User login

A closing column

As the year comes to an end, I have decided – after 9 years of writing for Pediatric News – to bring my column to a close. It has been a great joy to be a part of the pediatric community in this way, and I have been grateful for those of you who approach me at meetings, saying, “Hey, I recognize you – I really like your column!” or tell me you appreciated a particular topic or piece of advice.

As I reflected on the columns I have written, I realized there were two themes that repeatedly emerged as most meaningful to me. While these thoughts are nothing new, I thought they would be a fitting way to sum up my writings over the years.

First, and most important, is that patients and families are the best partners we have in the care we give. When we take the time to listen to them, involve them in decision making and think past what we see on the surface, kids are healthier. This is just as true for preventative “well-baby” care as it is for acute and specialty care. Understanding a family’s priorities, values, and the context in which they live is just as important as our medical knowledge and skills when taking care of patients. Pediatricians are expert at bringing all of these things together, grounded in the best and most up-to-date evidence available, and in doing so elevate the care of children.

Which leads me to the second theme – pediatricians are a strong and important voice for children, and it is important for us to learn to lead. Through our work, we have a window into the lives of children, both when they are healthy and when they are sick. That is a great privilege but also a great responsibility. We see the things that work well in our systems and the things that do not. We see the amazing things children are capable of, but also troubling and pervasive inequities in care, access, and education. We see children who aren’t having their basic needs met – things like food, shelter, and a safe place to play. We see how these inequities impact health and wellness – both now and as children grow into adults. These observations, and the things we learn by caring for children and families day in and day out, can be translated into action. For each of us that will mean something different, but it is imperative that we develop our talents as advocates and leaders so that we can catalyze change. Our best hope for making things better is if we each do our part to create solutions. And when that happens, children – a lot of children – are healthier.

Since I began my first column 9 years ago, a lot has changed for me, and I suspect for many of you. When I first began writing, my now tall, confident tween (who already wears the same shoe size as me!) was barely walking. Thank you to all who have listened and encouraged me along the way – it has been a fun journey, and I’ve appreciated your time.

Dr. Beers is assistant professor of pediatrics at Children’s National Medical Center and the George Washington University Medical Center, both in Washington. She is chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Residency Scholarships and immediate past president of the District of Columbia chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

As the year comes to an end, I have decided – after 9 years of writing for Pediatric News – to bring my column to a close. It has been a great joy to be a part of the pediatric community in this way, and I have been grateful for those of you who approach me at meetings, saying, “Hey, I recognize you – I really like your column!” or tell me you appreciated a particular topic or piece of advice.

As I reflected on the columns I have written, I realized there were two themes that repeatedly emerged as most meaningful to me. While these thoughts are nothing new, I thought they would be a fitting way to sum up my writings over the years.

First, and most important, is that patients and families are the best partners we have in the care we give. When we take the time to listen to them, involve them in decision making and think past what we see on the surface, kids are healthier. This is just as true for preventative “well-baby” care as it is for acute and specialty care. Understanding a family’s priorities, values, and the context in which they live is just as important as our medical knowledge and skills when taking care of patients. Pediatricians are expert at bringing all of these things together, grounded in the best and most up-to-date evidence available, and in doing so elevate the care of children.

Which leads me to the second theme – pediatricians are a strong and important voice for children, and it is important for us to learn to lead. Through our work, we have a window into the lives of children, both when they are healthy and when they are sick. That is a great privilege but also a great responsibility. We see the things that work well in our systems and the things that do not. We see the amazing things children are capable of, but also troubling and pervasive inequities in care, access, and education. We see children who aren’t having their basic needs met – things like food, shelter, and a safe place to play. We see how these inequities impact health and wellness – both now and as children grow into adults. These observations, and the things we learn by caring for children and families day in and day out, can be translated into action. For each of us that will mean something different, but it is imperative that we develop our talents as advocates and leaders so that we can catalyze change. Our best hope for making things better is if we each do our part to create solutions. And when that happens, children – a lot of children – are healthier.

Since I began my first column 9 years ago, a lot has changed for me, and I suspect for many of you. When I first began writing, my now tall, confident tween (who already wears the same shoe size as me!) was barely walking. Thank you to all who have listened and encouraged me along the way – it has been a fun journey, and I’ve appreciated your time.

Dr. Beers is assistant professor of pediatrics at Children’s National Medical Center and the George Washington University Medical Center, both in Washington. She is chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Residency Scholarships and immediate past president of the District of Columbia chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

As the year comes to an end, I have decided – after 9 years of writing for Pediatric News – to bring my column to a close. It has been a great joy to be a part of the pediatric community in this way, and I have been grateful for those of you who approach me at meetings, saying, “Hey, I recognize you – I really like your column!” or tell me you appreciated a particular topic or piece of advice.

As I reflected on the columns I have written, I realized there were two themes that repeatedly emerged as most meaningful to me. While these thoughts are nothing new, I thought they would be a fitting way to sum up my writings over the years.

First, and most important, is that patients and families are the best partners we have in the care we give. When we take the time to listen to them, involve them in decision making and think past what we see on the surface, kids are healthier. This is just as true for preventative “well-baby” care as it is for acute and specialty care. Understanding a family’s priorities, values, and the context in which they live is just as important as our medical knowledge and skills when taking care of patients. Pediatricians are expert at bringing all of these things together, grounded in the best and most up-to-date evidence available, and in doing so elevate the care of children.

Which leads me to the second theme – pediatricians are a strong and important voice for children, and it is important for us to learn to lead. Through our work, we have a window into the lives of children, both when they are healthy and when they are sick. That is a great privilege but also a great responsibility. We see the things that work well in our systems and the things that do not. We see the amazing things children are capable of, but also troubling and pervasive inequities in care, access, and education. We see children who aren’t having their basic needs met – things like food, shelter, and a safe place to play. We see how these inequities impact health and wellness – both now and as children grow into adults. These observations, and the things we learn by caring for children and families day in and day out, can be translated into action. For each of us that will mean something different, but it is imperative that we develop our talents as advocates and leaders so that we can catalyze change. Our best hope for making things better is if we each do our part to create solutions. And when that happens, children – a lot of children – are healthier.

Since I began my first column 9 years ago, a lot has changed for me, and I suspect for many of you. When I first began writing, my now tall, confident tween (who already wears the same shoe size as me!) was barely walking. Thank you to all who have listened and encouraged me along the way – it has been a fun journey, and I’ve appreciated your time.

Dr. Beers is assistant professor of pediatrics at Children’s National Medical Center and the George Washington University Medical Center, both in Washington. She is chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Residency Scholarships and immediate past president of the District of Columbia chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The Optum termination thunderbolt

One afternoon, after seeing your last patient, you’re doing the old-school thing, with your feet up, opening and reading your paper mail after a hard day’s work at the dermatology ranch. You see an odd form letter – a green sticker on the outside, certified mail – stating that you have been terminated from a Medicare advantage plan, no reason given.

At first, you don’t care so much. After all, this plan pays you only 95% of Medicare. Then you think about it and realize that this plan represents 50% of all Medicare beneficiaries in your area. You start to freak out, and you immediately go to the American Academy of Dermatology website where you read Rob Portman’s article about how to fight a termination notice and respond expeditiously.

Later that night, your spouse asks why you were singled out. “Are you a bad doctor? What did you do wrong? Can the kids still go to college?

The answer, most often, is that you did nothing wrong. You’ve just been caught up in the insurer’s network management software, Optum 360.

Optum 360 is a large health care information and management subsidiary of UnitedHealthcare. It was created as a joint venture by the Optum insight (health technology) unit of UnitedHealthcare, and Dignity Health (claims processing), forming Optum 360.

