should be prioritized and kept in balance with shared decision-making in individual patients suspected of having PCOS.

- March WA, Moore VM, Willson KJ, et al. The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in a community sample assessed under contrasting diagnostic criteria. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:544-551.

- Sivayoganathan D, Maruthini D, Glanville JM, et al. Full investigation of patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) presenting to four different clinical specialties reveals significant differences and undiagnosed morbidity. Hum Fertil. 2011;14:261-265.

- Schmidt TH, Shinkai K. Evidence-based approach to cutaneous hyperandrogenism in women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:672-690.

- Schmidt TH, Khanijow K, Cedars MI, et al. Cutaneous findings and systemic associations in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;152:391-398.

- Escobar-Morreale HF, Carmina E, Dewailly D, et al. Epidemiology, diagnosis and management of hirsutism: a consensus statement by the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society. Hum Reprod Update. 2012;18:146-170.

- Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D, et al. The Androgen Excess and PCOS Society criteria for the polycystic ovary syndrome: the complete task force report. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:456-488.

- Legro RS, Arslanian SA, Ehermann DA, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline [published online October 22, 2013]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:4565-4592.

- Goodman NF, Cobin RH, Futterweit W, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology, and Androgen Excess and PCOS Society disease state clinical review: guide to the best practices in the evaluation and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome—part 1. Endocr Pract. 2015;21:1291-1300.

- Healthcare Bluebook. https://healthcarebluebook.com. Accessed June 13, 2016.

- Azziz R, Sanchez LA, Knochenhauer ES, et al. Androgen excess in women: experience with over 1000 consecutive patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:453-462.

- Carmina E, Rosato F, Jannì A, et al. Relative prevalence of different androgen excess disorders in 950 women referred because of clinical hyperandrogenism [published online November 1, 2005]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2-6.

- Owens DK, Qaseem A, Chou R, et al. High-value, cost-conscious health care: concepts for clinicians to evaluate the benefits, harms, and costs of medical interventions. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:174-180.

- Nahuis MJ, Oude Lohuis E, Kose N, et al. Long-term follow-up of laparoscopic electrocautery of the ovaries versus ovulation induction with recombinant FSH in clomiphene citrate-resistant women with polycystic ovary syndrome: an economic evaluation. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2012;27:3577-3582.

- Moolenaar LM, Nahuis MJ, Hompes PG, et al. Cost-effectiveness of treatment strategies in women with PCOS who do not conceive after six cycles of clomiphene citrate. Reprod Biomed Online. 2014;28:606-613.

- Chogle A, Saps M. Yield and cost of performing screening tests for constipation in children. Can J Gastroenterol. 2013;27:E35-E38.

- Lee YH, Scharnitz TP, Muscat J, et al. Laboratory monitoring during isotretinoin therapy for acne: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:35-44.

- Shinkai K, McMichael A, Linos E. Isotretinoin laboratory test monitoring—a call to decrease testing in an era of high-value, cost-conscious care. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:17-19.

- March WA, Moore VM, Willson KJ, et al. The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in a community sample assessed under contrasting diagnostic criteria. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:544-551.

- Sivayoganathan D, Maruthini D, Glanville JM, et al. Full investigation of patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) presenting to four different clinical specialties reveals significant differences and undiagnosed morbidity. Hum Fertil. 2011;14:261-265.

- Schmidt TH, Shinkai K. Evidence-based approach to cutaneous hyperandrogenism in women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:672-690.

- Schmidt TH, Khanijow K, Cedars MI, et al. Cutaneous findings and systemic associations in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;152:391-398.

- Escobar-Morreale HF, Carmina E, Dewailly D, et al. Epidemiology, diagnosis and management of hirsutism: a consensus statement by the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society. Hum Reprod Update. 2012;18:146-170.

- Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D, et al. The Androgen Excess and PCOS Society criteria for the polycystic ovary syndrome: the complete task force report. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:456-488.

- Legro RS, Arslanian SA, Ehermann DA, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline [published online October 22, 2013]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:4565-4592.

- Goodman NF, Cobin RH, Futterweit W, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology, and Androgen Excess and PCOS Society disease state clinical review: guide to the best practices in the evaluation and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome—part 1. Endocr Pract. 2015;21:1291-1300.

- Healthcare Bluebook. https://healthcarebluebook.com. Accessed June 13, 2016.

- Azziz R, Sanchez LA, Knochenhauer ES, et al. Androgen excess in women: experience with over 1000 consecutive patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:453-462.

- Carmina E, Rosato F, Jannì A, et al. Relative prevalence of different androgen excess disorders in 950 women referred because of clinical hyperandrogenism [published online November 1, 2005]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2-6.

- Owens DK, Qaseem A, Chou R, et al. High-value, cost-conscious health care: concepts for clinicians to evaluate the benefits, harms, and costs of medical interventions. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:174-180.

- Nahuis MJ, Oude Lohuis E, Kose N, et al. Long-term follow-up of laparoscopic electrocautery of the ovaries versus ovulation induction with recombinant FSH in clomiphene citrate-resistant women with polycystic ovary syndrome: an economic evaluation. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2012;27:3577-3582.

- Moolenaar LM, Nahuis MJ, Hompes PG, et al. Cost-effectiveness of treatment strategies in women with PCOS who do not conceive after six cycles of clomiphene citrate. Reprod Biomed Online. 2014;28:606-613.

- Chogle A, Saps M. Yield and cost of performing screening tests for constipation in children. Can J Gastroenterol. 2013;27:E35-E38.

- Lee YH, Scharnitz TP, Muscat J, et al. Laboratory monitoring during isotretinoin therapy for acne: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:35-44.

- Shinkai K, McMichael A, Linos E. Isotretinoin laboratory test monitoring—a call to decrease testing in an era of high-value, cost-conscious care. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:17-19.

The hospitalist perspective on opioid prescribing

In the United States, we are currently experiencing an opioid epidemic. The rate of opioid-related overdose deaths has reached an all-time high. Hospitalists manage a large number of patients admitted to hospitals in the U.S., and pain is a frequent symptom among these patients.

My colleagues and I wanted to explore hospitalists’ attitudes, beliefs, and practices associated with opioid prescribing during hospitalization and at discharge. In this way, we can begin a conversation about how opioids have impacted the physician’s day to day clinical practice.

For our study, published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine (doi: 10.1002/jhm.2602), we recruited and interviewed 25 hospitalists working in a variety of hospital settings, including two university hospitals, a safety-net hospital, a Veterans Affairs hospital, and a private hospital, located in Colorado and South Carolina. All 25 hospitalists were trained in internal medicine and the majority of them had completed residency within the past 5 to 10 years (48%).

Hospitalists perceived limited success in managing acute exacerbations of chronic pain with opioids, but felt confident in their ability to control acute pain with opioids. They recounted negative sentinel events with their patients that impacted their opioid prescribing practices. Hospitalists described prescribing opioids as a pragmatic tool to facilitate hospital discharges or prevent readmissions, which left them feeling conflicted about how this practice could impact their patients over the long term.

Hospitalists also described feeling uncomfortable treating hospitalized patients with acute exacerbations of a chronic pain condition. One physician said of his experience, “You never get an adequate level of pain control and you keep adding the doses up, and they get habituated.” Another physician described his challenge with controlling chronic pain in hospitalized patients. He said, “Of course their pain is not controlled, because their pain is never going to be less than 5 out of 10. And no opioid is going to get them there, unless they are unconscious.”

Negative sentinel events influenced how hospitalists prescribed opioids in their clinical practice. One physician reflected on an avoidable in-hospital overdose death, which left her more guarded when prescribing opioids. “I’ve had an experience where my patient overdosed,” she said. “She crushed up the oxycodone we were giving her in the hospital, shot it up in her central line, and died.”

Hospitalists described past experiences with patients who altered opioid prescriptions for personal gain. One hospitalist recounted such an experience, saying the patient had “forged my script and changed it from 18 pills to 180 pills.” The physician added, “I got a call from the DEA... I think she [the patient] is in prison now.”

These experiences inspired hospitalists to adopt strategies around opioid prescribing that would make it hard for a patient to jeopardize their DEA license. One physician said, “When I write the prescription, I put the name of the patient on the paper prescription with the patient’s sticker on top. I don’t want the patients to pull it off and sell the prescriptions. Especially when it is my license.”

Hospitalists felt institutional pressure to reduce hospital readmissions and to facilitate discharges. Uncontrolled pain often prolongs a hospital admission. Physicians viewed opioid prescriptions as a pragmatic tool to buffer against readmission or long hospital stays, in order to save health care dollars. On physician described his thoughts on opioid prescribing and efficiency: “If the patient comes back [to the hospital] and gets readmitted when they don’t have pain medicine, it’s a $3,000, 2-day stay in the hospital. When they have pain medicine, they stay out of the hospital. That is utterly pragmatic.”

While opioid prescribing at discharge may improve efficiency and reduce health care costs, one hospitalist also described his discomfort with the practice: “At times, especially when a patient lacks a diagnosis which is known to cause pain [opioid prescribing to prevent readmissions], it can feel cheap and dirty.”

Our study concluded that strategies to provide adequate pain relief to hospitalized patients, which allowed hospitalists to safely and optimally prescribe opioids while maintaining current standards of efficiency, are urgently needed.

Currently, our group is developing predictive tools to be embedded within the electronic medical record to inform physicians about their patient’s future risk for chronic opioid use or opioid use disorders. The goal is to inform physicians, to assist them in making safe, patient-centered, and informed opioid prescribing decisions.

Dr. Calcaterra practices in the Department of Hospital Medicine, Denver Health Medical Center, and is Assistant Professor of Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora. She reported having no financial disclosures.

