User login

Ob.gyns. can help end the HIV epidemic

Despite staggering scientific and medical advances, the HIV epidemic in the United States has not changed significantly over the past decade. The estimated incidence of HIV infection has remained stable overall, with between 45,000 and 55,000 new HIV infections diagnosed per year.

This is disheartening because, even without a vaccine, I believe we have the tools today to drive the epidemic down to zero. First of all, we know how to effectively diagnose and treat the infection, and we have evidence that antiretroviral treatment is an effective prevention tool. Secondly, advances in chemoprophylaxis have made pre-exposure prophylaxis a reality.

Ob.gyns. played a central role in one of the greatest successes of the use of antiretroviral drugs: the virtual elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in the United States. Now, by fully utilizing the tools available today, ob.gyns. can play a critical role in ending the epidemic in the United States and beyond.

Tools for diagnosis and treatment

We have so many missed opportunities in fighting the HIV epidemic.

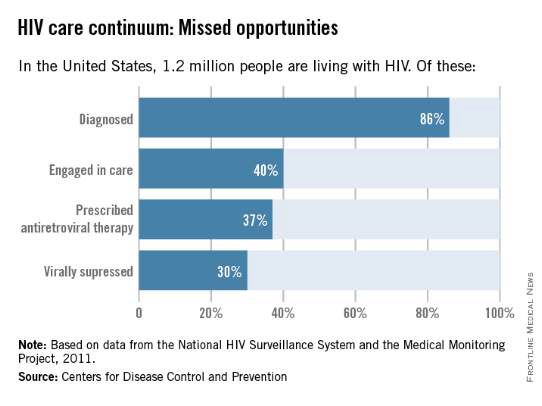

This is evident in data compiled for a model called the “HIV Care Continuum,” or HIV “Cascade of Care.” The model captures the sequential stages of HIV care from diagnosis to suppression of the virus. It was developed in 2011 by Dr. Edward Gardner, an infectious disease/HIV expert at Denver Public Health, and has since been used at the federal, state, and local levels to help identify gaps in HIV services.

Not too long ago, diagnosis was the biggest problem in reducing the public health burden of HIV. Today, the biggest problem is linking and keeping individuals in care. According to the latest analysis by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of the HIV Care Continuum, of the 1.2 million people estimated to be living with HIV in America in 2011, approximately 86% were diagnosed, but only 40% were linked to and stayed in care, 37% were prescribed antiretroviral therapy (ART), and 30% had achieved viral suppression.

Only 30% of Americans living with HIV infection today are effectively treated, according to these data, even though we have the drugs and drug regimens available to treat everyone effectively.

Other analyses have included an additional stage of being initially linked to care (rather than being linked to care and retained in care). This presentation of the cascade, or continuum, further illuminates the progressive drop-off and that shows why an effective, sustained linkage to care is a critical component to ending the HIV epidemic.

One of these studies – an analysis published in 2013 – showed that approximately 82% of people were diagnosed, 66% were linked to care, 37% were retained in care, 33% were prescribed antiretroviral therapy, and 25% had a suppressed viral load of 200 copies/mL or less (JAMA. Intern. Med. 2013;173:1337-44).

With regard to women specifically, the CDC estimates that one in four people living with HIV infection are women, and that only about half of the women who are diagnosed with the infection are staying in care. Even fewer – 4 in 10 – have viral suppression, according to the CDC.

Expanding the management of HIV in the primary care setting could move us closer to ensuring that everyone in the United States who is infected with HIV is aware of the infection, is committed to treatment, and is virologically suppressed.

Like other primary care physicians, ob.gyns often have some degree of long-term continuity with patients – or the ability to create such continuity – that can be helpful for ensuring treatment compliance.

Ob.gyns also have valuable contact with adolescents, who fare worse throughout the cascade and are significantly more likely than older individuals to have unknown infections. An analysis published in 2014 of data for youth ages 13-29 shows that only 40% of HIV-infected youth were aware of their diagnosis and that an estimated 6% or less of HIV-infected youth were virally suppressed (AIDS. Patient. Care. STDS. 2014;28:128-135).

HIV testing should occur much more frequently than a decade ago, given the move in 2006 by the CDC from targeted risk-based testing to routine opt-out testing for all patients aged 13-64.

Treatment, moreover, has become much simpler in many respects. We have available to us more than 30 different drugs for individualizing therapy and providing treatment that allows patients to live a natural lifetime.

While such a large array of options may require those ob.gyns. who see only a few HIV-infected patients a year to work in consultation with an expert, many of the regimens require only a single, once-a-day pill. And while there was much debate as recently as five years ago about when to start treatment, there now is consensus that treatment should be started immediately after diagnosis (even in pregnant women), rather than waiting for the immune system to show signs of decline.

In fact, there is growing evidence that early treatment is key for both the infected individual and for individuals at risk. In the HIV Prevention Trials Network 052 study of discordant couples, for instance, early antiretroviral therapy in an infected partner not only reduced the number of clinical events; it almost completely blocked sexual transmission of the virus to an HIV-negative partner (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:493-505).

The 052 study was a landmark “treatment as prevention” study. Other research has similarly shown that when the viral load of HIV-infected individuals is significantly reduced, their infectivity is reduced. And on a larger scale, research has shown that when we do this on a population basis, achieving widespread and continual treatment success, we can significantly impact the epidemic. This has been the case with the population of intravenous drug users in Vancouver, where the community viral load was significantly reduced by successful treatment that prevented new infections in this once-high-risk population.

Emerging data suggests that early diagnosis and treatment will likely also impact the likelihood of infected individuals achieving “functional cure.” The issue of functional cure – of achieving viral loads that are so low that drug therapy is no longer needed – has been receiving increasing attention in recent years, with the most promising findings reported thus far involving early treatment.

Tools for preexposure prophylaxis

For many years, we fit HIV care neatly into either the treatment or prevention category. More recently, we have come to appreciate that treatment is prevention, that a comprehensive prevention strategy must include treatment of infected individuals.

On the purely prevention side, it is important to continue educating women about safe sex behaviors. Most new HIV infections in women (84%) result from heterosexual contact, according to the CDC. For those who remain at risk of acquiring HIV despite education and counseling (eg., individuals who continue to engage in high-risk behaviors, or who have an HIV-positive partner), pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is now a safe and effective tool for preventing transmission. Patients deemed to be at high risk of acquiring HIV need to be made aware of this option.

PrEP originally was recommended only for gay or bisexual men, but in May 2014, the CDC recommended it for all individuals at risk and released the first comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for the prevention tool (www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/guidelines/PrEPguidelines2014.pdf).

The PrEP medication, Truvada, is a combination of two drugs (tenovovir and emtricitabine) that, when taken daily on a consistent basis, significantly reduces the risk of getting HIV infection. Several large national and international studies have documented risk reductions of 73% to 92% when the medication was taken every day or almost every day. It is clearly within the purview of any ob.gyn to prescribe, monitor, and manage such prevention therapy.

The availability and relative ease of such a tool, along with advances in treatment and knowledge gained from the HIV Care Continuum, should re-energize ob.gyns. to up the ante in efforts to end the epidemic.

Experience in our clinical program that provides care and treatment to patients in the Baltimore-Washington area has taught us that we do much better when we integrate HIV care within primary care. It’s much more likely that patients will “stay close” with their ob.gyn than to another specialist.

Certainly, HIV infection has its “hot spots” and areas of much lower prevalence, but regardless of where we reside, we must continue to appreciate that the epidemic has had a significant impact on women and that this will persist unless we can all better utilize our available tools, such as early diagnosis and effective treatment that are linked long-term with other primary care physicians.

For women, ob.gyns represent a great resource for our nation to make progress toward President Obama’s National HIV Strategy.