Optum claims that its software measures the efficiency of providers, saving insurers money and improving the quality of care – the Valhalla of health care managers everywhere. Unfortunately, Optum doesn’t deliver this vision of heaven on earth, at least not for dermatology.

Optum 360does little more than aggregate and average the costs of individual providers with no recognition of severity of disease or case mix. The physician with the most reimbursement during an episode of care for a given ICD-9 code (now for a group of ICD-10 codes) gets credited with all the expenses under that code. For example, you do two stages of Mohs surgery on a big basal cell on the nose that you send to plastics for repair. If the reimbursement for the Mohs surgery exceeds the plastics reimbursement, the Optum software designates you as the responsible provider. The cost of the plastics repair accrues to you; the hospital OR facility charges accrue to you (facilities are not considered a provider); and the anesthesiologist charges are credited to you. In addition, the superficial basal cell carcinoma on the patient’s back, treated a week later by the referring doctor, is also attributed to you as part of the original episode of care. There are no quality parameters and no subspecialty recognition.

If your patient load regularly includes patients who have Mohs surgery, the dermatologist down the street who does Mohs only once a week looks much better to Optum than you do. The referral-only medical dermatologist in town, who treats very sick patients and routinely prescribes biologics, and (heaven forbid) intravenous immunoglobulin, is similarly tagged for termination from the insurer’s network.

So it looks as though dermatologists who handle the toughest patients lose out. But who really loses the most? The sickest patients! The dermatologist can always fill the schedule with patients with other insurance coverage and reduce the backlog or, if worse comes to worse, he can take the Canadian cure and go on vacation. The sickest patients, however, get eliminated from the system when their doctors get eliminated by UnitedHealthcare’s software. Then patients often cannot find another doctor because most insurer’s physician rosters are 70% inaccurate (JAMA Dermatol. 2014 Dec;150[12]:1290-7).

In some circumstances, the sickest patients have reported either being unable to find other dermatologists willing to provide the special service they need or having to wait up to 6 months for an open appointment. These patients then try to drop back into fee-for-service Medicare, only to find they cannot afford the gap insurance, which costs five times as much. Why? Because those patients now have a preexisting condition. Yes, preexisting conditions still apply in the world of gap insurance.

This is obviously not optimal nor even acceptable. To quote Michael Keaton from the 1982 movie “Night Shift”: “Is this a great country or what?” The answer is a resounding “yes” for medical insurance companies who are booking record profits, but “no” for the sickest patients.

Dr. Coldiron is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. He is currently in private practice, but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. Reach him at [email protected].

One afternoon, after seeing your last patient, you’re doing the old-school thing, with your feet up, opening and reading your paper mail after a hard day’s work at the dermatology ranch. You see an odd form letter – a green sticker on the outside, certified mail – stating that you have been terminated from a Medicare advantage plan, no reason given.

At first, you don’t care so much. After all, this plan pays you only 95% of Medicare. Then you think about it and realize that this plan represents 50% of all Medicare beneficiaries in your area. You start to freak out, and you immediately go to the American Academy of Dermatology website where you read Rob Portman’s article about how to fight a termination notice and respond expeditiously.

Later that night, your spouse asks why you were singled out. “Are you a bad doctor? What did you do wrong? Can the kids still go to college?

The answer, most often, is that you did nothing wrong. You’ve just been caught up in the insurer’s network management software, Optum 360.

Optum 360 is a large health care information and management subsidiary of UnitedHealthcare. It was created as a joint venture by the Optum insight (health technology) unit of UnitedHealthcare, and Dignity Health (claims processing), forming Optum 360.

Optum claims that its software measures the efficiency of providers, saving insurers money and improving the quality of care – the Valhalla of health care managers everywhere. Unfortunately, Optum doesn’t deliver this vision of heaven on earth, at least not for dermatology.

Optum 360does little more than aggregate and average the costs of individual providers with no recognition of severity of disease or case mix. The physician with the most reimbursement during an episode of care for a given ICD-9 code (now for a group of ICD-10 codes) gets credited with all the expenses under that code. For example, you do two stages of Mohs surgery on a big basal cell on the nose that you send to plastics for repair. If the reimbursement for the Mohs surgery exceeds the plastics reimbursement, the Optum software designates you as the responsible provider. The cost of the plastics repair accrues to you; the hospital OR facility charges accrue to you (facilities are not considered a provider); and the anesthesiologist charges are credited to you. In addition, the superficial basal cell carcinoma on the patient’s back, treated a week later by the referring doctor, is also attributed to you as part of the original episode of care. There are no quality parameters and no subspecialty recognition.

If your patient load regularly includes patients who have Mohs surgery, the dermatologist down the street who does Mohs only once a week looks much better to Optum than you do. The referral-only medical dermatologist in town, who treats very sick patients and routinely prescribes biologics, and (heaven forbid) intravenous immunoglobulin, is similarly tagged for termination from the insurer’s network.

So it looks as though dermatologists who handle the toughest patients lose out. But who really loses the most? The sickest patients! The dermatologist can always fill the schedule with patients with other insurance coverage and reduce the backlog or, if worse comes to worse, he can take the Canadian cure and go on vacation. The sickest patients, however, get eliminated from the system when their doctors get eliminated by UnitedHealthcare’s software. Then patients often cannot find another doctor because most insurer’s physician rosters are 70% inaccurate (JAMA Dermatol. 2014 Dec;150[12]:1290-7).

In some circumstances, the sickest patients have reported either being unable to find other dermatologists willing to provide the special service they need or having to wait up to 6 months for an open appointment. These patients then try to drop back into fee-for-service Medicare, only to find they cannot afford the gap insurance, which costs five times as much. Why? Because those patients now have a preexisting condition. Yes, preexisting conditions still apply in the world of gap insurance.

This is obviously not optimal nor even acceptable. To quote Michael Keaton from the 1982 movie “Night Shift”: “Is this a great country or what?” The answer is a resounding “yes” for medical insurance companies who are booking record profits, but “no” for the sickest patients.

Dr. Coldiron is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. He is currently in private practice, but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. Reach him at [email protected].

One afternoon, after seeing your last patient, you’re doing the old-school thing, with your feet up, opening and reading your paper mail after a hard day’s work at the dermatology ranch. You see an odd form letter – a green sticker on the outside, certified mail – stating that you have been terminated from a Medicare advantage plan, no reason given.

At first, you don’t care so much. After all, this plan pays you only 95% of Medicare. Then you think about it and realize that this plan represents 50% of all Medicare beneficiaries in your area. You start to freak out, and you immediately go to the American Academy of Dermatology website where you read Rob Portman’s article about how to fight a termination notice and respond expeditiously.

Later that night, your spouse asks why you were singled out. “Are you a bad doctor? What did you do wrong? Can the kids still go to college?

The answer, most often, is that you did nothing wrong. You’ve just been caught up in the insurer’s network management software, Optum 360.

Optum 360 is a large health care information and management subsidiary of UnitedHealthcare. It was created as a joint venture by the Optum insight (health technology) unit of UnitedHealthcare, and Dignity Health (claims processing), forming Optum 360.

Optum claims that its software measures the efficiency of providers, saving insurers money and improving the quality of care – the Valhalla of health care managers everywhere. Unfortunately, Optum doesn’t deliver this vision of heaven on earth, at least not for dermatology.

