User login

Try to Remember …

How often do you misplace your keys or forget why you walked into a room? When I was younger, I dismissed things such as losing my train of thought (my nephew calls that a brain fart), a neglected errand (probably not important enough), or getting lost trying to go somewhere (never was good at directions anyway).

Know that I was never a “list maker.” I gave that up—because I often could not remember where I’d put it. Usually, once I wrote something down, I would eventually (in the same day) recall whatever was on it, so I wouldn’t fret about where I left that list.

Names? I could always tell you where we met, what you were wearing, and where you were sitting. But your name? Forget about it. (Those who have met me know the truth in that statement!)

During particularly stressful or busy times, if I found myself a bit more “absentminded” than usual, I would joke, “Of all the things I’ve lost, I miss my mind the most.”

Now I wonder: Just how serious are those instances of memory lapse? Yes, occasional memory lapses are part of normal aging. Just like our joints, our brains are not as young as they used to be. Even a 90-year-old with a healthy brain has experienced a loss of 10% brain cell volume.1 And let’s be honest, in celebrating major accomplishments (or failures), some of us have killed a few additional brain cells along the way (wink, wink).

We know that as we age, just as our stride has slowed, so too has the sharpness of our recall dulled. However, at what point are those misfires of our brain no longer a minor nuisance?

Data from the Administration on Aging document that in 2013, an estimated 44.7 million US residents were 65 or older.2 An estimated 5 million of them had Alzheimer disease. That translates to one in nine people—scary! This number, researchers predict, will increase to 13.8 million by 2050.3

Moreover, these statistics become more startling as we recognize that the cost of providing long-term and hospice care to people with Alzheimer disease (and other forms of dementia) is estimated to increase from $203 billion in 2013 to $1.2 trillion in 2050 (in 2013 dollars).4 Therefore, it is imperative for us, both as individuals and as health care professionals, to know the warning signs of dementia and be attentive to even seemingly subtle changes in behavior.

Early recognition that these changes are more than minor lapses in memory is important. Delays in diagnosis can result in a reduction of access to available treatments and resources. Yet, at what point do we start to consider those minor instances of forgetfulness not as normal but as indications of developing cognitive problems? My colleagues in gerontology tell us it is when those changes negatively affect activities of daily living and ability to function.

Continue for the difference between my lifelong “geographic handicap” and a form of dementia >>

What is the difference between my lifelong “geographic handicap” and a form of dementia? Would I (or any of my family or friends) recognize it? The diagnosis of dementia is not based on a sole symptom; rather, it requires the existence of at least two types of impairment that are significant and interfere with daily life.

Thankfully, I have adjusted to being “temporarily misplaced” (I don’t call it lost) and smiling at you whilst I try to remember your name. It may seem I jest or am insensitive to a grave health issue—but I am very serious about our need to pay attention to ourselves, to those we care for, and to those we care about (including neighbors). I now live in an area where a “silver alert” (missing elder) is an almost daily occurrence.

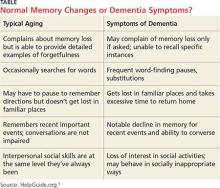

The table provides a comparison of normal-aging memory changes versus dementia symptoms; this is a tool we can use in practice and provide to our patients and their families.5 However, when changes in memory become so pervasive and severe that they are disrupting work, hobbies, social activities, and family relationships, we must recognize that they are the warning signs of Alzheimer disease.6 After reading multiple reports and guides, and witnessing the disease progression in neighbors, I share the three most significant hallmarks of the disease: impaired judgment, difficulty in recalling new information, and unusual behavior.7

It is important to remember—and to communicate to our patients—that memory loss itself does not meet the criteria for dementia. While some may be quick to fear that diagnosis, other factors that can contribute to cognitive problems are stress, depression, vitamin deficiency, thyroid disease, and even dehydration. All of these can be managed, with a resultant reversal of symptoms of memory loss.8 As always, a good health history, review of symptoms, and physical examination will guide us to an accurate diagnosis and plan of care.

There are multiple resources available for patients and families who receive a diagnosis of dementia or Alzheimer disease. Fear of the diagnosis need not blind us to the early warning signs. As NPs and PAs, despite our busy schedules, we must stop and listen to both the patient and the family, and ask the difficult questions about judgment and behavior in our aging patients.

REFERENCES

1. Doty L. Caregiving topics: early signs of dementia. http://alzonline.phhp.ufl.edu/en/reading/EarlySignsFeb08.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2015.

2. CDC. Older persons’ health. www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/older-american-health.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

3. Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DL. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology. 2013;80:1778-1783.

4. Alzheimer’s Association. 2013 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(2):20-245.

5. Wayne M, White M, Smith M. Understanding dementia. www.helpguide.org/articles/alzheimers-dementia/understanding-dementia.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

6. Smith M, Robinson L, Segal R. Age-related memory loss. www.helpguide.org/articles/memory/age-related-memory-loss.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

7. A guide to coping with Alzheimer’s disease: a Harvard Medical School Special Health Report. www.health.harvard.edu/special-health-reports/a-guide-to-coping-with-alzheimers-disease. Accessed December 11, 2015.

8. HelpGuide.org. What’s causing your memory loss? www.helpguide.org/harvard/whats-causing-your-memory-loss.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

How often do you misplace your keys or forget why you walked into a room? When I was younger, I dismissed things such as losing my train of thought (my nephew calls that a brain fart), a neglected errand (probably not important enough), or getting lost trying to go somewhere (never was good at directions anyway).

Know that I was never a “list maker.” I gave that up—because I often could not remember where I’d put it. Usually, once I wrote something down, I would eventually (in the same day) recall whatever was on it, so I wouldn’t fret about where I left that list.

Names? I could always tell you where we met, what you were wearing, and where you were sitting. But your name? Forget about it. (Those who have met me know the truth in that statement!)

During particularly stressful or busy times, if I found myself a bit more “absentminded” than usual, I would joke, “Of all the things I’ve lost, I miss my mind the most.”

Now I wonder: Just how serious are those instances of memory lapse? Yes, occasional memory lapses are part of normal aging. Just like our joints, our brains are not as young as they used to be. Even a 90-year-old with a healthy brain has experienced a loss of 10% brain cell volume.1 And let’s be honest, in celebrating major accomplishments (or failures), some of us have killed a few additional brain cells along the way (wink, wink).

We know that as we age, just as our stride has slowed, so too has the sharpness of our recall dulled. However, at what point are those misfires of our brain no longer a minor nuisance?

Data from the Administration on Aging document that in 2013, an estimated 44.7 million US residents were 65 or older.2 An estimated 5 million of them had Alzheimer disease. That translates to one in nine people—scary! This number, researchers predict, will increase to 13.8 million by 2050.3

Moreover, these statistics become more startling as we recognize that the cost of providing long-term and hospice care to people with Alzheimer disease (and other forms of dementia) is estimated to increase from $203 billion in 2013 to $1.2 trillion in 2050 (in 2013 dollars).4 Therefore, it is imperative for us, both as individuals and as health care professionals, to know the warning signs of dementia and be attentive to even seemingly subtle changes in behavior.

Early recognition that these changes are more than minor lapses in memory is important. Delays in diagnosis can result in a reduction of access to available treatments and resources. Yet, at what point do we start to consider those minor instances of forgetfulness not as normal but as indications of developing cognitive problems? My colleagues in gerontology tell us it is when those changes negatively affect activities of daily living and ability to function.

Continue for the difference between my lifelong “geographic handicap” and a form of dementia >>

What is the difference between my lifelong “geographic handicap” and a form of dementia? Would I (or any of my family or friends) recognize it? The diagnosis of dementia is not based on a sole symptom; rather, it requires the existence of at least two types of impairment that are significant and interfere with daily life.

Thankfully, I have adjusted to being “temporarily misplaced” (I don’t call it lost) and smiling at you whilst I try to remember your name. It may seem I jest or am insensitive to a grave health issue—but I am very serious about our need to pay attention to ourselves, to those we care for, and to those we care about (including neighbors). I now live in an area where a “silver alert” (missing elder) is an almost daily occurrence.

The table provides a comparison of normal-aging memory changes versus dementia symptoms; this is a tool we can use in practice and provide to our patients and their families.5 However, when changes in memory become so pervasive and severe that they are disrupting work, hobbies, social activities, and family relationships, we must recognize that they are the warning signs of Alzheimer disease.6 After reading multiple reports and guides, and witnessing the disease progression in neighbors, I share the three most significant hallmarks of the disease: impaired judgment, difficulty in recalling new information, and unusual behavior.7

It is important to remember—and to communicate to our patients—that memory loss itself does not meet the criteria for dementia. While some may be quick to fear that diagnosis, other factors that can contribute to cognitive problems are stress, depression, vitamin deficiency, thyroid disease, and even dehydration. All of these can be managed, with a resultant reversal of symptoms of memory loss.8 As always, a good health history, review of symptoms, and physical examination will guide us to an accurate diagnosis and plan of care.

There are multiple resources available for patients and families who receive a diagnosis of dementia or Alzheimer disease. Fear of the diagnosis need not blind us to the early warning signs. As NPs and PAs, despite our busy schedules, we must stop and listen to both the patient and the family, and ask the difficult questions about judgment and behavior in our aging patients.

REFERENCES

1. Doty L. Caregiving topics: early signs of dementia. http://alzonline.phhp.ufl.edu/en/reading/EarlySignsFeb08.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2015.

2. CDC. Older persons’ health. www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/older-american-health.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

3. Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DL. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology. 2013;80:1778-1783.

4. Alzheimer’s Association. 2013 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(2):20-245.

5. Wayne M, White M, Smith M. Understanding dementia. www.helpguide.org/articles/alzheimers-dementia/understanding-dementia.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

6. Smith M, Robinson L, Segal R. Age-related memory loss. www.helpguide.org/articles/memory/age-related-memory-loss.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

7. A guide to coping with Alzheimer’s disease: a Harvard Medical School Special Health Report. www.health.harvard.edu/special-health-reports/a-guide-to-coping-with-alzheimers-disease. Accessed December 11, 2015.

8. HelpGuide.org. What’s causing your memory loss? www.helpguide.org/harvard/whats-causing-your-memory-loss.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

How often do you misplace your keys or forget why you walked into a room? When I was younger, I dismissed things such as losing my train of thought (my nephew calls that a brain fart), a neglected errand (probably not important enough), or getting lost trying to go somewhere (never was good at directions anyway).

Know that I was never a “list maker.” I gave that up—because I often could not remember where I’d put it. Usually, once I wrote something down, I would eventually (in the same day) recall whatever was on it, so I wouldn’t fret about where I left that list.

Names? I could always tell you where we met, what you were wearing, and where you were sitting. But your name? Forget about it. (Those who have met me know the truth in that statement!)

During particularly stressful or busy times, if I found myself a bit more “absentminded” than usual, I would joke, “Of all the things I’ve lost, I miss my mind the most.”

Now I wonder: Just how serious are those instances of memory lapse? Yes, occasional memory lapses are part of normal aging. Just like our joints, our brains are not as young as they used to be. Even a 90-year-old with a healthy brain has experienced a loss of 10% brain cell volume.1 And let’s be honest, in celebrating major accomplishments (or failures), some of us have killed a few additional brain cells along the way (wink, wink).

We know that as we age, just as our stride has slowed, so too has the sharpness of our recall dulled. However, at what point are those misfires of our brain no longer a minor nuisance?

Data from the Administration on Aging document that in 2013, an estimated 44.7 million US residents were 65 or older.2 An estimated 5 million of them had Alzheimer disease. That translates to one in nine people—scary! This number, researchers predict, will increase to 13.8 million by 2050.3

Moreover, these statistics become more startling as we recognize that the cost of providing long-term and hospice care to people with Alzheimer disease (and other forms of dementia) is estimated to increase from $203 billion in 2013 to $1.2 trillion in 2050 (in 2013 dollars).4 Therefore, it is imperative for us, both as individuals and as health care professionals, to know the warning signs of dementia and be attentive to even seemingly subtle changes in behavior.

Early recognition that these changes are more than minor lapses in memory is important. Delays in diagnosis can result in a reduction of access to available treatments and resources. Yet, at what point do we start to consider those minor instances of forgetfulness not as normal but as indications of developing cognitive problems? My colleagues in gerontology tell us it is when those changes negatively affect activities of daily living and ability to function.

Continue for the difference between my lifelong “geographic handicap” and a form of dementia >>

What is the difference between my lifelong “geographic handicap” and a form of dementia? Would I (or any of my family or friends) recognize it? The diagnosis of dementia is not based on a sole symptom; rather, it requires the existence of at least two types of impairment that are significant and interfere with daily life.

Thankfully, I have adjusted to being “temporarily misplaced” (I don’t call it lost) and smiling at you whilst I try to remember your name. It may seem I jest or am insensitive to a grave health issue—but I am very serious about our need to pay attention to ourselves, to those we care for, and to those we care about (including neighbors). I now live in an area where a “silver alert” (missing elder) is an almost daily occurrence.

The table provides a comparison of normal-aging memory changes versus dementia symptoms; this is a tool we can use in practice and provide to our patients and their families.5 However, when changes in memory become so pervasive and severe that they are disrupting work, hobbies, social activities, and family relationships, we must recognize that they are the warning signs of Alzheimer disease.6 After reading multiple reports and guides, and witnessing the disease progression in neighbors, I share the three most significant hallmarks of the disease: impaired judgment, difficulty in recalling new information, and unusual behavior.7

It is important to remember—and to communicate to our patients—that memory loss itself does not meet the criteria for dementia. While some may be quick to fear that diagnosis, other factors that can contribute to cognitive problems are stress, depression, vitamin deficiency, thyroid disease, and even dehydration. All of these can be managed, with a resultant reversal of symptoms of memory loss.8 As always, a good health history, review of symptoms, and physical examination will guide us to an accurate diagnosis and plan of care.

There are multiple resources available for patients and families who receive a diagnosis of dementia or Alzheimer disease. Fear of the diagnosis need not blind us to the early warning signs. As NPs and PAs, despite our busy schedules, we must stop and listen to both the patient and the family, and ask the difficult questions about judgment and behavior in our aging patients.

REFERENCES

1. Doty L. Caregiving topics: early signs of dementia. http://alzonline.phhp.ufl.edu/en/reading/EarlySignsFeb08.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2015.

2. CDC. Older persons’ health. www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/older-american-health.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

3. Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DL. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology. 2013;80:1778-1783.

4. Alzheimer’s Association. 2013 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(2):20-245.

5. Wayne M, White M, Smith M. Understanding dementia. www.helpguide.org/articles/alzheimers-dementia/understanding-dementia.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

6. Smith M, Robinson L, Segal R. Age-related memory loss. www.helpguide.org/articles/memory/age-related-memory-loss.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

7. A guide to coping with Alzheimer’s disease: a Harvard Medical School Special Health Report. www.health.harvard.edu/special-health-reports/a-guide-to-coping-with-alzheimers-disease. Accessed December 11, 2015.

8. HelpGuide.org. What’s causing your memory loss? www.helpguide.org/harvard/whats-causing-your-memory-loss.htm. Accessed December 11, 2015.

Chutzpah

Chutzpah is a Yiddish word that entered American English, joining bagel and nosh. The usual translations of chutzpah – “nerve” or “effrontery” – are correct enough, but leave out the zest implied by chutzpah’s classic case: a man who kills his parents and throws himself on the mercy of the court because he is an orphan.

We all meet patients with chutzpah, which can be amusing, impressive – even breathtaking.

Take for instance the woman who paged me one evening last month. “I visit your nurse for cosmetic stuff,” she said when I called her back. “Your prices for laser hair removal were high, though, so I went to a spa where I could use a Groupon.”

How nice, I thought.

“Anyhow,” she continued, “I went for a treatment at the spa today, and now I have little red bumps all over my thighs. I thought it might be a reaction, and since you are my dermatologist I called to ask what to do.”

Good to be needed.

Then the next week I got another call, this time from a man I hadn’t seen in a long time. “I really like you as a dermatologist,” he began.

“Thank you,” I murmured.

“I saw this spot on my leg that worried me,” he said. “I was going to show it to you, but your office is in an old building, and old buildings don’t agree with me.”

As I scratched my head, he went on. “So I went to another dermatologist who works in a newer building. He did a biopsy and told me I have skin cancer. He said I should have surgery to take it off. I consider you my dermatologist, though, so I called to ask whether you think surgery is a good idea.”

I said I thought it was. I did not add that he should look for an old surgeon in a new building.

These patients are fresh in my mind, but it doesn’t take much effort to come up with others.

“Mr. Skillman wants a refill on his steroid cream,” says my secretary.

“Sure,” I tell her. “E-scribe it over.”

“No,” she says. “He wants a hard copy mailed to him.”

“Does he have one of those mail order pharmacies that requires a written script?”

“No.”

“But it’s so much simpler to call it in or do it by computer. Why does he have to have a hard copy?”

“I don’t know. But he insists on having one.”

I could go on and on. So could you, I’m sure.

When confronted with chutzpah, you have two options: challenge the person showing it and refuse to go along with his demands, or just sigh, comply, and move on. In general, I go with option #2.

First of all, anyone pushy enough to act this way will not react well to being pushed back. (“What’s your problem? Are you too busy to write a prescription? Too stingy to mail it?”)

Second, and perhaps more to the point, many people who display chutzpah don’t know that’s what they are doing. The woman who went for laser at the Groupon spa really has no idea I’d think it odd for her to call me about a complication instead of the spa personnel who lasered her legs. On some level, she figures that they probably don’t know (look how cheap they are), and thinks I should be flattered to be asked. After all, I’m her dermatologist.

Some people with chutzpah are aggressive and difficult and don’t care if they’re being offensive. A lot more are just clueless. The fellow who bores the daylights out of everyone at dinner parties with long, pointless stories doesn’t know he’s being tedious. He just doesn’t pick up social cues.

Most patients, like most people, are polite and deferential. The rest, though, are more memorable.

My building is indeed old. One hundred years ago it was the swankiest apartment house around. Every flat had rooms for a butler, a maid, and a chauffeur for their Packard motorcar. Then the builder went belly-up during the Depression, and the new owner converted it to medical offices. Downward mobility works for me.

Faced with chutzpah, I shrug, smile, and get on with it. Enough people can still tolerate old buildings, and old dermatologists.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. Write to him at [email protected].

Chutzpah is a Yiddish word that entered American English, joining bagel and nosh. The usual translations of chutzpah – “nerve” or “effrontery” – are correct enough, but leave out the zest implied by chutzpah’s classic case: a man who kills his parents and throws himself on the mercy of the court because he is an orphan.

We all meet patients with chutzpah, which can be amusing, impressive – even breathtaking.

Take for instance the woman who paged me one evening last month. “I visit your nurse for cosmetic stuff,” she said when I called her back. “Your prices for laser hair removal were high, though, so I went to a spa where I could use a Groupon.”

How nice, I thought.

“Anyhow,” she continued, “I went for a treatment at the spa today, and now I have little red bumps all over my thighs. I thought it might be a reaction, and since you are my dermatologist I called to ask what to do.”

Good to be needed.

Then the next week I got another call, this time from a man I hadn’t seen in a long time. “I really like you as a dermatologist,” he began.

“Thank you,” I murmured.

“I saw this spot on my leg that worried me,” he said. “I was going to show it to you, but your office is in an old building, and old buildings don’t agree with me.”

As I scratched my head, he went on. “So I went to another dermatologist who works in a newer building. He did a biopsy and told me I have skin cancer. He said I should have surgery to take it off. I consider you my dermatologist, though, so I called to ask whether you think surgery is a good idea.”

I said I thought it was. I did not add that he should look for an old surgeon in a new building.

These patients are fresh in my mind, but it doesn’t take much effort to come up with others.

“Mr. Skillman wants a refill on his steroid cream,” says my secretary.

“Sure,” I tell her. “E-scribe it over.”

“No,” she says. “He wants a hard copy mailed to him.”

“Does he have one of those mail order pharmacies that requires a written script?”

“No.”

“But it’s so much simpler to call it in or do it by computer. Why does he have to have a hard copy?”

“I don’t know. But he insists on having one.”

I could go on and on. So could you, I’m sure.

When confronted with chutzpah, you have two options: challenge the person showing it and refuse to go along with his demands, or just sigh, comply, and move on. In general, I go with option #2.

First of all, anyone pushy enough to act this way will not react well to being pushed back. (“What’s your problem? Are you too busy to write a prescription? Too stingy to mail it?”)

Second, and perhaps more to the point, many people who display chutzpah don’t know that’s what they are doing. The woman who went for laser at the Groupon spa really has no idea I’d think it odd for her to call me about a complication instead of the spa personnel who lasered her legs. On some level, she figures that they probably don’t know (look how cheap they are), and thinks I should be flattered to be asked. After all, I’m her dermatologist.

Some people with chutzpah are aggressive and difficult and don’t care if they’re being offensive. A lot more are just clueless. The fellow who bores the daylights out of everyone at dinner parties with long, pointless stories doesn’t know he’s being tedious. He just doesn’t pick up social cues.

Most patients, like most people, are polite and deferential. The rest, though, are more memorable.

My building is indeed old. One hundred years ago it was the swankiest apartment house around. Every flat had rooms for a butler, a maid, and a chauffeur for their Packard motorcar. Then the builder went belly-up during the Depression, and the new owner converted it to medical offices. Downward mobility works for me.

Faced with chutzpah, I shrug, smile, and get on with it. Enough people can still tolerate old buildings, and old dermatologists.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. Write to him at [email protected].

Chutzpah is a Yiddish word that entered American English, joining bagel and nosh. The usual translations of chutzpah – “nerve” or “effrontery” – are correct enough, but leave out the zest implied by chutzpah’s classic case: a man who kills his parents and throws himself on the mercy of the court because he is an orphan.

We all meet patients with chutzpah, which can be amusing, impressive – even breathtaking.

Take for instance the woman who paged me one evening last month. “I visit your nurse for cosmetic stuff,” she said when I called her back. “Your prices for laser hair removal were high, though, so I went to a spa where I could use a Groupon.”

How nice, I thought.

“Anyhow,” she continued, “I went for a treatment at the spa today, and now I have little red bumps all over my thighs. I thought it might be a reaction, and since you are my dermatologist I called to ask what to do.”