Dr. Redfield reported that he has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

Despite staggering scientific and medical advances, the HIV epidemic in the United States has not changed significantly over the past decade. The estimated incidence of HIV infection has remained stable overall, with between 45,000 and 55,000 new HIV infections diagnosed per year.

This is disheartening because, even without a vaccine, I believe we have the tools today to drive the epidemic down to zero. First of all, we know how to effectively diagnose and treat the infection, and we have evidence that antiretroviral treatment is an effective prevention tool. Secondly, advances in chemoprophylaxis have made pre-exposure prophylaxis a reality.

Ob.gyns. played a central role in one of the greatest successes of the use of antiretroviral drugs: the virtual elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in the United States. Now, by fully utilizing the tools available today, ob.gyns. can play a critical role in ending the epidemic in the United States and beyond.

Tools for diagnosis and treatment

We have so many missed opportunities in fighting the HIV epidemic.

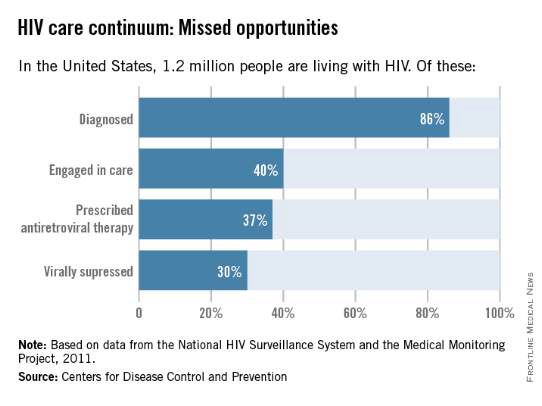

This is evident in data compiled for a model called the “HIV Care Continuum,” or HIV “Cascade of Care.” The model captures the sequential stages of HIV care from diagnosis to suppression of the virus. It was developed in 2011 by Dr. Edward Gardner, an infectious disease/HIV expert at Denver Public Health, and has since been used at the federal, state, and local levels to help identify gaps in HIV services.

Not too long ago, diagnosis was the biggest problem in reducing the public health burden of HIV. Today, the biggest problem is linking and keeping individuals in care. According to the latest analysis by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of the HIV Care Continuum, of the 1.2 million people estimated to be living with HIV in America in 2011, approximately 86% were diagnosed, but only 40% were linked to and stayed in care, 37% were prescribed antiretroviral therapy (ART), and 30% had achieved viral suppression.

Only 30% of Americans living with HIV infection today are effectively treated, according to these data, even though we have the drugs and drug regimens available to treat everyone effectively.

Other analyses have included an additional stage of being initially linked to care (rather than being linked to care and retained in care). This presentation of the cascade, or continuum, further illuminates the progressive drop-off and that shows why an effective, sustained linkage to care is a critical component to ending the HIV epidemic.

One of these studies – an analysis published in 2013 – showed that approximately 82% of people were diagnosed, 66% were linked to care, 37% were retained in care, 33% were prescribed antiretroviral therapy, and 25% had a suppressed viral load of 200 copies/mL or less (JAMA. Intern. Med. 2013;173:1337-44).

With regard to women specifically, the CDC estimates that one in four people living with HIV infection are women, and that only about half of the women who are diagnosed with the infection are staying in care. Even fewer – 4 in 10 – have viral suppression, according to the CDC.

Expanding the management of HIV in the primary care setting could move us closer to ensuring that everyone in the United States who is infected with HIV is aware of the infection, is committed to treatment, and is virologically suppressed.

Like other primary care physicians, ob.gyns often have some degree of long-term continuity with patients – or the ability to create such continuity – that can be helpful for ensuring treatment compliance.

Ob.gyns also have valuable contact with adolescents, who fare worse throughout the cascade and are significantly more likely than older individuals to have unknown infections. An analysis published in 2014 of data for youth ages 13-29 shows that only 40% of HIV-infected youth were aware of their diagnosis and that an estimated 6% or less of HIV-infected youth were virally suppressed (AIDS. Patient. Care. STDS. 2014;28:128-135).

HIV testing should occur much more frequently than a decade ago, given the move in 2006 by the CDC from targeted risk-based testing to routine opt-out testing for all patients aged 13-64.

Treatment, moreover, has become much simpler in many respects. We have available to us more than 30 different drugs for individualizing therapy and providing treatment that allows patients to live a natural lifetime.

While such a large array of options may require those ob.gyns. who see only a few HIV-infected patients a year to work in consultation with an expert, many of the regimens require only a single, once-a-day pill. And while there was much debate as recently as five years ago about when to start treatment, there now is consensus that treatment should be started immediately after diagnosis (even in pregnant women), rather than waiting for the immune system to show signs of decline.

In fact, there is growing evidence that early treatment is key for both the infected individual and for individuals at risk. In the HIV Prevention Trials Network 052 study of discordant couples, for instance, early antiretroviral therapy in an infected partner not only reduced the number of clinical events; it almost completely blocked sexual transmission of the virus to an HIV-negative partner (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:493-505).

The 052 study was a landmark “treatment as prevention” study. Other research has similarly shown that when the viral load of HIV-infected individuals is significantly reduced, their infectivity is reduced. And on a larger scale, research has shown that when we do this on a population basis, achieving widespread and continual treatment success, we can significantly impact the epidemic. This has been the case with the population of intravenous drug users in Vancouver, where the community viral load was significantly reduced by successful treatment that prevented new infections in this once-high-risk population.

Emerging data suggests that early diagnosis and treatment will likely also impact the likelihood of infected individuals achieving “functional cure.” The issue of functional cure – of achieving viral loads that are so low that drug therapy is no longer needed – has been receiving increasing attention in recent years, with the most promising findings reported thus far involving early treatment.

Tools for preexposure prophylaxis

For many years, we fit HIV care neatly into either the treatment or prevention category. More recently, we have come to appreciate that treatment is prevention, that a comprehensive prevention strategy must include treatment of infected individuals.

On the purely prevention side, it is important to continue educating women about safe sex behaviors. Most new HIV infections in women (84%) result from heterosexual contact, according to the CDC. For those who remain at risk of acquiring HIV despite education and counseling (eg., individuals who continue to engage in high-risk behaviors, or who have an HIV-positive partner), pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is now a safe and effective tool for preventing transmission. Patients deemed to be at high risk of acquiring HIV need to be made aware of this option.

PrEP originally was recommended only for gay or bisexual men, but in May 2014, the CDC recommended it for all individuals at risk and released the first comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for the prevention tool (www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/guidelines/PrEPguidelines2014.pdf).

The PrEP medication, Truvada, is a combination of two drugs (tenovovir and emtricitabine) that, when taken daily on a consistent basis, significantly reduces the risk of getting HIV infection. Several large national and international studies have documented risk reductions of 73% to 92% when the medication was taken every day or almost every day. It is clearly within the purview of any ob.gyn to prescribe, monitor, and manage such prevention therapy.

The availability and relative ease of such a tool, along with advances in treatment and knowledge gained from the HIV Care Continuum, should re-energize ob.gyns. to up the ante in efforts to end the epidemic.

Experience in our clinical program that provides care and treatment to patients in the Baltimore-Washington area has taught us that we do much better when we integrate HIV care within primary care. It’s much more likely that patients will “stay close” with their ob.gyn than to another specialist.

Certainly, HIV infection has its “hot spots” and areas of much lower prevalence, but regardless of where we reside, we must continue to appreciate that the epidemic has had a significant impact on women and that this will persist unless we can all better utilize our available tools, such as early diagnosis and effective treatment that are linked long-term with other primary care physicians.

For women, ob.gyns represent a great resource for our nation to make progress toward President Obama’s National HIV Strategy.