Optum 360does little more than aggregate and average the costs of individual providers with no recognition of severity of disease or case mix. The physician with the most reimbursement during an episode of care for a given ICD-9 code (now for a group of ICD-10 codes) gets credited with all the expenses under that code. For example, you do two stages of Mohs surgery on a big basal cell on the nose that you send to plastics for repair. If the reimbursement for the Mohs surgery exceeds the plastics reimbursement, the Optum software designates you as the responsible provider. The cost of the plastics repair accrues to you; the hospital OR facility charges accrue to you (facilities are not considered a provider); and the anesthesiologist charges are credited to you. In addition, the superficial basal cell carcinoma on the patient’s back, treated a week later by the referring doctor, is also attributed to you as part of the original episode of care. There are no quality parameters and no subspecialty recognition.

If your patient load regularly includes patients who have Mohs surgery, the dermatologist down the street who does Mohs only once a week looks much better to Optum than you do. The referral-only medical dermatologist in town, who treats very sick patients and routinely prescribes biologics, and (heaven forbid) intravenous immunoglobulin, is similarly tagged for termination from the insurer’s network.

So it looks as though dermatologists who handle the toughest patients lose out. But who really loses the most? The sickest patients! The dermatologist can always fill the schedule with patients with other insurance coverage and reduce the backlog or, if worse comes to worse, he can take the Canadian cure and go on vacation. The sickest patients, however, get eliminated from the system when their doctors get eliminated by UnitedHealthcare’s software. Then patients often cannot find another doctor because most insurer’s physician rosters are 70% inaccurate (JAMA Dermatol. 2014 Dec;150[12]:1290-7).

In some circumstances, the sickest patients have reported either being unable to find other dermatologists willing to provide the special service they need or having to wait up to 6 months for an open appointment. These patients then try to drop back into fee-for-service Medicare, only to find they cannot afford the gap insurance, which costs five times as much. Why? Because those patients now have a preexisting condition. Yes, preexisting conditions still apply in the world of gap insurance.

This is obviously not optimal nor even acceptable. To quote Michael Keaton from the 1982 movie “Night Shift”: “Is this a great country or what?” The answer is a resounding “yes” for medical insurance companies who are booking record profits, but “no” for the sickest patients.

Dr. Coldiron is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. He is currently in private practice, but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. Reach him at [email protected].

Career Development: A Focused Plan or Serendipity?

Fifth grade is a wonderful school year and fifth graders are interesting, enthusiastic, and busy people, but conflicts can arise amidst their many activities. We discovered that our fifth grader could not finish his homework, play on 3 sports teams, take bass lessons (and practice), join the city chorus, play outside with his friends, walk his dog, spend quality time with his parents, and do his chores—much less eat and sleep. Choices needed to be made. Unfortunately, in our community dropping out of the premier soccer club probably limits future possibilities in the sport; nevertheless, it would entail 6 to 8 hours of game and practice time per week (plus travel), as well as multiple 3-day tournaments. Therefore our son dropped soccer, as we decided the best strategy for our fifth grader to develop and mature was to do his personal best at his schoolwork while also exploring a greater variety of less intensive extracurricular experiences.

Most dermatologists appropriately adopt a different strategy during medical school and dermatology training. An intensive, single-minded focus gets us through hours in the anatomy laboratory, the first difficult clinical rotations, sleepless nights, grand rounds quizzing, and board examinations. Completion of our training does not, however, signal that development and maturation are complete; rather, we must then choose among a new set of options, such as the basic questions of whether to practice in an academic setting or group or solo practice and whether to emphasize a subspecialty. These choices involve some mutually exclusive options and exist in a milieu of adult (ie, nonacademic) dilemmas concerning family life, community and spiritual life, avocations, exercise regimens, housing and material goods, and other routine aspects of life. The professional options that are available may be limited by the lack of community opportunities, geographic need, or job availability in a preferred location or institution.

So how do dermatologists manage to start their careers, then develop and maintain them? A best practice is to be both introspective as well as aware of our external environments. Good questions to ask ourselves periodically (having different answers at different stages is highly recommended!) include: What are my core values and what do I want to accomplish? Pay attention to your gut. When do you lose track of time and what makes you want to scream in frustration? Regularly take an inventory of your strengths and find opportunities to acquire the competencies that can take you to the next level. What skill do I need to finesse and how do I finesse it? Do an external scan and understand limiting factors such as geographic saturation in your desired practice type or the lack of appropriate collaborators in your preferred area of interest. Search out people who are doing what you’d like to do and then identify their paths and what you can use from their experiences to help with your career development.

Once you have identified a few professional goals to pursue, utilize all the resources you can find. You might find helpful seminars at an academic institution or at conferences. Do you want to become the regional expert in sarcoidosis? Check out what has been written and find other experts in the subject and where they are speaking. Many organizations have practice management or leadership development courses and seminars. There also are books for everything—those that I have found most useful include Douglas Stone’s Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most1 and William L. Fisher and Roger Ury’s classic, Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In.2 Have to give a talk? There is a PowerPoint 2016 for Dummies.3 The same series also includes a book on the Microsoft® Excel spreadsheet. Also check out my all-time favorite—Brian Tracy’s Eat That Frog! 21 Ways to Stop Procrastinating and Get More Done in Less Time.4

It is important to experiment with different professional experiences and have an open mind when a new activity presents itself. Look for opportunities for new side ventures or interesting projects that will not take up much time so you can continue to do your best at your daily work. When I was a senior resident, a dermatologist from Maine asked me if I would help him find a dermatologist who would work regularly at a rural clinic in the northern part of the state. My answer was, why not me? For 8 years I worked in that clinic once to twice per month, seeing as many patients as I could for 8 to 12 hours a day on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, and then returning to Boston, Massachusetts, for my normal work week. I even took my 2 youngest children (who were born during that time) with me and found a family there who took excellent care of them while I worked. It ended up being one of the most important experiences, both intellectually and emotionally, of my professional career. I learned how to diagnose difficult and complex dermatology problems by myself in an environment with few resources (the closest dermatologist was 150 miles away), how to use primary care providers to manage patients remotely, how to set up a clinic and manage staff (I hired other part-time staff to help me), and how to lead an effort that I felt passionate about. I sometimes even took on residents, which helped me finesse my teaching and supervision style.

Unlike the achievement of becoming a board-certified dermatologist, a dermatology career does not develop in a straight line, and rarely at a steady pace. It seems to me that a shift from a single-minded focus during residency to the fifth-grade strategy of doing our personal best at the main tasks of everyday work as well as participating in a variety of other experiences successfully develops a career that encompasses excellence, enthusiasm, and the fulfillment of personal needs along with those of our practice or institution. When we do our personal best on the day-to-day matters, people will be beating down the doors to offer other valuable experiences. To paraphrase an old truism, if you want something done well, find a busy person who does other things well. Some of the experiences presented to us may question our basic assumptions and redirect our careers; others will fizzle out, but not before they garner self-confidence or even indirectly lead to something more substantial in our careers. Sometimes all that an experience teaches us is that we do not want to continue down that path.

Career development is a dynamic process. Strive for excellence in everything that you do, keep your eyes open for broadening experiences, and maintain your fifth-grade enthusiasm! I am not sure what I will be doing in 5 years, but I hope it will be fresh, varied, and exciting. Do dermatology careers develop through a focused plan or serendipity? At my mature age, with a well-developed career, my answer is mostly serendipity.

1. Stone D, Patton B, Heen S. Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 2010.

2. Fisher R, Ury W, Patton B. Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 2011.

3. Lowe D. PowerPoint 2016 for Dummies. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2015.

4. Tracy B. Eat That Frog! 21 Ways to Stop Procrastinating and Get More Done in Less Time. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 2007.

