User login

Psychotherapy

The term “psychotherapy” describes a variety of talk-based treatments for psychiatric illnesses. Its fundamental premise is that there are determinants of mood, anxiety, and behavior that are not fully in our conscious awareness. By becoming more aware or by developing skills in managing thoughts and feelings, patients can get relief from symptoms that often impair functioning. The focus on unconscious thoughts, feelings, and behaviors is the central principle of dynamic psychotherapy in which the therapist listens to the patients speak freely about important people and events in their day-to-day lives and takes note of themes that emerge. Eventually they offer “interpretations” to their patients about these patterns, and ways that current problems may connect to powerful experiences from their earlier lives.

Dynamic psychotherapy is often contrasted with supportive psychotherapy. This is not cheerleading, but instead refers to supporting the healthy ability to think about oneself, one’s thoughts and emotions, and one’s needs, and the tension that these can create with the expectations of society. In working with children and adolescents, therapists are almost always supporting the age-appropriate development of some of these skills, particularly if a child has gotten developmentally stuck because of depressive, anxious, or attentional symptoms. There are almost always supportive elements in psychotherapy with a school-age or teenage child.

For children with anxiety disorders or mild to moderate depression, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is an evidence-based first-line treatment. CBT is a structured psychotherapy that helps patients to identify specific thoughts that trigger or follow their mood or anxiety symptoms, and then sets about establishing new (less-distorted) thoughts or practicing avoided behaviors to help learn new responses. It appears to be especially effective for anxiety disorders (such as social phobia, panic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder) and for obsessive-compulsive disorder. There are specialized types of CBT that can be offered to patients (including children) who have been exposed to trauma and even for teenagers experiencing psychotic symptoms. It should be noted that one of the reasons that CBT has a robust evidence base supporting its use is that it is one of the most structured types of psychotherapy. It is standardized, reproducible, and easier to study than most other varieties of psychotherapy. Practicing CBT requires specific training, so in looking for a CBT therapist, one needs to ask whether she is CBT trained, and even whether she is trained in the type of CBT specific for the disorder you are treating.

A relative of CBT is dialectical behavioral therapy or DBT, developed to treat borderline personality disorder, a maladaptive pattern of identity uncertainty, emotional instability, and impulsivity that often starts in adolescence, causing stormy relationships and poor self-regulation that can contribute to self-injury, substance abuse, and chronic suicidality. DBT focuses on cognitive patterns, and utilizes a patient’s strengths to build new skills at managing challenging thoughts and feelings. The “dialectic” relates to interpersonal relationships, as this is where these patients often have great difficulty. High-quality DBT is often done with both individual and group therapy sessions. There is substantial evidence supporting the efficacy of this therapy in patients with borderline personality disorder.

Play therapy generally refers to the use of play (with toys, dolls, art, or games) in therapy with the youngest children. Such young children are unlikely to speak in a fluid manner about their relationships or struggles, as they may lack some of the cognitive means to be self-reflective. So instead, a therapist will watch for themes in their play (aggression, cheating, repetitive stories with dolls or art) that may reflect important themes, that they will then work on in play or in speaking, as tolerated. Therapists of older children also may use play to help these children feel more comfortable as they proceed with CBT or another talk therapy.

While gathering data from parents is always part of therapy for children, family therapy brings the whole family into a room with the therapist, who focuses on the roles each person may play in the family and patterns of communication (verbal and otherwise) that may be contributing to a young person’s symptoms. Family therapy can be very important in treating anorexia nervosa, somatoform illnesses, and conduct disorder in children and adolescents. While it can be a complex type of therapy to study, there is significant evidence supporting its efficacy in these very challenging disorders of youth.

There is a growing body of evidence in adults demonstrating neuroimaging changes after effective psychotherapies. Several studies of patients with OCD who were successfully treated with CBT have demonstrated decreased metabolism in the right caudate nucleus, and those treated effectively for phobias showed decreased activity in the limbic and paralimbic areas. Interestingly, patients with OCD and phobias who were effectively treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors demonstrated these same changes on functional neuroimaging (Mol Psychiatry. 2006 Jun;11[6]:528-38.). An Italian meta-analysis of patients treated for major depression with medications (usually selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) or with psychotherapy (usually CBT) demonstrated different, and possibly complementary brain changes in the two treatment groups (Brain Imaging Behav. 2015 Jul 12. [Epub ahead of print]). With time, these studies may help us to better understand the nature of specific illnesses and more about neuroplasticity, and may even help us to understand when medications, therapy, or both are indicated.

Finally, it is worth noting that multiple studies indicate that one of the most consistent predictors of a positive outcome in psychotherapy is the presence of a strong treatment alliance between the therapist and the patient. Studies have demonstrated that a strong alliance was a better predictor of positive outcomes than type of psychotherapy, and seemed to be a strong predictor of positive outcomes even in cases where the treatment was pharmacologic. This makes it critical that when you are trying to help your patient find a “good therapist,” you consider whether the patient may need a specialized therapy (CBT, DBT, or family therapy). But you should also instruct your patient and their parents that it is very important that they like their therapist, that after several meetings they should feel comfortable meeting and talking honestly with him, and that they should feel that the therapist cares about them and is committed to their health and well-being.

Dr. Swick is an attending psychiatrist in the division of child psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and director of the Parenting at a Challenging Time (PACT) Program at the Vernon Cancer Center at Newton (Mass.) Wellesley Hospital. Dr. Jellinek is professor of psychiatry and of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

The term “psychotherapy” describes a variety of talk-based treatments for psychiatric illnesses. Its fundamental premise is that there are determinants of mood, anxiety, and behavior that are not fully in our conscious awareness. By becoming more aware or by developing skills in managing thoughts and feelings, patients can get relief from symptoms that often impair functioning. The focus on unconscious thoughts, feelings, and behaviors is the central principle of dynamic psychotherapy in which the therapist listens to the patients speak freely about important people and events in their day-to-day lives and takes note of themes that emerge. Eventually they offer “interpretations” to their patients about these patterns, and ways that current problems may connect to powerful experiences from their earlier lives.

Dynamic psychotherapy is often contrasted with supportive psychotherapy. This is not cheerleading, but instead refers to supporting the healthy ability to think about oneself, one’s thoughts and emotions, and one’s needs, and the tension that these can create with the expectations of society. In working with children and adolescents, therapists are almost always supporting the age-appropriate development of some of these skills, particularly if a child has gotten developmentally stuck because of depressive, anxious, or attentional symptoms. There are almost always supportive elements in psychotherapy with a school-age or teenage child.

For children with anxiety disorders or mild to moderate depression, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is an evidence-based first-line treatment. CBT is a structured psychotherapy that helps patients to identify specific thoughts that trigger or follow their mood or anxiety symptoms, and then sets about establishing new (less-distorted) thoughts or practicing avoided behaviors to help learn new responses. It appears to be especially effective for anxiety disorders (such as social phobia, panic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder) and for obsessive-compulsive disorder. There are specialized types of CBT that can be offered to patients (including children) who have been exposed to trauma and even for teenagers experiencing psychotic symptoms. It should be noted that one of the reasons that CBT has a robust evidence base supporting its use is that it is one of the most structured types of psychotherapy. It is standardized, reproducible, and easier to study than most other varieties of psychotherapy. Practicing CBT requires specific training, so in looking for a CBT therapist, one needs to ask whether she is CBT trained, and even whether she is trained in the type of CBT specific for the disorder you are treating.