Dr. Redfield reported that he has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

Despite staggering scientific and medical advances, the HIV epidemic in the United States has not changed significantly over the past decade. The estimated incidence of HIV infection has remained stable overall, with between 45,000 and 55,000 new HIV infections diagnosed per year.

This is disheartening because, even without a vaccine, I believe we have the tools today to drive the epidemic down to zero. First of all, we know how to effectively diagnose and treat the infection, and we have evidence that antiretroviral treatment is an effective prevention tool. Secondly, advances in chemoprophylaxis have made pre-exposure prophylaxis a reality.

Ob.gyns. played a central role in one of the greatest successes of the use of antiretroviral drugs: the virtual elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in the United States. Now, by fully utilizing the tools available today, ob.gyns. can play a critical role in ending the epidemic in the United States and beyond.

Tools for diagnosis and treatment

We have so many missed opportunities in fighting the HIV epidemic.

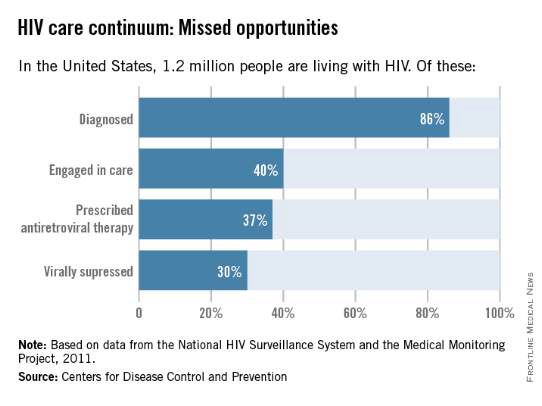

This is evident in data compiled for a model called the “HIV Care Continuum,” or HIV “Cascade of Care.” The model captures the sequential stages of HIV care from diagnosis to suppression of the virus. It was developed in 2011 by Dr. Edward Gardner, an infectious disease/HIV expert at Denver Public Health, and has since been used at the federal, state, and local levels to help identify gaps in HIV services.

Not too long ago, diagnosis was the biggest problem in reducing the public health burden of HIV. Today, the biggest problem is linking and keeping individuals in care. According to the latest analysis by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of the HIV Care Continuum, of the 1.2 million people estimated to be living with HIV in America in 2011, approximately 86% were diagnosed, but only 40% were linked to and stayed in care, 37% were prescribed antiretroviral therapy (ART), and 30% had achieved viral suppression.

Only 30% of Americans living with HIV infection today are effectively treated, according to these data, even though we have the drugs and drug regimens available to treat everyone effectively.

Other analyses have included an additional stage of being initially linked to care (rather than being linked to care and retained in care). This presentation of the cascade, or continuum, further illuminates the progressive drop-off and that shows why an effective, sustained linkage to care is a critical component to ending the HIV epidemic.

One of these studies – an analysis published in 2013 – showed that approximately 82% of people were diagnosed, 66% were linked to care, 37% were retained in care, 33% were prescribed antiretroviral therapy, and 25% had a suppressed viral load of 200 copies/mL or less (JAMA. Intern. Med. 2013;173:1337-44).

With regard to women specifically, the CDC estimates that one in four people living with HIV infection are women, and that only about half of the women who are diagnosed with the infection are staying in care. Even fewer – 4 in 10 – have viral suppression, according to the CDC.

Expanding the management of HIV in the primary care setting could move us closer to ensuring that everyone in the United States who is infected with HIV is aware of the infection, is committed to treatment, and is virologically suppressed.

Like other primary care physicians, ob.gyns often have some degree of long-term continuity with patients – or the ability to create such continuity – that can be helpful for ensuring treatment compliance.

Ob.gyns also have valuable contact with adolescents, who fare worse throughout the cascade and are significantly more likely than older individuals to have unknown infections. An analysis published in 2014 of data for youth ages 13-29 shows that only 40% of HIV-infected youth were aware of their diagnosis and that an estimated 6% or less of HIV-infected youth were virally suppressed (AIDS. Patient. Care. STDS. 2014;28:128-135).

HIV testing should occur much more frequently than a decade ago, given the move in 2006 by the CDC from targeted risk-based testing to routine opt-out testing for all patients aged 13-64.

Treatment, moreover, has become much simpler in many respects. We have available to us more than 30 different drugs for individualizing therapy and providing treatment that allows patients to live a natural lifetime.

While such a large array of options may require those ob.gyns. who see only a few HIV-infected patients a year to work in consultation with an expert, many of the regimens require only a single, once-a-day pill. And while there was much debate as recently as five years ago about when to start treatment, there now is consensus that treatment should be started immediately after diagnosis (even in pregnant women), rather than waiting for the immune system to show signs of decline.

In fact, there is growing evidence that early treatment is key for both the infected individual and for individuals at risk. In the HIV Prevention Trials Network 052 study of discordant couples, for instance, early antiretroviral therapy in an infected partner not only reduced the number of clinical events; it almost completely blocked sexual transmission of the virus to an HIV-negative partner (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:493-505).

The 052 study was a landmark “treatment as prevention” study. Other research has similarly shown that when the viral load of HIV-infected individuals is significantly reduced, their infectivity is reduced. And on a larger scale, research has shown that when we do this on a population basis, achieving widespread and continual treatment success, we can significantly impact the epidemic. This has been the case with the population of intravenous drug users in Vancouver, where the community viral load was significantly reduced by successful treatment that prevented new infections in this once-high-risk population.

Emerging data suggests that early diagnosis and treatment will likely also impact the likelihood of infected individuals achieving “functional cure.” The issue of functional cure – of achieving viral loads that are so low that drug therapy is no longer needed – has been receiving increasing attention in recent years, with the most promising findings reported thus far involving early treatment.

Tools for preexposure prophylaxis

For many years, we fit HIV care neatly into either the treatment or prevention category. More recently, we have come to appreciate that treatment is prevention, that a comprehensive prevention strategy must include treatment of infected individuals.

On the purely prevention side, it is important to continue educating women about safe sex behaviors. Most new HIV infections in women (84%) result from heterosexual contact, according to the CDC. For those who remain at risk of acquiring HIV despite education and counseling (eg., individuals who continue to engage in high-risk behaviors, or who have an HIV-positive partner), pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is now a safe and effective tool for preventing transmission. Patients deemed to be at high risk of acquiring HIV need to be made aware of this option.

PrEP originally was recommended only for gay or bisexual men, but in May 2014, the CDC recommended it for all individuals at risk and released the first comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for the prevention tool (www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/guidelines/PrEPguidelines2014.pdf).

The PrEP medication, Truvada, is a combination of two drugs (tenovovir and emtricitabine) that, when taken daily on a consistent basis, significantly reduces the risk of getting HIV infection. Several large national and international studies have documented risk reductions of 73% to 92% when the medication was taken every day or almost every day. It is clearly within the purview of any ob.gyn to prescribe, monitor, and manage such prevention therapy.

The availability and relative ease of such a tool, along with advances in treatment and knowledge gained from the HIV Care Continuum, should re-energize ob.gyns. to up the ante in efforts to end the epidemic.

Experience in our clinical program that provides care and treatment to patients in the Baltimore-Washington area has taught us that we do much better when we integrate HIV care within primary care. It’s much more likely that patients will “stay close” with their ob.gyn than to another specialist.

Certainly, HIV infection has its “hot spots” and areas of much lower prevalence, but regardless of where we reside, we must continue to appreciate that the epidemic has had a significant impact on women and that this will persist unless we can all better utilize our available tools, such as early diagnosis and effective treatment that are linked long-term with other primary care physicians.

For women, ob.gyns represent a great resource for our nation to make progress toward President Obama’s National HIV Strategy.