Fifth grade is a wonderful school year and fifth graders are interesting, enthusiastic, and busy people, but conflicts can arise amidst their many activities. We discovered that our fifth grader could not finish his homework, play on 3 sports teams, take bass lessons (and practice), join the city chorus, play outside with his friends, walk his dog, spend quality time with his parents, and do his chores—much less eat and sleep. Choices needed to be made. Unfortunately, in our community dropping out of the premier soccer club probably limits future possibilities in the sport; nevertheless, it would entail 6 to 8 hours of game and practice time per week (plus travel), as well as multiple 3-day tournaments. Therefore our son dropped soccer, as we decided the best strategy for our fifth grader to develop and mature was to do his personal best at his schoolwork while also exploring a greater variety of less intensive extracurricular experiences.

Most dermatologists appropriately adopt a different strategy during medical school and dermatology training. An intensive, single-minded focus gets us through hours in the anatomy laboratory, the first difficult clinical rotations, sleepless nights, grand rounds quizzing, and board examinations. Completion of our training does not, however, signal that development and maturation are complete; rather, we must then choose among a new set of options, such as the basic questions of whether to practice in an academic setting or group or solo practice and whether to emphasize a subspecialty. These choices involve some mutually exclusive options and exist in a milieu of adult (ie, nonacademic) dilemmas concerning family life, community and spiritual life, avocations, exercise regimens, housing and material goods, and other routine aspects of life. The professional options that are available may be limited by the lack of community opportunities, geographic need, or job availability in a preferred location or institution.

So how do dermatologists manage to start their careers, then develop and maintain them? A best practice is to be both introspective as well as aware of our external environments. Good questions to ask ourselves periodically (having different answers at different stages is highly recommended!) include: What are my core values and what do I want to accomplish? Pay attention to your gut. When do you lose track of time and what makes you want to scream in frustration? Regularly take an inventory of your strengths and find opportunities to acquire the competencies that can take you to the next level. What skill do I need to finesse and how do I finesse it? Do an external scan and understand limiting factors such as geographic saturation in your desired practice type or the lack of appropriate collaborators in your preferred area of interest. Search out people who are doing what you’d like to do and then identify their paths and what you can use from their experiences to help with your career development.

Once you have identified a few professional goals to pursue, utilize all the resources you can find. You might find helpful seminars at an academic institution or at conferences. Do you want to become the regional expert in sarcoidosis? Check out what has been written and find other experts in the subject and where they are speaking. Many organizations have practice management or leadership development courses and seminars. There also are books for everything—those that I have found most useful include Douglas Stone’s Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most1 and William L. Fisher and Roger Ury’s classic, Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In.2 Have to give a talk? There is a PowerPoint 2016 for Dummies.3 The same series also includes a book on the Microsoft® Excel spreadsheet. Also check out my all-time favorite—Brian Tracy’s Eat That Frog! 21 Ways to Stop Procrastinating and Get More Done in Less Time.4

It is important to experiment with different professional experiences and have an open mind when a new activity presents itself. Look for opportunities for new side ventures or interesting projects that will not take up much time so you can continue to do your best at your daily work. When I was a senior resident, a dermatologist from Maine asked me if I would help him find a dermatologist who would work regularly at a rural clinic in the northern part of the state. My answer was, why not me? For 8 years I worked in that clinic once to twice per month, seeing as many patients as I could for 8 to 12 hours a day on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, and then returning to Boston, Massachusetts, for my normal work week. I even took my 2 youngest children (who were born during that time) with me and found a family there who took excellent care of them while I worked. It ended up being one of the most important experiences, both intellectually and emotionally, of my professional career. I learned how to diagnose difficult and complex dermatology problems by myself in an environment with few resources (the closest dermatologist was 150 miles away), how to use primary care providers to manage patients remotely, how to set up a clinic and manage staff (I hired other part-time staff to help me), and how to lead an effort that I felt passionate about. I sometimes even took on residents, which helped me finesse my teaching and supervision style.

Unlike the achievement of becoming a board-certified dermatologist, a dermatology career does not develop in a straight line, and rarely at a steady pace. It seems to me that a shift from a single-minded focus during residency to the fifth-grade strategy of doing our personal best at the main tasks of everyday work as well as participating in a variety of other experiences successfully develops a career that encompasses excellence, enthusiasm, and the fulfillment of personal needs along with those of our practice or institution. When we do our personal best on the day-to-day matters, people will be beating down the doors to offer other valuable experiences. To paraphrase an old truism, if you want something done well, find a busy person who does other things well. Some of the experiences presented to us may question our basic assumptions and redirect our careers; others will fizzle out, but not before they garner self-confidence or even indirectly lead to something more substantial in our careers. Sometimes all that an experience teaches us is that we do not want to continue down that path.

Career development is a dynamic process. Strive for excellence in everything that you do, keep your eyes open for broadening experiences, and maintain your fifth-grade enthusiasm! I am not sure what I will be doing in 5 years, but I hope it will be fresh, varied, and exciting. Do dermatology careers develop through a focused plan or serendipity? At my mature age, with a well-developed career, my answer is mostly serendipity.

Fifth grade is a wonderful school year and fifth graders are interesting, enthusiastic, and busy people, but conflicts can arise amidst their many activities. We discovered that our fifth grader could not finish his homework, play on 3 sports teams, take bass lessons (and practice), join the city chorus, play outside with his friends, walk his dog, spend quality time with his parents, and do his chores—much less eat and sleep. Choices needed to be made. Unfortunately, in our community dropping out of the premier soccer club probably limits future possibilities in the sport; nevertheless, it would entail 6 to 8 hours of game and practice time per week (plus travel), as well as multiple 3-day tournaments. Therefore our son dropped soccer, as we decided the best strategy for our fifth grader to develop and mature was to do his personal best at his schoolwork while also exploring a greater variety of less intensive extracurricular experiences.

Most dermatologists appropriately adopt a different strategy during medical school and dermatology training. An intensive, single-minded focus gets us through hours in the anatomy laboratory, the first difficult clinical rotations, sleepless nights, grand rounds quizzing, and board examinations. Completion of our training does not, however, signal that development and maturation are complete; rather, we must then choose among a new set of options, such as the basic questions of whether to practice in an academic setting or group or solo practice and whether to emphasize a subspecialty. These choices involve some mutually exclusive options and exist in a milieu of adult (ie, nonacademic) dilemmas concerning family life, community and spiritual life, avocations, exercise regimens, housing and material goods, and other routine aspects of life. The professional options that are available may be limited by the lack of community opportunities, geographic need, or job availability in a preferred location or institution.

So how do dermatologists manage to start their careers, then develop and maintain them? A best practice is to be both introspective as well as aware of our external environments. Good questions to ask ourselves periodically (having different answers at different stages is highly recommended!) include: What are my core values and what do I want to accomplish? Pay attention to your gut. When do you lose track of time and what makes you want to scream in frustration? Regularly take an inventory of your strengths and find opportunities to acquire the competencies that can take you to the next level. What skill do I need to finesse and how do I finesse it? Do an external scan and understand limiting factors such as geographic saturation in your desired practice type or the lack of appropriate collaborators in your preferred area of interest. Search out people who are doing what you’d like to do and then identify their paths and what you can use from their experiences to help with your career development.