Good to be needed.

Then the next week I got another call, this time from a man I hadn’t seen in a long time. “I really like you as a dermatologist,” he began.

“Thank you,” I murmured.

“I saw this spot on my leg that worried me,” he said. “I was going to show it to you, but your office is in an old building, and old buildings don’t agree with me.”

As I scratched my head, he went on. “So I went to another dermatologist who works in a newer building. He did a biopsy and told me I have skin cancer. He said I should have surgery to take it off. I consider you my dermatologist, though, so I called to ask whether you think surgery is a good idea.”

I said I thought it was. I did not add that he should look for an old surgeon in a new building.

These patients are fresh in my mind, but it doesn’t take much effort to come up with others.

“Mr. Skillman wants a refill on his steroid cream,” says my secretary.

“Sure,” I tell her. “E-scribe it over.”

“No,” she says. “He wants a hard copy mailed to him.”

“Does he have one of those mail order pharmacies that requires a written script?”

“No.”

“But it’s so much simpler to call it in or do it by computer. Why does he have to have a hard copy?”

“I don’t know. But he insists on having one.”

I could go on and on. So could you, I’m sure.

When confronted with chutzpah, you have two options: challenge the person showing it and refuse to go along with his demands, or just sigh, comply, and move on. In general, I go with option #2.

First of all, anyone pushy enough to act this way will not react well to being pushed back. (“What’s your problem? Are you too busy to write a prescription? Too stingy to mail it?”)

Second, and perhaps more to the point, many people who display chutzpah don’t know that’s what they are doing. The woman who went for laser at the Groupon spa really has no idea I’d think it odd for her to call me about a complication instead of the spa personnel who lasered her legs. On some level, she figures that they probably don’t know (look how cheap they are), and thinks I should be flattered to be asked. After all, I’m her dermatologist.

Some people with chutzpah are aggressive and difficult and don’t care if they’re being offensive. A lot more are just clueless. The fellow who bores the daylights out of everyone at dinner parties with long, pointless stories doesn’t know he’s being tedious. He just doesn’t pick up social cues.

Most patients, like most people, are polite and deferential. The rest, though, are more memorable.

My building is indeed old. One hundred years ago it was the swankiest apartment house around. Every flat had rooms for a butler, a maid, and a chauffeur for their Packard motorcar. Then the builder went belly-up during the Depression, and the new owner converted it to medical offices. Downward mobility works for me.

Faced with chutzpah, I shrug, smile, and get on with it. Enough people can still tolerate old buildings, and old dermatologists.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. Write to him at [email protected].

Self-directed learning

Never before in history has medicine progressed as quickly as it does today. The half-life of knowledge and practices is shortening, and the ocean of literature continues to amass every day. In this context, it is simply not possible for training programs to teach in didactics everything residents must know to become competent, much less excellent, doctors. Self-directed learning has become a critical part of residents’ education.

How can we make self-directed learning a more successful process? Attending physicians are likely to answer with the old saying, ‘You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink!’ While this saying points to the fact that self-directed learning requires a thirsty horse, it takes for granted the role of the guide in showing where water is plentiful. We argue that residents’ self-directed learning can be made more successful by recognizing the role of attendings in this process.

In an era of infinite resources, the limiting factor to learning has become time. The more we learn, the more humbled we are by the vastness of what we don’t know. Self-directed learners must be smart in deciding what should be learned. Herein lies the value of attendings, who, whether we are aware or not, shape our learning simply by virtue of their example. We would do well to pay closer attention to them. No textbook can replace their vast experience, which allows them to hone in on relevant details, to quickly develop comprehensive differentials, or revise plans.

But this learning cannot be based on simply observing and blindly emulating our teachers. We refer to Dr. Bloom’s taxonomy for levels of cognitive learning, in saying that these steps will only get us to the most basic levels of learning, which is “knowing” a disease to the extent that we can apply that knowledge in patient care. These can be acquired without significant mental effort; just by listening to morning reports, reading quick tidbits in between taking care of patients, etc. The goal, however, should be utilizing this basic knowledge as a foundation to develop higher levels of learning, namely Analysis, Synthesis, and Evaluation.

An example for analysis would be quickly going over each of the differentials in a disease and learning what distinguishes them. Synthesis is integrating different ideas and creating a customized plan for the particular patient that is found in no book. Lastly, evaluation is the level of cognition needed to be able to appraise and critique the large volume of opinion that we come across, establish our own opinion, and be able to defend it.

Here again our attendings are valuable resources who can guide us in reaching each of these levels. We must be willing to challenge ourselves by challenging our attendings when things do not make sense. It means always questioning why your attending physician made one medical decision versus another. It means also to challenge what we think we know, in order to discover what we don’t know. … Returning to the old adage, perhaps the key to self-directed learning is for the horse to learn his masters’ ways to the well, so he may adapt to an ever-changing environment.

Dr. Hung and Dr. Ramakrishna are pediatric residents at the Metrohealth Medical Center in Cleveland, Ohio. Email them at [email protected].

Never before in history has medicine progressed as quickly as it does today. The half-life of knowledge and practices is shortening, and the ocean of literature continues to amass every day. In this context, it is simply not possible for training programs to teach in didactics everything residents must know to become competent, much less excellent, doctors. Self-directed learning has become a critical part of residents’ education.

How can we make self-directed learning a more successful process? Attending physicians are likely to answer with the old saying, ‘You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink!’ While this saying points to the fact that self-directed learning requires a thirsty horse, it takes for granted the role of the guide in showing where water is plentiful. We argue that residents’ self-directed learning can be made more successful by recognizing the role of attendings in this process.

In an era of infinite resources, the limiting factor to learning has become time. The more we learn, the more humbled we are by the vastness of what we don’t know. Self-directed learners must be smart in deciding what should be learned. Herein lies the value of attendings, who, whether we are aware or not, shape our learning simply by virtue of their example. We would do well to pay closer attention to them. No textbook can replace their vast experience, which allows them to hone in on relevant details, to quickly develop comprehensive differentials, or revise plans.

But this learning cannot be based on simply observing and blindly emulating our teachers. We refer to Dr. Bloom’s taxonomy for levels of cognitive learning, in saying that these steps will only get us to the most basic levels of learning, which is “knowing” a disease to the extent that we can apply that knowledge in patient care. These can be acquired without significant mental effort; just by listening to morning reports, reading quick tidbits in between taking care of patients, etc. The goal, however, should be utilizing this basic knowledge as a foundation to develop higher levels of learning, namely Analysis, Synthesis, and Evaluation.

An example for analysis would be quickly going over each of the differentials in a disease and learning what distinguishes them. Synthesis is integrating different ideas and creating a customized plan for the particular patient that is found in no book. Lastly, evaluation is the level of cognition needed to be able to appraise and critique the large volume of opinion that we come across, establish our own opinion, and be able to defend it.

Here again our attendings are valuable resources who can guide us in reaching each of these levels. We must be willing to challenge ourselves by challenging our attendings when things do not make sense. It means always questioning why your attending physician made one medical decision versus another. It means also to challenge what we think we know, in order to discover what we don’t know. … Returning to the old adage, perhaps the key to self-directed learning is for the horse to learn his masters’ ways to the well, so he may adapt to an ever-changing environment.

Dr. Hung and Dr. Ramakrishna are pediatric residents at the Metrohealth Medical Center in Cleveland, Ohio. Email them at [email protected].

Never before in history has medicine progressed as quickly as it does today. The half-life of knowledge and practices is shortening, and the ocean of literature continues to amass every day. In this context, it is simply not possible for training programs to teach in didactics everything residents must know to become competent, much less excellent, doctors. Self-directed learning has become a critical part of residents’ education.

How can we make self-directed learning a more successful process? Attending physicians are likely to answer with the old saying, ‘You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink!’ While this saying points to the fact that self-directed learning requires a thirsty horse, it takes for granted the role of the guide in showing where water is plentiful. We argue that residents’ self-directed learning can be made more successful by recognizing the role of attendings in this process.

In an era of infinite resources, the limiting factor to learning has become time. The more we learn, the more humbled we are by the vastness of what we don’t know. Self-directed learners must be smart in deciding what should be learned. Herein lies the value of attendings, who, whether we are aware or not, shape our learning simply by virtue of their example. We would do well to pay closer attention to them. No textbook can replace their vast experience, which allows them to hone in on relevant details, to quickly develop comprehensive differentials, or revise plans.

But this learning cannot be based on simply observing and blindly emulating our teachers. We refer to Dr. Bloom’s taxonomy for levels of cognitive learning, in saying that these steps will only get us to the most basic levels of learning, which is “knowing” a disease to the extent that we can apply that knowledge in patient care. These can be acquired without significant mental effort; just by listening to morning reports, reading quick tidbits in between taking care of patients, etc. The goal, however, should be utilizing this basic knowledge as a foundation to develop higher levels of learning, namely Analysis, Synthesis, and Evaluation.

An example for analysis would be quickly going over each of the differentials in a disease and learning what distinguishes them. Synthesis is integrating different ideas and creating a customized plan for the particular patient that is found in no book. Lastly, evaluation is the level of cognition needed to be able to appraise and critique the large volume of opinion that we come across, establish our own opinion, and be able to defend it.

Here again our attendings are valuable resources who can guide us in reaching each of these levels. We must be willing to challenge ourselves by challenging our attendings when things do not make sense. It means always questioning why your attending physician made one medical decision versus another. It means also to challenge what we think we know, in order to discover what we don’t know. … Returning to the old adage, perhaps the key to self-directed learning is for the horse to learn his masters’ ways to the well, so he may adapt to an ever-changing environment.

Dr. Hung and Dr. Ramakrishna are pediatric residents at the Metrohealth Medical Center in Cleveland, Ohio. Email them at [email protected].

Guidance for parents of LGBT youth

Two years ago, a mother of one of my patients asked me for advice. She knew that her daughter identified as lesbian, and she was fully supportive. One day, her daughter wanted to go to a sleepover at a female friend’s house. Her first reaction was to say yes, but then she had second thoughts: If her daughter were straight, and this friend were male, she would not allow her to go because of the potential for sexual activity. When she told her daughter she could not attend the sleepover, her daughter accused her of not letting her go because of her sexual orientation. And now, the dilemma: In her effort to be fair and consistent with her values, the mother is being accused of discrimination. What should she do?

Parents play an irreplaceable role in the life of any teen, especially in the lives of teens that identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT). But many LGBT youth face serious challenges with their parents. They face the potential of parental rejection of their sexual or gender identity. At the very worst, teens may face homelessness if they come out to homophobic parents.1 Youth whose parents are accepting, nevertheless, are less likely to have mental health problems or engage in substance use.2

As a clinical provider for children and adolescents, caregivers will ask you for advice on how to address parenting challenges. Because LGBT youth are at risk for many adverse health outcomes, and parental support is paramount in preventing them, this is an opportunity for you to help this vulnerable population.

If parents ask you how to be supportive of their LGBT children, here are some recommendations, which are based on an intervention by colleagues at the University of Utah:3

1. Let their affection show. Receiving news that a child is LGBT can be emotionally intense for parents.4 Because of this emotional intensity, parents may react negatively and neglect to show their love for their child, which is what the child is seeking. Parents showing affection is the first step in supporting their LGBT child. Remind parents to tell their child that they love them no matter what.

2. Avoid rejecting behaviors. This is sometimes hard, because some forms of rejection can be quite subtle. Avoid saying anything that may indicate a negative view of LGBT people, even if it is not intended. For example, saying that something is “gay” may seem innocent enough, but it sends the message that being gay is something to be ashamed of.

3. Express their pain away from their child. Evidence shows that minimizing a child’s exposure to parental conflict and stress is associated with better coping with these devastating events.5 Parents should avoid telling their children that news of their sexual orientation or gender identity upsets them, as this is another form of rejecting behavior.

4. Do good before they feel good. Previous studies suggest that changes in behavior can occur even though a person may feel otherwise.6 Negative feelings about a child’s sexual orientation or gender identity can last months or years.7 It’s okay to have these feelings, but showing support such as telling their child how they still love them can ultimately lead to acceptance.

Although it is important for parents to accept their child, it is only half the battle. If you remember Baumrind’s theory on parenting, there are two sides of parenting. The first side involves parents showing their affection, love, and support for their children, which I described earlier. The other side involves managing a child’s behaviors, whether parents create an environment that makes it difficult to engage in behaviors they disapprove of or teach their children how to make the right decision.8 Many LGBT youth engage in risky behaviors because it’s a way of coping in a homophobic environment. The parents’ job is to teach their children healthier coping strategies.

Research on this aspect of parenting in LGBT youth is still at its infancy, and some of it is not reassuring. One important behavior, parental monitoring, which is “a set of correlated parenting behaviors involving attention to and tracking of the child’s whereabouts, activities, and adaptations,”9 can prevent conduct disorders, substance use, and mental health problems in the typical teenager.10 Unfortunately, we don’t find the same results for sexual minorities. One study suggests that parental monitoring may not prevent high-risk sexual behavior for young gay males, even if the parent is aware of the young man’s sexual orientation.11

This doesn’t mean that parental monitoring isn’t helpful. This just means that parenting LGBT youth is different than parenting heterosexual youth. It’s not enough for parents to just accept their child’s sexual orientation. They also must help them make the right decisions taking into consideration the effect of stigma and discrimination on sexual minorities. There are a couple of things you can suggest to your parents to help them raise their LGBT children:

1. Be proactive. Join organizations that support parents of LGBT youth such as Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (PFLAG). Also, parents must be aware of their children’s behavior. If they are acting depressed, seek help. Having depression or anxiety increases the chances of engaging in risky behaviors, so the earlier parents address this, the better.

2. Make their child know what their views are on high risk-behaviors, such as substance use or having unprotected sex. They need to communicate their expectations clearly. If parents believe that drinking alcohol before the legal age is wrong, they should clearly let their children know that.

3. Make it easier for their child to tell parents what’s going on in their lives. Parents have to gain their children’s trust, be accessible (don’t answer texts while talking to them!), and be an active listener. LGBT youth may not ask parents for advice because they feel that because their parents are straight or cisgender, their life experiences do not apply. Being a member of an organization like PLFAG can be helpful, because parents can ask other parents who have experience raising LGBT youth for advice that works.

4. If parents’ children do something wrong, they should talk to them about how their actions were risky. Children will listen to parents if they view their parenting as legitimate and fair, which can only happen if there is a strong parent-child relationship. Being supportive of a child’s sexual orientation or gender identity is key here. And for the next time, it’s always good to role-play a scenario (for example, what to do if someone tries to make them drink at a party).

Parents of LGBT youth face many challenges. You can help these parents by encouraging them to accept and support their child’s sexual orientation or gender identity and provide parenting strategies relevant for LGBT youth. Most important of all, encourage them to seek support through organizations like PFLAG. With this support, parents can encourage healthy development in LGBT youth.

Resources for parents of LGBT youth

• The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has information on the health of LGBT Youth and advice on parental monitoring in general.

• The Family Acceptance Project is a project researching ways to improve parent-child relationships in LGBT Youth.

• PFLAG is an organization that provides support for families of LGBT youth.

• Lead with Love is a film about how various types of families react to their children coming out to them.

References

1. J Sex Res. 2004 Nov;41(4):329-42.

2. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010 Sep;44(9):774-83.

3. Huebner D. “Leading with Love: Interventions to Support Families of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Adolescents,” The Register Report, Vol. 39. National Register of Health Service Psychologists, Spring 2013.

4. J GLBT Fam Stud. 2014 Jan;10(1-2):36-57.

5. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2008 Apr;39(2):113-21.

6. “Behaviorism: Classic Studies” (Casper, Wyo: Endeavor Books/Mountain States Litho, 2009).

7. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling. 2008;2(2):126-58.

8. Genet Psychol Monogr. 1967;75(1):43-88.

9. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 1998 Mar;1(1):61-75.

10. “Parental Monitoring of Adolescents: Current Perspectives for Researchers and Practitioners” (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010).

11. AIDS Behav. 2014 Aug;18(8):1604-14.

Dr. Montano is an adolescent medicine fellow at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC and a postdoctoral fellow in the department of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh. Email him at [email protected].

Two years ago, a mother of one of my patients asked me for advice. She knew that her daughter identified as lesbian, and she was fully supportive. One day, her daughter wanted to go to a sleepover at a female friend’s house. Her first reaction was to say yes, but then she had second thoughts: If her daughter were straight, and this friend were male, she would not allow her to go because of the potential for sexual activity. When she told her daughter she could not attend the sleepover, her daughter accused her of not letting her go because of her sexual orientation. And now, the dilemma: In her effort to be fair and consistent with her values, the mother is being accused of discrimination. What should she do?

Parents play an irreplaceable role in the life of any teen, especially in the lives of teens that identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT). But many LGBT youth face serious challenges with their parents. They face the potential of parental rejection of their sexual or gender identity. At the very worst, teens may face homelessness if they come out to homophobic parents.1 Youth whose parents are accepting, nevertheless, are less likely to have mental health problems or engage in substance use.2

As a clinical provider for children and adolescents, caregivers will ask you for advice on how to address parenting challenges. Because LGBT youth are at risk for many adverse health outcomes, and parental support is paramount in preventing them, this is an opportunity for you to help this vulnerable population.

If parents ask you how to be supportive of their LGBT children, here are some recommendations, which are based on an intervention by colleagues at the University of Utah:3

1. Let their affection show. Receiving news that a child is LGBT can be emotionally intense for parents.4 Because of this emotional intensity, parents may react negatively and neglect to show their love for their child, which is what the child is seeking. Parents showing affection is the first step in supporting their LGBT child. Remind parents to tell their child that they love them no matter what.

2. Avoid rejecting behaviors. This is sometimes hard, because some forms of rejection can be quite subtle. Avoid saying anything that may indicate a negative view of LGBT people, even if it is not intended. For example, saying that something is “gay” may seem innocent enough, but it sends the message that being gay is something to be ashamed of.

3. Express their pain away from their child. Evidence shows that minimizing a child’s exposure to parental conflict and stress is associated with better coping with these devastating events.5 Parents should avoid telling their children that news of their sexual orientation or gender identity upsets them, as this is another form of rejecting behavior.

4. Do good before they feel good. Previous studies suggest that changes in behavior can occur even though a person may feel otherwise.6 Negative feelings about a child’s sexual orientation or gender identity can last months or years.7 It’s okay to have these feelings, but showing support such as telling their child how they still love them can ultimately lead to acceptance.

Although it is important for parents to accept their child, it is only half the battle. If you remember Baumrind’s theory on parenting, there are two sides of parenting. The first side involves parents showing their affection, love, and support for their children, which I described earlier. The other side involves managing a child’s behaviors, whether parents create an environment that makes it difficult to engage in behaviors they disapprove of or teach their children how to make the right decision.8 Many LGBT youth engage in risky behaviors because it’s a way of coping in a homophobic environment. The parents’ job is to teach their children healthier coping strategies.

Research on this aspect of parenting in LGBT youth is still at its infancy, and some of it is not reassuring. One important behavior, parental monitoring, which is “a set of correlated parenting behaviors involving attention to and tracking of the child’s whereabouts, activities, and adaptations,”9 can prevent conduct disorders, substance use, and mental health problems in the typical teenager.10 Unfortunately, we don’t find the same results for sexual minorities. One study suggests that parental monitoring may not prevent high-risk sexual behavior for young gay males, even if the parent is aware of the young man’s sexual orientation.11

This doesn’t mean that parental monitoring isn’t helpful. This just means that parenting LGBT youth is different than parenting heterosexual youth. It’s not enough for parents to just accept their child’s sexual orientation. They also must help them make the right decisions taking into consideration the effect of stigma and discrimination on sexual minorities. There are a couple of things you can suggest to your parents to help them raise their LGBT children:

1. Be proactive. Join organizations that support parents of LGBT youth such as Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (PFLAG). Also, parents must be aware of their children’s behavior. If they are acting depressed, seek help. Having depression or anxiety increases the chances of engaging in risky behaviors, so the earlier parents address this, the better.

2. Make their child know what their views are on high risk-behaviors, such as substance use or having unprotected sex. They need to communicate their expectations clearly. If parents believe that drinking alcohol before the legal age is wrong, they should clearly let their children know that.

3. Make it easier for their child to tell parents what’s going on in their lives. Parents have to gain their children’s trust, be accessible (don’t answer texts while talking to them!), and be an active listener. LGBT youth may not ask parents for advice because they feel that because their parents are straight or cisgender, their life experiences do not apply. Being a member of an organization like PLFAG can be helpful, because parents can ask other parents who have experience raising LGBT youth for advice that works.

4. If parents’ children do something wrong, they should talk to them about how their actions were risky. Children will listen to parents if they view their parenting as legitimate and fair, which can only happen if there is a strong parent-child relationship. Being supportive of a child’s sexual orientation or gender identity is key here. And for the next time, it’s always good to role-play a scenario (for example, what to do if someone tries to make them drink at a party).

Parents of LGBT youth face many challenges. You can help these parents by encouraging them to accept and support their child’s sexual orientation or gender identity and provide parenting strategies relevant for LGBT youth. Most important of all, encourage them to seek support through organizations like PFLAG. With this support, parents can encourage healthy development in LGBT youth.

Resources for parents of LGBT youth

• The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has information on the health of LGBT Youth and advice on parental monitoring in general.

• The Family Acceptance Project is a project researching ways to improve parent-child relationships in LGBT Youth.

• PFLAG is an organization that provides support for families of LGBT youth.

• Lead with Love is a film about how various types of families react to their children coming out to them.

References

1. J Sex Res. 2004 Nov;41(4):329-42.

2. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010 Sep;44(9):774-83.

3. Huebner D. “Leading with Love: Interventions to Support Families of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Adolescents,” The Register Report, Vol. 39. National Register of Health Service Psychologists, Spring 2013.

4. J GLBT Fam Stud. 2014 Jan;10(1-2):36-57.

5. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2008 Apr;39(2):113-21.

6. “Behaviorism: Classic Studies” (Casper, Wyo: Endeavor Books/Mountain States Litho, 2009).

7. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling. 2008;2(2):126-58.

8. Genet Psychol Monogr. 1967;75(1):43-88.

9. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 1998 Mar;1(1):61-75.

10. “Parental Monitoring of Adolescents: Current Perspectives for Researchers and Practitioners” (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010).

11. AIDS Behav. 2014 Aug;18(8):1604-14.

Dr. Montano is an adolescent medicine fellow at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC and a postdoctoral fellow in the department of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh. Email him at [email protected].

Two years ago, a mother of one of my patients asked me for advice. She knew that her daughter identified as lesbian, and she was fully supportive. One day, her daughter wanted to go to a sleepover at a female friend’s house. Her first reaction was to say yes, but then she had second thoughts: If her daughter were straight, and this friend were male, she would not allow her to go because of the potential for sexual activity. When she told her daughter she could not attend the sleepover, her daughter accused her of not letting her go because of her sexual orientation. And now, the dilemma: In her effort to be fair and consistent with her values, the mother is being accused of discrimination. What should she do?

Parents play an irreplaceable role in the life of any teen, especially in the lives of teens that identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT). But many LGBT youth face serious challenges with their parents. They face the potential of parental rejection of their sexual or gender identity. At the very worst, teens may face homelessness if they come out to homophobic parents.1 Youth whose parents are accepting, nevertheless, are less likely to have mental health problems or engage in substance use.2

As a clinical provider for children and adolescents, caregivers will ask you for advice on how to address parenting challenges. Because LGBT youth are at risk for many adverse health outcomes, and parental support is paramount in preventing them, this is an opportunity for you to help this vulnerable population.

If parents ask you how to be supportive of their LGBT children, here are some recommendations, which are based on an intervention by colleagues at the University of Utah:3

1. Let their affection show. Receiving news that a child is LGBT can be emotionally intense for parents.4 Because of this emotional intensity, parents may react negatively and neglect to show their love for their child, which is what the child is seeking. Parents showing affection is the first step in supporting their LGBT child. Remind parents to tell their child that they love them no matter what.

2. Avoid rejecting behaviors. This is sometimes hard, because some forms of rejection can be quite subtle. Avoid saying anything that may indicate a negative view of LGBT people, even if it is not intended. For example, saying that something is “gay” may seem innocent enough, but it sends the message that being gay is something to be ashamed of.

3. Express their pain away from their child. Evidence shows that minimizing a child’s exposure to parental conflict and stress is associated with better coping with these devastating events.5 Parents should avoid telling their children that news of their sexual orientation or gender identity upsets them, as this is another form of rejecting behavior.

4. Do good before they feel good. Previous studies suggest that changes in behavior can occur even though a person may feel otherwise.6 Negative feelings about a child’s sexual orientation or gender identity can last months or years.7 It’s okay to have these feelings, but showing support such as telling their child how they still love them can ultimately lead to acceptance.

Although it is important for parents to accept their child, it is only half the battle. If you remember Baumrind’s theory on parenting, there are two sides of parenting. The first side involves parents showing their affection, love, and support for their children, which I described earlier. The other side involves managing a child’s behaviors, whether parents create an environment that makes it difficult to engage in behaviors they disapprove of or teach their children how to make the right decision.8 Many LGBT youth engage in risky behaviors because it’s a way of coping in a homophobic environment. The parents’ job is to teach their children healthier coping strategies.

Research on this aspect of parenting in LGBT youth is still at its infancy, and some of it is not reassuring. One important behavior, parental monitoring, which is “a set of correlated parenting behaviors involving attention to and tracking of the child’s whereabouts, activities, and adaptations,”9 can prevent conduct disorders, substance use, and mental health problems in the typical teenager.10 Unfortunately, we don’t find the same results for sexual minorities. One study suggests that parental monitoring may not prevent high-risk sexual behavior for young gay males, even if the parent is aware of the young man’s sexual orientation.11

This doesn’t mean that parental monitoring isn’t helpful. This just means that parenting LGBT youth is different than parenting heterosexual youth. It’s not enough for parents to just accept their child’s sexual orientation. They also must help them make the right decisions taking into consideration the effect of stigma and discrimination on sexual minorities. There are a couple of things you can suggest to your parents to help them raise their LGBT children:

1. Be proactive. Join organizations that support parents of LGBT youth such as Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (PFLAG). Also, parents must be aware of their children’s behavior. If they are acting depressed, seek help. Having depression or anxiety increases the chances of engaging in risky behaviors, so the earlier parents address this, the better.

2. Make their child know what their views are on high risk-behaviors, such as substance use or having unprotected sex. They need to communicate their expectations clearly. If parents believe that drinking alcohol before the legal age is wrong, they should clearly let their children know that.

3. Make it easier for their child to tell parents what’s going on in their lives. Parents have to gain their children’s trust, be accessible (don’t answer texts while talking to them!), and be an active listener. LGBT youth may not ask parents for advice because they feel that because their parents are straight or cisgender, their life experiences do not apply. Being a member of an organization like PLFAG can be helpful, because parents can ask other parents who have experience raising LGBT youth for advice that works.

4. If parents’ children do something wrong, they should talk to them about how their actions were risky. Children will listen to parents if they view their parenting as legitimate and fair, which can only happen if there is a strong parent-child relationship. Being supportive of a child’s sexual orientation or gender identity is key here. And for the next time, it’s always good to role-play a scenario (for example, what to do if someone tries to make them drink at a party).

Parents of LGBT youth face many challenges. You can help these parents by encouraging them to accept and support their child’s sexual orientation or gender identity and provide parenting strategies relevant for LGBT youth. Most important of all, encourage them to seek support through organizations like PFLAG. With this support, parents can encourage healthy development in LGBT youth.

Resources for parents of LGBT youth

• The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has information on the health of LGBT Youth and advice on parental monitoring in general.

• The Family Acceptance Project is a project researching ways to improve parent-child relationships in LGBT Youth.

• PFLAG is an organization that provides support for families of LGBT youth.

• Lead with Love is a film about how various types of families react to their children coming out to them.

References

1. J Sex Res. 2004 Nov;41(4):329-42.

2. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010 Sep;44(9):774-83.

3. Huebner D. “Leading with Love: Interventions to Support Families of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Adolescents,” The Register Report, Vol. 39. National Register of Health Service Psychologists, Spring 2013.

4. J GLBT Fam Stud. 2014 Jan;10(1-2):36-57.

5. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2008 Apr;39(2):113-21.

6. “Behaviorism: Classic Studies” (Casper, Wyo: Endeavor Books/Mountain States Litho, 2009).

7. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling. 2008;2(2):126-58.

8. Genet Psychol Monogr. 1967;75(1):43-88.

9. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 1998 Mar;1(1):61-75.

10. “Parental Monitoring of Adolescents: Current Perspectives for Researchers and Practitioners” (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010).

11. AIDS Behav. 2014 Aug;18(8):1604-14.

Dr. Montano is an adolescent medicine fellow at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC and a postdoctoral fellow in the department of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh. Email him at [email protected].

The HPV vaccine

As physicians, we play a unique role in medicine. Drawing on research data, we provide a gateway of information to patients and families. Governing agencies use that data to make recommendations so that we can promote treatment with confidence. But we also have a responsibility if there is an ill outcome, so being well versed on vaccines and treatments is imperative.

Since the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines (Gardasil, Cervarix) were approved for the prevention of HPV, there has been controversy. Despite the ongoing reports of the vaccine’s success in lowering cervical cancer rates, many parents still feel that it puts their children at risk.

A 2012 study – a systematic review of parents’ knowledge of HPV – showed a decline from 2001 to 2011, with a rise in parents’ safety concerns, and fewer parents opting to have their children vaccinated (Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012. doi: 10.1155/2012/921236).

Several studies have shown the overwhelming decline in cervical cancer that is directly related to the implementation of the HPV vaccines. But there has been growing concern, as postural orthostatic hypotension (POTS), complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), and sudden death have been cited as side effects of theses vaccines. POTS and CRPS have been in the headlines recently, since a report came out linking the vaccine to these syndromes. Although a review by the European Medicines Agency found that the evidence does not support the notion of the HPV vaccine causing POTS or CRPS, many groups still promote a ban of the vaccine.

In 2013, Japan withdrew its recommendation for administration of the HPV vaccine after reports that many girls had been seriously harmed by it, and now calls for follow-up for patients who believe they are having side effects. Researchers argue that the basis for this action is poorly founded, and that many young women are being deprived of a vaccine that would be protective. But just as many say that more investigation needs to be done before the recommendation can be reinstated, given the number of reports about women being seriously injured from the vaccine. The Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology is pleading with the Japanese Health Ministry to commence recommending the HPV cancer-preventing vaccineonce again.

An Internet search of this topic shows there are several articles questioning the safety of the vaccine, and throughout the world, concerns are forcing more research to be done to ensure its safety. Although the research overwhelmingly shows that the risk-to-benefit ratio is in favor of the HPV vaccine, several sites are reporting injury.

In a study of 997,585 girls aged 10-17 years in Denmark and Sweden, among whom 296,826 received a total of 696,420 quadrivalent HPV vaccine doses, 1,043 (less than 1%) were found to have adverse reactions, compared with 11,944 (2%) of unvaccinated girls (BMJ 2013;347:f5906). Although some relationship between HPV vaccine and autoimmune disorders such as Behçet’s syndrome, Raynaud’s disease, and type 1 diabetes was apparent, no consistent evidence for a causal association was found.

“Analysis of data reported to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System revealed disproportionate reporting of venous thromboembolism,” noted Dr. Lisen Arnheim-Dahlström of the Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, lead author of the BMJ study, and associates. “A study by the Vaccine Safety Datalink, which involved eight outcomes, identified a nonsignificantly increased relative risk (1.98) of venous thromboembolism; medical record review could confirm five of the eight cases identified from databases using international classification of diseases codes, and all five had known risk factors for venous thromboembolism. In our analysis, based on 21 vaccine exposed cases, there was no significant association with venous thromboembolism within 90 days after exposure to [quadrivalent] HPV vaccine.”

These rising concerns are resulting in more parents declining the HPV vaccine, and more questions for the primary care physician to answer. Not only are parents alarmed, but so are the physicians who make the recommendations. Being aware of the most current research and reports for and against the vaccine’s use, and being able to discuss with the family the validity of this information, will help to dispel much of the anxiety.

Dr. Pearce is a pediatrician in Frankfort, Ill. To contact her, send email to [email protected].

As physicians, we play a unique role in medicine. Drawing on research data, we provide a gateway of information to patients and families. Governing agencies use that data to make recommendations so that we can promote treatment with confidence. But we also have a responsibility if there is an ill outcome, so being well versed on vaccines and treatments is imperative.

Since the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines (Gardasil, Cervarix) were approved for the prevention of HPV, there has been controversy. Despite the ongoing reports of the vaccine’s success in lowering cervical cancer rates, many parents still feel that it puts their children at risk.

A 2012 study – a systematic review of parents’ knowledge of HPV – showed a decline from 2001 to 2011, with a rise in parents’ safety concerns, and fewer parents opting to have their children vaccinated (Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012. doi: 10.1155/2012/921236).

Several studies have shown the overwhelming decline in cervical cancer that is directly related to the implementation of the HPV vaccines. But there has been growing concern, as postural orthostatic hypotension (POTS), complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), and sudden death have been cited as side effects of theses vaccines. POTS and CRPS have been in the headlines recently, since a report came out linking the vaccine to these syndromes. Although a review by the European Medicines Agency found that the evidence does not support the notion of the HPV vaccine causing POTS or CRPS, many groups still promote a ban of the vaccine.

In 2013, Japan withdrew its recommendation for administration of the HPV vaccine after reports that many girls had been seriously harmed by it, and now calls for follow-up for patients who believe they are having side effects. Researchers argue that the basis for this action is poorly founded, and that many young women are being deprived of a vaccine that would be protective. But just as many say that more investigation needs to be done before the recommendation can be reinstated, given the number of reports about women being seriously injured from the vaccine. The Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology is pleading with the Japanese Health Ministry to commence recommending the HPV cancer-preventing vaccineonce again.

An Internet search of this topic shows there are several articles questioning the safety of the vaccine, and throughout the world, concerns are forcing more research to be done to ensure its safety. Although the research overwhelmingly shows that the risk-to-benefit ratio is in favor of the HPV vaccine, several sites are reporting injury.

In a study of 997,585 girls aged 10-17 years in Denmark and Sweden, among whom 296,826 received a total of 696,420 quadrivalent HPV vaccine doses, 1,043 (less than 1%) were found to have adverse reactions, compared with 11,944 (2%) of unvaccinated girls (BMJ 2013;347:f5906). Although some relationship between HPV vaccine and autoimmune disorders such as Behçet’s syndrome, Raynaud’s disease, and type 1 diabetes was apparent, no consistent evidence for a causal association was found.

“Analysis of data reported to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System revealed disproportionate reporting of venous thromboembolism,” noted Dr. Lisen Arnheim-Dahlström of the Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, lead author of the BMJ study, and associates. “A study by the Vaccine Safety Datalink, which involved eight outcomes, identified a nonsignificantly increased relative risk (1.98) of venous thromboembolism; medical record review could confirm five of the eight cases identified from databases using international classification of diseases codes, and all five had known risk factors for venous thromboembolism. In our analysis, based on 21 vaccine exposed cases, there was no significant association with venous thromboembolism within 90 days after exposure to [quadrivalent] HPV vaccine.”

These rising concerns are resulting in more parents declining the HPV vaccine, and more questions for the primary care physician to answer. Not only are parents alarmed, but so are the physicians who make the recommendations. Being aware of the most current research and reports for and against the vaccine’s use, and being able to discuss with the family the validity of this information, will help to dispel much of the anxiety.

Dr. Pearce is a pediatrician in Frankfort, Ill. To contact her, send email to [email protected].

As physicians, we play a unique role in medicine. Drawing on research data, we provide a gateway of information to patients and families. Governing agencies use that data to make recommendations so that we can promote treatment with confidence. But we also have a responsibility if there is an ill outcome, so being well versed on vaccines and treatments is imperative.

Since the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines (Gardasil, Cervarix) were approved for the prevention of HPV, there has been controversy. Despite the ongoing reports of the vaccine’s success in lowering cervical cancer rates, many parents still feel that it puts their children at risk.

A 2012 study – a systematic review of parents’ knowledge of HPV – showed a decline from 2001 to 2011, with a rise in parents’ safety concerns, and fewer parents opting to have their children vaccinated (Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012. doi: 10.1155/2012/921236).

Several studies have shown the overwhelming decline in cervical cancer that is directly related to the implementation of the HPV vaccines. But there has been growing concern, as postural orthostatic hypotension (POTS), complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), and sudden death have been cited as side effects of theses vaccines. POTS and CRPS have been in the headlines recently, since a report came out linking the vaccine to these syndromes. Although a review by the European Medicines Agency found that the evidence does not support the notion of the HPV vaccine causing POTS or CRPS, many groups still promote a ban of the vaccine.