Dr. Redfield reported that he has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

HIV treatment adherence still a challenge

It’s hard to believe that it was 30 years ago that HIV was discovered as the cause of AIDS by Dr. Robert Gallo and Dr. Luc Montagnier. Since then, the medical community has focused on preventing and eradicating the virus and its transmission. Despite the advent of highly efficacious antiretroviral therapy, and education efforts to prevent transmission, the disease continues to cause significant morbidity and mortality.

Surveillance data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have indicated that screening and prevention efforts led to a decline in perinatally acquired HIV and AIDS by 80% and 93%, respectively. However, we still have far to go.

The CDC estimated that in 2010 more than 1 million people over age 13 were living with HIV, and approximately 50,000 new cases of HIV occur each year in the United States.

President Obama’s National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States, released in 2010, set ambitious goals for eradicating the disease in our country. We can only hope to achieve the President’s aims if the fight against the disease is taken up by all health care professionals, on multiple fronts, and throughout the many stages of a patient’s health.

In a 2011 Master Class, we addressed the importance of ob.gyns. testing nonpregnant women for HIV, as well as employing HIV prevention strategies to keep our female patients healthy, and prevent potential mother-to-baby transmission of the virus. Although transmission has decreased significantly, helping patients follow their treatment regimens remains a major barrier to eradicating the disease.

Ob.gyns. may be the only physicians who many women see throughout their lives. Therefore, we have a unique opportunity to educate our patients about seeking appropriate care and the need for adhering to treatment regimens.

Our guest author this month is Dr. Robert R. Redfield Jr., a distinguished professor in the department of medicine at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, and associate director of the university’s Institute of Human Virology, with clinical and research programs in virtually all countries in the continent of Africa. Dr. Redfield will discuss the role that physicians can play in terms of linking patients to care as a means of treating those with HIV and reducing the burden of disease. Dr. Redfield’s expertise in the area of novel therapeutics for the treatment of the virus, and his clinical experience in treating patients, provides a unique perspective into this important public health issue.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

It’s hard to believe that it was 30 years ago that HIV was discovered as the cause of AIDS by Dr. Robert Gallo and Dr. Luc Montagnier. Since then, the medical community has focused on preventing and eradicating the virus and its transmission. Despite the advent of highly efficacious antiretroviral therapy, and education efforts to prevent transmission, the disease continues to cause significant morbidity and mortality.

Surveillance data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have indicated that screening and prevention efforts led to a decline in perinatally acquired HIV and AIDS by 80% and 93%, respectively. However, we still have far to go.

The CDC estimated that in 2010 more than 1 million people over age 13 were living with HIV, and approximately 50,000 new cases of HIV occur each year in the United States.

President Obama’s National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States, released in 2010, set ambitious goals for eradicating the disease in our country. We can only hope to achieve the President’s aims if the fight against the disease is taken up by all health care professionals, on multiple fronts, and throughout the many stages of a patient’s health.

In a 2011 Master Class, we addressed the importance of ob.gyns. testing nonpregnant women for HIV, as well as employing HIV prevention strategies to keep our female patients healthy, and prevent potential mother-to-baby transmission of the virus. Although transmission has decreased significantly, helping patients follow their treatment regimens remains a major barrier to eradicating the disease.

Ob.gyns. may be the only physicians who many women see throughout their lives. Therefore, we have a unique opportunity to educate our patients about seeking appropriate care and the need for adhering to treatment regimens.

Our guest author this month is Dr. Robert R. Redfield Jr., a distinguished professor in the department of medicine at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, and associate director of the university’s Institute of Human Virology, with clinical and research programs in virtually all countries in the continent of Africa. Dr. Redfield will discuss the role that physicians can play in terms of linking patients to care as a means of treating those with HIV and reducing the burden of disease. Dr. Redfield’s expertise in the area of novel therapeutics for the treatment of the virus, and his clinical experience in treating patients, provides a unique perspective into this important public health issue.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

It’s hard to believe that it was 30 years ago that HIV was discovered as the cause of AIDS by Dr. Robert Gallo and Dr. Luc Montagnier. Since then, the medical community has focused on preventing and eradicating the virus and its transmission. Despite the advent of highly efficacious antiretroviral therapy, and education efforts to prevent transmission, the disease continues to cause significant morbidity and mortality.

Surveillance data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have indicated that screening and prevention efforts led to a decline in perinatally acquired HIV and AIDS by 80% and 93%, respectively. However, we still have far to go.

The CDC estimated that in 2010 more than 1 million people over age 13 were living with HIV, and approximately 50,000 new cases of HIV occur each year in the United States.

President Obama’s National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States, released in 2010, set ambitious goals for eradicating the disease in our country. We can only hope to achieve the President’s aims if the fight against the disease is taken up by all health care professionals, on multiple fronts, and throughout the many stages of a patient’s health.

In a 2011 Master Class, we addressed the importance of ob.gyns. testing nonpregnant women for HIV, as well as employing HIV prevention strategies to keep our female patients healthy, and prevent potential mother-to-baby transmission of the virus. Although transmission has decreased significantly, helping patients follow their treatment regimens remains a major barrier to eradicating the disease.

Ob.gyns. may be the only physicians who many women see throughout their lives. Therefore, we have a unique opportunity to educate our patients about seeking appropriate care and the need for adhering to treatment regimens.

Our guest author this month is Dr. Robert R. Redfield Jr., a distinguished professor in the department of medicine at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, and associate director of the university’s Institute of Human Virology, with clinical and research programs in virtually all countries in the continent of Africa. Dr. Redfield will discuss the role that physicians can play in terms of linking patients to care as a means of treating those with HIV and reducing the burden of disease. Dr. Redfield’s expertise in the area of novel therapeutics for the treatment of the virus, and his clinical experience in treating patients, provides a unique perspective into this important public health issue.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

Selling the better mousetrap

Despite all the hoopla about Ebola and measles this winter, the most common reason for admitting an infant or young child to the hospital continues to be bronchiolitis. Yet clinical practice guidelines for diagnosing and treating this common infection have not been incorporated into clinical practice.

The use of over-the-counter cold medications to treat upper respiratory infections in young children was shown by meta-analysis in the mid-1990’s to be ineffective, but that use continued until the Food and Drug Administration mandated revisions to packaging in 2008. Antibiotics have been commonly prescribed to treat the ear infections and sinusitis that frequently occur with bronchiolitis. But over the past 20 years, the use of antibiotics has become less prevalent. I date that trend to the work of Dr. Jack Paradise, professor emeritus of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh, and Dr. Ellen Wald, now chair of pediatrics at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, in the mid-1990’s. RespiGam was approved in 1996, then supplanted with palivizumab, as a medication to reduce the burden of respiratory syncytial virus disease. In the summer of 2014, an updated analysis of the costs, risks, and benefits of RSV prophylaxis led to new recommendations that curtailed the indications for that treatment (Pediatrics 2014:134;415-20). What do these trends have in common? The time frame.

It is often cited that it takes 17 years for new evidence to be assimilated into clinical practice (J.R. Soc. Med. 2011;104:510-20). An Institute of Medicine report in 2001, “Crossing the Quality Chasm,” emphasized the importance of becoming more efficient at making progress. Those recommendations themselves are now 14 years old, and I’m not expecting a revolution in human behavior within the next 3 years.

In the new clinical practice guideline issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics in November 2014 for the treatment of young children with bronchiolitis, Dr. Shawn L. Ralston and her colleagues assessed various treatment modalities, found many to be ineffective, and recommended discontinuing their routine use (Pediatrics 2014;134:e1474-e1502). Beta-agonists were at the forefront of this. Was the new guideline based on new data? For the most part, no. In my reading, itmostly reiterated the concerns about effectiveness that were expressed at the time of the prior guidelines from 2006, but removed the weasel words. I admire the dedication of this committee to evidence-based medicine. But will this revised clinical practice guideline actually change practice?