Once you have identified a few professional goals to pursue, utilize all the resources you can find. You might find helpful seminars at an academic institution or at conferences. Do you want to become the regional expert in sarcoidosis? Check out what has been written and find other experts in the subject and where they are speaking. Many organizations have practice management or leadership development courses and seminars. There also are books for everything—those that I have found most useful include Douglas Stone’s Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most1 and William L. Fisher and Roger Ury’s classic, Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In.2 Have to give a talk? There is a PowerPoint 2016 for Dummies.3 The same series also includes a book on the Microsoft® Excel spreadsheet. Also check out my all-time favorite—Brian Tracy’s Eat That Frog! 21 Ways to Stop Procrastinating and Get More Done in Less Time.4

It is important to experiment with different professional experiences and have an open mind when a new activity presents itself. Look for opportunities for new side ventures or interesting projects that will not take up much time so you can continue to do your best at your daily work. When I was a senior resident, a dermatologist from Maine asked me if I would help him find a dermatologist who would work regularly at a rural clinic in the northern part of the state. My answer was, why not me? For 8 years I worked in that clinic once to twice per month, seeing as many patients as I could for 8 to 12 hours a day on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, and then returning to Boston, Massachusetts, for my normal work week. I even took my 2 youngest children (who were born during that time) with me and found a family there who took excellent care of them while I worked. It ended up being one of the most important experiences, both intellectually and emotionally, of my professional career. I learned how to diagnose difficult and complex dermatology problems by myself in an environment with few resources (the closest dermatologist was 150 miles away), how to use primary care providers to manage patients remotely, how to set up a clinic and manage staff (I hired other part-time staff to help me), and how to lead an effort that I felt passionate about. I sometimes even took on residents, which helped me finesse my teaching and supervision style.

Unlike the achievement of becoming a board-certified dermatologist, a dermatology career does not develop in a straight line, and rarely at a steady pace. It seems to me that a shift from a single-minded focus during residency to the fifth-grade strategy of doing our personal best at the main tasks of everyday work as well as participating in a variety of other experiences successfully develops a career that encompasses excellence, enthusiasm, and the fulfillment of personal needs along with those of our practice or institution. When we do our personal best on the day-to-day matters, people will be beating down the doors to offer other valuable experiences. To paraphrase an old truism, if you want something done well, find a busy person who does other things well. Some of the experiences presented to us may question our basic assumptions and redirect our careers; others will fizzle out, but not before they garner self-confidence or even indirectly lead to something more substantial in our careers. Sometimes all that an experience teaches us is that we do not want to continue down that path.

Career development is a dynamic process. Strive for excellence in everything that you do, keep your eyes open for broadening experiences, and maintain your fifth-grade enthusiasm! I am not sure what I will be doing in 5 years, but I hope it will be fresh, varied, and exciting. Do dermatology careers develop through a focused plan or serendipity? At my mature age, with a well-developed career, my answer is mostly serendipity.

1. Stone D, Patton B, Heen S. Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 2010.

2. Fisher R, Ury W, Patton B. Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 2011.

3. Lowe D. PowerPoint 2016 for Dummies. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2015.

4. Tracy B. Eat That Frog! 21 Ways to Stop Procrastinating and Get More Done in Less Time. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 2007.

1. Stone D, Patton B, Heen S. Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 2010.

2. Fisher R, Ury W, Patton B. Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 2011.

3. Lowe D. PowerPoint 2016 for Dummies. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2015.

4. Tracy B. Eat That Frog! 21 Ways to Stop Procrastinating and Get More Done in Less Time. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 2007.

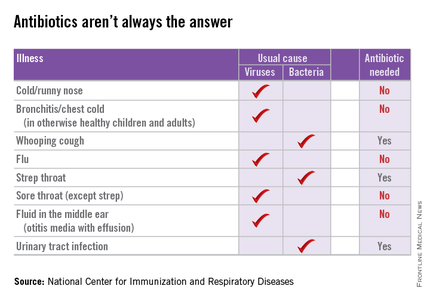

Judicious antibiotic use key in ambulatory settings

I was recently asked to evaluate a young child with a urinary tract infection caused by an extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)–producing Escherichia coli.

I’d just broken the bad news to the mother: There was no oral medication available to treat the baby, so she’d have to stay in the hospital for a full intravenous course.

“Has your child been treated with antibiotics recently?” I asked the mother, wondering how the baby had come to have such a resistant infection.

“She had a couple days of runny nose and a low-grade fever a couple of weeks ago,” she told me. “Her doctor treated her for a sinus infection.”

In 2011, doctors in outpatient settings across the United States wrote 262.5 million prescriptions for antibiotics – 73.7 million for children – and according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 50% of these were completely unnecessary because they were prescribed for viral respiratory tract infections (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 May 1;60[9]:1308-16).

Prescribing practices varied by region, with the highest rates in the South. Don’t think I’m judging. I live in Kentucky, the state with the highest rate of antibiotic prescribing at 1,281 prescriptions per 1,000 persons. Is it any wonder that we’re seeing kids with very resistant infections?

The CDC estimates that at least two million people in the United States are infected annually with antibiotic-resistant bacteria and at least 23,000 of them die as a result of these infections. It is estimated that prevention strategies that include better antibiotic prescribing could prevent as many as 619,000 infections and 37,000 deaths over 5 years. Fortunately, my little patient recovered fully, but it has made me think about antimicrobial stewardship, especially its role in the outpatient setting.

According the American Academy of Pediatrics, the goal of antimicrobial stewardship is “to optimize antimicrobial use, with the aim of decreasing inappropriate use that leads to unwarranted toxicity and to selection and spread of resistant organisms.”

Antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) are increasingly common in inpatient settings and have been shown to reduce antibiotic use. These programs can take many forms. The hospital where I work relies primarily on clinical guidelines emphasizing appropriate empiric therapy for a variety of common conditions. Other hospitals employ prospective audit and feedback, as well as a restricted formulary. Medicare and Medicaid Conditions of Participation will soon require hospitals that receive funds from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have an ASP.

Comparatively little has been published about ASPs in the outpatient setting. The American Academy of Pediatrics suggests that effective strategies include patient education, provider education, provider audit and feedback, and clinical decision support. We have at least some data that these work, at least in a research setting.

From 2000 to 2003, a controlled, cluster-randomized trial in 16 Massachusetts communities demonstrated that a 3-year, multifaceted, community-level intervention was “modestly successful” in reducing antibiotic use (Pediatrics. 2008 Jan;121[1]:e15-23). As a part of this intervention, parents received education via direct mail and in primary care settings, pharmacies, and child care centers while physicians received small-group education, frequent updates and educational materials, and prescribing feedback. Antibiotic prescribing was measured via health insurance claims data from all children who were 6 years of age or younger and resided in study communities, and were insured by one of four participating health plans. Coincident with the intervention, there was 4.2% decrease in antibiotic prescribing among children aged 24 to <48 months and a 6.7% decrease among those aged 48-72 months. The effect was greatest among Medicaid-insured children.

More recently, 18 primary care practices in Pennsylvania and New Jersey were randomized to an intervention that consisted of a 1-hour, on-site education session followed by 1 year of personalized, quarterly audit and feedback of prescribing for bacterial and viral acute respiratory tract infections (ARTIs), or usual practice (JAMA. 2013 Jun 12;309[22]:2345-52). The prescribing practices of 162 clinicians were included in the analysis.

Broad spectrum–antibiotic prescribing decreased in intervention practices, compared with controls (26.8% to 14.3% among intervention practices vs. 28.4% to 22.6% in controls), as did “off-guideline” prescribing for pneumonia and acute sinusitis. Antibiotic prescribing for viral infections was relatively low at baseline and did not change. The authors concluded that “extending antimicrobial stewardship to the ambulatory setting, where such programs have generally not been implemented, may have important health benefits.” Unfortunately, the positive effect in these practices was not sustained after the audit and feedback stopped (JAMA. 2014 Dec 17;312[23]:2569-70).