A relative of CBT is dialectical behavioral therapy or DBT, developed to treat borderline personality disorder, a maladaptive pattern of identity uncertainty, emotional instability, and impulsivity that often starts in adolescence, causing stormy relationships and poor self-regulation that can contribute to self-injury, substance abuse, and chronic suicidality. DBT focuses on cognitive patterns, and utilizes a patient’s strengths to build new skills at managing challenging thoughts and feelings. The “dialectic” relates to interpersonal relationships, as this is where these patients often have great difficulty. High-quality DBT is often done with both individual and group therapy sessions. There is substantial evidence supporting the efficacy of this therapy in patients with borderline personality disorder.

Play therapy generally refers to the use of play (with toys, dolls, art, or games) in therapy with the youngest children. Such young children are unlikely to speak in a fluid manner about their relationships or struggles, as they may lack some of the cognitive means to be self-reflective. So instead, a therapist will watch for themes in their play (aggression, cheating, repetitive stories with dolls or art) that may reflect important themes, that they will then work on in play or in speaking, as tolerated. Therapists of older children also may use play to help these children feel more comfortable as they proceed with CBT or another talk therapy.

While gathering data from parents is always part of therapy for children, family therapy brings the whole family into a room with the therapist, who focuses on the roles each person may play in the family and patterns of communication (verbal and otherwise) that may be contributing to a young person’s symptoms. Family therapy can be very important in treating anorexia nervosa, somatoform illnesses, and conduct disorder in children and adolescents. While it can be a complex type of therapy to study, there is significant evidence supporting its efficacy in these very challenging disorders of youth.

There is a growing body of evidence in adults demonstrating neuroimaging changes after effective psychotherapies. Several studies of patients with OCD who were successfully treated with CBT have demonstrated decreased metabolism in the right caudate nucleus, and those treated effectively for phobias showed decreased activity in the limbic and paralimbic areas. Interestingly, patients with OCD and phobias who were effectively treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors demonstrated these same changes on functional neuroimaging (Mol Psychiatry. 2006 Jun;11[6]:528-38.). An Italian meta-analysis of patients treated for major depression with medications (usually selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) or with psychotherapy (usually CBT) demonstrated different, and possibly complementary brain changes in the two treatment groups (Brain Imaging Behav. 2015 Jul 12. [Epub ahead of print]). With time, these studies may help us to better understand the nature of specific illnesses and more about neuroplasticity, and may even help us to understand when medications, therapy, or both are indicated.

Finally, it is worth noting that multiple studies indicate that one of the most consistent predictors of a positive outcome in psychotherapy is the presence of a strong treatment alliance between the therapist and the patient. Studies have demonstrated that a strong alliance was a better predictor of positive outcomes than type of psychotherapy, and seemed to be a strong predictor of positive outcomes even in cases where the treatment was pharmacologic. This makes it critical that when you are trying to help your patient find a “good therapist,” you consider whether the patient may need a specialized therapy (CBT, DBT, or family therapy). But you should also instruct your patient and their parents that it is very important that they like their therapist, that after several meetings they should feel comfortable meeting and talking honestly with him, and that they should feel that the therapist cares about them and is committed to their health and well-being.

Dr. Swick is an attending psychiatrist in the division of child psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and director of the Parenting at a Challenging Time (PACT) Program at the Vernon Cancer Center at Newton (Mass.) Wellesley Hospital. Dr. Jellinek is professor of psychiatry and of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

The term “psychotherapy” describes a variety of talk-based treatments for psychiatric illnesses. Its fundamental premise is that there are determinants of mood, anxiety, and behavior that are not fully in our conscious awareness. By becoming more aware or by developing skills in managing thoughts and feelings, patients can get relief from symptoms that often impair functioning. The focus on unconscious thoughts, feelings, and behaviors is the central principle of dynamic psychotherapy in which the therapist listens to the patients speak freely about important people and events in their day-to-day lives and takes note of themes that emerge. Eventually they offer “interpretations” to their patients about these patterns, and ways that current problems may connect to powerful experiences from their earlier lives.

Dynamic psychotherapy is often contrasted with supportive psychotherapy. This is not cheerleading, but instead refers to supporting the healthy ability to think about oneself, one’s thoughts and emotions, and one’s needs, and the tension that these can create with the expectations of society. In working with children and adolescents, therapists are almost always supporting the age-appropriate development of some of these skills, particularly if a child has gotten developmentally stuck because of depressive, anxious, or attentional symptoms. There are almost always supportive elements in psychotherapy with a school-age or teenage child.

For children with anxiety disorders or mild to moderate depression, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is an evidence-based first-line treatment. CBT is a structured psychotherapy that helps patients to identify specific thoughts that trigger or follow their mood or anxiety symptoms, and then sets about establishing new (less-distorted) thoughts or practicing avoided behaviors to help learn new responses. It appears to be especially effective for anxiety disorders (such as social phobia, panic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder) and for obsessive-compulsive disorder. There are specialized types of CBT that can be offered to patients (including children) who have been exposed to trauma and even for teenagers experiencing psychotic symptoms. It should be noted that one of the reasons that CBT has a robust evidence base supporting its use is that it is one of the most structured types of psychotherapy. It is standardized, reproducible, and easier to study than most other varieties of psychotherapy. Practicing CBT requires specific training, so in looking for a CBT therapist, one needs to ask whether she is CBT trained, and even whether she is trained in the type of CBT specific for the disorder you are treating.

A relative of CBT is dialectical behavioral therapy or DBT, developed to treat borderline personality disorder, a maladaptive pattern of identity uncertainty, emotional instability, and impulsivity that often starts in adolescence, causing stormy relationships and poor self-regulation that can contribute to self-injury, substance abuse, and chronic suicidality. DBT focuses on cognitive patterns, and utilizes a patient’s strengths to build new skills at managing challenging thoughts and feelings. The “dialectic” relates to interpersonal relationships, as this is where these patients often have great difficulty. High-quality DBT is often done with both individual and group therapy sessions. There is substantial evidence supporting the efficacy of this therapy in patients with borderline personality disorder.

Play therapy generally refers to the use of play (with toys, dolls, art, or games) in therapy with the youngest children. Such young children are unlikely to speak in a fluid manner about their relationships or struggles, as they may lack some of the cognitive means to be self-reflective. So instead, a therapist will watch for themes in their play (aggression, cheating, repetitive stories with dolls or art) that may reflect important themes, that they will then work on in play or in speaking, as tolerated. Therapists of older children also may use play to help these children feel more comfortable as they proceed with CBT or another talk therapy.

While gathering data from parents is always part of therapy for children, family therapy brings the whole family into a room with the therapist, who focuses on the roles each person may play in the family and patterns of communication (verbal and otherwise) that may be contributing to a young person’s symptoms. Family therapy can be very important in treating anorexia nervosa, somatoform illnesses, and conduct disorder in children and adolescents. While it can be a complex type of therapy to study, there is significant evidence supporting its efficacy in these very challenging disorders of youth.

There is a growing body of evidence in adults demonstrating neuroimaging changes after effective psychotherapies. Several studies of patients with OCD who were successfully treated with CBT have demonstrated decreased metabolism in the right caudate nucleus, and those treated effectively for phobias showed decreased activity in the limbic and paralimbic areas. Interestingly, patients with OCD and phobias who were effectively treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors demonstrated these same changes on functional neuroimaging (Mol Psychiatry. 2006 Jun;11[6]:528-38.). An Italian meta-analysis of patients treated for major depression with medications (usually selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) or with psychotherapy (usually CBT) demonstrated different, and possibly complementary brain changes in the two treatment groups (Brain Imaging Behav. 2015 Jul 12. [Epub ahead of print]). With time, these studies may help us to better understand the nature of specific illnesses and more about neuroplasticity, and may even help us to understand when medications, therapy, or both are indicated.