The saying is, “Build a better mousetrap and the world will beat a path to your door.” That quote has been attributed (without adequate documentation) to Ralph Waldo Emerson. He was a great poet, but not a scientist.

During the same month that the new bronchiolitis guidelinewas being released, America held some elections. In the post mortem, President Obama said, “There is a tendency sometimes for me to start thinking: As long as I get the policy right, then that’s what should matter.” He elaborated that “one thing that I do need to constantly remind myself and my team of is it’s not enough just to build the better mousetrap. People don’t automatically come beating to your door. We’ve got to sell it; we’ve got to reach out to the other side and where possible, persuade” (The Wall Street Journal, Nov. 10, 2014).

That isn’t poetry, but the President’s idea is probably more accurate than Emerson’s.

The bronchiolitis clinical practice guidelinewas written in a standardized fashion with 14 key action statements and 242 references. That makes for a good evidence-based medicine document, but is not the best sales pitch.

What will it take to translate these new guidelines into practice? One option is to teach new residents the new guidelines and expect dinosaurs such as myself to retire. If the average pediatrician works for about 34 years, then over a period of 17 years, we will have replaced half the miscreants simply by attrition.

A program of reaching out to the other side and persuading them to change is a better option.

In discussions about this topic on a listserv for pediatric hospitalists, I focused on my concerns. We need to clarify the harms associated with therapies such as beta-agonists, deep nasal suctioning, and continuous pulse oximetry. We need to clarify the goals of treatment, which might include a shorter length of stay, patient comfort, meeting parents’ expectations that we will do something, and/or explaining why we are contradicting any previous recommendations made to the parents. We need to mesh these bronchiolitis guidelines with the asthma action plans and medication lists advocated for wheezing children who are 24 months of age. My colleagues pointed out that all of that is just continuing to refine the policy.

Getting the policy right is necessary but insufficient. What we are really missing is a campaign strategy to sell it.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. He is also listserv moderator for the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine.

Despite all the hoopla about Ebola and measles this winter, the most common reason for admitting an infant or young child to the hospital continues to be bronchiolitis. Yet clinical practice guidelines for diagnosing and treating this common infection have not been incorporated into clinical practice.

The use of over-the-counter cold medications to treat upper respiratory infections in young children was shown by meta-analysis in the mid-1990’s to be ineffective, but that use continued until the Food and Drug Administration mandated revisions to packaging in 2008. Antibiotics have been commonly prescribed to treat the ear infections and sinusitis that frequently occur with bronchiolitis. But over the past 20 years, the use of antibiotics has become less prevalent. I date that trend to the work of Dr. Jack Paradise, professor emeritus of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh, and Dr. Ellen Wald, now chair of pediatrics at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, in the mid-1990’s. RespiGam was approved in 1996, then supplanted with palivizumab, as a medication to reduce the burden of respiratory syncytial virus disease. In the summer of 2014, an updated analysis of the costs, risks, and benefits of RSV prophylaxis led to new recommendations that curtailed the indications for that treatment (Pediatrics 2014:134;415-20). What do these trends have in common? The time frame.

It is often cited that it takes 17 years for new evidence to be assimilated into clinical practice (J.R. Soc. Med. 2011;104:510-20). An Institute of Medicine report in 2001, “Crossing the Quality Chasm,” emphasized the importance of becoming more efficient at making progress. Those recommendations themselves are now 14 years old, and I’m not expecting a revolution in human behavior within the next 3 years.

In the new clinical practice guideline issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics in November 2014 for the treatment of young children with bronchiolitis, Dr. Shawn L. Ralston and her colleagues assessed various treatment modalities, found many to be ineffective, and recommended discontinuing their routine use (Pediatrics 2014;134:e1474-e1502). Beta-agonists were at the forefront of this. Was the new guideline based on new data? For the most part, no. In my reading, itmostly reiterated the concerns about effectiveness that were expressed at the time of the prior guidelines from 2006, but removed the weasel words. I admire the dedication of this committee to evidence-based medicine. But will this revised clinical practice guideline actually change practice?

The saying is, “Build a better mousetrap and the world will beat a path to your door.” That quote has been attributed (without adequate documentation) to Ralph Waldo Emerson. He was a great poet, but not a scientist.

During the same month that the new bronchiolitis guidelinewas being released, America held some elections. In the post mortem, President Obama said, “There is a tendency sometimes for me to start thinking: As long as I get the policy right, then that’s what should matter.” He elaborated that “one thing that I do need to constantly remind myself and my team of is it’s not enough just to build the better mousetrap. People don’t automatically come beating to your door. We’ve got to sell it; we’ve got to reach out to the other side and where possible, persuade” (The Wall Street Journal, Nov. 10, 2014).

That isn’t poetry, but the President’s idea is probably more accurate than Emerson’s.

The bronchiolitis clinical practice guidelinewas written in a standardized fashion with 14 key action statements and 242 references. That makes for a good evidence-based medicine document, but is not the best sales pitch.

What will it take to translate these new guidelines into practice? One option is to teach new residents the new guidelines and expect dinosaurs such as myself to retire. If the average pediatrician works for about 34 years, then over a period of 17 years, we will have replaced half the miscreants simply by attrition.

A program of reaching out to the other side and persuading them to change is a better option.

In discussions about this topic on a listserv for pediatric hospitalists, I focused on my concerns. We need to clarify the harms associated with therapies such as beta-agonists, deep nasal suctioning, and continuous pulse oximetry. We need to clarify the goals of treatment, which might include a shorter length of stay, patient comfort, meeting parents’ expectations that we will do something, and/or explaining why we are contradicting any previous recommendations made to the parents. We need to mesh these bronchiolitis guidelines with the asthma action plans and medication lists advocated for wheezing children who are 24 months of age. My colleagues pointed out that all of that is just continuing to refine the policy.

Getting the policy right is necessary but insufficient. What we are really missing is a campaign strategy to sell it.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. He is also listserv moderator for the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine.

Despite all the hoopla about Ebola and measles this winter, the most common reason for admitting an infant or young child to the hospital continues to be bronchiolitis. Yet clinical practice guidelines for diagnosing and treating this common infection have not been incorporated into clinical practice.

The use of over-the-counter cold medications to treat upper respiratory infections in young children was shown by meta-analysis in the mid-1990’s to be ineffective, but that use continued until the Food and Drug Administration mandated revisions to packaging in 2008. Antibiotics have been commonly prescribed to treat the ear infections and sinusitis that frequently occur with bronchiolitis. But over the past 20 years, the use of antibiotics has become less prevalent. I date that trend to the work of Dr. Jack Paradise, professor emeritus of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh, and Dr. Ellen Wald, now chair of pediatrics at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, in the mid-1990’s. RespiGam was approved in 1996, then supplanted with palivizumab, as a medication to reduce the burden of respiratory syncytial virus disease. In the summer of 2014, an updated analysis of the costs, risks, and benefits of RSV prophylaxis led to new recommendations that curtailed the indications for that treatment (Pediatrics 2014:134;415-20). What do these trends have in common? The time frame.

It is often cited that it takes 17 years for new evidence to be assimilated into clinical practice (J.R. Soc. Med. 2011;104:510-20). An Institute of Medicine report in 2001, “Crossing the Quality Chasm,” emphasized the importance of becoming more efficient at making progress. Those recommendations themselves are now 14 years old, and I’m not expecting a revolution in human behavior within the next 3 years.