Not all antimicrobial stewardship interventions need to be time- and resource-intensive. Investigators in California found that providers who publicly pledged to reducing inappropriate antibiotic use for ARTIs by signing and posting a commitment letter in exam rooms actually prescribed fewer inappropriate antibiotic courses for their adult patients (JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Mar;174[3]:425-31).

“When you have a cough, sore throat, or other illness, your doctor will help you select the best possible treatments. If an antibiotic would do more harm than good, your doctor will explain this to you, and may offer other treatments that are better for you,” the letter read in part. There was a 19.7 absolute percentage reduction in inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for ARTIs among clinicians randomized to the commitment letter invention relative to controls.

Can antimicrobial strategies work in the “real” world, in a busy pediatrician’s office? According to Dr. Patricia Purcell, a physician with East Louisville Pediatrics in Louisville, Ky., the answer is “yes.”

“We actually start with education in the newborn period,” Dr. Purcell said. “We let parents know that we are not going to call in antibiotics over the phone, and we’re not going to prescribe them for an upper respiratory tract infection.”

Dr. Purcell and her partners have committed to following evidence-based guidelines for antibiotic practices, such as the AAP’s guidelines for otitis media and sinusitis. She also noted that at least one major insurance company is starting to provide the group feedback about their antibiotic-prescribing practices. “They want to make sure we are not prescribing antibiotics for viruses,” she said.

Still, the message that antibiotics are not always the answer can be a bitter pill for some parents to swallow. A pediatrician friend in Alabama notes: “I have these conversations every day, and a lot of parents are mad at me for not prescribing antibiotics for their child’s ‘terrible cold.’” Another friend notes that watchful waiting can be a burden for parents who have high copays or difficulties with transportation.

Still, many parents would welcome a frank discussion about the risks and benefits of antibiotics. After I shared some of the CDC information for parents with a nursing colleague, she told me that her daughter recently had a febrile illness and was diagnosed with otitis media. “I don’t like giving my kids meds they don’t need,” she told me. “However, if the doc says they need antibiotics and they prescribe them, I give them. I never say, ‘Do we really need antibiotics for that?’”

Now she is rethinking that approach. “Was 10 days of amoxicillin necessary for a ‘red’ eardrum?! I’m just a mom. ... I don’t know the answer to that! Was her ear red because she had been crying or because of her fever? Did she get ‘treatment’ she did not need? Did the doctor give me antibiotics without education because she assumed that is why I brought her in?”

This year’s “Get Smart About Antibiotics Week” was Nov. 16-22. This annual 1-week observance is intended to raise awareness of the threat of antibiotic resistance and the importance of appropriate prescribing and use. Kudos if you celebrated this in your office. If you missed it, it’s not too late to check out some of the activities suggested by the CDC, and try one or two in your own practice. Email me with your ideas about stewardship in the outpatient setting, and I’ll try to feature at least some of them in a future column.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Kosair Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. Dr. Bryant disclosed that she has been an investigator for clinical trials funded by Pfizer for the past 2 years. Email her at [email protected].

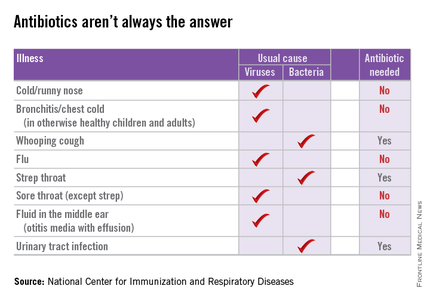

I was recently asked to evaluate a young child with a urinary tract infection caused by an extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)–producing Escherichia coli.

I’d just broken the bad news to the mother: There was no oral medication available to treat the baby, so she’d have to stay in the hospital for a full intravenous course.

“Has your child been treated with antibiotics recently?” I asked the mother, wondering how the baby had come to have such a resistant infection.

“She had a couple days of runny nose and a low-grade fever a couple of weeks ago,” she told me. “Her doctor treated her for a sinus infection.”

In 2011, doctors in outpatient settings across the United States wrote 262.5 million prescriptions for antibiotics – 73.7 million for children – and according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 50% of these were completely unnecessary because they were prescribed for viral respiratory tract infections (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 May 1;60[9]:1308-16).

Prescribing practices varied by region, with the highest rates in the South. Don’t think I’m judging. I live in Kentucky, the state with the highest rate of antibiotic prescribing at 1,281 prescriptions per 1,000 persons. Is it any wonder that we’re seeing kids with very resistant infections?

The CDC estimates that at least two million people in the United States are infected annually with antibiotic-resistant bacteria and at least 23,000 of them die as a result of these infections. It is estimated that prevention strategies that include better antibiotic prescribing could prevent as many as 619,000 infections and 37,000 deaths over 5 years. Fortunately, my little patient recovered fully, but it has made me think about antimicrobial stewardship, especially its role in the outpatient setting.

According the American Academy of Pediatrics, the goal of antimicrobial stewardship is “to optimize antimicrobial use, with the aim of decreasing inappropriate use that leads to unwarranted toxicity and to selection and spread of resistant organisms.”

Antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) are increasingly common in inpatient settings and have been shown to reduce antibiotic use. These programs can take many forms. The hospital where I work relies primarily on clinical guidelines emphasizing appropriate empiric therapy for a variety of common conditions. Other hospitals employ prospective audit and feedback, as well as a restricted formulary. Medicare and Medicaid Conditions of Participation will soon require hospitals that receive funds from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have an ASP.

Comparatively little has been published about ASPs in the outpatient setting. The American Academy of Pediatrics suggests that effective strategies include patient education, provider education, provider audit and feedback, and clinical decision support. We have at least some data that these work, at least in a research setting.

From 2000 to 2003, a controlled, cluster-randomized trial in 16 Massachusetts communities demonstrated that a 3-year, multifaceted, community-level intervention was “modestly successful” in reducing antibiotic use (Pediatrics. 2008 Jan;121[1]:e15-23). As a part of this intervention, parents received education via direct mail and in primary care settings, pharmacies, and child care centers while physicians received small-group education, frequent updates and educational materials, and prescribing feedback. Antibiotic prescribing was measured via health insurance claims data from all children who were 6 years of age or younger and resided in study communities, and were insured by one of four participating health plans. Coincident with the intervention, there was 4.2% decrease in antibiotic prescribing among children aged 24 to <48 months and a 6.7% decrease among those aged 48-72 months. The effect was greatest among Medicaid-insured children.

More recently, 18 primary care practices in Pennsylvania and New Jersey were randomized to an intervention that consisted of a 1-hour, on-site education session followed by 1 year of personalized, quarterly audit and feedback of prescribing for bacterial and viral acute respiratory tract infections (ARTIs), or usual practice (JAMA. 2013 Jun 12;309[22]:2345-52). The prescribing practices of 162 clinicians were included in the analysis.

Broad spectrum–antibiotic prescribing decreased in intervention practices, compared with controls (26.8% to 14.3% among intervention practices vs. 28.4% to 22.6% in controls), as did “off-guideline” prescribing for pneumonia and acute sinusitis. Antibiotic prescribing for viral infections was relatively low at baseline and did not change. The authors concluded that “extending antimicrobial stewardship to the ambulatory setting, where such programs have generally not been implemented, may have important health benefits.” Unfortunately, the positive effect in these practices was not sustained after the audit and feedback stopped (JAMA. 2014 Dec 17;312[23]:2569-70).

Not all antimicrobial stewardship interventions need to be time- and resource-intensive. Investigators in California found that providers who publicly pledged to reducing inappropriate antibiotic use for ARTIs by signing and posting a commitment letter in exam rooms actually prescribed fewer inappropriate antibiotic courses for their adult patients (JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Mar;174[3]:425-31).

