User login

How a medical recoding may limit cancer patients’ options for breast reconstruction

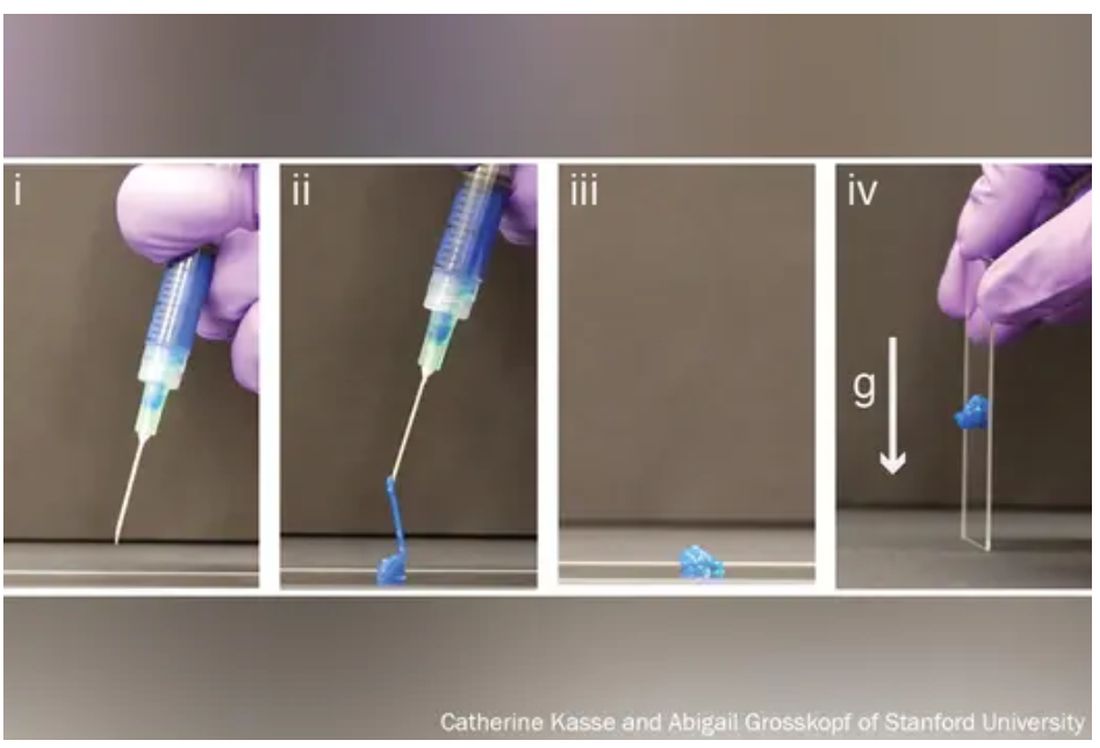

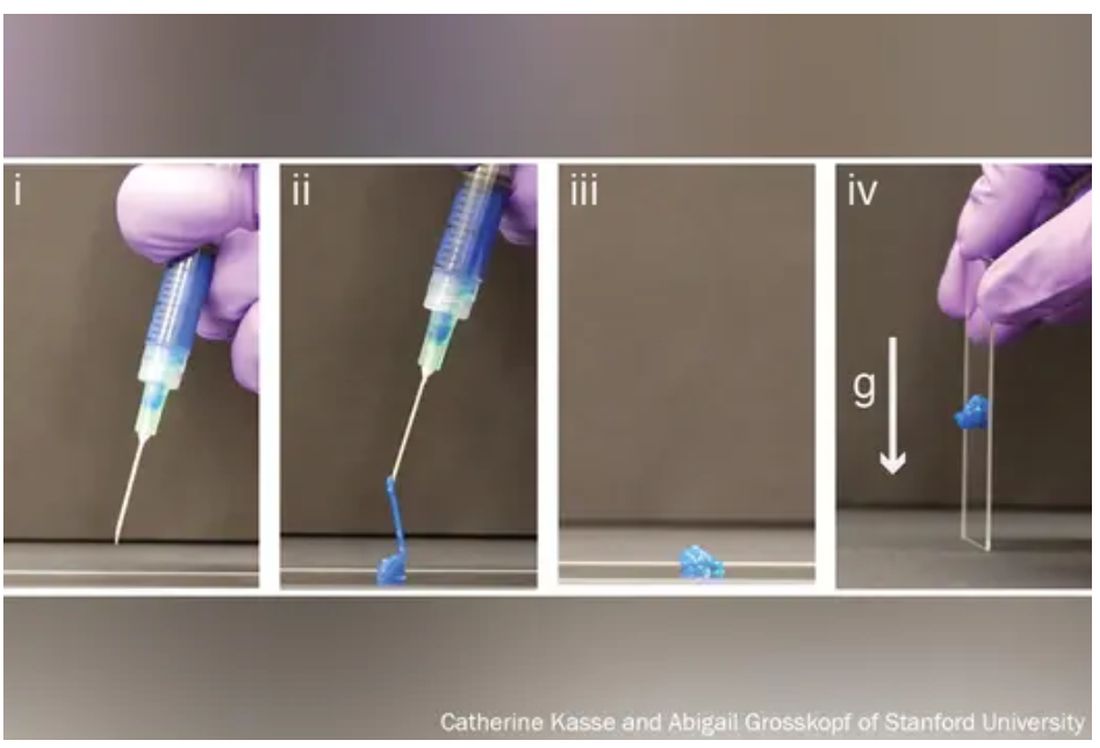

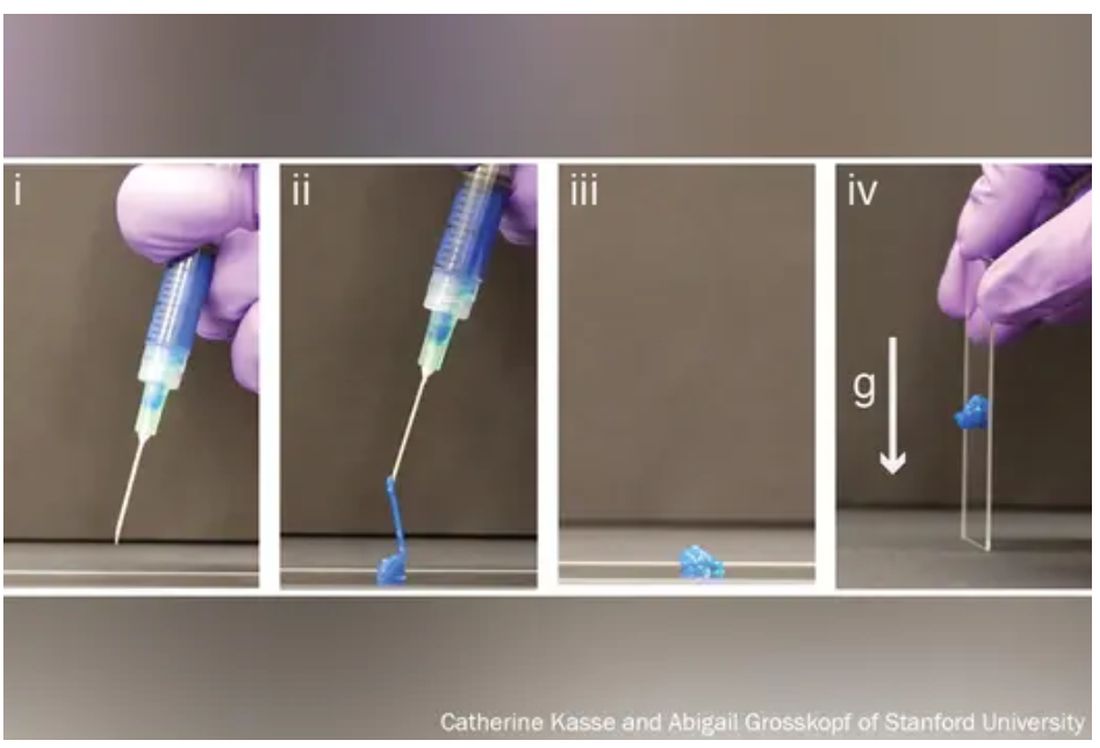

On June 1, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services plans to reexamine how doctors are paid for a type of breast reconstruction known as DIEP flap, in which skin, fat, and blood vessels are harvested from a woman’s abdomen to create a new breast.

The procedure offers potential advantages over implants and operations that take muscle from the abdomen. But it’s also more expensive. If patients go outside an insurance network for the operation, it can cost more than $50,000. And, if insurers pay significantly less for the surgery as a result of the government’s decision, some in-network surgeons would stop offering it, a plastic surgeons group has argued.

The DIEP flap controversy, spotlighted by CBS News in January, illustrates arcane and indirect ways the federal government can influence which medical options are available – even to people with private insurance. Often, the answers come down to billing codes – which identify specific medical services on forms doctors submit for reimbursement – and the competing pleas of groups whose interests are riding on them.

Medical coding is the backbone for “how business gets done in medicine,” said Karen Joynt Maddox, MD, MPH, a physician at Washington University in St. Louis who researches health economics and policy.

CMS, the agency overseeing Medicare and Medicaid, maintains a list of codes representing thousands of medical services and products. It regularly evaluates whether to add codes or revise or remove existing ones. In 2022, it decided to eliminate a code that has enabled doctors to collect much more money for DIEP flap operations than for simpler types of breast reconstruction.

In 2006, CMS established an “S” code – S2068 – for what was then a relatively new procedure: breast reconstructions with deep inferior epigastric perforator flap (DIEP flap). S codes temporarily fill gaps in a parallel system of billing codes known as CPT codes, which are maintained by the American Medical Association.

Codes don’t dictate the amounts private insurers pay for medical services; those reimbursements are generally worked out between insurance companies and medical providers. However, using the narrowly targeted S code, doctors and hospitals have been able to distinguish DIEP flap surgeries, which require complex microsurgical skills, from other forms of breast reconstruction that take less time to perform and generally yield lower insurance reimbursements.

CMS announced in 2022 that it planned to eliminate the S code at the end of 2024 – a move some doctors say would slash the amount surgeons are paid. (To be precise, CMS announced it would eliminate a series of three S codes for similar procedures, but some of the more outspoken critics have focused on one of them, S2068.) The agency’s decision is already changing the landscape of reconstructive surgery and creating anxiety for breast cancer patients.

Kate Getz, a single mother in Morton, Ill., learned she had cancer in January at age 30. As she grappled with her diagnosis, it was overwhelming to think about what her body would look like over the long term. She pictured herself getting married one day and wondered “how on earth I would be able to wear a wedding dress with only having one breast left,” she said.