In the new clinical practice guideline issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics in November 2014 for the treatment of young children with bronchiolitis, Dr. Shawn L. Ralston and her colleagues assessed various treatment modalities, found many to be ineffective, and recommended discontinuing their routine use (Pediatrics 2014;134:e1474-e1502). Beta-agonists were at the forefront of this. Was the new guideline based on new data? For the most part, no. In my reading, itmostly reiterated the concerns about effectiveness that were expressed at the time of the prior guidelines from 2006, but removed the weasel words. I admire the dedication of this committee to evidence-based medicine. But will this revised clinical practice guideline actually change practice?

The saying is, “Build a better mousetrap and the world will beat a path to your door.” That quote has been attributed (without adequate documentation) to Ralph Waldo Emerson. He was a great poet, but not a scientist.

During the same month that the new bronchiolitis guidelinewas being released, America held some elections. In the post mortem, President Obama said, “There is a tendency sometimes for me to start thinking: As long as I get the policy right, then that’s what should matter.” He elaborated that “one thing that I do need to constantly remind myself and my team of is it’s not enough just to build the better mousetrap. People don’t automatically come beating to your door. We’ve got to sell it; we’ve got to reach out to the other side and where possible, persuade” (The Wall Street Journal, Nov. 10, 2014).

That isn’t poetry, but the President’s idea is probably more accurate than Emerson’s.

The bronchiolitis clinical practice guidelinewas written in a standardized fashion with 14 key action statements and 242 references. That makes for a good evidence-based medicine document, but is not the best sales pitch.

What will it take to translate these new guidelines into practice? One option is to teach new residents the new guidelines and expect dinosaurs such as myself to retire. If the average pediatrician works for about 34 years, then over a period of 17 years, we will have replaced half the miscreants simply by attrition.

A program of reaching out to the other side and persuading them to change is a better option.

In discussions about this topic on a listserv for pediatric hospitalists, I focused on my concerns. We need to clarify the harms associated with therapies such as beta-agonists, deep nasal suctioning, and continuous pulse oximetry. We need to clarify the goals of treatment, which might include a shorter length of stay, patient comfort, meeting parents’ expectations that we will do something, and/or explaining why we are contradicting any previous recommendations made to the parents. We need to mesh these bronchiolitis guidelines with the asthma action plans and medication lists advocated for wheezing children who are 24 months of age. My colleagues pointed out that all of that is just continuing to refine the policy.

Getting the policy right is necessary but insufficient. What we are really missing is a campaign strategy to sell it.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. He is also listserv moderator for the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine.

Too sick to work?

By yesterday at lunch time, you knew you were sick. The sniffly nose and scratchy throat of the previous 2 days were maturing into a full-blown cold or worse. You woke this morning feeling achy and a bit feverish. The only thermometer in the house is a scary looking thing in the cutlery drawer next to the kitchen stove. There have been no cases of influenza reported in the country or even the state.

It is Thursday, and it is your partner’s traditional day off. You think you remember him saying that he was planning on driving out of state to visit his daughter who was struggling in her freshman year in college. Your new associate is in St. Louis taking her boards. The questions that need to be answered by 7:30 this morning are: Do I see if I can reach my partner before he leaves town and ask him if can work for me? If he is already on the road, do I call the office and tell them to cancel the day’s schedule because I am too sick to work?

This is the kind of scenario that most have us have faced more than once in our working lives. Who will I be putting at risk by going to work when I am sick? Of course, there are my patients. Is my patient population particularly fragile because of their age or immunological vulnerabilities? And there are my coworkers. Last of all, will going to work make me even sicker so that I will miss more work?

Where do you go for help in answering the question of whether you are too sick to go to work? Should you try to find a thermometer at an all-night convenience store? If you find one, exactly what temperature is the threshold that will prompt you to call in sick? How many sneezes per hour will render you too contagious to work? How many coughs? If your illness is primarily gastrointestinal, are you still a threat to your patients if your trips to the bathroom are spaced far enough apart to allow you to spend 15 minutes trapped in an examining room?

Would wearing a mask be of any benefit? My sense is that it wouldn’t help and may make you more of a threat if you keeping fiddling with it to readjust it for comfort. And a mask will certainly alarm some parents.

There are situations in which you look or sound worse than you are. I seem to develop laryngitis several days after the worst of my cold has passed. Unfortunately, this scenario is not one of those situations. If you show up in the office, you are going to sound and maybe look like you are as sick as you feel.

What are you going to do? I am embarrassed to admit that I was one of those masochists who would have gone to work regardless of my state of health. You would have had to tether me to an IV bottle to keep me at home. As a recovering workaholic, I have had to accept the fact that I may have jeopardized the health of some of my patients by my pigheaded and at times selfish devotion to showing up in the office come hell or high fever. But, on days when I was the only show in town, it was easy to fall into the trap of believing that I was indispensable. Although full-time emergency room physicians and hospitalists hadn’t been invented yet, there were a few other primary care physicians. I guess it was pride that prevented me from admitting that I could have called on them for help, even though they weren’t board certified pediatricians.

On the other hand, I still wonder how much harm I did by dragging myself to work when I was sick. Because Brunswick is a small town, I know my overly intense devotion to work didn’t result in any deaths. But how great was the collateral damage in the form of lost days from school and work for my patients, their parents, and my coworkers? There is no way to know, but I am sure there was some.

It is unreasonable to say, “I won’t ever go to work if I am ill.” I may have set the bar too high, but I am interested to hear how you decide when you are too sick to go to work.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “Coping with a Picky Eater.” E-mail him at [email protected].

By yesterday at lunch time, you knew you were sick. The sniffly nose and scratchy throat of the previous 2 days were maturing into a full-blown cold or worse. You woke this morning feeling achy and a bit feverish. The only thermometer in the house is a scary looking thing in the cutlery drawer next to the kitchen stove. There have been no cases of influenza reported in the country or even the state.

It is Thursday, and it is your partner’s traditional day off. You think you remember him saying that he was planning on driving out of state to visit his daughter who was struggling in her freshman year in college. Your new associate is in St. Louis taking her boards. The questions that need to be answered by 7:30 this morning are: Do I see if I can reach my partner before he leaves town and ask him if can work for me? If he is already on the road, do I call the office and tell them to cancel the day’s schedule because I am too sick to work?

This is the kind of scenario that most have us have faced more than once in our working lives. Who will I be putting at risk by going to work when I am sick? Of course, there are my patients. Is my patient population particularly fragile because of their age or immunological vulnerabilities? And there are my coworkers. Last of all, will going to work make me even sicker so that I will miss more work?

Where do you go for help in answering the question of whether you are too sick to go to work? Should you try to find a thermometer at an all-night convenience store? If you find one, exactly what temperature is the threshold that will prompt you to call in sick? How many sneezes per hour will render you too contagious to work? How many coughs? If your illness is primarily gastrointestinal, are you still a threat to your patients if your trips to the bathroom are spaced far enough apart to allow you to spend 15 minutes trapped in an examining room?

Would wearing a mask be of any benefit? My sense is that it wouldn’t help and may make you more of a threat if you keeping fiddling with it to readjust it for comfort. And a mask will certainly alarm some parents.

There are situations in which you look or sound worse than you are. I seem to develop laryngitis several days after the worst of my cold has passed. Unfortunately, this scenario is not one of those situations. If you show up in the office, you are going to sound and maybe look like you are as sick as you feel.

What are you going to do? I am embarrassed to admit that I was one of those masochists who would have gone to work regardless of my state of health. You would have had to tether me to an IV bottle to keep me at home. As a recovering workaholic, I have had to accept the fact that I may have jeopardized the health of some of my patients by my pigheaded and at times selfish devotion to showing up in the office come hell or high fever. But, on days when I was the only show in town, it was easy to fall into the trap of believing that I was indispensable. Although full-time emergency room physicians and hospitalists hadn’t been invented yet, there were a few other primary care physicians. I guess it was pride that prevented me from admitting that I could have called on them for help, even though they weren’t board certified pediatricians.

On the other hand, I still wonder how much harm I did by dragging myself to work when I was sick. Because Brunswick is a small town, I know my overly intense devotion to work didn’t result in any deaths. But how great was the collateral damage in the form of lost days from school and work for my patients, their parents, and my coworkers? There is no way to know, but I am sure there was some.

It is unreasonable to say, “I won’t ever go to work if I am ill.” I may have set the bar too high, but I am interested to hear how you decide when you are too sick to go to work.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “Coping with a Picky Eater.” E-mail him at [email protected].

By yesterday at lunch time, you knew you were sick. The sniffly nose and scratchy throat of the previous 2 days were maturing into a full-blown cold or worse. You woke this morning feeling achy and a bit feverish. The only thermometer in the house is a scary looking thing in the cutlery drawer next to the kitchen stove. There have been no cases of influenza reported in the country or even the state.

It is Thursday, and it is your partner’s traditional day off. You think you remember him saying that he was planning on driving out of state to visit his daughter who was struggling in her freshman year in college. Your new associate is in St. Louis taking her boards. The questions that need to be answered by 7:30 this morning are: Do I see if I can reach my partner before he leaves town and ask him if can work for me? If he is already on the road, do I call the office and tell them to cancel the day’s schedule because I am too sick to work?

This is the kind of scenario that most have us have faced more than once in our working lives. Who will I be putting at risk by going to work when I am sick? Of course, there are my patients. Is my patient population particularly fragile because of their age or immunological vulnerabilities? And there are my coworkers. Last of all, will going to work make me even sicker so that I will miss more work?

Where do you go for help in answering the question of whether you are too sick to go to work? Should you try to find a thermometer at an all-night convenience store? If you find one, exactly what temperature is the threshold that will prompt you to call in sick? How many sneezes per hour will render you too contagious to work? How many coughs? If your illness is primarily gastrointestinal, are you still a threat to your patients if your trips to the bathroom are spaced far enough apart to allow you to spend 15 minutes trapped in an examining room?

Would wearing a mask be of any benefit? My sense is that it wouldn’t help and may make you more of a threat if you keeping fiddling with it to readjust it for comfort. And a mask will certainly alarm some parents.

There are situations in which you look or sound worse than you are. I seem to develop laryngitis several days after the worst of my cold has passed. Unfortunately, this scenario is not one of those situations. If you show up in the office, you are going to sound and maybe look like you are as sick as you feel.

What are you going to do? I am embarrassed to admit that I was one of those masochists who would have gone to work regardless of my state of health. You would have had to tether me to an IV bottle to keep me at home. As a recovering workaholic, I have had to accept the fact that I may have jeopardized the health of some of my patients by my pigheaded and at times selfish devotion to showing up in the office come hell or high fever. But, on days when I was the only show in town, it was easy to fall into the trap of believing that I was indispensable. Although full-time emergency room physicians and hospitalists hadn’t been invented yet, there were a few other primary care physicians. I guess it was pride that prevented me from admitting that I could have called on them for help, even though they weren’t board certified pediatricians.

On the other hand, I still wonder how much harm I did by dragging myself to work when I was sick. Because Brunswick is a small town, I know my overly intense devotion to work didn’t result in any deaths. But how great was the collateral damage in the form of lost days from school and work for my patients, their parents, and my coworkers? There is no way to know, but I am sure there was some.

It is unreasonable to say, “I won’t ever go to work if I am ill.” I may have set the bar too high, but I am interested to hear how you decide when you are too sick to go to work.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “Coping with a Picky Eater.” E-mail him at [email protected].

The 2014 AAP COID update on palivizumab

The American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases released a 2014 policy statement (Pediatrics 2014:134;415-20) updating guidance on use of palivizumab in high-risk patients infected with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). The policy statement was accompanied by a detailed technical report to explain the committee’s rationale for the changes made since the previous update in 2012.

Since 2012, several observational studies were published related to risk factors associated with the need for hospitalization for RSV infection. The Committee on Infectious Diseases (COID) referred to these observational studies, along with other historical studies, in its 2014 technical report.

Some aspects of the updated guidance have met with controversy because the new advice limits palivizumab use among premature infants. The 2014 COID policy asserts that preterm infants born at greater than 29 weeks’ gestational age (GA) do not benefit substantially from palivizumab dosing during RSV season. This assertion has met with controversy because the justification detailed in the technical report cites several observational studies that don’t appear to support that conclusion. What percentage of a cohort would need to be hospitalized for RSV infection to identify them as high risk? COID doesn’t draw that line for us. Because approximately 3% of the term birth cohort is hospitalized with RSV, should we use this as the “baseline” and predetermine a percentage of hospitalization beyond baseline to define “at increased risk”?

The 2014 technical report states that RSV hospitalization rates from Stevens et al. (Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2000;154:55-61) were 7.5% and 4.4% for infants 28-30 weeks’ gestational age (GA) and 30-32 weeks’ GA, respectively. However, the rates quoted by COID were not the generalizable rates reported by Dr. T. P. Stevens and his team in their study. The authors calculated community-wide hospitalization rates for these groups to be 10% and 6.4%, respectively. These author-reported community-wide rates closely mirror rates reported in several other large observational studies, and still likely underestimate the true burden of RSV hospitalization based on the lower sensitivity of RSV detection testing done 15 years ago when that study was performed.

Similarly, the COID states that Dr. A.G. Winterstein’s study (JAMA Pediatrics 2013;167:1118-24) shows hospitalization rates among 32-34 weeks’ GA infants of 3.1% and 4.5% in two states based on health care insurance claims. Because fewer than half of infants are ever tested for RSV as the possible cause of their lower respiratory tract infection, these claims data are most certainly an underestimate of true rates. When active testing for RSV is done among hospitalized infants in this same GA category, using sensitive and specific PCR-based technology, hospitalization rates are 9.1%. Dr. Winterstein and associates also reported that RSV hospitalization rates increase as gestational age decreases.

In Dr. Caroline Breese Hall’s 2013 observational study (Pediatrics 2013;132:341-8) she and her associates recognized that hospitalization rates in children under 2 years of age were similar among term and preterm infants. The COID used these data in its 2014 technical report to suggest that preterm infants are no longer at high risk. The detail omitted from the report was that approximately 70% of eligible preterm infants in Dr. Hall’s study (according to the 2012 COID guidelines) had received palivizumab prophylaxis. This suggests that maintaining RSV prophylaxis according to the 2012 COID policy statement (and not the 2014 policy statement) can be successful in reducing the rate of RSV hospitalizations in preterm infants to that observed in term infants.

Finally, the technical report cites “overall declining incidence of hospitalizations for bronchiolitis in the United States” from the 2013 publication by Hasegawa et al. (Pediatrics 2013:132:28-36) without defining this observation for the AAP readers. While Hasegawa did report such a decline, the decline was specific to term infants, as no such decline was observed in the higher-risk preterm infants.

Based on careful review of several of the manuscripts referenced by COID, it’s difficult to determine why the committee’s recommendations changed so dramatically in the most recent iteration. It appears that the data need another look.

Dr. Domachowske is professor of pediatrics and professor of microbiology and immunology at the State University of New York Upstate Medical University in Syracuse. He serves on the New York State American Academy of Pediatrics Chapter 1 executive committee, volunteers as his district’s immunization champion, and is an appointed member of the New York State Immunization Advisory Council. He is a Pediatric News Editorial Advisory Board member. Dr. Domachowske disclosed he does consulting for the vaccine divisions of GlaxoSmithKline, Medimmune, Pfizer, Merck, Sanofi Pasteur, and Novartis; he performs clinical trials with GlaxoSmithKline, Medimmune, Merck, and Novartis; and he does basic and translational research with GlaxoSmithKline. E-mail him at [email protected].

The American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases released a 2014 policy statement (Pediatrics 2014:134;415-20) updating guidance on use of palivizumab in high-risk patients infected with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). The policy statement was accompanied by a detailed technical report to explain the committee’s rationale for the changes made since the previous update in 2012.

Since 2012, several observational studies were published related to risk factors associated with the need for hospitalization for RSV infection. The Committee on Infectious Diseases (COID) referred to these observational studies, along with other historical studies, in its 2014 technical report.

Some aspects of the updated guidance have met with controversy because the new advice limits palivizumab use among premature infants. The 2014 COID policy asserts that preterm infants born at greater than 29 weeks’ gestational age (GA) do not benefit substantially from palivizumab dosing during RSV season. This assertion has met with controversy because the justification detailed in the technical report cites several observational studies that don’t appear to support that conclusion. What percentage of a cohort would need to be hospitalized for RSV infection to identify them as high risk? COID doesn’t draw that line for us. Because approximately 3% of the term birth cohort is hospitalized with RSV, should we use this as the “baseline” and predetermine a percentage of hospitalization beyond baseline to define “at increased risk”?

The 2014 technical report states that RSV hospitalization rates from Stevens et al. (Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2000;154:55-61) were 7.5% and 4.4% for infants 28-30 weeks’ gestational age (GA) and 30-32 weeks’ GA, respectively. However, the rates quoted by COID were not the generalizable rates reported by Dr. T. P. Stevens and his team in their study. The authors calculated community-wide hospitalization rates for these groups to be 10% and 6.4%, respectively. These author-reported community-wide rates closely mirror rates reported in several other large observational studies, and still likely underestimate the true burden of RSV hospitalization based on the lower sensitivity of RSV detection testing done 15 years ago when that study was performed.

Similarly, the COID states that Dr. A.G. Winterstein’s study (JAMA Pediatrics 2013;167:1118-24) shows hospitalization rates among 32-34 weeks’ GA infants of 3.1% and 4.5% in two states based on health care insurance claims. Because fewer than half of infants are ever tested for RSV as the possible cause of their lower respiratory tract infection, these claims data are most certainly an underestimate of true rates. When active testing for RSV is done among hospitalized infants in this same GA category, using sensitive and specific PCR-based technology, hospitalization rates are 9.1%. Dr. Winterstein and associates also reported that RSV hospitalization rates increase as gestational age decreases.

In Dr. Caroline Breese Hall’s 2013 observational study (Pediatrics 2013;132:341-8) she and her associates recognized that hospitalization rates in children under 2 years of age were similar among term and preterm infants. The COID used these data in its 2014 technical report to suggest that preterm infants are no longer at high risk. The detail omitted from the report was that approximately 70% of eligible preterm infants in Dr. Hall’s study (according to the 2012 COID guidelines) had received palivizumab prophylaxis. This suggests that maintaining RSV prophylaxis according to the 2012 COID policy statement (and not the 2014 policy statement) can be successful in reducing the rate of RSV hospitalizations in preterm infants to that observed in term infants.

Finally, the technical report cites “overall declining incidence of hospitalizations for bronchiolitis in the United States” from the 2013 publication by Hasegawa et al. (Pediatrics 2013:132:28-36) without defining this observation for the AAP readers. While Hasegawa did report such a decline, the decline was specific to term infants, as no such decline was observed in the higher-risk preterm infants.

Based on careful review of several of the manuscripts referenced by COID, it’s difficult to determine why the committee’s recommendations changed so dramatically in the most recent iteration. It appears that the data need another look.

Dr. Domachowske is professor of pediatrics and professor of microbiology and immunology at the State University of New York Upstate Medical University in Syracuse. He serves on the New York State American Academy of Pediatrics Chapter 1 executive committee, volunteers as his district’s immunization champion, and is an appointed member of the New York State Immunization Advisory Council. He is a Pediatric News Editorial Advisory Board member. Dr. Domachowske disclosed he does consulting for the vaccine divisions of GlaxoSmithKline, Medimmune, Pfizer, Merck, Sanofi Pasteur, and Novartis; he performs clinical trials with GlaxoSmithKline, Medimmune, Merck, and Novartis; and he does basic and translational research with GlaxoSmithKline. E-mail him at [email protected].

The American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases released a 2014 policy statement (Pediatrics 2014:134;415-20) updating guidance on use of palivizumab in high-risk patients infected with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). The policy statement was accompanied by a detailed technical report to explain the committee’s rationale for the changes made since the previous update in 2012.

Since 2012, several observational studies were published related to risk factors associated with the need for hospitalization for RSV infection. The Committee on Infectious Diseases (COID) referred to these observational studies, along with other historical studies, in its 2014 technical report.

Some aspects of the updated guidance have met with controversy because the new advice limits palivizumab use among premature infants. The 2014 COID policy asserts that preterm infants born at greater than 29 weeks’ gestational age (GA) do not benefit substantially from palivizumab dosing during RSV season. This assertion has met with controversy because the justification detailed in the technical report cites several observational studies that don’t appear to support that conclusion. What percentage of a cohort would need to be hospitalized for RSV infection to identify them as high risk? COID doesn’t draw that line for us. Because approximately 3% of the term birth cohort is hospitalized with RSV, should we use this as the “baseline” and predetermine a percentage of hospitalization beyond baseline to define “at increased risk”?

The 2014 technical report states that RSV hospitalization rates from Stevens et al. (Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2000;154:55-61) were 7.5% and 4.4% for infants 28-30 weeks’ gestational age (GA) and 30-32 weeks’ GA, respectively. However, the rates quoted by COID were not the generalizable rates reported by Dr. T. P. Stevens and his team in their study. The authors calculated community-wide hospitalization rates for these groups to be 10% and 6.4%, respectively. These author-reported community-wide rates closely mirror rates reported in several other large observational studies, and still likely underestimate the true burden of RSV hospitalization based on the lower sensitivity of RSV detection testing done 15 years ago when that study was performed.

Similarly, the COID states that Dr. A.G. Winterstein’s study (JAMA Pediatrics 2013;167:1118-24) shows hospitalization rates among 32-34 weeks’ GA infants of 3.1% and 4.5% in two states based on health care insurance claims. Because fewer than half of infants are ever tested for RSV as the possible cause of their lower respiratory tract infection, these claims data are most certainly an underestimate of true rates. When active testing for RSV is done among hospitalized infants in this same GA category, using sensitive and specific PCR-based technology, hospitalization rates are 9.1%. Dr. Winterstein and associates also reported that RSV hospitalization rates increase as gestational age decreases.

In Dr. Caroline Breese Hall’s 2013 observational study (Pediatrics 2013;132:341-8) she and her associates recognized that hospitalization rates in children under 2 years of age were similar among term and preterm infants. The COID used these data in its 2014 technical report to suggest that preterm infants are no longer at high risk. The detail omitted from the report was that approximately 70% of eligible preterm infants in Dr. Hall’s study (according to the 2012 COID guidelines) had received palivizumab prophylaxis. This suggests that maintaining RSV prophylaxis according to the 2012 COID policy statement (and not the 2014 policy statement) can be successful in reducing the rate of RSV hospitalizations in preterm infants to that observed in term infants.

Finally, the technical report cites “overall declining incidence of hospitalizations for bronchiolitis in the United States” from the 2013 publication by Hasegawa et al. (Pediatrics 2013:132:28-36) without defining this observation for the AAP readers. While Hasegawa did report such a decline, the decline was specific to term infants, as no such decline was observed in the higher-risk preterm infants.

Based on careful review of several of the manuscripts referenced by COID, it’s difficult to determine why the committee’s recommendations changed so dramatically in the most recent iteration. It appears that the data need another look.