“When you have a cough, sore throat, or other illness, your doctor will help you select the best possible treatments. If an antibiotic would do more harm than good, your doctor will explain this to you, and may offer other treatments that are better for you,” the letter read in part. There was a 19.7 absolute percentage reduction in inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for ARTIs among clinicians randomized to the commitment letter invention relative to controls.

Can antimicrobial strategies work in the “real” world, in a busy pediatrician’s office? According to Dr. Patricia Purcell, a physician with East Louisville Pediatrics in Louisville, Ky., the answer is “yes.”

“We actually start with education in the newborn period,” Dr. Purcell said. “We let parents know that we are not going to call in antibiotics over the phone, and we’re not going to prescribe them for an upper respiratory tract infection.”

Dr. Purcell and her partners have committed to following evidence-based guidelines for antibiotic practices, such as the AAP’s guidelines for otitis media and sinusitis. She also noted that at least one major insurance company is starting to provide the group feedback about their antibiotic-prescribing practices. “They want to make sure we are not prescribing antibiotics for viruses,” she said.

Still, the message that antibiotics are not always the answer can be a bitter pill for some parents to swallow. A pediatrician friend in Alabama notes: “I have these conversations every day, and a lot of parents are mad at me for not prescribing antibiotics for their child’s ‘terrible cold.’” Another friend notes that watchful waiting can be a burden for parents who have high copays or difficulties with transportation.

Still, many parents would welcome a frank discussion about the risks and benefits of antibiotics. After I shared some of the CDC information for parents with a nursing colleague, she told me that her daughter recently had a febrile illness and was diagnosed with otitis media. “I don’t like giving my kids meds they don’t need,” she told me. “However, if the doc says they need antibiotics and they prescribe them, I give them. I never say, ‘Do we really need antibiotics for that?’”

Now she is rethinking that approach. “Was 10 days of amoxicillin necessary for a ‘red’ eardrum?! I’m just a mom. ... I don’t know the answer to that! Was her ear red because she had been crying or because of her fever? Did she get ‘treatment’ she did not need? Did the doctor give me antibiotics without education because she assumed that is why I brought her in?”

This year’s “Get Smart About Antibiotics Week” was Nov. 16-22. This annual 1-week observance is intended to raise awareness of the threat of antibiotic resistance and the importance of appropriate prescribing and use. Kudos if you celebrated this in your office. If you missed it, it’s not too late to check out some of the activities suggested by the CDC, and try one or two in your own practice. Email me with your ideas about stewardship in the outpatient setting, and I’ll try to feature at least some of them in a future column.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Kosair Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. Dr. Bryant disclosed that she has been an investigator for clinical trials funded by Pfizer for the past 2 years. Email her at [email protected].

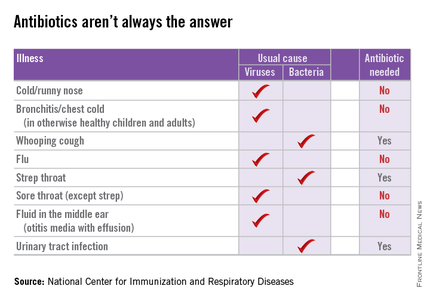

I was recently asked to evaluate a young child with a urinary tract infection caused by an extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)–producing Escherichia coli.

I’d just broken the bad news to the mother: There was no oral medication available to treat the baby, so she’d have to stay in the hospital for a full intravenous course.

“Has your child been treated with antibiotics recently?” I asked the mother, wondering how the baby had come to have such a resistant infection.

“She had a couple days of runny nose and a low-grade fever a couple of weeks ago,” she told me. “Her doctor treated her for a sinus infection.”

In 2011, doctors in outpatient settings across the United States wrote 262.5 million prescriptions for antibiotics – 73.7 million for children – and according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 50% of these were completely unnecessary because they were prescribed for viral respiratory tract infections (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 May 1;60[9]:1308-16).

Prescribing practices varied by region, with the highest rates in the South. Don’t think I’m judging. I live in Kentucky, the state with the highest rate of antibiotic prescribing at 1,281 prescriptions per 1,000 persons. Is it any wonder that we’re seeing kids with very resistant infections?

The CDC estimates that at least two million people in the United States are infected annually with antibiotic-resistant bacteria and at least 23,000 of them die as a result of these infections. It is estimated that prevention strategies that include better antibiotic prescribing could prevent as many as 619,000 infections and 37,000 deaths over 5 years. Fortunately, my little patient recovered fully, but it has made me think about antimicrobial stewardship, especially its role in the outpatient setting.

According the American Academy of Pediatrics, the goal of antimicrobial stewardship is “to optimize antimicrobial use, with the aim of decreasing inappropriate use that leads to unwarranted toxicity and to selection and spread of resistant organisms.”

Antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) are increasingly common in inpatient settings and have been shown to reduce antibiotic use. These programs can take many forms. The hospital where I work relies primarily on clinical guidelines emphasizing appropriate empiric therapy for a variety of common conditions. Other hospitals employ prospective audit and feedback, as well as a restricted formulary. Medicare and Medicaid Conditions of Participation will soon require hospitals that receive funds from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have an ASP.

Comparatively little has been published about ASPs in the outpatient setting. The American Academy of Pediatrics suggests that effective strategies include patient education, provider education, provider audit and feedback, and clinical decision support. We have at least some data that these work, at least in a research setting.

From 2000 to 2003, a controlled, cluster-randomized trial in 16 Massachusetts communities demonstrated that a 3-year, multifaceted, community-level intervention was “modestly successful” in reducing antibiotic use (Pediatrics. 2008 Jan;121[1]:e15-23). As a part of this intervention, parents received education via direct mail and in primary care settings, pharmacies, and child care centers while physicians received small-group education, frequent updates and educational materials, and prescribing feedback. Antibiotic prescribing was measured via health insurance claims data from all children who were 6 years of age or younger and resided in study communities, and were insured by one of four participating health plans. Coincident with the intervention, there was 4.2% decrease in antibiotic prescribing among children aged 24 to <48 months and a 6.7% decrease among those aged 48-72 months. The effect was greatest among Medicaid-insured children.

More recently, 18 primary care practices in Pennsylvania and New Jersey were randomized to an intervention that consisted of a 1-hour, on-site education session followed by 1 year of personalized, quarterly audit and feedback of prescribing for bacterial and viral acute respiratory tract infections (ARTIs), or usual practice (JAMA. 2013 Jun 12;309[22]:2345-52). The prescribing practices of 162 clinicians were included in the analysis.

Broad spectrum–antibiotic prescribing decreased in intervention practices, compared with controls (26.8% to 14.3% among intervention practices vs. 28.4% to 22.6% in controls), as did “off-guideline” prescribing for pneumonia and acute sinusitis. Antibiotic prescribing for viral infections was relatively low at baseline and did not change. The authors concluded that “extending antimicrobial stewardship to the ambulatory setting, where such programs have generally not been implemented, may have important health benefits.” Unfortunately, the positive effect in these practices was not sustained after the audit and feedback stopped (JAMA. 2014 Dec 17;312[23]:2569-70).

Not all antimicrobial stewardship interventions need to be time- and resource-intensive. Investigators in California found that providers who publicly pledged to reducing inappropriate antibiotic use for ARTIs by signing and posting a commitment letter in exam rooms actually prescribed fewer inappropriate antibiotic courses for their adult patients (JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Mar;174[3]:425-31).