She thought a DIEP flap was her best option and worried about having to undergo repeated surgeries if she got implants instead. Implants generally need to be replaced every 10 years or so. But after she spent more than a month trying to get answers about how her DIEP flap surgery would be covered, Ms. Getz’s insurer, Cigna, informed her it would use a lower-paying CPT code to reimburse her physician, Ms. Getz said. As far as she could see, that would have made it impossible for Ms. Getz to obtain the surgery.

Paying out of pocket was “not even an option.”

“I’m a single mom. We get by, right? But I’m not, not wealthy by any means,” she said.

Cost is not necessarily the only hurdle patients seeking DIEP flaps must overcome. Citing the complexity of the procedure, Ms. Getz said, a local plastic surgeon told her it would be difficult for him to perform. She ended up traveling from Illinois to Texas for the surgery.

The government’s plan to eliminate the three S codes was driven by the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, a major lobbying organization for health insurance companies. In 2021, the group asked CMS to discontinue the codes, arguing that they were no longer needed because the AMA had updated a CPT code to explicitly include DIEP flap surgery and the related operations, according to a CMS document.

For years, the AMA advised doctors that the CPT code was appropriate for DIEP flap procedures. But after the government’s decision, at least two major insurance companies told doctors they would no longer reimburse them under the higher-paying codes, prompting a backlash.

Physicians and advocacy groups for breast cancer patients, such as the nonprofit organization Susan G. Komen, have argued that many plastic surgeons would stop providing DIEP flap procedures for women with private insurance because they wouldn’t get paid enough.

Lawmakers from both parties have asked the agency to keep the S code, including Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-Fla.) and Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), who have had breast cancer, and Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.).

CMS at its June 1 meeting will consider whether to keep the three S codes or delay their expiration.

In a May 30 statement, Blue Cross Blue Shield Association spokesperson Kelly Parsons reiterated the organization’s view that “there is no longer a need to keep the S codes.”

In a profit-driven health care system, there’s a tug of war over reimbursements between providers and insurance companies, often at the expense of patients, said Dr. Joynt Maddox.

“We’re in this sort of constant battle” between hospital chains and insurance companies “about who’s going to wield more power at the bargaining table,” Dr. Joynt Maddox said. “And the clinical piece of that often gets lost, because it’s not often the clinical benefit and the clinical priority and the patient centeredness that’s at the middle of these conversations.”

Elisabeth Potter, MD, a plastic surgeon who specializes in DIEP flap surgeries, decided to perform Ms. Getz’s surgery at whatever price Cigna would pay.

According to Fair Health, a nonprofit that provides information on health care costs, in Austin, Tex. – where Dr. Potter is based – an insurer might pay an in-network doctor $9,323 for the surgery when it’s billed using the CPT code and $18,037 under the S code. Those amounts are not averages; rather, Fair Health estimated that 80% of payment rates are lower than or equal to those amounts.

Dr. Potter said her Cigna reimbursement “is significantly lower.”

Weeks before her May surgery, Ms. Getz received big news – Cigna had reversed itself and would cover her surgery under the S code. It “felt like a real victory,” she said.

But she still fears for other patients.

“I’m still asking these companies to do right by women,” Ms. Getz said. “I’m still asking them to provide the procedures we need to reimburse them at rates where women have access to them regardless of their wealth.”

In a statement, Cigna spokesperson Justine Sessions said the insurer remains “committed to ensuring that our customers have affordable coverage and access to the full range of breast reconstruction procedures and to quality surgeons who perform these complex surgeries.”

Medical costs that health insurers cover generally are passed along to consumers in the form of premiums, deductibles, and other out-of-pocket expenses.

For any type of breast reconstruction, there are benefits, risks, and trade-offs. A 2018 paper published in JAMA Surgery found that women who underwent DIEP flap surgery had higher odds of developing “reoperative complications” within 2 years than those who received artificial implants. However, DIEP flaps had lower odds of infection than implants.

Implants carry risks of additional surgery, pain, rupture, and even an uncommon type of immune system cancer.

Other flap procedures that take muscle from the abdomen can leave women with weakened abdominal walls and increase their risk of developing a hernia.

Academic research shows that insurance reimbursement affects which women can access DIEP flap breast reconstruction, creating a two-tiered system for private health insurance versus government programs like Medicare and Medicaid. Private insurance generally pays physicians more than government coverage, and Medicare doesn’t use S codes.

Lynn Damitz, a physician and board vice president of health policy and advocacy for the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, said the group supports continuing the S code temporarily or indefinitely. If reimbursements drop, some doctors won’t perform DIEP flaps anymore.

A study published in February found that, of patients who used their own tissue for breast reconstruction, privately insured patients were more likely than publicly insured patients to receive DIEP flap reconstruction.

To Dr. Potter, that shows what will happen if private insurance payments plummet. “If you’re a Medicare provider and you’re not paid to do DIEP flaps, you never tell a patient that it’s an option. You won’t perform it,” Dr. Potter said. “If you take private insurance and all of a sudden your reimbursement rate is cut from $15,000 down to $3,500, you’re not going to do that surgery. And I’m not saying that that’s the right thing to do, but that’s what happens.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

On June 1, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services plans to reexamine how doctors are paid for a type of breast reconstruction known as DIEP flap, in which skin, fat, and blood vessels are harvested from a woman’s abdomen to create a new breast.

The procedure offers potential advantages over implants and operations that take muscle from the abdomen. But it’s also more expensive. If patients go outside an insurance network for the operation, it can cost more than $50,000. And, if insurers pay significantly less for the surgery as a result of the government’s decision, some in-network surgeons would stop offering it, a plastic surgeons group has argued.

The DIEP flap controversy, spotlighted by CBS News in January, illustrates arcane and indirect ways the federal government can influence which medical options are available – even to people with private insurance. Often, the answers come down to billing codes – which identify specific medical services on forms doctors submit for reimbursement – and the competing pleas of groups whose interests are riding on them.

Medical coding is the backbone for “how business gets done in medicine,” said Karen Joynt Maddox, MD, MPH, a physician at Washington University in St. Louis who researches health economics and policy.

CMS, the agency overseeing Medicare and Medicaid, maintains a list of codes representing thousands of medical services and products. It regularly evaluates whether to add codes or revise or remove existing ones. In 2022, it decided to eliminate a code that has enabled doctors to collect much more money for DIEP flap operations than for simpler types of breast reconstruction.

In 2006, CMS established an “S” code – S2068 – for what was then a relatively new procedure: breast reconstructions with deep inferior epigastric perforator flap (DIEP flap). S codes temporarily fill gaps in a parallel system of billing codes known as CPT codes, which are maintained by the American Medical Association.

Codes don’t dictate the amounts private insurers pay for medical services; those reimbursements are generally worked out between insurance companies and medical providers. However, using the narrowly targeted S code, doctors and hospitals have been able to distinguish DIEP flap surgeries, which require complex microsurgical skills, from other forms of breast reconstruction that take less time to perform and generally yield lower insurance reimbursements.

CMS announced in 2022 that it planned to eliminate the S code at the end of 2024 – a move some doctors say would slash the amount surgeons are paid. (To be precise, CMS announced it would eliminate a series of three S codes for similar procedures, but some of the more outspoken critics have focused on one of them, S2068.) The agency’s decision is already changing the landscape of reconstructive surgery and creating anxiety for breast cancer patients.

Kate Getz, a single mother in Morton, Ill., learned she had cancer in January at age 30. As she grappled with her diagnosis, it was overwhelming to think about what her body would look like over the long term. She pictured herself getting married one day and wondered “how on earth I would be able to wear a wedding dress with only having one breast left,” she said.

She thought a DIEP flap was her best option and worried about having to undergo repeated surgeries if she got implants instead. Implants generally need to be replaced every 10 years or so. But after she spent more than a month trying to get answers about how her DIEP flap surgery would be covered, Ms. Getz’s insurer, Cigna, informed her it would use a lower-paying CPT code to reimburse her physician, Ms. Getz said. As far as she could see, that would have made it impossible for Ms. Getz to obtain the surgery.

Paying out of pocket was “not even an option.”

“I’m a single mom. We get by, right? But I’m not, not wealthy by any means,” she said.

Cost is not necessarily the only hurdle patients seeking DIEP flaps must overcome. Citing the complexity of the procedure, Ms. Getz said, a local plastic surgeon told her it would be difficult for him to perform. She ended up traveling from Illinois to Texas for the surgery.

The government’s plan to eliminate the three S codes was driven by the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, a major lobbying organization for health insurance companies. In 2021, the group asked CMS to discontinue the codes, arguing that they were no longer needed because the AMA had updated a CPT code to explicitly include DIEP flap surgery and the related operations, according to a CMS document.

For years, the AMA advised doctors that the CPT code was appropriate for DIEP flap procedures. But after the government’s decision, at least two major insurance companies told doctors they would no longer reimburse them under the higher-paying codes, prompting a backlash.

Physicians and advocacy groups for breast cancer patients, such as the nonprofit organization Susan G. Komen, have argued that many plastic surgeons would stop providing DIEP flap procedures for women with private insurance because they wouldn’t get paid enough.

Lawmakers from both parties have asked the agency to keep the S code, including Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-Fla.) and Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), who have had breast cancer, and Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.).

CMS at its June 1 meeting will consider whether to keep the three S codes or delay their expiration.

In a May 30 statement, Blue Cross Blue Shield Association spokesperson Kelly Parsons reiterated the organization’s view that “there is no longer a need to keep the S codes.”

In a profit-driven health care system, there’s a tug of war over reimbursements between providers and insurance companies, often at the expense of patients, said Dr. Joynt Maddox.

“We’re in this sort of constant battle” between hospital chains and insurance companies “about who’s going to wield more power at the bargaining table,” Dr. Joynt Maddox said. “And the clinical piece of that often gets lost, because it’s not often the clinical benefit and the clinical priority and the patient centeredness that’s at the middle of these conversations.”

Elisabeth Potter, MD, a plastic surgeon who specializes in DIEP flap surgeries, decided to perform Ms. Getz’s surgery at whatever price Cigna would pay.

According to Fair Health, a nonprofit that provides information on health care costs, in Austin, Tex. – where Dr. Potter is based – an insurer might pay an in-network doctor $9,323 for the surgery when it’s billed using the CPT code and $18,037 under the S code. Those amounts are not averages; rather, Fair Health estimated that 80% of payment rates are lower than or equal to those amounts.

Dr. Potter said her Cigna reimbursement “is significantly lower.”

Weeks before her May surgery, Ms. Getz received big news – Cigna had reversed itself and would cover her surgery under the S code. It “felt like a real victory,” she said.

But she still fears for other patients.

“I’m still asking these companies to do right by women,” Ms. Getz said. “I’m still asking them to provide the procedures we need to reimburse them at rates where women have access to them regardless of their wealth.”

In a statement, Cigna spokesperson Justine Sessions said the insurer remains “committed to ensuring that our customers have affordable coverage and access to the full range of breast reconstruction procedures and to quality surgeons who perform these complex surgeries.”

Medical costs that health insurers cover generally are passed along to consumers in the form of premiums, deductibles, and other out-of-pocket expenses.

For any type of breast reconstruction, there are benefits, risks, and trade-offs. A 2018 paper published in JAMA Surgery found that women who underwent DIEP flap surgery had higher odds of developing “reoperative complications” within 2 years than those who received artificial implants. However, DIEP flaps had lower odds of infection than implants.

Implants carry risks of additional surgery, pain, rupture, and even an uncommon type of immune system cancer.

Other flap procedures that take muscle from the abdomen can leave women with weakened abdominal walls and increase their risk of developing a hernia.

Academic research shows that insurance reimbursement affects which women can access DIEP flap breast reconstruction, creating a two-tiered system for private health insurance versus government programs like Medicare and Medicaid. Private insurance generally pays physicians more than government coverage, and Medicare doesn’t use S codes.

Lynn Damitz, a physician and board vice president of health policy and advocacy for the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, said the group supports continuing the S code temporarily or indefinitely. If reimbursements drop, some doctors won’t perform DIEP flaps anymore.

A study published in February found that, of patients who used their own tissue for breast reconstruction, privately insured patients were more likely than publicly insured patients to receive DIEP flap reconstruction.

To Dr. Potter, that shows what will happen if private insurance payments plummet. “If you’re a Medicare provider and you’re not paid to do DIEP flaps, you never tell a patient that it’s an option. You won’t perform it,” Dr. Potter said. “If you take private insurance and all of a sudden your reimbursement rate is cut from $15,000 down to $3,500, you’re not going to do that surgery. And I’m not saying that that’s the right thing to do, but that’s what happens.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

On June 1, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services plans to reexamine how doctors are paid for a type of breast reconstruction known as DIEP flap, in which skin, fat, and blood vessels are harvested from a woman’s abdomen to create a new breast.

The procedure offers potential advantages over implants and operations that take muscle from the abdomen. But it’s also more expensive. If patients go outside an insurance network for the operation, it can cost more than $50,000. And, if insurers pay significantly less for the surgery as a result of the government’s decision, some in-network surgeons would stop offering it, a plastic surgeons group has argued.

The DIEP flap controversy, spotlighted by CBS News in January, illustrates arcane and indirect ways the federal government can influence which medical options are available – even to people with private insurance. Often, the answers come down to billing codes – which identify specific medical services on forms doctors submit for reimbursement – and the competing pleas of groups whose interests are riding on them.

Medical coding is the backbone for “how business gets done in medicine,” said Karen Joynt Maddox, MD, MPH, a physician at Washington University in St. Louis who researches health economics and policy.

CMS, the agency overseeing Medicare and Medicaid, maintains a list of codes representing thousands of medical services and products. It regularly evaluates whether to add codes or revise or remove existing ones. In 2022, it decided to eliminate a code that has enabled doctors to collect much more money for DIEP flap operations than for simpler types of breast reconstruction.

In 2006, CMS established an “S” code – S2068 – for what was then a relatively new procedure: breast reconstructions with deep inferior epigastric perforator flap (DIEP flap). S codes temporarily fill gaps in a parallel system of billing codes known as CPT codes, which are maintained by the American Medical Association.

Codes don’t dictate the amounts private insurers pay for medical services; those reimbursements are generally worked out between insurance companies and medical providers. However, using the narrowly targeted S code, doctors and hospitals have been able to distinguish DIEP flap surgeries, which require complex microsurgical skills, from other forms of breast reconstruction that take less time to perform and generally yield lower insurance reimbursements.

CMS announced in 2022 that it planned to eliminate the S code at the end of 2024 – a move some doctors say would slash the amount surgeons are paid. (To be precise, CMS announced it would eliminate a series of three S codes for similar procedures, but some of the more outspoken critics have focused on one of them, S2068.) The agency’s decision is already changing the landscape of reconstructive surgery and creating anxiety for breast cancer patients.

Kate Getz, a single mother in Morton, Ill., learned she had cancer in January at age 30. As she grappled with her diagnosis, it was overwhelming to think about what her body would look like over the long term. She pictured herself getting married one day and wondered “how on earth I would be able to wear a wedding dress with only having one breast left,” she said.

She thought a DIEP flap was her best option and worried about having to undergo repeated surgeries if she got implants instead. Implants generally need to be replaced every 10 years or so. But after she spent more than a month trying to get answers about how her DIEP flap surgery would be covered, Ms. Getz’s insurer, Cigna, informed her it would use a lower-paying CPT code to reimburse her physician, Ms. Getz said. As far as she could see, that would have made it impossible for Ms. Getz to obtain the surgery.

Paying out of pocket was “not even an option.”

“I’m a single mom. We get by, right? But I’m not, not wealthy by any means,” she said.

Cost is not necessarily the only hurdle patients seeking DIEP flaps must overcome. Citing the complexity of the procedure, Ms. Getz said, a local plastic surgeon told her it would be difficult for him to perform. She ended up traveling from Illinois to Texas for the surgery.

The government’s plan to eliminate the three S codes was driven by the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, a major lobbying organization for health insurance companies. In 2021, the group asked CMS to discontinue the codes, arguing that they were no longer needed because the AMA had updated a CPT code to explicitly include DIEP flap surgery and the related operations, according to a CMS document.

For years, the AMA advised doctors that the CPT code was appropriate for DIEP flap procedures. But after the government’s decision, at least two major insurance companies told doctors they would no longer reimburse them under the higher-paying codes, prompting a backlash.

Physicians and advocacy groups for breast cancer patients, such as the nonprofit organization Susan G. Komen, have argued that many plastic surgeons would stop providing DIEP flap procedures for women with private insurance because they wouldn’t get paid enough.

Lawmakers from both parties have asked the agency to keep the S code, including Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-Fla.) and Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), who have had breast cancer, and Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.).

CMS at its June 1 meeting will consider whether to keep the three S codes or delay their expiration.

In a May 30 statement, Blue Cross Blue Shield Association spokesperson Kelly Parsons reiterated the organization’s view that “there is no longer a need to keep the S codes.”

In a profit-driven health care system, there’s a tug of war over reimbursements between providers and insurance companies, often at the expense of patients, said Dr. Joynt Maddox.

“We’re in this sort of constant battle” between hospital chains and insurance companies “about who’s going to wield more power at the bargaining table,” Dr. Joynt Maddox said. “And the clinical piece of that often gets lost, because it’s not often the clinical benefit and the clinical priority and the patient centeredness that’s at the middle of these conversations.”

Elisabeth Potter, MD, a plastic surgeon who specializes in DIEP flap surgeries, decided to perform Ms. Getz’s surgery at whatever price Cigna would pay.

According to Fair Health, a nonprofit that provides information on health care costs, in Austin, Tex. – where Dr. Potter is based – an insurer might pay an in-network doctor $9,323 for the surgery when it’s billed using the CPT code and $18,037 under the S code. Those amounts are not averages; rather, Fair Health estimated that 80% of payment rates are lower than or equal to those amounts.

Dr. Potter said her Cigna reimbursement “is significantly lower.”

Weeks before her May surgery, Ms. Getz received big news – Cigna had reversed itself and would cover her surgery under the S code. It “felt like a real victory,” she said.

But she still fears for other patients.

“I’m still asking these companies to do right by women,” Ms. Getz said. “I’m still asking them to provide the procedures we need to reimburse them at rates where women have access to them regardless of their wealth.”

In a statement, Cigna spokesperson Justine Sessions said the insurer remains “committed to ensuring that our customers have affordable coverage and access to the full range of breast reconstruction procedures and to quality surgeons who perform these complex surgeries.”

Medical costs that health insurers cover generally are passed along to consumers in the form of premiums, deductibles, and other out-of-pocket expenses.

For any type of breast reconstruction, there are benefits, risks, and trade-offs. A 2018 paper published in JAMA Surgery found that women who underwent DIEP flap surgery had higher odds of developing “reoperative complications” within 2 years than those who received artificial implants. However, DIEP flaps had lower odds of infection than implants.

Implants carry risks of additional surgery, pain, rupture, and even an uncommon type of immune system cancer.

Other flap procedures that take muscle from the abdomen can leave women with weakened abdominal walls and increase their risk of developing a hernia.

Academic research shows that insurance reimbursement affects which women can access DIEP flap breast reconstruction, creating a two-tiered system for private health insurance versus government programs like Medicare and Medicaid. Private insurance generally pays physicians more than government coverage, and Medicare doesn’t use S codes.

Lynn Damitz, a physician and board vice president of health policy and advocacy for the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, said the group supports continuing the S code temporarily or indefinitely. If reimbursements drop, some doctors won’t perform DIEP flaps anymore.

A study published in February found that, of patients who used their own tissue for breast reconstruction, privately insured patients were more likely than publicly insured patients to receive DIEP flap reconstruction.

To Dr. Potter, that shows what will happen if private insurance payments plummet. “If you’re a Medicare provider and you’re not paid to do DIEP flaps, you never tell a patient that it’s an option. You won’t perform it,” Dr. Potter said. “If you take private insurance and all of a sudden your reimbursement rate is cut from $15,000 down to $3,500, you’re not going to do that surgery. And I’m not saying that that’s the right thing to do, but that’s what happens.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Ancient plague, cyclical pandemics … history lesson?

Even the plague wanted to visit Stonehenge

We’re about to blow your mind: The history you learned in school was often inaccurate. Shocking, we know, so we’ll give you a minute to process this incredible news.

Better? Good. Now, let’s look back at high school European history. The Black Death, specifically. The common narrative is that the Mongols, while besieging a Crimean city belonging to the Genoese, catapulted dead bodies infected with some mystery disease that turned out to be the plague. The Genoese then brought the plague back to Italy, and from there, we all know the rest of the story.

The Black Death was certainly extremely important to the development of modern Europe as we know it, but the history books gloss over the much longer history of the plague. Yersinia pestis did not suddenly appear unbidden in a Mongol war camp in 1347. The Black Death wasn’t even the first horrific, continent-wide pandemic caused by the plague; the Plague of Justinian 800 years earlier crippled the Byzantine Empire during an expansionist phase and killed anywhere between 15 million and 100 million.

Today, though, LOTME looks even deeper into history, nearly beyond even history itself, back into the depths of early Bronze Age northern Europe. Specifically, to two ancient burial sites in England, where researchers have identified three 4,000-year-old cases of Y. pestis, the first recorded incidence of the disease in Britain.

Two of the individuals, identified through analysis of dental pulp, were young children buried at a mass grave in Somerset, while the third, a middle-aged woman, was found in a ring cairn in Cumbria. These sites are hundreds of miles apart, yet carbon dating suggests all three people lived and died at roughly the same time. The strain found is very similar to other samples of plague found across central and western Europe starting around 3,000 BCE, suggesting a single, easily spread disease affecting a large area in a relatively small period of time. In other words, a pandemic. Even in these ancient times, the world was connected. Not even the island of Britain could escape.

Beyond that though, the research helps confirm the cyclical nature of the plague; over time, it loses its effectiveness and goes into hiding, only to mutate and come roaring back. This is a story with absolutely no relevance at all to the modern world. Nope, no plagues or pandemics going around right now, no viruses fading into the background in any way. What a ridiculous inference to make.

Uncovering the invisible with artificial intelligence

This week in “What Else Can AI Do?” new research shows that a computer program can reveal brain injury that couldn’t be seen before with typical MRI.

The hot new AI, birthed by researchers at New York University, could potentially be a game changer by linking repeated head impacts with tiny, structural changes in the brains of athletes who have not been diagnosed with a concussion. By using machine learning to train the AI, the researchers were, for the first time, able to distinguish the brain of athletes who played contact sports (football, soccer, lacrosse) from those participating in noncontact sports such as baseball, basketball, and cross-country.

How did they do it? The investigators “designed statistical techniques that gave their computer program the ability to ‘learn’ how to predict exposure to repeated head impacts using mathematical models,” they explained in a written statement. Adding in data from the MRI scans of 81 male athletes with no known concussion diagnosis and the ability to identify unusual brain features between athletes with and without head trauma allowed the AI to predict results with accuracy even Miss Cleo would envy.

“This method may provide an important diagnostic tool not only for concussion, but also for detecting the damage that stems from subtler and more frequent head impacts,” said lead author Junbo Chen, an engineering doctoral candidate at NYU. That could make this new AI a valuable asset to science and medicine.

There are many things the human brain can do that AI can’t, and delegation could be one of them. Examining the data that represent the human brain in minute detail? Maybe we leave that to the machine.

Talk about your field promotions

If you’re a surgeon doing an amputation, the list of possible assistants pretty much starts and ends in only one place: Not the closest available janitor.

That may seem like an oddly obvious thing for us to say, but there’s at least one former Mainz (Germany) University Hospital physician who really needed to get this bit of advice before he attempted an unassisted toe amputation back in October of 2020. Yes, that does seem like kind of a long time ago for us to be reporting it now, but the details of the incident only just came to light a few days ago, thanks to German public broadcaster SWR.

Since it was just a toe, the surgeon thought he could perform the operation without any help. The toe, unfortunately, had other plans. The partially anesthetized patient got restless in the operating room, but with no actual trained nurse in the vicinity, the surgeon asked the closest available person – that would be the janitor – to lend a hand.

The surgical manager heard about these goings-on and got to the operating room too late to stop the procedure but soon enough to see the cleaning staffer “at the operating table with a bloody suction cup and a bloody compress in their hands,” SWR recently reported.

The incident was reported to the hospital’s medical director and the surgeon was fired, but since the patient experienced no complications not much fuss was made about it at the time.

Well, guess what? It’s toe-tally our job to make a fuss about these kinds of things. Or could it be that our job, much like the surgeon’s employment and the patient’s digit, is here toe-day and gone toe-morrow?

Even the plague wanted to visit Stonehenge

We’re about to blow your mind: The history you learned in school was often inaccurate. Shocking, we know, so we’ll give you a minute to process this incredible news.

Better? Good. Now, let’s look back at high school European history. The Black Death, specifically. The common narrative is that the Mongols, while besieging a Crimean city belonging to the Genoese, catapulted dead bodies infected with some mystery disease that turned out to be the plague. The Genoese then brought the plague back to Italy, and from there, we all know the rest of the story.

The Black Death was certainly extremely important to the development of modern Europe as we know it, but the history books gloss over the much longer history of the plague. Yersinia pestis did not suddenly appear unbidden in a Mongol war camp in 1347. The Black Death wasn’t even the first horrific, continent-wide pandemic caused by the plague; the Plague of Justinian 800 years earlier crippled the Byzantine Empire during an expansionist phase and killed anywhere between 15 million and 100 million.

Today, though, LOTME looks even deeper into history, nearly beyond even history itself, back into the depths of early Bronze Age northern Europe. Specifically, to two ancient burial sites in England, where researchers have identified three 4,000-year-old cases of Y. pestis, the first recorded incidence of the disease in Britain.

Two of the individuals, identified through analysis of dental pulp, were young children buried at a mass grave in Somerset, while the third, a middle-aged woman, was found in a ring cairn in Cumbria. These sites are hundreds of miles apart, yet carbon dating suggests all three people lived and died at roughly the same time. The strain found is very similar to other samples of plague found across central and western Europe starting around 3,000 BCE, suggesting a single, easily spread disease affecting a large area in a relatively small period of time. In other words, a pandemic. Even in these ancient times, the world was connected. Not even the island of Britain could escape.

Beyond that though, the research helps confirm the cyclical nature of the plague; over time, it loses its effectiveness and goes into hiding, only to mutate and come roaring back. This is a story with absolutely no relevance at all to the modern world. Nope, no plagues or pandemics going around right now, no viruses fading into the background in any way. What a ridiculous inference to make.

Uncovering the invisible with artificial intelligence

This week in “What Else Can AI Do?” new research shows that a computer program can reveal brain injury that couldn’t be seen before with typical MRI.

The hot new AI, birthed by researchers at New York University, could potentially be a game changer by linking repeated head impacts with tiny, structural changes in the brains of athletes who have not been diagnosed with a concussion. By using machine learning to train the AI, the researchers were, for the first time, able to distinguish the brain of athletes who played contact sports (football, soccer, lacrosse) from those participating in noncontact sports such as baseball, basketball, and cross-country.

How did they do it? The investigators “designed statistical techniques that gave their computer program the ability to ‘learn’ how to predict exposure to repeated head impacts using mathematical models,” they explained in a written statement. Adding in data from the MRI scans of 81 male athletes with no known concussion diagnosis and the ability to identify unusual brain features between athletes with and without head trauma allowed the AI to predict results with accuracy even Miss Cleo would envy.

“This method may provide an important diagnostic tool not only for concussion, but also for detecting the damage that stems from subtler and more frequent head impacts,” said lead author Junbo Chen, an engineering doctoral candidate at NYU. That could make this new AI a valuable asset to science and medicine.

There are many things the human brain can do that AI can’t, and delegation could be one of them. Examining the data that represent the human brain in minute detail? Maybe we leave that to the machine.

Talk about your field promotions

If you’re a surgeon doing an amputation, the list of possible assistants pretty much starts and ends in only one place: Not the closest available janitor.

That may seem like an oddly obvious thing for us to say, but there’s at least one former Mainz (Germany) University Hospital physician who really needed to get this bit of advice before he attempted an unassisted toe amputation back in October of 2020. Yes, that does seem like kind of a long time ago for us to be reporting it now, but the details of the incident only just came to light a few days ago, thanks to German public broadcaster SWR.

Since it was just a toe, the surgeon thought he could perform the operation without any help. The toe, unfortunately, had other plans. The partially anesthetized patient got restless in the operating room, but with no actual trained nurse in the vicinity, the surgeon asked the closest available person – that would be the janitor – to lend a hand.

The surgical manager heard about these goings-on and got to the operating room too late to stop the procedure but soon enough to see the cleaning staffer “at the operating table with a bloody suction cup and a bloody compress in their hands,” SWR recently reported.

The incident was reported to the hospital’s medical director and the surgeon was fired, but since the patient experienced no complications not much fuss was made about it at the time.

Well, guess what? It’s toe-tally our job to make a fuss about these kinds of things. Or could it be that our job, much like the surgeon’s employment and the patient’s digit, is here toe-day and gone toe-morrow?

Even the plague wanted to visit Stonehenge

We’re about to blow your mind: The history you learned in school was often inaccurate. Shocking, we know, so we’ll give you a minute to process this incredible news.

Better? Good. Now, let’s look back at high school European history. The Black Death, specifically. The common narrative is that the Mongols, while besieging a Crimean city belonging to the Genoese, catapulted dead bodies infected with some mystery disease that turned out to be the plague. The Genoese then brought the plague back to Italy, and from there, we all know the rest of the story.

The Black Death was certainly extremely important to the development of modern Europe as we know it, but the history books gloss over the much longer history of the plague. Yersinia pestis did not suddenly appear unbidden in a Mongol war camp in 1347. The Black Death wasn’t even the first horrific, continent-wide pandemic caused by the plague; the Plague of Justinian 800 years earlier crippled the Byzantine Empire during an expansionist phase and killed anywhere between 15 million and 100 million.

Today, though, LOTME looks even deeper into history, nearly beyond even history itself, back into the depths of early Bronze Age northern Europe. Specifically, to two ancient burial sites in England, where researchers have identified three 4,000-year-old cases of Y. pestis, the first recorded incidence of the disease in Britain.

Two of the individuals, identified through analysis of dental pulp, were young children buried at a mass grave in Somerset, while the third, a middle-aged woman, was found in a ring cairn in Cumbria. These sites are hundreds of miles apart, yet carbon dating suggests all three people lived and died at roughly the same time. The strain found is very similar to other samples of plague found across central and western Europe starting around 3,000 BCE, suggesting a single, easily spread disease affecting a large area in a relatively small period of time. In other words, a pandemic. Even in these ancient times, the world was connected. Not even the island of Britain could escape.

Beyond that though, the research helps confirm the cyclical nature of the plague; over time, it loses its effectiveness and goes into hiding, only to mutate and come roaring back. This is a story with absolutely no relevance at all to the modern world. Nope, no plagues or pandemics going around right now, no viruses fading into the background in any way. What a ridiculous inference to make.

Uncovering the invisible with artificial intelligence

This week in “What Else Can AI Do?” new research shows that a computer program can reveal brain injury that couldn’t be seen before with typical MRI.

The hot new AI, birthed by researchers at New York University, could potentially be a game changer by linking repeated head impacts with tiny, structural changes in the brains of athletes who have not been diagnosed with a concussion. By using machine learning to train the AI, the researchers were, for the first time, able to distinguish the brain of athletes who played contact sports (football, soccer, lacrosse) from those participating in noncontact sports such as baseball, basketball, and cross-country.

How did they do it? The investigators “designed statistical techniques that gave their computer program the ability to ‘learn’ how to predict exposure to repeated head impacts using mathematical models,” they explained in a written statement. Adding in data from the MRI scans of 81 male athletes with no known concussion diagnosis and the ability to identify unusual brain features between athletes with and without head trauma allowed the AI to predict results with accuracy even Miss Cleo would envy.

“This method may provide an important diagnostic tool not only for concussion, but also for detecting the damage that stems from subtler and more frequent head impacts,” said lead author Junbo Chen, an engineering doctoral candidate at NYU. That could make this new AI a valuable asset to science and medicine.

There are many things the human brain can do that AI can’t, and delegation could be one of them. Examining the data that represent the human brain in minute detail? Maybe we leave that to the machine.

Talk about your field promotions

If you’re a surgeon doing an amputation, the list of possible assistants pretty much starts and ends in only one place: Not the closest available janitor.

That may seem like an oddly obvious thing for us to say, but there’s at least one former Mainz (Germany) University Hospital physician who really needed to get this bit of advice before he attempted an unassisted toe amputation back in October of 2020. Yes, that does seem like kind of a long time ago for us to be reporting it now, but the details of the incident only just came to light a few days ago, thanks to German public broadcaster SWR.

Since it was just a toe, the surgeon thought he could perform the operation without any help. The toe, unfortunately, had other plans. The partially anesthetized patient got restless in the operating room, but with no actual trained nurse in the vicinity, the surgeon asked the closest available person – that would be the janitor – to lend a hand.

The surgical manager heard about these goings-on and got to the operating room too late to stop the procedure but soon enough to see the cleaning staffer “at the operating table with a bloody suction cup and a bloody compress in their hands,” SWR recently reported.

The incident was reported to the hospital’s medical director and the surgeon was fired, but since the patient experienced no complications not much fuss was made about it at the time.

Well, guess what? It’s toe-tally our job to make a fuss about these kinds of things. Or could it be that our job, much like the surgeon’s employment and the patient’s digit, is here toe-day and gone toe-morrow?

Survey: Family medicine earnings steady despite overall growth for physicians

according to the results of the Medscape Family Physician Compensation Report 2023.

Average compensation for the specialty, which has risen by 31% since 2015, was stagnant in 2022, showing no growth from the previous year. COVID, at least, had less of an effect on earnings, as 48% of family physicians cited pandemic-related income losses, compared with 64% in 2021, according to those who responded to Medscape’s annual survey, which was conducted from Oct. 2, 2022, to Jan. 17, 2023.

Comments from those respondents covered several areas that were already concerning physicians before the pandemic. One wrote that “decreasing Medicare reimbursement and poor payor mix destroy our income,” and another said that “patients have become rude and come with poor information from social media.” One respondent described the situation this way: “Overwhelming burnout. I had to reduce my hours to keep myself from quitting medicine completely.”

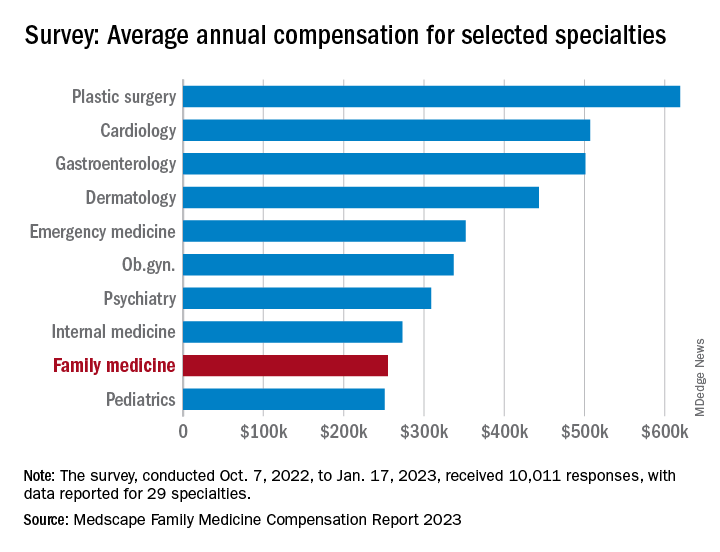

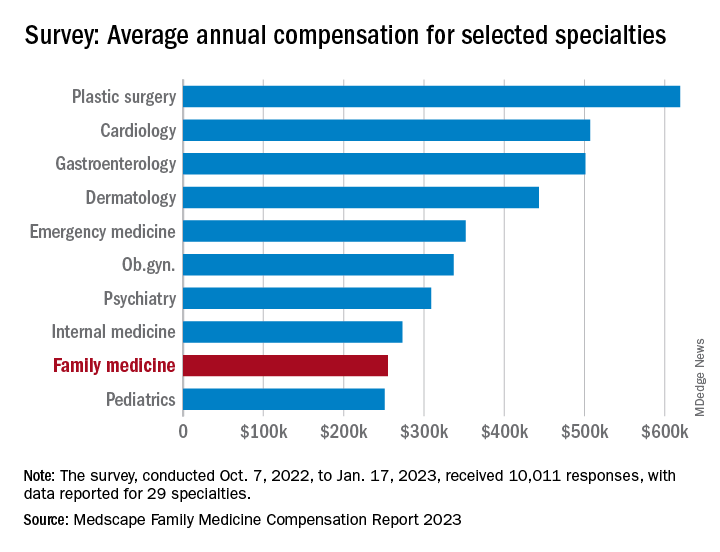

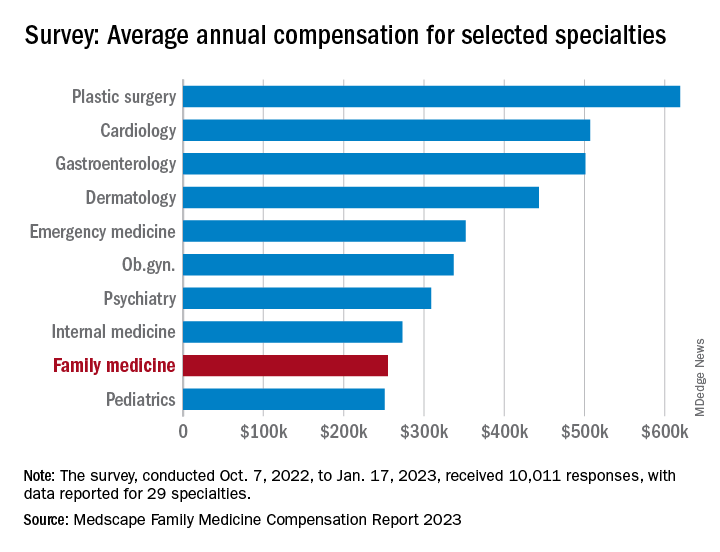

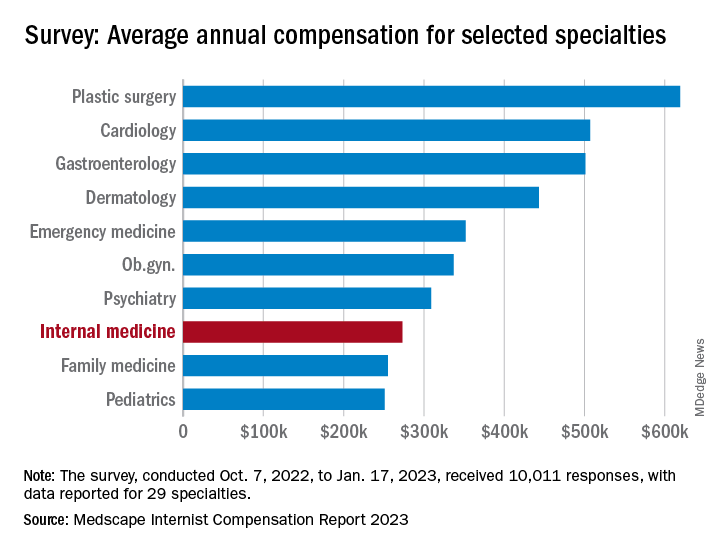

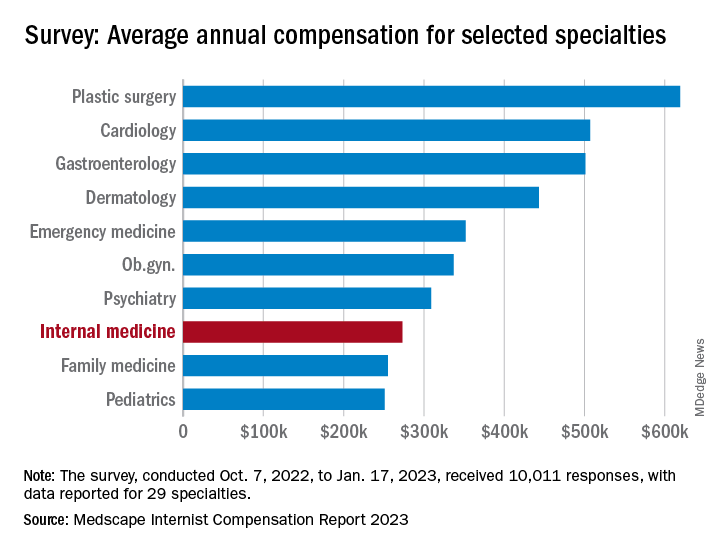

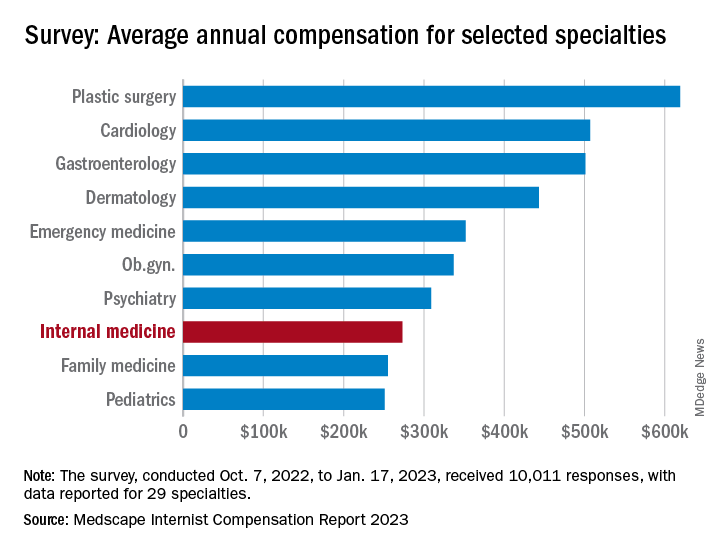

Overall physician compensation in 2022 was up by about 4% from 2021. For the 12% of the 10,011 respondents who practice family medicine, the average held at $255,000, where it had been the year before. Among the other primary care specialists, internists’ earnings were up by almost 4% and pediatricians did almost as well with a 3% increase, while ob.gyns. joined family physicians in the no-growth club, the Medscape results show.

For all physicians, average compensation in 2022 was $352,000, an increase of almost 18% since 2018. “Supply and demand is the biggest driver,” Mike Belkin, JD, of physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins, said in an interview. “Organizations understand it’s not getting any easier to get good candidates, and so for the most part, physicians are getting good offers.”

The lack of increase in FPs earnings among internists also included a decline of note: The disparity between mens’ and womens’ compensation dropped from 26% in 2021 to 23% in 2022. The 2022 disparity was only 16% for internists, however, even though family medicine has a considerably larger share of women (49% vs. 40%) among those surveyed, Medscape said.

Satisfaction with their compensation, on the other hand, was higher among the family physicians (50%), compared with internists (43%). In 2022, 55% of family physicians said that they had been fairly paid.

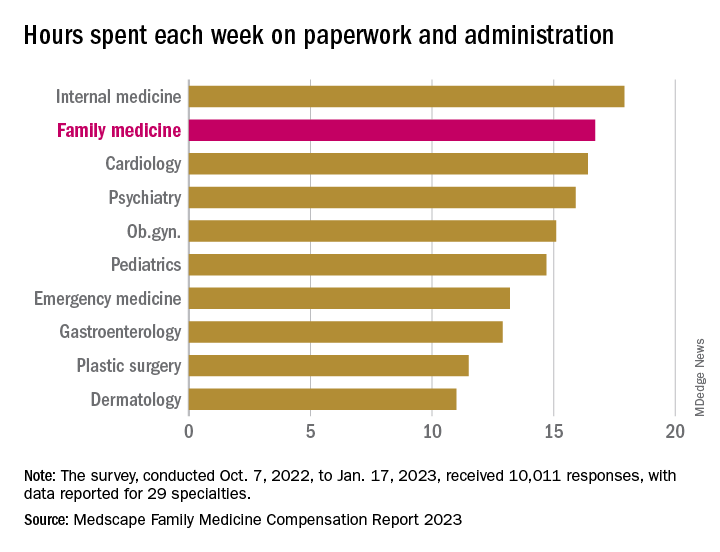

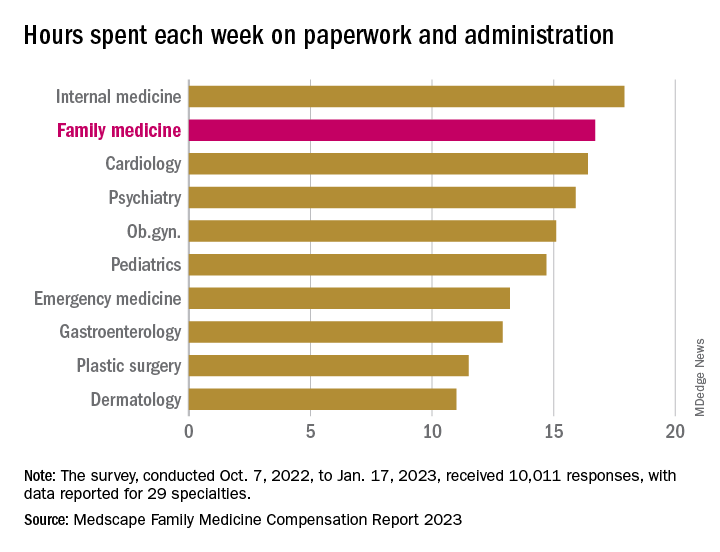

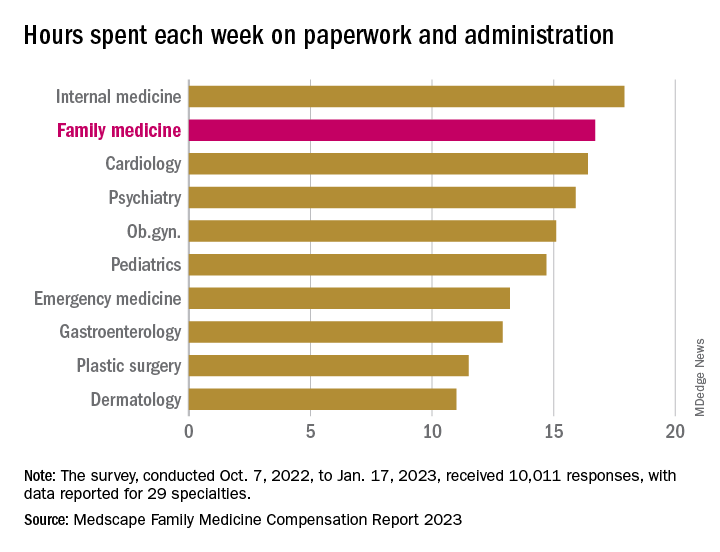

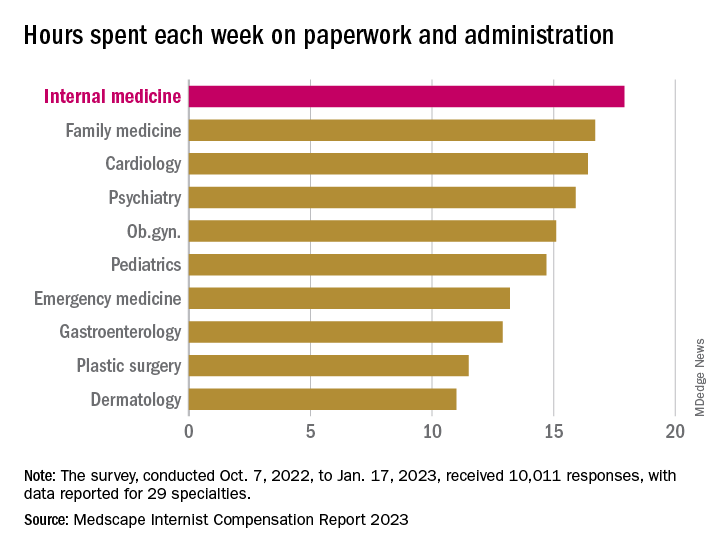

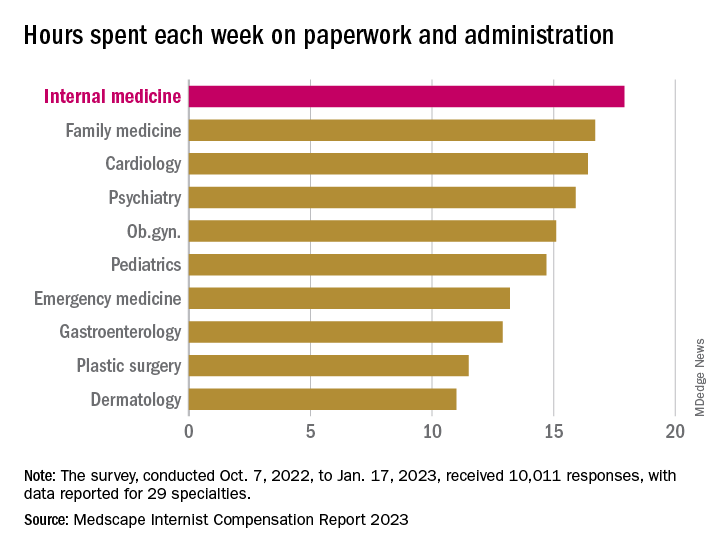

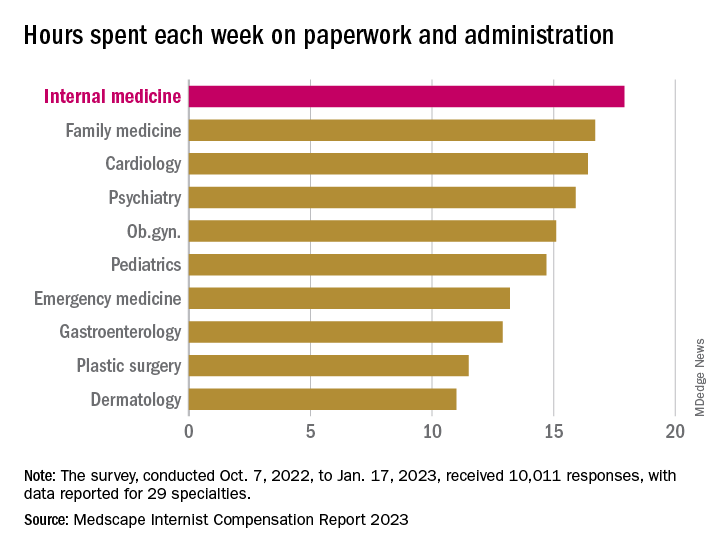

In 2022, FP respondents reported spending an average of 16.7 hours (up from 15.6 hours in 2021) each week on paperwork and administration, just below the survey leaders, physical medicine and rehabilitation (18.5 hours) and nephrology (18.1 hours) but well above anesthesiology, lowest of the 29 specialties at 9.0 hours, and the 2022 average of 15.5 hours for all physicians, Medscape said.

When asked if they would choose medicine again, 72% of family physician respondents and 73% of all physicians said yes, with emergency medicine (65%) and dermatology (86%) representing the two extremes. A question about specialty choice showed that 66% of FPs would choose it again, putting them 28th of the 29 included specialties in their eagerness to follow the same path, above only the internists (61%), Medscape reported.

Commenters among the survey respondents were not identified by specialty, but dissatisfaction on many fronts was a definite theme:

- “Our costs go up, and our reimbursement does not.”

- “Our practice was acquired by venture capital firms; they slashed costs.”

- “My productivity bonus should have come to $45,000. Instead I was paid only $15,000. Yet cardiologists and administrators who were working from home part of the year received their full bonus.”

- “I will no longer practice cookbook mediocrity.”

according to the results of the Medscape Family Physician Compensation Report 2023.

Average compensation for the specialty, which has risen by 31% since 2015, was stagnant in 2022, showing no growth from the previous year. COVID, at least, had less of an effect on earnings, as 48% of family physicians cited pandemic-related income losses, compared with 64% in 2021, according to those who responded to Medscape’s annual survey, which was conducted from Oct. 2, 2022, to Jan. 17, 2023.

Comments from those respondents covered several areas that were already concerning physicians before the pandemic. One wrote that “decreasing Medicare reimbursement and poor payor mix destroy our income,” and another said that “patients have become rude and come with poor information from social media.” One respondent described the situation this way: “Overwhelming burnout. I had to reduce my hours to keep myself from quitting medicine completely.”

Overall physician compensation in 2022 was up by about 4% from 2021. For the 12% of the 10,011 respondents who practice family medicine, the average held at $255,000, where it had been the year before. Among the other primary care specialists, internists’ earnings were up by almost 4% and pediatricians did almost as well with a 3% increase, while ob.gyns. joined family physicians in the no-growth club, the Medscape results show.

For all physicians, average compensation in 2022 was $352,000, an increase of almost 18% since 2018. “Supply and demand is the biggest driver,” Mike Belkin, JD, of physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins, said in an interview. “Organizations understand it’s not getting any easier to get good candidates, and so for the most part, physicians are getting good offers.”

The lack of increase in FPs earnings among internists also included a decline of note: The disparity between mens’ and womens’ compensation dropped from 26% in 2021 to 23% in 2022. The 2022 disparity was only 16% for internists, however, even though family medicine has a considerably larger share of women (49% vs. 40%) among those surveyed, Medscape said.

Satisfaction with their compensation, on the other hand, was higher among the family physicians (50%), compared with internists (43%). In 2022, 55% of family physicians said that they had been fairly paid.

In 2022, FP respondents reported spending an average of 16.7 hours (up from 15.6 hours in 2021) each week on paperwork and administration, just below the survey leaders, physical medicine and rehabilitation (18.5 hours) and nephrology (18.1 hours) but well above anesthesiology, lowest of the 29 specialties at 9.0 hours, and the 2022 average of 15.5 hours for all physicians, Medscape said.

When asked if they would choose medicine again, 72% of family physician respondents and 73% of all physicians said yes, with emergency medicine (65%) and dermatology (86%) representing the two extremes. A question about specialty choice showed that 66% of FPs would choose it again, putting them 28th of the 29 included specialties in their eagerness to follow the same path, above only the internists (61%), Medscape reported.

Commenters among the survey respondents were not identified by specialty, but dissatisfaction on many fronts was a definite theme:

- “Our costs go up, and our reimbursement does not.”

- “Our practice was acquired by venture capital firms; they slashed costs.”

- “My productivity bonus should have come to $45,000. Instead I was paid only $15,000. Yet cardiologists and administrators who were working from home part of the year received their full bonus.”

- “I will no longer practice cookbook mediocrity.”

according to the results of the Medscape Family Physician Compensation Report 2023.

Average compensation for the specialty, which has risen by 31% since 2015, was stagnant in 2022, showing no growth from the previous year. COVID, at least, had less of an effect on earnings, as 48% of family physicians cited pandemic-related income losses, compared with 64% in 2021, according to those who responded to Medscape’s annual survey, which was conducted from Oct. 2, 2022, to Jan. 17, 2023.

Comments from those respondents covered several areas that were already concerning physicians before the pandemic. One wrote that “decreasing Medicare reimbursement and poor payor mix destroy our income,” and another said that “patients have become rude and come with poor information from social media.” One respondent described the situation this way: “Overwhelming burnout. I had to reduce my hours to keep myself from quitting medicine completely.”

Overall physician compensation in 2022 was up by about 4% from 2021. For the 12% of the 10,011 respondents who practice family medicine, the average held at $255,000, where it had been the year before. Among the other primary care specialists, internists’ earnings were up by almost 4% and pediatricians did almost as well with a 3% increase, while ob.gyns. joined family physicians in the no-growth club, the Medscape results show.

For all physicians, average compensation in 2022 was $352,000, an increase of almost 18% since 2018. “Supply and demand is the biggest driver,” Mike Belkin, JD, of physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins, said in an interview. “Organizations understand it’s not getting any easier to get good candidates, and so for the most part, physicians are getting good offers.”

The lack of increase in FPs earnings among internists also included a decline of note: The disparity between mens’ and womens’ compensation dropped from 26% in 2021 to 23% in 2022. The 2022 disparity was only 16% for internists, however, even though family medicine has a considerably larger share of women (49% vs. 40%) among those surveyed, Medscape said.

Satisfaction with their compensation, on the other hand, was higher among the family physicians (50%), compared with internists (43%). In 2022, 55% of family physicians said that they had been fairly paid.

In 2022, FP respondents reported spending an average of 16.7 hours (up from 15.6 hours in 2021) each week on paperwork and administration, just below the survey leaders, physical medicine and rehabilitation (18.5 hours) and nephrology (18.1 hours) but well above anesthesiology, lowest of the 29 specialties at 9.0 hours, and the 2022 average of 15.5 hours for all physicians, Medscape said.

When asked if they would choose medicine again, 72% of family physician respondents and 73% of all physicians said yes, with emergency medicine (65%) and dermatology (86%) representing the two extremes. A question about specialty choice showed that 66% of FPs would choose it again, putting them 28th of the 29 included specialties in their eagerness to follow the same path, above only the internists (61%), Medscape reported.

Commenters among the survey respondents were not identified by specialty, but dissatisfaction on many fronts was a definite theme:

- “Our costs go up, and our reimbursement does not.”

- “Our practice was acquired by venture capital firms; they slashed costs.”

- “My productivity bonus should have come to $45,000. Instead I was paid only $15,000. Yet cardiologists and administrators who were working from home part of the year received their full bonus.”

- “I will no longer practice cookbook mediocrity.”

Blood cancer patient takes on bias and ‘gaslighting’

Diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma in 2021, Ms. Ngon underwent port surgery to allow chemotherapy to be administered. Her right arm lost circulation and went numb, so she sought guidance from her blood cancer specialist. He dismissed her worries, saying that her tumors were pinching a nerve. She’d get better, he predicted, after more chemo.

“I knew in my body that something was wrong,” Ms. Ngon recalled. When the oncologist continued to downplay her concerns, she and a fellow communications specialist sat down together in the hospital lobby to draft an email to her physician. “We were trying to articulate the urgency in an email that expresses that I’m not being dramatic. We had to do it in a way that didn’t insult his intelligence: ‘Respectfully, you’re the doctor, but I know something is wrong.’ ”

In essence, Ms. Ngon was trying to be diplomatic and not trigger her oncologist’s defenses, while still convincing him to take action. Her approach to getting her doctor’s attention worked. He referred Ms. Ngon to a radiologist, who discovered that she had blood clots in her arm. Ms. Ngon then landed in the ICU for a week, as clinicians tried to break up the clots.

“I was the perfect person for this to happen to, because of my job and education. But it makes me sad because I understand I was in a fortunate position, with a background in communication. Most people don’t have that,” Ms. Ngon said.

This and other negative experiences during her medical saga inspired Ms. Ngon to partner with the Lymphoma Research Foundation in order to spread the word about unique challenges facing patients like her: people of color.

Ms. Ngon, who is Black, said her goal as a patient advocate is to “empower communities of color to speak up for themselves and hold oncologists responsible for listening and understanding differences across cultures.” And she wants to take a stand against the “gaslighting” of patients.

African Americans with hematologic disease like Ms. Ngon face a higher risk of poor outcomes than Whites, even as they are less likely than Whites to develop certain blood cancers. The reasons for this disparity aren’t clear, but researchers suspect they’re related to factors such as poverty, lack of insurance, genetics, and limited access to high-quality care.

Some researchers have blamed another factor: racism. A 2022 study sought to explain why Black and Hispanic patients with acute myeloid leukemia in urban areas have higher mortality rates than Whites, “despite more favorable genetics and younger age” (hazard ratio, 1.59, 95% confidence interval, 1.15-2.22 and HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 0.88-1.79). The study authors determined that “structural racism” – which they measured by examining segregation and “disadvantage” in neighborhoods where patients lived – accounted for nearly all of the disparities.

Ms. Ngon said her experiences and her awareness about poorer outcomes in medicine for African Americans – such as higher death rates for Black women during pregnancy – affect how she interacts with clinicians. “I automatically assume a barrier between me and my doctors, and it’s their responsibility to dismantle it.”

Making an connection with a physician can make a huge difference, she said. “I walked into my primary care doctor’s office and saw that she was a Latino woman. My guard went down, and I could feel her care for me as a human being. Whether that was because she was also a woman of color or not, I don’t know. But I did feel more cared for.”

However, Ms. Ngon could not find a Black oncologist to care for her in New York City, and that’s no surprise.

Ethnic and gender diversity remains an immense challenge in the hematology/oncology field. According to the American Society of Clinical Oncology, only about a third of oncologists are women, and the percentages identifying themselves as Black/African American and Hispanic are just 2.3% and 5.8%, respectively.

These numbers don’t seem likely to budge much any time soon. An analysis of medical students in U.S. oncology training programs from 2015-2020 found that just 3.8% identified themselves as Black/African American and 5.1% as Hispanic/Latino versus 52.15% as White and 31% as Asian/Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian.

Ms. Ngon encountered challenges on other fronts during her cancer care. When she needed a wig during chemotherapy, a list of insurer-approved shops didn’t include any that catered to African Americans. Essentially, she said, she was being told that she couldn’t “purchase a wig from a place that makes you feel comfortable and from a woman who understand your needs as a Black woman. It needs to be from these specific shops that really don’t cater to my community.”

She also found it difficult to find fellow patients who shared her unique challenges. “I remember when I was diagnosed, I was looking through the support groups on Facebook, trying to find someone Black to ask about whether braiding my hair might stop it from falling out.”

Now, Ms. Ngon is in remission. And she’s happy with her oncologist, who’s White. “He listened to me, and he promised me that I would have the most boring recovery process ever, after everything I’d experienced. That explains a lot of why I felt so comfortable with him.”

She hopes to use her partnership with the Lymphoma Research Foundation to be a resource for people of color and alert them to the support that’s available for them. “I would love to let them know how to advocate for themselves as patients, how to trust their bodies, how to push back if they feel like they’re not getting the care that they deserve.”

Ms. Ngon would also like to see more support for medical students of color. “I hope to exist in a world one day where it wouldn’t be so hard to find an oncologist who looks like me in a city as large as this one,” she said.

As for oncologists, she urged them to “go the extra mile and really, really listen to what patients are saying. It’s easier said than done because there are natural biases in this world, and it’s hard to overcome those obstacles. But to not be heard and have to push every time. It was just exhausting to do that on top of trying to beat cancer.”

Diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma in 2021, Ms. Ngon underwent port surgery to allow chemotherapy to be administered. Her right arm lost circulation and went numb, so she sought guidance from her blood cancer specialist. He dismissed her worries, saying that her tumors were pinching a nerve. She’d get better, he predicted, after more chemo.

“I knew in my body that something was wrong,” Ms. Ngon recalled. When the oncologist continued to downplay her concerns, she and a fellow communications specialist sat down together in the hospital lobby to draft an email to her physician. “We were trying to articulate the urgency in an email that expresses that I’m not being dramatic. We had to do it in a way that didn’t insult his intelligence: ‘Respectfully, you’re the doctor, but I know something is wrong.’ ”

In essence, Ms. Ngon was trying to be diplomatic and not trigger her oncologist’s defenses, while still convincing him to take action. Her approach to getting her doctor’s attention worked. He referred Ms. Ngon to a radiologist, who discovered that she had blood clots in her arm. Ms. Ngon then landed in the ICU for a week, as clinicians tried to break up the clots.

“I was the perfect person for this to happen to, because of my job and education. But it makes me sad because I understand I was in a fortunate position, with a background in communication. Most people don’t have that,” Ms. Ngon said.

This and other negative experiences during her medical saga inspired Ms. Ngon to partner with the Lymphoma Research Foundation in order to spread the word about unique challenges facing patients like her: people of color.

Ms. Ngon, who is Black, said her goal as a patient advocate is to “empower communities of color to speak up for themselves and hold oncologists responsible for listening and understanding differences across cultures.” And she wants to take a stand against the “gaslighting” of patients.

African Americans with hematologic disease like Ms. Ngon face a higher risk of poor outcomes than Whites, even as they are less likely than Whites to develop certain blood cancers. The reasons for this disparity aren’t clear, but researchers suspect they’re related to factors such as poverty, lack of insurance, genetics, and limited access to high-quality care.

Some researchers have blamed another factor: racism. A 2022 study sought to explain why Black and Hispanic patients with acute myeloid leukemia in urban areas have higher mortality rates than Whites, “despite more favorable genetics and younger age” (hazard ratio, 1.59, 95% confidence interval, 1.15-2.22 and HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 0.88-1.79). The study authors determined that “structural racism” – which they measured by examining segregation and “disadvantage” in neighborhoods where patients lived – accounted for nearly all of the disparities.

Ms. Ngon said her experiences and her awareness about poorer outcomes in medicine for African Americans – such as higher death rates for Black women during pregnancy – affect how she interacts with clinicians. “I automatically assume a barrier between me and my doctors, and it’s their responsibility to dismantle it.”

Making an connection with a physician can make a huge difference, she said. “I walked into my primary care doctor’s office and saw that she was a Latino woman. My guard went down, and I could feel her care for me as a human being. Whether that was because she was also a woman of color or not, I don’t know. But I did feel more cared for.”

However, Ms. Ngon could not find a Black oncologist to care for her in New York City, and that’s no surprise.

Ethnic and gender diversity remains an immense challenge in the hematology/oncology field. According to the American Society of Clinical Oncology, only about a third of oncologists are women, and the percentages identifying themselves as Black/African American and Hispanic are just 2.3% and 5.8%, respectively.

These numbers don’t seem likely to budge much any time soon. An analysis of medical students in U.S. oncology training programs from 2015-2020 found that just 3.8% identified themselves as Black/African American and 5.1% as Hispanic/Latino versus 52.15% as White and 31% as Asian/Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian.

Ms. Ngon encountered challenges on other fronts during her cancer care. When she needed a wig during chemotherapy, a list of insurer-approved shops didn’t include any that catered to African Americans. Essentially, she said, she was being told that she couldn’t “purchase a wig from a place that makes you feel comfortable and from a woman who understand your needs as a Black woman. It needs to be from these specific shops that really don’t cater to my community.”

She also found it difficult to find fellow patients who shared her unique challenges. “I remember when I was diagnosed, I was looking through the support groups on Facebook, trying to find someone Black to ask about whether braiding my hair might stop it from falling out.”

Now, Ms. Ngon is in remission. And she’s happy with her oncologist, who’s White. “He listened to me, and he promised me that I would have the most boring recovery process ever, after everything I’d experienced. That explains a lot of why I felt so comfortable with him.”

She hopes to use her partnership with the Lymphoma Research Foundation to be a resource for people of color and alert them to the support that’s available for them. “I would love to let them know how to advocate for themselves as patients, how to trust their bodies, how to push back if they feel like they’re not getting the care that they deserve.”

Ms. Ngon would also like to see more support for medical students of color. “I hope to exist in a world one day where it wouldn’t be so hard to find an oncologist who looks like me in a city as large as this one,” she said.

As for oncologists, she urged them to “go the extra mile and really, really listen to what patients are saying. It’s easier said than done because there are natural biases in this world, and it’s hard to overcome those obstacles. But to not be heard and have to push every time. It was just exhausting to do that on top of trying to beat cancer.”

Diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma in 2021, Ms. Ngon underwent port surgery to allow chemotherapy to be administered. Her right arm lost circulation and went numb, so she sought guidance from her blood cancer specialist. He dismissed her worries, saying that her tumors were pinching a nerve. She’d get better, he predicted, after more chemo.

“I knew in my body that something was wrong,” Ms. Ngon recalled. When the oncologist continued to downplay her concerns, she and a fellow communications specialist sat down together in the hospital lobby to draft an email to her physician. “We were trying to articulate the urgency in an email that expresses that I’m not being dramatic. We had to do it in a way that didn’t insult his intelligence: ‘Respectfully, you’re the doctor, but I know something is wrong.’ ”

In essence, Ms. Ngon was trying to be diplomatic and not trigger her oncologist’s defenses, while still convincing him to take action. Her approach to getting her doctor’s attention worked. He referred Ms. Ngon to a radiologist, who discovered that she had blood clots in her arm. Ms. Ngon then landed in the ICU for a week, as clinicians tried to break up the clots.

“I was the perfect person for this to happen to, because of my job and education. But it makes me sad because I understand I was in a fortunate position, with a background in communication. Most people don’t have that,” Ms. Ngon said.

This and other negative experiences during her medical saga inspired Ms. Ngon to partner with the Lymphoma Research Foundation in order to spread the word about unique challenges facing patients like her: people of color.

Ms. Ngon, who is Black, said her goal as a patient advocate is to “empower communities of color to speak up for themselves and hold oncologists responsible for listening and understanding differences across cultures.” And she wants to take a stand against the “gaslighting” of patients.

African Americans with hematologic disease like Ms. Ngon face a higher risk of poor outcomes than Whites, even as they are less likely than Whites to develop certain blood cancers. The reasons for this disparity aren’t clear, but researchers suspect they’re related to factors such as poverty, lack of insurance, genetics, and limited access to high-quality care.

Some researchers have blamed another factor: racism. A 2022 study sought to explain why Black and Hispanic patients with acute myeloid leukemia in urban areas have higher mortality rates than Whites, “despite more favorable genetics and younger age” (hazard ratio, 1.59, 95% confidence interval, 1.15-2.22 and HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 0.88-1.79). The study authors determined that “structural racism” – which they measured by examining segregation and “disadvantage” in neighborhoods where patients lived – accounted for nearly all of the disparities.

Ms. Ngon said her experiences and her awareness about poorer outcomes in medicine for African Americans – such as higher death rates for Black women during pregnancy – affect how she interacts with clinicians. “I automatically assume a barrier between me and my doctors, and it’s their responsibility to dismantle it.”

Making an connection with a physician can make a huge difference, she said. “I walked into my primary care doctor’s office and saw that she was a Latino woman. My guard went down, and I could feel her care for me as a human being. Whether that was because she was also a woman of color or not, I don’t know. But I did feel more cared for.”

However, Ms. Ngon could not find a Black oncologist to care for her in New York City, and that’s no surprise.

Ethnic and gender diversity remains an immense challenge in the hematology/oncology field. According to the American Society of Clinical Oncology, only about a third of oncologists are women, and the percentages identifying themselves as Black/African American and Hispanic are just 2.3% and 5.8%, respectively.

These numbers don’t seem likely to budge much any time soon. An analysis of medical students in U.S. oncology training programs from 2015-2020 found that just 3.8% identified themselves as Black/African American and 5.1% as Hispanic/Latino versus 52.15% as White and 31% as Asian/Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian.

Ms. Ngon encountered challenges on other fronts during her cancer care. When she needed a wig during chemotherapy, a list of insurer-approved shops didn’t include any that catered to African Americans. Essentially, she said, she was being told that she couldn’t “purchase a wig from a place that makes you feel comfortable and from a woman who understand your needs as a Black woman. It needs to be from these specific shops that really don’t cater to my community.”

She also found it difficult to find fellow patients who shared her unique challenges. “I remember when I was diagnosed, I was looking through the support groups on Facebook, trying to find someone Black to ask about whether braiding my hair might stop it from falling out.”

Now, Ms. Ngon is in remission. And she’s happy with her oncologist, who’s White. “He listened to me, and he promised me that I would have the most boring recovery process ever, after everything I’d experienced. That explains a lot of why I felt so comfortable with him.”

She hopes to use her partnership with the Lymphoma Research Foundation to be a resource for people of color and alert them to the support that’s available for them. “I would love to let them know how to advocate for themselves as patients, how to trust their bodies, how to push back if they feel like they’re not getting the care that they deserve.”

Ms. Ngon would also like to see more support for medical students of color. “I hope to exist in a world one day where it wouldn’t be so hard to find an oncologist who looks like me in a city as large as this one,” she said.

As for oncologists, she urged them to “go the extra mile and really, really listen to what patients are saying. It’s easier said than done because there are natural biases in this world, and it’s hard to overcome those obstacles. But to not be heard and have to push every time. It was just exhausting to do that on top of trying to beat cancer.”

Exercise and empathy can help back pain patients in primary care

Treatment of chronic back pain remains a challenge for primary care physicians, and a new Cochrane Review confirms previous studies suggesting that analgesics and antidepressants fall short in terms of relief.

Data from another Cochrane Review support the value of exercise for chronic low back pain, although it is often underused, and the Food and Drug Administration’s recent approval of a spinal cord stimulation device for chronic back pain opens the door for another alternative.

Regardless of treatment type, however, patients report that empathy and clear communication from their doctors go a long way in their satisfaction with pain management, according to another recent study.

Exercise helps when patients adhere

The objective of the Cochrane Review on “Exercise therapy for chronic low back pain” was to determine whether exercise improves pain and functioning for people with chronic low back pain, compared with no treatment, usual care, or other common treatments, corresponding author Jill Hayden, PhD, of Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S., said in an interview.

When back pain is chronic, it is expensive in terms of health care costs and lost work hours, said Dr. Hayden. “Exercise is promoted in many guidelines and is often recommended for, and used by, people with chronic low back pain.” However, “systematic reviews have found only small treatment effects, with considerable variation across individual trials.”