In the United States, we are currently experiencing an opioid epidemic. The rate of opioid-related overdose deaths has reached an all-time high. Hospitalists manage a large number of patients admitted to hospitals in the U.S., and pain is a frequent symptom among these patients.

My colleagues and I wanted to explore hospitalists’ attitudes, beliefs, and practices associated with opioid prescribing during hospitalization and at discharge. In this way, we can begin a conversation about how opioids have impacted the physician’s day to day clinical practice.

For our study, published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine (doi: 10.1002/jhm.2602), we recruited and interviewed 25 hospitalists working in a variety of hospital settings, including two university hospitals, a safety-net hospital, a Veterans Affairs hospital, and a private hospital, located in Colorado and South Carolina. All 25 hospitalists were trained in internal medicine and the majority of them had completed residency within the past 5 to 10 years (48%).

Hospitalists perceived limited success in managing acute exacerbations of chronic pain with opioids, but felt confident in their ability to control acute pain with opioids. They recounted negative sentinel events with their patients that impacted their opioid prescribing practices. Hospitalists described prescribing opioids as a pragmatic tool to facilitate hospital discharges or prevent readmissions, which left them feeling conflicted about how this practice could impact their patients over the long term.

Hospitalists also described feeling uncomfortable treating hospitalized patients with acute exacerbations of a chronic pain condition. One physician said of his experience, “You never get an adequate level of pain control and you keep adding the doses up, and they get habituated.” Another physician described his challenge with controlling chronic pain in hospitalized patients. He said, “Of course their pain is not controlled, because their pain is never going to be less than 5 out of 10. And no opioid is going to get them there, unless they are unconscious.”

Negative sentinel events influenced how hospitalists prescribed opioids in their clinical practice. One physician reflected on an avoidable in-hospital overdose death, which left her more guarded when prescribing opioids. “I’ve had an experience where my patient overdosed,” she said. “She crushed up the oxycodone we were giving her in the hospital, shot it up in her central line, and died.”

Hospitalists described past experiences with patients who altered opioid prescriptions for personal gain. One hospitalist recounted such an experience, saying the patient had “forged my script and changed it from 18 pills to 180 pills.” The physician added, “I got a call from the DEA... I think she [the patient] is in prison now.”

These experiences inspired hospitalists to adopt strategies around opioid prescribing that would make it hard for a patient to jeopardize their DEA license. One physician said, “When I write the prescription, I put the name of the patient on the paper prescription with the patient’s sticker on top. I don’t want the patients to pull it off and sell the prescriptions. Especially when it is my license.”

Hospitalists felt institutional pressure to reduce hospital readmissions and to facilitate discharges. Uncontrolled pain often prolongs a hospital admission. Physicians viewed opioid prescriptions as a pragmatic tool to buffer against readmission or long hospital stays, in order to save health care dollars. On physician described his thoughts on opioid prescribing and efficiency: “If the patient comes back [to the hospital] and gets readmitted when they don’t have pain medicine, it’s a $3,000, 2-day stay in the hospital. When they have pain medicine, they stay out of the hospital. That is utterly pragmatic.”

While opioid prescribing at discharge may improve efficiency and reduce health care costs, one hospitalist also described his discomfort with the practice: “At times, especially when a patient lacks a diagnosis which is known to cause pain [opioid prescribing to prevent readmissions], it can feel cheap and dirty.”

Our study concluded that strategies to provide adequate pain relief to hospitalized patients, which allowed hospitalists to safely and optimally prescribe opioids while maintaining current standards of efficiency, are urgently needed.

Currently, our group is developing predictive tools to be embedded within the electronic medical record to inform physicians about their patient’s future risk for chronic opioid use or opioid use disorders. The goal is to inform physicians, to assist them in making safe, patient-centered, and informed opioid prescribing decisions.

Dr. Calcaterra practices in the Department of Hospital Medicine, Denver Health Medical Center, and is Assistant Professor of Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora. She reported having no financial disclosures.

In the United States, we are currently experiencing an opioid epidemic. The rate of opioid-related overdose deaths has reached an all-time high. Hospitalists manage a large number of patients admitted to hospitals in the U.S., and pain is a frequent symptom among these patients.

My colleagues and I wanted to explore hospitalists’ attitudes, beliefs, and practices associated with opioid prescribing during hospitalization and at discharge. In this way, we can begin a conversation about how opioids have impacted the physician’s day to day clinical practice.

For our study, published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine (doi: 10.1002/jhm.2602), we recruited and interviewed 25 hospitalists working in a variety of hospital settings, including two university hospitals, a safety-net hospital, a Veterans Affairs hospital, and a private hospital, located in Colorado and South Carolina. All 25 hospitalists were trained in internal medicine and the majority of them had completed residency within the past 5 to 10 years (48%).

Hospitalists perceived limited success in managing acute exacerbations of chronic pain with opioids, but felt confident in their ability to control acute pain with opioids. They recounted negative sentinel events with their patients that impacted their opioid prescribing practices. Hospitalists described prescribing opioids as a pragmatic tool to facilitate hospital discharges or prevent readmissions, which left them feeling conflicted about how this practice could impact their patients over the long term.

Hospitalists also described feeling uncomfortable treating hospitalized patients with acute exacerbations of a chronic pain condition. One physician said of his experience, “You never get an adequate level of pain control and you keep adding the doses up, and they get habituated.” Another physician described his challenge with controlling chronic pain in hospitalized patients. He said, “Of course their pain is not controlled, because their pain is never going to be less than 5 out of 10. And no opioid is going to get them there, unless they are unconscious.”

Negative sentinel events influenced how hospitalists prescribed opioids in their clinical practice. One physician reflected on an avoidable in-hospital overdose death, which left her more guarded when prescribing opioids. “I’ve had an experience where my patient overdosed,” she said. “She crushed up the oxycodone we were giving her in the hospital, shot it up in her central line, and died.”

Hospitalists described past experiences with patients who altered opioid prescriptions for personal gain. One hospitalist recounted such an experience, saying the patient had “forged my script and changed it from 18 pills to 180 pills.” The physician added, “I got a call from the DEA... I think she [the patient] is in prison now.”

These experiences inspired hospitalists to adopt strategies around opioid prescribing that would make it hard for a patient to jeopardize their DEA license. One physician said, “When I write the prescription, I put the name of the patient on the paper prescription with the patient’s sticker on top. I don’t want the patients to pull it off and sell the prescriptions. Especially when it is my license.”

Hospitalists felt institutional pressure to reduce hospital readmissions and to facilitate discharges. Uncontrolled pain often prolongs a hospital admission. Physicians viewed opioid prescriptions as a pragmatic tool to buffer against readmission or long hospital stays, in order to save health care dollars. On physician described his thoughts on opioid prescribing and efficiency: “If the patient comes back [to the hospital] and gets readmitted when they don’t have pain medicine, it’s a $3,000, 2-day stay in the hospital. When they have pain medicine, they stay out of the hospital. That is utterly pragmatic.”

While opioid prescribing at discharge may improve efficiency and reduce health care costs, one hospitalist also described his discomfort with the practice: “At times, especially when a patient lacks a diagnosis which is known to cause pain [opioid prescribing to prevent readmissions], it can feel cheap and dirty.”

Our study concluded that strategies to provide adequate pain relief to hospitalized patients, which allowed hospitalists to safely and optimally prescribe opioids while maintaining current standards of efficiency, are urgently needed.

Currently, our group is developing predictive tools to be embedded within the electronic medical record to inform physicians about their patient’s future risk for chronic opioid use or opioid use disorders. The goal is to inform physicians, to assist them in making safe, patient-centered, and informed opioid prescribing decisions.

Dr. Calcaterra practices in the Department of Hospital Medicine, Denver Health Medical Center, and is Assistant Professor of Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora. She reported having no financial disclosures.

Editorial Board Biographies

Struan H. Coleman, MD, PhD

Associate Editor for Practice Management/Economics

Dr. Coleman is a board-certified orthopedic surgeon specializing in hip preservation and sports medicine at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York and the Vincera Institute in Philadelphia, and currently is the Head Team Physician for the New York Mets. He earned a medical degree from Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons and holds a D.Phil in Microbiology from Oxford University in England. He completed his residency in Orthopedic Surgery and a fellowship in Sports Medicine at the Hospital for Special Surgery. Dr. Coleman focuses on the treatment of sports-related injuries of the hip, knee, and shoulder with a particular interest in hip arthroscopy and hip preservation. He has published multiple articles and book chapters, and holds numerous patents for technologies that are utilized by sports medicine physicians and surgeons.

Jack Farr II, MD

Associate Editor for Patellofemoral

Dr. Farr is a board-certified orthopedic surgeon and has a subspecialty practice in knee and cartilage restoration. He is affiliated with the OrthoIndy Hospital and Community Hospital South. He is also the Vice President of the Patellofemoral Foundation, is on the board for the International Cartilage Repair Society, holds a board position with the Cartilage Research Foundation, and holds a voluntary clinical full professorship in Orthopedic Surgery at the Indiana University Medical Center. Dr. Farr earned his medical degree from Indiana University, and completed his Orthopedic Surgery residency at Indiana University Medical Center. He was a design surgeon for a meniscal allograft transplant system and 2 knee patellofemoral osteotomy systems. He is also a member of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS), the Arthroscopy Association of North America (AANA), and the European Society of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery and Arthroscopy (ESSKA).

Kenneth Montgomery, MD

Associate Editor for Professional Sports

Dr. Montgomery is an orthopedic surgeon who is fellowship-trained in sports medicine and hand and upper extremity surgery. He is currently practicing at Tri-County Orthopedics and Sports Medicine in Morristown, New Jersey. He is also the Head Team Physician and Medical Director for the New York Jets. He served as a team orthopedist with the New York Islanders from 1997-2009, and was formerly the section chief of Sports Medicine at ProHEALTH Care Associates in Lake Success, New York. Dr. Montgomery completed his residency in Orthopedic Surgery at the Hospital for Special Surgery, and completed a Sports Medicine fellowship at Lenox Hill Hospital. He also completed a Hand and Upper Extremity fellowship at Harvard. He is one of the founders for OrthoNations, a nonprofit organization that helps educate orthopedic surgeons in developing countries. He is also one of the founding surgeons for Cayenne Medical, a medical device company specializing in sports medicine implants.

Struan H. Coleman, MD, PhD

Associate Editor for Practice Management/Economics

Dr. Coleman is a board-certified orthopedic surgeon specializing in hip preservation and sports medicine at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York and the Vincera Institute in Philadelphia, and currently is the Head Team Physician for the New York Mets. He earned a medical degree from Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons and holds a D.Phil in Microbiology from Oxford University in England. He completed his residency in Orthopedic Surgery and a fellowship in Sports Medicine at the Hospital for Special Surgery. Dr. Coleman focuses on the treatment of sports-related injuries of the hip, knee, and shoulder with a particular interest in hip arthroscopy and hip preservation. He has published multiple articles and book chapters, and holds numerous patents for technologies that are utilized by sports medicine physicians and surgeons.

Jack Farr II, MD

Associate Editor for Patellofemoral

Dr. Farr is a board-certified orthopedic surgeon and has a subspecialty practice in knee and cartilage restoration. He is affiliated with the OrthoIndy Hospital and Community Hospital South. He is also the Vice President of the Patellofemoral Foundation, is on the board for the International Cartilage Repair Society, holds a board position with the Cartilage Research Foundation, and holds a voluntary clinical full professorship in Orthopedic Surgery at the Indiana University Medical Center. Dr. Farr earned his medical degree from Indiana University, and completed his Orthopedic Surgery residency at Indiana University Medical Center. He was a design surgeon for a meniscal allograft transplant system and 2 knee patellofemoral osteotomy systems. He is also a member of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS), the Arthroscopy Association of North America (AANA), and the European Society of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery and Arthroscopy (ESSKA).

Kenneth Montgomery, MD

Associate Editor for Professional Sports

Dr. Montgomery is an orthopedic surgeon who is fellowship-trained in sports medicine and hand and upper extremity surgery. He is currently practicing at Tri-County Orthopedics and Sports Medicine in Morristown, New Jersey. He is also the Head Team Physician and Medical Director for the New York Jets. He served as a team orthopedist with the New York Islanders from 1997-2009, and was formerly the section chief of Sports Medicine at ProHEALTH Care Associates in Lake Success, New York. Dr. Montgomery completed his residency in Orthopedic Surgery at the Hospital for Special Surgery, and completed a Sports Medicine fellowship at Lenox Hill Hospital. He also completed a Hand and Upper Extremity fellowship at Harvard. He is one of the founders for OrthoNations, a nonprofit organization that helps educate orthopedic surgeons in developing countries. He is also one of the founding surgeons for Cayenne Medical, a medical device company specializing in sports medicine implants.

Struan H. Coleman, MD, PhD

Associate Editor for Practice Management/Economics

Dr. Coleman is a board-certified orthopedic surgeon specializing in hip preservation and sports medicine at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York and the Vincera Institute in Philadelphia, and currently is the Head Team Physician for the New York Mets. He earned a medical degree from Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons and holds a D.Phil in Microbiology from Oxford University in England. He completed his residency in Orthopedic Surgery and a fellowship in Sports Medicine at the Hospital for Special Surgery. Dr. Coleman focuses on the treatment of sports-related injuries of the hip, knee, and shoulder with a particular interest in hip arthroscopy and hip preservation. He has published multiple articles and book chapters, and holds numerous patents for technologies that are utilized by sports medicine physicians and surgeons.

Jack Farr II, MD

Associate Editor for Patellofemoral

Dr. Farr is a board-certified orthopedic surgeon and has a subspecialty practice in knee and cartilage restoration. He is affiliated with the OrthoIndy Hospital and Community Hospital South. He is also the Vice President of the Patellofemoral Foundation, is on the board for the International Cartilage Repair Society, holds a board position with the Cartilage Research Foundation, and holds a voluntary clinical full professorship in Orthopedic Surgery at the Indiana University Medical Center. Dr. Farr earned his medical degree from Indiana University, and completed his Orthopedic Surgery residency at Indiana University Medical Center. He was a design surgeon for a meniscal allograft transplant system and 2 knee patellofemoral osteotomy systems. He is also a member of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS), the Arthroscopy Association of North America (AANA), and the European Society of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery and Arthroscopy (ESSKA).

Kenneth Montgomery, MD

Associate Editor for Professional Sports

Dr. Montgomery is an orthopedic surgeon who is fellowship-trained in sports medicine and hand and upper extremity surgery. He is currently practicing at Tri-County Orthopedics and Sports Medicine in Morristown, New Jersey. He is also the Head Team Physician and Medical Director for the New York Jets. He served as a team orthopedist with the New York Islanders from 1997-2009, and was formerly the section chief of Sports Medicine at ProHEALTH Care Associates in Lake Success, New York. Dr. Montgomery completed his residency in Orthopedic Surgery at the Hospital for Special Surgery, and completed a Sports Medicine fellowship at Lenox Hill Hospital. He also completed a Hand and Upper Extremity fellowship at Harvard. He is one of the founders for OrthoNations, a nonprofit organization that helps educate orthopedic surgeons in developing countries. He is also one of the founding surgeons for Cayenne Medical, a medical device company specializing in sports medicine implants.

Clinical Guidelines: Update in acne treatment

Acne affects 85% of teenagers but can frequently persist into adulthood. It causes significant physical and psychological effects for patients including facial scarring, depression, and decreased self-esteem. The initial approach to acne is determined according to presenting severity, emphasizing topical treatment for milder disease and the addition of oral therapy as disease becomes more severe.

Treatment of mild acne can begin with either benzoyl peroxide (BP) or a topical retinoid (TR). Another option for slightly more severe acne is to start with the initially suggested treatment for moderately severe acne, which is topical combination therapy with BP plus a topical antibiotic; TR plus BP; or TR plus BP in combination with a topical antibiotic. Combination therapy can be given either with separate application of the different medicines or by using fixed combination products that include the separate components in one formulation.

BP is an antibacterial agent, with mild comedolytic properties, and it often is added to topical antibiotic therapy to increase effectiveness and reduce the development of resistance. BP is available in strengths from 2.5% to 10% and in a variety of formulations, which can be used as leave-on or wash-off agents. Common side effects include dose dependent skin irritation and bleaching of fabric.

Topical antibiotics, including clindamycin and erythromycin, work through both their antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory affects. Monotherapy with topical antibiotics is no longer recommended; instead they should be used in combination with BP to prevent bacterial resistance. The preferred topical antibiotic is clindamycin 1% solution or gel. Clindamycin is available in a combination with BP, which may enhance compliance with the treatment regimen.

Topical retinoids are vitamin A derivatives that are the core of treatment. They are effective for all forms of acne and should always be used in the treatment of comedonal acne. There are currently three active agents available: tretinoin (0.025%-0.1% in cream, gel, or microsphere gel vehicles), adapalene (0.1% and 0.3% cream or 0.1% lotion), and tazarotene (0.05% and 0.1% cream, gel, or foam). Combination products are available containing clindamycin and BP. The main side effects of retinoids include dryness, peeling, erythema, and skin irritation. Reducing the frequency of application or potency used may be helpful for limiting these side effects. Topical retinoids increase the risk of photosensitivity, so patients should be counseled on daily sunscreen use, and their use is contraindicated in pregnancy.

Dapsone is an alternative topical treatment for mild acne. Topical dapsone is primarily effective in reducing inflammatory lesions, and seems to be more beneficial for female patients. Dapsone can be combined with topical retinoids if comedonal lesions are present.

Moderate acne can be treated with either topical combination therapy as described above, or systemic antibiotics plus a TR and BP, with or without the addition of a topical antibiotic as well. Female patients may also consider combined oral contraceptives or spironolactone for the treatment of moderate acne.

Systemic antibiotics have been used in the treatment of acne vulgaris for many years, and they are indicated for use in moderate to severe acne. They should always be used in combination with topical therapies, specifically a retinoid or BP. Generally, systemic antibiotics should be used for the shortest possible duration, often 3 months, to prevent the development of bacterial resistance. Tetracyclines and macrolides have the strongest evidence for efficacy. Doxycycline and minocycline are considered equally effective and are the preferred first-line oral antibiotics. Azithromycin has been studied in a variety of pulse dose regimens, and is a good alternative for patients who are not candidates for tetracyclines.

Combined oral contraceptive pills (COCs) are another option for the treatment of acne in female patients. COCs improve acne through their antiandrogenic effects. Spironolactone also has antiandrogen properties, and while it is not FDA approved for the treatment of acne, the AAD guidelines support selective use in women. Spironolactone has been studied at doses from 50 to 200 mg daily and has shown clinically significant improvement in acne. Side effects include diuresis, menstrual irregularities, breast tenderness, and rare hyperkalemia.

Severe acne is treated with an oral antibiotic plus topical combination therapy, or oral isotretinoin, with the addition where appropriate of COCs or oral spironolactone.

Oral isotretinoin, an isomer of retinoic acid, is approved by the FDA for the treatment of severe recalcitrant acne. It causes decreased sebum production, acne lesions, and scarring. It can also be considered in the treatment of moderate acne that is resistant to other treatments, relapses quickly, or produces significant scarring or psychosocial distress. Serum cholesterol, triglycerides, and transaminases can rise during treatment, and should be monitored. Because of the risk of teratogenic effects, the FDA has mandated that all patients receiving isotretinoin must participate in the iPLEDGE risk management program, which requires abstinence or two forms of birth control. While isotretinoin requires monitoring and carries the possibility of significant side effects, it is an effective treatment option for patients with severe recalcitrant acne.

The bottom line

Acne is commonly treated by primary care physicians. A clear approach of graded treatment based on severity of disease yields improvement in outcomes. Mild acne should be treated with benzoyl peroxide, retinoids or a combinations of topical treatments. Systemic antibiotics should be combined with topical therapies for moderate to severe acne. Female patients may also consider using combined oral contraceptives and spironolactone. Oral isotretinoin is an effective option for severe acne, but requires close monitoring.

References

Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74[5]:945-73.e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037. Epub 2016 Feb 17).

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. Dr. Marriott is an attending family physician at Capital Health Primary Care in Hamilton, N.J.

Acne affects 85% of teenagers but can frequently persist into adulthood. It causes significant physical and psychological effects for patients including facial scarring, depression, and decreased self-esteem. The initial approach to acne is determined according to presenting severity, emphasizing topical treatment for milder disease and the addition of oral therapy as disease becomes more severe.

Treatment of mild acne can begin with either benzoyl peroxide (BP) or a topical retinoid (TR). Another option for slightly more severe acne is to start with the initially suggested treatment for moderately severe acne, which is topical combination therapy with BP plus a topical antibiotic; TR plus BP; or TR plus BP in combination with a topical antibiotic. Combination therapy can be given either with separate application of the different medicines or by using fixed combination products that include the separate components in one formulation.

BP is an antibacterial agent, with mild comedolytic properties, and it often is added to topical antibiotic therapy to increase effectiveness and reduce the development of resistance. BP is available in strengths from 2.5% to 10% and in a variety of formulations, which can be used as leave-on or wash-off agents. Common side effects include dose dependent skin irritation and bleaching of fabric.

Topical antibiotics, including clindamycin and erythromycin, work through both their antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory affects. Monotherapy with topical antibiotics is no longer recommended; instead they should be used in combination with BP to prevent bacterial resistance. The preferred topical antibiotic is clindamycin 1% solution or gel. Clindamycin is available in a combination with BP, which may enhance compliance with the treatment regimen.

Topical retinoids are vitamin A derivatives that are the core of treatment. They are effective for all forms of acne and should always be used in the treatment of comedonal acne. There are currently three active agents available: tretinoin (0.025%-0.1% in cream, gel, or microsphere gel vehicles), adapalene (0.1% and 0.3% cream or 0.1% lotion), and tazarotene (0.05% and 0.1% cream, gel, or foam). Combination products are available containing clindamycin and BP. The main side effects of retinoids include dryness, peeling, erythema, and skin irritation. Reducing the frequency of application or potency used may be helpful for limiting these side effects. Topical retinoids increase the risk of photosensitivity, so patients should be counseled on daily sunscreen use, and their use is contraindicated in pregnancy.

Dapsone is an alternative topical treatment for mild acne. Topical dapsone is primarily effective in reducing inflammatory lesions, and seems to be more beneficial for female patients. Dapsone can be combined with topical retinoids if comedonal lesions are present.

Moderate acne can be treated with either topical combination therapy as described above, or systemic antibiotics plus a TR and BP, with or without the addition of a topical antibiotic as well. Female patients may also consider combined oral contraceptives or spironolactone for the treatment of moderate acne.

Systemic antibiotics have been used in the treatment of acne vulgaris for many years, and they are indicated for use in moderate to severe acne. They should always be used in combination with topical therapies, specifically a retinoid or BP. Generally, systemic antibiotics should be used for the shortest possible duration, often 3 months, to prevent the development of bacterial resistance. Tetracyclines and macrolides have the strongest evidence for efficacy. Doxycycline and minocycline are considered equally effective and are the preferred first-line oral antibiotics. Azithromycin has been studied in a variety of pulse dose regimens, and is a good alternative for patients who are not candidates for tetracyclines.

Combined oral contraceptive pills (COCs) are another option for the treatment of acne in female patients. COCs improve acne through their antiandrogenic effects. Spironolactone also has antiandrogen properties, and while it is not FDA approved for the treatment of acne, the AAD guidelines support selective use in women. Spironolactone has been studied at doses from 50 to 200 mg daily and has shown clinically significant improvement in acne. Side effects include diuresis, menstrual irregularities, breast tenderness, and rare hyperkalemia.

Severe acne is treated with an oral antibiotic plus topical combination therapy, or oral isotretinoin, with the addition where appropriate of COCs or oral spironolactone.

Oral isotretinoin, an isomer of retinoic acid, is approved by the FDA for the treatment of severe recalcitrant acne. It causes decreased sebum production, acne lesions, and scarring. It can also be considered in the treatment of moderate acne that is resistant to other treatments, relapses quickly, or produces significant scarring or psychosocial distress. Serum cholesterol, triglycerides, and transaminases can rise during treatment, and should be monitored. Because of the risk of teratogenic effects, the FDA has mandated that all patients receiving isotretinoin must participate in the iPLEDGE risk management program, which requires abstinence or two forms of birth control. While isotretinoin requires monitoring and carries the possibility of significant side effects, it is an effective treatment option for patients with severe recalcitrant acne.

The bottom line

Acne is commonly treated by primary care physicians. A clear approach of graded treatment based on severity of disease yields improvement in outcomes. Mild acne should be treated with benzoyl peroxide, retinoids or a combinations of topical treatments. Systemic antibiotics should be combined with topical therapies for moderate to severe acne. Female patients may also consider using combined oral contraceptives and spironolactone. Oral isotretinoin is an effective option for severe acne, but requires close monitoring.

References

Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74[5]:945-73.e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037. Epub 2016 Feb 17).

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. Dr. Marriott is an attending family physician at Capital Health Primary Care in Hamilton, N.J.

Acne affects 85% of teenagers but can frequently persist into adulthood. It causes significant physical and psychological effects for patients including facial scarring, depression, and decreased self-esteem. The initial approach to acne is determined according to presenting severity, emphasizing topical treatment for milder disease and the addition of oral therapy as disease becomes more severe.

Treatment of mild acne can begin with either benzoyl peroxide (BP) or a topical retinoid (TR). Another option for slightly more severe acne is to start with the initially suggested treatment for moderately severe acne, which is topical combination therapy with BP plus a topical antibiotic; TR plus BP; or TR plus BP in combination with a topical antibiotic. Combination therapy can be given either with separate application of the different medicines or by using fixed combination products that include the separate components in one formulation.

BP is an antibacterial agent, with mild comedolytic properties, and it often is added to topical antibiotic therapy to increase effectiveness and reduce the development of resistance. BP is available in strengths from 2.5% to 10% and in a variety of formulations, which can be used as leave-on or wash-off agents. Common side effects include dose dependent skin irritation and bleaching of fabric.

Topical antibiotics, including clindamycin and erythromycin, work through both their antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory affects. Monotherapy with topical antibiotics is no longer recommended; instead they should be used in combination with BP to prevent bacterial resistance. The preferred topical antibiotic is clindamycin 1% solution or gel. Clindamycin is available in a combination with BP, which may enhance compliance with the treatment regimen.

Topical retinoids are vitamin A derivatives that are the core of treatment. They are effective for all forms of acne and should always be used in the treatment of comedonal acne. There are currently three active agents available: tretinoin (0.025%-0.1% in cream, gel, or microsphere gel vehicles), adapalene (0.1% and 0.3% cream or 0.1% lotion), and tazarotene (0.05% and 0.1% cream, gel, or foam). Combination products are available containing clindamycin and BP. The main side effects of retinoids include dryness, peeling, erythema, and skin irritation. Reducing the frequency of application or potency used may be helpful for limiting these side effects. Topical retinoids increase the risk of photosensitivity, so patients should be counseled on daily sunscreen use, and their use is contraindicated in pregnancy.

Dapsone is an alternative topical treatment for mild acne. Topical dapsone is primarily effective in reducing inflammatory lesions, and seems to be more beneficial for female patients. Dapsone can be combined with topical retinoids if comedonal lesions are present.

Moderate acne can be treated with either topical combination therapy as described above, or systemic antibiotics plus a TR and BP, with or without the addition of a topical antibiotic as well. Female patients may also consider combined oral contraceptives or spironolactone for the treatment of moderate acne.

Systemic antibiotics have been used in the treatment of acne vulgaris for many years, and they are indicated for use in moderate to severe acne. They should always be used in combination with topical therapies, specifically a retinoid or BP. Generally, systemic antibiotics should be used for the shortest possible duration, often 3 months, to prevent the development of bacterial resistance. Tetracyclines and macrolides have the strongest evidence for efficacy. Doxycycline and minocycline are considered equally effective and are the preferred first-line oral antibiotics. Azithromycin has been studied in a variety of pulse dose regimens, and is a good alternative for patients who are not candidates for tetracyclines.

Combined oral contraceptive pills (COCs) are another option for the treatment of acne in female patients. COCs improve acne through their antiandrogenic effects. Spironolactone also has antiandrogen properties, and while it is not FDA approved for the treatment of acne, the AAD guidelines support selective use in women. Spironolactone has been studied at doses from 50 to 200 mg daily and has shown clinically significant improvement in acne. Side effects include diuresis, menstrual irregularities, breast tenderness, and rare hyperkalemia.