Finally, it is worth noting that multiple studies indicate that one of the most consistent predictors of a positive outcome in psychotherapy is the presence of a strong treatment alliance between the therapist and the patient. Studies have demonstrated that a strong alliance was a better predictor of positive outcomes than type of psychotherapy, and seemed to be a strong predictor of positive outcomes even in cases where the treatment was pharmacologic. This makes it critical that when you are trying to help your patient find a “good therapist,” you consider whether the patient may need a specialized therapy (CBT, DBT, or family therapy). But you should also instruct your patient and their parents that it is very important that they like their therapist, that after several meetings they should feel comfortable meeting and talking honestly with him, and that they should feel that the therapist cares about them and is committed to their health and well-being.

Dr. Swick is an attending psychiatrist in the division of child psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and director of the Parenting at a Challenging Time (PACT) Program at the Vernon Cancer Center at Newton (Mass.) Wellesley Hospital. Dr. Jellinek is professor of psychiatry and of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

Precepting: I Love It, But ...

I have been a preceptor for more than 10 years. I originally started as a favor to a friend who was in NP school, but have grown to (mostly) love precepting. The university I have worked with the most has been very accommodating to my needs as a preceptor. I work part-time and am paid based on work revenue units/compensation and patient satisfaction scores. Therefore, I will only take students one day a week, and I am picky about which students I take. I have had some disastrous encounters with students who had very little to no work experience or had only outpatient experience. It is very important, in my opinion, that a student has several years working as a nurse in an inpatient setting before starting a DNP program.

What I have found throughout the years is that schools admit any nurse who can pass their admission requirements, without taking into account work experience or length of time as a nurse. Some students jump right to a DNP program after graduating with a BSN. Younger students can be overly confident in their abilities, which is problematic when they are learning new material. I have had to tell one online school that I couldn’t be a preceptor for their students, as they had too many rules about when their students do clinical and how many days a week they required me to give.

As far as compensation offered, I am able to take 10 CEU hours every 2 years toward my nursing license, have been given access to the university library, and once or twice would’ve been able to take a class for free. Unfortunately, work and life duties have not allowed me to take advantage of the classes. Being paid for my time would feel weird to me. I feel as though it is our duty to give back to students, just as others gave to us when we were in school.

My long-term patients are used to my students and sometimes even ask where the student is if they come on a day I am not working with them. All patients are given the option to have a student, and my medical assistants are very good at “pre-screening” for patients who may not be a good fit for a student. All in all, I enjoy working with students and seeing the “a-ha” moments when it all starts to click!

Shelly Sinatra, APN, CNP

St. Charles, IL

FOR MORE LETTERS TO THE EDITOR:

Do Veteran PAs Care Less, Or Are New PA Students Careless?

Has the Bar Been Lowered for RN/NP Programs?

Insurance and Billing Qualms Double the Work

Preceptor Tax Incentive Program: The Realities

I have been a preceptor for more than 10 years. I originally started as a favor to a friend who was in NP school, but have grown to (mostly) love precepting. The university I have worked with the most has been very accommodating to my needs as a preceptor. I work part-time and am paid based on work revenue units/compensation and patient satisfaction scores. Therefore, I will only take students one day a week, and I am picky about which students I take. I have had some disastrous encounters with students who had very little to no work experience or had only outpatient experience. It is very important, in my opinion, that a student has several years working as a nurse in an inpatient setting before starting a DNP program.

What I have found throughout the years is that schools admit any nurse who can pass their admission requirements, without taking into account work experience or length of time as a nurse. Some students jump right to a DNP program after graduating with a BSN. Younger students can be overly confident in their abilities, which is problematic when they are learning new material. I have had to tell one online school that I couldn’t be a preceptor for their students, as they had too many rules about when their students do clinical and how many days a week they required me to give.

As far as compensation offered, I am able to take 10 CEU hours every 2 years toward my nursing license, have been given access to the university library, and once or twice would’ve been able to take a class for free. Unfortunately, work and life duties have not allowed me to take advantage of the classes. Being paid for my time would feel weird to me. I feel as though it is our duty to give back to students, just as others gave to us when we were in school.

My long-term patients are used to my students and sometimes even ask where the student is if they come on a day I am not working with them. All patients are given the option to have a student, and my medical assistants are very good at “pre-screening” for patients who may not be a good fit for a student. All in all, I enjoy working with students and seeing the “a-ha” moments when it all starts to click!

Shelly Sinatra, APN, CNP

St. Charles, IL

FOR MORE LETTERS TO THE EDITOR:

Do Veteran PAs Care Less, Or Are New PA Students Careless?

Has the Bar Been Lowered for RN/NP Programs?

Insurance and Billing Qualms Double the Work

Preceptor Tax Incentive Program: The Realities

I have been a preceptor for more than 10 years. I originally started as a favor to a friend who was in NP school, but have grown to (mostly) love precepting. The university I have worked with the most has been very accommodating to my needs as a preceptor. I work part-time and am paid based on work revenue units/compensation and patient satisfaction scores. Therefore, I will only take students one day a week, and I am picky about which students I take. I have had some disastrous encounters with students who had very little to no work experience or had only outpatient experience. It is very important, in my opinion, that a student has several years working as a nurse in an inpatient setting before starting a DNP program.

What I have found throughout the years is that schools admit any nurse who can pass their admission requirements, without taking into account work experience or length of time as a nurse. Some students jump right to a DNP program after graduating with a BSN. Younger students can be overly confident in their abilities, which is problematic when they are learning new material. I have had to tell one online school that I couldn’t be a preceptor for their students, as they had too many rules about when their students do clinical and how many days a week they required me to give.

As far as compensation offered, I am able to take 10 CEU hours every 2 years toward my nursing license, have been given access to the university library, and once or twice would’ve been able to take a class for free. Unfortunately, work and life duties have not allowed me to take advantage of the classes. Being paid for my time would feel weird to me. I feel as though it is our duty to give back to students, just as others gave to us when we were in school.

My long-term patients are used to my students and sometimes even ask where the student is if they come on a day I am not working with them. All patients are given the option to have a student, and my medical assistants are very good at “pre-screening” for patients who may not be a good fit for a student. All in all, I enjoy working with students and seeing the “a-ha” moments when it all starts to click!

Shelly Sinatra, APN, CNP

St. Charles, IL

FOR MORE LETTERS TO THE EDITOR:

Do Veteran PAs Care Less, Or Are New PA Students Careless?

Has the Bar Been Lowered for RN/NP Programs?

Insurance and Billing Qualms Double the Work

Preceptor Tax Incentive Program: The Realities

Insurance and Billing Qualms Double the Work

An issue for me regarding precepting was that, according to our insurance people, I couldn't bill for work I delegated or oversaw. Consequently, the patient had to go through the exam twice, as I had to repeat everything the student did. I think our billing people were overreading the regulations, but as an NP, I really wasn't in a position to disagree.

Personally, I felt that was too disruptive for my patient and too time-consuming for my schedule.

You already addressed the other big issue; the students followed their course work curriculum, because that is who was testing them. Their curriculum did not follow their clinical schedule. I was in an Ob-Gyn practice. Often they saw me before they had a class on this subject; therefore, they were not prepared to work in my clinic. They were too busy following their class schedule, working for pay, and caring for their families. They did not feel the need to read up on my clinical area before they arrived in my exam room.

I retired in the fall of 2014, so I no longer have to do this.

Debbie Wright, NP, WHNP, BC, MSN (retired)

South Euclid, OH

FOR MORE LETTERS TO THE EDITOR:

Do Veteran PAs Care Less, Or Are New PA Students Careless?

Has the Bar Been Lowered for RN/NP Programs?

Precepting: I Love It, But ...

Preceptor Tax Incentive Program: The Realities

An issue for me regarding precepting was that, according to our insurance people, I couldn't bill for work I delegated or oversaw. Consequently, the patient had to go through the exam twice, as I had to repeat everything the student did. I think our billing people were overreading the regulations, but as an NP, I really wasn't in a position to disagree.

Personally, I felt that was too disruptive for my patient and too time-consuming for my schedule.

You already addressed the other big issue; the students followed their course work curriculum, because that is who was testing them. Their curriculum did not follow their clinical schedule. I was in an Ob-Gyn practice. Often they saw me before they had a class on this subject; therefore, they were not prepared to work in my clinic. They were too busy following their class schedule, working for pay, and caring for their families. They did not feel the need to read up on my clinical area before they arrived in my exam room.

I retired in the fall of 2014, so I no longer have to do this.

Debbie Wright, NP, WHNP, BC, MSN (retired)

South Euclid, OH

FOR MORE LETTERS TO THE EDITOR:

Do Veteran PAs Care Less, Or Are New PA Students Careless?

Has the Bar Been Lowered for RN/NP Programs?

Precepting: I Love It, But ...

Preceptor Tax Incentive Program: The Realities

An issue for me regarding precepting was that, according to our insurance people, I couldn't bill for work I delegated or oversaw. Consequently, the patient had to go through the exam twice, as I had to repeat everything the student did. I think our billing people were overreading the regulations, but as an NP, I really wasn't in a position to disagree.

Personally, I felt that was too disruptive for my patient and too time-consuming for my schedule.

You already addressed the other big issue; the students followed their course work curriculum, because that is who was testing them. Their curriculum did not follow their clinical schedule. I was in an Ob-Gyn practice. Often they saw me before they had a class on this subject; therefore, they were not prepared to work in my clinic. They were too busy following their class schedule, working for pay, and caring for their families. They did not feel the need to read up on my clinical area before they arrived in my exam room.

I retired in the fall of 2014, so I no longer have to do this.

Debbie Wright, NP, WHNP, BC, MSN (retired)

South Euclid, OH

FOR MORE LETTERS TO THE EDITOR:

Do Veteran PAs Care Less, Or Are New PA Students Careless?

Has the Bar Been Lowered for RN/NP Programs?

Precepting: I Love It, But ...

Preceptor Tax Incentive Program: The Realities

Preceptor Tax Incentive Program: The Realities

In follow-up to Dr. Danielsen’s mention of a tax incentive program in Georgia, here is more detail from the United Advanced Practice Registered Nurses of Georgia website:

“Gov. Nathan Deal signed into law April 15, 2014, legislation that creates tax deductions of up to $10,000 per year for physicians who provide training to medical, physician assistant, and nurse practitioner students.”

Georgia physicians (MDs and DOs) who clinically train health profession students (enrolled in in-state public or private medical/osteopathic, PA or NP programs) for a minimum of three rotations can claim a tax deduction of $1,000 per 160 hours of training.

The physicians, who cannot be compensated through any other source, can provide training for a maximum of 10 rotations. Rotations must be in family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics, Ob-Gyn, emergency medicine, psychiatry, or general surgery. Hours can be accrued from multiple programs and students, but the physician must complete three or more of these rotations per year in order to qualify (480 hours.)

As you referenced in your article, this Preceptor Tax Incentive Program would be a means to encourage preceptorship. Unfortunately, it did not pass for NPs or PAs to be awarded tax credit, but I think it could gain some momentum and can be tried again! One state at a time.

Amy Spearman, CRNP

Huntsville, AL

FOR MORE LETTERS TO THE EDITOR:

Do Veteran PAs Care Less, Or Are New PA Students Careless?

Has the Bar Been Lowered for RN/NP Programs?

Insurance and Billing Qualms Double the Work

Precepting: I Love It, But ...

In follow-up to Dr. Danielsen’s mention of a tax incentive program in Georgia, here is more detail from the United Advanced Practice Registered Nurses of Georgia website:

“Gov. Nathan Deal signed into law April 15, 2014, legislation that creates tax deductions of up to $10,000 per year for physicians who provide training to medical, physician assistant, and nurse practitioner students.”

Georgia physicians (MDs and DOs) who clinically train health profession students (enrolled in in-state public or private medical/osteopathic, PA or NP programs) for a minimum of three rotations can claim a tax deduction of $1,000 per 160 hours of training.

The physicians, who cannot be compensated through any other source, can provide training for a maximum of 10 rotations. Rotations must be in family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics, Ob-Gyn, emergency medicine, psychiatry, or general surgery. Hours can be accrued from multiple programs and students, but the physician must complete three or more of these rotations per year in order to qualify (480 hours.)

As you referenced in your article, this Preceptor Tax Incentive Program would be a means to encourage preceptorship. Unfortunately, it did not pass for NPs or PAs to be awarded tax credit, but I think it could gain some momentum and can be tried again! One state at a time.

Amy Spearman, CRNP

Huntsville, AL

FOR MORE LETTERS TO THE EDITOR:

Do Veteran PAs Care Less, Or Are New PA Students Careless?

Has the Bar Been Lowered for RN/NP Programs?

Insurance and Billing Qualms Double the Work

Precepting: I Love It, But ...

In follow-up to Dr. Danielsen’s mention of a tax incentive program in Georgia, here is more detail from the United Advanced Practice Registered Nurses of Georgia website:

“Gov. Nathan Deal signed into law April 15, 2014, legislation that creates tax deductions of up to $10,000 per year for physicians who provide training to medical, physician assistant, and nurse practitioner students.”

Georgia physicians (MDs and DOs) who clinically train health profession students (enrolled in in-state public or private medical/osteopathic, PA or NP programs) for a minimum of three rotations can claim a tax deduction of $1,000 per 160 hours of training.

The physicians, who cannot be compensated through any other source, can provide training for a maximum of 10 rotations. Rotations must be in family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics, Ob-Gyn, emergency medicine, psychiatry, or general surgery. Hours can be accrued from multiple programs and students, but the physician must complete three or more of these rotations per year in order to qualify (480 hours.)

As you referenced in your article, this Preceptor Tax Incentive Program would be a means to encourage preceptorship. Unfortunately, it did not pass for NPs or PAs to be awarded tax credit, but I think it could gain some momentum and can be tried again! One state at a time.

Amy Spearman, CRNP

Huntsville, AL

FOR MORE LETTERS TO THE EDITOR:

Do Veteran PAs Care Less, Or Are New PA Students Careless?

Has the Bar Been Lowered for RN/NP Programs?

Insurance and Billing Qualms Double the Work

Precepting: I Love It, But ...

A valuable string of PURLs

Since JFP’s launch of the PURL department in November of 2007, 122 PURLs—Priority Updates from the Research Literature—have been published. The Journal of Family Practice is the exclusive publication venue for these items. Because they have stood the test of time and are one of the more popular columns in JFP, I thought it would be worthwhile to describe the rigorous evaluation they undergo before they are published.

Many studies, but few PURLs. Each year, approximately 200,000 new human medical research studies are indexed on PubMed. Very few of these studies are pertinent to family medicine, however, and even fewer provide new patient-oriented evidence for primary care clinicians.

In 2005, the leaders of the Family Physician Inquiries Network (FPIN), which produces another popular JFP column, Clinical Inquiries, set about identifying high-priority research findings relevant to family medicine. A group of family physicians and librarians began combing the research literature monthly to find those rare randomized trials or high-quality observational studies that pertained to our specialty. To qualify as a PURL, a study had to meet 6 criteria. It had to be scientifically valid, relevant to family medicine, applicable in a medical care setting, immediately implementable, clinically meaningful, and practice changing. These criteria still stand today.

Making the cut. When a study is identified as a potential PURL, it is submitted to one of FPIN’s PURL review groups for a critical appraisal and rigorous peer review. If the group cannot convince the PURLs editors that the original research meets all 6 criteria, the study falls by the wayside. Most potential PURLs do not make the cut. I was one of the early PURL “divers,” and I was amazed at how few PURLs existed. Given the emphasis of research on subspecialties and the dearth of primary care research funding in the United States, I probably shouldn’t have been surprised.

Holding their value. I reviewed all 122 PURLs this week and am proud to say that nearly all still provide highly pertinent, practice-changing information for family physicians and other primary care clinicians. For a quick review of our string of PURLs, go to www.jfponline.com, select “Articles” in the banner, and then “PURLs,” and read the short practice changer box for each one. I guarantee it will be time well spent!

If you would like to become part of the PURLs process, either by nominating or reviewing a PURL, please contact the PURLs Project Manager at [email protected].

Since JFP’s launch of the PURL department in November of 2007, 122 PURLs—Priority Updates from the Research Literature—have been published. The Journal of Family Practice is the exclusive publication venue for these items. Because they have stood the test of time and are one of the more popular columns in JFP, I thought it would be worthwhile to describe the rigorous evaluation they undergo before they are published.

Many studies, but few PURLs. Each year, approximately 200,000 new human medical research studies are indexed on PubMed. Very few of these studies are pertinent to family medicine, however, and even fewer provide new patient-oriented evidence for primary care clinicians.

In 2005, the leaders of the Family Physician Inquiries Network (FPIN), which produces another popular JFP column, Clinical Inquiries, set about identifying high-priority research findings relevant to family medicine. A group of family physicians and librarians began combing the research literature monthly to find those rare randomized trials or high-quality observational studies that pertained to our specialty. To qualify as a PURL, a study had to meet 6 criteria. It had to be scientifically valid, relevant to family medicine, applicable in a medical care setting, immediately implementable, clinically meaningful, and practice changing. These criteria still stand today.

Making the cut. When a study is identified as a potential PURL, it is submitted to one of FPIN’s PURL review groups for a critical appraisal and rigorous peer review. If the group cannot convince the PURLs editors that the original research meets all 6 criteria, the study falls by the wayside. Most potential PURLs do not make the cut. I was one of the early PURL “divers,” and I was amazed at how few PURLs existed. Given the emphasis of research on subspecialties and the dearth of primary care research funding in the United States, I probably shouldn’t have been surprised.

Holding their value. I reviewed all 122 PURLs this week and am proud to say that nearly all still provide highly pertinent, practice-changing information for family physicians and other primary care clinicians. For a quick review of our string of PURLs, go to www.jfponline.com, select “Articles” in the banner, and then “PURLs,” and read the short practice changer box for each one. I guarantee it will be time well spent!

If you would like to become part of the PURLs process, either by nominating or reviewing a PURL, please contact the PURLs Project Manager at [email protected].

Since JFP’s launch of the PURL department in November of 2007, 122 PURLs—Priority Updates from the Research Literature—have been published. The Journal of Family Practice is the exclusive publication venue for these items. Because they have stood the test of time and are one of the more popular columns in JFP, I thought it would be worthwhile to describe the rigorous evaluation they undergo before they are published.

Many studies, but few PURLs. Each year, approximately 200,000 new human medical research studies are indexed on PubMed. Very few of these studies are pertinent to family medicine, however, and even fewer provide new patient-oriented evidence for primary care clinicians.

In 2005, the leaders of the Family Physician Inquiries Network (FPIN), which produces another popular JFP column, Clinical Inquiries, set about identifying high-priority research findings relevant to family medicine. A group of family physicians and librarians began combing the research literature monthly to find those rare randomized trials or high-quality observational studies that pertained to our specialty. To qualify as a PURL, a study had to meet 6 criteria. It had to be scientifically valid, relevant to family medicine, applicable in a medical care setting, immediately implementable, clinically meaningful, and practice changing. These criteria still stand today.

Making the cut. When a study is identified as a potential PURL, it is submitted to one of FPIN’s PURL review groups for a critical appraisal and rigorous peer review. If the group cannot convince the PURLs editors that the original research meets all 6 criteria, the study falls by the wayside. Most potential PURLs do not make the cut. I was one of the early PURL “divers,” and I was amazed at how few PURLs existed. Given the emphasis of research on subspecialties and the dearth of primary care research funding in the United States, I probably shouldn’t have been surprised.

Holding their value. I reviewed all 122 PURLs this week and am proud to say that nearly all still provide highly pertinent, practice-changing information for family physicians and other primary care clinicians. For a quick review of our string of PURLs, go to www.jfponline.com, select “Articles” in the banner, and then “PURLs,” and read the short practice changer box for each one. I guarantee it will be time well spent!

If you would like to become part of the PURLs process, either by nominating or reviewing a PURL, please contact the PURLs Project Manager at [email protected].

Sharing the lanes

A few weeks ago, Marilyn and I were left in charge of two of our grandchildren, 8 and 10 years old. The morning was overcast and drizzly, eliminating their first choice of going to the college athletic fields to practice their lacrosse skills. A game of Monopoly seemed like a good idea until it became obvious that someone was going to win and that another someone who doesn’t handle defeat very well was going to lose. So off we went to the bowling alley. As we pulled into the sparsely occupied parking lot, the ever-observant 8-year-old noted that almost all of the vehicles were vans.

As we checked in to rent our shoes, the explanation for the vans became clear. It turns out that on Thursday mornings, the bowling alley is the place to be if you are an adult with a mental disability in Brunswick, Maine.

Our grandchildren had a wonderful hour of bowling surrounded by the cacophony created by the several dozen adults with whom we were sharing the lanes. As my wife and I revisited our morning adventure that evening, we recalled how comfortable our grandchildren had been in the midst of a scenario that had the chaotic feel of a Hieronymus Bosch painting.

The explanation for their lack of discomfort lies in the fact that they have grown up in a time and in a town in which the individuals with chromosomal anomalies and birth injury are accepted and cared for in the community and not hidden away in an institution. Our grandchildren’s parents were born as this sea change was just beginning. In fact, when my son was born, I was moonlighting as the night emergency physician at an institution that housed a few hundred of these individuals, many of whom had disabilities similar to those of the folks with whom we had shared the bowling alley. It closed a few years later. And, by the time my son and his sisters entered middle school, they had become accustomed to having classmates with mental disabilities.

The next step in the evolution came when the children who had been “mainstreamed” grew too old for high school and began transitioning to the handful of small group homes that sprang up around the community. It was not always a smooth process and would not have happened without tireless pressure from their parents. Even today, funding and staffing problems continue. Despite initial concerns that some neighborhoods might resist the introduction of a group home, acceptance has not been a problem.

It has almost been a win-win situation. Our citizens with mental disabilities have a far richer life than they would have had in even the most progressive institution. And the rest of us have benefited by learning tolerance from having our challenged family members close by.

However, the transition from institutionalization to community-based support has not been without its downside, particularly for a small town like Brunswick, Maine. Federal and state mandates now place on the shoulders of the school a significant financial burden for the special services required by children with mental disabilities. Small communities with only a few students with disabilities can’t benefit from the economies of scale that allow larger school systems to staff their programs more efficiently and provide more specialized services. Smaller school districts can sometimes pool their resources. But if this solution necessitates transporting the students with mental disabilities out of their own school district to a central location, it runs the risk of robbing the other students, like my grandchildren, of an enriching experience that I wouldn’t want to see them lose.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

A few weeks ago, Marilyn and I were left in charge of two of our grandchildren, 8 and 10 years old. The morning was overcast and drizzly, eliminating their first choice of going to the college athletic fields to practice their lacrosse skills. A game of Monopoly seemed like a good idea until it became obvious that someone was going to win and that another someone who doesn’t handle defeat very well was going to lose. So off we went to the bowling alley. As we pulled into the sparsely occupied parking lot, the ever-observant 8-year-old noted that almost all of the vehicles were vans.

As we checked in to rent our shoes, the explanation for the vans became clear. It turns out that on Thursday mornings, the bowling alley is the place to be if you are an adult with a mental disability in Brunswick, Maine.

Our grandchildren had a wonderful hour of bowling surrounded by the cacophony created by the several dozen adults with whom we were sharing the lanes. As my wife and I revisited our morning adventure that evening, we recalled how comfortable our grandchildren had been in the midst of a scenario that had the chaotic feel of a Hieronymus Bosch painting.

The explanation for their lack of discomfort lies in the fact that they have grown up in a time and in a town in which the individuals with chromosomal anomalies and birth injury are accepted and cared for in the community and not hidden away in an institution. Our grandchildren’s parents were born as this sea change was just beginning. In fact, when my son was born, I was moonlighting as the night emergency physician at an institution that housed a few hundred of these individuals, many of whom had disabilities similar to those of the folks with whom we had shared the bowling alley. It closed a few years later. And, by the time my son and his sisters entered middle school, they had become accustomed to having classmates with mental disabilities.

The next step in the evolution came when the children who had been “mainstreamed” grew too old for high school and began transitioning to the handful of small group homes that sprang up around the community. It was not always a smooth process and would not have happened without tireless pressure from their parents. Even today, funding and staffing problems continue. Despite initial concerns that some neighborhoods might resist the introduction of a group home, acceptance has not been a problem.

It has almost been a win-win situation. Our citizens with mental disabilities have a far richer life than they would have had in even the most progressive institution. And the rest of us have benefited by learning tolerance from having our challenged family members close by.

However, the transition from institutionalization to community-based support has not been without its downside, particularly for a small town like Brunswick, Maine. Federal and state mandates now place on the shoulders of the school a significant financial burden for the special services required by children with mental disabilities. Small communities with only a few students with disabilities can’t benefit from the economies of scale that allow larger school systems to staff their programs more efficiently and provide more specialized services. Smaller school districts can sometimes pool their resources. But if this solution necessitates transporting the students with mental disabilities out of their own school district to a central location, it runs the risk of robbing the other students, like my grandchildren, of an enriching experience that I wouldn’t want to see them lose.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

A few weeks ago, Marilyn and I were left in charge of two of our grandchildren, 8 and 10 years old. The morning was overcast and drizzly, eliminating their first choice of going to the college athletic fields to practice their lacrosse skills. A game of Monopoly seemed like a good idea until it became obvious that someone was going to win and that another someone who doesn’t handle defeat very well was going to lose. So off we went to the bowling alley. As we pulled into the sparsely occupied parking lot, the ever-observant 8-year-old noted that almost all of the vehicles were vans.

As we checked in to rent our shoes, the explanation for the vans became clear. It turns out that on Thursday mornings, the bowling alley is the place to be if you are an adult with a mental disability in Brunswick, Maine.

Our grandchildren had a wonderful hour of bowling surrounded by the cacophony created by the several dozen adults with whom we were sharing the lanes. As my wife and I revisited our morning adventure that evening, we recalled how comfortable our grandchildren had been in the midst of a scenario that had the chaotic feel of a Hieronymus Bosch painting.

The explanation for their lack of discomfort lies in the fact that they have grown up in a time and in a town in which the individuals with chromosomal anomalies and birth injury are accepted and cared for in the community and not hidden away in an institution. Our grandchildren’s parents were born as this sea change was just beginning. In fact, when my son was born, I was moonlighting as the night emergency physician at an institution that housed a few hundred of these individuals, many of whom had disabilities similar to those of the folks with whom we had shared the bowling alley. It closed a few years later. And, by the time my son and his sisters entered middle school, they had become accustomed to having classmates with mental disabilities.

The next step in the evolution came when the children who had been “mainstreamed” grew too old for high school and began transitioning to the handful of small group homes that sprang up around the community. It was not always a smooth process and would not have happened without tireless pressure from their parents. Even today, funding and staffing problems continue. Despite initial concerns that some neighborhoods might resist the introduction of a group home, acceptance has not been a problem.

It has almost been a win-win situation. Our citizens with mental disabilities have a far richer life than they would have had in even the most progressive institution. And the rest of us have benefited by learning tolerance from having our challenged family members close by.

However, the transition from institutionalization to community-based support has not been without its downside, particularly for a small town like Brunswick, Maine. Federal and state mandates now place on the shoulders of the school a significant financial burden for the special services required by children with mental disabilities. Small communities with only a few students with disabilities can’t benefit from the economies of scale that allow larger school systems to staff their programs more efficiently and provide more specialized services. Smaller school districts can sometimes pool their resources. But if this solution necessitates transporting the students with mental disabilities out of their own school district to a central location, it runs the risk of robbing the other students, like my grandchildren, of an enriching experience that I wouldn’t want to see them lose.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Coldiron Truth: Office safety

Wait, I know what you’re thinking, boring, dry, and don’t scold me. I am not going to do any of that today, and instead am going to tell you how to easily improve patient care, save money, and improve staff morale.

The easiest things to do to improve safety in the office include better communications, infection control, correct patient/site identification, dealing with emergencies, and staff safety.

Staff communication is often surprisingly poor, and physicians often assume staff can read our minds (and if they have worked for you for many years, maybe they can!). Always make sure staff – and patients – repeat back complicated instructions (better to start by making them less complicated). Never assume your patients are literate, 14% of adults cannot read, so make sure your staff goes over printed materials with the patients.

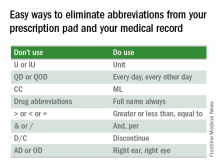

Something easy you can do is eliminate abbreviations from your prescription pad and your medical record.

Failure to follow up on path reports and lost biopsies is a frequent cause for lawsuits. You need to make sure you have a redundant system for tracking and reporting pathology results. In addition to the old reliable pathology log book, you need a sequential system ensuring that the specimen made it to the lab, that the result was generated and received, that the patient was notified, and that further action was taken if needed. If this is integrated into your electronic medical record, so much the better, but you still need a paper backup log book, “just in case.”

We all take basic infection precautions when performing procedures, including alcohol hand gel, eye protection, gloves, mask, and cleaning of surgical sites prior to excision. When there are wound infections, which should be rare, you should always culture, and if there is a cluster of infections, particularly with methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), you should consider culturing the anterior nares of the staff. Alternatively, you can preemptively treat the staff with intranasal topical mupirocin daily for 2 weeks.

Measuring the use of alcohol gel before and after staff education is an easy and beneficial quality improvement project. You and your staff are, of course, vaccinated for hepatitis B, and yearly for influenza, and you should consider PPD testing every 2 years for everyone. My asymptomatic receptionist converted, and needed prophylactic tuberculosis treatment and contact tracing.

Wrong-site surgery is a frequent problem for dermatologists. Many of our biopsies are tangential, heal almost invisibly, without marking sutures, and patients have battle-scarred skin, and are elderly. The patients may have trouble remembering or seeing where the biopsy was, so good charts and family members are helpful. Photographs of the biopsy sites can be priceless. If the site still cannot be identified, then rebiopsy, or close follow-up is indicated.

Emergencies are rare, but it is prudent to have an automatic external defibrillator in the office. These are automated, so Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support (ACLS), or even basic CPR is not required to operate them, and the survival rate after cardiac arrest increases from 2% to 50%. When it has to be replaced after 5 years, take the old one home and teach your spouse how to use it, and maybe they will.

If you do a lot of surgery you may want to get the ACLS training and buy the crash cart drug kit, but many of the drugs have become ferociously expensive, despite being generic.

Staff safety is a crucial consideration and showing concern boosts staff morale. You should dispose of sharps directly into a sharps container and remove the sharps from the tray at the end of the case. You should have a written protocol for needle sticks. I keep the red top tubes, and the first 2 days of HIV medication on site. Sometimes a patient is HIV positive, the sharp exposure is unknown (a cryostat tissue tease for example), or the patient refuses to have their blood drawn. Less obvious, but important to staff, are locks on doors, alarm systems, good parking lot lighting, and security cameras.

Office safety may seem mundane but a few simple measures can save you a fortune, boost employee morale, and most important of all, improve patient care.

Dr. Coldiron is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. He is currently in private practice, but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics.

Wait, I know what you’re thinking, boring, dry, and don’t scold me. I am not going to do any of that today, and instead am going to tell you how to easily improve patient care, save money, and improve staff morale.

The easiest things to do to improve safety in the office include better communications, infection control, correct patient/site identification, dealing with emergencies, and staff safety.

Staff communication is often surprisingly poor, and physicians often assume staff can read our minds (and if they have worked for you for many years, maybe they can!). Always make sure staff – and patients – repeat back complicated instructions (better to start by making them less complicated). Never assume your patients are literate, 14% of adults cannot read, so make sure your staff goes over printed materials with the patients.

Something easy you can do is eliminate abbreviations from your prescription pad and your medical record.

Failure to follow up on path reports and lost biopsies is a frequent cause for lawsuits. You need to make sure you have a redundant system for tracking and reporting pathology results. In addition to the old reliable pathology log book, you need a sequential system ensuring that the specimen made it to the lab, that the result was generated and received, that the patient was notified, and that further action was taken if needed. If this is integrated into your electronic medical record, so much the better, but you still need a paper backup log book, “just in case.”

We all take basic infection precautions when performing procedures, including alcohol hand gel, eye protection, gloves, mask, and cleaning of surgical sites prior to excision. When there are wound infections, which should be rare, you should always culture, and if there is a cluster of infections, particularly with methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), you should consider culturing the anterior nares of the staff. Alternatively, you can preemptively treat the staff with intranasal topical mupirocin daily for 2 weeks.

Measuring the use of alcohol gel before and after staff education is an easy and beneficial quality improvement project. You and your staff are, of course, vaccinated for hepatitis B, and yearly for influenza, and you should consider PPD testing every 2 years for everyone. My asymptomatic receptionist converted, and needed prophylactic tuberculosis treatment and contact tracing.

Wrong-site surgery is a frequent problem for dermatologists. Many of our biopsies are tangential, heal almost invisibly, without marking sutures, and patients have battle-scarred skin, and are elderly. The patients may have trouble remembering or seeing where the biopsy was, so good charts and family members are helpful. Photographs of the biopsy sites can be priceless. If the site still cannot be identified, then rebiopsy, or close follow-up is indicated.

Emergencies are rare, but it is prudent to have an automatic external defibrillator in the office. These are automated, so Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support (ACLS), or even basic CPR is not required to operate them, and the survival rate after cardiac arrest increases from 2% to 50%. When it has to be replaced after 5 years, take the old one home and teach your spouse how to use it, and maybe they will.

If you do a lot of surgery you may want to get the ACLS training and buy the crash cart drug kit, but many of the drugs have become ferociously expensive, despite being generic.

Staff safety is a crucial consideration and showing concern boosts staff morale. You should dispose of sharps directly into a sharps container and remove the sharps from the tray at the end of the case. You should have a written protocol for needle sticks. I keep the red top tubes, and the first 2 days of HIV medication on site. Sometimes a patient is HIV positive, the sharp exposure is unknown (a cryostat tissue tease for example), or the patient refuses to have their blood drawn. Less obvious, but important to staff, are locks on doors, alarm systems, good parking lot lighting, and security cameras.

Office safety may seem mundane but a few simple measures can save you a fortune, boost employee morale, and most important of all, improve patient care.

Dr. Coldiron is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. He is currently in private practice, but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics.

Wait, I know what you’re thinking, boring, dry, and don’t scold me. I am not going to do any of that today, and instead am going to tell you how to easily improve patient care, save money, and improve staff morale.

The easiest things to do to improve safety in the office include better communications, infection control, correct patient/site identification, dealing with emergencies, and staff safety.

Staff communication is often surprisingly poor, and physicians often assume staff can read our minds (and if they have worked for you for many years, maybe they can!). Always make sure staff – and patients – repeat back complicated instructions (better to start by making them less complicated). Never assume your patients are literate, 14% of adults cannot read, so make sure your staff goes over printed materials with the patients.

Something easy you can do is eliminate abbreviations from your prescription pad and your medical record.

Failure to follow up on path reports and lost biopsies is a frequent cause for lawsuits. You need to make sure you have a redundant system for tracking and reporting pathology results. In addition to the old reliable pathology log book, you need a sequential system ensuring that the specimen made it to the lab, that the result was generated and received, that the patient was notified, and that further action was taken if needed. If this is integrated into your electronic medical record, so much the better, but you still need a paper backup log book, “just in case.”

We all take basic infection precautions when performing procedures, including alcohol hand gel, eye protection, gloves, mask, and cleaning of surgical sites prior to excision. When there are wound infections, which should be rare, you should always culture, and if there is a cluster of infections, particularly with methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), you should consider culturing the anterior nares of the staff. Alternatively, you can preemptively treat the staff with intranasal topical mupirocin daily for 2 weeks.

Measuring the use of alcohol gel before and after staff education is an easy and beneficial quality improvement project. You and your staff are, of course, vaccinated for hepatitis B, and yearly for influenza, and you should consider PPD testing every 2 years for everyone. My asymptomatic receptionist converted, and needed prophylactic tuberculosis treatment and contact tracing.

Wrong-site surgery is a frequent problem for dermatologists. Many of our biopsies are tangential, heal almost invisibly, without marking sutures, and patients have battle-scarred skin, and are elderly. The patients may have trouble remembering or seeing where the biopsy was, so good charts and family members are helpful. Photographs of the biopsy sites can be priceless. If the site still cannot be identified, then rebiopsy, or close follow-up is indicated.

Emergencies are rare, but it is prudent to have an automatic external defibrillator in the office. These are automated, so Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support (ACLS), or even basic CPR is not required to operate them, and the survival rate after cardiac arrest increases from 2% to 50%. When it has to be replaced after 5 years, take the old one home and teach your spouse how to use it, and maybe they will.

If you do a lot of surgery you may want to get the ACLS training and buy the crash cart drug kit, but many of the drugs have become ferociously expensive, despite being generic.

Staff safety is a crucial consideration and showing concern boosts staff morale. You should dispose of sharps directly into a sharps container and remove the sharps from the tray at the end of the case. You should have a written protocol for needle sticks. I keep the red top tubes, and the first 2 days of HIV medication on site. Sometimes a patient is HIV positive, the sharp exposure is unknown (a cryostat tissue tease for example), or the patient refuses to have their blood drawn. Less obvious, but important to staff, are locks on doors, alarm systems, good parking lot lighting, and security cameras.

Office safety may seem mundane but a few simple measures can save you a fortune, boost employee morale, and most important of all, improve patient care.

Dr. Coldiron is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. He is currently in private practice, but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics.

Smooth hair – an acne-causing epidemic

Do you ask your acne patients about which hair products they use? This common question has recently brought our attention to popular hair products that are causing an acne epidemic. Have we forgotten about “Pomade acne”? Well, it’s making a comeback. Originally described in ethnic women, new frizz-fighting hair products have resurged and so has pomade acne in all skin types and in both men and women.

Smoothing serums, heat styling sprays, leave-in products popularly known as “It’s-a-10,” “Biosilk,” “anti-frizz serums,” “heat-protectants,” “thermal setting sprays,” and “shine sprays,” contain silicone-derived ingredients and oils to control frizz, add shine, and detangle the hair. They work by smoothing the hair cuticle, and for women with difficult-to-manage hair, they have become an essential part of the daily beauty regimen.

Men are not in the clear either. Hair waxes and pomades used to style men’s hair contain greasy wax-based ingredients that also clog pores, trap bacteria, and cause inflammatory breakouts.

As a general rule in skin and body care, most products work well for what they are made to do, but when misused, they can cause mishaps. You wouldn’t moisturize your face with your hair serum would you? It seems obvious that this could cause some skin issues; however, most people will not think to correlate their acne breakouts with their hair products until we mention it. These products rub off on the face or on the pillow at night. In addition, the less we wash our hair, the more we are going to bed and getting the daytime products all over our pillowcases. Our faces are rolling around in oily, waxy, hair products all night.

Makeup is known to cause acne, and some of the makeups that are well known culprits contain the same ingredients as in hair products. Foundations, primers, and popular “BB” creams often contain cyclopentasiloxane and dimethicone. They serve a similar purpose: smoothing the skin and smoothing the hair. Both should be avoided in acne-prone patients.

Common culprits in hair products include PVP/DMAPA acrylates, cyclopentasiloxane, panthenol, dimethicone, silicone, Quaternium-70, oils, and petrolatum.

The only way to eliminate acne caused by hair products is to completely eliminate the hair product from the daily routine. However, if your patients can’t live without their hair products, here are some tips to share with them to reduce breakouts:

• Choose a hairstyle that keeps the hair away from the face, or wear hair up to avoid prolonged contact with the face, particularly while sleeping.

• Change pillowcase often (every day if possible), especially for side sleepers. Regardless of the fabric, pillowcases trap oil, dirt, and bacteria.

• Shower at night and sleep with clean hair and clean skin.

• Style hair before applying makeup. Wash hands thoroughly to remove all hair products before touching the skin.

• Cover the face prior to applying any hair sprays.

• Cover the hair at bedtime; however, tight head coverings can stimulate sweat and cause scalp breakouts.

As a general rule, any patient with difficult-to-control acne, recalcitrant acne, or acne in areas on the cheeks or hairline should eliminate these hair products in their daily routine or avoid skin contact with these products.

References

1. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010 Apr;3(4):24-38.

2. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106 (6):843-50.

3. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003; 48:S127-33.

4. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101(5):580-584.

5. “Cosmetics in Dermatology,” Second Edition, by Zoe Diana Draelos (New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1995).

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub.

Do you ask your acne patients about which hair products they use? This common question has recently brought our attention to popular hair products that are causing an acne epidemic. Have we forgotten about “Pomade acne”? Well, it’s making a comeback. Originally described in ethnic women, new frizz-fighting hair products have resurged and so has pomade acne in all skin types and in both men and women.

Smoothing serums, heat styling sprays, leave-in products popularly known as “It’s-a-10,” “Biosilk,” “anti-frizz serums,” “heat-protectants,” “thermal setting sprays,” and “shine sprays,” contain silicone-derived ingredients and oils to control frizz, add shine, and detangle the hair. They work by smoothing the hair cuticle, and for women with difficult-to-manage hair, they have become an essential part of the daily beauty regimen.

Men are not in the clear either. Hair waxes and pomades used to style men’s hair contain greasy wax-based ingredients that also clog pores, trap bacteria, and cause inflammatory breakouts.

As a general rule in skin and body care, most products work well for what they are made to do, but when misused, they can cause mishaps. You wouldn’t moisturize your face with your hair serum would you? It seems obvious that this could cause some skin issues; however, most people will not think to correlate their acne breakouts with their hair products until we mention it. These products rub off on the face or on the pillow at night. In addition, the less we wash our hair, the more we are going to bed and getting the daytime products all over our pillowcases. Our faces are rolling around in oily, waxy, hair products all night.

Makeup is known to cause acne, and some of the makeups that are well known culprits contain the same ingredients as in hair products. Foundations, primers, and popular “BB” creams often contain cyclopentasiloxane and dimethicone. They serve a similar purpose: smoothing the skin and smoothing the hair. Both should be avoided in acne-prone patients.

Common culprits in hair products include PVP/DMAPA acrylates, cyclopentasiloxane, panthenol, dimethicone, silicone, Quaternium-70, oils, and petrolatum.

The only way to eliminate acne caused by hair products is to completely eliminate the hair product from the daily routine. However, if your patients can’t live without their hair products, here are some tips to share with them to reduce breakouts:

• Choose a hairstyle that keeps the hair away from the face, or wear hair up to avoid prolonged contact with the face, particularly while sleeping.

• Change pillowcase often (every day if possible), especially for side sleepers. Regardless of the fabric, pillowcases trap oil, dirt, and bacteria.

• Shower at night and sleep with clean hair and clean skin.

• Style hair before applying makeup. Wash hands thoroughly to remove all hair products before touching the skin.

• Cover the face prior to applying any hair sprays.

• Cover the hair at bedtime; however, tight head coverings can stimulate sweat and cause scalp breakouts.

As a general rule, any patient with difficult-to-control acne, recalcitrant acne, or acne in areas on the cheeks or hairline should eliminate these hair products in their daily routine or avoid skin contact with these products.

References

1. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010 Apr;3(4):24-38.

2. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106 (6):843-50.

3. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003; 48:S127-33.

4. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101(5):580-584.

5. “Cosmetics in Dermatology,” Second Edition, by Zoe Diana Draelos (New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1995).