“When you have a cough, sore throat, or other illness, your doctor will help you select the best possible treatments. If an antibiotic would do more harm than good, your doctor will explain this to you, and may offer other treatments that are better for you,” the letter read in part. There was a 19.7 absolute percentage reduction in inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for ARTIs among clinicians randomized to the commitment letter invention relative to controls.

Can antimicrobial strategies work in the “real” world, in a busy pediatrician’s office? According to Dr. Patricia Purcell, a physician with East Louisville Pediatrics in Louisville, Ky., the answer is “yes.”

“We actually start with education in the newborn period,” Dr. Purcell said. “We let parents know that we are not going to call in antibiotics over the phone, and we’re not going to prescribe them for an upper respiratory tract infection.”

Dr. Purcell and her partners have committed to following evidence-based guidelines for antibiotic practices, such as the AAP’s guidelines for otitis media and sinusitis. She also noted that at least one major insurance company is starting to provide the group feedback about their antibiotic-prescribing practices. “They want to make sure we are not prescribing antibiotics for viruses,” she said.

Still, the message that antibiotics are not always the answer can be a bitter pill for some parents to swallow. A pediatrician friend in Alabama notes: “I have these conversations every day, and a lot of parents are mad at me for not prescribing antibiotics for their child’s ‘terrible cold.’” Another friend notes that watchful waiting can be a burden for parents who have high copays or difficulties with transportation.

Still, many parents would welcome a frank discussion about the risks and benefits of antibiotics. After I shared some of the CDC information for parents with a nursing colleague, she told me that her daughter recently had a febrile illness and was diagnosed with otitis media. “I don’t like giving my kids meds they don’t need,” she told me. “However, if the doc says they need antibiotics and they prescribe them, I give them. I never say, ‘Do we really need antibiotics for that?’”

Now she is rethinking that approach. “Was 10 days of amoxicillin necessary for a ‘red’ eardrum?! I’m just a mom. ... I don’t know the answer to that! Was her ear red because she had been crying or because of her fever? Did she get ‘treatment’ she did not need? Did the doctor give me antibiotics without education because she assumed that is why I brought her in?”

This year’s “Get Smart About Antibiotics Week” was Nov. 16-22. This annual 1-week observance is intended to raise awareness of the threat of antibiotic resistance and the importance of appropriate prescribing and use. Kudos if you celebrated this in your office. If you missed it, it’s not too late to check out some of the activities suggested by the CDC, and try one or two in your own practice. Email me with your ideas about stewardship in the outpatient setting, and I’ll try to feature at least some of them in a future column.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Kosair Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. Dr. Bryant disclosed that she has been an investigator for clinical trials funded by Pfizer for the past 2 years. Email her at [email protected].

Assessment of High Staphylococcus aureus MIC and Poor Patient Outcomes

Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus) is a common cause of infection within the hospital and in the community.1 Treatment is based on the organism’s susceptibility to methicillin and is referred to as either MRSA (methicillin-resistant S aureus) or MSSA (methicillin-susceptible S aureus). As antibiotic resistance has evolved, patients with S aureus (especially MRSA) infections have become more difficult to treat. Susceptibility testing guides treatment of these infections and determines the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for each antibiotic. A MIC is the minimum concentration of an antibiotic that will inhibit the visible growth of the organism after incubation.

Related: Experts Debate Infection Control Merits of ‘Bare Beneath the Elbows’

Vancomycin has remained the mainstay for treatment of patients with MRSA infections. An increasing number of infections with high documented MICs to vancomycin are raising concern that resistance may be developing. Clinical controversy exists within the infectious disease community as to whether vancomycin is less effective against S aureus infections with a vancomycin MIC of ≥ 2 µg/mL, contributing to poor patient outcomes.2

The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) lowered the breakpoint for vancomycin in 2006 from > 4 µg/mL to > 2 µg/mL.3 Breakpoints delineate MIC values that are considered susceptible, nonsusceptible, or resistant to an antibiotic. The CLSI breakpoint change points to an increase in vancomycin resistance and supports the need for further discussion and insight.

A 2012 meta-analysis was conducted to determine whether an association exists between S aureus infections with vancomycin MIC values ≥ 2 µg/mL and the effectiveness of the therapy.2 Twenty-two studies were included with a primary outcome of 30-day mortality. A review of MRSA data revealed a statistically significant association between high vancomycin MICs (≥ 1.5 µg/mL) and increased mortality (P < .01), regardless of the source of infection. When limiting the data to Etest (bioMérieux, Marcy L’Etoile, France) MIC testing for MRSA bloodstream infections (BSIs), a vancomycin MIC ≥ 1.5 µg/mL was not associated with increased mortality (P = .08). Comparing data for MIC ≥ 2 µg/mL and ≤ 1.5 µg/mL, found that MICs ≥ 2 µg/mL were associated with increased mortality (P < .01). Analysis of the 11 studies that included data on treatment failure concluded that S aureus infections with a vancomycin MIC ≥ 1.5 µg/mL were associated with an increased risk of treatment failure in both MSSA and MRSA infections (P < .01) and that treatment failure was more likely in MRSA BSIs than in non-BSIs (P < .01).Evidence to support a possible correlation between high S aureus vancomycin MICs and poor patient outcomes came from a 2013 meta-analysis.3 The specific aim of this study was to examine the correlations between vancomycin MIC, patient mortality, and treatment failure. A MIC ≥ 1.5 µg/mL and ≥ 1.0 µg/mL were used to classify MICs as high when determined by Etest and broth microdilution (BMD), respectively. Analysis revealed an association between high vancomycin MICs and increased risk of treatment failure (relative risk [RR] 1.40, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.15-1.71) and overall mortality (RR 1.42, 95% CI 1.08-1.87). Similarly, a sensitivity analysis on S aureus BSIs with high vancomycin MICs revealed an increased risk of mortality (RR 1.46, 95% CI 1.06-2.01) and treatment failure (RR 1.37, 95% CI 1.09-1.73).

Related: The Importance of an Antimicrobial Stewardship Program

The most recent meta-analysis (published in 2014) included patients with S aureus bacteremia and evaluated the association of high S aureus vancomycin MIC with an increased risk of mortality.4 A high MIC was defined as ≥ 1.5 µg/mL by Etest and ≥ 2.0 µg/mL by BMD. The analysis of 38 studies found a nonstatistically significant difference in mortality risk (P = .43). Further analysis was performed to determine whether the vancomycin MIC cutoff plays a role in increased mortality. No statistically significant difference in mortality was found when using a vancomycin MIC ≥ 1.5 µg/mL, ≥ 2.0 µg/mL, ≥ 4.0 µg/mL, or ≥ 8.0 µg/mL. The authors argued that their differing conclusions from other meta-analyses may be due to the inclusion of only bacteremias rather than all infection types, and although there was not a statistically significant difference, increased risk of mortality could not be excluded.

Related: Results Mixed in Hospital Efforts to Tackle Antimicrobial Resistance

Although conclusions of published meta-analyses differ, the results highlight the necessity of using clinical judgment in treating patients with S aureus infections with high MIC values and to consider the primary source and severity of infection. A confounding factor to direct comparison of the literature is the variations based on the method of MIC determination and testing (Etest vs BMD).

Additionally, all 3 studies addressed the importance of considering clinical patient factors that may lead to poorer prognosis as well as the difficultly in achieving necessary vancomycin levels with limited toxicity. The risk of increased mortality in patients with high vancomycin MICs cannot be ruled out at this time. Therefore, additional patient factors as well as the potential toxicities that may result from vancomycin therapy should be considered when using vancomycin in treating patients with S aureus infections.

Additional Note

An earlier version of this article appeared in the Pharmacy Related Newsletter: The Capsule, of the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer